User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Case Series: Upadacitinib Effective for Granulomatous Cheilitis

TOPLINE:

in a small retrospective case series.

METHODOLOGY:

- Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare, nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammatory disorder characterized by intermittent or persistent swelling of the lips.

- In a retrospective case series of five patients (median age, 30 years; four women) with granulomatous cheilitis resistant to systemic treatments at a Belgian hospital between June 2023 and March 2024, all five were treated with a high dose of upadacitinib (30 mg daily).

- The primary endpoint was objective clinical improvement in lip swelling and infiltration over a median follow-up of 7.2 months.

- Three patients had concomitant dormant Crohn’s disease (CD); a secondary outcome was disease activity in these patients.

TAKEAWAY:

- Upadacitinib treatment resulted in a complete response in four patients (80%) within a median of 3.8 months and a partial response in one patient.

- CD remained dormant in the three patients with CD.

- The safety profile of upadacitinib was favorable, and no serious adverse events were reported. Two patients experienced headaches, acne, mild changes in lipids, and/or transaminitis.

IN PRACTICE:

“Upadacitinib was effective in treating patients with recalcitrant and long-lasting granulomatous cheilitis, even in cases of concomitant CD, which could substantially improve the quality of life of affected patients,” the authors wrote. More studies are needed to confirm these results in larger groups of patients over longer periods of time, “and with other JAK inhibitors.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Axel De Greef, MD, Department of Dermatology, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain), Brussels, Belgium. It was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The small sample size and short follow-up may limit the generalizability of the findings to a larger population of patients with granulomatous cheilitis.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not report any funding sources. Some authors reported receiving nonfinancial support and personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

in a small retrospective case series.

METHODOLOGY:

- Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare, nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammatory disorder characterized by intermittent or persistent swelling of the lips.

- In a retrospective case series of five patients (median age, 30 years; four women) with granulomatous cheilitis resistant to systemic treatments at a Belgian hospital between June 2023 and March 2024, all five were treated with a high dose of upadacitinib (30 mg daily).

- The primary endpoint was objective clinical improvement in lip swelling and infiltration over a median follow-up of 7.2 months.

- Three patients had concomitant dormant Crohn’s disease (CD); a secondary outcome was disease activity in these patients.

TAKEAWAY:

- Upadacitinib treatment resulted in a complete response in four patients (80%) within a median of 3.8 months and a partial response in one patient.

- CD remained dormant in the three patients with CD.

- The safety profile of upadacitinib was favorable, and no serious adverse events were reported. Two patients experienced headaches, acne, mild changes in lipids, and/or transaminitis.

IN PRACTICE:

“Upadacitinib was effective in treating patients with recalcitrant and long-lasting granulomatous cheilitis, even in cases of concomitant CD, which could substantially improve the quality of life of affected patients,” the authors wrote. More studies are needed to confirm these results in larger groups of patients over longer periods of time, “and with other JAK inhibitors.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Axel De Greef, MD, Department of Dermatology, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain), Brussels, Belgium. It was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The small sample size and short follow-up may limit the generalizability of the findings to a larger population of patients with granulomatous cheilitis.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not report any funding sources. Some authors reported receiving nonfinancial support and personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

in a small retrospective case series.

METHODOLOGY:

- Granulomatous cheilitis is a rare, nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammatory disorder characterized by intermittent or persistent swelling of the lips.

- In a retrospective case series of five patients (median age, 30 years; four women) with granulomatous cheilitis resistant to systemic treatments at a Belgian hospital between June 2023 and March 2024, all five were treated with a high dose of upadacitinib (30 mg daily).

- The primary endpoint was objective clinical improvement in lip swelling and infiltration over a median follow-up of 7.2 months.

- Three patients had concomitant dormant Crohn’s disease (CD); a secondary outcome was disease activity in these patients.

TAKEAWAY:

- Upadacitinib treatment resulted in a complete response in four patients (80%) within a median of 3.8 months and a partial response in one patient.

- CD remained dormant in the three patients with CD.

- The safety profile of upadacitinib was favorable, and no serious adverse events were reported. Two patients experienced headaches, acne, mild changes in lipids, and/or transaminitis.

IN PRACTICE:

“Upadacitinib was effective in treating patients with recalcitrant and long-lasting granulomatous cheilitis, even in cases of concomitant CD, which could substantially improve the quality of life of affected patients,” the authors wrote. More studies are needed to confirm these results in larger groups of patients over longer periods of time, “and with other JAK inhibitors.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Axel De Greef, MD, Department of Dermatology, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université catholique de Louvain (UCLouvain), Brussels, Belgium. It was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The small sample size and short follow-up may limit the generalizability of the findings to a larger population of patients with granulomatous cheilitis.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not report any funding sources. Some authors reported receiving nonfinancial support and personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Psychiatric, Autoimmune Comorbidities Increased in Patients with Alopecia Areata

TOPLINE:

and were at greater risk of developing those comorbidities after diagnosis.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated 63,384 patients with AA and 3,309,107 individuals without AA (aged 12-64 years) from the Merative MarketScan Research Databases.

- The matched cohorts included 16,512 patients with AA and 66,048 control individuals.

- Outcomes were the prevalence of psychiatric and autoimmune diseases at baseline and the incidence of new-onset psychiatric and autoimmune diseases during the year after diagnosis.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, patients with AA showed a greater prevalence of any psychiatric disease (30.9% vs 26.8%; P < .001) and any immune-mediated or autoimmune disease (16.1% vs 8.9%; P < .0001) than those with controls.

- In matched cohorts, patients with AA also showed a higher incidence of any new-onset psychiatric diseases (10.2% vs 6.8%; P < .001) or immune-mediated or autoimmune disease (6.2% vs 1.5%; P <.001) within the first 12 months of AA diagnosis than those with controls.

- Among patients with AA, the risk of developing a psychiatric comorbidity was higher (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.3; 95% CI, 1.3-1.4). The highest risks were seen for adjustment disorder (aHR, 1.5), panic disorder (aHR, 1.4), and sexual dysfunction (aHR, 1.4).

- Compared with controls, patients with AA were also at an increased risk of developing immune-mediated or autoimmune comorbidities (aHR, 2.7; 95% CI, 2.5-2.8), with the highest for systemic lupus (aHR, 5.7), atopic dermatitis (aHR, 4.3), and vitiligo (aHR, 3.8).

IN PRACTICE:

“Routine monitoring of patients with AA, especially those at risk of developing comorbidities, may permit earlier and more effective intervention,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Arash Mostaghimi, MD, MPA, MPH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston. It was published online on July 31, 2024, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Causality could not be inferred because of the retrospective nature of the study. Comorbidities were solely diagnosed on the basis of diagnostic codes, and researchers did not have access to characteristics such as lab values that could have indicated any underlying comorbidity before the AA diagnosis. This study also did not account for the varying levels of severity of the disease, which may have led to an underestimation of disease burden and the risk for comorbidities.

DISCLOSURES:

AbbVie provided funding for this study. Mostaghimi disclosed receiving personal fees from Abbvie and several other companies outside of this work. The other four authors were current or former employees of Abbvie and have or may have stock and/or stock options in AbbVie.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

and were at greater risk of developing those comorbidities after diagnosis.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated 63,384 patients with AA and 3,309,107 individuals without AA (aged 12-64 years) from the Merative MarketScan Research Databases.

- The matched cohorts included 16,512 patients with AA and 66,048 control individuals.

- Outcomes were the prevalence of psychiatric and autoimmune diseases at baseline and the incidence of new-onset psychiatric and autoimmune diseases during the year after diagnosis.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, patients with AA showed a greater prevalence of any psychiatric disease (30.9% vs 26.8%; P < .001) and any immune-mediated or autoimmune disease (16.1% vs 8.9%; P < .0001) than those with controls.

- In matched cohorts, patients with AA also showed a higher incidence of any new-onset psychiatric diseases (10.2% vs 6.8%; P < .001) or immune-mediated or autoimmune disease (6.2% vs 1.5%; P <.001) within the first 12 months of AA diagnosis than those with controls.

- Among patients with AA, the risk of developing a psychiatric comorbidity was higher (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.3; 95% CI, 1.3-1.4). The highest risks were seen for adjustment disorder (aHR, 1.5), panic disorder (aHR, 1.4), and sexual dysfunction (aHR, 1.4).

- Compared with controls, patients with AA were also at an increased risk of developing immune-mediated or autoimmune comorbidities (aHR, 2.7; 95% CI, 2.5-2.8), with the highest for systemic lupus (aHR, 5.7), atopic dermatitis (aHR, 4.3), and vitiligo (aHR, 3.8).

IN PRACTICE:

“Routine monitoring of patients with AA, especially those at risk of developing comorbidities, may permit earlier and more effective intervention,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Arash Mostaghimi, MD, MPA, MPH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston. It was published online on July 31, 2024, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Causality could not be inferred because of the retrospective nature of the study. Comorbidities were solely diagnosed on the basis of diagnostic codes, and researchers did not have access to characteristics such as lab values that could have indicated any underlying comorbidity before the AA diagnosis. This study also did not account for the varying levels of severity of the disease, which may have led to an underestimation of disease burden and the risk for comorbidities.

DISCLOSURES:

AbbVie provided funding for this study. Mostaghimi disclosed receiving personal fees from Abbvie and several other companies outside of this work. The other four authors were current or former employees of Abbvie and have or may have stock and/or stock options in AbbVie.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

and were at greater risk of developing those comorbidities after diagnosis.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers evaluated 63,384 patients with AA and 3,309,107 individuals without AA (aged 12-64 years) from the Merative MarketScan Research Databases.

- The matched cohorts included 16,512 patients with AA and 66,048 control individuals.

- Outcomes were the prevalence of psychiatric and autoimmune diseases at baseline and the incidence of new-onset psychiatric and autoimmune diseases during the year after diagnosis.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, patients with AA showed a greater prevalence of any psychiatric disease (30.9% vs 26.8%; P < .001) and any immune-mediated or autoimmune disease (16.1% vs 8.9%; P < .0001) than those with controls.

