User login

Rheumatologist prescribing rates predict chronic opioid use in RA patients

CHICAGO – A physician’s baseline opioid prescribing rate strongly predicts future chronic opioid use in rheumatoid arthritis patients, an analysis of data from the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America (Corrona) Rheumatoid Arthritis Registry suggests.

The baseline 12-month opioid prescribing rate of 148 physicians in the initial cohort varied widely from 0% to 70% (median, 27%), and among 9,337 patients in the registry beyond the baseline 12 months, physician opioid prescribing rates during the baseline period were significantly associated with risk for chronic opioid use, Yvonne C. Lee, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. She and her colleagues defined chronic opioid use as any opioid use during at least two consecutive study visits.

“It is important to understand the relative contributions of patient vs. physician characteristics on chronic opioid use,” said Dr. Lee of Northwestern University, Chicago. She that the goals of the current study were to identify the extent to which rheumatologists in the United States varied in baseline opioid prescribing rates and to determine the implications of baseline prescribing rates with respect to future chronic opioid use.

Compared with the lowest quartile of baseline opioid prescribing (rate of 18% or less), the second, third, and fourth quartiles of prescribing were associated with increasing odds of chronic opioid use (odds ratios of 1.16, 1.89, and 2.01 for the quartiles, respectively) during the study period, she said.

The researchers saw similar relationships when they used a stricter definition of opioid use and when they extended the cutoff between the baseline and study periods to 18 months. The relationships persisted after adjusting for numerous patient characteristics, such as age, sex, race, insurance status, RA duration, and treatments used, she said.

Subgroup analyses were also conducted to examine heterogeneity across clinical characteristics, including Clinical Disease Activity Index score (10 or less vs. greater than 10), pain intensity (scores of 40 or less, greater than 40 to 60, and greater than 60 out of 100), and use vs. nonuse of antidepressant medication. The relationships between physician baseline prescribing and chronic opioid use were similar across subgroups, she noted.

The findings help to characterize the role of rheumatologists’ prescribing rates in the ongoing opioid crisis even though the conclusions that can be reached are limited by the fact that some patients may receive opioid prescriptions from physicians outside the registry, by a lack of data on specific opioid types and doses, and by a lack of detailed information about physician characteristics, Dr. Lee said.

Physicians were included in the analysis only if they had contributed at least 10 RA patients to the registry within their first year of participation, and patients were included if they were patients of those physicians, if they had at least 12 months of follow-up data available, and if they were not prevalent opioid users at study entry.

A long-term goal is to target interventions to appropriate subgroups, she said, noting that 21%-29% of patients who are prescribed opioids for chronic pain misuse them, and more than 33,000 Americans die of opioid overdoses each year.

“Implications [of the findings] are that, in addition to targeting patients, we may also really want to consider interventions that target high-intensity prescribers. This may be useful for helping to decrease chronic opioid use in patients,” she concluded.

Dr. Lee has an investigator-initiated grant from Pfizer and owns stock in Express Scripts.

SOURCE: Lee Y et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10), Abstract 1917

CHICAGO – A physician’s baseline opioid prescribing rate strongly predicts future chronic opioid use in rheumatoid arthritis patients, an analysis of data from the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America (Corrona) Rheumatoid Arthritis Registry suggests.

The baseline 12-month opioid prescribing rate of 148 physicians in the initial cohort varied widely from 0% to 70% (median, 27%), and among 9,337 patients in the registry beyond the baseline 12 months, physician opioid prescribing rates during the baseline period were significantly associated with risk for chronic opioid use, Yvonne C. Lee, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. She and her colleagues defined chronic opioid use as any opioid use during at least two consecutive study visits.

“It is important to understand the relative contributions of patient vs. physician characteristics on chronic opioid use,” said Dr. Lee of Northwestern University, Chicago. She that the goals of the current study were to identify the extent to which rheumatologists in the United States varied in baseline opioid prescribing rates and to determine the implications of baseline prescribing rates with respect to future chronic opioid use.

Compared with the lowest quartile of baseline opioid prescribing (rate of 18% or less), the second, third, and fourth quartiles of prescribing were associated with increasing odds of chronic opioid use (odds ratios of 1.16, 1.89, and 2.01 for the quartiles, respectively) during the study period, she said.

The researchers saw similar relationships when they used a stricter definition of opioid use and when they extended the cutoff between the baseline and study periods to 18 months. The relationships persisted after adjusting for numerous patient characteristics, such as age, sex, race, insurance status, RA duration, and treatments used, she said.

Subgroup analyses were also conducted to examine heterogeneity across clinical characteristics, including Clinical Disease Activity Index score (10 or less vs. greater than 10), pain intensity (scores of 40 or less, greater than 40 to 60, and greater than 60 out of 100), and use vs. nonuse of antidepressant medication. The relationships between physician baseline prescribing and chronic opioid use were similar across subgroups, she noted.

The findings help to characterize the role of rheumatologists’ prescribing rates in the ongoing opioid crisis even though the conclusions that can be reached are limited by the fact that some patients may receive opioid prescriptions from physicians outside the registry, by a lack of data on specific opioid types and doses, and by a lack of detailed information about physician characteristics, Dr. Lee said.

Physicians were included in the analysis only if they had contributed at least 10 RA patients to the registry within their first year of participation, and patients were included if they were patients of those physicians, if they had at least 12 months of follow-up data available, and if they were not prevalent opioid users at study entry.

A long-term goal is to target interventions to appropriate subgroups, she said, noting that 21%-29% of patients who are prescribed opioids for chronic pain misuse them, and more than 33,000 Americans die of opioid overdoses each year.

“Implications [of the findings] are that, in addition to targeting patients, we may also really want to consider interventions that target high-intensity prescribers. This may be useful for helping to decrease chronic opioid use in patients,” she concluded.

Dr. Lee has an investigator-initiated grant from Pfizer and owns stock in Express Scripts.

SOURCE: Lee Y et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10), Abstract 1917

CHICAGO – A physician’s baseline opioid prescribing rate strongly predicts future chronic opioid use in rheumatoid arthritis patients, an analysis of data from the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America (Corrona) Rheumatoid Arthritis Registry suggests.

The baseline 12-month opioid prescribing rate of 148 physicians in the initial cohort varied widely from 0% to 70% (median, 27%), and among 9,337 patients in the registry beyond the baseline 12 months, physician opioid prescribing rates during the baseline period were significantly associated with risk for chronic opioid use, Yvonne C. Lee, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. She and her colleagues defined chronic opioid use as any opioid use during at least two consecutive study visits.

“It is important to understand the relative contributions of patient vs. physician characteristics on chronic opioid use,” said Dr. Lee of Northwestern University, Chicago. She that the goals of the current study were to identify the extent to which rheumatologists in the United States varied in baseline opioid prescribing rates and to determine the implications of baseline prescribing rates with respect to future chronic opioid use.

Compared with the lowest quartile of baseline opioid prescribing (rate of 18% or less), the second, third, and fourth quartiles of prescribing were associated with increasing odds of chronic opioid use (odds ratios of 1.16, 1.89, and 2.01 for the quartiles, respectively) during the study period, she said.

The researchers saw similar relationships when they used a stricter definition of opioid use and when they extended the cutoff between the baseline and study periods to 18 months. The relationships persisted after adjusting for numerous patient characteristics, such as age, sex, race, insurance status, RA duration, and treatments used, she said.

Subgroup analyses were also conducted to examine heterogeneity across clinical characteristics, including Clinical Disease Activity Index score (10 or less vs. greater than 10), pain intensity (scores of 40 or less, greater than 40 to 60, and greater than 60 out of 100), and use vs. nonuse of antidepressant medication. The relationships between physician baseline prescribing and chronic opioid use were similar across subgroups, she noted.

The findings help to characterize the role of rheumatologists’ prescribing rates in the ongoing opioid crisis even though the conclusions that can be reached are limited by the fact that some patients may receive opioid prescriptions from physicians outside the registry, by a lack of data on specific opioid types and doses, and by a lack of detailed information about physician characteristics, Dr. Lee said.

Physicians were included in the analysis only if they had contributed at least 10 RA patients to the registry within their first year of participation, and patients were included if they were patients of those physicians, if they had at least 12 months of follow-up data available, and if they were not prevalent opioid users at study entry.

