User login

Air pollution contribution to lung cancer may be underestimated

There is a growing body of evidence to show that air pollution is a major risk factor for lung cancer among never-smokers, although there is less certainty about the duration of exposure to fine particulate matter in ambient air as it relates to risk for lung cancer.

But as Canadian researchers now report, even 20 years of data on cumulative exposure to air pollution may underestimate the magnitude of the effect, especially among people diagnosed with lung cancer who have migrated from regions where heavy air pollution is the norm.

In a study of Canadian women with newly diagnosed lung cancer who never smoked, Renelle Myers, MD, FRCPC, from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and colleagues found that shorter-term assessment of cumulative exposure to ambient air particles smaller than 2.5 microns (PM2.5) may underestimate the health effects of chronic exposure to pollution, especially among those patients who had migrated to Canada after living in areas of high PM2.5 exposure for long periods of time.

“Our study points to the importance of incorporating this long-term cumulative exposure to air pollutants in the assessment of individual lung cancer risk, of course in combination with traditional risk factors, and depending on the country of residence, I think that even a 20-year cumulative exposure may underestimate the effects of PM2.5, as we’re not capturing childhood or adolescent exposure when the lung is developing, and what effect that will have,” she said in an oral abstract presented at the World Conference on Lung Cancer.

Satellite data on local pollution

With the objective of comparing cumulative 3-year vs. 20-year exposure to PM2.5 in women who had never smoked and had a new diagnosis of lung cancer, Dr. Myers and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study.

They recruited a total of 236 women and had them fill out a detailed residential history questionnaire, and demographic details including age, race, country of birth, arrival in Canada for those born out of the country, occupations, family history of lung cancer, and exposure to second-hand smoke.

The investigators linked local addresses or postal to satellite-derived data on local PM2.5 levels, which first became available in 1996.

The median age of participants was 66.1 years. Of the 236 participants, 190 (80.5%) were born outside of Canada, and came to the country at the median age of 45. About half of all participants came from mainland China or Hong Kong, and another one-third came from elsewhere in Asia.

Tumor histologies included adenocarcinomas in 219 patients, squamous cell carcinoma in 1, and other types in 16 patients. Slightly more than half of the patients (55.%) had stage III or IV disease at diagnosis. In all, 106 of 227 evaluable patients had EGFR mutations.

3 years not enough

Among the foreign-born patients, only 4 (2%) had 3-year cumulative PM2.5 exposure greater than 10 mcg/m3, but 38 (20%) had 20-year cumulative exposure greater than 10 mcg/m3 (P < .0001).

All of the patients had cumulative PM2.5 exposures greater than 5 mcg/m3.

Comparing patients with and without EGFR mutations, the investigators found that higher 3-year cumulative PM2.5 exposure was significantly associated with EGFR mutations compared with nonmutated cancers (P = .049), but there was no significant association with higher 20-year cumulative exposures.

“The significance of this study really captures that short term or at least less than 3-year cumulative exposure risk for PM2.5 will probably underestimate the adverse effects that chronic exposure to air pollution has, especially among patients who lived elsewhere that may have had higher exposure throughout their lifetime than where you actually meet them,” Dr. Myers said in a media briefing held prior to her presentation.

Lung cancer in female nonsmokers

During the oral abstract session, invited discussant Chang-Chuan Chan, ScD, National Taiwan University, Taipei, said that the study’s focus on female patients with lung cancer is important. He pointed to a 2019 study examining the relationship between air pollution and lung cancer among nonsmokers in Taiwan, in which the authors found that, although smoking levels among women remained low over time (about 5%), the incidence of lung adenocarcinomas among women increased from 7.05 per 100,000 in 1995, to 24.22 per 100,000 in 2015.

The authors of that study also found that changes in PM2.5 levels in Taiwan were predictive of fluctuations in lung cancer prevalence in never-smokers.

“We’re moving from 50-year studies of smoking to these new issues of air pollution, asbestos, and radon, and I think it’s better that these three factors can be combined together,” he said at the meeting sponsored by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

The study was supported by the BC Cancer Foundation, Terry Fox Research Institute, and VGH-UBC Hospital Foundation. Dr. Myers and Dr. Chan reported having no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

There is a growing body of evidence to show that air pollution is a major risk factor for lung cancer among never-smokers, although there is less certainty about the duration of exposure to fine particulate matter in ambient air as it relates to risk for lung cancer.

But as Canadian researchers now report, even 20 years of data on cumulative exposure to air pollution may underestimate the magnitude of the effect, especially among people diagnosed with lung cancer who have migrated from regions where heavy air pollution is the norm.

In a study of Canadian women with newly diagnosed lung cancer who never smoked, Renelle Myers, MD, FRCPC, from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and colleagues found that shorter-term assessment of cumulative exposure to ambient air particles smaller than 2.5 microns (PM2.5) may underestimate the health effects of chronic exposure to pollution, especially among those patients who had migrated to Canada after living in areas of high PM2.5 exposure for long periods of time.

“Our study points to the importance of incorporating this long-term cumulative exposure to air pollutants in the assessment of individual lung cancer risk, of course in combination with traditional risk factors, and depending on the country of residence, I think that even a 20-year cumulative exposure may underestimate the effects of PM2.5, as we’re not capturing childhood or adolescent exposure when the lung is developing, and what effect that will have,” she said in an oral abstract presented at the World Conference on Lung Cancer.

Satellite data on local pollution

With the objective of comparing cumulative 3-year vs. 20-year exposure to PM2.5 in women who had never smoked and had a new diagnosis of lung cancer, Dr. Myers and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study.

They recruited a total of 236 women and had them fill out a detailed residential history questionnaire, and demographic details including age, race, country of birth, arrival in Canada for those born out of the country, occupations, family history of lung cancer, and exposure to second-hand smoke.

The investigators linked local addresses or postal to satellite-derived data on local PM2.5 levels, which first became available in 1996.

The median age of participants was 66.1 years. Of the 236 participants, 190 (80.5%) were born outside of Canada, and came to the country at the median age of 45. About half of all participants came from mainland China or Hong Kong, and another one-third came from elsewhere in Asia.

Tumor histologies included adenocarcinomas in 219 patients, squamous cell carcinoma in 1, and other types in 16 patients. Slightly more than half of the patients (55.%) had stage III or IV disease at diagnosis. In all, 106 of 227 evaluable patients had EGFR mutations.

3 years not enough

Among the foreign-born patients, only 4 (2%) had 3-year cumulative PM2.5 exposure greater than 10 mcg/m3, but 38 (20%) had 20-year cumulative exposure greater than 10 mcg/m3 (P < .0001).

All of the patients had cumulative PM2.5 exposures greater than 5 mcg/m3.

Comparing patients with and without EGFR mutations, the investigators found that higher 3-year cumulative PM2.5 exposure was significantly associated with EGFR mutations compared with nonmutated cancers (P = .049), but there was no significant association with higher 20-year cumulative exposures.

“The significance of this study really captures that short term or at least less than 3-year cumulative exposure risk for PM2.5 will probably underestimate the adverse effects that chronic exposure to air pollution has, especially among patients who lived elsewhere that may have had higher exposure throughout their lifetime than where you actually meet them,” Dr. Myers said in a media briefing held prior to her presentation.

Lung cancer in female nonsmokers

During the oral abstract session, invited discussant Chang-Chuan Chan, ScD, National Taiwan University, Taipei, said that the study’s focus on female patients with lung cancer is important. He pointed to a 2019 study examining the relationship between air pollution and lung cancer among nonsmokers in Taiwan, in which the authors found that, although smoking levels among women remained low over time (about 5%), the incidence of lung adenocarcinomas among women increased from 7.05 per 100,000 in 1995, to 24.22 per 100,000 in 2015.

The authors of that study also found that changes in PM2.5 levels in Taiwan were predictive of fluctuations in lung cancer prevalence in never-smokers.

“We’re moving from 50-year studies of smoking to these new issues of air pollution, asbestos, and radon, and I think it’s better that these three factors can be combined together,” he said at the meeting sponsored by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

The study was supported by the BC Cancer Foundation, Terry Fox Research Institute, and VGH-UBC Hospital Foundation. Dr. Myers and Dr. Chan reported having no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

There is a growing body of evidence to show that air pollution is a major risk factor for lung cancer among never-smokers, although there is less certainty about the duration of exposure to fine particulate matter in ambient air as it relates to risk for lung cancer.

But as Canadian researchers now report, even 20 years of data on cumulative exposure to air pollution may underestimate the magnitude of the effect, especially among people diagnosed with lung cancer who have migrated from regions where heavy air pollution is the norm.

In a study of Canadian women with newly diagnosed lung cancer who never smoked, Renelle Myers, MD, FRCPC, from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and colleagues found that shorter-term assessment of cumulative exposure to ambient air particles smaller than 2.5 microns (PM2.5) may underestimate the health effects of chronic exposure to pollution, especially among those patients who had migrated to Canada after living in areas of high PM2.5 exposure for long periods of time.

“Our study points to the importance of incorporating this long-term cumulative exposure to air pollutants in the assessment of individual lung cancer risk, of course in combination with traditional risk factors, and depending on the country of residence, I think that even a 20-year cumulative exposure may underestimate the effects of PM2.5, as we’re not capturing childhood or adolescent exposure when the lung is developing, and what effect that will have,” she said in an oral abstract presented at the World Conference on Lung Cancer.

Satellite data on local pollution

With the objective of comparing cumulative 3-year vs. 20-year exposure to PM2.5 in women who had never smoked and had a new diagnosis of lung cancer, Dr. Myers and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study.

They recruited a total of 236 women and had them fill out a detailed residential history questionnaire, and demographic details including age, race, country of birth, arrival in Canada for those born out of the country, occupations, family history of lung cancer, and exposure to second-hand smoke.

The investigators linked local addresses or postal to satellite-derived data on local PM2.5 levels, which first became available in 1996.

The median age of participants was 66.1 years. Of the 236 participants, 190 (80.5%) were born outside of Canada, and came to the country at the median age of 45. About half of all participants came from mainland China or Hong Kong, and another one-third came from elsewhere in Asia.

Tumor histologies included adenocarcinomas in 219 patients, squamous cell carcinoma in 1, and other types in 16 patients. Slightly more than half of the patients (55.%) had stage III or IV disease at diagnosis. In all, 106 of 227 evaluable patients had EGFR mutations.

3 years not enough

Among the foreign-born patients, only 4 (2%) had 3-year cumulative PM2.5 exposure greater than 10 mcg/m3, but 38 (20%) had 20-year cumulative exposure greater than 10 mcg/m3 (P < .0001).

All of the patients had cumulative PM2.5 exposures greater than 5 mcg/m3.

Comparing patients with and without EGFR mutations, the investigators found that higher 3-year cumulative PM2.5 exposure was significantly associated with EGFR mutations compared with nonmutated cancers (P = .049), but there was no significant association with higher 20-year cumulative exposures.

“The significance of this study really captures that short term or at least less than 3-year cumulative exposure risk for PM2.5 will probably underestimate the adverse effects that chronic exposure to air pollution has, especially among patients who lived elsewhere that may have had higher exposure throughout their lifetime than where you actually meet them,” Dr. Myers said in a media briefing held prior to her presentation.

Lung cancer in female nonsmokers

During the oral abstract session, invited discussant Chang-Chuan Chan, ScD, National Taiwan University, Taipei, said that the study’s focus on female patients with lung cancer is important. He pointed to a 2019 study examining the relationship between air pollution and lung cancer among nonsmokers in Taiwan, in which the authors found that, although smoking levels among women remained low over time (about 5%), the incidence of lung adenocarcinomas among women increased from 7.05 per 100,000 in 1995, to 24.22 per 100,000 in 2015.

The authors of that study also found that changes in PM2.5 levels in Taiwan were predictive of fluctuations in lung cancer prevalence in never-smokers.

