User login

The Safety and Efficacy of AUC/MIC-Guided vs Trough-Guided Vancomycin Monitoring Among Veterans

Vancomycin is a commonly used glycopeptide antibiotic used to treat infections caused by gram-positive organisms. Vancomycin is most often used as a parenteral agent for empiric or definitive treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). It can also be used for the treatment of other susceptible Staphylococcus or Enterococcus species. Adverse effects of parenteral vancomycin include infusion-related reactions, ototoxicity, and nephrotoxicity.1 Higher vancomycin trough levels have been associated with an increased risk of nephrotoxicity.1-4 The major safety concern with vancomycin is acute kidney injury (AKI). Even mild AKI can prolong hospitalizations, increase the cost of health care, and increase morbidity.2

In March 2020, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists released a consensus statement and guidelines regarding the optimization of vancomycin dosing and monitoring for patients with suspected or definitive serious MRSA infections. Based on these guidelines, it is recommended to target an individualized area under the curve/minimum inhibitory concentration (AUC/MIC) ratio of 400 to 600 mg × h/L to maximize clinical efficacy and minimize the risk of AKI.2

Before March 2020, the vancomycin monitoring recommendation was to target trough levels of 10 to 20 mg/L. A goal trough of 15 to 20 mg/L was recommended for severe infections, including sepsis, endocarditis, hospital-acquired pneumonia, meningitis, and osteomyelitis, caused by MRSA. A goal trough of 10 to 15 mg/L was recommended for noninvasive infections, such as skin and soft tissue infections and urinary tract infections, caused by MRSA. Targeting these trough levels was thought to achieve an AUC/MIC ≥ 400 mg × h/L.5 Evidence has since shown that trough values may not be an optimal marker for AUC/MIC values.2

The updated vancomycin therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) guidelines recommend that health systems transition to AUC/MIC-guided monitoring for suspected or confirmed infections caused by MRSA. There is not enough evidence to recommend AUC/MIC-guided monitoring in patients with noninvasive infections or infections caused by other microbes.2

AUC/MIC-guided monitoring can be achieved in 2 ways. The first method is collecting Cmax (peak level) and Cmin (trough level) serum concentrations, preferably during the same dosing interval. Ideally, Cmax should be drawn 1 to 2 hours after the vancomycin infusion and Cmin should be drawn at the end of the dosing interval. First-order pharmacokinetic equations are used to estimate the AUC/MIC with this method. Bayesian software pharmacokinetic modeling based on 1 or 2 vancomycin concentrations with 1 trough level also can be used for monitoring. Preferably, 2 levels would be obtained to estimate the AUC/MIC when using Bayesian modeling.2

The bactericidal activity of vancomycin was achieved with AUC/MIC ratios of ≥ 400 mg × h/L. AUC/MIC ratios of < 400 mg × h/L increase the incidence of resistant and intermediate strains of S aureus. AUC/MIC-guided monitoring assumes an MIC of 1 mg/L. When the MIC is > 1 mg/L, it is less likely that an AUC/MIC ≥ 400 mg × h/L is achievable. Regardless of the TDM method used, AUC/MIC ratios ≥ 400 mg × h/L are not achievable with conventional dosing methods if the vancomycin MIC is > 2 mg/L in patients with normal renal function. Alternative therapy is recommended to be used for these patients.2

There are multiple studies investigating the therapeutic dosing of vancomycin and the associated incidence of AKI. Previous studies have correlated vancomycin AUC/MICs of 400 mg to 600 mg × h/L with clinical effectiveness.2,6 In 2017, Neely and colleagues looked at the therapeutic dosing of vancomycin in 252 adults with ≥ 1 vancomycin level.7 During this prospective trial, they evaluated patients for 1 year and targeted trough concentrations of 10 to 20 mg/L with infection-specific goal ranges of 10 to 15 mg/L and 15 to 20 mg/L for noninvasive and invasive infections, respectively. They also targeted AUC/MIC ratios ≥ 400 mg × h/L regardless of trough concentration using Bayesian estimated AUC/MICs for 2 years. They found only 19% of trough concentrations to be therapeutic compared with 70% of AUC/MICs. A secondary outcome assessed by Neely and colleagues was nephrotoxicity, which was identified in 8% of patients with trough targets and 2% of patients with AUC/MIC targets.8

Previous studies evaluating the use of vancomycin in the veteran population have focused on AKI incidence, general nephrotoxicity, and 30-day readmission rates.4,7,9,10 Poston-Blahnik and colleagues investigated the rates of AKI in 200 veterans using AUC/MIC-guided vancomycin TDM.5 They found an AKI incidence of 42% of patients with AUC/MICs ≥ 550 mg × h/L and 2% of patients with AUC/MICs < 550 mg × h/L.5 Gyamlani and colleagues investigated the rates of AKI in 33,527 veterans and found that serum vancomycin trough levels ≥ 20 mg/L were associated with a higher risk of AKI.8 Prabaker and colleagues investigated the association between vancomycin trough levels and nephrotoxicity, defined as 0.5 mg/L or a 50% increase in serum creatinine (sCr) in 348 veterans. They found nephrotoxicity in 8.9% of patients.10 Patel and colleagues investigated the effect of AKI on 30-day readmission rates in 216 veterans.10 AKI occurred in 8.8% of patients and of those 19.4% were readmitted within 30 days.10 Current literature lacks evidence regarding the comparison of the safety and efficacy of vancomycin trough-guided vs AUC/MIC-guided TDM in the veteran population. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the differences in the safety and efficacy of vancomycin TDM in the veteran population based on the different monitoring methods used.

METHODS

This study was a retrospective, single-center, quasi-experimental chart review conducted at the Sioux Falls Veterans Affairs Health Care System (SFVAHCS) in South Dakota. Data were collected from the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). The SFVAHCS transitioned from trough-guided to AUC/MIC-guided TDM in November 2020.

Patients included in this study were veterans aged ≥ 18 years with orders for parenteral vancomycin between February 1, 2020, and October 31, 2020, for the trough-guided TDM group and between December 1, 2020, and August 31, 2021, for the AUC/MIC-guided TDM group. Patients with vancomycin courses initiated during November 2020 were excluded as both TDM methods were being used at that time. Patients were excluded if their vancomycin course began before February 1, 2020, for the trough-guided TDM group or began during November 2020 for the AUC/MIC-guided TDM group. Patients were excluded if their vancomycin course extended past October 31, 2020, for the trough group or past August 31, 2021, for the AUC/MIC group. Patients on dialysis or missing Cmax, Cmin, or sCr levels were excluded.

