User login

Pay an annual visit to your office

that your patients might see?

We tend not to notice gradual deterioration in the workplace we inhabit every day: Carpets fade and dull with constant traffic and cleaning; wallpaper and paint accumulate dirt, stains, and damage; furniture gets dirty and dented, fabric rips, hardware goes missing; laminate peels off the edges of desks and cabinets.

When did you last take a good look at your waiting room? How clean is it? Patients expect cleanliness in doctor’s offices, and they expect the reception area to be neat. How are the carpeting and upholstery holding up? Sit in your chairs; how do they feel? Patients don’t appreciate a sore back or bottom from any chairs, especially in a medical office. Consider investing in new furniture that will be attractive and comfortable for your patients.

Look at the decor itself; is it dated or just plain “old-looking?” Any interior designer will tell you they can determine quite accurately when a space was last decorated, simply by the color and style of the materials used. If your office is stuck in the ‘90s, it’s probably time for a change. Even if you don’t find anything obvious, it’s wise to check periodically for subtle evidence of age: Find some patches of protected carpeting and flooring under stationary furniture and compare them to exposed floors.

If your color scheme is hopelessly out of date and style, or if you are just tired of it, change it. Wallpaper and carpeting should be long-wearing industrial quality; paint should be high-quality “eggshell” finish to facilitate cleaning, and everything should be professionally applied. (This is neither the time nor place for do-it-yourself experiments.) Consider updating your overhead lighting. The harsh glow of fluorescent lights amid an uninspired decor creates a sterile, uninviting atmosphere.

During renovation, get your building’s maintenance crew to fix any nagging plumbing, electrical, or heating/air conditioning problems while pipes, ducts, and wires are more readily accessible. This is also a good time to clear out old textbooks, journals, and files that you will never open again, in this digital age.

If your wall decorations are dated and unattractive, now would be a good time to replace at least some of them. This need not be an expensive proposition; a few years ago, I redecorated my exam room walls with framed photos from my travel adventures – to very positive responses from patients and staff alike. If you’re not an artist or photographer, invite a family member, or local artists or talented patients, to display some of their creations on your walls. If you get too many contributions, you can rotate them on a periodic basis.

Plants are great aesthetic accents, yet many offices have little or no plant life. Plants naturally aerate an office suite and help make it feel less stuffy. Also, multiple studies have found that plants promote productivity among office staff and create a sense of calm for apprehensive patients. Improvements like this can make a big difference. They show an attention to detail and a willingness to make your practice as inviting as possible for patients and employees alike.

Spruce-up time is also an excellent opportunity to inventory your medical equipment. We’ve all seen “vintage” offices full of gadgets that were state-of-the-art decades ago. Nostalgia is nice; but would you want to be treated by a physician whose office could be a Smithsonian exhibit titled, “Doctor’s Office Circa 1975?” Neither would your patients, for the most part; many – particularly younger ones – assume that doctors who don’t keep up with technological innovations don’t keep up with anything else, either.

If you’re planning a vacation this year (and I hope you are), that would be the perfect time for a re-do. Your patients will be spared the dust and turmoil, tradespeople won’t have to work around your office hours, and you won’t have to cancel any hours that weren’t already canceled. Best of all, you’ll come back to a clean, fresh environment.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

that your patients might see?

We tend not to notice gradual deterioration in the workplace we inhabit every day: Carpets fade and dull with constant traffic and cleaning; wallpaper and paint accumulate dirt, stains, and damage; furniture gets dirty and dented, fabric rips, hardware goes missing; laminate peels off the edges of desks and cabinets.

When did you last take a good look at your waiting room? How clean is it? Patients expect cleanliness in doctor’s offices, and they expect the reception area to be neat. How are the carpeting and upholstery holding up? Sit in your chairs; how do they feel? Patients don’t appreciate a sore back or bottom from any chairs, especially in a medical office. Consider investing in new furniture that will be attractive and comfortable for your patients.

Look at the decor itself; is it dated or just plain “old-looking?” Any interior designer will tell you they can determine quite accurately when a space was last decorated, simply by the color and style of the materials used. If your office is stuck in the ‘90s, it’s probably time for a change. Even if you don’t find anything obvious, it’s wise to check periodically for subtle evidence of age: Find some patches of protected carpeting and flooring under stationary furniture and compare them to exposed floors.

If your color scheme is hopelessly out of date and style, or if you are just tired of it, change it. Wallpaper and carpeting should be long-wearing industrial quality; paint should be high-quality “eggshell” finish to facilitate cleaning, and everything should be professionally applied. (This is neither the time nor place for do-it-yourself experiments.) Consider updating your overhead lighting. The harsh glow of fluorescent lights amid an uninspired decor creates a sterile, uninviting atmosphere.

During renovation, get your building’s maintenance crew to fix any nagging plumbing, electrical, or heating/air conditioning problems while pipes, ducts, and wires are more readily accessible. This is also a good time to clear out old textbooks, journals, and files that you will never open again, in this digital age.

If your wall decorations are dated and unattractive, now would be a good time to replace at least some of them. This need not be an expensive proposition; a few years ago, I redecorated my exam room walls with framed photos from my travel adventures – to very positive responses from patients and staff alike. If you’re not an artist or photographer, invite a family member, or local artists or talented patients, to display some of their creations on your walls. If you get too many contributions, you can rotate them on a periodic basis.

Plants are great aesthetic accents, yet many offices have little or no plant life. Plants naturally aerate an office suite and help make it feel less stuffy. Also, multiple studies have found that plants promote productivity among office staff and create a sense of calm for apprehensive patients. Improvements like this can make a big difference. They show an attention to detail and a willingness to make your practice as inviting as possible for patients and employees alike.

Spruce-up time is also an excellent opportunity to inventory your medical equipment. We’ve all seen “vintage” offices full of gadgets that were state-of-the-art decades ago. Nostalgia is nice; but would you want to be treated by a physician whose office could be a Smithsonian exhibit titled, “Doctor’s Office Circa 1975?” Neither would your patients, for the most part; many – particularly younger ones – assume that doctors who don’t keep up with technological innovations don’t keep up with anything else, either.

If you’re planning a vacation this year (and I hope you are), that would be the perfect time for a re-do. Your patients will be spared the dust and turmoil, tradespeople won’t have to work around your office hours, and you won’t have to cancel any hours that weren’t already canceled. Best of all, you’ll come back to a clean, fresh environment.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

that your patients might see?

We tend not to notice gradual deterioration in the workplace we inhabit every day: Carpets fade and dull with constant traffic and cleaning; wallpaper and paint accumulate dirt, stains, and damage; furniture gets dirty and dented, fabric rips, hardware goes missing; laminate peels off the edges of desks and cabinets.

When did you last take a good look at your waiting room? How clean is it? Patients expect cleanliness in doctor’s offices, and they expect the reception area to be neat. How are the carpeting and upholstery holding up? Sit in your chairs; how do they feel? Patients don’t appreciate a sore back or bottom from any chairs, especially in a medical office. Consider investing in new furniture that will be attractive and comfortable for your patients.

Look at the decor itself; is it dated or just plain “old-looking?” Any interior designer will tell you they can determine quite accurately when a space was last decorated, simply by the color and style of the materials used. If your office is stuck in the ‘90s, it’s probably time for a change. Even if you don’t find anything obvious, it’s wise to check periodically for subtle evidence of age: Find some patches of protected carpeting and flooring under stationary furniture and compare them to exposed floors.

If your color scheme is hopelessly out of date and style, or if you are just tired of it, change it. Wallpaper and carpeting should be long-wearing industrial quality; paint should be high-quality “eggshell” finish to facilitate cleaning, and everything should be professionally applied. (This is neither the time nor place for do-it-yourself experiments.) Consider updating your overhead lighting. The harsh glow of fluorescent lights amid an uninspired decor creates a sterile, uninviting atmosphere.

During renovation, get your building’s maintenance crew to fix any nagging plumbing, electrical, or heating/air conditioning problems while pipes, ducts, and wires are more readily accessible. This is also a good time to clear out old textbooks, journals, and files that you will never open again, in this digital age.

If your wall decorations are dated and unattractive, now would be a good time to replace at least some of them. This need not be an expensive proposition; a few years ago, I redecorated my exam room walls with framed photos from my travel adventures – to very positive responses from patients and staff alike. If you’re not an artist or photographer, invite a family member, or local artists or talented patients, to display some of their creations on your walls. If you get too many contributions, you can rotate them on a periodic basis.

Plants are great aesthetic accents, yet many offices have little or no plant life. Plants naturally aerate an office suite and help make it feel less stuffy. Also, multiple studies have found that plants promote productivity among office staff and create a sense of calm for apprehensive patients. Improvements like this can make a big difference. They show an attention to detail and a willingness to make your practice as inviting as possible for patients and employees alike.