“We’re moving from 50-year studies of smoking to these new issues of air pollution, asbestos, and radon, and I think it’s better that these three factors can be combined together,” he said at the meeting sponsored by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

The study was supported by the BC Cancer Foundation, Terry Fox Research Institute, and VGH-UBC Hospital Foundation. Dr. Myers and Dr. Chan reported having no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM WCLC

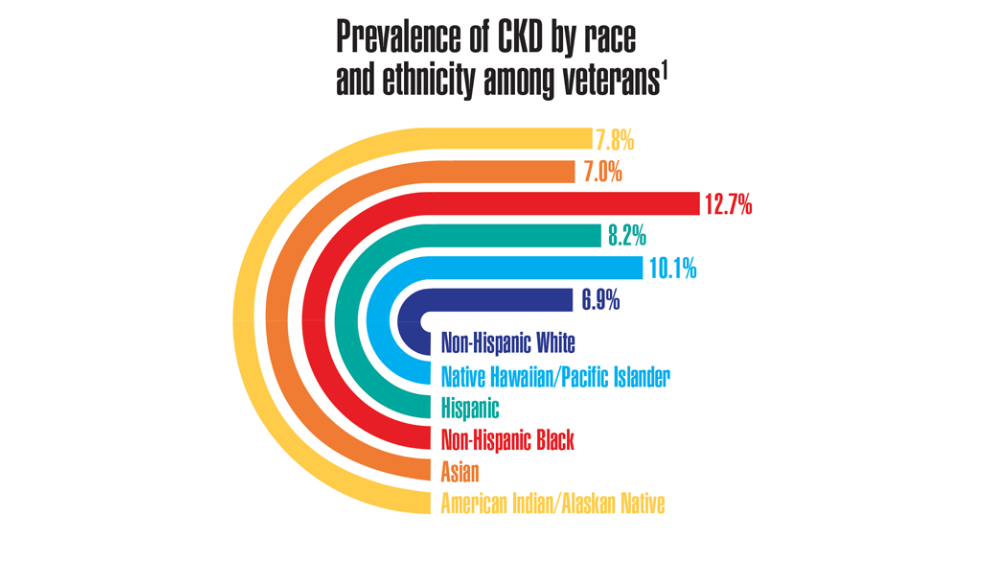

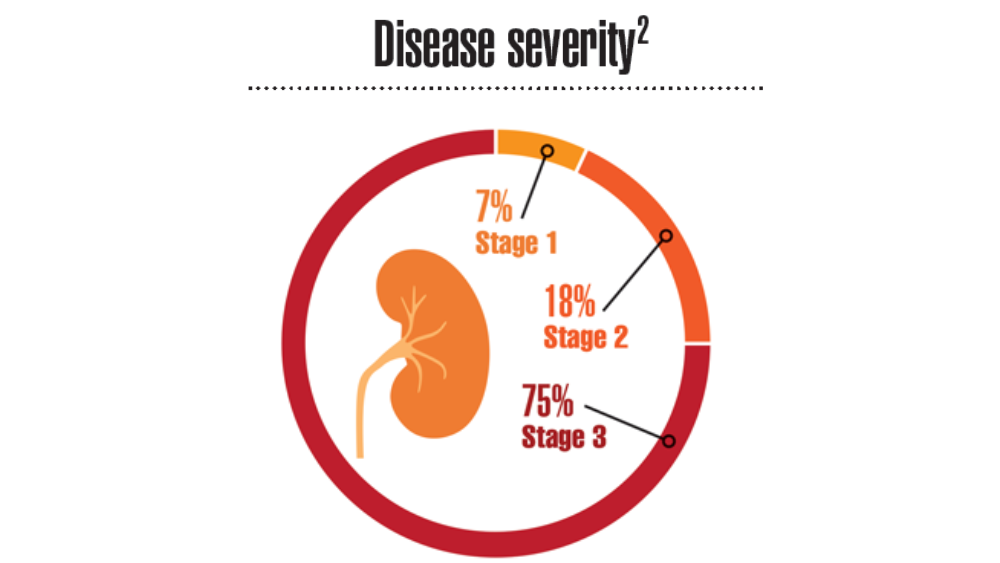

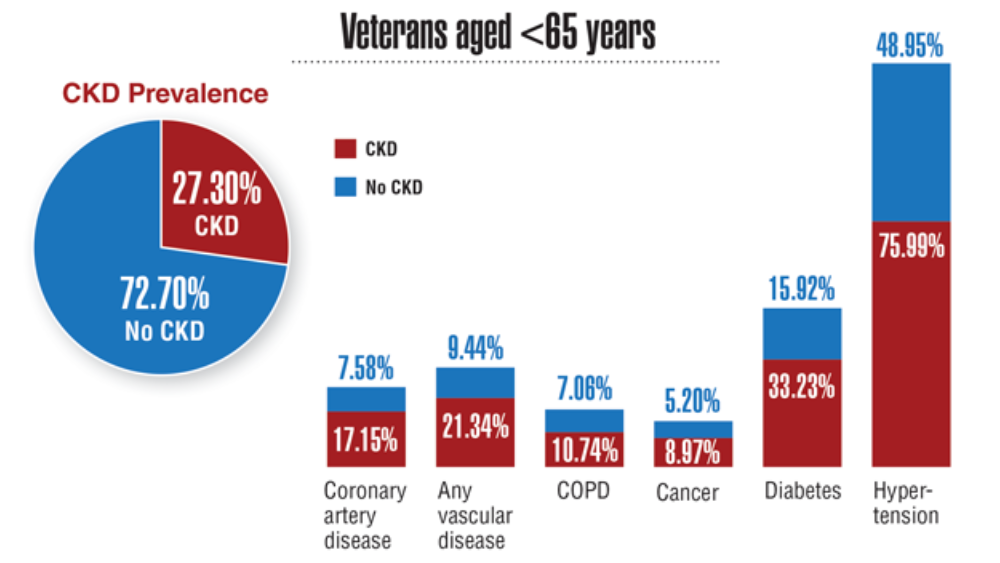

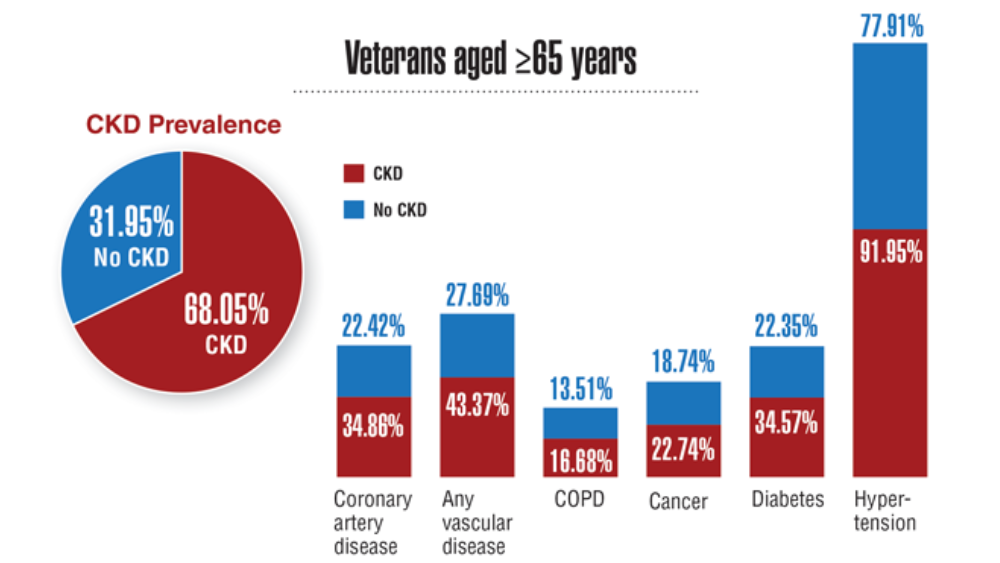

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: Chronic Kidney Disease

- Kidney disease in veterans. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Kidney_Disease_In_Veterans.asp

- Ozieh MN, Gebregziabher M, Ward RC, Taber DJ, Egede LE. Creating a 13-year National Longitudinal Cohort of veterans with chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:241. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-019-1430-y

- Patel N, Golzy M, Nainani N, et al. Prevalence of various comorbidities among veterans with chronic kidney disease and its comparison with other datasets. Ren Fail. 2016;38(2):204-208. http://doi.org/10.3109/0886022X.2015.1117924

- Kidney disease in veterans. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Kidney_Disease_In_Veterans.asp

- Ozieh MN, Gebregziabher M, Ward RC, Taber DJ, Egede LE. Creating a 13-year National Longitudinal Cohort of veterans with chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:241. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-019-1430-y

- Patel N, Golzy M, Nainani N, et al. Prevalence of various comorbidities among veterans with chronic kidney disease and its comparison with other datasets. Ren Fail. 2016;38(2):204-208. http://doi.org/10.3109/0886022X.2015.1117924

- Kidney disease in veterans. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Kidney_Disease_In_Veterans.asp

- Ozieh MN, Gebregziabher M, Ward RC, Taber DJ, Egede LE. Creating a 13-year National Longitudinal Cohort of veterans with chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:241. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-019-1430-y

- Patel N, Golzy M, Nainani N, et al. Prevalence of various comorbidities among veterans with chronic kidney disease and its comparison with other datasets. Ren Fail. 2016;38(2):204-208. http://doi.org/10.3109/0886022X.2015.1117924

