User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Saddled with med school debt, yet left out of loan forgiveness plans

In a recently obtained plan by Politico, the Biden administration is zeroing in on a broad student loan forgiveness plan to be released imminently. The plan would broadly forgive $10,000 in federal student loans, including graduate and PLUS loans. However, there’s a rub: The plan restricts the forgiveness to those with incomes below $150,000.

This would unfairly exclude many in health care from receiving this forgiveness, an egregious oversight given how much health care providers have sacrificed during the pandemic.

What was proposed?

Previously, it was reported that the Biden administration was considering this same amount of forgiveness, but with plans to exclude borrowers by either career or income. Student loan payments have been on an extended CARES Act forbearance since March 2020, with payment resumption planned for Aug. 31. The administration has said that they would deliver a plan for further extensions before this date and have repeatedly teased including forgiveness.

Forgiveness for some ...

Forgiving $10,000 of federal student loans would relieve some 15 million borrowers of student debt, roughly one-third of the 45 million borrowers with debt.

This would provide a massive boost to these borrowers (who disproportionately are female, low-income, and non-White), many of whom were targeted by predatory institutions whose education didn’t offer any actual tangible benefit to their earnings. While this is a group that absolutely ought to have their loans forgiven, drawing an income line inappropriately restricts those in health care from receiving any forgiveness.

... But not for others

Someone making an annual gross income of $150,000 is in the 80th percentile of earners in the United States (for comparison, the top 1% took home more than $505,000 in 2021). What student loan borrowers make up the remaining 20%? Overwhelmingly, health care providers occupy that tier: physicians, dentists, veterinarians, and advanced-practice nurses.

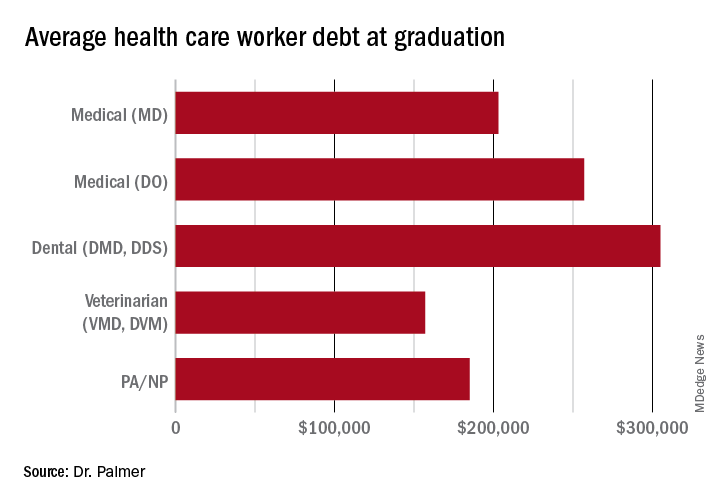

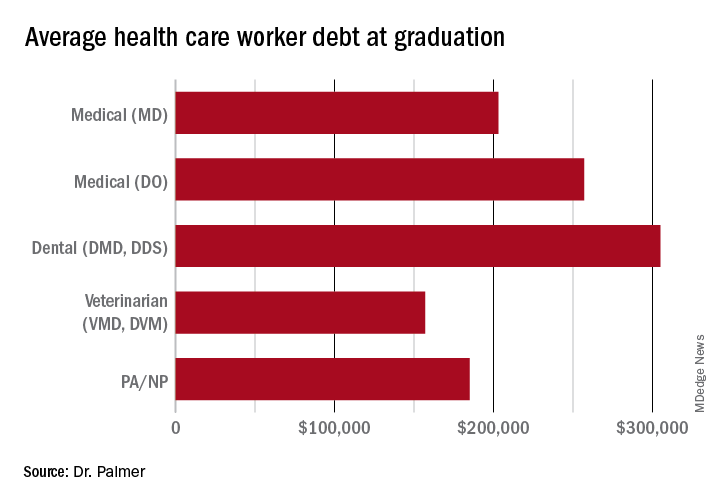

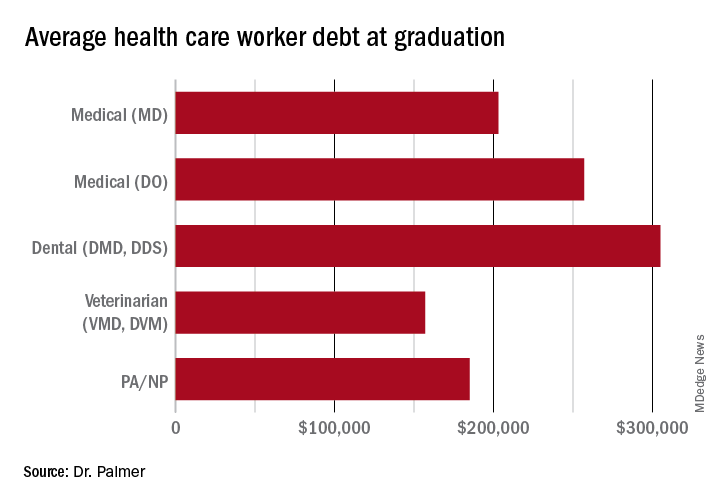

These schools leave their graduates with some of the highest student loan burdens, with veterinarians, dentists, and physicians having the highest debt-to-income ratios of any professional careers.

Flat forgiveness is regressive

Forgiving any student debt is the right direction. Too may have fallen victim to an industry without quality control, appropriate regulation, or price control. Quite the opposite, the blank-check model of student loan financing has led to an arms race as it comes to capital improvements in university spending.

The price of medical schools has risen more than four times as fast as inflation over the past 30 years, with dental and veterinary schools and nursing education showing similarly exaggerated price increases. Trainees in these fields are more likely to have taken on six-figure debt, with average debt loads at graduation in the table below. While $10,000 will move the proverbial needle less for these borrowers, does that mean they should be excluded?

Health care workers’ income declines during the pandemic

Now, over 2½ years since the start of the COVID pandemic, multiple reports have demonstrated that health care workers have suffered a loss in income. This loss in income was never compensated for, as the Paycheck Protection Program and the individual economic stimuli typically excluded doctors and high earners.

COVID and the hazard tax

As a provider during the COVID-19 pandemic, I didn’t ask for hazard pay. I supported those who did but recognized their requests were more ceremonial than they were likely to be successful.

However, I flatly reject the idea that my fellow health care practitioners are not deserving of student loan forgiveness simply based on an arbitrary income threshold. Health care providers are saddled with high debt burden, have suffered lost income, and have given of themselves during a devastating pandemic, where more than 1 million perished in the United States.

Bottom line

Health care workers should not be excluded from student loan forgiveness. Sadly, the Biden administration has signaled that they are dropping career-based exclusions in favor of more broadly harmful income-based forgiveness restrictions. This will disproportionately harm physicians and other health care workers.

These practitioners have suffered financially as a result of working through the COVID pandemic; should they also be forced to shoulder another financial injury by being excluded from student loan forgiveness?

Dr. Palmer is the chief operating officer and cofounder of Panacea Financial. He is also a practicing pediatric hospitalist at Boston Children’s Hospital and is on faculty at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a recently obtained plan by Politico, the Biden administration is zeroing in on a broad student loan forgiveness plan to be released imminently. The plan would broadly forgive $10,000 in federal student loans, including graduate and PLUS loans. However, there’s a rub: The plan restricts the forgiveness to those with incomes below $150,000.

This would unfairly exclude many in health care from receiving this forgiveness, an egregious oversight given how much health care providers have sacrificed during the pandemic.

What was proposed?

Previously, it was reported that the Biden administration was considering this same amount of forgiveness, but with plans to exclude borrowers by either career or income. Student loan payments have been on an extended CARES Act forbearance since March 2020, with payment resumption planned for Aug. 31. The administration has said that they would deliver a plan for further extensions before this date and have repeatedly teased including forgiveness.

Forgiveness for some ...

Forgiving $10,000 of federal student loans would relieve some 15 million borrowers of student debt, roughly one-third of the 45 million borrowers with debt.

This would provide a massive boost to these borrowers (who disproportionately are female, low-income, and non-White), many of whom were targeted by predatory institutions whose education didn’t offer any actual tangible benefit to their earnings. While this is a group that absolutely ought to have their loans forgiven, drawing an income line inappropriately restricts those in health care from receiving any forgiveness.

... But not for others

Someone making an annual gross income of $150,000 is in the 80th percentile of earners in the United States (for comparison, the top 1% took home more than $505,000 in 2021). What student loan borrowers make up the remaining 20%? Overwhelmingly, health care providers occupy that tier: physicians, dentists, veterinarians, and advanced-practice nurses.

