User login

Hospital to Home Transitions

Hospital readmissions, which account for a substantial proportion of healthcare expenditures, have increasingly become a focus for hospitals and health systems. Hospitals now assume greater responsibility for population health, and face financial penalties by federal and state agencies that consider readmissions a key measure of the quality of care provided during hospitalization. Consequently, there is broad interest in identifying approaches to reduce hospital reutilization, including emergency department (ED) revisits and hospital readmissions. In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Auger et al.[1] report the results of a systematic review, which evaluates the effect of discharge interventions on hospital reutilization among children.

As Auger et al. note, the transition from hospital to home is a vulnerable time for children and their families, with 1 in 5 parents reporting major challenges with such transitions.[2] Auger and colleagues identified 14 studies spanning 3 pediatric disease processes that addressed this issue. The authors concluded that several interventions were potentially effective, but individual studies frequently used multifactorial interventions, precluding determination of discrete elements essential to success. The larger body of care transitions literature in adult populations provides insights for interventions that may benefit pediatric patients, as well as informs future research and quality improvement priorities.

The authors identified some distinct interventions that may successfully decrease hospital reutilization, which share common themes from the adult literature. The first is the use of a dedicated transition coordinator (eg, nurse) or coordinating center to assist with the patient's transition home after discharge. In adult studies, this bridging strategy[3, 4] (ie, use of a dedicated transition coordinator or provider) is initiated during the hospitalization and continues postdischarge in the form of phone calls or home visits. The second theme illustrated in both this pediatric review[1] and adult reviews[3, 4, 5] focuses on enhanced or individualized patient education. Most studies have used a combination of these strategies. For example, the Care Transitions Intervention (one of the best validated adult discharge approaches) uses a transition coach to aid the patient in medication self‐management, creation of a patient‐centered record, scheduling follow‐up appointments, and understanding signs and symptoms of a worsening condition.[6] In a randomized study, this intervention demonstrated a reduction in readmissions within 90 days to 16.7% in the intervention group, compared with 22.5% in the control group.[6] One of the pediatric studies highlighted in the review by Auger et al. achieved a decrease in 14‐day ED revisits from 8% prior to implementation of the program to 2.7% following implementation of the program.[7] This program was for patients discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit and involved a nurse coordinator (similar to a transition coach) who worked closely with families and ensured adequate resources prior to discharge as well as a home visitation program.[7]

Although Auger et al. identify some effective approaches to reducing hospital reutilization after discharge in children, their review and the complementary adult literature bring to light 4 main unresolved questions for hospitalists seeking to improve care transitions: (1) how to dissect diverse and heterogeneous interventions to determine the key driver of success, (2) how to interpret and generally apply interventions from single centers where they may have been tailored to a specific healthcare environment, (3) how to generalize the findings of many disease‐specific interventions to other populations, and (4) how to evaluate the cost and assess the costbenefit of implementing many of the more resource intensive interventions. An example of a heterogeneous intervention addressed in this pediatric systematic review was described by Ng et al.,[8] in which the intervention group received a combination of an enhanced discharge education session, disease‐specific nurse evaluation, an animated education booklet, and postdischarge telephone follow‐up, whereas the control group received a shorter discharge education session, a disease‐specific nurse evaluation only if referred by a physician, a written education booklet, and no telephone follow‐up. Investigators found that intervention patients were less likely to be readmitted or revisit the ED as compared with controls. A similarly multifaceted intervention introduced by Taggart et al.[9] was unable to detect a difference in readmissions or ED revisits. It is unclear whether or not the differences in outcomes were related to differences in the intervention bundle itself or institutional or local contextual factors, thus limiting application to other hospitals. Generalizability of interventions is similarly complicated in adults.

The studies presented in this pediatric review article are specific to 3 disease processes: cancer, asthma, and neonatal intensive care (ie, premature) populations. Beyond these populations, there were no other pediatric conditions that met inclusion criteria, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings. As described by Rennke et al.,[3] adult systematic reviews that have focused only on disease‐specific interventions to reduce hospital reutilization are also difficult to generalize to broader populations. Two of the 3 recent adult transition intervention systematic reviews excluded disease‐specific interventions in an attempt to find more broadly applicable interventions but struggled with the same heterogeneity discussed in this review by Auger et al.[3, 4] Although disease‐specific interventions were included in the third adult systematic review and the evaluation was restricted to randomized controlled trials, the authors still grappled with finding 1 or 2 common, successful intervention components.[5] The fourth unresolved question involves understanding the financial burden of implementing more resource‐intensive interventions such as postdischarge home nurse visits. For example, it may be difficult to justify the business case for hiring a transition coach or initiating home nurse visits when the cost and financial implications are unclear. Neither the pediatric nor adult literature describes this well.

Some of the challenges in identifying effective interventions differ between adult and pediatric populations. Adults tend to have multiple comorbid conditions, making them more medically complex and at greater risk for adverse outcomes, medication errors, and hospital utilization.[10] Although a small subset of the pediatric population with complex chronic medical conditions accounts for a majority of hospital reutilization and cost,[11] most hospitalized pediatric patients are otherwise healthy with acute illnesses.[12] Additionally, pediatric patients have lower overall hospital reutilization rates when compared with adults. Adult 30‐day readmission rates are approximately 20%[13] compared with pediatric patients whose mean 30‐day readmission rate is 6.5%.[14] With readmission being an outcome upon which studies are basing intervention success or failure, the relatively low readmission rates in the pediatric population make shifting that outcome more challenging.

There is also controversy about whether policymakers should be focusing on decreasing 30‐day readmission rates as a measure of success. We believe that efforts should focus on identifying more meaningful outcomes, especially outcomes important to patients and their families. No single metric is likely to be an adequate measure of the quality of care transitions, but a combination of outcome measures could potentially be more informative both for patients and clinicians. Patient satisfaction with the discharge process is measured as part of standard patient experience surveys, and the 3‐question Care Transitions Measure[15] has been validated and endorsed as a measure of patient perception of discharge safety in adult populations. There is a growing consensus that 30‐day readmission rates are lacking as a measure of discharge quality, and therefore, measuring shorter‐term7‐ or 14‐dayreadmission rates along with short‐term ED utilization after discharge would likely be more helpful for identifying care transitions problems. Attention should also be paid to measuring rates of specific adverse events in the postdischarge period, such as adverse drug events or failure to follow up on pending test results, as these failures are often implicated in reutilization.

In reflecting upon the published data on adult and pediatric transitions of care interventions and the lingering unanswered questions, we propose a few considerations for future direction of the field. First, engagement of the primary care provider may be beneficial. In many interventions describing a care transition coordinator, nursing fulfilled this role; however, there are opportunities for the primary care provider to play a greater role in this arena. Second, the use of factorial design in future studies may help elucidate which specific parts of each intervention may be the most crucial.[16] Finally, readmission rates are a controversial quality measure in adults. Pediatric readmissions are relatively uncommon, making it difficult to track measurements and show improvement. Clinicians, patients, and policymakers should prioritize outcome measures that are most meaningful to patients and their families that occur at a much higher rate than that of readmissions.

- , , , . Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(0):000–000.

- , , , , . Are hospital characteristics associated with parental views of pediatric inpatient care quality? Pediatrics. 2003;111(2):308–314.

- , , , , , . Hospital‐initiated transitional care interventions as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5 pt 2):433–440.

- , , , , . Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- , , , et al. Improving patient handovers from hospital to primary care: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(6):417–428.

- , , , . The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828.

