User login

Oral antibiotics as effective as IV for stable endocarditis patients

Background: Patients with left-sided infective endocarditis often are treated with prolonged courses of intravenous (IV) antibiotics. The safety of switching from IV to oral antibiotics is unknown.

Study design: Randomized, multicenter, noninferiority study.

Setting: Cardiac centers in Denmark during July 2011–August 2017.

Synopsis: The study enrolled 400 patients with left-sided infective endocarditis and positive blood cultures from Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Staphylococcus aureus, or coagulase-negative staph (non–methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), without evidence of valvular abscess. Following at least 7 days (for those who required surgical intervention) or 10 days (for those who did not require surgical intervention) of IV antibiotics, patients with ongoing fever, leukocytosis, elevated C-reactive protein, or concurrent infections were excluded from the study. Patients were randomized to receive continued IV antibiotic treatment or switch to oral antibiotic treatment. The IV treatment group received a median of 19 additional days of therapy, compared with 17 days in the oral group. The primary composite outcome of death, unplanned cardiac surgery, embolic event, and relapse of bacteremia occurred in 12.1% in the IV therapy group and 9% in the oral therapy group (difference of 3.1%; 95% confidence interval, –3.4 to 9.6; P = .40), meeting the studies prespecified noninferiority criteria. Poor representation of women, obese patients, and patients who use IV drugs may limit the study’s generalizability. An accompanying editorial advocated for additional research before widespread change to current treatment recommendations are made.

Bottom line: For patients with left-sided infective endocarditis who have been stabilized on IV antibiotic treatment, transitioning to an oral antibiotic regimen may be a noninferior approach.

Citation: Iverson K et al. Partial oral versus intravenous antibiotic treatment of endocarditis. N Eng J Med. 2019 Jan 31;380(5):415-24.

Dr. Phillips is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Background: Patients with left-sided infective endocarditis often are treated with prolonged courses of intravenous (IV) antibiotics. The safety of switching from IV to oral antibiotics is unknown.

Study design: Randomized, multicenter, noninferiority study.

Setting: Cardiac centers in Denmark during July 2011–August 2017.

Synopsis: The study enrolled 400 patients with left-sided infective endocarditis and positive blood cultures from Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Staphylococcus aureus, or coagulase-negative staph (non–methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), without evidence of valvular abscess. Following at least 7 days (for those who required surgical intervention) or 10 days (for those who did not require surgical intervention) of IV antibiotics, patients with ongoing fever, leukocytosis, elevated C-reactive protein, or concurrent infections were excluded from the study. Patients were randomized to receive continued IV antibiotic treatment or switch to oral antibiotic treatment. The IV treatment group received a median of 19 additional days of therapy, compared with 17 days in the oral group. The primary composite outcome of death, unplanned cardiac surgery, embolic event, and relapse of bacteremia occurred in 12.1% in the IV therapy group and 9% in the oral therapy group (difference of 3.1%; 95% confidence interval, –3.4 to 9.6; P = .40), meeting the studies prespecified noninferiority criteria. Poor representation of women, obese patients, and patients who use IV drugs may limit the study’s generalizability. An accompanying editorial advocated for additional research before widespread change to current treatment recommendations are made.

Bottom line: For patients with left-sided infective endocarditis who have been stabilized on IV antibiotic treatment, transitioning to an oral antibiotic regimen may be a noninferior approach.

Citation: Iverson K et al. Partial oral versus intravenous antibiotic treatment of endocarditis. N Eng J Med. 2019 Jan 31;380(5):415-24.

Dr. Phillips is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Background: Patients with left-sided infective endocarditis often are treated with prolonged courses of intravenous (IV) antibiotics. The safety of switching from IV to oral antibiotics is unknown.

Study design: Randomized, multicenter, noninferiority study.

Setting: Cardiac centers in Denmark during July 2011–August 2017.

Synopsis: The study enrolled 400 patients with left-sided infective endocarditis and positive blood cultures from Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Staphylococcus aureus, or coagulase-negative staph (non–methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), without evidence of valvular abscess. Following at least 7 days (for those who required surgical intervention) or 10 days (for those who did not require surgical intervention) of IV antibiotics, patients with ongoing fever, leukocytosis, elevated C-reactive protein, or concurrent infections were excluded from the study. Patients were randomized to receive continued IV antibiotic treatment or switch to oral antibiotic treatment. The IV treatment group received a median of 19 additional days of therapy, compared with 17 days in the oral group. The primary composite outcome of death, unplanned cardiac surgery, embolic event, and relapse of bacteremia occurred in 12.1% in the IV therapy group and 9% in the oral therapy group (difference of 3.1%; 95% confidence interval, –3.4 to 9.6; P = .40), meeting the studies prespecified noninferiority criteria. Poor representation of women, obese patients, and patients who use IV drugs may limit the study’s generalizability. An accompanying editorial advocated for additional research before widespread change to current treatment recommendations are made.

Bottom line: For patients with left-sided infective endocarditis who have been stabilized on IV antibiotic treatment, transitioning to an oral antibiotic regimen may be a noninferior approach.

Citation: Iverson K et al. Partial oral versus intravenous antibiotic treatment of endocarditis. N Eng J Med. 2019 Jan 31;380(5):415-24.

Dr. Phillips is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Probiotics with Lactobacillus reduce loss in spine BMD for postmenopausal women

, according to recent research published in The Lancet Rheumatology.

“The menopausal and early postmenopausal lumbar spine bone loss is substantial in women, and by using a prevention therapy with bacteria naturally occurring in the human gut microbiota we observed a close to complete protection against lumbar spine bone loss in healthy postmenopausal women,” Per-Anders Jansson, MD, chief physician at the University of Gothenburg (Sweden), and colleagues wrote in their study.

Dr. Jansson and colleagues performed a double-blind trial at four centers in Sweden in which 249 postmenopausal women were randomized during April-November 2016 to receive probiotics consisting of three Lactobacillus strains or placebo once per day for 12 months. Participants were healthy women, neither underweight nor overweight, and were postmenopausal, which was defined as being 2-12 years or less from last menstruation. The Lactobacillus strains, L. paracasei 8700:2 (DSM 13434), L. plantarum Heal 9 (DSM 15312), and L. plantarum Heal 19 (DSM 15313), were equally represented in a capsule at a dose of 1 x 1010 colony-forming unit per capsule. The researchers measured the lumbar spine bone mineral density (LS-BMD) at baseline and at 12 months, and also evaluated the safety profile of participants in both the probiotic and placebo groups.

Overall, 234 participants (94%) had data available for analysis at the end of the study. There was a significant reduction in LS-BMD loss for participants who received the probiotic treatment, compared with women in the control group (mean difference, 0.71%; 95% confidence interval, 0.06%-1.35%), while there was a significant loss in LS-BMD for participants in the placebo group (percentage change, –0.72%; 95% CI, –1.22% to –0.22%) compared with loss in the probiotic group (percentage change, –0.01%; 95% CI, –0.50% to 0.48%). Using analysis of covariance, the researchers found the probiotic group had reduced LS-BMD loss after adjustment for factors such as study site, age at baseline, BMD at baseline, and number of years from menopause (mean difference, 7.44 mg/cm2; 95% CI, 0.38 to 14.50).

In a subgroup analysis of women above and below the median time since menopause at baseline (6 years), participants in the probiotic group who were below the median time saw a significant protective effect of Lactobacillus treatment (mean difference, 1.08%; 95% CI, 0.20%-1.96%), compared with women above the median time (mean difference, 0.31%; 95% CI, –0.62% to 1.23%).

Researchers also examined the effects of probiotic treatment on total hip and femoral neck BMD as secondary endpoints. Lactobacillus treatment did not appear to affect total hip (–1.01%; 95% CI, –1.65% to –0.37%) or trochanter BMD (–1.13%; 95% CI, –2.27% to 0.20%), but femoral neck BMD was reduced in the probiotic group (–1.34%; 95% CI, –2.09% to –0.58%), compared with the placebo group (–0.88%; 95% CI, –1.64% to –0.13%).

Limitations of the study included examining only one dose of Lactobacillus treatment and no analysis of the effect of short-chain fatty acids on LS-BMD. The researchers noted that “recent studies have shown that short-chain fatty acids, which are generated by fermentation of complex carbohydrates by the gut microbiota, are important regulators of both bone formation and resorption.”

The researchers also acknowledged that the LS-BMD effect size for the probiotic treatment over the 12 months was a lower magnitude, compared with first-line treatments for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women using bisphosphonates. “Further long-term studies should be done to evaluate if the bone-protective effect becomes more pronounced with prolonged treatment with the Lactobacillus strains used in the present study,” they said.

In a related editorial, Shivani Sahni, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Connie M. Weaver, PhD, of Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind., reiterated that the effect size of probiotics is “of far less magnitude” than such treatments as bisphosphonates and expressed concern about the reduction of femoral neck BMD in the probiotic group, which was not explained in the study (Lancet Rheumatol. 2019 Nov;1[3]:e135-e137. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30073-6). There is a need to learn the optimum dose of probiotics as well as which Lactobacillus strains should be used in future studies, as the strains chosen by Jansson et al. were based on results in mice.

In the meantime, patients might be better off choosing dietary interventions with proven bone protection and no documented negative effects on the hip, such as prebiotics like soluble corn fiber and dried prunes, in tandem with drug therapies, Dr. Sahni and Dr. Weaver said.

“Although Jansson and colleagues’ results are important, more work is needed before such probiotics are ready for consumers,” they concluded.

This study was funded by Probi, which employs two of the study’s authors. Three authors reported being coinventors of a patent involving the effects of probiotics in osteoporosis treatment, and one author is listed as an inventor on a pending patent application on probiotic compositions and uses. Dr. Sahni reported receiving grants from Dairy Management. Dr. Weaver reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jansson P-A et al. Lancet Rheumatol. 2019 Nov;1(3):e154-e162. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30068-2

, according to recent research published in The Lancet Rheumatology.

“The menopausal and early postmenopausal lumbar spine bone loss is substantial in women, and by using a prevention therapy with bacteria naturally occurring in the human gut microbiota we observed a close to complete protection against lumbar spine bone loss in healthy postmenopausal women,” Per-Anders Jansson, MD, chief physician at the University of Gothenburg (Sweden), and colleagues wrote in their study.

Dr. Jansson and colleagues performed a double-blind trial at four centers in Sweden in which 249 postmenopausal women were randomized during April-November 2016 to receive probiotics consisting of three Lactobacillus strains or placebo once per day for 12 months. Participants were healthy women, neither underweight nor overweight, and were postmenopausal, which was defined as being 2-12 years or less from last menstruation. The Lactobacillus strains, L. paracasei 8700:2 (DSM 13434), L. plantarum Heal 9 (DSM 15312), and L. plantarum Heal 19 (DSM 15313), were equally represented in a capsule at a dose of 1 x 1010 colony-forming unit per capsule. The researchers measured the lumbar spine bone mineral density (LS-BMD) at baseline and at 12 months, and also evaluated the safety profile of participants in both the probiotic and placebo groups.

Overall, 234 participants (94%) had data available for analysis at the end of the study. There was a significant reduction in LS-BMD loss for participants who received the probiotic treatment, compared with women in the control group (mean difference, 0.71%; 95% confidence interval, 0.06%-1.35%), while there was a significant loss in LS-BMD for participants in the placebo group (percentage change, –0.72%; 95% CI, –1.22% to –0.22%) compared with loss in the probiotic group (percentage change, –0.01%; 95% CI, –0.50% to 0.48%). Using analysis of covariance, the researchers found the probiotic group had reduced LS-BMD loss after adjustment for factors such as study site, age at baseline, BMD at baseline, and number of years from menopause (mean difference, 7.44 mg/cm2; 95% CI, 0.38 to 14.50).

In a subgroup analysis of women above and below the median time since menopause at baseline (6 years), participants in the probiotic group who were below the median time saw a significant protective effect of Lactobacillus treatment (mean difference, 1.08%; 95% CI, 0.20%-1.96%), compared with women above the median time (mean difference, 0.31%; 95% CI, –0.62% to 1.23%).

Researchers also examined the effects of probiotic treatment on total hip and femoral neck BMD as secondary endpoints. Lactobacillus treatment did not appear to affect total hip (–1.01%; 95% CI, –1.65% to –0.37%) or trochanter BMD (–1.13%; 95% CI, –2.27% to 0.20%), but femoral neck BMD was reduced in the probiotic group (–1.34%; 95% CI, –2.09% to –0.58%), compared with the placebo group (–0.88%; 95% CI, –1.64% to –0.13%).

Limitations of the study included examining only one dose of Lactobacillus treatment and no analysis of the effect of short-chain fatty acids on LS-BMD. The researchers noted that “recent studies have shown that short-chain fatty acids, which are generated by fermentation of complex carbohydrates by the gut microbiota, are important regulators of both bone formation and resorption.”

The researchers also acknowledged that the LS-BMD effect size for the probiotic treatment over the 12 months was a lower magnitude, compared with first-line treatments for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women using bisphosphonates. “Further long-term studies should be done to evaluate if the bone-protective effect becomes more pronounced with prolonged treatment with the Lactobacillus strains used in the present study,” they said.

