User login

Meaningful improvement for patients like Tante Ilse

Last year, after a long delay due to COVID, my father’s ashes were finally laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery. Among the loved ones who came was my favorite aunt, Tante Ilse, who was suffering from dementia. While she wasn’t “following” everything that was going on, she did perk up when she heard my father’s name and would comment on how she liked him and how wonderful he had been to her.

After the ceremony, our family of about 30 gathered at a restaurant where we shared stories and old pictures. Tante Ilse seemed to relish the photos and the time with family. She was doing so well that when we went back to my mom’s home after the reception, my cousins decided to bring Tante Ilse there, too. She had a great time, as evidenced by her famous total-body laugh. In the months before her death, we all commented about that day and how happy she seemed.

My aunt’s decline comes to mind as I reflect on media reports of 2 Alzheimer drugs— aducanumab and lecanemab—that have been billed by some as “gamechangers.” These new drugs are monoclonal antibodies directed at amyloid, one of several agents thought to cause Alzheimer disease. The details of aducanumab’s approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) generated a great deal of criticism—with good reason.

Two manufacturer-sponsored studies of aducanumab were halted due to futility of finding a benefit.1 The FDA’s scientific advisory panel recommended against approval due to a lack of evidence that it did anything more than remove amyloid plaque from the brain. And yet aducanumab received accelerated approval from the FDA. (This author collaborated on an additional analysis using data presented to the FDA, after its approval, which also reported no clinically meaningful effects.2) The other agent, lecanemab, also reduces markers of amyloid and was shown to be only moderately better than placebo in decreasing the rate of decline on various measures of cognition.3 Quite notably, both aducanumab and lecanemab, which are administered parenterally, cost more than $25,000 per year4,5 and cause amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (brain edema or hemorrhage).

Expensive agents without meaningful benefit. So far, neither of these agents has shown a reduction in things that are truly important to our patients and their families/caregivers: a reduction in caregiver burden and a reduction in the need for placement in long-term care facilities.

This is in contrast to cholinesterase inhibitors, which also slow the rate of cognitive decline.6 Among the differences that exist between these agents: Cholinesterase inhibitors are taken orally and are available as generics, which cost less than a thousand dollars per year.7 Limited data also suggest that they are associated with a lower risk for nursing home placement.8,9 (A February 2023 search of clinicaltrials.gov did not reveal any completed or planned head-to-head comparisons of monoclonal antibodies and anticholinergic agents.)

Our patients, their families, and caregivers hold out hope for something that will improve the patient’s cognition and extend the meaningful time they have with their loved ones. So far, the best we have to offer falls far short of these goals. I certainly would have hoped for something better than merely clearing amyloid for my aunt.

It’s time that the FDA adopt more rigorous standards requiring new drugs to, among other things, demonstrate meaningful clinical benefits, provide real cost savings, and be safer than currently available therapies. Other nations seem to be able to do this.10,11 It is bad enough to provide “hope in a bottle”; it is worse when what is offered is false hope.

1. Budd Haeberlein S, Aisen PS, Barkhof F, et al. Two randomized phase 3 studies of aducanumab in early Alzheimer’s disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2022;9:197-210. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2022.30

2. Ebell MH, Barry HC. Why physicians should not prescribe aducanumab for Alzheimer disease. Am Fam Physician. 2022;105:353-354.

3. van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:9-21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2212948

4. Reardon S. FDA approves Alzheimer’s drug lecanemab amid safety concerns. Nature. 2023; 613:227-228. doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-00030-3

5. Biogen announces reduced price for Aduhelm to improve access for patients with early Alzheimer’s disease. December 20, 2021. Accessed February 20, 2023. https://investors.biogen.com/news-releases/news-release-details/biogen-announces-reduced-price-aduhelmr-improve-access-patients

6. Takramah WK, Asem L. The efficacy of pharmacological interventions to improve cognitive and behavior symptoms in people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Sci Rep. 2022;5:e913. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.913

7. GoodRx. Donepezil generic Aricept. Accessed February 20, 2023. www.goodrx.com/donepezil

8. Howard R, McShane R, Lindesay J, et al. Nursing home placement in the donepezil and memantine in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease (DOMINO-AD) trial: secondary and post-hoc analyses. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:1171-1181. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00258-6

9. Geldmacher DS, Provenzano G, McRae T, et al. Donepezil is associated with delayed nursing home placement in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:937-944. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51306.x

10. Pham C, Le K, Draves M, et al. Assessment of FDA-approved drugs not recommended for use or reimbursement in other countries, 2017-2020. JAMA Intern Med. Published online February 13, 2023. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6787

11. Johnston JL, Ross JS, Ramachandran R. US Food and Drug Administration approval of drugs not meeting pivotal trial primary end points, 2018-2021. JAMA Intern Med. Published online February 13, 2023. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6444

Last year, after a long delay due to COVID, my father’s ashes were finally laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery. Among the loved ones who came was my favorite aunt, Tante Ilse, who was suffering from dementia. While she wasn’t “following” everything that was going on, she did perk up when she heard my father’s name and would comment on how she liked him and how wonderful he had been to her.

After the ceremony, our family of about 30 gathered at a restaurant where we shared stories and old pictures. Tante Ilse seemed to relish the photos and the time with family. She was doing so well that when we went back to my mom’s home after the reception, my cousins decided to bring Tante Ilse there, too. She had a great time, as evidenced by her famous total-body laugh. In the months before her death, we all commented about that day and how happy she seemed.

My aunt’s decline comes to mind as I reflect on media reports of 2 Alzheimer drugs— aducanumab and lecanemab—that have been billed by some as “gamechangers.” These new drugs are monoclonal antibodies directed at amyloid, one of several agents thought to cause Alzheimer disease. The details of aducanumab’s approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) generated a great deal of criticism—with good reason.

Two manufacturer-sponsored studies of aducanumab were halted due to futility of finding a benefit.1 The FDA’s scientific advisory panel recommended against approval due to a lack of evidence that it did anything more than remove amyloid plaque from the brain. And yet aducanumab received accelerated approval from the FDA. (This author collaborated on an additional analysis using data presented to the FDA, after its approval, which also reported no clinically meaningful effects.2) The other agent, lecanemab, also reduces markers of amyloid and was shown to be only moderately better than placebo in decreasing the rate of decline on various measures of cognition.3 Quite notably, both aducanumab and lecanemab, which are administered parenterally, cost more than $25,000 per year4,5 and cause amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (brain edema or hemorrhage).

Expensive agents without meaningful benefit. So far, neither of these agents has shown a reduction in things that are truly important to our patients and their families/caregivers: a reduction in caregiver burden and a reduction in the need for placement in long-term care facilities.

This is in contrast to cholinesterase inhibitors, which also slow the rate of cognitive decline.6 Among the differences that exist between these agents: Cholinesterase inhibitors are taken orally and are available as generics, which cost less than a thousand dollars per year.7 Limited data also suggest that they are associated with a lower risk for nursing home placement.8,9 (A February 2023 search of clinicaltrials.gov did not reveal any completed or planned head-to-head comparisons of monoclonal antibodies and anticholinergic agents.)

Our patients, their families, and caregivers hold out hope for something that will improve the patient’s cognition and extend the meaningful time they have with their loved ones. So far, the best we have to offer falls far short of these goals. I certainly would have hoped for something better than merely clearing amyloid for my aunt.

It’s time that the FDA adopt more rigorous standards requiring new drugs to, among other things, demonstrate meaningful clinical benefits, provide real cost savings, and be safer than currently available therapies. Other nations seem to be able to do this.10,11 It is bad enough to provide “hope in a bottle”; it is worse when what is offered is false hope.

Last year, after a long delay due to COVID, my father’s ashes were finally laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery. Among the loved ones who came was my favorite aunt, Tante Ilse, who was suffering from dementia. While she wasn’t “following” everything that was going on, she did perk up when she heard my father’s name and would comment on how she liked him and how wonderful he had been to her.

After the ceremony, our family of about 30 gathered at a restaurant where we shared stories and old pictures. Tante Ilse seemed to relish the photos and the time with family. She was doing so well that when we went back to my mom’s home after the reception, my cousins decided to bring Tante Ilse there, too. She had a great time, as evidenced by her famous total-body laugh. In the months before her death, we all commented about that day and how happy she seemed.

My aunt’s decline comes to mind as I reflect on media reports of 2 Alzheimer drugs— aducanumab and lecanemab—that have been billed by some as “gamechangers.” These new drugs are monoclonal antibodies directed at amyloid, one of several agents thought to cause Alzheimer disease. The details of aducanumab’s approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) generated a great deal of criticism—with good reason.

Two manufacturer-sponsored studies of aducanumab were halted due to futility of finding a benefit.1 The FDA’s scientific advisory panel recommended against approval due to a lack of evidence that it did anything more than remove amyloid plaque from the brain. And yet aducanumab received accelerated approval from the FDA. (This author collaborated on an additional analysis using data presented to the FDA, after its approval, which also reported no clinically meaningful effects.2) The other agent, lecanemab, also reduces markers of amyloid and was shown to be only moderately better than placebo in decreasing the rate of decline on various measures of cognition.3 Quite notably, both aducanumab and lecanemab, which are administered parenterally, cost more than $25,000 per year4,5 and cause amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (brain edema or hemorrhage).

Expensive agents without meaningful benefit. So far, neither of these agents has shown a reduction in things that are truly important to our patients and their families/caregivers: a reduction in caregiver burden and a reduction in the need for placement in long-term care facilities.

This is in contrast to cholinesterase inhibitors, which also slow the rate of cognitive decline.6 Among the differences that exist between these agents: Cholinesterase inhibitors are taken orally and are available as generics, which cost less than a thousand dollars per year.7 Limited data also suggest that they are associated with a lower risk for nursing home placement.8,9 (A February 2023 search of clinicaltrials.gov did not reveal any completed or planned head-to-head comparisons of monoclonal antibodies and anticholinergic agents.)

Our patients, their families, and caregivers hold out hope for something that will improve the patient’s cognition and extend the meaningful time they have with their loved ones. So far, the best we have to offer falls far short of these goals. I certainly would have hoped for something better than merely clearing amyloid for my aunt.

It’s time that the FDA adopt more rigorous standards requiring new drugs to, among other things, demonstrate meaningful clinical benefits, provide real cost savings, and be safer than currently available therapies. Other nations seem to be able to do this.10,11 It is bad enough to provide “hope in a bottle”; it is worse when what is offered is false hope.

1. Budd Haeberlein S, Aisen PS, Barkhof F, et al. Two randomized phase 3 studies of aducanumab in early Alzheimer’s disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2022;9:197-210. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2022.30

2. Ebell MH, Barry HC. Why physicians should not prescribe aducanumab for Alzheimer disease. Am Fam Physician. 2022;105:353-354.

3. van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:9-21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2212948

4. Reardon S. FDA approves Alzheimer’s drug lecanemab amid safety concerns. Nature. 2023; 613:227-228. doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-00030-3

5. Biogen announces reduced price for Aduhelm to improve access for patients with early Alzheimer’s disease. December 20, 2021. Accessed February 20, 2023. https://investors.biogen.com/news-releases/news-release-details/biogen-announces-reduced-price-aduhelmr-improve-access-patients

6. Takramah WK, Asem L. The efficacy of pharmacological interventions to improve cognitive and behavior symptoms in people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Sci Rep. 2022;5:e913. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.913

7. GoodRx. Donepezil generic Aricept. Accessed February 20, 2023. www.goodrx.com/donepezil

8. Howard R, McShane R, Lindesay J, et al. Nursing home placement in the donepezil and memantine in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease (DOMINO-AD) trial: secondary and post-hoc analyses. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:1171-1181. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00258-6

9. Geldmacher DS, Provenzano G, McRae T, et al. Donepezil is associated with delayed nursing home placement in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:937-944. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51306.x

10. Pham C, Le K, Draves M, et al. Assessment of FDA-approved drugs not recommended for use or reimbursement in other countries, 2017-2020. JAMA Intern Med. Published online February 13, 2023. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6787

11. Johnston JL, Ross JS, Ramachandran R. US Food and Drug Administration approval of drugs not meeting pivotal trial primary end points, 2018-2021. JAMA Intern Med. Published online February 13, 2023. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6444

1. Budd Haeberlein S, Aisen PS, Barkhof F, et al. Two randomized phase 3 studies of aducanumab in early Alzheimer’s disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2022;9:197-210. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2022.30

2. Ebell MH, Barry HC. Why physicians should not prescribe aducanumab for Alzheimer disease. Am Fam Physician. 2022;105:353-354.

3. van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:9-21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2212948

4. Reardon S. FDA approves Alzheimer’s drug lecanemab amid safety concerns. Nature. 2023; 613:227-228. doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-00030-3

5. Biogen announces reduced price for Aduhelm to improve access for patients with early Alzheimer’s disease. December 20, 2021. Accessed February 20, 2023. https://investors.biogen.com/news-releases/news-release-details/biogen-announces-reduced-price-aduhelmr-improve-access-patients

6. Takramah WK, Asem L. The efficacy of pharmacological interventions to improve cognitive and behavior symptoms in people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Sci Rep. 2022;5:e913. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.913

7. GoodRx. Donepezil generic Aricept. Accessed February 20, 2023. www.goodrx.com/donepezil

8. Howard R, McShane R, Lindesay J, et al. Nursing home placement in the donepezil and memantine in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease (DOMINO-AD) trial: secondary and post-hoc analyses. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:1171-1181. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00258-6

9. Geldmacher DS, Provenzano G, McRae T, et al. Donepezil is associated with delayed nursing home placement in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:937-944. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51306.x

10. Pham C, Le K, Draves M, et al. Assessment of FDA-approved drugs not recommended for use or reimbursement in other countries, 2017-2020. JAMA Intern Med. Published online February 13, 2023. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6787

11. Johnston JL, Ross JS, Ramachandran R. US Food and Drug Administration approval of drugs not meeting pivotal trial primary end points, 2018-2021. JAMA Intern Med. Published online February 13, 2023. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6444

5 non-COVID vaccine recommendations from ACIP

Much of the work of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) in 2022 was devoted to vaccines to protect against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19); details about the 4 available products can be found on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID vaccine website (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/index.html).1,2 However, ACIP also issued recommendations about 5 other (non-COVID) vaccines last year, and those are the focus of this Practice Alert.