- , , , , . Description and evaluation of a program for the early discharge of infants from a neonatal intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 1995;127(2):285–290.

- , , , , , . Effect of a structured asthma education program on hospitalized asthmatic children: a randomized controlled study. Pediatr Int. 2006;48(2):158–162.

- , , , et al. You Can Control Asthma: evaluation of an asthma education‐program for hospitalized inner‐city children. Patient Educ Couns. 1991;17(1):35–47.

- , , , et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. CMAJ. 2004;170(3):345–349.

- , , , et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children's hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682–690.

- , , , et al. Prioritization of comparative effectiveness research topics in hospital pediatrics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1155–1164.

- , , . Thirty‐day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305(7):675–681.

- , , , et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372–380.

- , , , . Assessing the quality of transitional care: further applications of the care transitions measure. Med Care. 2008;46(3):317–322.

- , , . Quality Improvement Through Planned Experimentation. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw‐Hill; 1999.

Hospital readmissions, which account for a substantial proportion of healthcare expenditures, have increasingly become a focus for hospitals and health systems. Hospitals now assume greater responsibility for population health, and face financial penalties by federal and state agencies that consider readmissions a key measure of the quality of care provided during hospitalization. Consequently, there is broad interest in identifying approaches to reduce hospital reutilization, including emergency department (ED) revisits and hospital readmissions. In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Auger et al.[1] report the results of a systematic review, which evaluates the effect of discharge interventions on hospital reutilization among children.

As Auger et al. note, the transition from hospital to home is a vulnerable time for children and their families, with 1 in 5 parents reporting major challenges with such transitions.[2] Auger and colleagues identified 14 studies spanning 3 pediatric disease processes that addressed this issue. The authors concluded that several interventions were potentially effective, but individual studies frequently used multifactorial interventions, precluding determination of discrete elements essential to success. The larger body of care transitions literature in adult populations provides insights for interventions that may benefit pediatric patients, as well as informs future research and quality improvement priorities.

The authors identified some distinct interventions that may successfully decrease hospital reutilization, which share common themes from the adult literature. The first is the use of a dedicated transition coordinator (eg, nurse) or coordinating center to assist with the patient's transition home after discharge. In adult studies, this bridging strategy[3, 4] (ie, use of a dedicated transition coordinator or provider) is initiated during the hospitalization and continues postdischarge in the form of phone calls or home visits. The second theme illustrated in both this pediatric review[1] and adult reviews[3, 4, 5] focuses on enhanced or individualized patient education. Most studies have used a combination of these strategies. For example, the Care Transitions Intervention (one of the best validated adult discharge approaches) uses a transition coach to aid the patient in medication self‐management, creation of a patient‐centered record, scheduling follow‐up appointments, and understanding signs and symptoms of a worsening condition.[6] In a randomized study, this intervention demonstrated a reduction in readmissions within 90 days to 16.7% in the intervention group, compared with 22.5% in the control group.[6] One of the pediatric studies highlighted in the review by Auger et al. achieved a decrease in 14‐day ED revisits from 8% prior to implementation of the program to 2.7% following implementation of the program.[7] This program was for patients discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit and involved a nurse coordinator (similar to a transition coach) who worked closely with families and ensured adequate resources prior to discharge as well as a home visitation program.[7]

Although Auger et al. identify some effective approaches to reducing hospital reutilization after discharge in children, their review and the complementary adult literature bring to light 4 main unresolved questions for hospitalists seeking to improve care transitions: (1) how to dissect diverse and heterogeneous interventions to determine the key driver of success, (2) how to interpret and generally apply interventions from single centers where they may have been tailored to a specific healthcare environment, (3) how to generalize the findings of many disease‐specific interventions to other populations, and (4) how to evaluate the cost and assess the costbenefit of implementing many of the more resource intensive interventions. An example of a heterogeneous intervention addressed in this pediatric systematic review was described by Ng et al.,[8] in which the intervention group received a combination of an enhanced discharge education session, disease‐specific nurse evaluation, an animated education booklet, and postdischarge telephone follow‐up, whereas the control group received a shorter discharge education session, a disease‐specific nurse evaluation only if referred by a physician, a written education booklet, and no telephone follow‐up. Investigators found that intervention patients were less likely to be readmitted or revisit the ED as compared with controls. A similarly multifaceted intervention introduced by Taggart et al.[9] was unable to detect a difference in readmissions or ED revisits. It is unclear whether or not the differences in outcomes were related to differences in the intervention bundle itself or institutional or local contextual factors, thus limiting application to other hospitals. Generalizability of interventions is similarly complicated in adults.

The studies presented in this pediatric review article are specific to 3 disease processes: cancer, asthma, and neonatal intensive care (ie, premature) populations. Beyond these populations, there were no other pediatric conditions that met inclusion criteria, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings. As described by Rennke et al.,[3] adult systematic reviews that have focused only on disease‐specific interventions to reduce hospital reutilization are also difficult to generalize to broader populations. Two of the 3 recent adult transition intervention systematic reviews excluded disease‐specific interventions in an attempt to find more broadly applicable interventions but struggled with the same heterogeneity discussed in this review by Auger et al.[3, 4] Although disease‐specific interventions were included in the third adult systematic review and the evaluation was restricted to randomized controlled trials, the authors still grappled with finding 1 or 2 common, successful intervention components.[5] The fourth unresolved question involves understanding the financial burden of implementing more resource‐intensive interventions such as postdischarge home nurse visits. For example, it may be difficult to justify the business case for hiring a transition coach or initiating home nurse visits when the cost and financial implications are unclear. Neither the pediatric nor adult literature describes this well.

Some of the challenges in identifying effective interventions differ between adult and pediatric populations. Adults tend to have multiple comorbid conditions, making them more medically complex and at greater risk for adverse outcomes, medication errors, and hospital utilization.[10] Although a small subset of the pediatric population with complex chronic medical conditions accounts for a majority of hospital reutilization and cost,[11] most hospitalized pediatric patients are otherwise healthy with acute illnesses.[12] Additionally, pediatric patients have lower overall hospital reutilization rates when compared with adults. Adult 30‐day readmission rates are approximately 20%[13] compared with pediatric patients whose mean 30‐day readmission rate is 6.5%.[14] With readmission being an outcome upon which studies are basing intervention success or failure, the relatively low readmission rates in the pediatric population make shifting that outcome more challenging.

There is also controversy about whether policymakers should be focusing on decreasing 30‐day readmission rates as a measure of success. We believe that efforts should focus on identifying more meaningful outcomes, especially outcomes important to patients and their families. No single metric is likely to be an adequate measure of the quality of care transitions, but a combination of outcome measures could potentially be more informative both for patients and clinicians. Patient satisfaction with the discharge process is measured as part of standard patient experience surveys, and the 3‐question Care Transitions Measure[15] has been validated and endorsed as a measure of patient perception of discharge safety in adult populations. There is a growing consensus that 30‐day readmission rates are lacking as a measure of discharge quality, and therefore, measuring shorter‐term7‐ or 14‐dayreadmission rates along with short‐term ED utilization after discharge would likely be more helpful for identifying care transitions problems. Attention should also be paid to measuring rates of specific adverse events in the postdischarge period, such as adverse drug events or failure to follow up on pending test results, as these failures are often implicated in reutilization.