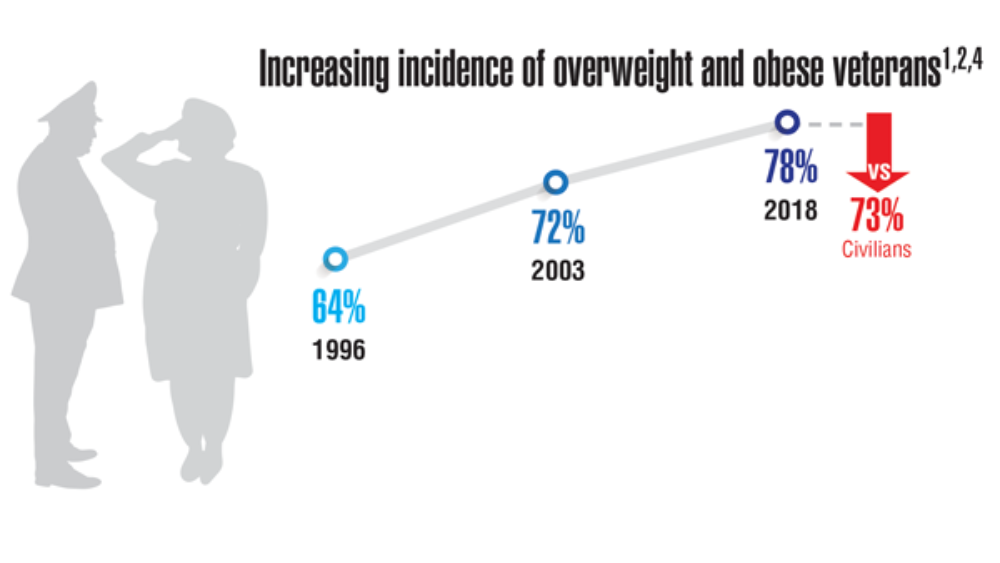

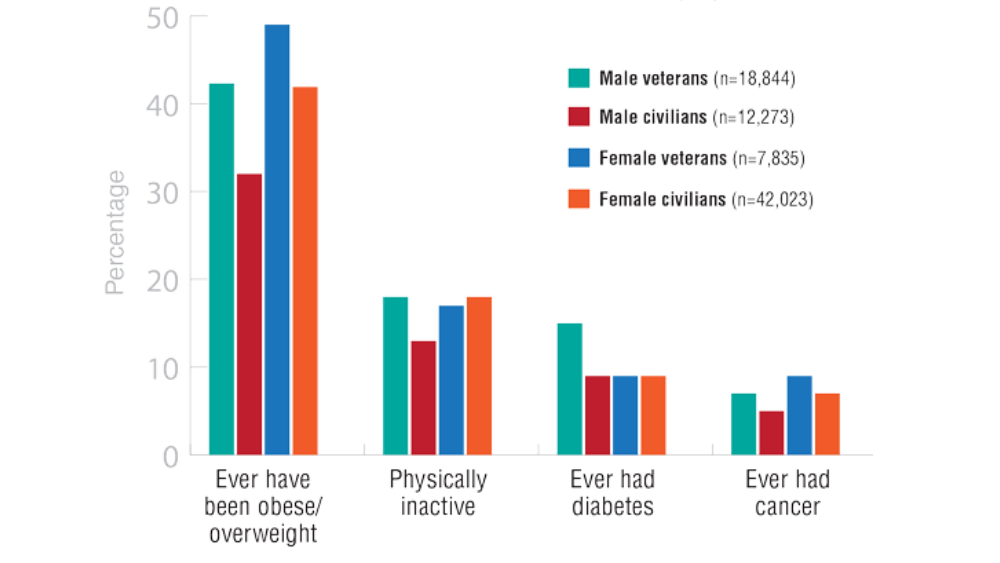

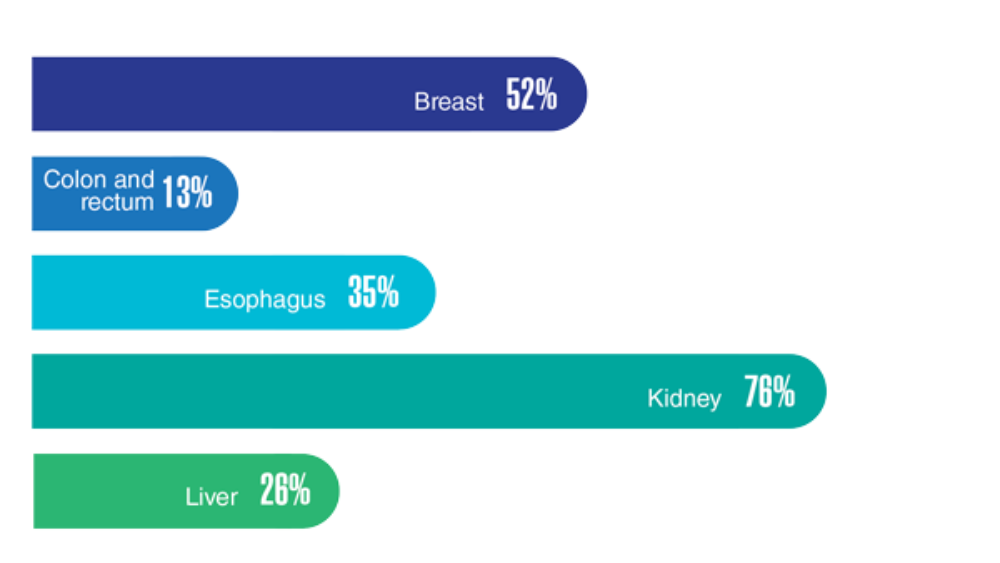

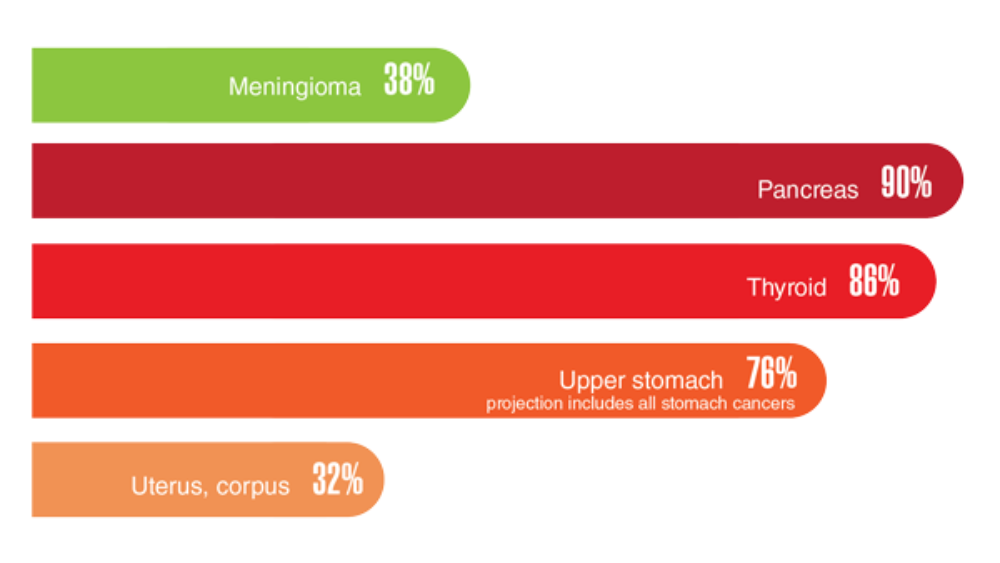

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: The Cancer-Obesity Connection

- VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of adult overweight and obesity. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Version 3.0. 2020. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/obesity/VADoDObesityCPGFinal5087242020.pdf

- Obesity and overweight. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated September 10, 2021. Accessed March 18, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm

- Obesity and cancer. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated February 18, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/obesity/index.htm

- Nelson KM. The burden of obesity among a national probability sample of veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):915-919. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00526.x

- Schult TM, Schmunk SK, Marzolf JR, Mohr DC. The health status of veteran employees compared to civilian employees in Veterans Health Administration. Mil Med. 2019;184(7-8):e218-e224. http://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy410

- Weir HK, Thompson TD, Stewart SL, White MC. Cancer incidence projections in the United States between 2015 and 2050. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E59. http://doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.210006

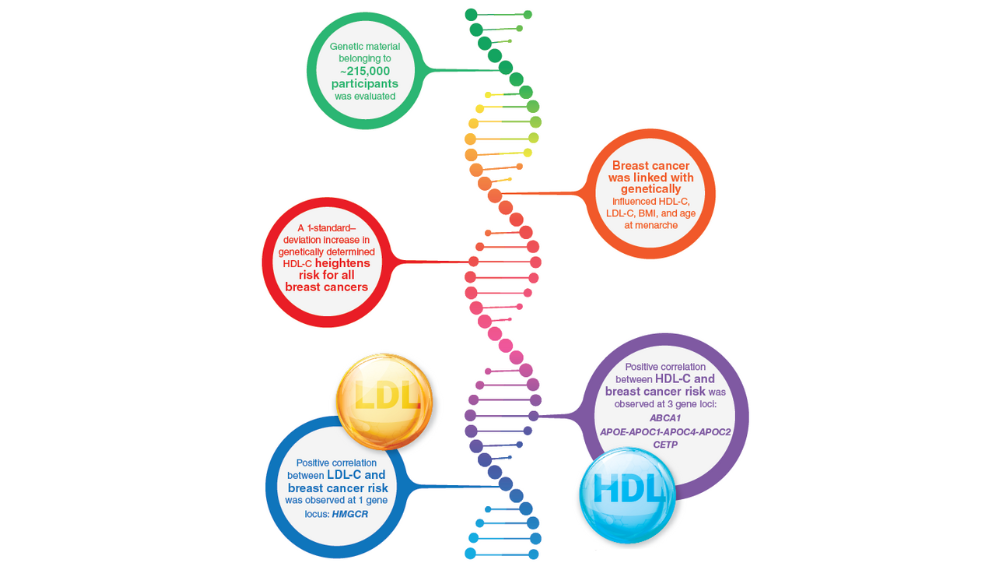

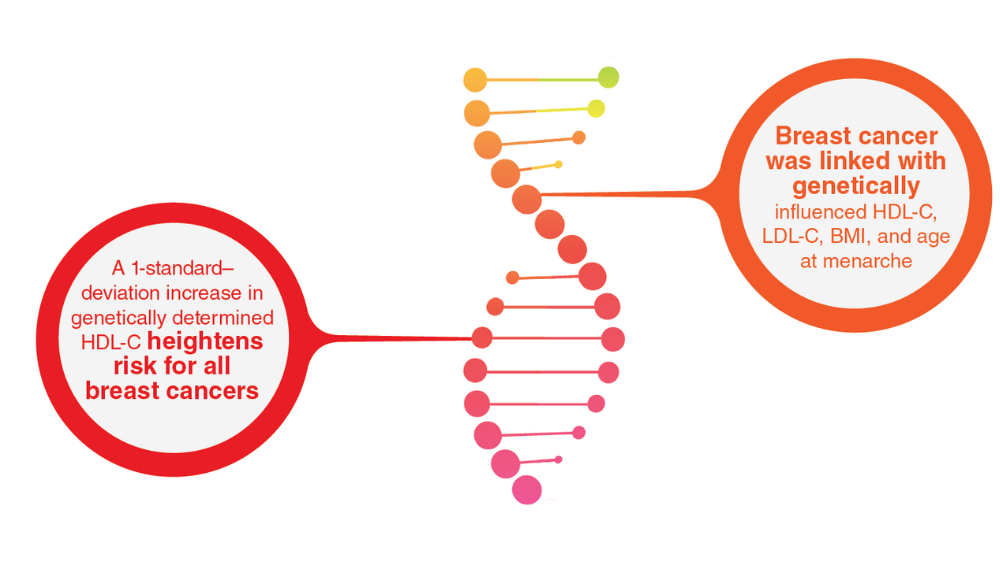

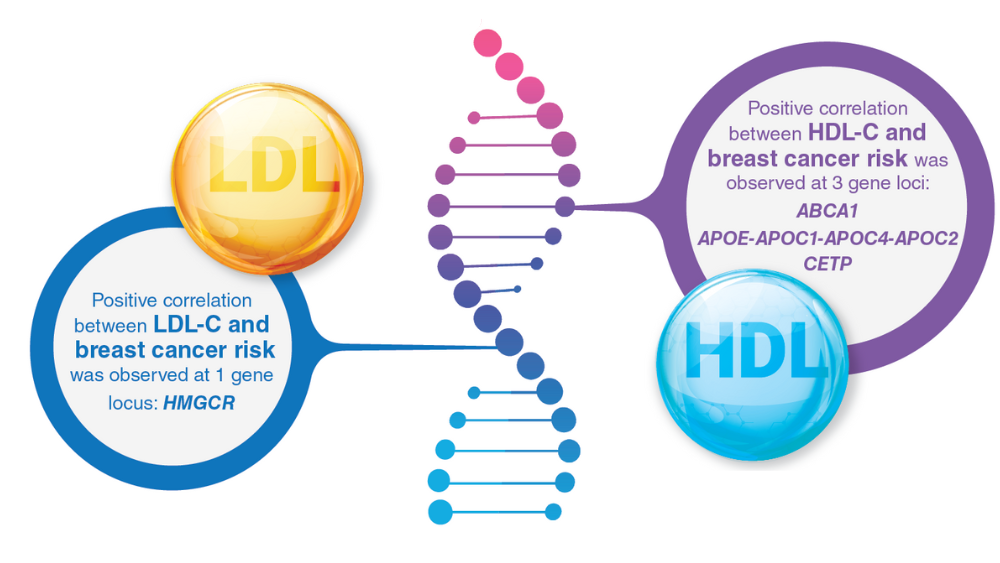

- Johnson KE, Siewert KM, Klarin D, et al. The relationship between circulating lipids and breast cancer risk: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(9):e1003302. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.100330

- MOVE! weight management program. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated May 2, 2022. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://www.move.va.gov/

- Gray KE, Hoerster KD, Spohr SA, Breland JY, Raffa SD. National Veterans Health Administration MOVE! weight management program participation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Chronic Dis. 2022;19:E11. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd19.210303

- VA Office of Patient Centered Care & Cultural Transformation (email, May 27, 2022).