A second MMR vaccine option

The United States has had only 1 measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine approved for use since 1978: M-M-R II (Merck). In June 2022, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a second MMR vaccine, PRIORIX (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals), which ACIP now recommends as an option when MMR vaccine is indicated.3

ACIP considers the 2 MMR options fully interchangeable.3 Both vaccines produce similar levels of immunogenicity and the safety profiles are also equivalent—including the rate of febrile seizures 6 to 11 days after vaccination, estimated at 3.3 to 8.7 per 10,000 doses.4 Since PRIORIX has been used in other countries since 1997, the MMR workgroup was able to include 13 studies on immunogenicity and 4 on safety in its evidence assessment; these are summarized on the CDC website.4

It is desirable to have multiple manufacturers of recommended vaccines to prevent shortages if there a disruption in the supply chain of 1 manufacturer, as well as to provide competition for cost control. A second MMR vaccine is therefore a welcome addition to the US vaccine supply. However, there remains only 1 combination measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccine approved for use in the United States: ProQuad (Merck).

Pneumococcal vaccine recommendations are revised and simplified

Adults. Last year, ACIP made recommendations regarding 2 new vaccine options for use against pneumococcal infections in adults: PCV15 (Vaxneuvance, Merck) and PCV20 (Prevnar20, Pfizer). These have been described in detail in a CDC publication and summarized in a recent Practice Alert.5,6

ACIP revised and simplified its recommendations on vaccination to prevent pneumococcal disease in adults as follows5:

1. Maintained the cutoff of age 65 years for universal pneumococcal vaccination

2. Recommended pneumococcal vaccination (with either PCV15 or PCV20) for all adults ages 65 years and older and for those younger than 65 years with chronic medical conditions or immunocompromise

3. Recommended that if PCV15 is used, it should be followed by 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23, Merck).

These revisions created a number of uncertain clinical situations, since patients could have already started and/or completed their pneumococcal vaccination with previously available products, including PCV7, PCV13, and PPSV23. At the October 2022 ACIP meeting, the pneumococcal workgroup addressed a number of “what if” clinical questions. These clinical considerations will soon be published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) but also can be reviewed by looking at the October ACIP meeting materials.7 The main considerations are summarized below7:

- For those who have previously received PCV7, either PCV15 or PCV20 should be given.

- If PPSV23 was inadvertently administered first, it should be followed by PCV15 or PCV20 at least 1 year later.

- Adults who have only received PPSV23 should receive a dose of either PCV20 or PCV15 at least 1 year after their last PPSV23 dose. When PCV15 is used in those with a history of PPSV23 receipt, it need not be followed by another dose of PPSV23.

- Adults who have received PCV13 only are recommended to complete their pneumococcal vaccine series by receiving either a dose of PCV20 at least 1 year after the PCV13 dose or PPSV23 as previously recommended.

- Shared clinical decision-making is recommended regarding administration of PCV20 for adults ages ≥ 65 years who have completed their recommended vaccine series with both PCV13 and PPSV23 but have not received PCV15 or PCV20. If a decision to administer PCV20 is made, a dose of PCV20 is recommended at least 5 years after the last pneumococcal vaccine dose.

Continue to: Children

Children. In 2022, PCV15 was licensed for use in children and adolescents ages 6 weeks to 17 years. PCV15 contains all the serotypes in the PCV13 vaccine, plus 22F and 33F. In June 2022, ACIP adopted recommendations regarding the use of PCV15 in children. The main recommendation is that PCV13 and PCV15 can be used interchangeably. The recommended schedule for PCV use in children and the catch-up schedule have not changed, nor has the use of PPSV23 in children with underlying medical conditions.8,9

Those who have been vaccinated with PCV13 do not need to be revaccinated with PCV15, and an incomplete series of PCV13 can be completed with PCV15. It is anticipated that in 2023, PCV20 will be FDA approved for use in children and adolescents, and this will probably change the recommendations for the use of PPSV23 in children with underlying medical conditions. The recommended routine immunization and catch-up immunization schedules are published on the CDC website,9 and the pneumococcal-specific recommendations are described in a recent MMWR.8

Preferential choice for influenza vaccine in those ≥ 65 years

The ACIP now recommends 1 of 3 influenza vaccines be used preferentially in those ages 65 years and older: the high-dose quadrivalent vaccine (HD-IIV4), Fluzone; the adjuvanted quadrivalent influenza vaccine (aIIV4), Fluad; or the recombinant quadrivalent influenza vaccine (RIV4), Flublok. However, if none of these options are available, a standard-dose vaccine is acceptable.

Both HD-IIV4 and aIIV4 are approved only for those ≥ 65 years of age. The RIV4 is approved for ages ≥ 18 years and is produced by a process that does not involve eggs. These 3 products produce better antibody levels and improved clinical outcomes in older adults compared to other, standard-dose flu vaccines, but there is no convincing evidence that any 1 of these is more effective than the others. A more in-depth discussion of flu vaccines and the considerations that went into this preferential recommendation were described in a previous Practice Alert.10

Updates for 2 travel vaccines

Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE). A TBE vaccine (Ticovac; Pfizer) has been available in other countries for more than 20 years, with no serious safety concerns identified. The vaccine was approved for use in the United States by the FDA in August 2021, and in early 2022, the ACIP made 3 recommendations for its use (to be discussed shortly).

TBE is a neuroinvasive flavivirus spread by ticks in parts of Europe and Asia. There are 3 main subtypes of the virus, and they cause serious illness, with a fatality rate of 1% to 20% and a sequelae rate of 10% to 50%.11 TBE infection is rare among US travelers, with only 11 cases documented between 2001 and 2020. There were 9 cases within the US military between 2006 and 2020.11

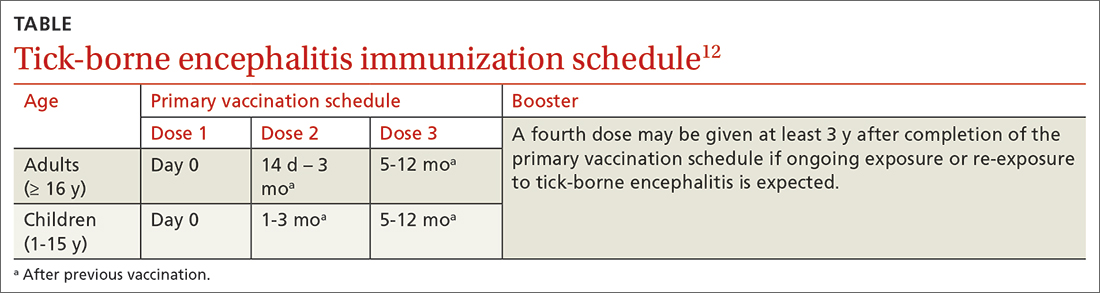

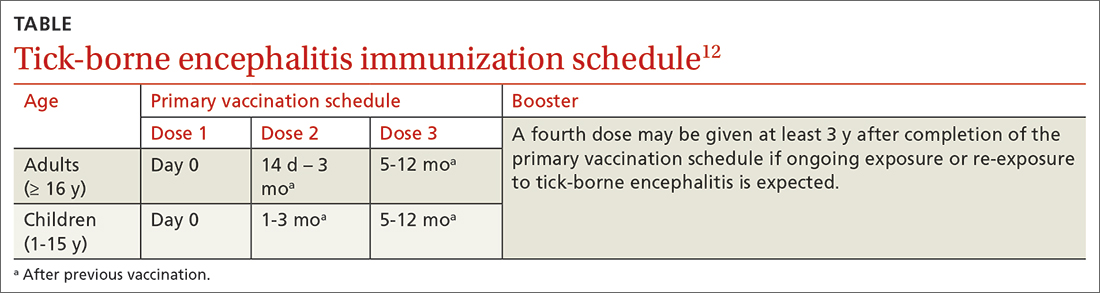

The TBE vaccine contains inactivated TBE virus, which is produced in chick embryo cells. It is administered in 3 doses over a 12-month timeframe, and those with continued exposure should receive a booster after 3 years.12 (See TABLE12 for administration schedule.) More information about the vaccine, contraindications, and rates of adverse reactions is available in the FDA package insert.13

Continue to: The ACIP has made...

The ACIP has made the following recommendations for the TBE vaccine11,12:

1. Vaccination is recommended for laboratory workers with a potential for exposure to TBE virus.

2. TBE vaccine also is recommended for individuals who are moving abroad or traveling to a TBE-endemic area and who will have extensive exposure to ticks based on their planned outdoor activities and itinerary.

3. TBE vaccine can be considered for people traveling or moving to a TBE-endemic area who might engage in outdoor activities in areas where ticks are likely to be found. The decision to vaccinate should be based on an assessment of the patient’s planned activities and itinerary, risk factors for a poorer medical outcome, and personal perception and tolerance of risk.

Cholera. ACIP now recommends CVD 103-HgR (PaxVax, VAXCHORA), a single-dose, live attenuated oral cholera vaccine, for travelers as young as 2 years who plan to visit an area that has active cholera transmission.14 In February 2022, ACIP expanded its recommendation for adults ages 18 to 64 years to include children and adolescents ages 2 to 17 years. This followed a 2020 FDA approval for the vaccine in the younger age group. Details about the vaccine were described in an MMWR publication.14

Cholera is caused by toxigenic bacteria. Infection occurs by ingestion of contaminated water or food and can be prevented by consumption of safe water and food, along with good sanitation and handwashing. Cholera produces a profuse watery diarrhea that can rapidly lead to death in 50% of those infected who do not receive rehydration therapy.15 Cholera is endemic is many countries and can cause large outbreaks. The World Health Organization estimates that 1 to 4 million cases of cholera and 21,000 to 143,000 related deaths occur globally each year.16

Staying current is moreimportant than ever

Vaccines are one of the most successful public health interventions of the past century, and maintaining a robust vaccine approval and safety monitoring system is an important priority. However, to gain the most benefit from vaccines, physicians need to stay current on vaccine recommendations—something that is becoming increasingly difficult to accomplish as the options expand. Consulting the literature and visiting the CDC’s website (www.cdc.gov) with frequency can be helpful to that end.

1. CDC. Summary document for interim clinical considerations for use of COVID-19 vaccines currently authorized or approved in the US. Published December 6, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/downloads/summary-interim-clinical-considerations.pdf

2. CDC. COVID-19 vaccine: interim COVID-19 immunization schedule for persons 6 months of age and older. Published December 8, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/downloads/COVID-19-immunization-schedule-ages-6months-older.pdf

3. Krow-Lucal E, Marin M, Shepersky L, et al. Measles, mumps, rubella vaccine (PRIORIX): recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1465-1470. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7146a1

4. CDC. ACIP evidence to recommendations framework for use of PRIORIX for prevention of measles, mumps, and rubella. Updated October 27, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recs/grade/mmr-PRIORIX-etr.html

5. Kobayashi M, Farrar JL, Gierke R, et al. Use of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine among US adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:109-117. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7104a1

6. Campos-Outcalt D. Vaccine update: the latest recommendations from ACIP. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:80-84. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0362

7. Kobayashi M. Proposed updates to clinical guidance on pneumococcal vaccine use among adults. Presented to the ACIP on October 19, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-10-19-20/04-Pneumococcal-Kobayashi-508.pdf

8. Kobayashi M, Farrar JL, Gierke R, et al. Use of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine among US children: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1174-1181. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7137a3

9. CDC. Immunization schedules. Updated February 17, 2022. Accessed February 6, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html

10. Campos-Outcalt D. Vaccine update for the 2022-2023 influenza season. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:362-365. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0487

11. Hills S. Tick-borne encephalitis. Presented to the ACIP on February 23, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-02-23-24/02-TBE-Hills-508.pdf

12. CDC. Tick-borne encephalitis. Updated March 11, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/tick-borne-encephalitis/

13. Ticovac. Package insert. Pfizer; 2022. Accessed February 6, 2023. www.fda.gov/media/151502/download

14. Collins JP, Ryan ET, Wong KK, et al. Cholera vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71:1-8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7102a1

15. Global Task Force on Cholera Control. Cholera outbreak response field manual. Published October 2019. Accessed February 16, 2023. www.gtfcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/gtfcc-cholera-outbreak-response-field-manual.pdf

16. WHO. Health topics: cholera. Accessed February 16, 2023. www.who.int/health-topics/cholera#tab=tab_1

Much of the work of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) in 2022 was devoted to vaccines to protect against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19); details about the 4 available products can be found on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID vaccine website (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/index.html).1,2 However, ACIP also issued recommendations about 5 other (non-COVID) vaccines last year, and those are the focus of this Practice Alert.

A second MMR vaccine option

The United States has had only 1 measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine approved for use since 1978: M-M-R II (Merck). In June 2022, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a second MMR vaccine, PRIORIX (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals), which ACIP now recommends as an option when MMR vaccine is indicated.3

ACIP considers the 2 MMR options fully interchangeable.3 Both vaccines produce similar levels of immunogenicity and the safety profiles are also equivalent—including the rate of febrile seizures 6 to 11 days after vaccination, estimated at 3.3 to 8.7 per 10,000 doses.4 Since PRIORIX has been used in other countries since 1997, the MMR workgroup was able to include 13 studies on immunogenicity and 4 on safety in its evidence assessment; these are summarized on the CDC website.4

It is desirable to have multiple manufacturers of recommended vaccines to prevent shortages if there a disruption in the supply chain of 1 manufacturer, as well as to provide competition for cost control. A second MMR vaccine is therefore a welcome addition to the US vaccine supply. However, there remains only 1 combination measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccine approved for use in the United States: ProQuad (Merck).

Pneumococcal vaccine recommendations are revised and simplified

Adults. Last year, ACIP made recommendations regarding 2 new vaccine options for use against pneumococcal infections in adults: PCV15 (Vaxneuvance, Merck) and PCV20 (Prevnar20, Pfizer). These have been described in detail in a CDC publication and summarized in a recent Practice Alert.5,6

ACIP revised and simplified its recommendations on vaccination to prevent pneumococcal disease in adults as follows5:

1. Maintained the cutoff of age 65 years for universal pneumococcal vaccination

2. Recommended pneumococcal vaccination (with either PCV15 or PCV20) for all adults ages 65 years and older and for those younger than 65 years with chronic medical conditions or immunocompromise

3. Recommended that if PCV15 is used, it should be followed by 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23, Merck).

