User login

Which children are at greatest risk for atopic dermatitis?

MADRID – A parental history of asthma or allergic rhinitis significantly increases the risk that a child will develop atopic dermatitis, and that risk doubles if a parent has a history of atopic dermatitis rather than another atopic disease, Nina H. Ravn reported at a meeting of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis held in conjunction with the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

She presented a comprehensive meta-analysis of 149 published studies addressing the risk of developing atopic dermatitis according to parental history of atopic disease. The studies included more than 656,000 participants. The picture that emerged from the meta-analysis was one of a stepwise increase in the risk of pediatric atopic dermatitis according to the type and number of parental atopic diseases present.

“This is something that hopefully can be useful when you talk with parents or parents-to-be with atopic diseases and they want to know how their disease might affect their child,” explained Ms. Ravn of the University of Copenhagen.

It’s also information that clinicians will find helpful in appropriately targeting primary prevention interventions if and when methods of proven efficacy become available. That’s a likely prospect, as this is now an extremely active field of research, she noted.

The meta-analysis showed that a parental history of atopic dermatitis was associated with a 3.3-fold greater risk of atopic dermatitis in the offspring than in families without a parental history of atopy. A parental history of asthma was associated with a 1.56-fold increased risk, while allergic rhinitis in a parent was linked to a 1.68-fold increased risk.

“It does matter what type of atopic disease the parents have,” she observed. “Those with a parental history of asthma or allergic rhinitis can be considered as being at more of an intermediate risk level, while those with a parental history of atopic dermatitis are a particularly high risk group.”

Of note, the risk of pediatric atopic dermatitis was the same regardless of whether the father or mother was the one with a history of atopic disease. If one parent had a history of an atopic disease, the pediatric risk was increased 1.3-fold compared to when the parental history was negative. If both parents had a history of atopic illness, the risk jumped to 2.08-fold. And if one parent had a history of more than one form of atopic disease, the pediatric risk of atopic dermatitis was increased 2.32-fold.

“An interesting result that was new to me what that fathers’ and mothers’ contribution to risk is equal,” said session cochair Andreas Wollenberg, MD, professor of dermatology at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. “For the past 2 decades we were always taught that the mother would have a greater impact on that risk.”

“I was also surprised by our findings,” Ms. Ravn replied. “But when we pooled all the data there really was no difference, nor in any of our subanalyses.”

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

SOURCE: Ravn NH. THE EADV CONGRESS.

MADRID – A parental history of asthma or allergic rhinitis significantly increases the risk that a child will develop atopic dermatitis, and that risk doubles if a parent has a history of atopic dermatitis rather than another atopic disease, Nina H. Ravn reported at a meeting of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis held in conjunction with the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

She presented a comprehensive meta-analysis of 149 published studies addressing the risk of developing atopic dermatitis according to parental history of atopic disease. The studies included more than 656,000 participants. The picture that emerged from the meta-analysis was one of a stepwise increase in the risk of pediatric atopic dermatitis according to the type and number of parental atopic diseases present.

“This is something that hopefully can be useful when you talk with parents or parents-to-be with atopic diseases and they want to know how their disease might affect their child,” explained Ms. Ravn of the University of Copenhagen.

It’s also information that clinicians will find helpful in appropriately targeting primary prevention interventions if and when methods of proven efficacy become available. That’s a likely prospect, as this is now an extremely active field of research, she noted.

The meta-analysis showed that a parental history of atopic dermatitis was associated with a 3.3-fold greater risk of atopic dermatitis in the offspring than in families without a parental history of atopy. A parental history of asthma was associated with a 1.56-fold increased risk, while allergic rhinitis in a parent was linked to a 1.68-fold increased risk.

“It does matter what type of atopic disease the parents have,” she observed. “Those with a parental history of asthma or allergic rhinitis can be considered as being at more of an intermediate risk level, while those with a parental history of atopic dermatitis are a particularly high risk group.”

Of note, the risk of pediatric atopic dermatitis was the same regardless of whether the father or mother was the one with a history of atopic disease. If one parent had a history of an atopic disease, the pediatric risk was increased 1.3-fold compared to when the parental history was negative. If both parents had a history of atopic illness, the risk jumped to 2.08-fold. And if one parent had a history of more than one form of atopic disease, the pediatric risk of atopic dermatitis was increased 2.32-fold.

“An interesting result that was new to me what that fathers’ and mothers’ contribution to risk is equal,” said session cochair Andreas Wollenberg, MD, professor of dermatology at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. “For the past 2 decades we were always taught that the mother would have a greater impact on that risk.”

“I was also surprised by our findings,” Ms. Ravn replied. “But when we pooled all the data there really was no difference, nor in any of our subanalyses.”

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

SOURCE: Ravn NH. THE EADV CONGRESS.

MADRID – A parental history of asthma or allergic rhinitis significantly increases the risk that a child will develop atopic dermatitis, and that risk doubles if a parent has a history of atopic dermatitis rather than another atopic disease, Nina H. Ravn reported at a meeting of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis held in conjunction with the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

She presented a comprehensive meta-analysis of 149 published studies addressing the risk of developing atopic dermatitis according to parental history of atopic disease. The studies included more than 656,000 participants. The picture that emerged from the meta-analysis was one of a stepwise increase in the risk of pediatric atopic dermatitis according to the type and number of parental atopic diseases present.

“This is something that hopefully can be useful when you talk with parents or parents-to-be with atopic diseases and they want to know how their disease might affect their child,” explained Ms. Ravn of the University of Copenhagen.

It’s also information that clinicians will find helpful in appropriately targeting primary prevention interventions if and when methods of proven efficacy become available. That’s a likely prospect, as this is now an extremely active field of research, she noted.

The meta-analysis showed that a parental history of atopic dermatitis was associated with a 3.3-fold greater risk of atopic dermatitis in the offspring than in families without a parental history of atopy. A parental history of asthma was associated with a 1.56-fold increased risk, while allergic rhinitis in a parent was linked to a 1.68-fold increased risk.

“It does matter what type of atopic disease the parents have,” she observed. “Those with a parental history of asthma or allergic rhinitis can be considered as being at more of an intermediate risk level, while those with a parental history of atopic dermatitis are a particularly high risk group.”

Of note, the risk of pediatric atopic dermatitis was the same regardless of whether the father or mother was the one with a history of atopic disease. If one parent had a history of an atopic disease, the pediatric risk was increased 1.3-fold compared to when the parental history was negative. If both parents had a history of atopic illness, the risk jumped to 2.08-fold. And if one parent had a history of more than one form of atopic disease, the pediatric risk of atopic dermatitis was increased 2.32-fold.

“An interesting result that was new to me what that fathers’ and mothers’ contribution to risk is equal,” said session cochair Andreas Wollenberg, MD, professor of dermatology at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. “For the past 2 decades we were always taught that the mother would have a greater impact on that risk.”

“I was also surprised by our findings,” Ms. Ravn replied. “But when we pooled all the data there really was no difference, nor in any of our subanalyses.”

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

SOURCE: Ravn NH. THE EADV CONGRESS.

REPORTING FROM The EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Pediatric atopic dermatitis risk varies according to type of parental history of atopic disease.

Major finding: A parental history of atopic dermatitis is associated with a 3.3-fold increased risk of atopic dermatitis in the child, twice the risk associated with parental asthma or allergic rhinitis.

Study details: This was a systematic review and meta-analysis of 149 published studies with 656,711 participants.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, conducted free of commercial support.

Source: Ravn NH. The EADV Congress.

FDA okays ubrogepant for acute migraine treatment

The Food and Drug Administration has approved ubrogepant (Ubrelvy, Allergan) for the acute treatment of migraine with or without aura in adults.

Ubrogepant is the first drug in the class of oral calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonists approved for the acute treatment of migraine. It is approved in two dose strengths (50 mg and 100 mg).

The drug is not indicated, however, for the preventive treatment of migraine.

“Migraine is an often disabling condition that affects an estimated 37 million people in the U.S.,” Billy Dunn, MD, acting director of the office of neuroscience in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in an FDA news release.

Ubrogepant represents “an important new option for the acute treatment of migraine in adults, as it is the first drug in its class approved for this indication. The FDA is pleased to approve a novel treatment for patients suffering from migraine and will continue to work with stakeholders to promote the development of new safe and effective migraine therapies,” added Dr. Dunn.

The safety and efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine was demonstrated in two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II). In total, 1,439 adults with a history of migraine, with and without aura, received ubrogepant to treat an ongoing migraine.

“Both 50-mg and 100-mg dose strengths demonstrated significantly greater rates of pain freedom and freedom from the most bothersome migraine-associated symptom at 2 hours, compared with placebo,” Allergan said in a news release announcing approval.

The most common side effects reported by patients in the clinical trials were nausea, tiredness, and dry mouth. Ubrogepant is contraindicated for coadministration with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors.

The company expects to have ubrogepant available in the first quarter of 2020.

