User login

Food allergy test breakthrough: Less risk, more useful results

What would you do if you believed you had a serious health issue, but the best way to find out for sure might kill you?

That’s the reality for patients who wish to confirm or rule out a food allergy, says Sindy Tang, PhD, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford (Calif.) University.

And it’s the reason Dr. Tang and her colleagues are developing a food allergy test that’s not only safer, but also more reliable than today’s tests. In a paper in the journal Lab on a Chip, Dr. Tang and her colleagues outline the basis for this future test, which isolates a food allergy marker from the blood using a magnetic field.

How today’s food allergy tests fall short

The gold standard for food allergy diagnosis is something called the oral food challenge. That’s when the patient eats gradually increasing amounts of a problem food – say, peanuts – every 15 to 30 minutes to see if symptoms occur. This means highly allergic patients may risk anaphylaxis, an allergic reaction that causes inflammation so severe that breathing becomes restricted and blood pressure drops. Because of that, a clinical team must be at the ready with treatments like oxygen, epinephrine, or albuterol.

“The test is very accurate, but it’s also potentially unsafe and even fatal in rare cases,” Dr. Tang says. “That’s led to many sham tests advertised online that claim to use hair samples for food tests, but those are inaccurate and potentially dangerous, since they may give someone a false sense of confidence about a food they should avoid.”

Less risky tests are available, such as skin-prick tests – those involve scratching a small amount of the food into a patient’s arm – as well as blood tests that measure allergen-specific antibodies.

“Unfortunately, both of those are not that accurate and have high false-positive rates,” Dr. Tang says. “The best method is the oral food challenge, which many patients are afraid to do, not surprisingly.”

The future of food allergy testing: faster, safer, more reliable

In their study, the Stanford researchers focused on a type of white blood cell known as basophils, which release histamine when triggered by allergens. By using magnetic nanoparticles that bind to some blood cells but not basophils, they were able to separate basophils from the blood with a magnetic field in just 10 minutes.

Once isolated, the basophils are exposed to potential allergens. If they react, that’s a sign of an allergy.

Basophils have been isolated in labs before but not nearly this quickly and efficiently, Dr. Tang says.

“For true basophil activation, you need the blood to be fresh, which is challenging when you have to send it to a lab,” Dr. Tang says. “Being able to do this kind of test within a clinic or an in-house lab would be a big step forward.”

Next steps

While this represents a breakthrough in basophil activation testing, more research is needed to fully develop the system for clinical use. It must be standardized, automated, and miniaturized, the researchers say.

That said, the results give hope to those with food allergies that tomorrow’s gold-standard test will require only a blood sample without an emergency team standing by.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

What would you do if you believed you had a serious health issue, but the best way to find out for sure might kill you?

That’s the reality for patients who wish to confirm or rule out a food allergy, says Sindy Tang, PhD, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford (Calif.) University.

And it’s the reason Dr. Tang and her colleagues are developing a food allergy test that’s not only safer, but also more reliable than today’s tests. In a paper in the journal Lab on a Chip, Dr. Tang and her colleagues outline the basis for this future test, which isolates a food allergy marker from the blood using a magnetic field.

How today’s food allergy tests fall short

The gold standard for food allergy diagnosis is something called the oral food challenge. That’s when the patient eats gradually increasing amounts of a problem food – say, peanuts – every 15 to 30 minutes to see if symptoms occur. This means highly allergic patients may risk anaphylaxis, an allergic reaction that causes inflammation so severe that breathing becomes restricted and blood pressure drops. Because of that, a clinical team must be at the ready with treatments like oxygen, epinephrine, or albuterol.

“The test is very accurate, but it’s also potentially unsafe and even fatal in rare cases,” Dr. Tang says. “That’s led to many sham tests advertised online that claim to use hair samples for food tests, but those are inaccurate and potentially dangerous, since they may give someone a false sense of confidence about a food they should avoid.”

Less risky tests are available, such as skin-prick tests – those involve scratching a small amount of the food into a patient’s arm – as well as blood tests that measure allergen-specific antibodies.

“Unfortunately, both of those are not that accurate and have high false-positive rates,” Dr. Tang says. “The best method is the oral food challenge, which many patients are afraid to do, not surprisingly.”

The future of food allergy testing: faster, safer, more reliable

In their study, the Stanford researchers focused on a type of white blood cell known as basophils, which release histamine when triggered by allergens. By using magnetic nanoparticles that bind to some blood cells but not basophils, they were able to separate basophils from the blood with a magnetic field in just 10 minutes.

Once isolated, the basophils are exposed to potential allergens. If they react, that’s a sign of an allergy.

Basophils have been isolated in labs before but not nearly this quickly and efficiently, Dr. Tang says.

“For true basophil activation, you need the blood to be fresh, which is challenging when you have to send it to a lab,” Dr. Tang says. “Being able to do this kind of test within a clinic or an in-house lab would be a big step forward.”

Next steps

While this represents a breakthrough in basophil activation testing, more research is needed to fully develop the system for clinical use. It must be standardized, automated, and miniaturized, the researchers say.

That said, the results give hope to those with food allergies that tomorrow’s gold-standard test will require only a blood sample without an emergency team standing by.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

What would you do if you believed you had a serious health issue, but the best way to find out for sure might kill you?

That’s the reality for patients who wish to confirm or rule out a food allergy, says Sindy Tang, PhD, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford (Calif.) University.

And it’s the reason Dr. Tang and her colleagues are developing a food allergy test that’s not only safer, but also more reliable than today’s tests. In a paper in the journal Lab on a Chip, Dr. Tang and her colleagues outline the basis for this future test, which isolates a food allergy marker from the blood using a magnetic field.

How today’s food allergy tests fall short

The gold standard for food allergy diagnosis is something called the oral food challenge. That’s when the patient eats gradually increasing amounts of a problem food – say, peanuts – every 15 to 30 minutes to see if symptoms occur. This means highly allergic patients may risk anaphylaxis, an allergic reaction that causes inflammation so severe that breathing becomes restricted and blood pressure drops. Because of that, a clinical team must be at the ready with treatments like oxygen, epinephrine, or albuterol.

“The test is very accurate, but it’s also potentially unsafe and even fatal in rare cases,” Dr. Tang says. “That’s led to many sham tests advertised online that claim to use hair samples for food tests, but those are inaccurate and potentially dangerous, since they may give someone a false sense of confidence about a food they should avoid.”

Less risky tests are available, such as skin-prick tests – those involve scratching a small amount of the food into a patient’s arm – as well as blood tests that measure allergen-specific antibodies.

“Unfortunately, both of those are not that accurate and have high false-positive rates,” Dr. Tang says. “The best method is the oral food challenge, which many patients are afraid to do, not surprisingly.”

The future of food allergy testing: faster, safer, more reliable

In their study, the Stanford researchers focused on a type of white blood cell known as basophils, which release histamine when triggered by allergens. By using magnetic nanoparticles that bind to some blood cells but not basophils, they were able to separate basophils from the blood with a magnetic field in just 10 minutes.

Once isolated, the basophils are exposed to potential allergens. If they react, that’s a sign of an allergy.

Basophils have been isolated in labs before but not nearly this quickly and efficiently, Dr. Tang says.

“For true basophil activation, you need the blood to be fresh, which is challenging when you have to send it to a lab,” Dr. Tang says. “Being able to do this kind of test within a clinic or an in-house lab would be a big step forward.”

Next steps

While this represents a breakthrough in basophil activation testing, more research is needed to fully develop the system for clinical use. It must be standardized, automated, and miniaturized, the researchers say.

That said, the results give hope to those with food allergies that tomorrow’s gold-standard test will require only a blood sample without an emergency team standing by.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Intravenous Immunoglobulin in Treating Nonventilated COVID-19 Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Hypoxia: A Pharmacoeconomic Analysis

From Sharp Memorial Hospital, San Diego, CA (Drs. Poremba, Dehner, Perreiter, Semma, and Mills), Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group, San Diego, CA (Dr. Sakoulas), and Collaborative to Halt Antibiotic-Resistant Microbes (CHARM), Department of Pediatrics, University of California San Diego School of Medicine, La Jolla, CA (Dr. Sakoulas).

Abstract

Objective: To compare the costs of hospitalization of patients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 who received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) with those of patients of similar comorbidity and illness severity who did not.

Design: Analysis 1 was a case-control study of 10 nonventilated, moderately to severely hypoxic patients with COVID-19 who received IVIG (Privigen [CSL Behring]) matched 1:2 with 20 control patients of similar age, body mass index, degree of hypoxemia, and comorbidities. Analysis 2 consisted of patients enrolled in a previously published, randomized, open-label prospective study of 14 patients with COVID-19 receiving standard of care vs 13 patients who received standard of care plus IVIG (Octagam 10% [Octapharma]).