In a related editorial, Shivani Sahni, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Connie M. Weaver, PhD, of Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind., reiterated that the effect size of probiotics is “of far less magnitude” than such treatments as bisphosphonates and expressed concern about the reduction of femoral neck BMD in the probiotic group, which was not explained in the study (Lancet Rheumatol. 2019 Nov;1[3]:e135-e137. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30073-6). There is a need to learn the optimum dose of probiotics as well as which Lactobacillus strains should be used in future studies, as the strains chosen by Jansson et al. were based on results in mice.

In the meantime, patients might be better off choosing dietary interventions with proven bone protection and no documented negative effects on the hip, such as prebiotics like soluble corn fiber and dried prunes, in tandem with drug therapies, Dr. Sahni and Dr. Weaver said.

“Although Jansson and colleagues’ results are important, more work is needed before such probiotics are ready for consumers,” they concluded.

This study was funded by Probi, which employs two of the study’s authors. Three authors reported being coinventors of a patent involving the effects of probiotics in osteoporosis treatment, and one author is listed as an inventor on a pending patent application on probiotic compositions and uses. Dr. Sahni reported receiving grants from Dairy Management. Dr. Weaver reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jansson P-A et al. Lancet Rheumatol. 2019 Nov;1(3):e154-e162. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30068-2

, according to recent research published in The Lancet Rheumatology.

“The menopausal and early postmenopausal lumbar spine bone loss is substantial in women, and by using a prevention therapy with bacteria naturally occurring in the human gut microbiota we observed a close to complete protection against lumbar spine bone loss in healthy postmenopausal women,” Per-Anders Jansson, MD, chief physician at the University of Gothenburg (Sweden), and colleagues wrote in their study.

Dr. Jansson and colleagues performed a double-blind trial at four centers in Sweden in which 249 postmenopausal women were randomized during April-November 2016 to receive probiotics consisting of three Lactobacillus strains or placebo once per day for 12 months. Participants were healthy women, neither underweight nor overweight, and were postmenopausal, which was defined as being 2-12 years or less from last menstruation. The Lactobacillus strains, L. paracasei 8700:2 (DSM 13434), L. plantarum Heal 9 (DSM 15312), and L. plantarum Heal 19 (DSM 15313), were equally represented in a capsule at a dose of 1 x 1010 colony-forming unit per capsule. The researchers measured the lumbar spine bone mineral density (LS-BMD) at baseline and at 12 months, and also evaluated the safety profile of participants in both the probiotic and placebo groups.

Overall, 234 participants (94%) had data available for analysis at the end of the study. There was a significant reduction in LS-BMD loss for participants who received the probiotic treatment, compared with women in the control group (mean difference, 0.71%; 95% confidence interval, 0.06%-1.35%), while there was a significant loss in LS-BMD for participants in the placebo group (percentage change, –0.72%; 95% CI, –1.22% to –0.22%) compared with loss in the probiotic group (percentage change, –0.01%; 95% CI, –0.50% to 0.48%). Using analysis of covariance, the researchers found the probiotic group had reduced LS-BMD loss after adjustment for factors such as study site, age at baseline, BMD at baseline, and number of years from menopause (mean difference, 7.44 mg/cm2; 95% CI, 0.38 to 14.50).

In a subgroup analysis of women above and below the median time since menopause at baseline (6 years), participants in the probiotic group who were below the median time saw a significant protective effect of Lactobacillus treatment (mean difference, 1.08%; 95% CI, 0.20%-1.96%), compared with women above the median time (mean difference, 0.31%; 95% CI, –0.62% to 1.23%).

Researchers also examined the effects of probiotic treatment on total hip and femoral neck BMD as secondary endpoints. Lactobacillus treatment did not appear to affect total hip (–1.01%; 95% CI, –1.65% to –0.37%) or trochanter BMD (–1.13%; 95% CI, –2.27% to 0.20%), but femoral neck BMD was reduced in the probiotic group (–1.34%; 95% CI, –2.09% to –0.58%), compared with the placebo group (–0.88%; 95% CI, –1.64% to –0.13%).

Limitations of the study included examining only one dose of Lactobacillus treatment and no analysis of the effect of short-chain fatty acids on LS-BMD. The researchers noted that “recent studies have shown that short-chain fatty acids, which are generated by fermentation of complex carbohydrates by the gut microbiota, are important regulators of both bone formation and resorption.”

The researchers also acknowledged that the LS-BMD effect size for the probiotic treatment over the 12 months was a lower magnitude, compared with first-line treatments for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women using bisphosphonates. “Further long-term studies should be done to evaluate if the bone-protective effect becomes more pronounced with prolonged treatment with the Lactobacillus strains used in the present study,” they said.

In a related editorial, Shivani Sahni, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Connie M. Weaver, PhD, of Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind., reiterated that the effect size of probiotics is “of far less magnitude” than such treatments as bisphosphonates and expressed concern about the reduction of femoral neck BMD in the probiotic group, which was not explained in the study (Lancet Rheumatol. 2019 Nov;1[3]:e135-e137. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30073-6). There is a need to learn the optimum dose of probiotics as well as which Lactobacillus strains should be used in future studies, as the strains chosen by Jansson et al. were based on results in mice.

In the meantime, patients might be better off choosing dietary interventions with proven bone protection and no documented negative effects on the hip, such as prebiotics like soluble corn fiber and dried prunes, in tandem with drug therapies, Dr. Sahni and Dr. Weaver said.

“Although Jansson and colleagues’ results are important, more work is needed before such probiotics are ready for consumers,” they concluded.

This study was funded by Probi, which employs two of the study’s authors. Three authors reported being coinventors of a patent involving the effects of probiotics in osteoporosis treatment, and one author is listed as an inventor on a pending patent application on probiotic compositions and uses. Dr. Sahni reported receiving grants from Dairy Management. Dr. Weaver reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jansson P-A et al. Lancet Rheumatol. 2019 Nov;1(3):e154-e162. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(19)30068-2

FROM THE LANCET RHEUMATOLOGY

Spinal progression found more often in men with ankylosing spondylitis

Patients with ankylosing spondylitis who are male, have evidence of spinal damage, or have higher levels of inflammatory markers may be at higher risk of disease progression, a study has found.

“Assessment of AS-related structural changes longitudinally is essential for understanding the natural course of progression and its underlying factors,” Ismail Sari, MD, of the University of Toronto and coauthors wrote in Arthritis Care & Research. “This could help identify the mechanisms responsible for progression and thereby personalizing treatment.”

The researchers found that nearly one-quarter (24.3%) of 350 individuals with ankylosing spondylitis in a longitudinal cohort study showed radiographic evidence of progression, defined as a change of 2 units on the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spinal Score (mSASSS) in 2 years. Overall, 76% of the group were males, and the group had a mean age of about 38 years with a mean symptom duration of nearly 15 years.

Over the 6-year follow-up, the mean mSASSS increased from 9.3 units at baseline to 17.7 units, with more progression seen in the cervical spine than the lumbar segments. During the first 2 years, the total mSASSS increased by a mean of 1.23 units; in years 2-4, it increased by a mean of 1.47 units, and from 4 to 6 years, it increased by a mean of 1.52 units.

Male sex was associated with more than double the risk of radiographic progression (hazard ratio, 2.46; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-5.76), while individuals with radiographic evidence of spinal damage at baseline had a nearly eightfold higher risk of progression (HR, 7.98; 95% CI, 3.98-16). The risk for disease progression also increased with higher levels of C-reactive protein.

The investigators also found that patients who had used tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy for at least 1 year had an 18% reduction in the rate of spinal progression.

However, other factors including symptom duration, presence of HLA-B27, smoking status, presence of radiographic hip disease, or use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or NSAIDs did not appear to influence the risk of disease progression.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Sari I et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1002/acr.24104.

Patients with ankylosing spondylitis who are male, have evidence of spinal damage, or have higher levels of inflammatory markers may be at higher risk of disease progression, a study has found.

“Assessment of AS-related structural changes longitudinally is essential for understanding the natural course of progression and its underlying factors,” Ismail Sari, MD, of the University of Toronto and coauthors wrote in Arthritis Care & Research. “This could help identify the mechanisms responsible for progression and thereby personalizing treatment.”

The researchers found that nearly one-quarter (24.3%) of 350 individuals with ankylosing spondylitis in a longitudinal cohort study showed radiographic evidence of progression, defined as a change of 2 units on the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spinal Score (mSASSS) in 2 years. Overall, 76% of the group were males, and the group had a mean age of about 38 years with a mean symptom duration of nearly 15 years.

Over the 6-year follow-up, the mean mSASSS increased from 9.3 units at baseline to 17.7 units, with more progression seen in the cervical spine than the lumbar segments. During the first 2 years, the total mSASSS increased by a mean of 1.23 units; in years 2-4, it increased by a mean of 1.47 units, and from 4 to 6 years, it increased by a mean of 1.52 units.

Male sex was associated with more than double the risk of radiographic progression (hazard ratio, 2.46; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-5.76), while individuals with radiographic evidence of spinal damage at baseline had a nearly eightfold higher risk of progression (HR, 7.98; 95% CI, 3.98-16). The risk for disease progression also increased with higher levels of C-reactive protein.

The investigators also found that patients who had used tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy for at least 1 year had an 18% reduction in the rate of spinal progression.

However, other factors including symptom duration, presence of HLA-B27, smoking status, presence of radiographic hip disease, or use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or NSAIDs did not appear to influence the risk of disease progression.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Sari I et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1002/acr.24104.

Patients with ankylosing spondylitis who are male, have evidence of spinal damage, or have higher levels of inflammatory markers may be at higher risk of disease progression, a study has found.

“Assessment of AS-related structural changes longitudinally is essential for understanding the natural course of progression and its underlying factors,” Ismail Sari, MD, of the University of Toronto and coauthors wrote in Arthritis Care & Research. “This could help identify the mechanisms responsible for progression and thereby personalizing treatment.”

The researchers found that nearly one-quarter (24.3%) of 350 individuals with ankylosing spondylitis in a longitudinal cohort study showed radiographic evidence of progression, defined as a change of 2 units on the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spinal Score (mSASSS) in 2 years. Overall, 76% of the group were males, and the group had a mean age of about 38 years with a mean symptom duration of nearly 15 years.

Over the 6-year follow-up, the mean mSASSS increased from 9.3 units at baseline to 17.7 units, with more progression seen in the cervical spine than the lumbar segments. During the first 2 years, the total mSASSS increased by a mean of 1.23 units; in years 2-4, it increased by a mean of 1.47 units, and from 4 to 6 years, it increased by a mean of 1.52 units.

Male sex was associated with more than double the risk of radiographic progression (hazard ratio, 2.46; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-5.76), while individuals with radiographic evidence of spinal damage at baseline had a nearly eightfold higher risk of progression (HR, 7.98; 95% CI, 3.98-16). The risk for disease progression also increased with higher levels of C-reactive protein.

The investigators also found that patients who had used tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy for at least 1 year had an 18% reduction in the rate of spinal progression.

However, other factors including symptom duration, presence of HLA-B27, smoking status, presence of radiographic hip disease, or use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs or NSAIDs did not appear to influence the risk of disease progression.

No funding or conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Sari I et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2019 Nov 1. doi: 10.1002/acr.24104.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Psoriatic Arthritis Types and Disease Pattern

Blocking TLR9 may halt brain edema in acute liver failure

A toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) antagonist may eventually be used to combat brain edema in acute liver failure, according to investigators.

This prediction is based on results of a recent study involving mouse models, which showed that ODN2088, a TLR9 antagonist, could stop ammonia-induced colocalization of DNA with TLR9 in innate immune cells, thereby blocking cytokine production and ensuant brain edema, reported lead author Godhev Kumar Manakkat Vijay of King’s College London and colleagues.

“Ammonia plays a pivotal role in the development of hepatic encephalopathy and brain edema in acute liver failure,” the investigators explained in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “A robust systemic inflammatory response and susceptibility to developing infection are common in acute liver failure, exacerbate the development of ammonia-induced brain edema and are major prognosticators. Experimental models have unequivocally associated ammonia exposure with astrocyte swelling and brain edema, potentiated by proinflammatory cytokines.”

The investigators added that, “although the evidence base supporting the relationship between ammonia, inflammation, and brain edema is robust in acute liver failure, there is a paucity of data characterizing the specific pathogenic mechanisms entailed.” Previous research suggested that TLR9 plays a key role in acetaminophen-induced liver inflammation, they noted, and that ammonia, in combination with DNA, triggers TLR9 expression in neutrophils, which brought TLR9 into focus for the present study.

Along with wild-type mice, the investigators relied upon two knockout models: TLR9–/– mice, in which TLR9 is entirely absent, and LysM-Cre TLR9fl/fl mice, in which TLR9 is absent from lysozyme-expressing cells (predominantly neutrophils and macrophages). Comparing against controls, the investigators assessed cytokine production and brain edema in each type of mouse when intraperitoneally injected with ammonium acetate (4 mmol/kg). Specifically, 6 hours after injection, they measured intracellular cytokines in splenic macrophages, CD8+ T cells, and CD4+ T cells. In addition, they recorded total plasma DNA and brain water, a measure of brain edema.

