User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

A 64-year-old woman presents with a history of asymptomatic erythematous grouped papules on the right breast

. Recurrences may occur. Rarely, lymph nodes, the gastrointestinal system, lung, bone and bone marrow may be involved as extracutaneous sites.

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas account for approximately 25% of all cutaneous lymphomas. Clinically, patients present with either solitary or multiple papules or plaques, typically on the upper extremities or trunk.

Histopathology is vital for the correct diagnosis. In this patient, the histologic report was written as follows: “The findings are those of a well-differentiated but atypical diffuse mixed small lymphocytic infiltrate representing a mixture of T-cells and B-cells. The minor component of the infiltrate is of T-cell lineage, whereby the cells do not show any phenotypic abnormalities. The background cell population is interpreted as reactive. However, the dominant cell population is in fact of B-cell lineage. It is extensively highlighted by CD20. Only a minor component of the B cell infiltrate appeared to be in the context of representing germinal centers as characterized by small foci of centrocytic and centroblastic infiltration highlighted by BCL6 and CD10. The overwhelming B-cell component is a non–germinal center small B cell that does demonstrate BCL2 positivity and significant immunoreactivity for CD23. This small lymphocytic infiltrate obscures the germinal centers. There are only a few plasma cells; they do not show light chain restriction.”

The pathologist remarked that “this type of morphology of a diffuse small B-cell lymphocytic infiltrate that is without any evidence of light chain restriction amidst plasma cells, whereby the B cell component is dominant over the T-cell component would in fact be consistent with a unique variant of marginal zone lymphoma derived from a naive mantle zone.”

PCMZL has an excellent prognosis. When limited to the skin, local radiation or excision are effective treatments. Intravenous rituximab has been used to treat multifocal PCMZL. This patient was found to have no extracutaneous involvement and was treated with radiation.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Virmani P et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2017 Jun 14;3(4):269-72.

Magro CM and Olson LC. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018 Jun;34:116-21.

. Recurrences may occur. Rarely, lymph nodes, the gastrointestinal system, lung, bone and bone marrow may be involved as extracutaneous sites.

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas account for approximately 25% of all cutaneous lymphomas. Clinically, patients present with either solitary or multiple papules or plaques, typically on the upper extremities or trunk.

Histopathology is vital for the correct diagnosis. In this patient, the histologic report was written as follows: “The findings are those of a well-differentiated but atypical diffuse mixed small lymphocytic infiltrate representing a mixture of T-cells and B-cells. The minor component of the infiltrate is of T-cell lineage, whereby the cells do not show any phenotypic abnormalities. The background cell population is interpreted as reactive. However, the dominant cell population is in fact of B-cell lineage. It is extensively highlighted by CD20. Only a minor component of the B cell infiltrate appeared to be in the context of representing germinal centers as characterized by small foci of centrocytic and centroblastic infiltration highlighted by BCL6 and CD10. The overwhelming B-cell component is a non–germinal center small B cell that does demonstrate BCL2 positivity and significant immunoreactivity for CD23. This small lymphocytic infiltrate obscures the germinal centers. There are only a few plasma cells; they do not show light chain restriction.”

The pathologist remarked that “this type of morphology of a diffuse small B-cell lymphocytic infiltrate that is without any evidence of light chain restriction amidst plasma cells, whereby the B cell component is dominant over the T-cell component would in fact be consistent with a unique variant of marginal zone lymphoma derived from a naive mantle zone.”

PCMZL has an excellent prognosis. When limited to the skin, local radiation or excision are effective treatments. Intravenous rituximab has been used to treat multifocal PCMZL. This patient was found to have no extracutaneous involvement and was treated with radiation.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Virmani P et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2017 Jun 14;3(4):269-72.

Magro CM and Olson LC. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018 Jun;34:116-21.

. Recurrences may occur. Rarely, lymph nodes, the gastrointestinal system, lung, bone and bone marrow may be involved as extracutaneous sites.

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas account for approximately 25% of all cutaneous lymphomas. Clinically, patients present with either solitary or multiple papules or plaques, typically on the upper extremities or trunk.

Histopathology is vital for the correct diagnosis. In this patient, the histologic report was written as follows: “The findings are those of a well-differentiated but atypical diffuse mixed small lymphocytic infiltrate representing a mixture of T-cells and B-cells. The minor component of the infiltrate is of T-cell lineage, whereby the cells do not show any phenotypic abnormalities. The background cell population is interpreted as reactive. However, the dominant cell population is in fact of B-cell lineage. It is extensively highlighted by CD20. Only a minor component of the B cell infiltrate appeared to be in the context of representing germinal centers as characterized by small foci of centrocytic and centroblastic infiltration highlighted by BCL6 and CD10. The overwhelming B-cell component is a non–germinal center small B cell that does demonstrate BCL2 positivity and significant immunoreactivity for CD23. This small lymphocytic infiltrate obscures the germinal centers. There are only a few plasma cells; they do not show light chain restriction.”

The pathologist remarked that “this type of morphology of a diffuse small B-cell lymphocytic infiltrate that is without any evidence of light chain restriction amidst plasma cells, whereby the B cell component is dominant over the T-cell component would in fact be consistent with a unique variant of marginal zone lymphoma derived from a naive mantle zone.”

PCMZL has an excellent prognosis. When limited to the skin, local radiation or excision are effective treatments. Intravenous rituximab has been used to treat multifocal PCMZL. This patient was found to have no extracutaneous involvement and was treated with radiation.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Virmani P et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2017 Jun 14;3(4):269-72.

Magro CM and Olson LC. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018 Jun;34:116-21.

Experts urge stopping melanoma trial because of failure and harm

New

The approach seemed promising, given the efficacy of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors in metastatic melanoma, and the relatively short response times to BRAF and MEK inhibitors could potentially be supplemented by longer response times associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The two categories also have different mechanisms of action and nonoverlapping toxicities, which led to an expectation that the combination would be well tolerated.

But the new study joins two previous randomized, controlled trials that also failed to show much clinical benefit. IMspire150 assigned BRAF V600–mutated melanoma patients to vemurafenib and cobimetinib plus the anti–PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab or placebo. The treatment arm had a small benefit in progression-free survival (hazard ratio, 0.78), which led to Food and Drug Administration approval of the combination, though there was no significant difference when the two cohorts were assessed by an independent review committee. The KEYNOTE-022 trial examined dabrafenib plus trametinib with or without the anti–PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab, and found no difference in investigator-assessed progression free survival.

The new study was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. In an accompanying editorial, Margaret K. Callahan, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and Paul B. Chapman, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, both in New York, speculated that the toxicity of the triplet combination might explain the latest failure, since patients in the triplet arm had more treatment interruptions and dose reductions than the doublet arm (32% received full-dose dabrafenib vs. 54% in the doublet arm), which may have undermined efficacy.

Citing the fact that there are now three randomized, controlled trials with discouraging results, “we believe that there are sufficient data now to be confident that the addition of anti–PD-1 or anti–PD-L1 antibodies to combination RAFi [RAF inhibitors] plus MEKi [MEK inhibitors] is not associated with a significant clinical benefit and should not be studied further in melanoma.

Moreover, “there is some evidence of harm,” the editorial authors wrote. “As the additional toxicity of triplet combination limited the delivery of combination RAFi plus MEKi therapy in COMBI-I. Focus should turn instead to optimizing doses and schedules of combination RAFi plus MEKi and checkpoint inhibitors, developing treatment strategies to overcome resistance to these therapies, and determining how best to sequence combination RAFi plus MEKi therapy and checkpoint inhibitors. Regarding the latter point, there are several sequential therapy trials currently underway in previously untreated patients with BRAF V600–mutated melanoma.”

In the study, patients were randomized to receive dabrafenib and trametinib plus the anti–PD receptor–1 antibody spartalizumab or placebo. After a median follow-up of 27.2 months, mean progression-free survival was 16.2 months in the spartalizumab arm and 12.0 months in the placebo arm (HR, 0.82; P = .042). The spartalizumab group had a 69% objective response rate versus 64% in the placebo group. 55% of the spartalizumab group experienced grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events, compared with 33% in the placebo group.

“These results do not support broad use of first-line immunotherapy plus targeted therapy combination, but they provide additional data toward understanding the optimal application of these therapeutic classes in patients with BRAF V600–mutant metastatic melanoma,” the authors of the study wrote.

The study was funded by F Hoffmann–La Roche and Genentech. Dr. Callahan has been employed at Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and Kleo Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Callahan has consulted for or advised AstraZeneca, Moderna Therapeutics, Merck, and Immunocore. Dr. Chapman has stock or ownership interest in Rgenix; has consulted for or advised Merck, Pfizer, and Black Diamond Therapeutics; and has received research funding from Genentech.

New

The approach seemed promising, given the efficacy of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors in metastatic melanoma, and the relatively short response times to BRAF and MEK inhibitors could potentially be supplemented by longer response times associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The two categories also have different mechanisms of action and nonoverlapping toxicities, which led to an expectation that the combination would be well tolerated.

