User login

Histologic Correlation of Dermoscopy Findings in a Sebaceous Nevus

To the Editor:

Sebaceous nevus (SN) is a relatively common hamartoma that presents most often as a single congenital hairless plaque on the scalp. After puberty, histologic features characteristically include papillomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis, a large number of mature or nearly mature sebaceous glands, and a lack of terminally differentiated hair follicles; however, histologic findings can be misleading during childhood when sebaceous glands are still underdeveloped. Bright yellow dots, which are thought to indicate the presence of sebaceous glands, may be seen on dermoscopy and can be useful in differentiating SN from aplasia cutis congenita in newborns.

We report a case of an SN in an 18-year-old woman and discuss how the histology findings correlated with features seen on dermoscopy.

An 18-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic, hairless plaque on the right parietal scalp that had been present since birth. The patient noted that the plaque had recently become larger in size. On physical examination, an 8×3-cm plaque with a smooth, flesh-colored surface was noted with central comedolike structures and an erythematous, verrucous periphery (Figure 1).

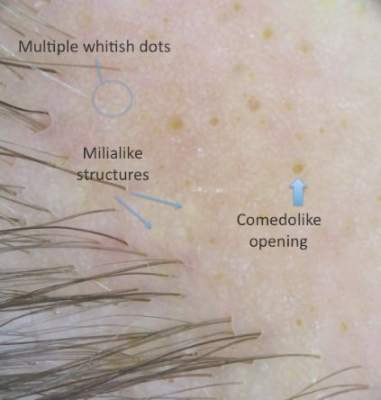

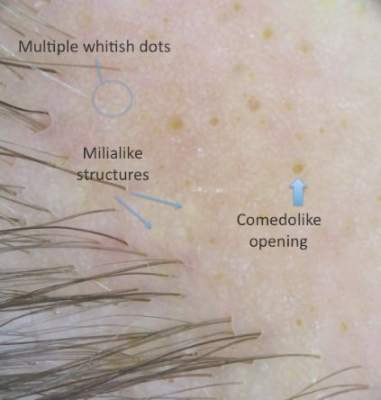

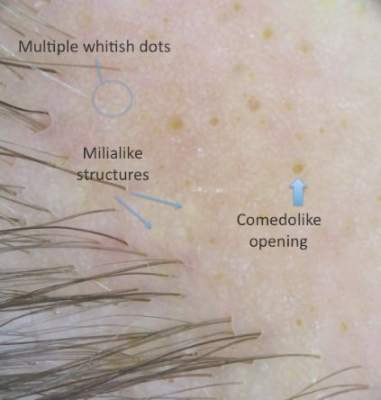

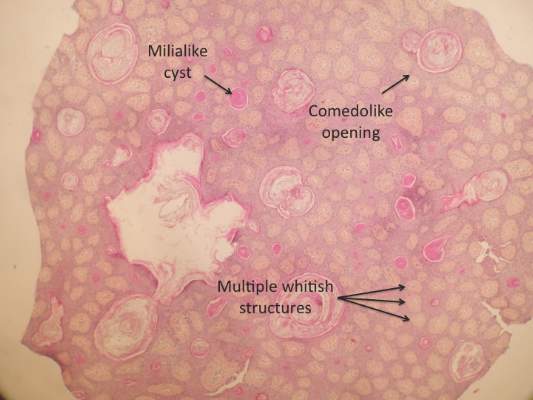

Dermoscopy (handheld dermoscope using polarized light) revealed 3 distinct types of round structures within the lesion: (1) comedolike openings (similar to those seen in seborrheic keratosis) that appeared as brownish-yellow, sharply circumscribed structures; (2) milialike cysts (also found in acanthotic seborrheic keratosis), which appeared as bright yellow structures; and (3) multiple whitish structures that were irregular in shape and size and covered the surface of the lesion where there were no other dermoscopic findings (Figure 2). The affected skin was pale to red in color and the verrucous aspect of the surface was better visualized at the edge of the lesion.

