User login

CRC: Troubling Mortality Rates for a Preventable Cancer

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

The American Cancer Society has just published its cancer statistics for 2024. This is an annual report, the latest version of which has some alarming news for gastroenterologists. Usually, we think of being “number one” as a positive thing, but that’s not the case this year when it comes to the projections for colorectal cancer.

But first, let’s discuss the report’s overall findings. That decline over the past four decades is due to reductions in smoking, earlier detection, and improved screening and treatments for localized or metastatic disease. But these gains are now threatened by some offsets that we’re seeing, with increasing rates of six of the top 10 cancers in the past several years.

Increasing Rates of Gastrointestinal Cancers

The incidence rate of pancreas cancer has increased from 0.6% to 1% annually.

Pancreas cancer has a 5-year relative survival rate of 13%, which ranks as one of the three worst rates for cancers. This cancer represents a real screening challenge for us, as it typically presents asymptomatically.

Women have experienced a 2%-3% annual increase in incidence rates for liver cancer.

I suspect that this is due to cases of fibrotic liver disease resulting from viral hepatitis and metabolic liver diseases with nonalcoholic fatty liver and advanced fibrosis (F3 and F4). These cases may be carried over from before, thereby contributing to the increasing incremental cancer risk.

We can’t overlook the need for risk reduction here and should focus on applying regular screening efforts in our female patients. However, it’s also true that we require better liver cancer screening tests to accomplish that goal.

In Those Under 50, CRC the Leading Cause of Cancer Death in Men, Second in Women

I really want to focus on the news around colorectal cancer.

To put this in perspective, in the late 1990s, colorectal cancer was the fourth leading cause of death in men and women. The current report extrapolated 2024 projections using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database ending in 2020, which was necessary given the incremental time it takes to develop cancers. The SEER database suggests that in 2024, colorectal cancer in those younger than 50 years of age will become the number-one leading cause of cancer death in men and number-two in women. The increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in younger people is probably the result of a number of epidemiologic and other reasons.

The current report offers evidence of racial disparities in cancer mortality rates in general, which are twofold higher in Black people compared with White people, particularly for gastric cancer. There is also an evident disparity in Native Americans, who have higher rates of gastric and liver cancer. This is a reminder of the increasing need for equity to address racial disparities across these populations.

But returning to colon cancer, it’s a marked change to go from being the fourth-leading cause of cancer death in those younger than 50 years of age to being number one for men and number two for women.

Being “number one” is supposed to make you famous. This “number one,” however, should in fact be infamous. It’s a travesty, because colorectal cancer is a potentially preventable disease.

As we move into March, which happens to be Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month, hopefully this fires up some of the conversations you have with your younger at-risk population, who may be reticent or resistant to colorectal cancer screening.

We have to do better at getting this message out to that population at large. “Number one” is not where we want to be for this potentially preventable problem.

Dr. Johnson is professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Virginia, and a past president of the American College of Gastroenterology. His primary focus is the clinical practice of gastroenterology. He has published extensively in the internal medicine/gastroenterology literature, with principal research interests in esophageal and colon disease, and more recently in sleep and microbiome effects on gastrointestinal health and disease. He has disclosed ties with ISOTHRIVE and Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

The American Cancer Society has just published its cancer statistics for 2024. This is an annual report, the latest version of which has some alarming news for gastroenterologists. Usually, we think of being “number one” as a positive thing, but that’s not the case this year when it comes to the projections for colorectal cancer.

But first, let’s discuss the report’s overall findings. That decline over the past four decades is due to reductions in smoking, earlier detection, and improved screening and treatments for localized or metastatic disease. But these gains are now threatened by some offsets that we’re seeing, with increasing rates of six of the top 10 cancers in the past several years.

Increasing Rates of Gastrointestinal Cancers

The incidence rate of pancreas cancer has increased from 0.6% to 1% annually.

Pancreas cancer has a 5-year relative survival rate of 13%, which ranks as one of the three worst rates for cancers. This cancer represents a real screening challenge for us, as it typically presents asymptomatically.

Women have experienced a 2%-3% annual increase in incidence rates for liver cancer.

I suspect that this is due to cases of fibrotic liver disease resulting from viral hepatitis and metabolic liver diseases with nonalcoholic fatty liver and advanced fibrosis (F3 and F4). These cases may be carried over from before, thereby contributing to the increasing incremental cancer risk.

We can’t overlook the need for risk reduction here and should focus on applying regular screening efforts in our female patients. However, it’s also true that we require better liver cancer screening tests to accomplish that goal.

In Those Under 50, CRC the Leading Cause of Cancer Death in Men, Second in Women

I really want to focus on the news around colorectal cancer.

To put this in perspective, in the late 1990s, colorectal cancer was the fourth leading cause of death in men and women. The current report extrapolated 2024 projections using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database ending in 2020, which was necessary given the incremental time it takes to develop cancers. The SEER database suggests that in 2024, colorectal cancer in those younger than 50 years of age will become the number-one leading cause of cancer death in men and number-two in women. The increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in younger people is probably the result of a number of epidemiologic and other reasons.

The current report offers evidence of racial disparities in cancer mortality rates in general, which are twofold higher in Black people compared with White people, particularly for gastric cancer. There is also an evident disparity in Native Americans, who have higher rates of gastric and liver cancer. This is a reminder of the increasing need for equity to address racial disparities across these populations.

But returning to colon cancer, it’s a marked change to go from being the fourth-leading cause of cancer death in those younger than 50 years of age to being number one for men and number two for women.

Being “number one” is supposed to make you famous. This “number one,” however, should in fact be infamous. It’s a travesty, because colorectal cancer is a potentially preventable disease.

As we move into March, which happens to be Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month, hopefully this fires up some of the conversations you have with your younger at-risk population, who may be reticent or resistant to colorectal cancer screening.

We have to do better at getting this message out to that population at large. “Number one” is not where we want to be for this potentially preventable problem.

Dr. Johnson is professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Virginia, and a past president of the American College of Gastroenterology. His primary focus is the clinical practice of gastroenterology. He has published extensively in the internal medicine/gastroenterology literature, with principal research interests in esophageal and colon disease, and more recently in sleep and microbiome effects on gastrointestinal health and disease. He has disclosed ties with ISOTHRIVE and Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

The American Cancer Society has just published its cancer statistics for 2024. This is an annual report, the latest version of which has some alarming news for gastroenterologists. Usually, we think of being “number one” as a positive thing, but that’s not the case this year when it comes to the projections for colorectal cancer.

But first, let’s discuss the report’s overall findings. That decline over the past four decades is due to reductions in smoking, earlier detection, and improved screening and treatments for localized or metastatic disease. But these gains are now threatened by some offsets that we’re seeing, with increasing rates of six of the top 10 cancers in the past several years.

Increasing Rates of Gastrointestinal Cancers

The incidence rate of pancreas cancer has increased from 0.6% to 1% annually.

Pancreas cancer has a 5-year relative survival rate of 13%, which ranks as one of the three worst rates for cancers. This cancer represents a real screening challenge for us, as it typically presents asymptomatically.

Women have experienced a 2%-3% annual increase in incidence rates for liver cancer.

I suspect that this is due to cases of fibrotic liver disease resulting from viral hepatitis and metabolic liver diseases with nonalcoholic fatty liver and advanced fibrosis (F3 and F4). These cases may be carried over from before, thereby contributing to the increasing incremental cancer risk.

We can’t overlook the need for risk reduction here and should focus on applying regular screening efforts in our female patients. However, it’s also true that we require better liver cancer screening tests to accomplish that goal.

In Those Under 50, CRC the Leading Cause of Cancer Death in Men, Second in Women

I really want to focus on the news around colorectal cancer.

To put this in perspective, in the late 1990s, colorectal cancer was the fourth leading cause of death in men and women. The current report extrapolated 2024 projections using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database ending in 2020, which was necessary given the incremental time it takes to develop cancers. The SEER database suggests that in 2024, colorectal cancer in those younger than 50 years of age will become the number-one leading cause of cancer death in men and number-two in women. The increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in younger people is probably the result of a number of epidemiologic and other reasons.

The current report offers evidence of racial disparities in cancer mortality rates in general, which are twofold higher in Black people compared with White people, particularly for gastric cancer. There is also an evident disparity in Native Americans, who have higher rates of gastric and liver cancer. This is a reminder of the increasing need for equity to address racial disparities across these populations.

But returning to colon cancer, it’s a marked change to go from being the fourth-leading cause of cancer death in those younger than 50 years of age to being number one for men and number two for women.

Being “number one” is supposed to make you famous. This “number one,” however, should in fact be infamous. It’s a travesty, because colorectal cancer is a potentially preventable disease.

As we move into March, which happens to be Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month, hopefully this fires up some of the conversations you have with your younger at-risk population, who may be reticent or resistant to colorectal cancer screening.

We have to do better at getting this message out to that population at large. “Number one” is not where we want to be for this potentially preventable problem.

Dr. Johnson is professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Virginia, and a past president of the American College of Gastroenterology. His primary focus is the clinical practice of gastroenterology. He has published extensively in the internal medicine/gastroenterology literature, with principal research interests in esophageal and colon disease, and more recently in sleep and microbiome effects on gastrointestinal health and disease. He has disclosed ties with ISOTHRIVE and Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The Daycare Petri Dish

I can’t remember where I heard it. Maybe I made it up myself. But, one definition of a family is a group of folks with whom you share your genes and germs. In that same vein, one could define daycare as a group of germ-sharing children. Of course that’s news to almost no one. Parents who decide, or are forced, to send their children to daycare expect that those children will get more colds, “stomach flu,” and ear infections than the children who spend their days in isolation at home. Everyone from the pediatrician to the little old lady next door has warned parents of the inevitable reality of daycare. Of course there are upsides that parents can cling to, including increased socialization and the hope that getting sick young will build a more robust immunity in the long run.