These schools leave their graduates with some of the highest student loan burdens, with veterinarians, dentists, and physicians having the highest debt-to-income ratios of any professional careers.

Flat forgiveness is regressive

Forgiving any student debt is the right direction. Too may have fallen victim to an industry without quality control, appropriate regulation, or price control. Quite the opposite, the blank-check model of student loan financing has led to an arms race as it comes to capital improvements in university spending.

The price of medical schools has risen more than four times as fast as inflation over the past 30 years, with dental and veterinary schools and nursing education showing similarly exaggerated price increases. Trainees in these fields are more likely to have taken on six-figure debt, with average debt loads at graduation in the table below. While $10,000 will move the proverbial needle less for these borrowers, does that mean they should be excluded?

Health care workers’ income declines during the pandemic

Now, over 2½ years since the start of the COVID pandemic, multiple reports have demonstrated that health care workers have suffered a loss in income. This loss in income was never compensated for, as the Paycheck Protection Program and the individual economic stimuli typically excluded doctors and high earners.

COVID and the hazard tax

As a provider during the COVID-19 pandemic, I didn’t ask for hazard pay. I supported those who did but recognized their requests were more ceremonial than they were likely to be successful.

However, I flatly reject the idea that my fellow health care practitioners are not deserving of student loan forgiveness simply based on an arbitrary income threshold. Health care providers are saddled with high debt burden, have suffered lost income, and have given of themselves during a devastating pandemic, where more than 1 million perished in the United States.

Bottom line

Health care workers should not be excluded from student loan forgiveness. Sadly, the Biden administration has signaled that they are dropping career-based exclusions in favor of more broadly harmful income-based forgiveness restrictions. This will disproportionately harm physicians and other health care workers.

These practitioners have suffered financially as a result of working through the COVID pandemic; should they also be forced to shoulder another financial injury by being excluded from student loan forgiveness?

Dr. Palmer is the chief operating officer and cofounder of Panacea Financial. He is also a practicing pediatric hospitalist at Boston Children’s Hospital and is on faculty at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a recently obtained plan by Politico, the Biden administration is zeroing in on a broad student loan forgiveness plan to be released imminently. The plan would broadly forgive $10,000 in federal student loans, including graduate and PLUS loans. However, there’s a rub: The plan restricts the forgiveness to those with incomes below $150,000.

This would unfairly exclude many in health care from receiving this forgiveness, an egregious oversight given how much health care providers have sacrificed during the pandemic.

What was proposed?

Previously, it was reported that the Biden administration was considering this same amount of forgiveness, but with plans to exclude borrowers by either career or income. Student loan payments have been on an extended CARES Act forbearance since March 2020, with payment resumption planned for Aug. 31. The administration has said that they would deliver a plan for further extensions before this date and have repeatedly teased including forgiveness.

Forgiveness for some ...

Forgiving $10,000 of federal student loans would relieve some 15 million borrowers of student debt, roughly one-third of the 45 million borrowers with debt.

This would provide a massive boost to these borrowers (who disproportionately are female, low-income, and non-White), many of whom were targeted by predatory institutions whose education didn’t offer any actual tangible benefit to their earnings. While this is a group that absolutely ought to have their loans forgiven, drawing an income line inappropriately restricts those in health care from receiving any forgiveness.

... But not for others

Someone making an annual gross income of $150,000 is in the 80th percentile of earners in the United States (for comparison, the top 1% took home more than $505,000 in 2021). What student loan borrowers make up the remaining 20%? Overwhelmingly, health care providers occupy that tier: physicians, dentists, veterinarians, and advanced-practice nurses.

These schools leave their graduates with some of the highest student loan burdens, with veterinarians, dentists, and physicians having the highest debt-to-income ratios of any professional careers.

Flat forgiveness is regressive

Forgiving any student debt is the right direction. Too may have fallen victim to an industry without quality control, appropriate regulation, or price control. Quite the opposite, the blank-check model of student loan financing has led to an arms race as it comes to capital improvements in university spending.

The price of medical schools has risen more than four times as fast as inflation over the past 30 years, with dental and veterinary schools and nursing education showing similarly exaggerated price increases. Trainees in these fields are more likely to have taken on six-figure debt, with average debt loads at graduation in the table below. While $10,000 will move the proverbial needle less for these borrowers, does that mean they should be excluded?

Health care workers’ income declines during the pandemic

Now, over 2½ years since the start of the COVID pandemic, multiple reports have demonstrated that health care workers have suffered a loss in income. This loss in income was never compensated for, as the Paycheck Protection Program and the individual economic stimuli typically excluded doctors and high earners.

COVID and the hazard tax

As a provider during the COVID-19 pandemic, I didn’t ask for hazard pay. I supported those who did but recognized their requests were more ceremonial than they were likely to be successful.

However, I flatly reject the idea that my fellow health care practitioners are not deserving of student loan forgiveness simply based on an arbitrary income threshold. Health care providers are saddled with high debt burden, have suffered lost income, and have given of themselves during a devastating pandemic, where more than 1 million perished in the United States.

Bottom line

Health care workers should not be excluded from student loan forgiveness. Sadly, the Biden administration has signaled that they are dropping career-based exclusions in favor of more broadly harmful income-based forgiveness restrictions. This will disproportionately harm physicians and other health care workers.

These practitioners have suffered financially as a result of working through the COVID pandemic; should they also be forced to shoulder another financial injury by being excluded from student loan forgiveness?

Dr. Palmer is the chief operating officer and cofounder of Panacea Financial. He is also a practicing pediatric hospitalist at Boston Children’s Hospital and is on faculty at Harvard Medical School, also in Boston.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Experts: EPA should assess risk of sunscreens’ UV filters

The , an expert panel of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) said on Aug. 9.

The assessment is urgently needed, the experts said, and the results should be shared with the Food and Drug Administration, which oversees sunscreens.

In its 400-page report, titled the Review of Fate, Exposure, and Effects of Sunscreens in Aquatic Environments and Implications for Sunscreen Usage and Human Health, the panel does not make recommendations but suggests that such an EPA risk assessment should highlight gaps in knowledge.

“We are teeing up the critical information that will be used to take on the challenge of risk assessment,” Charles A. Menzie, PhD, chair of the committee that wrote the report, said at a media briefing Aug. 9 when the report was released. Dr. Menzie is a principal at Exponent, Inc., an engineering and scientific consulting firm. He is former executive director of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry.

The EPA sponsored the study, which was conducted by a committee of the National Academy of Sciences, a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization authorized by Congress that studies issues related to science, technology, and medicine.

Balancing aquatic, human health concerns

Such an EPA assessment, Dr. Menzie said in a statement, will help inform efforts to understand the environmental effects of UV filters as well as clarify a path forward for managing sunscreens. For years, concerns have been raised about the potential toxicity of sunscreens regarding many marine and freshwater aquatic organisms, especially coral. That concern, however, must be balanced against the benefits of sunscreens, which are known to protect against skin cancer. A low percentage of people use sunscreen regularly, Dr. Menzie and other panel members said.

“Only about a third of the U.S. population regularly uses sunscreen,” Mark Cullen, MD, vice chair of the NAS committee and former director of the Center for Population Health Sciences, Stanford (Calif.) University, said at the briefing. About 70% or 80% of people use it at the beach or outdoors, he said.

Report background, details

UV filters are the active ingredients in physical as well as chemical sunscreen products. They decrease the amount of UV radiation that reaches the skin. They have been found in water, sediments, and marine organisms, both saltwater and freshwater.

