User login

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

A 64-year-old woman had a remote history of generalized fatigue, tightness of the hands, tingling and numbness of the face, joint stiffness, and bluish discoloration of the fingers that worsened with cold weather. Laboratory testing at that time had revealed an antinuclear antibody titer over 1:320 (reference range < 1:10), anti-Scl-70 antibody 100 U/mL (< 32 U/mL), and thyroid-stimulating hormone 10.78 mIU/L (0.4–5.5). Pulmonary function testing showed a pattern of restrictive lung disease. She was diagnosed with hypothyroidism, Raynaud phenomenon, and scleroderma. She was referred to a rheumatologist, who prescribed levothyroxine and penicillamine.

Despite treatment, she continued to feel fatigued, and she requested the addition of minocycline to the scleroderma treatment after seeing a report on television. Minocycline 100 mg twice daily was prescribed. She reported improvement of her symptoms for the next 2 years but was then lost to follow-up with the rheumatologist. She continued to take penicillamine and minocycline as prescribed by her primary care physician.

She presented to our clinic with bluish discoloration (Figure 1) that had started 1 year before as a small area but had spread to involve the entire face, fingers, gums, teeth, and sclera, and included a dark discoloration of the neck and upper chest. She had been taking minocycline for nearly 9 years. We referred her to a dermatologist, who diagnosed minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. Her minocycline was stopped. Skin biopsy was not done, as the dermatologist was confident making the diagnosis without biopsy. At 1 year later, she continued to have the widespread skin pigmentation with no improvement at all.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Hyperpigmentation is the darkening in the natural color of the skin, usually from increased deposition of melanin in the epidermis or dermis, or both. It can occur in different degrees of blue, brown, and black (from lightest to darkest). Less frequently, it may be caused by the deposition in the dermis of an endogenous or exogenous pigment, such as hemosiderin, iron, or heavy metal.1 The hyperpigmentation can be circumscribed or more diffuse.

The differential diagnosis of diffuse skin pigmentation includes Addison disease, hyperthyroidism, hemochromatosis, erythema dyschromicum perstans, cutaneous malignancies, sunburn, and drug-induced hyperpigmentation.1,2 Medications commonly cited as causing hyperpigmentation include minocycline, amiodarone, bleomycin, prostaglandins, oral contraceptives, phenothiazine, and antimalarial drugs.1,3 In Addison disease, the pigmentation is typically diffuse, with accentuation in sun-exposed areas, flexures, palmar and plantar creases, and areas of pressure or friction.2 The bronze discoloration of hemochromatosis is from a combination of hemosiderin deposition and increased melanin production.1 Erythema dyschromicum perstans presents with brownish oval-shaped macules and patches. Early lesions may have thin, raised, erythematous borders that typically involve the trunk, but they may spread to the neck, upper extremities, and face.4

The role of minocycline in the treatment of scleroderma is controversial. Early reports involving a small number of patients showed a benefit of minocycline in decreasing symptoms,5,6 but these findings were not achieved in a larger multicenter trial.7

Types of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

Three types of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation occur3,8:

- Type 1—blue-grey coloration on the face in areas of inflammation

- Type 2—blue-grey coloration on normal skin on the skin of the shins and forearms

- Type 3—the least common, characterized by diffuse muddy brown or blue-grey discoloration in sun-exposed areas, as in our patient.

The prevalence of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation varies between 2.4% and 41% and is highest in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.3,9 Type 1 pigmentation is not correlated with treatment duration or cumulative dose, while type 2 and 3 are associated with long-term therapy.8 In type 3, changes are nonspecific, consisting of increased melanin in basal keratinocytes and melanin-only staining dermal melanophages. Types 1 and 2 may resolve slowly, whereas type 3 can persist indefinitely.3,8,10

TREATMENT

Treatment involves early recognition, discontinuation of the drug, and avoidance of sun exposure. Treatment with pigment-specific lasers has shown promise.8,10

- Stulberg DL, Clark N, Tovey D. Common hyperpigmentation disorders in adults: Part I. Diagnostic approach, café au lait macules, diffuse hyperpigmentation, sun exposure, and phototoxic reactions. Am Fam Physician 2003; 68:1955–1960.

- Thiboutot DM. Clinical review 74: dermatological manifestations of endocrine disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995; 80:3082–3087.

- Geria AN, Tajirian AL, Kihiczak G, Schwartz RA. Minocycline-induced skin pigmentation: an update. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2009; 17:123–126.

- Schwartz RA. Erythema dyschromicum perstans: the continuing enigma of Cinderella or ashy dermatosis. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43:230–232.

- Le CH, Morales A, Trentham DE. Minocycline in early diffuse scleroderma. Lancet 1998; 352:1755–1756.

- Robertson LP, Marshall RW, Hickling P. Treatment of cutaneous calcinosis in limited systemic sclerosis with minocycline. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62:267–269.

- Mayes MD, O’Donnell D, Rothfield NF, Csuka ME. Minocycline is not effective in systemic sclerosis: results of an open-label multicenter trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50:553–557.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. London, UK: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011:125–126.

- Roberts G, Capell HA. The frequency and distribution of minocycline induced hyperpigmentation in a rheumatoid arthritis population. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:1254–1257.

- Vangipuram RK, DeLozier WL, Geddes E, Friedman PM. Complete resolution of minocycline pigmentation following a single treatment with non-ablative 1550-nm fractional resurfacing in combination with the 755-nm Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Surg Med 2016; 48:234–237.

A 64-year-old woman had a remote history of generalized fatigue, tightness of the hands, tingling and numbness of the face, joint stiffness, and bluish discoloration of the fingers that worsened with cold weather. Laboratory testing at that time had revealed an antinuclear antibody titer over 1:320 (reference range < 1:10), anti-Scl-70 antibody 100 U/mL (< 32 U/mL), and thyroid-stimulating hormone 10.78 mIU/L (0.4–5.5). Pulmonary function testing showed a pattern of restrictive lung disease. She was diagnosed with hypothyroidism, Raynaud phenomenon, and scleroderma. She was referred to a rheumatologist, who prescribed levothyroxine and penicillamine.

Despite treatment, she continued to feel fatigued, and she requested the addition of minocycline to the scleroderma treatment after seeing a report on television. Minocycline 100 mg twice daily was prescribed. She reported improvement of her symptoms for the next 2 years but was then lost to follow-up with the rheumatologist. She continued to take penicillamine and minocycline as prescribed by her primary care physician.

She presented to our clinic with bluish discoloration (Figure 1) that had started 1 year before as a small area but had spread to involve the entire face, fingers, gums, teeth, and sclera, and included a dark discoloration of the neck and upper chest. She had been taking minocycline for nearly 9 years. We referred her to a dermatologist, who diagnosed minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. Her minocycline was stopped. Skin biopsy was not done, as the dermatologist was confident making the diagnosis without biopsy. At 1 year later, she continued to have the widespread skin pigmentation with no improvement at all.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Hyperpigmentation is the darkening in the natural color of the skin, usually from increased deposition of melanin in the epidermis or dermis, or both. It can occur in different degrees of blue, brown, and black (from lightest to darkest). Less frequently, it may be caused by the deposition in the dermis of an endogenous or exogenous pigment, such as hemosiderin, iron, or heavy metal.1 The hyperpigmentation can be circumscribed or more diffuse.

The differential diagnosis of diffuse skin pigmentation includes Addison disease, hyperthyroidism, hemochromatosis, erythema dyschromicum perstans, cutaneous malignancies, sunburn, and drug-induced hyperpigmentation.1,2 Medications commonly cited as causing hyperpigmentation include minocycline, amiodarone, bleomycin, prostaglandins, oral contraceptives, phenothiazine, and antimalarial drugs.1,3 In Addison disease, the pigmentation is typically diffuse, with accentuation in sun-exposed areas, flexures, palmar and plantar creases, and areas of pressure or friction.2 The bronze discoloration of hemochromatosis is from a combination of hemosiderin deposition and increased melanin production.1 Erythema dyschromicum perstans presents with brownish oval-shaped macules and patches. Early lesions may have thin, raised, erythematous borders that typically involve the trunk, but they may spread to the neck, upper extremities, and face.4

The role of minocycline in the treatment of scleroderma is controversial. Early reports involving a small number of patients showed a benefit of minocycline in decreasing symptoms,5,6 but these findings were not achieved in a larger multicenter trial.7

Types of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

Three types of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation occur3,8:

- Type 1—blue-grey coloration on the face in areas of inflammation

- Type 2—blue-grey coloration on normal skin on the skin of the shins and forearms

- Type 3—the least common, characterized by diffuse muddy brown or blue-grey discoloration in sun-exposed areas, as in our patient.

