User login

Are Women Better Doctors Than Men?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s a battle of the sexes today as we dive into a paper that makes you say, “Wow, what an interesting study” and also “Boy, am I glad I didn’t do that study.” That’s because studies like this are always somewhat fraught; they say something about medicine but also something about society — and that makes this a bit precarious. But that’s never stopped us before. So, let’s go ahead and try to answer the question: Do women make better doctors than men?

On the surface, this question seems nearly impossible to answer. It’s too broad; what does it mean to be a “better” doctor? At first blush it seems that there are just too many variables to control for here: the type of doctor, the type of patient, the clinical scenario, and so on.

But this study, “Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates by physician and patient sex,” which appears in Annals of Internal Medicine, uses a fairly ingenious method to cut through all the bias by leveraging two simple facts: First, hospital medicine is largely conducted by hospitalists these days; second, due to the shift-based nature of hospitalist work, the hospitalist you get when you are admitted to the hospital is pretty much random.

In other words, if you are admitted to the hospital for an acute illness and get a hospitalist as your attending, you have no control over whether it is a man or a woman. Is this a randomized trial? No, but it’s not bad.

Researchers used Medicare claims data to identify adults over age 65 who had nonelective hospital admissions throughout the United States. The claims revealed the sex of the patient and the name of the attending physician. By linking to a medical provider database, they could determine the sex of the provider.

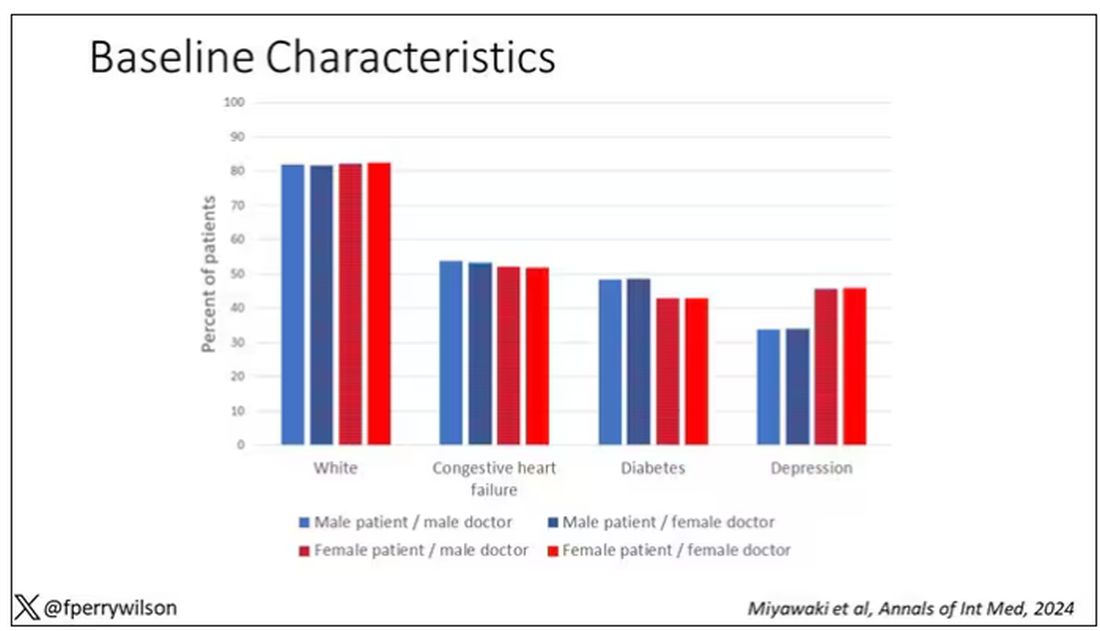

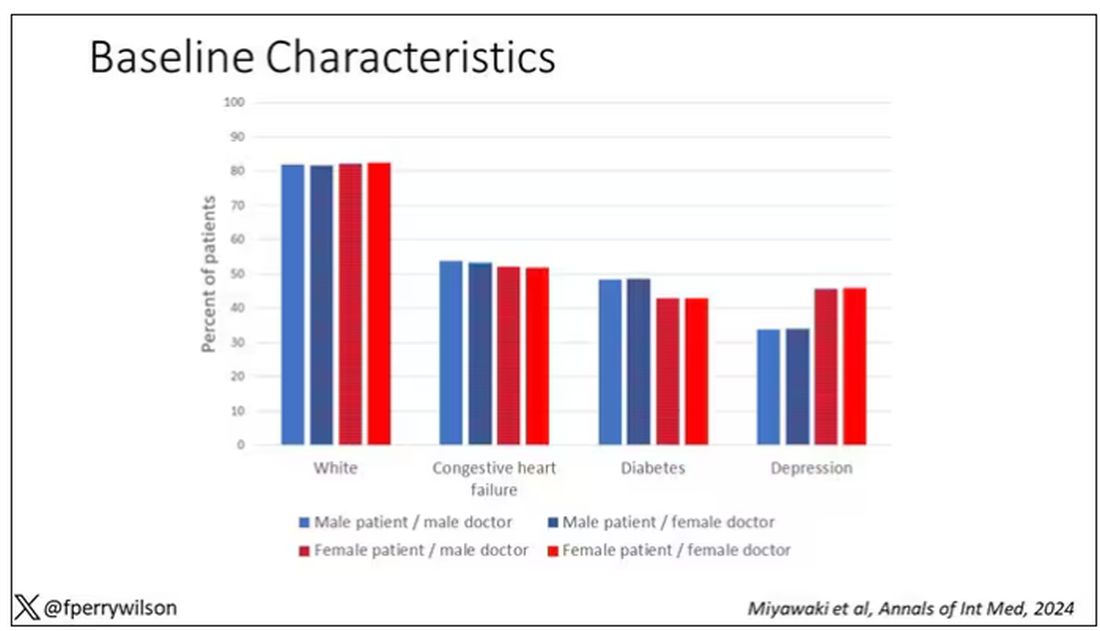

The goal was to look at outcomes across four dyads:

- Male patient – male doctor

- Male patient – female doctor

- Female patient – male doctor

- Female patient – female doctor

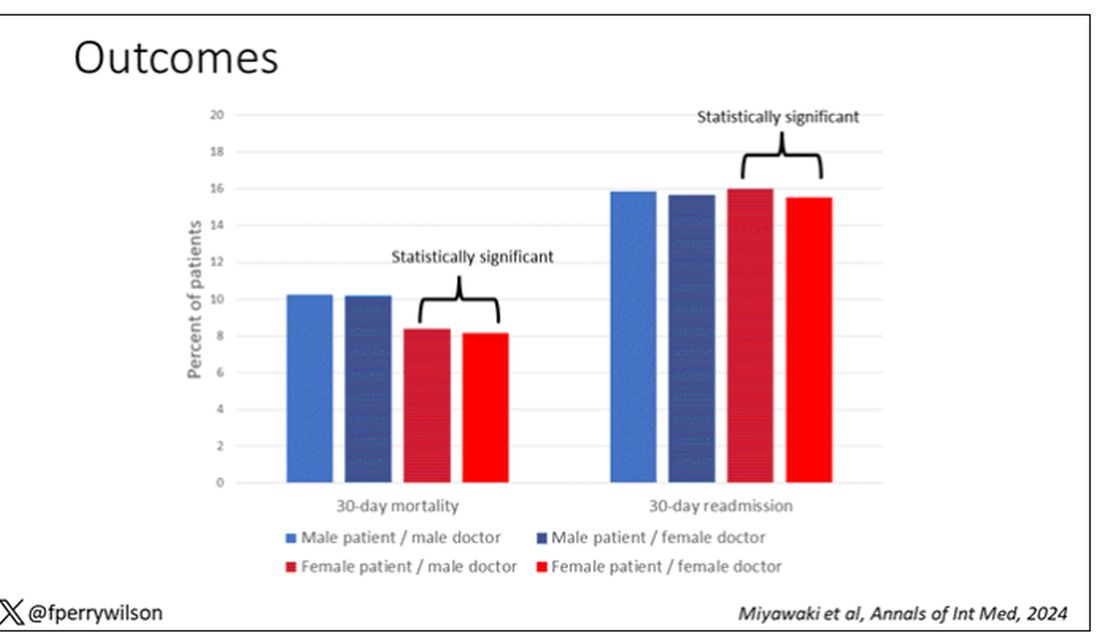

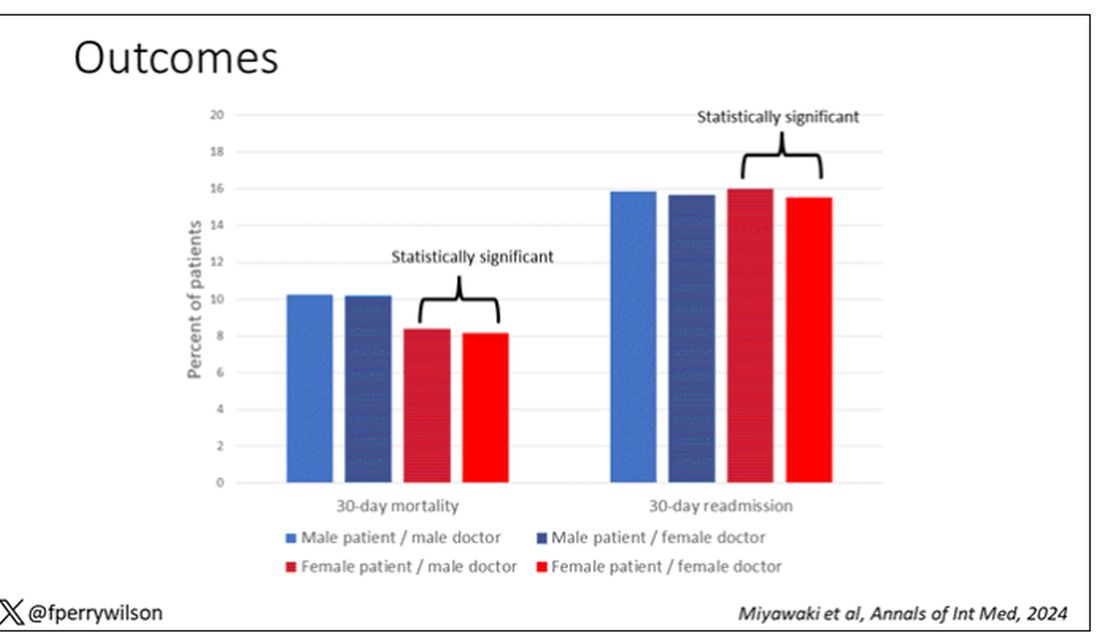

The primary outcome was 30-day mortality.