This study evaluated both safety (AKI incidence) and effectiveness (time spent in therapeutic range and time to therapeutic range). The primary endpoint was presence of vancomycin-induced AKI, which was based on the most recent Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) AKI definition: increased sCr of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL or by 50% from baseline sustained over 48 hours without any other explanation for the change.11 A secondary endpoint was the absence or presence of AKI.

Additional secondary endpoints included the presence of the initial trough or AUC/MIC of each vancomycin course within the therapeutic range and the percentage of all trough levels or AUC/MICs within therapeutic, subtherapeutic, and supratherapeutic ranges. The therapeutic range for AUC/MIC-guided TDM was 400 to 600 mg × h/L and 10 to 20 mg/L depending on indication for trough-guided TDM (15-20 mg/L for severe infections and 10-15 mg/L for less invasive infections). The percentage of trough levels or AUC/MICs within therapeutic, subtherapeutic, and supratherapeutic ranges were calculated as a ratio of levels within each range to total levels taken for each patient.

For AUC/MIC-guided TDM the Cmax levels were ideally drawn 1 to 2 hours after vancomycin infusion and Cmin levels were ideally drawn 30 minutes before the next dose. First-order pharmacokinetic equations were used to estimate the AUC/MIC.12 If the timing of a vancomycin level was inappropriate, actual levels were extrapolated based on the timing of the blood draw compared with the ideal Cmin or Cmax time. Extrapolated levels were used for both trough-guided and AUC/MIC-guided TDM groups when appropriate. Vancomycin levels were excluded if they were drawn during the vancomycin infusion.

Study participant age, sex, race, weight, baseline estimated glomerular filtration (eGFR) rate, baseline sCr, concomitant nephrotoxic medications, duration of vancomycin course, indication of vancomycin, and acuity of illness based on indication were collected. sCr levels were collected from the initial day vancomycin was ordered through 72 hours following completion of a vancomycin course to evaluate for AKI. Patients’ charts were reviewed for the use of the following nephrotoxic medications: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, aminoglycosides, piperacillin/tazobactam, loop diuretics, amphotericin B, acyclovir, intravenous contrast, and nephrotoxic chemotherapy (cisplatin). The category of concomitant nephrotoxic medications was also collected including the continuation of a home nephrotoxic medication vs the initiation of a new nephrotoxic medication.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint of the incidence of vancomycin-induced AKI was compared using a Fisher exact test. The secondary endpoint of the percentage of trough levels or AUC/MICs in the therapeutic, subtherapeutic, and supratherapeutic range were compared using a student t test. The secondary endpoint of first level or AUC/MIC within goal range was compared using a χ2 test. Continuous baseline characteristics were reported as a mean and compared using a student t test. Nominal baseline characteristics were reported as a percentage and compared using the χ2 test. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

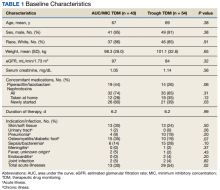

This study included 97 patients, 43 in the AUC/MIC group and 54 in the trough group.

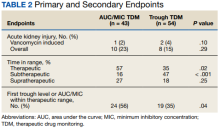

One (2%) patient in the AUC/MIC group and 2 (4%) patients in the trough group experienced vancomycin-induced AKI (P = .10) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

There was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups for the vancomycin-induced AKI (P = .10), the primary endpoint, or overall AKI (P = .29), the secondary endpoint. It should be noted that there was more overall AKI in the AUC/MIC group. Veterans in the AUC/MIC group were found to have their first AUC/MIC within the therapeutic range statistically significantly more often than the first trough level in the trough group (P = .04). The percentage of time spent within therapeutic range was statistically significantly higher in the AUC/MIC-guided TDM group (P = .02). The percentage of time spent subtherapeutic of goal range was statistically significantly higher in the trough-guided TDM group (P < .001). There was no statistically significant difference found in the percent of time spent supratherapeutic of goal range (P = .25). However, the observed percentage of time spent supratherapeutic of goal range was higher in the AUC/MIC group. These results indicate that AUC/MIC-guided TDM may be more efficacious with regard to time in therapeutic range and time to therapeutic range.

The finding of increased AKI with AUC/MIC-guided TDM does not align with previous studies.8 The prospective study by Neely and colleagues found that AUC/MIC-guided TDM resulted in more time in the therapeutic range as well as less nephrotoxicity compared with trough-guided TDM, although it was limited by its lack of randomization and did not account for other causes of nephrotoxicity.8 They found that only 19% of trough concentrations were therapeutic compared with 70% of AUC/MICs and found nephrotoxicity in 8% of trough-guided TDM patients compared with 2% of AUC/MIC-guided TDM patients.8

Unlike Nealy and colleagues, our study did not find lower nephrotoxicity associated with AUC/MIC-guided TDM. Multiple factors may have influenced our results. Our AUC/MIC group had significantly more newly started concomitant nephrotoxins and other nephrotoxic medications used during the vancomycin courses compared with the trough-guided group, which may have influenced AKI outcomes. It also should be noted that there was significantly more time spent subtherapeutic of the goal range and significantly less time in the goal range in the trough group compared with the AUC/MIC group. In our study, the trough-guided group had significantly more patients with acute illness compared with the AUC/MIC group (skin, soft tissue, and joint infections were similar between the groups). The group with more acutely ill patients would have been expected to have more nephrotoxicity. However, despite the acute illnesses, patients in the trough-guided group spent more time in the subtherapeutic range. This may explain the increased nephrotoxicity in the AUC/MIC group since those patients spent more time in the therapeutic range.

This study used the most recent KDIGO AKI definition: either an increase in sCr of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL or a 50% increase in sCr from baseline sustained over 48 hours without any other explanation for the change in renal function.11 This AKI definition is stricter than the previous definition, which was used by earlier studies, including Neely and colleagues, to evaluate rates of vancomycin-induced AKI.2,3 Therefore, the rates of overall AKI found in this study may be higher than in previous studies due to the definition of AKI used.

