User login

Waist-hip ratio a stronger mortality predictor than BMI

TOPLINE:

Compared with body mass index, waist-hip ratio (WHR) had the strongest and most consistent association with all-cause mortality and was the only measurement unaffected by BMI.

METHODOLOGY:

- Cohort study of incident deaths from the U.K. Biobank (2006-2022), including data from 22 centers across the United Kingdom.

- A total of 387,672 participants were divided into a discovery cohort (n = 337,078) and validation cohort (n = 50,594), with the latter consisting of 25,297 deaths and 2,297 controls.

- The discovery cohort was used to derive genetically determined adiposity measures while the validation cohort was used for analyses.

- Exposure-outcome associations were analyzed through observational and mendelian randomization analyses.

TAKEAWAY:

- In adjusted analysis, a J-shaped association was found for both measured BMI and fat mass index (FMI), whereas the association with WHR was linear (hazard ratio 1.41 per standard deviation increase).

- There was a significant association between all three adiposity measures and all-cause mortality, with odds ratio 1.29 per SD change in genetically determined BMI (P = 1.44×10-13), 1.45 per SD change in genetically determined FMI, 1.45 (P = 6.27×10-30), and 1.51 per SD change in genetically determined WHR (P = 2.11×10-9).

- Compared with BMI, WHR had the stronger association with all-cause mortality, although it was not significantly stronger than FMI.

- The association of genetically determined BMI and FMI with all-cause mortality varied across quantiles of observed BMI, but WHR did not (P = .04, P = .02, and P = .58, for BMI, FMI, and WHR, respectively).

IN PRACTICE:

“Current World Health Organization recommendations for optimal BMI range are inaccurate across individuals with various body compositions and therefore suboptimal for clinical guidelines.”

SOURCE:

Study by Irfan Khan, MSc, of the Population Health Research Institute, David Braley Cardiac, Vascular, and Stroke Research Institute, Hamilton, Ont., and colleagues. Published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Study population was genetically homogeneous, White, and British, so results may not be representative of other racial or ethnic groups.

DISCLOSURES:

Study was funded by, and Irfan Khan received support from, the Ontario Graduate Scholarship–Masters Scholarship, awarded by the government of Ontario.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Compared with body mass index, waist-hip ratio (WHR) had the strongest and most consistent association with all-cause mortality and was the only measurement unaffected by BMI.

METHODOLOGY:

- Cohort study of incident deaths from the U.K. Biobank (2006-2022), including data from 22 centers across the United Kingdom.

- A total of 387,672 participants were divided into a discovery cohort (n = 337,078) and validation cohort (n = 50,594), with the latter consisting of 25,297 deaths and 2,297 controls.

- The discovery cohort was used to derive genetically determined adiposity measures while the validation cohort was used for analyses.

- Exposure-outcome associations were analyzed through observational and mendelian randomization analyses.

TAKEAWAY:

- In adjusted analysis, a J-shaped association was found for both measured BMI and fat mass index (FMI), whereas the association with WHR was linear (hazard ratio 1.41 per standard deviation increase).

- There was a significant association between all three adiposity measures and all-cause mortality, with odds ratio 1.29 per SD change in genetically determined BMI (P = 1.44×10-13), 1.45 per SD change in genetically determined FMI, 1.45 (P = 6.27×10-30), and 1.51 per SD change in genetically determined WHR (P = 2.11×10-9).

- Compared with BMI, WHR had the stronger association with all-cause mortality, although it was not significantly stronger than FMI.

- The association of genetically determined BMI and FMI with all-cause mortality varied across quantiles of observed BMI, but WHR did not (P = .04, P = .02, and P = .58, for BMI, FMI, and WHR, respectively).

IN PRACTICE:

“Current World Health Organization recommendations for optimal BMI range are inaccurate across individuals with various body compositions and therefore suboptimal for clinical guidelines.”

SOURCE:

Study by Irfan Khan, MSc, of the Population Health Research Institute, David Braley Cardiac, Vascular, and Stroke Research Institute, Hamilton, Ont., and colleagues. Published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Study population was genetically homogeneous, White, and British, so results may not be representative of other racial or ethnic groups.

DISCLOSURES:

Study was funded by, and Irfan Khan received support from, the Ontario Graduate Scholarship–Masters Scholarship, awarded by the government of Ontario.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Compared with body mass index, waist-hip ratio (WHR) had the strongest and most consistent association with all-cause mortality and was the only measurement unaffected by BMI.

METHODOLOGY:

- Cohort study of incident deaths from the U.K. Biobank (2006-2022), including data from 22 centers across the United Kingdom.

- A total of 387,672 participants were divided into a discovery cohort (n = 337,078) and validation cohort (n = 50,594), with the latter consisting of 25,297 deaths and 2,297 controls.

- The discovery cohort was used to derive genetically determined adiposity measures while the validation cohort was used for analyses.

- Exposure-outcome associations were analyzed through observational and mendelian randomization analyses.

TAKEAWAY:

- In adjusted analysis, a J-shaped association was found for both measured BMI and fat mass index (FMI), whereas the association with WHR was linear (hazard ratio 1.41 per standard deviation increase).

- There was a significant association between all three adiposity measures and all-cause mortality, with odds ratio 1.29 per SD change in genetically determined BMI (P = 1.44×10-13), 1.45 per SD change in genetically determined FMI, 1.45 (P = 6.27×10-30), and 1.51 per SD change in genetically determined WHR (P = 2.11×10-9).

- Compared with BMI, WHR had the stronger association with all-cause mortality, although it was not significantly stronger than FMI.

- The association of genetically determined BMI and FMI with all-cause mortality varied across quantiles of observed BMI, but WHR did not (P = .04, P = .02, and P = .58, for BMI, FMI, and WHR, respectively).

IN PRACTICE:

“Current World Health Organization recommendations for optimal BMI range are inaccurate across individuals with various body compositions and therefore suboptimal for clinical guidelines.”

SOURCE:

Study by Irfan Khan, MSc, of the Population Health Research Institute, David Braley Cardiac, Vascular, and Stroke Research Institute, Hamilton, Ont., and colleagues. Published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Study population was genetically homogeneous, White, and British, so results may not be representative of other racial or ethnic groups.

DISCLOSURES:

Study was funded by, and Irfan Khan received support from, the Ontario Graduate Scholarship–Masters Scholarship, awarded by the government of Ontario.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

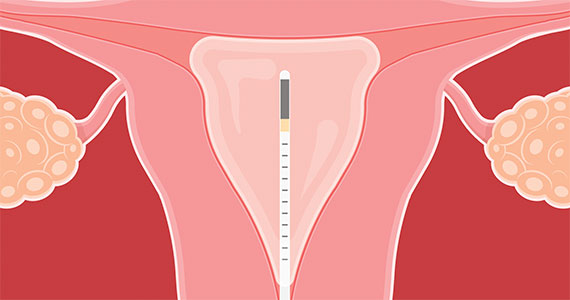

2023 Update on abnormal uterine bleeding

Endometrial ablation continues to be performed in significant numbers in the United States, with an estimated 500,000 cases annually. Several nonresectoscopic endometrial ablation devices have been approved for use, and some are now discontinued. The newest endometrial ablation therapy to gain US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and to have published outcomes is the Cerene cryotherapy ablation device (Channel Medsystems, Inc). The results of 36-month outcomes from the CLARITY study were published last year, and we have chosen to review these long-term data in addition to that of a second study in which investigators assessed the ability to access the endometrial cavity postcryoablation. We believe this is important because of concerns about the inability to access the endometrial cavity after ablation, as well as the potential for delay in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer. It is interesting that 2 publications simultaneously reviewed the incidence of endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation within the past 12 months, and we therefore present those findings as they provide valuable information.

Our second focus in this year’s Update is to provide additional information about the burgeoning data on gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists. We review evidence on linzagolix from the PRIMROSE 1 and PRIMROSE 2 trials and longer-term data on relugolix combination therapy for symptomatic uterine fibroids.