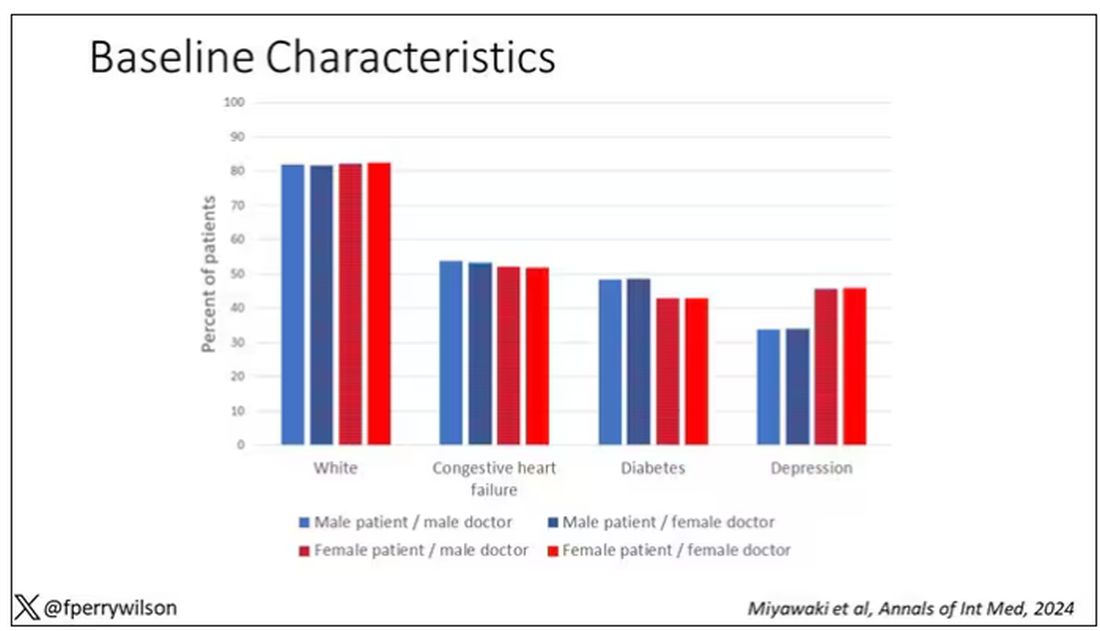

I told you that focusing on hospitalists produces some pseudorandomization, but let’s look at the data to be sure. Just under a million patients were treated by approximately 50,000 physicians, 30% of whom were female. And, though female patients and male patients differed, they did not differ with respect to the sex of their hospitalist. So, by physician sex, patients were similar in mean age, race, ethnicity, household income, eligibility for Medicaid, and comorbid conditions. The authors even created a “predicted mortality” score which was similar across the groups as well.

Now, the female physicians were a bit different from the male physicians. The female hospitalists were slightly more likely to have an osteopathic degree, had slightly fewer admissions per year, and were a bit younger.

So, we have broadly similar patients regardless of who their hospitalist was, but hospitalists differ by factors other than their sex. Fine.

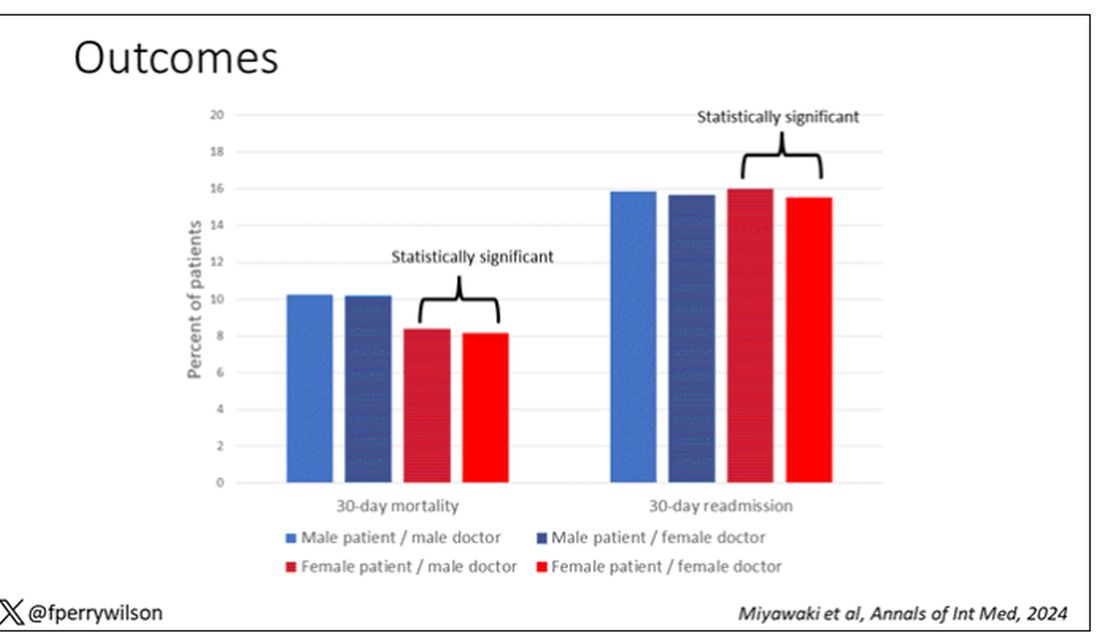

I’ve graphed the results here.

This is a relatively small effect, to be sure, but if you multiply it across the millions of hospitalist admissions per year, you can start to put up some real numbers.

So, what is going on here? I see four broad buckets of possibilities.

Let’s start with the obvious explanation: Women, on average, are better doctors than men. I am married to a woman doctor, and based on my personal experience, this explanation is undoubtedly true. But why would that be?

The authors cite data that suggest that female physicians are less likely than male physicians to dismiss patient concerns — and in particular, the concerns of female patients — perhaps leading to fewer missed diagnoses. But this is impossible to measure with administrative data, so this study can no more tell us whether these female hospitalists are more attentive than their male counterparts than it can suggest that the benefit is mediated by the shorter average height of female physicians. Perhaps the key is being closer to the patient?

The second possibility here is that this has nothing to do with the sex of the physician at all; it has to do with those other things that associate with the sex of the physician. We know, for example, that the female physicians saw fewer patients per year than the male physicians, but the study authors adjusted for this in the statistical models. Still, other unmeasured factors (confounders) could be present. By the way, confounders wouldn’t necessarily change the primary finding — you are better off being cared for by female physicians. It’s just not because they are female; it’s a convenient marker for some other quality, such as age.

The third possibility is that the study represents a phenomenon called collider bias. The idea here is that physicians only get into the study if they are hospitalists, and the quality of physicians who choose to become a hospitalist may differ by sex. When deciding on a specialty, a talented resident considering certain lifestyle issues may find hospital medicine particularly attractive — and that draw toward a more lifestyle-friendly specialty may differ by sex, as some prior studies have shown. If true, the pool of women hospitalists may be better than their male counterparts because male physicians of that caliber don’t become hospitalists.

Okay, don’t write in. I’m just trying to cite examples of how to think about collider bias. I can’t prove that this is the case, and in fact the authors do a sensitivity analysis of all physicians, not just hospitalists, and show the same thing. So this is probably not true, but epidemiology is fun, right?

And the fourth possibility: This is nothing but statistical noise. The effect size is incredibly small and just on the border of statistical significance. Especially when you’re working with very large datasets like this, you’ve got to be really careful about overinterpreting statistically significant findings that are nevertheless of small magnitude.

Regardless, it’s an interesting study, one that made me think and, of course, worry a bit about how I would present it. Forgive me if I’ve been indelicate in handling the complex issues of sex, gender, and society here. But I’m not sure what you expect; after all, I’m only a male doctor.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s a battle of the sexes today as we dive into a paper that makes you say, “Wow, what an interesting study” and also “Boy, am I glad I didn’t do that study.” That’s because studies like this are always somewhat fraught; they say something about medicine but also something about society — and that makes this a bit precarious. But that’s never stopped us before. So, let’s go ahead and try to answer the question: Do women make better doctors than men?

On the surface, this question seems nearly impossible to answer. It’s too broad; what does it mean to be a “better” doctor? At first blush it seems that there are just too many variables to control for here: the type of doctor, the type of patient, the clinical scenario, and so on.

But this study, “Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates by physician and patient sex,” which appears in Annals of Internal Medicine, uses a fairly ingenious method to cut through all the bias by leveraging two simple facts: First, hospital medicine is largely conducted by hospitalists these days; second, due to the shift-based nature of hospitalist work, the hospitalist you get when you are admitted to the hospital is pretty much random.

In other words, if you are admitted to the hospital for an acute illness and get a hospitalist as your attending, you have no control over whether it is a man or a woman. Is this a randomized trial? No, but it’s not bad.

Researchers used Medicare claims data to identify adults over age 65 who had nonelective hospital admissions throughout the United States. The claims revealed the sex of the patient and the name of the attending physician. By linking to a medical provider database, they could determine the sex of the provider.

The goal was to look at outcomes across four dyads:

- Male patient – male doctor

- Male patient – female doctor

- Female patient – male doctor

- Female patient – female doctor

The primary outcome was 30-day mortality.

I told you that focusing on hospitalists produces some pseudorandomization, but let’s look at the data to be sure. Just under a million patients were treated by approximately 50,000 physicians, 30% of whom were female. And, though female patients and male patients differed, they did not differ with respect to the sex of their hospitalist. So, by physician sex, patients were similar in mean age, race, ethnicity, household income, eligibility for Medicaid, and comorbid conditions. The authors even created a “predicted mortality” score which was similar across the groups as well.

Now, the female physicians were a bit different from the male physicians. The female hospitalists were slightly more likely to have an osteopathic degree, had slightly fewer admissions per year, and were a bit younger.

So, we have broadly similar patients regardless of who their hospitalist was, but hospitalists differ by factors other than their sex. Fine.

I’ve graphed the results here.

This is a relatively small effect, to be sure, but if you multiply it across the millions of hospitalist admissions per year, you can start to put up some real numbers.