Setting and participants: Patients with COVID-19 with moderate-to-severe hypoxemia hospitalized at a single site located in San Diego, California.

Measurements: Direct cost of hospitalization.

Results: In the first (case-control) population, mean total direct costs, including IVIG, for the treatment group were $21,982 per IVIG-treated case vs $42,431 per case for matched non-IVIG-receiving controls, representing a net cost reduction of $20,449 (48%) per case. For the second (randomized) group, mean total direct costs, including IVIG, for the treatment group were $28,268 per case vs $62,707 per case for untreated controls, representing a net cost reduction of $34,439 (55%) per case. Of the patients who did not receive IVIG, 24% had hospital costs exceeding $80,000; none of the IVIG-treated patients had costs exceeding this amount (P = .016, Fisher exact test).

Conclusion: If allocated early to the appropriate patient type (moderate-to-severe illness without end-organ comorbidities and age <70 years), IVIG can significantly reduce hospital costs in COVID-19 care. More important, in our study it reduced the demand for scarce critical care resources during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: IVIG, SARS-CoV-2, cost saving, direct hospital costs.

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) has been available in most hospitals for 4 decades, with broad therapeutic applications in the treatment of Kawasaki disease and a variety of inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, and viral diseases, via multifactorial mechanisms of immune modulation.1 Reports of COVID-19−associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults and children have supported the use of IVIG in treatment.2,3 Previous studies of IVIG treatment for COVID-19 have produced mixed results. Although retrospective studies have largely been positive,4-8 prospective clinical trials have been mixed, with some favorable results9-11 and another, more recent study showing no benefit.12 However, there is still considerable debate regarding whether some subgroups of patients with COVID-19 may benefit from IVIG; the studies that support this argument, however, have been diluted by broad clinical trials that lack granularity among the heterogeneity of patient characteristics and the timing of IVIG administration.13,14 One study suggests that patients with COVID-19 who may be particularly poised to benefit from IVIG are those who are younger, have fewer comorbidities, and are treated early.8

At our institution, we selectively utilized IVIG to treat patients within 48 hours of rapidly increasing oxygen requirements due to COVID-19, targeting those younger than 70 years, with no previous irreversible end-organ damage, no significant comorbidities (renal failure, heart failure, dementia, active cancer malignancies), and no active treatment for cancer. We analyzed the costs of care of these IVIG (Privigen) recipients and compared them to costs for patients with COVID-19 matched by comorbidities, age, and illness severity who did not receive IVIG. To look for consistency, we examined the cost of care of COVID-19 patients who received IVIG (Octagam) as compared to controls from a previously published pilot trial.10

Methods

Setting and Treatment

All patients in this study were hospitalized at a single site located in San Diego, California. Treatment patients in both cohorts received IVIG 0.5 g/kg adjusted for body weight daily for 3 consecutive days.

Patient Cohort #1: Retrospective Case-Control Trial

Intravenous immunoglobulin (Privigen 10%, CSL Behring) was utilized off-label to treat moderately to severely ill non-intensive care unit (ICU) patients with COVID-19 requiring ≥3 L of oxygen by nasal cannula who were not mechanically ventilated but were considered at high risk for respiratory failure. Preset exclusion criteria for off-label use of IVIG in the treatment of COVID-19 were age >70 years, active malignancy, organ transplant recipient, renal failure, heart failure, or dementia. Controls were obtained from a list of all admitted patients with COVID-19, matched to cases 2:1 on the basis of age (±10 years), body mass index (±1), gender, comorbidities present at admission (eg, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, lung disease, or history of tobacco use), and maximum oxygen requirements within the first 48 hours of admission. In situations where more than 2 potential matched controls were identified for a patient, the 2 controls closest in age to the treatment patient were selected. One IVIG patient was excluded because only 1 matched-age control could be found. Pregnant patients who otherwise fulfilled the criteria for IVIG administration were also excluded from this analysis.

Patient Cohort #2: Prospective, Randomized, Open-Label Trial

Use of IVIG (Octagam 10%, Octapharma) in COVID-19 was studied in a previously published, prospective, open-label randomized trial.10 This pilot trial included 16 IVIG-treated patients and 17 control patients, of which 13 and 14 patients, respectively, had hospital cost data available for analysis.10 Most notably, COVID-19 patients in this study were required to have ≥4 L of oxygen via nasal cannula to maintain arterial oxygen saturationof ≤96%.

Outcomes

Cost data were independently obtained from our finance team, which provided us with the total direct cost and the total pharmaceutical cost associated with each admission. We also compared total length of stay (LOS) and ICU LOS between treatment arms, as these were presumed to be the major drivers of cost difference.

Statistics

Nonparametric comparisons of medians were performed with the Mann-Whitney U test. Comparison of means was done by Student t test. Categorical data were analyzed by Fisher exact test.

This analysis was initiated as an internal quality assessment. It received approval from the Sharp Healthcare Institutional Review Board ([email protected]), and was granted a waiver of subject authorization and consent given the retrospective nature of the study.

Results

Case-Control Analysis

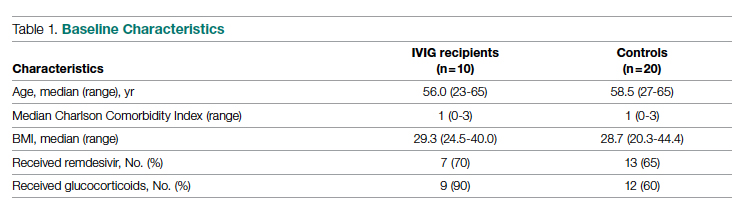

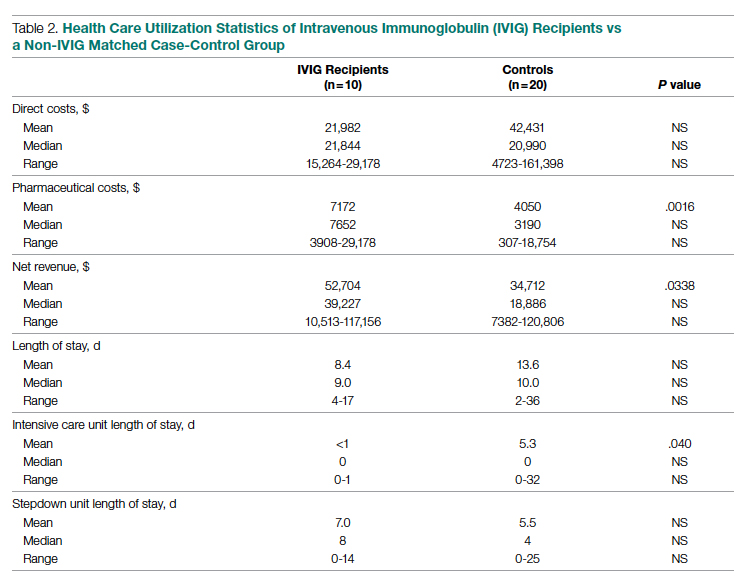

A total of 10 hypoxic patients with COVID-19 received Privigen IVIG outside of clinical trial settings. None of the patients was vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, as hospitalization occurred prior to vaccine availability. In addition, the original SARS-CoV-2 strain was circulating while these patients were hospitalized, preceding subsequent emerging variants. Oxygen requirements within the first 48 hours ranged from 3 L via nasal cannula to requiring bi-level positive pressure airway therapy with 100% oxygen; median age was 56 years and median Charlson comorbidity index was 1. These 10 patients were each matched to 2 control patients hospitalized during a comparable time period and who, based on oxygen requirements, did not receive IVIG. The 20 control patients had a median age of 58.5 years and a Charlson comorbidity index of 1 (Table 1). Rates of comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity, were identical in the 2 groups. None of the patients in either group died during the index hospitalization. Fewer control patients received glucocorticoids, which was reflective of lower illness severity/degree of hypoxia in some controls.