Three-year follow-up after endometrial cryoablation with the Cerene device found high patient satisfaction, low hysterectomy rates

Curlin HL, Cintron LC, Anderson TL. A prospective, multicenter, clinical trial evaluating the safety and effectiveness of the Cerene device to treat heavy menstrual bleeding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28;899-908.

Curlin HL, Anderson TL. Endometrial cryoablation for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding: 36-month outcomes from the CLARITY study. Int J Womens Health. 2022;14:1083-1092.

The 12-month data on the clinical safety and effectiveness of the Cerene cryoablation device were published in 2021 in the CLARITY trial.1 The 36-month outcomes were published in 2022 and showed sustained clinical effects through month 36 with a low risk of adverse outcomes.2 The interesting aspect of this trial is that although the amenorrhea rate was relatively low at 12 months (6.5%), it continued to remain relatively low compared with rates found with other devices, but the amenorrhea rate increased at 36 months (14.4%). This was the percentage of patients who reported, “I no longer get my period.”

Patient satisfaction was high

Despite a relatively low amenorrhea rate, study participants had a high satisfaction rate and a low 3-year hysterectomy rate. Eighty-five percent of the participants were satisfied or very satisfied, and the cumulative hysterectomy rate was low at 5%.

The overall reintervention rate was 8.7%. Six patients were treated with medications, 2 patients underwent repeat endometrial ablation, 1 received a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device, and 12 underwent hysterectomy.

At 36 months, 201 of the original 242 participants were available for assessment. Unfortunately, 5 pregnancies were reported through the 6-month posttreatment period, which emphasizes the importance of having reliable contraception. However, there were no reports of hematometra or postablation tubal sterilization syndrome (PATSS).

Effect on bleeding was long term

The main finding of the CLARITY study is that the Cerene cryoablation device appears to have a relatively stable effect on bleedingfor the first 3 years after therapy, with minimal risk of hematometra and PATSS. What we find interesting is that despite Cerene cryoablation having one of the lowest amenorrhea rates, it not only had a satisfaction rate in line with that of other devices but also had a low hysterectomy rate—only 5%—at 3 years.

The study authors pointed out that there is a lack of scarring within the endometrial cavity with the Cerene device. Some may find less endometrial scarring worth a low amenorrhea rate in the context of a favorable satisfaction rate. This begs the question, how well can the endometrial cavity be assessed? For answers, keep reading.

Can the endometrial cavity be reliably accessed after Cerene cryoablation?

Endometrial ablation has been associated with intracavitary scarring that results in hematometra, PATSS, and a concern for difficulty in performing an adequate endometrial assessment in patients who develop postablation abnormal uterine bleeding.

In a prospective study, 230 participants (of an initial 242) treated with Cerene cyroablation were studied with hysteroscopic evaluation of the endometrial cavity 12 months after surgery.3 The uterine cavity was accessible in 98.7% of participants. The cavity was not accessible in 3 participants due to pain or cervical stenosis.

Visualization of the uterine cavity was possible by hysteroscopy in 92.7% of study participants (204 of 220), with 1 or both tubal ostia identified in 89.2%. Both tubal ostia were visible in 78.4% and 1 ostium was visible in 10.8%. The cavity was not visualized in 16 of the 220 patients (7.2%) due to intrauterine adhesions, technical difficulties, or menstruation. Also of note, 97 of the 230 participants available at the 12-month follow-up had undergone tubal sterilization before cryoablation and none reported symptoms of PATSS or hematometra, which may be considered surrogate markers for adhesions.

Results of the CLARITY study demonstrated the clinical safety and effectiveness of the Cerene cryoablation device at 12 months, with sustained clinical effects through 36 months and a low risk of adverse outcomes. Patient satisfaction rates were high, and the hysterectomy rate was low. In addition, in a prospective study of patients treated with Cerene cryoablation, hysteroscopic evaluation at 12 months found the uterine cavity accessible in more than 98% of participants, and uterine visualization also was high. Therefore, the Cerene cryoablation device may provide the advantage of an easier evaluation of patients who eventually develop abnormal bleeding after endometrial ablation.

Continue to: Tissue effects differ with ablation technique...

Tissue effects differ with ablation technique

The study authors suggested that different tissue effects occur with freezing compared with heating ablation techniques. With freezing, over weeks to months the chronic inflammatory tissue is eventually replaced by a fibrous scar of collagen, with some preservation of the collagen matrix during tissue repair. This may be different from the charring and boiling of heated tissue that results in architectural tissue loss and may interfere with wound repair and tissue remodeling. Although the incidence of postoperative adhesions after endometrial ablation is not well studied, it is encouraging that most patients who received cryoablation with the Cerene device were able to undergo an evaluation of the endometrium without general anesthesia.

Key takeaway

The main idea from this study is that the endometrium can be assessed by office hysteroscopy in most patients who undergo cryoablation with the Cerene device. This may have advantages in terms of reducing the risk of PATSS and hematometra, and it may allow easier evaluation of the endometrium for patients who have postablation abnormal uterine bleeding. This begs the question, does intrauterine scarring influence the detection of endometrial cancer? For answers, keep reading.

Does endometrial ablation place a patient at higher risk for a delay in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer?

Radestad AF, Dahm-Kahler P, Holmberg E, et al. Long-term incidence of endometrial cancer after endometrial resection and ablation: a population based Swedish gynecologic cancer group (SweGCG) study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022;101:923-930.

Oderkerk TJ, van de Kar MRD, Cornel KMC, et al. Endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation: a systematic review. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022;32:1555-1560.

The answer to this question appears to be no, based on 2 different types of studies. One study was a 20-year population database review from Sweden,4 and the other was a systematic review of 11 cohort studies.5

Population-based study findings

The data from the Swedish population database is interesting because since 1994 all Swedish citizens have been allocated a unique personal identification number at birth or immigration that enables official registries and research. In reviewing their data from 1997 through 2017, Radestad and colleagues compared transcervical resection of the endometrium (TCRE) and other forms of endometrial ablation against the Swedish National Patient Register data for endometrial cancer.4 They found no increase in the incidence of endometrial cancer after TCRE (0.3%) or after endometrial ablation (0.02%) and suggested a significantly lower incidence of endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation.

This study is beneficial because it is the largest study to explore the long-term incidence of endometrial cancer after TCRE and endometrial ablation. The investigators hypothesized that, as an explanation for the difference between rates, ablation may burn deeper into the myometrium and treat adenomyosis compared with TCRE. However, they also were cautious to note that although this was a 20-year study, the incidence of endometrial carcinoma likely will reach a peak in the next few years.

Systematic review conclusions

In the systematic review, out of 890 publications from the authors’ database search, 11 articles were eventually included for review.5 A total of 29,102 patients with endometrial ablation were followed for a period of up to 25 years, and the incidence of endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation varied from 0.0% to 1.6%. A total of 38 cases of endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation have been described in the literature. Of those cases, bleeding was the most common presenting symptom of the disease. Endometrial sampling was successful in 89% of cases, and in 90% of cases, histological exam showed an early-stage endometrial adenocarcinoma.

Based on their review, the authors concluded that the incidence of endometrial cancer was not increased in patients who received endometrial ablation, and more importantly, there was no apparent delay in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation. They further suggested that diagnostic management with endometrial sampling did not appear to be a barrier.

The main findings from these 2 studies by Radestad and colleagues and Oderkerk and associates are that endometrial cancer does not appear to be more common after endometrial ablation, and it appears to be diagnosed with endometrial sampling in most cases.4,5 There may be some protection against endometrial cancer with nonresectoscopic endometrial ablation, although this needs to be verified by additional studies. To juxtapose this information with the prior information about cryotherapy, it emphasizes that the scarring within the endometrium will likely reduce the incidence of PATSS and hematometra, which are relatively low-incidence occurrences at 5% to 7%, but it likely does not affect the detection of endometrial cancer.

Longer-term data for relugolix combination treatment of symptomatic uterine bleeding from fibroids shows sustained efficacy

Al-Hendy A, Lukes AS, Poindexter AN, et al. Long-term relugolix combination therapy for symptomatic uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:920-930.