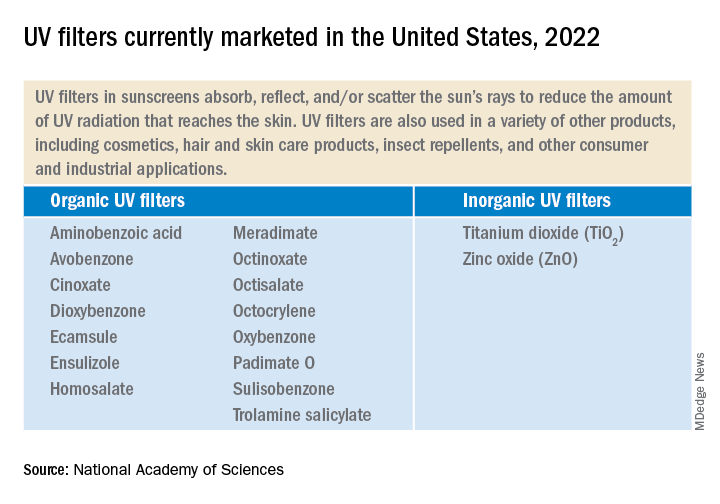

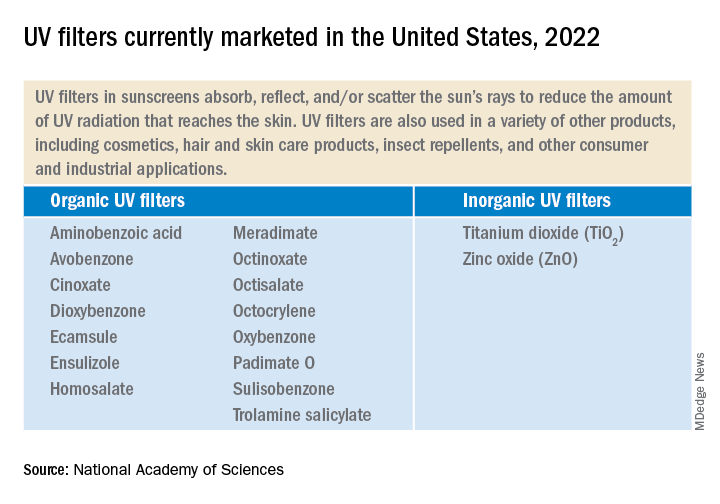

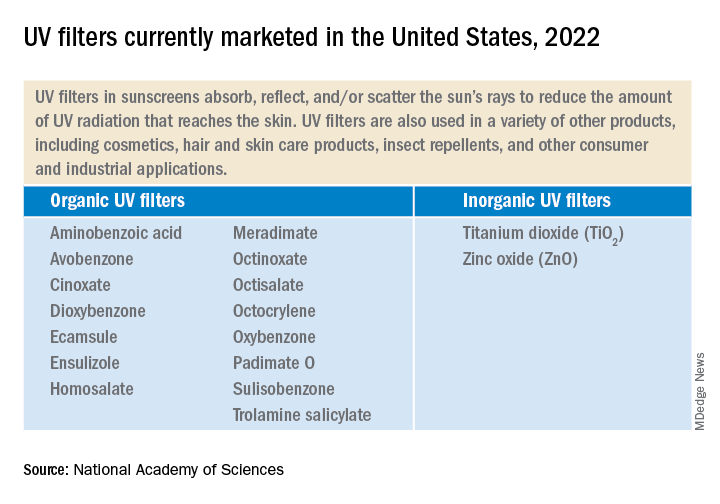

Currently, 17 UV filters are used in U.S. sunscreens; 15 of those are organic, such as oxybenzone and avobenzone, and are used in chemical sunscreens. They work by absorbing the rays before they damage the skin. In addition, two inorganic filters, which are used in physical sunscreens, sit on the skin and as a shield to block the rays.

UV filters enter bodies of water by direct release, as when sunscreens rinse off people while swimming or while engaging in other water activities. They also enter bodies of water in storm water runoff and wastewater.

Lab toxicity tests, which are the most widely used, provide effects data for ecologic risk assessment. The tests are more often used in the study of short-term, not long-term exposure. Test results have shown that in high enough concentrations, some UV filters can be toxic to algal, invertebrate, and fish species.

But much information is lacking, the experts said. Toxicity data for many species, for instance, are limited. There are few studies on the longer-term environmental effects of UV filter exposure. Not enough is known about the rate at which the filters degrade in the environment. The filters accumulate in higher amounts in different areas. Recreational water areas have higher concentrations.

The recommendations

The panel is urging the EPA to complete a formal risk assessment of the UV filters “with some urgency,” Dr. Cullen said. That will enable decisions to be made about the use of the products. The risks to aquatic life must be balanced against the need for sun protection to reduce skin cancer risk.

The experts made two recommendations:

- The EPA should conduct ecologic risk assessments for all the UV filters now marketed and for all new ones. The assessment should evaluate the filters individually as well as the risk from co-occurring filters. The assessments should take into account the different exposure scenarios.

- The EPA, along with partner agencies, and sunscreen and UV filter manufacturers should fund, support, and conduct research and share data. Research should include study of human health outcomes if usage and availability of sunscreens change.

Dermatologists should “continue to emphasize the importance of protection from UV radiation in every way that can be done,” Dr. Cullen said, including the use of sunscreen as well as other protective practices, such as wearing long sleeves and hats, seeking shade, and avoiding the sun during peak hours.

A dermatologist’s perspective

“I applaud their scientific curiosity to know one way or the other whether this is an issue,” said Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, DC. “I welcome this investigation.”

The multitude of studies, Dr. Friedman said, don’t always agree about whether the filters pose dangers. He noted that the concentration of UV filters detected in water is often lower than the concentrations found to be harmful in a lab setting to marine life, specifically coral.

However, he said, “these studies are snapshots.” For that reason, calling for more assessment of risk is desirable, Dr. Friedman said, but “I want to be sure the call to do more research is not an admission of guilt. It’s very easy to vilify sunscreens – but the facts we know are that UV light causes skin cancer and aging, and sunscreen protects us against this.”

Dr. Friedman has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The , an expert panel of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) said on Aug. 9.

The assessment is urgently needed, the experts said, and the results should be shared with the Food and Drug Administration, which oversees sunscreens.

In its 400-page report, titled the Review of Fate, Exposure, and Effects of Sunscreens in Aquatic Environments and Implications for Sunscreen Usage and Human Health, the panel does not make recommendations but suggests that such an EPA risk assessment should highlight gaps in knowledge.

“We are teeing up the critical information that will be used to take on the challenge of risk assessment,” Charles A. Menzie, PhD, chair of the committee that wrote the report, said at a media briefing Aug. 9 when the report was released. Dr. Menzie is a principal at Exponent, Inc., an engineering and scientific consulting firm. He is former executive director of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry.

The EPA sponsored the study, which was conducted by a committee of the National Academy of Sciences, a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization authorized by Congress that studies issues related to science, technology, and medicine.

Balancing aquatic, human health concerns

Such an EPA assessment, Dr. Menzie said in a statement, will help inform efforts to understand the environmental effects of UV filters as well as clarify a path forward for managing sunscreens. For years, concerns have been raised about the potential toxicity of sunscreens regarding many marine and freshwater aquatic organisms, especially coral. That concern, however, must be balanced against the benefits of sunscreens, which are known to protect against skin cancer. A low percentage of people use sunscreen regularly, Dr. Menzie and other panel members said.

“Only about a third of the U.S. population regularly uses sunscreen,” Mark Cullen, MD, vice chair of the NAS committee and former director of the Center for Population Health Sciences, Stanford (Calif.) University, said at the briefing. About 70% or 80% of people use it at the beach or outdoors, he said.

Report background, details

UV filters are the active ingredients in physical as well as chemical sunscreen products. They decrease the amount of UV radiation that reaches the skin. They have been found in water, sediments, and marine organisms, both saltwater and freshwater.

Currently, 17 UV filters are used in U.S. sunscreens; 15 of those are organic, such as oxybenzone and avobenzone, and are used in chemical sunscreens. They work by absorbing the rays before they damage the skin. In addition, two inorganic filters, which are used in physical sunscreens, sit on the skin and as a shield to block the rays.

UV filters enter bodies of water by direct release, as when sunscreens rinse off people while swimming or while engaging in other water activities. They also enter bodies of water in storm water runoff and wastewater.

Lab toxicity tests, which are the most widely used, provide effects data for ecologic risk assessment. The tests are more often used in the study of short-term, not long-term exposure. Test results have shown that in high enough concentrations, some UV filters can be toxic to algal, invertebrate, and fish species.

But much information is lacking, the experts said. Toxicity data for many species, for instance, are limited. There are few studies on the longer-term environmental effects of UV filter exposure. Not enough is known about the rate at which the filters degrade in the environment. The filters accumulate in higher amounts in different areas. Recreational water areas have higher concentrations.

The recommendations

The panel is urging the EPA to complete a formal risk assessment of the UV filters “with some urgency,” Dr. Cullen said. That will enable decisions to be made about the use of the products. The risks to aquatic life must be balanced against the need for sun protection to reduce skin cancer risk.

The experts made two recommendations:

- The EPA should conduct ecologic risk assessments for all the UV filters now marketed and for all new ones. The assessment should evaluate the filters individually as well as the risk from co-occurring filters. The assessments should take into account the different exposure scenarios.

- The EPA, along with partner agencies, and sunscreen and UV filter manufacturers should fund, support, and conduct research and share data. Research should include study of human health outcomes if usage and availability of sunscreens change.

Dermatologists should “continue to emphasize the importance of protection from UV radiation in every way that can be done,” Dr. Cullen said, including the use of sunscreen as well as other protective practices, such as wearing long sleeves and hats, seeking shade, and avoiding the sun during peak hours.

A dermatologist’s perspective

“I applaud their scientific curiosity to know one way or the other whether this is an issue,” said Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, DC. “I welcome this investigation.”