The prevalence of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation varies between 2.4% and 41% and is highest in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.3,9 Type 1 pigmentation is not correlated with treatment duration or cumulative dose, while type 2 and 3 are associated with long-term therapy.8 In type 3, changes are nonspecific, consisting of increased melanin in basal keratinocytes and melanin-only staining dermal melanophages. Types 1 and 2 may resolve slowly, whereas type 3 can persist indefinitely.3,8,10

TREATMENT

Treatment involves early recognition, discontinuation of the drug, and avoidance of sun exposure. Treatment with pigment-specific lasers has shown promise.8,10

A 64-year-old woman had a remote history of generalized fatigue, tightness of the hands, tingling and numbness of the face, joint stiffness, and bluish discoloration of the fingers that worsened with cold weather. Laboratory testing at that time had revealed an antinuclear antibody titer over 1:320 (reference range < 1:10), anti-Scl-70 antibody 100 U/mL (< 32 U/mL), and thyroid-stimulating hormone 10.78 mIU/L (0.4–5.5). Pulmonary function testing showed a pattern of restrictive lung disease. She was diagnosed with hypothyroidism, Raynaud phenomenon, and scleroderma. She was referred to a rheumatologist, who prescribed levothyroxine and penicillamine.

Despite treatment, she continued to feel fatigued, and she requested the addition of minocycline to the scleroderma treatment after seeing a report on television. Minocycline 100 mg twice daily was prescribed. She reported improvement of her symptoms for the next 2 years but was then lost to follow-up with the rheumatologist. She continued to take penicillamine and minocycline as prescribed by her primary care physician.

She presented to our clinic with bluish discoloration (Figure 1) that had started 1 year before as a small area but had spread to involve the entire face, fingers, gums, teeth, and sclera, and included a dark discoloration of the neck and upper chest. She had been taking minocycline for nearly 9 years. We referred her to a dermatologist, who diagnosed minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. Her minocycline was stopped. Skin biopsy was not done, as the dermatologist was confident making the diagnosis without biopsy. At 1 year later, she continued to have the widespread skin pigmentation with no improvement at all.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Hyperpigmentation is the darkening in the natural color of the skin, usually from increased deposition of melanin in the epidermis or dermis, or both. It can occur in different degrees of blue, brown, and black (from lightest to darkest). Less frequently, it may be caused by the deposition in the dermis of an endogenous or exogenous pigment, such as hemosiderin, iron, or heavy metal.1 The hyperpigmentation can be circumscribed or more diffuse.

The differential diagnosis of diffuse skin pigmentation includes Addison disease, hyperthyroidism, hemochromatosis, erythema dyschromicum perstans, cutaneous malignancies, sunburn, and drug-induced hyperpigmentation.1,2 Medications commonly cited as causing hyperpigmentation include minocycline, amiodarone, bleomycin, prostaglandins, oral contraceptives, phenothiazine, and antimalarial drugs.1,3 In Addison disease, the pigmentation is typically diffuse, with accentuation in sun-exposed areas, flexures, palmar and plantar creases, and areas of pressure or friction.2 The bronze discoloration of hemochromatosis is from a combination of hemosiderin deposition and increased melanin production.1 Erythema dyschromicum perstans presents with brownish oval-shaped macules and patches. Early lesions may have thin, raised, erythematous borders that typically involve the trunk, but they may spread to the neck, upper extremities, and face.4

The role of minocycline in the treatment of scleroderma is controversial. Early reports involving a small number of patients showed a benefit of minocycline in decreasing symptoms,5,6 but these findings were not achieved in a larger multicenter trial.7

Types of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation

Three types of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation occur3,8:

- Type 1—blue-grey coloration on the face in areas of inflammation

- Type 2—blue-grey coloration on normal skin on the skin of the shins and forearms

- Type 3—the least common, characterized by diffuse muddy brown or blue-grey discoloration in sun-exposed areas, as in our patient.

The prevalence of minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation varies between 2.4% and 41% and is highest in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.3,9 Type 1 pigmentation is not correlated with treatment duration or cumulative dose, while type 2 and 3 are associated with long-term therapy.8 In type 3, changes are nonspecific, consisting of increased melanin in basal keratinocytes and melanin-only staining dermal melanophages. Types 1 and 2 may resolve slowly, whereas type 3 can persist indefinitely.3,8,10

TREATMENT

Treatment involves early recognition, discontinuation of the drug, and avoidance of sun exposure. Treatment with pigment-specific lasers has shown promise.8,10

- Stulberg DL, Clark N, Tovey D. Common hyperpigmentation disorders in adults: Part I. Diagnostic approach, café au lait macules, diffuse hyperpigmentation, sun exposure, and phototoxic reactions. Am Fam Physician 2003; 68:1955–1960.

- Thiboutot DM. Clinical review 74: dermatological manifestations of endocrine disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995; 80:3082–3087.

- Geria AN, Tajirian AL, Kihiczak G, Schwartz RA. Minocycline-induced skin pigmentation: an update. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2009; 17:123–126.

- Schwartz RA. Erythema dyschromicum perstans: the continuing enigma of Cinderella or ashy dermatosis. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43:230–232.

- Le CH, Morales A, Trentham DE. Minocycline in early diffuse scleroderma. Lancet 1998; 352:1755–1756.

- Robertson LP, Marshall RW, Hickling P. Treatment of cutaneous calcinosis in limited systemic sclerosis with minocycline. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62:267–269.

- Mayes MD, O’Donnell D, Rothfield NF, Csuka ME. Minocycline is not effective in systemic sclerosis: results of an open-label multicenter trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50:553–557.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. London, UK: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011:125–126.

- Roberts G, Capell HA. The frequency and distribution of minocycline induced hyperpigmentation in a rheumatoid arthritis population. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:1254–1257.

- Vangipuram RK, DeLozier WL, Geddes E, Friedman PM. Complete resolution of minocycline pigmentation following a single treatment with non-ablative 1550-nm fractional resurfacing in combination with the 755-nm Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Surg Med 2016; 48:234–237.

- Stulberg DL, Clark N, Tovey D. Common hyperpigmentation disorders in adults: Part I. Diagnostic approach, café au lait macules, diffuse hyperpigmentation, sun exposure, and phototoxic reactions. Am Fam Physician 2003; 68:1955–1960.

- Thiboutot DM. Clinical review 74: dermatological manifestations of endocrine disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995; 80:3082–3087.

- Geria AN, Tajirian AL, Kihiczak G, Schwartz RA. Minocycline-induced skin pigmentation: an update. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 2009; 17:123–126.

- Schwartz RA. Erythema dyschromicum perstans: the continuing enigma of Cinderella or ashy dermatosis. Int J Dermatol 2004; 43:230–232.

- Le CH, Morales A, Trentham DE. Minocycline in early diffuse scleroderma. Lancet 1998; 352:1755–1756.

- Robertson LP, Marshall RW, Hickling P. Treatment of cutaneous calcinosis in limited systemic sclerosis with minocycline. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62:267–269.

- Mayes MD, O’Donnell D, Rothfield NF, Csuka ME. Minocycline is not effective in systemic sclerosis: results of an open-label multicenter trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50:553–557.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. London, UK: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011:125–126.

- Roberts G, Capell HA. The frequency and distribution of minocycline induced hyperpigmentation in a rheumatoid arthritis population. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:1254–1257.

- Vangipuram RK, DeLozier WL, Geddes E, Friedman PM. Complete resolution of minocycline pigmentation following a single treatment with non-ablative 1550-nm fractional resurfacing in combination with the 755-nm Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Surg Med 2016; 48:234–237.

When should an indwelling pleural catheter be considered for malignant pleural effusion?

