User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Psoriasis Therapy During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Should Patients Continue Biologics?

Amid hydroxychloroquine hopes, lupus patients face shortages

For almost a quarter century, Julie Powers, a 48-year-old non-profit professional from Maryland, has been taking the same medication for her lupus — and until recently, she never worried that her supply would run out. Now she’s terrified that she might lose access to a drug that prevents her immune system from attacking her heart, lungs, and skin. She describes a feeling akin to being underwater, near drowning: “That’s what my life would be like,” she said. “I’ll suffocate.”

Powers’ concerns began roughly a week ago when she learned that her lupus drug, hydroxychloroquine (hi-DROCK-see-KLORA-quin), may be helpful in the treatment of Covid-19, the illness caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus now racing across the planet. The medication was already being used around world to treat Covid-19 patients, but evidence of its effectiveness was largely anecdotal. Then, on March 16, a renowned infectious disease specialist, Didier Raoult, announced the results of a small clinical trial in France showing that patients receiving a combination of hydroxychloroquine and the common antibiotic azithromycin had notably lower levels of the virus in their bloodstream than those who did not receive the medication.

In the last week, this once obscure drug has been thrust into the national spotlight with everyone from doctors, to laypeople, to the U.S. president weighing in. The attention has so dramatically driven up demand that pharmacists are reporting depleted stocks of the drug, leaving many of the roughly 1.5 million lupus patients across the country unable to get their prescriptions filled. They now face an uncertain future as the public clings to one of the first signs of hope to appear since the coronavirus began sweeping across the U.S.

But scientists and physicians caution that this hope is based on studies that have been conducted outside of traditional scientific timelines. “The paper is interesting and certainly would warrant future more definitive studies,” Jeff Sparks, a rheumatologist and researcher at Harvard Medical School, said of the French study. “It might even be enough data to use the regimen off-label for sick and hospitalized patients.

“However,” he added, “it does not prove that the regimen actually works.”

Despite efforts to pin blame for the shortages on Trump alone, however, hydroxychloroquine scarcity was already setting in weeks ago, as doctors began responding on their own to percolating and preliminary research. Some evidence suggests that many doctors are now writing prescriptions prophylactically for patients with no known illness — as well as for themselves and family members — prompting at least one state pharmacy board to call an emergency meeting, scheduled for Sunday morning. The board planned to bar pharmacists from dispensing chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine for anyone other than confirmed Covid-19 patients without approval of the board's director.

A prolonged shortfall in supplies would likely have grave implications for people who depend on it — including Powers, who believes that she would not be alive today without the drug. “I guarantee you, it has saved my life,” she said. “It’s the only thing that’s protecting my organs. There’s nothing else.” Like others, she hopes that pharmaceutical companies that manufacture versions of the drug will be able to quickly ramp up production — something several have already promised to do. In the meantime, Powers has a message for the American public — one echoed by most lupus doctors: When it comes to hydroxychloroquine: “If you don’t need it, don’t get it.”

The origins of hydroxychloroquine can be traced back hundreds of years to South America, where the bark of the cinchona tree appears to have been used by Andean populations to treat shivering. European missionaries eventually brought the bark to Europe, where it was used to treat malaria. In 1820, French researchers isolated the substance in the bark responsible for its beneficial effects. They named it “quinine.” When the supply from South America began to dry up, the British and Dutch decided to grow the tree on plantations.

Over time, synthetic versions were developed, including a drug called chloroquine, which was created in the midst of World War II in an effort to spare overseas American troops from malaria. As it turned out, troops with rashes and arthritis saw an improvement in symptoms after using this anti-malarial medication. After the war, a related drug was created, one with fewer side-effects when taken long-term: hydroxychloroquine. It went on to be used to treat many types of autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. The latter, which disproportionately affects women, used to cut lives short — typically from failure of the kidneys. Those numbers have been reduced with strict management of the disease, but the Lupus Foundation of America estimates that 10 to 15 percent of patients die prematurely due to complications of the disease.

Jinoos Yazdany, a researcher and chief of the Division of Rheumatology at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, added that there is strong clinical trial data demonstrating that taking a group of lupus patients off of hydroxychloroquine results in lupus flares. “I am less concerned about a short interruption of a few weeks,” she said in an email message, “but anything longer than a month puts patients at risk.”

Whether or not that will happen is unclear, but Sparks said he has been receiving a raft queries from both lupus and non-lupus patients eager to know more about — and access — hydroxychloroquine: “Can I use this? Should I stockpile it? Can I get refills?” Sparks compares the current medication shortage to the ventilator shortage, where manufacturers make just enough of a certain supply to meet the demand. “We don’t have stockpiles of hydroxychloroquine sitting around,” he said.

Blazer understands that people are scared and says it’s natural that they would want to protect themselves. But she said, the medicine is a limited resource and should be reserved for people with a rheumatological disease or active Covid-19 infection. In order to minimize fallout from the pandemic, she says, “we all have to function as a community.”

As it turns out, there is an extreme paucity of data when it comes to hydroxychloroquine and Covid-19. On March 10, the Journal of Critical Care published online a systematic review of the safety and the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in treating Covid-19. The authors’ goal was to identify and summarize all available scientific evidence as of March 1 by searching scientific databases. They found six articles. (In contrast, a search of the database PubMed for hydroxychloroquine and lupus yields 1,654 results.)

“The articles themselves were kind of a menagerie of things that you don’t want to get data from,” said Michael Putman, a rheumatologist at Northwestern University, McGaw Medical Center, in his rheumatology podcast. The study authors found one narrative letter, one test tube study, one editorial, two national guidelines, and one expert consensus paper from China. Conspicuously missing were randomized controlled trials, which randomly assign human participants to an experimental group or a control group, with the experimental group receiving the treatment in question.

“It is kind of scary that that is all the data we had until March 1, for a drug that we are currently talking about rolling out en masse to the world,” said Putman.

Shortly after the systematic review appeared online, Didier Raoult announced the results of his team’s clinical trial. (The paper is now available online.) At first blush, the results are striking. Six days into the study, 70 percent of patients who received hydroxychloroquine were “virologically cured,” as evidenced from samples taken from the back of each patient’s nose. In contrast, just 12.5 percent of the control group, which did not receive the drug cocktail, were free of the virus.

A second potential issue: Patients who refused the treatment or had exclusion criteria served as controls. “It’s hard for me to describe just how problematic this is,” said Putman in his podcast. Ideally patients would be randomly assigned to one of the two treatment groups, said Putman. Patients with exclusion criteria — those unable to take the medication — are not the same as patients who are able to take it, he says. And the same is true for patients who refuse a drug vs. those who don’t.

Whether these and other potential problems with the research will prove salient in coming weeks and months is impossible to know — and most researchers concede that even amid lingering uncertainties, time is of the essence in the frantic hunt to find ways to slow the fast-moving Covid-19 pandemic. “A lot of this,” Kim said, “is the rush of trying to get something out.” On Friday, the University of Minnesota announced the launch of a 1,500-person trial aimed at further exploring the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine against SARS-CoV-2. And drug makers Novartis, Mylan, and Teva announced last week that they were fast-tracking production, with additional plans to donate hundreds of millions of tablets to hospitals around the country to help combat Covid-19 infections.

Still, reports of shortages are mounting. “It’s gone. It’s not in the pharmacy now,'' a physician in Queens told The Washington Post on Friday. The doctor admitted taking the drug himself in the hope of staving off infection, and that he’d prescribed it to 30 patients as a prophylactic.

These sorts of fast-multiplying, ad hoc transactions, are what worry lupus patients like Julie Powers. For now, she says she has enough hydroxychloroquine to last 90 days, and she added that her pharmacist in the Washington, D.C. area is currently hiding the medicine to be sure her regular lupus patients can get their prescriptions refilled.

Powers sounds almost amazed when she describes what that means to her: “I can walk outside,” she said, “and I can live.”

