User login

A “Solution” for Patients Unable to Swallow a Pill: Crushed Terbinafine Mixed With Syrup

Practice Gap

Terbinafine can be used safely and effectively in adult and pediatric patients to treat superficial fungal infections, including onychomycosis.1 These superficial fungal infections have become increasingly prevalent in children and often require oral therapy2; however, children are frequently unable to swallow a pill.

Until 2016, terbinafine was available as oral granules that could be sprinkled on food, but this formulation has been discontinued.3 In addition, terbinafine tablets have a bitter taste. Therefore, the inability to swallow a pill—typical of young children and other patients with pill dysphagia—is a barrier to prescribing terbinafine.

The Technique

For patients who cannot swallow a pill, a terbinafine tablet can be crushed and mixed with food or a syrup without loss of efficacy. Terbinafine in tablet form has been shown to have relatively unchanged properties after being crushed and mixed in solution, even several weeks after preparation.4 Crushing and mixing a terbinafine tablet with food or a syrup therefore is an effective option for patients who cannot swallow a pill but can safely swallow food.

The food or syrup used for this purpose should have a pH of at least 5 because greater acidity reduces absorption of terbinafine. Therefore, avoid mixing it with fruit juices, applesauce, or soda. Given the bitter taste of the terbinafine tablet, mixing it with a sweet food or syrup improves taste and compliance, which makes pudding a particularly good food option for this purpose.