Following ammonium acetate injection, wild-type mice developed brain edema and liver enlargement, while TLR9–/– mice and control-injected mice did not. After injection, total plasma DNA levels rose by comparable magnitudes in both wild-type mice and TLR9–/– mice, but did not change in control-injected mice, suggesting that ammonium-acetate injection was causing a release of DNA, which was binding with TLR9, resulting in activation of the innate immune system.

This hypothesis was supported by measurements of cytokines in T cells and splenic macrophages, which showed that wild-type mice had elevations of cytokines, whereas knockout mice did not. Further experiments showed that LysM-Cre TLR9fl/fl mice had similar outcomes as TLR9–/– mice, highlighting that macrophages and neutrophils are the key immune cells linking TLR9 activation with cytokine release, and therefore brain edema.

To ensure that brain edema was not directly caused by the acetate component of ammonium acetate, or acetate’s potential to increase pH, a different set of wild-type mice were injected with sodium acetate adjusted to the same pH as ammonium acetate. This had no impact on cytokine production, brain-water content, or liver-to-body weight ratio, confirming that acetate was not responsible for brain edema while providing further support for the role of TLR9.

Finally, the investigators treated wild-type mice immediately after ammonium acetate injection with the TLR9 antagonist ODN2088 (50 mcg/mouse). This treatment halted cytokine production, inflammation, and brain edema, strongly supporting the link between these ammonia-induced processes and TLR9 activation.

“These data are well supported by the findings of Imaeda et al. (J Clin Invest. 2009 Feb 2. doi: 10.1172/JCI35958), who in an acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity model established that inhibition of TLR9 using ODN2088 and IRS954, a TLR7/9 antagonist, down-regulated proinflammatory cytokine release and reduced mortality,” the investigators wrote. “The amelioration of brain edema and cytokine production by ODN2088 supports exploration of TLR9 antagonism as a therapeutic modality in early acute liver failure to prevent the development of brain edema and intracranial hypertension.”

The study was funded by the U.K. Institute of Liver Studies Charitable Fund and the National Institutes of Health. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Vijay GKM et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2019.08.002.

Acute liver failure is a devastating disease, which has a high mortality burden and often requires liver transplant. One of the major complications is cerebral edema that leads to encephalopathy and could be fatal. These brain changes are accompanied by inflammation, immune activation, and hyperammonemia, but further mechanistic approaches are needed.

This data adds to the growing literature about the interaction between immune dysfunction and brain diseases such as schizophrenia, autism, depression, and multiple sclerosis. However, further studies in models of brain edema with concomitant liver failure, which are closer to the human disease process, are needed. This exciting investigation of neuroimmune regulation of brain edema could set the basis for new therapeutic options for the prevention and treatment of this feared complication of acute liver failure.

Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, AGAF, is professor in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond. He reported no conflicts of interest.

Acute liver failure is a devastating disease, which has a high mortality burden and often requires liver transplant. One of the major complications is cerebral edema that leads to encephalopathy and could be fatal. These brain changes are accompanied by inflammation, immune activation, and hyperammonemia, but further mechanistic approaches are needed.

This data adds to the growing literature about the interaction between immune dysfunction and brain diseases such as schizophrenia, autism, depression, and multiple sclerosis. However, further studies in models of brain edema with concomitant liver failure, which are closer to the human disease process, are needed. This exciting investigation of neuroimmune regulation of brain edema could set the basis for new therapeutic options for the prevention and treatment of this feared complication of acute liver failure.

Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, AGAF, is professor in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond. He reported no conflicts of interest.

Acute liver failure is a devastating disease, which has a high mortality burden and often requires liver transplant. One of the major complications is cerebral edema that leads to encephalopathy and could be fatal. These brain changes are accompanied by inflammation, immune activation, and hyperammonemia, but further mechanistic approaches are needed.

This data adds to the growing literature about the interaction between immune dysfunction and brain diseases such as schizophrenia, autism, depression, and multiple sclerosis. However, further studies in models of brain edema with concomitant liver failure, which are closer to the human disease process, are needed. This exciting investigation of neuroimmune regulation of brain edema could set the basis for new therapeutic options for the prevention and treatment of this feared complication of acute liver failure.

Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, AGAF, is professor in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) antagonist may eventually be used to combat brain edema in acute liver failure, according to investigators.

This prediction is based on results of a recent study involving mouse models, which showed that ODN2088, a TLR9 antagonist, could stop ammonia-induced colocalization of DNA with TLR9 in innate immune cells, thereby blocking cytokine production and ensuant brain edema, reported lead author Godhev Kumar Manakkat Vijay of King’s College London and colleagues.

“Ammonia plays a pivotal role in the development of hepatic encephalopathy and brain edema in acute liver failure,” the investigators explained in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “A robust systemic inflammatory response and susceptibility to developing infection are common in acute liver failure, exacerbate the development of ammonia-induced brain edema and are major prognosticators. Experimental models have unequivocally associated ammonia exposure with astrocyte swelling and brain edema, potentiated by proinflammatory cytokines.”

The investigators added that, “although the evidence base supporting the relationship between ammonia, inflammation, and brain edema is robust in acute liver failure, there is a paucity of data characterizing the specific pathogenic mechanisms entailed.” Previous research suggested that TLR9 plays a key role in acetaminophen-induced liver inflammation, they noted, and that ammonia, in combination with DNA, triggers TLR9 expression in neutrophils, which brought TLR9 into focus for the present study.

Along with wild-type mice, the investigators relied upon two knockout models: TLR9–/– mice, in which TLR9 is entirely absent, and LysM-Cre TLR9fl/fl mice, in which TLR9 is absent from lysozyme-expressing cells (predominantly neutrophils and macrophages). Comparing against controls, the investigators assessed cytokine production and brain edema in each type of mouse when intraperitoneally injected with ammonium acetate (4 mmol/kg). Specifically, 6 hours after injection, they measured intracellular cytokines in splenic macrophages, CD8+ T cells, and CD4+ T cells. In addition, they recorded total plasma DNA and brain water, a measure of brain edema.

Following ammonium acetate injection, wild-type mice developed brain edema and liver enlargement, while TLR9–/– mice and control-injected mice did not. After injection, total plasma DNA levels rose by comparable magnitudes in both wild-type mice and TLR9–/– mice, but did not change in control-injected mice, suggesting that ammonium-acetate injection was causing a release of DNA, which was binding with TLR9, resulting in activation of the innate immune system.

This hypothesis was supported by measurements of cytokines in T cells and splenic macrophages, which showed that wild-type mice had elevations of cytokines, whereas knockout mice did not. Further experiments showed that LysM-Cre TLR9fl/fl mice had similar outcomes as TLR9–/– mice, highlighting that macrophages and neutrophils are the key immune cells linking TLR9 activation with cytokine release, and therefore brain edema.

To ensure that brain edema was not directly caused by the acetate component of ammonium acetate, or acetate’s potential to increase pH, a different set of wild-type mice were injected with sodium acetate adjusted to the same pH as ammonium acetate. This had no impact on cytokine production, brain-water content, or liver-to-body weight ratio, confirming that acetate was not responsible for brain edema while providing further support for the role of TLR9.

Finally, the investigators treated wild-type mice immediately after ammonium acetate injection with the TLR9 antagonist ODN2088 (50 mcg/mouse). This treatment halted cytokine production, inflammation, and brain edema, strongly supporting the link between these ammonia-induced processes and TLR9 activation.

“These data are well supported by the findings of Imaeda et al. (J Clin Invest. 2009 Feb 2. doi: 10.1172/JCI35958), who in an acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity model established that inhibition of TLR9 using ODN2088 and IRS954, a TLR7/9 antagonist, down-regulated proinflammatory cytokine release and reduced mortality,” the investigators wrote. “The amelioration of brain edema and cytokine production by ODN2088 supports exploration of TLR9 antagonism as a therapeutic modality in early acute liver failure to prevent the development of brain edema and intracranial hypertension.”

The study was funded by the U.K. Institute of Liver Studies Charitable Fund and the National Institutes of Health. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Vijay GKM et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2019.08.002.

A toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) antagonist may eventually be used to combat brain edema in acute liver failure, according to investigators.

This prediction is based on results of a recent study involving mouse models, which showed that ODN2088, a TLR9 antagonist, could stop ammonia-induced colocalization of DNA with TLR9 in innate immune cells, thereby blocking cytokine production and ensuant brain edema, reported lead author Godhev Kumar Manakkat Vijay of King’s College London and colleagues.

“Ammonia plays a pivotal role in the development of hepatic encephalopathy and brain edema in acute liver failure,” the investigators explained in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “A robust systemic inflammatory response and susceptibility to developing infection are common in acute liver failure, exacerbate the development of ammonia-induced brain edema and are major prognosticators. Experimental models have unequivocally associated ammonia exposure with astrocyte swelling and brain edema, potentiated by proinflammatory cytokines.”

The investigators added that, “although the evidence base supporting the relationship between ammonia, inflammation, and brain edema is robust in acute liver failure, there is a paucity of data characterizing the specific pathogenic mechanisms entailed.” Previous research suggested that TLR9 plays a key role in acetaminophen-induced liver inflammation, they noted, and that ammonia, in combination with DNA, triggers TLR9 expression in neutrophils, which brought TLR9 into focus for the present study.

Along with wild-type mice, the investigators relied upon two knockout models: TLR9–/– mice, in which TLR9 is entirely absent, and LysM-Cre TLR9fl/fl mice, in which TLR9 is absent from lysozyme-expressing cells (predominantly neutrophils and macrophages). Comparing against controls, the investigators assessed cytokine production and brain edema in each type of mouse when intraperitoneally injected with ammonium acetate (4 mmol/kg). Specifically, 6 hours after injection, they measured intracellular cytokines in splenic macrophages, CD8+ T cells, and CD4+ T cells. In addition, they recorded total plasma DNA and brain water, a measure of brain edema.

Following ammonium acetate injection, wild-type mice developed brain edema and liver enlargement, while TLR9–/– mice and control-injected mice did not. After injection, total plasma DNA levels rose by comparable magnitudes in both wild-type mice and TLR9–/– mice, but did not change in control-injected mice, suggesting that ammonium-acetate injection was causing a release of DNA, which was binding with TLR9, resulting in activation of the innate immune system.

This hypothesis was supported by measurements of cytokines in T cells and splenic macrophages, which showed that wild-type mice had elevations of cytokines, whereas knockout mice did not. Further experiments showed that LysM-Cre TLR9fl/fl mice had similar outcomes as TLR9–/– mice, highlighting that macrophages and neutrophils are the key immune cells linking TLR9 activation with cytokine release, and therefore brain edema.

To ensure that brain edema was not directly caused by the acetate component of ammonium acetate, or acetate’s potential to increase pH, a different set of wild-type mice were injected with sodium acetate adjusted to the same pH as ammonium acetate. This had no impact on cytokine production, brain-water content, or liver-to-body weight ratio, confirming that acetate was not responsible for brain edema while providing further support for the role of TLR9.

Finally, the investigators treated wild-type mice immediately after ammonium acetate injection with the TLR9 antagonist ODN2088 (50 mcg/mouse). This treatment halted cytokine production, inflammation, and brain edema, strongly supporting the link between these ammonia-induced processes and TLR9 activation.

“These data are well supported by the findings of Imaeda et al. (J Clin Invest. 2009 Feb 2. doi: 10.1172/JCI35958), who in an acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity model established that inhibition of TLR9 using ODN2088 and IRS954, a TLR7/9 antagonist, down-regulated proinflammatory cytokine release and reduced mortality,” the investigators wrote. “The amelioration of brain edema and cytokine production by ODN2088 supports exploration of TLR9 antagonism as a therapeutic modality in early acute liver failure to prevent the development of brain edema and intracranial hypertension.”

The study was funded by the U.K. Institute of Liver Studies Charitable Fund and the National Institutes of Health. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Vijay GKM et al. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2019.08.002.

