User login

When is an allergic reaction to raw plant food due to tree pollen?

A new guideline aims to help primary care doctors differentiate pollen food syndrome (PFS) – a cross-reactive allergic reaction to certain raw, but not cooked, plant foods – from other food allergies.

The guideline from the British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI) focuses on birch tree pollen, the major sensitizing PFS allergen in Northern Europe. Providers may be able to diagnose PFS related to birch pollen from clinical history alone, including the foods involved and the rapidity of symptom onset, write lead author Isabel J. Skypala, PhD, RD, of Imperial College London, and her colleagues.

The new BSACI guideline for diagnosis and management of PFS was published in Clinical & Experimental Allergy.

PFS is common and increasingly prevalent

PFS – also called oral allergy syndrome and pollen food allergy syndrome – is common and increasingly prevalent. PFS can begin at any age but usually starts in pollen-sensitized school-age children and adults with seasonal allergic rhinitis.

Symptoms from similar proteins in food

Mild to moderate allergic symptoms develop quickly when people sensitized to birch pollen eat raw plant foods that contain proteins similar to those in the pollen, such as pathogenesis-related protein PR-10. The allergens are broken down by cooking or processing.

Symptoms usually occur immediately or within 15 minutes of eating. Patients may have tingling; itching or soreness in the mouth, throat, or ears; mild lip and oral mucosa angioedema; itchy hands, sneezing, or eye symptoms; tongue or pharynx angioedema; perioral rash; cough; abdominal pain; nausea; and/or worsening of eczema. In children, itch and rash may predominate.

Triggers depend on pollen type

PFS triggers vary depending on a person’s pollen sensitization, which is affected by their geographic area and local dietary habits. In the United Kingdom, almost 70% of birch-allergic adults and more than 40% of birch-allergic children have PFS, the authors write.

Typical triggers include eating apples, stone fruits, kiwis, carrots, celery, hazelnuts, almonds, walnuts, soymilk, and peanuts, as well as peeling potatoes or other root vegetables. Freshly prepared vegetable or fruit smoothies or juices, celery, soymilk, raw nuts, large quantities of roasted nuts, and concentrated nut products can cause more severe reactions.

Diagnostic clinical history

If a patient answers yes to these questions, they almost certainly have PFS, the authors write:

- Are symptoms caused by raw fruits, nuts, carrots, or celery?

- Are the same trigger foods tolerated when they’re cooked well or roasted?

- Do symptoms come immediately or within a few minutes of eating?

- Do symptoms occur in the oropharynx and include tingling, itching, or swelling?

- Does the patient have seasonal allergic rhinitis or sensitization to pollen?

Testing needed for some cases

Allergy tests may be needed for people who report atypical or severe reactions or who also react to cooked or processed plant foods, such as roasted nuts, nuts in foods, fruits or vegetables in juices and smoothies, and soy products other than milk. Tests may also be needed for people who react to foods that are not linked with PFS, such as cashews, pistachios, macadamias, sesame seeds, beans, lentils, and chickpeas.

Whether PFS reactions also occur to roasted hazelnuts, almonds, walnuts, Brazil nuts, or peanuts, either alone or in composite foods such as chocolates, spreads, desserts, and snacks, is unclear.

An oral food challenge to confirm PFS is needed only if the history and diagnostic tests are inconclusive or if the patient is avoiding multiple foods.

Dietary management

PFS is managed by excluding known trigger foods. This becomes challenging for patients with preexisting food allergies and for vegetarians and vegans.

Personalized dietary advice is needed to avoid nutritional imbalance, minimize anxiety and unnecessary food restrictions, and improve quality of life. Reactions after accidental exposure often resolve without medication, and if antihistamines are needed, they rarely require self-injectable devices.

Guideline helpful beyond the United Kingdom and birch pollen

Allyson S. Larkin, MD, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, told this news organization in an email that the guideline summarizes in great detail the pathophysiology behind PFS and highlights how component testing may help diagnose patients and manage the condition.

“Patients worry very much about the progression and severity of allergic reactions,” said Dr. Larkin, who was not involved in the guideline development.

“As the authors note, recognizing the nutritional consequences of dietary restrictions is important, and nutrition consults and suitable alternative suggestions are very helpful for these patients, especially for those with food allergy or who are vegetarian or vegan.”

Jill A. Poole, MD, professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Allergy and Immunology at the University of Nebraska College of Medicine, Omaha, noted that PFS, although common, is underrecognized by the public and by health care providers.

“People are not allergic to the specific food, but they are allergic to a seasonal allergen, such as birch tree, that cross-reacts with the food protein, which is typically changed with cooking,” she explained in an email.

“This differs from reactions by those who have moderate to severe allergic food-specific reactions that may include systemic reactions like anaphylaxis from eating certain foods,” she said.

“Importantly, the number of cross-reacting foods with seasonal pollens continues to grow, and the extent of testing has expanded in recent years,” advised Dr. Poole, who also was not involved in the guideline development.

The authors recommend further related research into food immunotherapy and other novel PFS treatments. They also want to raise awareness of factors affecting PFS prevalence, such as increased spread and allergenicity of pollen due to climate change, pollution, the global consumption of previously local traditional foods, and the increase in vegetarian and vegan diets.

The authors, Dr. Larkin, and Dr. Poole report no relevant financial relationships involving this guideline. The guideline was not funded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new guideline aims to help primary care doctors differentiate pollen food syndrome (PFS) – a cross-reactive allergic reaction to certain raw, but not cooked, plant foods – from other food allergies.

The guideline from the British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI) focuses on birch tree pollen, the major sensitizing PFS allergen in Northern Europe. Providers may be able to diagnose PFS related to birch pollen from clinical history alone, including the foods involved and the rapidity of symptom onset, write lead author Isabel J. Skypala, PhD, RD, of Imperial College London, and her colleagues.

The new BSACI guideline for diagnosis and management of PFS was published in Clinical & Experimental Allergy.

PFS is common and increasingly prevalent

PFS – also called oral allergy syndrome and pollen food allergy syndrome – is common and increasingly prevalent. PFS can begin at any age but usually starts in pollen-sensitized school-age children and adults with seasonal allergic rhinitis.

Symptoms from similar proteins in food

Mild to moderate allergic symptoms develop quickly when people sensitized to birch pollen eat raw plant foods that contain proteins similar to those in the pollen, such as pathogenesis-related protein PR-10. The allergens are broken down by cooking or processing.

Symptoms usually occur immediately or within 15 minutes of eating. Patients may have tingling; itching or soreness in the mouth, throat, or ears; mild lip and oral mucosa angioedema; itchy hands, sneezing, or eye symptoms; tongue or pharynx angioedema; perioral rash; cough; abdominal pain; nausea; and/or worsening of eczema. In children, itch and rash may predominate.

Triggers depend on pollen type

PFS triggers vary depending on a person’s pollen sensitization, which is affected by their geographic area and local dietary habits. In the United Kingdom, almost 70% of birch-allergic adults and more than 40% of birch-allergic children have PFS, the authors write.

Typical triggers include eating apples, stone fruits, kiwis, carrots, celery, hazelnuts, almonds, walnuts, soymilk, and peanuts, as well as peeling potatoes or other root vegetables. Freshly prepared vegetable or fruit smoothies or juices, celery, soymilk, raw nuts, large quantities of roasted nuts, and concentrated nut products can cause more severe reactions.

Diagnostic clinical history

If a patient answers yes to these questions, they almost certainly have PFS, the authors write:

- Are symptoms caused by raw fruits, nuts, carrots, or celery?

- Are the same trigger foods tolerated when they’re cooked well or roasted?

- Do symptoms come immediately or within a few minutes of eating?

- Do symptoms occur in the oropharynx and include tingling, itching, or swelling?

- Does the patient have seasonal allergic rhinitis or sensitization to pollen?

Testing needed for some cases

Allergy tests may be needed for people who report atypical or severe reactions or who also react to cooked or processed plant foods, such as roasted nuts, nuts in foods, fruits or vegetables in juices and smoothies, and soy products other than milk. Tests may also be needed for people who react to foods that are not linked with PFS, such as cashews, pistachios, macadamias, sesame seeds, beans, lentils, and chickpeas.

Whether PFS reactions also occur to roasted hazelnuts, almonds, walnuts, Brazil nuts, or peanuts, either alone or in composite foods such as chocolates, spreads, desserts, and snacks, is unclear.

An oral food challenge to confirm PFS is needed only if the history and diagnostic tests are inconclusive or if the patient is avoiding multiple foods.

Dietary management

PFS is managed by excluding known trigger foods. This becomes challenging for patients with preexisting food allergies and for vegetarians and vegans.

Personalized dietary advice is needed to avoid nutritional imbalance, minimize anxiety and unnecessary food restrictions, and improve quality of life. Reactions after accidental exposure often resolve without medication, and if antihistamines are needed, they rarely require self-injectable devices.

Guideline helpful beyond the United Kingdom and birch pollen

Allyson S. Larkin, MD, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, told this news organization in an email that the guideline summarizes in great detail the pathophysiology behind PFS and highlights how component testing may help diagnose patients and manage the condition.

“Patients worry very much about the progression and severity of allergic reactions,” said Dr. Larkin, who was not involved in the guideline development.

“As the authors note, recognizing the nutritional consequences of dietary restrictions is important, and nutrition consults and suitable alternative suggestions are very helpful for these patients, especially for those with food allergy or who are vegetarian or vegan.”

Jill A. Poole, MD, professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Allergy and Immunology at the University of Nebraska College of Medicine, Omaha, noted that PFS, although common, is underrecognized by the public and by health care providers.

“People are not allergic to the specific food, but they are allergic to a seasonal allergen, such as birch tree, that cross-reacts with the food protein, which is typically changed with cooking,” she explained in an email.

