User login

Yellow Nodule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Solitary Sclerotic Fibroma

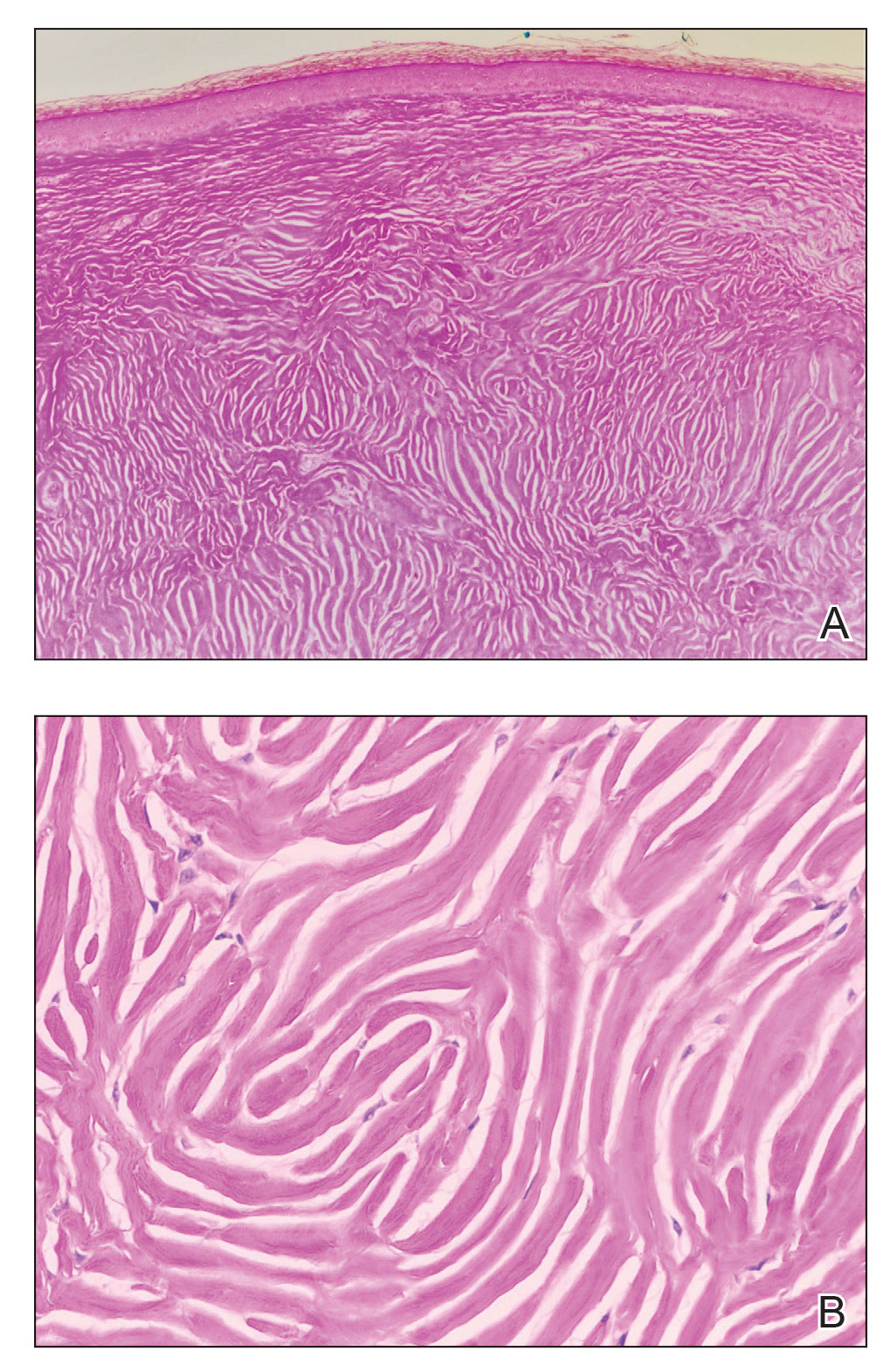

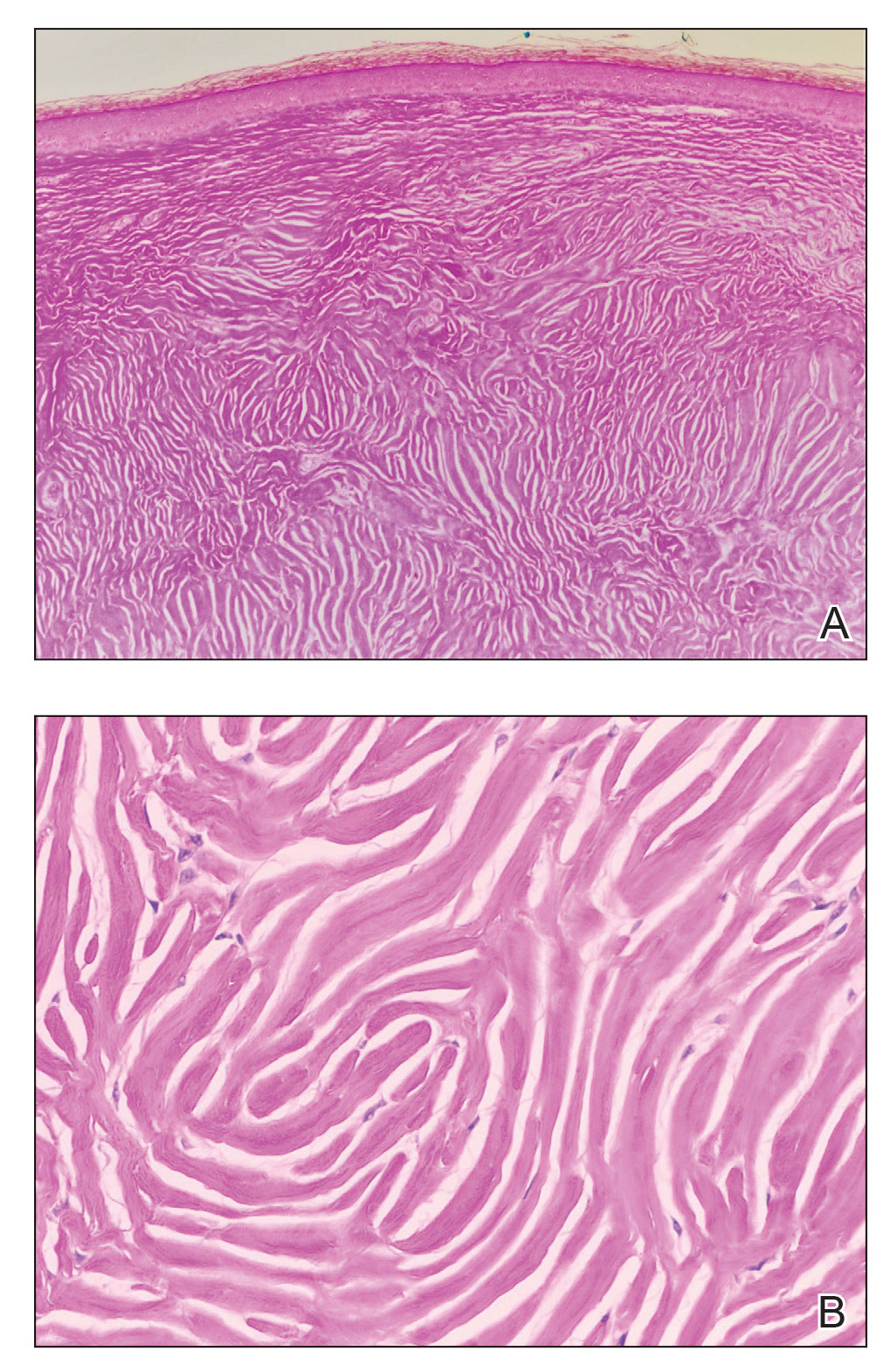

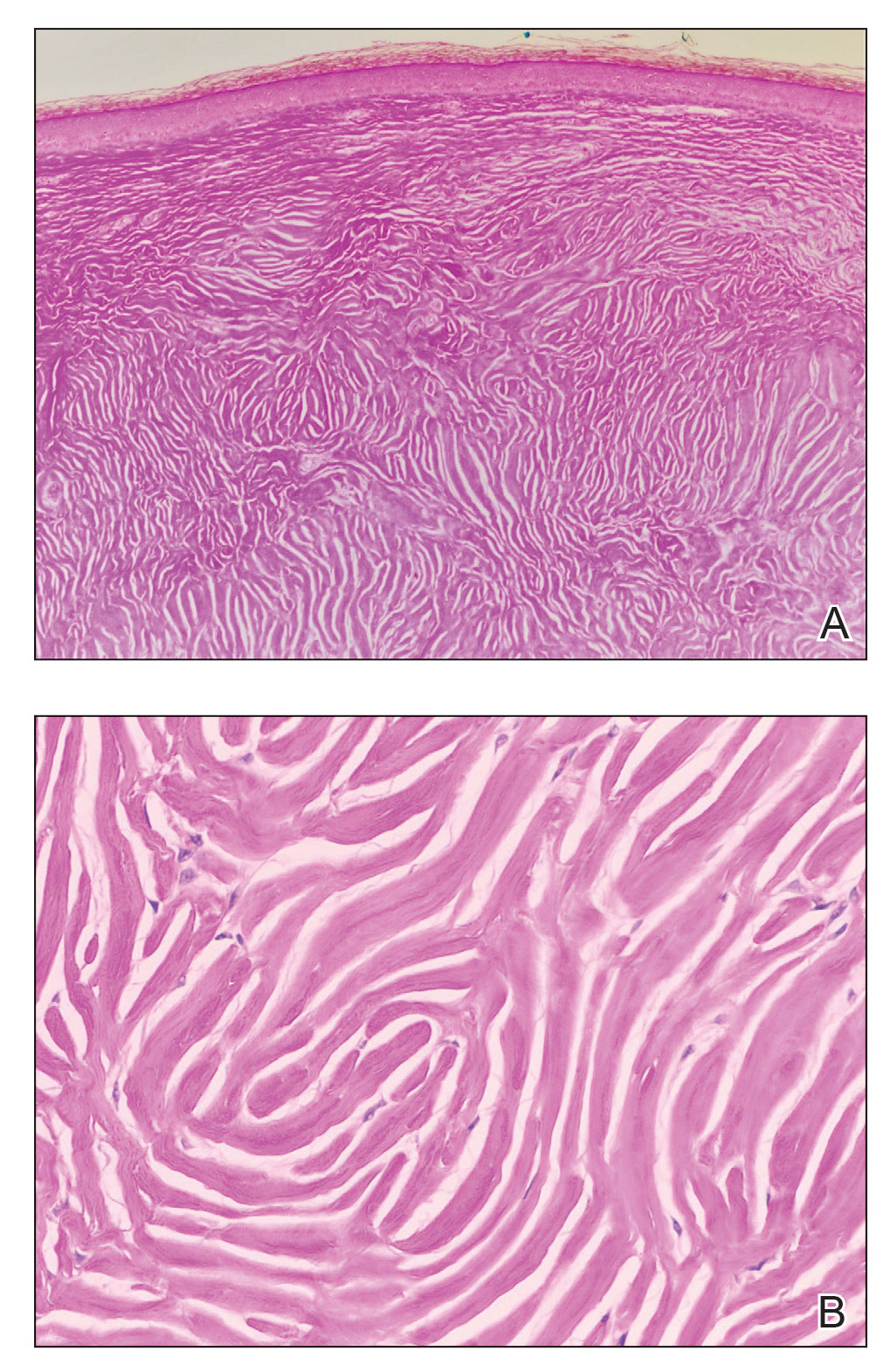

Based on the clinical and histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with solitary sclerotic fibroma (SF). Sclerotic fibroma is a rare benign tumor that first was described in 1972 by Weary et al1 in the oral mucosa of a patient with Cowden syndrome, a genodermatosis associated with multiple benign and malignant tumors. Rapini and Golitz2 reported solitary SF in 11 otherwise-healthy individuals with no signs of multiple hamartoma syndrome. Solitary SF is a sporadic benign condition, whereas multiple lesions are suggestive of Cowden syndrome. Solitary SF most commonly appears as an asymptomatic white-yellow papule or nodule on the head or neck, though larger tumors have been reported on the trunk and extremities.3 Histologic features of solitary SF include a well-circumscribed dermal nodule composed of eosinophilic dense collagen bundles arranged in a plywoodlike pattern (Figure). Immunohistochemistry is positive for CD34 and vimentin but negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, and neuron-specific enolase.4

The differential diagnosis of solitary SF of the head and neck includes sebaceous adenoma, pilar cyst, nodular basal cell carcinoma, and giant molluscum contagiosum. Sebaceous adenomas usually are solitary yellow nodules less than 1 cm in diameter and located on the head and neck. They are the most common sebaceous neoplasm associated with Muir-Torre syndrome, an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by sebaceous adenoma or carcinoma and colorectal cancer. Histopathology demonstrates well-circumscribed, round aggregations of mature lipid-filled sebocytes with a rim of basaloid germinative cells at the periphery. Pilar cysts typically are flesh-colored subcutaneous nodules on the scalp that are freely mobile over underlying tissue. Histopathology shows stratified squamous epithelium lining and trichilemmal keratinization. Nodular basal cell carcinoma has a pearly translucent appearance and arborizing telangiectases. Histopathology demonstrates nests of basaloid cells with palisading of the cells at the periphery. Giant solitary molluscum contagiosum is a dome-shaped, flesh-colored nodule with central umbilication. Histopathology reveals hyperplastic squamous epithelium with characteristic eosinophilic inclusion bodies above the basal layer.

Solitary SF can be difficult to diagnose based solely on the clinical presentation; thus biopsy with histologic evaluation is recommended. If SF is confirmed, the clinician should inquire about a family history of Cowden syndrome and then perform a total-body skin examination to check for multiple SF and other clinical hamartomas of Cowden syndrome such as trichilemmomas, acral keratosis, and oral papillomas.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry Jr WC, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden’s disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Rapini RP, Golitz LE. Sclerotic fibromas of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):266-271.

- Tosa M, Ansai S, Kuwahara H, et al. Two cases of sclerotic fibroma of the skin that mimicked keloids clinically. J Nippon Med Sch. 2018;85:283-286.

- High WA, Stewart D, Essary LR, et al. Sclerotic fibroma-like changes in various neoplastic and inflammatory skin lesions: is sclerotic fibroma a distinct entity? J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:373-378.

The Diagnosis: Solitary Sclerotic Fibroma

Based on the clinical and histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with solitary sclerotic fibroma (SF). Sclerotic fibroma is a rare benign tumor that first was described in 1972 by Weary et al1 in the oral mucosa of a patient with Cowden syndrome, a genodermatosis associated with multiple benign and malignant tumors. Rapini and Golitz2 reported solitary SF in 11 otherwise-healthy individuals with no signs of multiple hamartoma syndrome. Solitary SF is a sporadic benign condition, whereas multiple lesions are suggestive of Cowden syndrome. Solitary SF most commonly appears as an asymptomatic white-yellow papule or nodule on the head or neck, though larger tumors have been reported on the trunk and extremities.3 Histologic features of solitary SF include a well-circumscribed dermal nodule composed of eosinophilic dense collagen bundles arranged in a plywoodlike pattern (Figure). Immunohistochemistry is positive for CD34 and vimentin but negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, and neuron-specific enolase.4

