User login

Small Hospitals Concerned about Readmissions Avoidance

Small, rural, and community-based hospitals face many of the same concerns about readmissions as large ones. James Baumgartner, MD, chief hospitalist at Essentia Health-St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Brainerd, Minn., population 13,517, was asked if he sees the readmissions issue playing out differently in rural settings.

“I don’t think so, and I’ve practiced in bigger cities,” he says. “For the past two years, we’ve had a team-based approach here, with a multidisciplinary committee meeting monthly to work on making transitions of care better.”

The recent adoption of joint rounding by hospitalists and nurses also makes a difference, he says. To ensure that patients can get post-discharge medical appointments when they need them, Dr. Baumgartner’s group approached local PCPs within the same health system.

“They responded by reserving at least one open slot at the start of every day for seeing our recently discharged patients,” he says.

Kristi Howell, RN, director of quality initiatives at Richland Memorial Hospital, a 65-bed acute care facility in Olney, Ill., population 8,631, says the trend in smaller and rural hospitals is moving toward more personalized patient care and the use of one-on-one transitional care coordinators.

“We have the advantage of being closer to our patients and providing a more personalized discharge plan than may be possible at a larger facility,” she says. Nevertheless, Howell and her colleagues are “deeply concerned about readmissions.”

“Physicians in this area experience difficulty with readmissions due to our rural patients’ lack of access to larger facilities and medical specialties,” she says. “Noncompliance is another problem, mostly due to lack of health literacy and financial resources. Of course, it is well known that the shortage of primary care doctors is a contributor to poorer health outcomes for rural residents.”

Randy Ferrance, DC, MD, FAAP, SFHM, medical director of the hospitalist service at 47-bed Riverside Tappahannock Hospital in Tappahannock, Va., population 2,393, says he’s “tried all sorts of things, with little impact on readmissions,” although his five-member groups’ readmission rate is “actually low compared with the national average.”

“We make appointments for the first week after discharge,” he says. “We’re small enough that we can call the PCP. We know them. We all belong to the same medical group.”

Dr. Ferrance covers shifts in the ED on occasion. He says some patients in the community prefer to get their medical care at the ED. “And in the ED, if they don’t look well, they get admitted,” he says.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

Small, rural, and community-based hospitals face many of the same concerns about readmissions as large ones. James Baumgartner, MD, chief hospitalist at Essentia Health-St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Brainerd, Minn., population 13,517, was asked if he sees the readmissions issue playing out differently in rural settings.

“I don’t think so, and I’ve practiced in bigger cities,” he says. “For the past two years, we’ve had a team-based approach here, with a multidisciplinary committee meeting monthly to work on making transitions of care better.”

The recent adoption of joint rounding by hospitalists and nurses also makes a difference, he says. To ensure that patients can get post-discharge medical appointments when they need them, Dr. Baumgartner’s group approached local PCPs within the same health system.

“They responded by reserving at least one open slot at the start of every day for seeing our recently discharged patients,” he says.

Kristi Howell, RN, director of quality initiatives at Richland Memorial Hospital, a 65-bed acute care facility in Olney, Ill., population 8,631, says the trend in smaller and rural hospitals is moving toward more personalized patient care and the use of one-on-one transitional care coordinators.

“We have the advantage of being closer to our patients and providing a more personalized discharge plan than may be possible at a larger facility,” she says. Nevertheless, Howell and her colleagues are “deeply concerned about readmissions.”

“Physicians in this area experience difficulty with readmissions due to our rural patients’ lack of access to larger facilities and medical specialties,” she says. “Noncompliance is another problem, mostly due to lack of health literacy and financial resources. Of course, it is well known that the shortage of primary care doctors is a contributor to poorer health outcomes for rural residents.”

Randy Ferrance, DC, MD, FAAP, SFHM, medical director of the hospitalist service at 47-bed Riverside Tappahannock Hospital in Tappahannock, Va., population 2,393, says he’s “tried all sorts of things, with little impact on readmissions,” although his five-member groups’ readmission rate is “actually low compared with the national average.”

“We make appointments for the first week after discharge,” he says. “We’re small enough that we can call the PCP. We know them. We all belong to the same medical group.”

Dr. Ferrance covers shifts in the ED on occasion. He says some patients in the community prefer to get their medical care at the ED. “And in the ED, if they don’t look well, they get admitted,” he says.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

Small, rural, and community-based hospitals face many of the same concerns about readmissions as large ones. James Baumgartner, MD, chief hospitalist at Essentia Health-St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Brainerd, Minn., population 13,517, was asked if he sees the readmissions issue playing out differently in rural settings.

“I don’t think so, and I’ve practiced in bigger cities,” he says. “For the past two years, we’ve had a team-based approach here, with a multidisciplinary committee meeting monthly to work on making transitions of care better.”

The recent adoption of joint rounding by hospitalists and nurses also makes a difference, he says. To ensure that patients can get post-discharge medical appointments when they need them, Dr. Baumgartner’s group approached local PCPs within the same health system.

“They responded by reserving at least one open slot at the start of every day for seeing our recently discharged patients,” he says.

Kristi Howell, RN, director of quality initiatives at Richland Memorial Hospital, a 65-bed acute care facility in Olney, Ill., population 8,631, says the trend in smaller and rural hospitals is moving toward more personalized patient care and the use of one-on-one transitional care coordinators.

“We have the advantage of being closer to our patients and providing a more personalized discharge plan than may be possible at a larger facility,” she says. Nevertheless, Howell and her colleagues are “deeply concerned about readmissions.”

“Physicians in this area experience difficulty with readmissions due to our rural patients’ lack of access to larger facilities and medical specialties,” she says. “Noncompliance is another problem, mostly due to lack of health literacy and financial resources. Of course, it is well known that the shortage of primary care doctors is a contributor to poorer health outcomes for rural residents.”

Randy Ferrance, DC, MD, FAAP, SFHM, medical director of the hospitalist service at 47-bed Riverside Tappahannock Hospital in Tappahannock, Va., population 2,393, says he’s “tried all sorts of things, with little impact on readmissions,” although his five-member groups’ readmission rate is “actually low compared with the national average.”

“We make appointments for the first week after discharge,” he says. “We’re small enough that we can call the PCP. We know them. We all belong to the same medical group.”

Dr. Ferrance covers shifts in the ED on occasion. He says some patients in the community prefer to get their medical care at the ED. “And in the ED, if they don’t look well, they get admitted,” he says.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Alameda, Calif.

Plan Now for Society of Hospital Medicine's HM16

Are colleagues and co-workers who are coming back from HM15 with renewed enthusiasm for the hospital medicine movement making you jealous? Now is the time to start planning for next year. Mark your calendars and start coordinating schedules today for HM16. Registration is now open. For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/events.

Are colleagues and co-workers who are coming back from HM15 with renewed enthusiasm for the hospital medicine movement making you jealous? Now is the time to start planning for next year. Mark your calendars and start coordinating schedules today for HM16. Registration is now open. For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/events.

Are colleagues and co-workers who are coming back from HM15 with renewed enthusiasm for the hospital medicine movement making you jealous? Now is the time to start planning for next year. Mark your calendars and start coordinating schedules today for HM16. Registration is now open. For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/events.