- In matched cohorts, patients with AA also showed a higher incidence of any new-onset psychiatric diseases (10.2% vs 6.8%; P < .001) or immune-mediated or autoimmune disease (6.2% vs 1.5%; P <.001) within the first 12 months of AA diagnosis than those with controls.

- Among patients with AA, the risk of developing a psychiatric comorbidity was higher (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.3; 95% CI, 1.3-1.4). The highest risks were seen for adjustment disorder (aHR, 1.5), panic disorder (aHR, 1.4), and sexual dysfunction (aHR, 1.4).

- Compared with controls, patients with AA were also at an increased risk of developing immune-mediated or autoimmune comorbidities (aHR, 2.7; 95% CI, 2.5-2.8), with the highest for systemic lupus (aHR, 5.7), atopic dermatitis (aHR, 4.3), and vitiligo (aHR, 3.8).

IN PRACTICE:

“Routine monitoring of patients with AA, especially those at risk of developing comorbidities, may permit earlier and more effective intervention,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Arash Mostaghimi, MD, MPA, MPH, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston. It was published online on July 31, 2024, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Causality could not be inferred because of the retrospective nature of the study. Comorbidities were solely diagnosed on the basis of diagnostic codes, and researchers did not have access to characteristics such as lab values that could have indicated any underlying comorbidity before the AA diagnosis. This study also did not account for the varying levels of severity of the disease, which may have led to an underestimation of disease burden and the risk for comorbidities.

DISCLOSURES:

AbbVie provided funding for this study. Mostaghimi disclosed receiving personal fees from Abbvie and several other companies outside of this work. The other four authors were current or former employees of Abbvie and have or may have stock and/or stock options in AbbVie.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Expanded Surface Area Safe, Well-Tolerated for AK treatment

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- This phase 3 multicenter, single-arm trial evaluated the safety and tolerability of tirbanibulin ointment 1% in 105 adults with 4-12 clinically typical, visible, and discrete AKs on the face or balding scalp from June to December 2022 in the United States. (In June 2024, the Food and Drug Administration approved a supplemental new drug application for tirbanibulin 1%, a microtubule inhibitor, allowing the expansion of the surface area treated for AKs of the face or scalp from 25 cm2 to 100 cm2.)

- Participants applied tirbanibulin ointment 1% once daily for 5 days over a treatment field of about 100 cm2 on the face or balding scalp. A total of 102 patients completed the study.

- Safety and tolerability were evaluated with reports of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and a composite score of six local tolerability signs on days 5, 8, 15, and 29, and on completion of the evaluation period on day 57.

TAKEAWAY:

- The most common local effects of treatment were erythema (96.1% of patients) and flaking or scaling (84.4%), with severe cases reported in 5.8% and 8.7% of the patients, respectively.

- The mean maximum local tolerability composite score was 4.1 out of 18, which peaked around day 8 and returned to baseline by day 29.

- TEAEs considered related to the treatment were reported in 18.1% of patients; the most frequent were application site pruritus (10.5%) and application site pain (8.6%). No adverse events led to the discontinuation of treatment.

- The mean percent reduction in the lesion count from baseline was 77.8% at day 57, with a mean lesion count of 1.8 at the end of the study.

IN PRACTICE:

In this study, “local tolerability and safety profiles were well characterized in patients with 4-12 clinically typical, visible, and discrete AK lesions in a field of 100 cm2 and were consistent with those previously reported in patients with AK treated in pivotal trials with tirbanibulin over a smaller field (25 cm2),” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Neal Bhatia, MD, of Therapeutics Clinical Research, San Diego, was published online in JAAD International.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was limited by the lack of a placebo group and the absence of long-term follow-up.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by Almirall. Five authors reported being employees of Almirall. Other authors declared having ties with various other sources, including Almirall.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- This phase 3 multicenter, single-arm trial evaluated the safety and tolerability of tirbanibulin ointment 1% in 105 adults with 4-12 clinically typical, visible, and discrete AKs on the face or balding scalp from June to December 2022 in the United States. (In June 2024, the Food and Drug Administration approved a supplemental new drug application for tirbanibulin 1%, a microtubule inhibitor, allowing the expansion of the surface area treated for AKs of the face or scalp from 25 cm2 to 100 cm2.)

- Participants applied tirbanibulin ointment 1% once daily for 5 days over a treatment field of about 100 cm2 on the face or balding scalp. A total of 102 patients completed the study.

- Safety and tolerability were evaluated with reports of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and a composite score of six local tolerability signs on days 5, 8, 15, and 29, and on completion of the evaluation period on day 57.

TAKEAWAY:

- The most common local effects of treatment were erythema (96.1% of patients) and flaking or scaling (84.4%), with severe cases reported in 5.8% and 8.7% of the patients, respectively.

- The mean maximum local tolerability composite score was 4.1 out of 18, which peaked around day 8 and returned to baseline by day 29.

- TEAEs considered related to the treatment were reported in 18.1% of patients; the most frequent were application site pruritus (10.5%) and application site pain (8.6%). No adverse events led to the discontinuation of treatment.

- The mean percent reduction in the lesion count from baseline was 77.8% at day 57, with a mean lesion count of 1.8 at the end of the study.

IN PRACTICE:

In this study, “local tolerability and safety profiles were well characterized in patients with 4-12 clinically typical, visible, and discrete AK lesions in a field of 100 cm2 and were consistent with those previously reported in patients with AK treated in pivotal trials with tirbanibulin over a smaller field (25 cm2),” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Neal Bhatia, MD, of Therapeutics Clinical Research, San Diego, was published online in JAAD International.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was limited by the lack of a placebo group and the absence of long-term follow-up.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by Almirall. Five authors reported being employees of Almirall. Other authors declared having ties with various other sources, including Almirall.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- This phase 3 multicenter, single-arm trial evaluated the safety and tolerability of tirbanibulin ointment 1% in 105 adults with 4-12 clinically typical, visible, and discrete AKs on the face or balding scalp from June to December 2022 in the United States. (In June 2024, the Food and Drug Administration approved a supplemental new drug application for tirbanibulin 1%, a microtubule inhibitor, allowing the expansion of the surface area treated for AKs of the face or scalp from 25 cm2 to 100 cm2.)

- Participants applied tirbanibulin ointment 1% once daily for 5 days over a treatment field of about 100 cm2 on the face or balding scalp. A total of 102 patients completed the study.

- Safety and tolerability were evaluated with reports of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and a composite score of six local tolerability signs on days 5, 8, 15, and 29, and on completion of the evaluation period on day 57.

TAKEAWAY:

- The most common local effects of treatment were erythema (96.1% of patients) and flaking or scaling (84.4%), with severe cases reported in 5.8% and 8.7% of the patients, respectively.

- The mean maximum local tolerability composite score was 4.1 out of 18, which peaked around day 8 and returned to baseline by day 29.

- TEAEs considered related to the treatment were reported in 18.1% of patients; the most frequent were application site pruritus (10.5%) and application site pain (8.6%). No adverse events led to the discontinuation of treatment.

- The mean percent reduction in the lesion count from baseline was 77.8% at day 57, with a mean lesion count of 1.8 at the end of the study.

IN PRACTICE:

In this study, “local tolerability and safety profiles were well characterized in patients with 4-12 clinically typical, visible, and discrete AK lesions in a field of 100 cm2 and were consistent with those previously reported in patients with AK treated in pivotal trials with tirbanibulin over a smaller field (25 cm2),” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Neal Bhatia, MD, of Therapeutics Clinical Research, San Diego, was published online in JAAD International.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was limited by the lack of a placebo group and the absence of long-term follow-up.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by Almirall. Five authors reported being employees of Almirall. Other authors declared having ties with various other sources, including Almirall.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

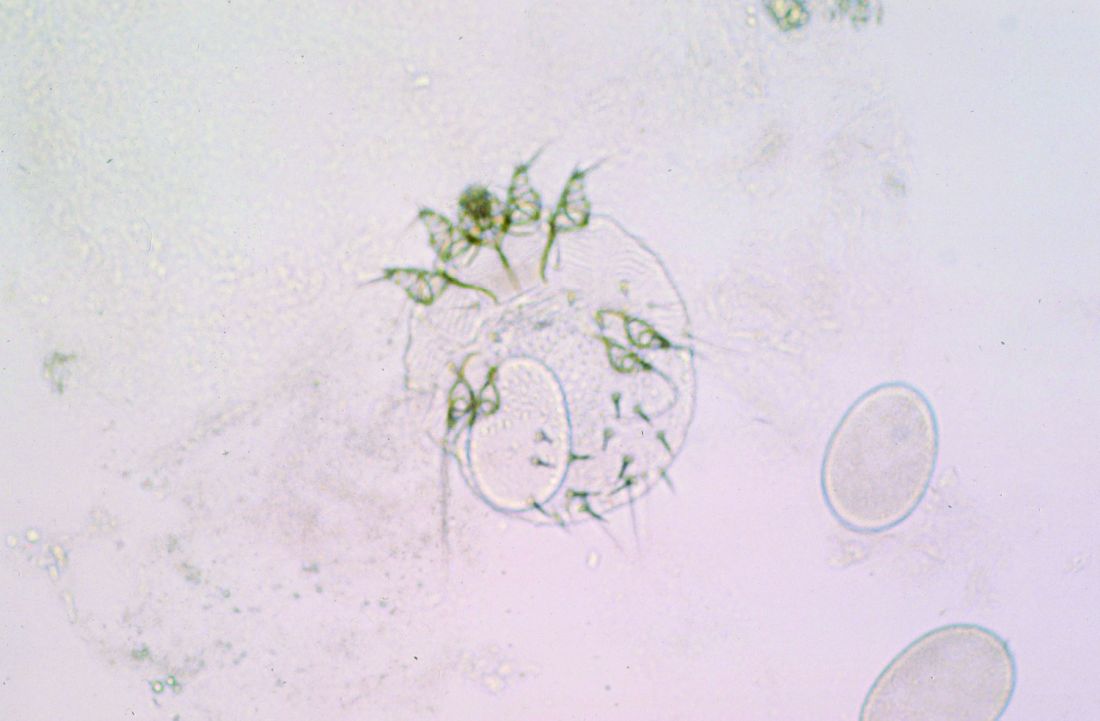

Skin Dxs in Children in Refugee Camps Include Fungal Infections, Leishmaniasis

on the topic, a literature review showed. However, likely culprits include infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations, such as pediculosis, tinea capitis, and scabies.