An indwelling pleural catheter should be considered when a malignant pleural effusion causes symptoms and recurs after thoracentesis, especially in patients with short to intermediate life expectancy or trapped lung, or who underwent unsuccessful pleurodesis.1

MALIGNANT PLEURAL EFFUSION

Malignant pleural effusion affects about 150,000 people in the United States each year. It occurs in 15% of patients with advanced malignancies, most often lung cancer, breast cancer, lymphoma, and ovarian cancer, which account for more than 50% of cases.2

In most patients with malignant pleural effusion, disabling dyspnea causes poor quality of life. The prognosis is unfavorable, with life expectancy of 3 to 12 months. Patients with poor performance status and lower glucose concentrations in the pleural fluid face a worse prognosis and a shorter life expectancy.2

In general, management focuses on relieving symptoms rather than on cure. Symptoms can be controlled by thoracentesis, but if the effusion recurs, the patient needs repeated visits to the emergency room or clinic or a hospital admission to drain the fluid. Frequent hospital visits can be grueling for a patient with a poor functional status, and so can the adverse effects of repeated thoracentesis. For that reason, an early palliative approach to malignant pleural effusion in patients with cancer and a poor prognosis leads to better symptom control and a better quality of life.3 Multiple treatments can be offered to control the symptoms in patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion (Table 1).

PLEURODESIS HAS BEEN THE TREATMENT OF CHOICE

Pleurodesis has been the treatment of choice for malignant pleural effusion for decades. In this procedure, adhesion of the visceral and parietal pleura is achxieved by inducing inflammation either mechanically or chemically between the pleural surfaces. Injection of a sclerosant into the pleural space generates the inflammation. The sclerosant can be introduced through a chest tube or thoracoscope such as in video-assisted thoracic surgery or medical pleuroscopy. The use of talc is associated with a higher success rate than other sclerosing agents such as bleomycin and doxycycline.4

The downside of this procedure is that pleural effusion recurs in 10% to 40% of cases, and patients require 2 to 4 days in the hospital. Also, the use of talc can lead to acute lung injury–acute respiratory distress syndrome, a rare but potentially life-threatening complication. The incidence of this complication may be related to particle size, with small particles posing a higher risk than large ones.5,6

PLACEMENT OF AN INDWELLING PLEURAL CATHETER

Indwelling pleural catheters are currently used as palliative therapy for patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion who suffer from respiratory distress due to rapid reaccumulation of pleural fluids that require multiple thoracentesis procedures.

An indwelling pleural catheter is contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled coagulopathy, multiloculated pleural effusions, or extensive malignancy in the skin.3 Other factors that need to be considered are the patient’s social circumstances: ie, the patient must be in a clean and safe environment and must have insurance coverage for the supplies.

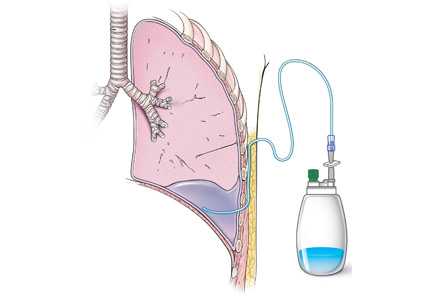

Catheters are 66 cm long and 15.5F and are made of silicone rubber with fenestrations along the distal 24 cm. They have a one-way valve at the proximal end that allows fluids and air to go out but not in (Figure 1).1 Several systems are commercially available in the United States.

The catheter is inserted and tunneled percutaneously with the patient under local anesthesia and conscious sedation (Figure 2). Insertion is a same-day outpatient procedure, and intermittent pleural fluid drainage can be done at home by a home heathcare provider or a trained family member.7

In a meta-analysis, insertion difficulties were reported in only 4% of cases, particularly in patients who underwent prior pleural interventions. Spontaneous pleurodesis occurred in 45% of patients at a mean of 52 days after insertion.8

After catheter insertion, the pleural space should be drained three times a week. No more than 1,000 mL of fluid should be removed at a time—or less if drainage causes chest pain or cough secondary to trapped lung (see below). When the drainage declines to 150 mL per session, the sessions can be reduced to twice a week. If the volume drops to less than 50 mL per session, imaging (computed tomography or bedside thoracic ultrasonography) is recommended to ensure the achievement of pleurodesis and to rule out catheter blockage.

A large multicenter randomized controlled trial9 compared indwelling pleural catheter therapy and chest tube insertion with talc pleurodesis. Both procedures relieved symptoms for the first 42 days, and there was no significant difference in quality of life. However, the median length of hospital stay was 4 days for the talc pleurodesis group compared with 0 days for the indwelling pleural catheter group. Twenty-two percent of the talc group required a further pleural procedure such as a video-assisted thoracic surgery or thoracoscopy, compared with 6% of the indwelling catheter group. On the other hand, 36% of those in the indwelling catheter group experienced nonserious adverse events such as pleural infections that mandated outpatient oral antibiotic therapy, cellulitis, and catheter blockage, compared with 7% of the talc group.9

Symptomatic, inoperable trapped lung is another condition for which an indwelling pleural catheter is a reasonable strategy compared with pleurodesis. Trapped lung is a condition in which the lung fails to fully expand despite proper pleural fluid removal, creating a vacuum space between the parietal and visceral pleura (Figure 3).

Patients with trapped lung complain of severe dull or sharp pain during drainage of pleural fluids due to stretching of the visceral pleura against the intrathoracic vacuum space. Trapped lung can be detected objectively by using intrathoracic manometry while draining fluids, looking for more than a 20-cm H2O drop in the intrathoracic pressure. Radiographically, this may be identified as a pneumothorax ex vacuo10 (ie, caused by inability of the lung to expand to fill the thoracic cavity after pleural fluid has been drained) and is not a procedure complication.

Placement of an indwelling pleural catheter is the treatment of choice for trapped lung, since chemical pleurodesis is not feasible without the potential of parietal and visceral pleural apposition. In a retrospective study of indwelling catheter placement for palliative symptom control, a catheter relieved symptoms, improved quality of life, and afforded a substantial increase in mobility.1,11

In another multicenter pilot study,12 rapid pleurodesis was achieved in 30 patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion by combining chemical pleurodesis and indwelling catheter placement. Both were done under direct vision with medical thoracoscopy. Pleurodesis succeeded in 92% of patients by day 8 after the procedure. The hospital stay was reduced to a mean of 2 days after the procedure. In the catheter group, fluids were drained three times in the first day after the procedure and twice a day on the second and third days. Of the 30 patients in this study, 2 had fever, 1 needed to have the catheter replaced, and 1 contracted empyema.

AN EFFECTIVE INITIAL TREATMENT

Placement of an indwelling pleural catheter is an effective initial treatment for recurrent malignant pleural effusion. Compared with chemical pleurodesis, it has a comparable success rate and complication rate. It offers the advantages of being a same-day surgical procedure entailing a shorter hospital stay and less need for further pleural intervention. This treatment should be considered for patients with symptomatic malignant pleural effusion, especially those in whom symptomatic malignant pleural effusion recurred after thoracentesis.8

- Roberts ME, Neville E, Berrisford RG, Antunes G, Ali NJ; BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Management of a malignant pleural effusion: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax 2010; 65(suppl 2):ii32–ii40.

- Thomas JM, Musani AI. Malignant pleural effusions: a review. Clin Chest Med 2013; 34:459–471.

- Thomas R, Francis R, Davies HE, Lee YC. Interventional therapies for malignant pleural effusions: the present and the future. Respirology 2014; 19:809–822.

- Rodriguez-Panadero F, Montes-Worboys A. Mechanisms of pleurodesis. Respiration 2012; 83:91–98.

- Gonzalez AV, Bezwada V, Beamis JF Jr, Villanueva AG. Lung injury following thoracoscopic talc insufflation: experience of a single North American center. Chest 2010; 137:1375–1381.

- Rossi VF, Vargas FS, Marchi E, et al. Acute inflammatory response secondary to intrapleural administration of two types of talc. Eur Respir J 2010; 35:396–401.

- Fysh ET, Waterer GW, Kendall PA, et al. Indwelling pleural catheters reduce inpatient days over pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusion. Chest 2012; 142:394–400.

- Kheir F, Shawwa K, Alokla K, Omballi M, Alraiyes AH. Tunneled pleural catheter for the treatment of malignant pleural effusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ther 2015 Feb 2. [Epub ahead of print]

- Davies HE, Mishra EK, Kahan BC, et al. Effect of an indwelling pleural catheter vs chest tube and talc pleurodesis for relieving dyspnea in patients with malignant pleural effusion: the TIME2 randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012; 307:2383–2389.

- Ponrartana S, Laberge JM, Kerlan RK, Wilson MW, Gordon RL. Management of patients with “ex vacuo” pneumothorax after thoracentesis. Acad Radiol 2005; 12:980–986.