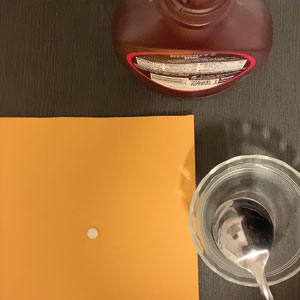

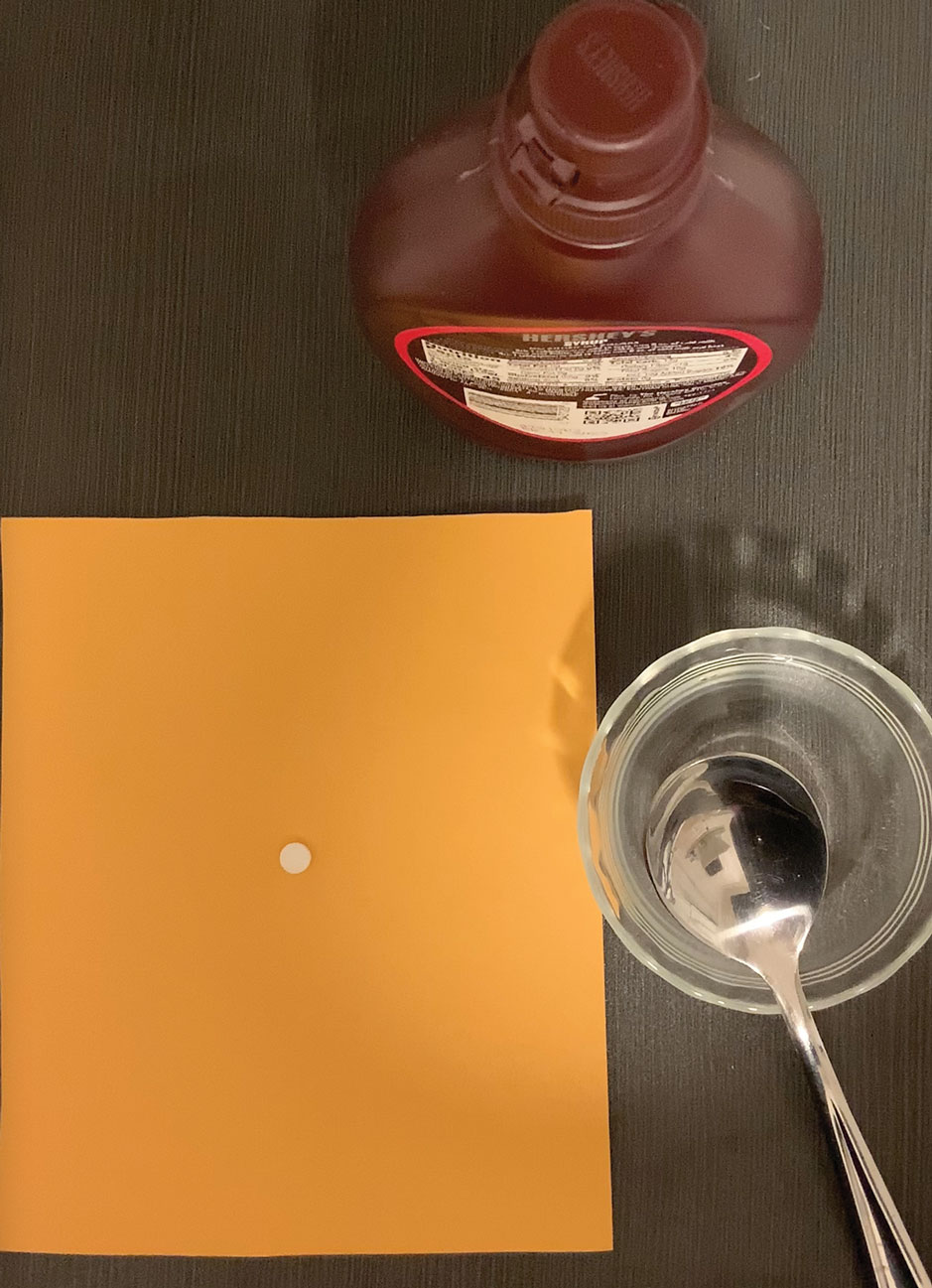

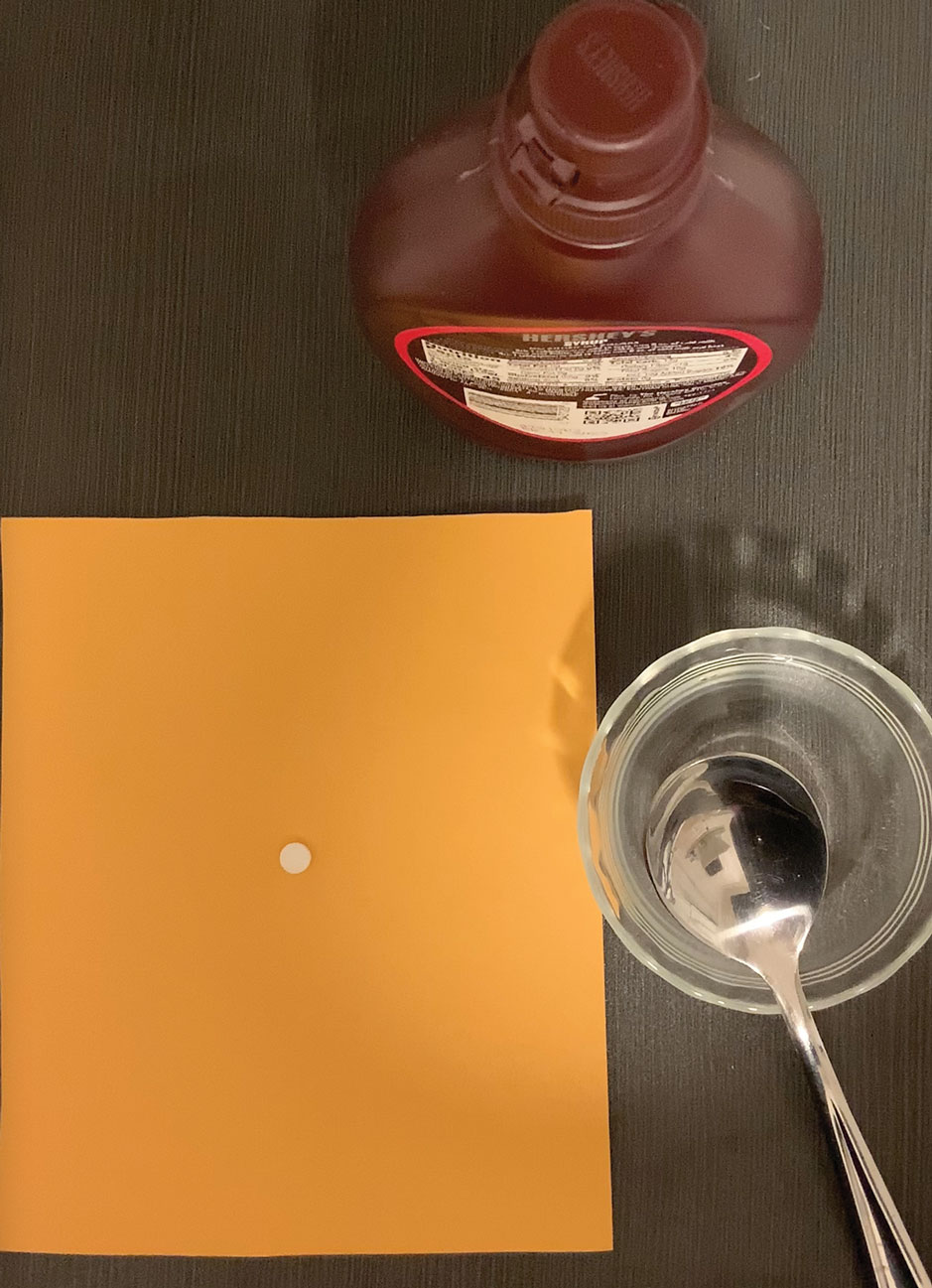

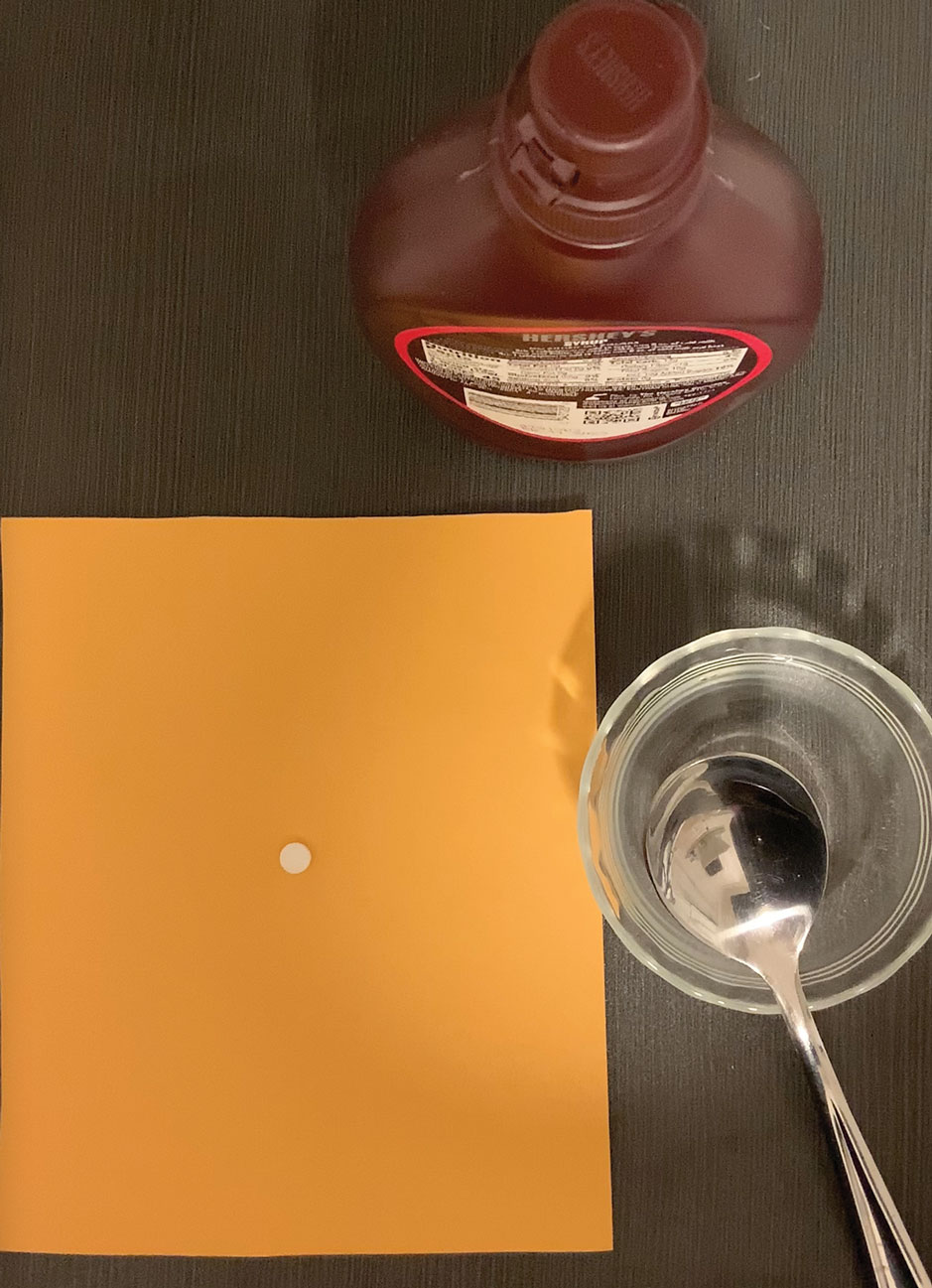

However, because younger patients might not finish an entire serving of pudding or other food into which the tablet has been crushed and mixed, inconsistent dosing might result. Therefore, we recommend mixing the crushed terbinafine tablet with 1 oz (30 mL) of chocolate syrup or corn syrup (Figure). This solution is sweet, easy to prepare and consume, widely available, and affordable (as low as $0.28/oz for corn syrup and as low as $0.10/oz for chocolate syrup, as priced on Amazon).

The tablet can be crushed using a pill crusher ($5–$10 at pharmacies or on Amazon) or by placing it on a piece of paper and crushing it with the back of a metal spoon. For children, the recommended dosing of terbinafine with a 250-mg tablet is based on weight: one-quarter of a tablet for a child weighing 10 to 20 kg; one-half of a tablet for a child weighing 20 to 40 kg; and a full tablet for a child weighing more than 40 kg.5 Because terbinafine tablets are not scored, a combined pill splitter–crusher can be used (also available at pharmacies or on Amazon; the price of this device is within the same price range as a pill crusher).

Practical Implication

Use of this method for crushing and mixing the terbinafine tablet allows patients who are unable to swallow a pill to safely and effectively use oral terbinafine.

- Solís-Arias MP, García-Romero MT. Onychomycosis in children. a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:123-130. doi:10.1111/ijd.13392

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of abnormal laboratory test results in pediatric patients prescribed terbinafine for superficial fungal infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1042-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.073

- Lamisil (terbinafine hydrochloride) oral granules. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation; 2013. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/022071s009lbl.pdf

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Nahata MC. Stability of terbinafine hydrochloride in an extemporaneously prepared oral suspension at 25 and 4 degrees C. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:243-245. doi:10.1093/ajhp/56.3.243

- Gupta AK, Adamiak A, Cooper EA. The efficacy and safety of terbinafine in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:627-640. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00691.x

Practice Gap

Terbinafine can be used safely and effectively in adult and pediatric patients to treat superficial fungal infections, including onychomycosis.1 These superficial fungal infections have become increasingly prevalent in children and often require oral therapy2; however, children are frequently unable to swallow a pill.

Until 2016, terbinafine was available as oral granules that could be sprinkled on food, but this formulation has been discontinued.3 In addition, terbinafine tablets have a bitter taste. Therefore, the inability to swallow a pill—typical of young children and other patients with pill dysphagia—is a barrier to prescribing terbinafine.

The Technique

For patients who cannot swallow a pill, a terbinafine tablet can be crushed and mixed with food or a syrup without loss of efficacy. Terbinafine in tablet form has been shown to have relatively unchanged properties after being crushed and mixed in solution, even several weeks after preparation.4 Crushing and mixing a terbinafine tablet with food or a syrup therefore is an effective option for patients who cannot swallow a pill but can safely swallow food.

The food or syrup used for this purpose should have a pH of at least 5 because greater acidity reduces absorption of terbinafine. Therefore, avoid mixing it with fruit juices, applesauce, or soda. Given the bitter taste of the terbinafine tablet, mixing it with a sweet food or syrup improves taste and compliance, which makes pudding a particularly good food option for this purpose.

However, because younger patients might not finish an entire serving of pudding or other food into which the tablet has been crushed and mixed, inconsistent dosing might result. Therefore, we recommend mixing the crushed terbinafine tablet with 1 oz (30 mL) of chocolate syrup or corn syrup (Figure). This solution is sweet, easy to prepare and consume, widely available, and affordable (as low as $0.28/oz for corn syrup and as low as $0.10/oz for chocolate syrup, as priced on Amazon).

The tablet can be crushed using a pill crusher ($5–$10 at pharmacies or on Amazon) or by placing it on a piece of paper and crushing it with the back of a metal spoon. For children, the recommended dosing of terbinafine with a 250-mg tablet is based on weight: one-quarter of a tablet for a child weighing 10 to 20 kg; one-half of a tablet for a child weighing 20 to 40 kg; and a full tablet for a child weighing more than 40 kg.5 Because terbinafine tablets are not scored, a combined pill splitter–crusher can be used (also available at pharmacies or on Amazon; the price of this device is within the same price range as a pill crusher).

Practical Implication

Use of this method for crushing and mixing the terbinafine tablet allows patients who are unable to swallow a pill to safely and effectively use oral terbinafine.

Practice Gap

Terbinafine can be used safely and effectively in adult and pediatric patients to treat superficial fungal infections, including onychomycosis.1 These superficial fungal infections have become increasingly prevalent in children and often require oral therapy2; however, children are frequently unable to swallow a pill.

Until 2016, terbinafine was available as oral granules that could be sprinkled on food, but this formulation has been discontinued.3 In addition, terbinafine tablets have a bitter taste. Therefore, the inability to swallow a pill—typical of young children and other patients with pill dysphagia—is a barrier to prescribing terbinafine.

The Technique

For patients who cannot swallow a pill, a terbinafine tablet can be crushed and mixed with food or a syrup without loss of efficacy. Terbinafine in tablet form has been shown to have relatively unchanged properties after being crushed and mixed in solution, even several weeks after preparation.4 Crushing and mixing a terbinafine tablet with food or a syrup therefore is an effective option for patients who cannot swallow a pill but can safely swallow food.

The food or syrup used for this purpose should have a pH of at least 5 because greater acidity reduces absorption of terbinafine. Therefore, avoid mixing it with fruit juices, applesauce, or soda. Given the bitter taste of the terbinafine tablet, mixing it with a sweet food or syrup improves taste and compliance, which makes pudding a particularly good food option for this purpose.