Spruce-up time is also an excellent opportunity to inventory your medical equipment. We’ve all seen “vintage” offices full of gadgets that were state-of-the-art decades ago. Nostalgia is nice; but would you want to be treated by a physician whose office could be a Smithsonian exhibit titled, “Doctor’s Office Circa 1975?” Neither would your patients, for the most part; many – particularly younger ones – assume that doctors who don’t keep up with technological innovations don’t keep up with anything else, either.

If you’re planning a vacation this year (and I hope you are), that would be the perfect time for a re-do. Your patients will be spared the dust and turmoil, tradespeople won’t have to work around your office hours, and you won’t have to cancel any hours that weren’t already canceled. Best of all, you’ll come back to a clean, fresh environment.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Black Veterans Disproportionately Denied VA Benefits

Black veterans are less likely to have their benefits claims processed and paid than are their White peers because of systemic problems within the US Department of Veterans Affairs, according to a lawsuit filed against the agency.

“A Black veteran who served honorably can walk into the VA, file a disability claim, and be at a significantly higher likelihood of having that claim denied,” said Adam Henderson, a student working with the Yale Law School Veterans Legal Services Clinic, one of several groups connected to the lawsuit.

“The VA has denied countless meritorious applications of Black veterans and thus deprived them and their families of the support that they are entitled to.”

The suit, filed in federal court by the clinic on behalf of Vietnam War veteran Conley Monk Jr., asks for “redress for the harms caused by the failure of VA staff and leaders to administer these benefits programs in a manner free from racial discrimination against Black veterans.”

In a press conference announcing the lawsuit, the effort received backing from Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D, Connecticut) who called it an “unacceptable” situation.

“Black veterans are denied benefits at a very significantly disproportionate rate,” he said. “We know the results. We want to know the reason why.”

The suit stems from an analysis of VA claims records released by the department following an earlier legal action. Between 2001 and 2020, the average denial rate for disability claims filed for Black veterans was 29.5%, significantly above the 24.2% for White veterans.

Attorneys allege the problems date back even further and that VA officials should have known about the racial disparities in the system from previous complaints.

“The negligence of VA leadership, and their failure to train, supervise, monitor and instruct agency officials to take steps to identify and correct racial disparities, led to systematic benefits obstruction for Black veterans,” the suit states.

Monk is a Black disabled Marine Corps veteran who previously sued the military to overturn his less-than-honorable military discharge due to complications from undiagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder.

He was subsequently granted access to a host of veterans benefits but not to retroactive payouts for claims he was denied in the 1970s.

“They didn’t fully compensate me or my family,” he said. “I wasn’t able to give my kids my educational benefits. We should have been receiving checks while they were growing up.”

Along with potential past benefits for Monk, individuals involved with the lawsuit said the move could force the VA to reassess thousands of other unfairly dismissed cases. “For decades [the US government] has allowed racially discriminatory practices to obstruct Black veterans from easily accessing veterans housing, education, and health care benefits with wide-reaching economic consequences for Black veterans and their families,” said Richard Brookshire, executive director of the Black Veterans Project.

“This lawsuit reckons with the shameful history of racism by the Department of Veteran Affairs and seeks to redress long-standing improprieties reverberating across generations of Black military service.”

In a statement, VA press secretary Terrence Hayes did not directly respond to the lawsuit but noted that “throughout history, there have been unacceptable disparities in both VA benefits decisions and military discharge status due to racism, which have wrongly left Black veterans without access to VA care and benefits.”

“We are actively working to right these wrongs, and we will stop at nothing to ensure that all Black veterans get the VA services they have earned and deserve,” he said. “We are currently studying racial disparities in benefits claims decisions, and we will publish the results of that study as soon as they are available.”

Hayes said the department has already begun targeted outreach to Black veterans to help them with claims and is “taking steps to ensure that our claims process combats institutional racism, rather than perpetuating it.”

Black veterans are less likely to have their benefits claims processed and paid than are their White peers because of systemic problems within the US Department of Veterans Affairs, according to a lawsuit filed against the agency.

“A Black veteran who served honorably can walk into the VA, file a disability claim, and be at a significantly higher likelihood of having that claim denied,” said Adam Henderson, a student working with the Yale Law School Veterans Legal Services Clinic, one of several groups connected to the lawsuit.

“The VA has denied countless meritorious applications of Black veterans and thus deprived them and their families of the support that they are entitled to.”

The suit, filed in federal court by the clinic on behalf of Vietnam War veteran Conley Monk Jr., asks for “redress for the harms caused by the failure of VA staff and leaders to administer these benefits programs in a manner free from racial discrimination against Black veterans.”

In a press conference announcing the lawsuit, the effort received backing from Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D, Connecticut) who called it an “unacceptable” situation.

“Black veterans are denied benefits at a very significantly disproportionate rate,” he said. “We know the results. We want to know the reason why.”

The suit stems from an analysis of VA claims records released by the department following an earlier legal action. Between 2001 and 2020, the average denial rate for disability claims filed for Black veterans was 29.5%, significantly above the 24.2% for White veterans.

Attorneys allege the problems date back even further and that VA officials should have known about the racial disparities in the system from previous complaints.

“The negligence of VA leadership, and their failure to train, supervise, monitor and instruct agency officials to take steps to identify and correct racial disparities, led to systematic benefits obstruction for Black veterans,” the suit states.

Monk is a Black disabled Marine Corps veteran who previously sued the military to overturn his less-than-honorable military discharge due to complications from undiagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder.

He was subsequently granted access to a host of veterans benefits but not to retroactive payouts for claims he was denied in the 1970s.

“They didn’t fully compensate me or my family,” he said. “I wasn’t able to give my kids my educational benefits. We should have been receiving checks while they were growing up.”

Along with potential past benefits for Monk, individuals involved with the lawsuit said the move could force the VA to reassess thousands of other unfairly dismissed cases. “For decades [the US government] has allowed racially discriminatory practices to obstruct Black veterans from easily accessing veterans housing, education, and health care benefits with wide-reaching economic consequences for Black veterans and their families,” said Richard Brookshire, executive director of the Black Veterans Project.

“This lawsuit reckons with the shameful history of racism by the Department of Veteran Affairs and seeks to redress long-standing improprieties reverberating across generations of Black military service.”

In a statement, VA press secretary Terrence Hayes did not directly respond to the lawsuit but noted that “throughout history, there have been unacceptable disparities in both VA benefits decisions and military discharge status due to racism, which have wrongly left Black veterans without access to VA care and benefits.”

“We are actively working to right these wrongs, and we will stop at nothing to ensure that all Black veterans get the VA services they have earned and deserve,” he said. “We are currently studying racial disparities in benefits claims decisions, and we will publish the results of that study as soon as they are available.”

Hayes said the department has already begun targeted outreach to Black veterans to help them with claims and is “taking steps to ensure that our claims process combats institutional racism, rather than perpetuating it.”

Black veterans are less likely to have their benefits claims processed and paid than are their White peers because of systemic problems within the US Department of Veterans Affairs, according to a lawsuit filed against the agency.

“A Black veteran who served honorably can walk into the VA, file a disability claim, and be at a significantly higher likelihood of having that claim denied,” said Adam Henderson, a student working with the Yale Law School Veterans Legal Services Clinic, one of several groups connected to the lawsuit.

“The VA has denied countless meritorious applications of Black veterans and thus deprived them and their families of the support that they are entitled to.”

The suit, filed in federal court by the clinic on behalf of Vietnam War veteran Conley Monk Jr., asks for “redress for the harms caused by the failure of VA staff and leaders to administer these benefits programs in a manner free from racial discrimination against Black veterans.”

In a press conference announcing the lawsuit, the effort received backing from Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D, Connecticut) who called it an “unacceptable” situation.

“Black veterans are denied benefits at a very significantly disproportionate rate,” he said. “We know the results. We want to know the reason why.”

The suit stems from an analysis of VA claims records released by the department following an earlier legal action. Between 2001 and 2020, the average denial rate for disability claims filed for Black veterans was 29.5%, significantly above the 24.2% for White veterans.

Attorneys allege the problems date back even further and that VA officials should have known about the racial disparities in the system from previous complaints.

“The negligence of VA leadership, and their failure to train, supervise, monitor and instruct agency officials to take steps to identify and correct racial disparities, led to systematic benefits obstruction for Black veterans,” the suit states.

Monk is a Black disabled Marine Corps veteran who previously sued the military to overturn his less-than-honorable military discharge due to complications from undiagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder.

He was subsequently granted access to a host of veterans benefits but not to retroactive payouts for claims he was denied in the 1970s.

“They didn’t fully compensate me or my family,” he said. “I wasn’t able to give my kids my educational benefits. We should have been receiving checks while they were growing up.”

Along with potential past benefits for Monk, individuals involved with the lawsuit said the move could force the VA to reassess thousands of other unfairly dismissed cases. “For decades [the US government] has allowed racially discriminatory practices to obstruct Black veterans from easily accessing veterans housing, education, and health care benefits with wide-reaching economic consequences for Black veterans and their families,” said Richard Brookshire, executive director of the Black Veterans Project.

