User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Chronic Retiform Purpura of the Abdomen and Thighs: A Fatal Case of Intravascular Large Cell Lymphoma

To the Editor:

Intravascular large cell lymphoma (ILCL) is a rare B-cell lymphoma that is defined by the presence of large neoplastic B cells in the lumen of blood vessels.1 At least 3 variants of ILCL have been described based on case reports and a small case series: classic, cutaneous, and hemophagocytic. The classic variant presents in elderly patients as nonspecific constitutional symptoms (fever or pain, or less frequently weight loss) or as signs of multiorgan failure (most commonly of the central nervous system). Skin involvement, which is present in nearly half of these patients, can take on multiple morphologies, including retiform purpura, ulcerated nodules, or pseudocellulitis. The cutaneous variant typically presents in middle-aged women with normal hematologic studies. Systemic involvement is less common in this variant of disease than the classic variant, which may partly explain why overall survival is superior in this variant. The hemophagocytic variant manifests as intravascular lymphoma accompanied by hemophagocytic syndrome (fever, hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, and bone marrow involvement).

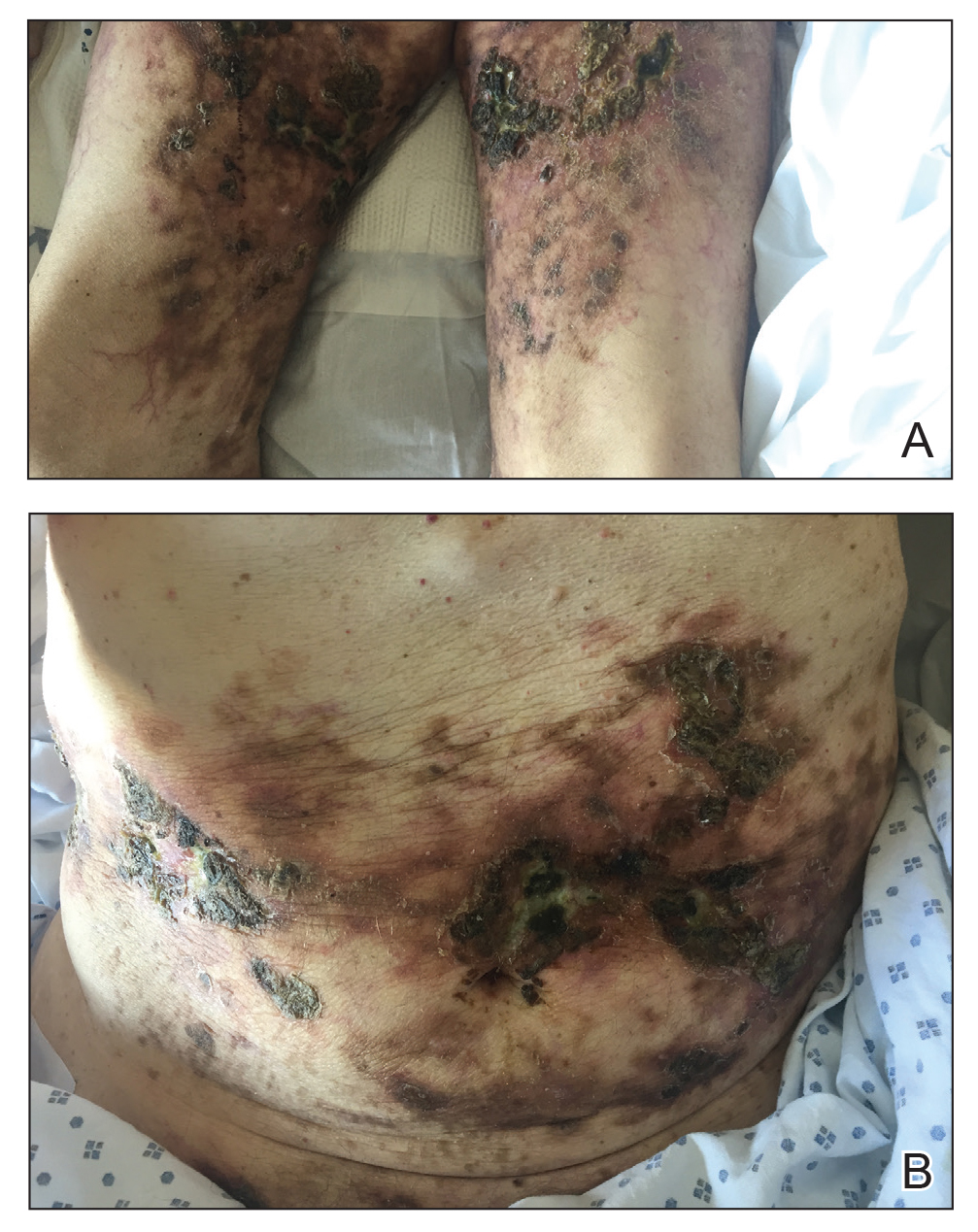

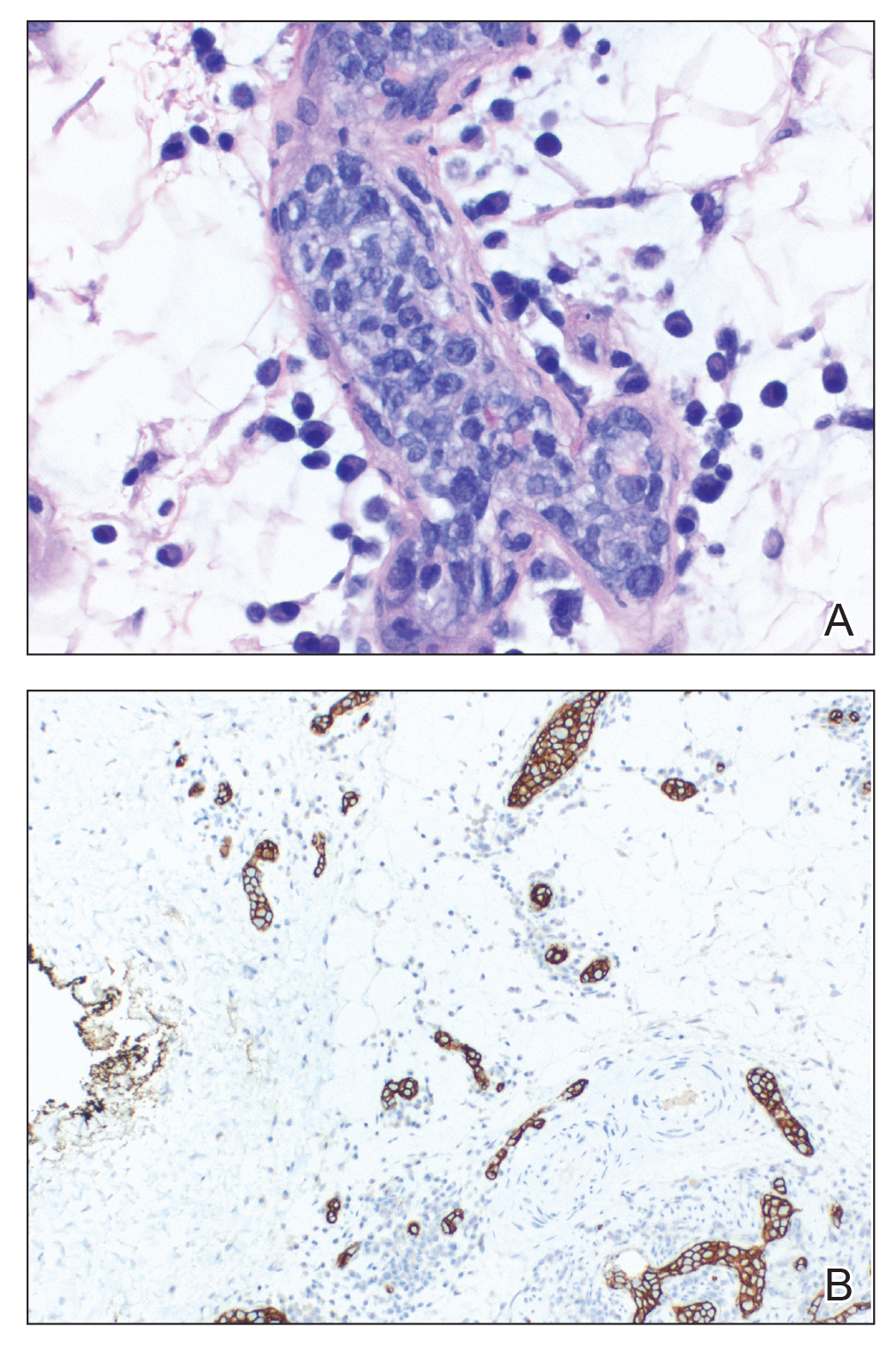

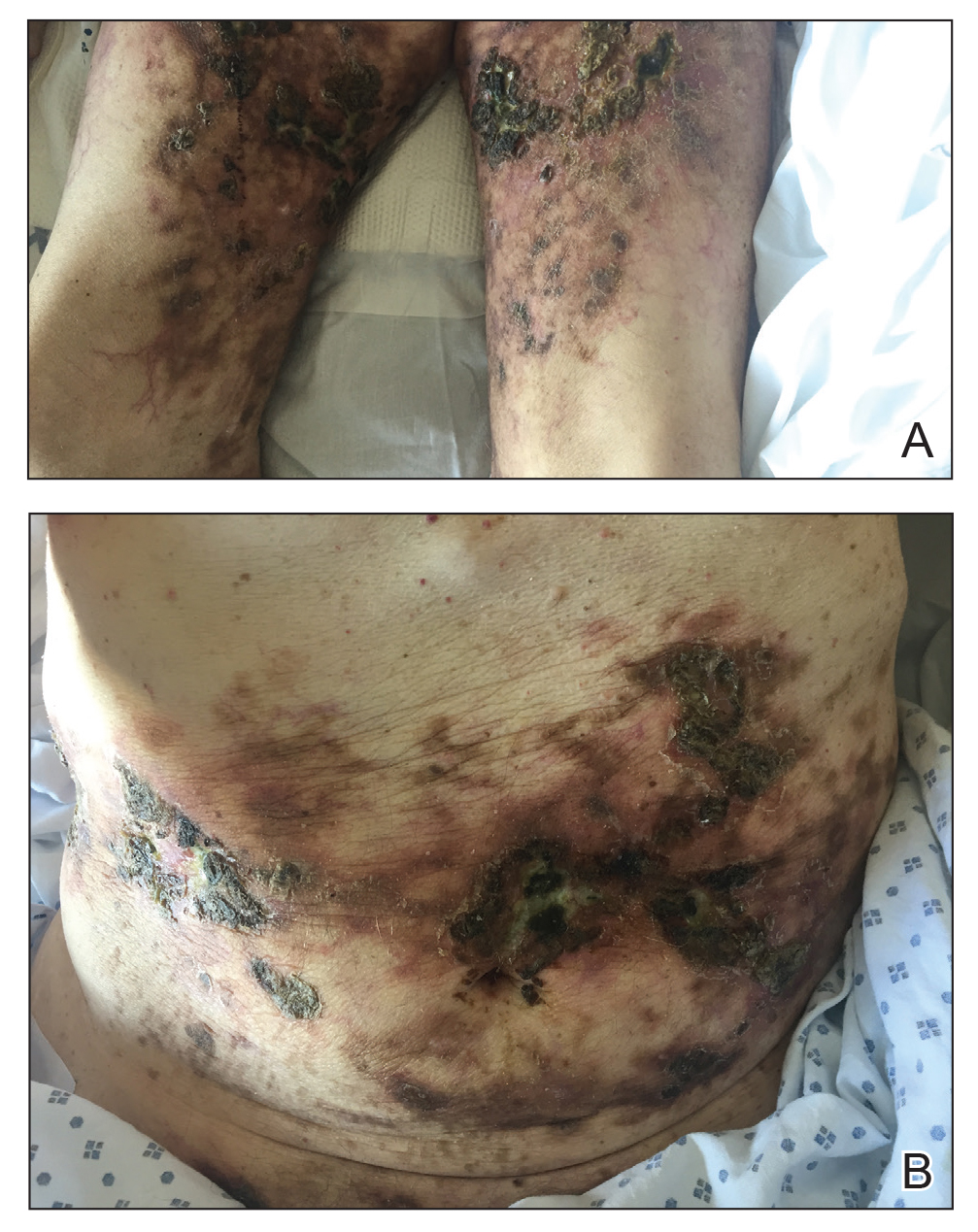

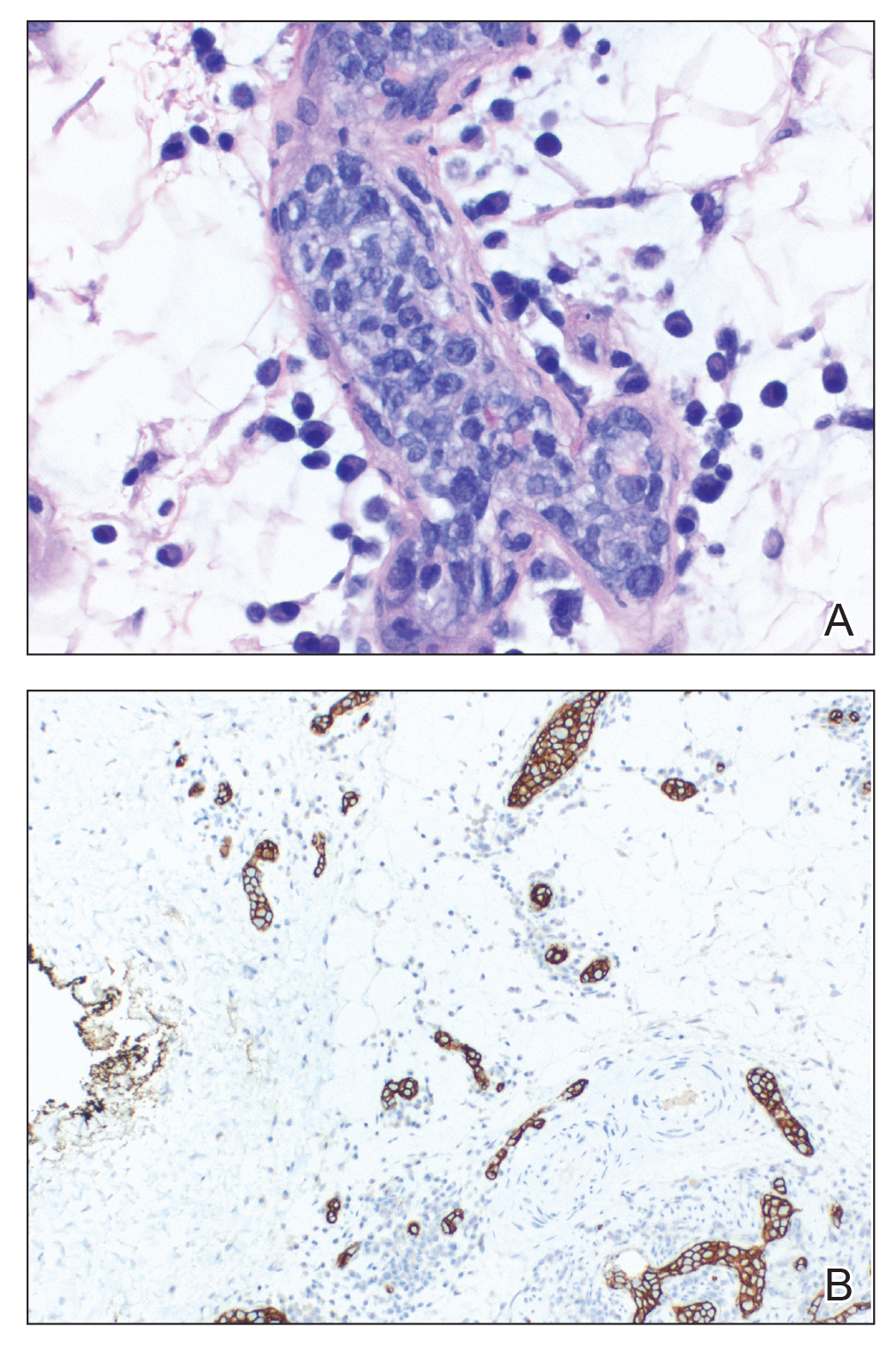

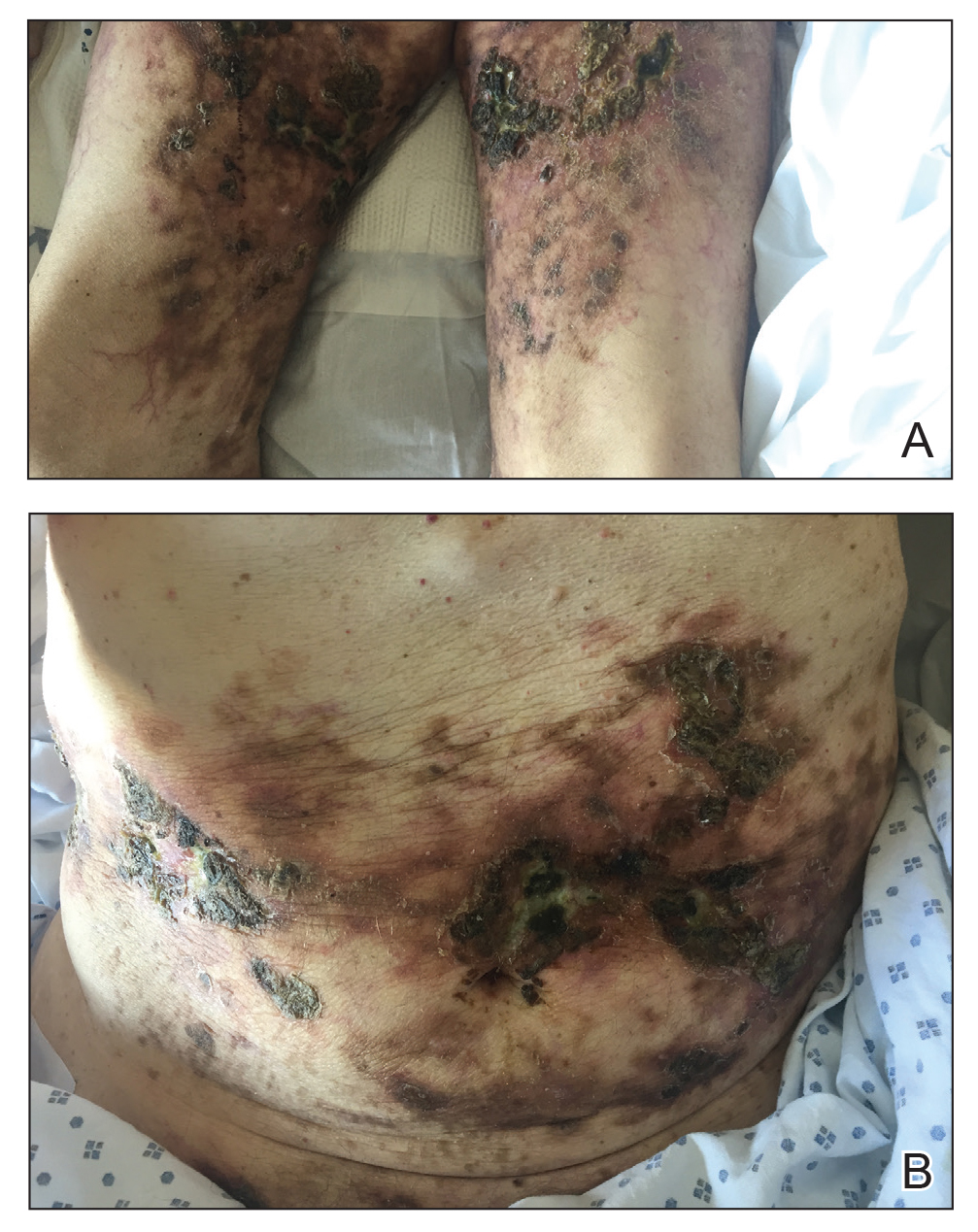

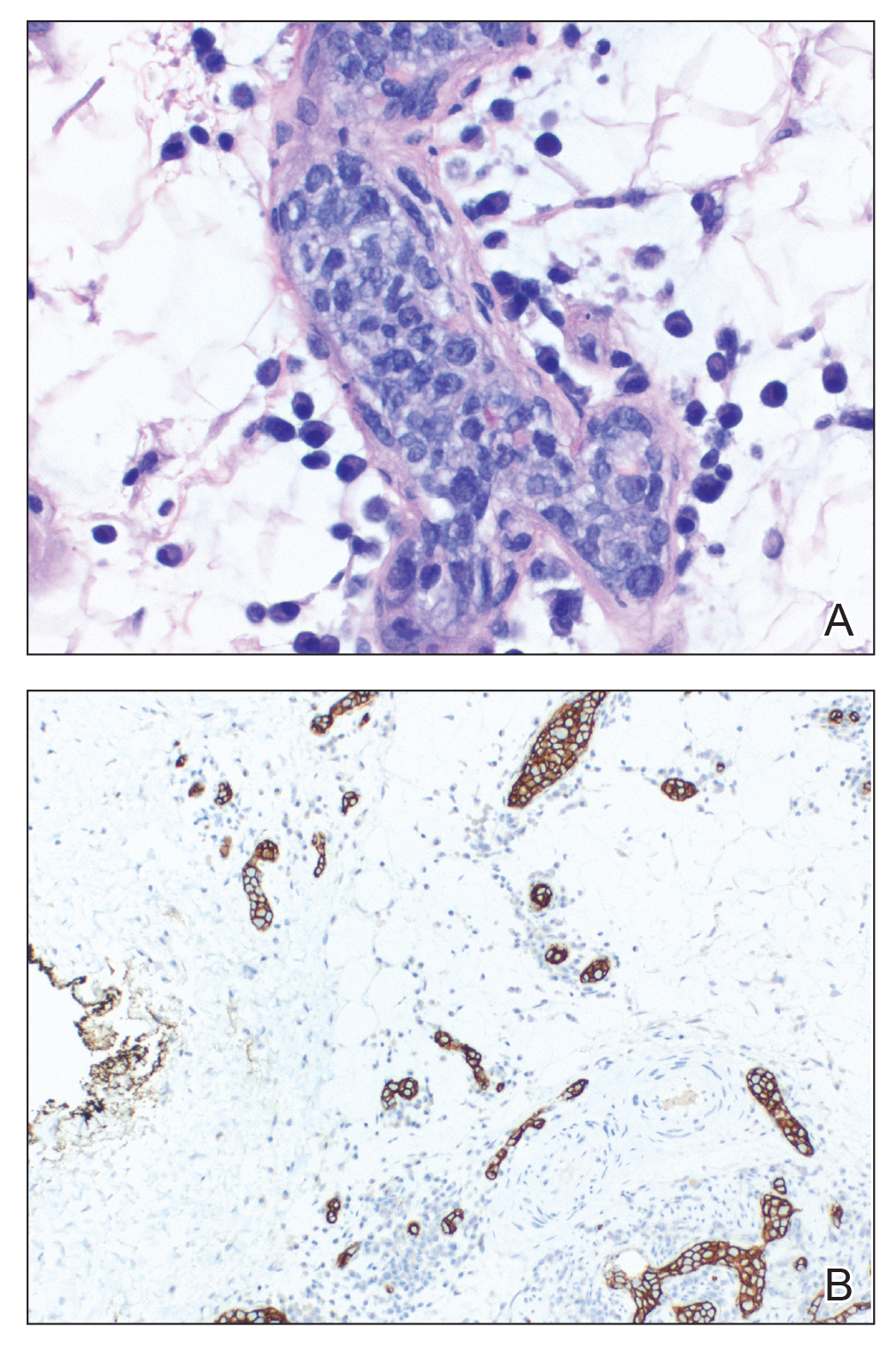

