User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

In one state, pandemic tamped down lice and scabies cases

.

When COVID-19 was declared a public health emergency by the World Health Organization in March 2020, many countries including the United States enacted lockdown and isolation measures to help contain the spread of the disease. Since scabies and lice are both spread by direct contact, “we hypothesized that the nationwide lockdown would influence the transmission of these two conditions among individuals,” wrote Marianne Bonanno, MD, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and colleagues.

“The pandemic created a unique opportunity for real-life observations following physical distancing measures being put in place,” coauthor Christopher Sayed, MD, associate professor of dermatology at UNC, said in an interview. “It makes intuitive sense that since lice and scabies spread by cost physical contact that rates would decrease with school closures and other physical distancing measures. Reports from other countries in which extended families more often live together and were forced to spend more time in close quarters saw increased rates so it was interesting to see this contrast,” he noted.

In the study, the researchers reviewed data from 1,858 cases of adult scabies, 893 cases of pediatric scabies, and 804 cases of pediatric lice reported in North Carolina between March 2017 and February 2021. They compared monthly cases of scabies and lice, and prescriptions during the period before the pandemic (March 2017 to February 2020), and during the pandemic (March 2020 to February 2021).

Pediatric lice cases decreased by 60.6% over the study period (P < .001). Significant decreases also occurred in adult scabies (31.1%, P < .001) and pediatric scabies (39%, P < .01).

The number of prescriptions for lice and scabies also decreased significantly (P < .01) during the study period, although these numbers differed from the actual cases. Prescriptions decreased by 41.4%, 29.9%, and 69.3% for pediatric scabies, adult scabies, and pediatric lice, respectively.

Both pediatric scabies and pediatric lice showed a greater drop in prescriptions than in cases, while the drop in prescriptions for adult scabies was slightly less than the drop in cases.

The difference in the decreased numbers between cases and prescriptions may stem from the decrease in close contacts during the pandemic, which decreased the need for multiple prescriptions, but other potential explanations could be examined in future studies, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design and potential underdiagnosis and underreporting, as well as the focus only on a population in a single state, which may limit generalizability, the researchers noted.

However, the results offer preliminary insights on the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on scabies and lice, and suggest the potential value of physical distancing to reduce transmission of both conditions, especially in settings such as schools and prisons, to help contain future outbreaks, they concluded.

The study findings reinforce physical contact as the likely route of disease transmission, for lice and scabies, Dr. Sayed said in the interview. “It’s possible distancing measures on a small scale could be considered for outbreaks in institutional settings, though the risks of these infestations are much lower than with COVID-19,” he said. “It will be interesting to observe trends as physical distancing measures end to see if cases rebound in the next few years,” he added.

Drop in cases likely temporary

“Examining the epidemiology of different infectious diseases over time is an interesting and important area of study,” said Sheilagh Maguiness, MD, associate professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, who was asked to comment on the results.

“The pandemic dramatically altered the daily lives of adults and children across the globe, and we can learn a lot from studying how social distancing and prolonged masking has made an impact on the incidence and prevalence of different infectious illnesses in the country and across the world,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Maguiness said she was not surprised by the study findings. “In fact, other countries have published similar studies documenting a reduction in both head lice and scabies infestations during the time of the pandemic,” she said. “In France, it was noted that during March to December 2020, there was a reduction in sales for topical head lice and scabies treatments of 44% and 14%, respectively. Similarly, a study from Argentina documented a decline in head lice infestations by about 25% among children,” she said.

“I personally noted a marked decrease in both of these diagnoses among children in my own clinic,” she added.

“Since both of these conditions are spread through close physical contact with others, it makes sense that there would be a steep decline in ectoparasitic infections during times of social distancing. However, anecdotally we are now diagnosing and treating these infestations again more regularly in our clinic,” said Dr. Maguiness. “As social distancing relaxes, I would expect that the incidence of both head lice and scabies will again increase.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Maguiness had no financial conflicts to disclose.

.

When COVID-19 was declared a public health emergency by the World Health Organization in March 2020, many countries including the United States enacted lockdown and isolation measures to help contain the spread of the disease. Since scabies and lice are both spread by direct contact, “we hypothesized that the nationwide lockdown would influence the transmission of these two conditions among individuals,” wrote Marianne Bonanno, MD, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and colleagues.

“The pandemic created a unique opportunity for real-life observations following physical distancing measures being put in place,” coauthor Christopher Sayed, MD, associate professor of dermatology at UNC, said in an interview. “It makes intuitive sense that since lice and scabies spread by cost physical contact that rates would decrease with school closures and other physical distancing measures. Reports from other countries in which extended families more often live together and were forced to spend more time in close quarters saw increased rates so it was interesting to see this contrast,” he noted.

In the study, the researchers reviewed data from 1,858 cases of adult scabies, 893 cases of pediatric scabies, and 804 cases of pediatric lice reported in North Carolina between March 2017 and February 2021. They compared monthly cases of scabies and lice, and prescriptions during the period before the pandemic (March 2017 to February 2020), and during the pandemic (March 2020 to February 2021).

Pediatric lice cases decreased by 60.6% over the study period (P < .001). Significant decreases also occurred in adult scabies (31.1%, P < .001) and pediatric scabies (39%, P < .01).

The number of prescriptions for lice and scabies also decreased significantly (P < .01) during the study period, although these numbers differed from the actual cases. Prescriptions decreased by 41.4%, 29.9%, and 69.3% for pediatric scabies, adult scabies, and pediatric lice, respectively.

Both pediatric scabies and pediatric lice showed a greater drop in prescriptions than in cases, while the drop in prescriptions for adult scabies was slightly less than the drop in cases.

The difference in the decreased numbers between cases and prescriptions may stem from the decrease in close contacts during the pandemic, which decreased the need for multiple prescriptions, but other potential explanations could be examined in future studies, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design and potential underdiagnosis and underreporting, as well as the focus only on a population in a single state, which may limit generalizability, the researchers noted.

However, the results offer preliminary insights on the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on scabies and lice, and suggest the potential value of physical distancing to reduce transmission of both conditions, especially in settings such as schools and prisons, to help contain future outbreaks, they concluded.

The study findings reinforce physical contact as the likely route of disease transmission, for lice and scabies, Dr. Sayed said in the interview. “It’s possible distancing measures on a small scale could be considered for outbreaks in institutional settings, though the risks of these infestations are much lower than with COVID-19,” he said. “It will be interesting to observe trends as physical distancing measures end to see if cases rebound in the next few years,” he added.

Drop in cases likely temporary

“Examining the epidemiology of different infectious diseases over time is an interesting and important area of study,” said Sheilagh Maguiness, MD, associate professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, who was asked to comment on the results.

“The pandemic dramatically altered the daily lives of adults and children across the globe, and we can learn a lot from studying how social distancing and prolonged masking has made an impact on the incidence and prevalence of different infectious illnesses in the country and across the world,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Maguiness said she was not surprised by the study findings. “In fact, other countries have published similar studies documenting a reduction in both head lice and scabies infestations during the time of the pandemic,” she said. “In France, it was noted that during March to December 2020, there was a reduction in sales for topical head lice and scabies treatments of 44% and 14%, respectively. Similarly, a study from Argentina documented a decline in head lice infestations by about 25% among children,” she said.

“I personally noted a marked decrease in both of these diagnoses among children in my own clinic,” she added.

“Since both of these conditions are spread through close physical contact with others, it makes sense that there would be a steep decline in ectoparasitic infections during times of social distancing. However, anecdotally we are now diagnosing and treating these infestations again more regularly in our clinic,” said Dr. Maguiness. “As social distancing relaxes, I would expect that the incidence of both head lice and scabies will again increase.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Maguiness had no financial conflicts to disclose.

.

When COVID-19 was declared a public health emergency by the World Health Organization in March 2020, many countries including the United States enacted lockdown and isolation measures to help contain the spread of the disease. Since scabies and lice are both spread by direct contact, “we hypothesized that the nationwide lockdown would influence the transmission of these two conditions among individuals,” wrote Marianne Bonanno, MD, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and colleagues.

“The pandemic created a unique opportunity for real-life observations following physical distancing measures being put in place,” coauthor Christopher Sayed, MD, associate professor of dermatology at UNC, said in an interview. “It makes intuitive sense that since lice and scabies spread by cost physical contact that rates would decrease with school closures and other physical distancing measures. Reports from other countries in which extended families more often live together and were forced to spend more time in close quarters saw increased rates so it was interesting to see this contrast,” he noted.

In the study, the researchers reviewed data from 1,858 cases of adult scabies, 893 cases of pediatric scabies, and 804 cases of pediatric lice reported in North Carolina between March 2017 and February 2021. They compared monthly cases of scabies and lice, and prescriptions during the period before the pandemic (March 2017 to February 2020), and during the pandemic (March 2020 to February 2021).

Pediatric lice cases decreased by 60.6% over the study period (P < .001). Significant decreases also occurred in adult scabies (31.1%, P < .001) and pediatric scabies (39%, P < .01).

The number of prescriptions for lice and scabies also decreased significantly (P < .01) during the study period, although these numbers differed from the actual cases. Prescriptions decreased by 41.4%, 29.9%, and 69.3% for pediatric scabies, adult scabies, and pediatric lice, respectively.

Both pediatric scabies and pediatric lice showed a greater drop in prescriptions than in cases, while the drop in prescriptions for adult scabies was slightly less than the drop in cases.

The difference in the decreased numbers between cases and prescriptions may stem from the decrease in close contacts during the pandemic, which decreased the need for multiple prescriptions, but other potential explanations could be examined in future studies, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design and potential underdiagnosis and underreporting, as well as the focus only on a population in a single state, which may limit generalizability, the researchers noted.

However, the results offer preliminary insights on the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on scabies and lice, and suggest the potential value of physical distancing to reduce transmission of both conditions, especially in settings such as schools and prisons, to help contain future outbreaks, they concluded.

The study findings reinforce physical contact as the likely route of disease transmission, for lice and scabies, Dr. Sayed said in the interview. “It’s possible distancing measures on a small scale could be considered for outbreaks in institutional settings, though the risks of these infestations are much lower than with COVID-19,” he said. “It will be interesting to observe trends as physical distancing measures end to see if cases rebound in the next few years,” he added.

Drop in cases likely temporary

“Examining the epidemiology of different infectious diseases over time is an interesting and important area of study,” said Sheilagh Maguiness, MD, associate professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, who was asked to comment on the results.

“The pandemic dramatically altered the daily lives of adults and children across the globe, and we can learn a lot from studying how social distancing and prolonged masking has made an impact on the incidence and prevalence of different infectious illnesses in the country and across the world,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Maguiness said she was not surprised by the study findings. “In fact, other countries have published similar studies documenting a reduction in both head lice and scabies infestations during the time of the pandemic,” she said. “In France, it was noted that during March to December 2020, there was a reduction in sales for topical head lice and scabies treatments of 44% and 14%, respectively. Similarly, a study from Argentina documented a decline in head lice infestations by about 25% among children,” she said.

“I personally noted a marked decrease in both of these diagnoses among children in my own clinic,” she added.

“Since both of these conditions are spread through close physical contact with others, it makes sense that there would be a steep decline in ectoparasitic infections during times of social distancing. However, anecdotally we are now diagnosing and treating these infestations again more regularly in our clinic,” said Dr. Maguiness. “As social distancing relaxes, I would expect that the incidence of both head lice and scabies will again increase.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Maguiness had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Climate change can worsen more than half of infectious diseases

An extensive new study shows that climate change can aggravate over half of known human pathogenic diseases. This comprehensive systematic review of the literature narrowed down 3,213 cases, linking 286 infectious diseases to specific climate change hazards. Of these, 58% were worsened, and only 9 conditions showed any benefit associated with environmental change.

The study was published online in Nature Climate Change. The complete list of cases, transmission pathways, and associated papers can be explored in detail – a remarkable, interactive data visualization.

To compile the data, investigators searched 10 keywords on the Global Infectious Disease and Epidemiology Network (GIDEON) and Center for Disease Control and Prevention databases. They then filled gaps by examining alternative names of the diseases, pathogens, and hazards.

Coauthor Tristan McKenzie, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, told this news organization: “If someone is interested in a certain pathway, it’s a beautiful starting point.” Or if someone wants to “do a modeling study and they want to focus on a specific area, the specific examples in the literature are already there” in the extensive database.

An early key finding is that warming and increased precipitation broadened the range of many pathogens through expansion of their habitat. This shift brings many pathogens closer to people. Examples are viruses (dengue, Chikungunya), bacteria (Lyme), protozoans (trypanosomes), and more. Warming has affected aquatic systems (for example, Vibrio) and higher altitudes and latitudes (malaria, dengue).

Pathogenic hazards are not just moving closer to people. People are also moving closer to the pathogenic hazards, with heat waves causing people to seek refuge with water activities, for example. This increases their exposure to pathogens, such as Vibrio, hepatitis, and water-borne gastroenteritis.

Some hazards, such as warming, can even make pathogens more virulent. Heat can upregulate Vibrio’s gene expression of proteins affecting transmission, adhesion, penetration, and host injury.

Heat and rainfall can increase stagnant water, enhancing mosquitoes’ breeding and growing grounds and enabling them to transmit many more infections.

People’s capacity to respond to climate hazards can also be impaired. For example, there is a reduced concentration of nutrients in crops under high CO2 levels, which can result in malnutrition. Lower crop yields can further fuel outbreaks of measles, cholera, or Cryptosporidium. Drought also likely forces people to drink contaminated water.

Among all this bad news, the authors found a small number of cases where climate hazards reduced the risk of infection. For example, droughts reduced the breeding grounds of mosquitoes, reducing the prevalence of malaria and chikungunya. But in other cases, the density of mosquitoes increased in some pools, causing an increased local risk of infection.