Hospitalists Encouraged to Complete HM15 Survey

Hospitalists are what make SHM’s annual meeting great. Feedback from hospitalists about what worked well and what SHM can do differently are an important part of making each meeting better than the next.

SHM has e-mailed a brief survey to all hospitalists, whether they attended HM15 or not, to ask how to make the next HM16 the most valuable conference for hospitalists possible. Please check your e-mail and fill out the survey. If you have not received the survey but would like to submit your feedback, please let us know at [email protected].

Hospitalists are what make SHM’s annual meeting great. Feedback from hospitalists about what worked well and what SHM can do differently are an important part of making each meeting better than the next.

SHM has e-mailed a brief survey to all hospitalists, whether they attended HM15 or not, to ask how to make the next HM16 the most valuable conference for hospitalists possible. Please check your e-mail and fill out the survey. If you have not received the survey but would like to submit your feedback, please let us know at [email protected].

Hospitalists are what make SHM’s annual meeting great. Feedback from hospitalists about what worked well and what SHM can do differently are an important part of making each meeting better than the next.

SHM has e-mailed a brief survey to all hospitalists, whether they attended HM15 or not, to ask how to make the next HM16 the most valuable conference for hospitalists possible. Please check your e-mail and fill out the survey. If you have not received the survey but would like to submit your feedback, please let us know at [email protected].

Society of Hospital Medicine Posts Content on Tumblr-Powered Website

Are you ready to meet and greet the next great generation of hospitalists? Or do you work with medical students and residents interested in becoming hospitalists?

For hospitalists and physicians in training in cities across the country, new events hosted by SHM will introduce medical students and residents to available opportunities. And for others, SHM is now providing content on the Tumblr-powered new website.

Are you ready to meet and greet the next great generation of hospitalists? Or do you work with medical students and residents interested in becoming hospitalists?

For hospitalists and physicians in training in cities across the country, new events hosted by SHM will introduce medical students and residents to available opportunities. And for others, SHM is now providing content on the Tumblr-powered new website.

Are you ready to meet and greet the next great generation of hospitalists? Or do you work with medical students and residents interested in becoming hospitalists?

For hospitalists and physicians in training in cities across the country, new events hosted by SHM will introduce medical students and residents to available opportunities. And for others, SHM is now providing content on the Tumblr-powered new website.

Educational Opportunities for Hospitalists in 2015

For hospitalists, learning doesn’t stop when SHM’s annual meeting ends. Instead, it’s a year-round endeavor to stay ahead of the trends in clinical practice, practice management, and quality improvement. That’s why SHM provides educational opportunities throughout the year:

Leadership Academy 2015

October 19-22

Austin, Texas

Want to show your boss you’re serious about career advancement and improving your hospital medicine group? SHM’s Leadership Academy helps hospitalists of all stripes become the leaders that today’s hospitals need. From management training to financial storytelling and creating culture change, Leadership Academy covers all of the topics that hospitalists need to work in a high-performance environment.

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership.

Also in October, SHM will be offering two other popular conferences: the Academic Hospitalist Academy and the Nurse Practitioner/Physician Assistant Boot Camp. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/events for details.

SHM’s Learning Portal

Stay up to speed on the latest CME modules from your own desk or living room using SHM’s Learning Portal. The portal now presents “Consultative & Perioperative Medicine Essentials for Hospitalists” from SHMConsults, including:

- SHMConsults Prerequisite Evaluation;

- Early Identification and Management of Severe Sepsis;

- Pulmonary Risk Management in the Perioperative Setting; and

- The Role of the Medical Consultant.

The Learning Portal also features online CME programs for education about anticoagulants:

- Management of Target Specific Oral Anticoagulants (TSOACs) in the Inpatient and Perioperative Setting;

- The Inpatient Management of Anticoagulation for Patients with Atrial Fibrillation;

- Anticoagulation for VTE & Management of VTE (a two-part module);

- Reversal of New Oral Anticoagulants;

- Establishing Inpatient Programs to Improve Anticoagulation Management; and

- Periprocedural Management of Anticoagulants.

For hospitalists, learning doesn’t stop when SHM’s annual meeting ends. Instead, it’s a year-round endeavor to stay ahead of the trends in clinical practice, practice management, and quality improvement. That’s why SHM provides educational opportunities throughout the year:

Leadership Academy 2015

October 19-22

Austin, Texas

Want to show your boss you’re serious about career advancement and improving your hospital medicine group? SHM’s Leadership Academy helps hospitalists of all stripes become the leaders that today’s hospitals need. From management training to financial storytelling and creating culture change, Leadership Academy covers all of the topics that hospitalists need to work in a high-performance environment.

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership.

Also in October, SHM will be offering two other popular conferences: the Academic Hospitalist Academy and the Nurse Practitioner/Physician Assistant Boot Camp. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/events for details.

SHM’s Learning Portal

Stay up to speed on the latest CME modules from your own desk or living room using SHM’s Learning Portal. The portal now presents “Consultative & Perioperative Medicine Essentials for Hospitalists” from SHMConsults, including:

- SHMConsults Prerequisite Evaluation;

- Early Identification and Management of Severe Sepsis;

- Pulmonary Risk Management in the Perioperative Setting; and

- The Role of the Medical Consultant.

The Learning Portal also features online CME programs for education about anticoagulants:

- Management of Target Specific Oral Anticoagulants (TSOACs) in the Inpatient and Perioperative Setting;

- The Inpatient Management of Anticoagulation for Patients with Atrial Fibrillation;

- Anticoagulation for VTE & Management of VTE (a two-part module);

- Reversal of New Oral Anticoagulants;

- Establishing Inpatient Programs to Improve Anticoagulation Management; and

- Periprocedural Management of Anticoagulants.

For hospitalists, learning doesn’t stop when SHM’s annual meeting ends. Instead, it’s a year-round endeavor to stay ahead of the trends in clinical practice, practice management, and quality improvement. That’s why SHM provides educational opportunities throughout the year:

Leadership Academy 2015

October 19-22

Austin, Texas

Want to show your boss you’re serious about career advancement and improving your hospital medicine group? SHM’s Leadership Academy helps hospitalists of all stripes become the leaders that today’s hospitals need. From management training to financial storytelling and creating culture change, Leadership Academy covers all of the topics that hospitalists need to work in a high-performance environment.

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership.

Also in October, SHM will be offering two other popular conferences: the Academic Hospitalist Academy and the Nurse Practitioner/Physician Assistant Boot Camp. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/events for details.

SHM’s Learning Portal

Stay up to speed on the latest CME modules from your own desk or living room using SHM’s Learning Portal. The portal now presents “Consultative & Perioperative Medicine Essentials for Hospitalists” from SHMConsults, including:

- SHMConsults Prerequisite Evaluation;

- Early Identification and Management of Severe Sepsis;

- Pulmonary Risk Management in the Perioperative Setting; and

- The Role of the Medical Consultant.