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved ubrogepant (Ubrelvy, Allergan) for the acute treatment of migraine with or without aura in adults.

Ubrogepant is the first drug in the class of oral calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonists approved for the acute treatment of migraine. It is approved in two dose strengths (50 mg and 100 mg).

The drug is not indicated, however, for the preventive treatment of migraine.

“Migraine is an often disabling condition that affects an estimated 37 million people in the U.S.,” Billy Dunn, MD, acting director of the office of neuroscience in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in an FDA news release.

Ubrogepant represents “an important new option for the acute treatment of migraine in adults, as it is the first drug in its class approved for this indication. The FDA is pleased to approve a novel treatment for patients suffering from migraine and will continue to work with stakeholders to promote the development of new safe and effective migraine therapies,” added Dr. Dunn.

The safety and efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine was demonstrated in two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II). In total, 1,439 adults with a history of migraine, with and without aura, received ubrogepant to treat an ongoing migraine.

“Both 50-mg and 100-mg dose strengths demonstrated significantly greater rates of pain freedom and freedom from the most bothersome migraine-associated symptom at 2 hours, compared with placebo,” Allergan said in a news release announcing approval.

The most common side effects reported by patients in the clinical trials were nausea, tiredness, and dry mouth. Ubrogepant is contraindicated for coadministration with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors.

The company expects to have ubrogepant available in the first quarter of 2020.

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved ubrogepant (Ubrelvy, Allergan) for the acute treatment of migraine with or without aura in adults.

Ubrogepant is the first drug in the class of oral calcitonin gene–related peptide receptor antagonists approved for the acute treatment of migraine. It is approved in two dose strengths (50 mg and 100 mg).

The drug is not indicated, however, for the preventive treatment of migraine.

“Migraine is an often disabling condition that affects an estimated 37 million people in the U.S.,” Billy Dunn, MD, acting director of the office of neuroscience in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in an FDA news release.

Ubrogepant represents “an important new option for the acute treatment of migraine in adults, as it is the first drug in its class approved for this indication. The FDA is pleased to approve a novel treatment for patients suffering from migraine and will continue to work with stakeholders to promote the development of new safe and effective migraine therapies,” added Dr. Dunn.

The safety and efficacy of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine was demonstrated in two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II). In total, 1,439 adults with a history of migraine, with and without aura, received ubrogepant to treat an ongoing migraine.

“Both 50-mg and 100-mg dose strengths demonstrated significantly greater rates of pain freedom and freedom from the most bothersome migraine-associated symptom at 2 hours, compared with placebo,” Allergan said in a news release announcing approval.

The most common side effects reported by patients in the clinical trials were nausea, tiredness, and dry mouth. Ubrogepant is contraindicated for coadministration with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors.

The company expects to have ubrogepant available in the first quarter of 2020.

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

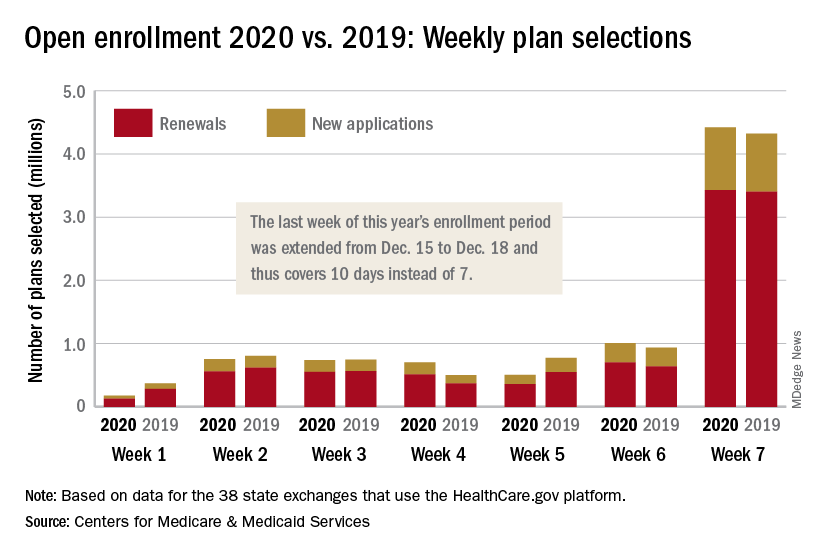

HealthCare.gov enrollment ends with unexpected extension

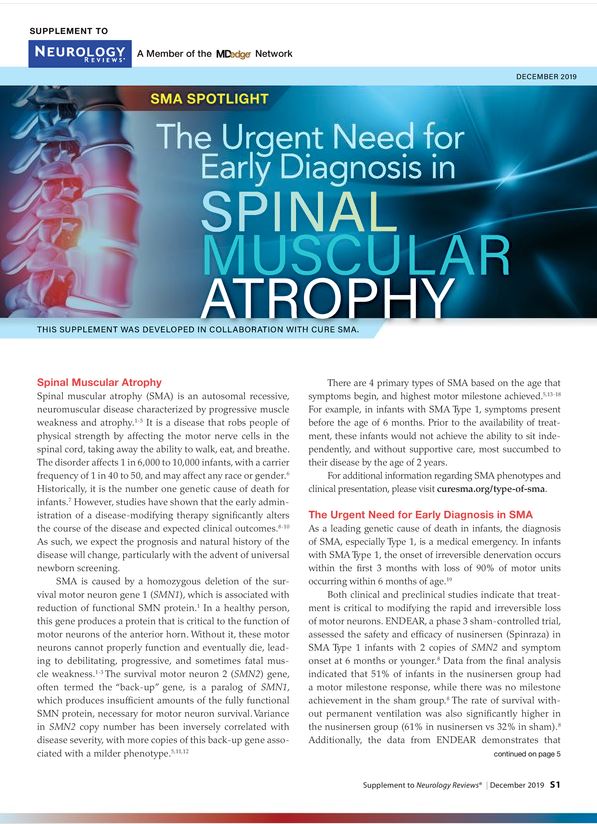

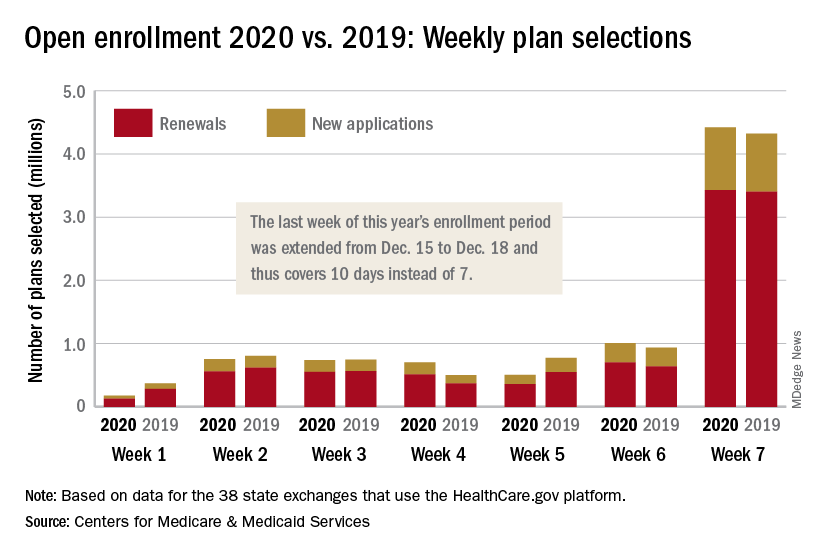

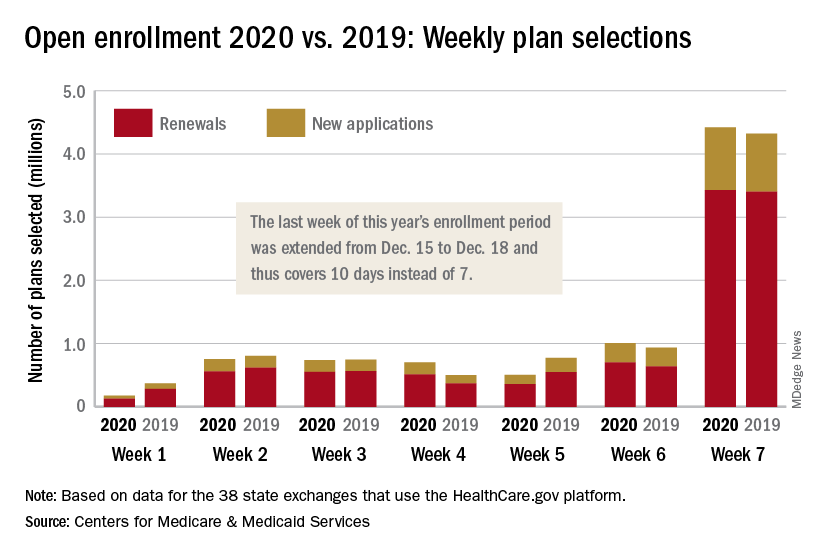

The 2020 open enrollment period on HealthCare.gov ended on Dec. 18 after an unplanned extension, but Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma touted the system’s stability.