FROM CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

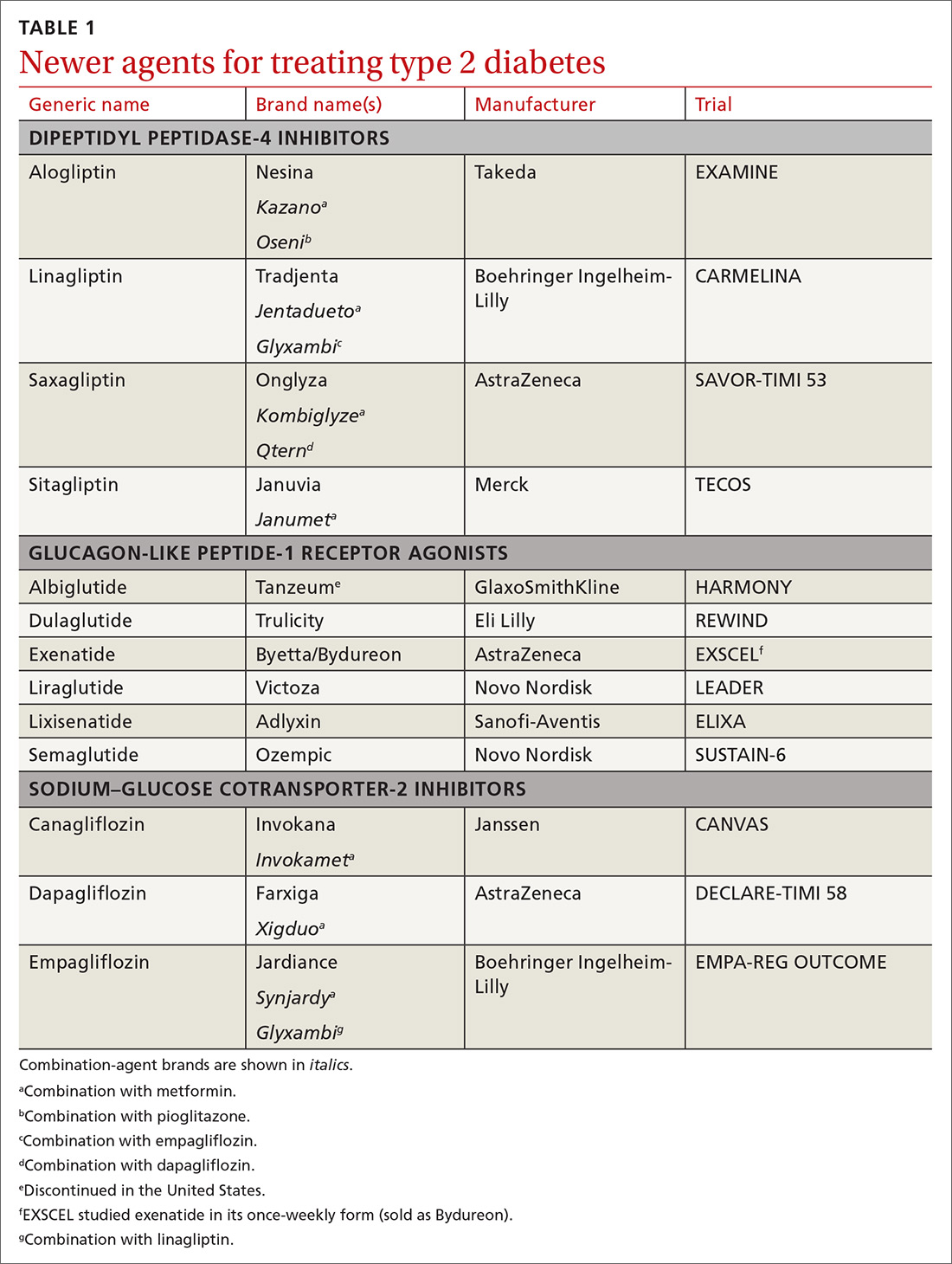

How to use type 2 diabetes meds to lower CV disease risk

The association between type 2 diabetes (T2D) and cardiovascular (CV) disease is well-established:

- Type 2 diabetes approximately doubles the risk of coronary artery disease, stroke, and peripheral arterial disease, independent of conventional risk factors1

- CV disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with T2D

- CV disease is the largest contributor to direct and indirect costs of the health care of patients who have T2D.2

