User login

Developments in wound healing include different treatment options

ORLANDO – , Hadar Lev-Tov, MD, said at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgery Conference.

At the meeting, Dr. Lev-Tov, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Miami, reviewed some of the latest developments in several conditions involving wound care.

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): In this condition, pustules or nodules become large ulcerations, and one-third of patients with PG have pathergy, exaggerated skin injury after a mild trauma such as a bump or a bruise.

“You want to look at the clues in the history because 20% of these patients had histories of PG elsewhere,” Dr. Lev-Tov said. “Ask them about other ulcers, maybe they had some wound dehiscence history.”

Criteria have been developed to help with the diagnosis of ulcerative PG, which includes one major criterion, a biopsy of the ulcer edge showing neutrophilic infiltrate, along with minor criteria, including exclusion of an infection, pathergy, and a history of inflammatory bowel disease or inflammatory arthritis.

“This is no longer a diagnosis of exclusion,” Dr. Lev-Tov said.

Cyclosporine and oral steroids have been found to work well, but it typically takes many months before healing occurs. Tacrolimus or topical steroids can work as well, but healing also takes a fairly long time with those medications, Dr. Lev-Tov said.

The tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker infliximab is another option. He had a patient who was referred to him who had been treated with cyclosporine for 3 years for PG on his feet, even though it had not been effective. Dr. Lev-Tov tried infliximab, and the wounds finally cleared, he said.

Apremilast, a phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4)-inhibitor, is another option for treating PG, he said. “Anecdotally, I used apremilast on three patients with recurrent PG for long-term suppression, with success,” he noted.

Epidermal grafting using suction and heat is an approach that might deserve further exploration for PG, Dr. Lev-Tov suggested. With this procedure, described in an article in 2014, heat and suction are used to induce blistering to separate and remove the epidermis from the dermis at the dermal-epidermal junction, creating an epidermal graft is placed over the wound to promote healing. Patients with PG who are immunosuppressed but demonstrate pathergy do not tend to experience pathergy when epidermal skin grafting is performed, he said.

The heat-suction procedure is simple, painless, and scarless, but better controlled data on this approach are needed, he said.

Corona phlebectatica: This disease involving abnormally dilated veins near the ankle has received formal recognition as a sign of venous insufficiency, in a 2020 update of a classification system for describing patients with chronic venous disorders, Dr. Lev-Tov said.

“We knew about it for years, but now there’s some data that can actually predict the severity of disease,” and, he said, it is now a part of the diagnostic criteria for venous insufficiency .

Venous leg ulcers: These often painful sores on the inside of the leg typically take more than a month to heal. A systematic review of placebo-controlled studies of pentoxifylline as a treatment for venous leg ulcers, published in 2021, supports its use for healing venous leg ulcers, Dr. Lev-Tov said. “It improved the healing rate and increased what [the researchers] called ‘significant improvement,’ ” a category they created to account for the varying methods across the studies, he said.

Topical beta-blockers can improve epithelialization and fibroblast migration in wound healing, he said. A study on topical timolol for various wounds found that a 0.5% formulation of topical timolol, with one drop applied per square centimeter as frequently as possible, was effective in healing. But the healing process was prolonged – a median of 90 days, said Dr. Lev-Tov, one of the study authors.

“When you start this, I don’t want you to expect the wound to heal tomorrow,” he said. “You’ve got to educate your patient.”

Dr. Lev-Tov reports relevant financial relationships with Abbvie, Novartis, Pfizer and other companies.

ORLANDO – , Hadar Lev-Tov, MD, said at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgery Conference.

At the meeting, Dr. Lev-Tov, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Miami, reviewed some of the latest developments in several conditions involving wound care.

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): In this condition, pustules or nodules become large ulcerations, and one-third of patients with PG have pathergy, exaggerated skin injury after a mild trauma such as a bump or a bruise.

“You want to look at the clues in the history because 20% of these patients had histories of PG elsewhere,” Dr. Lev-Tov said. “Ask them about other ulcers, maybe they had some wound dehiscence history.”

Criteria have been developed to help with the diagnosis of ulcerative PG, which includes one major criterion, a biopsy of the ulcer edge showing neutrophilic infiltrate, along with minor criteria, including exclusion of an infection, pathergy, and a history of inflammatory bowel disease or inflammatory arthritis.

“This is no longer a diagnosis of exclusion,” Dr. Lev-Tov said.

Cyclosporine and oral steroids have been found to work well, but it typically takes many months before healing occurs. Tacrolimus or topical steroids can work as well, but healing also takes a fairly long time with those medications, Dr. Lev-Tov said.

The tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker infliximab is another option. He had a patient who was referred to him who had been treated with cyclosporine for 3 years for PG on his feet, even though it had not been effective. Dr. Lev-Tov tried infliximab, and the wounds finally cleared, he said.

Apremilast, a phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4)-inhibitor, is another option for treating PG, he said. “Anecdotally, I used apremilast on three patients with recurrent PG for long-term suppression, with success,” he noted.

Epidermal grafting using suction and heat is an approach that might deserve further exploration for PG, Dr. Lev-Tov suggested. With this procedure, described in an article in 2014, heat and suction are used to induce blistering to separate and remove the epidermis from the dermis at the dermal-epidermal junction, creating an epidermal graft is placed over the wound to promote healing. Patients with PG who are immunosuppressed but demonstrate pathergy do not tend to experience pathergy when epidermal skin grafting is performed, he said.

The heat-suction procedure is simple, painless, and scarless, but better controlled data on this approach are needed, he said.

Corona phlebectatica: This disease involving abnormally dilated veins near the ankle has received formal recognition as a sign of venous insufficiency, in a 2020 update of a classification system for describing patients with chronic venous disorders, Dr. Lev-Tov said.

“We knew about it for years, but now there’s some data that can actually predict the severity of disease,” and, he said, it is now a part of the diagnostic criteria for venous insufficiency .

Venous leg ulcers: These often painful sores on the inside of the leg typically take more than a month to heal. A systematic review of placebo-controlled studies of pentoxifylline as a treatment for venous leg ulcers, published in 2021, supports its use for healing venous leg ulcers, Dr. Lev-Tov said. “It improved the healing rate and increased what [the researchers] called ‘significant improvement,’ ” a category they created to account for the varying methods across the studies, he said.

Topical beta-blockers can improve epithelialization and fibroblast migration in wound healing, he said. A study on topical timolol for various wounds found that a 0.5% formulation of topical timolol, with one drop applied per square centimeter as frequently as possible, was effective in healing. But the healing process was prolonged – a median of 90 days, said Dr. Lev-Tov, one of the study authors.

“When you start this, I don’t want you to expect the wound to heal tomorrow,” he said. “You’ve got to educate your patient.”

Dr. Lev-Tov reports relevant financial relationships with Abbvie, Novartis, Pfizer and other companies.

ORLANDO – , Hadar Lev-Tov, MD, said at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgery Conference.

At the meeting, Dr. Lev-Tov, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Miami, reviewed some of the latest developments in several conditions involving wound care.

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): In this condition, pustules or nodules become large ulcerations, and one-third of patients with PG have pathergy, exaggerated skin injury after a mild trauma such as a bump or a bruise.

“You want to look at the clues in the history because 20% of these patients had histories of PG elsewhere,” Dr. Lev-Tov said. “Ask them about other ulcers, maybe they had some wound dehiscence history.”

Criteria have been developed to help with the diagnosis of ulcerative PG, which includes one major criterion, a biopsy of the ulcer edge showing neutrophilic infiltrate, along with minor criteria, including exclusion of an infection, pathergy, and a history of inflammatory bowel disease or inflammatory arthritis.

“This is no longer a diagnosis of exclusion,” Dr. Lev-Tov said.

Cyclosporine and oral steroids have been found to work well, but it typically takes many months before healing occurs. Tacrolimus or topical steroids can work as well, but healing also takes a fairly long time with those medications, Dr. Lev-Tov said.

The tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker infliximab is another option. He had a patient who was referred to him who had been treated with cyclosporine for 3 years for PG on his feet, even though it had not been effective. Dr. Lev-Tov tried infliximab, and the wounds finally cleared, he said.

Apremilast, a phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4)-inhibitor, is another option for treating PG, he said. “Anecdotally, I used apremilast on three patients with recurrent PG for long-term suppression, with success,” he noted.

Epidermal grafting using suction and heat is an approach that might deserve further exploration for PG, Dr. Lev-Tov suggested. With this procedure, described in an article in 2014, heat and suction are used to induce blistering to separate and remove the epidermis from the dermis at the dermal-epidermal junction, creating an epidermal graft is placed over the wound to promote healing. Patients with PG who are immunosuppressed but demonstrate pathergy do not tend to experience pathergy when epidermal skin grafting is performed, he said.

The heat-suction procedure is simple, painless, and scarless, but better controlled data on this approach are needed, he said.

Corona phlebectatica: This disease involving abnormally dilated veins near the ankle has received formal recognition as a sign of venous insufficiency, in a 2020 update of a classification system for describing patients with chronic venous disorders, Dr. Lev-Tov said.

“We knew about it for years, but now there’s some data that can actually predict the severity of disease,” and, he said, it is now a part of the diagnostic criteria for venous insufficiency .

Venous leg ulcers: These often painful sores on the inside of the leg typically take more than a month to heal. A systematic review of placebo-controlled studies of pentoxifylline as a treatment for venous leg ulcers, published in 2021, supports its use for healing venous leg ulcers, Dr. Lev-Tov said. “It improved the healing rate and increased what [the researchers] called ‘significant improvement,’ ” a category they created to account for the varying methods across the studies, he said.

Topical beta-blockers can improve epithelialization and fibroblast migration in wound healing, he said. A study on topical timolol for various wounds found that a 0.5% formulation of topical timolol, with one drop applied per square centimeter as frequently as possible, was effective in healing. But the healing process was prolonged – a median of 90 days, said Dr. Lev-Tov, one of the study authors.

“When you start this, I don’t want you to expect the wound to heal tomorrow,” he said. “You’ve got to educate your patient.”

Dr. Lev-Tov reports relevant financial relationships with Abbvie, Novartis, Pfizer and other companies.