“This lawsuit reckons with the shameful history of racism by the Department of Veteran Affairs and seeks to redress long-standing improprieties reverberating across generations of Black military service.”

In a statement, VA press secretary Terrence Hayes did not directly respond to the lawsuit but noted that “throughout history, there have been unacceptable disparities in both VA benefits decisions and military discharge status due to racism, which have wrongly left Black veterans without access to VA care and benefits.”

“We are actively working to right these wrongs, and we will stop at nothing to ensure that all Black veterans get the VA services they have earned and deserve,” he said. “We are currently studying racial disparities in benefits claims decisions, and we will publish the results of that study as soon as they are available.”

Hayes said the department has already begun targeted outreach to Black veterans to help them with claims and is “taking steps to ensure that our claims process combats institutional racism, rather than perpetuating it.”

Metformin monotherapy not always best start in type 2 diabetes

Metformin failure in people with type 2 diabetes is very common, particularly among those with high hemoglobin A1c levels at the time of diagnosis, new findings suggest.

An analysis of electronic health record data for more than 22,000 patients starting metformin at three U.S. clinical sites found that over 40% experienced metformin failure.

This was defined as either failure to achieve or maintain A1c less than 7% within 18 months or the use of additional glucose-lowering medications.

Other predictors that metformin use wouldn’t be successful included increasing age, male sex, and race/ethnicity. However, the latter ceased to be linked after adjustment for other clinical risk factors.

“Our study results suggest increased monitoring with potentially earlier treatment intensification to achieve glycemic control may be appropriate in patients with clinical parameters described in this paper,” Suzette J. Bielinski, PhD, and colleagues wrote.

“Further, these results call into question the ubiquitous use of metformin as the first-line therapy and suggest a more individualized approach may be needed to optimize therapy,” they added in their article, published online in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

The study is also noteworthy in that it demonstrated the feasibility of using EHR data with a machine-learning approach to discover risk biomarkers, Dr. Bielinski, professor of epidemiology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said in an interview.

“We wanted to repurpose clinical data to answer questions ... I think more studies using these types of techniques repurposing data meant for one thing could potentially impact care in other domains. ... If we can get the bang for the buck from all these data that we generate on people I just think it will improve health care and maybe save health care dollars.”

Baseline A1c strongest predictor of metformin failure

The investigators identified a total of 22,047 metformin initiators from three clinical primary care sites: the University of Mississippi’s Jackson centers, which serves a mostly African American population, the Mountain Park Health Center in Arizona, a seven-clinic federally qualified community health center in Phoenix that serves a mostly Latino population, and the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which includes the Mayo Clinic and serves a primarily White population.

Overall, a total of 43% (9,407) of patients met one of two criteria for metformin failure by 18 months. Among those, median time to failure on metformin was 3.9 months.

Unadjusted failure rates were higher among African Americans, Hispanics, and other racial groups, compared with non-Hispanic White patients.

However, the racial groups also differed by baseline characteristics. Mean A1c was 7.7% overall, 8.1% for the African American group, 7.9% for Asians, and 8.2% for Hispanics, compared with 7.6% for non-Hispanic Whites.

Of 150 clinical factors examined, higher A1c was the strongest predictor of metformin failure, with a rapid increase in risk appearing between 7.5% and 8.0%.

“The slope is steep. It gives us some clinical guidance,” Dr. Bielinski said.

Other variables positively correlated with metformin failure included “diabetes with complications,” increased age, and higher levels of potassium, triglycerides, heart rate, and mean cell hemoglobin.

Factors inversely correlated with metformin failure were having received screening for other suspected conditions and medical examination/evaluation, and lower levels of sodium, albumin, and HDL cholesterol.

Three variables – body mass index, LDL cholesterol, and creatinine – had a U-shaped relationship with metformin failure, so that both high and low values were associated with increased risk.

“The racial/ethnic differences disappeared once other clinical factors were considered suggesting that the biological response to metformin is similar regardless of race/ethnicity,” Dr. Bielinski and colleagues wrote.

They also noted that the abnormal lab results which correlated with metformin failure “likely represent biomarkers for chronic illnesses. However, the effect size for lab abnormalities was small compared with that of baseline A1c.”

Dr. Bielinski urged caution in interpreting the findings. “Electronic health records data have limitations. We have evidence that these people were prescribed metformin. We have no idea if they took it. ... I would really be hesitant to be too strong in making clinical recommendations.”

However, she said that the data are “suggestive to say maybe we need to have some kind of threshold where if someone comes in with an A1c of X that they go on dual therapy right away. I think this is opening the door to that.”

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Metformin failure in people with type 2 diabetes is very common, particularly among those with high hemoglobin A1c levels at the time of diagnosis, new findings suggest.

An analysis of electronic health record data for more than 22,000 patients starting metformin at three U.S. clinical sites found that over 40% experienced metformin failure.

This was defined as either failure to achieve or maintain A1c less than 7% within 18 months or the use of additional glucose-lowering medications.

Other predictors that metformin use wouldn’t be successful included increasing age, male sex, and race/ethnicity. However, the latter ceased to be linked after adjustment for other clinical risk factors.

“Our study results suggest increased monitoring with potentially earlier treatment intensification to achieve glycemic control may be appropriate in patients with clinical parameters described in this paper,” Suzette J. Bielinski, PhD, and colleagues wrote.

“Further, these results call into question the ubiquitous use of metformin as the first-line therapy and suggest a more individualized approach may be needed to optimize therapy,” they added in their article, published online in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

The study is also noteworthy in that it demonstrated the feasibility of using EHR data with a machine-learning approach to discover risk biomarkers, Dr. Bielinski, professor of epidemiology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said in an interview.

“We wanted to repurpose clinical data to answer questions ... I think more studies using these types of techniques repurposing data meant for one thing could potentially impact care in other domains. ... If we can get the bang for the buck from all these data that we generate on people I just think it will improve health care and maybe save health care dollars.”

Baseline A1c strongest predictor of metformin failure

The investigators identified a total of 22,047 metformin initiators from three clinical primary care sites: the University of Mississippi’s Jackson centers, which serves a mostly African American population, the Mountain Park Health Center in Arizona, a seven-clinic federally qualified community health center in Phoenix that serves a mostly Latino population, and the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which includes the Mayo Clinic and serves a primarily White population.

Overall, a total of 43% (9,407) of patients met one of two criteria for metformin failure by 18 months. Among those, median time to failure on metformin was 3.9 months.

Unadjusted failure rates were higher among African Americans, Hispanics, and other racial groups, compared with non-Hispanic White patients.

However, the racial groups also differed by baseline characteristics. Mean A1c was 7.7% overall, 8.1% for the African American group, 7.9% for Asians, and 8.2% for Hispanics, compared with 7.6% for non-Hispanic Whites.

Of 150 clinical factors examined, higher A1c was the strongest predictor of metformin failure, with a rapid increase in risk appearing between 7.5% and 8.0%.

“The slope is steep. It gives us some clinical guidance,” Dr. Bielinski said.

Other variables positively correlated with metformin failure included “diabetes with complications,” increased age, and higher levels of potassium, triglycerides, heart rate, and mean cell hemoglobin.

Factors inversely correlated with metformin failure were having received screening for other suspected conditions and medical examination/evaluation, and lower levels of sodium, albumin, and HDL cholesterol.

Three variables – body mass index, LDL cholesterol, and creatinine – had a U-shaped relationship with metformin failure, so that both high and low values were associated with increased risk.

“The racial/ethnic differences disappeared once other clinical factors were considered suggesting that the biological response to metformin is similar regardless of race/ethnicity,” Dr. Bielinski and colleagues wrote.

They also noted that the abnormal lab results which correlated with metformin failure “likely represent biomarkers for chronic illnesses. However, the effect size for lab abnormalities was small compared with that of baseline A1c.”

Dr. Bielinski urged caution in interpreting the findings. “Electronic health records data have limitations. We have evidence that these people were prescribed metformin. We have no idea if they took it. ... I would really be hesitant to be too strong in making clinical recommendations.”

However, she said that the data are “suggestive to say maybe we need to have some kind of threshold where if someone comes in with an A1c of X that they go on dual therapy right away. I think this is opening the door to that.”

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Metformin failure in people with type 2 diabetes is very common, particularly among those with high hemoglobin A1c levels at the time of diagnosis, new findings suggest.

An analysis of electronic health record data for more than 22,000 patients starting metformin at three U.S. clinical sites found that over 40% experienced metformin failure.

This was defined as either failure to achieve or maintain A1c less than 7% within 18 months or the use of additional glucose-lowering medications.

Other predictors that metformin use wouldn’t be successful included increasing age, male sex, and race/ethnicity. However, the latter ceased to be linked after adjustment for other clinical risk factors.

“Our study results suggest increased monitoring with potentially earlier treatment intensification to achieve glycemic control may be appropriate in patients with clinical parameters described in this paper,” Suzette J. Bielinski, PhD, and colleagues wrote.