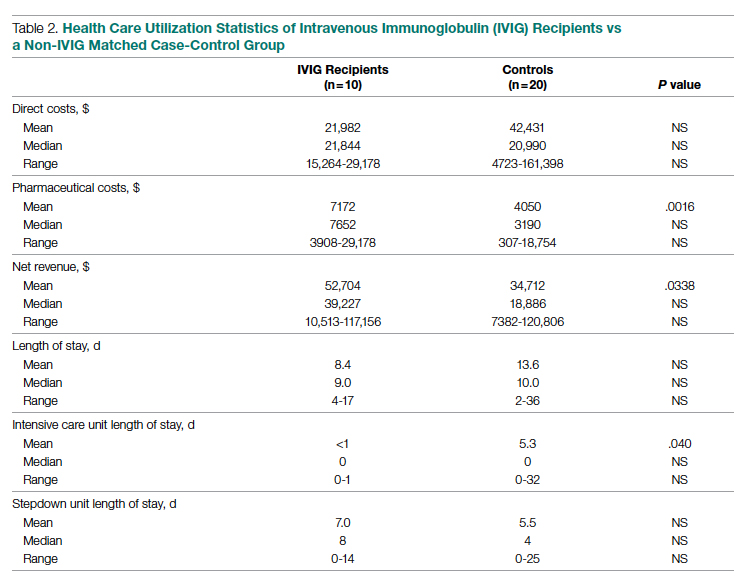

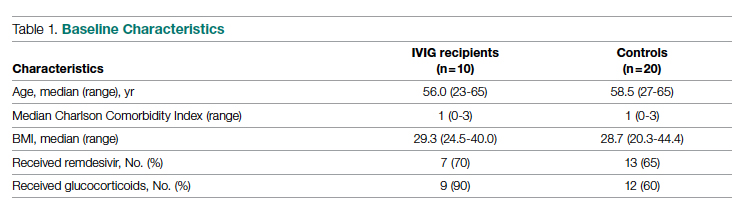

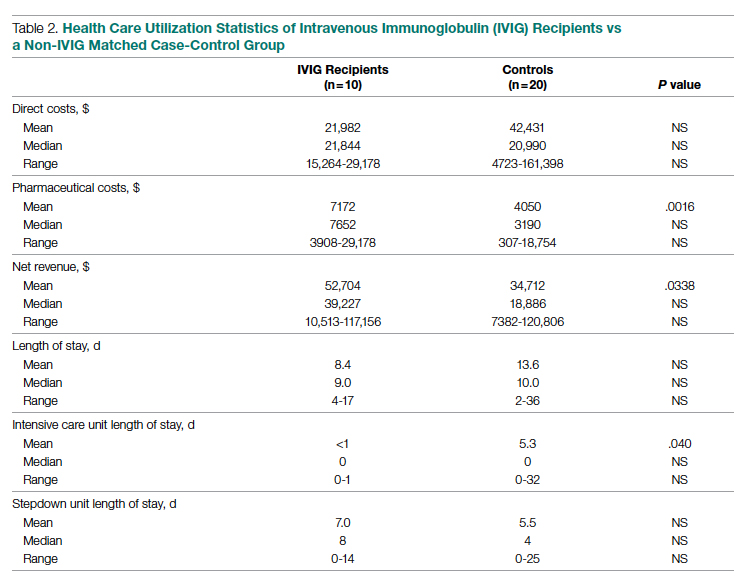

Health care utilization in terms of costs and hospital LOS between the 2 groups are shown in Table 2. The mean total direct hospital cost per case, including IVIG and other drug costs, for the 10 IVIG-treated COVID-19 patients was $21,982 vs $42,431 for the matched controls, a reduction of $20,449 (48%) per case (P = .6187) with IVIG. This difference was heavily driven by 4 control patients (20%) with hospital costs >$80,000, marked by need for ICU transfer, mechanical ventilation during admission, and longer hospital stays. This reduction in progression to mechanical ventilation was consistent with our previously published, open-label, randomized prospective IVIG study, the financial assessment of which is reviewed below. While total direct costs were lower in the treatment arm, the mean drug cost for the treatment arm was $3122 greater than the mean drug cost in the control arm (P = .001622), consistent with the high cost of IVIG therapy (Table 2).

LOS information was obtained, as this was thought to be a primary driver of direct costs. The average LOS in the IVIG arm was 8.4 days, and the average LOS in the control arm was 13.6 days (P = NS). The average ICU LOS in the IVIG arm was 0 days, while the average ICU LOS in the control arm was 5.3 days (P = .04). As with the differences in cost, the differences in LOS were primarily driven by the 4 outlier cases in our control arm, who each had a LOS >25 days, as well as an ICU LOS >20 days.

Randomized, Open-Label, Patient Cohort Analysis

Patient characteristics, LOS, and rates of mechanical ventilation for the IVIG and control patients were previously published and showed a reduction in mechanical ventilation and hospital LOS with IVIG treatment.10 In this group of patients, 1 patient treated with IVIG (6%) and 3 patients not treated with IVIG (18%) died. To determine the consistency of these results from the case-control patients with a set of patients obtained from clinical trial randomization, we examined the health care costs of patients from the prior study.10 As with the case-control group, patients in this portion of the analysis were hospitalized before vaccines were available and prior to any identified variants.

Comparing the hospital cost of the IVIG-treated patients to the control patients from this trial revealed results similar to the matched case-control analysis discussed earlier. Average total direct cost per case, including IVIG, for the IVIG treatment group was $28,268, vs $62,707 per case for non-IVIG controls. This represented a net cost reduction of $34,439 (55%) per case, very similar to that of the prior cohort.

IVIG Reduces Costly Outlier Cases

The case-control and randomized trial groups, yielding a combined 23 IVIG and 34 control patients, showed a median cost per case of $22,578 (range $10,115-$70,929) and $22,645 (range $4723-$279,797) for the IVIG and control groups, respectively. Cases with a cost >$80,000 were 0/23 (0%) vs 8/34 (24%) in the IVIG and control groups, respectively (P = .016, Fisher exact test).

Improving care while simultaneously keeping care costs below reimbursement payment levels received from third-party payers is paramount to the financial survival of health care systems. IVIG appears to do this by reducing the number of patients with COVID-19 who progress to ICU care. We compared the costs of care of our combined case-control and randomized trial cohorts to published data on average reimbursements hospitals receive for COVID-19 care from Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance (Figure).15 IVIG demonstrated a reduction in cases where costs exceed reimbursement. Indeed, a comparison of net revenue per case of the case-control group showed significantly higher revenue for the IVIG group compared to controls ($52,704 vs $34,712, P = .0338, Table 2).

Discussion

As reflected in at least 1 other study,16 our hospital had been successfully utilizing IVIG in the treatment of viral acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) prior to COVID-19. Therefore, we moved quickly to perform a randomized, open-label pilot study of IVIG (Octagam 10%) in COVID-19, and noted significant clinical benefit that might translate into hospital cost savings.10 Over the course of the pandemic, evidence has accumulated that IVIG may play an important role in COVID-19 therapeutics, as summarized in a recent review.17 However, despite promising but inconsistent results, the relatively high acquisition costs of IVIG raised questions as to its pharmacoeconomic value, particularly with such a high volume of COVID-19 patients with hypoxia, in light of limited clinical data.

COVID-19 therapeutics data can be categorized into either high-quality trials showing marginal benefit for some agents or low-quality trials showing greater benefit for other agents, with IVIG studies falling into the latter category.18 This phenomenon may speak to the pathophysiological heterogeneity of the COVID-19 patient population. High-quality trials enrolling broad patient types lack the granularity to capture and single out relevant patient subsets who would derive maximal therapeutic benefit, with those subsets diluted by other patient types for which no benefit is seen. Meanwhile, the more granular low-quality trials are criticized as underpowered and lacking in translatability to practice.

Positive results from our pilot trial allowed the use of IVIG (Privigen) off-label in hospitalized COVID-19 patients restricted to specific criteria. Patients had to be moderately to severely ill, requiring >3 L of oxygen via nasal cannula; show high risk of clinical deterioration based on respiratory rate and decline in respiratory status; and have underlying comorbidities (such as hypertension, obesity, or diabetes mellitus). However, older patients (>age 70 years) and those with underlying comorbidities marked by organ failure (such as heart failure, renal failure, dementia, or receipt of organ transplant) and active malignancy were excluded, as their clinical outcome in COVID-19 may be considered less modifiable by therapeutics, while simultaneously carrying potentially a higher risk of adverse events from IVIG (volume overload, renal failure). These exclusions are reflected in the overall low Charlson comorbidity index (mean of 1) of the patients in the case-control study arm. As anticipated, we found a net cost reduction: $20,449 (48%) per case among the 10 IVIG-treated patients compared to the 20 matched controls.

We then went back to the patients from the randomized prospective trial and compared costs for the 13 of 16 IVIG patients and 14 of 17 of the control patients for whom data were available. Among untreated controls, we found a net cost reduction of $34,439 (55%) per case. The higher costs seen in the randomized patient cohort compared to the latter case-control group may be due to a combination of the fact that the treated patients had slightly higher comorbidity indices than the case-control group (median Charlson comorbidity index of 2 in both groups) and the fact that they were treated earlier in the pandemic (May/June 2020), as opposed to the case-control group patients, who were treated in November/December 2020.

It was notable that the cost savings across both groups were derived largely from the reduction in the approximately 20% to 25% of control patients who went on to critical illness, including mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and prolonged ICU stays. Indeed, 8 of 34 of the control patients—but none of the 23 IVIG-treated patients—generated hospital costs in excess of $80,000, a difference that was statistically significant even for such a small sample size. Therefore, reducing these very costly outlier events translated into net savings across the board.