“This differs from reactions by those who have moderate to severe allergic food-specific reactions that may include systemic reactions like anaphylaxis from eating certain foods,” she said.

“Importantly, the number of cross-reacting foods with seasonal pollens continues to grow, and the extent of testing has expanded in recent years,” advised Dr. Poole, who also was not involved in the guideline development.

The authors recommend further related research into food immunotherapy and other novel PFS treatments. They also want to raise awareness of factors affecting PFS prevalence, such as increased spread and allergenicity of pollen due to climate change, pollution, the global consumption of previously local traditional foods, and the increase in vegetarian and vegan diets.

The authors, Dr. Larkin, and Dr. Poole report no relevant financial relationships involving this guideline. The guideline was not funded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new guideline aims to help primary care doctors differentiate pollen food syndrome (PFS) – a cross-reactive allergic reaction to certain raw, but not cooked, plant foods – from other food allergies.

The guideline from the British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI) focuses on birch tree pollen, the major sensitizing PFS allergen in Northern Europe. Providers may be able to diagnose PFS related to birch pollen from clinical history alone, including the foods involved and the rapidity of symptom onset, write lead author Isabel J. Skypala, PhD, RD, of Imperial College London, and her colleagues.

The new BSACI guideline for diagnosis and management of PFS was published in Clinical & Experimental Allergy.

PFS is common and increasingly prevalent

PFS – also called oral allergy syndrome and pollen food allergy syndrome – is common and increasingly prevalent. PFS can begin at any age but usually starts in pollen-sensitized school-age children and adults with seasonal allergic rhinitis.

Symptoms from similar proteins in food

Mild to moderate allergic symptoms develop quickly when people sensitized to birch pollen eat raw plant foods that contain proteins similar to those in the pollen, such as pathogenesis-related protein PR-10. The allergens are broken down by cooking or processing.

Symptoms usually occur immediately or within 15 minutes of eating. Patients may have tingling; itching or soreness in the mouth, throat, or ears; mild lip and oral mucosa angioedema; itchy hands, sneezing, or eye symptoms; tongue or pharynx angioedema; perioral rash; cough; abdominal pain; nausea; and/or worsening of eczema. In children, itch and rash may predominate.

Triggers depend on pollen type

PFS triggers vary depending on a person’s pollen sensitization, which is affected by their geographic area and local dietary habits. In the United Kingdom, almost 70% of birch-allergic adults and more than 40% of birch-allergic children have PFS, the authors write.

Typical triggers include eating apples, stone fruits, kiwis, carrots, celery, hazelnuts, almonds, walnuts, soymilk, and peanuts, as well as peeling potatoes or other root vegetables. Freshly prepared vegetable or fruit smoothies or juices, celery, soymilk, raw nuts, large quantities of roasted nuts, and concentrated nut products can cause more severe reactions.

Diagnostic clinical history

If a patient answers yes to these questions, they almost certainly have PFS, the authors write:

- Are symptoms caused by raw fruits, nuts, carrots, or celery?

- Are the same trigger foods tolerated when they’re cooked well or roasted?

- Do symptoms come immediately or within a few minutes of eating?

- Do symptoms occur in the oropharynx and include tingling, itching, or swelling?

- Does the patient have seasonal allergic rhinitis or sensitization to pollen?

Testing needed for some cases

Allergy tests may be needed for people who report atypical or severe reactions or who also react to cooked or processed plant foods, such as roasted nuts, nuts in foods, fruits or vegetables in juices and smoothies, and soy products other than milk. Tests may also be needed for people who react to foods that are not linked with PFS, such as cashews, pistachios, macadamias, sesame seeds, beans, lentils, and chickpeas.

Whether PFS reactions also occur to roasted hazelnuts, almonds, walnuts, Brazil nuts, or peanuts, either alone or in composite foods such as chocolates, spreads, desserts, and snacks, is unclear.

An oral food challenge to confirm PFS is needed only if the history and diagnostic tests are inconclusive or if the patient is avoiding multiple foods.

Dietary management

PFS is managed by excluding known trigger foods. This becomes challenging for patients with preexisting food allergies and for vegetarians and vegans.

Personalized dietary advice is needed to avoid nutritional imbalance, minimize anxiety and unnecessary food restrictions, and improve quality of life. Reactions after accidental exposure often resolve without medication, and if antihistamines are needed, they rarely require self-injectable devices.

Guideline helpful beyond the United Kingdom and birch pollen

Allyson S. Larkin, MD, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, told this news organization in an email that the guideline summarizes in great detail the pathophysiology behind PFS and highlights how component testing may help diagnose patients and manage the condition.

“Patients worry very much about the progression and severity of allergic reactions,” said Dr. Larkin, who was not involved in the guideline development.

“As the authors note, recognizing the nutritional consequences of dietary restrictions is important, and nutrition consults and suitable alternative suggestions are very helpful for these patients, especially for those with food allergy or who are vegetarian or vegan.”

Jill A. Poole, MD, professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Allergy and Immunology at the University of Nebraska College of Medicine, Omaha, noted that PFS, although common, is underrecognized by the public and by health care providers.

“People are not allergic to the specific food, but they are allergic to a seasonal allergen, such as birch tree, that cross-reacts with the food protein, which is typically changed with cooking,” she explained in an email.

“This differs from reactions by those who have moderate to severe allergic food-specific reactions that may include systemic reactions like anaphylaxis from eating certain foods,” she said.

“Importantly, the number of cross-reacting foods with seasonal pollens continues to grow, and the extent of testing has expanded in recent years,” advised Dr. Poole, who also was not involved in the guideline development.

The authors recommend further related research into food immunotherapy and other novel PFS treatments. They also want to raise awareness of factors affecting PFS prevalence, such as increased spread and allergenicity of pollen due to climate change, pollution, the global consumption of previously local traditional foods, and the increase in vegetarian and vegan diets.

The authors, Dr. Larkin, and Dr. Poole report no relevant financial relationships involving this guideline. The guideline was not funded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Improving Inpatient COVID-19 Vaccination Rates Among Adult Patients at a Tertiary Academic Medical Center

From the Department of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC.

Abstract

Objective: Inpatient vaccination initiatives are well described in the literature. During the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals began administering COVID-19 vaccines to hospitalized patients. Although vaccination rates increased, there remained many unvaccinated patients despite community efforts. This quality improvement project aimed to increase the COVID-19 vaccination rates of hospitalized patients on the medicine service at the George Washington University Hospital (GWUH).

Methods: From November 2021 through February 2022, we conducted a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle with 3 phases. Initial steps included gathering baseline data from the electronic health record and consulting stakeholders. The first 2 phases focused on educating housestaff on the availability, ordering process, and administration of the Pfizer vaccine. The third phase consisted of developing educational pamphlets for patients to be included in their admission packets.

Results: The baseline mean COVID-19 vaccination rate (August to October 2021) of eligible patients on the medicine service was 10.7%. In the months after we implemented the PDSA cycle (November 2021 to February 2022), the mean vaccination rate increased to 15.4%.

Conclusion: This quality improvement project implemented measures to increase administration of the Pfizer vaccine to eligible patients admitted to the medicine service at GWUH. The mean vaccination rate increased from 10.7% in the 3 months prior to implementation to 15.4% during the 4 months post implementation. Other measures to consider in the future include increasing the availability of other COVID-19 vaccines at our hospital and incorporating the vaccine into the admission order set to help facilitate vaccination early in the hospital course.

Keywords: housestaff, quality improvement, PDSA, COVID-19, BNT162b2 vaccine, patient education

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, case rates in the United States have fluctuated considerably, corresponding to epidemic waves. In 2021, US daily cases of COVID-19 peaked at nearly 300,000 in early January and reached a nadir of 8000 cases in mid-June.1 In September 2021, new cases had increased to 200,000 per day due to the prevalence of the Delta variant.1 Particularly with the emergence of new variants of SARS-CoV-2, vaccination efforts to limit the spread of infection and severity of illness are critical. Data have shown that 2 doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech) were largely protective against severe infection for approximately 6 months.2,3 When we began this quality improvement (QI) project in September 2021, only 179 million Americans had been fully vaccinated, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is just over half of the US population.4 An electronic survey conducted in the United States with more than 5 million responses found that, of those who were hesitant about receiving the vaccine, 49% reported a fear of adverse effects and 48% reported a lack of trust in the vaccine.5

This QI project sought to target unvaccinated individuals admitted to the internal medicine inpatient service. Vaccinating hospitalized patients is especially important since they are sicker than the general population and at higher risk of having poor outcomes from COVID-19. Inpatient vaccine initiatives, such as administering influenza vaccine prior to discharge, have been successfully implemented in the past.6 One large COVID-19 vaccination program featured an admission order set to increase the rates of vaccination among hospitalized patients.7 Our QI project piloted a multidisciplinary approach involving the nursing staff, pharmacy, information technology (IT) department, and internal medicine housestaff to increase COVID-19 vaccination rates among hospitalized patients on the medical service. This project aimed to increase inpatient vaccination rates through interventions targeting both primary providers as well as the patients themselves.

Methods

Setting and Interventions

This project was conducted at the George Washington University Hospital (GWUH) in Washington, DC. The clinicians involved in the study were the internal medicine housestaff, and the patients included were adults admitted to the resident medicine ward teams. The project was exempt by the institutional review board and did not require informed consent.