“We are reporting that for the third year in a row enrollment in the Federal Exchange remained stable,” she said in a statement. “For all our successes, too many Americans who do not qualify for subsidies still cannot afford premiums that remain in the stratosphere – constituting a new class of uninsured. The Affordable Care Act remains fundamentally broken and nothing less than wholesale reforms can fix it.”

The open enrollment period was scheduled to end on Dec. 15, but some individuals had problems signing up for coverage that day so the CMS extended the deadline to Dec. 18. During that last “week,” consumers selected over 4.4 million plans – 3.4 million were renewals and just under 1 million were new – bringing the cumulative total for the 2020 enrollment period to 8.3 million plans selected from Nov. 1 to Dec. 17, CMS reported.

Plans selected during the last 3 hours of open enrollment – 12:00 a.m. to 3:00 a.m. on Dec. 18 – are not included in the weekly or final counts, so it’s still possible that the 2020 enrollment could surpass last year’s total of 8.45 million plan selections. The fully updated enrollment data will be released during the second week of January, CMS said.

The 2020 open enrollment period on HealthCare.gov ended on Dec. 18 after an unplanned extension, but Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma touted the system’s stability.

“We are reporting that for the third year in a row enrollment in the Federal Exchange remained stable,” she said in a statement. “For all our successes, too many Americans who do not qualify for subsidies still cannot afford premiums that remain in the stratosphere – constituting a new class of uninsured. The Affordable Care Act remains fundamentally broken and nothing less than wholesale reforms can fix it.”

The open enrollment period was scheduled to end on Dec. 15, but some individuals had problems signing up for coverage that day so the CMS extended the deadline to Dec. 18. During that last “week,” consumers selected over 4.4 million plans – 3.4 million were renewals and just under 1 million were new – bringing the cumulative total for the 2020 enrollment period to 8.3 million plans selected from Nov. 1 to Dec. 17, CMS reported.

Plans selected during the last 3 hours of open enrollment – 12:00 a.m. to 3:00 a.m. on Dec. 18 – are not included in the weekly or final counts, so it’s still possible that the 2020 enrollment could surpass last year’s total of 8.45 million plan selections. The fully updated enrollment data will be released during the second week of January, CMS said.

The 2020 open enrollment period on HealthCare.gov ended on Dec. 18 after an unplanned extension, but Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma touted the system’s stability.

“We are reporting that for the third year in a row enrollment in the Federal Exchange remained stable,” she said in a statement. “For all our successes, too many Americans who do not qualify for subsidies still cannot afford premiums that remain in the stratosphere – constituting a new class of uninsured. The Affordable Care Act remains fundamentally broken and nothing less than wholesale reforms can fix it.”

The open enrollment period was scheduled to end on Dec. 15, but some individuals had problems signing up for coverage that day so the CMS extended the deadline to Dec. 18. During that last “week,” consumers selected over 4.4 million plans – 3.4 million were renewals and just under 1 million were new – bringing the cumulative total for the 2020 enrollment period to 8.3 million plans selected from Nov. 1 to Dec. 17, CMS reported.

Plans selected during the last 3 hours of open enrollment – 12:00 a.m. to 3:00 a.m. on Dec. 18 – are not included in the weekly or final counts, so it’s still possible that the 2020 enrollment could surpass last year’s total of 8.45 million plan selections. The fully updated enrollment data will be released during the second week of January, CMS said.

Appropriations bill, now law, eliminates ACA taxes, raises tobacco age

Congress took steps to permanently eliminate three taxes from within the Affordable Care Act that were enacted to help offset the law’s cost, but have been sporadically implemented.

The appropriations bill, H.R. 1865, signed into law Dec. 20 by President Trump, includes a number of other health-related provisions, including increasing the minimum age for purchasing tobacco to 21.

The repealed ACA-related taxes include the medical device tax (which previously had been delayed twice); the health insurance tax (which taxed insurers that offered fully insured health coverage in the individual market and has been under sporadic moratorium); and the so-called Cadillac tax on high-cost health plans, which is currently under suspension until the end of 2022.

The appropriations bill offers no offset for the lost revenue.

The tax repeals come on the heels of the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals’ ruling that the ACA’s individual mandate is unconstitutional, which is putting the ACA in its entirety in jeopardy should the district court rule that the individual mandate is not severable from the rest of the law, which would invalidate the ACA.

Other key provisions in H.R. 1865 include the short-term extension of a number of federal programs, including a delay in Medicaid disproportionate share hospital payment reductions, payments to community health centers, funding for teaching health centers, and the special diabetes program. Funding for these extenders will go through May 22, 2020.

H.R. 1865 is also notable for what is missing, including any broad provisions that address the price of prescription drugs and surprise billing.

The House of Representatives earlier this month passed a bill, H.R. 3, aimed at lowering the cost of prescription drugs, but that bill was essentially dead on arrival in the Senate, with Speaker Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) saying he would not bring it to the floor for consideration. There was also a veto threat from the White House hanging over it on the off chance it got past the upper chamber.

There was some optimism that surprise billing would be addressed in the appropriations bill after a bipartisan agreement was reached with the House Energy and Commerce Committee and the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, but that stalled after a different bipartisan agreement forged in the House Ways and Means Committee was introduced. More work is expected on surprise billing in the coming year.

One portion of H.R. 1865 that does address the cost of drugs is the Creating and Restoring Equal Access to Equivalent Samples (CREATES) Act, which is designed to allow generic manufacturers easier access to brand-name samples to help bring more generic drugs to market.

Another provision that gained applause from the American College of Physicians is the funding for research into gun violence.

“We are particularly encouraged that the legislation authorizes funding for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health to study gun violence and safety for the first time in decades,” ACP President Robert McLean, MD, said in a statement. “The key to solving any public health crisis is knowledge, and our efforts to prevent firearms-related injuries and deaths have been hampered by inadequate research. This funding is a promising first step.

However, ACP called for more action in this area.

“Congress should do more to reduce injuries and deaths from firearms,” Dr. McLean said. “The Senate should pass the Bipartisan Background Check Act and reauthorize the Violence Against Women Act, which would close the ‘domestic violence’ loophole in the background check system, as passed by the House of Representatives.”

H.R. 1865 also reauthorizes the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute for 10 additional years.

Congress took steps to permanently eliminate three taxes from within the Affordable Care Act that were enacted to help offset the law’s cost, but have been sporadically implemented.

The appropriations bill, H.R. 1865, signed into law Dec. 20 by President Trump, includes a number of other health-related provisions, including increasing the minimum age for purchasing tobacco to 21.

The repealed ACA-related taxes include the medical device tax (which previously had been delayed twice); the health insurance tax (which taxed insurers that offered fully insured health coverage in the individual market and has been under sporadic moratorium); and the so-called Cadillac tax on high-cost health plans, which is currently under suspension until the end of 2022.

The appropriations bill offers no offset for the lost revenue.

The tax repeals come on the heels of the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals’ ruling that the ACA’s individual mandate is unconstitutional, which is putting the ACA in its entirety in jeopardy should the district court rule that the individual mandate is not severable from the rest of the law, which would invalidate the ACA.

Other key provisions in H.R. 1865 include the short-term extension of a number of federal programs, including a delay in Medicaid disproportionate share hospital payment reductions, payments to community health centers, funding for teaching health centers, and the special diabetes program. Funding for these extenders will go through May 22, 2020.

H.R. 1865 is also notable for what is missing, including any broad provisions that address the price of prescription drugs and surprise billing.

The House of Representatives earlier this month passed a bill, H.R. 3, aimed at lowering the cost of prescription drugs, but that bill was essentially dead on arrival in the Senate, with Speaker Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) saying he would not bring it to the floor for consideration. There was also a veto threat from the White House hanging over it on the off chance it got past the upper chamber.

There was some optimism that surprise billing would be addressed in the appropriations bill after a bipartisan agreement was reached with the House Energy and Commerce Committee and the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, but that stalled after a different bipartisan agreement forged in the House Ways and Means Committee was introduced. More work is expected on surprise billing in the coming year.

One portion of H.R. 1865 that does address the cost of drugs is the Creating and Restoring Equal Access to Equivalent Samples (CREATES) Act, which is designed to allow generic manufacturers easier access to brand-name samples to help bring more generic drugs to market.

Another provision that gained applause from the American College of Physicians is the funding for research into gun violence.

“We are particularly encouraged that the legislation authorizes funding for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health to study gun violence and safety for the first time in decades,” ACP President Robert McLean, MD, said in a statement. “The key to solving any public health crisis is knowledge, and our efforts to prevent firearms-related injuries and deaths have been hampered by inadequate research. This funding is a promising first step.

However, ACP called for more action in this area.