But the new study joins two previous randomized, controlled trials that also failed to show much clinical benefit. IMspire150 assigned BRAF V600–mutated melanoma patients to vemurafenib and cobimetinib plus the anti–PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab or placebo. The treatment arm had a small benefit in progression-free survival (hazard ratio, 0.78), which led to Food and Drug Administration approval of the combination, though there was no significant difference when the two cohorts were assessed by an independent review committee. The KEYNOTE-022 trial examined dabrafenib plus trametinib with or without the anti–PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab, and found no difference in investigator-assessed progression free survival.

The new study was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. In an accompanying editorial, Margaret K. Callahan, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and Paul B. Chapman, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, both in New York, speculated that the toxicity of the triplet combination might explain the latest failure, since patients in the triplet arm had more treatment interruptions and dose reductions than the doublet arm (32% received full-dose dabrafenib vs. 54% in the doublet arm), which may have undermined efficacy.

Citing the fact that there are now three randomized, controlled trials with discouraging results, “we believe that there are sufficient data now to be confident that the addition of anti–PD-1 or anti–PD-L1 antibodies to combination RAFi [RAF inhibitors] plus MEKi [MEK inhibitors] is not associated with a significant clinical benefit and should not be studied further in melanoma.

Moreover, “there is some evidence of harm,” the editorial authors wrote. “As the additional toxicity of triplet combination limited the delivery of combination RAFi plus MEKi therapy in COMBI-I. Focus should turn instead to optimizing doses and schedules of combination RAFi plus MEKi and checkpoint inhibitors, developing treatment strategies to overcome resistance to these therapies, and determining how best to sequence combination RAFi plus MEKi therapy and checkpoint inhibitors. Regarding the latter point, there are several sequential therapy trials currently underway in previously untreated patients with BRAF V600–mutated melanoma.”

In the study, patients were randomized to receive dabrafenib and trametinib plus the anti–PD receptor–1 antibody spartalizumab or placebo. After a median follow-up of 27.2 months, mean progression-free survival was 16.2 months in the spartalizumab arm and 12.0 months in the placebo arm (HR, 0.82; P = .042). The spartalizumab group had a 69% objective response rate versus 64% in the placebo group. 55% of the spartalizumab group experienced grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events, compared with 33% in the placebo group.

“These results do not support broad use of first-line immunotherapy plus targeted therapy combination, but they provide additional data toward understanding the optimal application of these therapeutic classes in patients with BRAF V600–mutant metastatic melanoma,” the authors of the study wrote.

The study was funded by F Hoffmann–La Roche and Genentech. Dr. Callahan has been employed at Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and Kleo Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Callahan has consulted for or advised AstraZeneca, Moderna Therapeutics, Merck, and Immunocore. Dr. Chapman has stock or ownership interest in Rgenix; has consulted for or advised Merck, Pfizer, and Black Diamond Therapeutics; and has received research funding from Genentech.

New

The approach seemed promising, given the efficacy of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors in metastatic melanoma, and the relatively short response times to BRAF and MEK inhibitors could potentially be supplemented by longer response times associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The two categories also have different mechanisms of action and nonoverlapping toxicities, which led to an expectation that the combination would be well tolerated.

But the new study joins two previous randomized, controlled trials that also failed to show much clinical benefit. IMspire150 assigned BRAF V600–mutated melanoma patients to vemurafenib and cobimetinib plus the anti–PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab or placebo. The treatment arm had a small benefit in progression-free survival (hazard ratio, 0.78), which led to Food and Drug Administration approval of the combination, though there was no significant difference when the two cohorts were assessed by an independent review committee. The KEYNOTE-022 trial examined dabrafenib plus trametinib with or without the anti–PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab, and found no difference in investigator-assessed progression free survival.

The new study was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. In an accompanying editorial, Margaret K. Callahan, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and Paul B. Chapman, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, both in New York, speculated that the toxicity of the triplet combination might explain the latest failure, since patients in the triplet arm had more treatment interruptions and dose reductions than the doublet arm (32% received full-dose dabrafenib vs. 54% in the doublet arm), which may have undermined efficacy.

Citing the fact that there are now three randomized, controlled trials with discouraging results, “we believe that there are sufficient data now to be confident that the addition of anti–PD-1 or anti–PD-L1 antibodies to combination RAFi [RAF inhibitors] plus MEKi [MEK inhibitors] is not associated with a significant clinical benefit and should not be studied further in melanoma.

Moreover, “there is some evidence of harm,” the editorial authors wrote. “As the additional toxicity of triplet combination limited the delivery of combination RAFi plus MEKi therapy in COMBI-I. Focus should turn instead to optimizing doses and schedules of combination RAFi plus MEKi and checkpoint inhibitors, developing treatment strategies to overcome resistance to these therapies, and determining how best to sequence combination RAFi plus MEKi therapy and checkpoint inhibitors. Regarding the latter point, there are several sequential therapy trials currently underway in previously untreated patients with BRAF V600–mutated melanoma.”

In the study, patients were randomized to receive dabrafenib and trametinib plus the anti–PD receptor–1 antibody spartalizumab or placebo. After a median follow-up of 27.2 months, mean progression-free survival was 16.2 months in the spartalizumab arm and 12.0 months in the placebo arm (HR, 0.82; P = .042). The spartalizumab group had a 69% objective response rate versus 64% in the placebo group. 55% of the spartalizumab group experienced grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events, compared with 33% in the placebo group.

“These results do not support broad use of first-line immunotherapy plus targeted therapy combination, but they provide additional data toward understanding the optimal application of these therapeutic classes in patients with BRAF V600–mutant metastatic melanoma,” the authors of the study wrote.

The study was funded by F Hoffmann–La Roche and Genentech. Dr. Callahan has been employed at Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and Kleo Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Callahan has consulted for or advised AstraZeneca, Moderna Therapeutics, Merck, and Immunocore. Dr. Chapman has stock or ownership interest in Rgenix; has consulted for or advised Merck, Pfizer, and Black Diamond Therapeutics; and has received research funding from Genentech.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