“Current data indicates that one in two refugees are children,” one of the study investigators, Mehar Maju, MPH, a fourth-year student at of the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, said in an interview following the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, where the results were presented during a poster session.

“The number of refugees continues to rise to unprecedented levels every year,” and climate change continues to drive increases in migration, “impacting those residing in camps,” she said. “As we continue to think about what this means for best supporting those residing in camps, I think it’s also important to consider how to best support refugees, specifically children, when they arrive in the United States. Part of this is to know what conditions are most prevalent and what type of social support this vulnerable population needs.”

To identify the common dermatologic conditions among children living in refugee camps, Ms. Maju and fellow fourth-year University of Washington medical student Nadia Siddiqui searched PubMed and Google Scholar for studies that were published in English and reported on the skin disease prevalence and management for refugees who are children. Key search terms used included “refugees,” “children,” “dermatology,” and “skin disease.” Of approximately 105 potential studies identified, 19 underwent analysis. Of these, only five were included in the final review.

One of the five studies was conducted in rural Nyala, Sudan. The study found that 88.8% of those living in orphanages and refugee camps were reported to have a skin disorder, commonly fungal or bacterial infections and dermatitis. In a separate case series, researchers found that cutaneous leishmaniasis was rising among Syrian refugee children.

A study that looked at morbidity and disease burden in mainland Greece refugee camps found that the skin was the second-most common site of communicable diseases among children, behind those of the respiratory tract. In another study that investigated the health of children in Australian immigration detention centers, complaints related to skin conditions were significantly elevated among children who were detained offshore, compared with those who were detained onshore.

Finally, in a study of 125 children between the ages of 1 and 15 years at a Sierra Leone–based displacement camp, the prevalence of scabies was 77% among those aged < 5 years and peaked to 86% among those aged 5-9 years.

“It was surprising to see the limited information about dermatologic diseases impacting children in refugee camps,” Ms. Maju said. “I expected that there would be more information on the specific proportion of diseases beyond those of infectious etiology. For example, I had believed that we would have more information on the prevalence of atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, and other more chronic skin diseases.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, mainly the lack of published information on the skin health of pediatric refugees. “A study that evaluates the health status and dermatologic prevalence of disease among children residing in camps and those newly arrived in the United States from camps would provide unprecedented insight into this topic,” Ms. Maju said. “The results could guide public health efforts in improving care delivery and preparedness in camps and clinicians serving this particular population when they arrive in the United States.”

She and Ms. Siddiqui reported having no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

on the topic, a literature review showed. However, likely culprits include infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations, such as pediculosis, tinea capitis, and scabies.

“Current data indicates that one in two refugees are children,” one of the study investigators, Mehar Maju, MPH, a fourth-year student at of the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, said in an interview following the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, where the results were presented during a poster session.

“The number of refugees continues to rise to unprecedented levels every year,” and climate change continues to drive increases in migration, “impacting those residing in camps,” she said. “As we continue to think about what this means for best supporting those residing in camps, I think it’s also important to consider how to best support refugees, specifically children, when they arrive in the United States. Part of this is to know what conditions are most prevalent and what type of social support this vulnerable population needs.”

To identify the common dermatologic conditions among children living in refugee camps, Ms. Maju and fellow fourth-year University of Washington medical student Nadia Siddiqui searched PubMed and Google Scholar for studies that were published in English and reported on the skin disease prevalence and management for refugees who are children. Key search terms used included “refugees,” “children,” “dermatology,” and “skin disease.” Of approximately 105 potential studies identified, 19 underwent analysis. Of these, only five were included in the final review.

One of the five studies was conducted in rural Nyala, Sudan. The study found that 88.8% of those living in orphanages and refugee camps were reported to have a skin disorder, commonly fungal or bacterial infections and dermatitis. In a separate case series, researchers found that cutaneous leishmaniasis was rising among Syrian refugee children.

A study that looked at morbidity and disease burden in mainland Greece refugee camps found that the skin was the second-most common site of communicable diseases among children, behind those of the respiratory tract. In another study that investigated the health of children in Australian immigration detention centers, complaints related to skin conditions were significantly elevated among children who were detained offshore, compared with those who were detained onshore.

Finally, in a study of 125 children between the ages of 1 and 15 years at a Sierra Leone–based displacement camp, the prevalence of scabies was 77% among those aged < 5 years and peaked to 86% among those aged 5-9 years.

“It was surprising to see the limited information about dermatologic diseases impacting children in refugee camps,” Ms. Maju said. “I expected that there would be more information on the specific proportion of diseases beyond those of infectious etiology. For example, I had believed that we would have more information on the prevalence of atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, and other more chronic skin diseases.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, mainly the lack of published information on the skin health of pediatric refugees. “A study that evaluates the health status and dermatologic prevalence of disease among children residing in camps and those newly arrived in the United States from camps would provide unprecedented insight into this topic,” Ms. Maju said. “The results could guide public health efforts in improving care delivery and preparedness in camps and clinicians serving this particular population when they arrive in the United States.”

She and Ms. Siddiqui reported having no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

on the topic, a literature review showed. However, likely culprits include infectious diseases with cutaneous manifestations, such as pediculosis, tinea capitis, and scabies.

“Current data indicates that one in two refugees are children,” one of the study investigators, Mehar Maju, MPH, a fourth-year student at of the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, said in an interview following the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, where the results were presented during a poster session.

“The number of refugees continues to rise to unprecedented levels every year,” and climate change continues to drive increases in migration, “impacting those residing in camps,” she said. “As we continue to think about what this means for best supporting those residing in camps, I think it’s also important to consider how to best support refugees, specifically children, when they arrive in the United States. Part of this is to know what conditions are most prevalent and what type of social support this vulnerable population needs.”

To identify the common dermatologic conditions among children living in refugee camps, Ms. Maju and fellow fourth-year University of Washington medical student Nadia Siddiqui searched PubMed and Google Scholar for studies that were published in English and reported on the skin disease prevalence and management for refugees who are children. Key search terms used included “refugees,” “children,” “dermatology,” and “skin disease.” Of approximately 105 potential studies identified, 19 underwent analysis. Of these, only five were included in the final review.

One of the five studies was conducted in rural Nyala, Sudan. The study found that 88.8% of those living in orphanages and refugee camps were reported to have a skin disorder, commonly fungal or bacterial infections and dermatitis. In a separate case series, researchers found that cutaneous leishmaniasis was rising among Syrian refugee children.

A study that looked at morbidity and disease burden in mainland Greece refugee camps found that the skin was the second-most common site of communicable diseases among children, behind those of the respiratory tract. In another study that investigated the health of children in Australian immigration detention centers, complaints related to skin conditions were significantly elevated among children who were detained offshore, compared with those who were detained onshore.

Finally, in a study of 125 children between the ages of 1 and 15 years at a Sierra Leone–based displacement camp, the prevalence of scabies was 77% among those aged < 5 years and peaked to 86% among those aged 5-9 years.

“It was surprising to see the limited information about dermatologic diseases impacting children in refugee camps,” Ms. Maju said. “I expected that there would be more information on the specific proportion of diseases beyond those of infectious etiology. For example, I had believed that we would have more information on the prevalence of atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, and other more chronic skin diseases.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, mainly the lack of published information on the skin health of pediatric refugees. “A study that evaluates the health status and dermatologic prevalence of disease among children residing in camps and those newly arrived in the United States from camps would provide unprecedented insight into this topic,” Ms. Maju said. “The results could guide public health efforts in improving care delivery and preparedness in camps and clinicians serving this particular population when they arrive in the United States.”

She and Ms. Siddiqui reported having no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SPD 2024

Eruptive Syringoma Manifesting as a Widespread Rash in 3 Patients

To the Editor:

Syringoma is a relatively common benign adnexal neoplasm originating in the ducts of eccrine sweat glands. It can be