In addition to lowering costs, reducing progression to critical illness is extremely important during heavy waves of COVID-19, when the sheer volume of patients results in severe strain due to the relative scarcity of ICU beds, mechanical ventilators, and ECMO. Therefore, reducing the need for these resources would have a vital role that cannot be measured economically.

The major limitations of this study include the small sample size and the potential lack of generalizability of these results to all hospital centers and treating providers. Our group has considerable experience in IVIG utilization in COVID-19 and, as a result, has identified a “sweet spot,” where benefits were seen clinically and economically. However, it remains to be determined whether IVIG will benefit patients with greater illness severity, such as those in the ICU, on mechanical ventilation, or ECMO. Furthermore, while a significant morbidity and mortality burden of COVID-19 rests in extremely elderly patients and those with end-organ comorbidities such as renal failure and heart failure, it is uncertain whether their COVID-19 adverse outcomes can be improved with IVIG or other therapies. We believe such patients may limit the pharmacoeconomic value of IVIG due to their generally poorer prognosis, regardless of intervention. On the other hand, COVID-19 patients who are not that severely ill, with minimal to no hypoxia, generally will do well regardless of therapy. Therefore, IVIG intervention may be an unnecessary treatment expense. Evidence for this was suggested in our pilot trial10 and supported in a recent meta-analysis of IVIG therapy in COVID-19.19

Several other therapeutic options with high acquisition costs have seen an increase in use during the COVID-19 pandemic despite relatively lukewarm data. Remdesivir, the first drug found to have a beneficial effect on hospitalized patients with COVID-19, is priced at $3120 for a complete 5-day treatment course in the United States. This was in line with initial pricing models from the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) in May 2020, assuming a mortality benefit with remdesivir use. After the SOLIDARITY trial was published, which showed no mortality benefit associated with remdesivir, ICER updated their pricing models in June 2020 and released a statement that the price of remdesivir was too high to align with demonstrated benefits.20,21 More recent data demonstrate that remdesivir may be beneficial, but only if administered to patients with fewer than 6 days of symptoms.22 However, only a minority of patients present to the hospital early enough in their illness for remdesivir to be beneficial.22

Tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 inhibitor, saw an increase in use during the pandemic. An 800-mg treatment course for COVID-19 costs $3584. The efficacy of this treatment option came into question after the COVACTA trial failed to show a difference in clinical status or mortality in COVID-19 patients who received tocilizumab vs placebo.23,24 A more recent study pointed to a survival benefit of tocilizumab in COVID-19, driven by a very large sample size (>4000), yielding statistically significant, but perhaps clinically less significant, effects on survival.25 This latter study points to the extremely large sample sizes required to capture statistically significant benefits of expensive interventions in COVID-19, which our data demonstrate may benefit only a fraction of patients (20%-25% of patients in the case of IVIG). A more granular clinical assessment of these other interventions is needed to be able to capture the patient subtypes where tocilizumab, remdesivir, and other therapies will be cost effective in the treatment of COVID-19 or other virally mediated cases of ARDS.

Conclusion

While IVIG has a high acquisition cost, the drug’s use in hypoxic COVID-19 patients resulted in reduced costs per COVID-19 case of approximately 50% and use of less critical care resources. The difference was consistent between 2 cohorts (randomized trial vs off-label use in prespecified COVID-19 patient types), IVIG products used (Octagam 10% and Privigen), and time period in the pandemic (waves 1 and 2 in May/June 2020 vs wave 3 in November/December 2020), thereby adjusting for potential differences in circulating viral strains. Furthermore, patients from both groups predated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine availability and major circulating viral variants (eg, delta, omicron), thereby eliminating confounding on outcomes posed by these factors. Control patients’ higher costs of care were driven largely by the approximately 25% of patients who required costly hospital critical care resources, a group mitigated by IVIG. When allocated to the appropriate patient type (patients with moderate-to-severe but not critical illness, <age 70 without preexisting comorbidities of end-organ failure or active cancer), IVIG can reduce hospital costs for COVID-19 care. Identification of specific patient populations where IVIG has the most anticipated benefits in viral illness is needed.

Corresponding author: George Sakoulas, MD, Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group, 2020 Genesee Avenue, 2nd Floor, San Diego, CA 92123; [email protected]

Disclosures: Dr Sakoulas has worked as a consultant for Abbvie, Paratek, and Octapharma, has served as a speaker for Abbvie and Paratek, and has received research funding from Octapharma. The other authors did not report any disclosures.

1. Galeotti C, Kaveri SV, Bayry J. IVIG-mediated effector functions in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Int Immunol. 2017;29(11):491-498. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxx039

2. Verdoni L, Mazza A, Gervasoni A, et al. An outbreak of severe Kawasaki-like disease at the Italian epicentre of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1771-1778. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31103-X

3. Belhadjer Z, Méot M, Bajolle F, et al. Acute heart failure in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in the context of global SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Circulation. 2020;142(5):429-436. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048360

4. Shao Z, Feng Y, Zhong L, et al. Clinical efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in critical ill patients with COVID-19: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Clin Transl Immunology. 2020;9(10):e1192. doi:10.1002/cti2.1192

5. Xie Y, Cao S, Dong H, et al. Effect of regular intravenous immunoglobulin therapy on prognosis of severe pneumonia in patients with COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;81(2):318-356. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.044

6. Zhou ZG, Xie SM, Zhang J, et al. Short-term moderate-dose corticosteroid plus immunoglobulin effectively reverses COVID-19 patients who have failed low-dose therapy. Preprints. 2020:2020030065. doi:10.20944/preprints202003.0065.v1

7. Cao W, Liu X, Bai T, et al. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin as a therapeutic option for deteriorating patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(3):ofaa102. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofaa102

8. Cao W, Liu X, Hong K, et al. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin in severe coronavirus disease 2019: a multicenter retrospective study in China. Front Immunol. 2021;12:627844. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.627844

9. Gharebaghi N, Nejadrahim R, Mousavi SJ, Sadat-Ebrahimi SR, Hajizadeh R. The use of intravenous immunoglobulin gamma for the treatment of severe coronavirus disease 2019: a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind clinical trial. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):786. doi:10.1186/s12879-020-05507-4

10. Sakoulas G, Geriak M, Kullar R, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin plus methylprednisolone mitigate respiratory morbidity in coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2(11):e0280. doi:10.1097/CCE.0000000000000280

11. Raman RS, Bhagwan Barge V, Anil Kumar D, et al. A phase II safety and efficacy study on prognosis of moderate pneumonia in coronavirus disease 2019 patients with regular intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. J Infect Dis. 2021;223(9):1538-1543. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiab098

12. Mazeraud A, Jamme M, Mancusi RL, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulins in patients with COVID-19-associated moderate-to-severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ICAR): multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10(2):158-166. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00440-9

13. Kindgen-Milles D, Feldt T, Jensen BEO, Dimski T, Brandenburger T. Why the application of IVIG might be beneficial in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10(2):e15. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00549-X

14. Wilfong EM, Matthay MA. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for COVID-19 ARDS. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10(2):123-125. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00450-1

15. Bazell C, Kramer M, Mraz M, Silseth S. How much are hospitals paid for inpatient COVID-19 treatment? June 2020. https://us.milliman.com/-/media/milliman/pdfs/articles/how-much-hospitals-paid-for-inpatient-covid19-treatment.ashx

16. Liu X, Cao W, Li T. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulins in the treatment of severe acute viral pneumonia: the known mechanisms and clinical effects. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1660. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.01660

17. Danieli MG, Piga MA, Paladini A, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin as an important adjunct in prevention and therapy of coronavirus 19 disease. Scand J Immunol. 2021;94(5):e13101. doi:10.1111/sji.13101

18. Starshinova A, Malkova A, Zinchenko U, et al. Efficacy of different types of therapy for COVID-19: a comprehensive review. Life (Basel). 2021;11(8):753. doi:10.3390/life11080753

19. Xiang HR, Cheng X, Li Y, Luo WW, Zhang QZ, Peng WX. Efficacy of IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin) for corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;96:107732. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107732

20. ICER’s second update to pricing models of remdesivir for COVID-19. PharmacoEcon Outcomes News. 2020;867(1):2. doi:10.1007/s40274-020-7299-y

21. Pan H, Peto R, Henao-Restrepo AM, et al. Repurposed antiviral drugs for Covid-19—interim WHO solidarity trial results. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(6):497-511. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2023184

22. Garcia-Vidal C, Alonso R, Camon AM, et al. Impact of remdesivir according to the pre-admission symptom duration in patients with COVID-19. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;76(12):3296-3302. doi:10.1093/jac/dkab321

23. Golimumab (Simponi) IV: In combination with methotrexate (MTX) for the treatment of adult patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis [Internet]. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2015. Table 1: Cost comparison table for biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK349397/table/T34/

24. Rosas IO, Bräu N, Waters M, et al. Tocilizumab in hospitalized patients with severe Covid-19 pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(16):1503-1516. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2028700

25. RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Tocilizumab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10285):1637-1645. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00676-0

From Sharp Memorial Hospital, San Diego, CA (Drs. Poremba, Dehner, Perreiter, Semma, and Mills), Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group, San Diego, CA (Dr. Sakoulas), and Collaborative to Halt Antibiotic-Resistant Microbes (CHARM), Department of Pediatrics, University of California San Diego School of Medicine, La Jolla, CA (Dr. Sakoulas).