Naomi Hauser, MD, MPH, assistant clinical professor at UC Davis, Sacramento, told this news organization she was particularly impressed with the data visualization. “It really emphasizes the magnitude of what we’re dealing with. It makes you feel the weight of what they’re trying to represent,” she said.

On the other hand, Dr. Hauser said she would have liked “more emphasis on how the climate hazards interact with each other. It sort of made it sound like each of these climate hazards is in a vacuum – like when there’s floods, and that’s the problem. But there are a lot of other things ... like when we have warming and surface water temperature changes, it can also change the pH of the water and the salinity of the water, and those can also impact what we see with pathogens in the water.”

Dr. McKenzie explained one limitation: The study looked only at 10 keywords. So an example of a dust storm in Africa causing an increase in Vibrio in the United States could not be identified by this approach. “This also goes back to the scale of the problem, because we have something going on in the Sahara that’s impacting the East Coast of the United States,” he said. “And finding that link is not necessarily obvious – or at least not as obvious as [if] there [were] a hurricane and a bunch of people got sick from waterborne disease. So I think that really highlights the scale of this problem.”

Instead of looking at only one individual or group of pathogens, the study provided a much broader review of infections caused by an array of climate hazards. As Dr. McKenzie said, “no one’s actually done the work previously to really just try and get a comprehensive picture of what we might be dealing with. And so that was the goal for us.” The 58% estimate of diseases worsened by climate change is conservative, and, he says, “arguably, this is an even bigger problem than what we present.”

Dr. McKenzie concluded: “If we’re looking at the spread of some more serious or rare diseases in areas, to me then the answer is ... we need to be aggressively mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. Let’s start with the source.”

Dr. McKenzie and Dr. Hauser report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An extensive new study shows that climate change can aggravate over half of known human pathogenic diseases. This comprehensive systematic review of the literature narrowed down 3,213 cases, linking 286 infectious diseases to specific climate change hazards. Of these, 58% were worsened, and only 9 conditions showed any benefit associated with environmental change.

The study was published online in Nature Climate Change. The complete list of cases, transmission pathways, and associated papers can be explored in detail – a remarkable, interactive data visualization.

To compile the data, investigators searched 10 keywords on the Global Infectious Disease and Epidemiology Network (GIDEON) and Center for Disease Control and Prevention databases. They then filled gaps by examining alternative names of the diseases, pathogens, and hazards.

Coauthor Tristan McKenzie, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, told this news organization: “If someone is interested in a certain pathway, it’s a beautiful starting point.” Or if someone wants to “do a modeling study and they want to focus on a specific area, the specific examples in the literature are already there” in the extensive database.

An early key finding is that warming and increased precipitation broadened the range of many pathogens through expansion of their habitat. This shift brings many pathogens closer to people. Examples are viruses (dengue, Chikungunya), bacteria (Lyme), protozoans (trypanosomes), and more. Warming has affected aquatic systems (for example, Vibrio) and higher altitudes and latitudes (malaria, dengue).

Pathogenic hazards are not just moving closer to people. People are also moving closer to the pathogenic hazards, with heat waves causing people to seek refuge with water activities, for example. This increases their exposure to pathogens, such as Vibrio, hepatitis, and water-borne gastroenteritis.

Some hazards, such as warming, can even make pathogens more virulent. Heat can upregulate Vibrio’s gene expression of proteins affecting transmission, adhesion, penetration, and host injury.

Heat and rainfall can increase stagnant water, enhancing mosquitoes’ breeding and growing grounds and enabling them to transmit many more infections.

People’s capacity to respond to climate hazards can also be impaired. For example, there is a reduced concentration of nutrients in crops under high CO2 levels, which can result in malnutrition. Lower crop yields can further fuel outbreaks of measles, cholera, or Cryptosporidium. Drought also likely forces people to drink contaminated water.

Among all this bad news, the authors found a small number of cases where climate hazards reduced the risk of infection. For example, droughts reduced the breeding grounds of mosquitoes, reducing the prevalence of malaria and chikungunya. But in other cases, the density of mosquitoes increased in some pools, causing an increased local risk of infection.

Naomi Hauser, MD, MPH, assistant clinical professor at UC Davis, Sacramento, told this news organization she was particularly impressed with the data visualization. “It really emphasizes the magnitude of what we’re dealing with. It makes you feel the weight of what they’re trying to represent,” she said.

On the other hand, Dr. Hauser said she would have liked “more emphasis on how the climate hazards interact with each other. It sort of made it sound like each of these climate hazards is in a vacuum – like when there’s floods, and that’s the problem. But there are a lot of other things ... like when we have warming and surface water temperature changes, it can also change the pH of the water and the salinity of the water, and those can also impact what we see with pathogens in the water.”

Dr. McKenzie explained one limitation: The study looked only at 10 keywords. So an example of a dust storm in Africa causing an increase in Vibrio in the United States could not be identified by this approach. “This also goes back to the scale of the problem, because we have something going on in the Sahara that’s impacting the East Coast of the United States,” he said. “And finding that link is not necessarily obvious – or at least not as obvious as [if] there [were] a hurricane and a bunch of people got sick from waterborne disease. So I think that really highlights the scale of this problem.”

Instead of looking at only one individual or group of pathogens, the study provided a much broader review of infections caused by an array of climate hazards. As Dr. McKenzie said, “no one’s actually done the work previously to really just try and get a comprehensive picture of what we might be dealing with. And so that was the goal for us.” The 58% estimate of diseases worsened by climate change is conservative, and, he says, “arguably, this is an even bigger problem than what we present.”

Dr. McKenzie concluded: “If we’re looking at the spread of some more serious or rare diseases in areas, to me then the answer is ... we need to be aggressively mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. Let’s start with the source.”

Dr. McKenzie and Dr. Hauser report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An extensive new study shows that climate change can aggravate over half of known human pathogenic diseases. This comprehensive systematic review of the literature narrowed down 3,213 cases, linking 286 infectious diseases to specific climate change hazards. Of these, 58% were worsened, and only 9 conditions showed any benefit associated with environmental change.

The study was published online in Nature Climate Change. The complete list of cases, transmission pathways, and associated papers can be explored in detail – a remarkable, interactive data visualization.

To compile the data, investigators searched 10 keywords on the Global Infectious Disease and Epidemiology Network (GIDEON) and Center for Disease Control and Prevention databases. They then filled gaps by examining alternative names of the diseases, pathogens, and hazards.

Coauthor Tristan McKenzie, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, told this news organization: “If someone is interested in a certain pathway, it’s a beautiful starting point.” Or if someone wants to “do a modeling study and they want to focus on a specific area, the specific examples in the literature are already there” in the extensive database.

An early key finding is that warming and increased precipitation broadened the range of many pathogens through expansion of their habitat. This shift brings many pathogens closer to people. Examples are viruses (dengue, Chikungunya), bacteria (Lyme), protozoans (trypanosomes), and more. Warming has affected aquatic systems (for example, Vibrio) and higher altitudes and latitudes (malaria, dengue).

Pathogenic hazards are not just moving closer to people. People are also moving closer to the pathogenic hazards, with heat waves causing people to seek refuge with water activities, for example. This increases their exposure to pathogens, such as Vibrio, hepatitis, and water-borne gastroenteritis.

Some hazards, such as warming, can even make pathogens more virulent. Heat can upregulate Vibrio’s gene expression of proteins affecting transmission, adhesion, penetration, and host injury.

Heat and rainfall can increase stagnant water, enhancing mosquitoes’ breeding and growing grounds and enabling them to transmit many more infections.

People’s capacity to respond to climate hazards can also be impaired. For example, there is a reduced concentration of nutrients in crops under high CO2 levels, which can result in malnutrition. Lower crop yields can further fuel outbreaks of measles, cholera, or Cryptosporidium. Drought also likely forces people to drink contaminated water.

Among all this bad news, the authors found a small number of cases where climate hazards reduced the risk of infection. For example, droughts reduced the breeding grounds of mosquitoes, reducing the prevalence of malaria and chikungunya. But in other cases, the density of mosquitoes increased in some pools, causing an increased local risk of infection.

Naomi Hauser, MD, MPH, assistant clinical professor at UC Davis, Sacramento, told this news organization she was particularly impressed with the data visualization. “It really emphasizes the magnitude of what we’re dealing with. It makes you feel the weight of what they’re trying to represent,” she said.

On the other hand, Dr. Hauser said she would have liked “more emphasis on how the climate hazards interact with each other. It sort of made it sound like each of these climate hazards is in a vacuum – like when there’s floods, and that’s the problem. But there are a lot of other things ... like when we have warming and surface water temperature changes, it can also change the pH of the water and the salinity of the water, and those can also impact what we see with pathogens in the water.”

Dr. McKenzie explained one limitation: The study looked only at 10 keywords. So an example of a dust storm in Africa causing an increase in Vibrio in the United States could not be identified by this approach. “This also goes back to the scale of the problem, because we have something going on in the Sahara that’s impacting the East Coast of the United States,” he said. “And finding that link is not necessarily obvious – or at least not as obvious as [if] there [were] a hurricane and a bunch of people got sick from waterborne disease. So I think that really highlights the scale of this problem.”

Instead of looking at only one individual or group of pathogens, the study provided a much broader review of infections caused by an array of climate hazards. As Dr. McKenzie said, “no one’s actually done the work previously to really just try and get a comprehensive picture of what we might be dealing with. And so that was the goal for us.” The 58% estimate of diseases worsened by climate change is conservative, and, he says, “arguably, this is an even bigger problem than what we present.”

Dr. McKenzie concluded: “If we’re looking at the spread of some more serious or rare diseases in areas, to me then the answer is ... we need to be aggressively mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. Let’s start with the source.”

Dr. McKenzie and Dr. Hauser report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

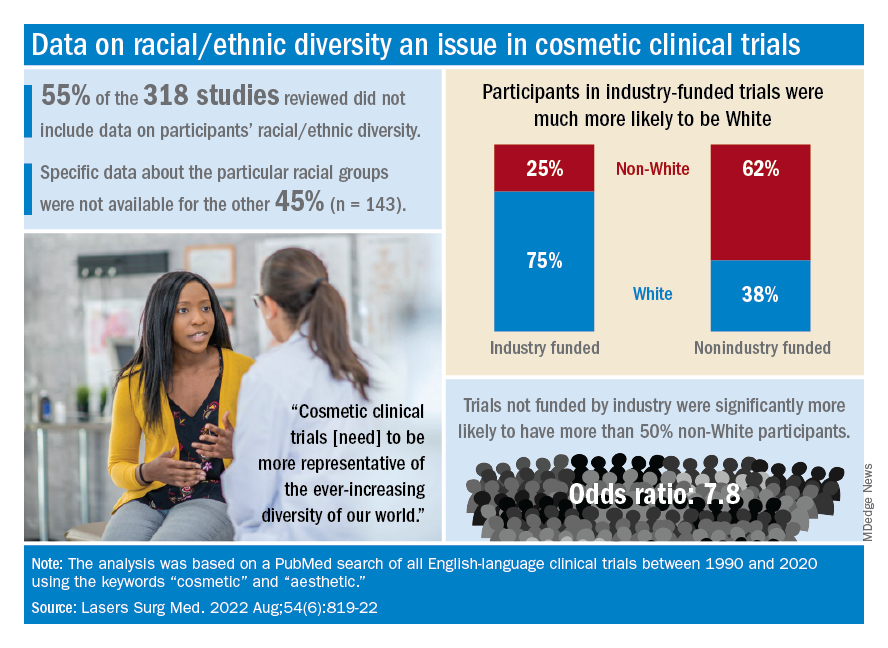

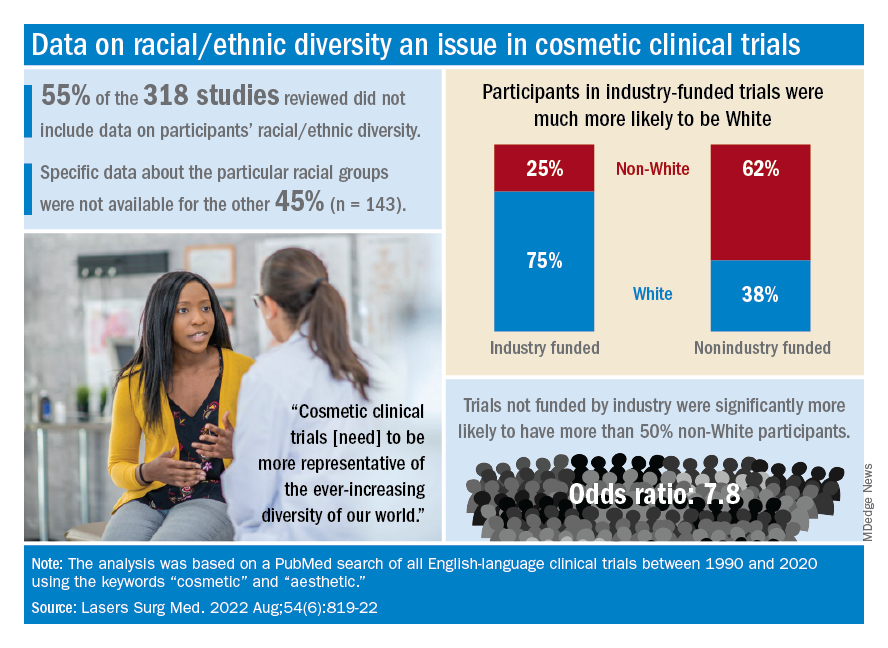

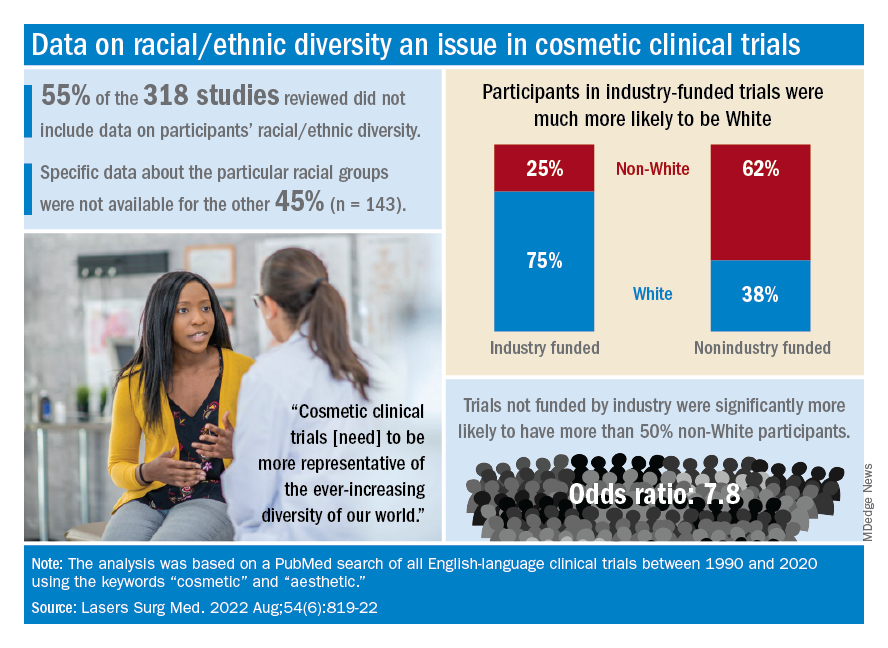

Funding of cosmetic clinical trials linked to racial/ethnic disparity

Individuals of nonwhite race/ethnicity are not underrepresented in cosmetic clinical trials, according to a recent literature review. The explanation for those contradictory conclusions comes down to money, or, more specifically, the source of the money.