These revisions created a number of uncertain clinical situations, since patients could have already started and/or completed their pneumococcal vaccination with previously available products, including PCV7, PCV13, and PPSV23. At the October 2022 ACIP meeting, the pneumococcal workgroup addressed a number of “what if” clinical questions. These clinical considerations will soon be published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) but also can be reviewed by looking at the October ACIP meeting materials.7 The main considerations are summarized below7:

- For those who have previously received PCV7, either PCV15 or PCV20 should be given.

- If PPSV23 was inadvertently administered first, it should be followed by PCV15 or PCV20 at least 1 year later.

- Adults who have only received PPSV23 should receive a dose of either PCV20 or PCV15 at least 1 year after their last PPSV23 dose. When PCV15 is used in those with a history of PPSV23 receipt, it need not be followed by another dose of PPSV23.

- Adults who have received PCV13 only are recommended to complete their pneumococcal vaccine series by receiving either a dose of PCV20 at least 1 year after the PCV13 dose or PPSV23 as previously recommended.

- Shared clinical decision-making is recommended regarding administration of PCV20 for adults ages ≥ 65 years who have completed their recommended vaccine series with both PCV13 and PPSV23 but have not received PCV15 or PCV20. If a decision to administer PCV20 is made, a dose of PCV20 is recommended at least 5 years after the last pneumococcal vaccine dose.

Continue to: Children

Children. In 2022, PCV15 was licensed for use in children and adolescents ages 6 weeks to 17 years. PCV15 contains all the serotypes in the PCV13 vaccine, plus 22F and 33F. In June 2022, ACIP adopted recommendations regarding the use of PCV15 in children. The main recommendation is that PCV13 and PCV15 can be used interchangeably. The recommended schedule for PCV use in children and the catch-up schedule have not changed, nor has the use of PPSV23 in children with underlying medical conditions.8,9

Those who have been vaccinated with PCV13 do not need to be revaccinated with PCV15, and an incomplete series of PCV13 can be completed with PCV15. It is anticipated that in 2023, PCV20 will be FDA approved for use in children and adolescents, and this will probably change the recommendations for the use of PPSV23 in children with underlying medical conditions. The recommended routine immunization and catch-up immunization schedules are published on the CDC website,9 and the pneumococcal-specific recommendations are described in a recent MMWR.8

Preferential choice for influenza vaccine in those ≥ 65 years

The ACIP now recommends 1 of 3 influenza vaccines be used preferentially in those ages 65 years and older: the high-dose quadrivalent vaccine (HD-IIV4), Fluzone; the adjuvanted quadrivalent influenza vaccine (aIIV4), Fluad; or the recombinant quadrivalent influenza vaccine (RIV4), Flublok. However, if none of these options are available, a standard-dose vaccine is acceptable.

Both HD-IIV4 and aIIV4 are approved only for those ≥ 65 years of age. The RIV4 is approved for ages ≥ 18 years and is produced by a process that does not involve eggs. These 3 products produce better antibody levels and improved clinical outcomes in older adults compared to other, standard-dose flu vaccines, but there is no convincing evidence that any 1 of these is more effective than the others. A more in-depth discussion of flu vaccines and the considerations that went into this preferential recommendation were described in a previous Practice Alert.10

Updates for 2 travel vaccines

Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE). A TBE vaccine (Ticovac; Pfizer) has been available in other countries for more than 20 years, with no serious safety concerns identified. The vaccine was approved for use in the United States by the FDA in August 2021, and in early 2022, the ACIP made 3 recommendations for its use (to be discussed shortly).

TBE is a neuroinvasive flavivirus spread by ticks in parts of Europe and Asia. There are 3 main subtypes of the virus, and they cause serious illness, with a fatality rate of 1% to 20% and a sequelae rate of 10% to 50%.11 TBE infection is rare among US travelers, with only 11 cases documented between 2001 and 2020. There were 9 cases within the US military between 2006 and 2020.11

The TBE vaccine contains inactivated TBE virus, which is produced in chick embryo cells. It is administered in 3 doses over a 12-month timeframe, and those with continued exposure should receive a booster after 3 years.12 (See TABLE12 for administration schedule.) More information about the vaccine, contraindications, and rates of adverse reactions is available in the FDA package insert.13

Continue to: The ACIP has made...

The ACIP has made the following recommendations for the TBE vaccine11,12:

1. Vaccination is recommended for laboratory workers with a potential for exposure to TBE virus.

2. TBE vaccine also is recommended for individuals who are moving abroad or traveling to a TBE-endemic area and who will have extensive exposure to ticks based on their planned outdoor activities and itinerary.

3. TBE vaccine can be considered for people traveling or moving to a TBE-endemic area who might engage in outdoor activities in areas where ticks are likely to be found. The decision to vaccinate should be based on an assessment of the patient’s planned activities and itinerary, risk factors for a poorer medical outcome, and personal perception and tolerance of risk.

Cholera. ACIP now recommends CVD 103-HgR (PaxVax, VAXCHORA), a single-dose, live attenuated oral cholera vaccine, for travelers as young as 2 years who plan to visit an area that has active cholera transmission.14 In February 2022, ACIP expanded its recommendation for adults ages 18 to 64 years to include children and adolescents ages 2 to 17 years. This followed a 2020 FDA approval for the vaccine in the younger age group. Details about the vaccine were described in an MMWR publication.14

Cholera is caused by toxigenic bacteria. Infection occurs by ingestion of contaminated water or food and can be prevented by consumption of safe water and food, along with good sanitation and handwashing. Cholera produces a profuse watery diarrhea that can rapidly lead to death in 50% of those infected who do not receive rehydration therapy.15 Cholera is endemic is many countries and can cause large outbreaks. The World Health Organization estimates that 1 to 4 million cases of cholera and 21,000 to 143,000 related deaths occur globally each year.16

Staying current is moreimportant than ever

Vaccines are one of the most successful public health interventions of the past century, and maintaining a robust vaccine approval and safety monitoring system is an important priority. However, to gain the most benefit from vaccines, physicians need to stay current on vaccine recommendations—something that is becoming increasingly difficult to accomplish as the options expand. Consulting the literature and visiting the CDC’s website (www.cdc.gov) with frequency can be helpful to that end.

Much of the work of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) in 2022 was devoted to vaccines to protect against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19); details about the 4 available products can be found on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID vaccine website (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/index.html).1,2 However, ACIP also issued recommendations about 5 other (non-COVID) vaccines last year, and those are the focus of this Practice Alert.

A second MMR vaccine option

The United States has had only 1 measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine approved for use since 1978: M-M-R II (Merck). In June 2022, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a second MMR vaccine, PRIORIX (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals), which ACIP now recommends as an option when MMR vaccine is indicated.3

ACIP considers the 2 MMR options fully interchangeable.3 Both vaccines produce similar levels of immunogenicity and the safety profiles are also equivalent—including the rate of febrile seizures 6 to 11 days after vaccination, estimated at 3.3 to 8.7 per 10,000 doses.4 Since PRIORIX has been used in other countries since 1997, the MMR workgroup was able to include 13 studies on immunogenicity and 4 on safety in its evidence assessment; these are summarized on the CDC website.4

It is desirable to have multiple manufacturers of recommended vaccines to prevent shortages if there a disruption in the supply chain of 1 manufacturer, as well as to provide competition for cost control. A second MMR vaccine is therefore a welcome addition to the US vaccine supply. However, there remains only 1 combination measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccine approved for use in the United States: ProQuad (Merck).

Pneumococcal vaccine recommendations are revised and simplified

Adults. Last year, ACIP made recommendations regarding 2 new vaccine options for use against pneumococcal infections in adults: PCV15 (Vaxneuvance, Merck) and PCV20 (Prevnar20, Pfizer). These have been described in detail in a CDC publication and summarized in a recent Practice Alert.5,6

ACIP revised and simplified its recommendations on vaccination to prevent pneumococcal disease in adults as follows5:

1. Maintained the cutoff of age 65 years for universal pneumococcal vaccination

2. Recommended pneumococcal vaccination (with either PCV15 or PCV20) for all adults ages 65 years and older and for those younger than 65 years with chronic medical conditions or immunocompromise

3. Recommended that if PCV15 is used, it should be followed by 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23, Merck).

These revisions created a number of uncertain clinical situations, since patients could have already started and/or completed their pneumococcal vaccination with previously available products, including PCV7, PCV13, and PPSV23. At the October 2022 ACIP meeting, the pneumococcal workgroup addressed a number of “what if” clinical questions. These clinical considerations will soon be published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) but also can be reviewed by looking at the October ACIP meeting materials.7 The main considerations are summarized below7:

- For those who have previously received PCV7, either PCV15 or PCV20 should be given.

- If PPSV23 was inadvertently administered first, it should be followed by PCV15 or PCV20 at least 1 year later.

- Adults who have only received PPSV23 should receive a dose of either PCV20 or PCV15 at least 1 year after their last PPSV23 dose. When PCV15 is used in those with a history of PPSV23 receipt, it need not be followed by another dose of PPSV23.

- Adults who have received PCV13 only are recommended to complete their pneumococcal vaccine series by receiving either a dose of PCV20 at least 1 year after the PCV13 dose or PPSV23 as previously recommended.

- Shared clinical decision-making is recommended regarding administration of PCV20 for adults ages ≥ 65 years who have completed their recommended vaccine series with both PCV13 and PPSV23 but have not received PCV15 or PCV20. If a decision to administer PCV20 is made, a dose of PCV20 is recommended at least 5 years after the last pneumococcal vaccine dose.

Continue to: Children

Children. In 2022, PCV15 was licensed for use in children and adolescents ages 6 weeks to 17 years. PCV15 contains all the serotypes in the PCV13 vaccine, plus 22F and 33F. In June 2022, ACIP adopted recommendations regarding the use of PCV15 in children. The main recommendation is that PCV13 and PCV15 can be used interchangeably. The recommended schedule for PCV use in children and the catch-up schedule have not changed, nor has the use of PPSV23 in children with underlying medical conditions.8,9

Those who have been vaccinated with PCV13 do not need to be revaccinated with PCV15, and an incomplete series of PCV13 can be completed with PCV15. It is anticipated that in 2023, PCV20 will be FDA approved for use in children and adolescents, and this will probably change the recommendations for the use of PPSV23 in children with underlying medical conditions. The recommended routine immunization and catch-up immunization schedules are published on the CDC website,9 and the pneumococcal-specific recommendations are described in a recent MMWR.8

Preferential choice for influenza vaccine in those ≥ 65 years

The ACIP now recommends 1 of 3 influenza vaccines be used preferentially in those ages 65 years and older: the high-dose quadrivalent vaccine (HD-IIV4), Fluzone; the adjuvanted quadrivalent influenza vaccine (aIIV4), Fluad; or the recombinant quadrivalent influenza vaccine (RIV4), Flublok. However, if none of these options are available, a standard-dose vaccine is acceptable.

Both HD-IIV4 and aIIV4 are approved only for those ≥ 65 years of age. The RIV4 is approved for ages ≥ 18 years and is produced by a process that does not involve eggs. These 3 products produce better antibody levels and improved clinical outcomes in older adults compared to other, standard-dose flu vaccines, but there is no convincing evidence that any 1 of these is more effective than the others. A more in-depth discussion of flu vaccines and the considerations that went into this preferential recommendation were described in a previous Practice Alert.10

Updates for 2 travel vaccines

Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE). A TBE vaccine (Ticovac; Pfizer) has been available in other countries for more than 20 years, with no serious safety concerns identified. The vaccine was approved for use in the United States by the FDA in August 2021, and in early 2022, the ACIP made 3 recommendations for its use (to be discussed shortly).

TBE is a neuroinvasive flavivirus spread by ticks in parts of Europe and Asia. There are 3 main subtypes of the virus, and they cause serious illness, with a fatality rate of 1% to 20% and a sequelae rate of 10% to 50%.11 TBE infection is rare among US travelers, with only 11 cases documented between 2001 and 2020. There were 9 cases within the US military between 2006 and 2020.11

The TBE vaccine contains inactivated TBE virus, which is produced in chick embryo cells. It is administered in 3 doses over a 12-month timeframe, and those with continued exposure should receive a booster after 3 years.12 (See TABLE12 for administration schedule.) More information about the vaccine, contraindications, and rates of adverse reactions is available in the FDA package insert.13

Continue to: The ACIP has made...

The ACIP has made the following recommendations for the TBE vaccine11,12:

1. Vaccination is recommended for laboratory workers with a potential for exposure to TBE virus.

2. TBE vaccine also is recommended for individuals who are moving abroad or traveling to a TBE-endemic area and who will have extensive exposure to ticks based on their planned outdoor activities and itinerary.

3. TBE vaccine can be considered for people traveling or moving to a TBE-endemic area who might engage in outdoor activities in areas where ticks are likely to be found. The decision to vaccinate should be based on an assessment of the patient’s planned activities and itinerary, risk factors for a poorer medical outcome, and personal perception and tolerance of risk.

Cholera. ACIP now recommends CVD 103-HgR (PaxVax, VAXCHORA), a single-dose, live attenuated oral cholera vaccine, for travelers as young as 2 years who plan to visit an area that has active cholera transmission.14 In February 2022, ACIP expanded its recommendation for adults ages 18 to 64 years to include children and adolescents ages 2 to 17 years. This followed a 2020 FDA approval for the vaccine in the younger age group. Details about the vaccine were described in an MMWR publication.14

Cholera is caused by toxigenic bacteria. Infection occurs by ingestion of contaminated water or food and can be prevented by consumption of safe water and food, along with good sanitation and handwashing. Cholera produces a profuse watery diarrhea that can rapidly lead to death in 50% of those infected who do not receive rehydration therapy.15 Cholera is endemic is many countries and can cause large outbreaks. The World Health Organization estimates that 1 to 4 million cases of cholera and 21,000 to 143,000 related deaths occur globally each year.16

Staying current is moreimportant than ever

Vaccines are one of the most successful public health interventions of the past century, and maintaining a robust vaccine approval and safety monitoring system is an important priority. However, to gain the most benefit from vaccines, physicians need to stay current on vaccine recommendations—something that is becoming increasingly difficult to accomplish as the options expand. Consulting the literature and visiting the CDC’s website (www.cdc.gov) with frequency can be helpful to that end.