The multitude of studies, Dr. Friedman said, don’t always agree about whether the filters pose dangers. He noted that the concentration of UV filters detected in water is often lower than the concentrations found to be harmful in a lab setting to marine life, specifically coral.

However, he said, “these studies are snapshots.” For that reason, calling for more assessment of risk is desirable, Dr. Friedman said, but “I want to be sure the call to do more research is not an admission of guilt. It’s very easy to vilify sunscreens – but the facts we know are that UV light causes skin cancer and aging, and sunscreen protects us against this.”

Dr. Friedman has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The , an expert panel of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) said on Aug. 9.

The assessment is urgently needed, the experts said, and the results should be shared with the Food and Drug Administration, which oversees sunscreens.

In its 400-page report, titled the Review of Fate, Exposure, and Effects of Sunscreens in Aquatic Environments and Implications for Sunscreen Usage and Human Health, the panel does not make recommendations but suggests that such an EPA risk assessment should highlight gaps in knowledge.

“We are teeing up the critical information that will be used to take on the challenge of risk assessment,” Charles A. Menzie, PhD, chair of the committee that wrote the report, said at a media briefing Aug. 9 when the report was released. Dr. Menzie is a principal at Exponent, Inc., an engineering and scientific consulting firm. He is former executive director of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry.

The EPA sponsored the study, which was conducted by a committee of the National Academy of Sciences, a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization authorized by Congress that studies issues related to science, technology, and medicine.

Balancing aquatic, human health concerns

Such an EPA assessment, Dr. Menzie said in a statement, will help inform efforts to understand the environmental effects of UV filters as well as clarify a path forward for managing sunscreens. For years, concerns have been raised about the potential toxicity of sunscreens regarding many marine and freshwater aquatic organisms, especially coral. That concern, however, must be balanced against the benefits of sunscreens, which are known to protect against skin cancer. A low percentage of people use sunscreen regularly, Dr. Menzie and other panel members said.

“Only about a third of the U.S. population regularly uses sunscreen,” Mark Cullen, MD, vice chair of the NAS committee and former director of the Center for Population Health Sciences, Stanford (Calif.) University, said at the briefing. About 70% or 80% of people use it at the beach or outdoors, he said.

Report background, details

UV filters are the active ingredients in physical as well as chemical sunscreen products. They decrease the amount of UV radiation that reaches the skin. They have been found in water, sediments, and marine organisms, both saltwater and freshwater.

Currently, 17 UV filters are used in U.S. sunscreens; 15 of those are organic, such as oxybenzone and avobenzone, and are used in chemical sunscreens. They work by absorbing the rays before they damage the skin. In addition, two inorganic filters, which are used in physical sunscreens, sit on the skin and as a shield to block the rays.

UV filters enter bodies of water by direct release, as when sunscreens rinse off people while swimming or while engaging in other water activities. They also enter bodies of water in storm water runoff and wastewater.

Lab toxicity tests, which are the most widely used, provide effects data for ecologic risk assessment. The tests are more often used in the study of short-term, not long-term exposure. Test results have shown that in high enough concentrations, some UV filters can be toxic to algal, invertebrate, and fish species.

But much information is lacking, the experts said. Toxicity data for many species, for instance, are limited. There are few studies on the longer-term environmental effects of UV filter exposure. Not enough is known about the rate at which the filters degrade in the environment. The filters accumulate in higher amounts in different areas. Recreational water areas have higher concentrations.

The recommendations

The panel is urging the EPA to complete a formal risk assessment of the UV filters “with some urgency,” Dr. Cullen said. That will enable decisions to be made about the use of the products. The risks to aquatic life must be balanced against the need for sun protection to reduce skin cancer risk.

The experts made two recommendations:

- The EPA should conduct ecologic risk assessments for all the UV filters now marketed and for all new ones. The assessment should evaluate the filters individually as well as the risk from co-occurring filters. The assessments should take into account the different exposure scenarios.

- The EPA, along with partner agencies, and sunscreen and UV filter manufacturers should fund, support, and conduct research and share data. Research should include study of human health outcomes if usage and availability of sunscreens change.

Dermatologists should “continue to emphasize the importance of protection from UV radiation in every way that can be done,” Dr. Cullen said, including the use of sunscreen as well as other protective practices, such as wearing long sleeves and hats, seeking shade, and avoiding the sun during peak hours.

A dermatologist’s perspective

“I applaud their scientific curiosity to know one way or the other whether this is an issue,” said Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, DC. “I welcome this investigation.”

The multitude of studies, Dr. Friedman said, don’t always agree about whether the filters pose dangers. He noted that the concentration of UV filters detected in water is often lower than the concentrations found to be harmful in a lab setting to marine life, specifically coral.

However, he said, “these studies are snapshots.” For that reason, calling for more assessment of risk is desirable, Dr. Friedman said, but “I want to be sure the call to do more research is not an admission of guilt. It’s very easy to vilify sunscreens – but the facts we know are that UV light causes skin cancer and aging, and sunscreen protects us against this.”

Dr. Friedman has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dermatologist arrested for allegedly poisoning radiologist husband

It is a story that has quickly gone viral around the world:

Yue Yu, MD, aged 45, was booked into the Orange County Jail on Aug. 4, after Irvine Police had been called to her residence that day by her husband, Jack Chen, MD, 53, a radiologist. Dr. Chen provided the police with video evidence that he said showed Dr. Yu pouring a drain-opening chemical into his hot lemonade drink.

“The victim sustained significant internal injuries but is expected to recover,” the Irvine police department said in a statement.

Dr. Yu was released after paying a $30,000 bond and has not been formally charged, according to the New York Post.

In a statement to the court on Aug. 5, Dr. Chen said he and the couple’s two children had long suffered verbal abuse from his wife and her mother, according to the Post. Multiple news organizations reported that Dr. Chen filed for divorce and also for a restraining order against Dr. Yu on that day.

After feeling ill for months – and being diagnosed with ulcers and esophageal inflammation – Dr. Chen reportedly set up video cameras in the couple’s house. He said he caught Dr. Yu on camera pouring something into his drink on several occasions in July.

According to NBC News, Dr. Yu’s attorney, David E. Wohl, said that Dr. Yu “vehemently and unequivocally denies ever attempting to poison her husband or anyone else.”

Dr. Yu received her medical degree from Washington University in St. Louis in 2006 and has no disciplinary actions against her, according to the Medical Board of California. She was head of dermatology at Mission Heritage Medical Group, but her name and information have been scrubbed from that group’s website. Mission Heritage is affiliated with Providence Mission Hospital. A spokesperson for the hospital told NBC News that it is cooperating with the police investigation and that no patients are in danger.

The dermatologist is due to report back to court in November, NBC News said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It is a story that has quickly gone viral around the world:

Yue Yu, MD, aged 45, was booked into the Orange County Jail on Aug. 4, after Irvine Police had been called to her residence that day by her husband, Jack Chen, MD, 53, a radiologist. Dr. Chen provided the police with video evidence that he said showed Dr. Yu pouring a drain-opening chemical into his hot lemonade drink.

“The victim sustained significant internal injuries but is expected to recover,” the Irvine police department said in a statement.

Dr. Yu was released after paying a $30,000 bond and has not been formally charged, according to the New York Post.

In a statement to the court on Aug. 5, Dr. Chen said he and the couple’s two children had long suffered verbal abuse from his wife and her mother, according to the Post. Multiple news organizations reported that Dr. Chen filed for divorce and also for a restraining order against Dr. Yu on that day.

After feeling ill for months – and being diagnosed with ulcers and esophageal inflammation – Dr. Chen reportedly set up video cameras in the couple’s house. He said he caught Dr. Yu on camera pouring something into his drink on several occasions in July.

According to NBC News, Dr. Yu’s attorney, David E. Wohl, said that Dr. Yu “vehemently and unequivocally denies ever attempting to poison her husband or anyone else.”

Dr. Yu received her medical degree from Washington University in St. Louis in 2006 and has no disciplinary actions against her, according to the Medical Board of California. She was head of dermatology at Mission Heritage Medical Group, but her name and information have been scrubbed from that group’s website. Mission Heritage is affiliated with Providence Mission Hospital. A spokesperson for the hospital told NBC News that it is cooperating with the police investigation and that no patients are in danger.

The dermatologist is due to report back to court in November, NBC News said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It is a story that has quickly gone viral around the world:

Yue Yu, MD, aged 45, was booked into the Orange County Jail on Aug. 4, after Irvine Police had been called to her residence that day by her husband, Jack Chen, MD, 53, a radiologist. Dr. Chen provided the police with video evidence that he said showed Dr. Yu pouring a drain-opening chemical into his hot lemonade drink.