- Efthymiou CA, Masudi T, Thorpe JA, Papagiannopoulos K. Malignant pleural effusion in the presence of trapped lung. Five-year experience of PleurX tunnelled catheters. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2009; 9:961–964.

- Reddy C, Ernst A, Lamb C, Feller-Kopman D. Rapid pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusions: a pilot study. Chest 2011; 139:1419–1423.

An indwelling pleural catheter should be considered when a malignant pleural effusion causes symptoms and recurs after thoracentesis, especially in patients with short to intermediate life expectancy or trapped lung, or who underwent unsuccessful pleurodesis.1

MALIGNANT PLEURAL EFFUSION

Malignant pleural effusion affects about 150,000 people in the United States each year. It occurs in 15% of patients with advanced malignancies, most often lung cancer, breast cancer, lymphoma, and ovarian cancer, which account for more than 50% of cases.2

In most patients with malignant pleural effusion, disabling dyspnea causes poor quality of life. The prognosis is unfavorable, with life expectancy of 3 to 12 months. Patients with poor performance status and lower glucose concentrations in the pleural fluid face a worse prognosis and a shorter life expectancy.2

In general, management focuses on relieving symptoms rather than on cure. Symptoms can be controlled by thoracentesis, but if the effusion recurs, the patient needs repeated visits to the emergency room or clinic or a hospital admission to drain the fluid. Frequent hospital visits can be grueling for a patient with a poor functional status, and so can the adverse effects of repeated thoracentesis. For that reason, an early palliative approach to malignant pleural effusion in patients with cancer and a poor prognosis leads to better symptom control and a better quality of life.3 Multiple treatments can be offered to control the symptoms in patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion (Table 1).

PLEURODESIS HAS BEEN THE TREATMENT OF CHOICE

Pleurodesis has been the treatment of choice for malignant pleural effusion for decades. In this procedure, adhesion of the visceral and parietal pleura is achxieved by inducing inflammation either mechanically or chemically between the pleural surfaces. Injection of a sclerosant into the pleural space generates the inflammation. The sclerosant can be introduced through a chest tube or thoracoscope such as in video-assisted thoracic surgery or medical pleuroscopy. The use of talc is associated with a higher success rate than other sclerosing agents such as bleomycin and doxycycline.4

The downside of this procedure is that pleural effusion recurs in 10% to 40% of cases, and patients require 2 to 4 days in the hospital. Also, the use of talc can lead to acute lung injury–acute respiratory distress syndrome, a rare but potentially life-threatening complication. The incidence of this complication may be related to particle size, with small particles posing a higher risk than large ones.5,6

PLACEMENT OF AN INDWELLING PLEURAL CATHETER

Indwelling pleural catheters are currently used as palliative therapy for patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion who suffer from respiratory distress due to rapid reaccumulation of pleural fluids that require multiple thoracentesis procedures.

An indwelling pleural catheter is contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled coagulopathy, multiloculated pleural effusions, or extensive malignancy in the skin.3 Other factors that need to be considered are the patient’s social circumstances: ie, the patient must be in a clean and safe environment and must have insurance coverage for the supplies.

Catheters are 66 cm long and 15.5F and are made of silicone rubber with fenestrations along the distal 24 cm. They have a one-way valve at the proximal end that allows fluids and air to go out but not in (Figure 1).1 Several systems are commercially available in the United States.

The catheter is inserted and tunneled percutaneously with the patient under local anesthesia and conscious sedation (Figure 2). Insertion is a same-day outpatient procedure, and intermittent pleural fluid drainage can be done at home by a home heathcare provider or a trained family member.7

In a meta-analysis, insertion difficulties were reported in only 4% of cases, particularly in patients who underwent prior pleural interventions. Spontaneous pleurodesis occurred in 45% of patients at a mean of 52 days after insertion.8

After catheter insertion, the pleural space should be drained three times a week. No more than 1,000 mL of fluid should be removed at a time—or less if drainage causes chest pain or cough secondary to trapped lung (see below). When the drainage declines to 150 mL per session, the sessions can be reduced to twice a week. If the volume drops to less than 50 mL per session, imaging (computed tomography or bedside thoracic ultrasonography) is recommended to ensure the achievement of pleurodesis and to rule out catheter blockage.

A large multicenter randomized controlled trial9 compared indwelling pleural catheter therapy and chest tube insertion with talc pleurodesis. Both procedures relieved symptoms for the first 42 days, and there was no significant difference in quality of life. However, the median length of hospital stay was 4 days for the talc pleurodesis group compared with 0 days for the indwelling pleural catheter group. Twenty-two percent of the talc group required a further pleural procedure such as a video-assisted thoracic surgery or thoracoscopy, compared with 6% of the indwelling catheter group. On the other hand, 36% of those in the indwelling catheter group experienced nonserious adverse events such as pleural infections that mandated outpatient oral antibiotic therapy, cellulitis, and catheter blockage, compared with 7% of the talc group.9

Symptomatic, inoperable trapped lung is another condition for which an indwelling pleural catheter is a reasonable strategy compared with pleurodesis. Trapped lung is a condition in which the lung fails to fully expand despite proper pleural fluid removal, creating a vacuum space between the parietal and visceral pleura (Figure 3).

Patients with trapped lung complain of severe dull or sharp pain during drainage of pleural fluids due to stretching of the visceral pleura against the intrathoracic vacuum space. Trapped lung can be detected objectively by using intrathoracic manometry while draining fluids, looking for more than a 20-cm H2O drop in the intrathoracic pressure. Radiographically, this may be identified as a pneumothorax ex vacuo10 (ie, caused by inability of the lung to expand to fill the thoracic cavity after pleural fluid has been drained) and is not a procedure complication.

Placement of an indwelling pleural catheter is the treatment of choice for trapped lung, since chemical pleurodesis is not feasible without the potential of parietal and visceral pleural apposition. In a retrospective study of indwelling catheter placement for palliative symptom control, a catheter relieved symptoms, improved quality of life, and afforded a substantial increase in mobility.1,11

In another multicenter pilot study,12 rapid pleurodesis was achieved in 30 patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion by combining chemical pleurodesis and indwelling catheter placement. Both were done under direct vision with medical thoracoscopy. Pleurodesis succeeded in 92% of patients by day 8 after the procedure. The hospital stay was reduced to a mean of 2 days after the procedure. In the catheter group, fluids were drained three times in the first day after the procedure and twice a day on the second and third days. Of the 30 patients in this study, 2 had fever, 1 needed to have the catheter replaced, and 1 contracted empyema.

AN EFFECTIVE INITIAL TREATMENT

Placement of an indwelling pleural catheter is an effective initial treatment for recurrent malignant pleural effusion. Compared with chemical pleurodesis, it has a comparable success rate and complication rate. It offers the advantages of being a same-day surgical procedure entailing a shorter hospital stay and less need for further pleural intervention. This treatment should be considered for patients with symptomatic malignant pleural effusion, especially those in whom symptomatic malignant pleural effusion recurred after thoracentesis.8

An indwelling pleural catheter should be considered when a malignant pleural effusion causes symptoms and recurs after thoracentesis, especially in patients with short to intermediate life expectancy or trapped lung, or who underwent unsuccessful pleurodesis.1

MALIGNANT PLEURAL EFFUSION

Malignant pleural effusion affects about 150,000 people in the United States each year. It occurs in 15% of patients with advanced malignancies, most often lung cancer, breast cancer, lymphoma, and ovarian cancer, which account for more than 50% of cases.2

In most patients with malignant pleural effusion, disabling dyspnea causes poor quality of life. The prognosis is unfavorable, with life expectancy of 3 to 12 months. Patients with poor performance status and lower glucose concentrations in the pleural fluid face a worse prognosis and a shorter life expectancy.2

In general, management focuses on relieving symptoms rather than on cure. Symptoms can be controlled by thoracentesis, but if the effusion recurs, the patient needs repeated visits to the emergency room or clinic or a hospital admission to drain the fluid. Frequent hospital visits can be grueling for a patient with a poor functional status, and so can the adverse effects of repeated thoracentesis. For that reason, an early palliative approach to malignant pleural effusion in patients with cancer and a poor prognosis leads to better symptom control and a better quality of life.3 Multiple treatments can be offered to control the symptoms in patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion (Table 1).

