User login

Comparing Outcomes and Toxicities With Standard and Reduced Dose Melphalan in Autologous Stem Cell Transplant Patients With Multiple Myeloma

BACKGROUND

Multiple myeloma, an incurable plasma cell malignancy, has an average age of diagnosis over 65 years. For transplant-eligible patients, high-dose melphalan 200 mg/m2 (MEL200), followed by autologous stem cell rescue (ASCR) is the standard in consolidation therapy. Most clinical trials evaluating MEL200 with ASCR excluded patients over 65 due to concerns for toxicity and treatment-related mortality, leading to use of reduced dose melphalan 140 mg/m2 (MEL140) in clinical practice for older patients. As this dose has limited studies surrounding its reduction, the purpose of this study was to compare outcomes and toxicities of MEL140 in patients over the age of 65 to MEL200 in patients 65 and under.

METHODS

This single-center institutional review board approved retrospective study was conducted at VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System. All multiple myeloma patients greater than 18 years of age who received melphalan with ASCR from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2021, were included. Patients were divided into two arms: age < 65 treated with MEL200 and age >65 treated with MEL140. The primary endpoint was oneyear progression-free survival (PFS). The secondary endpoints were one-year overall survival (OS), treatment related mortality, time to neutrophil engraftment, and toxicities including febrile neutropenia, diarrhea, mucositis, infection, and intensive care unit transfers.

RESULTS

A total of 222 patients were included, 114 patients in the MEL200 arm and 108 patients in the MEL140 arm. The primary endpoint of one-year PFS had no significant difference, with 103 (90.4%) patients in the MEL200 group compared to 99 (91.7%) patients in the MEL140 group (p=0.732). Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference in the secondary endpoint of one-year OS with 112 (98.3%) patients in the MEL200 group compared to 106 (98.2%) in the MEL140 group (p=0.956). Toxicities were similar; however, grade 3 mucositis was higher in the MEL200 arm.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study found no difference in oneyear PFS or one-year OS when comparing MEL140 to MEL200 with minimal differences in regimen-related toxicities. Although not powered to detect statistical difference, results suggests that dose reduction with MEL140 in patients >65 years does not impact one-year PFS when compared to patients <65 receiving standard MEL200.

BACKGROUND

Multiple myeloma, an incurable plasma cell malignancy, has an average age of diagnosis over 65 years. For transplant-eligible patients, high-dose melphalan 200 mg/m2 (MEL200), followed by autologous stem cell rescue (ASCR) is the standard in consolidation therapy. Most clinical trials evaluating MEL200 with ASCR excluded patients over 65 due to concerns for toxicity and treatment-related mortality, leading to use of reduced dose melphalan 140 mg/m2 (MEL140) in clinical practice for older patients. As this dose has limited studies surrounding its reduction, the purpose of this study was to compare outcomes and toxicities of MEL140 in patients over the age of 65 to MEL200 in patients 65 and under.

METHODS

This single-center institutional review board approved retrospective study was conducted at VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System. All multiple myeloma patients greater than 18 years of age who received melphalan with ASCR from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2021, were included. Patients were divided into two arms: age < 65 treated with MEL200 and age >65 treated with MEL140. The primary endpoint was oneyear progression-free survival (PFS). The secondary endpoints were one-year overall survival (OS), treatment related mortality, time to neutrophil engraftment, and toxicities including febrile neutropenia, diarrhea, mucositis, infection, and intensive care unit transfers.

RESULTS

A total of 222 patients were included, 114 patients in the MEL200 arm and 108 patients in the MEL140 arm. The primary endpoint of one-year PFS had no significant difference, with 103 (90.4%) patients in the MEL200 group compared to 99 (91.7%) patients in the MEL140 group (p=0.732). Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference in the secondary endpoint of one-year OS with 112 (98.3%) patients in the MEL200 group compared to 106 (98.2%) in the MEL140 group (p=0.956). Toxicities were similar; however, grade 3 mucositis was higher in the MEL200 arm.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study found no difference in oneyear PFS or one-year OS when comparing MEL140 to MEL200 with minimal differences in regimen-related toxicities. Although not powered to detect statistical difference, results suggests that dose reduction with MEL140 in patients >65 years does not impact one-year PFS when compared to patients <65 receiving standard MEL200.

BACKGROUND

Multiple myeloma, an incurable plasma cell malignancy, has an average age of diagnosis over 65 years. For transplant-eligible patients, high-dose melphalan 200 mg/m2 (MEL200), followed by autologous stem cell rescue (ASCR) is the standard in consolidation therapy. Most clinical trials evaluating MEL200 with ASCR excluded patients over 65 due to concerns for toxicity and treatment-related mortality, leading to use of reduced dose melphalan 140 mg/m2 (MEL140) in clinical practice for older patients. As this dose has limited studies surrounding its reduction, the purpose of this study was to compare outcomes and toxicities of MEL140 in patients over the age of 65 to MEL200 in patients 65 and under.

METHODS

This single-center institutional review board approved retrospective study was conducted at VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System. All multiple myeloma patients greater than 18 years of age who received melphalan with ASCR from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2021, were included. Patients were divided into two arms: age < 65 treated with MEL200 and age >65 treated with MEL140. The primary endpoint was oneyear progression-free survival (PFS). The secondary endpoints were one-year overall survival (OS), treatment related mortality, time to neutrophil engraftment, and toxicities including febrile neutropenia, diarrhea, mucositis, infection, and intensive care unit transfers.

RESULTS

A total of 222 patients were included, 114 patients in the MEL200 arm and 108 patients in the MEL140 arm. The primary endpoint of one-year PFS had no significant difference, with 103 (90.4%) patients in the MEL200 group compared to 99 (91.7%) patients in the MEL140 group (p=0.732). Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference in the secondary endpoint of one-year OS with 112 (98.3%) patients in the MEL200 group compared to 106 (98.2%) in the MEL140 group (p=0.956). Toxicities were similar; however, grade 3 mucositis was higher in the MEL200 arm.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study found no difference in oneyear PFS or one-year OS when comparing MEL140 to MEL200 with minimal differences in regimen-related toxicities. Although not powered to detect statistical difference, results suggests that dose reduction with MEL140 in patients >65 years does not impact one-year PFS when compared to patients <65 receiving standard MEL200.

Quality Improvement Project of All Resected Lung Specimens for Pathologic Findings and Synoptic Surgical Reports for Accuracy in Staging: A Critical Review of 91 Specimens

BACKGROUND

In 2017, the Thoracic Tumor Board realized that there were patients whose lung resections had critical review of the slides and reports prior to presentation. Errors were found which resulted in a change of the pathology Tumor Nodal Metastases (pTNM) staging for the patient. The impacts were important for determining appropriate therapy. It was decided to systematically review all lung cancer resections for accuracy before determining definitive therapy recommendations.

METHODS

All lung resections for malignancy were examined prior and up to 2 days of completion for accuracy of tumor type, tumor size, tumor grade, lymph node metastases and pathologic stage (pTNM). Any errors found were given to the original pathologist for a change in the report before release or for a modified report to be issued.

RESULTS

From June 2017 to December 2020, there were 91 lung resections with 28 (30.77%) errors. Errors included: 16 incorrect pathologic staging, 5 missed tumors in lung and lymph nodes, 2 unexamined stapled surgical margins, 1 wrong site, 1 incorrect lymph node number and 2 missed tumor vascular invasion.

IMPLICATIONS

Quality improvement (QI) review of lung resections by a second pathologist is important and may clearly improve pathologic staging for lung cancer patients. It can be added to QI programs currently used in Surgical Pathology. It is important in directing appropriate postsurgical therapies.

BACKGROUND

In 2017, the Thoracic Tumor Board realized that there were patients whose lung resections had critical review of the slides and reports prior to presentation. Errors were found which resulted in a change of the pathology Tumor Nodal Metastases (pTNM) staging for the patient. The impacts were important for determining appropriate therapy. It was decided to systematically review all lung cancer resections for accuracy before determining definitive therapy recommendations.

METHODS

All lung resections for malignancy were examined prior and up to 2 days of completion for accuracy of tumor type, tumor size, tumor grade, lymph node metastases and pathologic stage (pTNM). Any errors found were given to the original pathologist for a change in the report before release or for a modified report to be issued.

RESULTS

From June 2017 to December 2020, there were 91 lung resections with 28 (30.77%) errors. Errors included: 16 incorrect pathologic staging, 5 missed tumors in lung and lymph nodes, 2 unexamined stapled surgical margins, 1 wrong site, 1 incorrect lymph node number and 2 missed tumor vascular invasion.

IMPLICATIONS

Quality improvement (QI) review of lung resections by a second pathologist is important and may clearly improve pathologic staging for lung cancer patients. It can be added to QI programs currently used in Surgical Pathology. It is important in directing appropriate postsurgical therapies.

BACKGROUND

In 2017, the Thoracic Tumor Board realized that there were patients whose lung resections had critical review of the slides and reports prior to presentation. Errors were found which resulted in a change of the pathology Tumor Nodal Metastases (pTNM) staging for the patient. The impacts were important for determining appropriate therapy. It was decided to systematically review all lung cancer resections for accuracy before determining definitive therapy recommendations.

METHODS

All lung resections for malignancy were examined prior and up to 2 days of completion for accuracy of tumor type, tumor size, tumor grade, lymph node metastases and pathologic stage (pTNM). Any errors found were given to the original pathologist for a change in the report before release or for a modified report to be issued.

RESULTS

From June 2017 to December 2020, there were 91 lung resections with 28 (30.77%) errors. Errors included: 16 incorrect pathologic staging, 5 missed tumors in lung and lymph nodes, 2 unexamined stapled surgical margins, 1 wrong site, 1 incorrect lymph node number and 2 missed tumor vascular invasion.

IMPLICATIONS

Quality improvement (QI) review of lung resections by a second pathologist is important and may clearly improve pathologic staging for lung cancer patients. It can be added to QI programs currently used in Surgical Pathology. It is important in directing appropriate postsurgical therapies.

A Multi-Disciplinary Approach to Increasing Germline Genetic Testing for Prostate Cancer

PURPOSE

This quality improvement project aims to enhance the rate of germline genetic testing for prostate cancer at the Stratton VA Medical Center, improving risk reduction strategies and therapeutic options for patients.

BACKGROUND

Prostate cancer is prevalent at the Stratton VA Medical Center, yet the rate of genetic evaluation for prostate cancer remains suboptimal. National guidelines recommend genetic counseling and testing in specific patient populations. To address this gap, an interdisciplinary working group conducted gap analysis and root cause analysis, identifying four significant barriers.

METHODS

The working group comprised medical oncologists, urologists, primary care physicians, genetics counselors, data experts, and a LEAN coach. Interventions included implementing a prostate cancer pathway to educate staff on genetic testing indications and integrating genetic testing screening into clinic visits. After the interventions were implemented in January 2022, patient charts were reviewed for all genetic referrals and new prostate cancer diagnoses from January to December 2022.

DATA ANALYSIS

Descriptive analysis was conducted on referral rates, evaluation visit completion rates, and genetic testing outcomes among prostate cancer patients.

RESULTS

During the study period, 59 prostate cancer patients were referred for genetic evaluation. Notably, this was a large increase from no genetic referrals for prostate cancer in the previous year. Among them, 43 completed the evaluation visit, and 34 underwent genetic testing. Noteworthy findings were observed in 5 patients, including 3 variants of unknown significance and 2 pathogenic germline variants: HOXB13 and BRCA2 mutations.

IMPLICATIONS

This project highlights the power of a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to overcome barriers and enhance the quality of care for prostate cancer patients. The team’s use of gap analysis and root cause analysis successfully identified barriers and proposed solutions, leading to increased referrals and the identification of significant genetic findings. Continued efforts to improve access to germline genetic testing are crucial for enhanced patient care and improved outcomes.

PURPOSE

This quality improvement project aims to enhance the rate of germline genetic testing for prostate cancer at the Stratton VA Medical Center, improving risk reduction strategies and therapeutic options for patients.

BACKGROUND

Prostate cancer is prevalent at the Stratton VA Medical Center, yet the rate of genetic evaluation for prostate cancer remains suboptimal. National guidelines recommend genetic counseling and testing in specific patient populations. To address this gap, an interdisciplinary working group conducted gap analysis and root cause analysis, identifying four significant barriers.

METHODS

The working group comprised medical oncologists, urologists, primary care physicians, genetics counselors, data experts, and a LEAN coach. Interventions included implementing a prostate cancer pathway to educate staff on genetic testing indications and integrating genetic testing screening into clinic visits. After the interventions were implemented in January 2022, patient charts were reviewed for all genetic referrals and new prostate cancer diagnoses from January to December 2022.

DATA ANALYSIS

Descriptive analysis was conducted on referral rates, evaluation visit completion rates, and genetic testing outcomes among prostate cancer patients.

RESULTS

During the study period, 59 prostate cancer patients were referred for genetic evaluation. Notably, this was a large increase from no genetic referrals for prostate cancer in the previous year. Among them, 43 completed the evaluation visit, and 34 underwent genetic testing. Noteworthy findings were observed in 5 patients, including 3 variants of unknown significance and 2 pathogenic germline variants: HOXB13 and BRCA2 mutations.

IMPLICATIONS

This project highlights the power of a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to overcome barriers and enhance the quality of care for prostate cancer patients. The team’s use of gap analysis and root cause analysis successfully identified barriers and proposed solutions, leading to increased referrals and the identification of significant genetic findings. Continued efforts to improve access to germline genetic testing are crucial for enhanced patient care and improved outcomes.

PURPOSE

This quality improvement project aims to enhance the rate of germline genetic testing for prostate cancer at the Stratton VA Medical Center, improving risk reduction strategies and therapeutic options for patients.

BACKGROUND

Prostate cancer is prevalent at the Stratton VA Medical Center, yet the rate of genetic evaluation for prostate cancer remains suboptimal. National guidelines recommend genetic counseling and testing in specific patient populations. To address this gap, an interdisciplinary working group conducted gap analysis and root cause analysis, identifying four significant barriers.

METHODS

The working group comprised medical oncologists, urologists, primary care physicians, genetics counselors, data experts, and a LEAN coach. Interventions included implementing a prostate cancer pathway to educate staff on genetic testing indications and integrating genetic testing screening into clinic visits. After the interventions were implemented in January 2022, patient charts were reviewed for all genetic referrals and new prostate cancer diagnoses from January to December 2022.