“Further, these results call into question the ubiquitous use of metformin as the first-line therapy and suggest a more individualized approach may be needed to optimize therapy,” they added in their article, published online in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

The study is also noteworthy in that it demonstrated the feasibility of using EHR data with a machine-learning approach to discover risk biomarkers, Dr. Bielinski, professor of epidemiology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said in an interview.

“We wanted to repurpose clinical data to answer questions ... I think more studies using these types of techniques repurposing data meant for one thing could potentially impact care in other domains. ... If we can get the bang for the buck from all these data that we generate on people I just think it will improve health care and maybe save health care dollars.”

Baseline A1c strongest predictor of metformin failure

The investigators identified a total of 22,047 metformin initiators from three clinical primary care sites: the University of Mississippi’s Jackson centers, which serves a mostly African American population, the Mountain Park Health Center in Arizona, a seven-clinic federally qualified community health center in Phoenix that serves a mostly Latino population, and the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which includes the Mayo Clinic and serves a primarily White population.

Overall, a total of 43% (9,407) of patients met one of two criteria for metformin failure by 18 months. Among those, median time to failure on metformin was 3.9 months.

Unadjusted failure rates were higher among African Americans, Hispanics, and other racial groups, compared with non-Hispanic White patients.

However, the racial groups also differed by baseline characteristics. Mean A1c was 7.7% overall, 8.1% for the African American group, 7.9% for Asians, and 8.2% for Hispanics, compared with 7.6% for non-Hispanic Whites.

Of 150 clinical factors examined, higher A1c was the strongest predictor of metformin failure, with a rapid increase in risk appearing between 7.5% and 8.0%.

“The slope is steep. It gives us some clinical guidance,” Dr. Bielinski said.

Other variables positively correlated with metformin failure included “diabetes with complications,” increased age, and higher levels of potassium, triglycerides, heart rate, and mean cell hemoglobin.

Factors inversely correlated with metformin failure were having received screening for other suspected conditions and medical examination/evaluation, and lower levels of sodium, albumin, and HDL cholesterol.

Three variables – body mass index, LDL cholesterol, and creatinine – had a U-shaped relationship with metformin failure, so that both high and low values were associated with increased risk.

“The racial/ethnic differences disappeared once other clinical factors were considered suggesting that the biological response to metformin is similar regardless of race/ethnicity,” Dr. Bielinski and colleagues wrote.

They also noted that the abnormal lab results which correlated with metformin failure “likely represent biomarkers for chronic illnesses. However, the effect size for lab abnormalities was small compared with that of baseline A1c.”

Dr. Bielinski urged caution in interpreting the findings. “Electronic health records data have limitations. We have evidence that these people were prescribed metformin. We have no idea if they took it. ... I would really be hesitant to be too strong in making clinical recommendations.”

However, she said that the data are “suggestive to say maybe we need to have some kind of threshold where if someone comes in with an A1c of X that they go on dual therapy right away. I think this is opening the door to that.”

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Atrial failure or insufficiency: A new syndrome

Atrial dysfunction, widely considered a marker or consequence of other heart diseases, is a relevant clinical entity, which is why it is justified to define atrial failure or insufficiency as “a new syndrome that all cardiologists should be aware of,” said Adrián Baranchuk, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., during the 2022 48th Argentine Congress of Cardiology in Buenos Aires.

“The atria are like the heart’s silly sisters and can fail just like the ventricle fails. Understanding their function and dysfunction helps us to understand heart failure. And as electrophysiologists and clinical cardiologists, we have to embrace this concept and understand it in depth,” Dr. Baranchuk, president-elect of the Inter-American Society of Cardiology, said in an interview.

The specialist first proposed atrial failure as an entity or syndrome in early 2020 in an article in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. His four collaborators included the experienced Eugene Braunwald, MD, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Antoni Bayés de Luna, PhD, from the department of medicine of the autonomous University of Barcelona.

Pathology despite function

“In many patients with heart failure, the pump function is preserved, but what causes the pathology? For the last 5-10 years, attention has been focused on the ventricle: whether it contracts poorly or whether it contracts properly and relaxes poorly. However, we have also seen patients in whom the ventricle contracts properly and relaxes properly. Where else can we look? We started looking at atrial contraction, especially the left atrium,” recalled Dr. Baranchuk.

He and his colleagues proposed the following consensus definition of atrial failure or insufficiency: any atrial dysfunction (anatomical, mechanical, electrical, and rheological, including blood homeostasis) that causes impaired function, heart symptoms, and a worsening of quality of life (or life expectancy) in the absence of significant valvular or ventricular abnormalities.

In his presentation, recorded and projected by video from Canada, Dr. Baranchuk pointed out that there are two large groups of causes of atrial failure: one that has to do with electrical disorders of atrial and interatrial contraction and another related to the progressive development of fibrosis, which gradually leads to dyssynchrony in interatrial contraction, pump failure, and impaired atrial function as a reservoir and as a conduit.

“In turn, these mechanisms trigger neurohormonal alterations that perpetuate atrial failure, so it is not just a matter of progressive fibrosis, which is very difficult to treat, but also of constant neurohormonal activation that guarantees that these phenomena never resolve,” said Dr. Baranchuk. The manifestations or end point of this cascade of events are the known ones: stroke, ischemia, and heart failure.

New entity necessary?

Defining atrial failure or insufficiency as a clinical entity not only restores the hierarchy of the atria in cardiac function, which was already postulated by William Harvey in 1628, but also enables new lines of research that would eventually allow timely preventive interventions.

One key is early recognition of partial or total interatrial block by analyzing the characteristics of the P wave on the electrocardiogram, which could serve to prevent progression to atrial fibrillation. Left atrial enlargement can also be detected by echocardiography.

“When the contractile impairment is severe and you are in atrial fibrillation, all that remains is to apply patches. The strategy is to correct risk factors beforehand, such as high blood pressure, sleep apnea, or high-dose alcohol consumption, as well as tirelessly searching for atrial fibrillation, with Holter electrocardiograms, continuous monitoring devices, such as Apple Watch, KardiaMobile, or an implantable loop recorder,” Dr. Baranchuk said in an interview.

Two ongoing or planned studies, ARCADIA and AMIABLE, will seek to determine whether anticoagulation in patients with elevated cardiovascular risk scores and any of these atrial disorders that have not yet led to atrial fibrillation could reduce the incidence of stroke.

The strategy has a rational basis. In a subanalysis of raw data from the NAVIGATE ESUS study in patients with embolic stroke of unknown cause, Dr. Baranchuk estimated that the presence of interatrial block was a tenfold higher predictor of the risk of experiencing a second stroke. Another 2018 observational study in which he participated found that in outpatients with heart failure, advanced interatrial block approximately tripled the risk of developing atrial fibrillation and ischemic stroke.

For Dr. Baranchuk, other questions that still need to be answered include whether drugs used for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction can be useful in primary atrial failure or whether specific drugs can be repositioned or developed to suppress or slow the process of fibrosis. “From generating the clinical concept, many lines of research are enabled.”

“The concept of atrial failure is very interesting and opens our eyes to treatments,” another speaker at the session, Alejo Tronconi, MD, a cardiologist and electrophysiologist at the Cardiovascular Institute of the South, Cipolletti, Argentina, said in an interview.

“It is necessary to cut circuits that have been extensively studied in heart failure models, and now we are beginning to see their participation in atrial dysfunction,” he said.

Dr. Baranchuk and Dr. Tronconi declared no relevant financial conflict of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Atrial dysfunction, widely considered a marker or consequence of other heart diseases, is a relevant clinical entity, which is why it is justified to define atrial failure or insufficiency as “a new syndrome that all cardiologists should be aware of,” said Adrián Baranchuk, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., during the 2022 48th Argentine Congress of Cardiology in Buenos Aires.

“The atria are like the heart’s silly sisters and can fail just like the ventricle fails. Understanding their function and dysfunction helps us to understand heart failure. And as electrophysiologists and clinical cardiologists, we have to embrace this concept and understand it in depth,” Dr. Baranchuk, president-elect of the Inter-American Society of Cardiology, said in an interview.

The specialist first proposed atrial failure as an entity or syndrome in early 2020 in an article in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. His four collaborators included the experienced Eugene Braunwald, MD, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Antoni Bayés de Luna, PhD, from the department of medicine of the autonomous University of Barcelona.

Pathology despite function

“In many patients with heart failure, the pump function is preserved, but what causes the pathology? For the last 5-10 years, attention has been focused on the ventricle: whether it contracts poorly or whether it contracts properly and relaxes poorly. However, we have also seen patients in whom the ventricle contracts properly and relaxes properly. Where else can we look? We started looking at atrial contraction, especially the left atrium,” recalled Dr. Baranchuk.

He and his colleagues proposed the following consensus definition of atrial failure or insufficiency: any atrial dysfunction (anatomical, mechanical, electrical, and rheological, including blood homeostasis) that causes impaired function, heart symptoms, and a worsening of quality of life (or life expectancy) in the absence of significant valvular or ventricular abnormalities.