AT ODAC 2023

Chronic Ulcerative Lesion

The Diagnosis: Marjolin Ulcer

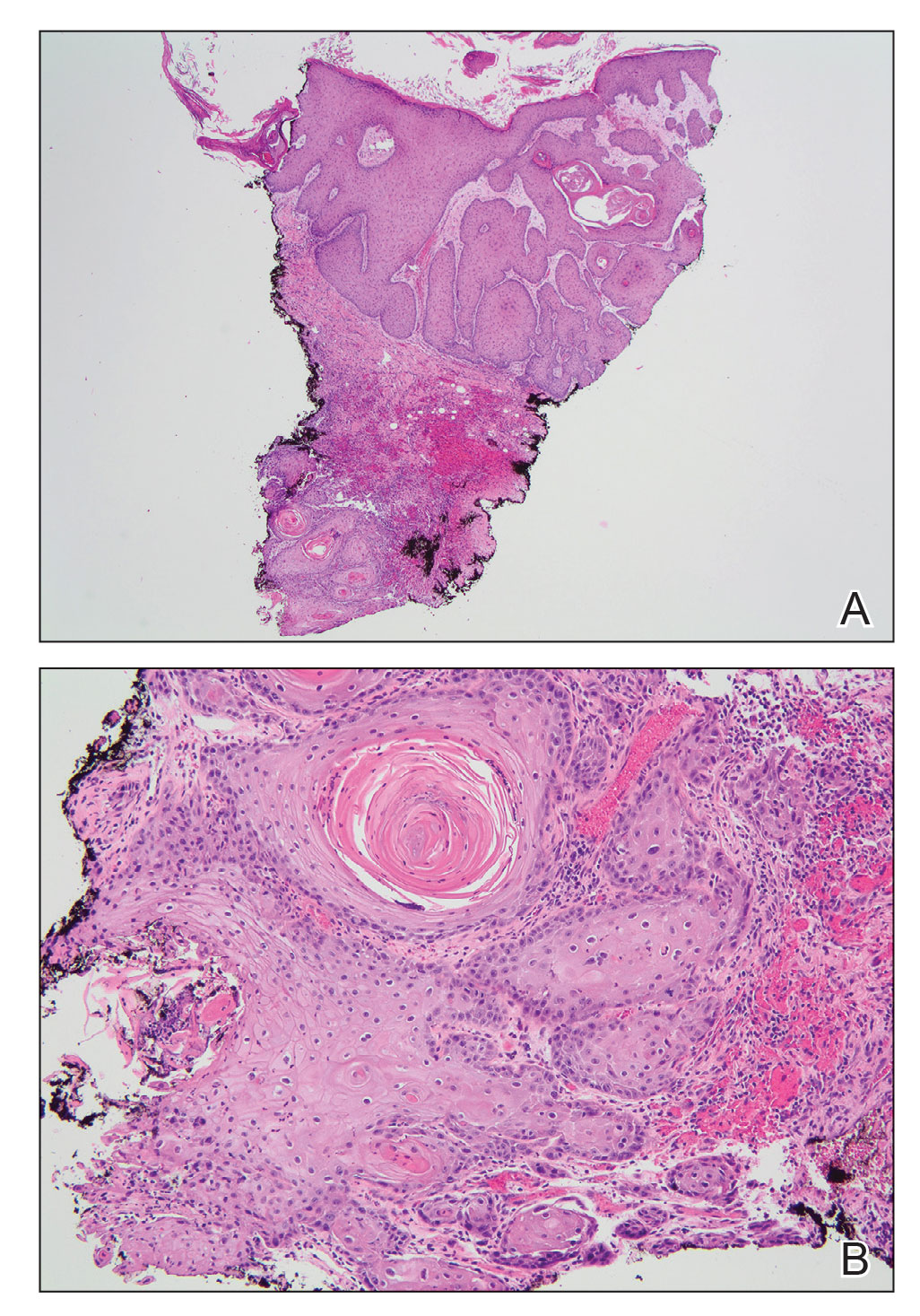

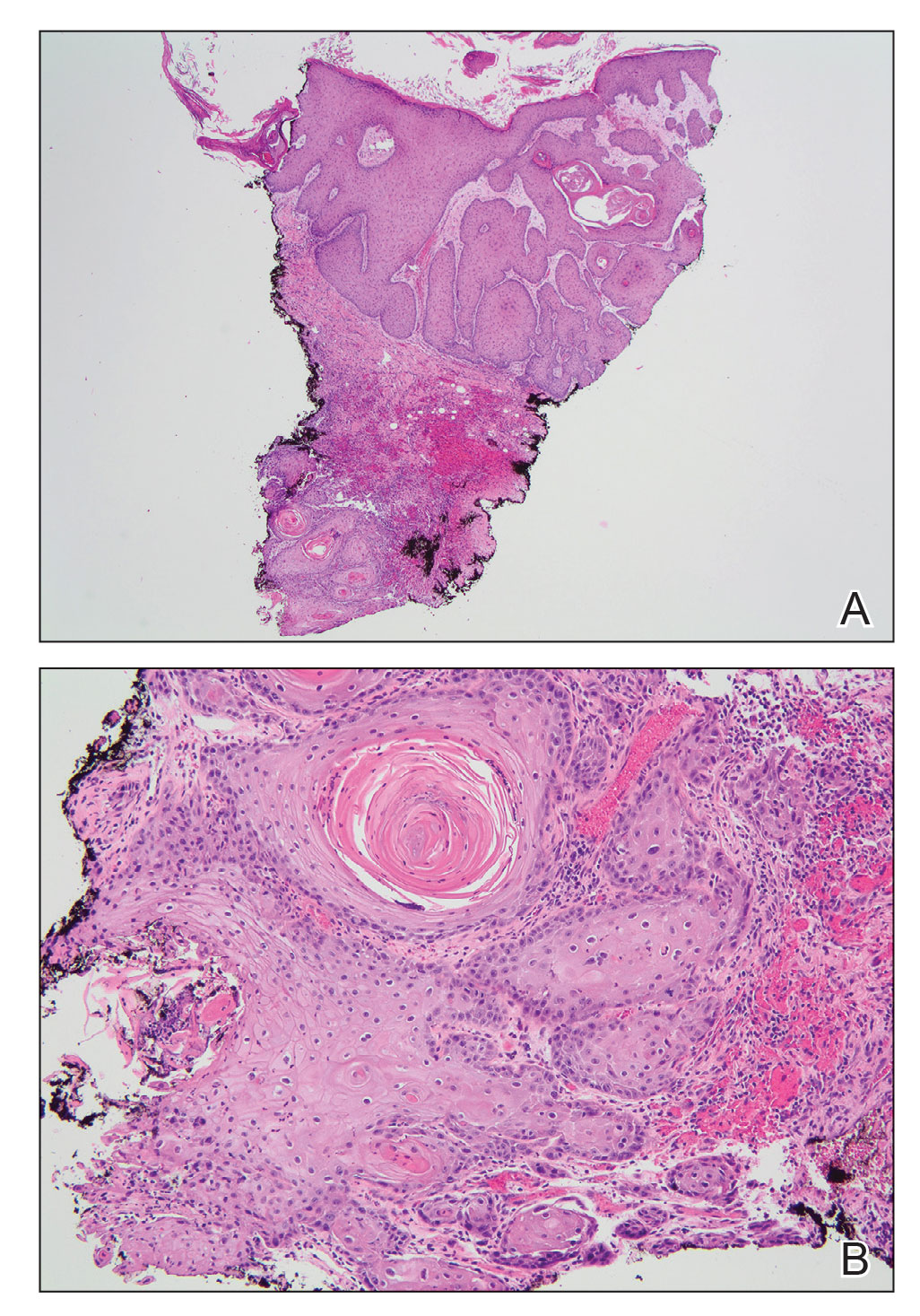

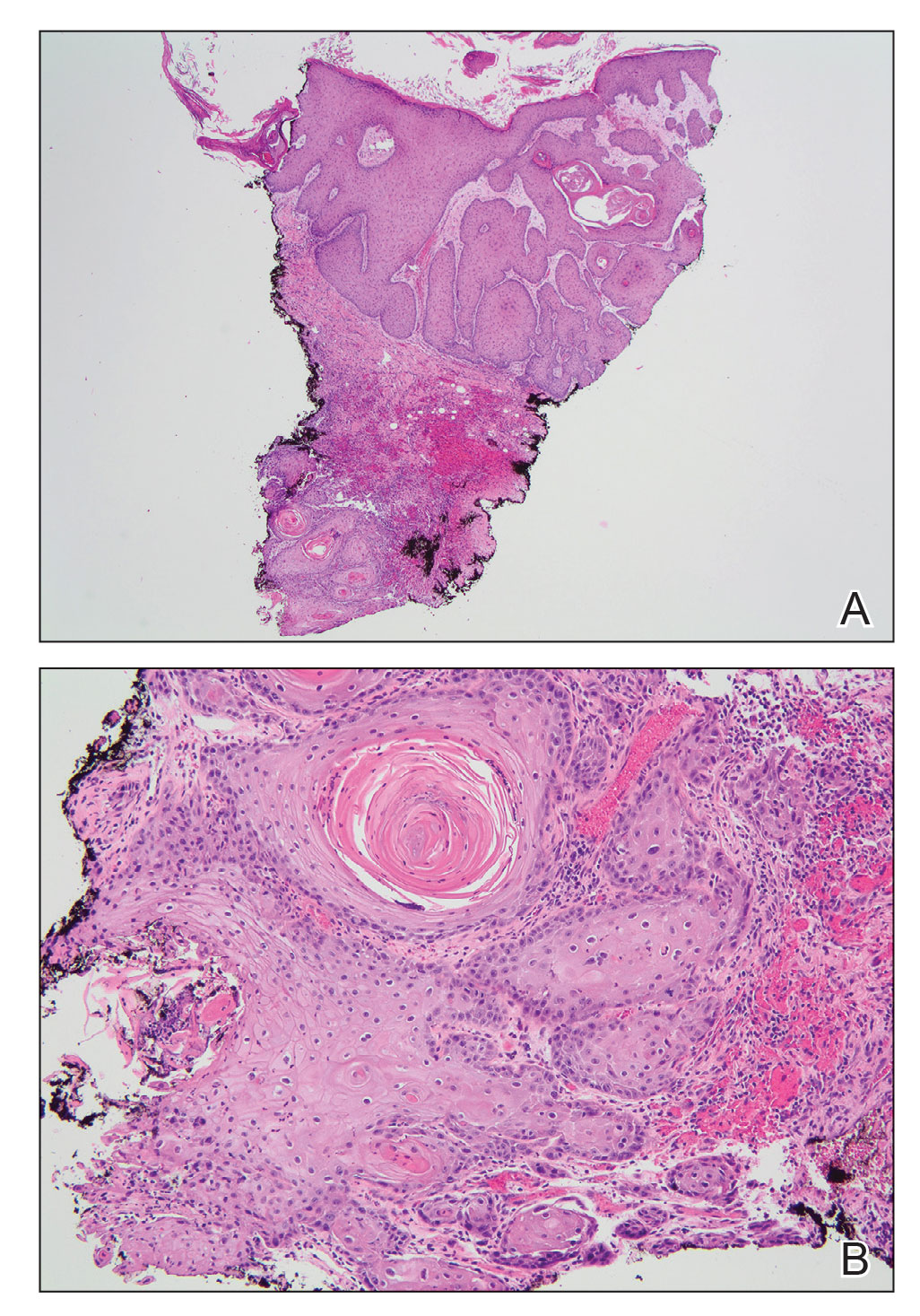

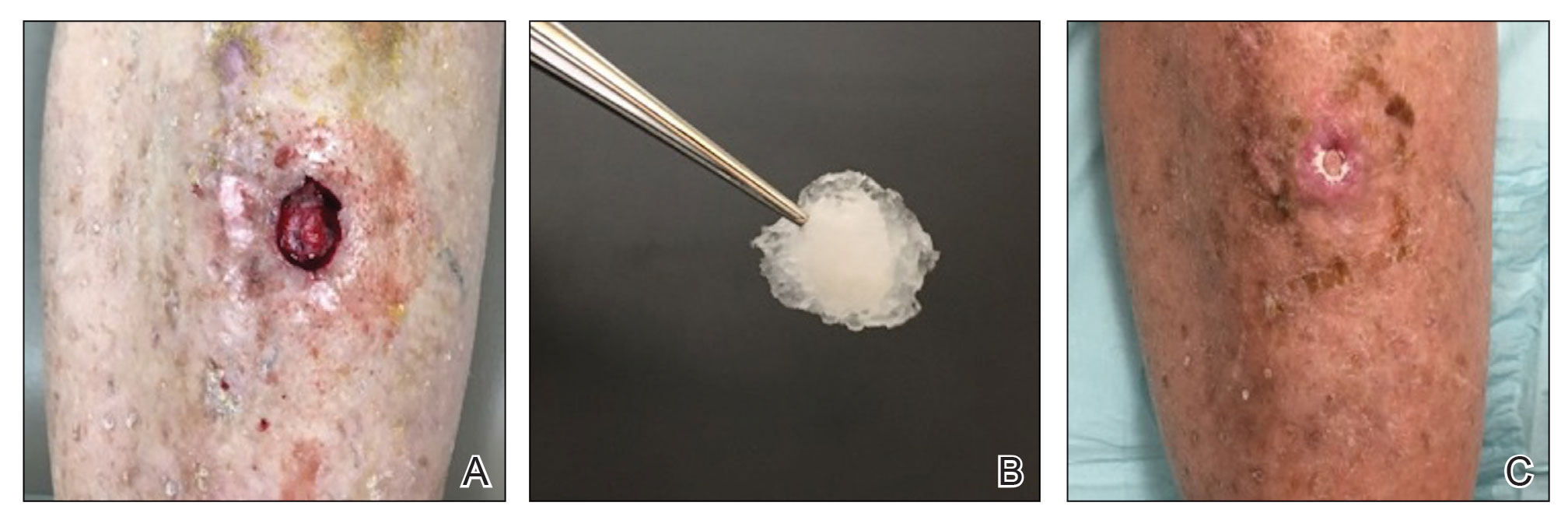

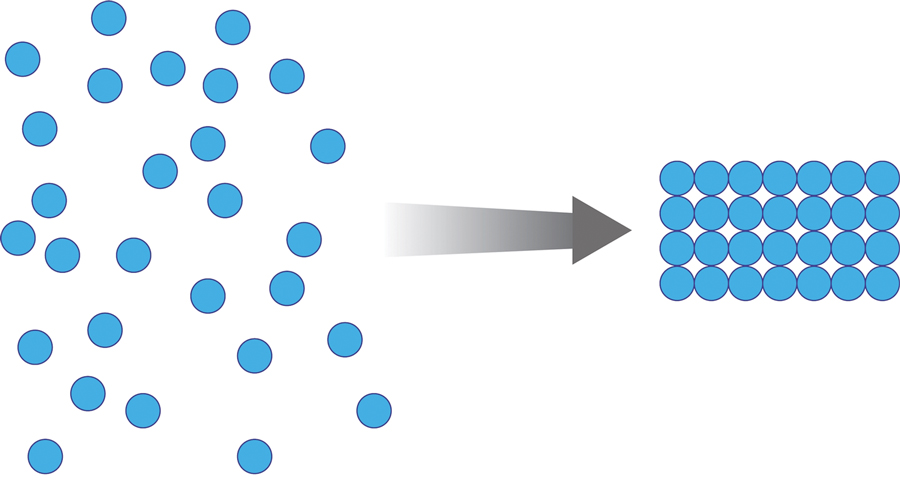

A skin biopsy during his prior hospital admission demonstrated an ulcer with granulation tissue and mixed inflammation, and the patient was discharged with close outpatient follow-up. Two repeat skin biopsies from the peripheral margin at the time of the outpatient follow-up confirmed an invasive, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Figure), consistent with a Marjolin ulcer. Radiography demonstrated multiple left iliac chain and inguinal lymphadenopathies with extensive subcutaneous disease overlying the left medial tibia. After tumor board discussion, surgery was not recommended due to the size and likely penetration into the muscle. The patient began treatment with cemiplimab-rwlc, a PD-1 inhibitor. Within 4 cycles of treatment, he had improved pain and ambulation, and a 3-month follow-up positron emission tomography scan revealed decreased lymph node and cutaneous metabolic activity as well as clinical improvement.

Marjolin ulcers are rare and aggressive squamous cell carcinomas that arise from chronic wounds such as burn scars or pressure ulcers.1 Although an underlying well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma is the most common etiology, patients also may present with underlying basal cell carcinomas, melanomas, or angiosarcomas.2 The exact pathogenesis underlying the malignant degeneration is unclear but appears to be driven by chronic inflammation. Patients classically present with a nonhealing ulcer associated with raised, friable, or crusty borders, as well as surrounding scar tissue. There is a median latency of 30 years after the trauma, though acute transformation within 12 months of an injury is possible.3 The diagnosis is confirmed with a peripheral wound biopsy. Surgical excision with wide margins remains the most common and effective intervention, especially for localized disease.1 The addition of lymph node dissection remains controversial, but treatment decisions can be guided by radiographic staging.4

The prognosis of Marjolin ulcers remains poor, with a predicted 5-year survival rate ranging from 43% to 58%.1 Dermatologists and trainees should be aware of Marjolin ulcers, especially as a mimicker of other chronic ulcerating conditions. Among the differential diagnosis, ulcerative lichen planus is a condition that commonly affects the oral and genital regions; however, patients with erosive lichen planus may develop an increased risk for the subsequent development of squamous cell carcinoma in the region.5 Furthermore, arterial ulcers typically develop on the distal lower extremities with other signs of chronic ischemia, including absent peripheral pulses, atrophic skin, hair loss, and ankle-brachial indices less than 0.5. Conversely, a venous ulcer classically affects the medial malleolus and will have evidence of venous insufficiency, including stasis dermatitis and peripheral edema.6

- Iqbal FM, Sinha Y, Jaffe W. Marjolin’s ulcer: a rare entity with a call for early diagnosis [published online July 15, 2015]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-208176

- Kanth AM, Heiman AJ, Nair L, et al. Current trends in management of Marjolin’s ulcer: a systematic review. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:144-151. doi:10.1093/jbcr/iraa128

- Copcu E. Marjolin’s ulcer: a preventable complication of burns? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:E156-E164. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a8082e

- Pekarek B, Buck S, Osher L. A comprehensive review on Marjolin’s ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Coll Certif Wound Spec. 2011; 3:60-64. doi:10.1016/j.jcws.2012.04.001

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Spentzouris G, Labropoulos N. The evaluation of lower-extremity ulcers. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26:286-295. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1242204

The Diagnosis: Marjolin Ulcer

A skin biopsy during his prior hospital admission demonstrated an ulcer with granulation tissue and mixed inflammation, and the patient was discharged with close outpatient follow-up. Two repeat skin biopsies from the peripheral margin at the time of the outpatient follow-up confirmed an invasive, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Figure), consistent with a Marjolin ulcer. Radiography demonstrated multiple left iliac chain and inguinal lymphadenopathies with extensive subcutaneous disease overlying the left medial tibia. After tumor board discussion, surgery was not recommended due to the size and likely penetration into the muscle. The patient began treatment with cemiplimab-rwlc, a PD-1 inhibitor. Within 4 cycles of treatment, he had improved pain and ambulation, and a 3-month follow-up positron emission tomography scan revealed decreased lymph node and cutaneous metabolic activity as well as clinical improvement.

Marjolin ulcers are rare and aggressive squamous cell carcinomas that arise from chronic wounds such as burn scars or pressure ulcers.1 Although an underlying well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma is the most common etiology, patients also may present with underlying basal cell carcinomas, melanomas, or angiosarcomas.2 The exact pathogenesis underlying the malignant degeneration is unclear but appears to be driven by chronic inflammation. Patients classically present with a nonhealing ulcer associated with raised, friable, or crusty borders, as well as surrounding scar tissue. There is a median latency of 30 years after the trauma, though acute transformation within 12 months of an injury is possible.3 The diagnosis is confirmed with a peripheral wound biopsy. Surgical excision with wide margins remains the most common and effective intervention, especially for localized disease.1 The addition of lymph node dissection remains controversial, but treatment decisions can be guided by radiographic staging.4

The prognosis of Marjolin ulcers remains poor, with a predicted 5-year survival rate ranging from 43% to 58%.1 Dermatologists and trainees should be aware of Marjolin ulcers, especially as a mimicker of other chronic ulcerating conditions. Among the differential diagnosis, ulcerative lichen planus is a condition that commonly affects the oral and genital regions; however, patients with erosive lichen planus may develop an increased risk for the subsequent development of squamous cell carcinoma in the region.5 Furthermore, arterial ulcers typically develop on the distal lower extremities with other signs of chronic ischemia, including absent peripheral pulses, atrophic skin, hair loss, and ankle-brachial indices less than 0.5. Conversely, a venous ulcer classically affects the medial malleolus and will have evidence of venous insufficiency, including stasis dermatitis and peripheral edema.6

The Diagnosis: Marjolin Ulcer

A skin biopsy during his prior hospital admission demonstrated an ulcer with granulation tissue and mixed inflammation, and the patient was discharged with close outpatient follow-up. Two repeat skin biopsies from the peripheral margin at the time of the outpatient follow-up confirmed an invasive, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Figure), consistent with a Marjolin ulcer. Radiography demonstrated multiple left iliac chain and inguinal lymphadenopathies with extensive subcutaneous disease overlying the left medial tibia. After tumor board discussion, surgery was not recommended due to the size and likely penetration into the muscle. The patient began treatment with cemiplimab-rwlc, a PD-1 inhibitor. Within 4 cycles of treatment, he had improved pain and ambulation, and a 3-month follow-up positron emission tomography scan revealed decreased lymph node and cutaneous metabolic activity as well as clinical improvement.

