User login

Proposed Medicare bill would raise docs’ pay with inflation

Introduced by four physician U.S. House representatives, HR 2474 would link Medicare fee schedule updates to the Medicare Economic Index, a measure of inflation related to physicians’ practice costs and wages.

That’s a long-sought goal of the American Medical Association, which is leading 120 state medical societies and medical specialty groups in championing the bill.

The legislation is essential to enabling physician practices to better absorb payment distributions triggered by budget neutrality rules, performance adjustments, and periods of high inflation, the groups wrote in a joint letter sent to the bill’s sponsors. The sponsors say they hope the legislation will improve access to care, as low reimbursements cause some physicians to limit their number of Medicare patients.

Physicians groups for years have urged federal lawmakers to scrap short-term fixes staving off Medicare pay cuts in favor of permanent reforms. Unlike nearly all other Medicare clinicians including hospitals, physicians’ Medicare payment updates aren’t currently tied to inflation.

Adjusted for inflation, Medicare payments to physicians have declined 26% between 2001 and 2023, including a 2% payment reduction in 2023, according to the AMA. Small and rural physician practices have been disproportionately affected by these reductions, as have doctors treating low-income or uninsured patients, the AMA said.

Last month, an influential federal advisory panel recommended permanently tying Medicare physician pay increases to inflation. Clinicians’ cost of providing services, measured by the Medicare Economic Index, rose by 2.6% in 2021 and are estimated to have risen 4.7% in 2022, significantly more than in recent years, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Introduced by four physician U.S. House representatives, HR 2474 would link Medicare fee schedule updates to the Medicare Economic Index, a measure of inflation related to physicians’ practice costs and wages.

That’s a long-sought goal of the American Medical Association, which is leading 120 state medical societies and medical specialty groups in championing the bill.

The legislation is essential to enabling physician practices to better absorb payment distributions triggered by budget neutrality rules, performance adjustments, and periods of high inflation, the groups wrote in a joint letter sent to the bill’s sponsors. The sponsors say they hope the legislation will improve access to care, as low reimbursements cause some physicians to limit their number of Medicare patients.

Physicians groups for years have urged federal lawmakers to scrap short-term fixes staving off Medicare pay cuts in favor of permanent reforms. Unlike nearly all other Medicare clinicians including hospitals, physicians’ Medicare payment updates aren’t currently tied to inflation.

Adjusted for inflation, Medicare payments to physicians have declined 26% between 2001 and 2023, including a 2% payment reduction in 2023, according to the AMA. Small and rural physician practices have been disproportionately affected by these reductions, as have doctors treating low-income or uninsured patients, the AMA said.

Last month, an influential federal advisory panel recommended permanently tying Medicare physician pay increases to inflation. Clinicians’ cost of providing services, measured by the Medicare Economic Index, rose by 2.6% in 2021 and are estimated to have risen 4.7% in 2022, significantly more than in recent years, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Introduced by four physician U.S. House representatives, HR 2474 would link Medicare fee schedule updates to the Medicare Economic Index, a measure of inflation related to physicians’ practice costs and wages.

That’s a long-sought goal of the American Medical Association, which is leading 120 state medical societies and medical specialty groups in championing the bill.

The legislation is essential to enabling physician practices to better absorb payment distributions triggered by budget neutrality rules, performance adjustments, and periods of high inflation, the groups wrote in a joint letter sent to the bill’s sponsors. The sponsors say they hope the legislation will improve access to care, as low reimbursements cause some physicians to limit their number of Medicare patients.

Physicians groups for years have urged federal lawmakers to scrap short-term fixes staving off Medicare pay cuts in favor of permanent reforms. Unlike nearly all other Medicare clinicians including hospitals, physicians’ Medicare payment updates aren’t currently tied to inflation.

Adjusted for inflation, Medicare payments to physicians have declined 26% between 2001 and 2023, including a 2% payment reduction in 2023, according to the AMA. Small and rural physician practices have been disproportionately affected by these reductions, as have doctors treating low-income or uninsured patients, the AMA said.

Last month, an influential federal advisory panel recommended permanently tying Medicare physician pay increases to inflation. Clinicians’ cost of providing services, measured by the Medicare Economic Index, rose by 2.6% in 2021 and are estimated to have risen 4.7% in 2022, significantly more than in recent years, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Medicare expands CGM coverage to more with type 2 diabetes

Medicare is now covering continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) for all beneficiaries with diabetes who use insulin, as well as those with a “history of problematic hypoglycemia.”

The new policy decision, announced earlier this year by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, means that coverage is expanded to those who take even just a single dose of basal insulin daily or who don’t take insulin but who for other reasons experience “problematic” hypoglycemia, defined as a history of more than one level 2 event (glucose < 54 mg/dL) or at least one level 3 event (< 54 mg/dL requiring assistance).

Previously, coverage was limited to those taking frequent daily insulin doses.

The additional number of people covered, most with type 2 diabetes, is estimated to be at least 1.5 million. That number could more than double if private insurers follow suit, reported an industry analyst.

Chuck Henderson, chief executive officer of the American Diabetes Association, said in a statement: “We applaud CMS’ decision allowing for all insulin-dependent people as well as others who have a history of problematic hypoglycemia to have access to a continuous glucose monitor, a potentially life-saving tool for diabetes management.”

According to Dexcom, which manufacturers the G6 and the recently approved G7 CGMs, the decision was based in part on their MOBILE study. The trial demonstrated the benefit of CGM in people with type 2 diabetes who use only basal insulin or have a history of problematic hypoglycemic events.

On April 14, Abbott, which manufactures the Freestyle Libre 2 and the recently approved Libre 3, received clearance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the Libre 3’s stand-alone reader device. Previously, the Libre 3 had been approved for use only with a smartphone app. The small handheld reader is considered durable medical equipment, making it eligible for Medicare coverage. Abbott is “working on having the FreeStyle Libre 3 system available to Medicare beneficiaries,” the company said in a statement.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medicare is now covering continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) for all beneficiaries with diabetes who use insulin, as well as those with a “history of problematic hypoglycemia.”

The new policy decision, announced earlier this year by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, means that coverage is expanded to those who take even just a single dose of basal insulin daily or who don’t take insulin but who for other reasons experience “problematic” hypoglycemia, defined as a history of more than one level 2 event (glucose < 54 mg/dL) or at least one level 3 event (< 54 mg/dL requiring assistance).

Previously, coverage was limited to those taking frequent daily insulin doses.

The additional number of people covered, most with type 2 diabetes, is estimated to be at least 1.5 million. That number could more than double if private insurers follow suit, reported an industry analyst.

Chuck Henderson, chief executive officer of the American Diabetes Association, said in a statement: “We applaud CMS’ decision allowing for all insulin-dependent people as well as others who have a history of problematic hypoglycemia to have access to a continuous glucose monitor, a potentially life-saving tool for diabetes management.”

According to Dexcom, which manufacturers the G6 and the recently approved G7 CGMs, the decision was based in part on their MOBILE study. The trial demonstrated the benefit of CGM in people with type 2 diabetes who use only basal insulin or have a history of problematic hypoglycemic events.

On April 14, Abbott, which manufactures the Freestyle Libre 2 and the recently approved Libre 3, received clearance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the Libre 3’s stand-alone reader device. Previously, the Libre 3 had been approved for use only with a smartphone app. The small handheld reader is considered durable medical equipment, making it eligible for Medicare coverage. Abbott is “working on having the FreeStyle Libre 3 system available to Medicare beneficiaries,” the company said in a statement.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medicare is now covering continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) for all beneficiaries with diabetes who use insulin, as well as those with a “history of problematic hypoglycemia.”

The new policy decision, announced earlier this year by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, means that coverage is expanded to those who take even just a single dose of basal insulin daily or who don’t take insulin but who for other reasons experience “problematic” hypoglycemia, defined as a history of more than one level 2 event (glucose < 54 mg/dL) or at least one level 3 event (< 54 mg/dL requiring assistance).

Previously, coverage was limited to those taking frequent daily insulin doses.

The additional number of people covered, most with type 2 diabetes, is estimated to be at least 1.5 million. That number could more than double if private insurers follow suit, reported an industry analyst.

Chuck Henderson, chief executive officer of the American Diabetes Association, said in a statement: “We applaud CMS’ decision allowing for all insulin-dependent people as well as others who have a history of problematic hypoglycemia to have access to a continuous glucose monitor, a potentially life-saving tool for diabetes management.”

According to Dexcom, which manufacturers the G6 and the recently approved G7 CGMs, the decision was based in part on their MOBILE study. The trial demonstrated the benefit of CGM in people with type 2 diabetes who use only basal insulin or have a history of problematic hypoglycemic events.

On April 14, Abbott, which manufactures the Freestyle Libre 2 and the recently approved Libre 3, received clearance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the Libre 3’s stand-alone reader device. Previously, the Libre 3 had been approved for use only with a smartphone app. The small handheld reader is considered durable medical equipment, making it eligible for Medicare coverage. Abbott is “working on having the FreeStyle Libre 3 system available to Medicare beneficiaries,” the company said in a statement.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Single bivalent COVID booster is enough for now: CDC

“If you have completed your updated booster dose, you are currently up to date. There is not a recommendation to get another updated booster dose,” the CDC website now explains.

In January, the nation’s expert COVID panel recommended that the United States move toward an annual COVID booster shot in the fall, similar to the annual flu shot, that targets the most widely circulating strains of the virus. Recent studies have shown that booster strength wanes after a few months, spurring discussions of whether people at high risk of getting a severe case of COVID may need more than one annual shot.

September was the last time a new booster dose was recommended, when, at the time, the bivalent booster was released, offering new protection against Omicron variants of the virus. Health officials’ focus is now shifting from preventing infections to reducing the likelihood of severe ones, the San Francisco Chronicle reported.

“The bottom line is that there is some waning of protection for those who got boosters more than six months ago and haven’t had an intervening infection,” said Bob Wachter, MD, head of the University of California–San Francisco’s department of medicine, according to the Chronicle. “But the level of protection versus severe infection continues to be fairly high, good enough that people who aren’t at super high risk are probably fine waiting until a new booster comes out in the fall.”

