User login

Is hemoglobin A1c an accurate measure of glycemic control in all diabetic patients?

No. Hemoglobin A1c has been validated as a predictor of diabetes-related complications and is a standard measure of the adequacy of glucose control. But sometimes we need to regard its values with suspicion, especially when they are not concordant with the patient’s self-monitored blood glucose levels.

UNIVERSALLY USED

Measuring glycated hemoglobin has become an essential tool for detecting impaired glucose tolerance (when levels are between 5.7% and 6.5%), for diagnosing diabetes mellitus (when levels are ≥ 6.5%), and for following the adequacy of control in established disease. The results reflect glycemic control over the preceding 2 to 3 months and possibly indicate the risk of complications, particularly microvascular disease in the long term.

The significance of hemoglobin A1c was further accentuated with the results of the DETECT-2 project,1 which showed that the risk of diabetic retinopathy is insignificant with levels lower than 6% and rises substantially when it is greater than 6.5%.

However, because the biochemical hallmark of diabetes is hyperglycemia (and not the glycation of proteins), concerns have been raised about the universal validity of hemoglobin A1c in all diabetic patients, especially when it is used to monitor glucose control in the long term.2

FACTORS THAT AFFECT THE GLYCATED HEMOGLOBIN LEVEL

Altered glycation

Although the hemoglobin A1c value correlates well with the mean blood glucose level over the previous months, it is affected more by the most recent glucose levels than by earlier levels, and it is especially affected by the most recent peak in blood glucose.3 It is estimated that approximately 50% of the hemoglobin A1c level is determined by the plasma glucose level during the preceding 1-month period.3

Other factors that affect levels of glycated hemoglobin independently of the average glucose level during the previous months include genetic predisposition (some people are “rapid glycators”), labile glycation (ie, transient glycation of hemoglobin when exposed to very high concentrations of glucose), and the 2,3-diphosphoglycerate concentration and pH of the blood.2

Hemoglobin factors

Age of red blood cells. Red blood cells last about 120 days, and the mean age of all red blood cells in circulation ranges from 38 to 60 days (50 on average). Turnover is dictated by a number of factors, including ethnicity, which in turn significantly affect hemoglobin A1c values.

Race and ethnicity. African American, Asian, and Hispanic patients may have higher hemoglobin A1c values than white people who have the same blood glucose levels. In one study of racial and ethnic differences in mean plasma glucose, levels were higher by 0.37% in African American patients, 0.27% in Hispanics, and 0.33% in Asians than in white patients, and the differences were statistically significant.4 However, there is no clear evidence that these differences are associated with differences in the incidence of microvascular disease.5

Effects due to heritable factors could vary among ethnic groups. Racial differences in hemoglobin A1c may be ascribed to the degree of glycation, caused by multiple factors, and to socioeconomic status. Interestingly, many of the interracial differences in conditions that affect erythrocyte turnover would in theory lead to a lower hemoglobin A1c in nonwhites, which is not the case.6

Pregnancy. The mechanisms of hemoglobin A1c discrepancy in pregnancy are not clear. It has been demonstrated that pregnant women may have lower hemoglobin A1c levels than nonpregnant women.7–9 Hemodilution and increased cell turnover have been postulated to account for the decrease, although a mechanism has not been described. Interestingly, conflicting data have been reported regarding hemoglobin A1c in the last trimester of pregnancy (increase, decrease, or no change). Iron deficiency has been presumed to cause the increase of hemoglobin A1c in the last trimester.10

Moreover, hemoglobin A1c may reflect glucose levels during a shorter time because of increased turnover of red blood cells that occurs during this state. Erythropoietin and erythrocyte production are increased during normal pregnancy while hemoglobin and hematocrit continuously dilute into the third trimester. In normal pregnancy, the red blood cell life span is decreased due to “emergency hemopoiesis” in response to these elevated erythropoietin levels.

Anemia. Hemolytic anemia, acute bleeding, and iron-deficiency anemia all influence glycated hemoglobin levels. The formation of reticulocytes whose hemoglobin lacks glycosylation may lead to falsely low hemoglobin A1c values. Interestingly, iron deficiency by itself has been observed to cause elevation of hemoglobin A1c through unclear mechanisms11; however, iron replacement may lead to reticulocytosis. Alternatively, asplenic patients may have deceptively higher hemoglobin A1c values because of the increased life span of their red blood cells.12

Hemoglobinopathy. Hemoglobin F may cause overestimation of hemoglobin A1c levels, whereas hemoglobin S and hemoglobin C may cause underestimation. Of note, these effects are method-specific, and newer immunoassay techniques are relatively robust even in the presence of common hemoglobin variants. Clinicians should be aware of their institution’s laboratory method for measuring glycated hemoglobin.13

Comorbidities

Chronic illnesses can cause fluctuation in hemoglobin A1c and make it unreliable. Uremia, severe hypertriglyceridemia, severe hyperbilirubinemia, chronic alcoholism, chronic salicylate use, chronic opioid use, and lead poisoning all can falsely increase hemoglobin A1c levels.

Vitamin and mineral deficiencies (eg, deficiencies of vitamin B12 and iron) can reduce red blood cell turnover and therefore falsely elevate hemoglobin A1c levels. Conversely, medical replacement of these deficiencies could lead to higher red blood cell turnover and reduced hemoglobin A1c levels.

Blood transfusions. Recent reports suggest that red blood cell transfusions reduce the hemoglobin A1c concentration in diabetic patients. This effect was most pronounced in patients who received large transfusion volumes or who had a high hemoglobin A1c level before the transfusion.14

Renal failure. Patients with renal failure have higher levels of carbamylated hemoglobin, which is reported to interfere with measurement and interpretation of hemoglobin A1c. Moreover, there is concern that hemoglobin A1c values may be falsely low in these patients because of shortened erythrocyte survival. Other factors that influence hemoglobin A1c and cause the measured levels to be misleadingly low in renal failure patients include use of recombinant human erythropoietin, the uremic environment, and blood transfusions.15

It has been suggested that glycated albumin may be a better marker for assessing glycemic control in patients with severe chronic kidney disease.16

Medications and supplements that affect hemoglobin

Drugs that may cause hemolysis could lower hemoglobin A1c levels. Examples are dapsone, ribavirin, and sulfonamides. Other drugs can change the structure of hemoglobin. For example, hydroxyurea alters hemoglobin A into hemoglobin F, thus lowering the hemoglobin A1c level. Chronic opiate use has been reported to increase hemoglobin A1c levels through mechanisms yet unclear.

Aspirin, vitamin C, and vitamin E have been postulated to interfere with hemoglobin A1c measurement assays, although studies have not been consistent in demonstrating these effects.

Labile diabetes

In some patients with diabetes, blood glucose levels are labile and oscillate between states of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, despite optimal hemoglobin A1c levels.17 In these patients, the average blood glucose level may very well correlate appropriately with the glycated hemoglobin level, but the degree of control would not be acceptable. Fasting hyperglycemia or postprandial hyperglycemia, or both, especially in the setting of significant glycemic variability over the month before testing, may not be captured by the hemoglobin A1c measurement. These glycemic excursions may be important, as data suggest that this variability may independently worsen microvascular complications in diabetic patients.18

ALTERNATIVES TO MEASURING THE GLYCATED HEMOGLOBIN

When hemoglobin A1c levels are suspected to be inaccurate, other tests of the adequacy of glycemic control can be used.19

Continuous glucose monitoring is the gold standard and precisely shows the degree of glycemic variability, usually over 5 days. It is often used when hypoglycemia and wide fluctuations in within-day and day-to-day glucose levels are suspected. In addition, we believe that continuous monitoring could be used to confirm the validity of hemoglobin A1c testing. In a clinical setting in which the level does not seem to match the fingerstick blood glucose readings, it can be a useful tool to assess the range and variation in glycemic control.

This method, however, is not practical in all diabetic patients, and it certainly does not have the same long-term predictive prognostic value. Yet it may still have a role in validating measures of long-term glycemic control (eg, hemoglobin A1c). There is evidence that using continuous glucose monitoring periodically can improve glycemic control, lower hemoglobin A1c levels, and lead to fewer hypoglycemic events.20 As discussed earlier, patients who have labile glycemic excursions and higher risk of microvascular complications can still have “normal” hemoglobin A1c levels; in this scenario, the use of continuous glucose monitoring can lead to lower risk and better control.