PLEURODESIS HAS BEEN THE TREATMENT OF CHOICE

Pleurodesis has been the treatment of choice for malignant pleural effusion for decades. In this procedure, adhesion of the visceral and parietal pleura is achxieved by inducing inflammation either mechanically or chemically between the pleural surfaces. Injection of a sclerosant into the pleural space generates the inflammation. The sclerosant can be introduced through a chest tube or thoracoscope such as in video-assisted thoracic surgery or medical pleuroscopy. The use of talc is associated with a higher success rate than other sclerosing agents such as bleomycin and doxycycline.4

The downside of this procedure is that pleural effusion recurs in 10% to 40% of cases, and patients require 2 to 4 days in the hospital. Also, the use of talc can lead to acute lung injury–acute respiratory distress syndrome, a rare but potentially life-threatening complication. The incidence of this complication may be related to particle size, with small particles posing a higher risk than large ones.5,6

PLACEMENT OF AN INDWELLING PLEURAL CATHETER

Indwelling pleural catheters are currently used as palliative therapy for patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion who suffer from respiratory distress due to rapid reaccumulation of pleural fluids that require multiple thoracentesis procedures.

An indwelling pleural catheter is contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled coagulopathy, multiloculated pleural effusions, or extensive malignancy in the skin.3 Other factors that need to be considered are the patient’s social circumstances: ie, the patient must be in a clean and safe environment and must have insurance coverage for the supplies.

Catheters are 66 cm long and 15.5F and are made of silicone rubber with fenestrations along the distal 24 cm. They have a one-way valve at the proximal end that allows fluids and air to go out but not in (Figure 1).1 Several systems are commercially available in the United States.

The catheter is inserted and tunneled percutaneously with the patient under local anesthesia and conscious sedation (Figure 2). Insertion is a same-day outpatient procedure, and intermittent pleural fluid drainage can be done at home by a home heathcare provider or a trained family member.7

In a meta-analysis, insertion difficulties were reported in only 4% of cases, particularly in patients who underwent prior pleural interventions. Spontaneous pleurodesis occurred in 45% of patients at a mean of 52 days after insertion.8

After catheter insertion, the pleural space should be drained three times a week. No more than 1,000 mL of fluid should be removed at a time—or less if drainage causes chest pain or cough secondary to trapped lung (see below). When the drainage declines to 150 mL per session, the sessions can be reduced to twice a week. If the volume drops to less than 50 mL per session, imaging (computed tomography or bedside thoracic ultrasonography) is recommended to ensure the achievement of pleurodesis and to rule out catheter blockage.

A large multicenter randomized controlled trial9 compared indwelling pleural catheter therapy and chest tube insertion with talc pleurodesis. Both procedures relieved symptoms for the first 42 days, and there was no significant difference in quality of life. However, the median length of hospital stay was 4 days for the talc pleurodesis group compared with 0 days for the indwelling pleural catheter group. Twenty-two percent of the talc group required a further pleural procedure such as a video-assisted thoracic surgery or thoracoscopy, compared with 6% of the indwelling catheter group. On the other hand, 36% of those in the indwelling catheter group experienced nonserious adverse events such as pleural infections that mandated outpatient oral antibiotic therapy, cellulitis, and catheter blockage, compared with 7% of the talc group.9

Symptomatic, inoperable trapped lung is another condition for which an indwelling pleural catheter is a reasonable strategy compared with pleurodesis. Trapped lung is a condition in which the lung fails to fully expand despite proper pleural fluid removal, creating a vacuum space between the parietal and visceral pleura (Figure 3).

Patients with trapped lung complain of severe dull or sharp pain during drainage of pleural fluids due to stretching of the visceral pleura against the intrathoracic vacuum space. Trapped lung can be detected objectively by using intrathoracic manometry while draining fluids, looking for more than a 20-cm H2O drop in the intrathoracic pressure. Radiographically, this may be identified as a pneumothorax ex vacuo10 (ie, caused by inability of the lung to expand to fill the thoracic cavity after pleural fluid has been drained) and is not a procedure complication.

Placement of an indwelling pleural catheter is the treatment of choice for trapped lung, since chemical pleurodesis is not feasible without the potential of parietal and visceral pleural apposition. In a retrospective study of indwelling catheter placement for palliative symptom control, a catheter relieved symptoms, improved quality of life, and afforded a substantial increase in mobility.1,11

In another multicenter pilot study,12 rapid pleurodesis was achieved in 30 patients with recurrent malignant pleural effusion by combining chemical pleurodesis and indwelling catheter placement. Both were done under direct vision with medical thoracoscopy. Pleurodesis succeeded in 92% of patients by day 8 after the procedure. The hospital stay was reduced to a mean of 2 days after the procedure. In the catheter group, fluids were drained three times in the first day after the procedure and twice a day on the second and third days. Of the 30 patients in this study, 2 had fever, 1 needed to have the catheter replaced, and 1 contracted empyema.

AN EFFECTIVE INITIAL TREATMENT

Placement of an indwelling pleural catheter is an effective initial treatment for recurrent malignant pleural effusion. Compared with chemical pleurodesis, it has a comparable success rate and complication rate. It offers the advantages of being a same-day surgical procedure entailing a shorter hospital stay and less need for further pleural intervention. This treatment should be considered for patients with symptomatic malignant pleural effusion, especially those in whom symptomatic malignant pleural effusion recurred after thoracentesis.8

- Roberts ME, Neville E, Berrisford RG, Antunes G, Ali NJ; BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Management of a malignant pleural effusion: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax 2010; 65(suppl 2):ii32–ii40.

- Thomas JM, Musani AI. Malignant pleural effusions: a review. Clin Chest Med 2013; 34:459–471.

- Thomas R, Francis R, Davies HE, Lee YC. Interventional therapies for malignant pleural effusions: the present and the future. Respirology 2014; 19:809–822.

- Rodriguez-Panadero F, Montes-Worboys A. Mechanisms of pleurodesis. Respiration 2012; 83:91–98.

- Gonzalez AV, Bezwada V, Beamis JF Jr, Villanueva AG. Lung injury following thoracoscopic talc insufflation: experience of a single North American center. Chest 2010; 137:1375–1381.

- Rossi VF, Vargas FS, Marchi E, et al. Acute inflammatory response secondary to intrapleural administration of two types of talc. Eur Respir J 2010; 35:396–401.

- Fysh ET, Waterer GW, Kendall PA, et al. Indwelling pleural catheters reduce inpatient days over pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusion. Chest 2012; 142:394–400.

- Kheir F, Shawwa K, Alokla K, Omballi M, Alraiyes AH. Tunneled pleural catheter for the treatment of malignant pleural effusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ther 2015 Feb 2. [Epub ahead of print]

- Davies HE, Mishra EK, Kahan BC, et al. Effect of an indwelling pleural catheter vs chest tube and talc pleurodesis for relieving dyspnea in patients with malignant pleural effusion: the TIME2 randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012; 307:2383–2389.

- Ponrartana S, Laberge JM, Kerlan RK, Wilson MW, Gordon RL. Management of patients with “ex vacuo” pneumothorax after thoracentesis. Acad Radiol 2005; 12:980–986.

- Efthymiou CA, Masudi T, Thorpe JA, Papagiannopoulos K. Malignant pleural effusion in the presence of trapped lung. Five-year experience of PleurX tunnelled catheters. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2009; 9:961–964.

- Reddy C, Ernst A, Lamb C, Feller-Kopman D. Rapid pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusions: a pilot study. Chest 2011; 139:1419–1423.

- Roberts ME, Neville E, Berrisford RG, Antunes G, Ali NJ; BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Management of a malignant pleural effusion: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax 2010; 65(suppl 2):ii32–ii40.

- Thomas JM, Musani AI. Malignant pleural effusions: a review. Clin Chest Med 2013; 34:459–471.

- Thomas R, Francis R, Davies HE, Lee YC. Interventional therapies for malignant pleural effusions: the present and the future. Respirology 2014; 19:809–822.

- Rodriguez-Panadero F, Montes-Worboys A. Mechanisms of pleurodesis. Respiration 2012; 83:91–98.

- Gonzalez AV, Bezwada V, Beamis JF Jr, Villanueva AG. Lung injury following thoracoscopic talc insufflation: experience of a single North American center. Chest 2010; 137:1375–1381.

- Rossi VF, Vargas FS, Marchi E, et al. Acute inflammatory response secondary to intrapleural administration of two types of talc. Eur Respir J 2010; 35:396–401.