1. CDC. Summary document for interim clinical considerations for use of COVID-19 vaccines currently authorized or approved in the US. Published December 6, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/downloads/summary-interim-clinical-considerations.pdf

2. CDC. COVID-19 vaccine: interim COVID-19 immunization schedule for persons 6 months of age and older. Published December 8, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/downloads/COVID-19-immunization-schedule-ages-6months-older.pdf

3. Krow-Lucal E, Marin M, Shepersky L, et al. Measles, mumps, rubella vaccine (PRIORIX): recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1465-1470. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7146a1

4. CDC. ACIP evidence to recommendations framework for use of PRIORIX for prevention of measles, mumps, and rubella. Updated October 27, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recs/grade/mmr-PRIORIX-etr.html

5. Kobayashi M, Farrar JL, Gierke R, et al. Use of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine among US adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:109-117. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7104a1

6. Campos-Outcalt D. Vaccine update: the latest recommendations from ACIP. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:80-84. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0362

7. Kobayashi M. Proposed updates to clinical guidance on pneumococcal vaccine use among adults. Presented to the ACIP on October 19, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-10-19-20/04-Pneumococcal-Kobayashi-508.pdf

8. Kobayashi M, Farrar JL, Gierke R, et al. Use of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine among US children: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1174-1181. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7137a3

9. CDC. Immunization schedules. Updated February 17, 2022. Accessed February 6, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html

10. Campos-Outcalt D. Vaccine update for the 2022-2023 influenza season. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:362-365. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0487

11. Hills S. Tick-borne encephalitis. Presented to the ACIP on February 23, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-02-23-24/02-TBE-Hills-508.pdf

12. CDC. Tick-borne encephalitis. Updated March 11, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/tick-borne-encephalitis/

13. Ticovac. Package insert. Pfizer; 2022. Accessed February 6, 2023. www.fda.gov/media/151502/download

14. Collins JP, Ryan ET, Wong KK, et al. Cholera vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71:1-8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7102a1

15. Global Task Force on Cholera Control. Cholera outbreak response field manual. Published October 2019. Accessed February 16, 2023. www.gtfcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/gtfcc-cholera-outbreak-response-field-manual.pdf

16. WHO. Health topics: cholera. Accessed February 16, 2023. www.who.int/health-topics/cholera#tab=tab_1

1. CDC. Summary document for interim clinical considerations for use of COVID-19 vaccines currently authorized or approved in the US. Published December 6, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/downloads/summary-interim-clinical-considerations.pdf

2. CDC. COVID-19 vaccine: interim COVID-19 immunization schedule for persons 6 months of age and older. Published December 8, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/downloads/COVID-19-immunization-schedule-ages-6months-older.pdf

3. Krow-Lucal E, Marin M, Shepersky L, et al. Measles, mumps, rubella vaccine (PRIORIX): recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1465-1470. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7146a1

4. CDC. ACIP evidence to recommendations framework for use of PRIORIX for prevention of measles, mumps, and rubella. Updated October 27, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recs/grade/mmr-PRIORIX-etr.html

5. Kobayashi M, Farrar JL, Gierke R, et al. Use of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine among US adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:109-117. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7104a1

6. Campos-Outcalt D. Vaccine update: the latest recommendations from ACIP. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:80-84. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0362

7. Kobayashi M. Proposed updates to clinical guidance on pneumococcal vaccine use among adults. Presented to the ACIP on October 19, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-10-19-20/04-Pneumococcal-Kobayashi-508.pdf

8. Kobayashi M, Farrar JL, Gierke R, et al. Use of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine among US children: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1174-1181. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7137a3

9. CDC. Immunization schedules. Updated February 17, 2022. Accessed February 6, 2022. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html

10. Campos-Outcalt D. Vaccine update for the 2022-2023 influenza season. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:362-365. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0487

11. Hills S. Tick-borne encephalitis. Presented to the ACIP on February 23, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2022-02-23-24/02-TBE-Hills-508.pdf

12. CDC. Tick-borne encephalitis. Updated March 11, 2022. Accessed February 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/tick-borne-encephalitis/

13. Ticovac. Package insert. Pfizer; 2022. Accessed February 6, 2023. www.fda.gov/media/151502/download

14. Collins JP, Ryan ET, Wong KK, et al. Cholera vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71:1-8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7102a1

15. Global Task Force on Cholera Control. Cholera outbreak response field manual. Published October 2019. Accessed February 16, 2023. www.gtfcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/gtfcc-cholera-outbreak-response-field-manual.pdf

16. WHO. Health topics: cholera. Accessed February 16, 2023. www.who.int/health-topics/cholera#tab=tab_1

Pulmonary hypertension: An update of Dx and Tx guidelines

New guidelines that redefine pulmonary hypertension (PH) by a lower mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) have led to a reported increase in the number of patients given a diagnosis of PH. Although the evaluation and treatment of PH relies on the specialist, as we explain here, family physicians play a pivotal role in the diagnosis, reduction or elimination of risk factors for PH, and timely referral to a pulmonologist or cardiologist who has expertise in managing the disease. We also address the important finding that adult patients who have been evaluated, treated, and followed based on guidelines—updated just last year—have a longer life expectancy than patients who have not been treated properly or not treated at all.

Last, we summarize the etiology, evaluation, and management of PH in the pediatric population.

What is pulmonary hypertension? A revised definition

Prior to 2018, PH was defined as mPAP (measured by right heart catheterization [RHC]) ≥ 25 mm Hg at rest. Now, based on guidelines developed at the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension (WSPH) in 2018, PH is defined as mPAP > 20 mm Hg.1,2 That change was based on studies in which researchers noted higher mortality in adults who had mPAP below the traditional threshold.3,4 There is no evidence, however, of increased mortality in the pediatric population in this lower mPAP range.5

PH is estimated to be present in approximately 1% of the population.6 PH due to other diseases—eg, cardiac disease, lung disease, or a chronic thromboembolic condition—reflects the prevalence of the causative disease.7

How is pulmonary hypertension classified?