In his presentation, recorded and projected by video from Canada, Dr. Baranchuk pointed out that there are two large groups of causes of atrial failure: one that has to do with electrical disorders of atrial and interatrial contraction and another related to the progressive development of fibrosis, which gradually leads to dyssynchrony in interatrial contraction, pump failure, and impaired atrial function as a reservoir and as a conduit.

“In turn, these mechanisms trigger neurohormonal alterations that perpetuate atrial failure, so it is not just a matter of progressive fibrosis, which is very difficult to treat, but also of constant neurohormonal activation that guarantees that these phenomena never resolve,” said Dr. Baranchuk. The manifestations or end point of this cascade of events are the known ones: stroke, ischemia, and heart failure.

New entity necessary?

Defining atrial failure or insufficiency as a clinical entity not only restores the hierarchy of the atria in cardiac function, which was already postulated by William Harvey in 1628, but also enables new lines of research that would eventually allow timely preventive interventions.

One key is early recognition of partial or total interatrial block by analyzing the characteristics of the P wave on the electrocardiogram, which could serve to prevent progression to atrial fibrillation. Left atrial enlargement can also be detected by echocardiography.

“When the contractile impairment is severe and you are in atrial fibrillation, all that remains is to apply patches. The strategy is to correct risk factors beforehand, such as high blood pressure, sleep apnea, or high-dose alcohol consumption, as well as tirelessly searching for atrial fibrillation, with Holter electrocardiograms, continuous monitoring devices, such as Apple Watch, KardiaMobile, or an implantable loop recorder,” Dr. Baranchuk said in an interview.

Two ongoing or planned studies, ARCADIA and AMIABLE, will seek to determine whether anticoagulation in patients with elevated cardiovascular risk scores and any of these atrial disorders that have not yet led to atrial fibrillation could reduce the incidence of stroke.

The strategy has a rational basis. In a subanalysis of raw data from the NAVIGATE ESUS study in patients with embolic stroke of unknown cause, Dr. Baranchuk estimated that the presence of interatrial block was a tenfold higher predictor of the risk of experiencing a second stroke. Another 2018 observational study in which he participated found that in outpatients with heart failure, advanced interatrial block approximately tripled the risk of developing atrial fibrillation and ischemic stroke.

For Dr. Baranchuk, other questions that still need to be answered include whether drugs used for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction can be useful in primary atrial failure or whether specific drugs can be repositioned or developed to suppress or slow the process of fibrosis. “From generating the clinical concept, many lines of research are enabled.”

“The concept of atrial failure is very interesting and opens our eyes to treatments,” another speaker at the session, Alejo Tronconi, MD, a cardiologist and electrophysiologist at the Cardiovascular Institute of the South, Cipolletti, Argentina, said in an interview.

“It is necessary to cut circuits that have been extensively studied in heart failure models, and now we are beginning to see their participation in atrial dysfunction,” he said.

Dr. Baranchuk and Dr. Tronconi declared no relevant financial conflict of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Atrial dysfunction, widely considered a marker or consequence of other heart diseases, is a relevant clinical entity, which is why it is justified to define atrial failure or insufficiency as “a new syndrome that all cardiologists should be aware of,” said Adrián Baranchuk, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., during the 2022 48th Argentine Congress of Cardiology in Buenos Aires.

“The atria are like the heart’s silly sisters and can fail just like the ventricle fails. Understanding their function and dysfunction helps us to understand heart failure. And as electrophysiologists and clinical cardiologists, we have to embrace this concept and understand it in depth,” Dr. Baranchuk, president-elect of the Inter-American Society of Cardiology, said in an interview.

The specialist first proposed atrial failure as an entity or syndrome in early 2020 in an article in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. His four collaborators included the experienced Eugene Braunwald, MD, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and Antoni Bayés de Luna, PhD, from the department of medicine of the autonomous University of Barcelona.

Pathology despite function

“In many patients with heart failure, the pump function is preserved, but what causes the pathology? For the last 5-10 years, attention has been focused on the ventricle: whether it contracts poorly or whether it contracts properly and relaxes poorly. However, we have also seen patients in whom the ventricle contracts properly and relaxes properly. Where else can we look? We started looking at atrial contraction, especially the left atrium,” recalled Dr. Baranchuk.

He and his colleagues proposed the following consensus definition of atrial failure or insufficiency: any atrial dysfunction (anatomical, mechanical, electrical, and rheological, including blood homeostasis) that causes impaired function, heart symptoms, and a worsening of quality of life (or life expectancy) in the absence of significant valvular or ventricular abnormalities.

In his presentation, recorded and projected by video from Canada, Dr. Baranchuk pointed out that there are two large groups of causes of atrial failure: one that has to do with electrical disorders of atrial and interatrial contraction and another related to the progressive development of fibrosis, which gradually leads to dyssynchrony in interatrial contraction, pump failure, and impaired atrial function as a reservoir and as a conduit.

“In turn, these mechanisms trigger neurohormonal alterations that perpetuate atrial failure, so it is not just a matter of progressive fibrosis, which is very difficult to treat, but also of constant neurohormonal activation that guarantees that these phenomena never resolve,” said Dr. Baranchuk. The manifestations or end point of this cascade of events are the known ones: stroke, ischemia, and heart failure.

New entity necessary?

Defining atrial failure or insufficiency as a clinical entity not only restores the hierarchy of the atria in cardiac function, which was already postulated by William Harvey in 1628, but also enables new lines of research that would eventually allow timely preventive interventions.

One key is early recognition of partial or total interatrial block by analyzing the characteristics of the P wave on the electrocardiogram, which could serve to prevent progression to atrial fibrillation. Left atrial enlargement can also be detected by echocardiography.

“When the contractile impairment is severe and you are in atrial fibrillation, all that remains is to apply patches. The strategy is to correct risk factors beforehand, such as high blood pressure, sleep apnea, or high-dose alcohol consumption, as well as tirelessly searching for atrial fibrillation, with Holter electrocardiograms, continuous monitoring devices, such as Apple Watch, KardiaMobile, or an implantable loop recorder,” Dr. Baranchuk said in an interview.

Two ongoing or planned studies, ARCADIA and AMIABLE, will seek to determine whether anticoagulation in patients with elevated cardiovascular risk scores and any of these atrial disorders that have not yet led to atrial fibrillation could reduce the incidence of stroke.

The strategy has a rational basis. In a subanalysis of raw data from the NAVIGATE ESUS study in patients with embolic stroke of unknown cause, Dr. Baranchuk estimated that the presence of interatrial block was a tenfold higher predictor of the risk of experiencing a second stroke. Another 2018 observational study in which he participated found that in outpatients with heart failure, advanced interatrial block approximately tripled the risk of developing atrial fibrillation and ischemic stroke.

For Dr. Baranchuk, other questions that still need to be answered include whether drugs used for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction can be useful in primary atrial failure or whether specific drugs can be repositioned or developed to suppress or slow the process of fibrosis. “From generating the clinical concept, many lines of research are enabled.”

“The concept of atrial failure is very interesting and opens our eyes to treatments,” another speaker at the session, Alejo Tronconi, MD, a cardiologist and electrophysiologist at the Cardiovascular Institute of the South, Cipolletti, Argentina, said in an interview.

“It is necessary to cut circuits that have been extensively studied in heart failure models, and now we are beginning to see their participation in atrial dysfunction,” he said.

Dr. Baranchuk and Dr. Tronconi declared no relevant financial conflict of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Exophytic Firm Papulonodule on the Labia in a Patient With Nonspecific Gastrointestinal Symptoms