However, because younger patients might not finish an entire serving of pudding or other food into which the tablet has been crushed and mixed, inconsistent dosing might result. Therefore, we recommend mixing the crushed terbinafine tablet with 1 oz (30 mL) of chocolate syrup or corn syrup (Figure). This solution is sweet, easy to prepare and consume, widely available, and affordable (as low as $0.28/oz for corn syrup and as low as $0.10/oz for chocolate syrup, as priced on Amazon).

The tablet can be crushed using a pill crusher ($5–$10 at pharmacies or on Amazon) or by placing it on a piece of paper and crushing it with the back of a metal spoon. For children, the recommended dosing of terbinafine with a 250-mg tablet is based on weight: one-quarter of a tablet for a child weighing 10 to 20 kg; one-half of a tablet for a child weighing 20 to 40 kg; and a full tablet for a child weighing more than 40 kg.5 Because terbinafine tablets are not scored, a combined pill splitter–crusher can be used (also available at pharmacies or on Amazon; the price of this device is within the same price range as a pill crusher).

Practical Implication

Use of this method for crushing and mixing the terbinafine tablet allows patients who are unable to swallow a pill to safely and effectively use oral terbinafine.

- Solís-Arias MP, García-Romero MT. Onychomycosis in children. a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:123-130. doi:10.1111/ijd.13392

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of abnormal laboratory test results in pediatric patients prescribed terbinafine for superficial fungal infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1042-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.073

- Lamisil (terbinafine hydrochloride) oral granules. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation; 2013. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/022071s009lbl.pdf

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Nahata MC. Stability of terbinafine hydrochloride in an extemporaneously prepared oral suspension at 25 and 4 degrees C. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:243-245. doi:10.1093/ajhp/56.3.243

- Gupta AK, Adamiak A, Cooper EA. The efficacy and safety of terbinafine in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:627-640. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00691.x

- Solís-Arias MP, García-Romero MT. Onychomycosis in children. a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:123-130. doi:10.1111/ijd.13392

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of abnormal laboratory test results in pediatric patients prescribed terbinafine for superficial fungal infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1042-1044. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.073

- Lamisil (terbinafine hydrochloride) oral granules. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation; 2013. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/022071s009lbl.pdf

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Nahata MC. Stability of terbinafine hydrochloride in an extemporaneously prepared oral suspension at 25 and 4 degrees C. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:243-245. doi:10.1093/ajhp/56.3.243

- Gupta AK, Adamiak A, Cooper EA. The efficacy and safety of terbinafine in children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:627-640. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00691.x

Portable MRI has potential for MS

, suggesting that it could have potential for use in screening high-risk patients.

Although previous studies had shown that the approach could hold up to high-field MRI, the new study was a blind comparison in which raters did not have access to the high-field images.

In addition to portability, the device has potential advantages over high-field MRI, including low cost and no need for high-field physical shielding. It could be used for point-of-care testing, especially in remote or low-resource areas. It does not produce ionizing radiation, and has been used in intensive care units and pediatric facilities.

Advantages and limitations

The device isn’t ready for general use in MS. It performed well in periventricular lesions but less well in other areas. Ongoing research could improve its performance, including multiplanar imaging and image analysis.

“I think it still needs some work, but to me if it’s less expensive it will be particularly better for third-world countries and that sort of place, or possibly for use in the field in the United States or in North America. If something is detected, you can then bring the person in for a better scan, but I don’t know how sensitive it is – how much pathology you might miss. But in countries where there are no MRIs, it’s certainly better than nothing,” said Anne Cross, MD, who comoderated the session at the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, where the study was presented.

She also noted that the device is potentially safer than high-field MRI. “I don’t think it would be something insurance companies or patients would want to pay $1,000 for when they could get a better scan somewhere, but it’ll get better,” said Dr. Cross, who is a professor of neurology and chair of neuroimmunology at Washington University in St. Louis.

How reliable are low-field images?

In previous work, in which evaluators compared the two scans side by side, the researchers showed in 36 patients that the device performed well, compared with a 64mT scanner. “When we look at tandem evaluations, we can identify dissemination in space in 80%. When a patient has at least one lesion that is larger than 4 millimeters in its largest diameter, we are able to detect it in the ultralow field MRI with 100% sensitivity. The open question here is, what is the diagnostic utility of these scanners when we don’t have any information about the high-field images?” said Serhat Okar, MD, during his presentation of the study. Dr. Okar is a neurologist and postdoctoral researcher at the National Institutes of Health.

To answer that question, the researchers asked two raters to examine scans from the low-field MRI, but only an independent party evaluator had access to both scans.

The study included 55 MS patients who were seen for either clinical or research purposes. The average age was 41 years, and 43 patients were female. Two neuroradiologists served as scan raters. Rater 1 had 17 years of experience, and rater 2 had 9 years of experience. They each conducted assessments for periventricular, juxtacortical, infratentorial, deep white matter, and deep gray matter lesions, as well as dissemination in space. They marked the scan and filled out an online form with number of observed lesions and whether they observed dissemination in space, with responses checked against a high-field image by an independent neuroradiologist for true positive and false positive findings.

There was significant discordance between raters for observation of dissemination in space, with rater 1 reporting 81% positivity and reader 2, 49%. False positive analyses revealed a difference in their approaches: Rater 1 was more conservative in marking lesions, which led to fewer true positive and fewer false positive findings. Both raters had good performance in the periventricular lesions with similar, low rates of false positives.

Other areas were a different story. Both raters found a greater number of true positive and false positive areas in the juxtacortical, deep white matter, and deep gray matter areas.

The study was funded by Hyperfine. Dr. Okar and Dr. Cross have no relevant financial disclosures.

, suggesting that it could have potential for use in screening high-risk patients.

Although previous studies had shown that the approach could hold up to high-field MRI, the new study was a blind comparison in which raters did not have access to the high-field images.

In addition to portability, the device has potential advantages over high-field MRI, including low cost and no need for high-field physical shielding. It could be used for point-of-care testing, especially in remote or low-resource areas. It does not produce ionizing radiation, and has been used in intensive care units and pediatric facilities.

Advantages and limitations

The device isn’t ready for general use in MS. It performed well in periventricular lesions but less well in other areas. Ongoing research could improve its performance, including multiplanar imaging and image analysis.

“I think it still needs some work, but to me if it’s less expensive it will be particularly better for third-world countries and that sort of place, or possibly for use in the field in the United States or in North America. If something is detected, you can then bring the person in for a better scan, but I don’t know how sensitive it is – how much pathology you might miss. But in countries where there are no MRIs, it’s certainly better than nothing,” said Anne Cross, MD, who comoderated the session at the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, where the study was presented.

She also noted that the device is potentially safer than high-field MRI. “I don’t think it would be something insurance companies or patients would want to pay $1,000 for when they could get a better scan somewhere, but it’ll get better,” said Dr. Cross, who is a professor of neurology and chair of neuroimmunology at Washington University in St. Louis.

How reliable are low-field images?

In previous work, in which evaluators compared the two scans side by side, the researchers showed in 36 patients that the device performed well, compared with a 64mT scanner. “When we look at tandem evaluations, we can identify dissemination in space in 80%. When a patient has at least one lesion that is larger than 4 millimeters in its largest diameter, we are able to detect it in the ultralow field MRI with 100% sensitivity. The open question here is, what is the diagnostic utility of these scanners when we don’t have any information about the high-field images?” said Serhat Okar, MD, during his presentation of the study. Dr. Okar is a neurologist and postdoctoral researcher at the National Institutes of Health.

To answer that question, the researchers asked two raters to examine scans from the low-field MRI, but only an independent party evaluator had access to both scans.

The study included 55 MS patients who were seen for either clinical or research purposes. The average age was 41 years, and 43 patients were female. Two neuroradiologists served as scan raters. Rater 1 had 17 years of experience, and rater 2 had 9 years of experience. They each conducted assessments for periventricular, juxtacortical, infratentorial, deep white matter, and deep gray matter lesions, as well as dissemination in space. They marked the scan and filled out an online form with number of observed lesions and whether they observed dissemination in space, with responses checked against a high-field image by an independent neuroradiologist for true positive and false positive findings.

There was significant discordance between raters for observation of dissemination in space, with rater 1 reporting 81% positivity and reader 2, 49%. False positive analyses revealed a difference in their approaches: Rater 1 was more conservative in marking lesions, which led to fewer true positive and fewer false positive findings. Both raters had good performance in the periventricular lesions with similar, low rates of false positives.

Other areas were a different story. Both raters found a greater number of true positive and false positive areas in the juxtacortical, deep white matter, and deep gray matter areas.

The study was funded by Hyperfine. Dr. Okar and Dr. Cross have no relevant financial disclosures.

, suggesting that it could have potential for use in screening high-risk patients.

Although previous studies had shown that the approach could hold up to high-field MRI, the new study was a blind comparison in which raters did not have access to the high-field images.

In addition to portability, the device has potential advantages over high-field MRI, including low cost and no need for high-field physical shielding. It could be used for point-of-care testing, especially in remote or low-resource areas. It does not produce ionizing radiation, and has been used in intensive care units and pediatric facilities.

Advantages and limitations

The device isn’t ready for general use in MS. It performed well in periventricular lesions but less well in other areas. Ongoing research could improve its performance, including multiplanar imaging and image analysis.