DATA ANALYSIS

Descriptive analysis was conducted on referral rates, evaluation visit completion rates, and genetic testing outcomes among prostate cancer patients.

RESULTS

During the study period, 59 prostate cancer patients were referred for genetic evaluation. Notably, this was a large increase from no genetic referrals for prostate cancer in the previous year. Among them, 43 completed the evaluation visit, and 34 underwent genetic testing. Noteworthy findings were observed in 5 patients, including 3 variants of unknown significance and 2 pathogenic germline variants: HOXB13 and BRCA2 mutations.

IMPLICATIONS

This project highlights the power of a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to overcome barriers and enhance the quality of care for prostate cancer patients. The team’s use of gap analysis and root cause analysis successfully identified barriers and proposed solutions, leading to increased referrals and the identification of significant genetic findings. Continued efforts to improve access to germline genetic testing are crucial for enhanced patient care and improved outcomes.

Results From the First Annual Association of Professors of Dermatology Program Directors Survey

Educational organizations across several specialties, including internal medicine and obstetrics and gynecology, have formal surveys1; however, the field of dermatology has been without one. This study aimed to establish a formal survey for dermatology program directors (PDs) and clinician-educators. Because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and American Board of Dermatology surveys do not capture all metrics relevant to dermatology residency educators, an annual survey for our specialty may be helpful to compare dermatology-specific data among programs. Responses could provide context and perspective to faculty and residents who respond to the ACGME annual survey, as our Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) survey asks more in-depth questions, such as how often didactics occur and who leads them. Resident commute time and faculty demographics and training also are covered. Current ad hoc surveys disseminated through listserves of various medical associations contain overlapping questions and reflect relatively low response rates; dermatology PDs may benefit from a survey with a high response rate to which they can contribute future questions and topics that reflect recent trends and current needs in graduate medical education. As future surveys are administered, the results can be captured in a centralized database accessible by dermatology PDs.

Methods

A survey of PDs from 141 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs was conducted by the Residency Program Director Steering Committee of the APD from November 2022 to January 2023 using a prevalidated questionnaire. Personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each PD’s email listed in the ACGME accreditation data system. All survey responses were captured anonymously, with a number assigned to keep de-identified responses separate and organized. The survey consisted of 137 survey questions addressing topics that included program characteristics, PD demographics, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinical rotation and educational conferences, available resident resources, quality improvement, clinical and didactic instruction, research content, diversity and inclusion, wellness, professionalism, evaluation systems, and graduate outcomes.

Data were collected using Qualtrics survey tools. After removing duplicate and incomplete surveys, data were analyzed using Qualtrics reports and Microsoft Excel for data plotting, averages, and range calculations.

Results

One hundred forty-one personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each program’s filed email obtained from the APD listserv. Fifty-three responses were recorded after removing duplicate or incomplete surveys (38% [53/141] response rate). As of May 2023, there were 144 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs due to 3 newly accredited programs in 2022-2023 academic year, which were not included in our survey population.

Program Characteristics—Forty-four respondents (83%) were from a university-based program. Fifty respondents (94%) were from programs that were ACGME accredited prior to 2020, while 3 programs (6%) were American Osteopathic Association accredited prior to singular accreditation. Seventy-one percent (38/53) of respondents had 1 or more associate PDs.

PD Demographics—Eighty-seven percent (45/52) of PDs who responded to the survey graduated from a US allopathic medical school (MD), 10% (5/52) graduated from a US osteopathic medical school (DO), and 4% (2/52) graduated from an international medical school. Seventy-four percent (35/47) of respondents were White, 17% (8/47) were Asian, and 2% (1/47) were Black or African American; this data was not provided for 4 respondents. Forty-eight percent (23/48) of PDs identified as cisgender man, 48% (23/48) identified as cisgender woman, and 4% (2/48) preferred not to answer. Eighty-one percent (38/47) of PDs identified as heterosexual or straight, 15% (7/47) identified as gay or lesbian, and 4% (2/47) preferred not to answer.

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Residency Training—Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 88% (45/51) of respondents incorporated telemedicine into the resident clinical rotation schedule. Moving forward, 75% (38/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to continue to incorporate telemedicine into the rotation schedule. Based on 50 responses, the average of educational conferences that became virtual at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic was 87%; based on 46 responses, the percentage of educational conferences that will remain virtual moving forward is 46%, while 90% (46/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to use virtual conferences in some capacity moving forward. Seventy-three percent (37/51) of respondents indicated that they plan to use virtual interviews as part of residency recruitment moving forward.

Available Resources—Twenty-four percent (11/46) of respondents indicated that residents in their program do not get protected time or time off for CORE examinations. Seventy-five percent (33/44) of PDs said their program provides funding for residents to participate in board review courses. The chief residents at 63% (31/49) of programs receive additional compensation, and 69% (34/49) provide additional administrative time to chief residents. Seventy-one percent (24/34) of PDs reported their programs have scribes for attendings, and 12% (4/34) have scribes for residents. Support staff help residents with callbacks and in-basket messages according to 76% (35/46) of respondents. The majority (98% [45/46]) of PDs indicated that residents follow-up on results and messages from patients seen in resident clinics, and 43% (20/46) of programs have residents follow-up with patients seen in faculty clinics. Only 15% (7/46) of PDs responded they have schedules with residents dedicated to handle these tasks. According to respondents, 33% (17/52) have residents who are required to travel more than 25 miles to distant clinical sites. Of them, 35% (6/17) provide accommodations.

Quality Improvement—Seventy-one percent (35/49) of respondents indicated their department has a quality improvement/patient safety team or committee, and 94% (33/35) of these teams include residents. A lecture series on quality improvement and patient safety is offered at 67% (33/49) of the respondents’ programs, while morbidity and mortality conferences are offered in 73% (36/49).