Relugolix combination therapy was previously reported to be effective for the treatment of fibroids based on the 24-week trials LIBERTY 1 and LIBERTY 2. We now have information about longer-term therapy for up to 52 weeks of treatment.6

Relugolix combination therapy is a once-daily single tablet for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding thought to be due to uterine fibroids in premenopausal women. It is comprised of relugolix 40 mg (a GnRH antagonist), estradiol 1.0 mg, and norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg.

Continue to: Extension study showed sustained efficacy...

Extension study showed sustained efficacy

The study by Al-Hendy and colleagues showed that the relugolix combination not only was well tolerated but also that there was sustained improvement in heavy bleeding, with the average patient having an approximately 90% decrease in menstrual bleeding from baseline.6 It was noted that 70.6% of patients achieved amenorrhea over the last 35 days of treatment.

Importantly, the treatment effect was independent of race, body mass index, baseline menstrual blood loss, and uterine fibroid volume. The bone mineral density (BMD) change trajectory was similar to what was observed in the pivotal study. No new safety concerns were identified, and BMD generally was preserved.

The extension study by Al-Hendy and colleagues demonstrated that that the reduced fibroid-associated bleeding treated with relugolix combination therapy is sustained throughout the 52-week period, with no new safety concerns.

Linzagolix is the newest GnRH antagonist to be studied in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial

Donnez J, Taylor HS, Stewart EA, et al. Linzagolix with and without hormonal add-back therapy for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids: two randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2022;400:896-907.

At the time of this writing, linzagolix was not approved by the FDA. The results of the PRIMROSE 1 (P1) and PRIMROSE 2 (P2) trials were published last year as 2 identical 52-week randomized, parallel, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials.7 The difference between the development of linzagolix as a GnRH antagonist and other similar medications is the strategy of potential partial hypothalamic pituitary ovarian axis suppression at 100 mg versus complete suppression at 200 mg. In this trial by Donnez and colleagues, both linzagolix doses were evaluated with and without add-back hormonal therapy and also were compared with placebo in a 1:1:1:1:1 ratio.7

Study details and results

To be eligible for this study, participants had to have heavy menstrual bleeding, defined as more than 80 mL for at least 2 cycles, and have at least 1 fibroid that was 2 cm in diameter or multiple small fibroids with the calculated uterine volume of more than 200 cm3. No fibroid larger than 12 cm in diameter was included.

The primary end point was a menstrual blood loss of 80 mL or less and a 50% or more reduction in menstrual blood loss from baseline in the 28 days before week 24. Uterine fibroid volume reduction and a safety assessment, including BMD assessment, also were studied.

In the P1 trial, which was conducted in US sites, the response rate for the primary objective was 56.4% in the linzagolix 100-mg group, 66.4% in the 100-mg plus add-back therapy group, 71.4% in the 200-mg group, and 75.5% in the 200-mg plus add-back group, compared with 35.0% in the placebo group.

In the P2 trial, which included sites in both Europe and the United States, the response rates were 56.7% in the 100-mg group, 77.2% in the 100-mg plus add-back therapy group, 77.7% in the 200-mg group, and 93.9% in the 200-mg plus add-back therapy group, compared with 29.4% in the placebo group. Thus, in both trials a significantly higher proportion of menstrual reduction occurred in all linzagolix treatment groups compared with placebo.

As expected, the incidence of hot flushes was the highest in participants taking the linzagolix 200-mg dose without add-back hormonal therapy, with hot flushes occurring in 35% (P1) and 32% (P2) of patients, compared with all other groups, which was 3% to 14%. All treatment groups showed improvement in quality-of-life scores compared with placebo. Of note, to achieve reduction of fibroid volume in the 40% to 50% range, this was observed consistently only with the linzagolix 200-mg alone dose.

Linzagolix effect on bone

Decreases in BMD appeared to be dose dependent, as lumbar spine losses of up to 4% were noted with the linzgolix 200-mg dose, and a 2% loss was observed with the 100-mg dose at 24 weeks. However, these were improved with add-back therapy. There were continued BMD decreases at 52 weeks, with up to 2.4% with 100 mg of linzagolix and up to 1.5% with 100 mg plus add-back therapy, and up to 2% with 200 mg of linzagolix plus add-back therapy. ●

Results of the P1 and P2 trials suggest that there could be a potential niche for linzagolix in patients who need chronic use (> 6 months) without the need for concomitant add-back hormone therapy at lower doses. The non-add-back option may be a possibility for women who have both a contraindication to estrogen and an increased risk for hormone-related adverse events.

- Curlin HL, Cintron LC, Anderson TL. A prospective, multicenter, clinical trial evaluating the safety and effectiveness of the Cerene device to treat heavy menstrual bleeding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28;899-908.

- Curlin HL, Anderson TL. Endometrial cryoablation for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding: 36-month outcomes from the CLARITY study. Int J Womens Health. 2022;14:1083-1092.

- Curlin H, Cholkeri-Singh A, Leal JGG, et al. Hysteroscopic access and uterine cavity evaluation 12 months after endometrial ablation with the Cerene cryotherapy device. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022;29:440-447.

- Radestad AF, Dahm-Kahler P, Holmberg E, et al. Longterm incidence of endometrial cancer after endometrial resection and ablation: a population based Swedish gynecologic cancer group (SweGCG) study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022;101:923-930.

- Oderkerk TJ, van de Kar MRD, Cornel KMC, et al. Endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation: a systematic review. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022;32:1555-1560.

- Al-Hendy A, Lukes AS, Poindexter AN, et al. Long-term relugolix combination therapy for symptomatic uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:920-930.

- Donnez J, Taylor HS, Stewart EA, et al. Linzagolix with and without hormonal add-back therapy for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids: two randomised, placebo- controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2022;400:896-907.

Endometrial ablation continues to be performed in significant numbers in the United States, with an estimated 500,000 cases annually. Several nonresectoscopic endometrial ablation devices have been approved for use, and some are now discontinued. The newest endometrial ablation therapy to gain US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and to have published outcomes is the Cerene cryotherapy ablation device (Channel Medsystems, Inc). The results of 36-month outcomes from the CLARITY study were published last year, and we have chosen to review these long-term data in addition to that of a second study in which investigators assessed the ability to access the endometrial cavity postcryoablation. We believe this is important because of concerns about the inability to access the endometrial cavity after ablation, as well as the potential for delay in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer. It is interesting that 2 publications simultaneously reviewed the incidence of endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation within the past 12 months, and we therefore present those findings as they provide valuable information.

Our second focus in this year’s Update is to provide additional information about the burgeoning data on gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists. We review evidence on linzagolix from the PRIMROSE 1 and PRIMROSE 2 trials and longer-term data on relugolix combination therapy for symptomatic uterine fibroids.

Three-year follow-up after endometrial cryoablation with the Cerene device found high patient satisfaction, low hysterectomy rates

Curlin HL, Cintron LC, Anderson TL. A prospective, multicenter, clinical trial evaluating the safety and effectiveness of the Cerene device to treat heavy menstrual bleeding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28;899-908.

Curlin HL, Anderson TL. Endometrial cryoablation for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding: 36-month outcomes from the CLARITY study. Int J Womens Health. 2022;14:1083-1092.

The 12-month data on the clinical safety and effectiveness of the Cerene cryoablation device were published in 2021 in the CLARITY trial.1 The 36-month outcomes were published in 2022 and showed sustained clinical effects through month 36 with a low risk of adverse outcomes.2 The interesting aspect of this trial is that although the amenorrhea rate was relatively low at 12 months (6.5%), it continued to remain relatively low compared with rates found with other devices, but the amenorrhea rate increased at 36 months (14.4%). This was the percentage of patients who reported, “I no longer get my period.”

Patient satisfaction was high

Despite a relatively low amenorrhea rate, study participants had a high satisfaction rate and a low 3-year hysterectomy rate. Eighty-five percent of the participants were satisfied or very satisfied, and the cumulative hysterectomy rate was low at 5%.