“I think it still needs some work, but to me if it’s less expensive it will be particularly better for third-world countries and that sort of place, or possibly for use in the field in the United States or in North America. If something is detected, you can then bring the person in for a better scan, but I don’t know how sensitive it is – how much pathology you might miss. But in countries where there are no MRIs, it’s certainly better than nothing,” said Anne Cross, MD, who comoderated the session at the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, where the study was presented.

She also noted that the device is potentially safer than high-field MRI. “I don’t think it would be something insurance companies or patients would want to pay $1,000 for when they could get a better scan somewhere, but it’ll get better,” said Dr. Cross, who is a professor of neurology and chair of neuroimmunology at Washington University in St. Louis.

How reliable are low-field images?

In previous work, in which evaluators compared the two scans side by side, the researchers showed in 36 patients that the device performed well, compared with a 64mT scanner. “When we look at tandem evaluations, we can identify dissemination in space in 80%. When a patient has at least one lesion that is larger than 4 millimeters in its largest diameter, we are able to detect it in the ultralow field MRI with 100% sensitivity. The open question here is, what is the diagnostic utility of these scanners when we don’t have any information about the high-field images?” said Serhat Okar, MD, during his presentation of the study. Dr. Okar is a neurologist and postdoctoral researcher at the National Institutes of Health.

To answer that question, the researchers asked two raters to examine scans from the low-field MRI, but only an independent party evaluator had access to both scans.

The study included 55 MS patients who were seen for either clinical or research purposes. The average age was 41 years, and 43 patients were female. Two neuroradiologists served as scan raters. Rater 1 had 17 years of experience, and rater 2 had 9 years of experience. They each conducted assessments for periventricular, juxtacortical, infratentorial, deep white matter, and deep gray matter lesions, as well as dissemination in space. They marked the scan and filled out an online form with number of observed lesions and whether they observed dissemination in space, with responses checked against a high-field image by an independent neuroradiologist for true positive and false positive findings.

There was significant discordance between raters for observation of dissemination in space, with rater 1 reporting 81% positivity and reader 2, 49%. False positive analyses revealed a difference in their approaches: Rater 1 was more conservative in marking lesions, which led to fewer true positive and fewer false positive findings. Both raters had good performance in the periventricular lesions with similar, low rates of false positives.

Other areas were a different story. Both raters found a greater number of true positive and false positive areas in the juxtacortical, deep white matter, and deep gray matter areas.

The study was funded by Hyperfine. Dr. Okar and Dr. Cross have no relevant financial disclosures.

AT ACTRIMS FORUM 2023

Mini-invasive MV repair as safe, effective as sternotomy surgery but has advantages: UK Mini-Mitral Trial

Patients with degenerative mitral valve (MV) regurgitation that calls for surgery may, for the most part, safely choose either a standard procedure requiring a midline sternotomy or one performed through a minithoracotomy, suggests a randomized comparison of the two techniques.

Still, the minimally invasive approach showed some advantages in the study. Patients’ quality of recovery was about the same with both procedures at 12 weeks, but those who had the minimally invasive thoracoscopy-guided surgery had shown greater improvement 6 weeks earlier.

Also in the UK Mini Mitral Trial, hospital length of stay (LOS) was significantly shorter for patients who underwent the mini-thoracotomy procedure, and that group spent fewer days in the hospital over the following months.

But neither procedure had an edge in terms of postoperative clinical risk in the study. Rates of clinical events, such as death or hospitalization for heart failure (HHF), were about the same over 1 year.

Patients in this trial had been deemed suitable for either of the two surgeries, which were always performed by surgeons specially chosen by the steering committee for their experience and expertise.

This first randomized head-to-head comparison of the two approaches in such patients should make both patients and clinicians more confident about choosing the minimally invasive surgery for degenerative MV disease, said Enoch Akowuah, MD, Newcastle (England) University, United Kingdom.

Dr. Akowuah presented the UK Mini-Mitral Trial at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation.

A “main takeaway” for clinical practice from the trial would be that minithoracotomy MV repair “is as safe and effective as conventional sternotomy for degenerative mitral regurgitation,” said discussant Amy E. Simone, PA-C, following Dr. Akowuah’s presentation.

“I think this study is unique in that its focus is on delivering high-quality, cost-efficient care for mitral regurgitation, but also with an emphasis on patients’ goals and wishes,” said Ms. Simone, who directs the Marcus Heart Valve Center of the Piedmont Heart Institute, Atlanta.

Cardiac surgeon Thomas MacGillivray, MD, another discussant, agreed that the data presented from at least this study suggest neither the minithoracotomy nor sternotomy approach is better than the other. But he questioned whether that would hold true if applied to broader clinical practice.

Dr. MacGillivray, of MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, observed that only 330 patients were randomly assigned among a total of 1,167 candidates for candidates for MV repair surgery.

Indeed, he noted, more than 200 declined and about 600 were declared ineligible for the study, “even though it had seemed as if all were appropriate for mitral valve repair. That could be viewed as a significant limitation in terms of scalability in the real world.”

Some of those patients weren’t randomly assigned because they ultimately were not considered appropriate for both procedures, and some expressed a preference for one or the other approach, Dr. Akowuah replied. Those were the most common reasons. Many others did not enter the study, he said, because their mitral regurgitation was functional, not degenerative.

The two randomization groups fared similarly for the primary endpoint reflecting recovery from surgery, so the trial was actually “negative,” Dr. Akowuah said in an interview. However, “I see it as very much a win for minithoracotomy. The outstanding questions for clinicians and patients have been about the clinical efficacy and safety of the technique. And we’ve shown in this trial that minithoracotomy is safe and effective.”

If the minithoracotomy procedure is available, he continued, “and it’s just as clinically effective and safe – and we weren’t sure that was the case until we did this trial – and the repair is almost as durable, then why have a sternotomy?”

The researchers assigned 330 patients with degenerative MV disease who were deemed suitable for either type of surgery to undergo the standard operation via sternotomy or the minithoracotomy procedure at 10 centers in the United Kingdom. The steering committee had hand-selected its 28 experienced surgeons, each of whom performed only one of the two surgeries consistently for the trial’s patients.

The technically more demanding minithoracotomy procedure took longer to perform by a mean of 44 minutes, it prolonged cross-clamp time by 11 minutes, and it required 30 minutes more cardiopulmonary bypass support, Dr. Akowuah reported.

The two patient groups showed no significant differences in the primary endpoint of physical function and ability to return to usual activity levels at 12 weeks, as assessed by scores on the 36-Item Short Form Survey and wrist-worn accelerometer monitoring. At 6 weeks, however, the mini-thoracotomy patients had shown a significant early but temporary advantage for those recovery measures.

The minithoracotomy group clearly fared better, however, on some secondary endpoints. For example, their median hospital LOS was 5 days, compared with 6 days for the sternotomy group (P = .003), and 33.1% of the mini-thoracotomy patients were discharged within 4 days of the surgery, compared with only 15.3% of patients who had the standard procedure (P < .001).

The minithoracotomy group also had marginally more days alive out of the hospital at both 30 days (23.6 days vs. 22.4 days in the sternotomy group) and 90 days (82.7 days and 80.5 days, respectively) after the surgery (P = .03 for both differences).

Safety outcomes at 12 weeks were similar, with no significant differences in rate of death, strokes, MI, or renal impairment, or in ICU length of stay or need for more than 48 hours of mechanical ventilation, Dr. Akowuah reported.

Safety outcomes at 1 year were also similar. Mortality by then was 2.4% for the minithoracotomy patients and 2.5% for the sternotomy group, nor were there significant differences in HHF rates or need for repeat MV surgical repair.

Dr. Akowuah said the patients will be followed for up to 5 years for the primary outcomes, echocardiographic changes, and clinical events.

The minithoracotomy surgery’s longer operative times and specialized equipment make it more a expensive procedure than the standard surgery, he said. “So we need to work out in a cost-effectiveness analysis whether that is offset by the benefits,” such as shorter hospital stays or perhaps fewer transfusions or readmissions.

The study was funded by the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Research. Dr. Akowuah reported no relevant financial relationships with industry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with degenerative mitral valve (MV) regurgitation that calls for surgery may, for the most part, safely choose either a standard procedure requiring a midline sternotomy or one performed through a minithoracotomy, suggests a randomized comparison of the two techniques.

Still, the minimally invasive approach showed some advantages in the study. Patients’ quality of recovery was about the same with both procedures at 12 weeks, but those who had the minimally invasive thoracoscopy-guided surgery had shown greater improvement 6 weeks earlier.

Also in the UK Mini Mitral Trial, hospital length of stay (LOS) was significantly shorter for patients who underwent the mini-thoracotomy procedure, and that group spent fewer days in the hospital over the following months.

But neither procedure had an edge in terms of postoperative clinical risk in the study. Rates of clinical events, such as death or hospitalization for heart failure (HHF), were about the same over 1 year.

Patients in this trial had been deemed suitable for either of the two surgeries, which were always performed by surgeons specially chosen by the steering committee for their experience and expertise.

This first randomized head-to-head comparison of the two approaches in such patients should make both patients and clinicians more confident about choosing the minimally invasive surgery for degenerative MV disease, said Enoch Akowuah, MD, Newcastle (England) University, United Kingdom.

Dr. Akowuah presented the UK Mini-Mitral Trial at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation.