Limitations

This study was limited by its retrospective nature, lack of randomization, and small sample size. To decrease the potential for error in this study, analysis of power and a larger study sample would have been beneficial. During the COVID-19 pandemic, increased pneumonia cases may have hidden bacterial causes and caused an undercount. Nephrotoxicity may also be related to volume depletion, severe systemic illness, dehydration, or hypotension. Screening was completed via chart review for these alternative causes of nephrotoxicity in this study but may not be completely accounted for due to lack of documentation and the retrospective nature of this study.

CONCLUSIONS

This study did not find a significant difference in the rates of vancomycin-induced or overall AKI between AUC/MIC-guided and trough-guided TDM. However, this study may not have been powered to detect a significant difference in the primary endpoint. This study indicated that AUC/MIC-guided TDM of vancomycin resulted in a quicker time to the therapeutic range and a higher percentage of overall time in the therapeutic range as compared with trough-guided TDM. The results of this study indicated that trough-guided monitoring resulted in a higher percentage of time in a subtherapeutic range. This study also found that the first AUC/MIC calculated was within therapeutic range more often than the first trough level collected.

These results indicate that AUC/MIC-guided TDM may be more effective than trough-guided TDM in the veteran population. However, while AUC/MIC-guided TDM may be more effective with regards to time in therapeutic range and time to therapeutic range, this study did not indicate any safety benefit of AUC/MIC-guided over trough-guided TDM with regards to AKI incidence. Our data indicate that AUC/MIC-guided TDM increases the amount of time in the therapeutic range compared with trough-guided TDM and is not more nephrotoxic. The findings of this study support the recommendation to transition to the use of AUC/MIC-guided TDM of vancomycin in the veteran population.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with the use of facilities and resources from the Sioux Falls Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

1. Gallagher J, MacDougall C. Glycopeptides and short-acting lipoglycopeptides In: Antibiotics Simplified. Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2018.

2. Rybak MJ, Le J, Lodise TP, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin for serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: a revised consensus guideline and review by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(11):835-864. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa036

3. Hermsen ED, Hanson M, Sankaranarayanan J, Stoner JA, Florescu MC, Rupp ME. Clinical outcomes and nephrotoxicity associated with vancomycin trough concentrations during treatment of deep-seated infections. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2010;9(1):9-14. doi:10.1517/14740330903413514

4. Poston-Blahnik A, Moenster R. Association between vancomycin area under the curve and nephrotoxicity: a single center, retrospective cohort study in a veteran population. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(5):ofab094. Published 2021 Mar 12. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab094

5. Rybak M, Lomaestro B, Rotschafer JC, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adult patients: a consensus review of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66(1):82-98. doi:10.2146/ajhp080434

6. Moise-Broder PA, Forrest A, Birmingham MC, Schentag JJ. Pharmacodynamics of vancomycin and other antimicrobials in patients with Staphylococcus aureus lower respiratory tract infections. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(13):925-942. doi:10.2165/00003088-200443130-00005

7. Gyamlani G, Potukuchi PK, Thomas F, et al. Vancomycin-Associated Acute Kidney Injury in a Large Veteran Population. Am J Nephrol. 2019;49(2):133-142. doi:10.1159/000496484

8. Neely MN, Kato L, Youn G, et al. Prospective Trial on the Use of Trough Concentration versus Area under the Curve To Determine Therapeutic Vancomycin Dosing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(2):e02042-17. Published 2018 Jan 25. doi:10.1128/AAC.02042-17

9. Prabaker KK, Tran TP, Pratummas T, Goetz MB, Graber CJ. Elevated vancomycin trough is not associated with nephrotoxicity among inpatient veterans. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(2):91-97. doi:10.1002/jhm.946

10. Patel N, Stornelli N, Sangiovanni RJ, Huang DB, Lodise TP. Effect of vancomycin-associated acute kidney injury on incidence of 30-day readmissions among hospitalized Veterans Affairs patients with skin and skin structure infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64(10):e01268-20. Published 2020 Sep 21. doi:10.1128/AAC.01268-20

11. Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int. 2012;2(suppl 1):1-138.

12. Pai MP, Neely M, Rodvold KA, Lodise TP. Innovative approaches to optimizing the delivery of vancomycin in individual patients. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;77:50-57. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2014.05.016

Vancomycin is a commonly used glycopeptide antibiotic used to treat infections caused by gram-positive organisms. Vancomycin is most often used as a parenteral agent for empiric or definitive treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). It can also be used for the treatment of other susceptible Staphylococcus or Enterococcus species. Adverse effects of parenteral vancomycin include infusion-related reactions, ototoxicity, and nephrotoxicity.1 Higher vancomycin trough levels have been associated with an increased risk of nephrotoxicity.1-4 The major safety concern with vancomycin is acute kidney injury (AKI). Even mild AKI can prolong hospitalizations, increase the cost of health care, and increase morbidity.2

In March 2020, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists released a consensus statement and guidelines regarding the optimization of vancomycin dosing and monitoring for patients with suspected or definitive serious MRSA infections. Based on these guidelines, it is recommended to target an individualized area under the curve/minimum inhibitory concentration (AUC/MIC) ratio of 400 to 600 mg × h/L to maximize clinical efficacy and minimize the risk of AKI.2

Before March 2020, the vancomycin monitoring recommendation was to target trough levels of 10 to 20 mg/L. A goal trough of 15 to 20 mg/L was recommended for severe infections, including sepsis, endocarditis, hospital-acquired pneumonia, meningitis, and osteomyelitis, caused by MRSA. A goal trough of 10 to 15 mg/L was recommended for noninvasive infections, such as skin and soft tissue infections and urinary tract infections, caused by MRSA. Targeting these trough levels was thought to achieve an AUC/MIC ≥ 400 mg × h/L.5 Evidence has since shown that trough values may not be an optimal marker for AUC/MIC values.2

The updated vancomycin therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) guidelines recommend that health systems transition to AUC/MIC-guided monitoring for suspected or confirmed infections caused by MRSA. There is not enough evidence to recommend AUC/MIC-guided monitoring in patients with noninvasive infections or infections caused by other microbes.2