Marjolin ulcers are rare and aggressive squamous cell carcinomas that arise from chronic wounds such as burn scars or pressure ulcers.1 Although an underlying well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma is the most common etiology, patients also may present with underlying basal cell carcinomas, melanomas, or angiosarcomas.2 The exact pathogenesis underlying the malignant degeneration is unclear but appears to be driven by chronic inflammation. Patients classically present with a nonhealing ulcer associated with raised, friable, or crusty borders, as well as surrounding scar tissue. There is a median latency of 30 years after the trauma, though acute transformation within 12 months of an injury is possible.3 The diagnosis is confirmed with a peripheral wound biopsy. Surgical excision with wide margins remains the most common and effective intervention, especially for localized disease.1 The addition of lymph node dissection remains controversial, but treatment decisions can be guided by radiographic staging.4

The prognosis of Marjolin ulcers remains poor, with a predicted 5-year survival rate ranging from 43% to 58%.1 Dermatologists and trainees should be aware of Marjolin ulcers, especially as a mimicker of other chronic ulcerating conditions. Among the differential diagnosis, ulcerative lichen planus is a condition that commonly affects the oral and genital regions; however, patients with erosive lichen planus may develop an increased risk for the subsequent development of squamous cell carcinoma in the region.5 Furthermore, arterial ulcers typically develop on the distal lower extremities with other signs of chronic ischemia, including absent peripheral pulses, atrophic skin, hair loss, and ankle-brachial indices less than 0.5. Conversely, a venous ulcer classically affects the medial malleolus and will have evidence of venous insufficiency, including stasis dermatitis and peripheral edema.6

- Iqbal FM, Sinha Y, Jaffe W. Marjolin’s ulcer: a rare entity with a call for early diagnosis [published online July 15, 2015]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-208176

- Kanth AM, Heiman AJ, Nair L, et al. Current trends in management of Marjolin’s ulcer: a systematic review. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:144-151. doi:10.1093/jbcr/iraa128

- Copcu E. Marjolin’s ulcer: a preventable complication of burns? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:E156-E164. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a8082e

- Pekarek B, Buck S, Osher L. A comprehensive review on Marjolin’s ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Coll Certif Wound Spec. 2011; 3:60-64. doi:10.1016/j.jcws.2012.04.001

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Spentzouris G, Labropoulos N. The evaluation of lower-extremity ulcers. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26:286-295. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1242204

- Iqbal FM, Sinha Y, Jaffe W. Marjolin’s ulcer: a rare entity with a call for early diagnosis [published online July 15, 2015]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-208176

- Kanth AM, Heiman AJ, Nair L, et al. Current trends in management of Marjolin’s ulcer: a systematic review. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:144-151. doi:10.1093/jbcr/iraa128

- Copcu E. Marjolin’s ulcer: a preventable complication of burns? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:E156-E164. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a8082e

- Pekarek B, Buck S, Osher L. A comprehensive review on Marjolin’s ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Coll Certif Wound Spec. 2011; 3:60-64. doi:10.1016/j.jcws.2012.04.001

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Spentzouris G, Labropoulos N. The evaluation of lower-extremity ulcers. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26:286-295. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1242204

A 46-year-old man with a history of a left leg burn during childhood that was unsuccessfully treated with multiple skin grafts presented as a hospital follow-up for outpatient management of an ulcer. The patient had an ulcer that gradually increased in size over 7 years. Over the course of 2 weeks prior to the hospital presentation, he noted increased pain and severe difficulty with ambulation but remained afebrile without other systemic symptoms. Prior to the outpatient follow-up, he had been admitted to the hospital where he underwent imaging, laboratory studies, and skin biopsy, as well as treatment with empiric vancomycin. Physical examination revealed a large undermined ulcer with an elevated peripheral margin and crusting on the left lower leg with surrounding chronic scarring.

Microneedling With Bimatoprost to Treat Hypopigmented Skin Caused by Burn Scars

To the Editor:

Microneedling is a percutaneous collagen induction therapy frequently used in cosmetic dermatology to promote skin rejuvenation and hair growth and to treat scars by taking advantage of the body’s natural wound-healing cascade.1 The procedure works by generating thousands of microscopic wounds in the dermis with minimal damage to the epidermis, thus initiating the wound-healing cascade and subsequently promoting collagen production in a manner safe for all Fitzpatrick classification skin types.1-3 This therapy effectively treats scars by breaking down scarred collagen and replacing it with new healthy collagen. Microneedling also has application in drug delivery by increasing the permeability of the skin; the microwounds generated can serve as a portal for drug delivery.4

Bimatoprost is a prostaglandin analogue typically used to treat hypotrichosis and open-angle glaucoma.5-7 A known side effect of bimatoprost is hyperpigmentation of surrounding skin; the drug increases melanogenesis, melanocyte proliferation, and melanocyte dendricity, resulting in activation of the inflammatory response and subsequent prostaglandin release, which stimulates melanogenesis. This effect is similar to UV radiation–induced inflammation and hyperpigmentation.6,8

Capitalizing on this effect, a novel application of bimatoprost has been proposed—treating vitiligo, in which hypopigmentation results from destruction of melanocytes in certain areas of the skin. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% utilized as an off-label treatment for vitiligo has been shown to notably increase melanogenesis and return pigmentation to hypopigmented areas.8-10

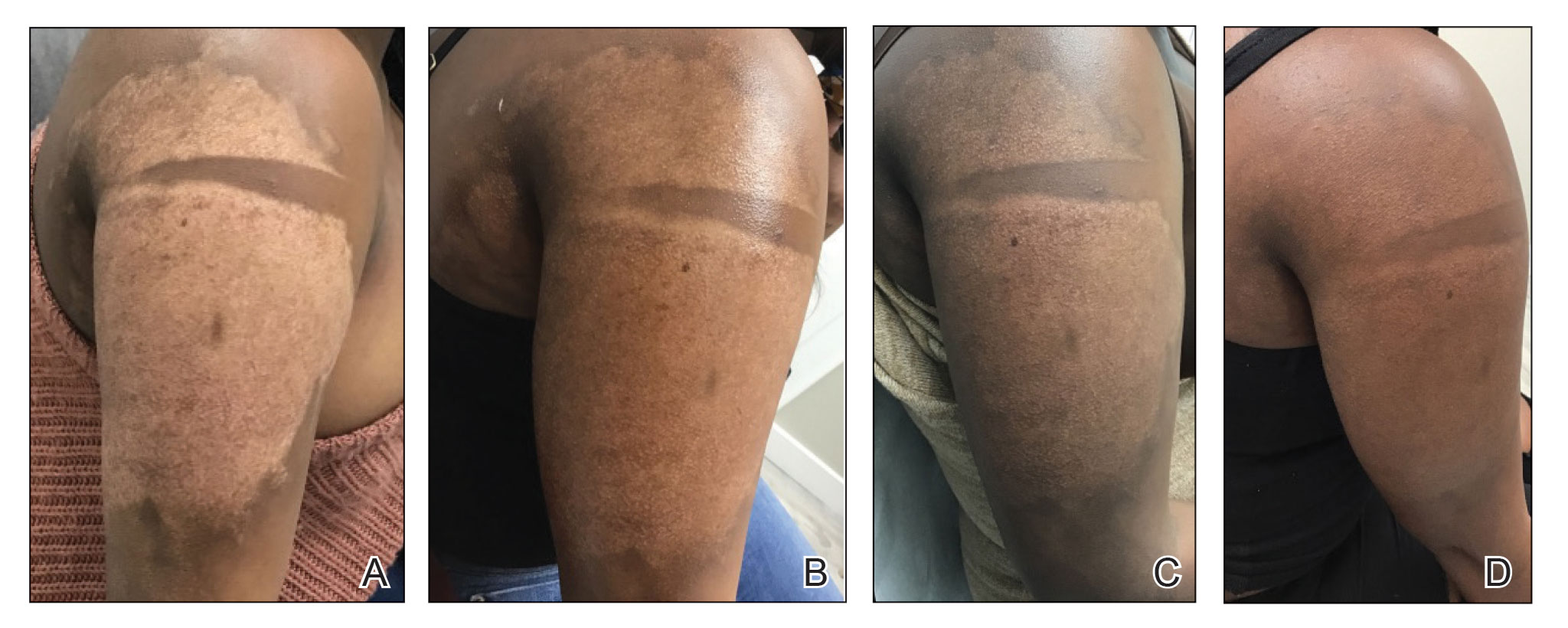

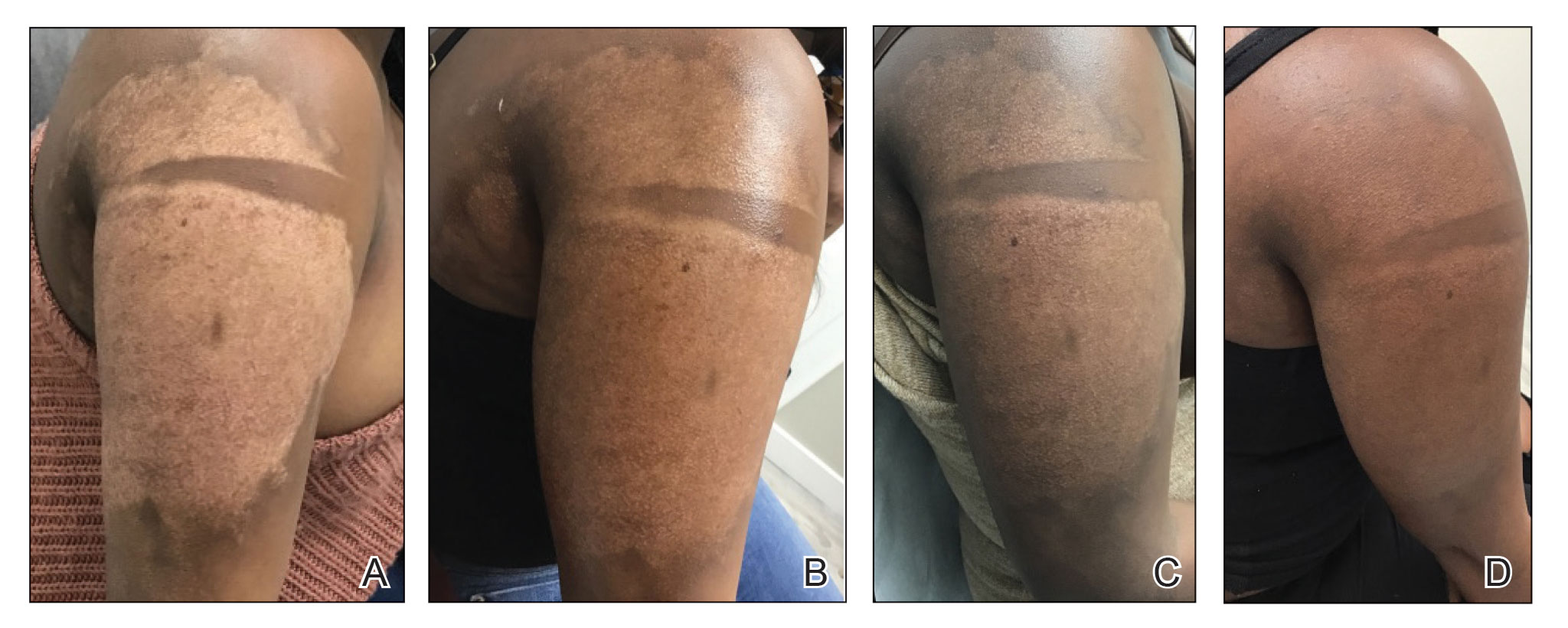

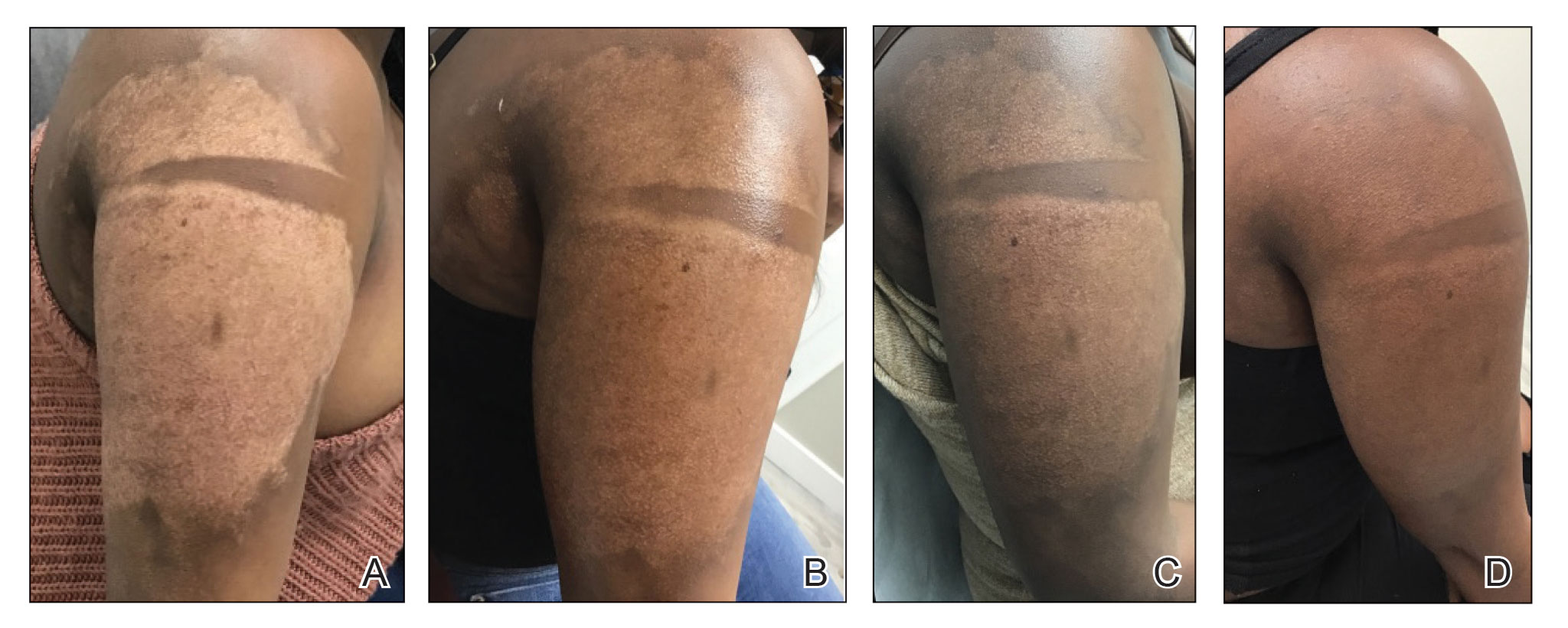

A 32-year-old Black woman presented to our clinic with a 40×15-cm scar that was marked by postinflammatory hypopigmentation from a second-degree burn on the right proximal arm. The patient had been burned 5 months prior by boiling water that was spilled on the arm while cooking. She had immediately sought treatment at an emergency department and subsequently in a burn unit, where the burn was debrided twice; medication was not prescribed to continue treatment. The patient reported that the scarring and hypopigmentation had taken a psychologic toll; her hope was to have pigmentation restored to the affected area to boost her confidence.

Physical examination revealed that the burn wound had healed but visible scarring and severe hypopigmentation due to destroyed melanocytes remained (Figure 1). To inhibit inflammation and stimulate repigmentation, we prescribed the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus ointment 0.1% to be applied daily to the affected area. The patient returned to the clinic 1 month later. Perifollicular hyperpigmentation was noted at the site of the scar.

Monthly microneedling sessions with bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% were started. To avoid damaging any potentially remaining unhealed hypodermis and vasculature, the first microneedling session was performed with 9 needles set at minimal needle depth and frequency. The number of needles and their depth and frequency gradually were increased with each subsequent treatment. The patient continued tacrolimus ointment 0.1% throughout the course of treatment.

For each microneedling procedure, a handheld motorized microneedling device was applied to the skin at a depth of 0.25 mm, which was gradually increased until pinpoint petechiae were achieved. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% was then painted on the skin and allowed to absorb. Microneedling was performed again, ensuring that bimatoprost entered the skin in the area of the burn scar.

Microneedling procedures were performed monthly for 6 months, then once 3 months later, and once more 3 months later—8 treatments in total over the course of 1 year. Improvement in skin pigmentation was noted at each visit (Figure 2). Repigmentation was first noticed surrounding hair follicles; after later visits, it was observed that pigmentation began to spread from hair follicles to fill in remaining skin. The darkest areas of pigmentation were first noted around hair follicles; over time, melanocytes appeared to spontaneously regenerate and fill in surrounding areas as the scar continued to heal. The patient continued use of tacrolimus during the entire course of microneedling treatments and for the following 4 months. Sixteen months after initiation of treatment, the appearance of the skin was texturally smooth and returned to almost its original pigmentation (Figure 3).

We report a successful outcome in a patient with a hypopigmented burn scar who was treated with bimatoprost administered with traditional microneedling and alongside a tacrolimus regimen. Tacrolimus ointment inhibited the inflammatory response to allow melanocytes to heal and regenerate; bimatoprost and microneedling promoted hyperpigmentation of hair follicles in the affected area, eventually restoring pigmentation to the entire area. Our patient was extremely satisfied with the results of this combination treatment. She has reported feeling more confident going out and wearing short-sleeved clothing. Percutaneous drug delivery of bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% combined with topical tacrolimus may be an effective treatment for skin repigmentation. Further investigation of this regimen is needed to develop standardized treatment protocols.

