User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

FDA OKs emergency use of Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine

The much-anticipated emergency use authorization (EUA) of this vaccine — the first such approval in the United States — was greeted with optimism by infectious disease and pulmonary experts, although unanswered questions remain regarding use in people with allergic hypersensitivity, safety in pregnant women, and how smooth distribution will be.

“I am delighted. This is a first, firm step on a long path to getting this COVID pandemic under control,” William Schaffner, MD, professor of infectious diseases at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee, said in an interview.

The FDA gave the green light after the December 10 recommendation from the agency’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) meeting. The committee voted 17-4 in favor of the emergency authorization.

The COVID-19 vaccine is “going to have a major impact here in the US. I’m very optimistic about it,” Dial Hewlett, MD, a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of American (IDSA), told this news organization.

Daniel Culver, DO, chair of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, is likewise hopeful. “My understanding is that supplies of the vaccine are already in place in hubs and will be shipped relatively quickly. The hope would be we can start vaccinating people as early as next week.”

Allergic reactions reported in the UK

After vaccinations with the Pfizer vaccine began in the UK on December 8, reports surfaced of two healthcare workers who experienced allergic reactions. They have since recovered, but officials warned that people with a history of severe allergic reactions should not receive the Pfizer vaccine at this time.

“For the moment, they are asking people who have had notable allergic reactions to step aside while this is investigated. It shows you that the system is working,” Schaffner said.

Both vaccine recipients who experienced anaphylaxis carried EpiPens, as they were at high risk for allergic reactions, Hewlett said. Also, if other COVID-19 vaccines are approved for use in the future, people allergic to the Pfizer vaccine might have another option, he added.

Reassuring role models

Schaffner supports the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) decision to start vaccinations with healthcare workers and residents of long-term care facilities.

“Vaccinating healthcare workers, in particular, will be a model for the general public,” said Schaffner, who is also a former member of the IDSA board of directors. “If they see those of us in white coats and blue scrubs lining up for the vaccine, that will provide confidence.”

To further increase acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine, public health officials need to provide information and reassure the general public, Schaffner said.

Hewlett agreed. “I know there are a lot of people in the population who are very hesitant about vaccines. As infection disease specialists and people in public health, we are trying to allay a lot of concerns people have.”

Reassurance will be especially important in minority communities. “They have been disproportionately affected by the virus, and they have a traditional history of not being optimally vaccinated,” Schaffner said. “We need to reach them in particular with good information and reassurance…so they can make good decisions for themselves and their families.”

No vaccine is 100% effective or completely free of side effects. “There is always a chance there can be adverse reactions, but we think for the most part this is going to be a safe and effective vaccine,” said Hewlett, medical director at the Division of Disease Control and deputy to commissioner of health at the Westchester County Department of Health in White Plains, New York.

Distribution: Smooth or full of strife?

In addition to the concern that some people will not take advantage of vaccination against COVID-19, there could be vaccine supply issues down the road, Schaffner said.

Culver agreed. “In the early phases, I expect that there will be some kinks to work out, but because the numbers are relatively small, this should be okay,” he said.

“I think when we start to get into larger-scale vaccination programs — the supply chain, transport, and storage will be a Herculean undertaking,” Culver added. “It will take careful coordination between healthcare providers, distributors, suppliers, and public health officials to pull this off.”

Planning and distribution also should focus beyond US borders. Any issues in vaccine distribution or administration in the United States “will only be multiplied in several other parts of the world,” Culver said. Because COVID-19 is a pandemic, “we need to think about vaccinating globally.”

Investigating adverse events

Adverse events common to vaccinations in general — injection site pain, headaches, and fever — would not be unexpected with the COVID-19 vaccines. However, experts remain concerned that other, unrelated adverse events might be erroneously attributed to vaccination. For example, if a fall, heart attack, or death occurs within days of immunization, some might immediately blame the vaccine product.

“It’s important to remember that any new, highly touted medical therapy like this will receive a lot of scrutiny, so it would be unusual not to hear about something happening to somebody,” Culver said. Vaccine companies and health agencies will be carefully evaluating any reported adverse events to ensure no safety signal was missed in the trials.

“Fortunately, there are systems in place to investigate these events immediately,” Schaffner said.

Pregnancy recommendations pending

One question still looms: Is the COVID-19 vaccination safe for pregnant women? This isn’t just a question for the general public, either, Schaffner said. He estimated that about 70 percent of healthcare workers are women, and data suggests about 300,000 of these healthcare workers are pregnant.

“The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will speak to that just as soon as the EUA is issued,” he added.

Patients are asking Culver about the priority order for vaccination. He said it’s difficult to provide firm guidance at this point.

People also have “lingering skepticism” about whether vaccine development was done in a prudent way, Culver said. Some people question whether the Pfizer vaccine and others were rushed to market. “So we try to spend time with the patients, reassuring them that all the usual safety evaluations were carefully done,” he said.

Another concern is whether mRNA vaccines can interact with human DNA. “The quick, short, and definitive answer is no,” Schaffner said. The m stands for messenger — the vaccines transmit information. "Once it gets into a cell, the mRNA does not go anywhere near the DNA, and once it transmits its information to the cell appropriately, it gets metabolized, and we excrete all the remnants."

Hewlett pointed out that investigations and surveillance will continue. Because this is an EUA and not full approval, “that essentially means they will still be obligated to collect a lot more data than they would ordinarily,” he said.

How long immunoprotection will last also remains an unknown. “The big question left on the table now is the durability,” Culver said. “Of course, we won’t know the answer to that for quite some time.”

Schaffner and Culver have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Hewlett was an employee of Pfizer until mid-2019. His previous work as Pfizer’s senior medical director of global medical product evaluation was not associated with development of the COVID-19 vaccine.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The much-anticipated emergency use authorization (EUA) of this vaccine — the first such approval in the United States — was greeted with optimism by infectious disease and pulmonary experts, although unanswered questions remain regarding use in people with allergic hypersensitivity, safety in pregnant women, and how smooth distribution will be.

“I am delighted. This is a first, firm step on a long path to getting this COVID pandemic under control,” William Schaffner, MD, professor of infectious diseases at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee, said in an interview.

The FDA gave the green light after the December 10 recommendation from the agency’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) meeting. The committee voted 17-4 in favor of the emergency authorization.

The COVID-19 vaccine is “going to have a major impact here in the US. I’m very optimistic about it,” Dial Hewlett, MD, a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of American (IDSA), told this news organization.

Daniel Culver, DO, chair of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, is likewise hopeful. “My understanding is that supplies of the vaccine are already in place in hubs and will be shipped relatively quickly. The hope would be we can start vaccinating people as early as next week.”

Allergic reactions reported in the UK

After vaccinations with the Pfizer vaccine began in the UK on December 8, reports surfaced of two healthcare workers who experienced allergic reactions. They have since recovered, but officials warned that people with a history of severe allergic reactions should not receive the Pfizer vaccine at this time.

“For the moment, they are asking people who have had notable allergic reactions to step aside while this is investigated. It shows you that the system is working,” Schaffner said.

Both vaccine recipients who experienced anaphylaxis carried EpiPens, as they were at high risk for allergic reactions, Hewlett said. Also, if other COVID-19 vaccines are approved for use in the future, people allergic to the Pfizer vaccine might have another option, he added.

Reassuring role models

Schaffner supports the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) decision to start vaccinations with healthcare workers and residents of long-term care facilities.

“Vaccinating healthcare workers, in particular, will be a model for the general public,” said Schaffner, who is also a former member of the IDSA board of directors. “If they see those of us in white coats and blue scrubs lining up for the vaccine, that will provide confidence.”

To further increase acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine, public health officials need to provide information and reassure the general public, Schaffner said.

Hewlett agreed. “I know there are a lot of people in the population who are very hesitant about vaccines. As infection disease specialists and people in public health, we are trying to allay a lot of concerns people have.”

Reassurance will be especially important in minority communities. “They have been disproportionately affected by the virus, and they have a traditional history of not being optimally vaccinated,” Schaffner said. “We need to reach them in particular with good information and reassurance…so they can make good decisions for themselves and their families.”

No vaccine is 100% effective or completely free of side effects. “There is always a chance there can be adverse reactions, but we think for the most part this is going to be a safe and effective vaccine,” said Hewlett, medical director at the Division of Disease Control and deputy to commissioner of health at the Westchester County Department of Health in White Plains, New York.

Distribution: Smooth or full of strife?

In addition to the concern that some people will not take advantage of vaccination against COVID-19, there could be vaccine supply issues down the road, Schaffner said.

Culver agreed. “In the early phases, I expect that there will be some kinks to work out, but because the numbers are relatively small, this should be okay,” he said.

“I think when we start to get into larger-scale vaccination programs — the supply chain, transport, and storage will be a Herculean undertaking,” Culver added. “It will take careful coordination between healthcare providers, distributors, suppliers, and public health officials to pull this off.”

Planning and distribution also should focus beyond US borders. Any issues in vaccine distribution or administration in the United States “will only be multiplied in several other parts of the world,” Culver said. Because COVID-19 is a pandemic, “we need to think about vaccinating globally.”

Investigating adverse events

Adverse events common to vaccinations in general — injection site pain, headaches, and fever — would not be unexpected with the COVID-19 vaccines. However, experts remain concerned that other, unrelated adverse events might be erroneously attributed to vaccination. For example, if a fall, heart attack, or death occurs within days of immunization, some might immediately blame the vaccine product.

“It’s important to remember that any new, highly touted medical therapy like this will receive a lot of scrutiny, so it would be unusual not to hear about something happening to somebody,” Culver said. Vaccine companies and health agencies will be carefully evaluating any reported adverse events to ensure no safety signal was missed in the trials.

“Fortunately, there are systems in place to investigate these events immediately,” Schaffner said.

Pregnancy recommendations pending

One question still looms: Is the COVID-19 vaccination safe for pregnant women? This isn’t just a question for the general public, either, Schaffner said. He estimated that about 70 percent of healthcare workers are women, and data suggests about 300,000 of these healthcare workers are pregnant.