In reflecting upon the published data on adult and pediatric transitions of care interventions and the lingering unanswered questions, we propose a few considerations for future direction of the field. First, engagement of the primary care provider may be beneficial. In many interventions describing a care transition coordinator, nursing fulfilled this role; however, there are opportunities for the primary care provider to play a greater role in this arena. Second, the use of factorial design in future studies may help elucidate which specific parts of each intervention may be the most crucial.[16] Finally, readmission rates are a controversial quality measure in adults. Pediatric readmissions are relatively uncommon, making it difficult to track measurements and show improvement. Clinicians, patients, and policymakers should prioritize outcome measures that are most meaningful to patients and their families that occur at a much higher rate than that of readmissions.

Hospital readmissions, which account for a substantial proportion of healthcare expenditures, have increasingly become a focus for hospitals and health systems. Hospitals now assume greater responsibility for population health, and face financial penalties by federal and state agencies that consider readmissions a key measure of the quality of care provided during hospitalization. Consequently, there is broad interest in identifying approaches to reduce hospital reutilization, including emergency department (ED) revisits and hospital readmissions. In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Auger et al.[1] report the results of a systematic review, which evaluates the effect of discharge interventions on hospital reutilization among children.

As Auger et al. note, the transition from hospital to home is a vulnerable time for children and their families, with 1 in 5 parents reporting major challenges with such transitions.[2] Auger and colleagues identified 14 studies spanning 3 pediatric disease processes that addressed this issue. The authors concluded that several interventions were potentially effective, but individual studies frequently used multifactorial interventions, precluding determination of discrete elements essential to success. The larger body of care transitions literature in adult populations provides insights for interventions that may benefit pediatric patients, as well as informs future research and quality improvement priorities.

The authors identified some distinct interventions that may successfully decrease hospital reutilization, which share common themes from the adult literature. The first is the use of a dedicated transition coordinator (eg, nurse) or coordinating center to assist with the patient's transition home after discharge. In adult studies, this bridging strategy[3, 4] (ie, use of a dedicated transition coordinator or provider) is initiated during the hospitalization and continues postdischarge in the form of phone calls or home visits. The second theme illustrated in both this pediatric review[1] and adult reviews[3, 4, 5] focuses on enhanced or individualized patient education. Most studies have used a combination of these strategies. For example, the Care Transitions Intervention (one of the best validated adult discharge approaches) uses a transition coach to aid the patient in medication self‐management, creation of a patient‐centered record, scheduling follow‐up appointments, and understanding signs and symptoms of a worsening condition.[6] In a randomized study, this intervention demonstrated a reduction in readmissions within 90 days to 16.7% in the intervention group, compared with 22.5% in the control group.[6] One of the pediatric studies highlighted in the review by Auger et al. achieved a decrease in 14‐day ED revisits from 8% prior to implementation of the program to 2.7% following implementation of the program.[7] This program was for patients discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit and involved a nurse coordinator (similar to a transition coach) who worked closely with families and ensured adequate resources prior to discharge as well as a home visitation program.[7]

Although Auger et al. identify some effective approaches to reducing hospital reutilization after discharge in children, their review and the complementary adult literature bring to light 4 main unresolved questions for hospitalists seeking to improve care transitions: (1) how to dissect diverse and heterogeneous interventions to determine the key driver of success, (2) how to interpret and generally apply interventions from single centers where they may have been tailored to a specific healthcare environment, (3) how to generalize the findings of many disease‐specific interventions to other populations, and (4) how to evaluate the cost and assess the costbenefit of implementing many of the more resource intensive interventions. An example of a heterogeneous intervention addressed in this pediatric systematic review was described by Ng et al.,[8] in which the intervention group received a combination of an enhanced discharge education session, disease‐specific nurse evaluation, an animated education booklet, and postdischarge telephone follow‐up, whereas the control group received a shorter discharge education session, a disease‐specific nurse evaluation only if referred by a physician, a written education booklet, and no telephone follow‐up. Investigators found that intervention patients were less likely to be readmitted or revisit the ED as compared with controls. A similarly multifaceted intervention introduced by Taggart et al.[9] was unable to detect a difference in readmissions or ED revisits. It is unclear whether or not the differences in outcomes were related to differences in the intervention bundle itself or institutional or local contextual factors, thus limiting application to other hospitals. Generalizability of interventions is similarly complicated in adults.

The studies presented in this pediatric review article are specific to 3 disease processes: cancer, asthma, and neonatal intensive care (ie, premature) populations. Beyond these populations, there were no other pediatric conditions that met inclusion criteria, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings. As described by Rennke et al.,[3] adult systematic reviews that have focused only on disease‐specific interventions to reduce hospital reutilization are also difficult to generalize to broader populations. Two of the 3 recent adult transition intervention systematic reviews excluded disease‐specific interventions in an attempt to find more broadly applicable interventions but struggled with the same heterogeneity discussed in this review by Auger et al.[3, 4] Although disease‐specific interventions were included in the third adult systematic review and the evaluation was restricted to randomized controlled trials, the authors still grappled with finding 1 or 2 common, successful intervention components.[5] The fourth unresolved question involves understanding the financial burden of implementing more resource‐intensive interventions such as postdischarge home nurse visits. For example, it may be difficult to justify the business case for hiring a transition coach or initiating home nurse visits when the cost and financial implications are unclear. Neither the pediatric nor adult literature describes this well.

Some of the challenges in identifying effective interventions differ between adult and pediatric populations. Adults tend to have multiple comorbid conditions, making them more medically complex and at greater risk for adverse outcomes, medication errors, and hospital utilization.[10] Although a small subset of the pediatric population with complex chronic medical conditions accounts for a majority of hospital reutilization and cost,[11] most hospitalized pediatric patients are otherwise healthy with acute illnesses.[12] Additionally, pediatric patients have lower overall hospital reutilization rates when compared with adults. Adult 30‐day readmission rates are approximately 20%[13] compared with pediatric patients whose mean 30‐day readmission rate is 6.5%.[14] With readmission being an outcome upon which studies are basing intervention success or failure, the relatively low readmission rates in the pediatric population make shifting that outcome more challenging.

There is also controversy about whether policymakers should be focusing on decreasing 30‐day readmission rates as a measure of success. We believe that efforts should focus on identifying more meaningful outcomes, especially outcomes important to patients and their families. No single metric is likely to be an adequate measure of the quality of care transitions, but a combination of outcome measures could potentially be more informative both for patients and clinicians. Patient satisfaction with the discharge process is measured as part of standard patient experience surveys, and the 3‐question Care Transitions Measure[15] has been validated and endorsed as a measure of patient perception of discharge safety in adult populations. There is a growing consensus that 30‐day readmission rates are lacking as a measure of discharge quality, and therefore, measuring shorter‐term7‐ or 14‐dayreadmission rates along with short‐term ED utilization after discharge would likely be more helpful for identifying care transitions problems. Attention should also be paid to measuring rates of specific adverse events in the postdischarge period, such as adverse drug events or failure to follow up on pending test results, as these failures are often implicated in reutilization.

In reflecting upon the published data on adult and pediatric transitions of care interventions and the lingering unanswered questions, we propose a few considerations for future direction of the field. First, engagement of the primary care provider may be beneficial. In many interventions describing a care transition coordinator, nursing fulfilled this role; however, there are opportunities for the primary care provider to play a greater role in this arena. Second, the use of factorial design in future studies may help elucidate which specific parts of each intervention may be the most crucial.[16] Finally, readmission rates are a controversial quality measure in adults. Pediatric readmissions are relatively uncommon, making it difficult to track measurements and show improvement. Clinicians, patients, and policymakers should prioritize outcome measures that are most meaningful to patients and their families that occur at a much higher rate than that of readmissions.

- , , , . Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(0):000–000.

- , , , , . Are hospital characteristics associated with parental views of pediatric inpatient care quality? Pediatrics. 2003;111(2):308–314.

- , , , , , . Hospital‐initiated transitional care interventions as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5 pt 2):433–440.

- , , , , . Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- , , , et al. Improving patient handovers from hospital to primary care: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(6):417–428.

- , , , . The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828.

- , , , , . Description and evaluation of a program for the early discharge of infants from a neonatal intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 1995;127(2):285–290.

- , , , , , . Effect of a structured asthma education program on hospitalized asthmatic children: a randomized controlled study. Pediatr Int. 2006;48(2):158–162.

- , , , et al. You Can Control Asthma: evaluation of an asthma education‐program for hospitalized inner‐city children. Patient Educ Couns. 1991;17(1):35–47.

- , , , et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. CMAJ. 2004;170(3):345–349.

- , , , et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children's hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682–690.

- , , , et al. Prioritization of comparative effectiveness research topics in hospital pediatrics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1155–1164.

- , , . Thirty‐day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305(7):675–681.

- , , , et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372–380.

- , , , . Assessing the quality of transitional care: further applications of the care transitions measure. Med Care. 2008;46(3):317–322.

- , , . Quality Improvement Through Planned Experimentation. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw‐Hill; 1999.

- , , , . Pediatric hospital discharge interventions to reduce subsequent utilization: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(0):000–000.

- , , , , . Are hospital characteristics associated with parental views of pediatric inpatient care quality? Pediatrics. 2003;111(2):308–314.

- , , , , , . Hospital‐initiated transitional care interventions as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5 pt 2):433–440.

- , , , , . Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- , , , et al. Improving patient handovers from hospital to primary care: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(6):417–428.

- , , , . The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828.

- , , , , . Description and evaluation of a program for the early discharge of infants from a neonatal intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 1995;127(2):285–290.

- , , , , , . Effect of a structured asthma education program on hospitalized asthmatic children: a randomized controlled study. Pediatr Int. 2006;48(2):158–162.

- , , , et al. You Can Control Asthma: evaluation of an asthma education‐program for hospitalized inner‐city children. Patient Educ Couns. 1991;17(1):35–47.

- , , , et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. CMAJ. 2004;170(3):345–349.

- , , , et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children's hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682–690.

- , , , et al. Prioritization of comparative effectiveness research topics in hospital pediatrics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1155–1164.

- , , . Thirty‐day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305(7):675–681.

- , , , et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372–380.

- , , , . Assessing the quality of transitional care: further applications of the care transitions measure. Med Care. 2008;46(3):317–322.

- , , . Quality Improvement Through Planned Experimentation. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw‐Hill; 1999.

AAN issues nonvalvular atrial fibrillation stroke prevention guideline

A new evidence-based guideline on how to identify and treat patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation to prevent cardioembolic stroke from the American Academy of Neurology suggests when to conduct cardiac rhythm monitoring and offer anticoagulation, including newer agents in place of warfarin.

But the guideline might already be outdated in not considering the results of the recent CRYSTAL-AF study, in which long-term cardiac rhythm monitoring of patients with a previous cryptogenic stroke detected asymptomatic patients at a significantly higher rate than did standard monitoring methods.

The guideline also extends the routine use of anticoagulation for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) who are generally undertreated or whose health was thought a possible barrier to their use, such as those aged 75 years or older, those with mild dementia, and those at moderate risk of falls.

"Cognizant of the global reach of the AAN [American Academy of Neurology], the guideline also examines the evidence base for a treatment alternative to warfarin or its analogues for patients in developing countries who may not have access to the new oral anticoagulants," said lead author Dr. Antonio Culebras in an interview.

"The World Health Organization has determined that atrial fibrillation has reached near-epidemic proportions," observed Dr. Culebras of the State University of New York, Syracuse. "Approximately 1 in 20 individuals with AF will have a stroke unless treated appropriately."

The risk for stroke among patients with NVAF is highest in those with a history of transient ischemic attack (TIA) or prior stroke, at an absolute value of around 10% per year. Patients with "lone NVAF," meaning they have no additional risk factors, have less than a 2% increased risk of stroke per year.

The AAN issued a practice parameter on this topic in 1998 (Neurology 1998;51:671-3). At the time, warfarin, adjusted to an international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.0, was, and largely remains, the recommended standard for patients at risk for cardioembolic stroke. Aspirin was the only recommended alterative for those unable to receive the vitamin K antagonist or who were deemed to be at low risk of stroke, although the evidence was scanty.

Since then, several new oral anticoagulant agents have become available, including the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran (Pradaxa), and two factor Xa inhibitors – rivaroxaban (Xarelto) and apixaban (Eliquis) – which have been shown to be at least as effective as, if not more effective than, warfarin. Cardiac rhythm monitoring via a variety of methods has also been introduced as a means to try to detect NVAF in asymptomatic patients.

The aim of the AAN guideline (Neurology 2014;82:716-24) was therefore to look at the latest evidence on the detection of AF using new technologies, as well as the use of treatments to reduce the risk of stroke without increasing the risk of hemorrhage versus the long-standing standard of therapy, warfarin. Data published from 1998 to March 2013 were considered in the preparation of the guideline.

Cardiac rhythm monitoring for NVAF

Seventeen studies were found that examined the use of cardiac monitoring technologies to detect new cases of NVAF. The most common methods used were 24-hour Holter monitoring and serial electrocardiograms, but some emerging evidence on newer technologies was included. The proportion of patients identified with NVAF ranged from 0% to 23%, with the average detection rate 10.7% in all of the studies included.

"The guideline addresses the question of long-term monitoring of patients with NVAF," Dr. Culebras said. "It recommends that clinicians ‘might’ [level C evidence] obtain outpatient cardiac rhythm studies in patients with cryptogenic stroke without known NVAF to identify patients with occult NVAF." He added that the guideline also recommends that monitoring might be needed for prolonged periods of 1 or more weeks rather than for shorter periods, such as 24 hours.

However, at the time the guideline was being prepared, recent data from the CRYSTAL-AF study were not available, and this means the guideline is already outdated, Dr. Richard A. Bernstein, professor of neurology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an interview. He was not a guideline author.

Dr. Bernstein was on the steering committee for the CRYSTAL-AF trial, which assessed the performance of Medtronic’s Reveal XT Insertable Cardiac Monitor and found that the implanted device could detect NVAF better than serial ECGs or Holter monitoring (8.6% vs. 1.4%; P = .0006); most (74%) cases of NVAF found were asymptomatic.*

"CRYSTAL-AF represents the state of the art for cardiac monitoring in cryptogenic stroke patients and makes the AAN guidelines obsolete," Dr. Berstein said. "[The study] shows that even intermediate-term monitoring (less than 1 month) will miss the majority of AF in this population, and that most of the AF we find with long-term (greater than 1 year) monitoring is likely to be clinically significant."

With regard to the AAN guideline, he added: "There is no discussion of truly long-term monitoring in the guideline, which is unfortunate." That said, "anything that gets neurologists thinking about long-term cardiac monitoring is likely to be beneficial."

Anticoagulation for stroke prevention

The AAN guideline also provides general recommendations on the use of novel oral anticoagulant agents (NOACs) as alternatives to warfarin. Specifically, it notes that in comparison with warfarin, these NOACs are probably at least as effective (rivaroxaban) or more effective (dabigatran and apixaban). Additionally, while apixaban is also likely to be more effective than aspirin, it is associated with a similar risk for bleeding. NOACs have the following advantages over warfarin: an overall lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage and no need for routine anticoagulant monitoring.