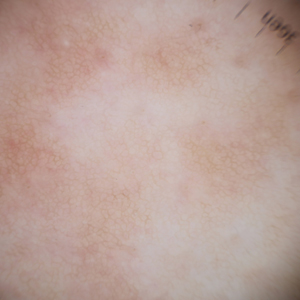

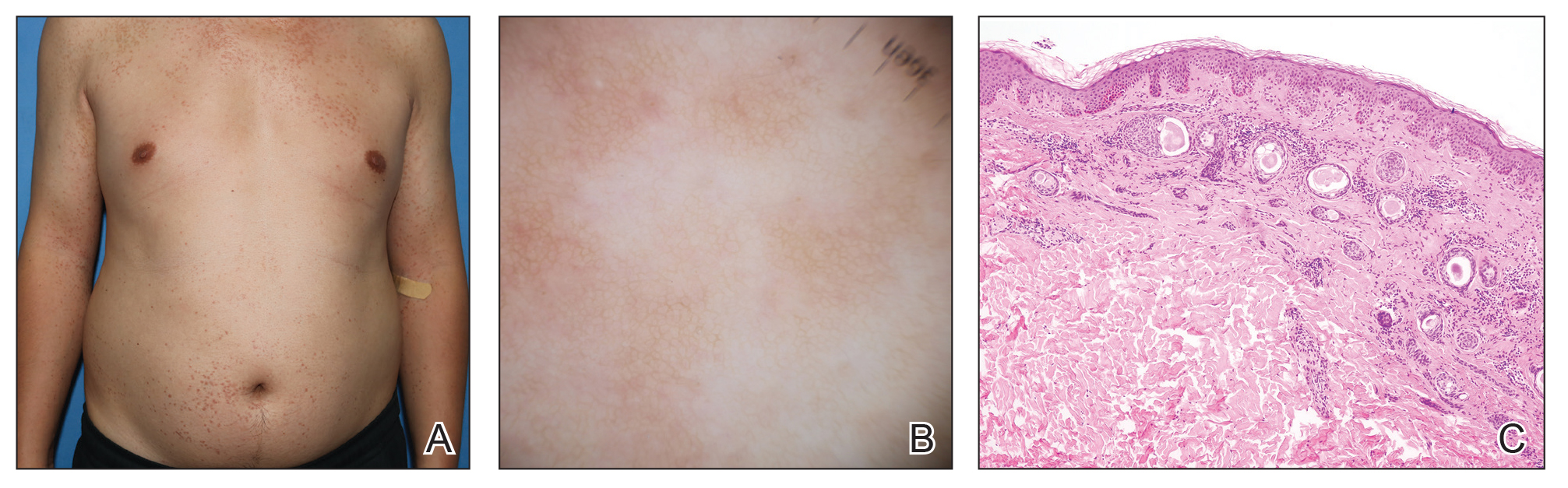

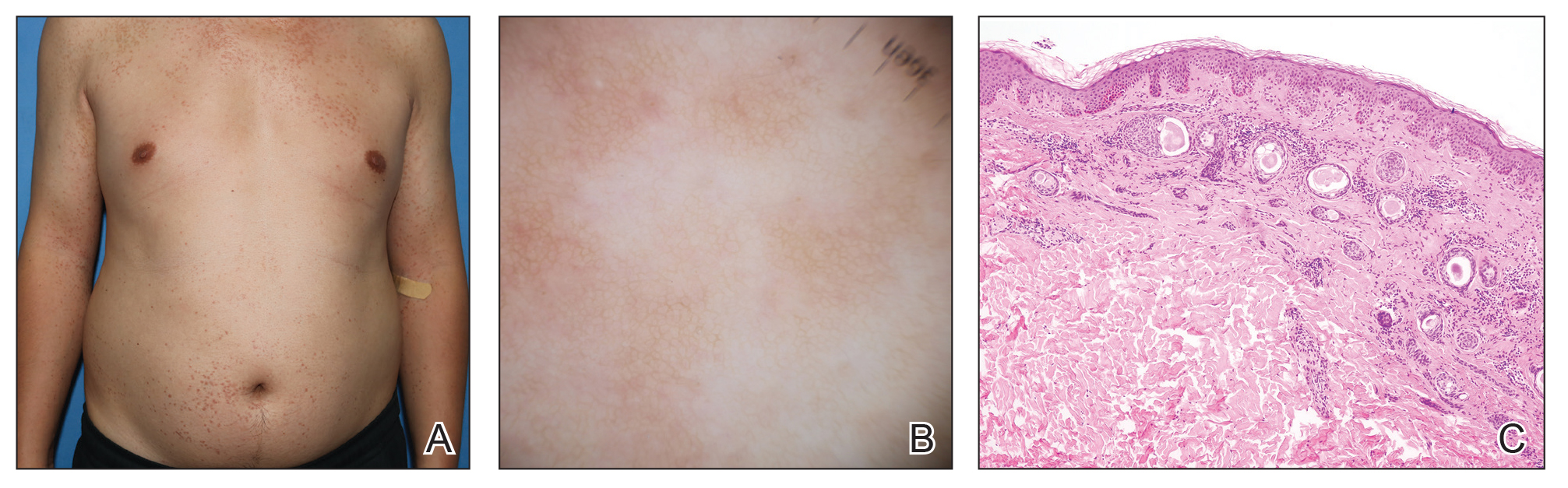

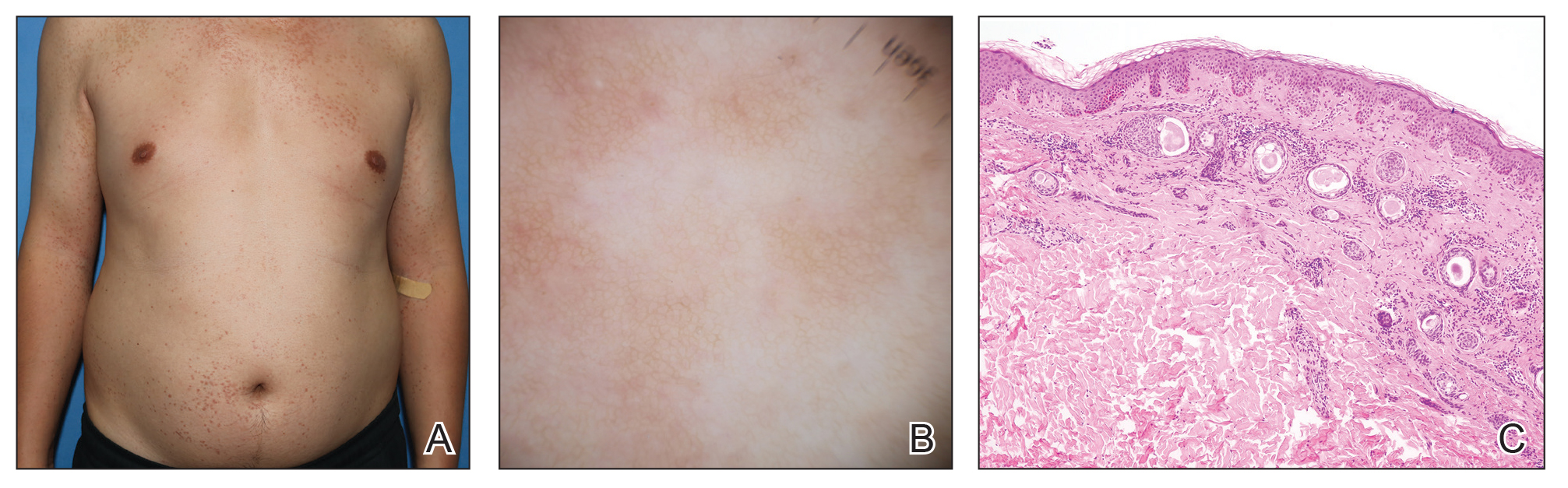

A 28-year-old man presented with multiple asymptomatic papules on the trunk and upper arms of 20 years’ duration (patient 1). He had been diagnosed with Darier disease 3 years prior to the current presentation and was treated with oral and topical retinoic acid without a response. After 3 months of oral treatment, the retinoic acid was stopped due to elevated liver enzymes. Physical examination at the current presentation revealed multiple smooth, firm, nonfused, 1- to 4-mm

