User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Estimating insulin resistance may help predict stroke, death in T2D

Calculating the estimated glucose disposal rate (eGDR) as a proxy for the level of insulin resistance may be useful way to determine if someone with type 2 diabetes (T2D) is at risk for having a first stroke, Swedish researchers have found.

In a large population-based study, the lower the eGDR score went, the higher the risk for having a first stroke became.

The eGDR score was also predictive of the chance of dying from any or a cardiovascular cause, Alexander Zabala, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (Abstract OP 01-4).

The link between insulin resistance and an increased risk for stroke has been known for some time, and not just in people with T2D. However, the current way of determining insulin resistance is not suitable for widespread practice.

“The goal standard technique for measuring insulin resistance is the euglycemic clamp method,” said Dr. Zabala, an internal medical resident at Södersjukhuset hospital and researcher at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm.

“For that reason, [the eGDR], a method based on readily available clinical factors – waist circumference, hypertension, and glycosylated hemoglobin was developed,” he explained. Body mass index can also be used in place of waist circumference, he qualified.

The eGDR has already been proven to be very precise in people with type 1 diabetes, said Dr. Zabala, and could be an “excellent tool to measure insulin resistance in a large patient population.”

Investigating the link between eGDR and first stroke risk

The aim of the study he presented was to see if changes in the eGDR were associated with changes in the risk of someone with T2D experiencing a first stroke, or dying from a cardiovascular or other cause.

An observational cohort was formed by first considering data on all adult patients with T2D who were logged in the Swedish National Diabetes Registry (NDR) during 2004-2016. Then anyone with a history of stroke, or with any missing data on the clinical variables needed to calculate the eGDR, were excluded.

This resulted in an overall population of 104,697 individuals, aged a mean of 63 years, who had developed T2D at around the age of 59 years. About 44% of the study population were women. The mean eGDR for the whole population was 5.6 mg/kg per min.

The study subjects were grouped according to four eGDR levels: 24,706 were in the lowest quartile of eGDR (less than 4 mg/kg per min), signifying the highest level of insulin resistance, and 18,762 were in the upper quartile of eGDR (greater than 8 mg/kg per min), signifying the lowest level of insulin resistance. The middle two groups had an eGDR between 4 and 6 mg/kg per min (40,187), and 6 and 8 mg/kg/min (21,042).

Data from the NDR were then combined with the Swedish Cause of Death register, the Swedish In-patient Care Diagnoses registry, and the Longitudinal Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies (LISA) to determine the rates of stroke, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, all-cause mortality, and cardiovascular mortality.

Increasing insulin resistance ups risk for stroke, death

After a median follow-up of 5.6 years, 4% (4,201) of the study population had had a stroke.

“We clearly see an increased occurrence of first-time stroke in the group with the lowest eGDR, indicating worst insulin resistance, in comparison with the group with the highest eGDR, indicating less insulin resistance,” Dr. Zabala reported.

After adjustment for potential confounding factors, including age at baseline, gender, diabetes duration, among other variables, the risk for stroke was lowest in those with a high eGDR value and highest for those with a low eGDR value.

Using individuals with the lowest eGDR (less than 4 mg/kg per min) and thus greatest risk of stroke as the reference, adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) for first-time stroke were: 0.60, 0.68, and 0.77 for those with an eGDR of greater than 8, 6-8, and 4-6 mg/kg per min, respectively.

The corresponding values for risk of ischemic stroke were 0.55, 0.68, and 0.75. Regarding hemorrhagic stroke, there was no statistically significant correlation between eGDR levels and stroke occurrence. This was due to the small number of cases recorded.

As for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, a similar pattern was seen, with higher rates of death linked to increasing insulin resistance. Adjusted hazard ratios according to increasing insulin resistance (decreasing eGDR scores) for all-cause death were 0.68, 0.75, and 0.82 and for cardiovascular mortality were 0.65, 0.75, and 0.82.

A sensitivity analysis, using BMI instead of waist circumference to calculate the eGDR, showed a similar pattern, and “interestingly, a correlation between eGDR levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke.” Dr. Zabala said.

Limitations and take-homes

Of course, this is an observational cohort study, so no conclusions on causality can be made and there are no data on the use of anti-diabetic treatments specifically. But there are strengths such as covering almost all adults with T2D in Sweden and a relatively long-follow-up time.

The findings suggest that “eGDR, which may reflect insulin resistance may be a useful risk marker for stroke and death in people with type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Zabala.

“You had a very large cohort, and that certainly makes your results very valid,” observed Peter Novodvorsky, MUDr. (Hons), PhD, MRCP, a consultant diabetologist in Trenčín, Slovakia.

Dr. Novodvorsky, who chaired the session, picked up on the lack of information about how many people were taking newer diabetes drugs, such as the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor antagonists and sodium glucose-lowering transport 2 inhibitors.

“As we all know, these might have protective effects which are not necessarily related to the glucose lowering or insulin resistance-lowering” effects, so could have influenced the results. In terms of how practical the eGDR is for clinical practice, Dr. Zabala observed in a press release: “eGDR could be used to help T2D patients better understand and manage their risk of stroke and death.

“It could also be of importance in research. In this era of personalized medicine, better stratification of type 2 diabetes patients will help optimize clinical trials and further vital research into treatment, diagnosis, care and prevention.”

The research was a collaboration between the Karolinska Institutet, Gothenburg University and the Swedish National Diabetes Registry. Dr. Zabala and coauthors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Calculating the estimated glucose disposal rate (eGDR) as a proxy for the level of insulin resistance may be useful way to determine if someone with type 2 diabetes (T2D) is at risk for having a first stroke, Swedish researchers have found.

In a large population-based study, the lower the eGDR score went, the higher the risk for having a first stroke became.

The eGDR score was also predictive of the chance of dying from any or a cardiovascular cause, Alexander Zabala, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (Abstract OP 01-4).

The link between insulin resistance and an increased risk for stroke has been known for some time, and not just in people with T2D. However, the current way of determining insulin resistance is not suitable for widespread practice.

“The goal standard technique for measuring insulin resistance is the euglycemic clamp method,” said Dr. Zabala, an internal medical resident at Södersjukhuset hospital and researcher at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm.

“For that reason, [the eGDR], a method based on readily available clinical factors – waist circumference, hypertension, and glycosylated hemoglobin was developed,” he explained. Body mass index can also be used in place of waist circumference, he qualified.

The eGDR has already been proven to be very precise in people with type 1 diabetes, said Dr. Zabala, and could be an “excellent tool to measure insulin resistance in a large patient population.”

Investigating the link between eGDR and first stroke risk

The aim of the study he presented was to see if changes in the eGDR were associated with changes in the risk of someone with T2D experiencing a first stroke, or dying from a cardiovascular or other cause.

An observational cohort was formed by first considering data on all adult patients with T2D who were logged in the Swedish National Diabetes Registry (NDR) during 2004-2016. Then anyone with a history of stroke, or with any missing data on the clinical variables needed to calculate the eGDR, were excluded.

This resulted in an overall population of 104,697 individuals, aged a mean of 63 years, who had developed T2D at around the age of 59 years. About 44% of the study population were women. The mean eGDR for the whole population was 5.6 mg/kg per min.

The study subjects were grouped according to four eGDR levels: 24,706 were in the lowest quartile of eGDR (less than 4 mg/kg per min), signifying the highest level of insulin resistance, and 18,762 were in the upper quartile of eGDR (greater than 8 mg/kg per min), signifying the lowest level of insulin resistance. The middle two groups had an eGDR between 4 and 6 mg/kg per min (40,187), and 6 and 8 mg/kg/min (21,042).

Data from the NDR were then combined with the Swedish Cause of Death register, the Swedish In-patient Care Diagnoses registry, and the Longitudinal Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies (LISA) to determine the rates of stroke, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, all-cause mortality, and cardiovascular mortality.