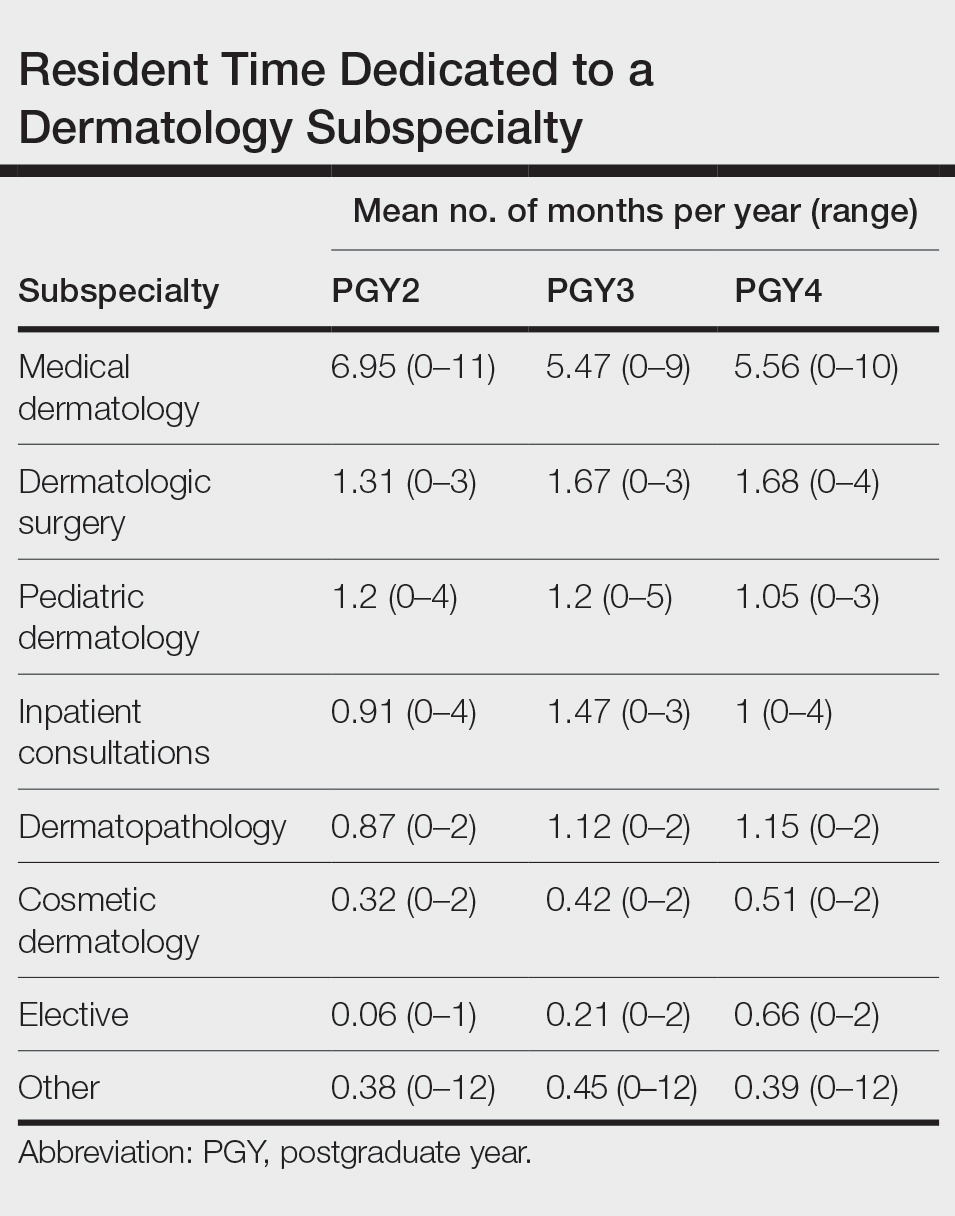

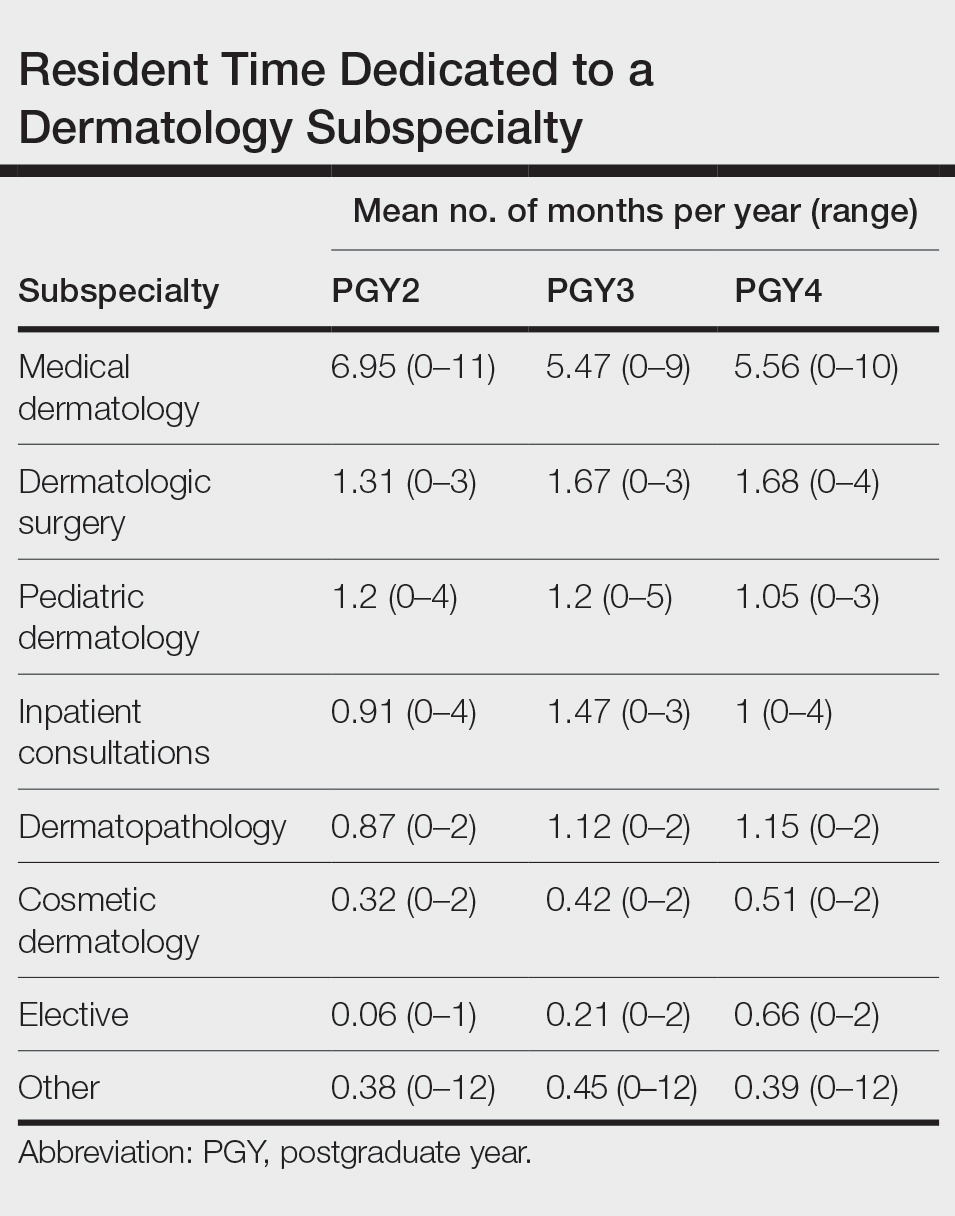

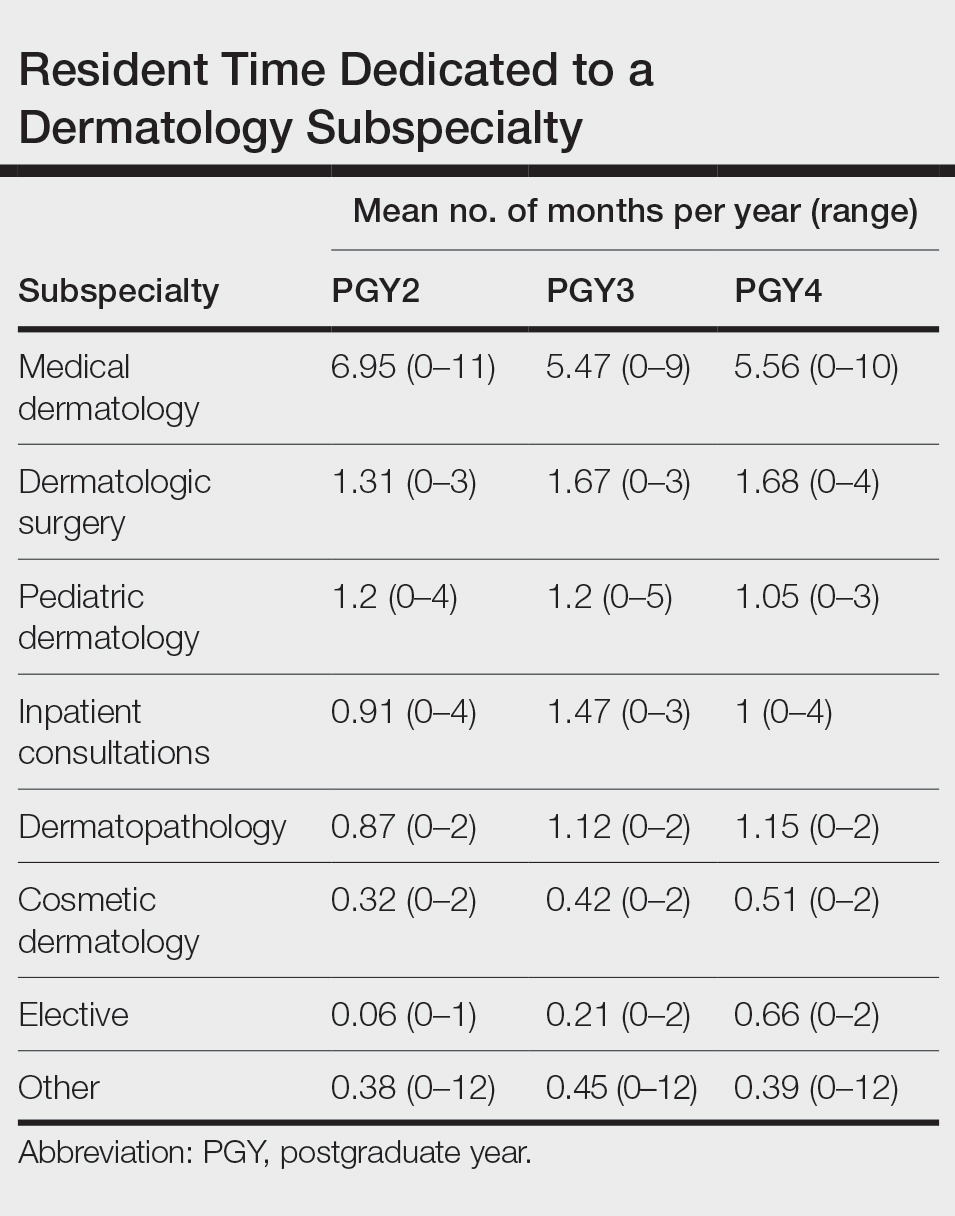

Clinical Instruction—Our survey asked PDs how many months each residency year spends on a certain rotational service. Based on 46 respondents, the average number of months dedicated to medical dermatology is 7, 5, and 6 months for postgraduate year (PGY) 2, PGY3, and PGY4, respectively. The average number of months spent in other subspecialties is provided in the Table. On average, PGY2 residents spend 8 half-days per week seeing patients in clinic, while PGY3 and PGY4 residents see patients for 7 half-days. The median and mean number of patients staffed by a single attending per hour in teaching clinics are 6 and 5.88, respectively. Respondents indicated that residents participate in the following specialty clinics: pediatric dermatology (96% [44/46]), laser/cosmetic (87% [40/44]), high-risk skin cancer (ie, immunosuppressed/transplant patient)(65% [30/44]), pigmented lesion/melanoma (52% [24/44]), connective tissue disease (52% [24/44]), teledermatology (50% [23/44]), free clinic for homeless and/or indigent populations (48% [22/44]), contact dermatitis (43% [20/44]), skin of color (43% [20/44]), oncodermatology (41% [19/44]), and bullous disease (33% [15/44]).

Additionally, in 87% (40/46) of programs, residents participate in a dedicated inpatient consultation service. Most respondents (98% [45/46]) responded that they utilize in-person consultations with a teledermatology supplement. Fifteen percent (7/46) utilize virtual teledermatology (live video-based consultations), and 57% (26/46) utilize asynchronous teledermatology (picture-based consultations). All respondents (n=46) indicated that 0% to 25% of patient encounters involving residents are teledermatology visits. Thirty-three percent (6/18) of programs have a global health special training track, 56% (10/18) have a Specialty Training and Advanced Research/Physician-Scientist Research Training track, 28% (5/18) have a diversity training track, and 50% (9/18) have a clinician educator training track.

Didactic Instruction—Five programs have a full day per week dedicated to didactics, while 36 programs have at least one half-day per week for didactics. On average, didactics in 57% (26/46) of programs are led by faculty alone, while 43% (20/46) are led at least in part by residents or fellows.

Research Content—Fifty percent (23/46) of programs have a specific research requirement for residents beyond general ACGME requirements, and 35% (16/46) require residents to participate in a longitudinal research project over the course of residency. There is a dedicated research coordinator for resident support at 63% (29/46) of programs. Dedicated biostatistics research support is available for resident projects at 42% (19/45) of programs. Additionally, at 42% (19/45) of programs, there is a dedicated faculty member for oversight of resident research.