From a practical perspective, the AAN guideline suggests that clinicians have the following options available: warfarin to reach an INR of 2.0-3.0, dabigatran 150 mg twice daily, rivaroxaban 15-20 mg/dL, apixaban 2.5-5 mg twice a day, and triflusal 600 mg plus acenocoumarol to reach an INR target of 1.25-2.0. If a patient is already taking warfarin and is well controlled, then they should remain on that therapy and not switch to a newer oral anticoagulant.

The guideline also notes that clopidogrel plus aspirin is probably less effective than warfarin, but the combination is probably better than aspirin alone. However, the risk of hemorrhage is higher.

Where used, triflusal plus acenocoumarol is "likely more effective" than acenocoumarol alone. Triflusal is an antiplatelet drug related to aspirin, used in Europe, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. Acenocoumarol is mostly used in European countries.

Dr. Culebras explained that the guideline was not intended to dictate which treatment to use. "The guideline leaves room on purpose for clinicians to use their judgment," he said. "The overall objective of the guideline is to reduce therapeutic uncertainty and not to issue commandments for treatment."

Although Dr. Bernstein was critical of the guidelines for not advocating the use of anticoagulants strongly enough, he said that the recommendations on anticoagulant choice are "reasonable in that they impute potential clinical profiles of patients who might particularly benefit from one NOAC over another, without making a claim that these recommendations are based on solid data. This reflects how doctors make decisions when we don’t have direct comparative studies, and I think that is helpful."

The guideline was developed with financial support from the American Academy of Neurology. None of the authors received reimbursement, honoraria, or stipends for their participation in the development of the guideline.

Dr. Culebras has received one-time funding for travel from J. Uriach & Co, and he serves on the editorial boards of MedLink, UpToDate.com, and the International Journal of Stroke. He has received royalties from Informa Healthcare and Cambridge University Press, and has held stock in Clinical Stroke Research. Other authors reported current or past ties to companies marketing oral anticoagulants and stroke treatments.

Dr. Bernstein was on the steering committee for the CRYSTAL-AF study and is a paid speaker, researcher, and consultant for Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Lifewatch.

*Correction, 4/8/2014: The article previously misstated what the implantable device was detecting in the CRYSTAL-AF study.

|

|

These guidelines are a missed opportunity to empower neurologists to advocate in favor of anticoagulation to prevent stroke. The biggest public health problem in AF is that only half of patients who need anticoagulation are getting it. This disgraceful state of affairs results in patients having cardioembolic strokes that are fatal or worse and that could have been prevented. We neurologists see these complications of inadequate treatment and should be on the front lines of prevention. These tepid guidelines give as much space to bleeding as they do to ischemic stroke prevention, which is inappropriate, and I fear will make neurologists, who are not terribly assertive under any circumstances, even less willing to push doctors to use anticoagulants.

I would have been happier with a single page that said: "Stop using aspirin. Patients fear major stroke more than they fear bleeding or death, and they are right. Stop undertreating your patients and start preventing strokes."

Dr. Richard A. Bernstein is professor of neurology and director of the stroke program at Northwestern University, Chicago.

|

|

These guidelines are a missed opportunity to empower neurologists to advocate in favor of anticoagulation to prevent stroke. The biggest public health problem in AF is that only half of patients who need anticoagulation are getting it. This disgraceful state of affairs results in patients having cardioembolic strokes that are fatal or worse and that could have been prevented. We neurologists see these complications of inadequate treatment and should be on the front lines of prevention. These tepid guidelines give as much space to bleeding as they do to ischemic stroke prevention, which is inappropriate, and I fear will make neurologists, who are not terribly assertive under any circumstances, even less willing to push doctors to use anticoagulants.

I would have been happier with a single page that said: "Stop using aspirin. Patients fear major stroke more than they fear bleeding or death, and they are right. Stop undertreating your patients and start preventing strokes."

Dr. Richard A. Bernstein is professor of neurology and director of the stroke program at Northwestern University, Chicago.

|

|

These guidelines are a missed opportunity to empower neurologists to advocate in favor of anticoagulation to prevent stroke. The biggest public health problem in AF is that only half of patients who need anticoagulation are getting it. This disgraceful state of affairs results in patients having cardioembolic strokes that are fatal or worse and that could have been prevented. We neurologists see these complications of inadequate treatment and should be on the front lines of prevention. These tepid guidelines give as much space to bleeding as they do to ischemic stroke prevention, which is inappropriate, and I fear will make neurologists, who are not terribly assertive under any circumstances, even less willing to push doctors to use anticoagulants.

I would have been happier with a single page that said: "Stop using aspirin. Patients fear major stroke more than they fear bleeding or death, and they are right. Stop undertreating your patients and start preventing strokes."

Dr. Richard A. Bernstein is professor of neurology and director of the stroke program at Northwestern University, Chicago.

A new evidence-based guideline on how to identify and treat patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation to prevent cardioembolic stroke from the American Academy of Neurology suggests when to conduct cardiac rhythm monitoring and offer anticoagulation, including newer agents in place of warfarin.

But the guideline might already be outdated in not considering the results of the recent CRYSTAL-AF study, in which long-term cardiac rhythm monitoring of patients with a previous cryptogenic stroke detected asymptomatic patients at a significantly higher rate than did standard monitoring methods.

The guideline also extends the routine use of anticoagulation for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) who are generally undertreated or whose health was thought a possible barrier to their use, such as those aged 75 years or older, those with mild dementia, and those at moderate risk of falls.

"Cognizant of the global reach of the AAN [American Academy of Neurology], the guideline also examines the evidence base for a treatment alternative to warfarin or its analogues for patients in developing countries who may not have access to the new oral anticoagulants," said lead author Dr. Antonio Culebras in an interview.

"The World Health Organization has determined that atrial fibrillation has reached near-epidemic proportions," observed Dr. Culebras of the State University of New York, Syracuse. "Approximately 1 in 20 individuals with AF will have a stroke unless treated appropriately."

The risk for stroke among patients with NVAF is highest in those with a history of transient ischemic attack (TIA) or prior stroke, at an absolute value of around 10% per year. Patients with "lone NVAF," meaning they have no additional risk factors, have less than a 2% increased risk of stroke per year.

The AAN issued a practice parameter on this topic in 1998 (Neurology 1998;51:671-3). At the time, warfarin, adjusted to an international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.0, was, and largely remains, the recommended standard for patients at risk for cardioembolic stroke. Aspirin was the only recommended alterative for those unable to receive the vitamin K antagonist or who were deemed to be at low risk of stroke, although the evidence was scanty.

Since then, several new oral anticoagulant agents have become available, including the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran (Pradaxa), and two factor Xa inhibitors – rivaroxaban (Xarelto) and apixaban (Eliquis) – which have been shown to be at least as effective as, if not more effective than, warfarin. Cardiac rhythm monitoring via a variety of methods has also been introduced as a means to try to detect NVAF in asymptomatic patients.

The aim of the AAN guideline (Neurology 2014;82:716-24) was therefore to look at the latest evidence on the detection of AF using new technologies, as well as the use of treatments to reduce the risk of stroke without increasing the risk of hemorrhage versus the long-standing standard of therapy, warfarin. Data published from 1998 to March 2013 were considered in the preparation of the guideline.