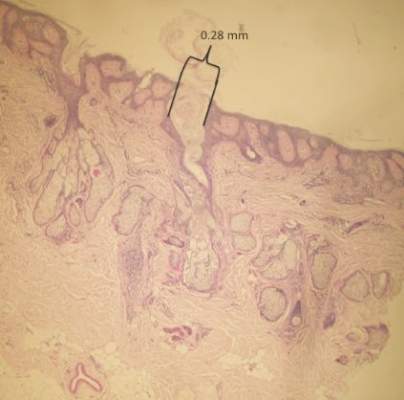

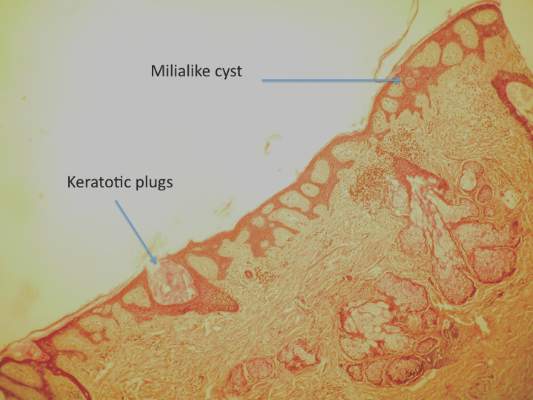

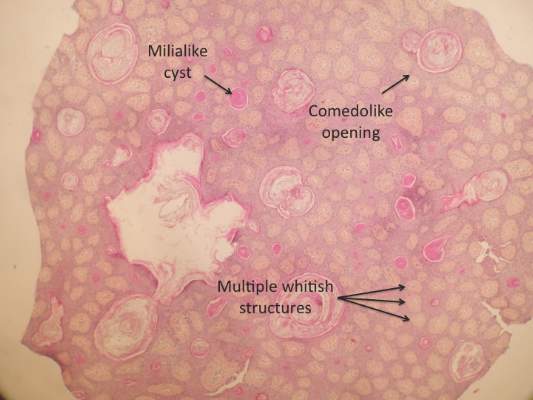

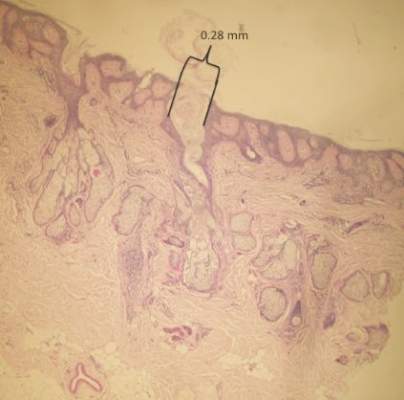

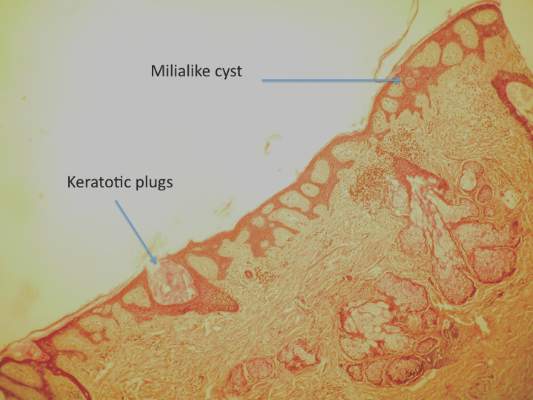

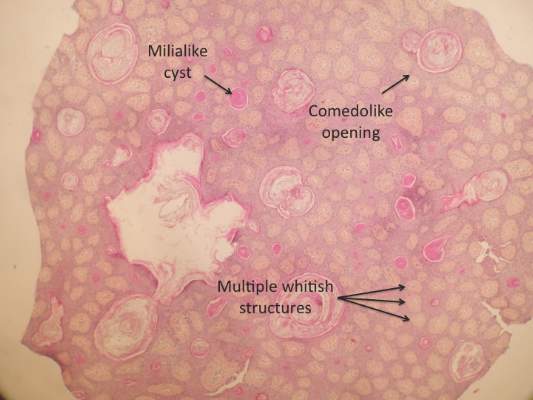

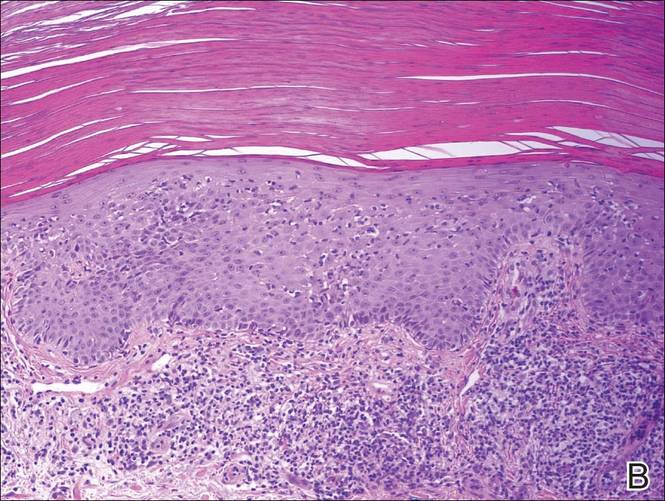

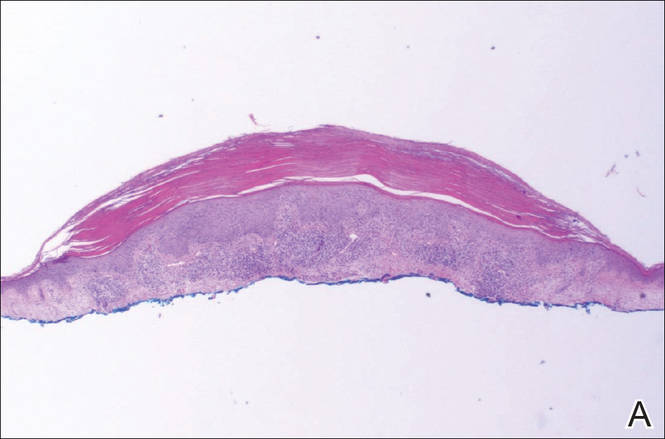

Two 4-mm punch biopsies were performed following dermoscopy: one for horizontal sectioning and one for vertical sectioning. Histologic analysis showed an acanthotic epidermis with an anastomosing network of elongated rete ridges in the superficial dermis. Numerous hyperplasic sebaceous glands were found in the mid dermis, with some also located above this level. Immature hair follicles were present and sebaceous gland ducts communicated directly with the epidermis through dilated hyperkeratinized pathways. Eccrine glands were normal, but no apocrine glands were present. A lymphocytic infiltrate was noted around the sebaceous glands and immature hair follicles and also around dilated capillaries in the superficial dermis. Moderate spongiosis and lymphocytic exocytosis were noted in the glandular epithelium and in the basal layer of the hair follicles and the epidermis. Superficial slides of horizontal sections of the biopsy specimen showed a correlation between the histology findings and dermoscopy images: multiple normal-appearing papilla surrounded by a network of anastomosing rete ridges correlated with multiple whitish structures, keratotic cysts with compact keratin corresponded to bright yellow dots, and larger conglomerates of loose lamelar keratin correlated with comedolike openings. Due to the presence of eczematous changes (eg, epithelial spongiosis, inflammatory cells) observed on histology, a diagnosis of an irritated sebaceous nevus was made, which explained the recent enlargement of the congenital lesion.

Sebaceous nevus is a benign, epidermal appendageal tumor with differentiation towards sebaceous glands that is composed of mature or nearly mature skin structures. Histologically, it is classified as a hamartoma.1 It commonly arises on the scalp as a yellowish or flesh-colored, hairless plaque of variable size. At birth, its surface is smooth and the differential diagnoses include aplasia cutis congenita, congenital triangular alopecia, and alopecia areata.2 As the patient ages, hormones stimulate the proliferation of sebaceous glands and the epidermis, and the lesion gradually acquires a verrucous, waxy surface.3 Benign appendageal tumors often develop inside SN. Basal cell epitheliomas are rarely found.4 Surgical excision is recommended for aesthetic purposes or to prevent the development of tumors.

Histology also varies with the patient’s age and can be misleading in childhood because the sebaceous glands are underdeveloped.5,6 After adrenarche, histology becomes more diagnostic, showing a dermis almost completely filled with sebaceous glands with varying degrees of maturity.2 The presence of incompletely differentiated follicles without hair shafts can be found in newborns and children and may be helpful for the correct histological diagnosis before puberty.1,5 The epidermis presents no abnormalities at birth but develops acanthosis and papillomatosis as the patient ages. Ectopic dilated apocrine glands sometimes can be found deeper in the dermis in the late stage of the lesion.5

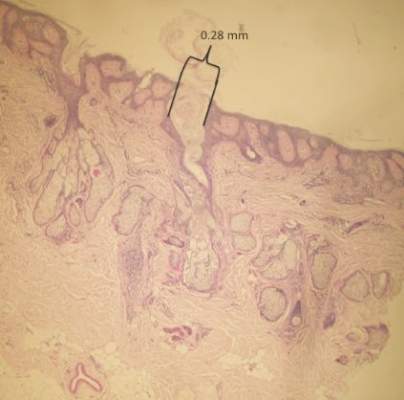

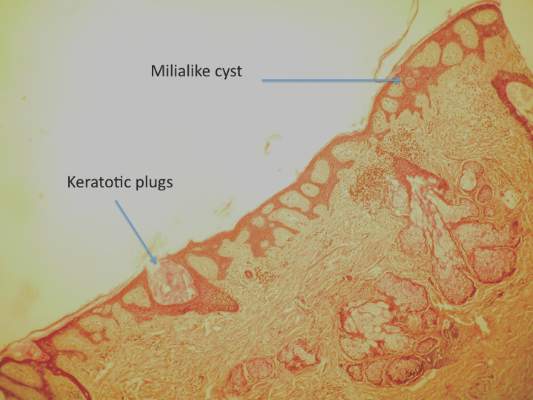

In a report by Neri et al,7 multiple bright yellow dots were noted on dermoscopy in 2 children with SN. The investigators concluded that this characteristic feature, which was thought to represent the sebaceous glands, can be useful in differentiating SN from aplasia cutis congenita in early infancy, but no histologic analyses were performed.7 In our patient, we identified 3 different dermoscopic features that correlated with histologic findings. Comedolike openings correlated with the accumulated keratin (ie, keratotic plugs) inside dilated sebaceous gland ducts directly connected to the epidermis. The brownish-yellow color of these openings observed on dermoscopy may be due to the oxidation of kerat-inous material, such as those in seborrheic keratosis lesions (Figure 3). We also noted bright yellow dots similar to those reported by Neri et al7; however, histologic analysis in our patient showed these dots more closely correlated with keratotic cysts similar to milialike structures seen in acanthotic seborrheic keratosis. The material remained lightly colored because no oxidation process had occurred (Figure 4). The third structure found on dermoscopy in our patient was multiple whitish structures that were irregular in shape and size. According to our comparison of superficial horizontal histology slides with dermoscopy images, we hypothesized this finding was the result of epidermal papillomatosis over a dermis filled with enlarged sebaceous glands (Figure 5). This finding was likely absent in the cases previously reported by Neri et al7 because epidermal and glandular changes occur later in the evolution of SN and the patients in these cases were younger than 4 months old.

Our correlation of dermoscopic features with histology findings in an 18-year-old woman with an irritated SN highlights the need for more studies needed in order to establish the prevalence of certain dermoscopic findings in this setting, particularly considering the important morphological changes that occur in these lesions as patients age as well as the histological variation among different hamartomas. Over the last decade, dermoscopy has proven to be a useful tool in the diagnosis of various hair and scalp diseases.8 Histologic correlation of dermoscopy findings is essential for more precise understanding of this new imaging technique and should be conducted whenever possible.

- Lever WF, Schaumburg-Lever G. Tumors of the epidermal appendages. In: Lever WF, Schaumburg-Lever G, eds. Histopathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Co; 1975:498-502.

- Civatte J. Tumeurs du cuir chevelu. In: Bouhanna P, Reygagne P, eds. Pathologie du Cheveu et du Cuir Cheveulu. Paris, France: Masson Co; 1999:208-209.

- Gruβendorf-Conen E-I. Adnexal cysts and tumors of the scalp. In: Orfanos CE, Happle R, eds. Hair and Hair Diseases. 1st ed. Berlin Germany: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg Co; 1990:710-711.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceous: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2 pt 1):263-268.

- Camacho F. Tumeurs du cuir chevelu. In: Camacho F, Montagna W, eds. Trichologie: Maladie du Follicule Pilosébacé. Madrid, Spain: Grupo Aula Medica; 1997:515-516.

- Wechsler J. Hamartome sebace. In: Wechsler J, Fraitag S, Moulonguet I, eds. Pathologie Cutanee Tumorale. Montpelier, France: Sauramps Medical Co; 2009:100-102.

- Neri I, Savoia F, Giacomini F, et al. Usefulness of dermatoscopy for the early diagnosis of sebaceous naevus and differentiation from aplasia cutis congenita [published online ahead of print May 5, 2009]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e50-e52.

- Miteva M, Tosti A. Hair and scalp dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1040-1048.

To the Editor:

Sebaceous nevus (SN) is a relatively common hamartoma that presents most often as a single congenital hairless plaque on the scalp. After puberty, histologic features characteristically include papillomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis, a large number of mature or nearly mature sebaceous glands, and a lack of terminally differentiated hair follicles; however, histologic findings can be misleading during childhood when sebaceous glands are still underdeveloped. Bright yellow dots, which are thought to indicate the presence of sebaceous glands, may be seen on dermoscopy and can be useful in differentiating SN from aplasia cutis congenita in newborns.

We report a case of an SN in an 18-year-old woman and discuss how the histology findings correlated with features seen on dermoscopy.

An 18-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic, hairless plaque on the right parietal scalp that had been present since birth. The patient noted that the plaque had recently become larger in size. On physical examination, an 8×3-cm plaque with a smooth, flesh-colored surface was noted with central comedolike structures and an erythematous, verrucous periphery (Figure 1).

Dermoscopy (handheld dermoscope using polarized light) revealed 3 distinct types of round structures within the lesion: (1) comedolike openings (similar to those seen in seborrheic keratosis) that appeared as brownish-yellow, sharply circumscribed structures; (2) milialike cysts (also found in acanthotic seborrheic keratosis), which appeared as bright yellow structures; and (3) multiple whitish structures that were irregular in shape and size and covered the surface of the lesion where there were no other dermoscopic findings (Figure 2). The affected skin was pale to red in color and the verrucous aspect of the surface was better visualized at the edge of the lesion.

Two 4-mm punch biopsies were performed following dermoscopy: one for horizontal sectioning and one for vertical sectioning. Histologic analysis showed an acanthotic epidermis with an anastomosing network of elongated rete ridges in the superficial dermis. Numerous hyperplasic sebaceous glands were found in the mid dermis, with some also located above this level. Immature hair follicles were present and sebaceous gland ducts communicated directly with the epidermis through dilated hyperkeratinized pathways. Eccrine glands were normal, but no apocrine glands were present. A lymphocytic infiltrate was noted around the sebaceous glands and immature hair follicles and also around dilated capillaries in the superficial dermis. Moderate spongiosis and lymphocytic exocytosis were noted in the glandular epithelium and in the basal layer of the hair follicles and the epidermis. Superficial slides of horizontal sections of the biopsy specimen showed a correlation between the histology findings and dermoscopy images: multiple normal-appearing papilla surrounded by a network of anastomosing rete ridges correlated with multiple whitish structures, keratotic cysts with compact keratin corresponded to bright yellow dots, and larger conglomerates of loose lamelar keratin correlated with comedolike openings. Due to the presence of eczematous changes (eg, epithelial spongiosis, inflammatory cells) observed on histology, a diagnosis of an irritated sebaceous nevus was made, which explained the recent enlargement of the congenital lesion.