“The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will speak to that just as soon as the EUA is issued,” he added.

Patients are asking Culver about the priority order for vaccination. He said it’s difficult to provide firm guidance at this point.

People also have “lingering skepticism” about whether vaccine development was done in a prudent way, Culver said. Some people question whether the Pfizer vaccine and others were rushed to market. “So we try to spend time with the patients, reassuring them that all the usual safety evaluations were carefully done,” he said.

Another concern is whether mRNA vaccines can interact with human DNA. “The quick, short, and definitive answer is no,” Schaffner said. The m stands for messenger — the vaccines transmit information. "Once it gets into a cell, the mRNA does not go anywhere near the DNA, and once it transmits its information to the cell appropriately, it gets metabolized, and we excrete all the remnants."

Hewlett pointed out that investigations and surveillance will continue. Because this is an EUA and not full approval, “that essentially means they will still be obligated to collect a lot more data than they would ordinarily,” he said.

How long immunoprotection will last also remains an unknown. “The big question left on the table now is the durability,” Culver said. “Of course, we won’t know the answer to that for quite some time.”

Schaffner and Culver have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Hewlett was an employee of Pfizer until mid-2019. His previous work as Pfizer’s senior medical director of global medical product evaluation was not associated with development of the COVID-19 vaccine.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The much-anticipated emergency use authorization (EUA) of this vaccine — the first such approval in the United States — was greeted with optimism by infectious disease and pulmonary experts, although unanswered questions remain regarding use in people with allergic hypersensitivity, safety in pregnant women, and how smooth distribution will be.

“I am delighted. This is a first, firm step on a long path to getting this COVID pandemic under control,” William Schaffner, MD, professor of infectious diseases at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee, said in an interview.

The FDA gave the green light after the December 10 recommendation from the agency’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) meeting. The committee voted 17-4 in favor of the emergency authorization.

The COVID-19 vaccine is “going to have a major impact here in the US. I’m very optimistic about it,” Dial Hewlett, MD, a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of American (IDSA), told this news organization.

Daniel Culver, DO, chair of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, is likewise hopeful. “My understanding is that supplies of the vaccine are already in place in hubs and will be shipped relatively quickly. The hope would be we can start vaccinating people as early as next week.”

Allergic reactions reported in the UK

After vaccinations with the Pfizer vaccine began in the UK on December 8, reports surfaced of two healthcare workers who experienced allergic reactions. They have since recovered, but officials warned that people with a history of severe allergic reactions should not receive the Pfizer vaccine at this time.

“For the moment, they are asking people who have had notable allergic reactions to step aside while this is investigated. It shows you that the system is working,” Schaffner said.

Both vaccine recipients who experienced anaphylaxis carried EpiPens, as they were at high risk for allergic reactions, Hewlett said. Also, if other COVID-19 vaccines are approved for use in the future, people allergic to the Pfizer vaccine might have another option, he added.

Reassuring role models

Schaffner supports the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) decision to start vaccinations with healthcare workers and residents of long-term care facilities.

“Vaccinating healthcare workers, in particular, will be a model for the general public,” said Schaffner, who is also a former member of the IDSA board of directors. “If they see those of us in white coats and blue scrubs lining up for the vaccine, that will provide confidence.”

To further increase acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine, public health officials need to provide information and reassure the general public, Schaffner said.

Hewlett agreed. “I know there are a lot of people in the population who are very hesitant about vaccines. As infection disease specialists and people in public health, we are trying to allay a lot of concerns people have.”

Reassurance will be especially important in minority communities. “They have been disproportionately affected by the virus, and they have a traditional history of not being optimally vaccinated,” Schaffner said. “We need to reach them in particular with good information and reassurance…so they can make good decisions for themselves and their families.”

No vaccine is 100% effective or completely free of side effects. “There is always a chance there can be adverse reactions, but we think for the most part this is going to be a safe and effective vaccine,” said Hewlett, medical director at the Division of Disease Control and deputy to commissioner of health at the Westchester County Department of Health in White Plains, New York.

Distribution: Smooth or full of strife?

In addition to the concern that some people will not take advantage of vaccination against COVID-19, there could be vaccine supply issues down the road, Schaffner said.

Culver agreed. “In the early phases, I expect that there will be some kinks to work out, but because the numbers are relatively small, this should be okay,” he said.

“I think when we start to get into larger-scale vaccination programs — the supply chain, transport, and storage will be a Herculean undertaking,” Culver added. “It will take careful coordination between healthcare providers, distributors, suppliers, and public health officials to pull this off.”

Planning and distribution also should focus beyond US borders. Any issues in vaccine distribution or administration in the United States “will only be multiplied in several other parts of the world,” Culver said. Because COVID-19 is a pandemic, “we need to think about vaccinating globally.”

Investigating adverse events

Adverse events common to vaccinations in general — injection site pain, headaches, and fever — would not be unexpected with the COVID-19 vaccines. However, experts remain concerned that other, unrelated adverse events might be erroneously attributed to vaccination. For example, if a fall, heart attack, or death occurs within days of immunization, some might immediately blame the vaccine product.

“It’s important to remember that any new, highly touted medical therapy like this will receive a lot of scrutiny, so it would be unusual not to hear about something happening to somebody,” Culver said. Vaccine companies and health agencies will be carefully evaluating any reported adverse events to ensure no safety signal was missed in the trials.

“Fortunately, there are systems in place to investigate these events immediately,” Schaffner said.

Pregnancy recommendations pending

One question still looms: Is the COVID-19 vaccination safe for pregnant women? This isn’t just a question for the general public, either, Schaffner said. He estimated that about 70 percent of healthcare workers are women, and data suggests about 300,000 of these healthcare workers are pregnant.

“The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will speak to that just as soon as the EUA is issued,” he added.

Patients are asking Culver about the priority order for vaccination. He said it’s difficult to provide firm guidance at this point.

People also have “lingering skepticism” about whether vaccine development was done in a prudent way, Culver said. Some people question whether the Pfizer vaccine and others were rushed to market. “So we try to spend time with the patients, reassuring them that all the usual safety evaluations were carefully done,” he said.

Another concern is whether mRNA vaccines can interact with human DNA. “The quick, short, and definitive answer is no,” Schaffner said. The m stands for messenger — the vaccines transmit information. "Once it gets into a cell, the mRNA does not go anywhere near the DNA, and once it transmits its information to the cell appropriately, it gets metabolized, and we excrete all the remnants."

Hewlett pointed out that investigations and surveillance will continue. Because this is an EUA and not full approval, “that essentially means they will still be obligated to collect a lot more data than they would ordinarily,” he said.

How long immunoprotection will last also remains an unknown. “The big question left on the table now is the durability,” Culver said. “Of course, we won’t know the answer to that for quite some time.”

Schaffner and Culver have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Hewlett was an employee of Pfizer until mid-2019. His previous work as Pfizer’s senior medical director of global medical product evaluation was not associated with development of the COVID-19 vaccine.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Consider this Rx for patients with high triglycerides?

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 63-year-old man with a medical history significant for myocardial infarction (MI) 5 years ago presents to you for an annual exam. His medications include a daily aspirin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, beta-blocker, and a high-intensity statin for coronary artery disease (CAD). On his fasting lipid panel, his low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level is 70 mg/dL, but his triglycerides remain elevated at 200 mg/dL despite dietary changes.

In addition to lifestyle modifications, what can be done to reduce his risk of another MI?

Patients with known cardiovascular disease (CVD) or multiple risk factors for CVD are at high risk of cardiovascular events, even when taking primary or secondary preventive medications such as statins.2,3 In these patients, elevated triglycerides are an independent risk factor for increased rates of cardiovascular events.4,5

The 2018 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for the treatment of blood cholesterol recommend statin therapy for moderate (175-499 mg/dL) to severe (≥ 500 mg/dL) hypertriglyceridemia in appropriate patients with atherosclerotic CVD risk ≥ 7.5%, after appropriately addressing secondary causes of hypertriglycidemia.6

Previous studies have shown no benefit from combination therapy with triglyceride-lowering medications (eg, extended-release niacin and fibrates) and statins, compared with statin monotherapy.7 A recent meta-analysis concluded that omega-3 fatty acid supplements offer no reduction in cardiovascular morbidity or mortality, whether taken with or without statins.8

Interestingly, the randomized controlled Japan EPA Lipid Intervention Study (JELIS) demonstrated fewer major coronary events in patients with elevated cholesterol, with or without CAD, who took eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)—a subtype of omega-3 fatty acids—plus a statin, compared with statin monotherapy.9

The REDUCE-IT trial evaluated icosapent ethyl, a highly purified EPA that has been shown to reduce triglycerides and, at the time this study was conducted, was approved for use solely for the reduction of triglyceride levels in adults with severe hypertriglyceridemia.10,11

Continue to: Study Summary

STUDY SUMMARY

Patients with known CVD had fewercardiovascular events on icosapent ethyl

The multicenter, randomized controlled REDUCE-IT trial evaluated the effectiveness of icosapent ethyl, 2 g orally twice daily, on cardiovascular outcomes.1 A total of 8179 patients, ≥ 45 years of age with hypertriglyceridemia and known CVD or ≥ 50 years with diabetes and at least 1 additional risk factor and no known CVD, were enrolled at 473 participating sites in 11 countries, including the United States.

Patients had a triglyceride level of 150 to 499 mg/dL and an LDL cholesterol level of 41 to 100 mg/dL, and were taking a stable dose of a statin for at least 4 weeks. The enrollment protocol was amended to increase the lower limit of triglycerides from 150 to 200 mg/dL about one-third of the way through the study. Among the study population, 70.7% of patients were enrolled for secondary prevention (ie, had established CVD) and 29.3% of patients were enrolled for primary prevention (ie, had diabetes and at least 1 additional risk factor but no known CVD). Exclusion criteria included severe heart failure, active severe liver disease, glycated hemoglobin > 10%, a planned surgical cardiac intervention, history of pancreatitis, or allergies to fish or shellfish products.

