User login

Systemic Treatment for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma

From the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Division of Hematology Oncology, Birmingham, AL, and the University of South Alabama, Division of Hematology Oncology, Mobile, AL. Dr. Paluri and Dr. Hatic contributed equally to this article.

Abstract

- Objective: To review systemic treatment options for patients with locally advanced unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: The paradigm of what constitutes first-line treatment for advanced HCC is shifting. Until recently, many patients with advanced HCC were treated with repeated locoregional therapies, such as transartertial embolization (TACE). However, retrospective studies suggest that continuing TACE after refractoriness or failure may not be beneficial and may delay subsequent treatments because of deterioration of liver function or declines in performance status. With recent approvals of several systemic therapy options, including immunotherapy, it is vital to conduct a risk-benefit assessment prior to repeating TACE after failure, so that patients are not denied the use of available systemic therapeutic options due to declined performance status or organ function from these procedures. The optimal timing and the sequence of systemic and locoregional therapy must be carefully evaluated by a multidisciplinary team.

- Conclusion: Randomized clinical trials to improve patient selection and determine the proper sequence of treatments are needed. Given the heterogeneity of HCC, molecular profiling of the tumor to differentiate responders from nonresponders may elucidate potential biomarkers to effectively guide treatment recommendations.

Keywords: liver cancer; molecular therapy; immunotherapy.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents 90% of primary liver malignancies. It is the fifth most common malignancy in males and the ninth most common in females worldwide.1 In contrast to other major cancers (colon, breast, prostate), the incidence of and mortality from HCC has increased over the past decade, following a brief decline between 1999 and 2004.2 The epidemiology and incidence of HCC is closely linked to chronic liver disease and conditions predisposing to liver cirrhosis. Worldwide, hepatitis B virus infection is the leading cause of liver cirrhosis and, hence, HCC. In the United States, 50% of HCC cases are linked to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Diabetes mellitus and alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are the other major etiologies of HCC. Indeed, the metabolic syndrome, independent of other factors, is associated with a 2-fold increase in the risk of HCC.3

Although most cases of HCC are predated by liver cirrhosis, in about 20% of patients HCC occurs without liver cirrhosis.4 Similar to other malignancies, surgery in the form of resection (for isolated lesions in the context of good liver function) or liver transplant (for low-volume disease with mildly impaired liver function) provides the best chance of a cure. Locoregional therapies involving hepatic artery–directed therapy are offered for patients with more advanced disease that is limited to the liver, while systemic therapy is offered for advanced unresectable disease that involves portal vein invasion, lymph nodes, and distant metastasis. The

Molecular Pathogenesis

Similar to other malignancies, a multistep process of carcinogenesis, with accumulation of genomic alterations at the molecular and cellular levels, is recognized in HCC. In about 80% of cases, repeated and chronic injury, inflammation, and repair lead to a distortion of normal liver architecture and development of cirrhotic nodules. Exome sequencing of HCC tissues has identified risk factor–specific mutational signatures, including those related to the tumor microenvironment, and defined the extensive landscape of altered genes and pathways in HCC (eg, angiogenic and MET pathways).7 In the Schulze et al study, the frequency of alterations that could be targeted by available Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved drugs comprised either amplifications or mutations of FLTs (6%), FGF3 or 4 or 19 (4%), PDGFRs (3%), VEGFA (1%), HGF (3%), MTOR (2%), EGFR (1%), FGFRs (1%), and MET (1%).7 Epigenetic modification of growth-factor expression, particularly insulin-like growth factor 2 and transforming growth factor alpha, and structural alterations that lead to loss of heterozygosity are early events that cause hepatocyte proliferation and progression of dysplastic nodules.8,9 Advances in whole-exome sequencing have identified TERT promoter mutations, leading to activation of telomerase, as an early event in HCC pathogenesis. Other commonly altered genes include CTNNB1 (B-Catenin) and TP53. As a group, alterations in the MAP kinase pathway genes occur in about 40% of HCC cases.

Actionable oncogenic driver alterations are not as common as tumor suppressor pathway alterations in HCC, making targeted drug development challenging.10,11 The FGFR (fibroblast growth factor receptor) pathway, which plays a critical role in carcinogenesis-related cell growth, survival, neo-angiogenesis, and acquired resistance to other cancer treatments, is being explored as a treatment target.12 The molecular characterization of HCC may help with identifying new biomarkers and present opportunities for developing therapeutic targets.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 61-year-old man with a history of chronic hepatitis C and hypertension presents to his primary care physician due to right upper quadrant pain. Laboratory evaluation shows transaminases elevated 2 times the upper limit of normal. This leads to an ultrasound and follow-up magnetic resonance imaging. Imaging shows diffuse cirrhotic changes, with a 6-cm, well-circumscribed lesion within the left lobe of the liver that shows rapid arterial enhancement with venous washout. These vascular characteristics are consistent with HCC. In addition, 2 satellite lesions in the left lobe and sonographic evidence of invasion into the portal vein are present. Periportal lymph nodes are pathologically enlarged.

The physical examination is unremarkable, except for mild tenderness over the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Serum bilirubin, albumin, platelets, and international normalized ratio are normal, and alpha fetoprotein (AFP) is elevated at 1769 ng/mL. The patient’s family history is unremarkable for any major illness or cancer. Computed tomography scan of the chest and pelvis shows no evidence of other lesions. His liver disease is classified as Child–Pugh A. Due to locally advanced presentation, the tumor is deemed to be nontransplantable and unresectable, and is staged as BCLC-C. The patient continues to work and his performance status is ECOG (

What systemic treatment would you recommend for this patient with locally advanced unresectable HCC with nodal metastasis?

First-Line Therapeutic Options

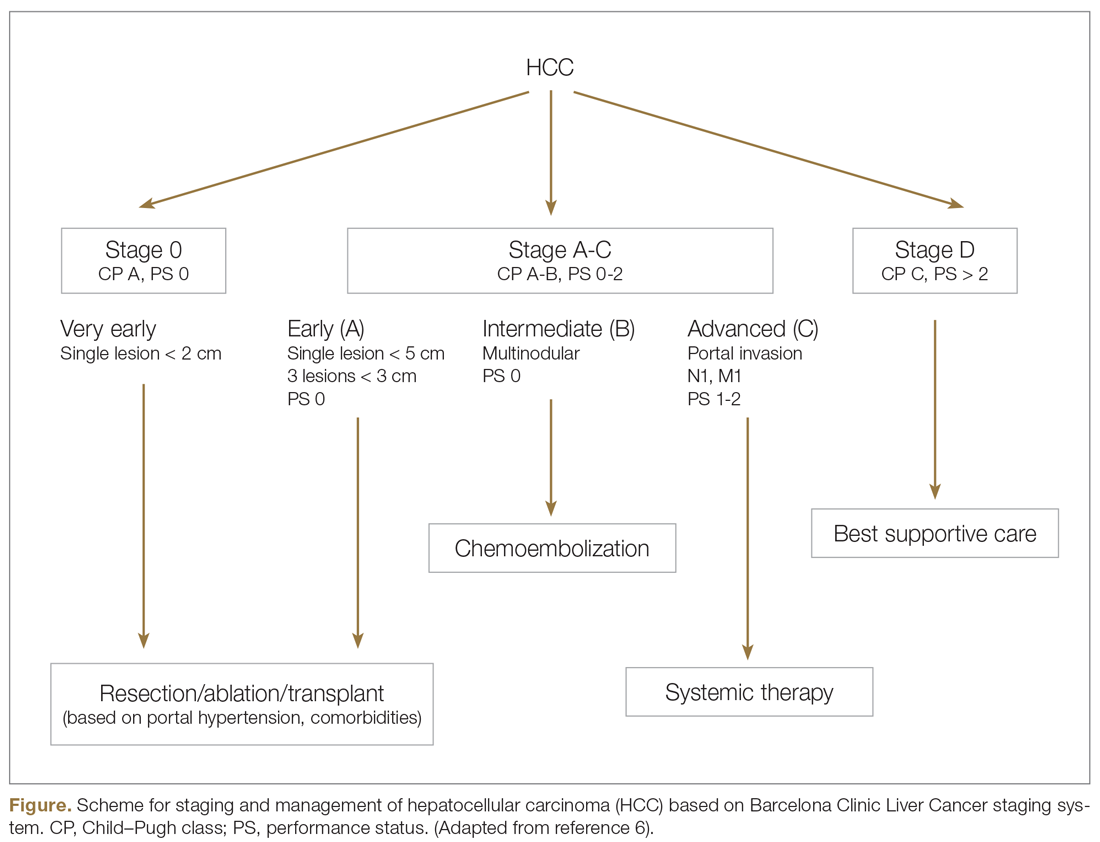

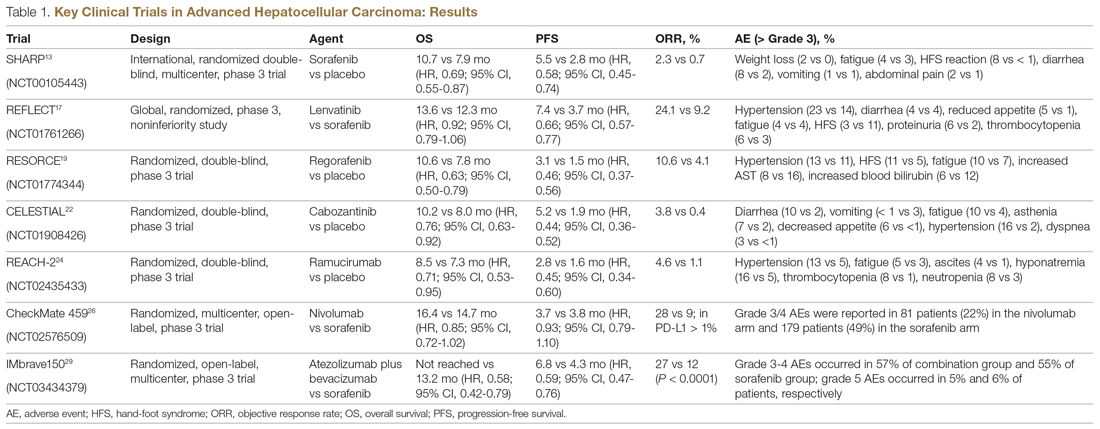

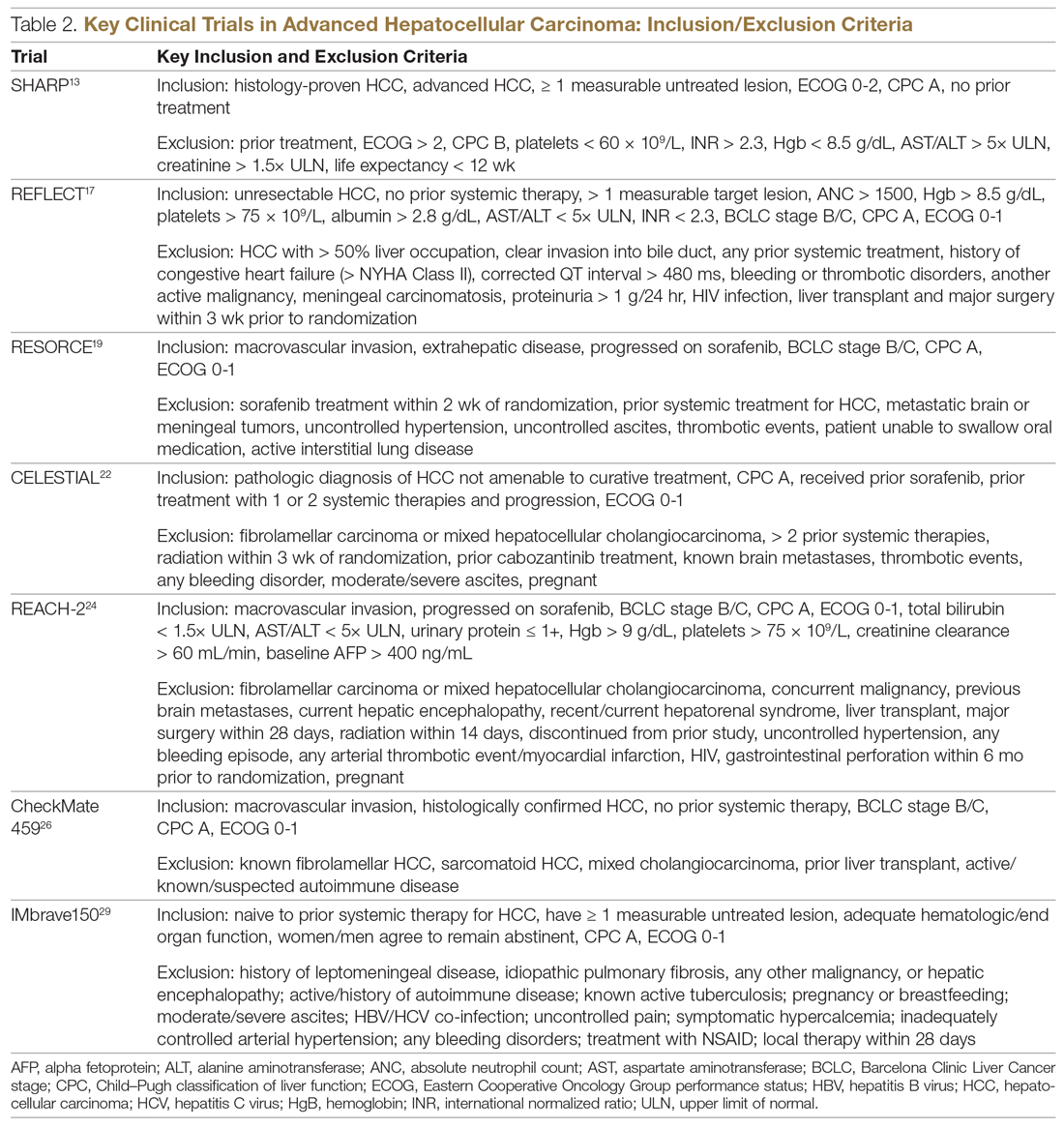

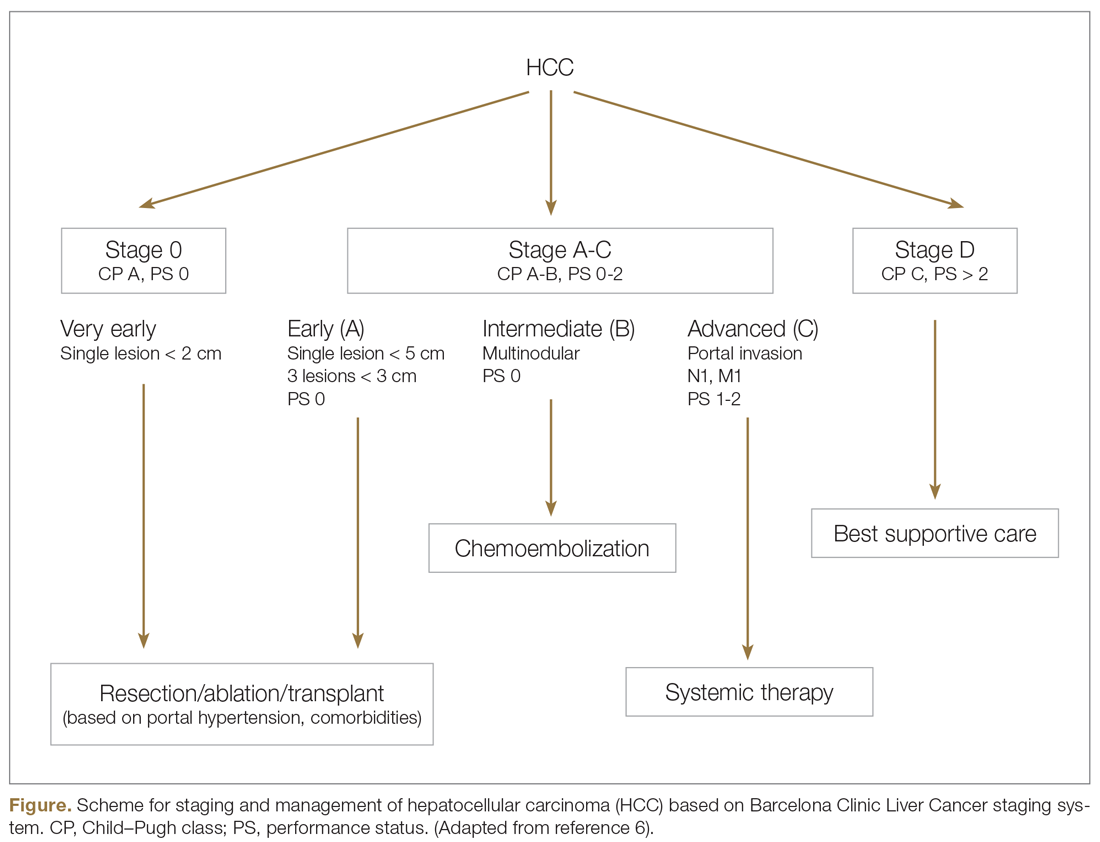

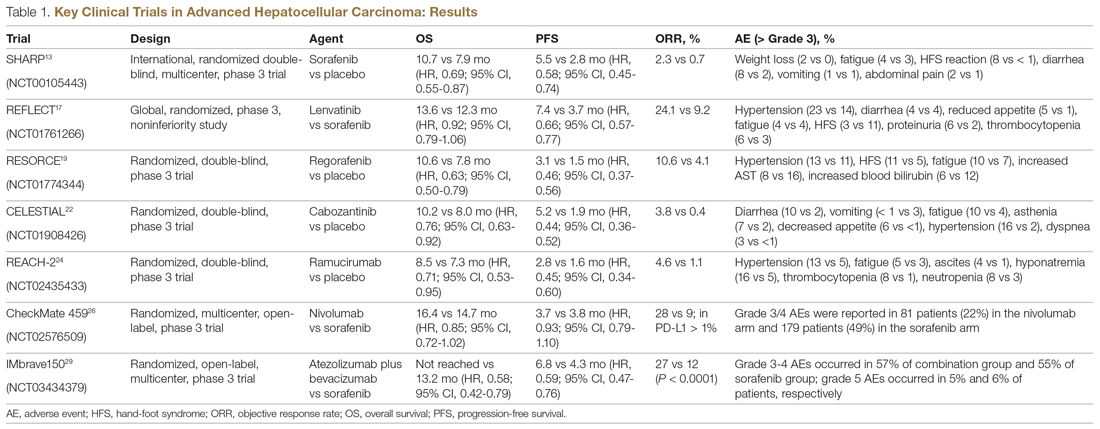

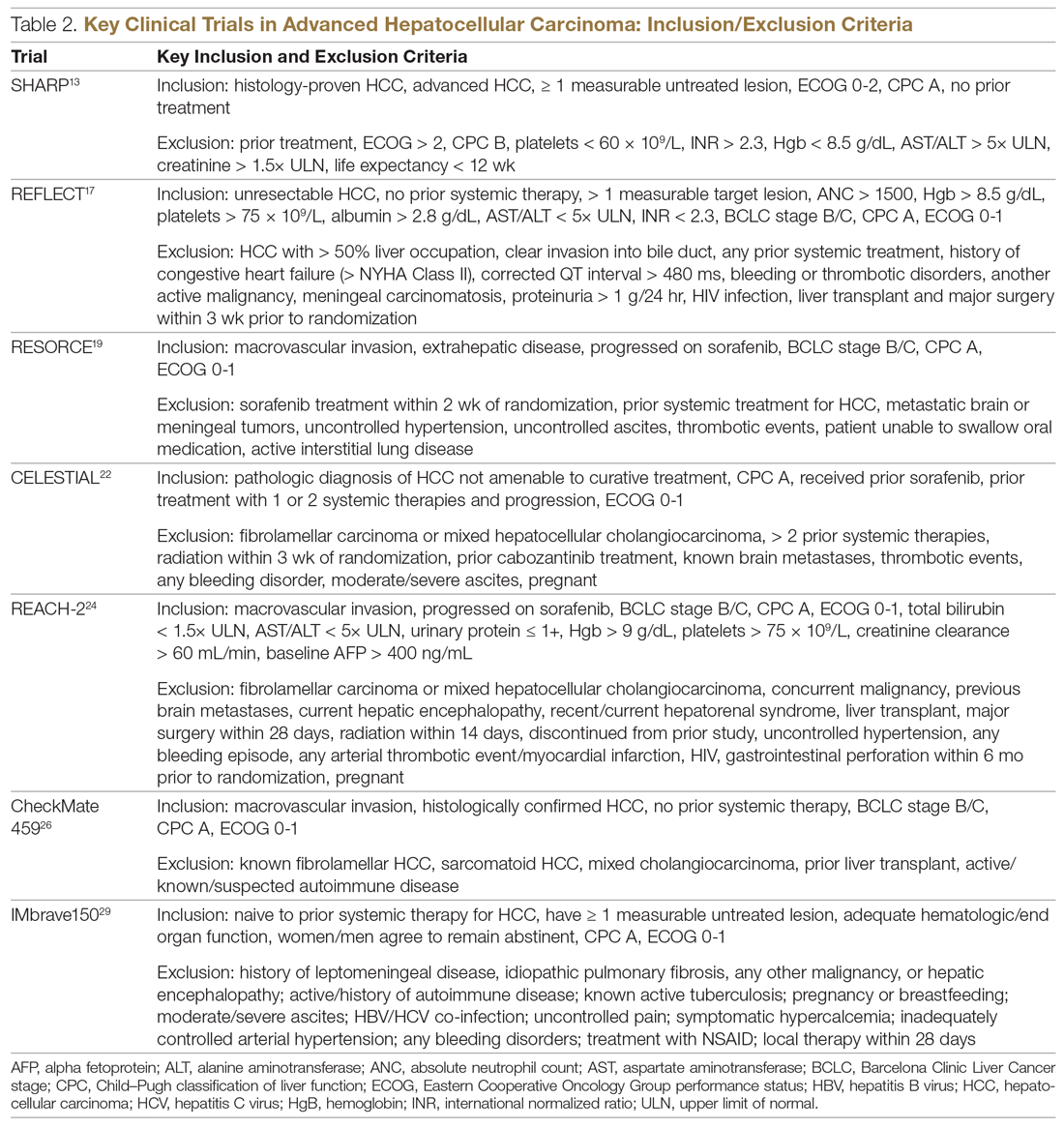

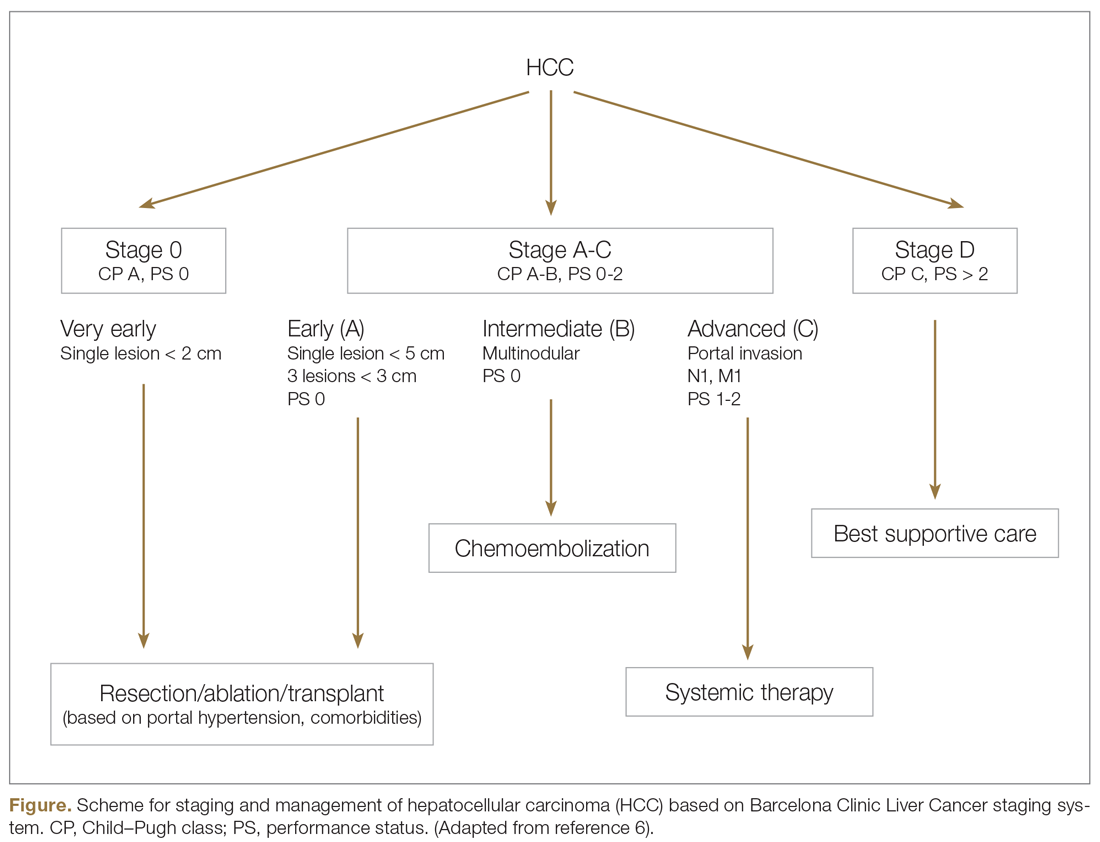

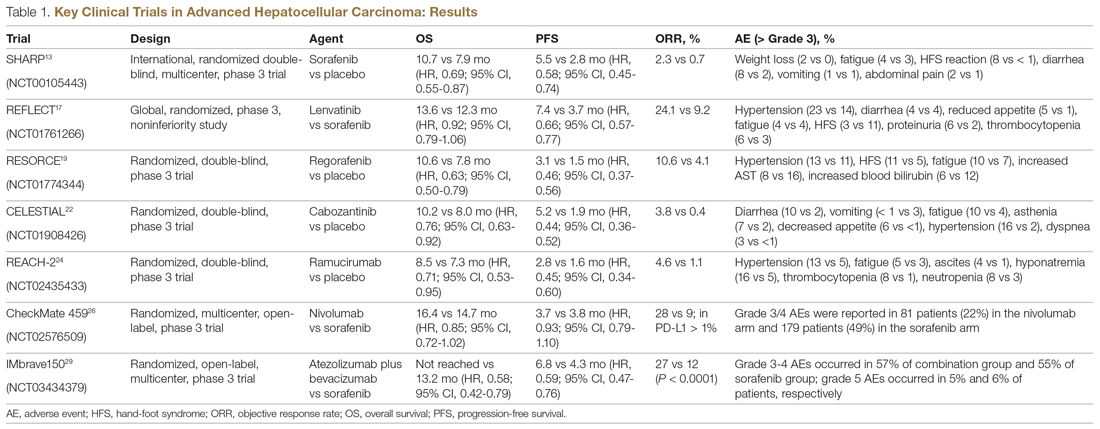

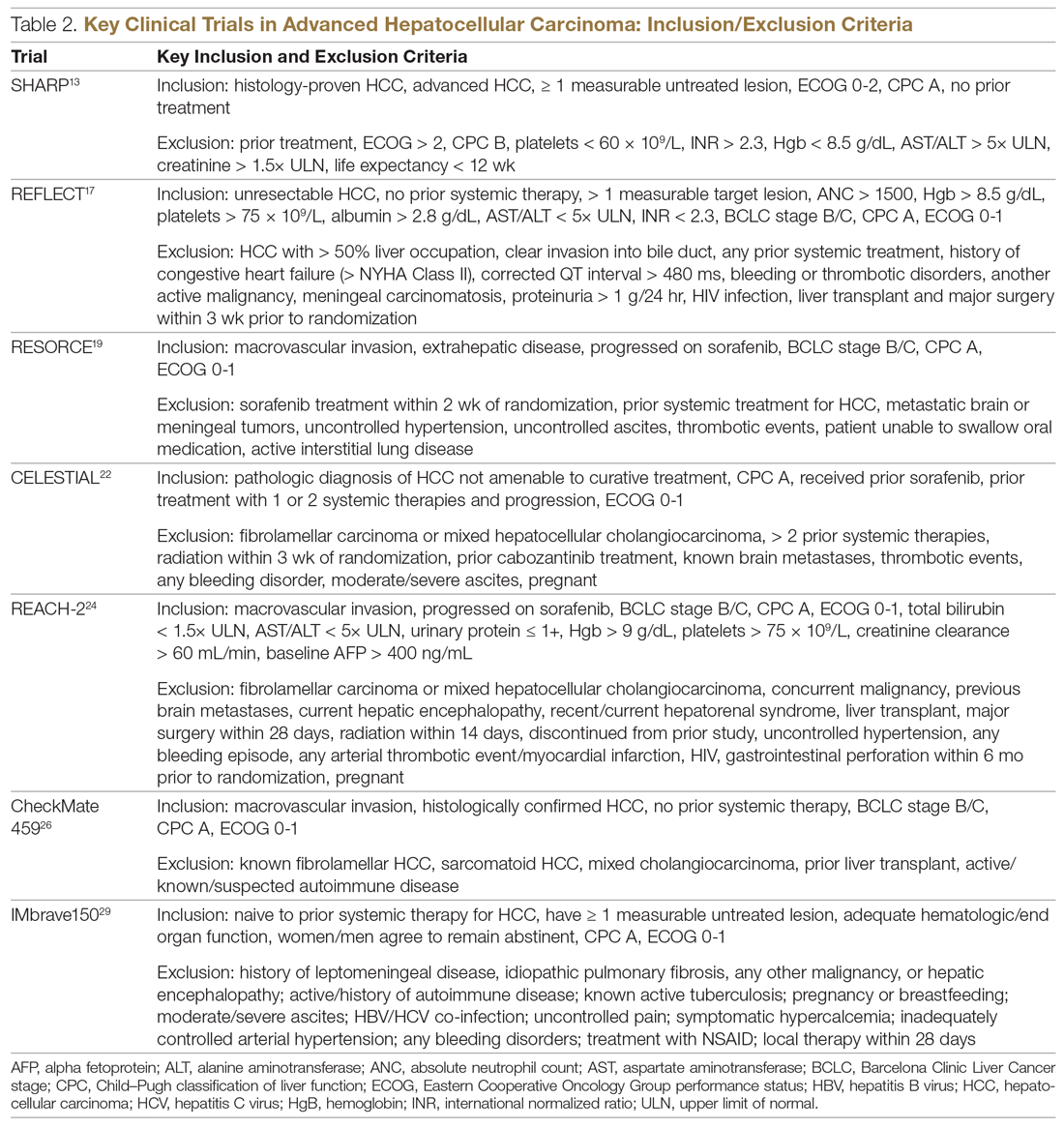

Systemic treatment of HCC is challenging because of the underlying liver cirrhosis and hepatic dysfunction present in most patients. Overall prognosis is therefore dependent on the disease biology and burden and on the degree of hepatic dysfunction. These factors must be considered in patients with advanced disease who present for systemic therapy. As such, patients with BCLC class D HCC with poor performance status and impaired liver function are better off with best supportive care and hospice services (Figure). Table 1 and Table 2 outline the landmark trials that led to the approval of agents for advanced HCC treatment.

Sorafenib

In the patient with BCLC class C HCC who has preserved liver function (traditionally based on a Child–Pugh score of ≤ 6 and a decent functional status [ECOG performance status 1-2]), sorafenib is the first FDA-approved first-line treatment. Sorafenib is a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) kinase signaling, in addition to many other tyrosine kinase pathways (including the platelet-derived growth factor and Raf-Ras pathways). Evidence for the clinical benefit of sorafenib comes from the SHARP trial.13 This was a multinational, but primarily European, randomized phase 3 study that compared sorafenib to best supportive care for advanced HCC in patients with a Child–Pugh score ≤ 6A and a robust performance status (ECOG 0 and 1). Overall survival (OS) with placebo and sorafenib was 7.9 months and 10.7 months, respectively. There was no difference in time to radiologic progression, and the progression-free survival (PFS) at 4 months was 62% with sorafenib and 42% with placebo. Patients with HCV-associated HCC appeared to derive a more substantial benefit from sorafenib.14 In a smaller randomized study of sorafenib in Asian patients with predominantly hepatitis B–associated HCC, OS in the sorafenib and best supportive care arms was lower than that reported in the SHARP study (6.5 months vs 4.2 months), although OS still was longer in the sorafenib group.15

Significant adverse events reported with sorafenib include fatigue (30%), hand and foot syndrome (30%), diarrhea (15%), and mucositis (10%). Major proportions of patients in the clinical setting have not tolerated the standard dose of 400 mg twice daily. Dose-adjusted administration of sorafenib has been advocated in patients with more impaired liver function (Child–Pugh class 7B) and bilirubin of 1.5 to 3 times the upper limit of normal, although it is unclear whether these patients are deriving any benefit from sorafenib.16 At this time, in a patient with preserved liver function, starting with 400 mg twice daily, followed by dose reduction based on toxicity, remains standard.

Lenvatinib

After multiple attempts to develop newer first-line treatments for HCC,

Second-Line Therapeutic Options

Following the sorafenib approval, clinical studies of several other agents did not meet their primary endpoint and failed to show improvement in clinical outcomes compared to sorafenib. However, over the past years the treatment landscape for advanced HCC has been changed with the approval of several agents in the second line. The overall response rate (ORR) has become the new theme for management of advanced disease. With multiple therapeutic options available, optimal sequencing now plays a critical role, especially for transitioning from locoregional to systemic therapy. Five drugs are now indicated for second-line treatment of patients who progressed on or were intolerant to sorafenib: regorafenib, cabozantinib, ramucirumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab.

Regorafenib

Regorafenib was evaluated in the advanced HCC setting in a single-arm, phase 2 trial involving 36 patients with Child–Pugh class A liver disease who had progressed on prior sorafenib.18 Patients received regorafenib 160 mg orally once daily for 3 weeks on/1 week off cycles. Disease control was achieved in 72% of patients, with stable disease in 25 patients (69%). Based on these results, regorafenib was further evaluated in the multicenter, phase 3, 2:1 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled RESORCE study, which enrolled 573 patients.19 Due to the overlapping safety profiles of sorafenib and regorafenib, the inclusion criteria required patients to have tolerated a sorafenib dose of at least 400 mg daily for 20 of the past 28 days of treatment prior to enrollment. The primary endpoint of the study, OS, was met (median OS of 10.6 months in regorafenib arm versus 7.8 months in placebo arm; hazard ratio [HR], 0.63; P < 0.0001).

Cabozantinib

CELESTIAL was a phase 3, double-blind study that assessed the efficacy of cabozantinib versus placebo in patients with advanced HCC who had received prior sorafenib.22 In this study, 707 patients with Child–Pugh class A liver disease who progressed on at least 1 prior systemic therapy were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to treatment with cabozantinib at 60 mg daily or placebo. Patients treated with cabozantinib had a longer OS (10.2 months vs 8.0 months), resulting in a 24% reduction in the risk of death (HR, 0.76), and a longer median PFS (5.2 months versus 1.9 months). The disease control rate was higher with cabozantinib (64% vs 33%) as well. The incidence of high‐grade adverse events in the cabozantinib group was twice that of the placebo group. Common adverse events reported with cabozantinib included HFSR (17%), hypertension (16%), increased aspartate aminotransferase (12%), fatigue (10%), and diarrhea (10%).

Ramucirumab

REACH was a phase 3 study exploring the efficacy of ramucirumab that did not meet its primary endpoint; however, the subgroup analysis in AFP-high patients showed an OS improvement with ramucirumab.23 This led to the phase 3 REACH-2 trial, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind biomarker study in patients with advanced HCC who either progressed on or were intolerant to sorafenib and had an AFP level ≥ 400 ng/mL.24 Patients were randomized to ramucirumab 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks or placebo. The study met its primary endpoint, showing improved OS (8.5 months vs 7.3 months; P = 0.0059). The most common treatment-related adverse events in the ramucirumab group were ascites (5%), hypertension (12%), asthenia (5%), malignant neoplasm progression (6%), increased aspartate aminotransferase concentration (5%), and thrombocytopenia.

Immunotherapy

HCC is considered an inflammation-induced cancer, which renders immunotherapeutic strategies more appealing. The PD-L1/PD-1 pathway is the critical immune checkpoint mechanism and is an important target for treatment. HCC uses a complex, overlapping set of mechanisms to evade cancer-specific immunity and to suppress the immune system. Initial efforts to develop immunotherapies for HCC focused on anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies. CheckMate 040 evaluated nivolumab in 262 sorafenib-naïve and -treated patients with advanced HCC (98% with Child–Pugh scores of 5 or 6), with a median follow-up of 12.9 months.25 In sorafenib-naïve patients (n = 80), the ORR was 23%, and the disease control rate was 63%. In sorafenib-treated patients (n = 182), the ORR was 18%. Response was not associated with PD-L1 expression. Durable objective responses, a manageable safety profile, and promising efficacy led the FDA to grant accelerated approval of nivolumab for the treatment of patients with HCC who have been previously treated with sorafenib. Based on this, the phase 3 randomized CheckMate-459 trial evaluated the efficacy of nivolumab versus sorafenib in the first-line. Median OS and ORR were better with nivolumab (16.4 months vs 14.7 months; HR 0.85; P = 0.752; and 15% [with 5 complete responses] vs 7%), as was the safety profile (22% vs 49% reporting grade 3 and 4 adverse events). 26

The KEYNOTE-224 study27 evaluated pembrolizumab in 104 patients with previously treated advanced HCC. This study showed an ORR of 17%, with 1 complete response and 17 partial responses. One-third of the patients had progressive disease, while 46 had stable disease. Among those who responded, 56% maintained a durable response for more than 1 year. Subsequently, in KEYNOTE 240, pembrolizumab showed an improvement in OS (13.9 months vs 10.6 months; HR, 0.78; P = 0.0238) and PFS (3.0 months versus 2.8 months; HR, 0.78; P = 0.0186) compared with placebo.28 The ORR for pembrolizumab was 16.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 12.7%-21.8%) versus 2.2% (95% CI, 0.5%-6.4%; P = 0.00001) for placebo. Mean duration of response was 13.8 months.

In the IMbrave150 trial, atezolizumab/bevacizumab combination, compared to sorafenib, had better OS (not estimable vs 13.2 months; P = 0.0006), PFS (6.8 months vs 4.5 months, P < 0.0001), and ORR (33% vs 13%, P < 0.0001), but grade 3-4 events were similar.29 This combination has potential for first-line approval. The COSMIC–312 study is comparing the combination of cabozantinib and atezolizumab to sorafenib monotherapy and cabozantinib monotherapy in advanced HCC.

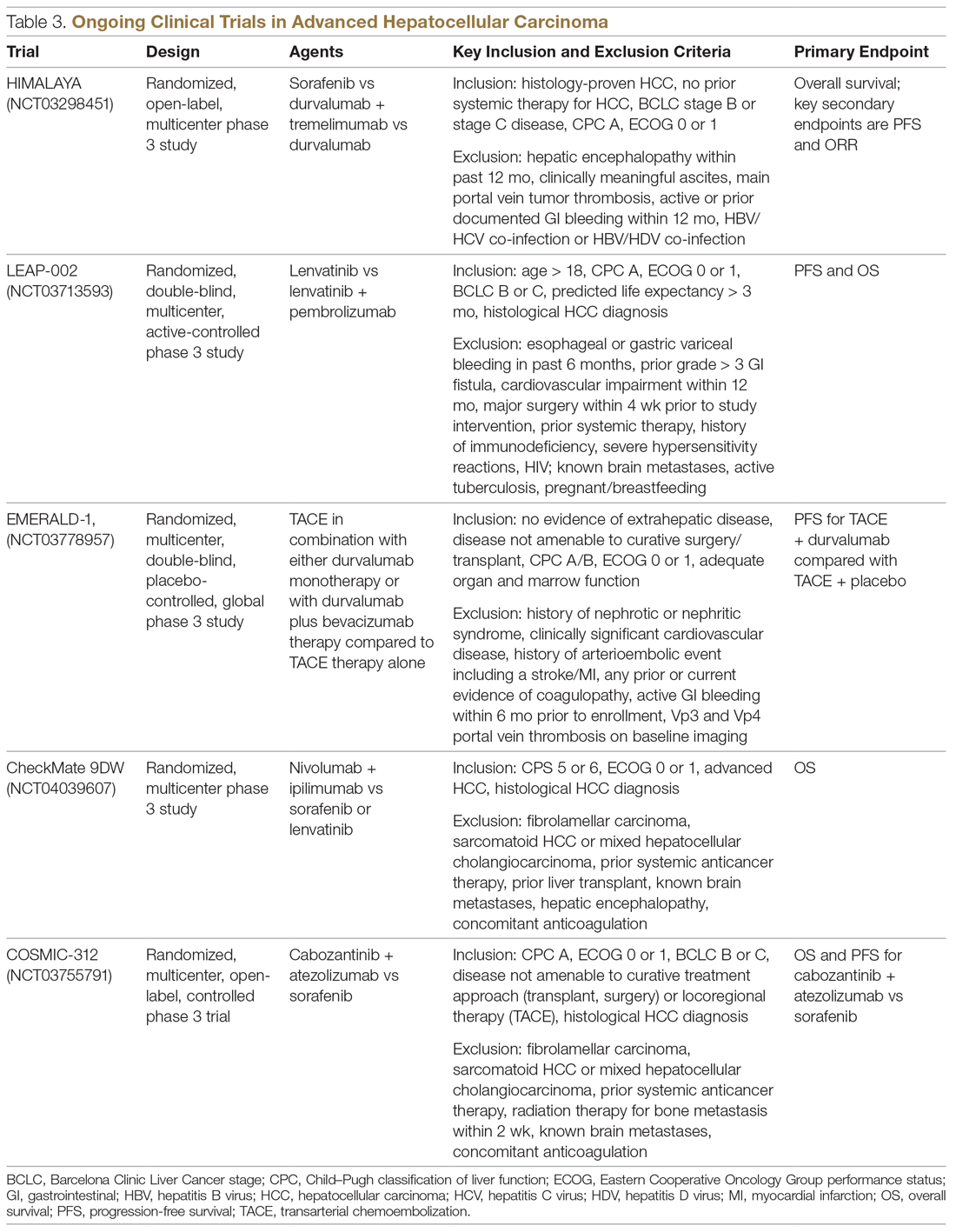

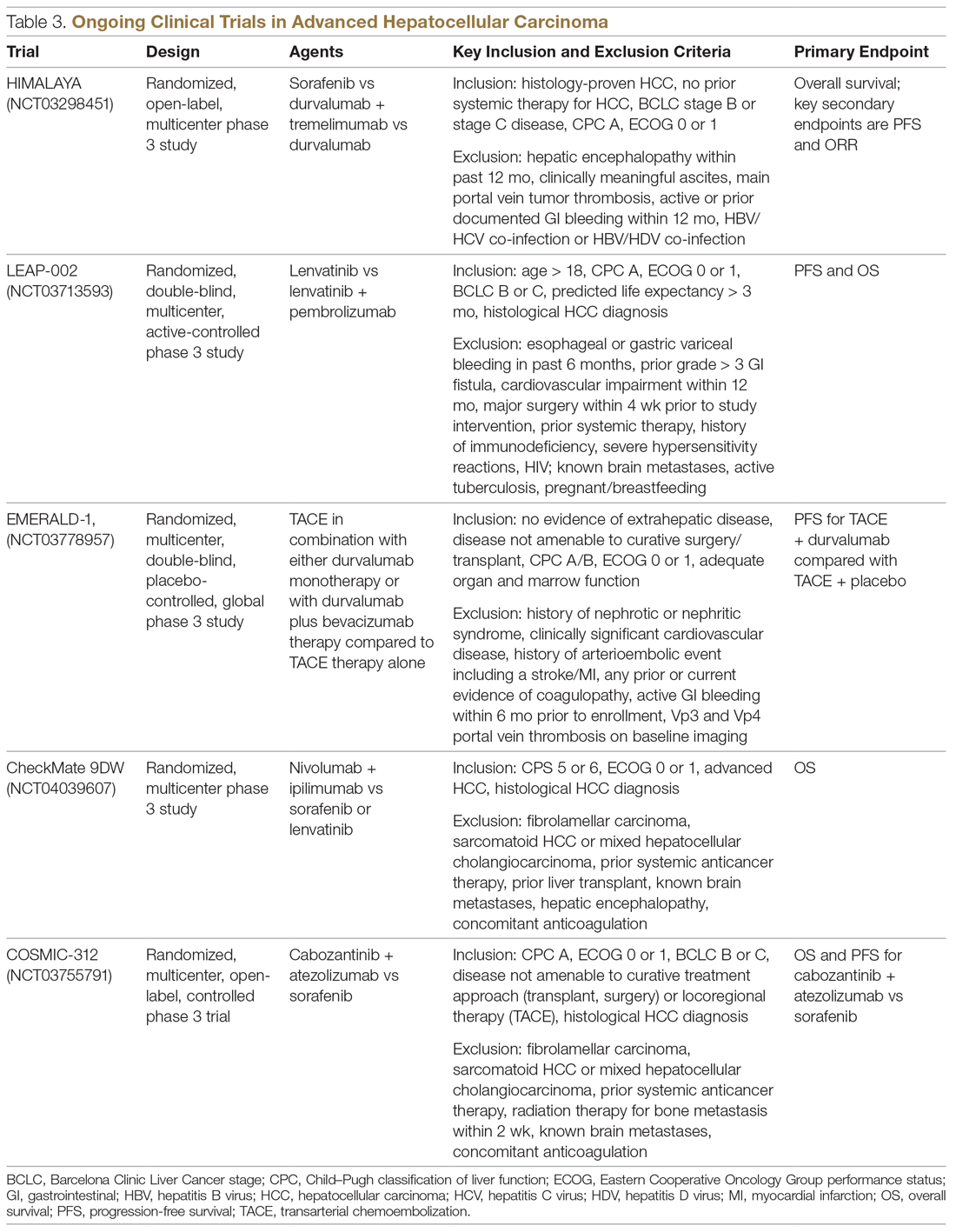

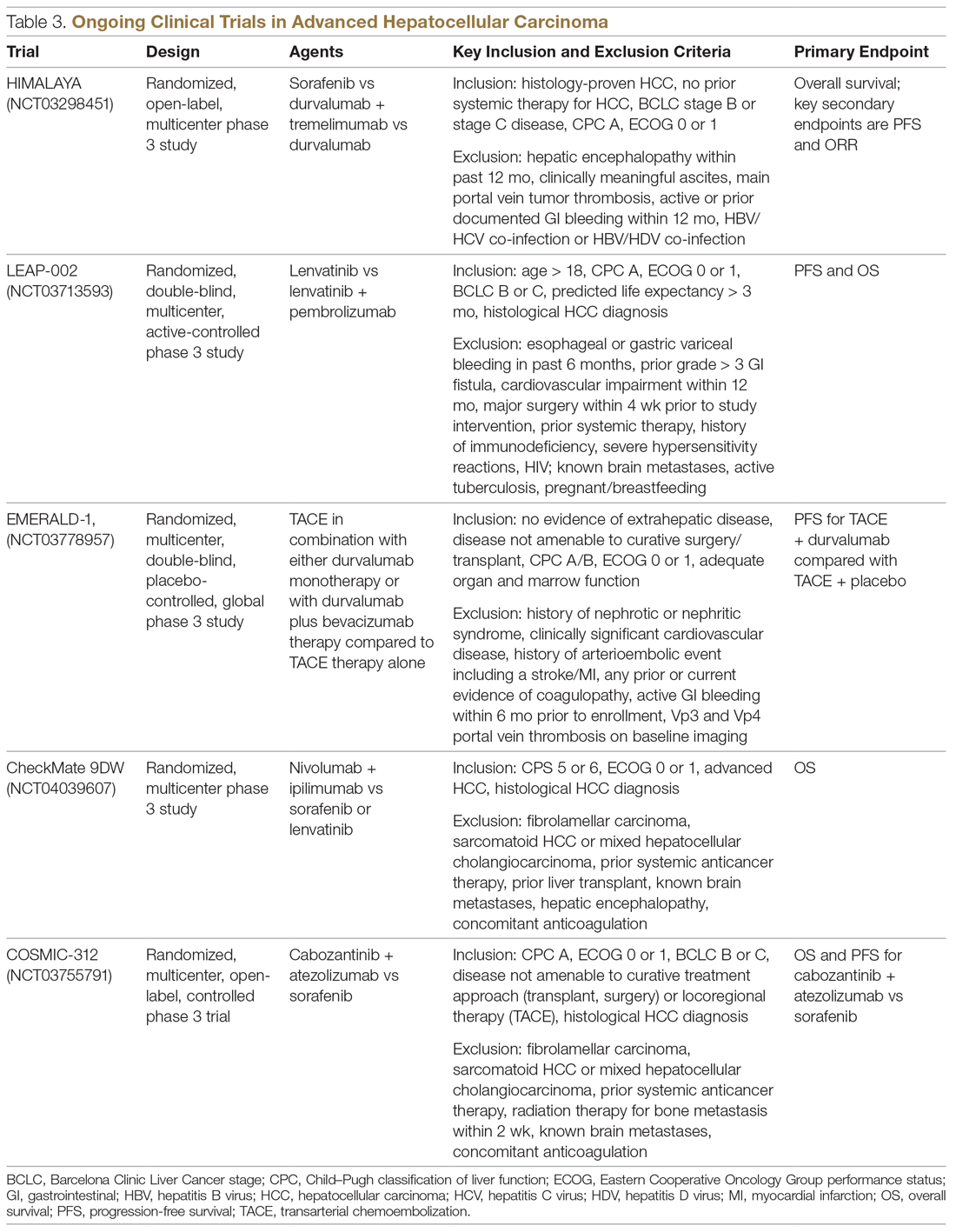

Resistance to immunotherapy can be extrinsic, associated with activation mechanisms of T-cells, or intrinsic, related to immune recognition, gene expression, and cell-signaling pathways.30 Tumor-immune heterogeneity and antigen presentation contribute to complex resistance mechanisms.31,32 Although clinical outcomes have improved with immune checkpoint inhibitors, the response rate is low and responses are inconsistent, likely due to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.33 Therefore, several novel combinations of checkpoint inhibitors and targeted drugs are being evaluated to bypass some of the resistance mechanisms (Table 3).

Chemotherapy

Multiple combinations of cytotoxic regimens have been evaluated, but efficacy has been modest, suggesting the limited role for traditional chemotherapy in the systemic management of advanced HCC. Response rates to chemotherapy are low and responses are not durable. Gemcitabine- and doxorubicin-based treatment and FOLFOX (5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin) are some regimens that have been studied, with a median OS of less than 1 year for these regimens.34-36 FOLFOX had a higher response rate (8.15% vs 2.67%; P = 0.02) and longer median OS (6.40 months versus 4.97 months; HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.63-1.02; P = 0.07) than doxorubicin.34 With the gemcitabine/oxaliplatin combination, ORR was 18%, with stable disease in 58% of patients, and median PFS and OS were 6.3 months and 11.5 months, respectively.35 In a study that compared doxorubicin and PIAF (cisplatin/interferon a-2b/doxorubicin/5-fluorouracil), median OS was 6.83 months and 8.67 months, respectively (P = 0.83). The hazard ratio for death from any cause in the PIAF group compared with the doxorubicin group was 0.97 (95% CI, 0.71-1.32). PIAF had a higher ORR (20.9%; 95% CI, 12.5%-29.2%) than doxorubicin (10.5%; 95% CI, 3.9%-16.9%).

The phase 3 ALLIANCE study evaluated the combination of sorafenib and doxorubicin in treatment-naïve HCC patients with Child–Pugh class A liver disease, and did not demonstrate superiority with the addition of cytotoxic chemotherapy.37 Indeed, the combination of chemotherapy with sorafenib appears harmful in terms of lower OS (9.3 months vs 10.6 months; HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.8-1.4) and worse toxicity. Patients treated with the combination experienced more hematologic (37.8% vs 8.1%) and nonhematologic adverse events (63.6% vs 61.5%).

Locoregional Therapy

The role of locoregional therapy in advanced HCC remains the subject of intense debate. Patients with BCLC stage C HCC with metastatic disease and those with lymph node involvement are candidates for systemic therapy. The optimal candidate for locoregional therapy is the patient with localized intermediate-stage disease, particularly hepatic artery–delivered therapeutic interventions. However, the presence of a solitary large tumor or portal vein involvement constitutes gray areas regarding which therapy to deliver directly to the tumor via the hepatic artery, and increasingly stereotactic body radiation therapy is being offered.

Transarterial Chemoembolization

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), with or without chemotherapy, is the most widely adopted locoregional therapy in the management of HCC. TACE exploits the differential vascular supply to the HCC and normal liver parenchyma. Normal liver receives only one-fourth of its blood supply from the hepatic artery (three-fourths from the portal vein), whereas HCC is mainly supplied by the hepatic artery. A survival benefit for TACE compared to best supportive care is widely acknowledged for intermediate-stage HCC, and transarterial embolization (TAE) with gelatin sponge or microspheres is noninferior to TACE.38,39 Overall safety profile and efficacy inform therapy selection in advanced HCC, although the evidence for TACE in advanced HCC is less robust. Although single-institution experiences suggest survival numbers similar to and even superior to sorafenib,40,41 there is a scarcity of large randomized clinical trial data to back this up. Based on this, patients with advanced HCC should only be offered liver-directed therapy within a clinical trial or on a case-by-case basis under multidisciplinary tumor board consensus.

A serious adverse effect of TACE is post-embolization syndrome, which occurs in about 30% of patients and may be associated with poor prognosis.42 The syndrome consists of right upper quadrant abdominal pain, malaise, and worsening nausea/vomiting following the embolization procedure. Laboratory abnormalities and other complications may persist for up to 30 days after the procedure. This is a concern, because post-embolization syndrome may affect the ability to deliver systemic therapy.

Transarterial Radioembolization

In the past few years, there has been an uptick in the utilization of transarterial radioembolization (TARE), which instead of delivering glass beads, as done in TAE, or chemotherapy-infused beads, as done in TACE, delivers the radioisotope Y-90 to the tumor via the hepatic artery. TARE is able to administer larger doses of radiation to the tumor while avoiding normal liver tissue, as compared to external-beam radiation. There has been no head-to-head comparison of these different intra-arterial therapy approaches, but TARE with Y-90 has been shown to be safe in patients with portal vein thrombosis. A recent multicenter retrospective study of TARE demonstrated a median OS of 8.8 to 10.8 months in patients with BCLC C HCC,43 and in a large randomized study of Y-90 compared to sorafenib in advanced and previously treated intermediate HCC, there was no difference in median OS between the treatment modalities (8 months for selective internal radiotherapy, 9 months for sorafenib; P = 0.18). Treatment with Y-90 was better tolerated.44 A major impediment to the adoption of TARE is the time it takes to order, plan, and deliver Y-90 to patients. Radio-embolization-induced liver disease, similar to post-embolization syndrome, is characterized by jaundice and ascites, which may occur 4 to 8 weeks postprocedure and is more common in patients with HCC who do not have cirrhosis. Compared to TACE, TARE may offer a better adverse effect profile, with improvement in quality of life.

Combination of Systemic and Locoregional Therapy

Even in carefully selected patients with intermediate- and advanced-stage HCC, locoregional therapy is not curative. Tumor embolization may promote more angiogenesis, and hence tumor progression, by causing hypoxia and upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor.45 This upregulation of angiogenesis as a resistance mechanism to tumor embolization provides a rationale for combining systemic therapy (typically based on abrogating angiogenesis) with TACE/TAE. Most of the experience has been with sorafenib in intermediate-stage disease, and the results have been disappointing. The administration of sorafenib after at least a partial response with TACE did not provide additional benefit in terms of time to progression.46 Similarly, in the SPACE trial, concurrent therapy with TACE-doxorubicin-eluting beads and sorafenib compared to TACE-doxorubicin-eluting beads and placebo yielded similar time to progression numbers for both treatment modalities.47 While the data have been disappointing in intermediate-stage disease, as described earlier, registry data suggest that patients with advanced-stage disease may benefit from this approach.48

In the phase 2 TACTICS trial, 156 patients with unresectable HCC were randomized to receive TACE alone or sorafenib plus TACE, with a novel endpoint, time to untreatable progression (TTUP) and/or progression to TACE refractoriness.49 Treatment with sorafenib following TACE was continued until TTUP, decline in liver function to Child–Pugh class C, or the development of vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread. Development of new lesions while on sorafenib was not considered as progressive disease as long as the lesions were amenable to TACE. In this study, PFS was longer with sorafenib-TACE compared to TACE alone (26.7 months vs 20.6 months; P = 0.02). However, the TTUP endpoint needs further validation, and we are still awaiting the survival outcomes of this study. At this time, there are insufficient data to recommend the combination of liver-directed locoregional therapy and sorafenib or other systemic therapy options outside of a clinical trial setting.

Current Treatment Approach for Advanced HCC (BCLC-C)

Although progress is being made in the development of effective therapies, advanced HCC is generally incurable. These patients experience significant symptom burden throughout the course of the disease. Therefore, the optimal treatment plan must focus on improving or maintaining quality of life, in addition to overall efficacy. It is important to actively involve patients in treatment decisions for an individualized treatment plan, and to discuss the best strategy for incorporating current advances in targeted and immunotherapies. The paradigm of what constitutes first-line treatment for advanced HCC is shifting due to the recent systemic therapy approvals. Prior to the availability of these therapies, many patients with advanced HCC were treated with repeated locoregional therapies. For instance, TACE was often used to treat unresectable HCC multiple times beyond progression. There was no consensus on the definition of TACE failure, and hence it was used in broader, unselected populations. Retrospective studies suggest that continuing TACE after refractoriness or failure may not be beneficial, and may delay subsequent treatments because of deterioration of liver function or declines in performance status. With recent approvals of several systemic therapy options, including immunotherapy, it is vital to conduct a risk-benefit assessment prior to repeating TACE after failure, so that patients are not denied the use of available systemic therapeutic options due to declined performance status or organ function from these procedures. The optimal timing and the sequence of systemic and locoregional therapy must be carefully evaluated by a multidisciplinary team.

CASE CONCLUSION

An important part of evaluating a new patient with HCC is to determine whether they are a candidate for curative therapies, such as transplant or surgical resection. These are no longer an option for patients with intermediate disease. For patients with advanced disease characteristics, such as vascular invasion or systemic metastasis, the evidence supports using systemic therapy with sorafenib or lenvatinib. Lenvatinib, with a better tolerance profile and response rate, is the treatment of choice for the patient described in the case scenario. Lenvatinib is also indicated for first-line treatment of advanced HCC, and is useful in very aggressive tumors, such as those with an AFP level exceeding 200 ng/mL.

Future Directions

The emerging role of novel systemic therapeutics, including immunotherapy, has drastically changed the treatment landscape for hepatocellular cancers, with 6 new drugs for treating advanced hepatocellular cancers approved recently. While these systemic drugs have improved survival in advanced HCC in the past decade, patient selection and treatment sequencing remain a challenge, due to a lack of biomarkers capable of predicting antitumor responses. In addition, there is an unmet need for treatment options for patients with Child–Pugh class B7 and C liver disease and poor performance status.

The goal of future management should be to achieve personalized care aimed at improved safety and efficacy by targeting multiple cancer pathways in the HCC cascade with combination treatments. Randomized clinical trials to improve patient selection and determine the proper sequence of treatments are needed. Given the heterogeneity of HCC, molecular profiling of the tumor to differentiate responders from nonresponders may elucidate potential biomarkers to effectively guide treatment recommendations.

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424.

2. Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Reichman ME. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1485-1491.

3. Welzel TM, Graubard BI, Zeuzem S, et al. Metabolic syndrome increases the risk of primary liver cancer in the United States: a study in the SEER-Medicare database. Hepatology. 2011;54:463-471.

4. Schutte K, Schulz C, Poranzke J, et al. Characterization and prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the non-cirrhotic liver. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:117.

5. Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:329-338.

6. Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;391:1301-1314.

7. Schulze K, Imbeaud S, Letouzé E, et al. Exome sequencing of hepatocellular carcinomas identifies new mutational signatures and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Genet. 2015;47:505-511.

8. Thorgeirsson SS, Grisham JW. Molecular pathogenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2002;31:339-346.

9. Dhanasekaran R, Bandoh S, Roberts LR. Molecular pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma and impact of therapeutic advances. F1000Res. 2016;5.

10. Schulze K, Imbeaud S, Letouze E, et al. Exome sequencing of hepatocellular carcinomas identifies new mutational signatures and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Genet. 2015;47:505-511.

11. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Electronic address: [email protected]; Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive and integrative genomic characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. 2017;169:1327-1134.

12. Chae YK, Ranganath K, Hammerman PS, et al: Inhibition of the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) pathway: the current landscape and barriers to clinical application. Oncotarget. 2016;8:16052-16074.

13. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378-390.

14. Jackson R, Psarelli EE, Berhane S, et al. Impact of viral status on survival in patients receiving sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized phase III trials. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:622-628.

15. Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25-34.

16. Da Fonseca LG, Barroso-Sousa R, Bento AD, et al. Safety and efficacy of sorafenib in patients with Child-Pugh B advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3:793-796.

17. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1163-1173.

18. Bruix J, Tak W-Y, Gasbarrini A, et al. Regorafenib as second-line therapy for intermediate or advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Multicentre, open-label, phase II safety study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:3412-3419.

19. Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:56-66.

20. Bruix J, Merle P, Granito A, et al. Hand-foot skin reaction (HFSR) and overall survival (OS) in the phase 3 RESORCE trial of regorafenib for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) progressing on sorafenib. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:412-412.

21. Finn RS, Merle P, Granito A, et al. Outcomes of sequential treatment with sorafenib followed by regorafenib for HCC: Additional analyses from the phase III RESORCE trial. J Hepatol. 2018;69:353-358.

22. Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng A-L, et al. Cabozantinib (C) versus placebo (P) in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who have received prior sorafenib: Results from the randomized phase III CELESTIAL trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:207-207.

23. Zhu AX, Park JO, Ryoo B-Y, et al. Ramucirumab versus placebo as second-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma following first-line therapy with sorafenib (REACH): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncology. 2015;16:859-870.

24. Zhu AX, Kang Y-K, Yen C-J, et al. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased αfetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncology. 2019;20:282-296.

25. El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2492-2502.

26. Yau T, Park JW, Finn RS, et al. CheckMate 459: A randomized, multi-center phase III study of nivolumab (NIVO) vs sorafenib (SOR) as first-line (1L) treatment in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC). Ann Oncol. 2020;30:v874-v875.

27. Zhu AX, Finn RS, Cattan S, et al. KEYNOTE-224: Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:942-952.

28. Finn RS, Ryoo BY, Merle P, et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in KEYNOTE-240: a randomized, double-blind, phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:193-202.

29. Cheng A-L, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. IMbrave150: efficacy and safety results from a ph III study evaluating atezolizumab (atezo) + bevacizumab (bev) vs sorafenib (sor) as first treatment (tx) for patients (pts) with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Ann Oncol. 2019;30 (suppl_9):ix183-ix202.

30. Jiang Y, Han Q-J, Zhang J. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Mechanisms of progression and immunotherapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:3151-3167.

31. Xu F, Jin T, Zhu Y, et al. Immune checkpoint therapy in liver cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:110.

32. Koyama S, Akbay EA, Li YY, et al. Adaptive resistance to therapeutic PD-1 blockade is associated with upregulation of alternative immune checkpoints. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10501.

33. Prieto J, Melero I, Sangro B. Immunological landscape and immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:681-700.

34. Qin S, Bai Y, Lim HY, et al. Randomized, multicenter, open-label study of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil/leucovorin versus doxorubicin as palliative chemotherapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma from Asia. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3501-3508.

35. Louafi S, Boige V, Ducreux M, et al. Gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin (GEMOX) in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Cancer. 2007;109:1384-1390.

36. Tang A, Chan AT, Zee B, et al. A randomized phase iii study of doxorubicin versus cisplatin/interferon α-2b/doxorubicin/fluorouracil (PIAF) combination chemotherapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1532-1538.

37. Abou-Alfa GK, Niedzwieski D, Knox JJ, et al. Phase III randomized study of sorafenib plus doxorubicin versus sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): CALGB 80802 (Alliance). J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:192.

38. Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1734-1739.

39. Brown KT, Do RK, Gonen M, et al. randomized trial of hepatic artery embolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using doxorubicin-eluting microspheres compared with embolization with microspheres alone. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2046-2053.

40. Kirstein MM, Voigtlander T, Schweitzer N, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization versus sorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and extrahepatic disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:238-246.

41. Pinter M, Hucke F, Graziadei I, et al. Advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: transarterial chemoembolization versus sorafenib. Radiology. 2012;263:590-599.

42. Mason MC, Massarweh NN, Salami A, et al. Post-embolization syndrome as an early predictor of overall survival after transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2015;17:1137-1144.

43. Sangro B, Maini CL, Ettorre GM, et al. Radioembolisation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma that have previously received liver-directed therapies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45:1721-1730.

44. Vilgrain V, Pereira H, Assenat E, et al. Efficacy and safety of selective internal radiotherapy with yttrium-90 resin microspheres compared with sorafenib in locally advanced and inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma (SARAH): an open-label randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1624-1636.

45. Sergio A, Cristofori C, Cardin R, et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): the role of angiogenesis and invasiveness. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:914-921.

46. Kudo M, Imanaka K, Chida N, et al. Phase III study of sorafenib after transarterial chemoembolisation in Japanese and Korean patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2117-2127.

47. Lencioni R, Llovet JM, Han G, et al. Sorafenib or placebo plus TACE with doxorubicin-eluting beads for intermediate stage HCC: The SPACE trial. J Hepatol. 2016;64:1090-1098.

48. Geschwind JF, Chapiro J. Sorafenib in combination with transarterial chemoembolization for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2016;14:585-587.

49. Kudo M, Ueshima K, Ikeda M, et al. Randomized, open label, multicenter, phase II trial comparing transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) plus sorafenib with TACE alone in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): TACTICS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:206.

From the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Division of Hematology Oncology, Birmingham, AL, and the University of South Alabama, Division of Hematology Oncology, Mobile, AL. Dr. Paluri and Dr. Hatic contributed equally to this article.

Abstract

- Objective: To review systemic treatment options for patients with locally advanced unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: The paradigm of what constitutes first-line treatment for advanced HCC is shifting. Until recently, many patients with advanced HCC were treated with repeated locoregional therapies, such as transartertial embolization (TACE). However, retrospective studies suggest that continuing TACE after refractoriness or failure may not be beneficial and may delay subsequent treatments because of deterioration of liver function or declines in performance status. With recent approvals of several systemic therapy options, including immunotherapy, it is vital to conduct a risk-benefit assessment prior to repeating TACE after failure, so that patients are not denied the use of available systemic therapeutic options due to declined performance status or organ function from these procedures. The optimal timing and the sequence of systemic and locoregional therapy must be carefully evaluated by a multidisciplinary team.

- Conclusion: Randomized clinical trials to improve patient selection and determine the proper sequence of treatments are needed. Given the heterogeneity of HCC, molecular profiling of the tumor to differentiate responders from nonresponders may elucidate potential biomarkers to effectively guide treatment recommendations.

Keywords: liver cancer; molecular therapy; immunotherapy.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents 90% of primary liver malignancies. It is the fifth most common malignancy in males and the ninth most common in females worldwide.1 In contrast to other major cancers (colon, breast, prostate), the incidence of and mortality from HCC has increased over the past decade, following a brief decline between 1999 and 2004.2 The epidemiology and incidence of HCC is closely linked to chronic liver disease and conditions predisposing to liver cirrhosis. Worldwide, hepatitis B virus infection is the leading cause of liver cirrhosis and, hence, HCC. In the United States, 50% of HCC cases are linked to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Diabetes mellitus and alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are the other major etiologies of HCC. Indeed, the metabolic syndrome, independent of other factors, is associated with a 2-fold increase in the risk of HCC.3

Although most cases of HCC are predated by liver cirrhosis, in about 20% of patients HCC occurs without liver cirrhosis.4 Similar to other malignancies, surgery in the form of resection (for isolated lesions in the context of good liver function) or liver transplant (for low-volume disease with mildly impaired liver function) provides the best chance of a cure. Locoregional therapies involving hepatic artery–directed therapy are offered for patients with more advanced disease that is limited to the liver, while systemic therapy is offered for advanced unresectable disease that involves portal vein invasion, lymph nodes, and distant metastasis. The

Molecular Pathogenesis

Similar to other malignancies, a multistep process of carcinogenesis, with accumulation of genomic alterations at the molecular and cellular levels, is recognized in HCC. In about 80% of cases, repeated and chronic injury, inflammation, and repair lead to a distortion of normal liver architecture and development of cirrhotic nodules. Exome sequencing of HCC tissues has identified risk factor–specific mutational signatures, including those related to the tumor microenvironment, and defined the extensive landscape of altered genes and pathways in HCC (eg, angiogenic and MET pathways).7 In the Schulze et al study, the frequency of alterations that could be targeted by available Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved drugs comprised either amplifications or mutations of FLTs (6%), FGF3 or 4 or 19 (4%), PDGFRs (3%), VEGFA (1%), HGF (3%), MTOR (2%), EGFR (1%), FGFRs (1%), and MET (1%).7 Epigenetic modification of growth-factor expression, particularly insulin-like growth factor 2 and transforming growth factor alpha, and structural alterations that lead to loss of heterozygosity are early events that cause hepatocyte proliferation and progression of dysplastic nodules.8,9 Advances in whole-exome sequencing have identified TERT promoter mutations, leading to activation of telomerase, as an early event in HCC pathogenesis. Other commonly altered genes include CTNNB1 (B-Catenin) and TP53. As a group, alterations in the MAP kinase pathway genes occur in about 40% of HCC cases.

Actionable oncogenic driver alterations are not as common as tumor suppressor pathway alterations in HCC, making targeted drug development challenging.10,11 The FGFR (fibroblast growth factor receptor) pathway, which plays a critical role in carcinogenesis-related cell growth, survival, neo-angiogenesis, and acquired resistance to other cancer treatments, is being explored as a treatment target.12 The molecular characterization of HCC may help with identifying new biomarkers and present opportunities for developing therapeutic targets.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 61-year-old man with a history of chronic hepatitis C and hypertension presents to his primary care physician due to right upper quadrant pain. Laboratory evaluation shows transaminases elevated 2 times the upper limit of normal. This leads to an ultrasound and follow-up magnetic resonance imaging. Imaging shows diffuse cirrhotic changes, with a 6-cm, well-circumscribed lesion within the left lobe of the liver that shows rapid arterial enhancement with venous washout. These vascular characteristics are consistent with HCC. In addition, 2 satellite lesions in the left lobe and sonographic evidence of invasion into the portal vein are present. Periportal lymph nodes are pathologically enlarged.

The physical examination is unremarkable, except for mild tenderness over the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Serum bilirubin, albumin, platelets, and international normalized ratio are normal, and alpha fetoprotein (AFP) is elevated at 1769 ng/mL. The patient’s family history is unremarkable for any major illness or cancer. Computed tomography scan of the chest and pelvis shows no evidence of other lesions. His liver disease is classified as Child–Pugh A. Due to locally advanced presentation, the tumor is deemed to be nontransplantable and unresectable, and is staged as BCLC-C. The patient continues to work and his performance status is ECOG (

What systemic treatment would you recommend for this patient with locally advanced unresectable HCC with nodal metastasis?

First-Line Therapeutic Options

Systemic treatment of HCC is challenging because of the underlying liver cirrhosis and hepatic dysfunction present in most patients. Overall prognosis is therefore dependent on the disease biology and burden and on the degree of hepatic dysfunction. These factors must be considered in patients with advanced disease who present for systemic therapy. As such, patients with BCLC class D HCC with poor performance status and impaired liver function are better off with best supportive care and hospice services (Figure). Table 1 and Table 2 outline the landmark trials that led to the approval of agents for advanced HCC treatment.

Sorafenib

In the patient with BCLC class C HCC who has preserved liver function (traditionally based on a Child–Pugh score of ≤ 6 and a decent functional status [ECOG performance status 1-2]), sorafenib is the first FDA-approved first-line treatment. Sorafenib is a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) kinase signaling, in addition to many other tyrosine kinase pathways (including the platelet-derived growth factor and Raf-Ras pathways). Evidence for the clinical benefit of sorafenib comes from the SHARP trial.13 This was a multinational, but primarily European, randomized phase 3 study that compared sorafenib to best supportive care for advanced HCC in patients with a Child–Pugh score ≤ 6A and a robust performance status (ECOG 0 and 1). Overall survival (OS) with placebo and sorafenib was 7.9 months and 10.7 months, respectively. There was no difference in time to radiologic progression, and the progression-free survival (PFS) at 4 months was 62% with sorafenib and 42% with placebo. Patients with HCV-associated HCC appeared to derive a more substantial benefit from sorafenib.14 In a smaller randomized study of sorafenib in Asian patients with predominantly hepatitis B–associated HCC, OS in the sorafenib and best supportive care arms was lower than that reported in the SHARP study (6.5 months vs 4.2 months), although OS still was longer in the sorafenib group.15

Significant adverse events reported with sorafenib include fatigue (30%), hand and foot syndrome (30%), diarrhea (15%), and mucositis (10%). Major proportions of patients in the clinical setting have not tolerated the standard dose of 400 mg twice daily. Dose-adjusted administration of sorafenib has been advocated in patients with more impaired liver function (Child–Pugh class 7B) and bilirubin of 1.5 to 3 times the upper limit of normal, although it is unclear whether these patients are deriving any benefit from sorafenib.16 At this time, in a patient with preserved liver function, starting with 400 mg twice daily, followed by dose reduction based on toxicity, remains standard.

Lenvatinib

After multiple attempts to develop newer first-line treatments for HCC,

Second-Line Therapeutic Options

Following the sorafenib approval, clinical studies of several other agents did not meet their primary endpoint and failed to show improvement in clinical outcomes compared to sorafenib. However, over the past years the treatment landscape for advanced HCC has been changed with the approval of several agents in the second line. The overall response rate (ORR) has become the new theme for management of advanced disease. With multiple therapeutic options available, optimal sequencing now plays a critical role, especially for transitioning from locoregional to systemic therapy. Five drugs are now indicated for second-line treatment of patients who progressed on or were intolerant to sorafenib: regorafenib, cabozantinib, ramucirumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab.

Regorafenib

Regorafenib was evaluated in the advanced HCC setting in a single-arm, phase 2 trial involving 36 patients with Child–Pugh class A liver disease who had progressed on prior sorafenib.18 Patients received regorafenib 160 mg orally once daily for 3 weeks on/1 week off cycles. Disease control was achieved in 72% of patients, with stable disease in 25 patients (69%). Based on these results, regorafenib was further evaluated in the multicenter, phase 3, 2:1 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled RESORCE study, which enrolled 573 patients.19 Due to the overlapping safety profiles of sorafenib and regorafenib, the inclusion criteria required patients to have tolerated a sorafenib dose of at least 400 mg daily for 20 of the past 28 days of treatment prior to enrollment. The primary endpoint of the study, OS, was met (median OS of 10.6 months in regorafenib arm versus 7.8 months in placebo arm; hazard ratio [HR], 0.63; P < 0.0001).

Cabozantinib

CELESTIAL was a phase 3, double-blind study that assessed the efficacy of cabozantinib versus placebo in patients with advanced HCC who had received prior sorafenib.22 In this study, 707 patients with Child–Pugh class A liver disease who progressed on at least 1 prior systemic therapy were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to treatment with cabozantinib at 60 mg daily or placebo. Patients treated with cabozantinib had a longer OS (10.2 months vs 8.0 months), resulting in a 24% reduction in the risk of death (HR, 0.76), and a longer median PFS (5.2 months versus 1.9 months). The disease control rate was higher with cabozantinib (64% vs 33%) as well. The incidence of high‐grade adverse events in the cabozantinib group was twice that of the placebo group. Common adverse events reported with cabozantinib included HFSR (17%), hypertension (16%), increased aspartate aminotransferase (12%), fatigue (10%), and diarrhea (10%).

Ramucirumab

REACH was a phase 3 study exploring the efficacy of ramucirumab that did not meet its primary endpoint; however, the subgroup analysis in AFP-high patients showed an OS improvement with ramucirumab.23 This led to the phase 3 REACH-2 trial, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind biomarker study in patients with advanced HCC who either progressed on or were intolerant to sorafenib and had an AFP level ≥ 400 ng/mL.24 Patients were randomized to ramucirumab 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks or placebo. The study met its primary endpoint, showing improved OS (8.5 months vs 7.3 months; P = 0.0059). The most common treatment-related adverse events in the ramucirumab group were ascites (5%), hypertension (12%), asthenia (5%), malignant neoplasm progression (6%), increased aspartate aminotransferase concentration (5%), and thrombocytopenia.

Immunotherapy

HCC is considered an inflammation-induced cancer, which renders immunotherapeutic strategies more appealing. The PD-L1/PD-1 pathway is the critical immune checkpoint mechanism and is an important target for treatment. HCC uses a complex, overlapping set of mechanisms to evade cancer-specific immunity and to suppress the immune system. Initial efforts to develop immunotherapies for HCC focused on anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies. CheckMate 040 evaluated nivolumab in 262 sorafenib-naïve and -treated patients with advanced HCC (98% with Child–Pugh scores of 5 or 6), with a median follow-up of 12.9 months.25 In sorafenib-naïve patients (n = 80), the ORR was 23%, and the disease control rate was 63%. In sorafenib-treated patients (n = 182), the ORR was 18%. Response was not associated with PD-L1 expression. Durable objective responses, a manageable safety profile, and promising efficacy led the FDA to grant accelerated approval of nivolumab for the treatment of patients with HCC who have been previously treated with sorafenib. Based on this, the phase 3 randomized CheckMate-459 trial evaluated the efficacy of nivolumab versus sorafenib in the first-line. Median OS and ORR were better with nivolumab (16.4 months vs 14.7 months; HR 0.85; P = 0.752; and 15% [with 5 complete responses] vs 7%), as was the safety profile (22% vs 49% reporting grade 3 and 4 adverse events). 26

The KEYNOTE-224 study27 evaluated pembrolizumab in 104 patients with previously treated advanced HCC. This study showed an ORR of 17%, with 1 complete response and 17 partial responses. One-third of the patients had progressive disease, while 46 had stable disease. Among those who responded, 56% maintained a durable response for more than 1 year. Subsequently, in KEYNOTE 240, pembrolizumab showed an improvement in OS (13.9 months vs 10.6 months; HR, 0.78; P = 0.0238) and PFS (3.0 months versus 2.8 months; HR, 0.78; P = 0.0186) compared with placebo.28 The ORR for pembrolizumab was 16.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 12.7%-21.8%) versus 2.2% (95% CI, 0.5%-6.4%; P = 0.00001) for placebo. Mean duration of response was 13.8 months.

In the IMbrave150 trial, atezolizumab/bevacizumab combination, compared to sorafenib, had better OS (not estimable vs 13.2 months; P = 0.0006), PFS (6.8 months vs 4.5 months, P < 0.0001), and ORR (33% vs 13%, P < 0.0001), but grade 3-4 events were similar.29 This combination has potential for first-line approval. The COSMIC–312 study is comparing the combination of cabozantinib and atezolizumab to sorafenib monotherapy and cabozantinib monotherapy in advanced HCC.

Resistance to immunotherapy can be extrinsic, associated with activation mechanisms of T-cells, or intrinsic, related to immune recognition, gene expression, and cell-signaling pathways.30 Tumor-immune heterogeneity and antigen presentation contribute to complex resistance mechanisms.31,32 Although clinical outcomes have improved with immune checkpoint inhibitors, the response rate is low and responses are inconsistent, likely due to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.33 Therefore, several novel combinations of checkpoint inhibitors and targeted drugs are being evaluated to bypass some of the resistance mechanisms (Table 3).

Chemotherapy

Multiple combinations of cytotoxic regimens have been evaluated, but efficacy has been modest, suggesting the limited role for traditional chemotherapy in the systemic management of advanced HCC. Response rates to chemotherapy are low and responses are not durable. Gemcitabine- and doxorubicin-based treatment and FOLFOX (5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin) are some regimens that have been studied, with a median OS of less than 1 year for these regimens.34-36 FOLFOX had a higher response rate (8.15% vs 2.67%; P = 0.02) and longer median OS (6.40 months versus 4.97 months; HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.63-1.02; P = 0.07) than doxorubicin.34 With the gemcitabine/oxaliplatin combination, ORR was 18%, with stable disease in 58% of patients, and median PFS and OS were 6.3 months and 11.5 months, respectively.35 In a study that compared doxorubicin and PIAF (cisplatin/interferon a-2b/doxorubicin/5-fluorouracil), median OS was 6.83 months and 8.67 months, respectively (P = 0.83). The hazard ratio for death from any cause in the PIAF group compared with the doxorubicin group was 0.97 (95% CI, 0.71-1.32). PIAF had a higher ORR (20.9%; 95% CI, 12.5%-29.2%) than doxorubicin (10.5%; 95% CI, 3.9%-16.9%).

The phase 3 ALLIANCE study evaluated the combination of sorafenib and doxorubicin in treatment-naïve HCC patients with Child–Pugh class A liver disease, and did not demonstrate superiority with the addition of cytotoxic chemotherapy.37 Indeed, the combination of chemotherapy with sorafenib appears harmful in terms of lower OS (9.3 months vs 10.6 months; HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.8-1.4) and worse toxicity. Patients treated with the combination experienced more hematologic (37.8% vs 8.1%) and nonhematologic adverse events (63.6% vs 61.5%).

Locoregional Therapy

The role of locoregional therapy in advanced HCC remains the subject of intense debate. Patients with BCLC stage C HCC with metastatic disease and those with lymph node involvement are candidates for systemic therapy. The optimal candidate for locoregional therapy is the patient with localized intermediate-stage disease, particularly hepatic artery–delivered therapeutic interventions. However, the presence of a solitary large tumor or portal vein involvement constitutes gray areas regarding which therapy to deliver directly to the tumor via the hepatic artery, and increasingly stereotactic body radiation therapy is being offered.

Transarterial Chemoembolization

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), with or without chemotherapy, is the most widely adopted locoregional therapy in the management of HCC. TACE exploits the differential vascular supply to the HCC and normal liver parenchyma. Normal liver receives only one-fourth of its blood supply from the hepatic artery (three-fourths from the portal vein), whereas HCC is mainly supplied by the hepatic artery. A survival benefit for TACE compared to best supportive care is widely acknowledged for intermediate-stage HCC, and transarterial embolization (TAE) with gelatin sponge or microspheres is noninferior to TACE.38,39 Overall safety profile and efficacy inform therapy selection in advanced HCC, although the evidence for TACE in advanced HCC is less robust. Although single-institution experiences suggest survival numbers similar to and even superior to sorafenib,40,41 there is a scarcity of large randomized clinical trial data to back this up. Based on this, patients with advanced HCC should only be offered liver-directed therapy within a clinical trial or on a case-by-case basis under multidisciplinary tumor board consensus.

A serious adverse effect of TACE is post-embolization syndrome, which occurs in about 30% of patients and may be associated with poor prognosis.42 The syndrome consists of right upper quadrant abdominal pain, malaise, and worsening nausea/vomiting following the embolization procedure. Laboratory abnormalities and other complications may persist for up to 30 days after the procedure. This is a concern, because post-embolization syndrome may affect the ability to deliver systemic therapy.

Transarterial Radioembolization

In the past few years, there has been an uptick in the utilization of transarterial radioembolization (TARE), which instead of delivering glass beads, as done in TAE, or chemotherapy-infused beads, as done in TACE, delivers the radioisotope Y-90 to the tumor via the hepatic artery. TARE is able to administer larger doses of radiation to the tumor while avoiding normal liver tissue, as compared to external-beam radiation. There has been no head-to-head comparison of these different intra-arterial therapy approaches, but TARE with Y-90 has been shown to be safe in patients with portal vein thrombosis. A recent multicenter retrospective study of TARE demonstrated a median OS of 8.8 to 10.8 months in patients with BCLC C HCC,43 and in a large randomized study of Y-90 compared to sorafenib in advanced and previously treated intermediate HCC, there was no difference in median OS between the treatment modalities (8 months for selective internal radiotherapy, 9 months for sorafenib; P = 0.18). Treatment with Y-90 was better tolerated.44 A major impediment to the adoption of TARE is the time it takes to order, plan, and deliver Y-90 to patients. Radio-embolization-induced liver disease, similar to post-embolization syndrome, is characterized by jaundice and ascites, which may occur 4 to 8 weeks postprocedure and is more common in patients with HCC who do not have cirrhosis. Compared to TACE, TARE may offer a better adverse effect profile, with improvement in quality of life.

Combination of Systemic and Locoregional Therapy

Even in carefully selected patients with intermediate- and advanced-stage HCC, locoregional therapy is not curative. Tumor embolization may promote more angiogenesis, and hence tumor progression, by causing hypoxia and upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor.45 This upregulation of angiogenesis as a resistance mechanism to tumor embolization provides a rationale for combining systemic therapy (typically based on abrogating angiogenesis) with TACE/TAE. Most of the experience has been with sorafenib in intermediate-stage disease, and the results have been disappointing. The administration of sorafenib after at least a partial response with TACE did not provide additional benefit in terms of time to progression.46 Similarly, in the SPACE trial, concurrent therapy with TACE-doxorubicin-eluting beads and sorafenib compared to TACE-doxorubicin-eluting beads and placebo yielded similar time to progression numbers for both treatment modalities.47 While the data have been disappointing in intermediate-stage disease, as described earlier, registry data suggest that patients with advanced-stage disease may benefit from this approach.48

In the phase 2 TACTICS trial, 156 patients with unresectable HCC were randomized to receive TACE alone or sorafenib plus TACE, with a novel endpoint, time to untreatable progression (TTUP) and/or progression to TACE refractoriness.49 Treatment with sorafenib following TACE was continued until TTUP, decline in liver function to Child–Pugh class C, or the development of vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread. Development of new lesions while on sorafenib was not considered as progressive disease as long as the lesions were amenable to TACE. In this study, PFS was longer with sorafenib-TACE compared to TACE alone (26.7 months vs 20.6 months; P = 0.02). However, the TTUP endpoint needs further validation, and we are still awaiting the survival outcomes of this study. At this time, there are insufficient data to recommend the combination of liver-directed locoregional therapy and sorafenib or other systemic therapy options outside of a clinical trial setting.

Current Treatment Approach for Advanced HCC (BCLC-C)

Although progress is being made in the development of effective therapies, advanced HCC is generally incurable. These patients experience significant symptom burden throughout the course of the disease. Therefore, the optimal treatment plan must focus on improving or maintaining quality of life, in addition to overall efficacy. It is important to actively involve patients in treatment decisions for an individualized treatment plan, and to discuss the best strategy for incorporating current advances in targeted and immunotherapies. The paradigm of what constitutes first-line treatment for advanced HCC is shifting due to the recent systemic therapy approvals. Prior to the availability of these therapies, many patients with advanced HCC were treated with repeated locoregional therapies. For instance, TACE was often used to treat unresectable HCC multiple times beyond progression. There was no consensus on the definition of TACE failure, and hence it was used in broader, unselected populations. Retrospective studies suggest that continuing TACE after refractoriness or failure may not be beneficial, and may delay subsequent treatments because of deterioration of liver function or declines in performance status. With recent approvals of several systemic therapy options, including immunotherapy, it is vital to conduct a risk-benefit assessment prior to repeating TACE after failure, so that patients are not denied the use of available systemic therapeutic options due to declined performance status or organ function from these procedures. The optimal timing and the sequence of systemic and locoregional therapy must be carefully evaluated by a multidisciplinary team.

CASE CONCLUSION

An important part of evaluating a new patient with HCC is to determine whether they are a candidate for curative therapies, such as transplant or surgical resection. These are no longer an option for patients with intermediate disease. For patients with advanced disease characteristics, such as vascular invasion or systemic metastasis, the evidence supports using systemic therapy with sorafenib or lenvatinib. Lenvatinib, with a better tolerance profile and response rate, is the treatment of choice for the patient described in the case scenario. Lenvatinib is also indicated for first-line treatment of advanced HCC, and is useful in very aggressive tumors, such as those with an AFP level exceeding 200 ng/mL.

Future Directions

The emerging role of novel systemic therapeutics, including immunotherapy, has drastically changed the treatment landscape for hepatocellular cancers, with 6 new drugs for treating advanced hepatocellular cancers approved recently. While these systemic drugs have improved survival in advanced HCC in the past decade, patient selection and treatment sequencing remain a challenge, due to a lack of biomarkers capable of predicting antitumor responses. In addition, there is an unmet need for treatment options for patients with Child–Pugh class B7 and C liver disease and poor performance status.

The goal of future management should be to achieve personalized care aimed at improved safety and efficacy by targeting multiple cancer pathways in the HCC cascade with combination treatments. Randomized clinical trials to improve patient selection and determine the proper sequence of treatments are needed. Given the heterogeneity of HCC, molecular profiling of the tumor to differentiate responders from nonresponders may elucidate potential biomarkers to effectively guide treatment recommendations.

From the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Division of Hematology Oncology, Birmingham, AL, and the University of South Alabama, Division of Hematology Oncology, Mobile, AL. Dr. Paluri and Dr. Hatic contributed equally to this article.

Abstract

- Objective: To review systemic treatment options for patients with locally advanced unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: The paradigm of what constitutes first-line treatment for advanced HCC is shifting. Until recently, many patients with advanced HCC were treated with repeated locoregional therapies, such as transartertial embolization (TACE). However, retrospective studies suggest that continuing TACE after refractoriness or failure may not be beneficial and may delay subsequent treatments because of deterioration of liver function or declines in performance status. With recent approvals of several systemic therapy options, including immunotherapy, it is vital to conduct a risk-benefit assessment prior to repeating TACE after failure, so that patients are not denied the use of available systemic therapeutic options due to declined performance status or organ function from these procedures. The optimal timing and the sequence of systemic and locoregional therapy must be carefully evaluated by a multidisciplinary team.

- Conclusion: Randomized clinical trials to improve patient selection and determine the proper sequence of treatments are needed. Given the heterogeneity of HCC, molecular profiling of the tumor to differentiate responders from nonresponders may elucidate potential biomarkers to effectively guide treatment recommendations.

Keywords: liver cancer; molecular therapy; immunotherapy.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents 90% of primary liver malignancies. It is the fifth most common malignancy in males and the ninth most common in females worldwide.1 In contrast to other major cancers (colon, breast, prostate), the incidence of and mortality from HCC has increased over the past decade, following a brief decline between 1999 and 2004.2 The epidemiology and incidence of HCC is closely linked to chronic liver disease and conditions predisposing to liver cirrhosis. Worldwide, hepatitis B virus infection is the leading cause of liver cirrhosis and, hence, HCC. In the United States, 50% of HCC cases are linked to hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Diabetes mellitus and alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are the other major etiologies of HCC. Indeed, the metabolic syndrome, independent of other factors, is associated with a 2-fold increase in the risk of HCC.3

Although most cases of HCC are predated by liver cirrhosis, in about 20% of patients HCC occurs without liver cirrhosis.4 Similar to other malignancies, surgery in the form of resection (for isolated lesions in the context of good liver function) or liver transplant (for low-volume disease with mildly impaired liver function) provides the best chance of a cure. Locoregional therapies involving hepatic artery–directed therapy are offered for patients with more advanced disease that is limited to the liver, while systemic therapy is offered for advanced unresectable disease that involves portal vein invasion, lymph nodes, and distant metastasis. The

Molecular Pathogenesis

Similar to other malignancies, a multistep process of carcinogenesis, with accumulation of genomic alterations at the molecular and cellular levels, is recognized in HCC. In about 80% of cases, repeated and chronic injury, inflammation, and repair lead to a distortion of normal liver architecture and development of cirrhotic nodules. Exome sequencing of HCC tissues has identified risk factor–specific mutational signatures, including those related to the tumor microenvironment, and defined the extensive landscape of altered genes and pathways in HCC (eg, angiogenic and MET pathways).7 In the Schulze et al study, the frequency of alterations that could be targeted by available Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved drugs comprised either amplifications or mutations of FLTs (6%), FGF3 or 4 or 19 (4%), PDGFRs (3%), VEGFA (1%), HGF (3%), MTOR (2%), EGFR (1%), FGFRs (1%), and MET (1%).7 Epigenetic modification of growth-factor expression, particularly insulin-like growth factor 2 and transforming growth factor alpha, and structural alterations that lead to loss of heterozygosity are early events that cause hepatocyte proliferation and progression of dysplastic nodules.8,9 Advances in whole-exome sequencing have identified TERT promoter mutations, leading to activation of telomerase, as an early event in HCC pathogenesis. Other commonly altered genes include CTNNB1 (B-Catenin) and TP53. As a group, alterations in the MAP kinase pathway genes occur in about 40% of HCC cases.

Actionable oncogenic driver alterations are not as common as tumor suppressor pathway alterations in HCC, making targeted drug development challenging.10,11 The FGFR (fibroblast growth factor receptor) pathway, which plays a critical role in carcinogenesis-related cell growth, survival, neo-angiogenesis, and acquired resistance to other cancer treatments, is being explored as a treatment target.12 The molecular characterization of HCC may help with identifying new biomarkers and present opportunities for developing therapeutic targets.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 61-year-old man with a history of chronic hepatitis C and hypertension presents to his primary care physician due to right upper quadrant pain. Laboratory evaluation shows transaminases elevated 2 times the upper limit of normal. This leads to an ultrasound and follow-up magnetic resonance imaging. Imaging shows diffuse cirrhotic changes, with a 6-cm, well-circumscribed lesion within the left lobe of the liver that shows rapid arterial enhancement with venous washout. These vascular characteristics are consistent with HCC. In addition, 2 satellite lesions in the left lobe and sonographic evidence of invasion into the portal vein are present. Periportal lymph nodes are pathologically enlarged.

The physical examination is unremarkable, except for mild tenderness over the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Serum bilirubin, albumin, platelets, and international normalized ratio are normal, and alpha fetoprotein (AFP) is elevated at 1769 ng/mL. The patient’s family history is unremarkable for any major illness or cancer. Computed tomography scan of the chest and pelvis shows no evidence of other lesions. His liver disease is classified as Child–Pugh A. Due to locally advanced presentation, the tumor is deemed to be nontransplantable and unresectable, and is staged as BCLC-C. The patient continues to work and his performance status is ECOG (

What systemic treatment would you recommend for this patient with locally advanced unresectable HCC with nodal metastasis?

First-Line Therapeutic Options

Systemic treatment of HCC is challenging because of the underlying liver cirrhosis and hepatic dysfunction present in most patients. Overall prognosis is therefore dependent on the disease biology and burden and on the degree of hepatic dysfunction. These factors must be considered in patients with advanced disease who present for systemic therapy. As such, patients with BCLC class D HCC with poor performance status and impaired liver function are better off with best supportive care and hospice services (Figure). Table 1 and Table 2 outline the landmark trials that led to the approval of agents for advanced HCC treatment.

Sorafenib

In the patient with BCLC class C HCC who has preserved liver function (traditionally based on a Child–Pugh score of ≤ 6 and a decent functional status [ECOG performance status 1-2]), sorafenib is the first FDA-approved first-line treatment. Sorafenib is a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) kinase signaling, in addition to many other tyrosine kinase pathways (including the platelet-derived growth factor and Raf-Ras pathways). Evidence for the clinical benefit of sorafenib comes from the SHARP trial.13 This was a multinational, but primarily European, randomized phase 3 study that compared sorafenib to best supportive care for advanced HCC in patients with a Child–Pugh score ≤ 6A and a robust performance status (ECOG 0 and 1). Overall survival (OS) with placebo and sorafenib was 7.9 months and 10.7 months, respectively. There was no difference in time to radiologic progression, and the progression-free survival (PFS) at 4 months was 62% with sorafenib and 42% with placebo. Patients with HCV-associated HCC appeared to derive a more substantial benefit from sorafenib.14 In a smaller randomized study of sorafenib in Asian patients with predominantly hepatitis B–associated HCC, OS in the sorafenib and best supportive care arms was lower than that reported in the SHARP study (6.5 months vs 4.2 months), although OS still was longer in the sorafenib group.15

Significant adverse events reported with sorafenib include fatigue (30%), hand and foot syndrome (30%), diarrhea (15%), and mucositis (10%). Major proportions of patients in the clinical setting have not tolerated the standard dose of 400 mg twice daily. Dose-adjusted administration of sorafenib has been advocated in patients with more impaired liver function (Child–Pugh class 7B) and bilirubin of 1.5 to 3 times the upper limit of normal, although it is unclear whether these patients are deriving any benefit from sorafenib.16 At this time, in a patient with preserved liver function, starting with 400 mg twice daily, followed by dose reduction based on toxicity, remains standard.

Lenvatinib

After multiple attempts to develop newer first-line treatments for HCC,

Second-Line Therapeutic Options

Following the sorafenib approval, clinical studies of several other agents did not meet their primary endpoint and failed to show improvement in clinical outcomes compared to sorafenib. However, over the past years the treatment landscape for advanced HCC has been changed with the approval of several agents in the second line. The overall response rate (ORR) has become the new theme for management of advanced disease. With multiple therapeutic options available, optimal sequencing now plays a critical role, especially for transitioning from locoregional to systemic therapy. Five drugs are now indicated for second-line treatment of patients who progressed on or were intolerant to sorafenib: regorafenib, cabozantinib, ramucirumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab.

Regorafenib

Regorafenib was evaluated in the advanced HCC setting in a single-arm, phase 2 trial involving 36 patients with Child–Pugh class A liver disease who had progressed on prior sorafenib.18 Patients received regorafenib 160 mg orally once daily for 3 weeks on/1 week off cycles. Disease control was achieved in 72% of patients, with stable disease in 25 patients (69%). Based on these results, regorafenib was further evaluated in the multicenter, phase 3, 2:1 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled RESORCE study, which enrolled 573 patients.19 Due to the overlapping safety profiles of sorafenib and regorafenib, the inclusion criteria required patients to have tolerated a sorafenib dose of at least 400 mg daily for 20 of the past 28 days of treatment prior to enrollment. The primary endpoint of the study, OS, was met (median OS of 10.6 months in regorafenib arm versus 7.8 months in placebo arm; hazard ratio [HR], 0.63; P < 0.0001).

Cabozantinib

CELESTIAL was a phase 3, double-blind study that assessed the efficacy of cabozantinib versus placebo in patients with advanced HCC who had received prior sorafenib.22 In this study, 707 patients with Child–Pugh class A liver disease who progressed on at least 1 prior systemic therapy were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to treatment with cabozantinib at 60 mg daily or placebo. Patients treated with cabozantinib had a longer OS (10.2 months vs 8.0 months), resulting in a 24% reduction in the risk of death (HR, 0.76), and a longer median PFS (5.2 months versus 1.9 months). The disease control rate was higher with cabozantinib (64% vs 33%) as well. The incidence of high‐grade adverse events in the cabozantinib group was twice that of the placebo group. Common adverse events reported with cabozantinib included HFSR (17%), hypertension (16%), increased aspartate aminotransferase (12%), fatigue (10%), and diarrhea (10%).

Ramucirumab