- Juhasz MLW, Cohen JL. Micro-needling for the treatment of scars: an update for clinicians. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2020;13:997-1003. doi:10.2147/CCID.S267192

- Alster TS, Li MKY. Micro-needling of scars: a large prospective study with long-term follow-up. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145:358-364. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000006462

- Aust MC, Knobloch K, Reimers K, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction therapy: an alternative treatment for burn scars. Burns. 2010;36:836-843. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2009.11.014

- Kim Y-C, Park J-H, Prausnitz MR. Microneedles for drug and vaccine delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:1547-1568. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2012.04.005

- Doshi M, Edward DP, Osmanovic S. Clinical course of bimatoprost-induced periocular skin changes in Caucasians. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1961-1967. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.041

- Kapur R, Osmanovic S, Toyran S, et al. Bimatoprost-induced periocular skin hyperpigmentation: histopathological study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1541-1546. doi:10.1001/archopht.123.11.1541

- Priluck JC, Fu S. Latisse-induced periocular skin hyperpigmentation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:792-793. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.89

- Grimes PE. Bimatoprost 0.03% solution for the treatment of nonfacial vitiligo. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:703-710.

- Barbulescu C, Goldstein N, Roop D, et al. Harnessing the power of regenerative therapy for vitiligo and alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140: 29-37. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2019.03.1142

- Kanokrungsee S, Pruettivorawongse D, Rajatanavin N. Clinicaloutcomes of topical bimatoprost for nonsegmental facial vitiligo: a preliminary study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:812-818. doi.org/10.1111/jocd.13648

To the Editor:

Microneedling is a percutaneous collagen induction therapy frequently used in cosmetic dermatology to promote skin rejuvenation and hair growth and to treat scars by taking advantage of the body’s natural wound-healing cascade.1 The procedure works by generating thousands of microscopic wounds in the dermis with minimal damage to the epidermis, thus initiating the wound-healing cascade and subsequently promoting collagen production in a manner safe for all Fitzpatrick classification skin types.1-3 This therapy effectively treats scars by breaking down scarred collagen and replacing it with new healthy collagen. Microneedling also has application in drug delivery by increasing the permeability of the skin; the microwounds generated can serve as a portal for drug delivery.4

Bimatoprost is a prostaglandin analogue typically used to treat hypotrichosis and open-angle glaucoma.5-7 A known side effect of bimatoprost is hyperpigmentation of surrounding skin; the drug increases melanogenesis, melanocyte proliferation, and melanocyte dendricity, resulting in activation of the inflammatory response and subsequent prostaglandin release, which stimulates melanogenesis. This effect is similar to UV radiation–induced inflammation and hyperpigmentation.6,8

Capitalizing on this effect, a novel application of bimatoprost has been proposed—treating vitiligo, in which hypopigmentation results from destruction of melanocytes in certain areas of the skin. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% utilized as an off-label treatment for vitiligo has been shown to notably increase melanogenesis and return pigmentation to hypopigmented areas.8-10

A 32-year-old Black woman presented to our clinic with a 40×15-cm scar that was marked by postinflammatory hypopigmentation from a second-degree burn on the right proximal arm. The patient had been burned 5 months prior by boiling water that was spilled on the arm while cooking. She had immediately sought treatment at an emergency department and subsequently in a burn unit, where the burn was debrided twice; medication was not prescribed to continue treatment. The patient reported that the scarring and hypopigmentation had taken a psychologic toll; her hope was to have pigmentation restored to the affected area to boost her confidence.

Physical examination revealed that the burn wound had healed but visible scarring and severe hypopigmentation due to destroyed melanocytes remained (Figure 1). To inhibit inflammation and stimulate repigmentation, we prescribed the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus ointment 0.1% to be applied daily to the affected area. The patient returned to the clinic 1 month later. Perifollicular hyperpigmentation was noted at the site of the scar.

Monthly microneedling sessions with bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% were started. To avoid damaging any potentially remaining unhealed hypodermis and vasculature, the first microneedling session was performed with 9 needles set at minimal needle depth and frequency. The number of needles and their depth and frequency gradually were increased with each subsequent treatment. The patient continued tacrolimus ointment 0.1% throughout the course of treatment.

For each microneedling procedure, a handheld motorized microneedling device was applied to the skin at a depth of 0.25 mm, which was gradually increased until pinpoint petechiae were achieved. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% was then painted on the skin and allowed to absorb. Microneedling was performed again, ensuring that bimatoprost entered the skin in the area of the burn scar.

Microneedling procedures were performed monthly for 6 months, then once 3 months later, and once more 3 months later—8 treatments in total over the course of 1 year. Improvement in skin pigmentation was noted at each visit (Figure 2). Repigmentation was first noticed surrounding hair follicles; after later visits, it was observed that pigmentation began to spread from hair follicles to fill in remaining skin. The darkest areas of pigmentation were first noted around hair follicles; over time, melanocytes appeared to spontaneously regenerate and fill in surrounding areas as the scar continued to heal. The patient continued use of tacrolimus during the entire course of microneedling treatments and for the following 4 months. Sixteen months after initiation of treatment, the appearance of the skin was texturally smooth and returned to almost its original pigmentation (Figure 3).

We report a successful outcome in a patient with a hypopigmented burn scar who was treated with bimatoprost administered with traditional microneedling and alongside a tacrolimus regimen. Tacrolimus ointment inhibited the inflammatory response to allow melanocytes to heal and regenerate; bimatoprost and microneedling promoted hyperpigmentation of hair follicles in the affected area, eventually restoring pigmentation to the entire area. Our patient was extremely satisfied with the results of this combination treatment. She has reported feeling more confident going out and wearing short-sleeved clothing. Percutaneous drug delivery of bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% combined with topical tacrolimus may be an effective treatment for skin repigmentation. Further investigation of this regimen is needed to develop standardized treatment protocols.

To the Editor:

Microneedling is a percutaneous collagen induction therapy frequently used in cosmetic dermatology to promote skin rejuvenation and hair growth and to treat scars by taking advantage of the body’s natural wound-healing cascade.1 The procedure works by generating thousands of microscopic wounds in the dermis with minimal damage to the epidermis, thus initiating the wound-healing cascade and subsequently promoting collagen production in a manner safe for all Fitzpatrick classification skin types.1-3 This therapy effectively treats scars by breaking down scarred collagen and replacing it with new healthy collagen. Microneedling also has application in drug delivery by increasing the permeability of the skin; the microwounds generated can serve as a portal for drug delivery.4

Bimatoprost is a prostaglandin analogue typically used to treat hypotrichosis and open-angle glaucoma.5-7 A known side effect of bimatoprost is hyperpigmentation of surrounding skin; the drug increases melanogenesis, melanocyte proliferation, and melanocyte dendricity, resulting in activation of the inflammatory response and subsequent prostaglandin release, which stimulates melanogenesis. This effect is similar to UV radiation–induced inflammation and hyperpigmentation.6,8

Capitalizing on this effect, a novel application of bimatoprost has been proposed—treating vitiligo, in which hypopigmentation results from destruction of melanocytes in certain areas of the skin. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% utilized as an off-label treatment for vitiligo has been shown to notably increase melanogenesis and return pigmentation to hypopigmented areas.8-10

A 32-year-old Black woman presented to our clinic with a 40×15-cm scar that was marked by postinflammatory hypopigmentation from a second-degree burn on the right proximal arm. The patient had been burned 5 months prior by boiling water that was spilled on the arm while cooking. She had immediately sought treatment at an emergency department and subsequently in a burn unit, where the burn was debrided twice; medication was not prescribed to continue treatment. The patient reported that the scarring and hypopigmentation had taken a psychologic toll; her hope was to have pigmentation restored to the affected area to boost her confidence.

Physical examination revealed that the burn wound had healed but visible scarring and severe hypopigmentation due to destroyed melanocytes remained (Figure 1). To inhibit inflammation and stimulate repigmentation, we prescribed the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus ointment 0.1% to be applied daily to the affected area. The patient returned to the clinic 1 month later. Perifollicular hyperpigmentation was noted at the site of the scar.

Monthly microneedling sessions with bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% were started. To avoid damaging any potentially remaining unhealed hypodermis and vasculature, the first microneedling session was performed with 9 needles set at minimal needle depth and frequency. The number of needles and their depth and frequency gradually were increased with each subsequent treatment. The patient continued tacrolimus ointment 0.1% throughout the course of treatment.

For each microneedling procedure, a handheld motorized microneedling device was applied to the skin at a depth of 0.25 mm, which was gradually increased until pinpoint petechiae were achieved. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% was then painted on the skin and allowed to absorb. Microneedling was performed again, ensuring that bimatoprost entered the skin in the area of the burn scar.

Microneedling procedures were performed monthly for 6 months, then once 3 months later, and once more 3 months later—8 treatments in total over the course of 1 year. Improvement in skin pigmentation was noted at each visit (Figure 2). Repigmentation was first noticed surrounding hair follicles; after later visits, it was observed that pigmentation began to spread from hair follicles to fill in remaining skin. The darkest areas of pigmentation were first noted around hair follicles; over time, melanocytes appeared to spontaneously regenerate and fill in surrounding areas as the scar continued to heal. The patient continued use of tacrolimus during the entire course of microneedling treatments and for the following 4 months. Sixteen months after initiation of treatment, the appearance of the skin was texturally smooth and returned to almost its original pigmentation (Figure 3).

We report a successful outcome in a patient with a hypopigmented burn scar who was treated with bimatoprost administered with traditional microneedling and alongside a tacrolimus regimen. Tacrolimus ointment inhibited the inflammatory response to allow melanocytes to heal and regenerate; bimatoprost and microneedling promoted hyperpigmentation of hair follicles in the affected area, eventually restoring pigmentation to the entire area. Our patient was extremely satisfied with the results of this combination treatment. She has reported feeling more confident going out and wearing short-sleeved clothing. Percutaneous drug delivery of bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.3% combined with topical tacrolimus may be an effective treatment for skin repigmentation. Further investigation of this regimen is needed to develop standardized treatment protocols.

- Juhasz MLW, Cohen JL. Micro-needling for the treatment of scars: an update for clinicians. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2020;13:997-1003. doi:10.2147/CCID.S267192

- Alster TS, Li MKY. Micro-needling of scars: a large prospective study with long-term follow-up. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145:358-364. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000006462

- Aust MC, Knobloch K, Reimers K, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction therapy: an alternative treatment for burn scars. Burns. 2010;36:836-843. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2009.11.014

- Kim Y-C, Park J-H, Prausnitz MR. Microneedles for drug and vaccine delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:1547-1568. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2012.04.005

- Doshi M, Edward DP, Osmanovic S. Clinical course of bimatoprost-induced periocular skin changes in Caucasians. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1961-1967. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.041

- Kapur R, Osmanovic S, Toyran S, et al. Bimatoprost-induced periocular skin hyperpigmentation: histopathological study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1541-1546. doi:10.1001/archopht.123.11.1541

- Priluck JC, Fu S. Latisse-induced periocular skin hyperpigmentation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:792-793. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.89

- Grimes PE. Bimatoprost 0.03% solution for the treatment of nonfacial vitiligo. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:703-710.

- Barbulescu C, Goldstein N, Roop D, et al. Harnessing the power of regenerative therapy for vitiligo and alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140: 29-37. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2019.03.1142

- Kanokrungsee S, Pruettivorawongse D, Rajatanavin N. Clinicaloutcomes of topical bimatoprost for nonsegmental facial vitiligo: a preliminary study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:812-818. doi.org/10.1111/jocd.13648

- Juhasz MLW, Cohen JL. Micro-needling for the treatment of scars: an update for clinicians. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2020;13:997-1003. doi:10.2147/CCID.S267192

- Alster TS, Li MKY. Micro-needling of scars: a large prospective study with long-term follow-up. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145:358-364. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000006462

- Aust MC, Knobloch K, Reimers K, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction therapy: an alternative treatment for burn scars. Burns. 2010;36:836-843. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2009.11.014

- Kim Y-C, Park J-H, Prausnitz MR. Microneedles for drug and vaccine delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:1547-1568. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2012.04.005

- Doshi M, Edward DP, Osmanovic S. Clinical course of bimatoprost-induced periocular skin changes in Caucasians. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1961-1967. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.041

- Kapur R, Osmanovic S, Toyran S, et al. Bimatoprost-induced periocular skin hyperpigmentation: histopathological study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1541-1546. doi:10.1001/archopht.123.11.1541

- Priluck JC, Fu S. Latisse-induced periocular skin hyperpigmentation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:792-793. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.89

- Grimes PE. Bimatoprost 0.03% solution for the treatment of nonfacial vitiligo. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:703-710.

- Barbulescu C, Goldstein N, Roop D, et al. Harnessing the power of regenerative therapy for vitiligo and alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140: 29-37. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2019.03.1142

- Kanokrungsee S, Pruettivorawongse D, Rajatanavin N. Clinicaloutcomes of topical bimatoprost for nonsegmental facial vitiligo: a preliminary study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:812-818. doi.org/10.1111/jocd.13648

PRACTICE POINTS

- Microneedling is a percutaneous collagen induction therapy that also may be used in drug delivery.

- Hypopigmentation can cause considerable distress for patients with skin of color.

- Percutaneous drug delivery of bimatoprost may be helpful in skin repigmentation.

Methacrylate Polymer Powder Dressing for a Lower Leg Surgical Defect

To the Editor:

Surgical wounds on the lower leg are challenging to manage because venous stasis, bacterial colonization, and high tension may contribute to protracted healing. Advances in technology led to the development of novel, polymer-based wound-healing modalities that hold promise for the management of these wounds.

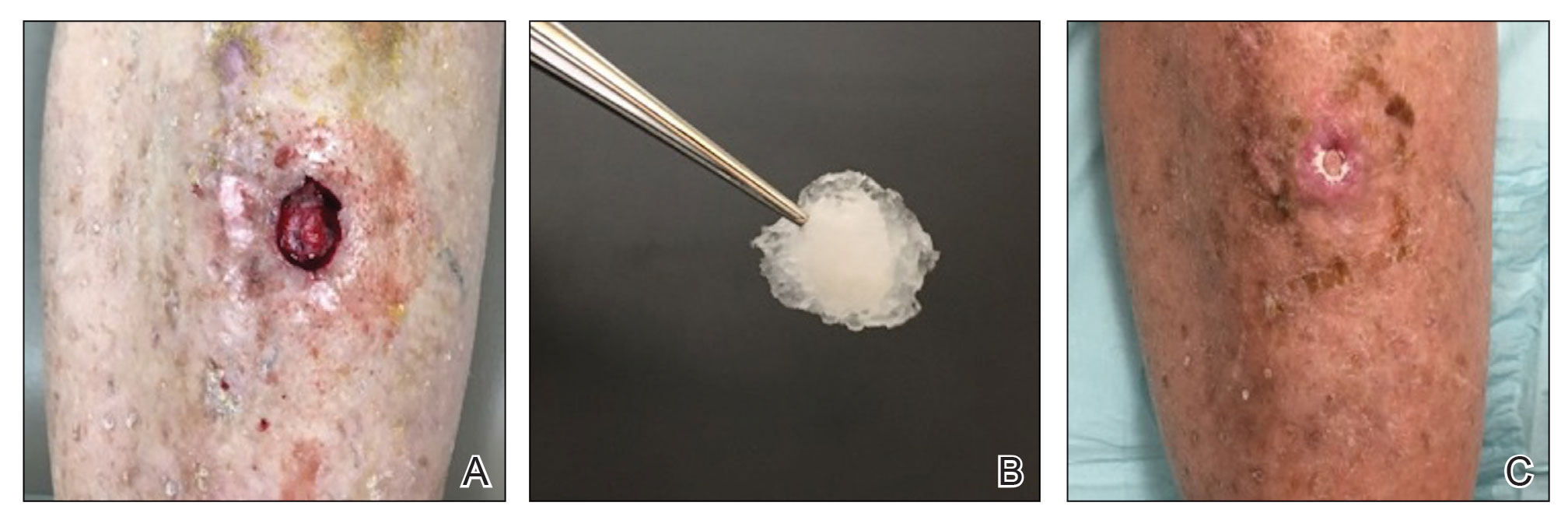

A 75-year-old man presented with a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with a 3-mm depth of invasion on the left pretibial region. His comorbidities were notable for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, varicose veins, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, and a 32 pack-year cigarette smoking history. Current medications included clopidogrel bisulfate and warfarin sodium to manage a recently placed coronary artery stent.