Outcomes. The primary end point was a composite outcome of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, coronary revascularization, or unstable angina.

Results. The median duration of follow-up was 4.9 years. From baseline to 1 year, the median change in triglycerides was an 18% reduction in the icosapent ethyl group but a 2% increase in the placebo group. Fewer patients in the icosapent ethyl group than the placebo group had a composite outcome event (17% vs 22%, respectively; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.75; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.68-0.83; number needed to treat [NNT] to avoid 1 primary end point event = 21). Patients with known CVD had fewer composite outcome events in the icosapent ethyl group than the placebo group (19% vs 26%; HR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.65-0.81; NNT = 14) but not in the primary prevention group vs the placebo group (12% vs 14%; HR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.70-1.1).

In the entire population, all individual outcomes in the composite were significantly fewer in the icosapent ethyl group (cardiovascular death: HR = 0.8; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98; fatal or nonfatal MI: HR = 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58-0.81; revascularization: HR = 0.65; 95% CI, 0.55-0.78; unstable angina: HR = 0.68; 95% CI, 0.53-0.87; and fatal or nonfatal stroke: HR = 0.72; 95% CI, 0.55-0.93). All-cause mortality did not differ between groups (HR = 0.87; 95% CI, 0.74-1.02).

No significant differences in adverse events leading to discontinuation of the drug were reported between groups. Atrial fibrillation occurred more frequently in the icosapent ethyl group (5.3% vs 3.9%), but anemia (4.7% vs 5.8%) and gastrointestinal adverse events (33% vs 35%) were less common.

Continue to: What's New

WHAT’S NEW

First RCT to demonstrate valueof pairing icosapent ethyl with a statin

Many prior studies on use of omega-3 fatty acid supplements to treat hypertriglyceridemia did not show any benefit, possibly due to a low dose or low ratio of EPA in the study drug.8 One trial (JELIS) with favorable results was an open-label study, limited to patients in Japan. The REDUCE-IT study was the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial to show that icosapent ethyl treatment for hypertriglyceridemia in patients with known CVD who are taking a statin results in fewer cardiovascular events than statin use alone.

Also worth noting: Since publication of the REDUCE-IT study, the FDA has approved an expanded indication for icosapent ethyl for reduction of risk of cardiovascular events in statin-treated patients with hypertriglyceridemia and established CVD or diabetes and ≥ 2 additional cardiovascular risk factors.11

CAVEATS

Drug’s benefit was not linkedto triglyceride level reductions

The cardiovascular benefits of icosapent ethyl were obtained irrespective of triglyceride levels achieved. This raises the question of other potential mechanisms of action of icosapent ethyl in achieving cardiovascular benefit. However, this should not preclude the use of icosapent ethyl for secondary prevention in appropriate patients.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Medication is pricey

Icosapent ethyl is an expensive medication, currently priced at an estimated $351/month using a nationally available discount pharmacy plan, although additional manufacturer’s discounts may apply.12,13 The cost of the medication could be a consideration for widespread implementation of this recommendation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2020. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

1. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22.

2. Bhatt DL, Eagle KA, Ohman EM, et al; REACH Registry Investigators. Comparative determinants of 4-year cardiovascular event rates in stable outpatients at risk of or with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2010;304:1350-1357.

3. Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al; Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22 Investigators. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2006;354:778]. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495-1504.

4. Klempfner R, Erez A, Sagit BZ, et al. Elevated triglyceride level is independently associated with increased all-cause mortality in patients with established coronary heart disease: twenty-two-year follow-up of the Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention Study and Registry [published correction appears in Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:613]. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:100-108.

5. Nichols GA, Philip S, Reynolds K, Granowitz CB, Fazio S. Increased cardiovascular risk in hypertriglyceridemic patients with statin-controlled LDL cholesterol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:3019-3027.

6. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3237-3241]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:e285-e350.

7. Ganda OP, Bhatt DL, Mason RP, Miller M, Boden WE. Unmet need for adjunctive dyslipidemia therapy in hypertriglyceridemia management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:330-343.

8. Aung T, Halsey J, Kromhout D, et al; Omega-3 Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Associations of omega-3 fatty acid supplement use with cardiovascular disease risks: meta-analysis of 10 trials involving 77 917 individuals. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:225-234.

9. Yokoyama M, Origasa H, Matsuzaki M, et al; Japan EPA lipid intervention study (JELIS) Investigators. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients (JELIS): a randomised open-label, blinded endpoint analysis [published correction appears in Lancet. 2007;370:220]. Lancet. 2007;369:1090-1098.

10. Ballantyne CM, Bays HE, Kastelein JJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester (AMR101) therapy in statin-treated patients with persistent high triglycerides (from the ANCHOR study). Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:984-992.

11. FDA approves use of drug to reduce risk of cardiovascular events in certain adult patient groups [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; December 13, 2019. www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-use-drug-reduce-risk-cardiovascular-events-certain-adult-patient-groups. Accessed November 30, 2020.

12. Vascepa. GoodRx. www.goodrx.com/vascepa. Accessed November 30, 2020.

13. The VASCEPA Savings Program. www.vascepa.com/getting-started/savings-card/. Accessed November 30, 2020.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 63-year-old man with a medical history significant for myocardial infarction (MI) 5 years ago presents to you for an annual exam. His medications include a daily aspirin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, beta-blocker, and a high-intensity statin for coronary artery disease (CAD). On his fasting lipid panel, his low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level is 70 mg/dL, but his triglycerides remain elevated at 200 mg/dL despite dietary changes.

In addition to lifestyle modifications, what can be done to reduce his risk of another MI?

Patients with known cardiovascular disease (CVD) or multiple risk factors for CVD are at high risk of cardiovascular events, even when taking primary or secondary preventive medications such as statins.2,3 In these patients, elevated triglycerides are an independent risk factor for increased rates of cardiovascular events.4,5

The 2018 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for the treatment of blood cholesterol recommend statin therapy for moderate (175-499 mg/dL) to severe (≥ 500 mg/dL) hypertriglyceridemia in appropriate patients with atherosclerotic CVD risk ≥ 7.5%, after appropriately addressing secondary causes of hypertriglycidemia.6

Previous studies have shown no benefit from combination therapy with triglyceride-lowering medications (eg, extended-release niacin and fibrates) and statins, compared with statin monotherapy.7 A recent meta-analysis concluded that omega-3 fatty acid supplements offer no reduction in cardiovascular morbidity or mortality, whether taken with or without statins.8

Interestingly, the randomized controlled Japan EPA Lipid Intervention Study (JELIS) demonstrated fewer major coronary events in patients with elevated cholesterol, with or without CAD, who took eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)—a subtype of omega-3 fatty acids—plus a statin, compared with statin monotherapy.9

The REDUCE-IT trial evaluated icosapent ethyl, a highly purified EPA that has been shown to reduce triglycerides and, at the time this study was conducted, was approved for use solely for the reduction of triglyceride levels in adults with severe hypertriglyceridemia.10,11

Continue to: Study Summary

STUDY SUMMARY

Patients with known CVD had fewercardiovascular events on icosapent ethyl

The multicenter, randomized controlled REDUCE-IT trial evaluated the effectiveness of icosapent ethyl, 2 g orally twice daily, on cardiovascular outcomes.1 A total of 8179 patients, ≥ 45 years of age with hypertriglyceridemia and known CVD or ≥ 50 years with diabetes and at least 1 additional risk factor and no known CVD, were enrolled at 473 participating sites in 11 countries, including the United States.

Patients had a triglyceride level of 150 to 499 mg/dL and an LDL cholesterol level of 41 to 100 mg/dL, and were taking a stable dose of a statin for at least 4 weeks. The enrollment protocol was amended to increase the lower limit of triglycerides from 150 to 200 mg/dL about one-third of the way through the study. Among the study population, 70.7% of patients were enrolled for secondary prevention (ie, had established CVD) and 29.3% of patients were enrolled for primary prevention (ie, had diabetes and at least 1 additional risk factor but no known CVD). Exclusion criteria included severe heart failure, active severe liver disease, glycated hemoglobin > 10%, a planned surgical cardiac intervention, history of pancreatitis, or allergies to fish or shellfish products.

Outcomes. The primary end point was a composite outcome of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, coronary revascularization, or unstable angina.

Results. The median duration of follow-up was 4.9 years. From baseline to 1 year, the median change in triglycerides was an 18% reduction in the icosapent ethyl group but a 2% increase in the placebo group. Fewer patients in the icosapent ethyl group than the placebo group had a composite outcome event (17% vs 22%, respectively; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.75; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.68-0.83; number needed to treat [NNT] to avoid 1 primary end point event = 21). Patients with known CVD had fewer composite outcome events in the icosapent ethyl group than the placebo group (19% vs 26%; HR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.65-0.81; NNT = 14) but not in the primary prevention group vs the placebo group (12% vs 14%; HR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.70-1.1).

In the entire population, all individual outcomes in the composite were significantly fewer in the icosapent ethyl group (cardiovascular death: HR = 0.8; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98; fatal or nonfatal MI: HR = 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58-0.81; revascularization: HR = 0.65; 95% CI, 0.55-0.78; unstable angina: HR = 0.68; 95% CI, 0.53-0.87; and fatal or nonfatal stroke: HR = 0.72; 95% CI, 0.55-0.93). All-cause mortality did not differ between groups (HR = 0.87; 95% CI, 0.74-1.02).

No significant differences in adverse events leading to discontinuation of the drug were reported between groups. Atrial fibrillation occurred more frequently in the icosapent ethyl group (5.3% vs 3.9%), but anemia (4.7% vs 5.8%) and gastrointestinal adverse events (33% vs 35%) were less common.