“Congress should do more to reduce injuries and deaths from firearms,” Dr. McLean said. “The Senate should pass the Bipartisan Background Check Act and reauthorize the Violence Against Women Act, which would close the ‘domestic violence’ loophole in the background check system, as passed by the House of Representatives.”

H.R. 1865 also reauthorizes the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute for 10 additional years.

Congress took steps to permanently eliminate three taxes from within the Affordable Care Act that were enacted to help offset the law’s cost, but have been sporadically implemented.

The appropriations bill, H.R. 1865, signed into law Dec. 20 by President Trump, includes a number of other health-related provisions, including increasing the minimum age for purchasing tobacco to 21.

The repealed ACA-related taxes include the medical device tax (which previously had been delayed twice); the health insurance tax (which taxed insurers that offered fully insured health coverage in the individual market and has been under sporadic moratorium); and the so-called Cadillac tax on high-cost health plans, which is currently under suspension until the end of 2022.

The appropriations bill offers no offset for the lost revenue.

The tax repeals come on the heels of the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals’ ruling that the ACA’s individual mandate is unconstitutional, which is putting the ACA in its entirety in jeopardy should the district court rule that the individual mandate is not severable from the rest of the law, which would invalidate the ACA.

Other key provisions in H.R. 1865 include the short-term extension of a number of federal programs, including a delay in Medicaid disproportionate share hospital payment reductions, payments to community health centers, funding for teaching health centers, and the special diabetes program. Funding for these extenders will go through May 22, 2020.

H.R. 1865 is also notable for what is missing, including any broad provisions that address the price of prescription drugs and surprise billing.

The House of Representatives earlier this month passed a bill, H.R. 3, aimed at lowering the cost of prescription drugs, but that bill was essentially dead on arrival in the Senate, with Speaker Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) saying he would not bring it to the floor for consideration. There was also a veto threat from the White House hanging over it on the off chance it got past the upper chamber.

There was some optimism that surprise billing would be addressed in the appropriations bill after a bipartisan agreement was reached with the House Energy and Commerce Committee and the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, but that stalled after a different bipartisan agreement forged in the House Ways and Means Committee was introduced. More work is expected on surprise billing in the coming year.

One portion of H.R. 1865 that does address the cost of drugs is the Creating and Restoring Equal Access to Equivalent Samples (CREATES) Act, which is designed to allow generic manufacturers easier access to brand-name samples to help bring more generic drugs to market.

Another provision that gained applause from the American College of Physicians is the funding for research into gun violence.

“We are particularly encouraged that the legislation authorizes funding for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health to study gun violence and safety for the first time in decades,” ACP President Robert McLean, MD, said in a statement. “The key to solving any public health crisis is knowledge, and our efforts to prevent firearms-related injuries and deaths have been hampered by inadequate research. This funding is a promising first step.

However, ACP called for more action in this area.

“Congress should do more to reduce injuries and deaths from firearms,” Dr. McLean said. “The Senate should pass the Bipartisan Background Check Act and reauthorize the Violence Against Women Act, which would close the ‘domestic violence’ loophole in the background check system, as passed by the House of Representatives.”

H.R. 1865 also reauthorizes the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute for 10 additional years.

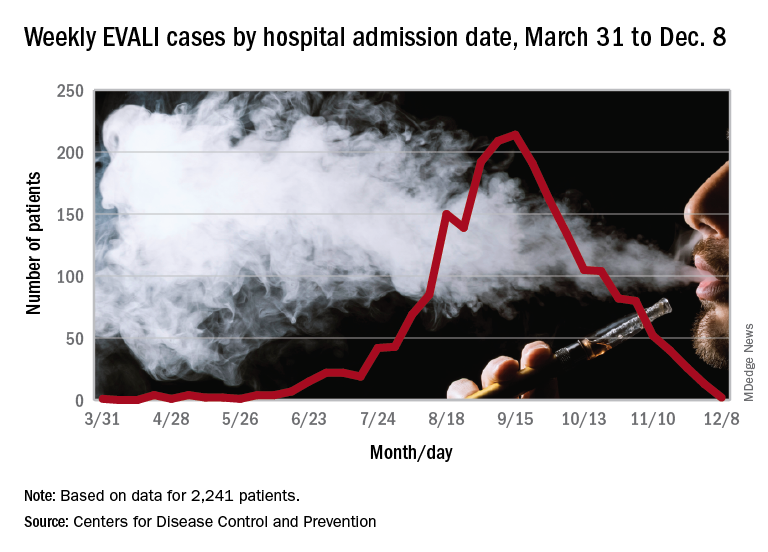

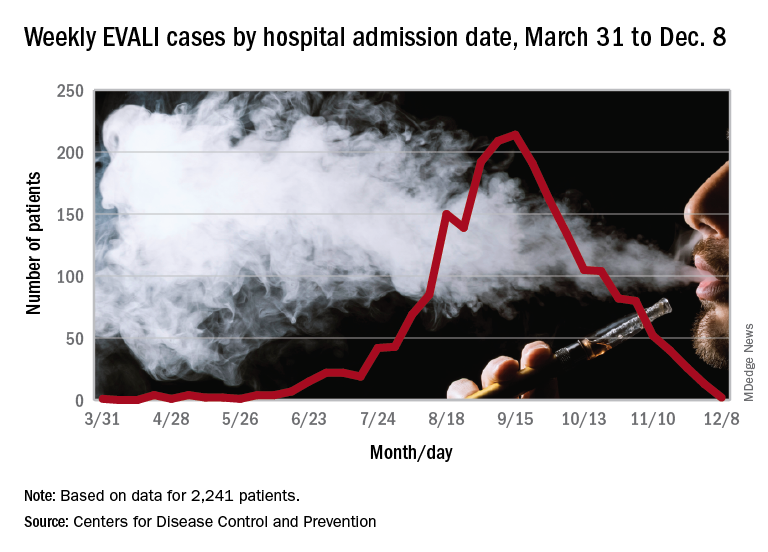

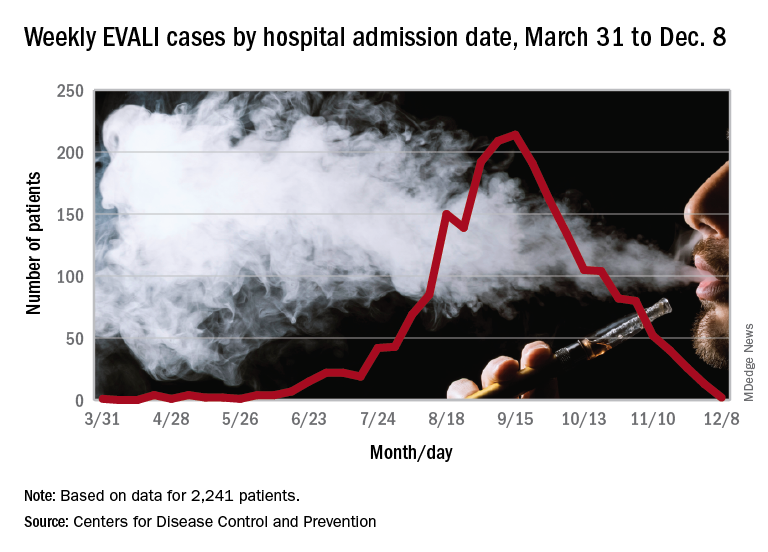

EVALI readmissions and deaths prompt guideline change

Those who required rehospitalization for e-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) and those who died after discharge were more likely to have one or more chronic conditions than were other EVALI patients, and those “who died also were more likely to have been admitted to an intensive care unit, experienced respiratory failure necessitating intubation and mechanical ventilation, and were significantly older,” Christina A. Mikosz, MD, and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Their analysis included the 1,139 EVALI patients who were discharged on or after Oct. 31, 2019. Of that group, 31 (2.7%) patients were rehospitalized and subsequently discharged and another 7 died after the initial discharge. The median age was 54 years for those who died, 27 years for those who were rehospitalized, and 23 for those who survived without rehospitalization, said Dr. Mikosz of the CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Atlanta, and associates.

Those findings, along with the rates of one or more comorbidities – 83% for those who died, 71% for those who were rehospitalized, and 26% for those who did not die or get readmitted – prompted the CDC to update its guidance for postdischarge follow-up of EVALI patients.

That update involves six specific recommendations to determine readiness for discharge, which include “confirming no clinically significant fluctuations in vital signs for at least 24-48 hours before discharge [and] preparation for hospital discharge and postdischarge care coordination to reduce risk of rehospitalization and death,” Mary E. Evans, MD, and associates said in a separate CDC communication (MMWR. 2019 Dec. 20. 68[early release]:1-6).

As of Dec. 17, the CDC reports that 2,506 patients have been hospitalized with EVALI since March 31, 2019, and 54 deaths have been confirmed in 27 states and the District of Columbia. The outbreak appears to have peaked in September, but cases are still being reported: 13 during the week of Dec. 1-7 and one case for the week of Dec. 8-14.