Sebaceous nevus is a benign, epidermal appendageal tumor with differentiation towards sebaceous glands that is composed of mature or nearly mature skin structures. Histologically, it is classified as a hamartoma.1 It commonly arises on the scalp as a yellowish or flesh-colored, hairless plaque of variable size. At birth, its surface is smooth and the differential diagnoses include aplasia cutis congenita, congenital triangular alopecia, and alopecia areata.2 As the patient ages, hormones stimulate the proliferation of sebaceous glands and the epidermis, and the lesion gradually acquires a verrucous, waxy surface.3 Benign appendageal tumors often develop inside SN. Basal cell epitheliomas are rarely found.4 Surgical excision is recommended for aesthetic purposes or to prevent the development of tumors.

Histology also varies with the patient’s age and can be misleading in childhood because the sebaceous glands are underdeveloped.5,6 After adrenarche, histology becomes more diagnostic, showing a dermis almost completely filled with sebaceous glands with varying degrees of maturity.2 The presence of incompletely differentiated follicles without hair shafts can be found in newborns and children and may be helpful for the correct histological diagnosis before puberty.1,5 The epidermis presents no abnormalities at birth but develops acanthosis and papillomatosis as the patient ages. Ectopic dilated apocrine glands sometimes can be found deeper in the dermis in the late stage of the lesion.5

In a report by Neri et al,7 multiple bright yellow dots were noted on dermoscopy in 2 children with SN. The investigators concluded that this characteristic feature, which was thought to represent the sebaceous glands, can be useful in differentiating SN from aplasia cutis congenita in early infancy, but no histologic analyses were performed.7 In our patient, we identified 3 different dermoscopic features that correlated with histologic findings. Comedolike openings correlated with the accumulated keratin (ie, keratotic plugs) inside dilated sebaceous gland ducts directly connected to the epidermis. The brownish-yellow color of these openings observed on dermoscopy may be due to the oxidation of kerat-inous material, such as those in seborrheic keratosis lesions (Figure 3). We also noted bright yellow dots similar to those reported by Neri et al7; however, histologic analysis in our patient showed these dots more closely correlated with keratotic cysts similar to milialike structures seen in acanthotic seborrheic keratosis. The material remained lightly colored because no oxidation process had occurred (Figure 4). The third structure found on dermoscopy in our patient was multiple whitish structures that were irregular in shape and size. According to our comparison of superficial horizontal histology slides with dermoscopy images, we hypothesized this finding was the result of epidermal papillomatosis over a dermis filled with enlarged sebaceous glands (Figure 5). This finding was likely absent in the cases previously reported by Neri et al7 because epidermal and glandular changes occur later in the evolution of SN and the patients in these cases were younger than 4 months old.

Our correlation of dermoscopic features with histology findings in an 18-year-old woman with an irritated SN highlights the need for more studies needed in order to establish the prevalence of certain dermoscopic findings in this setting, particularly considering the important morphological changes that occur in these lesions as patients age as well as the histological variation among different hamartomas. Over the last decade, dermoscopy has proven to be a useful tool in the diagnosis of various hair and scalp diseases.8 Histologic correlation of dermoscopy findings is essential for more precise understanding of this new imaging technique and should be conducted whenever possible.

To the Editor:

Sebaceous nevus (SN) is a relatively common hamartoma that presents most often as a single congenital hairless plaque on the scalp. After puberty, histologic features characteristically include papillomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis, a large number of mature or nearly mature sebaceous glands, and a lack of terminally differentiated hair follicles; however, histologic findings can be misleading during childhood when sebaceous glands are still underdeveloped. Bright yellow dots, which are thought to indicate the presence of sebaceous glands, may be seen on dermoscopy and can be useful in differentiating SN from aplasia cutis congenita in newborns.

We report a case of an SN in an 18-year-old woman and discuss how the histology findings correlated with features seen on dermoscopy.

An 18-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic, hairless plaque on the right parietal scalp that had been present since birth. The patient noted that the plaque had recently become larger in size. On physical examination, an 8×3-cm plaque with a smooth, flesh-colored surface was noted with central comedolike structures and an erythematous, verrucous periphery (Figure 1).

Dermoscopy (handheld dermoscope using polarized light) revealed 3 distinct types of round structures within the lesion: (1) comedolike openings (similar to those seen in seborrheic keratosis) that appeared as brownish-yellow, sharply circumscribed structures; (2) milialike cysts (also found in acanthotic seborrheic keratosis), which appeared as bright yellow structures; and (3) multiple whitish structures that were irregular in shape and size and covered the surface of the lesion where there were no other dermoscopic findings (Figure 2). The affected skin was pale to red in color and the verrucous aspect of the surface was better visualized at the edge of the lesion.

Two 4-mm punch biopsies were performed following dermoscopy: one for horizontal sectioning and one for vertical sectioning. Histologic analysis showed an acanthotic epidermis with an anastomosing network of elongated rete ridges in the superficial dermis. Numerous hyperplasic sebaceous glands were found in the mid dermis, with some also located above this level. Immature hair follicles were present and sebaceous gland ducts communicated directly with the epidermis through dilated hyperkeratinized pathways. Eccrine glands were normal, but no apocrine glands were present. A lymphocytic infiltrate was noted around the sebaceous glands and immature hair follicles and also around dilated capillaries in the superficial dermis. Moderate spongiosis and lymphocytic exocytosis were noted in the glandular epithelium and in the basal layer of the hair follicles and the epidermis. Superficial slides of horizontal sections of the biopsy specimen showed a correlation between the histology findings and dermoscopy images: multiple normal-appearing papilla surrounded by a network of anastomosing rete ridges correlated with multiple whitish structures, keratotic cysts with compact keratin corresponded to bright yellow dots, and larger conglomerates of loose lamelar keratin correlated with comedolike openings. Due to the presence of eczematous changes (eg, epithelial spongiosis, inflammatory cells) observed on histology, a diagnosis of an irritated sebaceous nevus was made, which explained the recent enlargement of the congenital lesion.

Sebaceous nevus is a benign, epidermal appendageal tumor with differentiation towards sebaceous glands that is composed of mature or nearly mature skin structures. Histologically, it is classified as a hamartoma.1 It commonly arises on the scalp as a yellowish or flesh-colored, hairless plaque of variable size. At birth, its surface is smooth and the differential diagnoses include aplasia cutis congenita, congenital triangular alopecia, and alopecia areata.2 As the patient ages, hormones stimulate the proliferation of sebaceous glands and the epidermis, and the lesion gradually acquires a verrucous, waxy surface.3 Benign appendageal tumors often develop inside SN. Basal cell epitheliomas are rarely found.4 Surgical excision is recommended for aesthetic purposes or to prevent the development of tumors.

Histology also varies with the patient’s age and can be misleading in childhood because the sebaceous glands are underdeveloped.5,6 After adrenarche, histology becomes more diagnostic, showing a dermis almost completely filled with sebaceous glands with varying degrees of maturity.2 The presence of incompletely differentiated follicles without hair shafts can be found in newborns and children and may be helpful for the correct histological diagnosis before puberty.1,5 The epidermis presents no abnormalities at birth but develops acanthosis and papillomatosis as the patient ages. Ectopic dilated apocrine glands sometimes can be found deeper in the dermis in the late stage of the lesion.5

In a report by Neri et al,7 multiple bright yellow dots were noted on dermoscopy in 2 children with SN. The investigators concluded that this characteristic feature, which was thought to represent the sebaceous glands, can be useful in differentiating SN from aplasia cutis congenita in early infancy, but no histologic analyses were performed.7 In our patient, we identified 3 different dermoscopic features that correlated with histologic findings. Comedolike openings correlated with the accumulated keratin (ie, keratotic plugs) inside dilated sebaceous gland ducts directly connected to the epidermis. The brownish-yellow color of these openings observed on dermoscopy may be due to the oxidation of kerat-inous material, such as those in seborrheic keratosis lesions (Figure 3). We also noted bright yellow dots similar to those reported by Neri et al7; however, histologic analysis in our patient showed these dots more closely correlated with keratotic cysts similar to milialike structures seen in acanthotic seborrheic keratosis. The material remained lightly colored because no oxidation process had occurred (Figure 4). The third structure found on dermoscopy in our patient was multiple whitish structures that were irregular in shape and size. According to our comparison of superficial horizontal histology slides with dermoscopy images, we hypothesized this finding was the result of epidermal papillomatosis over a dermis filled with enlarged sebaceous glands (Figure 5). This finding was likely absent in the cases previously reported by Neri et al7 because epidermal and glandular changes occur later in the evolution of SN and the patients in these cases were younger than 4 months old.

Our correlation of dermoscopic features with histology findings in an 18-year-old woman with an irritated SN highlights the need for more studies needed in order to establish the prevalence of certain dermoscopic findings in this setting, particularly considering the important morphological changes that occur in these lesions as patients age as well as the histological variation among different hamartomas. Over the last decade, dermoscopy has proven to be a useful tool in the diagnosis of various hair and scalp diseases.8 Histologic correlation of dermoscopy findings is essential for more precise understanding of this new imaging technique and should be conducted whenever possible.