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

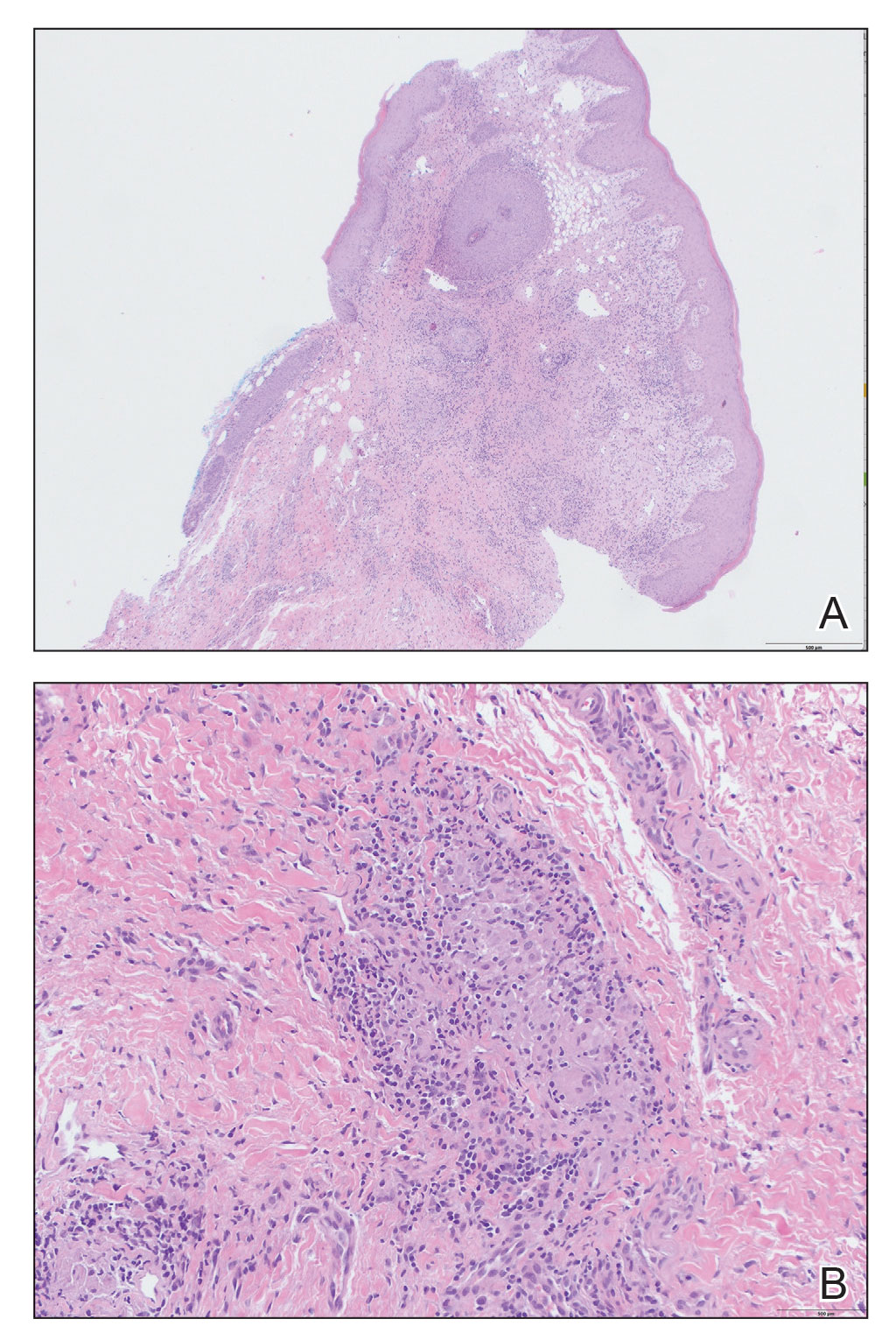

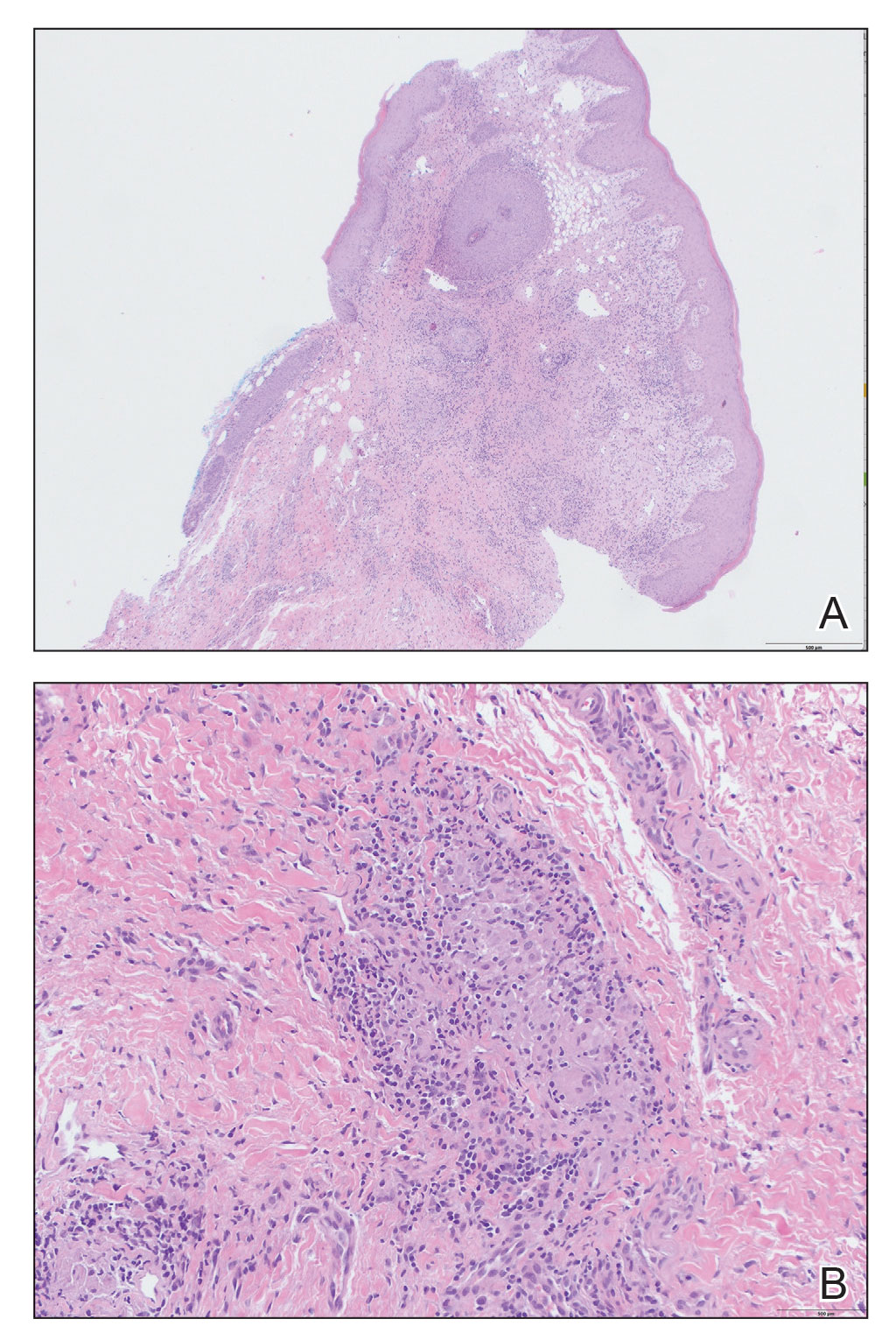

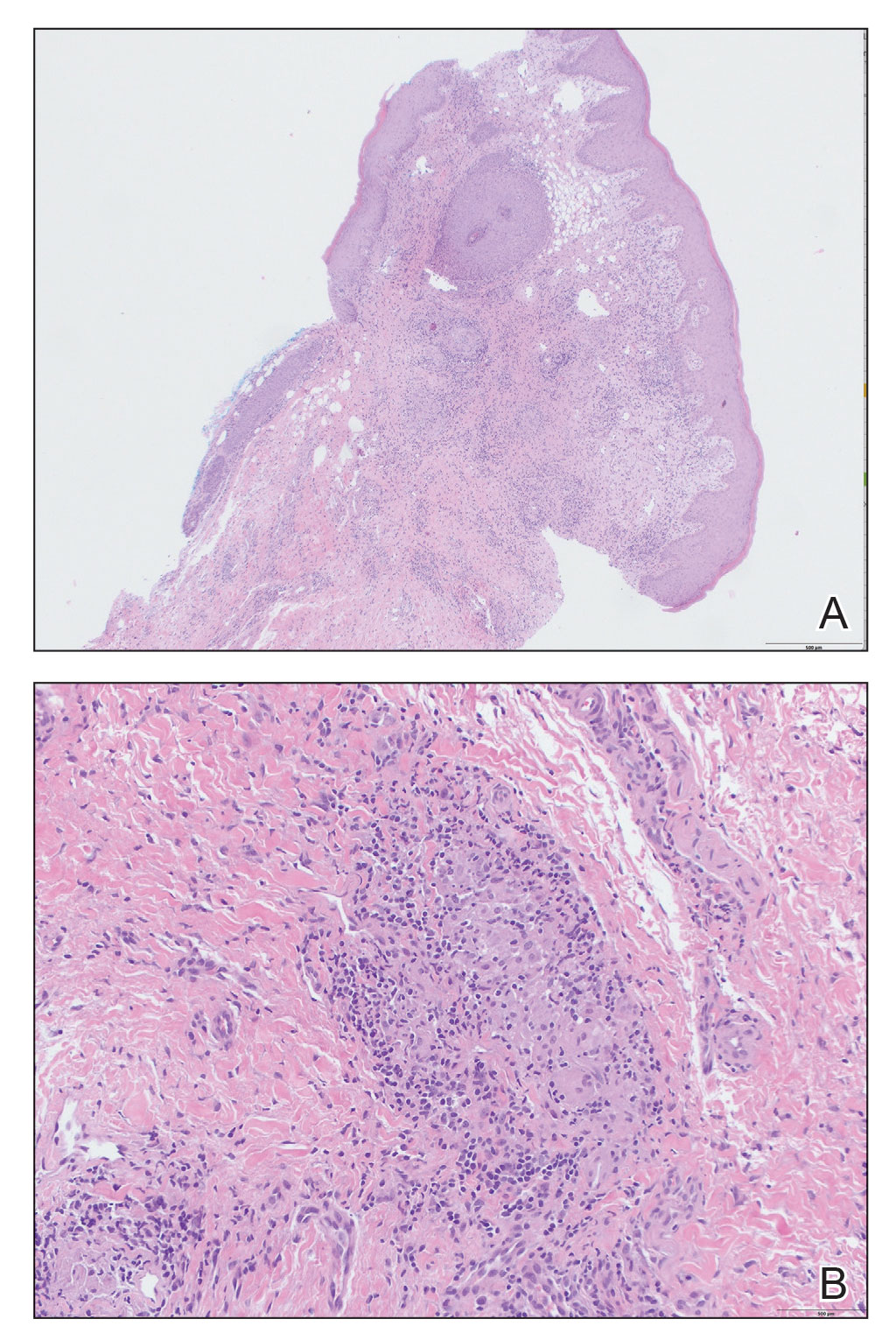

Kinyoun and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the labial biopsy were negative for mycobacteria and fungi, respectively. A complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, celiac disease serologies, stool occult blood, and stool calprotectin laboratory test results were within reference range. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis demonstrated an anal fissure extending from the anal verge at the 6 o’clock position, abnormal T2 bright signal in the skin of the buttocks and perineum extending to the labia, and mild mucosal enhancement of the rectal and anal mucosa. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and magnetic resonance elastography were unremarkable. Colonoscopy demonstrated scattered superficial erythematous patches and erosions in the rectum. Histologically, there was mild to moderately active colitis in the rectum with no evidence of chronicity. Given our patient’s labial edema and exophytic papulonodule (Figure 1) in the setting of nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and granulomatous dermatitis seen on pathology (Figure 2), she was diagnosed with cutaneous Crohn disease (CD).

In our patient, labial biopsy was necessary to definitively diagnose CD. Prior to biopsy of the lesion, our patient was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation leading to an anal fissure and skin tag due to lack of laboratory, imaging, and colonoscopy findings commonly associated with CD. Her biopsy results and gastrointestinal symptoms made these diagnoses, as well as condyloma or a large sentinel skin tag, less likely.

Extraintestinal findings of CD, especially cutaneous manifestations, are relatively frequent and may be present in as many as 44% of patients.1,2 Cutaneous CD often is characterized based on pathogenic mechanisms as either reactive, associated, or CD specific. Reactive cutaneous manifestations include erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, and oral aphthae. Associated cutaneous manifestations include vitiligo, palmar erythema, and palmoplantar pustulosis.2 Crohn disease–specific manifestations, including genital or extragenital metastatic CD (MCD), fistulas, and oral involvement, are granulomatous in nature, similar to intestinal CD. Genital manifestations of MCD include edema, erythema, fissures, and/or ulceration of the vulva, penis, or scrotum. Labial swelling is the most common presenting symptom of MCD in females in both pediatric and adult age groups.2 Lymphedema, skin tags, and condylomalike growths also can be seen but are relatively less common.2

Given the labial edema, exophytic papulonodule, and granulomatous dermatitis seen on histopathology, our patient likely fit into the MCD category.2 In adults, most instances of MCD arise in the setting of well-established intestinal CD disease,3 whereas in children 86% of cases occur in patients without concurrent intestinal CD.2

Given the nonspecific and variable presentation of MCD, the differential diagnosis is broad. The differential diagnosis could include infectious etiologies such as condyloma acuminatum (human papillomavirus); syphilitic chancre; or mycobacterial, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic vulvovaginitis. Sexual abuse, sarcoidosis, Behçet disease, or hidradenitis suppurativa, among other diagnoses, also should be considered. Diagnostic workup should include biopsy of the lesion with special stains, polarizing microscopy, and tissue cultures.4 A thorough evaluation for gastrointestinal CD should be completed after diagnosis.3

The clinical course of vulvar CD can be unpredictable, with some cases healing spontaneously but most persisting despite treatment and sometimes prompting surgical removal.2,4 Early recognition is crucial, as long-standing MCD lesions can be therapy resistant.5 Due to the rarity of the condition and lack of data, there is a lack of treatment consensus for MCD. In 2014, the American Academy of Dermatology published treatment guidelines recommending superpotent topical steroids or topical tacrolimus as first-line therapy. Next-line therapy includes oral metronidazole, followed by prednisolone if still symptomatic.3 Treatment-resistant disease can warrant treatment with immunomodulators or tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors. Our patient was started on adalimumab; after just 2 months of therapy, the labial swelling decreased and the exophytic nodule was less firm and smaller.

Metastatic CD is a rare manifestation of cutaneous CD and can be present in the absence of gastrointestinal disease.3 This case demonstrates the importance of recognizing the cutaneous signs of CD and the necessity of lesional biopsy for the diagnosis of MCD, as our patient presented with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and a diagnostic workup, including endoscopies, that proved inconclusive for the diagnosis of CD.

- Antonelli E, Bassotti G, Tramontana M, et al. Dermatological manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1-16. doi:10.3390/JCM10020364