However, there has been little research exploring the nuances of the germ sharing that we all know is happening in these and other social settings.

A team of evolutionary biologists at Harvard is working to better define the “social microbiome” and its “role in individuals’ susceptibility to, and resilience against, both communicable and noncommunicable diseases.” These researchers point out that while we harbor our own unique collection of microbes, we share those with the microbiomes of the people with whom we interact socially. They report that studies by other investigators have shown that residents of a household share a significant proportion of their gastrointestinal flora. There are other studies that have shown that villages can be identified by their own social biome. There are few social settings more intimately involved in microbe sharing than daycares. I have a friends who calls them “petri dishes.”

The biologists point out that antibiotic-resistant microbes can become part of an individual’s microbiome and can be shared with other individuals in their social group, who can then go on and share them in a different social environment. Imagine there is one popular physician in a community whose sense of antibiotic stewardship is, shall we say, somewhat lacking. By inappropriately prescribing antibiotics to a child or two in a daycare, he may be altering the social biome in that daycare, which could then jeopardize the health of all the children and eventually their own home-based social biomes, that may include an immune deficient individual.

The researchers also remind us that different cultures and countries may have different antibiotic usage patterns. Does this mean I am taking a risk by traveling in these “culture-dependent transmission landscapes”? Am I more likely to encounter an antibiotic-resistant microbe when I am visiting a country whose healthcare providers are less prudent prescribers?

However, as these evolutionary biologists point out, not all shared microbes are bad. There is some evidence in animals that individuals can share microbes that have been found to “increase resilience against colitis or improve their responsiveness to cancer therapy.” If a microbe can contribute to a disease that was once considered to be “noncommunicable,” we may need to redefine “communicable” in the light this more nuanced view of the social biome.

It became standard practice during the COVID pandemic to test dormitory and community sewage water to determine the level of infection. Can sewage water be used as a proxy for a social biome? If a parent is lucky enough to have a choice of daycares, would knowing each facility’s biome, as reflected in an analysis of its sewage effluent, help him or her decide? Should a daycare ask for a stool sample from each child before accepting him or her? Seems like this would raise some privacy issues, not to mention the logistical messiness of the process. As we learn more about social biomes, can we imagine a time when a daycare or country or region might proudly advertise itself as having the healthiest spectrum of microbes in its sewage system?

Communal living certainly has its benefits, not just for children but also adults as we realize how loneliness is eating its way into our society. However,

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

I can’t remember where I heard it. Maybe I made it up myself. But, one definition of a family is a group of folks with whom you share your genes and germs. In that same vein, one could define daycare as a group of germ-sharing children. Of course that’s news to almost no one. Parents who decide, or are forced, to send their children to daycare expect that those children will get more colds, “stomach flu,” and ear infections than the children who spend their days in isolation at home. Everyone from the pediatrician to the little old lady next door has warned parents of the inevitable reality of daycare. Of course there are upsides that parents can cling to, including increased socialization and the hope that getting sick young will build a more robust immunity in the long run.

However, there has been little research exploring the nuances of the germ sharing that we all know is happening in these and other social settings.

A team of evolutionary biologists at Harvard is working to better define the “social microbiome” and its “role in individuals’ susceptibility to, and resilience against, both communicable and noncommunicable diseases.” These researchers point out that while we harbor our own unique collection of microbes, we share those with the microbiomes of the people with whom we interact socially. They report that studies by other investigators have shown that residents of a household share a significant proportion of their gastrointestinal flora. There are other studies that have shown that villages can be identified by their own social biome. There are few social settings more intimately involved in microbe sharing than daycares. I have a friends who calls them “petri dishes.”

The biologists point out that antibiotic-resistant microbes can become part of an individual’s microbiome and can be shared with other individuals in their social group, who can then go on and share them in a different social environment. Imagine there is one popular physician in a community whose sense of antibiotic stewardship is, shall we say, somewhat lacking. By inappropriately prescribing antibiotics to a child or two in a daycare, he may be altering the social biome in that daycare, which could then jeopardize the health of all the children and eventually their own home-based social biomes, that may include an immune deficient individual.

The researchers also remind us that different cultures and countries may have different antibiotic usage patterns. Does this mean I am taking a risk by traveling in these “culture-dependent transmission landscapes”? Am I more likely to encounter an antibiotic-resistant microbe when I am visiting a country whose healthcare providers are less prudent prescribers?

However, as these evolutionary biologists point out, not all shared microbes are bad. There is some evidence in animals that individuals can share microbes that have been found to “increase resilience against colitis or improve their responsiveness to cancer therapy.” If a microbe can contribute to a disease that was once considered to be “noncommunicable,” we may need to redefine “communicable” in the light this more nuanced view of the social biome.

It became standard practice during the COVID pandemic to test dormitory and community sewage water to determine the level of infection. Can sewage water be used as a proxy for a social biome? If a parent is lucky enough to have a choice of daycares, would knowing each facility’s biome, as reflected in an analysis of its sewage effluent, help him or her decide? Should a daycare ask for a stool sample from each child before accepting him or her? Seems like this would raise some privacy issues, not to mention the logistical messiness of the process. As we learn more about social biomes, can we imagine a time when a daycare or country or region might proudly advertise itself as having the healthiest spectrum of microbes in its sewage system?

Communal living certainly has its benefits, not just for children but also adults as we realize how loneliness is eating its way into our society. However,

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

I can’t remember where I heard it. Maybe I made it up myself. But, one definition of a family is a group of folks with whom you share your genes and germs. In that same vein, one could define daycare as a group of germ-sharing children. Of course that’s news to almost no one. Parents who decide, or are forced, to send their children to daycare expect that those children will get more colds, “stomach flu,” and ear infections than the children who spend their days in isolation at home. Everyone from the pediatrician to the little old lady next door has warned parents of the inevitable reality of daycare. Of course there are upsides that parents can cling to, including increased socialization and the hope that getting sick young will build a more robust immunity in the long run.

However, there has been little research exploring the nuances of the germ sharing that we all know is happening in these and other social settings.

A team of evolutionary biologists at Harvard is working to better define the “social microbiome” and its “role in individuals’ susceptibility to, and resilience against, both communicable and noncommunicable diseases.” These researchers point out that while we harbor our own unique collection of microbes, we share those with the microbiomes of the people with whom we interact socially. They report that studies by other investigators have shown that residents of a household share a significant proportion of their gastrointestinal flora. There are other studies that have shown that villages can be identified by their own social biome. There are few social settings more intimately involved in microbe sharing than daycares. I have a friends who calls them “petri dishes.”

The biologists point out that antibiotic-resistant microbes can become part of an individual’s microbiome and can be shared with other individuals in their social group, who can then go on and share them in a different social environment. Imagine there is one popular physician in a community whose sense of antibiotic stewardship is, shall we say, somewhat lacking. By inappropriately prescribing antibiotics to a child or two in a daycare, he may be altering the social biome in that daycare, which could then jeopardize the health of all the children and eventually their own home-based social biomes, that may include an immune deficient individual.

The researchers also remind us that different cultures and countries may have different antibiotic usage patterns. Does this mean I am taking a risk by traveling in these “culture-dependent transmission landscapes”? Am I more likely to encounter an antibiotic-resistant microbe when I am visiting a country whose healthcare providers are less prudent prescribers?

However, as these evolutionary biologists point out, not all shared microbes are bad. There is some evidence in animals that individuals can share microbes that have been found to “increase resilience against colitis or improve their responsiveness to cancer therapy.” If a microbe can contribute to a disease that was once considered to be “noncommunicable,” we may need to redefine “communicable” in the light this more nuanced view of the social biome.

It became standard practice during the COVID pandemic to test dormitory and community sewage water to determine the level of infection. Can sewage water be used as a proxy for a social biome? If a parent is lucky enough to have a choice of daycares, would knowing each facility’s biome, as reflected in an analysis of its sewage effluent, help him or her decide? Should a daycare ask for a stool sample from each child before accepting him or her? Seems like this would raise some privacy issues, not to mention the logistical messiness of the process. As we learn more about social biomes, can we imagine a time when a daycare or country or region might proudly advertise itself as having the healthiest spectrum of microbes in its sewage system?

Communal living certainly has its benefits, not just for children but also adults as we realize how loneliness is eating its way into our society. However,

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Unleashing Our Immune Response to Quash Cancer

This article was originally published on February 10 in Eric Topol’s substack “Ground Truths.”

It’s astounding how devious cancer cells and tumor tissue can be. This week in Science we learned how certain lung cancer cells can function like “Catch Me If You Can” — changing their driver mutation and cell identity to escape targeted therapy. This histologic transformation, as seen in an experimental model, is just one of so many cancer tricks that we are learning about.

Recently, as shown by single-cell sequencing, cancer cells can steal the mitochondria from T cells, a double whammy that turbocharges cancer cells with the hijacked fuel supply and, at the same time, dismantles the immune response.

Last week, we saw how tumor cells can release a virus-like protein that unleashes a vicious autoimmune response.

And then there’s the finding that cancer cell spread predominantly is occurring while we sleep.

As I previously reviewed, the ability for cancer cells to hijack neurons and neural circuits is now well established, no less their ability to reprogram neurons to become adrenergic and stimulate tumor progression, and interfere with the immune response. Stay tuned on that for a new Ground Truths podcast with Prof Michelle Monje, a leader in cancer neuroscience, which will post soon.

Add advancing age’s immunosenescence as yet another challenge to the long and growing list of formidable ways that cancer cells, and the tumor microenvironment, evade our immune response.

An Ever-Expanding Armamentarium

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

The field of immunotherapies took off with the immune checkpoint inhibitors, first approved by the FDA in 2011, that take the brakes off of T cells, with the programmed death-1 (PD-1), PD-ligand1, and anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies.