SOURCE: Mikosz CA et al. MMWR. 2019 Dec. 20. 68[early release]:1-7.

Those who required rehospitalization for e-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) and those who died after discharge were more likely to have one or more chronic conditions than were other EVALI patients, and those “who died also were more likely to have been admitted to an intensive care unit, experienced respiratory failure necessitating intubation and mechanical ventilation, and were significantly older,” Christina A. Mikosz, MD, and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Their analysis included the 1,139 EVALI patients who were discharged on or after Oct. 31, 2019. Of that group, 31 (2.7%) patients were rehospitalized and subsequently discharged and another 7 died after the initial discharge. The median age was 54 years for those who died, 27 years for those who were rehospitalized, and 23 for those who survived without rehospitalization, said Dr. Mikosz of the CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Atlanta, and associates.

Those findings, along with the rates of one or more comorbidities – 83% for those who died, 71% for those who were rehospitalized, and 26% for those who did not die or get readmitted – prompted the CDC to update its guidance for postdischarge follow-up of EVALI patients.

That update involves six specific recommendations to determine readiness for discharge, which include “confirming no clinically significant fluctuations in vital signs for at least 24-48 hours before discharge [and] preparation for hospital discharge and postdischarge care coordination to reduce risk of rehospitalization and death,” Mary E. Evans, MD, and associates said in a separate CDC communication (MMWR. 2019 Dec. 20. 68[early release]:1-6).

As of Dec. 17, the CDC reports that 2,506 patients have been hospitalized with EVALI since March 31, 2019, and 54 deaths have been confirmed in 27 states and the District of Columbia. The outbreak appears to have peaked in September, but cases are still being reported: 13 during the week of Dec. 1-7 and one case for the week of Dec. 8-14.

SOURCE: Mikosz CA et al. MMWR. 2019 Dec. 20. 68[early release]:1-7.

Those who required rehospitalization for e-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) and those who died after discharge were more likely to have one or more chronic conditions than were other EVALI patients, and those “who died also were more likely to have been admitted to an intensive care unit, experienced respiratory failure necessitating intubation and mechanical ventilation, and were significantly older,” Christina A. Mikosz, MD, and associates wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Their analysis included the 1,139 EVALI patients who were discharged on or after Oct. 31, 2019. Of that group, 31 (2.7%) patients were rehospitalized and subsequently discharged and another 7 died after the initial discharge. The median age was 54 years for those who died, 27 years for those who were rehospitalized, and 23 for those who survived without rehospitalization, said Dr. Mikosz of the CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Atlanta, and associates.

Those findings, along with the rates of one or more comorbidities – 83% for those who died, 71% for those who were rehospitalized, and 26% for those who did not die or get readmitted – prompted the CDC to update its guidance for postdischarge follow-up of EVALI patients.

That update involves six specific recommendations to determine readiness for discharge, which include “confirming no clinically significant fluctuations in vital signs for at least 24-48 hours before discharge [and] preparation for hospital discharge and postdischarge care coordination to reduce risk of rehospitalization and death,” Mary E. Evans, MD, and associates said in a separate CDC communication (MMWR. 2019 Dec. 20. 68[early release]:1-6).

As of Dec. 17, the CDC reports that 2,506 patients have been hospitalized with EVALI since March 31, 2019, and 54 deaths have been confirmed in 27 states and the District of Columbia. The outbreak appears to have peaked in September, but cases are still being reported: 13 during the week of Dec. 1-7 and one case for the week of Dec. 8-14.

SOURCE: Mikosz CA et al. MMWR. 2019 Dec. 20. 68[early release]:1-7.

FROM MMWR

FDA approves Dayvigo for insomnia

Lemborexant will be available in 5-mg and 10-mg tablets after the Drug Enforcement Administration schedules the drug, which is expected to occur within 90 days, according to a statement from Eisai.

Lemborexant is an orexin receptor antagonist. Its approval is based on two phase 3 studies, SUNRISE 1 and SUNRISE 2, that included approximately 2,000 adults with insomnia. Investigators assessed lemborexant versus active comparators for as long as 1 month and versus placebo for 6 months.

In these studies, lemborexant significantly improved objective and subjective measures of sleep onset and sleep maintenance, compared with placebo. The medication was not associated with rebound insomnia or withdrawal effects after treatment discontinuation.

In the phase 3 trials, somnolence was the most common adverse reaction that occurred in at least 5% of patients who received lemborexant and at twice the rate in patients who received placebo (lemborexant 10 mg, 10%; lemborexant 5 mg, 7%; placebo, 1%).

In a middle-of-the-night safety study, lemborexant was associated with dose-dependent worsening on measures of attention and memory, compared with placebo. Treatment did not meaningfully affect ability to awaken to sound, however.

Previously reported data showed that lemborexant was effective in male and female patients and was well tolerated by both sexes and that the medication did not impair postural stability and driving performance.

Lemborexant will be available in 5-mg and 10-mg tablets after the Drug Enforcement Administration schedules the drug, which is expected to occur within 90 days, according to a statement from Eisai.

Lemborexant is an orexin receptor antagonist. Its approval is based on two phase 3 studies, SUNRISE 1 and SUNRISE 2, that included approximately 2,000 adults with insomnia. Investigators assessed lemborexant versus active comparators for as long as 1 month and versus placebo for 6 months.

In these studies, lemborexant significantly improved objective and subjective measures of sleep onset and sleep maintenance, compared with placebo. The medication was not associated with rebound insomnia or withdrawal effects after treatment discontinuation.

In the phase 3 trials, somnolence was the most common adverse reaction that occurred in at least 5% of patients who received lemborexant and at twice the rate in patients who received placebo (lemborexant 10 mg, 10%; lemborexant 5 mg, 7%; placebo, 1%).

In a middle-of-the-night safety study, lemborexant was associated with dose-dependent worsening on measures of attention and memory, compared with placebo. Treatment did not meaningfully affect ability to awaken to sound, however.

Previously reported data showed that lemborexant was effective in male and female patients and was well tolerated by both sexes and that the medication did not impair postural stability and driving performance.

Lemborexant will be available in 5-mg and 10-mg tablets after the Drug Enforcement Administration schedules the drug, which is expected to occur within 90 days, according to a statement from Eisai.

Lemborexant is an orexin receptor antagonist. Its approval is based on two phase 3 studies, SUNRISE 1 and SUNRISE 2, that included approximately 2,000 adults with insomnia. Investigators assessed lemborexant versus active comparators for as long as 1 month and versus placebo for 6 months.

In these studies, lemborexant significantly improved objective and subjective measures of sleep onset and sleep maintenance, compared with placebo. The medication was not associated with rebound insomnia or withdrawal effects after treatment discontinuation.

In the phase 3 trials, somnolence was the most common adverse reaction that occurred in at least 5% of patients who received lemborexant and at twice the rate in patients who received placebo (lemborexant 10 mg, 10%; lemborexant 5 mg, 7%; placebo, 1%).

In a middle-of-the-night safety study, lemborexant was associated with dose-dependent worsening on measures of attention and memory, compared with placebo. Treatment did not meaningfully affect ability to awaken to sound, however.

Previously reported data showed that lemborexant was effective in male and female patients and was well tolerated by both sexes and that the medication did not impair postural stability and driving performance.

Inhibitor appears to strengthen anti-BCMA CAR T cells in myeloma patients

ORLANDO – A gamma secretase inhibitor could enhance the efficacy of B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, a phase 1 trial suggests.

The inhibitor, JSMD194, increased BCMA expression in all 10 patients studied. All patients responded to anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy, including three patients who had previously failed BCMA-directed therapy.

Nine patients remain alive and in response at a median follow-up of 20 weeks, with two patients being followed for more than a year. One patient experienced dose-limiting toxicity and died, which prompted a change to the study’s eligibility criteria.

Andrew J. Cowan, MD, of the University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, presented these results at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Dr. Cowan and colleagues previously showed that treatment with a gamma secretase inhibitor increased BCMA expression on tumor cells and improved the efficacy of BCMA-targeted CAR T cells in a mouse model of multiple myeloma. The team also showed that a gamma secretase inhibitor could “markedly” increase the percentage of BCMA-positive tumor cells in myeloma patients (Blood. 2019 Nov 7;134[19]:1585-97).

To expand upon these findings, the researchers began a phase 1 trial of BCMA-directed CAR T cells and the oral gamma secretase inhibitor JSMD194 in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.

Ten patients have been treated, five men and five women. The patients’ median age at baseline was 66 years (range, 44-74 years). They received a median of 10 prior therapies (range, 4-23). Nine patients had received at least one autologous stem cell transplant, and one patient had two. One patient underwent allogeneic transplant (as well as autologous transplant).

Three patients had received prior BCMA-directed therapy. Two patients had received BCMA-directed CAR T cells. One of them did not respond, and the other responded but relapsed. The third patient received a BCMA-targeted bispecific T-cell engager and did not respond.

