User login

Advanced Primary Care program boosts COVID-19 results

The better outcomes were seen in higher vaccination rates and fewer infections, hospitalizations, and deaths from the disease, according to study authors, led by Emily Gruber, MBA, MPH, with the Maryland Primary Care Program, Maryland Department of Health in Baltimore.

The results were published online in JAMA Network Open.

The study population was divided into MDPCP participants (n = 208,146) and a matched cohort (n = 37,203) of beneficiaries not attributed to MDPCP practices but who met eligibility criteria for study participation from Jan. 1, 2020, through Dec. 31, 2021.

More vaccinations, more antibody treatments

Researchers broke down the comparisons of better outcomes: 84.47% of MDPCP beneficiaries were fully vaccinated vs. 77.93% of nonparticipating beneficiaries (P less than .001). COVID-19–positive program beneficiaries also received monoclonal antibody treatment more often (8.45% vs. 6.11%; P less than .001).

Plus, program participants received more care via telehealth (62.95% vs. 54.53%; P less than .001) compared with those not participating.

Regarding secondary outcomes, MDPCP beneficiaries had lower rates of COVID cases (6.55% vs. 7.09%; P less than .001), lower rates of COVID-19 hospitalizations (1.81% vs. 2.06%; P = .001), and lower rates of death due to COVID-19 (0.56% vs. 0.77%; P less than .001).

Program components

Enrollment in the MDPCP is voluntary, and primary care practices can apply each year to be part of the program.

The model integrates primary care and public health in the pandemic response. It was created by the Maryland Department of Health (MDH) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

It expands the role of primary care to include services such as expanded care management, integrated behavioral health, data-driven care, and screenings and referrals to address social needs.

Coauthor Howard Haft, MD, MMM, with the Maryland Department of Public Health, said in an interview that among the most important factors in the program’s success were giving providers vaccines to distribute and then giving providers data on how many patients are vaccinated, and who’s not vaccinated but at high risk, and how those rates compare to other practices.

As to whether this could be a widespread model, Dr. Haft said, “It’s highly replicable.”

“Every state in the nation overall has all of these resources. It’s a matter of having the operational and political will to put those resources together. Almost every state has the technological ability to use their health information exchange to help tie pieces together.”

Vaccines and testing made available to providers

Making ample vaccines and testing available to providers in their offices helped patients get those services in a place they trust, Dr. Haft said.

The model also included a payment system for providers that included a significant amount of non–visit-based payments when many locations were closed in the height of the pandemic.

“That helped financially,” as did providing free telehealth platforms to practices with training on how to use them, Dr. Haft said.

‘Innovative and important’

Renu Tipirneni, MD, an assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan and at the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation in Ann Arbor, said Maryland is out front putting into practice what practices nationwide aspire to do – coordinating physical and mental health and social needs and integrating primary and public health. Dr. Tipirneni, who was not involved with the study, said she was impressed the researchers were able to show statistically significant improvement with COVID-19 outcomes in the first 2 years.

“In terms of health outcomes, we often have to wait longer to see good outcomes,” she said. “It’s a really innovative and important model.”

She said states can learn from each other and this model is an example.

Integrating primary care and public health and addressing social needs may be the biggest challenges for states, she said, as those realms typically have been siloed.

“But they may be the key components to achieving these outcomes,” she said.

Take-home message

The most important benefit of the program is that data suggest it saves lives, according to Dr. Haft. While the actual difference between COVID deaths in the program and nonprogram groups was small, multiplying that savings across the nation shows substantial potential benefit, he explained.

“At a time when we were losing lives at an unconscionable rate, we were able to make a difference in saving lives,” Dr. Haft said.

Authors report no relevant financial disclosures.

The study received financial support from the Maryland Department of Health.

Dr. Tiperneni is helping evaluate Michigan’s Medicaid contract.

The better outcomes were seen in higher vaccination rates and fewer infections, hospitalizations, and deaths from the disease, according to study authors, led by Emily Gruber, MBA, MPH, with the Maryland Primary Care Program, Maryland Department of Health in Baltimore.

The results were published online in JAMA Network Open.

The study population was divided into MDPCP participants (n = 208,146) and a matched cohort (n = 37,203) of beneficiaries not attributed to MDPCP practices but who met eligibility criteria for study participation from Jan. 1, 2020, through Dec. 31, 2021.

More vaccinations, more antibody treatments

Researchers broke down the comparisons of better outcomes: 84.47% of MDPCP beneficiaries were fully vaccinated vs. 77.93% of nonparticipating beneficiaries (P less than .001). COVID-19–positive program beneficiaries also received monoclonal antibody treatment more often (8.45% vs. 6.11%; P less than .001).

Plus, program participants received more care via telehealth (62.95% vs. 54.53%; P less than .001) compared with those not participating.

Regarding secondary outcomes, MDPCP beneficiaries had lower rates of COVID cases (6.55% vs. 7.09%; P less than .001), lower rates of COVID-19 hospitalizations (1.81% vs. 2.06%; P = .001), and lower rates of death due to COVID-19 (0.56% vs. 0.77%; P less than .001).

Program components

Enrollment in the MDPCP is voluntary, and primary care practices can apply each year to be part of the program.

The model integrates primary care and public health in the pandemic response. It was created by the Maryland Department of Health (MDH) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

It expands the role of primary care to include services such as expanded care management, integrated behavioral health, data-driven care, and screenings and referrals to address social needs.

Coauthor Howard Haft, MD, MMM, with the Maryland Department of Public Health, said in an interview that among the most important factors in the program’s success were giving providers vaccines to distribute and then giving providers data on how many patients are vaccinated, and who’s not vaccinated but at high risk, and how those rates compare to other practices.

As to whether this could be a widespread model, Dr. Haft said, “It’s highly replicable.”

“Every state in the nation overall has all of these resources. It’s a matter of having the operational and political will to put those resources together. Almost every state has the technological ability to use their health information exchange to help tie pieces together.”

Vaccines and testing made available to providers

Making ample vaccines and testing available to providers in their offices helped patients get those services in a place they trust, Dr. Haft said.

The model also included a payment system for providers that included a significant amount of non–visit-based payments when many locations were closed in the height of the pandemic.

“That helped financially,” as did providing free telehealth platforms to practices with training on how to use them, Dr. Haft said.

‘Innovative and important’

Renu Tipirneni, MD, an assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan and at the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation in Ann Arbor, said Maryland is out front putting into practice what practices nationwide aspire to do – coordinating physical and mental health and social needs and integrating primary and public health. Dr. Tipirneni, who was not involved with the study, said she was impressed the researchers were able to show statistically significant improvement with COVID-19 outcomes in the first 2 years.

“In terms of health outcomes, we often have to wait longer to see good outcomes,” she said. “It’s a really innovative and important model.”

She said states can learn from each other and this model is an example.

Integrating primary care and public health and addressing social needs may be the biggest challenges for states, she said, as those realms typically have been siloed.

“But they may be the key components to achieving these outcomes,” she said.

Take-home message

The most important benefit of the program is that data suggest it saves lives, according to Dr. Haft. While the actual difference between COVID deaths in the program and nonprogram groups was small, multiplying that savings across the nation shows substantial potential benefit, he explained.

“At a time when we were losing lives at an unconscionable rate, we were able to make a difference in saving lives,” Dr. Haft said.

Authors report no relevant financial disclosures.

The study received financial support from the Maryland Department of Health.

Dr. Tiperneni is helping evaluate Michigan’s Medicaid contract.

The better outcomes were seen in higher vaccination rates and fewer infections, hospitalizations, and deaths from the disease, according to study authors, led by Emily Gruber, MBA, MPH, with the Maryland Primary Care Program, Maryland Department of Health in Baltimore.

The results were published online in JAMA Network Open.

The study population was divided into MDPCP participants (n = 208,146) and a matched cohort (n = 37,203) of beneficiaries not attributed to MDPCP practices but who met eligibility criteria for study participation from Jan. 1, 2020, through Dec. 31, 2021.

More vaccinations, more antibody treatments

Researchers broke down the comparisons of better outcomes: 84.47% of MDPCP beneficiaries were fully vaccinated vs. 77.93% of nonparticipating beneficiaries (P less than .001). COVID-19–positive program beneficiaries also received monoclonal antibody treatment more often (8.45% vs. 6.11%; P less than .001).

Plus, program participants received more care via telehealth (62.95% vs. 54.53%; P less than .001) compared with those not participating.

Regarding secondary outcomes, MDPCP beneficiaries had lower rates of COVID cases (6.55% vs. 7.09%; P less than .001), lower rates of COVID-19 hospitalizations (1.81% vs. 2.06%; P = .001), and lower rates of death due to COVID-19 (0.56% vs. 0.77%; P less than .001).

Program components

Enrollment in the MDPCP is voluntary, and primary care practices can apply each year to be part of the program.

The model integrates primary care and public health in the pandemic response. It was created by the Maryland Department of Health (MDH) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

It expands the role of primary care to include services such as expanded care management, integrated behavioral health, data-driven care, and screenings and referrals to address social needs.

Coauthor Howard Haft, MD, MMM, with the Maryland Department of Public Health, said in an interview that among the most important factors in the program’s success were giving providers vaccines to distribute and then giving providers data on how many patients are vaccinated, and who’s not vaccinated but at high risk, and how those rates compare to other practices.