But we’re clearly learning they are not enough to prevail over cancer with common recurrences, only short term success in most patients, with some notable exceptions. Adding other immune response strategies, such as a vaccine, or antibody-drug conjugates, or engineered T cells, are showing improved chances for success.

Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines

There are many therapeutic cancer vaccines in the works, as reviewed in depth here.

Here’s a list of ongoing clinical trials of cancer vaccines. You’ll note most of these are on top of a checkpoint inhibitor and use personalized neoantigens (cancer cell surface proteins) derived from sequencing (whole-exome or whole genome, RNA-sequencing and HLA-profiling) the patient’s tumor.

An example of positive findings is with the combination of an mRNA-nanoparticle vaccine with up to 34 personalized neoantigens and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) vs pembrolizumab alone in advanced melanoma after resection, with improved outcomes at 3-year follow-up, cutting death or relapse rate in half.

Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADC)

There is considerable excitement about antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) whereby a linker is used to attach a chemotherapy agent to the checkpoint inhibitor antibody, specifically targeting the cancer cell and facilitating entry of the chemotherapy into the cell. Akin to these are bispecific antibodies (BiTEs, binding to a tumor antigen and T cell receptor simultaneously), both of these conjugates acting as “biologic” or “guided” missiles.

A very good example of the potency of an ADC was seen in a “HER2-low” breast cancer randomized trial. The absence or very low expression or amplification of the HER2 receptor is common in breast cancer and successful treatment has been elusive. A randomized trial of an ADC (trastuzumab deruxtecan) compared to physician’s choice therapy demonstrated a marked success for progression-free survival in HER2-low patients, which was characterized as “unheard-of success” by media coverage.

This strategy is being used to target some of the most difficult cancer driver mutations such as TP53 and KRAS.

Oncolytic Viruses

Modifying viruses to infect the tumor and make it more visible to the immune system, potentiating anti-tumor responses, known as oncolytic viruses, have been proposed as a way to rev up the immune response for a long time but without positive Phase 3 clinical trials.

After decades of failure, a recent trial in refractory bladder cancer showed marked success, along with others, summarized here, now providing very encouraging results. It looks like oncolytic viruses are on a comeback path.

Engineering T Cells (Chimeric Antigen Receptor [CAR-T])

As I recently reviewed, there are over 500 ongoing clinical trials to build on the success of the first CAR-T approval for leukemia 7 years ago. I won’t go through that all again here, but to reiterate most of the success to date has been in “liquid” blood (leukemia and lymphoma) cancer tumors. This week in Nature is the discovery of a T cell cancer mutation, a gene fusion CARD11-PIK3R3, from a T cell lymphoma that can potentially be used to augment CAR-T efficacy. It has pronounced and prolonged effects in the experimental model. Instead of 1 million cells needed for treatment, even 20,000 were enough to melt the tumor. This is a noteworthy discovery since CAR-T work to date has largely not exploited such naturally occurring mutations, while instead concentrating on those seen in the patient’s set of key tumor mutations.

As currently conceived, CAR-T, and what is being referred to more broadly as adoptive cell therapies, involves removing T cells from the patient’s body and engineering their activation, then reintroducing them back to the patient. This is laborious, technically difficult, and very expensive. Recently, the idea of achieving all of this via an injection of virus that specifically infects T cells and inserts the genes needed, was advanced by two biotech companies with preclinical results, one in non-human primates.

Gearing up to meet the challenge of solid tumor CAR-T intervention, there’s more work using CRISPR genome editing of T cell receptors. A.I. is increasingly being exploited to process the data from sequencing and identify optimal neoantigens.

Instead of just CAR-T, we’re seeing the emergence of CAR-macrophage and CAR-natural killer (NK) cells strategies, and rapidly expanding potential combinations of all the strategies I’ve mentioned. No less, there’s been maturation of on-off suicide switches programmed in, to limit cytokine release and promote safety of these interventions. Overall, major side effects of immunotherapies are not only cytokine release syndromes, but also include interstitial pneumonitis and neurotoxicity.

Summary

Given the multitude of ways cancer cells and tumor tissue can evade our immune response, durably successful treatment remains a daunting challenge. But the ingenuity of so many different approaches to unleash our immune response, and their combinations, provides considerable hope that we’ll increasingly meet the challenge in the years ahead. We have clearly learned that combining different immunotherapy strategies will be essential for many patients with the most resilient solid tumors.

Of concern, as noted by a recent editorial in The Lancet, entitled “Cancer Research Equity: Innovations For The Many, Not The Few,” is that these individualized, sophisticated strategies are not scalable; they will have limited reach and benefit. The movement towards “off the shelf” CAR-T and inexpensive, orally active checkpoint inhibitors may help mitigate this issue.

Notwithstanding this important concern, we’re seeing an array of diverse and potent immunotherapy strategies that are providing highly encouraging results, engendering more excitement than we’ve seen in this space for some time. These should propel substantial improvements in outcomes for patients in the years ahead. It can’t happen soon enough.

Thanks for reading this edition of Ground Truths. If you found it informative, please share it with your colleagues.

Dr. Topol has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Dexcom; Illumina; Molecular Stethoscope; Quest Diagnostics; Blue Cross Blue Shield Association. Received research grant from National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was originally published on February 10 in Eric Topol’s substack “Ground Truths.”

It’s astounding how devious cancer cells and tumor tissue can be. This week in Science we learned how certain lung cancer cells can function like “Catch Me If You Can” — changing their driver mutation and cell identity to escape targeted therapy. This histologic transformation, as seen in an experimental model, is just one of so many cancer tricks that we are learning about.

Recently, as shown by single-cell sequencing, cancer cells can steal the mitochondria from T cells, a double whammy that turbocharges cancer cells with the hijacked fuel supply and, at the same time, dismantles the immune response.

Last week, we saw how tumor cells can release a virus-like protein that unleashes a vicious autoimmune response.

And then there’s the finding that cancer cell spread predominantly is occurring while we sleep.

As I previously reviewed, the ability for cancer cells to hijack neurons and neural circuits is now well established, no less their ability to reprogram neurons to become adrenergic and stimulate tumor progression, and interfere with the immune response. Stay tuned on that for a new Ground Truths podcast with Prof Michelle Monje, a leader in cancer neuroscience, which will post soon.

Add advancing age’s immunosenescence as yet another challenge to the long and growing list of formidable ways that cancer cells, and the tumor microenvironment, evade our immune response.

An Ever-Expanding Armamentarium

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

The field of immunotherapies took off with the immune checkpoint inhibitors, first approved by the FDA in 2011, that take the brakes off of T cells, with the programmed death-1 (PD-1), PD-ligand1, and anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies.

But we’re clearly learning they are not enough to prevail over cancer with common recurrences, only short term success in most patients, with some notable exceptions. Adding other immune response strategies, such as a vaccine, or antibody-drug conjugates, or engineered T cells, are showing improved chances for success.

Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines

There are many therapeutic cancer vaccines in the works, as reviewed in depth here.

Here’s a list of ongoing clinical trials of cancer vaccines. You’ll note most of these are on top of a checkpoint inhibitor and use personalized neoantigens (cancer cell surface proteins) derived from sequencing (whole-exome or whole genome, RNA-sequencing and HLA-profiling) the patient’s tumor.

An example of positive findings is with the combination of an mRNA-nanoparticle vaccine with up to 34 personalized neoantigens and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) vs pembrolizumab alone in advanced melanoma after resection, with improved outcomes at 3-year follow-up, cutting death or relapse rate in half.

Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADC)

There is considerable excitement about antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) whereby a linker is used to attach a chemotherapy agent to the checkpoint inhibitor antibody, specifically targeting the cancer cell and facilitating entry of the chemotherapy into the cell. Akin to these are bispecific antibodies (BiTEs, binding to a tumor antigen and T cell receptor simultaneously), both of these conjugates acting as “biologic” or “guided” missiles.

A very good example of the potency of an ADC was seen in a “HER2-low” breast cancer randomized trial. The absence or very low expression or amplification of the HER2 receptor is common in breast cancer and successful treatment has been elusive. A randomized trial of an ADC (trastuzumab deruxtecan) compared to physician’s choice therapy demonstrated a marked success for progression-free survival in HER2-low patients, which was characterized as “unheard-of success” by media coverage.

This strategy is being used to target some of the most difficult cancer driver mutations such as TP53 and KRAS.

Oncolytic Viruses

Modifying viruses to infect the tumor and make it more visible to the immune system, potentiating anti-tumor responses, known as oncolytic viruses, have been proposed as a way to rev up the immune response for a long time but without positive Phase 3 clinical trials.

After decades of failure, a recent trial in refractory bladder cancer showed marked success, along with others, summarized here, now providing very encouraging results. It looks like oncolytic viruses are on a comeback path.

Engineering T Cells (Chimeric Antigen Receptor [CAR-T])

As I recently reviewed, there are over 500 ongoing clinical trials to build on the success of the first CAR-T approval for leukemia 7 years ago. I won’t go through that all again here, but to reiterate most of the success to date has been in “liquid” blood (leukemia and lymphoma) cancer tumors. This week in Nature is the discovery of a T cell cancer mutation, a gene fusion CARD11-PIK3R3, from a T cell lymphoma that can potentially be used to augment CAR-T efficacy. It has pronounced and prolonged effects in the experimental model. Instead of 1 million cells needed for treatment, even 20,000 were enough to melt the tumor. This is a noteworthy discovery since CAR-T work to date has largely not exploited such naturally occurring mutations, while instead concentrating on those seen in the patient’s set of key tumor mutations.