“The victim sustained significant internal injuries but is expected to recover,” the Irvine police department said in a statement.

Dr. Yu was released after paying a $30,000 bond and has not been formally charged, according to the New York Post.

In a statement to the court on Aug. 5, Dr. Chen said he and the couple’s two children had long suffered verbal abuse from his wife and her mother, according to the Post. Multiple news organizations reported that Dr. Chen filed for divorce and also for a restraining order against Dr. Yu on that day.

After feeling ill for months – and being diagnosed with ulcers and esophageal inflammation – Dr. Chen reportedly set up video cameras in the couple’s house. He said he caught Dr. Yu on camera pouring something into his drink on several occasions in July.

According to NBC News, Dr. Yu’s attorney, David E. Wohl, said that Dr. Yu “vehemently and unequivocally denies ever attempting to poison her husband or anyone else.”

Dr. Yu received her medical degree from Washington University in St. Louis in 2006 and has no disciplinary actions against her, according to the Medical Board of California. She was head of dermatology at Mission Heritage Medical Group, but her name and information have been scrubbed from that group’s website. Mission Heritage is affiliated with Providence Mission Hospital. A spokesperson for the hospital told NBC News that it is cooperating with the police investigation and that no patients are in danger.

The dermatologist is due to report back to court in November, NBC News said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long COVID’s grip will likely tighten as infections continue

COVID-19 is far from done in the United States, with more than 111,000 new cases being recorded a day in the second week of August, according to Johns Hopkins University, and 625 deaths being reported every day. , a condition that already has affected between 7.7 million and 23 million Americans, according to U.S. government estimates.

“It is evident that long COVID is real, that it already impacts a substantial number of people, and that this number may continue to grow as new infections occur,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) said in a research action plan released Aug. 4.

“We are heading towards a big problem on our hands,” says Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research and development at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in St. Louis. “It’s like if we are falling in a plane, hurtling towards the ground. It doesn’t matter at what speed we are falling; what matters is that we are all falling, and falling fast. It’s a real problem. We needed to bring attention to this, yesterday,” he said.

Bryan Lau, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and co-lead of a long COVID study there, says whether it’s 5% of the 92 million officially recorded U.S. COVID-19 cases, or 30% – on the higher end of estimates – that means anywhere between 4.5 million and 27 million Americans will have the effects of long COVID.

Other experts put the estimates even higher.

“If we conservatively assume 100 million working-age adults have been infected, that implies 10 to 33 million may have long COVID,” Alice Burns, PhD, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, wrote in an analysis.

And even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says only a fraction of cases have been recorded.

That, in turn, means tens of millions of people who struggle to work, to get to school, and to take care of their families – and who will be making demands on an already stressed U.S. health care system.

The HHS said in its Aug. 4 report that long COVID could keep 1 million people a day out of work, with a loss of $50 billion in annual pay.

Dr. Lau said health workers and policymakers are woefully unprepared.

“If you have a family unit, and the mom or dad can’t work, or has trouble taking their child to activities, where does the question of support come into play? Where is there potential for food issues, or housing issues?” he asked. “I see the potential for the burden to be extremely large in that capacity.”

Dr. Lau said he has yet to see any strong estimates of how many cases of long COVID might develop. Because a person has to get COVID-19 to ultimately get long COVID, the two are linked. In other words, as COVID-19 cases rise, so will cases of long COVID, and vice versa.

Evidence from the Kaiser Family Foundation analysis suggests a significant impact on employment: Surveys showed more than half of adults with long COVID who worked before becoming infected are either out of work or working fewer hours. Conditions associated with long COVID – such as fatigue, malaise, or problems concentrating – limit people’s ability to work, even if they have jobs that allow for accommodations.

Two surveys of people with long COVID who had worked before becoming infected showed that between 22% and 27% of them were out of work after getting long COVID. In comparison, among all working-age adults in 2019, only 7% were out of work. Given the sheer number of working-age adults with long COVID, the effects on employment may be profound and are likely to involve more people over time. One study estimates that long COVID already accounts for 15% of unfilled jobs.

The most severe symptoms of long COVID include brain fog and heart complications, known to persist for weeks for months after a COVID-19 infection.

A study from the University of Norway published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found 53% of people tested had at least one symptom of thinking problems 13 months after infection with COVID-19. According to the HHS’ latest report on long COVID, people with thinking problems, heart conditions, mobility issues, and other symptoms are going to need a considerable amount of care. Many will need lengthy periods of rehabilitation.

Dr. Al-Aly worries that long COVID has already severely affected the labor force and the job market, all while burdening the country’s health care system.

“While there are variations in how individuals respond and cope with long COVID, the unifying thread is that with the level of disability it causes, more people will be struggling to keep up with the demands of the workforce and more people will be out on disability than ever before,” he said.

Studies from Johns Hopkins and the University of Washington estimate that 5%-30% of people could get long COVID in the future. Projections beyond that are hazy.

“So far, all the studies we have done on long COVID have been reactionary. Much of the activism around long COVID has been patient led. We are seeing more and more people with lasting symptoms. We need our research to catch up,” Dr. Lau said.

Theo Vos, MD, PhD, professor of health sciences at University of Washington, Seattle, said the main reasons for the huge range of predictions are the variety of methods used, as well as differences in sample size. Also, much long COVID data is self-reported, making it difficult for epidemiologists to track.

“With self-reported data, you can’t plug people into a machine and say this is what they have or this is what they don’t have. At the population level, the only thing you can do is ask questions. There is no systematic way to define long COVID,” he said.

Dr. Vos’s most recent study, which is being peer-reviewed and revised, found that most people with long COVID have symptoms similar to those seen in other autoimmune diseases. But sometimes the immune system can overreact, causing the more severe symptoms, such as brain fog and heart problems, associated with long COVID.

One reason that researchers struggle to come up with numbers, said Dr. Al-Aly, is the rapid rise of new variants. These variants appear to sometimes cause less severe disease than previous ones, but it’s not clear whether that means different risks for long COVID.

“There’s a wide diversity in severity. Someone can have long COVID and be fully functional, while others are not functional at all. We still have a long way to go before we figure out why,” Dr. Lau said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID-19 is far from done in the United States, with more than 111,000 new cases being recorded a day in the second week of August, according to Johns Hopkins University, and 625 deaths being reported every day. , a condition that already has affected between 7.7 million and 23 million Americans, according to U.S. government estimates.

“It is evident that long COVID is real, that it already impacts a substantial number of people, and that this number may continue to grow as new infections occur,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) said in a research action plan released Aug. 4.

“We are heading towards a big problem on our hands,” says Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research and development at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in St. Louis. “It’s like if we are falling in a plane, hurtling towards the ground. It doesn’t matter at what speed we are falling; what matters is that we are all falling, and falling fast. It’s a real problem. We needed to bring attention to this, yesterday,” he said.

Bryan Lau, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and co-lead of a long COVID study there, says whether it’s 5% of the 92 million officially recorded U.S. COVID-19 cases, or 30% – on the higher end of estimates – that means anywhere between 4.5 million and 27 million Americans will have the effects of long COVID.

Other experts put the estimates even higher.

“If we conservatively assume 100 million working-age adults have been infected, that implies 10 to 33 million may have long COVID,” Alice Burns, PhD, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, wrote in an analysis.

And even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says only a fraction of cases have been recorded.

That, in turn, means tens of millions of people who struggle to work, to get to school, and to take care of their families – and who will be making demands on an already stressed U.S. health care system.

The HHS said in its Aug. 4 report that long COVID could keep 1 million people a day out of work, with a loss of $50 billion in annual pay.

Dr. Lau said health workers and policymakers are woefully unprepared.

“If you have a family unit, and the mom or dad can’t work, or has trouble taking their child to activities, where does the question of support come into play? Where is there potential for food issues, or housing issues?” he asked. “I see the potential for the burden to be extremely large in that capacity.”

Dr. Lau said he has yet to see any strong estimates of how many cases of long COVID might develop. Because a person has to get COVID-19 to ultimately get long COVID, the two are linked. In other words, as COVID-19 cases rise, so will cases of long COVID, and vice versa.

Evidence from the Kaiser Family Foundation analysis suggests a significant impact on employment: Surveys showed more than half of adults with long COVID who worked before becoming infected are either out of work or working fewer hours. Conditions associated with long COVID – such as fatigue, malaise, or problems concentrating – limit people’s ability to work, even if they have jobs that allow for accommodations.

Two surveys of people with long COVID who had worked before becoming infected showed that between 22% and 27% of them were out of work after getting long COVID. In comparison, among all working-age adults in 2019, only 7% were out of work. Given the sheer number of working-age adults with long COVID, the effects on employment may be profound and are likely to involve more people over time. One study estimates that long COVID already accounts for 15% of unfilled jobs.

