User login

ACIP recommendations for COVID-19 vaccines—and more

The year 2020 was challenging for public health agencies and especially for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). In a normal year, the ACIP meets in person 3 times for a total of 6 days of deliberations. In 2020, there were 10 meetings (all but 1 using Zoom) covering 14 days. Much of the time was dedicated to the COVID-19 pandemic, the vaccines being developed to prevent COVID-19, and the prioritization of those who should receive the vaccines first.

The ACIP also made recommendations for the use of influenza vaccines in the 2020-2021 season, approved the adult and pediatric immunization schedules for 2021, and approved the use of 2 new vaccines, one to protect against meningococcal meningitis and the other to prevent Ebola virus disease. The influenza recommendations were covered in the October 2020 Practice Alert,1 and the immunization schedules can be found on the CDC website at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html.

COVID-19 vaccines

Two COVID-19 vaccines have been approved for use in the United States. The first was the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on December 11 and recommended for use by the ACIP on December 12.2 The second vaccine, from Moderna, was approved by the FDA on December 18 and recommended by the ACIP on December 19.3 Both were approved by the FDA under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) and were approved by the ACIP for use while the EUA is in effect. Both vaccines must eventually undergo regular approval by the FDA and will be reconsidered by the ACIP regarding use in non–public health emergency conditions. A description of the EUA process and measures taken to assure efficacy and safety, before and after approval, were discussed in the September 2020 audiocast.

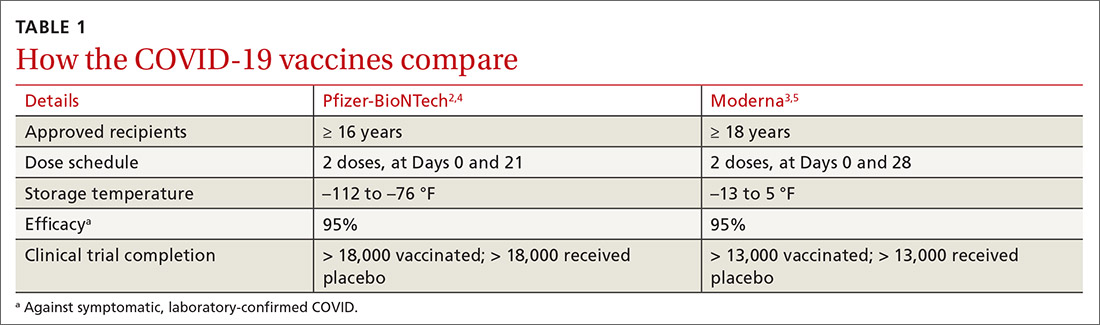

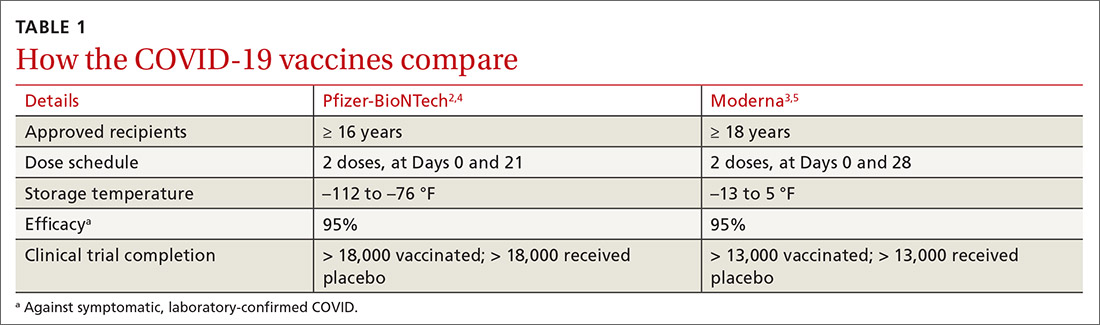

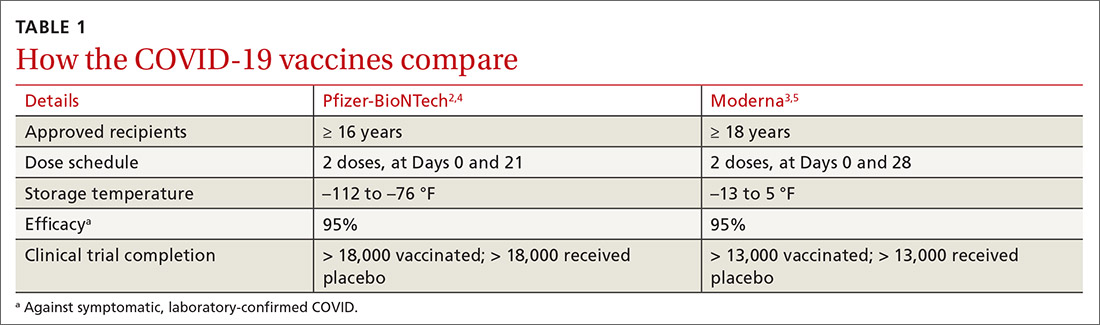

Both COVID-19 vaccines consist of nucleoside-modified mRNA encapsulated with lipid nanoparticles, which encode for a spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Both vaccines require 2 doses (separated by 3 weeks for the Pfizer vaccine and 4 weeks for the Moderna vaccine) and are approved for use only in adults and older adolescents (ages ≥ 16 years for the Pfizer vaccine and ≥ 18 years for the Moderna vaccine) (TABLE 12-5).