Study treatment

Patients had BCMA expression measured at baseline, then underwent apheresis for CAR T-cell production.

Patients received JSMD194 at 25 mg on days 1, 3, and 5. Then, they received cyclophosphamide at 300 mg and fludarabine at 25 mg for 3 days.

Next, patients received a single CAR T-cell infusion at a dose of 50 x 106 (n = 5), 150 x 106 (n = 3), or 300 x 106 (n = 2). They also received JSMD194 at 25 mg three times a week for 3 weeks.

Safety

“Nearly all patients had a serious adverse event, which was typically admission to the hospital for neutropenic fever,” Dr. Cowan said.

One patient experienced dose-limiting toxicity and died at day 33. The patient had a disseminating fungal infection, grade 4 cytokine release syndrome (CRS), and neurotoxicity. The patient’s death prompted the researchers to include performance status in the study’s eligibility criteria.

All patients developed CRS. Only the aforementioned patient had grade 4 CRS, and three patients had grade 3 CRS. Six patients experienced neurotoxicity. There were no cases of tumor lysis syndrome.

Efficacy

“All patients experienced an increase of cells expressing BCMA,” Dr. Cowan said. “While there was significant variability in BCMA expression at baseline, all cells expressed BCMA after three doses of the gamma secretase inhibitor.”

The median BCMA expression after JSMD194 treatment was 99% (range, 96%-100%), and there was a median 20-fold (range, 8- to 157-fold) increase in BCMA surface density.

The overall response rate was 100%. Two patients achieved a stringent complete response (CR), one achieved a CR, five patients had a very good partial response, and two had a partial response.

The patient with a CR received the 50 x 106 dose of CAR T cells, and the patients with stringent CRs received the 150 x 106 and 300 x 106 doses.

Of the three patients who previously received BCMA-directed therapy, two achieved a very good partial response, and one had a partial response.

Nine of the 10 patients are still alive and in response, with a median follow-up of 20 weeks. The longest follow-up is 444 days.

“To date, all patients have evidence of durable responses,” Dr. Cowan said. “Moreover, all patients had dramatic reductions in involved serum free light chain ... and serum monoclonal proteins.”

Dr. Cowan noted that longer follow-up is needed to assess CAR T-cell persistence and the durability of response.

This trial is sponsored by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute. Two researchers involved in this work are employees of Juno Therapeutics. Dr. Cowan reported relationships with Juno Therapeutics, Janssen, Celgene, AbbVie, Cellectar, and Sanofi.

SOURCE: Cowan AJ et al. ASH 2019. Abstract 204.

ORLANDO – A gamma secretase inhibitor could enhance the efficacy of B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, a phase 1 trial suggests.

The inhibitor, JSMD194, increased BCMA expression in all 10 patients studied. All patients responded to anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy, including three patients who had previously failed BCMA-directed therapy.

Nine patients remain alive and in response at a median follow-up of 20 weeks, with two patients being followed for more than a year. One patient experienced dose-limiting toxicity and died, which prompted a change to the study’s eligibility criteria.

Andrew J. Cowan, MD, of the University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, presented these results at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Dr. Cowan and colleagues previously showed that treatment with a gamma secretase inhibitor increased BCMA expression on tumor cells and improved the efficacy of BCMA-targeted CAR T cells in a mouse model of multiple myeloma. The team also showed that a gamma secretase inhibitor could “markedly” increase the percentage of BCMA-positive tumor cells in myeloma patients (Blood. 2019 Nov 7;134[19]:1585-97).

To expand upon these findings, the researchers began a phase 1 trial of BCMA-directed CAR T cells and the oral gamma secretase inhibitor JSMD194 in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.

Ten patients have been treated, five men and five women. The patients’ median age at baseline was 66 years (range, 44-74 years). They received a median of 10 prior therapies (range, 4-23). Nine patients had received at least one autologous stem cell transplant, and one patient had two. One patient underwent allogeneic transplant (as well as autologous transplant).

Three patients had received prior BCMA-directed therapy. Two patients had received BCMA-directed CAR T cells. One of them did not respond, and the other responded but relapsed. The third patient received a BCMA-targeted bispecific T-cell engager and did not respond.

Study treatment

Patients had BCMA expression measured at baseline, then underwent apheresis for CAR T-cell production.

Patients received JSMD194 at 25 mg on days 1, 3, and 5. Then, they received cyclophosphamide at 300 mg and fludarabine at 25 mg for 3 days.

Next, patients received a single CAR T-cell infusion at a dose of 50 x 106 (n = 5), 150 x 106 (n = 3), or 300 x 106 (n = 2). They also received JSMD194 at 25 mg three times a week for 3 weeks.

Safety

“Nearly all patients had a serious adverse event, which was typically admission to the hospital for neutropenic fever,” Dr. Cowan said.

One patient experienced dose-limiting toxicity and died at day 33. The patient had a disseminating fungal infection, grade 4 cytokine release syndrome (CRS), and neurotoxicity. The patient’s death prompted the researchers to include performance status in the study’s eligibility criteria.

All patients developed CRS. Only the aforementioned patient had grade 4 CRS, and three patients had grade 3 CRS. Six patients experienced neurotoxicity. There were no cases of tumor lysis syndrome.

Efficacy

“All patients experienced an increase of cells expressing BCMA,” Dr. Cowan said. “While there was significant variability in BCMA expression at baseline, all cells expressed BCMA after three doses of the gamma secretase inhibitor.”

The median BCMA expression after JSMD194 treatment was 99% (range, 96%-100%), and there was a median 20-fold (range, 8- to 157-fold) increase in BCMA surface density.

The overall response rate was 100%. Two patients achieved a stringent complete response (CR), one achieved a CR, five patients had a very good partial response, and two had a partial response.

The patient with a CR received the 50 x 106 dose of CAR T cells, and the patients with stringent CRs received the 150 x 106 and 300 x 106 doses.

Of the three patients who previously received BCMA-directed therapy, two achieved a very good partial response, and one had a partial response.

Nine of the 10 patients are still alive and in response, with a median follow-up of 20 weeks. The longest follow-up is 444 days.

“To date, all patients have evidence of durable responses,” Dr. Cowan said. “Moreover, all patients had dramatic reductions in involved serum free light chain ... and serum monoclonal proteins.”

Dr. Cowan noted that longer follow-up is needed to assess CAR T-cell persistence and the durability of response.

This trial is sponsored by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute. Two researchers involved in this work are employees of Juno Therapeutics. Dr. Cowan reported relationships with Juno Therapeutics, Janssen, Celgene, AbbVie, Cellectar, and Sanofi.

SOURCE: Cowan AJ et al. ASH 2019. Abstract 204.

ORLANDO – A gamma secretase inhibitor could enhance the efficacy of B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, a phase 1 trial suggests.

The inhibitor, JSMD194, increased BCMA expression in all 10 patients studied. All patients responded to anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy, including three patients who had previously failed BCMA-directed therapy.

Nine patients remain alive and in response at a median follow-up of 20 weeks, with two patients being followed for more than a year. One patient experienced dose-limiting toxicity and died, which prompted a change to the study’s eligibility criteria.

Andrew J. Cowan, MD, of the University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, presented these results at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Dr. Cowan and colleagues previously showed that treatment with a gamma secretase inhibitor increased BCMA expression on tumor cells and improved the efficacy of BCMA-targeted CAR T cells in a mouse model of multiple myeloma. The team also showed that a gamma secretase inhibitor could “markedly” increase the percentage of BCMA-positive tumor cells in myeloma patients (Blood. 2019 Nov 7;134[19]:1585-97).

To expand upon these findings, the researchers began a phase 1 trial of BCMA-directed CAR T cells and the oral gamma secretase inhibitor JSMD194 in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.

Ten patients have been treated, five men and five women. The patients’ median age at baseline was 66 years (range, 44-74 years). They received a median of 10 prior therapies (range, 4-23). Nine patients had received at least one autologous stem cell transplant, and one patient had two. One patient underwent allogeneic transplant (as well as autologous transplant).

Three patients had received prior BCMA-directed therapy. Two patients had received BCMA-directed CAR T cells. One of them did not respond, and the other responded but relapsed. The third patient received a BCMA-targeted bispecific T-cell engager and did not respond.

Study treatment

Patients had BCMA expression measured at baseline, then underwent apheresis for CAR T-cell production.

Patients received JSMD194 at 25 mg on days 1, 3, and 5. Then, they received cyclophosphamide at 300 mg and fludarabine at 25 mg for 3 days.

Next, patients received a single CAR T-cell infusion at a dose of 50 x 106 (n = 5), 150 x 106 (n = 3), or 300 x 106 (n = 2). They also received JSMD194 at 25 mg three times a week for 3 weeks.

Safety

“Nearly all patients had a serious adverse event, which was typically admission to the hospital for neutropenic fever,” Dr. Cowan said.