Among the cosmetic studies funded by industry, non-Whites represented about 25% of the patient populations. That proportion, however, rose to 62% for studies that were funded by universities/governments or had no funding source reported, Lisa Akintilo, MD, and associates said in their review.

“Lack of inclusion of diverse patient populations is both a medical and moral issue as conclusions of such homogeneous studies may not be generalizable. In the realm of cosmetic dermatology, diverse research cohorts are needed to identify potential disparities in therapies for cosmetic concerns and fully investigate effective treatments for all,” wrote Dr. Akintilo of New York University and coauthors.

Data from the U.S. Census show that non-Hispanic Whites made up 60% of the population in 2019, with that proportion falling to about 50% by 2045, the investigators noted. A report from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that about 34% of cosmetic patients identified as skin of color in 2020.

The availability of data was an issue in the review of the literature from 1990 to 2020, as 55% of the 318 randomized controlled trials that were reviewed did not include any information on racial/ethnic diversity and the other 143 studies offered only enough to determine White/non-White status, they explained.

That limitation meant that those 143 studies had to form the basis of the funding analysis, which also indicated that the studies with funding outside of industry were significantly more likely (odds ratio, 7.8) to have more than 50% non-White participants, compared with the industry-funded trials. The projects with industry backing, however, had a larger mean sample size than did those without: 139 vs. 81, Dr. Akintilo and associates said.

“The protocols of cosmetic trials should be questioned, as many target Caucasian‐centric treatment goals that may not be in alignment with the goals of skin of color patients,” they wrote. “It is important for cosmetic providers to recognize the well-established anatomical variations between different races and ethnicities and how they can inform desired cosmetic procedures.”

The investigators said that they had no conflicts of interest.

Individuals of nonwhite race/ethnicity are not underrepresented in cosmetic clinical trials, according to a recent literature review. The explanation for those contradictory conclusions comes down to money, or, more specifically, the source of the money.

Among the cosmetic studies funded by industry, non-Whites represented about 25% of the patient populations. That proportion, however, rose to 62% for studies that were funded by universities/governments or had no funding source reported, Lisa Akintilo, MD, and associates said in their review.

“Lack of inclusion of diverse patient populations is both a medical and moral issue as conclusions of such homogeneous studies may not be generalizable. In the realm of cosmetic dermatology, diverse research cohorts are needed to identify potential disparities in therapies for cosmetic concerns and fully investigate effective treatments for all,” wrote Dr. Akintilo of New York University and coauthors.

Data from the U.S. Census show that non-Hispanic Whites made up 60% of the population in 2019, with that proportion falling to about 50% by 2045, the investigators noted. A report from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that about 34% of cosmetic patients identified as skin of color in 2020.

The availability of data was an issue in the review of the literature from 1990 to 2020, as 55% of the 318 randomized controlled trials that were reviewed did not include any information on racial/ethnic diversity and the other 143 studies offered only enough to determine White/non-White status, they explained.

That limitation meant that those 143 studies had to form the basis of the funding analysis, which also indicated that the studies with funding outside of industry were significantly more likely (odds ratio, 7.8) to have more than 50% non-White participants, compared with the industry-funded trials. The projects with industry backing, however, had a larger mean sample size than did those without: 139 vs. 81, Dr. Akintilo and associates said.

“The protocols of cosmetic trials should be questioned, as many target Caucasian‐centric treatment goals that may not be in alignment with the goals of skin of color patients,” they wrote. “It is important for cosmetic providers to recognize the well-established anatomical variations between different races and ethnicities and how they can inform desired cosmetic procedures.”

The investigators said that they had no conflicts of interest.

Individuals of nonwhite race/ethnicity are not underrepresented in cosmetic clinical trials, according to a recent literature review. The explanation for those contradictory conclusions comes down to money, or, more specifically, the source of the money.

Among the cosmetic studies funded by industry, non-Whites represented about 25% of the patient populations. That proportion, however, rose to 62% for studies that were funded by universities/governments or had no funding source reported, Lisa Akintilo, MD, and associates said in their review.

“Lack of inclusion of diverse patient populations is both a medical and moral issue as conclusions of such homogeneous studies may not be generalizable. In the realm of cosmetic dermatology, diverse research cohorts are needed to identify potential disparities in therapies for cosmetic concerns and fully investigate effective treatments for all,” wrote Dr. Akintilo of New York University and coauthors.

Data from the U.S. Census show that non-Hispanic Whites made up 60% of the population in 2019, with that proportion falling to about 50% by 2045, the investigators noted. A report from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that about 34% of cosmetic patients identified as skin of color in 2020.

The availability of data was an issue in the review of the literature from 1990 to 2020, as 55% of the 318 randomized controlled trials that were reviewed did not include any information on racial/ethnic diversity and the other 143 studies offered only enough to determine White/non-White status, they explained.

That limitation meant that those 143 studies had to form the basis of the funding analysis, which also indicated that the studies with funding outside of industry were significantly more likely (odds ratio, 7.8) to have more than 50% non-White participants, compared with the industry-funded trials. The projects with industry backing, however, had a larger mean sample size than did those without: 139 vs. 81, Dr. Akintilo and associates said.

“The protocols of cosmetic trials should be questioned, as many target Caucasian‐centric treatment goals that may not be in alignment with the goals of skin of color patients,” they wrote. “It is important for cosmetic providers to recognize the well-established anatomical variations between different races and ethnicities and how they can inform desired cosmetic procedures.”

The investigators said that they had no conflicts of interest.

FROM LASERS IN SURGERY AND MEDICINE

Firm Exophytic Tumor on the Shin

The Diagnosis: Leiomyosarcoma

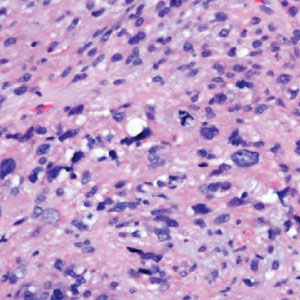

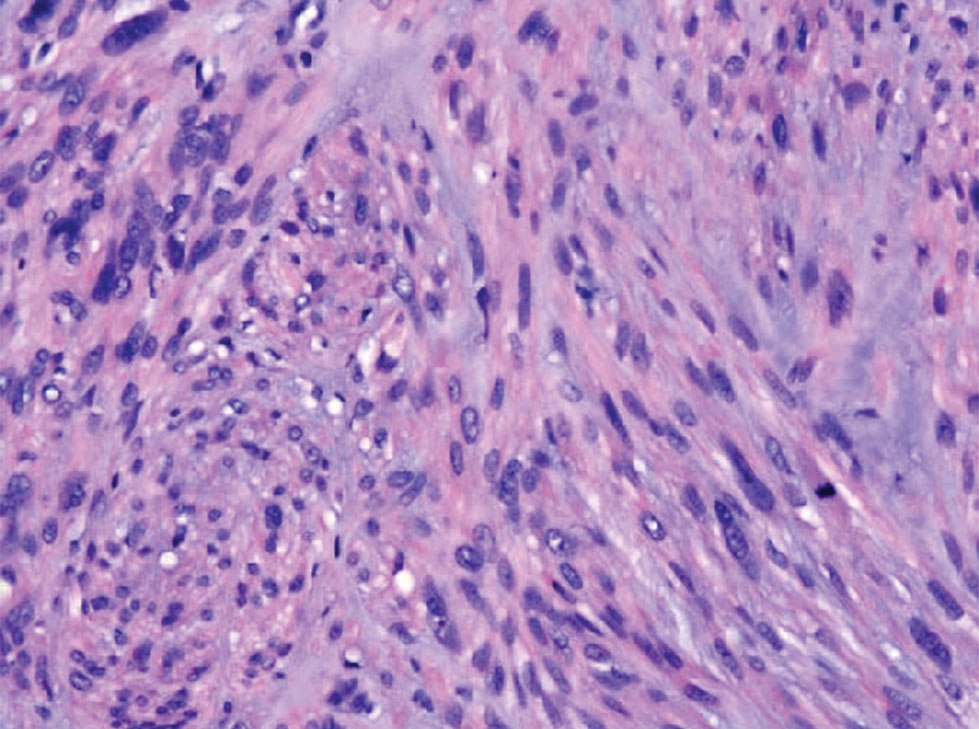

Cutaneous leiomyosarcomas are relatively rare neoplasms that favor the head, neck, and extremities of older adults.1 Dermal leiomyosarcomas originate from arrector pili and are locally aggressive, whereas subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas arise from vascular smooth muscle and metastasize in 30% to 60% of cases.2 Clinically, leiomyosarcomas present as solitary, firm, well-circumscribed nodules with possible ulceration and crusting.3 Histopathology of leiomyosarcoma shows fascicles of atypical spindle cells with blunt-ended nuclei and perinuclear glycogen vacuoles, variable atypia, and mitotic figures (quiz images). Definitive diagnosis is based on positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin and smooth muscle actin.4 Treatment entails complete removal via wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.5

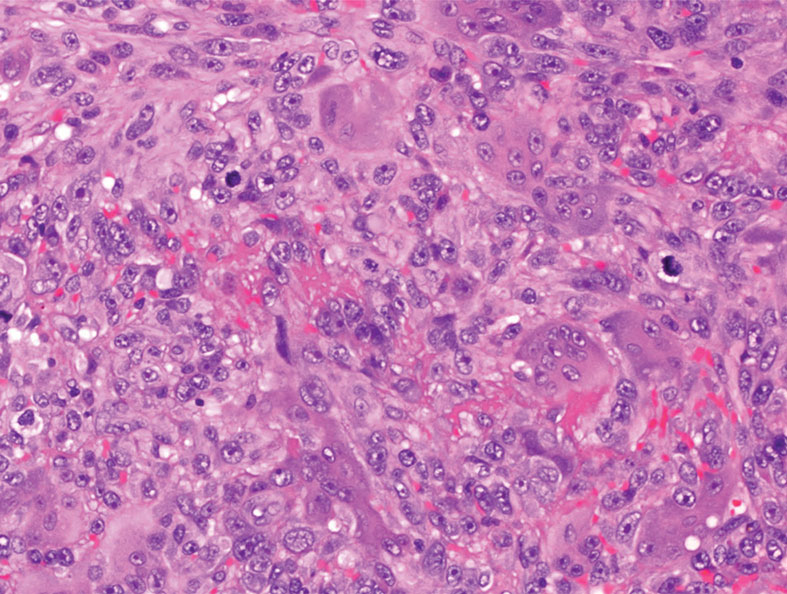

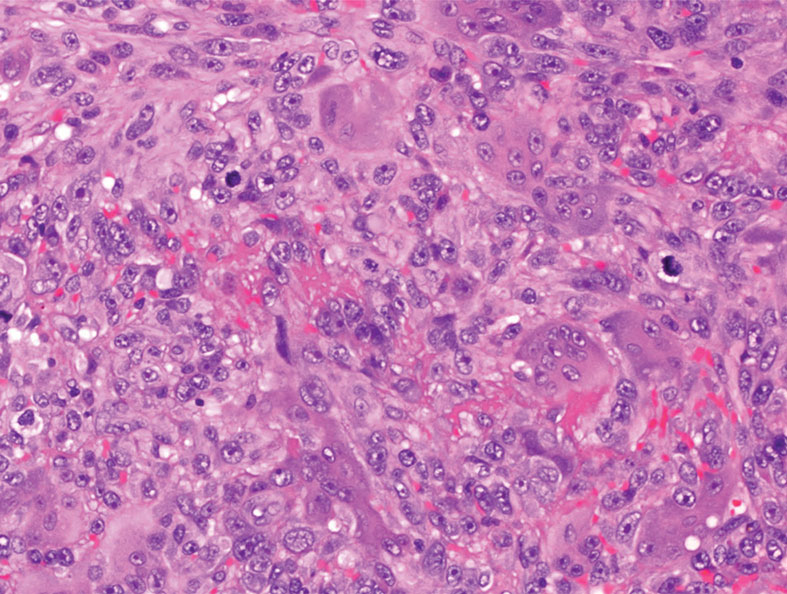

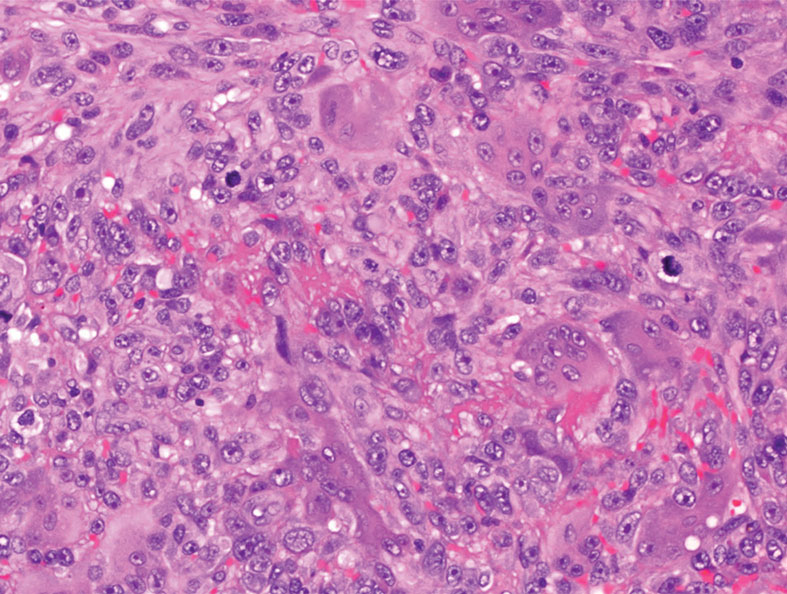

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a malignant fibrohistiocytic neoplasm that arises in the dermis and preferentially affects the head and neck in older individuals.3 Atypical fibroxanthoma presents as a nonspecific, pinkred, sometimes ulcerated papule on sun-damaged skin that may clinically resemble a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or basal cell carcinoma.6 Histopathology shows pleomorphic spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm mixed with multinucleated giant cells and scattered mitotic figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry is essential for distinguishing AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms. Atypical fibroxanthoma stains positively for vimentin, procollagen-1, CD10, and CD68 but is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, desmin, cytokeratin, p40, and p63.6 Treatment includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