Cardiac rhythm monitoring for NVAF

Seventeen studies were found that examined the use of cardiac monitoring technologies to detect new cases of NVAF. The most common methods used were 24-hour Holter monitoring and serial electrocardiograms, but some emerging evidence on newer technologies was included. The proportion of patients identified with NVAF ranged from 0% to 23%, with the average detection rate 10.7% in all of the studies included.

"The guideline addresses the question of long-term monitoring of patients with NVAF," Dr. Culebras said. "It recommends that clinicians ‘might’ [level C evidence] obtain outpatient cardiac rhythm studies in patients with cryptogenic stroke without known NVAF to identify patients with occult NVAF." He added that the guideline also recommends that monitoring might be needed for prolonged periods of 1 or more weeks rather than for shorter periods, such as 24 hours.

However, at the time the guideline was being prepared, recent data from the CRYSTAL-AF study were not available, and this means the guideline is already outdated, Dr. Richard A. Bernstein, professor of neurology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an interview. He was not a guideline author.

Dr. Bernstein was on the steering committee for the CRYSTAL-AF trial, which assessed the performance of Medtronic’s Reveal XT Insertable Cardiac Monitor and found that the implanted device could detect NVAF better than serial ECGs or Holter monitoring (8.6% vs. 1.4%; P = .0006); most (74%) cases of NVAF found were asymptomatic.*

"CRYSTAL-AF represents the state of the art for cardiac monitoring in cryptogenic stroke patients and makes the AAN guidelines obsolete," Dr. Berstein said. "[The study] shows that even intermediate-term monitoring (less than 1 month) will miss the majority of AF in this population, and that most of the AF we find with long-term (greater than 1 year) monitoring is likely to be clinically significant."

With regard to the AAN guideline, he added: "There is no discussion of truly long-term monitoring in the guideline, which is unfortunate." That said, "anything that gets neurologists thinking about long-term cardiac monitoring is likely to be beneficial."

Anticoagulation for stroke prevention

The AAN guideline also provides general recommendations on the use of novel oral anticoagulant agents (NOACs) as alternatives to warfarin. Specifically, it notes that in comparison with warfarin, these NOACs are probably at least as effective (rivaroxaban) or more effective (dabigatran and apixaban). Additionally, while apixaban is also likely to be more effective than aspirin, it is associated with a similar risk for bleeding. NOACs have the following advantages over warfarin: an overall lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage and no need for routine anticoagulant monitoring.

From a practical perspective, the AAN guideline suggests that clinicians have the following options available: warfarin to reach an INR of 2.0-3.0, dabigatran 150 mg twice daily, rivaroxaban 15-20 mg/dL, apixaban 2.5-5 mg twice a day, and triflusal 600 mg plus acenocoumarol to reach an INR target of 1.25-2.0. If a patient is already taking warfarin and is well controlled, then they should remain on that therapy and not switch to a newer oral anticoagulant.

The guideline also notes that clopidogrel plus aspirin is probably less effective than warfarin, but the combination is probably better than aspirin alone. However, the risk of hemorrhage is higher.

Where used, triflusal plus acenocoumarol is "likely more effective" than acenocoumarol alone. Triflusal is an antiplatelet drug related to aspirin, used in Europe, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. Acenocoumarol is mostly used in European countries.

Dr. Culebras explained that the guideline was not intended to dictate which treatment to use. "The guideline leaves room on purpose for clinicians to use their judgment," he said. "The overall objective of the guideline is to reduce therapeutic uncertainty and not to issue commandments for treatment."

Although Dr. Bernstein was critical of the guidelines for not advocating the use of anticoagulants strongly enough, he said that the recommendations on anticoagulant choice are "reasonable in that they impute potential clinical profiles of patients who might particularly benefit from one NOAC over another, without making a claim that these recommendations are based on solid data. This reflects how doctors make decisions when we don’t have direct comparative studies, and I think that is helpful."

The guideline was developed with financial support from the American Academy of Neurology. None of the authors received reimbursement, honoraria, or stipends for their participation in the development of the guideline.

Dr. Culebras has received one-time funding for travel from J. Uriach & Co, and he serves on the editorial boards of MedLink, UpToDate.com, and the International Journal of Stroke. He has received royalties from Informa Healthcare and Cambridge University Press, and has held stock in Clinical Stroke Research. Other authors reported current or past ties to companies marketing oral anticoagulants and stroke treatments.

Dr. Bernstein was on the steering committee for the CRYSTAL-AF study and is a paid speaker, researcher, and consultant for Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Lifewatch.

*Correction, 4/8/2014: The article previously misstated what the implantable device was detecting in the CRYSTAL-AF study.

A new evidence-based guideline on how to identify and treat patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation to prevent cardioembolic stroke from the American Academy of Neurology suggests when to conduct cardiac rhythm monitoring and offer anticoagulation, including newer agents in place of warfarin.

But the guideline might already be outdated in not considering the results of the recent CRYSTAL-AF study, in which long-term cardiac rhythm monitoring of patients with a previous cryptogenic stroke detected asymptomatic patients at a significantly higher rate than did standard monitoring methods.

The guideline also extends the routine use of anticoagulation for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) who are generally undertreated or whose health was thought a possible barrier to their use, such as those aged 75 years or older, those with mild dementia, and those at moderate risk of falls.

"Cognizant of the global reach of the AAN [American Academy of Neurology], the guideline also examines the evidence base for a treatment alternative to warfarin or its analogues for patients in developing countries who may not have access to the new oral anticoagulants," said lead author Dr. Antonio Culebras in an interview.

"The World Health Organization has determined that atrial fibrillation has reached near-epidemic proportions," observed Dr. Culebras of the State University of New York, Syracuse. "Approximately 1 in 20 individuals with AF will have a stroke unless treated appropriately."

The risk for stroke among patients with NVAF is highest in those with a history of transient ischemic attack (TIA) or prior stroke, at an absolute value of around 10% per year. Patients with "lone NVAF," meaning they have no additional risk factors, have less than a 2% increased risk of stroke per year.

The AAN issued a practice parameter on this topic in 1998 (Neurology 1998;51:671-3). At the time, warfarin, adjusted to an international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.0, was, and largely remains, the recommended standard for patients at risk for cardioembolic stroke. Aspirin was the only recommended alterative for those unable to receive the vitamin K antagonist or who were deemed to be at low risk of stroke, although the evidence was scanty.

Since then, several new oral anticoagulant agents have become available, including the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran (Pradaxa), and two factor Xa inhibitors – rivaroxaban (Xarelto) and apixaban (Eliquis) – which have been shown to be at least as effective as, if not more effective than, warfarin. Cardiac rhythm monitoring via a variety of methods has also been introduced as a means to try to detect NVAF in asymptomatic patients.

The aim of the AAN guideline (Neurology 2014;82:716-24) was therefore to look at the latest evidence on the detection of AF using new technologies, as well as the use of treatments to reduce the risk of stroke without increasing the risk of hemorrhage versus the long-standing standard of therapy, warfarin. Data published from 1998 to March 2013 were considered in the preparation of the guideline.

Cardiac rhythm monitoring for NVAF

Seventeen studies were found that examined the use of cardiac monitoring technologies to detect new cases of NVAF. The most common methods used were 24-hour Holter monitoring and serial electrocardiograms, but some emerging evidence on newer technologies was included. The proportion of patients identified with NVAF ranged from 0% to 23%, with the average detection rate 10.7% in all of the studies included.