Sara Talpos is a senior editor at Undark and a freelance writer whose recent work has been published in Science, Mosaic, and the Kenyon Review’s special issue on science writing.

Disclosure: The author’s spouse is a rheumatologist at Michigan Medicine.

UPDATES: This story has been updated to clarify Alfred Kim's view on several patients who dropped out of a small French study on the efficacy of using hydroxychloroquine to treat Covid-19 cases. The piece was also edited to include information noting that one state pharmacy board is now taking steps to curtail prescriptions of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine for Covid-19 prophylaxis.

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.

For almost a quarter century, Julie Powers, a 48-year-old non-profit professional from Maryland, has been taking the same medication for her lupus — and until recently, she never worried that her supply would run out. Now she’s terrified that she might lose access to a drug that prevents her immune system from attacking her heart, lungs, and skin. She describes a feeling akin to being underwater, near drowning: “That’s what my life would be like,” she said. “I’ll suffocate.”

Powers’ concerns began roughly a week ago when she learned that her lupus drug, hydroxychloroquine (hi-DROCK-see-KLORA-quin), may be helpful in the treatment of Covid-19, the illness caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus now racing across the planet. The medication was already being used around world to treat Covid-19 patients, but evidence of its effectiveness was largely anecdotal. Then, on March 16, a renowned infectious disease specialist, Didier Raoult, announced the results of a small clinical trial in France showing that patients receiving a combination of hydroxychloroquine and the common antibiotic azithromycin had notably lower levels of the virus in their bloodstream than those who did not receive the medication.

In the last week, this once obscure drug has been thrust into the national spotlight with everyone from doctors, to laypeople, to the U.S. president weighing in. The attention has so dramatically driven up demand that pharmacists are reporting depleted stocks of the drug, leaving many of the roughly 1.5 million lupus patients across the country unable to get their prescriptions filled. They now face an uncertain future as the public clings to one of the first signs of hope to appear since the coronavirus began sweeping across the U.S.

But scientists and physicians caution that this hope is based on studies that have been conducted outside of traditional scientific timelines. “The paper is interesting and certainly would warrant future more definitive studies,” Jeff Sparks, a rheumatologist and researcher at Harvard Medical School, said of the French study. “It might even be enough data to use the regimen off-label for sick and hospitalized patients.

“However,” he added, “it does not prove that the regimen actually works.”

Despite efforts to pin blame for the shortages on Trump alone, however, hydroxychloroquine scarcity was already setting in weeks ago, as doctors began responding on their own to percolating and preliminary research. Some evidence suggests that many doctors are now writing prescriptions prophylactically for patients with no known illness — as well as for themselves and family members — prompting at least one state pharmacy board to call an emergency meeting, scheduled for Sunday morning. The board planned to bar pharmacists from dispensing chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine for anyone other than confirmed Covid-19 patients without approval of the board's director.

A prolonged shortfall in supplies would likely have grave implications for people who depend on it — including Powers, who believes that she would not be alive today without the drug. “I guarantee you, it has saved my life,” she said. “It’s the only thing that’s protecting my organs. There’s nothing else.” Like others, she hopes that pharmaceutical companies that manufacture versions of the drug will be able to quickly ramp up production — something several have already promised to do. In the meantime, Powers has a message for the American public — one echoed by most lupus doctors: When it comes to hydroxychloroquine: “If you don’t need it, don’t get it.”

The origins of hydroxychloroquine can be traced back hundreds of years to South America, where the bark of the cinchona tree appears to have been used by Andean populations to treat shivering. European missionaries eventually brought the bark to Europe, where it was used to treat malaria. In 1820, French researchers isolated the substance in the bark responsible for its beneficial effects. They named it “quinine.” When the supply from South America began to dry up, the British and Dutch decided to grow the tree on plantations.

Over time, synthetic versions were developed, including a drug called chloroquine, which was created in the midst of World War II in an effort to spare overseas American troops from malaria. As it turned out, troops with rashes and arthritis saw an improvement in symptoms after using this anti-malarial medication. After the war, a related drug was created, one with fewer side-effects when taken long-term: hydroxychloroquine. It went on to be used to treat many types of autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. The latter, which disproportionately affects women, used to cut lives short — typically from failure of the kidneys. Those numbers have been reduced with strict management of the disease, but the Lupus Foundation of America estimates that 10 to 15 percent of patients die prematurely due to complications of the disease.

Jinoos Yazdany, a researcher and chief of the Division of Rheumatology at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, added that there is strong clinical trial data demonstrating that taking a group of lupus patients off of hydroxychloroquine results in lupus flares. “I am less concerned about a short interruption of a few weeks,” she said in an email message, “but anything longer than a month puts patients at risk.”

Whether or not that will happen is unclear, but Sparks said he has been receiving a raft queries from both lupus and non-lupus patients eager to know more about — and access — hydroxychloroquine: “Can I use this? Should I stockpile it? Can I get refills?” Sparks compares the current medication shortage to the ventilator shortage, where manufacturers make just enough of a certain supply to meet the demand. “We don’t have stockpiles of hydroxychloroquine sitting around,” he said.

Blazer understands that people are scared and says it’s natural that they would want to protect themselves. But she said, the medicine is a limited resource and should be reserved for people with a rheumatological disease or active Covid-19 infection. In order to minimize fallout from the pandemic, she says, “we all have to function as a community.”

As it turns out, there is an extreme paucity of data when it comes to hydroxychloroquine and Covid-19. On March 10, the Journal of Critical Care published online a systematic review of the safety and the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in treating Covid-19. The authors’ goal was to identify and summarize all available scientific evidence as of March 1 by searching scientific databases. They found six articles. (In contrast, a search of the database PubMed for hydroxychloroquine and lupus yields 1,654 results.)

“The articles themselves were kind of a menagerie of things that you don’t want to get data from,” said Michael Putman, a rheumatologist at Northwestern University, McGaw Medical Center, in his rheumatology podcast. The study authors found one narrative letter, one test tube study, one editorial, two national guidelines, and one expert consensus paper from China. Conspicuously missing were randomized controlled trials, which randomly assign human participants to an experimental group or a control group, with the experimental group receiving the treatment in question.

“It is kind of scary that that is all the data we had until March 1, for a drug that we are currently talking about rolling out en masse to the world,” said Putman.

Shortly after the systematic review appeared online, Didier Raoult announced the results of his team’s clinical trial. (The paper is now available online.) At first blush, the results are striking. Six days into the study, 70 percent of patients who received hydroxychloroquine were “virologically cured,” as evidenced from samples taken from the back of each patient’s nose. In contrast, just 12.5 percent of the control group, which did not receive the drug cocktail, were free of the virus.

A second potential issue: Patients who refused the treatment or had exclusion criteria served as controls. “It’s hard for me to describe just how problematic this is,” said Putman in his podcast. Ideally patients would be randomly assigned to one of the two treatment groups, said Putman. Patients with exclusion criteria — those unable to take the medication — are not the same as patients who are able to take it, he says. And the same is true for patients who refuse a drug vs. those who don’t.

Whether these and other potential problems with the research will prove salient in coming weeks and months is impossible to know — and most researchers concede that even amid lingering uncertainties, time is of the essence in the frantic hunt to find ways to slow the fast-moving Covid-19 pandemic. “A lot of this,” Kim said, “is the rush of trying to get something out.” On Friday, the University of Minnesota announced the launch of a 1,500-person trial aimed at further exploring the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine against SARS-CoV-2. And drug makers Novartis, Mylan, and Teva announced last week that they were fast-tracking production, with additional plans to donate hundreds of millions of tablets to hospitals around the country to help combat Covid-19 infections.

Still, reports of shortages are mounting. “It’s gone. It’s not in the pharmacy now,'' a physician in Queens told The Washington Post on Friday. The doctor admitted taking the drug himself in the hope of staving off infection, and that he’d prescribed it to 30 patients as a prophylactic.