The Learning Portal also features online CME programs for education about anticoagulants:

- Management of Target Specific Oral Anticoagulants (TSOACs) in the Inpatient and Perioperative Setting;

- The Inpatient Management of Anticoagulation for Patients with Atrial Fibrillation;

- Anticoagulation for VTE & Management of VTE (a two-part module);

- Reversal of New Oral Anticoagulants;

- Establishing Inpatient Programs to Improve Anticoagulation Management; and

- Periprocedural Management of Anticoagulants.

Project BOOST Can Bring Quality Improvement to Your Hospital

Every hospital wants to bring health to its community, and hospitalists can play a major role in bringing that value to patients—both during and after their hospital stays. From handoffs to managing diabetic patients to many of the other issues hospitalists tackle on a daily basis, SHM provides resources and access to the experts—all from its website.

Project BOOST now accepts applications year-round for the program and will be presenting a free webinar on April 15 to present Project BOOST’s new program offerings.

To register for the webinar, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost.

Every hospital wants to bring health to its community, and hospitalists can play a major role in bringing that value to patients—both during and after their hospital stays. From handoffs to managing diabetic patients to many of the other issues hospitalists tackle on a daily basis, SHM provides resources and access to the experts—all from its website.

Project BOOST now accepts applications year-round for the program and will be presenting a free webinar on April 15 to present Project BOOST’s new program offerings.

To register for the webinar, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost.

Every hospital wants to bring health to its community, and hospitalists can play a major role in bringing that value to patients—both during and after their hospital stays. From handoffs to managing diabetic patients to many of the other issues hospitalists tackle on a daily basis, SHM provides resources and access to the experts—all from its website.

Project BOOST now accepts applications year-round for the program and will be presenting a free webinar on April 15 to present Project BOOST’s new program offerings.

To register for the webinar, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost.

Society of Hospital Medicine New Merchandise Available

Want to showcase your new FHM or SFHM certificate in a snazzy frame? Need to stay hydrated at work? Or maybe the hospital hallways are too chilly?

SHM’s eStore has you covered with brand new merchandise, including certificate frames, branded water bottles, and zip-up hoodies with the SHM logo on the front. To browse SHM merchandise, click on “eStore”.

Want to showcase your new FHM or SFHM certificate in a snazzy frame? Need to stay hydrated at work? Or maybe the hospital hallways are too chilly?

SHM’s eStore has you covered with brand new merchandise, including certificate frames, branded water bottles, and zip-up hoodies with the SHM logo on the front. To browse SHM merchandise, click on “eStore”.

Want to showcase your new FHM or SFHM certificate in a snazzy frame? Need to stay hydrated at work? Or maybe the hospital hallways are too chilly?

SHM’s eStore has you covered with brand new merchandise, including certificate frames, branded water bottles, and zip-up hoodies with the SHM logo on the front. To browse SHM merchandise, click on “eStore”.

TeamHealth's Dr. Jasen Gunderson Designs Own Path to Hospital Medicine

Jasen Gundersen, MD, MBA, CPE, SFHM, didn’t take the straightest path to HM. First, as he entered University of Connecticut School of Medicine in Farmington, he thought he’d be an emergency medicine physician. Then he thought about being a rural primary care physician. To that end, he did his residency in family medicine at UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester.

And yet, somehow, he became a hospitalist.

“I found that I liked spending all my time in the hospital. I could spend all my time with patients and deal with higher-acuity issues,” says Dr. Gundersen, president of TeamHealth Hospital Medicine in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. “I found that I’d rather deal with acute and more complicated [cases] in the hospital setting than work in an office setting. I like the pace of working in an acute care setting.”

The move to HM, and later to an administrative role, shocked some of his friends and colleagues. But in medical school, the nature of emergency room crises became clear: For a cardiac case, the cardiologist would take over. For a surgical issue, surgeons rolled in.

“I found that if I was going to be doing primary care for folks, which is what happens in a lot of emergency rooms, I didn’t want to do it in a quick, in-and-out setting, where you don’t really get to know the patient,” he says.

Now, Dr. Gundersen is bringing his off-the-beaten path career insights to Team Hospitalist. He’s one of six new members of the volunteer editorial advisory board of The Hospitalist.

—Dr. Gundersen

Question: Was there a mentor who pushed you to HM?

Answer: It just kind of happened. I liked working in the hospital. I was really excited about my weeks in the hospital and when I was in the office, I was thinking about working in the hospital.

Q: How did HM help prepare you for your current position, in terms of growing and building a business?

A: It’s a rapidly growing field. The timing was perfect for me to be in the field and have a background in hospital medicine and grow in a leadership role. I think my background of knowing hospitals made it easier to be a HM leader, but along the way I had hospital leadership roles. The experience working in the hospital, as a hospitalist, touching all aspects of patient care, really set me up well for a leadership role in a hospital. That was a springboard for me, managing doctors, to step into the role I have now with TeamHealth.

Q: What do you miss most about clinical work, given that you spend most of your time now in business development?

A: The simplicity of it, compared to the complicated aspects of running a huge company. It’s nice to be able to just go in and be a doctor sometimes. You know, talk to patients about their illness, work through the systems, and just be a doc. Not thinking about fixing something and managing people.

Q: What is the best advice you’ve ever received?

A: Be honest. Always be honest. That’s be honest with yourself about what your abilities are, where your limitations are, and what your goals are and why you have them. And then be honest with all the people you work with about what you can do and can’t do. That is probably the most important thing. If you are a hospitalist and want to be a leader, be honest with yourself [about] why you want to do it. Is it because you enjoy it? Is it because you think you are going to have more time or make more money? Are you capable of handling the stress of being a leader?

Q: What is the worst piece of advice you’ve ever received?

A: I don’t know, probably because I just ignored it.

Q: Where do you see the field in five to 10 years?

A: I think the field of hospital medicine needs to be cautious of the pace [at which] we are growing, and some of the limitations and demands we have been trying to put on it. I think we need to embrace the growth and embrace what people are asking us to do. I think the role of hospitalists will get bigger and bigger. I think what has really happened is that we have transitioned into two types of physicians in general, and I think that is because of the hospitalist movement. Medical staffs will be made up of outpatient physicians and inpatient physicians.

Q: Any concerns about that growth?

A: I think we need to be cautious as we grow that we don’t overspecialize the hospital and that we realize that what has allowed us to grow is our flexibility. The ‘scope creep’ of what we cover and what we do is going to continue, and we’re going to have to work with it and seize that opportunity.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Jasen Gundersen, MD, MBA, CPE, SFHM, didn’t take the straightest path to HM. First, as he entered University of Connecticut School of Medicine in Farmington, he thought he’d be an emergency medicine physician. Then he thought about being a rural primary care physician. To that end, he did his residency in family medicine at UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester.

And yet, somehow, he became a hospitalist.

“I found that I liked spending all my time in the hospital. I could spend all my time with patients and deal with higher-acuity issues,” says Dr. Gundersen, president of TeamHealth Hospital Medicine in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. “I found that I’d rather deal with acute and more complicated [cases] in the hospital setting than work in an office setting. I like the pace of working in an acute care setting.”

The move to HM, and later to an administrative role, shocked some of his friends and colleagues. But in medical school, the nature of emergency room crises became clear: For a cardiac case, the cardiologist would take over. For a surgical issue, surgeons rolled in.