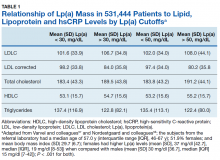

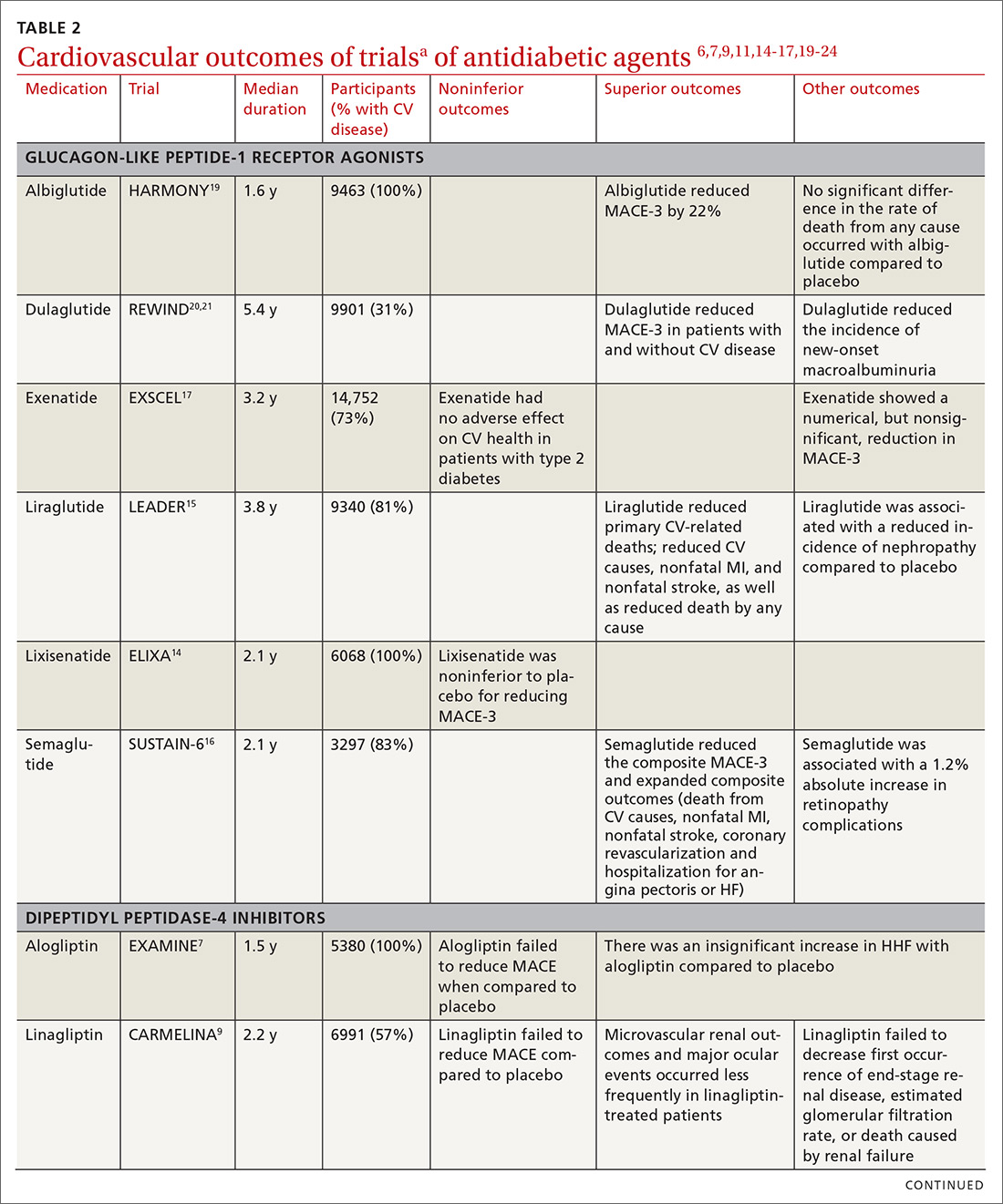

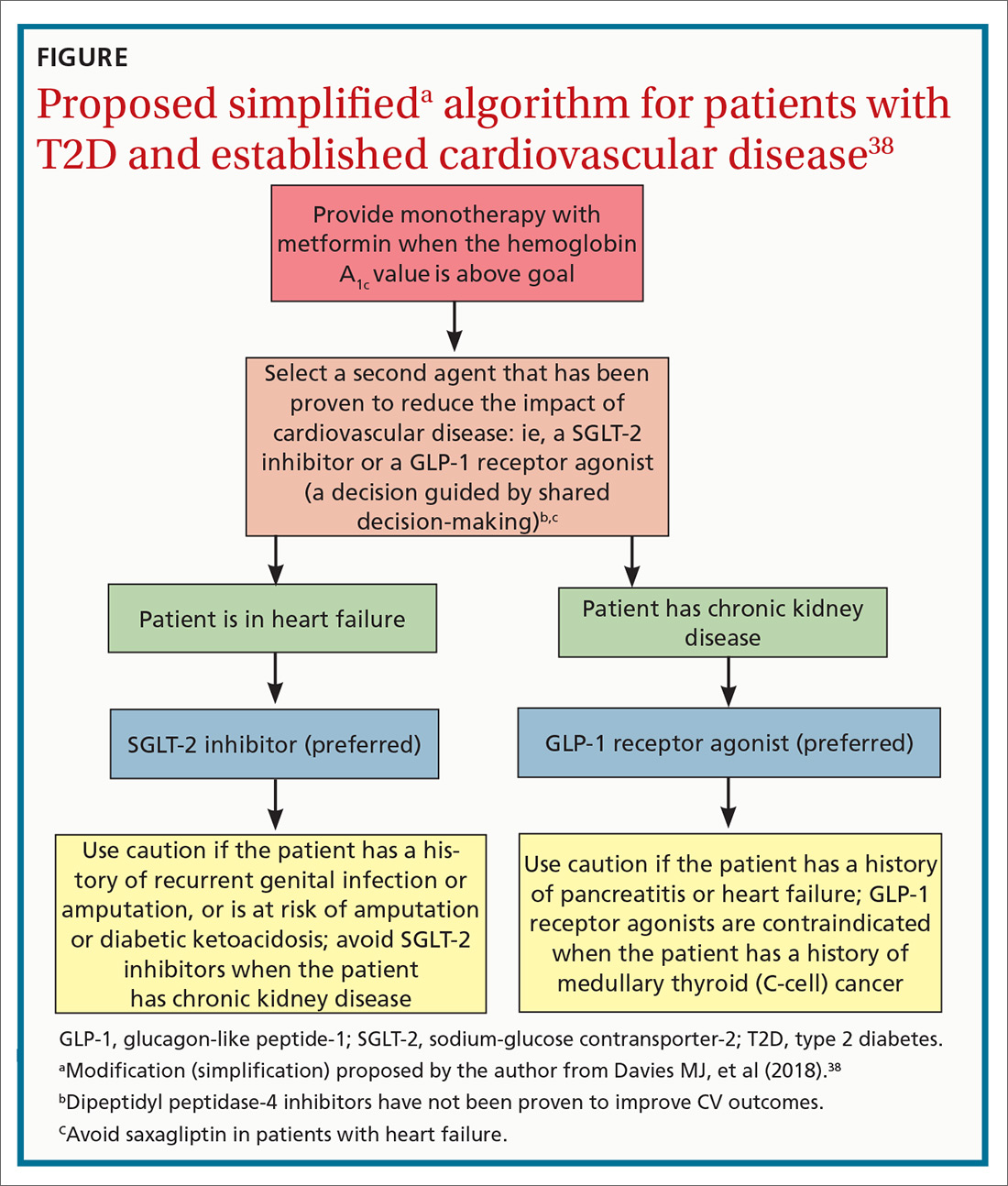

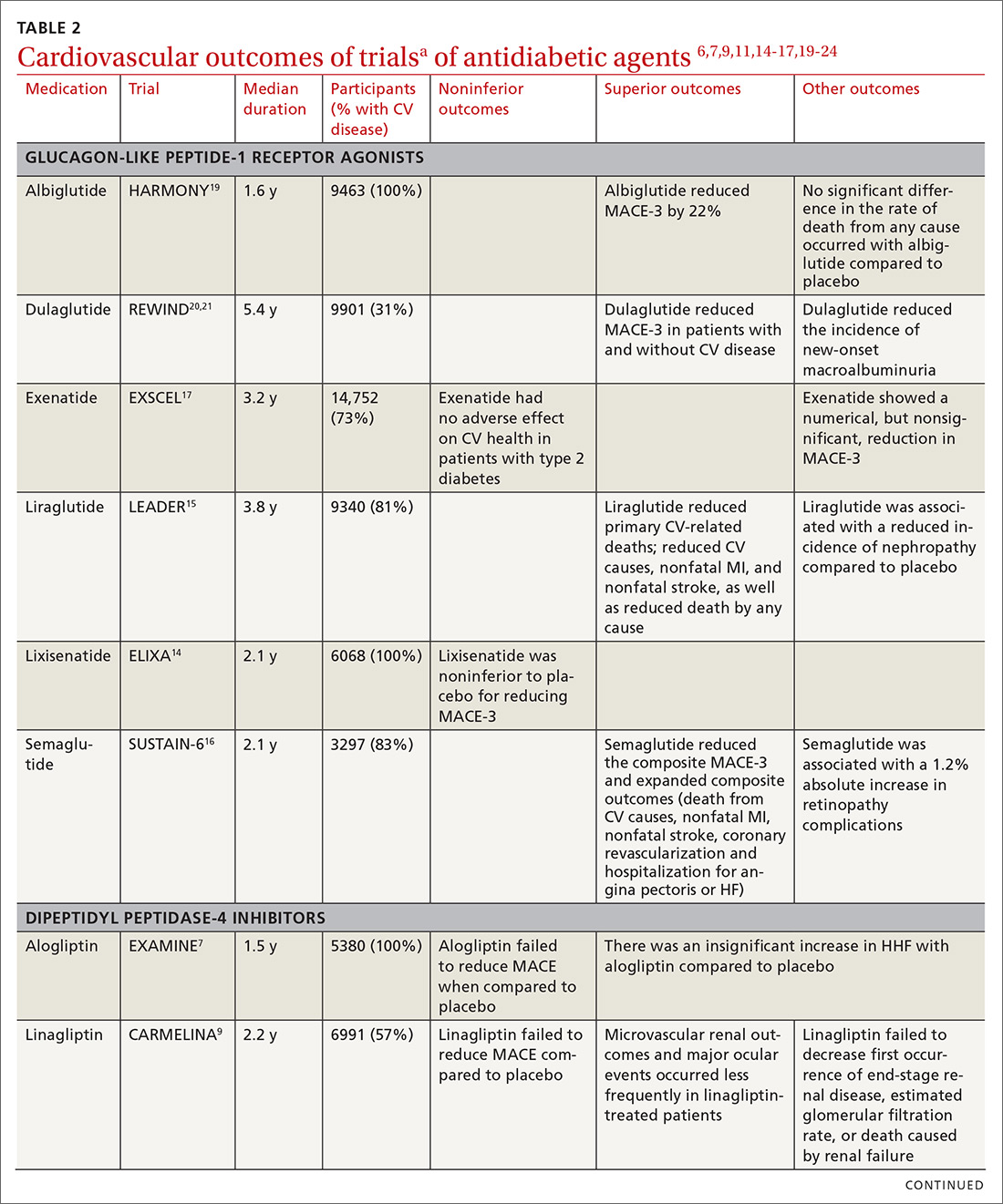

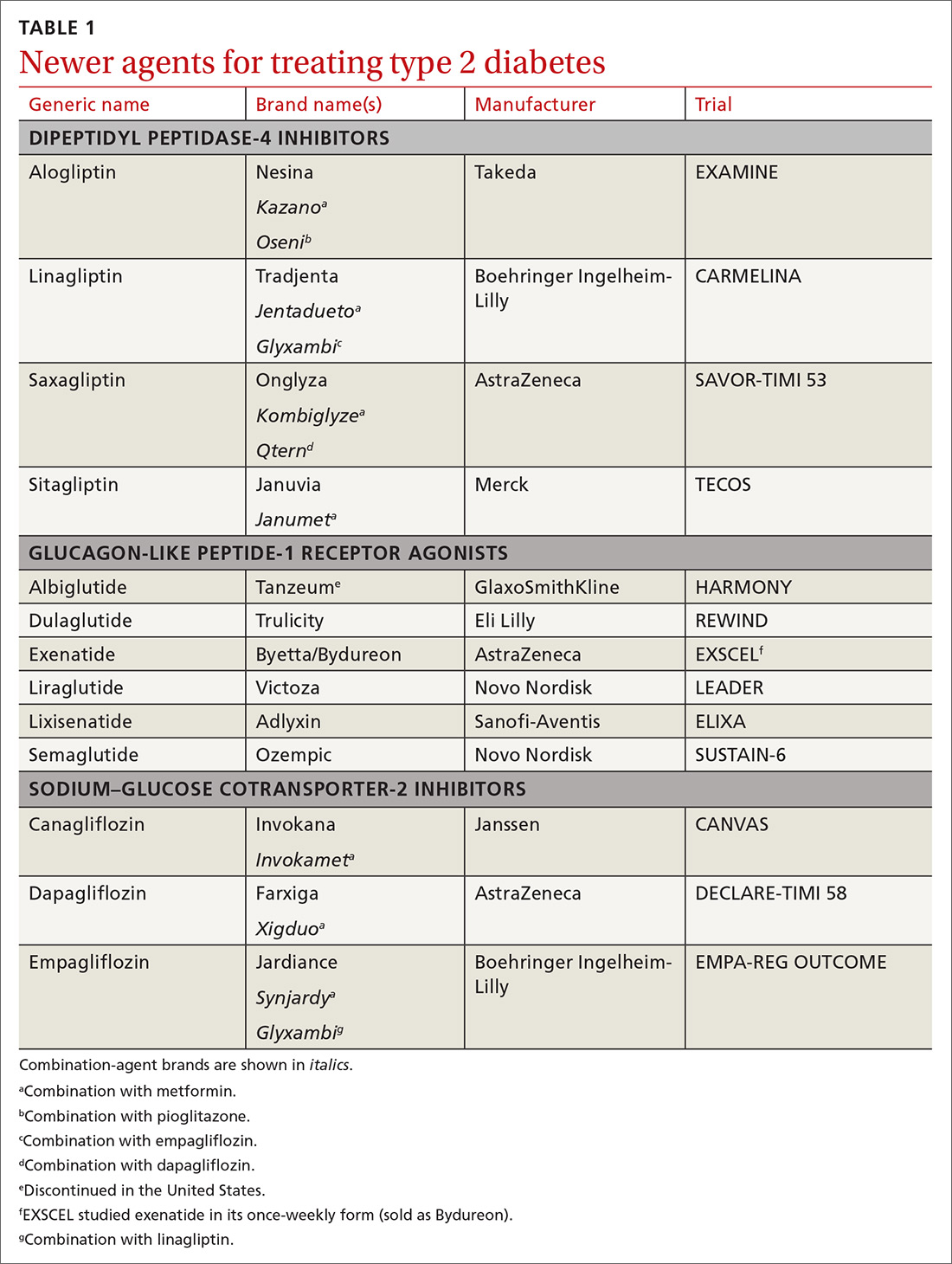

In recent years, new classes of agents for treating T2D have been introduced (TABLE 1). Prior to 2008, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drugs in those new classes based simply on their effectiveness in reducing the blood glucose level. Concerns about the CV safety of specific drugs (eg, rosiglitazone, muraglitazar) emerged from a number of trials, suggesting that these agents might increase the risk of CV events.3,4

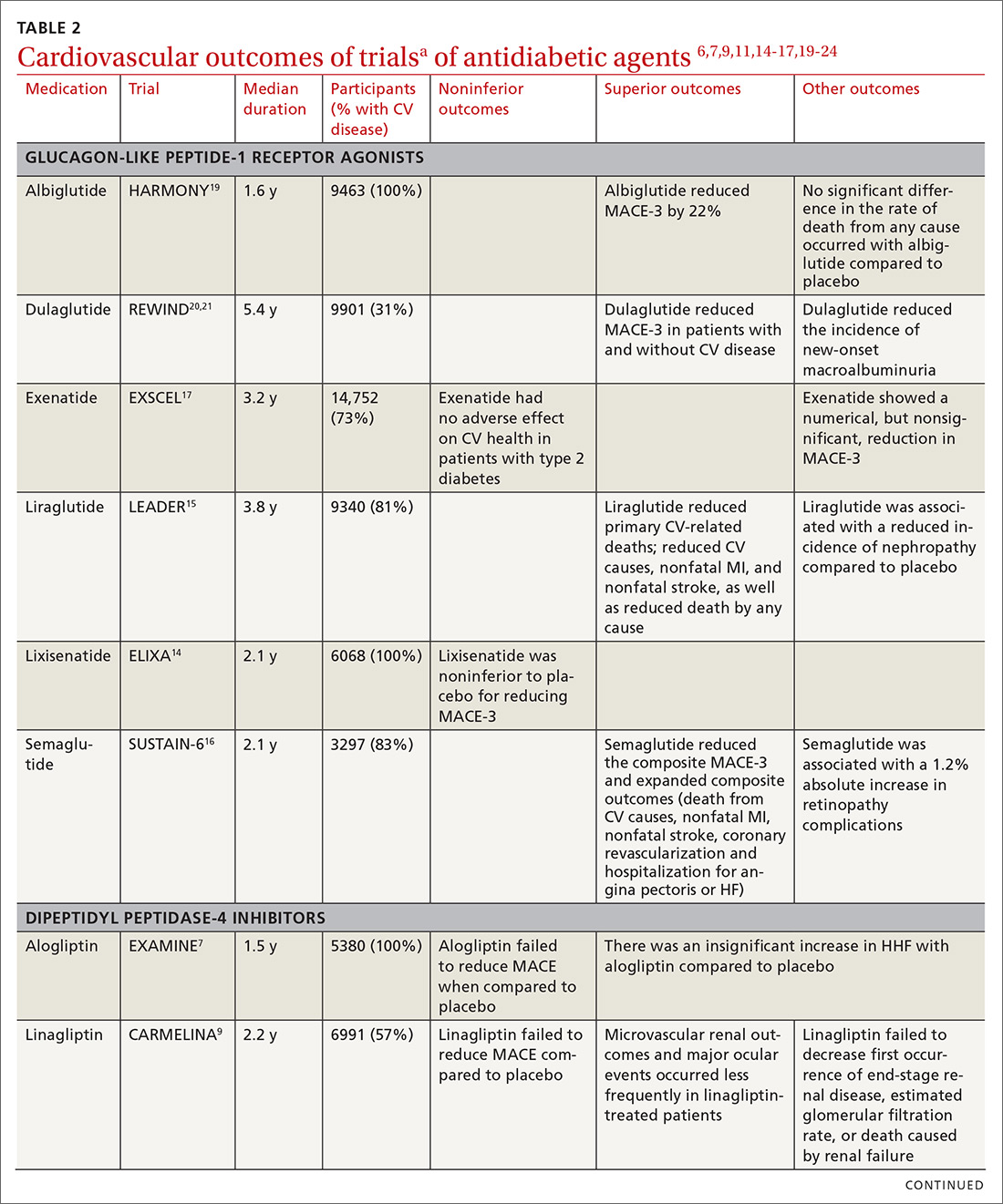

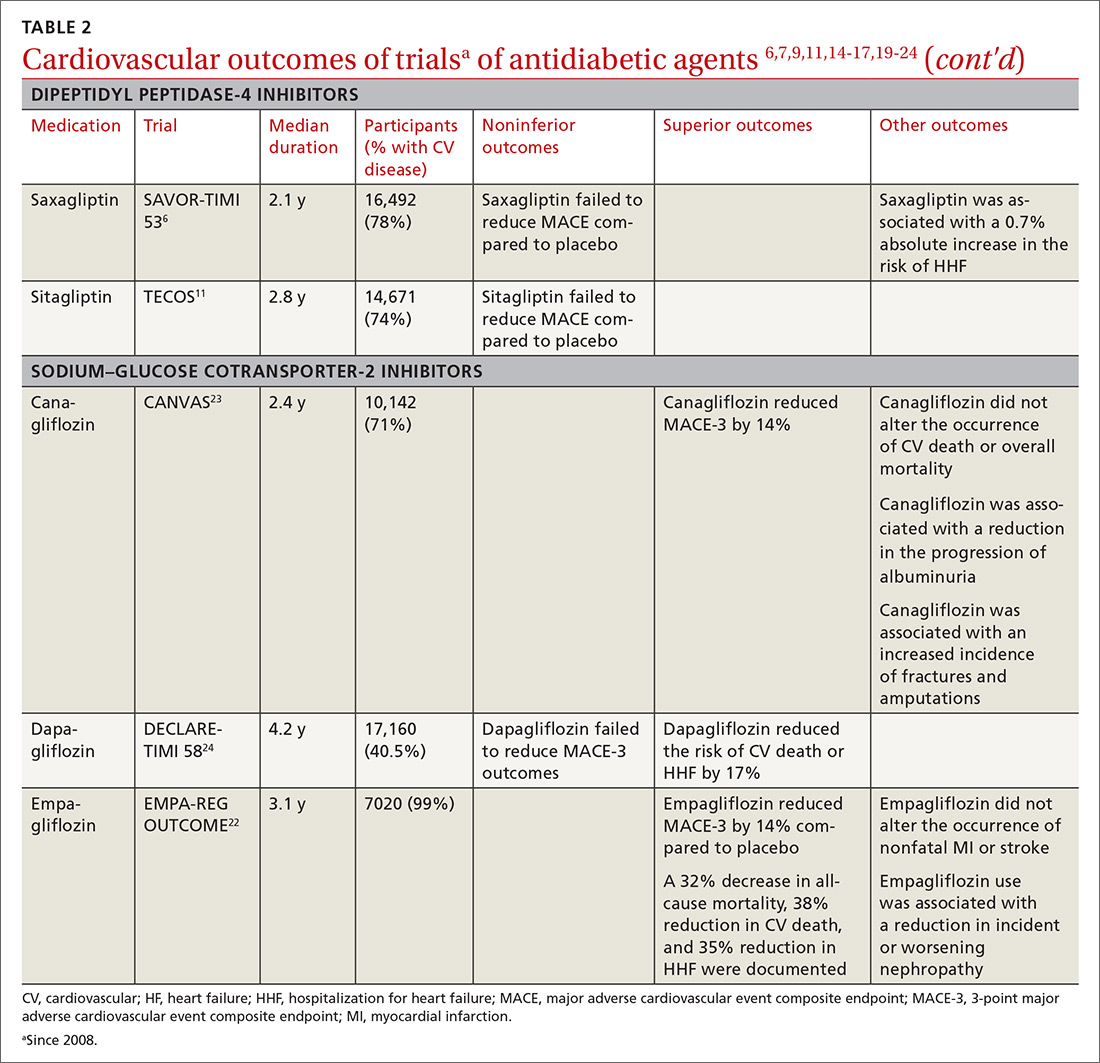

Consequently, in 2008, the FDA issued guidance to the pharmaceutical industry: Preapproval and postapproval trials of all new antidiabetic drugs must now assess potential excess CV risk.5 CV outcomes trials (CVOTs), performed in accordance with FDA guidelines, have therefore become the focus of evaluating novel treatment options. In most CVOTs, combined primary CV endpoints have included CV mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), and nonfatal stroke—taken together, what is known as the composite of these 3 major adverse CV events, or MACE-3.