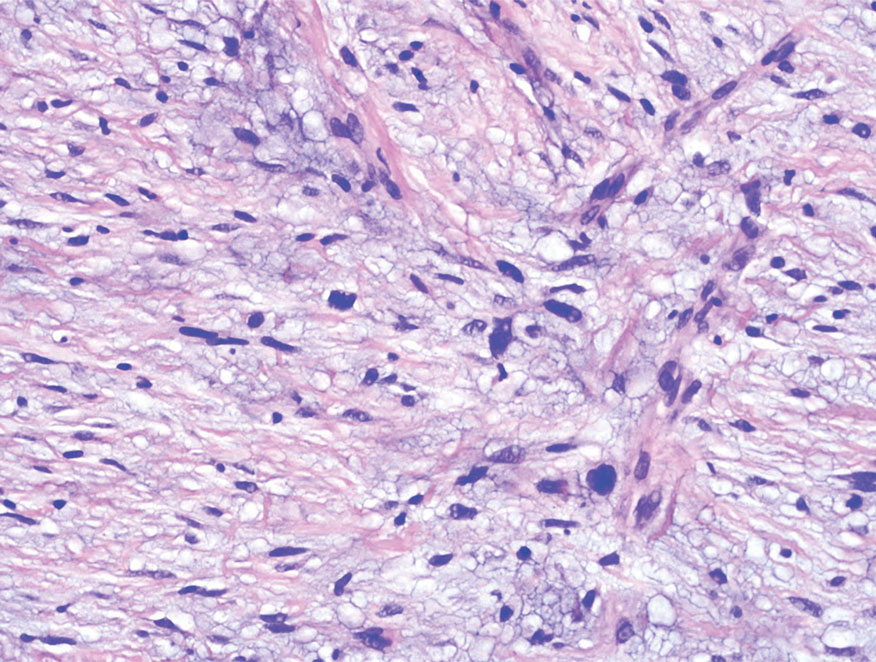

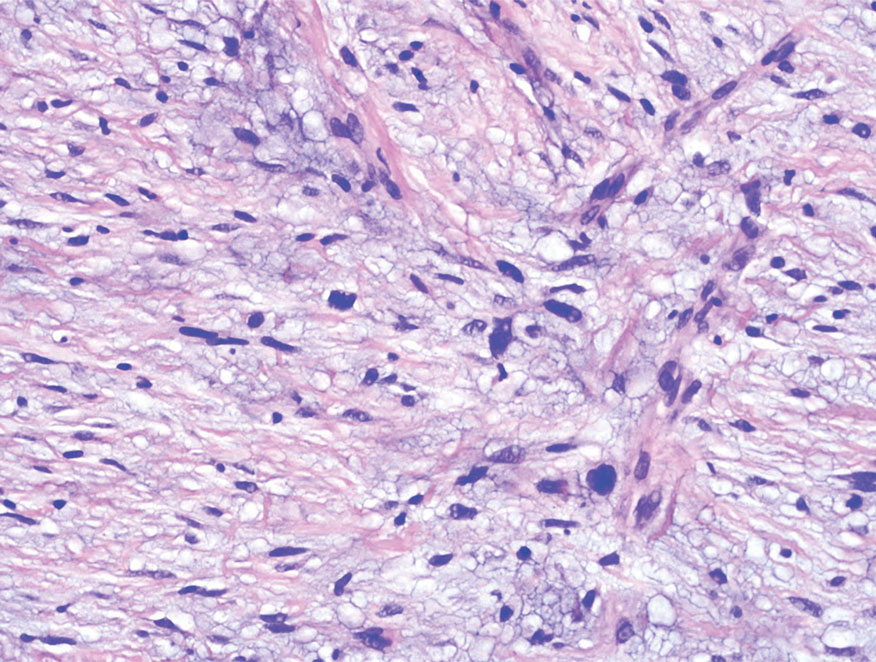

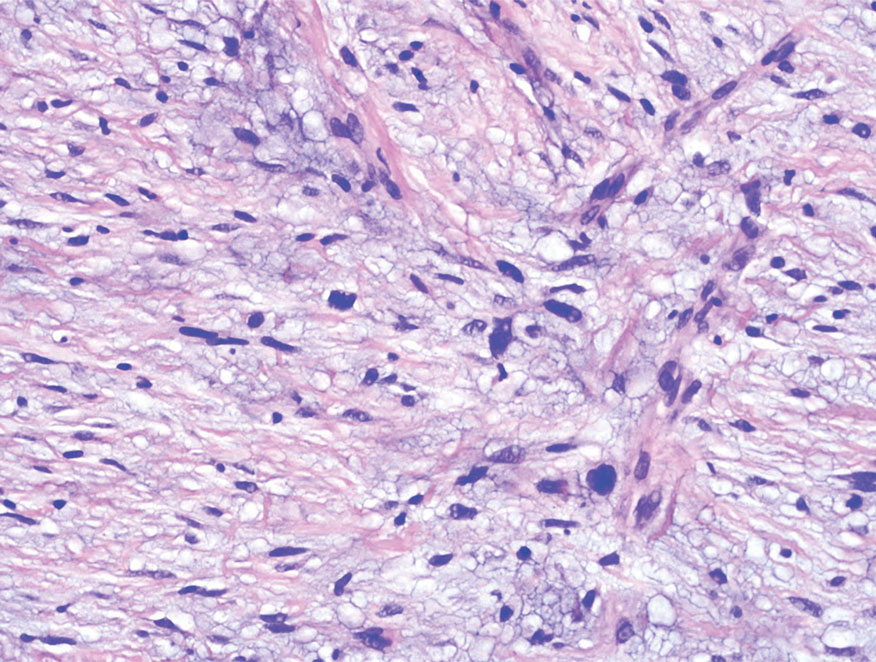

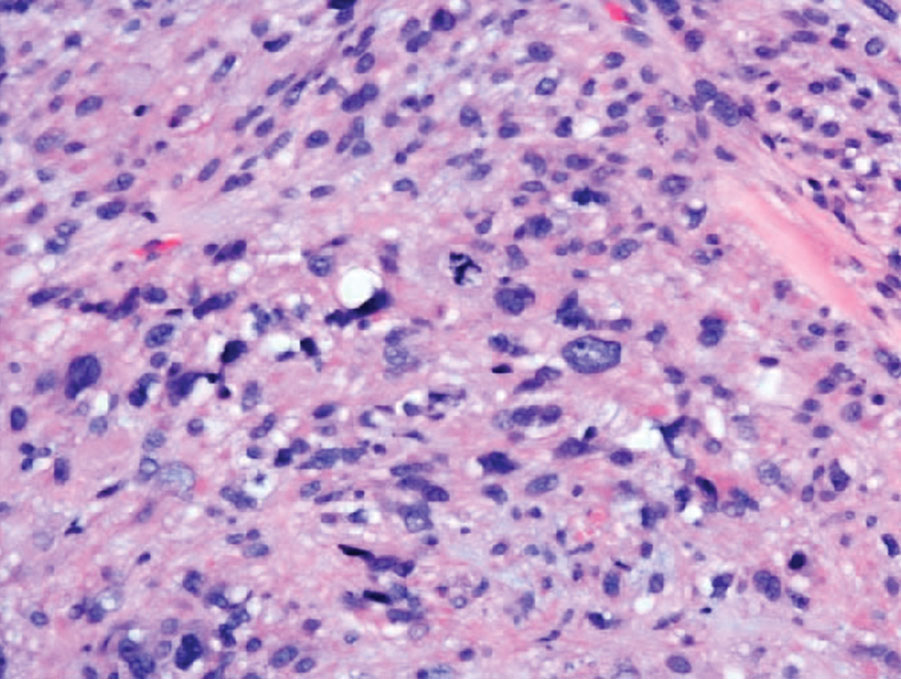

Melanoma is an aggressive cancer with the propensity to metastasize. Both desmoplastic and spindle cell variants demonstrate atypical spindled melanocytes on histology, and desmoplasia is seen in the desmoplastic variant (Figure 2). In some cases, evaluation of the epidermis for melanoma in situ may aid in diagnosis.7 Clinical and prognostic features differ between the 2 variants. Desmoplastic melanomas usually present on the head and neck as scarlike nodules with a low rate of nodal involvement, while spindle cell melanomas can occur anywhere on the body, often are amelanotic, and are associated with widespread metastatic disease at the time of presentation.8 SOX10 (SRY-box transcription factor 10) and S-100 may be the only markers that are positive in desmoplastic melanoma.9,10 Treatment depends on the thickness of the lesion.11