A 27-year-old woman presented with widespread asymptomatic papules

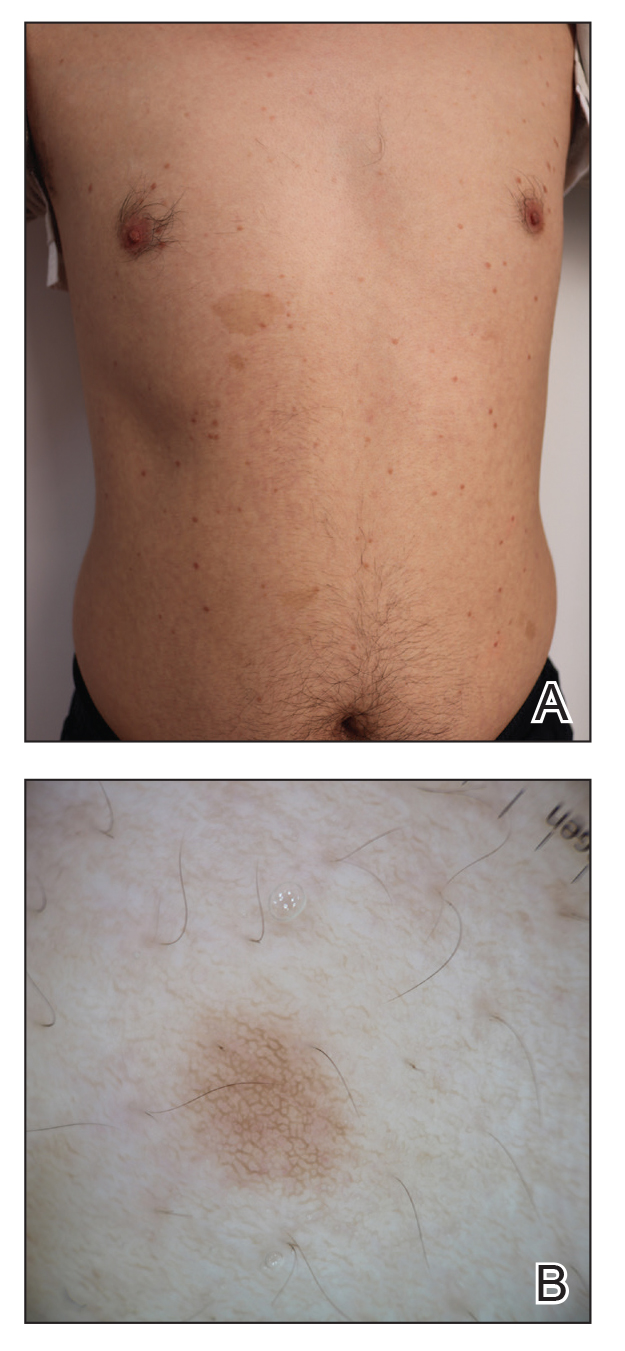

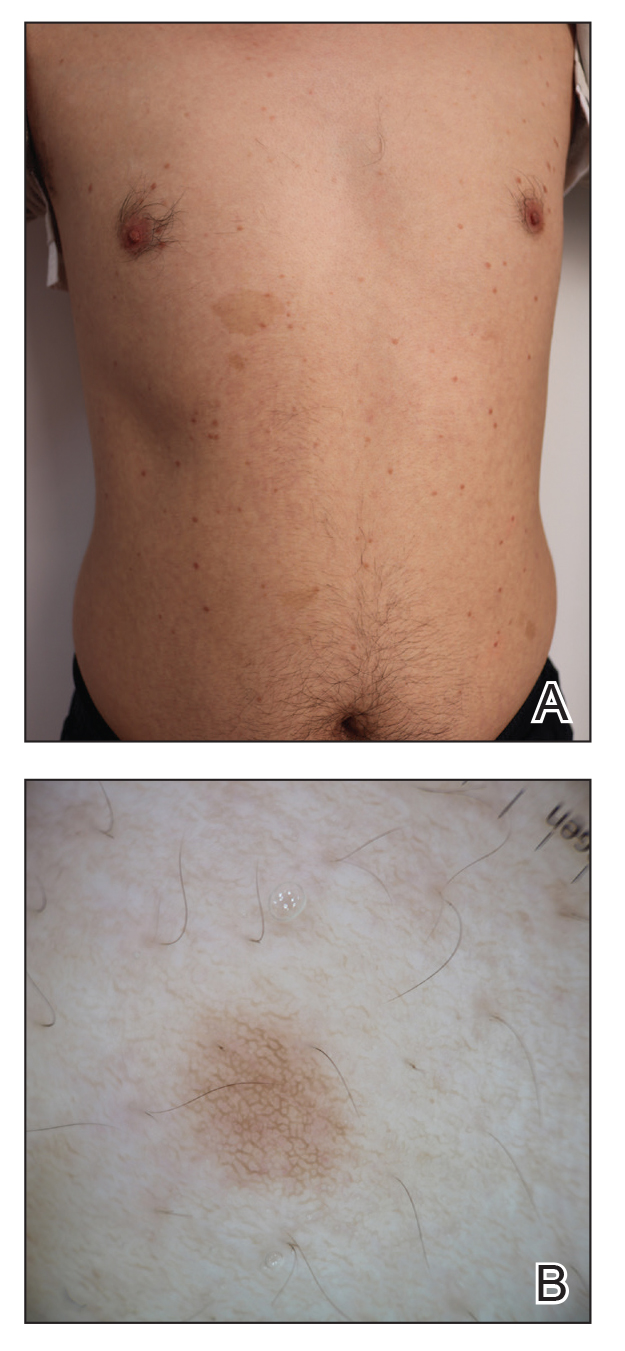

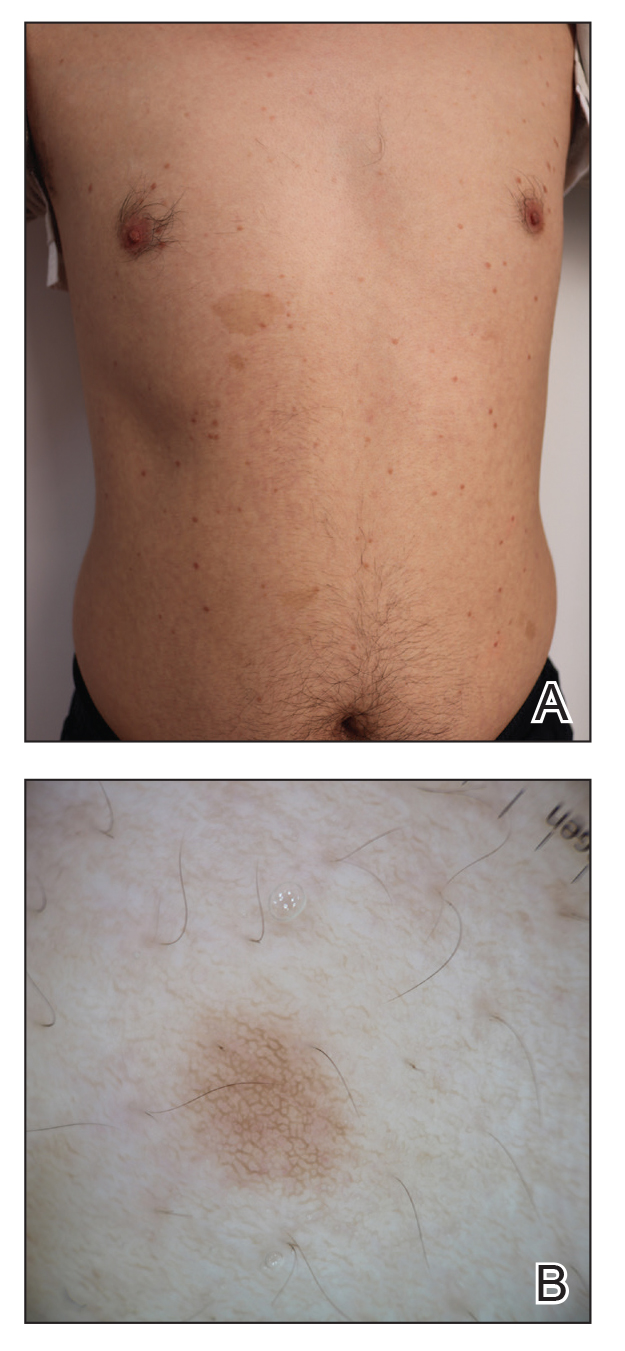

A 43-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with brownish flat-topped papules on the chest and abdomen of 19 years’ duration (Figure 3A)(patient 3). The lesions had remained stable and did not progress. He denied any treatment.

All 3 patients demonstrated classic histopathologic features of syringoma, and none had a family history of similar skin lesions. The clinical and dermoscopic findings along with the histopathology in all 3 patients were consistent with ES.

The pathogenesis of ES is

- Williams K, Shinkai K. Evaluation and management of the patient with multiple syringomas: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1234-1240.e1239. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.006

- Jacquet L, Darier J.

Hidradénomes éruptifs, I.épithéliomes adenoids des glandes sudoripares ou adénomes sudoripares. Ann Dermatol Venerol. 1887;8:317-323. - Huang A, Taylor G, Liebman TN. Generalized eruptive syringomas. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt0hb8q22g..

- Maeda T, Natsuga K, Nishie W, et al. Extensive eruptive syringoma after liver transplantation. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:119-120. doi:10.2340/00015555-2814

- Lerner TH, Barr RJ, Dolezal JF, et al. Syringomatous hyperplasia and eccrine squamous syringometaplasia associated with benoxaprofen therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1202-1204. doi:10.1001/archderm.1987.01660330113022

- Ozturk F, Ermertcan AT, Bilac C, et al.

A case report of postpubertal eruptive syringoma triggered with antiepileptic drugs. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:707-710. - Guitart J, Rosenbaum MM, Requena L. ‘Eruptive syringoma’: a misnomer for a reactive eccrine gland ductal proliferation? J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:202-205. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.00023.x

- Dupre A, Carrere S, Bonafe JL, et al. Eruptive generalized syringomas, milium and atrophoderma vermiculata. Nicolau and Balus’ syndrome (author’s transl). Dermatologica. 1981;162:281-286.

- Schepis C, Torre V, Siragusa M, et al. Eruptive syringomas with calcium deposits in a young woman with Down’s syndrome. Dermatology. 2001;203:345-347. doi:10.1159/000051788

- Samia AM, Donthi D, Nenow J, et al. A case study and review of literature of eruptive syringoma in a six-year-old. Cureus. 2021;13:E14634. doi:10.7759/cureus.14634

- Soler-Carrillo J, Estrach T, Mascaró JM. Eruptive syringoma: 27 new cases and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:242-246. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00235.x

- Aleissa M, Aljarbou O, AlJasser MI. Dermoscopy of eruptive syringoma. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:401-403. doi:10.1159/000515443

- Botsali A, Caliskan E, Coskun A, et al. Eruptive syringoma: two cases with dermoscopic features. Skin Appendage Disord. 2020;6:319-322. doi:10.1159/000508656

- Dutra Rezende H, Madia ACT, Elias BM, et al. Comment on: eruptive syringoma—two cases with dermoscopic features. Skin Appendage Disord. 2022;8:81-82. doi:10.1159/000518158

- Silva-Hirschberg C, Cabrera R, Rollán MP, et al. Darier disease: the use of dermoscopy in monitoring acitretin treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2022;97:644-647. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2021.05.021

- Singal A, Kaur I, Jakhar D. Fox-Fordyce disease: dermoscopic perspective. Skin Appendage Disord. 2020;6:247-249. doi:10.1159/000508201

- Brau Javier CN, Morales A, Sanchez JL. Histopathology attributes of Fox-Fordyce disease. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1313-1318. doi:10.1159/000508201

- Horie K, Shinkuma S, Fujita Y, et al. Efficacy of N-(3,4-dimethoxycinnamoyl)-anthranilic acid (tranilast) against eruptive syringoma: report of two cases and review of published work. J Dermatol. 2012;39:1044-1046. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01612.x

- Sanchez TS, Dauden E, Casas AP, et al. Eruptive pruritic syringomas: treatment with topical atropine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:148-149. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.109854

To the Editor:

Syringoma is a relatively common benign adnexal neoplasm originating in the ducts of eccrine sweat glands. It can be

A 28-year-old man presented with multiple asymptomatic papules on the trunk and upper arms of 20 years’ duration (patient 1). He had been diagnosed with Darier disease 3 years prior to the current presentation and was treated with oral and topical retinoic acid without a response. After 3 months of oral treatment, the retinoic acid was stopped due to elevated liver enzymes. Physical examination at the current presentation revealed multiple smooth, firm, nonfused, 1- to 4-mm

A 27-year-old woman presented with widespread asymptomatic papules

A 43-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with brownish flat-topped papules on the chest and abdomen of 19 years’ duration (Figure 3A)(patient 3). The lesions had remained stable and did not progress. He denied any treatment.

All 3 patients demonstrated classic histopathologic features of syringoma, and none had a family history of similar skin lesions. The clinical and dermoscopic findings along with the histopathology in all 3 patients were consistent with ES.

The pathogenesis of ES is

To the Editor:

Syringoma is a relatively common benign adnexal neoplasm originating in the ducts of eccrine sweat glands. It can be

A 28-year-old man presented with multiple asymptomatic papules on the trunk and upper arms of 20 years’ duration (patient 1). He had been diagnosed with Darier disease 3 years prior to the current presentation and was treated with oral and topical retinoic acid without a response. After 3 months of oral treatment, the retinoic acid was stopped due to elevated liver enzymes. Physical examination at the current presentation revealed multiple smooth, firm, nonfused, 1- to 4-mm

A 27-year-old woman presented with widespread asymptomatic papules

A 43-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with brownish flat-topped papules on the chest and abdomen of 19 years’ duration (Figure 3A)(patient 3). The lesions had remained stable and did not progress. He denied any treatment.

All 3 patients demonstrated classic histopathologic features of syringoma, and none had a family history of similar skin lesions. The clinical and dermoscopic findings along with the histopathology in all 3 patients were consistent with ES.

The pathogenesis of ES is

- Williams K, Shinkai K. Evaluation and management of the patient with multiple syringomas: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1234-1240.e1239. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.006

- Jacquet L, Darier J.