So, what is going on here? I see four broad buckets of possibilities.

Let’s start with the obvious explanation: Women, on average, are better doctors than men. I am married to a woman doctor, and based on my personal experience, this explanation is undoubtedly true. But why would that be?

The authors cite data that suggest that female physicians are less likely than male physicians to dismiss patient concerns — and in particular, the concerns of female patients — perhaps leading to fewer missed diagnoses. But this is impossible to measure with administrative data, so this study can no more tell us whether these female hospitalists are more attentive than their male counterparts than it can suggest that the benefit is mediated by the shorter average height of female physicians. Perhaps the key is being closer to the patient?

The second possibility here is that this has nothing to do with the sex of the physician at all; it has to do with those other things that associate with the sex of the physician. We know, for example, that the female physicians saw fewer patients per year than the male physicians, but the study authors adjusted for this in the statistical models. Still, other unmeasured factors (confounders) could be present. By the way, confounders wouldn’t necessarily change the primary finding — you are better off being cared for by female physicians. It’s just not because they are female; it’s a convenient marker for some other quality, such as age.

The third possibility is that the study represents a phenomenon called collider bias. The idea here is that physicians only get into the study if they are hospitalists, and the quality of physicians who choose to become a hospitalist may differ by sex. When deciding on a specialty, a talented resident considering certain lifestyle issues may find hospital medicine particularly attractive — and that draw toward a more lifestyle-friendly specialty may differ by sex, as some prior studies have shown. If true, the pool of women hospitalists may be better than their male counterparts because male physicians of that caliber don’t become hospitalists.

Okay, don’t write in. I’m just trying to cite examples of how to think about collider bias. I can’t prove that this is the case, and in fact the authors do a sensitivity analysis of all physicians, not just hospitalists, and show the same thing. So this is probably not true, but epidemiology is fun, right?

And the fourth possibility: This is nothing but statistical noise. The effect size is incredibly small and just on the border of statistical significance. Especially when you’re working with very large datasets like this, you’ve got to be really careful about overinterpreting statistically significant findings that are nevertheless of small magnitude.

Regardless, it’s an interesting study, one that made me think and, of course, worry a bit about how I would present it. Forgive me if I’ve been indelicate in handling the complex issues of sex, gender, and society here. But I’m not sure what you expect; after all, I’m only a male doctor.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s a battle of the sexes today as we dive into a paper that makes you say, “Wow, what an interesting study” and also “Boy, am I glad I didn’t do that study.” That’s because studies like this are always somewhat fraught; they say something about medicine but also something about society — and that makes this a bit precarious. But that’s never stopped us before. So, let’s go ahead and try to answer the question: Do women make better doctors than men?

On the surface, this question seems nearly impossible to answer. It’s too broad; what does it mean to be a “better” doctor? At first blush it seems that there are just too many variables to control for here: the type of doctor, the type of patient, the clinical scenario, and so on.

But this study, “Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates by physician and patient sex,” which appears in Annals of Internal Medicine, uses a fairly ingenious method to cut through all the bias by leveraging two simple facts: First, hospital medicine is largely conducted by hospitalists these days; second, due to the shift-based nature of hospitalist work, the hospitalist you get when you are admitted to the hospital is pretty much random.

In other words, if you are admitted to the hospital for an acute illness and get a hospitalist as your attending, you have no control over whether it is a man or a woman. Is this a randomized trial? No, but it’s not bad.

Researchers used Medicare claims data to identify adults over age 65 who had nonelective hospital admissions throughout the United States. The claims revealed the sex of the patient and the name of the attending physician. By linking to a medical provider database, they could determine the sex of the provider.

The goal was to look at outcomes across four dyads:

- Male patient – male doctor

- Male patient – female doctor

- Female patient – male doctor

- Female patient – female doctor

The primary outcome was 30-day mortality.

I told you that focusing on hospitalists produces some pseudorandomization, but let’s look at the data to be sure. Just under a million patients were treated by approximately 50,000 physicians, 30% of whom were female. And, though female patients and male patients differed, they did not differ with respect to the sex of their hospitalist. So, by physician sex, patients were similar in mean age, race, ethnicity, household income, eligibility for Medicaid, and comorbid conditions. The authors even created a “predicted mortality” score which was similar across the groups as well.

Now, the female physicians were a bit different from the male physicians. The female hospitalists were slightly more likely to have an osteopathic degree, had slightly fewer admissions per year, and were a bit younger.

So, we have broadly similar patients regardless of who their hospitalist was, but hospitalists differ by factors other than their sex. Fine.

I’ve graphed the results here.

This is a relatively small effect, to be sure, but if you multiply it across the millions of hospitalist admissions per year, you can start to put up some real numbers.

So, what is going on here? I see four broad buckets of possibilities.

Let’s start with the obvious explanation: Women, on average, are better doctors than men. I am married to a woman doctor, and based on my personal experience, this explanation is undoubtedly true. But why would that be?

The authors cite data that suggest that female physicians are less likely than male physicians to dismiss patient concerns — and in particular, the concerns of female patients — perhaps leading to fewer missed diagnoses. But this is impossible to measure with administrative data, so this study can no more tell us whether these female hospitalists are more attentive than their male counterparts than it can suggest that the benefit is mediated by the shorter average height of female physicians. Perhaps the key is being closer to the patient?

The second possibility here is that this has nothing to do with the sex of the physician at all; it has to do with those other things that associate with the sex of the physician. We know, for example, that the female physicians saw fewer patients per year than the male physicians, but the study authors adjusted for this in the statistical models. Still, other unmeasured factors (confounders) could be present. By the way, confounders wouldn’t necessarily change the primary finding — you are better off being cared for by female physicians. It’s just not because they are female; it’s a convenient marker for some other quality, such as age.

The third possibility is that the study represents a phenomenon called collider bias. The idea here is that physicians only get into the study if they are hospitalists, and the quality of physicians who choose to become a hospitalist may differ by sex. When deciding on a specialty, a talented resident considering certain lifestyle issues may find hospital medicine particularly attractive — and that draw toward a more lifestyle-friendly specialty may differ by sex, as some prior studies have shown. If true, the pool of women hospitalists may be better than their male counterparts because male physicians of that caliber don’t become hospitalists.

Okay, don’t write in. I’m just trying to cite examples of how to think about collider bias. I can’t prove that this is the case, and in fact the authors do a sensitivity analysis of all physicians, not just hospitalists, and show the same thing. So this is probably not true, but epidemiology is fun, right?

And the fourth possibility: This is nothing but statistical noise. The effect size is incredibly small and just on the border of statistical significance. Especially when you’re working with very large datasets like this, you’ve got to be really careful about overinterpreting statistically significant findings that are nevertheless of small magnitude.

Regardless, it’s an interesting study, one that made me think and, of course, worry a bit about how I would present it. Forgive me if I’ve been indelicate in handling the complex issues of sex, gender, and society here. But I’m not sure what you expect; after all, I’m only a male doctor.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Avoidance Predicts Worse Long-term Outcomes From Intensive OCD Treatment

BOSTON — , a new analysis shows.

Although avoidant patients with OCD reported symptom improvement immediately after treatment, baseline avoidance was associated with significantly worse outcomes 1 year later.

“Avoidance is often overlooked in OCD,” said lead investigator Michael Wheaton, PhD, an assistant professor of psychology at Barnard College in New York. “It’s really important clinically to focus on that.”

The findings were presented at the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA) annual conference and published online in the Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders.

The Avoidance Question

Although ERP is often included in treatment for OCD, between 38% and 60% of patients have residual symptoms after treatment and as many as a quarter don’t respond at all, Dr. Wheaton said.

Severe pretreatment avoidance could affect the efficacy of ERP, which involves exposing patients to situations and stimuli they may usually avoid. But prior research to identify predictors of ERP outcomes have largely excluded severity of pretreatment avoidance as a factor.

The new study analyzed data from 161 Norwegian adults with treatment-resistant OCD who participated in a concentrated ERP therapy called the Bergen 4-day Exposure and Response Prevention (B4DT) treatment. This method delivers intensive treatment over 4 consecutive days in small groups with a 1:1 ratio of therapists to patients.

B4DT is common throughout Norway, with the treatment offered at 55 clinics, and has been trialed in other countries including the United States, Nepal, Ecuador, and Kenya.

Symptom severity was measured using the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS) at baseline, immediately after treatment, and 3 and 12 months later. Functional impairment was measured 12 months after treatment using the Work and Social Adjustment Scale.

Although the formal scoring of the YBOCS does not include any questions about avoidance, one question in the auxiliary items does: “Have you been avoiding doing anything, going anyplace or being with anyone because of obsessional thoughts or out of a need to perform compulsions?”

Dr. Wheaton used this response, which is rated on a five-point scale, to measure avoidance. Overall, 18.8% of participants had no deliberate avoidance, 15% were rated as having mild avoidance, 36% moderate, 23% severe, and 6.8% extreme.

Long-Term Outcomes

Overall, 84% of participants responded to treatment, with a change in mean YBOCS scores from 26.98 at baseline to 12.28 immediately after treatment. Acute outcomes were similar between avoidant and nonavoidant patients.

But at 12-month follow-up, even after controlling for pretreatment OCD severity, patients with more extensive avoidance at baseline had worse long-term outcomes — both more severe OCD symptoms (P = .031) and greater functional impairment (P = .002).

Across all patients, average avoidance decreased significantly immediately after the concentrated ERP treatment. Average avoidance increased somewhat at 3- and 12-month follow-up but remained significantly improved from pretreatment.

Interestingly, patients’ change in avoidance immediately post-treatment to 3 months post-treatment predicted worsening of OCD severity at 12 months. This change could potentially identify people at risk of relapse, Dr. Wheaton said.

Previous research has shown that pretreatment OCD severity, measured using the YBOCS, does not significantly predict ERP outcomes, and this study found the same.

Relapse Prevention

“The fact that they did equally well in the short run I think was great,” Dr. Wheaton said.

Previous research, including 2018 and 2023 papers from Wheaton’s team, has shown that more avoidant patients have worse outcomes from standard 12-week ERP programs.

One possible explanation for this difference is that in the Bergen treatment, most exposures happen during face-to-face time with a therapist instead of as homework, which may be easier to avoid, he said.

