User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Nurse practitioner fined $20k for advertising herself as ‘Doctor Sarah’

Last month, the San Luis Obispo County, California, District Attorney Dan Dow filed a complaint against Sarah Erny, RN, NP, citing unfair business practices and unprofessional conduct.

According to court documents, California’s Medical Practice Act does not permit individuals to refer to themselves as “doctor, physician, or any other terms or letters indicating or implying that he or she is a physician and surgeon ... without having ... a certificate as a physician and surgeon.”

Individuals who misrepresent themselves are subject to misdemeanor charges and civil penalties.

In addition to the fine, Ms. Erny agreed to refrain from referring to herself as a doctor in her practice and on social media. She has already deleted her Twitter account.

The case underscores tensions between physicians fighting to preserve their scope of practice and the allied professionals that U.S. lawmakers increasingly see as a less expensive way to improve access to health care.

The American Medical Association and specialty groups strongly oppose a new bill, the Improving Care and Access to Nurses Act, that would expand the scope of practice for nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

Court records show that Ms. Erny earned a doctor of nursing practice (DNP) degree from Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and that she met the state requirements to obtain licensure as a registered nurse and nurse practitioner. In 2018, she opened a practice in Arroyo Grande, California, called Holistic Women’s Healing, where she provided medical services and drug supplements to patients.

She also entered a collaborative agreement with ob.gyn. Anika Moore, MD, for approximately 3 years. Dr. Moore’s medical practice was in another county and state, and the physician returned every 2 to 3 months to review a portion of Ms. Erny’s patient files.

Ms. Erny and Dr. Moore terminated the collaborative agreement in March, according to court documents.

However, Mr. Dow alleged that Ms. Erny regularly referred to herself as “Dr. Sarah” or “Dr. Sarah Erny” in her online advertising and social media accounts. Her patients “were so proud of her” that they called her doctor, and her supervising physician instructed staff to do the same.

Mr. Dow said Ms. Erny did not clearly advise the public that she was not a medical doctor and failed to identify her supervising physician. “Simply put, there is a great need for health care providers to state their level of training and licensing clearly and honestly in all of their advertising and marketing materials,” he said in a press release.

In California, nurse practitioners who have been certified by the Board of Registered Nursing may use the following titles: Advanced Practice Registered Nurse; Certified Nurse Practitioner; APRN-CNP; RN and NP; or a combination of other letters or words to identify specialization, such as adult nurse practitioner, pediatric nurse practitioner, obstetrical-gynecological nurse practitioner, and family nurse practitioner.

As educational requirements shift for advanced practice clinicians, similar cases will likely emerge, said Grant Martsolf, PhD, MPH, RN, FAAN, professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

“Scope of practice is governed by states, [so they] will have to figure [it] out as more professional disciplines move to clinical doctorates as the entry to practice. Pharma, [physical therapy], and [occupational therapy] have already done this, and advanced practice nursing is on its way. [Certified registered nurse anesthetists] are already required to get a DNP to sit for certification,” he said.

More guidance is needed, especially when considering other professions like dentists, clinical psychologists, and individuals with clinical or research doctorates who often call themselves doctors, Dr. Martsolf said.

“It seems that the honorific of ‘Dr.’ emerges from the degree, not from being a physician or surgeon,” he said.

Beyond the false advertising, Mr. Dow alleged that Ms. Erny did not file a fictitious business name statement for 2020 and 2021 – a requirement under the California Business and Professions Code to identify who is operating the business.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Last month, the San Luis Obispo County, California, District Attorney Dan Dow filed a complaint against Sarah Erny, RN, NP, citing unfair business practices and unprofessional conduct.

According to court documents, California’s Medical Practice Act does not permit individuals to refer to themselves as “doctor, physician, or any other terms or letters indicating or implying that he or she is a physician and surgeon ... without having ... a certificate as a physician and surgeon.”

Individuals who misrepresent themselves are subject to misdemeanor charges and civil penalties.

In addition to the fine, Ms. Erny agreed to refrain from referring to herself as a doctor in her practice and on social media. She has already deleted her Twitter account.

The case underscores tensions between physicians fighting to preserve their scope of practice and the allied professionals that U.S. lawmakers increasingly see as a less expensive way to improve access to health care.

The American Medical Association and specialty groups strongly oppose a new bill, the Improving Care and Access to Nurses Act, that would expand the scope of practice for nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

Court records show that Ms. Erny earned a doctor of nursing practice (DNP) degree from Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and that she met the state requirements to obtain licensure as a registered nurse and nurse practitioner. In 2018, she opened a practice in Arroyo Grande, California, called Holistic Women’s Healing, where she provided medical services and drug supplements to patients.

She also entered a collaborative agreement with ob.gyn. Anika Moore, MD, for approximately 3 years. Dr. Moore’s medical practice was in another county and state, and the physician returned every 2 to 3 months to review a portion of Ms. Erny’s patient files.

Ms. Erny and Dr. Moore terminated the collaborative agreement in March, according to court documents.

However, Mr. Dow alleged that Ms. Erny regularly referred to herself as “Dr. Sarah” or “Dr. Sarah Erny” in her online advertising and social media accounts. Her patients “were so proud of her” that they called her doctor, and her supervising physician instructed staff to do the same.

Mr. Dow said Ms. Erny did not clearly advise the public that she was not a medical doctor and failed to identify her supervising physician. “Simply put, there is a great need for health care providers to state their level of training and licensing clearly and honestly in all of their advertising and marketing materials,” he said in a press release.

In California, nurse practitioners who have been certified by the Board of Registered Nursing may use the following titles: Advanced Practice Registered Nurse; Certified Nurse Practitioner; APRN-CNP; RN and NP; or a combination of other letters or words to identify specialization, such as adult nurse practitioner, pediatric nurse practitioner, obstetrical-gynecological nurse practitioner, and family nurse practitioner.

As educational requirements shift for advanced practice clinicians, similar cases will likely emerge, said Grant Martsolf, PhD, MPH, RN, FAAN, professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

“Scope of practice is governed by states, [so they] will have to figure [it] out as more professional disciplines move to clinical doctorates as the entry to practice. Pharma, [physical therapy], and [occupational therapy] have already done this, and advanced practice nursing is on its way. [Certified registered nurse anesthetists] are already required to get a DNP to sit for certification,” he said.

More guidance is needed, especially when considering other professions like dentists, clinical psychologists, and individuals with clinical or research doctorates who often call themselves doctors, Dr. Martsolf said.

“It seems that the honorific of ‘Dr.’ emerges from the degree, not from being a physician or surgeon,” he said.

Beyond the false advertising, Mr. Dow alleged that Ms. Erny did not file a fictitious business name statement for 2020 and 2021 – a requirement under the California Business and Professions Code to identify who is operating the business.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Last month, the San Luis Obispo County, California, District Attorney Dan Dow filed a complaint against Sarah Erny, RN, NP, citing unfair business practices and unprofessional conduct.

According to court documents, California’s Medical Practice Act does not permit individuals to refer to themselves as “doctor, physician, or any other terms or letters indicating or implying that he or she is a physician and surgeon ... without having ... a certificate as a physician and surgeon.”

Individuals who misrepresent themselves are subject to misdemeanor charges and civil penalties.

In addition to the fine, Ms. Erny agreed to refrain from referring to herself as a doctor in her practice and on social media. She has already deleted her Twitter account.

The case underscores tensions between physicians fighting to preserve their scope of practice and the allied professionals that U.S. lawmakers increasingly see as a less expensive way to improve access to health care.

The American Medical Association and specialty groups strongly oppose a new bill, the Improving Care and Access to Nurses Act, that would expand the scope of practice for nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

Court records show that Ms. Erny earned a doctor of nursing practice (DNP) degree from Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and that she met the state requirements to obtain licensure as a registered nurse and nurse practitioner. In 2018, she opened a practice in Arroyo Grande, California, called Holistic Women’s Healing, where she provided medical services and drug supplements to patients.

She also entered a collaborative agreement with ob.gyn. Anika Moore, MD, for approximately 3 years. Dr. Moore’s medical practice was in another county and state, and the physician returned every 2 to 3 months to review a portion of Ms. Erny’s patient files.

Ms. Erny and Dr. Moore terminated the collaborative agreement in March, according to court documents.

However, Mr. Dow alleged that Ms. Erny regularly referred to herself as “Dr. Sarah” or “Dr. Sarah Erny” in her online advertising and social media accounts. Her patients “were so proud of her” that they called her doctor, and her supervising physician instructed staff to do the same.