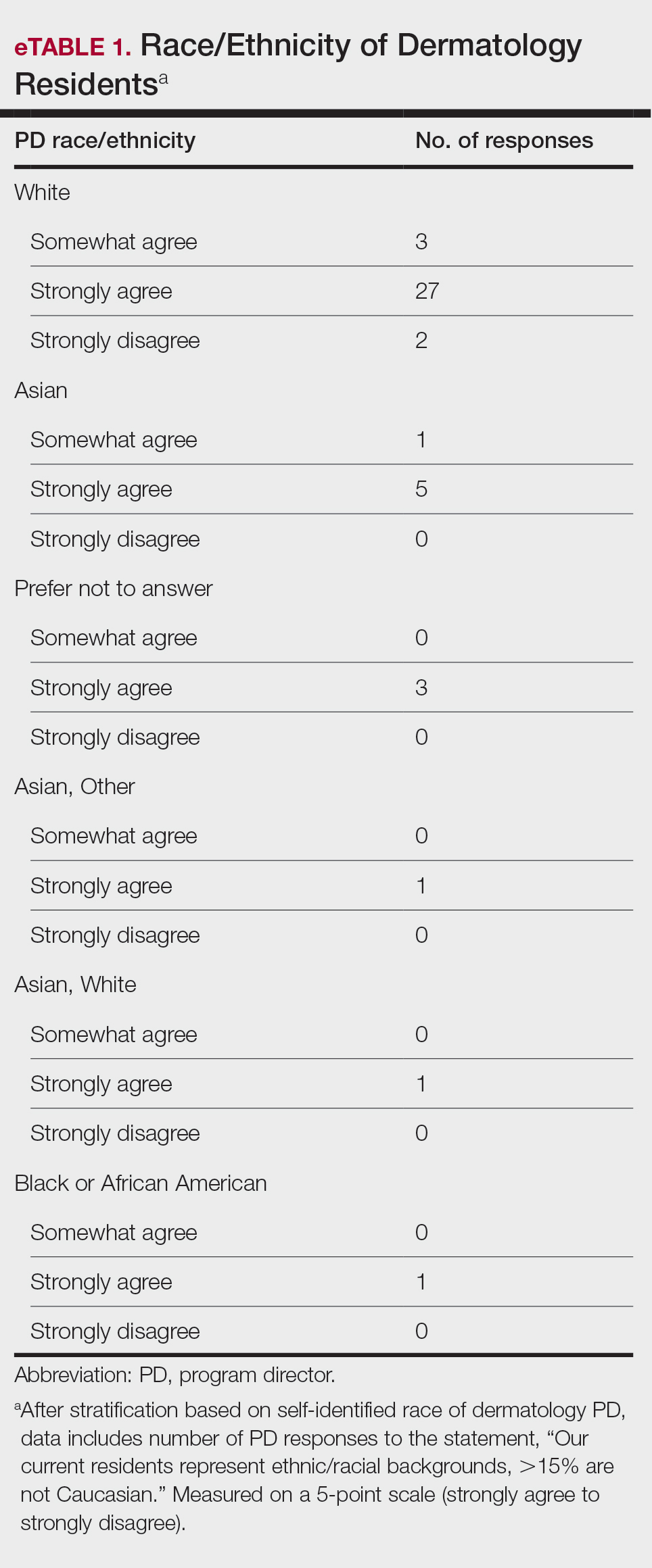

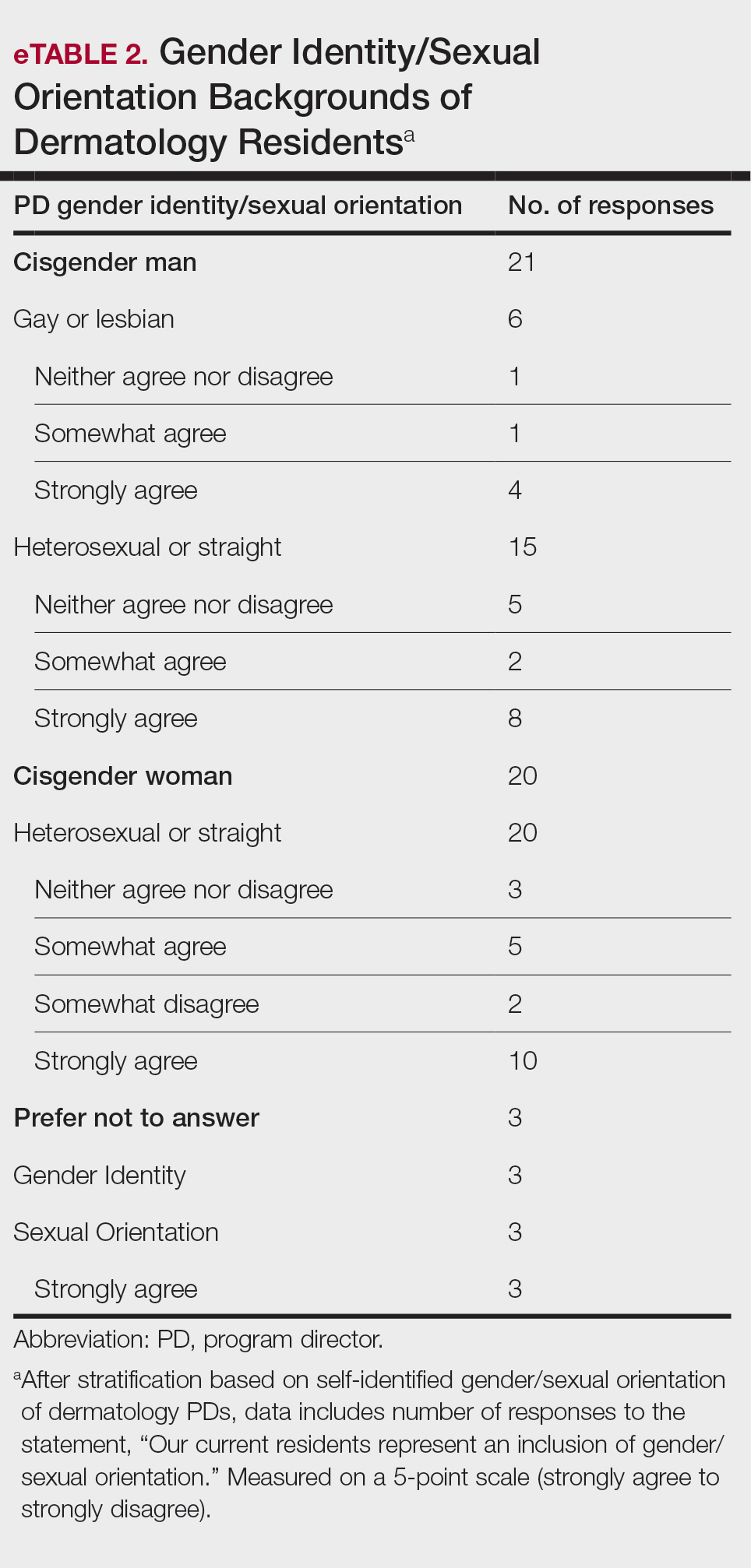

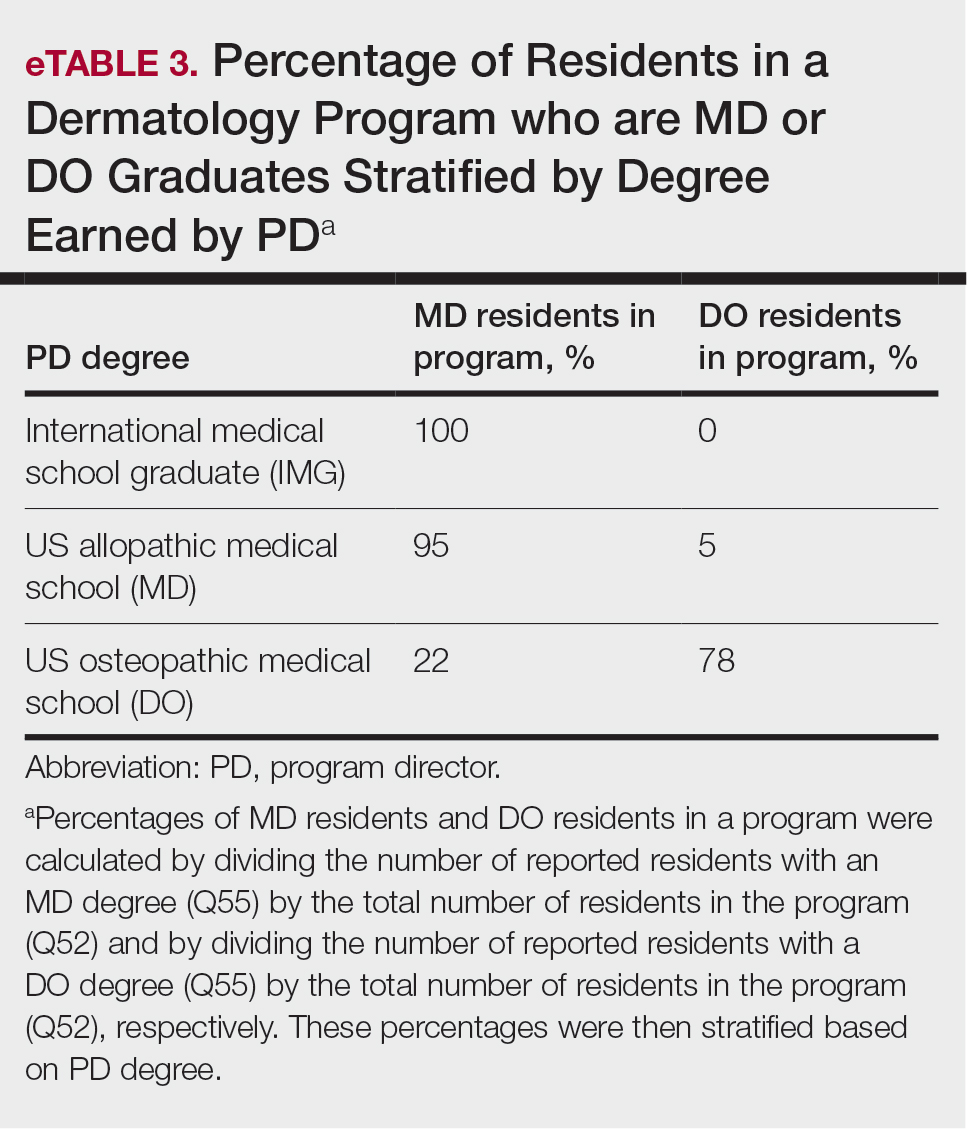

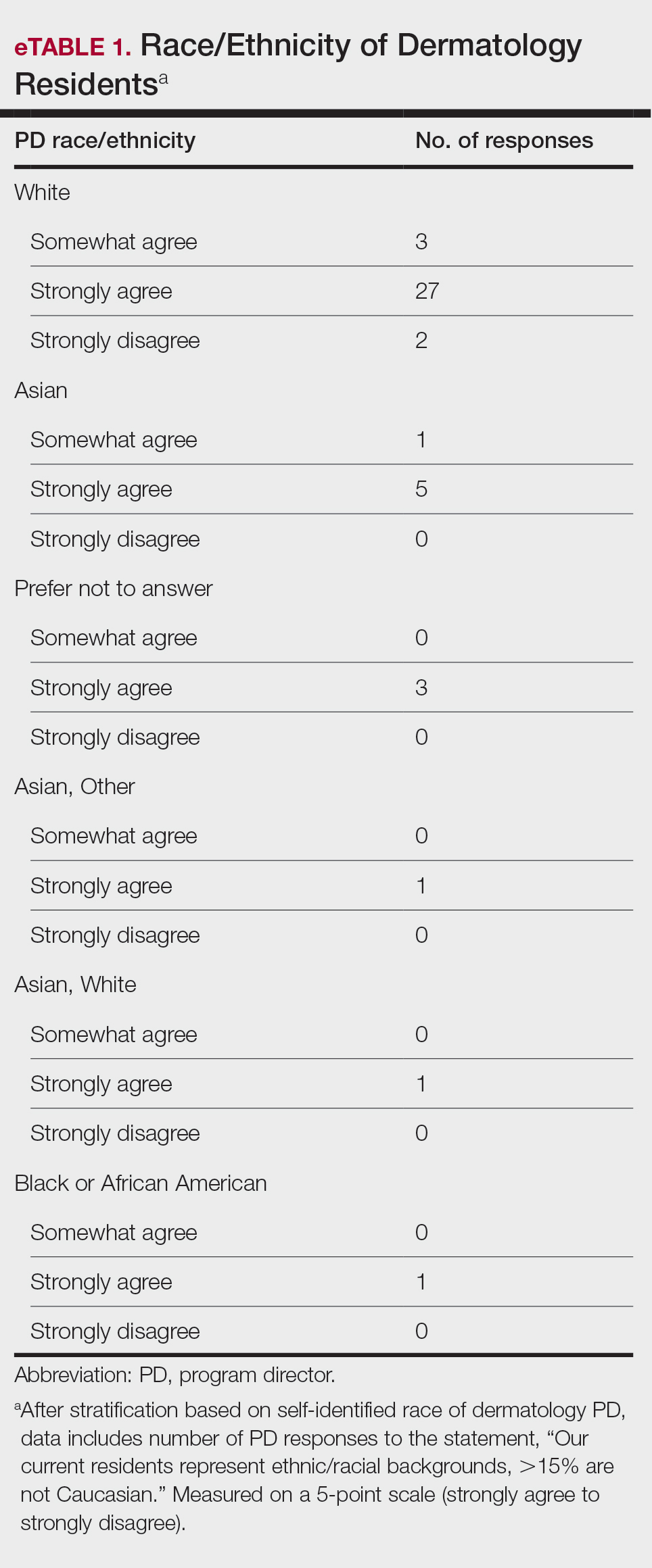

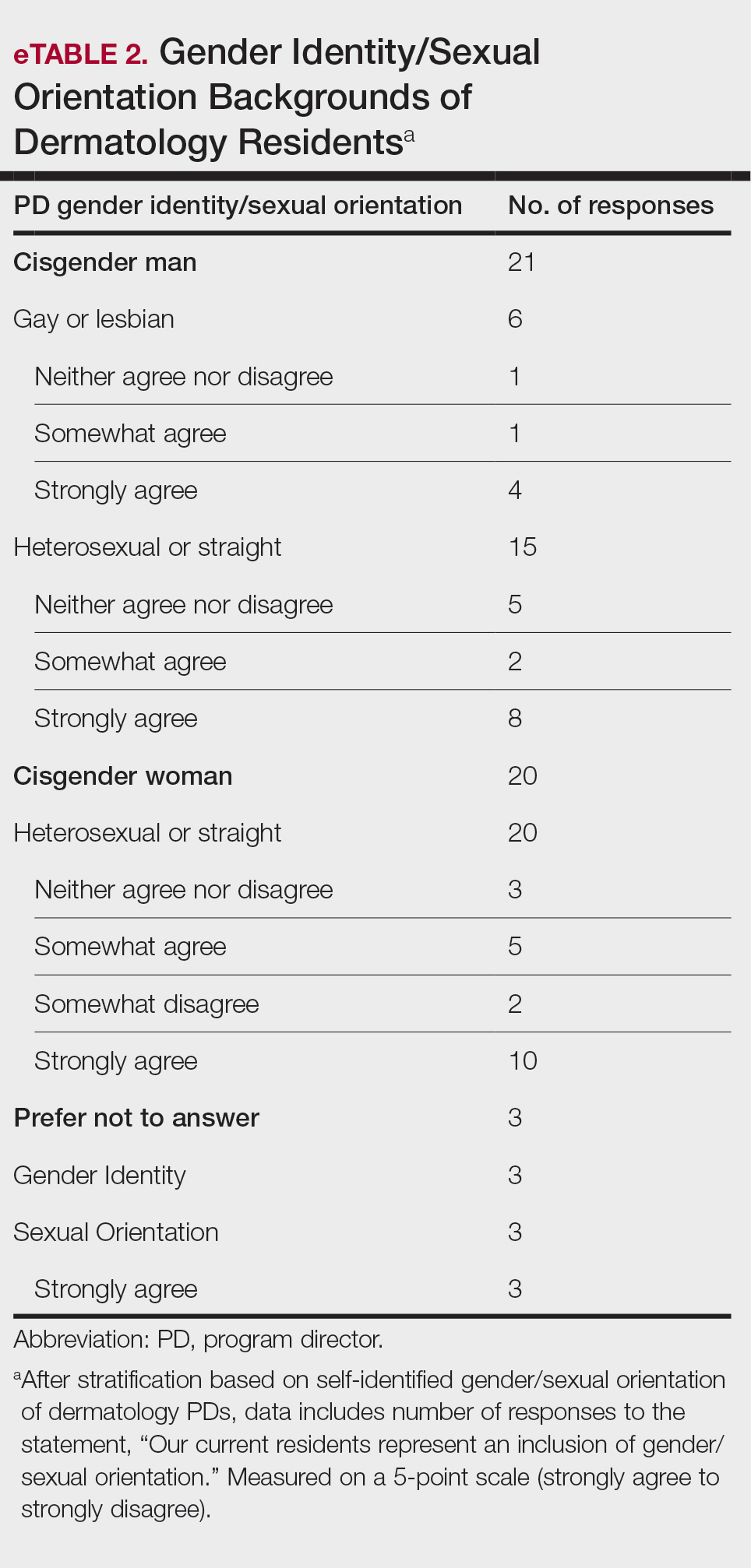

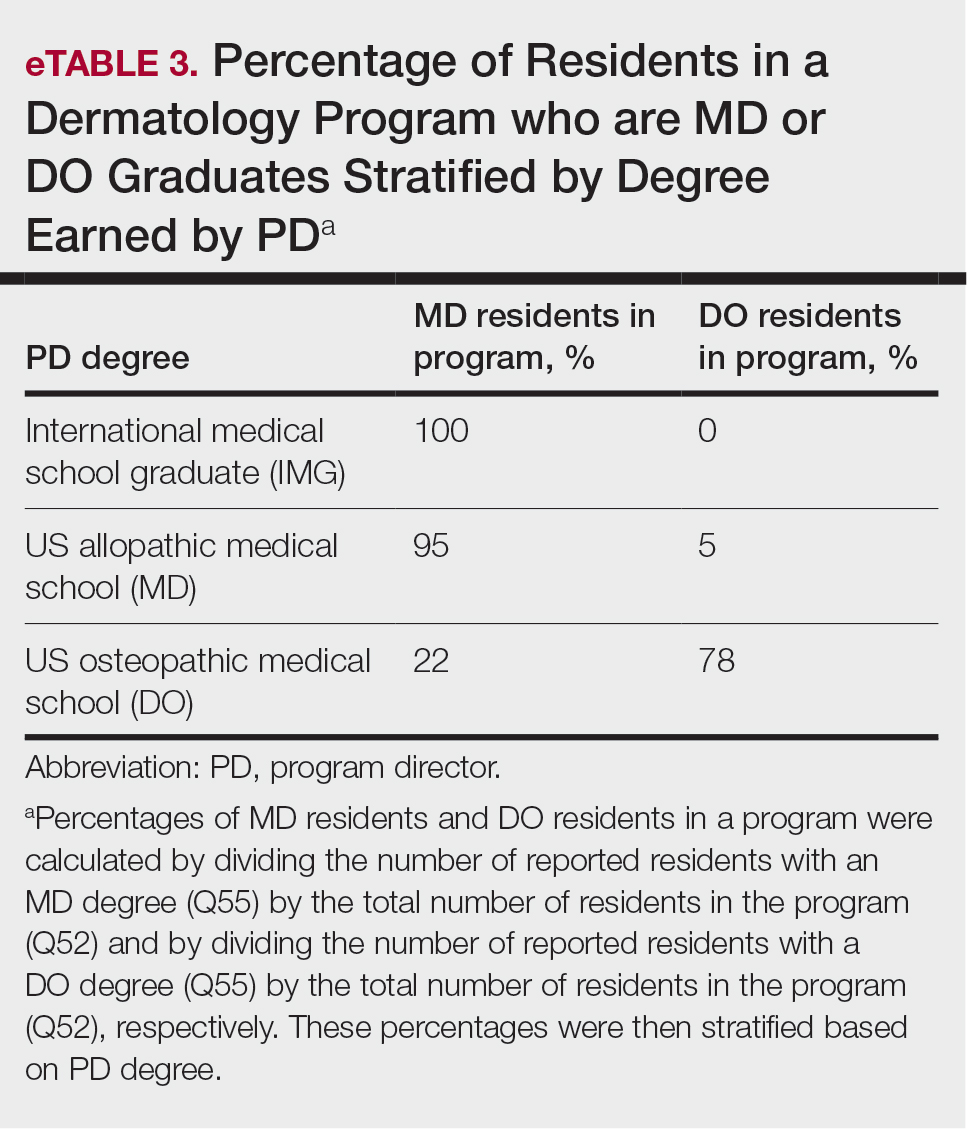

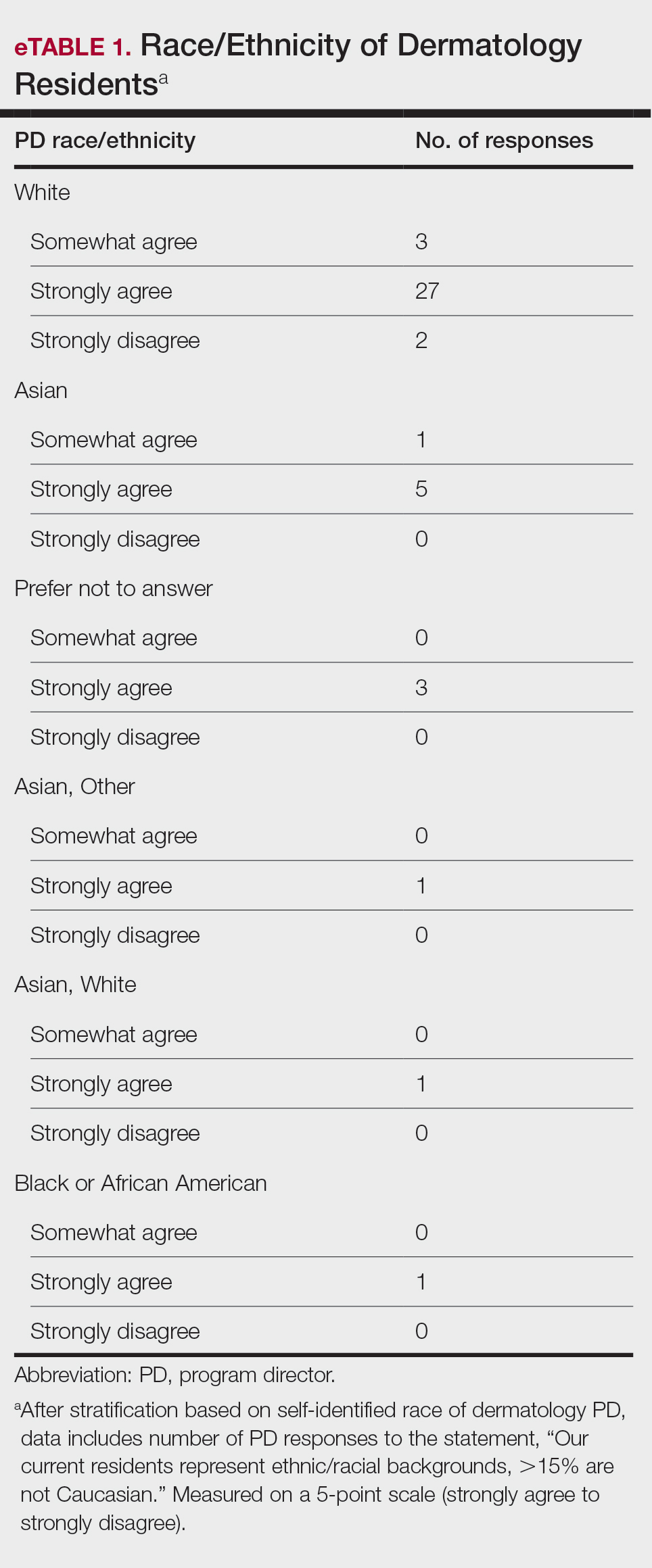

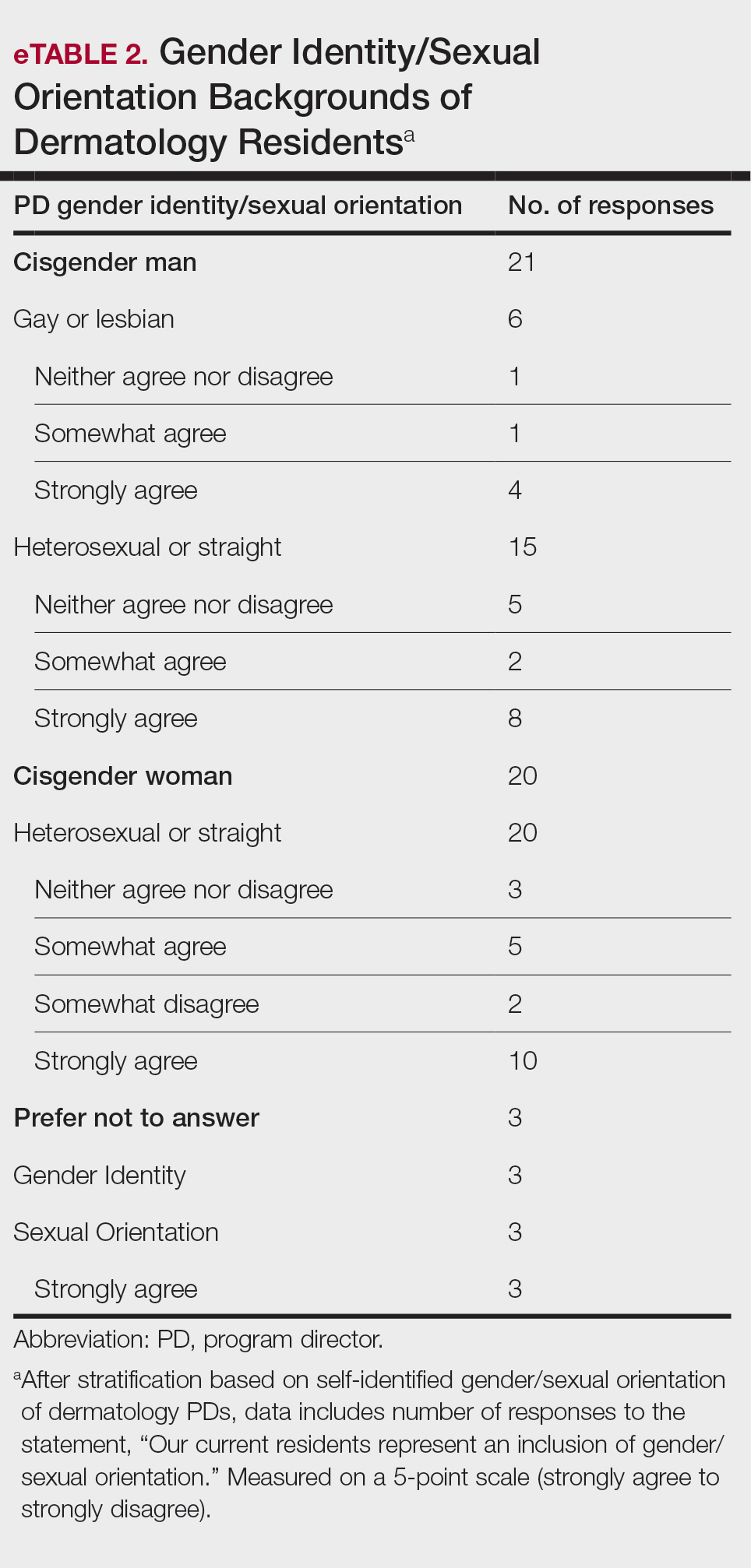

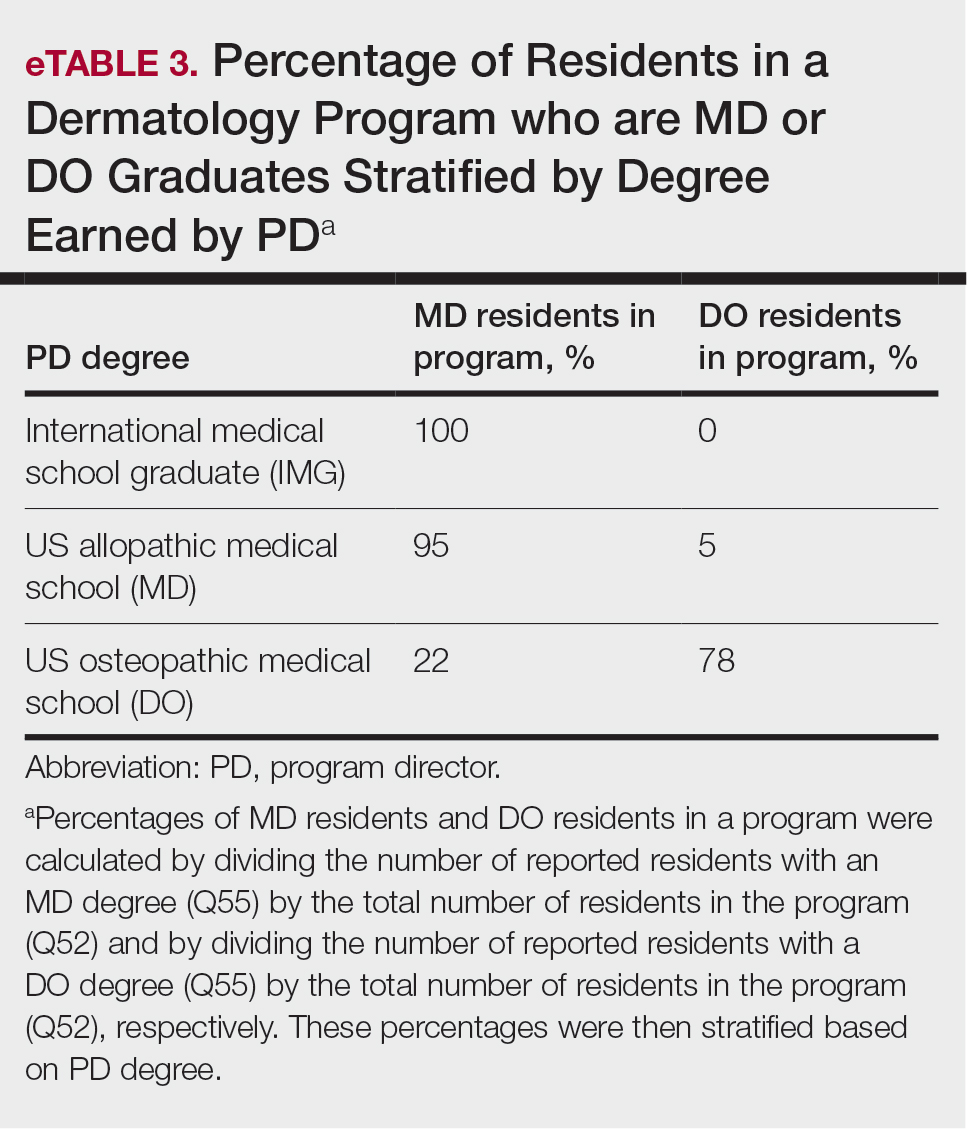

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion—Seventy-three percent (29/40) of programs have special diversity, equity, and inclusion programs or meetings specific to residency, 60% (24/40) have residency initiatives, and 55% (22/40) have a residency diversity committee. Eighty-six percent (42/49) of respondents strongly agreed that their current residents represent diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds (ie, >15% are not White). eTable 1 shows PD responses to this statement, which were stratified based on self-identified race. eTable 2 shows PD responses to the statement, “Our current residents represent an inclusion of gender/sexual orientation,” which were stratified based on self-identified gender identity/sexual orientation. Lastly, eTable 3 highlights the percentage of residents with an MD and DO degree, stratified based on PD degree.

Wellness—Forty-eight percent (20/42) of respondents indicated they are under stress and do not always have as much energy as before becoming a PD but do not feel burned out. Thirty-one percent (13/42) indicated they have 1 or more symptoms of burnout, such as emotional exhaustion. Eighty-six percent (36/42) are satisfied with their jobs overall (43% agree and 43% strongly agree [18/42 each]).

Evaluation System—Seventy-five percent (33/44) of programs deliver evaluations of residents by faculty online, 86% (38/44) of programs have PDs discuss evaluations in-person, and 20% (9/44) of programs have faculty evaluators discuss evaluations in-person. Seventy-seven percent (34/44) of programs have formal faculty-resident mentor-mentee programs. Clinical competency committee chair positions are filled by PDs, assistant PDs, or core faculty members 47%, 38%, and 16% of the time, respectively.

Graduation Outcomes of PGY4 Residents—About 28% (55/199) of graduating residents applied to a fellowship position, with the majority (15% [29/55]) matching into Mohs micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology (MSDO) fellowships. Approximately 5% (9/199) and 4% (7/199) of graduates matched into dermatopathology and pediatric dermatology, respectively. The remaining 5% (10/199) of graduating residents applied to a fellowship but did not match. The majority (45% [91/199]) of residency graduates entered private practice after graduation. Approximately 21% (42/199) of graduating residents chose an academic practice with 17% (33/199), 2% (4/199), and 2% (3/199) of those positions being full-time, part-time, and adjunct, respectively.

Comment

The first annual APD survey is a novel data source and provides opportunities for areas of discussion and investigation. Evaluating the similarities and differences among dermatology residency programs across the United States can strengthen individual programs through collaboration and provide areas of cohesion among programs.

Diversity of PDs—An important area of discussion is diversity and PD demographics. Although DO students make up 1 in 4 US graduating medical students, they are not interviewed or ranked as often as MD students.2 Diversity in PD race and ethnicity may be worthy of investigation in future studies, as match rates and recruitment of diverse medical school applicants may be impacted by these demographics.

Continued Use of Telemedicine in Training—Since 2020, the benefits of virtual residency recruitment have been debated among PDs across all medical specialties. Points in favor of virtual interviews include cost savings for programs and especially for applicants, as well as time efficiency, reduced burden of travel, and reduced carbon footprint. A problem posed by virtual interviews is that candidates are unable to fully learn institutional cultures and social environments of the programs.3 Likewise, telehealth was an important means of clinical teaching for residents during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, with benefits that included cost-effectiveness and reduction of disparities in access to dermatologic care.4 Seventy-five percent (38/51) of PDs indicated that their program plans to include telemedicine in resident clinical rotation moving forward.

Resources Available—Our survey showed that resources available for residents, delivery of lectures and program time allocated to didactics, protected academic or study time for residents, and allocation of program time for CORE examinations are highly variable across programs. This could inspire future studies to be done to determine the differences in success of the resident on CORE examinations and in digesting material.