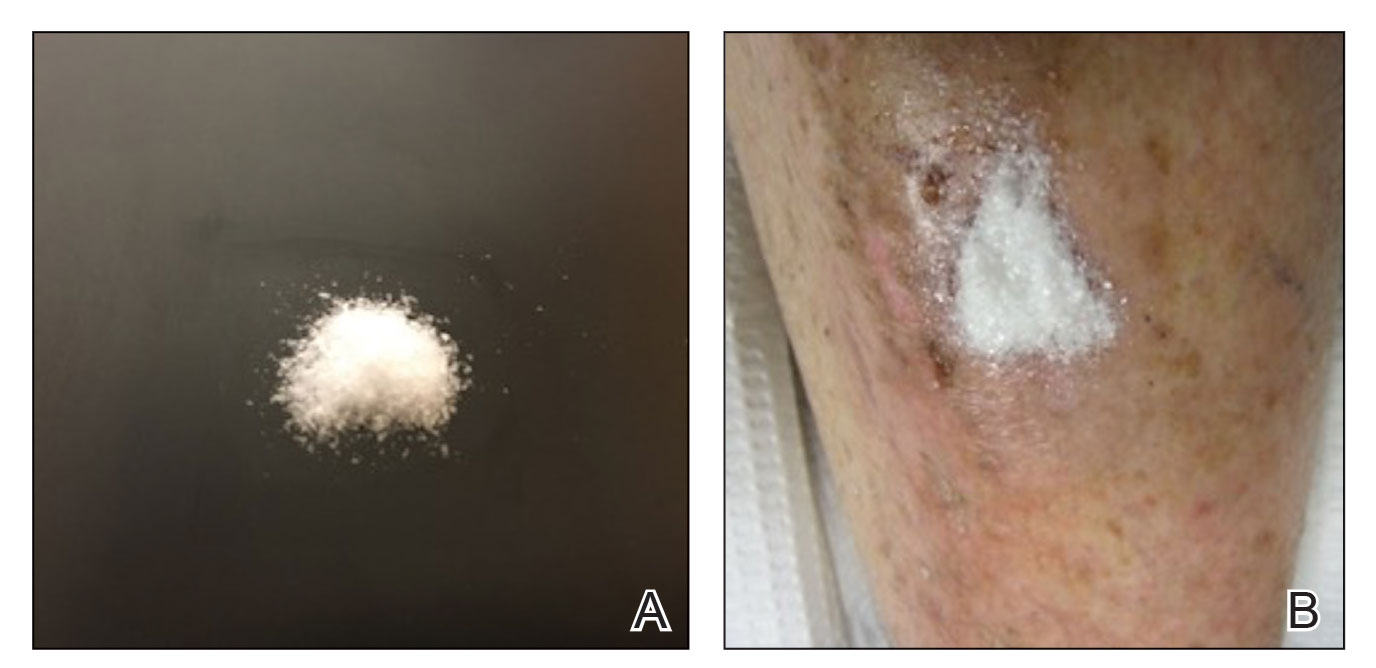

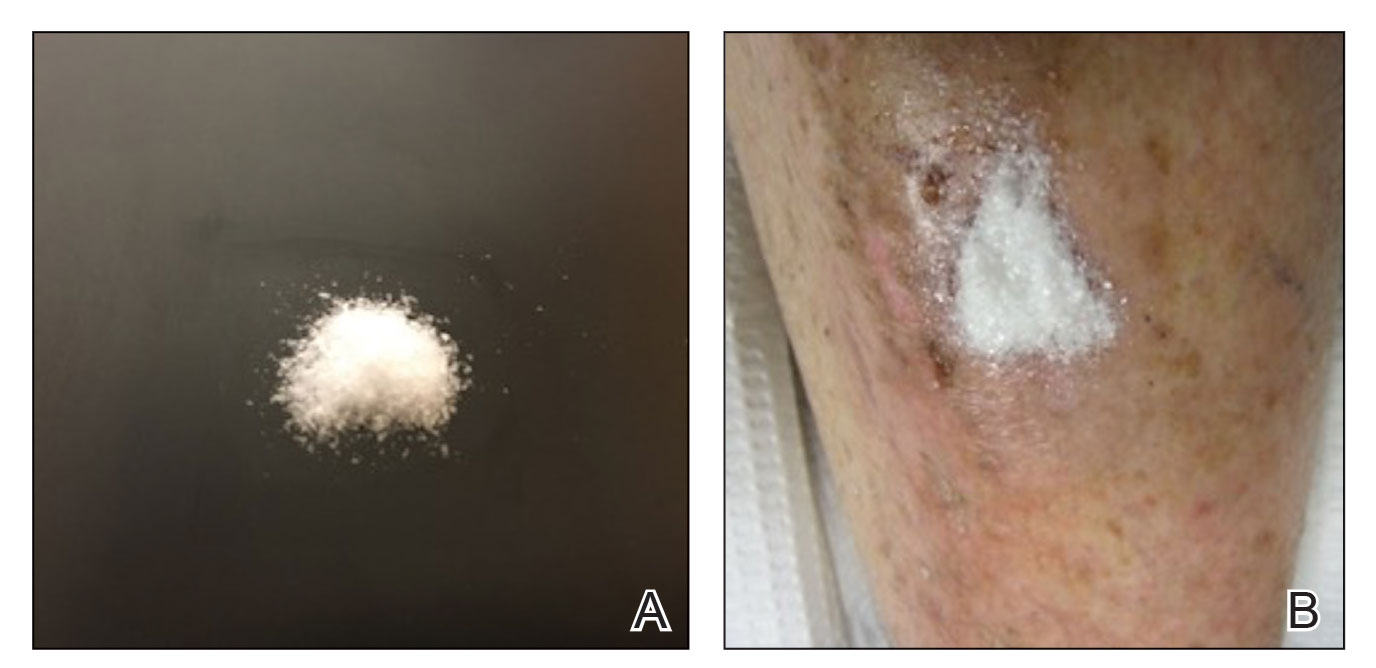

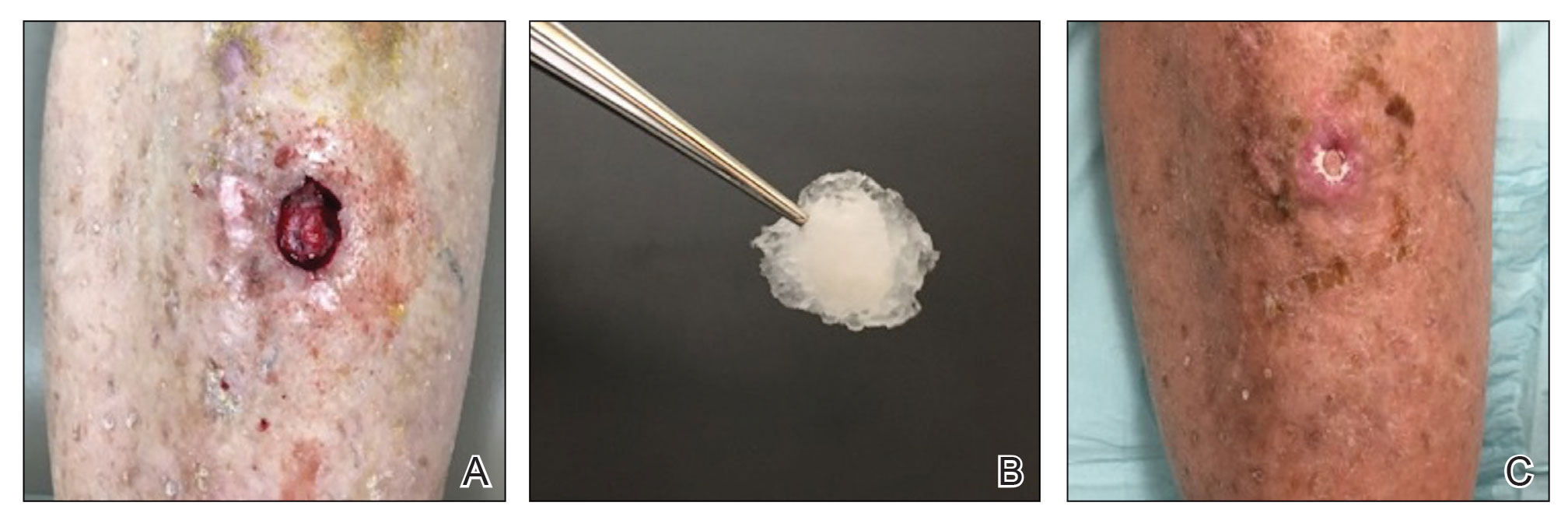

The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs micrographic surgery with excision down to tibialis anterior fascia (Figure 1A). The resultant defect measured 43×33 mm in area and 9 mm in depth (wound size, 12,771 mm3). Reconstructive options were discussed, including random-pattern flap repair and skin graft. Given the patient’s risk of bleeding, the decision was made to forego a flap repair. Additionally, the patient was a heavy smoker and could not comply with the wound care and elevation and ambulation restrictions required for optimal skin graft care. Therefore, a decision was made to proceed with secondary intention healing using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing.

After achieving hemostasis, a novel 10-mg sterile, biologically inert methacrylate polymer powder dressing was poured over the wound in a uniform layer to fill and seal the entire wound surface (Figure 1B). Sterile normal saline 0.1 mL was sprayed onto the powder to activate particle aggregation. No secondary dressing was used, and the patient was permitted to get the dressing wet after 48 hours.

The dressing was changed in a similar fashion 4 weeks after application, following gentle debridement with gauze and normal saline. Eight weeks after surgery, the wound exhibited healthy granulation tissue and measured 5×6 mm in area and 2 mm in depth (wound size, 60 mm3), which represented a 99.5% reduction in wound size (Figure 1C). The dressing was not painful, and there were no reported adverse effects. The patient continued to smoke and ambulate fully throughout this period. No antibiotics were used.

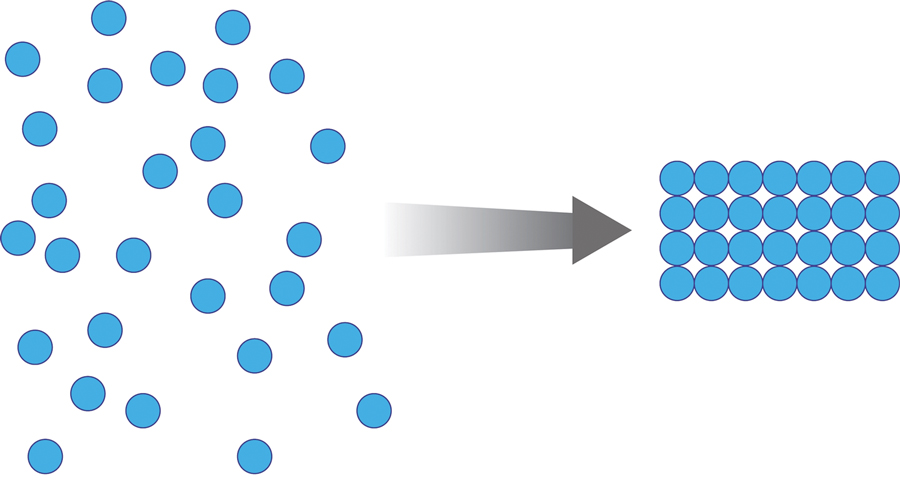

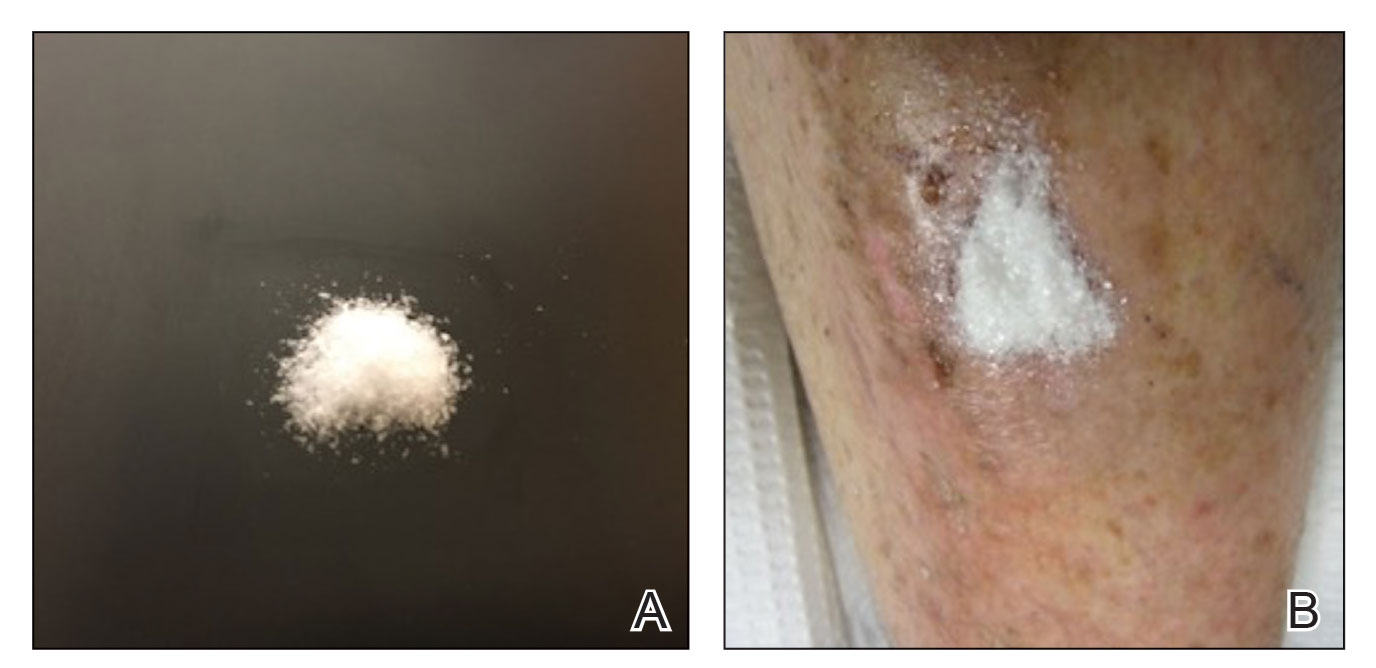

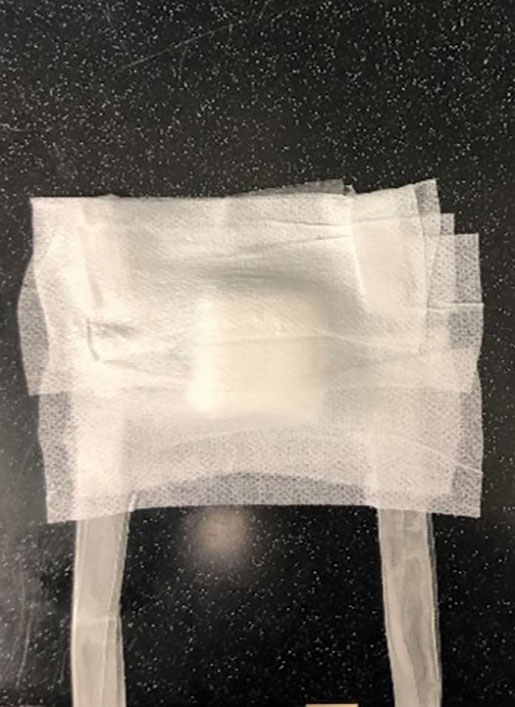

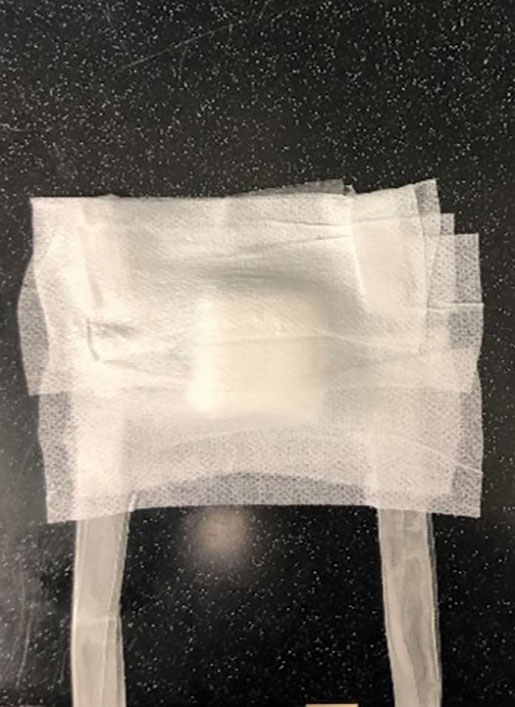

Methacrylate polymer powder dressings are a novel and sophisticated dressing modality with great promise for the management of surgical wounds on the lower limb. The dressing is a sterile powder consisting of 84.8% poly-2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate, 14.9% poly-2-hydroxypropylmethacrylate, and 0.3% sodium deoxycholate. These hydrophilic polymers have a covalent methacrylate backbone with a hydroxyl aliphatic side chain. When saline or wound exudate contacts the powder, the spheres hydrate and nonreversibly aggregate to form a moist, flexible dressing that conforms to the topography of the wound and seals it (Figure 2).1

Once the spheres have aggregated, they are designed to orient in a honeycomb formation with 4- to 10-nm openings that serve as capillary channels (Figure 3). This porous architecture of the polymer is essential for adequate moisture management. It allows for vapor transpiration at a rate of 12 L/m2 per day, which ensures the capillary flow from the moist wound surface is evenly distributed through the dressing, contributing to its 68% water content. Notably, this approximately three-fifths water composition is similar to the water makeup of human skin. Optimized moisture management is theorized to enhance epithelial migration, stimulate angiogenesis, retain growth factors, promote autolytic debridement, and maintain ideal voltage and oxygen gradients for wound healing. The risk for infection is not increased by the existence of these pores, as their small size does not allow for bacterial migration.1

This case demonstrates the effectiveness of using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing to promote timely wound healing in a poorly vascularized lower leg surgical wound. The low maintenance, user-friendly dressing was changed at monthly intervals, which spared the patient the inconvenience and pain associated with the repeated application of more conventional primary and secondary dressings. The dressing was well tolerated and resulted in a 99.5% reduction in wound size. Further studies are needed to investigate the utility of this promising technology.