The most severe symptoms of long COVID include brain fog and heart complications, known to persist for weeks for months after a COVID-19 infection.

A study from the University of Norway published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found 53% of people tested had at least one symptom of thinking problems 13 months after infection with COVID-19. According to the HHS’ latest report on long COVID, people with thinking problems, heart conditions, mobility issues, and other symptoms are going to need a considerable amount of care. Many will need lengthy periods of rehabilitation.

Dr. Al-Aly worries that long COVID has already severely affected the labor force and the job market, all while burdening the country’s health care system.

“While there are variations in how individuals respond and cope with long COVID, the unifying thread is that with the level of disability it causes, more people will be struggling to keep up with the demands of the workforce and more people will be out on disability than ever before,” he said.

Studies from Johns Hopkins and the University of Washington estimate that 5%-30% of people could get long COVID in the future. Projections beyond that are hazy.

“So far, all the studies we have done on long COVID have been reactionary. Much of the activism around long COVID has been patient led. We are seeing more and more people with lasting symptoms. We need our research to catch up,” Dr. Lau said.

Theo Vos, MD, PhD, professor of health sciences at University of Washington, Seattle, said the main reasons for the huge range of predictions are the variety of methods used, as well as differences in sample size. Also, much long COVID data is self-reported, making it difficult for epidemiologists to track.

“With self-reported data, you can’t plug people into a machine and say this is what they have or this is what they don’t have. At the population level, the only thing you can do is ask questions. There is no systematic way to define long COVID,” he said.

Dr. Vos’s most recent study, which is being peer-reviewed and revised, found that most people with long COVID have symptoms similar to those seen in other autoimmune diseases. But sometimes the immune system can overreact, causing the more severe symptoms, such as brain fog and heart problems, associated with long COVID.

One reason that researchers struggle to come up with numbers, said Dr. Al-Aly, is the rapid rise of new variants. These variants appear to sometimes cause less severe disease than previous ones, but it’s not clear whether that means different risks for long COVID.

“There’s a wide diversity in severity. Someone can have long COVID and be fully functional, while others are not functional at all. We still have a long way to go before we figure out why,” Dr. Lau said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID-19 is far from done in the United States, with more than 111,000 new cases being recorded a day in the second week of August, according to Johns Hopkins University, and 625 deaths being reported every day. , a condition that already has affected between 7.7 million and 23 million Americans, according to U.S. government estimates.

“It is evident that long COVID is real, that it already impacts a substantial number of people, and that this number may continue to grow as new infections occur,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) said in a research action plan released Aug. 4.

“We are heading towards a big problem on our hands,” says Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research and development at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in St. Louis. “It’s like if we are falling in a plane, hurtling towards the ground. It doesn’t matter at what speed we are falling; what matters is that we are all falling, and falling fast. It’s a real problem. We needed to bring attention to this, yesterday,” he said.

Bryan Lau, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and co-lead of a long COVID study there, says whether it’s 5% of the 92 million officially recorded U.S. COVID-19 cases, or 30% – on the higher end of estimates – that means anywhere between 4.5 million and 27 million Americans will have the effects of long COVID.

Other experts put the estimates even higher.

“If we conservatively assume 100 million working-age adults have been infected, that implies 10 to 33 million may have long COVID,” Alice Burns, PhD, associate director for the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, wrote in an analysis.

And even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says only a fraction of cases have been recorded.

That, in turn, means tens of millions of people who struggle to work, to get to school, and to take care of their families – and who will be making demands on an already stressed U.S. health care system.

The HHS said in its Aug. 4 report that long COVID could keep 1 million people a day out of work, with a loss of $50 billion in annual pay.

Dr. Lau said health workers and policymakers are woefully unprepared.

“If you have a family unit, and the mom or dad can’t work, or has trouble taking their child to activities, where does the question of support come into play? Where is there potential for food issues, or housing issues?” he asked. “I see the potential for the burden to be extremely large in that capacity.”

Dr. Lau said he has yet to see any strong estimates of how many cases of long COVID might develop. Because a person has to get COVID-19 to ultimately get long COVID, the two are linked. In other words, as COVID-19 cases rise, so will cases of long COVID, and vice versa.

Evidence from the Kaiser Family Foundation analysis suggests a significant impact on employment: Surveys showed more than half of adults with long COVID who worked before becoming infected are either out of work or working fewer hours. Conditions associated with long COVID – such as fatigue, malaise, or problems concentrating – limit people’s ability to work, even if they have jobs that allow for accommodations.

Two surveys of people with long COVID who had worked before becoming infected showed that between 22% and 27% of them were out of work after getting long COVID. In comparison, among all working-age adults in 2019, only 7% were out of work. Given the sheer number of working-age adults with long COVID, the effects on employment may be profound and are likely to involve more people over time. One study estimates that long COVID already accounts for 15% of unfilled jobs.

The most severe symptoms of long COVID include brain fog and heart complications, known to persist for weeks for months after a COVID-19 infection.

A study from the University of Norway published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases found 53% of people tested had at least one symptom of thinking problems 13 months after infection with COVID-19. According to the HHS’ latest report on long COVID, people with thinking problems, heart conditions, mobility issues, and other symptoms are going to need a considerable amount of care. Many will need lengthy periods of rehabilitation.

Dr. Al-Aly worries that long COVID has already severely affected the labor force and the job market, all while burdening the country’s health care system.

“While there are variations in how individuals respond and cope with long COVID, the unifying thread is that with the level of disability it causes, more people will be struggling to keep up with the demands of the workforce and more people will be out on disability than ever before,” he said.

Studies from Johns Hopkins and the University of Washington estimate that 5%-30% of people could get long COVID in the future. Projections beyond that are hazy.

“So far, all the studies we have done on long COVID have been reactionary. Much of the activism around long COVID has been patient led. We are seeing more and more people with lasting symptoms. We need our research to catch up,” Dr. Lau said.

Theo Vos, MD, PhD, professor of health sciences at University of Washington, Seattle, said the main reasons for the huge range of predictions are the variety of methods used, as well as differences in sample size. Also, much long COVID data is self-reported, making it difficult for epidemiologists to track.

“With self-reported data, you can’t plug people into a machine and say this is what they have or this is what they don’t have. At the population level, the only thing you can do is ask questions. There is no systematic way to define long COVID,” he said.

Dr. Vos’s most recent study, which is being peer-reviewed and revised, found that most people with long COVID have symptoms similar to those seen in other autoimmune diseases. But sometimes the immune system can overreact, causing the more severe symptoms, such as brain fog and heart problems, associated with long COVID.

One reason that researchers struggle to come up with numbers, said Dr. Al-Aly, is the rapid rise of new variants. These variants appear to sometimes cause less severe disease than previous ones, but it’s not clear whether that means different risks for long COVID.

“There’s a wide diversity in severity. Someone can have long COVID and be fully functional, while others are not functional at all. We still have a long way to go before we figure out why,” Dr. Lau said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Does hidradenitis suppurativa worsen during pregnancy?