Mr. Dow said Ms. Erny did not clearly advise the public that she was not a medical doctor and failed to identify her supervising physician. “Simply put, there is a great need for health care providers to state their level of training and licensing clearly and honestly in all of their advertising and marketing materials,” he said in a press release.

In California, nurse practitioners who have been certified by the Board of Registered Nursing may use the following titles: Advanced Practice Registered Nurse; Certified Nurse Practitioner; APRN-CNP; RN and NP; or a combination of other letters or words to identify specialization, such as adult nurse practitioner, pediatric nurse practitioner, obstetrical-gynecological nurse practitioner, and family nurse practitioner.

As educational requirements shift for advanced practice clinicians, similar cases will likely emerge, said Grant Martsolf, PhD, MPH, RN, FAAN, professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

“Scope of practice is governed by states, [so they] will have to figure [it] out as more professional disciplines move to clinical doctorates as the entry to practice. Pharma, [physical therapy], and [occupational therapy] have already done this, and advanced practice nursing is on its way. [Certified registered nurse anesthetists] are already required to get a DNP to sit for certification,” he said.

More guidance is needed, especially when considering other professions like dentists, clinical psychologists, and individuals with clinical or research doctorates who often call themselves doctors, Dr. Martsolf said.

“It seems that the honorific of ‘Dr.’ emerges from the degree, not from being a physician or surgeon,” he said.

Beyond the false advertising, Mr. Dow alleged that Ms. Erny did not file a fictitious business name statement for 2020 and 2021 – a requirement under the California Business and Professions Code to identify who is operating the business.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Diffuse Papular Eruption With Erosions and Ulcerations

The Diagnosis: Immunotherapy-Related Lichenoid Drug Eruption

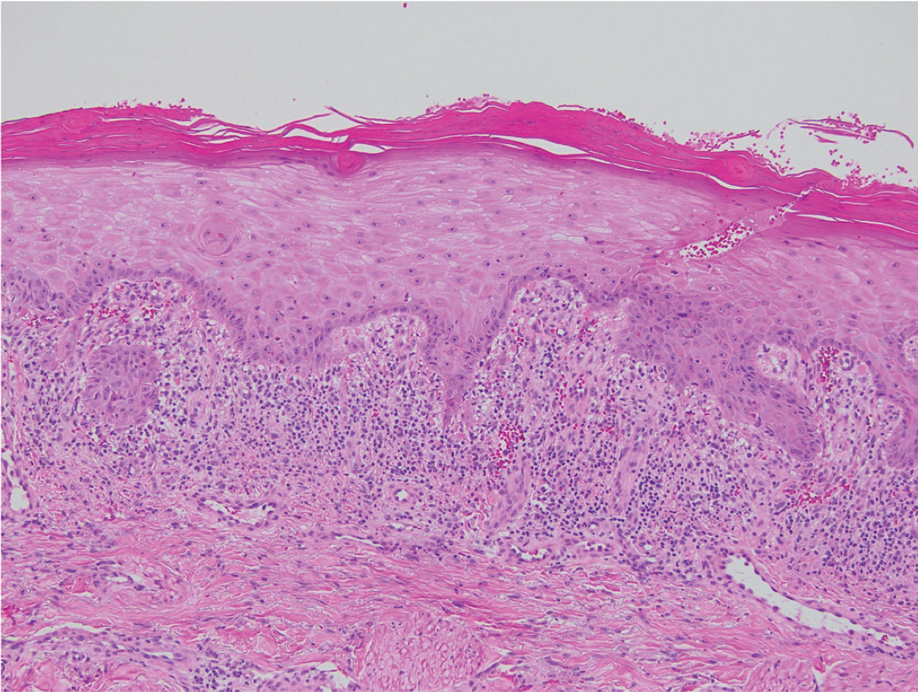

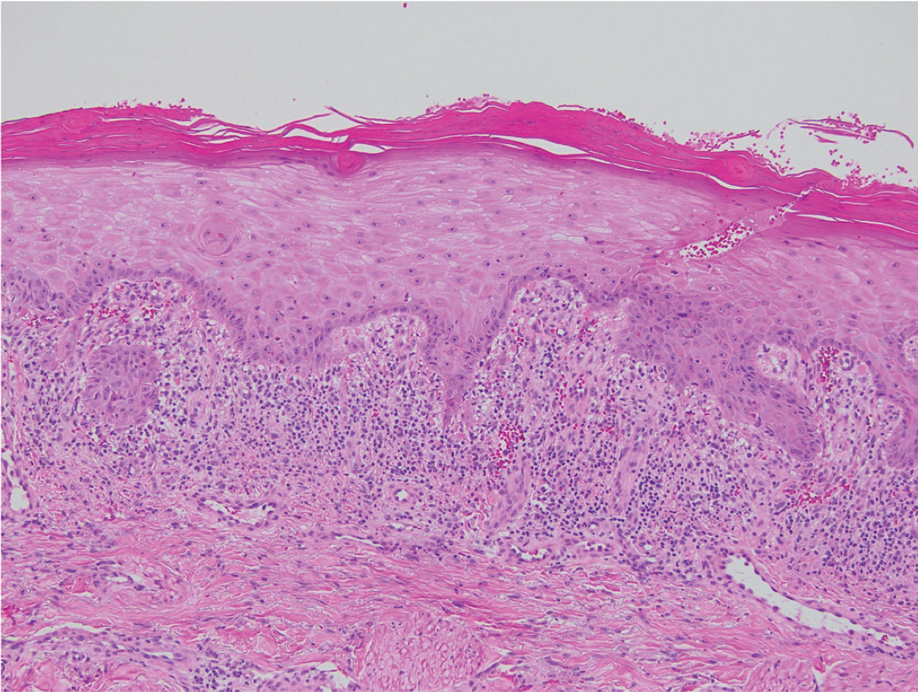

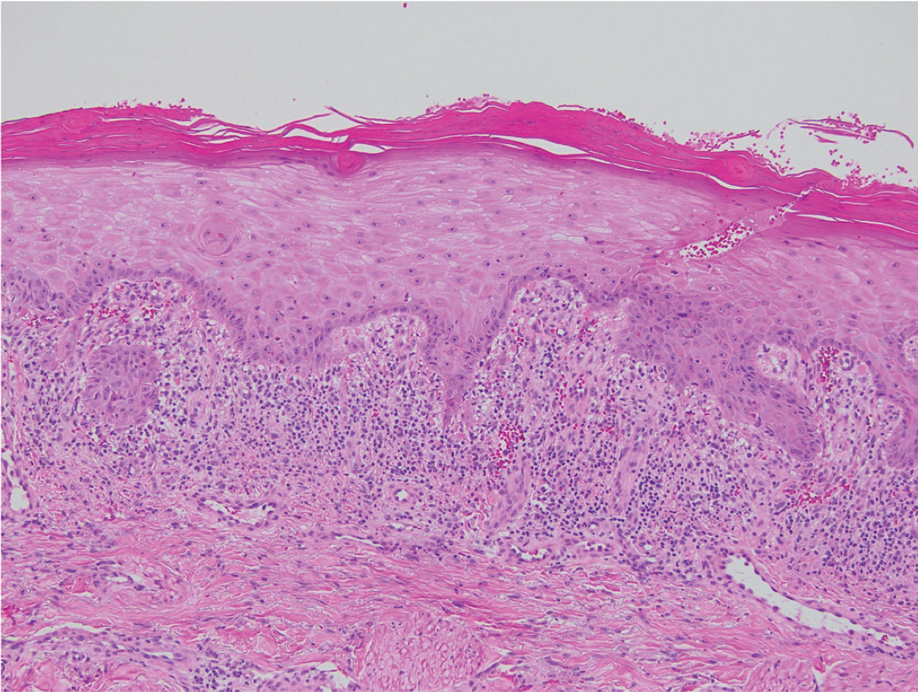

Direct immunofluorescence was negative, and histopathology revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis, minimal parakeratosis, and saw-toothed rete ridges (Figure 1). He was diagnosed with an immunotherapyrelated lichenoid drug eruption based on the morphology of the skin lesions and clinicopathologic correlation. Bullous pemphigoid and lichen planus pemphigoides were ruled out given the negative direct immunofluorescence findings. Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) was not consistent with the clinical presentation, especially given the lack of mucosal findings. The histology also was not consistent, as the biopsy specimen lacked apoptotic and necrotic keratinocytes to the degree seen in SJS/TEN and also had a greater degree of inflammatory infiltrate. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome was ruled out given the lack of systemic findings, including facial swelling and lymphadenopathy and the clinical appearance of the rash. No morbilliform features were present, which is the most common presentation of DRESS syndrome.