Continue to: What's New

WHAT’S NEW

First RCT to demonstrate valueof pairing icosapent ethyl with a statin

Many prior studies on use of omega-3 fatty acid supplements to treat hypertriglyceridemia did not show any benefit, possibly due to a low dose or low ratio of EPA in the study drug.8 One trial (JELIS) with favorable results was an open-label study, limited to patients in Japan. The REDUCE-IT study was the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial to show that icosapent ethyl treatment for hypertriglyceridemia in patients with known CVD who are taking a statin results in fewer cardiovascular events than statin use alone.

Also worth noting: Since publication of the REDUCE-IT study, the FDA has approved an expanded indication for icosapent ethyl for reduction of risk of cardiovascular events in statin-treated patients with hypertriglyceridemia and established CVD or diabetes and ≥ 2 additional cardiovascular risk factors.11

CAVEATS

Drug’s benefit was not linkedto triglyceride level reductions

The cardiovascular benefits of icosapent ethyl were obtained irrespective of triglyceride levels achieved. This raises the question of other potential mechanisms of action of icosapent ethyl in achieving cardiovascular benefit. However, this should not preclude the use of icosapent ethyl for secondary prevention in appropriate patients.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Medication is pricey

Icosapent ethyl is an expensive medication, currently priced at an estimated $351/month using a nationally available discount pharmacy plan, although additional manufacturer’s discounts may apply.12,13 The cost of the medication could be a consideration for widespread implementation of this recommendation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2020. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 63-year-old man with a medical history significant for myocardial infarction (MI) 5 years ago presents to you for an annual exam. His medications include a daily aspirin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, beta-blocker, and a high-intensity statin for coronary artery disease (CAD). On his fasting lipid panel, his low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level is 70 mg/dL, but his triglycerides remain elevated at 200 mg/dL despite dietary changes.

In addition to lifestyle modifications, what can be done to reduce his risk of another MI?

Patients with known cardiovascular disease (CVD) or multiple risk factors for CVD are at high risk of cardiovascular events, even when taking primary or secondary preventive medications such as statins.2,3 In these patients, elevated triglycerides are an independent risk factor for increased rates of cardiovascular events.4,5

The 2018 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for the treatment of blood cholesterol recommend statin therapy for moderate (175-499 mg/dL) to severe (≥ 500 mg/dL) hypertriglyceridemia in appropriate patients with atherosclerotic CVD risk ≥ 7.5%, after appropriately addressing secondary causes of hypertriglycidemia.6

Previous studies have shown no benefit from combination therapy with triglyceride-lowering medications (eg, extended-release niacin and fibrates) and statins, compared with statin monotherapy.7 A recent meta-analysis concluded that omega-3 fatty acid supplements offer no reduction in cardiovascular morbidity or mortality, whether taken with or without statins.8

Interestingly, the randomized controlled Japan EPA Lipid Intervention Study (JELIS) demonstrated fewer major coronary events in patients with elevated cholesterol, with or without CAD, who took eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)—a subtype of omega-3 fatty acids—plus a statin, compared with statin monotherapy.9

The REDUCE-IT trial evaluated icosapent ethyl, a highly purified EPA that has been shown to reduce triglycerides and, at the time this study was conducted, was approved for use solely for the reduction of triglyceride levels in adults with severe hypertriglyceridemia.10,11

Continue to: Study Summary

STUDY SUMMARY

Patients with known CVD had fewercardiovascular events on icosapent ethyl

The multicenter, randomized controlled REDUCE-IT trial evaluated the effectiveness of icosapent ethyl, 2 g orally twice daily, on cardiovascular outcomes.1 A total of 8179 patients, ≥ 45 years of age with hypertriglyceridemia and known CVD or ≥ 50 years with diabetes and at least 1 additional risk factor and no known CVD, were enrolled at 473 participating sites in 11 countries, including the United States.

Patients had a triglyceride level of 150 to 499 mg/dL and an LDL cholesterol level of 41 to 100 mg/dL, and were taking a stable dose of a statin for at least 4 weeks. The enrollment protocol was amended to increase the lower limit of triglycerides from 150 to 200 mg/dL about one-third of the way through the study. Among the study population, 70.7% of patients were enrolled for secondary prevention (ie, had established CVD) and 29.3% of patients were enrolled for primary prevention (ie, had diabetes and at least 1 additional risk factor but no known CVD). Exclusion criteria included severe heart failure, active severe liver disease, glycated hemoglobin > 10%, a planned surgical cardiac intervention, history of pancreatitis, or allergies to fish or shellfish products.

Outcomes. The primary end point was a composite outcome of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, coronary revascularization, or unstable angina.

Results. The median duration of follow-up was 4.9 years. From baseline to 1 year, the median change in triglycerides was an 18% reduction in the icosapent ethyl group but a 2% increase in the placebo group. Fewer patients in the icosapent ethyl group than the placebo group had a composite outcome event (17% vs 22%, respectively; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.75; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.68-0.83; number needed to treat [NNT] to avoid 1 primary end point event = 21). Patients with known CVD had fewer composite outcome events in the icosapent ethyl group than the placebo group (19% vs 26%; HR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.65-0.81; NNT = 14) but not in the primary prevention group vs the placebo group (12% vs 14%; HR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.70-1.1).

In the entire population, all individual outcomes in the composite were significantly fewer in the icosapent ethyl group (cardiovascular death: HR = 0.8; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98; fatal or nonfatal MI: HR = 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58-0.81; revascularization: HR = 0.65; 95% CI, 0.55-0.78; unstable angina: HR = 0.68; 95% CI, 0.53-0.87; and fatal or nonfatal stroke: HR = 0.72; 95% CI, 0.55-0.93). All-cause mortality did not differ between groups (HR = 0.87; 95% CI, 0.74-1.02).

No significant differences in adverse events leading to discontinuation of the drug were reported between groups. Atrial fibrillation occurred more frequently in the icosapent ethyl group (5.3% vs 3.9%), but anemia (4.7% vs 5.8%) and gastrointestinal adverse events (33% vs 35%) were less common.

Continue to: What's New

WHAT’S NEW

First RCT to demonstrate valueof pairing icosapent ethyl with a statin

Many prior studies on use of omega-3 fatty acid supplements to treat hypertriglyceridemia did not show any benefit, possibly due to a low dose or low ratio of EPA in the study drug.8 One trial (JELIS) with favorable results was an open-label study, limited to patients in Japan. The REDUCE-IT study was the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial to show that icosapent ethyl treatment for hypertriglyceridemia in patients with known CVD who are taking a statin results in fewer cardiovascular events than statin use alone.

Also worth noting: Since publication of the REDUCE-IT study, the FDA has approved an expanded indication for icosapent ethyl for reduction of risk of cardiovascular events in statin-treated patients with hypertriglyceridemia and established CVD or diabetes and ≥ 2 additional cardiovascular risk factors.11

CAVEATS

Drug’s benefit was not linkedto triglyceride level reductions

The cardiovascular benefits of icosapent ethyl were obtained irrespective of triglyceride levels achieved. This raises the question of other potential mechanisms of action of icosapent ethyl in achieving cardiovascular benefit. However, this should not preclude the use of icosapent ethyl for secondary prevention in appropriate patients.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Medication is pricey

Icosapent ethyl is an expensive medication, currently priced at an estimated $351/month using a nationally available discount pharmacy plan, although additional manufacturer’s discounts may apply.12,13 The cost of the medication could be a consideration for widespread implementation of this recommendation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2020. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

1. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22.

2. Bhatt DL, Eagle KA, Ohman EM, et al; REACH Registry Investigators. Comparative determinants of 4-year cardiovascular event rates in stable outpatients at risk of or with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2010;304:1350-1357.

3. Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al; Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22 Investigators. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2006;354:778]. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495-1504.

4. Klempfner R, Erez A, Sagit BZ, et al. Elevated triglyceride level is independently associated with increased all-cause mortality in patients with established coronary heart disease: twenty-two-year follow-up of the Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention Study and Registry [published correction appears in Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:613]. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:100-108.

5. Nichols GA, Philip S, Reynolds K, Granowitz CB, Fazio S. Increased cardiovascular risk in hypertriglyceridemic patients with statin-controlled LDL cholesterol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:3019-3027.

6. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3237-3241]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:e285-e350.

7. Ganda OP, Bhatt DL, Mason RP, Miller M, Boden WE. Unmet need for adjunctive dyslipidemia therapy in hypertriglyceridemia management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:330-343.

8. Aung T, Halsey J, Kromhout D, et al; Omega-3 Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Associations of omega-3 fatty acid supplement use with cardiovascular disease risks: meta-analysis of 10 trials involving 77 917 individuals. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:225-234.

9. Yokoyama M, Origasa H, Matsuzaki M, et al; Japan EPA lipid intervention study (JELIS) Investigators. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients (JELIS): a randomised open-label, blinded endpoint analysis [published correction appears in Lancet. 2007;370:220]. Lancet. 2007;369:1090-1098.

10. Ballantyne CM, Bays HE, Kastelein JJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester (AMR101) therapy in statin-treated patients with persistent high triglycerides (from the ANCHOR study). Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:984-992.

11. FDA approves use of drug to reduce risk of cardiovascular events in certain adult patient groups [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; December 13, 2019. www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-use-drug-reduce-risk-cardiovascular-events-certain-adult-patient-groups. Accessed November 30, 2020.

12. Vascepa. GoodRx. www.goodrx.com/vascepa. Accessed November 30, 2020.

13. The VASCEPA Savings Program. www.vascepa.com/getting-started/savings-card/. Accessed November 30, 2020.

1. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22.

2. Bhatt DL, Eagle KA, Ohman EM, et al; REACH Registry Investigators. Comparative determinants of 4-year cardiovascular event rates in stable outpatients at risk of or with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2010;304:1350-1357.

3. Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al; Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22 Investigators. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2006;354:778]. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495-1504.

4. Klempfner R, Erez A, Sagit BZ, et al. Elevated triglyceride level is independently associated with increased all-cause mortality in patients with established coronary heart disease: twenty-two-year follow-up of the Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention Study and Registry [published correction appears in Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:613]. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:100-108.

5. Nichols GA, Philip S, Reynolds K, Granowitz CB, Fazio S. Increased cardiovascular risk in hypertriglyceridemic patients with statin-controlled LDL cholesterol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:3019-3027.

6. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3237-3241]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:e285-e350.

7. Ganda OP, Bhatt DL, Mason RP, Miller M, Boden WE. Unmet need for adjunctive dyslipidemia therapy in hypertriglyceridemia management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:330-343.

8. Aung T, Halsey J, Kromhout D, et al; Omega-3 Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Associations of omega-3 fatty acid supplement use with cardiovascular disease risks: meta-analysis of 10 trials involving 77 917 individuals. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:225-234.

9. Yokoyama M, Origasa H, Matsuzaki M, et al; Japan EPA lipid intervention study (JELIS) Investigators. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients (JELIS): a randomised open-label, blinded endpoint analysis [published correction appears in Lancet. 2007;370:220]. Lancet. 2007;369:1090-1098.

10. Ballantyne CM, Bays HE, Kastelein JJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester (AMR101) therapy in statin-treated patients with persistent high triglycerides (from the ANCHOR study). Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:984-992.

11. FDA approves use of drug to reduce risk of cardiovascular events in certain adult patient groups [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; December 13, 2019. www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-use-drug-reduce-risk-cardiovascular-events-certain-adult-patient-groups. Accessed November 30, 2020.

12. Vascepa. GoodRx. www.goodrx.com/vascepa. Accessed November 30, 2020.

13. The VASCEPA Savings Program. www.vascepa.com/getting-started/savings-card/. Accessed November 30, 2020.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider icosapent ethyl, 2 g twice daily, for secondary prevention of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with elevated triglycerides who are already taking a statin.

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single, good-quality, multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22.1

Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22.1

Worsening skin lesions but no diagnosis

A 50-year-old woman presented to her family physician for a urinary tract infection (UTI) and an itchy rash. She said the rash had developed 2 years earlier and had gotten worse, with additional lesions emerging on her skin as time went on. She noted that other physicians had evaluated the rash but provided no clear diagnosis and had done no testing.

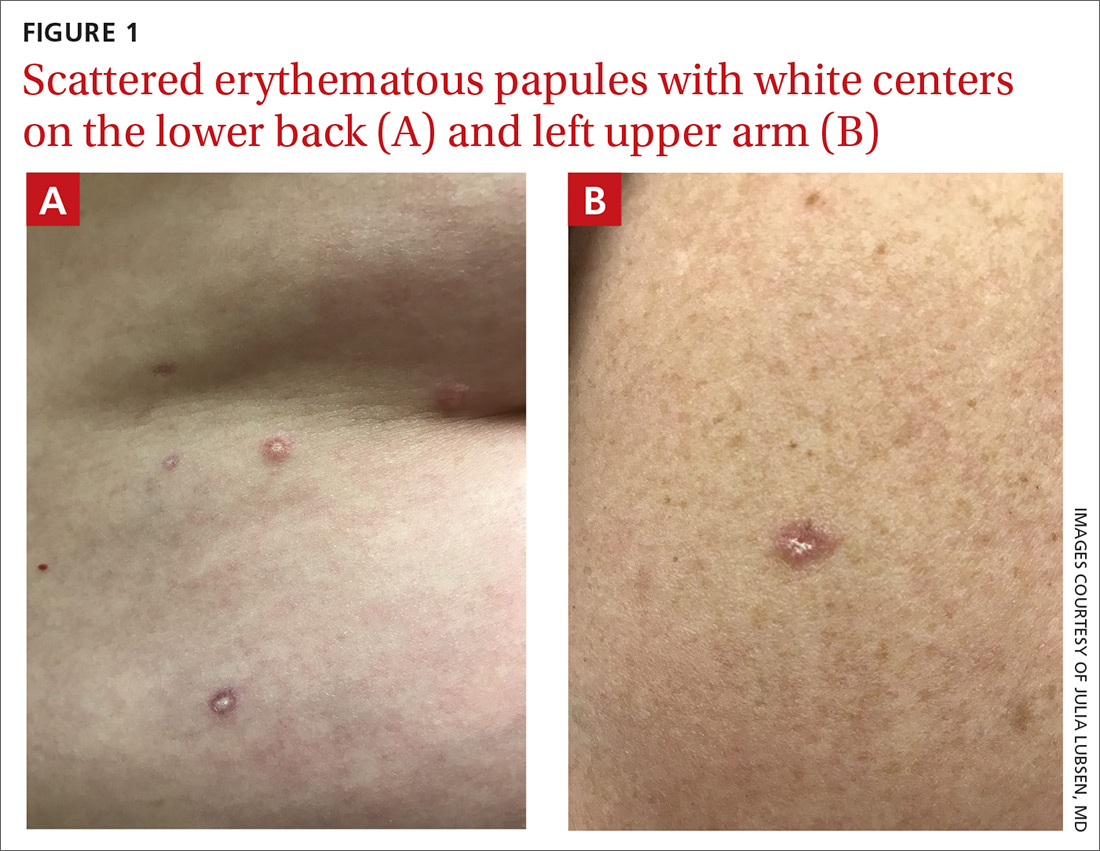

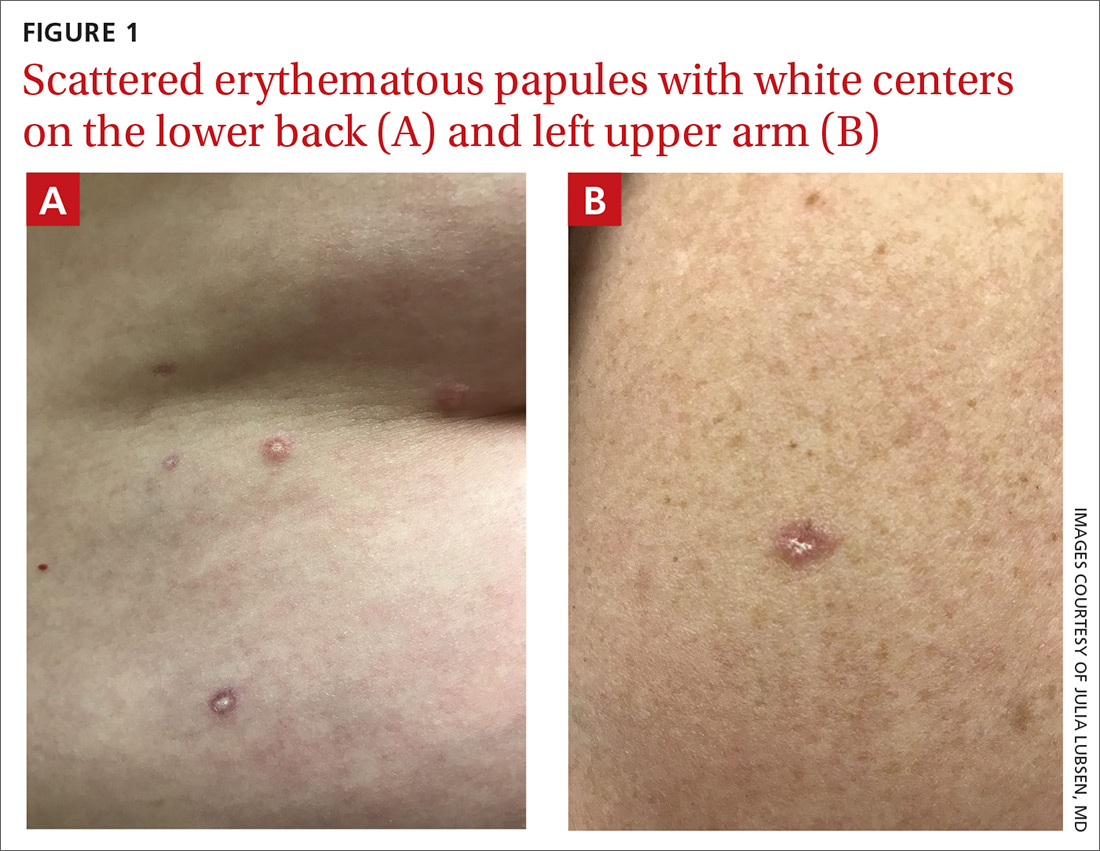

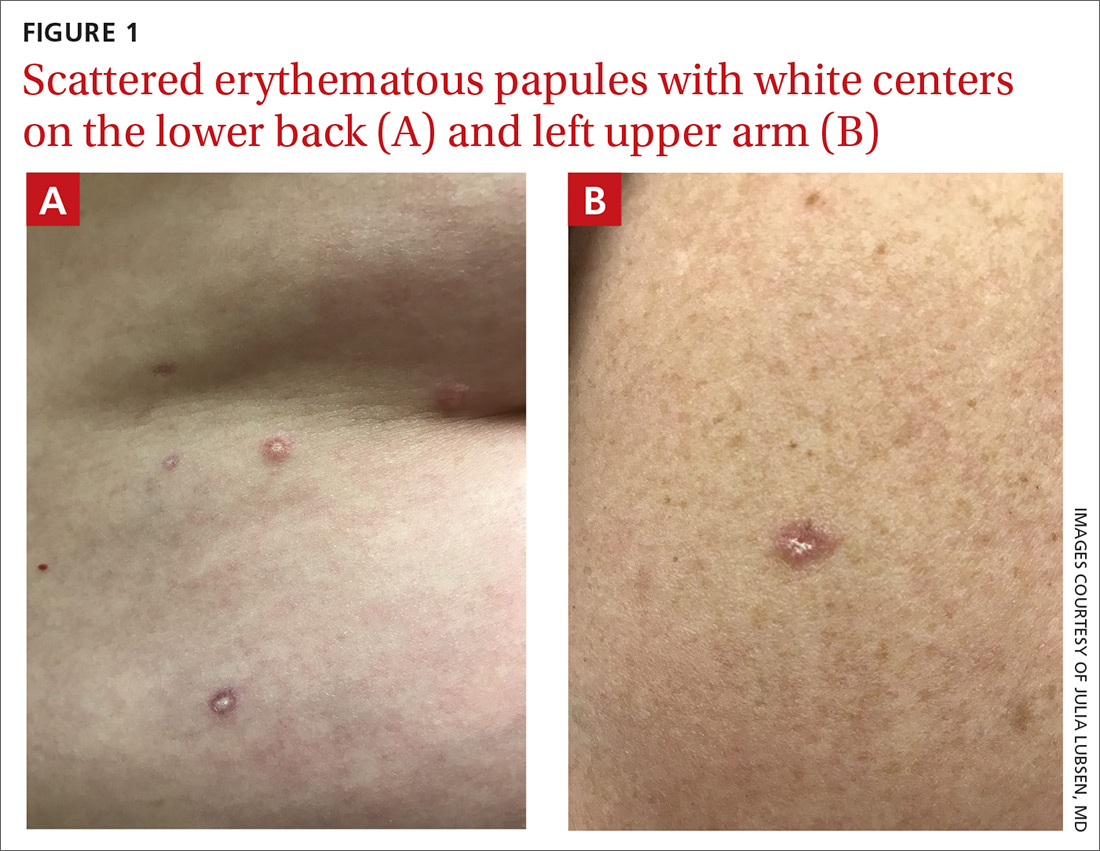

A physical exam revealed scattered erythematous papules with white centers on the patient’s trunk, arms, and legs (FIGURE 1). The patient’s medical history was significant for asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease, urinary incontinence, and depression. Her medications included montelukast, inhaled fluticasone, albuterol, tolterodine, omeprazole, and fluoxetine.