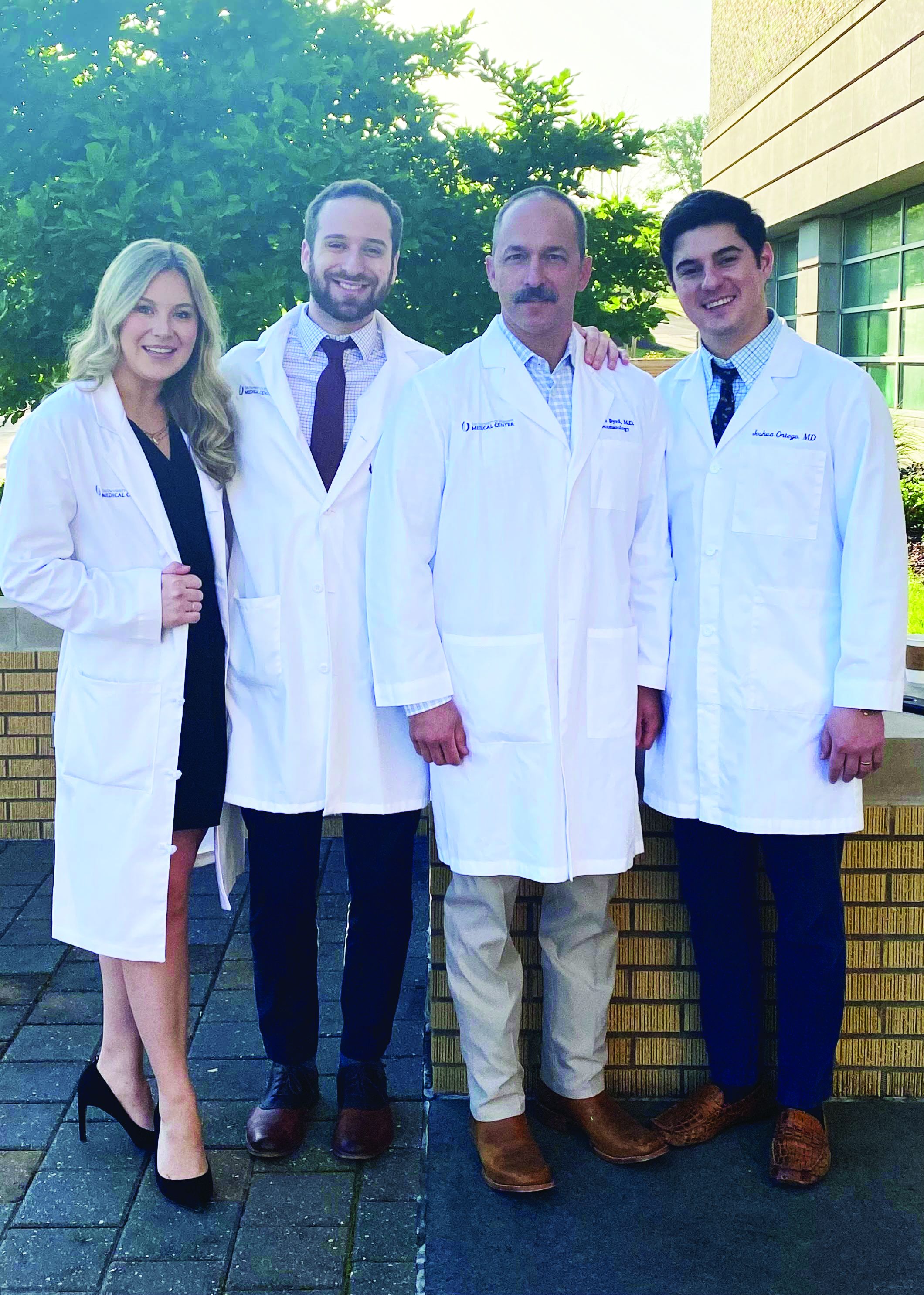

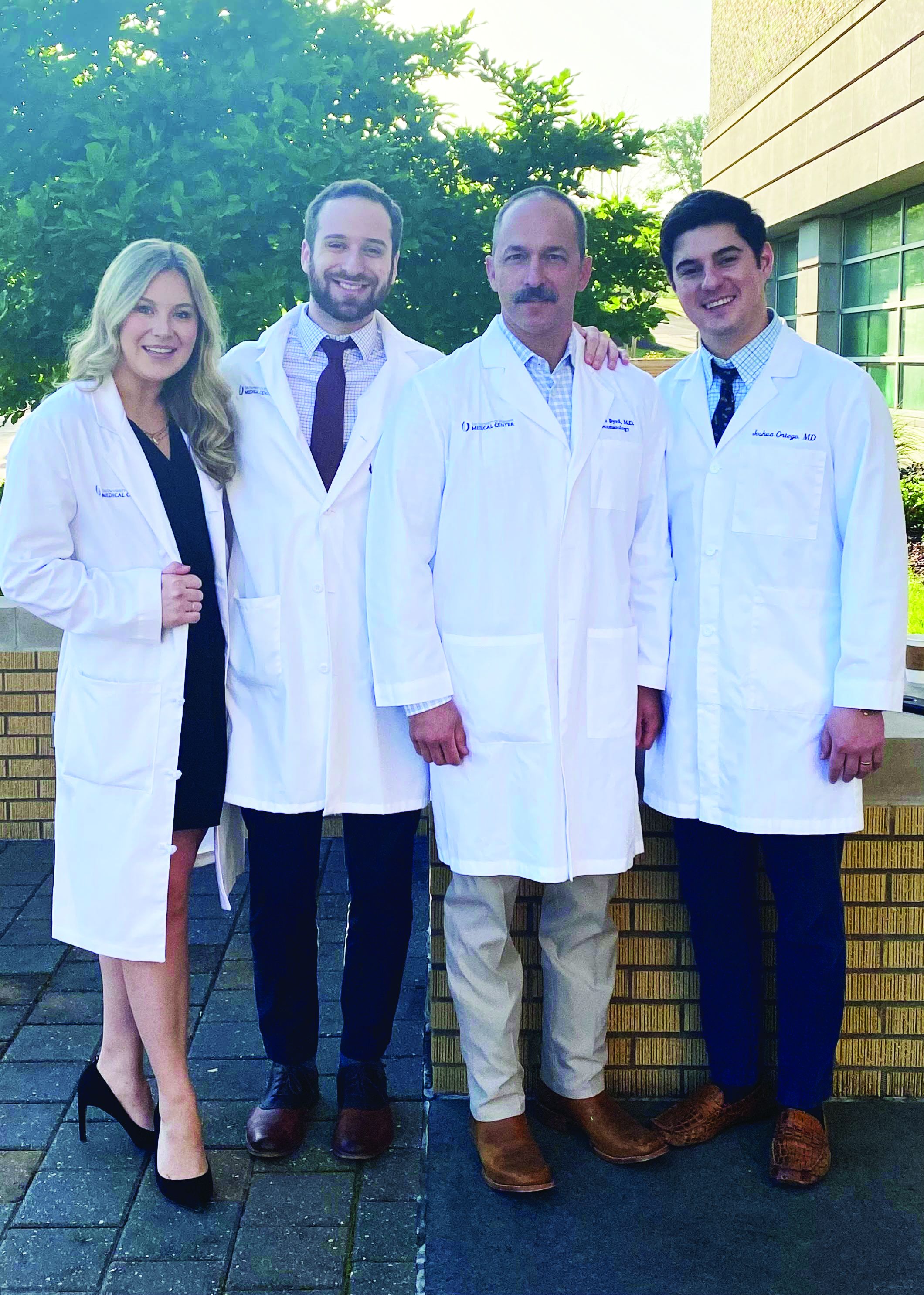

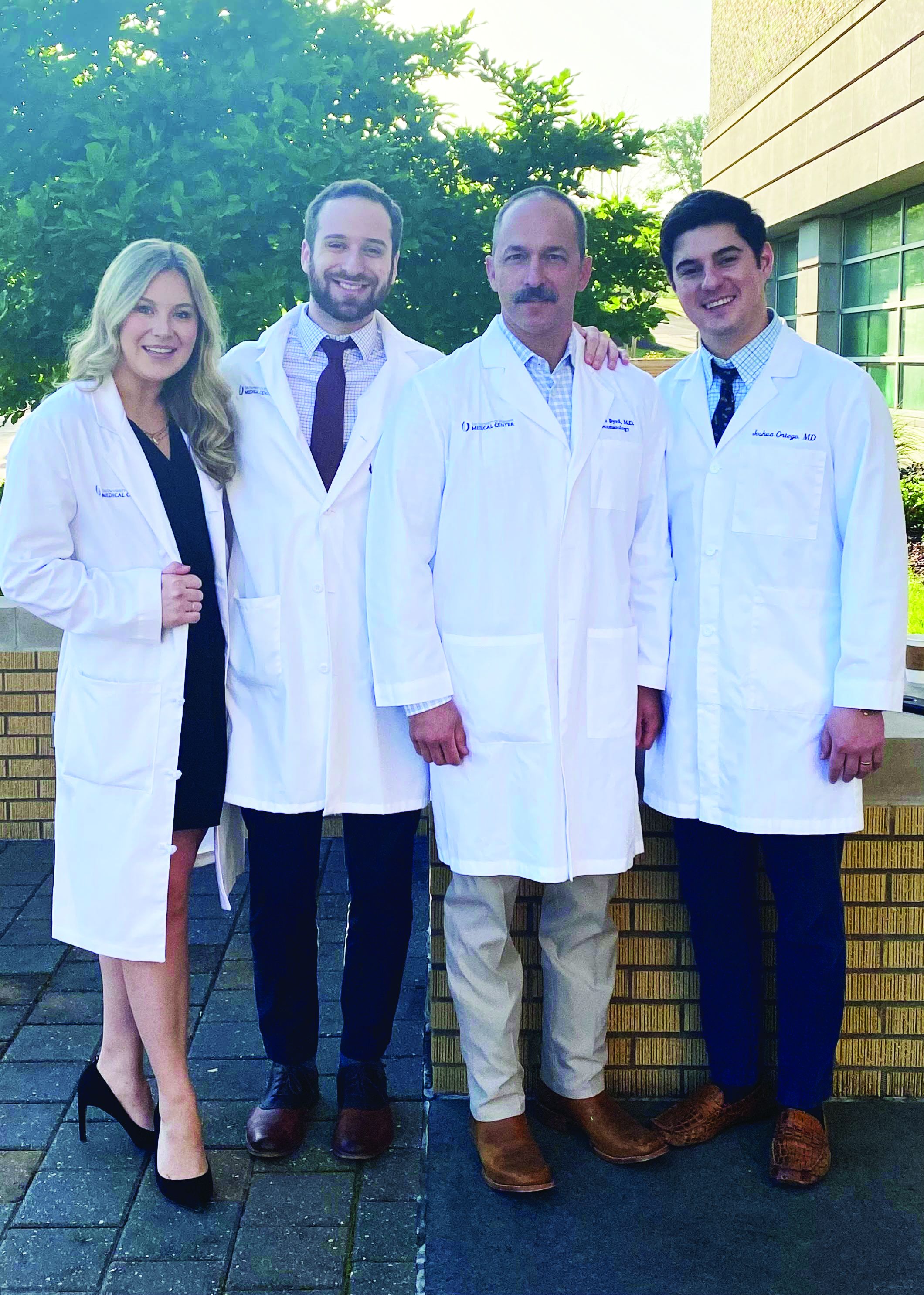

Are physician white coats becoming obsolete? How docs dress for work now

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Trisha Pasricha, MD, a gastroenterologist and research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, was talking to a patient who had been hospitalized for a peptic ulcer.