Checkpoint inhibitor (CPI) therapy has become the cornerstone in management of certain advanced malignancies.1 Checkpoint inhibitors block cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4, programmed cell death-1, and/or programmed cell death ligand-1, allowing activated T cells to infiltrate the tumor microenvironment and destroy malignant cells. Checkpoint inhibitors are approved for the treatment of melanoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma and are being investigated in various other cutaneous and soft tissue malignancies.1-3

Although CPIs have shown substantial efficacy in the management of advanced malignancies, immune-related adverse events (AEs) are common due to nonspecific immune activation.2 Immune-related cutaneous AEs are the most common immune-related AEs, occurring in 30% to 50% of patients who undergo treatment.2-5 Common immune-related cutaneous AEs include maculopapular, psoriasiform, and lichenoid dermatitis, as well as pruritus without dermatitis.2,3,6 Other reactions include but are not limited to bullous pemphigoid, vitiligolike depigmentation, and alopecia.2,3 Immune-related cutaneous AEs usually are self-limited; however, severe life-threatening reactions such as the spectrum of SJS/TEN and DRESS syndrome also can occur.2-4 Immune-related cutaneous AEs are graded based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: grade 1 reactions are asymptomatic and cover less than 10% of the patient’s body surface area (BSA), grade 2 reactions have mild symptoms and cover 10% to 30% of the patient’s BSA, grade 3 reactions have moderate to severe symptoms and cover greater than 30% of the patient’s BSA, and grade 4 reactions are life-threatening.2,3 With prompt recognition and adequate treatment, mild to moderate immune-related cutaneous AEs—grades 1 and 2—largely are reversible, and less than 5% require discontinuation of therapy.2,3,6 It has been suggested that immune-related cutaneous AEs may be a positive prognostic factor in the treatment of underlying malignancy, indicating adequate immune activation targeting the malignant cells.6

Although our patient had some typical violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques with Wickham striae, he also had atypical findings for a lichenoid reaction. Given the endorsement of blisters, it is possible that some of these lesions initially were bullous and subsequently ruptured, leaving behind erosions. However, in other areas, there also were eroded papules and ulcerations without a reported history of excoriation, scratching, picking, or prior bullae, including difficult-to-reach areas such as the back. It is favored that these lesions represented a robust lichenoid dermatitis leading to erosive and ulcerated lesions, similar to the formation of bullous lichen planus. Lichenoid eruptions secondary to immunotherapy are well-known phenomena, but a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms ulcer, lichenoid, and immunotherapy revealed only 2 cases of ulcerative lichenoid eruptions: a localized digital erosive lichenoid dermatitis and a widespread ulcerative lichenoid drug eruption without true erosions.7,8 However, widespread erosive and ulcerated lichenoid reactions are rare.

Lichenoid eruptions most strongly are associated with anti–programmed cell death-1/ programmed cell death ligand-1 therapy, occurring in 20% of patients undergoing treatment.3 Lichenoid eruptions present as discrete, pruritic, erythematous, violaceous papules and plaques on the chest and back and rarely may involve the limbs, palmoplantar surfaces, and oral mucosa.2,3,6 Histopathologic features include a dense bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis with scattered apoptotic keratinocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis.2,4,6 Grades 1 to 2 lesions can be managed with high-potency topical corticosteroids without CPI dose interruption, with more extensive grade 2 lesions requiring systemic corticosteroids.2,6,9 Lichenoid eruptions grade 3 or higher also require systemic corticosteroid therapy CPI therapy cessation until the eruption has receded to grade 0 to 1.2 Alternative treatment options for high-grade toxicity include phototherapy and acitretin.2,4,9

Our patient was treated with cessation of immunotherapy and initiation of a systemic corticosteroid taper, acitretin, and narrowband UVB therapy. After 6 weeks of treatment, the pain and pruritus improved and the rash had resolved in some areas while it had taken on a more classic lichenoid appearance with violaceous scaly papules and plaques (Figure 2) in areas of prior ulcers and erosions. He no longer had any bullae, erosions, or ulcers.

- Barrios DM, Do MH, Phillips GS, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat cutaneous malignancies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1239-1253. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.131

- Geisler AN, Phillips GS, Barrios DM, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1255-1268. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.132

- Tattersall IW, Leventhal JS. Cutaneous toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors: the role of the dermatologist. Yale J Biol Med. 2020;93:123-132.

- Si X, He C, Zhang L, et al. Management of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. Thorac Cancer. 2020;11:488-492. doi:10.1111/1759-7714.13275

- Eggermont AMM, Kicinski M, Blank CU, et al. Association between immune-related adverse events and recurrence-free survival among patients with stage III melanoma randomized to receive pembrolizumab or placebo: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:519-527. doi:10.1001 /jamaoncol.2019.5570

- Sibaud V, Meyer N, Lamant L, et al. Dermatologic complications of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28:254-263. doi:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000290

- Martínez-Doménech Á, García-Legaz Martínez M, Magdaleno-Tapial J, et al. Digital ulcerative lichenoid dermatitis in a patient receiving anti-PD-1 therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt8sm0j7t7.

- Davis MJ, Wilken R, Fung MA, et al. Debilitating erosive lichenoid interface dermatitis from checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt3vq6b04v.

- Apalla Z, Papageorgiou C, Lallas A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a literature review [published online January 29, 2021]. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:E2021155. doi:10.5826/dpc.1101a155

The Diagnosis: Immunotherapy-Related Lichenoid Drug Eruption

Direct immunofluorescence was negative, and histopathology revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis, minimal parakeratosis, and saw-toothed rete ridges (Figure 1). He was diagnosed with an immunotherapyrelated lichenoid drug eruption based on the morphology of the skin lesions and clinicopathologic correlation. Bullous pemphigoid and lichen planus pemphigoides were ruled out given the negative direct immunofluorescence findings. Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) was not consistent with the clinical presentation, especially given the lack of mucosal findings. The histology also was not consistent, as the biopsy specimen lacked apoptotic and necrotic keratinocytes to the degree seen in SJS/TEN and also had a greater degree of inflammatory infiltrate. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome was ruled out given the lack of systemic findings, including facial swelling and lymphadenopathy and the clinical appearance of the rash. No morbilliform features were present, which is the most common presentation of DRESS syndrome.

Checkpoint inhibitor (CPI) therapy has become the cornerstone in management of certain advanced malignancies.1 Checkpoint inhibitors block cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4, programmed cell death-1, and/or programmed cell death ligand-1, allowing activated T cells to infiltrate the tumor microenvironment and destroy malignant cells. Checkpoint inhibitors are approved for the treatment of melanoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma and are being investigated in various other cutaneous and soft tissue malignancies.1-3

Although CPIs have shown substantial efficacy in the management of advanced malignancies, immune-related adverse events (AEs) are common due to nonspecific immune activation.2 Immune-related cutaneous AEs are the most common immune-related AEs, occurring in 30% to 50% of patients who undergo treatment.2-5 Common immune-related cutaneous AEs include maculopapular, psoriasiform, and lichenoid dermatitis, as well as pruritus without dermatitis.2,3,6 Other reactions include but are not limited to bullous pemphigoid, vitiligolike depigmentation, and alopecia.2,3 Immune-related cutaneous AEs usually are self-limited; however, severe life-threatening reactions such as the spectrum of SJS/TEN and DRESS syndrome also can occur.2-4 Immune-related cutaneous AEs are graded based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: grade 1 reactions are asymptomatic and cover less than 10% of the patient’s body surface area (BSA), grade 2 reactions have mild symptoms and cover 10% to 30% of the patient’s BSA, grade 3 reactions have moderate to severe symptoms and cover greater than 30% of the patient’s BSA, and grade 4 reactions are life-threatening.2,3 With prompt recognition and adequate treatment, mild to moderate immune-related cutaneous AEs—grades 1 and 2—largely are reversible, and less than 5% require discontinuation of therapy.2,3,6 It has been suggested that immune-related cutaneous AEs may be a positive prognostic factor in the treatment of underlying malignancy, indicating adequate immune activation targeting the malignant cells.6

Although our patient had some typical violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques with Wickham striae, he also had atypical findings for a lichenoid reaction. Given the endorsement of blisters, it is possible that some of these lesions initially were bullous and subsequently ruptured, leaving behind erosions. However, in other areas, there also were eroded papules and ulcerations without a reported history of excoriation, scratching, picking, or prior bullae, including difficult-to-reach areas such as the back. It is favored that these lesions represented a robust lichenoid dermatitis leading to erosive and ulcerated lesions, similar to the formation of bullous lichen planus. Lichenoid eruptions secondary to immunotherapy are well-known phenomena, but a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms ulcer, lichenoid, and immunotherapy revealed only 2 cases of ulcerative lichenoid eruptions: a localized digital erosive lichenoid dermatitis and a widespread ulcerative lichenoid drug eruption without true erosions.7,8 However, widespread erosive and ulcerated lichenoid reactions are rare.