“But then the finding was that their symptoms were worsening over time — their avoidance was sliding back into old habits,” said Dr. Wheaton.

He would like to see the study replicated in diverse populations outside Norway and in treatment-naive people. Dr. Wheaton also noted that the study assessed avoidance with only a single item.

Future work is needed to test ways to improve relapse prevention. For example, clinicians may be able to monitor for avoidance behaviors post-treatment, which could be the start of a relapse, said Dr. Wheaton.

Although clinicians consider avoidance when treating phobias, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder, “somehow avoidance got relegated to item 11 on the YBOCS that isn’t scored,” Helen Blair Simpson, MD, PhD, director of the Center for OCD and Related Disorders at Columbia University, New York, New York, said during the presentation.

A direct implication of Dr. Wheaton’s findings to clinical practice is to “talk to people about their avoidance right up front,” said Dr. Simpson, who was not part of the study.

Clinicians who deliver ERP in their practices “can apply this tomorrow,” Dr. Simpson added.

Dr. Wheaton reported no disclosures. Dr. Simpson reported a stipend from the American Medical Association for serving as associate editor of JAMA Psychiatry and royalties from UpToDate, Inc for articles on OCD and from Cambridge University Press for editing a book on anxiety disorders.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

BOSTON — , a new analysis shows.

Although avoidant patients with OCD reported symptom improvement immediately after treatment, baseline avoidance was associated with significantly worse outcomes 1 year later.

“Avoidance is often overlooked in OCD,” said lead investigator Michael Wheaton, PhD, an assistant professor of psychology at Barnard College in New York. “It’s really important clinically to focus on that.”

The findings were presented at the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA) annual conference and published online in the Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders.

The Avoidance Question

Although ERP is often included in treatment for OCD, between 38% and 60% of patients have residual symptoms after treatment and as many as a quarter don’t respond at all, Dr. Wheaton said.

Severe pretreatment avoidance could affect the efficacy of ERP, which involves exposing patients to situations and stimuli they may usually avoid. But prior research to identify predictors of ERP outcomes have largely excluded severity of pretreatment avoidance as a factor.

The new study analyzed data from 161 Norwegian adults with treatment-resistant OCD who participated in a concentrated ERP therapy called the Bergen 4-day Exposure and Response Prevention (B4DT) treatment. This method delivers intensive treatment over 4 consecutive days in small groups with a 1:1 ratio of therapists to patients.

B4DT is common throughout Norway, with the treatment offered at 55 clinics, and has been trialed in other countries including the United States, Nepal, Ecuador, and Kenya.

Symptom severity was measured using the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS) at baseline, immediately after treatment, and 3 and 12 months later. Functional impairment was measured 12 months after treatment using the Work and Social Adjustment Scale.

Although the formal scoring of the YBOCS does not include any questions about avoidance, one question in the auxiliary items does: “Have you been avoiding doing anything, going anyplace or being with anyone because of obsessional thoughts or out of a need to perform compulsions?”

Dr. Wheaton used this response, which is rated on a five-point scale, to measure avoidance. Overall, 18.8% of participants had no deliberate avoidance, 15% were rated as having mild avoidance, 36% moderate, 23% severe, and 6.8% extreme.

Long-Term Outcomes

Overall, 84% of participants responded to treatment, with a change in mean YBOCS scores from 26.98 at baseline to 12.28 immediately after treatment. Acute outcomes were similar between avoidant and nonavoidant patients.

But at 12-month follow-up, even after controlling for pretreatment OCD severity, patients with more extensive avoidance at baseline had worse long-term outcomes — both more severe OCD symptoms (P = .031) and greater functional impairment (P = .002).

Across all patients, average avoidance decreased significantly immediately after the concentrated ERP treatment. Average avoidance increased somewhat at 3- and 12-month follow-up but remained significantly improved from pretreatment.

Interestingly, patients’ change in avoidance immediately post-treatment to 3 months post-treatment predicted worsening of OCD severity at 12 months. This change could potentially identify people at risk of relapse, Dr. Wheaton said.

Previous research has shown that pretreatment OCD severity, measured using the YBOCS, does not significantly predict ERP outcomes, and this study found the same.

Relapse Prevention

“The fact that they did equally well in the short run I think was great,” Dr. Wheaton said.

Previous research, including 2018 and 2023 papers from Wheaton’s team, has shown that more avoidant patients have worse outcomes from standard 12-week ERP programs.

One possible explanation for this difference is that in the Bergen treatment, most exposures happen during face-to-face time with a therapist instead of as homework, which may be easier to avoid, he said.

“But then the finding was that their symptoms were worsening over time — their avoidance was sliding back into old habits,” said Dr. Wheaton.

He would like to see the study replicated in diverse populations outside Norway and in treatment-naive people. Dr. Wheaton also noted that the study assessed avoidance with only a single item.

Future work is needed to test ways to improve relapse prevention. For example, clinicians may be able to monitor for avoidance behaviors post-treatment, which could be the start of a relapse, said Dr. Wheaton.

Although clinicians consider avoidance when treating phobias, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder, “somehow avoidance got relegated to item 11 on the YBOCS that isn’t scored,” Helen Blair Simpson, MD, PhD, director of the Center for OCD and Related Disorders at Columbia University, New York, New York, said during the presentation.

A direct implication of Dr. Wheaton’s findings to clinical practice is to “talk to people about their avoidance right up front,” said Dr. Simpson, who was not part of the study.

Clinicians who deliver ERP in their practices “can apply this tomorrow,” Dr. Simpson added.

Dr. Wheaton reported no disclosures. Dr. Simpson reported a stipend from the American Medical Association for serving as associate editor of JAMA Psychiatry and royalties from UpToDate, Inc for articles on OCD and from Cambridge University Press for editing a book on anxiety disorders.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

BOSTON — , a new analysis shows.

Although avoidant patients with OCD reported symptom improvement immediately after treatment, baseline avoidance was associated with significantly worse outcomes 1 year later.

“Avoidance is often overlooked in OCD,” said lead investigator Michael Wheaton, PhD, an assistant professor of psychology at Barnard College in New York. “It’s really important clinically to focus on that.”

The findings were presented at the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA) annual conference and published online in the Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders.

The Avoidance Question

Although ERP is often included in treatment for OCD, between 38% and 60% of patients have residual symptoms after treatment and as many as a quarter don’t respond at all, Dr. Wheaton said.

Severe pretreatment avoidance could affect the efficacy of ERP, which involves exposing patients to situations and stimuli they may usually avoid. But prior research to identify predictors of ERP outcomes have largely excluded severity of pretreatment avoidance as a factor.

The new study analyzed data from 161 Norwegian adults with treatment-resistant OCD who participated in a concentrated ERP therapy called the Bergen 4-day Exposure and Response Prevention (B4DT) treatment. This method delivers intensive treatment over 4 consecutive days in small groups with a 1:1 ratio of therapists to patients.

B4DT is common throughout Norway, with the treatment offered at 55 clinics, and has been trialed in other countries including the United States, Nepal, Ecuador, and Kenya.

Symptom severity was measured using the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS) at baseline, immediately after treatment, and 3 and 12 months later. Functional impairment was measured 12 months after treatment using the Work and Social Adjustment Scale.

Although the formal scoring of the YBOCS does not include any questions about avoidance, one question in the auxiliary items does: “Have you been avoiding doing anything, going anyplace or being with anyone because of obsessional thoughts or out of a need to perform compulsions?”

Dr. Wheaton used this response, which is rated on a five-point scale, to measure avoidance. Overall, 18.8% of participants had no deliberate avoidance, 15% were rated as having mild avoidance, 36% moderate, 23% severe, and 6.8% extreme.

Long-Term Outcomes

Overall, 84% of participants responded to treatment, with a change in mean YBOCS scores from 26.98 at baseline to 12.28 immediately after treatment. Acute outcomes were similar between avoidant and nonavoidant patients.

But at 12-month follow-up, even after controlling for pretreatment OCD severity, patients with more extensive avoidance at baseline had worse long-term outcomes — both more severe OCD symptoms (P = .031) and greater functional impairment (P = .002).

Across all patients, average avoidance decreased significantly immediately after the concentrated ERP treatment. Average avoidance increased somewhat at 3- and 12-month follow-up but remained significantly improved from pretreatment.

Interestingly, patients’ change in avoidance immediately post-treatment to 3 months post-treatment predicted worsening of OCD severity at 12 months. This change could potentially identify people at risk of relapse, Dr. Wheaton said.

Previous research has shown that pretreatment OCD severity, measured using the YBOCS, does not significantly predict ERP outcomes, and this study found the same.

Relapse Prevention

“The fact that they did equally well in the short run I think was great,” Dr. Wheaton said.

Previous research, including 2018 and 2023 papers from Wheaton’s team, has shown that more avoidant patients have worse outcomes from standard 12-week ERP programs.

One possible explanation for this difference is that in the Bergen treatment, most exposures happen during face-to-face time with a therapist instead of as homework, which may be easier to avoid, he said.

“But then the finding was that their symptoms were worsening over time — their avoidance was sliding back into old habits,” said Dr. Wheaton.

He would like to see the study replicated in diverse populations outside Norway and in treatment-naive people. Dr. Wheaton also noted that the study assessed avoidance with only a single item.

Future work is needed to test ways to improve relapse prevention. For example, clinicians may be able to monitor for avoidance behaviors post-treatment, which could be the start of a relapse, said Dr. Wheaton.

Although clinicians consider avoidance when treating phobias, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder, “somehow avoidance got relegated to item 11 on the YBOCS that isn’t scored,” Helen Blair Simpson, MD, PhD, director of the Center for OCD and Related Disorders at Columbia University, New York, New York, said during the presentation.

A direct implication of Dr. Wheaton’s findings to clinical practice is to “talk to people about their avoidance right up front,” said Dr. Simpson, who was not part of the study.

Clinicians who deliver ERP in their practices “can apply this tomorrow,” Dr. Simpson added.

Dr. Wheaton reported no disclosures. Dr. Simpson reported a stipend from the American Medical Association for serving as associate editor of JAMA Psychiatry and royalties from UpToDate, Inc for articles on OCD and from Cambridge University Press for editing a book on anxiety disorders.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ADAA 2024

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: Which Drug for Which Patient?