The overall reintervention rate was 8.7%. Six patients were treated with medications, 2 patients underwent repeat endometrial ablation, 1 received a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device, and 12 underwent hysterectomy.

At 36 months, 201 of the original 242 participants were available for assessment. Unfortunately, 5 pregnancies were reported through the 6-month posttreatment period, which emphasizes the importance of having reliable contraception. However, there were no reports of hematometra or postablation tubal sterilization syndrome (PATSS).

Effect on bleeding was long term

The main finding of the CLARITY study is that the Cerene cryoablation device appears to have a relatively stable effect on bleedingfor the first 3 years after therapy, with minimal risk of hematometra and PATSS. What we find interesting is that despite Cerene cryoablation having one of the lowest amenorrhea rates, it not only had a satisfaction rate in line with that of other devices but also had a low hysterectomy rate—only 5%—at 3 years.

The study authors pointed out that there is a lack of scarring within the endometrial cavity with the Cerene device. Some may find less endometrial scarring worth a low amenorrhea rate in the context of a favorable satisfaction rate. This begs the question, how well can the endometrial cavity be assessed? For answers, keep reading.

Can the endometrial cavity be reliably accessed after Cerene cryoablation?

Endometrial ablation has been associated with intracavitary scarring that results in hematometra, PATSS, and a concern for difficulty in performing an adequate endometrial assessment in patients who develop postablation abnormal uterine bleeding.

In a prospective study, 230 participants (of an initial 242) treated with Cerene cyroablation were studied with hysteroscopic evaluation of the endometrial cavity 12 months after surgery.3 The uterine cavity was accessible in 98.7% of participants. The cavity was not accessible in 3 participants due to pain or cervical stenosis.

Visualization of the uterine cavity was possible by hysteroscopy in 92.7% of study participants (204 of 220), with 1 or both tubal ostia identified in 89.2%. Both tubal ostia were visible in 78.4% and 1 ostium was visible in 10.8%. The cavity was not visualized in 16 of the 220 patients (7.2%) due to intrauterine adhesions, technical difficulties, or menstruation. Also of note, 97 of the 230 participants available at the 12-month follow-up had undergone tubal sterilization before cryoablation and none reported symptoms of PATSS or hematometra, which may be considered surrogate markers for adhesions.

Results of the CLARITY study demonstrated the clinical safety and effectiveness of the Cerene cryoablation device at 12 months, with sustained clinical effects through 36 months and a low risk of adverse outcomes. Patient satisfaction rates were high, and the hysterectomy rate was low. In addition, in a prospective study of patients treated with Cerene cryoablation, hysteroscopic evaluation at 12 months found the uterine cavity accessible in more than 98% of participants, and uterine visualization also was high. Therefore, the Cerene cryoablation device may provide the advantage of an easier evaluation of patients who eventually develop abnormal bleeding after endometrial ablation.

Continue to: Tissue effects differ with ablation technique...

Tissue effects differ with ablation technique

The study authors suggested that different tissue effects occur with freezing compared with heating ablation techniques. With freezing, over weeks to months the chronic inflammatory tissue is eventually replaced by a fibrous scar of collagen, with some preservation of the collagen matrix during tissue repair. This may be different from the charring and boiling of heated tissue that results in architectural tissue loss and may interfere with wound repair and tissue remodeling. Although the incidence of postoperative adhesions after endometrial ablation is not well studied, it is encouraging that most patients who received cryoablation with the Cerene device were able to undergo an evaluation of the endometrium without general anesthesia.

Key takeaway

The main idea from this study is that the endometrium can be assessed by office hysteroscopy in most patients who undergo cryoablation with the Cerene device. This may have advantages in terms of reducing the risk of PATSS and hematometra, and it may allow easier evaluation of the endometrium for patients who have postablation abnormal uterine bleeding. This begs the question, does intrauterine scarring influence the detection of endometrial cancer? For answers, keep reading.

Does endometrial ablation place a patient at higher risk for a delay in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer?

Radestad AF, Dahm-Kahler P, Holmberg E, et al. Long-term incidence of endometrial cancer after endometrial resection and ablation: a population based Swedish gynecologic cancer group (SweGCG) study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022;101:923-930.

Oderkerk TJ, van de Kar MRD, Cornel KMC, et al. Endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation: a systematic review. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022;32:1555-1560.

The answer to this question appears to be no, based on 2 different types of studies. One study was a 20-year population database review from Sweden,4 and the other was a systematic review of 11 cohort studies.5

Population-based study findings

The data from the Swedish population database is interesting because since 1994 all Swedish citizens have been allocated a unique personal identification number at birth or immigration that enables official registries and research. In reviewing their data from 1997 through 2017, Radestad and colleagues compared transcervical resection of the endometrium (TCRE) and other forms of endometrial ablation against the Swedish National Patient Register data for endometrial cancer.4 They found no increase in the incidence of endometrial cancer after TCRE (0.3%) or after endometrial ablation (0.02%) and suggested a significantly lower incidence of endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation.

This study is beneficial because it is the largest study to explore the long-term incidence of endometrial cancer after TCRE and endometrial ablation. The investigators hypothesized that, as an explanation for the difference between rates, ablation may burn deeper into the myometrium and treat adenomyosis compared with TCRE. However, they also were cautious to note that although this was a 20-year study, the incidence of endometrial carcinoma likely will reach a peak in the next few years.

Systematic review conclusions

In the systematic review, out of 890 publications from the authors’ database search, 11 articles were eventually included for review.5 A total of 29,102 patients with endometrial ablation were followed for a period of up to 25 years, and the incidence of endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation varied from 0.0% to 1.6%. A total of 38 cases of endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation have been described in the literature. Of those cases, bleeding was the most common presenting symptom of the disease. Endometrial sampling was successful in 89% of cases, and in 90% of cases, histological exam showed an early-stage endometrial adenocarcinoma.

Based on their review, the authors concluded that the incidence of endometrial cancer was not increased in patients who received endometrial ablation, and more importantly, there was no apparent delay in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation. They further suggested that diagnostic management with endometrial sampling did not appear to be a barrier.

The main findings from these 2 studies by Radestad and colleagues and Oderkerk and associates are that endometrial cancer does not appear to be more common after endometrial ablation, and it appears to be diagnosed with endometrial sampling in most cases.4,5 There may be some protection against endometrial cancer with nonresectoscopic endometrial ablation, although this needs to be verified by additional studies. To juxtapose this information with the prior information about cryotherapy, it emphasizes that the scarring within the endometrium will likely reduce the incidence of PATSS and hematometra, which are relatively low-incidence occurrences at 5% to 7%, but it likely does not affect the detection of endometrial cancer.

Longer-term data for relugolix combination treatment of symptomatic uterine bleeding from fibroids shows sustained efficacy

Al-Hendy A, Lukes AS, Poindexter AN, et al. Long-term relugolix combination therapy for symptomatic uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:920-930.

Relugolix combination therapy was previously reported to be effective for the treatment of fibroids based on the 24-week trials LIBERTY 1 and LIBERTY 2. We now have information about longer-term therapy for up to 52 weeks of treatment.6

Relugolix combination therapy is a once-daily single tablet for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding thought to be due to uterine fibroids in premenopausal women. It is comprised of relugolix 40 mg (a GnRH antagonist), estradiol 1.0 mg, and norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg.

Continue to: Extension study showed sustained efficacy...

Extension study showed sustained efficacy

The study by Al-Hendy and colleagues showed that the relugolix combination not only was well tolerated but also that there was sustained improvement in heavy bleeding, with the average patient having an approximately 90% decrease in menstrual bleeding from baseline.6 It was noted that 70.6% of patients achieved amenorrhea over the last 35 days of treatment.

Importantly, the treatment effect was independent of race, body mass index, baseline menstrual blood loss, and uterine fibroid volume. The bone mineral density (BMD) change trajectory was similar to what was observed in the pivotal study. No new safety concerns were identified, and BMD generally was preserved.

The extension study by Al-Hendy and colleagues demonstrated that that the reduced fibroid-associated bleeding treated with relugolix combination therapy is sustained throughout the 52-week period, with no new safety concerns.