Lichenoid eruptions most strongly are associated with anti–programmed cell death-1/ programmed cell death ligand-1 therapy, occurring in 20% of patients undergoing treatment.3 Lichenoid eruptions present as discrete, pruritic, erythematous, violaceous papules and plaques on the chest and back and rarely may involve the limbs, palmoplantar surfaces, and oral mucosa.2,3,6 Histopathologic features include a dense bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis with scattered apoptotic keratinocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis.2,4,6 Grades 1 to 2 lesions can be managed with high-potency topical corticosteroids without CPI dose interruption, with more extensive grade 2 lesions requiring systemic corticosteroids.2,6,9 Lichenoid eruptions grade 3 or higher also require systemic corticosteroid therapy CPI therapy cessation until the eruption has receded to grade 0 to 1.2 Alternative treatment options for high-grade toxicity include phototherapy and acitretin.2,4,9

Our patient was treated with cessation of immunotherapy and initiation of a systemic corticosteroid taper, acitretin, and narrowband UVB therapy. After 6 weeks of treatment, the pain and pruritus improved and the rash had resolved in some areas while it had taken on a more classic lichenoid appearance with violaceous scaly papules and plaques (Figure 2) in areas of prior ulcers and erosions. He no longer had any bullae, erosions, or ulcers.

The Diagnosis: Immunotherapy-Related Lichenoid Drug Eruption

Direct immunofluorescence was negative, and histopathology revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis, minimal parakeratosis, and saw-toothed rete ridges (Figure 1). He was diagnosed with an immunotherapyrelated lichenoid drug eruption based on the morphology of the skin lesions and clinicopathologic correlation. Bullous pemphigoid and lichen planus pemphigoides were ruled out given the negative direct immunofluorescence findings. Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) was not consistent with the clinical presentation, especially given the lack of mucosal findings. The histology also was not consistent, as the biopsy specimen lacked apoptotic and necrotic keratinocytes to the degree seen in SJS/TEN and also had a greater degree of inflammatory infiltrate. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome was ruled out given the lack of systemic findings, including facial swelling and lymphadenopathy and the clinical appearance of the rash. No morbilliform features were present, which is the most common presentation of DRESS syndrome.

Checkpoint inhibitor (CPI) therapy has become the cornerstone in management of certain advanced malignancies.1 Checkpoint inhibitors block cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4, programmed cell death-1, and/or programmed cell death ligand-1, allowing activated T cells to infiltrate the tumor microenvironment and destroy malignant cells. Checkpoint inhibitors are approved for the treatment of melanoma, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma and are being investigated in various other cutaneous and soft tissue malignancies.1-3

Although CPIs have shown substantial efficacy in the management of advanced malignancies, immune-related adverse events (AEs) are common due to nonspecific immune activation.2 Immune-related cutaneous AEs are the most common immune-related AEs, occurring in 30% to 50% of patients who undergo treatment.2-5 Common immune-related cutaneous AEs include maculopapular, psoriasiform, and lichenoid dermatitis, as well as pruritus without dermatitis.2,3,6 Other reactions include but are not limited to bullous pemphigoid, vitiligolike depigmentation, and alopecia.2,3 Immune-related cutaneous AEs usually are self-limited; however, severe life-threatening reactions such as the spectrum of SJS/TEN and DRESS syndrome also can occur.2-4 Immune-related cutaneous AEs are graded based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events: grade 1 reactions are asymptomatic and cover less than 10% of the patient’s body surface area (BSA), grade 2 reactions have mild symptoms and cover 10% to 30% of the patient’s BSA, grade 3 reactions have moderate to severe symptoms and cover greater than 30% of the patient’s BSA, and grade 4 reactions are life-threatening.2,3 With prompt recognition and adequate treatment, mild to moderate immune-related cutaneous AEs—grades 1 and 2—largely are reversible, and less than 5% require discontinuation of therapy.2,3,6 It has been suggested that immune-related cutaneous AEs may be a positive prognostic factor in the treatment of underlying malignancy, indicating adequate immune activation targeting the malignant cells.6

Although our patient had some typical violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques with Wickham striae, he also had atypical findings for a lichenoid reaction. Given the endorsement of blisters, it is possible that some of these lesions initially were bullous and subsequently ruptured, leaving behind erosions. However, in other areas, there also were eroded papules and ulcerations without a reported history of excoriation, scratching, picking, or prior bullae, including difficult-to-reach areas such as the back. It is favored that these lesions represented a robust lichenoid dermatitis leading to erosive and ulcerated lesions, similar to the formation of bullous lichen planus. Lichenoid eruptions secondary to immunotherapy are well-known phenomena, but a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms ulcer, lichenoid, and immunotherapy revealed only 2 cases of ulcerative lichenoid eruptions: a localized digital erosive lichenoid dermatitis and a widespread ulcerative lichenoid drug eruption without true erosions.7,8 However, widespread erosive and ulcerated lichenoid reactions are rare.

Lichenoid eruptions most strongly are associated with anti–programmed cell death-1/ programmed cell death ligand-1 therapy, occurring in 20% of patients undergoing treatment.3 Lichenoid eruptions present as discrete, pruritic, erythematous, violaceous papules and plaques on the chest and back and rarely may involve the limbs, palmoplantar surfaces, and oral mucosa.2,3,6 Histopathologic features include a dense bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis with scattered apoptotic keratinocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis.2,4,6 Grades 1 to 2 lesions can be managed with high-potency topical corticosteroids without CPI dose interruption, with more extensive grade 2 lesions requiring systemic corticosteroids.2,6,9 Lichenoid eruptions grade 3 or higher also require systemic corticosteroid therapy CPI therapy cessation until the eruption has receded to grade 0 to 1.2 Alternative treatment options for high-grade toxicity include phototherapy and acitretin.2,4,9

Our patient was treated with cessation of immunotherapy and initiation of a systemic corticosteroid taper, acitretin, and narrowband UVB therapy. After 6 weeks of treatment, the pain and pruritus improved and the rash had resolved in some areas while it had taken on a more classic lichenoid appearance with violaceous scaly papules and plaques (Figure 2) in areas of prior ulcers and erosions. He no longer had any bullae, erosions, or ulcers.

- Barrios DM, Do MH, Phillips GS, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat cutaneous malignancies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1239-1253. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.131

- Geisler AN, Phillips GS, Barrios DM, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1255-1268. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.132

- Tattersall IW, Leventhal JS. Cutaneous toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors: the role of the dermatologist. Yale J Biol Med. 2020;93:123-132.

- Si X, He C, Zhang L, et al. Management of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. Thorac Cancer. 2020;11:488-492. doi:10.1111/1759-7714.13275

- Eggermont AMM, Kicinski M, Blank CU, et al. Association between immune-related adverse events and recurrence-free survival among patients with stage III melanoma randomized to receive pembrolizumab or placebo: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:519-527. doi:10.1001 /jamaoncol.2019.5570

- Sibaud V, Meyer N, Lamant L, et al. Dermatologic complications of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28:254-263. doi:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000290

- Martínez-Doménech Á, García-Legaz Martínez M, Magdaleno-Tapial J, et al. Digital ulcerative lichenoid dermatitis in a patient receiving anti-PD-1 therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt8sm0j7t7.

- Davis MJ, Wilken R, Fung MA, et al. Debilitating erosive lichenoid interface dermatitis from checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt3vq6b04v.

- Apalla Z, Papageorgiou C, Lallas A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a literature review [published online January 29, 2021]. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:E2021155. doi:10.5826/dpc.1101a155

- Barrios DM, Do MH, Phillips GS, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat cutaneous malignancies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1239-1253. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.131

- Geisler AN, Phillips GS, Barrios DM, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1255-1268. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.132

- Tattersall IW, Leventhal JS. Cutaneous toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors: the role of the dermatologist. Yale J Biol Med. 2020;93:123-132.