With all the excitement about GLP-1 agonists,

Of course, we want to make sure that we’re treating the right condition. If the patient has type 2 diabetes, we tend to give them medication that is indicated for type 2 diabetes. Many GLP-1 agonists are available in a diabetes version and a chronic weight management or obesity version. If a patient has diabetes and obesity, they can receive either one. If a patient has only diabetes but not obesity, they should be prescribed the diabetes version. For obesity without diabetes, we tend to stick with the drugs that are indicated for chronic weight management.

Let’s go through them.

Exenatide. In chronological order of approval, the first GLP-1 drug that was used for diabetes dates back to exenatide (Bydureon). Bydureon had a partner called Byetta (also exenatide), both of which are still on the market but infrequently used. Some patients reported that these medications were inconvenient because they required twice-daily injections and caused painful injection-site nodules.

Diabetes drugs in more common use include liraglutide (Victoza) for type 2 diabetes. It is a daily injection and has various doses. We always start low and increase with tolerance and desired effect for A1c.

Liraglutide. Victoza has an antiobesity counterpart called Saxenda. The Saxenda pen looks very similar to the Victoza pen. It is a daily GLP-1 agonist for chronic weight management. The SCALE trial demonstrated 8%-12% weight loss with Saxenda.

Those are the daily injections: Victoza for diabetes and Saxenda for weight loss.

Our patients are very excited about the advent of weekly injections for diabetes and weight management. Ozempic is very popular. It is a weekly GLP-1 agonist for type 2 diabetes. Many patients come in asking for Ozempic, and we must make sure that we’re moving them in the right direction depending on their condition.

Semaglutide. Ozempic has a few different doses. It is a weekly injection and has been found to be quite efficacious for treating diabetes. The drug’s weight loss counterpart is called Wegovy, which comes in a different pen. Both forms contain the compound semaglutide. While all of these GLP-1 agonists are indicated to treat type 2 diabetes or for weight management, Wegovy has a special indication that none of the others have. In March 2024, Wegovy acquired an indication to decrease cardiac risk in those with a BMI ≥ 27 and a previous cardiac history. This will really change the accessibility of this medication because patients with heart conditions who are on Medicare are expected to have access to Wegovy.

Tirzepatide. Another weekly injection for treatment of type 2 diabetes is called Mounjaro. Its counterpart for weight management is called Zepbound, which was found to have about 20.9% weight loss over 72 weeks. These medications have similar side effects in differing degrees, but the most-often reported are nausea, stool changes, abdominal pain, and reflux. There are some other potential side effects; I recommend that you read the individual prescribing information available for each drug to have more clarity about that.

It is important that we stay on label for using the GLP-1 receptor agonists, for many reasons. One, it increases our patients’ accessibility to the right medication for them, and we can also make sure that we’re treating the patient with the right drug according to the clinical trials. When the clinical trials are done, the study populations demonstrate safety and efficacy for that population. But if we’re prescribing a GLP-1 for a different population, it is considered off-label use.

Dr. Lofton, an obesity medicine specialist, is clinical associate professor of surgery and medicine at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, and director of the medical weight management program at NYU Langone Weight Management Center, New York. She disclosed ties to Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

With all the excitement about GLP-1 agonists,

Of course, we want to make sure that we’re treating the right condition. If the patient has type 2 diabetes, we tend to give them medication that is indicated for type 2 diabetes. Many GLP-1 agonists are available in a diabetes version and a chronic weight management or obesity version. If a patient has diabetes and obesity, they can receive either one. If a patient has only diabetes but not obesity, they should be prescribed the diabetes version. For obesity without diabetes, we tend to stick with the drugs that are indicated for chronic weight management.

Let’s go through them.

Exenatide. In chronological order of approval, the first GLP-1 drug that was used for diabetes dates back to exenatide (Bydureon). Bydureon had a partner called Byetta (also exenatide), both of which are still on the market but infrequently used. Some patients reported that these medications were inconvenient because they required twice-daily injections and caused painful injection-site nodules.

Diabetes drugs in more common use include liraglutide (Victoza) for type 2 diabetes. It is a daily injection and has various doses. We always start low and increase with tolerance and desired effect for A1c.

Liraglutide. Victoza has an antiobesity counterpart called Saxenda. The Saxenda pen looks very similar to the Victoza pen. It is a daily GLP-1 agonist for chronic weight management. The SCALE trial demonstrated 8%-12% weight loss with Saxenda.

Those are the daily injections: Victoza for diabetes and Saxenda for weight loss.

Our patients are very excited about the advent of weekly injections for diabetes and weight management. Ozempic is very popular. It is a weekly GLP-1 agonist for type 2 diabetes. Many patients come in asking for Ozempic, and we must make sure that we’re moving them in the right direction depending on their condition.

Semaglutide. Ozempic has a few different doses. It is a weekly injection and has been found to be quite efficacious for treating diabetes. The drug’s weight loss counterpart is called Wegovy, which comes in a different pen. Both forms contain the compound semaglutide. While all of these GLP-1 agonists are indicated to treat type 2 diabetes or for weight management, Wegovy has a special indication that none of the others have. In March 2024, Wegovy acquired an indication to decrease cardiac risk in those with a BMI ≥ 27 and a previous cardiac history. This will really change the accessibility of this medication because patients with heart conditions who are on Medicare are expected to have access to Wegovy.

Tirzepatide. Another weekly injection for treatment of type 2 diabetes is called Mounjaro. Its counterpart for weight management is called Zepbound, which was found to have about 20.9% weight loss over 72 weeks. These medications have similar side effects in differing degrees, but the most-often reported are nausea, stool changes, abdominal pain, and reflux. There are some other potential side effects; I recommend that you read the individual prescribing information available for each drug to have more clarity about that.

It is important that we stay on label for using the GLP-1 receptor agonists, for many reasons. One, it increases our patients’ accessibility to the right medication for them, and we can also make sure that we’re treating the patient with the right drug according to the clinical trials. When the clinical trials are done, the study populations demonstrate safety and efficacy for that population. But if we’re prescribing a GLP-1 for a different population, it is considered off-label use.

Dr. Lofton, an obesity medicine specialist, is clinical associate professor of surgery and medicine at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, and director of the medical weight management program at NYU Langone Weight Management Center, New York. She disclosed ties to Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

With all the excitement about GLP-1 agonists,

Of course, we want to make sure that we’re treating the right condition. If the patient has type 2 diabetes, we tend to give them medication that is indicated for type 2 diabetes. Many GLP-1 agonists are available in a diabetes version and a chronic weight management or obesity version. If a patient has diabetes and obesity, they can receive either one. If a patient has only diabetes but not obesity, they should be prescribed the diabetes version. For obesity without diabetes, we tend to stick with the drugs that are indicated for chronic weight management.

Let’s go through them.

Exenatide. In chronological order of approval, the first GLP-1 drug that was used for diabetes dates back to exenatide (Bydureon). Bydureon had a partner called Byetta (also exenatide), both of which are still on the market but infrequently used. Some patients reported that these medications were inconvenient because they required twice-daily injections and caused painful injection-site nodules.

Diabetes drugs in more common use include liraglutide (Victoza) for type 2 diabetes. It is a daily injection and has various doses. We always start low and increase with tolerance and desired effect for A1c.

Liraglutide. Victoza has an antiobesity counterpart called Saxenda. The Saxenda pen looks very similar to the Victoza pen. It is a daily GLP-1 agonist for chronic weight management. The SCALE trial demonstrated 8%-12% weight loss with Saxenda.

Those are the daily injections: Victoza for diabetes and Saxenda for weight loss.

Our patients are very excited about the advent of weekly injections for diabetes and weight management. Ozempic is very popular. It is a weekly GLP-1 agonist for type 2 diabetes. Many patients come in asking for Ozempic, and we must make sure that we’re moving them in the right direction depending on their condition.

Semaglutide. Ozempic has a few different doses. It is a weekly injection and has been found to be quite efficacious for treating diabetes. The drug’s weight loss counterpart is called Wegovy, which comes in a different pen. Both forms contain the compound semaglutide. While all of these GLP-1 agonists are indicated to treat type 2 diabetes or for weight management, Wegovy has a special indication that none of the others have. In March 2024, Wegovy acquired an indication to decrease cardiac risk in those with a BMI ≥ 27 and a previous cardiac history. This will really change the accessibility of this medication because patients with heart conditions who are on Medicare are expected to have access to Wegovy.

Tirzepatide. Another weekly injection for treatment of type 2 diabetes is called Mounjaro. Its counterpart for weight management is called Zepbound, which was found to have about 20.9% weight loss over 72 weeks. These medications have similar side effects in differing degrees, but the most-often reported are nausea, stool changes, abdominal pain, and reflux. There are some other potential side effects; I recommend that you read the individual prescribing information available for each drug to have more clarity about that.

It is important that we stay on label for using the GLP-1 receptor agonists, for many reasons. One, it increases our patients’ accessibility to the right medication for them, and we can also make sure that we’re treating the patient with the right drug according to the clinical trials. When the clinical trials are done, the study populations demonstrate safety and efficacy for that population. But if we’re prescribing a GLP-1 for a different population, it is considered off-label use.

Dr. Lofton, an obesity medicine specialist, is clinical associate professor of surgery and medicine at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, and director of the medical weight management program at NYU Langone Weight Management Center, New York. She disclosed ties to Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Is Osimertinib Better Alone or With Chemotherapy in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer?

SAN DIEGO —

That is a question brewing among some oncologists now that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca) for both indications in patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations.

An answer began to emerge in research presented at the American Association for Cancer Research annual meeting.

An exploratory analysis of the FLAURA2 trial found that, when patients have EGFR mutations on baseline circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) testing, the combination treatment can extend progression-free survival (PFS). In this patient group, those receiving osimertinib alongside pemetrexed plus cisplatin or carboplatin had a 9-month PFS advantage compared with those who received osimertinib alone.

Conversely, when patients do not have EGFR mutations following baseline ctDNA testing, osimertinib alone appears to offer similar PFS outcomes to the combination therapy, but with less toxicity.

“Baseline detection of plasma EGFR mutations may identify a subgroup of patients who derive most benefit from the addition of platinum-pemetrexed to osimertinib as first-line treatment of EGFR-mutated advance non–small cell lung cancer,” investigator Pasi A. Jänne, MD, PhD, a lung cancer oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, said during his presentation.