“I found that if I was going to be doing primary care for folks, which is what happens in a lot of emergency rooms, I didn’t want to do it in a quick, in-and-out setting, where you don’t really get to know the patient,” he says.

Now, Dr. Gundersen is bringing his off-the-beaten path career insights to Team Hospitalist. He’s one of six new members of the volunteer editorial advisory board of The Hospitalist.

—Dr. Gundersen

Question: Was there a mentor who pushed you to HM?

Answer: It just kind of happened. I liked working in the hospital. I was really excited about my weeks in the hospital and when I was in the office, I was thinking about working in the hospital.

Q: How did HM help prepare you for your current position, in terms of growing and building a business?

A: It’s a rapidly growing field. The timing was perfect for me to be in the field and have a background in hospital medicine and grow in a leadership role. I think my background of knowing hospitals made it easier to be a HM leader, but along the way I had hospital leadership roles. The experience working in the hospital, as a hospitalist, touching all aspects of patient care, really set me up well for a leadership role in a hospital. That was a springboard for me, managing doctors, to step into the role I have now with TeamHealth.

Q: What do you miss most about clinical work, given that you spend most of your time now in business development?

A: The simplicity of it, compared to the complicated aspects of running a huge company. It’s nice to be able to just go in and be a doctor sometimes. You know, talk to patients about their illness, work through the systems, and just be a doc. Not thinking about fixing something and managing people.

Q: What is the best advice you’ve ever received?

A: Be honest. Always be honest. That’s be honest with yourself about what your abilities are, where your limitations are, and what your goals are and why you have them. And then be honest with all the people you work with about what you can do and can’t do. That is probably the most important thing. If you are a hospitalist and want to be a leader, be honest with yourself [about] why you want to do it. Is it because you enjoy it? Is it because you think you are going to have more time or make more money? Are you capable of handling the stress of being a leader?

Q: What is the worst piece of advice you’ve ever received?

A: I don’t know, probably because I just ignored it.

Q: Where do you see the field in five to 10 years?

A: I think the field of hospital medicine needs to be cautious of the pace [at which] we are growing, and some of the limitations and demands we have been trying to put on it. I think we need to embrace the growth and embrace what people are asking us to do. I think the role of hospitalists will get bigger and bigger. I think what has really happened is that we have transitioned into two types of physicians in general, and I think that is because of the hospitalist movement. Medical staffs will be made up of outpatient physicians and inpatient physicians.

Q: Any concerns about that growth?

A: I think we need to be cautious as we grow that we don’t overspecialize the hospital and that we realize that what has allowed us to grow is our flexibility. The ‘scope creep’ of what we cover and what we do is going to continue, and we’re going to have to work with it and seize that opportunity.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Jasen Gundersen, MD, MBA, CPE, SFHM, didn’t take the straightest path to HM. First, as he entered University of Connecticut School of Medicine in Farmington, he thought he’d be an emergency medicine physician. Then he thought about being a rural primary care physician. To that end, he did his residency in family medicine at UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester.

And yet, somehow, he became a hospitalist.

“I found that I liked spending all my time in the hospital. I could spend all my time with patients and deal with higher-acuity issues,” says Dr. Gundersen, president of TeamHealth Hospital Medicine in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. “I found that I’d rather deal with acute and more complicated [cases] in the hospital setting than work in an office setting. I like the pace of working in an acute care setting.”

The move to HM, and later to an administrative role, shocked some of his friends and colleagues. But in medical school, the nature of emergency room crises became clear: For a cardiac case, the cardiologist would take over. For a surgical issue, surgeons rolled in.

“I found that if I was going to be doing primary care for folks, which is what happens in a lot of emergency rooms, I didn’t want to do it in a quick, in-and-out setting, where you don’t really get to know the patient,” he says.

Now, Dr. Gundersen is bringing his off-the-beaten path career insights to Team Hospitalist. He’s one of six new members of the volunteer editorial advisory board of The Hospitalist.

—Dr. Gundersen

Question: Was there a mentor who pushed you to HM?

Answer: It just kind of happened. I liked working in the hospital. I was really excited about my weeks in the hospital and when I was in the office, I was thinking about working in the hospital.

Q: How did HM help prepare you for your current position, in terms of growing and building a business?

A: It’s a rapidly growing field. The timing was perfect for me to be in the field and have a background in hospital medicine and grow in a leadership role. I think my background of knowing hospitals made it easier to be a HM leader, but along the way I had hospital leadership roles. The experience working in the hospital, as a hospitalist, touching all aspects of patient care, really set me up well for a leadership role in a hospital. That was a springboard for me, managing doctors, to step into the role I have now with TeamHealth.

Q: What do you miss most about clinical work, given that you spend most of your time now in business development?

A: The simplicity of it, compared to the complicated aspects of running a huge company. It’s nice to be able to just go in and be a doctor sometimes. You know, talk to patients about their illness, work through the systems, and just be a doc. Not thinking about fixing something and managing people.

Q: What is the best advice you’ve ever received?

A: Be honest. Always be honest. That’s be honest with yourself about what your abilities are, where your limitations are, and what your goals are and why you have them. And then be honest with all the people you work with about what you can do and can’t do. That is probably the most important thing. If you are a hospitalist and want to be a leader, be honest with yourself [about] why you want to do it. Is it because you enjoy it? Is it because you think you are going to have more time or make more money? Are you capable of handling the stress of being a leader?

Q: What is the worst piece of advice you’ve ever received?

A: I don’t know, probably because I just ignored it.

Q: Where do you see the field in five to 10 years?

A: I think the field of hospital medicine needs to be cautious of the pace [at which] we are growing, and some of the limitations and demands we have been trying to put on it. I think we need to embrace the growth and embrace what people are asking us to do. I think the role of hospitalists will get bigger and bigger. I think what has really happened is that we have transitioned into two types of physicians in general, and I think that is because of the hospitalist movement. Medical staffs will be made up of outpatient physicians and inpatient physicians.

Q: Any concerns about that growth?

A: I think we need to be cautious as we grow that we don’t overspecialize the hospital and that we realize that what has allowed us to grow is our flexibility. The ‘scope creep’ of what we cover and what we do is going to continue, and we’re going to have to work with it and seize that opportunity.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Rapid-Response Teams Help Hospitalists Manage Non-Medical Distress

A team that could respond quickly to social and behavioral concerns—and not medical issues per se—would have tremendous benefits for patients and caregivers.

I think there has been a steady increase, over the last 20 years or so, in the number of very unhappy, angry, or misbehaving patients (e.g. abusive/threatening to staff). In some cases, the hospital and caregivers have failed the patient. In other cases, their frustration arises out of things outside the hospital’s direct control, such as Medicare observation status, or perhaps the patient or family is just unreasonable or suffering from a psychiatric or substance abuse disorder.

I’m not talking about the common occurrence of a disappointed patient or family who might calmly complain about something. Instead, I want to focus on those patients who, whether we perceive them as justifiably unhappy or not, are so angry that they become very time consuming and distressing to deal with. Maybe they shout about how their lawyer will be suing us and the newspaper will be writing a story about how awful we are. Or they shout and throw things, and staff become afraid of them.

In my May 2013 column, I discussed care plans for patients like this who are admitted frequently, but such plans are not sufficient in every case.