Like other physicians in her institution, Dr. Pasricha was wearing scrubs instead of a white coat, out of concern that the white coat might be more prone to accumulating or transmitting COVID-19 pathogens. Her badge identified her as a physician, and she introduced herself clearly as “Dr. Pasricha.”

The patient “required an emergent procedure, which I discussed with him,” Dr. Pasricha told this news organization. “I went over what the procedure entailed, the risks and benefits, and the need for informed consent. The patient nodded and seemed to understand, but at the end of the discussion he said: ‘That all sounds fine, but I need to speak to the doctor first.’ ”

Dr. Pasricha was taken aback. She wondered: “Who did he think I was the whole time that I was reviewing medical concerns, explaining medical concepts, and describing a procedure in a way that a physician would describe it?”

She realized the reason he didn’t correctly identify her was that, clad only in scrubs, she was less easily recognizable as a physician. And to be misidentified as technicians, nurses, physician assistants, or other health care professionals, according to Dr. Pasricha.

Dr. Pasricha said she has been the recipient of this “implicit bias” not only from patients but also from members of the health care team, and added that other female colleagues have told her that they’ve had similar experiences, especially when they’re not wearing a white coat.

Changing times, changing trends

When COVID-19 began to spread, “there was an initial concern that COVID-19 was passed through surfaces, and concerns about whether white coats could carry viral particles,” according to Jordan Steinberg, MD, PhD, surgical director of the craniofacial program at Nicklaus Children’s Pediatric Specialists/Nicklaus Children’s Health System, Miami. “Hospitals didn’t want to launder the white coats as frequently as scrubs, due to cost concerns. There was also a concern raised that a necktie might dangle in patients’ faces, coming in closer contact with pathogens, so more physicians were wearing scrubs.”

Yet even before the pandemic, physician attire in hospital and outpatient settings had started to change. Dr. Steinberg, who is also a clinical associate professor at Florida International University, Miami, told this news organization that, in his previous appointment at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, he and his colleagues “had noticed in our institution, as well as other facilities, an increasing trend that moved from white coats worn over professional attire toward more casual dress among medical staff – increased wearing of casual fleece or softshell jackets with the institutional logo.”

This was especially true with trainees and the “younger generation,” who were preferring “what I would almost call ‘warm-up clothes,’ gym clothes, and less shirt-tie-white-coat attire for men or white-coats-and-business attire for women.” Dr. Steinberg thinks that some physicians prefer the fleece with the institutional logo “because it’s like wearing your favorite sports team jersey. It gives a sense of belonging.”

Todd Shaffer, MD, MBA, a family physician at University Physicians Associates, Truman Medical Centers and the Lakewood Medical Pavilion, Kansas City, Mo., has been at his institution for 30 years and has seen a similar trend. “At one point, things were very formal,” he told this news organization. But attire was already becoming less formal before the pandemic, and new changes took place during the pandemic, as physicians began wearing scrubs instead of white coats because of fears of viral contamination.

Now, there is less concern about potential viral contamination with the white coat. Yet many physicians continue to wear scrubs – especially those who interact with patients with COVID – and it has become more acceptable to do so, or to wear personal protective equipment (PPE) over ordinary clothing, but it is less common in routine clinical practice, said Dr. Shaffer, a member of the board of directors of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

“The world has changed since COVID. People feel more comfortable dressing more casually during professional Zoom calls, when they have the convenience of working from home,” said Dr. Shaffer, who is also a professor of family medicine at University of Missouri–Kansas City.

Dr. Shaffer himself hasn’t worn a white coat for years. “I’m more likely to wear medium casual pants. I’ve bought some nicer shirts, so I still look professional and upbeat. I don’t always tuck in my shirt, and I don’t dress as formally.” He wears PPE and a mask and/or face shield when treating patients with COVID-19. And he wears a white coat “when someone wants a photograph taken with the doctors – with the stethoscope draped around my neck.”

Traditional symbol of medicine

Because of the changing mores, Dr. Steinberg and colleagues at Johns Hopkins wondered if there might still be a role for professional attire and white coats and what patients prefer. To investigate the question, they surveyed 487 U.S. adults in the spring of 2020.

Respondents were asked where and how frequently they see health care professionals wearing white coats, scrubs, and fleece or softshell jackets. They were also shown photographs depicting models wearing various types of attire commonly seen in health care settings and were asked to rank the “health care provider’s” level of experience, professionalism, and friendliness.

The majority of participants said they had seen health care practitioners in white coats “most of the time,” in scrubs “sometimes,” and in fleece or softshell jackets “rarely.” Models in white coats were regarded by respondents as more experienced and professional, although those in softshell jackets were perceived as friendlier.

There were age as well as regional differences in the responses, Dr. Steinberg said. Older respondents were significantly more likely than their younger counterparts to perceive a model wearing a white coat over business attire as being more experienced, and – in all regions of the United States except the West coast – respondents gave lower professionalism scores to providers wearing fleece jackets with scrubs underneath.

Respondents tended to prefer surgeons wearing a white coat with scrubs underneath, while a white coat over business attire was the preferred dress code for family physicians and dermatologists.

“People tended to respond as if there was a more professional element in the white coat. The age-old symbol of the white coat still marked something important,” Dr. Steinberg said. “Our data suggest that the white coat isn’t ready to die just yet. People still see an air of authority and a traditional symbol of medicine. Nevertheless, I do think it will become less common than it used to be, especially in certain regions of the country.”

Organic, subtle changes

Christopher Petrilli, MD, assistant professor at New York University, conducted research in 2018 regarding physician attire by surveying over 4,000 patients in 10 U.S. academic hospitals. His team found that most patients continued to prefer physicians to wear formal attire under a white coat, especially older respondents.

Dr. Petrilli and colleagues have been studying the issue of physician attire since 2015. “The big issue when we did our initial study – which might not be accurate anymore – is that few hospitals actually had a uniform dress code,” said Dr. Petrilli, the medical director of clinical documentation improvement and the clinical lead of value-based medicine at NYU Langone Hospitals. “When we looked at ‘honor roll hospitals’ during our study, we cold-called these hospitals and also looked online for their dress code policies. Except for the Mayo Clinic, hospitals that had dress code policies were more generic.”

For example, the American Medical Association guidance merely states that attire should be “clean, unsoiled, and appropriate to the setting of care” and recommends weighing research findings regarding textile transmission of health care–associated infections when individual institutions determine their dress code policies. The AMA’s last policy discussion took place in 2015 and its guidance has not changed since the pandemic.

Regardless of what institutions and patients prefer, some research suggests that many physicians would prefer to stay with wearing scrubs rather than reverting to the white coat. One study of 151 hospitalists, conducted in Ireland, found that three-quarters wanted scrubs to remain standard attire, despite the fact that close to half had experienced changes in patients› perception in the absence of their white coat and “professional attire.”

Jennifer Workman, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics, division of pediatric critical care, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, said in an interview that, as the pandemic has “waxed and waned, some trends have reverted to what they were prepandemic, but other physicians have stayed with wearing scrubs.”

Much depends on practice setting, said Dr. Workman, who is also the medical director of pediatric sepsis at Intermountain Care. In pediatrics, for example, many physicians prefer not to wear white coats when they are interacting with young children or adolescents.

Like Dr. Shaffer, Dr. Workman has seen changes in physicians’ attire during video meetings, where they often dress more casually, perhaps wearing sweatshirts. And in the hospital, more are continuing to wear scrubs. “But I don’t see it as people trying to consciously experiment or push boundaries,” she said. “I see it as a more organic, subtle shift.”

Dr. Petrilli thinks that, at this juncture, it’s “pretty heterogeneous as to who is going to return to formal attire and a white coat and who won’t.” Further research needs to be done into currently evolving trends. “We need a more thorough survey looking at changes. We need to ask [physician respondents]: ‘What is your current attire, and how has it changed?’ ”

Navigating the gender divide

In their study, Dr. Steinberg and colleagues found that respondents perceived a male model wearing business attire underneath any type of outerwear (white coat or fleece) to be significantly more professional than a female model wearing the same attire. Respondents also perceived males wearing scrubs to be more professional than females wearing scrubs.

Male models in white coats over business attire were also more likely to be identified as physicians, compared with female models in the same attire. Females were also more likely to be misidentified as nonphysician health care professionals.

Shikha Jain, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Illinois Cancer Center in Chicago, said that Dr. Steinberg’s study confirmed experiences that she and other female physicians have had. Wearing a white coat makes it more likely that a patient will identify you as a physician, but women are less likely to be identified as physicians, regardless of what they wear.

“I think that individuals of color and especially people with intersectional identities – such as women of color – are even more frequently targeted and stereotyped. Numerous studies have shown that a person of color is less likely to be seen as an authority figure, and studies have shown that physicians of color are less likely to be identified as ‘physicians,’ compared to a Caucasian individual,” she said.

Does that mean that female physicians should revert back to prepandemic white coats rather than scrubs or more casual attire? Not necessarily, according to Dr. Jain.