1. Fitzgerald RH, Bharara M, Mills JL, et al. Use of a nanoflex powder dressing for wound management following debridement for necrotising fasciitis in the diabetic foot. Int Wound J. 2009;6:133-139.

To the Editor:

Surgical wounds on the lower leg are challenging to manage because venous stasis, bacterial colonization, and high tension may contribute to protracted healing. Advances in technology led to the development of novel, polymer-based wound-healing modalities that hold promise for the management of these wounds.

A 75-year-old man presented with a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with a 3-mm depth of invasion on the left pretibial region. His comorbidities were notable for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, varicose veins, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, and a 32 pack-year cigarette smoking history. Current medications included clopidogrel bisulfate and warfarin sodium to manage a recently placed coronary artery stent.

The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs micrographic surgery with excision down to tibialis anterior fascia (Figure 1A). The resultant defect measured 43×33 mm in area and 9 mm in depth (wound size, 12,771 mm3). Reconstructive options were discussed, including random-pattern flap repair and skin graft. Given the patient’s risk of bleeding, the decision was made to forego a flap repair. Additionally, the patient was a heavy smoker and could not comply with the wound care and elevation and ambulation restrictions required for optimal skin graft care. Therefore, a decision was made to proceed with secondary intention healing using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing.

After achieving hemostasis, a novel 10-mg sterile, biologically inert methacrylate polymer powder dressing was poured over the wound in a uniform layer to fill and seal the entire wound surface (Figure 1B). Sterile normal saline 0.1 mL was sprayed onto the powder to activate particle aggregation. No secondary dressing was used, and the patient was permitted to get the dressing wet after 48 hours.

The dressing was changed in a similar fashion 4 weeks after application, following gentle debridement with gauze and normal saline. Eight weeks after surgery, the wound exhibited healthy granulation tissue and measured 5×6 mm in area and 2 mm in depth (wound size, 60 mm3), which represented a 99.5% reduction in wound size (Figure 1C). The dressing was not painful, and there were no reported adverse effects. The patient continued to smoke and ambulate fully throughout this period. No antibiotics were used.

Methacrylate polymer powder dressings are a novel and sophisticated dressing modality with great promise for the management of surgical wounds on the lower limb. The dressing is a sterile powder consisting of 84.8% poly-2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate, 14.9% poly-2-hydroxypropylmethacrylate, and 0.3% sodium deoxycholate. These hydrophilic polymers have a covalent methacrylate backbone with a hydroxyl aliphatic side chain. When saline or wound exudate contacts the powder, the spheres hydrate and nonreversibly aggregate to form a moist, flexible dressing that conforms to the topography of the wound and seals it (Figure 2).1

Once the spheres have aggregated, they are designed to orient in a honeycomb formation with 4- to 10-nm openings that serve as capillary channels (Figure 3). This porous architecture of the polymer is essential for adequate moisture management. It allows for vapor transpiration at a rate of 12 L/m2 per day, which ensures the capillary flow from the moist wound surface is evenly distributed through the dressing, contributing to its 68% water content. Notably, this approximately three-fifths water composition is similar to the water makeup of human skin. Optimized moisture management is theorized to enhance epithelial migration, stimulate angiogenesis, retain growth factors, promote autolytic debridement, and maintain ideal voltage and oxygen gradients for wound healing. The risk for infection is not increased by the existence of these pores, as their small size does not allow for bacterial migration.1

This case demonstrates the effectiveness of using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing to promote timely wound healing in a poorly vascularized lower leg surgical wound. The low maintenance, user-friendly dressing was changed at monthly intervals, which spared the patient the inconvenience and pain associated with the repeated application of more conventional primary and secondary dressings. The dressing was well tolerated and resulted in a 99.5% reduction in wound size. Further studies are needed to investigate the utility of this promising technology.

To the Editor:

Surgical wounds on the lower leg are challenging to manage because venous stasis, bacterial colonization, and high tension may contribute to protracted healing. Advances in technology led to the development of novel, polymer-based wound-healing modalities that hold promise for the management of these wounds.

A 75-year-old man presented with a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with a 3-mm depth of invasion on the left pretibial region. His comorbidities were notable for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, varicose veins, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, and a 32 pack-year cigarette smoking history. Current medications included clopidogrel bisulfate and warfarin sodium to manage a recently placed coronary artery stent.

The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs micrographic surgery with excision down to tibialis anterior fascia (Figure 1A). The resultant defect measured 43×33 mm in area and 9 mm in depth (wound size, 12,771 mm3). Reconstructive options were discussed, including random-pattern flap repair and skin graft. Given the patient’s risk of bleeding, the decision was made to forego a flap repair. Additionally, the patient was a heavy smoker and could not comply with the wound care and elevation and ambulation restrictions required for optimal skin graft care. Therefore, a decision was made to proceed with secondary intention healing using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing.

After achieving hemostasis, a novel 10-mg sterile, biologically inert methacrylate polymer powder dressing was poured over the wound in a uniform layer to fill and seal the entire wound surface (Figure 1B). Sterile normal saline 0.1 mL was sprayed onto the powder to activate particle aggregation. No secondary dressing was used, and the patient was permitted to get the dressing wet after 48 hours.

The dressing was changed in a similar fashion 4 weeks after application, following gentle debridement with gauze and normal saline. Eight weeks after surgery, the wound exhibited healthy granulation tissue and measured 5×6 mm in area and 2 mm in depth (wound size, 60 mm3), which represented a 99.5% reduction in wound size (Figure 1C). The dressing was not painful, and there were no reported adverse effects. The patient continued to smoke and ambulate fully throughout this period. No antibiotics were used.

Methacrylate polymer powder dressings are a novel and sophisticated dressing modality with great promise for the management of surgical wounds on the lower limb. The dressing is a sterile powder consisting of 84.8% poly-2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate, 14.9% poly-2-hydroxypropylmethacrylate, and 0.3% sodium deoxycholate. These hydrophilic polymers have a covalent methacrylate backbone with a hydroxyl aliphatic side chain. When saline or wound exudate contacts the powder, the spheres hydrate and nonreversibly aggregate to form a moist, flexible dressing that conforms to the topography of the wound and seals it (Figure 2).1

Once the spheres have aggregated, they are designed to orient in a honeycomb formation with 4- to 10-nm openings that serve as capillary channels (Figure 3). This porous architecture of the polymer is essential for adequate moisture management. It allows for vapor transpiration at a rate of 12 L/m2 per day, which ensures the capillary flow from the moist wound surface is evenly distributed through the dressing, contributing to its 68% water content. Notably, this approximately three-fifths water composition is similar to the water makeup of human skin. Optimized moisture management is theorized to enhance epithelial migration, stimulate angiogenesis, retain growth factors, promote autolytic debridement, and maintain ideal voltage and oxygen gradients for wound healing. The risk for infection is not increased by the existence of these pores, as their small size does not allow for bacterial migration.1

This case demonstrates the effectiveness of using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing to promote timely wound healing in a poorly vascularized lower leg surgical wound. The low maintenance, user-friendly dressing was changed at monthly intervals, which spared the patient the inconvenience and pain associated with the repeated application of more conventional primary and secondary dressings. The dressing was well tolerated and resulted in a 99.5% reduction in wound size. Further studies are needed to investigate the utility of this promising technology.

1. Fitzgerald RH, Bharara M, Mills JL, et al. Use of a nanoflex powder dressing for wound management following debridement for necrotising fasciitis in the diabetic foot. Int Wound J. 2009;6:133-139.

1. Fitzgerald RH, Bharara M, Mills JL, et al. Use of a nanoflex powder dressing for wound management following debridement for necrotising fasciitis in the diabetic foot. Int Wound J. 2009;6:133-139.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Lower leg surgical wounds are difficult to manage, as venous stasis, bacterial colonization, and high tension may contribute to protracted healing.

- A methacrylate polymer powder dressing is user friendly and facilitates granulation and reduction in size of difficult lower leg wounds.

How to Optimize Wound Closure in Thin Skin

Practice Gap

Cutaneous surgery involves many areas where skin is quite thin and fragile, which often is encountered in elderly patients; the forearms and lower legs are the most frequent locations for thin skin.1 Dermatologic surgeons frequently encounter these situations, making this a highly practical arena for technical improvements.

For many of these patients, there is little meaningful dermis for placement of subcutaneous sutures. Therefore, a common approach following surgery, particularly following Mohs micrographic surgery in which tumors and defects typically are larger, is healing by secondary intention.2 Although healing by secondary intention often is a reasonable option, we have found that maximizing the use of epidermal skin for primary closure can be an effective means of closing many such defects. Antimicrobial reinforced skin closure strips have been incorporated in wound closure for thin skin. However, earlier efforts involving reinforcement perpendicular to the wound lacked critical details or used a different technique.3

The Technique

We developed a novel effective closure technique that minimizes these problems. Our technique has been used on the wounds of hundreds of patients with satisfying results. Early on, we used multiple variations to optimize outcomes, including different sizes of sutures and reinforced skin closure strips, application of medical liquid adhesive, liquid adhesive, and varying postoperative dressings. For 3 years, we tracked outcomes in-house and gradually narrowed down our successes into a single, user-friendly paradigm.

Supplies—To perform this technique, required supplies include:

• 2-0 Polypropylene suture with a PS-2 needle, or the equivalent. Polyglactin or silk suture can be utilized if a less-rigid suture is desired; however, we primarily have used polypropylene for repairs with good results. Each repair requires at least 2 sutures.

• Reinforced skin closure strips (1×5 inches). This width affords increased strength.

• Conforming stretch bandage and elastic self-adherent wrap.

• Polysporin (bacitracin zinc, polymyxin B sulfate, and petrolatum)(Johnson & Johnson).

• All usual surgical instruments and supplies, including paper tape and nonadherent gauze (surgeon dependent).

Step-by-step Technique—Close the wound using the following steps:

1. Once the defect is finalized following Mohs micrographic surgery or excision, excise the ellipse to be utilized for the closure and perform complete hemostasis.