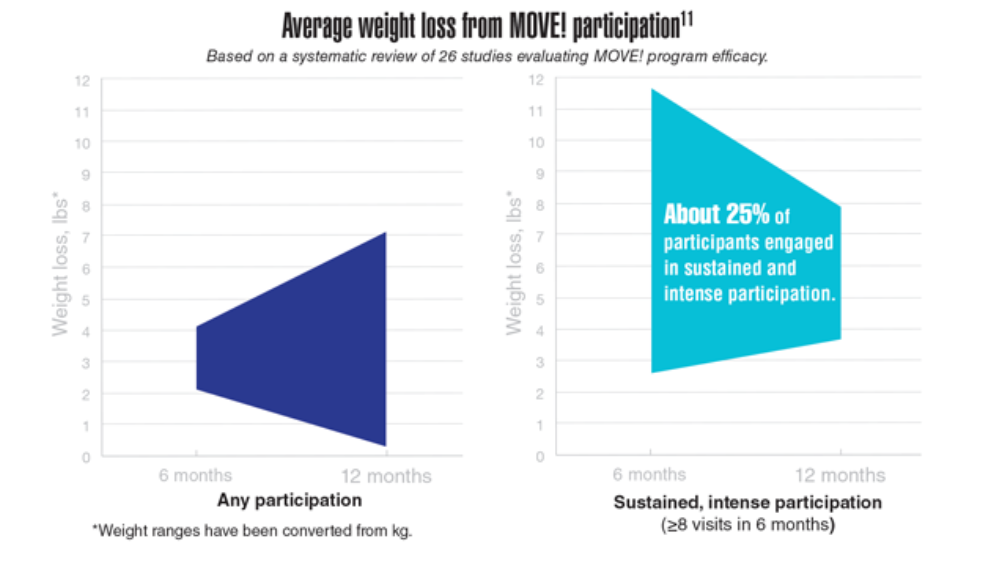

- Maciejewski ML, Shepherd-Banigan M, Raffa SD, Weidenbacher HJ. Systematic review of behavioral weight management program MOVE! for veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(5):704-714. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.029

- VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of adult overweight and obesity. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Version 3.0. 2020. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/obesity/VADoDObesityCPGFinal5087242020.pdf

- Obesity and overweight. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated September 10, 2021. Accessed March 18, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm

- Obesity and cancer. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated February 18, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/obesity/index.htm

- Nelson KM. The burden of obesity among a national probability sample of veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):915-919. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00526.x

- Schult TM, Schmunk SK, Marzolf JR, Mohr DC. The health status of veteran employees compared to civilian employees in Veterans Health Administration. Mil Med. 2019;184(7-8):e218-e224. http://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy410

- Weir HK, Thompson TD, Stewart SL, White MC. Cancer incidence projections in the United States between 2015 and 2050. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E59. http://doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.210006

- Johnson KE, Siewert KM, Klarin D, et al. The relationship between circulating lipids and breast cancer risk: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(9):e1003302. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.100330

- MOVE! weight management program. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated May 2, 2022. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://www.move.va.gov/

- Gray KE, Hoerster KD, Spohr SA, Breland JY, Raffa SD. National Veterans Health Administration MOVE! weight management program participation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Chronic Dis. 2022;19:E11. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd19.210303

- VA Office of Patient Centered Care & Cultural Transformation (email, May 27, 2022).

- Maciejewski ML, Shepherd-Banigan M, Raffa SD, Weidenbacher HJ. Systematic review of behavioral weight management program MOVE! for veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(5):704-714. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.029

- VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of adult overweight and obesity. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Version 3.0. 2020. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/CD/obesity/VADoDObesityCPGFinal5087242020.pdf

- Obesity and overweight. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated September 10, 2021. Accessed March 18, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm

- Obesity and cancer. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated February 18, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/obesity/index.htm

- Nelson KM. The burden of obesity among a national probability sample of veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):915-919. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00526.x

- Schult TM, Schmunk SK, Marzolf JR, Mohr DC. The health status of veteran employees compared to civilian employees in Veterans Health Administration. Mil Med. 2019;184(7-8):e218-e224. http://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usy410

- Weir HK, Thompson TD, Stewart SL, White MC. Cancer incidence projections in the United States between 2015 and 2050. Prev Chronic Dis. 2021;18:E59. http://doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.210006

- Johnson KE, Siewert KM, Klarin D, et al. The relationship between circulating lipids and breast cancer risk: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 2020;17(9):e1003302. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.100330

- MOVE! weight management program. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated May 2, 2022. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://www.move.va.gov/

- Gray KE, Hoerster KD, Spohr SA, Breland JY, Raffa SD. National Veterans Health Administration MOVE! weight management program participation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Chronic Dis. 2022;19:E11. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd19.210303

- VA Office of Patient Centered Care & Cultural Transformation (email, May 27, 2022).

- Maciejewski ML, Shepherd-Banigan M, Raffa SD, Weidenbacher HJ. Systematic review of behavioral weight management program MOVE! for veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(5):704-714. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.029

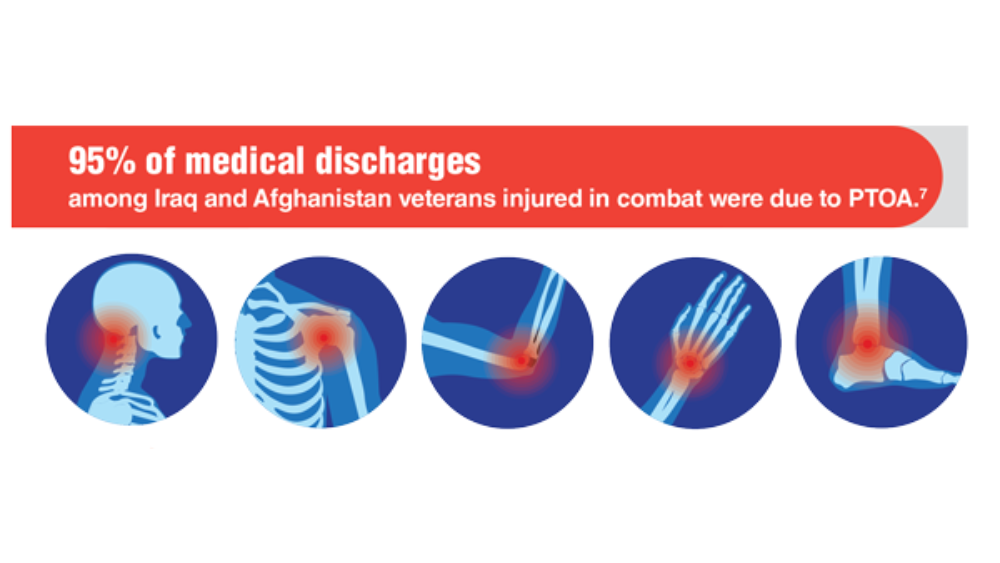

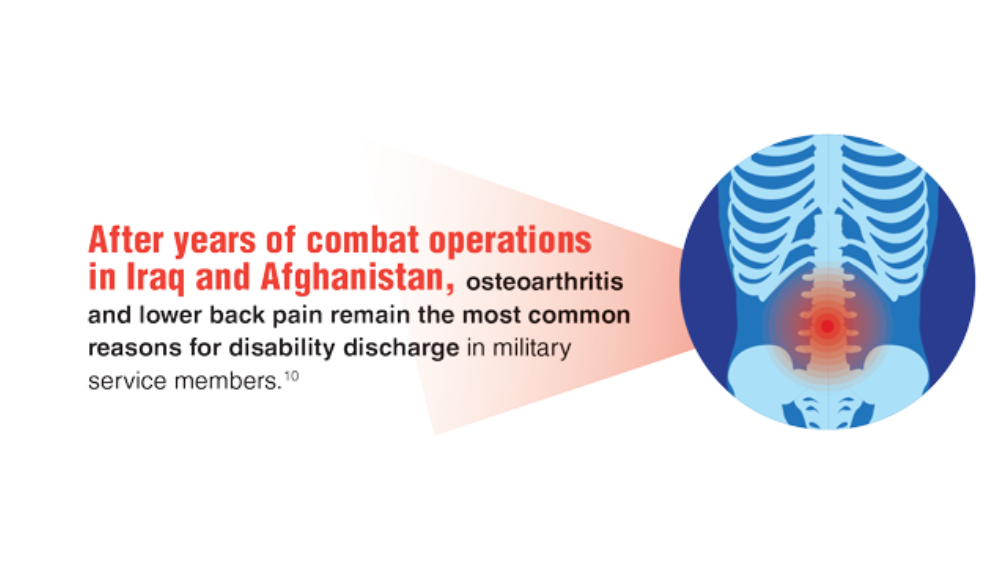

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: Rheumatologic Diseases

- Arthritis help for veterans. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 10, 2020. Accessed March 20, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/communications/features/arthritis-among-veterans.html

- Cameron KL, Hsiao MS, Owens BD, Burks R, Svoboda SJ. Incidence of physician-diagnosed osteoarthritis among active duty United States military service members. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):2974-2982. http://doi.org/10.1002/art.30498

- Ebel AV, Lutt G, Poole JA, et al. Association of agricultural, occupational, and military inhalants with autoantibodies and disease features in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(3):392-400. http://doi.org/10.1002/art.41559

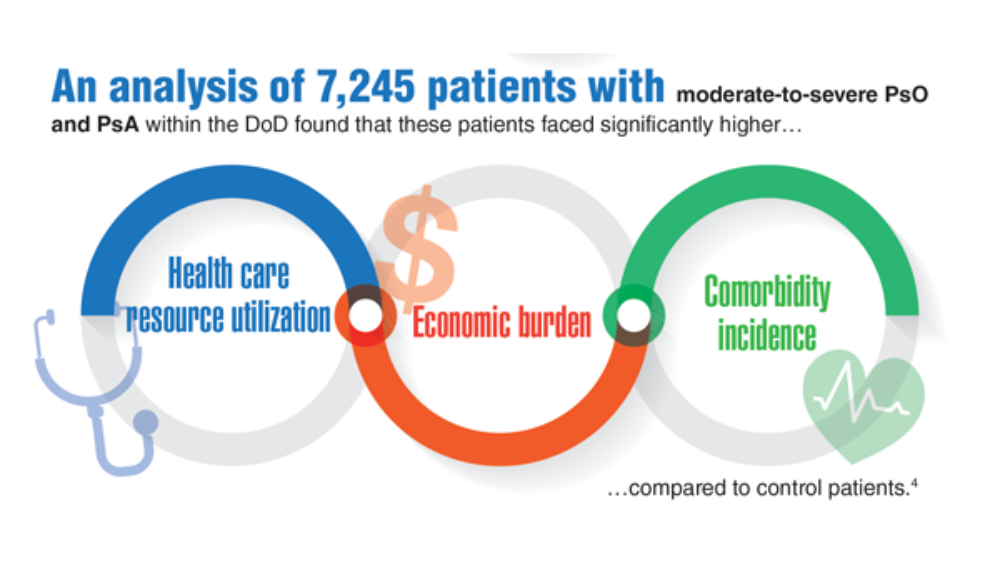

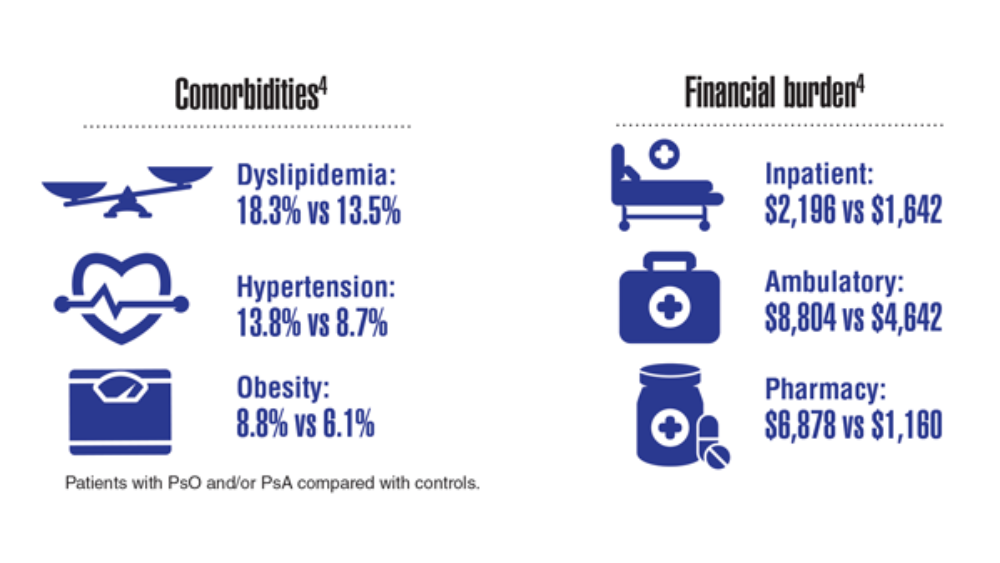

- Lee S, Xie L, Wang Y, Vaidya N, Baser O. Comorbidity and economic burden among moderate-to-severe psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis patients in the US Department of Defense population. J Med Econ. 2018;21(6):564-570. http://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2018.1431921