- Si X, He C, Zhang L, et al. Management of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. Thorac Cancer. 2020;11:488-492. doi:10.1111/1759-7714.13275

- Eggermont AMM, Kicinski M, Blank CU, et al. Association between immune-related adverse events and recurrence-free survival among patients with stage III melanoma randomized to receive pembrolizumab or placebo: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:519-527. doi:10.1001 /jamaoncol.2019.5570

- Sibaud V, Meyer N, Lamant L, et al. Dermatologic complications of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28:254-263. doi:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000290

- Martínez-Doménech Á, García-Legaz Martínez M, Magdaleno-Tapial J, et al. Digital ulcerative lichenoid dermatitis in a patient receiving anti-PD-1 therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt8sm0j7t7.

- Davis MJ, Wilken R, Fung MA, et al. Debilitating erosive lichenoid interface dermatitis from checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt3vq6b04v.

- Apalla Z, Papageorgiou C, Lallas A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a literature review [published online January 29, 2021]. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:E2021155. doi:10.5826/dpc.1101a155

A 70-year-old man presented with a painful, pruritic, diffuse eruption on the trunk, legs, and arms of 2 months’ duration. He had a history of stage IV pleomorphic cell sarcoma of the retroperitoneum and was started on pembrolizumab therapy 6 weeks prior to the eruption. Physical examination revealed violaceous papules and plaques with shiny reticulated scaling as well as multiple scattered eroded papules and shallow ulcerations. The oral mucosa and genitals were spared. The patient endorsed blisters followed by open sores that were both itchy and painful. He denied self-infliction. Both the patient and his wife denied scratching. Two biopsies for direct immunofluorescence and histopathology were performed.

Add tezepelumab to SCIT to improve cat allergy symptoms?

according to results of a phase 1/2 clinical trial.

“One year of allergen immunotherapy [AIT] combined with tezepelumab was significantly more effective than SCIT alone in reducing the nasal response to allergen challenge both at the end of treatment and one year after stopping treatment,” lead study author Jonathan Corren, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues wrote in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

“This persistent improvement in clinical response was paralleled by reductions in nasal transcripts for multiple immunologic pathways, including mast cell activation.”

The study was cited in a news release from the National Institutes of Health that said that the approach may work in a similar way with other allergens.

The Food and Drug Administration recently approved tezepelumab for the treatment of severe asthma in people aged 12 years and older. Tezelumab, a monoclonal antibody, works by blocking the cytokine thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP).

“Cells that cover the surface of organs like the skin and intestines or that line the inside of the nose and lungs rapidly secrete TSLP in response to signals of potential danger,” according to the NIH news release. “In allergic disease, TSLP helps initiate an overreactive immune response to otherwise harmless substances like cat dander, provoking airway inflammation that leads to the symptoms of allergic rhinitis.”

Testing an enhanced strategy

The double-blind CATNIP trial was conducted by Dr. Corren and colleagues at nine sites in the United States. The trial included patients aged 18-65 years who’d had moderate to severe cat-induced allergic rhinitis for at least 2 years from 2015 to 2019.

The researchers excluded patients with recurrent acute or chronic sinusitis. They excluded patients who had undergone SCIT with cat allergen within the past 10 years or seasonal or perennial allergen sensitivity during nasal challenges. They also excluded persons with a history of persistent asthma.

In the parallel-design study, 121 participants were randomly allocated into four groups: 32 patients were treated with intravenous tezepelumab plus cat SCIT, 31 received the allergy shots alone, 30 received tezepelumab alone, and 28 received placebo alone for 52 weeks, followed by 52 weeks of observation.

Participants received SCIT (10,000 bioequivalent allergy units per milliliter) or matched placebo via subcutaneous injections weekly in increasing doses for around 12 weeks, followed by monthly maintenance injections (4,000 BAU or maximum tolerated dose) until week 48.

They received tezepelumab (700 mg IV) or matched placebo 1-3 days prior to the SCIT or placebo SCIT injections once every 4 weeks through week 24, then before or on the same day as the SCIT or placebo injections through week 48.

Measures of effectiveness

Participants were also given nasal allergy challenges – one spritz of a nasal spray containing cat allergen extract in each nostril at screening, baseline, and weeks 26, 52, 78, and 104. The researchers recorded participants’ total nasal symptom score (TNSS) and peak nasal inspiratory flow at 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes after being sprayed and hourly for up to 6 hours post challenge. Blood and nasal cell samples were also collected.

The research team performed skin prick tests using serial dilutions of cat extract and an intradermal skin test (IDST) using the concentration of allergen that produced an early response of at least 15 mm at baseline. They measured early-phase responses for the both tests at 15 minutes and late-phase response to the IDST at 6 hours.

They measured serum levels of cat dander–specific IgE, IgG4, and total IgE using fluoroenzyme immunoassay. They measured serum interleukin-5 and IL-13 using high-sensitivity single-molecule digital immunoassay and performed nasal brushing using a 3-mm cytology brush 6 hours after a nasal allergy challenge. They performed whole-genome transcriptional profiling on the extracted RNA.

Combination therapy worked better and longer

The combined therapy worked better while being administered. Although the allergy shots alone stopped working after they were discontinued, the combination continued to benefit participants 1 year after that therapy ended.

At week 52, statistically significant reductions in TNSS induced by nasal allergy challenges occurred in patients receiving tezepelumab plus SCIT compared with patients receiving SCIT alone.

At week 104, 1 year after treatment ended, the primary endpoint TNSS was not significantly different in the tezepelumab-plus-SCIT group than in the SCIT-alone group, but TNSS peak 0–1 hour was significantly lower in the combination treatment group than in the SCIT-alone group.

In analysis of gene expression from nasal epithelial samples, participants who had been treated with the combination but not with either therapy by itself showed persistent modulation of the nasal immunologic environment, including diminished mast cell function. This was explained in large part by decreased transcription of the gene TPSAB1 (tryptase). Tryptase protein in nasal fluid was also decreased in the combination group, compared with the SCIT-alone group.

Adverse and serious adverse events, including infections and infestations as well as respiratory, thoracic, mediastinal, gastrointestinal, immune system, and nervous system disorders, did not differ significantly between treatment groups.

Four independent experts welcome the results

Patricia Lynne Lugar, MD, associate professor of medicine in the division of pulmonology, allergy, and critical care medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C., found the results, especially the 1-year posttreatment response durability, surprising.

“AIT is a very effective treatment that often provides prolonged symptom improvement and is ‘curative’ in many cases,” she said in an interview. “If further studies show that tezepelumab offers long-term results, more patients might opt for combination therapy.

“A significant strength of the study is its evaluation of responses of the combination therapy on cellular output and gene expression,” Dr. Lugar added. “The mechanism by which AIT modulates the allergic response is largely understood. Tezepelumab may augment this modulation to alter the Th2 response upon exposure to the allergens.”

Will payors cover the prohibitively costly biologic?

Scott Frank, MD, associate professor in the department of family medicine and community health at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, called the study well designed and rigorous.

“The practicality of the approach may be limited by the need for intravenous administration of tezepelumab in addition to the traditional allergy shot,” he noted by email, “and the cost of this therapeutic approach is not addressed.”

Christopher Brooks, MD, clinical assistant professor of allergy and immunology in the department of otolaryngology at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, also pointed out the drug’s cost.

“Tezepelumab is currently an expensive biologic, so it remains to be seen whether patients and payors will be willing to pay for this add-on medication when AIT by itself still remains very effective,” he said by email.

“AIT is most effective when given for 5 years, so it also remains to be seen whether the results and conclusions of this study would still hold true if done for the typical 5-year treatment period,” he added.

Stokes Peebles, MD, professor of medicine in the division of allergy, pulmonary, and critical care medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., called the study “very well designed by a highly respected group of investigators using well-matched study populations.

“Tezepelumab has been shown to work in asthma, and there is no reason to think it would not work in allergic rhinitis,” he said in an interview.

“However, while the results of the combined therapy were statistically significant, their clinical significance was not clear. Patients do not care about statistical significance. They want to know whether a drug will be clinically significant,” he added.

Many people avoid cat allergy symptoms by avoiding cats and, in some cases, by avoiding people who live with cats, he said. Medical therapy, usually involving nasal corticosteroids and antihistamines, helps most people avoid cat allergy symptoms.