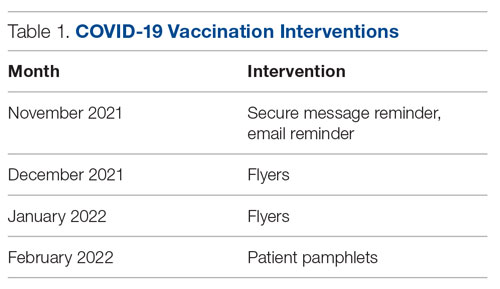

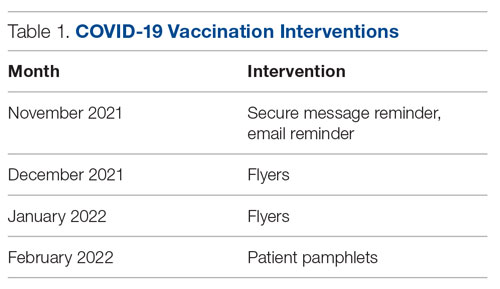

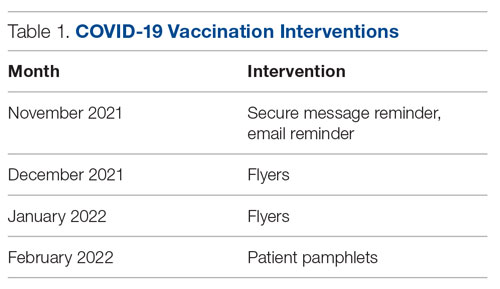

The quality improvement initiative had 3 phases, each featuring a different intervention (Table 1). The first phase involved sending a weekly announcement (via email and a secure health care messaging app) to current residents rotating on the inpatient medicine service. The announcement contained information regarding COVID-19 vaccine availability at the hospital, instructions on ordering the vaccine, and the process of coordinating with pharmacy to facilitate vaccine administration. Thereafter, residents were educated on the process of giving a COVID-19 vaccine to a patient from start to finish. Due to the nature of the residency schedule, different housestaff members rotated in and out of the medicine wards during the intervention periods. The weekly email was sent to the entire internal medicine housestaff, informing all residents about the QI project, while the weekly secure messages served as reminders and were only sent to residents currently on the medicine wards.

In the second phase, we posted paper flyers throughout the hospital to remind housestaff to give the vaccine and again educate them on the process of ordering the vaccine. For the third intervention, a COVID-19 vaccine educational pamphlet was developed for distribution to inpatients at GWUH. The pamphlet included information on vaccine efficacy, safety, side effects, and eligibility. The pamphlet was incorporated in the admission packet that every patient receives upon admission to the hospital. The patients reviewed the pamphlets with nursing staff, who would answer any questions, with residents available to discuss any outstanding concerns.

Measures and Data Gathering

The primary endpoint of the study was inpatient vaccination rate, defined as the number of COVID-19 vaccines administered divided by the number of patients eligible to receive a vaccine (not fully vaccinated). During initial triage, nursing staff documented vaccination status in the electronic health record (EHR), checking a box in a data entry form if a patient had received 0, 1, or 2 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. The GWUH IT department generated data from this form to determine the number of patients eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Data were extracted from the medication administration record in the EHR to determine the number of vaccines that were administered to patients during their hospitalization on the inpatient medical service. Each month, the IT department extracted data for the number of eligible patients and the number of vaccines administered. This yielded the monthly vaccination rates. The monthly vaccination rates in the period prior to starting the QI initiative were compared to the rates in the period after the interventions were implemented.

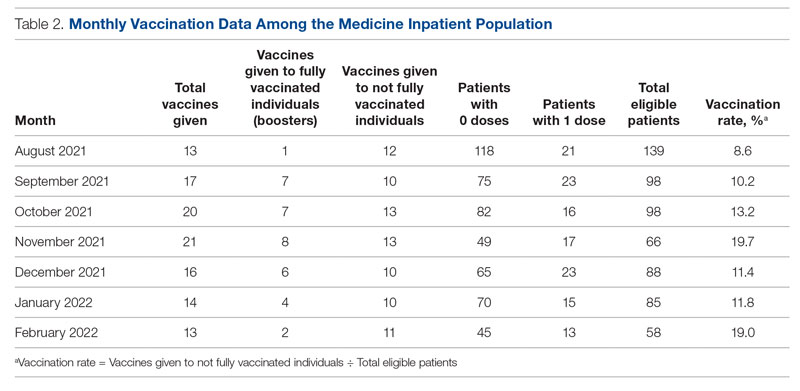

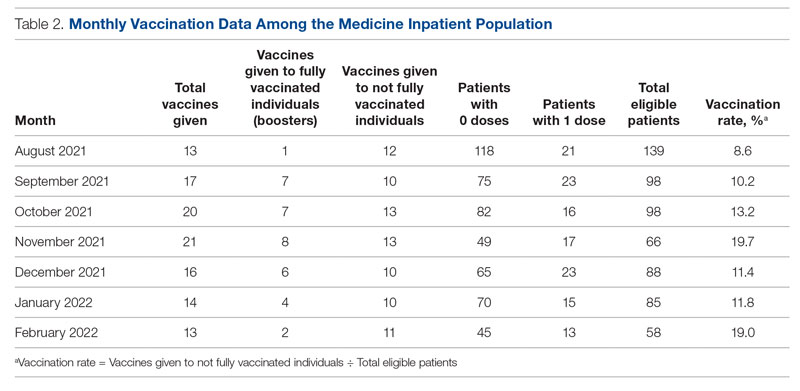

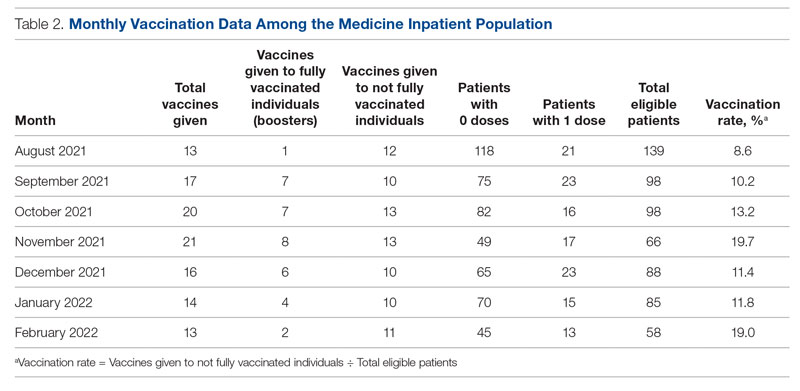

Of note, during the course of this project, patients became eligible for a third COVID-19 vaccine (booster). We decided to continue with the original aim of vaccinating adults who had only received 0 or 1 dose of the vaccine. Therefore, the eligibility criteria remained the same throughout the study. We obtained retrospective data to ensure that the vaccines being counted toward the vaccination rate were vaccines given to patients not yet fully vaccinated and not vaccines given as boosters.