Postgraduate Career Plans and Fellowship Matches—Residents of programs that have a home MSDO fellowship are more likely to successfully match into a MSDO fellowship.5 Based on this survey, approximately 28% of graduating residents applied to a fellowship position, with 15%, 5%, and 3% matching into desired MSDO, dermatopathology, and pediatric dermatology fellowships, respectively. Additional studies are needed to determine advantages and disadvantages that lead to residents reaching their career goals.

Limitations—Limitations of this study include a small sample size that may not adequately represent all ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs and selection bias toward respondents who are more likely to participate in survey-based research.

Conclusion

The APD plans to continue to administer this survey on an annual basis, with updates to the content and questions based on input from PDs. This survey will continue to provide valuable information to drive collaboration among residency programs and optimize the learning experience for residents. Our hope is that the response rate will increase in coming years, allowing us to draw more generalizable conclusions. Nonetheless, the survey data allow individual dermatology residency programs to compare their specific characteristics to other programs.

- Maciejko L, Cope A, Mara K, et al. A national survey of obstetrics and gynecology emergency training and deficits in office emergency preparation [A53]. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:16S. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000826548.05758.26

- Lavertue SM, Terry R. A comparison of surgical subspecialty match rates in 2022 in the United States. Cureus. 2023;15:E37178. doi:10.7759/cureus.37178

- Domingo A, Rdesinski RE, Stenson A, et al. Virtual residency interviews: applicant perceptions regarding virtual interview effectiveness, advantages, and barriers. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14:224-228. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-21-00675.1

- Rustad AM, Lio PA. Pandemic pressure: teledermatology and health care disparities. J Patient Exp. 2021;8:2374373521996982. doi:10.1177/2374373521996982

- Rickstrew J, Rajpara A, Hocker TLH. Dermatology residency program influences chance of successful surgery fellowship match. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1040-1042. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002859

Educational organizations across several specialties, including internal medicine and obstetrics and gynecology, have formal surveys1; however, the field of dermatology has been without one. This study aimed to establish a formal survey for dermatology program directors (PDs) and clinician-educators. Because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and American Board of Dermatology surveys do not capture all metrics relevant to dermatology residency educators, an annual survey for our specialty may be helpful to compare dermatology-specific data among programs. Responses could provide context and perspective to faculty and residents who respond to the ACGME annual survey, as our Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) survey asks more in-depth questions, such as how often didactics occur and who leads them. Resident commute time and faculty demographics and training also are covered. Current ad hoc surveys disseminated through listserves of various medical associations contain overlapping questions and reflect relatively low response rates; dermatology PDs may benefit from a survey with a high response rate to which they can contribute future questions and topics that reflect recent trends and current needs in graduate medical education. As future surveys are administered, the results can be captured in a centralized database accessible by dermatology PDs.

Methods

A survey of PDs from 141 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs was conducted by the Residency Program Director Steering Committee of the APD from November 2022 to January 2023 using a prevalidated questionnaire. Personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each PD’s email listed in the ACGME accreditation data system. All survey responses were captured anonymously, with a number assigned to keep de-identified responses separate and organized. The survey consisted of 137 survey questions addressing topics that included program characteristics, PD demographics, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinical rotation and educational conferences, available resident resources, quality improvement, clinical and didactic instruction, research content, diversity and inclusion, wellness, professionalism, evaluation systems, and graduate outcomes.