1,5-anhydroglucitol and fructosamine are circulating biomarkers that reflect short-term glucose control, ie, over 2 to 3 weeks. The higher the average blood glucose level, the lower the 1,5-anhydroglucitol level, since higher glucose levels competitively inhibit renal reabsorption of this molecule. However, its utility is limited in renal failure, liver disease, and pregnancy.

Fructosamines are nonenzymatically glycated proteins. As markers, they are reliable in renal disease but are unreliable in hypoproteinemic states such as liver disease, nephrosis, and lipemia. This group of proteins represents all of serum-stable glycated proteins; they are strongly influenced by the concentration of serum proteins, as well as by coexisting low-molecular-weight substances in the plasma.

Glycated albumin is superior to glycated hemoglobin in reflecting glycemic control, as it has a faster metabolic turnover than hemoglobin and is not affected by hemoglobin-opathies. Unlike fructosamines, it is not influenced by the serum albumin concentration. Moreover, it may be superior to the hemoglobin A1c in patients who have postprandial hypoglycemia.21

Interestingly, recent cross-sectional analyses suggest that fructosamines and glycated albumin are at least as strongly associated with microvascular complications as the hemoglobin A1c is.22

BE ALERT TO FACTORS THAT AFFECT GLYCATED HEMOGLOBIN

Hemoglobin A1c reflects exposure of red blood cells to glucose. Multiple factors—pathologic, physiologic, and environmental—can influence the glycation process, red blood cell turnover, and the hemoglobin structure in ways that can decrease the reliability of the hemoglobin A1c measurement.

Clinicians should be vigilant for the various clinical situations in which hemoglobin A1c is hard to interpret, and they should be familiar with alternative tests (eg, continuous glucose monitoring, 1,5-anhydroglucitol, fructosamines) that can be used to monitor adequate glycemic control in these patients.

- Colaguiri S, Lee CM, Wong TY, Balkau B, Shaw JE, Borch-Johnsen K; DETECT-2 Collaboration Writing Group. Glycemic thresholds for diabetes-specific retinopathy: implications for diagnostic criteria for diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011; 34:145–150.

- Bonora E, Tuomilehto J. The pros and cons of diagnosing diabetes with A1C. Diabetes Care 2011; 34(suppl 2):S184–S190.

- Rohlfing CL, Wiedmeyer HM, Little RR, England JD, Tennill A, Goldstein DE. Defining the relationship between plasma glucose and HbA(1c): analysis of glucose profiles and HbA(1c) in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Care 2002; 25:275–278.

- Herman WH, Dungan KM, Wolffenbuttel BH, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in mean plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and 1,5-anhydroglucitol in over 2000 patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94:1689–1694.

- Selvin E, Steffes MW, Zhu H, et al. Glycated hemoglobin, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk in nondiabetic adults. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:800–811.

- Tahara Y, Shima K. The response of GHb to stepwise plasma glucose change over time in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 1993; 16:1313–1314.

- Radder JK, van Roosmalen J. HbA1c in healthy, pregnant women. Neth J Med 2005; 63:256–259.

- Mosca A, Paleari R, Dalfra MG, et al. Reference intervals for hemoglobin A1c in pregnant women: data from an Italian multicenter study. Clin Chem 2006; 52:1138–1143.

- Nielsen LR, Ekbom P, Damm P, et al. HbA1c levels are significantly lower in early and late pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2004; 27:1200–1201.

- Makris K, Spanou L. Is there a relationship between mean blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin? J Diabetes Sci Technol 2011; 5:1572–1583.

- Tarim O, Kucukerdogan A, Gunay U, Eralp O, Ercan I. Effects of iron deficiency anemia on hemoglobin A1c in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Int 1999; 41:357–362.

- Panzer S, Kronik G, Lechner K, Bettelheim P, Neumann E, Dudczak R. Glycosylated hemoglobins (GHb): an index of red cell survival. Blood 1982; 59:1348–1350.

- National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program. HbA1c assay interferences. www.ngsp.org/interf.asp. Accessed December 27, 2013.

- Spencer DH, Grossman BJ, Scott MG. Red cell transfusion decreases hemoglobin A1c in patients with diabetes. Clin Chem 2011; 57:344–346.

- Little RR, Rohlfing CL, Tennill AL, et al. Measurement of Hba(1C) in patients with chronic renal failure. Clin Chim Acta 2013; 418:73–76.

- Vos FE, Schollum JB, Walker RJ. Glycated albumin is the preferred marker for assessing glycaemic control in advanced chronic kidney disease. NDT Plus 2011; 4:368–375.

- Kilpatrick ES, Rigby AS, Goode K, Atkin SL. Relating mean blood glucose and glucose variability to the risk of multiple episodes of hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2007; 50:2553–2561.

- Monnier L, Mas E, Ginet C, et al. Activation of oxidative stress by acute glucose fluctuations compared with sustained chronic hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2006; 295:1681–1687.

- Radin MS. Pitfalls in hemoglobin A1c measurement: when results may be misleading. J Gen Intern Med 2013; Sep 4 [epub ahead of print]. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11606-013-2595-x/fulltext.html. Accessed January 29, 2014.

- Leinung M, Nardacci E, Patel N, Bettadahalli S, Paika K, Thompson S. Benefits of short-term professional continuous glucose monitoring in clinical practice. Diabetes Technol Ther 2013; 15:744–747.

- Koga M, Kasayama S. Clinical impact of glycated albumin as another glycemic control marker. Endocr J 2010; 57:751–762.

- Selvin E, Francis LM, Ballantyne CM, et al. Nontraditional markers of glycemia: associations with microvascular conditions. Diabetes Care 2011; 34:960–967.

No. Hemoglobin A1c has been validated as a predictor of diabetes-related complications and is a standard measure of the adequacy of glucose control. But sometimes we need to regard its values with suspicion, especially when they are not concordant with the patient’s self-monitored blood glucose levels.

UNIVERSALLY USED

Measuring glycated hemoglobin has become an essential tool for detecting impaired glucose tolerance (when levels are between 5.7% and 6.5%), for diagnosing diabetes mellitus (when levels are ≥ 6.5%), and for following the adequacy of control in established disease. The results reflect glycemic control over the preceding 2 to 3 months and possibly indicate the risk of complications, particularly microvascular disease in the long term.

The significance of hemoglobin A1c was further accentuated with the results of the DETECT-2 project,1 which showed that the risk of diabetic retinopathy is insignificant with levels lower than 6% and rises substantially when it is greater than 6.5%.

However, because the biochemical hallmark of diabetes is hyperglycemia (and not the glycation of proteins), concerns have been raised about the universal validity of hemoglobin A1c in all diabetic patients, especially when it is used to monitor glucose control in the long term.2

FACTORS THAT AFFECT THE GLYCATED HEMOGLOBIN LEVEL

Altered glycation

Although the hemoglobin A1c value correlates well with the mean blood glucose level over the previous months, it is affected more by the most recent glucose levels than by earlier levels, and it is especially affected by the most recent peak in blood glucose.3 It is estimated that approximately 50% of the hemoglobin A1c level is determined by the plasma glucose level during the preceding 1-month period.3

Other factors that affect levels of glycated hemoglobin independently of the average glucose level during the previous months include genetic predisposition (some people are “rapid glycators”), labile glycation (ie, transient glycation of hemoglobin when exposed to very high concentrations of glucose), and the 2,3-diphosphoglycerate concentration and pH of the blood.2

Hemoglobin factors

Age of red blood cells. Red blood cells last about 120 days, and the mean age of all red blood cells in circulation ranges from 38 to 60 days (50 on average). Turnover is dictated by a number of factors, including ethnicity, which in turn significantly affect hemoglobin A1c values.