“Patients with bad allergies who have not done well with SCIT may consider adding tezepelumab, but it incurs a major cost. If medical therapy doesn’t work, allergy shots are available at roughly $3,000 per year. Adding tezepelumab costs around $40,000 more per year,” he explained. “Does the slight clinical benefit justify the greatly increased cost?”

The authors and uninvolved experts recommend further related research.

The research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. AstraZeneca and Amgen donated the drug used in the study. Dr. Corren reported financial relationships with AstraZeneca, and one coauthor reported relevant financial relationships with Amgen and other pharmaceutical companies. The remaining coauthors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to results of a phase 1/2 clinical trial.

“One year of allergen immunotherapy [AIT] combined with tezepelumab was significantly more effective than SCIT alone in reducing the nasal response to allergen challenge both at the end of treatment and one year after stopping treatment,” lead study author Jonathan Corren, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues wrote in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

“This persistent improvement in clinical response was paralleled by reductions in nasal transcripts for multiple immunologic pathways, including mast cell activation.”

The study was cited in a news release from the National Institutes of Health that said that the approach may work in a similar way with other allergens.

The Food and Drug Administration recently approved tezepelumab for the treatment of severe asthma in people aged 12 years and older. Tezelumab, a monoclonal antibody, works by blocking the cytokine thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP).

“Cells that cover the surface of organs like the skin and intestines or that line the inside of the nose and lungs rapidly secrete TSLP in response to signals of potential danger,” according to the NIH news release. “In allergic disease, TSLP helps initiate an overreactive immune response to otherwise harmless substances like cat dander, provoking airway inflammation that leads to the symptoms of allergic rhinitis.”

Testing an enhanced strategy

The double-blind CATNIP trial was conducted by Dr. Corren and colleagues at nine sites in the United States. The trial included patients aged 18-65 years who’d had moderate to severe cat-induced allergic rhinitis for at least 2 years from 2015 to 2019.

The researchers excluded patients with recurrent acute or chronic sinusitis. They excluded patients who had undergone SCIT with cat allergen within the past 10 years or seasonal or perennial allergen sensitivity during nasal challenges. They also excluded persons with a history of persistent asthma.

In the parallel-design study, 121 participants were randomly allocated into four groups: 32 patients were treated with intravenous tezepelumab plus cat SCIT, 31 received the allergy shots alone, 30 received tezepelumab alone, and 28 received placebo alone for 52 weeks, followed by 52 weeks of observation.

Participants received SCIT (10,000 bioequivalent allergy units per milliliter) or matched placebo via subcutaneous injections weekly in increasing doses for around 12 weeks, followed by monthly maintenance injections (4,000 BAU or maximum tolerated dose) until week 48.

They received tezepelumab (700 mg IV) or matched placebo 1-3 days prior to the SCIT or placebo SCIT injections once every 4 weeks through week 24, then before or on the same day as the SCIT or placebo injections through week 48.

Measures of effectiveness

Participants were also given nasal allergy challenges – one spritz of a nasal spray containing cat allergen extract in each nostril at screening, baseline, and weeks 26, 52, 78, and 104. The researchers recorded participants’ total nasal symptom score (TNSS) and peak nasal inspiratory flow at 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes after being sprayed and hourly for up to 6 hours post challenge. Blood and nasal cell samples were also collected.

The research team performed skin prick tests using serial dilutions of cat extract and an intradermal skin test (IDST) using the concentration of allergen that produced an early response of at least 15 mm at baseline. They measured early-phase responses for the both tests at 15 minutes and late-phase response to the IDST at 6 hours.

They measured serum levels of cat dander–specific IgE, IgG4, and total IgE using fluoroenzyme immunoassay. They measured serum interleukin-5 and IL-13 using high-sensitivity single-molecule digital immunoassay and performed nasal brushing using a 3-mm cytology brush 6 hours after a nasal allergy challenge. They performed whole-genome transcriptional profiling on the extracted RNA.

Combination therapy worked better and longer

The combined therapy worked better while being administered. Although the allergy shots alone stopped working after they were discontinued, the combination continued to benefit participants 1 year after that therapy ended.

At week 52, statistically significant reductions in TNSS induced by nasal allergy challenges occurred in patients receiving tezepelumab plus SCIT compared with patients receiving SCIT alone.

At week 104, 1 year after treatment ended, the primary endpoint TNSS was not significantly different in the tezepelumab-plus-SCIT group than in the SCIT-alone group, but TNSS peak 0–1 hour was significantly lower in the combination treatment group than in the SCIT-alone group.

In analysis of gene expression from nasal epithelial samples, participants who had been treated with the combination but not with either therapy by itself showed persistent modulation of the nasal immunologic environment, including diminished mast cell function. This was explained in large part by decreased transcription of the gene TPSAB1 (tryptase). Tryptase protein in nasal fluid was also decreased in the combination group, compared with the SCIT-alone group.

Adverse and serious adverse events, including infections and infestations as well as respiratory, thoracic, mediastinal, gastrointestinal, immune system, and nervous system disorders, did not differ significantly between treatment groups.

Four independent experts welcome the results

Patricia Lynne Lugar, MD, associate professor of medicine in the division of pulmonology, allergy, and critical care medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C., found the results, especially the 1-year posttreatment response durability, surprising.

“AIT is a very effective treatment that often provides prolonged symptom improvement and is ‘curative’ in many cases,” she said in an interview. “If further studies show that tezepelumab offers long-term results, more patients might opt for combination therapy.

“A significant strength of the study is its evaluation of responses of the combination therapy on cellular output and gene expression,” Dr. Lugar added. “The mechanism by which AIT modulates the allergic response is largely understood. Tezepelumab may augment this modulation to alter the Th2 response upon exposure to the allergens.”

Will payors cover the prohibitively costly biologic?

Scott Frank, MD, associate professor in the department of family medicine and community health at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, called the study well designed and rigorous.

“The practicality of the approach may be limited by the need for intravenous administration of tezepelumab in addition to the traditional allergy shot,” he noted by email, “and the cost of this therapeutic approach is not addressed.”

Christopher Brooks, MD, clinical assistant professor of allergy and immunology in the department of otolaryngology at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, also pointed out the drug’s cost.

“Tezepelumab is currently an expensive biologic, so it remains to be seen whether patients and payors will be willing to pay for this add-on medication when AIT by itself still remains very effective,” he said by email.

“AIT is most effective when given for 5 years, so it also remains to be seen whether the results and conclusions of this study would still hold true if done for the typical 5-year treatment period,” he added.

Stokes Peebles, MD, professor of medicine in the division of allergy, pulmonary, and critical care medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., called the study “very well designed by a highly respected group of investigators using well-matched study populations.

“Tezepelumab has been shown to work in asthma, and there is no reason to think it would not work in allergic rhinitis,” he said in an interview.

“However, while the results of the combined therapy were statistically significant, their clinical significance was not clear. Patients do not care about statistical significance. They want to know whether a drug will be clinically significant,” he added.

Many people avoid cat allergy symptoms by avoiding cats and, in some cases, by avoiding people who live with cats, he said. Medical therapy, usually involving nasal corticosteroids and antihistamines, helps most people avoid cat allergy symptoms.

“Patients with bad allergies who have not done well with SCIT may consider adding tezepelumab, but it incurs a major cost. If medical therapy doesn’t work, allergy shots are available at roughly $3,000 per year. Adding tezepelumab costs around $40,000 more per year,” he explained. “Does the slight clinical benefit justify the greatly increased cost?”

The authors and uninvolved experts recommend further related research.

The research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. AstraZeneca and Amgen donated the drug used in the study. Dr. Corren reported financial relationships with AstraZeneca, and one coauthor reported relevant financial relationships with Amgen and other pharmaceutical companies. The remaining coauthors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to results of a phase 1/2 clinical trial.

“One year of allergen immunotherapy [AIT] combined with tezepelumab was significantly more effective than SCIT alone in reducing the nasal response to allergen challenge both at the end of treatment and one year after stopping treatment,” lead study author Jonathan Corren, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues wrote in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

“This persistent improvement in clinical response was paralleled by reductions in nasal transcripts for multiple immunologic pathways, including mast cell activation.”

The study was cited in a news release from the National Institutes of Health that said that the approach may work in a similar way with other allergens.

The Food and Drug Administration recently approved tezepelumab for the treatment of severe asthma in people aged 12 years and older. Tezelumab, a monoclonal antibody, works by blocking the cytokine thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP).