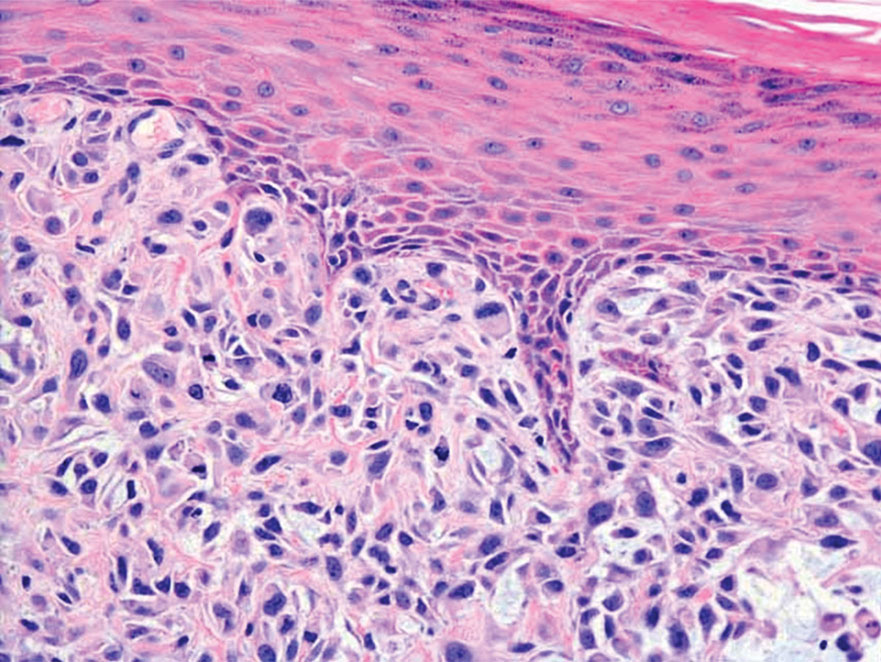

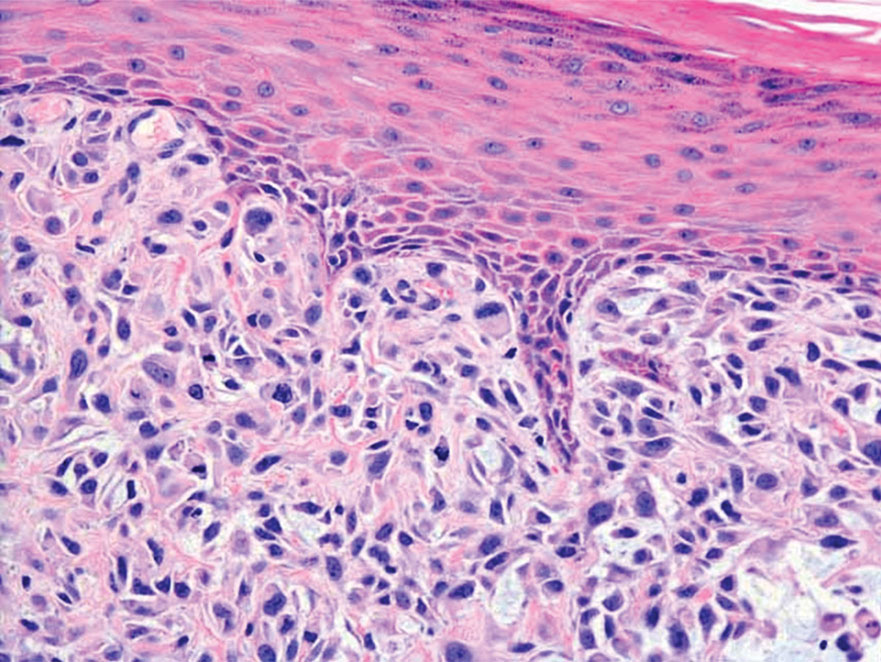

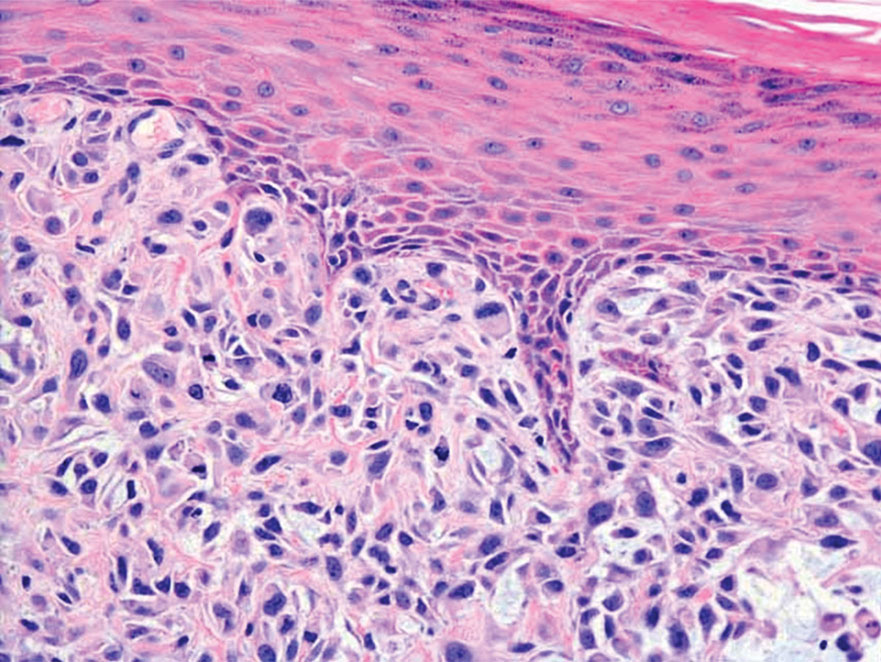

Spindle cell SCC is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by spindled epithelial cells. Spindle cell SCC typically presents as an ulcerated or exophytic mass in sun-exposed areas or areas exposed to ionizing radiation, or in immunocompromised individuals. Histopathology shows spindled pleomorphic keratinocytes with elongated nuclei infiltrating the dermis and minimal keratinization (Figure 3).12 Immunohistochemistry is necessary to distinguish spindle cell SCC from other spindle cell tumors such as spindle cell melanoma, AFX, and leiomyosarcoma. Spindle cell SCC is positive for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, p40, and p63. Mohs micrographic surgery provides the highest cure rate, and radiation therapy may be considered when clear surgical margins cannot be obtained.6

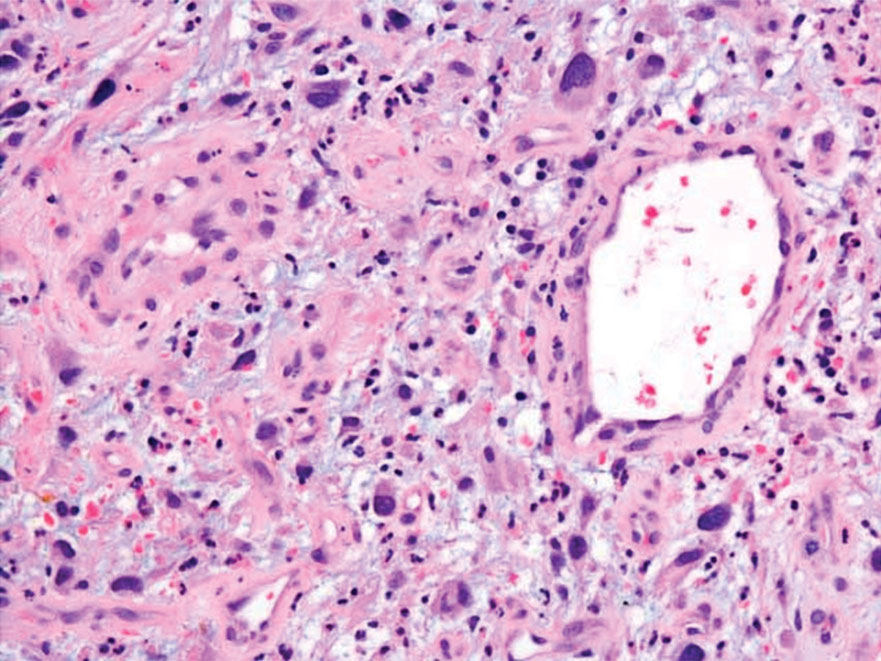

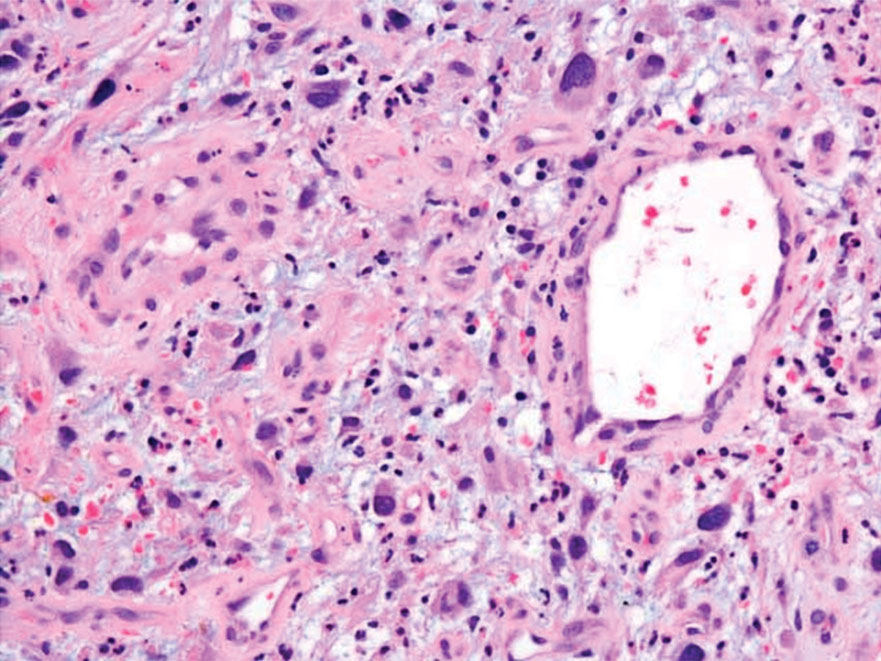

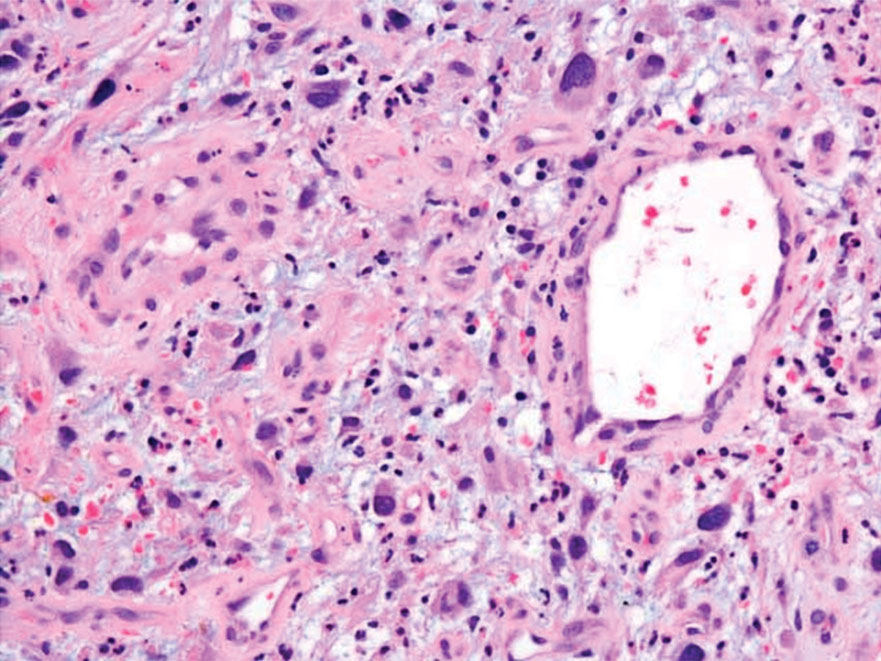

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) (formerly known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma) describes tumors that resemble AFX but are more invasive. They commonly involve the soft tissue with a higher risk for both recurrence and metastasis than AFX.13 Histopathology shows marked cytologic pleomorphism, bizarre cellular forms, atypical mitoses, and ulceration (Figure 4).14 Diagnosis of UPS is by exclusion and is dependent on immunohistochemical studies. In contrast to AFX, UPS is more likely to be positive for LN-2 (CD74).6 Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma has been treated with surgical excision in combination with chemical and radiation therapy, but due to limited data, optimal management is less clear compared to AFX.15 There is a substantial risk for local recurrence and metastasis, and the lungs are the most common sites of distant metastasis.13 In a study of 23 individuals with high-grade UPS, 5-year metastasis-free survival and local recurrence-free survival were 26% and 16%, respectively.10

- Massi D, Franchi A, Alos L, et al. Primary cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathological analysis of 36 cases. Histopathology. 2010;56: 251-262. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03471.x

- Ciurea ME, Georgescu CV, Radu CC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma—case report [published online June 25, 2014]. J Med Life. 2014;7:270-273.

- Fleury LFF, Sanches JA. Primary cutaneous sarcomas. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:207-221. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962006000300002

- Murback NDN, de Castro BC, Takita LC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma on the face. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:262-264. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186715

- Winchester DS, Hocker TL, Brewer JD, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the skin: clinical, histopathologic, and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:919-925. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2014.07.020

- Hollmig ST, Sachdev R, Cockerell CJ, et al. Spindle cell neoplasms encountered in dermatologic surgery: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:825-850. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02296.x

- De Almeida LS, Requena L, Rütten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0B013E3181716E6B

- Weissinger SE, Keil P, Silvers DN, et al. A diagnostic algorithm to distinguish desmoplastic from spindle cell melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:524-534. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2013.162

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00891.x

- Delisca GO, Mesko NW, Alamanda VK, et al. MFH and highgrade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma—what’s in a name? [published online September 12, 2014]. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:173-177. doi:10.1002/jso.23787

- Baron PL, Nguyen CL. Malignant of melanoma. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem- Oriented. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK6877

- Wernheden E, Trøstrup H, Pedersen Pilt A. Unusual presentation of cutaneous spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:70-75. doi:10.1159/000507358

- Ramsey JK, Chen JL, Schoenfield L, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma metastatic to the orbit. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34:E193-E195. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001240

- Winchester D, Lehman J, Tello T, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: factors predictive of adverse outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:853-859. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.022

- Soleymani T, Tyler Hollmig S. Conception and management of a poorly understood spectrum of dermatologic neoplasms: atypical fibroxanthoma, pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18:50. doi:10.1007 /s11864-017-0489-6

The Diagnosis: Leiomyosarcoma

Cutaneous leiomyosarcomas are relatively rare neoplasms that favor the head, neck, and extremities of older adults.1 Dermal leiomyosarcomas originate from arrector pili and are locally aggressive, whereas subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas arise from vascular smooth muscle and metastasize in 30% to 60% of cases.2 Clinically, leiomyosarcomas present as solitary, firm, well-circumscribed nodules with possible ulceration and crusting.3 Histopathology of leiomyosarcoma shows fascicles of atypical spindle cells with blunt-ended nuclei and perinuclear glycogen vacuoles, variable atypia, and mitotic figures (quiz images). Definitive diagnosis is based on positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin and smooth muscle actin.4 Treatment entails complete removal via wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.5

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a malignant fibrohistiocytic neoplasm that arises in the dermis and preferentially affects the head and neck in older individuals.3 Atypical fibroxanthoma presents as a nonspecific, pinkred, sometimes ulcerated papule on sun-damaged skin that may clinically resemble a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or basal cell carcinoma.6 Histopathology shows pleomorphic spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm mixed with multinucleated giant cells and scattered mitotic figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry is essential for distinguishing AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms. Atypical fibroxanthoma stains positively for vimentin, procollagen-1, CD10, and CD68 but is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, desmin, cytokeratin, p40, and p63.6 Treatment includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Melanoma is an aggressive cancer with the propensity to metastasize. Both desmoplastic and spindle cell variants demonstrate atypical spindled melanocytes on histology, and desmoplasia is seen in the desmoplastic variant (Figure 2). In some cases, evaluation of the epidermis for melanoma in situ may aid in diagnosis.7 Clinical and prognostic features differ between the 2 variants. Desmoplastic melanomas usually present on the head and neck as scarlike nodules with a low rate of nodal involvement, while spindle cell melanomas can occur anywhere on the body, often are amelanotic, and are associated with widespread metastatic disease at the time of presentation.8 SOX10 (SRY-box transcription factor 10) and S-100 may be the only markers that are positive in desmoplastic melanoma.9,10 Treatment depends on the thickness of the lesion.11

Spindle cell SCC is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by spindled epithelial cells. Spindle cell SCC typically presents as an ulcerated or exophytic mass in sun-exposed areas or areas exposed to ionizing radiation, or in immunocompromised individuals. Histopathology shows spindled pleomorphic keratinocytes with elongated nuclei infiltrating the dermis and minimal keratinization (Figure 3).12 Immunohistochemistry is necessary to distinguish spindle cell SCC from other spindle cell tumors such as spindle cell melanoma, AFX, and leiomyosarcoma. Spindle cell SCC is positive for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, p40, and p63. Mohs micrographic surgery provides the highest cure rate, and radiation therapy may be considered when clear surgical margins cannot be obtained.6