“The typical dress code guidance is that physicians should dress ‘professionally,’ but what that means is a question that needs to be addressed,” Dr. Jain said. “Medicine has evolved from the days of house calls, in which one’s patient population is a very small, intimate group of people in the physician’s community. Yet now, we’ve given rebirth to the ‘house call’ when we do telemedicine with a patient in his or her home. And in the old days, doctors often had offices their homes and now, with telemedicine, patients often see the interior of their physician’s home.” As the delivery of medicine evolves, concepts of “professionalism” – what is defined as “casual” and what is defined as “formal” – is also evolving.

The more important issue, according to Dr. Jain, is to “continue the conversation” about the discrepancies between how men and women are treated in medicine. Attire is one arena in which this issue plays out, and it’s a “bigger picture” that goes beyond the white coat.

Dr. Jain has been “told by patients that a particular outfit doesn’t make me look like a doctor or that scrubs make me look younger. I don’t think my male colleagues have been subjected to these types of remarks, but my female colleagues have heard them as well.”

Even fellow health care providers have commented on Dr. Jain’s clothing. She was presenting at a major medical conference via video and was wearing a similar outfit to the one she wore for her headshot. “Thirty seconds before beginning my talk, one of the male physicians said: ‘Are you wearing the same outfit you wore for your headshot?’ I can’t imagine a man commenting that another man was wearing the same jacket or tie that he wore in the photograph. I found it odd that this was something that someone felt the need to comment on right before I was about to address a large group of people in a professional capacity.”

Addressing these systemic issues “needs to be done and amplified not only by women but also by men in medicine,” said Dr. Jain, founder and director of Women in Medicine, an organization consisting of women physicians whose goal is to “find and implement solutions to gender inequity.”

Dr. Jain said the organization offers an Inclusive Leadership Development Lab – a course specifically for men in health care leadership positions to learn how to be more equitable, inclusive leaders.

A personal decision

Dr. Pasricha hopes she “handled the patient’s misidentification graciously.” She explained to him that she would be the physician conducting the procedure. The patient was initially “a little embarrassed” that he had misidentified her, but she put him at ease and “we moved forward quickly.”

At this point, although some of her colleagues have continued to wear scrubs or have returned to wearing fleeces with hospital logos, Dr. Pasricha prefers to wear a white coat in both inpatient and outpatient settings because it reduces the likelihood of misidentification.

And white coats can be more convenient – for example, Dr. Jain likes the fact that the white coat has pockets where she can put her stethoscope and other items, while some of her professional clothes don’t always have pockets.

Dr. Jain noted that there are some institutions where everyone seems to wear white coats, not only the physician – “from the chaplain to the phlebotomist to the social worker.” In those settings, the white coat no longer distinguishes physicians from nonphysicians, and so wearing a white coat may not confer additional credibility as a physician.

Nevertheless, “if you want to wear a white coat, if you feel it gives you that added level of authority, if you feel it tells people more clearly that you’re a physician, by all means go ahead and do so,” she said. “There’s no ‘one-size-fits-all’ strategy or solution. What’s more important than your clothing is your professionalism.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Trisha Pasricha, MD, a gastroenterologist and research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, was talking to a patient who had been hospitalized for a peptic ulcer.

Like other physicians in her institution, Dr. Pasricha was wearing scrubs instead of a white coat, out of concern that the white coat might be more prone to accumulating or transmitting COVID-19 pathogens. Her badge identified her as a physician, and she introduced herself clearly as “Dr. Pasricha.”

The patient “required an emergent procedure, which I discussed with him,” Dr. Pasricha told this news organization. “I went over what the procedure entailed, the risks and benefits, and the need for informed consent. The patient nodded and seemed to understand, but at the end of the discussion he said: ‘That all sounds fine, but I need to speak to the doctor first.’ ”

Dr. Pasricha was taken aback. She wondered: “Who did he think I was the whole time that I was reviewing medical concerns, explaining medical concepts, and describing a procedure in a way that a physician would describe it?”

She realized the reason he didn’t correctly identify her was that, clad only in scrubs, she was less easily recognizable as a physician. And to be misidentified as technicians, nurses, physician assistants, or other health care professionals, according to Dr. Pasricha.

Dr. Pasricha said she has been the recipient of this “implicit bias” not only from patients but also from members of the health care team, and added that other female colleagues have told her that they’ve had similar experiences, especially when they’re not wearing a white coat.

Changing times, changing trends

When COVID-19 began to spread, “there was an initial concern that COVID-19 was passed through surfaces, and concerns about whether white coats could carry viral particles,” according to Jordan Steinberg, MD, PhD, surgical director of the craniofacial program at Nicklaus Children’s Pediatric Specialists/Nicklaus Children’s Health System, Miami. “Hospitals didn’t want to launder the white coats as frequently as scrubs, due to cost concerns. There was also a concern raised that a necktie might dangle in patients’ faces, coming in closer contact with pathogens, so more physicians were wearing scrubs.”

Yet even before the pandemic, physician attire in hospital and outpatient settings had started to change. Dr. Steinberg, who is also a clinical associate professor at Florida International University, Miami, told this news organization that, in his previous appointment at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, he and his colleagues “had noticed in our institution, as well as other facilities, an increasing trend that moved from white coats worn over professional attire toward more casual dress among medical staff – increased wearing of casual fleece or softshell jackets with the institutional logo.”

This was especially true with trainees and the “younger generation,” who were preferring “what I would almost call ‘warm-up clothes,’ gym clothes, and less shirt-tie-white-coat attire for men or white-coats-and-business attire for women.” Dr. Steinberg thinks that some physicians prefer the fleece with the institutional logo “because it’s like wearing your favorite sports team jersey. It gives a sense of belonging.”

Todd Shaffer, MD, MBA, a family physician at University Physicians Associates, Truman Medical Centers and the Lakewood Medical Pavilion, Kansas City, Mo., has been at his institution for 30 years and has seen a similar trend. “At one point, things were very formal,” he told this news organization. But attire was already becoming less formal before the pandemic, and new changes took place during the pandemic, as physicians began wearing scrubs instead of white coats because of fears of viral contamination.

Now, there is less concern about potential viral contamination with the white coat. Yet many physicians continue to wear scrubs – especially those who interact with patients with COVID – and it has become more acceptable to do so, or to wear personal protective equipment (PPE) over ordinary clothing, but it is less common in routine clinical practice, said Dr. Shaffer, a member of the board of directors of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

“The world has changed since COVID. People feel more comfortable dressing more casually during professional Zoom calls, when they have the convenience of working from home,” said Dr. Shaffer, who is also a professor of family medicine at University of Missouri–Kansas City.

Dr. Shaffer himself hasn’t worn a white coat for years. “I’m more likely to wear medium casual pants. I’ve bought some nicer shirts, so I still look professional and upbeat. I don’t always tuck in my shirt, and I don’t dress as formally.” He wears PPE and a mask and/or face shield when treating patients with COVID-19. And he wears a white coat “when someone wants a photograph taken with the doctors – with the stethoscope draped around my neck.”

Traditional symbol of medicine

Because of the changing mores, Dr. Steinberg and colleagues at Johns Hopkins wondered if there might still be a role for professional attire and white coats and what patients prefer. To investigate the question, they surveyed 487 U.S. adults in the spring of 2020.

Respondents were asked where and how frequently they see health care professionals wearing white coats, scrubs, and fleece or softshell jackets. They were also shown photographs depicting models wearing various types of attire commonly seen in health care settings and were asked to rank the “health care provider’s” level of experience, professionalism, and friendliness.

The majority of participants said they had seen health care practitioners in white coats “most of the time,” in scrubs “sometimes,” and in fleece or softshell jackets “rarely.” Models in white coats were regarded by respondents as more experienced and professional, although those in softshell jackets were perceived as friendlier.

There were age as well as regional differences in the responses, Dr. Steinberg said. Older respondents were significantly more likely than their younger counterparts to perceive a model wearing a white coat over business attire as being more experienced, and – in all regions of the United States except the West coast – respondents gave lower professionalism scores to providers wearing fleece jackets with scrubs underneath.

Respondents tended to prefer surgeons wearing a white coat with scrubs underneath, while a white coat over business attire was the preferred dress code for family physicians and dermatologists.

“People tended to respond as if there was a more professional element in the white coat. The age-old symbol of the white coat still marked something important,” Dr. Steinberg said. “Our data suggest that the white coat isn’t ready to die just yet. People still see an air of authority and a traditional symbol of medicine. Nevertheless, I do think it will become less common than it used to be, especially in certain regions of the country.”

Organic, subtle changes

Christopher Petrilli, MD, assistant professor at New York University, conducted research in 2018 regarding physician attire by surveying over 4,000 patients in 10 U.S. academic hospitals. His team found that most patients continued to prefer physicians to wear formal attire under a white coat, especially older respondents.