AUC/MIC-guided monitoring can be achieved in 2 ways. The first method is collecting Cmax (peak level) and Cmin (trough level) serum concentrations, preferably during the same dosing interval. Ideally, Cmax should be drawn 1 to 2 hours after the vancomycin infusion and Cmin should be drawn at the end of the dosing interval. First-order pharmacokinetic equations are used to estimate the AUC/MIC with this method. Bayesian software pharmacokinetic modeling based on 1 or 2 vancomycin concentrations with 1 trough level also can be used for monitoring. Preferably, 2 levels would be obtained to estimate the AUC/MIC when using Bayesian modeling.2

The bactericidal activity of vancomycin was achieved with AUC/MIC ratios of ≥ 400 mg × h/L. AUC/MIC ratios of < 400 mg × h/L increase the incidence of resistant and intermediate strains of S aureus. AUC/MIC-guided monitoring assumes an MIC of 1 mg/L. When the MIC is > 1 mg/L, it is less likely that an AUC/MIC ≥ 400 mg × h/L is achievable. Regardless of the TDM method used, AUC/MIC ratios ≥ 400 mg × h/L are not achievable with conventional dosing methods if the vancomycin MIC is > 2 mg/L in patients with normal renal function. Alternative therapy is recommended to be used for these patients.2

There are multiple studies investigating the therapeutic dosing of vancomycin and the associated incidence of AKI. Previous studies have correlated vancomycin AUC/MICs of 400 mg to 600 mg × h/L with clinical effectiveness.2,6 In 2017, Neely and colleagues looked at the therapeutic dosing of vancomycin in 252 adults with ≥ 1 vancomycin level.7 During this prospective trial, they evaluated patients for 1 year and targeted trough concentrations of 10 to 20 mg/L with infection-specific goal ranges of 10 to 15 mg/L and 15 to 20 mg/L for noninvasive and invasive infections, respectively. They also targeted AUC/MIC ratios ≥ 400 mg × h/L regardless of trough concentration using Bayesian estimated AUC/MICs for 2 years. They found only 19% of trough concentrations to be therapeutic compared with 70% of AUC/MICs. A secondary outcome assessed by Neely and colleagues was nephrotoxicity, which was identified in 8% of patients with trough targets and 2% of patients with AUC/MIC targets.8

Previous studies evaluating the use of vancomycin in the veteran population have focused on AKI incidence, general nephrotoxicity, and 30-day readmission rates.4,7,9,10 Poston-Blahnik and colleagues investigated the rates of AKI in 200 veterans using AUC/MIC-guided vancomycin TDM.5 They found an AKI incidence of 42% of patients with AUC/MICs ≥ 550 mg × h/L and 2% of patients with AUC/MICs < 550 mg × h/L.5 Gyamlani and colleagues investigated the rates of AKI in 33,527 veterans and found that serum vancomycin trough levels ≥ 20 mg/L were associated with a higher risk of AKI.8 Prabaker and colleagues investigated the association between vancomycin trough levels and nephrotoxicity, defined as 0.5 mg/L or a 50% increase in serum creatinine (sCr) in 348 veterans. They found nephrotoxicity in 8.9% of patients.10 Patel and colleagues investigated the effect of AKI on 30-day readmission rates in 216 veterans.10 AKI occurred in 8.8% of patients and of those 19.4% were readmitted within 30 days.10 Current literature lacks evidence regarding the comparison of the safety and efficacy of vancomycin trough-guided vs AUC/MIC-guided TDM in the veteran population. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the differences in the safety and efficacy of vancomycin TDM in the veteran population based on the different monitoring methods used.

METHODS

This study was a retrospective, single-center, quasi-experimental chart review conducted at the Sioux Falls Veterans Affairs Health Care System (SFVAHCS) in South Dakota. Data were collected from the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). The SFVAHCS transitioned from trough-guided to AUC/MIC-guided TDM in November 2020.

Patients included in this study were veterans aged ≥ 18 years with orders for parenteral vancomycin between February 1, 2020, and October 31, 2020, for the trough-guided TDM group and between December 1, 2020, and August 31, 2021, for the AUC/MIC-guided TDM group. Patients with vancomycin courses initiated during November 2020 were excluded as both TDM methods were being used at that time. Patients were excluded if their vancomycin course began before February 1, 2020, for the trough-guided TDM group or began during November 2020 for the AUC/MIC-guided TDM group. Patients were excluded if their vancomycin course extended past October 31, 2020, for the trough group or past August 31, 2021, for the AUC/MIC group. Patients on dialysis or missing Cmax, Cmin, or sCr levels were excluded.

This study evaluated both safety (AKI incidence) and effectiveness (time spent in therapeutic range and time to therapeutic range). The primary endpoint was presence of vancomycin-induced AKI, which was based on the most recent Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) AKI definition: increased sCr of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL or by 50% from baseline sustained over 48 hours without any other explanation for the change.11 A secondary endpoint was the absence or presence of AKI.

Additional secondary endpoints included the presence of the initial trough or AUC/MIC of each vancomycin course within the therapeutic range and the percentage of all trough levels or AUC/MICs within therapeutic, subtherapeutic, and supratherapeutic ranges. The therapeutic range for AUC/MIC-guided TDM was 400 to 600 mg × h/L and 10 to 20 mg/L depending on indication for trough-guided TDM (15-20 mg/L for severe infections and 10-15 mg/L for less invasive infections). The percentage of trough levels or AUC/MICs within therapeutic, subtherapeutic, and supratherapeutic ranges were calculated as a ratio of levels within each range to total levels taken for each patient.

For AUC/MIC-guided TDM the Cmax levels were ideally drawn 1 to 2 hours after vancomycin infusion and Cmin levels were ideally drawn 30 minutes before the next dose. First-order pharmacokinetic equations were used to estimate the AUC/MIC.12 If the timing of a vancomycin level was inappropriate, actual levels were extrapolated based on the timing of the blood draw compared with the ideal Cmin or Cmax time. Extrapolated levels were used for both trough-guided and AUC/MIC-guided TDM groups when appropriate. Vancomycin levels were excluded if they were drawn during the vancomycin infusion.