A 69-year-old man presented to the emergency department for failure to thrive and nonhealing wounds of 1 year’s duration. His medical history was notable for poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, progressive multifocal ischemic and hemorrhagic cerebral infarcts, and bilateral deep venous thromboses. Physical examination revealed large purpuric to brown plaques in a retiform configuration with central necrotic eschars on the thighs and abdomen (Figure 1). There was no palpable lymphadenopathy. Laboratory tests revealed normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 10.5 g/dL (reference range, 12–18 g/dL), elevated lactate dehydrogenase level of 525 U/L (reference range, 118–242 U/L), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 73 mm/h (reference range, <20 mm/h), antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:2560 (reference range, <1:80), and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. The patient’s white blood cell and platelet counts, creatinine level, and liver function tests were within reference range. Cryoglobulins, coagulation studies, and cardiolipin antibodies were negative. Chest and abdominal imaging also were negative. An incisional skin biopsy and skin punch biopsy showed thrombotic coagulopathy and dilated vessels. A bone marrow biopsy revealed a hypercellular marrow but no plasma cell neoplasm. A repeat incisional skin biopsy demonstrated large CD20+ and CD45+ atypical lymphocytes within the small capillaries of the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat (Figure 2), which confirmed ILCL. Too deconditioned to tolerate chemotherapy, the patient opted for palliative care and died 18 months after initial presentation.