To date, 15 CVOTs have been completed, assessing 3 novel classes of antihyperglycemic agents:

- dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors

- glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists

- sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors.

None of these trials identified any increased incidence of MACE; 7 found CV benefit. This review summarizes what the CVOTs revealed about these antihyperglycemic agents and their ability to yield a reduction in MACE and a decrease in all-cause mortality in patients with T2D and elevated CV disease risk. Armed with this information, you will have the tools you need to offer patients with T2D CV benefit while managing their primary disease.

Cardiovascular outcomes trials: DPP-4 inhibitors

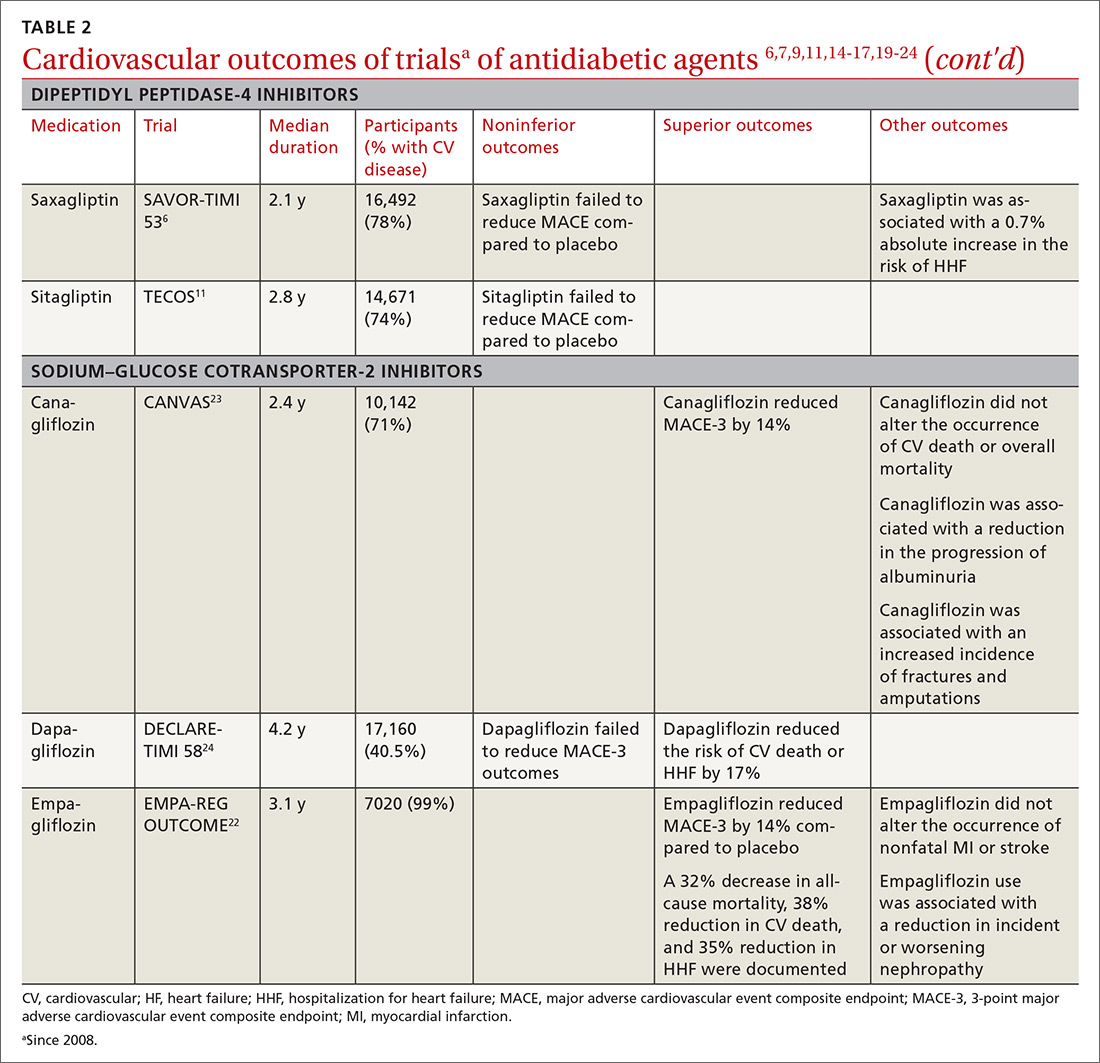

Four trials. Trials of DPP-4 inhibitors that have been completed and reported are of saxagliptin (SAVOR-TIMI 536), alogliptin (EXAMINE7), sitagliptin (TECOS8), and linagliptin (CARMELINA9); others are in progress. In general, researchers enrolled patients at high risk of CV events, although inclusion criteria varied substantially. Consistently, these studies demonstrated that DPP-4 inhibition neither increased nor decreased (ie, were noninferior) the 3-point MACE (SAVOR-TIMI 53 noninferiority, P < .001; EXAMINE, P < .001; TECOS, P < .001).

Continue to: Rather than improve...

Rather than improve CV outcomes, there was some evidence that DPP-4 inhibitors might be associated with an increased risk of hospitalization for heart failure (HHF). In the SAVOR-TIMI 53 trial, patients randomized to saxagliptin had a 0.7% absolute increase in risk of HHF (P = .98).6 In the EXAMINE trial, patients treated with alogliptin showed a nonsignificant trend for HHF.10 In both the TECOS and CARMELINA trials, no difference was recorded in the rate of HHF.8,9,11 Subsequent meta-analysis that summarized the risk of HHF in CVOTs with DPP-4 inhibitors indicated a nonsignificant trend to increased risk.12

From these trials alone, it appears that DPP-4 inhibitors are unlikely to provide CV benefit. Data from additional trials are needed to evaluate the possible association between these medications and heart failure (HF). However, largely as a result of the findings from SAVOR-TIMI 53 and EXAMINE, the FDA issued a Drug Safety Communication in April 2016, adding warnings about HF to the labeling of saxagliptin and alogliptin.13

CARMELINA was designed to also evaluate kidney outcomes in patients with T2D. As with other DPP-4 inhibitor trials, the primary aim was to establish noninferiority, compared with placebo, for time to MACE-3 (P < .001). Secondary outcomes were defined as time to first occurrence of end-stage renal disease, death due to renal failure, and sustained decrease from baseline of ≥ 40% in the estimated glomerular filtration rate. The incidence of the secondary kidney composite results was not significantly different between groups randomized to linagliptin or placebo.9

Cardiovascular outcomes trials: GLP-1 receptor agonists

ELIXA. The CV safety of GLP-1 receptor agonists has been evaluated in several randomized clinical trials. The Evaluation of Lixisenatide in Acute Coronary Syndrome (ELIXA) trial was the first14: Lixisenatide was studied in 6068 patients with recent hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome. Lixisenatide therapy was neutral with regard to CV outcomes, which met the primary endpoint: noninferiority to placebo (P < .001). There was no increase in either HF or HHF.

Continue to: LEADER

LEADER. The Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results trial (LEADER) evaluated long-term effects of liraglutide, compared to placebo, on CV events in patients with T2D.15 It was a multicenter, double-blind, placebocontrolled study that followed 9340 participants, most (81%) of whom had established CV disease, over 5 years. LEADER is considered a landmark study because it was the first large CVOT to show significant benefit for a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

Liraglutide demonstrated reductions in first occurrence of death from CV causes, nonfatal MI or nonfatal stroke, overall CV mortality, and all-cause mortality. The composite MACE-3 showed a relative risk reduction (RRR) of 13%, equivalent to an absolute risk reduction (ARR) of 1.9% (noninferiority, P < .001; superiority, P < .01). The RRR was 22% for death from CV causes, with an ARR of 1.3% (P = .007); the RRR for death from any cause was 15%, with an ARR of 1.4% (P = .02).

In addition, there was a lower rate of nephropathy (1.5 events for every 100 patient–years in the liraglutide group [P = .003], compared with 1.9 events every 100 patient–years in the placebo group).15

Results clearly demonstrated benefit. No significant difference was seen in the liraglutide rate of HHF, compared to the rate in the placebo group.

SUSTAIN-6. Evidence for the CV benefit of GLP-1 receptor agonists was also demonstrated in the phase 3 Trial to Evaluate Cardiovascular and Other Long-term Outcomes With Semaglutide in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes (SUSTAIN-6).16 This was a study of 3297 patients with T2D at high risk of CV disease and with a mean hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) value of 8.7%, 83% of whom had established CV disease. Patients were randomized to semaglutide or placebo. Note: SUSTAIN-6 was a noninferiority safety study; as such, it was not actually designed to assess or establish superiority.

Continue to: The incidence of MACE-3...

The incidence of MACE-3 was significantly reduced among patients treated with semaglutide (P = .02) after median followup of 2.1 years. The expanded composite outcome (death from CV causes, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, coronary revascularization, or hospitalization for unstable angina or HF), also showed a significant reduction with semaglutide (P = .002), compared with placebo. There was no difference in the overall hospitalization rate or rate of death from any cause.

EXSCEL. The Exenatide Study of Cardiovascular Event Lowering trial (EXSCEL)17,18 was a phase III/IV, double-blind, pragmatic placebo-controlled study of 14,752 patients at any level of CV risk, for a median 3.2 years. The study population was intentionally more diverse than in earlier GLP-1 receptor agonist studies. The researchers hypothesized that patients at increased risk of MACE would experience a comparatively greater relative treatment benefit with exenatide than those at lower risk. That did not prove to be the case.

EXSCEL did confirm noninferiority compared with placebo (P < .001), but once-weekly exenatide resulted in a nonsignificant reduction in major adverse CV events, and a trend for RRR in all-cause mortality (RRR = 14%; ARR = 1% [P = .06]).

HARMONY OUTCOMES. The Albiglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease study (HARMONY OUTCOMES)19 was a double-blind, randomized, placebocontrolled trial conducted at 610 sites across 28 countries. The study investigated albiglutide, 30 to 50 mg once weekly, compared with placebo. It included 9463 patients ages ≥ 40 years with T2D who had an HbA1c > 7% (median value, 8.7%) and established CV disease. Patients were evaluated for a median 1.6 years.

Albiglutide reduced the risk of CV causes of death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke by an RRR of 22%, (ARR, 2%) (noninferiority, P < .0001; superiority, P < .0006).

Continue to: REWIND

REWIND. The Researching Cardiovascular Events with a Weekly INcretin in Diabetes trial (REWIND),20 the most recently completed GLP-1 receptor agonist CVOT (presented at the 2019 American Diabetes Association [ADA] Conference in June and published simultaneously in The Lancet), was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial designed to assess the effect of weekly dulaglutide, 1.5 mg, compared with placebo, in 9901 participants enrolled at 371 sites in 24 countries. Mean patient age was 66.2 years, with women constituting 4589 (46.3%) of participants.

REWIND was distinct from other CVOTs in several ways:

- Other CVOTs were designed to show noninferiority compared with placebo regarding CV events; REWIND was designed to establish superiority

- In contrast to trials of other GLP-1 receptor agonists, in which most patients had established CV disease, only 31% of REWIND participants had a history of CV disease or a prior CV event (although 69% did have CV risk factors without underlying disease)

- REWIND was much longer (median follow-up, 5.4 years) than other GLP-1 receptor agonist trials (median follow-up, 1.5 to 3.8 years).

In REWIND, the primary composite outcome of MACE-3 occurred in 12% of participants assigned to dulaglutide, compared with 13.1% assigned to placebo (P = .026). This equated to 2.4 events for every 100 person– years on dulaglutide, compared with 2.7 events for every 100 person–years on placebo. There was a consistent effect on all MACE-3 components, although the greatest reductions were observed in nonfatal stroke (P = .017). Overall risk reduction was the same for primary and secondary prevention cohorts (P = .97), as well as in patients with either an HbA1c value < 7.2% or ≥ 7.2% (P = .75). Risk reduction was consistent across age, sex, duration of T2D, and body mass index.

Dulaglutide did not significantly affect the incidence of all-cause mortality, heart failure, revascularization, or hospital admission. Forty-seven percent of patients taking dulaglutide reported gastrointestinal adverse effects (P = .0001).

In a separate analysis of secondary outcomes, 21 dulaglutide reduced the composite renal outcomes of new-onset macroalbuminuria (P = .0001); decline of ≥ 30% in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (P = .066); and chronic renal replacement therapy (P = .39). Investigators estimated that 1 composite renal outcome event would be prevented for every 31 patients treated with dulaglutide for a median 5.4 years.

Continue to: Cardiovascular outcomes trials...

Cardiovascular outcomes trials: SGLT-2 inhibitors

EMPA-REG OUTCOME. The Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes trial (EMPA-REG OUTCOME) was also a landmark study because it was the first dedicated CVOT to show that an antihyperglycemic agent 1) decreased CV mortality and all-cause mortality, and 2) reduced HHF in patients with T2D and established CV disease.22 In this trial, 7020 patients with T2D who were at high risk of CV events were randomized and treated with empagliflozin, 10 or 25 mg, or placebo, in addition to standard care, and were followed for a median 2.6 years.