The differential diagnosis of solitary SF of the head and neck includes sebaceous adenoma, pilar cyst, nodular basal cell carcinoma, and giant molluscum contagiosum. Sebaceous adenomas usually are solitary yellow nodules less than 1 cm in diameter and located on the head and neck. They are the most common sebaceous neoplasm associated with Muir-Torre syndrome, an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by sebaceous adenoma or carcinoma and colorectal cancer. Histopathology demonstrates well-circumscribed, round aggregations of mature lipid-filled sebocytes with a rim of basaloid germinative cells at the periphery. Pilar cysts typically are flesh-colored subcutaneous nodules on the scalp that are freely mobile over underlying tissue. Histopathology shows stratified squamous epithelium lining and trichilemmal keratinization. Nodular basal cell carcinoma has a pearly translucent appearance and arborizing telangiectases. Histopathology demonstrates nests of basaloid cells with palisading of the cells at the periphery. Giant solitary molluscum contagiosum is a dome-shaped, flesh-colored nodule with central umbilication. Histopathology reveals hyperplastic squamous epithelium with characteristic eosinophilic inclusion bodies above the basal layer.

Solitary SF can be difficult to diagnose based solely on the clinical presentation; thus biopsy with histologic evaluation is recommended. If SF is confirmed, the clinician should inquire about a family history of Cowden syndrome and then perform a total-body skin examination to check for multiple SF and other clinical hamartomas of Cowden syndrome such as trichilemmomas, acral keratosis, and oral papillomas.

The Diagnosis: Solitary Sclerotic Fibroma

Based on the clinical and histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with solitary sclerotic fibroma (SF). Sclerotic fibroma is a rare benign tumor that first was described in 1972 by Weary et al1 in the oral mucosa of a patient with Cowden syndrome, a genodermatosis associated with multiple benign and malignant tumors. Rapini and Golitz2 reported solitary SF in 11 otherwise-healthy individuals with no signs of multiple hamartoma syndrome. Solitary SF is a sporadic benign condition, whereas multiple lesions are suggestive of Cowden syndrome. Solitary SF most commonly appears as an asymptomatic white-yellow papule or nodule on the head or neck, though larger tumors have been reported on the trunk and extremities.3 Histologic features of solitary SF include a well-circumscribed dermal nodule composed of eosinophilic dense collagen bundles arranged in a plywoodlike pattern (Figure). Immunohistochemistry is positive for CD34 and vimentin but negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, and neuron-specific enolase.4

The differential diagnosis of solitary SF of the head and neck includes sebaceous adenoma, pilar cyst, nodular basal cell carcinoma, and giant molluscum contagiosum. Sebaceous adenomas usually are solitary yellow nodules less than 1 cm in diameter and located on the head and neck. They are the most common sebaceous neoplasm associated with Muir-Torre syndrome, an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by sebaceous adenoma or carcinoma and colorectal cancer. Histopathology demonstrates well-circumscribed, round aggregations of mature lipid-filled sebocytes with a rim of basaloid germinative cells at the periphery. Pilar cysts typically are flesh-colored subcutaneous nodules on the scalp that are freely mobile over underlying tissue. Histopathology shows stratified squamous epithelium lining and trichilemmal keratinization. Nodular basal cell carcinoma has a pearly translucent appearance and arborizing telangiectases. Histopathology demonstrates nests of basaloid cells with palisading of the cells at the periphery. Giant solitary molluscum contagiosum is a dome-shaped, flesh-colored nodule with central umbilication. Histopathology reveals hyperplastic squamous epithelium with characteristic eosinophilic inclusion bodies above the basal layer.