"The guideline addresses the question of long-term monitoring of patients with NVAF," Dr. Culebras said. "It recommends that clinicians ‘might’ [level C evidence] obtain outpatient cardiac rhythm studies in patients with cryptogenic stroke without known NVAF to identify patients with occult NVAF." He added that the guideline also recommends that monitoring might be needed for prolonged periods of 1 or more weeks rather than for shorter periods, such as 24 hours.

However, at the time the guideline was being prepared, recent data from the CRYSTAL-AF study were not available, and this means the guideline is already outdated, Dr. Richard A. Bernstein, professor of neurology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an interview. He was not a guideline author.

Dr. Bernstein was on the steering committee for the CRYSTAL-AF trial, which assessed the performance of Medtronic’s Reveal XT Insertable Cardiac Monitor and found that the implanted device could detect NVAF better than serial ECGs or Holter monitoring (8.6% vs. 1.4%; P = .0006); most (74%) cases of NVAF found were asymptomatic.*

"CRYSTAL-AF represents the state of the art for cardiac monitoring in cryptogenic stroke patients and makes the AAN guidelines obsolete," Dr. Berstein said. "[The study] shows that even intermediate-term monitoring (less than 1 month) will miss the majority of AF in this population, and that most of the AF we find with long-term (greater than 1 year) monitoring is likely to be clinically significant."

With regard to the AAN guideline, he added: "There is no discussion of truly long-term monitoring in the guideline, which is unfortunate." That said, "anything that gets neurologists thinking about long-term cardiac monitoring is likely to be beneficial."

Anticoagulation for stroke prevention

The AAN guideline also provides general recommendations on the use of novel oral anticoagulant agents (NOACs) as alternatives to warfarin. Specifically, it notes that in comparison with warfarin, these NOACs are probably at least as effective (rivaroxaban) or more effective (dabigatran and apixaban). Additionally, while apixaban is also likely to be more effective than aspirin, it is associated with a similar risk for bleeding. NOACs have the following advantages over warfarin: an overall lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage and no need for routine anticoagulant monitoring.

From a practical perspective, the AAN guideline suggests that clinicians have the following options available: warfarin to reach an INR of 2.0-3.0, dabigatran 150 mg twice daily, rivaroxaban 15-20 mg/dL, apixaban 2.5-5 mg twice a day, and triflusal 600 mg plus acenocoumarol to reach an INR target of 1.25-2.0. If a patient is already taking warfarin and is well controlled, then they should remain on that therapy and not switch to a newer oral anticoagulant.

The guideline also notes that clopidogrel plus aspirin is probably less effective than warfarin, but the combination is probably better than aspirin alone. However, the risk of hemorrhage is higher.

Where used, triflusal plus acenocoumarol is "likely more effective" than acenocoumarol alone. Triflusal is an antiplatelet drug related to aspirin, used in Europe, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. Acenocoumarol is mostly used in European countries.

Dr. Culebras explained that the guideline was not intended to dictate which treatment to use. "The guideline leaves room on purpose for clinicians to use their judgment," he said. "The overall objective of the guideline is to reduce therapeutic uncertainty and not to issue commandments for treatment."

Although Dr. Bernstein was critical of the guidelines for not advocating the use of anticoagulants strongly enough, he said that the recommendations on anticoagulant choice are "reasonable in that they impute potential clinical profiles of patients who might particularly benefit from one NOAC over another, without making a claim that these recommendations are based on solid data. This reflects how doctors make decisions when we don’t have direct comparative studies, and I think that is helpful."

The guideline was developed with financial support from the American Academy of Neurology. None of the authors received reimbursement, honoraria, or stipends for their participation in the development of the guideline.

Dr. Culebras has received one-time funding for travel from J. Uriach & Co, and he serves on the editorial boards of MedLink, UpToDate.com, and the International Journal of Stroke. He has received royalties from Informa Healthcare and Cambridge University Press, and has held stock in Clinical Stroke Research. Other authors reported current or past ties to companies marketing oral anticoagulants and stroke treatments.

Dr. Bernstein was on the steering committee for the CRYSTAL-AF study and is a paid speaker, researcher, and consultant for Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Lifewatch.

*Correction, 4/8/2014: The article previously misstated what the implantable device was detecting in the CRYSTAL-AF study.

FROM NEUROLOGY

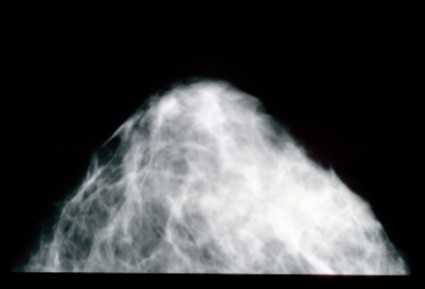

Mammogram data are not to die for

I remember that day like it was yesterday, though it occurred more than a decade ago. I stood leaning over a black entertainment center in my family room, legs wobbly, heart weary – a surreal and solemn snapshot in time. From a speaker streamed a now-favorite Donnie McClurkin song, called "Stand," with its introspective lyrics: "You’ve prayed and you’ve cried ... . After you’ve done all you can, you just stand."

In the next room I could hear her softly gurgling on her secretions. I needed a moment, no, two or three moments, to collect my thoughts and pull myself together before I returned to face the nightmare I was living. My mother was actively dying in my guestroom. Why? I believed then and, today, many years later, believe just as strongly it was because she had not been getting her mammograms.

As a writer, sometimes I struggle with how personal to get in my blogs, but rest assured. I got her permission to share her story while she was still very lucid and competent. You see, she did not want others’ lives to end as hers was ending. She realized, in her final stages of life, that things would have likely been much different had she had her screening mammograms as recommended.

By the time of her diagnosis in her early 60s, the cancer had already spread. Would a mammogram in her late 50s have saved her life? I believe so, and I’m not alone. So I take issue with a recent article published in BMJ that downplays the significance of mammography (BMJ 2014;348:g366).

In 1980, Canadian researchers randomized 89,835 women, aged 40-59 to receive five annual mammograms or physical breast examinations. They followed these women over a 25-year period, and concluded that yearly mammography in women aged 40-59 did not decrease breast cancer mortality "beyond that of physical examination or usual care when adjuvant therapy for breast cancer is freely available."

Well, how many of us have taken care of women in their 50s, 40s, and even 30s with terminal breast cancer? How many of us would advise a mother, aunt, sister (or self) not to have routine mammography? Not many, I’m sure. There is the art of medicine and the science of medicine. Sometimes these two clash, but I believe the art of medicine is realizing that the science of medicine really doesn’t matter to dying patients and their family members. Sometimes, we have to act in the best interest of individual patients and not rely too heavily on the "data." Data changes, risk factors emerge, or research findings may prove to be skewed or wrong in hindsight. Explains Dr. Poornima Sharma, an oncologist/hematologist at the University of Maryland Baltimore-Washington Medical Center: "While the methodology, mammographic technique, and equipment used in the Canadian study is being assessed and compared to the mammography standards used in the United States, the standard in this country remains annual mammography starting at age 40."

Still, many women consider themselves at low risk for breast cancer if they have no close relatives with the disease. As erroneous as this assumption may be, this subset of women may be particularly vulnerable to the implication that yearly mammography is not needed.

So do this: Discuss screening mammography with your own family and then use those feelings when a teachable moment presents itself at bedside.

Our patients rely on us to look into their eyes and give them our best advice. Even though I am a hospitalist, there are still those women I feel compelled to counsel about screening mammography, and this study will not lessen my fervor.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

I remember that day like it was yesterday, though it occurred more than a decade ago. I stood leaning over a black entertainment center in my family room, legs wobbly, heart weary – a surreal and solemn snapshot in time. From a speaker streamed a now-favorite Donnie McClurkin song, called "Stand," with its introspective lyrics: "You’ve prayed and you’ve cried ... . After you’ve done all you can, you just stand."