A Haphazard Approach

Most hospitals have an informal process of dealing with these patients; it starts with the bedside nurse and/or doctor trying to apologize or make adjustments to satisfy and calm the patient. If that fails, then perhaps the manager of the nursing unit gets involved. Others may be recruited, such as someone from the hospital’s risk management or “patient advocate” departments and hospital executives such as the CNO, CMO, or CEO. Sometimes several of these people may meet as a group in an effort to come up with a plan to address the situation. But, most institutions do not have a clear and consistent approach to this important work, so the hospital personnel involved end up “reinventing the wheel” each time.

The growing awareness that hospital personnel don’t seem to have a robust and confident approach to addressing this type of situation can increase a patient’s distress, and it may embolden some to become even more demanding or threatening.

And all of this takes a significant toll on bedside caregivers, who often spend so much time dealing with the angry patient that they have less time to devote to other patients, who are in turn at least a little more likely to become unhappy or suffer as a result of a distressed and busy caregiver.

A Consistent Approach: RRT for Non-Medical Distress

I think the potential benefit for patients and caregivers is significant enough that hospitals should develop a standardized approach to managing such patients, and rapid response teams (RRTs) could serve as a model. To be clear, I’m not advocating that RRTs add management of very angry or distressed patients to their current role. Let’s call it an “RRT for non-medical distress.” And, while I think it is a worthwhile idea, and I am in the early steps of trying to develop it at “my” hospital, I’m not aware of any such team in place anywhere now.

To make it practical, I think this team should be available only during weekday business hours and would comprise something like six to 10 people with clinical backgrounds who do mostly administrative work. For example, the team members could include two nursing unit directors, a risk manager, a patient advocate (or patient satisfaction “czar”), a psychiatrist, the hospitalist medical director, the chief medical officer, and a few other individuals selected for their communication skills.

One of the team members would be on call for a day or week at a time and would carry the team’s pager during business hours. Any hospital caregiver could send a page requesting the team’s assistance, and the on-call team member would respond immediately by phone or, if possible, in person. After the on-call team member’s initial assessment, the whole team would meet later the same day or early the next day. On most days, a few members of the team would be off and unable to attend the meeting. So, if the team has eight members, each meeting of the team might average about five participants.

Non-Medical Distress RRT Processes

When meeting to establish a plan for addressing an extraordinarily distressed patient/family, the team should follow a standardized written approach. A designated person should lead the conversation—perhaps the on-call team member who responded first—and another should take notes. Using a form developed for this purpose, the note-taker would capture a standardized data set that is likely to be useful in determining a course of action, as well as valuable in helping the team fine-tune its approach by reviewing trends in aggregate data. The form might include things like patient demographics; the patient’s complaints and demands; potential complicating patient issues such as substance abuse, psychoactive drugs, or psychiatric history; location in the hospital; and names of bedside caregivers. Every effort should be made to keep the meetings efficient and as brief as practical—typically 30-60 minutes.

I’m convinced that when deciding how to respond to the situation, the team should try to limit itself to choosing one or more of eight to 10 standard interventions, rather than aiming for an entirely customized response in every case. Among the standardized interventions:

- Service recovery tools, such as a handwritten apology letter;

- A meeting between the patient/family and the hospital CEO or CMO;

- Security guard(s) at the door, on “high alert” to help if called; or

- A behavioral contract specifying the expectations for both patient and hospital staff behavior.

You might think of additional “tools” this team could have in their standardized response set.

Why limit the team as much as possible to a small set of standardized interventions? Developing customized responses in each situation is time consuming and, arguably, has a higher risk of failure, since it will be difficult to ensure that all staff caring for the patient can understand and execute them effectively. And the small set of interventions will make it easier to track their effectiveness over multiple patients so that the whole process can be improved over time.

Set a High Bar

The team should not be activated for every unhappy or difficult patient; that would be overkill and would result in many activations requiring dedicated staff with no other duties to serve on the team each day. Instead, I think the team should be activated only for the most difficult and distressing cases, at least for the first few years. In a 300-bed hospital, this would be approximately one to 1.5 activations per week.

Bedside caregivers would likely feel some reassurance knowing that they can reliably get help managing the most difficult patients, and, if the plan is executed well, these patients may get care that is safer for both themselves and staff. Who knows, medical outcomes might be improved for these patients also.

A team that could respond quickly to social and behavioral concerns—and not medical issues per se—would have tremendous benefits for patients and caregivers.

I think there has been a steady increase, over the last 20 years or so, in the number of very unhappy, angry, or misbehaving patients (e.g. abusive/threatening to staff). In some cases, the hospital and caregivers have failed the patient. In other cases, their frustration arises out of things outside the hospital’s direct control, such as Medicare observation status, or perhaps the patient or family is just unreasonable or suffering from a psychiatric or substance abuse disorder.

I’m not talking about the common occurrence of a disappointed patient or family who might calmly complain about something. Instead, I want to focus on those patients who, whether we perceive them as justifiably unhappy or not, are so angry that they become very time consuming and distressing to deal with. Maybe they shout about how their lawyer will be suing us and the newspaper will be writing a story about how awful we are. Or they shout and throw things, and staff become afraid of them.

In my May 2013 column, I discussed care plans for patients like this who are admitted frequently, but such plans are not sufficient in every case.

A Haphazard Approach

Most hospitals have an informal process of dealing with these patients; it starts with the bedside nurse and/or doctor trying to apologize or make adjustments to satisfy and calm the patient. If that fails, then perhaps the manager of the nursing unit gets involved. Others may be recruited, such as someone from the hospital’s risk management or “patient advocate” departments and hospital executives such as the CNO, CMO, or CEO. Sometimes several of these people may meet as a group in an effort to come up with a plan to address the situation. But, most institutions do not have a clear and consistent approach to this important work, so the hospital personnel involved end up “reinventing the wheel” each time.

The growing awareness that hospital personnel don’t seem to have a robust and confident approach to addressing this type of situation can increase a patient’s distress, and it may embolden some to become even more demanding or threatening.

And all of this takes a significant toll on bedside caregivers, who often spend so much time dealing with the angry patient that they have less time to devote to other patients, who are in turn at least a little more likely to become unhappy or suffer as a result of a distressed and busy caregiver.

A Consistent Approach: RRT for Non-Medical Distress

I think the potential benefit for patients and caregivers is significant enough that hospitals should develop a standardized approach to managing such patients, and rapid response teams (RRTs) could serve as a model. To be clear, I’m not advocating that RRTs add management of very angry or distressed patients to their current role. Let’s call it an “RRT for non-medical distress.” And, while I think it is a worthwhile idea, and I am in the early steps of trying to develop it at “my” hospital, I’m not aware of any such team in place anywhere now.

To make it practical, I think this team should be available only during weekday business hours and would comprise something like six to 10 people with clinical backgrounds who do mostly administrative work. For example, the team members could include two nursing unit directors, a risk manager, a patient advocate (or patient satisfaction “czar”), a psychiatrist, the hospitalist medical director, the chief medical officer, and a few other individuals selected for their communication skills.