Linzagolix is the newest GnRH antagonist to be studied in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial

Donnez J, Taylor HS, Stewart EA, et al. Linzagolix with and without hormonal add-back therapy for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids: two randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2022;400:896-907.

At the time of this writing, linzagolix was not approved by the FDA. The results of the PRIMROSE 1 (P1) and PRIMROSE 2 (P2) trials were published last year as 2 identical 52-week randomized, parallel, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials.7 The difference between the development of linzagolix as a GnRH antagonist and other similar medications is the strategy of potential partial hypothalamic pituitary ovarian axis suppression at 100 mg versus complete suppression at 200 mg. In this trial by Donnez and colleagues, both linzagolix doses were evaluated with and without add-back hormonal therapy and also were compared with placebo in a 1:1:1:1:1 ratio.7

Study details and results

To be eligible for this study, participants had to have heavy menstrual bleeding, defined as more than 80 mL for at least 2 cycles, and have at least 1 fibroid that was 2 cm in diameter or multiple small fibroids with the calculated uterine volume of more than 200 cm3. No fibroid larger than 12 cm in diameter was included.

The primary end point was a menstrual blood loss of 80 mL or less and a 50% or more reduction in menstrual blood loss from baseline in the 28 days before week 24. Uterine fibroid volume reduction and a safety assessment, including BMD assessment, also were studied.

In the P1 trial, which was conducted in US sites, the response rate for the primary objective was 56.4% in the linzagolix 100-mg group, 66.4% in the 100-mg plus add-back therapy group, 71.4% in the 200-mg group, and 75.5% in the 200-mg plus add-back group, compared with 35.0% in the placebo group.

In the P2 trial, which included sites in both Europe and the United States, the response rates were 56.7% in the 100-mg group, 77.2% in the 100-mg plus add-back therapy group, 77.7% in the 200-mg group, and 93.9% in the 200-mg plus add-back therapy group, compared with 29.4% in the placebo group. Thus, in both trials a significantly higher proportion of menstrual reduction occurred in all linzagolix treatment groups compared with placebo.

As expected, the incidence of hot flushes was the highest in participants taking the linzagolix 200-mg dose without add-back hormonal therapy, with hot flushes occurring in 35% (P1) and 32% (P2) of patients, compared with all other groups, which was 3% to 14%. All treatment groups showed improvement in quality-of-life scores compared with placebo. Of note, to achieve reduction of fibroid volume in the 40% to 50% range, this was observed consistently only with the linzagolix 200-mg alone dose.

Linzagolix effect on bone

Decreases in BMD appeared to be dose dependent, as lumbar spine losses of up to 4% were noted with the linzgolix 200-mg dose, and a 2% loss was observed with the 100-mg dose at 24 weeks. However, these were improved with add-back therapy. There were continued BMD decreases at 52 weeks, with up to 2.4% with 100 mg of linzagolix and up to 1.5% with 100 mg plus add-back therapy, and up to 2% with 200 mg of linzagolix plus add-back therapy. ●

Results of the P1 and P2 trials suggest that there could be a potential niche for linzagolix in patients who need chronic use (> 6 months) without the need for concomitant add-back hormone therapy at lower doses. The non-add-back option may be a possibility for women who have both a contraindication to estrogen and an increased risk for hormone-related adverse events.

Endometrial ablation continues to be performed in significant numbers in the United States, with an estimated 500,000 cases annually. Several nonresectoscopic endometrial ablation devices have been approved for use, and some are now discontinued. The newest endometrial ablation therapy to gain US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and to have published outcomes is the Cerene cryotherapy ablation device (Channel Medsystems, Inc). The results of 36-month outcomes from the CLARITY study were published last year, and we have chosen to review these long-term data in addition to that of a second study in which investigators assessed the ability to access the endometrial cavity postcryoablation. We believe this is important because of concerns about the inability to access the endometrial cavity after ablation, as well as the potential for delay in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer. It is interesting that 2 publications simultaneously reviewed the incidence of endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation within the past 12 months, and we therefore present those findings as they provide valuable information.

Our second focus in this year’s Update is to provide additional information about the burgeoning data on gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists. We review evidence on linzagolix from the PRIMROSE 1 and PRIMROSE 2 trials and longer-term data on relugolix combination therapy for symptomatic uterine fibroids.

Three-year follow-up after endometrial cryoablation with the Cerene device found high patient satisfaction, low hysterectomy rates

Curlin HL, Cintron LC, Anderson TL. A prospective, multicenter, clinical trial evaluating the safety and effectiveness of the Cerene device to treat heavy menstrual bleeding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28;899-908.

Curlin HL, Anderson TL. Endometrial cryoablation for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding: 36-month outcomes from the CLARITY study. Int J Womens Health. 2022;14:1083-1092.

The 12-month data on the clinical safety and effectiveness of the Cerene cryoablation device were published in 2021 in the CLARITY trial.1 The 36-month outcomes were published in 2022 and showed sustained clinical effects through month 36 with a low risk of adverse outcomes.2 The interesting aspect of this trial is that although the amenorrhea rate was relatively low at 12 months (6.5%), it continued to remain relatively low compared with rates found with other devices, but the amenorrhea rate increased at 36 months (14.4%). This was the percentage of patients who reported, “I no longer get my period.”

Patient satisfaction was high

Despite a relatively low amenorrhea rate, study participants had a high satisfaction rate and a low 3-year hysterectomy rate. Eighty-five percent of the participants were satisfied or very satisfied, and the cumulative hysterectomy rate was low at 5%.

The overall reintervention rate was 8.7%. Six patients were treated with medications, 2 patients underwent repeat endometrial ablation, 1 received a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device, and 12 underwent hysterectomy.

At 36 months, 201 of the original 242 participants were available for assessment. Unfortunately, 5 pregnancies were reported through the 6-month posttreatment period, which emphasizes the importance of having reliable contraception. However, there were no reports of hematometra or postablation tubal sterilization syndrome (PATSS).

Effect on bleeding was long term

The main finding of the CLARITY study is that the Cerene cryoablation device appears to have a relatively stable effect on bleedingfor the first 3 years after therapy, with minimal risk of hematometra and PATSS. What we find interesting is that despite Cerene cryoablation having one of the lowest amenorrhea rates, it not only had a satisfaction rate in line with that of other devices but also had a low hysterectomy rate—only 5%—at 3 years.

The study authors pointed out that there is a lack of scarring within the endometrial cavity with the Cerene device. Some may find less endometrial scarring worth a low amenorrhea rate in the context of a favorable satisfaction rate. This begs the question, how well can the endometrial cavity be assessed? For answers, keep reading.

Can the endometrial cavity be reliably accessed after Cerene cryoablation?

Endometrial ablation has been associated with intracavitary scarring that results in hematometra, PATSS, and a concern for difficulty in performing an adequate endometrial assessment in patients who develop postablation abnormal uterine bleeding.

In a prospective study, 230 participants (of an initial 242) treated with Cerene cyroablation were studied with hysteroscopic evaluation of the endometrial cavity 12 months after surgery.3 The uterine cavity was accessible in 98.7% of participants. The cavity was not accessible in 3 participants due to pain or cervical stenosis.

Visualization of the uterine cavity was possible by hysteroscopy in 92.7% of study participants (204 of 220), with 1 or both tubal ostia identified in 89.2%. Both tubal ostia were visible in 78.4% and 1 ostium was visible in 10.8%. The cavity was not visualized in 16 of the 220 patients (7.2%) due to intrauterine adhesions, technical difficulties, or menstruation. Also of note, 97 of the 230 participants available at the 12-month follow-up had undergone tubal sterilization before cryoablation and none reported symptoms of PATSS or hematometra, which may be considered surrogate markers for adhesions.