Dr. Petrilli and colleagues have been studying the issue of physician attire since 2015. “The big issue when we did our initial study – which might not be accurate anymore – is that few hospitals actually had a uniform dress code,” said Dr. Petrilli, the medical director of clinical documentation improvement and the clinical lead of value-based medicine at NYU Langone Hospitals. “When we looked at ‘honor roll hospitals’ during our study, we cold-called these hospitals and also looked online for their dress code policies. Except for the Mayo Clinic, hospitals that had dress code policies were more generic.”

For example, the American Medical Association guidance merely states that attire should be “clean, unsoiled, and appropriate to the setting of care” and recommends weighing research findings regarding textile transmission of health care–associated infections when individual institutions determine their dress code policies. The AMA’s last policy discussion took place in 2015 and its guidance has not changed since the pandemic.

Regardless of what institutions and patients prefer, some research suggests that many physicians would prefer to stay with wearing scrubs rather than reverting to the white coat. One study of 151 hospitalists, conducted in Ireland, found that three-quarters wanted scrubs to remain standard attire, despite the fact that close to half had experienced changes in patients› perception in the absence of their white coat and “professional attire.”

Jennifer Workman, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics, division of pediatric critical care, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, said in an interview that, as the pandemic has “waxed and waned, some trends have reverted to what they were prepandemic, but other physicians have stayed with wearing scrubs.”

Much depends on practice setting, said Dr. Workman, who is also the medical director of pediatric sepsis at Intermountain Care. In pediatrics, for example, many physicians prefer not to wear white coats when they are interacting with young children or adolescents.

Like Dr. Shaffer, Dr. Workman has seen changes in physicians’ attire during video meetings, where they often dress more casually, perhaps wearing sweatshirts. And in the hospital, more are continuing to wear scrubs. “But I don’t see it as people trying to consciously experiment or push boundaries,” she said. “I see it as a more organic, subtle shift.”

Dr. Petrilli thinks that, at this juncture, it’s “pretty heterogeneous as to who is going to return to formal attire and a white coat and who won’t.” Further research needs to be done into currently evolving trends. “We need a more thorough survey looking at changes. We need to ask [physician respondents]: ‘What is your current attire, and how has it changed?’ ”

Navigating the gender divide

In their study, Dr. Steinberg and colleagues found that respondents perceived a male model wearing business attire underneath any type of outerwear (white coat or fleece) to be significantly more professional than a female model wearing the same attire. Respondents also perceived males wearing scrubs to be more professional than females wearing scrubs.

Male models in white coats over business attire were also more likely to be identified as physicians, compared with female models in the same attire. Females were also more likely to be misidentified as nonphysician health care professionals.

Shikha Jain, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Illinois Cancer Center in Chicago, said that Dr. Steinberg’s study confirmed experiences that she and other female physicians have had. Wearing a white coat makes it more likely that a patient will identify you as a physician, but women are less likely to be identified as physicians, regardless of what they wear.

“I think that individuals of color and especially people with intersectional identities – such as women of color – are even more frequently targeted and stereotyped. Numerous studies have shown that a person of color is less likely to be seen as an authority figure, and studies have shown that physicians of color are less likely to be identified as ‘physicians,’ compared to a Caucasian individual,” she said.

Does that mean that female physicians should revert back to prepandemic white coats rather than scrubs or more casual attire? Not necessarily, according to Dr. Jain.

“The typical dress code guidance is that physicians should dress ‘professionally,’ but what that means is a question that needs to be addressed,” Dr. Jain said. “Medicine has evolved from the days of house calls, in which one’s patient population is a very small, intimate group of people in the physician’s community. Yet now, we’ve given rebirth to the ‘house call’ when we do telemedicine with a patient in his or her home. And in the old days, doctors often had offices their homes and now, with telemedicine, patients often see the interior of their physician’s home.” As the delivery of medicine evolves, concepts of “professionalism” – what is defined as “casual” and what is defined as “formal” – is also evolving.

The more important issue, according to Dr. Jain, is to “continue the conversation” about the discrepancies between how men and women are treated in medicine. Attire is one arena in which this issue plays out, and it’s a “bigger picture” that goes beyond the white coat.

Dr. Jain has been “told by patients that a particular outfit doesn’t make me look like a doctor or that scrubs make me look younger. I don’t think my male colleagues have been subjected to these types of remarks, but my female colleagues have heard them as well.”

Even fellow health care providers have commented on Dr. Jain’s clothing. She was presenting at a major medical conference via video and was wearing a similar outfit to the one she wore for her headshot. “Thirty seconds before beginning my talk, one of the male physicians said: ‘Are you wearing the same outfit you wore for your headshot?’ I can’t imagine a man commenting that another man was wearing the same jacket or tie that he wore in the photograph. I found it odd that this was something that someone felt the need to comment on right before I was about to address a large group of people in a professional capacity.”

Addressing these systemic issues “needs to be done and amplified not only by women but also by men in medicine,” said Dr. Jain, founder and director of Women in Medicine, an organization consisting of women physicians whose goal is to “find and implement solutions to gender inequity.”

Dr. Jain said the organization offers an Inclusive Leadership Development Lab – a course specifically for men in health care leadership positions to learn how to be more equitable, inclusive leaders.

A personal decision

Dr. Pasricha hopes she “handled the patient’s misidentification graciously.” She explained to him that she would be the physician conducting the procedure. The patient was initially “a little embarrassed” that he had misidentified her, but she put him at ease and “we moved forward quickly.”

At this point, although some of her colleagues have continued to wear scrubs or have returned to wearing fleeces with hospital logos, Dr. Pasricha prefers to wear a white coat in both inpatient and outpatient settings because it reduces the likelihood of misidentification.

And white coats can be more convenient – for example, Dr. Jain likes the fact that the white coat has pockets where she can put her stethoscope and other items, while some of her professional clothes don’t always have pockets.

Dr. Jain noted that there are some institutions where everyone seems to wear white coats, not only the physician – “from the chaplain to the phlebotomist to the social worker.” In those settings, the white coat no longer distinguishes physicians from nonphysicians, and so wearing a white coat may not confer additional credibility as a physician.

Nevertheless, “if you want to wear a white coat, if you feel it gives you that added level of authority, if you feel it tells people more clearly that you’re a physician, by all means go ahead and do so,” she said. “There’s no ‘one-size-fits-all’ strategy or solution. What’s more important than your clothing is your professionalism.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Trisha Pasricha, MD, a gastroenterologist and research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, was talking to a patient who had been hospitalized for a peptic ulcer.

Like other physicians in her institution, Dr. Pasricha was wearing scrubs instead of a white coat, out of concern that the white coat might be more prone to accumulating or transmitting COVID-19 pathogens. Her badge identified her as a physician, and she introduced herself clearly as “Dr. Pasricha.”

The patient “required an emergent procedure, which I discussed with him,” Dr. Pasricha told this news organization. “I went over what the procedure entailed, the risks and benefits, and the need for informed consent. The patient nodded and seemed to understand, but at the end of the discussion he said: ‘That all sounds fine, but I need to speak to the doctor first.’ ”

Dr. Pasricha was taken aback. She wondered: “Who did he think I was the whole time that I was reviewing medical concerns, explaining medical concepts, and describing a procedure in a way that a physician would describe it?”

She realized the reason he didn’t correctly identify her was that, clad only in scrubs, she was less easily recognizable as a physician. And to be misidentified as technicians, nurses, physician assistants, or other health care professionals, according to Dr. Pasricha.

Dr. Pasricha said she has been the recipient of this “implicit bias” not only from patients but also from members of the health care team, and added that other female colleagues have told her that they’ve had similar experiences, especially when they’re not wearing a white coat.

Changing times, changing trends

When COVID-19 began to spread, “there was an initial concern that COVID-19 was passed through surfaces, and concerns about whether white coats could carry viral particles,” according to Jordan Steinberg, MD, PhD, surgical director of the craniofacial program at Nicklaus Children’s Pediatric Specialists/Nicklaus Children’s Health System, Miami. “Hospitals didn’t want to launder the white coats as frequently as scrubs, due to cost concerns. There was also a concern raised that a necktie might dangle in patients’ faces, coming in closer contact with pathogens, so more physicians were wearing scrubs.”

Yet even before the pandemic, physician attire in hospital and outpatient settings had started to change. Dr. Steinberg, who is also a clinical associate professor at Florida International University, Miami, told this news organization that, in his previous appointment at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, he and his colleagues “had noticed in our institution, as well as other facilities, an increasing trend that moved from white coats worn over professional attire toward more casual dress among medical staff – increased wearing of casual fleece or softshell jackets with the institutional logo.”

This was especially true with trainees and the “younger generation,” who were preferring “what I would almost call ‘warm-up clothes,’ gym clothes, and less shirt-tie-white-coat attire for men or white-coats-and-business attire for women.” Dr. Steinberg thinks that some physicians prefer the fleece with the institutional logo “because it’s like wearing your favorite sports team jersey. It gives a sense of belonging.”