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) (formerly known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma) describes tumors that resemble AFX but are more invasive. They commonly involve the soft tissue with a higher risk for both recurrence and metastasis than AFX.13 Histopathology shows marked cytologic pleomorphism, bizarre cellular forms, atypical mitoses, and ulceration (Figure 4).14 Diagnosis of UPS is by exclusion and is dependent on immunohistochemical studies. In contrast to AFX, UPS is more likely to be positive for LN-2 (CD74).6 Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma has been treated with surgical excision in combination with chemical and radiation therapy, but due to limited data, optimal management is less clear compared to AFX.15 There is a substantial risk for local recurrence and metastasis, and the lungs are the most common sites of distant metastasis.13 In a study of 23 individuals with high-grade UPS, 5-year metastasis-free survival and local recurrence-free survival were 26% and 16%, respectively.10

The Diagnosis: Leiomyosarcoma

Cutaneous leiomyosarcomas are relatively rare neoplasms that favor the head, neck, and extremities of older adults.1 Dermal leiomyosarcomas originate from arrector pili and are locally aggressive, whereas subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas arise from vascular smooth muscle and metastasize in 30% to 60% of cases.2 Clinically, leiomyosarcomas present as solitary, firm, well-circumscribed nodules with possible ulceration and crusting.3 Histopathology of leiomyosarcoma shows fascicles of atypical spindle cells with blunt-ended nuclei and perinuclear glycogen vacuoles, variable atypia, and mitotic figures (quiz images). Definitive diagnosis is based on positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin and smooth muscle actin.4 Treatment entails complete removal via wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.5

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a malignant fibrohistiocytic neoplasm that arises in the dermis and preferentially affects the head and neck in older individuals.3 Atypical fibroxanthoma presents as a nonspecific, pinkred, sometimes ulcerated papule on sun-damaged skin that may clinically resemble a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or basal cell carcinoma.6 Histopathology shows pleomorphic spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm mixed with multinucleated giant cells and scattered mitotic figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry is essential for distinguishing AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms. Atypical fibroxanthoma stains positively for vimentin, procollagen-1, CD10, and CD68 but is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, desmin, cytokeratin, p40, and p63.6 Treatment includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Melanoma is an aggressive cancer with the propensity to metastasize. Both desmoplastic and spindle cell variants demonstrate atypical spindled melanocytes on histology, and desmoplasia is seen in the desmoplastic variant (Figure 2). In some cases, evaluation of the epidermis for melanoma in situ may aid in diagnosis.7 Clinical and prognostic features differ between the 2 variants. Desmoplastic melanomas usually present on the head and neck as scarlike nodules with a low rate of nodal involvement, while spindle cell melanomas can occur anywhere on the body, often are amelanotic, and are associated with widespread metastatic disease at the time of presentation.8 SOX10 (SRY-box transcription factor 10) and S-100 may be the only markers that are positive in desmoplastic melanoma.9,10 Treatment depends on the thickness of the lesion.11

Spindle cell SCC is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by spindled epithelial cells. Spindle cell SCC typically presents as an ulcerated or exophytic mass in sun-exposed areas or areas exposed to ionizing radiation, or in immunocompromised individuals. Histopathology shows spindled pleomorphic keratinocytes with elongated nuclei infiltrating the dermis and minimal keratinization (Figure 3).12 Immunohistochemistry is necessary to distinguish spindle cell SCC from other spindle cell tumors such as spindle cell melanoma, AFX, and leiomyosarcoma. Spindle cell SCC is positive for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, p40, and p63. Mohs micrographic surgery provides the highest cure rate, and radiation therapy may be considered when clear surgical margins cannot be obtained.6

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) (formerly known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma) describes tumors that resemble AFX but are more invasive. They commonly involve the soft tissue with a higher risk for both recurrence and metastasis than AFX.13 Histopathology shows marked cytologic pleomorphism, bizarre cellular forms, atypical mitoses, and ulceration (Figure 4).14 Diagnosis of UPS is by exclusion and is dependent on immunohistochemical studies. In contrast to AFX, UPS is more likely to be positive for LN-2 (CD74).6 Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma has been treated with surgical excision in combination with chemical and radiation therapy, but due to limited data, optimal management is less clear compared to AFX.15 There is a substantial risk for local recurrence and metastasis, and the lungs are the most common sites of distant metastasis.13 In a study of 23 individuals with high-grade UPS, 5-year metastasis-free survival and local recurrence-free survival were 26% and 16%, respectively.10

- Massi D, Franchi A, Alos L, et al. Primary cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathological analysis of 36 cases. Histopathology. 2010;56: 251-262. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03471.x

- Ciurea ME, Georgescu CV, Radu CC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma—case report [published online June 25, 2014]. J Med Life. 2014;7:270-273.

- Fleury LFF, Sanches JA. Primary cutaneous sarcomas. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:207-221. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962006000300002

- Murback NDN, de Castro BC, Takita LC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma on the face. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:262-264. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186715

- Winchester DS, Hocker TL, Brewer JD, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the skin: clinical, histopathologic, and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:919-925. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2014.07.020

- Hollmig ST, Sachdev R, Cockerell CJ, et al. Spindle cell neoplasms encountered in dermatologic surgery: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:825-850. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02296.x

- De Almeida LS, Requena L, Rütten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0B013E3181716E6B

- Weissinger SE, Keil P, Silvers DN, et al. A diagnostic algorithm to distinguish desmoplastic from spindle cell melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:524-534. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2013.162

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00891.x

- Delisca GO, Mesko NW, Alamanda VK, et al. MFH and highgrade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma—what’s in a name? [published online September 12, 2014]. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:173-177. doi:10.1002/jso.23787

- Baron PL, Nguyen CL. Malignant of melanoma. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem- Oriented. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK6877

- Wernheden E, Trøstrup H, Pedersen Pilt A. Unusual presentation of cutaneous spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:70-75. doi:10.1159/000507358

- Ramsey JK, Chen JL, Schoenfield L, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma metastatic to the orbit. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34:E193-E195. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001240

- Winchester D, Lehman J, Tello T, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: factors predictive of adverse outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:853-859. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.022

- Soleymani T, Tyler Hollmig S. Conception and management of a poorly understood spectrum of dermatologic neoplasms: atypical fibroxanthoma, pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18:50. doi:10.1007 /s11864-017-0489-6

- Massi D, Franchi A, Alos L, et al. Primary cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathological analysis of 36 cases. Histopathology. 2010;56: 251-262. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03471.x

- Ciurea ME, Georgescu CV, Radu CC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma—case report [published online June 25, 2014]. J Med Life. 2014;7:270-273.

- Fleury LFF, Sanches JA. Primary cutaneous sarcomas. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:207-221. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962006000300002

- Murback NDN, de Castro BC, Takita LC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma on the face. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:262-264. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186715

- Winchester DS, Hocker TL, Brewer JD, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the skin: clinical, histopathologic, and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:919-925. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2014.07.020

- Hollmig ST, Sachdev R, Cockerell CJ, et al. Spindle cell neoplasms encountered in dermatologic surgery: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:825-850. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02296.x

- De Almeida LS, Requena L, Rütten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0B013E3181716E6B

- Weissinger SE, Keil P, Silvers DN, et al. A diagnostic algorithm to distinguish desmoplastic from spindle cell melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:524-534. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2013.162

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00891.x

- Delisca GO, Mesko NW, Alamanda VK, et al. MFH and highgrade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma—what’s in a name? [published online September 12, 2014]. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:173-177. doi:10.1002/jso.23787

- Baron PL, Nguyen CL. Malignant of melanoma. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem- Oriented. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK6877

- Wernheden E, Trøstrup H, Pedersen Pilt A. Unusual presentation of cutaneous spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:70-75. doi:10.1159/000507358

- Ramsey JK, Chen JL, Schoenfield L, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma metastatic to the orbit. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34:E193-E195. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001240

- Winchester D, Lehman J, Tello T, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: factors predictive of adverse outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:853-859. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.022

- Soleymani T, Tyler Hollmig S. Conception and management of a poorly understood spectrum of dermatologic neoplasms: atypical fibroxanthoma, pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18:50. doi:10.1007 /s11864-017-0489-6

A 62-year-old man presented with a firm, exophytic, 2.8×1.5-cm tumor on the left shin of 6 to 7 years’ duration. An excisional biopsy was obtained for histopathologic evaluation.

FDA acts against sales of unapproved mole and skin tag products on Amazon, other sites

according to a press release issued on Aug. 9.

In addition to Amazon.com, the other two companies are Ariella Naturals, and Justified Laboratories.

Currently, no over-the-counter products are FDA-approved for the at-home removal of moles and skin tags, and use of unapproved products could be dangerous to consumers, according to the statement. These products may be sold as ointments, gels, sticks, or liquids, and may contain high concentrations of salicylic acid or other harmful ingredients. Introducing unapproved products in to interstate commerce violates the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

Two products sold on Amazon are the “Deisana Skin Tag Remover, Mole Remover and Repair Gel Set” and “Skincell Mole Skin Tag Corrector Serum,” according to the letter sent to Amazon.

The warning letters alert the three companies that they have 15 days from receipt to address any violations. However, warning letters are not a final FDA action, according to the statement.

“The agency’s rigorous surveillance works to identify threats to public health and stop these products from reaching our communities,” Donald D. Ashley, JD, director of the Office of Compliance in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release. “This includes where online retailers like Amazon are involved in the interstate sale of unapproved drug products. We will continue to work diligently to ensure that online retailers do not sell products that violate federal law,” he added.

The statement emphasized that moles should be evaluated by a health care professional, as attempts at self-diagnosis and at-home treatment could lead to a delayed cancer diagnosis, and potentially to cancer progression.

Products marketed to consumers for at-home removal of moles, skin tags, and other skin lesions could cause injuries, infections, and scarring, according to a related consumer update first posted by the FDA in June, which was updated after the warning letters were sent out.

Consumers and health care professionals are encouraged to report any adverse events related to mole removal or skin tag removal products to the agency’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program.

The FDA also offers an online guide, BeSafeRx, with advice for consumers about potential risks of using online pharmacies and how to do so safely.

according to a press release issued on Aug. 9.

In addition to Amazon.com, the other two companies are Ariella Naturals, and Justified Laboratories.

Currently, no over-the-counter products are FDA-approved for the at-home removal of moles and skin tags, and use of unapproved products could be dangerous to consumers, according to the statement. These products may be sold as ointments, gels, sticks, or liquids, and may contain high concentrations of salicylic acid or other harmful ingredients. Introducing unapproved products in to interstate commerce violates the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

Two products sold on Amazon are the “Deisana Skin Tag Remover, Mole Remover and Repair Gel Set” and “Skincell Mole Skin Tag Corrector Serum,” according to the letter sent to Amazon.

The warning letters alert the three companies that they have 15 days from receipt to address any violations. However, warning letters are not a final FDA action, according to the statement.

“The agency’s rigorous surveillance works to identify threats to public health and stop these products from reaching our communities,” Donald D. Ashley, JD, director of the Office of Compliance in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release. “This includes where online retailers like Amazon are involved in the interstate sale of unapproved drug products. We will continue to work diligently to ensure that online retailers do not sell products that violate federal law,” he added.

The statement emphasized that moles should be evaluated by a health care professional, as attempts at self-diagnosis and at-home treatment could lead to a delayed cancer diagnosis, and potentially to cancer progression.

Products marketed to consumers for at-home removal of moles, skin tags, and other skin lesions could cause injuries, infections, and scarring, according to a related consumer update first posted by the FDA in June, which was updated after the warning letters were sent out.

Consumers and health care professionals are encouraged to report any adverse events related to mole removal or skin tag removal products to the agency’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program.

The FDA also offers an online guide, BeSafeRx, with advice for consumers about potential risks of using online pharmacies and how to do so safely.

according to a press release issued on Aug. 9.

In addition to Amazon.com, the other two companies are Ariella Naturals, and Justified Laboratories.

Currently, no over-the-counter products are FDA-approved for the at-home removal of moles and skin tags, and use of unapproved products could be dangerous to consumers, according to the statement. These products may be sold as ointments, gels, sticks, or liquids, and may contain high concentrations of salicylic acid or other harmful ingredients. Introducing unapproved products in to interstate commerce violates the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

Two products sold on Amazon are the “Deisana Skin Tag Remover, Mole Remover and Repair Gel Set” and “Skincell Mole Skin Tag Corrector Serum,” according to the letter sent to Amazon.

The warning letters alert the three companies that they have 15 days from receipt to address any violations. However, warning letters are not a final FDA action, according to the statement.

“The agency’s rigorous surveillance works to identify threats to public health and stop these products from reaching our communities,” Donald D. Ashley, JD, director of the Office of Compliance in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release. “This includes where online retailers like Amazon are involved in the interstate sale of unapproved drug products. We will continue to work diligently to ensure that online retailers do not sell products that violate federal law,” he added.

The statement emphasized that moles should be evaluated by a health care professional, as attempts at self-diagnosis and at-home treatment could lead to a delayed cancer diagnosis, and potentially to cancer progression.

Products marketed to consumers for at-home removal of moles, skin tags, and other skin lesions could cause injuries, infections, and scarring, according to a related consumer update first posted by the FDA in June, which was updated after the warning letters were sent out.

Consumers and health care professionals are encouraged to report any adverse events related to mole removal or skin tag removal products to the agency’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program.

The FDA also offers an online guide, BeSafeRx, with advice for consumers about potential risks of using online pharmacies and how to do so safely.