Race and ethnicity. African American, Asian, and Hispanic patients may have higher hemoglobin A1c values than white people who have the same blood glucose levels. In one study of racial and ethnic differences in mean plasma glucose, levels were higher by 0.37% in African American patients, 0.27% in Hispanics, and 0.33% in Asians than in white patients, and the differences were statistically significant.4 However, there is no clear evidence that these differences are associated with differences in the incidence of microvascular disease.5

Effects due to heritable factors could vary among ethnic groups. Racial differences in hemoglobin A1c may be ascribed to the degree of glycation, caused by multiple factors, and to socioeconomic status. Interestingly, many of the interracial differences in conditions that affect erythrocyte turnover would in theory lead to a lower hemoglobin A1c in nonwhites, which is not the case.6

Pregnancy. The mechanisms of hemoglobin A1c discrepancy in pregnancy are not clear. It has been demonstrated that pregnant women may have lower hemoglobin A1c levels than nonpregnant women.7–9 Hemodilution and increased cell turnover have been postulated to account for the decrease, although a mechanism has not been described. Interestingly, conflicting data have been reported regarding hemoglobin A1c in the last trimester of pregnancy (increase, decrease, or no change). Iron deficiency has been presumed to cause the increase of hemoglobin A1c in the last trimester.10

Moreover, hemoglobin A1c may reflect glucose levels during a shorter time because of increased turnover of red blood cells that occurs during this state. Erythropoietin and erythrocyte production are increased during normal pregnancy while hemoglobin and hematocrit continuously dilute into the third trimester. In normal pregnancy, the red blood cell life span is decreased due to “emergency hemopoiesis” in response to these elevated erythropoietin levels.

Anemia. Hemolytic anemia, acute bleeding, and iron-deficiency anemia all influence glycated hemoglobin levels. The formation of reticulocytes whose hemoglobin lacks glycosylation may lead to falsely low hemoglobin A1c values. Interestingly, iron deficiency by itself has been observed to cause elevation of hemoglobin A1c through unclear mechanisms11; however, iron replacement may lead to reticulocytosis. Alternatively, asplenic patients may have deceptively higher hemoglobin A1c values because of the increased life span of their red blood cells.12

Hemoglobinopathy. Hemoglobin F may cause overestimation of hemoglobin A1c levels, whereas hemoglobin S and hemoglobin C may cause underestimation. Of note, these effects are method-specific, and newer immunoassay techniques are relatively robust even in the presence of common hemoglobin variants. Clinicians should be aware of their institution’s laboratory method for measuring glycated hemoglobin.13

Comorbidities

Chronic illnesses can cause fluctuation in hemoglobin A1c and make it unreliable. Uremia, severe hypertriglyceridemia, severe hyperbilirubinemia, chronic alcoholism, chronic salicylate use, chronic opioid use, and lead poisoning all can falsely increase hemoglobin A1c levels.

Vitamin and mineral deficiencies (eg, deficiencies of vitamin B12 and iron) can reduce red blood cell turnover and therefore falsely elevate hemoglobin A1c levels. Conversely, medical replacement of these deficiencies could lead to higher red blood cell turnover and reduced hemoglobin A1c levels.

Blood transfusions. Recent reports suggest that red blood cell transfusions reduce the hemoglobin A1c concentration in diabetic patients. This effect was most pronounced in patients who received large transfusion volumes or who had a high hemoglobin A1c level before the transfusion.14

Renal failure. Patients with renal failure have higher levels of carbamylated hemoglobin, which is reported to interfere with measurement and interpretation of hemoglobin A1c. Moreover, there is concern that hemoglobin A1c values may be falsely low in these patients because of shortened erythrocyte survival. Other factors that influence hemoglobin A1c and cause the measured levels to be misleadingly low in renal failure patients include use of recombinant human erythropoietin, the uremic environment, and blood transfusions.15

It has been suggested that glycated albumin may be a better marker for assessing glycemic control in patients with severe chronic kidney disease.16

Medications and supplements that affect hemoglobin

Drugs that may cause hemolysis could lower hemoglobin A1c levels. Examples are dapsone, ribavirin, and sulfonamides. Other drugs can change the structure of hemoglobin. For example, hydroxyurea alters hemoglobin A into hemoglobin F, thus lowering the hemoglobin A1c level. Chronic opiate use has been reported to increase hemoglobin A1c levels through mechanisms yet unclear.

Aspirin, vitamin C, and vitamin E have been postulated to interfere with hemoglobin A1c measurement assays, although studies have not been consistent in demonstrating these effects.

Labile diabetes

In some patients with diabetes, blood glucose levels are labile and oscillate between states of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, despite optimal hemoglobin A1c levels.17 In these patients, the average blood glucose level may very well correlate appropriately with the glycated hemoglobin level, but the degree of control would not be acceptable. Fasting hyperglycemia or postprandial hyperglycemia, or both, especially in the setting of significant glycemic variability over the month before testing, may not be captured by the hemoglobin A1c measurement. These glycemic excursions may be important, as data suggest that this variability may independently worsen microvascular complications in diabetic patients.18

ALTERNATIVES TO MEASURING THE GLYCATED HEMOGLOBIN

When hemoglobin A1c levels are suspected to be inaccurate, other tests of the adequacy of glycemic control can be used.19

Continuous glucose monitoring is the gold standard and precisely shows the degree of glycemic variability, usually over 5 days. It is often used when hypoglycemia and wide fluctuations in within-day and day-to-day glucose levels are suspected. In addition, we believe that continuous monitoring could be used to confirm the validity of hemoglobin A1c testing. In a clinical setting in which the level does not seem to match the fingerstick blood glucose readings, it can be a useful tool to assess the range and variation in glycemic control.

This method, however, is not practical in all diabetic patients, and it certainly does not have the same long-term predictive prognostic value. Yet it may still have a role in validating measures of long-term glycemic control (eg, hemoglobin A1c). There is evidence that using continuous glucose monitoring periodically can improve glycemic control, lower hemoglobin A1c levels, and lead to fewer hypoglycemic events.20 As discussed earlier, patients who have labile glycemic excursions and higher risk of microvascular complications can still have “normal” hemoglobin A1c levels; in this scenario, the use of continuous glucose monitoring can lead to lower risk and better control.

1,5-anhydroglucitol and fructosamine are circulating biomarkers that reflect short-term glucose control, ie, over 2 to 3 weeks. The higher the average blood glucose level, the lower the 1,5-anhydroglucitol level, since higher glucose levels competitively inhibit renal reabsorption of this molecule. However, its utility is limited in renal failure, liver disease, and pregnancy.

Fructosamines are nonenzymatically glycated proteins. As markers, they are reliable in renal disease but are unreliable in hypoproteinemic states such as liver disease, nephrosis, and lipemia. This group of proteins represents all of serum-stable glycated proteins; they are strongly influenced by the concentration of serum proteins, as well as by coexisting low-molecular-weight substances in the plasma.

Glycated albumin is superior to glycated hemoglobin in reflecting glycemic control, as it has a faster metabolic turnover than hemoglobin and is not affected by hemoglobin-opathies. Unlike fructosamines, it is not influenced by the serum albumin concentration. Moreover, it may be superior to the hemoglobin A1c in patients who have postprandial hypoglycemia.21

Interestingly, recent cross-sectional analyses suggest that fructosamines and glycated albumin are at least as strongly associated with microvascular complications as the hemoglobin A1c is.22

BE ALERT TO FACTORS THAT AFFECT GLYCATED HEMOGLOBIN

Hemoglobin A1c reflects exposure of red blood cells to glucose. Multiple factors—pathologic, physiologic, and environmental—can influence the glycation process, red blood cell turnover, and the hemoglobin structure in ways that can decrease the reliability of the hemoglobin A1c measurement.

Clinicians should be vigilant for the various clinical situations in which hemoglobin A1c is hard to interpret, and they should be familiar with alternative tests (eg, continuous glucose monitoring, 1,5-anhydroglucitol, fructosamines) that can be used to monitor adequate glycemic control in these patients.

No. Hemoglobin A1c has been validated as a predictor of diabetes-related complications and is a standard measure of the adequacy of glucose control. But sometimes we need to regard its values with suspicion, especially when they are not concordant with the patient’s self-monitored blood glucose levels.

UNIVERSALLY USED

Measuring glycated hemoglobin has become an essential tool for detecting impaired glucose tolerance (when levels are between 5.7% and 6.5%), for diagnosing diabetes mellitus (when levels are ≥ 6.5%), and for following the adequacy of control in established disease. The results reflect glycemic control over the preceding 2 to 3 months and possibly indicate the risk of complications, particularly microvascular disease in the long term.

The significance of hemoglobin A1c was further accentuated with the results of the DETECT-2 project,1 which showed that the risk of diabetic retinopathy is insignificant with levels lower than 6% and rises substantially when it is greater than 6.5%.