Data were collected using Qualtrics survey tools. After removing duplicate and incomplete surveys, data were analyzed using Qualtrics reports and Microsoft Excel for data plotting, averages, and range calculations.

Results

One hundred forty-one personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each program’s filed email obtained from the APD listserv. Fifty-three responses were recorded after removing duplicate or incomplete surveys (38% [53/141] response rate). As of May 2023, there were 144 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs due to 3 newly accredited programs in 2022-2023 academic year, which were not included in our survey population.

Program Characteristics—Forty-four respondents (83%) were from a university-based program. Fifty respondents (94%) were from programs that were ACGME accredited prior to 2020, while 3 programs (6%) were American Osteopathic Association accredited prior to singular accreditation. Seventy-one percent (38/53) of respondents had 1 or more associate PDs.

PD Demographics—Eighty-seven percent (45/52) of PDs who responded to the survey graduated from a US allopathic medical school (MD), 10% (5/52) graduated from a US osteopathic medical school (DO), and 4% (2/52) graduated from an international medical school. Seventy-four percent (35/47) of respondents were White, 17% (8/47) were Asian, and 2% (1/47) were Black or African American; this data was not provided for 4 respondents. Forty-eight percent (23/48) of PDs identified as cisgender man, 48% (23/48) identified as cisgender woman, and 4% (2/48) preferred not to answer. Eighty-one percent (38/47) of PDs identified as heterosexual or straight, 15% (7/47) identified as gay or lesbian, and 4% (2/47) preferred not to answer.

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Residency Training—Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 88% (45/51) of respondents incorporated telemedicine into the resident clinical rotation schedule. Moving forward, 75% (38/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to continue to incorporate telemedicine into the rotation schedule. Based on 50 responses, the average of educational conferences that became virtual at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic was 87%; based on 46 responses, the percentage of educational conferences that will remain virtual moving forward is 46%, while 90% (46/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to use virtual conferences in some capacity moving forward. Seventy-three percent (37/51) of respondents indicated that they plan to use virtual interviews as part of residency recruitment moving forward.

Available Resources—Twenty-four percent (11/46) of respondents indicated that residents in their program do not get protected time or time off for CORE examinations. Seventy-five percent (33/44) of PDs said their program provides funding for residents to participate in board review courses. The chief residents at 63% (31/49) of programs receive additional compensation, and 69% (34/49) provide additional administrative time to chief residents. Seventy-one percent (24/34) of PDs reported their programs have scribes for attendings, and 12% (4/34) have scribes for residents. Support staff help residents with callbacks and in-basket messages according to 76% (35/46) of respondents. The majority (98% [45/46]) of PDs indicated that residents follow-up on results and messages from patients seen in resident clinics, and 43% (20/46) of programs have residents follow-up with patients seen in faculty clinics. Only 15% (7/46) of PDs responded they have schedules with residents dedicated to handle these tasks. According to respondents, 33% (17/52) have residents who are required to travel more than 25 miles to distant clinical sites. Of them, 35% (6/17) provide accommodations.

Quality Improvement—Seventy-one percent (35/49) of respondents indicated their department has a quality improvement/patient safety team or committee, and 94% (33/35) of these teams include residents. A lecture series on quality improvement and patient safety is offered at 67% (33/49) of the respondents’ programs, while morbidity and mortality conferences are offered in 73% (36/49).

Clinical Instruction—Our survey asked PDs how many months each residency year spends on a certain rotational service. Based on 46 respondents, the average number of months dedicated to medical dermatology is 7, 5, and 6 months for postgraduate year (PGY) 2, PGY3, and PGY4, respectively. The average number of months spent in other subspecialties is provided in the Table. On average, PGY2 residents spend 8 half-days per week seeing patients in clinic, while PGY3 and PGY4 residents see patients for 7 half-days. The median and mean number of patients staffed by a single attending per hour in teaching clinics are 6 and 5.88, respectively. Respondents indicated that residents participate in the following specialty clinics: pediatric dermatology (96% [44/46]), laser/cosmetic (87% [40/44]), high-risk skin cancer (ie, immunosuppressed/transplant patient)(65% [30/44]), pigmented lesion/melanoma (52% [24/44]), connective tissue disease (52% [24/44]), teledermatology (50% [23/44]), free clinic for homeless and/or indigent populations (48% [22/44]), contact dermatitis (43% [20/44]), skin of color (43% [20/44]), oncodermatology (41% [19/44]), and bullous disease (33% [15/44]).

Additionally, in 87% (40/46) of programs, residents participate in a dedicated inpatient consultation service. Most respondents (98% [45/46]) responded that they utilize in-person consultations with a teledermatology supplement. Fifteen percent (7/46) utilize virtual teledermatology (live video-based consultations), and 57% (26/46) utilize asynchronous teledermatology (picture-based consultations). All respondents (n=46) indicated that 0% to 25% of patient encounters involving residents are teledermatology visits. Thirty-three percent (6/18) of programs have a global health special training track, 56% (10/18) have a Specialty Training and Advanced Research/Physician-Scientist Research Training track, 28% (5/18) have a diversity training track, and 50% (9/18) have a clinician educator training track.

Didactic Instruction—Five programs have a full day per week dedicated to didactics, while 36 programs have at least one half-day per week for didactics. On average, didactics in 57% (26/46) of programs are led by faculty alone, while 43% (20/46) are led at least in part by residents or fellows.

Research Content—Fifty percent (23/46) of programs have a specific research requirement for residents beyond general ACGME requirements, and 35% (16/46) require residents to participate in a longitudinal research project over the course of residency. There is a dedicated research coordinator for resident support at 63% (29/46) of programs. Dedicated biostatistics research support is available for resident projects at 42% (19/45) of programs. Additionally, at 42% (19/45) of programs, there is a dedicated faculty member for oversight of resident research.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion—Seventy-three percent (29/40) of programs have special diversity, equity, and inclusion programs or meetings specific to residency, 60% (24/40) have residency initiatives, and 55% (22/40) have a residency diversity committee. Eighty-six percent (42/49) of respondents strongly agreed that their current residents represent diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds (ie, >15% are not White). eTable 1 shows PD responses to this statement, which were stratified based on self-identified race. eTable 2 shows PD responses to the statement, “Our current residents represent an inclusion of gender/sexual orientation,” which were stratified based on self-identified gender identity/sexual orientation. Lastly, eTable 3 highlights the percentage of residents with an MD and DO degree, stratified based on PD degree.

Wellness—Forty-eight percent (20/42) of respondents indicated they are under stress and do not always have as much energy as before becoming a PD but do not feel burned out. Thirty-one percent (13/42) indicated they have 1 or more symptoms of burnout, such as emotional exhaustion. Eighty-six percent (36/42) are satisfied with their jobs overall (43% agree and 43% strongly agree [18/42 each]).

Evaluation System—Seventy-five percent (33/44) of programs deliver evaluations of residents by faculty online, 86% (38/44) of programs have PDs discuss evaluations in-person, and 20% (9/44) of programs have faculty evaluators discuss evaluations in-person. Seventy-seven percent (34/44) of programs have formal faculty-resident mentor-mentee programs. Clinical competency committee chair positions are filled by PDs, assistant PDs, or core faculty members 47%, 38%, and 16% of the time, respectively.

Graduation Outcomes of PGY4 Residents—About 28% (55/199) of graduating residents applied to a fellowship position, with the majority (15% [29/55]) matching into Mohs micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology (MSDO) fellowships. Approximately 5% (9/199) and 4% (7/199) of graduates matched into dermatopathology and pediatric dermatology, respectively. The remaining 5% (10/199) of graduating residents applied to a fellowship but did not match. The majority (45% [91/199]) of residency graduates entered private practice after graduation. Approximately 21% (42/199) of graduating residents chose an academic practice with 17% (33/199), 2% (4/199), and 2% (3/199) of those positions being full-time, part-time, and adjunct, respectively.

Comment

The first annual APD survey is a novel data source and provides opportunities for areas of discussion and investigation. Evaluating the similarities and differences among dermatology residency programs across the United States can strengthen individual programs through collaboration and provide areas of cohesion among programs.

Diversity of PDs—An important area of discussion is diversity and PD demographics. Although DO students make up 1 in 4 US graduating medical students, they are not interviewed or ranked as often as MD students.2 Diversity in PD race and ethnicity may be worthy of investigation in future studies, as match rates and recruitment of diverse medical school applicants may be impacted by these demographics.

Continued Use of Telemedicine in Training—Since 2020, the benefits of virtual residency recruitment have been debated among PDs across all medical specialties. Points in favor of virtual interviews include cost savings for programs and especially for applicants, as well as time efficiency, reduced burden of travel, and reduced carbon footprint. A problem posed by virtual interviews is that candidates are unable to fully learn institutional cultures and social environments of the programs.3 Likewise, telehealth was an important means of clinical teaching for residents during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, with benefits that included cost-effectiveness and reduction of disparities in access to dermatologic care.4 Seventy-five percent (38/51) of PDs indicated that their program plans to include telemedicine in resident clinical rotation moving forward.

Resources Available—Our survey showed that resources available for residents, delivery of lectures and program time allocated to didactics, protected academic or study time for residents, and allocation of program time for CORE examinations are highly variable across programs. This could inspire future studies to be done to determine the differences in success of the resident on CORE examinations and in digesting material.

Postgraduate Career Plans and Fellowship Matches—Residents of programs that have a home MSDO fellowship are more likely to successfully match into a MSDO fellowship.5 Based on this survey, approximately 28% of graduating residents applied to a fellowship position, with 15%, 5%, and 3% matching into desired MSDO, dermatopathology, and pediatric dermatology fellowships, respectively. Additional studies are needed to determine advantages and disadvantages that lead to residents reaching their career goals.

Limitations—Limitations of this study include a small sample size that may not adequately represent all ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs and selection bias toward respondents who are more likely to participate in survey-based research.

Conclusion

The APD plans to continue to administer this survey on an annual basis, with updates to the content and questions based on input from PDs. This survey will continue to provide valuable information to drive collaboration among residency programs and optimize the learning experience for residents. Our hope is that the response rate will increase in coming years, allowing us to draw more generalizable conclusions. Nonetheless, the survey data allow individual dermatology residency programs to compare their specific characteristics to other programs.

Educational organizations across several specialties, including internal medicine and obstetrics and gynecology, have formal surveys1; however, the field of dermatology has been without one. This study aimed to establish a formal survey for dermatology program directors (PDs) and clinician-educators. Because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and American Board of Dermatology surveys do not capture all metrics relevant to dermatology residency educators, an annual survey for our specialty may be helpful to compare dermatology-specific data among programs. Responses could provide context and perspective to faculty and residents who respond to the ACGME annual survey, as our Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) survey asks more in-depth questions, such as how often didactics occur and who leads them. Resident commute time and faculty demographics and training also are covered. Current ad hoc surveys disseminated through listserves of various medical associations contain overlapping questions and reflect relatively low response rates; dermatology PDs may benefit from a survey with a high response rate to which they can contribute future questions and topics that reflect recent trends and current needs in graduate medical education. As future surveys are administered, the results can be captured in a centralized database accessible by dermatology PDs.

Methods

A survey of PDs from 141 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs was conducted by the Residency Program Director Steering Committee of the APD from November 2022 to January 2023 using a prevalidated questionnaire. Personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each PD’s email listed in the ACGME accreditation data system. All survey responses were captured anonymously, with a number assigned to keep de-identified responses separate and organized. The survey consisted of 137 survey questions addressing topics that included program characteristics, PD demographics, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinical rotation and educational conferences, available resident resources, quality improvement, clinical and didactic instruction, research content, diversity and inclusion, wellness, professionalism, evaluation systems, and graduate outcomes.

Data were collected using Qualtrics survey tools. After removing duplicate and incomplete surveys, data were analyzed using Qualtrics reports and Microsoft Excel for data plotting, averages, and range calculations.

Results

One hundred forty-one personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each program’s filed email obtained from the APD listserv. Fifty-three responses were recorded after removing duplicate or incomplete surveys (38% [53/141] response rate). As of May 2023, there were 144 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs due to 3 newly accredited programs in 2022-2023 academic year, which were not included in our survey population.

Program Characteristics—Forty-four respondents (83%) were from a university-based program. Fifty respondents (94%) were from programs that were ACGME accredited prior to 2020, while 3 programs (6%) were American Osteopathic Association accredited prior to singular accreditation. Seventy-one percent (38/53) of respondents had 1 or more associate PDs.

PD Demographics—Eighty-seven percent (45/52) of PDs who responded to the survey graduated from a US allopathic medical school (MD), 10% (5/52) graduated from a US osteopathic medical school (DO), and 4% (2/52) graduated from an international medical school. Seventy-four percent (35/47) of respondents were White, 17% (8/47) were Asian, and 2% (1/47) were Black or African American; this data was not provided for 4 respondents. Forty-eight percent (23/48) of PDs identified as cisgender man, 48% (23/48) identified as cisgender woman, and 4% (2/48) preferred not to answer. Eighty-one percent (38/47) of PDs identified as heterosexual or straight, 15% (7/47) identified as gay or lesbian, and 4% (2/47) preferred not to answer.

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Residency Training—Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 88% (45/51) of respondents incorporated telemedicine into the resident clinical rotation schedule. Moving forward, 75% (38/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to continue to incorporate telemedicine into the rotation schedule. Based on 50 responses, the average of educational conferences that became virtual at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic was 87%; based on 46 responses, the percentage of educational conferences that will remain virtual moving forward is 46%, while 90% (46/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to use virtual conferences in some capacity moving forward. Seventy-three percent (37/51) of respondents indicated that they plan to use virtual interviews as part of residency recruitment moving forward.

Available Resources—Twenty-four percent (11/46) of respondents indicated that residents in their program do not get protected time or time off for CORE examinations. Seventy-five percent (33/44) of PDs said their program provides funding for residents to participate in board review courses. The chief residents at 63% (31/49) of programs receive additional compensation, and 69% (34/49) provide additional administrative time to chief residents. Seventy-one percent (24/34) of PDs reported their programs have scribes for attendings, and 12% (4/34) have scribes for residents. Support staff help residents with callbacks and in-basket messages according to 76% (35/46) of respondents. The majority (98% [45/46]) of PDs indicated that residents follow-up on results and messages from patients seen in resident clinics, and 43% (20/46) of programs have residents follow-up with patients seen in faculty clinics. Only 15% (7/46) of PDs responded they have schedules with residents dedicated to handle these tasks. According to respondents, 33% (17/52) have residents who are required to travel more than 25 miles to distant clinical sites. Of them, 35% (6/17) provide accommodations.