A “main takeaway” for clinical practice from the trial would be that minithoracotomy MV repair “is as safe and effective as conventional sternotomy for degenerative mitral regurgitation,” said discussant Amy E. Simone, PA-C, following Dr. Akowuah’s presentation.

“I think this study is unique in that its focus is on delivering high-quality, cost-efficient care for mitral regurgitation, but also with an emphasis on patients’ goals and wishes,” said Ms. Simone, who directs the Marcus Heart Valve Center of the Piedmont Heart Institute, Atlanta.

Cardiac surgeon Thomas MacGillivray, MD, another discussant, agreed that the data presented from at least this study suggest neither the minithoracotomy nor sternotomy approach is better than the other. But he questioned whether that would hold true if applied to broader clinical practice.

Dr. MacGillivray, of MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, observed that only 330 patients were randomly assigned among a total of 1,167 candidates for candidates for MV repair surgery.

Indeed, he noted, more than 200 declined and about 600 were declared ineligible for the study, “even though it had seemed as if all were appropriate for mitral valve repair. That could be viewed as a significant limitation in terms of scalability in the real world.”

Some of those patients weren’t randomly assigned because they ultimately were not considered appropriate for both procedures, and some expressed a preference for one or the other approach, Dr. Akowuah replied. Those were the most common reasons. Many others did not enter the study, he said, because their mitral regurgitation was functional, not degenerative.

The two randomization groups fared similarly for the primary endpoint reflecting recovery from surgery, so the trial was actually “negative,” Dr. Akowuah said in an interview. However, “I see it as very much a win for minithoracotomy. The outstanding questions for clinicians and patients have been about the clinical efficacy and safety of the technique. And we’ve shown in this trial that minithoracotomy is safe and effective.”

If the minithoracotomy procedure is available, he continued, “and it’s just as clinically effective and safe – and we weren’t sure that was the case until we did this trial – and the repair is almost as durable, then why have a sternotomy?”

The researchers assigned 330 patients with degenerative MV disease who were deemed suitable for either type of surgery to undergo the standard operation via sternotomy or the minithoracotomy procedure at 10 centers in the United Kingdom. The steering committee had hand-selected its 28 experienced surgeons, each of whom performed only one of the two surgeries consistently for the trial’s patients.

The technically more demanding minithoracotomy procedure took longer to perform by a mean of 44 minutes, it prolonged cross-clamp time by 11 minutes, and it required 30 minutes more cardiopulmonary bypass support, Dr. Akowuah reported.

The two patient groups showed no significant differences in the primary endpoint of physical function and ability to return to usual activity levels at 12 weeks, as assessed by scores on the 36-Item Short Form Survey and wrist-worn accelerometer monitoring. At 6 weeks, however, the mini-thoracotomy patients had shown a significant early but temporary advantage for those recovery measures.

The minithoracotomy group clearly fared better, however, on some secondary endpoints. For example, their median hospital LOS was 5 days, compared with 6 days for the sternotomy group (P = .003), and 33.1% of the mini-thoracotomy patients were discharged within 4 days of the surgery, compared with only 15.3% of patients who had the standard procedure (P < .001).

The minithoracotomy group also had marginally more days alive out of the hospital at both 30 days (23.6 days vs. 22.4 days in the sternotomy group) and 90 days (82.7 days and 80.5 days, respectively) after the surgery (P = .03 for both differences).

Safety outcomes at 12 weeks were similar, with no significant differences in rate of death, strokes, MI, or renal impairment, or in ICU length of stay or need for more than 48 hours of mechanical ventilation, Dr. Akowuah reported.

Safety outcomes at 1 year were also similar. Mortality by then was 2.4% for the minithoracotomy patients and 2.5% for the sternotomy group, nor were there significant differences in HHF rates or need for repeat MV surgical repair.

Dr. Akowuah said the patients will be followed for up to 5 years for the primary outcomes, echocardiographic changes, and clinical events.

The minithoracotomy surgery’s longer operative times and specialized equipment make it more a expensive procedure than the standard surgery, he said. “So we need to work out in a cost-effectiveness analysis whether that is offset by the benefits,” such as shorter hospital stays or perhaps fewer transfusions or readmissions.

The study was funded by the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Research. Dr. Akowuah reported no relevant financial relationships with industry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with degenerative mitral valve (MV) regurgitation that calls for surgery may, for the most part, safely choose either a standard procedure requiring a midline sternotomy or one performed through a minithoracotomy, suggests a randomized comparison of the two techniques.

Still, the minimally invasive approach showed some advantages in the study. Patients’ quality of recovery was about the same with both procedures at 12 weeks, but those who had the minimally invasive thoracoscopy-guided surgery had shown greater improvement 6 weeks earlier.

Also in the UK Mini Mitral Trial, hospital length of stay (LOS) was significantly shorter for patients who underwent the mini-thoracotomy procedure, and that group spent fewer days in the hospital over the following months.

But neither procedure had an edge in terms of postoperative clinical risk in the study. Rates of clinical events, such as death or hospitalization for heart failure (HHF), were about the same over 1 year.

Patients in this trial had been deemed suitable for either of the two surgeries, which were always performed by surgeons specially chosen by the steering committee for their experience and expertise.

This first randomized head-to-head comparison of the two approaches in such patients should make both patients and clinicians more confident about choosing the minimally invasive surgery for degenerative MV disease, said Enoch Akowuah, MD, Newcastle (England) University, United Kingdom.

Dr. Akowuah presented the UK Mini-Mitral Trial at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation.

A “main takeaway” for clinical practice from the trial would be that minithoracotomy MV repair “is as safe and effective as conventional sternotomy for degenerative mitral regurgitation,” said discussant Amy E. Simone, PA-C, following Dr. Akowuah’s presentation.

“I think this study is unique in that its focus is on delivering high-quality, cost-efficient care for mitral regurgitation, but also with an emphasis on patients’ goals and wishes,” said Ms. Simone, who directs the Marcus Heart Valve Center of the Piedmont Heart Institute, Atlanta.

Cardiac surgeon Thomas MacGillivray, MD, another discussant, agreed that the data presented from at least this study suggest neither the minithoracotomy nor sternotomy approach is better than the other. But he questioned whether that would hold true if applied to broader clinical practice.

Dr. MacGillivray, of MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, observed that only 330 patients were randomly assigned among a total of 1,167 candidates for candidates for MV repair surgery.

Indeed, he noted, more than 200 declined and about 600 were declared ineligible for the study, “even though it had seemed as if all were appropriate for mitral valve repair. That could be viewed as a significant limitation in terms of scalability in the real world.”

Some of those patients weren’t randomly assigned because they ultimately were not considered appropriate for both procedures, and some expressed a preference for one or the other approach, Dr. Akowuah replied. Those were the most common reasons. Many others did not enter the study, he said, because their mitral regurgitation was functional, not degenerative.

The two randomization groups fared similarly for the primary endpoint reflecting recovery from surgery, so the trial was actually “negative,” Dr. Akowuah said in an interview. However, “I see it as very much a win for minithoracotomy. The outstanding questions for clinicians and patients have been about the clinical efficacy and safety of the technique. And we’ve shown in this trial that minithoracotomy is safe and effective.”

If the minithoracotomy procedure is available, he continued, “and it’s just as clinically effective and safe – and we weren’t sure that was the case until we did this trial – and the repair is almost as durable, then why have a sternotomy?”

The researchers assigned 330 patients with degenerative MV disease who were deemed suitable for either type of surgery to undergo the standard operation via sternotomy or the minithoracotomy procedure at 10 centers in the United Kingdom. The steering committee had hand-selected its 28 experienced surgeons, each of whom performed only one of the two surgeries consistently for the trial’s patients.

The technically more demanding minithoracotomy procedure took longer to perform by a mean of 44 minutes, it prolonged cross-clamp time by 11 minutes, and it required 30 minutes more cardiopulmonary bypass support, Dr. Akowuah reported.

The two patient groups showed no significant differences in the primary endpoint of physical function and ability to return to usual activity levels at 12 weeks, as assessed by scores on the 36-Item Short Form Survey and wrist-worn accelerometer monitoring. At 6 weeks, however, the mini-thoracotomy patients had shown a significant early but temporary advantage for those recovery measures.

The minithoracotomy group clearly fared better, however, on some secondary endpoints. For example, their median hospital LOS was 5 days, compared with 6 days for the sternotomy group (P = .003), and 33.1% of the mini-thoracotomy patients were discharged within 4 days of the surgery, compared with only 15.3% of patients who had the standard procedure (P < .001).

The minithoracotomy group also had marginally more days alive out of the hospital at both 30 days (23.6 days vs. 22.4 days in the sternotomy group) and 90 days (82.7 days and 80.5 days, respectively) after the surgery (P = .03 for both differences).

Safety outcomes at 12 weeks were similar, with no significant differences in rate of death, strokes, MI, or renal impairment, or in ICU length of stay or need for more than 48 hours of mechanical ventilation, Dr. Akowuah reported.

Safety outcomes at 1 year were also similar. Mortality by then was 2.4% for the minithoracotomy patients and 2.5% for the sternotomy group, nor were there significant differences in HHF rates or need for repeat MV surgical repair.

Dr. Akowuah said the patients will be followed for up to 5 years for the primary outcomes, echocardiographic changes, and clinical events.

The minithoracotomy surgery’s longer operative times and specialized equipment make it more a expensive procedure than the standard surgery, he said. “So we need to work out in a cost-effectiveness analysis whether that is offset by the benefits,” such as shorter hospital stays or perhaps fewer transfusions or readmissions.