Compared with placebo, empagliflozin resulted in an RRR of 14% (ARR, 1.6%) in the primary endpoint of CV death, nonfatal MI, and stroke, confirming study drug superiority (P = .04). When compared with placebo, the empagliflozin group had an RRR of 38% in CV mortality, (ARR < 2.2%) (P < .001); an RRR of 35% in HHF (ARR, 1.4%) (P = .002); and an RRR of 32% (ARR, 2.6%) in death from any cause (P < .001).

CANVAS. The Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study (CANVAS) integrated 2 multicenter, placebo-controlled, randomized trials with 10,142 participants and a mean follow-up of 3.6 years.23 Patients were randomized to receive canagliflozin (100-300 mg/d) or placebo. Approximately two-thirds of patients had a history of CV disease (therefore representing secondary prevention); one-third had CV risk factors only (primary prevention).

In CANVAS, patients receiving canagliflozin had a risk reduction in MACE-3, establishing superiority compared with placebo (P < .001). There was also a significant reduction in progression of albuminuria (P < .05). Superiority was not shown for the secondary outcome of death from any cause. Canagliflozin had no effect on the primary endpoint (MACE-3) in the subgroup of participants who did not have a history of CV disease. Similar to what was found with empagliflozin in EMPA-REG OUTCOME, CANVAS participants had a reduced risk of HHF.

Continue to: Patients on canagliflozin...

Patients on canagliflozin unexpectedly had an increased incidence of amputations (6.3 participants, compared with 3.4 participants, for every 1000 patient–years). This finding led to a black box warning for canagliflozin about the risk of lower-limb amputation.

DECLARE-TIMI 58. The Dapagliflozin Effect of Cardiovascular Events-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 58 trial (DECLARETIMI 58) was the largest SGLT-2 inhibitor outcomes trial to date, enrolling 17,160 patients with T2D who also had established CV disease or multiple risk factors for atherosclerotic CV disease. The trial compared dapagliflozin, 10 mg/d, and placebo, following patients for a median 4.2 years.24 Unlike CANVAS and EMPA-REG OUTCOME, DECLARE-TIMI 58 included CV death and HHF as primary outcomes, in addition to MACE-3.

Dapagliflozin was noninferior to placebo with regard to MACE-3. However, its use did result in a lower rate of CV death and HHF by an RRR of 17% (ARR, 1.9%). Risk reduction was greatest in patients with HF who had a reduced ejection fraction (ARR = 9.2%).25

In October, the FDA approved dapagliflozin to reduce the risk of HHF in adults with T2D and established CV disease or multiple CV risk factors. Before initiating the drug, physicians should evaluate the patient's renal function and monitor periodically.

Meta-analyses of SGLT-2 inhibitors

Systematic review. Usman et al released a meta-analysis in 2018 that included 35 randomized, placebo-controlled trials (including EMPA-REG OUTCOME, CANVAS, and DECLARE-TIMI 58) that had assessed the use of SGLT-2 inhibitors in nearly 35,000 patients with T2D.26 This review concluded that, as a class, SGLT-2 inhibitors reduce all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiac events, nonfatal MI, and HF and HHF, compared with placebo.

Continue to: CVD-REAL

CVD-REAL. A separate study, Comparative Effectiveness of Cardiovascular Outcomes in New Users of SGLT-2 Inhibitors (CVD-REAL), of 154,528 patients who were treated with canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, or empagliflozin, showed that initiation of SGLT-2 inhibitors, compared with other glucose- lowering therapies, was associated with a 39% reduction in HHF; a 51% reduction in death from any cause; and a 46% reduction in the composite of HHF or death (P < .001).27

CVD-REAL was unique because it was the largest real-world study to assess the effectiveness of SGLT-2 inhibitors on HHF and mortality. The study utilized data from patients in the United States, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Germany, and the United Kingdom, based on information obtained from medical claims, primary care and hospital records, and national registries that compared patients who were either newly started on an SGLT-2 inhibitor or another glucose-lowering drug. The drug used by most patients in the trial was canagliflozin (53%), followed by dapagliflozin (42%), and empagliflozin (5%).

In this meta-analysis, similar therapeutic effects were seen across countries, regardless of geographic differences, in the use of specific SGLT-2 inhibitors, suggesting a class effect. Of particular significance was that most (87%) patients enrolled in CVD-REAL did not have prior CV disease. Despite this, results for examined outcomes in CVD-REAL were similar to what was seen in other SGLT-2 inhibitor trials that were designed to study patients with established CV disease.

Risk of adverse effects of newer antidiabetic agents

DPP-4 inhibitors. Alogliptin and sitagliptin carry a black-box warning about potential risk of HF. In SAVOR-TIMI, a 27% increase was detected in the rate of HHF after approximately 2 years of saxagliptin therapy.6 Although HF should not be considered a class effect for DPP-4 inhibitors, patients who have risk factors for HF should be monitored for signs and symptoms of HF.

Continue to: Cases of acute pancreatitis...

Cases of acute pancreatitis have been reported in association with all DPP-4 inhibitors available in the United States. A combined analysis of DDP-4 inhibitor trials suggested an increased relative risk of 79% and an absolute risk of 0.13%, which translates to 1 or 2 additional cases of acute pancreatitis for every 1000 patients treated for 2 years.28

There have been numerous postmarketing reports of severe joint pain in patients taking a DPP-4 inhibitor. Most recently, cases of bullous pemphigoid have been reported after initiation of DPP-4 inhibitor therapy.29

GLP-1 receptor agonists carry a black box warning for medullary thyroid (C-cell) tumor risk. GLP-1 receptor agonists are contraindicated in patients with a personal or family history of this cancer, although this FDA warning is based solely on observations from animal models.

In addition, GLP-1 receptor agonists can increase the risk of cholecystitis and pancreatitis. Not uncommonly, they cause gastrointestinal symptoms when first started and when the dosage is titrated upward. Most GLP-1 receptor agonists can be used in patients with renal impairment, although data regarding their use in Stages 4 and 5 chronic kidney disease are limited.30 Semaglutide was found, in the SUSTAIN-6 trial, to be associated with an increased rate of complications of retinopathy, including vitreous hemorrhage and blindness (P = .02)31

SGLT-2 inhibitors are associated with an increased incidence of genitourinary infection, bone fracture (canagliflozin), amputation (canagliflozin), and euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis. Agents in this class should be avoided in patients with moderate or severe renal impairment, primarily due to a lack of efficacy. They are contraindicated in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. (Dapagliflozin is not recommended when eGFR is < 45 mL/min/ 1.73 m2.) These agents carry an FDA warning about the risk of acute kidney injury.30

Continue to: Summing up

Summing up

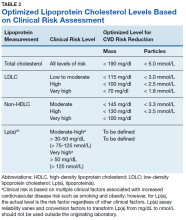

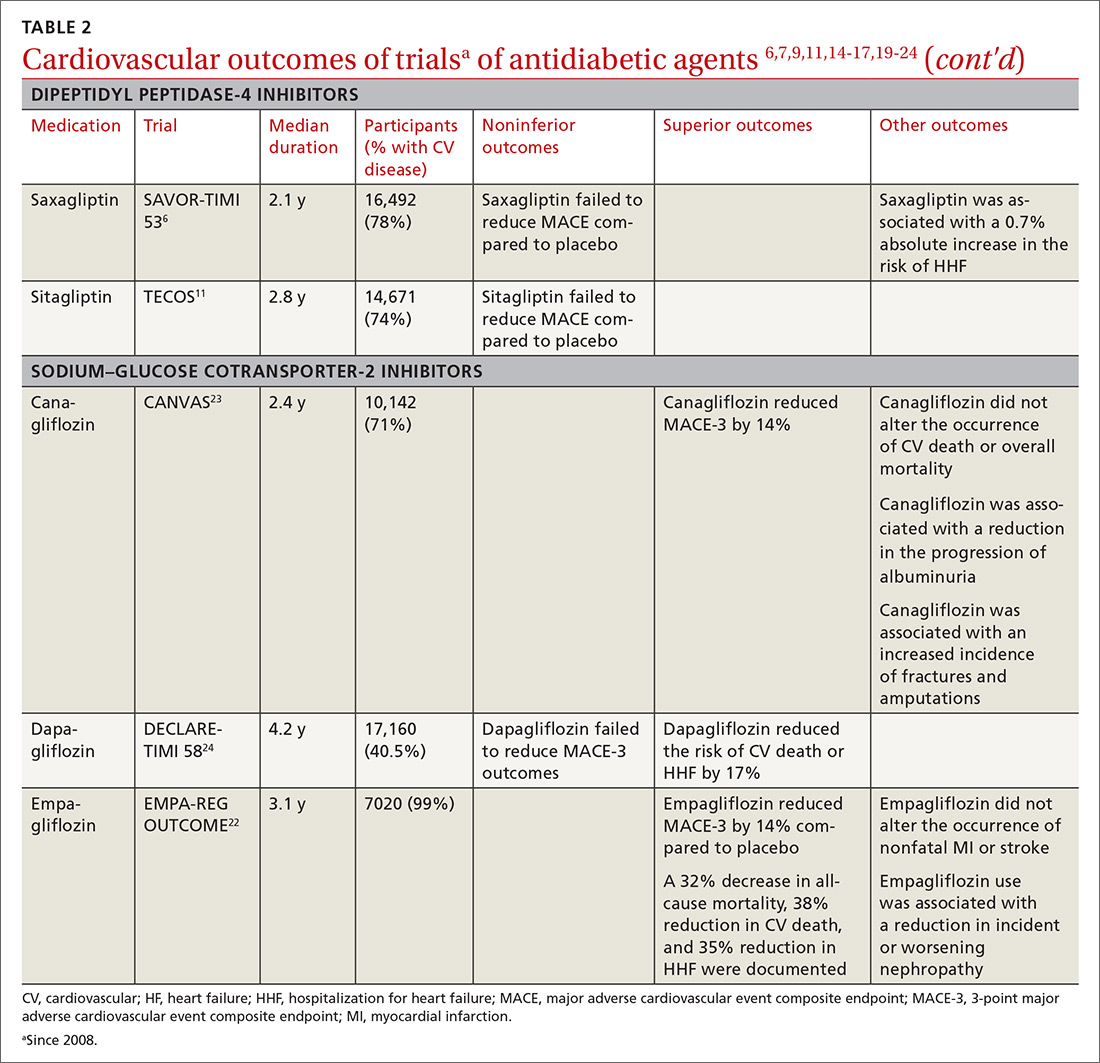

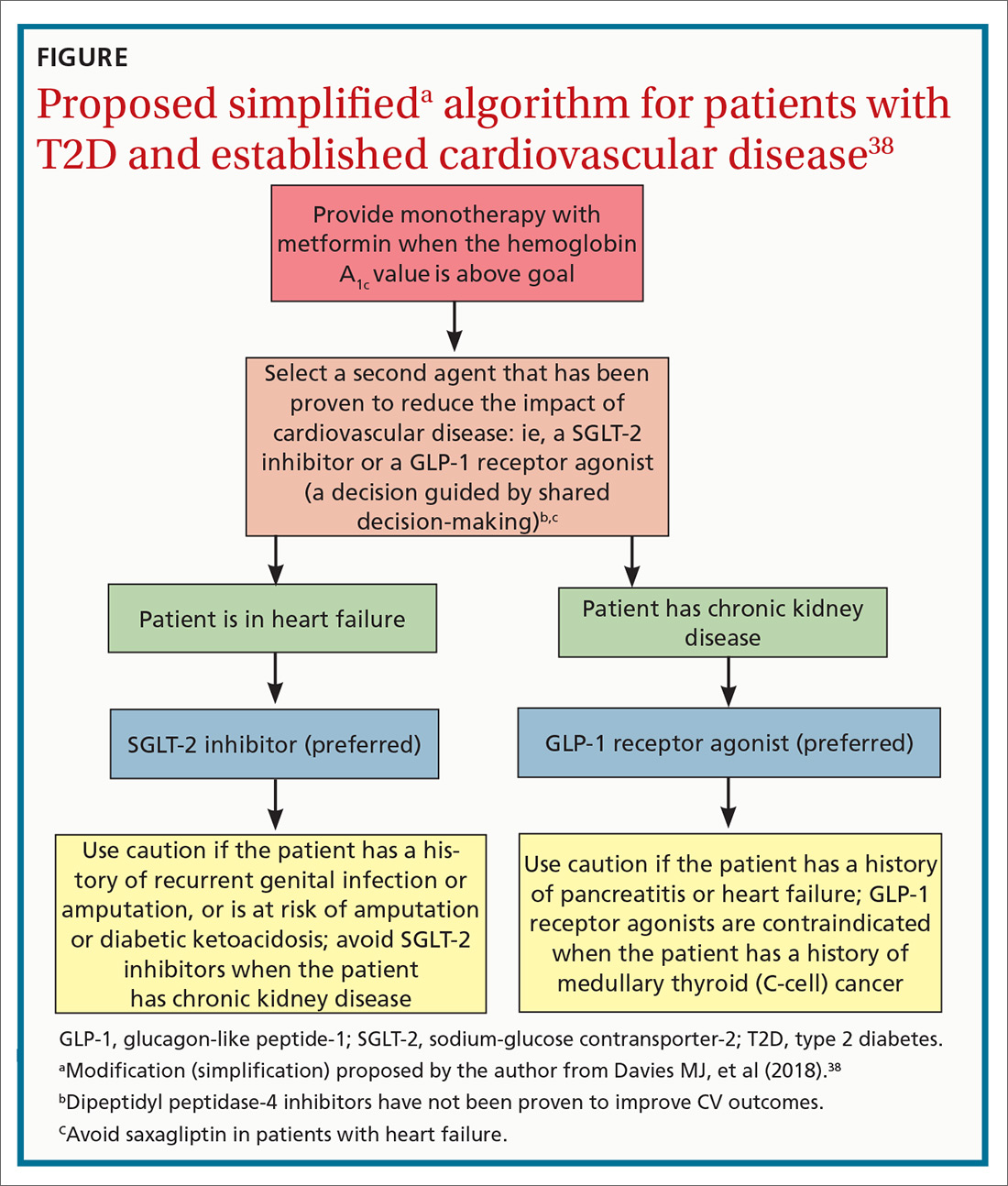

All glucose-lowering medications used to treat T2D are not equally effective in reducing CV complications. Recent CVOTs have uncovered evidence that certain antidiabetic agents might confer CV and all-cause mortality benefits (TABLE 26,7,9,11,14-17,19-24).