The patient was prescribed nitrofurantoin, 100 mg twice daily for 5 days, to treat her UTI, and a punch biopsy was performed on one of the patient’s lesions to determine the cause of the rash.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

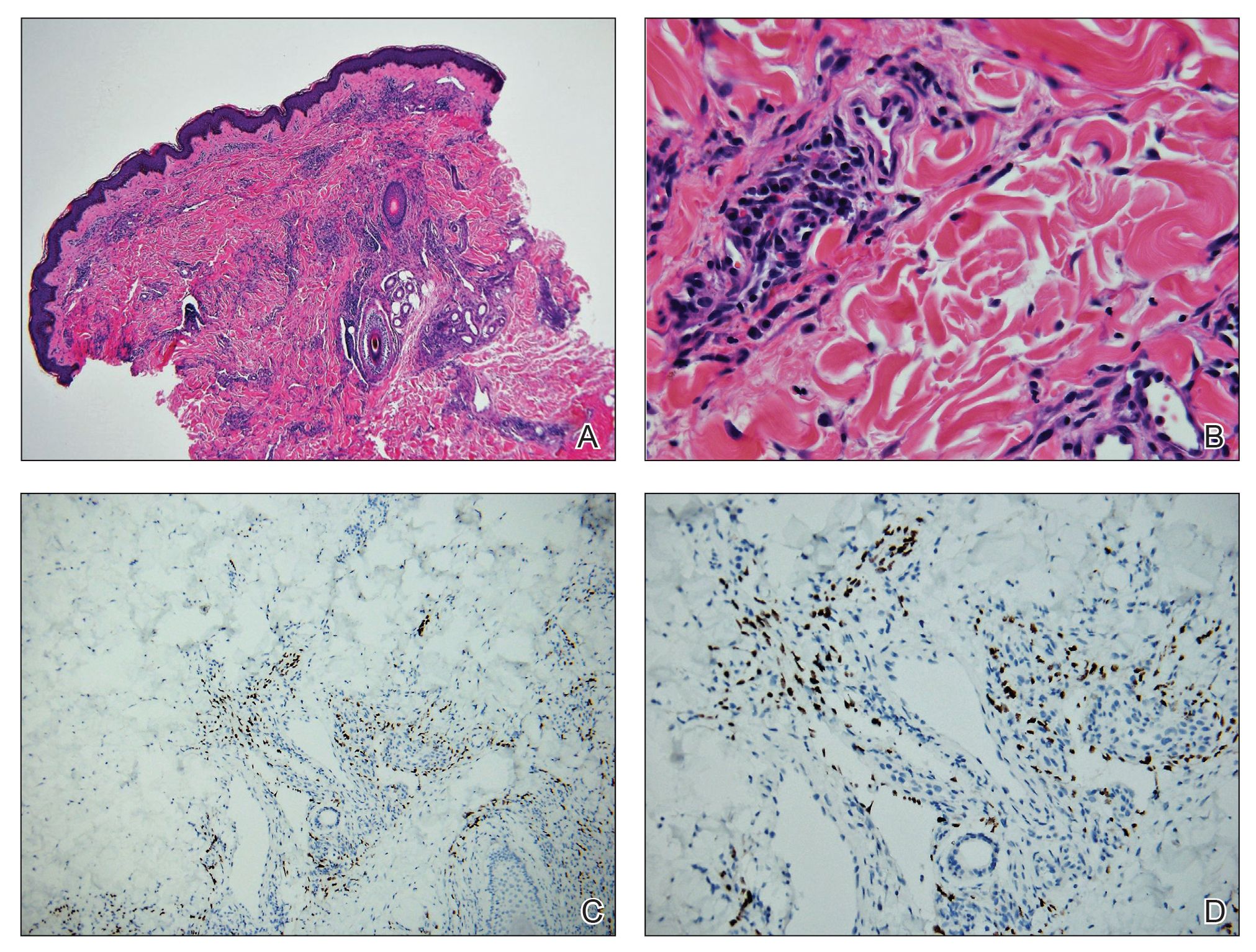

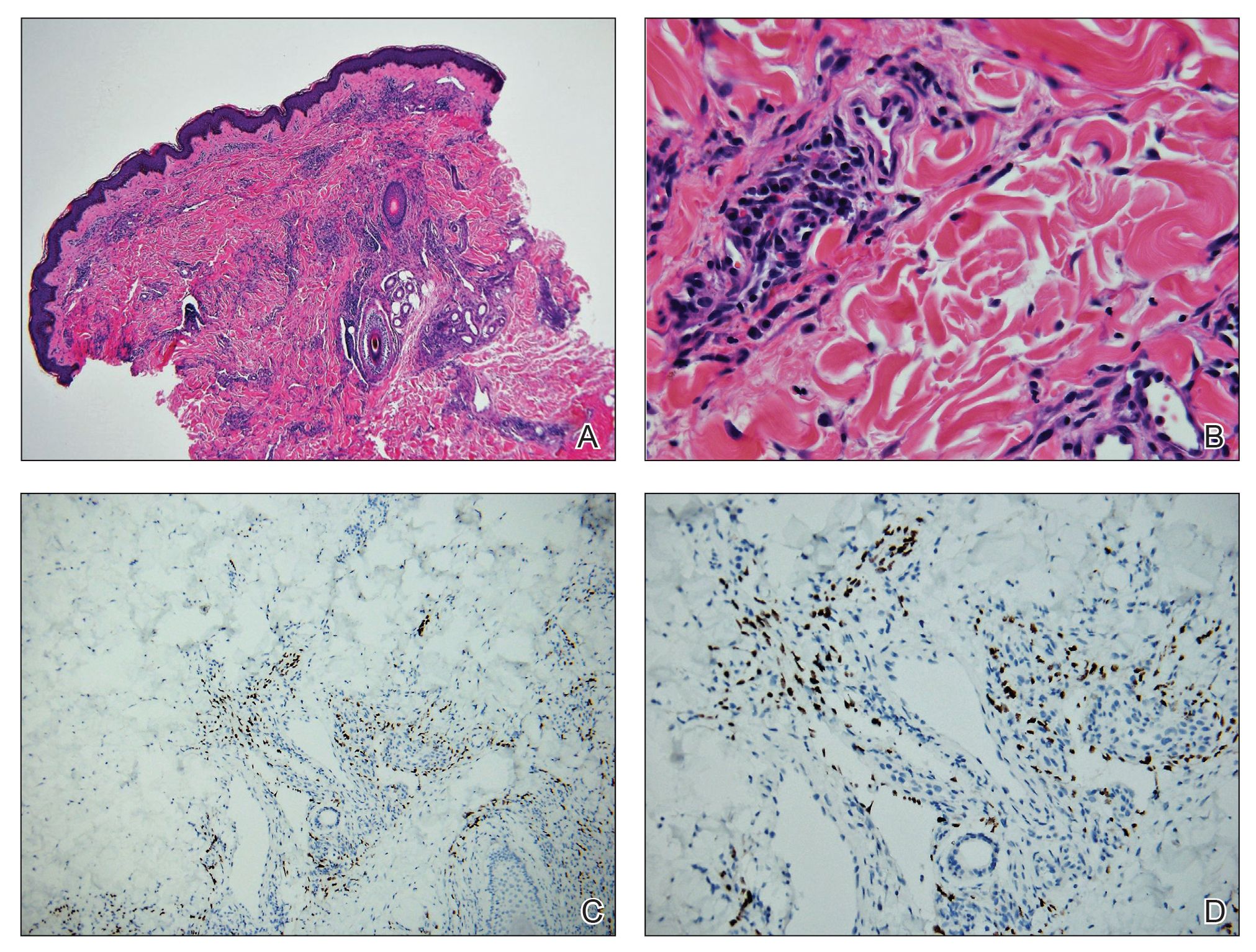

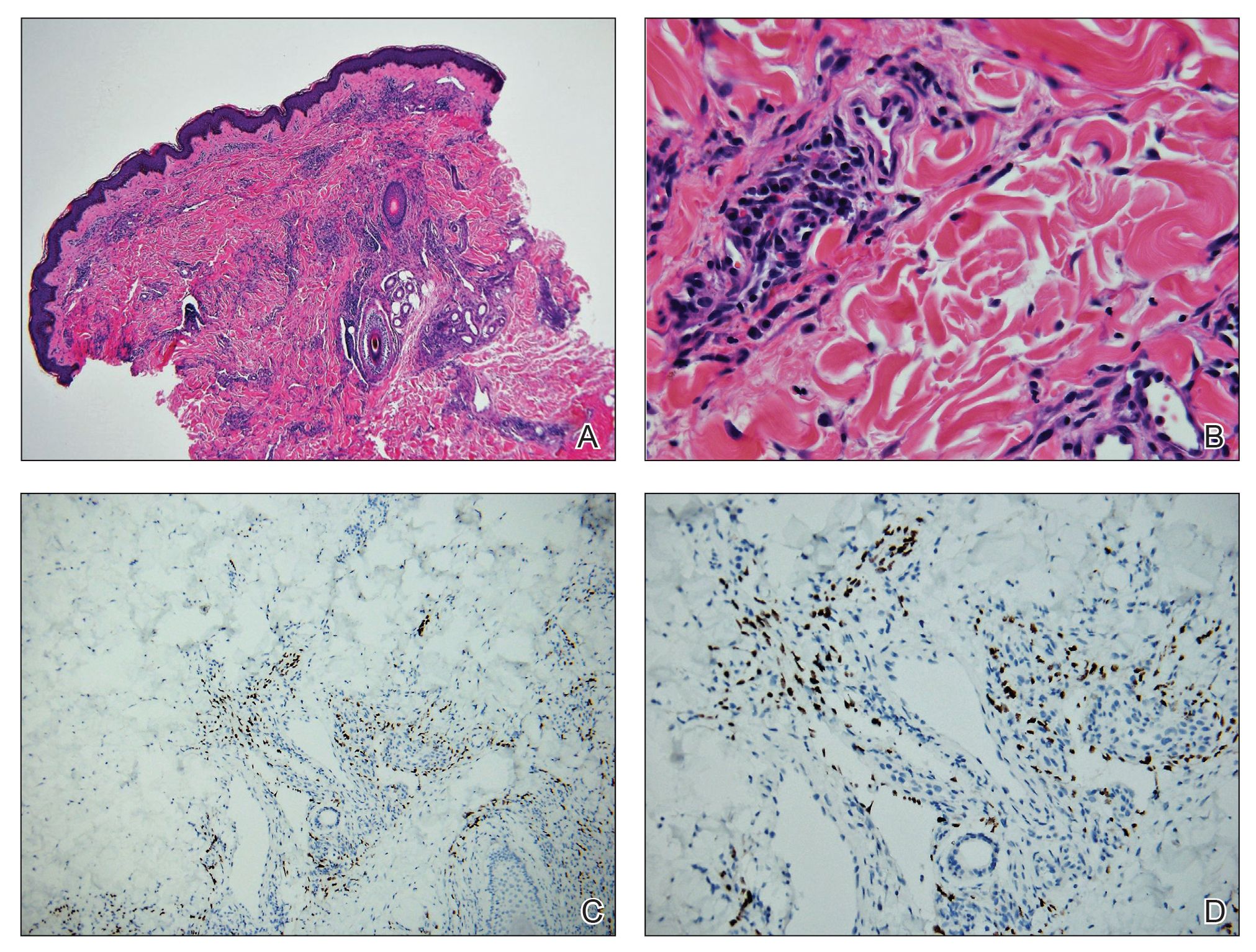

Diagnosis: Atrophic papulosis

Pathology suggested a diagnosis of atrophic papulosis. A consultation with a dermatologist and additional biopsies confirmed the diagnosis. The biopsies showed wedge-shaped areas of superficial dermal sclerosis with thinning of the overlying epidermis. The superficial dermal vessels contained scattered, small thrombi at the periphery of the areas of sclerosis.

Atrophic papulosis (also known as Degos disease or Kölmeier-Degos disease) is a vasculopathy characterized by thrombotic occlusion of small arteries.1 Although rare—with fewer than 200 published case reports in the literature—it is likely underdiagnosed.1 Atrophic papulosis can be distinguished by hallmark skin findings, including 0.5- to 1-cm papular skin lesions with central porcelain-white atrophy and an erythematous, telangiectatic rim.1 It usually manifests between ages 20 to 50 but can occur in infants and children.1 The etiology is unknown, but case evidence suggests the condition is sometimes familial.1,2

Easy to confuse with common conditions

Clinical presentation of atrophic papulosis can vary, but evaluation should rule out systemic lupus erythematosus and other connective tissue diseases.1 In addition, the lesions can easily be confused with other common conditions such as molluscum contagiosum or insect bites.

The hallmark finding of molluscum contagiosum is raised papules with central umbilication, whereas atrophic papulosis lesions are characterized by white centers. While insect bites typically disappear within weeks, atrophic papulosis lesions persist for years or are even lifelong.1

Is it benign or malignant?

Benign atrophic papulosis is limited to the skin.1 The probability of a patient having benign atrophic papulosis is about 70% at the onset of skin lesions and 97% after 7 years without other symptoms.2

Malignant atrophic papulosis—although less common—is systemic and life-threatening. About 30% of patients with atrophic papulosis develop lesions manifesting both on the skin and in internal organs.1,2 Systemic involvement can develop at any time, sometimes years after the appearance of skin lesions, but the risk declines over time.2 In a case series, systemic signs were shown to develop, on average, 1 year after skin lesions.2 Some evidence suggests a mortality rate of 50% within 2 to 3 years of the onset of systemic involvement, making regular follow-up necessary.1

Continue to: Patients with malignant atrophic papulosis...

Patients with malignant atrophic papulosis may have systemic involvement in multiple organ systems. Gastrointestinal (GI) involvement can cause bowel perforation. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement may put the patient at risk for stroke, intracranial bleeding, meningitis, and encephalitis.1,3 There can also be cardiopulmonary involvement that causes pleuritis and pericarditis.1 Ocular involvement can affect the eyelids, conjunctiva, retina, sclera, and choroid plexus.1 Renal involvement has been noted in a few cases.2

In a prospective, single-center cohort study of 39 patients with atrophic papulosis, systemic involvement (malignant atrophic papulosis) was reported in 29% (n = 11) of the patients.2 In these patients, involved organ systems included the GI tract (73%; n = 8), CNS (64%; n = 7), eye (18%; n = 2), heart (18%; n = 2), and lungs (9%; n = 1); 64% (n = 7) had multiorgan involvement. Mortality was reported in 73% of the patients with systemic disease.

Ongoing testing is required

For a patient presenting with atrophic papulosis, initial and follow-up visits should include evaluation for systemic manifestations through a full skin examination, fecal occult blood test, and ocular fundus examination.1,2 If the patient shows any symptoms that suggest systemic involvement, further testing is advised, including evaluation of renal function, colonoscopy, endoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, an echocardiogram, and chest computed tomography.