The diagnosis of ILCL often is delayed for several reasons.2 Patients can present with a variety of signs and symptoms related to small vessel occlusion that can be misattributed to other conditions.3,4 In our case, the patient’s recurrent infarcts were thought to be due to his poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, which was diagnosed a few weeks prior, and a positive ANA, even though the workup for antiphospholipid syndrome was negative. Interestingly, a positive ANA (without signs or symptoms of lupus or other autoimmune conditions) has been reported in patients with lymphoma.3 A positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody level (without symptoms or other signs of vasculitis) has been reported in patients with ILCL.4,5 Therefore, distractors are common.

Multiple incisional skin biopsies in the absence of clinical findings (ie, random skin biopsy) are moderately sensitive (77.8%) for the diagnosis of ILCL.2 In a study by Matsue et al,2 111 suspected cases of ILCL underwent 3 incisional biopsies of fat-containing areas of the skin, such as the thigh, abdomen, and upper arm. Intravascular large cell lymphoma was confirmed in 26 cases. Seven additional cases were diagnosed as ILCL, 2 by additional skin biopsies (1 by a second round and 1 by a third round) and 5 by internal organ biopsy (4 bone marrow and 1 adrenal gland). The remaining cases ultimately were found to be a diagnostic mimicker of ILCL, including non-ILCL.2 Although random skin biopsies are reasonably sensitive for ILCL, multiple biopsies are needed, and in some cases, sampling of an internal organ may be required to establish the diagnosis of ILCL.

The prognosis of ILCL is poor; the 3-year overall survival rate for classic and cutaneous variants is 22% and 56%, respectively.6 Anthracycline-based chemotherapy, such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), is considered first-line treatment, and the addition of rituximab to the CHOP regimen may improve remission rates and survival.7

- Ponzoni M, Campo E, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a chameleon with multiple faces and many masks [published online August 15, 2018]. Blood. 2018;132:1561-1567. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-04-737445

- Matsue K, Abe Y, Kitadate A, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of incisional random skin biopsy for diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2019;133:1257-1259.

- Altintas A, Cil T, Pasa S, et al. Clinical significance of elevated antinuclear antibody test in patients with Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Minerva Med. 2008;99:7-14.

- Shinkawa Y, Hatachi S, Yagita M. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with a high titer of proteinase-3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody mimicking granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2019;29:195-197.

- Sugiyama A, Kobayashi M, Daizo A, et al. Diffuse cerebral vasoconstriction in a intravascular lymphoma patient with a high serum MPO-ANCA level. Intern Med. 2017;56:1715-1718.

- Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Seymour JF, et al. Intravascular lymphoma: clinical presentation, natural history, management and prognostic factors in a series of 38 cases, with special emphasis on the ‘cutaneous variant.’ Br J Haematol. 2004;127:173-183.

- Ferreri AJM, Dognini GP, Bairey O, et al; International Extranodal Lyphoma Study Group. The addition of rituximab to anthracycline-based chemotherapy significantly improves outcome in ‘Western’ patients with intravascular large B-cell lymphoma [published online August 10, 2008]. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:253-257. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07338.x

To the Editor:

Intravascular large cell lymphoma (ILCL) is a rare B-cell lymphoma that is defined by the presence of large neoplastic B cells in the lumen of blood vessels.1 At least 3 variants of ILCL have been described based on case reports and a small case series: classic, cutaneous, and hemophagocytic. The classic variant presents in elderly patients as nonspecific constitutional symptoms (fever or pain, or less frequently weight loss) or as signs of multiorgan failure (most commonly of the central nervous system). Skin involvement, which is present in nearly half of these patients, can take on multiple morphologies, including retiform purpura, ulcerated nodules, or pseudocellulitis. The cutaneous variant typically presents in middle-aged women with normal hematologic studies. Systemic involvement is less common in this variant of disease than the classic variant, which may partly explain why overall survival is superior in this variant. The hemophagocytic variant manifests as intravascular lymphoma accompanied by hemophagocytic syndrome (fever, hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, and bone marrow involvement).

A 69-year-old man presented to the emergency department for failure to thrive and nonhealing wounds of 1 year’s duration. His medical history was notable for poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, progressive multifocal ischemic and hemorrhagic cerebral infarcts, and bilateral deep venous thromboses. Physical examination revealed large purpuric to brown plaques in a retiform configuration with central necrotic eschars on the thighs and abdomen (Figure 1). There was no palpable lymphadenopathy. Laboratory tests revealed normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 10.5 g/dL (reference range, 12–18 g/dL), elevated lactate dehydrogenase level of 525 U/L (reference range, 118–242 U/L), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 73 mm/h (reference range, <20 mm/h), antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:2560 (reference range, <1:80), and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. The patient’s white blood cell and platelet counts, creatinine level, and liver function tests were within reference range. Cryoglobulins, coagulation studies, and cardiolipin antibodies were negative. Chest and abdominal imaging also were negative. An incisional skin biopsy and skin punch biopsy showed thrombotic coagulopathy and dilated vessels. A bone marrow biopsy revealed a hypercellular marrow but no plasma cell neoplasm. A repeat incisional skin biopsy demonstrated large CD20+ and CD45+ atypical lymphocytes within the small capillaries of the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat (Figure 2), which confirmed ILCL. Too deconditioned to tolerate chemotherapy, the patient opted for palliative care and died 18 months after initial presentation.

The diagnosis of ILCL often is delayed for several reasons.2 Patients can present with a variety of signs and symptoms related to small vessel occlusion that can be misattributed to other conditions.3,4 In our case, the patient’s recurrent infarcts were thought to be due to his poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, which was diagnosed a few weeks prior, and a positive ANA, even though the workup for antiphospholipid syndrome was negative. Interestingly, a positive ANA (without signs or symptoms of lupus or other autoimmune conditions) has been reported in patients with lymphoma.3 A positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody level (without symptoms or other signs of vasculitis) has been reported in patients with ILCL.4,5 Therefore, distractors are common.

Multiple incisional skin biopsies in the absence of clinical findings (ie, random skin biopsy) are moderately sensitive (77.8%) for the diagnosis of ILCL.2 In a study by Matsue et al,2 111 suspected cases of ILCL underwent 3 incisional biopsies of fat-containing areas of the skin, such as the thigh, abdomen, and upper arm. Intravascular large cell lymphoma was confirmed in 26 cases. Seven additional cases were diagnosed as ILCL, 2 by additional skin biopsies (1 by a second round and 1 by a third round) and 5 by internal organ biopsy (4 bone marrow and 1 adrenal gland). The remaining cases ultimately were found to be a diagnostic mimicker of ILCL, including non-ILCL.2 Although random skin biopsies are reasonably sensitive for ILCL, multiple biopsies are needed, and in some cases, sampling of an internal organ may be required to establish the diagnosis of ILCL.

The prognosis of ILCL is poor; the 3-year overall survival rate for classic and cutaneous variants is 22% and 56%, respectively.6 Anthracycline-based chemotherapy, such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), is considered first-line treatment, and the addition of rituximab to the CHOP regimen may improve remission rates and survival.7

To the Editor:

Intravascular large cell lymphoma (ILCL) is a rare B-cell lymphoma that is defined by the presence of large neoplastic B cells in the lumen of blood vessels.1 At least 3 variants of ILCL have been described based on case reports and a small case series: classic, cutaneous, and hemophagocytic. The classic variant presents in elderly patients as nonspecific constitutional symptoms (fever or pain, or less frequently weight loss) or as signs of multiorgan failure (most commonly of the central nervous system). Skin involvement, which is present in nearly half of these patients, can take on multiple morphologies, including retiform purpura, ulcerated nodules, or pseudocellulitis. The cutaneous variant typically presents in middle-aged women with normal hematologic studies. Systemic involvement is less common in this variant of disease than the classic variant, which may partly explain why overall survival is superior in this variant. The hemophagocytic variant manifests as intravascular lymphoma accompanied by hemophagocytic syndrome (fever, hepatosplenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, and bone marrow involvement).

A 69-year-old man presented to the emergency department for failure to thrive and nonhealing wounds of 1 year’s duration. His medical history was notable for poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, progressive multifocal ischemic and hemorrhagic cerebral infarcts, and bilateral deep venous thromboses. Physical examination revealed large purpuric to brown plaques in a retiform configuration with central necrotic eschars on the thighs and abdomen (Figure 1). There was no palpable lymphadenopathy. Laboratory tests revealed normocytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 10.5 g/dL (reference range, 12–18 g/dL), elevated lactate dehydrogenase level of 525 U/L (reference range, 118–242 U/L), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 73 mm/h (reference range, <20 mm/h), antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:2560 (reference range, <1:80), and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. The patient’s white blood cell and platelet counts, creatinine level, and liver function tests were within reference range. Cryoglobulins, coagulation studies, and cardiolipin antibodies were negative. Chest and abdominal imaging also were negative. An incisional skin biopsy and skin punch biopsy showed thrombotic coagulopathy and dilated vessels. A bone marrow biopsy revealed a hypercellular marrow but no plasma cell neoplasm. A repeat incisional skin biopsy demonstrated large CD20+ and CD45+ atypical lymphocytes within the small capillaries of the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat (Figure 2), which confirmed ILCL. Too deconditioned to tolerate chemotherapy, the patient opted for palliative care and died 18 months after initial presentation.

The diagnosis of ILCL often is delayed for several reasons.2 Patients can present with a variety of signs and symptoms related to small vessel occlusion that can be misattributed to other conditions.3,4 In our case, the patient’s recurrent infarcts were thought to be due to his poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, which was diagnosed a few weeks prior, and a positive ANA, even though the workup for antiphospholipid syndrome was negative. Interestingly, a positive ANA (without signs or symptoms of lupus or other autoimmune conditions) has been reported in patients with lymphoma.3 A positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody level (without symptoms or other signs of vasculitis) has been reported in patients with ILCL.4,5 Therefore, distractors are common.

Multiple incisional skin biopsies in the absence of clinical findings (ie, random skin biopsy) are moderately sensitive (77.8%) for the diagnosis of ILCL.2 In a study by Matsue et al,2 111 suspected cases of ILCL underwent 3 incisional biopsies of fat-containing areas of the skin, such as the thigh, abdomen, and upper arm. Intravascular large cell lymphoma was confirmed in 26 cases. Seven additional cases were diagnosed as ILCL, 2 by additional skin biopsies (1 by a second round and 1 by a third round) and 5 by internal organ biopsy (4 bone marrow and 1 adrenal gland). The remaining cases ultimately were found to be a diagnostic mimicker of ILCL, including non-ILCL.2 Although random skin biopsies are reasonably sensitive for ILCL, multiple biopsies are needed, and in some cases, sampling of an internal organ may be required to establish the diagnosis of ILCL.

The prognosis of ILCL is poor; the 3-year overall survival rate for classic and cutaneous variants is 22% and 56%, respectively.6 Anthracycline-based chemotherapy, such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), is considered first-line treatment, and the addition of rituximab to the CHOP regimen may improve remission rates and survival.7

- Ponzoni M, Campo E, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a chameleon with multiple faces and many masks [published online August 15, 2018]. Blood. 2018;132:1561-1567. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-04-737445

- Matsue K, Abe Y, Kitadate A, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of incisional random skin biopsy for diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2019;133:1257-1259.