- Lever WF, Schaumburg-Lever G. Tumors of the epidermal appendages. In: Lever WF, Schaumburg-Lever G, eds. Histopathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Co; 1975:498-502.

- Civatte J. Tumeurs du cuir chevelu. In: Bouhanna P, Reygagne P, eds. Pathologie du Cheveu et du Cuir Cheveulu. Paris, France: Masson Co; 1999:208-209.

- Gruβendorf-Conen E-I. Adnexal cysts and tumors of the scalp. In: Orfanos CE, Happle R, eds. Hair and Hair Diseases. 1st ed. Berlin Germany: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg Co; 1990:710-711.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceous: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2 pt 1):263-268.

- Camacho F. Tumeurs du cuir chevelu. In: Camacho F, Montagna W, eds. Trichologie: Maladie du Follicule Pilosébacé. Madrid, Spain: Grupo Aula Medica; 1997:515-516.

- Wechsler J. Hamartome sebace. In: Wechsler J, Fraitag S, Moulonguet I, eds. Pathologie Cutanee Tumorale. Montpelier, France: Sauramps Medical Co; 2009:100-102.

- Neri I, Savoia F, Giacomini F, et al. Usefulness of dermatoscopy for the early diagnosis of sebaceous naevus and differentiation from aplasia cutis congenita [published online ahead of print May 5, 2009]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e50-e52.

- Miteva M, Tosti A. Hair and scalp dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1040-1048.

- Lever WF, Schaumburg-Lever G. Tumors of the epidermal appendages. In: Lever WF, Schaumburg-Lever G, eds. Histopathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Co; 1975:498-502.

- Civatte J. Tumeurs du cuir chevelu. In: Bouhanna P, Reygagne P, eds. Pathologie du Cheveu et du Cuir Cheveulu. Paris, France: Masson Co; 1999:208-209.

- Gruβendorf-Conen E-I. Adnexal cysts and tumors of the scalp. In: Orfanos CE, Happle R, eds. Hair and Hair Diseases. 1st ed. Berlin Germany: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg Co; 1990:710-711.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceous: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2 pt 1):263-268.

- Camacho F. Tumeurs du cuir chevelu. In: Camacho F, Montagna W, eds. Trichologie: Maladie du Follicule Pilosébacé. Madrid, Spain: Grupo Aula Medica; 1997:515-516.

- Wechsler J. Hamartome sebace. In: Wechsler J, Fraitag S, Moulonguet I, eds. Pathologie Cutanee Tumorale. Montpelier, France: Sauramps Medical Co; 2009:100-102.

- Neri I, Savoia F, Giacomini F, et al. Usefulness of dermatoscopy for the early diagnosis of sebaceous naevus and differentiation from aplasia cutis congenita [published online ahead of print May 5, 2009]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e50-e52.

- Miteva M, Tosti A. Hair and scalp dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1040-1048.

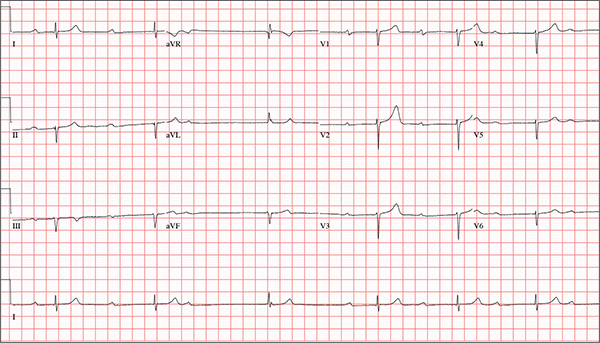

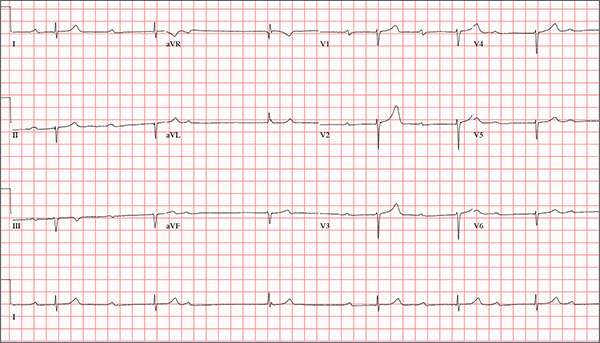

Cardiovascular risk assessment required with use of TKIs for CML

Treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) entails effective but mostly noncurative long-term use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) that require proactive, rational approaches to minimizing cardiovascular toxicities, according to a recent review.

Survival rates of patients with newly diagnosed CML are about 90%, and in those with a complete cytogenetic response, survival is comparable to that of age-matched controls. Although second-generation TKIs have increased efficacy, survival rates are similar to those of imatinib, possibly due in part to mortality from non-CML causes.

TKIs used in CML therapy target BCR-ABL1, but their potencies vary against other kinases, including receptors for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF). The relationship between off-target activities and adverse events (AEs) remains unclear, and AE management is largely empirical, said Dr. Javid Moslehi of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and Dr. Michael Deininger, professor at the University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City.

“Reports of cardiovascular AEs with nilotinib, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) on dasatinib, and frequent cardiovascular AEs with ponatinib have caused a reassessment of the situation,” they noted.

“Given the high population frequency of cardiovascular disease and the increased frequency of vascular events with nilotinib and ponatinib, cardiovascular risk assessment and, if necessary, treatment need to be integrated into the management of patients with CML on TKIs,” they wrote (J Clin Onc. 2015 Dec 10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.4718).

Retrospective studies have indicated that imatinib may have favorable metabolic and vascular effects, but prospective controlled trials are lacking. Defining the cardiovascular baseline risk of the specific CML population under study will be crucial in future studies.

Dasatinib was approved for front-line CML treatment based on superior cytogenic response rates, compared with imatinib, but in 2011 the Food and Drug Administration warned against cardiopulmonary risks and recommended that patients be evaluated for signs and symptoms of cardiopulmonary disease before and during dasatinib treatment. Results of DASISION (Dasatinib Versus Imatinib Study in Treatment-Naive CML Patients) showed that, at 36 months of follow-up, PAH was reported in 3% of patients on dasatinib and 0% on imatinib.

Nilotinib has shown superior efficacy to imatinib and was FDA approved for first-line therapy, with recommendations for arrhythmia monitoring and avoidance of QT interval–prolonging medications. There have been no subsequent reports of ventricular arrhythmias with nilotinib, but 36% of patients on nilotinib experienced hyperglycemia in the ENESTnd (Evaluating Nilotinib Efficacy and Safety in Clinical Trials–Newly Diagnosed Patients) study, compared with 20% on imatinib. Nilotinib also has been associated with hyperlipidemia and increased body mass. Recent results point to vascular toxicity with nilotinib. At the 6-year follow-up of the ENESTnd study, 10% of patients on nilotinib 300 mg twice per day and 16% on nilotinib 400 mg twice per day had cardiovascular events, compared with 2.5% of patients taking imatinib 400 mg once per day. The dose-dependent increased risk implicates a drug-dependent process.

Ponatinib is the only clinical TKI active against the BCR-ABL1T315I mutation. It is a potent inhibitor of numerous other kinases as well, including VEGF receptors. In the PACE (Ponatinib Ph-positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and CML Evaluation) study, 26% of patients on ponatinib developed hypertension, and traditional atherosclerosis risk factors (age, hypertension, and diabetes) predisposed patients to serious vascular AEs. Cardiovascular toxicity was shown to be dose dependent, and older patients with history of diabetes or ischemic events are the least tolerant of high dose intensity. A subset of patients will benefit from ponatinib, particularly those with BCR-ABL1T315I, but leukemia-related and cardiovascular risks must both be assessed.

Dr. Moslehi reported financial ties with Novartis, ARIAD, Takeda/Millennium, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Acceleron Pharma. Dr. Deininger reported ties to Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Incyte, ARIAD, Pfizer, and Cellgene.

Treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) entails effective but mostly noncurative long-term use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) that require proactive, rational approaches to minimizing cardiovascular toxicities, according to a recent review.

Survival rates of patients with newly diagnosed CML are about 90%, and in those with a complete cytogenetic response, survival is comparable to that of age-matched controls. Although second-generation TKIs have increased efficacy, survival rates are similar to those of imatinib, possibly due in part to mortality from non-CML causes.

TKIs used in CML therapy target BCR-ABL1, but their potencies vary against other kinases, including receptors for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF). The relationship between off-target activities and adverse events (AEs) remains unclear, and AE management is largely empirical, said Dr. Javid Moslehi of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and Dr. Michael Deininger, professor at the University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City.

“Reports of cardiovascular AEs with nilotinib, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) on dasatinib, and frequent cardiovascular AEs with ponatinib have caused a reassessment of the situation,” they noted.

“Given the high population frequency of cardiovascular disease and the increased frequency of vascular events with nilotinib and ponatinib, cardiovascular risk assessment and, if necessary, treatment need to be integrated into the management of patients with CML on TKIs,” they wrote (J Clin Onc. 2015 Dec 10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.4718).

Retrospective studies have indicated that imatinib may have favorable metabolic and vascular effects, but prospective controlled trials are lacking. Defining the cardiovascular baseline risk of the specific CML population under study will be crucial in future studies.

Dasatinib was approved for front-line CML treatment based on superior cytogenic response rates, compared with imatinib, but in 2011 the Food and Drug Administration warned against cardiopulmonary risks and recommended that patients be evaluated for signs and symptoms of cardiopulmonary disease before and during dasatinib treatment. Results of DASISION (Dasatinib Versus Imatinib Study in Treatment-Naive CML Patients) showed that, at 36 months of follow-up, PAH was reported in 3% of patients on dasatinib and 0% on imatinib.