However, because the biochemical hallmark of diabetes is hyperglycemia (and not the glycation of proteins), concerns have been raised about the universal validity of hemoglobin A1c in all diabetic patients, especially when it is used to monitor glucose control in the long term.2

FACTORS THAT AFFECT THE GLYCATED HEMOGLOBIN LEVEL

Altered glycation

Although the hemoglobin A1c value correlates well with the mean blood glucose level over the previous months, it is affected more by the most recent glucose levels than by earlier levels, and it is especially affected by the most recent peak in blood glucose.3 It is estimated that approximately 50% of the hemoglobin A1c level is determined by the plasma glucose level during the preceding 1-month period.3

Other factors that affect levels of glycated hemoglobin independently of the average glucose level during the previous months include genetic predisposition (some people are “rapid glycators”), labile glycation (ie, transient glycation of hemoglobin when exposed to very high concentrations of glucose), and the 2,3-diphosphoglycerate concentration and pH of the blood.2

Hemoglobin factors

Age of red blood cells. Red blood cells last about 120 days, and the mean age of all red blood cells in circulation ranges from 38 to 60 days (50 on average). Turnover is dictated by a number of factors, including ethnicity, which in turn significantly affect hemoglobin A1c values.

Race and ethnicity. African American, Asian, and Hispanic patients may have higher hemoglobin A1c values than white people who have the same blood glucose levels. In one study of racial and ethnic differences in mean plasma glucose, levels were higher by 0.37% in African American patients, 0.27% in Hispanics, and 0.33% in Asians than in white patients, and the differences were statistically significant.4 However, there is no clear evidence that these differences are associated with differences in the incidence of microvascular disease.5

Effects due to heritable factors could vary among ethnic groups. Racial differences in hemoglobin A1c may be ascribed to the degree of glycation, caused by multiple factors, and to socioeconomic status. Interestingly, many of the interracial differences in conditions that affect erythrocyte turnover would in theory lead to a lower hemoglobin A1c in nonwhites, which is not the case.6

Pregnancy. The mechanisms of hemoglobin A1c discrepancy in pregnancy are not clear. It has been demonstrated that pregnant women may have lower hemoglobin A1c levels than nonpregnant women.7–9 Hemodilution and increased cell turnover have been postulated to account for the decrease, although a mechanism has not been described. Interestingly, conflicting data have been reported regarding hemoglobin A1c in the last trimester of pregnancy (increase, decrease, or no change). Iron deficiency has been presumed to cause the increase of hemoglobin A1c in the last trimester.10

Moreover, hemoglobin A1c may reflect glucose levels during a shorter time because of increased turnover of red blood cells that occurs during this state. Erythropoietin and erythrocyte production are increased during normal pregnancy while hemoglobin and hematocrit continuously dilute into the third trimester. In normal pregnancy, the red blood cell life span is decreased due to “emergency hemopoiesis” in response to these elevated erythropoietin levels.

Anemia. Hemolytic anemia, acute bleeding, and iron-deficiency anemia all influence glycated hemoglobin levels. The formation of reticulocytes whose hemoglobin lacks glycosylation may lead to falsely low hemoglobin A1c values. Interestingly, iron deficiency by itself has been observed to cause elevation of hemoglobin A1c through unclear mechanisms11; however, iron replacement may lead to reticulocytosis. Alternatively, asplenic patients may have deceptively higher hemoglobin A1c values because of the increased life span of their red blood cells.12

Hemoglobinopathy. Hemoglobin F may cause overestimation of hemoglobin A1c levels, whereas hemoglobin S and hemoglobin C may cause underestimation. Of note, these effects are method-specific, and newer immunoassay techniques are relatively robust even in the presence of common hemoglobin variants. Clinicians should be aware of their institution’s laboratory method for measuring glycated hemoglobin.13

Comorbidities

Chronic illnesses can cause fluctuation in hemoglobin A1c and make it unreliable. Uremia, severe hypertriglyceridemia, severe hyperbilirubinemia, chronic alcoholism, chronic salicylate use, chronic opioid use, and lead poisoning all can falsely increase hemoglobin A1c levels.

Vitamin and mineral deficiencies (eg, deficiencies of vitamin B12 and iron) can reduce red blood cell turnover and therefore falsely elevate hemoglobin A1c levels. Conversely, medical replacement of these deficiencies could lead to higher red blood cell turnover and reduced hemoglobin A1c levels.

Blood transfusions. Recent reports suggest that red blood cell transfusions reduce the hemoglobin A1c concentration in diabetic patients. This effect was most pronounced in patients who received large transfusion volumes or who had a high hemoglobin A1c level before the transfusion.14

Renal failure. Patients with renal failure have higher levels of carbamylated hemoglobin, which is reported to interfere with measurement and interpretation of hemoglobin A1c. Moreover, there is concern that hemoglobin A1c values may be falsely low in these patients because of shortened erythrocyte survival. Other factors that influence hemoglobin A1c and cause the measured levels to be misleadingly low in renal failure patients include use of recombinant human erythropoietin, the uremic environment, and blood transfusions.15

It has been suggested that glycated albumin may be a better marker for assessing glycemic control in patients with severe chronic kidney disease.16

Medications and supplements that affect hemoglobin

Drugs that may cause hemolysis could lower hemoglobin A1c levels. Examples are dapsone, ribavirin, and sulfonamides. Other drugs can change the structure of hemoglobin. For example, hydroxyurea alters hemoglobin A into hemoglobin F, thus lowering the hemoglobin A1c level. Chronic opiate use has been reported to increase hemoglobin A1c levels through mechanisms yet unclear.

Aspirin, vitamin C, and vitamin E have been postulated to interfere with hemoglobin A1c measurement assays, although studies have not been consistent in demonstrating these effects.

Labile diabetes

In some patients with diabetes, blood glucose levels are labile and oscillate between states of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, despite optimal hemoglobin A1c levels.17 In these patients, the average blood glucose level may very well correlate appropriately with the glycated hemoglobin level, but the degree of control would not be acceptable. Fasting hyperglycemia or postprandial hyperglycemia, or both, especially in the setting of significant glycemic variability over the month before testing, may not be captured by the hemoglobin A1c measurement. These glycemic excursions may be important, as data suggest that this variability may independently worsen microvascular complications in diabetic patients.18

ALTERNATIVES TO MEASURING THE GLYCATED HEMOGLOBIN

When hemoglobin A1c levels are suspected to be inaccurate, other tests of the adequacy of glycemic control can be used.19

Continuous glucose monitoring is the gold standard and precisely shows the degree of glycemic variability, usually over 5 days. It is often used when hypoglycemia and wide fluctuations in within-day and day-to-day glucose levels are suspected. In addition, we believe that continuous monitoring could be used to confirm the validity of hemoglobin A1c testing. In a clinical setting in which the level does not seem to match the fingerstick blood glucose readings, it can be a useful tool to assess the range and variation in glycemic control.

This method, however, is not practical in all diabetic patients, and it certainly does not have the same long-term predictive prognostic value. Yet it may still have a role in validating measures of long-term glycemic control (eg, hemoglobin A1c). There is evidence that using continuous glucose monitoring periodically can improve glycemic control, lower hemoglobin A1c levels, and lead to fewer hypoglycemic events.20 As discussed earlier, patients who have labile glycemic excursions and higher risk of microvascular complications can still have “normal” hemoglobin A1c levels; in this scenario, the use of continuous glucose monitoring can lead to lower risk and better control.

1,5-anhydroglucitol and fructosamine are circulating biomarkers that reflect short-term glucose control, ie, over 2 to 3 weeks. The higher the average blood glucose level, the lower the 1,5-anhydroglucitol level, since higher glucose levels competitively inhibit renal reabsorption of this molecule. However, its utility is limited in renal failure, liver disease, and pregnancy.

Fructosamines are nonenzymatically glycated proteins. As markers, they are reliable in renal disease but are unreliable in hypoproteinemic states such as liver disease, nephrosis, and lipemia. This group of proteins represents all of serum-stable glycated proteins; they are strongly influenced by the concentration of serum proteins, as well as by coexisting low-molecular-weight substances in the plasma.