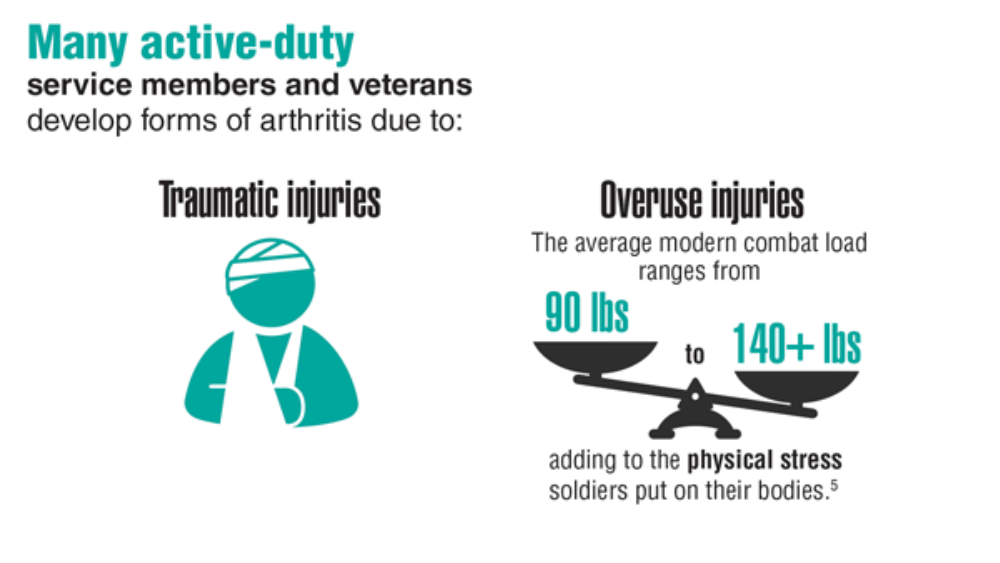

- Fish L, Scharre P. The soldier’s heavy load. Center for a New American Security. Published September 26, 2018. Accessed April 27, 2022. https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/the-soldiers-heavy-load-1

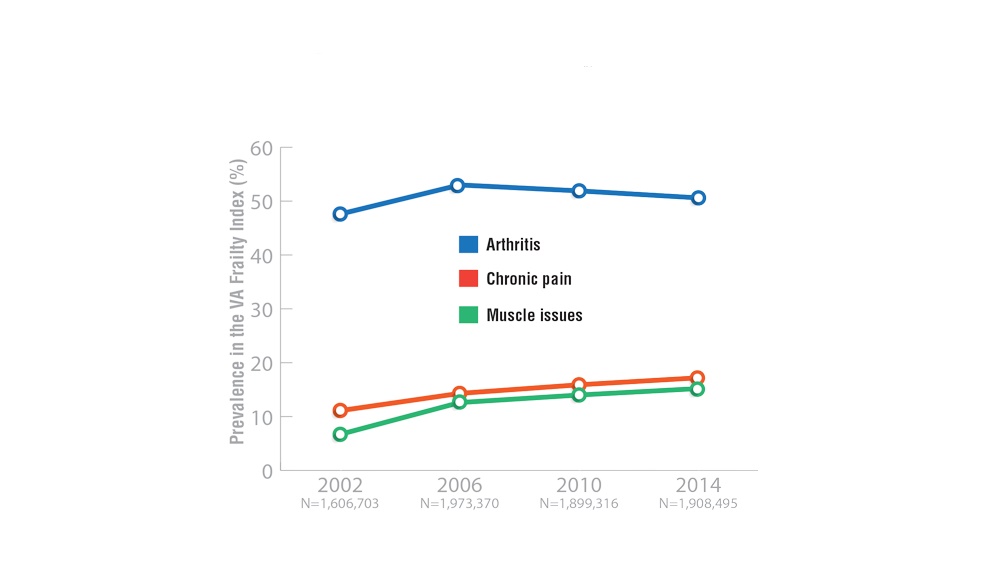

- Shrauner W, Lord EM, Nguyen XMT, et al. Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US veterans. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):818-826. http://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850

- Tyrer J. Military service leads to post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Published April 2021. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.arthritis.org/diseases/more-about/military-service-leads-to-post-traumatic-osteoarth

- Cameron KL, Shing TL, Kardouni JR. The incidence of post-traumatic osteoarthritis in the knee in active duty military personnel compared to estimates in the general population. Presented at the Osteoarthritis Research Society International World Congress on Osteoarthritis, April 27-30, 2017, Las Vegas, NV.

- Rivera JD, Wenke JC, Buckwalter JA, Ficke JR, Johnson AE. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis caused by battlefield injuries: The primary source of disability in warriors. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(01):S64-S69. http://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S64

- Patzkowski JC, Rivera JC, FIcke JR, Wenke JC. The changing face of disability in the US Army: The Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom Effect. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012; 20(S1): S23-S30. http://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S23

- Related conditions of psoriasis. National Psoriasis Foundation. Updated October 8, 2020. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.psoriasis.org/related-conditions/

- Arthritis help for veterans. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 10, 2020. Accessed March 20, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/communications/features/arthritis-among-veterans.html

- Cameron KL, Hsiao MS, Owens BD, Burks R, Svoboda SJ. Incidence of physician-diagnosed osteoarthritis among active duty United States military service members. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):2974-2982. http://doi.org/10.1002/art.30498

- Ebel AV, Lutt G, Poole JA, et al. Association of agricultural, occupational, and military inhalants with autoantibodies and disease features in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(3):392-400. http://doi.org/10.1002/art.41559

- Lee S, Xie L, Wang Y, Vaidya N, Baser O. Comorbidity and economic burden among moderate-to-severe psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis patients in the US Department of Defense population. J Med Econ. 2018;21(6):564-570. http://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2018.1431921

- Fish L, Scharre P. The soldier’s heavy load. Center for a New American Security. Published September 26, 2018. Accessed April 27, 2022. https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/the-soldiers-heavy-load-1

- Shrauner W, Lord EM, Nguyen XMT, et al. Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US veterans. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):818-826. http://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850

- Tyrer J. Military service leads to post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Published April 2021. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.arthritis.org/diseases/more-about/military-service-leads-to-post-traumatic-osteoarth

- Cameron KL, Shing TL, Kardouni JR. The incidence of post-traumatic osteoarthritis in the knee in active duty military personnel compared to estimates in the general population. Presented at the Osteoarthritis Research Society International World Congress on Osteoarthritis, April 27-30, 2017, Las Vegas, NV.

- Rivera JD, Wenke JC, Buckwalter JA, Ficke JR, Johnson AE. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis caused by battlefield injuries: The primary source of disability in warriors. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(01):S64-S69. http://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S64

- Patzkowski JC, Rivera JC, FIcke JR, Wenke JC. The changing face of disability in the US Army: The Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom Effect. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012; 20(S1): S23-S30. http://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S23

- Related conditions of psoriasis. National Psoriasis Foundation. Updated October 8, 2020. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.psoriasis.org/related-conditions/

- Arthritis help for veterans. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 10, 2020. Accessed March 20, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/communications/features/arthritis-among-veterans.html

- Cameron KL, Hsiao MS, Owens BD, Burks R, Svoboda SJ. Incidence of physician-diagnosed osteoarthritis among active duty United States military service members. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):2974-2982. http://doi.org/10.1002/art.30498

- Ebel AV, Lutt G, Poole JA, et al. Association of agricultural, occupational, and military inhalants with autoantibodies and disease features in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(3):392-400. http://doi.org/10.1002/art.41559

- Lee S, Xie L, Wang Y, Vaidya N, Baser O. Comorbidity and economic burden among moderate-to-severe psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis patients in the US Department of Defense population. J Med Econ. 2018;21(6):564-570. http://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2018.1431921

- Fish L, Scharre P. The soldier’s heavy load. Center for a New American Security. Published September 26, 2018. Accessed April 27, 2022. https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/the-soldiers-heavy-load-1

- Shrauner W, Lord EM, Nguyen XMT, et al. Frailty and cardiovascular mortality in more than 3 million US veterans. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):818-826. http://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab850

- Tyrer J. Military service leads to post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Published April 2021. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.arthritis.org/diseases/more-about/military-service-leads-to-post-traumatic-osteoarth

- Cameron KL, Shing TL, Kardouni JR. The incidence of post-traumatic osteoarthritis in the knee in active duty military personnel compared to estimates in the general population. Presented at the Osteoarthritis Research Society International World Congress on Osteoarthritis, April 27-30, 2017, Las Vegas, NV.

- Rivera JD, Wenke JC, Buckwalter JA, Ficke JR, Johnson AE. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis caused by battlefield injuries: The primary source of disability in warriors. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(01):S64-S69. http://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S64

- Patzkowski JC, Rivera JC, FIcke JR, Wenke JC. The changing face of disability in the US Army: The Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom Effect. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012; 20(S1): S23-S30. http://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-20-08-S23

- Related conditions of psoriasis. National Psoriasis Foundation. Updated October 8, 2020. Accessed March 25, 2022. https://www.psoriasis.org/related-conditions/

Meet a champion climber with type 1 diabetes

Managing type 1 diabetes is never easy. But if you ask 16-year-old climbing star Katie Bone, she’ll tell you that she will never let this disease get in the way of her goals.

“My motto is the same one as Bethany Hamilton’s – the surfer who lost her arm in a shark attack: ‘I don’t need easy, I just need possible,” said Ms. Bone, who lives in Albuquerque and has been a competitive rock climber since she was 8 years old. “That really stuck with me.”

Just watching her compete on NBC’s hit reality show American Ninja Warrior in June is proof of that. Not only did the nationally ranked climber fly through the obstacles with grace and grit, but she proudly showed off her two monitoring devices: a glucose monitor on one arm and a tubeless insulin pump on the other.

“I specifically decided to keep my devices visible when I went on the show,” she said. “It’s part of my life, and I wanted to show that I’m not ashamed to wear medical devices.”

Still, it has been a long journey since Bone was diagnosed in 2017. She was just 11 years old at the time and had recently done a climbing competition when she started feeling ill.

“I didn’t perform well,” she said. “I needed to go to the bathroom a lot and felt really nauseous. Three days later, we ended up in urgent care.”

When her doctor first told her she had diabetes, she started crying.

“My grandma had type 1 and was extremely sick and died from complications,” she said. “That was all I knew about diabetes, and it was scary to think my life could be like that.”

But her outlook brightened when her doctor assured her that she could keep climbing.

“When I was told that I could keep competing, a switch flipped for me and I made a decision that nothing would hold me back,” she says.

But every day isn’t easy.

“It’s sometimes really hard to manage my diabetes during competitions,” she said. “When we climb, for example, we’re not allowed to have our phones, and I manage my [glucose monitor] through my phone. This means accommodations have to be made for me.”

And managing her diabetes can be unpredictable at times.

“If my blood sugar is low or high, I might be put last in a competition,” she said. “That messes up my warm-up and my mental game. It’s a never-ending battle.”