The Wall Street Journal reported recently that many people have been asking their doctors to give them another booster, which is not authorized by the Food and Drug Administration.

About 8 in 10 people in the United States got the initial set of COVID-19 vaccines, which were first approved in August 2021. But just 16.4% of people in the United States have gotten the latest booster that was released in September, CDC data show.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

“If you have completed your updated booster dose, you are currently up to date. There is not a recommendation to get another updated booster dose,” the CDC website now explains.

In January, the nation’s expert COVID panel recommended that the United States move toward an annual COVID booster shot in the fall, similar to the annual flu shot, that targets the most widely circulating strains of the virus. Recent studies have shown that booster strength wanes after a few months, spurring discussions of whether people at high risk of getting a severe case of COVID may need more than one annual shot.

September was the last time a new booster dose was recommended, when, at the time, the bivalent booster was released, offering new protection against Omicron variants of the virus. Health officials’ focus is now shifting from preventing infections to reducing the likelihood of severe ones, the San Francisco Chronicle reported.

“The bottom line is that there is some waning of protection for those who got boosters more than six months ago and haven’t had an intervening infection,” said Bob Wachter, MD, head of the University of California–San Francisco’s department of medicine, according to the Chronicle. “But the level of protection versus severe infection continues to be fairly high, good enough that people who aren’t at super high risk are probably fine waiting until a new booster comes out in the fall.”

The Wall Street Journal reported recently that many people have been asking their doctors to give them another booster, which is not authorized by the Food and Drug Administration.

About 8 in 10 people in the United States got the initial set of COVID-19 vaccines, which were first approved in August 2021. But just 16.4% of people in the United States have gotten the latest booster that was released in September, CDC data show.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

“If you have completed your updated booster dose, you are currently up to date. There is not a recommendation to get another updated booster dose,” the CDC website now explains.

In January, the nation’s expert COVID panel recommended that the United States move toward an annual COVID booster shot in the fall, similar to the annual flu shot, that targets the most widely circulating strains of the virus. Recent studies have shown that booster strength wanes after a few months, spurring discussions of whether people at high risk of getting a severe case of COVID may need more than one annual shot.

September was the last time a new booster dose was recommended, when, at the time, the bivalent booster was released, offering new protection against Omicron variants of the virus. Health officials’ focus is now shifting from preventing infections to reducing the likelihood of severe ones, the San Francisco Chronicle reported.

“The bottom line is that there is some waning of protection for those who got boosters more than six months ago and haven’t had an intervening infection,” said Bob Wachter, MD, head of the University of California–San Francisco’s department of medicine, according to the Chronicle. “But the level of protection versus severe infection continues to be fairly high, good enough that people who aren’t at super high risk are probably fine waiting until a new booster comes out in the fall.”

The Wall Street Journal reported recently that many people have been asking their doctors to give them another booster, which is not authorized by the Food and Drug Administration.

About 8 in 10 people in the United States got the initial set of COVID-19 vaccines, which were first approved in August 2021. But just 16.4% of people in the United States have gotten the latest booster that was released in September, CDC data show.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

Kickback Scheme Nets Prison Time for Philadelphia VAMC Service Chief

A former manager at the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) has been sentenced to 6 months in federal prison for his part in a bribery scheme.

Ralph Johnson was convicted of accepting $30,000 in kickbacks and bribes for steering contracts to Earron and Carlicha Starks, who ran Ekno Medical Supply and Collondale Medical Supply from 2009 to 2019. Johnson served as chief of environmental services at the medical center. He admitted to receiving cash in binders and packages mailed to his home between 2018 and 2019.

The Starkses pleaded guilty first to paying kickbacks on $7 million worth of contracts to Florida VA facilities, then participated in a sting that implicated Johnson.

The VA Office of Inspector General began investigating Johnson in 2018 after the Starkses, who were indicted for bribing staff at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals in Miami and West Palm Beach, Florida, said they also paid officials in VA facilities on the East Coast.

According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, the judge credited Johnson’s past military service and his “extensive cooperation” with federal authorities investigating fraud within the VA. Johnson apologized to his former employers: “Throughout these 2 and a half years [since the arrest] there’s not a day I don’t think about the wrongness that I did.”

In addition to the prison sentence, Johnson has been ordered to pay back, at $50 a month, the $440,000-plus he cost the Philadelphia VAMC in fraudulent and bloated contracts.

Johnson is at least the third Philadelphia VAMC employee indicted or sentenced for fraud since 2020.

A former manager at the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) has been sentenced to 6 months in federal prison for his part in a bribery scheme.

Ralph Johnson was convicted of accepting $30,000 in kickbacks and bribes for steering contracts to Earron and Carlicha Starks, who ran Ekno Medical Supply and Collondale Medical Supply from 2009 to 2019. Johnson served as chief of environmental services at the medical center. He admitted to receiving cash in binders and packages mailed to his home between 2018 and 2019.

The Starkses pleaded guilty first to paying kickbacks on $7 million worth of contracts to Florida VA facilities, then participated in a sting that implicated Johnson.

The VA Office of Inspector General began investigating Johnson in 2018 after the Starkses, who were indicted for bribing staff at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals in Miami and West Palm Beach, Florida, said they also paid officials in VA facilities on the East Coast.

According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, the judge credited Johnson’s past military service and his “extensive cooperation” with federal authorities investigating fraud within the VA. Johnson apologized to his former employers: “Throughout these 2 and a half years [since the arrest] there’s not a day I don’t think about the wrongness that I did.”

In addition to the prison sentence, Johnson has been ordered to pay back, at $50 a month, the $440,000-plus he cost the Philadelphia VAMC in fraudulent and bloated contracts.

Johnson is at least the third Philadelphia VAMC employee indicted or sentenced for fraud since 2020.

A former manager at the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) has been sentenced to 6 months in federal prison for his part in a bribery scheme.

Ralph Johnson was convicted of accepting $30,000 in kickbacks and bribes for steering contracts to Earron and Carlicha Starks, who ran Ekno Medical Supply and Collondale Medical Supply from 2009 to 2019. Johnson served as chief of environmental services at the medical center. He admitted to receiving cash in binders and packages mailed to his home between 2018 and 2019.

The Starkses pleaded guilty first to paying kickbacks on $7 million worth of contracts to Florida VA facilities, then participated in a sting that implicated Johnson.

The VA Office of Inspector General began investigating Johnson in 2018 after the Starkses, who were indicted for bribing staff at US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals in Miami and West Palm Beach, Florida, said they also paid officials in VA facilities on the East Coast.

According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, the judge credited Johnson’s past military service and his “extensive cooperation” with federal authorities investigating fraud within the VA. Johnson apologized to his former employers: “Throughout these 2 and a half years [since the arrest] there’s not a day I don’t think about the wrongness that I did.”

In addition to the prison sentence, Johnson has been ordered to pay back, at $50 a month, the $440,000-plus he cost the Philadelphia VAMC in fraudulent and bloated contracts.

Johnson is at least the third Philadelphia VAMC employee indicted or sentenced for fraud since 2020.

Frustration over iPLEDGE evident at FDA meeting

During 2 days of after the chaotic rollout of the new REMS platform at the end of 2021.

On March 29, at the end of the FDA’s joint meeting of two advisory committees that addressed ways to improve the iPLEDGE program, most panelists voted to change the 19-day lockout period for patients who can become pregnant, and the requirement that every month, providers must document counseling of those who cannot get pregnant and are taking the drug for acne.

However, there was no consensus on whether there should be a lockout at all or for how long, and what an appropriate interval for counseling those who cannot get pregnant would be, if not monthly. Those voting on the questions repeatedly cited a lack of data to make well-informed decisions.

The meeting of the two panels, the FDA’s Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee and the Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee, was held March 28-29, to discuss proposed changes to iPLEDGE requirements, to minimize the program’s burden on patients, prescribers, and pharmacies – while maintaining safe use of the highly teratogenic drug.

Lockout based on outdated reasoning

John S. Barbieri, MD, a dermatologist and epidemiologist, and director of the Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, speaking as deputy chair of the American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA) iPLEDGE work group, described the burden of getting the drug to patients. He was not on the panel, but spoke during the open public hearing.

“Compared to other acne medications, the time it takes to successfully go from prescribed (isotretinoin) to when the patient actually has it in their hands is 5- to 10-fold higher,” he said.

Among the barriers is the 19-day lockout period for people who can get pregnant and miss the 7-day window for picking up their prescriptions. They must then wait 19 days to get a pregnancy test to clear them for receiving the medication.

Gregory Wedin, PharmD, pharmacovigilance and risk management director of Upsher-Smith Laboratories, who spoke on behalf of the Isotretinoin Products Manufacturer Group (IPMG), which manages iPLEDGE, said, “The rationale for the 19-day wait is to ensure the next confirmatory pregnancy test is completed after the most fertile period of the menstrual cycle is passed.”

Many don’t have a monthly cycle

But Dr. Barbieri said that reasoning is outdated.

“The current program’s focus on the menstrual cycle is really an antiquated approach,” he said. “Many patients do not have a monthly cycle due to medical conditions like polycystic ovarian syndrome, or due to [certain kinds of] contraception.”

He added, “By removing this 19-day lockout and, really, the archaic timing around the menstrual cycle in general in this program, we can simplify the program, improve it, and better align it with the real-world biology of our patients.” He added that patients are often missing the 7-day window for picking up their prescriptions through no fault of their own. Speakers at the hearing also mentioned insurance hassles and ordering delays.

Communication with IPMG

Ilona Frieden, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco, and outgoing chair of the AADA iPLEDGE work group, cited difficulty in working with IPMG on modifications as another barrier. She also spoke during the open public hearing.

“Despite many, many attempts to work with the IPMG, we are not aware of any organizational structure or key leaders to communicate with. Instead we have been given repeatedly a generic email address for trying to establish a working relationship and we believe this may explain the inaction of the IPMG since our proposals 4 years ago in 2019.”

Among those proposals, she said, were allowing telemedicine visits as part of the iPLEDGE REMS program and reducing counseling attestation to every 6 months instead of monthly for those who cannot become pregnant.

She pointed to the chaotic rollout of modifications to the iPLEDGE program on a new website at the end of 2021.

In 2021, she said, “despite 6 months of notification, no prescriber input was solicited before revamping the website. This lack of transparency and accountability has been a major hurdle in improving iPLEDGE.”

Dr. Barbieri called the rollout “a debacle” that could have been mitigated with communication with IPMG. “We warned about every issue that happened and talked about ways to mitigate it and were largely ignored,” he said.

“By including dermatologists and key stakeholders in these discussions, as we move forward with changes to improve this program, we can make sure that it’s patient-centered.”

IPMG did not address the specific complaints about the working relationship with the AADA workgroup at the meeting.

Monthly attestation for counseling patients who cannot get pregnant

Dr. Barbieri said the monthly requirement to counsel patients who cannot get pregnant and document that counseling unfairly burdens clinicians and patients. “We’re essentially asking patients to come in monthly just to tell them not to share their drugs [or] donate blood,” he said.

Ken Katz, MD, MSc, a dermatologist at Kaiser Permanente in San Francisco, was among the panel members voting not to continue the 19-day lockout.

“I think this places an unduly high burden physically and psychologically on our patients. It seems arbitrary,” he said. “Likely we will miss some pregnancies; we are missing some already. But the burden is not matched by the benefit.”

IPMG representative Dr. Wedin, said, “while we cannot support eliminating or extending the confirmation interval to a year, the [iPLEDGE] sponsors are agreeable [to] a 120-day confirmation interval.”

He said that while an extension to 120 days would reduce burden on prescribers, it comes with the risk in reducing oversight by a certified iPLEDGE prescriber and potentially increasing the risk for drug sharing.

“A patient may be more likely to share their drug with another person the further along with therapy they get as their condition improves,” Dr. Wedin said.

Home pregnancy testing

The advisory groups were also tasked with discussing whether home pregnancy tests, allowed during the COVID-19 public health emergency, should continue to be allowed. Most committee members and those in the public hearing who spoke on the issue agreed that home tests should continue in an effort to increase access and decrease burden.

During the pandemic, iPLEDGE rules have been relaxed from having a pregnancy test done only at a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratory.

Lindsey Crist, PharmD, a risk management analyst at the FDA, who presented the FDA review committee’s analysis, said that the FDA’s review committee recommends ending the allowance of home tests, citing insufficient data on use and the discovery of instances of falsification of pregnancy tests.

“One study at an academic medical center reviewed the medical records of 89 patients who used home pregnancy tests while taking isotretinoin during the public health emergency. It found that 15.7% submitted falsified pregnancy test results,” Dr. Crist said.

Dr. Crist added, however, that the review committee recommends allowing the tests to be done in a provider’s office as an alternative.

Workaround to avoid falsification

Advisory committee member Brian P. Green, DO, associate professor of dermatology at Penn State University, Hershey, Pa., spoke in support of home pregnancy tests.

“What we have people do for telemedicine is take the stick, write their name, write the date on it, and send a picture of that the same day as their visit,” he said. “That way we have the pregnancy test the same day. Allowing this to continue to happen at home is important. Bringing people in is burdensome and costly.”

Emmy Graber, MD, a dermatologist who practices in Boston, and a director of the American Acne and Rosacea Society (AARS), relayed an example of the burden for a patient using isotretinoin who lives 1.5 hours away from the dermatology office. She is able to meet the requirements of iPLEDGE only through telehealth.

“Home pregnancy tests are highly sensitive, equal to the ones done in CLIA-certified labs, and highly accurate when interpreted by a dermatology provider,” said Dr. Graber, who spoke on behalf of the AARS during the open public hearing.

“Notably, CLIA [Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments] certification is not required by other REMS programs” for teratogenic drugs, she added.

Dr. Graber said it’s important to note that in the time the pandemic exceptions have been made for isotretinoin patients, “there has been no reported spike in pregnancy in the past three years.

“We do have some data to show that it is not imposing additional harms,” she said.

Suggestions for improvement

At the end of the hearing, advisory committee members were asked to propose improvements to the iPLEDGE REMS program.

Dr. Green advocated for the addition of an iPLEDGE mobile app.

“Most people go to their phones rather than their computers, particularly teenagers and younger people,” he noted.

Advisory committee member Megha M. Tollefson, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatric and adolescent medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., echoed the need for an iPLEDGE app.

The young patients getting isotretinoin “don’t respond to email, they don’t necessarily go onto web pages. If we’re going to be as effective as possible, it’s going to have to be through an app-based system.”

Dr. Tollefson said she would like to see patient counseling standardized through the app. “I think there’s a lot of variability in what counseling is given when it’s left to the individual prescriber or practice,” she said.

Exceptions for long-acting contraceptives?

Advisory committee member Abbey B. Berenson, MD, PhD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, said that patients taking long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) may need to be considered differently when deciding the intervals for attestation or whether to have a lockout period.

“LARC methods’ rate of failure is extremely low,” she said. “While it is true, as it has been pointed out, that all methods can fail, when they’re over 99% effective, I think that we can treat those methods differently than we treat methods such as birth control pills or abstinence that fail far more often. That is one way we could minimize burden on the providers and the patients.”

She also suggested using members of the health care team other than physicians to complete counseling, such as a nurse or pharmacist.

Prescriptions for emergency contraception

Advisory committee member Sascha Dublin, MD, PhD, senior scientific investigator for Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle, said most patients taking the drug who can get pregnant should get a prescription for emergency contraception at the time of the first isotretinoin prescription.

“They don’t have to buy it, but to make it available at the very beginning sets the expectation that it would be good to have in your medicine cabinet, particularly if the [contraception] choice is abstinence or birth control pills.”

Dr. Dublin also called for better transparency surrounding the role of IPMG.

She said IPMG should be expected to collect data in a way that allows examination of health disparities, including by race and ethnicity and insurance status. Dr. Dublin added that she was concerned about the poor communication between dermatological societies and IPMG.

“The FDA should really require that IPMG hold periodic, regularly scheduled stakeholder forums,” she said. “There has to be a mechanism in place for IPMG to listen to those concerns in real time and respond.”

The advisory committees’ recommendations to the FDA are nonbinding, but the FDA generally follows the recommendations of advisory panels.

During 2 days of after the chaotic rollout of the new REMS platform at the end of 2021.

On March 29, at the end of the FDA’s joint meeting of two advisory committees that addressed ways to improve the iPLEDGE program, most panelists voted to change the 19-day lockout period for patients who can become pregnant, and the requirement that every month, providers must document counseling of those who cannot get pregnant and are taking the drug for acne.

However, there was no consensus on whether there should be a lockout at all or for how long, and what an appropriate interval for counseling those who cannot get pregnant would be, if not monthly. Those voting on the questions repeatedly cited a lack of data to make well-informed decisions.

The meeting of the two panels, the FDA’s Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee and the Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee, was held March 28-29, to discuss proposed changes to iPLEDGE requirements, to minimize the program’s burden on patients, prescribers, and pharmacies – while maintaining safe use of the highly teratogenic drug.

Lockout based on outdated reasoning

John S. Barbieri, MD, a dermatologist and epidemiologist, and director of the Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, speaking as deputy chair of the American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA) iPLEDGE work group, described the burden of getting the drug to patients. He was not on the panel, but spoke during the open public hearing.

“Compared to other acne medications, the time it takes to successfully go from prescribed (isotretinoin) to when the patient actually has it in their hands is 5- to 10-fold higher,” he said.

Among the barriers is the 19-day lockout period for people who can get pregnant and miss the 7-day window for picking up their prescriptions. They must then wait 19 days to get a pregnancy test to clear them for receiving the medication.

Gregory Wedin, PharmD, pharmacovigilance and risk management director of Upsher-Smith Laboratories, who spoke on behalf of the Isotretinoin Products Manufacturer Group (IPMG), which manages iPLEDGE, said, “The rationale for the 19-day wait is to ensure the next confirmatory pregnancy test is completed after the most fertile period of the menstrual cycle is passed.”

Many don’t have a monthly cycle

But Dr. Barbieri said that reasoning is outdated.

“The current program’s focus on the menstrual cycle is really an antiquated approach,” he said. “Many patients do not have a monthly cycle due to medical conditions like polycystic ovarian syndrome, or due to [certain kinds of] contraception.”

He added, “By removing this 19-day lockout and, really, the archaic timing around the menstrual cycle in general in this program, we can simplify the program, improve it, and better align it with the real-world biology of our patients.” He added that patients are often missing the 7-day window for picking up their prescriptions through no fault of their own. Speakers at the hearing also mentioned insurance hassles and ordering delays.

Communication with IPMG

Ilona Frieden, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco, and outgoing chair of the AADA iPLEDGE work group, cited difficulty in working with IPMG on modifications as another barrier. She also spoke during the open public hearing.

“Despite many, many attempts to work with the IPMG, we are not aware of any organizational structure or key leaders to communicate with. Instead we have been given repeatedly a generic email address for trying to establish a working relationship and we believe this may explain the inaction of the IPMG since our proposals 4 years ago in 2019.”

Among those proposals, she said, were allowing telemedicine visits as part of the iPLEDGE REMS program and reducing counseling attestation to every 6 months instead of monthly for those who cannot become pregnant.

She pointed to the chaotic rollout of modifications to the iPLEDGE program on a new website at the end of 2021.

In 2021, she said, “despite 6 months of notification, no prescriber input was solicited before revamping the website. This lack of transparency and accountability has been a major hurdle in improving iPLEDGE.”

Dr. Barbieri called the rollout “a debacle” that could have been mitigated with communication with IPMG. “We warned about every issue that happened and talked about ways to mitigate it and were largely ignored,” he said.

“By including dermatologists and key stakeholders in these discussions, as we move forward with changes to improve this program, we can make sure that it’s patient-centered.”

IPMG did not address the specific complaints about the working relationship with the AADA workgroup at the meeting.

Monthly attestation for counseling patients who cannot get pregnant

Dr. Barbieri said the monthly requirement to counsel patients who cannot get pregnant and document that counseling unfairly burdens clinicians and patients. “We’re essentially asking patients to come in monthly just to tell them not to share their drugs [or] donate blood,” he said.

Ken Katz, MD, MSc, a dermatologist at Kaiser Permanente in San Francisco, was among the panel members voting not to continue the 19-day lockout.

“I think this places an unduly high burden physically and psychologically on our patients. It seems arbitrary,” he said. “Likely we will miss some pregnancies; we are missing some already. But the burden is not matched by the benefit.”

IPMG representative Dr. Wedin, said, “while we cannot support eliminating or extending the confirmation interval to a year, the [iPLEDGE] sponsors are agreeable [to] a 120-day confirmation interval.”

He said that while an extension to 120 days would reduce burden on prescribers, it comes with the risk in reducing oversight by a certified iPLEDGE prescriber and potentially increasing the risk for drug sharing.

“A patient may be more likely to share their drug with another person the further along with therapy they get as their condition improves,” Dr. Wedin said.

Home pregnancy testing

The advisory groups were also tasked with discussing whether home pregnancy tests, allowed during the COVID-19 public health emergency, should continue to be allowed. Most committee members and those in the public hearing who spoke on the issue agreed that home tests should continue in an effort to increase access and decrease burden.

During the pandemic, iPLEDGE rules have been relaxed from having a pregnancy test done only at a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratory.

Lindsey Crist, PharmD, a risk management analyst at the FDA, who presented the FDA review committee’s analysis, said that the FDA’s review committee recommends ending the allowance of home tests, citing insufficient data on use and the discovery of instances of falsification of pregnancy tests.

“One study at an academic medical center reviewed the medical records of 89 patients who used home pregnancy tests while taking isotretinoin during the public health emergency. It found that 15.7% submitted falsified pregnancy test results,” Dr. Crist said.

Dr. Crist added, however, that the review committee recommends allowing the tests to be done in a provider’s office as an alternative.

Workaround to avoid falsification

Advisory committee member Brian P. Green, DO, associate professor of dermatology at Penn State University, Hershey, Pa., spoke in support of home pregnancy tests.

“What we have people do for telemedicine is take the stick, write their name, write the date on it, and send a picture of that the same day as their visit,” he said. “That way we have the pregnancy test the same day. Allowing this to continue to happen at home is important. Bringing people in is burdensome and costly.”

Emmy Graber, MD, a dermatologist who practices in Boston, and a director of the American Acne and Rosacea Society (AARS), relayed an example of the burden for a patient using isotretinoin who lives 1.5 hours away from the dermatology office. She is able to meet the requirements of iPLEDGE only through telehealth.

“Home pregnancy tests are highly sensitive, equal to the ones done in CLIA-certified labs, and highly accurate when interpreted by a dermatology provider,” said Dr. Graber, who spoke on behalf of the AARS during the open public hearing.

“Notably, CLIA [Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments] certification is not required by other REMS programs” for teratogenic drugs, she added.

Dr. Graber said it’s important to note that in the time the pandemic exceptions have been made for isotretinoin patients, “there has been no reported spike in pregnancy in the past three years.

“We do have some data to show that it is not imposing additional harms,” she said.

Suggestions for improvement

At the end of the hearing, advisory committee members were asked to propose improvements to the iPLEDGE REMS program.

Dr. Green advocated for the addition of an iPLEDGE mobile app.

“Most people go to their phones rather than their computers, particularly teenagers and younger people,” he noted.

Advisory committee member Megha M. Tollefson, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatric and adolescent medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., echoed the need for an iPLEDGE app.

The young patients getting isotretinoin “don’t respond to email, they don’t necessarily go onto web pages. If we’re going to be as effective as possible, it’s going to have to be through an app-based system.”

Dr. Tollefson said she would like to see patient counseling standardized through the app. “I think there’s a lot of variability in what counseling is given when it’s left to the individual prescriber or practice,” she said.

Exceptions for long-acting contraceptives?

Advisory committee member Abbey B. Berenson, MD, PhD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, said that patients taking long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) may need to be considered differently when deciding the intervals for attestation or whether to have a lockout period.

“LARC methods’ rate of failure is extremely low,” she said. “While it is true, as it has been pointed out, that all methods can fail, when they’re over 99% effective, I think that we can treat those methods differently than we treat methods such as birth control pills or abstinence that fail far more often. That is one way we could minimize burden on the providers and the patients.”

She also suggested using members of the health care team other than physicians to complete counseling, such as a nurse or pharmacist.

Prescriptions for emergency contraception

Advisory committee member Sascha Dublin, MD, PhD, senior scientific investigator for Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle, said most patients taking the drug who can get pregnant should get a prescription for emergency contraception at the time of the first isotretinoin prescription.

“They don’t have to buy it, but to make it available at the very beginning sets the expectation that it would be good to have in your medicine cabinet, particularly if the [contraception] choice is abstinence or birth control pills.”

Dr. Dublin also called for better transparency surrounding the role of IPMG.

She said IPMG should be expected to collect data in a way that allows examination of health disparities, including by race and ethnicity and insurance status. Dr. Dublin added that she was concerned about the poor communication between dermatological societies and IPMG.

“The FDA should really require that IPMG hold periodic, regularly scheduled stakeholder forums,” she said. “There has to be a mechanism in place for IPMG to listen to those concerns in real time and respond.”

The advisory committees’ recommendations to the FDA are nonbinding, but the FDA generally follows the recommendations of advisory panels.

During 2 days of after the chaotic rollout of the new REMS platform at the end of 2021.

On March 29, at the end of the FDA’s joint meeting of two advisory committees that addressed ways to improve the iPLEDGE program, most panelists voted to change the 19-day lockout period for patients who can become pregnant, and the requirement that every month, providers must document counseling of those who cannot get pregnant and are taking the drug for acne.

However, there was no consensus on whether there should be a lockout at all or for how long, and what an appropriate interval for counseling those who cannot get pregnant would be, if not monthly. Those voting on the questions repeatedly cited a lack of data to make well-informed decisions.

The meeting of the two panels, the FDA’s Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee and the Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee, was held March 28-29, to discuss proposed changes to iPLEDGE requirements, to minimize the program’s burden on patients, prescribers, and pharmacies – while maintaining safe use of the highly teratogenic drug.

Lockout based on outdated reasoning

John S. Barbieri, MD, a dermatologist and epidemiologist, and director of the Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, speaking as deputy chair of the American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA) iPLEDGE work group, described the burden of getting the drug to patients. He was not on the panel, but spoke during the open public hearing.

“Compared to other acne medications, the time it takes to successfully go from prescribed (isotretinoin) to when the patient actually has it in their hands is 5- to 10-fold higher,” he said.

Among the barriers is the 19-day lockout period for people who can get pregnant and miss the 7-day window for picking up their prescriptions. They must then wait 19 days to get a pregnancy test to clear them for receiving the medication.

Gregory Wedin, PharmD, pharmacovigilance and risk management director of Upsher-Smith Laboratories, who spoke on behalf of the Isotretinoin Products Manufacturer Group (IPMG), which manages iPLEDGE, said, “The rationale for the 19-day wait is to ensure the next confirmatory pregnancy test is completed after the most fertile period of the menstrual cycle is passed.”

Many don’t have a monthly cycle

But Dr. Barbieri said that reasoning is outdated.

“The current program’s focus on the menstrual cycle is really an antiquated approach,” he said. “Many patients do not have a monthly cycle due to medical conditions like polycystic ovarian syndrome, or due to [certain kinds of] contraception.”

He added, “By removing this 19-day lockout and, really, the archaic timing around the menstrual cycle in general in this program, we can simplify the program, improve it, and better align it with the real-world biology of our patients.” He added that patients are often missing the 7-day window for picking up their prescriptions through no fault of their own. Speakers at the hearing also mentioned insurance hassles and ordering delays.

Communication with IPMG

Ilona Frieden, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco, and outgoing chair of the AADA iPLEDGE work group, cited difficulty in working with IPMG on modifications as another barrier. She also spoke during the open public hearing.

“Despite many, many attempts to work with the IPMG, we are not aware of any organizational structure or key leaders to communicate with. Instead we have been given repeatedly a generic email address for trying to establish a working relationship and we believe this may explain the inaction of the IPMG since our proposals 4 years ago in 2019.”

Among those proposals, she said, were allowing telemedicine visits as part of the iPLEDGE REMS program and reducing counseling attestation to every 6 months instead of monthly for those who cannot become pregnant.

She pointed to the chaotic rollout of modifications to the iPLEDGE program on a new website at the end of 2021.

In 2021, she said, “despite 6 months of notification, no prescriber input was solicited before revamping the website. This lack of transparency and accountability has been a major hurdle in improving iPLEDGE.”

Dr. Barbieri called the rollout “a debacle” that could have been mitigated with communication with IPMG. “We warned about every issue that happened and talked about ways to mitigate it and were largely ignored,” he said.

“By including dermatologists and key stakeholders in these discussions, as we move forward with changes to improve this program, we can make sure that it’s patient-centered.”

IPMG did not address the specific complaints about the working relationship with the AADA workgroup at the meeting.

Monthly attestation for counseling patients who cannot get pregnant

Dr. Barbieri said the monthly requirement to counsel patients who cannot get pregnant and document that counseling unfairly burdens clinicians and patients. “We’re essentially asking patients to come in monthly just to tell them not to share their drugs [or] donate blood,” he said.

Ken Katz, MD, MSc, a dermatologist at Kaiser Permanente in San Francisco, was among the panel members voting not to continue the 19-day lockout.

“I think this places an unduly high burden physically and psychologically on our patients. It seems arbitrary,” he said. “Likely we will miss some pregnancies; we are missing some already. But the burden is not matched by the benefit.”

IPMG representative Dr. Wedin, said, “while we cannot support eliminating or extending the confirmation interval to a year, the [iPLEDGE] sponsors are agreeable [to] a 120-day confirmation interval.”

He said that while an extension to 120 days would reduce burden on prescribers, it comes with the risk in reducing oversight by a certified iPLEDGE prescriber and potentially increasing the risk for drug sharing.

“A patient may be more likely to share their drug with another person the further along with therapy they get as their condition improves,” Dr. Wedin said.

Home pregnancy testing

The advisory groups were also tasked with discussing whether home pregnancy tests, allowed during the COVID-19 public health emergency, should continue to be allowed. Most committee members and those in the public hearing who spoke on the issue agreed that home tests should continue in an effort to increase access and decrease burden.

During the pandemic, iPLEDGE rules have been relaxed from having a pregnancy test done only at a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratory.

Lindsey Crist, PharmD, a risk management analyst at the FDA, who presented the FDA review committee’s analysis, said that the FDA’s review committee recommends ending the allowance of home tests, citing insufficient data on use and the discovery of instances of falsification of pregnancy tests.

“One study at an academic medical center reviewed the medical records of 89 patients who used home pregnancy tests while taking isotretinoin during the public health emergency. It found that 15.7% submitted falsified pregnancy test results,” Dr. Crist said.

Dr. Crist added, however, that the review committee recommends allowing the tests to be done in a provider’s office as an alternative.

Workaround to avoid falsification

Advisory committee member Brian P. Green, DO, associate professor of dermatology at Penn State University, Hershey, Pa., spoke in support of home pregnancy tests.

“What we have people do for telemedicine is take the stick, write their name, write the date on it, and send a picture of that the same day as their visit,” he said. “That way we have the pregnancy test the same day. Allowing this to continue to happen at home is important. Bringing people in is burdensome and costly.”

Emmy Graber, MD, a dermatologist who practices in Boston, and a director of the American Acne and Rosacea Society (AARS), relayed an example of the burden for a patient using isotretinoin who lives 1.5 hours away from the dermatology office. She is able to meet the requirements of iPLEDGE only through telehealth.

“Home pregnancy tests are highly sensitive, equal to the ones done in CLIA-certified labs, and highly accurate when interpreted by a dermatology provider,” said Dr. Graber, who spoke on behalf of the AARS during the open public hearing.

“Notably, CLIA [Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments] certification is not required by other REMS programs” for teratogenic drugs, she added.

Dr. Graber said it’s important to note that in the time the pandemic exceptions have been made for isotretinoin patients, “there has been no reported spike in pregnancy in the past three years.

“We do have some data to show that it is not imposing additional harms,” she said.

Suggestions for improvement

At the end of the hearing, advisory committee members were asked to propose improvements to the iPLEDGE REMS program.

Dr. Green advocated for the addition of an iPLEDGE mobile app.

“Most people go to their phones rather than their computers, particularly teenagers and younger people,” he noted.

Advisory committee member Megha M. Tollefson, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatric and adolescent medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., echoed the need for an iPLEDGE app.

The young patients getting isotretinoin “don’t respond to email, they don’t necessarily go onto web pages. If we’re going to be as effective as possible, it’s going to have to be through an app-based system.”

Dr. Tollefson said she would like to see patient counseling standardized through the app. “I think there’s a lot of variability in what counseling is given when it’s left to the individual prescriber or practice,” she said.

Exceptions for long-acting contraceptives?

Advisory committee member Abbey B. Berenson, MD, PhD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, said that patients taking long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) may need to be considered differently when deciding the intervals for attestation or whether to have a lockout period.

“LARC methods’ rate of failure is extremely low,” she said. “While it is true, as it has been pointed out, that all methods can fail, when they’re over 99% effective, I think that we can treat those methods differently than we treat methods such as birth control pills or abstinence that fail far more often. That is one way we could minimize burden on the providers and the patients.”

She also suggested using members of the health care team other than physicians to complete counseling, such as a nurse or pharmacist.

Prescriptions for emergency contraception

Advisory committee member Sascha Dublin, MD, PhD, senior scientific investigator for Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle, said most patients taking the drug who can get pregnant should get a prescription for emergency contraception at the time of the first isotretinoin prescription.

“They don’t have to buy it, but to make it available at the very beginning sets the expectation that it would be good to have in your medicine cabinet, particularly if the [contraception] choice is abstinence or birth control pills.”

Dr. Dublin also called for better transparency surrounding the role of IPMG.

She said IPMG should be expected to collect data in a way that allows examination of health disparities, including by race and ethnicity and insurance status. Dr. Dublin added that she was concerned about the poor communication between dermatological societies and IPMG.

“The FDA should really require that IPMG hold periodic, regularly scheduled stakeholder forums,” she said. “There has to be a mechanism in place for IPMG to listen to those concerns in real time and respond.”

The advisory committees’ recommendations to the FDA are nonbinding, but the FDA generally follows the recommendations of advisory panels.

New state bill could protect docs prescribing abortion pills to out-of-state patients

California lawmakers are considering legislation to protect California physicians and pharmacists who prescribe abortion pills to out-of-state patients. The proposed law would shield health care providers who are legally performing their jobs in California from facing prosecution in another state or being extradited.

State Sen. Nancy Skinner, who introduced the bill, said the legislation is necessary in a fractured, post-Roe legal landscape where doctors in some states can face felony charges or civil penalties for providing reproductive health care. It’s part of a package of 17 new bills aiming to “strengthen California’s standing as a safe haven for abortion, contraception, and pregnancy care,” according to a press release.

“I’m trying to protect our healthcare practitioners so they can do their jobs, without fear,” Ms. Skinner said in a statement on March 24.

Most abortions are banned in 14 states after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. Lawmakers in those states have established a variety of penalties for doctors, pharmacists, and other clinicians to provide abortion care or assist patients in obtaining abortions, including jail time, fines, and loss of professional licenses.

As a result, doctors in restrictive states have anguished over having to delay treatment for patients experiencing miscarriages, ectopic pregnancies, and other conditions until their lives are enough at risk to satisfy exceptions to state abortion laws.

“As a physician, I believe everyone deserves the care they need, regardless of where they live,” said Daniel Grossman, MD, a University of California, San Francisco, ob.gyn. professor who directs the university’s Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health program.

“Since the fall of Roe v. Wade, patients are being forced to travel long distances – often over 500 miles – to access abortion care in a clinic. People should be able to access this essential care closer to home, including by telemedicine, which has been shown to be safe and effective. I am hopeful that SB 345 will provide additional legal protections that would allow California clinicians to help patients in other states,” he stated.

Other states, including New York, Vermont, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, have passed or are considering similar legislation to protect doctors using telemedicine to prescribe abortion medication to out-of-state patients. These laws come amid a growing push by some states and anti-abortion groups to severely restrict access to abortion pills.

Wyoming is the first state to explicitly ban the pills, although a judge on March 22 blocked that ban. And, in a closely watched case, a conservative federal judge could soon rule to ban sales of mifepristone, one of the medications in a two-pill regimen approved for abortions early in pregnancy.

California’s legislation protects clinicians from losing their California professional licenses if an out-of-state medical board takes action against them. It also allows clinicians to sue anyone who tries to legally interfere with the care they are providing.

It also covers California physicians prescribing contraceptives or gender-affirming care to out-of-state patients. At least 21 states are considering restrictions on gender-affirming care for minors and another 9 states have passed them, according to the advocacy group Human Rights Campaign. Courts have blocked the restrictions in some states.

“It’s understandable that states like California want to reassure their doctors ... that, if one of their patients is caught in one of those states and can’t get help locally, they can step up to help and feel safe in doing so,” said Matthew Wynia, MD, MPH, FACP, director of the Center for Bioethics and Humanities at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

“This is also a crazy development in terms of the law. It’s just one part of the legal mayhem that was predicted when the Supreme Court overturned Roe,” Dr. Wynia said of the growing number of bills protecting in-state doctors. These bills “will almost certainly end up being litigated over issues of interstate commerce, cross-state licensure and practice compacts, FDA regulations and authorities, and maybe more. It’s a huge mess, in which both doctors and patients are being hurt.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

California lawmakers are considering legislation to protect California physicians and pharmacists who prescribe abortion pills to out-of-state patients. The proposed law would shield health care providers who are legally performing their jobs in California from facing prosecution in another state or being extradited.

State Sen. Nancy Skinner, who introduced the bill, said the legislation is necessary in a fractured, post-Roe legal landscape where doctors in some states can face felony charges or civil penalties for providing reproductive health care. It’s part of a package of 17 new bills aiming to “strengthen California’s standing as a safe haven for abortion, contraception, and pregnancy care,” according to a press release.

“I’m trying to protect our healthcare practitioners so they can do their jobs, without fear,” Ms. Skinner said in a statement on March 24.

Most abortions are banned in 14 states after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. Lawmakers in those states have established a variety of penalties for doctors, pharmacists, and other clinicians to provide abortion care or assist patients in obtaining abortions, including jail time, fines, and loss of professional licenses.

As a result, doctors in restrictive states have anguished over having to delay treatment for patients experiencing miscarriages, ectopic pregnancies, and other conditions until their lives are enough at risk to satisfy exceptions to state abortion laws.

“As a physician, I believe everyone deserves the care they need, regardless of where they live,” said Daniel Grossman, MD, a University of California, San Francisco, ob.gyn. professor who directs the university’s Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health program.

“Since the fall of Roe v. Wade, patients are being forced to travel long distances – often over 500 miles – to access abortion care in a clinic. People should be able to access this essential care closer to home, including by telemedicine, which has been shown to be safe and effective. I am hopeful that SB 345 will provide additional legal protections that would allow California clinicians to help patients in other states,” he stated.

Other states, including New York, Vermont, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, have passed or are considering similar legislation to protect doctors using telemedicine to prescribe abortion medication to out-of-state patients. These laws come amid a growing push by some states and anti-abortion groups to severely restrict access to abortion pills.

Wyoming is the first state to explicitly ban the pills, although a judge on March 22 blocked that ban. And, in a closely watched case, a conservative federal judge could soon rule to ban sales of mifepristone, one of the medications in a two-pill regimen approved for abortions early in pregnancy.

California’s legislation protects clinicians from losing their California professional licenses if an out-of-state medical board takes action against them. It also allows clinicians to sue anyone who tries to legally interfere with the care they are providing.

It also covers California physicians prescribing contraceptives or gender-affirming care to out-of-state patients. At least 21 states are considering restrictions on gender-affirming care for minors and another 9 states have passed them, according to the advocacy group Human Rights Campaign. Courts have blocked the restrictions in some states.

“It’s understandable that states like California want to reassure their doctors ... that, if one of their patients is caught in one of those states and can’t get help locally, they can step up to help and feel safe in doing so,” said Matthew Wynia, MD, MPH, FACP, director of the Center for Bioethics and Humanities at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

“This is also a crazy development in terms of the law. It’s just one part of the legal mayhem that was predicted when the Supreme Court overturned Roe,” Dr. Wynia said of the growing number of bills protecting in-state doctors. These bills “will almost certainly end up being litigated over issues of interstate commerce, cross-state licensure and practice compacts, FDA regulations and authorities, and maybe more. It’s a huge mess, in which both doctors and patients are being hurt.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

California lawmakers are considering legislation to protect California physicians and pharmacists who prescribe abortion pills to out-of-state patients. The proposed law would shield health care providers who are legally performing their jobs in California from facing prosecution in another state or being extradited.

State Sen. Nancy Skinner, who introduced the bill, said the legislation is necessary in a fractured, post-Roe legal landscape where doctors in some states can face felony charges or civil penalties for providing reproductive health care. It’s part of a package of 17 new bills aiming to “strengthen California’s standing as a safe haven for abortion, contraception, and pregnancy care,” according to a press release.

“I’m trying to protect our healthcare practitioners so they can do their jobs, without fear,” Ms. Skinner said in a statement on March 24.

Most abortions are banned in 14 states after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. Lawmakers in those states have established a variety of penalties for doctors, pharmacists, and other clinicians to provide abortion care or assist patients in obtaining abortions, including jail time, fines, and loss of professional licenses.

As a result, doctors in restrictive states have anguished over having to delay treatment for patients experiencing miscarriages, ectopic pregnancies, and other conditions until their lives are enough at risk to satisfy exceptions to state abortion laws.

“As a physician, I believe everyone deserves the care they need, regardless of where they live,” said Daniel Grossman, MD, a University of California, San Francisco, ob.gyn. professor who directs the university’s Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health program.

“Since the fall of Roe v. Wade, patients are being forced to travel long distances – often over 500 miles – to access abortion care in a clinic. People should be able to access this essential care closer to home, including by telemedicine, which has been shown to be safe and effective. I am hopeful that SB 345 will provide additional legal protections that would allow California clinicians to help patients in other states,” he stated.

Other states, including New York, Vermont, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, have passed or are considering similar legislation to protect doctors using telemedicine to prescribe abortion medication to out-of-state patients. These laws come amid a growing push by some states and anti-abortion groups to severely restrict access to abortion pills.

Wyoming is the first state to explicitly ban the pills, although a judge on March 22 blocked that ban. And, in a closely watched case, a conservative federal judge could soon rule to ban sales of mifepristone, one of the medications in a two-pill regimen approved for abortions early in pregnancy.

California’s legislation protects clinicians from losing their California professional licenses if an out-of-state medical board takes action against them. It also allows clinicians to sue anyone who tries to legally interfere with the care they are providing.

It also covers California physicians prescribing contraceptives or gender-affirming care to out-of-state patients. At least 21 states are considering restrictions on gender-affirming care for minors and another 9 states have passed them, according to the advocacy group Human Rights Campaign. Courts have blocked the restrictions in some states.

“It’s understandable that states like California want to reassure their doctors ... that, if one of their patients is caught in one of those states and can’t get help locally, they can step up to help and feel safe in doing so,” said Matthew Wynia, MD, MPH, FACP, director of the Center for Bioethics and Humanities at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

“This is also a crazy development in terms of the law. It’s just one part of the legal mayhem that was predicted when the Supreme Court overturned Roe,” Dr. Wynia said of the growing number of bills protecting in-state doctors. These bills “will almost certainly end up being litigated over issues of interstate commerce, cross-state licensure and practice compacts, FDA regulations and authorities, and maybe more. It’s a huge mess, in which both doctors and patients are being hurt.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Meet the JCOM Author with Dr. Barkoudah: Leading for High Reliability During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Meet the JCOM Author with Dr. Barkoudah: Residence Characteristics and Nursing Home Compare Quality Measures

Relationships Between Residence Characteristics and Nursing Home Compare Database Quality Measures

From the University of Nebraska, Lincoln (Mr. Puckett and Dr. Ryherd), University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha (Dr. Manley), and the University of Nebraska, Omaha (Dr. Ryan).

ABSTRACT

Objective: This study evaluated relationships between physical characteristics of nursing home residences and quality-of-care measures.