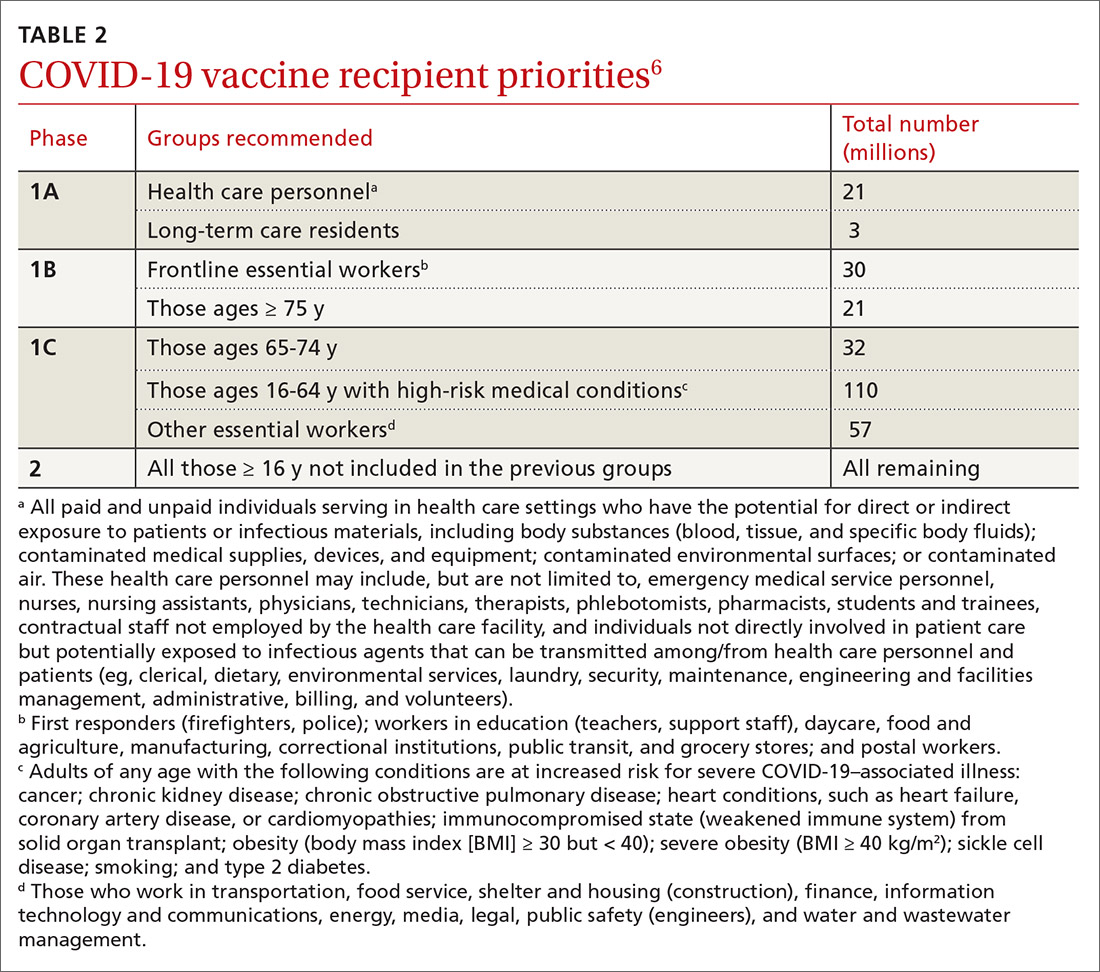

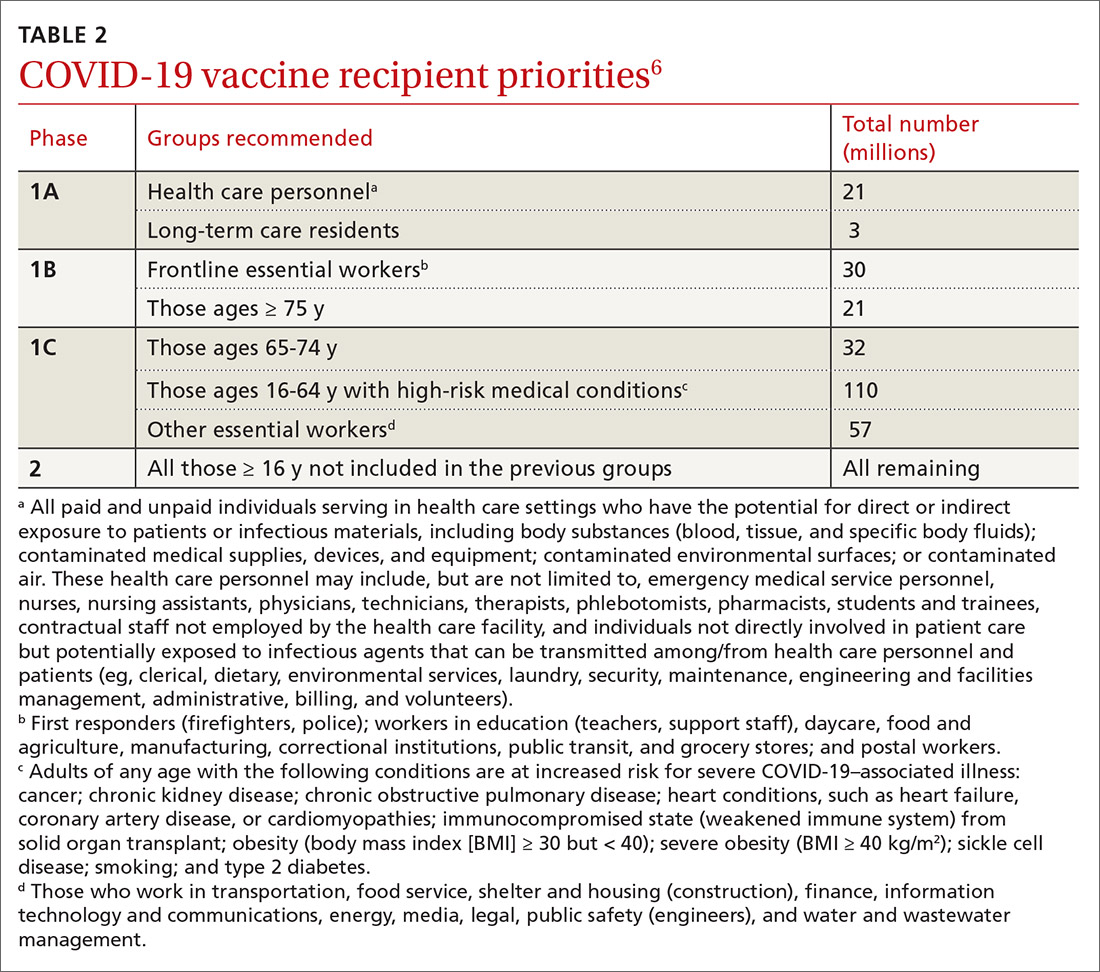

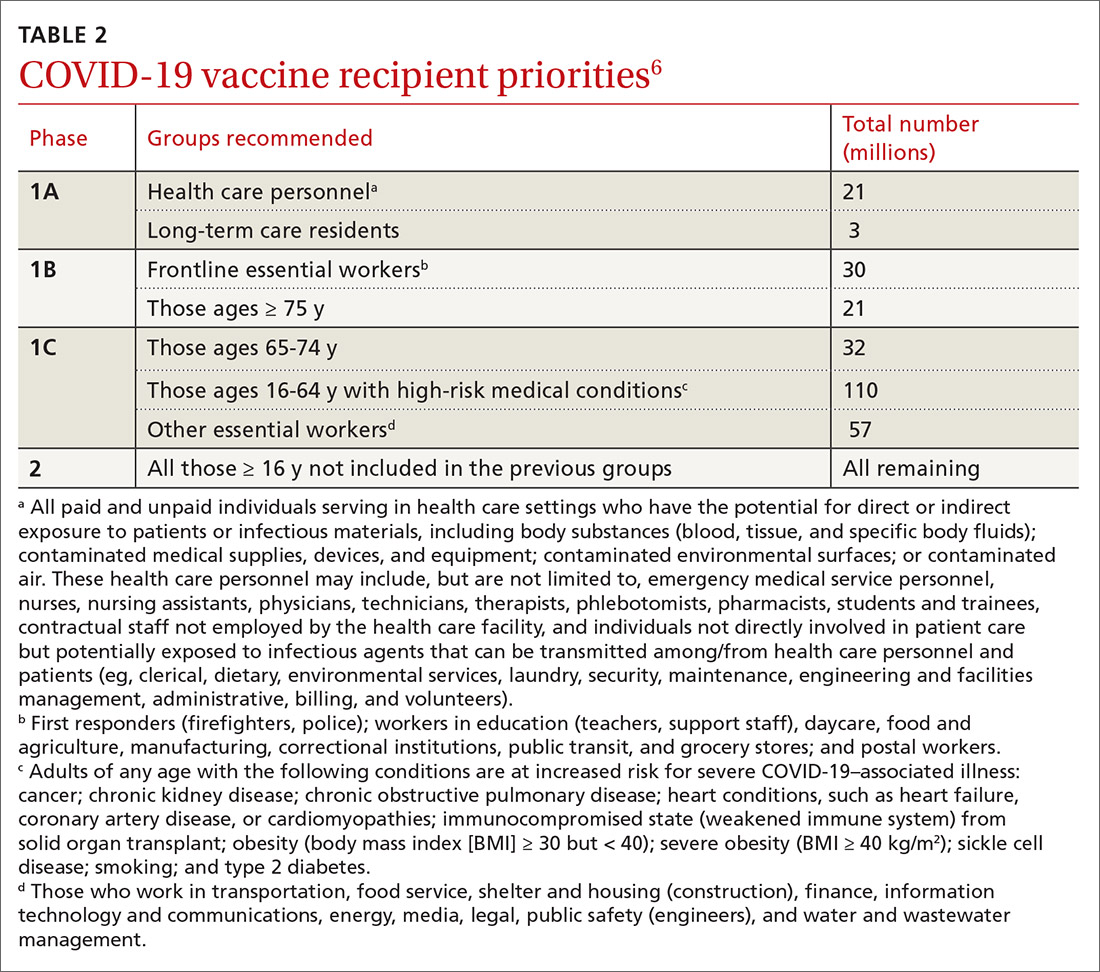

In anticipation of vaccine shortages immediately after approval for use and a high demand for the vaccine, the ACIP developed a list of high-priority groups who should receive the vaccine in ranked order.6 States are encouraged, but not required, to follow this priority list (TABLE 26).

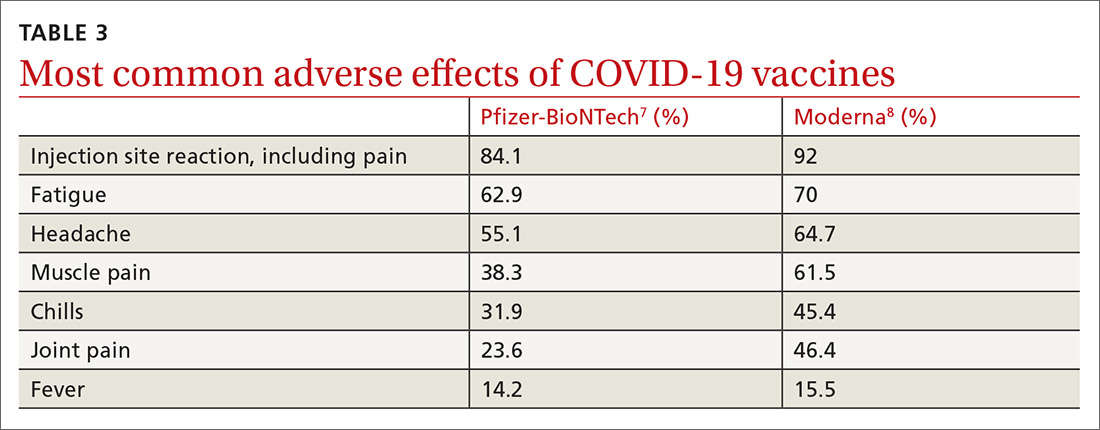

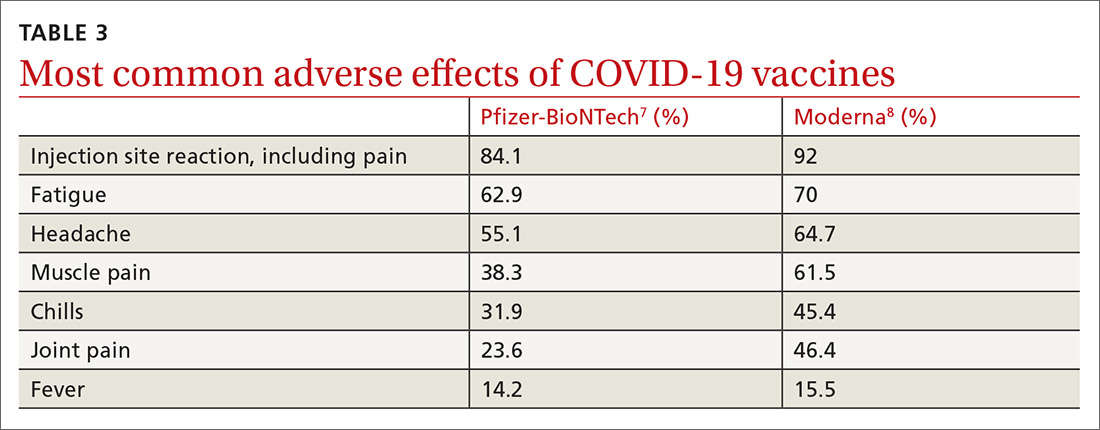

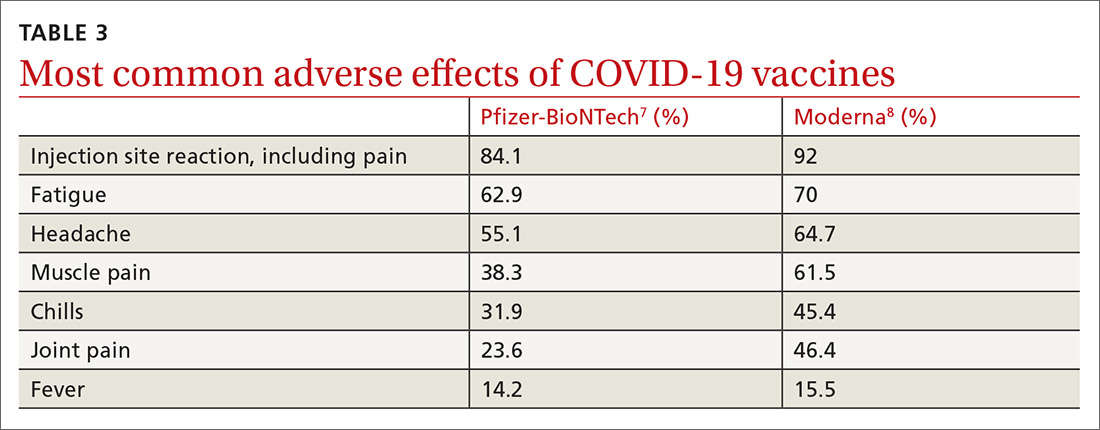

Caveats with usage. Both COVID-19 vaccines are very reactogenic, causing local and systemic adverse effects that patients should be warned about (TABLE 37,8). These reactions are usually mild to moderate and last 24 hours or less. Acetaminophen can alleviate these symptoms but should not be used to prevent them. In addition, both vaccines have stringent cold-storage requirements; once the vaccines are thawed, they must be used within a defined time-period.

Neither vaccine is listed as preferred. And they are not interchangeable; both recommended doses should be completed with the same vaccine. More details about the use of these vaccines were discussed in the January 2021 audiocast (www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/234239/coronavirus-updates/covid-19-vaccines-rollout-risks-and-reason-still) and can be located on the CDC website (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/pfizer/reactogenicity.html; www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/moderna/reactogenicity.html).

Continue to: Much remains unknown...

Much remains unknown regarding the use of these COVID-19 vaccines:

- What is their duration of protection, and will booster doses be needed?

- Will they protect against asymptomatic infection and carrier states, and thereby prevent transmission?

- Can they be co-administered with other vaccines?

- Will they be efficacious and safe to use during pregnancy and breastfeeding?

These issues will need to be addressed before they are recommended for non–public health emergency use.

Quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY)

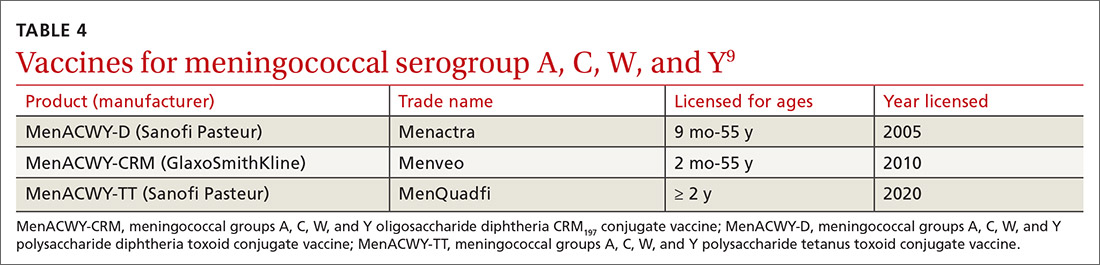

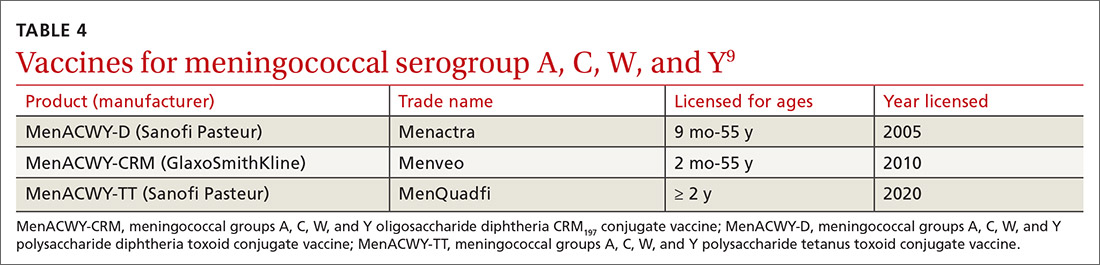

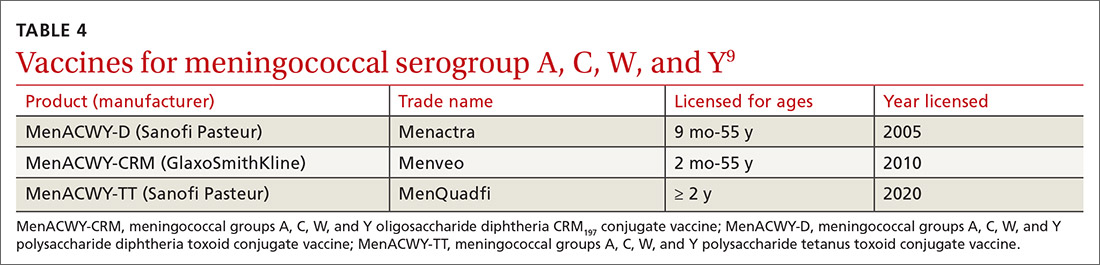

In June 2020, the ACIP added a third quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine to its recommended list of vaccines that are FDA-approved for meningococcal disease (TABLE 49). The new vaccine fills a void left by the meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine (MPSV4), which is no longer marketed in the United States. MPSV4 was previously the only meningococcal vaccine approved for individuals 55 years and older.

The new vaccine, MenACWY-TT (MenQuadfi), is approved for those ages 2 years and older, including those > 55 years. It is anticipated that MenQuadfi will, in the near future, be licensed and approved for individuals 6 months and older and will replace MenACWY-D (Menactra). (Both are manufactured by Sanofi Pasteur.)

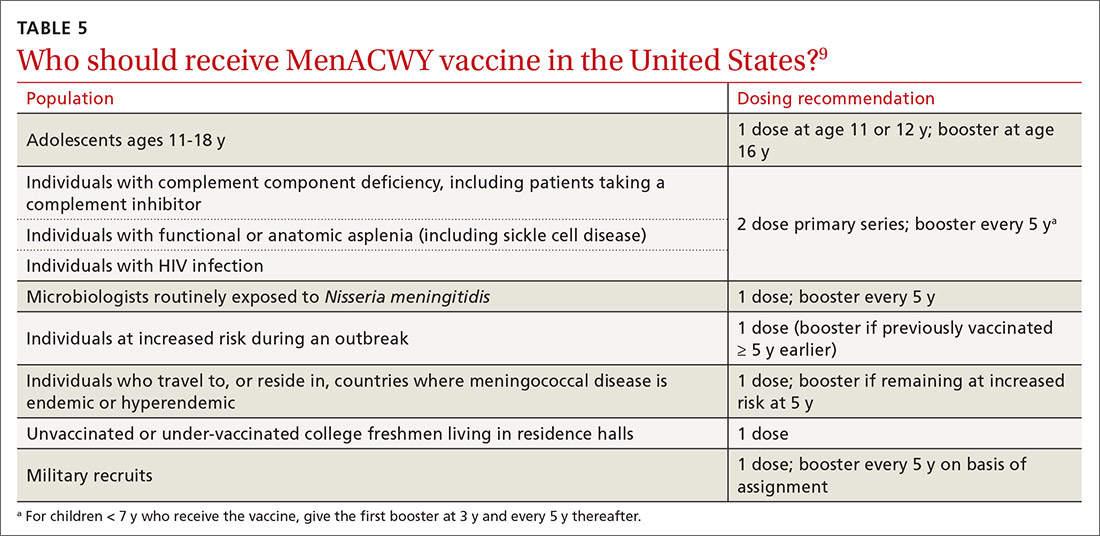

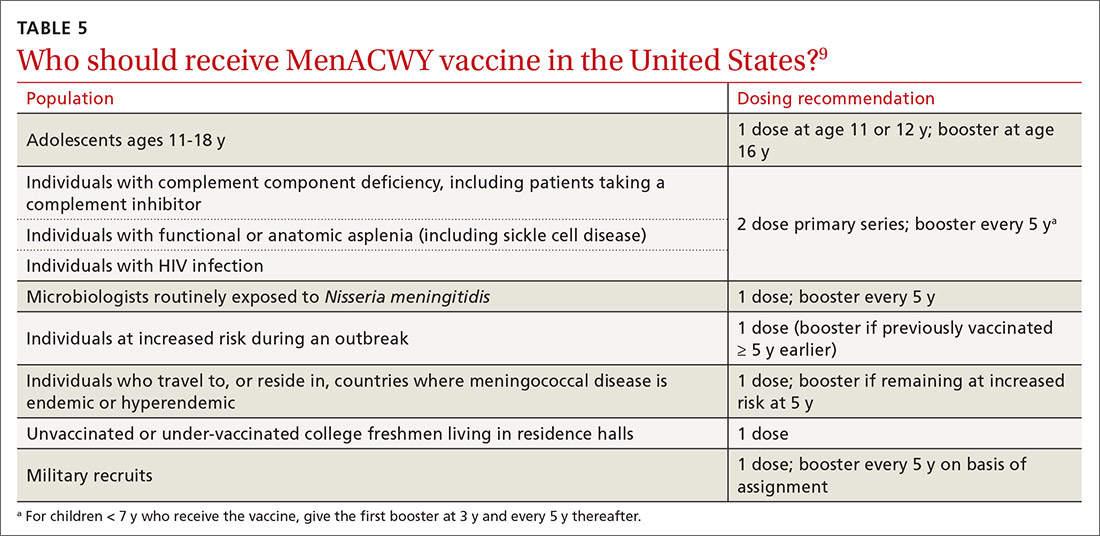

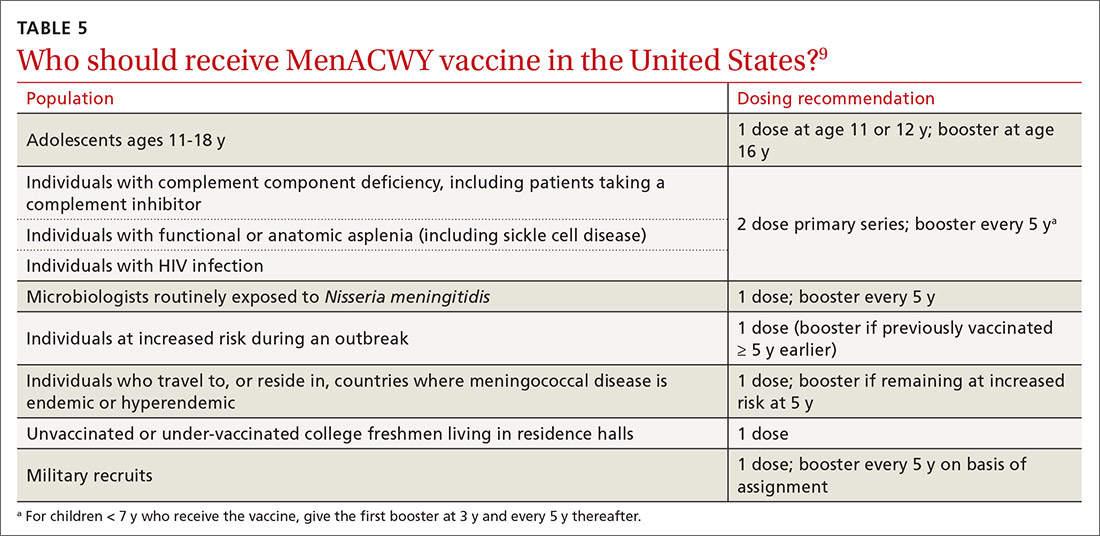

Groups for whom a MenACWY vaccine is recommended are listed in TABLE 5.9 A full description of current, updated recommendations for the prevention of meningococcal disease is also available.9

Continue to: Ebola virus (EBOV) vaccine

Ebola virus (EBOV) vaccine

A vaccine to prevent Ebola virus disease (EVD) is available by special request in the United States. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus-based Ebola virus vaccine, abbreviated as rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (brand name, ERVBO) is manufactured by Merck and received approval by the FDA on December 19, 2019, for use in those ages 18 years and older. It is a live, attenuated vaccine.

The ACIP has recommended pre-exposure vaccination with rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP for adults 18 years or older who are at risk of exposure to EBOV while responding to an outbreak of EVD; while working as health care personnel at a federally designated Ebola Treatment Center; or while working at biosafety-level 4 facilities.10 The vaccine is protective against just 1 of 4 EBOV species, Zaire ebolavirus, which has been the cause of most reported EVD outbreaks, including the 2 largest EVD outbreaks in history that occurred in West Africa and the Republic of Congo.

It is estimated that EBOV outbreaks have infected more than 31,000 people and resulted in more than 12,000 deaths worldwide.11 Only 11 people infected with EBOV have been treated in the United States, all related to the 2014-2016 large outbreaks in West Africa. Nine of these cases were imported and only 1 resulted in transmission, to 2 people.10 The mammalian species that are suspected as intermediate hosts for EBOV are not present in the United States, which prevents EBOV from becoming endemic here.

The rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine was tested in a large trial in Africa during the 2014 outbreak. Its effectiveness was 100% (95% confidence interval, 63.5%-100%). The most common adverse effects were injection site pain, swelling, and redness. Mild-to-moderate systemic symptoms can occur within the first 2 days following vaccination, and include headache (37%), fever (34%), muscle pain (33%), fatigue (19%), joint pain (18%), nausea (8%), arthritis (5%), rash (4%), and

Since the vaccine contains a live virus that causes stomatitis in animals, it is possible that the virus could be transmitted to humans and other animals through close contact. Accordingly, the CDC has published some precautions including, but not limited to, not donating blood and, for 6 weeks after vaccination, avoiding contact with those who are immunosuppressed.10 The vaccine is not commercially available in the United States and must be obtained from the CDC. Information on requesting the vaccine is available at www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/clinicians/vaccine/.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Prospects and challenges for the upcoming influenza season. J Fam Pract 2020;69:406-411.

2. Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for use of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine-United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1922-1924.

3. Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for use of Moderna COVID-19 vaccine-United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69:1653-1656.

4. CDC. Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/pfizer/index.html

5. CDC. Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/moderna/index.html#:~:text=How%20to%20Store%20the%20Moderna%20COVID%2D19%20Vaccine&text=Vaccine%20may%20be%20stored%20in,for%20this%20vaccine%20is%20tighter

6. Dooling K, Marin M, Wallace M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ updated interim recommendation for allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine—United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69:1657-1660.