- Schneider SL, Foster K, Patel D, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of metastatic Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:566-574. doi:10.1111/PDE.13565

- Kurtzman DJB, Jones T, Lian F, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2014.04.002

- Barret M, De Parades V, Battistella M, et al. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:563-570. doi:10.1016/J.CROHNS.2013.10.009

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder [published online January 3, 2017]. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150. doi:10.1155/2017/8192150

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

Kinyoun and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the labial biopsy were negative for mycobacteria and fungi, respectively. A complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, celiac disease serologies, stool occult blood, and stool calprotectin laboratory test results were within reference range. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis demonstrated an anal fissure extending from the anal verge at the 6 o’clock position, abnormal T2 bright signal in the skin of the buttocks and perineum extending to the labia, and mild mucosal enhancement of the rectal and anal mucosa. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and magnetic resonance elastography were unremarkable. Colonoscopy demonstrated scattered superficial erythematous patches and erosions in the rectum. Histologically, there was mild to moderately active colitis in the rectum with no evidence of chronicity. Given our patient’s labial edema and exophytic papulonodule (Figure 1) in the setting of nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and granulomatous dermatitis seen on pathology (Figure 2), she was diagnosed with cutaneous Crohn disease (CD).

In our patient, labial biopsy was necessary to definitively diagnose CD. Prior to biopsy of the lesion, our patient was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation leading to an anal fissure and skin tag due to lack of laboratory, imaging, and colonoscopy findings commonly associated with CD. Her biopsy results and gastrointestinal symptoms made these diagnoses, as well as condyloma or a large sentinel skin tag, less likely.

Extraintestinal findings of CD, especially cutaneous manifestations, are relatively frequent and may be present in as many as 44% of patients.1,2 Cutaneous CD often is characterized based on pathogenic mechanisms as either reactive, associated, or CD specific. Reactive cutaneous manifestations include erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, and oral aphthae. Associated cutaneous manifestations include vitiligo, palmar erythema, and palmoplantar pustulosis.2 Crohn disease–specific manifestations, including genital or extragenital metastatic CD (MCD), fistulas, and oral involvement, are granulomatous in nature, similar to intestinal CD. Genital manifestations of MCD include edema, erythema, fissures, and/or ulceration of the vulva, penis, or scrotum. Labial swelling is the most common presenting symptom of MCD in females in both pediatric and adult age groups.2 Lymphedema, skin tags, and condylomalike growths also can be seen but are relatively less common.2

Given the labial edema, exophytic papulonodule, and granulomatous dermatitis seen on histopathology, our patient likely fit into the MCD category.2 In adults, most instances of MCD arise in the setting of well-established intestinal CD disease,3 whereas in children 86% of cases occur in patients without concurrent intestinal CD.2

Given the nonspecific and variable presentation of MCD, the differential diagnosis is broad. The differential diagnosis could include infectious etiologies such as condyloma acuminatum (human papillomavirus); syphilitic chancre; or mycobacterial, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic vulvovaginitis. Sexual abuse, sarcoidosis, Behçet disease, or hidradenitis suppurativa, among other diagnoses, also should be considered. Diagnostic workup should include biopsy of the lesion with special stains, polarizing microscopy, and tissue cultures.4 A thorough evaluation for gastrointestinal CD should be completed after diagnosis.3

The clinical course of vulvar CD can be unpredictable, with some cases healing spontaneously but most persisting despite treatment and sometimes prompting surgical removal.2,4 Early recognition is crucial, as long-standing MCD lesions can be therapy resistant.5 Due to the rarity of the condition and lack of data, there is a lack of treatment consensus for MCD. In 2014, the American Academy of Dermatology published treatment guidelines recommending superpotent topical steroids or topical tacrolimus as first-line therapy. Next-line therapy includes oral metronidazole, followed by prednisolone if still symptomatic.3 Treatment-resistant disease can warrant treatment with immunomodulators or tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors. Our patient was started on adalimumab; after just 2 months of therapy, the labial swelling decreased and the exophytic nodule was less firm and smaller.