These sorts of fast-multiplying, ad hoc transactions, are what worry lupus patients like Julie Powers. For now, she says she has enough hydroxychloroquine to last 90 days, and she added that her pharmacist in the Washington, D.C. area is currently hiding the medicine to be sure her regular lupus patients can get their prescriptions refilled.

Powers sounds almost amazed when she describes what that means to her: “I can walk outside,” she said, “and I can live.”

Sara Talpos is a senior editor at Undark and a freelance writer whose recent work has been published in Science, Mosaic, and the Kenyon Review’s special issue on science writing.

Disclosure: The author’s spouse is a rheumatologist at Michigan Medicine.

UPDATES: This story has been updated to clarify Alfred Kim's view on several patients who dropped out of a small French study on the efficacy of using hydroxychloroquine to treat Covid-19 cases. The piece was also edited to include information noting that one state pharmacy board is now taking steps to curtail prescriptions of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine for Covid-19 prophylaxis.

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.

For almost a quarter century, Julie Powers, a 48-year-old non-profit professional from Maryland, has been taking the same medication for her lupus — and until recently, she never worried that her supply would run out. Now she’s terrified that she might lose access to a drug that prevents her immune system from attacking her heart, lungs, and skin. She describes a feeling akin to being underwater, near drowning: “That’s what my life would be like,” she said. “I’ll suffocate.”

Powers’ concerns began roughly a week ago when she learned that her lupus drug, hydroxychloroquine (hi-DROCK-see-KLORA-quin), may be helpful in the treatment of Covid-19, the illness caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus now racing across the planet. The medication was already being used around world to treat Covid-19 patients, but evidence of its effectiveness was largely anecdotal. Then, on March 16, a renowned infectious disease specialist, Didier Raoult, announced the results of a small clinical trial in France showing that patients receiving a combination of hydroxychloroquine and the common antibiotic azithromycin had notably lower levels of the virus in their bloodstream than those who did not receive the medication.

In the last week, this once obscure drug has been thrust into the national spotlight with everyone from doctors, to laypeople, to the U.S. president weighing in. The attention has so dramatically driven up demand that pharmacists are reporting depleted stocks of the drug, leaving many of the roughly 1.5 million lupus patients across the country unable to get their prescriptions filled. They now face an uncertain future as the public clings to one of the first signs of hope to appear since the coronavirus began sweeping across the U.S.

But scientists and physicians caution that this hope is based on studies that have been conducted outside of traditional scientific timelines. “The paper is interesting and certainly would warrant future more definitive studies,” Jeff Sparks, a rheumatologist and researcher at Harvard Medical School, said of the French study. “It might even be enough data to use the regimen off-label for sick and hospitalized patients.

“However,” he added, “it does not prove that the regimen actually works.”

Despite efforts to pin blame for the shortages on Trump alone, however, hydroxychloroquine scarcity was already setting in weeks ago, as doctors began responding on their own to percolating and preliminary research. Some evidence suggests that many doctors are now writing prescriptions prophylactically for patients with no known illness — as well as for themselves and family members — prompting at least one state pharmacy board to call an emergency meeting, scheduled for Sunday morning. The board planned to bar pharmacists from dispensing chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine for anyone other than confirmed Covid-19 patients without approval of the board's director.

A prolonged shortfall in supplies would likely have grave implications for people who depend on it — including Powers, who believes that she would not be alive today without the drug. “I guarantee you, it has saved my life,” she said. “It’s the only thing that’s protecting my organs. There’s nothing else.” Like others, she hopes that pharmaceutical companies that manufacture versions of the drug will be able to quickly ramp up production — something several have already promised to do. In the meantime, Powers has a message for the American public — one echoed by most lupus doctors: When it comes to hydroxychloroquine: “If you don’t need it, don’t get it.”

The origins of hydroxychloroquine can be traced back hundreds of years to South America, where the bark of the cinchona tree appears to have been used by Andean populations to treat shivering. European missionaries eventually brought the bark to Europe, where it was used to treat malaria. In 1820, French researchers isolated the substance in the bark responsible for its beneficial effects. They named it “quinine.” When the supply from South America began to dry up, the British and Dutch decided to grow the tree on plantations.

Over time, synthetic versions were developed, including a drug called chloroquine, which was created in the midst of World War II in an effort to spare overseas American troops from malaria. As it turned out, troops with rashes and arthritis saw an improvement in symptoms after using this anti-malarial medication. After the war, a related drug was created, one with fewer side-effects when taken long-term: hydroxychloroquine. It went on to be used to treat many types of autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. The latter, which disproportionately affects women, used to cut lives short — typically from failure of the kidneys. Those numbers have been reduced with strict management of the disease, but the Lupus Foundation of America estimates that 10 to 15 percent of patients die prematurely due to complications of the disease.

Jinoos Yazdany, a researcher and chief of the Division of Rheumatology at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, added that there is strong clinical trial data demonstrating that taking a group of lupus patients off of hydroxychloroquine results in lupus flares. “I am less concerned about a short interruption of a few weeks,” she said in an email message, “but anything longer than a month puts patients at risk.”

Whether or not that will happen is unclear, but Sparks said he has been receiving a raft queries from both lupus and non-lupus patients eager to know more about — and access — hydroxychloroquine: “Can I use this? Should I stockpile it? Can I get refills?” Sparks compares the current medication shortage to the ventilator shortage, where manufacturers make just enough of a certain supply to meet the demand. “We don’t have stockpiles of hydroxychloroquine sitting around,” he said.

Blazer understands that people are scared and says it’s natural that they would want to protect themselves. But she said, the medicine is a limited resource and should be reserved for people with a rheumatological disease or active Covid-19 infection. In order to minimize fallout from the pandemic, she says, “we all have to function as a community.”

As it turns out, there is an extreme paucity of data when it comes to hydroxychloroquine and Covid-19. On March 10, the Journal of Critical Care published online a systematic review of the safety and the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in treating Covid-19. The authors’ goal was to identify and summarize all available scientific evidence as of March 1 by searching scientific databases. They found six articles. (In contrast, a search of the database PubMed for hydroxychloroquine and lupus yields 1,654 results.)

“The articles themselves were kind of a menagerie of things that you don’t want to get data from,” said Michael Putman, a rheumatologist at Northwestern University, McGaw Medical Center, in his rheumatology podcast. The study authors found one narrative letter, one test tube study, one editorial, two national guidelines, and one expert consensus paper from China. Conspicuously missing were randomized controlled trials, which randomly assign human participants to an experimental group or a control group, with the experimental group receiving the treatment in question.

“It is kind of scary that that is all the data we had until March 1, for a drug that we are currently talking about rolling out en masse to the world,” said Putman.

Shortly after the systematic review appeared online, Didier Raoult announced the results of his team’s clinical trial. (The paper is now available online.) At first blush, the results are striking. Six days into the study, 70 percent of patients who received hydroxychloroquine were “virologically cured,” as evidenced from samples taken from the back of each patient’s nose. In contrast, just 12.5 percent of the control group, which did not receive the drug cocktail, were free of the virus.

A second potential issue: Patients who refused the treatment or had exclusion criteria served as controls. “It’s hard for me to describe just how problematic this is,” said Putman in his podcast. Ideally patients would be randomly assigned to one of the two treatment groups, said Putman. Patients with exclusion criteria — those unable to take the medication — are not the same as patients who are able to take it, he says. And the same is true for patients who refuse a drug vs. those who don’t.

Whether these and other potential problems with the research will prove salient in coming weeks and months is impossible to know — and most researchers concede that even amid lingering uncertainties, time is of the essence in the frantic hunt to find ways to slow the fast-moving Covid-19 pandemic. “A lot of this,” Kim said, “is the rush of trying to get something out.” On Friday, the University of Minnesota announced the launch of a 1,500-person trial aimed at further exploring the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine against SARS-CoV-2. And drug makers Novartis, Mylan, and Teva announced last week that they were fast-tracking production, with additional plans to donate hundreds of millions of tablets to hospitals around the country to help combat Covid-19 infections.