The study was funded by the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Research. Dr. Akowuah reported no relevant financial relationships with industry.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACC 2023

Spreading Painful Lesions on the Legs

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

A punch biopsy of the skin showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis with dermal granulomatous and suppurative inflammation; tissue cultures remained sterile. Polymerase chain reaction testing of the skin revealed the presence of Leishmania guyanensis complex. Leishmaniasis is a widespread parasitic disease transmitted via sandflies that often is seen in children and young adults.1 Although leishmaniasis is endemic to several countries within Southeast Asia, East Africa, and Latin America, an increase in international travel has brought the disease to nonendemic regions. Therefore, it is crucial to obtain a detailed history of travel and exposure to sandflies in patients who have recently returned from endemic regions.

Leishmaniasis may present in 3 forms: cutaneous, mucocutaneous, or visceral. Cutaneous clinical findings vary depending on disease stage, causative species, and host immune activation. Presentation following a sandfly bite typically includes a papule that progresses to an erythematous nodule. Cutaneous leishmaniasis commonly occurs in areas of the body that are easily accessible to sandflies, such as the face, neck, and limbs. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis presents with nasal or oral involvement several years after the onset of cutaneous leishmaniasis; however, it can coexist with cutaneous involvement. Without treatment, mucocutaneous leishmaniasis may lead to perforation of the nasal septum, destruction of the mouth, and life-threatening airway obstruction.1 Determining the specific species is important due to the variation in treatment options and prognosis. Because Leishmania organisms are fastidious, obtaining a positive culture often is challenging. Polymerase chain reaction can be utilized for identification, with detection rates of 97%.1 Systemic treatment is indicated for patients with multiple or large lesions; lesions on the hands, feet, face, or joints; or immunocompromised patients. Antimonial drugs are the first-line treatment for most forms of leishmaniasis, though increasing resistance has led to a decrease in efficacy.1 Our patient ultimately was treated with 4 weeks of miltefosine 50 mg 3 times daily. She obtained full resolution of the lesions with no further treatment indicated.

Pemphigus vegetans may present with various clinical manifestations that often can lead to a delay in diagnosis. The Hallopeau subtype typically presents as pustular lesions, while the Neumann subtype may present as large vesiculobullous erosive lesions that rupture and form verrucous, crusted, vegetative plaques. The groin, inguinal folds, axillae, thighs, and flexural areas commonly are affected, but reports of nasal, vaginal, and conjunctival involvement also exist.2

Granuloma inguinale is a sexually transmitted ulcerative disease that is caused by infection with Klebsiella granulomatis. It typically is found in tropical and subtropical climates, including Australia, Brazil, India, and South Africa. The initial presentation includes a single papule or multiple papules or nodules in the genital area that progress to a painless ulcer. It can be diagnosed via biopsies or tissue smears, which will demonstrate the presence of inclusion bodies known as Donovan bodies.3

Cutaneous tuberculosis (TB) can have variable clinical presentations and may be acquired exogenously or endogenously. Cutaneous TB can be divided into 2 categories: exogenous TB caused by inoculation and endogenous TB due to direct spread or autoinoculation. Exogenous TB subtypes include tuberculous chancre and TB verrucosa cutis, while endogenous TB includes scrofuloderma, orificial TB, and lupus vulgaris.4 Patches and plaques are found in patients with lupus vulgaris and TB verrucosa cutis. Scrofuloderma, tuberculous chancre, and orificial TB can present as ulcerative or erosive lesions. Cutaneous TB infection can be diagnosed through a smear, culture, or polymerase chain reaction.4

Deep cutaneous fungal infections most commonly present in immunocompromised individuals, particularly those who are severely neutropenic and are receiving broad-spectrum systemic antimicrobial agents. Deep cutaneous fungal infections initially present as a papule and evolve into a pustule followed by a necrotic ulcer. The lesions typically are accompanied by a fever and/or vital sign abnormalities.5

- Pace D. Leishmaniasis [published online September 17, 2014]. J Infect. 2014;69(suppl 1):S10-S18. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2014.07.016

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Ornelas J, Kiuru M, Konia T, et al. Granuloma inguinale in a 51-year-old man. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt52k0c4hj.

- Chen Q, Chen W, Hao F. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2019;37:192-199.

- Marcoux D, Jafarian F, Joncas V, et al. Deep cutaneous fungal infections in immunocompromised children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:857-864.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

A punch biopsy of the skin showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis with dermal granulomatous and suppurative inflammation; tissue cultures remained sterile. Polymerase chain reaction testing of the skin revealed the presence of Leishmania guyanensis complex. Leishmaniasis is a widespread parasitic disease transmitted via sandflies that often is seen in children and young adults.1 Although leishmaniasis is endemic to several countries within Southeast Asia, East Africa, and Latin America, an increase in international travel has brought the disease to nonendemic regions. Therefore, it is crucial to obtain a detailed history of travel and exposure to sandflies in patients who have recently returned from endemic regions.

Leishmaniasis may present in 3 forms: cutaneous, mucocutaneous, or visceral. Cutaneous clinical findings vary depending on disease stage, causative species, and host immune activation. Presentation following a sandfly bite typically includes a papule that progresses to an erythematous nodule. Cutaneous leishmaniasis commonly occurs in areas of the body that are easily accessible to sandflies, such as the face, neck, and limbs. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis presents with nasal or oral involvement several years after the onset of cutaneous leishmaniasis; however, it can coexist with cutaneous involvement. Without treatment, mucocutaneous leishmaniasis may lead to perforation of the nasal septum, destruction of the mouth, and life-threatening airway obstruction.1 Determining the specific species is important due to the variation in treatment options and prognosis. Because Leishmania organisms are fastidious, obtaining a positive culture often is challenging. Polymerase chain reaction can be utilized for identification, with detection rates of 97%.1 Systemic treatment is indicated for patients with multiple or large lesions; lesions on the hands, feet, face, or joints; or immunocompromised patients. Antimonial drugs are the first-line treatment for most forms of leishmaniasis, though increasing resistance has led to a decrease in efficacy.1 Our patient ultimately was treated with 4 weeks of miltefosine 50 mg 3 times daily. She obtained full resolution of the lesions with no further treatment indicated.

Pemphigus vegetans may present with various clinical manifestations that often can lead to a delay in diagnosis. The Hallopeau subtype typically presents as pustular lesions, while the Neumann subtype may present as large vesiculobullous erosive lesions that rupture and form verrucous, crusted, vegetative plaques. The groin, inguinal folds, axillae, thighs, and flexural areas commonly are affected, but reports of nasal, vaginal, and conjunctival involvement also exist.2

Granuloma inguinale is a sexually transmitted ulcerative disease that is caused by infection with Klebsiella granulomatis. It typically is found in tropical and subtropical climates, including Australia, Brazil, India, and South Africa. The initial presentation includes a single papule or multiple papules or nodules in the genital area that progress to a painless ulcer. It can be diagnosed via biopsies or tissue smears, which will demonstrate the presence of inclusion bodies known as Donovan bodies.3

Cutaneous tuberculosis (TB) can have variable clinical presentations and may be acquired exogenously or endogenously. Cutaneous TB can be divided into 2 categories: exogenous TB caused by inoculation and endogenous TB due to direct spread or autoinoculation. Exogenous TB subtypes include tuberculous chancre and TB verrucosa cutis, while endogenous TB includes scrofuloderma, orificial TB, and lupus vulgaris.4 Patches and plaques are found in patients with lupus vulgaris and TB verrucosa cutis. Scrofuloderma, tuberculous chancre, and orificial TB can present as ulcerative or erosive lesions. Cutaneous TB infection can be diagnosed through a smear, culture, or polymerase chain reaction.4

Deep cutaneous fungal infections most commonly present in immunocompromised individuals, particularly those who are severely neutropenic and are receiving broad-spectrum systemic antimicrobial agents. Deep cutaneous fungal infections initially present as a papule and evolve into a pustule followed by a necrotic ulcer. The lesions typically are accompanied by a fever and/or vital sign abnormalities.5

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

A punch biopsy of the skin showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis with dermal granulomatous and suppurative inflammation; tissue cultures remained sterile. Polymerase chain reaction testing of the skin revealed the presence of Leishmania guyanensis complex. Leishmaniasis is a widespread parasitic disease transmitted via sandflies that often is seen in children and young adults.1 Although leishmaniasis is endemic to several countries within Southeast Asia, East Africa, and Latin America, an increase in international travel has brought the disease to nonendemic regions. Therefore, it is crucial to obtain a detailed history of travel and exposure to sandflies in patients who have recently returned from endemic regions.

Leishmaniasis may present in 3 forms: cutaneous, mucocutaneous, or visceral. Cutaneous clinical findings vary depending on disease stage, causative species, and host immune activation. Presentation following a sandfly bite typically includes a papule that progresses to an erythematous nodule. Cutaneous leishmaniasis commonly occurs in areas of the body that are easily accessible to sandflies, such as the face, neck, and limbs. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis presents with nasal or oral involvement several years after the onset of cutaneous leishmaniasis; however, it can coexist with cutaneous involvement. Without treatment, mucocutaneous leishmaniasis may lead to perforation of the nasal septum, destruction of the mouth, and life-threatening airway obstruction.1 Determining the specific species is important due to the variation in treatment options and prognosis. Because Leishmania organisms are fastidious, obtaining a positive culture often is challenging. Polymerase chain reaction can be utilized for identification, with detection rates of 97%.1 Systemic treatment is indicated for patients with multiple or large lesions; lesions on the hands, feet, face, or joints; or immunocompromised patients. Antimonial drugs are the first-line treatment for most forms of leishmaniasis, though increasing resistance has led to a decrease in efficacy.1 Our patient ultimately was treated with 4 weeks of miltefosine 50 mg 3 times daily. She obtained full resolution of the lesions with no further treatment indicated.