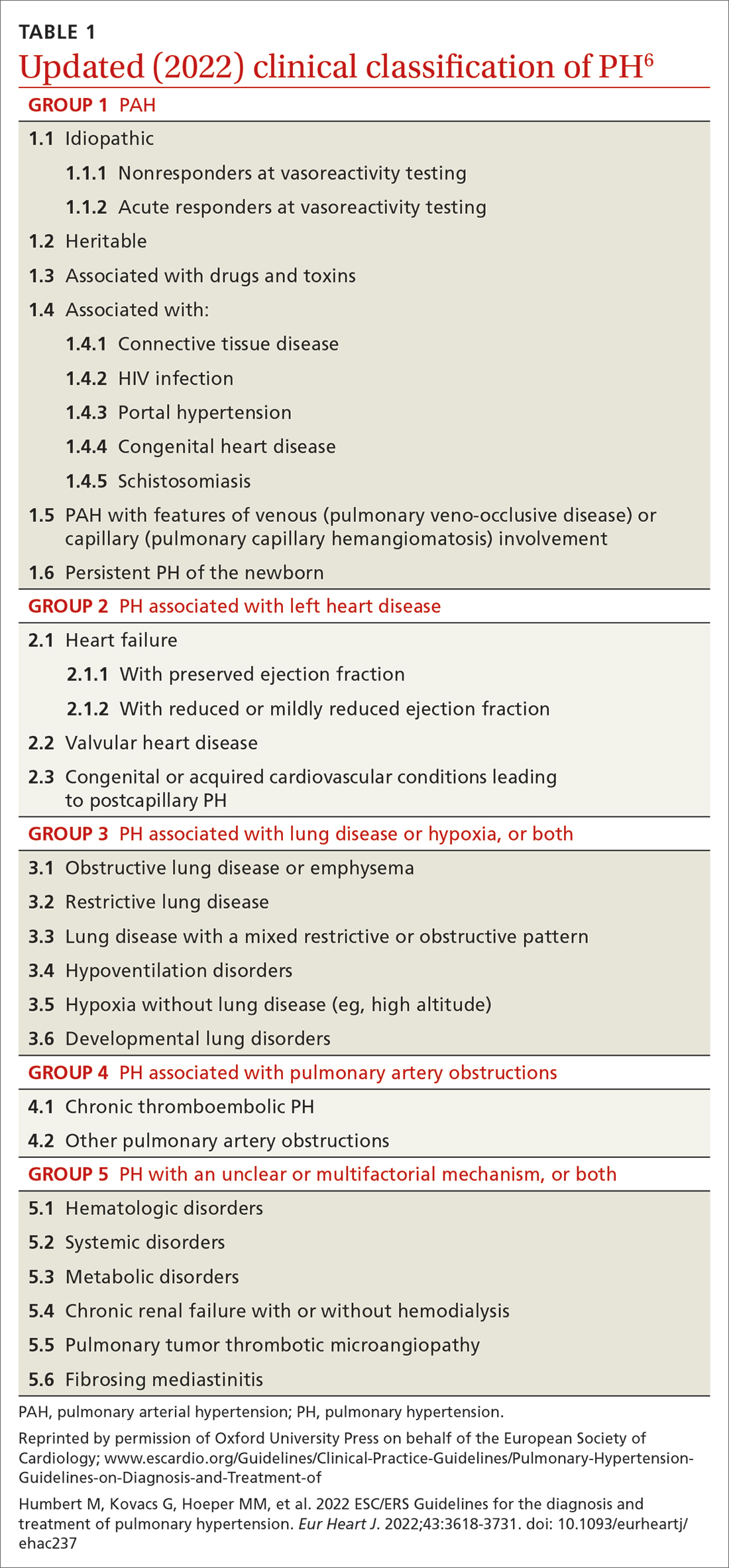

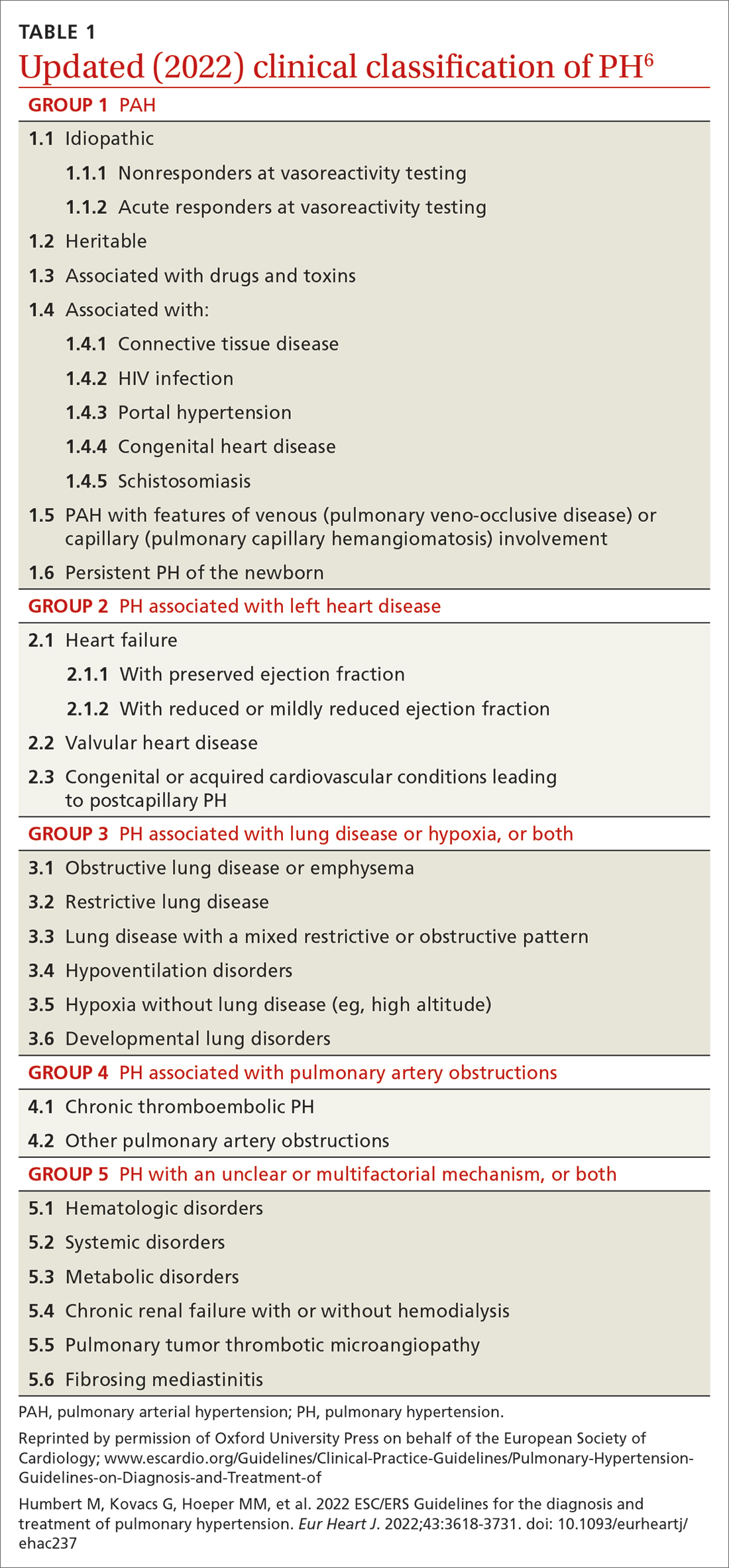

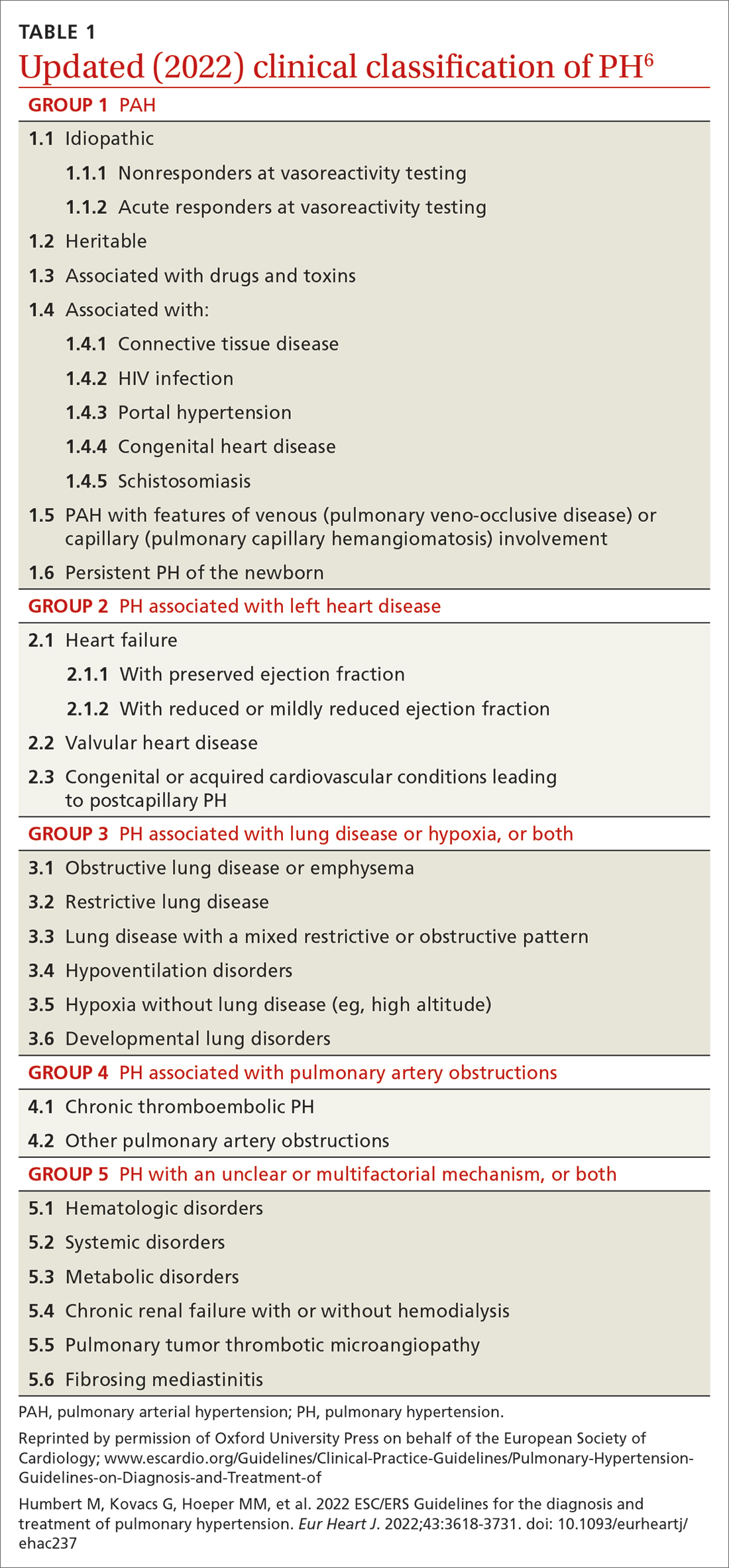

Based on the work of a Task Force of the 6th WSPH, PH is classified by underlying pathophysiology, hemodynamics, and functional status. Clinical classification comprises 5 categories, or “groups,” based on underlying pathophysiology (TABLE 16).

Clinical classification

Group 1 PH includes patients with primary pulmonary hypertension, also referred to (including in this article) as pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Hemodynamic criteria that define PAH include pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) > 2 Woods unitsa and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure > 15 mm Hg. Idiopathic PAH is the most common diagnosis in this group.

The incidence of PAH is approximately 6 cases for every 1 million adults; prevalence is 48 to 55 cases for every 1 million adults. PAH is more common in women.6

Continue to: Less common causes...

Less common causes in Group 1 includ

Group 2 PH comprises patients whose disease results from left heart dysfunction, the most common cause of PH. This subgroup has an elevated pulmonary artery wedge pressure > 15 mm Hg.8 Patients have either isolated postcapillary PH or combined pre-capillary and postcapillary PH.

Group 3 PH comprises patients whose PH is secondary to chronic and hypoxic lung disease. Patients in this group have pre-capillary PH; even a modest elevation in mPAP (20-29 mm Hg) is associated with a poor prognosis. Group 3 patients have elevated PVR, even with mild PH.2 Exertional dyspnea disproportionate to the results of pulmonary function testing, low carbon monoxide diffusion capacity, and rapid decline of arterial oxygenation with exercise all point to severe PH in these patients.9

Group 4 PH encompasses patients with pulmonary artery obstruction, the most common cause of which is related to chronic thromboembolism. Other causes include obstruction of the pulmonary artery from an extrinsic source. Patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) also have pre-capillary PH, resulting from elevated pulmonary pressures secondary to thromboembolic burden, as well as pulmonary remodeling in unobstructed small arterioles.

Group 5 PH is a miscellaneous group secondary to unclear or multiple causes, including chronic hematologic anemia (eg, sickle cell disease), systemic disorders (eg, sarcoidosis), and metabolic disorders (eg, glycogen storage disease). Patients in Group 5 can have both pre-capillary and postcapillary hypertension.

Classification by functional status

The World Health Organization (WHO) Functional Classification of Patients with Pulmonary Hypertension is divided into 4 classes.10 This system is used to guide treatment and for prognostic purposes:

Class I. Patients have no limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause undue dyspnea or fatigue, chest pain, or near-syncope.

Continue to: Class II

Class II. Patients have slight limitation of physical activity. They are comfortable at rest but daily physical activity causes dyspnea, fatigue, chest pain, or near-syncope.

Class III. These patients have marked limitation of physical activity. They are comfortable at rest, but less-than-ordinary activity causes dyspnea, fatigue, chest pain, or near-syncope.

Class IV. Patients are unable to carry out any physical activity without symptoms. They manifest signs of right heart failure. Dyspnea or fatigue, or both, might be present even at rest.

How is the pathophysiology of PH described?

The term pulmonary hypertension refers to an elevation in PAP that can result from any number of causes. Pulmonary arterial hypertension is a subcategory of PH in which a rise in PAP is due to primary pathology in the arteries proper.

As noted, PH results from a variety of pathophysiologic mechanisms, reflected in the classification in TABLE 1.6

WSPH Group 1 patients are considered to have PAH; for most, disease is idiopathic. In small-caliber pulmonary arteries, hypertrophy of smooth muscle, endothelial cells, and adventitia leads to increased resistance. Production of nitric oxide and prostacyclins is also impaired in endothelial cells. Genetic mutation, environmental factors such as exposure to stimulant use, and collagen vascular disease have a role in different subtypes of PAH. Portopulmonary hypertension is a subtype of PAH in patients with portal hypertension.

WSPH Groups 2-5. Increased PVR can result from pulmonary vascular congestion due to left heart dysfunction; destruction of the alveolar capillary bed; chronic hypoxic vasoconstriction; and vascular occlusion from thromboembolism.

Continue to: Once approximately...

Once approximately 30% of the pulmonary vasculature is involved, pressure in the pulmonary circulation starts to rise. In all WSPH groups, this increase in PVR results in increased right ventricular afterload that, over time, leads to right ventricular dysfunction.7,11,12

How does PH manifest?

Patients who have PH usually present with dyspnea, fatigue, chest pain, near-syncope, syncope, or lower-extremity edema, or any combination of these symptoms. The nonspecificity of presenting symptoms can lead to a delay in diagnosis.

In addition, suspicion of PH should be raised when a patient:

- presents with skin discoloration (light or dark) or a telangiectatic rash

- presents with difficulty swallowing

- has a history of connective tissue disease or hemolytic anemia

- has risk factors for HIV infection or liver disease

- takes an appetite suppressant

- has been exposed to other toxins known to increase the risk of PH.

A detailed medical history—looking for chronic lung or heart disease, thromboembolism, sleep-disordered breathing, a thyroid disorder, chronic renal failure, or a metabolic disorder—should be obtained.

Common findings on the physical exam in PH include:

- an increased P2 heart sound (pulmonic closure)

- high-pitched holosystolic murmur from tricuspid regurgitation

- pulmonic insufficiency murmur

- jugular venous distension

- hepatojugular reflux

- peripheral edema.

These findings are not specific to PH but, again, their presence warrants consideration of PH.

How best to approach evaluation and diagnosis?