- Altintas A, Cil T, Pasa S, et al. Clinical significance of elevated antinuclear antibody test in patients with Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Minerva Med. 2008;99:7-14.

- Shinkawa Y, Hatachi S, Yagita M. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with a high titer of proteinase-3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody mimicking granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2019;29:195-197.

- Sugiyama A, Kobayashi M, Daizo A, et al. Diffuse cerebral vasoconstriction in a intravascular lymphoma patient with a high serum MPO-ANCA level. Intern Med. 2017;56:1715-1718.

- Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Seymour JF, et al. Intravascular lymphoma: clinical presentation, natural history, management and prognostic factors in a series of 38 cases, with special emphasis on the ‘cutaneous variant.’ Br J Haematol. 2004;127:173-183.

- Ferreri AJM, Dognini GP, Bairey O, et al; International Extranodal Lyphoma Study Group. The addition of rituximab to anthracycline-based chemotherapy significantly improves outcome in ‘Western’ patients with intravascular large B-cell lymphoma [published online August 10, 2008]. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:253-257. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07338.x

- Ponzoni M, Campo E, Nakamura S. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: a chameleon with multiple faces and many masks [published online August 15, 2018]. Blood. 2018;132:1561-1567. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-04-737445

- Matsue K, Abe Y, Kitadate A, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of incisional random skin biopsy for diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2019;133:1257-1259.

- Altintas A, Cil T, Pasa S, et al. Clinical significance of elevated antinuclear antibody test in patients with Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Minerva Med. 2008;99:7-14.

- Shinkawa Y, Hatachi S, Yagita M. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with a high titer of proteinase-3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody mimicking granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Mod Rheumatol. 2019;29:195-197.

- Sugiyama A, Kobayashi M, Daizo A, et al. Diffuse cerebral vasoconstriction in a intravascular lymphoma patient with a high serum MPO-ANCA level. Intern Med. 2017;56:1715-1718.

- Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Seymour JF, et al. Intravascular lymphoma: clinical presentation, natural history, management and prognostic factors in a series of 38 cases, with special emphasis on the ‘cutaneous variant.’ Br J Haematol. 2004;127:173-183.

- Ferreri AJM, Dognini GP, Bairey O, et al; International Extranodal Lyphoma Study Group. The addition of rituximab to anthracycline-based chemotherapy significantly improves outcome in ‘Western’ patients with intravascular large B-cell lymphoma [published online August 10, 2008]. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:253-257. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07338.x

Practice Points

- Intravascular large cell lymphoma (ILCL) is a life-threatening malignancy that can present with retiform purpura and other symptoms of vascular occlusion.

- The diagnosis of ILCL can be challenging because of the presence of distractors, and multiple biopsies may be required to establish pathology.

Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitor–Induced Lupuslike Syndrome in a Patient Prescribed Certolizumab Pegol

To the Editor:

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome (TAILS) is a newly described entity that refers to the onset of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) during drug therapy with TNF-α antagonists. The condition is unique because it is thought to occur via a separate pathophysiologic mechanism than all other agents implicated in the development of drug-induced lupus erythematosus (DILE). Infliximab and etanercept are the 2 most common TNF-α antagonists associated with TAILS. Although rare, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol have been reported to induce this state of autoimmunity. We report an uncommon presentation of TAILS in a patient taking certolizumab pegol with a brief discussion of the pathogenesis underlying TAILS.

A 71-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash located on the arms, face, and trunk that she reported as having been present for months. She had a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and currently was receiving certolizumab pegol injections. Physical examination revealed erythematous patches and plaques with overlying scaling and evidence of atrophic scarring on sun-exposed areas of the body. The lesions predominantly were in a symmetrical distribution across the extensor surfaces of both outer arms as well as the posterior superior thoracic region extending anteriorly along the bilateral supraclavicular area (Figures 1 and 2). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent for histologic analysis, along with a sample of the patient’s serum for antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing.