Pemphigus vegetans may present with various clinical manifestations that often can lead to a delay in diagnosis. The Hallopeau subtype typically presents as pustular lesions, while the Neumann subtype may present as large vesiculobullous erosive lesions that rupture and form verrucous, crusted, vegetative plaques. The groin, inguinal folds, axillae, thighs, and flexural areas commonly are affected, but reports of nasal, vaginal, and conjunctival involvement also exist.2

Granuloma inguinale is a sexually transmitted ulcerative disease that is caused by infection with Klebsiella granulomatis. It typically is found in tropical and subtropical climates, including Australia, Brazil, India, and South Africa. The initial presentation includes a single papule or multiple papules or nodules in the genital area that progress to a painless ulcer. It can be diagnosed via biopsies or tissue smears, which will demonstrate the presence of inclusion bodies known as Donovan bodies.3

Cutaneous tuberculosis (TB) can have variable clinical presentations and may be acquired exogenously or endogenously. Cutaneous TB can be divided into 2 categories: exogenous TB caused by inoculation and endogenous TB due to direct spread or autoinoculation. Exogenous TB subtypes include tuberculous chancre and TB verrucosa cutis, while endogenous TB includes scrofuloderma, orificial TB, and lupus vulgaris.4 Patches and plaques are found in patients with lupus vulgaris and TB verrucosa cutis. Scrofuloderma, tuberculous chancre, and orificial TB can present as ulcerative or erosive lesions. Cutaneous TB infection can be diagnosed through a smear, culture, or polymerase chain reaction.4

Deep cutaneous fungal infections most commonly present in immunocompromised individuals, particularly those who are severely neutropenic and are receiving broad-spectrum systemic antimicrobial agents. Deep cutaneous fungal infections initially present as a papule and evolve into a pustule followed by a necrotic ulcer. The lesions typically are accompanied by a fever and/or vital sign abnormalities.5

- Pace D. Leishmaniasis [published online September 17, 2014]. J Infect. 2014;69(suppl 1):S10-S18. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2014.07.016

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Ornelas J, Kiuru M, Konia T, et al. Granuloma inguinale in a 51-year-old man. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt52k0c4hj.

- Chen Q, Chen W, Hao F. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2019;37:192-199.

- Marcoux D, Jafarian F, Joncas V, et al. Deep cutaneous fungal infections in immunocompromised children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:857-864.

- Pace D. Leishmaniasis [published online September 17, 2014]. J Infect. 2014;69(suppl 1):S10-S18. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2014.07.016

- Messersmith L, Krauland K. Pemphigus vegetans. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Ornelas J, Kiuru M, Konia T, et al. Granuloma inguinale in a 51-year-old man. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt52k0c4hj.

- Chen Q, Chen W, Hao F. Cutaneous tuberculosis: a great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2019;37:192-199.

- Marcoux D, Jafarian F, Joncas V, et al. Deep cutaneous fungal infections in immunocompromised children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:857-864.

A 14-year-old adolescent girl presented with spreading painful lesions on the legs and left forearm of 2 years’ duration. Her travel history included several countries in South and Central America, traversing the Colombian jungle on foot. Near the end of the jungle trip, she noted a skin lesion on the left forearm around the site of an insect bite. Within 1 month, the lesions spread to the legs. She was treated with topical corticosteroids without improvement. Physical examination revealed verrucous, reddish-brown plaques on the legs and left forearm. Intranasal examination revealed a red rounded lesion inside the left nostril.

How to help pediatricians apply peanut allergy guidelines

Despite the profound shift in guidelines for preventing peanut allergies in infants after the landmark LEAP study, national surveys in 2021 showed that 70% of parents and caregivers said that they hadn’t heard the new recommendations, and fewer than one-third of pediatricians were following them.

Now, in a 5-year National Institutes of Health–funded study called iREACH, researchers are testing whether a two-part intervention, which includes training videos and a clinical decision support tool, helps pediatricians follow the guidelines and ultimately reduces peanut allergy.

Early results from iREACH, presented at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology 2023 annual meeting in San Antonio, showed mixed results with a sharp rise in clinician knowledge of the guidelines but only a modest increase in their real-world implementation with high-risk infants.

Raising a food-allergic child while working as a pediatrician herself, Ruchi Gupta, MD, MPH, director of the Center for Food Allergy and Asthma Research at Northwestern University, Chicago, understands the importance and challenge of translating published findings into practice.

During a typical 4- to 6-month well-child visit, pediatricians must check the baby’s growth, perform a physical exam, discuss milestones, field questions about sleep and poop and colic and – if they’re up on the latest guidelines – explain why it’s important to feed peanuts early and often.

“Pediatricians get stuff from every single specialty, and guidelines are always changing,” she told this news organization.

The current feeding guidelines, published in 2017 after the landmark LEAP study, switched from “ ‘don’t introduce peanuts until age 3’ to ‘introduce peanuts now,’ ” said Dr. Gupta.

But the recommendations aren’t entirely straightforward. They require pediatricians to make an assessment when the baby is around 4 months old. If the child is high-risk (has severe eczema or an egg allergy), they need a peanut-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) test. If the test is negative, the pediatrician should encourage peanut introduction. If positive, they should refer the child to an allergist.

“It’s a little complicated,” Dr. Gupta said.

To boost understanding and adherence, Dr. Gupta’s team created the intervention tested in the iREACH study. It includes a set of training videos, a clinical decision support tool that embeds into the electronic health record (EHR) with pop-ups reminding the physician to discuss early introduction, menus for ordering peanut IgE tests or referring to an allergist if needed, and a caregiver handout that explains how to add peanuts to the baby’s diet. (These resources can be found here.)

The study enrolled 290 pediatric clinicians at 30 local practices, examining 18,460 babies from diverse backgrounds, about one-quarter of whom were from families on public insurance. About half of the clinicians received the intervention, whereas the other half served as the control arm.

The training videos seemed effective. Clinicians’ knowledge of the guidelines rose from 72.6% at baseline to 94.5% after the intervention, and their ability to identify severe eczema went up from 63.4% to 97.6%. This translated to 70.4% success with applying the guidelines when presented various clinical scenarios, up from 29% at baseline. These results are in press at JAMA Network Open.

The next set of analyses, preliminary and unpublished, monitored real-world adherence using natural language processing to pull EHR data from 4- and 6-month well-check visits. It was “AI [artificial intelligence] for notes,” Dr. Gupta said.

For low-risk infants, the training and EHR-embedded support tool greatly improved clinician adherence. Eighty percent of clinicians in the intervention arm followed the guidelines, compared with 26% in the control group.

In high-risk infants, the impact was much weaker. Even after the video-based training, only 17% of pediatric clinicians followed the guidelines – that is, ordered a peanut IgE test or referred to an allergist – compared with 8% in the control group.

Why such a low uptake?

Pediatricians are time-pressed. “How do you add [early introduction] to the other 10 or 15 things you want to talk to a parent about at the 4-month visit?” said Jonathan Necheles, MD, MPH, a pediatrician at Children’s Healthcare Associates in Chicago.

It can also be hard to tell if a baby’s eczema is “severe” or “mild to moderate.” The EHR-integrated support tool included a scorecard for judging eczema severity across a range of skin tones. The condition can be hard to recognize in patients of color. “You don’t get the redness in the same way,” said Dr. Necheles, who worked with Dr. Gupta to develop the iREACH intervention.

Curiously, even though the AI analysis found that less than one-fifth of pediatricians put the guidelines into action for high-risk infants, 69% of them recommended peanut introduction.

One interpretation is that busy pediatricians may be “doing the minimum” – introducing the concept of early introduction and telling parents to try it “but not giving any additional sort of guidance as far as who’s high risk, who’s low risk, who should see the allergist, who should get screened,” said Edwin Kim, MD, allergist-immunologist and director of the Food Allergy Initiative at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The ultimate impact of iREACH has yet to be seen. “The end goal is, if pediatricians recommend, will parents follow, and will we reduce peanut allergy?” Dr. Gupta said.

Dr. Gupta consults or serves as an advisor for Genentech, Novartis, Aimmune, Allergenis, and Food Allergy Research & Education; receives research funding from Novartis, Genentech, FARE, Melchiorre Family Foundation, and Sunshine Charitable Foundation; and reports ownership interest from Yobee Care. Dr. Necheles reports no financial disclosures. Dr. Kim reports consultancy with Allergy Therapeutics, Belhaven Biopharma, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Genentech, Nutricia, and Revolo; advisory board membership with ALK, Kenota Health, and Ukko; and grant support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Immune Tolerance Network, and Food Allergy Research and Education.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite the profound shift in guidelines for preventing peanut allergies in infants after the landmark LEAP study, national surveys in 2021 showed that 70% of parents and caregivers said that they hadn’t heard the new recommendations, and fewer than one-third of pediatricians were following them.