Glycated albumin is superior to glycated hemoglobin in reflecting glycemic control, as it has a faster metabolic turnover than hemoglobin and is not affected by hemoglobin-opathies. Unlike fructosamines, it is not influenced by the serum albumin concentration. Moreover, it may be superior to the hemoglobin A1c in patients who have postprandial hypoglycemia.21

Interestingly, recent cross-sectional analyses suggest that fructosamines and glycated albumin are at least as strongly associated with microvascular complications as the hemoglobin A1c is.22

BE ALERT TO FACTORS THAT AFFECT GLYCATED HEMOGLOBIN

Hemoglobin A1c reflects exposure of red blood cells to glucose. Multiple factors—pathologic, physiologic, and environmental—can influence the glycation process, red blood cell turnover, and the hemoglobin structure in ways that can decrease the reliability of the hemoglobin A1c measurement.

Clinicians should be vigilant for the various clinical situations in which hemoglobin A1c is hard to interpret, and they should be familiar with alternative tests (eg, continuous glucose monitoring, 1,5-anhydroglucitol, fructosamines) that can be used to monitor adequate glycemic control in these patients.

- Colaguiri S, Lee CM, Wong TY, Balkau B, Shaw JE, Borch-Johnsen K; DETECT-2 Collaboration Writing Group. Glycemic thresholds for diabetes-specific retinopathy: implications for diagnostic criteria for diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011; 34:145–150.

- Bonora E, Tuomilehto J. The pros and cons of diagnosing diabetes with A1C. Diabetes Care 2011; 34(suppl 2):S184–S190.

- Rohlfing CL, Wiedmeyer HM, Little RR, England JD, Tennill A, Goldstein DE. Defining the relationship between plasma glucose and HbA(1c): analysis of glucose profiles and HbA(1c) in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Care 2002; 25:275–278.

- Herman WH, Dungan KM, Wolffenbuttel BH, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in mean plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and 1,5-anhydroglucitol in over 2000 patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94:1689–1694.

- Selvin E, Steffes MW, Zhu H, et al. Glycated hemoglobin, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk in nondiabetic adults. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:800–811.

- Tahara Y, Shima K. The response of GHb to stepwise plasma glucose change over time in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 1993; 16:1313–1314.

- Radder JK, van Roosmalen J. HbA1c in healthy, pregnant women. Neth J Med 2005; 63:256–259.

- Mosca A, Paleari R, Dalfra MG, et al. Reference intervals for hemoglobin A1c in pregnant women: data from an Italian multicenter study. Clin Chem 2006; 52:1138–1143.

- Nielsen LR, Ekbom P, Damm P, et al. HbA1c levels are significantly lower in early and late pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2004; 27:1200–1201.

- Makris K, Spanou L. Is there a relationship between mean blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin? J Diabetes Sci Technol 2011; 5:1572–1583.

- Tarim O, Kucukerdogan A, Gunay U, Eralp O, Ercan I. Effects of iron deficiency anemia on hemoglobin A1c in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Int 1999; 41:357–362.

- Panzer S, Kronik G, Lechner K, Bettelheim P, Neumann E, Dudczak R. Glycosylated hemoglobins (GHb): an index of red cell survival. Blood 1982; 59:1348–1350.

- National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program. HbA1c assay interferences. www.ngsp.org/interf.asp. Accessed December 27, 2013.

- Spencer DH, Grossman BJ, Scott MG. Red cell transfusion decreases hemoglobin A1c in patients with diabetes. Clin Chem 2011; 57:344–346.

- Little RR, Rohlfing CL, Tennill AL, et al. Measurement of Hba(1C) in patients with chronic renal failure. Clin Chim Acta 2013; 418:73–76.

- Vos FE, Schollum JB, Walker RJ. Glycated albumin is the preferred marker for assessing glycaemic control in advanced chronic kidney disease. NDT Plus 2011; 4:368–375.

- Kilpatrick ES, Rigby AS, Goode K, Atkin SL. Relating mean blood glucose and glucose variability to the risk of multiple episodes of hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2007; 50:2553–2561.

- Monnier L, Mas E, Ginet C, et al. Activation of oxidative stress by acute glucose fluctuations compared with sustained chronic hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2006; 295:1681–1687.

- Radin MS. Pitfalls in hemoglobin A1c measurement: when results may be misleading. J Gen Intern Med 2013; Sep 4 [epub ahead of print]. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11606-013-2595-x/fulltext.html. Accessed January 29, 2014.

- Leinung M, Nardacci E, Patel N, Bettadahalli S, Paika K, Thompson S. Benefits of short-term professional continuous glucose monitoring in clinical practice. Diabetes Technol Ther 2013; 15:744–747.

- Koga M, Kasayama S. Clinical impact of glycated albumin as another glycemic control marker. Endocr J 2010; 57:751–762.

- Selvin E, Francis LM, Ballantyne CM, et al. Nontraditional markers of glycemia: associations with microvascular conditions. Diabetes Care 2011; 34:960–967.

- Colaguiri S, Lee CM, Wong TY, Balkau B, Shaw JE, Borch-Johnsen K; DETECT-2 Collaboration Writing Group. Glycemic thresholds for diabetes-specific retinopathy: implications for diagnostic criteria for diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011; 34:145–150.

- Bonora E, Tuomilehto J. The pros and cons of diagnosing diabetes with A1C. Diabetes Care 2011; 34(suppl 2):S184–S190.

- Rohlfing CL, Wiedmeyer HM, Little RR, England JD, Tennill A, Goldstein DE. Defining the relationship between plasma glucose and HbA(1c): analysis of glucose profiles and HbA(1c) in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Care 2002; 25:275–278.

- Herman WH, Dungan KM, Wolffenbuttel BH, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in mean plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and 1,5-anhydroglucitol in over 2000 patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94:1689–1694.

- Selvin E, Steffes MW, Zhu H, et al. Glycated hemoglobin, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk in nondiabetic adults. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:800–811.

- Tahara Y, Shima K. The response of GHb to stepwise plasma glucose change over time in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 1993; 16:1313–1314.

- Radder JK, van Roosmalen J. HbA1c in healthy, pregnant women. Neth J Med 2005; 63:256–259.

- Mosca A, Paleari R, Dalfra MG, et al. Reference intervals for hemoglobin A1c in pregnant women: data from an Italian multicenter study. Clin Chem 2006; 52:1138–1143.

- Nielsen LR, Ekbom P, Damm P, et al. HbA1c levels are significantly lower in early and late pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2004; 27:1200–1201.

- Makris K, Spanou L. Is there a relationship between mean blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin? J Diabetes Sci Technol 2011; 5:1572–1583.

- Tarim O, Kucukerdogan A, Gunay U, Eralp O, Ercan I. Effects of iron deficiency anemia on hemoglobin A1c in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Int 1999; 41:357–362.

- Panzer S, Kronik G, Lechner K, Bettelheim P, Neumann E, Dudczak R. Glycosylated hemoglobins (GHb): an index of red cell survival. Blood 1982; 59:1348–1350.

- National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program. HbA1c assay interferences. www.ngsp.org/interf.asp. Accessed December 27, 2013.

- Spencer DH, Grossman BJ, Scott MG. Red cell transfusion decreases hemoglobin A1c in patients with diabetes. Clin Chem 2011; 57:344–346.

- Little RR, Rohlfing CL, Tennill AL, et al. Measurement of Hba(1C) in patients with chronic renal failure. Clin Chim Acta 2013; 418:73–76.

- Vos FE, Schollum JB, Walker RJ. Glycated albumin is the preferred marker for assessing glycaemic control in advanced chronic kidney disease. NDT Plus 2011; 4:368–375.

- Kilpatrick ES, Rigby AS, Goode K, Atkin SL. Relating mean blood glucose and glucose variability to the risk of multiple episodes of hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2007; 50:2553–2561.

- Monnier L, Mas E, Ginet C, et al. Activation of oxidative stress by acute glucose fluctuations compared with sustained chronic hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2006; 295:1681–1687.

- Radin MS. Pitfalls in hemoglobin A1c measurement: when results may be misleading. J Gen Intern Med 2013; Sep 4 [epub ahead of print]. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11606-013-2595-x/fulltext.html. Accessed January 29, 2014.

- Leinung M, Nardacci E, Patel N, Bettadahalli S, Paika K, Thompson S. Benefits of short-term professional continuous glucose monitoring in clinical practice. Diabetes Technol Ther 2013; 15:744–747.