Solitary SF can be difficult to diagnose based solely on the clinical presentation; thus biopsy with histologic evaluation is recommended. If SF is confirmed, the clinician should inquire about a family history of Cowden syndrome and then perform a total-body skin examination to check for multiple SF and other clinical hamartomas of Cowden syndrome such as trichilemmomas, acral keratosis, and oral papillomas.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry Jr WC, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden’s disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Rapini RP, Golitz LE. Sclerotic fibromas of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):266-271.

- Tosa M, Ansai S, Kuwahara H, et al. Two cases of sclerotic fibroma of the skin that mimicked keloids clinically. J Nippon Med Sch. 2018;85:283-286.

- High WA, Stewart D, Essary LR, et al. Sclerotic fibroma-like changes in various neoplastic and inflammatory skin lesions: is sclerotic fibroma a distinct entity? J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:373-378.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry Jr WC, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden’s disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Rapini RP, Golitz LE. Sclerotic fibromas of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):266-271.

- Tosa M, Ansai S, Kuwahara H, et al. Two cases of sclerotic fibroma of the skin that mimicked keloids clinically. J Nippon Med Sch. 2018;85:283-286.

- High WA, Stewart D, Essary LR, et al. Sclerotic fibroma-like changes in various neoplastic and inflammatory skin lesions: is sclerotic fibroma a distinct entity? J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:373-378.

A 45-year-old woman was referred to dermatology by a primary care physician for evaluation of a raised skin lesion on the scalp. She was otherwise healthy. The lesion had been present for many years but recently grew in size. The patient reported that the lesion was subject to recurrent physical trauma and she wanted it removed. Physical examination revealed a 6×6-mm, domeshaped, yellow nodule on the left inferior parietal scalp. There were no similar lesions located elsewhere on the body. A shave removal was performed and sent for histopathologic evaluation.

DEI advances in dermatology unremarkable to date, studies find

suggest.

To evaluate diversity and career goals of graduating allopathic medical students pursuing careers in dermatology, corresponding author Matthew Mansh, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues drew from the 2016-2019 Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire for their study. The main outcome measures were the proportion of female students, students from racial and ethnic groups underrepresented in medicine (URM), and sexual minority (SM) students pursuing dermatology versus those pursuing other specialties, as well as the proportions and multivariable adjusted odds of intended career goals between students pursuing dermatology and those pursuing other specialties, and by sex, race, and ethnicity, and sexual orientation among students pursuing dermatology.

Of the 58,077 graduating students, 49% were women, 15% were URM, and 6% were SM. The researchers found that women pursuing dermatology were significantly less likely than women pursuing other specialties to identify as URM (11.6% vs. 17.2%; P < .001) or SM (1.9% vs. 5.7%; P < .001).

In multivariable-adjusted analyses of all students, those pursuing dermatology compared with other specialties had decreased odds of intending to care for underserved populations (18.3% vs. 34%; adjusted odd ratio, 0.40; P < .001), practice in underserved areas (12.7% vs. 25.9%; aOR, 0.40; P < .001), and practice public health (17% vs. 30.2%; aOR, 0.44; P < .001). The odds for pursuing research in their careers was greater among those pursuing dermatology (64.7% vs. 51.7%; aOR, 1.76; P < .001).

“Addressing health inequities and improving care for underserved patients is the responsibility of all dermatologists, and efforts are needed to increase diversity and interest in careers focused on underserved care among trainees in the dermatology workforce pipeline,” the authors concluded. They acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including lack of data delineating sex, sex assigned at birth, and gender identity, and lack of intersectional analyses between multiple minority identities and multiple career goals. “Importantly, diversity factors and their relationship to underserved care is likely multidimensional, and many students pursuing dermatology identified with multiple minority identities, highlighting the need for future studies focused on intersectionality,” they wrote.

Trends over 15 years

In a separate study, Jazzmin C. Williams, a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco, and coauthors drew from an Association of American Medical Colleges report of trainees’ and applicants’ self-reported race and ethnicity by specialty from 2005 to 2020 to evaluate diversity trends over the 15-year period. They found that Black and Latinx trainees were underrepresented in all specialties, but even more so in dermatology (mean annual rate ratios of 0.32 and 0.14, respectively), compared with those in primary care (mean annual RRs of 0.54 and 0.23) and those in specialty care (mean annual RRs of 0.39 and 0.18).

In other findings, the annual representation of Black trainees remained unchanged in dermatology between 2005 and 2020, but down-trended for primary (P < .001) and specialty care (P = .001). At the same time, representation of Latinx trainees remained unchanged in dermatology and specialty care but increased in primary care (P < .001). Finally, Black and Latinx race and ethnicity comprised a lower mean proportion of matriculating dermatology trainees (postgraduate year-2s) compared with annual dermatology applicants (4.01% vs. 5.97%, respectively, and 2.06% vs. 6.37% among Latinx; P < .001 for all associations).

“Much of these disparities can be attributed to the leaky pipeline – the disproportionate, stepwise reduction in racial and ethnic minority representation along the path to medicine,” the authors wrote. “This leaky pipeline is the direct result of structural racism, which includes, but is not limited to, historical and contemporary economic disinvestment from majority-minority schools, kindergarten through grade 12.” They concluded by stating that “dermatologists must intervene throughout the educational pipeline, including residency selection and mentorship, to effectively increase diversity.”

Solutions to address diversity

In an editorial accompanying the two studies published in the same issue of JAMA Dermatology, Ellen N. Pritchett, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology at Howard University, Washington, and Andrew J. Park, MD, MBA, and Rebecca Vasquez, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, offered several solutions to address diversity in the dermatology work force. They include:

Go beyond individual bias in recruitment. “A residency selection framework that meaningfully incorporates diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) will require more than strategies that address individual bias,” they wrote. “Departmental recruitment committees must become familiar with systems that serve to perpetuate individual bias, like institutional racism or practices that disproportionately favor non-URM versus URM individuals.”

Challenge the myth of meritocracy. “The inaccurate notion of meritocracy – that success purely derives from individual effort has become the foundation of residency selection,” the authors wrote. “Unfortunately, this view ignores the inequitably distributed sociostructural resources that limit the rewards of individual effort.”

Avoid tokenism in retention strategies. Tokenism, which they defined as “a symbolic addition of members from a marginalized group to give the impression of social inclusiveness and diversity without meaningful incorporation of DEI in the policies, processes, and culture,” can lead to depression, burnout, and attrition, they wrote. They advise leaders of dermatology departments to “review their residency selection framework to ensure that it allows for meaningful representation, inclusion, and equity among trainees and faculty to better support URM individuals at all levels.”

Omar N. Qutub, MD, a Portland, Ore.–based dermatologist who was asked to comment on the studies, characterized the findings by Dr. Mansh and colleagues as sobering. “It appears that there is work to do as far as improving diversity in the dermatology workforce that will likely benefit greatly from an honest and steadfast approach to equitable application standards as well as mentorship during all stages of the application process,” such as medical school and residency, said Dr. Qutub, who is the director of equity, diversity, and inclusion of the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference. “With a focused attempt, we are likely to matriculate more racial minorities into our residency programs, maximizing patient outcomes.”

As for the study by Ms. Williams and colleagues, he told this news organization that efforts toward recruiting URM students as well as sexual minority students “is likely to not only improve health inequities in underserved areas, but will also enrich the specialty as a whole, allowing for better understanding of our diverse patient population and [for us to] to deliver quality care more readily for people and in areas where the focus has often been limited.”

In an interview, Chesahna Kindred, MD, a Columbia, Md.–based dermatologist and immediate past chair of the National Medical Association dermatology section, pointed out that the number of Black physicians in the United States has increased by only 4% in the last 120 years. The study by Dr. Mansh and colleagues, she commented, “underscores what I’ve recognized in the last couple of years: Where are the Black male dermatologists? NMA Derm started recruiting this demographic aggressively about a year ago and started the Black Men in Derm events. Black male members of NMA Derm travel to the Student National Medical Association and NMA conference and hold a panel to expose Black male students into dermatology. This article provides the numbers needed to measure how successful this and other programs are to closing the equity gap.”