Increasing insulin resistance ups risk for stroke, death

After a median follow-up of 5.6 years, 4% (4,201) of the study population had had a stroke.

“We clearly see an increased occurrence of first-time stroke in the group with the lowest eGDR, indicating worst insulin resistance, in comparison with the group with the highest eGDR, indicating less insulin resistance,” Dr. Zabala reported.

After adjustment for potential confounding factors, including age at baseline, gender, diabetes duration, among other variables, the risk for stroke was lowest in those with a high eGDR value and highest for those with a low eGDR value.

Using individuals with the lowest eGDR (less than 4 mg/kg per min) and thus greatest risk of stroke as the reference, adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) for first-time stroke were: 0.60, 0.68, and 0.77 for those with an eGDR of greater than 8, 6-8, and 4-6 mg/kg per min, respectively.

The corresponding values for risk of ischemic stroke were 0.55, 0.68, and 0.75. Regarding hemorrhagic stroke, there was no statistically significant correlation between eGDR levels and stroke occurrence. This was due to the small number of cases recorded.

As for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, a similar pattern was seen, with higher rates of death linked to increasing insulin resistance. Adjusted hazard ratios according to increasing insulin resistance (decreasing eGDR scores) for all-cause death were 0.68, 0.75, and 0.82 and for cardiovascular mortality were 0.65, 0.75, and 0.82.

A sensitivity analysis, using BMI instead of waist circumference to calculate the eGDR, showed a similar pattern, and “interestingly, a correlation between eGDR levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke.” Dr. Zabala said.

Limitations and take-homes

Of course, this is an observational cohort study, so no conclusions on causality can be made and there are no data on the use of anti-diabetic treatments specifically. But there are strengths such as covering almost all adults with T2D in Sweden and a relatively long-follow-up time.

The findings suggest that “eGDR, which may reflect insulin resistance may be a useful risk marker for stroke and death in people with type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Zabala.

“You had a very large cohort, and that certainly makes your results very valid,” observed Peter Novodvorsky, MUDr. (Hons), PhD, MRCP, a consultant diabetologist in Trenčín, Slovakia.

Dr. Novodvorsky, who chaired the session, picked up on the lack of information about how many people were taking newer diabetes drugs, such as the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor antagonists and sodium glucose-lowering transport 2 inhibitors.

“As we all know, these might have protective effects which are not necessarily related to the glucose lowering or insulin resistance-lowering” effects, so could have influenced the results. In terms of how practical the eGDR is for clinical practice, Dr. Zabala observed in a press release: “eGDR could be used to help T2D patients better understand and manage their risk of stroke and death.

“It could also be of importance in research. In this era of personalized medicine, better stratification of type 2 diabetes patients will help optimize clinical trials and further vital research into treatment, diagnosis, care and prevention.”

The research was a collaboration between the Karolinska Institutet, Gothenburg University and the Swedish National Diabetes Registry. Dr. Zabala and coauthors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Calculating the estimated glucose disposal rate (eGDR) as a proxy for the level of insulin resistance may be useful way to determine if someone with type 2 diabetes (T2D) is at risk for having a first stroke, Swedish researchers have found.

In a large population-based study, the lower the eGDR score went, the higher the risk for having a first stroke became.

The eGDR score was also predictive of the chance of dying from any or a cardiovascular cause, Alexander Zabala, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (Abstract OP 01-4).

The link between insulin resistance and an increased risk for stroke has been known for some time, and not just in people with T2D. However, the current way of determining insulin resistance is not suitable for widespread practice.

“The goal standard technique for measuring insulin resistance is the euglycemic clamp method,” said Dr. Zabala, an internal medical resident at Södersjukhuset hospital and researcher at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm.

“For that reason, [the eGDR], a method based on readily available clinical factors – waist circumference, hypertension, and glycosylated hemoglobin was developed,” he explained. Body mass index can also be used in place of waist circumference, he qualified.

The eGDR has already been proven to be very precise in people with type 1 diabetes, said Dr. Zabala, and could be an “excellent tool to measure insulin resistance in a large patient population.”

Investigating the link between eGDR and first stroke risk

The aim of the study he presented was to see if changes in the eGDR were associated with changes in the risk of someone with T2D experiencing a first stroke, or dying from a cardiovascular or other cause.

An observational cohort was formed by first considering data on all adult patients with T2D who were logged in the Swedish National Diabetes Registry (NDR) during 2004-2016. Then anyone with a history of stroke, or with any missing data on the clinical variables needed to calculate the eGDR, were excluded.

This resulted in an overall population of 104,697 individuals, aged a mean of 63 years, who had developed T2D at around the age of 59 years. About 44% of the study population were women. The mean eGDR for the whole population was 5.6 mg/kg per min.

The study subjects were grouped according to four eGDR levels: 24,706 were in the lowest quartile of eGDR (less than 4 mg/kg per min), signifying the highest level of insulin resistance, and 18,762 were in the upper quartile of eGDR (greater than 8 mg/kg per min), signifying the lowest level of insulin resistance. The middle two groups had an eGDR between 4 and 6 mg/kg per min (40,187), and 6 and 8 mg/kg/min (21,042).

Data from the NDR were then combined with the Swedish Cause of Death register, the Swedish In-patient Care Diagnoses registry, and the Longitudinal Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies (LISA) to determine the rates of stroke, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, all-cause mortality, and cardiovascular mortality.

Increasing insulin resistance ups risk for stroke, death

After a median follow-up of 5.6 years, 4% (4,201) of the study population had had a stroke.

“We clearly see an increased occurrence of first-time stroke in the group with the lowest eGDR, indicating worst insulin resistance, in comparison with the group with the highest eGDR, indicating less insulin resistance,” Dr. Zabala reported.

After adjustment for potential confounding factors, including age at baseline, gender, diabetes duration, among other variables, the risk for stroke was lowest in those with a high eGDR value and highest for those with a low eGDR value.

Using individuals with the lowest eGDR (less than 4 mg/kg per min) and thus greatest risk of stroke as the reference, adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) for first-time stroke were: 0.60, 0.68, and 0.77 for those with an eGDR of greater than 8, 6-8, and 4-6 mg/kg per min, respectively.

The corresponding values for risk of ischemic stroke were 0.55, 0.68, and 0.75. Regarding hemorrhagic stroke, there was no statistically significant correlation between eGDR levels and stroke occurrence. This was due to the small number of cases recorded.

As for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, a similar pattern was seen, with higher rates of death linked to increasing insulin resistance. Adjusted hazard ratios according to increasing insulin resistance (decreasing eGDR scores) for all-cause death were 0.68, 0.75, and 0.82 and for cardiovascular mortality were 0.65, 0.75, and 0.82.

A sensitivity analysis, using BMI instead of waist circumference to calculate the eGDR, showed a similar pattern, and “interestingly, a correlation between eGDR levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke.” Dr. Zabala said.

Limitations and take-homes

Of course, this is an observational cohort study, so no conclusions on causality can be made and there are no data on the use of anti-diabetic treatments specifically. But there are strengths such as covering almost all adults with T2D in Sweden and a relatively long-follow-up time.

The findings suggest that “eGDR, which may reflect insulin resistance may be a useful risk marker for stroke and death in people with type 2 diabetes,” said Dr. Zabala.

“You had a very large cohort, and that certainly makes your results very valid,” observed Peter Novodvorsky, MUDr. (Hons), PhD, MRCP, a consultant diabetologist in Trenčín, Slovakia.

Dr. Novodvorsky, who chaired the session, picked up on the lack of information about how many people were taking newer diabetes drugs, such as the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor antagonists and sodium glucose-lowering transport 2 inhibitors.

“As we all know, these might have protective effects which are not necessarily related to the glucose lowering or insulin resistance-lowering” effects, so could have influenced the results. In terms of how practical the eGDR is for clinical practice, Dr. Zabala observed in a press release: “eGDR could be used to help T2D patients better understand and manage their risk of stroke and death.