Ultimately, Ms. Bone’s goal is to inspire others and advocate for diabetes awareness. She says she’s been overwhelmed by viewer responses to her appearance on the show.

“I heard from so many parents and kids,” she said. “I want the world to know that wearing a pump on your arm only makes you more amazing.”

She also draws inspiration from others with diabetes.

“Everyone with this disease is a role model for me, since everyone is fighting their own battles,” she said. “Diabetes is different for everyone, and seeing how people can do what they do despite the diagnosis has been incredibly inspiring.”

For now, the rising high school junior plans to continue training and competing.

“My goal is to make the 2024 Olympic climbing team in Paris,” she said. “I’ve always wanted to compete in the Olympics since I was a little kid. Nothing can stop me.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Managing type 1 diabetes is never easy. But if you ask 16-year-old climbing star Katie Bone, she’ll tell you that she will never let this disease get in the way of her goals.

“My motto is the same one as Bethany Hamilton’s – the surfer who lost her arm in a shark attack: ‘I don’t need easy, I just need possible,” said Ms. Bone, who lives in Albuquerque and has been a competitive rock climber since she was 8 years old. “That really stuck with me.”

Just watching her compete on NBC’s hit reality show American Ninja Warrior in June is proof of that. Not only did the nationally ranked climber fly through the obstacles with grace and grit, but she proudly showed off her two monitoring devices: a glucose monitor on one arm and a tubeless insulin pump on the other.

“I specifically decided to keep my devices visible when I went on the show,” she said. “It’s part of my life, and I wanted to show that I’m not ashamed to wear medical devices.”

Still, it has been a long journey since Bone was diagnosed in 2017. She was just 11 years old at the time and had recently done a climbing competition when she started feeling ill.

“I didn’t perform well,” she said. “I needed to go to the bathroom a lot and felt really nauseous. Three days later, we ended up in urgent care.”

When her doctor first told her she had diabetes, she started crying.

“My grandma had type 1 and was extremely sick and died from complications,” she said. “That was all I knew about diabetes, and it was scary to think my life could be like that.”

But her outlook brightened when her doctor assured her that she could keep climbing.

“When I was told that I could keep competing, a switch flipped for me and I made a decision that nothing would hold me back,” she says.

But every day isn’t easy.

“It’s sometimes really hard to manage my diabetes during competitions,” she said. “When we climb, for example, we’re not allowed to have our phones, and I manage my [glucose monitor] through my phone. This means accommodations have to be made for me.”

And managing her diabetes can be unpredictable at times.

“If my blood sugar is low or high, I might be put last in a competition,” she said. “That messes up my warm-up and my mental game. It’s a never-ending battle.”

Ultimately, Ms. Bone’s goal is to inspire others and advocate for diabetes awareness. She says she’s been overwhelmed by viewer responses to her appearance on the show.

“I heard from so many parents and kids,” she said. “I want the world to know that wearing a pump on your arm only makes you more amazing.”

She also draws inspiration from others with diabetes.

“Everyone with this disease is a role model for me, since everyone is fighting their own battles,” she said. “Diabetes is different for everyone, and seeing how people can do what they do despite the diagnosis has been incredibly inspiring.”

For now, the rising high school junior plans to continue training and competing.

“My goal is to make the 2024 Olympic climbing team in Paris,” she said. “I’ve always wanted to compete in the Olympics since I was a little kid. Nothing can stop me.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Managing type 1 diabetes is never easy. But if you ask 16-year-old climbing star Katie Bone, she’ll tell you that she will never let this disease get in the way of her goals.

“My motto is the same one as Bethany Hamilton’s – the surfer who lost her arm in a shark attack: ‘I don’t need easy, I just need possible,” said Ms. Bone, who lives in Albuquerque and has been a competitive rock climber since she was 8 years old. “That really stuck with me.”

Just watching her compete on NBC’s hit reality show American Ninja Warrior in June is proof of that. Not only did the nationally ranked climber fly through the obstacles with grace and grit, but she proudly showed off her two monitoring devices: a glucose monitor on one arm and a tubeless insulin pump on the other.

“I specifically decided to keep my devices visible when I went on the show,” she said. “It’s part of my life, and I wanted to show that I’m not ashamed to wear medical devices.”

Still, it has been a long journey since Bone was diagnosed in 2017. She was just 11 years old at the time and had recently done a climbing competition when she started feeling ill.

“I didn’t perform well,” she said. “I needed to go to the bathroom a lot and felt really nauseous. Three days later, we ended up in urgent care.”

When her doctor first told her she had diabetes, she started crying.

“My grandma had type 1 and was extremely sick and died from complications,” she said. “That was all I knew about diabetes, and it was scary to think my life could be like that.”

But her outlook brightened when her doctor assured her that she could keep climbing.

“When I was told that I could keep competing, a switch flipped for me and I made a decision that nothing would hold me back,” she says.

But every day isn’t easy.

“It’s sometimes really hard to manage my diabetes during competitions,” she said. “When we climb, for example, we’re not allowed to have our phones, and I manage my [glucose monitor] through my phone. This means accommodations have to be made for me.”

And managing her diabetes can be unpredictable at times.

“If my blood sugar is low or high, I might be put last in a competition,” she said. “That messes up my warm-up and my mental game. It’s a never-ending battle.”

Ultimately, Ms. Bone’s goal is to inspire others and advocate for diabetes awareness. She says she’s been overwhelmed by viewer responses to her appearance on the show.

“I heard from so many parents and kids,” she said. “I want the world to know that wearing a pump on your arm only makes you more amazing.”

She also draws inspiration from others with diabetes.

“Everyone with this disease is a role model for me, since everyone is fighting their own battles,” she said. “Diabetes is different for everyone, and seeing how people can do what they do despite the diagnosis has been incredibly inspiring.”

For now, the rising high school junior plans to continue training and competing.

“My goal is to make the 2024 Olympic climbing team in Paris,” she said. “I’ve always wanted to compete in the Olympics since I was a little kid. Nothing can stop me.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Value of a Pharmacy-Adjudicated Community Care Prior Authorization Drug Request Service

Veterans’ access to medical care was expanded outside of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities with the inception of the 2014 Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act (Choice Act).1 This legislation aimed to remove barriers some veterans were experiencing, specifically access to health care. In subsequent years, approximately 17% of veterans receiving care from the VA did so under the Choice Act.2 The Choice Act positively impacted medical care access for veterans but presented new challenges for VA pharmacies processing community care (CC) prescriptions, including limited access to outside health records, lack of interface between CC prescribers and the VA order entry system, and limited awareness of the VA national formulary.3,4 These factors made it difficult for VA pharmacies to assess prescriptions for clinical appropriateness, evaluate patient safety parameters, and manage expenditures.

In 2019, the Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act, which expanded CC support and better defined which veterans are able to receive care outside the VA, updated the Choice Act.4,5 However, VA pharmacies faced challenges in managing pharmacy drug costs and ensuring clinical appropriateness of prescription drug therapy. As a result, VA pharmacy departments have adjusted how they allocate workload, time, and funds.5

Pharmacists improve clinical outcomes and reduce health care costs by decreasing medication errors, unnecessary prescribing, and adverse drug events.6-12 Pharmacist-driven formulary management through evaluation of prior authorization drug requests (PADRs) has shown economic value.13,14 VA pharmacy review of community care PADRs is important because outside health care professionals (HCPs) might not be familiar with the VA formulary. This could lead to high volume of PADRs that do not meet criteria and could result in increased potential for medication misuse, adverse drug events, medication errors, and cost to the health system. It is imperative that CC orders are evaluated as critically as traditional orders.

The value of a centralized CC pharmacy team has not been assessed in the literature. The primary objective of this study was to assess the direct cost savings achieved through a centralized CC PADR process. Secondary objectives were to characterize the CC PADRs submitted to the site, including approval rate, reason for nonapproval, which medications were requested and by whom, and to compare CC prescriptions with other high-complexity (1a) VA facilities.

Community Care Pharmacy

VA health systems are stratified according to complexity, which reflects size, patient population, and services offered. This study was conducted at the Durham Veterans Affairs Health Care System (DVAHCS), North Carolina, a high-complexity, 251-bed, tertiary care referral, teaching, and research system. DVAHCS provides general and specialty medical, surgical, inpatient psychiatric, and ambulatory services, and serves as a major referral center.

DVAHCS created a centralized pharmacy team for processing CC prescriptions and managing customer service. This team’s goal is to increase CC prescription processing efficiency and transparency, ensure accountability of the health care team, and promote veteran-centric customer service. The pharmacy team includes a pharmacist program manager and a dedicated CC pharmacist with administrative support from a health benefits assistant and 4 pharmacy technicians. The CC pharmacy team assesses every new prescription to ensure the veteran is authorized to receive care in the community. Once eligibility is verified, a pharmacy technician or pharmacist evaluates the prescription to ensure it contains all required information, then contacts the prescriber for any missing data. If clinically appropriate, the pharmacist processes the prescription.

In 2020, the CC pharmacy team implemented a new process for reviewing and documenting CC prescriptions that require a PADR. The closed national VA formulary is set up so that all nonformulary medications and some formulary medications, including those that are restricted because of safety and/or cost, require a PADR.15 After a CC pharmacy technician confirms a veteran’s eligibility, the technician assesses whether the requested medication requires submitting a PADR to the VA internal electronic health record. The PADR is then adjudicated by a formulary management pharmacist, CC program manager, or CC pharmacist who reviews health records to determine whether the CC prescription meets VA medication use policy requirements.

If additional information is needed or an alternate medication is suggested, the pharmacist comments back on the PADR and a CC pharmacy technician contacts the prescriber. The PADR is canceled administratively then resubmitted once all information is obtained. While waiting for a response from the prescriber, the CC pharmacy technician contacts that veteran to give an update on the prescription status, as appropriate. Once there is sufficient information to adjudicate the PADR, the outcome is documented, and if approved, the order is processed.

Methods

The DVAHCS Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective review of CC PADRs submitted from June 1, 2020, through November 30, 2020. CC PADRs were excluded if they were duplicates or were reactivated administratively but had an initial submission date before the study period. Local data were collected for nonapproved CC PADRs including drug requested, dosage and directions, medication specialty, alternative drug recommended, drug acquisition cost, PADR submission date, PADR completion date, PADR nonapproval rationale, and documented time spent per PADR. Additional data was obtained for CC prescriptions at all 42 high-complexity VA facilities from the VA national CC prescription database for the study time interval and included total PADRs, PADR approval status, total CC prescription cost, and total CC fills.

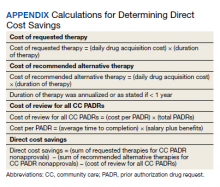

Direct cost savings were calculated by assessing the cost of requested therapy that was not approved minus the cost of recommended therapy and cost to review all PADRs, as described by Britt and colleagues.13 The cost of the requested and recommended therapy was calculated based on VA drug acquisition cost at time of data collection and multiplied by the expected duration of therapy up to 1 year. For each CC prescription, duration of therapy was based on the duration limit in the prescription or annualized if no duration limit was documented. Cost of PADR review was calculated based on the total time pharmacists and pharmacy technicians documented for each step of the review process for a representative sample of 100 nonapproved PADRs and then multiplied by the salary plus benefits of an entry-level pharmacist and pharmacy technician.16 The eAppendix describes specific equations used for determining direct cost savings. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate study results.

Results

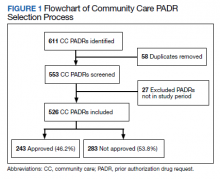

During the 6-month study period, 611 CC PADRs were submitted to the pharmacy and 526 met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Of those, 243 (46.2%) were approved and 283 (53.8%) were not approved. The cost of requested therapies for nonapproved CC PADRs totaled $584,565.48 and the cost of all recommended therapies was $57,473.59. The mean time per CC PADR was 24 minutes; 16 minutes for pharmacists and 8 minutes for pharmacy technicians. Given an hourly wage (plus benefits) of $67.25 for a pharmacist and $25.53 for a pharmacy technician, the total cost of review per CC PADR was $21.33. After subtracting the costs of all recommended therapies and review of all included CC PADRs, the process generated $515,872.31 in direct cost savings. After factoring in administrative lag time, such as HCP communication, an average of 8 calendar days was needed to complete a nonapproved PADR.