Now, in a 5-year National Institutes of Health–funded study called iREACH, researchers are testing whether a two-part intervention, which includes training videos and a clinical decision support tool, helps pediatricians follow the guidelines and ultimately reduces peanut allergy.

Early results from iREACH, presented at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology 2023 annual meeting in San Antonio, showed mixed results with a sharp rise in clinician knowledge of the guidelines but only a modest increase in their real-world implementation with high-risk infants.

Raising a food-allergic child while working as a pediatrician herself, Ruchi Gupta, MD, MPH, director of the Center for Food Allergy and Asthma Research at Northwestern University, Chicago, understands the importance and challenge of translating published findings into practice.

During a typical 4- to 6-month well-child visit, pediatricians must check the baby’s growth, perform a physical exam, discuss milestones, field questions about sleep and poop and colic and – if they’re up on the latest guidelines – explain why it’s important to feed peanuts early and often.

“Pediatricians get stuff from every single specialty, and guidelines are always changing,” she told this news organization.

The current feeding guidelines, published in 2017 after the landmark LEAP study, switched from “ ‘don’t introduce peanuts until age 3’ to ‘introduce peanuts now,’ ” said Dr. Gupta.

But the recommendations aren’t entirely straightforward. They require pediatricians to make an assessment when the baby is around 4 months old. If the child is high-risk (has severe eczema or an egg allergy), they need a peanut-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) test. If the test is negative, the pediatrician should encourage peanut introduction. If positive, they should refer the child to an allergist.

“It’s a little complicated,” Dr. Gupta said.

To boost understanding and adherence, Dr. Gupta’s team created the intervention tested in the iREACH study. It includes a set of training videos, a clinical decision support tool that embeds into the electronic health record (EHR) with pop-ups reminding the physician to discuss early introduction, menus for ordering peanut IgE tests or referring to an allergist if needed, and a caregiver handout that explains how to add peanuts to the baby’s diet. (These resources can be found here.)

The study enrolled 290 pediatric clinicians at 30 local practices, examining 18,460 babies from diverse backgrounds, about one-quarter of whom were from families on public insurance. About half of the clinicians received the intervention, whereas the other half served as the control arm.

The training videos seemed effective. Clinicians’ knowledge of the guidelines rose from 72.6% at baseline to 94.5% after the intervention, and their ability to identify severe eczema went up from 63.4% to 97.6%. This translated to 70.4% success with applying the guidelines when presented various clinical scenarios, up from 29% at baseline. These results are in press at JAMA Network Open.

The next set of analyses, preliminary and unpublished, monitored real-world adherence using natural language processing to pull EHR data from 4- and 6-month well-check visits. It was “AI [artificial intelligence] for notes,” Dr. Gupta said.

For low-risk infants, the training and EHR-embedded support tool greatly improved clinician adherence. Eighty percent of clinicians in the intervention arm followed the guidelines, compared with 26% in the control group.

In high-risk infants, the impact was much weaker. Even after the video-based training, only 17% of pediatric clinicians followed the guidelines – that is, ordered a peanut IgE test or referred to an allergist – compared with 8% in the control group.

Why such a low uptake?

Pediatricians are time-pressed. “How do you add [early introduction] to the other 10 or 15 things you want to talk to a parent about at the 4-month visit?” said Jonathan Necheles, MD, MPH, a pediatrician at Children’s Healthcare Associates in Chicago.

It can also be hard to tell if a baby’s eczema is “severe” or “mild to moderate.” The EHR-integrated support tool included a scorecard for judging eczema severity across a range of skin tones. The condition can be hard to recognize in patients of color. “You don’t get the redness in the same way,” said Dr. Necheles, who worked with Dr. Gupta to develop the iREACH intervention.

Curiously, even though the AI analysis found that less than one-fifth of pediatricians put the guidelines into action for high-risk infants, 69% of them recommended peanut introduction.

One interpretation is that busy pediatricians may be “doing the minimum” – introducing the concept of early introduction and telling parents to try it “but not giving any additional sort of guidance as far as who’s high risk, who’s low risk, who should see the allergist, who should get screened,” said Edwin Kim, MD, allergist-immunologist and director of the Food Allergy Initiative at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The ultimate impact of iREACH has yet to be seen. “The end goal is, if pediatricians recommend, will parents follow, and will we reduce peanut allergy?” Dr. Gupta said.

Dr. Gupta consults or serves as an advisor for Genentech, Novartis, Aimmune, Allergenis, and Food Allergy Research & Education; receives research funding from Novartis, Genentech, FARE, Melchiorre Family Foundation, and Sunshine Charitable Foundation; and reports ownership interest from Yobee Care. Dr. Necheles reports no financial disclosures. Dr. Kim reports consultancy with Allergy Therapeutics, Belhaven Biopharma, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Genentech, Nutricia, and Revolo; advisory board membership with ALK, Kenota Health, and Ukko; and grant support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Immune Tolerance Network, and Food Allergy Research and Education.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite the profound shift in guidelines for preventing peanut allergies in infants after the landmark LEAP study, national surveys in 2021 showed that 70% of parents and caregivers said that they hadn’t heard the new recommendations, and fewer than one-third of pediatricians were following them.

Now, in a 5-year National Institutes of Health–funded study called iREACH, researchers are testing whether a two-part intervention, which includes training videos and a clinical decision support tool, helps pediatricians follow the guidelines and ultimately reduces peanut allergy.

Early results from iREACH, presented at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology 2023 annual meeting in San Antonio, showed mixed results with a sharp rise in clinician knowledge of the guidelines but only a modest increase in their real-world implementation with high-risk infants.

Raising a food-allergic child while working as a pediatrician herself, Ruchi Gupta, MD, MPH, director of the Center for Food Allergy and Asthma Research at Northwestern University, Chicago, understands the importance and challenge of translating published findings into practice.

During a typical 4- to 6-month well-child visit, pediatricians must check the baby’s growth, perform a physical exam, discuss milestones, field questions about sleep and poop and colic and – if they’re up on the latest guidelines – explain why it’s important to feed peanuts early and often.

“Pediatricians get stuff from every single specialty, and guidelines are always changing,” she told this news organization.

The current feeding guidelines, published in 2017 after the landmark LEAP study, switched from “ ‘don’t introduce peanuts until age 3’ to ‘introduce peanuts now,’ ” said Dr. Gupta.

But the recommendations aren’t entirely straightforward. They require pediatricians to make an assessment when the baby is around 4 months old. If the child is high-risk (has severe eczema or an egg allergy), they need a peanut-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) test. If the test is negative, the pediatrician should encourage peanut introduction. If positive, they should refer the child to an allergist.

“It’s a little complicated,” Dr. Gupta said.

To boost understanding and adherence, Dr. Gupta’s team created the intervention tested in the iREACH study. It includes a set of training videos, a clinical decision support tool that embeds into the electronic health record (EHR) with pop-ups reminding the physician to discuss early introduction, menus for ordering peanut IgE tests or referring to an allergist if needed, and a caregiver handout that explains how to add peanuts to the baby’s diet. (These resources can be found here.)

The study enrolled 290 pediatric clinicians at 30 local practices, examining 18,460 babies from diverse backgrounds, about one-quarter of whom were from families on public insurance. About half of the clinicians received the intervention, whereas the other half served as the control arm.

The training videos seemed effective. Clinicians’ knowledge of the guidelines rose from 72.6% at baseline to 94.5% after the intervention, and their ability to identify severe eczema went up from 63.4% to 97.6%. This translated to 70.4% success with applying the guidelines when presented various clinical scenarios, up from 29% at baseline. These results are in press at JAMA Network Open.

The next set of analyses, preliminary and unpublished, monitored real-world adherence using natural language processing to pull EHR data from 4- and 6-month well-check visits. It was “AI [artificial intelligence] for notes,” Dr. Gupta said.

For low-risk infants, the training and EHR-embedded support tool greatly improved clinician adherence. Eighty percent of clinicians in the intervention arm followed the guidelines, compared with 26% in the control group.

In high-risk infants, the impact was much weaker. Even after the video-based training, only 17% of pediatric clinicians followed the guidelines – that is, ordered a peanut IgE test or referred to an allergist – compared with 8% in the control group.

Why such a low uptake?

Pediatricians are time-pressed. “How do you add [early introduction] to the other 10 or 15 things you want to talk to a parent about at the 4-month visit?” said Jonathan Necheles, MD, MPH, a pediatrician at Children’s Healthcare Associates in Chicago.

It can also be hard to tell if a baby’s eczema is “severe” or “mild to moderate.” The EHR-integrated support tool included a scorecard for judging eczema severity across a range of skin tones. The condition can be hard to recognize in patients of color. “You don’t get the redness in the same way,” said Dr. Necheles, who worked with Dr. Gupta to develop the iREACH intervention.

Curiously, even though the AI analysis found that less than one-fifth of pediatricians put the guidelines into action for high-risk infants, 69% of them recommended peanut introduction.

One interpretation is that busy pediatricians may be “doing the minimum” – introducing the concept of early introduction and telling parents to try it “but not giving any additional sort of guidance as far as who’s high risk, who’s low risk, who should see the allergist, who should get screened,” said Edwin Kim, MD, allergist-immunologist and director of the Food Allergy Initiative at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The ultimate impact of iREACH has yet to be seen. “The end goal is, if pediatricians recommend, will parents follow, and will we reduce peanut allergy?” Dr. Gupta said.