“Cells that cover the surface of organs like the skin and intestines or that line the inside of the nose and lungs rapidly secrete TSLP in response to signals of potential danger,” according to the NIH news release. “In allergic disease, TSLP helps initiate an overreactive immune response to otherwise harmless substances like cat dander, provoking airway inflammation that leads to the symptoms of allergic rhinitis.”

Testing an enhanced strategy

The double-blind CATNIP trial was conducted by Dr. Corren and colleagues at nine sites in the United States. The trial included patients aged 18-65 years who’d had moderate to severe cat-induced allergic rhinitis for at least 2 years from 2015 to 2019.

The researchers excluded patients with recurrent acute or chronic sinusitis. They excluded patients who had undergone SCIT with cat allergen within the past 10 years or seasonal or perennial allergen sensitivity during nasal challenges. They also excluded persons with a history of persistent asthma.

In the parallel-design study, 121 participants were randomly allocated into four groups: 32 patients were treated with intravenous tezepelumab plus cat SCIT, 31 received the allergy shots alone, 30 received tezepelumab alone, and 28 received placebo alone for 52 weeks, followed by 52 weeks of observation.

Participants received SCIT (10,000 bioequivalent allergy units per milliliter) or matched placebo via subcutaneous injections weekly in increasing doses for around 12 weeks, followed by monthly maintenance injections (4,000 BAU or maximum tolerated dose) until week 48.

They received tezepelumab (700 mg IV) or matched placebo 1-3 days prior to the SCIT or placebo SCIT injections once every 4 weeks through week 24, then before or on the same day as the SCIT or placebo injections through week 48.

Measures of effectiveness

Participants were also given nasal allergy challenges – one spritz of a nasal spray containing cat allergen extract in each nostril at screening, baseline, and weeks 26, 52, 78, and 104. The researchers recorded participants’ total nasal symptom score (TNSS) and peak nasal inspiratory flow at 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes after being sprayed and hourly for up to 6 hours post challenge. Blood and nasal cell samples were also collected.

The research team performed skin prick tests using serial dilutions of cat extract and an intradermal skin test (IDST) using the concentration of allergen that produced an early response of at least 15 mm at baseline. They measured early-phase responses for the both tests at 15 minutes and late-phase response to the IDST at 6 hours.

They measured serum levels of cat dander–specific IgE, IgG4, and total IgE using fluoroenzyme immunoassay. They measured serum interleukin-5 and IL-13 using high-sensitivity single-molecule digital immunoassay and performed nasal brushing using a 3-mm cytology brush 6 hours after a nasal allergy challenge. They performed whole-genome transcriptional profiling on the extracted RNA.

Combination therapy worked better and longer

The combined therapy worked better while being administered. Although the allergy shots alone stopped working after they were discontinued, the combination continued to benefit participants 1 year after that therapy ended.

At week 52, statistically significant reductions in TNSS induced by nasal allergy challenges occurred in patients receiving tezepelumab plus SCIT compared with patients receiving SCIT alone.

At week 104, 1 year after treatment ended, the primary endpoint TNSS was not significantly different in the tezepelumab-plus-SCIT group than in the SCIT-alone group, but TNSS peak 0–1 hour was significantly lower in the combination treatment group than in the SCIT-alone group.

In analysis of gene expression from nasal epithelial samples, participants who had been treated with the combination but not with either therapy by itself showed persistent modulation of the nasal immunologic environment, including diminished mast cell function. This was explained in large part by decreased transcription of the gene TPSAB1 (tryptase). Tryptase protein in nasal fluid was also decreased in the combination group, compared with the SCIT-alone group.

Adverse and serious adverse events, including infections and infestations as well as respiratory, thoracic, mediastinal, gastrointestinal, immune system, and nervous system disorders, did not differ significantly between treatment groups.

Four independent experts welcome the results

Patricia Lynne Lugar, MD, associate professor of medicine in the division of pulmonology, allergy, and critical care medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C., found the results, especially the 1-year posttreatment response durability, surprising.

“AIT is a very effective treatment that often provides prolonged symptom improvement and is ‘curative’ in many cases,” she said in an interview. “If further studies show that tezepelumab offers long-term results, more patients might opt for combination therapy.

“A significant strength of the study is its evaluation of responses of the combination therapy on cellular output and gene expression,” Dr. Lugar added. “The mechanism by which AIT modulates the allergic response is largely understood. Tezepelumab may augment this modulation to alter the Th2 response upon exposure to the allergens.”

Will payors cover the prohibitively costly biologic?

Scott Frank, MD, associate professor in the department of family medicine and community health at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, called the study well designed and rigorous.

“The practicality of the approach may be limited by the need for intravenous administration of tezepelumab in addition to the traditional allergy shot,” he noted by email, “and the cost of this therapeutic approach is not addressed.”

Christopher Brooks, MD, clinical assistant professor of allergy and immunology in the department of otolaryngology at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, also pointed out the drug’s cost.

“Tezepelumab is currently an expensive biologic, so it remains to be seen whether patients and payors will be willing to pay for this add-on medication when AIT by itself still remains very effective,” he said by email.

“AIT is most effective when given for 5 years, so it also remains to be seen whether the results and conclusions of this study would still hold true if done for the typical 5-year treatment period,” he added.

Stokes Peebles, MD, professor of medicine in the division of allergy, pulmonary, and critical care medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., called the study “very well designed by a highly respected group of investigators using well-matched study populations.

“Tezepelumab has been shown to work in asthma, and there is no reason to think it would not work in allergic rhinitis,” he said in an interview.

“However, while the results of the combined therapy were statistically significant, their clinical significance was not clear. Patients do not care about statistical significance. They want to know whether a drug will be clinically significant,” he added.

Many people avoid cat allergy symptoms by avoiding cats and, in some cases, by avoiding people who live with cats, he said. Medical therapy, usually involving nasal corticosteroids and antihistamines, helps most people avoid cat allergy symptoms.

“Patients with bad allergies who have not done well with SCIT may consider adding tezepelumab, but it incurs a major cost. If medical therapy doesn’t work, allergy shots are available at roughly $3,000 per year. Adding tezepelumab costs around $40,000 more per year,” he explained. “Does the slight clinical benefit justify the greatly increased cost?”

The authors and uninvolved experts recommend further related research.

The research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. AstraZeneca and Amgen donated the drug used in the study. Dr. Corren reported financial relationships with AstraZeneca, and one coauthor reported relevant financial relationships with Amgen and other pharmaceutical companies. The remaining coauthors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY

Why your professional persona may be considered unprofessional

On one of the first days of medical school, Adaira Landry, MD, applied her favorite dark shade of lipstick and headed to her orientation. She was eager to learn about program expectations and connect with fellow aspiring physicians. But when Dr. Landry got there, one of her brand-new peers turned to her and asked, “Why do you wear your lipstick like an angry Black woman?”

“Imagine hearing that,” Dr. Landry, now an emergency medical physician in Boston, says. “It was so hurtful.”

So, what is a “standard-issue doctor” expected to look like? Physicians manage their appearances in myriad ways: through clothes, accessories, hair style, makeup; through a social media presence or lack thereof; in the rhythms and nuances of their interactions with patients and colleagues. These things add up to a professional “persona” – the Latin word for “mask,” or the face on display for the world to see.

While the health care field itself is diversifying, its guidelines for professionalism appear slower to change, often excluding or frowning upon expressions of individual personality or identity.

“Medicine is run primarily by men. It’s an objective truth,” Dr. Landry says. “Currently and historically, the standard of professionalism, especially in the physical sense, was set by them. As we increase diversity and welcome people bringing their authentic self to work, the prior definitions of professionalism are obviously in need of change.”

Split social media personalities

In August 2020, the Journal of Vascular Surgery published a study on the “prevalence of unprofessional social media content among young vascular surgeons.” The content that was deemed “unprofessional” included opinions on political issues like abortion and gun control. Photos of physicians holding alcoholic drinks or wearing “inappropriate/offensive attire,” including underwear, “provocative Halloween costumes,” and “bikinis/swimwear” were also censured. Six men and one woman worked on the study, and three of the male researchers took on the task of seeking out the “unprofessional” photos on social media. The resulting paper was reviewed by an all-male editorial board.

The study sparked immediate backlash and prompted hundreds of health care professionals to post photos of themselves in bathing suits with the hashtag “#medbikini.” The journal then retracted the study and issued an apology on Twitter, recognizing “errors in the design of the study with regards to conscious and unconscious bias.”