Still, reports of shortages are mounting. “It’s gone. It’s not in the pharmacy now,'' a physician in Queens told The Washington Post on Friday. The doctor admitted taking the drug himself in the hope of staving off infection, and that he’d prescribed it to 30 patients as a prophylactic.

These sorts of fast-multiplying, ad hoc transactions, are what worry lupus patients like Julie Powers. For now, she says she has enough hydroxychloroquine to last 90 days, and she added that her pharmacist in the Washington, D.C. area is currently hiding the medicine to be sure her regular lupus patients can get their prescriptions refilled.

Powers sounds almost amazed when she describes what that means to her: “I can walk outside,” she said, “and I can live.”

Sara Talpos is a senior editor at Undark and a freelance writer whose recent work has been published in Science, Mosaic, and the Kenyon Review’s special issue on science writing.

Disclosure: The author’s spouse is a rheumatologist at Michigan Medicine.

UPDATES: This story has been updated to clarify Alfred Kim's view on several patients who dropped out of a small French study on the efficacy of using hydroxychloroquine to treat Covid-19 cases. The piece was also edited to include information noting that one state pharmacy board is now taking steps to curtail prescriptions of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine for Covid-19 prophylaxis.

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.

Webinar confronts unique issues for the bleeding disorders community facing COVID-19

In a webinar conducted on March 20, Leonard Valentino, MD, president and CEO of the National Hemophilia Foundation (NHF), provided

Overall, the risk of comorbidities is no different in the bleeding disorders population than in the general population, and similar precautions should be maintained, Dr. Valentino stated. He listed some of the at-risk populations as designated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In particular, he pointed out that, when the CDC referred to a greater risk of COVID-19 to individuals with bleeding disorders, the organization was referring to patients with HIV and sickle cell disease. The CDC was not referring to patients with other forms of bleeding disorders, such as hemophilia, Dr. Valentino stated.

All individuals should be following CDC and state and federal recommendations with regard to social distancing and hygiene. However, with regard to immunocompromised individuals, “the two populations we [in the bleeding disorders community] have to be concerned about are those in gene therapy clinical trials and those with inhibitors,” said Dr. Valentino.

Patients in a gene therapy clinical trial should exercise additional precautions because the use of steroids, common in these trials. “Steroids are an immunosuppressive drug, and this would increase one’s risk of infection, including COVID-19,” according to Dr. Valentino.

In addition, “I will say, if you have hemophilia and an inhibitor [an antibody to clotting factor treatment], that may alter the immune system, and we don’t know what the implication of that is in terms of coronavirus infection and COVID-19 disease. So people with an inhibitor should take special precautions to limit their exposures.”

Patients with a port should not need to have extra concerns regarding COVID-19, but they should continue to exercise the good hygiene that has always been essential, according to Dr. Valentino.

Dr. Valentino asked: Are patients with a bleeding disorder who become infected with COVID-19 more susceptible to a bleed? “You shouldn’t be more susceptible to bleeding except if you have severe cough, and that cough could result in bleeding to the head,” he answered.

If a patient needs to go to the emergency department for a bleed or possible COVID-19 infection, they should wear a face mask if they are sick to prevent spreading of disease. “This is really the only instance where a face mask may be beneficial” in that it limits other people’s exposure to your infection. It is especially important to call ahead before visiting the doctor or going to the emergency department. “Make sure that they’re aware that you’re coming.”

Of particular concern to patients is the amount of factor product they should have on hand. The current CDC recommendation is a 30-day supply of medicines, but that is misleading, because it refers to general medications, such as high-blood pressure medicine, and not factor products. “The current MASAC [NHF’s Medical and Scientific Advisory Council] recommendation is to have a 14-day supply of factor products available to you,” said Dr. Valentino, “and one should reorder when you have a 1-week supply.”

MASAC has issued a letter on the crisis on the NHF website.

These recommendations should not be exceeded in order to ensure that there is enough factor available to all patients, he added. Hoarding is discouraged, and there are no concerns as yet of factor running out. “We have had conversations with manufacturers and … the supply chain is robust.” The greater concern is with regard to ancillary supplies in the hospital that a hemophilia patient may require during treatment.

Patients and practitioners should consult the COVID-19 pages of both the NHF and Hemophilia Federation of America (HFA) websites. This includes a Health and Wellness update by Dr. Valentino.

With regard to financial issues, he and Sharon Meyers, CEO and president of the HFA, spoke, stating that both NHF and HFA have advocacy for patients seeking to deal with insurance issues or in paying for their products, urging people to go to the organizational websites and to also use their emails: [email protected] and [email protected].

She also announced that the annual meeting of the HFA was being postponed to Aug. 24-26 at the Hilton Inner Harbor Baltimore, Md.

Dr. Valentino and Ms. Meyers did not provide any disclosure information.

In a webinar conducted on March 20, Leonard Valentino, MD, president and CEO of the National Hemophilia Foundation (NHF), provided

Overall, the risk of comorbidities is no different in the bleeding disorders population than in the general population, and similar precautions should be maintained, Dr. Valentino stated. He listed some of the at-risk populations as designated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In particular, he pointed out that, when the CDC referred to a greater risk of COVID-19 to individuals with bleeding disorders, the organization was referring to patients with HIV and sickle cell disease. The CDC was not referring to patients with other forms of bleeding disorders, such as hemophilia, Dr. Valentino stated.

All individuals should be following CDC and state and federal recommendations with regard to social distancing and hygiene. However, with regard to immunocompromised individuals, “the two populations we [in the bleeding disorders community] have to be concerned about are those in gene therapy clinical trials and those with inhibitors,” said Dr. Valentino.

Patients in a gene therapy clinical trial should exercise additional precautions because the use of steroids, common in these trials. “Steroids are an immunosuppressive drug, and this would increase one’s risk of infection, including COVID-19,” according to Dr. Valentino.

In addition, “I will say, if you have hemophilia and an inhibitor [an antibody to clotting factor treatment], that may alter the immune system, and we don’t know what the implication of that is in terms of coronavirus infection and COVID-19 disease. So people with an inhibitor should take special precautions to limit their exposures.”

Patients with a port should not need to have extra concerns regarding COVID-19, but they should continue to exercise the good hygiene that has always been essential, according to Dr. Valentino.

Dr. Valentino asked: Are patients with a bleeding disorder who become infected with COVID-19 more susceptible to a bleed? “You shouldn’t be more susceptible to bleeding except if you have severe cough, and that cough could result in bleeding to the head,” he answered.

If a patient needs to go to the emergency department for a bleed or possible COVID-19 infection, they should wear a face mask if they are sick to prevent spreading of disease. “This is really the only instance where a face mask may be beneficial” in that it limits other people’s exposure to your infection. It is especially important to call ahead before visiting the doctor or going to the emergency department. “Make sure that they’re aware that you’re coming.”

Of particular concern to patients is the amount of factor product they should have on hand. The current CDC recommendation is a 30-day supply of medicines, but that is misleading, because it refers to general medications, such as high-blood pressure medicine, and not factor products. “The current MASAC [NHF’s Medical and Scientific Advisory Council] recommendation is to have a 14-day supply of factor products available to you,” said Dr. Valentino, “and one should reorder when you have a 1-week supply.”

MASAC has issued a letter on the crisis on the NHF website.

These recommendations should not be exceeded in order to ensure that there is enough factor available to all patients, he added. Hoarding is discouraged, and there are no concerns as yet of factor running out. “We have had conversations with manufacturers and … the supply chain is robust.” The greater concern is with regard to ancillary supplies in the hospital that a hemophilia patient may require during treatment.