Ms. Williams reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Mansh reported receiving grants from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences outside the submitted work. Dr. Pritchett and colleagues reported having no relevant financial disclosures, as did Dr. Qutub and Dr. Kindred.

suggest.

To evaluate diversity and career goals of graduating allopathic medical students pursuing careers in dermatology, corresponding author Matthew Mansh, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues drew from the 2016-2019 Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire for their study. The main outcome measures were the proportion of female students, students from racial and ethnic groups underrepresented in medicine (URM), and sexual minority (SM) students pursuing dermatology versus those pursuing other specialties, as well as the proportions and multivariable adjusted odds of intended career goals between students pursuing dermatology and those pursuing other specialties, and by sex, race, and ethnicity, and sexual orientation among students pursuing dermatology.

Of the 58,077 graduating students, 49% were women, 15% were URM, and 6% were SM. The researchers found that women pursuing dermatology were significantly less likely than women pursuing other specialties to identify as URM (11.6% vs. 17.2%; P < .001) or SM (1.9% vs. 5.7%; P < .001).

In multivariable-adjusted analyses of all students, those pursuing dermatology compared with other specialties had decreased odds of intending to care for underserved populations (18.3% vs. 34%; adjusted odd ratio, 0.40; P < .001), practice in underserved areas (12.7% vs. 25.9%; aOR, 0.40; P < .001), and practice public health (17% vs. 30.2%; aOR, 0.44; P < .001). The odds for pursuing research in their careers was greater among those pursuing dermatology (64.7% vs. 51.7%; aOR, 1.76; P < .001).

“Addressing health inequities and improving care for underserved patients is the responsibility of all dermatologists, and efforts are needed to increase diversity and interest in careers focused on underserved care among trainees in the dermatology workforce pipeline,” the authors concluded. They acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including lack of data delineating sex, sex assigned at birth, and gender identity, and lack of intersectional analyses between multiple minority identities and multiple career goals. “Importantly, diversity factors and their relationship to underserved care is likely multidimensional, and many students pursuing dermatology identified with multiple minority identities, highlighting the need for future studies focused on intersectionality,” they wrote.

Trends over 15 years

In a separate study, Jazzmin C. Williams, a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco, and coauthors drew from an Association of American Medical Colleges report of trainees’ and applicants’ self-reported race and ethnicity by specialty from 2005 to 2020 to evaluate diversity trends over the 15-year period. They found that Black and Latinx trainees were underrepresented in all specialties, but even more so in dermatology (mean annual rate ratios of 0.32 and 0.14, respectively), compared with those in primary care (mean annual RRs of 0.54 and 0.23) and those in specialty care (mean annual RRs of 0.39 and 0.18).

In other findings, the annual representation of Black trainees remained unchanged in dermatology between 2005 and 2020, but down-trended for primary (P < .001) and specialty care (P = .001). At the same time, representation of Latinx trainees remained unchanged in dermatology and specialty care but increased in primary care (P < .001). Finally, Black and Latinx race and ethnicity comprised a lower mean proportion of matriculating dermatology trainees (postgraduate year-2s) compared with annual dermatology applicants (4.01% vs. 5.97%, respectively, and 2.06% vs. 6.37% among Latinx; P < .001 for all associations).

“Much of these disparities can be attributed to the leaky pipeline – the disproportionate, stepwise reduction in racial and ethnic minority representation along the path to medicine,” the authors wrote. “This leaky pipeline is the direct result of structural racism, which includes, but is not limited to, historical and contemporary economic disinvestment from majority-minority schools, kindergarten through grade 12.” They concluded by stating that “dermatologists must intervene throughout the educational pipeline, including residency selection and mentorship, to effectively increase diversity.”

Solutions to address diversity

In an editorial accompanying the two studies published in the same issue of JAMA Dermatology, Ellen N. Pritchett, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology at Howard University, Washington, and Andrew J. Park, MD, MBA, and Rebecca Vasquez, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, offered several solutions to address diversity in the dermatology work force. They include:

Go beyond individual bias in recruitment. “A residency selection framework that meaningfully incorporates diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) will require more than strategies that address individual bias,” they wrote. “Departmental recruitment committees must become familiar with systems that serve to perpetuate individual bias, like institutional racism or practices that disproportionately favor non-URM versus URM individuals.”

Challenge the myth of meritocracy. “The inaccurate notion of meritocracy – that success purely derives from individual effort has become the foundation of residency selection,” the authors wrote. “Unfortunately, this view ignores the inequitably distributed sociostructural resources that limit the rewards of individual effort.”

Avoid tokenism in retention strategies. Tokenism, which they defined as “a symbolic addition of members from a marginalized group to give the impression of social inclusiveness and diversity without meaningful incorporation of DEI in the policies, processes, and culture,” can lead to depression, burnout, and attrition, they wrote. They advise leaders of dermatology departments to “review their residency selection framework to ensure that it allows for meaningful representation, inclusion, and equity among trainees and faculty to better support URM individuals at all levels.”

Omar N. Qutub, MD, a Portland, Ore.–based dermatologist who was asked to comment on the studies, characterized the findings by Dr. Mansh and colleagues as sobering. “It appears that there is work to do as far as improving diversity in the dermatology workforce that will likely benefit greatly from an honest and steadfast approach to equitable application standards as well as mentorship during all stages of the application process,” such as medical school and residency, said Dr. Qutub, who is the director of equity, diversity, and inclusion of the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference. “With a focused attempt, we are likely to matriculate more racial minorities into our residency programs, maximizing patient outcomes.”

As for the study by Ms. Williams and colleagues, he told this news organization that efforts toward recruiting URM students as well as sexual minority students “is likely to not only improve health inequities in underserved areas, but will also enrich the specialty as a whole, allowing for better understanding of our diverse patient population and [for us to] to deliver quality care more readily for people and in areas where the focus has often been limited.”

In an interview, Chesahna Kindred, MD, a Columbia, Md.–based dermatologist and immediate past chair of the National Medical Association dermatology section, pointed out that the number of Black physicians in the United States has increased by only 4% in the last 120 years. The study by Dr. Mansh and colleagues, she commented, “underscores what I’ve recognized in the last couple of years: Where are the Black male dermatologists? NMA Derm started recruiting this demographic aggressively about a year ago and started the Black Men in Derm events. Black male members of NMA Derm travel to the Student National Medical Association and NMA conference and hold a panel to expose Black male students into dermatology. This article provides the numbers needed to measure how successful this and other programs are to closing the equity gap.”

Ms. Williams reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Mansh reported receiving grants from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences outside the submitted work. Dr. Pritchett and colleagues reported having no relevant financial disclosures, as did Dr. Qutub and Dr. Kindred.

suggest.

To evaluate diversity and career goals of graduating allopathic medical students pursuing careers in dermatology, corresponding author Matthew Mansh, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues drew from the 2016-2019 Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire for their study. The main outcome measures were the proportion of female students, students from racial and ethnic groups underrepresented in medicine (URM), and sexual minority (SM) students pursuing dermatology versus those pursuing other specialties, as well as the proportions and multivariable adjusted odds of intended career goals between students pursuing dermatology and those pursuing other specialties, and by sex, race, and ethnicity, and sexual orientation among students pursuing dermatology.

Of the 58,077 graduating students, 49% were women, 15% were URM, and 6% were SM. The researchers found that women pursuing dermatology were significantly less likely than women pursuing other specialties to identify as URM (11.6% vs. 17.2%; P < .001) or SM (1.9% vs. 5.7%; P < .001).

In multivariable-adjusted analyses of all students, those pursuing dermatology compared with other specialties had decreased odds of intending to care for underserved populations (18.3% vs. 34%; adjusted odd ratio, 0.40; P < .001), practice in underserved areas (12.7% vs. 25.9%; aOR, 0.40; P < .001), and practice public health (17% vs. 30.2%; aOR, 0.44; P < .001). The odds for pursuing research in their careers was greater among those pursuing dermatology (64.7% vs. 51.7%; aOR, 1.76; P < .001).

“Addressing health inequities and improving care for underserved patients is the responsibility of all dermatologists, and efforts are needed to increase diversity and interest in careers focused on underserved care among trainees in the dermatology workforce pipeline,” the authors concluded. They acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including lack of data delineating sex, sex assigned at birth, and gender identity, and lack of intersectional analyses between multiple minority identities and multiple career goals. “Importantly, diversity factors and their relationship to underserved care is likely multidimensional, and many students pursuing dermatology identified with multiple minority identities, highlighting the need for future studies focused on intersectionality,” they wrote.

Trends over 15 years

In a separate study, Jazzmin C. Williams, a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco, and coauthors drew from an Association of American Medical Colleges report of trainees’ and applicants’ self-reported race and ethnicity by specialty from 2005 to 2020 to evaluate diversity trends over the 15-year period. They found that Black and Latinx trainees were underrepresented in all specialties, but even more so in dermatology (mean annual rate ratios of 0.32 and 0.14, respectively), compared with those in primary care (mean annual RRs of 0.54 and 0.23) and those in specialty care (mean annual RRs of 0.39 and 0.18).