Abstract

Objective: To compare the costs of hospitalization of patients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 who received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) with those of patients of similar comorbidity and illness severity who did not.

Design: Analysis 1 was a case-control study of 10 nonventilated, moderately to severely hypoxic patients with COVID-19 who received IVIG (Privigen [CSL Behring]) matched 1:2 with 20 control patients of similar age, body mass index, degree of hypoxemia, and comorbidities. Analysis 2 consisted of patients enrolled in a previously published, randomized, open-label prospective study of 14 patients with COVID-19 receiving standard of care vs 13 patients who received standard of care plus IVIG (Octagam 10% [Octapharma]).

Setting and participants: Patients with COVID-19 with moderate-to-severe hypoxemia hospitalized at a single site located in San Diego, California.

Measurements: Direct cost of hospitalization.

Results: In the first (case-control) population, mean total direct costs, including IVIG, for the treatment group were $21,982 per IVIG-treated case vs $42,431 per case for matched non-IVIG-receiving controls, representing a net cost reduction of $20,449 (48%) per case. For the second (randomized) group, mean total direct costs, including IVIG, for the treatment group were $28,268 per case vs $62,707 per case for untreated controls, representing a net cost reduction of $34,439 (55%) per case. Of the patients who did not receive IVIG, 24% had hospital costs exceeding $80,000; none of the IVIG-treated patients had costs exceeding this amount (P = .016, Fisher exact test).

Conclusion: If allocated early to the appropriate patient type (moderate-to-severe illness without end-organ comorbidities and age <70 years), IVIG can significantly reduce hospital costs in COVID-19 care. More important, in our study it reduced the demand for scarce critical care resources during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: IVIG, SARS-CoV-2, cost saving, direct hospital costs.

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) has been available in most hospitals for 4 decades, with broad therapeutic applications in the treatment of Kawasaki disease and a variety of inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, and viral diseases, via multifactorial mechanisms of immune modulation.1 Reports of COVID-19−associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults and children have supported the use of IVIG in treatment.2,3 Previous studies of IVIG treatment for COVID-19 have produced mixed results. Although retrospective studies have largely been positive,4-8 prospective clinical trials have been mixed, with some favorable results9-11 and another, more recent study showing no benefit.12 However, there is still considerable debate regarding whether some subgroups of patients with COVID-19 may benefit from IVIG; the studies that support this argument, however, have been diluted by broad clinical trials that lack granularity among the heterogeneity of patient characteristics and the timing of IVIG administration.13,14 One study suggests that patients with COVID-19 who may be particularly poised to benefit from IVIG are those who are younger, have fewer comorbidities, and are treated early.8

At our institution, we selectively utilized IVIG to treat patients within 48 hours of rapidly increasing oxygen requirements due to COVID-19, targeting those younger than 70 years, with no previous irreversible end-organ damage, no significant comorbidities (renal failure, heart failure, dementia, active cancer malignancies), and no active treatment for cancer. We analyzed the costs of care of these IVIG (Privigen) recipients and compared them to costs for patients with COVID-19 matched by comorbidities, age, and illness severity who did not receive IVIG. To look for consistency, we examined the cost of care of COVID-19 patients who received IVIG (Octagam) as compared to controls from a previously published pilot trial.10

Methods

Setting and Treatment

All patients in this study were hospitalized at a single site located in San Diego, California. Treatment patients in both cohorts received IVIG 0.5 g/kg adjusted for body weight daily for 3 consecutive days.

Patient Cohort #1: Retrospective Case-Control Trial

Intravenous immunoglobulin (Privigen 10%, CSL Behring) was utilized off-label to treat moderately to severely ill non-intensive care unit (ICU) patients with COVID-19 requiring ≥3 L of oxygen by nasal cannula who were not mechanically ventilated but were considered at high risk for respiratory failure. Preset exclusion criteria for off-label use of IVIG in the treatment of COVID-19 were age >70 years, active malignancy, organ transplant recipient, renal failure, heart failure, or dementia. Controls were obtained from a list of all admitted patients with COVID-19, matched to cases 2:1 on the basis of age (±10 years), body mass index (±1), gender, comorbidities present at admission (eg, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, lung disease, or history of tobacco use), and maximum oxygen requirements within the first 48 hours of admission. In situations where more than 2 potential matched controls were identified for a patient, the 2 controls closest in age to the treatment patient were selected. One IVIG patient was excluded because only 1 matched-age control could be found. Pregnant patients who otherwise fulfilled the criteria for IVIG administration were also excluded from this analysis.

Patient Cohort #2: Prospective, Randomized, Open-Label Trial

Use of IVIG (Octagam 10%, Octapharma) in COVID-19 was studied in a previously published, prospective, open-label randomized trial.10 This pilot trial included 16 IVIG-treated patients and 17 control patients, of which 13 and 14 patients, respectively, had hospital cost data available for analysis.10 Most notably, COVID-19 patients in this study were required to have ≥4 L of oxygen via nasal cannula to maintain arterial oxygen saturationof ≤96%.

Outcomes

Cost data were independently obtained from our finance team, which provided us with the total direct cost and the total pharmaceutical cost associated with each admission. We also compared total length of stay (LOS) and ICU LOS between treatment arms, as these were presumed to be the major drivers of cost difference.

Statistics

Nonparametric comparisons of medians were performed with the Mann-Whitney U test. Comparison of means was done by Student t test. Categorical data were analyzed by Fisher exact test.

This analysis was initiated as an internal quality assessment. It received approval from the Sharp Healthcare Institutional Review Board ([email protected]), and was granted a waiver of subject authorization and consent given the retrospective nature of the study.

Results

Case-Control Analysis

A total of 10 hypoxic patients with COVID-19 received Privigen IVIG outside of clinical trial settings. None of the patients was vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, as hospitalization occurred prior to vaccine availability. In addition, the original SARS-CoV-2 strain was circulating while these patients were hospitalized, preceding subsequent emerging variants. Oxygen requirements within the first 48 hours ranged from 3 L via nasal cannula to requiring bi-level positive pressure airway therapy with 100% oxygen; median age was 56 years and median Charlson comorbidity index was 1. These 10 patients were each matched to 2 control patients hospitalized during a comparable time period and who, based on oxygen requirements, did not receive IVIG. The 20 control patients had a median age of 58.5 years and a Charlson comorbidity index of 1 (Table 1). Rates of comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity, were identical in the 2 groups. None of the patients in either group died during the index hospitalization. Fewer control patients received glucocorticoids, which was reflective of lower illness severity/degree of hypoxia in some controls.

Health care utilization in terms of costs and hospital LOS between the 2 groups are shown in Table 2. The mean total direct hospital cost per case, including IVIG and other drug costs, for the 10 IVIG-treated COVID-19 patients was $21,982 vs $42,431 for the matched controls, a reduction of $20,449 (48%) per case (P = .6187) with IVIG. This difference was heavily driven by 4 control patients (20%) with hospital costs >$80,000, marked by need for ICU transfer, mechanical ventilation during admission, and longer hospital stays. This reduction in progression to mechanical ventilation was consistent with our previously published, open-label, randomized prospective IVIG study, the financial assessment of which is reviewed below. While total direct costs were lower in the treatment arm, the mean drug cost for the treatment arm was $3122 greater than the mean drug cost in the control arm (P = .001622), consistent with the high cost of IVIG therapy (Table 2).

LOS information was obtained, as this was thought to be a primary driver of direct costs. The average LOS in the IVIG arm was 8.4 days, and the average LOS in the control arm was 13.6 days (P = NS). The average ICU LOS in the IVIG arm was 0 days, while the average ICU LOS in the control arm was 5.3 days (P = .04). As with the differences in cost, the differences in LOS were primarily driven by the 4 outlier cases in our control arm, who each had a LOS >25 days, as well as an ICU LOS >20 days.