Todd Shaffer, MD, MBA, a family physician at University Physicians Associates, Truman Medical Centers and the Lakewood Medical Pavilion, Kansas City, Mo., has been at his institution for 30 years and has seen a similar trend. “At one point, things were very formal,” he told this news organization. But attire was already becoming less formal before the pandemic, and new changes took place during the pandemic, as physicians began wearing scrubs instead of white coats because of fears of viral contamination.

Now, there is less concern about potential viral contamination with the white coat. Yet many physicians continue to wear scrubs – especially those who interact with patients with COVID – and it has become more acceptable to do so, or to wear personal protective equipment (PPE) over ordinary clothing, but it is less common in routine clinical practice, said Dr. Shaffer, a member of the board of directors of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

“The world has changed since COVID. People feel more comfortable dressing more casually during professional Zoom calls, when they have the convenience of working from home,” said Dr. Shaffer, who is also a professor of family medicine at University of Missouri–Kansas City.

Dr. Shaffer himself hasn’t worn a white coat for years. “I’m more likely to wear medium casual pants. I’ve bought some nicer shirts, so I still look professional and upbeat. I don’t always tuck in my shirt, and I don’t dress as formally.” He wears PPE and a mask and/or face shield when treating patients with COVID-19. And he wears a white coat “when someone wants a photograph taken with the doctors – with the stethoscope draped around my neck.”

Traditional symbol of medicine

Because of the changing mores, Dr. Steinberg and colleagues at Johns Hopkins wondered if there might still be a role for professional attire and white coats and what patients prefer. To investigate the question, they surveyed 487 U.S. adults in the spring of 2020.

Respondents were asked where and how frequently they see health care professionals wearing white coats, scrubs, and fleece or softshell jackets. They were also shown photographs depicting models wearing various types of attire commonly seen in health care settings and were asked to rank the “health care provider’s” level of experience, professionalism, and friendliness.

The majority of participants said they had seen health care practitioners in white coats “most of the time,” in scrubs “sometimes,” and in fleece or softshell jackets “rarely.” Models in white coats were regarded by respondents as more experienced and professional, although those in softshell jackets were perceived as friendlier.

There were age as well as regional differences in the responses, Dr. Steinberg said. Older respondents were significantly more likely than their younger counterparts to perceive a model wearing a white coat over business attire as being more experienced, and – in all regions of the United States except the West coast – respondents gave lower professionalism scores to providers wearing fleece jackets with scrubs underneath.

Respondents tended to prefer surgeons wearing a white coat with scrubs underneath, while a white coat over business attire was the preferred dress code for family physicians and dermatologists.

“People tended to respond as if there was a more professional element in the white coat. The age-old symbol of the white coat still marked something important,” Dr. Steinberg said. “Our data suggest that the white coat isn’t ready to die just yet. People still see an air of authority and a traditional symbol of medicine. Nevertheless, I do think it will become less common than it used to be, especially in certain regions of the country.”

Organic, subtle changes

Christopher Petrilli, MD, assistant professor at New York University, conducted research in 2018 regarding physician attire by surveying over 4,000 patients in 10 U.S. academic hospitals. His team found that most patients continued to prefer physicians to wear formal attire under a white coat, especially older respondents.

Dr. Petrilli and colleagues have been studying the issue of physician attire since 2015. “The big issue when we did our initial study – which might not be accurate anymore – is that few hospitals actually had a uniform dress code,” said Dr. Petrilli, the medical director of clinical documentation improvement and the clinical lead of value-based medicine at NYU Langone Hospitals. “When we looked at ‘honor roll hospitals’ during our study, we cold-called these hospitals and also looked online for their dress code policies. Except for the Mayo Clinic, hospitals that had dress code policies were more generic.”

For example, the American Medical Association guidance merely states that attire should be “clean, unsoiled, and appropriate to the setting of care” and recommends weighing research findings regarding textile transmission of health care–associated infections when individual institutions determine their dress code policies. The AMA’s last policy discussion took place in 2015 and its guidance has not changed since the pandemic.

Regardless of what institutions and patients prefer, some research suggests that many physicians would prefer to stay with wearing scrubs rather than reverting to the white coat. One study of 151 hospitalists, conducted in Ireland, found that three-quarters wanted scrubs to remain standard attire, despite the fact that close to half had experienced changes in patients› perception in the absence of their white coat and “professional attire.”

Jennifer Workman, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics, division of pediatric critical care, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, said in an interview that, as the pandemic has “waxed and waned, some trends have reverted to what they were prepandemic, but other physicians have stayed with wearing scrubs.”

Much depends on practice setting, said Dr. Workman, who is also the medical director of pediatric sepsis at Intermountain Care. In pediatrics, for example, many physicians prefer not to wear white coats when they are interacting with young children or adolescents.

Like Dr. Shaffer, Dr. Workman has seen changes in physicians’ attire during video meetings, where they often dress more casually, perhaps wearing sweatshirts. And in the hospital, more are continuing to wear scrubs. “But I don’t see it as people trying to consciously experiment or push boundaries,” she said. “I see it as a more organic, subtle shift.”

Dr. Petrilli thinks that, at this juncture, it’s “pretty heterogeneous as to who is going to return to formal attire and a white coat and who won’t.” Further research needs to be done into currently evolving trends. “We need a more thorough survey looking at changes. We need to ask [physician respondents]: ‘What is your current attire, and how has it changed?’ ”

Navigating the gender divide

In their study, Dr. Steinberg and colleagues found that respondents perceived a male model wearing business attire underneath any type of outerwear (white coat or fleece) to be significantly more professional than a female model wearing the same attire. Respondents also perceived males wearing scrubs to be more professional than females wearing scrubs.

Male models in white coats over business attire were also more likely to be identified as physicians, compared with female models in the same attire. Females were also more likely to be misidentified as nonphysician health care professionals.

Shikha Jain, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Illinois Cancer Center in Chicago, said that Dr. Steinberg’s study confirmed experiences that she and other female physicians have had. Wearing a white coat makes it more likely that a patient will identify you as a physician, but women are less likely to be identified as physicians, regardless of what they wear.

“I think that individuals of color and especially people with intersectional identities – such as women of color – are even more frequently targeted and stereotyped. Numerous studies have shown that a person of color is less likely to be seen as an authority figure, and studies have shown that physicians of color are less likely to be identified as ‘physicians,’ compared to a Caucasian individual,” she said.

Does that mean that female physicians should revert back to prepandemic white coats rather than scrubs or more casual attire? Not necessarily, according to Dr. Jain.

“The typical dress code guidance is that physicians should dress ‘professionally,’ but what that means is a question that needs to be addressed,” Dr. Jain said. “Medicine has evolved from the days of house calls, in which one’s patient population is a very small, intimate group of people in the physician’s community. Yet now, we’ve given rebirth to the ‘house call’ when we do telemedicine with a patient in his or her home. And in the old days, doctors often had offices their homes and now, with telemedicine, patients often see the interior of their physician’s home.” As the delivery of medicine evolves, concepts of “professionalism” – what is defined as “casual” and what is defined as “formal” – is also evolving.

The more important issue, according to Dr. Jain, is to “continue the conversation” about the discrepancies between how men and women are treated in medicine. Attire is one arena in which this issue plays out, and it’s a “bigger picture” that goes beyond the white coat.

Dr. Jain has been “told by patients that a particular outfit doesn’t make me look like a doctor or that scrubs make me look younger. I don’t think my male colleagues have been subjected to these types of remarks, but my female colleagues have heard them as well.”

Even fellow health care providers have commented on Dr. Jain’s clothing. She was presenting at a major medical conference via video and was wearing a similar outfit to the one she wore for her headshot. “Thirty seconds before beginning my talk, one of the male physicians said: ‘Are you wearing the same outfit you wore for your headshot?’ I can’t imagine a man commenting that another man was wearing the same jacket or tie that he wore in the photograph. I found it odd that this was something that someone felt the need to comment on right before I was about to address a large group of people in a professional capacity.”

Addressing these systemic issues “needs to be done and amplified not only by women but also by men in medicine,” said Dr. Jain, founder and director of Women in Medicine, an organization consisting of women physicians whose goal is to “find and implement solutions to gender inequity.”

Dr. Jain said the organization offers an Inclusive Leadership Development Lab – a course specifically for men in health care leadership positions to learn how to be more equitable, inclusive leaders.

A personal decision

Dr. Pasricha hopes she “handled the patient’s misidentification graciously.” She explained to him that she would be the physician conducting the procedure. The patient was initially “a little embarrassed” that he had misidentified her, but she put him at ease and “we moved forward quickly.”

At this point, although some of her colleagues have continued to wear scrubs or have returned to wearing fleeces with hospital logos, Dr. Pasricha prefers to wear a white coat in both inpatient and outpatient settings because it reduces the likelihood of misidentification.

And white coats can be more convenient – for example, Dr. Jain likes the fact that the white coat has pockets where she can put her stethoscope and other items, while some of her professional clothes don’t always have pockets.

Dr. Jain noted that there are some institutions where everyone seems to wear white coats, not only the physician – “from the chaplain to the phlebotomist to the social worker.” In those settings, the white coat no longer distinguishes physicians from nonphysicians, and so wearing a white coat may not confer additional credibility as a physician.