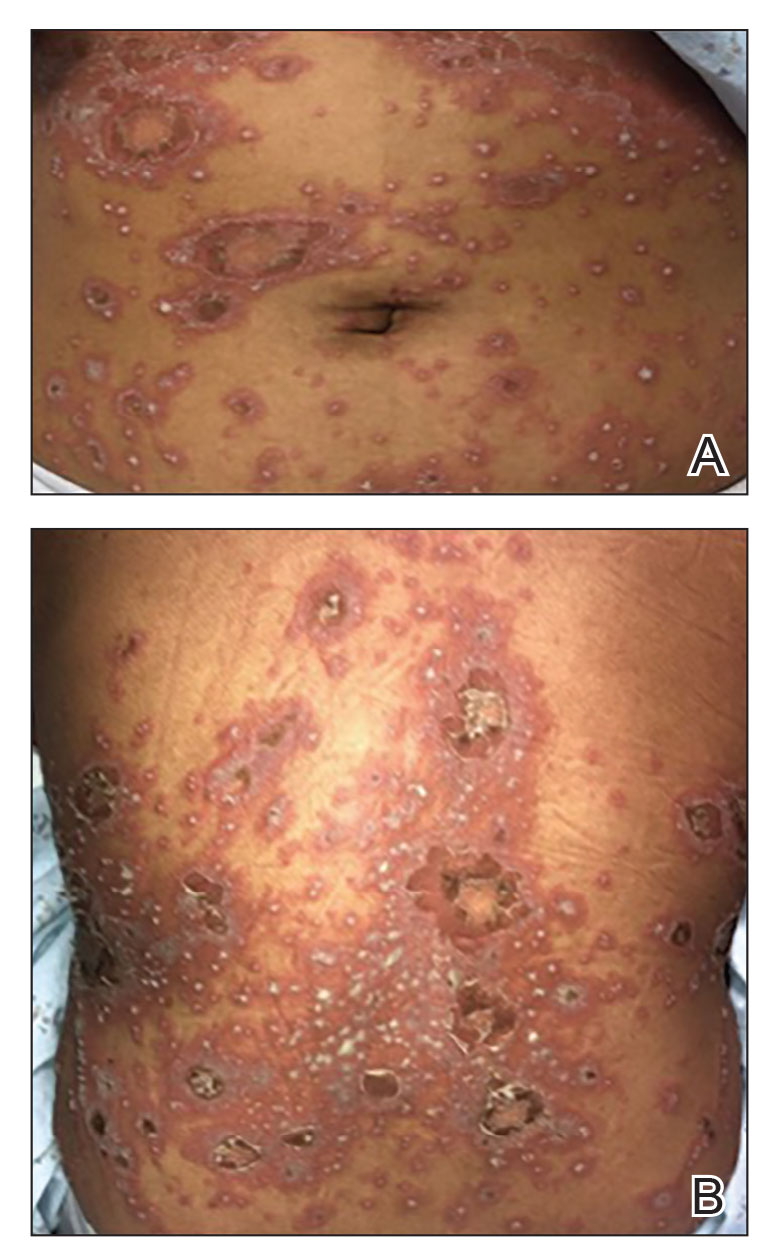

PORTLAND, ORE. – The recurrent boils, abscesses, and nodules of the chronic inflammatory skin condition hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) may improve during pregnancy for a subset of women, but for many, pregnancy does not change the disease course and may worsen symptoms.

In addition, HS appears to be a risk factor for adverse pregnancy and maternal outcomes.

“This is relevant, because in the United States, HS disproportionately impacts women compared with men by a ratio of about 3:1,” Jennifer Hsiao, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

“Also, the highest prevalence of HS is among people in their 20s and 30s, so in their practice, clinicians will encounter female patients with HS who are either pregnant or actively thinking about getting pregnant,” she said.

During a wide-ranging presentation, Dr. Hsiao of the department of dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, described the impact of pregnancy on HS, identified appropriate treatment options for this population of patients, and discussed HS comorbidities that may be exacerbated during pregnancy.

She began by noting that levels of progesterone and estrogen both rise during pregnancy. Progesterone is known to suppress development and function of Th1 and Th17 T cells, but the effect of estrogen on inflammation is less well known. At the same time, serum levels of interleukin (IL)-1 receptor antagonist and soluble TNF-alpha receptor both increase during pregnancy.

“This would lead to serum IL-1 and TNF-alpha falling, sort of like the way that we give anti–IL-1 and TNF blockers as HS treatments,” she explained. “So, presumably that might be helpful during HS in pregnancy. On the flip side, pregnancy weight gain can exacerbate HS, with increased friction between skin folds. In addition, just having more adipocytes can promote secretion of proinflammatory cytokines like TNF-alpha.”

To better understand the effect of pregnancy on patients with HS, Dr. Hsiao and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on the topic published in Dermatology. They included eight studies in which a total of 672 patients self-reported their HS disease course during pregnancy and 164 self-reported whether they had a postpartum HS flare or not. On pooled analyses, HS improved in 24% of patients but worsened in 20%. In addition, 60% of patients experienced a postpartum flare.

“So, at this point in time, based on the literature, it would be fair to tell your patient that during pregnancy, HS has a mixed response,” Dr. Hsiao said. “About 25% may have improvement, but for the rest, HS symptoms may be unchanged or even worsen. That’s why it’s so important to be in contact with your pregnant patients, because not only may they have to stay on treatment, but they might also have to escalate [their treatment] during pregnancy.”

Lifestyle modifications to discuss with pregnant HS patients include appropriate weight gain during pregnancy, smoking cessation, and avoidance of tight-fitting clothing, “since friction can make things worse,” she said. Topical antibiotics safe to use during pregnancy for patients with mild HS include clindamycin 1%, erythromycin 2%, and metronidazole 0.75% applied twice per day to active lesions, she continued.

As for systemic therapies, some data exist to support the use of metformin 500 mg once daily, titrating up to twice or – if needed and tolerated – three times daily for patients with mild to moderate HS, she said, referencing a paper published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Zinc gluconate is another potential option. Of 22 nonpregnant HS patients with Hurley stage I-II disease who were treated with zinc gluconate 90 mg daily, 8 had a complete remission of HS and 14 had partial remission, according to a report in Dermatology.

“Zinc supplementation of up to 50 mg daily has shown no effect on neonatal or maternal outcomes at birth based on existing medical literature,” Dr. Hsiao added.

Among antibiotics, injections of intralesional Kenalog 5-10 mg/mL have been shown to decrease pain and inflammation in acute HS lesions and are unlikely to pose significant risks during pregnancy, but a course of systemic antibiotics may be warranted in moderate to severe disease, she said. These include, but are not limited to, clindamycin, erythromycin base, cephalexin, or metronidazole.

“In addition, some of my HS colleagues and I will also use other antibiotics such as Augmentin [amoxicillin/clavulanate] or cefdinir for HS and these are also generally considered safe to use in pregnancy,” she said. “Caution is advised with using rifampin, dapsone, and moxifloxacin during pregnancy.”

As for biologic agents, the first-line option is adalimumab, which is currently the only Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for HS.

“There is also good efficacy data for infliximab,” she said. “Etanercept has less placental transfer than adalimumab or infliximab so it’s safer to use in pregnancy, but it has inconsistent data for efficacy in HS, so I would generally avoid using it to treat HS and reach for adalimumab or infliximab instead.”

Data on TNF-alpha inhibitors from the GI and rheumatology literature have demonstrated that there is minimal placental transport of maternal antibodies during the first two trimesters of pregnancy.

“It’s at the beginning of the third trimester that the placental transfer of antibodies picks up,” she said. “At that point in time, you can have a discussion with the patient: do you want to stay on treatment and treat through, or do you want to consider being taken off the medication? I think this is a discussion that needs to be had, because let’s say you peel off adalimumab or infliximab and they have severe HS flares. I’m not sure that leads to a better outcome. I usually treat through for my pregnant patients.”

To better understand clinician practice patterns on the management of HS in pregnancy, Dr. Hsiao and Erin Collier, MD, MPH, of University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues distributed an online survey to HS specialists in North America. They reported the findings in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

Of the 49 respondents, 36 (73%) directed an HS specialty clinic and 29 (59%) reported having prescribed or continued a biologic agent in a pregnant HS patient. The top three biologics prescribed were adalimumab (90%), infliximab (41%), and certolizumab pegol (34%). Dr. Hsiao noted that certolizumab pegol is a pegylated anti-TNF, so it lacks an Fc region on the medication.

“This means that it cannot be actively transported by the neonatal Fc receptor on the placenta, thus resulting in minimal placental transmission,” she said. “The main issue is that there is little data on its efficacy in HS, but it’s a reasonable option to consider in a pregnant patient, especially in a patient with severe HS who asks, ‘what’s the safest biologic that I can go on?’ But you’d have to discuss with the patient that in terms of efficacy data, there is much less in the literature compared to adalimumab or infliximab.”

Breastfeeding while on anti–TNF-alpha biologics is considered safe. “There are minimal amounts of medication in breast milk,” she said. “If any gets through, infant gastric digestion is thought to take care of the rest. Of note, babies born to mothers who are continually treated with biologic agents should not be given live vaccinations for 6 months after birth.”

In a single-center study, Dr. Hsiao and colleagues retrospectively examined pregnancy complications, pregnancy outcomes, and neonatal outcomes in patients with HS. The study population included 202 pregnancies in 127 HS patients. Of 134 babies born to mothers with HS, 74% were breastfed and 24% were bottle-fed, and presence of HS lesions on the breast was significantly associated with not breastfeeding.

“So, when we see these patients, if moms decide to breastfeed and they have lesions on the breast, it would be helpful to discuss expectations and perhaps treat HS breast lesions early, so the breastfeeding process may go more smoothly for them after they deliver,” said Dr. Hsiao, who is one of the editors of the textbook “A Comprehensive Guide to Hidradenitis Suppurativa” (Elsevier, 2021). Safety-related resources that she recommends for clinicians include Mother to Baby and the Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed).

Dr. Hsiao concluded her presentation by spotlighting the influence of pregnancy on HS comorbidities. Patients with HS already have a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety compared to controls. “Pregnancy can exacerbate underlying mood disorders in patients,” she said. “That’s why monitoring the patient’s mood and coordinating mental health care with the patient’s primary care physician and ob.gyn. is important.”