In other findings, the annual representation of Black trainees remained unchanged in dermatology between 2005 and 2020, but down-trended for primary (P < .001) and specialty care (P = .001). At the same time, representation of Latinx trainees remained unchanged in dermatology and specialty care but increased in primary care (P < .001). Finally, Black and Latinx race and ethnicity comprised a lower mean proportion of matriculating dermatology trainees (postgraduate year-2s) compared with annual dermatology applicants (4.01% vs. 5.97%, respectively, and 2.06% vs. 6.37% among Latinx; P < .001 for all associations).

“Much of these disparities can be attributed to the leaky pipeline – the disproportionate, stepwise reduction in racial and ethnic minority representation along the path to medicine,” the authors wrote. “This leaky pipeline is the direct result of structural racism, which includes, but is not limited to, historical and contemporary economic disinvestment from majority-minority schools, kindergarten through grade 12.” They concluded by stating that “dermatologists must intervene throughout the educational pipeline, including residency selection and mentorship, to effectively increase diversity.”

Solutions to address diversity

In an editorial accompanying the two studies published in the same issue of JAMA Dermatology, Ellen N. Pritchett, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology at Howard University, Washington, and Andrew J. Park, MD, MBA, and Rebecca Vasquez, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, offered several solutions to address diversity in the dermatology work force. They include:

Go beyond individual bias in recruitment. “A residency selection framework that meaningfully incorporates diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) will require more than strategies that address individual bias,” they wrote. “Departmental recruitment committees must become familiar with systems that serve to perpetuate individual bias, like institutional racism or practices that disproportionately favor non-URM versus URM individuals.”

Challenge the myth of meritocracy. “The inaccurate notion of meritocracy – that success purely derives from individual effort has become the foundation of residency selection,” the authors wrote. “Unfortunately, this view ignores the inequitably distributed sociostructural resources that limit the rewards of individual effort.”

Avoid tokenism in retention strategies. Tokenism, which they defined as “a symbolic addition of members from a marginalized group to give the impression of social inclusiveness and diversity without meaningful incorporation of DEI in the policies, processes, and culture,” can lead to depression, burnout, and attrition, they wrote. They advise leaders of dermatology departments to “review their residency selection framework to ensure that it allows for meaningful representation, inclusion, and equity among trainees and faculty to better support URM individuals at all levels.”

Omar N. Qutub, MD, a Portland, Ore.–based dermatologist who was asked to comment on the studies, characterized the findings by Dr. Mansh and colleagues as sobering. “It appears that there is work to do as far as improving diversity in the dermatology workforce that will likely benefit greatly from an honest and steadfast approach to equitable application standards as well as mentorship during all stages of the application process,” such as medical school and residency, said Dr. Qutub, who is the director of equity, diversity, and inclusion of the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference. “With a focused attempt, we are likely to matriculate more racial minorities into our residency programs, maximizing patient outcomes.”

As for the study by Ms. Williams and colleagues, he told this news organization that efforts toward recruiting URM students as well as sexual minority students “is likely to not only improve health inequities in underserved areas, but will also enrich the specialty as a whole, allowing for better understanding of our diverse patient population and [for us to] to deliver quality care more readily for people and in areas where the focus has often been limited.”

In an interview, Chesahna Kindred, MD, a Columbia, Md.–based dermatologist and immediate past chair of the National Medical Association dermatology section, pointed out that the number of Black physicians in the United States has increased by only 4% in the last 120 years. The study by Dr. Mansh and colleagues, she commented, “underscores what I’ve recognized in the last couple of years: Where are the Black male dermatologists? NMA Derm started recruiting this demographic aggressively about a year ago and started the Black Men in Derm events. Black male members of NMA Derm travel to the Student National Medical Association and NMA conference and hold a panel to expose Black male students into dermatology. This article provides the numbers needed to measure how successful this and other programs are to closing the equity gap.”

Ms. Williams reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Mansh reported receiving grants from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences outside the submitted work. Dr. Pritchett and colleagues reported having no relevant financial disclosures, as did Dr. Qutub and Dr. Kindred.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Advancing health equity in neurology is essential to patient care

Black and Latinx older adults are up to three times as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than non-Latinx White adults and tend to experience onset at a younger age with more severe symptoms, according to Monica Rivera-Mindt, PhD, a professor of psychology at Fordham University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Looking ahead, that means by 2030, nearly 40% of the 8.4 million Americans affected by Alzheimer’s disease will be Black and/or Latinx, she said. These facts were among the stark disparities in health care outcomes Dr. Rivera-Mindt discussed in her presentation on brain health equity at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Dr. Rivera-Mindt’s presentation opened the ANA’s plenary session on health disparities and inequities. The plenary, “Advancing Neurologic Equity: Challenges and Paths Forward,” did not simply enumerate racial and ethnic disparities that exist with various neurological conditions. Rather it went beyond the discussion of what disparities exist into understanding the roots of them as well as tips, tools, and resources that can aid clinicians in addressing or ameliorating them.

Roy Hamilton, MD, an associate professor of neurology and physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said. “If clinicians are unaware of these disparities or don’t have any sense of how to start to address or think about them, then they’re really missing out on an important component of their education as persons who take care of patients with brain disorders.”

Dr. Hamilton, who organized the plenary, noted that awareness of these disparities is crucial to comprehensively caring for patients.

Missed opportunities

“We’re talking about disadvantages that are structural and large scale, but those disadvantages play themselves out in the individual encounter,” Dr. Hamilton said. “When physicians see patients, they have to treat the whole patient in front of them,” which means being aware of the risks and factors that could affect a patient’s clinical presentation. “Being aware of disparities has practical impacts on physician judgment,” he said.

For example, recent research in multiple sclerosis (MS) has highlighted how clinicians may be missing diagnosis of this condition in non-White populations because the condition has been regarded for so long as a “White person’s” disease, Dr. Hamilton said. In non-White patients exhibiting MS symptoms, then, clinicians may have been less likely to consider MS as a possibility, thereby delaying diagnosis and treatment.

Those patterns may partly explain why the mortality rate for MS is greater in Black patients, who also show more rapid neurodegeneration than White patients with MS, Lilyana Amezcua, MD, an associate professor of neurology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, reported in the plenary’s second presentation.

Transgender issues

The third session, presented by Nicole Rosendale, MD, an assistant professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of the San Francisco General Hospital neurology inpatient services, examined disparities in neurology within the LGBTQ+ community through representative case studies and then offered specific ways that neurologists could make their practices more inclusive and equitable for sexual and gender minorities.

Her first case study was a 52-year-old man who presented with new-onset seizures, right hemiparesis, and aphasia. A brain biopsy consistent with adenocarcinoma eventually led his physician to discover he had metastatic breast cancer. It turned out the man was transgender and, despite a family history of breast cancer, hadn’t been advised to get breast cancer screenings.

“Breast cancer was not initially on the differential as no one had identified that the patient was transmasculine,” Dr. Rosendale said. A major challenge to providing care to transgender patients is a dearth of data on risks and screening recommendations. Another barrier is low knowledge of LGBTQ+ health among neurologists, Dr. Rosendale said while sharing findings from her 2019 study on the topic and calling for more research in LGBTQ+ populations.

Dr. Rosendale’s second case study dealt with a nonbinary patient who suffered from debilitating headaches for decades, first because they lacked access to health insurance and then because negative experiences with providers dissuaded them from seeking care. In data from the Center for American Progress she shared, 8% of LGB respondents and 22% of transgender respondents said they had avoided or delayed care because of fear of discrimination or mistreatment.

“So it’s not only access but also what experiences people are having when they go in and whether they’re actually even getting access to care or being taken care of,” Dr. Rosendale said. Other findings from the CAP found that:

- 8% of LGB patients and 29% of transgender patients reported having a clinician refuse to see them.

- 6% of LGB patients and 12% of transgender patients reported that a clinician refused to give them health care.

- 9% of LGB patients and 21% of transgender patients experienced harsh or abusive language during a health care experience.

- 7% of LGB patients and nearly a third (29%) of transgender patients experienced unwanted physical contact, such as fondling or sexual assault.

Reducing the disparities

Adys Mendizabal, MD, an assistant professor of neurology at the Institute of Society and Genetics at the University of California, Los Angeles, who attended the presentation, was grateful to see how the various lectures enriched the discussion beyond stating the fact of racial/ethnic disparities and dug into the nuances on how to think about and address these disparities. She particularly appreciated discussion about the need to go out of the way to recruit diverse patient populations for clinical trials while also providing them care.

“It is definitely complicated, but it’s not impossible for an individual neurologist or an individual department to do something to reduce some of the disparities,” Dr. Mendizabal said. “It starts with just knowing that they exist and being aware of some of the things that may be impacting care for a particular patient.”

Tools to counter disparity

In the final presentation, Amy Kind, MD, PhD, the associate dean for social health sciences and programs at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, rounded out the discussion by exploring social determinants of health and their influence on outcomes.