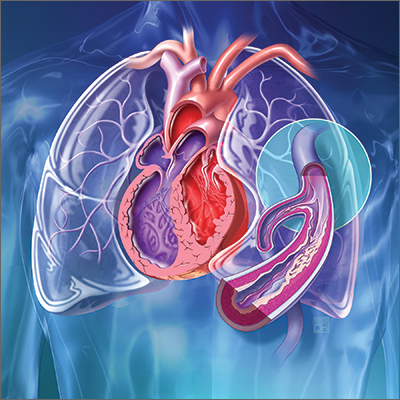

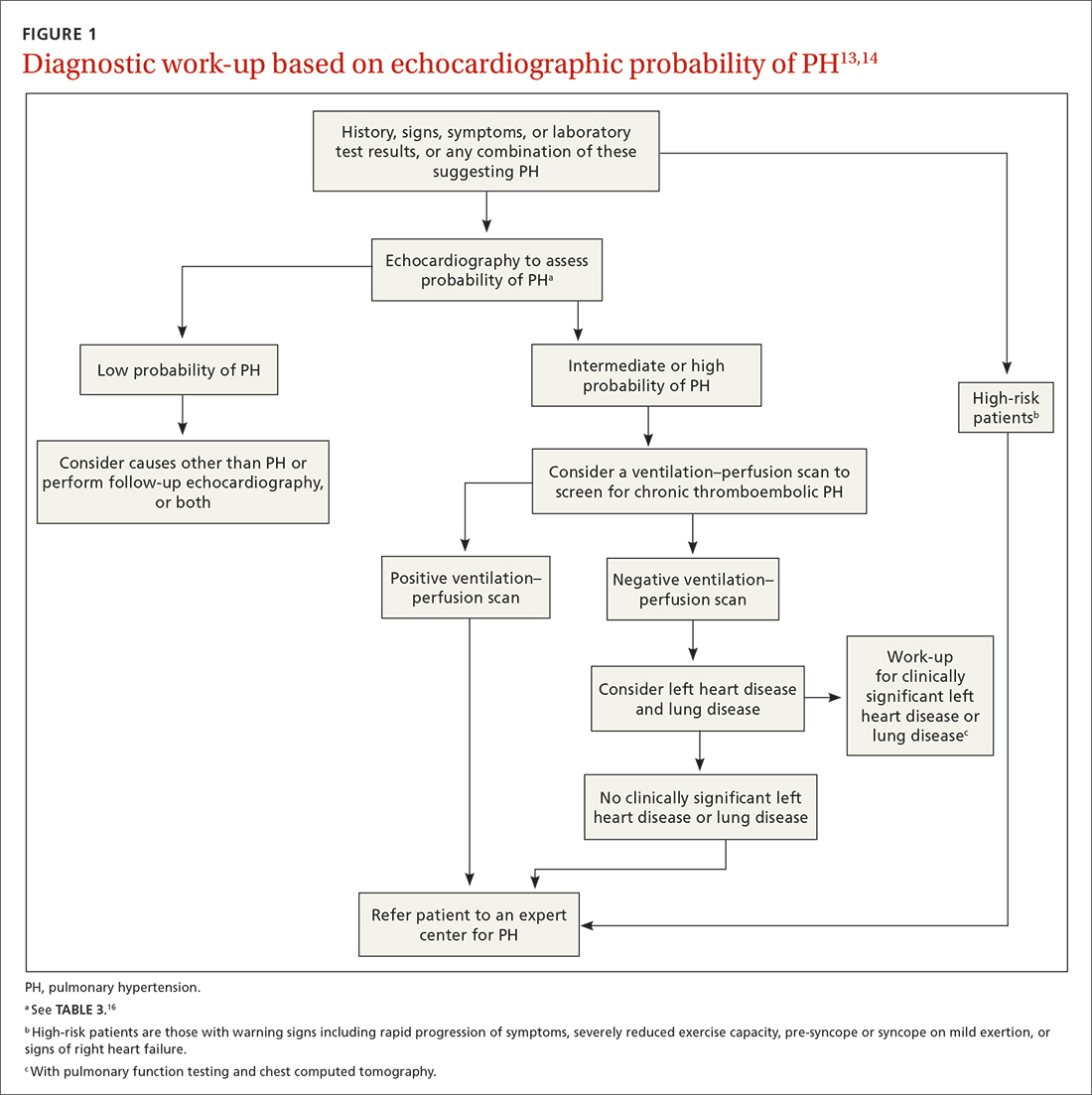

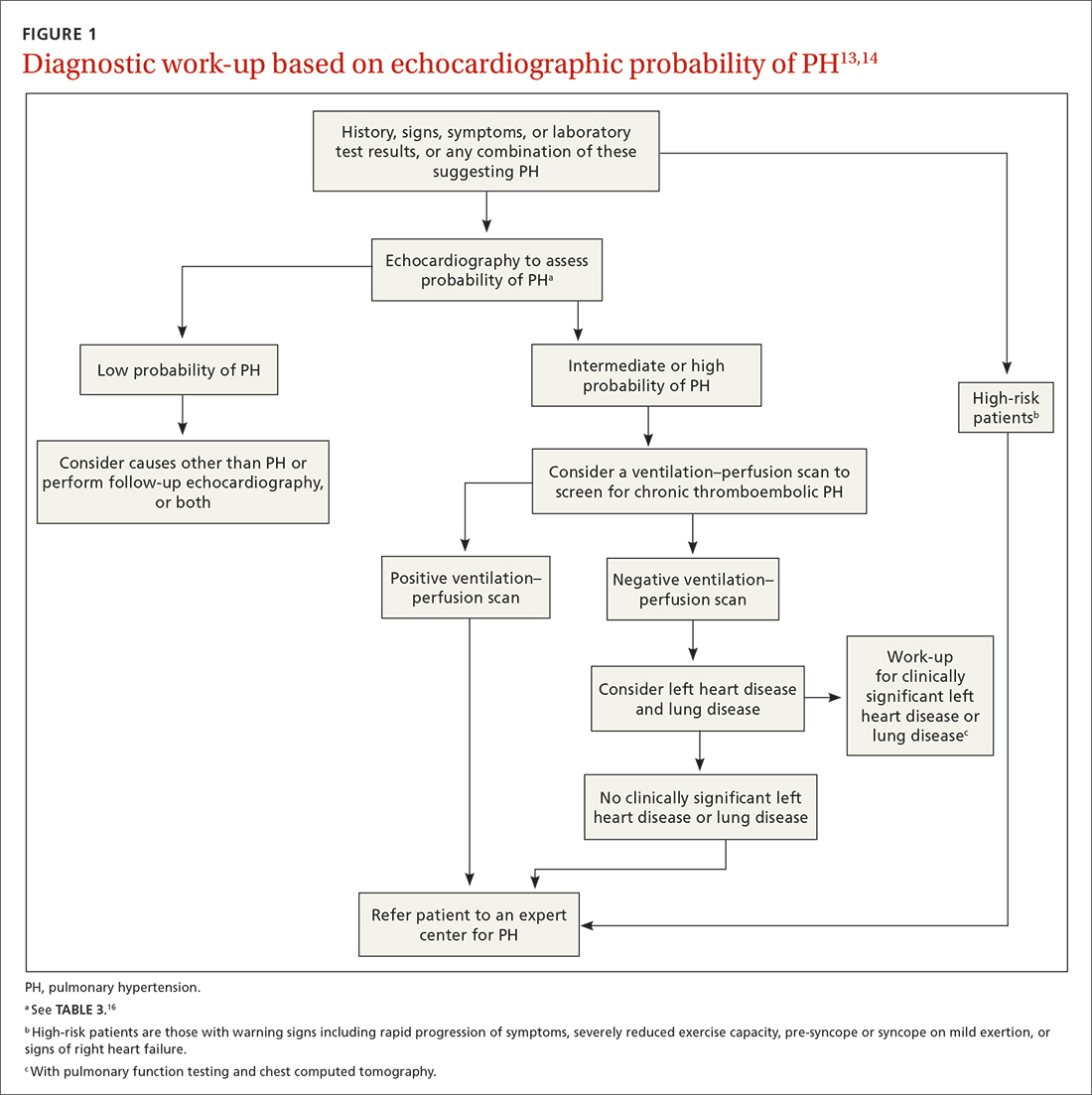

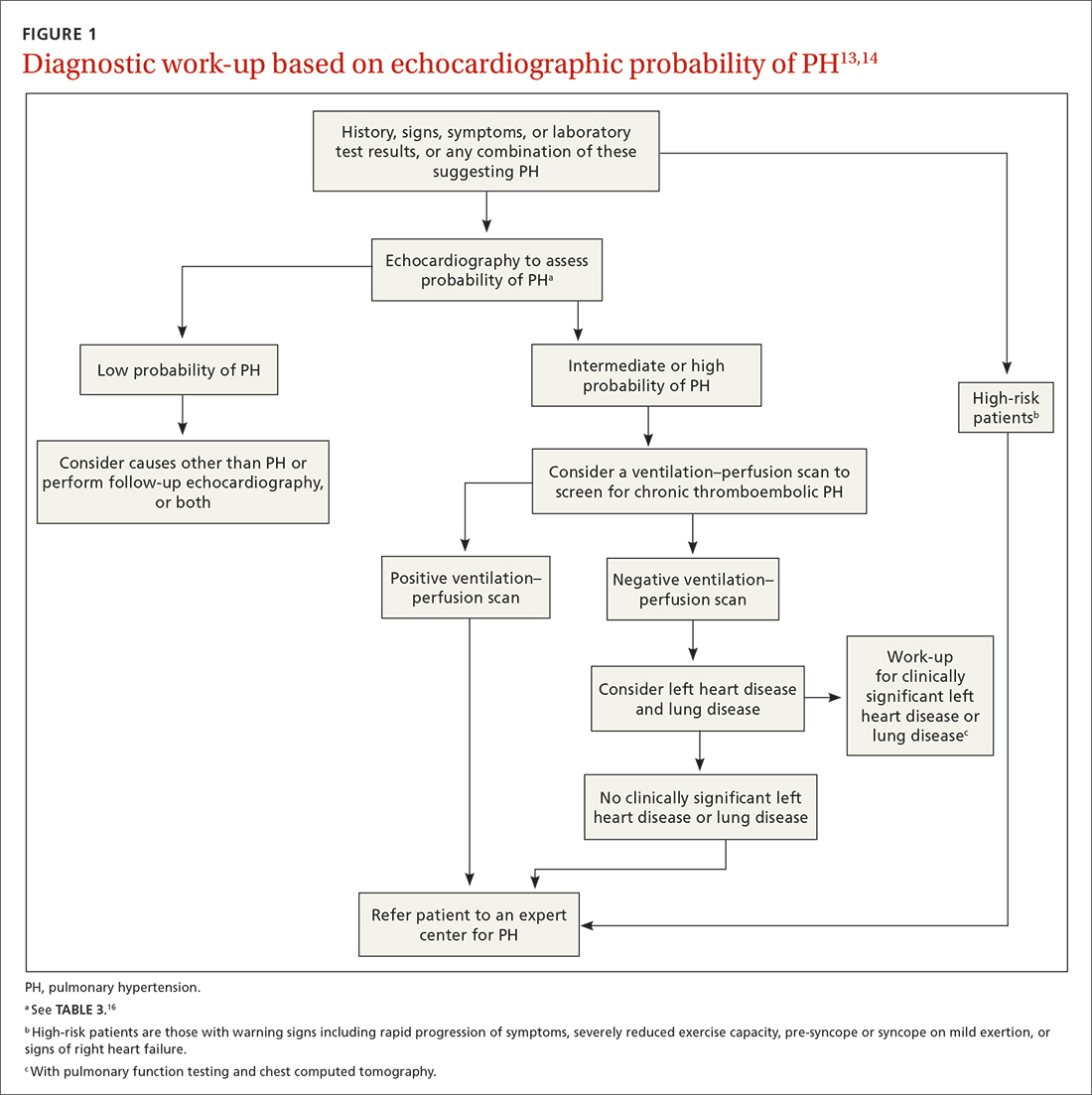

The work-up for PH is broad; FIGURE 113,14 provides an outline of how to proceed when there is a concern for PH. For the work-up of symptoms and signs listed earlier, chest radiography and electrocardiography are recommended.

Continue to: Radiographic findings

Radiographic findings that suggest PH include enlargement of central pulmonary arteries and the right ventricle and dilation of the right atrium. Pulmonary vascular congestion might also be seen, secondary to left heart disease.7

Electrocardiographic findings of PH are demonstrated by signs of left ventricular hypertrophy, especially in Group 2 PH. Upright R waves in V1-V2 with deeper S waves in V5-V6 might represent right ventricular hypertrophy or right heart strain. Frequent premature atrial contractions and multifocal atrial tachycardia are also associated with PH.7

Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal (NT) proBNP. The level of BNP might be elevated in PH, but its role in the diagnostic process has not been established. BNP can, however, be used to monitor treatment effectiveness and prognosis.15 A normal electrocardiogram in tandem with a normal level of BNP or NT-proBNP is associated with a low likelihood of PH.6