As currently conceived, CAR-T, and what is being referred to more broadly as adoptive cell therapies, involves removing T cells from the patient’s body and engineering their activation, then reintroducing them back to the patient. This is laborious, technically difficult, and very expensive. Recently, the idea of achieving all of this via an injection of virus that specifically infects T cells and inserts the genes needed, was advanced by two biotech companies with preclinical results, one in non-human primates.

Gearing up to meet the challenge of solid tumor CAR-T intervention, there’s more work using CRISPR genome editing of T cell receptors. A.I. is increasingly being exploited to process the data from sequencing and identify optimal neoantigens.

Instead of just CAR-T, we’re seeing the emergence of CAR-macrophage and CAR-natural killer (NK) cells strategies, and rapidly expanding potential combinations of all the strategies I’ve mentioned. No less, there’s been maturation of on-off suicide switches programmed in, to limit cytokine release and promote safety of these interventions. Overall, major side effects of immunotherapies are not only cytokine release syndromes, but also include interstitial pneumonitis and neurotoxicity.

Summary

Given the multitude of ways cancer cells and tumor tissue can evade our immune response, durably successful treatment remains a daunting challenge. But the ingenuity of so many different approaches to unleash our immune response, and their combinations, provides considerable hope that we’ll increasingly meet the challenge in the years ahead. We have clearly learned that combining different immunotherapy strategies will be essential for many patients with the most resilient solid tumors.

Of concern, as noted by a recent editorial in The Lancet, entitled “Cancer Research Equity: Innovations For The Many, Not The Few,” is that these individualized, sophisticated strategies are not scalable; they will have limited reach and benefit. The movement towards “off the shelf” CAR-T and inexpensive, orally active checkpoint inhibitors may help mitigate this issue.

Notwithstanding this important concern, we’re seeing an array of diverse and potent immunotherapy strategies that are providing highly encouraging results, engendering more excitement than we’ve seen in this space for some time. These should propel substantial improvements in outcomes for patients in the years ahead. It can’t happen soon enough.

Thanks for reading this edition of Ground Truths. If you found it informative, please share it with your colleagues.

Dr. Topol has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Dexcom; Illumina; Molecular Stethoscope; Quest Diagnostics; Blue Cross Blue Shield Association. Received research grant from National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was originally published on February 10 in Eric Topol’s substack “Ground Truths.”

It’s astounding how devious cancer cells and tumor tissue can be. This week in Science we learned how certain lung cancer cells can function like “Catch Me If You Can” — changing their driver mutation and cell identity to escape targeted therapy. This histologic transformation, as seen in an experimental model, is just one of so many cancer tricks that we are learning about.

Recently, as shown by single-cell sequencing, cancer cells can steal the mitochondria from T cells, a double whammy that turbocharges cancer cells with the hijacked fuel supply and, at the same time, dismantles the immune response.

Last week, we saw how tumor cells can release a virus-like protein that unleashes a vicious autoimmune response.

And then there’s the finding that cancer cell spread predominantly is occurring while we sleep.

As I previously reviewed, the ability for cancer cells to hijack neurons and neural circuits is now well established, no less their ability to reprogram neurons to become adrenergic and stimulate tumor progression, and interfere with the immune response. Stay tuned on that for a new Ground Truths podcast with Prof Michelle Monje, a leader in cancer neuroscience, which will post soon.

Add advancing age’s immunosenescence as yet another challenge to the long and growing list of formidable ways that cancer cells, and the tumor microenvironment, evade our immune response.

An Ever-Expanding Armamentarium

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

The field of immunotherapies took off with the immune checkpoint inhibitors, first approved by the FDA in 2011, that take the brakes off of T cells, with the programmed death-1 (PD-1), PD-ligand1, and anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies.

But we’re clearly learning they are not enough to prevail over cancer with common recurrences, only short term success in most patients, with some notable exceptions. Adding other immune response strategies, such as a vaccine, or antibody-drug conjugates, or engineered T cells, are showing improved chances for success.

Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines

There are many therapeutic cancer vaccines in the works, as reviewed in depth here.

Here’s a list of ongoing clinical trials of cancer vaccines. You’ll note most of these are on top of a checkpoint inhibitor and use personalized neoantigens (cancer cell surface proteins) derived from sequencing (whole-exome or whole genome, RNA-sequencing and HLA-profiling) the patient’s tumor.

An example of positive findings is with the combination of an mRNA-nanoparticle vaccine with up to 34 personalized neoantigens and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) vs pembrolizumab alone in advanced melanoma after resection, with improved outcomes at 3-year follow-up, cutting death or relapse rate in half.

Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADC)

There is considerable excitement about antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) whereby a linker is used to attach a chemotherapy agent to the checkpoint inhibitor antibody, specifically targeting the cancer cell and facilitating entry of the chemotherapy into the cell. Akin to these are bispecific antibodies (BiTEs, binding to a tumor antigen and T cell receptor simultaneously), both of these conjugates acting as “biologic” or “guided” missiles.

A very good example of the potency of an ADC was seen in a “HER2-low” breast cancer randomized trial. The absence or very low expression or amplification of the HER2 receptor is common in breast cancer and successful treatment has been elusive. A randomized trial of an ADC (trastuzumab deruxtecan) compared to physician’s choice therapy demonstrated a marked success for progression-free survival in HER2-low patients, which was characterized as “unheard-of success” by media coverage.

This strategy is being used to target some of the most difficult cancer driver mutations such as TP53 and KRAS.

Oncolytic Viruses

Modifying viruses to infect the tumor and make it more visible to the immune system, potentiating anti-tumor responses, known as oncolytic viruses, have been proposed as a way to rev up the immune response for a long time but without positive Phase 3 clinical trials.

After decades of failure, a recent trial in refractory bladder cancer showed marked success, along with others, summarized here, now providing very encouraging results. It looks like oncolytic viruses are on a comeback path.

Engineering T Cells (Chimeric Antigen Receptor [CAR-T])

As I recently reviewed, there are over 500 ongoing clinical trials to build on the success of the first CAR-T approval for leukemia 7 years ago. I won’t go through that all again here, but to reiterate most of the success to date has been in “liquid” blood (leukemia and lymphoma) cancer tumors. This week in Nature is the discovery of a T cell cancer mutation, a gene fusion CARD11-PIK3R3, from a T cell lymphoma that can potentially be used to augment CAR-T efficacy. It has pronounced and prolonged effects in the experimental model. Instead of 1 million cells needed for treatment, even 20,000 were enough to melt the tumor. This is a noteworthy discovery since CAR-T work to date has largely not exploited such naturally occurring mutations, while instead concentrating on those seen in the patient’s set of key tumor mutations.

As currently conceived, CAR-T, and what is being referred to more broadly as adoptive cell therapies, involves removing T cells from the patient’s body and engineering their activation, then reintroducing them back to the patient. This is laborious, technically difficult, and very expensive. Recently, the idea of achieving all of this via an injection of virus that specifically infects T cells and inserts the genes needed, was advanced by two biotech companies with preclinical results, one in non-human primates.

Gearing up to meet the challenge of solid tumor CAR-T intervention, there’s more work using CRISPR genome editing of T cell receptors. A.I. is increasingly being exploited to process the data from sequencing and identify optimal neoantigens.

Instead of just CAR-T, we’re seeing the emergence of CAR-macrophage and CAR-natural killer (NK) cells strategies, and rapidly expanding potential combinations of all the strategies I’ve mentioned. No less, there’s been maturation of on-off suicide switches programmed in, to limit cytokine release and promote safety of these interventions. Overall, major side effects of immunotherapies are not only cytokine release syndromes, but also include interstitial pneumonitis and neurotoxicity.

Summary

Given the multitude of ways cancer cells and tumor tissue can evade our immune response, durably successful treatment remains a daunting challenge. But the ingenuity of so many different approaches to unleash our immune response, and their combinations, provides considerable hope that we’ll increasingly meet the challenge in the years ahead. We have clearly learned that combining different immunotherapy strategies will be essential for many patients with the most resilient solid tumors.

Of concern, as noted by a recent editorial in The Lancet, entitled “Cancer Research Equity: Innovations For The Many, Not The Few,” is that these individualized, sophisticated strategies are not scalable; they will have limited reach and benefit. The movement towards “off the shelf” CAR-T and inexpensive, orally active checkpoint inhibitors may help mitigate this issue.

Notwithstanding this important concern, we’re seeing an array of diverse and potent immunotherapy strategies that are providing highly encouraging results, engendering more excitement than we’ve seen in this space for some time. These should propel substantial improvements in outcomes for patients in the years ahead. It can’t happen soon enough.

Thanks for reading this edition of Ground Truths. If you found it informative, please share it with your colleagues.

Dr. Topol has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Dexcom; Illumina; Molecular Stethoscope; Quest Diagnostics; Blue Cross Blue Shield Association. Received research grant from National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-Term Follow-Up Emphasizes HPV Vaccination Importance

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I want to briefly discuss a critically important topic that cannot be overly emphasized. It is the relevance, the importance, the benefits, and the outcome of HPV vaccination.

The paper I’m referring to was published in Pediatrics in October 2023. It’s titled, “Ten-Year Follow-up of 9-Valent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Immunogenicity, Effectiveness, and Safety.”

Let me emphasize that we’re talking about a 10-year follow-up. In this particular paper and analysis, 301 boys — I emphasize boys — were included and 971 girls at 40 different sites in 13 countries, who received the 9-valent vaccine, which includes HPV 16, 18, and seven other types.

Most importantly, there was not a single case. Not one. Let me repeat this: There was not a single case of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, or worse, or condyloma in either males or females. There was not a single case in over 1000 individuals with a follow-up of more than 10 years.

It is difficult to overstate the magnitude of the benefit associated with HPV vaccination for our children and young adults on their risk of developing highly relevant, life-changing, potentially deadly cancers.