In the next room I could hear her softly gurgling on her secretions. I needed a moment, no, two or three moments, to collect my thoughts and pull myself together before I returned to face the nightmare I was living. My mother was actively dying in my guestroom. Why? I believed then and, today, many years later, believe just as strongly it was because she had not been getting her mammograms.

As a writer, sometimes I struggle with how personal to get in my blogs, but rest assured. I got her permission to share her story while she was still very lucid and competent. You see, she did not want others’ lives to end as hers was ending. She realized, in her final stages of life, that things would have likely been much different had she had her screening mammograms as recommended.

By the time of her diagnosis in her early 60s, the cancer had already spread. Would a mammogram in her late 50s have saved her life? I believe so, and I’m not alone. So I take issue with a recent article published in BMJ that downplays the significance of mammography (BMJ 2014;348:g366).

In 1980, Canadian researchers randomized 89,835 women, aged 40-59 to receive five annual mammograms or physical breast examinations. They followed these women over a 25-year period, and concluded that yearly mammography in women aged 40-59 did not decrease breast cancer mortality "beyond that of physical examination or usual care when adjuvant therapy for breast cancer is freely available."

Well, how many of us have taken care of women in their 50s, 40s, and even 30s with terminal breast cancer? How many of us would advise a mother, aunt, sister (or self) not to have routine mammography? Not many, I’m sure. There is the art of medicine and the science of medicine. Sometimes these two clash, but I believe the art of medicine is realizing that the science of medicine really doesn’t matter to dying patients and their family members. Sometimes, we have to act in the best interest of individual patients and not rely too heavily on the "data." Data changes, risk factors emerge, or research findings may prove to be skewed or wrong in hindsight. Explains Dr. Poornima Sharma, an oncologist/hematologist at the University of Maryland Baltimore-Washington Medical Center: "While the methodology, mammographic technique, and equipment used in the Canadian study is being assessed and compared to the mammography standards used in the United States, the standard in this country remains annual mammography starting at age 40."

Still, many women consider themselves at low risk for breast cancer if they have no close relatives with the disease. As erroneous as this assumption may be, this subset of women may be particularly vulnerable to the implication that yearly mammography is not needed.

So do this: Discuss screening mammography with your own family and then use those feelings when a teachable moment presents itself at bedside.

Our patients rely on us to look into their eyes and give them our best advice. Even though I am a hospitalist, there are still those women I feel compelled to counsel about screening mammography, and this study will not lessen my fervor.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

I remember that day like it was yesterday, though it occurred more than a decade ago. I stood leaning over a black entertainment center in my family room, legs wobbly, heart weary – a surreal and solemn snapshot in time. From a speaker streamed a now-favorite Donnie McClurkin song, called "Stand," with its introspective lyrics: "You’ve prayed and you’ve cried ... . After you’ve done all you can, you just stand."

In the next room I could hear her softly gurgling on her secretions. I needed a moment, no, two or three moments, to collect my thoughts and pull myself together before I returned to face the nightmare I was living. My mother was actively dying in my guestroom. Why? I believed then and, today, many years later, believe just as strongly it was because she had not been getting her mammograms.

As a writer, sometimes I struggle with how personal to get in my blogs, but rest assured. I got her permission to share her story while she was still very lucid and competent. You see, she did not want others’ lives to end as hers was ending. She realized, in her final stages of life, that things would have likely been much different had she had her screening mammograms as recommended.

By the time of her diagnosis in her early 60s, the cancer had already spread. Would a mammogram in her late 50s have saved her life? I believe so, and I’m not alone. So I take issue with a recent article published in BMJ that downplays the significance of mammography (BMJ 2014;348:g366).

In 1980, Canadian researchers randomized 89,835 women, aged 40-59 to receive five annual mammograms or physical breast examinations. They followed these women over a 25-year period, and concluded that yearly mammography in women aged 40-59 did not decrease breast cancer mortality "beyond that of physical examination or usual care when adjuvant therapy for breast cancer is freely available."

Well, how many of us have taken care of women in their 50s, 40s, and even 30s with terminal breast cancer? How many of us would advise a mother, aunt, sister (or self) not to have routine mammography? Not many, I’m sure. There is the art of medicine and the science of medicine. Sometimes these two clash, but I believe the art of medicine is realizing that the science of medicine really doesn’t matter to dying patients and their family members. Sometimes, we have to act in the best interest of individual patients and not rely too heavily on the "data." Data changes, risk factors emerge, or research findings may prove to be skewed or wrong in hindsight. Explains Dr. Poornima Sharma, an oncologist/hematologist at the University of Maryland Baltimore-Washington Medical Center: "While the methodology, mammographic technique, and equipment used in the Canadian study is being assessed and compared to the mammography standards used in the United States, the standard in this country remains annual mammography starting at age 40."

Still, many women consider themselves at low risk for breast cancer if they have no close relatives with the disease. As erroneous as this assumption may be, this subset of women may be particularly vulnerable to the implication that yearly mammography is not needed.

So do this: Discuss screening mammography with your own family and then use those feelings when a teachable moment presents itself at bedside.

Our patients rely on us to look into their eyes and give them our best advice. Even though I am a hospitalist, there are still those women I feel compelled to counsel about screening mammography, and this study will not lessen my fervor.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

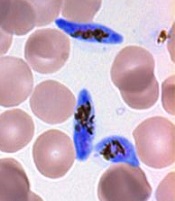

Protein appears essential to malaria transmission

gametocyte stage (blue) and

uninfected red blood cells

Credit: The Llinás lab

Results of 2 new studies suggest that a single regulatory protein acts as a master switch to trigger development of the sexual forms of malaria parasites.

It appears that the protein, AP2-G, is necessary for activating a set of genes that initiate the development of Plasmodium gametocytes, the only forms of the parasite that are infectious to mosquitoes.

This suggests that if researchers can target AP2-G, they can stop sexual parasites from forming.

And if the sexual forms of the parasite never develop in an infected person’s blood, none will enter the mosquito’s gut, and the mosquito will be unable to infect anyone else with malaria.

“Exciting opportunities now lie ahead for finding an effective way to break the chain of malaria transmission by preventing the malaria parasite from completing its full lifecycle,” said Manuel Llinás, PhD, a professor at Pennsylvania State University who was involved in both studies.

The 2 studies, which were published as letters to Nature, had remarkably similar results, despite the fact that the groups worked with 2 different malaria parasites—Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium berghei.

In one study, researchers analyzed the whole-genome sequences of 2 P falciparum strains that were unable to produce gametocytes. The only mutated, non-functional gene common to both strains was the AP2-G gene.

In the other study, researchers sequenced P berghei parasites that had lost their ability to make gametocytes. Again, the only common mutated gene in these parasites was AP2-G.

To confirm these observations, both groups of researchers disabled the AP2-G gene in parasites that could generate gametocytes.

As expected, disabling the gene prevented the parasites from producing gametocytes. But the parasites regained their ability to make gametocytes when the mutated gene was repaired.

These results, as well as results of additional experiments, suggest that sexual-stage malaria parasites are produced only when the AP2-G protein is in working order.

“Our research has demonstrated unequivocally that the AP2-G transcription factor protein is essential for flipping the switch that initiates the transformation of malaria parasites in the blood from the asexual stage to the critical sexual stage of their life cycle,” Dr Llinás said.