Results of the CLARITY study demonstrated the clinical safety and effectiveness of the Cerene cryoablation device at 12 months, with sustained clinical effects through 36 months and a low risk of adverse outcomes. Patient satisfaction rates were high, and the hysterectomy rate was low. In addition, in a prospective study of patients treated with Cerene cryoablation, hysteroscopic evaluation at 12 months found the uterine cavity accessible in more than 98% of participants, and uterine visualization also was high. Therefore, the Cerene cryoablation device may provide the advantage of an easier evaluation of patients who eventually develop abnormal bleeding after endometrial ablation.

Continue to: Tissue effects differ with ablation technique...

Tissue effects differ with ablation technique

The study authors suggested that different tissue effects occur with freezing compared with heating ablation techniques. With freezing, over weeks to months the chronic inflammatory tissue is eventually replaced by a fibrous scar of collagen, with some preservation of the collagen matrix during tissue repair. This may be different from the charring and boiling of heated tissue that results in architectural tissue loss and may interfere with wound repair and tissue remodeling. Although the incidence of postoperative adhesions after endometrial ablation is not well studied, it is encouraging that most patients who received cryoablation with the Cerene device were able to undergo an evaluation of the endometrium without general anesthesia.

Key takeaway

The main idea from this study is that the endometrium can be assessed by office hysteroscopy in most patients who undergo cryoablation with the Cerene device. This may have advantages in terms of reducing the risk of PATSS and hematometra, and it may allow easier evaluation of the endometrium for patients who have postablation abnormal uterine bleeding. This begs the question, does intrauterine scarring influence the detection of endometrial cancer? For answers, keep reading.

Does endometrial ablation place a patient at higher risk for a delay in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer?

Radestad AF, Dahm-Kahler P, Holmberg E, et al. Long-term incidence of endometrial cancer after endometrial resection and ablation: a population based Swedish gynecologic cancer group (SweGCG) study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022;101:923-930.

Oderkerk TJ, van de Kar MRD, Cornel KMC, et al. Endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation: a systematic review. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022;32:1555-1560.

The answer to this question appears to be no, based on 2 different types of studies. One study was a 20-year population database review from Sweden,4 and the other was a systematic review of 11 cohort studies.5

Population-based study findings

The data from the Swedish population database is interesting because since 1994 all Swedish citizens have been allocated a unique personal identification number at birth or immigration that enables official registries and research. In reviewing their data from 1997 through 2017, Radestad and colleagues compared transcervical resection of the endometrium (TCRE) and other forms of endometrial ablation against the Swedish National Patient Register data for endometrial cancer.4 They found no increase in the incidence of endometrial cancer after TCRE (0.3%) or after endometrial ablation (0.02%) and suggested a significantly lower incidence of endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation.

This study is beneficial because it is the largest study to explore the long-term incidence of endometrial cancer after TCRE and endometrial ablation. The investigators hypothesized that, as an explanation for the difference between rates, ablation may burn deeper into the myometrium and treat adenomyosis compared with TCRE. However, they also were cautious to note that although this was a 20-year study, the incidence of endometrial carcinoma likely will reach a peak in the next few years.

Systematic review conclusions

In the systematic review, out of 890 publications from the authors’ database search, 11 articles were eventually included for review.5 A total of 29,102 patients with endometrial ablation were followed for a period of up to 25 years, and the incidence of endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation varied from 0.0% to 1.6%. A total of 38 cases of endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation have been described in the literature. Of those cases, bleeding was the most common presenting symptom of the disease. Endometrial sampling was successful in 89% of cases, and in 90% of cases, histological exam showed an early-stage endometrial adenocarcinoma.

Based on their review, the authors concluded that the incidence of endometrial cancer was not increased in patients who received endometrial ablation, and more importantly, there was no apparent delay in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation. They further suggested that diagnostic management with endometrial sampling did not appear to be a barrier.

The main findings from these 2 studies by Radestad and colleagues and Oderkerk and associates are that endometrial cancer does not appear to be more common after endometrial ablation, and it appears to be diagnosed with endometrial sampling in most cases.4,5 There may be some protection against endometrial cancer with nonresectoscopic endometrial ablation, although this needs to be verified by additional studies. To juxtapose this information with the prior information about cryotherapy, it emphasizes that the scarring within the endometrium will likely reduce the incidence of PATSS and hematometra, which are relatively low-incidence occurrences at 5% to 7%, but it likely does not affect the detection of endometrial cancer.

Longer-term data for relugolix combination treatment of symptomatic uterine bleeding from fibroids shows sustained efficacy

Al-Hendy A, Lukes AS, Poindexter AN, et al. Long-term relugolix combination therapy for symptomatic uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:920-930.

Relugolix combination therapy was previously reported to be effective for the treatment of fibroids based on the 24-week trials LIBERTY 1 and LIBERTY 2. We now have information about longer-term therapy for up to 52 weeks of treatment.6

Relugolix combination therapy is a once-daily single tablet for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding thought to be due to uterine fibroids in premenopausal women. It is comprised of relugolix 40 mg (a GnRH antagonist), estradiol 1.0 mg, and norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg.

Continue to: Extension study showed sustained efficacy...

Extension study showed sustained efficacy

The study by Al-Hendy and colleagues showed that the relugolix combination not only was well tolerated but also that there was sustained improvement in heavy bleeding, with the average patient having an approximately 90% decrease in menstrual bleeding from baseline.6 It was noted that 70.6% of patients achieved amenorrhea over the last 35 days of treatment.

Importantly, the treatment effect was independent of race, body mass index, baseline menstrual blood loss, and uterine fibroid volume. The bone mineral density (BMD) change trajectory was similar to what was observed in the pivotal study. No new safety concerns were identified, and BMD generally was preserved.

The extension study by Al-Hendy and colleagues demonstrated that that the reduced fibroid-associated bleeding treated with relugolix combination therapy is sustained throughout the 52-week period, with no new safety concerns.

Linzagolix is the newest GnRH antagonist to be studied in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial

Donnez J, Taylor HS, Stewart EA, et al. Linzagolix with and without hormonal add-back therapy for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids: two randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2022;400:896-907.

At the time of this writing, linzagolix was not approved by the FDA. The results of the PRIMROSE 1 (P1) and PRIMROSE 2 (P2) trials were published last year as 2 identical 52-week randomized, parallel, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials.7 The difference between the development of linzagolix as a GnRH antagonist and other similar medications is the strategy of potential partial hypothalamic pituitary ovarian axis suppression at 100 mg versus complete suppression at 200 mg. In this trial by Donnez and colleagues, both linzagolix doses were evaluated with and without add-back hormonal therapy and also were compared with placebo in a 1:1:1:1:1 ratio.7

Study details and results

To be eligible for this study, participants had to have heavy menstrual bleeding, defined as more than 80 mL for at least 2 cycles, and have at least 1 fibroid that was 2 cm in diameter or multiple small fibroids with the calculated uterine volume of more than 200 cm3. No fibroid larger than 12 cm in diameter was included.

The primary end point was a menstrual blood loss of 80 mL or less and a 50% or more reduction in menstrual blood loss from baseline in the 28 days before week 24. Uterine fibroid volume reduction and a safety assessment, including BMD assessment, also were studied.

In the P1 trial, which was conducted in US sites, the response rate for the primary objective was 56.4% in the linzagolix 100-mg group, 66.4% in the 100-mg plus add-back therapy group, 71.4% in the 200-mg group, and 75.5% in the 200-mg plus add-back group, compared with 35.0% in the placebo group.

In the P2 trial, which included sites in both Europe and the United States, the response rates were 56.7% in the 100-mg group, 77.2% in the 100-mg plus add-back therapy group, 77.7% in the 200-mg group, and 93.9% in the 200-mg plus add-back therapy group, compared with 29.4% in the placebo group. Thus, in both trials a significantly higher proportion of menstrual reduction occurred in all linzagolix treatment groups compared with placebo.

As expected, the incidence of hot flushes was the highest in participants taking the linzagolix 200-mg dose without add-back hormonal therapy, with hot flushes occurring in 35% (P1) and 32% (P2) of patients, compared with all other groups, which was 3% to 14%. All treatment groups showed improvement in quality-of-life scores compared with placebo. Of note, to achieve reduction of fibroid volume in the 40% to 50% range, this was observed consistently only with the linzagolix 200-mg alone dose.