As to whether this could be a widespread model, Dr. Haft said, “It’s highly replicable.”

“Every state in the nation overall has all of these resources. It’s a matter of having the operational and political will to put those resources together. Almost every state has the technological ability to use their health information exchange to help tie pieces together.”

Vaccines and testing made available to providers

Making ample vaccines and testing available to providers in their offices helped patients get those services in a place they trust, Dr. Haft said.

The model also included a payment system for providers that included a significant amount of non–visit-based payments when many locations were closed in the height of the pandemic.

“That helped financially,” as did providing free telehealth platforms to practices with training on how to use them, Dr. Haft said.

‘Innovative and important’

Renu Tipirneni, MD, an assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan and at the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation in Ann Arbor, said Maryland is out front putting into practice what practices nationwide aspire to do – coordinating physical and mental health and social needs and integrating primary and public health. Dr. Tipirneni, who was not involved with the study, said she was impressed the researchers were able to show statistically significant improvement with COVID-19 outcomes in the first 2 years.

“In terms of health outcomes, we often have to wait longer to see good outcomes,” she said. “It’s a really innovative and important model.”

She said states can learn from each other and this model is an example.

Integrating primary care and public health and addressing social needs may be the biggest challenges for states, she said, as those realms typically have been siloed.

“But they may be the key components to achieving these outcomes,” she said.

Take-home message

The most important benefit of the program is that data suggest it saves lives, according to Dr. Haft. While the actual difference between COVID deaths in the program and nonprogram groups was small, multiplying that savings across the nation shows substantial potential benefit, he explained.

“At a time when we were losing lives at an unconscionable rate, we were able to make a difference in saving lives,” Dr. Haft said.

Authors report no relevant financial disclosures.

The study received financial support from the Maryland Department of Health.

Dr. Tiperneni is helping evaluate Michigan’s Medicaid contract.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Pediatric vaccination rates have failed to recover

I guess we shouldn’t be surprised that vaccination rates in this country fell during the frenzy created by the COVID pandemic. We had a lot on our plates. Schools closed and many of us retreated into what seemed to be the safety of our homes. Parents were reluctant to take their children anywhere, let alone a pediatrician’s office. State health agencies wisely focused on collecting case figures and then shepherding the efforts to immunize against SARS-CoV-2 once vaccines were available. Tracking and promoting the existing children’s vaccinations fell off the priority list, even in places with exemplary vaccination rates.

Whether or not the pandemic is over continues to be a topic for debate, but there is clearly a general shift toward a new normalcy. However, vaccination rates of our children have not rebounded to prepandemic levels. In fact, in some areas they are continuing to fall.

In a recent guest essay in the New York Times, Ezekiel J. Emmanuel, MD, PhD, a physician and professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania, and Matthew Guido, his research assistant, explore the reasons for this lack of a significant rebound. The authors cite recent outbreaks of measles in Ohio and polio in New York City as examples of the peril we are facing if we fail to reverse the trend. In some areas measles vaccine rates alarmingly have dipped below the threshold for herd immunity.

While Dr. Emmanuel and Mr. Guido acknowledge that the pandemic was a major driver of the falling vaccination rates they lay blame on the persistent decline on three factors that they view as correctable: nonmedical exemptions, our failure to vigorously enforce existing vaccine requirements, and inadequate public health campaigns.

The authors underestimate the lingering effect of the pandemic on parents’ vaccine hesitancy. As a septuagenarian who often hangs out with other septuagenarians I view the rapid development and effectiveness of the COVID vaccine as astounding and a boost for vaccines in general. However, were I much younger I might treat the vaccine’s success with a shrug. After some initial concern, the younger half of the population didn’t seem to see the illness as much of a threat to themselves or their peers. This attitude was reinforced by the fact that few of their peers, including those who were unvaccinated, were getting seriously ill. Despite all the hype, most parents and their children never ended up getting seriously ill.

You can understand why many parents might be quick to toss what you and I consider a successful COVID vaccine onto what they view as a growing pile of vaccines for diseases that in their experience have never sickened or killed anyone they have known.

Let’s be honest: Over the last half century we have produced several generations of parents who have little knowledge and certainly no personal experience with a childhood disease on the order or magnitude of polio. The vaccines that we have developed during their lifetimes have been targeted at diseases such as haemophilus influenzae meningitis that, while serious and anxiety provoking for pediatricians, occur so sporadically that most parents have no personal experience to motivate them to vaccinate their children.

Dr. Emmanuel and Mr. Guido are correct in advocating for the broader elimination of nonmedical exemptions and urging us to find the political will to vigorously enforce the vaccine requirements we have already enacted. I agree that our promotional campaigns need to be more robust. But, this will be a difficult challenge unless we can impress our audience with our straight talk and honesty. We must acknowledge and then explain why all vaccines are not created equal and that some are of more critical importance than others.

We are slowly learning that education isn’t the cure-all for vaccine hesitancy we once thought it was. And using scare tactics can backfire and create dysfunctional anxiety. We must choosing our words and target audience carefully. And ... having the political will to force parents into doing the right thing will be critical if we wish to restore our vaccination rates.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

I guess we shouldn’t be surprised that vaccination rates in this country fell during the frenzy created by the COVID pandemic. We had a lot on our plates. Schools closed and many of us retreated into what seemed to be the safety of our homes. Parents were reluctant to take their children anywhere, let alone a pediatrician’s office. State health agencies wisely focused on collecting case figures and then shepherding the efforts to immunize against SARS-CoV-2 once vaccines were available. Tracking and promoting the existing children’s vaccinations fell off the priority list, even in places with exemplary vaccination rates.

Whether or not the pandemic is over continues to be a topic for debate, but there is clearly a general shift toward a new normalcy. However, vaccination rates of our children have not rebounded to prepandemic levels. In fact, in some areas they are continuing to fall.

In a recent guest essay in the New York Times, Ezekiel J. Emmanuel, MD, PhD, a physician and professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania, and Matthew Guido, his research assistant, explore the reasons for this lack of a significant rebound. The authors cite recent outbreaks of measles in Ohio and polio in New York City as examples of the peril we are facing if we fail to reverse the trend. In some areas measles vaccine rates alarmingly have dipped below the threshold for herd immunity.

While Dr. Emmanuel and Mr. Guido acknowledge that the pandemic was a major driver of the falling vaccination rates they lay blame on the persistent decline on three factors that they view as correctable: nonmedical exemptions, our failure to vigorously enforce existing vaccine requirements, and inadequate public health campaigns.

The authors underestimate the lingering effect of the pandemic on parents’ vaccine hesitancy. As a septuagenarian who often hangs out with other septuagenarians I view the rapid development and effectiveness of the COVID vaccine as astounding and a boost for vaccines in general. However, were I much younger I might treat the vaccine’s success with a shrug. After some initial concern, the younger half of the population didn’t seem to see the illness as much of a threat to themselves or their peers. This attitude was reinforced by the fact that few of their peers, including those who were unvaccinated, were getting seriously ill. Despite all the hype, most parents and their children never ended up getting seriously ill.

You can understand why many parents might be quick to toss what you and I consider a successful COVID vaccine onto what they view as a growing pile of vaccines for diseases that in their experience have never sickened or killed anyone they have known.

Let’s be honest: Over the last half century we have produced several generations of parents who have little knowledge and certainly no personal experience with a childhood disease on the order or magnitude of polio. The vaccines that we have developed during their lifetimes have been targeted at diseases such as haemophilus influenzae meningitis that, while serious and anxiety provoking for pediatricians, occur so sporadically that most parents have no personal experience to motivate them to vaccinate their children.

Dr. Emmanuel and Mr. Guido are correct in advocating for the broader elimination of nonmedical exemptions and urging us to find the political will to vigorously enforce the vaccine requirements we have already enacted. I agree that our promotional campaigns need to be more robust. But, this will be a difficult challenge unless we can impress our audience with our straight talk and honesty. We must acknowledge and then explain why all vaccines are not created equal and that some are of more critical importance than others.

We are slowly learning that education isn’t the cure-all for vaccine hesitancy we once thought it was. And using scare tactics can backfire and create dysfunctional anxiety. We must choosing our words and target audience carefully. And ... having the political will to force parents into doing the right thing will be critical if we wish to restore our vaccination rates.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

I guess we shouldn’t be surprised that vaccination rates in this country fell during the frenzy created by the COVID pandemic. We had a lot on our plates. Schools closed and many of us retreated into what seemed to be the safety of our homes. Parents were reluctant to take their children anywhere, let alone a pediatrician’s office. State health agencies wisely focused on collecting case figures and then shepherding the efforts to immunize against SARS-CoV-2 once vaccines were available. Tracking and promoting the existing children’s vaccinations fell off the priority list, even in places with exemplary vaccination rates.

Whether or not the pandemic is over continues to be a topic for debate, but there is clearly a general shift toward a new normalcy. However, vaccination rates of our children have not rebounded to prepandemic levels. In fact, in some areas they are continuing to fall.

In a recent guest essay in the New York Times, Ezekiel J. Emmanuel, MD, PhD, a physician and professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania, and Matthew Guido, his research assistant, explore the reasons for this lack of a significant rebound. The authors cite recent outbreaks of measles in Ohio and polio in New York City as examples of the peril we are facing if we fail to reverse the trend. In some areas measles vaccine rates alarmingly have dipped below the threshold for herd immunity.