A long-term goal is to target interventions to appropriate subgroups, she said, noting that 21%-29% of patients who are prescribed opioids for chronic pain misuse them, and more than 33,000 Americans die of opioid overdoses each year.

“Implications [of the findings] are that, in addition to targeting patients, we may also really want to consider interventions that target high-intensity prescribers. This may be useful for helping to decrease chronic opioid use in patients,” she concluded.

Dr. Lee has an investigator-initiated grant from Pfizer and owns stock in Express Scripts.

SOURCE: Lee Y et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10), Abstract 1917

REPORTING FROM THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The odds of chronic opioid use increased with rising baseline prescribing rates (odds ratios, 1.16, 1.89, and 2.01 for 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quartiles vs. 1st quartile of prescribing, respectively).

Study details: An analysis of data from 148 physicians and 9,337 Corrona RA Registry patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Lee has an investigator-initiated grant from Pfizer and owns stock in Express Scripts.

Source: Lee Y et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Suppl 10), Abstract 1917

Phase 3 data support apixaban for cancer-associated VTE

SAN DIEGO – according to the Phase 3 ADAM VTE trial.

The rates of major bleeding and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding in patients who received apixaban were similar to those in patients who received dalteparin. However, the rate of VTE recurrence was significantly lower with apixaban than it was with dalteparin.

“[A]pixaban was associated with very low bleeding rates and venous thrombosis recurrence rates compared to dalteparin,” said Robert D. McBane II, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

The trial included 300 adults (aged 18 years and older) with active cancer and acute VTE who were randomized to receive apixaban (n = 150) or dalteparin (n = 150). The dose and schedule for oral apixaban was 10 mg twice daily for 7 days followed by 5 mg twice daily for 6 months. Dalteparin was given subcutaneously at 200 IU/kg per day for 1 month followed by 150 IU/kg daily for 6 months. Among the patients in the study, 145 patients in the apixaban arm and 142 in the dalteparin arm ultimately received their assigned treatment.

Every month, patients completed an anticoagulation satisfaction survey and bruise survey (a modification of the Duke Anticoagulation Satisfaction Scale). They also underwent lab testing (complete blood count, liver and renal function testing) and were assessed for outcomes, medication reconciliation, drug compliance, and ECOG status on a monthly basis.

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The mean age was 64 years in both arms, and roughly half of patients in both arms were female. Hematologic malignancies were present in 9% of patients in the apixaban arm and 11% in the dalteparin arm. Others included lung, colorectal,

pancreatic/hepatobiliary, gynecologic, breast, genitourinary, upper gastrointestinal, and brain cancers.

Of patients in the study, 65% of those in the apixaban arm and 66% in the dalteparin arm had distant metastasis, and 74% of patients in both arms were receiving chemotherapy while on study.

Patients had the following qualifying thrombotic events:

- Any pulmonary embolism (PE) – 55% of patients in the apixaban arm and 51% in the dalteparin arm

- Any deep vein thrombosis (DVT) – 48% and 47%, respectively

- PE only – 44% and 39%, respectively

- PE with DVT – 12% in both arms

- DVT only – 37% and 35%, respectively

- Lower extremity DVT – 31% and 34%, respectively

- Upper extremity DVT – 17% and 14%, respectively

- Cerebral venous thrombosis (VT) – 1% and 0%, respectively

- Splanchnic VT – 8% and 18%, respectively.

Bleeding, thrombosis, and death

The study’s primary endpoint was major bleeding, which did not occur in any of the apixaban-treated patients. However, major bleeding did occur in two (1.4%) patients in the dalteparin arm (P = .14).

A secondary endpoint was major bleeding plus clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding. This occurred in nine (6.2%) patients in the apixaban arm and nine (6.3%) in the dalteparin arm (P = .88).

The researchers also assessed VTE recurrence. One patient in the apixaban arm (0.7%) and nine in the dalteparin arm (6.3%) had VTE recurrence (P = .03).

The patient in the apixaban arm experienced cerebral VT, and the patients with recurrence in the dalteparin arm had leg (n = 4) or arm (n = 2) VTE, PE (n = 1), or splanchnic VT (n = 2).

One patient in each arm (0.7%) had arterial thrombosis.

There was no significant difference in cumulative mortality between the treatment arms (hazard ratio, 1.40; P = .3078).

Satisfaction and discontinuation

Overall, apixaban fared better than dalteparin in the monthly patient satisfaction surveys. At various time points, apixaban-treated patients were significantly less likely to be concerned about excessive bruising, find anticoagulant treatment a burden or difficult to carry out, or say anticoagulant treatment added stress to their lives, negatively impacted their quality of life, or caused them “a great deal” of worry, irritation, or frustration.

However, apixaban-treated patients were less likely than dalteparin recipients to have confidence that their drug protected them from VTE recurrence, while the apixaban recipients were more likely than the dalteparin group to report overall satisfaction with their treatment.

In addition, premature treatment discontinuation was more common in the dalteparin group than in the apixaban group – 15% and 4%, respectively (P = .0012).

“Apixaban was well tolerated with superior patient safety satisfaction, as well as significantly fewer study drug discontinuations compared to dalteparin,” Dr. McBane said. “I believe that these data support the use of apixaban for the acute treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism.”

This study was funded by BMS/Pfizer Alliance. Dr. McBane declared no other conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: McBane RD et al. ASH 2018, Abstract 421.

SAN DIEGO – according to the Phase 3 ADAM VTE trial.

The rates of major bleeding and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding in patients who received apixaban were similar to those in patients who received dalteparin. However, the rate of VTE recurrence was significantly lower with apixaban than it was with dalteparin.

“[A]pixaban was associated with very low bleeding rates and venous thrombosis recurrence rates compared to dalteparin,” said Robert D. McBane II, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

The trial included 300 adults (aged 18 years and older) with active cancer and acute VTE who were randomized to receive apixaban (n = 150) or dalteparin (n = 150). The dose and schedule for oral apixaban was 10 mg twice daily for 7 days followed by 5 mg twice daily for 6 months. Dalteparin was given subcutaneously at 200 IU/kg per day for 1 month followed by 150 IU/kg daily for 6 months. Among the patients in the study, 145 patients in the apixaban arm and 142 in the dalteparin arm ultimately received their assigned treatment.

Every month, patients completed an anticoagulation satisfaction survey and bruise survey (a modification of the Duke Anticoagulation Satisfaction Scale). They also underwent lab testing (complete blood count, liver and renal function testing) and were assessed for outcomes, medication reconciliation, drug compliance, and ECOG status on a monthly basis.

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The mean age was 64 years in both arms, and roughly half of patients in both arms were female. Hematologic malignancies were present in 9% of patients in the apixaban arm and 11% in the dalteparin arm. Others included lung, colorectal,

pancreatic/hepatobiliary, gynecologic, breast, genitourinary, upper gastrointestinal, and brain cancers.

Of patients in the study, 65% of those in the apixaban arm and 66% in the dalteparin arm had distant metastasis, and 74% of patients in both arms were receiving chemotherapy while on study.

Patients had the following qualifying thrombotic events:

- Any pulmonary embolism (PE) – 55% of patients in the apixaban arm and 51% in the dalteparin arm

- Any deep vein thrombosis (DVT) – 48% and 47%, respectively

- PE only – 44% and 39%, respectively

- PE with DVT – 12% in both arms

- DVT only – 37% and 35%, respectively

- Lower extremity DVT – 31% and 34%, respectively

- Upper extremity DVT – 17% and 14%, respectively

- Cerebral venous thrombosis (VT) – 1% and 0%, respectively

- Splanchnic VT – 8% and 18%, respectively.

Bleeding, thrombosis, and death

The study’s primary endpoint was major bleeding, which did not occur in any of the apixaban-treated patients. However, major bleeding did occur in two (1.4%) patients in the dalteparin arm (P = .14).

A secondary endpoint was major bleeding plus clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding. This occurred in nine (6.2%) patients in the apixaban arm and nine (6.3%) in the dalteparin arm (P = .88).

The researchers also assessed VTE recurrence. One patient in the apixaban arm (0.7%) and nine in the dalteparin arm (6.3%) had VTE recurrence (P = .03).

The patient in the apixaban arm experienced cerebral VT, and the patients with recurrence in the dalteparin arm had leg (n = 4) or arm (n = 2) VTE, PE (n = 1), or splanchnic VT (n = 2).

One patient in each arm (0.7%) had arterial thrombosis.

There was no significant difference in cumulative mortality between the treatment arms (hazard ratio, 1.40; P = .3078).

Satisfaction and discontinuation

Overall, apixaban fared better than dalteparin in the monthly patient satisfaction surveys. At various time points, apixaban-treated patients were significantly less likely to be concerned about excessive bruising, find anticoagulant treatment a burden or difficult to carry out, or say anticoagulant treatment added stress to their lives, negatively impacted their quality of life, or caused them “a great deal” of worry, irritation, or frustration.

However, apixaban-treated patients were less likely than dalteparin recipients to have confidence that their drug protected them from VTE recurrence, while the apixaban recipients were more likely than the dalteparin group to report overall satisfaction with their treatment.

In addition, premature treatment discontinuation was more common in the dalteparin group than in the apixaban group – 15% and 4%, respectively (P = .0012).

“Apixaban was well tolerated with superior patient safety satisfaction, as well as significantly fewer study drug discontinuations compared to dalteparin,” Dr. McBane said. “I believe that these data support the use of apixaban for the acute treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism.”

This study was funded by BMS/Pfizer Alliance. Dr. McBane declared no other conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: McBane RD et al. ASH 2018, Abstract 421.

SAN DIEGO – according to the Phase 3 ADAM VTE trial.

The rates of major bleeding and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding in patients who received apixaban were similar to those in patients who received dalteparin. However, the rate of VTE recurrence was significantly lower with apixaban than it was with dalteparin.

“[A]pixaban was associated with very low bleeding rates and venous thrombosis recurrence rates compared to dalteparin,” said Robert D. McBane II, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

The trial included 300 adults (aged 18 years and older) with active cancer and acute VTE who were randomized to receive apixaban (n = 150) or dalteparin (n = 150). The dose and schedule for oral apixaban was 10 mg twice daily for 7 days followed by 5 mg twice daily for 6 months. Dalteparin was given subcutaneously at 200 IU/kg per day for 1 month followed by 150 IU/kg daily for 6 months. Among the patients in the study, 145 patients in the apixaban arm and 142 in the dalteparin arm ultimately received their assigned treatment.

Every month, patients completed an anticoagulation satisfaction survey and bruise survey (a modification of the Duke Anticoagulation Satisfaction Scale). They also underwent lab testing (complete blood count, liver and renal function testing) and were assessed for outcomes, medication reconciliation, drug compliance, and ECOG status on a monthly basis.

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The mean age was 64 years in both arms, and roughly half of patients in both arms were female. Hematologic malignancies were present in 9% of patients in the apixaban arm and 11% in the dalteparin arm. Others included lung, colorectal,

pancreatic/hepatobiliary, gynecologic, breast, genitourinary, upper gastrointestinal, and brain cancers.

Of patients in the study, 65% of those in the apixaban arm and 66% in the dalteparin arm had distant metastasis, and 74% of patients in both arms were receiving chemotherapy while on study.

Patients had the following qualifying thrombotic events:

- Any pulmonary embolism (PE) – 55% of patients in the apixaban arm and 51% in the dalteparin arm

- Any deep vein thrombosis (DVT) – 48% and 47%, respectively

- PE only – 44% and 39%, respectively

- PE with DVT – 12% in both arms

- DVT only – 37% and 35%, respectively

- Lower extremity DVT – 31% and 34%, respectively

- Upper extremity DVT – 17% and 14%, respectively

- Cerebral venous thrombosis (VT) – 1% and 0%, respectively

- Splanchnic VT – 8% and 18%, respectively.

Bleeding, thrombosis, and death

The study’s primary endpoint was major bleeding, which did not occur in any of the apixaban-treated patients. However, major bleeding did occur in two (1.4%) patients in the dalteparin arm (P = .14).

A secondary endpoint was major bleeding plus clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding. This occurred in nine (6.2%) patients in the apixaban arm and nine (6.3%) in the dalteparin arm (P = .88).

The researchers also assessed VTE recurrence. One patient in the apixaban arm (0.7%) and nine in the dalteparin arm (6.3%) had VTE recurrence (P = .03).

The patient in the apixaban arm experienced cerebral VT, and the patients with recurrence in the dalteparin arm had leg (n = 4) or arm (n = 2) VTE, PE (n = 1), or splanchnic VT (n = 2).

One patient in each arm (0.7%) had arterial thrombosis.

There was no significant difference in cumulative mortality between the treatment arms (hazard ratio, 1.40; P = .3078).

Satisfaction and discontinuation

Overall, apixaban fared better than dalteparin in the monthly patient satisfaction surveys. At various time points, apixaban-treated patients were significantly less likely to be concerned about excessive bruising, find anticoagulant treatment a burden or difficult to carry out, or say anticoagulant treatment added stress to their lives, negatively impacted their quality of life, or caused them “a great deal” of worry, irritation, or frustration.

However, apixaban-treated patients were less likely than dalteparin recipients to have confidence that their drug protected them from VTE recurrence, while the apixaban recipients were more likely than the dalteparin group to report overall satisfaction with their treatment.

In addition, premature treatment discontinuation was more common in the dalteparin group than in the apixaban group – 15% and 4%, respectively (P = .0012).

“Apixaban was well tolerated with superior patient safety satisfaction, as well as significantly fewer study drug discontinuations compared to dalteparin,” Dr. McBane said. “I believe that these data support the use of apixaban for the acute treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism.”

This study was funded by BMS/Pfizer Alliance. Dr. McBane declared no other conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: McBane RD et al. ASH 2018, Abstract 421.

REPORTING FROM ASH 2018

Key clinical point: Apixaban is associated with a similar risk of major bleeding and a lower risk of VTE recurrence when compared with dalteparin in patients with cancer-associated VTE.

Major finding: There were no major bleeding events in the apixaban arm and two in the dalteparin arm (P = .14).

Study details: Phase 3 study of 300 patients.

Disclosures: This study was funded by BMS/Pfizer Alliance.

Source: McBane RD et al. ASH 2018, Abstract 421.

Rural teleprescribing for opioid use disorder shows success

BONITA SPRINGS, FLA. – Clinician shortages and alarming opioid overdose rates are prompting rural health care centers to turn to telemedicine for delivering treatments for opioid use disorder (OUD). Several studies suggest that these treatments are being delivered effectively, experts said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

In both Maryland and West Virginia, for example, success using a telehealth approach has been reported recently, said David Moore, MD, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Specifically, in rural Maryland, physicians used telemedicine to provide buprenorphine treatment for OUD at a treatment center in August 2015. Researchers at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, looked at the first 177 of the patients treated with the approach. They found that retention in treatment was 91% at 1 month and 57% at 3 months. Of patients still in treatment at 3 months, 86% had urine that was opioid negative, researchers said (Am J Addict. 2018 Dec;27[8]:612-17).

And in West Virginia, researchers reviewed the records of 100 patients receiving buprenorphine treatment to compare outcomes of those treated with telemedicine and those treated face-to-face. They found no significant differences between the groups in additional substance use, time to achieve 30 days and 90 days of abstinence, or retention rates at 3 months and 1 year (J Addict Med. 2017 Mar-Apr;11[2]:138-44).

In addition, Dr. Moore said, he has had success with home inductions in the northern reaches of Maine. His first home induction involved a 55-year-old veteran with a history of oxycodone and hydrocodone use who used illicit buprenorphine when he could. Dr. Moore said the man was referred to him on a Monday. He called in a prescription for the drug the next day and gave the patient a handout on how to do a home induction. “Then he had a phone check-in, and we followed up on Thursday. It actually worked really well,” Dr. Moore said.

The dearth of buprenorphine providers in northern Maine makes those kinds of arrangements attractive, he said. In Maine’s Piscataquis County, he said, there is one buprenorphine provider for every 2,000 square miles. “We have about 1 in every 5 square miles in New Haven,” he said. “Thinking about the distance you have to travel, it gets to be pretty daunting.”

The ability of clinicians to provide buprenorphine with telemedicine varies by state. Among the resources needed to provide telemedicine services are reliable Internet access and an ability for a patient to consent to the treatment.

Nationwide, 56.3% of rural counties have no buprenorphine provider, according to a recent study, said Lewei (Allison) Lin, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. A survey of 1,100 rural providers, results of which were included in that study, found that 48% of them said concerns about substance diversion or misuse were a barrier to providing buprenorphine, and 44% cited a lack of mental health or psychosocial support services.

“Although this country still has a major issue with access to treatment, we see that the access problem is about double in rural areas,” she said. “If you add on the distance issue and time, this becomes an even greater challenge.”

Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are now able to obtain a Drug Enforcement Administration waiver that will allow them to prescribe OUD, thanks to the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016.

BONITA SPRINGS, FLA. – Clinician shortages and alarming opioid overdose rates are prompting rural health care centers to turn to telemedicine for delivering treatments for opioid use disorder (OUD). Several studies suggest that these treatments are being delivered effectively, experts said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

In both Maryland and West Virginia, for example, success using a telehealth approach has been reported recently, said David Moore, MD, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Specifically, in rural Maryland, physicians used telemedicine to provide buprenorphine treatment for OUD at a treatment center in August 2015. Researchers at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, looked at the first 177 of the patients treated with the approach. They found that retention in treatment was 91% at 1 month and 57% at 3 months. Of patients still in treatment at 3 months, 86% had urine that was opioid negative, researchers said (Am J Addict. 2018 Dec;27[8]:612-17).

And in West Virginia, researchers reviewed the records of 100 patients receiving buprenorphine treatment to compare outcomes of those treated with telemedicine and those treated face-to-face. They found no significant differences between the groups in additional substance use, time to achieve 30 days and 90 days of abstinence, or retention rates at 3 months and 1 year (J Addict Med. 2017 Mar-Apr;11[2]:138-44).

In addition, Dr. Moore said, he has had success with home inductions in the northern reaches of Maine. His first home induction involved a 55-year-old veteran with a history of oxycodone and hydrocodone use who used illicit buprenorphine when he could. Dr. Moore said the man was referred to him on a Monday. He called in a prescription for the drug the next day and gave the patient a handout on how to do a home induction. “Then he had a phone check-in, and we followed up on Thursday. It actually worked really well,” Dr. Moore said.

The dearth of buprenorphine providers in northern Maine makes those kinds of arrangements attractive, he said. In Maine’s Piscataquis County, he said, there is one buprenorphine provider for every 2,000 square miles. “We have about 1 in every 5 square miles in New Haven,” he said. “Thinking about the distance you have to travel, it gets to be pretty daunting.”

The ability of clinicians to provide buprenorphine with telemedicine varies by state. Among the resources needed to provide telemedicine services are reliable Internet access and an ability for a patient to consent to the treatment.

Nationwide, 56.3% of rural counties have no buprenorphine provider, according to a recent study, said Lewei (Allison) Lin, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. A survey of 1,100 rural providers, results of which were included in that study, found that 48% of them said concerns about substance diversion or misuse were a barrier to providing buprenorphine, and 44% cited a lack of mental health or psychosocial support services.

“Although this country still has a major issue with access to treatment, we see that the access problem is about double in rural areas,” she said. “If you add on the distance issue and time, this becomes an even greater challenge.”

Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are now able to obtain a Drug Enforcement Administration waiver that will allow them to prescribe OUD, thanks to the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016.

BONITA SPRINGS, FLA. – Clinician shortages and alarming opioid overdose rates are prompting rural health care centers to turn to telemedicine for delivering treatments for opioid use disorder (OUD). Several studies suggest that these treatments are being delivered effectively, experts said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry.

In both Maryland and West Virginia, for example, success using a telehealth approach has been reported recently, said David Moore, MD, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Specifically, in rural Maryland, physicians used telemedicine to provide buprenorphine treatment for OUD at a treatment center in August 2015. Researchers at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, looked at the first 177 of the patients treated with the approach. They found that retention in treatment was 91% at 1 month and 57% at 3 months. Of patients still in treatment at 3 months, 86% had urine that was opioid negative, researchers said (Am J Addict. 2018 Dec;27[8]:612-17).

And in West Virginia, researchers reviewed the records of 100 patients receiving buprenorphine treatment to compare outcomes of those treated with telemedicine and those treated face-to-face. They found no significant differences between the groups in additional substance use, time to achieve 30 days and 90 days of abstinence, or retention rates at 3 months and 1 year (J Addict Med. 2017 Mar-Apr;11[2]:138-44).

In addition, Dr. Moore said, he has had success with home inductions in the northern reaches of Maine. His first home induction involved a 55-year-old veteran with a history of oxycodone and hydrocodone use who used illicit buprenorphine when he could. Dr. Moore said the man was referred to him on a Monday. He called in a prescription for the drug the next day and gave the patient a handout on how to do a home induction. “Then he had a phone check-in, and we followed up on Thursday. It actually worked really well,” Dr. Moore said.

The dearth of buprenorphine providers in northern Maine makes those kinds of arrangements attractive, he said. In Maine’s Piscataquis County, he said, there is one buprenorphine provider for every 2,000 square miles. “We have about 1 in every 5 square miles in New Haven,” he said. “Thinking about the distance you have to travel, it gets to be pretty daunting.”

The ability of clinicians to provide buprenorphine with telemedicine varies by state. Among the resources needed to provide telemedicine services are reliable Internet access and an ability for a patient to consent to the treatment.

Nationwide, 56.3% of rural counties have no buprenorphine provider, according to a recent study, said Lewei (Allison) Lin, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. A survey of 1,100 rural providers, results of which were included in that study, found that 48% of them said concerns about substance diversion or misuse were a barrier to providing buprenorphine, and 44% cited a lack of mental health or psychosocial support services.

“Although this country still has a major issue with access to treatment, we see that the access problem is about double in rural areas,” she said. “If you add on the distance issue and time, this becomes an even greater challenge.”

Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are now able to obtain a Drug Enforcement Administration waiver that will allow them to prescribe OUD, thanks to the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016.

REPORTING FROM AAAP 2018

AHA: Statins associated with high degree of safety

The benefits of statins highly offset the associated risks in appropriate patients, according to a scientific statement issued by the American Heart Association.

“The review covers the general patient population, as well as demographic subgroups, including the elderly, children, pregnant women, East Asians, and patients with specific conditions.” wrote Connie B. Newman, MD, of New York University, together with her colleagues. The report is in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology.

After an extensive review of the literature pertaining to statin safety and tolerability, Dr. Newman and her colleagues reported the compiled findings from several randomized controlled trials, in addition to observational data, where required. They found that the risk of serious muscle complications, such as rhabdomyolysis, attributable to statin use was less than 0.1%. Furthermore, they noted that the risk of serious hepatotoxicity was even less likely, occurring in about 1 in 10,000 patients treated with therapy.

“There is no convincing evidence for a causal relationship between statins and cancer, cataracts, cognitive dysfunction, peripheral neuropathy, erectile dysfunction, or tendinitis,” the experts wrote. “In U.S. clinical practices, roughly 10% of patients stop taking a statin because of subjective complaints, most commonly muscle symptoms without raised creatine kinase,” they further reported.

Contrastingly, data from randomized trials have shown that the change in the incidence of muscle-related symptoms in patients treated with statins versus placebo is less than 1%. Moreover, the incidence is even lower, with an estimated rate of 0.1%, in those who stopped statin therapy because of these symptoms. Given these results, Dr. Newman and her colleagues said that muscle-related symptoms among statin-treated patients are not due to the pharmacological activity of the statin.

“Restarting statin therapy in these patients can be challenging, but it is important, especially in patients at high risk of cardiovascular events, for whom prevention of these events is a priority,” they added.

A large proportion of the population takes statin therapy to lower the risk of major cardiovascular events, including ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and other adverse effects of cardiovascular disease. At maximal doses, statins may decrease LDL-cholesterol levels by roughly 55%-60%. In addition, given the multitude of available generics, statins are an economical treatment option for most patients.

However, Dr. Newman and her colleagues suggested that, when considering statin therapy in special populations, particularly in patients with end-stage renal failure or severe hepatic disease, commencing treatment is not recommended.

“The lack of proof of cardiovascular benefit in patients with end-stage renal disease suggests that initiating statin treatment in these patients is generally not warranted,” the experts wrote. “Data on safety in people with more serious liver disease are insufficient, and statin treatment is generally discouraged,” they added.

With respect to statin-induced adverse effects, they are usually reversible upon discontinuation of therapy, with the exception of hemorrhagic stroke. However, damage from an ischemic stroke or myocardial infarction may result in death. As a result, in patients who would benefit from statin therapy, based on most recent guidelines, cardiovascular benefits greatly exceed potential safety concerns.

Dr. Newman and her coauthors disclosed financial affiliations with Amgen, Kowa, Regeneron, Sanofi, and others.

SOURCE: Newman CB et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018 Dec 10. doi: 10.1161/ATV.0000000000000073

The benefits of statins highly offset the associated risks in appropriate patients, according to a scientific statement issued by the American Heart Association.

“The review covers the general patient population, as well as demographic subgroups, including the elderly, children, pregnant women, East Asians, and patients with specific conditions.” wrote Connie B. Newman, MD, of New York University, together with her colleagues. The report is in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology.

After an extensive review of the literature pertaining to statin safety and tolerability, Dr. Newman and her colleagues reported the compiled findings from several randomized controlled trials, in addition to observational data, where required. They found that the risk of serious muscle complications, such as rhabdomyolysis, attributable to statin use was less than 0.1%. Furthermore, they noted that the risk of serious hepatotoxicity was even less likely, occurring in about 1 in 10,000 patients treated with therapy.

“There is no convincing evidence for a causal relationship between statins and cancer, cataracts, cognitive dysfunction, peripheral neuropathy, erectile dysfunction, or tendinitis,” the experts wrote. “In U.S. clinical practices, roughly 10% of patients stop taking a statin because of subjective complaints, most commonly muscle symptoms without raised creatine kinase,” they further reported.

Contrastingly, data from randomized trials have shown that the change in the incidence of muscle-related symptoms in patients treated with statins versus placebo is less than 1%. Moreover, the incidence is even lower, with an estimated rate of 0.1%, in those who stopped statin therapy because of these symptoms. Given these results, Dr. Newman and her colleagues said that muscle-related symptoms among statin-treated patients are not due to the pharmacological activity of the statin.

“Restarting statin therapy in these patients can be challenging, but it is important, especially in patients at high risk of cardiovascular events, for whom prevention of these events is a priority,” they added.

A large proportion of the population takes statin therapy to lower the risk of major cardiovascular events, including ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and other adverse effects of cardiovascular disease. At maximal doses, statins may decrease LDL-cholesterol levels by roughly 55%-60%. In addition, given the multitude of available generics, statins are an economical treatment option for most patients.

However, Dr. Newman and her colleagues suggested that, when considering statin therapy in special populations, particularly in patients with end-stage renal failure or severe hepatic disease, commencing treatment is not recommended.

“The lack of proof of cardiovascular benefit in patients with end-stage renal disease suggests that initiating statin treatment in these patients is generally not warranted,” the experts wrote. “Data on safety in people with more serious liver disease are insufficient, and statin treatment is generally discouraged,” they added.

With respect to statin-induced adverse effects, they are usually reversible upon discontinuation of therapy, with the exception of hemorrhagic stroke. However, damage from an ischemic stroke or myocardial infarction may result in death. As a result, in patients who would benefit from statin therapy, based on most recent guidelines, cardiovascular benefits greatly exceed potential safety concerns.

Dr. Newman and her coauthors disclosed financial affiliations with Amgen, Kowa, Regeneron, Sanofi, and others.

SOURCE: Newman CB et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018 Dec 10. doi: 10.1161/ATV.0000000000000073

The benefits of statins highly offset the associated risks in appropriate patients, according to a scientific statement issued by the American Heart Association.

“The review covers the general patient population, as well as demographic subgroups, including the elderly, children, pregnant women, East Asians, and patients with specific conditions.” wrote Connie B. Newman, MD, of New York University, together with her colleagues. The report is in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology.

After an extensive review of the literature pertaining to statin safety and tolerability, Dr. Newman and her colleagues reported the compiled findings from several randomized controlled trials, in addition to observational data, where required. They found that the risk of serious muscle complications, such as rhabdomyolysis, attributable to statin use was less than 0.1%. Furthermore, they noted that the risk of serious hepatotoxicity was even less likely, occurring in about 1 in 10,000 patients treated with therapy.

“There is no convincing evidence for a causal relationship between statins and cancer, cataracts, cognitive dysfunction, peripheral neuropathy, erectile dysfunction, or tendinitis,” the experts wrote. “In U.S. clinical practices, roughly 10% of patients stop taking a statin because of subjective complaints, most commonly muscle symptoms without raised creatine kinase,” they further reported.

Contrastingly, data from randomized trials have shown that the change in the incidence of muscle-related symptoms in patients treated with statins versus placebo is less than 1%. Moreover, the incidence is even lower, with an estimated rate of 0.1%, in those who stopped statin therapy because of these symptoms. Given these results, Dr. Newman and her colleagues said that muscle-related symptoms among statin-treated patients are not due to the pharmacological activity of the statin.

“Restarting statin therapy in these patients can be challenging, but it is important, especially in patients at high risk of cardiovascular events, for whom prevention of these events is a priority,” they added.

A large proportion of the population takes statin therapy to lower the risk of major cardiovascular events, including ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and other adverse effects of cardiovascular disease. At maximal doses, statins may decrease LDL-cholesterol levels by roughly 55%-60%. In addition, given the multitude of available generics, statins are an economical treatment option for most patients.

However, Dr. Newman and her colleagues suggested that, when considering statin therapy in special populations, particularly in patients with end-stage renal failure or severe hepatic disease, commencing treatment is not recommended.

“The lack of proof of cardiovascular benefit in patients with end-stage renal disease suggests that initiating statin treatment in these patients is generally not warranted,” the experts wrote. “Data on safety in people with more serious liver disease are insufficient, and statin treatment is generally discouraged,” they added.

With respect to statin-induced adverse effects, they are usually reversible upon discontinuation of therapy, with the exception of hemorrhagic stroke. However, damage from an ischemic stroke or myocardial infarction may result in death. As a result, in patients who would benefit from statin therapy, based on most recent guidelines, cardiovascular benefits greatly exceed potential safety concerns.

Dr. Newman and her coauthors disclosed financial affiliations with Amgen, Kowa, Regeneron, Sanofi, and others.

SOURCE: Newman CB et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018 Dec 10. doi: 10.1161/ATV.0000000000000073

FROM ARTERIOSCLEROSIS, THROMBOSIS, AND VASCULAR BIOLOGY

Key clinical point: After rigorous review, the benefits of statin therapy were found to markedly exceed associated risks.

Major finding: .

Study details: A scientific statement on statin safety and associated adverse events from the American Heart Association.

Disclosures: Several writing group members disclosed financial affiliations with Amgen, Kowa, Regeneron, Sanofi, and others.

Source: Newman CB et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018 Dec 10. doi: 10.1161/ATV.0000000000000073.

Beta-cell therapies for type 1 diabetes: Transplants and bionics

With intensive insulin regimens and home blood glucose monitoring, patients with type 1 diabetes are controlling their blood glucose better than in the past. Nevertheless, glucose regulation is still imperfect and tedious, and striving for tight glycemic control poses the risk of hypoglycemia.

Prominent among the challenges are the sheer numbers involved. Some 1.25 million Americans have type 1 diabetes, and another 30 million have type 2, but only about 7,000 to 8,000 pancreases are available for transplant each year.1 While awaiting a breakthrough—perhaps involving stem cells, perhaps involving organs obtained from animals—an insulin pump may offer better diabetes control for many. Another possibility is a closed-loop system with a continuous glucose monitor that drives a dual-infusion pump, delivering insulin when glucose levels rise too high, and glucagon when they dip too low.

DIABETES WAS KNOWN IN ANCIENT TIMES

About 3,000 years ago, Egyptians described the syndrome of thirst, emaciation, and sweet urine that attracted ants. The term diabetes (Greek for siphon) was first recorded in 1425; mellitus (Latin for sweet with honey) was not added until 1675.

In 1857, Bernard hypothesized that diabetes was caused by overproduction of glucose in the liver. This idea was replaced in 1889, when Mering and Minkowski proposed the dysfunctional pancreas theory that eventually led to the discovery of the beta cell.2

In 1921, Banting and Best isolated insulin, and for the past 100 years subcutaneous insulin replacement has been the mainstay of treatment. But starting about 50 years ago, researchers have been looking for safe and long-lasting ways to replace beta cells and eliminate the need for exogenous insulin replacement.

TRANSPLANTING THE WHOLE PANCREAS

The first whole-pancreas transplant was performed in 1966 by Kelly et al,3 followed by 13 more by 1973.4 These first transplant grafts were short-lived, with only 1 graft surviving longer than 1 year. Since then, more than 12,000 pancreases have been transplanted worldwide, as refinements in surgical techniques and immunosuppressive therapies have improved patient and graft survival rates.4

Today, most pancreas transplants are in patients who have both type 1 diabetes and end-stage renal disease due to diabetic nephropathy, and most receive both a kidney and a pancreas at the same time. Far fewer patients receive a pancreas after previously receiving a kidney, or receive a pancreas alone.

The bile duct of the transplanted pancreas is usually routed into the patient’s small intestine, as nature intended, and less often into the bladder. Although bladder drainage is associated with urinary complications, it has the advantage of allowing measurement of pancreatic amylase levels in the urine to monitor for graft rejection. With simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplant, the serum creatinine concentration can also be monitored for rejection of the kidney graft.

Current immunosuppressive regimens vary but generally consist of anti-T-cell antibodies at the time of surgery, followed by lifelong treatment with the combination of a calcineurin inhibitor (cyclosporine or tacrolimus) and an antimetabolite (mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine).

Outcomes are good. The rates of patient and graft survival are highest with simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant, and somewhat lower with pancreas-after-kidney and pancreas-alone transplant.

Benefits of pancreas transplant

Most recipients can stop taking insulin immediately after the procedure, and their hemoglobin A1c levels normalize and stay low for the life of the graft. Lipid levels also decrease, although this has not been directly correlated with lower risk of vascular disease.4

Transplant also reduces or eliminates some complications of diabetes, including retinopathy, nephropathy, cardiomyopathy, and gastropathy.

For example, in patients undergoing simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant, diabetic nephropathy does not recur in the new kidney. Fioretto et al5 reported that nephropathy lesions reversed during the 10 years after pancreas transplant.

Kennedy et al6,7 found that preexisting diabetic neuropathy improved slightly (although neurologic status did not completely return to normal) over a period of up to 42 months in a group of patients who received a pancreas transplant, whereas it tended to worsen in a control group. Both groups were assessed at baseline and at 12 and 24 months, with a subgroup followed through 42 months, and they underwent testing of motor, sensory, and autonomic function.6,7

Disadvantages of pancreas transplant

Disadvantages of whole-pancreas transplant include hypoglycemia (usually mild), adverse effects of immunosuppression, potential for surgical complications including an increased rate of death in the first 90 days after the procedure, and cost.

In an analysis comparing the 5-year estimated costs of dialysis, kidney transplant alone from cadavers or live donors, or simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant for diabetic patients with end-stage renal disease, the least expensive option was kidney transplant from a live donor.8 The most expensive option was simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant, but quality of life was better with this option. The analysis did not consider the potential cost of long-term treatments for complications related to diabetes that could be saved with a pancreas transplant.

Data conflict regarding the risk of death with different types of pancreas transplants. A retrospective cohort study of data from 124 US transplant centers reported in 2003 found higher mortality rates in pancreas-alone transplant recipients than in patients on a transplant waiting list receiving conventional therapy.9 In contrast, a 2004 study reported that after the first 90 days, when the risk of death was clearly higher, mortality rates were lower after simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant and pancreas-after-kidney transplant.10 After pancreas-alone transplant, however, mortality rates were higher than with exogenous insulin therapy.

Although outcomes have improved, fewer patients with type 1 diabetes are undergoing pancreas transplant in recent years.

Interestingly, more simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants are being successfully performed in patients with type 2 diabetes, who now account for 8% of all simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant recipients.11 Outcomes of pancreas transplant appear to be similar regardless of diabetes type.

Bottom line

Pancreas transplant is a viable option for certain cases of complicated diabetes.

TRANSPLANTING ISLET CELLS

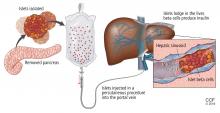

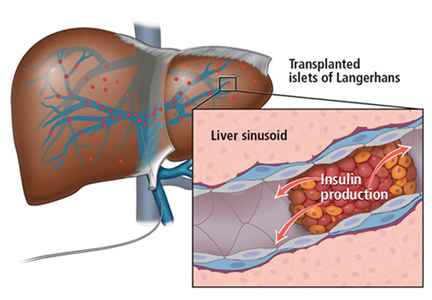

Despite its successes, pancreas transplant is major surgery and requires lifetime immunosuppression. Research is ongoing into a less-invasive procedure that, it is hoped, would require less immunosuppression: transplanting islets by themselves.

Islet autotransplant after pancreatectomy

For some patients with chronic pancreatitis, the only option to relieve chronic pain, narcotic dependence, and poor quality of life is to remove the pancreas. In the past, this desperate measure would instantly and inevitably cause diabetes, but not anymore.

Alpha cells and glucagon are a different story; a complication of islet transplant is hypoglycemia. In 2016, Lin et al12 reported spontaneous hypoglycemia in 6 of 12 patients who maintained insulin independence after autotransplant of islets. Although the transplanted islets had functional alpha cells that could in theory produce glucagon, as well as beta cells that produce insulin and C-peptide, apparently the alpha cells were not secreting glucagon in response to the hypoglycemia.

Location may matter. Gupta et al,13 in a 1997 study in dogs, found that more hypoglycemia occurs if islets are autotransplanted into the liver than if they are transplanted into the peritoneal cavity. A possible explanation may have to do with the glycemic environment of the liver.

Islet allotransplant

Islets can also be taken from cadaver donors and transplanted into patients with type 1 diabetes, who do not have enough working beta cells.

Success of allotransplant increased after the publication of observational data from the program in Edmonton in Canada, in which 7 consecutive patients with type 1 diabetes achieved initial insulin independence after islet allotransplant using steroid-free immunosuppression.14 Six recipients required islets from 2 donors, and 1 required islets from 4 donors, so they all received large volumes of at least 11,000 islet equivalents (IEQ) per kilogram of body weight.

In a subsequent report from the same team,15 16 (44%) of 36 patients remained insulin-free at 1 year, and C-peptide secretion was detectable in 70% at 2 years. But despite the elevated C-peptide levels, only 5 patients remained insulin-independent by 2 years. Lower hemoglobin A1c levels and decreases in hypoglycemic events from baseline also were noted.

The Clinical Islet Transplantation Consortium (CITC)16 and Collaborative Islet Transplant Registry (CITR)17 were established in 2004 to combine data and resources from centers around the world, including several that specialize in islet isolation and purification. Currently, more than 80 studies are being conducted.

The CITC and CITR now have data on more than 1,000 allogeneic islet transplant recipients (islet transplant alone, after kidney transplant, or simultaneous with it). The primary outcomes are hemoglobin A1c levels below 7% fasting C-peptide levels 0.3 ng/mL or higher, and fasting blood glucose of 60 to 140 mg/dL with no severe hypoglycemic events. The best results for islet-alone transplant have been in recipients over age 35 who received at least 325,000 IEQs with use of tumor necrosis factor antagonists for induction and calcineurin inhibitors or mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors for maintenance.17

The best success for islet-after-kidney transplant was achieved with the same protocol but with insulin given to the donor during hospitalization before pancreas procurement. For participants with favorable factors, a hemoglobin A1c at or below 6.5% was achieved in about 80% at 1 year after last infusion, with more than 80% maintaining their fasting blood glucose level goals. About 70% of these patients were insulin-independent at 1 year. Hypoglycemia unawareness resolved in these patients even 5 years after infusion. Although there were no deaths or disabilities related to these transplants, bleeding occurred in 1 of 15 procedures. There was also a notable decline in estimated glomerular filtration rates with calcineurin inhibitor-based immunosuppression.17

Making islets go farther

One of the greatest challenges to islet transplant is the need for multiple donors to provide enough islet cells to overcome the loss of cells during transplant. Pancreases are already in short supply, and if each recipient needs more than 1, this makes the shortage worse. Some centers have achieved transplant with fewer donors,18,19 possibly by selecting pancreases from young donors who had a high body mass index and more islet cells, and harvesting and using them with a shorter cold ischemic time.

The number of viable, functioning islet cells drastically decreases after transplant, especially when transplanted into the portal system. This phenomenon is linked to an instant, blood-mediated inflammatory reaction involving antibody binding, complement and coagulation cascade activation, and platelet aggregation. The reaction, part of the innate immune system, damages the islet cells and leads to insulin dumping and early graft loss in studies in vitro and in vivo. Another factor affecting the survival of the graft cells is the low oxygen tension in the portal system.

For this reason, sites such as the pancreas, gastric submucosa, genitourinary tract, muscle, omentum, bone marrow, kidney capsule, peritoneum, anterior eye chamber, testis, and thymus are being explored.20

To create a more supportive environment for the transplanted cells, biotechnicians are trying to encapsulate islets in a semipermeable membrane that would protect them from the immune system while still allowing oxygen, nutrients, waste products, and, critically, insulin to diffuse in and out. Currently, no site or encapsulated product has been more successful than the current practice of implanting naked islets in the portal system.20

Bottom line

Without advances in transplant sites or increasing the yield of islet cells to allow single-donor transplants, islet cell allotransplant will not be feasible for most patients with type 1 diabetes.

Xenotransplant: Can pig cells make up the shortage?

Use of animal kidneys (xenotransplant) is a potential solution to the shortage of human organs for transplant.

In theory, pigs could be a source. Porcine insulin is similar to human insulin (differing by only 1 amino acid), and it should be possible to breed “knockout” pigs that lack the antigens responsible for acute humoral rejection.21

On the other hand, transplant of porcine islets poses several immunologic, physiologic, ethical, legal, and infectious concerns. For example, porcine tissue could carry pig viruses, such as porcine endogenous retroviruses.21 And even if the pigs are genetically modified, patients will still require immunosuppressive therapy.

A review of 17 studies of pig islet xenotransplant into nonhuman primates found that in 5 of the studies (4 using diabetic primates) the grafts survived at least 3 months.22 Of these, 1 study used encapsulation, and the rest used intensive and toxic immunosuppression.

More research is needed to make xenotransplant a clinical option.

Transplanting stem cells or beta cells grown from stem cells

Stem cells provide an exciting potential alternative to the limited donor pool. During the past decade, several studies have shown success using human pluripotent stem cells (embryonic stem cells and human-induced pluripotent stem cells), mesenchymal stem cells isolated from adult tissues, and directly programmed somatic cells. Researchers have created stable cultures of pluripotent stem cells from embryonic stem cells, which could possibly be produced on a large scale and banked.23

Human pluripotent stem cells derived from pancreatic progenitors have been shown to mature into more functional, islet-like structures in vivo. They transform into subtypes of islet cells including alpha, beta, and delta cells, ghrelin-producing cells, and pancreatic polypeptide hormone-producing cells. This process takes 2 to 6 weeks. In mice, these cells have been shown to maintain glucose homeostasis.24 Phase 1 and 2 trials in humans are now being conducted.

Pagliuca et al25 generated functional human pancreatic beta cells in vitro from embryonic stem cells. Rezania et al24 reversed diabetes with insulin-producing cells derived in vitro from human pluripotent stem cells. The techniques used in these studies contributed to the success of a study by Vegas et al,26 who achieved successful long-term glycemic control in mice using polymer-encapsulated human stem cell-derived beta cells.

Reversal of autoimmunity is an important step that needs to be overcome in stem cell transplant for type 1 diabetes. Nikolic et al27 have achieved mixed allogeneic chimerism across major histocompatibility complex barriers with nonmyeloablative conditioning in advanced-diabetic nonobese diabetic mice. However, conditioning alone (ie, without bone marrow transplant) does not permit acceptance of allogeneic islets and does not reverse autoimmunity or allow islet regeneration.28 Adding allogeneic bone marrow transplant to conditioned nonobese diabetic mice leads to tolerance to the donor and reverses autoimmunity.

THE ‘BIONIC’ PANCREAS

While we wait for advances in islet cell transplant, improved insulin pumps hold promise.

One such experimental device, the iLet (Beta Bionics, Boston, MA), designed by Damiano et al, consists of 2 infusion pumps (1 for insulin, 1 for glucagon) linked to a continuous glucose monitor via a smartphone app.

The monitor measures the glucose level every 5 minutes and transmits the information wirelessly to the phone app, which calculates the amount of insulin and glucagon required to stabilize the blood glucose: more insulin if too high, more glucagon if too low. The phone transmits this information to the pumps.

Dubbed the “bionic” pancreas, this closed-loop system frees patients from the tasks of measuring their glucose multiple times a day, calculating the appropriate dose, and giving multiple insulin injections.

The 2016 summer camp study29 followed 19 preteens wearing the bionic pancreas for 5 days. During this time, the patients had lower mean glucose levels and less hypoglycemia than during control periods. No episodes of severe hypoglycemia were recorded.

El-Khatib et al30 randomly assigned 43 patients to treatment with either the bihormonal bionic pancreas or usual care (a conventional insulin pump or a sensor-augmented insulin pump) for 11 days, followed by 11 days of the opposite treatment. All participants continued their normal activities. The bionic pancreas system was superior to the insulin pump in terms of the mean glucose concentration and mean time in the hypoglycemic range (P < .0001 for both results).

Bottom line

As the search continues for better solutions, advances in technology such as the bionic pancreas could provide a safer (ie, less hypoglycemic) and more successful alternative for insulin replacement in the near future.

- American Diabetes Association. Statistics about diabetes: overall numbers, diabetes and prediabetes. www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statistics/. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Ahmed AM. History of diabetes mellitus. Saudi Med J 2002; 23(4):373–378. pmid:11953758

- Kelly WD, Lillehei RC, Merkel FK, Idezuki Y, Goetz FC. Allotransplantation of the pancreas and duodenum along with the kidney in diabetic nephropathy. Surgery 1967; 61:827–837. pmid: 5338113

- Sutherland DE, Gruessner RW, Dunn DL, et al. Lessons learned from more than 1,000 pancreas transplants at a single institution. Ann Surg 2001; 233(4):463–501. pmid:11303130

- Fioretto P, Steffes MW, Sutherland DE, Goetz FC, Mauer M. Reversal of lesions of diabetic nephropathy after pancreas transplantation. N Engl J Med 1998; 339(2):69–75. doi:10.1056/NEJM199807093390202

- Kennedy WR, Navarro X, Goetz FC, Sutherland DE, Najarian JS. Effects of pancreatic transplantation on diabetic neuropathy. N Engl J Med 1990; 322(15):1031–1037. doi:10.1056/NEJM199004123221503

- Kennedy WR, Navarro X, Sutherland DER. Neuropathy profile of diabetic patients in a pancreas transplantation program. Neurology 1995; 45(4):773–780. pmid:7723969

- Douzdjian V, Ferrara D, Silvestri G. Treatment strategies for insulin-dependent diabetics with ESRD: a cost-effectiveness decision analysis model. Am J Kidney Dis 1998; 31(5):794–802. pmid:9590189

- Venstrom JM, McBride MA, Rother KI, Hirshberg B, Orchard TJ, Harlan DM. Survival after pancreas transplantation in patients with diabetes and preserved kidney function. JAMA 2003; 290(21):2817–2823. doi:10.1001/jama.290.21.2817

- Gruessner RW, Sutherland DE, Gruessner AC. Mortality assessment for pancreas transplants. Am J Transplant 2004; 4(12):2018–2026. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00667.x

- Redfield RR, Scalea JR, Odorico JS. Simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplantation: current trends and future directions. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2015; 20(1):94-102. doi:10.1097/MOT.0000000000000146

- Lin YK, Faiman C, Johnston PC, et al. Spontaneous hypoglycemia after islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016; 101(10):3669–3675. doi:10.1210/jc.2016-2111

- Gupta V, Wahoff DC, Rooney DP, et al. The defective glucagon response from transplanted intrahepatic pancreatic islets during hypoglycemia is transplantation site-determined. Diabetes 1997; 46(1):28–33. pmid:8971077

- Shapiro AM, Lakey JR, Ryan EA, et al. Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med 2000; 343(4):230–238. doi:10.1056/NEJM200007273430401

- Shapiro AM, Ricordi C, Hering BJ, et al. International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation. N Engl J Med 2006; 355(13):1318–1330. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061267

- Clinical Islet Transplantation (CIT) Consortium. www.citisletstudy.org. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Collaborative Islet Transplantation Registry (CITR). CITR 10th Annual Report. https://citregistry.org/system/files/10th_AR.pdf. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- Hering BJ, Kandaswamy R, Harmon JV, et al. Transplantation of cultured islets from two-layer preserved pancreases in type 1 diabetes with anti-CD3 antibody. Am J Transplant 2004; 4(3):390–401. pmid:14961992

- Posselt AM, Bellin MD, Tavakol M, et al. Islet transplantation in type 1 diabetics using an immunosuppressive protocol based on the anti-LFA-1 antibody efalizumab. Am J Transplant 2010; 10(8):1870–1880. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03073.x

- Cantarelli E, Piemonti L. Alternative transplantation sites for pancreatic islet grafts. Curr Diab Rep 2011; 11(5):364–374. doi:10.1007/s11892-011-0216-9

- Cooper DK, Gollackner B, Knosalla C, Teranishi K. Xenotransplantation—how far have we come? Transpl Immunol 2002; 9(2–4):251–256. pmid:12180839

- Marigliano M, Bertera S, Grupillo M, Trucco M, Bottino R. Pig-to-nonhuman primates pancreatic islet xenotransplantation: an overview. Curr Diab Rep 2011; 11(5):402–412. doi:10.1007/s11892-011-0213-z

- Bartlett ST, Markmann JF, Johnson P, et al. Report from IPITA-TTS opinion leaders meeting on the future of beta-cell replacement. Transplantation 2016; 100(suppl 2):S1–S44. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000001055

- Rezania A, Bruin JE, Arora P, et al. Reversal of diabetes with insulin-producing cells derived in vitro from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 2014; 32(11):1121–1133. doi:10.1038/nbt.3033

- Pagliuca FW, Millman JR, Gurtler M, et al. Generation of functional human pancreatic beta cells in vitro. Cell 2014; 159(2):428–439. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.040

- Vegas AJ, Veiseh O, Gurtler M, et al. Long-term glycemic control using polymer-encapsulated human stem cell-derived beta cells in immune-competent mice. Nat Med 2016; 22(3):306–311. doi:10.1038/nm.4030

- Nikolic B, Takeuchi Y, Leykin I, Fudaba Y, Smith RN, Sykes M. Mixed hematopoietic chimerism allows cure of autoimmune tolerance and reversal of autoimmunity. Diabetes 2004; 53(2):376–383. pmid:14747288

- Li HW, Sykes M. Emerging concepts in haematopoietic cell transplantation. Nat Rev Immunol 2012; 12(6):403–416. doi:10.1038/nri3226

- Russell SJ, Hillard MA, Balliro C, et al. Day and night glycaemic control with a bionic pancreas versus conventional insulin pump therapy in preadolescent children with type 1 diabetes: a randomised crossover trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016; 4(3):233–243. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00489-1

- El-Khatib FH, Balliro C, Hillard MA, et al. Home use of a bihormonal bionic pancreas versus insulin pump therapy in adults with type 1 diabetes: a multicenter randomized crossover trial. Lancet 2017; 389(10067):369–380. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32567-3

With intensive insulin regimens and home blood glucose monitoring, patients with type 1 diabetes are controlling their blood glucose better than in the past. Nevertheless, glucose regulation is still imperfect and tedious, and striving for tight glycemic control poses the risk of hypoglycemia.

Prominent among the challenges are the sheer numbers involved. Some 1.25 million Americans have type 1 diabetes, and another 30 million have type 2, but only about 7,000 to 8,000 pancreases are available for transplant each year.1 While awaiting a breakthrough—perhaps involving stem cells, perhaps involving organs obtained from animals—an insulin pump may offer better diabetes control for many. Another possibility is a closed-loop system with a continuous glucose monitor that drives a dual-infusion pump, delivering insulin when glucose levels rise too high, and glucagon when they dip too low.

DIABETES WAS KNOWN IN ANCIENT TIMES

About 3,000 years ago, Egyptians described the syndrome of thirst, emaciation, and sweet urine that attracted ants. The term diabetes (Greek for siphon) was first recorded in 1425; mellitus (Latin for sweet with honey) was not added until 1675.

In 1857, Bernard hypothesized that diabetes was caused by overproduction of glucose in the liver. This idea was replaced in 1889, when Mering and Minkowski proposed the dysfunctional pancreas theory that eventually led to the discovery of the beta cell.2

In 1921, Banting and Best isolated insulin, and for the past 100 years subcutaneous insulin replacement has been the mainstay of treatment. But starting about 50 years ago, researchers have been looking for safe and long-lasting ways to replace beta cells and eliminate the need for exogenous insulin replacement.

TRANSPLANTING THE WHOLE PANCREAS

The first whole-pancreas transplant was performed in 1966 by Kelly et al,3 followed by 13 more by 1973.4 These first transplant grafts were short-lived, with only 1 graft surviving longer than 1 year. Since then, more than 12,000 pancreases have been transplanted worldwide, as refinements in surgical techniques and immunosuppressive therapies have improved patient and graft survival rates.4

Today, most pancreas transplants are in patients who have both type 1 diabetes and end-stage renal disease due to diabetic nephropathy, and most receive both a kidney and a pancreas at the same time. Far fewer patients receive a pancreas after previously receiving a kidney, or receive a pancreas alone.

The bile duct of the transplanted pancreas is usually routed into the patient’s small intestine, as nature intended, and less often into the bladder. Although bladder drainage is associated with urinary complications, it has the advantage of allowing measurement of pancreatic amylase levels in the urine to monitor for graft rejection. With simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplant, the serum creatinine concentration can also be monitored for rejection of the kidney graft.

Current immunosuppressive regimens vary but generally consist of anti-T-cell antibodies at the time of surgery, followed by lifelong treatment with the combination of a calcineurin inhibitor (cyclosporine or tacrolimus) and an antimetabolite (mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine).

Outcomes are good. The rates of patient and graft survival are highest with simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant, and somewhat lower with pancreas-after-kidney and pancreas-alone transplant.

Benefits of pancreas transplant

Most recipients can stop taking insulin immediately after the procedure, and their hemoglobin A1c levels normalize and stay low for the life of the graft. Lipid levels also decrease, although this has not been directly correlated with lower risk of vascular disease.4

Transplant also reduces or eliminates some complications of diabetes, including retinopathy, nephropathy, cardiomyopathy, and gastropathy.

For example, in patients undergoing simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant, diabetic nephropathy does not recur in the new kidney. Fioretto et al5 reported that nephropathy lesions reversed during the 10 years after pancreas transplant.

Kennedy et al6,7 found that preexisting diabetic neuropathy improved slightly (although neurologic status did not completely return to normal) over a period of up to 42 months in a group of patients who received a pancreas transplant, whereas it tended to worsen in a control group. Both groups were assessed at baseline and at 12 and 24 months, with a subgroup followed through 42 months, and they underwent testing of motor, sensory, and autonomic function.6,7

Disadvantages of pancreas transplant

Disadvantages of whole-pancreas transplant include hypoglycemia (usually mild), adverse effects of immunosuppression, potential for surgical complications including an increased rate of death in the first 90 days after the procedure, and cost.