Patients and practitioners should consult the COVID-19 pages of both the NHF and Hemophilia Federation of America (HFA) websites. This includes a Health and Wellness update by Dr. Valentino.

With regard to financial issues, he and Sharon Meyers, CEO and president of the HFA, spoke, stating that both NHF and HFA have advocacy for patients seeking to deal with insurance issues or in paying for their products, urging people to go to the organizational websites and to also use their emails: [email protected] and [email protected].

She also announced that the annual meeting of the HFA was being postponed to Aug. 24-26 at the Hilton Inner Harbor Baltimore, Md.

Dr. Valentino and Ms. Meyers did not provide any disclosure information.

In a webinar conducted on March 20, Leonard Valentino, MD, president and CEO of the National Hemophilia Foundation (NHF), provided

Overall, the risk of comorbidities is no different in the bleeding disorders population than in the general population, and similar precautions should be maintained, Dr. Valentino stated. He listed some of the at-risk populations as designated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In particular, he pointed out that, when the CDC referred to a greater risk of COVID-19 to individuals with bleeding disorders, the organization was referring to patients with HIV and sickle cell disease. The CDC was not referring to patients with other forms of bleeding disorders, such as hemophilia, Dr. Valentino stated.

All individuals should be following CDC and state and federal recommendations with regard to social distancing and hygiene. However, with regard to immunocompromised individuals, “the two populations we [in the bleeding disorders community] have to be concerned about are those in gene therapy clinical trials and those with inhibitors,” said Dr. Valentino.

Patients in a gene therapy clinical trial should exercise additional precautions because the use of steroids, common in these trials. “Steroids are an immunosuppressive drug, and this would increase one’s risk of infection, including COVID-19,” according to Dr. Valentino.

In addition, “I will say, if you have hemophilia and an inhibitor [an antibody to clotting factor treatment], that may alter the immune system, and we don’t know what the implication of that is in terms of coronavirus infection and COVID-19 disease. So people with an inhibitor should take special precautions to limit their exposures.”

Patients with a port should not need to have extra concerns regarding COVID-19, but they should continue to exercise the good hygiene that has always been essential, according to Dr. Valentino.

Dr. Valentino asked: Are patients with a bleeding disorder who become infected with COVID-19 more susceptible to a bleed? “You shouldn’t be more susceptible to bleeding except if you have severe cough, and that cough could result in bleeding to the head,” he answered.

If a patient needs to go to the emergency department for a bleed or possible COVID-19 infection, they should wear a face mask if they are sick to prevent spreading of disease. “This is really the only instance where a face mask may be beneficial” in that it limits other people’s exposure to your infection. It is especially important to call ahead before visiting the doctor or going to the emergency department. “Make sure that they’re aware that you’re coming.”

Of particular concern to patients is the amount of factor product they should have on hand. The current CDC recommendation is a 30-day supply of medicines, but that is misleading, because it refers to general medications, such as high-blood pressure medicine, and not factor products. “The current MASAC [NHF’s Medical and Scientific Advisory Council] recommendation is to have a 14-day supply of factor products available to you,” said Dr. Valentino, “and one should reorder when you have a 1-week supply.”

MASAC has issued a letter on the crisis on the NHF website.

These recommendations should not be exceeded in order to ensure that there is enough factor available to all patients, he added. Hoarding is discouraged, and there are no concerns as yet of factor running out. “We have had conversations with manufacturers and … the supply chain is robust.” The greater concern is with regard to ancillary supplies in the hospital that a hemophilia patient may require during treatment.

Patients and practitioners should consult the COVID-19 pages of both the NHF and Hemophilia Federation of America (HFA) websites. This includes a Health and Wellness update by Dr. Valentino.

With regard to financial issues, he and Sharon Meyers, CEO and president of the HFA, spoke, stating that both NHF and HFA have advocacy for patients seeking to deal with insurance issues or in paying for their products, urging people to go to the organizational websites and to also use their emails: [email protected] and [email protected].

She also announced that the annual meeting of the HFA was being postponed to Aug. 24-26 at the Hilton Inner Harbor Baltimore, Md.

Dr. Valentino and Ms. Meyers did not provide any disclosure information.

Should patients with COVID-19 avoid ibuprofen or RAAS antagonists?

Researchers have hypothesized that treatments that increase angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) may also increase the risk of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). This speculation and other concerns have led some officials and organizations to question whether ibuprofen or other drugs such as renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) antagonists should be avoided as treatments in patients with COVID-19. Health agencies and professional organizations have said they are not recommending against these medications.

The Food and Drug Administration on March 19 advised patients that it was “not aware of scientific evidence connecting” nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen “with worsening COVID-19 symptoms.”

“The agency is investigating this issue further and will communicate publicly when more information is available,” the FDA said. “However, all prescription NSAID labels warn that ‘the pharmacological activity of NSAIDs in reducing inflammation, and possibly fever, may diminish the utility of diagnostic signs in detecting infections.’ ” The FDA also noted that other over-the-counter and prescription medications are available for pain relief and fever reduction, and patients who “are concerned about taking NSAIDs and rely on these medications to treat chronic diseases” should talk to a health care provider.

A World Health Organization spokesperson said during a press conference on March 17 that the organization was looking into concerns about ibuprofen use in patients with COVID-19 and suggested that in the meantime patients take acetaminophen for fever instead. On March 18, the WHO said that it was not recommending against the use of ibuprofen.

“At present, based on currently available information, WHO does not recommend against the use of ibuprofen,” the organization said. “We are also consulting with physicians treating COVID-19 patients and are not aware of reports of any negative effects of ibuprofen, beyond the usual known side effects that limit its use in certain populations. WHO is not aware of published clinical or population-based data on this topic.”

A spokesperson for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases said on March 18, “More research is needed to evaluate reports that ibruprofen and other over-the-counter anti-inflammatory drugs may affect the course of COVID-19. Currently, there is no conclusive evidence that ibuprofen and other over-the-counter anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of serious complications or of acquiring the virus that causes COVID-19. There is also no conclusive evidence that taking over-the-counter anti-inflammatory drugs is harmful for other respiratory infections.”

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) on March 18 said, “There is currently no scientific evidence establishing a link between ibuprofen and worsening of COVID‑19. EMA is monitoring the situation closely and will review any new information that becomes available on this issue in the context of the pandemic.”

In correspondence published March 11 in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine, Lei Fang, MD, of the department of biomedicine at University Hospital Basel (Switzerland), and colleagues suggested that patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus may be at increased risk of COVID-19 because these comorbidities “are often treated with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.” In addition, “ACE2 polymorphisms that have been linked to diabetes mellitus, cerebral stroke, and hypertension” also may play a role, the researchers said (Lancet Respir Med. 2020 Mar 11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8).

“ACE2 is substantially increased in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, who are treated with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II type-I receptor blockers (ARBs). Hypertension is also treated with ACE inhibitors and ARBs, which results in an upregulation of ACE2. ACE2 can also be increased by thiazolidinediones and ibuprofen.”

A March 16 statement from the Heart Failure Society of America (HSFC), American College of Cardiology (ACC), and American Heart Association (AHA) addressed concerns about using RAAS antagonists in COVID-19.

“Patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases appear to have an increased risk for adverse outcomes with [COVID-19],” the organizations said. “Although the clinical manifestations of COVID-19 are dominated by respiratory symptoms, some patients also may have severe cardiovascular damage. [ACE2] receptors have been shown to be the entry point into human cells for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. In a few experimental studies with animal models, both [ACE] inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been shown to upregulate ACE2 expression in the heart. Though these have not been shown in human studies, or in the setting of COVID-19, such potential upregulation of ACE2 by ACE inhibitors or ARBs has resulted in a speculation of potential increased risk for COVID-19 infection in patients with background treatment of these medications.”