While Dr. Emmanuel and Mr. Guido acknowledge that the pandemic was a major driver of the falling vaccination rates they lay blame on the persistent decline on three factors that they view as correctable: nonmedical exemptions, our failure to vigorously enforce existing vaccine requirements, and inadequate public health campaigns.

The authors underestimate the lingering effect of the pandemic on parents’ vaccine hesitancy. As a septuagenarian who often hangs out with other septuagenarians I view the rapid development and effectiveness of the COVID vaccine as astounding and a boost for vaccines in general. However, were I much younger I might treat the vaccine’s success with a shrug. After some initial concern, the younger half of the population didn’t seem to see the illness as much of a threat to themselves or their peers. This attitude was reinforced by the fact that few of their peers, including those who were unvaccinated, were getting seriously ill. Despite all the hype, most parents and their children never ended up getting seriously ill.

You can understand why many parents might be quick to toss what you and I consider a successful COVID vaccine onto what they view as a growing pile of vaccines for diseases that in their experience have never sickened or killed anyone they have known.

Let’s be honest: Over the last half century we have produced several generations of parents who have little knowledge and certainly no personal experience with a childhood disease on the order or magnitude of polio. The vaccines that we have developed during their lifetimes have been targeted at diseases such as haemophilus influenzae meningitis that, while serious and anxiety provoking for pediatricians, occur so sporadically that most parents have no personal experience to motivate them to vaccinate their children.

Dr. Emmanuel and Mr. Guido are correct in advocating for the broader elimination of nonmedical exemptions and urging us to find the political will to vigorously enforce the vaccine requirements we have already enacted. I agree that our promotional campaigns need to be more robust. But, this will be a difficult challenge unless we can impress our audience with our straight talk and honesty. We must acknowledge and then explain why all vaccines are not created equal and that some are of more critical importance than others.

We are slowly learning that education isn’t the cure-all for vaccine hesitancy we once thought it was. And using scare tactics can backfire and create dysfunctional anxiety. We must choosing our words and target audience carefully. And ... having the political will to force parents into doing the right thing will be critical if we wish to restore our vaccination rates.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Berdazimer gel under review at FDA for treating molluscum contagiosum

, the manufacturer announced.

If the submission is accepted by the FDA, the topical product could be approved in the first quarter of 2024, according to a press release from Novan, the manufacturer. If approved, it would be the first-in-class topical treatment for MC, the common, contagious viral skin infection that affects approximately six million individuals in the United States each year, most of them children aged 1-14 years, the statement noted. No FDA-approved therapies currently exist for the condition, which causes unsightly lesions on the face, trunk, limbs, and axillae that may persist untreated for a period of years.

The active ingredient in berdazimer gel 10.3% is berdazimer sodium, a nitric oxide–releasing agent. A 3.4% formulation is in development for the topical treatment of acne, according to the company.

The submission for FDA approval is based on data from the B-SIMPLE4 study, a phase 3 randomized trial of nearly 900 individuals with MC aged 6 months and older (mean age, 6.6 years), with 3-70 raised lesions. Participants were randomized to treatment with berdazimer gel 10.3% or a vehicle gel applied in a thin layer to all lesions once daily for 12 weeks. The results were published in JAMA Dermatology.

The primary outcome was complete clearance of all lesions. At 12 weeks, 32.4% of patients in the berdazimer group achieved this outcome vs. 19.7% of those in the vehicle group (P < .001). Overall adverse event rates were low in both groups; 4.1% of patients on berdazimer and 0.7% of those on the vehicle experienced adverse events that led to discontinuation of treatment. The most common adverse events across both groups were application-site pain and erythema, and most of these were mild or moderate.

, the manufacturer announced.

If the submission is accepted by the FDA, the topical product could be approved in the first quarter of 2024, according to a press release from Novan, the manufacturer. If approved, it would be the first-in-class topical treatment for MC, the common, contagious viral skin infection that affects approximately six million individuals in the United States each year, most of them children aged 1-14 years, the statement noted. No FDA-approved therapies currently exist for the condition, which causes unsightly lesions on the face, trunk, limbs, and axillae that may persist untreated for a period of years.

The active ingredient in berdazimer gel 10.3% is berdazimer sodium, a nitric oxide–releasing agent. A 3.4% formulation is in development for the topical treatment of acne, according to the company.

The submission for FDA approval is based on data from the B-SIMPLE4 study, a phase 3 randomized trial of nearly 900 individuals with MC aged 6 months and older (mean age, 6.6 years), with 3-70 raised lesions. Participants were randomized to treatment with berdazimer gel 10.3% or a vehicle gel applied in a thin layer to all lesions once daily for 12 weeks. The results were published in JAMA Dermatology.

The primary outcome was complete clearance of all lesions. At 12 weeks, 32.4% of patients in the berdazimer group achieved this outcome vs. 19.7% of those in the vehicle group (P < .001). Overall adverse event rates were low in both groups; 4.1% of patients on berdazimer and 0.7% of those on the vehicle experienced adverse events that led to discontinuation of treatment. The most common adverse events across both groups were application-site pain and erythema, and most of these were mild or moderate.

, the manufacturer announced.

If the submission is accepted by the FDA, the topical product could be approved in the first quarter of 2024, according to a press release from Novan, the manufacturer. If approved, it would be the first-in-class topical treatment for MC, the common, contagious viral skin infection that affects approximately six million individuals in the United States each year, most of them children aged 1-14 years, the statement noted. No FDA-approved therapies currently exist for the condition, which causes unsightly lesions on the face, trunk, limbs, and axillae that may persist untreated for a period of years.

The active ingredient in berdazimer gel 10.3% is berdazimer sodium, a nitric oxide–releasing agent. A 3.4% formulation is in development for the topical treatment of acne, according to the company.

The submission for FDA approval is based on data from the B-SIMPLE4 study, a phase 3 randomized trial of nearly 900 individuals with MC aged 6 months and older (mean age, 6.6 years), with 3-70 raised lesions. Participants were randomized to treatment with berdazimer gel 10.3% or a vehicle gel applied in a thin layer to all lesions once daily for 12 weeks. The results were published in JAMA Dermatology.

The primary outcome was complete clearance of all lesions. At 12 weeks, 32.4% of patients in the berdazimer group achieved this outcome vs. 19.7% of those in the vehicle group (P < .001). Overall adverse event rates were low in both groups; 4.1% of patients on berdazimer and 0.7% of those on the vehicle experienced adverse events that led to discontinuation of treatment. The most common adverse events across both groups were application-site pain and erythema, and most of these were mild or moderate.