7. FDA. Fact sheet for healthcare providers administering vaccine. [Pfizer–BioNTech]. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.fda.gov/media/144413/download

8. FDA. Fact sheet for healthcare providers administering vaccine. [Moderna]. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.fda.gov/media/144637/download

9. Mbaeyi SA, Bozio CH, Duffy J, et al. Meningococcal vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1-41.

10. Choi MJ, Cossaboom CM, Whitesell AN, et al. Use of Ebola vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-12.

11. CDC. Ebola background. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2020-02/Ebola-02-Choi-508.pdf

The year 2020 was challenging for public health agencies and especially for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). In a normal year, the ACIP meets in person 3 times for a total of 6 days of deliberations. In 2020, there were 10 meetings (all but 1 using Zoom) covering 14 days. Much of the time was dedicated to the COVID-19 pandemic, the vaccines being developed to prevent COVID-19, and the prioritization of those who should receive the vaccines first.

The ACIP also made recommendations for the use of influenza vaccines in the 2020-2021 season, approved the adult and pediatric immunization schedules for 2021, and approved the use of 2 new vaccines, one to protect against meningococcal meningitis and the other to prevent Ebola virus disease. The influenza recommendations were covered in the October 2020 Practice Alert,1 and the immunization schedules can be found on the CDC website at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html.

COVID-19 vaccines

Two COVID-19 vaccines have been approved for use in the United States. The first was the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on December 11 and recommended for use by the ACIP on December 12.2 The second vaccine, from Moderna, was approved by the FDA on December 18 and recommended by the ACIP on December 19.3 Both were approved by the FDA under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) and were approved by the ACIP for use while the EUA is in effect. Both vaccines must eventually undergo regular approval by the FDA and will be reconsidered by the ACIP regarding use in non–public health emergency conditions. A description of the EUA process and measures taken to assure efficacy and safety, before and after approval, were discussed in the September 2020 audiocast.

Both COVID-19 vaccines consist of nucleoside-modified mRNA encapsulated with lipid nanoparticles, which encode for a spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Both vaccines require 2 doses (separated by 3 weeks for the Pfizer vaccine and 4 weeks for the Moderna vaccine) and are approved for use only in adults and older adolescents (ages ≥ 16 years for the Pfizer vaccine and ≥ 18 years for the Moderna vaccine) (TABLE 12-5).

In anticipation of vaccine shortages immediately after approval for use and a high demand for the vaccine, the ACIP developed a list of high-priority groups who should receive the vaccine in ranked order.6 States are encouraged, but not required, to follow this priority list (TABLE 26).

Caveats with usage. Both COVID-19 vaccines are very reactogenic, causing local and systemic adverse effects that patients should be warned about (TABLE 37,8). These reactions are usually mild to moderate and last 24 hours or less. Acetaminophen can alleviate these symptoms but should not be used to prevent them. In addition, both vaccines have stringent cold-storage requirements; once the vaccines are thawed, they must be used within a defined time-period.

Neither vaccine is listed as preferred. And they are not interchangeable; both recommended doses should be completed with the same vaccine. More details about the use of these vaccines were discussed in the January 2021 audiocast (www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/234239/coronavirus-updates/covid-19-vaccines-rollout-risks-and-reason-still) and can be located on the CDC website (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/pfizer/reactogenicity.html; www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/moderna/reactogenicity.html).

Continue to: Much remains unknown...

Much remains unknown regarding the use of these COVID-19 vaccines:

- What is their duration of protection, and will booster doses be needed?

- Will they protect against asymptomatic infection and carrier states, and thereby prevent transmission?

- Can they be co-administered with other vaccines?

- Will they be efficacious and safe to use during pregnancy and breastfeeding?

These issues will need to be addressed before they are recommended for non–public health emergency use.

Quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY)

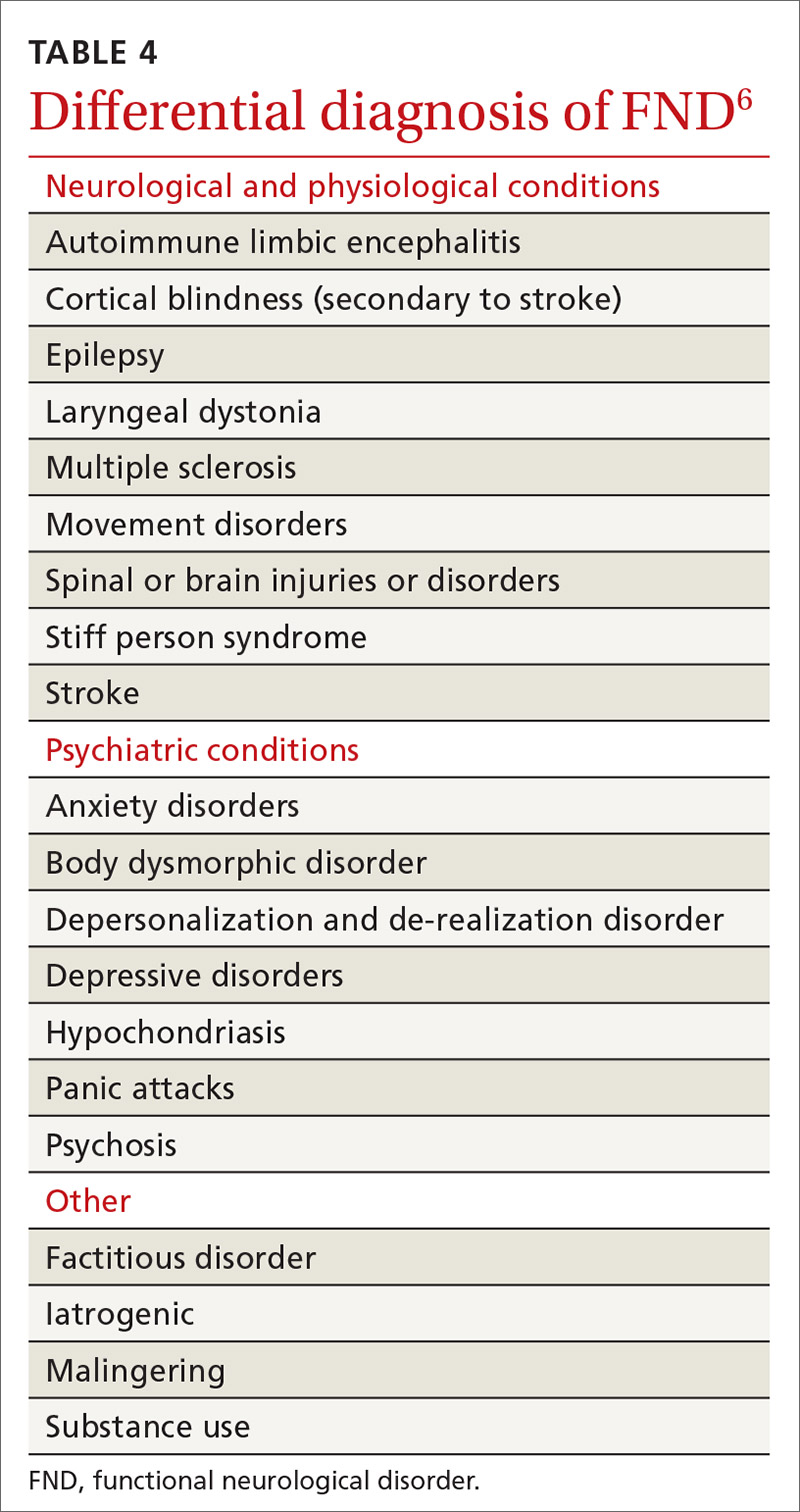

In June 2020, the ACIP added a third quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine to its recommended list of vaccines that are FDA-approved for meningococcal disease (TABLE 49). The new vaccine fills a void left by the meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine (MPSV4), which is no longer marketed in the United States. MPSV4 was previously the only meningococcal vaccine approved for individuals 55 years and older.

The new vaccine, MenACWY-TT (MenQuadfi), is approved for those ages 2 years and older, including those > 55 years. It is anticipated that MenQuadfi will, in the near future, be licensed and approved for individuals 6 months and older and will replace MenACWY-D (Menactra). (Both are manufactured by Sanofi Pasteur.)

Groups for whom a MenACWY vaccine is recommended are listed in TABLE 5.9 A full description of current, updated recommendations for the prevention of meningococcal disease is also available.9

Continue to: Ebola virus (EBOV) vaccine

Ebola virus (EBOV) vaccine

A vaccine to prevent Ebola virus disease (EVD) is available by special request in the United States. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus-based Ebola virus vaccine, abbreviated as rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (brand name, ERVBO) is manufactured by Merck and received approval by the FDA on December 19, 2019, for use in those ages 18 years and older. It is a live, attenuated vaccine.

The ACIP has recommended pre-exposure vaccination with rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP for adults 18 years or older who are at risk of exposure to EBOV while responding to an outbreak of EVD; while working as health care personnel at a federally designated Ebola Treatment Center; or while working at biosafety-level 4 facilities.10 The vaccine is protective against just 1 of 4 EBOV species, Zaire ebolavirus, which has been the cause of most reported EVD outbreaks, including the 2 largest EVD outbreaks in history that occurred in West Africa and the Republic of Congo.

It is estimated that EBOV outbreaks have infected more than 31,000 people and resulted in more than 12,000 deaths worldwide.11 Only 11 people infected with EBOV have been treated in the United States, all related to the 2014-2016 large outbreaks in West Africa. Nine of these cases were imported and only 1 resulted in transmission, to 2 people.10 The mammalian species that are suspected as intermediate hosts for EBOV are not present in the United States, which prevents EBOV from becoming endemic here.

The rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine was tested in a large trial in Africa during the 2014 outbreak. Its effectiveness was 100% (95% confidence interval, 63.5%-100%). The most common adverse effects were injection site pain, swelling, and redness. Mild-to-moderate systemic symptoms can occur within the first 2 days following vaccination, and include headache (37%), fever (34%), muscle pain (33%), fatigue (19%), joint pain (18%), nausea (8%), arthritis (5%), rash (4%), and

Since the vaccine contains a live virus that causes stomatitis in animals, it is possible that the virus could be transmitted to humans and other animals through close contact. Accordingly, the CDC has published some precautions including, but not limited to, not donating blood and, for 6 weeks after vaccination, avoiding contact with those who are immunosuppressed.10 The vaccine is not commercially available in the United States and must be obtained from the CDC. Information on requesting the vaccine is available at www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/clinicians/vaccine/.

The year 2020 was challenging for public health agencies and especially for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). In a normal year, the ACIP meets in person 3 times for a total of 6 days of deliberations. In 2020, there were 10 meetings (all but 1 using Zoom) covering 14 days. Much of the time was dedicated to the COVID-19 pandemic, the vaccines being developed to prevent COVID-19, and the prioritization of those who should receive the vaccines first.

The ACIP also made recommendations for the use of influenza vaccines in the 2020-2021 season, approved the adult and pediatric immunization schedules for 2021, and approved the use of 2 new vaccines, one to protect against meningococcal meningitis and the other to prevent Ebola virus disease. The influenza recommendations were covered in the October 2020 Practice Alert,1 and the immunization schedules can be found on the CDC website at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html.