Linzagolix effect on bone

Decreases in BMD appeared to be dose dependent, as lumbar spine losses of up to 4% were noted with the linzgolix 200-mg dose, and a 2% loss was observed with the 100-mg dose at 24 weeks. However, these were improved with add-back therapy. There were continued BMD decreases at 52 weeks, with up to 2.4% with 100 mg of linzagolix and up to 1.5% with 100 mg plus add-back therapy, and up to 2% with 200 mg of linzagolix plus add-back therapy. ●

Results of the P1 and P2 trials suggest that there could be a potential niche for linzagolix in patients who need chronic use (> 6 months) without the need for concomitant add-back hormone therapy at lower doses. The non-add-back option may be a possibility for women who have both a contraindication to estrogen and an increased risk for hormone-related adverse events.

- Curlin HL, Cintron LC, Anderson TL. A prospective, multicenter, clinical trial evaluating the safety and effectiveness of the Cerene device to treat heavy menstrual bleeding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28;899-908.

- Curlin HL, Anderson TL. Endometrial cryoablation for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding: 36-month outcomes from the CLARITY study. Int J Womens Health. 2022;14:1083-1092.

- Curlin H, Cholkeri-Singh A, Leal JGG, et al. Hysteroscopic access and uterine cavity evaluation 12 months after endometrial ablation with the Cerene cryotherapy device. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022;29:440-447.

- Radestad AF, Dahm-Kahler P, Holmberg E, et al. Longterm incidence of endometrial cancer after endometrial resection and ablation: a population based Swedish gynecologic cancer group (SweGCG) study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022;101:923-930.

- Oderkerk TJ, van de Kar MRD, Cornel KMC, et al. Endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation: a systematic review. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022;32:1555-1560.

- Al-Hendy A, Lukes AS, Poindexter AN, et al. Long-term relugolix combination therapy for symptomatic uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:920-930.

- Donnez J, Taylor HS, Stewart EA, et al. Linzagolix with and without hormonal add-back therapy for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids: two randomised, placebo- controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2022;400:896-907.

- Curlin HL, Cintron LC, Anderson TL. A prospective, multicenter, clinical trial evaluating the safety and effectiveness of the Cerene device to treat heavy menstrual bleeding. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28;899-908.

- Curlin HL, Anderson TL. Endometrial cryoablation for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding: 36-month outcomes from the CLARITY study. Int J Womens Health. 2022;14:1083-1092.

- Curlin H, Cholkeri-Singh A, Leal JGG, et al. Hysteroscopic access and uterine cavity evaluation 12 months after endometrial ablation with the Cerene cryotherapy device. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022;29:440-447.

- Radestad AF, Dahm-Kahler P, Holmberg E, et al. Longterm incidence of endometrial cancer after endometrial resection and ablation: a population based Swedish gynecologic cancer group (SweGCG) study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022;101:923-930.

- Oderkerk TJ, van de Kar MRD, Cornel KMC, et al. Endometrial cancer after endometrial ablation: a systematic review. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022;32:1555-1560.

- Al-Hendy A, Lukes AS, Poindexter AN, et al. Long-term relugolix combination therapy for symptomatic uterine leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140:920-930.

- Donnez J, Taylor HS, Stewart EA, et al. Linzagolix with and without hormonal add-back therapy for the treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids: two randomised, placebo- controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2022;400:896-907.

News & Perspectives from Ob.Gyn. News

COMMENTARY

Answering the protein question when prescribing plant-based diets

Science supports the use of a whole food, predominantly plant-based dietary pattern for optimal health, including reduced risk for chronic disease, and best practice in treatment of leading chronic disease.

But clinicians who prescribe such eating patterns encounter a common concern from patients whose health may benefit.

“Where will I get my protein?”

We’ve all heard it, and it’s understandable

To ensure that patients have all the facts when making dietary decisions, clinicians need to be prepared to respond to concerns about protein adequacy and quality with evidence-based information. A good starting point for these conversations is to assess how much protein patients are already consuming. A review of the 2015-2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that women normally consume an average of 69 g and men an average of 97 g of protein daily.

As a general point of reference, the recommended dietary allowance for protein is about 0.8 g/kg of bodyweight (or 0.36 g/lb), which equates to about 52 g of protein per day for a 145-lb woman and 65 g for a 180-lb man. But for many patients, it may be best to get a more precise recommendation based upon age, gender and physical activity level by using a handy Department of Agriculture tool for health care professionals to calculate daily protein and other nutrient needs. Patients can also use one of countless apps to track their protein and other nutrient intake. By using the tool and a tracking app, both clinician and patients can be fully informed whether protein needs are being met.

LATEST NEWS

Continuous glucose monitors for pregnant patients?

Patients with pregestational diabetes may benefit from use of a continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion pump paired with a continuous glucose monitor. Use of the tools has been associated with a reduction in maternal and neonatal morbidity, a recent study found.

“We were seeing an unacceptable burden of both maternal and fetal disease in our diabetic population,” said Neil Hamill, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Methodist Women’s Hospital, Omaha, Neb., and an author of the study. “We thought the success with this technology in the nonpregnant population would and should translate into the pregnant population.”

Dr. Hamill and his colleagues analyzed data from 55 pregnant patients who received care at the Women’s Hospital Perinatal Center at the Nebraska Methodist Health System between October 2019 and October 2022. Everyone in the cohort had pregestational diabetes and required insulin prior to week 20 of pregnancy. They used CGMs for more than 2 weeks. The study set blood glucose levels of less than 140 mg/dL as a healthy benchmark.

Participants who had severe preeclampsia, who had delivered preterm, who had delivered a neonate with respiratory distress syndrome, and/or who had given birth to a larger-than-expected infant spent less time in the safe zone — having a blood glucose level below 140 mg/dL—than women who did not have those risk factors.

“When blood sugar control is better, maternal and fetal outcomes are improved,” Dr. Hamill said.

Neetu Sodhi, MD, an ob.gyn. at Providence Cedars-Sinai Tarzana Medical Center, Los Angeles, expressed optimism that use of blood glucose monitors and insulin pumps can improve outcomes for pregnant patients with pregestational diabetes.

“This is just another case for why it’s so important for patients to have access to these types of devices that really, really improve their outcomes and their health, and now it’s proven in the case of pregnancy outcomes too – or at least suggested strongly with this data,” Dr. Sodhi said.

Continue to: It may be time to pay attention to COVID again...

It may be time to pay attention to COVID again

More than 3 years into the COVID-19 era, most Americans have settled back into their prepandemic lifestyles. But a new dominant variant and rising hospitalization numbers may give way to another summer surge.

Since April, a new COVID variant has cropped up. According to recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, EG.5—from the Omicron family—now makes up 17% of all cases in the United States, up from 7.5% in the first week of July.

A summary from the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota says that EG.5, nicknamed “Eris” by health trackers, is nearly the same as its parent strain, XBB.1.9.2, but has one extra spike mutation.

Along with the news of EG.5’s growing prevalence, COVID-related hospitalization rates have increased by 12.5% during the week ending on July 29—the most significant uptick since December. Still, no connection has been made between the new variant and rising hospital admissions. And so far, experts have found no difference in the severity of illness or symptoms between Eris and the strains that came before it.

Cause for concern?

The COVID virus has a great tendency to mutate, said William Schaffner, MD, a professor of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

“Fortunately, these are relatively minor mutations.” Even so, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, continues to be highly contagious. “There isn’t any doubt that it’s spreading—but it’s not more serious.”

So, Dr. Schaffner doesn’t think it’s time to panic. He prefers calling it an “uptick” in cases instead of a “surge,” because a surge “sounds too big.”