“It could also be of importance in research. In this era of personalized medicine, better stratification of type 2 diabetes patients will help optimize clinical trials and further vital research into treatment, diagnosis, care and prevention.”

The research was a collaboration between the Karolinska Institutet, Gothenburg University and the Swedish National Diabetes Registry. Dr. Zabala and coauthors reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM EASD 2021

Comorbidities larger factor than race in COVID ICU deaths?

Racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality rates may be related more to comorbidities than to demographics, suggest authors of a new study.

Researchers compared the length of stay in intensive care units in two suburban hospitals for patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infections. Their study shows that although the incidence of comorbidities and rates of use of mechanical ventilation and death were higher among Black patients than among patients of other races, length of stay in the ICU was generally similar for patients of all races. The study was conducted by Tripti Kumar, DO, from Lankenau Medical Center, Wynnewood, Pennsylvania, and colleagues.

“Racial disparities are observed in the United States concerning COVID-19, and studies have discovered that minority populations are at ongoing risk for health inequity,” Dr. Kumar said in a narrated e-poster presented during the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) 2021 Annual Meeting.

“Primary prevention initiatives should take precedence in mitigating the effect that comorbidities have on these vulnerable populations to help reduce necessity for mechanical ventilation, hospital length of stay, and overall mortality,” she said.

Higher death rates for Black patients

At the time the study was conducted, the COVID-19 death rate in the United States had topped 500,000 (as of this writing, it stands at 726,000). Of those who died, 22.4% were Black, 18.1% were Hispanic, and 3.6% were of Asian descent. The numbers of COVID-19 diagnoses and deaths were significantly higher in U.S. counties where the proportions of Black residents were higher, the authors note.

To see whether differences in COVID-19 outcomes were reflected in ICU length of stay, the researchers conducted a retrospective chart review of data on 162 patients admitted to ICUs at Paoli Hospital and Lankenau Medical Center, both in the suburban Philadelphia town of Wynnewood.

All patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 from March through June 2020.

In all, 60% of the study population were Black, 35% were White, 3% were Asian, and 2% were Hispanic. Women composed 46% of the sample.

The average length of ICU stay, which was the primary endpoint, was similar among Black patients (15.4 days), White patients (15.5 days), and Asians (16 days). The shortest average hospital stay was among Hispanic patients, at 11.3 days.

The investigators determined that among all races, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and smoking was highest among Black patients.

Overall, nearly 85% of patients required mechanical ventilation. Among the patients who required it, 86% were Black, 84% were White, 66% were Hispanic, and 75% were Asian.

Overall mortality was 62%. It was higher among Black patients, at 60%, than among White patients, at 33%. The investigators did not report mortality rates for Hispanic or Asian patients.

Missing data

Demondes Haynes, MD, FCCP, professor of medicine in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care and associate dean for admissions at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and School of Medicine, Jackson, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization that there are some gaps in the study that make it difficult to draw strong conclusions about the findings.

“For sure, comorbidities contribute a great deal to mortality, but is there something else going on? I think this poster is incomplete in that it cannot answer that question,” he said in an interview.

He noted that the use of retrospective rather than prospective data makes it hard to account for potential confounders.

“I agree that these findings show the potential contribution of comorbidities, but to me, this is a little incomplete to make that a definitive statement,” he said.

“I can’t argue with their recommendation for primary prevention – we definitely want to do primary prevention to decrease comorbidities. Would it decrease overall mortality? It might, it sure might, for just COVID-19 I’d say no, we need more information.”

No funding source for the study was reported. Dr. Kumar and colleagues and Dr. Haynes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality rates may be related more to comorbidities than to demographics, suggest authors of a new study.

Researchers compared the length of stay in intensive care units in two suburban hospitals for patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infections. Their study shows that although the incidence of comorbidities and rates of use of mechanical ventilation and death were higher among Black patients than among patients of other races, length of stay in the ICU was generally similar for patients of all races. The study was conducted by Tripti Kumar, DO, from Lankenau Medical Center, Wynnewood, Pennsylvania, and colleagues.

“Racial disparities are observed in the United States concerning COVID-19, and studies have discovered that minority populations are at ongoing risk for health inequity,” Dr. Kumar said in a narrated e-poster presented during the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) 2021 Annual Meeting.

“Primary prevention initiatives should take precedence in mitigating the effect that comorbidities have on these vulnerable populations to help reduce necessity for mechanical ventilation, hospital length of stay, and overall mortality,” she said.

Higher death rates for Black patients

At the time the study was conducted, the COVID-19 death rate in the United States had topped 500,000 (as of this writing, it stands at 726,000). Of those who died, 22.4% were Black, 18.1% were Hispanic, and 3.6% were of Asian descent. The numbers of COVID-19 diagnoses and deaths were significantly higher in U.S. counties where the proportions of Black residents were higher, the authors note.

To see whether differences in COVID-19 outcomes were reflected in ICU length of stay, the researchers conducted a retrospective chart review of data on 162 patients admitted to ICUs at Paoli Hospital and Lankenau Medical Center, both in the suburban Philadelphia town of Wynnewood.

All patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 from March through June 2020.

In all, 60% of the study population were Black, 35% were White, 3% were Asian, and 2% were Hispanic. Women composed 46% of the sample.

The average length of ICU stay, which was the primary endpoint, was similar among Black patients (15.4 days), White patients (15.5 days), and Asians (16 days). The shortest average hospital stay was among Hispanic patients, at 11.3 days.

The investigators determined that among all races, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and smoking was highest among Black patients.

Overall, nearly 85% of patients required mechanical ventilation. Among the patients who required it, 86% were Black, 84% were White, 66% were Hispanic, and 75% were Asian.

Overall mortality was 62%. It was higher among Black patients, at 60%, than among White patients, at 33%. The investigators did not report mortality rates for Hispanic or Asian patients.

Missing data

Demondes Haynes, MD, FCCP, professor of medicine in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care and associate dean for admissions at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and School of Medicine, Jackson, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization that there are some gaps in the study that make it difficult to draw strong conclusions about the findings.

“For sure, comorbidities contribute a great deal to mortality, but is there something else going on? I think this poster is incomplete in that it cannot answer that question,” he said in an interview.

He noted that the use of retrospective rather than prospective data makes it hard to account for potential confounders.

“I agree that these findings show the potential contribution of comorbidities, but to me, this is a little incomplete to make that a definitive statement,” he said.

“I can’t argue with their recommendation for primary prevention – we definitely want to do primary prevention to decrease comorbidities. Would it decrease overall mortality? It might, it sure might, for just COVID-19 I’d say no, we need more information.”

No funding source for the study was reported. Dr. Kumar and colleagues and Dr. Haynes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality rates may be related more to comorbidities than to demographics, suggest authors of a new study.

Researchers compared the length of stay in intensive care units in two suburban hospitals for patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infections. Their study shows that although the incidence of comorbidities and rates of use of mechanical ventilation and death were higher among Black patients than among patients of other races, length of stay in the ICU was generally similar for patients of all races. The study was conducted by Tripti Kumar, DO, from Lankenau Medical Center, Wynnewood, Pennsylvania, and colleagues.

“Racial disparities are observed in the United States concerning COVID-19, and studies have discovered that minority populations are at ongoing risk for health inequity,” Dr. Kumar said in a narrated e-poster presented during the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) 2021 Annual Meeting.

“Primary prevention initiatives should take precedence in mitigating the effect that comorbidities have on these vulnerable populations to help reduce necessity for mechanical ventilation, hospital length of stay, and overall mortality,” she said.