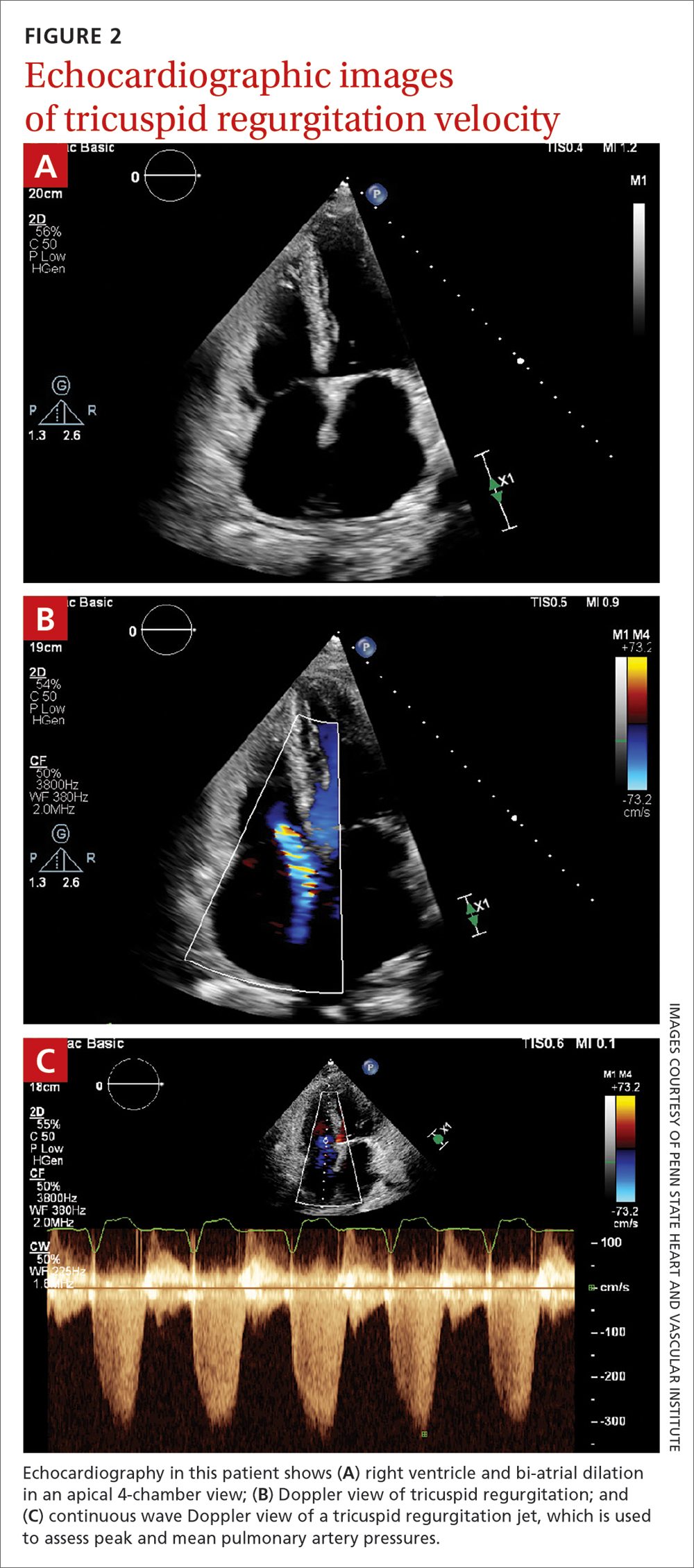

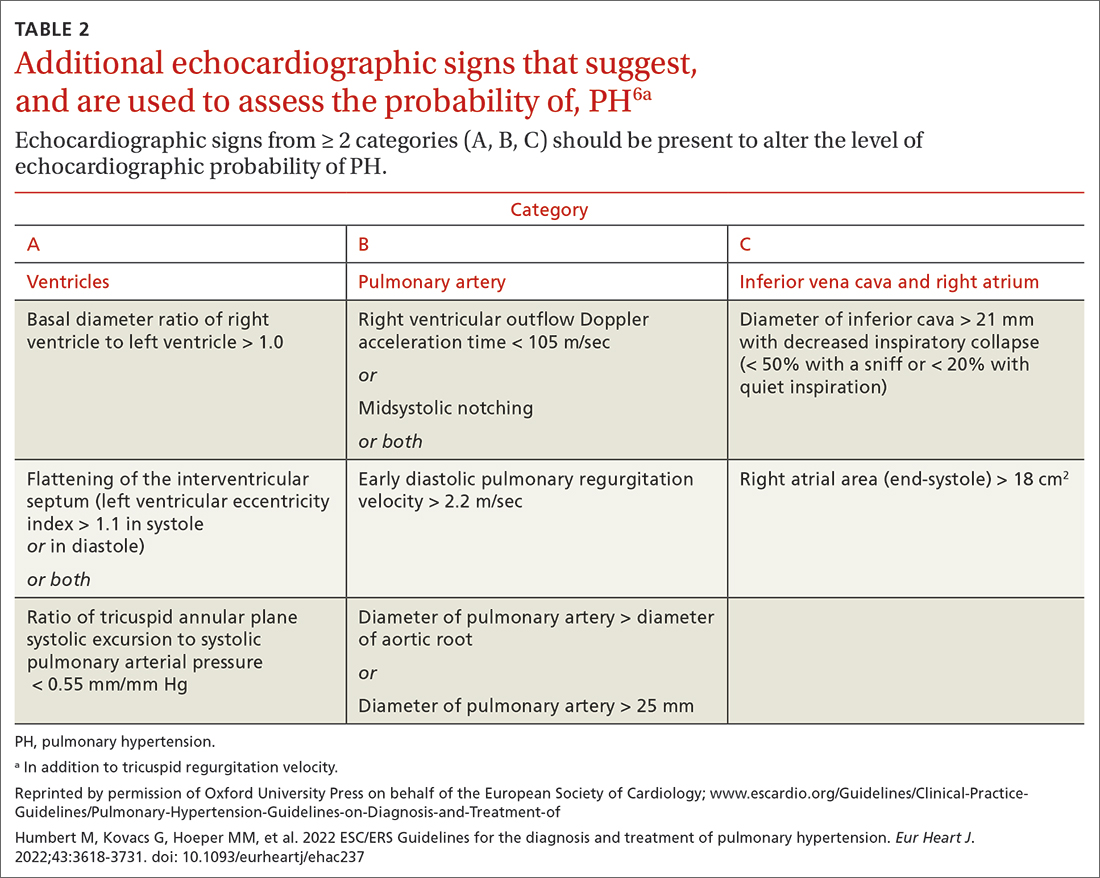

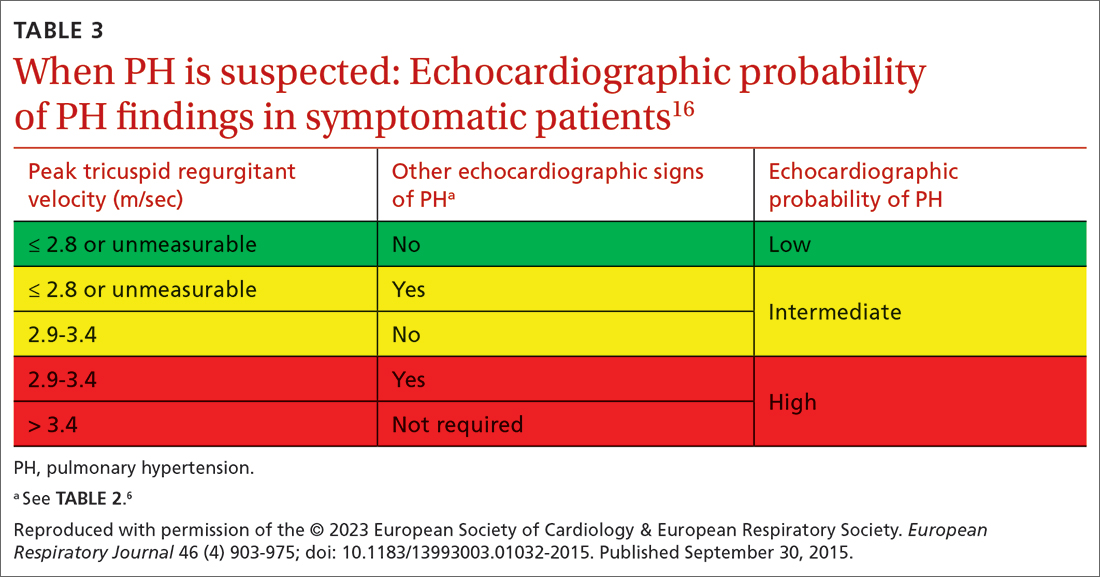

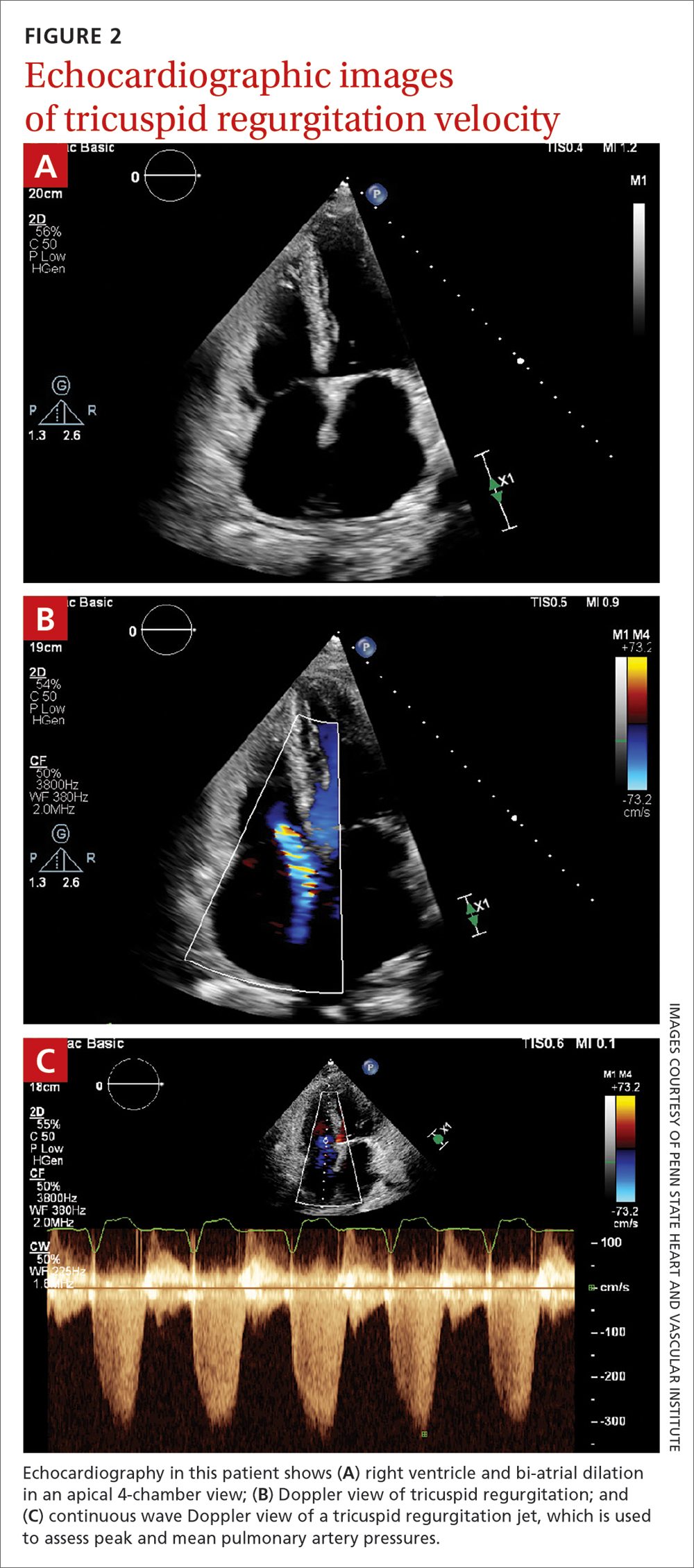

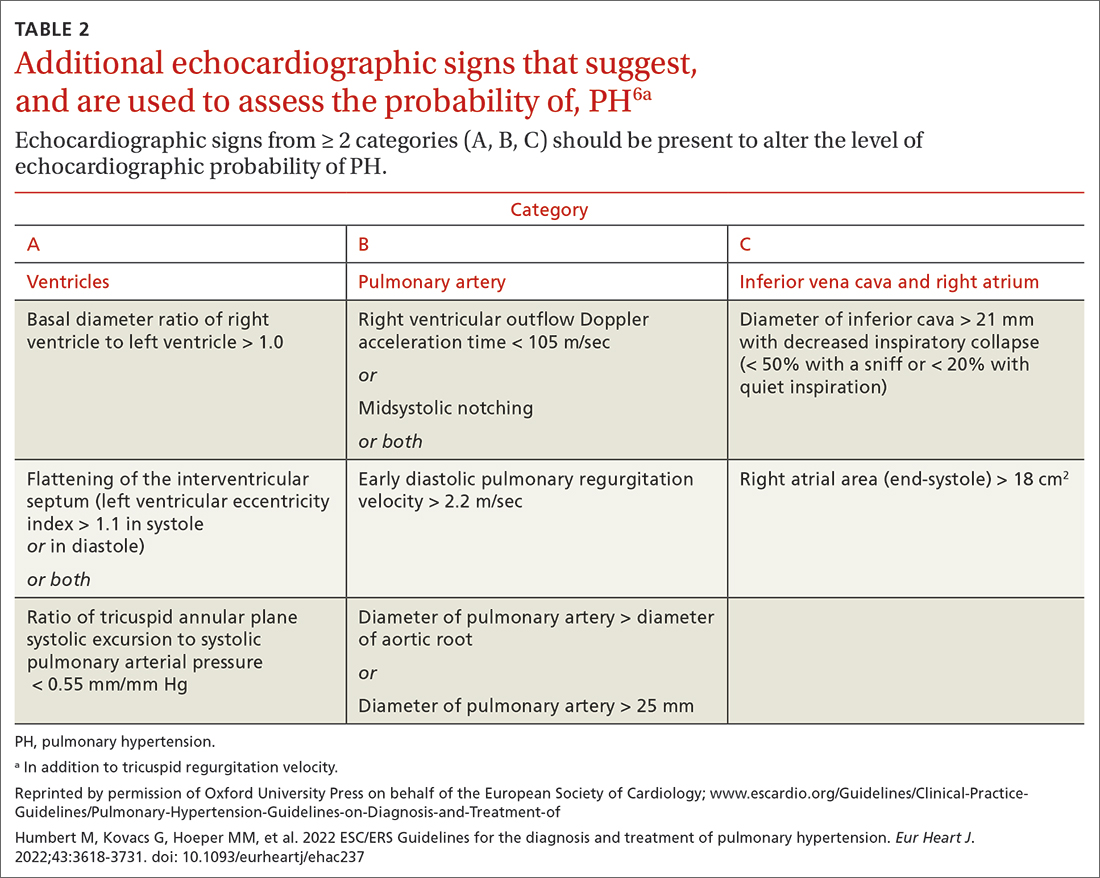

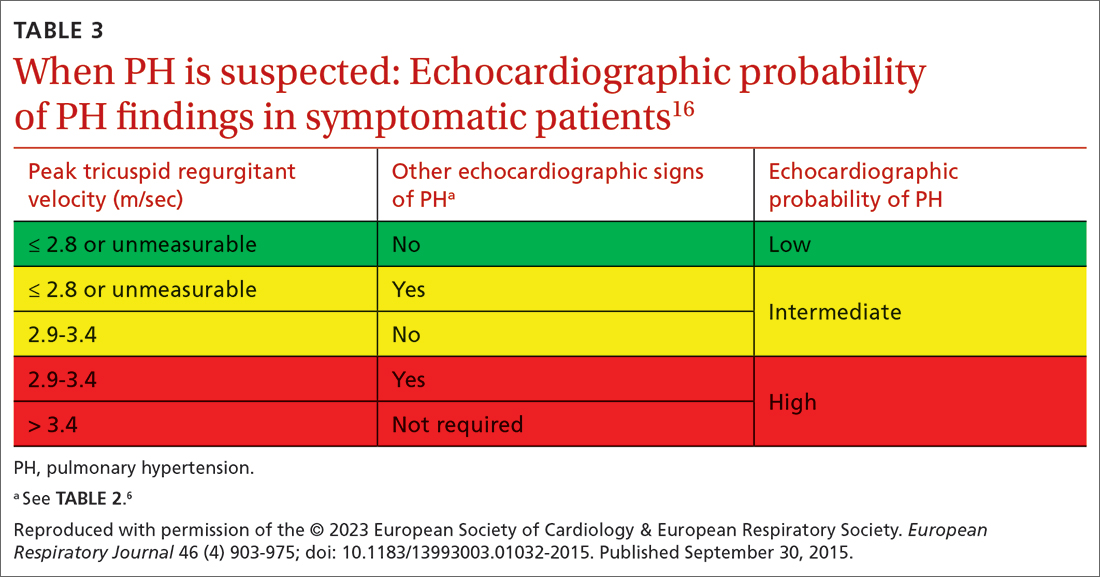

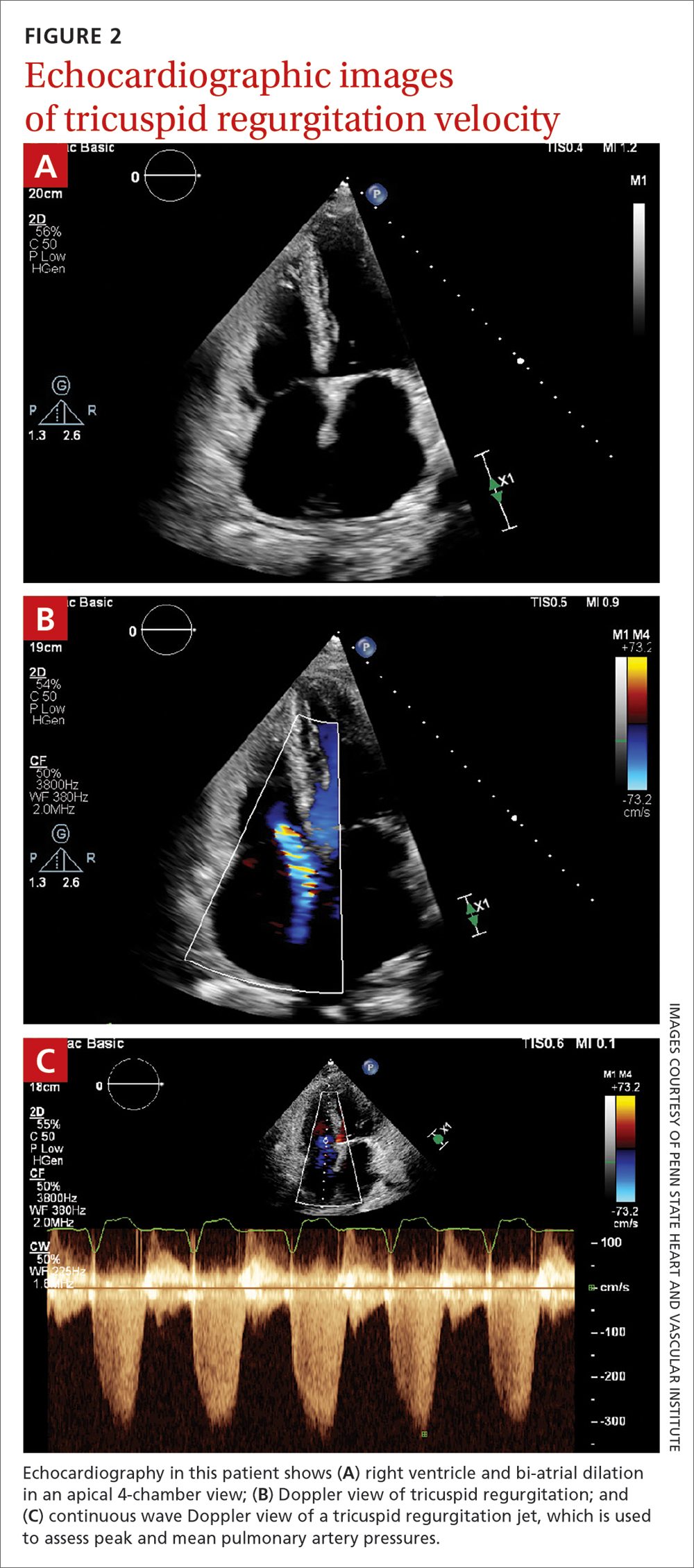

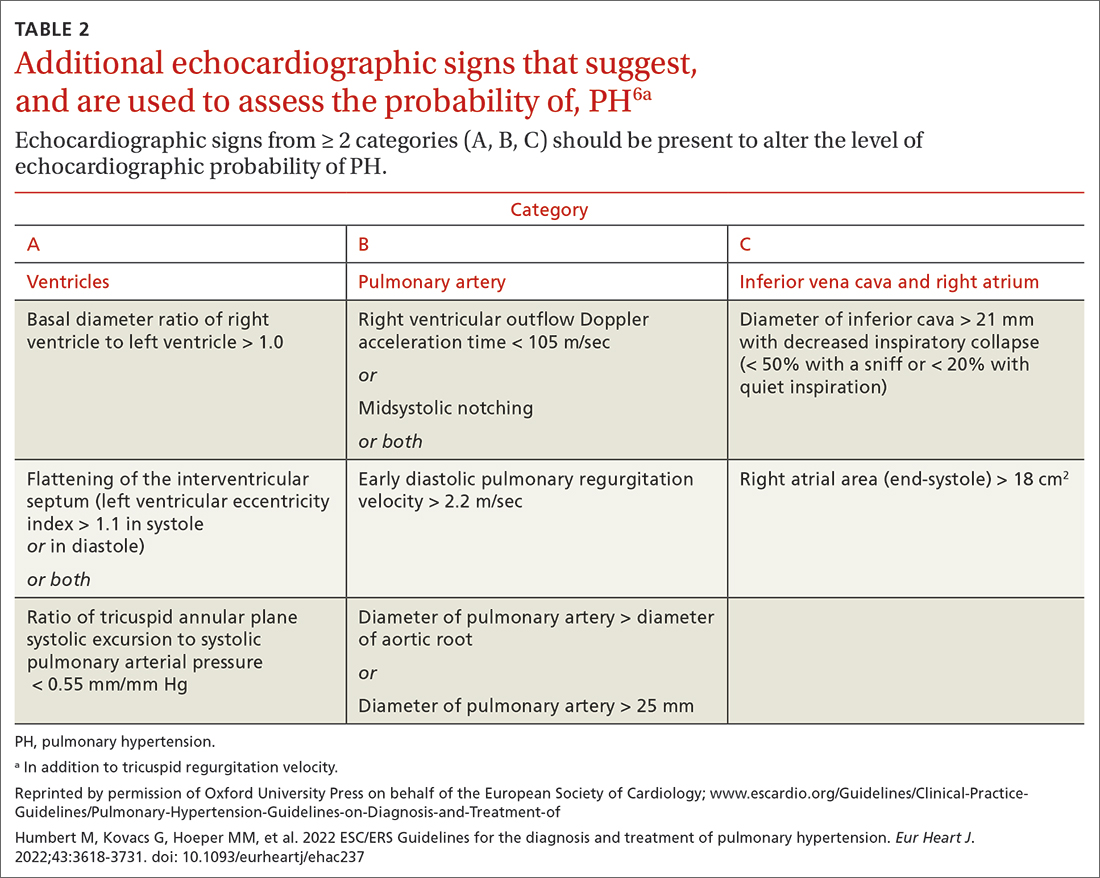

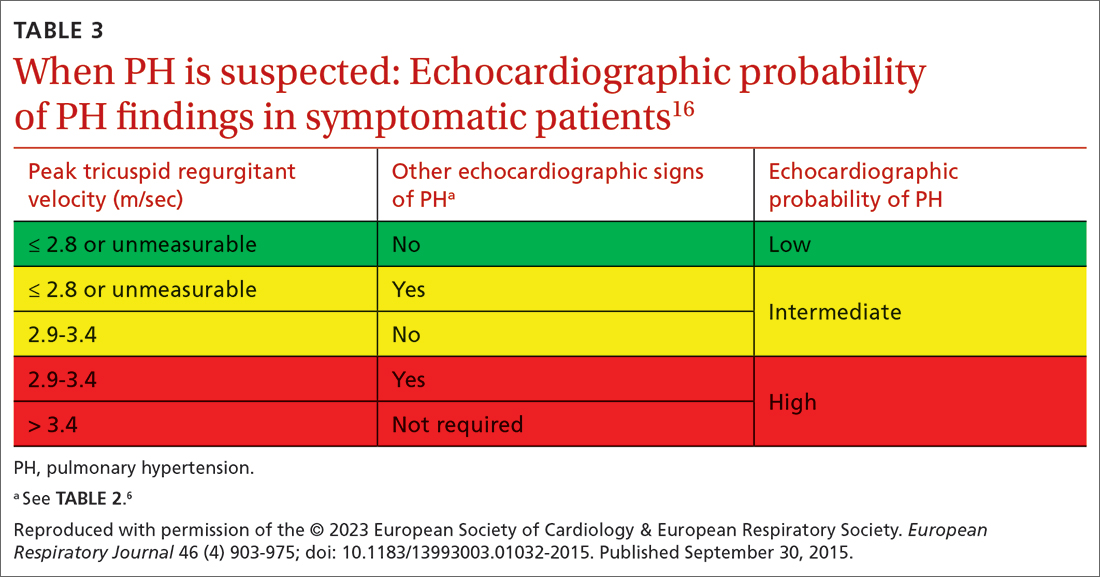

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is the initial evaluation tool whenever PH is suspected. Echocardiographic findings suggestive of PH include a combination of tricuspid regurgitation velocity > 2.8 m/s (FIGURE 2); estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure > 35 mm Hg in younger adults and > 40 mm Hg in older adults; right ventricular hypertrophy or strain; or a combination of these. Other TTE findings suggestive of PH are related to the ventricles, pulmonary artery, inferior vena cava, and right atrium (TABLE 26). The probability of PH based on TTE findings is categorized as low, intermediate, or high (see TABLE 26 and TABLE 316 for details).

Older guidelines, still used by some, rely on the estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure (ePASP) reading on echocardiography.13,17 However, studies have reported poor correlation between ePASP readings and values obtained from RHC.18

TTE also provides findings of left heart disease, such as left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction and left-sided valvular pathology. Patients with suspected PH in whom evidence of left heart disease on TTE is insufficient for making the diagnosis should receive further evaluation for their possible status in Groups 3-5 PH.

Ventilation–perfusion (VQ) scan. If CTEPH is suspected, a VQ scan should be performed. The scan is highly sensitive for CTEPH; a normal VQ scan excludes CTEPH. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest is not helpful for identifying chronic thromboembolism.13

Continue to: Coagulation assays

Coagulation assays. When CTEPH is suspected, coagulopathy can be assessed by measuring anticardiolipin antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, and anti-b-2-glycoprotein antibodies.13

Chest CT will show radiographic findings in greater detail. An enlarged pulmonary artery (diameter ≥ 29 mm) or a ratio ≥ 1 of the diameter of the main pulmonary artery to the diameter of the ascending aorta is suggestive of PH.

Other tests. Overnight oximetry and testing for sleep-disordered breathing, performed in an appropriate setting, can be considered.13,14,19

Pulmonary function testing with diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide, high-resolution chest CT, and a 6-minute walk test (6MWT) can be considered in patients who have risk factors for chronic lung disease. Pulmonary function testing, including measurement of the diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide, arterial blood gas analysis, and CT, is used to aid in interpreting echocardiographic findings in patients with lung disease in whom PH is suspected.

Testing for comorbidities. A given patient’s predisposing conditions for PH might already be known; if not, laboratory evaluation for conditions such as sickle cell disease, liver disease, thyroid dysfunction, connective tissue disorders (antibody tests of antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, anticentromere, anti-topoisomerase, anti-RNA polymerase III, anti-double stranded DNA, anti-Ro, anti-La, and anti-U1-RNP), and vasculitis (anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies) should be undertaken.

Analysis of stool and urine for Schistosoma spp parasites can be considered in an appropriate clinical setting.13

Right heart catheterization. Once alternative diagnoses are excluded, RHC is recommended to make a definitive diagnosis and assess the contribution of left heart disease. Vasoreactivity—defined as a reduction in mPAP ≥ 10 mm Hg to reach an absolute value of mPAP ≤ 40 mm Hg with increased or unchanged cardiac output—is assessed during RHC by administering nitric oxide or another vasodilator. This definition of vasoreactivity helps guide medical management in patients with PAH.7,20

Continue to: 6MWT

6MWT. Once the diagnosis of PH is made, a 6MWT helps establish baseline functional performance and will help you to monitor disease progression.

Who can benefit from screening for PH?

Annual evaluation of the risk of PAH is recommended for patients with systemic sclerosis or portal hypertension13 and can be considered in patients who have connective tissue disease with overlap features of systemic sclerosis.

Assessment for CTEPH or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease is recommended for patients with persistent or new-onset dyspnea or exercise limitation after pulmonary embolism.

Screening echocardiography for PH is recommended for patients who have been referred for liver transplantation.6

How risk is stratified

Risk stratification is used to manage PH and assess prognosis.

At diagnosis. Application of a 3-strata model of risk assessment (low, intermediate, high) is recommended.6 Pertinent data to determine risk include signs of right heart failure, progression of symptoms and clinical manifestations, report of syncope, WHO functional class, 6MWT, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, biomarkers (BNP or NT-proBNP), echocardiography, presence of pericardial effusion, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.

At follow-up. Use of a 4-strata model (low, intermediate–low, intermediate–high, and high risk) is recommended. Data used are WHO functional class, 6MWT, and results of either BNP or NT-proBNP testing.6

Continue to: When to refer

When to refer

Specialty consultation21-23 is recommended for:

- all patients with PAH

- PH patients in clinical Groups 2 and 3 whose disease is disproportionate to the extent of their left heart disease or hypoxic lung disease

- patients in whom there is concern about CTEPH and who therefore require early referral to a specialist for definitive treatment

- patients in whom the cause of PH is unclear or multifactorial (ie, clinical Group 5).

What are the options for managing PH?

Management of PH is based on the cause and classification of the individual patient’s disease.

Treatment for WSPH Group 1

Patients require referral to a specialty clinic for diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of progression.10

First, regrettably, none of the medications approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treating PAH prevent progression.7