Discussion of proposed mechanisms for CV outcome superiority of these agents is beyond the scope of this review. It is generally believed that benefits result from mechanisms other than a reduction in the serum glucose level, given the relatively short time frame of the studies and the magnitude of the CV benefit. It is almost certain that mechanisms of CV benefit in the 2 landmark studies—LEADER and EMPA-REG OUTCOME—are distinct from each other.32

See “When planning T2D pharmacotherapy, include newer agents that offer CV benefit,” 33-38 for a stepwise approach to treating T2D, including the role of agents that have efficacy in modifying the risk of CV disease.

SIDEBAR

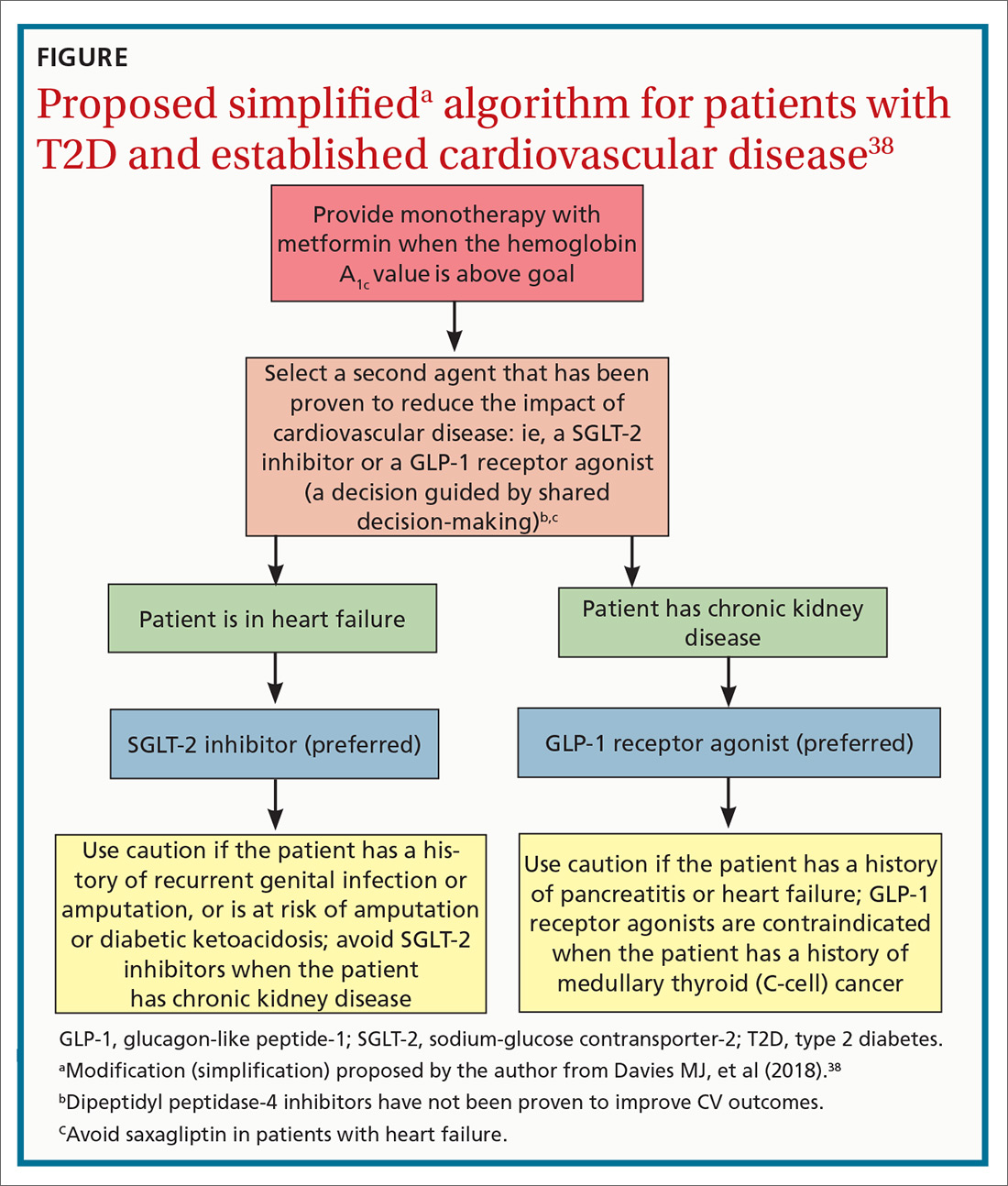

When planning T2D pharmacotherapy, include newer agents that offer CV benefit33-38

First-line management. The 2019 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes Guidelines established by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommend metformin as first-line pharmacotherapy for type 2 diabetes (T2D).33 This recommendation is based on metformin’s efficacy in reducing the blood glucose level and hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C); safety; tolerability; extensive clinical experience; and findings from the UK Prospective Diabetes Study demonstrating a substantial beneficial effect of metformin on cardiovascular (CV) disease.34 Additional benefits of metformin include a decrease in body weight, low-density lipoprotein level, and the need for insulin.

Second-line additive benefit. In addition, ADA guidelines make a highest level (Level-A) recommendation that patients with T2D and established atherosclerotic CV disease be treated with one of the sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors or glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists that have demonstrated efficacy in CV disease risk reduction as part of an antihyperglycemic regimen.35 Seven agents described in this article from these 2 unique classes of medications meet the CV disease benefit criterion: liraglutide, semaglutide, albiglutide, dulaglutide, empagliflozin, canagliflozin, and dapagliflozin. Only empagliflozin and liraglutide have received a US Food and Drug Administration indication for risk reduction in major CV events in adults with T2D and established CV disease.

Regarding dulaglutide, although the findings of REWIND are encouraging, results were not robust; further analysis is necessary to make a recommendation for treating patients who do not have a history of established CV disease with this medication.

Individualized decision-making. From a clinical perspective, patient-specific considerations and shared decision-making should be incorporated into T2D treatment decisions:

- For patients with T2D and established atherosclerotic CV disease, SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists are recommended agents after metformin.

- SGLT-2 inhibitors are preferred in T2D patients with established CV disease and a history of heart failure.

- GLP-1 receptor agonists with proven CV disease benefit are preferred in patients with established CV disease and chronic kidney disease.

Add-on Tx. In ADA guidelines, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DDP-4) inhibitors are recommended as an optional add-on for patients without clinical atherosclerotic CV disease who are unable to reach their HbA1C goal after taking metformin for 3 months.33 Furthermore, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists lists DPP-4 inhibitors as alternatives for patients with an HbA1C < 7.5% in whom metformin is contraindicated.36 DPP-4 inhibitors are not an ideal choice as a second agent when the patient has a history of heart failure, and should not be recommended over GLP-1 receptor agonists or SGLT-2 inhibitors as second-line agents in patients with T2D and CV disease.

Individualizing management. The current algorithm for T2D management,37 based primarily on HbA1C reduction, is shifting toward concurrent attention to reduction of CV risk (FIGURE38). Our challenge, as physicians, is to translate the results of recent CV outcomes trials into a more targeted management strategy that focuses on eligible populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Linda Speer, MD, Kevin Phelps, DO, and Jay Shubrook, DO, provided support and editorial assistance.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert Gotfried, DO, FAAFP, Department of Family Medicine, University of Toledo College of Medicine, 3333 Glendale Avenue, Toledo, OH 43614; [email protected].

1. Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration; Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SR, et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet. 2010;375:2215-2222.

2. Chamberlain JJ, Johnson EL, Leal S, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: review of the American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2018. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:640-650.

3. Nissen SE, Wolski K, Topol EJ. Effect of muraglitazar on death and major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2005;294:2581-2586.

4. Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2457-2471.

5. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance document: Diabetes mellitus—evaluating cardiovascular risk in new antidiabetic therapies to treat type 2 diabetes. www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidance

complianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm071627.pdf. Published December 2008. Accessed October 4, 2019.

6. Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, et al; SAVOR-TIMI 53 Steering Committee and Investigators. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1317-1326.

7. White WB, Canon CP, Heller SR, et al; EXAMINE Investigators. Alogliptin after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1327-1335.

8. Green JB, Bethel MA, Armstrong PW, et al; TECOS Study Group. Effect of sitagliptin on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:232-242.

9. Rosenstock J, Perkovic V, Johansen OE, et al; CARMELINA Investigators. Effect of linagliptin vs placebo on major cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular and renal risk: the CARMELINA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:69-79.

10. Zannad F, Cannon CP, Cushman WC, et al. EXAMINE Investigators. Heart failure and mortality outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes taking alogliptin versus placebo in EXAMINE: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2067-2076.

11. McGuire DK, Van de Werf F, Armstrong PW, et al; Trial Evaluating Cardiovascular Outcomes with Sitagliptin Study Group. Association between sitagliptin use and heart failure hospitalization and related outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:126-135.

12. Toh S, Hampp C, Reichman ME, et al. Risk for hospitalized heart failure among new users of saxagliptin, sitagliptin, and other antihyperglycemic drugs: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:705-714.

13. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: FDA adds warning about heart failure risk to labels of type 2 diabetes medicines containing saxagliptin and alogliptin. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm486096.htm. Updated April 5, 2016. Accessed October 4, 2019.

14. Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Diaz R, et al. Lixisenatide in patient with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2247-2257.

15. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al; LEADER Trial Investigators. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-322.

16. Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al; SUSTAIN-6 Investigators. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1834-1844.

17. Mentz RJ, Bethel MA, Merrill P, et al; EXSCEL Study Group. Effect of once-weekly exenatide on clinical outcomes according to baseline risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: insights from the EXSCEL Trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009304.

18. Holman RR, Bethel MA, George J, et al. Rationale and design of the EXenatide Study of Cardiovascular Event Lowering (EXSCEL) trial. Am Heart J. 2016;174:103-110.

19. Hernandez AF, Green JB, Janmohamed S, et al; Harmony Outcomes committees and investigators. Albiglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Harmony Outcomes): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392:1519-1529.

20. Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al; REWIND Investigators. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:121-130.

21. Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al; REWIND Investigators. Dulaglutide and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: an exploratory analysis of the REWIND randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:131-138.

22. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al; EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators. Empaglifozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2117-2128.

23. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al; CANVAS Program Collaborative Group. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:644-657.

24. Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al; DECLARE–TIMI 58 Investigators. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:347-357.

25. Kato ET, Silverman MG, Mosenzon O, et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on heart failure and mortality in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2019;139:2528-2536.

26. Usman MS, Siddiqi TJ, Memon MM, et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25:495-502.

27. Kosiborod M, Cavender MA, Fu AZ, et al; CVD-REAL Investigators and Study Group. Lower risk of heart failure and death in patients initiated on sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors versus other glucose-lowering drugs: the CVD-REAL study (Comparative Effectiveness of Cardiovascular Outcomes in New Users of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors). Circulation. 2017;136:249-259.

28. Tkáč I, Raz I. Combined analysis of three large interventional trials with gliptins indicates increased incidence of acute pancreatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:284-286.

29. Schaffer C, Buclin T, Jornayvaz FR, et al. Use of dipeptidyl-peptidase IV inhibitors and bullous pemphigoid. Dermatology. 2017;233:401-403.

30. Madievsky R. Spotlight on antidiabetic agents with cardiovascular or renoprotective benefits. Perm J. 2018;22:18-034.

31. Vilsbøll T, Bain SC, Leiter LA, et al. Semaglutide, reduction in glycated hemoglobin and the risk of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:889-897.

32. Kosiborod M. Following the LEADER–why this and other recent trials signal a major paradigm shift in the management of type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31:517-519.

33. American Diabetes Association. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S90-S102.

34. Holman R. Metformin as first choice in oral diabetes treatment: the UKPDS experience. Journ Annu Diabetol Hotel Dieu. 2007:13-20.

35. American Diabetes Association. 10. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S103-S123.

36. Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm–2018 executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2018;24:91-120.