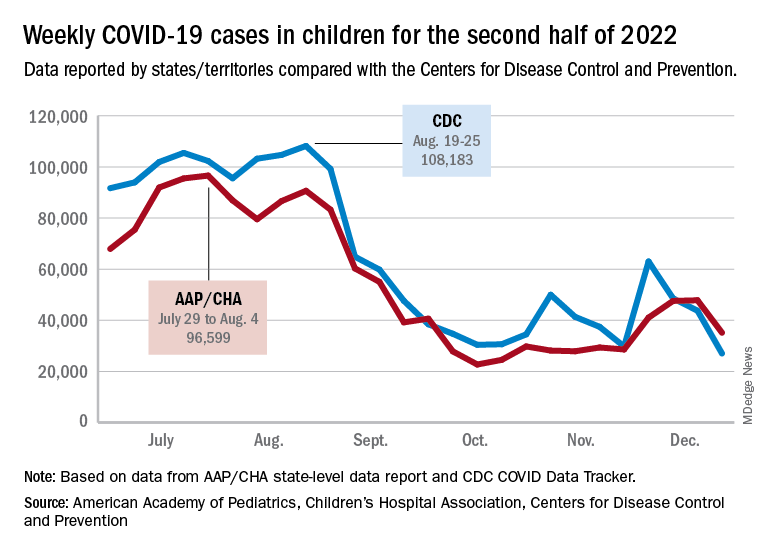

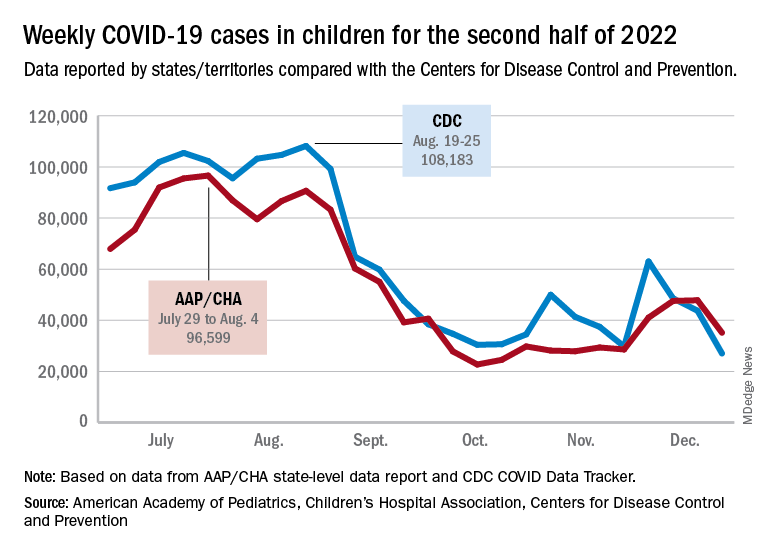

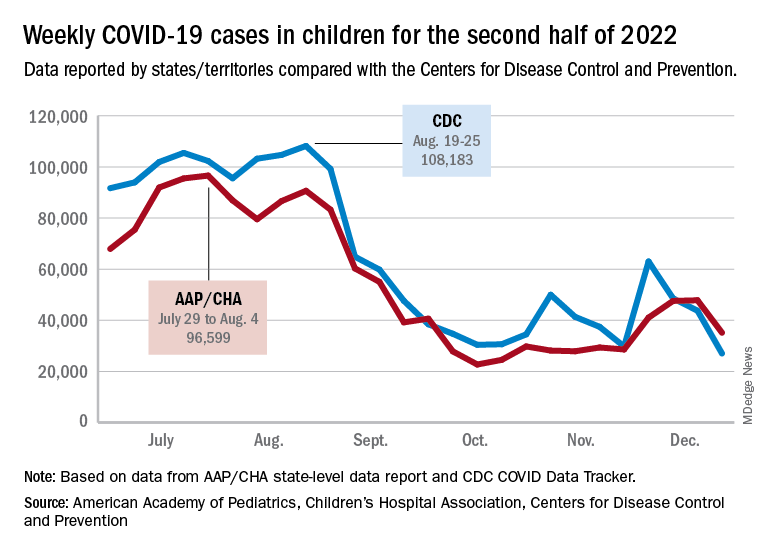

Children and COVID: New cases fell as the old year ended

The end of 2022 saw a drop in new COVID-19 cases in children, even as rates of emergency department visits continued upward trends that began in late October.

New cases for the week of Dec. 23-29 fell for the first time since late November, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The AAP/CHA analysis of publicly available state data differs somewhat from figures reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has new cases for the latest available week, Dec.18-24, at just over 27,000 after 3 straight weeks of declines from a count of almost 63,000 for the week ending Nov. 26. The CDC, however, updates previously reported data on a regular basis, so that 27,000 is likely to increase in the coming weeks.

The CDC line on the graph also shows a peak for the week of Oct. 30 to Nov. 5 when new cases reached almost 50,000, compared with almost 30,000 reported for the week of Oct. 28 to Nov. 3 by the AAP and CHA in their report of state-level data. The AAP and CHA put the total number of child COVID cases since the start of the pandemic at 15.2 million as of Dec. 29, while the CDC reports 16.2 million cases as of Dec. 28.

There have been 1,975 deaths from COVID-19 in children aged 0-17 years, according to the CDC, which amounts to just over 0.2% of all COVID deaths for which age group data were available.

CDC data on emergency department visits involving diagnosed COVID-19 have been rising since late October. In children aged 0-11 years, for example, COVID was involved in 1.0% of ED visits (7-day average) as late as Nov. 4, but by Dec. 27 that rate was 2.6%. Children aged 12-15 years went from 0.6% on Oct. 28 to 1.5% on Dec. 27, while 16- to 17-year-olds had ED visit rates of 0.6% on Oct. 19 and 1.7% on Dec. 27, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

New hospital admissions with diagnosed COVID, which had been following the same upward trend as ED visits since late October, halted that rise in children aged 0-17 years and have gone no higher than 0.29 per 100,000 population since Dec. 9, the CDC data show.

The end of 2022 saw a drop in new COVID-19 cases in children, even as rates of emergency department visits continued upward trends that began in late October.

New cases for the week of Dec. 23-29 fell for the first time since late November, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The AAP/CHA analysis of publicly available state data differs somewhat from figures reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has new cases for the latest available week, Dec.18-24, at just over 27,000 after 3 straight weeks of declines from a count of almost 63,000 for the week ending Nov. 26. The CDC, however, updates previously reported data on a regular basis, so that 27,000 is likely to increase in the coming weeks.

The CDC line on the graph also shows a peak for the week of Oct. 30 to Nov. 5 when new cases reached almost 50,000, compared with almost 30,000 reported for the week of Oct. 28 to Nov. 3 by the AAP and CHA in their report of state-level data. The AAP and CHA put the total number of child COVID cases since the start of the pandemic at 15.2 million as of Dec. 29, while the CDC reports 16.2 million cases as of Dec. 28.

There have been 1,975 deaths from COVID-19 in children aged 0-17 years, according to the CDC, which amounts to just over 0.2% of all COVID deaths for which age group data were available.

CDC data on emergency department visits involving diagnosed COVID-19 have been rising since late October. In children aged 0-11 years, for example, COVID was involved in 1.0% of ED visits (7-day average) as late as Nov. 4, but by Dec. 27 that rate was 2.6%. Children aged 12-15 years went from 0.6% on Oct. 28 to 1.5% on Dec. 27, while 16- to 17-year-olds had ED visit rates of 0.6% on Oct. 19 and 1.7% on Dec. 27, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

New hospital admissions with diagnosed COVID, which had been following the same upward trend as ED visits since late October, halted that rise in children aged 0-17 years and have gone no higher than 0.29 per 100,000 population since Dec. 9, the CDC data show.

The end of 2022 saw a drop in new COVID-19 cases in children, even as rates of emergency department visits continued upward trends that began in late October.

New cases for the week of Dec. 23-29 fell for the first time since late November, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The AAP/CHA analysis of publicly available state data differs somewhat from figures reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has new cases for the latest available week, Dec.18-24, at just over 27,000 after 3 straight weeks of declines from a count of almost 63,000 for the week ending Nov. 26. The CDC, however, updates previously reported data on a regular basis, so that 27,000 is likely to increase in the coming weeks.

The CDC line on the graph also shows a peak for the week of Oct. 30 to Nov. 5 when new cases reached almost 50,000, compared with almost 30,000 reported for the week of Oct. 28 to Nov. 3 by the AAP and CHA in their report of state-level data. The AAP and CHA put the total number of child COVID cases since the start of the pandemic at 15.2 million as of Dec. 29, while the CDC reports 16.2 million cases as of Dec. 28.

There have been 1,975 deaths from COVID-19 in children aged 0-17 years, according to the CDC, which amounts to just over 0.2% of all COVID deaths for which age group data were available.

CDC data on emergency department visits involving diagnosed COVID-19 have been rising since late October. In children aged 0-11 years, for example, COVID was involved in 1.0% of ED visits (7-day average) as late as Nov. 4, but by Dec. 27 that rate was 2.6%. Children aged 12-15 years went from 0.6% on Oct. 28 to 1.5% on Dec. 27, while 16- to 17-year-olds had ED visit rates of 0.6% on Oct. 19 and 1.7% on Dec. 27, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

New hospital admissions with diagnosed COVID, which had been following the same upward trend as ED visits since late October, halted that rise in children aged 0-17 years and have gone no higher than 0.29 per 100,000 population since Dec. 9, the CDC data show.

Latent TB: The case for vigilance

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released draft recommendations on screening for tuberculosis (TB).1 The USPSTF continues to recommend screening for latent TB infection (LTBI) in those at high risk.

Why is this important? Up to one-quarter of the world’s population has been infected with TB, according to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates. In 2021, active TB was diagnosed in 10.6 million people, and it caused 1.6 million deaths.2 Worldwide, TB is still a major cause of mortality: It is the 13th leading cause of death and is the leading cause of infectious disease mortality in non-COVID years.

Although the rate of active TB in the United States has been declining for decades (from 30.7/100,000 in 1960 to 2.4/100,000 in 2021), 7882 cases were reported in 2021, and an estimated 13 million people in the United States have LTBI.3 If not treated, 5% to 10% of LTBI cases will progress to active TB. This risk is higher in those with certain medical conditions.3 People born outside the United States currently account for 71.4% of reported TB cases in the United States.3

To reduce the morbidity and mortality of TB, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), WHO, and USPSTF all recommend screening for and treating LTBI. An effective approach to TB control also includes early detection and completion of treatment for active TB, as well as testing contacts of active TB cases.

Who should be screened? Those at high risk for LTBI include those who were born in, or who have resided in, countries with high rates of TB (eg, Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, and Russia); those who have lived in a correctional facility or homeless shelter; household and other close contacts of active TB cases; and health care workers who provide care to patients with TB.

Some chronic medical conditions can increase risk for progression to active TB in those with LTBI. Patients who should be tested for LTBI as part of their routine care include those who are HIV positive; are receiving immunosuppressive therapy (chemotherapy, biological immune suppressants); have received an organ transplant; have silicosis; use illicit injected drugs; and/or have had a gastrectomy or jejunoileal bypass.

In addition, local communities may have populations or geographic regions in which TB rates are high. Family physicians can obtain this information from their state or local health departments.

There are 2 screening tests for LTBI: TB blood tests (interferon-gamma release assays [IGRAs]) and the Mantoux tuberculin skin test (TST). Two TB blood tests are available in the United States: QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus (QFT-Plus) and T-SPOT.TB test (T-Spot).

There are advantages and disadvantages to both types of tests. A TST requires accurate administration and interpretation and 2 clinic visits, 48 to 72 hours apart. The cutoff on a positive test (5, 10, or 15 mm) depends on the patient’s age and risk.4 An IGRA should be processed within 8 to 32 hours and is more expensive. However, a major advantage is that it is more specific, because it is unaffected by previous vaccination with bacille Calmette-Guérin or by most nontuberculous mycobacteria infections.

To rule out active TB ... If a TB screening test is positive, the recommended work-up is to ask about TB symptoms and perform a chest x-ray to rule out active pulmonary TB. Sputum collection for acid-fast smear and culture should be ordered for anyone with a suspicious chest x-ray, respiratory symptoms consistent with TB, or HIV infection.