One of the team members would be on call for a day or week at a time and would carry the team’s pager during business hours. Any hospital caregiver could send a page requesting the team’s assistance, and the on-call team member would respond immediately by phone or, if possible, in person. After the on-call team member’s initial assessment, the whole team would meet later the same day or early the next day. On most days, a few members of the team would be off and unable to attend the meeting. So, if the team has eight members, each meeting of the team might average about five participants.

Non-Medical Distress RRT Processes

When meeting to establish a plan for addressing an extraordinarily distressed patient/family, the team should follow a standardized written approach. A designated person should lead the conversation—perhaps the on-call team member who responded first—and another should take notes. Using a form developed for this purpose, the note-taker would capture a standardized data set that is likely to be useful in determining a course of action, as well as valuable in helping the team fine-tune its approach by reviewing trends in aggregate data. The form might include things like patient demographics; the patient’s complaints and demands; potential complicating patient issues such as substance abuse, psychoactive drugs, or psychiatric history; location in the hospital; and names of bedside caregivers. Every effort should be made to keep the meetings efficient and as brief as practical—typically 30-60 minutes.

I’m convinced that when deciding how to respond to the situation, the team should try to limit itself to choosing one or more of eight to 10 standard interventions, rather than aiming for an entirely customized response in every case. Among the standardized interventions:

- Service recovery tools, such as a handwritten apology letter;

- A meeting between the patient/family and the hospital CEO or CMO;

- Security guard(s) at the door, on “high alert” to help if called; or

- A behavioral contract specifying the expectations for both patient and hospital staff behavior.

You might think of additional “tools” this team could have in their standardized response set.

Why limit the team as much as possible to a small set of standardized interventions? Developing customized responses in each situation is time consuming and, arguably, has a higher risk of failure, since it will be difficult to ensure that all staff caring for the patient can understand and execute them effectively. And the small set of interventions will make it easier to track their effectiveness over multiple patients so that the whole process can be improved over time.

Set a High Bar

The team should not be activated for every unhappy or difficult patient; that would be overkill and would result in many activations requiring dedicated staff with no other duties to serve on the team each day. Instead, I think the team should be activated only for the most difficult and distressing cases, at least for the first few years. In a 300-bed hospital, this would be approximately one to 1.5 activations per week.

Bedside caregivers would likely feel some reassurance knowing that they can reliably get help managing the most difficult patients, and, if the plan is executed well, these patients may get care that is safer for both themselves and staff. Who knows, medical outcomes might be improved for these patients also.

A team that could respond quickly to social and behavioral concerns—and not medical issues per se—would have tremendous benefits for patients and caregivers.

I think there has been a steady increase, over the last 20 years or so, in the number of very unhappy, angry, or misbehaving patients (e.g. abusive/threatening to staff). In some cases, the hospital and caregivers have failed the patient. In other cases, their frustration arises out of things outside the hospital’s direct control, such as Medicare observation status, or perhaps the patient or family is just unreasonable or suffering from a psychiatric or substance abuse disorder.

I’m not talking about the common occurrence of a disappointed patient or family who might calmly complain about something. Instead, I want to focus on those patients who, whether we perceive them as justifiably unhappy or not, are so angry that they become very time consuming and distressing to deal with. Maybe they shout about how their lawyer will be suing us and the newspaper will be writing a story about how awful we are. Or they shout and throw things, and staff become afraid of them.

In my May 2013 column, I discussed care plans for patients like this who are admitted frequently, but such plans are not sufficient in every case.

A Haphazard Approach

Most hospitals have an informal process of dealing with these patients; it starts with the bedside nurse and/or doctor trying to apologize or make adjustments to satisfy and calm the patient. If that fails, then perhaps the manager of the nursing unit gets involved. Others may be recruited, such as someone from the hospital’s risk management or “patient advocate” departments and hospital executives such as the CNO, CMO, or CEO. Sometimes several of these people may meet as a group in an effort to come up with a plan to address the situation. But, most institutions do not have a clear and consistent approach to this important work, so the hospital personnel involved end up “reinventing the wheel” each time.

The growing awareness that hospital personnel don’t seem to have a robust and confident approach to addressing this type of situation can increase a patient’s distress, and it may embolden some to become even more demanding or threatening.

And all of this takes a significant toll on bedside caregivers, who often spend so much time dealing with the angry patient that they have less time to devote to other patients, who are in turn at least a little more likely to become unhappy or suffer as a result of a distressed and busy caregiver.

A Consistent Approach: RRT for Non-Medical Distress

I think the potential benefit for patients and caregivers is significant enough that hospitals should develop a standardized approach to managing such patients, and rapid response teams (RRTs) could serve as a model. To be clear, I’m not advocating that RRTs add management of very angry or distressed patients to their current role. Let’s call it an “RRT for non-medical distress.” And, while I think it is a worthwhile idea, and I am in the early steps of trying to develop it at “my” hospital, I’m not aware of any such team in place anywhere now.

To make it practical, I think this team should be available only during weekday business hours and would comprise something like six to 10 people with clinical backgrounds who do mostly administrative work. For example, the team members could include two nursing unit directors, a risk manager, a patient advocate (or patient satisfaction “czar”), a psychiatrist, the hospitalist medical director, the chief medical officer, and a few other individuals selected for their communication skills.

One of the team members would be on call for a day or week at a time and would carry the team’s pager during business hours. Any hospital caregiver could send a page requesting the team’s assistance, and the on-call team member would respond immediately by phone or, if possible, in person. After the on-call team member’s initial assessment, the whole team would meet later the same day or early the next day. On most days, a few members of the team would be off and unable to attend the meeting. So, if the team has eight members, each meeting of the team might average about five participants.

Non-Medical Distress RRT Processes

When meeting to establish a plan for addressing an extraordinarily distressed patient/family, the team should follow a standardized written approach. A designated person should lead the conversation—perhaps the on-call team member who responded first—and another should take notes. Using a form developed for this purpose, the note-taker would capture a standardized data set that is likely to be useful in determining a course of action, as well as valuable in helping the team fine-tune its approach by reviewing trends in aggregate data. The form might include things like patient demographics; the patient’s complaints and demands; potential complicating patient issues such as substance abuse, psychoactive drugs, or psychiatric history; location in the hospital; and names of bedside caregivers. Every effort should be made to keep the meetings efficient and as brief as practical—typically 30-60 minutes.

I’m convinced that when deciding how to respond to the situation, the team should try to limit itself to choosing one or more of eight to 10 standard interventions, rather than aiming for an entirely customized response in every case. Among the standardized interventions:

- Service recovery tools, such as a handwritten apology letter;

- A meeting between the patient/family and the hospital CEO or CMO;

- Security guard(s) at the door, on “high alert” to help if called; or

- A behavioral contract specifying the expectations for both patient and hospital staff behavior.

You might think of additional “tools” this team could have in their standardized response set.

Why limit the team as much as possible to a small set of standardized interventions? Developing customized responses in each situation is time consuming and, arguably, has a higher risk of failure, since it will be difficult to ensure that all staff caring for the patient can understand and execute them effectively. And the small set of interventions will make it easier to track their effectiveness over multiple patients so that the whole process can be improved over time.