The FLAURA2 trial randomized 557 patients equally to daily osimertinib either alone or with pemetrexed plus cisplatin or carboplatin every 3 weeks for four cycles followed by pemetrexed every 3 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Patients were tested for Ex19del or L858R EGFR mutations at baseline and at 3 and 6 weeks; baseline mutations were found in 73% of evaluable patients.

In patients with baseline mutations, the median PFS was 24.8 months with the combination therapy vs 13.9 months with osimertinib alone (hazard ratio [HR], 0.60).

In patients without baseline mutations, the median PFS was similar in both groups — 33.3 months with the combination vs 30.3 months with monotherapy (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.51-1.72).

The investigators also found that having baseline mutations was associated with worse outcomes regardless of study arm, and mutation clearance was associated with improved outcomes. Clearance occurred more quickly among patients receiving the combination treatment, but almost 90% of patients in both arms cleared their mutations by week 6.

“As we move forward and think about which of our patients we would treat with the combination ... the presence of baseline EGFR mutations in ctDNA may be one of the features that goes into the conversation,” Dr. Jänne said.

Study discussant Marina Chiara Garassino, MD, a thoracic oncologist at the University of Chicago, agreed that this trial can help oncologists make this kind of treatment decision.

Patients with baseline EGFR mutations also tended to have larger tumors, more brain metastases, and worse performance scores; the combination therapy makes sense when such factors are present in patients with baseline EGFR mutations, Dr. Garassino said.

The wrinkle in the findings is that the study used digital droplet polymerase chain reaction (Biodesix) to test for EGFR mutations, which is not commonly used. Clinicians often use next-generation sequencing, which is less sensitive and can lead to false negatives.

It makes it difficult to know how to apply the findings to everyday practice, but Janne hopes a study will be done to correlate next-generation sequencing detection with outcomes.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca, maker of osimertinib, and researchers included AstraZeneca employees. Dr. Jänne is a consultant for and reported research funding from the company. He is a co-inventor on an EGFR mutations patent. Dr. Garassino is also an AstraZeneca consultant and reported institutional financial interests in the company.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO —

That is a question brewing among some oncologists now that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca) for both indications in patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations.

An answer began to emerge in research presented at the American Association for Cancer Research annual meeting.

An exploratory analysis of the FLAURA2 trial found that, when patients have EGFR mutations on baseline circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) testing, the combination treatment can extend progression-free survival (PFS). In this patient group, those receiving osimertinib alongside pemetrexed plus cisplatin or carboplatin had a 9-month PFS advantage compared with those who received osimertinib alone.

Conversely, when patients do not have EGFR mutations following baseline ctDNA testing, osimertinib alone appears to offer similar PFS outcomes to the combination therapy, but with less toxicity.

“Baseline detection of plasma EGFR mutations may identify a subgroup of patients who derive most benefit from the addition of platinum-pemetrexed to osimertinib as first-line treatment of EGFR-mutated advance non–small cell lung cancer,” investigator Pasi A. Jänne, MD, PhD, a lung cancer oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, said during his presentation.

The FLAURA2 trial randomized 557 patients equally to daily osimertinib either alone or with pemetrexed plus cisplatin or carboplatin every 3 weeks for four cycles followed by pemetrexed every 3 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Patients were tested for Ex19del or L858R EGFR mutations at baseline and at 3 and 6 weeks; baseline mutations were found in 73% of evaluable patients.

In patients with baseline mutations, the median PFS was 24.8 months with the combination therapy vs 13.9 months with osimertinib alone (hazard ratio [HR], 0.60).

In patients without baseline mutations, the median PFS was similar in both groups — 33.3 months with the combination vs 30.3 months with monotherapy (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.51-1.72).

The investigators also found that having baseline mutations was associated with worse outcomes regardless of study arm, and mutation clearance was associated with improved outcomes. Clearance occurred more quickly among patients receiving the combination treatment, but almost 90% of patients in both arms cleared their mutations by week 6.

“As we move forward and think about which of our patients we would treat with the combination ... the presence of baseline EGFR mutations in ctDNA may be one of the features that goes into the conversation,” Dr. Jänne said.

Study discussant Marina Chiara Garassino, MD, a thoracic oncologist at the University of Chicago, agreed that this trial can help oncologists make this kind of treatment decision.

Patients with baseline EGFR mutations also tended to have larger tumors, more brain metastases, and worse performance scores; the combination therapy makes sense when such factors are present in patients with baseline EGFR mutations, Dr. Garassino said.

The wrinkle in the findings is that the study used digital droplet polymerase chain reaction (Biodesix) to test for EGFR mutations, which is not commonly used. Clinicians often use next-generation sequencing, which is less sensitive and can lead to false negatives.

It makes it difficult to know how to apply the findings to everyday practice, but Janne hopes a study will be done to correlate next-generation sequencing detection with outcomes.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca, maker of osimertinib, and researchers included AstraZeneca employees. Dr. Jänne is a consultant for and reported research funding from the company. He is a co-inventor on an EGFR mutations patent. Dr. Garassino is also an AstraZeneca consultant and reported institutional financial interests in the company.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO —

That is a question brewing among some oncologists now that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved osimertinib (Tagrisso, AstraZeneca) for both indications in patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations.

An answer began to emerge in research presented at the American Association for Cancer Research annual meeting.

An exploratory analysis of the FLAURA2 trial found that, when patients have EGFR mutations on baseline circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) testing, the combination treatment can extend progression-free survival (PFS). In this patient group, those receiving osimertinib alongside pemetrexed plus cisplatin or carboplatin had a 9-month PFS advantage compared with those who received osimertinib alone.

Conversely, when patients do not have EGFR mutations following baseline ctDNA testing, osimertinib alone appears to offer similar PFS outcomes to the combination therapy, but with less toxicity.

“Baseline detection of plasma EGFR mutations may identify a subgroup of patients who derive most benefit from the addition of platinum-pemetrexed to osimertinib as first-line treatment of EGFR-mutated advance non–small cell lung cancer,” investigator Pasi A. Jänne, MD, PhD, a lung cancer oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, said during his presentation.

The FLAURA2 trial randomized 557 patients equally to daily osimertinib either alone or with pemetrexed plus cisplatin or carboplatin every 3 weeks for four cycles followed by pemetrexed every 3 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Patients were tested for Ex19del or L858R EGFR mutations at baseline and at 3 and 6 weeks; baseline mutations were found in 73% of evaluable patients.

In patients with baseline mutations, the median PFS was 24.8 months with the combination therapy vs 13.9 months with osimertinib alone (hazard ratio [HR], 0.60).

In patients without baseline mutations, the median PFS was similar in both groups — 33.3 months with the combination vs 30.3 months with monotherapy (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.51-1.72).

The investigators also found that having baseline mutations was associated with worse outcomes regardless of study arm, and mutation clearance was associated with improved outcomes. Clearance occurred more quickly among patients receiving the combination treatment, but almost 90% of patients in both arms cleared their mutations by week 6.

“As we move forward and think about which of our patients we would treat with the combination ... the presence of baseline EGFR mutations in ctDNA may be one of the features that goes into the conversation,” Dr. Jänne said.

Study discussant Marina Chiara Garassino, MD, a thoracic oncologist at the University of Chicago, agreed that this trial can help oncologists make this kind of treatment decision.

Patients with baseline EGFR mutations also tended to have larger tumors, more brain metastases, and worse performance scores; the combination therapy makes sense when such factors are present in patients with baseline EGFR mutations, Dr. Garassino said.

The wrinkle in the findings is that the study used digital droplet polymerase chain reaction (Biodesix) to test for EGFR mutations, which is not commonly used. Clinicians often use next-generation sequencing, which is less sensitive and can lead to false negatives.

It makes it difficult to know how to apply the findings to everyday practice, but Janne hopes a study will be done to correlate next-generation sequencing detection with outcomes.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca, maker of osimertinib, and researchers included AstraZeneca employees. Dr. Jänne is a consultant for and reported research funding from the company. He is a co-inventor on an EGFR mutations patent. Dr. Garassino is also an AstraZeneca consultant and reported institutional financial interests in the company.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AACR

FDA Approves New Bladder Cancer Drug

Specifically, the agent is approved to treat patients with BCG-unresponsive non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer carcinoma in situ with or without Ta or T1 papillary disease.

The FDA declined an initial approval for the combination in May 2023 because of deficiencies the agency observed during its prelicense inspection of third-party manufacturing organizations. In October 2023, ImmunityBio resubmitted the Biologics License Application, which was accepted.

The new therapy represents addresses “an unmet need” in this high-risk bladder cancer population, the company stated in a press release announcing the initial study findings. Typically, patients with intermediate or high-risk disease undergo bladder tumor resection followed by treatment with BCG, but the cancer recurs in up to 50% of patients, including those who experience a complete response, explained ImmunityBio, which acquired Altor BioScience.

Approval was based on findings from the single arm, phase 2/3 open-label QUILT-3.032 study, which included 77 patients with BCG-unresponsive, high-risk disease following transurethral resection. All had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-2.

Patients received nogapendekin alfa inbakicept-pmln induction via intravesical instillation with BCG followed by maintenance therapy for up to 37 months.

According to the FDA’s press release, 62% of patients had a complete response, defined as a negative cystoscopy and urine cytology; 58% of those with a complete response had a duration of response lasting at least 12 months and 40% had a duration of response lasting 24 months or longer.

The safety of the combination was evaluated in a cohort of 88 patients. Serious adverse reactions occurred in 16% of patients. The most common treatment-emergent adverse effects included dysuria, pollakiuria, and hematuria, which are associated with intravesical BCG; 86% of these events were grade 1 or 2. Overall, 7% of patients discontinued the combination owing to adverse reactions.

The recommended dose is 400 mcg administered intravesically with BCG once a week for 6 weeks as induction therapy, with an option for a second induction course if patients don’t achieve a complete response at 3 months. The recommended maintenance therapy dose is 400 mcg with BCG once a week for 3 weeks at months 4, 7, 10, 13, and 19. Patients who achieve a complete response at 25 months and beyond may receive maintenance instillations with BCG once a week for 3 weeks at months 25, 31, and 37. The maximum treatment duration is 37 months.

The FDA recommends discontinuing treatment if disease persists after second induction or owing to disease recurrence, progression, or unacceptable toxicity.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Specifically, the agent is approved to treat patients with BCG-unresponsive non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer carcinoma in situ with or without Ta or T1 papillary disease.