Randomized, Open-Label, Patient Cohort Analysis

Patient characteristics, LOS, and rates of mechanical ventilation for the IVIG and control patients were previously published and showed a reduction in mechanical ventilation and hospital LOS with IVIG treatment.10 In this group of patients, 1 patient treated with IVIG (6%) and 3 patients not treated with IVIG (18%) died. To determine the consistency of these results from the case-control patients with a set of patients obtained from clinical trial randomization, we examined the health care costs of patients from the prior study.10 As with the case-control group, patients in this portion of the analysis were hospitalized before vaccines were available and prior to any identified variants.

Comparing the hospital cost of the IVIG-treated patients to the control patients from this trial revealed results similar to the matched case-control analysis discussed earlier. Average total direct cost per case, including IVIG, for the IVIG treatment group was $28,268, vs $62,707 per case for non-IVIG controls. This represented a net cost reduction of $34,439 (55%) per case, very similar to that of the prior cohort.

IVIG Reduces Costly Outlier Cases

The case-control and randomized trial groups, yielding a combined 23 IVIG and 34 control patients, showed a median cost per case of $22,578 (range $10,115-$70,929) and $22,645 (range $4723-$279,797) for the IVIG and control groups, respectively. Cases with a cost >$80,000 were 0/23 (0%) vs 8/34 (24%) in the IVIG and control groups, respectively (P = .016, Fisher exact test).

Improving care while simultaneously keeping care costs below reimbursement payment levels received from third-party payers is paramount to the financial survival of health care systems. IVIG appears to do this by reducing the number of patients with COVID-19 who progress to ICU care. We compared the costs of care of our combined case-control and randomized trial cohorts to published data on average reimbursements hospitals receive for COVID-19 care from Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance (Figure).15 IVIG demonstrated a reduction in cases where costs exceed reimbursement. Indeed, a comparison of net revenue per case of the case-control group showed significantly higher revenue for the IVIG group compared to controls ($52,704 vs $34,712, P = .0338, Table 2).

Discussion

As reflected in at least 1 other study,16 our hospital had been successfully utilizing IVIG in the treatment of viral acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) prior to COVID-19. Therefore, we moved quickly to perform a randomized, open-label pilot study of IVIG (Octagam 10%) in COVID-19, and noted significant clinical benefit that might translate into hospital cost savings.10 Over the course of the pandemic, evidence has accumulated that IVIG may play an important role in COVID-19 therapeutics, as summarized in a recent review.17 However, despite promising but inconsistent results, the relatively high acquisition costs of IVIG raised questions as to its pharmacoeconomic value, particularly with such a high volume of COVID-19 patients with hypoxia, in light of limited clinical data.

COVID-19 therapeutics data can be categorized into either high-quality trials showing marginal benefit for some agents or low-quality trials showing greater benefit for other agents, with IVIG studies falling into the latter category.18 This phenomenon may speak to the pathophysiological heterogeneity of the COVID-19 patient population. High-quality trials enrolling broad patient types lack the granularity to capture and single out relevant patient subsets who would derive maximal therapeutic benefit, with those subsets diluted by other patient types for which no benefit is seen. Meanwhile, the more granular low-quality trials are criticized as underpowered and lacking in translatability to practice.

Positive results from our pilot trial allowed the use of IVIG (Privigen) off-label in hospitalized COVID-19 patients restricted to specific criteria. Patients had to be moderately to severely ill, requiring >3 L of oxygen via nasal cannula; show high risk of clinical deterioration based on respiratory rate and decline in respiratory status; and have underlying comorbidities (such as hypertension, obesity, or diabetes mellitus). However, older patients (>age 70 years) and those with underlying comorbidities marked by organ failure (such as heart failure, renal failure, dementia, or receipt of organ transplant) and active malignancy were excluded, as their clinical outcome in COVID-19 may be considered less modifiable by therapeutics, while simultaneously carrying potentially a higher risk of adverse events from IVIG (volume overload, renal failure). These exclusions are reflected in the overall low Charlson comorbidity index (mean of 1) of the patients in the case-control study arm. As anticipated, we found a net cost reduction: $20,449 (48%) per case among the 10 IVIG-treated patients compared to the 20 matched controls.

We then went back to the patients from the randomized prospective trial and compared costs for the 13 of 16 IVIG patients and 14 of 17 of the control patients for whom data were available. Among untreated controls, we found a net cost reduction of $34,439 (55%) per case. The higher costs seen in the randomized patient cohort compared to the latter case-control group may be due to a combination of the fact that the treated patients had slightly higher comorbidity indices than the case-control group (median Charlson comorbidity index of 2 in both groups) and the fact that they were treated earlier in the pandemic (May/June 2020), as opposed to the case-control group patients, who were treated in November/December 2020.

It was notable that the cost savings across both groups were derived largely from the reduction in the approximately 20% to 25% of control patients who went on to critical illness, including mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and prolonged ICU stays. Indeed, 8 of 34 of the control patients—but none of the 23 IVIG-treated patients—generated hospital costs in excess of $80,000, a difference that was statistically significant even for such a small sample size. Therefore, reducing these very costly outlier events translated into net savings across the board.

In addition to lowering costs, reducing progression to critical illness is extremely important during heavy waves of COVID-19, when the sheer volume of patients results in severe strain due to the relative scarcity of ICU beds, mechanical ventilators, and ECMO. Therefore, reducing the need for these resources would have a vital role that cannot be measured economically.

The major limitations of this study include the small sample size and the potential lack of generalizability of these results to all hospital centers and treating providers. Our group has considerable experience in IVIG utilization in COVID-19 and, as a result, has identified a “sweet spot,” where benefits were seen clinically and economically. However, it remains to be determined whether IVIG will benefit patients with greater illness severity, such as those in the ICU, on mechanical ventilation, or ECMO. Furthermore, while a significant morbidity and mortality burden of COVID-19 rests in extremely elderly patients and those with end-organ comorbidities such as renal failure and heart failure, it is uncertain whether their COVID-19 adverse outcomes can be improved with IVIG or other therapies. We believe such patients may limit the pharmacoeconomic value of IVIG due to their generally poorer prognosis, regardless of intervention. On the other hand, COVID-19 patients who are not that severely ill, with minimal to no hypoxia, generally will do well regardless of therapy. Therefore, IVIG intervention may be an unnecessary treatment expense. Evidence for this was suggested in our pilot trial10 and supported in a recent meta-analysis of IVIG therapy in COVID-19.19

Several other therapeutic options with high acquisition costs have seen an increase in use during the COVID-19 pandemic despite relatively lukewarm data. Remdesivir, the first drug found to have a beneficial effect on hospitalized patients with COVID-19, is priced at $3120 for a complete 5-day treatment course in the United States. This was in line with initial pricing models from the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) in May 2020, assuming a mortality benefit with remdesivir use. After the SOLIDARITY trial was published, which showed no mortality benefit associated with remdesivir, ICER updated their pricing models in June 2020 and released a statement that the price of remdesivir was too high to align with demonstrated benefits.20,21 More recent data demonstrate that remdesivir may be beneficial, but only if administered to patients with fewer than 6 days of symptoms.22 However, only a minority of patients present to the hospital early enough in their illness for remdesivir to be beneficial.22

Tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 inhibitor, saw an increase in use during the pandemic. An 800-mg treatment course for COVID-19 costs $3584. The efficacy of this treatment option came into question after the COVACTA trial failed to show a difference in clinical status or mortality in COVID-19 patients who received tocilizumab vs placebo.23,24 A more recent study pointed to a survival benefit of tocilizumab in COVID-19, driven by a very large sample size (>4000), yielding statistically significant, but perhaps clinically less significant, effects on survival.25 This latter study points to the extremely large sample sizes required to capture statistically significant benefits of expensive interventions in COVID-19, which our data demonstrate may benefit only a fraction of patients (20%-25% of patients in the case of IVIG). A more granular clinical assessment of these other interventions is needed to be able to capture the patient subtypes where tocilizumab, remdesivir, and other therapies will be cost effective in the treatment of COVID-19 or other virally mediated cases of ARDS.

Conclusion

While IVIG has a high acquisition cost, the drug’s use in hypoxic COVID-19 patients resulted in reduced costs per COVID-19 case of approximately 50% and use of less critical care resources. The difference was consistent between 2 cohorts (randomized trial vs off-label use in prespecified COVID-19 patient types), IVIG products used (Octagam 10% and Privigen), and time period in the pandemic (waves 1 and 2 in May/June 2020 vs wave 3 in November/December 2020), thereby adjusting for potential differences in circulating viral strains. Furthermore, patients from both groups predated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine availability and major circulating viral variants (eg, delta, omicron), thereby eliminating confounding on outcomes posed by these factors. Control patients’ higher costs of care were driven largely by the approximately 25% of patients who required costly hospital critical care resources, a group mitigated by IVIG. When allocated to the appropriate patient type (patients with moderate-to-severe but not critical illness, <age 70 without preexisting comorbidities of end-organ failure or active cancer), IVIG can reduce hospital costs for COVID-19 care. Identification of specific patient populations where IVIG has the most anticipated benefits in viral illness is needed.

Corresponding author: George Sakoulas, MD, Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group, 2020 Genesee Avenue, 2nd Floor, San Diego, CA 92123; [email protected]

Disclosures: Dr Sakoulas has worked as a consultant for Abbvie, Paratek, and Octapharma, has served as a speaker for Abbvie and Paratek, and has received research funding from Octapharma. The other authors did not report any disclosures.

From Sharp Memorial Hospital, San Diego, CA (Drs. Poremba, Dehner, Perreiter, Semma, and Mills), Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group, San Diego, CA (Dr. Sakoulas), and Collaborative to Halt Antibiotic-Resistant Microbes (CHARM), Department of Pediatrics, University of California San Diego School of Medicine, La Jolla, CA (Dr. Sakoulas).

Abstract

Objective: To compare the costs of hospitalization of patients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 who received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) with those of patients of similar comorbidity and illness severity who did not.

Design: Analysis 1 was a case-control study of 10 nonventilated, moderately to severely hypoxic patients with COVID-19 who received IVIG (Privigen [CSL Behring]) matched 1:2 with 20 control patients of similar age, body mass index, degree of hypoxemia, and comorbidities. Analysis 2 consisted of patients enrolled in a previously published, randomized, open-label prospective study of 14 patients with COVID-19 receiving standard of care vs 13 patients who received standard of care plus IVIG (Octagam 10% [Octapharma]).

Setting and participants: Patients with COVID-19 with moderate-to-severe hypoxemia hospitalized at a single site located in San Diego, California.

Measurements: Direct cost of hospitalization.

Results: In the first (case-control) population, mean total direct costs, including IVIG, for the treatment group were $21,982 per IVIG-treated case vs $42,431 per case for matched non-IVIG-receiving controls, representing a net cost reduction of $20,449 (48%) per case. For the second (randomized) group, mean total direct costs, including IVIG, for the treatment group were $28,268 per case vs $62,707 per case for untreated controls, representing a net cost reduction of $34,439 (55%) per case. Of the patients who did not receive IVIG, 24% had hospital costs exceeding $80,000; none of the IVIG-treated patients had costs exceeding this amount (P = .016, Fisher exact test).

Conclusion: If allocated early to the appropriate patient type (moderate-to-severe illness without end-organ comorbidities and age <70 years), IVIG can significantly reduce hospital costs in COVID-19 care. More important, in our study it reduced the demand for scarce critical care resources during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: IVIG, SARS-CoV-2, cost saving, direct hospital costs.

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) has been available in most hospitals for 4 decades, with broad therapeutic applications in the treatment of Kawasaki disease and a variety of inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, and viral diseases, via multifactorial mechanisms of immune modulation.1 Reports of COVID-19−associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults and children have supported the use of IVIG in treatment.2,3 Previous studies of IVIG treatment for COVID-19 have produced mixed results. Although retrospective studies have largely been positive,4-8 prospective clinical trials have been mixed, with some favorable results9-11 and another, more recent study showing no benefit.12 However, there is still considerable debate regarding whether some subgroups of patients with COVID-19 may benefit from IVIG; the studies that support this argument, however, have been diluted by broad clinical trials that lack granularity among the heterogeneity of patient characteristics and the timing of IVIG administration.13,14 One study suggests that patients with COVID-19 who may be particularly poised to benefit from IVIG are those who are younger, have fewer comorbidities, and are treated early.8

At our institution, we selectively utilized IVIG to treat patients within 48 hours of rapidly increasing oxygen requirements due to COVID-19, targeting those younger than 70 years, with no previous irreversible end-organ damage, no significant comorbidities (renal failure, heart failure, dementia, active cancer malignancies), and no active treatment for cancer. We analyzed the costs of care of these IVIG (Privigen) recipients and compared them to costs for patients with COVID-19 matched by comorbidities, age, and illness severity who did not receive IVIG. To look for consistency, we examined the cost of care of COVID-19 patients who received IVIG (Octagam) as compared to controls from a previously published pilot trial.10

Methods

Setting and Treatment

All patients in this study were hospitalized at a single site located in San Diego, California. Treatment patients in both cohorts received IVIG 0.5 g/kg adjusted for body weight daily for 3 consecutive days.

Patient Cohort #1: Retrospective Case-Control Trial

Intravenous immunoglobulin (Privigen 10%, CSL Behring) was utilized off-label to treat moderately to severely ill non-intensive care unit (ICU) patients with COVID-19 requiring ≥3 L of oxygen by nasal cannula who were not mechanically ventilated but were considered at high risk for respiratory failure. Preset exclusion criteria for off-label use of IVIG in the treatment of COVID-19 were age >70 years, active malignancy, organ transplant recipient, renal failure, heart failure, or dementia. Controls were obtained from a list of all admitted patients with COVID-19, matched to cases 2:1 on the basis of age (±10 years), body mass index (±1), gender, comorbidities present at admission (eg, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, lung disease, or history of tobacco use), and maximum oxygen requirements within the first 48 hours of admission. In situations where more than 2 potential matched controls were identified for a patient, the 2 controls closest in age to the treatment patient were selected. One IVIG patient was excluded because only 1 matched-age control could be found. Pregnant patients who otherwise fulfilled the criteria for IVIG administration were also excluded from this analysis.

Patient Cohort #2: Prospective, Randomized, Open-Label Trial

Use of IVIG (Octagam 10%, Octapharma) in COVID-19 was studied in a previously published, prospective, open-label randomized trial.10 This pilot trial included 16 IVIG-treated patients and 17 control patients, of which 13 and 14 patients, respectively, had hospital cost data available for analysis.10 Most notably, COVID-19 patients in this study were required to have ≥4 L of oxygen via nasal cannula to maintain arterial oxygen saturationof ≤96%.

Outcomes

Cost data were independently obtained from our finance team, which provided us with the total direct cost and the total pharmaceutical cost associated with each admission. We also compared total length of stay (LOS) and ICU LOS between treatment arms, as these were presumed to be the major drivers of cost difference.

Statistics

Nonparametric comparisons of medians were performed with the Mann-Whitney U test. Comparison of means was done by Student t test. Categorical data were analyzed by Fisher exact test.

This analysis was initiated as an internal quality assessment. It received approval from the Sharp Healthcare Institutional Review Board ([email protected]), and was granted a waiver of subject authorization and consent given the retrospective nature of the study.

Results

Case-Control Analysis

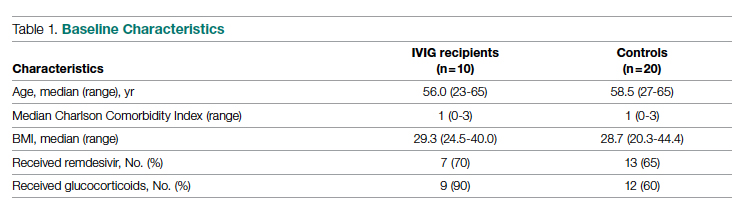

A total of 10 hypoxic patients with COVID-19 received Privigen IVIG outside of clinical trial settings. None of the patients was vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, as hospitalization occurred prior to vaccine availability. In addition, the original SARS-CoV-2 strain was circulating while these patients were hospitalized, preceding subsequent emerging variants. Oxygen requirements within the first 48 hours ranged from 3 L via nasal cannula to requiring bi-level positive pressure airway therapy with 100% oxygen; median age was 56 years and median Charlson comorbidity index was 1. These 10 patients were each matched to 2 control patients hospitalized during a comparable time period and who, based on oxygen requirements, did not receive IVIG. The 20 control patients had a median age of 58.5 years and a Charlson comorbidity index of 1 (Table 1). Rates of comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity, were identical in the 2 groups. None of the patients in either group died during the index hospitalization. Fewer control patients received glucocorticoids, which was reflective of lower illness severity/degree of hypoxia in some controls.

Health care utilization in terms of costs and hospital LOS between the 2 groups are shown in Table 2. The mean total direct hospital cost per case, including IVIG and other drug costs, for the 10 IVIG-treated COVID-19 patients was $21,982 vs $42,431 for the matched controls, a reduction of $20,449 (48%) per case (P = .6187) with IVIG. This difference was heavily driven by 4 control patients (20%) with hospital costs >$80,000, marked by need for ICU transfer, mechanical ventilation during admission, and longer hospital stays. This reduction in progression to mechanical ventilation was consistent with our previously published, open-label, randomized prospective IVIG study, the financial assessment of which is reviewed below. While total direct costs were lower in the treatment arm, the mean drug cost for the treatment arm was $3122 greater than the mean drug cost in the control arm (P = .001622), consistent with the high cost of IVIG therapy (Table 2).