Study participant age, sex, race, weight, baseline estimated glomerular filtration (eGFR) rate, baseline sCr, concomitant nephrotoxic medications, duration of vancomycin course, indication of vancomycin, and acuity of illness based on indication were collected. sCr levels were collected from the initial day vancomycin was ordered through 72 hours following completion of a vancomycin course to evaluate for AKI. Patients’ charts were reviewed for the use of the following nephrotoxic medications: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, aminoglycosides, piperacillin/tazobactam, loop diuretics, amphotericin B, acyclovir, intravenous contrast, and nephrotoxic chemotherapy (cisplatin). The category of concomitant nephrotoxic medications was also collected including the continuation of a home nephrotoxic medication vs the initiation of a new nephrotoxic medication.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint of the incidence of vancomycin-induced AKI was compared using a Fisher exact test. The secondary endpoint of the percentage of trough levels or AUC/MICs in the therapeutic, subtherapeutic, and supratherapeutic range were compared using a student t test. The secondary endpoint of first level or AUC/MIC within goal range was compared using a χ2 test. Continuous baseline characteristics were reported as a mean and compared using a student t test. Nominal baseline characteristics were reported as a percentage and compared using the χ2 test. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

This study included 97 patients, 43 in the AUC/MIC group and 54 in the trough group.

One (2%) patient in the AUC/MIC group and 2 (4%) patients in the trough group experienced vancomycin-induced AKI (P = .10) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

There was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups for the vancomycin-induced AKI (P = .10), the primary endpoint, or overall AKI (P = .29), the secondary endpoint. It should be noted that there was more overall AKI in the AUC/MIC group. Veterans in the AUC/MIC group were found to have their first AUC/MIC within the therapeutic range statistically significantly more often than the first trough level in the trough group (P = .04). The percentage of time spent within therapeutic range was statistically significantly higher in the AUC/MIC-guided TDM group (P = .02). The percentage of time spent subtherapeutic of goal range was statistically significantly higher in the trough-guided TDM group (P < .001). There was no statistically significant difference found in the percent of time spent supratherapeutic of goal range (P = .25). However, the observed percentage of time spent supratherapeutic of goal range was higher in the AUC/MIC group. These results indicate that AUC/MIC-guided TDM may be more efficacious with regard to time in therapeutic range and time to therapeutic range.

The finding of increased AKI with AUC/MIC-guided TDM does not align with previous studies.8 The prospective study by Neely and colleagues found that AUC/MIC-guided TDM resulted in more time in the therapeutic range as well as less nephrotoxicity compared with trough-guided TDM, although it was limited by its lack of randomization and did not account for other causes of nephrotoxicity.8 They found that only 19% of trough concentrations were therapeutic compared with 70% of AUC/MICs and found nephrotoxicity in 8% of trough-guided TDM patients compared with 2% of AUC/MIC-guided TDM patients.8

Unlike Nealy and colleagues, our study did not find lower nephrotoxicity associated with AUC/MIC-guided TDM. Multiple factors may have influenced our results. Our AUC/MIC group had significantly more newly started concomitant nephrotoxins and other nephrotoxic medications used during the vancomycin courses compared with the trough-guided group, which may have influenced AKI outcomes. It also should be noted that there was significantly more time spent subtherapeutic of the goal range and significantly less time in the goal range in the trough group compared with the AUC/MIC group. In our study, the trough-guided group had significantly more patients with acute illness compared with the AUC/MIC group (skin, soft tissue, and joint infections were similar between the groups). The group with more acutely ill patients would have been expected to have more nephrotoxicity. However, despite the acute illnesses, patients in the trough-guided group spent more time in the subtherapeutic range. This may explain the increased nephrotoxicity in the AUC/MIC group since those patients spent more time in the therapeutic range.

This study used the most recent KDIGO AKI definition: either an increase in sCr of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL or a 50% increase in sCr from baseline sustained over 48 hours without any other explanation for the change in renal function.11 This AKI definition is stricter than the previous definition, which was used by earlier studies, including Neely and colleagues, to evaluate rates of vancomycin-induced AKI.2,3 Therefore, the rates of overall AKI found in this study may be higher than in previous studies due to the definition of AKI used.

Limitations

This study was limited by its retrospective nature, lack of randomization, and small sample size. To decrease the potential for error in this study, analysis of power and a larger study sample would have been beneficial. During the COVID-19 pandemic, increased pneumonia cases may have hidden bacterial causes and caused an undercount. Nephrotoxicity may also be related to volume depletion, severe systemic illness, dehydration, or hypotension. Screening was completed via chart review for these alternative causes of nephrotoxicity in this study but may not be completely accounted for due to lack of documentation and the retrospective nature of this study.

CONCLUSIONS

This study did not find a significant difference in the rates of vancomycin-induced or overall AKI between AUC/MIC-guided and trough-guided TDM. However, this study may not have been powered to detect a significant difference in the primary endpoint. This study indicated that AUC/MIC-guided TDM of vancomycin resulted in a quicker time to the therapeutic range and a higher percentage of overall time in the therapeutic range as compared with trough-guided TDM. The results of this study indicated that trough-guided monitoring resulted in a higher percentage of time in a subtherapeutic range. This study also found that the first AUC/MIC calculated was within therapeutic range more often than the first trough level collected.

These results indicate that AUC/MIC-guided TDM may be more effective than trough-guided TDM in the veteran population. However, while AUC/MIC-guided TDM may be more effective with regards to time in therapeutic range and time to therapeutic range, this study did not indicate any safety benefit of AUC/MIC-guided over trough-guided TDM with regards to AKI incidence. Our data indicate that AUC/MIC-guided TDM increases the amount of time in the therapeutic range compared with trough-guided TDM and is not more nephrotoxic. The findings of this study support the recommendation to transition to the use of AUC/MIC-guided TDM of vancomycin in the veteran population.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with the use of facilities and resources from the Sioux Falls Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

Vancomycin is a commonly used glycopeptide antibiotic used to treat infections caused by gram-positive organisms. Vancomycin is most often used as a parenteral agent for empiric or definitive treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). It can also be used for the treatment of other susceptible Staphylococcus or Enterococcus species. Adverse effects of parenteral vancomycin include infusion-related reactions, ototoxicity, and nephrotoxicity.1 Higher vancomycin trough levels have been associated with an increased risk of nephrotoxicity.1-4 The major safety concern with vancomycin is acute kidney injury (AKI). Even mild AKI can prolong hospitalizations, increase the cost of health care, and increase morbidity.2

In March 2020, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists released a consensus statement and guidelines regarding the optimization of vancomycin dosing and monitoring for patients with suspected or definitive serious MRSA infections. Based on these guidelines, it is recommended to target an individualized area under the curve/minimum inhibitory concentration (AUC/MIC) ratio of 400 to 600 mg × h/L to maximize clinical efficacy and minimize the risk of AKI.2

Before March 2020, the vancomycin monitoring recommendation was to target trough levels of 10 to 20 mg/L. A goal trough of 15 to 20 mg/L was recommended for severe infections, including sepsis, endocarditis, hospital-acquired pneumonia, meningitis, and osteomyelitis, caused by MRSA. A goal trough of 10 to 15 mg/L was recommended for noninvasive infections, such as skin and soft tissue infections and urinary tract infections, caused by MRSA. Targeting these trough levels was thought to achieve an AUC/MIC ≥ 400 mg × h/L.5 Evidence has since shown that trough values may not be an optimal marker for AUC/MIC values.2

The updated vancomycin therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) guidelines recommend that health systems transition to AUC/MIC-guided monitoring for suspected or confirmed infections caused by MRSA. There is not enough evidence to recommend AUC/MIC-guided monitoring in patients with noninvasive infections or infections caused by other microbes.2

AUC/MIC-guided monitoring can be achieved in 2 ways. The first method is collecting Cmax (peak level) and Cmin (trough level) serum concentrations, preferably during the same dosing interval. Ideally, Cmax should be drawn 1 to 2 hours after the vancomycin infusion and Cmin should be drawn at the end of the dosing interval. First-order pharmacokinetic equations are used to estimate the AUC/MIC with this method. Bayesian software pharmacokinetic modeling based on 1 or 2 vancomycin concentrations with 1 trough level also can be used for monitoring. Preferably, 2 levels would be obtained to estimate the AUC/MIC when using Bayesian modeling.2

The bactericidal activity of vancomycin was achieved with AUC/MIC ratios of ≥ 400 mg × h/L. AUC/MIC ratios of < 400 mg × h/L increase the incidence of resistant and intermediate strains of S aureus. AUC/MIC-guided monitoring assumes an MIC of 1 mg/L. When the MIC is > 1 mg/L, it is less likely that an AUC/MIC ≥ 400 mg × h/L is achievable. Regardless of the TDM method used, AUC/MIC ratios ≥ 400 mg × h/L are not achievable with conventional dosing methods if the vancomycin MIC is > 2 mg/L in patients with normal renal function. Alternative therapy is recommended to be used for these patients.2

There are multiple studies investigating the therapeutic dosing of vancomycin and the associated incidence of AKI. Previous studies have correlated vancomycin AUC/MICs of 400 mg to 600 mg × h/L with clinical effectiveness.2,6 In 2017, Neely and colleagues looked at the therapeutic dosing of vancomycin in 252 adults with ≥ 1 vancomycin level.7 During this prospective trial, they evaluated patients for 1 year and targeted trough concentrations of 10 to 20 mg/L with infection-specific goal ranges of 10 to 15 mg/L and 15 to 20 mg/L for noninvasive and invasive infections, respectively. They also targeted AUC/MIC ratios ≥ 400 mg × h/L regardless of trough concentration using Bayesian estimated AUC/MICs for 2 years. They found only 19% of trough concentrations to be therapeutic compared with 70% of AUC/MICs. A secondary outcome assessed by Neely and colleagues was nephrotoxicity, which was identified in 8% of patients with trough targets and 2% of patients with AUC/MIC targets.8

Previous studies evaluating the use of vancomycin in the veteran population have focused on AKI incidence, general nephrotoxicity, and 30-day readmission rates.4,7,9,10 Poston-Blahnik and colleagues investigated the rates of AKI in 200 veterans using AUC/MIC-guided vancomycin TDM.5 They found an AKI incidence of 42% of patients with AUC/MICs ≥ 550 mg × h/L and 2% of patients with AUC/MICs < 550 mg × h/L.5 Gyamlani and colleagues investigated the rates of AKI in 33,527 veterans and found that serum vancomycin trough levels ≥ 20 mg/L were associated with a higher risk of AKI.8 Prabaker and colleagues investigated the association between vancomycin trough levels and nephrotoxicity, defined as 0.5 mg/L or a 50% increase in serum creatinine (sCr) in 348 veterans. They found nephrotoxicity in 8.9% of patients.10 Patel and colleagues investigated the effect of AKI on 30-day readmission rates in 216 veterans.10 AKI occurred in 8.8% of patients and of those 19.4% were readmitted within 30 days.10 Current literature lacks evidence regarding the comparison of the safety and efficacy of vancomycin trough-guided vs AUC/MIC-guided TDM in the veteran population. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the differences in the safety and efficacy of vancomycin TDM in the veteran population based on the different monitoring methods used.

METHODS

This study was a retrospective, single-center, quasi-experimental chart review conducted at the Sioux Falls Veterans Affairs Health Care System (SFVAHCS) in South Dakota. Data were collected from the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). The SFVAHCS transitioned from trough-guided to AUC/MIC-guided TDM in November 2020.

Patients included in this study were veterans aged ≥ 18 years with orders for parenteral vancomycin between February 1, 2020, and October 31, 2020, for the trough-guided TDM group and between December 1, 2020, and August 31, 2021, for the AUC/MIC-guided TDM group. Patients with vancomycin courses initiated during November 2020 were excluded as both TDM methods were being used at that time. Patients were excluded if their vancomycin course began before February 1, 2020, for the trough-guided TDM group or began during November 2020 for the AUC/MIC-guided TDM group. Patients were excluded if their vancomycin course extended past October 31, 2020, for the trough group or past August 31, 2021, for the AUC/MIC group. Patients on dialysis or missing Cmax, Cmin, or sCr levels were excluded.

This study evaluated both safety (AKI incidence) and effectiveness (time spent in therapeutic range and time to therapeutic range). The primary endpoint was presence of vancomycin-induced AKI, which was based on the most recent Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) AKI definition: increased sCr of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL or by 50% from baseline sustained over 48 hours without any other explanation for the change.11 A secondary endpoint was the absence or presence of AKI.

Additional secondary endpoints included the presence of the initial trough or AUC/MIC of each vancomycin course within the therapeutic range and the percentage of all trough levels or AUC/MICs within therapeutic, subtherapeutic, and supratherapeutic ranges. The therapeutic range for AUC/MIC-guided TDM was 400 to 600 mg × h/L and 10 to 20 mg/L depending on indication for trough-guided TDM (15-20 mg/L for severe infections and 10-15 mg/L for less invasive infections). The percentage of trough levels or AUC/MICs within therapeutic, subtherapeutic, and supratherapeutic ranges were calculated as a ratio of levels within each range to total levels taken for each patient.

For AUC/MIC-guided TDM the Cmax levels were ideally drawn 1 to 2 hours after vancomycin infusion and Cmin levels were ideally drawn 30 minutes before the next dose. First-order pharmacokinetic equations were used to estimate the AUC/MIC.12 If the timing of a vancomycin level was inappropriate, actual levels were extrapolated based on the timing of the blood draw compared with the ideal Cmin or Cmax time. Extrapolated levels were used for both trough-guided and AUC/MIC-guided TDM groups when appropriate. Vancomycin levels were excluded if they were drawn during the vancomycin infusion.

Study participant age, sex, race, weight, baseline estimated glomerular filtration (eGFR) rate, baseline sCr, concomitant nephrotoxic medications, duration of vancomycin course, indication of vancomycin, and acuity of illness based on indication were collected. sCr levels were collected from the initial day vancomycin was ordered through 72 hours following completion of a vancomycin course to evaluate for AKI. Patients’ charts were reviewed for the use of the following nephrotoxic medications: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, aminoglycosides, piperacillin/tazobactam, loop diuretics, amphotericin B, acyclovir, intravenous contrast, and nephrotoxic chemotherapy (cisplatin). The category of concomitant nephrotoxic medications was also collected including the continuation of a home nephrotoxic medication vs the initiation of a new nephrotoxic medication.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint of the incidence of vancomycin-induced AKI was compared using a Fisher exact test. The secondary endpoint of the percentage of trough levels or AUC/MICs in the therapeutic, subtherapeutic, and supratherapeutic range were compared using a student t test. The secondary endpoint of first level or AUC/MIC within goal range was compared using a χ2 test. Continuous baseline characteristics were reported as a mean and compared using a student t test. Nominal baseline characteristics were reported as a percentage and compared using the χ2 test. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

This study included 97 patients, 43 in the AUC/MIC group and 54 in the trough group.

One (2%) patient in the AUC/MIC group and 2 (4%) patients in the trough group experienced vancomycin-induced AKI (P = .10) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

There was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups for the vancomycin-induced AKI (P = .10), the primary endpoint, or overall AKI (P = .29), the secondary endpoint. It should be noted that there was more overall AKI in the AUC/MIC group. Veterans in the AUC/MIC group were found to have their first AUC/MIC within the therapeutic range statistically significantly more often than the first trough level in the trough group (P = .04). The percentage of time spent within therapeutic range was statistically significantly higher in the AUC/MIC-guided TDM group (P = .02). The percentage of time spent subtherapeutic of goal range was statistically significantly higher in the trough-guided TDM group (P < .001). There was no statistically significant difference found in the percent of time spent supratherapeutic of goal range (P = .25). However, the observed percentage of time spent supratherapeutic of goal range was higher in the AUC/MIC group. These results indicate that AUC/MIC-guided TDM may be more efficacious with regard to time in therapeutic range and time to therapeutic range.

The finding of increased AKI with AUC/MIC-guided TDM does not align with previous studies.8 The prospective study by Neely and colleagues found that AUC/MIC-guided TDM resulted in more time in the therapeutic range as well as less nephrotoxicity compared with trough-guided TDM, although it was limited by its lack of randomization and did not account for other causes of nephrotoxicity.8 They found that only 19% of trough concentrations were therapeutic compared with 70% of AUC/MICs and found nephrotoxicity in 8% of trough-guided TDM patients compared with 2% of AUC/MIC-guided TDM patients.8

Unlike Nealy and colleagues, our study did not find lower nephrotoxicity associated with AUC/MIC-guided TDM. Multiple factors may have influenced our results. Our AUC/MIC group had significantly more newly started concomitant nephrotoxins and other nephrotoxic medications used during the vancomycin courses compared with the trough-guided group, which may have influenced AKI outcomes. It also should be noted that there was significantly more time spent subtherapeutic of the goal range and significantly less time in the goal range in the trough group compared with the AUC/MIC group. In our study, the trough-guided group had significantly more patients with acute illness compared with the AUC/MIC group (skin, soft tissue, and joint infections were similar between the groups). The group with more acutely ill patients would have been expected to have more nephrotoxicity. However, despite the acute illnesses, patients in the trough-guided group spent more time in the subtherapeutic range. This may explain the increased nephrotoxicity in the AUC/MIC group since those patients spent more time in the therapeutic range.

This study used the most recent KDIGO AKI definition: either an increase in sCr of ≥ 0.3 mg/dL or a 50% increase in sCr from baseline sustained over 48 hours without any other explanation for the change in renal function.11 This AKI definition is stricter than the previous definition, which was used by earlier studies, including Neely and colleagues, to evaluate rates of vancomycin-induced AKI.2,3 Therefore, the rates of overall AKI found in this study may be higher than in previous studies due to the definition of AKI used.

Limitations

This study was limited by its retrospective nature, lack of randomization, and small sample size. To decrease the potential for error in this study, analysis of power and a larger study sample would have been beneficial. During the COVID-19 pandemic, increased pneumonia cases may have hidden bacterial causes and caused an undercount. Nephrotoxicity may also be related to volume depletion, severe systemic illness, dehydration, or hypotension. Screening was completed via chart review for these alternative causes of nephrotoxicity in this study but may not be completely accounted for due to lack of documentation and the retrospective nature of this study.

CONCLUSIONS

This study did not find a significant difference in the rates of vancomycin-induced or overall AKI between AUC/MIC-guided and trough-guided TDM. However, this study may not have been powered to detect a significant difference in the primary endpoint. This study indicated that AUC/MIC-guided TDM of vancomycin resulted in a quicker time to the therapeutic range and a higher percentage of overall time in the therapeutic range as compared with trough-guided TDM. The results of this study indicated that trough-guided monitoring resulted in a higher percentage of time in a subtherapeutic range. This study also found that the first AUC/MIC calculated was within therapeutic range more often than the first trough level collected.