The FDA declined an initial approval for the combination in May 2023 because of deficiencies the agency observed during its prelicense inspection of third-party manufacturing organizations. In October 2023, ImmunityBio resubmitted the Biologics License Application, which was accepted.

The new therapy represents addresses “an unmet need” in this high-risk bladder cancer population, the company stated in a press release announcing the initial study findings. Typically, patients with intermediate or high-risk disease undergo bladder tumor resection followed by treatment with BCG, but the cancer recurs in up to 50% of patients, including those who experience a complete response, explained ImmunityBio, which acquired Altor BioScience.

Approval was based on findings from the single arm, phase 2/3 open-label QUILT-3.032 study, which included 77 patients with BCG-unresponsive, high-risk disease following transurethral resection. All had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-2.

Patients received nogapendekin alfa inbakicept-pmln induction via intravesical instillation with BCG followed by maintenance therapy for up to 37 months.

According to the FDA’s press release, 62% of patients had a complete response, defined as a negative cystoscopy and urine cytology; 58% of those with a complete response had a duration of response lasting at least 12 months and 40% had a duration of response lasting 24 months or longer.

The safety of the combination was evaluated in a cohort of 88 patients. Serious adverse reactions occurred in 16% of patients. The most common treatment-emergent adverse effects included dysuria, pollakiuria, and hematuria, which are associated with intravesical BCG; 86% of these events were grade 1 or 2. Overall, 7% of patients discontinued the combination owing to adverse reactions.

The recommended dose is 400 mcg administered intravesically with BCG once a week for 6 weeks as induction therapy, with an option for a second induction course if patients don’t achieve a complete response at 3 months. The recommended maintenance therapy dose is 400 mcg with BCG once a week for 3 weeks at months 4, 7, 10, 13, and 19. Patients who achieve a complete response at 25 months and beyond may receive maintenance instillations with BCG once a week for 3 weeks at months 25, 31, and 37. The maximum treatment duration is 37 months.

The FDA recommends discontinuing treatment if disease persists after second induction or owing to disease recurrence, progression, or unacceptable toxicity.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Specifically, the agent is approved to treat patients with BCG-unresponsive non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer carcinoma in situ with or without Ta or T1 papillary disease.

The FDA declined an initial approval for the combination in May 2023 because of deficiencies the agency observed during its prelicense inspection of third-party manufacturing organizations. In October 2023, ImmunityBio resubmitted the Biologics License Application, which was accepted.

The new therapy represents addresses “an unmet need” in this high-risk bladder cancer population, the company stated in a press release announcing the initial study findings. Typically, patients with intermediate or high-risk disease undergo bladder tumor resection followed by treatment with BCG, but the cancer recurs in up to 50% of patients, including those who experience a complete response, explained ImmunityBio, which acquired Altor BioScience.

Approval was based on findings from the single arm, phase 2/3 open-label QUILT-3.032 study, which included 77 patients with BCG-unresponsive, high-risk disease following transurethral resection. All had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-2.

Patients received nogapendekin alfa inbakicept-pmln induction via intravesical instillation with BCG followed by maintenance therapy for up to 37 months.

According to the FDA’s press release, 62% of patients had a complete response, defined as a negative cystoscopy and urine cytology; 58% of those with a complete response had a duration of response lasting at least 12 months and 40% had a duration of response lasting 24 months or longer.

The safety of the combination was evaluated in a cohort of 88 patients. Serious adverse reactions occurred in 16% of patients. The most common treatment-emergent adverse effects included dysuria, pollakiuria, and hematuria, which are associated with intravesical BCG; 86% of these events were grade 1 or 2. Overall, 7% of patients discontinued the combination owing to adverse reactions.

The recommended dose is 400 mcg administered intravesically with BCG once a week for 6 weeks as induction therapy, with an option for a second induction course if patients don’t achieve a complete response at 3 months. The recommended maintenance therapy dose is 400 mcg with BCG once a week for 3 weeks at months 4, 7, 10, 13, and 19. Patients who achieve a complete response at 25 months and beyond may receive maintenance instillations with BCG once a week for 3 weeks at months 25, 31, and 37. The maximum treatment duration is 37 months.

The FDA recommends discontinuing treatment if disease persists after second induction or owing to disease recurrence, progression, or unacceptable toxicity.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Inflammation Affects Association Between Furan Exposure and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

TOPLINE:

Exposure to furan, a chemical present in agricultural products, stabilizers, pharmaceuticals, and heat-processed foods, shows a significant positive correlation with the prevalence and respiratory mortality of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers reviewed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database from 2013 to 2018 and identified 270 adults with a diagnosis of COPD and 7212 without.

- The researchers used a restricted cubic spline analysis to examine the association between COPD risk and blood furan levels and mediating analysis to explore the impact of inflammation.

- The primary outcome of the study was respiratory mortality.

TAKEAWAY:

- Ten COPD patients died of respiratory diseases; adjusted analysis showed a positive correlation between log10-transformed blood furan levels and respiratory mortality in COPD patients (hazard ratio, 41.00, P = .003).

- In a logistic regression analysis, log10-transformed blood furan levels were significantly associated with increased risk for COPD; individuals in the fifth quartile had significantly increased risk compared with the first quartile (odds ratio, 4.47; P = .006).

- COPD demonstrated a significant positive association with monocytes, neutrophils, and basophils, which showed mediated proportions of 8.73%, 20.90%, and 10.94%, respectively, in the relationship between furan exposure and prevalence of COPD (P < .05 for all).

IN PRACTICE:

“The implication [of the findings] is that reducing exposure to furan in the environment could potentially lower the incidence of COPD and improve the prognosis for COPD patients,” but large-scale prospective cohort studies are needed, the researchers wrote in their conclusion.

SOURCE:

The lead author of the study was Di Sun, MD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, China. The study was published online in BMC Public Health.

LIMITATIONS:

The cross-sectional design prevented establishment of a causal relationship between furan exposure and COPD; lack of data on the conditions of furan exposure and the reliance on self-reports for COPD diagnosis were among the factors that limited the study findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the High Level Public Health Technology Talent Construction Project and Reform and Development Program of Beijing Institute of Respiratory Medicine. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Exposure to furan, a chemical present in agricultural products, stabilizers, pharmaceuticals, and heat-processed foods, shows a significant positive correlation with the prevalence and respiratory mortality of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers reviewed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database from 2013 to 2018 and identified 270 adults with a diagnosis of COPD and 7212 without.

- The researchers used a restricted cubic spline analysis to examine the association between COPD risk and blood furan levels and mediating analysis to explore the impact of inflammation.

- The primary outcome of the study was respiratory mortality.

TAKEAWAY:

- Ten COPD patients died of respiratory diseases; adjusted analysis showed a positive correlation between log10-transformed blood furan levels and respiratory mortality in COPD patients (hazard ratio, 41.00, P = .003).

- In a logistic regression analysis, log10-transformed blood furan levels were significantly associated with increased risk for COPD; individuals in the fifth quartile had significantly increased risk compared with the first quartile (odds ratio, 4.47; P = .006).

- COPD demonstrated a significant positive association with monocytes, neutrophils, and basophils, which showed mediated proportions of 8.73%, 20.90%, and 10.94%, respectively, in the relationship between furan exposure and prevalence of COPD (P < .05 for all).

IN PRACTICE:

“The implication [of the findings] is that reducing exposure to furan in the environment could potentially lower the incidence of COPD and improve the prognosis for COPD patients,” but large-scale prospective cohort studies are needed, the researchers wrote in their conclusion.

SOURCE:

The lead author of the study was Di Sun, MD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, China. The study was published online in BMC Public Health.

LIMITATIONS:

The cross-sectional design prevented establishment of a causal relationship between furan exposure and COPD; lack of data on the conditions of furan exposure and the reliance on self-reports for COPD diagnosis were among the factors that limited the study findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the High Level Public Health Technology Talent Construction Project and Reform and Development Program of Beijing Institute of Respiratory Medicine. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Exposure to furan, a chemical present in agricultural products, stabilizers, pharmaceuticals, and heat-processed foods, shows a significant positive correlation with the prevalence and respiratory mortality of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers reviewed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database from 2013 to 2018 and identified 270 adults with a diagnosis of COPD and 7212 without.

- The researchers used a restricted cubic spline analysis to examine the association between COPD risk and blood furan levels and mediating analysis to explore the impact of inflammation.

- The primary outcome of the study was respiratory mortality.

TAKEAWAY:

- Ten COPD patients died of respiratory diseases; adjusted analysis showed a positive correlation between log10-transformed blood furan levels and respiratory mortality in COPD patients (hazard ratio, 41.00, P = .003).

- In a logistic regression analysis, log10-transformed blood furan levels were significantly associated with increased risk for COPD; individuals in the fifth quartile had significantly increased risk compared with the first quartile (odds ratio, 4.47; P = .006).

- COPD demonstrated a significant positive association with monocytes, neutrophils, and basophils, which showed mediated proportions of 8.73%, 20.90%, and 10.94%, respectively, in the relationship between furan exposure and prevalence of COPD (P < .05 for all).

IN PRACTICE:

“The implication [of the findings] is that reducing exposure to furan in the environment could potentially lower the incidence of COPD and improve the prognosis for COPD patients,” but large-scale prospective cohort studies are needed, the researchers wrote in their conclusion.

SOURCE:

The lead author of the study was Di Sun, MD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, China. The study was published online in BMC Public Health.