LOS information was obtained, as this was thought to be a primary driver of direct costs. The average LOS in the IVIG arm was 8.4 days, and the average LOS in the control arm was 13.6 days (P = NS). The average ICU LOS in the IVIG arm was 0 days, while the average ICU LOS in the control arm was 5.3 days (P = .04). As with the differences in cost, the differences in LOS were primarily driven by the 4 outlier cases in our control arm, who each had a LOS >25 days, as well as an ICU LOS >20 days.

Randomized, Open-Label, Patient Cohort Analysis

Patient characteristics, LOS, and rates of mechanical ventilation for the IVIG and control patients were previously published and showed a reduction in mechanical ventilation and hospital LOS with IVIG treatment.10 In this group of patients, 1 patient treated with IVIG (6%) and 3 patients not treated with IVIG (18%) died. To determine the consistency of these results from the case-control patients with a set of patients obtained from clinical trial randomization, we examined the health care costs of patients from the prior study.10 As with the case-control group, patients in this portion of the analysis were hospitalized before vaccines were available and prior to any identified variants.

Comparing the hospital cost of the IVIG-treated patients to the control patients from this trial revealed results similar to the matched case-control analysis discussed earlier. Average total direct cost per case, including IVIG, for the IVIG treatment group was $28,268, vs $62,707 per case for non-IVIG controls. This represented a net cost reduction of $34,439 (55%) per case, very similar to that of the prior cohort.

IVIG Reduces Costly Outlier Cases

The case-control and randomized trial groups, yielding a combined 23 IVIG and 34 control patients, showed a median cost per case of $22,578 (range $10,115-$70,929) and $22,645 (range $4723-$279,797) for the IVIG and control groups, respectively. Cases with a cost >$80,000 were 0/23 (0%) vs 8/34 (24%) in the IVIG and control groups, respectively (P = .016, Fisher exact test).

Improving care while simultaneously keeping care costs below reimbursement payment levels received from third-party payers is paramount to the financial survival of health care systems. IVIG appears to do this by reducing the number of patients with COVID-19 who progress to ICU care. We compared the costs of care of our combined case-control and randomized trial cohorts to published data on average reimbursements hospitals receive for COVID-19 care from Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance (Figure).15 IVIG demonstrated a reduction in cases where costs exceed reimbursement. Indeed, a comparison of net revenue per case of the case-control group showed significantly higher revenue for the IVIG group compared to controls ($52,704 vs $34,712, P = .0338, Table 2).

Discussion

As reflected in at least 1 other study,16 our hospital had been successfully utilizing IVIG in the treatment of viral acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) prior to COVID-19. Therefore, we moved quickly to perform a randomized, open-label pilot study of IVIG (Octagam 10%) in COVID-19, and noted significant clinical benefit that might translate into hospital cost savings.10 Over the course of the pandemic, evidence has accumulated that IVIG may play an important role in COVID-19 therapeutics, as summarized in a recent review.17 However, despite promising but inconsistent results, the relatively high acquisition costs of IVIG raised questions as to its pharmacoeconomic value, particularly with such a high volume of COVID-19 patients with hypoxia, in light of limited clinical data.

COVID-19 therapeutics data can be categorized into either high-quality trials showing marginal benefit for some agents or low-quality trials showing greater benefit for other agents, with IVIG studies falling into the latter category.18 This phenomenon may speak to the pathophysiological heterogeneity of the COVID-19 patient population. High-quality trials enrolling broad patient types lack the granularity to capture and single out relevant patient subsets who would derive maximal therapeutic benefit, with those subsets diluted by other patient types for which no benefit is seen. Meanwhile, the more granular low-quality trials are criticized as underpowered and lacking in translatability to practice.

Positive results from our pilot trial allowed the use of IVIG (Privigen) off-label in hospitalized COVID-19 patients restricted to specific criteria. Patients had to be moderately to severely ill, requiring >3 L of oxygen via nasal cannula; show high risk of clinical deterioration based on respiratory rate and decline in respiratory status; and have underlying comorbidities (such as hypertension, obesity, or diabetes mellitus). However, older patients (>age 70 years) and those with underlying comorbidities marked by organ failure (such as heart failure, renal failure, dementia, or receipt of organ transplant) and active malignancy were excluded, as their clinical outcome in COVID-19 may be considered less modifiable by therapeutics, while simultaneously carrying potentially a higher risk of adverse events from IVIG (volume overload, renal failure). These exclusions are reflected in the overall low Charlson comorbidity index (mean of 1) of the patients in the case-control study arm. As anticipated, we found a net cost reduction: $20,449 (48%) per case among the 10 IVIG-treated patients compared to the 20 matched controls.

We then went back to the patients from the randomized prospective trial and compared costs for the 13 of 16 IVIG patients and 14 of 17 of the control patients for whom data were available. Among untreated controls, we found a net cost reduction of $34,439 (55%) per case. The higher costs seen in the randomized patient cohort compared to the latter case-control group may be due to a combination of the fact that the treated patients had slightly higher comorbidity indices than the case-control group (median Charlson comorbidity index of 2 in both groups) and the fact that they were treated earlier in the pandemic (May/June 2020), as opposed to the case-control group patients, who were treated in November/December 2020.

It was notable that the cost savings across both groups were derived largely from the reduction in the approximately 20% to 25% of control patients who went on to critical illness, including mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and prolonged ICU stays. Indeed, 8 of 34 of the control patients—but none of the 23 IVIG-treated patients—generated hospital costs in excess of $80,000, a difference that was statistically significant even for such a small sample size. Therefore, reducing these very costly outlier events translated into net savings across the board.

In addition to lowering costs, reducing progression to critical illness is extremely important during heavy waves of COVID-19, when the sheer volume of patients results in severe strain due to the relative scarcity of ICU beds, mechanical ventilators, and ECMO. Therefore, reducing the need for these resources would have a vital role that cannot be measured economically.

The major limitations of this study include the small sample size and the potential lack of generalizability of these results to all hospital centers and treating providers. Our group has considerable experience in IVIG utilization in COVID-19 and, as a result, has identified a “sweet spot,” where benefits were seen clinically and economically. However, it remains to be determined whether IVIG will benefit patients with greater illness severity, such as those in the ICU, on mechanical ventilation, or ECMO. Furthermore, while a significant morbidity and mortality burden of COVID-19 rests in extremely elderly patients and those with end-organ comorbidities such as renal failure and heart failure, it is uncertain whether their COVID-19 adverse outcomes can be improved with IVIG or other therapies. We believe such patients may limit the pharmacoeconomic value of IVIG due to their generally poorer prognosis, regardless of intervention. On the other hand, COVID-19 patients who are not that severely ill, with minimal to no hypoxia, generally will do well regardless of therapy. Therefore, IVIG intervention may be an unnecessary treatment expense. Evidence for this was suggested in our pilot trial10 and supported in a recent meta-analysis of IVIG therapy in COVID-19.19

Several other therapeutic options with high acquisition costs have seen an increase in use during the COVID-19 pandemic despite relatively lukewarm data. Remdesivir, the first drug found to have a beneficial effect on hospitalized patients with COVID-19, is priced at $3120 for a complete 5-day treatment course in the United States. This was in line with initial pricing models from the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) in May 2020, assuming a mortality benefit with remdesivir use. After the SOLIDARITY trial was published, which showed no mortality benefit associated with remdesivir, ICER updated their pricing models in June 2020 and released a statement that the price of remdesivir was too high to align with demonstrated benefits.20,21 More recent data demonstrate that remdesivir may be beneficial, but only if administered to patients with fewer than 6 days of symptoms.22 However, only a minority of patients present to the hospital early enough in their illness for remdesivir to be beneficial.22

Tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 inhibitor, saw an increase in use during the pandemic. An 800-mg treatment course for COVID-19 costs $3584. The efficacy of this treatment option came into question after the COVACTA trial failed to show a difference in clinical status or mortality in COVID-19 patients who received tocilizumab vs placebo.23,24 A more recent study pointed to a survival benefit of tocilizumab in COVID-19, driven by a very large sample size (>4000), yielding statistically significant, but perhaps clinically less significant, effects on survival.25 This latter study points to the extremely large sample sizes required to capture statistically significant benefits of expensive interventions in COVID-19, which our data demonstrate may benefit only a fraction of patients (20%-25% of patients in the case of IVIG). A more granular clinical assessment of these other interventions is needed to be able to capture the patient subtypes where tocilizumab, remdesivir, and other therapies will be cost effective in the treatment of COVID-19 or other virally mediated cases of ARDS.

Conclusion