- Koga M, Kasayama S. Clinical impact of glycated albumin as another glycemic control marker. Endocr J 2010; 57:751–762.

- Selvin E, Francis LM, Ballantyne CM, et al. Nontraditional markers of glycemia: associations with microvascular conditions. Diabetes Care 2011; 34:960–967.

New practice guidelines: Constrained or enhanced by the evidence?

Recent guidelines have revisited the management of two major modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular morbidity: hypercholesterolemia and hypertension. The authors of each purposefully emphasized high-grade evidence in generating their recommendations. But, as pointed out by Thomas et al in this issue of the Journal,1 the authors of the hypertension guidelines still resorted to “expert opinion” in five of their 10 recommendations.

The authors of the new hypertension guidelines from the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8),2 as well as the new cholesterol guidelines3 discussed by Raymond et al in the January 2014 issue of the Journal,4 relied on interventional clinical trial evidence for their recommendations. The good news in the context of pay-for-performance metrics is that both of these new guidelines are easier to adhere to than the previous ones. But will the new guidelines really help us achieve better patient outcomes?

Concerns about these guidelines spring directly from their assumed major strength—ie, that they are based on interventional trial data. Well-run, randomized, controlled trials are the brass ring of evidence-based medical practice, presumably providing the cleanest demonstration of therapeutic efficacy. But with “clean” data potentially come sterile, non-real-world conclusions that may advise but should not limit our practice decisions. Most of our patients do not fit neatly into trial inclusion and exclusion criteria, nor do they exactly match the demographics of trial volunteers. Patients who participate in clinical trials are not the same as the patients who populate our clinics. Nor, unfortunately, is the blood pressure measurement technique likely the same in the clinical trial setting as in many of our offices.

In the clinic, it seems obvious not to be overly zealous about blood pressure control in an elderly, frail, hypertensive patient. But at the same time, aiming for a systolic pressure lower than 150 mm Hg (which is looser than in the last set of guidelines) as a target for those over age 60 is incredibly arbitrary, given that physiology and biologic risk rarely act in a step-function manner. Biologic metrics tend to behave as a continuum. If we recognize that the blood pressure can be readily and safely reduced further in a given patient, and if there are observational data to support the concept that risk for cardiovascular events roughly parallels the systolic blood pressure in a continuous manner to lower than 150 mm Hg, why aim to lower it only slightly? Trial-based guidelines are valuable, but they should not replace sound physiologic reasoning and common sense (also known as “expert opinion”). Yet we must temper this logical reasoning with lessons learned from trials such as ACCORD,5 which showed that overly vigorous efforts at reaching theoretical therapeutic targets may be fraught with unexpected adverse outcomes.

Our challenge is to appropriately individualize therapy, usually in the absence of relevant comparative efficacy studies. Trying to apply homogenized clinical trial data to the individual patient in the examination room is not always reasonable. Treating a 59-year-old who has a slowly escalating systolic pressure of 142 mm Hg is not the same as treating a 32-year-old who has a chronic pressure of 138 and an audible S4.

The new hypertension guidelines should be easier to implement than the previous ones in JNC 7. I like some of the specificity of the new recommendations and the disappearance of beta-blockers from the list of recommended early therapies. Yet I think that in the presence of comorbidities and end-organ damage, they may be too lax. And certain groups are left relatively undiscussed, such as patients with cerebrovascular disease, known hypertensive vascular injury, and obstructive sleep apnea, as there were limited trial data to provide guidance (although for some clinical subsets we do have very suggestive observational and experiential data). We can’t always wait for the perfect trial to be done in order to make clinical decisions.

To paraphrase Thomas et al,1 for these guidelines, one size fits many, but we still must do significant custom tailoring in the office. In the months ahead, we will try to provide some guidance on how to effectively deal with those situations where robust trial evidence is insufficient to direct clinical decision-making.

- Thomas G, Shishehbor M, Brill D, Nally JV Jr. New hypertension guidelines: one size fits most? Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:178–188.

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 2013; doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427.

- Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; doi: 10.1016/jacc.2013.11.002.

- Raymond C, Cho L, Rocco M, Hazen SL. New cholesterol guidelines: worth the wait? Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:11–19.

- Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al; ACCORD Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1575–1585.

Recent guidelines have revisited the management of two major modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular morbidity: hypercholesterolemia and hypertension. The authors of each purposefully emphasized high-grade evidence in generating their recommendations. But, as pointed out by Thomas et al in this issue of the Journal,1 the authors of the hypertension guidelines still resorted to “expert opinion” in five of their 10 recommendations.

The authors of the new hypertension guidelines from the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8),2 as well as the new cholesterol guidelines3 discussed by Raymond et al in the January 2014 issue of the Journal,4 relied on interventional clinical trial evidence for their recommendations. The good news in the context of pay-for-performance metrics is that both of these new guidelines are easier to adhere to than the previous ones. But will the new guidelines really help us achieve better patient outcomes?

Concerns about these guidelines spring directly from their assumed major strength—ie, that they are based on interventional trial data. Well-run, randomized, controlled trials are the brass ring of evidence-based medical practice, presumably providing the cleanest demonstration of therapeutic efficacy. But with “clean” data potentially come sterile, non-real-world conclusions that may advise but should not limit our practice decisions. Most of our patients do not fit neatly into trial inclusion and exclusion criteria, nor do they exactly match the demographics of trial volunteers. Patients who participate in clinical trials are not the same as the patients who populate our clinics. Nor, unfortunately, is the blood pressure measurement technique likely the same in the clinical trial setting as in many of our offices.

In the clinic, it seems obvious not to be overly zealous about blood pressure control in an elderly, frail, hypertensive patient. But at the same time, aiming for a systolic pressure lower than 150 mm Hg (which is looser than in the last set of guidelines) as a target for those over age 60 is incredibly arbitrary, given that physiology and biologic risk rarely act in a step-function manner. Biologic metrics tend to behave as a continuum. If we recognize that the blood pressure can be readily and safely reduced further in a given patient, and if there are observational data to support the concept that risk for cardiovascular events roughly parallels the systolic blood pressure in a continuous manner to lower than 150 mm Hg, why aim to lower it only slightly? Trial-based guidelines are valuable, but they should not replace sound physiologic reasoning and common sense (also known as “expert opinion”). Yet we must temper this logical reasoning with lessons learned from trials such as ACCORD,5 which showed that overly vigorous efforts at reaching theoretical therapeutic targets may be fraught with unexpected adverse outcomes.

Our challenge is to appropriately individualize therapy, usually in the absence of relevant comparative efficacy studies. Trying to apply homogenized clinical trial data to the individual patient in the examination room is not always reasonable. Treating a 59-year-old who has a slowly escalating systolic pressure of 142 mm Hg is not the same as treating a 32-year-old who has a chronic pressure of 138 and an audible S4.

The new hypertension guidelines should be easier to implement than the previous ones in JNC 7. I like some of the specificity of the new recommendations and the disappearance of beta-blockers from the list of recommended early therapies. Yet I think that in the presence of comorbidities and end-organ damage, they may be too lax. And certain groups are left relatively undiscussed, such as patients with cerebrovascular disease, known hypertensive vascular injury, and obstructive sleep apnea, as there were limited trial data to provide guidance (although for some clinical subsets we do have very suggestive observational and experiential data). We can’t always wait for the perfect trial to be done in order to make clinical decisions.

To paraphrase Thomas et al,1 for these guidelines, one size fits many, but we still must do significant custom tailoring in the office. In the months ahead, we will try to provide some guidance on how to effectively deal with those situations where robust trial evidence is insufficient to direct clinical decision-making.

Recent guidelines have revisited the management of two major modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular morbidity: hypercholesterolemia and hypertension. The authors of each purposefully emphasized high-grade evidence in generating their recommendations. But, as pointed out by Thomas et al in this issue of the Journal,1 the authors of the hypertension guidelines still resorted to “expert opinion” in five of their 10 recommendations.

The authors of the new hypertension guidelines from the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8),2 as well as the new cholesterol guidelines3 discussed by Raymond et al in the January 2014 issue of the Journal,4 relied on interventional clinical trial evidence for their recommendations. The good news in the context of pay-for-performance metrics is that both of these new guidelines are easier to adhere to than the previous ones. But will the new guidelines really help us achieve better patient outcomes?