- Fysh ET, Waterer GW, Kendall PA, et al. Indwelling pleural catheters reduce inpatient days over pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusion. Chest 2012; 142:394–400.

- Kheir F, Shawwa K, Alokla K, Omballi M, Alraiyes AH. Tunneled pleural catheter for the treatment of malignant pleural effusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ther 2015 Feb 2. [Epub ahead of print]

- Davies HE, Mishra EK, Kahan BC, et al. Effect of an indwelling pleural catheter vs chest tube and talc pleurodesis for relieving dyspnea in patients with malignant pleural effusion: the TIME2 randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012; 307:2383–2389.

- Ponrartana S, Laberge JM, Kerlan RK, Wilson MW, Gordon RL. Management of patients with “ex vacuo” pneumothorax after thoracentesis. Acad Radiol 2005; 12:980–986.

- Efthymiou CA, Masudi T, Thorpe JA, Papagiannopoulos K. Malignant pleural effusion in the presence of trapped lung. Five-year experience of PleurX tunnelled catheters. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2009; 9:961–964.

- Reddy C, Ernst A, Lamb C, Feller-Kopman D. Rapid pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusions: a pilot study. Chest 2011; 139:1419–1423.

Women’s health 2016: An update for internists

Women's health encompasses a variety of topics relevant to the daily practice of internists. Staying up to date with the evidence in this wide field is a challenge.

This article reviews important studies published in 2015 and early 2016 on treatment of urinary tract infections, the optimal duration of bisphosphonate use, ovarian cancer screening, the impact of oral contraceptives and lactation on mortality rates, and the risks and benefits of intrauterine contraception. We critically appraised the studies and judged that their methodology was strong and appropriate for inclusion in this review.

IBUPROFEN FOR URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

A 36-year-old woman reports 4 days of mild to moderate dysuria, frequency, and urgency. She denies fever, nausea, or back pain. Her last urinary tract infection was 2 years ago. Office urinalysis reveals leukocyte esterase and nitrites. She has read an article about antibiotic resistance and Clostridium difficile infection and asks you if antibiotics are truly necessary. What do you recommend?

Urinary tract infections are often self-limited

Uncomplicated urinary tract infections account for 25% of antibiotic prescriptions in primary care.1

Several small studies have suggested that many of these infections are self-limited, resolving within 3 to 14 days without antibiotics (Table 1).2–6 A potential disadvantage of withholding treatment is slower bacterial clearance and resolution of symptoms, but reducing the number of antibiotic prescriptions may help slow antibiotic resistance.7,8 Surveys and qualitative studies have suggested that women are concerned about the harms of antibiotic treatment and so may be willing to avoid or postpone antibiotic use.9–11

Ibuprofen vs fosfomycin

Gágyor et al6 conducted a double-blind, randomized multicenter trial in 42 general practices in Germany to assess whether treating the symptoms of uncomplicated urinary tract infection with ibuprofen would reduce antibiotic use without worsening outcomes.

Of the 779 eligible women with suspected urinary tract infection, 281 declined to participate in the study, 4 did not participate for reasons not specified, 246 received a single dose of fosfomycin 3 g, and 248 were treated with ibuprofen 400 mg three times a day for 3 days. Participants scored their daily symptoms and activity impairment, and safety data were collected for adverse events and relapses up to day 28 and within 6 and 12 months. In both groups, if symptoms worsened or persisted, antibiotic therapy was initiated at the discretion of the treating physician.

Exclusion criteria included fever, “loin” (back) tenderness, pregnancy, renal disease, a previous urinary tract infection within 2 weeks, urinary catheterization, and a contraindication to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications.

Results. Within 28 days of symptom onset, women in the ibuprofen group had received 81 courses of antibiotics for symptoms of urinary tract infection (plus another 13 courses for other reasons), compared with 277 courses for urinary tract infection in the fosfomycin group (plus 6 courses for other reasons), for a relative rate reduction in antibiotic use of 66.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] 58.8%–74.4%, P < .001). The women who received ibuprofen were more likely to need antibiotics after initial treatment because of refractory symptoms but were still less likely to receive antibiotics overall (Table 1).

The mean duration of symptoms was slightly shorter in the fosfomycin group (4.6 vs 5.6 days, P < .001). However, the percentage of patients who had a recurrent urinary tract infection within 2 to 4 weeks was higher in the fosfomycin-treated patients (11% vs 6% P = .049).

Although the study was not powered to show significant differences in pyelonephritis, five patients in the ibuprofen group developed pyelonephritis compared with one in the antibiotic-treated group (P = .12).

An important limitation of the study was that nonparticipants had higher symptom scores, which may mean that the results are not generalizable to women who have recurrent urinary tract infections, longer duration of symptoms, or symptoms that are more severe. The strengths of the study were that more than half of all potentially eligible women were enrolled, and baseline data were collected from nonparticipants.

Can our patient avoid antibiotics?

Given the mild nature of her symptoms, the clinician should discuss with her the risks vs benefits of delaying antibiotics, once it has been determined that she has no risk factors for severe urinary tract infection. Her symptoms are likely to resolve within 1 week even if she declines antibiotic treatment, though they may last a day longer with ibuprofen alone than if she had received antibiotics. She should watch for symptoms of pyelonephritis (eg, flank pain, fever, chills, vomiting) and should seek prompt medical care if such symptoms occur.

DISCONTINUING BISPHOSPHONATES

A 64-year-old woman has taken alendronate for her osteoporosis for 5 years. She has no history of fractures. Her original bone density scans showed a T-score of –2.6 at the spine and –1.5 at the hip. Since she started to take alendronate, there has been no further loss in bone mineral density. She is tolerating the drug well and does not take any other medications. Should she continue the bisphosphonate?

Optimal duration of therapy unknown

The risks and benefits of long-term bisphosphonate use are debated.

In the Fracture Intervention Trial (FIT),12 women with low bone mineral density of the femoral neck were randomized to receive alendronate or placebo and were followed for 36 months. The alendronate group had significantly fewer vertebral fractures and clinical fractures overall. Then, in the FIT Long-term Extension (FLEX) study,13 1,009 alendronate-treated women in the FIT study were rerandomized to receive 5 years of additional treatment or to stop treatment. Bone density in the untreated women decreased, although not to the level it was before treatment. At the end of the study, there was no difference in hip fracture rate between the two groups (3% of each group had had a hip fracture), although women in the treated group had a lower rate of clinical vertebral fracture (2% vs 5%, relative risk 0.5, 95% CI 0.2–0.8).

In addition, rare but serious risks have been associated with bisphosphonate use, specifically atypical femoral fracture and osteonecrosis of the jaw. A US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) evaluation of long-term bisphosphonate use concluded that there was evidence of an increased risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw with longer duration of use, but causality was not established. The evaluation also noted conflicting results about the association with atypical femoral fracture.14

Based on this report and focusing on the absence of nonspine benefit after 5 years, the FDA suggested that bisphosphonates may be safely discontinued in some patients without compromising therapeutic gains, but no adequate clinical trial has yet delineated how long the benefits of treatment are maintained after cessation. A periodic reevaluation of continued need was recommended.14

New recommendations from the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research

Age is the greatest risk factor for fracture.15 Therefore, deciding whether to discontinue a bisphosphonate when a woman is older, and hence at higher risk, is a challenge.

A task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR) has developed an evidence-based guideline on managing osteoporosis in patients on long-term bisphosphonate treatment.16 The goal was to provide guidance on the duration of bisphosphonate therapy from the perspective of risk vs benefit. The authors conducted a systematic review focusing on two randomized controlled trials (FLEX13 and the Health Outcomes and Reduced Incidence With Zoledronic Acid Once Yearly Pivotal Fracture Trial17) that provided data on long-term bisphosphonate use.

The task force recommended16 that after 5 years of oral bisphosphonates or 3 years of intravenous bisphosphonates, risk should be reassessed. In women at high fracture risk, they recommended continuing the oral bisphosphonate for 10 years or the intravenous bisphosphonate for 6 years. Factors that favored continuation of bisphosphonate therapy were as follows:

- An osteoporotic fracture before or during therapy

- A hip bone mineral density T-score ≤ –2.5

- High risk of fracture, defined as age older than 70 or 75, other strong risk factors for fracture, or a FRAX fracture risk score18 above a country-specific threshold.