One patient experienced dose-limiting toxicity and died at day 33. The patient had a disseminating fungal infection, grade 4 cytokine release syndrome (CRS), and neurotoxicity. The patient’s death prompted the researchers to include performance status in the study’s eligibility criteria.

All patients developed CRS. Only the aforementioned patient had grade 4 CRS, and three patients had grade 3 CRS. Six patients experienced neurotoxicity. There were no cases of tumor lysis syndrome.

Efficacy

“All patients experienced an increase of cells expressing BCMA,” Dr. Cowan said. “While there was significant variability in BCMA expression at baseline, all cells expressed BCMA after three doses of the gamma secretase inhibitor.”

The median BCMA expression after JSMD194 treatment was 99% (range, 96%-100%), and there was a median 20-fold (range, 8- to 157-fold) increase in BCMA surface density.

The overall response rate was 100%. Two patients achieved a stringent complete response (CR), one achieved a CR, five patients had a very good partial response, and two had a partial response.

The patient with a CR received the 50 x 106 dose of CAR T cells, and the patients with stringent CRs received the 150 x 106 and 300 x 106 doses.

Of the three patients who previously received BCMA-directed therapy, two achieved a very good partial response, and one had a partial response.

Nine of the 10 patients are still alive and in response, with a median follow-up of 20 weeks. The longest follow-up is 444 days.

“To date, all patients have evidence of durable responses,” Dr. Cowan said. “Moreover, all patients had dramatic reductions in involved serum free light chain ... and serum monoclonal proteins.”

Dr. Cowan noted that longer follow-up is needed to assess CAR T-cell persistence and the durability of response.

This trial is sponsored by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute. Two researchers involved in this work are employees of Juno Therapeutics. Dr. Cowan reported relationships with Juno Therapeutics, Janssen, Celgene, AbbVie, Cellectar, and Sanofi.

SOURCE: Cowan AJ et al. ASH 2019. Abstract 204.

REPORTING FROM ASH 2019

Spotlight on SMA: The urgent need for early diagnosis in spinal muscular atrophy

The diagnosis of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), especially Type 1, is a medical emergency, as SMA is a leading genetic cause of death in infants. In infants with SMA Type 1, the onset of irreversible denervation occurs within the first 3 months with loss of 90% of motor units occurring within 6 months of age.

This supplement examines the clinical implications of delayed diagnosis of SMA, as well as assessment tools, treatment methods, and resources that are available for physicians, patients, and caregivers to better manage this rare disease.

The diagnosis of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), especially Type 1, is a medical emergency, as SMA is a leading genetic cause of death in infants. In infants with SMA Type 1, the onset of irreversible denervation occurs within the first 3 months with loss of 90% of motor units occurring within 6 months of age.

This supplement examines the clinical implications of delayed diagnosis of SMA, as well as assessment tools, treatment methods, and resources that are available for physicians, patients, and caregivers to better manage this rare disease.

The diagnosis of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), especially Type 1, is a medical emergency, as SMA is a leading genetic cause of death in infants. In infants with SMA Type 1, the onset of irreversible denervation occurs within the first 3 months with loss of 90% of motor units occurring within 6 months of age.

This supplement examines the clinical implications of delayed diagnosis of SMA, as well as assessment tools, treatment methods, and resources that are available for physicians, patients, and caregivers to better manage this rare disease.

FDA approves Caplyta to treat schizophrenia in adults

The Food and Drug Administration has approved lumateperone for the treatment of schizophrenia in adults.

Lumateperone, an atypical antipsychotic, will be marketed by Intra-Cellular Therapies as Caplyta, according to a Dec. 23 statement from the company.

In the first, 335 patients with schizophrenia were randomized to two doses of lumateperone, an active comparator, or placebo. Those randomized to the approved 42-mg dose of lumateperone showed a statistically significant reduction in total score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), compared with patients in the other groups. The median age in this study was 42 years; 17% of patients were female, 19% were white, and 78% were black.

In the second study, 450 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia were randomized in a double-blind fashion to one of two doses of lumateperone or placebo. Patients taking the approved dose showed a statistically significant reduction from baseline to day 28 in PANSS total score. In this study, patients’ median age was 44 years; 23% were female, 26% were white, and 66% were black.

Treatment with lumateperone appears to feature a more favorable cardiometabolic profile than that of other approved antipsychotic agents.

Patients treated with lumateperone for at least a year showed significant reductions in LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, serum prolactin, and body weight, compared with baseline values recorded when participants were on various standard-of-care antipsychotics prior to switching, Suresh Durgam, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. Other cardiometabolic parameters, including fasting blood glucose, insulin, triglycerides, and HDL cholesterol, showed only negligible change over the course of study, according to Dr. Durgam, a psychiatrist and senior vice president for late-stage clinical development and medical affairs at Intra-Cellular Therapies.

The most common adverse events with lumateperone were somnolence (24% vs. 10% on placebo) and dry mouth (6% vs. 2%).

Approval of lumateperone hit a snag last summer when the FDA canceled the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee meeting it previously had called for to review the new drug application for lumateperone. The agency said the meeting was canceled because of “new information regarding the application.”

At the time, Intra-Cellular Therapies noted that it had provided additional information to the FDA to meet agency requests. This information was related to nonclinical studies.

“The FDA canceled the advisory committee meeting to allow sufficient time to review this new and any forthcoming information as they continue” to review the new drug application for lumateperone, Intra-Cellular said a statement.

The company plans to launch Caplyta late in the first quarter of 2020.

Bruce Jancin and Kerry Dooley Young contributed to this report.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved lumateperone for the treatment of schizophrenia in adults.

Lumateperone, an atypical antipsychotic, will be marketed by Intra-Cellular Therapies as Caplyta, according to a Dec. 23 statement from the company.

In the first, 335 patients with schizophrenia were randomized to two doses of lumateperone, an active comparator, or placebo. Those randomized to the approved 42-mg dose of lumateperone showed a statistically significant reduction in total score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), compared with patients in the other groups. The median age in this study was 42 years; 17% of patients were female, 19% were white, and 78% were black.

In the second study, 450 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia were randomized in a double-blind fashion to one of two doses of lumateperone or placebo. Patients taking the approved dose showed a statistically significant reduction from baseline to day 28 in PANSS total score. In this study, patients’ median age was 44 years; 23% were female, 26% were white, and 66% were black.

Treatment with lumateperone appears to feature a more favorable cardiometabolic profile than that of other approved antipsychotic agents.

Patients treated with lumateperone for at least a year showed significant reductions in LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, serum prolactin, and body weight, compared with baseline values recorded when participants were on various standard-of-care antipsychotics prior to switching, Suresh Durgam, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. Other cardiometabolic parameters, including fasting blood glucose, insulin, triglycerides, and HDL cholesterol, showed only negligible change over the course of study, according to Dr. Durgam, a psychiatrist and senior vice president for late-stage clinical development and medical affairs at Intra-Cellular Therapies.

The most common adverse events with lumateperone were somnolence (24% vs. 10% on placebo) and dry mouth (6% vs. 2%).

Approval of lumateperone hit a snag last summer when the FDA canceled the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee meeting it previously had called for to review the new drug application for lumateperone. The agency said the meeting was canceled because of “new information regarding the application.”

At the time, Intra-Cellular Therapies noted that it had provided additional information to the FDA to meet agency requests. This information was related to nonclinical studies.

“The FDA canceled the advisory committee meeting to allow sufficient time to review this new and any forthcoming information as they continue” to review the new drug application for lumateperone, Intra-Cellular said a statement.

The company plans to launch Caplyta late in the first quarter of 2020.

Bruce Jancin and Kerry Dooley Young contributed to this report.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved lumateperone for the treatment of schizophrenia in adults.

Lumateperone, an atypical antipsychotic, will be marketed by Intra-Cellular Therapies as Caplyta, according to a Dec. 23 statement from the company.

In the first, 335 patients with schizophrenia were randomized to two doses of lumateperone, an active comparator, or placebo. Those randomized to the approved 42-mg dose of lumateperone showed a statistically significant reduction in total score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), compared with patients in the other groups. The median age in this study was 42 years; 17% of patients were female, 19% were white, and 78% were black.

In the second study, 450 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia were randomized in a double-blind fashion to one of two doses of lumateperone or placebo. Patients taking the approved dose showed a statistically significant reduction from baseline to day 28 in PANSS total score. In this study, patients’ median age was 44 years; 23% were female, 26% were white, and 66% were black.

Treatment with lumateperone appears to feature a more favorable cardiometabolic profile than that of other approved antipsychotic agents.

Patients treated with lumateperone for at least a year showed significant reductions in LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, serum prolactin, and body weight, compared with baseline values recorded when participants were on various standard-of-care antipsychotics prior to switching, Suresh Durgam, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. Other cardiometabolic parameters, including fasting blood glucose, insulin, triglycerides, and HDL cholesterol, showed only negligible change over the course of study, according to Dr. Durgam, a psychiatrist and senior vice president for late-stage clinical development and medical affairs at Intra-Cellular Therapies.