Results

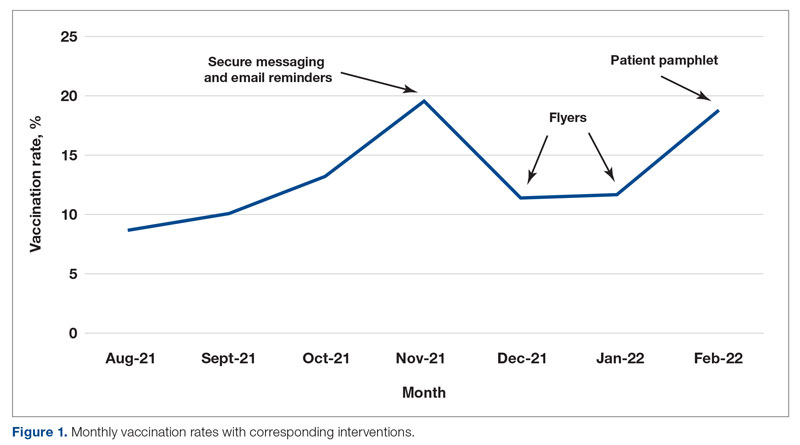

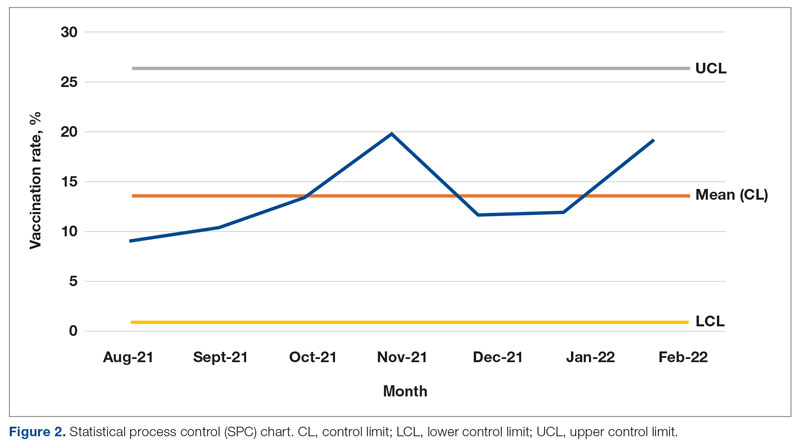

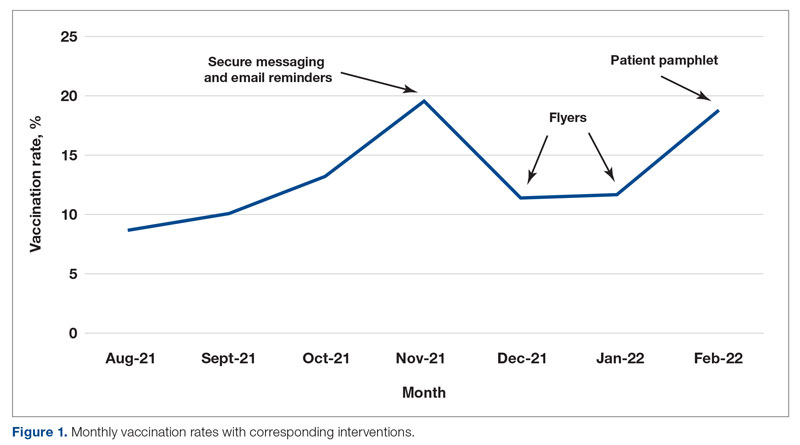

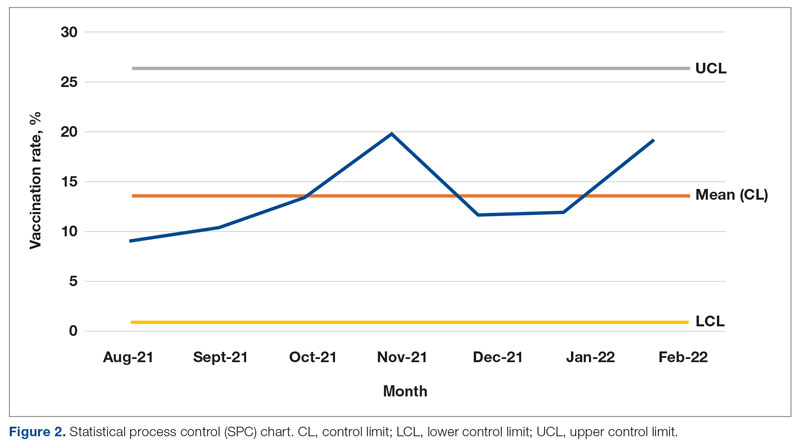

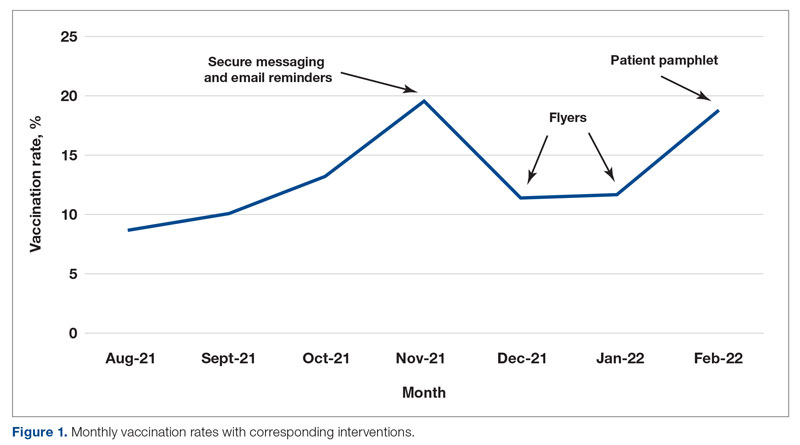

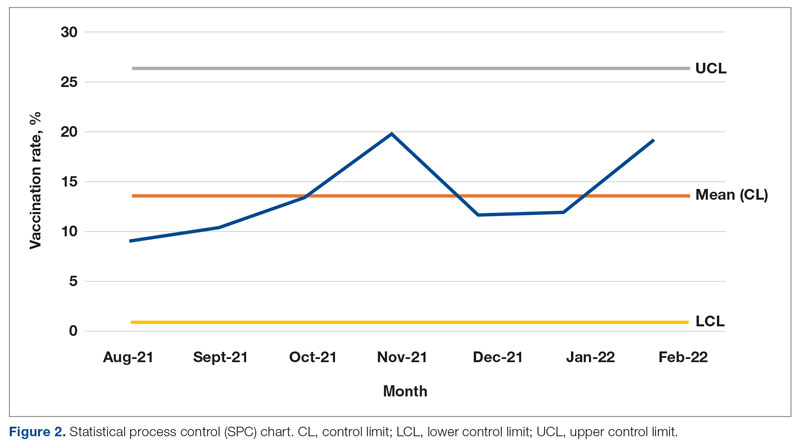

From August to October 2021, the baseline average monthly vaccination rate of patients on the medicine service who were eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine was 10.7%. After the first intervention, the vaccination rate increased to 19.7% in November 2021 (Table 2). The second intervention yielded vaccination rates of 11.4% and 11.8% in December 2021 and January 2022, respectively. During the final phase in February 2022, the vaccination rate was 19.0%. At the conclusion of the study, the mean vaccination rate for the intervention months was 15.4% (Figure 1). Process stability and variation are demonstrated with a statistical process control chart (Figure 2).

Discussion

For this housestaff-driven QI project, we implemented an inpatient COVID-19 vaccination campaign consisting of 3 phases that targeted both providers and patients. During the intervention period, we observed an increased vaccination rate compared to the period just prior to implementation of the QI project. While our interventions may certainly have boosted vaccination rates, we understand other variables could have contributed to increased rates as well. The emergence of variants in the United States, such as omicron in December 2021,8 could have precipitated a demand for vaccinations among patients. Holidays in November and December may also have increased patients’ desire to get vaccinated before travel.

We encountered a number of roadblocks that challenged our project, including difficulty identifying patients who were eligible for the vaccine, logistical vaccine administration challenges, and hesitancy among the inpatient population. Accurately identifying patients who were eligible for a vaccine in the EHR was especially challenging in the setting of rapidly changing guidelines regarding COVID-19 vaccination. In September 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration authorized the Pfizer booster for certain populations and later, in November 2021, for all adults. This meant that some fully vaccinated hospitalized patients (those with 2 doses) then qualified for an additional dose of the vaccine and received a dose during hospitalization. To determine the true vaccination rate, we obtained retrospective data that allowed us to track each vaccine administered. If a patient had already received 2 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine, the vaccine administered was counted as a booster and excluded from the calculation of the vaccination rate. Future PDSA cycles could include updating the EHR to capture the whole range of COVID-19 vaccination status (unvaccinated, partially vaccinated, fully vaccinated, fully vaccinated with 1 booster, fully vaccinated with 2 boosters).

We also encountered logistical challenges with the administration of the COVID-19 vaccine to hospitalized patients. During the intervention period, our pharmacy department required 5 COVID-19 vaccination orders before opening a vial and administering the vaccine doses in order to reduce waste. This policy may have limited our ability to vaccinate eligible inpatients because we were not always able to identify 5 patients simultaneously on the service who were eligible and consented to the vaccine.

The majority of patients who were interested in receiving COVID-19 vaccination had already been vaccinated in the outpatient setting. This fact made the inpatient internal medicine subset of patients a particularly challenging population to target, given their possible hesitancy regarding vaccination. By utilizing a multidisciplinary team and increasing communication of providers and nursing staff, we helped to increase the COVID-19 vaccination rates at our hospital from 10.7% to 15.4%.

Future Directions

Future interventions to consider include increasing the availability of other approved COVID-19 vaccines at our hospital besides the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Furthermore, incorporating the vaccine into the admission order set would help initiate the vaccination process early in the hospital course. We encourage other institutions to utilize similar approaches to not only remind providers about inpatient vaccination, but also educate and encourage patients to receive the vaccine. These measures will help institutions increase inpatient COVID-19 vaccination rates in a high-risk population.

Corresponding author: Anna Rubin, MD, Department of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Trends in number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the US reported to CDC, by state/territory. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_dailycases

2. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162B2 MRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603-2615. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2034577

3. Hall V, Foulkes S, Insalata F, et al. Protection against SARS-COV-2 after covid-19 vaccination and previous infection. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(13):1207-1220. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2118691

4. Trends in number of COVID-19 vaccinations in the US. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-trends_vacctrends-fully-cum

5. King WC, Rubinstein M, Reinhart A, Mejia R. Time trends, factors associated with, and reasons for covid-19 vaccine hesitancy: A massive online survey of US adults from January-May 2021. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(12). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260731

6. Cohen ES, Ogrinc G, Taylor T, et al. Influenza vaccination rates for hospitalised patients: A multiyear quality improvement effort. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(3):221-227. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003556

7. Berger RE, Diaz DC, Chacko S, et al. Implementation of an inpatient covid-19 vaccination program. NEJM Catalyst. 2021;2(10). doi:10.1056/cat.21.0235

8. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) Variant - United States, December 1-8, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(50):1731-1734. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7050e1

From the Department of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC.

Abstract

Objective: Inpatient vaccination initiatives are well described in the literature. During the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals began administering COVID-19 vaccines to hospitalized patients. Although vaccination rates increased, there remained many unvaccinated patients despite community efforts. This quality improvement project aimed to increase the COVID-19 vaccination rates of hospitalized patients on the medicine service at the George Washington University Hospital (GWUH).

Methods: From November 2021 through February 2022, we conducted a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle with 3 phases. Initial steps included gathering baseline data from the electronic health record and consulting stakeholders. The first 2 phases focused on educating housestaff on the availability, ordering process, and administration of the Pfizer vaccine. The third phase consisted of developing educational pamphlets for patients to be included in their admission packets.

Results: The baseline mean COVID-19 vaccination rate (August to October 2021) of eligible patients on the medicine service was 10.7%. In the months after we implemented the PDSA cycle (November 2021 to February 2022), the mean vaccination rate increased to 15.4%.

Conclusion: This quality improvement project implemented measures to increase administration of the Pfizer vaccine to eligible patients admitted to the medicine service at GWUH. The mean vaccination rate increased from 10.7% in the 3 months prior to implementation to 15.4% during the 4 months post implementation. Other measures to consider in the future include increasing the availability of other COVID-19 vaccines at our hospital and incorporating the vaccine into the admission order set to help facilitate vaccination early in the hospital course.