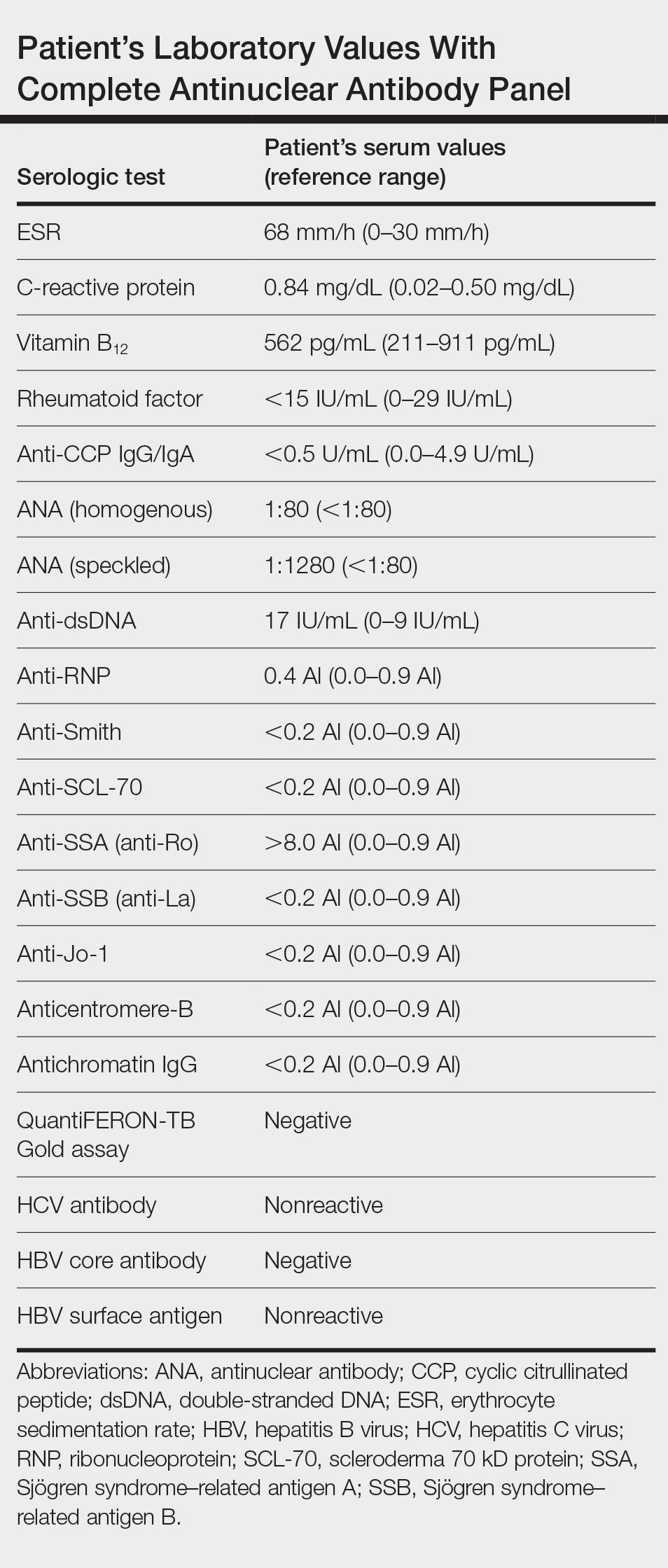

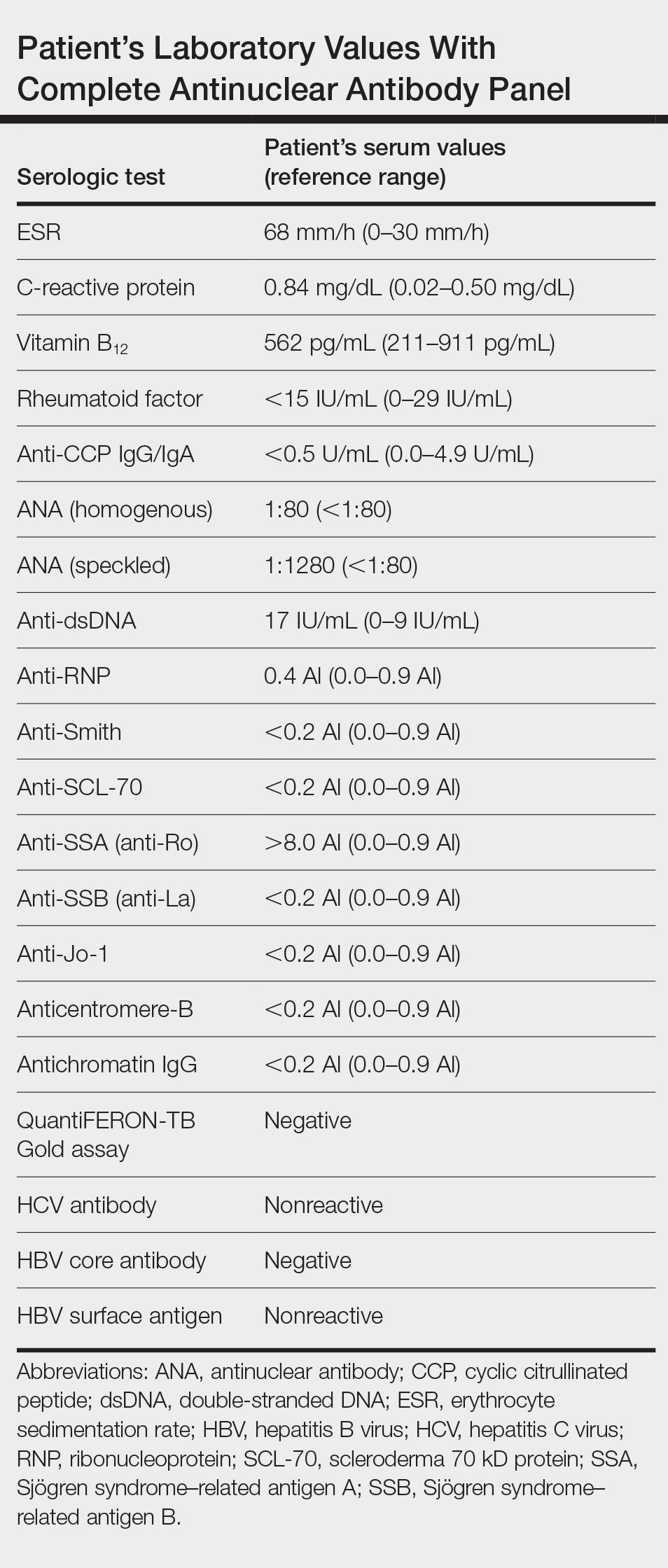

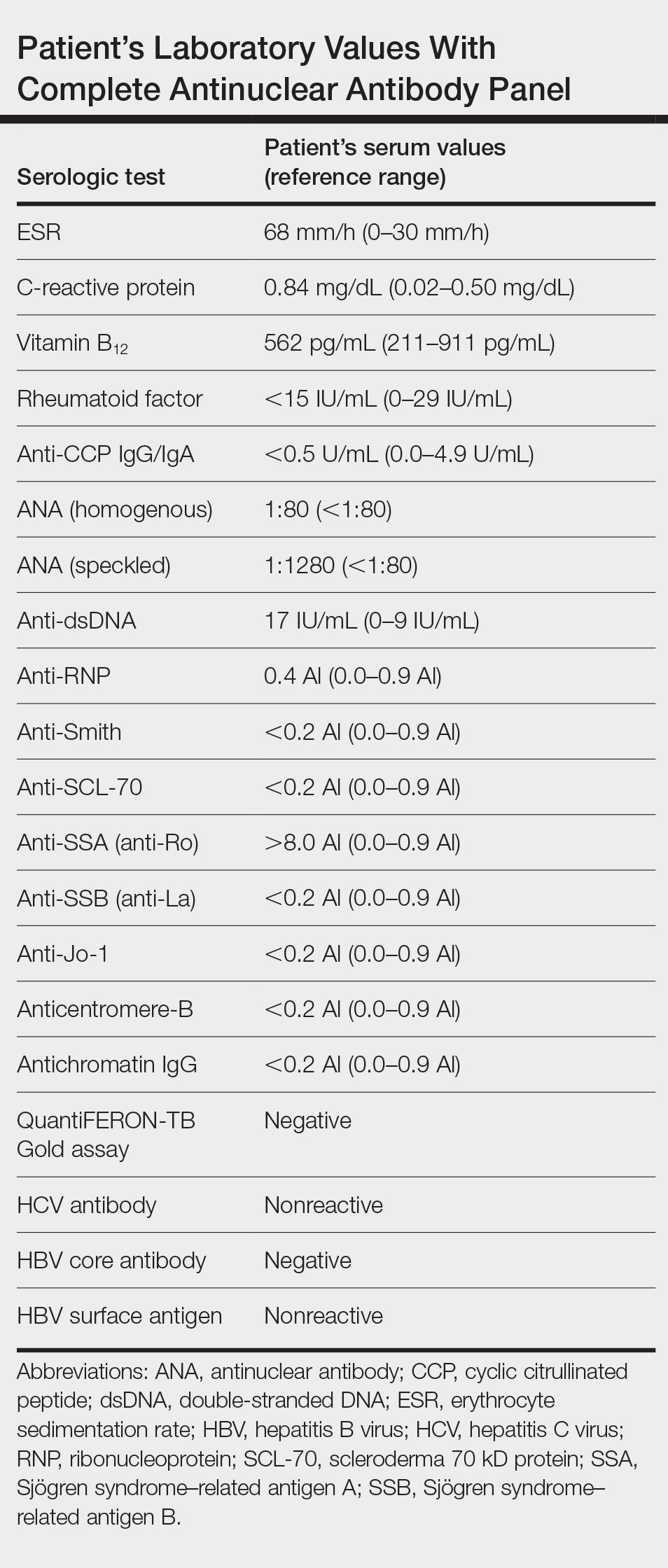

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained tissue sections of the right superior thoracic lesions revealed epidermal atrophy, hyperkeratosis, and vacuolar alteration of the basal layer with apoptosis, consistent with a lichenoid tissue reaction. In addition, both superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates were observed as well as increased dermal mucin. Serologic testing was performed with a comprehensive ANA panel of the patient’s serum (Table). Of note, there was a speckled ANA pattern (1:1280), with elevated anti–double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A (anti-SSA)(also called anti-Ro antibodies) levels. The patient’s rheumatologist was consulted; certolizumab pegol was removed from the current drug regimen and switched to a daily regimen of hydroxychloroquine and prednisone. Seven weeks after discontinuation of certolizumab pegol, the patient was symptom free and without any cutaneous involvement. Based on the histologic analysis, presence of anti-SSA (Ro) autoantibodies, and the resolution of symptoms following withdrawal of anti–TNF-α therapy, a diagnosis of TAILS was made.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, the most common subset of DILE, typically presents with annular polycyclic or papulosquamous skin eruptions on the legs; patients often test positive for anti-SSA/Ro and/or anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen B (also called anti-La) antibodies. Pharmaceutical agents linked to the development of SCLE are calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, thiazide diuretics, terbinafine, the chemotherapeutic agent gemcitabine, and TNF-α antagonists.1,2 Tumor necrosis factor α antagonists are biologic agents that commonly are used in the management of systemic inflammatory diseases such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, seronegative spondyloarthropathies, and rheumatoid arthritis. Among this family of therapeutics includes adalimumab (humanized monoclonal antibody), infliximab (chimeric monoclonal TNF-α antagonist), etanercept (soluble receptor fusion protein), certolizumab pegol (Fab fraction of a human IgG monoclonal antibody), and golimumab (humanized monoclonal antibody).

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome most commonly occurs in women in the fifth decade of life, and it is seen more often in those using infliximab or entanercept.3 Although reports do exist, TAILS rarely complicates treatment with adalimumab, golimumab, or certolizumab.4,5 Due to the lack of reports, there are no diagnostic criteria nor an acceptable theory regarding the pathogenesis. In one study in France, the estimated incidence was thought to be 0.19% for infliximab and 0.18% for etanercept.6 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome is unique in that it is thought to occur by a different mechanism than that of other known offending agents in the development of DILE. Molecular mimicry, direct cytotoxicity, altered T-cell gene expression, and disruption of central immune tolerance have all been hypothesized to cause drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus, SCLE, and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, are postulated to cause the induction of SCLE via an independent route separate from not only other drugs that cause SCLE but also all forms of DILE as a whole, making it a distinctive player within the realm of agents known to cause a lupuslike syndrome. The following hypotheses may explain this occurrence:

1. Increased humoral autoimmunity: Under normal circumstances, TNF-α activation leads to upregulation in the production of cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes. The upregulation of CD8+ T lymphocytes concurrently leads to a simultaneous suppression of B lymphocytes. Inhibiting the effects of TNF-α on the other hand promotes cytotoxic T-lymphocyte suppression, leading to an increased synthesis of B cells and subsequently a state of increased humoral autoimmunity.7

2. Infection: The immunosuppressive effects of TNF-α inhibitors are well known, and the propensity to develop microbial infections, such as tuberculosis, is markedly increased on the use of these agents. Infections brought on by TNF-α inhibitor usage are hypothesized to induce a widespread activation of polyclonal B lymphocytes, eventually leading to the formation of antibodies against these polyclonal B lymphocytes and subsequently SCLE.8

3. Helper T cell (TH2) response: The inhibition of TH1 CD4+ lymphocytes by TNF-α inversely leads to an increased production of TH2 CD4+ lymphocytes. This increase in the levels of circulating TH2 CD4+ lymphocytes brought on by the action of anti–TNF-α agents is thought to promote the development of SCLE.9,10

4. Apoptosis theory: Molecules of TNF-α inhibitors are capable of binding to TNF-α receptors on the cell surface. In doing so, cellular apoptosis is triggered, resulting in the release of nucleosomal autoantigens from the apoptotic cells. In susceptible individuals, autoantibodies then begin to form against the nucleosomal autoantigens, leading to an autoimmune reaction that is characterized by SCLE.11,12

Major histone compatibility (MHC) antigen testing performed by Sontheimer et al12 established the presence of the HLA class I, HLA-B8, and/or HLA-DR3 haplotypes in patients with SCLE.13,14 Furthermore, there is a well-known association between the antinuclear profile of known SCLE patients and the presence of anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies.13 Therefore, we propose that in susceptible individuals, such as those with the HLA class I, HLA-B8, or HLA-DR3 haplotypes, the initiation of a TNF-α inhibitor causes cellular apoptosis with the subsequent release of nucleosomal and cytoplasmic components (namely that of the Ro autoantigens), inducing a state of autoimmunity. An ensuing immunogenic response is then initiated in predisposed individuals for which anti-SSA (Ro) autoantibodies are produced against these previously mentioned autoantigens.

Drug-induced SCLE is most common in females (71%), with a median age of 58 years. The most common site of cutaneous manifestations is the legs.15 Although our patient was in the eighth decade of life with predominant cutaneous involvement of the upper extremity, the erythematous plaques with a symmetric, annular, polycyclic appearance in photosensitive regions raised a heightened suspicion for lupus erythematosus. Histology classically involves an interface dermatitis with vacuolar or hydropic change and lymphocytic infiltrates,16 consistent with the analysis of tissue sections from our patient. Moreover, the speckled ANA profile with positive anti-dsDNA and anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies in the absence of a negative rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies strongly favored the diagnosis of SCLE over alternative diagnoses.2

The supraclavicular rash in our patient raises clinical suspicion for the shawl sign of dermatomyositis, which also is associated with musculoskeletal pain and photosensitivity. In addition, skin biopsy revealed vacuolar alteration of the basement membrane zoneand dermal mucin in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis; therefore, skin biopsy is of little use in distinguishing the 2 conditions, and antibody testing must be performed. Although anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies commonly are associated with SCLE, there are reports involving positivity for the extractable nuclear antigen in cases of dermatomyositis.17 Based on our patient’s current drug regimen, including that of a known offending agent for SCLE, a presumptive diagnosis of TAILS was made. Following withdrawal of certolizumab pegol injections and subsequent resolution of the skin lesions, our patient was given a definitive diagnosis of TAILS based on clinical and pathological assessments.

The clinical diagnosis of TAILS should be made according to the triad of at least 1 serologic and 1 nonserologic American College of Rheumatology criteria, such as anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies and a photosensitive rash, respectively, as well as a relationship between the onset of symptoms and TNF-α inhibitor therapy.18 Both the definitive diagnosis and the treatment of TAILS can be made via withdrawal of the TNF-α inhibitor, which was true in our case whereby chronologically the onset of use with a TNF-α inhibitor was associated with disease onset. Furthermore, withdrawal led to complete improvement of all signs and symptoms, collectively supporting a diagnosis of TAILS. Notably, switching to a different TNF-α inhibitor has been shown to be safe and effective.19

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Crosti C. Drug-induced lupus: an update on its dermatological aspects. Lupus. 2009;18:935-940.

- Wiznia LE, Subtil A, Choi JN. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced by chemotherapy: gemcitabine as a causative agent. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1071-1075.

- Williams VL, Cohen PR. TNF alpha antagonist-induced lupus-like syndrome: report and review of the literature with implications for treatment with alternative TNF alpha antagonists. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:619-625.

- Pasut G. Pegylation of biological molecules and potential benefits: pharmacological properties of certolizumab pegol. Bio Drugs. 2014;28(suppl 1):15-23.

- Mudduluru BM, Shah S, Shamah S. et al. TNF-alpha antagonist induced lupus on three different agents. Postgrad Med. 2017;129:304-306.

- De Bandt M. Anti-TNF-alpha-induced lupus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:235.

- Costa MF, Said NR, Zimmermann B. Drug-induced lupus due to anti-tumor necrosis factor alfa agents. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;37:381-387.

- Caramaschi P, Biasi D, Colombatti M. Anti-TNF alpha therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmunity. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:209-214.

- Yung RL, Quddus J, Chrisp CE, et al. Mechanism of drug-induced lupus. I. cloned Th2 cells modified with DNA methylation inhibitors in vitro cause autoimmunity in vivo. J Immunol. 1995;154:3025-3035.

- Yung R, Powers D, Johnson K, et al. Mechanisms of drug-induced lupus. II. T cells overexpressing lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 become autoreactive and cause a lupuslike disease in syngeneic mice. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2866-2871.

- Sontheimer RD, Stastny P, Gilliam JN. Human histocompatibility antigen associations in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1981;67:312-316.

- Sontheimer RD, Maddison PJ, Reichlin M, et al. Serologic and HLA associations in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, a clinical subset of lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97:664-671.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

- Deutscher SL, Harley JB, Keene JD. Molecular analysis of the 60-kDa human Ro ribonucleoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:9479-9483.

- DalleVedove C, Simon JC, Girolomoni G. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus with emphasis on skin manifestations and the role of anti-TNFα agents [article in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:889-897.

- Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:391-404.

- Schulte-Pelkum J, Fritzler M, Mahler M. Latest update on the Ro/SS-A autoantibody system. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:632-637.

- De Bandt M, Sibilia J, Le Loët X, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus induced by anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapy: a French national survey. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R545-R551.

- Lupu A, Tieranu C, Constantinescu CL, et al. TNFα inhibitor induced lupus-like syndrome (TAILS) in a patient with IBD. Current Health Sci J. 2014;40:285-288.

To the Editor:

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome (TAILS) is a newly described entity that refers to the onset of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) during drug therapy with TNF-α antagonists. The condition is unique because it is thought to occur via a separate pathophysiologic mechanism than all other agents implicated in the development of drug-induced lupus erythematosus (DILE). Infliximab and etanercept are the 2 most common TNF-α antagonists associated with TAILS. Although rare, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol have been reported to induce this state of autoimmunity. We report an uncommon presentation of TAILS in a patient taking certolizumab pegol with a brief discussion of the pathogenesis underlying TAILS.