Nilotinib has shown superior efficacy to imatinib and was FDA approved for first-line therapy, with recommendations for arrhythmia monitoring and avoidance of QT interval–prolonging medications. There have been no subsequent reports of ventricular arrhythmias with nilotinib, but 36% of patients on nilotinib experienced hyperglycemia in the ENESTnd (Evaluating Nilotinib Efficacy and Safety in Clinical Trials–Newly Diagnosed Patients) study, compared with 20% on imatinib. Nilotinib also has been associated with hyperlipidemia and increased body mass. Recent results point to vascular toxicity with nilotinib. At the 6-year follow-up of the ENESTnd study, 10% of patients on nilotinib 300 mg twice per day and 16% on nilotinib 400 mg twice per day had cardiovascular events, compared with 2.5% of patients taking imatinib 400 mg once per day. The dose-dependent increased risk implicates a drug-dependent process.

Ponatinib is the only clinical TKI active against the BCR-ABL1T315I mutation. It is a potent inhibitor of numerous other kinases as well, including VEGF receptors. In the PACE (Ponatinib Ph-positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and CML Evaluation) study, 26% of patients on ponatinib developed hypertension, and traditional atherosclerosis risk factors (age, hypertension, and diabetes) predisposed patients to serious vascular AEs. Cardiovascular toxicity was shown to be dose dependent, and older patients with history of diabetes or ischemic events are the least tolerant of high dose intensity. A subset of patients will benefit from ponatinib, particularly those with BCR-ABL1T315I, but leukemia-related and cardiovascular risks must both be assessed.

Dr. Moslehi reported financial ties with Novartis, ARIAD, Takeda/Millennium, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Acceleron Pharma. Dr. Deininger reported ties to Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Incyte, ARIAD, Pfizer, and Cellgene.

Treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) entails effective but mostly noncurative long-term use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) that require proactive, rational approaches to minimizing cardiovascular toxicities, according to a recent review.

Survival rates of patients with newly diagnosed CML are about 90%, and in those with a complete cytogenetic response, survival is comparable to that of age-matched controls. Although second-generation TKIs have increased efficacy, survival rates are similar to those of imatinib, possibly due in part to mortality from non-CML causes.

TKIs used in CML therapy target BCR-ABL1, but their potencies vary against other kinases, including receptors for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF). The relationship between off-target activities and adverse events (AEs) remains unclear, and AE management is largely empirical, said Dr. Javid Moslehi of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and Dr. Michael Deininger, professor at the University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City.

“Reports of cardiovascular AEs with nilotinib, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) on dasatinib, and frequent cardiovascular AEs with ponatinib have caused a reassessment of the situation,” they noted.

“Given the high population frequency of cardiovascular disease and the increased frequency of vascular events with nilotinib and ponatinib, cardiovascular risk assessment and, if necessary, treatment need to be integrated into the management of patients with CML on TKIs,” they wrote (J Clin Onc. 2015 Dec 10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.4718).

Retrospective studies have indicated that imatinib may have favorable metabolic and vascular effects, but prospective controlled trials are lacking. Defining the cardiovascular baseline risk of the specific CML population under study will be crucial in future studies.

Dasatinib was approved for front-line CML treatment based on superior cytogenic response rates, compared with imatinib, but in 2011 the Food and Drug Administration warned against cardiopulmonary risks and recommended that patients be evaluated for signs and symptoms of cardiopulmonary disease before and during dasatinib treatment. Results of DASISION (Dasatinib Versus Imatinib Study in Treatment-Naive CML Patients) showed that, at 36 months of follow-up, PAH was reported in 3% of patients on dasatinib and 0% on imatinib.

Nilotinib has shown superior efficacy to imatinib and was FDA approved for first-line therapy, with recommendations for arrhythmia monitoring and avoidance of QT interval–prolonging medications. There have been no subsequent reports of ventricular arrhythmias with nilotinib, but 36% of patients on nilotinib experienced hyperglycemia in the ENESTnd (Evaluating Nilotinib Efficacy and Safety in Clinical Trials–Newly Diagnosed Patients) study, compared with 20% on imatinib. Nilotinib also has been associated with hyperlipidemia and increased body mass. Recent results point to vascular toxicity with nilotinib. At the 6-year follow-up of the ENESTnd study, 10% of patients on nilotinib 300 mg twice per day and 16% on nilotinib 400 mg twice per day had cardiovascular events, compared with 2.5% of patients taking imatinib 400 mg once per day. The dose-dependent increased risk implicates a drug-dependent process.

Ponatinib is the only clinical TKI active against the BCR-ABL1T315I mutation. It is a potent inhibitor of numerous other kinases as well, including VEGF receptors. In the PACE (Ponatinib Ph-positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and CML Evaluation) study, 26% of patients on ponatinib developed hypertension, and traditional atherosclerosis risk factors (age, hypertension, and diabetes) predisposed patients to serious vascular AEs. Cardiovascular toxicity was shown to be dose dependent, and older patients with history of diabetes or ischemic events are the least tolerant of high dose intensity. A subset of patients will benefit from ponatinib, particularly those with BCR-ABL1T315I, but leukemia-related and cardiovascular risks must both be assessed.

Dr. Moslehi reported financial ties with Novartis, ARIAD, Takeda/Millennium, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Acceleron Pharma. Dr. Deininger reported ties to Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Incyte, ARIAD, Pfizer, and Cellgene.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Most patients with chronic myeloid leukemia require long-term tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy, and cardiovascular effects are critical factors in treatment decisions.

Major finding: Second- and third-generation TKIs have been associated with more cardiovascular risk than first-generation imatinib.

Data source: Review of current literature on cardiovascular toxicity of BCR-ABL1 TKIs for treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia.

Disclosures: Dr. Moslehi reported financial ties with Novartis, ARIAD, Takeda/Millennium, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Acceleron Pharma. Dr. Deininger reported ties to Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Incyte, ARIAD, Pfizer, and Cellgene.

Erythematous Scaly Papules on the Shins and Calves

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans

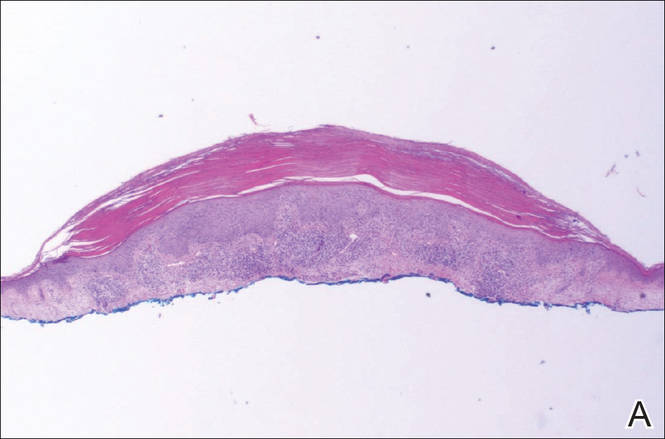

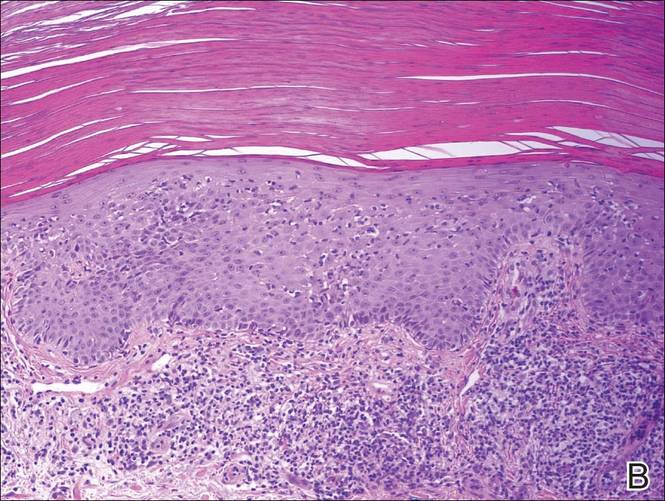

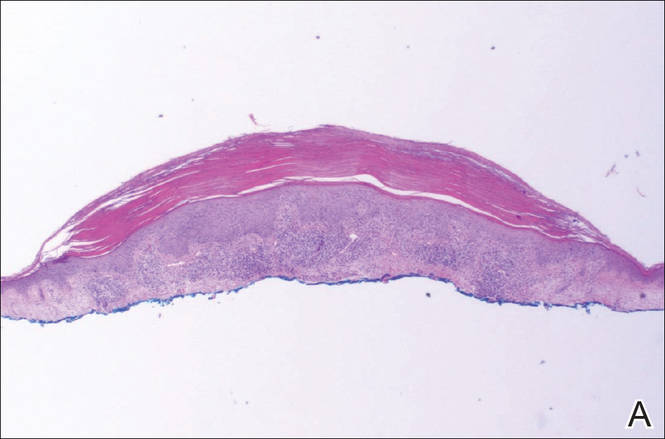

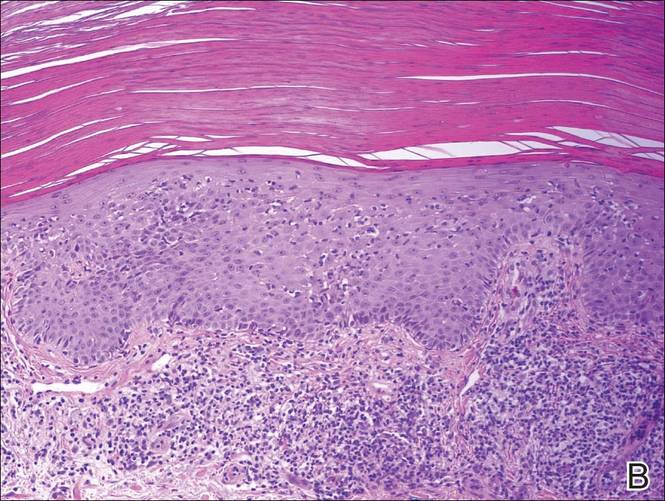

A shave biopsy of a lesion on the right leg was performed. Histopathology revealed a discrete papule with overlying compact hyperkeratosis. There was parakeratosis with an absent granular layer and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate within the papillary dermis (Figure). Given the clinical context, these changes were consistent with a diagnosis of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), also known as Flegel disease.