Unique Treatment for Alopecia Areata Combining Epinephrine With an Intralesional Steroid

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by transient hair loss with preservation of the hair follicle (HF). The lifetime incidence risk of AA is approximately 2%,1 with a mean age of onset of 25 to 36 years and with no clinically relevant significant differences between sex or ethnicity.2 Most commonly, it presents as round, well-demarcated patches of alopecia on the scalp and spontaneously resolves in nearly 30% of patients. However, severe disease is associated with younger age of presentation and can progress to a total loss of scalp or body hair—referred to as alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis, respectively—thus severely impacting quality of life.3,4

First-line treatment options for AA include potent topical steroids5,6 and intralesional (IL) steroids, most commonly IL triamcinolone acetonide (ILTA). Intralesional steroids have been found to be more effective than topicals in stimulating hair growth at the injection site.7,8 A recent systemic therapy—the Janus kinase inhibitor baricitinib—was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for AA.9 Other systemic therapies such as oral corticosteroids have been studied in small trials with promising results.10 However, the risks of systemic therapies may outweigh the benefits.9,10

Another less common topical therapy is contact immunotherapy, which involves topical application of an unlicensed non–pharmaceutical-grade agent to areas affected with AA. It is reported to have a wide range of response rates (29%–87%).11

We report 2 cases of extensive AA that were treated with a novel combination regimen— 2.5 mg/mL of ILTA diluted with lidocaine 1% and epinephrine 1:100,000 in place of normal saline (NS)— which is a modification to an already widely used first-line treatment.

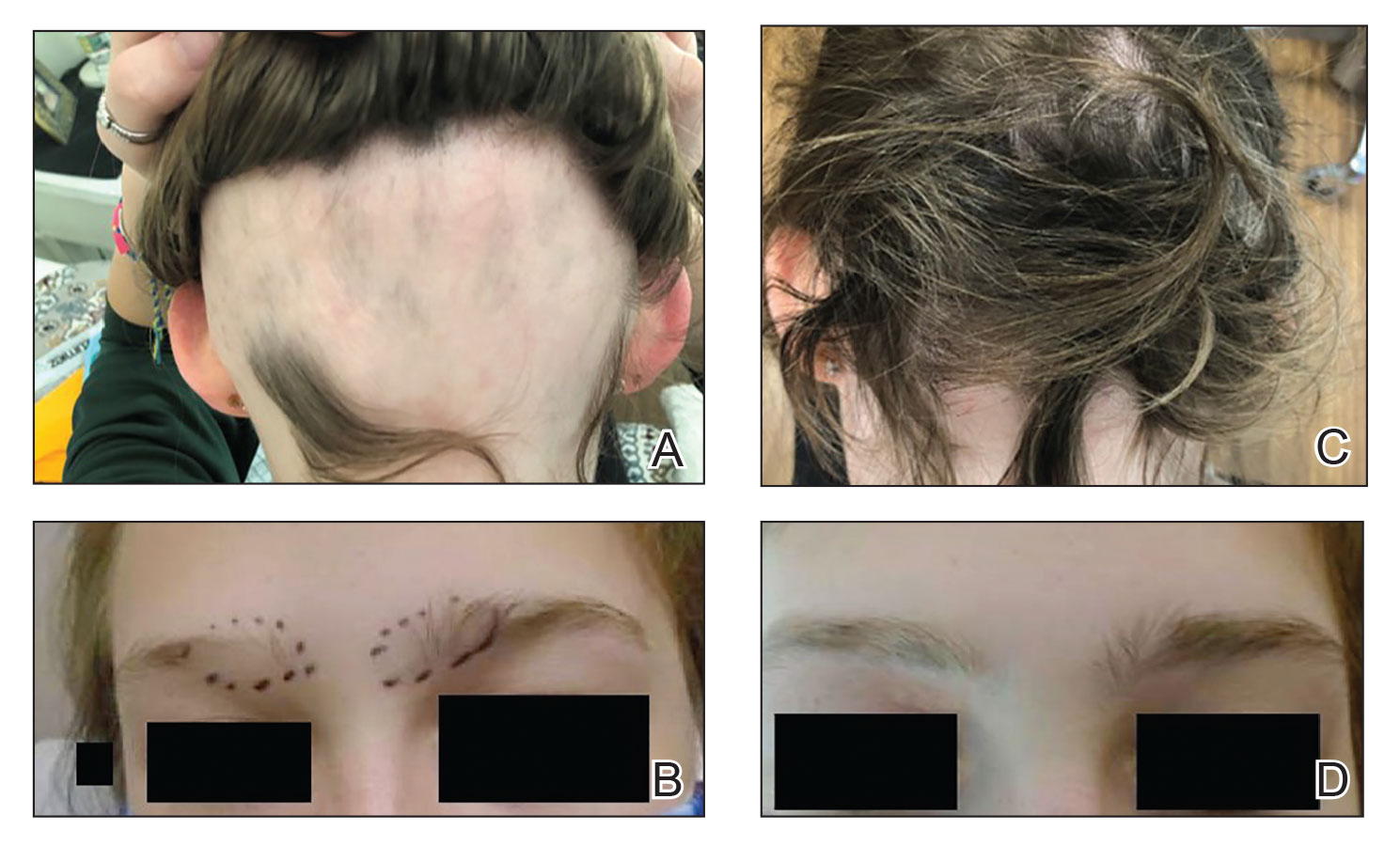

Case Reports

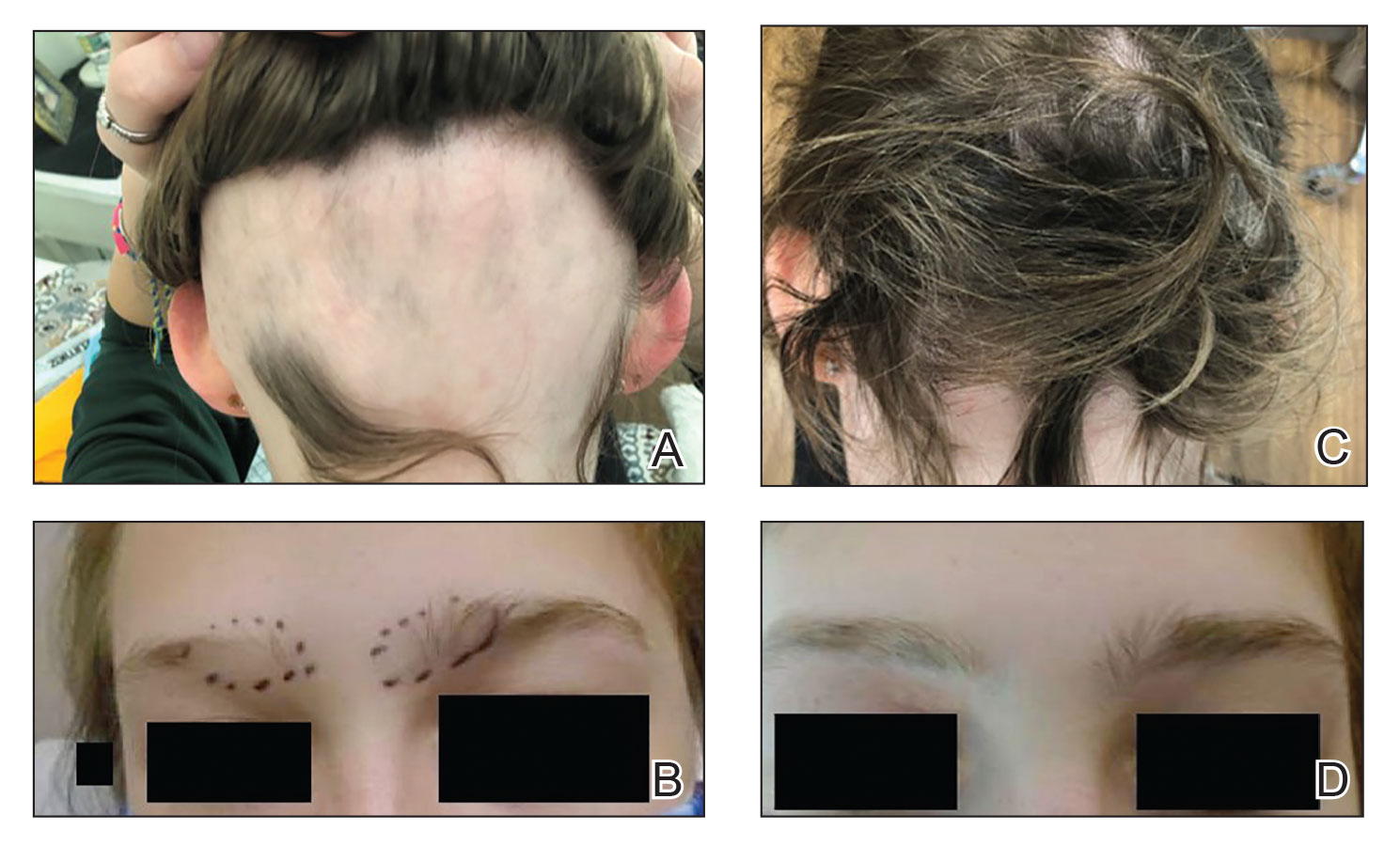

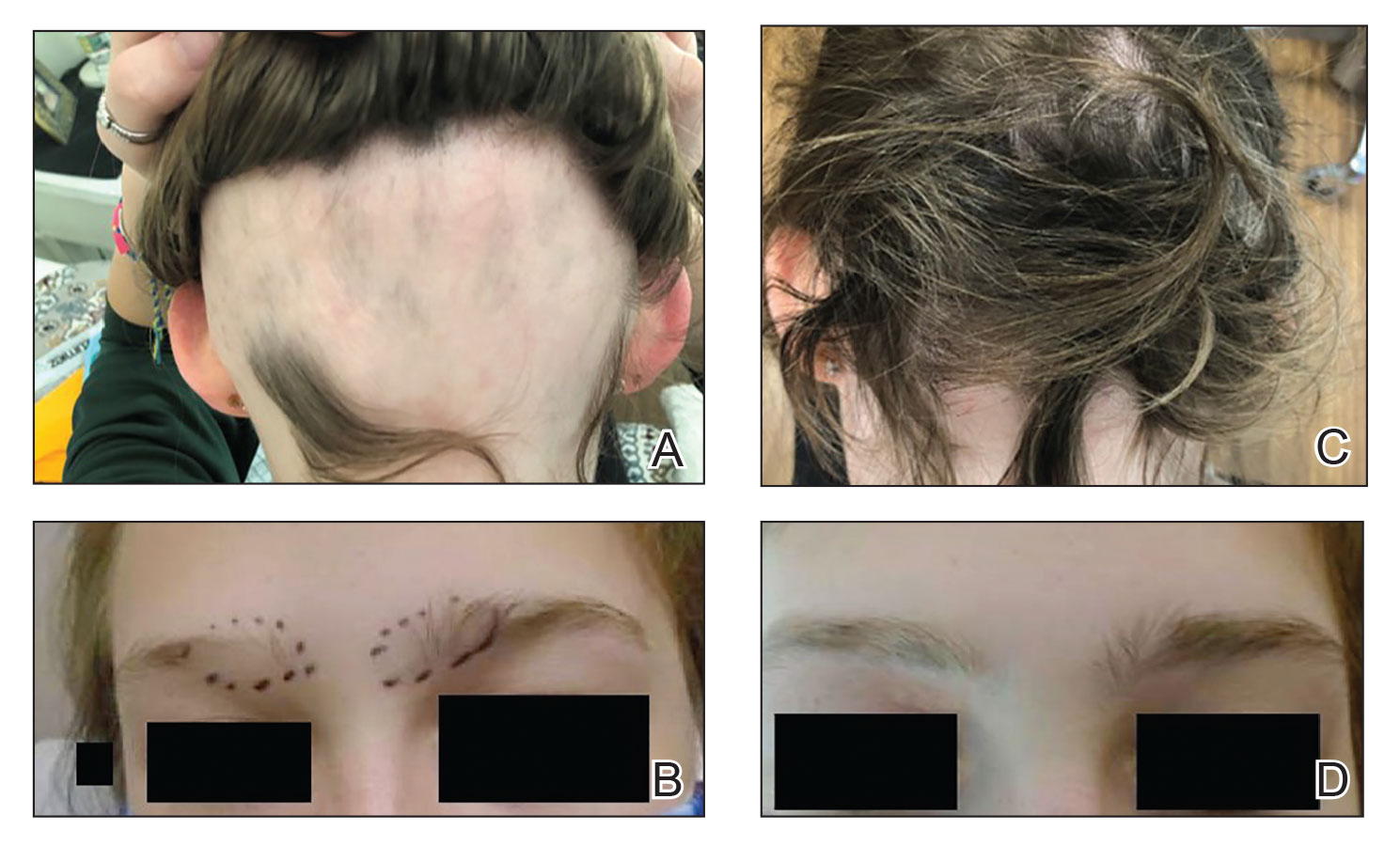

Patient 1—An 11-year-old girl presented with nonscarring alopecia of the vertex and occipital scalp. Three years prior she was treated with topical and IL corticosteroids by a different provider. Physical examination revealed almost complete alopecia involving the bottom two-thirds of the occipital scalp as well as the medial eyebrows (Figures 1A and 1B). Over the span of 1 year she was treated with betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05% and several rounds of ILTA 2.5 mg/mL buffered with NS, with minimal improvement. A year after the initial presentation, the decision was made to initiate monthly injections of ILTA 2.5 mg/mL buffered with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine 1:100,000. Some hair regrowth of the occipital scalp was noted by 3 months, with near-complete regrowth of the scalp hair and eyebrows by 7 months and 5 months, respectively (Figures 1C and 1D). During this period, the patient continued to develop new areas of alopecia of the scalp and eyebrows, which also were injected with this combination. In total, the patient received 8 rounds of IL injections 4 to 6 weeks apart in the scalp and 6 rounds in the eyebrows. The treated areas showed resolution over a follow-up period of 14 months, though there was recurrence at the right medial eyebrow at 5 months. No localized skin atrophy or other adverse effects were noted.