Nevertheless, “if you want to wear a white coat, if you feel it gives you that added level of authority, if you feel it tells people more clearly that you’re a physician, by all means go ahead and do so,” she said. “There’s no ‘one-size-fits-all’ strategy or solution. What’s more important than your clothing is your professionalism.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Myositis guidelines aim to standardize adult and pediatric care

All patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM) should be screened for swallowing difficulties, according to the first evidence-based guideline to be produced.

The guideline, which has been developed by a working group of the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR), also advises that all diagnosed patients should have their myositis antibody levels checked and have their overall well-being assessed. Other recommendations for all patients include the use of glucocorticoids to reduce muscle inflammation and conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) for long-term treatment.

“Finally, now, we’re able to standardize the way we treat adults and children with IIM,” senior guideline author Hector Chinoy, PhD, said at the society’s annual meeting.

It has been a long labor of love, however, taking 4 years to get the guideline published, said Dr. Chinoy, professor of rheumatology and neuromuscular disease at the University of Manchester (England), and a consultant at Salford (England) Royal Hospital.

“We’re not covering diagnosis, classification, or the investigation of suspected IIM,” said Dr. Chinoy. Inclusion body myositis also is not included.

Altogether, there are 13 recommendations that have been developed using a PICO (patient or population, intervention, comparison, outcome) format, graded based on the quality of the available evidence, and then voted on by the working group members to give a score of the strength of agreement. Dr. Chinoy noted that there was a checklist included in the Supplementary Data section of the guideline to help follow the recommendations.

“The target audience for the guideline reflects the variety of clinicians caring for patients with IIM,” Dr. Chinoy said. So that is not just pediatric and adult rheumatologists, but also neurologists, dermatologists, respiratory physicians, oncologists, gastroenterologists, cardiologists, and of course other health care professionals. This includes rheumatology and neurology nurses, psychologists, speech and language therapists, and podiatrists, as well as rheumatology specialist pharmacists, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists.

With reference to the latter, Liza McCann, MBBS, who co-led the development of the guideline, said in a statement released by the BSR that the guideline “highlights the importance of exercise, led and monitored by specialist physiotherapists and occupational therapists.”

Dr. McCann, a consultant pediatric rheumatologist at Alder Hey Hospital, Liverpool, England, and Honorary Clinical Lecturer at the University of Liverpool, added that the guidelines also cover “the need to address psychological wellbeing as an integral part of treatment, in parallel with pharmacological therapies.”

Recommendation highlights

Some of the highlights of the recommendations include the use of high-dose glucocorticoids to manage skeletal muscle inflammation at the time of treatment induction, with specific guidance on the different doses to use in adults and in children. There also is guidance on the use of csDMARDs in both populations and what to use if there is refractory disease – with the strongest evidence supporting the use of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or cyclophosphamide, and possibly rituximab and abatacept.

“There is insufficient evidence to recommend JAK inhibition,” Dr. Chinoy said. The data search used to develop the guideline had a cutoff of October 2020, but even now there is only anecdotal evidence from case studies, he added.

Importantly, the guidelines recognize that childhood IIM differs from adult disease and call for children to be managed by pediatric specialists.

“Routine assessment of dysphagia should be considered in all patients,” Dr. Chinoy said, “so ask the question.” The recommendation is that a swallowing assessment should involve a speech and language therapist or gastroenterologist, and that IVIG be considered for active disease and dysphagia that is resistant to other treatments.

There also are recommendations to screen adult patients for interstitial lung disease, consider fracture risk, and screen adult patients for cancer if they have specific risk factors that include older age at onset, male gender, dysphagia, and rapid disease onset, among others.

Separate cancer screening guidelines on cards

“Around one in four patients with myositis will develop cancer within the 3 years either before or after myositis onset,” Alexander Oldroyd, MBChB, PhD, said in a separate presentation at the BSR annual meeting.

“It’s a hugely increased risk compared to the general population, and a great worry for patients,” he added. Exactly why there is an increased risk is not known, but “there’s a big link between the biological onset of cancer and myositis.”

Dr. Oldroyd, who is an NIHR Academic Clinical Lecturer at the University of Manchester in England and a coauthor of the BSR myositis guideline, is part of a special interest group set up by the International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group (IMACS) that is in the process of developing separate guidelines for cancer screening in people newly diagnosed with IIM.

The aim was to produce evidence-based recommendations that were both “pragmatic and practical,” that could help clinicians answer patient’s questions on their risk and how best and how often to screen them, Dr. Oldroyd explained. Importantly, IMACS has endeavored to create recommendations that should be applicable across different countries and health care systems.

“We had to acknowledge that there’s not a lot of evidence base there,” Dr. Oldroyd said, noting that he and colleagues conducted a systematic literature review and meta-analysis and used a Delphi process to draft 20 recommendations. These cover identifying risk factors for cancer in people with myositis and categorizing people into low, medium, and high-risk categories. The recommendations also cover what should constitute basic and enhanced screening, and how often someone should be screened.

Moreover, the authors make recommendations on the use of imaging modalities such as PET and CT scans, as well as upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy and naso-endoscopy.

“As rheumatologists, we don’t talk about cancer a lot,” Dr. Oldroyd said. “We pick up a lot of incidental cancers, but we don’t usually talk about cancer screening with patients.” That’s something that needs to change, he said.

“It’s important – just get it out in the open, talk to people about it,” Dr. Oldroyd said.

“Tell them what you’re wanting to do, how you’re wanting to investigate for it, clearly communicate their risk,” he said. “But also acknowledge the limited evidence as well, and clearly communicate the results.”

Dr. Chinoy acknowledged he had received fees for presentations (UCB, Biogen), consultancy (Alexion, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Orphazyme, AstraZeneca), or grant support (Eli Lilly, UCB) that had been paid via his institution for the purpose of furthering myositis research. Dr. Oldroyd had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

All patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM) should be screened for swallowing difficulties, according to the first evidence-based guideline to be produced.

The guideline, which has been developed by a working group of the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR), also advises that all diagnosed patients should have their myositis antibody levels checked and have their overall well-being assessed. Other recommendations for all patients include the use of glucocorticoids to reduce muscle inflammation and conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) for long-term treatment.

“Finally, now, we’re able to standardize the way we treat adults and children with IIM,” senior guideline author Hector Chinoy, PhD, said at the society’s annual meeting.

It has been a long labor of love, however, taking 4 years to get the guideline published, said Dr. Chinoy, professor of rheumatology and neuromuscular disease at the University of Manchester (England), and a consultant at Salford (England) Royal Hospital.

“We’re not covering diagnosis, classification, or the investigation of suspected IIM,” said Dr. Chinoy. Inclusion body myositis also is not included.

Altogether, there are 13 recommendations that have been developed using a PICO (patient or population, intervention, comparison, outcome) format, graded based on the quality of the available evidence, and then voted on by the working group members to give a score of the strength of agreement. Dr. Chinoy noted that there was a checklist included in the Supplementary Data section of the guideline to help follow the recommendations.

“The target audience for the guideline reflects the variety of clinicians caring for patients with IIM,” Dr. Chinoy said. So that is not just pediatric and adult rheumatologists, but also neurologists, dermatologists, respiratory physicians, oncologists, gastroenterologists, cardiologists, and of course other health care professionals. This includes rheumatology and neurology nurses, psychologists, speech and language therapists, and podiatrists, as well as rheumatology specialist pharmacists, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists.

With reference to the latter, Liza McCann, MBBS, who co-led the development of the guideline, said in a statement released by the BSR that the guideline “highlights the importance of exercise, led and monitored by specialist physiotherapists and occupational therapists.”

Dr. McCann, a consultant pediatric rheumatologist at Alder Hey Hospital, Liverpool, England, and Honorary Clinical Lecturer at the University of Liverpool, added that the guidelines also cover “the need to address psychological wellbeing as an integral part of treatment, in parallel with pharmacological therapies.”

Recommendation highlights

Some of the highlights of the recommendations include the use of high-dose glucocorticoids to manage skeletal muscle inflammation at the time of treatment induction, with specific guidance on the different doses to use in adults and in children. There also is guidance on the use of csDMARDs in both populations and what to use if there is refractory disease – with the strongest evidence supporting the use of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or cyclophosphamide, and possibly rituximab and abatacept.

“There is insufficient evidence to recommend JAK inhibition,” Dr. Chinoy said. The data search used to develop the guideline had a cutoff of October 2020, but even now there is only anecdotal evidence from case studies, he added.

Importantly, the guidelines recognize that childhood IIM differs from adult disease and call for children to be managed by pediatric specialists.

“Routine assessment of dysphagia should be considered in all patients,” Dr. Chinoy said, “so ask the question.” The recommendation is that a swallowing assessment should involve a speech and language therapist or gastroenterologist, and that IVIG be considered for active disease and dysphagia that is resistant to other treatments.