The researchers’ original definition of professionalism suggests that physicians should manage their personae even outside of work hours. “I think medicine in general is a very conservative and hierarchical field of study and of work, to say the least,” says Sarah Fraser, MD, a family medicine physician in Nova Scotia, Canada. “There’s this view that we have to have completely separate personal and professional lives, like church and state.”

The #medbikini controversy inspired Dr. Fraser to write an op-ed for the British Medical Journal blog about the flaws of requiring physicians to keep their personal and professional selves separate. The piece referenced Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 Gothic novella “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” in which the respected scientist Dr. Jekyll creates an alter ego so he can express his evil urges without experiencing guilt, punishment, or loss of livelihood. Dr. Fraser likened this story to the pressure physicians feel to shrink or split themselves to squeeze into a narrow definition of professionalism.

But Dr. Landry points out that some elements of expression seen as unprofessional cannot be entirely separated from a physician’s fundamental identity. “For Black women, our daily behaviors and forms of expression that are deemed ‘unprofessional’ are much more subtle than being able to wear a bikini on social media,” she says. “The way we wear our hair, the tone of our voice, the color of our lipstick, the way we wear scrub caps are parts of us that are called into question.”

Keeping up appearances

The stereotype of what a doctor should look like starts to shape physicians’ professional personae in medical school. When Jennifer Caputo-Seidler, MD, started medical school in 2008, the dress code requirements for male students were simple: pants, a button-down shirt, a tie. But then there were the rules for women: Hair should be tied back. Minimal makeup. No flashy jewelry. Nothing without sleeves. Neutral colors. High necklines. Low hemlines. “The message I got was that we need to dress like the men in order to be taken seriously and to be seen as professional,” says Dr. Caputo-Seidler, now an assistant professor of medicine at the University of South Florida, Tampa, “and so that’s what I did.”

A 2018 analysis of 78 “draw-a-scientist” studies found that children have overwhelmingly associated scientific fields with men for the last 50 years. Overall, children drew 73% of scientists as men. The drawings grew more gender diverse over time, but even as more women entered scientific fields, both boys and girls continued to draw significantly more male than female scientists.

Not everyone at Dr. Caputo-Seidler’s medical school adhered to the environment’s gendered expectations. One resident she worked with often wore voluminous hairstyles, lipstick, and high heels. Dr. Caputo-Seidler overheard her peers as they gossiped behind the resident’s back, ridiculing the way she looked.

“She was good at her job,” Dr. Caputo-Seidler says. “She knew her patients. She had things down. She was, by all measures, very competent. But when people saw her dressing outside the norm and being forward with her femininity, there was definitely a lot of chatter about it.”

While expectations for a conservative appearance may disproportionately affect women, and particularly women of color, they also affect men who deviate from the norm. “As an LGBTQ+ person working as a ‘professional,’ I have countless stories and moments where I had my professionalism questioned,” Blair Peters, MD, a plastic surgeon and assistant professor at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, wrote on Twitter. “Why is it ‘unprofessional’ to have colored hair? Why is it ‘unprofessional’ to have a visible tattoo? Why is it ‘unprofessional’ to wear bright colors and patterns?”

Dr. Fraser remembers a fellow medical student who had full-sleeve tattoos on both of his arms. A preceptor made a comment about it to Dr. Fraser, and then instructed the student to cover up his tattoos. “I think that there are scenarios when having tattoos or having different-colored hair or expressing your individual personality could help you even better bond with your patients,” Dr. Fraser says, “especially if you’re, for example, working with youth.”

Unmasking health care

Beyond the facets of dress codes and social media posts, the issue of professional personae speaks to the deeper issue of inclusion in medicine. As the field grows increasingly diverse, health care institutions and those they serve may need to expand their definitions of professionalism to include more truthful expressions of who contemporary health care professionals are as people.

Dr. Fraser suggests that the benefits of physicians embracing self-expression – rather than assimilating to an outdated model of professionalism – extend beyond the individual.

“Whether it comes to what you choose to wear to the clinic on a day-to-day basis, or what you choose to share on a social media account, as long as it’s not harming others, then I think that it’s a positive thing to be able to be yourself and express yourself,” she says. “I feel like doctors are expected to have a different personality when we’re at the clinic, and usually it’s more conservative or objective or aloof. But I think that by being open about who we are, we’ll actually help build a trusting relationship with both patients and society.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On one of the first days of medical school, Adaira Landry, MD, applied her favorite dark shade of lipstick and headed to her orientation. She was eager to learn about program expectations and connect with fellow aspiring physicians. But when Dr. Landry got there, one of her brand-new peers turned to her and asked, “Why do you wear your lipstick like an angry Black woman?”

“Imagine hearing that,” Dr. Landry, now an emergency medical physician in Boston, says. “It was so hurtful.”

So, what is a “standard-issue doctor” expected to look like? Physicians manage their appearances in myriad ways: through clothes, accessories, hair style, makeup; through a social media presence or lack thereof; in the rhythms and nuances of their interactions with patients and colleagues. These things add up to a professional “persona” – the Latin word for “mask,” or the face on display for the world to see.

While the health care field itself is diversifying, its guidelines for professionalism appear slower to change, often excluding or frowning upon expressions of individual personality or identity.

“Medicine is run primarily by men. It’s an objective truth,” Dr. Landry says. “Currently and historically, the standard of professionalism, especially in the physical sense, was set by them. As we increase diversity and welcome people bringing their authentic self to work, the prior definitions of professionalism are obviously in need of change.”

Split social media personalities

In August 2020, the Journal of Vascular Surgery published a study on the “prevalence of unprofessional social media content among young vascular surgeons.” The content that was deemed “unprofessional” included opinions on political issues like abortion and gun control. Photos of physicians holding alcoholic drinks or wearing “inappropriate/offensive attire,” including underwear, “provocative Halloween costumes,” and “bikinis/swimwear” were also censured. Six men and one woman worked on the study, and three of the male researchers took on the task of seeking out the “unprofessional” photos on social media. The resulting paper was reviewed by an all-male editorial board.

The study sparked immediate backlash and prompted hundreds of health care professionals to post photos of themselves in bathing suits with the hashtag “#medbikini.” The journal then retracted the study and issued an apology on Twitter, recognizing “errors in the design of the study with regards to conscious and unconscious bias.”

The researchers’ original definition of professionalism suggests that physicians should manage their personae even outside of work hours. “I think medicine in general is a very conservative and hierarchical field of study and of work, to say the least,” says Sarah Fraser, MD, a family medicine physician in Nova Scotia, Canada. “There’s this view that we have to have completely separate personal and professional lives, like church and state.”

The #medbikini controversy inspired Dr. Fraser to write an op-ed for the British Medical Journal blog about the flaws of requiring physicians to keep their personal and professional selves separate. The piece referenced Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 Gothic novella “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” in which the respected scientist Dr. Jekyll creates an alter ego so he can express his evil urges without experiencing guilt, punishment, or loss of livelihood. Dr. Fraser likened this story to the pressure physicians feel to shrink or split themselves to squeeze into a narrow definition of professionalism.

But Dr. Landry points out that some elements of expression seen as unprofessional cannot be entirely separated from a physician’s fundamental identity. “For Black women, our daily behaviors and forms of expression that are deemed ‘unprofessional’ are much more subtle than being able to wear a bikini on social media,” she says. “The way we wear our hair, the tone of our voice, the color of our lipstick, the way we wear scrub caps are parts of us that are called into question.”

Keeping up appearances

The stereotype of what a doctor should look like starts to shape physicians’ professional personae in medical school. When Jennifer Caputo-Seidler, MD, started medical school in 2008, the dress code requirements for male students were simple: pants, a button-down shirt, a tie. But then there were the rules for women: Hair should be tied back. Minimal makeup. No flashy jewelry. Nothing without sleeves. Neutral colors. High necklines. Low hemlines. “The message I got was that we need to dress like the men in order to be taken seriously and to be seen as professional,” says Dr. Caputo-Seidler, now an assistant professor of medicine at the University of South Florida, Tampa, “and so that’s what I did.”

A 2018 analysis of 78 “draw-a-scientist” studies found that children have overwhelmingly associated scientific fields with men for the last 50 years. Overall, children drew 73% of scientists as men. The drawings grew more gender diverse over time, but even as more women entered scientific fields, both boys and girls continued to draw significantly more male than female scientists.

Not everyone at Dr. Caputo-Seidler’s medical school adhered to the environment’s gendered expectations. One resident she worked with often wore voluminous hairstyles, lipstick, and high heels. Dr. Caputo-Seidler overheard her peers as they gossiped behind the resident’s back, ridiculing the way she looked.