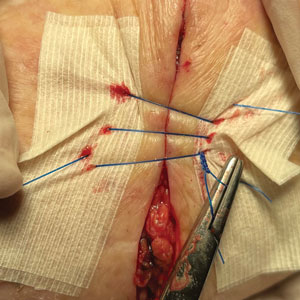

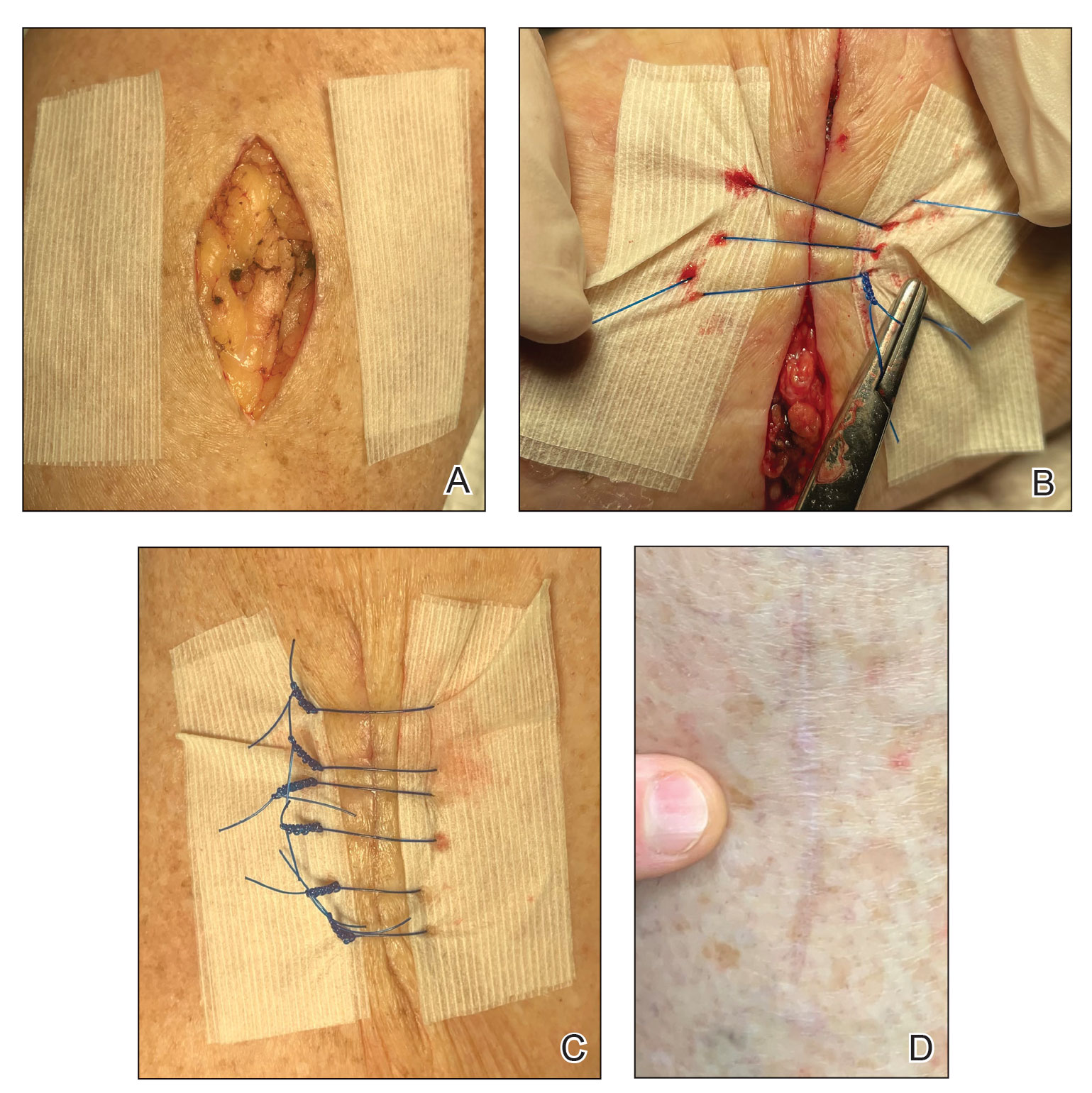

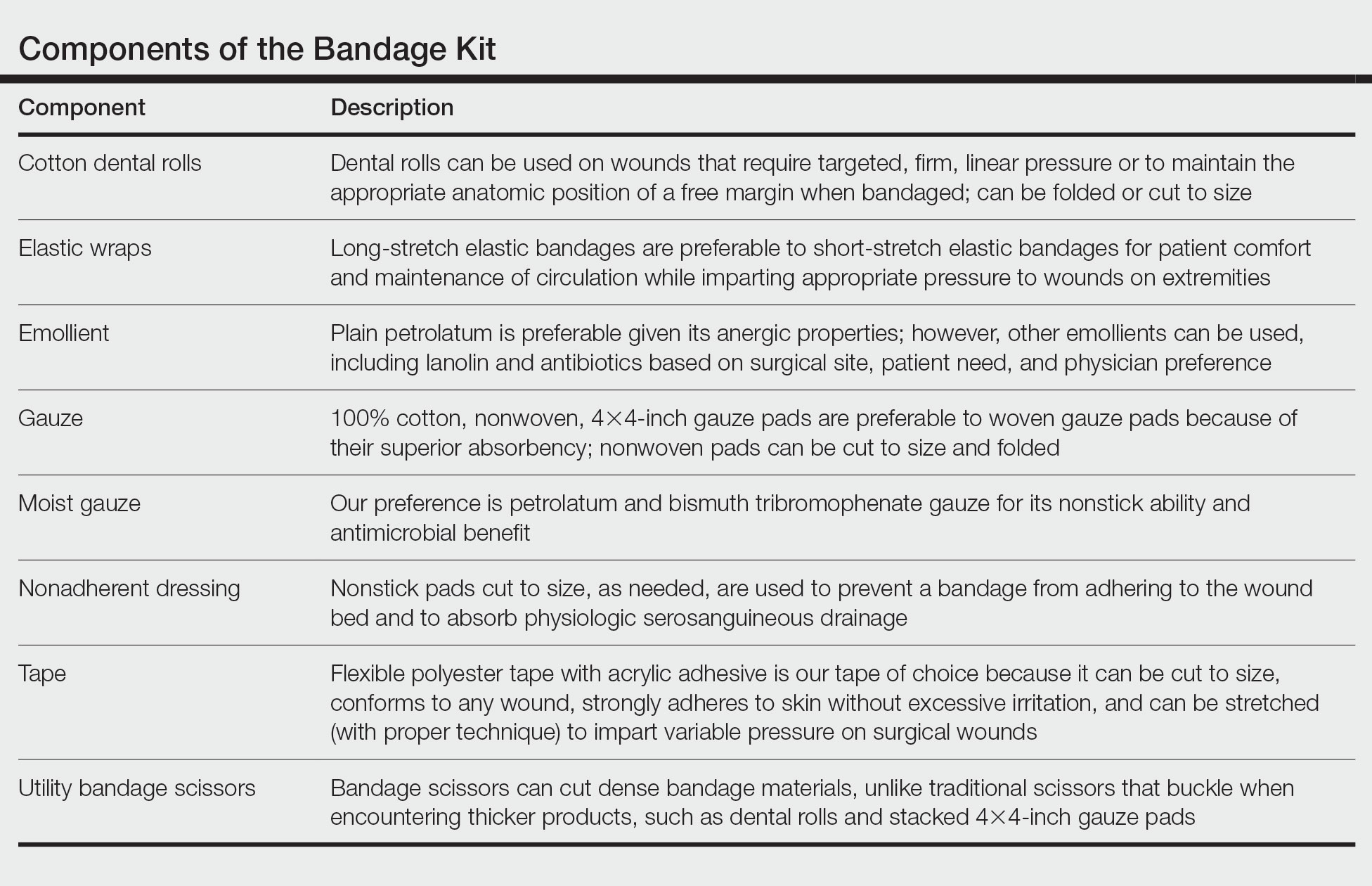

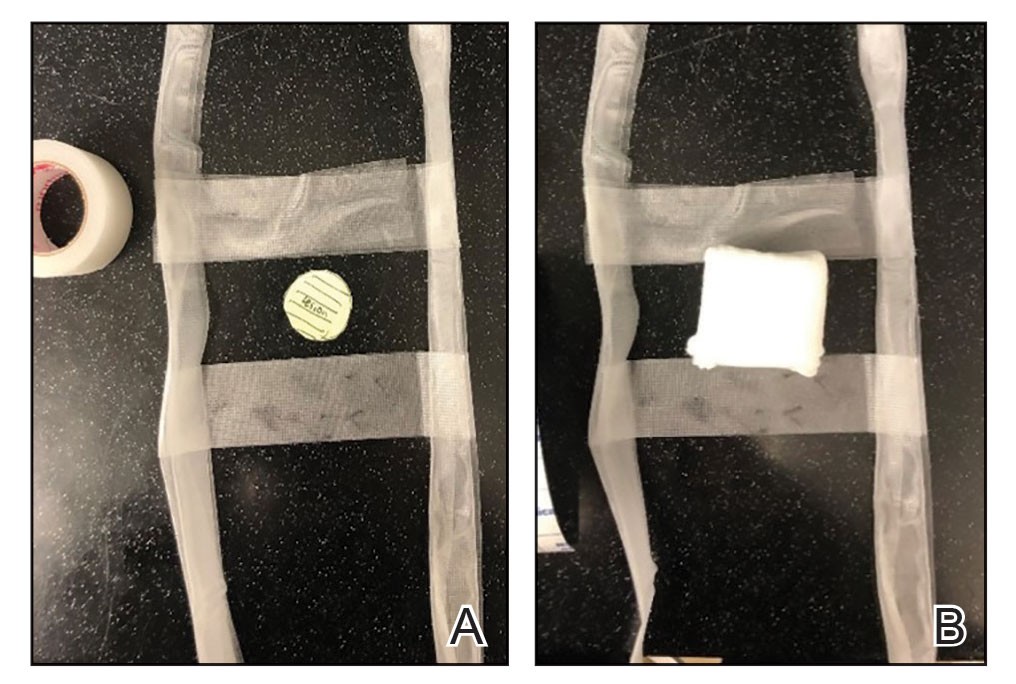

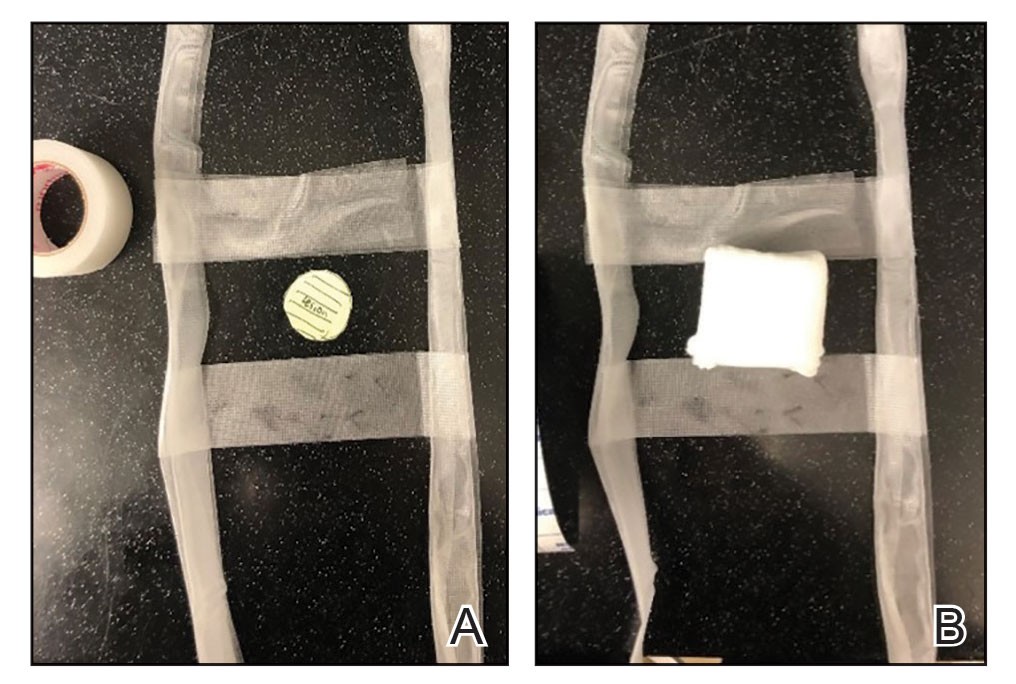

2. Place 2 layers of reinforced skin closure strips—one on top of the other—along each side of the defect, leaving approximately 1 cm of uncovered skin between the wound edges and the reinforced skin closure strips (Figure, A).

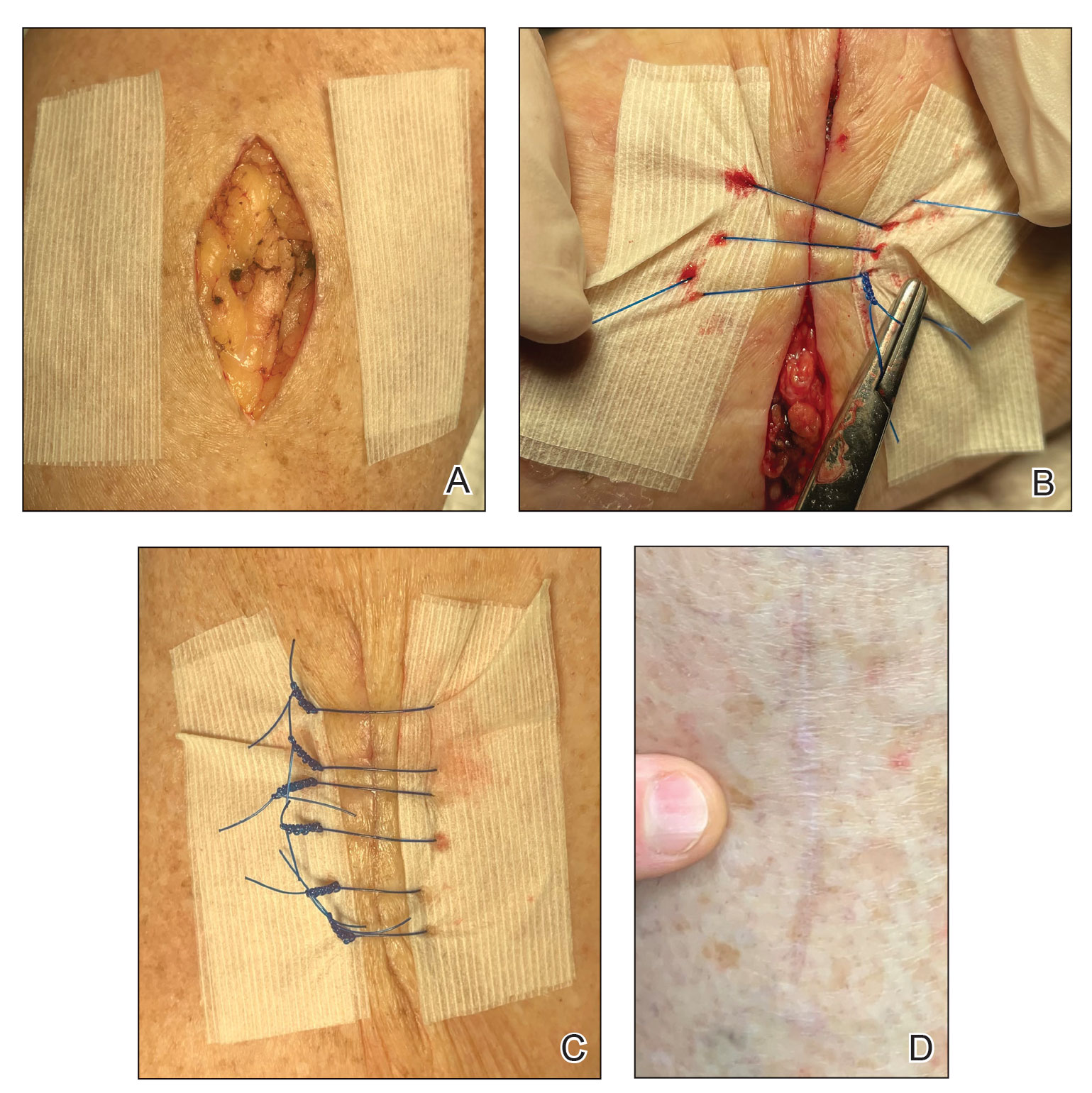

3. Take a big-bite pulley suture about one-third of the way from one end of the ellipse, with both punctures passing through the reinforced skin closure strips. Leave that in place or have the assistant hold it and wait. Place a second suture immediately adjacent to the pulley suture. Once that suture is placed but still untied, have the assistant carefully pull the pulley suture outward away from the wound edge while you carefully bring the suture together and tie it off gently (Figure, B). Doing this utilizes the pulley ability of the suture to protect the skin from tearing and releases sufficient pressure on the single suture so that it can be easily tightened without risk to the fragile skin.

4. Repeat step 3, this time placing a pulley suture near the midline of the ellipse and the subsequent single suture adjacent to it.

5. Take pulley sutures repeatedly as in steps 3 and 4 until multiple sutures are secured in place. Replace the pulley sutures with single sutures because the double-pulley sutures in areas of lower vascularity tend to have, in our experience, a slightly increased incidence of focal necrosis in comparison to single sutures.

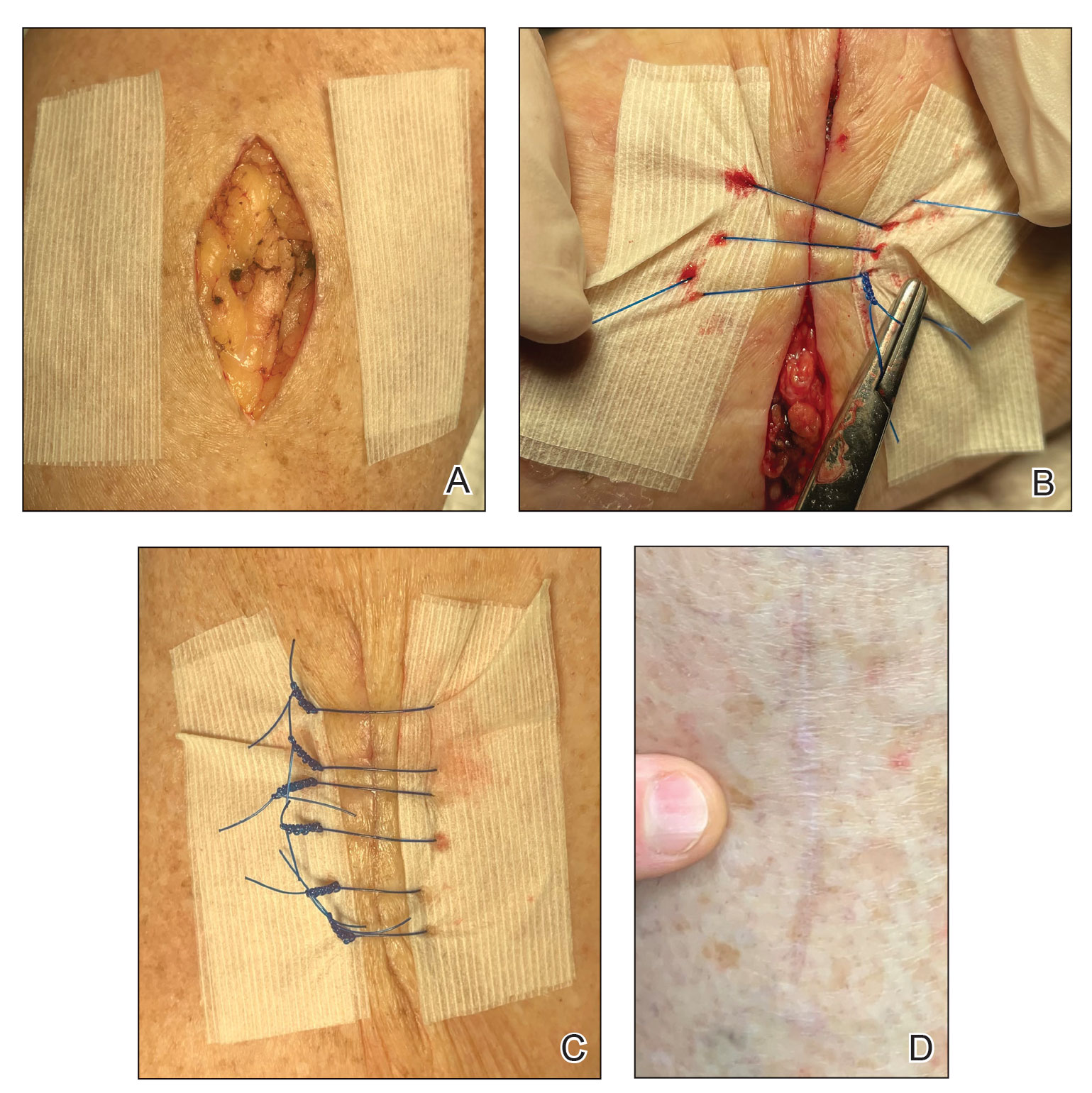

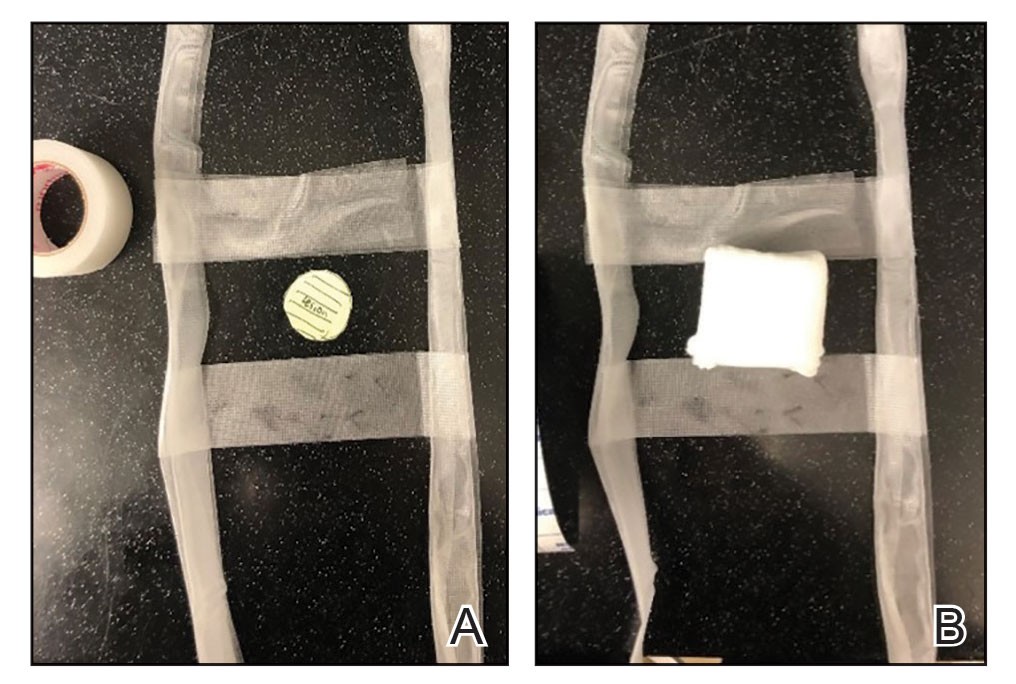

6. Make a concerted attempt to keep as much blood as possible off the reinforced skin closure strips throughout the procedure; the less dried blood on the reinforced skin closure strips, the cleaner and better the final closure (Figure, C).