A 71-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash located on the arms, face, and trunk that she reported as having been present for months. She had a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and currently was receiving certolizumab pegol injections. Physical examination revealed erythematous patches and plaques with overlying scaling and evidence of atrophic scarring on sun-exposed areas of the body. The lesions predominantly were in a symmetrical distribution across the extensor surfaces of both outer arms as well as the posterior superior thoracic region extending anteriorly along the bilateral supraclavicular area (Figures 1 and 2). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent for histologic analysis, along with a sample of the patient’s serum for antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing.

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained tissue sections of the right superior thoracic lesions revealed epidermal atrophy, hyperkeratosis, and vacuolar alteration of the basal layer with apoptosis, consistent with a lichenoid tissue reaction. In addition, both superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates were observed as well as increased dermal mucin. Serologic testing was performed with a comprehensive ANA panel of the patient’s serum (Table). Of note, there was a speckled ANA pattern (1:1280), with elevated anti–double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A (anti-SSA)(also called anti-Ro antibodies) levels. The patient’s rheumatologist was consulted; certolizumab pegol was removed from the current drug regimen and switched to a daily regimen of hydroxychloroquine and prednisone. Seven weeks after discontinuation of certolizumab pegol, the patient was symptom free and without any cutaneous involvement. Based on the histologic analysis, presence of anti-SSA (Ro) autoantibodies, and the resolution of symptoms following withdrawal of anti–TNF-α therapy, a diagnosis of TAILS was made.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, the most common subset of DILE, typically presents with annular polycyclic or papulosquamous skin eruptions on the legs; patients often test positive for anti-SSA/Ro and/or anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen B (also called anti-La) antibodies. Pharmaceutical agents linked to the development of SCLE are calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, thiazide diuretics, terbinafine, the chemotherapeutic agent gemcitabine, and TNF-α antagonists.1,2 Tumor necrosis factor α antagonists are biologic agents that commonly are used in the management of systemic inflammatory diseases such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, seronegative spondyloarthropathies, and rheumatoid arthritis. Among this family of therapeutics includes adalimumab (humanized monoclonal antibody), infliximab (chimeric monoclonal TNF-α antagonist), etanercept (soluble receptor fusion protein), certolizumab pegol (Fab fraction of a human IgG monoclonal antibody), and golimumab (humanized monoclonal antibody).

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome most commonly occurs in women in the fifth decade of life, and it is seen more often in those using infliximab or entanercept.3 Although reports do exist, TAILS rarely complicates treatment with adalimumab, golimumab, or certolizumab.4,5 Due to the lack of reports, there are no diagnostic criteria nor an acceptable theory regarding the pathogenesis. In one study in France, the estimated incidence was thought to be 0.19% for infliximab and 0.18% for etanercept.6 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome is unique in that it is thought to occur by a different mechanism than that of other known offending agents in the development of DILE. Molecular mimicry, direct cytotoxicity, altered T-cell gene expression, and disruption of central immune tolerance have all been hypothesized to cause drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus, SCLE, and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, are postulated to cause the induction of SCLE via an independent route separate from not only other drugs that cause SCLE but also all forms of DILE as a whole, making it a distinctive player within the realm of agents known to cause a lupuslike syndrome. The following hypotheses may explain this occurrence:

1. Increased humoral autoimmunity: Under normal circumstances, TNF-α activation leads to upregulation in the production of cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes. The upregulation of CD8+ T lymphocytes concurrently leads to a simultaneous suppression of B lymphocytes. Inhibiting the effects of TNF-α on the other hand promotes cytotoxic T-lymphocyte suppression, leading to an increased synthesis of B cells and subsequently a state of increased humoral autoimmunity.7

2. Infection: The immunosuppressive effects of TNF-α inhibitors are well known, and the propensity to develop microbial infections, such as tuberculosis, is markedly increased on the use of these agents. Infections brought on by TNF-α inhibitor usage are hypothesized to induce a widespread activation of polyclonal B lymphocytes, eventually leading to the formation of antibodies against these polyclonal B lymphocytes and subsequently SCLE.8

3. Helper T cell (TH2) response: The inhibition of TH1 CD4+ lymphocytes by TNF-α inversely leads to an increased production of TH2 CD4+ lymphocytes. This increase in the levels of circulating TH2 CD4+ lymphocytes brought on by the action of anti–TNF-α agents is thought to promote the development of SCLE.9,10

4. Apoptosis theory: Molecules of TNF-α inhibitors are capable of binding to TNF-α receptors on the cell surface. In doing so, cellular apoptosis is triggered, resulting in the release of nucleosomal autoantigens from the apoptotic cells. In susceptible individuals, autoantibodies then begin to form against the nucleosomal autoantigens, leading to an autoimmune reaction that is characterized by SCLE.11,12

Major histone compatibility (MHC) antigen testing performed by Sontheimer et al12 established the presence of the HLA class I, HLA-B8, and/or HLA-DR3 haplotypes in patients with SCLE.13,14 Furthermore, there is a well-known association between the antinuclear profile of known SCLE patients and the presence of anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies.13 Therefore, we propose that in susceptible individuals, such as those with the HLA class I, HLA-B8, or HLA-DR3 haplotypes, the initiation of a TNF-α inhibitor causes cellular apoptosis with the subsequent release of nucleosomal and cytoplasmic components (namely that of the Ro autoantigens), inducing a state of autoimmunity. An ensuing immunogenic response is then initiated in predisposed individuals for which anti-SSA (Ro) autoantibodies are produced against these previously mentioned autoantigens.

Drug-induced SCLE is most common in females (71%), with a median age of 58 years. The most common site of cutaneous manifestations is the legs.15 Although our patient was in the eighth decade of life with predominant cutaneous involvement of the upper extremity, the erythematous plaques with a symmetric, annular, polycyclic appearance in photosensitive regions raised a heightened suspicion for lupus erythematosus. Histology classically involves an interface dermatitis with vacuolar or hydropic change and lymphocytic infiltrates,16 consistent with the analysis of tissue sections from our patient. Moreover, the speckled ANA profile with positive anti-dsDNA and anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies in the absence of a negative rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies strongly favored the diagnosis of SCLE over alternative diagnoses.2

The supraclavicular rash in our patient raises clinical suspicion for the shawl sign of dermatomyositis, which also is associated with musculoskeletal pain and photosensitivity. In addition, skin biopsy revealed vacuolar alteration of the basement membrane zoneand dermal mucin in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis; therefore, skin biopsy is of little use in distinguishing the 2 conditions, and antibody testing must be performed. Although anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies commonly are associated with SCLE, there are reports involving positivity for the extractable nuclear antigen in cases of dermatomyositis.17 Based on our patient’s current drug regimen, including that of a known offending agent for SCLE, a presumptive diagnosis of TAILS was made. Following withdrawal of certolizumab pegol injections and subsequent resolution of the skin lesions, our patient was given a definitive diagnosis of TAILS based on clinical and pathological assessments.

The clinical diagnosis of TAILS should be made according to the triad of at least 1 serologic and 1 nonserologic American College of Rheumatology criteria, such as anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies and a photosensitive rash, respectively, as well as a relationship between the onset of symptoms and TNF-α inhibitor therapy.18 Both the definitive diagnosis and the treatment of TAILS can be made via withdrawal of the TNF-α inhibitor, which was true in our case whereby chronologically the onset of use with a TNF-α inhibitor was associated with disease onset. Furthermore, withdrawal led to complete improvement of all signs and symptoms, collectively supporting a diagnosis of TAILS. Notably, switching to a different TNF-α inhibitor has been shown to be safe and effective.19

To the Editor:

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome (TAILS) is a newly described entity that refers to the onset of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) during drug therapy with TNF-α antagonists. The condition is unique because it is thought to occur via a separate pathophysiologic mechanism than all other agents implicated in the development of drug-induced lupus erythematosus (DILE). Infliximab and etanercept are the 2 most common TNF-α antagonists associated with TAILS. Although rare, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol have been reported to induce this state of autoimmunity. We report an uncommon presentation of TAILS in a patient taking certolizumab pegol with a brief discussion of the pathogenesis underlying TAILS.

A 71-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash located on the arms, face, and trunk that she reported as having been present for months. She had a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and currently was receiving certolizumab pegol injections. Physical examination revealed erythematous patches and plaques with overlying scaling and evidence of atrophic scarring on sun-exposed areas of the body. The lesions predominantly were in a symmetrical distribution across the extensor surfaces of both outer arms as well as the posterior superior thoracic region extending anteriorly along the bilateral supraclavicular area (Figures 1 and 2). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent for histologic analysis, along with a sample of the patient’s serum for antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing.

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained tissue sections of the right superior thoracic lesions revealed epidermal atrophy, hyperkeratosis, and vacuolar alteration of the basal layer with apoptosis, consistent with a lichenoid tissue reaction. In addition, both superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates were observed as well as increased dermal mucin. Serologic testing was performed with a comprehensive ANA panel of the patient’s serum (Table). Of note, there was a speckled ANA pattern (1:1280), with elevated anti–double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A (anti-SSA)(also called anti-Ro antibodies) levels. The patient’s rheumatologist was consulted; certolizumab pegol was removed from the current drug regimen and switched to a daily regimen of hydroxychloroquine and prednisone. Seven weeks after discontinuation of certolizumab pegol, the patient was symptom free and without any cutaneous involvement. Based on the histologic analysis, presence of anti-SSA (Ro) autoantibodies, and the resolution of symptoms following withdrawal of anti–TNF-α therapy, a diagnosis of TAILS was made.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, the most common subset of DILE, typically presents with annular polycyclic or papulosquamous skin eruptions on the legs; patients often test positive for anti-SSA/Ro and/or anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen B (also called anti-La) antibodies. Pharmaceutical agents linked to the development of SCLE are calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, thiazide diuretics, terbinafine, the chemotherapeutic agent gemcitabine, and TNF-α antagonists.1,2 Tumor necrosis factor α antagonists are biologic agents that commonly are used in the management of systemic inflammatory diseases such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, seronegative spondyloarthropathies, and rheumatoid arthritis. Among this family of therapeutics includes adalimumab (humanized monoclonal antibody), infliximab (chimeric monoclonal TNF-α antagonist), etanercept (soluble receptor fusion protein), certolizumab pegol (Fab fraction of a human IgG monoclonal antibody), and golimumab (humanized monoclonal antibody).

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome most commonly occurs in women in the fifth decade of life, and it is seen more often in those using infliximab or entanercept.3 Although reports do exist, TAILS rarely complicates treatment with adalimumab, golimumab, or certolizumab.4,5 Due to the lack of reports, there are no diagnostic criteria nor an acceptable theory regarding the pathogenesis. In one study in France, the estimated incidence was thought to be 0.19% for infliximab and 0.18% for etanercept.6 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome is unique in that it is thought to occur by a different mechanism than that of other known offending agents in the development of DILE. Molecular mimicry, direct cytotoxicity, altered T-cell gene expression, and disruption of central immune tolerance have all been hypothesized to cause drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus, SCLE, and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, are postulated to cause the induction of SCLE via an independent route separate from not only other drugs that cause SCLE but also all forms of DILE as a whole, making it a distinctive player within the realm of agents known to cause a lupuslike syndrome. The following hypotheses may explain this occurrence:

1. Increased humoral autoimmunity: Under normal circumstances, TNF-α activation leads to upregulation in the production of cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes. The upregulation of CD8+ T lymphocytes concurrently leads to a simultaneous suppression of B lymphocytes. Inhibiting the effects of TNF-α on the other hand promotes cytotoxic T-lymphocyte suppression, leading to an increased synthesis of B cells and subsequently a state of increased humoral autoimmunity.7

2. Infection: The immunosuppressive effects of TNF-α inhibitors are well known, and the propensity to develop microbial infections, such as tuberculosis, is markedly increased on the use of these agents. Infections brought on by TNF-α inhibitor usage are hypothesized to induce a widespread activation of polyclonal B lymphocytes, eventually leading to the formation of antibodies against these polyclonal B lymphocytes and subsequently SCLE.8

3. Helper T cell (TH2) response: The inhibition of TH1 CD4+ lymphocytes by TNF-α inversely leads to an increased production of TH2 CD4+ lymphocytes. This increase in the levels of circulating TH2 CD4+ lymphocytes brought on by the action of anti–TNF-α agents is thought to promote the development of SCLE.9,10

4. Apoptosis theory: Molecules of TNF-α inhibitors are capable of binding to TNF-α receptors on the cell surface. In doing so, cellular apoptosis is triggered, resulting in the release of nucleosomal autoantigens from the apoptotic cells. In susceptible individuals, autoantibodies then begin to form against the nucleosomal autoantigens, leading to an autoimmune reaction that is characterized by SCLE.11,12

Major histone compatibility (MHC) antigen testing performed by Sontheimer et al12 established the presence of the HLA class I, HLA-B8, and/or HLA-DR3 haplotypes in patients with SCLE.13,14 Furthermore, there is a well-known association between the antinuclear profile of known SCLE patients and the presence of anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies.13 Therefore, we propose that in susceptible individuals, such as those with the HLA class I, HLA-B8, or HLA-DR3 haplotypes, the initiation of a TNF-α inhibitor causes cellular apoptosis with the subsequent release of nucleosomal and cytoplasmic components (namely that of the Ro autoantigens), inducing a state of autoimmunity. An ensuing immunogenic response is then initiated in predisposed individuals for which anti-SSA (Ro) autoantibodies are produced against these previously mentioned autoantigens.