For those of you who are interested in this topic — which should include almost all of you, if not all of you — I encourage you to read this very important follow-up paper, again, demonstrating the simple, overwhelming magnitude of the benefit of HPV vaccination. I thank you for your attention.

Dr. Markman is a professor in the department of medical oncology and therapeutics research, City of Hope, Duarte, California, and president of medicine and science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, and Phoenix. He disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline; AstraZeneca.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I want to briefly discuss a critically important topic that cannot be overly emphasized. It is the relevance, the importance, the benefits, and the outcome of HPV vaccination.

The paper I’m referring to was published in Pediatrics in October 2023. It’s titled, “Ten-Year Follow-up of 9-Valent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Immunogenicity, Effectiveness, and Safety.”

Let me emphasize that we’re talking about a 10-year follow-up. In this particular paper and analysis, 301 boys — I emphasize boys — were included and 971 girls at 40 different sites in 13 countries, who received the 9-valent vaccine, which includes HPV 16, 18, and seven other types.

Most importantly, there was not a single case. Not one. Let me repeat this: There was not a single case of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, or worse, or condyloma in either males or females. There was not a single case in over 1000 individuals with a follow-up of more than 10 years.

It is difficult to overstate the magnitude of the benefit associated with HPV vaccination for our children and young adults on their risk of developing highly relevant, life-changing, potentially deadly cancers.

For those of you who are interested in this topic — which should include almost all of you, if not all of you — I encourage you to read this very important follow-up paper, again, demonstrating the simple, overwhelming magnitude of the benefit of HPV vaccination. I thank you for your attention.

Dr. Markman is a professor in the department of medical oncology and therapeutics research, City of Hope, Duarte, California, and president of medicine and science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, and Phoenix. He disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline; AstraZeneca.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I want to briefly discuss a critically important topic that cannot be overly emphasized. It is the relevance, the importance, the benefits, and the outcome of HPV vaccination.

The paper I’m referring to was published in Pediatrics in October 2023. It’s titled, “Ten-Year Follow-up of 9-Valent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Immunogenicity, Effectiveness, and Safety.”

Let me emphasize that we’re talking about a 10-year follow-up. In this particular paper and analysis, 301 boys — I emphasize boys — were included and 971 girls at 40 different sites in 13 countries, who received the 9-valent vaccine, which includes HPV 16, 18, and seven other types.

Most importantly, there was not a single case. Not one. Let me repeat this: There was not a single case of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, or worse, or condyloma in either males or females. There was not a single case in over 1000 individuals with a follow-up of more than 10 years.

It is difficult to overstate the magnitude of the benefit associated with HPV vaccination for our children and young adults on their risk of developing highly relevant, life-changing, potentially deadly cancers.

For those of you who are interested in this topic — which should include almost all of you, if not all of you — I encourage you to read this very important follow-up paper, again, demonstrating the simple, overwhelming magnitude of the benefit of HPV vaccination. I thank you for your attention.

Dr. Markman is a professor in the department of medical oncology and therapeutics research, City of Hope, Duarte, California, and president of medicine and science, City of Hope Atlanta, Chicago, and Phoenix. He disclosed ties with GlaxoSmithKline; AstraZeneca.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians as First Responders II

I recently wrote about a fledgling program here in Maine in which some emergency room physicians were being outfitted with equipment and communications gear that would allow them to respond on the fly to emergencies in the field when they weren’t working in the hospital. I questioned the rationale of using in-house personnel, already in short supply, for the few situations in which trained EMT personnel would usually be called. At the same time, I promised to return to the broader subject of the role of physicians as first responders in a future letter. And, here it is.

Have you ever been on a plane or at a large public gathering and the public addressed system crackled, “Is there a doctor on board” or in the audience? Or have you been on the highway and come upon a fresh accident in which it appears that there may have been injuries? Or at a youth soccer game in which a player has been injured and is still on the ground?

How do you usually respond in situations like this? Do you immediately identify yourself as a physician? Or, do you routinely shy away from involvement? What thoughts run through your head?

Do you feel your training and experience with emergencies is so outdated that you doubt you could be of any assistance? Has your practice become so specialized that you aren’t comfortable with anything outside of your specialty? Maybe getting involved is likely to throw your already tight travel schedule into disarray? Or are you afraid that should something go wrong while you were helping out you could be sued?

Keeping in mind that I am a retired septuagenarian pediatrician more than a decade removed from active practice, I would describe my usual response to these situations as “attentive hovering.” I position myself to have a good view of the victim and watch to see if there are any other responders. Either because of their personality or their experience, often there is someone who steps forward to help. Trained EMTs seem to have no hesitancy going into action. If I sense things aren’t going well, or the victim is a child, I will identify myself as a retired pediatrician and offer my assistance. Even if the response given by others seems appropriate, I may still eventually identify myself, maybe to lend an air of legitimacy to the process.

What are the roots of my hesitancy? I have found that I generally have little to add when there is a trained first responder on hand. They have been-there-and-done-that far more recently than I have. They know how to stabilize potential or obvious fractures. They know how to position the victim for transport. Even when I am in an environment where my medical background is already known, I yield to the more recently experienced first responders.

I don’t particularly worry about being sued. Every state has Good Samaritan laws. Although the laws vary from state to state, here in Maine I feel comfortable with the good sense of my fellow citizens. I understand if you live or practice in a more litigious environment you may be more concerned. On an airplane there is the Aviation Medical Assistant Act, which became law in 1998, and provides us with some extra protection.

What if there is a situation in which even with my outdated skills I seem to be the only show in town? Fortunately, that situation hasn’t occurred for me in quite a few years, but the odds are that one might occur. In almost 1 out of 600 airline flights, there is an inflight emergency. I tend to hang out with other septuagenarians and octogenarians doing active things. And I frequent youth athletic events where there is unlikely to be a first responder assigned to the event.

Should I be doing more to update my skills? It’s been a while since I refreshed by CPR techniques. I can’t recall the last time I handled a defibrillator. Should I be learning more about exsanguination prevention techniques?

Every so often there are some rumblings to mandate that all physicians should be required to update these first responder skills to maintain their license or certification. That wouldn’t cover those of us who are retired or who no longer practice medicine. And, I’m not sure we need to add another layer to the system. I think there are enough of us out there who would like to add ourselves to the first responder population, maybe not as fully trained experts but as folks who would like to be more ready to help by updating old or seldom-used skills.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

I recently wrote about a fledgling program here in Maine in which some emergency room physicians were being outfitted with equipment and communications gear that would allow them to respond on the fly to emergencies in the field when they weren’t working in the hospital. I questioned the rationale of using in-house personnel, already in short supply, for the few situations in which trained EMT personnel would usually be called. At the same time, I promised to return to the broader subject of the role of physicians as first responders in a future letter. And, here it is.

Have you ever been on a plane or at a large public gathering and the public addressed system crackled, “Is there a doctor on board” or in the audience? Or have you been on the highway and come upon a fresh accident in which it appears that there may have been injuries? Or at a youth soccer game in which a player has been injured and is still on the ground?

How do you usually respond in situations like this? Do you immediately identify yourself as a physician? Or, do you routinely shy away from involvement? What thoughts run through your head?

Do you feel your training and experience with emergencies is so outdated that you doubt you could be of any assistance? Has your practice become so specialized that you aren’t comfortable with anything outside of your specialty? Maybe getting involved is likely to throw your already tight travel schedule into disarray? Or are you afraid that should something go wrong while you were helping out you could be sued?

Keeping in mind that I am a retired septuagenarian pediatrician more than a decade removed from active practice, I would describe my usual response to these situations as “attentive hovering.” I position myself to have a good view of the victim and watch to see if there are any other responders. Either because of their personality or their experience, often there is someone who steps forward to help. Trained EMTs seem to have no hesitancy going into action. If I sense things aren’t going well, or the victim is a child, I will identify myself as a retired pediatrician and offer my assistance. Even if the response given by others seems appropriate, I may still eventually identify myself, maybe to lend an air of legitimacy to the process.

What are the roots of my hesitancy? I have found that I generally have little to add when there is a trained first responder on hand. They have been-there-and-done-that far more recently than I have. They know how to stabilize potential or obvious fractures. They know how to position the victim for transport. Even when I am in an environment where my medical background is already known, I yield to the more recently experienced first responders.

I don’t particularly worry about being sued. Every state has Good Samaritan laws. Although the laws vary from state to state, here in Maine I feel comfortable with the good sense of my fellow citizens. I understand if you live or practice in a more litigious environment you may be more concerned. On an airplane there is the Aviation Medical Assistant Act, which became law in 1998, and provides us with some extra protection.

What if there is a situation in which even with my outdated skills I seem to be the only show in town? Fortunately, that situation hasn’t occurred for me in quite a few years, but the odds are that one might occur. In almost 1 out of 600 airline flights, there is an inflight emergency. I tend to hang out with other septuagenarians and octogenarians doing active things. And I frequent youth athletic events where there is unlikely to be a first responder assigned to the event.

Should I be doing more to update my skills? It’s been a while since I refreshed by CPR techniques. I can’t recall the last time I handled a defibrillator. Should I be learning more about exsanguination prevention techniques?

Every so often there are some rumblings to mandate that all physicians should be required to update these first responder skills to maintain their license or certification. That wouldn’t cover those of us who are retired or who no longer practice medicine. And, I’m not sure we need to add another layer to the system. I think there are enough of us out there who would like to add ourselves to the first responder population, maybe not as fully trained experts but as folks who would like to be more ready to help by updating old or seldom-used skills.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

I recently wrote about a fledgling program here in Maine in which some emergency room physicians were being outfitted with equipment and communications gear that would allow them to respond on the fly to emergencies in the field when they weren’t working in the hospital. I questioned the rationale of using in-house personnel, already in short supply, for the few situations in which trained EMT personnel would usually be called. At the same time, I promised to return to the broader subject of the role of physicians as first responders in a future letter. And, here it is.