Quality Improvement—Seventy-one percent (35/49) of respondents indicated their department has a quality improvement/patient safety team or committee, and 94% (33/35) of these teams include residents. A lecture series on quality improvement and patient safety is offered at 67% (33/49) of the respondents’ programs, while morbidity and mortality conferences are offered in 73% (36/49).

Clinical Instruction—Our survey asked PDs how many months each residency year spends on a certain rotational service. Based on 46 respondents, the average number of months dedicated to medical dermatology is 7, 5, and 6 months for postgraduate year (PGY) 2, PGY3, and PGY4, respectively. The average number of months spent in other subspecialties is provided in the Table. On average, PGY2 residents spend 8 half-days per week seeing patients in clinic, while PGY3 and PGY4 residents see patients for 7 half-days. The median and mean number of patients staffed by a single attending per hour in teaching clinics are 6 and 5.88, respectively. Respondents indicated that residents participate in the following specialty clinics: pediatric dermatology (96% [44/46]), laser/cosmetic (87% [40/44]), high-risk skin cancer (ie, immunosuppressed/transplant patient)(65% [30/44]), pigmented lesion/melanoma (52% [24/44]), connective tissue disease (52% [24/44]), teledermatology (50% [23/44]), free clinic for homeless and/or indigent populations (48% [22/44]), contact dermatitis (43% [20/44]), skin of color (43% [20/44]), oncodermatology (41% [19/44]), and bullous disease (33% [15/44]).

Additionally, in 87% (40/46) of programs, residents participate in a dedicated inpatient consultation service. Most respondents (98% [45/46]) responded that they utilize in-person consultations with a teledermatology supplement. Fifteen percent (7/46) utilize virtual teledermatology (live video-based consultations), and 57% (26/46) utilize asynchronous teledermatology (picture-based consultations). All respondents (n=46) indicated that 0% to 25% of patient encounters involving residents are teledermatology visits. Thirty-three percent (6/18) of programs have a global health special training track, 56% (10/18) have a Specialty Training and Advanced Research/Physician-Scientist Research Training track, 28% (5/18) have a diversity training track, and 50% (9/18) have a clinician educator training track.

Didactic Instruction—Five programs have a full day per week dedicated to didactics, while 36 programs have at least one half-day per week for didactics. On average, didactics in 57% (26/46) of programs are led by faculty alone, while 43% (20/46) are led at least in part by residents or fellows.

Research Content—Fifty percent (23/46) of programs have a specific research requirement for residents beyond general ACGME requirements, and 35% (16/46) require residents to participate in a longitudinal research project over the course of residency. There is a dedicated research coordinator for resident support at 63% (29/46) of programs. Dedicated biostatistics research support is available for resident projects at 42% (19/45) of programs. Additionally, at 42% (19/45) of programs, there is a dedicated faculty member for oversight of resident research.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion—Seventy-three percent (29/40) of programs have special diversity, equity, and inclusion programs or meetings specific to residency, 60% (24/40) have residency initiatives, and 55% (22/40) have a residency diversity committee. Eighty-six percent (42/49) of respondents strongly agreed that their current residents represent diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds (ie, >15% are not White). eTable 1 shows PD responses to this statement, which were stratified based on self-identified race. eTable 2 shows PD responses to the statement, “Our current residents represent an inclusion of gender/sexual orientation,” which were stratified based on self-identified gender identity/sexual orientation. Lastly, eTable 3 highlights the percentage of residents with an MD and DO degree, stratified based on PD degree.

Wellness—Forty-eight percent (20/42) of respondents indicated they are under stress and do not always have as much energy as before becoming a PD but do not feel burned out. Thirty-one percent (13/42) indicated they have 1 or more symptoms of burnout, such as emotional exhaustion. Eighty-six percent (36/42) are satisfied with their jobs overall (43% agree and 43% strongly agree [18/42 each]).

Evaluation System—Seventy-five percent (33/44) of programs deliver evaluations of residents by faculty online, 86% (38/44) of programs have PDs discuss evaluations in-person, and 20% (9/44) of programs have faculty evaluators discuss evaluations in-person. Seventy-seven percent (34/44) of programs have formal faculty-resident mentor-mentee programs. Clinical competency committee chair positions are filled by PDs, assistant PDs, or core faculty members 47%, 38%, and 16% of the time, respectively.

Graduation Outcomes of PGY4 Residents—About 28% (55/199) of graduating residents applied to a fellowship position, with the majority (15% [29/55]) matching into Mohs micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology (MSDO) fellowships. Approximately 5% (9/199) and 4% (7/199) of graduates matched into dermatopathology and pediatric dermatology, respectively. The remaining 5% (10/199) of graduating residents applied to a fellowship but did not match. The majority (45% [91/199]) of residency graduates entered private practice after graduation. Approximately 21% (42/199) of graduating residents chose an academic practice with 17% (33/199), 2% (4/199), and 2% (3/199) of those positions being full-time, part-time, and adjunct, respectively.

Comment

The first annual APD survey is a novel data source and provides opportunities for areas of discussion and investigation. Evaluating the similarities and differences among dermatology residency programs across the United States can strengthen individual programs through collaboration and provide areas of cohesion among programs.

Diversity of PDs—An important area of discussion is diversity and PD demographics. Although DO students make up 1 in 4 US graduating medical students, they are not interviewed or ranked as often as MD students.2 Diversity in PD race and ethnicity may be worthy of investigation in future studies, as match rates and recruitment of diverse medical school applicants may be impacted by these demographics.

Continued Use of Telemedicine in Training—Since 2020, the benefits of virtual residency recruitment have been debated among PDs across all medical specialties. Points in favor of virtual interviews include cost savings for programs and especially for applicants, as well as time efficiency, reduced burden of travel, and reduced carbon footprint. A problem posed by virtual interviews is that candidates are unable to fully learn institutional cultures and social environments of the programs.3 Likewise, telehealth was an important means of clinical teaching for residents during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, with benefits that included cost-effectiveness and reduction of disparities in access to dermatologic care.4 Seventy-five percent (38/51) of PDs indicated that their program plans to include telemedicine in resident clinical rotation moving forward.

Resources Available—Our survey showed that resources available for residents, delivery of lectures and program time allocated to didactics, protected academic or study time for residents, and allocation of program time for CORE examinations are highly variable across programs. This could inspire future studies to be done to determine the differences in success of the resident on CORE examinations and in digesting material.

Postgraduate Career Plans and Fellowship Matches—Residents of programs that have a home MSDO fellowship are more likely to successfully match into a MSDO fellowship.5 Based on this survey, approximately 28% of graduating residents applied to a fellowship position, with 15%, 5%, and 3% matching into desired MSDO, dermatopathology, and pediatric dermatology fellowships, respectively. Additional studies are needed to determine advantages and disadvantages that lead to residents reaching their career goals.

Limitations—Limitations of this study include a small sample size that may not adequately represent all ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs and selection bias toward respondents who are more likely to participate in survey-based research.

Conclusion

The APD plans to continue to administer this survey on an annual basis, with updates to the content and questions based on input from PDs. This survey will continue to provide valuable information to drive collaboration among residency programs and optimize the learning experience for residents. Our hope is that the response rate will increase in coming years, allowing us to draw more generalizable conclusions. Nonetheless, the survey data allow individual dermatology residency programs to compare their specific characteristics to other programs.

- Maciejko L, Cope A, Mara K, et al. A national survey of obstetrics and gynecology emergency training and deficits in office emergency preparation [A53]. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:16S. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000826548.05758.26

- Lavertue SM, Terry R. A comparison of surgical subspecialty match rates in 2022 in the United States. Cureus. 2023;15:E37178. doi:10.7759/cureus.37178

- Domingo A, Rdesinski RE, Stenson A, et al. Virtual residency interviews: applicant perceptions regarding virtual interview effectiveness, advantages, and barriers. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14:224-228. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-21-00675.1

- Rustad AM, Lio PA. Pandemic pressure: teledermatology and health care disparities. J Patient Exp. 2021;8:2374373521996982. doi:10.1177/2374373521996982

- Rickstrew J, Rajpara A, Hocker TLH. Dermatology residency program influences chance of successful surgery fellowship match. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1040-1042. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002859

- Maciejko L, Cope A, Mara K, et al. A national survey of obstetrics and gynecology emergency training and deficits in office emergency preparation [A53]. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:16S. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000826548.05758.26

- Lavertue SM, Terry R. A comparison of surgical subspecialty match rates in 2022 in the United States. Cureus. 2023;15:E37178. doi:10.7759/cureus.37178

- Domingo A, Rdesinski RE, Stenson A, et al. Virtual residency interviews: applicant perceptions regarding virtual interview effectiveness, advantages, and barriers. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14:224-228. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-21-00675.1

- Rustad AM, Lio PA. Pandemic pressure: teledermatology and health care disparities. J Patient Exp. 2021;8:2374373521996982. doi:10.1177/2374373521996982

- Rickstrew J, Rajpara A, Hocker TLH. Dermatology residency program influences chance of successful surgery fellowship match. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1040-1042. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002859

Practice Points

- The first annual Association of Professors of Dermatology program directors survey allows faculty to compare their programs to other dermatology residency programs across the United States.

- The results should inspire opportunities for growth, improvement, and collaboration among dermatology residency programs.

Effect of COVID-19 Vaccination on Disease Severity in Patients With Stable Plaque Psoriasis: A Cross-sectional Study

To the Editor:

COVID-19 infection has resulted in 6.9 million deaths worldwide. India has the third highest mortality from COVID-19 infection after the United States and Brazil.1 Vaccination plays a crucial role in containing COVID-19 infection and reducing its severity. At present, 11 vaccines have been approved by the World Health Organization. India started its vaccination program on January 16, 2021, with approval for use of Covaxin (Bharat Biotech) and Covishield (Oxford/AstraZeneca formulation)(Serum Institute of India). More than 2 billion doses have been administered since then.2,3

Patients with psoriasis are prone to develop a severe form of COVID-19 due to comorbidities and the intake of immunosuppressive drugs.4 These patients often are hesitant to receive the vaccine without an expert opinion. COVID-19 vaccines are considered to increase tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells. Tumor necrosis factor α is a key proinflammatory cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccines induce elevation of IL-6 and helper T cells (TH17), which can induce a flare of psoriasis in a subset of patients.5The International Psoriasis Council recommends that patients with psoriasis receive one of the vaccines approved to prevent COVID-19 infection as soon as possible.6 Reports of new-onset psoriasis and flare of psoriasis after the use of COVID-19 vaccines, such as those manufactured by Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca, have been published from different parts of the world.7 India used locally developed whole virion inactivated BBV152 (Covaxin) and nonreplicating viral vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Covishield) in its vaccination program and exported them to other developing countries. There is a dearth of data on the safety of these vaccines in patients with psoriasis, which needs to be assessed. Later, Covaxin, ZyCoV-D (DNA plasmid vaccine; Cadila Healthcare), and CorbeVax (protein subunit vaccine; Biological E) were approved for usage in children.8 We conducted a cross-sectional study using the direct interview method.

Patients with psoriasis who attended the outpatient department of the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (Chandigarh, India) from April 2022 to June 2022 were invited to participate in the study after written informed consent was received. Patients 18 years and older with chronic plaque psoriasis who had received a COVID-19 vaccine dose in the last 90 days were enrolled. Data on demographics, comorbidities, treatment received for psoriasis, vaccination concerns, history of COVID-19 infection, type of vaccine received with doses, adverse effects, and psoriasis flare after receiving the vaccine (considered up to 2 weeks from the date of vaccination) were collected. Ordinal logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with a psoriasis flare following vaccination. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