While the numbers are still low, compared with 2022’s summer surge, experts still urge people to stay aware of changes in the virus. “I do not think that there is any cause for alarm,” agreed Bernard Camins, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

So why the higher number of cases? “There has been an increase in COVID cases this summer, probably related to travel, socializing, and dwindling masking,” said Anne Liu, MD, an allergy, immunology, and infectious disease specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University. Even so, “because of an existing level of immunity from vaccination and prior infections, it has been limited and case severity has been lower than in prior surges.” ●

COMMENTARY

Answering the protein question when prescribing plant-based diets

Science supports the use of a whole food, predominantly plant-based dietary pattern for optimal health, including reduced risk for chronic disease, and best practice in treatment of leading chronic disease.

But clinicians who prescribe such eating patterns encounter a common concern from patients whose health may benefit.

“Where will I get my protein?”

We’ve all heard it, and it’s understandable

To ensure that patients have all the facts when making dietary decisions, clinicians need to be prepared to respond to concerns about protein adequacy and quality with evidence-based information. A good starting point for these conversations is to assess how much protein patients are already consuming. A review of the 2015-2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that women normally consume an average of 69 g and men an average of 97 g of protein daily.

As a general point of reference, the recommended dietary allowance for protein is about 0.8 g/kg of bodyweight (or 0.36 g/lb), which equates to about 52 g of protein per day for a 145-lb woman and 65 g for a 180-lb man. But for many patients, it may be best to get a more precise recommendation based upon age, gender and physical activity level by using a handy Department of Agriculture tool for health care professionals to calculate daily protein and other nutrient needs. Patients can also use one of countless apps to track their protein and other nutrient intake. By using the tool and a tracking app, both clinician and patients can be fully informed whether protein needs are being met.

LATEST NEWS

Continuous glucose monitors for pregnant patients?

Patients with pregestational diabetes may benefit from use of a continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion pump paired with a continuous glucose monitor. Use of the tools has been associated with a reduction in maternal and neonatal morbidity, a recent study found.

“We were seeing an unacceptable burden of both maternal and fetal disease in our diabetic population,” said Neil Hamill, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Methodist Women’s Hospital, Omaha, Neb., and an author of the study. “We thought the success with this technology in the nonpregnant population would and should translate into the pregnant population.”

Dr. Hamill and his colleagues analyzed data from 55 pregnant patients who received care at the Women’s Hospital Perinatal Center at the Nebraska Methodist Health System between October 2019 and October 2022. Everyone in the cohort had pregestational diabetes and required insulin prior to week 20 of pregnancy. They used CGMs for more than 2 weeks. The study set blood glucose levels of less than 140 mg/dL as a healthy benchmark.

Participants who had severe preeclampsia, who had delivered preterm, who had delivered a neonate with respiratory distress syndrome, and/or who had given birth to a larger-than-expected infant spent less time in the safe zone — having a blood glucose level below 140 mg/dL—than women who did not have those risk factors.

“When blood sugar control is better, maternal and fetal outcomes are improved,” Dr. Hamill said.

Neetu Sodhi, MD, an ob.gyn. at Providence Cedars-Sinai Tarzana Medical Center, Los Angeles, expressed optimism that use of blood glucose monitors and insulin pumps can improve outcomes for pregnant patients with pregestational diabetes.

“This is just another case for why it’s so important for patients to have access to these types of devices that really, really improve their outcomes and their health, and now it’s proven in the case of pregnancy outcomes too – or at least suggested strongly with this data,” Dr. Sodhi said.

Continue to: It may be time to pay attention to COVID again...

It may be time to pay attention to COVID again

More than 3 years into the COVID-19 era, most Americans have settled back into their prepandemic lifestyles. But a new dominant variant and rising hospitalization numbers may give way to another summer surge.

Since April, a new COVID variant has cropped up. According to recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, EG.5—from the Omicron family—now makes up 17% of all cases in the United States, up from 7.5% in the first week of July.

A summary from the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota says that EG.5, nicknamed “Eris” by health trackers, is nearly the same as its parent strain, XBB.1.9.2, but has one extra spike mutation.

Along with the news of EG.5’s growing prevalence, COVID-related hospitalization rates have increased by 12.5% during the week ending on July 29—the most significant uptick since December. Still, no connection has been made between the new variant and rising hospital admissions. And so far, experts have found no difference in the severity of illness or symptoms between Eris and the strains that came before it.

Cause for concern?

The COVID virus has a great tendency to mutate, said William Schaffner, MD, a professor of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

“Fortunately, these are relatively minor mutations.” Even so, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, continues to be highly contagious. “There isn’t any doubt that it’s spreading—but it’s not more serious.”

So, Dr. Schaffner doesn’t think it’s time to panic. He prefers calling it an “uptick” in cases instead of a “surge,” because a surge “sounds too big.”

While the numbers are still low, compared with 2022’s summer surge, experts still urge people to stay aware of changes in the virus. “I do not think that there is any cause for alarm,” agreed Bernard Camins, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

So why the higher number of cases? “There has been an increase in COVID cases this summer, probably related to travel, socializing, and dwindling masking,” said Anne Liu, MD, an allergy, immunology, and infectious disease specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University. Even so, “because of an existing level of immunity from vaccination and prior infections, it has been limited and case severity has been lower than in prior surges.” ●

COMMENTARY

Answering the protein question when prescribing plant-based diets

Science supports the use of a whole food, predominantly plant-based dietary pattern for optimal health, including reduced risk for chronic disease, and best practice in treatment of leading chronic disease.

But clinicians who prescribe such eating patterns encounter a common concern from patients whose health may benefit.

“Where will I get my protein?”

We’ve all heard it, and it’s understandable

To ensure that patients have all the facts when making dietary decisions, clinicians need to be prepared to respond to concerns about protein adequacy and quality with evidence-based information. A good starting point for these conversations is to assess how much protein patients are already consuming. A review of the 2015-2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that women normally consume an average of 69 g and men an average of 97 g of protein daily.

As a general point of reference, the recommended dietary allowance for protein is about 0.8 g/kg of bodyweight (or 0.36 g/lb), which equates to about 52 g of protein per day for a 145-lb woman and 65 g for a 180-lb man. But for many patients, it may be best to get a more precise recommendation based upon age, gender and physical activity level by using a handy Department of Agriculture tool for health care professionals to calculate daily protein and other nutrient needs. Patients can also use one of countless apps to track their protein and other nutrient intake. By using the tool and a tracking app, both clinician and patients can be fully informed whether protein needs are being met.

LATEST NEWS

Continuous glucose monitors for pregnant patients?

Patients with pregestational diabetes may benefit from use of a continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion pump paired with a continuous glucose monitor. Use of the tools has been associated with a reduction in maternal and neonatal morbidity, a recent study found.

“We were seeing an unacceptable burden of both maternal and fetal disease in our diabetic population,” said Neil Hamill, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Methodist Women’s Hospital, Omaha, Neb., and an author of the study. “We thought the success with this technology in the nonpregnant population would and should translate into the pregnant population.”

Dr. Hamill and his colleagues analyzed data from 55 pregnant patients who received care at the Women’s Hospital Perinatal Center at the Nebraska Methodist Health System between October 2019 and October 2022. Everyone in the cohort had pregestational diabetes and required insulin prior to week 20 of pregnancy. They used CGMs for more than 2 weeks. The study set blood glucose levels of less than 140 mg/dL as a healthy benchmark.

Participants who had severe preeclampsia, who had delivered preterm, who had delivered a neonate with respiratory distress syndrome, and/or who had given birth to a larger-than-expected infant spent less time in the safe zone — having a blood glucose level below 140 mg/dL—than women who did not have those risk factors.

“When blood sugar control is better, maternal and fetal outcomes are improved,” Dr. Hamill said.

Neetu Sodhi, MD, an ob.gyn. at Providence Cedars-Sinai Tarzana Medical Center, Los Angeles, expressed optimism that use of blood glucose monitors and insulin pumps can improve outcomes for pregnant patients with pregestational diabetes.

“This is just another case for why it’s so important for patients to have access to these types of devices that really, really improve their outcomes and their health, and now it’s proven in the case of pregnancy outcomes too – or at least suggested strongly with this data,” Dr. Sodhi said.

Continue to: It may be time to pay attention to COVID again...

It may be time to pay attention to COVID again