COVID-19 vaccines

Two COVID-19 vaccines have been approved for use in the United States. The first was the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on December 11 and recommended for use by the ACIP on December 12.2 The second vaccine, from Moderna, was approved by the FDA on December 18 and recommended by the ACIP on December 19.3 Both were approved by the FDA under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) and were approved by the ACIP for use while the EUA is in effect. Both vaccines must eventually undergo regular approval by the FDA and will be reconsidered by the ACIP regarding use in non–public health emergency conditions. A description of the EUA process and measures taken to assure efficacy and safety, before and after approval, were discussed in the September 2020 audiocast.

Both COVID-19 vaccines consist of nucleoside-modified mRNA encapsulated with lipid nanoparticles, which encode for a spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Both vaccines require 2 doses (separated by 3 weeks for the Pfizer vaccine and 4 weeks for the Moderna vaccine) and are approved for use only in adults and older adolescents (ages ≥ 16 years for the Pfizer vaccine and ≥ 18 years for the Moderna vaccine) (TABLE 12-5).

In anticipation of vaccine shortages immediately after approval for use and a high demand for the vaccine, the ACIP developed a list of high-priority groups who should receive the vaccine in ranked order.6 States are encouraged, but not required, to follow this priority list (TABLE 26).

Caveats with usage. Both COVID-19 vaccines are very reactogenic, causing local and systemic adverse effects that patients should be warned about (TABLE 37,8). These reactions are usually mild to moderate and last 24 hours or less. Acetaminophen can alleviate these symptoms but should not be used to prevent them. In addition, both vaccines have stringent cold-storage requirements; once the vaccines are thawed, they must be used within a defined time-period.

Neither vaccine is listed as preferred. And they are not interchangeable; both recommended doses should be completed with the same vaccine. More details about the use of these vaccines were discussed in the January 2021 audiocast (www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/234239/coronavirus-updates/covid-19-vaccines-rollout-risks-and-reason-still) and can be located on the CDC website (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/pfizer/reactogenicity.html; www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/moderna/reactogenicity.html).

Continue to: Much remains unknown...

Much remains unknown regarding the use of these COVID-19 vaccines:

- What is their duration of protection, and will booster doses be needed?

- Will they protect against asymptomatic infection and carrier states, and thereby prevent transmission?

- Can they be co-administered with other vaccines?

- Will they be efficacious and safe to use during pregnancy and breastfeeding?

These issues will need to be addressed before they are recommended for non–public health emergency use.

Quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY)

In June 2020, the ACIP added a third quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate vaccine to its recommended list of vaccines that are FDA-approved for meningococcal disease (TABLE 49). The new vaccine fills a void left by the meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine (MPSV4), which is no longer marketed in the United States. MPSV4 was previously the only meningococcal vaccine approved for individuals 55 years and older.

The new vaccine, MenACWY-TT (MenQuadfi), is approved for those ages 2 years and older, including those > 55 years. It is anticipated that MenQuadfi will, in the near future, be licensed and approved for individuals 6 months and older and will replace MenACWY-D (Menactra). (Both are manufactured by Sanofi Pasteur.)

Groups for whom a MenACWY vaccine is recommended are listed in TABLE 5.9 A full description of current, updated recommendations for the prevention of meningococcal disease is also available.9

Continue to: Ebola virus (EBOV) vaccine

Ebola virus (EBOV) vaccine

A vaccine to prevent Ebola virus disease (EVD) is available by special request in the United States. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus-based Ebola virus vaccine, abbreviated as rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (brand name, ERVBO) is manufactured by Merck and received approval by the FDA on December 19, 2019, for use in those ages 18 years and older. It is a live, attenuated vaccine.

The ACIP has recommended pre-exposure vaccination with rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP for adults 18 years or older who are at risk of exposure to EBOV while responding to an outbreak of EVD; while working as health care personnel at a federally designated Ebola Treatment Center; or while working at biosafety-level 4 facilities.10 The vaccine is protective against just 1 of 4 EBOV species, Zaire ebolavirus, which has been the cause of most reported EVD outbreaks, including the 2 largest EVD outbreaks in history that occurred in West Africa and the Republic of Congo.

It is estimated that EBOV outbreaks have infected more than 31,000 people and resulted in more than 12,000 deaths worldwide.11 Only 11 people infected with EBOV have been treated in the United States, all related to the 2014-2016 large outbreaks in West Africa. Nine of these cases were imported and only 1 resulted in transmission, to 2 people.10 The mammalian species that are suspected as intermediate hosts for EBOV are not present in the United States, which prevents EBOV from becoming endemic here.

The rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine was tested in a large trial in Africa during the 2014 outbreak. Its effectiveness was 100% (95% confidence interval, 63.5%-100%). The most common adverse effects were injection site pain, swelling, and redness. Mild-to-moderate systemic symptoms can occur within the first 2 days following vaccination, and include headache (37%), fever (34%), muscle pain (33%), fatigue (19%), joint pain (18%), nausea (8%), arthritis (5%), rash (4%), and

Since the vaccine contains a live virus that causes stomatitis in animals, it is possible that the virus could be transmitted to humans and other animals through close contact. Accordingly, the CDC has published some precautions including, but not limited to, not donating blood and, for 6 weeks after vaccination, avoiding contact with those who are immunosuppressed.10 The vaccine is not commercially available in the United States and must be obtained from the CDC. Information on requesting the vaccine is available at www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/clinicians/vaccine/.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Prospects and challenges for the upcoming influenza season. J Fam Pract 2020;69:406-411.

2. Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for use of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine-United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1922-1924.

3. Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for use of Moderna COVID-19 vaccine-United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69:1653-1656.

4. CDC. Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/pfizer/index.html

5. CDC. Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/moderna/index.html#:~:text=How%20to%20Store%20the%20Moderna%20COVID%2D19%20Vaccine&text=Vaccine%20may%20be%20stored%20in,for%20this%20vaccine%20is%20tighter

6. Dooling K, Marin M, Wallace M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ updated interim recommendation for allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine—United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69:1657-1660.

7. FDA. Fact sheet for healthcare providers administering vaccine. [Pfizer–BioNTech]. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.fda.gov/media/144413/download

8. FDA. Fact sheet for healthcare providers administering vaccine. [Moderna]. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.fda.gov/media/144637/download

9. Mbaeyi SA, Bozio CH, Duffy J, et al. Meningococcal vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1-41.

10. Choi MJ, Cossaboom CM, Whitesell AN, et al. Use of Ebola vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-12.

11. CDC. Ebola background. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2020-02/Ebola-02-Choi-508.pdf

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Prospects and challenges for the upcoming influenza season. J Fam Pract 2020;69:406-411.

2. Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for use of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine-United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1922-1924.

3. Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for use of Moderna COVID-19 vaccine-United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69:1653-1656.

4. CDC. Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/pfizer/index.html

5. CDC. Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/moderna/index.html#:~:text=How%20to%20Store%20the%20Moderna%20COVID%2D19%20Vaccine&text=Vaccine%20may%20be%20stored%20in,for%20this%20vaccine%20is%20tighter

6. Dooling K, Marin M, Wallace M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ updated interim recommendation for allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine—United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69:1657-1660.

7. FDA. Fact sheet for healthcare providers administering vaccine. [Pfizer–BioNTech]. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.fda.gov/media/144413/download

8. FDA. Fact sheet for healthcare providers administering vaccine. [Moderna]. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.fda.gov/media/144637/download

9. Mbaeyi SA, Bozio CH, Duffy J, et al. Meningococcal vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1-41.

10. Choi MJ, Cossaboom CM, Whitesell AN, et al. Use of Ebola vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:1-12.

11. CDC. Ebola background. Accessed February 17, 2021. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2020-02/Ebola-02-Choi-508.pdf

AT PRESS TIME

The US Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization for a third COVID-19 vaccine. The single-dose vaccine was developed by the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson. For more information, go to www.mdedge.com/familymedicine

Conservative or surgical management for that shoulder dislocation?

The shoulder, or glenohumeral joint, is the most commonly dislocated large joint; dislocation occurs at a rate of 23.9 per 100,000 person/years.1,2 There are 2 types of dislocation: traumatic anterior dislocation, which accounts for roughly 90% of dislocations, and posterior dislocation (10%).3 Anterior dislocation typically occurs when the patient’s shoulder is forcefully abducted and externally rotated.

The diagnosis is made after review of the history and mechanism of injury and performance of a complete physical exam with imaging studies—the most critical component of diagnosis.4 Standard radiographs (anteroposterior, axillary, and scapular Y) can confirm the presence of a dislocation; once the diagnosis is confirmed, closed reduction of the joint should be performed.1 (Methods of reduction are beyond the scope of this article but have been recently reviewed.5)

Risk for recurrence drives management choices

Following an initial shoulder dislocation, the risk of recurrence is high.6,7 Rates vary based on age, pathology after dislocation, activity level, type of immobilization, and whether surgery was performed. Overall, age is the strongest predictor of recurrence: 72% of patients ages 12 to 22 years, 56% of those ages 23 to 29 years, and 27% of those older than 30 years experience recurrence.6 Patients who have recurrent dislocations are at risk for arthropathy, fear of instability, and worsening surgical outcomes.6

Reducing the risk of a recurrent shoulder dislocation has been the focus of intense study. Proponents of surgical stabilization argue that surgery—rather than a trial of conservative treatment—is best when you consider the high risk of recurrence in young athletes (the population primarily studied), the soft-tissue and bony damage caused by recurrent instability, and the predictable improvement in quality of life following surgery.

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, there was evidence that, for first-time traumatic shoulder dislocations, early surgery led to fewer repeat shoulder dislocations (number needed to treat [NNT] = 2-4.7). However, a significant number of patients primarily treated nonoperatively did not experience a repeat shoulder dislocation within 2 years.2

The conflicting results from randomized trials comparing operative intervention to conservative management have led surgeons and physicians in other specialties to take different approaches to the management of shoulder dislocation.2 In this review, we aim to summarize considerations for conservative vs surgical management and provide clinical guidance for primary care physicians.

When to try conservative management

Although the initial treatment after a traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation has been debated, a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed that at least half of first-time dislocations are successfully treated with conservative management.2 Management can include immobilization for comfort and/or physical therapy. Age will play a role, as mentioned earlier; in general, patients older than 30 have a significant decrease in recurrence rate and are good candidates for conservative therapy.6 It should be noted that much of the research with regard to management of shoulder dislocations has been done in an athletic population.

Continue to: Immobilization may benefit some

Immobilization may benefit some

Recent evidence has determined that the duration of immobilization in internal rotation does not impact recurrent instability.8,9 In patients older than 30, the rate of repeat dislocation is lower, and early mobilization after 1 week is advocated to avoid joint stiffness and minimize the risk of adhesive capsulitis.10

Arm position during immobilization remains controversial.11 In a classic study by Itoi et al, immobilization for 3 weeks in internal rotation vs 10° of external rotation was associated with a recurrence rate of 42% vs 26%, respectively.12 In this study, immobilization in 10° of external rotation was especially beneficial for patients ages 30 years or younger.12

Cadaveric and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have shown external rotation may improve the odds of labral tear healing by positioning the damaged and intact parts of the glenoid labrum in closer proximity.13 While this is theoretically plausible, a recent Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to determine whether immobilization in external rotation has any benefits beyond those offered by internal rotation.14 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that immobilization in external rotation vs internal rotation after a first-time traumatic shoulder dislocation did not change outcomes.2 With that said, most would prefer to immobilize in the internal rotation position for ease.