The patient was started on tretinoin cream 0.1% nightly for 3 months and triamcinolone ointment 0.1% as needed for pruritus but showed no clinical response. Given the benign nature of the condition and because the lesions were asymptomatic, additional treatment options were not pursued.

Originally described by Flegel1 in 1958, HLP is a rare skin disorder commonly seen in white individuals with onset in the fourth or fifth decades of life.1,2 While most cases are sporadic,3-6 HLP also has been associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.7-10

Patients with HLP typically present with multiple 1- to 5-mm reddish-brown, hyperkeratotic, scaly papules that reveal a moist, erythematous base with pinpoint bleeding upon removal of the scale. Lesions usually are distributed symmetrically and most commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and dorsal feet.1,2,7 Lesions also may appear on the extensor surfaces of the arms, pinna, periocular region, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and oral mucosa and also may present as pits on the palms and soles.2,4,7,8 Furthermore, unilateral and localized variants of HLP have been described.11,12 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans usually is asymptomatic but can present with mild pruritus or burning.3,5,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of HLP are unknown. Exposure to UV light has been implicated as an inciting factor14; however, reports of spontaneous resolution in the summer13 and upon treatment with psoralen plus UVA therapy15 make the role of UV light unclear. Furthermore, investigators disagree as to whether the primary pathogenic event in HLP is an inflammatory process or one of abnormal keratinization.1,3,7,10 Fernandez-Flores and Manjon16 suggested HLP is an inflammatory process with periods of exacerbations and remissions after finding mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils arranged in different strata in the stratum corneum.

Histologically, compact hyperkeratosis usually is noted, often with associated parakeratosis, epidermal atrophy with thinning or absence of the granular layer, and a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.1-3 Histopathologic differences between recent-onset versus longstanding lesions have been found, with old lesions lacking an inflammatory infiltrate.3 Furthermore, new lesions often show abnormalities in quantity and/or morphology of membrane-coating granules, also known as Odland bodies, in keratinocytes on electron microscopy,3,10,17 while old lesions do not.3 Odland bodies are involved in normal desquamation, leading some to speculate on their role in HLP.10 Currently, it is unclear whether abnormalities in these organelles cause the retention hyperkeratosis seen in HLP or if such abnormalities are a secondary phenomenon.3,17

There are questionable associations between HLP and diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperthyroidism, basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, and gastrointestinal malignancy.4,9,18 Our patient had a history of basal cell carcinoma on the face, diet-controlled diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism. Given the high prevalence of these diseases in the general population, however, it is difficult to ascertain whether a true association with HLP exists.

While HLP can slowly progress to involve additional body sites, it is overall a benign condition that does not require treatment. Therapeutic options are based on case reports, with no single treatment showing a consistent response. From review of the literature, therapies that have been most effective include dermabrasion, excision,19 topical 5-fluorouracil,2,17,20 and oral retinoids.8 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans generally is resistant to topical steroids, retinoids, and vitamin D3 analogs, although success with betamethasone dipropionate,5 isotretinoin

gel 0.05%,11 and calcipotriol have been reported.6 A case of HLP with clinical response to psoralen plus UVA therapy also has been described.15

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Pearson LH, Smith JG, Chalker DK. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:190-195.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodríguez-Rey E, Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, or Flegel disease, with palmoplantar involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:157-159.

- Sterneberg-Vos H, van Marion AM, Frank J, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease)—successful treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:38-41.

- Bayramgürler D, Apaydin R, Dökmeci S, et al. Flegel’s disease: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:161-162.

- Price ML, Jones EW, MacDonald DM. A clinicopathological study of Flegel’s disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans). Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:681-691.

- Krishnan A, Kar S. Photoletter to the editor: hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. response to isotretinoin therapy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:93-95.

- Beveridge GW, Langlands AO. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans associated with tumours of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:453-458.

- Frenk E, Tapernoux B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel): a biological model for keratinization occurring in the absence of Odland bodies? Dermatologica. 1976;153:253-262.

- Miranda-Romero A, Sánchez Sambucety P, Bajo del Pozo C, et al. Unilateral hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:655-657.

- Gutiérrez MC, Hasson A, Arias MD, et al. Localized hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Cutis. 1991;48:201-204.

- Fathy S, Azadeh B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:120-121.

- Rosdahl I, Rosen K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans: report on two cases. Acta Derm Venerol. 1985;65:562-564.

- Cooper SM, George S. Flegel's disease treated with psoralen ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:340-342.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Manjon JA. Morphological evidence of periodical exacerbation of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:16-19.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Ishibashi A, Tsuboi R, Fujita K. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. associated with cancers of the digestive organs. J Dermatol. 1984;11:407-409.

- Cunha Filho RR, Almeida Jr HL. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S76-S77.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)—lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans

A shave biopsy of a lesion on the right leg was performed. Histopathology revealed a discrete papule with overlying compact hyperkeratosis. There was parakeratosis with an absent granular layer and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate within the papillary dermis (Figure). Given the clinical context, these changes were consistent with a diagnosis of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), also known as Flegel disease.

The patient was started on tretinoin cream 0.1% nightly for 3 months and triamcinolone ointment 0.1% as needed for pruritus but showed no clinical response. Given the benign nature of the condition and because the lesions were asymptomatic, additional treatment options were not pursued.

Originally described by Flegel1 in 1958, HLP is a rare skin disorder commonly seen in white individuals with onset in the fourth or fifth decades of life.1,2 While most cases are sporadic,3-6 HLP also has been associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.7-10

Patients with HLP typically present with multiple 1- to 5-mm reddish-brown, hyperkeratotic, scaly papules that reveal a moist, erythematous base with pinpoint bleeding upon removal of the scale. Lesions usually are distributed symmetrically and most commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and dorsal feet.1,2,7 Lesions also may appear on the extensor surfaces of the arms, pinna, periocular region, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and oral mucosa and also may present as pits on the palms and soles.2,4,7,8 Furthermore, unilateral and localized variants of HLP have been described.11,12 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans usually is asymptomatic but can present with mild pruritus or burning.3,5,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of HLP are unknown. Exposure to UV light has been implicated as an inciting factor14; however, reports of spontaneous resolution in the summer13 and upon treatment with psoralen plus UVA therapy15 make the role of UV light unclear. Furthermore, investigators disagree as to whether the primary pathogenic event in HLP is an inflammatory process or one of abnormal keratinization.1,3,7,10 Fernandez-Flores and Manjon16 suggested HLP is an inflammatory process with periods of exacerbations and remissions after finding mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils arranged in different strata in the stratum corneum.

Histologically, compact hyperkeratosis usually is noted, often with associated parakeratosis, epidermal atrophy with thinning or absence of the granular layer, and a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.1-3 Histopathologic differences between recent-onset versus longstanding lesions have been found, with old lesions lacking an inflammatory infiltrate.3 Furthermore, new lesions often show abnormalities in quantity and/or morphology of membrane-coating granules, also known as Odland bodies, in keratinocytes on electron microscopy,3,10,17 while old lesions do not.3 Odland bodies are involved in normal desquamation, leading some to speculate on their role in HLP.10 Currently, it is unclear whether abnormalities in these organelles cause the retention hyperkeratosis seen in HLP or if such abnormalities are a secondary phenomenon.3,17

There are questionable associations between HLP and diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperthyroidism, basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, and gastrointestinal malignancy.4,9,18 Our patient had a history of basal cell carcinoma on the face, diet-controlled diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism. Given the high prevalence of these diseases in the general population, however, it is difficult to ascertain whether a true association with HLP exists.

While HLP can slowly progress to involve additional body sites, it is overall a benign condition that does not require treatment. Therapeutic options are based on case reports, with no single treatment showing a consistent response. From review of the literature, therapies that have been most effective include dermabrasion, excision,19 topical 5-fluorouracil,2,17,20 and oral retinoids.8 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans generally is resistant to topical steroids, retinoids, and vitamin D3 analogs, although success with betamethasone dipropionate,5 isotretinoin

gel 0.05%,11 and calcipotriol have been reported.6 A case of HLP with clinical response to psoralen plus UVA therapy also has been described.15

The Diagnosis: Hyperkeratosis Lenticularis Perstans

A shave biopsy of a lesion on the right leg was performed. Histopathology revealed a discrete papule with overlying compact hyperkeratosis. There was parakeratosis with an absent granular layer and a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate within the papillary dermis (Figure). Given the clinical context, these changes were consistent with a diagnosis of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (HLP), also known as Flegel disease.

The patient was started on tretinoin cream 0.1% nightly for 3 months and triamcinolone ointment 0.1% as needed for pruritus but showed no clinical response. Given the benign nature of the condition and because the lesions were asymptomatic, additional treatment options were not pursued.