Keywords: housestaff, quality improvement, PDSA, COVID-19, BNT162b2 vaccine, patient education

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, case rates in the United States have fluctuated considerably, corresponding to epidemic waves. In 2021, US daily cases of COVID-19 peaked at nearly 300,000 in early January and reached a nadir of 8000 cases in mid-June.1 In September 2021, new cases had increased to 200,000 per day due to the prevalence of the Delta variant.1 Particularly with the emergence of new variants of SARS-CoV-2, vaccination efforts to limit the spread of infection and severity of illness are critical. Data have shown that 2 doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech) were largely protective against severe infection for approximately 6 months.2,3 When we began this quality improvement (QI) project in September 2021, only 179 million Americans had been fully vaccinated, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is just over half of the US population.4 An electronic survey conducted in the United States with more than 5 million responses found that, of those who were hesitant about receiving the vaccine, 49% reported a fear of adverse effects and 48% reported a lack of trust in the vaccine.5

This QI project sought to target unvaccinated individuals admitted to the internal medicine inpatient service. Vaccinating hospitalized patients is especially important since they are sicker than the general population and at higher risk of having poor outcomes from COVID-19. Inpatient vaccine initiatives, such as administering influenza vaccine prior to discharge, have been successfully implemented in the past.6 One large COVID-19 vaccination program featured an admission order set to increase the rates of vaccination among hospitalized patients.7 Our QI project piloted a multidisciplinary approach involving the nursing staff, pharmacy, information technology (IT) department, and internal medicine housestaff to increase COVID-19 vaccination rates among hospitalized patients on the medical service. This project aimed to increase inpatient vaccination rates through interventions targeting both primary providers as well as the patients themselves.

Methods

Setting and Interventions

This project was conducted at the George Washington University Hospital (GWUH) in Washington, DC. The clinicians involved in the study were the internal medicine housestaff, and the patients included were adults admitted to the resident medicine ward teams. The project was exempt by the institutional review board and did not require informed consent.

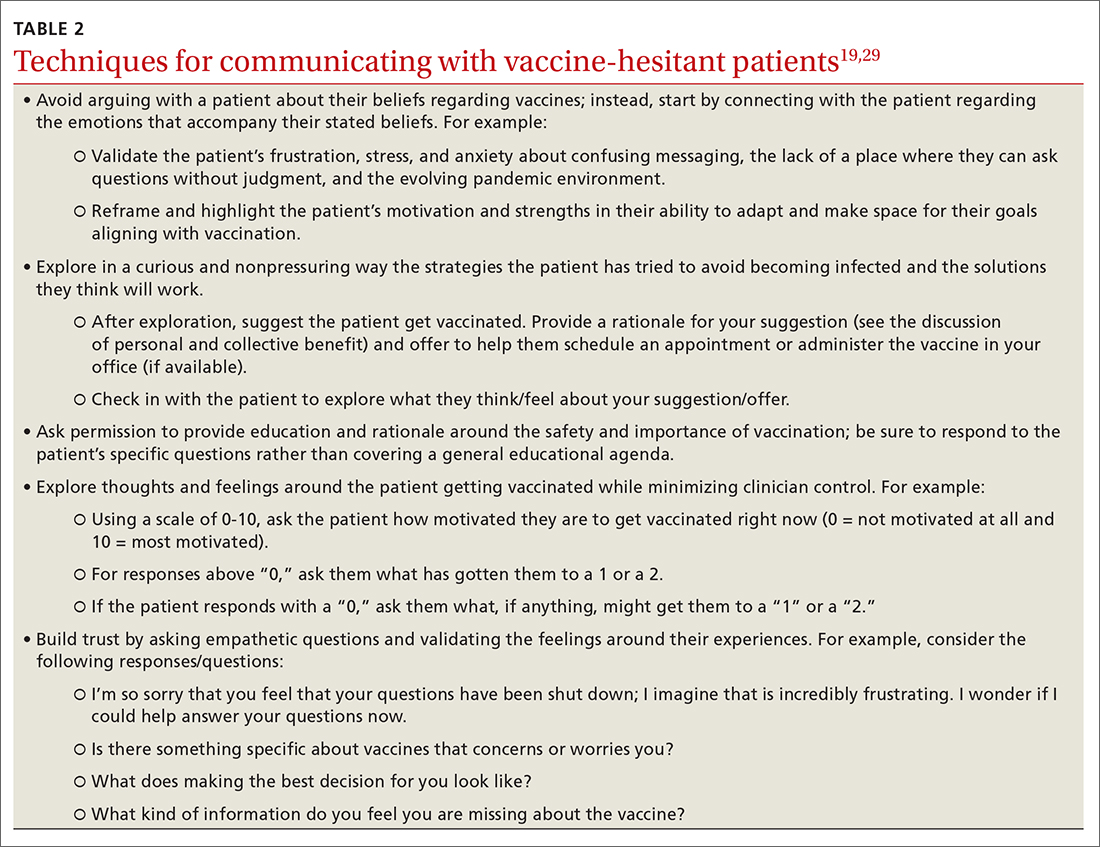

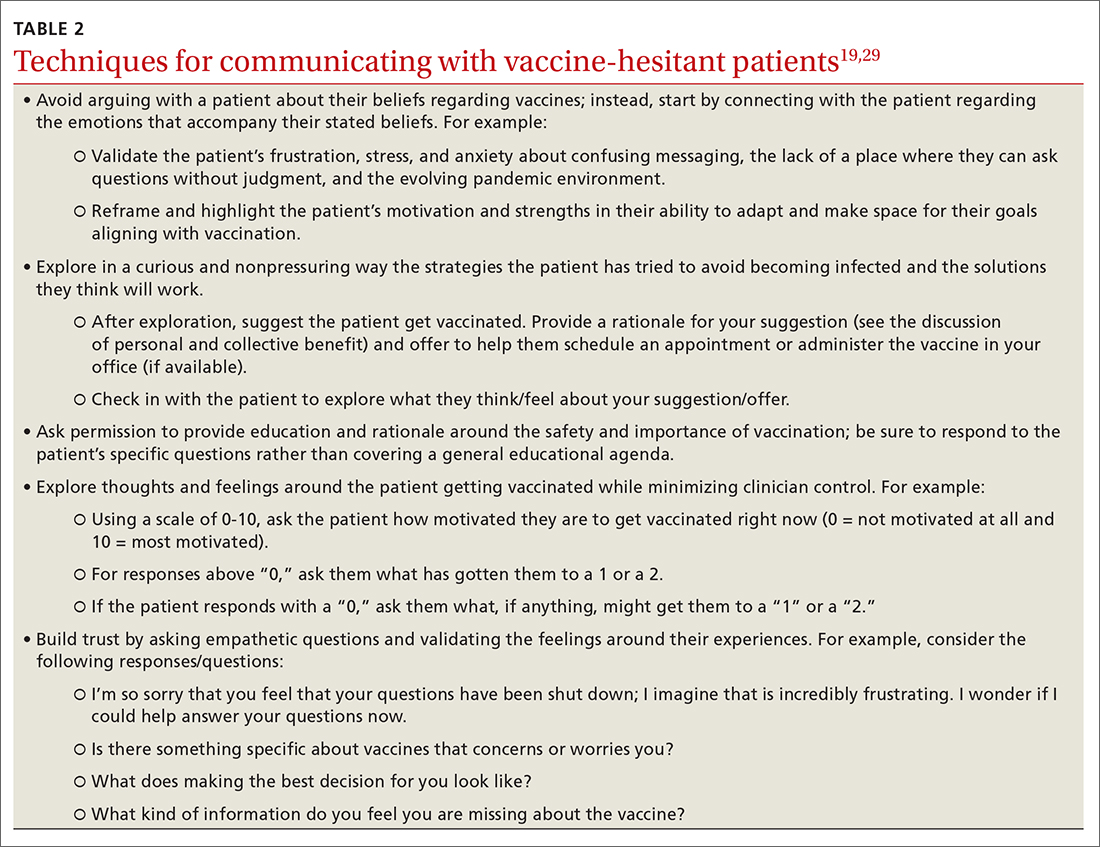

The quality improvement initiative had 3 phases, each featuring a different intervention (Table 1). The first phase involved sending a weekly announcement (via email and a secure health care messaging app) to current residents rotating on the inpatient medicine service. The announcement contained information regarding COVID-19 vaccine availability at the hospital, instructions on ordering the vaccine, and the process of coordinating with pharmacy to facilitate vaccine administration. Thereafter, residents were educated on the process of giving a COVID-19 vaccine to a patient from start to finish. Due to the nature of the residency schedule, different housestaff members rotated in and out of the medicine wards during the intervention periods. The weekly email was sent to the entire internal medicine housestaff, informing all residents about the QI project, while the weekly secure messages served as reminders and were only sent to residents currently on the medicine wards.

In the second phase, we posted paper flyers throughout the hospital to remind housestaff to give the vaccine and again educate them on the process of ordering the vaccine. For the third intervention, a COVID-19 vaccine educational pamphlet was developed for distribution to inpatients at GWUH. The pamphlet included information on vaccine efficacy, safety, side effects, and eligibility. The pamphlet was incorporated in the admission packet that every patient receives upon admission to the hospital. The patients reviewed the pamphlets with nursing staff, who would answer any questions, with residents available to discuss any outstanding concerns.

Measures and Data Gathering

The primary endpoint of the study was inpatient vaccination rate, defined as the number of COVID-19 vaccines administered divided by the number of patients eligible to receive a vaccine (not fully vaccinated). During initial triage, nursing staff documented vaccination status in the electronic health record (EHR), checking a box in a data entry form if a patient had received 0, 1, or 2 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. The GWUH IT department generated data from this form to determine the number of patients eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Data were extracted from the medication administration record in the EHR to determine the number of vaccines that were administered to patients during their hospitalization on the inpatient medical service. Each month, the IT department extracted data for the number of eligible patients and the number of vaccines administered. This yielded the monthly vaccination rates. The monthly vaccination rates in the period prior to starting the QI initiative were compared to the rates in the period after the interventions were implemented.

Of note, during the course of this project, patients became eligible for a third COVID-19 vaccine (booster). We decided to continue with the original aim of vaccinating adults who had only received 0 or 1 dose of the vaccine. Therefore, the eligibility criteria remained the same throughout the study. We obtained retrospective data to ensure that the vaccines being counted toward the vaccination rate were vaccines given to patients not yet fully vaccinated and not vaccines given as boosters.

Results

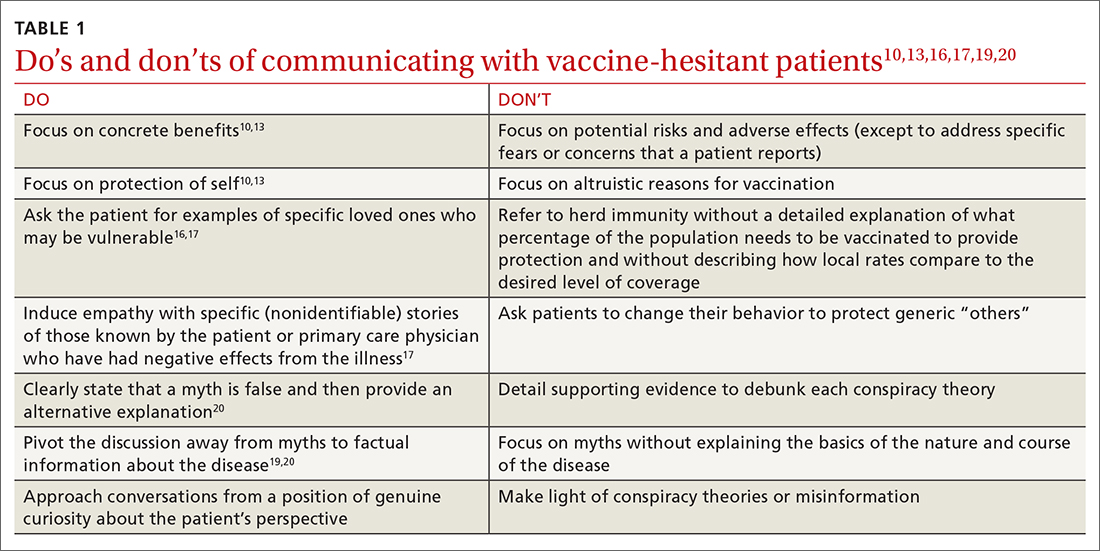

From August to October 2021, the baseline average monthly vaccination rate of patients on the medicine service who were eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine was 10.7%. After the first intervention, the vaccination rate increased to 19.7% in November 2021 (Table 2). The second intervention yielded vaccination rates of 11.4% and 11.8% in December 2021 and January 2022, respectively. During the final phase in February 2022, the vaccination rate was 19.0%. At the conclusion of the study, the mean vaccination rate for the intervention months was 15.4% (Figure 1). Process stability and variation are demonstrated with a statistical process control chart (Figure 2).

Discussion

For this housestaff-driven QI project, we implemented an inpatient COVID-19 vaccination campaign consisting of 3 phases that targeted both providers and patients. During the intervention period, we observed an increased vaccination rate compared to the period just prior to implementation of the QI project. While our interventions may certainly have boosted vaccination rates, we understand other variables could have contributed to increased rates as well. The emergence of variants in the United States, such as omicron in December 2021,8 could have precipitated a demand for vaccinations among patients. Holidays in November and December may also have increased patients’ desire to get vaccinated before travel.

We encountered a number of roadblocks that challenged our project, including difficulty identifying patients who were eligible for the vaccine, logistical vaccine administration challenges, and hesitancy among the inpatient population. Accurately identifying patients who were eligible for a vaccine in the EHR was especially challenging in the setting of rapidly changing guidelines regarding COVID-19 vaccination. In September 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration authorized the Pfizer booster for certain populations and later, in November 2021, for all adults. This meant that some fully vaccinated hospitalized patients (those with 2 doses) then qualified for an additional dose of the vaccine and received a dose during hospitalization. To determine the true vaccination rate, we obtained retrospective data that allowed us to track each vaccine administered. If a patient had already received 2 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine, the vaccine administered was counted as a booster and excluded from the calculation of the vaccination rate. Future PDSA cycles could include updating the EHR to capture the whole range of COVID-19 vaccination status (unvaccinated, partially vaccinated, fully vaccinated, fully vaccinated with 1 booster, fully vaccinated with 2 boosters).

We also encountered logistical challenges with the administration of the COVID-19 vaccine to hospitalized patients. During the intervention period, our pharmacy department required 5 COVID-19 vaccination orders before opening a vial and administering the vaccine doses in order to reduce waste. This policy may have limited our ability to vaccinate eligible inpatients because we were not always able to identify 5 patients simultaneously on the service who were eligible and consented to the vaccine.

The majority of patients who were interested in receiving COVID-19 vaccination had already been vaccinated in the outpatient setting. This fact made the inpatient internal medicine subset of patients a particularly challenging population to target, given their possible hesitancy regarding vaccination. By utilizing a multidisciplinary team and increasing communication of providers and nursing staff, we helped to increase the COVID-19 vaccination rates at our hospital from 10.7% to 15.4%.

Future Directions

Future interventions to consider include increasing the availability of other approved COVID-19 vaccines at our hospital besides the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Furthermore, incorporating the vaccine into the admission order set would help initiate the vaccination process early in the hospital course. We encourage other institutions to utilize similar approaches to not only remind providers about inpatient vaccination, but also educate and encourage patients to receive the vaccine. These measures will help institutions increase inpatient COVID-19 vaccination rates in a high-risk population.

Corresponding author: Anna Rubin, MD, Department of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

From the Department of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC.

Abstract

Objective: Inpatient vaccination initiatives are well described in the literature. During the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals began administering COVID-19 vaccines to hospitalized patients. Although vaccination rates increased, there remained many unvaccinated patients despite community efforts. This quality improvement project aimed to increase the COVID-19 vaccination rates of hospitalized patients on the medicine service at the George Washington University Hospital (GWUH).

Methods: From November 2021 through February 2022, we conducted a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle with 3 phases. Initial steps included gathering baseline data from the electronic health record and consulting stakeholders. The first 2 phases focused on educating housestaff on the availability, ordering process, and administration of the Pfizer vaccine. The third phase consisted of developing educational pamphlets for patients to be included in their admission packets.

Results: The baseline mean COVID-19 vaccination rate (August to October 2021) of eligible patients on the medicine service was 10.7%. In the months after we implemented the PDSA cycle (November 2021 to February 2022), the mean vaccination rate increased to 15.4%.

Conclusion: This quality improvement project implemented measures to increase administration of the Pfizer vaccine to eligible patients admitted to the medicine service at GWUH. The mean vaccination rate increased from 10.7% in the 3 months prior to implementation to 15.4% during the 4 months post implementation. Other measures to consider in the future include increasing the availability of other COVID-19 vaccines at our hospital and incorporating the vaccine into the admission order set to help facilitate vaccination early in the hospital course.

Keywords: housestaff, quality improvement, PDSA, COVID-19, BNT162b2 vaccine, patient education

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, case rates in the United States have fluctuated considerably, corresponding to epidemic waves. In 2021, US daily cases of COVID-19 peaked at nearly 300,000 in early January and reached a nadir of 8000 cases in mid-June.1 In September 2021, new cases had increased to 200,000 per day due to the prevalence of the Delta variant.1 Particularly with the emergence of new variants of SARS-CoV-2, vaccination efforts to limit the spread of infection and severity of illness are critical. Data have shown that 2 doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech) were largely protective against severe infection for approximately 6 months.2,3 When we began this quality improvement (QI) project in September 2021, only 179 million Americans had been fully vaccinated, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is just over half of the US population.4 An electronic survey conducted in the United States with more than 5 million responses found that, of those who were hesitant about receiving the vaccine, 49% reported a fear of adverse effects and 48% reported a lack of trust in the vaccine.5

This QI project sought to target unvaccinated individuals admitted to the internal medicine inpatient service. Vaccinating hospitalized patients is especially important since they are sicker than the general population and at higher risk of having poor outcomes from COVID-19. Inpatient vaccine initiatives, such as administering influenza vaccine prior to discharge, have been successfully implemented in the past.6 One large COVID-19 vaccination program featured an admission order set to increase the rates of vaccination among hospitalized patients.7 Our QI project piloted a multidisciplinary approach involving the nursing staff, pharmacy, information technology (IT) department, and internal medicine housestaff to increase COVID-19 vaccination rates among hospitalized patients on the medical service. This project aimed to increase inpatient vaccination rates through interventions targeting both primary providers as well as the patients themselves.

Methods

Setting and Interventions

This project was conducted at the George Washington University Hospital (GWUH) in Washington, DC. The clinicians involved in the study were the internal medicine housestaff, and the patients included were adults admitted to the resident medicine ward teams. The project was exempt by the institutional review board and did not require informed consent.

The quality improvement initiative had 3 phases, each featuring a different intervention (Table 1). The first phase involved sending a weekly announcement (via email and a secure health care messaging app) to current residents rotating on the inpatient medicine service. The announcement contained information regarding COVID-19 vaccine availability at the hospital, instructions on ordering the vaccine, and the process of coordinating with pharmacy to facilitate vaccine administration. Thereafter, residents were educated on the process of giving a COVID-19 vaccine to a patient from start to finish. Due to the nature of the residency schedule, different housestaff members rotated in and out of the medicine wards during the intervention periods. The weekly email was sent to the entire internal medicine housestaff, informing all residents about the QI project, while the weekly secure messages served as reminders and were only sent to residents currently on the medicine wards.

In the second phase, we posted paper flyers throughout the hospital to remind housestaff to give the vaccine and again educate them on the process of ordering the vaccine. For the third intervention, a COVID-19 vaccine educational pamphlet was developed for distribution to inpatients at GWUH. The pamphlet included information on vaccine efficacy, safety, side effects, and eligibility. The pamphlet was incorporated in the admission packet that every patient receives upon admission to the hospital. The patients reviewed the pamphlets with nursing staff, who would answer any questions, with residents available to discuss any outstanding concerns.

Measures and Data Gathering

The primary endpoint of the study was inpatient vaccination rate, defined as the number of COVID-19 vaccines administered divided by the number of patients eligible to receive a vaccine (not fully vaccinated). During initial triage, nursing staff documented vaccination status in the electronic health record (EHR), checking a box in a data entry form if a patient had received 0, 1, or 2 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. The GWUH IT department generated data from this form to determine the number of patients eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Data were extracted from the medication administration record in the EHR to determine the number of vaccines that were administered to patients during their hospitalization on the inpatient medical service. Each month, the IT department extracted data for the number of eligible patients and the number of vaccines administered. This yielded the monthly vaccination rates. The monthly vaccination rates in the period prior to starting the QI initiative were compared to the rates in the period after the interventions were implemented.

Of note, during the course of this project, patients became eligible for a third COVID-19 vaccine (booster). We decided to continue with the original aim of vaccinating adults who had only received 0 or 1 dose of the vaccine. Therefore, the eligibility criteria remained the same throughout the study. We obtained retrospective data to ensure that the vaccines being counted toward the vaccination rate were vaccines given to patients not yet fully vaccinated and not vaccines given as boosters.

Results

From August to October 2021, the baseline average monthly vaccination rate of patients on the medicine service who were eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine was 10.7%. After the first intervention, the vaccination rate increased to 19.7% in November 2021 (Table 2). The second intervention yielded vaccination rates of 11.4% and 11.8% in December 2021 and January 2022, respectively. During the final phase in February 2022, the vaccination rate was 19.0%. At the conclusion of the study, the mean vaccination rate for the intervention months was 15.4% (Figure 1). Process stability and variation are demonstrated with a statistical process control chart (Figure 2).

Discussion

For this housestaff-driven QI project, we implemented an inpatient COVID-19 vaccination campaign consisting of 3 phases that targeted both providers and patients. During the intervention period, we observed an increased vaccination rate compared to the period just prior to implementation of the QI project. While our interventions may certainly have boosted vaccination rates, we understand other variables could have contributed to increased rates as well. The emergence of variants in the United States, such as omicron in December 2021,8 could have precipitated a demand for vaccinations among patients. Holidays in November and December may also have increased patients’ desire to get vaccinated before travel.

We encountered a number of roadblocks that challenged our project, including difficulty identifying patients who were eligible for the vaccine, logistical vaccine administration challenges, and hesitancy among the inpatient population. Accurately identifying patients who were eligible for a vaccine in the EHR was especially challenging in the setting of rapidly changing guidelines regarding COVID-19 vaccination. In September 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration authorized the Pfizer booster for certain populations and later, in November 2021, for all adults. This meant that some fully vaccinated hospitalized patients (those with 2 doses) then qualified for an additional dose of the vaccine and received a dose during hospitalization. To determine the true vaccination rate, we obtained retrospective data that allowed us to track each vaccine administered. If a patient had already received 2 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine, the vaccine administered was counted as a booster and excluded from the calculation of the vaccination rate. Future PDSA cycles could include updating the EHR to capture the whole range of COVID-19 vaccination status (unvaccinated, partially vaccinated, fully vaccinated, fully vaccinated with 1 booster, fully vaccinated with 2 boosters).

We also encountered logistical challenges with the administration of the COVID-19 vaccine to hospitalized patients. During the intervention period, our pharmacy department required 5 COVID-19 vaccination orders before opening a vial and administering the vaccine doses in order to reduce waste. This policy may have limited our ability to vaccinate eligible inpatients because we were not always able to identify 5 patients simultaneously on the service who were eligible and consented to the vaccine.

The majority of patients who were interested in receiving COVID-19 vaccination had already been vaccinated in the outpatient setting. This fact made the inpatient internal medicine subset of patients a particularly challenging population to target, given their possible hesitancy regarding vaccination. By utilizing a multidisciplinary team and increasing communication of providers and nursing staff, we helped to increase the COVID-19 vaccination rates at our hospital from 10.7% to 15.4%.

Future Directions

Future interventions to consider include increasing the availability of other approved COVID-19 vaccines at our hospital besides the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Furthermore, incorporating the vaccine into the admission order set would help initiate the vaccination process early in the hospital course. We encourage other institutions to utilize similar approaches to not only remind providers about inpatient vaccination, but also educate and encourage patients to receive the vaccine. These measures will help institutions increase inpatient COVID-19 vaccination rates in a high-risk population.

Corresponding author: Anna Rubin, MD, Department of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Trends in number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the US reported to CDC, by state/territory. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_dailycases

2. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162B2 MRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603-2615. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2034577

3. Hall V, Foulkes S, Insalata F, et al. Protection against SARS-COV-2 after covid-19 vaccination and previous infection. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(13):1207-1220. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2118691

4. Trends in number of COVID-19 vaccinations in the US. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-trends_vacctrends-fully-cum

5. King WC, Rubinstein M, Reinhart A, Mejia R. Time trends, factors associated with, and reasons for covid-19 vaccine hesitancy: A massive online survey of US adults from January-May 2021. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(12). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260731

6. Cohen ES, Ogrinc G, Taylor T, et al. Influenza vaccination rates for hospitalised patients: A multiyear quality improvement effort. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(3):221-227. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003556

7. Berger RE, Diaz DC, Chacko S, et al. Implementation of an inpatient covid-19 vaccination program. NEJM Catalyst. 2021;2(10). doi:10.1056/cat.21.0235

8. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) Variant - United States, December 1-8, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(50):1731-1734. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7050e1

1. Trends in number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the US reported to CDC, by state/territory. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_dailycases

2. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162B2 MRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603-2615. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2034577

3. Hall V, Foulkes S, Insalata F, et al. Protection against SARS-COV-2 after covid-19 vaccination and previous infection. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(13):1207-1220. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2118691

4. Trends in number of COVID-19 vaccinations in the US. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-trends_vacctrends-fully-cum

5. King WC, Rubinstein M, Reinhart A, Mejia R. Time trends, factors associated with, and reasons for covid-19 vaccine hesitancy: A massive online survey of US adults from January-May 2021. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(12). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260731

6. Cohen ES, Ogrinc G, Taylor T, et al. Influenza vaccination rates for hospitalised patients: A multiyear quality improvement effort. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(3):221-227. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003556

7. Berger RE, Diaz DC, Chacko S, et al. Implementation of an inpatient covid-19 vaccination program. NEJM Catalyst. 2021;2(10). doi:10.1056/cat.21.0235

8. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) Variant - United States, December 1-8, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(50):1731-1734. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7050e1

Many young kids with COVID may show no symptoms

BY WILL PASS

Just 14% of adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were asymptomatic, versus 37% of children aged 0-4 years, in the paper. This raises concern that parents, childcare providers, and preschools may be underestimating infection in seemingly healthy young kids who have been exposed to COVID, wrote lead author Ruth A. Karron, MD, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open.

Methods

The new research involved 690 individuals from 175 households in Maryland who were monitored closely between November 2020 and October 2021. Every week for 8 months, participants completed online symptom checks and underwent PCR testing using nasal swabs, with symptomatic individuals submitting additional swabs for analysis.

“What was different about our study [compared with previous studies] was the intensity of our collection, and the fact that we collected specimens from asymptomatic people,” said Dr. Karron, a pediatrician and professor in the department of international health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in an interview. “You shed more virus earlier in the infection than later, and the fact that we were sampling every single week meant that we could pick up those early infections.”

The study also stands out for its focus on young children, Dr. Karron said. Enrollment required all households to have at least one child aged 0-4 years, so 256 out of 690 participants (37.1%) were in this youngest age group. The remainder of the population consisted of 100 older children aged 5-17 years (14.5%) and 334 adults aged 18-74 years (48.4%).

Children 4 and under more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic

By the end of the study, 51 participants had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, among whom 14 had no symptoms. A closer look showed that children 0-4 years of age who contracted COVID were more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic as infected adults (36.8% vs. 14.3%).

The relationship between symptoms and viral load also differed between adults and young children.

While adults with high viral loads – suggesting greater contagiousness – typically had more severe COVID symptoms, no correlation was found in young kids, meaning children with mild or no symptoms could still be highly contagious.

Dr. Karron said these findings should help parents and other stakeholders make better-informed decisions based on known risks. She recommended testing young, asymptomatic children for COVID if they have been exposed to infected individuals, then acting accordingly based on the results.

“If a family is infected with the virus, and the 2-year-old is asymptomatic, and people are thinking about a visit to elderly grandparents who may be frail, one shouldn’t assume that the 2-year-old is uninfected,” Dr. Karron said. “That child should be tested along with other family members.”

Testing should also be considered for young children exposed to COVID at childcare facilities, she added.

But not every expert consulted for this piece shared these opinions of Dr. Karron.

“I question whether that effort is worth it,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at UC Davis Health, Sacramento, Calif.

He noted that recent Food and Drug Administration guidance for COVID testing calls for three negative at-home antigen tests to confirm lack of infection.

“That would take 4 days to get those tests done,” he said. “So, it’s a lot of testing. It’s a lot of record keeping, it’s inconvenient, it’s uncomfortable to be tested, and I just question whether it’s worth that effort.”

Applicability of findings to today questioned

Dr. Blumberg also questioned whether the study, which was completed almost a year ago, reflects the current pandemic landscape.

“At the time this study was done, it was predominantly Delta [variant instead of Omicron],” Dr. Blumberg said. “The other issue [with the study] is that … most of the children didn’t have preexisting immunity, so you have to take that into account.”

Preexisting immunity – whether from exposure or vaccination – could lower viral loads, so asymptomatic children today really could be less contagious than they were when the study was done, according to Dr. Blumberg. Kids without symptoms are also less likely to spread the virus, because they aren’t coughing or sneezing, he added.