Concerns about these guidelines spring directly from their assumed major strength—ie, that they are based on interventional trial data. Well-run, randomized, controlled trials are the brass ring of evidence-based medical practice, presumably providing the cleanest demonstration of therapeutic efficacy. But with “clean” data potentially come sterile, non-real-world conclusions that may advise but should not limit our practice decisions. Most of our patients do not fit neatly into trial inclusion and exclusion criteria, nor do they exactly match the demographics of trial volunteers. Patients who participate in clinical trials are not the same as the patients who populate our clinics. Nor, unfortunately, is the blood pressure measurement technique likely the same in the clinical trial setting as in many of our offices.

In the clinic, it seems obvious not to be overly zealous about blood pressure control in an elderly, frail, hypertensive patient. But at the same time, aiming for a systolic pressure lower than 150 mm Hg (which is looser than in the last set of guidelines) as a target for those over age 60 is incredibly arbitrary, given that physiology and biologic risk rarely act in a step-function manner. Biologic metrics tend to behave as a continuum. If we recognize that the blood pressure can be readily and safely reduced further in a given patient, and if there are observational data to support the concept that risk for cardiovascular events roughly parallels the systolic blood pressure in a continuous manner to lower than 150 mm Hg, why aim to lower it only slightly? Trial-based guidelines are valuable, but they should not replace sound physiologic reasoning and common sense (also known as “expert opinion”). Yet we must temper this logical reasoning with lessons learned from trials such as ACCORD,5 which showed that overly vigorous efforts at reaching theoretical therapeutic targets may be fraught with unexpected adverse outcomes.

Our challenge is to appropriately individualize therapy, usually in the absence of relevant comparative efficacy studies. Trying to apply homogenized clinical trial data to the individual patient in the examination room is not always reasonable. Treating a 59-year-old who has a slowly escalating systolic pressure of 142 mm Hg is not the same as treating a 32-year-old who has a chronic pressure of 138 and an audible S4.

The new hypertension guidelines should be easier to implement than the previous ones in JNC 7. I like some of the specificity of the new recommendations and the disappearance of beta-blockers from the list of recommended early therapies. Yet I think that in the presence of comorbidities and end-organ damage, they may be too lax. And certain groups are left relatively undiscussed, such as patients with cerebrovascular disease, known hypertensive vascular injury, and obstructive sleep apnea, as there were limited trial data to provide guidance (although for some clinical subsets we do have very suggestive observational and experiential data). We can’t always wait for the perfect trial to be done in order to make clinical decisions.

To paraphrase Thomas et al,1 for these guidelines, one size fits many, but we still must do significant custom tailoring in the office. In the months ahead, we will try to provide some guidance on how to effectively deal with those situations where robust trial evidence is insufficient to direct clinical decision-making.

- Thomas G, Shishehbor M, Brill D, Nally JV Jr. New hypertension guidelines: one size fits most? Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:178–188.

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 2013; doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427.

- Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; doi: 10.1016/jacc.2013.11.002.

- Raymond C, Cho L, Rocco M, Hazen SL. New cholesterol guidelines: worth the wait? Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:11–19.

- Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al; ACCORD Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1575–1585.

- Thomas G, Shishehbor M, Brill D, Nally JV Jr. New hypertension guidelines: one size fits most? Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:178–188.

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 2013; doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427.

- Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; doi: 10.1016/jacc.2013.11.002.

- Raymond C, Cho L, Rocco M, Hazen SL. New cholesterol guidelines: worth the wait? Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:11–19.

- Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al; ACCORD Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1575–1585.

New hypertension guidelines: One size fits most?

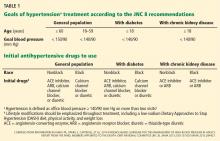

The report of the panel appointed to the eighth Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 8),1 published in December 2013 after considerable delay, contains some important changes from earlier guidelines from this group.2 For example:

- The blood pressure goal has been changed to less than 150/90 mm Hg in people age 60 and older. Formerly, the goal was less than 140/90 mm Hg.

- The goal has been changed to less than 140/90 mm Hg in all others, including people with diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. Formerly, those two groups had a goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg.

- The initial choice of therapy can be from any of four classes of drugs: thiazide-type diuretics, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). Formerly, the list also contained beta-blockers. Also, thiazide-type diuretics have lost their “preferred” status.

The new guidelines are evidence-based and are intended to simplify the way that hypertension is managed. Below, we summarize them—how they were developed, their strengths and limitations, and the main changes from earlier JNC reports.

WHOSE GUIDELINES ARE THESE?

The JNC has issued guidelines for managing hypertension since 1976, traditionally sanctioned by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health. The guidelines have generally been updated every 4 to 5 years, with the last update, JNC 7,2 published in 2003.

The JNC 8 panel, consisting of 17 members, was commissioned by the NHLBI in 2008. However, in June 2013, the NHLBI announced it was withdrawing from guideline development and was delegating it to selected specialty organizations.3,4 In the interest of bringing the already delayed guidelines to the public in a timely manner, the JNC 8 panel decided to pursue publication independently and submitted the report to a medical journal. It is therefore not an official NHLBI-sanctioned report.

Here, we will refer to the new guidelines as “JNC 8,” but they are officially from “panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8).”

THREE QUESTIONS THAT GUIDED THE GUIDELINES

Epidemiologic studies clearly show a close relationship between blood pressure and the risk of heart disease, stroke, and kidney disease, these risks being lowest at a blood pressure of around 115/75 mm Hg.5 However, clinical trials have failed to show any evidence to justify treatment with antihypertensive medications to such a low level once hypertension has been diagnosed.

Patients and health care providers thus face questions about when to begin treatment, how low to aim for, and which antihypertensive medications to use. The JNC 8 panel focused on these three questions, believing them to be of greatest relevance to primary care providers.

A RIGOROUS PROCESS OF EVIDENCE REVIEW AND GUIDELINE DEVELOPMENT

The JNC 8 panel followed the guideline-development pathway outlined by the Institute of Medicine report, Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust.6

Studies published from January 1966 through December 2009 that met specified criteria were selected for evidence review. Specifically, the studies had to be randomized controlled trials—no observational studies, systematic reviews, or meta-analyses, which were allowed in the JNC 7 report—with sample sizes of more than 100. Follow-up had to be for more than 1 year. Participants had to be age 18 or older and have hypertension—studies with patients with normal blood pressure or prehypertension were excluded. Health outcomes had to be reported, ie, “hard” end points such as rates of death, myocardial infarction, heart failure, hospitalization for heart failure, stroke, revascularization, and end-stage renal disease. Post hoc analyses were not allowed. The studies had to be rated by the NHLBI’s standardized quality rating tool as “good” (which has the least risk of bias, with valid results) or “fair (which is susceptible to some bias, but not enough to invalidate the results).

Subsequently, another search was conducted for relevant studies published from December 2009 through August 2013. In addition to meeting all the other criteria, this bridging search further restricted selection to major multicenter studies with sample sizes of more than 2,000.

An external methodology team performed the initial literature review and summarized the data. The JNC panel then crafted evidence statements and clinical recommendations using the evidence quality rating and grading systems developed by the NHLBI. In January 2013, the NHLBI submitted the guidelines for external review by individual reviewers with expertise in hypertension and to federal agencies, and a revised document was framed based on their comments and suggestions.

The evidence statements are detailed in an online 300-page supplemental review, and the panel members have indicated that reviewer comments and responses from the presubmission review process will be made available on request.

NINE RECOMMENDATIONS AND ONE COROLLARY

The panel made nine recommendations and one corollary recommendation based on a review of the evidence. Of the 10 total recommendations, five are based on expert opinion. Another two were rated as “moderate” in strength, one was “weak,” and only two were rated as “strong” (ie, based on high-quality evidence).

Recommendation 1: < 150/90 for those 60 and older

In the general population age 60 and older, the JNC 8 recommends starting drug treatment if the systolic pressure is 150 mm Hg or higher or if the diastolic pressure is 90 mm Hg or higher, and aiming for a systolic goal of less than 150 mm Hg and a diastolic goal of less than 90 mm Hg.

Strength of recommendation—strong (grade A).

Comments. Of all the recommendations, this one will probably have the greatest impact on clinical practice. Consider a frail 70-year-old patient at risk of falls who is taking two antihypertensive medications and whose blood pressure is 148/85 mm Hg. This level would have been considered too high under JNC 7 but is now acceptable, and the patient’s therapy does not have to be escalated.