Hidradénomes éruptifs, I.épithéliomes adenoids des glandes sudoripares ou adénomes sudoripares. Ann Dermatol Venerol. 1887;8:317-323. - Huang A, Taylor G, Liebman TN. Generalized eruptive syringomas. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt0hb8q22g..

- Maeda T, Natsuga K, Nishie W, et al. Extensive eruptive syringoma after liver transplantation. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:119-120. doi:10.2340/00015555-2814

- Lerner TH, Barr RJ, Dolezal JF, et al. Syringomatous hyperplasia and eccrine squamous syringometaplasia associated with benoxaprofen therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1202-1204. doi:10.1001/archderm.1987.01660330113022

- Ozturk F, Ermertcan AT, Bilac C, et al.

A case report of postpubertal eruptive syringoma triggered with antiepileptic drugs. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:707-710. - Guitart J, Rosenbaum MM, Requena L. ‘Eruptive syringoma’: a misnomer for a reactive eccrine gland ductal proliferation? J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:202-205. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.00023.x

- Dupre A, Carrere S, Bonafe JL, et al. Eruptive generalized syringomas, milium and atrophoderma vermiculata. Nicolau and Balus’ syndrome (author’s transl). Dermatologica. 1981;162:281-286.

- Schepis C, Torre V, Siragusa M, et al. Eruptive syringomas with calcium deposits in a young woman with Down’s syndrome. Dermatology. 2001;203:345-347. doi:10.1159/000051788

- Samia AM, Donthi D, Nenow J, et al. A case study and review of literature of eruptive syringoma in a six-year-old. Cureus. 2021;13:E14634. doi:10.7759/cureus.14634

- Soler-Carrillo J, Estrach T, Mascaró JM. Eruptive syringoma: 27 new cases and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:242-246. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00235.x

- Aleissa M, Aljarbou O, AlJasser MI. Dermoscopy of eruptive syringoma. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:401-403. doi:10.1159/000515443

- Botsali A, Caliskan E, Coskun A, et al. Eruptive syringoma: two cases with dermoscopic features. Skin Appendage Disord. 2020;6:319-322. doi:10.1159/000508656

- Dutra Rezende H, Madia ACT, Elias BM, et al. Comment on: eruptive syringoma—two cases with dermoscopic features. Skin Appendage Disord. 2022;8:81-82. doi:10.1159/000518158

- Silva-Hirschberg C, Cabrera R, Rollán MP, et al. Darier disease: the use of dermoscopy in monitoring acitretin treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2022;97:644-647. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2021.05.021

- Singal A, Kaur I, Jakhar D. Fox-Fordyce disease: dermoscopic perspective. Skin Appendage Disord. 2020;6:247-249. doi:10.1159/000508201

- Brau Javier CN, Morales A, Sanchez JL. Histopathology attributes of Fox-Fordyce disease. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1313-1318. doi:10.1159/000508201

- Horie K, Shinkuma S, Fujita Y, et al. Efficacy of N-(3,4-dimethoxycinnamoyl)-anthranilic acid (tranilast) against eruptive syringoma: report of two cases and review of published work. J Dermatol. 2012;39:1044-1046. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01612.x

- Sanchez TS, Dauden E, Casas AP, et al. Eruptive pruritic syringomas: treatment with topical atropine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:148-149. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.109854

- Williams K, Shinkai K. Evaluation and management of the patient with multiple syringomas: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1234-1240.e1239. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.006

- Jacquet L, Darier J.

Hidradénomes éruptifs, I.épithéliomes adenoids des glandes sudoripares ou adénomes sudoripares. Ann Dermatol Venerol. 1887;8:317-323. - Huang A, Taylor G, Liebman TN. Generalized eruptive syringomas. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt0hb8q22g..

- Maeda T, Natsuga K, Nishie W, et al. Extensive eruptive syringoma after liver transplantation. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:119-120. doi:10.2340/00015555-2814

- Lerner TH, Barr RJ, Dolezal JF, et al. Syringomatous hyperplasia and eccrine squamous syringometaplasia associated with benoxaprofen therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1202-1204. doi:10.1001/archderm.1987.01660330113022

- Ozturk F, Ermertcan AT, Bilac C, et al.

A case report of postpubertal eruptive syringoma triggered with antiepileptic drugs. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:707-710. - Guitart J, Rosenbaum MM, Requena L. ‘Eruptive syringoma’: a misnomer for a reactive eccrine gland ductal proliferation? J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:202-205. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2003.00023.x

- Dupre A, Carrere S, Bonafe JL, et al. Eruptive generalized syringomas, milium and atrophoderma vermiculata. Nicolau and Balus’ syndrome (author’s transl). Dermatologica. 1981;162:281-286.

- Schepis C, Torre V, Siragusa M, et al. Eruptive syringomas with calcium deposits in a young woman with Down’s syndrome. Dermatology. 2001;203:345-347. doi:10.1159/000051788

- Samia AM, Donthi D, Nenow J, et al. A case study and review of literature of eruptive syringoma in a six-year-old. Cureus. 2021;13:E14634. doi:10.7759/cureus.14634

- Soler-Carrillo J, Estrach T, Mascaró JM. Eruptive syringoma: 27 new cases and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:242-246. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00235.x

- Aleissa M, Aljarbou O, AlJasser MI. Dermoscopy of eruptive syringoma. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:401-403. doi:10.1159/000515443

- Botsali A, Caliskan E, Coskun A, et al. Eruptive syringoma: two cases with dermoscopic features. Skin Appendage Disord. 2020;6:319-322. doi:10.1159/000508656

- Dutra Rezende H, Madia ACT, Elias BM, et al. Comment on: eruptive syringoma—two cases with dermoscopic features. Skin Appendage Disord. 2022;8:81-82. doi:10.1159/000518158

- Silva-Hirschberg C, Cabrera R, Rollán MP, et al. Darier disease: the use of dermoscopy in monitoring acitretin treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2022;97:644-647. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2021.05.021

- Singal A, Kaur I, Jakhar D. Fox-Fordyce disease: dermoscopic perspective. Skin Appendage Disord. 2020;6:247-249. doi:10.1159/000508201

- Brau Javier CN, Morales A, Sanchez JL. Histopathology attributes of Fox-Fordyce disease. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1313-1318. doi:10.1159/000508201

- Horie K, Shinkuma S, Fujita Y, et al. Efficacy of N-(3,4-dimethoxycinnamoyl)-anthranilic acid (tranilast) against eruptive syringoma: report of two cases and review of published work. J Dermatol. 2012;39:1044-1046. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01612.x

- Sanchez TS, Dauden E, Casas AP, et al. Eruptive pruritic syringomas: treatment with topical atropine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:148-149. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.109854

Practice Points

- Eruptive syringoma (ES) is a benign cutaneous adnexal neoplasm that typically does not require treatment.

- Dermoscopy and biopsy are helpful for the diagnosis of ES, which often is missed or misdiagnosed clinically.

Saxophone Penis: A Forgotten Manifestation of Hidradenitis Suppurativa

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a multifactorial chronic inflammatory skin disease affecting 1% to 4% of Europeans. It is characterized by recurrent inflamed nodules, abscesses, and sinus tracts in intertriginous regions.1 The genital area is affected in 11% of cases2 and usually is connected to severe forms of HS in both men and women.3 The prevalence of HS-associated genital lymphedema remains unknown.

Saxophone penis is a specific penile malformation characterized by a saxophone shape due to inflammation of the major penile lymphatic vessels that cause fibrosis of the surrounding connective tissue. Poor blood flow further causes contracture and distortion of the penile axis.4 Saxophone penis also has been associated with primary lymphedema, lymphogranuloma venereum, filariasis,5 and administration of paraffin injections.6 We describe 3 men with HS who presented with saxophone penis.

A 33-year-old man with Hurley stage III HS presented with a medical history of groin lesions and progressive penoscrotal edema of 13 years’ duration. He had a body mass index (BMI) of 37, no family history of HS or comorbidities, and a 15-year history of smoking 20 cigarettes per day. After repeated surgical drainage of the HS lesions as well as antibiotic treatment with clindamycin 600 mg/d and rifampicin 600 mg/d, the patient was kept on a maintenance therapy with adalimumab 40 mg/wk. Due to lack of response, treatment was discontinued at week 16. Clindamycin and rifampicin 300 mg were immediately reintroduced with no benefit on the genital lesions. The patient underwent genital reconstruction, including penile degloving, scrotoplasty, infrapubic fat pad removal, and perineoplasty (Figure 1). The patient currently is not undergoing any therapies.

A 55-year-old man presented with Hurley stage II HS of 33 years’ duration. He had a BMI of 52; a history of hypertension, hyperuricemia, severe hip and knee osteoarthritis, and orchiopexy in childhood; a smoking history of 40 cigarettes per day; and an alcohol consumption history of 200 mL per day since 18 years of age. He had radical excision of axillary lesions 8 years prior. One year later, he was treated with concomitant clindamycin and rifampicin 300 mg twice daily for 3 months with no desirable effects. Adalimumab 40 mg/wk was initiated. After 12 weeks of treatment, he experienced 80% improvement in all areas except the genital region. He continued adalimumab for 3 years with good clinical response in all HS-affected sites except the genital region.

A 66-year-old man presented with Hurley stage III HS of 37 years’ duration. He had a smoking history of 10 cigarettes per day for 30 years, a BMI of 24.6, and a medical history of long-standing hypertension and hypothyroidism. A 3-month course of clindamycin and rifampicin 600 mg/d was ineffective; adalimumab 40 mg/wk was initiated. All affected areas improved, except for the saxophone penis. He continues his fifth year of therapy with adalimumab (Figure 2).

Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with chronic pain, purulent malodor, and scarring with structural deformity. Repetitive inflammation causes fibrosis, scar formation, and soft-tissue destruction of lymphatic vessels, leading to lymphedema; primary lymphedema of the genitals in men has been reported to result in a saxophone penis.4

The only approved biologic treatments for moderate to severe HS are the tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor adalimumab and anti-IL-17 secukinumab.1 All 3 of our patients with HS were treated with adalimumab with reasonable success; however, the penile condition remained refractory, which we speculate may be due to adalimumab’s ability to control only active inflammatory lesions but not scars or fibrotic tissue.7 Higher adalimumab dosages were unlikely to be beneficial for their penile condition; some improvements have been reported following fluoroquinolone therapy. To our knowledge, there is no effective medical treatment for saxophone penis. However, surgery showed good results in one of our patients. Among our 3 adalimumab-treated patients, only 1 patient had corrective surgery that resulted in improvement in the penile deformity, further confirming adalimumab’s limited role in genital lymphedema.7 Extensive resection of the lymphedematous tissue, scrotoplasty, and Charles procedure are treatment options.8

Genital lymphedema has been associated with lymphangiectasia, lymphangioma circumscriptum, infections, and neoplasms such as lymphangiosarcoma and squamous cell carcinoma.9 Our patients reported discomfort, hygiene issues, and swelling. One patient reported micturition, and 2 patients reported sexual dysfunction.

Saxophone penis remains a disabling sequela of HS. Early diagnosis and treatment of HS may help prevent development of this condition.

- Lee EY, Alhusayen R, Lansang P, et al. What is hidradenitis suppurativa? Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:114-120.

- Fertitta L, Hotz C, Wolkenstein P, et al. Efficacy and satisfaction of surgical treatment for hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:839-845.

- Micieli R, Alavi A. Lymphedema in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review of published literature. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1471-1480.

- Maatouk I, Moutran R. Saxophone penis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:802.

- Koley S, Mandal RK. Saxophone penis after unilateral inguinal bubo of lymphogranuloma venereum. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2013;34:149-151.

- D’Antuono A, Lambertini M, Gaspari V, et al. Visual dermatology: self-induced chronic saxophone penis due to paraffin injections. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:330.

- Musumeci ML, Scilletta A, Sorci F, et al. Genital lymphedema associated with hidradenitis suppurativa unresponsive to adalimumab treatment. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:326-328.

- Jain V, Singh S, Garge S, et al. Saxophone penis due to primary lymphoedema. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2009;14:230-231.

- Moosbrugger EA, Mutasim DF. Hidradenitis suppurativa complicated by severe lymphedema and lymphangiectasias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1223-1224.

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a multifactorial chronic inflammatory skin disease affecting 1% to 4% of Europeans. It is characterized by recurrent inflamed nodules, abscesses, and sinus tracts in intertriginous regions.1 The genital area is affected in 11% of cases2 and usually is connected to severe forms of HS in both men and women.3 The prevalence of HS-associated genital lymphedema remains unknown.

Saxophone penis is a specific penile malformation characterized by a saxophone shape due to inflammation of the major penile lymphatic vessels that cause fibrosis of the surrounding connective tissue. Poor blood flow further causes contracture and distortion of the penile axis.4 Saxophone penis also has been associated with primary lymphedema, lymphogranuloma venereum, filariasis,5 and administration of paraffin injections.6 We describe 3 men with HS who presented with saxophone penis.

A 33-year-old man with Hurley stage III HS presented with a medical history of groin lesions and progressive penoscrotal edema of 13 years’ duration. He had a body mass index (BMI) of 37, no family history of HS or comorbidities, and a 15-year history of smoking 20 cigarettes per day. After repeated surgical drainage of the HS lesions as well as antibiotic treatment with clindamycin 600 mg/d and rifampicin 600 mg/d, the patient was kept on a maintenance therapy with adalimumab 40 mg/wk. Due to lack of response, treatment was discontinued at week 16. Clindamycin and rifampicin 300 mg were immediately reintroduced with no benefit on the genital lesions. The patient underwent genital reconstruction, including penile degloving, scrotoplasty, infrapubic fat pad removal, and perineoplasty (Figure 1). The patient currently is not undergoing any therapies.

A 55-year-old man presented with Hurley stage II HS of 33 years’ duration. He had a BMI of 52; a history of hypertension, hyperuricemia, severe hip and knee osteoarthritis, and orchiopexy in childhood; a smoking history of 40 cigarettes per day; and an alcohol consumption history of 200 mL per day since 18 years of age. He had radical excision of axillary lesions 8 years prior. One year later, he was treated with concomitant clindamycin and rifampicin 300 mg twice daily for 3 months with no desirable effects. Adalimumab 40 mg/wk was initiated. After 12 weeks of treatment, he experienced 80% improvement in all areas except the genital region. He continued adalimumab for 3 years with good clinical response in all HS-affected sites except the genital region.

A 66-year-old man presented with Hurley stage III HS of 37 years’ duration. He had a smoking history of 10 cigarettes per day for 30 years, a BMI of 24.6, and a medical history of long-standing hypertension and hypothyroidism. A 3-month course of clindamycin and rifampicin 600 mg/d was ineffective; adalimumab 40 mg/wk was initiated. All affected areas improved, except for the saxophone penis. He continues his fifth year of therapy with adalimumab (Figure 2).

Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with chronic pain, purulent malodor, and scarring with structural deformity. Repetitive inflammation causes fibrosis, scar formation, and soft-tissue destruction of lymphatic vessels, leading to lymphedema; primary lymphedema of the genitals in men has been reported to result in a saxophone penis.4

The only approved biologic treatments for moderate to severe HS are the tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor adalimumab and anti-IL-17 secukinumab.1 All 3 of our patients with HS were treated with adalimumab with reasonable success; however, the penile condition remained refractory, which we speculate may be due to adalimumab’s ability to control only active inflammatory lesions but not scars or fibrotic tissue.7 Higher adalimumab dosages were unlikely to be beneficial for their penile condition; some improvements have been reported following fluoroquinolone therapy. To our knowledge, there is no effective medical treatment for saxophone penis. However, surgery showed good results in one of our patients. Among our 3 adalimumab-treated patients, only 1 patient had corrective surgery that resulted in improvement in the penile deformity, further confirming adalimumab’s limited role in genital lymphedema.7 Extensive resection of the lymphedematous tissue, scrotoplasty, and Charles procedure are treatment options.8

Genital lymphedema has been associated with lymphangiectasia, lymphangioma circumscriptum, infections, and neoplasms such as lymphangiosarcoma and squamous cell carcinoma.9 Our patients reported discomfort, hygiene issues, and swelling. One patient reported micturition, and 2 patients reported sexual dysfunction.

Saxophone penis remains a disabling sequela of HS. Early diagnosis and treatment of HS may help prevent development of this condition.

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a multifactorial chronic inflammatory skin disease affecting 1% to 4% of Europeans. It is characterized by recurrent inflamed nodules, abscesses, and sinus tracts in intertriginous regions.1 The genital area is affected in 11% of cases2 and usually is connected to severe forms of HS in both men and women.3 The prevalence of HS-associated genital lymphedema remains unknown.

Saxophone penis is a specific penile malformation characterized by a saxophone shape due to inflammation of the major penile lymphatic vessels that cause fibrosis of the surrounding connective tissue. Poor blood flow further causes contracture and distortion of the penile axis.4 Saxophone penis also has been associated with primary lymphedema, lymphogranuloma venereum, filariasis,5 and administration of paraffin injections.6 We describe 3 men with HS who presented with saxophone penis.

A 33-year-old man with Hurley stage III HS presented with a medical history of groin lesions and progressive penoscrotal edema of 13 years’ duration. He had a body mass index (BMI) of 37, no family history of HS or comorbidities, and a 15-year history of smoking 20 cigarettes per day. After repeated surgical drainage of the HS lesions as well as antibiotic treatment with clindamycin 600 mg/d and rifampicin 600 mg/d, the patient was kept on a maintenance therapy with adalimumab 40 mg/wk. Due to lack of response, treatment was discontinued at week 16. Clindamycin and rifampicin 300 mg were immediately reintroduced with no benefit on the genital lesions. The patient underwent genital reconstruction, including penile degloving, scrotoplasty, infrapubic fat pad removal, and perineoplasty (Figure 1). The patient currently is not undergoing any therapies.

A 55-year-old man presented with Hurley stage II HS of 33 years’ duration. He had a BMI of 52; a history of hypertension, hyperuricemia, severe hip and knee osteoarthritis, and orchiopexy in childhood; a smoking history of 40 cigarettes per day; and an alcohol consumption history of 200 mL per day since 18 years of age. He had radical excision of axillary lesions 8 years prior. One year later, he was treated with concomitant clindamycin and rifampicin 300 mg twice daily for 3 months with no desirable effects. Adalimumab 40 mg/wk was initiated. After 12 weeks of treatment, he experienced 80% improvement in all areas except the genital region. He continued adalimumab for 3 years with good clinical response in all HS-affected sites except the genital region.

A 66-year-old man presented with Hurley stage III HS of 37 years’ duration. He had a smoking history of 10 cigarettes per day for 30 years, a BMI of 24.6, and a medical history of long-standing hypertension and hypothyroidism. A 3-month course of clindamycin and rifampicin 600 mg/d was ineffective; adalimumab 40 mg/wk was initiated. All affected areas improved, except for the saxophone penis. He continues his fifth year of therapy with adalimumab (Figure 2).

Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with chronic pain, purulent malodor, and scarring with structural deformity. Repetitive inflammation causes fibrosis, scar formation, and soft-tissue destruction of lymphatic vessels, leading to lymphedema; primary lymphedema of the genitals in men has been reported to result in a saxophone penis.4

The only approved biologic treatments for moderate to severe HS are the tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor adalimumab and anti-IL-17 secukinumab.1 All 3 of our patients with HS were treated with adalimumab with reasonable success; however, the penile condition remained refractory, which we speculate may be due to adalimumab’s ability to control only active inflammatory lesions but not scars or fibrotic tissue.7 Higher adalimumab dosages were unlikely to be beneficial for their penile condition; some improvements have been reported following fluoroquinolone therapy. To our knowledge, there is no effective medical treatment for saxophone penis. However, surgery showed good results in one of our patients. Among our 3 adalimumab-treated patients, only 1 patient had corrective surgery that resulted in improvement in the penile deformity, further confirming adalimumab’s limited role in genital lymphedema.7 Extensive resection of the lymphedematous tissue, scrotoplasty, and Charles procedure are treatment options.8

Genital lymphedema has been associated with lymphangiectasia, lymphangioma circumscriptum, infections, and neoplasms such as lymphangiosarcoma and squamous cell carcinoma.9 Our patients reported discomfort, hygiene issues, and swelling. One patient reported micturition, and 2 patients reported sexual dysfunction.