Higher death rates for Black patients

At the time the study was conducted, the COVID-19 death rate in the United States had topped 500,000 (as of this writing, it stands at 726,000). Of those who died, 22.4% were Black, 18.1% were Hispanic, and 3.6% were of Asian descent. The numbers of COVID-19 diagnoses and deaths were significantly higher in U.S. counties where the proportions of Black residents were higher, the authors note.

To see whether differences in COVID-19 outcomes were reflected in ICU length of stay, the researchers conducted a retrospective chart review of data on 162 patients admitted to ICUs at Paoli Hospital and Lankenau Medical Center, both in the suburban Philadelphia town of Wynnewood.

All patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 from March through June 2020.

In all, 60% of the study population were Black, 35% were White, 3% were Asian, and 2% were Hispanic. Women composed 46% of the sample.

The average length of ICU stay, which was the primary endpoint, was similar among Black patients (15.4 days), White patients (15.5 days), and Asians (16 days). The shortest average hospital stay was among Hispanic patients, at 11.3 days.

The investigators determined that among all races, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and smoking was highest among Black patients.

Overall, nearly 85% of patients required mechanical ventilation. Among the patients who required it, 86% were Black, 84% were White, 66% were Hispanic, and 75% were Asian.

Overall mortality was 62%. It was higher among Black patients, at 60%, than among White patients, at 33%. The investigators did not report mortality rates for Hispanic or Asian patients.

Missing data

Demondes Haynes, MD, FCCP, professor of medicine in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care and associate dean for admissions at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and School of Medicine, Jackson, who was not involved in the study, told this news organization that there are some gaps in the study that make it difficult to draw strong conclusions about the findings.

“For sure, comorbidities contribute a great deal to mortality, but is there something else going on? I think this poster is incomplete in that it cannot answer that question,” he said in an interview.

He noted that the use of retrospective rather than prospective data makes it hard to account for potential confounders.

“I agree that these findings show the potential contribution of comorbidities, but to me, this is a little incomplete to make that a definitive statement,” he said.

“I can’t argue with their recommendation for primary prevention – we definitely want to do primary prevention to decrease comorbidities. Would it decrease overall mortality? It might, it sure might, for just COVID-19 I’d say no, we need more information.”

No funding source for the study was reported. Dr. Kumar and colleagues and Dr. Haynes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

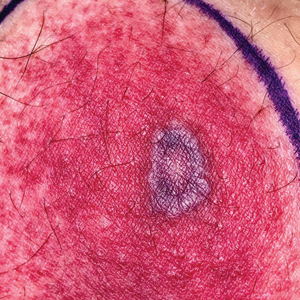

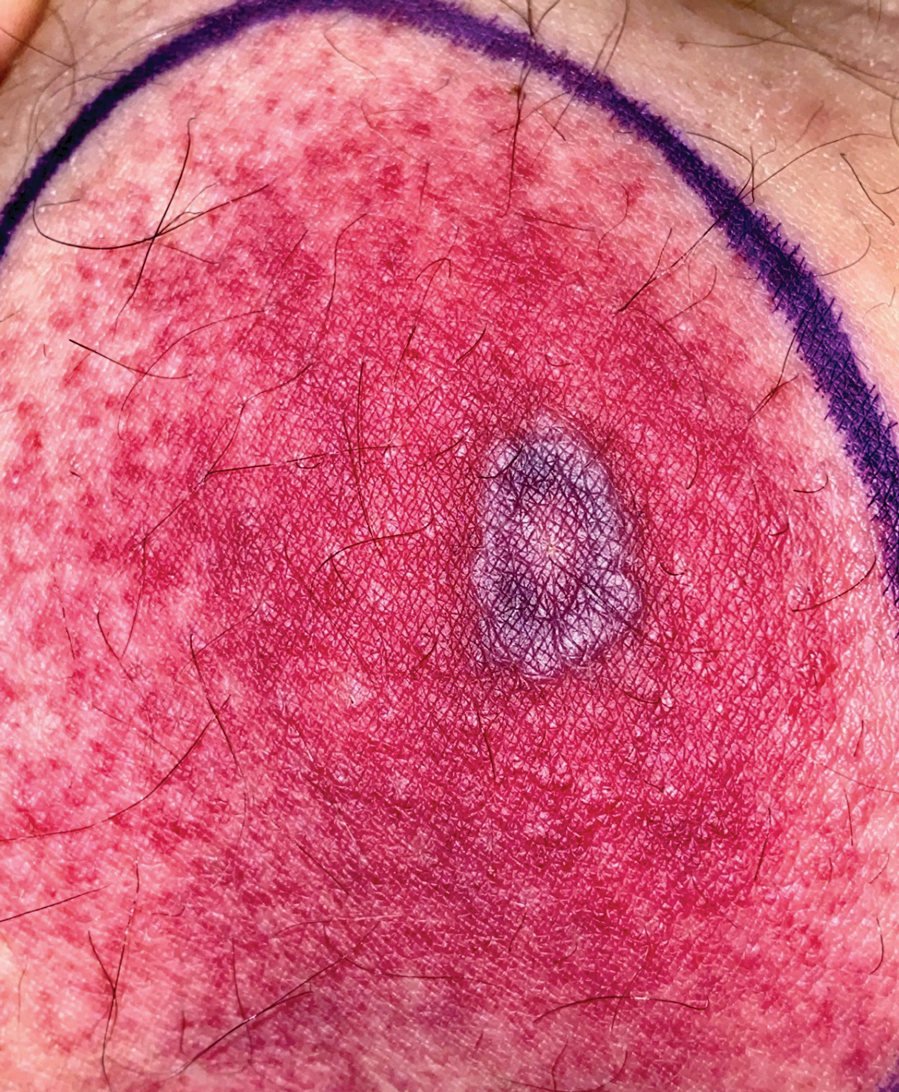

Yellow pruritic eruption

This pruritic, eruption with yellowing atrophy and telangiectasias on the lower extremities is a classic presentation for necrobiosis lipoidica (NL).

NL is a chronic granulomatous disorder with a predilection for the lower extremities. Patients with NL present with progressive, yellow-brown atrophic plaques on the pretibial aspect of the legs. The plaques have underlying telangiectasias, revealed by the atrophy, and may ulcerate. While these lesions are primarily asymptomatic, associated symptoms may include pruritus, pain, or altered sensation on the affected skin. The classic pathology of NL is notable for altered collagen bundles layered with palisading granulomas extending deep into the dermis. Other notable findings may include mixed inflammatory cells, multinucleated giant cells, and plasma cells; mucin is notably absent.

There is an established relationship between NL and diabetes. When these 2 entities are present, the skin eruption may be referred to as “necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum” or “NLD.” Only a small percentage of patients with diabetes will develop NL. Furthermore, there is growing evidence to suggest that NL may be associated with other comorbidities, such as obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and thyroid disease.1 Additionally, squamous cell carcinoma has been reported as arising within skin affected by NL.2

The etiology of NL is not completely understood. Current theories suggest that blood vessel inflammation related to autoimmune factors may be at work.2 The differential diagnosis of NL includes granuloma annulare, pretibial myxedema, stasis dermatitis, panniculitis, morphea, and lichen sclerosis.

NL can be refractory to therapy. Paramount to management is the avoidance of trauma to the affected skin. Topical therapies include corticosteroids, tretinoin, and tacrolimus. Systemic immunomodulation with infliximab, etanercept, thalidomide, and cyclosporine has also been trialed. There is evidence for the utility of pentoxifylline (400 mg po tid), a xanthine derivative often used for peripheral artery disease, to reverse ulceration that can arise in NL.

The patient in this case opted for topical therapy with clobetasol 0.05% ointment and tacrolimus 0.1% ointment. She was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Image courtesy of Cyrelle Fermin, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque. Text courtesy of Cyrelle Fermin, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Hashemi DA, Brown-Joel ZO, Tkachenko E, et al. Clinical features and comorbidities of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica with or without diabetes. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:455-459. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5635

2. Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

This pruritic, eruption with yellowing atrophy and telangiectasias on the lower extremities is a classic presentation for necrobiosis lipoidica (NL).