In addition, pregnancy-related changes in body mass index, blood pressure, lipid metabolism, and glucose tolerance trend toward changes seen in metabolic syndrome, she said, and HS patients are already at higher risk of metabolic syndrome compared with the general population.

HS may also compromise a patient’s ability to have a healthy pregnancy. Dr. Hsiao worked with Amit Garg, MD, and colleagues on a study that drew from the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims Database to evaluate adverse pregnancy and maternal outcomes in women with HS between Jan. 1, 2011, and Sept. 30, 2015.

After the researchers adjusted for age, race, smoking status, and other comorbidities, they found that HS pregnancies were independently associated with spontaneous abortion (odds ratio, 1.20), gestational diabetes (OR, 1.26), and cesarean section (OR, 1.09). The findings were published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

A separate study that used the same database found comparable results, also published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. “What I say to patients right now is, ‘there are many women with HS who have healthy pregnancies and deliver healthy babies, but HS could be a risk factor for a higher-risk pregnancy.’ It’s important that these patients are established with an ob.gyn. and are closely monitored to make sure that we optimize their care and give them the best outcome possible for mom and baby.”

Dr. Hsiao disclosed that she is on the board of directors for the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation. She has also served as an advisor for Novartis, UCB, and Boehringer Ingelheim and as a speaker and advisor for AbbVie.

PORTLAND, ORE. – The recurrent boils, abscesses, and nodules of the chronic inflammatory skin condition hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) may improve during pregnancy for a subset of women, but for many, pregnancy does not change the disease course and may worsen symptoms.

In addition, HS appears to be a risk factor for adverse pregnancy and maternal outcomes.

“This is relevant, because in the United States, HS disproportionately impacts women compared with men by a ratio of about 3:1,” Jennifer Hsiao, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

“Also, the highest prevalence of HS is among people in their 20s and 30s, so in their practice, clinicians will encounter female patients with HS who are either pregnant or actively thinking about getting pregnant,” she said.

During a wide-ranging presentation, Dr. Hsiao of the department of dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, described the impact of pregnancy on HS, identified appropriate treatment options for this population of patients, and discussed HS comorbidities that may be exacerbated during pregnancy.

She began by noting that levels of progesterone and estrogen both rise during pregnancy. Progesterone is known to suppress development and function of Th1 and Th17 T cells, but the effect of estrogen on inflammation is less well known. At the same time, serum levels of interleukin (IL)-1 receptor antagonist and soluble TNF-alpha receptor both increase during pregnancy.

“This would lead to serum IL-1 and TNF-alpha falling, sort of like the way that we give anti–IL-1 and TNF blockers as HS treatments,” she explained. “So, presumably that might be helpful during HS in pregnancy. On the flip side, pregnancy weight gain can exacerbate HS, with increased friction between skin folds. In addition, just having more adipocytes can promote secretion of proinflammatory cytokines like TNF-alpha.”

To better understand the effect of pregnancy on patients with HS, Dr. Hsiao and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on the topic published in Dermatology. They included eight studies in which a total of 672 patients self-reported their HS disease course during pregnancy and 164 self-reported whether they had a postpartum HS flare or not. On pooled analyses, HS improved in 24% of patients but worsened in 20%. In addition, 60% of patients experienced a postpartum flare.

“So, at this point in time, based on the literature, it would be fair to tell your patient that during pregnancy, HS has a mixed response,” Dr. Hsiao said. “About 25% may have improvement, but for the rest, HS symptoms may be unchanged or even worsen. That’s why it’s so important to be in contact with your pregnant patients, because not only may they have to stay on treatment, but they might also have to escalate [their treatment] during pregnancy.”

Lifestyle modifications to discuss with pregnant HS patients include appropriate weight gain during pregnancy, smoking cessation, and avoidance of tight-fitting clothing, “since friction can make things worse,” she said. Topical antibiotics safe to use during pregnancy for patients with mild HS include clindamycin 1%, erythromycin 2%, and metronidazole 0.75% applied twice per day to active lesions, she continued.

As for systemic therapies, some data exist to support the use of metformin 500 mg once daily, titrating up to twice or – if needed and tolerated – three times daily for patients with mild to moderate HS, she said, referencing a paper published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Zinc gluconate is another potential option. Of 22 nonpregnant HS patients with Hurley stage I-II disease who were treated with zinc gluconate 90 mg daily, 8 had a complete remission of HS and 14 had partial remission, according to a report in Dermatology.

“Zinc supplementation of up to 50 mg daily has shown no effect on neonatal or maternal outcomes at birth based on existing medical literature,” Dr. Hsiao added.

Among antibiotics, injections of intralesional Kenalog 5-10 mg/mL have been shown to decrease pain and inflammation in acute HS lesions and are unlikely to pose significant risks during pregnancy, but a course of systemic antibiotics may be warranted in moderate to severe disease, she said. These include, but are not limited to, clindamycin, erythromycin base, cephalexin, or metronidazole.

“In addition, some of my HS colleagues and I will also use other antibiotics such as Augmentin [amoxicillin/clavulanate] or cefdinir for HS and these are also generally considered safe to use in pregnancy,” she said. “Caution is advised with using rifampin, dapsone, and moxifloxacin during pregnancy.”

As for biologic agents, the first-line option is adalimumab, which is currently the only Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for HS.

“There is also good efficacy data for infliximab,” she said. “Etanercept has less placental transfer than adalimumab or infliximab so it’s safer to use in pregnancy, but it has inconsistent data for efficacy in HS, so I would generally avoid using it to treat HS and reach for adalimumab or infliximab instead.”

Data on TNF-alpha inhibitors from the GI and rheumatology literature have demonstrated that there is minimal placental transport of maternal antibodies during the first two trimesters of pregnancy.

“It’s at the beginning of the third trimester that the placental transfer of antibodies picks up,” she said. “At that point in time, you can have a discussion with the patient: do you want to stay on treatment and treat through, or do you want to consider being taken off the medication? I think this is a discussion that needs to be had, because let’s say you peel off adalimumab or infliximab and they have severe HS flares. I’m not sure that leads to a better outcome. I usually treat through for my pregnant patients.”

To better understand clinician practice patterns on the management of HS in pregnancy, Dr. Hsiao and Erin Collier, MD, MPH, of University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues distributed an online survey to HS specialists in North America. They reported the findings in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

Of the 49 respondents, 36 (73%) directed an HS specialty clinic and 29 (59%) reported having prescribed or continued a biologic agent in a pregnant HS patient. The top three biologics prescribed were adalimumab (90%), infliximab (41%), and certolizumab pegol (34%). Dr. Hsiao noted that certolizumab pegol is a pegylated anti-TNF, so it lacks an Fc region on the medication.

“This means that it cannot be actively transported by the neonatal Fc receptor on the placenta, thus resulting in minimal placental transmission,” she said. “The main issue is that there is little data on its efficacy in HS, but it’s a reasonable option to consider in a pregnant patient, especially in a patient with severe HS who asks, ‘what’s the safest biologic that I can go on?’ But you’d have to discuss with the patient that in terms of efficacy data, there is much less in the literature compared to adalimumab or infliximab.”

Breastfeeding while on anti–TNF-alpha biologics is considered safe. “There are minimal amounts of medication in breast milk,” she said. “If any gets through, infant gastric digestion is thought to take care of the rest. Of note, babies born to mothers who are continually treated with biologic agents should not be given live vaccinations for 6 months after birth.”

In a single-center study, Dr. Hsiao and colleagues retrospectively examined pregnancy complications, pregnancy outcomes, and neonatal outcomes in patients with HS. The study population included 202 pregnancies in 127 HS patients. Of 134 babies born to mothers with HS, 74% were breastfed and 24% were bottle-fed, and presence of HS lesions on the breast was significantly associated with not breastfeeding.

“So, when we see these patients, if moms decide to breastfeed and they have lesions on the breast, it would be helpful to discuss expectations and perhaps treat HS breast lesions early, so the breastfeeding process may go more smoothly for them after they deliver,” said Dr. Hsiao, who is one of the editors of the textbook “A Comprehensive Guide to Hidradenitis Suppurativa” (Elsevier, 2021). Safety-related resources that she recommends for clinicians include Mother to Baby and the Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed).

Dr. Hsiao concluded her presentation by spotlighting the influence of pregnancy on HS comorbidities. Patients with HS already have a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety compared to controls. “Pregnancy can exacerbate underlying mood disorders in patients,” she said. “That’s why monitoring the patient’s mood and coordinating mental health care with the patient’s primary care physician and ob.gyn. is important.”

In addition, pregnancy-related changes in body mass index, blood pressure, lipid metabolism, and glucose tolerance trend toward changes seen in metabolic syndrome, she said, and HS patients are already at higher risk of metabolic syndrome compared with the general population.