Treatment for LTBI markedly reduces the risk for active TB. There are 4 options:

- Isoniazid (INH) plus rifapentine (RPT) once per week for 3 months.

- Rifampin (RIF) daily for 4 months.

- INH plus RIF daily for 3 months.

- INH daily for 6 or 9 months.

Details about the variables to consider in choosing a regimen are described on the CDC website.4,5

Know your resources. Local and state public health departments should have TB control programs and are sources of information on TB diagnosis and treatment; they also can assist with follow-up of TB contacts.6 Although LTBI is a reportable condition only in young children, any suspicion of community spread of active TB should be reported to the public health department.

1. USPSTF. Latent tuberculosis infection in adults: screening. Draft recommendation statement. Published November 22, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/latent-tuberculosis-infection-adults

2. WHO. Tuberculosis: key facts. Updated October 27, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

3. CDC. Tuberculosis: data and statistics. Updated November 29, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/default.htm

4. CDC. Latent TB infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Updated February 3, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/pdf/LTBIbooklet508.pdf

5. CDC. Treatment regimens for latent TB infection. Updated February 13, 2020. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm

6. CDC. TB control offices. Updated March 28, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/links/tboffices.htm

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released draft recommendations on screening for tuberculosis (TB).1 The USPSTF continues to recommend screening for latent TB infection (LTBI) in those at high risk.

Why is this important? Up to one-quarter of the world’s population has been infected with TB, according to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates. In 2021, active TB was diagnosed in 10.6 million people, and it caused 1.6 million deaths.2 Worldwide, TB is still a major cause of mortality: It is the 13th leading cause of death and is the leading cause of infectious disease mortality in non-COVID years.

Although the rate of active TB in the United States has been declining for decades (from 30.7/100,000 in 1960 to 2.4/100,000 in 2021), 7882 cases were reported in 2021, and an estimated 13 million people in the United States have LTBI.3 If not treated, 5% to 10% of LTBI cases will progress to active TB. This risk is higher in those with certain medical conditions.3 People born outside the United States currently account for 71.4% of reported TB cases in the United States.3

To reduce the morbidity and mortality of TB, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), WHO, and USPSTF all recommend screening for and treating LTBI. An effective approach to TB control also includes early detection and completion of treatment for active TB, as well as testing contacts of active TB cases.

Who should be screened? Those at high risk for LTBI include those who were born in, or who have resided in, countries with high rates of TB (eg, Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, and Russia); those who have lived in a correctional facility or homeless shelter; household and other close contacts of active TB cases; and health care workers who provide care to patients with TB.

Some chronic medical conditions can increase risk for progression to active TB in those with LTBI. Patients who should be tested for LTBI as part of their routine care include those who are HIV positive; are receiving immunosuppressive therapy (chemotherapy, biological immune suppressants); have received an organ transplant; have silicosis; use illicit injected drugs; and/or have had a gastrectomy or jejunoileal bypass.

In addition, local communities may have populations or geographic regions in which TB rates are high. Family physicians can obtain this information from their state or local health departments.

There are 2 screening tests for LTBI: TB blood tests (interferon-gamma release assays [IGRAs]) and the Mantoux tuberculin skin test (TST). Two TB blood tests are available in the United States: QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus (QFT-Plus) and T-SPOT.TB test (T-Spot).

There are advantages and disadvantages to both types of tests. A TST requires accurate administration and interpretation and 2 clinic visits, 48 to 72 hours apart. The cutoff on a positive test (5, 10, or 15 mm) depends on the patient’s age and risk.4 An IGRA should be processed within 8 to 32 hours and is more expensive. However, a major advantage is that it is more specific, because it is unaffected by previous vaccination with bacille Calmette-Guérin or by most nontuberculous mycobacteria infections.

To rule out active TB ... If a TB screening test is positive, the recommended work-up is to ask about TB symptoms and perform a chest x-ray to rule out active pulmonary TB. Sputum collection for acid-fast smear and culture should be ordered for anyone with a suspicious chest x-ray, respiratory symptoms consistent with TB, or HIV infection.

Treatment for LTBI markedly reduces the risk for active TB. There are 4 options:

- Isoniazid (INH) plus rifapentine (RPT) once per week for 3 months.

- Rifampin (RIF) daily for 4 months.

- INH plus RIF daily for 3 months.

- INH daily for 6 or 9 months.

Details about the variables to consider in choosing a regimen are described on the CDC website.4,5

Know your resources. Local and state public health departments should have TB control programs and are sources of information on TB diagnosis and treatment; they also can assist with follow-up of TB contacts.6 Although LTBI is a reportable condition only in young children, any suspicion of community spread of active TB should be reported to the public health department.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released draft recommendations on screening for tuberculosis (TB).1 The USPSTF continues to recommend screening for latent TB infection (LTBI) in those at high risk.

Why is this important? Up to one-quarter of the world’s population has been infected with TB, according to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates. In 2021, active TB was diagnosed in 10.6 million people, and it caused 1.6 million deaths.2 Worldwide, TB is still a major cause of mortality: It is the 13th leading cause of death and is the leading cause of infectious disease mortality in non-COVID years.

Although the rate of active TB in the United States has been declining for decades (from 30.7/100,000 in 1960 to 2.4/100,000 in 2021), 7882 cases were reported in 2021, and an estimated 13 million people in the United States have LTBI.3 If not treated, 5% to 10% of LTBI cases will progress to active TB. This risk is higher in those with certain medical conditions.3 People born outside the United States currently account for 71.4% of reported TB cases in the United States.3

To reduce the morbidity and mortality of TB, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), WHO, and USPSTF all recommend screening for and treating LTBI. An effective approach to TB control also includes early detection and completion of treatment for active TB, as well as testing contacts of active TB cases.

Who should be screened? Those at high risk for LTBI include those who were born in, or who have resided in, countries with high rates of TB (eg, Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, and Russia); those who have lived in a correctional facility or homeless shelter; household and other close contacts of active TB cases; and health care workers who provide care to patients with TB.

Some chronic medical conditions can increase risk for progression to active TB in those with LTBI. Patients who should be tested for LTBI as part of their routine care include those who are HIV positive; are receiving immunosuppressive therapy (chemotherapy, biological immune suppressants); have received an organ transplant; have silicosis; use illicit injected drugs; and/or have had a gastrectomy or jejunoileal bypass.

In addition, local communities may have populations or geographic regions in which TB rates are high. Family physicians can obtain this information from their state or local health departments.

There are 2 screening tests for LTBI: TB blood tests (interferon-gamma release assays [IGRAs]) and the Mantoux tuberculin skin test (TST). Two TB blood tests are available in the United States: QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus (QFT-Plus) and T-SPOT.TB test (T-Spot).

There are advantages and disadvantages to both types of tests. A TST requires accurate administration and interpretation and 2 clinic visits, 48 to 72 hours apart. The cutoff on a positive test (5, 10, or 15 mm) depends on the patient’s age and risk.4 An IGRA should be processed within 8 to 32 hours and is more expensive. However, a major advantage is that it is more specific, because it is unaffected by previous vaccination with bacille Calmette-Guérin or by most nontuberculous mycobacteria infections.

To rule out active TB ... If a TB screening test is positive, the recommended work-up is to ask about TB symptoms and perform a chest x-ray to rule out active pulmonary TB. Sputum collection for acid-fast smear and culture should be ordered for anyone with a suspicious chest x-ray, respiratory symptoms consistent with TB, or HIV infection.

Treatment for LTBI markedly reduces the risk for active TB. There are 4 options:

- Isoniazid (INH) plus rifapentine (RPT) once per week for 3 months.

- Rifampin (RIF) daily for 4 months.

- INH plus RIF daily for 3 months.

- INH daily for 6 or 9 months.

Details about the variables to consider in choosing a regimen are described on the CDC website.4,5

Know your resources. Local and state public health departments should have TB control programs and are sources of information on TB diagnosis and treatment; they also can assist with follow-up of TB contacts.6 Although LTBI is a reportable condition only in young children, any suspicion of community spread of active TB should be reported to the public health department.