Because internal organ involvement in malignant atrophic papulosis can develop within years of (benign) cutaneous manifestations, regular follow-up is recommended.1 Research suggests evaluation of patients with benign atrophic papulosis every 6 months for the first 7 years after disease onset and then yearly between 7 and 10 years after onset.2

Treatment options are limited

Antiplatelet agents (aspirin, pentoxifylline, dipyridamole, and ticlodipine) and anticoagulants (heparin) have led to partial regression of skin lesions in case reports.1 Some lesions seem to disappear after treatment, but due to limited evidence, it is difficult to determine whether treatment leads to a reduction of future lesions.

When it comes to malignant atrophic papulosis, there is no uniformly effective treatment. Antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants are often used as initial treatment, but efficacy has not been clearly demonstrated. In case reports, eculizumab and treprostinil have shown effectiveness in treating CNS involvement, but there are no uniform dosage recommendations.3,4

In this case, the patient had mild GI symptoms. A colonoscopy showed evidence of microscopic colitis, but there was no evidence of atrophic papulosis in the GI tract.

Additional laboratory work-up was ordered to evaluate for signs of organ involvement and to rule out any associated connective tissue disease or hypercoagulable state. Her results showed a mildly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (29 mm/h) and a positive antinuclear antibodies assay (1:640, speckled pattern). She was referred to a rheumatologist, who found no evidence of a connective tissue disorder. A complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, and hypercoagulability work-up were all within normal limits. A complete eye exam was also normal.

The patient was started on aspirin 81 mg/d. Because she continued to develop new lesions, her dermatologist added pentoxifylline extended release and gradually increased the dose to 400 mg in the morning and 800 mg in the evening. About 4 years after onset of the rash, the patient showed no signs of systemic involvement, but her skin lesions were still present.

1. Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC, et al. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease)—a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:10.

2. Theodoridis A, Konstantinidou A, Makrantonaki E, et al. Malignant and benign forms of atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease): systemic involvement determines the prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:110-115.

3. Huang YC, Wang JD, Lee FY, et al. Pediatric malignant atrophic papulosis. Pediatrics. 2018;141(suppl 5):S481-S484.

4. Shapiro LS, Toledo-Garcia AE, Farrell JF. Effective treatment of malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease) with treprostinil—early experience. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:52.

A 50-year-old woman presented to her family physician for a urinary tract infection (UTI) and an itchy rash. She said the rash had developed 2 years earlier and had gotten worse, with additional lesions emerging on her skin as time went on. She noted that other physicians had evaluated the rash but provided no clear diagnosis and had done no testing.

A physical exam revealed scattered erythematous papules with white centers on the patient’s trunk, arms, and legs (FIGURE 1). The patient’s medical history was significant for asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease, urinary incontinence, and depression. Her medications included montelukast, inhaled fluticasone, albuterol, tolterodine, omeprazole, and fluoxetine.

The patient was prescribed nitrofurantoin, 100 mg twice daily for 5 days, to treat her UTI, and a punch biopsy was performed on one of the patient’s lesions to determine the cause of the rash.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Atrophic papulosis

Pathology suggested a diagnosis of atrophic papulosis. A consultation with a dermatologist and additional biopsies confirmed the diagnosis. The biopsies showed wedge-shaped areas of superficial dermal sclerosis with thinning of the overlying epidermis. The superficial dermal vessels contained scattered, small thrombi at the periphery of the areas of sclerosis.