The most common adverse events with lumateperone were somnolence (24% vs. 10% on placebo) and dry mouth (6% vs. 2%).

Approval of lumateperone hit a snag last summer when the FDA canceled the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee meeting it previously had called for to review the new drug application for lumateperone. The agency said the meeting was canceled because of “new information regarding the application.”

At the time, Intra-Cellular Therapies noted that it had provided additional information to the FDA to meet agency requests. This information was related to nonclinical studies.

“The FDA canceled the advisory committee meeting to allow sufficient time to review this new and any forthcoming information as they continue” to review the new drug application for lumateperone, Intra-Cellular said a statement.

The company plans to launch Caplyta late in the first quarter of 2020.

Bruce Jancin and Kerry Dooley Young contributed to this report.

Top picks for online diabetes information for doctors and patients

BUSAN, SOUTH KOREA – says endocrinologist Irl B. Hirsch, MD, professor of medicine and diabetes treatment and teaching chair at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Speaking at the recent International Diabetes Federation Congress, Dr. Hirsch offered the international audience a list of sites he considers reliable and helpful, but with the caveat that “this is by no means a complete list, but these are some of my favorites.”

Session moderator David M. Maahs, MD, PhD, chief of pediatric endocrinology at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview that it is now pointless to try to tell patients not to look things up online. “Everyone is going to go on the Internet, so point people in the right direction for reliable information,” he advised.

For general diabetes information, Dr. Hirsch said society websites are a good place for clinicians and patients to start. Among the best of these, he said, are:

- American Diabetes Association (ADA).

- Diabetes Australia.

- Diabetes UK.

- European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD).

- International Diabetes Federation (IDF).

- JDRF (type 1 diabetes).

Sites for type 1 diabetes

He pointed out in his talk that he was able to find many more reliable sites for type 1 diabetes than for type 2 diabetes. Among his top picks was the Children with Diabetes (CWD) website, which he said was “an outstanding site for type 1 diabetes for children, parents, grandparents, and also adults with type 1 diabetes.” Its content includes up-to-date information about all aspects of type 1 diabetes research, frequent polls of common questions, and discussion forums.

“It’s not just the United States. People from all over the world are looking at this site,” Dr. Hirsch noted.

For 2 decades, the CWD has sponsored the Friends for Life conference, which takes place in Orlando every July. The event is now attended by around 3,000 children and young adults with type 1 diabetes and their family members, he noted.

Dr. Maahs seconded Dr. Hirsch’s CWD recommendation. “They’ve continued to have a wonderful website, a great source of information. The conference is great. They’ll put you in touch with people in your area.”

Another good type 1 diabetes site for patients and families is that of the JDRF (formerly the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation), which provides “an outstanding review of type 1 diabetes research and social action,” Dr. Hirsch commented. In addition to the main site, there are also regional JDRF sites in Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada.

Beyond Type 1 is part of a network that also includes Beyond Type 2 and Spanish-language sites for both Beyond Type 1 and Beyond Type 2. The sites feature news, stories, self-help, and resources.

The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) has a site for clinicians and families with type 1 diabetes, according to Dr. Hirsch. It provides information about events, resources, and guidelines. A recent article, for example, addresses fasting during Ramadan or young people with diabetes.

Dr. Maahs, who is secretary general of ISPAD and edited the organization’s 2018 Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines, noted that all of the clinical guidelines and patient education materials are free on the site, as are conference presentations from the past 3 years. A lot of the material is also available in different languages, he noted.

He also pointed out that ISPAD’s recommendations for pediatric diabetes are mostly in line with that of the ADA, but they include far more information – 25 chapters versus just one ADA chapter. Also, in 2018, ISPAD lowered its A1c target for children from 7.5% to 7.0%, which aligns with Scandinavian but not U.S. recommendations.

In addition to the type 1 diabetes sites that Dr. Hirsch listed, Dr. Maahs added the T1D Exchange online community site Glu, which he said was a good patient advocacy site.

Sites for type 2 diabetes

Dr. Hirsch recommended several sites for patients with type 2 diabetes, including:

- The Johns Hopkins Patient Guide to Diabetes, one of his favorite type 2 diabetes sites because of its “artistry, the graphics – you get it from just looking at the pictures. There’s a tech corner, videos, and patient stories. There’s just a lot here for patients.”

- Diabetes Sisters, specifically for women with diabetes.

- Diabetes Strong, which focuses on exercise.

- Wildly Fluctuating, with topics “from humor to serious stuff to miscellaneous musings on the diabetes news of the week by a type 2 diabetes patient/expert.”

Sites for clinicians

For clinicians, Dr. Hirsch said the following sites provide free and up-to-date information on the management of type 2 diabetes (some also include type 1 diabetes):

- ADA/EASD Standards of Care.

- Diabetes Canada 2018 Guidelines.

- American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Type 2 Diabetes Management Algorithm.

- UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, which Dr. Hirsch called “extensive evidence-based guidelines. They really dig into the evidence as much, if not more, than most of the national standards of care around the world.”

- Clinical Diabetes, an ADA journal that provides “outstanding articles geared for nonspecialists free to clinicians online 6 months after publication.” It includes some primary data articles, but it is mostly review, he noted.

Regional sites

Dr. Hirsch included information about regional sites as well:

- Dr. Mohan’s Diabetes Specialties Centre, “a very good site for those living in India.”

- HealthDirect in Australia.

- Diabetes UK.

Dr. Hirsch is a consultant for Abbott Diabetes Care, Roche, and Bigfoot; conducts research for Medtronic; and is an editor on diabetes for UpToDate. Dr. Maahs has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, JDRF, National Science Foundation, and Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and has consulted for Abbott, Helmsley, Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, and Insulet.

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

BUSAN, SOUTH KOREA – says endocrinologist Irl B. Hirsch, MD, professor of medicine and diabetes treatment and teaching chair at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Speaking at the recent International Diabetes Federation Congress, Dr. Hirsch offered the international audience a list of sites he considers reliable and helpful, but with the caveat that “this is by no means a complete list, but these are some of my favorites.”

Session moderator David M. Maahs, MD, PhD, chief of pediatric endocrinology at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview that it is now pointless to try to tell patients not to look things up online. “Everyone is going to go on the Internet, so point people in the right direction for reliable information,” he advised.

For general diabetes information, Dr. Hirsch said society websites are a good place for clinicians and patients to start. Among the best of these, he said, are:

- American Diabetes Association (ADA).

- Diabetes Australia.

- Diabetes UK.

- European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD).

- International Diabetes Federation (IDF).

- JDRF (type 1 diabetes).

Sites for type 1 diabetes

He pointed out in his talk that he was able to find many more reliable sites for type 1 diabetes than for type 2 diabetes. Among his top picks was the Children with Diabetes (CWD) website, which he said was “an outstanding site for type 1 diabetes for children, parents, grandparents, and also adults with type 1 diabetes.” Its content includes up-to-date information about all aspects of type 1 diabetes research, frequent polls of common questions, and discussion forums.

“It’s not just the United States. People from all over the world are looking at this site,” Dr. Hirsch noted.

For 2 decades, the CWD has sponsored the Friends for Life conference, which takes place in Orlando every July. The event is now attended by around 3,000 children and young adults with type 1 diabetes and their family members, he noted.

Dr. Maahs seconded Dr. Hirsch’s CWD recommendation. “They’ve continued to have a wonderful website, a great source of information. The conference is great. They’ll put you in touch with people in your area.”

Another good type 1 diabetes site for patients and families is that of the JDRF (formerly the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation), which provides “an outstanding review of type 1 diabetes research and social action,” Dr. Hirsch commented. In addition to the main site, there are also regional JDRF sites in Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada.

Beyond Type 1 is part of a network that also includes Beyond Type 2 and Spanish-language sites for both Beyond Type 1 and Beyond Type 2. The sites feature news, stories, self-help, and resources.

The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) has a site for clinicians and families with type 1 diabetes, according to Dr. Hirsch. It provides information about events, resources, and guidelines. A recent article, for example, addresses fasting during Ramadan or young people with diabetes.

Dr. Maahs, who is secretary general of ISPAD and edited the organization’s 2018 Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines, noted that all of the clinical guidelines and patient education materials are free on the site, as are conference presentations from the past 3 years. A lot of the material is also available in different languages, he noted.

He also pointed out that ISPAD’s recommendations for pediatric diabetes are mostly in line with that of the ADA, but they include far more information – 25 chapters versus just one ADA chapter. Also, in 2018, ISPAD lowered its A1c target for children from 7.5% to 7.0%, which aligns with Scandinavian but not U.S. recommendations.

In addition to the type 1 diabetes sites that Dr. Hirsch listed, Dr. Maahs added the T1D Exchange online community site Glu, which he said was a good patient advocacy site.

Sites for type 2 diabetes

Dr. Hirsch recommended several sites for patients with type 2 diabetes, including: