User login

Antidepressants for chronic pain

Approximately 55 years ago, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) began to be used to treat neuropathic pain.1 Eventually, clinical trials emerged suggesting the utility of TCAs for other chronic pain conditions, such as fibromyalgia (FM) and migraine prophylaxis. However, despite TCAs’ effectiveness in mitigating painful conditions, their adverse effects limited their use.

Pharmacologic advancements have led to the development of other antidepressant classes, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and the use of these agents has come to eclipse that of TCAs. In the realm of pain management, such developments have raised the hope of possible alternative co-analgesic agents that could avoid the adverse effects associated with TCAs. Some of these agents have demonstrated efficacy for managing chronic pain states, while others have demonstrated only limited utility.

This article provides a synopsis of systematic reviews and meta-analyses examining the role of antidepressant therapy for managing several chronic pain conditions, including pain associated with neuropathy, FM, headache, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Because the literature base is rapidly evolving, it is necessary to revisit the information gleaned from clinical data with respect to treatment effectiveness, and to clarify how antidepressants might be positioned in the management of chronic pain.

The effectiveness of antidepressants for pain

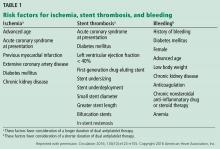

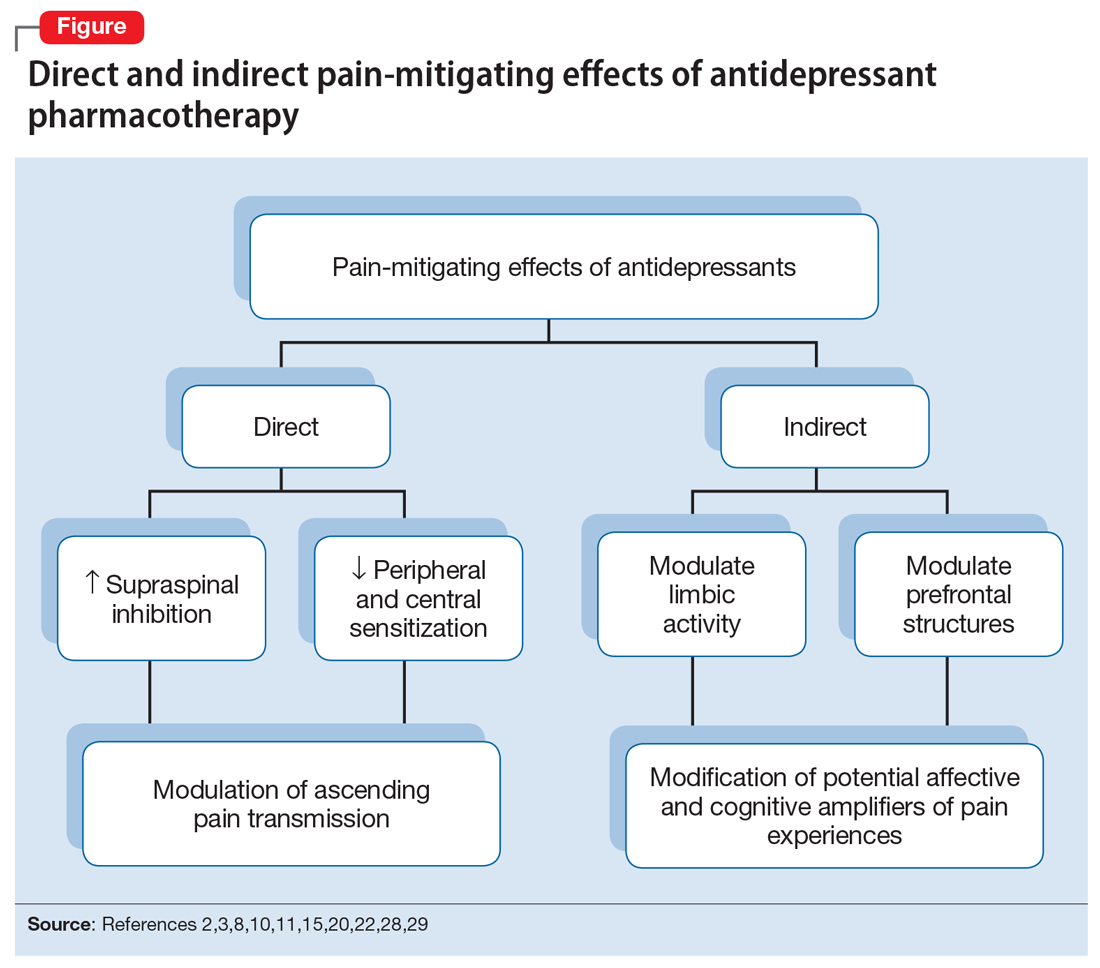

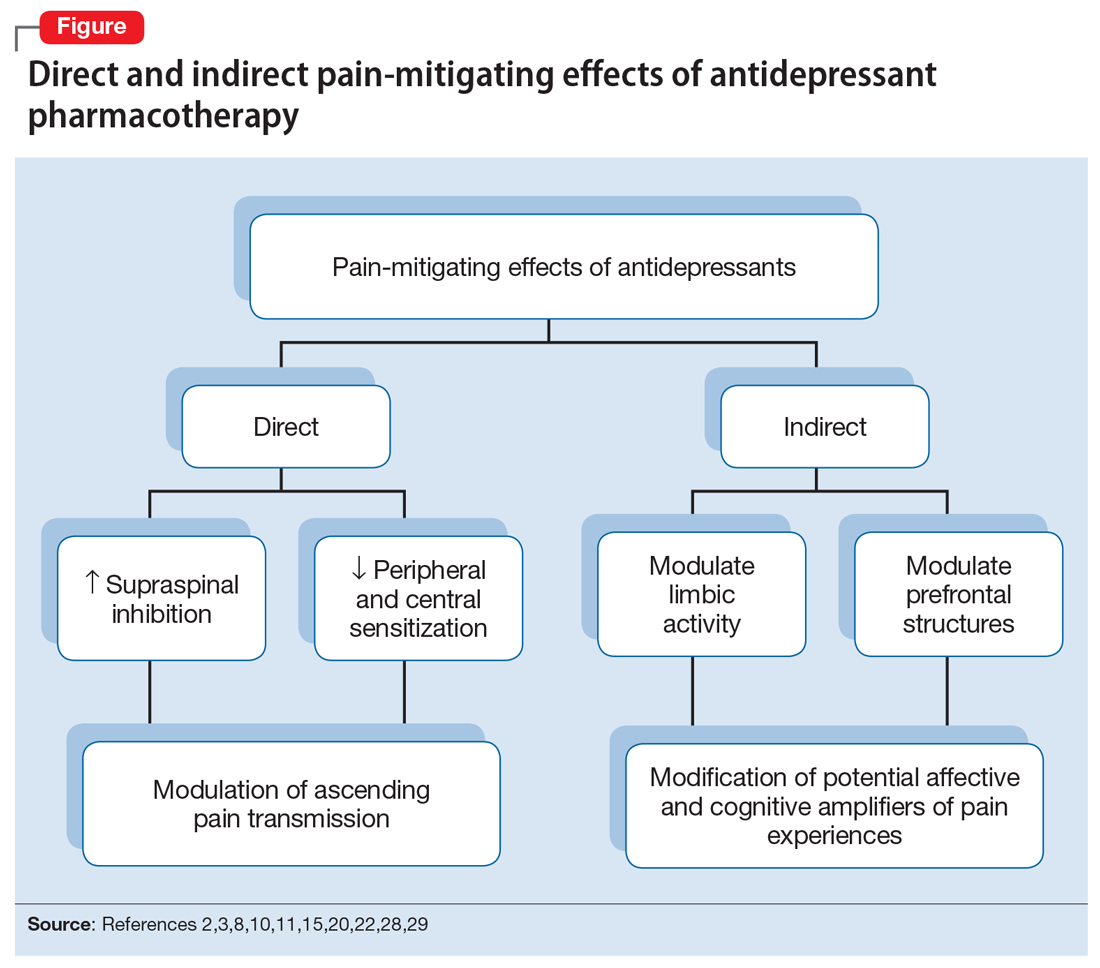

The pathophysiologic processes that precipitate and maintain chronic pain conditions are complex (Box 12-10). The pain-mitigating effects of antidepressants can be thought of in terms of direct analgesic effects and indirect effects (Box 22,3,8,10,11-33).

Box 1

The pathophysiologic processes precipitating and maintaining chronic pain conditions are complex. Persistent and chronic pain results from changes in sensitivity within both ascending pathways (relaying pain information from the periphery to the spinal cord and brain) and descending pain pathways (functioning to modulate ascending pain information).2,3 Tissue damage or peripheral nerve injury can lead to a cascade of neuroplastic changes within the CNS, resulting in hyperexcitability within the ascending pain pathways.

The descending pain pathways consist of the midbrain periaqueductal gray area (PGA), the rostroventral medulla (RVM), and the dorsolateral pontomesencephalic tegmentum (DLPT). The axons of the RVM (the outflow of which is serotonergic) and DLPT (the outflow of which is noradrenergic) terminate in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord,4 and thereby dampen pain signals arising from the periphery. Diminished output from descending pain pathways can heighten the pain experience. Input from the cortex, hypothalamus, and amygdala (among other structures) converges upon the PGA, RVM and DLPT, and can influence the degree of pain modulation emerging from descending pathways. In this way, thoughts, appraisals, and mood are believed to comprise cognitive and affective modifiers of pain experiences.

Devising effective chronic pain treatment becomes challenging; multimodal treatment approaches often are advocated, including pharmacologic treatment with analgesics in combination with co-analgesic medications such as antidepressants. Although a description of multimodal treatment is beyond the scope of this article, such treatment also would encompass physical therapy, occupational therapy, and psychotherapeutic interventions to augment rehabilitative efforts and the functional capabilities of patients who struggle with persisting pain.

Although the direct pain-mitigating effects of antidepressants are not fully understood, it is believed that augmentation of monoamine neurotransmission from supraspinal nuclei (ie, the RVM and DLPT) modulate pain transmission from the periphery.5,6 In addition, there is evidence that some effects of tricyclic antidepressants can modulate several other functions that impact peripheral and central sensitization.7-10

During the last several decades, antidepressants have been used to address—and have demonstrated clinical utility for—a variety of chronic pain states. However, antidepressants are not a panacea; some chronic pain conditions are more responsive to antidepressants than are others. The chronic painful states most amenable to antidepressants are those that result primarily from a process of neural sensitization, as opposed to acute somatic or visceral nociception. Hence, several meta-analyses and evidence-based reviews have long suggested the usefulness of antidepressants for mitigating pain associated with neuropathy,34,35 FM,36,37 headache,38 and IBS.39,40

Box 2

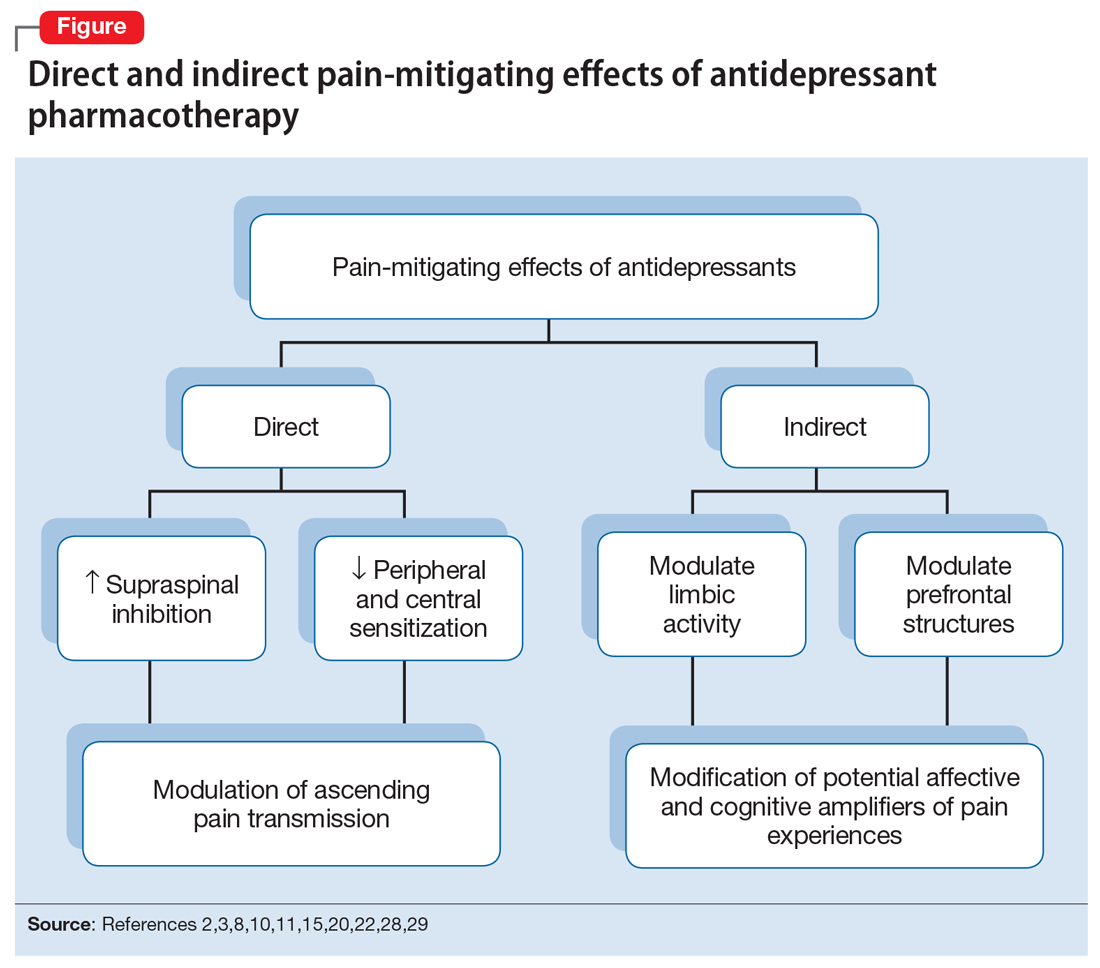

The pain-mitigating effects of antidepressants can be thought of in terms of direct analgesic effects (impacting neurotransmission of descending pathways independent of influences on mood) and indirect effects (presumably impacting cortical and limbic output to the periaqueductal gray area, the rostroventral medulla, and the dorsolateral pontomesencephalic tegmentum brought about by improvement in mood and/or cognitive appraisals) (Figure2,3,8,10,11,15,20,22,28,29). Support for the direct analgesic effects has been garnered from initial empirical work that demonstrated pain relief among patients with pain who are not depressed. Additionally, among patients who have depression and experience pain, analgesia reportedly often occurs within 2 weeks, which is before antidepressant effects are appreciated,11-15 and, at least for some antidepressants, occurs at doses far lower than those required to produce mood-elevating effects.11,12,16

On the other hand, it is well established that significant comorbidities exist between chronic pain states and psychiatric disorders (eg, depression and somatic symptom and related disorders).17-21 There may be common physiological substrates underlying chronic pain and depression.20,22 There are bidirectional influences of limbic (affective) systems and those CNS structures involved in pain processing and integration. The effects of pain and depression are reciprocal; the presence of one makes the management of the other more challenging.23-27 Mood disturbances can, therefore, impact pain processing by acting as affective and cognitive amplifiers of pain by leading to catastrophizing, pain severity augmentation, poor coping with pain-related stress, etc.28,29 It is plausible that the mood-elevating effects of antidepressants can improve pain by indirect effects, by modulating limbic activity, which in turn, impacts coping, cognitive appraisals of pain, etc.

Patients with somatoform disorders (using pre-DSM-5 terminology) frequently present with chronic pain, often in multiple sites.19 Such patients are characterized by hypervigilance for, and a predisposition to focus on, physical sensations and to appraise these sensations as reflecting a pathological state.30 Neuroimaging studies have begun to identify those neural circuits involved in somatoform disorders, many of which act as cognitive and affective amplifiers of visceral-somatic sensory processing. Many of these neural circuits overlap, and interact with, those involved in pain processing.31 Antidepressants can mitigate the severity of unexplained physical complaints, including pain, among patients who somatize32,33; however, due to the heterogeneity of studies upon which this claim is based, the quality of the evidence is reportedly low.33 There is uncertainty whether, or to what extent, antidepressant benefits among patients who somatize are due to a direct impact on pain modulation, or indirect effects on mood or cognitive appraisals/perceptions.

Despite the uncertainties about the exact mechanisms through which antidepressants exert analgesic effects, antidepressants can be appropriately used to treat patients with selected chronic pain syndromes, regardless of whether or not the patient has a psychiatric comorbidity. For those patients with pain and psychiatric comorbidities, the benefits may be brought about via direct mechanisms, indirect mechanisms, or a combination of both.

Continue to: Neuropathic pain

Neuropathic pain

Several treatment guidelines advocate for the use of antidepressants for neuropathic pain.41-44 For decades, TCAs have been employed off-label to successfully treat many patients with neuropathic pain states. Early investigations suggested that TCAs were robustly efficacious in managing patients with neuropathy.45-48 Calculated number-needed-to-treat (NNT) values for TCAs were quite low (ie, reflecting that few patients would need to be treated to yield a positive response in one patient compared with placebo), and were comparable to, if not slightly better than, the NNTs generated for anticonvulsants and α2-δ ligands, such as gabapentin or pregabalin.45-48

Unfortunately, early studies involving TCAs conducted many years ago do not meet contemporary standards of methodological rigor; they featured relatively small samples of patients assessed for brief post-treatment intervals with variable outcome measures. Thus, the NNT values obtained in meta-analyses based on these studies may overestimate treatment benefits.49 Further, NNT values derived from meta-analyses tended to combine all drugs within a particular antidepressant class (eg, amitriptyline, nortriptyline, desipramine, and imipramine among the TCAs) employed at diverse doses. Taken together, these limitations raise questions about the results of those meta-analyses.

Subsequent meta-analyses, which employed strict criteria to eliminate data from studies with potential sources of bias and used a primary outcome of frequencies of patients reporting at least 30% pain reduction compared with a placebo-controlled sample, suggest that the effectiveness of TCAs as a class for treating neuropathic pain is not as compelling as once was thought. Meta-analyses of studies employing specific TCAs revealed that there was little evidence to support the use of desipramine,50 imipramine,51 or nortriptyline52 in managing diabetic neuropathy or postherpetic neuralgia. Studies evaluating amitriptyline (dose range 12.5 to 150 mg/d), found low-level evidence of effectiveness; the benefit was expected to be present for a small subset (approximately 25%) of patients with neuropathic pain.53

There is moderate-quality evidence that duloxetine (60 to 120 mg/d) can produce a ≥50% improvement in pain severity ratings among patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy.54 Although head-to-head studies with other antidepressants are limited, it appears that duloxetine and amitriptyline have comparable efficacy, even though the NNTs for amitriptyline were derived from lower-quality studies than those for duloxetine. Duloxetine is the only antidepressant to receive FDA approval for managing diabetic neuropathy. By contrast, studies assessing the utility of venlafaxine in neuropathic pain comprised small samples for brief durations, which limits the ability to draw clear (unbiased) support for its usefulness.55

Given the diversity of pathophysiologic processes underlying the disturbances that cause neuropathic pain disorders, it is unsurprising that the effectiveness of amitriptyline and duloxetine were not generalizable to all neuropathic pain states. Although amitriptyline produced pain-mitigating effects in patients with diabetic neuropathy and post-herpetic neuralgia, and duloxetine mitigated pain among patients with diabetic neuropathy, there was no evidence to suggest their effectiveness in phantom limb pain or human immunodeficiency virus-related and spinal cord-related neuropathies.35,53,54,56-58

Continue to: Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia

As with the issues encountered in interpreting the effectiveness of antidepressants in neuropathic pain, interpreting results gleaned from clinical trials of antidepressants for treating FM are fraught with similar difficulties. Although amitriptyline has been a first-line treatment for FM for many years, the evidence upon which such recommendations were based consisted of low-level studies that had a significant potential for bias.59 Large randomized trials would offer more compelling data regarding the efficacy of amitriptyline, but the prohibitive costs of such studies makes it unlikely they will be conducted. Amitriptyline (25 to 50 mg/d) was effective in mitigating FM-related pain in a small percentage of patients studied, with an estimated NNT of 4.59 Adverse effects, often contributing to treatment discontinuation, were encountered more frequently among patients who received amitriptyline compared with placebo.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors failed to demonstrate significant pain relief (estimated NNT of 10), or improvement in fatigue or sleep problems, even though the studies upon which such conclusions were based were low-level studies with a high potential for bias.60 Although SSRIs have limited utility for mitigating pain, they are still quite useful for reducing depression among patients with FM.60

By contrast, the SNRIs duloxetine and milnacipran provided clinically relevant benefit over placebo in the frequency of patients reporting pain relief of ≥30%, as well as patients’ global impression of change.61 These agents, however, failed to provide clinically relevant benefit over placebo in improving health-related quality of life, reducing sleep problems, or improving fatigue. Nonetheless, duloxetine and milnacipran are FDA-approved for managing pain in FM. Studies assessing the efficacy of venlafaxine in the treatment of FM to date have been limited by small sample sizes, inconsistent dosing, lack of a placebo control, and lack of blinding, which limits the ability to clearly delineate the role of venlafaxine in managing FM.62

Mirtazapine (15 to 45 mg/d) showed a clinically relevant benefit compared with placebo for participant-reported pain relief of ≥30% and sleep disturbances. There was no benefit in terms of participant-reported improvement of quality of life, fatigue, or negative mood.63 The evidence was considered to be of low quality overall.

Headache

Amitriptyline has been employed off-label to address headache prophylaxis since 1964.64 Compared with placebo, it is efficacious in ameliorating migraine frequency and intensity as well as the frequency of tension headache.65,66 However, SSRIs and SNRIs (venlafaxine) failed to produce significant reductions in migraine frequency or severity or the frequencies of tension headache when compared with placebo.67,68

Continue to: Irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome

Early studies addressing antidepressant efficacy in IBS reveal inconsistencies. For example, whereas some suggest that TCAs are effective in mitigating chronic, severe abdominal pain,39,40 others concluded that TCAs failed to demonstrate a significant analgesic benefit.69 A recent meta-analysis that restricted analysis of efficacy to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with more rigorous methodological adherence found that pain relief in IBS is possible with both TCAs as well as SSRIs. However, adverse effects were more commonly encountered with TCAs than with SSRIs. Some of the inconsistencies in treatment efficacy reported in early studies may be due to variations in responsiveness of subsets of IBS patients. Specifically, the utility of TCAs appears to be best among patients with diarrheal-type (as opposed to constipation-type) IBS, presumably due to TCAs’ anticholinergic effects, whereas SSRIs may provide more of a benefit for patients with predominantly constipation-type IBS.40,70

Other chronic pain conditions

Antidepressants have been used to assist in the management of several other pain conditions, including oral-facial pain, interstitial cystitis, non-cardiac chest pain, and others. The role of antidepressants for such conditions remains unclear due to limitations in the prevailing empirical work, such as few trials, small sample sizes, variations in outcome measures, and insufficient randomization and blinding.71-76 The interpretation of results from systematic reviews and meta-analyses is limited because of these shortcomings.77 Hence, it has not always been possible to determine whether, and to what extent, patients with such conditions may benefit from antidepressants.

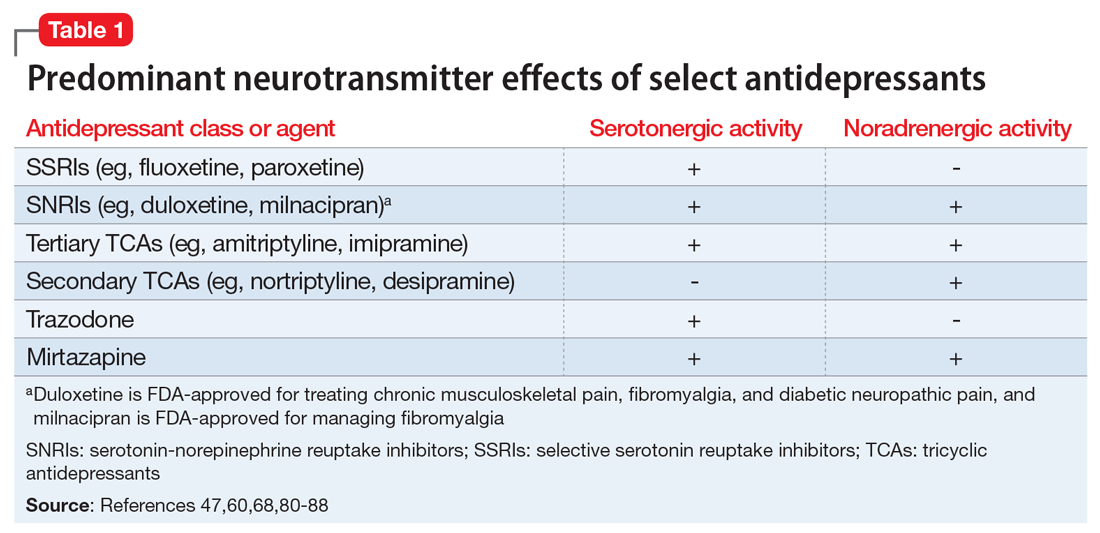

Neuromodulatory effects and efficacy for pain

The interplay of norepinephrine (NE) and serotonin (5-HT) neurotransmitter systems and cellular mechanisms involved in the descending modulation of pain pathways is complex. Experimental animal models of pain modulation suggest that 5-HT can both inhibit as well as promote pain perception by different physiological mechanisms, in contrast to NE, which is predominately inhibitory. While 5-HT in the descending modulating system can inhibit pain transmission ascending to the brain from the periphery, it appears that an intact noradrenergic system is necessary for the inhibitory influences of the serotonergic system to be appreciated.16,78,79 Deficiencies in one or both of these neurotransmitter systems may contribute to hyperactive pain processing, and thereby precipitate or maintain chronic pain.

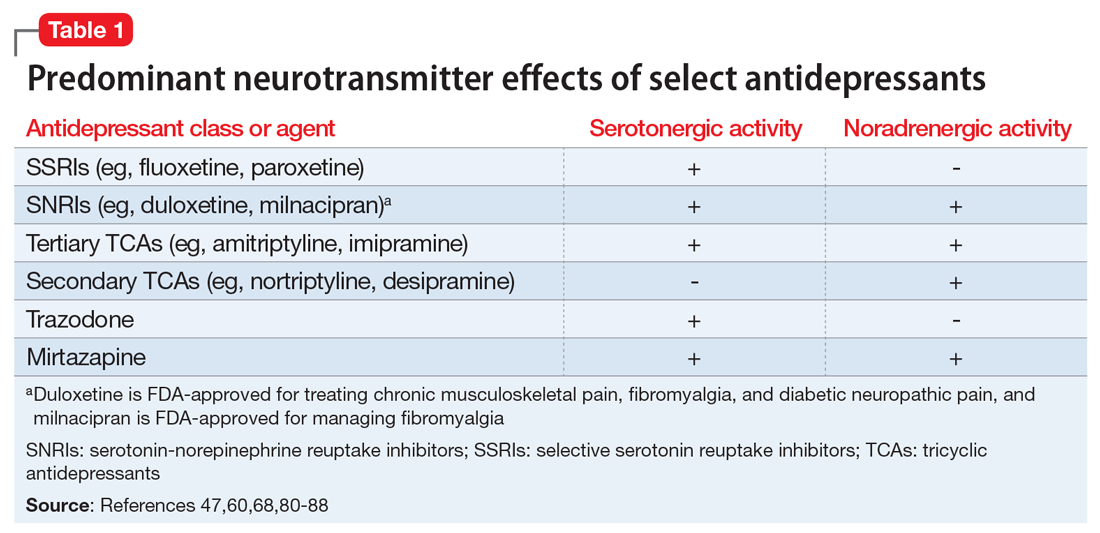

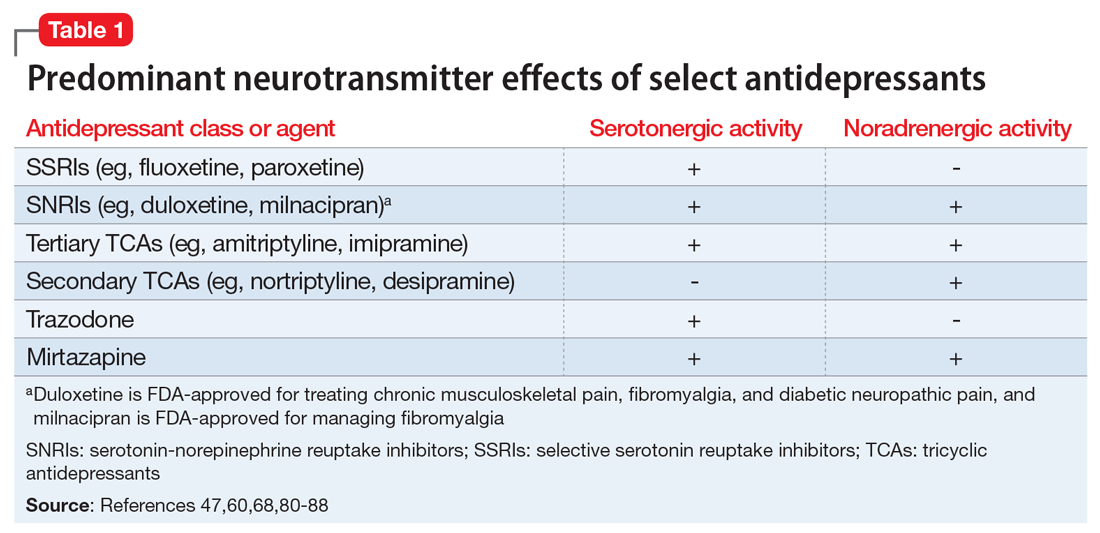

Pain mitigation may be achieved best by enhancing both neurotransmitters simultaneously, less so by enhancing NE alone, and least by enhancing 5-HT alone.6 The ability to impact pain modulation would, therefore, depend on the degree to which an antidepressant capitalizes on both noradrenergic and serotonergic neurotransmission. Antidepressants commonly employed to manage pain are presented in Table 147,60,68,80-88 according to their primary neurotransmitter effects. Thus, the literature summarized above suggests that antidepressants that influence both NE and 5-HT transmission have greater analgesic effects than antidepressants with more specific effects, such as influencing 5-HT reuptake alone.80-85 It is unsurprising, therefore, that the SSRIs have not been demonstrated to be as consistently analgesic.47,60,68,80,86-88

Similarly, pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic differences within antidepressant classes may influence analgesic effectiveness. Simultaneous effects on NE and 5-HT are achieved at low doses with duloxetine and milnacipran. By contrast, 5-HT effects predominate at low doses for venlafaxine. To achieve pain-mitigating effects, higher doses of venlafaxine generally are required.89 Therefore, inconsistencies across studies regarding the analgesic benefits of venlafaxine may be attributable to variability in dosing; patients treated with lower doses may not have experienced sufficient NE effects to garner positive results.

Continue to: The differences in analgesic efficacy...

The differences in analgesic efficacy among specific TCAs may be understood in a similar fashion. Specifically, tertiary TCAs (imipramine and amitriptyline) inhibit both 5-HT and NE reuptake.6,90 Secondary amines (desipramine and nortriptyline) predominantly impact NE reuptake, possibly accounting for the lesser pain-mitigating benefit achieved with these agents, such as for treating neuropathic pain. Further, in vivo imipramine and amitriptyline are rapidly metabolized to secondary amines that are potent and selective NE reuptake inhibitors. In this way, the secondary amines may substantially lose the ability to modulate pain transmission because of the loss of concurrent 5-HT influences.90

Clinical pearls

The following practical points can help guide clinicians regarding the usefulness of antidepressants for pain management:

- Antidepressants can alleviate symptoms of depression and pain. The pain-mitigating effects of antidepressants are possible even among chronic pain patients who are not depressed. Antidepressants may confer benefits for chronic pain patients with depression and other comorbid conditions, such as somatic symptom and related disorders.

- Antidepressants are useful for select chronic pain states. Although the noradrenergic and serotonergic antidepressants (SNRIs and, to some extent, amitriptyline) appear to have efficacy for neuropathic pain and FM, the benefits of SSRIs appear to be less robust. On the other hand, SSRIs and TCAs may have potential benefit for patients with IBS. However, the results of meta-analyses are limited in the ability to provide information about which patients will best respond to which specific antidepressant or how well. Future research directed at identifying characteristics that can predict which patients are likely to benefit from one antidepressant vs another would help inform how best to tailor treatment to individual needs.

- The pain-mitigating effects of antidepressants often emerge early in the course of treatment (often before mood-elevating effects are observed). For example, in the case of amitriptyline, pain relief may be possible for some patients at doses generally lower than those required for mood-elevating effects. To date, there is limited information in the literature to determine what constitutes a sufficient duration of treatment, or when treatment should be modified.

- Failure to reduce pain should raise questions about whether the dose should be increased, an alternative agent should be tried, or combinations with other analgesic agents should be considered. Failure to achieve pain-mitigating effects with one antidepressant does not mean failure with others. Hence, failure to achieve desired effects with one agent might warrant an empirical trial with another agent. Presently, too few double-blind RCTs have been conducted to assess the pain-mitigating effects of other antidepressants (eg, bupropion and newer SNRIs such as desvenlafaxine and levomilnacipran). Meta-analysis of the analgesic effectiveness of these agents or comparisons to the efficacy of other antidepressant classes is, therefore, impossible at this time.

Because many chronic pain states are complex, patients will seldom experience clinically relevant benefit from any one intervention.53 The bigger implication for clinical research is to determine whether there is a sequence or combination of medication use that will provide overall better clinical effectiveness.53 Only limited data are available exploring the utility of combining pharmacologic approaches to address pain.91 For example, preliminary evidence suggests that combinations of complementary strategies, such as duloxetine combined with pregabalin, may result in significantly greater numbers of FM patients achieving ≥30% pain reduction compared with monotherapy with either agent alone or placebo.92

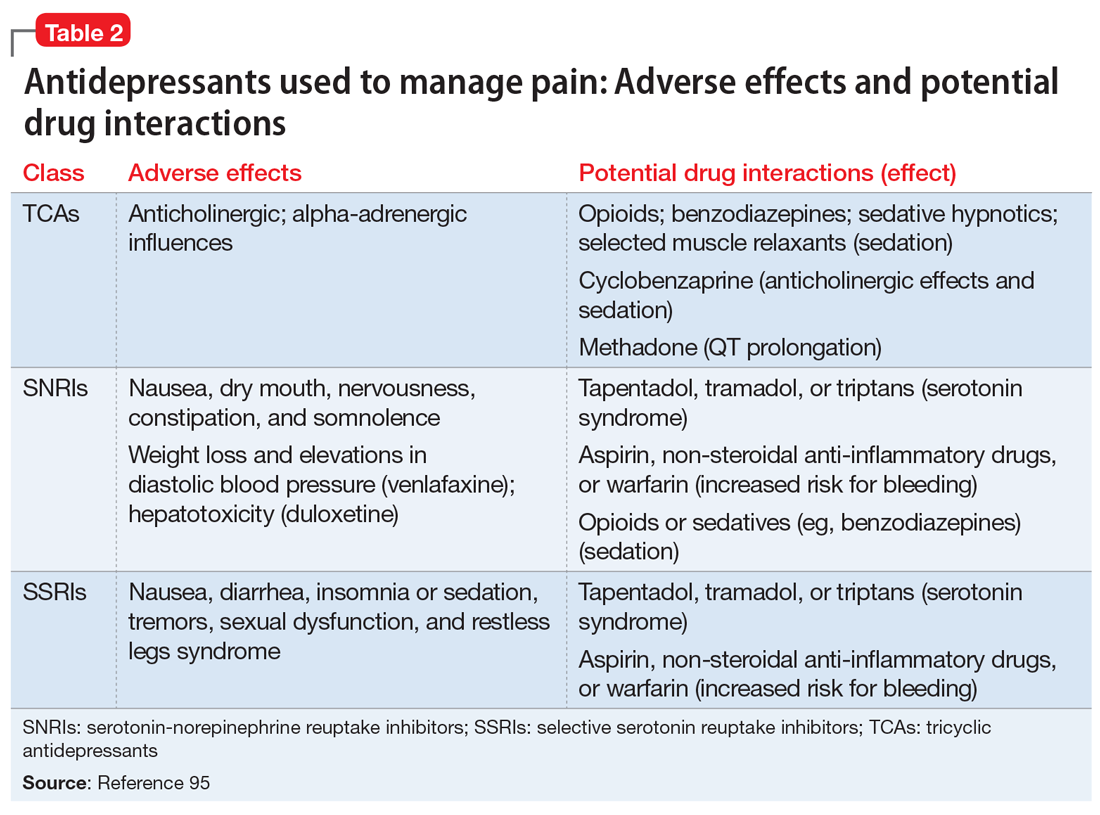

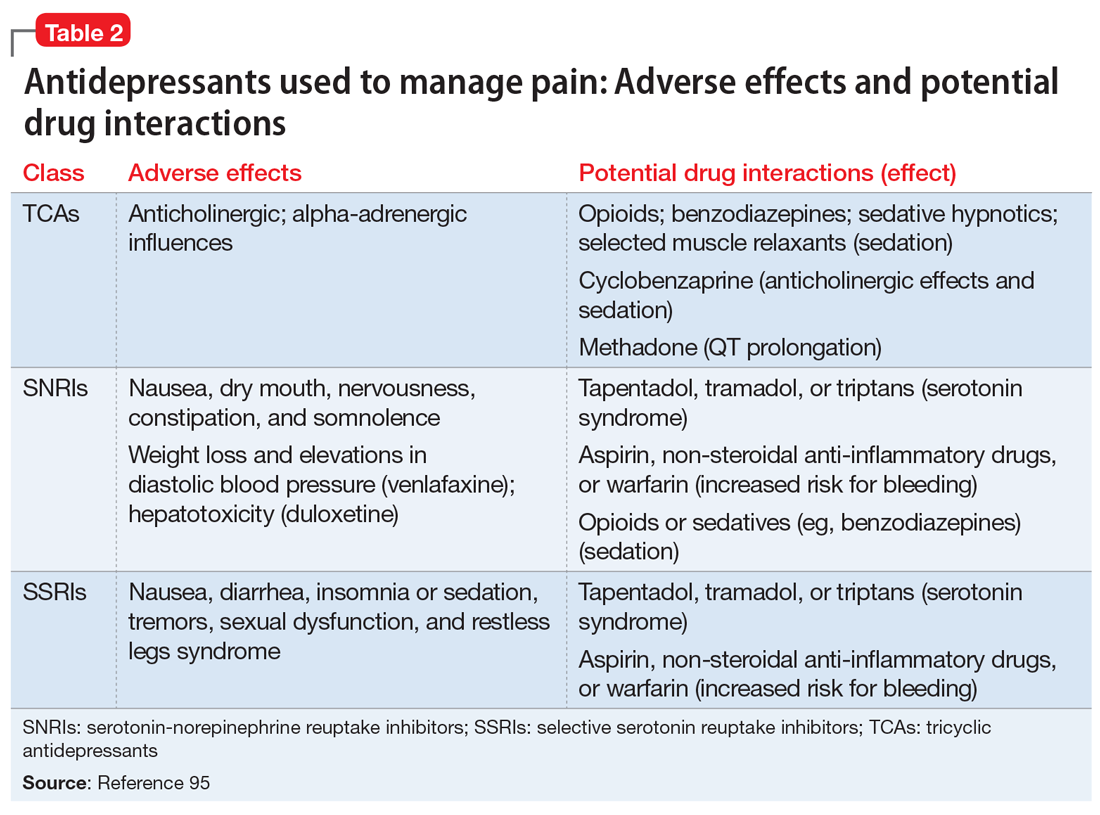

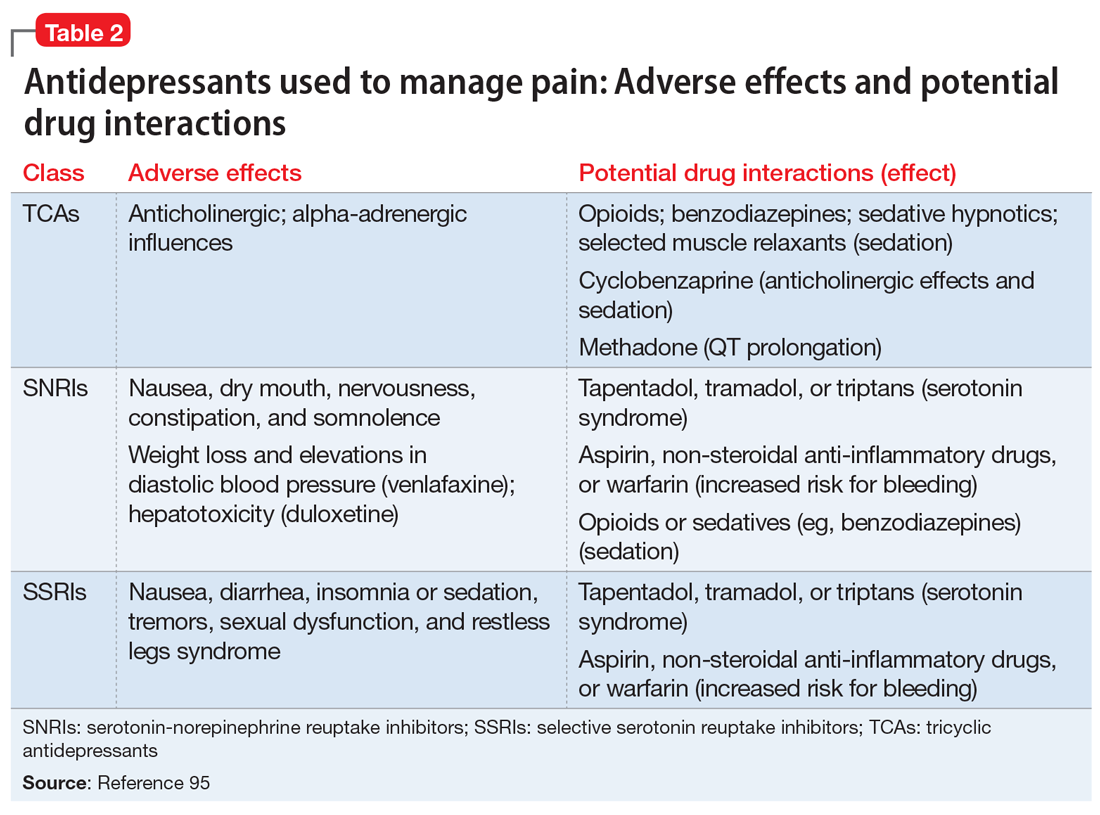

- Antidepressant selection may need to be based on medication-related adverse effect profiles and the potential for drug interactions. These factors are useful to consider in delineating multimodal treatment regimens for chronic pain in light of patients’ comorbidities and co-medication regimen. For example, the adverse effects of TCAs (anticholinergic and alpha-adrenergic influences) limit their utility for treating pain. Some of these effects can be more problematic in select populations, such as older adults or those with orthostatic difficulties, among others. TCAs are contraindicated in patients with closed-angle glaucoma, recent myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmias, poorly controlled seizures, or severe benign prostatic hypertrophy. Although the pain-mitigating effects of SNRIs have not been demonstrated to significantly exceed those of TCAs,68,93,94 SNRIs would offer an advantage of greater tolerability of adverse effects and relative safety in patients with comorbid medical conditions that would otherwise preclude TCA use. The adverse effects and common drug interactions associated with antidepressants are summarized in Table 295.

Conclusion

Chronic, nonmalignant pain conditions afflict many patients and significantly impair their ability to function. Because of heightened concerns related to the appropriateness of, and restricting inordinate access to, long-term opioid analgesics, clinicians need to explore the usefulness of co-analgesic agents, such as antidepressants. Significant comorbidities exist between psychiatric disorders and chronic pain, and psychiatrists are uniquely positioned to diagnose and treat psychiatric comorbidities, as well as pain, among their patients, especially since they understand the kinetics and dynamics of antidepressants.

Bottom Line

Antidepressants can alleviate symptoms of depression and pain. Noradrenergic and serotonergic antidepressants appear to have efficacy for pain associated with neuropathy and fibromyalgia, while selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants may have benefit for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. However, evidence regarding which patients will best respond to which specific antidepressant is limited.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Williams AM, Knox ED. When to prescribe antidepressants to treat comorbid depression and pain disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):55-58.

- Maletic V, Demuri B. Chronic pain and depression: treatment of 2 culprits in common. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(3):41,47-50,52.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil, Endep

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Carisoprodol • Rela, Soma

Cyclobenzaprine • Amrix, Flexeril

Desipramine • Norpramin

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Gabapentin • Horizant, Neurontin

Imipramine • Tofranil

Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

Milnacipran • Savella

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Paroxetine • Paxil

Pregabalin • Lyrica, Lyrica CR

Tapentadol • Nucynta

Tramadol • Ultram

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Warfarin • Coumadin, Jantoven

1. Paoli F, Darcourt G, Cossa P. Preliminary note on the action of imipramine in painful states [in French]. Rev Neurol (Paris). 1960;102:503-504.

2. Fields HL, Heinricher MM, Mason P. Neurotransmitters in nociceptive modulatory circuits. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1991;14:219-245.

3. Hunt SP, Mantyh PW. The molecular dynamics of pain control. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(2):83-91.

4. Lamont LA, Tranquilli WJ, Grimm KA. Physiology of pain. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2000;30(4):703-728, v.

5. Fields HL, Basbaum AI, Heinricher MM. Central nervous system mechanisms of pain modulation. In: McMahon S, Koltzenburg M, eds. Wall and Melzack’s Textbook of Pain. 5th ed. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:125-142.

6. Marks DM, Shah MJ, Patkar AA, et al. Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for pain control: premise and promise. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2009;7(4):331-336.

7. Baba H, Shimoji K, Yoshimura M. Norepinephrine facilitates inhibitory transmission in substantia gelatinosa of adult rat spinal cord (part 1): effects on axon terminals of GABAergic and glycinergic neurons. Anesthesiology. 2000;92(2):473-484.

8. Carter GT, Sullivan MD. Antidepressants in pain management. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3(3):454-458.

9. Kawasaki Y, Kumamoto E, Furue H, et al. Alpha 2 adrenoceptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition of primary afferent glutamatergic transmission in rat substantia gelatinosa neurons. Anesthesiology. 2003;98(3):682-689.

10. McCleane G. Antidepressants as analgesics. CNS Drugs. 2008;22(2):139-156.

11. Ansari A. The efficacy of newer antidepressants in the treatment of chronic pain: a review of current literature. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2000;7(5):257-277.

12. Egbunike IG, Chaffee BJ. Antidepressants in the management of chronic pain syndromes. Pharmacotherapy. 1990;10(4):262-270.

13. Fishbain DA. Evidence-based data on pain relief with antidepressants. Ann Med. 2000;32(5):305-316.

14. Fishbain DA, Detke MJ, Wernicke J, et al. The relationship between antidepressant and analgesic responses: findings from six placebo-controlled trials assessing the efficacy of duloxetine in patients with major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(11):3105-3115.

15. Harada E, Tokuoka H, Fujikoshi S, et al. Is duloxetine’s effect on painful physical symptoms in depression an indirect result of improvement of depressive symptoms? Pooled analyses of three randomized controlled trials. Pain. 2016;157(3):577-584.

16. Kehoe WA. Antidepressants for chronic pain: selection and dosing considerations. Am J Pain Med. 1993;3(4):161-165.

17. Damush TM, Kroenke K, Bair MJ, et al. Pain self-management training increases self-efficacy, self-management behaviours and pain and depression outcomes. Eur J Pain. 2016;20(2):1070-1078.

18. DeVeaugh-Geiss AM, West SL, Miller WC, et al. The adverse effects of comorbid pain on depression outcomes in primary care patients: results from the ARTIST trial. Pain Medicine. 2010;11(5):732-741.

19. Egloff N, Cámara RJ, von Känel R, et al. Hypersensitivity and hyperalgesia in somatoform pain disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(3):284-290.

20. Goesling J, Clauw DW, Hassett AL. Pain and depression: an integrative review of neurobiological and psychological factors. Curr Psych Reports. 2013;15(12):421.

21. Kroenke K, Wu J, Bair MJ, et al. Reciprocal relationship between pain and depression: a 12-Month longitudinal analysis in primary care. J Pain. 2011;12(9):964-973.

22. Leo RJ. Chronic pain and comorbid depression. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2005;7(5):403-412.

23. Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Eckert GJ, et al. Impact of pain on depression treatment response in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(1):17-22.

24. Karp JF, Scott J, Houck P, et al. Pain predicts longer time to remission during treatment of recurrent depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(5):591-597.

25. Kroenke K, Shen J, Oxman TE, et al. Impact of pain on the outcomes of depression treatment: results from the RESPECT trial. Pain. 2008;134(1-2):209-215.

26. Mavandadi S, Ten Have TR, Katz IR, et al. Effect of depression treatment on depressive symptoms in older adulthood: the moderating role of pain. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):202-211.

27. Thielke SM, Fan MY, Sullivan M, et al. Pain limits the effectiveness of collaborative care for depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(8):699-707.

28. Arnow BA, Hunkeler EM, Blasey CM, et al. Comorbid depression, chronic pain, and disability in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(2):262-268.

29. Demyttenaere K, Bonnewyn A, Bruffaerts R, et al. Comorbid painful physical symptoms and depression: Prevalence, work loss, and help seeking. J Affect Disord. 2006;92(2-3):185-193.

30. Nakao M, Barsky AJ. Clinical application of somatosensory amplification in psychosomatic medicine. Biopsychosoc Med. 2007;1:17.

31. Perez DL, Barsky AJ, Vago DR, et al. A neural circuit framework for somatosensory amplification in somatoform disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;27(1):e40-e50.

32. Fishbain DA, Cutler RB, Rosomoff HL, et al. Do antidepressants have an analgesic effect in psychogenic pain and somatoform pain disorder? A meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 1998;60(4):503-509.

33. Kleinstäuber M, Witthöft M, Steffanowski A, et al. Pharmacological interventions for somatoform disorders in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(11):CD010628.

34. Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuay HJ, et al. Antidepressants and anticonvulsants for diabetic neuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia: a quantitative systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20(6):449-458.

35. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain: a Cochrane review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(12):1372-1373.

36. Arnold LM, Keck PE, Welge JA. Antidepressant treatment of fibromyalgia. A meta-analysis and review. Psychosomatics. 2000;41(2):104-113.

37. O’Malley PG, Balden E, Tomkins G, et al. Treatment of fibromyalgia with antidepressants: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(9):659-666.

38. Tomkins GE, Jackson JL, O’Malley PG, et al. Treatment of chronic headache with antidepressants: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2001;111(1):54-63.

39. Jackson JL, O’Malley PG, Tomkins G, et al. Treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders with antidepressant medications: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2000;108(1):65-72.

40. Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Michetti P, Fried M et al. Meta-analysis: the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(11-12):1253-1269.

41. Centre for Clinical Practice at NICE (UK). Neuropathic pain: the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain in adults in non-specialist settings. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, (UK); 2013.

42. O’Connor AB, Dworkin RH. Treatment of neuropathic pain: an overview of recent guidelines. Am J Med. 2009;122(suppl 10):S22-S32.

43. Moulin D, Boulanger A, Clark AJ, et al; Canadian Pain Society. Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain: revised consensus statement from the Canadian Pain Society. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(6):328-35.

44. Mu A, Weinberg E, Moulin DE, et al. Pharmacologic management of chronic neuropathic pain: Review of the Canadian Pain Society consensus statement. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(11):844-852.

45. Finnerup NB, Otto M, McQuay HJ, et al. Algorithm for neuropathic pain treatment: an evidence based proposal. Pain. 2005;118(3):289-305.

46. Hempenstall K, Nurmikko TJ, Johnson RW, et al. Analgesic therapy in postherpetic neuralgia: a quantitative systematic review. PLoS Med. 2005;2(7):e164.

47. Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. Efficacy of pharmacological treatments of neuropathic pain: an update and effect related to mechanism of drug action. Pain. 1999;83(3):389-400.

48. Wu CL, Raja SN. An update on the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. J Pain. 2008;9(suppl 1):S19-S30.

49. Kroenke K, Krebs EE, Bair MJ. Pharmacotherapy of chronic pain: a synthesis of recommendations from systematic reviews. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(3):206-219.

50. Hearn L, Moore RA, Derry S, et al. Desipramine for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(9):CD011003.

51. Hearn L, Derry S, Phillips T, et al. Imipramine for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(5):CD010769.

52. Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Aldington D, et al. Nortriptyline for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD011209.

53. Moore R, Derry S, Aldington D, et al. Amitriptyline for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(7):CD008242.

54. Lunn MP, Hughes RA, Wiffen PJ. Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy, chronic pain or fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1):CD007115.

55. Gallagher HC, Gallagher RM, Butler M, et al. Venlafaxine for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(8):CD011091.

56. Alviar MJ, Hale T, Dungca M. Pharmacologic interventions for treating phantom limb pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD006380.

57. Dinat N, Marinda E, Moch S, et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Crossover Trial of Amitriptyline for Analgesia in Painful HIV-Associated Sensory Neuropathy. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126297.eCollection 2015.

58. Mehta S, McIntyre A, Janzen S, et al; Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence Team. Systematic review of pharmacologic treatments of pain after spinal cord injury: an update. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(8):1381-1391.e1.

59. Moore RA, Derry S, Aldington D, et al. Amitriptyline for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(12):CD008242..

60. Walitt B, Urrútia G, Nishishinya MB, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for fibromyalgia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(6):CD011735.

61. Welsch P, Üçeyler N, Klose P, et al. Serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;(2):CD010292.

62. VanderWeide LA, Smith SM, Trinkley KE. A systematic review of the efficacy of venlafaxine for the treatment of fibromyalgia. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2015;40(1):1-6.

63. Welsch P, Bernardy K, Derry S, et al. Mirtazapine for fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;(8):CD012708.

64. Lance JW, Curran DA. Treatment of chronic tension headache. Lancet. 1964;283(7345):1236-1239.

65. Jackson JL, William S, Laura S, et al. Tricyclic antidepressants and headaches: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c5222. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c5222

66. Xu XM, Liu Y, Dong MX, et al. Tricyclic antidepressants for preventing migraine in adults. Medicine. 2017;96(22):e6989. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006989.

67. Banzi R, Cusi C, Randazzo C, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) for the prevention of migraine in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(4):CD002919.

68. Banzi R, Cusi C, Randazzo C, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) for the prevention of tension-type headache in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(5):CD011681.

69. Quartero AO, Meineche-Schmidt V, Muris J, et al. Bulking agents, antispasmodic and antidepressant medication for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD003460.

70. Ford AC, Talley NJ, Schoenfeld PS, et al. Efficacy of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2009;58(3):367-378.

71. Coss-Adame E, Erdogan A, Rao SS. Treatment of esophageal (noncardiac) chest pain: an expert review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(8):1224-1245.

72. Kelada E, Jones A. Interstitial cystitis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;275(4):223-229.

73. Leo RJ, Dewani S. A systematic review of the utility of antidepressant pharmacotherapy in the treatment of vulvodynia pain. J Sex Med. 2013;10(10):2497-2505.

74. McMillan R, Forssell H, Buchanan JA, et al. Interventions for treating burning mouth syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD002779.

75. Patel DN. Inconclusive results of a systematic review of efficacy of antidepressants on orofacial pain disorders. Evid Based Dent. 2013;14(2):55-56.

76. Wang W, Sun YH, Wang YY, et al. Treatment of functional chest pain with antidepressants: a meta-analysis. Pain Physician. 2012;15(2):E131-E142.

77. Lavis JN. How can we support the use of systematic reviews in policymaking? PLoS Med. 2009;6(11):e1000141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000141.

78. Sorkin L. Nociceptive transmission within the spinal cord. Mt Sinai J Med. 1991;58(3):208-216.

79. Yokogawa F, Kiuchi Y, Ishikawa Y, et al. An investigation of monoamine receptors involved in antinociceptive effects of antidepressants. Anesth Analg. 2002;95(1):163-168, table of contents.

80. Lynch ME. Antidepressants as analgesics: a review of randomized controlled trials. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2001;26(1):30-36.

81. Max MB. Treatment of post-herpetic neuralgia: antidepressants. Ann Neurol. 1994;35(suppl):S50-S53.

82. Max MB, Lynch SA, Muir J, et al. Effects of desipramine, amitriptyline, and fluoxetine on pain in diabetic neuropathy. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(19):1250-1256.

83. McQuay HJ, Tramèr M, Nye BA, et al. A systematic review of antidepressants in neuropathic pain. Pain. 1996;68(2-3):217-227.

84. Mochizucki D. Serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors in animal models of pain. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2004;19(suppl 1):15-19.

85. Sussman N. SNRIs versus SSRIs: mechanisms of action in treating depression and painful physical symptoms. Primary Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;5(suppl 7):19-26.

86. Bundeff AW, Woodis CB. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(6):777-784.

87. Jung AC, Staiger T, Sullivan M. The efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the management of chronic pain. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(6):384-389.

88. Xie C, Tang Y, Wang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0127815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127815. eCollection 2015.

89. Zijlstra TR , Barendregt PJ , van de Laar MA. Venlafaxine in fibromyalgia: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(suppl 9):S105.

90. Bymaster FP, Dreshfield-Ahmad LJ, Threlkeld PG. Comparative affinity of duloxetine and venlafaxine for serotonin and norepinephrine transporters in vitro and in vivo, human serotonin receptor subtypes, and other neuronal receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(6):871-880.

91. Thorpe J, Shum B, Moore RA, et al. Combination pharmacotherapy for the treatment of fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;(2):CD010585.

92. Gilron I, Chaparro LE, Tu D, et al. Combination of pregabalin with duloxetine for fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2016;157(7):1532-1540.

93. Häuser W, Petzke F, Üçeyler N, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of amitriptyline, duloxetine and milnacipran in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(3):532-543.

94. Hossain SM, Hussain SM, Ekram AR. Duloxetine in painful diabetic neuropathy: a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(11):1005-1010.

95. Riediger C, Schuster T, Barlinn K, et al. Adverse effects of antidepressants for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2017;8:307.

Approximately 55 years ago, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) began to be used to treat neuropathic pain.1 Eventually, clinical trials emerged suggesting the utility of TCAs for other chronic pain conditions, such as fibromyalgia (FM) and migraine prophylaxis. However, despite TCAs’ effectiveness in mitigating painful conditions, their adverse effects limited their use.

Pharmacologic advancements have led to the development of other antidepressant classes, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and the use of these agents has come to eclipse that of TCAs. In the realm of pain management, such developments have raised the hope of possible alternative co-analgesic agents that could avoid the adverse effects associated with TCAs. Some of these agents have demonstrated efficacy for managing chronic pain states, while others have demonstrated only limited utility.

This article provides a synopsis of systematic reviews and meta-analyses examining the role of antidepressant therapy for managing several chronic pain conditions, including pain associated with neuropathy, FM, headache, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Because the literature base is rapidly evolving, it is necessary to revisit the information gleaned from clinical data with respect to treatment effectiveness, and to clarify how antidepressants might be positioned in the management of chronic pain.

The effectiveness of antidepressants for pain

The pathophysiologic processes that precipitate and maintain chronic pain conditions are complex (Box 12-10). The pain-mitigating effects of antidepressants can be thought of in terms of direct analgesic effects and indirect effects (Box 22,3,8,10,11-33).

Box 1

The pathophysiologic processes precipitating and maintaining chronic pain conditions are complex. Persistent and chronic pain results from changes in sensitivity within both ascending pathways (relaying pain information from the periphery to the spinal cord and brain) and descending pain pathways (functioning to modulate ascending pain information).2,3 Tissue damage or peripheral nerve injury can lead to a cascade of neuroplastic changes within the CNS, resulting in hyperexcitability within the ascending pain pathways.

The descending pain pathways consist of the midbrain periaqueductal gray area (PGA), the rostroventral medulla (RVM), and the dorsolateral pontomesencephalic tegmentum (DLPT). The axons of the RVM (the outflow of which is serotonergic) and DLPT (the outflow of which is noradrenergic) terminate in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord,4 and thereby dampen pain signals arising from the periphery. Diminished output from descending pain pathways can heighten the pain experience. Input from the cortex, hypothalamus, and amygdala (among other structures) converges upon the PGA, RVM and DLPT, and can influence the degree of pain modulation emerging from descending pathways. In this way, thoughts, appraisals, and mood are believed to comprise cognitive and affective modifiers of pain experiences.

Devising effective chronic pain treatment becomes challenging; multimodal treatment approaches often are advocated, including pharmacologic treatment with analgesics in combination with co-analgesic medications such as antidepressants. Although a description of multimodal treatment is beyond the scope of this article, such treatment also would encompass physical therapy, occupational therapy, and psychotherapeutic interventions to augment rehabilitative efforts and the functional capabilities of patients who struggle with persisting pain.

Although the direct pain-mitigating effects of antidepressants are not fully understood, it is believed that augmentation of monoamine neurotransmission from supraspinal nuclei (ie, the RVM and DLPT) modulate pain transmission from the periphery.5,6 In addition, there is evidence that some effects of tricyclic antidepressants can modulate several other functions that impact peripheral and central sensitization.7-10

During the last several decades, antidepressants have been used to address—and have demonstrated clinical utility for—a variety of chronic pain states. However, antidepressants are not a panacea; some chronic pain conditions are more responsive to antidepressants than are others. The chronic painful states most amenable to antidepressants are those that result primarily from a process of neural sensitization, as opposed to acute somatic or visceral nociception. Hence, several meta-analyses and evidence-based reviews have long suggested the usefulness of antidepressants for mitigating pain associated with neuropathy,34,35 FM,36,37 headache,38 and IBS.39,40

Box 2

The pain-mitigating effects of antidepressants can be thought of in terms of direct analgesic effects (impacting neurotransmission of descending pathways independent of influences on mood) and indirect effects (presumably impacting cortical and limbic output to the periaqueductal gray area, the rostroventral medulla, and the dorsolateral pontomesencephalic tegmentum brought about by improvement in mood and/or cognitive appraisals) (Figure2,3,8,10,11,15,20,22,28,29). Support for the direct analgesic effects has been garnered from initial empirical work that demonstrated pain relief among patients with pain who are not depressed. Additionally, among patients who have depression and experience pain, analgesia reportedly often occurs within 2 weeks, which is before antidepressant effects are appreciated,11-15 and, at least for some antidepressants, occurs at doses far lower than those required to produce mood-elevating effects.11,12,16

On the other hand, it is well established that significant comorbidities exist between chronic pain states and psychiatric disorders (eg, depression and somatic symptom and related disorders).17-21 There may be common physiological substrates underlying chronic pain and depression.20,22 There are bidirectional influences of limbic (affective) systems and those CNS structures involved in pain processing and integration. The effects of pain and depression are reciprocal; the presence of one makes the management of the other more challenging.23-27 Mood disturbances can, therefore, impact pain processing by acting as affective and cognitive amplifiers of pain by leading to catastrophizing, pain severity augmentation, poor coping with pain-related stress, etc.28,29 It is plausible that the mood-elevating effects of antidepressants can improve pain by indirect effects, by modulating limbic activity, which in turn, impacts coping, cognitive appraisals of pain, etc.

Patients with somatoform disorders (using pre-DSM-5 terminology) frequently present with chronic pain, often in multiple sites.19 Such patients are characterized by hypervigilance for, and a predisposition to focus on, physical sensations and to appraise these sensations as reflecting a pathological state.30 Neuroimaging studies have begun to identify those neural circuits involved in somatoform disorders, many of which act as cognitive and affective amplifiers of visceral-somatic sensory processing. Many of these neural circuits overlap, and interact with, those involved in pain processing.31 Antidepressants can mitigate the severity of unexplained physical complaints, including pain, among patients who somatize32,33; however, due to the heterogeneity of studies upon which this claim is based, the quality of the evidence is reportedly low.33 There is uncertainty whether, or to what extent, antidepressant benefits among patients who somatize are due to a direct impact on pain modulation, or indirect effects on mood or cognitive appraisals/perceptions.

Despite the uncertainties about the exact mechanisms through which antidepressants exert analgesic effects, antidepressants can be appropriately used to treat patients with selected chronic pain syndromes, regardless of whether or not the patient has a psychiatric comorbidity. For those patients with pain and psychiatric comorbidities, the benefits may be brought about via direct mechanisms, indirect mechanisms, or a combination of both.

Continue to: Neuropathic pain

Neuropathic pain

Several treatment guidelines advocate for the use of antidepressants for neuropathic pain.41-44 For decades, TCAs have been employed off-label to successfully treat many patients with neuropathic pain states. Early investigations suggested that TCAs were robustly efficacious in managing patients with neuropathy.45-48 Calculated number-needed-to-treat (NNT) values for TCAs were quite low (ie, reflecting that few patients would need to be treated to yield a positive response in one patient compared with placebo), and were comparable to, if not slightly better than, the NNTs generated for anticonvulsants and α2-δ ligands, such as gabapentin or pregabalin.45-48

Unfortunately, early studies involving TCAs conducted many years ago do not meet contemporary standards of methodological rigor; they featured relatively small samples of patients assessed for brief post-treatment intervals with variable outcome measures. Thus, the NNT values obtained in meta-analyses based on these studies may overestimate treatment benefits.49 Further, NNT values derived from meta-analyses tended to combine all drugs within a particular antidepressant class (eg, amitriptyline, nortriptyline, desipramine, and imipramine among the TCAs) employed at diverse doses. Taken together, these limitations raise questions about the results of those meta-analyses.

Subsequent meta-analyses, which employed strict criteria to eliminate data from studies with potential sources of bias and used a primary outcome of frequencies of patients reporting at least 30% pain reduction compared with a placebo-controlled sample, suggest that the effectiveness of TCAs as a class for treating neuropathic pain is not as compelling as once was thought. Meta-analyses of studies employing specific TCAs revealed that there was little evidence to support the use of desipramine,50 imipramine,51 or nortriptyline52 in managing diabetic neuropathy or postherpetic neuralgia. Studies evaluating amitriptyline (dose range 12.5 to 150 mg/d), found low-level evidence of effectiveness; the benefit was expected to be present for a small subset (approximately 25%) of patients with neuropathic pain.53

There is moderate-quality evidence that duloxetine (60 to 120 mg/d) can produce a ≥50% improvement in pain severity ratings among patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy.54 Although head-to-head studies with other antidepressants are limited, it appears that duloxetine and amitriptyline have comparable efficacy, even though the NNTs for amitriptyline were derived from lower-quality studies than those for duloxetine. Duloxetine is the only antidepressant to receive FDA approval for managing diabetic neuropathy. By contrast, studies assessing the utility of venlafaxine in neuropathic pain comprised small samples for brief durations, which limits the ability to draw clear (unbiased) support for its usefulness.55

Given the diversity of pathophysiologic processes underlying the disturbances that cause neuropathic pain disorders, it is unsurprising that the effectiveness of amitriptyline and duloxetine were not generalizable to all neuropathic pain states. Although amitriptyline produced pain-mitigating effects in patients with diabetic neuropathy and post-herpetic neuralgia, and duloxetine mitigated pain among patients with diabetic neuropathy, there was no evidence to suggest their effectiveness in phantom limb pain or human immunodeficiency virus-related and spinal cord-related neuropathies.35,53,54,56-58

Continue to: Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia

As with the issues encountered in interpreting the effectiveness of antidepressants in neuropathic pain, interpreting results gleaned from clinical trials of antidepressants for treating FM are fraught with similar difficulties. Although amitriptyline has been a first-line treatment for FM for many years, the evidence upon which such recommendations were based consisted of low-level studies that had a significant potential for bias.59 Large randomized trials would offer more compelling data regarding the efficacy of amitriptyline, but the prohibitive costs of such studies makes it unlikely they will be conducted. Amitriptyline (25 to 50 mg/d) was effective in mitigating FM-related pain in a small percentage of patients studied, with an estimated NNT of 4.59 Adverse effects, often contributing to treatment discontinuation, were encountered more frequently among patients who received amitriptyline compared with placebo.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors failed to demonstrate significant pain relief (estimated NNT of 10), or improvement in fatigue or sleep problems, even though the studies upon which such conclusions were based were low-level studies with a high potential for bias.60 Although SSRIs have limited utility for mitigating pain, they are still quite useful for reducing depression among patients with FM.60

By contrast, the SNRIs duloxetine and milnacipran provided clinically relevant benefit over placebo in the frequency of patients reporting pain relief of ≥30%, as well as patients’ global impression of change.61 These agents, however, failed to provide clinically relevant benefit over placebo in improving health-related quality of life, reducing sleep problems, or improving fatigue. Nonetheless, duloxetine and milnacipran are FDA-approved for managing pain in FM. Studies assessing the efficacy of venlafaxine in the treatment of FM to date have been limited by small sample sizes, inconsistent dosing, lack of a placebo control, and lack of blinding, which limits the ability to clearly delineate the role of venlafaxine in managing FM.62

Mirtazapine (15 to 45 mg/d) showed a clinically relevant benefit compared with placebo for participant-reported pain relief of ≥30% and sleep disturbances. There was no benefit in terms of participant-reported improvement of quality of life, fatigue, or negative mood.63 The evidence was considered to be of low quality overall.

Headache

Amitriptyline has been employed off-label to address headache prophylaxis since 1964.64 Compared with placebo, it is efficacious in ameliorating migraine frequency and intensity as well as the frequency of tension headache.65,66 However, SSRIs and SNRIs (venlafaxine) failed to produce significant reductions in migraine frequency or severity or the frequencies of tension headache when compared with placebo.67,68

Continue to: Irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome

Early studies addressing antidepressant efficacy in IBS reveal inconsistencies. For example, whereas some suggest that TCAs are effective in mitigating chronic, severe abdominal pain,39,40 others concluded that TCAs failed to demonstrate a significant analgesic benefit.69 A recent meta-analysis that restricted analysis of efficacy to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with more rigorous methodological adherence found that pain relief in IBS is possible with both TCAs as well as SSRIs. However, adverse effects were more commonly encountered with TCAs than with SSRIs. Some of the inconsistencies in treatment efficacy reported in early studies may be due to variations in responsiveness of subsets of IBS patients. Specifically, the utility of TCAs appears to be best among patients with diarrheal-type (as opposed to constipation-type) IBS, presumably due to TCAs’ anticholinergic effects, whereas SSRIs may provide more of a benefit for patients with predominantly constipation-type IBS.40,70

Other chronic pain conditions

Antidepressants have been used to assist in the management of several other pain conditions, including oral-facial pain, interstitial cystitis, non-cardiac chest pain, and others. The role of antidepressants for such conditions remains unclear due to limitations in the prevailing empirical work, such as few trials, small sample sizes, variations in outcome measures, and insufficient randomization and blinding.71-76 The interpretation of results from systematic reviews and meta-analyses is limited because of these shortcomings.77 Hence, it has not always been possible to determine whether, and to what extent, patients with such conditions may benefit from antidepressants.

Neuromodulatory effects and efficacy for pain

The interplay of norepinephrine (NE) and serotonin (5-HT) neurotransmitter systems and cellular mechanisms involved in the descending modulation of pain pathways is complex. Experimental animal models of pain modulation suggest that 5-HT can both inhibit as well as promote pain perception by different physiological mechanisms, in contrast to NE, which is predominately inhibitory. While 5-HT in the descending modulating system can inhibit pain transmission ascending to the brain from the periphery, it appears that an intact noradrenergic system is necessary for the inhibitory influences of the serotonergic system to be appreciated.16,78,79 Deficiencies in one or both of these neurotransmitter systems may contribute to hyperactive pain processing, and thereby precipitate or maintain chronic pain.

Pain mitigation may be achieved best by enhancing both neurotransmitters simultaneously, less so by enhancing NE alone, and least by enhancing 5-HT alone.6 The ability to impact pain modulation would, therefore, depend on the degree to which an antidepressant capitalizes on both noradrenergic and serotonergic neurotransmission. Antidepressants commonly employed to manage pain are presented in Table 147,60,68,80-88 according to their primary neurotransmitter effects. Thus, the literature summarized above suggests that antidepressants that influence both NE and 5-HT transmission have greater analgesic effects than antidepressants with more specific effects, such as influencing 5-HT reuptake alone.80-85 It is unsurprising, therefore, that the SSRIs have not been demonstrated to be as consistently analgesic.47,60,68,80,86-88

Similarly, pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic differences within antidepressant classes may influence analgesic effectiveness. Simultaneous effects on NE and 5-HT are achieved at low doses with duloxetine and milnacipran. By contrast, 5-HT effects predominate at low doses for venlafaxine. To achieve pain-mitigating effects, higher doses of venlafaxine generally are required.89 Therefore, inconsistencies across studies regarding the analgesic benefits of venlafaxine may be attributable to variability in dosing; patients treated with lower doses may not have experienced sufficient NE effects to garner positive results.

Continue to: The differences in analgesic efficacy...

The differences in analgesic efficacy among specific TCAs may be understood in a similar fashion. Specifically, tertiary TCAs (imipramine and amitriptyline) inhibit both 5-HT and NE reuptake.6,90 Secondary amines (desipramine and nortriptyline) predominantly impact NE reuptake, possibly accounting for the lesser pain-mitigating benefit achieved with these agents, such as for treating neuropathic pain. Further, in vivo imipramine and amitriptyline are rapidly metabolized to secondary amines that are potent and selective NE reuptake inhibitors. In this way, the secondary amines may substantially lose the ability to modulate pain transmission because of the loss of concurrent 5-HT influences.90

Clinical pearls

The following practical points can help guide clinicians regarding the usefulness of antidepressants for pain management:

- Antidepressants can alleviate symptoms of depression and pain. The pain-mitigating effects of antidepressants are possible even among chronic pain patients who are not depressed. Antidepressants may confer benefits for chronic pain patients with depression and other comorbid conditions, such as somatic symptom and related disorders.

- Antidepressants are useful for select chronic pain states. Although the noradrenergic and serotonergic antidepressants (SNRIs and, to some extent, amitriptyline) appear to have efficacy for neuropathic pain and FM, the benefits of SSRIs appear to be less robust. On the other hand, SSRIs and TCAs may have potential benefit for patients with IBS. However, the results of meta-analyses are limited in the ability to provide information about which patients will best respond to which specific antidepressant or how well. Future research directed at identifying characteristics that can predict which patients are likely to benefit from one antidepressant vs another would help inform how best to tailor treatment to individual needs.

- The pain-mitigating effects of antidepressants often emerge early in the course of treatment (often before mood-elevating effects are observed). For example, in the case of amitriptyline, pain relief may be possible for some patients at doses generally lower than those required for mood-elevating effects. To date, there is limited information in the literature to determine what constitutes a sufficient duration of treatment, or when treatment should be modified.

- Failure to reduce pain should raise questions about whether the dose should be increased, an alternative agent should be tried, or combinations with other analgesic agents should be considered. Failure to achieve pain-mitigating effects with one antidepressant does not mean failure with others. Hence, failure to achieve desired effects with one agent might warrant an empirical trial with another agent. Presently, too few double-blind RCTs have been conducted to assess the pain-mitigating effects of other antidepressants (eg, bupropion and newer SNRIs such as desvenlafaxine and levomilnacipran). Meta-analysis of the analgesic effectiveness of these agents or comparisons to the efficacy of other antidepressant classes is, therefore, impossible at this time.

Because many chronic pain states are complex, patients will seldom experience clinically relevant benefit from any one intervention.53 The bigger implication for clinical research is to determine whether there is a sequence or combination of medication use that will provide overall better clinical effectiveness.53 Only limited data are available exploring the utility of combining pharmacologic approaches to address pain.91 For example, preliminary evidence suggests that combinations of complementary strategies, such as duloxetine combined with pregabalin, may result in significantly greater numbers of FM patients achieving ≥30% pain reduction compared with monotherapy with either agent alone or placebo.92

- Antidepressant selection may need to be based on medication-related adverse effect profiles and the potential for drug interactions. These factors are useful to consider in delineating multimodal treatment regimens for chronic pain in light of patients’ comorbidities and co-medication regimen. For example, the adverse effects of TCAs (anticholinergic and alpha-adrenergic influences) limit their utility for treating pain. Some of these effects can be more problematic in select populations, such as older adults or those with orthostatic difficulties, among others. TCAs are contraindicated in patients with closed-angle glaucoma, recent myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmias, poorly controlled seizures, or severe benign prostatic hypertrophy. Although the pain-mitigating effects of SNRIs have not been demonstrated to significantly exceed those of TCAs,68,93,94 SNRIs would offer an advantage of greater tolerability of adverse effects and relative safety in patients with comorbid medical conditions that would otherwise preclude TCA use. The adverse effects and common drug interactions associated with antidepressants are summarized in Table 295.

Conclusion

Chronic, nonmalignant pain conditions afflict many patients and significantly impair their ability to function. Because of heightened concerns related to the appropriateness of, and restricting inordinate access to, long-term opioid analgesics, clinicians need to explore the usefulness of co-analgesic agents, such as antidepressants. Significant comorbidities exist between psychiatric disorders and chronic pain, and psychiatrists are uniquely positioned to diagnose and treat psychiatric comorbidities, as well as pain, among their patients, especially since they understand the kinetics and dynamics of antidepressants.

Bottom Line

Antidepressants can alleviate symptoms of depression and pain. Noradrenergic and serotonergic antidepressants appear to have efficacy for pain associated with neuropathy and fibromyalgia, while selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants may have benefit for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. However, evidence regarding which patients will best respond to which specific antidepressant is limited.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Williams AM, Knox ED. When to prescribe antidepressants to treat comorbid depression and pain disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):55-58.

- Maletic V, Demuri B. Chronic pain and depression: treatment of 2 culprits in common. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(3):41,47-50,52.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil, Endep

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Carisoprodol • Rela, Soma

Cyclobenzaprine • Amrix, Flexeril

Desipramine • Norpramin

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Gabapentin • Horizant, Neurontin

Imipramine • Tofranil

Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

Milnacipran • Savella

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Paroxetine • Paxil

Pregabalin • Lyrica, Lyrica CR

Tapentadol • Nucynta

Tramadol • Ultram

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Warfarin • Coumadin, Jantoven

Approximately 55 years ago, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) began to be used to treat neuropathic pain.1 Eventually, clinical trials emerged suggesting the utility of TCAs for other chronic pain conditions, such as fibromyalgia (FM) and migraine prophylaxis. However, despite TCAs’ effectiveness in mitigating painful conditions, their adverse effects limited their use.

Pharmacologic advancements have led to the development of other antidepressant classes, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and the use of these agents has come to eclipse that of TCAs. In the realm of pain management, such developments have raised the hope of possible alternative co-analgesic agents that could avoid the adverse effects associated with TCAs. Some of these agents have demonstrated efficacy for managing chronic pain states, while others have demonstrated only limited utility.

This article provides a synopsis of systematic reviews and meta-analyses examining the role of antidepressant therapy for managing several chronic pain conditions, including pain associated with neuropathy, FM, headache, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Because the literature base is rapidly evolving, it is necessary to revisit the information gleaned from clinical data with respect to treatment effectiveness, and to clarify how antidepressants might be positioned in the management of chronic pain.

The effectiveness of antidepressants for pain

The pathophysiologic processes that precipitate and maintain chronic pain conditions are complex (Box 12-10). The pain-mitigating effects of antidepressants can be thought of in terms of direct analgesic effects and indirect effects (Box 22,3,8,10,11-33).

Box 1

The pathophysiologic processes precipitating and maintaining chronic pain conditions are complex. Persistent and chronic pain results from changes in sensitivity within both ascending pathways (relaying pain information from the periphery to the spinal cord and brain) and descending pain pathways (functioning to modulate ascending pain information).2,3 Tissue damage or peripheral nerve injury can lead to a cascade of neuroplastic changes within the CNS, resulting in hyperexcitability within the ascending pain pathways.

The descending pain pathways consist of the midbrain periaqueductal gray area (PGA), the rostroventral medulla (RVM), and the dorsolateral pontomesencephalic tegmentum (DLPT). The axons of the RVM (the outflow of which is serotonergic) and DLPT (the outflow of which is noradrenergic) terminate in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord,4 and thereby dampen pain signals arising from the periphery. Diminished output from descending pain pathways can heighten the pain experience. Input from the cortex, hypothalamus, and amygdala (among other structures) converges upon the PGA, RVM and DLPT, and can influence the degree of pain modulation emerging from descending pathways. In this way, thoughts, appraisals, and mood are believed to comprise cognitive and affective modifiers of pain experiences.

Devising effective chronic pain treatment becomes challenging; multimodal treatment approaches often are advocated, including pharmacologic treatment with analgesics in combination with co-analgesic medications such as antidepressants. Although a description of multimodal treatment is beyond the scope of this article, such treatment also would encompass physical therapy, occupational therapy, and psychotherapeutic interventions to augment rehabilitative efforts and the functional capabilities of patients who struggle with persisting pain.

Although the direct pain-mitigating effects of antidepressants are not fully understood, it is believed that augmentation of monoamine neurotransmission from supraspinal nuclei (ie, the RVM and DLPT) modulate pain transmission from the periphery.5,6 In addition, there is evidence that some effects of tricyclic antidepressants can modulate several other functions that impact peripheral and central sensitization.7-10

During the last several decades, antidepressants have been used to address—and have demonstrated clinical utility for—a variety of chronic pain states. However, antidepressants are not a panacea; some chronic pain conditions are more responsive to antidepressants than are others. The chronic painful states most amenable to antidepressants are those that result primarily from a process of neural sensitization, as opposed to acute somatic or visceral nociception. Hence, several meta-analyses and evidence-based reviews have long suggested the usefulness of antidepressants for mitigating pain associated with neuropathy,34,35 FM,36,37 headache,38 and IBS.39,40

Box 2

The pain-mitigating effects of antidepressants can be thought of in terms of direct analgesic effects (impacting neurotransmission of descending pathways independent of influences on mood) and indirect effects (presumably impacting cortical and limbic output to the periaqueductal gray area, the rostroventral medulla, and the dorsolateral pontomesencephalic tegmentum brought about by improvement in mood and/or cognitive appraisals) (Figure2,3,8,10,11,15,20,22,28,29). Support for the direct analgesic effects has been garnered from initial empirical work that demonstrated pain relief among patients with pain who are not depressed. Additionally, among patients who have depression and experience pain, analgesia reportedly often occurs within 2 weeks, which is before antidepressant effects are appreciated,11-15 and, at least for some antidepressants, occurs at doses far lower than those required to produce mood-elevating effects.11,12,16

On the other hand, it is well established that significant comorbidities exist between chronic pain states and psychiatric disorders (eg, depression and somatic symptom and related disorders).17-21 There may be common physiological substrates underlying chronic pain and depression.20,22 There are bidirectional influences of limbic (affective) systems and those CNS structures involved in pain processing and integration. The effects of pain and depression are reciprocal; the presence of one makes the management of the other more challenging.23-27 Mood disturbances can, therefore, impact pain processing by acting as affective and cognitive amplifiers of pain by leading to catastrophizing, pain severity augmentation, poor coping with pain-related stress, etc.28,29 It is plausible that the mood-elevating effects of antidepressants can improve pain by indirect effects, by modulating limbic activity, which in turn, impacts coping, cognitive appraisals of pain, etc.

Patients with somatoform disorders (using pre-DSM-5 terminology) frequently present with chronic pain, often in multiple sites.19 Such patients are characterized by hypervigilance for, and a predisposition to focus on, physical sensations and to appraise these sensations as reflecting a pathological state.30 Neuroimaging studies have begun to identify those neural circuits involved in somatoform disorders, many of which act as cognitive and affective amplifiers of visceral-somatic sensory processing. Many of these neural circuits overlap, and interact with, those involved in pain processing.31 Antidepressants can mitigate the severity of unexplained physical complaints, including pain, among patients who somatize32,33; however, due to the heterogeneity of studies upon which this claim is based, the quality of the evidence is reportedly low.33 There is uncertainty whether, or to what extent, antidepressant benefits among patients who somatize are due to a direct impact on pain modulation, or indirect effects on mood or cognitive appraisals/perceptions.

Despite the uncertainties about the exact mechanisms through which antidepressants exert analgesic effects, antidepressants can be appropriately used to treat patients with selected chronic pain syndromes, regardless of whether or not the patient has a psychiatric comorbidity. For those patients with pain and psychiatric comorbidities, the benefits may be brought about via direct mechanisms, indirect mechanisms, or a combination of both.

Continue to: Neuropathic pain

Neuropathic pain

Several treatment guidelines advocate for the use of antidepressants for neuropathic pain.41-44 For decades, TCAs have been employed off-label to successfully treat many patients with neuropathic pain states. Early investigations suggested that TCAs were robustly efficacious in managing patients with neuropathy.45-48 Calculated number-needed-to-treat (NNT) values for TCAs were quite low (ie, reflecting that few patients would need to be treated to yield a positive response in one patient compared with placebo), and were comparable to, if not slightly better than, the NNTs generated for anticonvulsants and α2-δ ligands, such as gabapentin or pregabalin.45-48

Unfortunately, early studies involving TCAs conducted many years ago do not meet contemporary standards of methodological rigor; they featured relatively small samples of patients assessed for brief post-treatment intervals with variable outcome measures. Thus, the NNT values obtained in meta-analyses based on these studies may overestimate treatment benefits.49 Further, NNT values derived from meta-analyses tended to combine all drugs within a particular antidepressant class (eg, amitriptyline, nortriptyline, desipramine, and imipramine among the TCAs) employed at diverse doses. Taken together, these limitations raise questions about the results of those meta-analyses.

Subsequent meta-analyses, which employed strict criteria to eliminate data from studies with potential sources of bias and used a primary outcome of frequencies of patients reporting at least 30% pain reduction compared with a placebo-controlled sample, suggest that the effectiveness of TCAs as a class for treating neuropathic pain is not as compelling as once was thought. Meta-analyses of studies employing specific TCAs revealed that there was little evidence to support the use of desipramine,50 imipramine,51 or nortriptyline52 in managing diabetic neuropathy or postherpetic neuralgia. Studies evaluating amitriptyline (dose range 12.5 to 150 mg/d), found low-level evidence of effectiveness; the benefit was expected to be present for a small subset (approximately 25%) of patients with neuropathic pain.53

There is moderate-quality evidence that duloxetine (60 to 120 mg/d) can produce a ≥50% improvement in pain severity ratings among patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy.54 Although head-to-head studies with other antidepressants are limited, it appears that duloxetine and amitriptyline have comparable efficacy, even though the NNTs for amitriptyline were derived from lower-quality studies than those for duloxetine. Duloxetine is the only antidepressant to receive FDA approval for managing diabetic neuropathy. By contrast, studies assessing the utility of venlafaxine in neuropathic pain comprised small samples for brief durations, which limits the ability to draw clear (unbiased) support for its usefulness.55