More research is needed. A Cochrane review highlighted the need for continued research.14 Additionally, most of the available randomized controlled trials to date have consisted of young men, with the majority of dislocations related to sports activities. Women, nonathletes, and older patients have been understudied to date; extrapolating current research to those groups of patients may not be appropriate and should be a focus for future research.2

Physical therapy: The conservative standard of care

Rehabilitation after glenohumeral joint dislocation is the current standard of care in conservative management to reduce the risk for repeat dislocation.15 Depending on the specific characteristics of the instability pattern, the approach may be adapted to the patient. A recent review focused on the following 4 key points: (1) restoration of rotator cuff strength, focusing on the eccentric capacity of the external rotators, (2) normalization of rotational range of motion with particular focus on internal range of motion, (3) optimization of the flexibility and muscle performance of the scapular muscles, and (4) increasing the functional sport-specific load on the shoulder girdle.

Continue to: A common approach to the care of...

A common approach to the care of a patient after a glenohumeral joint dislocation is to place the patient’s shoulder in a sling for comfort, with permitted pain-free isometric exercise along with passive and assisted elevation up to 100°.16 This is followed by a nonaggressive rehabilitation protocol for 2 months until full recovery, which includes progressive range of motion, strength, proprioception, and return to functional activities.16

More aggressive return-to-play protocols with accelerated timelines and functional progression have been studied, including in a multicenter observational study that followed 45 contact intercollegiate athletes prospectively after in-season anterior glenohumeral instability. Thirty-three of 45 (73%) athletes returned to sport for either all or part of the season after a median 5 days lost from competition, with 12 athletes (27%) successfully completing the season without recurrence. Athletes with a subluxation event were 5.3 times more likely to return to sport during the same season, compared with those with dislocations.17

Dynamic bracing may also allow for a safe and quicker return to sport in athletes18 but recently was shown to not impact recurrent dislocation risk.19

Return to play should be based on subjective assessment as well as objective measurements of range of motion, strength, and dynamic function.15 Patients who continue to have significant weakness and pain at 2 to 3 weeks post injury despite physical therapy should be re-evaluated with an MRI for concomitant rotator cuff tears and need for surgical referral.20

When to consider surgical intervention

In a recent meta-analysis, recurrent dislocation and instability occurred at a rate of 52.9% following nonsurgical treatment.2 The decision to perform surgical intervention is typically made following failure of conservative management. Other considerations include age, gender, bone loss, and cartilage defect.21,22 Age younger than 30 years, participation in competition, contact sports, and male gender have been associated with an increased risk of recurrence.23-25 For this reason, obtaining an MRI at time of first dislocation can help facilitate surgical decisions if the patient is at high risk for surgical need.26

Continue to: An increasing number...

An increasing number of dislocations portends a poor outcome with nonoperative treatment. Kao et al demonstrated a second dislocation leads to another dislocation in 19.6% of cases, while 44.3% of those with a third dislocation event will sustain another dislocation.24 Surgery should be considered for patients with recurrent instability events to prevent persistent instability and decrease the amount of bone loss that can occur with repetitive dislocations.

What are the surgical options?

Several surgical options exist to remedy the unstable shoulder. Procedures can range from an arthroscopic repair to an open stabilization combined with structural bone graft to replace a bone defect caused by repetitive dislocations.

Arthroscopic techniques have become the mainstay of treatment and account for 71% of stabilization procedures performed.21 These techniques cause less pain in the early postoperative period and provide for a faster return to work.27 Arthroscopy has the additional advantage of allowing for complete visualization of the glenohumeral joint to identify and address concomitant pathology, such as intra-articular loose bodies or rotator cuff tears.

Open repair was the mainstay of treatment prior to development of arthroscopic techniques. Some surgeons still prefer this method—especially in high-risk groups—because of a lower risk of recurrent disloca-tion.28 Open techniques often involve detachment and repair of the upper subscapularis tendon and are more likely to produce long-term losses in external rotation range of motion.28

Which one is appropriate for your patient? The decision to pursue an open or arthroscopic procedure and to augment with bone graft depends on the amount of glenoid and humeral head bone loss, patient activity level, risk of recurrent dislocation, and surgeon preference.

Continue to: For the nonathletic population...

For the nonathletic population, the timing of injury is less critical and surgery is typically recommended after conservative treatment has failed. In an athletic population, the timing of injury is a necessary consideration. An injury midseason may be “rehabbed” in hopes of returning to play. Individuals with injuries occurring at the end of a season, who are unable to regain desired function, and/or with peri-articular fractures or associated full-thickness rotator cuff tears may benefit from sooner surgical intervention.21

Owens et al have described appropriate surgical indications and recommendations for an in-season athlete.21 In this particular algorithm, the authors suggest obtaining an MRI for decision making, but this is specific to in-season athletes wishing to return to play. In general, an MRI is not always indicated for patients who wish to receive conservative therapy but would be indicated for surgical considerations. The algorithm otherwise uses bone and soft-tissue injury, recurrent instability, and timing in the season to help determine management.21

Outcomes: Surgery has advantages …

Recurrence rates following surgical intervention are considerably lower than with conservative management, especially among young, active individuals. A recent systematic review by Donohue et al demonstrated recurrent instability rates following surgical intervention as low as 2.4%.29 One study comparing the outcome of arthroscopic repair vs conservative management showed that the risk of postoperative instability was reduced by 20% compared to other treatments.7 Furthermore, early surgical fixation can improve quality of life, produce better functional outcomes, decrease time away from activity, increase patient satisfaction, and slow the development of glenohumeral osteoarthritis produced from recurrent instability.2,7

Complications. Surgery does carry inherent risks of infection, anesthesia effects, surgical complications, and surgical failure. Recurrent instability is the most common complication following surgical shoulder stabilization. Rates of recurrent instability after surgical stabilization depend on patient age, activity level, and amount of bone loss: males younger than 18 years who participate in contact competitive sports and have significant bone loss are more likely to have recurrent dislocation after surgery.23 The type of surgical procedure selected may decrease this risk.

While the open procedures decrease risk of postoperative instability, these surgeries can pose a significant risk of complications. Major complications for specific open techniques have been reported in up to 30% of patients30 and are associated with lower levels of surgeon experience.31 While the healing of bones and ligaments is always a concern, 1 of the most feared complications following stabilization surgery is iatrogenic nerve injury. Because of the axillary nerve’s close proximity to the inferior glenoid, this nerve can be injured without meticulous care and can result in paralysis of the deltoid muscle. This injury poses a major impediment to normal shoulder function. Some procedures may cause nerve injuries in up to 10% of patients, although most injuries are transient.32

Continue to: Bottom line

Bottom line

Due to the void of evidence-based guidelines for conservative vs surgical management of primary shoulder dislocation, it would be prudent to have a risk-benefit discussion with patients regarding treatment options.

Patients older than 30 years and those with uncomplicated injuries are best suited for conservative management of primary shoulder dislocations. Immobilization is debated and may not change outcomes, but a progressive rehabilitative program after the initial acute injury is helpful. Risk factors for failing conservative management include recurrent dislocation, subsequent arthropathy, and additional concomitant bone or soft-tissue injuries.

Patients younger than 30 years who have complicated injuries with bone or cartilage loss, rotator cuff tears, or recurrent instability, and highly physically active individuals are best suited for surgical management. Shoulder arthroscopy has become the mainstay of surgical treatment for shoulder dislocations. Outcomes are favorable and dislocation recurrence is low after surgical repair. Surgery does carry its own inherent risks of infection, anesthesia effects, complications during surgery, and surgical failure leading to recurrent instability.

Cayce Onks, DO, MS, ATC, Penn State Hershey, Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Penn State College of Medicine, Family and Community Medicine H154, 500 University Drive, PO Box 850, Hershey, PA 17033-0850; [email protected]

1. Lin K, James E, Spitzer E, et al. Pediatric and adolescent anterior shoulder instability: clinical management of first time dislocators. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2018;30:49-56.

2. Kavaja L, Lähdeoja T, Malmivaara A, et al. Treatment after traumatic shoulder dislocation: a systematic review with a network meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:1498-1506.

3. Brelin A, Dickens JF. Posterior shoulder instability. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2017;25:136-143.

4. Galvin JW, Ernat JJ, Waterman BR, et al. The epidemiology and natural history of anterior shoulder dislocation. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10:411-424.

5. Rozzi SL, Anderson JM, Doberstein ST, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: immediate management of appendicular joint dislocations. J Athl Train. 2018;53:1117-1128.

6. Hovelius L, Saeboe M. Arthropathy after primary anterior shoulder dislocation: 223 shoulders prospectively followed up for twenty-five years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:339-347.

7. Polyzois I, Dattani R, Gupta R, et al. Traumatic first time shoulder dislocation: surgery vs non-operative treatment. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2016;4:104-108.

8. Cox CL, Kuhn JE. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of acute shoulder dislocation in the athlete. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2008;7:263-268.

9. Kuhn JE. Treating the initial anterior shoulder dislocation—an evidence-based medicine approach. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2006;14:192-198.

10. Smith TO. Immobilization following traumatic anterior glenohumeral joint dislocation: a literature review. Injury. 2006;37:228-237.

11. Liavaag S, Brox JI, Pripp AH, et al. Immobilization in external rotation after primary shoulder dislocation did not reduce the risk of recurrence: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:897-904.

12. Itoi E, Hatakeyama Y, Sato T, et al. Immobilization in external rotation after shoulder dislocation reduces the risk of recurrence: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2124-2131.

13. Miller BS, Sonnabend DH, Hatrick C, et al. Should acute anterior dislocations of the shoulder be immobilized in external rotation? A cadaveric study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:589-592.

14. Hanchard NCA, Goodchild LM, Kottam L. Conservative management following closed reduction of traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD004962.

15. Cools AM, Borms D, Castelein B, et al. Evidence-based rehabilitation of athletes with glenohumeral instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:382-389.

16. Lafuente JLA, Marco SM, Pequerul JMG. Controversies in the management of the first time shoulder dislocation. Open Orthop J. 2017;11:1001-1010.

17. Dickens JF, Owens BD, Cameron KL, et al. Return to play and recurrent instability after in-season anterior shoulder instability: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2842-2850.

18. Conti M, Garofalo R, Castagna A, et al. Dynamic brace is a good option to treat first anterior shoulder dislocation in season. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017;101(suppl 2):169-173.

19. Shanley E, Thigpen C, Brooks J, et al. Return to sport as an outcome measure for shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:1062-1067.

20. Gombera MM, Sekiya JK. Rotator cuff tear and glenohumeral instability. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2448-2456.

21. Owens BD, Dickens JF, Kilcoyne KG, et al. Management of mid-season traumatic anterior shoulder instability in athletes. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:518-526.

22. Ozturk BY, Maak TG, Fabricant P, et al. Return to sports after arthroscopic anterior stabilization in patients aged younger than 25 years. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:1922-1931.

23. Balg F, Boileau P. The instability severity index score. A simple preoperative score to select patients for arthroscopic or open shoulder stabilisation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1470-1477.

24. Kao J-T, Chang C-L, Su W-R, et al. Incidence of recurrence after shoulder dislocation: a nationwide database study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:1519-1525.

25. Porcillini G, Campi F, Pegreffi F, et al. Predisposing factors for recurrent shoulder dislocation after arthroscopic treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2537-2542.

26. Magee T. 3T MRI of the shoulder: is MR arthrography necessary? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:86-92.