“Social determinants impact brain health, and brain health is not distributed equally,” Dr. Kind told attendees. “We have known this for decades, yet disparities persist.”

Dr. Kind described the “exposome,” a “measure of all the exposures of an individual in a lifetime and how those exposures relate to health,” according to the CDC, and then introduced a tool clinicians can use to better understand social determinants of health in specific geographic areas. The Neighborhood Atlas, which Dr. Kind described in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2018, measures 17 social determinants across small population-sensitive areas and provides an area deprivation index. A high area deprivation index is linked to a range of negative outcomes, including reshopitalization, later diagnoses, less comprehensive diagnostic evaluation, increased risk of postsurgical complications, and decreased life expectancy.

“One of the things that really stood out to me about Dr. Kind’s discussion of the use of the area deprivation index was the fact that understanding and quantifying these kinds of risks and exposures is the vehicle for creating the kinds of social changes, including policy changes, that will actually lead to addressing and mitigating some of these lifelong risks and exposures,” Dr. Hamilton said. “It is implausible to think that a specific group of people would be genetically more susceptible to basically every disease that we know,” he added. “It makes much more sense to think that groups of individuals have been subjected systematically to conditions that impair health in a variety of ways.”

Not just race, ethnicity, sex, and gender

Following the four presentations from researchers in health inequities was an Emerging Scholar presentation in which Jay B. Lusk, an MD/MBA candidate at Duke University, Durham, N.C., shared new research findings on the role of neighborhood disadvantage in predicting mortality from coma, stroke, and other neurologic conditions. His findings revealed that living in a neighborhood with greater deprivation substantially increased risk of mortality even after accounting for individual wealth and demographics.

Maria Eugenia Diaz-Ortiz, PhD, of the department of neurology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said she found the five presentations to be an excellent introduction to people like herself who are in the earlier stages of learning about health equity research.

“I think they introduced various important concepts and frameworks and provided tools for people who don’t know about them,” Dr. Diaz-Ortiz said. “Then they asked important questions and provided some solutions to them.”

Dr. Diaz-Ortiz also appreciated seemingly minor but actually important details in how the speakers presented themselves, such as Dr. Rivera-Mindt opening with a land acknowledgment and her disclosures of “positionality.” The former recognized the traditional Native American custodians of the land on which she lives and works, and the latter revealed details about her as an individual – such as being the Afro-Latinx daughter of immigrants yet being cisgender, able-bodied, and U.S.-born – that show where she falls on the axis of adversity and axis of privilege.

Implications for research

The biggest takeaway for Dr. Diaz-Ortiz, however, came from the first Q&A session when someone asked how to increase underrepresented populations in dementia research. Dr. Rivera-Mindt described her experience engaging these communities by employing “community-based participatory research practices, which involves making yourself a part of the community and making the community active participants in the research,” Dr. Diaz-Ortiz said. “It’s an evidence-based approach that has been shown to increase participation in research not only in her work but in the work of others.”

Preaching to the choir

Dr. Diaz-Ortiz was pleased overall with the plenary but disappointed in its placement at the end of the meeting, when attendance is always lower as attendees head home.

“The people who stayed were people who already know and recognize the value of health equity work, so I think that was a missed opportunity where the session could have been included on day one or two to boost attendance and also to educate like a broader group of neurologists,” Dr. Diaz-Ortiz said in an interview.

Dr. Mendizabal felt similarly, appreciating the plenary but noting it was “definitely overdue” and that it should not be the last session. Instead, sessions on health equity should be as easy as possible to attend to bring in larger audiences. “Perhaps having that session on a Saturday or Sunday would have a higher likelihood of greater attendance than on a Tuesday,” she said. That said, Dr. Mendizabal also noticed that greater attention to health care disparities was woven into many other sessions throughout the conference, which is “the best way of addressing health equity instead of trying to just designate a session,” she said.

Dr. Mendizabal hopes that plenaries like this one and the weaving of health equity issues into presentations throughout neurology conferences continue.

“After the racial reckoning in 2020, there was a big impetus and a big wave of energy in addressing health disparities in the field, and I hope that that momentum is not starting to wane,” Dr. Mendizabal said. “It’s important because not talking about is not going to make this issue go away.”

Dr. Hamilton agreed that it is important that the conversation continue and that physicians recognize the importance of understanding health care disparities and determinants of health, regardless of where they fall on the political spectrum or whether they choose to get involved in policy or advocacy.

“Irrespective of whether you think race or ethnicity or socioeconomic status are political issues or not, it is the case that you’re obligated to have an objective understanding of the factors that contribute to your patient’s health and as points of intervention,” Dr. Hamilton said. “So even if you don’t want to sit down and jot off that email to your senator, you still have to take these factors into account when you’re treating the person who’s sitting right in front of you, and that’s not political. That’s the promise of being a physician.”

Dr. Amezcua has received personal compensation for consulting, speaking, or serving on steering committees or advisory boards for Biogen Idec, Novartis, Genentech, and EMD Serono, and she has received research support from Biogen Idec and Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation. Dr. Kind reported support from the Alzheimer’s Association. Dr. Diaz-Ortiz is coinventor of a provisional patent submitted by the University of Pennsylvania that relates to a potential therapeutic in Parkinson’s disease. Mr. Lusk reported fellowship support from American Heart Association and travel support from the American Neurological Association. No other speakers or sources had relevant disclosures.

Black and Latinx older adults are up to three times as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than non-Latinx White adults and tend to experience onset at a younger age with more severe symptoms, according to Monica Rivera-Mindt, PhD, a professor of psychology at Fordham University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Looking ahead, that means by 2030, nearly 40% of the 8.4 million Americans affected by Alzheimer’s disease will be Black and/or Latinx, she said. These facts were among the stark disparities in health care outcomes Dr. Rivera-Mindt discussed in her presentation on brain health equity at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Dr. Rivera-Mindt’s presentation opened the ANA’s plenary session on health disparities and inequities. The plenary, “Advancing Neurologic Equity: Challenges and Paths Forward,” did not simply enumerate racial and ethnic disparities that exist with various neurological conditions. Rather it went beyond the discussion of what disparities exist into understanding the roots of them as well as tips, tools, and resources that can aid clinicians in addressing or ameliorating them.

Roy Hamilton, MD, an associate professor of neurology and physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said. “If clinicians are unaware of these disparities or don’t have any sense of how to start to address or think about them, then they’re really missing out on an important component of their education as persons who take care of patients with brain disorders.”

Dr. Hamilton, who organized the plenary, noted that awareness of these disparities is crucial to comprehensively caring for patients.

Missed opportunities

“We’re talking about disadvantages that are structural and large scale, but those disadvantages play themselves out in the individual encounter,” Dr. Hamilton said. “When physicians see patients, they have to treat the whole patient in front of them,” which means being aware of the risks and factors that could affect a patient’s clinical presentation. “Being aware of disparities has practical impacts on physician judgment,” he said.

For example, recent research in multiple sclerosis (MS) has highlighted how clinicians may be missing diagnosis of this condition in non-White populations because the condition has been regarded for so long as a “White person’s” disease, Dr. Hamilton said. In non-White patients exhibiting MS symptoms, then, clinicians may have been less likely to consider MS as a possibility, thereby delaying diagnosis and treatment.

Those patterns may partly explain why the mortality rate for MS is greater in Black patients, who also show more rapid neurodegeneration than White patients with MS, Lilyana Amezcua, MD, an associate professor of neurology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, reported in the plenary’s second presentation.

Transgender issues

The third session, presented by Nicole Rosendale, MD, an assistant professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of the San Francisco General Hospital neurology inpatient services, examined disparities in neurology within the LGBTQ+ community through representative case studies and then offered specific ways that neurologists could make their practices more inclusive and equitable for sexual and gender minorities.

Her first case study was a 52-year-old man who presented with new-onset seizures, right hemiparesis, and aphasia. A brain biopsy consistent with adenocarcinoma eventually led his physician to discover he had metastatic breast cancer. It turned out the man was transgender and, despite a family history of breast cancer, hadn’t been advised to get breast cancer screenings.

“Breast cancer was not initially on the differential as no one had identified that the patient was transmasculine,” Dr. Rosendale said. A major challenge to providing care to transgender patients is a dearth of data on risks and screening recommendations. Another barrier is low knowledge of LGBTQ+ health among neurologists, Dr. Rosendale said while sharing findings from her 2019 study on the topic and calling for more research in LGBTQ+ populations.

Dr. Rosendale’s second case study dealt with a nonbinary patient who suffered from debilitating headaches for decades, first because they lacked access to health insurance and then because negative experiences with providers dissuaded them from seeking care. In data from the Center for American Progress she shared, 8% of LGB respondents and 22% of transgender respondents said they had avoided or delayed care because of fear of discrimination or mistreatment.

“So it’s not only access but also what experiences people are having when they go in and whether they’re actually even getting access to care or being taken care of,” Dr. Rosendale said. Other findings from the CAP found that:

- 8% of LGB patients and 29% of transgender patients reported having a clinician refuse to see them.

- 6% of LGB patients and 12% of transgender patients reported that a clinician refused to give them health care.

- 9% of LGB patients and 21% of transgender patients experienced harsh or abusive language during a health care experience.

- 7% of LGB patients and nearly a third (29%) of transgender patients experienced unwanted physical contact, such as fondling or sexual assault.

Reducing the disparities

Adys Mendizabal, MD, an assistant professor of neurology at the Institute of Society and Genetics at the University of California, Los Angeles, who attended the presentation, was grateful to see how the various lectures enriched the discussion beyond stating the fact of racial/ethnic disparities and dug into the nuances on how to think about and address these disparities. She particularly appreciated discussion about the need to go out of the way to recruit diverse patient populations for clinical trials while also providing them care.

“It is definitely complicated, but it’s not impossible for an individual neurologist or an individual department to do something to reduce some of the disparities,” Dr. Mendizabal said. “It starts with just knowing that they exist and being aware of some of the things that may be impacting care for a particular patient.”

Tools to counter disparity

In the final presentation, Amy Kind, MD, PhD, the associate dean for social health sciences and programs at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, rounded out the discussion by exploring social determinants of health and their influence on outcomes.

“Social determinants impact brain health, and brain health is not distributed equally,” Dr. Kind told attendees. “We have known this for decades, yet disparities persist.”

Dr. Kind described the “exposome,” a “measure of all the exposures of an individual in a lifetime and how those exposures relate to health,” according to the CDC, and then introduced a tool clinicians can use to better understand social determinants of health in specific geographic areas. The Neighborhood Atlas, which Dr. Kind described in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2018, measures 17 social determinants across small population-sensitive areas and provides an area deprivation index. A high area deprivation index is linked to a range of negative outcomes, including reshopitalization, later diagnoses, less comprehensive diagnostic evaluation, increased risk of postsurgical complications, and decreased life expectancy.

“One of the things that really stood out to me about Dr. Kind’s discussion of the use of the area deprivation index was the fact that understanding and quantifying these kinds of risks and exposures is the vehicle for creating the kinds of social changes, including policy changes, that will actually lead to addressing and mitigating some of these lifelong risks and exposures,” Dr. Hamilton said. “It is implausible to think that a specific group of people would be genetically more susceptible to basically every disease that we know,” he added. “It makes much more sense to think that groups of individuals have been subjected systematically to conditions that impair health in a variety of ways.”

Not just race, ethnicity, sex, and gender

Following the four presentations from researchers in health inequities was an Emerging Scholar presentation in which Jay B. Lusk, an MD/MBA candidate at Duke University, Durham, N.C., shared new research findings on the role of neighborhood disadvantage in predicting mortality from coma, stroke, and other neurologic conditions. His findings revealed that living in a neighborhood with greater deprivation substantially increased risk of mortality even after accounting for individual wealth and demographics.

Maria Eugenia Diaz-Ortiz, PhD, of the department of neurology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said she found the five presentations to be an excellent introduction to people like herself who are in the earlier stages of learning about health equity research.

“I think they introduced various important concepts and frameworks and provided tools for people who don’t know about them,” Dr. Diaz-Ortiz said. “Then they asked important questions and provided some solutions to them.”

Dr. Diaz-Ortiz also appreciated seemingly minor but actually important details in how the speakers presented themselves, such as Dr. Rivera-Mindt opening with a land acknowledgment and her disclosures of “positionality.” The former recognized the traditional Native American custodians of the land on which she lives and works, and the latter revealed details about her as an individual – such as being the Afro-Latinx daughter of immigrants yet being cisgender, able-bodied, and U.S.-born – that show where she falls on the axis of adversity and axis of privilege.

Implications for research

The biggest takeaway for Dr. Diaz-Ortiz, however, came from the first Q&A session when someone asked how to increase underrepresented populations in dementia research. Dr. Rivera-Mindt described her experience engaging these communities by employing “community-based participatory research practices, which involves making yourself a part of the community and making the community active participants in the research,” Dr. Diaz-Ortiz said. “It’s an evidence-based approach that has been shown to increase participation in research not only in her work but in the work of others.”

Preaching to the choir

Dr. Diaz-Ortiz was pleased overall with the plenary but disappointed in its placement at the end of the meeting, when attendance is always lower as attendees head home.

“The people who stayed were people who already know and recognize the value of health equity work, so I think that was a missed opportunity where the session could have been included on day one or two to boost attendance and also to educate like a broader group of neurologists,” Dr. Diaz-Ortiz said in an interview.

Dr. Mendizabal felt similarly, appreciating the plenary but noting it was “definitely overdue” and that it should not be the last session. Instead, sessions on health equity should be as easy as possible to attend to bring in larger audiences. “Perhaps having that session on a Saturday or Sunday would have a higher likelihood of greater attendance than on a Tuesday,” she said. That said, Dr. Mendizabal also noticed that greater attention to health care disparities was woven into many other sessions throughout the conference, which is “the best way of addressing health equity instead of trying to just designate a session,” she said.

Dr. Mendizabal hopes that plenaries like this one and the weaving of health equity issues into presentations throughout neurology conferences continue.

“After the racial reckoning in 2020, there was a big impetus and a big wave of energy in addressing health disparities in the field, and I hope that that momentum is not starting to wane,” Dr. Mendizabal said. “It’s important because not talking about is not going to make this issue go away.”

Dr. Hamilton agreed that it is important that the conversation continue and that physicians recognize the importance of understanding health care disparities and determinants of health, regardless of where they fall on the political spectrum or whether they choose to get involved in policy or advocacy.

“Irrespective of whether you think race or ethnicity or socioeconomic status are political issues or not, it is the case that you’re obligated to have an objective understanding of the factors that contribute to your patient’s health and as points of intervention,” Dr. Hamilton said. “So even if you don’t want to sit down and jot off that email to your senator, you still have to take these factors into account when you’re treating the person who’s sitting right in front of you, and that’s not political. That’s the promise of being a physician.”

Dr. Amezcua has received personal compensation for consulting, speaking, or serving on steering committees or advisory boards for Biogen Idec, Novartis, Genentech, and EMD Serono, and she has received research support from Biogen Idec and Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation. Dr. Kind reported support from the Alzheimer’s Association. Dr. Diaz-Ortiz is coinventor of a provisional patent submitted by the University of Pennsylvania that relates to a potential therapeutic in Parkinson’s disease. Mr. Lusk reported fellowship support from American Heart Association and travel support from the American Neurological Association. No other speakers or sources had relevant disclosures.

Black and Latinx older adults are up to three times as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than non-Latinx White adults and tend to experience onset at a younger age with more severe symptoms, according to Monica Rivera-Mindt, PhD, a professor of psychology at Fordham University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Looking ahead, that means by 2030, nearly 40% of the 8.4 million Americans affected by Alzheimer’s disease will be Black and/or Latinx, she said. These facts were among the stark disparities in health care outcomes Dr. Rivera-Mindt discussed in her presentation on brain health equity at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Dr. Rivera-Mindt’s presentation opened the ANA’s plenary session on health disparities and inequities. The plenary, “Advancing Neurologic Equity: Challenges and Paths Forward,” did not simply enumerate racial and ethnic disparities that exist with various neurological conditions. Rather it went beyond the discussion of what disparities exist into understanding the roots of them as well as tips, tools, and resources that can aid clinicians in addressing or ameliorating them.

Roy Hamilton, MD, an associate professor of neurology and physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said. “If clinicians are unaware of these disparities or don’t have any sense of how to start to address or think about them, then they’re really missing out on an important component of their education as persons who take care of patients with brain disorders.”

Dr. Hamilton, who organized the plenary, noted that awareness of these disparities is crucial to comprehensively caring for patients.

Missed opportunities

“We’re talking about disadvantages that are structural and large scale, but those disadvantages play themselves out in the individual encounter,” Dr. Hamilton said. “When physicians see patients, they have to treat the whole patient in front of them,” which means being aware of the risks and factors that could affect a patient’s clinical presentation. “Being aware of disparities has practical impacts on physician judgment,” he said.

For example, recent research in multiple sclerosis (MS) has highlighted how clinicians may be missing diagnosis of this condition in non-White populations because the condition has been regarded for so long as a “White person’s” disease, Dr. Hamilton said. In non-White patients exhibiting MS symptoms, then, clinicians may have been less likely to consider MS as a possibility, thereby delaying diagnosis and treatment.

Those patterns may partly explain why the mortality rate for MS is greater in Black patients, who also show more rapid neurodegeneration than White patients with MS, Lilyana Amezcua, MD, an associate professor of neurology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, reported in the plenary’s second presentation.

Transgender issues

The third session, presented by Nicole Rosendale, MD, an assistant professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of the San Francisco General Hospital neurology inpatient services, examined disparities in neurology within the LGBTQ+ community through representative case studies and then offered specific ways that neurologists could make their practices more inclusive and equitable for sexual and gender minorities.

Her first case study was a 52-year-old man who presented with new-onset seizures, right hemiparesis, and aphasia. A brain biopsy consistent with adenocarcinoma eventually led his physician to discover he had metastatic breast cancer. It turned out the man was transgender and, despite a family history of breast cancer, hadn’t been advised to get breast cancer screenings.