NL is a chronic granulomatous disorder with a predilection for the lower extremities. Patients with NL present with progressive, yellow-brown atrophic plaques on the pretibial aspect of the legs. The plaques have underlying telangiectasias, revealed by the atrophy, and may ulcerate. While these lesions are primarily asymptomatic, associated symptoms may include pruritus, pain, or altered sensation on the affected skin. The classic pathology of NL is notable for altered collagen bundles layered with palisading granulomas extending deep into the dermis. Other notable findings may include mixed inflammatory cells, multinucleated giant cells, and plasma cells; mucin is notably absent.

There is an established relationship between NL and diabetes. When these 2 entities are present, the skin eruption may be referred to as “necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum” or “NLD.” Only a small percentage of patients with diabetes will develop NL. Furthermore, there is growing evidence to suggest that NL may be associated with other comorbidities, such as obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and thyroid disease.1 Additionally, squamous cell carcinoma has been reported as arising within skin affected by NL.2

The etiology of NL is not completely understood. Current theories suggest that blood vessel inflammation related to autoimmune factors may be at work.2 The differential diagnosis of NL includes granuloma annulare, pretibial myxedema, stasis dermatitis, panniculitis, morphea, and lichen sclerosis.

NL can be refractory to therapy. Paramount to management is the avoidance of trauma to the affected skin. Topical therapies include corticosteroids, tretinoin, and tacrolimus. Systemic immunomodulation with infliximab, etanercept, thalidomide, and cyclosporine has also been trialed. There is evidence for the utility of pentoxifylline (400 mg po tid), a xanthine derivative often used for peripheral artery disease, to reverse ulceration that can arise in NL.

The patient in this case opted for topical therapy with clobetasol 0.05% ointment and tacrolimus 0.1% ointment. She was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Image courtesy of Cyrelle Fermin, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque. Text courtesy of Cyrelle Fermin, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

This pruritic, eruption with yellowing atrophy and telangiectasias on the lower extremities is a classic presentation for necrobiosis lipoidica (NL).

NL is a chronic granulomatous disorder with a predilection for the lower extremities. Patients with NL present with progressive, yellow-brown atrophic plaques on the pretibial aspect of the legs. The plaques have underlying telangiectasias, revealed by the atrophy, and may ulcerate. While these lesions are primarily asymptomatic, associated symptoms may include pruritus, pain, or altered sensation on the affected skin. The classic pathology of NL is notable for altered collagen bundles layered with palisading granulomas extending deep into the dermis. Other notable findings may include mixed inflammatory cells, multinucleated giant cells, and plasma cells; mucin is notably absent.

There is an established relationship between NL and diabetes. When these 2 entities are present, the skin eruption may be referred to as “necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum” or “NLD.” Only a small percentage of patients with diabetes will develop NL. Furthermore, there is growing evidence to suggest that NL may be associated with other comorbidities, such as obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and thyroid disease.1 Additionally, squamous cell carcinoma has been reported as arising within skin affected by NL.2

The etiology of NL is not completely understood. Current theories suggest that blood vessel inflammation related to autoimmune factors may be at work.2 The differential diagnosis of NL includes granuloma annulare, pretibial myxedema, stasis dermatitis, panniculitis, morphea, and lichen sclerosis.

NL can be refractory to therapy. Paramount to management is the avoidance of trauma to the affected skin. Topical therapies include corticosteroids, tretinoin, and tacrolimus. Systemic immunomodulation with infliximab, etanercept, thalidomide, and cyclosporine has also been trialed. There is evidence for the utility of pentoxifylline (400 mg po tid), a xanthine derivative often used for peripheral artery disease, to reverse ulceration that can arise in NL.

The patient in this case opted for topical therapy with clobetasol 0.05% ointment and tacrolimus 0.1% ointment. She was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Image courtesy of Cyrelle Fermin, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque. Text courtesy of Cyrelle Fermin, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Hashemi DA, Brown-Joel ZO, Tkachenko E, et al. Clinical features and comorbidities of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica with or without diabetes. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:455-459. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5635

2. Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

1. Hashemi DA, Brown-Joel ZO, Tkachenko E, et al. Clinical features and comorbidities of patients with necrobiosis lipoidica with or without diabetes. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:455-459. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5635

2. Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

FDA authorizes boosters for Moderna, J&J, allows mix-and-match

in people who are eligible to get them.

The move to amend the Emergency Use Authorization for these vaccines gives the vaccine experts on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices latitude to recommend a mix-and-match strategy if they feel the science supports it.

The committee convenes Oct. 21 for a day-long meeting to make its recommendations for additional doses.

People who’ve previously received two doses of the Moderna mRNA vaccine, which is now called Spikevax, are eligible for a third dose of any COVID-19 vaccine if they are 6 months past their second dose and are:

- 65 years of age or older

- 18 to 64 years of age, but at high risk for severe COVID-19 because of an underlying health condition

- 18 to 64 years of age and at high risk for exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus because they live in a group setting, such as a prison or care home, or work in a risky occupation, such as healthcare

People who’ve previously received a dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine are eligible for a second dose of any COVID-19 vaccine if they are over the age of 18 and at least 2 months past their vaccination.

“Today’s actions demonstrate our commitment to public health in proactively fighting against the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, in a news release. “As the pandemic continues to impact the country, science has shown that vaccination continues to be the safest and most effective way to prevent COVID-19, including the most serious consequences of the disease, such as hospitalization and death.

“The available data suggest waning immunity in some populations who are fully vaccinated. The availability of these authorized boosters is important for continued protection against COVID-19 disease.”

A version of this article was first published on Medscape.com.

in people who are eligible to get them.

The move to amend the Emergency Use Authorization for these vaccines gives the vaccine experts on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices latitude to recommend a mix-and-match strategy if they feel the science supports it.

The committee convenes Oct. 21 for a day-long meeting to make its recommendations for additional doses.

People who’ve previously received two doses of the Moderna mRNA vaccine, which is now called Spikevax, are eligible for a third dose of any COVID-19 vaccine if they are 6 months past their second dose and are:

- 65 years of age or older

- 18 to 64 years of age, but at high risk for severe COVID-19 because of an underlying health condition

- 18 to 64 years of age and at high risk for exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus because they live in a group setting, such as a prison or care home, or work in a risky occupation, such as healthcare

People who’ve previously received a dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine are eligible for a second dose of any COVID-19 vaccine if they are over the age of 18 and at least 2 months past their vaccination.

“Today’s actions demonstrate our commitment to public health in proactively fighting against the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, in a news release. “As the pandemic continues to impact the country, science has shown that vaccination continues to be the safest and most effective way to prevent COVID-19, including the most serious consequences of the disease, such as hospitalization and death.

“The available data suggest waning immunity in some populations who are fully vaccinated. The availability of these authorized boosters is important for continued protection against COVID-19 disease.”

A version of this article was first published on Medscape.com.

in people who are eligible to get them.

The move to amend the Emergency Use Authorization for these vaccines gives the vaccine experts on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices latitude to recommend a mix-and-match strategy if they feel the science supports it.

The committee convenes Oct. 21 for a day-long meeting to make its recommendations for additional doses.

People who’ve previously received two doses of the Moderna mRNA vaccine, which is now called Spikevax, are eligible for a third dose of any COVID-19 vaccine if they are 6 months past their second dose and are:

- 65 years of age or older

- 18 to 64 years of age, but at high risk for severe COVID-19 because of an underlying health condition

- 18 to 64 years of age and at high risk for exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus because they live in a group setting, such as a prison or care home, or work in a risky occupation, such as healthcare

People who’ve previously received a dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine are eligible for a second dose of any COVID-19 vaccine if they are over the age of 18 and at least 2 months past their vaccination.