Sara R. Kim, MD, and Janet A. Englund, MD, of the Seattle Children’s Research Institute, University of Washington, said it’s challenging to know how applicable the findings are, although they sided more with the investigators than Dr. Blumberg.

“Given the higher rate of transmissibility and infectivity of the Omicron variant, it is difficult to make direct associations between findings reported during this study period and those present in the current era during which the Omicron variant is circulating,” they wrote in an accompanying editorial. “However, the higher rates of asymptomatic infection observed among children in this study are likely to be consistent with those observed for current and future viral variants.”

Although the experts offered different interpretations of the findings, they shared similar perspectives on vaccination.

“The most important thing that parents can do is get their kids vaccinated, be vaccinated themselves, and have everybody in the household vaccinated and up to date for all doses that are indicated,” Dr. Blumberg said.

Dr. Karron noted that vaccination will be increasingly important in the coming months.

“Summer is ending; school is starting,” she said. “We’re going to be in large groups indoors again very soon. To keep young children safe, I think it’s really important for them to get vaccinated.”

The study was funded by the CDC. The investigators disclosed no other relationships. Dr. Englund disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and others. Dr. Kim and Dr. Blumberg disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

BY WILL PASS

Just 14% of adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were asymptomatic, versus 37% of children aged 0-4 years, in the paper. This raises concern that parents, childcare providers, and preschools may be underestimating infection in seemingly healthy young kids who have been exposed to COVID, wrote lead author Ruth A. Karron, MD, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open.

Methods

The new research involved 690 individuals from 175 households in Maryland who were monitored closely between November 2020 and October 2021. Every week for 8 months, participants completed online symptom checks and underwent PCR testing using nasal swabs, with symptomatic individuals submitting additional swabs for analysis.

“What was different about our study [compared with previous studies] was the intensity of our collection, and the fact that we collected specimens from asymptomatic people,” said Dr. Karron, a pediatrician and professor in the department of international health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in an interview. “You shed more virus earlier in the infection than later, and the fact that we were sampling every single week meant that we could pick up those early infections.”

The study also stands out for its focus on young children, Dr. Karron said. Enrollment required all households to have at least one child aged 0-4 years, so 256 out of 690 participants (37.1%) were in this youngest age group. The remainder of the population consisted of 100 older children aged 5-17 years (14.5%) and 334 adults aged 18-74 years (48.4%).

Children 4 and under more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic

By the end of the study, 51 participants had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, among whom 14 had no symptoms. A closer look showed that children 0-4 years of age who contracted COVID were more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic as infected adults (36.8% vs. 14.3%).

The relationship between symptoms and viral load also differed between adults and young children.

While adults with high viral loads – suggesting greater contagiousness – typically had more severe COVID symptoms, no correlation was found in young kids, meaning children with mild or no symptoms could still be highly contagious.

Dr. Karron said these findings should help parents and other stakeholders make better-informed decisions based on known risks. She recommended testing young, asymptomatic children for COVID if they have been exposed to infected individuals, then acting accordingly based on the results.

“If a family is infected with the virus, and the 2-year-old is asymptomatic, and people are thinking about a visit to elderly grandparents who may be frail, one shouldn’t assume that the 2-year-old is uninfected,” Dr. Karron said. “That child should be tested along with other family members.”

Testing should also be considered for young children exposed to COVID at childcare facilities, she added.

But not every expert consulted for this piece shared these opinions of Dr. Karron.

“I question whether that effort is worth it,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at UC Davis Health, Sacramento, Calif.

He noted that recent Food and Drug Administration guidance for COVID testing calls for three negative at-home antigen tests to confirm lack of infection.

“That would take 4 days to get those tests done,” he said. “So, it’s a lot of testing. It’s a lot of record keeping, it’s inconvenient, it’s uncomfortable to be tested, and I just question whether it’s worth that effort.”

Applicability of findings to today questioned

Dr. Blumberg also questioned whether the study, which was completed almost a year ago, reflects the current pandemic landscape.

“At the time this study was done, it was predominantly Delta [variant instead of Omicron],” Dr. Blumberg said. “The other issue [with the study] is that … most of the children didn’t have preexisting immunity, so you have to take that into account.”

Preexisting immunity – whether from exposure or vaccination – could lower viral loads, so asymptomatic children today really could be less contagious than they were when the study was done, according to Dr. Blumberg. Kids without symptoms are also less likely to spread the virus, because they aren’t coughing or sneezing, he added.

Sara R. Kim, MD, and Janet A. Englund, MD, of the Seattle Children’s Research Institute, University of Washington, said it’s challenging to know how applicable the findings are, although they sided more with the investigators than Dr. Blumberg.

“Given the higher rate of transmissibility and infectivity of the Omicron variant, it is difficult to make direct associations between findings reported during this study period and those present in the current era during which the Omicron variant is circulating,” they wrote in an accompanying editorial. “However, the higher rates of asymptomatic infection observed among children in this study are likely to be consistent with those observed for current and future viral variants.”

Although the experts offered different interpretations of the findings, they shared similar perspectives on vaccination.

“The most important thing that parents can do is get their kids vaccinated, be vaccinated themselves, and have everybody in the household vaccinated and up to date for all doses that are indicated,” Dr. Blumberg said.

Dr. Karron noted that vaccination will be increasingly important in the coming months.

“Summer is ending; school is starting,” she said. “We’re going to be in large groups indoors again very soon. To keep young children safe, I think it’s really important for them to get vaccinated.”

The study was funded by the CDC. The investigators disclosed no other relationships. Dr. Englund disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and others. Dr. Kim and Dr. Blumberg disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

BY WILL PASS

Just 14% of adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were asymptomatic, versus 37% of children aged 0-4 years, in the paper. This raises concern that parents, childcare providers, and preschools may be underestimating infection in seemingly healthy young kids who have been exposed to COVID, wrote lead author Ruth A. Karron, MD, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open.

Methods

The new research involved 690 individuals from 175 households in Maryland who were monitored closely between November 2020 and October 2021. Every week for 8 months, participants completed online symptom checks and underwent PCR testing using nasal swabs, with symptomatic individuals submitting additional swabs for analysis.

“What was different about our study [compared with previous studies] was the intensity of our collection, and the fact that we collected specimens from asymptomatic people,” said Dr. Karron, a pediatrician and professor in the department of international health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in an interview. “You shed more virus earlier in the infection than later, and the fact that we were sampling every single week meant that we could pick up those early infections.”

The study also stands out for its focus on young children, Dr. Karron said. Enrollment required all households to have at least one child aged 0-4 years, so 256 out of 690 participants (37.1%) were in this youngest age group. The remainder of the population consisted of 100 older children aged 5-17 years (14.5%) and 334 adults aged 18-74 years (48.4%).

Children 4 and under more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic

By the end of the study, 51 participants had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, among whom 14 had no symptoms. A closer look showed that children 0-4 years of age who contracted COVID were more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic as infected adults (36.8% vs. 14.3%).

The relationship between symptoms and viral load also differed between adults and young children.

While adults with high viral loads – suggesting greater contagiousness – typically had more severe COVID symptoms, no correlation was found in young kids, meaning children with mild or no symptoms could still be highly contagious.

Dr. Karron said these findings should help parents and other stakeholders make better-informed decisions based on known risks. She recommended testing young, asymptomatic children for COVID if they have been exposed to infected individuals, then acting accordingly based on the results.

“If a family is infected with the virus, and the 2-year-old is asymptomatic, and people are thinking about a visit to elderly grandparents who may be frail, one shouldn’t assume that the 2-year-old is uninfected,” Dr. Karron said. “That child should be tested along with other family members.”

Testing should also be considered for young children exposed to COVID at childcare facilities, she added.

But not every expert consulted for this piece shared these opinions of Dr. Karron.

“I question whether that effort is worth it,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at UC Davis Health, Sacramento, Calif.

He noted that recent Food and Drug Administration guidance for COVID testing calls for three negative at-home antigen tests to confirm lack of infection.

“That would take 4 days to get those tests done,” he said. “So, it’s a lot of testing. It’s a lot of record keeping, it’s inconvenient, it’s uncomfortable to be tested, and I just question whether it’s worth that effort.”

Applicability of findings to today questioned

Dr. Blumberg also questioned whether the study, which was completed almost a year ago, reflects the current pandemic landscape.

“At the time this study was done, it was predominantly Delta [variant instead of Omicron],” Dr. Blumberg said. “The other issue [with the study] is that … most of the children didn’t have preexisting immunity, so you have to take that into account.”

Preexisting immunity – whether from exposure or vaccination – could lower viral loads, so asymptomatic children today really could be less contagious than they were when the study was done, according to Dr. Blumberg. Kids without symptoms are also less likely to spread the virus, because they aren’t coughing or sneezing, he added.

Sara R. Kim, MD, and Janet A. Englund, MD, of the Seattle Children’s Research Institute, University of Washington, said it’s challenging to know how applicable the findings are, although they sided more with the investigators than Dr. Blumberg.

“Given the higher rate of transmissibility and infectivity of the Omicron variant, it is difficult to make direct associations between findings reported during this study period and those present in the current era during which the Omicron variant is circulating,” they wrote in an accompanying editorial. “However, the higher rates of asymptomatic infection observed among children in this study are likely to be consistent with those observed for current and future viral variants.”

Although the experts offered different interpretations of the findings, they shared similar perspectives on vaccination.

“The most important thing that parents can do is get their kids vaccinated, be vaccinated themselves, and have everybody in the household vaccinated and up to date for all doses that are indicated,” Dr. Blumberg said.

Dr. Karron noted that vaccination will be increasingly important in the coming months.

“Summer is ending; school is starting,” she said. “We’re going to be in large groups indoors again very soon. To keep young children safe, I think it’s really important for them to get vaccinated.”