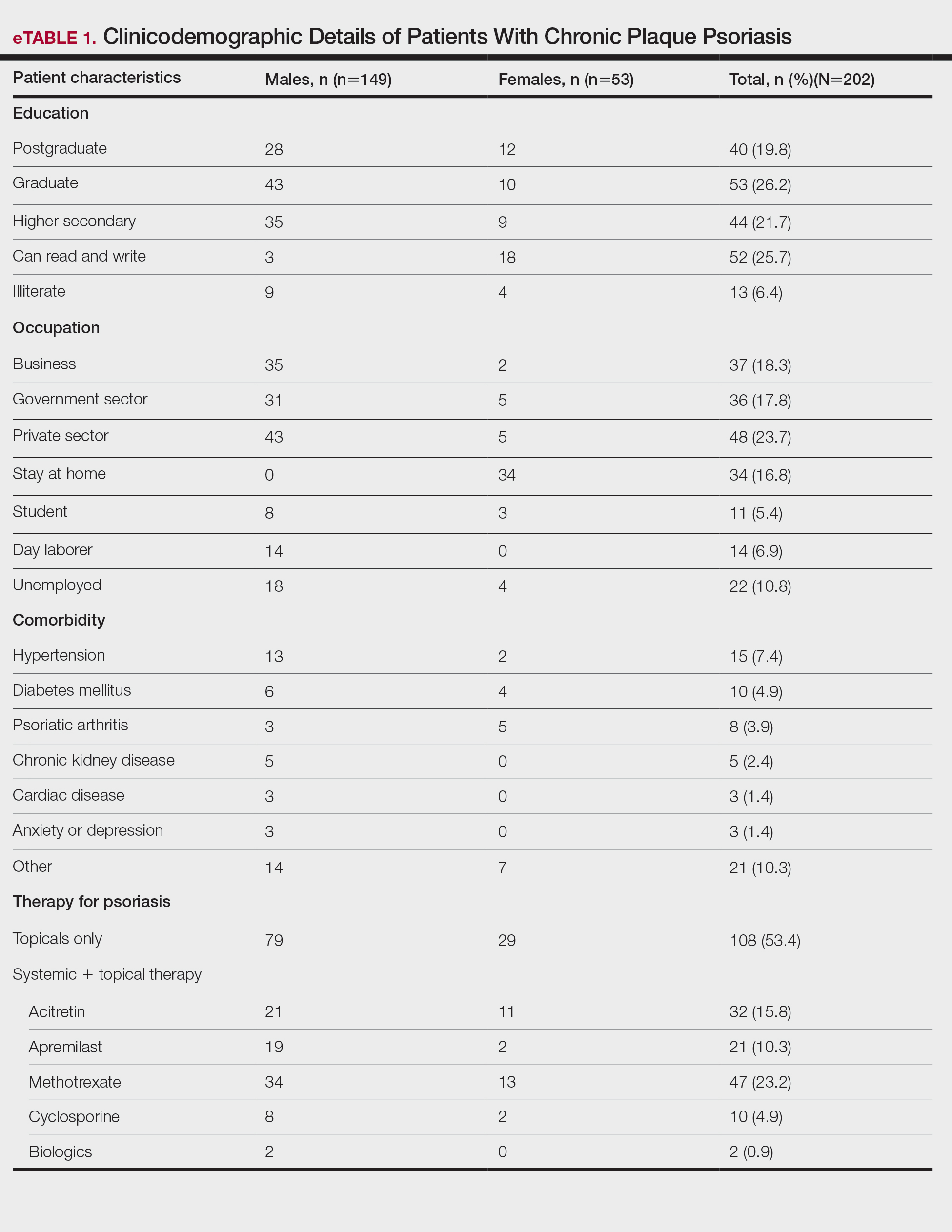

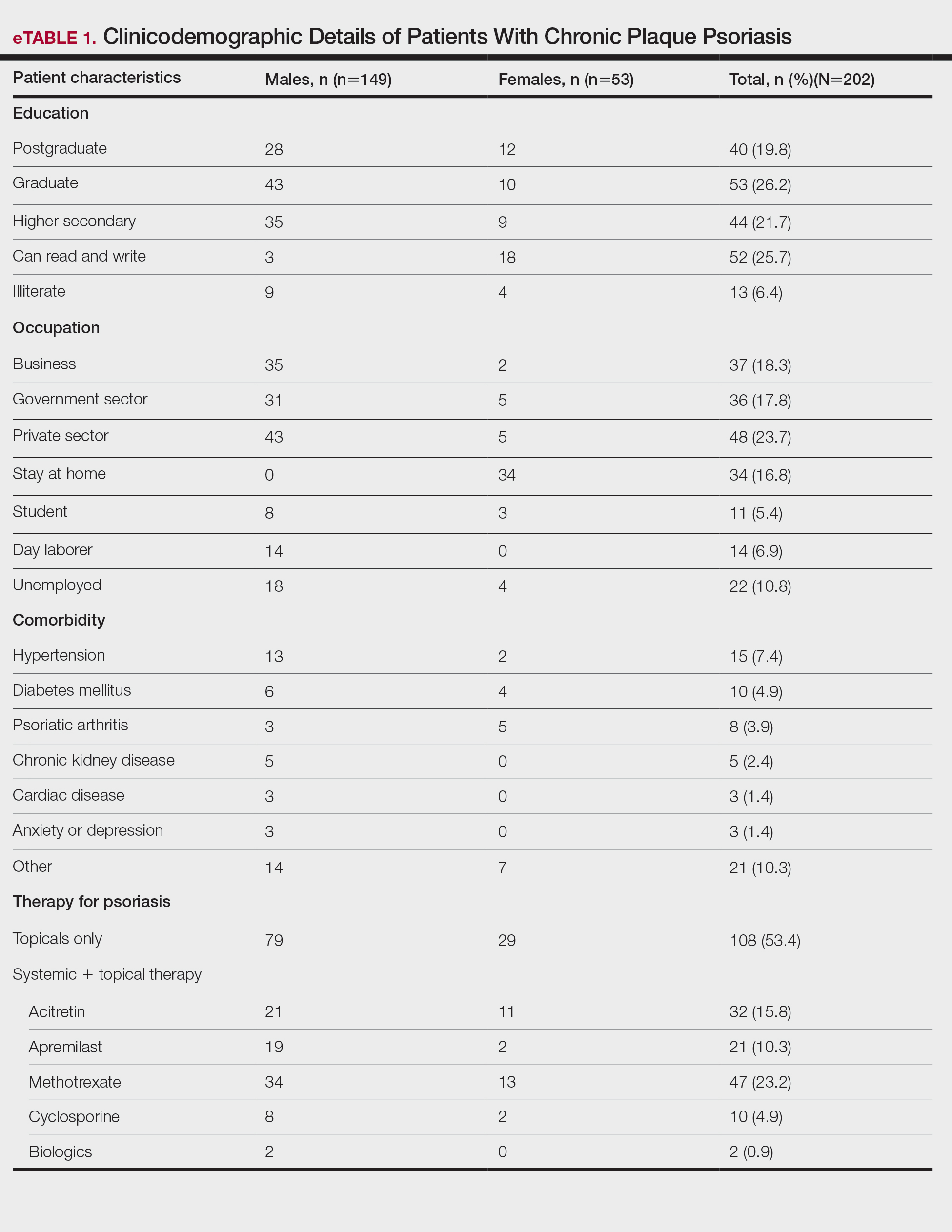

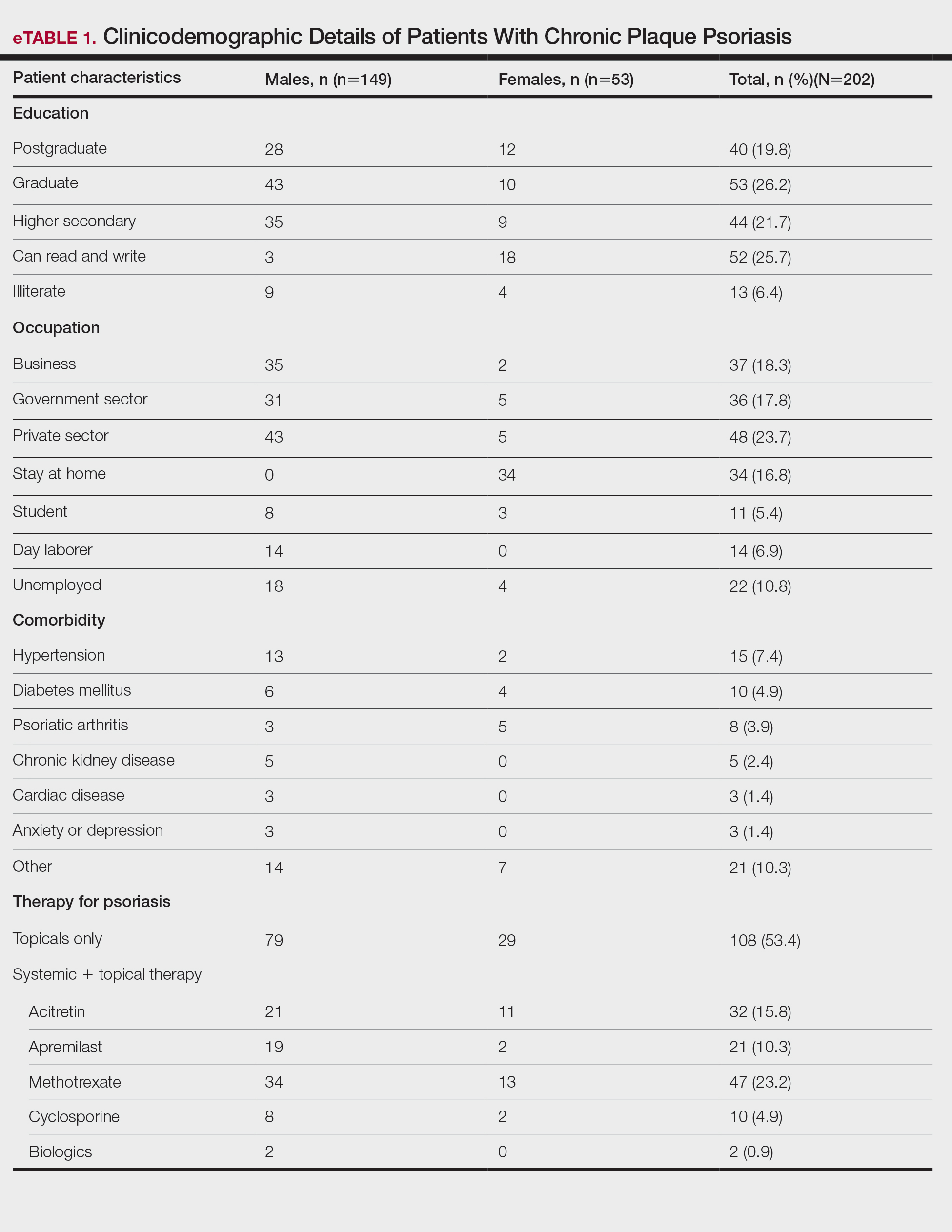

A total of 202 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis who received either Covaxin or Covishield were enrolled during the study period. The mean age (SD) was 40.3 (13.1) years, and 149 (73.8%) patients were male. One hundred thirty-five (66.8%) patients completed 2 doses of the vaccine. eTable 1 provides the clinicodemographic details of the patients. Eighty-three (41.1%) patients had a fear of psoriasis flare after vaccination. Seventy-two (35.6%) patients received the vaccine after clearance from their treating physician/dermatologist. One hundred sixty-four (81.2%) patients received the Covishield vaccine, and 38 (18.8%) patients received Covaxin. Eighty-three (41.1%) patients reported flulike symptoms, such as fever, myalgia, or body pain, within the first week of vaccination. Sixty-one (30.2%) patients reported a psoriasis flare after vaccination in the form of new lesions or worsening of pre-existing lesions. Of these patients, 51 reported a flare after receiving the first dose of vaccine, 8 patients reported a flare after receiving the second dose of vaccine, and 2 patients reported a flare after receiving both doses of vaccine. The mean (SD) flare onset was 8.1 (3.4) days after the vaccination. Eighteen patients considered the flare to be severe. Seventeen (8.4%) patients reported a positive history of COVID-19 infection before vaccination. None of the patients reported breakthrough COVID-19 infection or pustular aggravation of psoriasis following the vaccination.

The self-reported psoriasis flare after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine was significantly higher in patients who experienced immediate adverse effects (P=.005), which included fever, myalgia, joint pain, and injection-site reaction. The reported postvaccination psoriasis flare was not significantly associated with patient sex, history of COVID-19 infection, type of vaccine received, comorbidities, or therapy for psoriasis (eTable 2).

Nearly 30% of our patients reported a postvaccination psoriasis flare, which was more common after the first vaccine dose. Sotiriou et al7 reported 14 cases of psoriasis flare in patients after receiving Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines. These patients experienced an exacerbation of disease soon after the second dose of vaccine (mean [SD], 10.36 [7.71] days), and 21% of the 713 enrolled patients wanted to forego the immunization due to concern of a postvaccination psoriasis flare.7 In another report, 14 (27%) patients developed a psoriasis flare after COVID-19 vaccination; the mean (SD) flare onset was 9.3 (4.3) days after vaccination.9

Data on the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine in patients using immunosuppressive drugs are limited. We did not find a significant association between the psoriasis flare and use of immunosuppressive drugs or type of vaccine received. Huang and Tsai9 observed similar results, with no association between psoriasis flare and use of immunosuppressive drugs or biologics, while Damiani et al10 demonstrated a protective role of biologics in preventing vaccine-induced psoriasis flare.

Similar to another study from India,11 the immediate adverse effects due to immunization with Covaxin and Covishield were mild in our study and resolved within a week. The incidence of psoriasis flare was significantly higher in patients who reported adverse effects (P=.005). Activation of immune response after vaccination leads to the release of proinflammatory and pyrogenic cytokines (ie, IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α), which may explain the higher incidence of psoriasis flare in patients experiencing adverse effects to vaccination.12

Our study showed approximately 30% of patients developed a psoriasis flare after COVID-19 vaccination, with no patients experiencing any vaccine-related serious adverse events, which suggests that Covaxin and Covishield are safe for patients with psoriasis in India. Limitations of our study include potential inaccuracy of the patient’s self-assessment of symptoms and disease flare, recall bias that may lead to errors in estimating patient-reported outcomes, the flare of psoriasis potentially being a part of disease fluctuation, and flare being enhanced by the psychological stress of vaccination.

Considering a high risk for severe COVID-19 infection in patients with psoriasis with comorbidities and those using immunosuppressive drugs, Covaxin and Covishield can be safely recommended in India. However, caution needs to be exercised when vaccinating patients with an unstable disease or severe psoriasis.

- COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic: weekly trends. Worldometer. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- National COVID-19 vaccination programme meets its goals by overcoming R&D and logistical challenges, says economic survey 2022-23. Government of India Press Information Bureau website. Published January 31, 2023. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1894907

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. CoWIN. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.cowin.gov.in/

- Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, et al. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397:1301-1315.

- Wu D, Yang XO. TH17 responses in cytokine storm of COVID-19: anemerging target of JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:368-370.

- International Psoriasis Council. Revised IPC statement on COVID-19. Published December 19, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://psoriasiscouncil.org/covid-19/revised-statement-covid-19/

- Sotiriou E, Tsentemeidou A, Bakirtzi K, et al. Psoriasis exacerbation after COVID-19 vaccination: a report of 14 cases from a single centre. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E857-E859.

- Kaul R. India clears 2 vaccines for kids under 12 years. Hindustan Times. Published April 27, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-clears-2-vaccines-for-kids-under-12-years-101650998027336.html

- Huang YW, Tsai TF. Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination: report from a single center. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:812010.

- Damiani G, Allocco F, Young Dermatologists Italian Network, et al. COVID-19 vaccination and patients with psoriasis under biologics: real-life evidence on safety and effectiveness from Italian vaccinated healthcare workers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;460:1106-1108.

- Joshi RK, Muralidharan CG, Gulati DS, et al. Higher incidence of reported adverse events following immunisation (AEFI) after first dose of COVID-19 vaccine among previously infected health care workers. Med J Armed Forces India. 2021;77(suppl 2):S505-S507.

- Hervé C, Laupèze B, Del Giudice G, et al. The how’s and what’s of vaccine reactogenicity. NPJ Vaccines. 2019;4:39.

To the Editor:

COVID-19 infection has resulted in 6.9 million deaths worldwide. India has the third highest mortality from COVID-19 infection after the United States and Brazil.1 Vaccination plays a crucial role in containing COVID-19 infection and reducing its severity. At present, 11 vaccines have been approved by the World Health Organization. India started its vaccination program on January 16, 2021, with approval for use of Covaxin (Bharat Biotech) and Covishield (Oxford/AstraZeneca formulation)(Serum Institute of India). More than 2 billion doses have been administered since then.2,3