Have you ever been on a plane or at a large public gathering and the public addressed system crackled, “Is there a doctor on board” or in the audience? Or have you been on the highway and come upon a fresh accident in which it appears that there may have been injuries? Or at a youth soccer game in which a player has been injured and is still on the ground?

How do you usually respond in situations like this? Do you immediately identify yourself as a physician? Or, do you routinely shy away from involvement? What thoughts run through your head?

Do you feel your training and experience with emergencies is so outdated that you doubt you could be of any assistance? Has your practice become so specialized that you aren’t comfortable with anything outside of your specialty? Maybe getting involved is likely to throw your already tight travel schedule into disarray? Or are you afraid that should something go wrong while you were helping out you could be sued?

Keeping in mind that I am a retired septuagenarian pediatrician more than a decade removed from active practice, I would describe my usual response to these situations as “attentive hovering.” I position myself to have a good view of the victim and watch to see if there are any other responders. Either because of their personality or their experience, often there is someone who steps forward to help. Trained EMTs seem to have no hesitancy going into action. If I sense things aren’t going well, or the victim is a child, I will identify myself as a retired pediatrician and offer my assistance. Even if the response given by others seems appropriate, I may still eventually identify myself, maybe to lend an air of legitimacy to the process.

What are the roots of my hesitancy? I have found that I generally have little to add when there is a trained first responder on hand. They have been-there-and-done-that far more recently than I have. They know how to stabilize potential or obvious fractures. They know how to position the victim for transport. Even when I am in an environment where my medical background is already known, I yield to the more recently experienced first responders.

I don’t particularly worry about being sued. Every state has Good Samaritan laws. Although the laws vary from state to state, here in Maine I feel comfortable with the good sense of my fellow citizens. I understand if you live or practice in a more litigious environment you may be more concerned. On an airplane there is the Aviation Medical Assistant Act, which became law in 1998, and provides us with some extra protection.

What if there is a situation in which even with my outdated skills I seem to be the only show in town? Fortunately, that situation hasn’t occurred for me in quite a few years, but the odds are that one might occur. In almost 1 out of 600 airline flights, there is an inflight emergency. I tend to hang out with other septuagenarians and octogenarians doing active things. And I frequent youth athletic events where there is unlikely to be a first responder assigned to the event.

Should I be doing more to update my skills? It’s been a while since I refreshed by CPR techniques. I can’t recall the last time I handled a defibrillator. Should I be learning more about exsanguination prevention techniques?

Every so often there are some rumblings to mandate that all physicians should be required to update these first responder skills to maintain their license or certification. That wouldn’t cover those of us who are retired or who no longer practice medicine. And, I’m not sure we need to add another layer to the system. I think there are enough of us out there who would like to add ourselves to the first responder population, maybe not as fully trained experts but as folks who would like to be more ready to help by updating old or seldom-used skills.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Bivalent Vaccines Protect Even Children Who’ve Had COVID

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It was only 3 years ago when we called the pathogen we now refer to as the coronavirus “nCOV-19.” It was, in many ways, more descriptive than what we have today. The little “n” there stood for “novel” — and it was really that little “n” that caused us all the trouble.

You see, coronaviruses themselves were not really new to us. Understudied, perhaps, but with four strains running around the globe at any time giving rise to the common cold, these were viruses our bodies understood.

But Instead of acting like a cold, it acted like nothing we had seen before, at least in our lifetime. The story of the pandemic is very much a bildungsroman of our immune systems — a story of how our immunity grew up.

The difference between the start of 2020 and now, when infections with the coronavirus remain common but not as deadly, can be measured in terms of immune education. Some of our immune systems were educated by infection, some by vaccination, and many by both.

When the first vaccines emerged in December 2020, the opportunity to educate our immune systems was still huge. Though, at the time, an estimated 20 million had been infected in the US and 350,000 had died, there was a large population that remained immunologically naive. I was one of them.

If 2020 into early 2021 was the era of immune education, the postvaccine period was the era of the variant. From one COVID strain to two, to five, to innumerable, our immune memory — trained on a specific version of the virus or its spike protein — became imperfect again. Not naive; these variants were not “novel” in the way COVID-19 was novel, but they were different. And different enough to cause infection.

Following the playbook of another virus that loves to come dressed up in different outfits, the flu virus, we find ourselves in the booster era — a world where yearly doses of a vaccine, ideally matched to the variants circulating when the vaccine is given, are the recommendation if not the norm.

But questions remain about the vaccination program, particularly around who should get it. And two populations with big question marks over their heads are (1) people who have already been infected and (2) kids, because their risk for bad outcomes is so much lower.

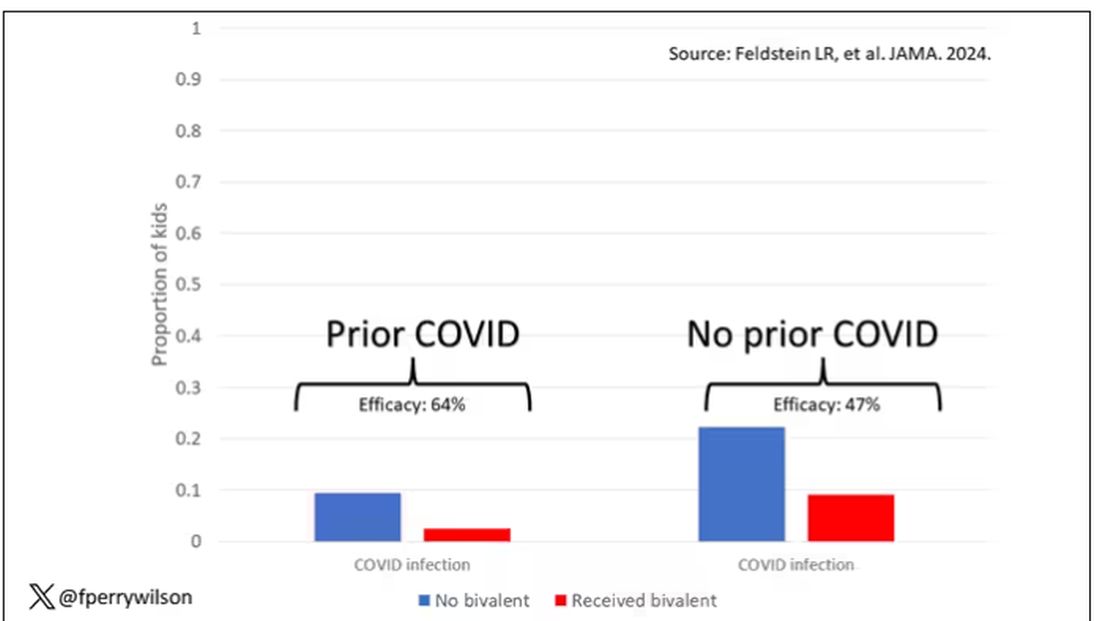

This week, we finally have some evidence that can shed light on these questions. The study under the spotlight is this one, appearing in JAMA, which tries to analyze the ability of the bivalent vaccine — that’s the second one to come out, around September 2022 — to protect kids from COVID-19.

Now, right off the bat, this was not a randomized trial. The studies that established the viability of the mRNA vaccine platform were; they happened before the vaccine was authorized. But trials of the bivalent vaccine were mostly limited to proving immune response, not protection from disease.

Nevertheless, with some good observational methods and some statistics, we can try to tease out whether bivalent vaccines in kids worked.

The study combines three prospective cohort studies. The details are in the paper, but what you need to know is that the special sauce of these studies was that the kids were tested for COVID-19 on a weekly basis, whether they had symptoms or not. This is critical because asymptomatic infections can transmit COVID-19.

Let’s do the variables of interest. First and foremost, the bivalent vaccine. Some of these kids got the bivalent vaccine, some didn’t. Other key variables include prior vaccination with the monovalent vaccine. Some had been vaccinated with the monovalent vaccine before, some hadn’t. And, of course, prior infection. Some had been infected before (based on either nasal swabs or blood tests).