The age cutoff of 60 years for this recommendation is debatable. The Japanese Trial to Assess Optimal Systolic Blood Pressure in Elderly Hypertensive Patients (JATOS)7 included patients ages 60 to 85 (mean age 74) and found no difference in outcomes comparing a goal systolic pressure of less than 140 mm Hg (this group achieved a mean systolic pressure of 135.9 mm Hg) and a goal systolic pressure of 140 to 160 mm Hg (achieved systolic pressure 145.6 mm Hg).

Similarly, the Valsartan in Elderly Isolated Systolic Hypertension (VALISH) trial8 included patients ages 70 to 84 (mean age 76.1) and found no difference in outcomes between a goal systolic pressure of less than 140 mm Hg (achieved systolic pressure 136.6 mm Hg) and a goal of 140 to 150 mm Hg (achieved systolic pressure 142 mm Hg).

The Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET)9 found lower rates of stroke, death, and heart failure in patients age 80 and older when their systolic pressure was less than 150 mm Hg.

While these trials support a goal pressure of less than 150 mm Hg in the elderly, it is unclear whether this goal should be applied beginning at age 60. Other guidelines, including those recently released jointly by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension, recommend a systolic goal of less than 150 mm Hg in people age 80 and older—not age 60.10

The recommendation for a goal systolic pressure of less than 150 mm Hg in people age 60 and older was not unanimous; some panel members recommended continuing the JNC 7 goal of less than 140 mm Hg based on expert opinion, as they believed that the evidence was insufficient, especially in high-risk subgroups such as black people and those with cerebrovascular disease and other risk factors.

A subsequent minority report from five panel members discusses in more detail why they believe the systolic target should be kept lower than 140 mm Hg in patients age 60 or older until the risks and benefits of a higher target become clearer.11

Corollary recommendation: No need to down-titrate if lower than 140

In the general population age 60 and older, dosages do not have to be adjusted downward if the patient’s systolic pressure is already lower than 140 mm Hg and treatment is well tolerated without adverse effects on health or quality of life.

Strength of recommendation—expert opinion (grade E).

Comments. In the studies that supported a systolic goal lower than 150 mm Hg, many participants actually achieved a systolic pressure lower than 140 mm Hg without any adverse events. Trials that showed no benefit from a systolic goal lower than 140 mm Hg were graded as lower in quality. Thus, the possibility remains that a systolic goal lower than 140 mm Hg could have a clinically important benefit. Therefore, medications do not have to be adjusted so that blood pressure can “ride up.”

For example, therapy does not need to be down-titrated in a 65-year-old patient whose blood pressure is 138/85 mm Hg on two medications that he or she is tolerating well. On the other hand, based on Recommendation 1, therapy can be down-titrated in a 65-year-old whose pressure is 138/85 mm Hg on four medications that are causing side effects.

Recommendation 2: Diastolic < 90 for those younger than 60

In the general population younger than 60 years, JNC 8 recommends starting pharmacologic treatment if the diastolic pressure is 90 mm Hg or higher and aiming for a goal diastolic pressure of less than 90 mm Hg.

Strength of recommendation—strong (grade A) for ages 30 to 59, expert opinion (grade E) for ages 18 to 29.

Comments. The panel found no evidence to support a goal diastolic pressure of 80 mm Hg or less (or 85 mm Hg or less) compared with 90 mm Hg or less in this population.

It is reasonable to aim for the same diastolic goal in younger persons (under age 30), given the higher prevalence of diastolic hypertension in younger people.

Recommendation 3: Systolic < 140 for those younger than 60

In the general population younger than 60 years, we should start drug treatment at a systolic pressure of 140 mm Hg or higher and treat to a systolic goal of less than 140 mm Hg.

Strength of recommendation—expert opinion (grade E).

Comments. Although evidence was insufficient to support this recommendation, the panel decided to keep the same systolic goal for people younger than 60 as in the JNC 7 recommendations, for the following two reasons.

First, there is strong evidence supporting a diastolic goal of less than 90 mm Hg in this population (Recommendation 2), and many study participants who achieved a diastolic pressure lower than 90 mm Hg also achieved a systolic pressure lower than 140. Therefore, it is not possible to tease out whether the outcome benefits were due to lower systolic pressure or to lower diastolic pressure, or to both.

Second, the panel believed the guidelines would be simpler to implement if the systolic goals were the same in the general population as in those with chronic kidney disease or diabetes (see below).

Recommendation 4: < 140/90 in chronic kidney disease

In patients age 18 and older with chronic kidney disease, JNC 8 recommends starting drug treatment at a systolic pressure of 140 mm Hg or higher or a diastolic pressure of 90 mm Hg or higher and treating to a goal systolic pressure of less than 140 mm Hg and a diastolic pressure of less than 90 mm Hg.

Chronic kidney disease is defined as either a glomerular filtration rate (estimated or measured) less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 in people up to age 70, or albuminuria, defined as more than 30 mg/g of creatinine at any glomerular filtration rate at any age.

Strength of recommendation—expert opinion (grade E).

Comments. There was insufficient evidence that aiming for a lower goal of 130/80 mm Hg (as in the JNC 7 recommendations) had any beneficial effect on cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, or mortality outcomes compared with 140/90 mm Hg, and there was moderate-quality evidence showing that treatment to lower goal (< 130/80 mm Hg) did not slow the progression of chronic kidney disease any better than a goal of less than 140/90 mm Hg. (One study that did find better renal outcomes with a lower blood pressure goal was a post hoc analysis of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study data in patients with proteinuria of more than 3 g per day.12)

We believe that decisions should be individualized regarding goal blood pressures and pharmacologic therapy in patients with chronic kidney disease and proteinuria, who may benefit from lower blood pressure goals (<130/80 mm Hg), based on low-level evidence.13,14 Risks and benefits should also be weighed in considering the blood pressure goal in the elderly with chronic kidney disease, taking into account functional status, comorbidities, and level of proteinuria.

Recommendation 5: < 140/90 for people with diabetes

In patients with diabetes who are age 18 and older, JNC 8 says to start drug treatment at a systolic pressure of 140 mm Hg or higher or diastolic pressure of 90 mm Hg or higher, and treat to goal systolic pressure of less than 140 mm Hg and a diastolic pressure of less than 90 mm Hg.

Strength of recommendation—expert opinion (grade E).

Comments. Moderate-quality evidence showed cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and mortality outcome benefits with treatment to a systolic goal of less than 150 mm Hg in patients with diabetes and hypertension.

The panel found no randomized controlled trials that compared a treatment goal of less than 140 mm Hg with one of less than 150 mm Hg for outcome benefits, but decided to base its recommendations on the results of the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes—Blood-pressure-lowering Arm (ACCORD-BP) trial.15 The control group in this trial had a goal systolic pressure of less than 140 mm Hg and had similar outcomes compared with a lower goal.

The panel found no evidence to support a lower blood pressure goal (< 130/80) as in JNC 7. ACCORD-BP showed no differences in outcomes with a systolic goal lower than 140 mm Hg vs lower than 120 mm Hg except for a small reduction in stroke, and the risks of trying to achieve intensive lowering of blood pressure may outweigh the benefit of a small reduction in stroke.12 There was no evidence for a goal diastolic pressure below 80 mm Hg.

Recommendation 6: In nonblack patients, start with a thiazide-type diuretic, calcium channel blocker, ACE inhibitor, or ARB

In the general nonblack population, including those with diabetes, initial drug treatment should include a thiazide-type diuretic, calcium channel blocker, ACE inhibitor, or ARB.

Strength of recommendation—moderate (grade B).

Comments. All these drug classes had comparable outcome benefits in terms of rates of death, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, and kidney disease, but not heart failure. For improving heart failure outcomes, thiazide-type diuretics are better than ACE inhibitors, which in turn are better than calcium channel blockers.

Thiazide-type diuretics (eg, hydrochlorothiazide, chlorthalidone, and indapamide) were recommended as first-line therapy for most patients in JNC 7, but they no longer carry this preferred status in JNC 8. In addition, the panel did not address preferential use of chlorthalidone as opposed to hydrochlorothiazide, or the use of spironolactone in resistant hypertension.