Originally described by Flegel1 in 1958, HLP is a rare skin disorder commonly seen in white individuals with onset in the fourth or fifth decades of life.1,2 While most cases are sporadic,3-6 HLP also has been associated with autosomal dominant inheritance.7-10

Patients with HLP typically present with multiple 1- to 5-mm reddish-brown, hyperkeratotic, scaly papules that reveal a moist, erythematous base with pinpoint bleeding upon removal of the scale. Lesions usually are distributed symmetrically and most commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the lower legs and dorsal feet.1,2,7 Lesions also may appear on the extensor surfaces of the arms, pinna, periocular region, antecubital and popliteal fossae, and oral mucosa and also may present as pits on the palms and soles.2,4,7,8 Furthermore, unilateral and localized variants of HLP have been described.11,12 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans usually is asymptomatic but can present with mild pruritus or burning.3,5,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of HLP are unknown. Exposure to UV light has been implicated as an inciting factor14; however, reports of spontaneous resolution in the summer13 and upon treatment with psoralen plus UVA therapy15 make the role of UV light unclear. Furthermore, investigators disagree as to whether the primary pathogenic event in HLP is an inflammatory process or one of abnormal keratinization.1,3,7,10 Fernandez-Flores and Manjon16 suggested HLP is an inflammatory process with periods of exacerbations and remissions after finding mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils arranged in different strata in the stratum corneum.

Histologically, compact hyperkeratosis usually is noted, often with associated parakeratosis, epidermal atrophy with thinning or absence of the granular layer, and a bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis.1-3 Histopathologic differences between recent-onset versus longstanding lesions have been found, with old lesions lacking an inflammatory infiltrate.3 Furthermore, new lesions often show abnormalities in quantity and/or morphology of membrane-coating granules, also known as Odland bodies, in keratinocytes on electron microscopy,3,10,17 while old lesions do not.3 Odland bodies are involved in normal desquamation, leading some to speculate on their role in HLP.10 Currently, it is unclear whether abnormalities in these organelles cause the retention hyperkeratosis seen in HLP or if such abnormalities are a secondary phenomenon.3,17

There are questionable associations between HLP and diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperthyroidism, basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, and gastrointestinal malignancy.4,9,18 Our patient had a history of basal cell carcinoma on the face, diet-controlled diabetes mellitus, and hypothyroidism. Given the high prevalence of these diseases in the general population, however, it is difficult to ascertain whether a true association with HLP exists.

While HLP can slowly progress to involve additional body sites, it is overall a benign condition that does not require treatment. Therapeutic options are based on case reports, with no single treatment showing a consistent response. From review of the literature, therapies that have been most effective include dermabrasion, excision,19 topical 5-fluorouracil,2,17,20 and oral retinoids.8 Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans generally is resistant to topical steroids, retinoids, and vitamin D3 analogs, although success with betamethasone dipropionate,5 isotretinoin

gel 0.05%,11 and calcipotriol have been reported.6 A case of HLP with clinical response to psoralen plus UVA therapy also has been described.15

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Pearson LH, Smith JG, Chalker DK. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:190-195.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodríguez-Rey E, Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, or Flegel disease, with palmoplantar involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:157-159.

- Sterneberg-Vos H, van Marion AM, Frank J, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease)—successful treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:38-41.

- Bayramgürler D, Apaydin R, Dökmeci S, et al. Flegel’s disease: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:161-162.

- Price ML, Jones EW, MacDonald DM. A clinicopathological study of Flegel’s disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans). Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:681-691.

- Krishnan A, Kar S. Photoletter to the editor: hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. response to isotretinoin therapy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:93-95.

- Beveridge GW, Langlands AO. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans associated with tumours of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:453-458.

- Frenk E, Tapernoux B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel): a biological model for keratinization occurring in the absence of Odland bodies? Dermatologica. 1976;153:253-262.

- Miranda-Romero A, Sánchez Sambucety P, Bajo del Pozo C, et al. Unilateral hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:655-657.

- Gutiérrez MC, Hasson A, Arias MD, et al. Localized hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Cutis. 1991;48:201-204.

- Fathy S, Azadeh B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:120-121.

- Rosdahl I, Rosen K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans: report on two cases. Acta Derm Venerol. 1985;65:562-564.

- Cooper SM, George S. Flegel's disease treated with psoralen ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:340-342.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Manjon JA. Morphological evidence of periodical exacerbation of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:16-19.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Ishibashi A, Tsuboi R, Fujita K. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. associated with cancers of the digestive organs. J Dermatol. 1984;11:407-409.

- Cunha Filho RR, Almeida Jr HL. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S76-S77.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)—lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

- Flegel H. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Hautarzt. 1958;9:363-364.

- Pearson LH, Smith JG, Chalker DK. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:190-195.

- Ando K, Hattori H, Yamauchi Y. Histopathological differences between early and old lesions of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:122-126.

- Fernández-Crehuet P, Rodríguez-Rey E, Ríos-Martín JJ, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans, or Flegel disease, with palmoplantar involvement. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:157-159.

- Sterneberg-Vos H, van Marion AM, Frank J, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease)—successful treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:38-41.

- Bayramgürler D, Apaydin R, Dökmeci S, et al. Flegel’s disease: treatment with topical calcipotriol. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:161-162.

- Price ML, Jones EW, MacDonald DM. A clinicopathological study of Flegel’s disease (hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans). Br J Dermatol. 1987;116:681-691.

- Krishnan A, Kar S. Photoletter to the editor: hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) with unusual clinical presentation. response to isotretinoin therapy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:93-95.

- Beveridge GW, Langlands AO. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans associated with tumours of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1973;88:453-458.

- Frenk E, Tapernoux B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel): a biological model for keratinization occurring in the absence of Odland bodies? Dermatologica. 1976;153:253-262.

- Miranda-Romero A, Sánchez Sambucety P, Bajo del Pozo C, et al. Unilateral hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:655-657.

- Gutiérrez MC, Hasson A, Arias MD, et al. Localized hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). Cutis. 1991;48:201-204.

- Fathy S, Azadeh B. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:120-121.

- Rosdahl I, Rosen K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans: report on two cases. Acta Derm Venerol. 1985;65:562-564.

- Cooper SM, George S. Flegel's disease treated with psoralen ultraviolet A. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:340-342.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Manjon JA. Morphological evidence of periodical exacerbation of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2009;17:16-19.

- Langer K, Zonzits E, Konrad K. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease). ultrastructural study of lesional and perilesional skin and therapeutic trial of topical tretinoin versus 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:812-816.

- Ishibashi A, Tsuboi R, Fujita K. Familial hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. associated with cancers of the digestive organs. J Dermatol. 1984;11:407-409.

- Cunha Filho RR, Almeida Jr HL. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S76-S77.

- Blaheta HJ, Metzler G, Rassner G, et al. Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel's disease)—lack of response to treatment with tacalcitol and calcipotriol. Dermatology. 2001;202:255-258.

Drug disappoints in phase 3 HSCT trial

The antiviral drug brincidofovir did not meet the primary endpoint of the phase 3 SUPPRESS trial, according to the drug’s developer, Chimerix.

Brincidofovir did not prevent clinically significant cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection through week 24 after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

However, the president and CEO of Chimerix said the company still believes there is a “viable path forward” for the drug.

Brincidofovir is an oral nucleotide analog that has shown in vitro antiviral activity against all 5 families of DNA viruses that affect humans, including herpes viruses and adenovirus.

The SUPPRESS trial, which was initiated in August 2013 and fully enrolled in June 2015, was informed by a successful phase 2 trial conducted in HSCT recipients.

The SUPPRESS trial enrolled and treated 452 adults who received allogeneic HSCTs from more than 40 transplant centers in the US, Canada, and Europe.

Subjects received twice-weekly brincidofovir or placebo (2:1 ratio) from the early post-transplant period through week 14 post-transplant, the period of highest risk for viral infections.

All patients in the trial were CMV-seropositive, placing them at high risk of CMV infection. The most common indications leading to HSCT were acute myelogenous leukemia (43% of patients), myelodysplasia (17%), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (10%), and acute lymphocytic leukemia (9%).

During the on-treatment period through week 14 after HSCT, fewer patients in the brincidofovir arm had a CMV infection, which was consistent with results from the phase 2 study of the drug.

However, during the 10 weeks off treatment from week 14 to week 24, there was an increase in CMV infections in the brincidofovir arm compared to the control arm. And there was a non-statistically significant increase in mortality in the brincidofovir arm compared to the control arm.

Preliminary analysis suggests the failure in preventing CMV infections and the increased mortality in the brincidofovir arm were driven by confirmed cases of graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD), which resulted in a significantly higher use of corticosteroids than in the control arm.

Both GVHD and the use of corticosteroids are risk factors for “late” CMV infection that occurs after the discontinuation of the antiviral in HSCT recipients.

The rate of study drug discontinuation for gastrointestinal events was less than 10% in this study, which is comparable to that observed in the phase 2 trial of brincidofovir in a similar HSCT population.

“While we are clearly disappointed in the top-line results from SUPPRESS, we remain committed to better understanding the full data set as we consider potential paths forward for brincidofovir,” said M. Michelle Berrey, MD, president and CEO of Chimerix.

“We will be evaluating the subgroups of patients within SUPPRESS, such as T-cell-depleted transplant recipients who have a lower risk of GVHD, to better understand these results and inform our next steps,” said W. Garrett Nichols, MD, Chimerix’s chief medical officer.

“We are reaching out to investigators and other experts to help us assess the complete data set to understand what may have caused the results of the SUPPRESS trial to differ substantially from those seen in the phase 2 study. Additionally, we are in communication with the US Food and Drug Administration and other regulatory bodies and will share any updates on the brincidofovir clinical program when we can.”

“With data currently in hand, we believe that brincidofovir may ultimately demonstrate a positive risk-benefit profile for the treatment of adenovirus and smallpox, as well as use in other populations in need of a novel compound for DNA viral infections.”

Chimerix plans to continue the programs testing brincidofovir in serious adenovirus infections and in smallpox. Pending the availability of complete data from SUPPRESS, including secondary endpoints in other dsDNA viral infections, Chimerix has elected to pause further enrollment in the phase 3 SUSTAIN and SURPASS trials in kidney transplant recipients.