The most common rationale for PADR nonapproval was that the formulary alternative was not exhausted. Ondansetron orally disintegrating tablets was the most commonly nonapproved medication and azelastine was the most commonly approved medication. Dulaglutide was the most expensive nonapproved and tafamidis was the most expensive approved PADR (Table 1). Gastroenterology, endocrinology, and neurology were the top specialties for nonapproved PADRs while neurology, pulmonology, and endocrinology were the top specialties for approved PADRs (Table 2).

Several high-complexity VA facilities had no reported data; we used the median for the analysis to account for these outliers (Figure 2). The median (IQR) adjudicated CC PADRs for all facilities was 97 (20-175), median (IQR) CC PADR approval rate was 80.9% (63.7%-96.8%), median (IQR) total CC prescriptions was 8440 (2464-14,466), and median (IQR) cost per fill was $136.05 ($76.27-$221.28).

Discussion

This study demonstrated direct cost savings of $515,872.31 over 6 months with theadjudication of CC PADRs by a centralized CC pharmacy team. This could result in > $1,000,000 of cost savings per fiscal year.

The CC PADRs observed at DVAHCS had a 46.2% approval rate; almost one-half the approval rate of 84.1% of all PADRs submitted to the study site by VA HCPs captured by Britt and colleagues.13 Results from this study showed that coordination of care for nonapproved CC PADRs between the VA pharmacy and non-VA prescriber took an average of 8 calendar days. The noted CC PADR approval rate and administrative burden might be because of lack of familiarity of non-VA providers regarding the VA national formulary. The National VA Pharmacy Benefits Management determines the formulary using cost-effectiveness criteria that considers the medical literature and VA-specific contract pricing and prepares extensive guidance for restricted medications via relevant criteria for use.15 HCPs outside the VA might not know this information is available online. Because gastroenterology, endocrinology, and neurology specialty medications were among the most frequently nonapproved PADRs, VA formulary education could begin with CC HCPs in these practice areas.

This study showed that the CC PADR process was not solely driven by cost, but also included patient safety. Nonapproval rationale for some requests included submission without an indication, submission by a prescriber that did not have the authority to prescribe a type of medication, or contraindication based on patient-specific factors.

Compared with other VA high-complexity facilities, DVAHCS was among the top health care systems for total volume of CC prescriptions (n = 16,096) and among the lowest for cost/fill ($75.74). Similarly, DVAHCS was among the top sites for total adjudicated CC PADRs within the 6-month study period (n = 611) and the lowest approval rate (44.2%). This study shows that despite high volumes of overall CC prescriptions and CC PADRs, it is possible to maintain a low overall CC prescription cost/fill compared with other similarly complex sites across the country. Wide variance in reported results exists across high-complexity VA facilities because some sites had low to no CC fills and/or CC PADRs. This is likely a result of administrative differences when handling CC prescriptions and presents an opportunity to standardize this process nationally.

Limitations

CC PADRs were assessed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which might have resulted in lower-than-normal CC prescription and PADR volumes, therefore underestimating the potential for direct cost savings. Entry-level salary was used to demonstrate cost savings potential from the perspective of a newly hired CC team; however, the cost savings might have been less if the actual salaries of site personnel were higher. National contract pricing data were gathered at the time of data collection and might have been different than at the time of PADR submission. Chronic medication prescriptions were annualized, which could overestimate cost savings if the medication was discontinued or changed to an alternative therapy within that time period.

The study’s exclusion criteria could only be applied locally and did not include data received from the VA CC prescription database. This can be seen by the discrepancy in CC PADR approval rates from the local and national data (46.2% vs 44.2%, respectively) and CC PADR volume. High-complexity VA facility data were captured without assessing the CC prescription process at each site. As a result, definitive conclusions cannot be made regarding the impact of a centralized CC pharmacy team compared with other facilities.

Conclusions

Adjudication of CC PADRs by a centralized CC pharmacy team over a 6-month period provided > $500,000 in direct cost savings to a VA health care system. Considering the CC PADR approval rate seen in this study, the VA could allocate resources to educate CC providers about the VA formulary to increase the PADR approval rate and reduce administrative burden for VA pharmacies and prescribers. Future research should evaluate CC prescription handling practices at other VA facilities to compare the effectiveness among varying approaches and develop recommendations for a nationally standardized process.

Acknowledgments

Concept and design (AJJ, JNB, RBB, LAM, MD, MGH); acquisition of data (AJJ, MGH); analysis and interpretation of data (AJJ, JNB, RBB, LAM, MD, MGH); drafting of the manuscript (AJJ); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (AJJ, JNB, RBB, LAM, MD, MGH); statistical analysis (AJJ); administrative, technical, or logistic support (LAM, MGH); and supervision (MGH).

1. Gellad WF, Cunningham FE, Good CB, et al. Pharmacy use in the first year of the Veterans Choice Program: a mixed-methods evaluation. Med Care. 2017(7 suppl 1);55:S26. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000661

2. Mattocks KM, Yehia B. Evaluating the veterans choice program: lessons for developing a high-performing integrated network. Med Care. 2017(7 suppl 1);55:S1-S3. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000743.

3. Mattocks KM, Mengeling M, Sadler A, Baldor R, Bastian L. The Veterans Choice Act: a qualitative examination of rapid policy implementation in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2017;55(7 suppl 1):S71-S75. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000667

4. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1108.08: VHA formulary management process. November 2, 2016. Accessed June 9, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=3291

5. Massarweh NN, Itani KMF, Morris MS. The VA MISSION act and the future of veterans’ access to quality health care. JAMA. 2020;324:343-344. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4505

6. Jourdan JP, Muzard A, Goyer I, et al. Impact of pharmacist interventions on clinical outcome and cost avoidance in a university teaching hospital. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(6):1474-1481. doi:10.1007/s11096-018-0733-6

7. Lee AJ, Boro MS, Knapp KK, Meier JL, Korman NE. Clinical and economic outcomes of pharmacist recommendations in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(21):2070-2077. doi:10.1093/ajhp/59.21.2070

8. Dalton K, Byrne S. Role of the pharmacist in reducing healthcare costs: current insights. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2017;6:37-46. doi:10.2147/IPRP.S108047

9. De Rijdt T, Willems L, Simoens S. Economic effects of clinical pharmacy interventions: a literature review. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(12):1161-1172. doi:10.2146/ajhp070506

10. Perez A, Doloresco F, Hoffman J, et al. Economic evaluation of clinical pharmacy services: 2001-2005. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(1):128. doi:10.1592/phco.29.1.128

11. Nesbit TW, Shermock KM, Bobek MB, et al. Implementation and pharmacoeconomic analysis of a clinical staff pharmacist practice model. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(9):784-790. doi:10.1093/ajhp/58.9.784

12. Yang S, Britt RB, Hashem MG, Brown JN. Outcomes of pharmacy-led hepatitis C direct-acting antiviral utilization management at a Veterans Affairs medical center. J Manag Care Pharm. 2017;23(3):364-369. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.3.364

13. Britt RB, Hashem MG, Bryan WE III, Kothapalli R, Brown JN. Economic outcomes associated with a pharmacist-adjudicated formulary consult service in a Veterans Affairs medical center. J Manag Care Pharm. 2016;22(9):1051-1061. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.9.1051

14. Jacob S, Britt RB, Bryan WE, Hashem MG, Hale JC, Brown JN. Economic outcomes associated with safety interventions by a pharmacist-adjudicated prior authorization consult service. J Manag Care Pharm. 2019;25(3):411-416. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2019.25.3.411

15. Aspinall SL, Sales MM, Good CB, et al. Pharmacy benefits management in the Veterans Health Administration revisited: a decade of advancements, 2004-2014. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(9):1058-1063. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.9.1058

16. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer. Title 38 Pay Schedules. Updated January 26, 2022. Accessed June 9, 2022. https://www.va.gov/ohrm/pay

Veterans’ access to medical care was expanded outside of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities with the inception of the 2014 Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act (Choice Act).1 This legislation aimed to remove barriers some veterans were experiencing, specifically access to health care. In subsequent years, approximately 17% of veterans receiving care from the VA did so under the Choice Act.2 The Choice Act positively impacted medical care access for veterans but presented new challenges for VA pharmacies processing community care (CC) prescriptions, including limited access to outside health records, lack of interface between CC prescribers and the VA order entry system, and limited awareness of the VA national formulary.3,4 These factors made it difficult for VA pharmacies to assess prescriptions for clinical appropriateness, evaluate patient safety parameters, and manage expenditures.

In 2019, the Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act, which expanded CC support and better defined which veterans are able to receive care outside the VA, updated the Choice Act.4,5 However, VA pharmacies faced challenges in managing pharmacy drug costs and ensuring clinical appropriateness of prescription drug therapy. As a result, VA pharmacy departments have adjusted how they allocate workload, time, and funds.5

Pharmacists improve clinical outcomes and reduce health care costs by decreasing medication errors, unnecessary prescribing, and adverse drug events.6-12 Pharmacist-driven formulary management through evaluation of prior authorization drug requests (PADRs) has shown economic value.13,14 VA pharmacy review of community care PADRs is important because outside health care professionals (HCPs) might not be familiar with the VA formulary. This could lead to high volume of PADRs that do not meet criteria and could result in increased potential for medication misuse, adverse drug events, medication errors, and cost to the health system. It is imperative that CC orders are evaluated as critically as traditional orders.

The value of a centralized CC pharmacy team has not been assessed in the literature. The primary objective of this study was to assess the direct cost savings achieved through a centralized CC PADR process. Secondary objectives were to characterize the CC PADRs submitted to the site, including approval rate, reason for nonapproval, which medications were requested and by whom, and to compare CC prescriptions with other high-complexity (1a) VA facilities.

Community Care Pharmacy

VA health systems are stratified according to complexity, which reflects size, patient population, and services offered. This study was conducted at the Durham Veterans Affairs Health Care System (DVAHCS), North Carolina, a high-complexity, 251-bed, tertiary care referral, teaching, and research system. DVAHCS provides general and specialty medical, surgical, inpatient psychiatric, and ambulatory services, and serves as a major referral center.

DVAHCS created a centralized pharmacy team for processing CC prescriptions and managing customer service. This team’s goal is to increase CC prescription processing efficiency and transparency, ensure accountability of the health care team, and promote veteran-centric customer service. The pharmacy team includes a pharmacist program manager and a dedicated CC pharmacist with administrative support from a health benefits assistant and 4 pharmacy technicians. The CC pharmacy team assesses every new prescription to ensure the veteran is authorized to receive care in the community. Once eligibility is verified, a pharmacy technician or pharmacist evaluates the prescription to ensure it contains all required information, then contacts the prescriber for any missing data. If clinically appropriate, the pharmacist processes the prescription.

In 2020, the CC pharmacy team implemented a new process for reviewing and documenting CC prescriptions that require a PADR. The closed national VA formulary is set up so that all nonformulary medications and some formulary medications, including those that are restricted because of safety and/or cost, require a PADR.15 After a CC pharmacy technician confirms a veteran’s eligibility, the technician assesses whether the requested medication requires submitting a PADR to the VA internal electronic health record. The PADR is then adjudicated by a formulary management pharmacist, CC program manager, or CC pharmacist who reviews health records to determine whether the CC prescription meets VA medication use policy requirements.

If additional information is needed or an alternate medication is suggested, the pharmacist comments back on the PADR and a CC pharmacy technician contacts the prescriber. The PADR is canceled administratively then resubmitted once all information is obtained. While waiting for a response from the prescriber, the CC pharmacy technician contacts that veteran to give an update on the prescription status, as appropriate. Once there is sufficient information to adjudicate the PADR, the outcome is documented, and if approved, the order is processed.