ACE2, ACE, angiotensin II, and other RAAS system interactions “are quite complex, and at times, paradoxical,” the statement says. “In experimental studies, both ACE inhibitors and ARBs have been shown to reduce severe lung injury in certain viral pneumonias, and it has been speculated that these agents could be beneficial in COVID-19.

“Currently there are no experimental or clinical data demonstrating beneficial or adverse outcomes with background use of ACE inhibitors, ARBs or other RAAS antagonists in COVID-19 or among COVID-19 patients with a history of cardiovascular disease treated with such agents. The HFSA, ACC, and AHA recommend continuation of RAAS antagonists for those patients who are currently prescribed such agents for indications for which these agents are known to be beneficial, such as heart failure, hypertension, or ischemic heart disease. In the event patients with cardiovascular disease are diagnosed with COVID-19, individualized treatment decisions should be made according to each patient’s hemodynamic status and clinical presentation. Therefore, be advised not to add or remove any RAAS-related treatments, beyond actions based on standard clinical practice.

“These theoretical concerns and findings of cardiovascular involvement with COVID-19 deserve much more detailed research, and quickly. As further research and developments related to this issue evolve, we will update these recommendations as needed.”

Dr. Fang and colleagues had no competing interests.

SOURCE: Fang L et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8.

Researchers have hypothesized that treatments that increase angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) may also increase the risk of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). This speculation and other concerns have led some officials and organizations to question whether ibuprofen or other drugs such as renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) antagonists should be avoided as treatments in patients with COVID-19. Health agencies and professional organizations have said they are not recommending against these medications.

The Food and Drug Administration on March 19 advised patients that it was “not aware of scientific evidence connecting” nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen “with worsening COVID-19 symptoms.”

“The agency is investigating this issue further and will communicate publicly when more information is available,” the FDA said. “However, all prescription NSAID labels warn that ‘the pharmacological activity of NSAIDs in reducing inflammation, and possibly fever, may diminish the utility of diagnostic signs in detecting infections.’ ” The FDA also noted that other over-the-counter and prescription medications are available for pain relief and fever reduction, and patients who “are concerned about taking NSAIDs and rely on these medications to treat chronic diseases” should talk to a health care provider.

A World Health Organization spokesperson said during a press conference on March 17 that the organization was looking into concerns about ibuprofen use in patients with COVID-19 and suggested that in the meantime patients take acetaminophen for fever instead. On March 18, the WHO said that it was not recommending against the use of ibuprofen.

“At present, based on currently available information, WHO does not recommend against the use of ibuprofen,” the organization said. “We are also consulting with physicians treating COVID-19 patients and are not aware of reports of any negative effects of ibuprofen, beyond the usual known side effects that limit its use in certain populations. WHO is not aware of published clinical or population-based data on this topic.”

A spokesperson for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases said on March 18, “More research is needed to evaluate reports that ibruprofen and other over-the-counter anti-inflammatory drugs may affect the course of COVID-19. Currently, there is no conclusive evidence that ibuprofen and other over-the-counter anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of serious complications or of acquiring the virus that causes COVID-19. There is also no conclusive evidence that taking over-the-counter anti-inflammatory drugs is harmful for other respiratory infections.”

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) on March 18 said, “There is currently no scientific evidence establishing a link between ibuprofen and worsening of COVID‑19. EMA is monitoring the situation closely and will review any new information that becomes available on this issue in the context of the pandemic.”

In correspondence published March 11 in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine, Lei Fang, MD, of the department of biomedicine at University Hospital Basel (Switzerland), and colleagues suggested that patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus may be at increased risk of COVID-19 because these comorbidities “are often treated with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.” In addition, “ACE2 polymorphisms that have been linked to diabetes mellitus, cerebral stroke, and hypertension” also may play a role, the researchers said (Lancet Respir Med. 2020 Mar 11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8).

“ACE2 is substantially increased in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, who are treated with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II type-I receptor blockers (ARBs). Hypertension is also treated with ACE inhibitors and ARBs, which results in an upregulation of ACE2. ACE2 can also be increased by thiazolidinediones and ibuprofen.”

A March 16 statement from the Heart Failure Society of America (HSFC), American College of Cardiology (ACC), and American Heart Association (AHA) addressed concerns about using RAAS antagonists in COVID-19.

“Patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases appear to have an increased risk for adverse outcomes with [COVID-19],” the organizations said. “Although the clinical manifestations of COVID-19 are dominated by respiratory symptoms, some patients also may have severe cardiovascular damage. [ACE2] receptors have been shown to be the entry point into human cells for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. In a few experimental studies with animal models, both [ACE] inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been shown to upregulate ACE2 expression in the heart. Though these have not been shown in human studies, or in the setting of COVID-19, such potential upregulation of ACE2 by ACE inhibitors or ARBs has resulted in a speculation of potential increased risk for COVID-19 infection in patients with background treatment of these medications.”

ACE2, ACE, angiotensin II, and other RAAS system interactions “are quite complex, and at times, paradoxical,” the statement says. “In experimental studies, both ACE inhibitors and ARBs have been shown to reduce severe lung injury in certain viral pneumonias, and it has been speculated that these agents could be beneficial in COVID-19.

“Currently there are no experimental or clinical data demonstrating beneficial or adverse outcomes with background use of ACE inhibitors, ARBs or other RAAS antagonists in COVID-19 or among COVID-19 patients with a history of cardiovascular disease treated with such agents. The HFSA, ACC, and AHA recommend continuation of RAAS antagonists for those patients who are currently prescribed such agents for indications for which these agents are known to be beneficial, such as heart failure, hypertension, or ischemic heart disease. In the event patients with cardiovascular disease are diagnosed with COVID-19, individualized treatment decisions should be made according to each patient’s hemodynamic status and clinical presentation. Therefore, be advised not to add or remove any RAAS-related treatments, beyond actions based on standard clinical practice.

“These theoretical concerns and findings of cardiovascular involvement with COVID-19 deserve much more detailed research, and quickly. As further research and developments related to this issue evolve, we will update these recommendations as needed.”

Dr. Fang and colleagues had no competing interests.

SOURCE: Fang L et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8.

Researchers have hypothesized that treatments that increase angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) may also increase the risk of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). This speculation and other concerns have led some officials and organizations to question whether ibuprofen or other drugs such as renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) antagonists should be avoided as treatments in patients with COVID-19. Health agencies and professional organizations have said they are not recommending against these medications.

The Food and Drug Administration on March 19 advised patients that it was “not aware of scientific evidence connecting” nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen “with worsening COVID-19 symptoms.”

“The agency is investigating this issue further and will communicate publicly when more information is available,” the FDA said. “However, all prescription NSAID labels warn that ‘the pharmacological activity of NSAIDs in reducing inflammation, and possibly fever, may diminish the utility of diagnostic signs in detecting infections.’ ” The FDA also noted that other over-the-counter and prescription medications are available for pain relief and fever reduction, and patients who “are concerned about taking NSAIDs and rely on these medications to treat chronic diseases” should talk to a health care provider.

A World Health Organization spokesperson said during a press conference on March 17 that the organization was looking into concerns about ibuprofen use in patients with COVID-19 and suggested that in the meantime patients take acetaminophen for fever instead. On March 18, the WHO said that it was not recommending against the use of ibuprofen.

“At present, based on currently available information, WHO does not recommend against the use of ibuprofen,” the organization said. “We are also consulting with physicians treating COVID-19 patients and are not aware of reports of any negative effects of ibuprofen, beyond the usual known side effects that limit its use in certain populations. WHO is not aware of published clinical or population-based data on this topic.”

A spokesperson for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases said on March 18, “More research is needed to evaluate reports that ibruprofen and other over-the-counter anti-inflammatory drugs may affect the course of COVID-19. Currently, there is no conclusive evidence that ibuprofen and other over-the-counter anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of serious complications or of acquiring the virus that causes COVID-19. There is also no conclusive evidence that taking over-the-counter anti-inflammatory drugs is harmful for other respiratory infections.”