Patients with idiopathic, hereditary, or drug-induced PAH with positive vasoreactivity are treated with a calcium channel blocker (CCB). The dosage is titrated to optimize therapy for the individual patient.

The patient is then reassessed after 3 to 6 months of medical therapy. Current treatment is continued if the following goals have been met:

- WHO functional classification is I or II

- BNP < 50 ng/L or NT-proBNP < 300 ng/L

- hemodynamics are normal or near-normal (mPAP ≤ 30 mm Hg and PVR ≤ 4 WU).

If these goals have not been met, treatment is adjusted by following the algorithm described below.

Continue to: The treatment algorithm...

The treatment algorithm for idiopathic-, heritable-, drug-induced, and connective tissue disease–associated PAH highlights the importance of cardiopulmonary comorbidities and risk strata at the time treatment is initiated and then during follow-up.

Cardiopulmonary comorbidities are conditions associated with an increased risk of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, including obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and coronary artery disease. Pulmonary comorbidities can include signs of mild parenchymal lung disease and are often associated with a low carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (< 45% of predicted value).

The management algorithm proceeds as follows:

- For patients without cardiopulmonary comorbidities and who are at low or intermediate risk, treatment of PAH with an endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA) plus a phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitor is recommended.

- For patients without cardiopulmonary comorbidities and who are at high risk, treatment with an ERA, a PDE5 inhibitor, and either an IV or subcutaneous prostacyclin analogue (PCA) can be considered.

- Patients in either of the preceding 2 categories should have regular follow-up assessment; at such follow-up, their risk should be stratified based on 4 strata (see “How risk is stratified”):

- Low risk: Continue initial therapy.

- Low-to-intermediate risk: Consider adding a prostacyclin receptor agonist to the initial regimen or switch to a PDE5 inhibitor or a soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator.

- Intermediate-to-high or high risk: Consider adding a PCA (IV epoprostenol or IV or subcutaneous treprostinil). In addition, or alternatively, have the patient evaluated for lung transplantation.

- For patients with cardiopulmonary comorbidity—in any risk category—consider oral monotherapy with a PDE5 inhibitor or an ERA. Provide regular follow-up and individualize therapy.6

Treatment for WSPH Groups 2 and 3

Treatment is focused on the underlying cause of PH:

- Patients who have left heart disease with either severe pre-capillary component PH or markers of right ventricular dysfunction, or both, should be referred to a PH center.

- Patients with combined pre-capillary and postcapillary PH in whom pre-capillary PH is severe should be considered for an individualized approach.

- Consider prescribing the ERA bosentan in specific scenarios (eg, the Eisenmenger syndrome of left-right shunting resulting from a congenital cardiac defect) to improve exercise capacity. If PAH persists after corrected adult congenital heart disease, follow the PAH treatment algorithm for Group 1 patients (described earlier).

- For patients in Group 3, those who have severe PH should be referred to a PH center.

- Consider prescribing inhaled treprostinil in PH with interstitial lung disease.

Treatment for WSPH Group 4

Patients with CTEPH are the only ones for whom pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA), the treatment of choice, might be curative. Balloon angioplasty can be considered for inoperable cases6; these patients should be placed on lifelong anticoagulant therapy.

Symptomatic patients who have inoperable CTEPH or persistent recurrent PH after PEA are medically managed; the agent of choice is riociguat. Patients who have undergone PEA or balloon angioplasty and those receiving pharmacotherapy should be followed long term.

Treatment for WSPH Group 5

Management of these patients focuses on associated conditions.

Continue to: Which medications for PAH?

Which medications for PAH?

CCBs. Four options in this class have shown utility, notably in patients who have had a positive vasoreactivity test (see “How best to approach evaluation and diagnosis?”):

- Nifedipine is started at 10 mg tid; target dosage is 20 to 60 mg, bid or tid.

- Diltiazem is started at 60 mg bid; target dosage is 120 to 360 mg bid.

- Amlodipine is started at 5 mg/d; target dosage is 15 to 30 mg/d.

- Felodipine is started at 5 mg/d; target dosage is 15 to 30 mg/d.

Felodipine and amlodipine have longer half-lives than other CCBs and are well tolerated.

ERA. Used as vasodilators are ambrinsentan (starting dosage, 5 mg/d; target dosage, 10 mg/d), macitentan (starting and target dosage, 10 mg/d), and bosentan (starting dosage, 62.5 mg bid; target dosage, 125 mg bid).

Nitric oxide–cyclic guanosine monophosphate enhancers. These are the PDE5 inhibitors sildenafil (starting and target dosages, 20 mg tid) and tadalafil (starting dosage, 20 or 40 mg/d; target dosage, 40 mg/d), and the guanylate cyclase stimulant riociguat (starting dosage, 1 mg tid; target dosage, 2.5 mg tid). All 3 agents enhance production of the potent vasodilator nitric oxide, production of which is impaired in PH.

Prostanoids. Several options are available:

- Beraprost sodium. For this oral prostacyclin analogue, starting dosage is 20 μg tid; target dosage is the maximum tolerated dosage (as high as 40 μg tid).

- Extended-release beraprost. Starting dosage is 60 μg bid; target dosage is the maximum tolerated dosage (as high as 180 μg bid).

- Oral treprostinil. Starting dosage is 0.25 mg bid or 0.125 mg tid; target dosage is the maximum tolerated dosage.

- Inhaled iloprost. Starting dosage of this prostacyclin analogue is 2.5 μg, 6 to 9 times per day; target dosage is 5 μg, 6 to 9 times per day.

- Inhaled treprostinil. Starting dosage is 18 μg qid; target dosage is 54 to 72 μg qid.

- Eproprostenol is administered by continuous IV infusion, at a starting dosage of 2 ng/kg/min; target dosage is determined by tolerability and effectiveness (typically, 30 ng/kg/min).

- IV treprostinil. Starting dosage 1.25 ng/kg/min; target dosage is determined by tolerability and effectiveness, with a typical dosage of 60 ng/kg/min.

Combination treatment with the agents listed above is often utilized.