“Today’s actions demonstrate our commitment to public health in proactively fighting against the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, in a news release. “As the pandemic continues to impact the country, science has shown that vaccination continues to be the safest and most effective way to prevent COVID-19, including the most serious consequences of the disease, such as hospitalization and death.

“The available data suggest waning immunity in some populations who are fully vaccinated. The availability of these authorized boosters is important for continued protection against COVID-19 disease.”

A version of this article was first published on Medscape.com.

Bone risk: Is time since menopause a better predictor than age?

Although early menopause is linked to increased risks in bone loss and fracture, new research indicates that, even among the majority of women who have menopause after age 45, the time since the final menstrual period can be a stronger predictor than chronological age for key risks in bone health and fracture.

In a large longitudinal cohort, the number of years since a woman’s final menstrual period specifically showed a stronger association with femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) than chronological age, while an earlier age at menopause – even among those over 45 years, was linked to an increased risk of fracture.

“Most of our clinical tools to predict osteoporosis-related outcomes use chronological age,” first author Albert Shieh, MD, told this news organization.

“Our findings suggest that more research should be done to examine whether ovarian age (time since final menstrual period) should be used in these tools as well.”

An increased focus on the significance of age at the time of the final menstrual period, compared with chronological age, has gained interest in risk assessment because of the known acceleration in the decline of BMD that occurs 1 year prior to the final menstrual period and continues at a rapid pace for 3 years afterwards before slowing.

To further investigate the association with BMD, Dr. Shieh, an endocrinologist specializing in osteoporosis at the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues turned to data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a longitudinal cohort study of ambulatory women with pre- or early perimenopausal baseline data and 15 annual follow-up assessments.

Outcomes regarding postmenopausal lumbar spine (LS) or femoral neck (FN) BMD were evaluated in 1,038 women, while the time to fracture in relation to the final menstrual period was separately evaluated in 1,554 women.

In both cohorts, the women had a known final menstrual period at age 45 or older, and on average, their final menstrual period occurred at age 52.

After a multivariate adjustment for age, body mass index, and various other factors, they found that each additional year after a woman’s final menstrual period was associated with a significant (0.006 g/cm2) reduction in postmenopausal lumbar spine BMD and a 0.004 g/cm2 reduction femoral neck BMD (both P < .0001).

Conversely, chronological age was not associated with a change in femoral neck BMD when evaluated independently of years since the final menstrual period, the researchers reported in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Regarding lumbar spine BMD, chronological age was unexpectedly associated not just with change, but in fact with increases in lumbar spine BMD (P < .0001 per year). However, the authors speculate the change “is likely a reflection of age-associated degenerative changes causing false elevations in BMD measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.”

Fracture risk with earlier menopause

In terms of the fracture risk analysis, despite the women all being aged 45 or older, earlier age at menopause was still tied to an increased risk of incident fracture, with a 5% increase in risk for each earlier year in age at the time of the final menstrual period (P = .02).

Compared with women who had their final menstrual period at age 55, for instance, those who finished menstruating at age 47 had a 6.3% greater 20-year cumulative fracture risk, the authors note.

While previous findings from the Malmo Perimenopausal Study showed menopause prior to the age of 47 to be associated with an 83% and 59% greater risk of densitometric osteoporosis and fracture, respectively, by age 77, the authors note that the new study is unique in including only women who had a final menstrual period over the age of 45, therefore reducing the potential confounding of data on women under 45.

The new results “add to a growing body of literature suggesting that the endocrine changes that occur during the menopause transition trigger a pathophysiologic cascade that leads to organ dysfunction,” the authors note.

In terms of implications in risk assessment, “future studies should examine whether years since the final menstrual period predicts major osteoporotic fractures and hip fractures, specifically, and, if so, whether replacing chronological age with years since the final menstrual period improves the performance of clinical prediction tools, such as FRAX [Fracture Risk Assessment Tool],” they add.

Addition to guidelines?

Commenting on the findings, Peter Ebeling, MD, the current president of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research, noted that the study importantly “confirms what we had previously anticipated, that in women with menopause who are 45 years of age or older a lower age of final menstrual period is associated with lower spine and hip BMD and more fractures.”

“We had already known this for women with premature ovarian insufficiency or an early menopause, and this extends the observation to the vast majority of women – more than 90% – with a normal menopause age,” said Dr. Ebeling, professor of medicine at Monash Health, Monash University, in Melbourne.

Despite the known importance of the time since final menstrual period, guidelines still focus on age in terms of chronology, rather than biology, emphasizing the risk among women over 50, in general, rather than the time since the last menstrual period, he noted.

“There is an important difference [between those two], as shown by this study,” he said. “Guidelines could be easily adapted to reflect this.”

Specifically, the association between lower age of final menstrual period and lower spine and hip BMD and more fractures requires “more formal assessment to determine whether adding age of final menstrual period to existing fracture risk calculator tools, like FRAX, can improve absolute fracture risk prediction,” Dr. Ebeling noted.

The authors and Dr. Ebeling had no disclosures to report.

Although early menopause is linked to increased risks in bone loss and fracture, new research indicates that, even among the majority of women who have menopause after age 45, the time since the final menstrual period can be a stronger predictor than chronological age for key risks in bone health and fracture.

In a large longitudinal cohort, the number of years since a woman’s final menstrual period specifically showed a stronger association with femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) than chronological age, while an earlier age at menopause – even among those over 45 years, was linked to an increased risk of fracture.

“Most of our clinical tools to predict osteoporosis-related outcomes use chronological age,” first author Albert Shieh, MD, told this news organization.

“Our findings suggest that more research should be done to examine whether ovarian age (time since final menstrual period) should be used in these tools as well.”

An increased focus on the significance of age at the time of the final menstrual period, compared with chronological age, has gained interest in risk assessment because of the known acceleration in the decline of BMD that occurs 1 year prior to the final menstrual period and continues at a rapid pace for 3 years afterwards before slowing.

To further investigate the association with BMD, Dr. Shieh, an endocrinologist specializing in osteoporosis at the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues turned to data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a longitudinal cohort study of ambulatory women with pre- or early perimenopausal baseline data and 15 annual follow-up assessments.

Outcomes regarding postmenopausal lumbar spine (LS) or femoral neck (FN) BMD were evaluated in 1,038 women, while the time to fracture in relation to the final menstrual period was separately evaluated in 1,554 women.

In both cohorts, the women had a known final menstrual period at age 45 or older, and on average, their final menstrual period occurred at age 52.

After a multivariate adjustment for age, body mass index, and various other factors, they found that each additional year after a woman’s final menstrual period was associated with a significant (0.006 g/cm2) reduction in postmenopausal lumbar spine BMD and a 0.004 g/cm2 reduction femoral neck BMD (both P < .0001).

Conversely, chronological age was not associated with a change in femoral neck BMD when evaluated independently of years since the final menstrual period, the researchers reported in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Regarding lumbar spine BMD, chronological age was unexpectedly associated not just with change, but in fact with increases in lumbar spine BMD (P < .0001 per year). However, the authors speculate the change “is likely a reflection of age-associated degenerative changes causing false elevations in BMD measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.”

Fracture risk with earlier menopause

In terms of the fracture risk analysis, despite the women all being aged 45 or older, earlier age at menopause was still tied to an increased risk of incident fracture, with a 5% increase in risk for each earlier year in age at the time of the final menstrual period (P = .02).

Compared with women who had their final menstrual period at age 55, for instance, those who finished menstruating at age 47 had a 6.3% greater 20-year cumulative fracture risk, the authors note.

While previous findings from the Malmo Perimenopausal Study showed menopause prior to the age of 47 to be associated with an 83% and 59% greater risk of densitometric osteoporosis and fracture, respectively, by age 77, the authors note that the new study is unique in including only women who had a final menstrual period over the age of 45, therefore reducing the potential confounding of data on women under 45.

The new results “add to a growing body of literature suggesting that the endocrine changes that occur during the menopause transition trigger a pathophysiologic cascade that leads to organ dysfunction,” the authors note.

In terms of implications in risk assessment, “future studies should examine whether years since the final menstrual period predicts major osteoporotic fractures and hip fractures, specifically, and, if so, whether replacing chronological age with years since the final menstrual period improves the performance of clinical prediction tools, such as FRAX [Fracture Risk Assessment Tool],” they add.

Addition to guidelines?

Commenting on the findings, Peter Ebeling, MD, the current president of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research, noted that the study importantly “confirms what we had previously anticipated, that in women with menopause who are 45 years of age or older a lower age of final menstrual period is associated with lower spine and hip BMD and more fractures.”

“We had already known this for women with premature ovarian insufficiency or an early menopause, and this extends the observation to the vast majority of women – more than 90% – with a normal menopause age,” said Dr. Ebeling, professor of medicine at Monash Health, Monash University, in Melbourne.

Despite the known importance of the time since final menstrual period, guidelines still focus on age in terms of chronology, rather than biology, emphasizing the risk among women over 50, in general, rather than the time since the last menstrual period, he noted.

“There is an important difference [between those two], as shown by this study,” he said. “Guidelines could be easily adapted to reflect this.”

Specifically, the association between lower age of final menstrual period and lower spine and hip BMD and more fractures requires “more formal assessment to determine whether adding age of final menstrual period to existing fracture risk calculator tools, like FRAX, can improve absolute fracture risk prediction,” Dr. Ebeling noted.

The authors and Dr. Ebeling had no disclosures to report.

Although early menopause is linked to increased risks in bone loss and fracture, new research indicates that, even among the majority of women who have menopause after age 45, the time since the final menstrual period can be a stronger predictor than chronological age for key risks in bone health and fracture.

In a large longitudinal cohort, the number of years since a woman’s final menstrual period specifically showed a stronger association with femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) than chronological age, while an earlier age at menopause – even among those over 45 years, was linked to an increased risk of fracture.

“Most of our clinical tools to predict osteoporosis-related outcomes use chronological age,” first author Albert Shieh, MD, told this news organization.

“Our findings suggest that more research should be done to examine whether ovarian age (time since final menstrual period) should be used in these tools as well.”

An increased focus on the significance of age at the time of the final menstrual period, compared with chronological age, has gained interest in risk assessment because of the known acceleration in the decline of BMD that occurs 1 year prior to the final menstrual period and continues at a rapid pace for 3 years afterwards before slowing.

To further investigate the association with BMD, Dr. Shieh, an endocrinologist specializing in osteoporosis at the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues turned to data from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), a longitudinal cohort study of ambulatory women with pre- or early perimenopausal baseline data and 15 annual follow-up assessments.

Outcomes regarding postmenopausal lumbar spine (LS) or femoral neck (FN) BMD were evaluated in 1,038 women, while the time to fracture in relation to the final menstrual period was separately evaluated in 1,554 women.

In both cohorts, the women had a known final menstrual period at age 45 or older, and on average, their final menstrual period occurred at age 52.

After a multivariate adjustment for age, body mass index, and various other factors, they found that each additional year after a woman’s final menstrual period was associated with a significant (0.006 g/cm2) reduction in postmenopausal lumbar spine BMD and a 0.004 g/cm2 reduction femoral neck BMD (both P < .0001).

Conversely, chronological age was not associated with a change in femoral neck BMD when evaluated independently of years since the final menstrual period, the researchers reported in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Regarding lumbar spine BMD, chronological age was unexpectedly associated not just with change, but in fact with increases in lumbar spine BMD (P < .0001 per year). However, the authors speculate the change “is likely a reflection of age-associated degenerative changes causing false elevations in BMD measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.”

Fracture risk with earlier menopause

In terms of the fracture risk analysis, despite the women all being aged 45 or older, earlier age at menopause was still tied to an increased risk of incident fracture, with a 5% increase in risk for each earlier year in age at the time of the final menstrual period (P = .02).

Compared with women who had their final menstrual period at age 55, for instance, those who finished menstruating at age 47 had a 6.3% greater 20-year cumulative fracture risk, the authors note.

While previous findings from the Malmo Perimenopausal Study showed menopause prior to the age of 47 to be associated with an 83% and 59% greater risk of densitometric osteoporosis and fracture, respectively, by age 77, the authors note that the new study is unique in including only women who had a final menstrual period over the age of 45, therefore reducing the potential confounding of data on women under 45.

The new results “add to a growing body of literature suggesting that the endocrine changes that occur during the menopause transition trigger a pathophysiologic cascade that leads to organ dysfunction,” the authors note.

In terms of implications in risk assessment, “future studies should examine whether years since the final menstrual period predicts major osteoporotic fractures and hip fractures, specifically, and, if so, whether replacing chronological age with years since the final menstrual period improves the performance of clinical prediction tools, such as FRAX [Fracture Risk Assessment Tool],” they add.

Addition to guidelines?

Commenting on the findings, Peter Ebeling, MD, the current president of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research, noted that the study importantly “confirms what we had previously anticipated, that in women with menopause who are 45 years of age or older a lower age of final menstrual period is associated with lower spine and hip BMD and more fractures.”

“We had already known this for women with premature ovarian insufficiency or an early menopause, and this extends the observation to the vast majority of women – more than 90% – with a normal menopause age,” said Dr. Ebeling, professor of medicine at Monash Health, Monash University, in Melbourne.

Despite the known importance of the time since final menstrual period, guidelines still focus on age in terms of chronology, rather than biology, emphasizing the risk among women over 50, in general, rather than the time since the last menstrual period, he noted.

“There is an important difference [between those two], as shown by this study,” he said. “Guidelines could be easily adapted to reflect this.”

Specifically, the association between lower age of final menstrual period and lower spine and hip BMD and more fractures requires “more formal assessment to determine whether adding age of final menstrual period to existing fracture risk calculator tools, like FRAX, can improve absolute fracture risk prediction,” Dr. Ebeling noted.

The authors and Dr. Ebeling had no disclosures to report.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY AND METABOLISM

White House announces vaccination plans for younger children

States were allowed to begin preordering the shots this week. But they can’t be delivered into kids’ arms until the FDA and CDC sign off. The shots could be available in early November.

“We know millions of parents have been waiting for COVID-19 vaccine for kids in this age group, and should the FDA and CDC authorize the vaccine, we will be ready to get shots in arms,” Jeff Zients, the White House COVID-19 response coordinator, said at a briefing Oct. 20.

Asked whether announcing plans to deliver a vaccine to children might put pressure on the agencies considering the evidence for their use, Mr. Zients defended the Biden administration’s plans.

“This is the right way to do things: To be operationally ready,” he said. Mr. Zients said they had learned a lesson from the prior administration.

“The decision was made by the FDA and CDC, and the operations weren’t ready. And that meant that adults at the time were not able to receive their vaccines as efficiently, equitably as possible. And this will enable us to be ready for kids,” he said.

Pfizer submitted data to the FDA in late September from its test of the vaccine in 2,200 children. The company said the shots had a favorable safety profile and generated “robust” antibody responses.

An FDA panel is scheduled to meet on Oct. 26 to consider Pfizer’s application. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will meet the following week, on Nov. 2 and 3.

Laying the groundwork

Doctors applauded the advance planning.

“Laying this advance groundwork, ensuring supply is available at physician practices, and that a patient’s own physician is available to answer questions, is critical to the continued success of this rollout,” Gerald Harmon, MD, president of the American Medical Association, said in a written statement.

The shots planned for children are 10 micrograms, a smaller dose than is given to adults. To be fully immunized, kids get two doses, spaced about 21 days apart. Vaccines for younger children are packaged in smaller vials and injected through smaller needles, too.