Set a High Bar

The team should not be activated for every unhappy or difficult patient; that would be overkill and would result in many activations requiring dedicated staff with no other duties to serve on the team each day. Instead, I think the team should be activated only for the most difficult and distressing cases, at least for the first few years. In a 300-bed hospital, this would be approximately one to 1.5 activations per week.

Bedside caregivers would likely feel some reassurance knowing that they can reliably get help managing the most difficult patients, and, if the plan is executed well, these patients may get care that is safer for both themselves and staff. Who knows, medical outcomes might be improved for these patients also.

Hospitalist Training Helps Phuoc Le, MD, MPH, Fight Global Health Inequality

Phuoc Le, MD, MPH, was born a year after the Vietnam War ended and was five when he and his family fled Vietnam by boat to seek asylum in Hong Kong. At a refugee camp there, he had his first contact with a functional public health system and, within days, was cured of the parasitic disease that had made him ill since he was a toddler. Later, as an undergraduate at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., he realized he had been one of the health disparity victims described by medical anthropologist Paul E. Farmer, PhD, MD, in his books.

“For the vast majority of people, it doesn’t turn out the way it did for me,” says Dr. Le. “As much as I’ve been blessed with, what I expect of myself is to focus on health disparities and have it be my life’s work.”

Dr. Le’s personal mission led him to co-found the Global Health Core within the division of hospital medicine at the University of California San Francisco, which aims to train hospitalists to work in resource-poor settings. The program recently was honored with the 2015 SHM Award for Excellence in Humanitarian Service.

Dr. Le, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), where he co-directs the Global Health-Hospital Medicine Fellowship, recently spoke with The Hospitalist about his work.

Question: What was your first trip as a physician abroad like?

Answer: I was a resident at Harvard [University in Cambridge, Mass.] in 2007 when I went to Haiti with Paul Farmer and a few other residents involved in the [nonprofit] Partners in Health. I’ll never forget that the trip from Port-au-Prince to the hospital was only about 120 miles, and it took eight hours in a four-wheel drive vehicle to get there. They didn’t want us residents to suffer that trip, so they got a bunch of volunteer pilots to fly us in a single-engine plane, which took about 20 minutes.

We got there, had lunch and dinner, and it was during dinner that the group coming by vehicle finally arrived. It just dawned on me. These are things you don’t have a visceral feeling for until you see them. These people were tired because they had driven all day. What if I had been a patient and had to travel 120 miles and was sick? Would I have lasted eight hours to go that small distance?

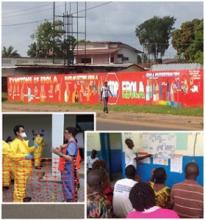

This is just one example of many structural problems that need to be addressed. The same conditions are impeding the progress in [controlling] Ebola in West Africa. I was there in November. The problems that led to [the] Ebola [outbreak] were absolutely predictable and avoidable if the global community had paid more attention to this injustice before Ebola started—or responded much earlier. It could have saved lives [and] money, and we probably wouldn’t have had the huge scare in the U.S. that we did.

Q: What compelled you to go to Liberia just as the Ebola outbreak began?

A: To me, there was no question in my mind that I needed to go. It was a situation where I had the expertise. I’m a physician, a public health expert, [I’ve] worked in places with tropical diseases and have experience responding to emergencies like the cholera epidemic in Haiti and the Haiti earthquake. We also had a relationship with an NGO [non-governmental organization] in Liberia for several years. My colleagues and I at UCSF started the nation’s first global health hospital medicine fellowship, and our fellows had been going to Liberia for the last three years. For us, it was a matter of solidarity.

Q: You trained at the CDC prior to your trip. How did that training prepare you?

A: During those three days at the CDC, we were taught how to put on and take off personal protective equipment every day, and so we understood how difficult it was, especially in searing heat. It is very challenging, and we were able to teach those skills in Liberia.

Q: In a paper recently published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, you call on hospitalists to join the ranks of global health hospitalists. Can you explain?

A: Whether it’s Navajo Nation in Arizona or rural Haiti, the healthcare needs of the poor are very similar. Global health hospitalists play an important role in capacity building, running a health system, improving quality while reducing costs, working in teams to provide holistic care for the inpatient, and improving transitions to the outpatient setting.

Q: How do the skills learned in resource-poor settings apply back home?

A: Let’s say you have a patient with tuberculosis, which is very common in places like Liberia, and you suspect fluid in the lungs. [In Liberia], you would insert a needle and remove the fluid. In the U.S., a lot of providers would not be able to remove the fluid without getting an ultrasound and multiple other studies. Those costs add up. Global health hospitalists are very well versed in the skills of ultrasonography because there are no ultrasonographers in the field working with us.

Q: You said it was in Haiti where you began to notice volunteers arriving with good intentions but without needed skills. What exactly did you learn?

A: I spent a lot of time there, responding to the earthquake and also the cholera epidemic in 2010. I came across dozens of healthcare volunteers who had passion and commitment but really came ill prepared, not through any fault of their own, but because they never had an opportunity to learn the skills needed to be effective in the field. For example, take a nurse from an ivory tower hospital and suddenly put her where she doesn’t have IVs to work with or the right type of fluids or tubing. Well, suddenly she feels like her efficacy has gone way down. That could easily lead to a lot of frustration and potential burnout.

Stephanie Mackiewicz is a freelance writer in Los Angeles.

Phuoc Le, MD, MPH, was born a year after the Vietnam War ended and was five when he and his family fled Vietnam by boat to seek asylum in Hong Kong. At a refugee camp there, he had his first contact with a functional public health system and, within days, was cured of the parasitic disease that had made him ill since he was a toddler. Later, as an undergraduate at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., he realized he had been one of the health disparity victims described by medical anthropologist Paul E. Farmer, PhD, MD, in his books.

“For the vast majority of people, it doesn’t turn out the way it did for me,” says Dr. Le. “As much as I’ve been blessed with, what I expect of myself is to focus on health disparities and have it be my life’s work.”

Dr. Le’s personal mission led him to co-found the Global Health Core within the division of hospital medicine at the University of California San Francisco, which aims to train hospitalists to work in resource-poor settings. The program recently was honored with the 2015 SHM Award for Excellence in Humanitarian Service.

Dr. Le, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), where he co-directs the Global Health-Hospital Medicine Fellowship, recently spoke with The Hospitalist about his work.

Question: What was your first trip as a physician abroad like?

Answer: I was a resident at Harvard [University in Cambridge, Mass.] in 2007 when I went to Haiti with Paul Farmer and a few other residents involved in the [nonprofit] Partners in Health. I’ll never forget that the trip from Port-au-Prince to the hospital was only about 120 miles, and it took eight hours in a four-wheel drive vehicle to get there. They didn’t want us residents to suffer that trip, so they got a bunch of volunteer pilots to fly us in a single-engine plane, which took about 20 minutes.

We got there, had lunch and dinner, and it was during dinner that the group coming by vehicle finally arrived. It just dawned on me. These are things you don’t have a visceral feeling for until you see them. These people were tired because they had driven all day. What if I had been a patient and had to travel 120 miles and was sick? Would I have lasted eight hours to go that small distance?