“Breast cancer was not initially on the differential as no one had identified that the patient was transmasculine,” Dr. Rosendale said. A major challenge to providing care to transgender patients is a dearth of data on risks and screening recommendations. Another barrier is low knowledge of LGBTQ+ health among neurologists, Dr. Rosendale said while sharing findings from her 2019 study on the topic and calling for more research in LGBTQ+ populations.

Dr. Rosendale’s second case study dealt with a nonbinary patient who suffered from debilitating headaches for decades, first because they lacked access to health insurance and then because negative experiences with providers dissuaded them from seeking care. In data from the Center for American Progress she shared, 8% of LGB respondents and 22% of transgender respondents said they had avoided or delayed care because of fear of discrimination or mistreatment.

“So it’s not only access but also what experiences people are having when they go in and whether they’re actually even getting access to care or being taken care of,” Dr. Rosendale said. Other findings from the CAP found that:

- 8% of LGB patients and 29% of transgender patients reported having a clinician refuse to see them.

- 6% of LGB patients and 12% of transgender patients reported that a clinician refused to give them health care.

- 9% of LGB patients and 21% of transgender patients experienced harsh or abusive language during a health care experience.

- 7% of LGB patients and nearly a third (29%) of transgender patients experienced unwanted physical contact, such as fondling or sexual assault.

Reducing the disparities

Adys Mendizabal, MD, an assistant professor of neurology at the Institute of Society and Genetics at the University of California, Los Angeles, who attended the presentation, was grateful to see how the various lectures enriched the discussion beyond stating the fact of racial/ethnic disparities and dug into the nuances on how to think about and address these disparities. She particularly appreciated discussion about the need to go out of the way to recruit diverse patient populations for clinical trials while also providing them care.

“It is definitely complicated, but it’s not impossible for an individual neurologist or an individual department to do something to reduce some of the disparities,” Dr. Mendizabal said. “It starts with just knowing that they exist and being aware of some of the things that may be impacting care for a particular patient.”

Tools to counter disparity

In the final presentation, Amy Kind, MD, PhD, the associate dean for social health sciences and programs at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, rounded out the discussion by exploring social determinants of health and their influence on outcomes.

“Social determinants impact brain health, and brain health is not distributed equally,” Dr. Kind told attendees. “We have known this for decades, yet disparities persist.”

Dr. Kind described the “exposome,” a “measure of all the exposures of an individual in a lifetime and how those exposures relate to health,” according to the CDC, and then introduced a tool clinicians can use to better understand social determinants of health in specific geographic areas. The Neighborhood Atlas, which Dr. Kind described in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2018, measures 17 social determinants across small population-sensitive areas and provides an area deprivation index. A high area deprivation index is linked to a range of negative outcomes, including reshopitalization, later diagnoses, less comprehensive diagnostic evaluation, increased risk of postsurgical complications, and decreased life expectancy.

“One of the things that really stood out to me about Dr. Kind’s discussion of the use of the area deprivation index was the fact that understanding and quantifying these kinds of risks and exposures is the vehicle for creating the kinds of social changes, including policy changes, that will actually lead to addressing and mitigating some of these lifelong risks and exposures,” Dr. Hamilton said. “It is implausible to think that a specific group of people would be genetically more susceptible to basically every disease that we know,” he added. “It makes much more sense to think that groups of individuals have been subjected systematically to conditions that impair health in a variety of ways.”

Not just race, ethnicity, sex, and gender

Following the four presentations from researchers in health inequities was an Emerging Scholar presentation in which Jay B. Lusk, an MD/MBA candidate at Duke University, Durham, N.C., shared new research findings on the role of neighborhood disadvantage in predicting mortality from coma, stroke, and other neurologic conditions. His findings revealed that living in a neighborhood with greater deprivation substantially increased risk of mortality even after accounting for individual wealth and demographics.

Maria Eugenia Diaz-Ortiz, PhD, of the department of neurology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said she found the five presentations to be an excellent introduction to people like herself who are in the earlier stages of learning about health equity research.

“I think they introduced various important concepts and frameworks and provided tools for people who don’t know about them,” Dr. Diaz-Ortiz said. “Then they asked important questions and provided some solutions to them.”

Dr. Diaz-Ortiz also appreciated seemingly minor but actually important details in how the speakers presented themselves, such as Dr. Rivera-Mindt opening with a land acknowledgment and her disclosures of “positionality.” The former recognized the traditional Native American custodians of the land on which she lives and works, and the latter revealed details about her as an individual – such as being the Afro-Latinx daughter of immigrants yet being cisgender, able-bodied, and U.S.-born – that show where she falls on the axis of adversity and axis of privilege.

Implications for research

The biggest takeaway for Dr. Diaz-Ortiz, however, came from the first Q&A session when someone asked how to increase underrepresented populations in dementia research. Dr. Rivera-Mindt described her experience engaging these communities by employing “community-based participatory research practices, which involves making yourself a part of the community and making the community active participants in the research,” Dr. Diaz-Ortiz said. “It’s an evidence-based approach that has been shown to increase participation in research not only in her work but in the work of others.”

Preaching to the choir

Dr. Diaz-Ortiz was pleased overall with the plenary but disappointed in its placement at the end of the meeting, when attendance is always lower as attendees head home.

“The people who stayed were people who already know and recognize the value of health equity work, so I think that was a missed opportunity where the session could have been included on day one or two to boost attendance and also to educate like a broader group of neurologists,” Dr. Diaz-Ortiz said in an interview.

Dr. Mendizabal felt similarly, appreciating the plenary but noting it was “definitely overdue” and that it should not be the last session. Instead, sessions on health equity should be as easy as possible to attend to bring in larger audiences. “Perhaps having that session on a Saturday or Sunday would have a higher likelihood of greater attendance than on a Tuesday,” she said. That said, Dr. Mendizabal also noticed that greater attention to health care disparities was woven into many other sessions throughout the conference, which is “the best way of addressing health equity instead of trying to just designate a session,” she said.

Dr. Mendizabal hopes that plenaries like this one and the weaving of health equity issues into presentations throughout neurology conferences continue.

“After the racial reckoning in 2020, there was a big impetus and a big wave of energy in addressing health disparities in the field, and I hope that that momentum is not starting to wane,” Dr. Mendizabal said. “It’s important because not talking about is not going to make this issue go away.”

Dr. Hamilton agreed that it is important that the conversation continue and that physicians recognize the importance of understanding health care disparities and determinants of health, regardless of where they fall on the political spectrum or whether they choose to get involved in policy or advocacy.

“Irrespective of whether you think race or ethnicity or socioeconomic status are political issues or not, it is the case that you’re obligated to have an objective understanding of the factors that contribute to your patient’s health and as points of intervention,” Dr. Hamilton said. “So even if you don’t want to sit down and jot off that email to your senator, you still have to take these factors into account when you’re treating the person who’s sitting right in front of you, and that’s not political. That’s the promise of being a physician.”

Dr. Amezcua has received personal compensation for consulting, speaking, or serving on steering committees or advisory boards for Biogen Idec, Novartis, Genentech, and EMD Serono, and she has received research support from Biogen Idec and Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation. Dr. Kind reported support from the Alzheimer’s Association. Dr. Diaz-Ortiz is coinventor of a provisional patent submitted by the University of Pennsylvania that relates to a potential therapeutic in Parkinson’s disease. Mr. Lusk reported fellowship support from American Heart Association and travel support from the American Neurological Association. No other speakers or sources had relevant disclosures.

FROM ANA 2022

Cardiovascular societies less apt to recognize women, minorities

Major cardiovascular societies are more apt to give out awards to men and White individuals than to women and minorities, according to a look at 2 decades’ worth of data.

“Women received significantly fewer awards than men in all societies, countries, and award categories,” author Martha Gulati, MD, director of preventive cardiology at Smidt Heart Institute at Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, said in a news release. “This bias may be responsible for preventing underrepresented groups from ascending the academic ladder and receiving senior awards like lifetime achievement awards.”

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

A slow climb

The findings are based on a review of honors given from 2000 to 2021 by the ACC, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, the Heart Rhythm Society, the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society.

Among the 173 unique awards, 94 were given by the AHA, 27 by the HRS, 17 by the ACC, 16 by the CCS, 8 by the ASE, 7 by the ESC, and 4 by the SCAI. There were 3,044 recipients of these awards, including 2,830 unique awardees.

The vast majority of the awardees were White (75.2%), with Asian, Hispanic/Latino, and Black awardees representing just 18.9%, 4.5%, and 1.4% of the total awardees, respectively.

In a gender analysis, the researchers looked at 169 awards after excluding female-specific awards. These 169 awards were distributed to 2,995 recipients. More than three-quarters of these awardees (76.2%) were men, with women making up less than one-quarter (23.8%).

Encouragingly, there was an increasing trend in recognition of women over time, with 7.7% of female awardees in 2000 and climbing to 31.2% in 2021 (average annual percentage change, 6.6%; P < .05).