1. USPSTF. Latent tuberculosis infection in adults: screening. Draft recommendation statement. Published November 22, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/latent-tuberculosis-infection-adults

2. WHO. Tuberculosis: key facts. Updated October 27, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

3. CDC. Tuberculosis: data and statistics. Updated November 29, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/default.htm

4. CDC. Latent TB infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Updated February 3, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/pdf/LTBIbooklet508.pdf

5. CDC. Treatment regimens for latent TB infection. Updated February 13, 2020. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm

6. CDC. TB control offices. Updated March 28, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/links/tboffices.htm

1. USPSTF. Latent tuberculosis infection in adults: screening. Draft recommendation statement. Published November 22, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/latent-tuberculosis-infection-adults

2. WHO. Tuberculosis: key facts. Updated October 27, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

3. CDC. Tuberculosis: data and statistics. Updated November 29, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/default.htm

4. CDC. Latent TB infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Updated February 3, 2021. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/pdf/LTBIbooklet508.pdf

5. CDC. Treatment regimens for latent TB infection. Updated February 13, 2020. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm

6. CDC. TB control offices. Updated March 28, 2022. Accessed December 14, 2022. www.cdc.gov/tb/links/tboffices.htm

Atypical Keratotic Nodule on the Knuckle

The Diagnosis: Atypical Mycobacterial Infection

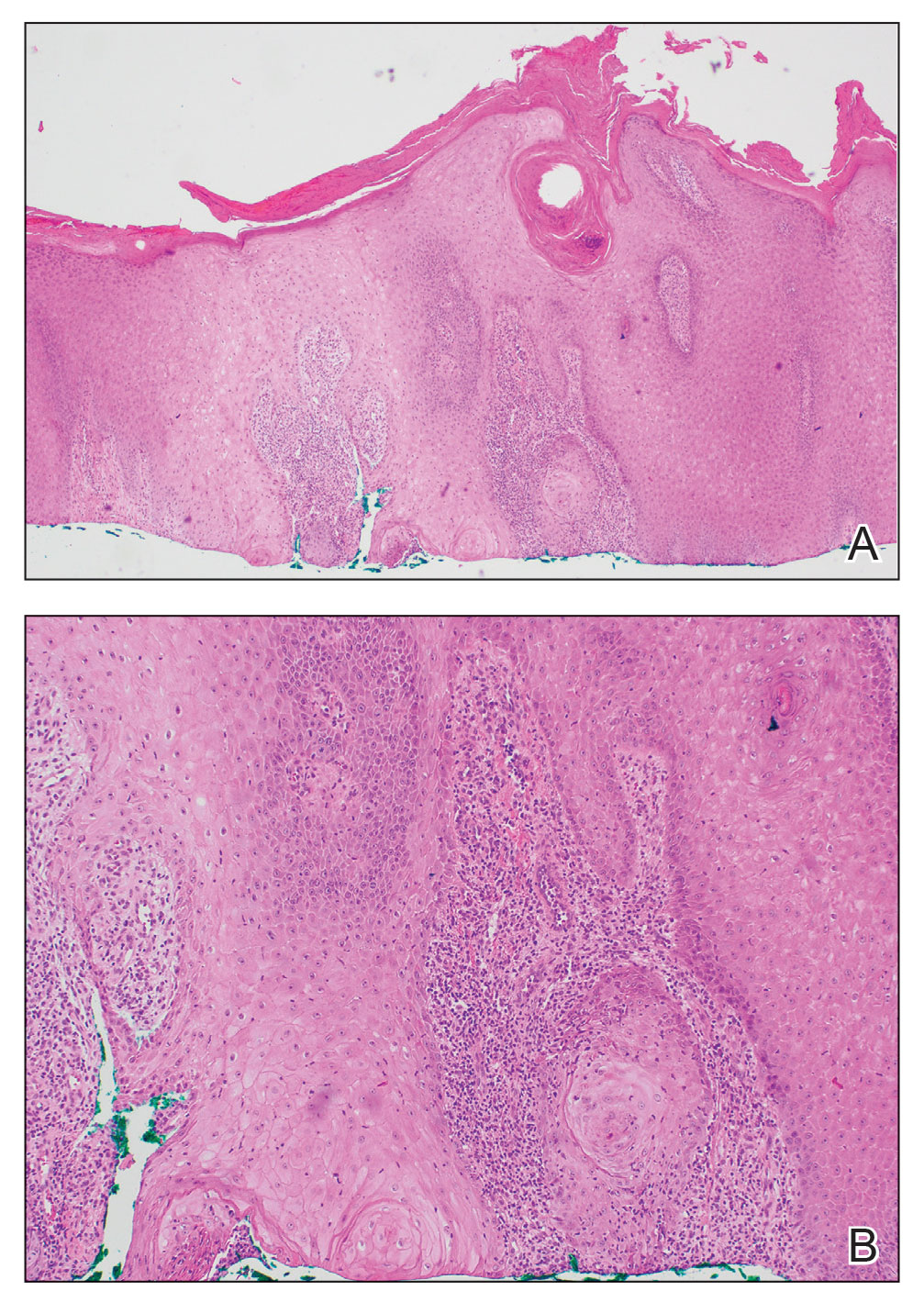

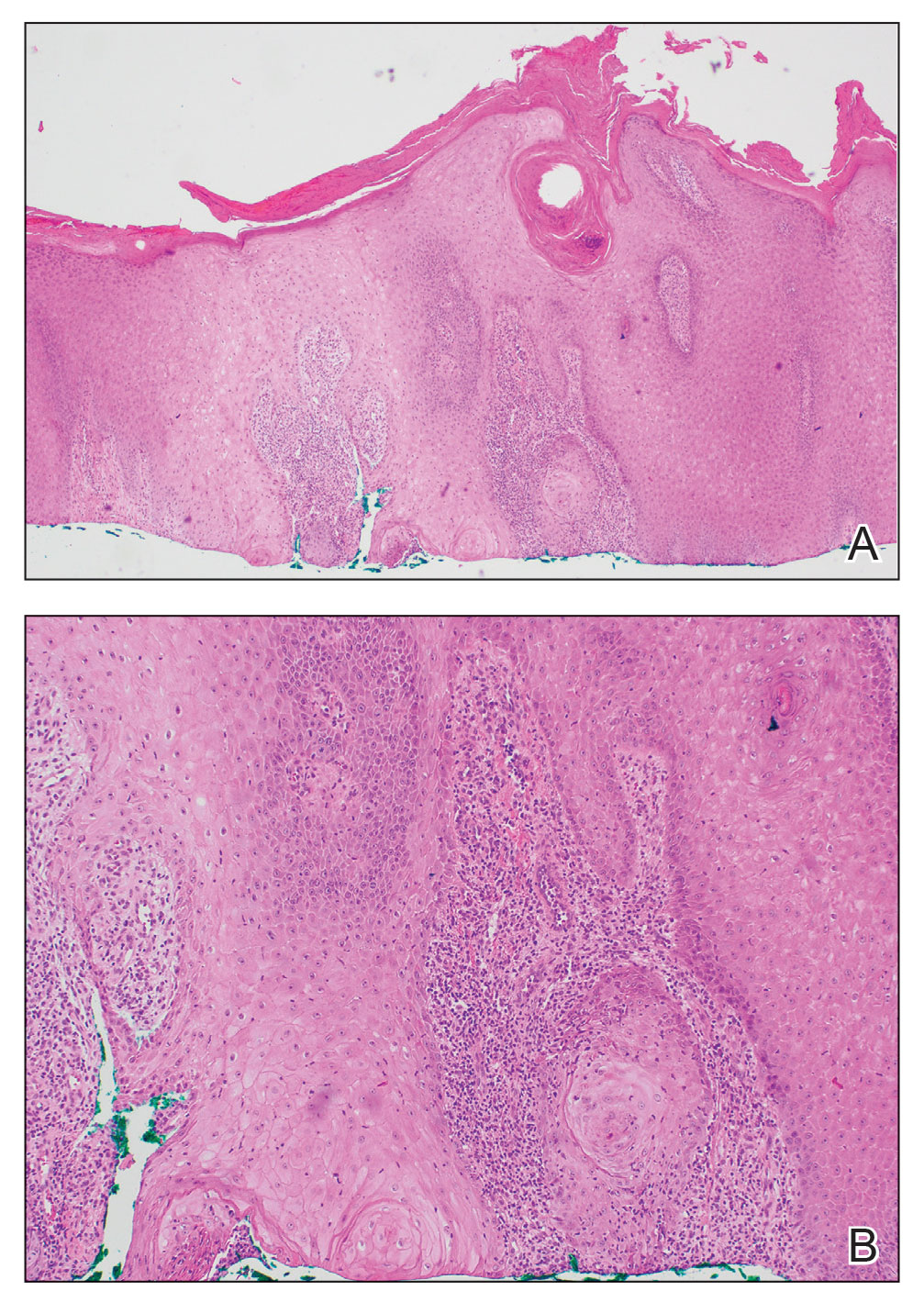

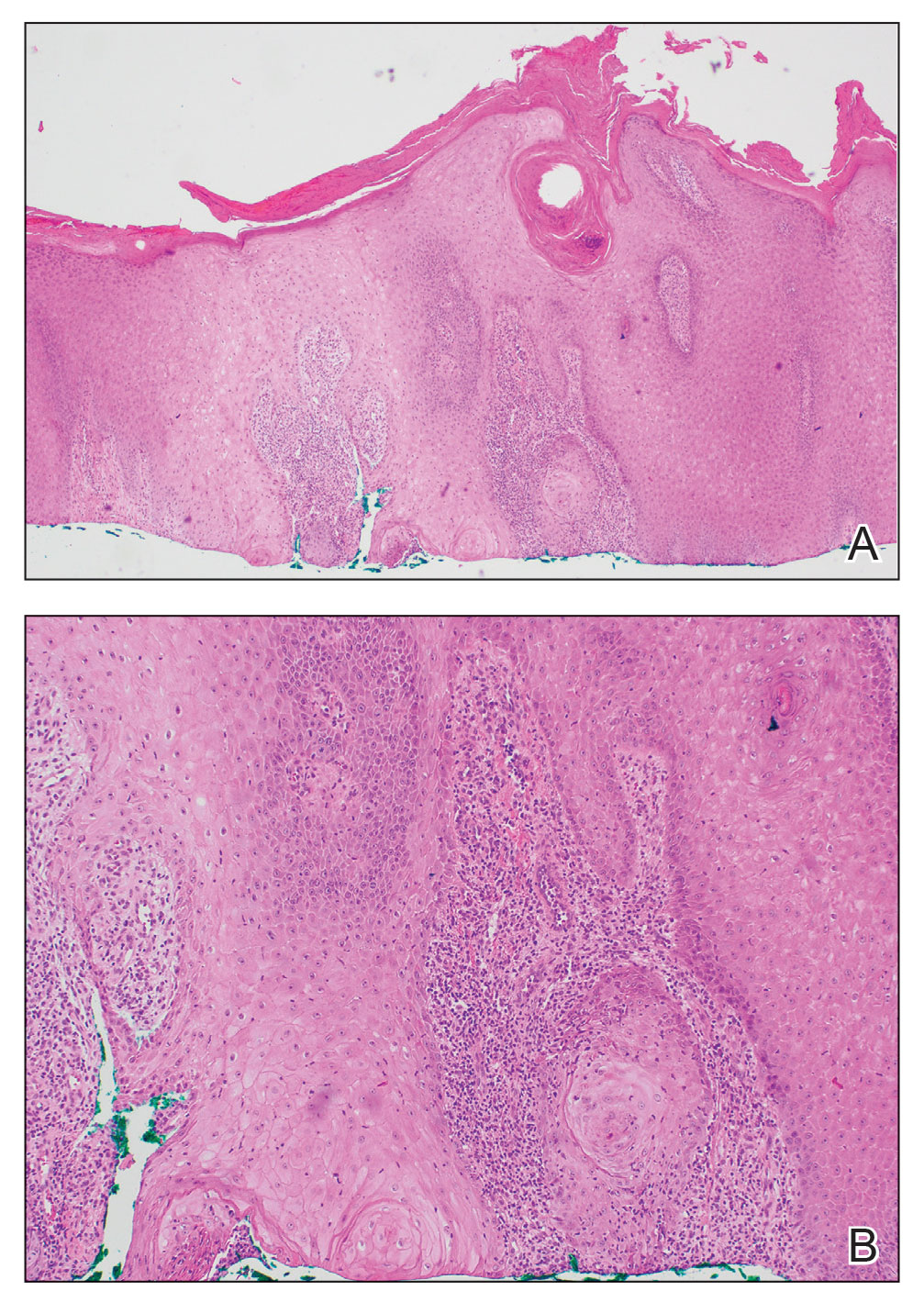

The history of rapid growth followed by shrinkage as well as the craterlike clinical appearance of our patient’s lesion were suspicious for the keratoacanthoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Periodic acid–Schiff green staining was negative for fungal or bacterial organisms, and the biopsy findings of keratinocyte atypia and irregular epidermal proliferation seemed to confirm our suspicion for well-differentiated SCC (Figure 1). Our patient subsequently was scheduled for Mohs micrographic surgery. Fortunately, a sample of tissue had been sent for panculture—bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial—to rule out infectious etiologies, given the history of possible traumatic inoculation, and returned positive for Mycobacterium marinum infection prior to the surgery. Mohs surgery was canceled, and he was referred to an infectious disease specialist who started antibiotic treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. After 1 month of treatment the lesion substantially improved (Figure 2), further supporting the diagnosis of M marinum infection over SCC.

The differential diagnosis also included sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and chromoblastomycosis. Sporotrichosis lesions typically develop as multiple nodules and ulcers along a path of lymphatic drainage and can exhibit asteroid bodies and cigar-shaped yeast forms on histology. Chromoblastomycosis may display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and granulomatous inflammation; however, pathognomonic pigmented Medlar bodies also likely would be present.1 Leishmaniasis has a wide variety of presentations; however, it typically occurs in patients with exposure to endemic areas outside of the United States. Although leishmaniasis may demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and mixed inflammation on histology, it also likely would show amastigotes within dermal macrophages.2

Atypical mycobacterial infections initially may be misdiagnosed as SCC due to their tendency to induce irregular acanthosis in the form of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia as well as mild keratinocyte atypia secondary to inflammation.3,4 Our case is unique because it occurred with M marinum infection specifically. The histopathologic findings of M marinum infections are variable and may additionally include granulomas, most commonly suppurative; intraepithelial abscesses; small vessel proliferation; dermal fibrosis; multinucleated giant cells; and transepidermal elimination.4,5 Periodic acid–Schiff, Ziehl-Neelsen (acid-fast bacilli), and Fite staining may be used to distinguish M marinum infection from SCC but have low sensitivities (approximately 30%). Culture remains the most reliable test, with a sensitivity of nearly 80%.5-7 In our patient, a Periodic acid–Schiff stain was obtained prior to receiving culture results, and acid-fast bacilli and Fite staining were added after the culture returned positive; however, all 3 stains failed to highlight any mycobacteria.

The primary risk factor for infection with M marinum is contact with aquatic environments or marine animals, and most cases involve the fingers or the hand.6 After we reached the diagnosis and further discussed the patient’s history, he recalled fishing for and cleaning raw shrimp around the time that he had a splinter. The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends a treatment course extending 1 to 2 months after clinical symptoms resolve with ethambutol in addition to clarithromycin or azithromycin.8 If the infection is near a joint, rifampin should be empirically added to account for a potentially deeper infection. Imaging should be obtained to evaluate for joint space involvement, with magnetic resonance imaging being the preferred modality. If joint space involvement is confirmed, surgical debridement is indicated. Surgical debridement also is indicated for infections that fail to respond to antibiotic therapy.8