(The FRAX score is based on age, sex, weight, height, previous fracture, hip fracture in a parent, current smoking, use of glucocorticoids, rheumatoid arthritis, secondary osteoporosis, alcohol use, and bone mineral density in the femoral neck. It gives an estimate of the 10-year risk of major osteoporotic fracture and hip fracture. High risk would be a 10-year risk of major osteoporotic fracture greater than 20% or a 10-year risk of hip fracture greater than 3%.)

For women at high risk, the risks of atypical femoral fracture and osteonecrosis of the jaw are outweighed by the benefit of a reduction in vertebral fracture risk. For women not at high risk of fracture, a drug holiday of 2 to 3 years can be considered after 3 to 5 years of treatment.

Although the task force recommended reassessment after 2 to 3 years of drug holiday, how best to do this is not clear. The task force did not recommend a specific approach to reassessment, so decisions about when to restart therapy after a drug holiday could potentially be informed by subsequent bone mineral density testing if it were to show persistent bone loss. Another option could be to restart bisphosphonates after a defined amount of time (eg, 3–5 years) for women who have previously experienced benefit.

The task force recommendations are in line with those of other societies, the FDA, and expert opinion.19–23

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommends considering a drug holiday in low-risk patients after 4 to 5 years of treatment. For high-risk patients, they recommend 1 to 2 years of drug holiday after 10 years of treatment. They encourage restarting treatment if bone mineral density decreases, bone turnover markers rise, or fracture occurs.19 This is a grade C recommendation, meaning the advice is based on descriptive studies and expert opinion.

Although some clinicians restart bisphosphonates when markers of bone turnover such as NTX (N-telopeptide of type 1 collagen) rise to premenopausal levels, there is no evidence to support this strategy.24

The task force recommendations are based on limited evidence that primarily comes from white postmenopausal women. Another important limitation is that the outcomes are primarily vertebral fractures. However, until additional evidence is available, these guidelines can be useful in guiding decision-making.

Should our patient continue therapy?

Our patient is relatively young and does not have any of the high-risk features noted within the task force recommendations. She has responded well to bisphosphonate treatment and so can consider a drug holiday at this time.

OVARIAN CANCER SCREENING

A 50-year-old woman requests screening for ovarian cancer. She is postmenopausal and has no personal or family history of cancer. She is concerned because a friend forwarded an e-mail stating, “Please tell all your female friends and relatives to insist on a cancer antigen (CA) 125 blood test every year as part of their annual exam. This is an inexpensive and simple blood test. Don’t take no for an answer. If I had known then what I know now, we would have caught my cancer much earlier, before it was stage III!” What should you tell the patient?

Ovarian cancer is the most deadly of female reproductive cancers, largely because in most patients the cancer has already spread beyond the ovary by the time of clinical detection. Death rates from ovarian cancer have decreased only slightly in the past 30 years.

Little benefit and considerable harm of screening

In 2011, the Prostate Lung Colorectal Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening trial25 randomized more than 68,000 women ages 55 to 74 from the general US population to annual screening with CA 125 testing and transvaginal ultrasonography compared with usual care. They were followed for a median of 12.4 years.

Screening did not affect stage at diagnosis (77%–78% were in stage III or IV in both the screening and usual care groups), nor did it reduce the rate of death from ovarian cancer. In addition, false-positive findings led to some harm: nearly one in three women who had a positive screening test underwent surgery. Of 3,285 women with false-positive results, 1,080 underwent surgery, and 15% of these had at least one serious complication. The trial was stopped early due to evidence of futility.

A new UK study also found no benefit from screening

In the PLCO study, a CA 125 result of 35 U/mL or greater was classified as abnormal. However, researchers in the United Kingdom postulated that instead of using a single cutoff for a normal or abnormal CA 125 level, it would be better to interpret the CA 125 result according to a somewhat complicated (and proprietary) algorithm called the Risk of Ovarian Cancer Algorithm (ROCA).26,27 The ROCA takes into account a woman’s age, menopausal status, known genetic mutations (BRCA 1 or 2 or Lynch syndrome), Ashkenazi Jewish descent, and family history of ovarian or breast cancer, as well as any change in CA 125 level over time.

In a 2016 UK study,26 202,638 postmenopausal women ages 50 to 74 were randomized to no screening, annual screening with transvaginal ultrasonography, or multimodal screening with an annual CA 125 blood test interpreted with the ROCA algorithm, adding transvaginal ultrasonography as a second-line test when needed if the CA 125 level was abnormal based on the ROCA. Women with abnormal findings on multimodal screening or ultrasonography had repeat tests, and women with persistent abnormalities underwent clinical evaluation and, when appropriate, surgery.

Participants were at average risk of ovarian cancer; those with suspected familial ovarian cancer syndrome were excluded, as were those with a personal history of ovarian cancer or other active cancer.

Results. At a median follow-up of 11.1 years, the percentage of women who were diagnosed with ovarian cancer was 0.7% in the multimodal screening group, 0.6% in the screening ultrasonography group, and 0.6% in the no-screening group. Comparing either multimodal or screening ultrasonography with no screening, there was no statistically significant reduction in mortality rate over 14 years of follow-up.

Screening had significant costs and potential harms. For every ovarian or peritoneal cancer detected by screening, an additional 2 women in the multimodal screening group and 10 women in the ultrasonography group underwent needless surgery.

Strengths of this trial included its large size, allowing adequate power to detect differences in outcomes, its multicenter setting, its high compliance rate, and the low crossover rate in the no-screening group. However, the design of the study makes it difficult to anticipate the late effects of screening. Also, the patient must purchase ROCA testing online and must also pay a consultation fee. Insurance providers do not cover this test.

Should our patient proceed with ovarian cancer screening?

No. Current evidence shows no clear benefit to ovarian cancer screening for average-risk women, and we should not recommend yearly ultrasonography and CA 125 level testing, as they are likely to cause harm without providing benefit. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends against screening for ovarian cancer.28 For premenopausal women, pregnancy, hormonal contraception, and breastfeeding all significantly decrease ovarian cancer risk by suppressing ovulation.29–31

REPRODUCTIVE FACTORS AND THE RISK OF DEATH

A 26-year-old woman comes in to discuss her contraceptive options. She has been breastfeeding since the birth of her first baby 6 months ago, and wonders how lactation and contraception may affect her long-term health.

Questions about the safety of contraceptive options are common, especially in breastfeeding mothers.

In 2010, the long-term Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraceptive Study reported that the all-cause mortality rate was actually lower in women who used oral contraceptives.32 Similarly, in 2013, an Oxford study that followed 17,032 women for over 30 years reported no association between oral contraceptives and breast cancer.33

However, in 2014, results from the Nurses’ Health Study indicated that breast cancer rates were higher in oral contraceptive users, although reassuringly, the study found no difference in all-cause mortality rates in women who had used oral contraception.34

The European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition

To further characterize relationships between reproductive characteristics and mortality rates, investigators analyzed data from the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition,35 which recruited 322,972 women from 10 countries between 1992 and 2000. Analyses were stratified by study center and participant age and were adjusted for body mass index, physical activity, education level, smoking, and menopausal status; alcohol intake was examined as a potential confounder but was excluded from final models.

Findings. Over an average 13 years of follow-up, the rate of all-cause mortality was 20% lower in parous than in nulliparous women. In parous women, the all-cause mortality rate was additionally 18% lower in those who had breastfed vs those who had never breastfed, although breastfeeding duration was not associated with mortality. Use of oral contraceptives lowered all-cause mortality by 10% among nonsmokers; in smokers, no association with all-cause mortality was seen for oral contraceptive use, as smoking is such a powerful risk factor for mortality. The primary contributor to all-cause mortality appeared to be ischemic heart disease, the incidence of which was significantly lower in parous women (by 14%) and those who breastfed (by 20%) and was not related to oral contraceptive use.35

Strengths of this study included the large sample size recruited from countries across Europe, with varying rates of breastfeeding and contraceptive use. However, as with all observational studies, it remains subject to the possibility of residual confounding.

What should we tell this patient?

After congratulating her for breastfeeding, we can reassure her about the safety of all available contraceptives. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),36 after 42 days postpartum most women can use combined hormonal contraception. All other methods can be used immediately postpartum, including progestin-only pills.

As lactational amenorrhea is only effective while mothers are exclusively breastfeeding, and short interpregnancy intervals have been associated with higher rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes,37 this patient will likely benefit from promptly starting a prescription contraceptive.

HIGHLY EFFECTIVE REVERSIBLE CONTRACEPTION

This same 26-year-old patient is concerned that she will not remember to take an oral contraceptive every day, and expresses interest in a more convenient method of contraception. However, she is concerned about the potential risks.