LIMITATIONS:

The cross-sectional design prevented establishment of a causal relationship between furan exposure and COPD; lack of data on the conditions of furan exposure and the reliance on self-reports for COPD diagnosis were among the factors that limited the study findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the High Level Public Health Technology Talent Construction Project and Reform and Development Program of Beijing Institute of Respiratory Medicine. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Occipital Scalp Nodule in a Newborn

The Diagnosis: Subcutaneous Fat Necrosis

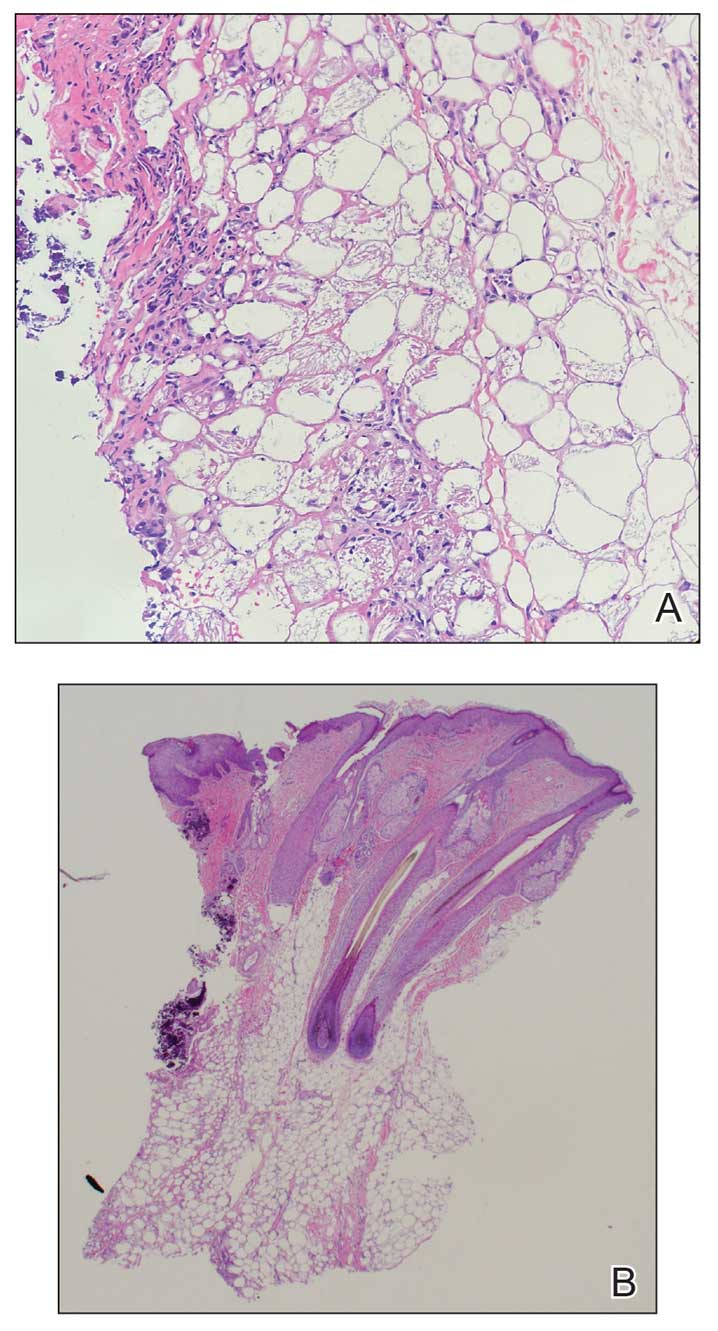

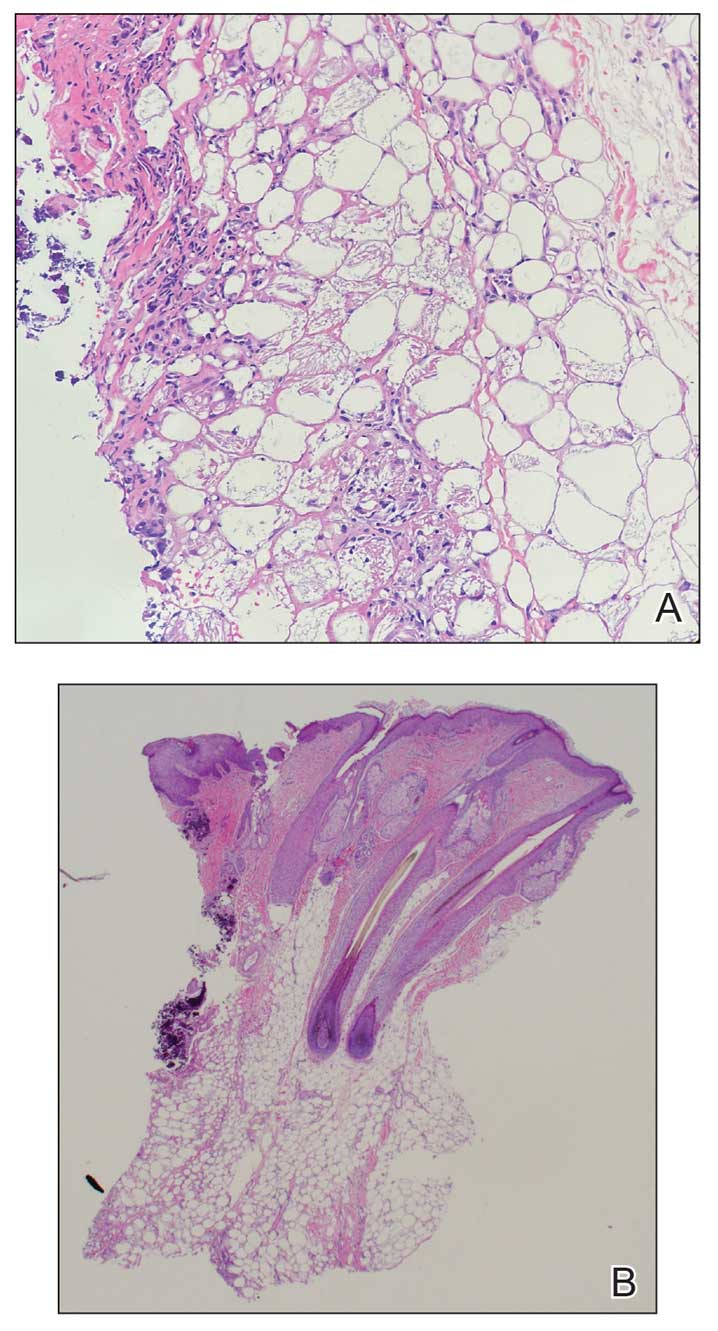

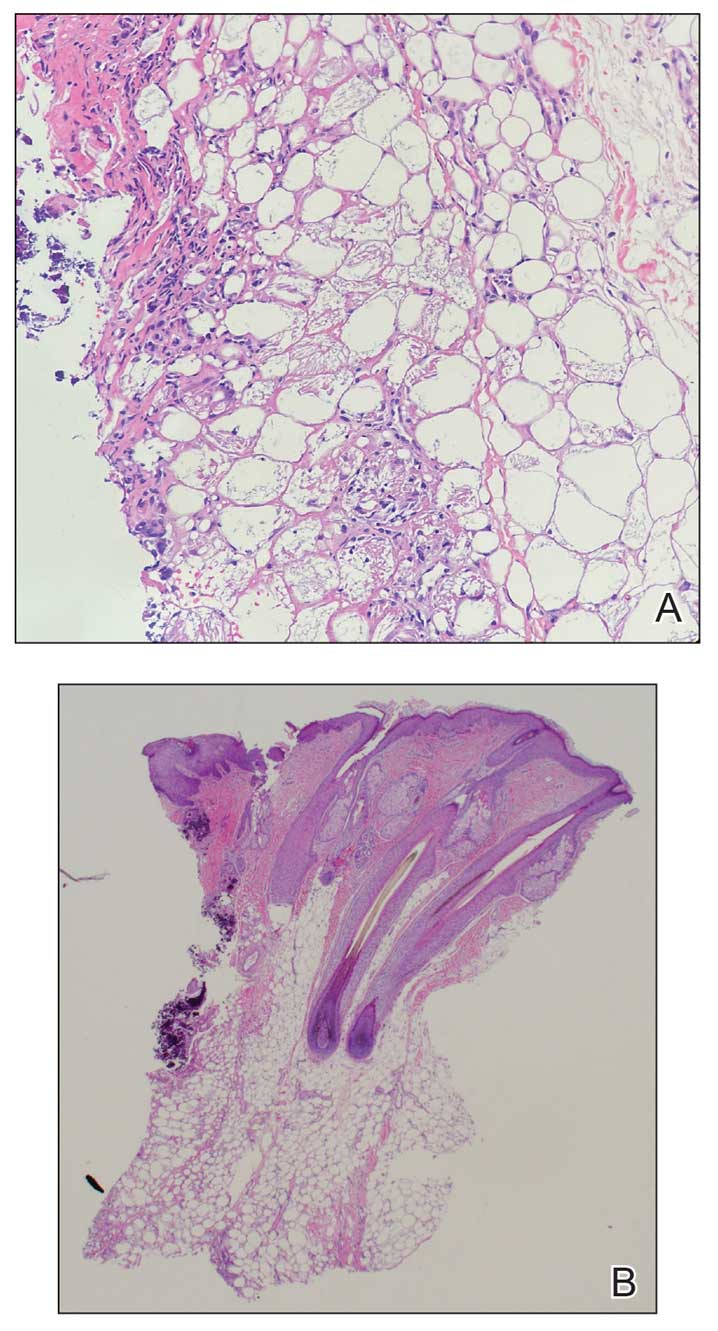

Histopathology revealed lobular panniculitis with lymphohistiocytic inflammation, lipid crystals, and calcifications in our patient (Figure). Subcutaneous fat necrosis (SCFN) was diagnosed based on these characteristic histopathologic findings. No further treatment was pursued.

Subcutaneous fat necrosis is a rare, self-limiting panniculitis that typically resolves within several weeks to months without scarring. It manifests as red or violaceous subcutaneous nodules or plaques most commonly on the buttocks, trunk, proximal arms and legs, and cheeks.1 Histopathology reveals lobular panniculitis with dense granulomatous infiltrates of histiocytes, eosinophils, and multinucleated giant cells with needle-shaped crystals. Focal areas of fat necrosis with calcification also can be seen.2

The epidemiology of SCFN is unknown. Most cases occur in healthy full-term to postterm neonates who experience hypoxia, other prenatal stressors, or therapeutic hypothermia for the treatment of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.3 Although the etiology is unclear, certain inciting factors such as local tissue hypoxia, cold exposure, meconium aspiration, maternal diabetes, preeclampsia, and mechanical pressure have been proposed. Our patient underwent hypothermic cooling protocol, and it has been suggested that the increased saturated to unsaturated fat concentration in the skin of newborns increases the melting point, thus predisposing them to fat crystalization.4 Cases of SCFN involving the scalp are rare; therefore, any newborns receiving hypothermic therapy for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy should have a thorough skin examination with possible biopsy of lesions that are characteristic of SCFN, such as red or violaceous subcutaneous nodules or plaques, for specific disease identification.