The vaccine for younger children will roll out slightly differently than it has for adults and teens. While adults mostly got their COVID-19 vaccines through pop-up mass vaccination sites, health departments, and other community locations, the strategy to get children immunized against COVID is centered on the offices of pediatricians and primary care doctors.

The White House says 25,000 doctors have already signed up to give the vaccines.

The vaccination campaign will get underway at a tough moment for pediatricians.

The voicemail message at Roswell Pediatrics Center in the suburbs north of Atlanta, for instance, warns parents to be patient.

“Due to the current, new COVID-19 surge, we are experiencing extremely high call volume, as well as suffering from the same staffing shortages that most businesses are having,” the message says, adding that they’re working around the clock to answer questions and return phone calls.

Jesse Hackell, MD, says he knows the feeling. He’s the chief operating officer of Pomona Pediatrics in Pomona, N.Y., and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“We’re swamped now by kids who get sent home from school because they sneezed once and they have to be cleared before they can go back to school,” he said. “We’re seeing kids who we don’t need to see in terms of the degree of illness because the school requires them to be cleared [of COVID-19].”

Dr. Hackell has been offering the vaccines to kids ages 12 and up since May. He’s planning to offer it to younger children too.

“Adding the vaccines to it is going to be a challenge, but you know we’ll get up to speed and we’ll make it happen,” he said, adding that pediatricians have done many large-scale vaccination campaigns, like those for the H1N1 influenza vaccine in 2009.

Dr. Hackell helped to draft a new policy in New York that will require COVID-19 vaccines for schoolchildren once they are granted full approval from the FDA. Other states may follow with their own vaccination requirements.

He said ultimately, vaccinating school-age children is going to make them safer, will help prevent the virus from mutating and spreading, and will help society as a whole get back to normal.

“We’re the vaccine experts in pediatrics. This is what we do. It’s a huge part of our practice like no other specialty. If we can’t get it right, how can anyone else be expected to?” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

States were allowed to begin preordering the shots this week. But they can’t be delivered into kids’ arms until the FDA and CDC sign off. The shots could be available in early November.

“We know millions of parents have been waiting for COVID-19 vaccine for kids in this age group, and should the FDA and CDC authorize the vaccine, we will be ready to get shots in arms,” Jeff Zients, the White House COVID-19 response coordinator, said at a briefing Oct. 20.

Asked whether announcing plans to deliver a vaccine to children might put pressure on the agencies considering the evidence for their use, Mr. Zients defended the Biden administration’s plans.

“This is the right way to do things: To be operationally ready,” he said. Mr. Zients said they had learned a lesson from the prior administration.

“The decision was made by the FDA and CDC, and the operations weren’t ready. And that meant that adults at the time were not able to receive their vaccines as efficiently, equitably as possible. And this will enable us to be ready for kids,” he said.

Pfizer submitted data to the FDA in late September from its test of the vaccine in 2,200 children. The company said the shots had a favorable safety profile and generated “robust” antibody responses.

An FDA panel is scheduled to meet on Oct. 26 to consider Pfizer’s application. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will meet the following week, on Nov. 2 and 3.

Laying the groundwork

Doctors applauded the advance planning.

“Laying this advance groundwork, ensuring supply is available at physician practices, and that a patient’s own physician is available to answer questions, is critical to the continued success of this rollout,” Gerald Harmon, MD, president of the American Medical Association, said in a written statement.

The shots planned for children are 10 micrograms, a smaller dose than is given to adults. To be fully immunized, kids get two doses, spaced about 21 days apart. Vaccines for younger children are packaged in smaller vials and injected through smaller needles, too.

The vaccine for younger children will roll out slightly differently than it has for adults and teens. While adults mostly got their COVID-19 vaccines through pop-up mass vaccination sites, health departments, and other community locations, the strategy to get children immunized against COVID is centered on the offices of pediatricians and primary care doctors.

The White House says 25,000 doctors have already signed up to give the vaccines.

The vaccination campaign will get underway at a tough moment for pediatricians.

The voicemail message at Roswell Pediatrics Center in the suburbs north of Atlanta, for instance, warns parents to be patient.

“Due to the current, new COVID-19 surge, we are experiencing extremely high call volume, as well as suffering from the same staffing shortages that most businesses are having,” the message says, adding that they’re working around the clock to answer questions and return phone calls.

Jesse Hackell, MD, says he knows the feeling. He’s the chief operating officer of Pomona Pediatrics in Pomona, N.Y., and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“We’re swamped now by kids who get sent home from school because they sneezed once and they have to be cleared before they can go back to school,” he said. “We’re seeing kids who we don’t need to see in terms of the degree of illness because the school requires them to be cleared [of COVID-19].”

Dr. Hackell has been offering the vaccines to kids ages 12 and up since May. He’s planning to offer it to younger children too.

“Adding the vaccines to it is going to be a challenge, but you know we’ll get up to speed and we’ll make it happen,” he said, adding that pediatricians have done many large-scale vaccination campaigns, like those for the H1N1 influenza vaccine in 2009.

Dr. Hackell helped to draft a new policy in New York that will require COVID-19 vaccines for schoolchildren once they are granted full approval from the FDA. Other states may follow with their own vaccination requirements.

He said ultimately, vaccinating school-age children is going to make them safer, will help prevent the virus from mutating and spreading, and will help society as a whole get back to normal.

“We’re the vaccine experts in pediatrics. This is what we do. It’s a huge part of our practice like no other specialty. If we can’t get it right, how can anyone else be expected to?” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

States were allowed to begin preordering the shots this week. But they can’t be delivered into kids’ arms until the FDA and CDC sign off. The shots could be available in early November.

“We know millions of parents have been waiting for COVID-19 vaccine for kids in this age group, and should the FDA and CDC authorize the vaccine, we will be ready to get shots in arms,” Jeff Zients, the White House COVID-19 response coordinator, said at a briefing Oct. 20.

Asked whether announcing plans to deliver a vaccine to children might put pressure on the agencies considering the evidence for their use, Mr. Zients defended the Biden administration’s plans.

“This is the right way to do things: To be operationally ready,” he said. Mr. Zients said they had learned a lesson from the prior administration.

“The decision was made by the FDA and CDC, and the operations weren’t ready. And that meant that adults at the time were not able to receive their vaccines as efficiently, equitably as possible. And this will enable us to be ready for kids,” he said.

Pfizer submitted data to the FDA in late September from its test of the vaccine in 2,200 children. The company said the shots had a favorable safety profile and generated “robust” antibody responses.

An FDA panel is scheduled to meet on Oct. 26 to consider Pfizer’s application. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will meet the following week, on Nov. 2 and 3.

Laying the groundwork

Doctors applauded the advance planning.

“Laying this advance groundwork, ensuring supply is available at physician practices, and that a patient’s own physician is available to answer questions, is critical to the continued success of this rollout,” Gerald Harmon, MD, president of the American Medical Association, said in a written statement.

The shots planned for children are 10 micrograms, a smaller dose than is given to adults. To be fully immunized, kids get two doses, spaced about 21 days apart. Vaccines for younger children are packaged in smaller vials and injected through smaller needles, too.

The vaccine for younger children will roll out slightly differently than it has for adults and teens. While adults mostly got their COVID-19 vaccines through pop-up mass vaccination sites, health departments, and other community locations, the strategy to get children immunized against COVID is centered on the offices of pediatricians and primary care doctors.

The White House says 25,000 doctors have already signed up to give the vaccines.

The vaccination campaign will get underway at a tough moment for pediatricians.

The voicemail message at Roswell Pediatrics Center in the suburbs north of Atlanta, for instance, warns parents to be patient.

“Due to the current, new COVID-19 surge, we are experiencing extremely high call volume, as well as suffering from the same staffing shortages that most businesses are having,” the message says, adding that they’re working around the clock to answer questions and return phone calls.