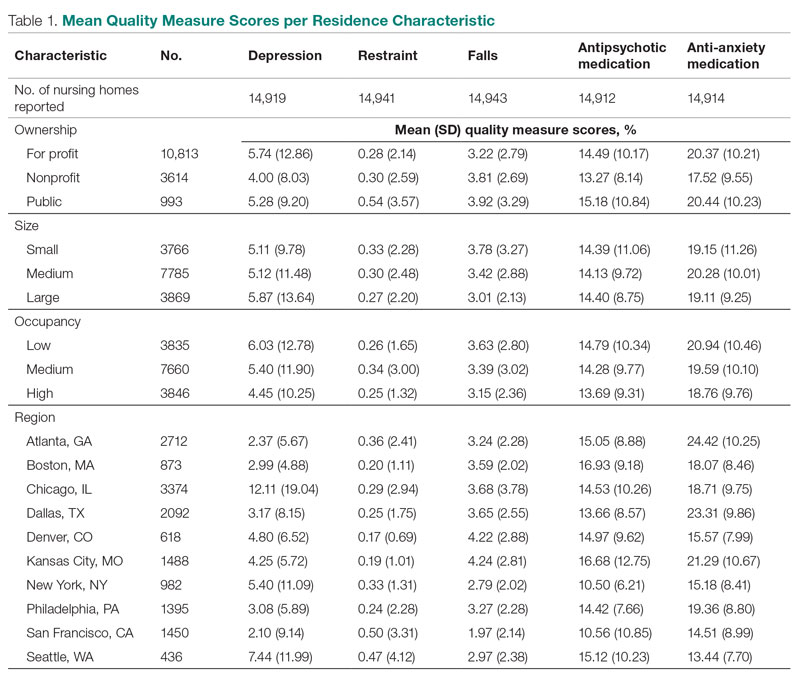

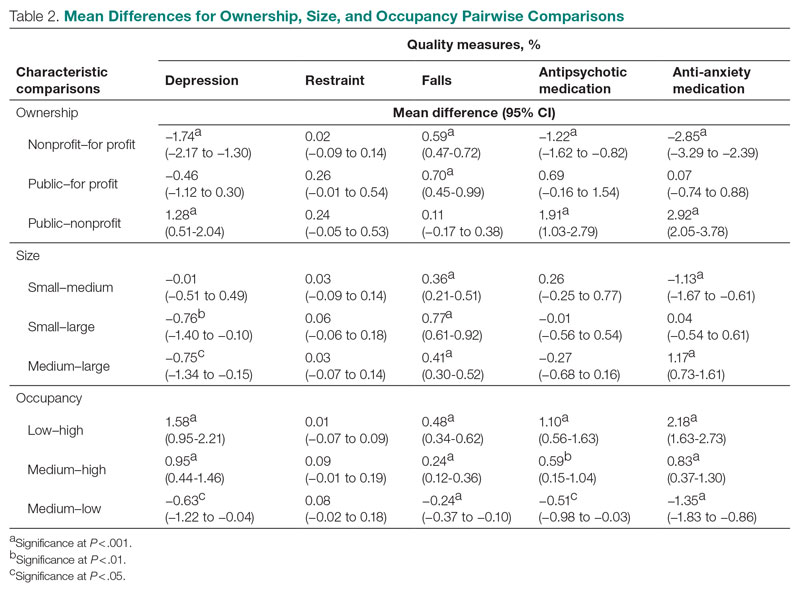

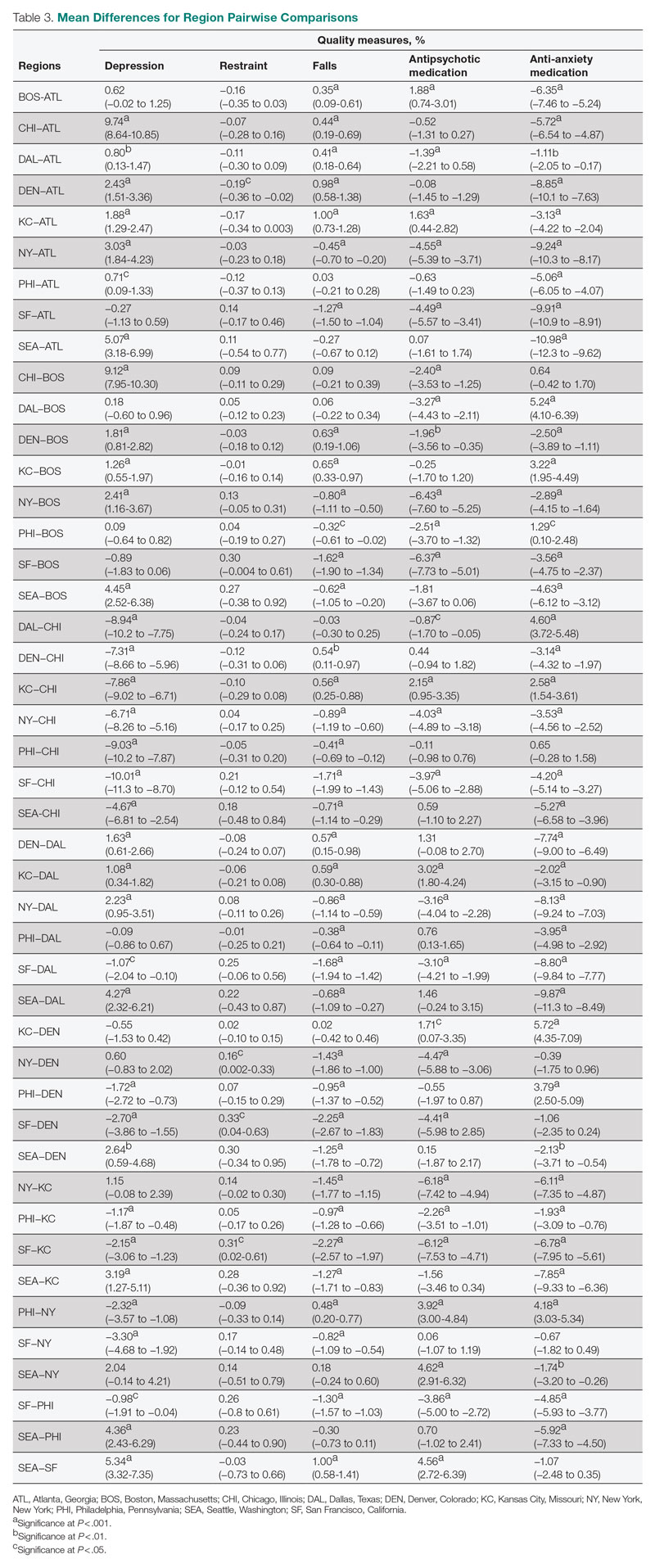

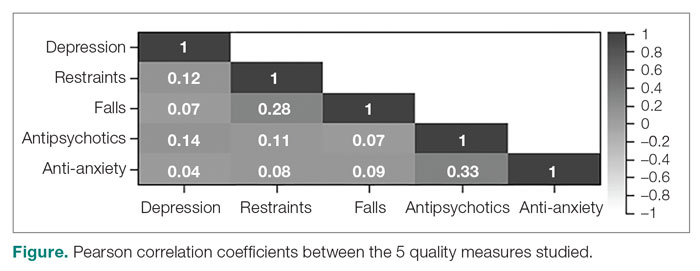

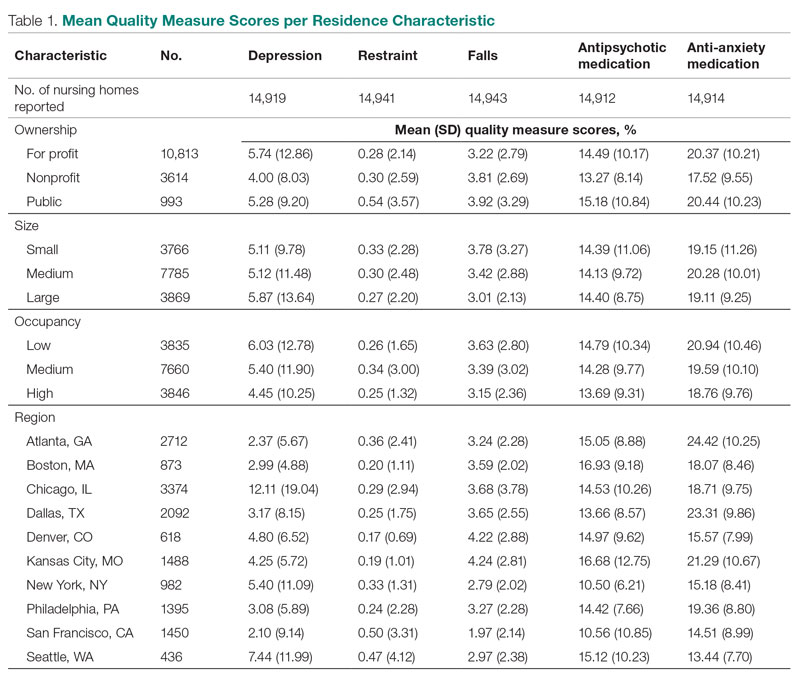

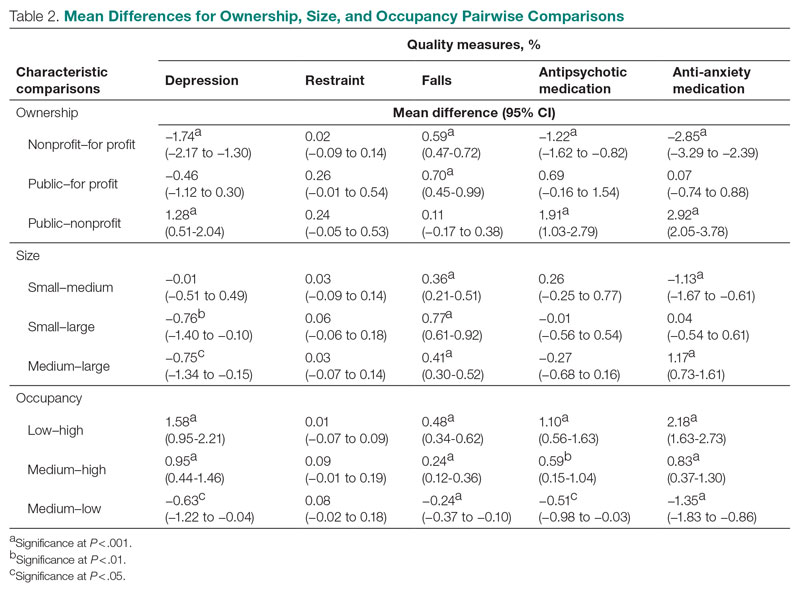

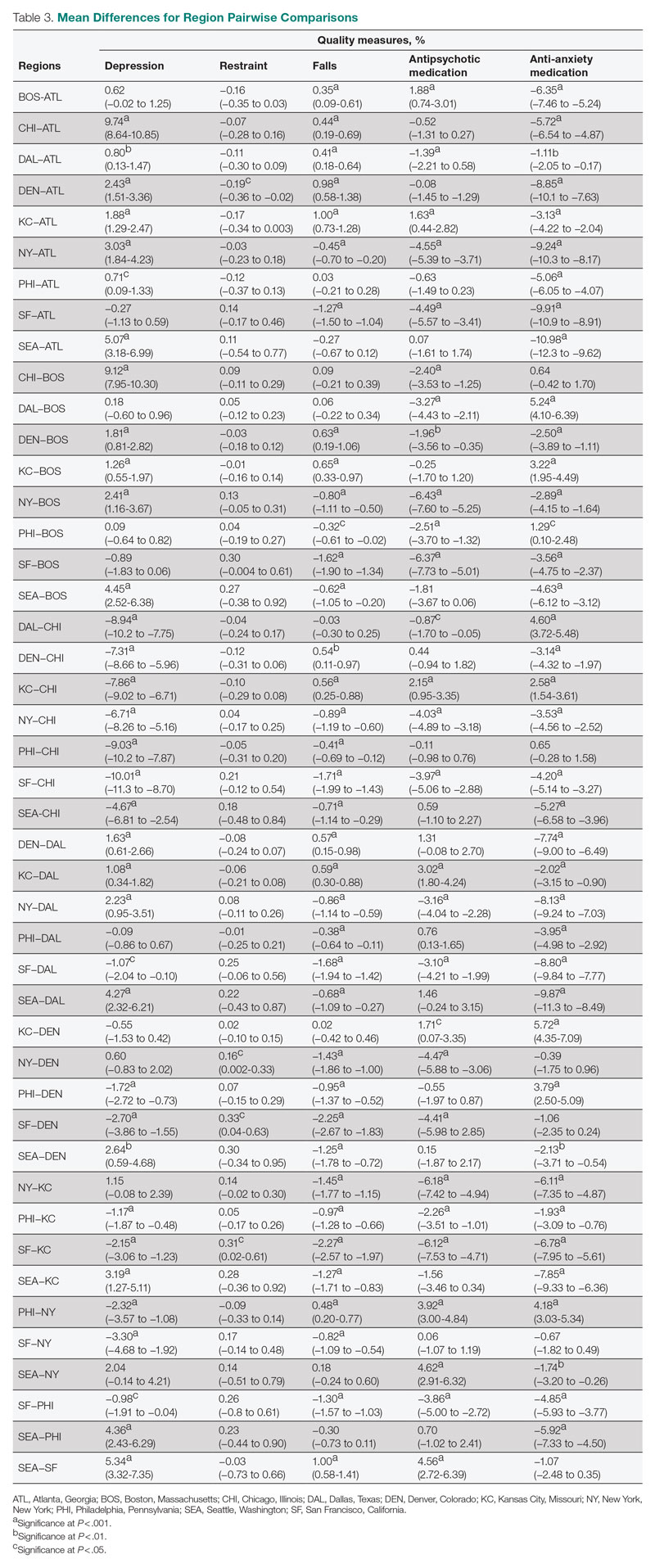

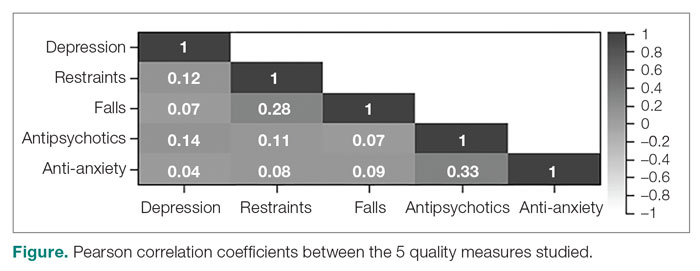

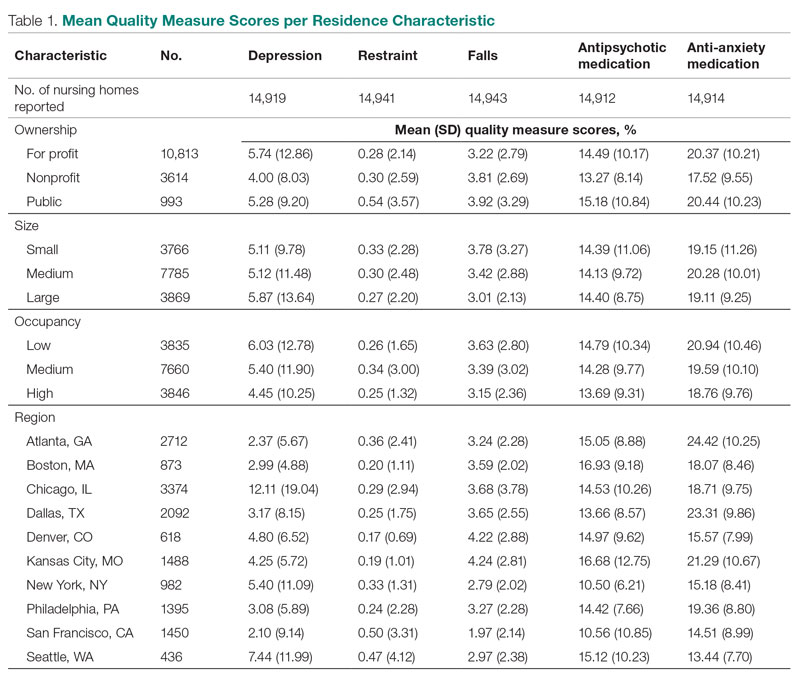

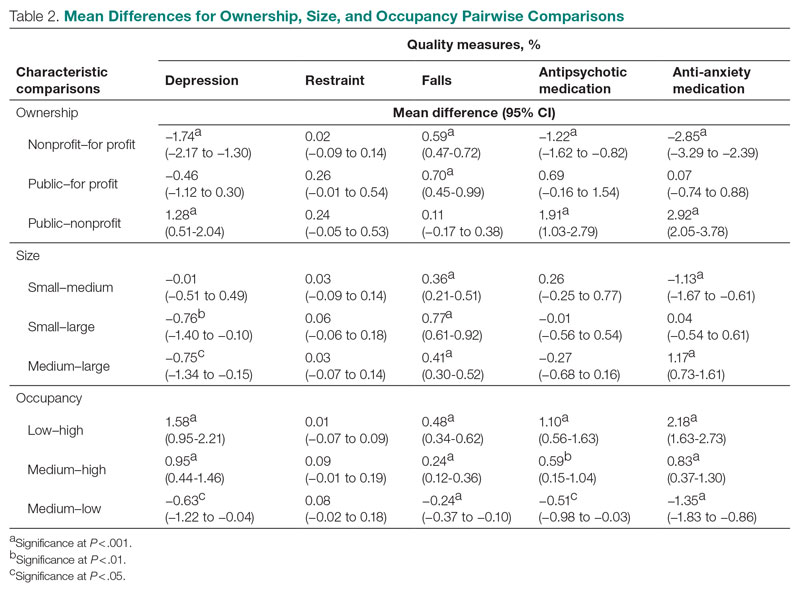

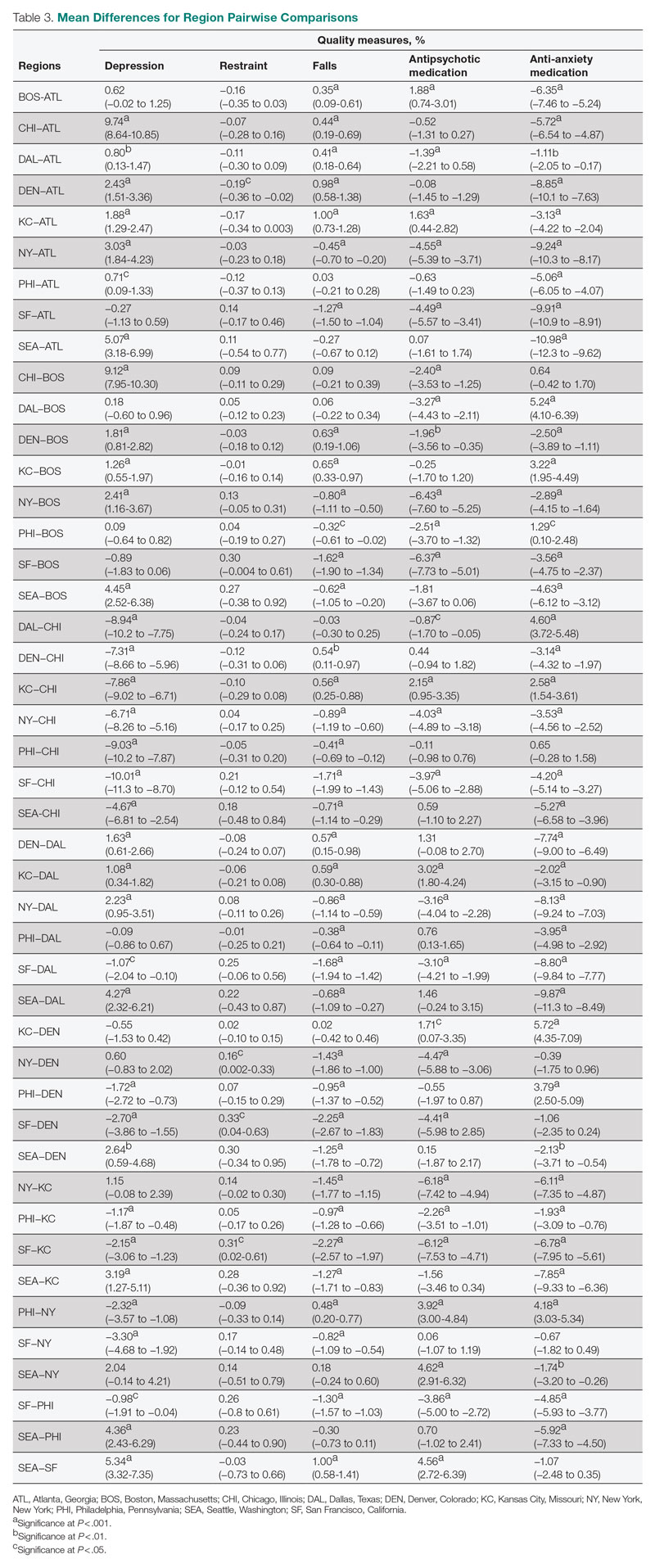

Design: This was a cross-sectional ecologic study. The dependent variables were 5 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Nursing Home Compare database long-stay quality measures (QMs) during 2019: percentage of residents who displayed depressive symptoms, percentage of residents who were physically restrained, percentage of residents who experienced 1 or more falls resulting in injury, percentage of residents who received antipsychotic medication, and percentage of residents who received anti-anxiety medication. The independent variables were 4 residence characteristics: ownership type, size, occupancy, and region within the United States. We explored how different types of each residence characteristic compare for each QM.

Setting, participants, and measurements: Quality measure values from 15,420 CMS-supported nursing homes across the United States averaged over the 4 quarters of 2019 reporting were used. Welch’s analysis of variance was performed to examine whether the mean QM values for groups within each residential characteristic were statistically different.

Results: Publicly owned and low-occupancy residences had the highest mean QM values, indicating the poorest performance. Nonprofit and high-occupancy residences generally had the lowest (ie, best) mean QM values. There were significant differences in mean QM values among nursing home sizes and regions.

Conclusion: This study suggests that residence characteristics are related to 5 nursing home QMs. Results suggest that physical characteristics may be related to overall quality of life in nursing homes.

Keywords: quality of care, quality measures, residence characteristics, Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

More than 55 million people worldwide are living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD).1 With the aging of the Baby Boomer population, this number is expected to rise to more than 78 million worldwide by 2030.1 Given the growing number of cognitively impaired older adults, there is an increased need for residences designed for the specialized care of this population. Although there are dozens of living options for the elderly, and although most specialized establishments have the resources to meet the immediate needs of their residents, many facilities lack universal design features that support a high quality of life for someone with ADRD or mild cognitive impairment. Previous research has shown relationships between behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and environmental characteristics such as acoustics, lighting, and indoor air temperature.2,3 Physical behaviors of BPSD, including aggression and wandering, and psychological symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, and delusions, put residents at risk of injury.4 Additionally, BPSD is correlated with caregiver burden and stress.5-8 Patients with dementia may also experience a lower stress threshold, changes in perception of space, and decreased short-term memory, creating environmental difficulties for those with ADRD9 that lead them to exhibit BPSD due to poor environmental design. Thus, there is a need to learn more about design features that minimize BPSD and promote a high quality of life for those with ADRD.10

Although research has shown relationships between physical environmental characteristics and BPSD, in this work we study relationships between possible BPSD indicators and 4 residence-level characteristics: ownership type, size, occupancy, and region in the United States (determined by location of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] regional offices). We analyzed data from the CMS Nursing Home Compare database for the year 2019.11 This database publishes quarterly data and star ratings for quality-of-care measures (QMs), staffing levels, and health inspections for every nursing home supported by CMS. Previous research has investigated the accuracy of QM reporting for resident falls, the impact of residential characteristics on administration of antipsychotic medication, the influence of profit status on resident outcomes and quality of care, and the effect of nursing home size on quality of life.12-16 Additionally, research suggests that residential characteristics such as size and location could be associated with infection control in nursing homes.17

Certain QMs, such as psychotropic drug administration, resident falls, and physical restraint, provide indicators of agitation, disorientation, or aggression, which are often signals of BPSD episodes. We hypothesized that residence types are associated with different QM scores, which could indicate different occurrences of BPSD. We selected 5 QMs for long-stay residents that could potentially be used as indicators of BPSD. Short-stay resident data were not included in this work to control for BPSD that could be a result of sheer unfamiliarity with the environment and confusion from being in a new home.

Methods

Design and Data Collection

This was a cross-sectional ecologic study aimed at exploring relationships between aggregate residential characteristics and QMs. Data were retrieved from the 2019 annual archives found in the CMS provider data catalog on nursing homes, including rehabilitation services.11 The dataset provides general residence information, such as ownership, number of beds, number of residents, and location, as well as residence quality metrics, such as QMs, staffing data, and inspection data. Residence characteristics and 4-quarter averages of QMs were retrieved and used as cross-sectional data. The data used are from 15,420 residences across the United States. Nursing homes located in Guam, the US Pacific Territories, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands, while supported by CMS and included in the dataset, were excluded from the study due to a severe absence of QM data.

Dependent Variables