Methods

The DVAHCS Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective review of CC PADRs submitted from June 1, 2020, through November 30, 2020. CC PADRs were excluded if they were duplicates or were reactivated administratively but had an initial submission date before the study period. Local data were collected for nonapproved CC PADRs including drug requested, dosage and directions, medication specialty, alternative drug recommended, drug acquisition cost, PADR submission date, PADR completion date, PADR nonapproval rationale, and documented time spent per PADR. Additional data was obtained for CC prescriptions at all 42 high-complexity VA facilities from the VA national CC prescription database for the study time interval and included total PADRs, PADR approval status, total CC prescription cost, and total CC fills.

Direct cost savings were calculated by assessing the cost of requested therapy that was not approved minus the cost of recommended therapy and cost to review all PADRs, as described by Britt and colleagues.13 The cost of the requested and recommended therapy was calculated based on VA drug acquisition cost at time of data collection and multiplied by the expected duration of therapy up to 1 year. For each CC prescription, duration of therapy was based on the duration limit in the prescription or annualized if no duration limit was documented. Cost of PADR review was calculated based on the total time pharmacists and pharmacy technicians documented for each step of the review process for a representative sample of 100 nonapproved PADRs and then multiplied by the salary plus benefits of an entry-level pharmacist and pharmacy technician.16 The eAppendix describes specific equations used for determining direct cost savings. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate study results.

Results

During the 6-month study period, 611 CC PADRs were submitted to the pharmacy and 526 met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Of those, 243 (46.2%) were approved and 283 (53.8%) were not approved. The cost of requested therapies for nonapproved CC PADRs totaled $584,565.48 and the cost of all recommended therapies was $57,473.59. The mean time per CC PADR was 24 minutes; 16 minutes for pharmacists and 8 minutes for pharmacy technicians. Given an hourly wage (plus benefits) of $67.25 for a pharmacist and $25.53 for a pharmacy technician, the total cost of review per CC PADR was $21.33. After subtracting the costs of all recommended therapies and review of all included CC PADRs, the process generated $515,872.31 in direct cost savings. After factoring in administrative lag time, such as HCP communication, an average of 8 calendar days was needed to complete a nonapproved PADR.

The most common rationale for PADR nonapproval was that the formulary alternative was not exhausted. Ondansetron orally disintegrating tablets was the most commonly nonapproved medication and azelastine was the most commonly approved medication. Dulaglutide was the most expensive nonapproved and tafamidis was the most expensive approved PADR (Table 1). Gastroenterology, endocrinology, and neurology were the top specialties for nonapproved PADRs while neurology, pulmonology, and endocrinology were the top specialties for approved PADRs (Table 2).

Several high-complexity VA facilities had no reported data; we used the median for the analysis to account for these outliers (Figure 2). The median (IQR) adjudicated CC PADRs for all facilities was 97 (20-175), median (IQR) CC PADR approval rate was 80.9% (63.7%-96.8%), median (IQR) total CC prescriptions was 8440 (2464-14,466), and median (IQR) cost per fill was $136.05 ($76.27-$221.28).

Discussion

This study demonstrated direct cost savings of $515,872.31 over 6 months with theadjudication of CC PADRs by a centralized CC pharmacy team. This could result in > $1,000,000 of cost savings per fiscal year.

The CC PADRs observed at DVAHCS had a 46.2% approval rate; almost one-half the approval rate of 84.1% of all PADRs submitted to the study site by VA HCPs captured by Britt and colleagues.13 Results from this study showed that coordination of care for nonapproved CC PADRs between the VA pharmacy and non-VA prescriber took an average of 8 calendar days. The noted CC PADR approval rate and administrative burden might be because of lack of familiarity of non-VA providers regarding the VA national formulary. The National VA Pharmacy Benefits Management determines the formulary using cost-effectiveness criteria that considers the medical literature and VA-specific contract pricing and prepares extensive guidance for restricted medications via relevant criteria for use.15 HCPs outside the VA might not know this information is available online. Because gastroenterology, endocrinology, and neurology specialty medications were among the most frequently nonapproved PADRs, VA formulary education could begin with CC HCPs in these practice areas.

This study showed that the CC PADR process was not solely driven by cost, but also included patient safety. Nonapproval rationale for some requests included submission without an indication, submission by a prescriber that did not have the authority to prescribe a type of medication, or contraindication based on patient-specific factors.

Compared with other VA high-complexity facilities, DVAHCS was among the top health care systems for total volume of CC prescriptions (n = 16,096) and among the lowest for cost/fill ($75.74). Similarly, DVAHCS was among the top sites for total adjudicated CC PADRs within the 6-month study period (n = 611) and the lowest approval rate (44.2%). This study shows that despite high volumes of overall CC prescriptions and CC PADRs, it is possible to maintain a low overall CC prescription cost/fill compared with other similarly complex sites across the country. Wide variance in reported results exists across high-complexity VA facilities because some sites had low to no CC fills and/or CC PADRs. This is likely a result of administrative differences when handling CC prescriptions and presents an opportunity to standardize this process nationally.

Limitations

CC PADRs were assessed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which might have resulted in lower-than-normal CC prescription and PADR volumes, therefore underestimating the potential for direct cost savings. Entry-level salary was used to demonstrate cost savings potential from the perspective of a newly hired CC team; however, the cost savings might have been less if the actual salaries of site personnel were higher. National contract pricing data were gathered at the time of data collection and might have been different than at the time of PADR submission. Chronic medication prescriptions were annualized, which could overestimate cost savings if the medication was discontinued or changed to an alternative therapy within that time period.

The study’s exclusion criteria could only be applied locally and did not include data received from the VA CC prescription database. This can be seen by the discrepancy in CC PADR approval rates from the local and national data (46.2% vs 44.2%, respectively) and CC PADR volume. High-complexity VA facility data were captured without assessing the CC prescription process at each site. As a result, definitive conclusions cannot be made regarding the impact of a centralized CC pharmacy team compared with other facilities.

Conclusions

Adjudication of CC PADRs by a centralized CC pharmacy team over a 6-month period provided > $500,000 in direct cost savings to a VA health care system. Considering the CC PADR approval rate seen in this study, the VA could allocate resources to educate CC providers about the VA formulary to increase the PADR approval rate and reduce administrative burden for VA pharmacies and prescribers. Future research should evaluate CC prescription handling practices at other VA facilities to compare the effectiveness among varying approaches and develop recommendations for a nationally standardized process.

Acknowledgments

Concept and design (AJJ, JNB, RBB, LAM, MD, MGH); acquisition of data (AJJ, MGH); analysis and interpretation of data (AJJ, JNB, RBB, LAM, MD, MGH); drafting of the manuscript (AJJ); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (AJJ, JNB, RBB, LAM, MD, MGH); statistical analysis (AJJ); administrative, technical, or logistic support (LAM, MGH); and supervision (MGH).

Veterans’ access to medical care was expanded outside of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities with the inception of the 2014 Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act (Choice Act).1 This legislation aimed to remove barriers some veterans were experiencing, specifically access to health care. In subsequent years, approximately 17% of veterans receiving care from the VA did so under the Choice Act.2 The Choice Act positively impacted medical care access for veterans but presented new challenges for VA pharmacies processing community care (CC) prescriptions, including limited access to outside health records, lack of interface between CC prescribers and the VA order entry system, and limited awareness of the VA national formulary.3,4 These factors made it difficult for VA pharmacies to assess prescriptions for clinical appropriateness, evaluate patient safety parameters, and manage expenditures.

In 2019, the Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act, which expanded CC support and better defined which veterans are able to receive care outside the VA, updated the Choice Act.4,5 However, VA pharmacies faced challenges in managing pharmacy drug costs and ensuring clinical appropriateness of prescription drug therapy. As a result, VA pharmacy departments have adjusted how they allocate workload, time, and funds.5

Pharmacists improve clinical outcomes and reduce health care costs by decreasing medication errors, unnecessary prescribing, and adverse drug events.6-12 Pharmacist-driven formulary management through evaluation of prior authorization drug requests (PADRs) has shown economic value.13,14 VA pharmacy review of community care PADRs is important because outside health care professionals (HCPs) might not be familiar with the VA formulary. This could lead to high volume of PADRs that do not meet criteria and could result in increased potential for medication misuse, adverse drug events, medication errors, and cost to the health system. It is imperative that CC orders are evaluated as critically as traditional orders.

The value of a centralized CC pharmacy team has not been assessed in the literature. The primary objective of this study was to assess the direct cost savings achieved through a centralized CC PADR process. Secondary objectives were to characterize the CC PADRs submitted to the site, including approval rate, reason for nonapproval, which medications were requested and by whom, and to compare CC prescriptions with other high-complexity (1a) VA facilities.

Community Care Pharmacy

VA health systems are stratified according to complexity, which reflects size, patient population, and services offered. This study was conducted at the Durham Veterans Affairs Health Care System (DVAHCS), North Carolina, a high-complexity, 251-bed, tertiary care referral, teaching, and research system. DVAHCS provides general and specialty medical, surgical, inpatient psychiatric, and ambulatory services, and serves as a major referral center.

DVAHCS created a centralized pharmacy team for processing CC prescriptions and managing customer service. This team’s goal is to increase CC prescription processing efficiency and transparency, ensure accountability of the health care team, and promote veteran-centric customer service. The pharmacy team includes a pharmacist program manager and a dedicated CC pharmacist with administrative support from a health benefits assistant and 4 pharmacy technicians. The CC pharmacy team assesses every new prescription to ensure the veteran is authorized to receive care in the community. Once eligibility is verified, a pharmacy technician or pharmacist evaluates the prescription to ensure it contains all required information, then contacts the prescriber for any missing data. If clinically appropriate, the pharmacist processes the prescription.

In 2020, the CC pharmacy team implemented a new process for reviewing and documenting CC prescriptions that require a PADR. The closed national VA formulary is set up so that all nonformulary medications and some formulary medications, including those that are restricted because of safety and/or cost, require a PADR.15 After a CC pharmacy technician confirms a veteran’s eligibility, the technician assesses whether the requested medication requires submitting a PADR to the VA internal electronic health record. The PADR is then adjudicated by a formulary management pharmacist, CC program manager, or CC pharmacist who reviews health records to determine whether the CC prescription meets VA medication use policy requirements.

If additional information is needed or an alternate medication is suggested, the pharmacist comments back on the PADR and a CC pharmacy technician contacts the prescriber. The PADR is canceled administratively then resubmitted once all information is obtained. While waiting for a response from the prescriber, the CC pharmacy technician contacts that veteran to give an update on the prescription status, as appropriate. Once there is sufficient information to adjudicate the PADR, the outcome is documented, and if approved, the order is processed.

Methods

The DVAHCS Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective review of CC PADRs submitted from June 1, 2020, through November 30, 2020. CC PADRs were excluded if they were duplicates or were reactivated administratively but had an initial submission date before the study period. Local data were collected for nonapproved CC PADRs including drug requested, dosage and directions, medication specialty, alternative drug recommended, drug acquisition cost, PADR submission date, PADR completion date, PADR nonapproval rationale, and documented time spent per PADR. Additional data was obtained for CC prescriptions at all 42 high-complexity VA facilities from the VA national CC prescription database for the study time interval and included total PADRs, PADR approval status, total CC prescription cost, and total CC fills.

Direct cost savings were calculated by assessing the cost of requested therapy that was not approved minus the cost of recommended therapy and cost to review all PADRs, as described by Britt and colleagues.13 The cost of the requested and recommended therapy was calculated based on VA drug acquisition cost at time of data collection and multiplied by the expected duration of therapy up to 1 year. For each CC prescription, duration of therapy was based on the duration limit in the prescription or annualized if no duration limit was documented. Cost of PADR review was calculated based on the total time pharmacists and pharmacy technicians documented for each step of the review process for a representative sample of 100 nonapproved PADRs and then multiplied by the salary plus benefits of an entry-level pharmacist and pharmacy technician.16 The eAppendix describes specific equations used for determining direct cost savings. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate study results.

Results