Drug-induced SCLE is most common in females (71%), with a median age of 58 years. The most common site of cutaneous manifestations is the legs.15 Although our patient was in the eighth decade of life with predominant cutaneous involvement of the upper extremity, the erythematous plaques with a symmetric, annular, polycyclic appearance in photosensitive regions raised a heightened suspicion for lupus erythematosus. Histology classically involves an interface dermatitis with vacuolar or hydropic change and lymphocytic infiltrates,16 consistent with the analysis of tissue sections from our patient. Moreover, the speckled ANA profile with positive anti-dsDNA and anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies in the absence of a negative rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies strongly favored the diagnosis of SCLE over alternative diagnoses.2

The supraclavicular rash in our patient raises clinical suspicion for the shawl sign of dermatomyositis, which also is associated with musculoskeletal pain and photosensitivity. In addition, skin biopsy revealed vacuolar alteration of the basement membrane zoneand dermal mucin in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis; therefore, skin biopsy is of little use in distinguishing the 2 conditions, and antibody testing must be performed. Although anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies commonly are associated with SCLE, there are reports involving positivity for the extractable nuclear antigen in cases of dermatomyositis.17 Based on our patient’s current drug regimen, including that of a known offending agent for SCLE, a presumptive diagnosis of TAILS was made. Following withdrawal of certolizumab pegol injections and subsequent resolution of the skin lesions, our patient was given a definitive diagnosis of TAILS based on clinical and pathological assessments.

The clinical diagnosis of TAILS should be made according to the triad of at least 1 serologic and 1 nonserologic American College of Rheumatology criteria, such as anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies and a photosensitive rash, respectively, as well as a relationship between the onset of symptoms and TNF-α inhibitor therapy.18 Both the definitive diagnosis and the treatment of TAILS can be made via withdrawal of the TNF-α inhibitor, which was true in our case whereby chronologically the onset of use with a TNF-α inhibitor was associated with disease onset. Furthermore, withdrawal led to complete improvement of all signs and symptoms, collectively supporting a diagnosis of TAILS. Notably, switching to a different TNF-α inhibitor has been shown to be safe and effective.19

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Crosti C. Drug-induced lupus: an update on its dermatological aspects. Lupus. 2009;18:935-940.

- Wiznia LE, Subtil A, Choi JN. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced by chemotherapy: gemcitabine as a causative agent. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1071-1075.

- Williams VL, Cohen PR. TNF alpha antagonist-induced lupus-like syndrome: report and review of the literature with implications for treatment with alternative TNF alpha antagonists. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:619-625.

- Pasut G. Pegylation of biological molecules and potential benefits: pharmacological properties of certolizumab pegol. Bio Drugs. 2014;28(suppl 1):15-23.

- Mudduluru BM, Shah S, Shamah S. et al. TNF-alpha antagonist induced lupus on three different agents. Postgrad Med. 2017;129:304-306.

- De Bandt M. Anti-TNF-alpha-induced lupus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:235.

- Costa MF, Said NR, Zimmermann B. Drug-induced lupus due to anti-tumor necrosis factor alfa agents. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;37:381-387.

- Caramaschi P, Biasi D, Colombatti M. Anti-TNF alpha therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmunity. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:209-214.

- Yung RL, Quddus J, Chrisp CE, et al. Mechanism of drug-induced lupus. I. cloned Th2 cells modified with DNA methylation inhibitors in vitro cause autoimmunity in vivo. J Immunol. 1995;154:3025-3035.

- Yung R, Powers D, Johnson K, et al. Mechanisms of drug-induced lupus. II. T cells overexpressing lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 become autoreactive and cause a lupuslike disease in syngeneic mice. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2866-2871.

- Sontheimer RD, Stastny P, Gilliam JN. Human histocompatibility antigen associations in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1981;67:312-316.

- Sontheimer RD, Maddison PJ, Reichlin M, et al. Serologic and HLA associations in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, a clinical subset of lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97:664-671.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

- Deutscher SL, Harley JB, Keene JD. Molecular analysis of the 60-kDa human Ro ribonucleoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:9479-9483.

- DalleVedove C, Simon JC, Girolomoni G. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus with emphasis on skin manifestations and the role of anti-TNFα agents [article in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:889-897.

- Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:391-404.

- Schulte-Pelkum J, Fritzler M, Mahler M. Latest update on the Ro/SS-A autoantibody system. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:632-637.

- De Bandt M, Sibilia J, Le Loët X, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus induced by anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapy: a French national survey. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R545-R551.

- Lupu A, Tieranu C, Constantinescu CL, et al. TNFα inhibitor induced lupus-like syndrome (TAILS) in a patient with IBD. Current Health Sci J. 2014;40:285-288.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Crosti C. Drug-induced lupus: an update on its dermatological aspects. Lupus. 2009;18:935-940.

- Wiznia LE, Subtil A, Choi JN. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced by chemotherapy: gemcitabine as a causative agent. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1071-1075.

- Williams VL, Cohen PR. TNF alpha antagonist-induced lupus-like syndrome: report and review of the literature with implications for treatment with alternative TNF alpha antagonists. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:619-625.

- Pasut G. Pegylation of biological molecules and potential benefits: pharmacological properties of certolizumab pegol. Bio Drugs. 2014;28(suppl 1):15-23.

- Mudduluru BM, Shah S, Shamah S. et al. TNF-alpha antagonist induced lupus on three different agents. Postgrad Med. 2017;129:304-306.

- De Bandt M. Anti-TNF-alpha-induced lupus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:235.

- Costa MF, Said NR, Zimmermann B. Drug-induced lupus due to anti-tumor necrosis factor alfa agents. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;37:381-387.

- Caramaschi P, Biasi D, Colombatti M. Anti-TNF alpha therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmunity. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:209-214.

- Yung RL, Quddus J, Chrisp CE, et al. Mechanism of drug-induced lupus. I. cloned Th2 cells modified with DNA methylation inhibitors in vitro cause autoimmunity in vivo. J Immunol. 1995;154:3025-3035.

- Yung R, Powers D, Johnson K, et al. Mechanisms of drug-induced lupus. II. T cells overexpressing lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 become autoreactive and cause a lupuslike disease in syngeneic mice. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2866-2871.

- Sontheimer RD, Stastny P, Gilliam JN. Human histocompatibility antigen associations in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1981;67:312-316.

- Sontheimer RD, Maddison PJ, Reichlin M, et al. Serologic and HLA associations in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, a clinical subset of lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97:664-671.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

- Deutscher SL, Harley JB, Keene JD. Molecular analysis of the 60-kDa human Ro ribonucleoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:9479-9483.

- DalleVedove C, Simon JC, Girolomoni G. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus with emphasis on skin manifestations and the role of anti-TNFα agents [article in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:889-897.

- Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:391-404.

- Schulte-Pelkum J, Fritzler M, Mahler M. Latest update on the Ro/SS-A autoantibody system. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:632-637.

- De Bandt M, Sibilia J, Le Loët X, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus induced by anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapy: a French national survey. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R545-R551.

- Lupu A, Tieranu C, Constantinescu CL, et al. TNFα inhibitor induced lupus-like syndrome (TAILS) in a patient with IBD. Current Health Sci J. 2014;40:285-288.

Practice Points

- Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome (TAILS) is a form of drug-induced lupus specific to patients on anti–TNF-α therapy.

- The underlying mechanism of disease development is unique compared to other types of drug-induced lupus.

- TAILS most commonly is associated with the use of infliximab and etanercept but also has been reported with adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol.

Nodules on the Anterior Neck Following Poly-L-lactic Acid Injection

Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) is a synthetic biologic polymer that is suspended in solution and can be injected for soft-tissue augmentation. The stimulatory molecule functions to increase collagen synthesis as a by-product of its degradation.1 Poly-L-lactic acid measures 40 to 63 μm and is irregularly shaped, which inhibits product mobility and allows for precise tissue augmentation.2 Clinical trials of injectable PLLA have proven its safety with no reported cases of infection, allergies, or serious adverse reactions.3-5 The most common patient concerns generally are transient in nature, such as swelling, tenderness, pain, bruising, and bleeding. Persistent adverse events of PLLA primarily are papule and nodule formation.6 Clinical trials showed a variable incidence of papule/nodule formation between 6% and 44%.2 Nodule formation remains a major challenge to achieving optimal results from injectable PLLA. We present a case in which a hyperdiluted formulation of PLLA produced a relatively acute (3-week) onset of multiple nodule formations dispersed on the anterior neck. The nodules were resistant to less-invasive treatment modalities and were further requested to be surgically excised.

Case Report

A 38-year-old woman presented for soft-tissue augmentation of the anterior neck using PLLA to achieve correction of skin laxity and static rhytides. She had a history of successful PLLA injections in the temples, knees, chest, and buttocks over a 5-year period. Forty-eight hours prior to injection, 1 PLLA vial was hydrated with 7 cc bacteriostatic water by using a continuous rotation suspension method over the 48 hours. On the day of injection, the PLLA was further hyperdiluted with 2 cc of 2% lidocaine and an additional 7 cc of bacteriostatic water, for a total of 16 cc diluent. The product was injected using a cannula in the anterior and lateral neck. According to the patient, 3 weeks after the procedure she noticed that some nodules began to form at the cannula insertion sites, while others formed distant from those sites; a total of 10 nodules had formed on the anterior neck (Figure 1).

The bacteriostatic water, lidocaine, and PLLA vial were all confirmed not to be expired. The manufacturer was contacted, and no other adverse reactions have been reported with this particular lot number of PLLA. The nodules initially were treated with injections of large boluses of bacteriostatic saline, which was ineffective. Treatment was then attempted using injections of a solution containing 1.0 mL of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) 50 mg/mL, 0.4 mL of dexamethasone 4 mg/mL, 0.1 mL of triamcinolone 10 mg/mL, and 0.3 mL hyaluronidase. A series of 4 injections was performed in 2- to 4-week intervals. Two of the nodules resolved completely with this treatment. The remaining 8 nodules subjectively improved in size and softened to palpation but did not resolve completely. At 2 of the injection sites, treatment was complicated with steroid atrophy of the overlying skin. At the patient’s request, the remaining nodules were surgically excised (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed exogenous foreign material consistent with dermal filler (Figure 3).

Comment

Causes of Nodule Formation—Two factors that could contribute to nodule formation are inadequate dispersion of molecules and an insufficient volume of dilution. One study demonstrated that hydration for at least 24 hours is required for adequate PLLA dispersion. Furthermore, sonification for 5 minutes after a 2-hour hydration disperses molecules similarly to the 48-hour hydration.7 The PLLA in the current case was hydrated for 48 hours using a continuous rotation suspension method. Therefore, this likely did not play a role in our patient’s nodule formation. The volume of dilution has been shown to impact the incidence of nodule formation.8 At present, most injectors (60.4%) reconstitute each vial of PLLA with 9 to 10 mL of diluent.9 The PLLA in our patient was reconstituted with 16 mL; therefore, we believe that the anatomic location was the main contributor of nodule formation.