This case highlights M marinum infection as a potential mimicker of SCC, particularly if the biopsy is relatively superficial, as often occurs when obtained via the common shave technique. The distinction is critical, as M marinum infection is highly treatable and inappropriate surgery on the typical hand and finger locations may subject patients to substantial morbidity, such as the need for a skin graft, reduced mobility from scarring, or risk for serious wound infection.9 For superficial biopsies of an atypical squamous process, pathologists also may consider routinely recommending tissue culture, especially for hand and finger locations or when a history of local trauma is reported, instead of recommending complete excision or repeat biopsy alone.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1329-1363.

- Bravo FG. Protozoa and worms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1470-1502.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-122; quiz 123-126. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e3181fcfb47

- Li JJ, Beresford R, Fyfe J, et al. Clinical and histopathological features of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection: a review of 13 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:433-443. doi:10.1111/cup.12903

- Abbas O, Marrouch N, Kattar MM, et al. Cutaneous non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections: a clinical and histopathological study of 17 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:33-42. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03684.x

- Johnson MG, Stout JE. Twenty-eight cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: retrospective case series and literature review. Infection. 2015;43:655-662. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0776-8

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

- Alam M, Ibrahim O, Nodzenski M, et al. Adverse events associated with Mohs micrographic surgery: multicenter prospective cohort study of 20,821 cases at 23 centers. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1378-1385. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6255

The Diagnosis: Atypical Mycobacterial Infection

The history of rapid growth followed by shrinkage as well as the craterlike clinical appearance of our patient’s lesion were suspicious for the keratoacanthoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Periodic acid–Schiff green staining was negative for fungal or bacterial organisms, and the biopsy findings of keratinocyte atypia and irregular epidermal proliferation seemed to confirm our suspicion for well-differentiated SCC (Figure 1). Our patient subsequently was scheduled for Mohs micrographic surgery. Fortunately, a sample of tissue had been sent for panculture—bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial—to rule out infectious etiologies, given the history of possible traumatic inoculation, and returned positive for Mycobacterium marinum infection prior to the surgery. Mohs surgery was canceled, and he was referred to an infectious disease specialist who started antibiotic treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. After 1 month of treatment the lesion substantially improved (Figure 2), further supporting the diagnosis of M marinum infection over SCC.

The differential diagnosis also included sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and chromoblastomycosis. Sporotrichosis lesions typically develop as multiple nodules and ulcers along a path of lymphatic drainage and can exhibit asteroid bodies and cigar-shaped yeast forms on histology. Chromoblastomycosis may display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and granulomatous inflammation; however, pathognomonic pigmented Medlar bodies also likely would be present.1 Leishmaniasis has a wide variety of presentations; however, it typically occurs in patients with exposure to endemic areas outside of the United States. Although leishmaniasis may demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and mixed inflammation on histology, it also likely would show amastigotes within dermal macrophages.2

Atypical mycobacterial infections initially may be misdiagnosed as SCC due to their tendency to induce irregular acanthosis in the form of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia as well as mild keratinocyte atypia secondary to inflammation.3,4 Our case is unique because it occurred with M marinum infection specifically. The histopathologic findings of M marinum infections are variable and may additionally include granulomas, most commonly suppurative; intraepithelial abscesses; small vessel proliferation; dermal fibrosis; multinucleated giant cells; and transepidermal elimination.4,5 Periodic acid–Schiff, Ziehl-Neelsen (acid-fast bacilli), and Fite staining may be used to distinguish M marinum infection from SCC but have low sensitivities (approximately 30%). Culture remains the most reliable test, with a sensitivity of nearly 80%.5-7 In our patient, a Periodic acid–Schiff stain was obtained prior to receiving culture results, and acid-fast bacilli and Fite staining were added after the culture returned positive; however, all 3 stains failed to highlight any mycobacteria.