A full analysis of the SUPPRESS trial results is ongoing. The data are scheduled to be presented at the BMT Tandem Meetings in Honolulu, Hawaii, in February. ![]()

The antiviral drug brincidofovir did not meet the primary endpoint of the phase 3 SUPPRESS trial, according to the drug’s developer, Chimerix.

Brincidofovir did not prevent clinically significant cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection through week 24 after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

However, the president and CEO of Chimerix said the company still believes there is a “viable path forward” for the drug.

Brincidofovir is an oral nucleotide analog that has shown in vitro antiviral activity against all 5 families of DNA viruses that affect humans, including herpes viruses and adenovirus.

The SUPPRESS trial, which was initiated in August 2013 and fully enrolled in June 2015, was informed by a successful phase 2 trial conducted in HSCT recipients.

The SUPPRESS trial enrolled and treated 452 adults who received allogeneic HSCTs from more than 40 transplant centers in the US, Canada, and Europe.

Subjects received twice-weekly brincidofovir or placebo (2:1 ratio) from the early post-transplant period through week 14 post-transplant, the period of highest risk for viral infections.

All patients in the trial were CMV-seropositive, placing them at high risk of CMV infection. The most common indications leading to HSCT were acute myelogenous leukemia (43% of patients), myelodysplasia (17%), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (10%), and acute lymphocytic leukemia (9%).

During the on-treatment period through week 14 after HSCT, fewer patients in the brincidofovir arm had a CMV infection, which was consistent with results from the phase 2 study of the drug.

However, during the 10 weeks off treatment from week 14 to week 24, there was an increase in CMV infections in the brincidofovir arm compared to the control arm. And there was a non-statistically significant increase in mortality in the brincidofovir arm compared to the control arm.

Preliminary analysis suggests the failure in preventing CMV infections and the increased mortality in the brincidofovir arm were driven by confirmed cases of graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD), which resulted in a significantly higher use of corticosteroids than in the control arm.

Both GVHD and the use of corticosteroids are risk factors for “late” CMV infection that occurs after the discontinuation of the antiviral in HSCT recipients.

The rate of study drug discontinuation for gastrointestinal events was less than 10% in this study, which is comparable to that observed in the phase 2 trial of brincidofovir in a similar HSCT population.

“While we are clearly disappointed in the top-line results from SUPPRESS, we remain committed to better understanding the full data set as we consider potential paths forward for brincidofovir,” said M. Michelle Berrey, MD, president and CEO of Chimerix.

“We will be evaluating the subgroups of patients within SUPPRESS, such as T-cell-depleted transplant recipients who have a lower risk of GVHD, to better understand these results and inform our next steps,” said W. Garrett Nichols, MD, Chimerix’s chief medical officer.

“We are reaching out to investigators and other experts to help us assess the complete data set to understand what may have caused the results of the SUPPRESS trial to differ substantially from those seen in the phase 2 study. Additionally, we are in communication with the US Food and Drug Administration and other regulatory bodies and will share any updates on the brincidofovir clinical program when we can.”

“With data currently in hand, we believe that brincidofovir may ultimately demonstrate a positive risk-benefit profile for the treatment of adenovirus and smallpox, as well as use in other populations in need of a novel compound for DNA viral infections.”

Chimerix plans to continue the programs testing brincidofovir in serious adenovirus infections and in smallpox. Pending the availability of complete data from SUPPRESS, including secondary endpoints in other dsDNA viral infections, Chimerix has elected to pause further enrollment in the phase 3 SUSTAIN and SURPASS trials in kidney transplant recipients.

A full analysis of the SUPPRESS trial results is ongoing. The data are scheduled to be presented at the BMT Tandem Meetings in Honolulu, Hawaii, in February. ![]()

The antiviral drug brincidofovir did not meet the primary endpoint of the phase 3 SUPPRESS trial, according to the drug’s developer, Chimerix.

Brincidofovir did not prevent clinically significant cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection through week 24 after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

However, the president and CEO of Chimerix said the company still believes there is a “viable path forward” for the drug.

Brincidofovir is an oral nucleotide analog that has shown in vitro antiviral activity against all 5 families of DNA viruses that affect humans, including herpes viruses and adenovirus.

The SUPPRESS trial, which was initiated in August 2013 and fully enrolled in June 2015, was informed by a successful phase 2 trial conducted in HSCT recipients.

The SUPPRESS trial enrolled and treated 452 adults who received allogeneic HSCTs from more than 40 transplant centers in the US, Canada, and Europe.

Subjects received twice-weekly brincidofovir or placebo (2:1 ratio) from the early post-transplant period through week 14 post-transplant, the period of highest risk for viral infections.

All patients in the trial were CMV-seropositive, placing them at high risk of CMV infection. The most common indications leading to HSCT were acute myelogenous leukemia (43% of patients), myelodysplasia (17%), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (10%), and acute lymphocytic leukemia (9%).

During the on-treatment period through week 14 after HSCT, fewer patients in the brincidofovir arm had a CMV infection, which was consistent with results from the phase 2 study of the drug.

However, during the 10 weeks off treatment from week 14 to week 24, there was an increase in CMV infections in the brincidofovir arm compared to the control arm. And there was a non-statistically significant increase in mortality in the brincidofovir arm compared to the control arm.

Preliminary analysis suggests the failure in preventing CMV infections and the increased mortality in the brincidofovir arm were driven by confirmed cases of graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD), which resulted in a significantly higher use of corticosteroids than in the control arm.

Both GVHD and the use of corticosteroids are risk factors for “late” CMV infection that occurs after the discontinuation of the antiviral in HSCT recipients.

The rate of study drug discontinuation for gastrointestinal events was less than 10% in this study, which is comparable to that observed in the phase 2 trial of brincidofovir in a similar HSCT population.

“While we are clearly disappointed in the top-line results from SUPPRESS, we remain committed to better understanding the full data set as we consider potential paths forward for brincidofovir,” said M. Michelle Berrey, MD, president and CEO of Chimerix.

“We will be evaluating the subgroups of patients within SUPPRESS, such as T-cell-depleted transplant recipients who have a lower risk of GVHD, to better understand these results and inform our next steps,” said W. Garrett Nichols, MD, Chimerix’s chief medical officer.

“We are reaching out to investigators and other experts to help us assess the complete data set to understand what may have caused the results of the SUPPRESS trial to differ substantially from those seen in the phase 2 study. Additionally, we are in communication with the US Food and Drug Administration and other regulatory bodies and will share any updates on the brincidofovir clinical program when we can.”

“With data currently in hand, we believe that brincidofovir may ultimately demonstrate a positive risk-benefit profile for the treatment of adenovirus and smallpox, as well as use in other populations in need of a novel compound for DNA viral infections.”

Chimerix plans to continue the programs testing brincidofovir in serious adenovirus infections and in smallpox. Pending the availability of complete data from SUPPRESS, including secondary endpoints in other dsDNA viral infections, Chimerix has elected to pause further enrollment in the phase 3 SUSTAIN and SURPASS trials in kidney transplant recipients.

A full analysis of the SUPPRESS trial results is ongoing. The data are scheduled to be presented at the BMT Tandem Meetings in Honolulu, Hawaii, in February. ![]()

Study reveals germline variants in AML, other cancers

A study published in Nature Communications has shed light on the hereditary elements of 12 cancer types.

Investigators looked for rare germline mutations in genes known to be associated with cancer and found the frequency of these mutations varied widely, from 4% in the acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cases studied to 19% in cases of ovarian cancer.

The team’s analysis also revealed an unexpected inherited component to stomach cancer and provided some clarity on the consequences of certain mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes.

Li Ding, PhD, of Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, Missouri, and her colleagues conducted this study, analyzing genetic information from more than 4000 cancer cases included in The Cancer Genome Atlas project.

“In general, we have known that ovarian and breast cancers have a significant inherited component, and others, such as acute myeloid leukemia and lung cancer, have a much smaller inherited genetic contribution,” Dr Ding said. “But this is the first time, on a large scale, that we’ve been able to pinpoint gene culprits or even the actual mutations responsible for cancer susceptibility.”

To help tease out cancer’s inherited components, Dr Ding and her colleagues looked for germline truncations in 114 genes known to be associated with cancer.

“We looked for germline mutations in the tumor, but it was not enough for the mutations simply to be present,” Dr Ding said. “They needed to be enriched in the tumor—present at higher frequency. If a mutation is present in the germline and amplified in the tumor, there is a high likelihood it is playing a role in the cancer.”

The investigators found germline truncations in all 12 cancer types analyzed, but the mutations occurred in varying frequencies depending on the cancer.

The percentage of tumors with truncations in the germline was 4% for AML and glioblastoma; 5% for kidney cancer; 7% for lung adenocarcinoma and endometrial cancer; 8% for head and neck cancer, glioma, lung squamous cell carcinoma, and prostate cancer; 9% for breast cancer; 11% for stomach cancer; and 19% for ovarian cancer.

“We also found a significant number of germline truncations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes present in tumor types other than breast cancer, including stomach and prostate cancers, for example,” Dr Ding said. “This suggests we should pay attention to the potential involvement of these 2 genes in other cancer types.”

The investigators said they identified 13 cancer genes with significant enrichment of rare truncations. Some of these were associated with specific cancers—for example, RAD51C in AML, PALB2 in stomach cancer, and MSH6 in endometrial cancer.

And the team observed significant, tumor-specific loss of heterozygosity in 9 genes—ATM, BAP1, BRCA1/2, BRIP1, FANCM, PALB2, and RAD51C/D.

Dr Ding said more research is needed to confirm these results before they can be used to advise patients making healthcare decisions.