Metastatic CD is a rare manifestation of cutaneous CD and can be present in the absence of gastrointestinal disease.3 This case demonstrates the importance of recognizing the cutaneous signs of CD and the necessity of lesional biopsy for the diagnosis of MCD, as our patient presented with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and a diagnostic workup, including endoscopies, that proved inconclusive for the diagnosis of CD.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

Kinyoun and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining of the labial biopsy were negative for mycobacteria and fungi, respectively. A complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, celiac disease serologies, stool occult blood, and stool calprotectin laboratory test results were within reference range. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis demonstrated an anal fissure extending from the anal verge at the 6 o’clock position, abnormal T2 bright signal in the skin of the buttocks and perineum extending to the labia, and mild mucosal enhancement of the rectal and anal mucosa. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and magnetic resonance elastography were unremarkable. Colonoscopy demonstrated scattered superficial erythematous patches and erosions in the rectum. Histologically, there was mild to moderately active colitis in the rectum with no evidence of chronicity. Given our patient’s labial edema and exophytic papulonodule (Figure 1) in the setting of nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and granulomatous dermatitis seen on pathology (Figure 2), she was diagnosed with cutaneous Crohn disease (CD).

In our patient, labial biopsy was necessary to definitively diagnose CD. Prior to biopsy of the lesion, our patient was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation leading to an anal fissure and skin tag due to lack of laboratory, imaging, and colonoscopy findings commonly associated with CD. Her biopsy results and gastrointestinal symptoms made these diagnoses, as well as condyloma or a large sentinel skin tag, less likely.

Extraintestinal findings of CD, especially cutaneous manifestations, are relatively frequent and may be present in as many as 44% of patients.1,2 Cutaneous CD often is characterized based on pathogenic mechanisms as either reactive, associated, or CD specific. Reactive cutaneous manifestations include erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, and oral aphthae. Associated cutaneous manifestations include vitiligo, palmar erythema, and palmoplantar pustulosis.2 Crohn disease–specific manifestations, including genital or extragenital metastatic CD (MCD), fistulas, and oral involvement, are granulomatous in nature, similar to intestinal CD. Genital manifestations of MCD include edema, erythema, fissures, and/or ulceration of the vulva, penis, or scrotum. Labial swelling is the most common presenting symptom of MCD in females in both pediatric and adult age groups.2 Lymphedema, skin tags, and condylomalike growths also can be seen but are relatively less common.2

Given the labial edema, exophytic papulonodule, and granulomatous dermatitis seen on histopathology, our patient likely fit into the MCD category.2 In adults, most instances of MCD arise in the setting of well-established intestinal CD disease,3 whereas in children 86% of cases occur in patients without concurrent intestinal CD.2

Given the nonspecific and variable presentation of MCD, the differential diagnosis is broad. The differential diagnosis could include infectious etiologies such as condyloma acuminatum (human papillomavirus); syphilitic chancre; or mycobacterial, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic vulvovaginitis. Sexual abuse, sarcoidosis, Behçet disease, or hidradenitis suppurativa, among other diagnoses, also should be considered. Diagnostic workup should include biopsy of the lesion with special stains, polarizing microscopy, and tissue cultures.4 A thorough evaluation for gastrointestinal CD should be completed after diagnosis.3

The clinical course of vulvar CD can be unpredictable, with some cases healing spontaneously but most persisting despite treatment and sometimes prompting surgical removal.2,4 Early recognition is crucial, as long-standing MCD lesions can be therapy resistant.5 Due to the rarity of the condition and lack of data, there is a lack of treatment consensus for MCD. In 2014, the American Academy of Dermatology published treatment guidelines recommending superpotent topical steroids or topical tacrolimus as first-line therapy. Next-line therapy includes oral metronidazole, followed by prednisolone if still symptomatic.3 Treatment-resistant disease can warrant treatment with immunomodulators or tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors. Our patient was started on adalimumab; after just 2 months of therapy, the labial swelling decreased and the exophytic nodule was less firm and smaller.

Metastatic CD is a rare manifestation of cutaneous CD and can be present in the absence of gastrointestinal disease.3 This case demonstrates the importance of recognizing the cutaneous signs of CD and the necessity of lesional biopsy for the diagnosis of MCD, as our patient presented with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and a diagnostic workup, including endoscopies, that proved inconclusive for the diagnosis of CD.

- Antonelli E, Bassotti G, Tramontana M, et al. Dermatological manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1-16. doi:10.3390/JCM10020364

- Schneider SL, Foster K, Patel D, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of metastatic Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:566-574. doi:10.1111/PDE.13565

- Kurtzman DJB, Jones T, Lian F, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2014.04.002

- Barret M, De Parades V, Battistella M, et al. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:563-570. doi:10.1016/J.CROHNS.2013.10.009

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder [published online January 3, 2017]. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150. doi:10.1155/2017/8192150

- Antonelli E, Bassotti G, Tramontana M, et al. Dermatological manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1-16. doi:10.3390/JCM10020364

- Schneider SL, Foster K, Patel D, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of metastatic Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:566-574. doi:10.1111/PDE.13565

- Kurtzman DJB, Jones T, Lian F, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2014.04.002

- Barret M, De Parades V, Battistella M, et al. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:563-570. doi:10.1016/J.CROHNS.2013.10.009

- Aberumand B, Howard J, Howard J. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: an approach to an uncommon but important cutaneous disorder [published online January 3, 2017]. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:8192150. doi:10.1155/2017/8192150

An 18-year-old woman with chronic constipation presented with an enlarging, painful, and edematous “lump” in the perineum of 1 year’s duration. The lesion became firmer and more painful with bowel movements. Physical examination revealed an enlarged right labia majora, as well as a pink to flesh-colored, exophytic, firm papulonodule in the perineum posterior to the right labia. The patient concomitantly was following with gastroenterology due to abdominal pain that worsened with eating, as well as constipation, nausea, weight loss, and rectal bleeding of 5 years’ duration. The patient denied rash, joint arthralgia, or oral ulcers. A biopsy from the labial lesion was performed.

Dietary zinc seen reducing migraine risk

, according to results from a cross-sectional study of more than 11,000 American adults.

For their research, published online in Headache, Huanxian Liu, MD, and colleagues at Chinese PLA General Hospital in Beijing, analyzed publicly available data from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to determine whether people self-reporting migraine or severe headache saw lower zinc intake, compared with people without migraine. The data used in the analysis was collected between 1999 and 2004, and contained information on foods and drinks consumed by participants in a 24-hour period, along with additional health information.

An inverse relationship

The investigators divided their study’s 11,088 participants (mean age, 46.5 years; 50% female) into quintiles based on dietary zinc consumption as inferred from foods eaten. They also considered zinc supplementation, for which data was available for 4,324 participants, of whom 2,607 reported use of supplements containing zinc.

Some 20% of the cohort (n = 2,236) reported migraine or severe headache within the previous 3 months. Pregnant women were excluded from analysis, and the investigators adjusted for a range of covariates, including age, sex, ethnicity, education level, body mass, smoking, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and nutritional factors.

Dr. Liu and colleagues reported an inverse association between dietary zinc consumption and migraine, with the highest-consuming quintile of the cohort (15.8 mg or more zinc per day) seeing lowest risk of migraine (odds ratio, 0.70; 95% confidence interval, 0.52-0.94; P = .029), compared with the low-consuming quintile (5.9 mg or less daily). Among people getting high levels of zinc (19.3-32.5 mg daily) through supplements, risk of migraine was lower still, to between an OR of 0.62 (95% CI: 0.46–0.83, P = 0.019) and an OR of 0.67 (95% CI, 0.49–0.91; P = .045).

While the investigators acknowledged limitations of the study, including its cross-sectional design and use of a broad question to discern prevalence of migraine, the findings suggest that “zinc is an important nutrient that influences migraine,” they wrote, citing evidence for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.

The importance of nutritional factors

Commenting on the research findings, Deborah I. Friedman, MD, MPH, a headache specialist in Dallas, said that Dr. Liu and colleagues’ findings added to a growing information base about nutritional factors and migraine. For example, “low magnesium levels are common in people with migraine, and magnesium supplementation is a recommended preventive treatment for migraine.”

Dr. Friedman cited a recent study showing that vitamin B12 and magnesium supplementation in women (, combined with high-intensity interval training, “silenced” the inflammation signaling pathway, helped migraine pain and decreased levels of calcitonin gene-related peptide. A 2022 randomized trial found that alpha lipoic acid supplementation reduced migraine severity, frequency and disability in women with episodic migraine.

Vitamin D levels are also lower in people with migraine, compared with controls, Dr. Friedman noted, and a randomized trial of 2,000 IU of vitamin D3 daily saw reduced monthly headache days, attack duration, severe headaches, and analgesic use, compared with placebo. Other nutrients implicated in migraine include coenzyme Q10, calcium, folic acid, vitamin B6, and vitamin B1.