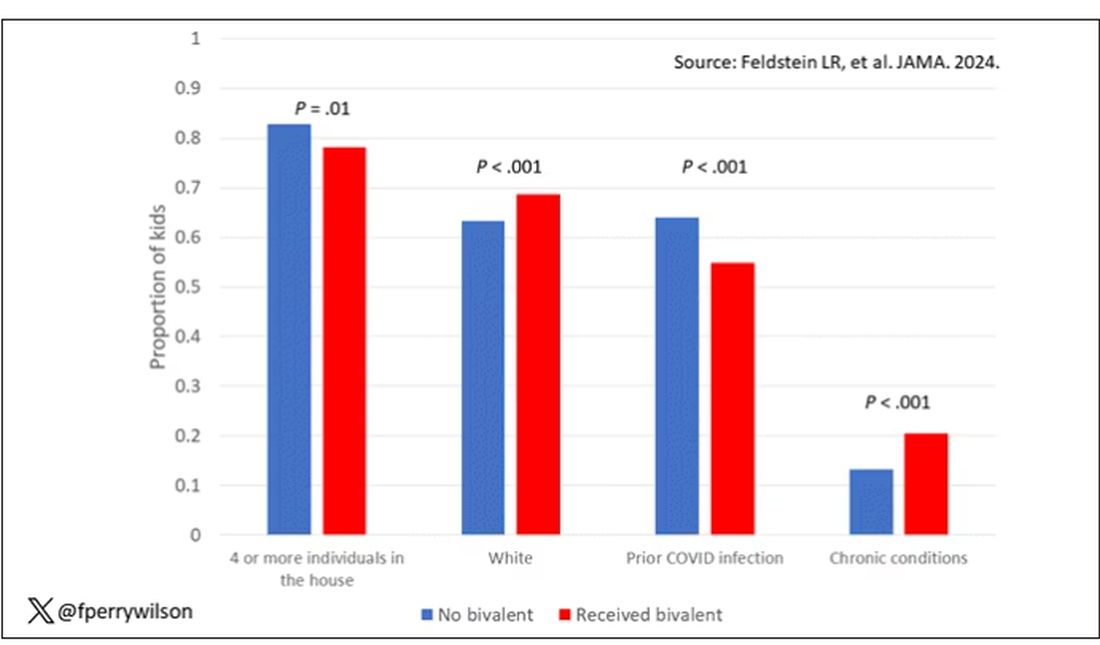

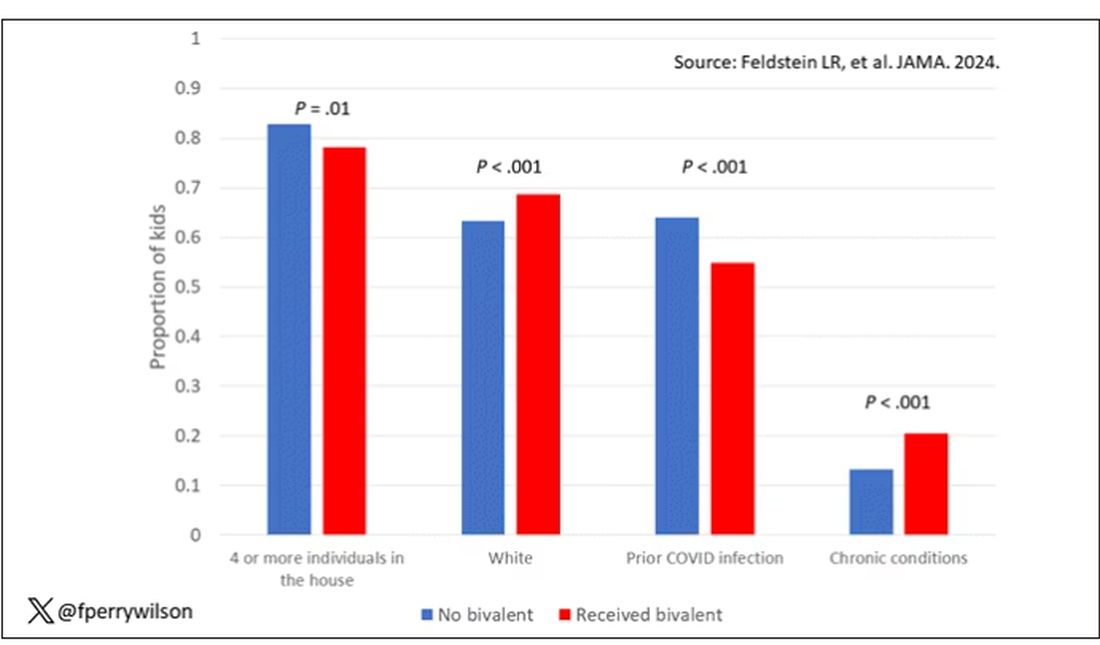

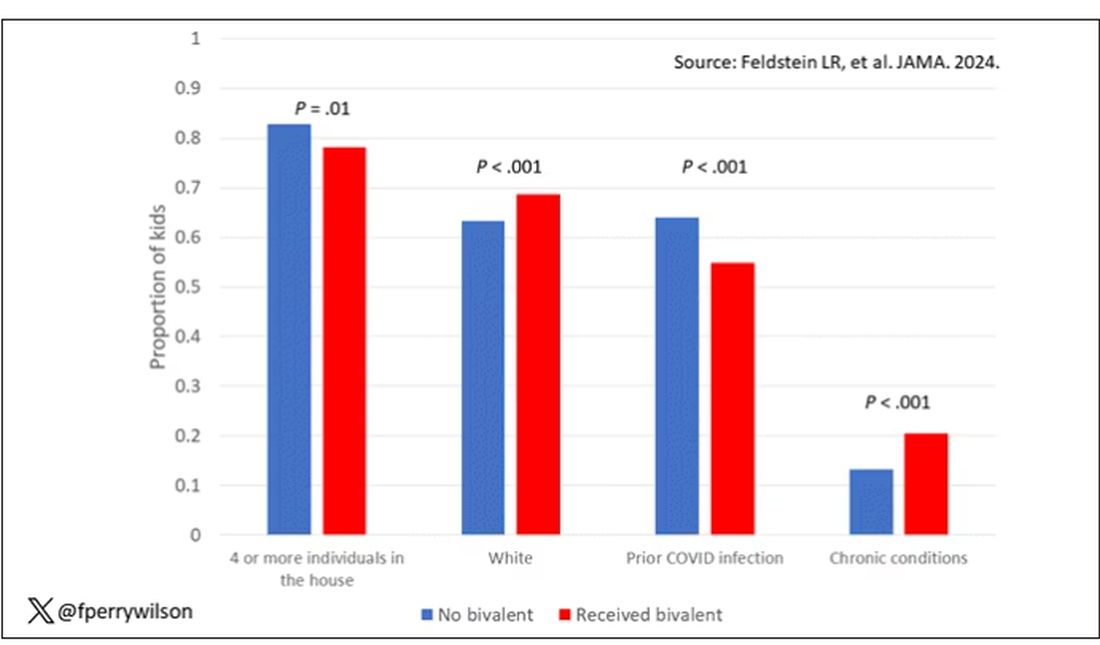

Let’s focus first on the primary exposure of interest: getting that bivalent vaccine. Again, this was not randomly assigned; kids who got the bivalent vaccine were different from those who did not. In general, they lived in smaller households, they were more likely to be White, less likely to have had a prior COVID infection, and quite a bit more likely to have at least one chronic condition.

To me, this constellation of factors describes a slightly higher-risk group; it makes sense that they were more likely to get the second vaccine.