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) on March 18 said, “There is currently no scientific evidence establishing a link between ibuprofen and worsening of COVID‑19. EMA is monitoring the situation closely and will review any new information that becomes available on this issue in the context of the pandemic.”

In correspondence published March 11 in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine, Lei Fang, MD, of the department of biomedicine at University Hospital Basel (Switzerland), and colleagues suggested that patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus may be at increased risk of COVID-19 because these comorbidities “are often treated with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.” In addition, “ACE2 polymorphisms that have been linked to diabetes mellitus, cerebral stroke, and hypertension” also may play a role, the researchers said (Lancet Respir Med. 2020 Mar 11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8).

“ACE2 is substantially increased in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, who are treated with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II type-I receptor blockers (ARBs). Hypertension is also treated with ACE inhibitors and ARBs, which results in an upregulation of ACE2. ACE2 can also be increased by thiazolidinediones and ibuprofen.”

A March 16 statement from the Heart Failure Society of America (HSFC), American College of Cardiology (ACC), and American Heart Association (AHA) addressed concerns about using RAAS antagonists in COVID-19.

“Patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases appear to have an increased risk for adverse outcomes with [COVID-19],” the organizations said. “Although the clinical manifestations of COVID-19 are dominated by respiratory symptoms, some patients also may have severe cardiovascular damage. [ACE2] receptors have been shown to be the entry point into human cells for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. In a few experimental studies with animal models, both [ACE] inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) have been shown to upregulate ACE2 expression in the heart. Though these have not been shown in human studies, or in the setting of COVID-19, such potential upregulation of ACE2 by ACE inhibitors or ARBs has resulted in a speculation of potential increased risk for COVID-19 infection in patients with background treatment of these medications.”

ACE2, ACE, angiotensin II, and other RAAS system interactions “are quite complex, and at times, paradoxical,” the statement says. “In experimental studies, both ACE inhibitors and ARBs have been shown to reduce severe lung injury in certain viral pneumonias, and it has been speculated that these agents could be beneficial in COVID-19.

“Currently there are no experimental or clinical data demonstrating beneficial or adverse outcomes with background use of ACE inhibitors, ARBs or other RAAS antagonists in COVID-19 or among COVID-19 patients with a history of cardiovascular disease treated with such agents. The HFSA, ACC, and AHA recommend continuation of RAAS antagonists for those patients who are currently prescribed such agents for indications for which these agents are known to be beneficial, such as heart failure, hypertension, or ischemic heart disease. In the event patients with cardiovascular disease are diagnosed with COVID-19, individualized treatment decisions should be made according to each patient’s hemodynamic status and clinical presentation. Therefore, be advised not to add or remove any RAAS-related treatments, beyond actions based on standard clinical practice.

“These theoretical concerns and findings of cardiovascular involvement with COVID-19 deserve much more detailed research, and quickly. As further research and developments related to this issue evolve, we will update these recommendations as needed.”

Dr. Fang and colleagues had no competing interests.

SOURCE: Fang L et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8.

Managing the COVID-19 isolation floor at UCSF Medical Center

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, chair of the department of medicine at UCSF, interviewed Armond Esmaili, MD, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UCSF, who is the leader of the Respiratory Isolation Unit at UCSF Medical Center, where the institution's COVID-19 and rule-out COVID-19 patients are being cohorted.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, chair of the department of medicine at UCSF, interviewed Armond Esmaili, MD, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UCSF, who is the leader of the Respiratory Isolation Unit at UCSF Medical Center, where the institution's COVID-19 and rule-out COVID-19 patients are being cohorted.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, chair of the department of medicine at UCSF, interviewed Armond Esmaili, MD, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at UCSF, who is the leader of the Respiratory Isolation Unit at UCSF Medical Center, where the institution's COVID-19 and rule-out COVID-19 patients are being cohorted.

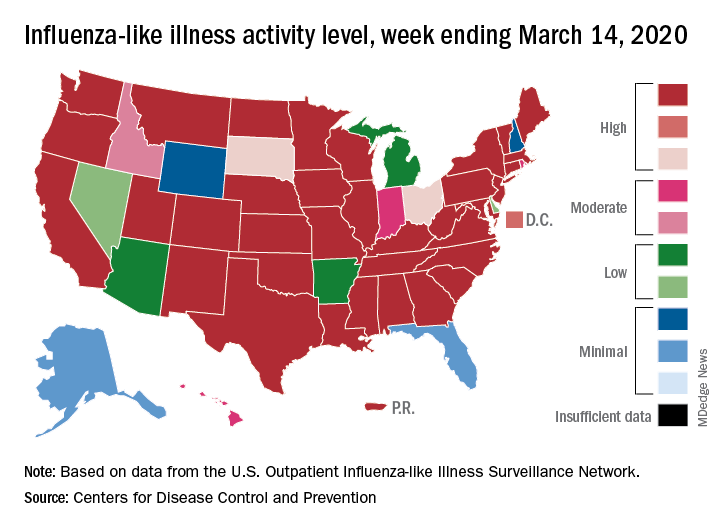

Flu now riding on COVID-19’s coattails

The viral tsunami that is COVID-19 has hit the United States, and influenza appears to be riding the crest of the wave.

according to the Centers for Disease Control. Flu-related visits went from 5.2% of all outpatient visits the week before to 5.8% during the week ending March 14.

“The COVID-19 outbreak unfolding in the United States may affect healthcare seeking behavior which in turn would impact data from” the U.S. Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network, the CDC explained.

Data from clinical laboratories show that, despite the increased activity, fewer respiratory specimens tested positive for influenza: 15.3% for the week of March 8-14, compared with 21.1% the week before, the CDC’s influenza division said in its latest FluView report.

Influenza activity also increased slightly among the states, with 35 states and Puerto Rico at the highest level on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, versus 34 states and Puerto Rico the previous week. The count was down to 33 for the last week of February, CDC data show.

Severity measures remain mixed as overall hospitalization continues to be moderate but rates for children aged 0-4 years and adults aged 18-49 years are the highest on record and rates for children aged 5-17 years are the highest since the 2009 pandemic, the influenza division said.

Mortality data present a similar picture: The overall death rate is low, but the 149 flu-related deaths reported among children is the most for this point of the season since 2009, the CDC said.

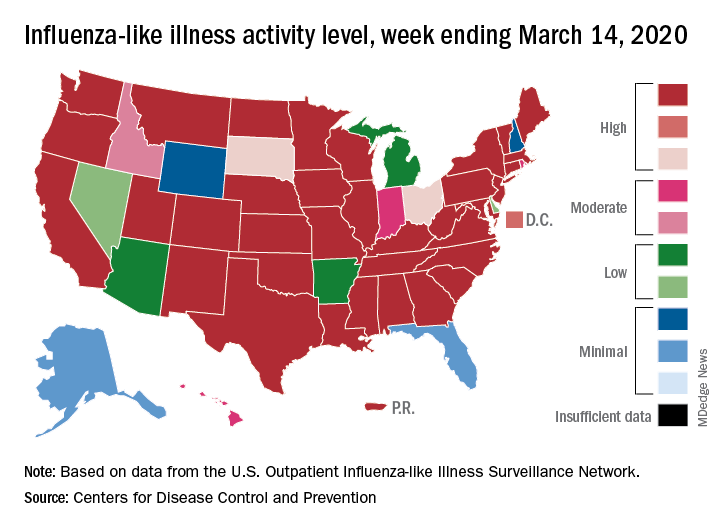

The viral tsunami that is COVID-19 has hit the United States, and influenza appears to be riding the crest of the wave.

according to the Centers for Disease Control. Flu-related visits went from 5.2% of all outpatient visits the week before to 5.8% during the week ending March 14.

“The COVID-19 outbreak unfolding in the United States may affect healthcare seeking behavior which in turn would impact data from” the U.S. Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network, the CDC explained.