The primary risk factor for infection with M marinum is contact with aquatic environments or marine animals, and most cases involve the fingers or the hand.6 After we reached the diagnosis and further discussed the patient’s history, he recalled fishing for and cleaning raw shrimp around the time that he had a splinter. The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends a treatment course extending 1 to 2 months after clinical symptoms resolve with ethambutol in addition to clarithromycin or azithromycin.8 If the infection is near a joint, rifampin should be empirically added to account for a potentially deeper infection. Imaging should be obtained to evaluate for joint space involvement, with magnetic resonance imaging being the preferred modality. If joint space involvement is confirmed, surgical debridement is indicated. Surgical debridement also is indicated for infections that fail to respond to antibiotic therapy.8

This case highlights M marinum infection as a potential mimicker of SCC, particularly if the biopsy is relatively superficial, as often occurs when obtained via the common shave technique. The distinction is critical, as M marinum infection is highly treatable and inappropriate surgery on the typical hand and finger locations may subject patients to substantial morbidity, such as the need for a skin graft, reduced mobility from scarring, or risk for serious wound infection.9 For superficial biopsies of an atypical squamous process, pathologists also may consider routinely recommending tissue culture, especially for hand and finger locations or when a history of local trauma is reported, instead of recommending complete excision or repeat biopsy alone.

The Diagnosis: Atypical Mycobacterial Infection

The history of rapid growth followed by shrinkage as well as the craterlike clinical appearance of our patient’s lesion were suspicious for the keratoacanthoma variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Periodic acid–Schiff green staining was negative for fungal or bacterial organisms, and the biopsy findings of keratinocyte atypia and irregular epidermal proliferation seemed to confirm our suspicion for well-differentiated SCC (Figure 1). Our patient subsequently was scheduled for Mohs micrographic surgery. Fortunately, a sample of tissue had been sent for panculture—bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial—to rule out infectious etiologies, given the history of possible traumatic inoculation, and returned positive for Mycobacterium marinum infection prior to the surgery. Mohs surgery was canceled, and he was referred to an infectious disease specialist who started antibiotic treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. After 1 month of treatment the lesion substantially improved (Figure 2), further supporting the diagnosis of M marinum infection over SCC.

The differential diagnosis also included sporotrichosis, leishmaniasis, and chromoblastomycosis. Sporotrichosis lesions typically develop as multiple nodules and ulcers along a path of lymphatic drainage and can exhibit asteroid bodies and cigar-shaped yeast forms on histology. Chromoblastomycosis may display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and granulomatous inflammation; however, pathognomonic pigmented Medlar bodies also likely would be present.1 Leishmaniasis has a wide variety of presentations; however, it typically occurs in patients with exposure to endemic areas outside of the United States. Although leishmaniasis may demonstrate pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, ulceration, and mixed inflammation on histology, it also likely would show amastigotes within dermal macrophages.2

Atypical mycobacterial infections initially may be misdiagnosed as SCC due to their tendency to induce irregular acanthosis in the form of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia as well as mild keratinocyte atypia secondary to inflammation.3,4 Our case is unique because it occurred with M marinum infection specifically. The histopathologic findings of M marinum infections are variable and may additionally include granulomas, most commonly suppurative; intraepithelial abscesses; small vessel proliferation; dermal fibrosis; multinucleated giant cells; and transepidermal elimination.4,5 Periodic acid–Schiff, Ziehl-Neelsen (acid-fast bacilli), and Fite staining may be used to distinguish M marinum infection from SCC but have low sensitivities (approximately 30%). Culture remains the most reliable test, with a sensitivity of nearly 80%.5-7 In our patient, a Periodic acid–Schiff stain was obtained prior to receiving culture results, and acid-fast bacilli and Fite staining were added after the culture returned positive; however, all 3 stains failed to highlight any mycobacteria.

The primary risk factor for infection with M marinum is contact with aquatic environments or marine animals, and most cases involve the fingers or the hand.6 After we reached the diagnosis and further discussed the patient’s history, he recalled fishing for and cleaning raw shrimp around the time that he had a splinter. The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends a treatment course extending 1 to 2 months after clinical symptoms resolve with ethambutol in addition to clarithromycin or azithromycin.8 If the infection is near a joint, rifampin should be empirically added to account for a potentially deeper infection. Imaging should be obtained to evaluate for joint space involvement, with magnetic resonance imaging being the preferred modality. If joint space involvement is confirmed, surgical debridement is indicated. Surgical debridement also is indicated for infections that fail to respond to antibiotic therapy.8

This case highlights M marinum infection as a potential mimicker of SCC, particularly if the biopsy is relatively superficial, as often occurs when obtained via the common shave technique. The distinction is critical, as M marinum infection is highly treatable and inappropriate surgery on the typical hand and finger locations may subject patients to substantial morbidity, such as the need for a skin graft, reduced mobility from scarring, or risk for serious wound infection.9 For superficial biopsies of an atypical squamous process, pathologists also may consider routinely recommending tissue culture, especially for hand and finger locations or when a history of local trauma is reported, instead of recommending complete excision or repeat biopsy alone.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1329-1363.

- Bravo FG. Protozoa and worms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1470-1502.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-122; quiz 123-126. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e3181fcfb47

- Li JJ, Beresford R, Fyfe J, et al. Clinical and histopathological features of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection: a review of 13 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:433-443. doi:10.1111/cup.12903

- Abbas O, Marrouch N, Kattar MM, et al. Cutaneous non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections: a clinical and histopathological study of 17 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:33-42. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03684.x

- Johnson MG, Stout JE. Twenty-eight cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: retrospective case series and literature review. Infection. 2015;43:655-662. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0776-8

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

- Alam M, Ibrahim O, Nodzenski M, et al. Adverse events associated with Mohs micrographic surgery: multicenter prospective cohort study of 20,821 cases at 23 centers. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1378-1385. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6255

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1329-1363.

- Bravo FG. Protozoa and worms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1470-1502.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-122; quiz 123-126. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e3181fcfb47

- Li JJ, Beresford R, Fyfe J, et al. Clinical and histopathological features of cutaneous nontuberculous mycobacterial infection: a review of 13 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:433-443. doi:10.1111/cup.12903

- Abbas O, Marrouch N, Kattar MM, et al. Cutaneous non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections: a clinical and histopathological study of 17 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:33-42. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03684.x

- Johnson MG, Stout JE. Twenty-eight cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: retrospective case series and literature review. Infection. 2015;43:655-662. doi:10.1007/s15010-015-0776-8

- Aubry A, Mougari F, Reibel F, et al. Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0038-2016

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

- Alam M, Ibrahim O, Nodzenski M, et al. Adverse events associated with Mohs micrographic surgery: multicenter prospective cohort study of 20,821 cases at 23 centers. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1378-1385. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6255

A 75-year-old man presented with a lesion on the knuckle of 5 months’ duration. He reported that the lesion initially grew very quickly before shrinking down to its current size. He denied any bleeding or pain but thought he may have had a splinter in the area around the time the lesion appeared. He reported spending a lot of time outdoors and noted several recent insect and tick bites. He also owned a boat and frequently went fishing. He previously had been treated for actinic keratoses but had no history of skin cancer and no family history of melanoma. Physical examination revealed a 2-cm erythematous nodule with central hyperkeratosis overlying the metacarpophalangeal joint of the right index finger. A shave biopsy was performed.

Meningococcal B vaccine protects against gonorrhea

PARIS – All the way back in 1907, The Lancet published an article on a gonorrhea vaccine trial. Today, after continuous research throughout the intervening 110-plus years, scientists may finally have achieved success. Sébastien Fouéré, MD, discussed the details at a press conference that focused on the highlights of the Dermatology Days of Paris conference. Dr. Fouéré is the head of the genital dermatology and sexually transmitted infections unit at Saint-Louis Hospital, Paris.

Twin bacteria

Although the gonorrhea vaccine has long been the subject of research, Dr. Fouéré views 2017 as a turning point. This was when the results of a study led by Helen Petousis-Harris, PhD, were published.

“She tried to formalize the not completely indisputable results published by Cuba, where it seemed there were fewer gonococci in individuals vaccinated against meningococcal group B,” he noted.

Dr. Petousis-Harris, an immunologist, conducted a retrospective case-control study involving 11 clinics in New Zealand. The participants were aged 15-30 years, were eligible to receive the meningococcal B vaccine, and had been diagnosed with gonorrhea, chlamydia, or both. The researchers found that receiving the meningococcal B vaccine in childhood provides around 30% protection against Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections.

“It’s not perhaps a coincidence that a meningococcal B vaccine would be protective against gonorrhea,” Dr. Fouéré pointed out. He considers this protection logical, even expected, insofar as “meningococcus and gonococcus are almost twins.” There is 90% and 100% homology between membrane proteins of the two bacteria.

Vaccine is effective

Two retrospective case-control studies confirm that the vaccine is protective. One of the studies, carried out by an Australian team, found that the effectiveness was 32%, quite close to that reported by Petousis-Harris. In the other study, a U.S. team brought to light a dose-response relationship. while a complete vaccination series (two MenB-4C doses) was 40% effective.

Prospective studies are in progress, which will provide a higher level of evidence. The ANRS DOXYVAC trial has been underway since January 2021. The participants are men who have sex with men, who are highly exposed to the risk of sexually transmitted infections, and who presented with at least one STI in the year before their participation in the study. “The study is being conducted by Jean-Michel Molina of Saint-Louis Hospital. What they’re trying to do is protect our cohort of pre-exposure prophylaxis patients with meningococcal vaccine,” explained Dr. Fouéré.