This is just one example of many structural problems that need to be addressed. The same conditions are impeding the progress in [controlling] Ebola in West Africa. I was there in November. The problems that led to [the] Ebola [outbreak] were absolutely predictable and avoidable if the global community had paid more attention to this injustice before Ebola started—or responded much earlier. It could have saved lives [and] money, and we probably wouldn’t have had the huge scare in the U.S. that we did.

Q: What compelled you to go to Liberia just as the Ebola outbreak began?

A: To me, there was no question in my mind that I needed to go. It was a situation where I had the expertise. I’m a physician, a public health expert, [I’ve] worked in places with tropical diseases and have experience responding to emergencies like the cholera epidemic in Haiti and the Haiti earthquake. We also had a relationship with an NGO [non-governmental organization] in Liberia for several years. My colleagues and I at UCSF started the nation’s first global health hospital medicine fellowship, and our fellows had been going to Liberia for the last three years. For us, it was a matter of solidarity.

Q: You trained at the CDC prior to your trip. How did that training prepare you?

A: During those three days at the CDC, we were taught how to put on and take off personal protective equipment every day, and so we understood how difficult it was, especially in searing heat. It is very challenging, and we were able to teach those skills in Liberia.

Q: In a paper recently published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, you call on hospitalists to join the ranks of global health hospitalists. Can you explain?

A: Whether it’s Navajo Nation in Arizona or rural Haiti, the healthcare needs of the poor are very similar. Global health hospitalists play an important role in capacity building, running a health system, improving quality while reducing costs, working in teams to provide holistic care for the inpatient, and improving transitions to the outpatient setting.

Q: How do the skills learned in resource-poor settings apply back home?

A: Let’s say you have a patient with tuberculosis, which is very common in places like Liberia, and you suspect fluid in the lungs. [In Liberia], you would insert a needle and remove the fluid. In the U.S., a lot of providers would not be able to remove the fluid without getting an ultrasound and multiple other studies. Those costs add up. Global health hospitalists are very well versed in the skills of ultrasonography because there are no ultrasonographers in the field working with us.

Q: You said it was in Haiti where you began to notice volunteers arriving with good intentions but without needed skills. What exactly did you learn?

A: I spent a lot of time there, responding to the earthquake and also the cholera epidemic in 2010. I came across dozens of healthcare volunteers who had passion and commitment but really came ill prepared, not through any fault of their own, but because they never had an opportunity to learn the skills needed to be effective in the field. For example, take a nurse from an ivory tower hospital and suddenly put her where she doesn’t have IVs to work with or the right type of fluids or tubing. Well, suddenly she feels like her efficacy has gone way down. That could easily lead to a lot of frustration and potential burnout.

Stephanie Mackiewicz is a freelance writer in Los Angeles.

Phuoc Le, MD, MPH, was born a year after the Vietnam War ended and was five when he and his family fled Vietnam by boat to seek asylum in Hong Kong. At a refugee camp there, he had his first contact with a functional public health system and, within days, was cured of the parasitic disease that had made him ill since he was a toddler. Later, as an undergraduate at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., he realized he had been one of the health disparity victims described by medical anthropologist Paul E. Farmer, PhD, MD, in his books.

“For the vast majority of people, it doesn’t turn out the way it did for me,” says Dr. Le. “As much as I’ve been blessed with, what I expect of myself is to focus on health disparities and have it be my life’s work.”

Dr. Le’s personal mission led him to co-found the Global Health Core within the division of hospital medicine at the University of California San Francisco, which aims to train hospitalists to work in resource-poor settings. The program recently was honored with the 2015 SHM Award for Excellence in Humanitarian Service.

Dr. Le, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), where he co-directs the Global Health-Hospital Medicine Fellowship, recently spoke with The Hospitalist about his work.

Question: What was your first trip as a physician abroad like?

Answer: I was a resident at Harvard [University in Cambridge, Mass.] in 2007 when I went to Haiti with Paul Farmer and a few other residents involved in the [nonprofit] Partners in Health. I’ll never forget that the trip from Port-au-Prince to the hospital was only about 120 miles, and it took eight hours in a four-wheel drive vehicle to get there. They didn’t want us residents to suffer that trip, so they got a bunch of volunteer pilots to fly us in a single-engine plane, which took about 20 minutes.

We got there, had lunch and dinner, and it was during dinner that the group coming by vehicle finally arrived. It just dawned on me. These are things you don’t have a visceral feeling for until you see them. These people were tired because they had driven all day. What if I had been a patient and had to travel 120 miles and was sick? Would I have lasted eight hours to go that small distance?

This is just one example of many structural problems that need to be addressed. The same conditions are impeding the progress in [controlling] Ebola in West Africa. I was there in November. The problems that led to [the] Ebola [outbreak] were absolutely predictable and avoidable if the global community had paid more attention to this injustice before Ebola started—or responded much earlier. It could have saved lives [and] money, and we probably wouldn’t have had the huge scare in the U.S. that we did.

Q: What compelled you to go to Liberia just as the Ebola outbreak began?

A: To me, there was no question in my mind that I needed to go. It was a situation where I had the expertise. I’m a physician, a public health expert, [I’ve] worked in places with tropical diseases and have experience responding to emergencies like the cholera epidemic in Haiti and the Haiti earthquake. We also had a relationship with an NGO [non-governmental organization] in Liberia for several years. My colleagues and I at UCSF started the nation’s first global health hospital medicine fellowship, and our fellows had been going to Liberia for the last three years. For us, it was a matter of solidarity.

Q: You trained at the CDC prior to your trip. How did that training prepare you?

A: During those three days at the CDC, we were taught how to put on and take off personal protective equipment every day, and so we understood how difficult it was, especially in searing heat. It is very challenging, and we were able to teach those skills in Liberia.

Q: In a paper recently published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, you call on hospitalists to join the ranks of global health hospitalists. Can you explain?

A: Whether it’s Navajo Nation in Arizona or rural Haiti, the healthcare needs of the poor are very similar. Global health hospitalists play an important role in capacity building, running a health system, improving quality while reducing costs, working in teams to provide holistic care for the inpatient, and improving transitions to the outpatient setting.

Q: How do the skills learned in resource-poor settings apply back home?

A: Let’s say you have a patient with tuberculosis, which is very common in places like Liberia, and you suspect fluid in the lungs. [In Liberia], you would insert a needle and remove the fluid. In the U.S., a lot of providers would not be able to remove the fluid without getting an ultrasound and multiple other studies. Those costs add up. Global health hospitalists are very well versed in the skills of ultrasonography because there are no ultrasonographers in the field working with us.

Q: You said it was in Haiti where you began to notice volunteers arriving with good intentions but without needed skills. What exactly did you learn?

A: I spent a lot of time there, responding to the earthquake and also the cholera epidemic in 2010. I came across dozens of healthcare volunteers who had passion and commitment but really came ill prepared, not through any fault of their own, but because they never had an opportunity to learn the skills needed to be effective in the field. For example, take a nurse from an ivory tower hospital and suddenly put her where she doesn’t have IVs to work with or the right type of fluids or tubing. Well, suddenly she feels like her efficacy has gone way down. That could easily lead to a lot of frustration and potential burnout.

Stephanie Mackiewicz is a freelance writer in Los Angeles.