Although intrauterine contraceptives (IUCs) are typically 20 times more effective than oral contraceptives38 and have been used by millions of women worldwide, rates of use in the United States have been lower than in many other countries.39

A study of intrauterine contraception

To clarify the safety of IUCs, researchers followed 61,448 women who underwent IUC placement in six European countries between 2006 and 2013.40 Most participants received an IUC containing levonorgestrel, while 30% received a copper IUC.

Findings. Overall, rates of uterine perforation were low (approximately 1 per 1,000 insertions). The most significant risk factors for perforation were breastfeeding at the time of insertion and insertion less than 36 weeks after the last delivery. None of the perforations in the study led to serious illness or injury of intra-abdominal or pelvic structures. Interestingly, women using a levonorgestrel IUC were considerably less likely to experience a contraceptive failure than those using a copper IUC.41

Strengths of this study included the prospective data collection and power to examine rare clinical outcomes. However, it was industry-funded.

The risk of pelvic infection with an IUC is so low that the CDC does not recommend prophylactic antibiotics with the insertion procedure. If women have other indications for testing for sexually transmitted disease, an IUC can be placed the same day as testing, and before results are available.42 If a woman is found to have a sexually transmitted disease while she has an IUC in place, she should be treated with antibiotics, and there is no need to remove the IUC.43

Subdermal implants

Another highly effective contraceptive option for this patient is the progestin-only subdermal contraceptive implant (marketed in the United States as Nexplanon). Implants have been well-studied and found to have no adverse effect on lactation.44

Learning to place a subdermal contraceptive is far easier than learning to place an IUC, but it requires a few hours of FDA-mandated in-person training. Unfortunately, relatively few clinicians have obtained this training.45 As placing a subdermal contraceptive is like placing an intravenous line without needing to hit the vein, this procedure can easily be incorporated into a primary care practice. Training from the manufacturer is available to providers who request it.

What should we tell this patient?

An IUC is a great option for many women. When pregnancy is desired, the device is easily removed. Of the three IUCs now available in the United States, those containing 52 mg of levonorgestrel (marketed in the United States as Mirena and Liletta) are the most effective.

The only option more effective than these IUCs is subdermal contraception.46 These reversible contraceptives are typically more effective than permanent contraceptives (ie, tubal ligation)47 and can be removed at any time if a patient wishes to switch to another method or to become pregnant.

Pregnancy rates following attempts at “sterilization” are higher than many realize. There are a variety of approaches to “tying tubes,” some of which may not result in complete tubal occlusion. The failure rate of the laparoscopic approach, according to the US Collaborative Review of Sterilization, ranges from 7.5 per 1,000 procedures for unipolar coagulation to a high of 36.5 per 1,000 for the spring clip.48 The relatively commonly used Filshie clip was not included in this study, but its failure rate is reported to be between 1% and 2%.

- Hooton TM. Clinical practice. Uncomplicated urinary tract infection. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1028–1037.

- Christiaens TC, De Meyere M, Verschraegen G, et al. Randomised controlled trial of nitrofurantoin versus placebo in the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection in adult women. Br J Gen Pract 2002; 52:729–734.

- Bleidorn J, Gágyor I, Kochen MM, Wegscheider K, Hummers-Pradier E. Symptomatic treatment (ibuprofen) or antibiotics (ciprofloxacin) for uncomplicated urinary tract infection?—results of a randomized controlled pilot trial. BMC Med 2010; 8:30. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-30.

- Little P, Moore MV, Turner S, et al. Effectiveness of five different approaches in management of urinary tract infection: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010; 340:c199.

- Ferry SA, Holm SE, Stenlund H, Lundholm R, Monsen TJ. The natural course of uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection in women illustrated by a randomized placebo controlled study. Scand J Infect Dis 2004; 36:296–301.

- Gágyor I, Bleidorn J, Kochen MM, Schmiemann G, Wegscheider K, Hummers-Pradier E. Ibuprofen versus fosfomycin for uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2015; 351:h6544. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6544.

- Butler CC, Dunstan F, Heginbothom M, et al. Containing antibiotic resistance: decreased antibiotic-resistant coliform urinary tract infections with reduction in antibiotic prescribing by general practices. Br J Gen Pract 2007; 57:785–792.

- Gottesman BS, Carmeli Y, Shitrit P, Chowers M. Impact of quinolone restriction on resistance patterns of Escherichia coli isolated from urine by culture in a community setting. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49:869–875.

- Knottnerus BJ, Geerlings SE, Moll van Charante EP, ter Riet G. Women with symptoms of uncomplicated urinary tract infection are often willing to delay antibiotic treatment: a prospective cohort study. BMC Fam Pract 2013; 14:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-71.

- Leydon GM, Turner S, Smith H, Little P; UTIS team. Women’s views about management and cause of urinary tract infection: qualitative interview study. BMJ 2010; 340:c279. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c279.

- Willems CS, van den Broek D’Obrenan J, Numans ME, Verheij TJ, van der Velden AW. Cystitis: antibiotic prescribing, consultation, attitudes and opinions. Fam Pract 2014; 31:149–155.

- Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet 1996; 348:1535–1541.

- Black DM, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE, et al; FLEX Research Group. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment: the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. JAMA 2006; 296:2927–2938.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Background document for meeting of Advisory Committee for Reproductive Health Drugs and Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee. www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/DrugSafetyandRiskManagementAdvisoryCommittee/UCM270958.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2016.

- Kanis JA, Borgstrom F, De Laet C, et al. Assessment of fracture risk. Osteoporos Int 2005; 16:581–589.

- Adler RA, El-Hajj Fuleihan G, Bauer DC, et al. Managing osteoporosis in patients on long-term bisphosphonate treatment: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res 2016; 31:16–35.

- Black DM, Reid IR, Boonen S, et al. The effect of 3 versus 6 years of zoledronic acid treatment of osteoporosis: a randomized extension to the HORIZON-Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT). J Bone Miner Res 2012; 27:243–254.

- World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases. FRAX WHO fracture risk assessment tool. www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/. Accessed October 7, 2016.

- Watts NB, Bilezikian JP, Camacho PM, et al; AACE Osteoporosis Task Force. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Endocr Pract 2010; 16(suppl 3):1–37.

- Whitaker M, Guo J, Kehoe T, Benson G. Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis—where do we go from here? N Engl J Med 2012; 366:2048–2051.

- Black DM, Bauer DC, Schwartz AV, Cummings SR, Rosen CJ. Continuing bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis—for whom and for how long? N Engl J Med 2012; 366:2051–2053.

- Brown JP, Morin S, Leslie W, et al. Bisphosphonates for treatment of osteoporosis: expected benefits, potential harms, and drug holidays. Can Fam Physician 2014; 60:324–333.

- Watts NB, Diab DL. Long-term use of bisphosphonates in osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95:1555–1565.

- Bauer DC, Schwartz A, Palermo L, et al. Fracture prediction after discontinuation of 4 to 5 years of alendronate therapy: the FLEX study. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174:1126–1134.

- Buys SS, Partridge E, Black A, et al; PLCO Project Team. Effect of screening on ovarian cancer mortality: the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2011; 305:2295–2303.

- Jacobs IJ, Menon U, Ryan A, et al. Ovarian cancer screening and mortality in the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387:945–956.

- Abcodia Inc. The ROCA test. www.therocatest.co.uk/for-clinicians/about-roca. Accessed November 3, 2016.

- Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for ovarian cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157:900–904.

- Titus-Ernstoff L, Perez K, Cramer DW, Harlow BL, Baron JA, Greenberg ER. Menstrual and reproductive factors in relation to ovarian cancer risk. Br J Cancer 2001; 84:714–721.

- Collaborative Group on Epidemiological Studies of Ovarian Cancer, Beral V, Doll R, Hermon C, Peto R, Reeves G. Ovarian cancer and oral contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of data from 45 epidemiological studies including 23,257 women with ovarian cancer and 87,303 controls. Lancet 2008; 371:303–314.

- Chowdhury R, Sinha B, Sankar MJ, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr 2015; 104:96–113.

- Hannaford PC, Iversen L, Macfarlane TV, Elliott AM, Angus V, Lee AJ. Mortality among contraceptive pill users: cohort evidence from Royal College of General Practitioners’ Oral Contraception Study. BMJ 2010; 340:c927. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c927.