7. Most of these cases involve the forearms and the legs below the knees. Because any increase in pressure or swelling on the wound can result in skin breakdown, postoperative dressing is critical. We use a layered approach; the following sequence can be modified to the preference of the surgeon: Polysporin (bacitracin zinc, polymyxin B sulfate, and petrolatum), nonadherent gauze, paper tape, conforming stretch bandage, and elastic self-adherent wrap. Minimizing swelling and infection are the primary goals. The wrap is left on for 1 week and should be kept dry.

8. Have the patient return to the office in 1 week. Unwrap the entire wound; trim back the reinforced skin closure strips; and have the patient utilize typical wound care at home thereafter consisting of cleaning and application of Polysporin or plain petrolatum, nonadherent gauze, and a paper-tape bandage. Because liquid adhesive is not utilized in this technique, the reinforced skin closure strips can be carefully removed without tearing skin. Leave sutures in for 3 weeks for arm procedures and 4 weeks for leg procedures, unless irritation develops or rapid suture overgrowth occurs in either location.

Complications

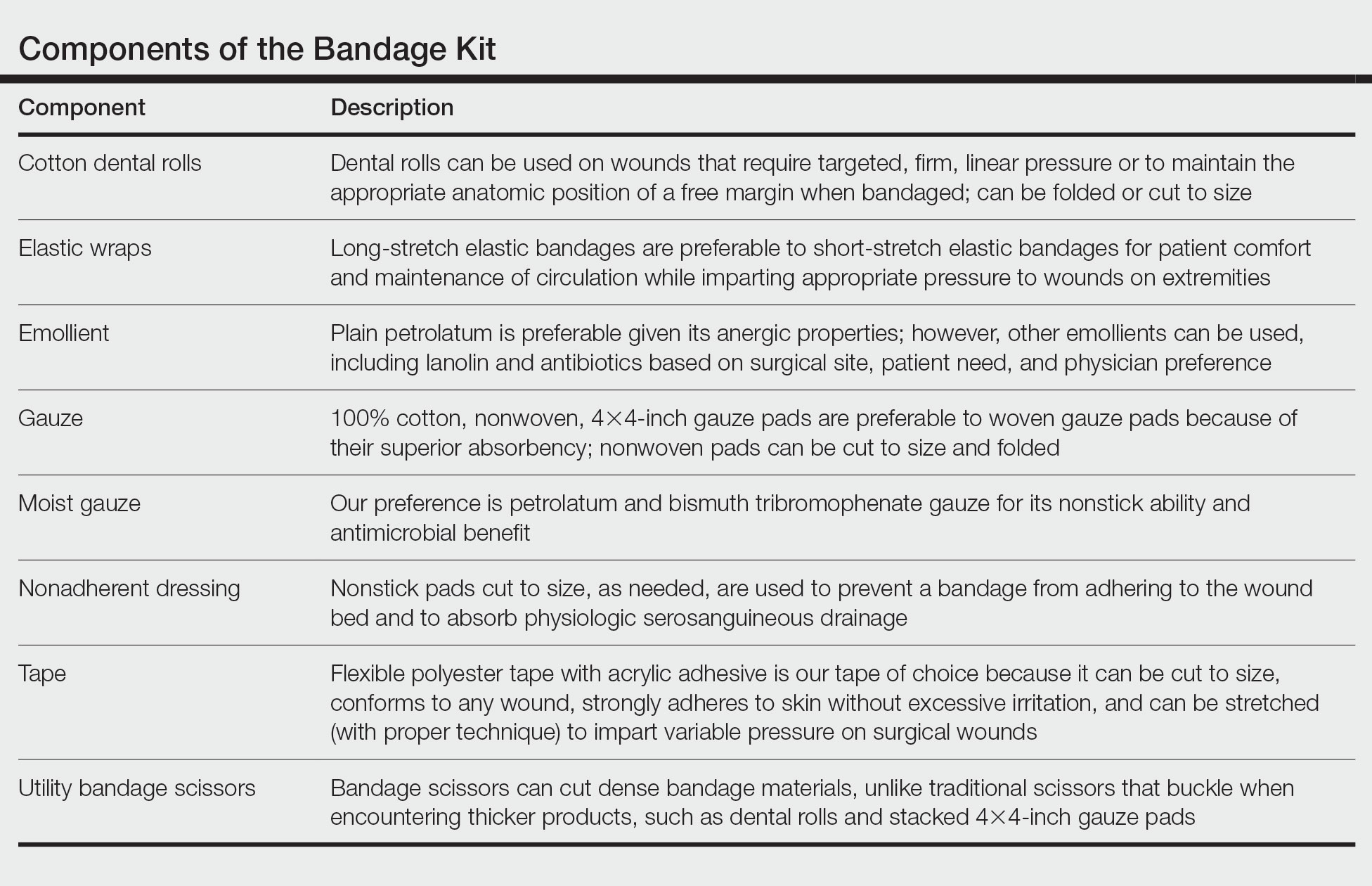

Most outcomes after using this technique are typical of optimized linear surgeries, with reduced scarring and complete wound healing (Figure, D). We seldom see complications but the following are possible:

• Bleeding occurs but rarely; the weeklong wrap likely provides great benefit.

• Infection is rare but does occur occasionally, as in any surgical procedure.

• Breakdown of the entire wound is rare; however, we occasionally see focal necrosis near 1 stitch—or rarely 2 stitches—that does not require intervention, apart from longer use of topical Polysporin or petrolatum alone to maximize healing by secondary intention in those small areas.• Despite simple suture placement far from the edge of the wound, wound inversion is seldom a problem because these taut closures have a tendency to expand slightly due to postoperative swelling.

Practice Implications

Any experienced dermatologic surgeon can perfect this technique for closing a wound in thin skin. Because wound closure in areas of fragile skin frequently is encountered in cutaneous surgery, we hope that utilizing this technique results in an optimal outcome for many patients.

- Shuster S, Black MM, McVitie E. The influence of age and sex on skin thickness, skin collagen and density. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93:639-643. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1975.tb05113.x

- Molina GE, Yu SH, Neel VA. Observations regarding infection risk in lower-extremity wound healing by second intention. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:1342-1344. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002094

- Davis M, Nakhdjevani A, Lidder S. Suture/Steri-Strip combination for the management of lacerations in thin-skinned individuals. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:322-323. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.05.077

Practice Gap

Cutaneous surgery involves many areas where skin is quite thin and fragile, which often is encountered in elderly patients; the forearms and lower legs are the most frequent locations for thin skin.1 Dermatologic surgeons frequently encounter these situations, making this a highly practical arena for technical improvements.

For many of these patients, there is little meaningful dermis for placement of subcutaneous sutures. Therefore, a common approach following surgery, particularly following Mohs micrographic surgery in which tumors and defects typically are larger, is healing by secondary intention.2 Although healing by secondary intention often is a reasonable option, we have found that maximizing the use of epidermal skin for primary closure can be an effective means of closing many such defects. Antimicrobial reinforced skin closure strips have been incorporated in wound closure for thin skin. However, earlier efforts involving reinforcement perpendicular to the wound lacked critical details or used a different technique.3

The Technique

We developed a novel effective closure technique that minimizes these problems. Our technique has been used on the wounds of hundreds of patients with satisfying results. Early on, we used multiple variations to optimize outcomes, including different sizes of sutures and reinforced skin closure strips, application of medical liquid adhesive, liquid adhesive, and varying postoperative dressings. For 3 years, we tracked outcomes in-house and gradually narrowed down our successes into a single, user-friendly paradigm.

Supplies—To perform this technique, required supplies include:

• 2-0 Polypropylene suture with a PS-2 needle, or the equivalent. Polyglactin or silk suture can be utilized if a less-rigid suture is desired; however, we primarily have used polypropylene for repairs with good results. Each repair requires at least 2 sutures.

• Reinforced skin closure strips (1×5 inches). This width affords increased strength.

• Conforming stretch bandage and elastic self-adherent wrap.

• Polysporin (bacitracin zinc, polymyxin B sulfate, and petrolatum)(Johnson & Johnson).

• All usual surgical instruments and supplies, including paper tape and nonadherent gauze (surgeon dependent).

Step-by-step Technique—Close the wound using the following steps:

1. Once the defect is finalized following Mohs micrographic surgery or excision, excise the ellipse to be utilized for the closure and perform complete hemostasis.

2. Place 2 layers of reinforced skin closure strips—one on top of the other—along each side of the defect, leaving approximately 1 cm of uncovered skin between the wound edges and the reinforced skin closure strips (Figure, A).

3. Take a big-bite pulley suture about one-third of the way from one end of the ellipse, with both punctures passing through the reinforced skin closure strips. Leave that in place or have the assistant hold it and wait. Place a second suture immediately adjacent to the pulley suture. Once that suture is placed but still untied, have the assistant carefully pull the pulley suture outward away from the wound edge while you carefully bring the suture together and tie it off gently (Figure, B). Doing this utilizes the pulley ability of the suture to protect the skin from tearing and releases sufficient pressure on the single suture so that it can be easily tightened without risk to the fragile skin.

4. Repeat step 3, this time placing a pulley suture near the midline of the ellipse and the subsequent single suture adjacent to it.

5. Take pulley sutures repeatedly as in steps 3 and 4 until multiple sutures are secured in place. Replace the pulley sutures with single sutures because the double-pulley sutures in areas of lower vascularity tend to have, in our experience, a slightly increased incidence of focal necrosis in comparison to single sutures.

6. Make a concerted attempt to keep as much blood as possible off the reinforced skin closure strips throughout the procedure; the less dried blood on the reinforced skin closure strips, the cleaner and better the final closure (Figure, C).

7. Most of these cases involve the forearms and the legs below the knees. Because any increase in pressure or swelling on the wound can result in skin breakdown, postoperative dressing is critical. We use a layered approach; the following sequence can be modified to the preference of the surgeon: Polysporin (bacitracin zinc, polymyxin B sulfate, and petrolatum), nonadherent gauze, paper tape, conforming stretch bandage, and elastic self-adherent wrap. Minimizing swelling and infection are the primary goals. The wrap is left on for 1 week and should be kept dry.

8. Have the patient return to the office in 1 week. Unwrap the entire wound; trim back the reinforced skin closure strips; and have the patient utilize typical wound care at home thereafter consisting of cleaning and application of Polysporin or plain petrolatum, nonadherent gauze, and a paper-tape bandage. Because liquid adhesive is not utilized in this technique, the reinforced skin closure strips can be carefully removed without tearing skin. Leave sutures in for 3 weeks for arm procedures and 4 weeks for leg procedures, unless irritation develops or rapid suture overgrowth occurs in either location.

Complications

Most outcomes after using this technique are typical of optimized linear surgeries, with reduced scarring and complete wound healing (Figure, D). We seldom see complications but the following are possible:

• Bleeding occurs but rarely; the weeklong wrap likely provides great benefit.

• Infection is rare but does occur occasionally, as in any surgical procedure.

• Breakdown of the entire wound is rare; however, we occasionally see focal necrosis near 1 stitch—or rarely 2 stitches—that does not require intervention, apart from longer use of topical Polysporin or petrolatum alone to maximize healing by secondary intention in those small areas.• Despite simple suture placement far from the edge of the wound, wound inversion is seldom a problem because these taut closures have a tendency to expand slightly due to postoperative swelling.

Practice Implications

Any experienced dermatologic surgeon can perfect this technique for closing a wound in thin skin. Because wound closure in areas of fragile skin frequently is encountered in cutaneous surgery, we hope that utilizing this technique results in an optimal outcome for many patients.

Practice Gap

Cutaneous surgery involves many areas where skin is quite thin and fragile, which often is encountered in elderly patients; the forearms and lower legs are the most frequent locations for thin skin.1 Dermatologic surgeons frequently encounter these situations, making this a highly practical arena for technical improvements.

For many of these patients, there is little meaningful dermis for placement of subcutaneous sutures. Therefore, a common approach following surgery, particularly following Mohs micrographic surgery in which tumors and defects typically are larger, is healing by secondary intention.2 Although healing by secondary intention often is a reasonable option, we have found that maximizing the use of epidermal skin for primary closure can be an effective means of closing many such defects. Antimicrobial reinforced skin closure strips have been incorporated in wound closure for thin skin. However, earlier efforts involving reinforcement perpendicular to the wound lacked critical details or used a different technique.3

The Technique

We developed a novel effective closure technique that minimizes these problems. Our technique has been used on the wounds of hundreds of patients with satisfying results. Early on, we used multiple variations to optimize outcomes, including different sizes of sutures and reinforced skin closure strips, application of medical liquid adhesive, liquid adhesive, and varying postoperative dressings. For 3 years, we tracked outcomes in-house and gradually narrowed down our successes into a single, user-friendly paradigm.

Supplies—To perform this technique, required supplies include:

• 2-0 Polypropylene suture with a PS-2 needle, or the equivalent. Polyglactin or silk suture can be utilized if a less-rigid suture is desired; however, we primarily have used polypropylene for repairs with good results. Each repair requires at least 2 sutures.

• Reinforced skin closure strips (1×5 inches). This width affords increased strength.

• Conforming stretch bandage and elastic self-adherent wrap.

• Polysporin (bacitracin zinc, polymyxin B sulfate, and petrolatum)(Johnson & Johnson).

• All usual surgical instruments and supplies, including paper tape and nonadherent gauze (surgeon dependent).

Step-by-step Technique—Close the wound using the following steps:

1. Once the defect is finalized following Mohs micrographic surgery or excision, excise the ellipse to be utilized for the closure and perform complete hemostasis.

2. Place 2 layers of reinforced skin closure strips—one on top of the other—along each side of the defect, leaving approximately 1 cm of uncovered skin between the wound edges and the reinforced skin closure strips (Figure, A).

3. Take a big-bite pulley suture about one-third of the way from one end of the ellipse, with both punctures passing through the reinforced skin closure strips. Leave that in place or have the assistant hold it and wait. Place a second suture immediately adjacent to the pulley suture. Once that suture is placed but still untied, have the assistant carefully pull the pulley suture outward away from the wound edge while you carefully bring the suture together and tie it off gently (Figure, B). Doing this utilizes the pulley ability of the suture to protect the skin from tearing and releases sufficient pressure on the single suture so that it can be easily tightened without risk to the fragile skin.

4. Repeat step 3, this time placing a pulley suture near the midline of the ellipse and the subsequent single suture adjacent to it.

5. Take pulley sutures repeatedly as in steps 3 and 4 until multiple sutures are secured in place. Replace the pulley sutures with single sutures because the double-pulley sutures in areas of lower vascularity tend to have, in our experience, a slightly increased incidence of focal necrosis in comparison to single sutures.

6. Make a concerted attempt to keep as much blood as possible off the reinforced skin closure strips throughout the procedure; the less dried blood on the reinforced skin closure strips, the cleaner and better the final closure (Figure, C).