Fillers should be injected in the subcutaneous or deep dermal plane of tissue.10 The platysma is a superficial muscle that is intimately involved with the overlying skin of the anterior neck, and injections in this area could inadvertently be intramuscular. Intramuscular injections have a higher incidence of nodule formation.1 Our patient had prior PLLA injections without adverse reactions in numerous other sites, supporting the claim that the anterior neck is prone to nodule formation from PLLA injections.

Management of Noninflammatory Nodules—Initial treatment of nodules with injections of saline was ineffective. This treatment can be used in an attempt to disperse the product. Treatment was then attempted with injections of a solution containing 5-FU, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and hyaluronidase. Combination steroid therapy may be superior to monotherapy.11 Dexamethasone may exhibit a cytoprotective effect on cells such as fibroblasts when used in combination with triamcinolone; monotherapy steroid use with triamcinolone alone induced fibroblast apoptosis at a much higher level.12 Hyaluronidase works by breaking cross-links in hyaluronic acid, a glycosaminoglycan polysaccharide prevalent in the skin and connective tissue, which increases tissue permeability and aids in delivery of the other injected fluids.13 5-Fluorouracil is an antimetabolite that may aid in treating nodules by discouraging additional fibroblast activity and fibrosis.14

The combination of 5-FU, dexamethasone, and triamcinolone has been shown to be successful in treating noninflammatory nodules in as few as 1 treatment.14 In our patient, hyaluronidase also was used in an attempt to aid delivery of the other injected fluids. If nodules do not resolve with 1 injection, it is recommended to wait at least 8 weeks before repeating the injection to prevent steroid atrophy of the overlying skin. In our patient, the intramuscular placement of the filler contributed to the nodules being resistant to this treatment. During excision, the nodules were tightly embedded in the underlying tissue, which may have prevented the solution from being delivered to the nodule (Figure 2).

Conclusion

Injectable PLLA is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for soft-tissue augmentation of deep nasolabial folds and facial wrinkles. Off-label use of this product may cause higher incidence of nodule formation. Injectors should be cautious of injecting into the anterior neck. If nodules do form, treatment can be attempted with injections of saline. If that treatment fails, another treatment option is injection(s) of a mixture of 5-FU, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and hyaluronidase separated by 8-week intervals. Finally, surgical excision is a viable treatment option, as presented in our case.

- Bartus C, William HC, Daro-Kaftan E. A decade of experience with injectable poly-L-lactic acid: a focus on safety. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:698-705.

- Engelhard P, Humble G, Mest D. Safety of Sculptra: a review of clinical trial data. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2005;7:201-205.

- Mest DR, Humble G. Safety and efficacy of poly-L-lactic acid injections in persons with HIV-associated lipoatrophy: the US experience. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1336-1345.

- Burgess CM, Quiroga RM. Assessment of the safety and efficacy of poly-L-lactic acid for the treatment of HIV associated facial lipoatrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:233-239.

- Cattelan AM, Bauer U, Trevenzoli M, et al. Use of polylactic acid implants to correct facial lipoatrophy in human immunodeficiency virus 1-positive individuals receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:329-334.

- Sculptra. Package insert. sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC; 2009.

- Li CN, Wang CC, Huang CC, et al. A novel, optimized method to accelerate the preparation of injectable poly-L-lactic acid by sonication. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:894-898.

- Rossner F, Rossner M, Hartmann V, et al. Decrease of reported adverse events to injectable polylactic acid after recommending an increased dilution: 8-year results from the Injectable Filler Safety study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8:14-18.

- Lin MJ, Dubin DP, Goldberg DJ, et al. Practices in the usage and reconstitution of poly-L-lactic acid. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:880-886.

- Sieber DA, Scheuer JF 3rd, Villanueva NL, et al. Review of 3-dimensional facial anatomy: injecting fillers and neuromodulators. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(12 suppl Anatomy and Safety in Cosmetic Medicine: Cosmetic Bootcamp):E1166.

- Syed F, Singh S, Bayat A. Superior effect of combination vs. single steroid therapy in keloid disease: a comparative in vitro analysis of glucocorticoids. Wound Repair Regen. 2013;21:88-102.

- Brody HJ. Use of hyaluronidase in the treatment of granulomatous hyaluronic acid reactions or unwanted hyaluronic acid misplacement. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:893-897.

- Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin Cosm Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:295-316.

- Aguilera SB, Aristizabal M, Reed A. Successful treatment of calcium hydroxylapatite nodules with intralesional 5-fluorouracil, dexamethasone, and triamcinolone. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:1142-1143.

Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) is a synthetic biologic polymer that is suspended in solution and can be injected for soft-tissue augmentation. The stimulatory molecule functions to increase collagen synthesis as a by-product of its degradation.1 Poly-L-lactic acid measures 40 to 63 μm and is irregularly shaped, which inhibits product mobility and allows for precise tissue augmentation.2 Clinical trials of injectable PLLA have proven its safety with no reported cases of infection, allergies, or serious adverse reactions.3-5 The most common patient concerns generally are transient in nature, such as swelling, tenderness, pain, bruising, and bleeding. Persistent adverse events of PLLA primarily are papule and nodule formation.6 Clinical trials showed a variable incidence of papule/nodule formation between 6% and 44%.2 Nodule formation remains a major challenge to achieving optimal results from injectable PLLA. We present a case in which a hyperdiluted formulation of PLLA produced a relatively acute (3-week) onset of multiple nodule formations dispersed on the anterior neck. The nodules were resistant to less-invasive treatment modalities and were further requested to be surgically excised.

Case Report

A 38-year-old woman presented for soft-tissue augmentation of the anterior neck using PLLA to achieve correction of skin laxity and static rhytides. She had a history of successful PLLA injections in the temples, knees, chest, and buttocks over a 5-year period. Forty-eight hours prior to injection, 1 PLLA vial was hydrated with 7 cc bacteriostatic water by using a continuous rotation suspension method over the 48 hours. On the day of injection, the PLLA was further hyperdiluted with 2 cc of 2% lidocaine and an additional 7 cc of bacteriostatic water, for a total of 16 cc diluent. The product was injected using a cannula in the anterior and lateral neck. According to the patient, 3 weeks after the procedure she noticed that some nodules began to form at the cannula insertion sites, while others formed distant from those sites; a total of 10 nodules had formed on the anterior neck (Figure 1).

The bacteriostatic water, lidocaine, and PLLA vial were all confirmed not to be expired. The manufacturer was contacted, and no other adverse reactions have been reported with this particular lot number of PLLA. The nodules initially were treated with injections of large boluses of bacteriostatic saline, which was ineffective. Treatment was then attempted using injections of a solution containing 1.0 mL of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) 50 mg/mL, 0.4 mL of dexamethasone 4 mg/mL, 0.1 mL of triamcinolone 10 mg/mL, and 0.3 mL hyaluronidase. A series of 4 injections was performed in 2- to 4-week intervals. Two of the nodules resolved completely with this treatment. The remaining 8 nodules subjectively improved in size and softened to palpation but did not resolve completely. At 2 of the injection sites, treatment was complicated with steroid atrophy of the overlying skin. At the patient’s request, the remaining nodules were surgically excised (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed exogenous foreign material consistent with dermal filler (Figure 3).

Comment

Causes of Nodule Formation—Two factors that could contribute to nodule formation are inadequate dispersion of molecules and an insufficient volume of dilution. One study demonstrated that hydration for at least 24 hours is required for adequate PLLA dispersion. Furthermore, sonification for 5 minutes after a 2-hour hydration disperses molecules similarly to the 48-hour hydration.7 The PLLA in the current case was hydrated for 48 hours using a continuous rotation suspension method. Therefore, this likely did not play a role in our patient’s nodule formation. The volume of dilution has been shown to impact the incidence of nodule formation.8 At present, most injectors (60.4%) reconstitute each vial of PLLA with 9 to 10 mL of diluent.9 The PLLA in our patient was reconstituted with 16 mL; therefore, we believe that the anatomic location was the main contributor of nodule formation.

Fillers should be injected in the subcutaneous or deep dermal plane of tissue.10 The platysma is a superficial muscle that is intimately involved with the overlying skin of the anterior neck, and injections in this area could inadvertently be intramuscular. Intramuscular injections have a higher incidence of nodule formation.1 Our patient had prior PLLA injections without adverse reactions in numerous other sites, supporting the claim that the anterior neck is prone to nodule formation from PLLA injections.

Management of Noninflammatory Nodules—Initial treatment of nodules with injections of saline was ineffective. This treatment can be used in an attempt to disperse the product. Treatment was then attempted with injections of a solution containing 5-FU, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and hyaluronidase. Combination steroid therapy may be superior to monotherapy.11 Dexamethasone may exhibit a cytoprotective effect on cells such as fibroblasts when used in combination with triamcinolone; monotherapy steroid use with triamcinolone alone induced fibroblast apoptosis at a much higher level.12 Hyaluronidase works by breaking cross-links in hyaluronic acid, a glycosaminoglycan polysaccharide prevalent in the skin and connective tissue, which increases tissue permeability and aids in delivery of the other injected fluids.13 5-Fluorouracil is an antimetabolite that may aid in treating nodules by discouraging additional fibroblast activity and fibrosis.14

The combination of 5-FU, dexamethasone, and triamcinolone has been shown to be successful in treating noninflammatory nodules in as few as 1 treatment.14 In our patient, hyaluronidase also was used in an attempt to aid delivery of the other injected fluids. If nodules do not resolve with 1 injection, it is recommended to wait at least 8 weeks before repeating the injection to prevent steroid atrophy of the overlying skin. In our patient, the intramuscular placement of the filler contributed to the nodules being resistant to this treatment. During excision, the nodules were tightly embedded in the underlying tissue, which may have prevented the solution from being delivered to the nodule (Figure 2).

Conclusion

Injectable PLLA is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for soft-tissue augmentation of deep nasolabial folds and facial wrinkles. Off-label use of this product may cause higher incidence of nodule formation. Injectors should be cautious of injecting into the anterior neck. If nodules do form, treatment can be attempted with injections of saline. If that treatment fails, another treatment option is injection(s) of a mixture of 5-FU, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and hyaluronidase separated by 8-week intervals. Finally, surgical excision is a viable treatment option, as presented in our case.

Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) is a synthetic biologic polymer that is suspended in solution and can be injected for soft-tissue augmentation. The stimulatory molecule functions to increase collagen synthesis as a by-product of its degradation.1 Poly-L-lactic acid measures 40 to 63 μm and is irregularly shaped, which inhibits product mobility and allows for precise tissue augmentation.2 Clinical trials of injectable PLLA have proven its safety with no reported cases of infection, allergies, or serious adverse reactions.3-5 The most common patient concerns generally are transient in nature, such as swelling, tenderness, pain, bruising, and bleeding. Persistent adverse events of PLLA primarily are papule and nodule formation.6 Clinical trials showed a variable incidence of papule/nodule formation between 6% and 44%.2 Nodule formation remains a major challenge to achieving optimal results from injectable PLLA. We present a case in which a hyperdiluted formulation of PLLA produced a relatively acute (3-week) onset of multiple nodule formations dispersed on the anterior neck. The nodules were resistant to less-invasive treatment modalities and were further requested to be surgically excised.

Case Report

A 38-year-old woman presented for soft-tissue augmentation of the anterior neck using PLLA to achieve correction of skin laxity and static rhytides. She had a history of successful PLLA injections in the temples, knees, chest, and buttocks over a 5-year period. Forty-eight hours prior to injection, 1 PLLA vial was hydrated with 7 cc bacteriostatic water by using a continuous rotation suspension method over the 48 hours. On the day of injection, the PLLA was further hyperdiluted with 2 cc of 2% lidocaine and an additional 7 cc of bacteriostatic water, for a total of 16 cc diluent. The product was injected using a cannula in the anterior and lateral neck. According to the patient, 3 weeks after the procedure she noticed that some nodules began to form at the cannula insertion sites, while others formed distant from those sites; a total of 10 nodules had formed on the anterior neck (Figure 1).