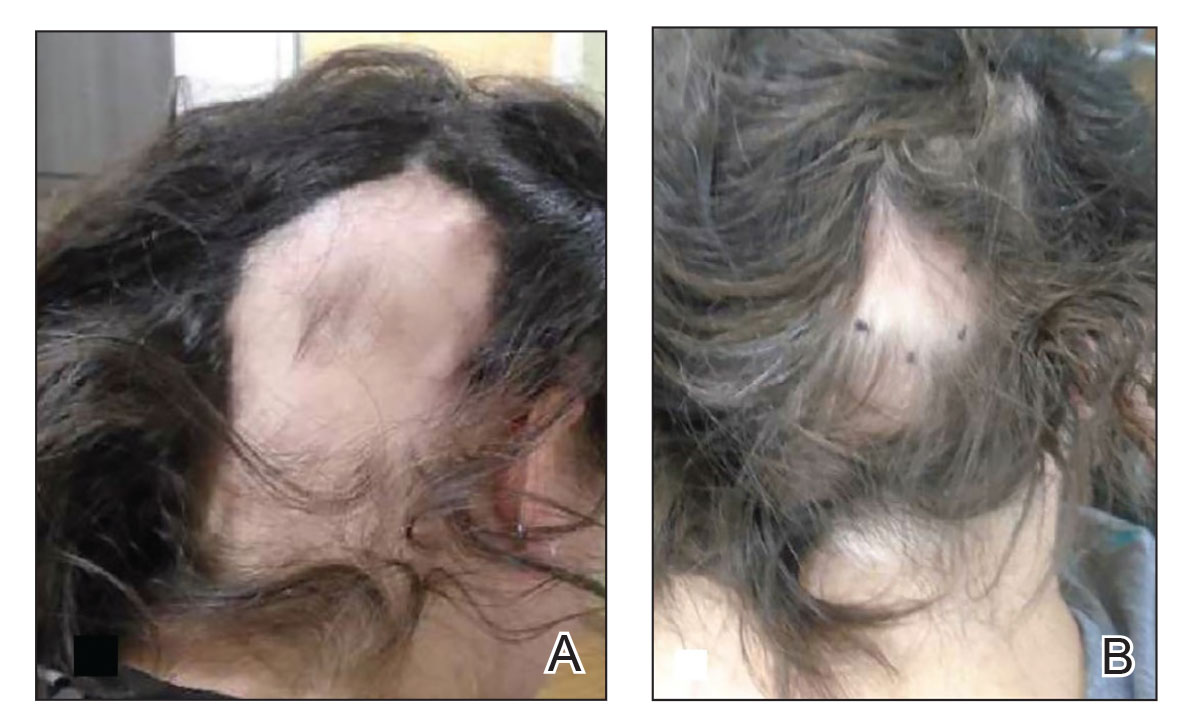

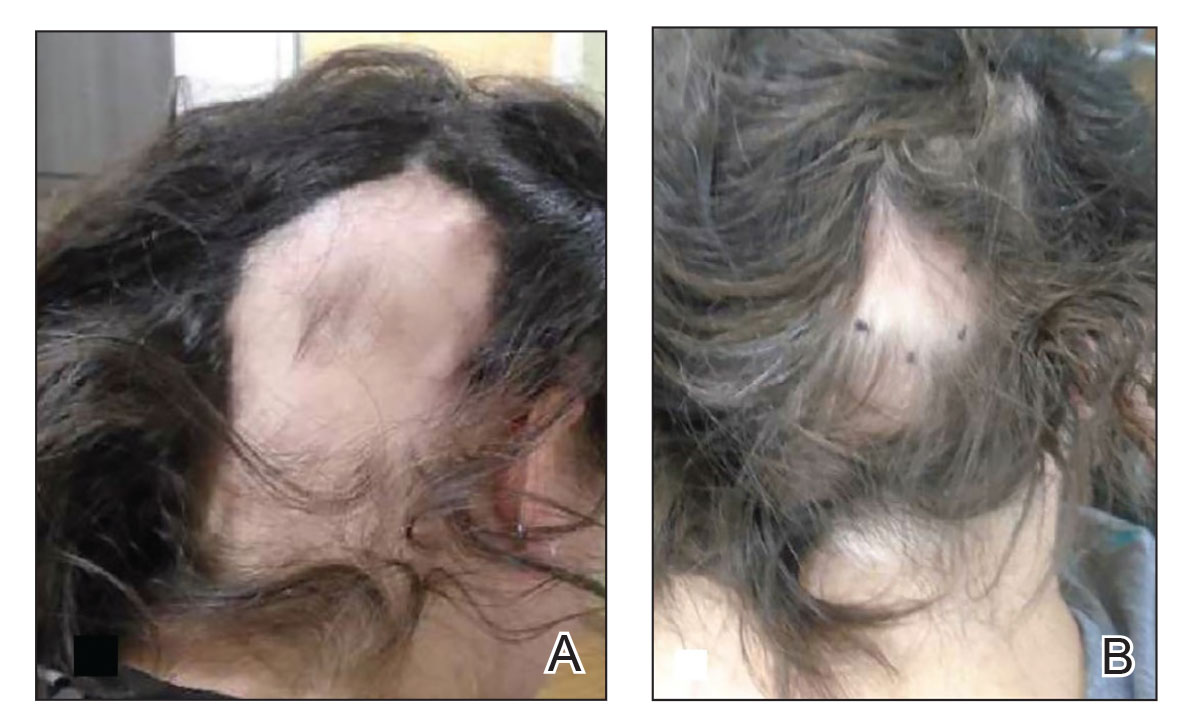

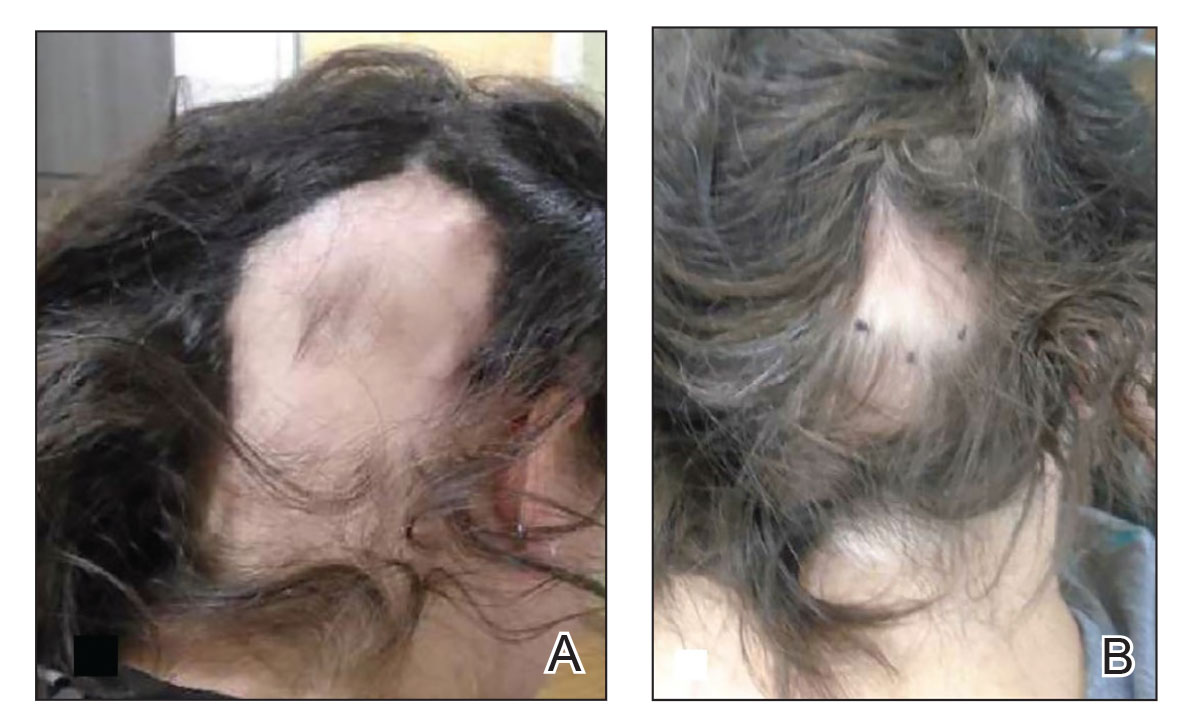

Patient 2—A 34-year-old woman who was otherwise healthy presented with previously untreated AA involving the scalp of 2 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed the following areas of nonscarring alopecia: a 10×10-cm area of the right occipital scalp with some regrowth; a 10×14-cm area of the left parieto-occipital scalp; and a 1-cm area posterior to the vertex (Figure 2A). Given the extensive involvement, the decision was made to initiate ILTA 2.5 mg/mL buffered with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine 1:100,000 once monthly. Appreciable hair regrowth was noted within 1 month, mostly on the parietal scalp. Substantial improvement was noted after 3 months in all affected areas of the hair-bearing scalp, with near-complete regrowth on the left occipital scalp and greater than 50% regrowth on the right occipital scalp (Figure 2B). No adverse effects were noted. She currently has no alopecia.

Comment

Alopecia Pathogenesis—The most widely adopted theory of AA etiology implicates an aberrant immune response. The HF, which is a dynamic “mini-organ” with its own immune and hormonal microenvironment, is considered an “immune-privileged site”—meaning it is less exposed to immune responses than most other body areas. It is hypothesized that AA results from a breakdown in this immune privilege, with the subsequent attack on the peribulbar part of the follicle by CD8+ T lymphocytes. This lymphocytic infiltrate induces apoptosis in the HF keratinocytes, resulting in inhibition of hair shaft production.12 Other theories suggest a link to the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary system and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.13

Therapies for Alopecia—Topical and IL corticosteroids are the first-line therapies for localized AA in patients with less than 50% scalp involvement. Triamcinolone acetonide generally is the IL steroid of choice because it is widely available and less atrophogenic than other steroids. Unlike topicals, ILTA bypasses the epidermis when injected, achieving direct access to the HF.14

High-quality controlled studies regarding the use of ILTA in AA are scarce. A meta-analysis concluded that 5 mg/mL and 10 mg/mL of ILTA diluted in NS were equally effective (80.9% [P<.05] vs 76.4% [P<.005], respectively). Concentrations of less than 5 mg/mL of ILTA resulted in lower rates of hair regrowth (62.3%; P=.04).15 The role of diluents other than NS has not been studied.

Benefits of Epinephrine in ILTA Therapy—The role of epinephrine 1:100,000 is to decrease the rate of clearance of triamcinolone acetonide from the HF, allowing for a better therapeutic effect. Laser Doppler blood flowmeter studies have shown that epinephrine 1:100,000 injected in the scalp causes vasoconstriction, thereby decreasing the blood flow rate of clearance of other substances in the same solution.16 Also, a more gradual systemic absorption is achieved, decreasing systemic side effects such as osteoporosis.17

Another potential benefit of epinephrine has been suggested in animal studies that demonstrate the important role of the sympathetic nervous system in HF growth. In a mouse study, chemical sympathectomy led to diminished norepinephrine levels in the skin, accompanied by a decreased keratinocyte proliferation and hair growth. Conversely, norepinephrine was found to promote HF growth in an organotypic skin culture model.18 Topically applied isoproterenol, a panadrenergic receptor agonist, accelerated HF growth in an organotypic skin culture. It also has been shown that external light and temperature changes stimulate hair growth via the sympathetic nervous system, promoting anagen HF growth in cultured skin explants, further linking HF activity with sympathetic nerve activity.19

In our experience, cases of AA that at first failed ILTA 5 mg/mL in NS have been successfully treated with 2.5 mg/mL ILTA in 1% lidocaine and epinephrine 1:100,000. One such case was alopecia totalis, though we do not have high-quality photographs to present for this report. The 2 cases presented here are the ones with the best photographs to demonstrate our outcomes. Both were treated with 2.5 mg/mL ILTA in 1% lidocaine and epinephrine 1:100,000 administered using a 0.5-in long 30-gauge needle, with 0.05 to 0.1 mL per injection approximately 0.51-cm apart. The treatment intervals were 4 weeks, with a maximal dose of 20 mg per session. In addition to the 2 cases reported here, the Table includes 2 other patients in our practice who were successfully treated with this novel regimen.

Prior to adopting this combination regimen, our standard therapy for AA was 5 mg/mL ILTA buffered with NS. Instead of NS, we now use the widely available 1% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000 and dilute the ILTA to 2.5 mg/mL. We postulate that epinephrine 1:100,000 enhances therapeutic efficacy via local vasoconstriction, thus keeping the ILTA in situ longer than NS. This effect allows for a lower concentration of ILTA (2.5 mg/mL) to be effective. Furthermore, epinephrine 1:100,000 may have an independent effect, as suggested in mouse studies.18

Our first case demonstrated the ophiasis subtype of AA (symmetric bandlike hair loss), which has a poorer prognosis and is less responsive to therapy.20 In this patient, prior treatment with topical corticosteroids and ILTA in NS failed to induce a response. After a series of injections with 2.5 mg/mL ILTA in 1% lidocaine and epinephrine 1:100,000, she entered remission. Our second case is one of alopecia subtotalis, which responded quickly, and the patient entered remission after just 3 months of treatment. These 2 cases are illustrative of the results that we regularly get and have come to expect with this treatment.

Conclusion

Our novel modified regimen of 2.5 mg/mL ILTA diluted with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine 1:100,000 has yielded a series of excellent outcomes in many of our most challenging AA cases without any untoward effects. Two cases are presented here. Higher-powered studies are needed to validate this new yet simple approach. A split-scalp or split-lesion study comparing ILTA with and without epinephrine 1:100,000 would be warranted for further investigation.

- Mirzoyev SA, Schrum AG, Davis MDP, et al. Lifetime incidence risk of alopecia areata estimated at 2.1 percent by Rochester Epidemiology Project, 1990-2009. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1141-1142.

- Villasante Fricke AC, Miteva M. Epidemiology and burden of alopecia areata: a systematic review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:397-403.