Saxophone penis remains a disabling sequela of HS. Early diagnosis and treatment of HS may help prevent development of this condition.

- Lee EY, Alhusayen R, Lansang P, et al. What is hidradenitis suppurativa? Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:114-120.

- Fertitta L, Hotz C, Wolkenstein P, et al. Efficacy and satisfaction of surgical treatment for hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:839-845.

- Micieli R, Alavi A. Lymphedema in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review of published literature. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1471-1480.

- Maatouk I, Moutran R. Saxophone penis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:802.

- Koley S, Mandal RK. Saxophone penis after unilateral inguinal bubo of lymphogranuloma venereum. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2013;34:149-151.

- D’Antuono A, Lambertini M, Gaspari V, et al. Visual dermatology: self-induced chronic saxophone penis due to paraffin injections. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:330.

- Musumeci ML, Scilletta A, Sorci F, et al. Genital lymphedema associated with hidradenitis suppurativa unresponsive to adalimumab treatment. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:326-328.

- Jain V, Singh S, Garge S, et al. Saxophone penis due to primary lymphoedema. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2009;14:230-231.

- Moosbrugger EA, Mutasim DF. Hidradenitis suppurativa complicated by severe lymphedema and lymphangiectasias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1223-1224.

- Lee EY, Alhusayen R, Lansang P, et al. What is hidradenitis suppurativa? Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:114-120.

- Fertitta L, Hotz C, Wolkenstein P, et al. Efficacy and satisfaction of surgical treatment for hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:839-845.

- Micieli R, Alavi A. Lymphedema in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review of published literature. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1471-1480.

- Maatouk I, Moutran R. Saxophone penis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:802.

- Koley S, Mandal RK. Saxophone penis after unilateral inguinal bubo of lymphogranuloma venereum. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2013;34:149-151.

- D’Antuono A, Lambertini M, Gaspari V, et al. Visual dermatology: self-induced chronic saxophone penis due to paraffin injections. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:330.

- Musumeci ML, Scilletta A, Sorci F, et al. Genital lymphedema associated with hidradenitis suppurativa unresponsive to adalimumab treatment. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:326-328.

- Jain V, Singh S, Garge S, et al. Saxophone penis due to primary lymphoedema. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2009;14:230-231.

- Moosbrugger EA, Mutasim DF. Hidradenitis suppurativa complicated by severe lymphedema and lymphangiectasias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1223-1224.

Practice Points

- Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a multifactorial chronic inflammatory skin disease.

- Saxophone penis is a specific penile malformation characterized by a saxophone shape due to inflammation.

- Repetitive inflammation within the context of HS may cause structural deformity of the penis, resulting in a saxophone penis.

- Early diagnosis and treatment of HS may help prevent development of this condition.

Government Accuses Health System of Paying Docs Outrageous Salaries for Patient Referrals

Strapped for cash and searching for new profits, Tennessee-based Erlanger Health System illegally paid excessive salaries to physicians in exchange for patient referrals, the US government alleged in a federal lawsuit.

Erlanger changed its compensation model to entice revenue-generating doctors, paying some two to three times the median salary for their specialty, according to the complaint.

The physicians in turn referred numerous patients to Erlanger, and the health system submitted claims to Medicare for the referred services in violation of the Stark Law, according to the suit, filed in US District Court for the Western District of North Carolina.

The government’s complaint “serves as a warning” to healthcare providers who try to boost profits through improper financial arrangements with referring physicians, said Tamala E. Miles, Special Agent in Charge for the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG).

In a statement provided to this news organization, Erlanger denied the allegations and said it would “vigorously” defend the lawsuit.

“Erlanger paid physicians based on amounts that outside experts advised was fair market value,” Erlanger officials said in the statement. “Erlanger did not pay for referrals. A complete picture of the facts will demonstrate that the allegations lack merit and tell a very different story than what the government now claims.”

The Erlanger case is a reminder to physicians to consult their own knowledgeable advisors when considering financial arrangements with hospitals, said William Sarraille, JD, adjunct professor for the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law in Baltimore and a regulatory consultant.

“There is a tendency by physicians when contracting ... to rely on [hospitals’] perceived compliance and legal expertise,” Mr. Sarraille told this news organization. “This case illustrates the risks in doing so. Sometimes bigger doesn’t translate into more sophisticated or more effective from a compliance perspective.”

Stark Law Prohibits Kickbacks

The Stark Law prohibits hospitals from billing the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for services referred by a physician with whom the hospital has an improper financial relationship.

CMS paid Erlanger about $27.8 million for claims stemming from the improper financial arrangements, the government contends.

“HHS-OIG will continue to investigate such deals to prevent financial arrangements that could compromise impartial medical judgment, increase healthcare costs, and erode public trust in the healthcare system,” Ms. Miles said in a statement.

Suit: Health System’s Money Woes Led to Illegal Arrangements

Erlanger’s financial troubles allegedly started after a previous run-in with the US government over false claims.

In 2005, Erlanger Health System agreed to pay the government $40 million to resolve allegations that it knowingly submitted false claims to Medicare, according to the government’s complaint. At the time, Erlanger entered into a Corporate Integrity Agreement (CIA) with the OIG that required Erlanger to put controls in place to ensure its financial relationships did not violate the Stark Law.

Erlanger’s agreement with OIG ended in 2010. Over the next 3 years, the health system lost nearly $32 million and in fiscal year 2013, had only 65 days of cash on hand, according to the government’s lawsuit.

Beginning in 2013, Erlanger allegedly implemented a strategy to increase profits by employing more physicians, particularly specialists from competing hospitals whose patients would need costly hospital stays, according to the complaint.

Once hired, Erlanger’s physicians were expected to treat patients at Erlanger’s hospitals and refer them to other providers within the health system, the suit claims. Erlanger also relaxed or eliminated the oversight and controls on physician compensation put in place under the CIA. For example, Erlanger’s CEO signed some compensation contracts before its chief compliance officer could review them and no longer allowed the compliance officer to vote on whether to approve compensation arrangements, according to the complaint.

Erlanger also changed its compensation model to include large salaries for medical director and academic positions and allegedly paid such salaries to physicians without ensuring the required work was performed. As a result, Erlanger physicians with profitable referrals were among the highest paid in the nation for their specialties, the government claims. For example, according to the complaint:

- Erlanger paid an electrophysiologist an annual clinical salary of $816,701, a medical director salary of $101,080, an academic salary of $59,322, and a productivity incentive based on work relative value units (wRVUs). The medical director and academic salaries paid were near the 90th percentile of comparable salaries in the specialty.

- The health system paid a neurosurgeon a base salary of $654,735, a productivity incentive based on wRVUs, and payments for excess call coverage ranging from $400 to $1000 per 24-hour shift. In 2016, the neurosurgeon made $500,000 in excess call payments.

- Erlanger paid a cardiothoracic surgeon a base clinical salary of $1,070,000, a sign-on bonus of $150,000, a retention bonus of $100,000 (payable in the 4th year of the contract), and a program incentive of up to $150,000 per year.

In addition, Erlanger ignored patient safety concerns about some of its high revenue-generating physicians, the government claims.

For instance, Erlanger received multiple complaints that a cardiothoracic surgeon was misusing an expensive form of life support in which pumps and oxygenators take over heart and lung function. Overuse of the equipment prolonged patients’ hospital stays and increased the hospital fees generated by the surgeon, according to the complaint. Staff also raised concerns about the cardiothoracic surgeon’s patient outcomes.

But Erlanger disregarded the concerns and in 2018, increased the cardiothoracic surgeon’s retention bonus from $100,000 to $250,000, the suit alleges. A year later, the health system increased his base salary from $1,070,000 to $1,195,000.

Health care compensation and billing consultants alerted Erlanger that it was overpaying salaries and handing out bonuses based on measures that overstated the work physicians were performing, but Erlanger ignored the warnings, according to the complaint.

Administrators allegedly resisted efforts by the chief compliance officer to hire an outside consultant to review its compensation models. Erlanger fired the compliance officer in 2019.

The former chief compliance officer and another administrator filed a whistleblower lawsuit against Erlanger in 2021. The two administrators are relators in the government’s July 2024 lawsuit.

How to Protect Yourself From Illegal Hospital Deals

The Erlanger case is the latest in a series of recent complaints by the federal government involving financial arrangements between hospitals and physicians.

In December 2023, Indianapolis-based Community Health Network Inc. agreed to pay the government $345 million to resolve claims that it paid physicians above fair market value and awarded bonuses tied to referrals in violation of the Stark Law.

Also in 2023, Saginaw, Michigan–based Covenant HealthCare and two physicians paid the government $69 million to settle allegations that administrators engaged in improper financial arrangements with referring physicians and a physician-owned investment group. In another 2023 case, Massachusetts Eye and Ear in Boston agreed to pay $5.7 million to resolve claims that some of its physician compensation plans violated the Stark Law.

Before you enter into a financial arrangement with a hospital, it’s also important to examine what percentile the aggregate compensation would reflect, law professor Mr. Sarraille said. The Erlanger case highlights federal officials’ suspicion of compensation, in aggregate, that exceeds the 90th percentile and increased attention to compensation that exceeds the 75th percentile, he said.

To research compensation levels, doctors can review the Medical Group Management Association’s annual compensation report or search its compensation data.

Before signing any contracts, Mr. Sarraille suggests, physicians should also consider whether the hospital shares the same values. Ask physicians at the hospital what they have to say about the hospital’s culture, vision, and values. Have physicians left the hospital after their practices were acquired? Consider speaking with them to learn why.

Keep in mind that a doctor’s reputation could be impacted by a compliance complaint, regardless of whether it’s directed at the hospital and not the employed physician, Mr. Sarraille said.

“The [Erlanger] complaint focuses on the compensation of specific, named physicians saying they were wildly overcompensated,” he said. “The implication is that they sold their referral power in exchange for a pay day. It’s a bad look, no matter how the case evolves from here.”