Atrophic papulosis (also known as Degos disease or Kölmeier-Degos disease) is a vasculopathy characterized by thrombotic occlusion of small arteries.1 Although rare—with fewer than 200 published case reports in the literature—it is likely underdiagnosed.1 Atrophic papulosis can be distinguished by hallmark skin findings, including 0.5- to 1-cm papular skin lesions with central porcelain-white atrophy and an erythematous, telangiectatic rim.1 It usually manifests between ages 20 to 50 but can occur in infants and children.1 The etiology is unknown, but case evidence suggests the condition is sometimes familial.1,2

Easy to confuse with common conditions

Clinical presentation of atrophic papulosis can vary, but evaluation should rule out systemic lupus erythematosus and other connective tissue diseases.1 In addition, the lesions can easily be confused with other common conditions such as molluscum contagiosum or insect bites.

The hallmark finding of molluscum contagiosum is raised papules with central umbilication, whereas atrophic papulosis lesions are characterized by white centers. While insect bites typically disappear within weeks, atrophic papulosis lesions persist for years or are even lifelong.1

Is it benign or malignant?

Benign atrophic papulosis is limited to the skin.1 The probability of a patient having benign atrophic papulosis is about 70% at the onset of skin lesions and 97% after 7 years without other symptoms.2

Malignant atrophic papulosis—although less common—is systemic and life-threatening. About 30% of patients with atrophic papulosis develop lesions manifesting both on the skin and in internal organs.1,2 Systemic involvement can develop at any time, sometimes years after the appearance of skin lesions, but the risk declines over time.2 In a case series, systemic signs were shown to develop, on average, 1 year after skin lesions.2 Some evidence suggests a mortality rate of 50% within 2 to 3 years of the onset of systemic involvement, making regular follow-up necessary.1

Continue to: Patients with malignant atrophic papulosis...

Patients with malignant atrophic papulosis may have systemic involvement in multiple organ systems. Gastrointestinal (GI) involvement can cause bowel perforation. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement may put the patient at risk for stroke, intracranial bleeding, meningitis, and encephalitis.1,3 There can also be cardiopulmonary involvement that causes pleuritis and pericarditis.1 Ocular involvement can affect the eyelids, conjunctiva, retina, sclera, and choroid plexus.1 Renal involvement has been noted in a few cases.2

In a prospective, single-center cohort study of 39 patients with atrophic papulosis, systemic involvement (malignant atrophic papulosis) was reported in 29% (n = 11) of the patients.2 In these patients, involved organ systems included the GI tract (73%; n = 8), CNS (64%; n = 7), eye (18%; n = 2), heart (18%; n = 2), and lungs (9%; n = 1); 64% (n = 7) had multiorgan involvement. Mortality was reported in 73% of the patients with systemic disease.

Ongoing testing is required

For a patient presenting with atrophic papulosis, initial and follow-up visits should include evaluation for systemic manifestations through a full skin examination, fecal occult blood test, and ocular fundus examination.1,2 If the patient shows any symptoms that suggest systemic involvement, further testing is advised, including evaluation of renal function, colonoscopy, endoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, an echocardiogram, and chest computed tomography.

Because internal organ involvement in malignant atrophic papulosis can develop within years of (benign) cutaneous manifestations, regular follow-up is recommended.1 Research suggests evaluation of patients with benign atrophic papulosis every 6 months for the first 7 years after disease onset and then yearly between 7 and 10 years after onset.2

Treatment options are limited

Antiplatelet agents (aspirin, pentoxifylline, dipyridamole, and ticlodipine) and anticoagulants (heparin) have led to partial regression of skin lesions in case reports.1 Some lesions seem to disappear after treatment, but due to limited evidence, it is difficult to determine whether treatment leads to a reduction of future lesions.

When it comes to malignant atrophic papulosis, there is no uniformly effective treatment. Antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants are often used as initial treatment, but efficacy has not been clearly demonstrated. In case reports, eculizumab and treprostinil have shown effectiveness in treating CNS involvement, but there are no uniform dosage recommendations.3,4

In this case, the patient had mild GI symptoms. A colonoscopy showed evidence of microscopic colitis, but there was no evidence of atrophic papulosis in the GI tract.

Additional laboratory work-up was ordered to evaluate for signs of organ involvement and to rule out any associated connective tissue disease or hypercoagulable state. Her results showed a mildly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (29 mm/h) and a positive antinuclear antibodies assay (1:640, speckled pattern). She was referred to a rheumatologist, who found no evidence of a connective tissue disorder. A complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, and hypercoagulability work-up were all within normal limits. A complete eye exam was also normal.

The patient was started on aspirin 81 mg/d. Because she continued to develop new lesions, her dermatologist added pentoxifylline extended release and gradually increased the dose to 400 mg in the morning and 800 mg in the evening. About 4 years after onset of the rash, the patient showed no signs of systemic involvement, but her skin lesions were still present.

A 50-year-old woman presented to her family physician for a urinary tract infection (UTI) and an itchy rash. She said the rash had developed 2 years earlier and had gotten worse, with additional lesions emerging on her skin as time went on. She noted that other physicians had evaluated the rash but provided no clear diagnosis and had done no testing.

A physical exam revealed scattered erythematous papules with white centers on the patient’s trunk, arms, and legs (FIGURE 1). The patient’s medical history was significant for asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease, urinary incontinence, and depression. Her medications included montelukast, inhaled fluticasone, albuterol, tolterodine, omeprazole, and fluoxetine.

The patient was prescribed nitrofurantoin, 100 mg twice daily for 5 days, to treat her UTI, and a punch biopsy was performed on one of the patient’s lesions to determine the cause of the rash.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Atrophic papulosis

Pathology suggested a diagnosis of atrophic papulosis. A consultation with a dermatologist and additional biopsies confirmed the diagnosis. The biopsies showed wedge-shaped areas of superficial dermal sclerosis with thinning of the overlying epidermis. The superficial dermal vessels contained scattered, small thrombi at the periphery of the areas of sclerosis.

Atrophic papulosis (also known as Degos disease or Kölmeier-Degos disease) is a vasculopathy characterized by thrombotic occlusion of small arteries.1 Although rare—with fewer than 200 published case reports in the literature—it is likely underdiagnosed.1 Atrophic papulosis can be distinguished by hallmark skin findings, including 0.5- to 1-cm papular skin lesions with central porcelain-white atrophy and an erythematous, telangiectatic rim.1 It usually manifests between ages 20 to 50 but can occur in infants and children.1 The etiology is unknown, but case evidence suggests the condition is sometimes familial.1,2

Easy to confuse with common conditions

Clinical presentation of atrophic papulosis can vary, but evaluation should rule out systemic lupus erythematosus and other connective tissue diseases.1 In addition, the lesions can easily be confused with other common conditions such as molluscum contagiosum or insect bites.

The hallmark finding of molluscum contagiosum is raised papules with central umbilication, whereas atrophic papulosis lesions are characterized by white centers. While insect bites typically disappear within weeks, atrophic papulosis lesions persist for years or are even lifelong.1

Is it benign or malignant?

Benign atrophic papulosis is limited to the skin.1 The probability of a patient having benign atrophic papulosis is about 70% at the onset of skin lesions and 97% after 7 years without other symptoms.2

Malignant atrophic papulosis—although less common—is systemic and life-threatening. About 30% of patients with atrophic papulosis develop lesions manifesting both on the skin and in internal organs.1,2 Systemic involvement can develop at any time, sometimes years after the appearance of skin lesions, but the risk declines over time.2 In a case series, systemic signs were shown to develop, on average, 1 year after skin lesions.2 Some evidence suggests a mortality rate of 50% within 2 to 3 years of the onset of systemic involvement, making regular follow-up necessary.1

Continue to: Patients with malignant atrophic papulosis...

Patients with malignant atrophic papulosis may have systemic involvement in multiple organ systems. Gastrointestinal (GI) involvement can cause bowel perforation. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement may put the patient at risk for stroke, intracranial bleeding, meningitis, and encephalitis.1,3 There can also be cardiopulmonary involvement that causes pleuritis and pericarditis.1 Ocular involvement can affect the eyelids, conjunctiva, retina, sclera, and choroid plexus.1 Renal involvement has been noted in a few cases.2

In a prospective, single-center cohort study of 39 patients with atrophic papulosis, systemic involvement (malignant atrophic papulosis) was reported in 29% (n = 11) of the patients.2 In these patients, involved organ systems included the GI tract (73%; n = 8), CNS (64%; n = 7), eye (18%; n = 2), heart (18%; n = 2), and lungs (9%; n = 1); 64% (n = 7) had multiorgan involvement. Mortality was reported in 73% of the patients with systemic disease.

Ongoing testing is required

For a patient presenting with atrophic papulosis, initial and follow-up visits should include evaluation for systemic manifestations through a full skin examination, fecal occult blood test, and ocular fundus examination.1,2 If the patient shows any symptoms that suggest systemic involvement, further testing is advised, including evaluation of renal function, colonoscopy, endoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, an echocardiogram, and chest computed tomography.

Because internal organ involvement in malignant atrophic papulosis can develop within years of (benign) cutaneous manifestations, regular follow-up is recommended.1 Research suggests evaluation of patients with benign atrophic papulosis every 6 months for the first 7 years after disease onset and then yearly between 7 and 10 years after onset.2

Treatment options are limited

Antiplatelet agents (aspirin, pentoxifylline, dipyridamole, and ticlodipine) and anticoagulants (heparin) have led to partial regression of skin lesions in case reports.1 Some lesions seem to disappear after treatment, but due to limited evidence, it is difficult to determine whether treatment leads to a reduction of future lesions.

When it comes to malignant atrophic papulosis, there is no uniformly effective treatment. Antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants are often used as initial treatment, but efficacy has not been clearly demonstrated. In case reports, eculizumab and treprostinil have shown effectiveness in treating CNS involvement, but there are no uniform dosage recommendations.3,4

In this case, the patient had mild GI symptoms. A colonoscopy showed evidence of microscopic colitis, but there was no evidence of atrophic papulosis in the GI tract.