27. Green MR, Christensen KP. Arthroscopic versus open Bankart procedures: a comparison of early morbidity and complications. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:371-374.

28. Khatri K, Arora H, Chaudhary S, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials involving anterior shoulder instability. Open Orthop J. 2018;12:411-418.

29. Donohue MA, Owens BD, Dickens JF. Return to play following anterior shoulder dislocations and stabilization surgery. Clin Sports Med. 2016;35:545-561.

30. Griesser MJ, Harris JD, McCoy BW, et al. Complications and re-operations after Bristow-Latarjet shoulder stabilization: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:286-292.

31. Ekhtiari S, Horner NS, Bedi A, et al. The learning curve for the Latarjet procedure: a systematic review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6:2325967118786930.

32. Shah AA, Butler RB, Romanowski J, et al. Short-term complications of the Latarjet procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:495-501.

The shoulder, or glenohumeral joint, is the most commonly dislocated large joint; dislocation occurs at a rate of 23.9 per 100,000 person/years.1,2 There are 2 types of dislocation: traumatic anterior dislocation, which accounts for roughly 90% of dislocations, and posterior dislocation (10%).3 Anterior dislocation typically occurs when the patient’s shoulder is forcefully abducted and externally rotated.

The diagnosis is made after review of the history and mechanism of injury and performance of a complete physical exam with imaging studies—the most critical component of diagnosis.4 Standard radiographs (anteroposterior, axillary, and scapular Y) can confirm the presence of a dislocation; once the diagnosis is confirmed, closed reduction of the joint should be performed.1 (Methods of reduction are beyond the scope of this article but have been recently reviewed.5)

Risk for recurrence drives management choices

Following an initial shoulder dislocation, the risk of recurrence is high.6,7 Rates vary based on age, pathology after dislocation, activity level, type of immobilization, and whether surgery was performed. Overall, age is the strongest predictor of recurrence: 72% of patients ages 12 to 22 years, 56% of those ages 23 to 29 years, and 27% of those older than 30 years experience recurrence.6 Patients who have recurrent dislocations are at risk for arthropathy, fear of instability, and worsening surgical outcomes.6

Reducing the risk of a recurrent shoulder dislocation has been the focus of intense study. Proponents of surgical stabilization argue that surgery—rather than a trial of conservative treatment—is best when you consider the high risk of recurrence in young athletes (the population primarily studied), the soft-tissue and bony damage caused by recurrent instability, and the predictable improvement in quality of life following surgery.

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, there was evidence that, for first-time traumatic shoulder dislocations, early surgery led to fewer repeat shoulder dislocations (number needed to treat [NNT] = 2-4.7). However, a significant number of patients primarily treated nonoperatively did not experience a repeat shoulder dislocation within 2 years.2

The conflicting results from randomized trials comparing operative intervention to conservative management have led surgeons and physicians in other specialties to take different approaches to the management of shoulder dislocation.2 In this review, we aim to summarize considerations for conservative vs surgical management and provide clinical guidance for primary care physicians.

When to try conservative management

Although the initial treatment after a traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation has been debated, a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed that at least half of first-time dislocations are successfully treated with conservative management.2 Management can include immobilization for comfort and/or physical therapy. Age will play a role, as mentioned earlier; in general, patients older than 30 have a significant decrease in recurrence rate and are good candidates for conservative therapy.6 It should be noted that much of the research with regard to management of shoulder dislocations has been done in an athletic population.

Continue to: Immobilization may benefit some

Immobilization may benefit some

Recent evidence has determined that the duration of immobilization in internal rotation does not impact recurrent instability.8,9 In patients older than 30, the rate of repeat dislocation is lower, and early mobilization after 1 week is advocated to avoid joint stiffness and minimize the risk of adhesive capsulitis.10

Arm position during immobilization remains controversial.11 In a classic study by Itoi et al, immobilization for 3 weeks in internal rotation vs 10° of external rotation was associated with a recurrence rate of 42% vs 26%, respectively.12 In this study, immobilization in 10° of external rotation was especially beneficial for patients ages 30 years or younger.12

Cadaveric and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have shown external rotation may improve the odds of labral tear healing by positioning the damaged and intact parts of the glenoid labrum in closer proximity.13 While this is theoretically plausible, a recent Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to determine whether immobilization in external rotation has any benefits beyond those offered by internal rotation.14 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that immobilization in external rotation vs internal rotation after a first-time traumatic shoulder dislocation did not change outcomes.2 With that said, most would prefer to immobilize in the internal rotation position for ease.

More research is needed. A Cochrane review highlighted the need for continued research.14 Additionally, most of the available randomized controlled trials to date have consisted of young men, with the majority of dislocations related to sports activities. Women, nonathletes, and older patients have been understudied to date; extrapolating current research to those groups of patients may not be appropriate and should be a focus for future research.2

Physical therapy: The conservative standard of care

Rehabilitation after glenohumeral joint dislocation is the current standard of care in conservative management to reduce the risk for repeat dislocation.15 Depending on the specific characteristics of the instability pattern, the approach may be adapted to the patient. A recent review focused on the following 4 key points: (1) restoration of rotator cuff strength, focusing on the eccentric capacity of the external rotators, (2) normalization of rotational range of motion with particular focus on internal range of motion, (3) optimization of the flexibility and muscle performance of the scapular muscles, and (4) increasing the functional sport-specific load on the shoulder girdle.

Continue to: A common approach to the care of...

A common approach to the care of a patient after a glenohumeral joint dislocation is to place the patient’s shoulder in a sling for comfort, with permitted pain-free isometric exercise along with passive and assisted elevation up to 100°.16 This is followed by a nonaggressive rehabilitation protocol for 2 months until full recovery, which includes progressive range of motion, strength, proprioception, and return to functional activities.16

More aggressive return-to-play protocols with accelerated timelines and functional progression have been studied, including in a multicenter observational study that followed 45 contact intercollegiate athletes prospectively after in-season anterior glenohumeral instability. Thirty-three of 45 (73%) athletes returned to sport for either all or part of the season after a median 5 days lost from competition, with 12 athletes (27%) successfully completing the season without recurrence. Athletes with a subluxation event were 5.3 times more likely to return to sport during the same season, compared with those with dislocations.17

Dynamic bracing may also allow for a safe and quicker return to sport in athletes18 but recently was shown to not impact recurrent dislocation risk.19

Return to play should be based on subjective assessment as well as objective measurements of range of motion, strength, and dynamic function.15 Patients who continue to have significant weakness and pain at 2 to 3 weeks post injury despite physical therapy should be re-evaluated with an MRI for concomitant rotator cuff tears and need for surgical referral.20

When to consider surgical intervention

In a recent meta-analysis, recurrent dislocation and instability occurred at a rate of 52.9% following nonsurgical treatment.2 The decision to perform surgical intervention is typically made following failure of conservative management. Other considerations include age, gender, bone loss, and cartilage defect.21,22 Age younger than 30 years, participation in competition, contact sports, and male gender have been associated with an increased risk of recurrence.23-25 For this reason, obtaining an MRI at time of first dislocation can help facilitate surgical decisions if the patient is at high risk for surgical need.26

Continue to: An increasing number...

An increasing number of dislocations portends a poor outcome with nonoperative treatment. Kao et al demonstrated a second dislocation leads to another dislocation in 19.6% of cases, while 44.3% of those with a third dislocation event will sustain another dislocation.24 Surgery should be considered for patients with recurrent instability events to prevent persistent instability and decrease the amount of bone loss that can occur with repetitive dislocations.

What are the surgical options?

Several surgical options exist to remedy the unstable shoulder. Procedures can range from an arthroscopic repair to an open stabilization combined with structural bone graft to replace a bone defect caused by repetitive dislocations.

Arthroscopic techniques have become the mainstay of treatment and account for 71% of stabilization procedures performed.21 These techniques cause less pain in the early postoperative period and provide for a faster return to work.27 Arthroscopy has the additional advantage of allowing for complete visualization of the glenohumeral joint to identify and address concomitant pathology, such as intra-articular loose bodies or rotator cuff tears.

Open repair was the mainstay of treatment prior to development of arthroscopic techniques. Some surgeons still prefer this method—especially in high-risk groups—because of a lower risk of recurrent disloca-tion.28 Open techniques often involve detachment and repair of the upper subscapularis tendon and are more likely to produce long-term losses in external rotation range of motion.28

Which one is appropriate for your patient? The decision to pursue an open or arthroscopic procedure and to augment with bone graft depends on the amount of glenoid and humeral head bone loss, patient activity level, risk of recurrent dislocation, and surgeon preference.

Continue to: For the nonathletic population...

For the nonathletic population, the timing of injury is less critical and surgery is typically recommended after conservative treatment has failed. In an athletic population, the timing of injury is a necessary consideration. An injury midseason may be “rehabbed” in hopes of returning to play. Individuals with injuries occurring at the end of a season, who are unable to regain desired function, and/or with peri-articular fractures or associated full-thickness rotator cuff tears may benefit from sooner surgical intervention.21

Owens et al have described appropriate surgical indications and recommendations for an in-season athlete.21 In this particular algorithm, the authors suggest obtaining an MRI for decision making, but this is specific to in-season athletes wishing to return to play. In general, an MRI is not always indicated for patients who wish to receive conservative therapy but would be indicated for surgical considerations. The algorithm otherwise uses bone and soft-tissue injury, recurrent instability, and timing in the season to help determine management.21

Outcomes: Surgery has advantages …

Recurrence rates following surgical intervention are considerably lower than with conservative management, especially among young, active individuals. A recent systematic review by Donohue et al demonstrated recurrent instability rates following surgical intervention as low as 2.4%.29 One study comparing the outcome of arthroscopic repair vs conservative management showed that the risk of postoperative instability was reduced by 20% compared to other treatments.7 Furthermore, early surgical fixation can improve quality of life, produce better functional outcomes, decrease time away from activity, increase patient satisfaction, and slow the development of glenohumeral osteoarthritis produced from recurrent instability.2,7

Complications. Surgery does carry inherent risks of infection, anesthesia effects, surgical complications, and surgical failure. Recurrent instability is the most common complication following surgical shoulder stabilization. Rates of recurrent instability after surgical stabilization depend on patient age, activity level, and amount of bone loss: males younger than 18 years who participate in contact competitive sports and have significant bone loss are more likely to have recurrent dislocation after surgery.23 The type of surgical procedure selected may decrease this risk.

While the open procedures decrease risk of postoperative instability, these surgeries can pose a significant risk of complications. Major complications for specific open techniques have been reported in up to 30% of patients30 and are associated with lower levels of surgeon experience.31 While the healing of bones and ligaments is always a concern, 1 of the most feared complications following stabilization surgery is iatrogenic nerve injury. Because of the axillary nerve’s close proximity to the inferior glenoid, this nerve can be injured without meticulous care and can result in paralysis of the deltoid muscle. This injury poses a major impediment to normal shoulder function. Some procedures may cause nerve injuries in up to 10% of patients, although most injuries are transient.32

Continue to: Bottom line

Bottom line

Due to the void of evidence-based guidelines for conservative vs surgical management of primary shoulder dislocation, it would be prudent to have a risk-benefit discussion with patients regarding treatment options.

Patients older than 30 years and those with uncomplicated injuries are best suited for conservative management of primary shoulder dislocations. Immobilization is debated and may not change outcomes, but a progressive rehabilitative program after the initial acute injury is helpful. Risk factors for failing conservative management include recurrent dislocation, subsequent arthropathy, and additional concomitant bone or soft-tissue injuries.