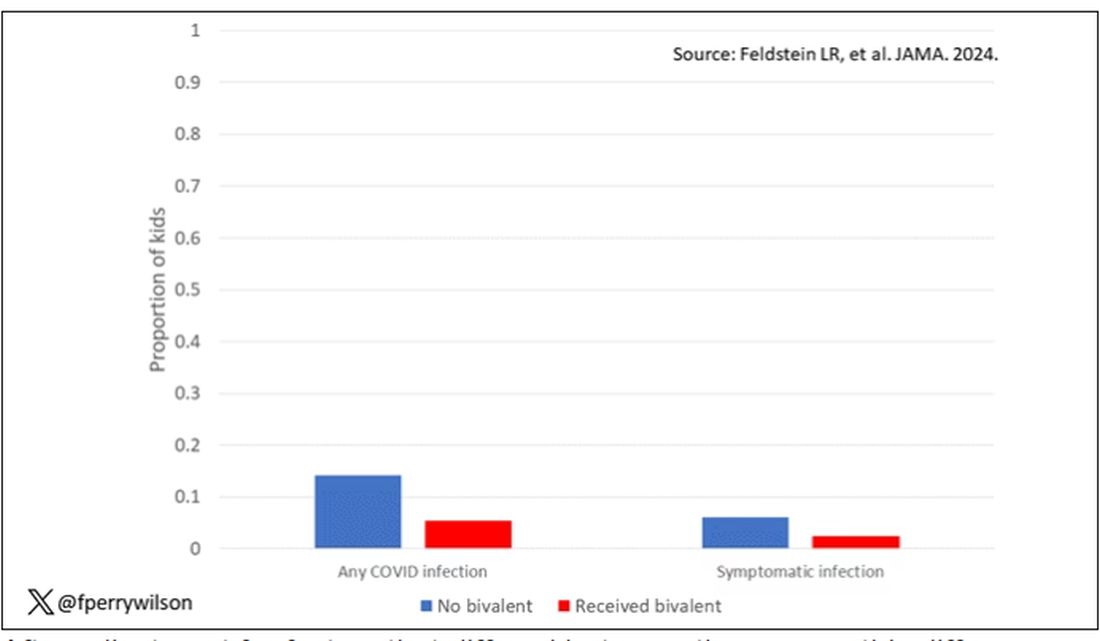

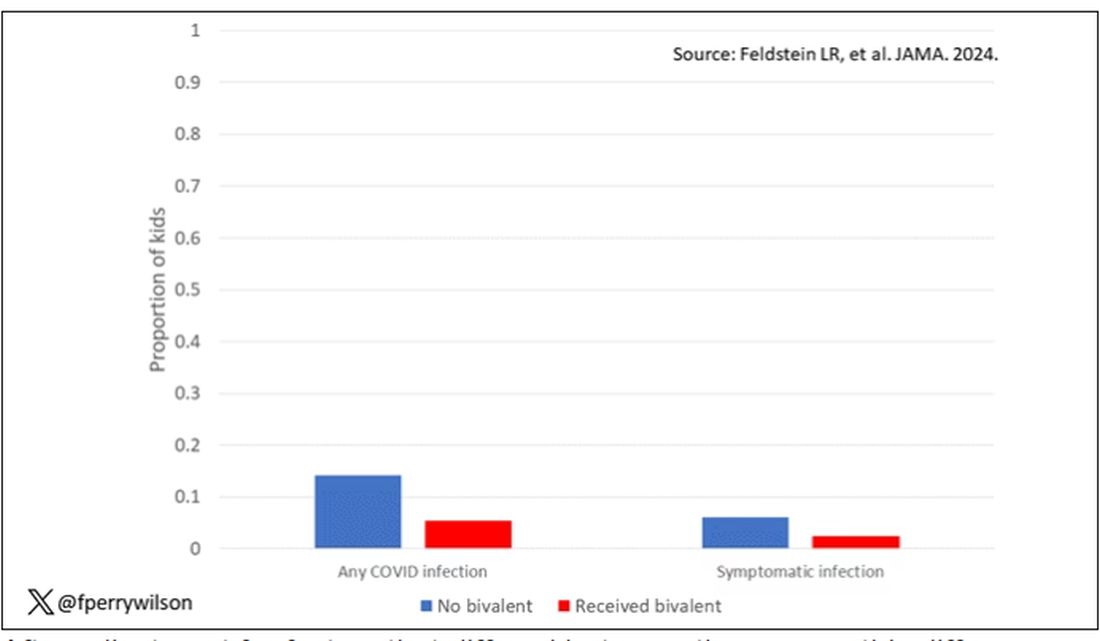

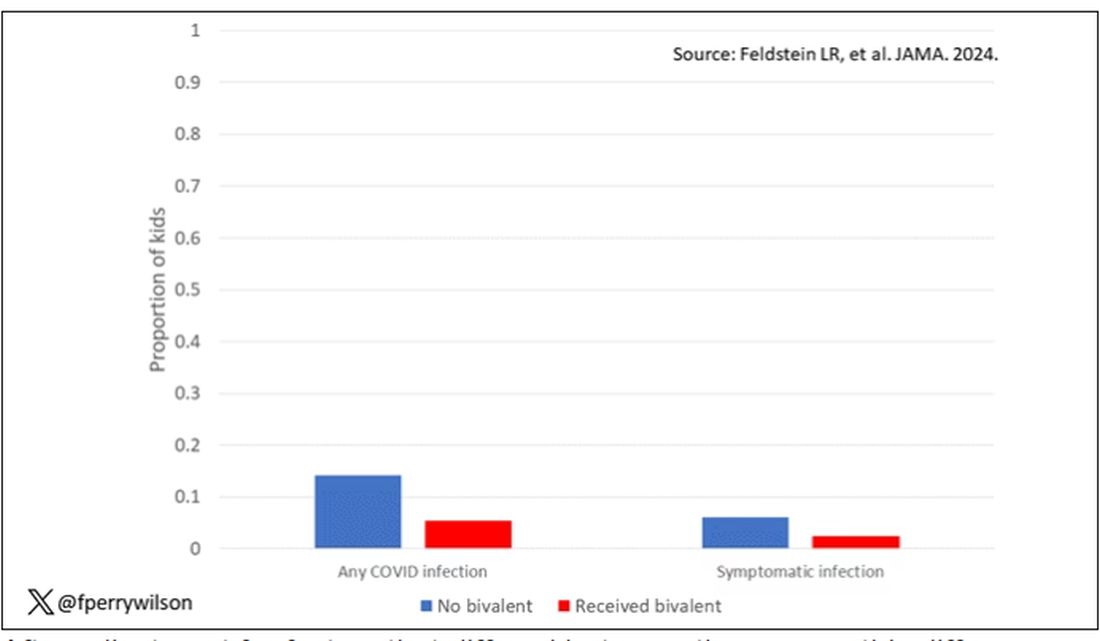

Given those factors, what were the rates of COVID infection? After nearly a year of follow-up, around 15% of the kids who hadn’t received the bivalent vaccine got infected compared with 5% of the vaccinated kids. Symptomatic infections represented roughly half of all infections in both groups.

After adjustment for factors that differed between the groups, this difference translated into a vaccine efficacy of about 50% in this population. That’s our first data point. Yes, the bivalent vaccine worked. Not amazingly, of course. But it worked.

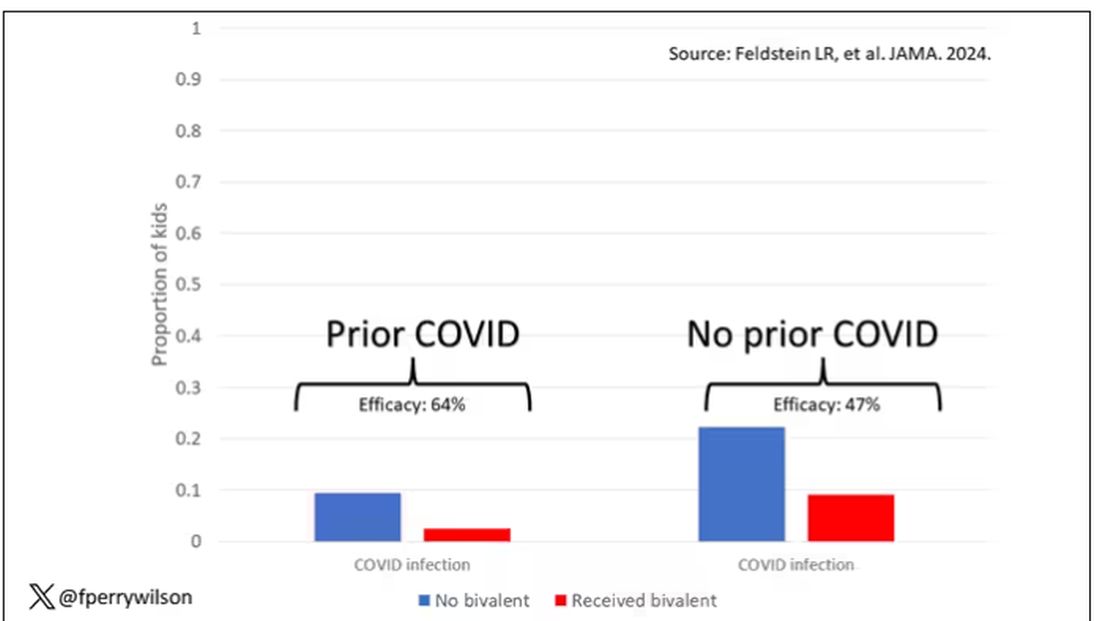

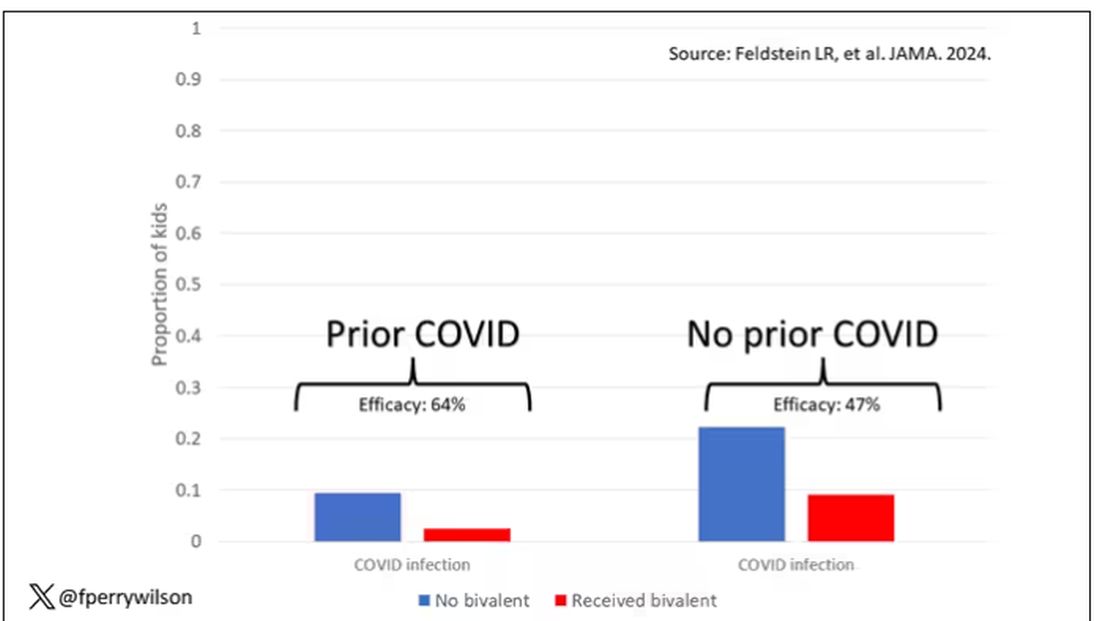

What about the kids who had had a prior COVID infection? Somewhat surprisingly, the vaccine was just as effective in this population, despite the fact that their immune systems already had some knowledge of COVID. Ten percent of unvaccinated kids got infected, even though they had been infected before. Just 2.5% of kids who received the bivalent vaccine got infected, suggesting some synergy between prior infection and vaccination.

These data suggest that the bivalent vaccine did reduce the risk for COVID infection in kids. All good. But the piece still missing is how severe these infections were. It doesn’t appear that any of the 426 infections documented in this study resulted in hospitalization or death, fortunately. And no data are presented on the incidence of multisystem inflammatory syndrome of children, though given the rarity, I’d be surprised if any of these kids have this either.

So where are we? Well, it seems that the narrative out there that says “the vaccines don’t work” or “the vaccines don’t work if you’ve already been infected” is probably not true. They do work. This study and others in adults show that. If they work to reduce infections, as this study shows, they will also work to reduce deaths. It’s just that death is fortunately so rare in children that the number needed to vaccinate to prevent one death is very large. In that situation, the decision to vaccinate comes down to the risks associated with vaccination. So far, those risk seem very minimal.

Perhaps falling into a flu-like yearly vaccination schedule is not simply the result of old habits dying hard. Maybe it’s actually not a bad idea.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It was only 3 years ago when we called the pathogen we now refer to as the coronavirus “nCOV-19.” It was, in many ways, more descriptive than what we have today. The little “n” there stood for “novel” — and it was really that little “n” that caused us all the trouble.

You see, coronaviruses themselves were not really new to us. Understudied, perhaps, but with four strains running around the globe at any time giving rise to the common cold, these were viruses our bodies understood.