Data from clinical laboratories show that, despite the increased activity, fewer respiratory specimens tested positive for influenza: 15.3% for the week of March 8-14, compared with 21.1% the week before, the CDC’s influenza division said in its latest FluView report.

Influenza activity also increased slightly among the states, with 35 states and Puerto Rico at the highest level on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, versus 34 states and Puerto Rico the previous week. The count was down to 33 for the last week of February, CDC data show.

Severity measures remain mixed as overall hospitalization continues to be moderate but rates for children aged 0-4 years and adults aged 18-49 years are the highest on record and rates for children aged 5-17 years are the highest since the 2009 pandemic, the influenza division said.

Mortality data present a similar picture: The overall death rate is low, but the 149 flu-related deaths reported among children is the most for this point of the season since 2009, the CDC said.

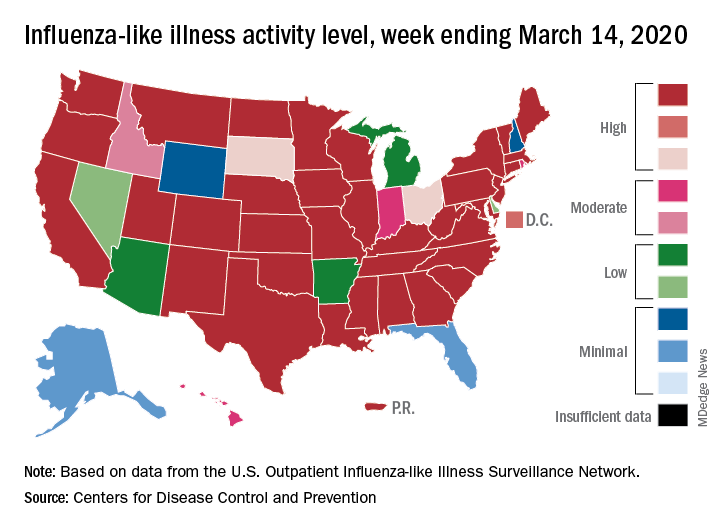

The viral tsunami that is COVID-19 has hit the United States, and influenza appears to be riding the crest of the wave.

according to the Centers for Disease Control. Flu-related visits went from 5.2% of all outpatient visits the week before to 5.8% during the week ending March 14.

“The COVID-19 outbreak unfolding in the United States may affect healthcare seeking behavior which in turn would impact data from” the U.S. Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network, the CDC explained.

Data from clinical laboratories show that, despite the increased activity, fewer respiratory specimens tested positive for influenza: 15.3% for the week of March 8-14, compared with 21.1% the week before, the CDC’s influenza division said in its latest FluView report.

Influenza activity also increased slightly among the states, with 35 states and Puerto Rico at the highest level on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, versus 34 states and Puerto Rico the previous week. The count was down to 33 for the last week of February, CDC data show.

Severity measures remain mixed as overall hospitalization continues to be moderate but rates for children aged 0-4 years and adults aged 18-49 years are the highest on record and rates for children aged 5-17 years are the highest since the 2009 pandemic, the influenza division said.

Mortality data present a similar picture: The overall death rate is low, but the 149 flu-related deaths reported among children is the most for this point of the season since 2009, the CDC said.

Preventable diseases could gain a foothold because of COVID-19

There is a highly infectious virus spreading around the world and it is targeting the most vulnerable among us. It is among the most contagious of human diseases, spreading through the air unseen. No, it isn’t the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. It’s measles.

Remember measles? Outbreaks in recent years have brought the disease, which once was declared eliminated in the United States, back into the news and public awareness, but measles never has really gone away. Every year there are millions of cases worldwide – in 2018 alone there were nearly 10 million estimated cases and 142,300 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. The good news is that measles vaccination is highly effective, at about 97% after the recommended two doses. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “because of vaccination, more than 21 million lives have been saved and measles deaths have been reduced by 80% since 2000.” This is a tremendous public health success and a cause for celebration. But our work is not done. The recent increases in vaccine hesitancy and refusal in many countries has contributed to the resurgence of measles worldwide.

Influenza still is in full swing with the CDC reporting high activity in 1 states for the week ending April 4th. Seasonal influenza, according to currently available data, has a lower fatality rate than COVID-19, but that doesn’t mean it is harmless. Thus far in the 2019-2020 flu season, there have been at least 24,000 deaths because of influenza in the United States alone, 166 of which were among pediatric patients.*

Like many pediatricians, I have seen firsthand the impact of vaccine-preventable illnesses like influenza, pertussis, and varicella. I have personally cared for an infant with pertussis who had to be intubated and on a ventilator for nearly a week. I have told the family of a child with cancer that they would have to be admitted to the hospital yet again for intravenous antiviral medication because that little rash turned out to be varicella. I have performed CPR on a previously healthy teenager with the flu whose heart was failing despite maximum ventilator support. All these illnesses might have been prevented had these patients or those around them been appropriately vaccinated.

Right now, the United States and governments around the world are taking unprecedented public health measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19, directing the public to stay home, avoid unnecessary contact with other people, practice good hand-washing and infection-control techniques. In order to promote social distancing, many primary care clinics are canceling nonurgent appointments or converting them to virtual visits, including some visits for routine vaccinations for older children, teens, and adults. This is a responsible choice to keep potentially asymptomatic people from spreading COVID-19, but once restrictions begin to lift, we all will need to act to help our patients catch up on these missing vaccinations.

This pandemic has made it more apparent than ever that we all rely upon each other to stay healthy. While this pandemic has disrupted nearly every aspect of daily life, we can’t let it disrupt one of the great successes in health care today: the prevention of serious illnesses. As soon as it is safe to do so, we must help and encourage patients to catch up on missing vaccinations. It’s rare that preventative public health measures and vaccine developments are in the nightly news, so we should use this increased public awareness to ensure patients are well educated and protected from every disease. As part of this, we must continue our efforts to share accurate information on the safety and efficacy of routine vaccination. And when there is a vaccine for COVID-19? Let’s make sure everyone gets that too.

Dr. Leighton is a pediatrician in the ED at Children’s National Hospital and currently is completing her MPH in health policy at George Washington University, both in Washington. She had no relevant financial disclosures.*

* This article was updated 4/10/2020.

There is a highly infectious virus spreading around the world and it is targeting the most vulnerable among us. It is among the most contagious of human diseases, spreading through the air unseen. No, it isn’t the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. It’s measles.

Remember measles? Outbreaks in recent years have brought the disease, which once was declared eliminated in the United States, back into the news and public awareness, but measles never has really gone away. Every year there are millions of cases worldwide – in 2018 alone there were nearly 10 million estimated cases and 142,300 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. The good news is that measles vaccination is highly effective, at about 97% after the recommended two doses. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “because of vaccination, more than 21 million lives have been saved and measles deaths have been reduced by 80% since 2000.” This is a tremendous public health success and a cause for celebration. But our work is not done. The recent increases in vaccine hesitancy and refusal in many countries has contributed to the resurgence of measles worldwide.

Influenza still is in full swing with the CDC reporting high activity in 1 states for the week ending April 4th. Seasonal influenza, according to currently available data, has a lower fatality rate than COVID-19, but that doesn’t mean it is harmless. Thus far in the 2019-2020 flu season, there have been at least 24,000 deaths because of influenza in the United States alone, 166 of which were among pediatric patients.*

Like many pediatricians, I have seen firsthand the impact of vaccine-preventable illnesses like influenza, pertussis, and varicella. I have personally cared for an infant with pertussis who had to be intubated and on a ventilator for nearly a week. I have told the family of a child with cancer that they would have to be admitted to the hospital yet again for intravenous antiviral medication because that little rash turned out to be varicella. I have performed CPR on a previously healthy teenager with the flu whose heart was failing despite maximum ventilator support. All these illnesses might have been prevented had these patients or those around them been appropriately vaccinated.