Patients younger than 30 years who have complicated injuries with bone or cartilage loss, rotator cuff tears, or recurrent instability, and highly physically active individuals are best suited for surgical management. Shoulder arthroscopy has become the mainstay of surgical treatment for shoulder dislocations. Outcomes are favorable and dislocation recurrence is low after surgical repair. Surgery does carry its own inherent risks of infection, anesthesia effects, complications during surgery, and surgical failure leading to recurrent instability.

Cayce Onks, DO, MS, ATC, Penn State Hershey, Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Penn State College of Medicine, Family and Community Medicine H154, 500 University Drive, PO Box 850, Hershey, PA 17033-0850; [email protected]

The shoulder, or glenohumeral joint, is the most commonly dislocated large joint; dislocation occurs at a rate of 23.9 per 100,000 person/years.1,2 There are 2 types of dislocation: traumatic anterior dislocation, which accounts for roughly 90% of dislocations, and posterior dislocation (10%).3 Anterior dislocation typically occurs when the patient’s shoulder is forcefully abducted and externally rotated.

The diagnosis is made after review of the history and mechanism of injury and performance of a complete physical exam with imaging studies—the most critical component of diagnosis.4 Standard radiographs (anteroposterior, axillary, and scapular Y) can confirm the presence of a dislocation; once the diagnosis is confirmed, closed reduction of the joint should be performed.1 (Methods of reduction are beyond the scope of this article but have been recently reviewed.5)

Risk for recurrence drives management choices

Following an initial shoulder dislocation, the risk of recurrence is high.6,7 Rates vary based on age, pathology after dislocation, activity level, type of immobilization, and whether surgery was performed. Overall, age is the strongest predictor of recurrence: 72% of patients ages 12 to 22 years, 56% of those ages 23 to 29 years, and 27% of those older than 30 years experience recurrence.6 Patients who have recurrent dislocations are at risk for arthropathy, fear of instability, and worsening surgical outcomes.6

Reducing the risk of a recurrent shoulder dislocation has been the focus of intense study. Proponents of surgical stabilization argue that surgery—rather than a trial of conservative treatment—is best when you consider the high risk of recurrence in young athletes (the population primarily studied), the soft-tissue and bony damage caused by recurrent instability, and the predictable improvement in quality of life following surgery.

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, there was evidence that, for first-time traumatic shoulder dislocations, early surgery led to fewer repeat shoulder dislocations (number needed to treat [NNT] = 2-4.7). However, a significant number of patients primarily treated nonoperatively did not experience a repeat shoulder dislocation within 2 years.2

The conflicting results from randomized trials comparing operative intervention to conservative management have led surgeons and physicians in other specialties to take different approaches to the management of shoulder dislocation.2 In this review, we aim to summarize considerations for conservative vs surgical management and provide clinical guidance for primary care physicians.

When to try conservative management

Although the initial treatment after a traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation has been debated, a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed that at least half of first-time dislocations are successfully treated with conservative management.2 Management can include immobilization for comfort and/or physical therapy. Age will play a role, as mentioned earlier; in general, patients older than 30 have a significant decrease in recurrence rate and are good candidates for conservative therapy.6 It should be noted that much of the research with regard to management of shoulder dislocations has been done in an athletic population.

Continue to: Immobilization may benefit some

Immobilization may benefit some

Recent evidence has determined that the duration of immobilization in internal rotation does not impact recurrent instability.8,9 In patients older than 30, the rate of repeat dislocation is lower, and early mobilization after 1 week is advocated to avoid joint stiffness and minimize the risk of adhesive capsulitis.10

Arm position during immobilization remains controversial.11 In a classic study by Itoi et al, immobilization for 3 weeks in internal rotation vs 10° of external rotation was associated with a recurrence rate of 42% vs 26%, respectively.12 In this study, immobilization in 10° of external rotation was especially beneficial for patients ages 30 years or younger.12

Cadaveric and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have shown external rotation may improve the odds of labral tear healing by positioning the damaged and intact parts of the glenoid labrum in closer proximity.13 While this is theoretically plausible, a recent Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to determine whether immobilization in external rotation has any benefits beyond those offered by internal rotation.14 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that immobilization in external rotation vs internal rotation after a first-time traumatic shoulder dislocation did not change outcomes.2 With that said, most would prefer to immobilize in the internal rotation position for ease.

More research is needed. A Cochrane review highlighted the need for continued research.14 Additionally, most of the available randomized controlled trials to date have consisted of young men, with the majority of dislocations related to sports activities. Women, nonathletes, and older patients have been understudied to date; extrapolating current research to those groups of patients may not be appropriate and should be a focus for future research.2

Physical therapy: The conservative standard of care

Rehabilitation after glenohumeral joint dislocation is the current standard of care in conservative management to reduce the risk for repeat dislocation.15 Depending on the specific characteristics of the instability pattern, the approach may be adapted to the patient. A recent review focused on the following 4 key points: (1) restoration of rotator cuff strength, focusing on the eccentric capacity of the external rotators, (2) normalization of rotational range of motion with particular focus on internal range of motion, (3) optimization of the flexibility and muscle performance of the scapular muscles, and (4) increasing the functional sport-specific load on the shoulder girdle.

Continue to: A common approach to the care of...

A common approach to the care of a patient after a glenohumeral joint dislocation is to place the patient’s shoulder in a sling for comfort, with permitted pain-free isometric exercise along with passive and assisted elevation up to 100°.16 This is followed by a nonaggressive rehabilitation protocol for 2 months until full recovery, which includes progressive range of motion, strength, proprioception, and return to functional activities.16

More aggressive return-to-play protocols with accelerated timelines and functional progression have been studied, including in a multicenter observational study that followed 45 contact intercollegiate athletes prospectively after in-season anterior glenohumeral instability. Thirty-three of 45 (73%) athletes returned to sport for either all or part of the season after a median 5 days lost from competition, with 12 athletes (27%) successfully completing the season without recurrence. Athletes with a subluxation event were 5.3 times more likely to return to sport during the same season, compared with those with dislocations.17

Dynamic bracing may also allow for a safe and quicker return to sport in athletes18 but recently was shown to not impact recurrent dislocation risk.19

Return to play should be based on subjective assessment as well as objective measurements of range of motion, strength, and dynamic function.15 Patients who continue to have significant weakness and pain at 2 to 3 weeks post injury despite physical therapy should be re-evaluated with an MRI for concomitant rotator cuff tears and need for surgical referral.20

When to consider surgical intervention

In a recent meta-analysis, recurrent dislocation and instability occurred at a rate of 52.9% following nonsurgical treatment.2 The decision to perform surgical intervention is typically made following failure of conservative management. Other considerations include age, gender, bone loss, and cartilage defect.21,22 Age younger than 30 years, participation in competition, contact sports, and male gender have been associated with an increased risk of recurrence.23-25 For this reason, obtaining an MRI at time of first dislocation can help facilitate surgical decisions if the patient is at high risk for surgical need.26

Continue to: An increasing number...

An increasing number of dislocations portends a poor outcome with nonoperative treatment. Kao et al demonstrated a second dislocation leads to another dislocation in 19.6% of cases, while 44.3% of those with a third dislocation event will sustain another dislocation.24 Surgery should be considered for patients with recurrent instability events to prevent persistent instability and decrease the amount of bone loss that can occur with repetitive dislocations.

What are the surgical options?

Several surgical options exist to remedy the unstable shoulder. Procedures can range from an arthroscopic repair to an open stabilization combined with structural bone graft to replace a bone defect caused by repetitive dislocations.

Arthroscopic techniques have become the mainstay of treatment and account for 71% of stabilization procedures performed.21 These techniques cause less pain in the early postoperative period and provide for a faster return to work.27 Arthroscopy has the additional advantage of allowing for complete visualization of the glenohumeral joint to identify and address concomitant pathology, such as intra-articular loose bodies or rotator cuff tears.

Open repair was the mainstay of treatment prior to development of arthroscopic techniques. Some surgeons still prefer this method—especially in high-risk groups—because of a lower risk of recurrent disloca-tion.28 Open techniques often involve detachment and repair of the upper subscapularis tendon and are more likely to produce long-term losses in external rotation range of motion.28

Which one is appropriate for your patient? The decision to pursue an open or arthroscopic procedure and to augment with bone graft depends on the amount of glenoid and humeral head bone loss, patient activity level, risk of recurrent dislocation, and surgeon preference.

Continue to: For the nonathletic population...

For the nonathletic population, the timing of injury is less critical and surgery is typically recommended after conservative treatment has failed. In an athletic population, the timing of injury is a necessary consideration. An injury midseason may be “rehabbed” in hopes of returning to play. Individuals with injuries occurring at the end of a season, who are unable to regain desired function, and/or with peri-articular fractures or associated full-thickness rotator cuff tears may benefit from sooner surgical intervention.21

Owens et al have described appropriate surgical indications and recommendations for an in-season athlete.21 In this particular algorithm, the authors suggest obtaining an MRI for decision making, but this is specific to in-season athletes wishing to return to play. In general, an MRI is not always indicated for patients who wish to receive conservative therapy but would be indicated for surgical considerations. The algorithm otherwise uses bone and soft-tissue injury, recurrent instability, and timing in the season to help determine management.21

Outcomes: Surgery has advantages …

Recurrence rates following surgical intervention are considerably lower than with conservative management, especially among young, active individuals. A recent systematic review by Donohue et al demonstrated recurrent instability rates following surgical intervention as low as 2.4%.29 One study comparing the outcome of arthroscopic repair vs conservative management showed that the risk of postoperative instability was reduced by 20% compared to other treatments.7 Furthermore, early surgical fixation can improve quality of life, produce better functional outcomes, decrease time away from activity, increase patient satisfaction, and slow the development of glenohumeral osteoarthritis produced from recurrent instability.2,7

Complications. Surgery does carry inherent risks of infection, anesthesia effects, surgical complications, and surgical failure. Recurrent instability is the most common complication following surgical shoulder stabilization. Rates of recurrent instability after surgical stabilization depend on patient age, activity level, and amount of bone loss: males younger than 18 years who participate in contact competitive sports and have significant bone loss are more likely to have recurrent dislocation after surgery.23 The type of surgical procedure selected may decrease this risk.

While the open procedures decrease risk of postoperative instability, these surgeries can pose a significant risk of complications. Major complications for specific open techniques have been reported in up to 30% of patients30 and are associated with lower levels of surgeon experience.31 While the healing of bones and ligaments is always a concern, 1 of the most feared complications following stabilization surgery is iatrogenic nerve injury. Because of the axillary nerve’s close proximity to the inferior glenoid, this nerve can be injured without meticulous care and can result in paralysis of the deltoid muscle. This injury poses a major impediment to normal shoulder function. Some procedures may cause nerve injuries in up to 10% of patients, although most injuries are transient.32

Continue to: Bottom line

Bottom line

Due to the void of evidence-based guidelines for conservative vs surgical management of primary shoulder dislocation, it would be prudent to have a risk-benefit discussion with patients regarding treatment options.

Patients older than 30 years and those with uncomplicated injuries are best suited for conservative management of primary shoulder dislocations. Immobilization is debated and may not change outcomes, but a progressive rehabilitative program after the initial acute injury is helpful. Risk factors for failing conservative management include recurrent dislocation, subsequent arthropathy, and additional concomitant bone or soft-tissue injuries.