These results indicate that AUC/MIC-guided TDM may be more effective than trough-guided TDM in the veteran population. However, while AUC/MIC-guided TDM may be more effective with regards to time in therapeutic range and time to therapeutic range, this study did not indicate any safety benefit of AUC/MIC-guided over trough-guided TDM with regards to AKI incidence. Our data indicate that AUC/MIC-guided TDM increases the amount of time in the therapeutic range compared with trough-guided TDM and is not more nephrotoxic. The findings of this study support the recommendation to transition to the use of AUC/MIC-guided TDM of vancomycin in the veteran population.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with the use of facilities and resources from the Sioux Falls Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

1. Gallagher J, MacDougall C. Glycopeptides and short-acting lipoglycopeptides In: Antibiotics Simplified. Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2018.

2. Rybak MJ, Le J, Lodise TP, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin for serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: a revised consensus guideline and review by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(11):835-864. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa036

3. Hermsen ED, Hanson M, Sankaranarayanan J, Stoner JA, Florescu MC, Rupp ME. Clinical outcomes and nephrotoxicity associated with vancomycin trough concentrations during treatment of deep-seated infections. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2010;9(1):9-14. doi:10.1517/14740330903413514

4. Poston-Blahnik A, Moenster R. Association between vancomycin area under the curve and nephrotoxicity: a single center, retrospective cohort study in a veteran population. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(5):ofab094. Published 2021 Mar 12. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab094

5. Rybak M, Lomaestro B, Rotschafer JC, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adult patients: a consensus review of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66(1):82-98. doi:10.2146/ajhp080434

6. Moise-Broder PA, Forrest A, Birmingham MC, Schentag JJ. Pharmacodynamics of vancomycin and other antimicrobials in patients with Staphylococcus aureus lower respiratory tract infections. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(13):925-942. doi:10.2165/00003088-200443130-00005

7. Gyamlani G, Potukuchi PK, Thomas F, et al. Vancomycin-Associated Acute Kidney Injury in a Large Veteran Population. Am J Nephrol. 2019;49(2):133-142. doi:10.1159/000496484

8. Neely MN, Kato L, Youn G, et al. Prospective Trial on the Use of Trough Concentration versus Area under the Curve To Determine Therapeutic Vancomycin Dosing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(2):e02042-17. Published 2018 Jan 25. doi:10.1128/AAC.02042-17

9. Prabaker KK, Tran TP, Pratummas T, Goetz MB, Graber CJ. Elevated vancomycin trough is not associated with nephrotoxicity among inpatient veterans. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(2):91-97. doi:10.1002/jhm.946

10. Patel N, Stornelli N, Sangiovanni RJ, Huang DB, Lodise TP. Effect of vancomycin-associated acute kidney injury on incidence of 30-day readmissions among hospitalized Veterans Affairs patients with skin and skin structure infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64(10):e01268-20. Published 2020 Sep 21. doi:10.1128/AAC.01268-20

11. Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int. 2012;2(suppl 1):1-138.

12. Pai MP, Neely M, Rodvold KA, Lodise TP. Innovative approaches to optimizing the delivery of vancomycin in individual patients. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;77:50-57. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2014.05.016

1. Gallagher J, MacDougall C. Glycopeptides and short-acting lipoglycopeptides In: Antibiotics Simplified. Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2018.

2. Rybak MJ, Le J, Lodise TP, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin for serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: a revised consensus guideline and review by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(11):835-864. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa036

3. Hermsen ED, Hanson M, Sankaranarayanan J, Stoner JA, Florescu MC, Rupp ME. Clinical outcomes and nephrotoxicity associated with vancomycin trough concentrations during treatment of deep-seated infections. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2010;9(1):9-14. doi:10.1517/14740330903413514

4. Poston-Blahnik A, Moenster R. Association between vancomycin area under the curve and nephrotoxicity: a single center, retrospective cohort study in a veteran population. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(5):ofab094. Published 2021 Mar 12. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab094

5. Rybak M, Lomaestro B, Rotschafer JC, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adult patients: a consensus review of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66(1):82-98. doi:10.2146/ajhp080434

6. Moise-Broder PA, Forrest A, Birmingham MC, Schentag JJ. Pharmacodynamics of vancomycin and other antimicrobials in patients with Staphylococcus aureus lower respiratory tract infections. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(13):925-942. doi:10.2165/00003088-200443130-00005

7. Gyamlani G, Potukuchi PK, Thomas F, et al. Vancomycin-Associated Acute Kidney Injury in a Large Veteran Population. Am J Nephrol. 2019;49(2):133-142. doi:10.1159/000496484

8. Neely MN, Kato L, Youn G, et al. Prospective Trial on the Use of Trough Concentration versus Area under the Curve To Determine Therapeutic Vancomycin Dosing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(2):e02042-17. Published 2018 Jan 25. doi:10.1128/AAC.02042-17

9. Prabaker KK, Tran TP, Pratummas T, Goetz MB, Graber CJ. Elevated vancomycin trough is not associated with nephrotoxicity among inpatient veterans. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(2):91-97. doi:10.1002/jhm.946

10. Patel N, Stornelli N, Sangiovanni RJ, Huang DB, Lodise TP. Effect of vancomycin-associated acute kidney injury on incidence of 30-day readmissions among hospitalized Veterans Affairs patients with skin and skin structure infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64(10):e01268-20. Published 2020 Sep 21. doi:10.1128/AAC.01268-20

11. Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int. 2012;2(suppl 1):1-138.

12. Pai MP, Neely M, Rodvold KA, Lodise TP. Innovative approaches to optimizing the delivery of vancomycin in individual patients. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;77:50-57. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2014.05.016

COVID leading cause of death among law enforcement for third year

A new report says 70 officers died of COVID-related causes after getting the virus while on the job. The number is down dramatically from 2021, when 405 officer deaths were attributed to COVID.

The annual count was published Wednesday by the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund.

In total, 226 officers died in the line of duty in 2022, which is a decrease of 61% from 2021.

The decrease “is almost entirely related to the significant reduction in COVID-19 deaths,” the report stated. The authors said the decline was likely due to “reduced infection rates and the broad availability and use of vaccinations.”

Reported deaths included federal, state, tribal, and local law enforcement officers.

Firearms-related fatalities were the second-leading cause of death among officers, with 64 in 2022. That count sustains a 21% increase seen in 2021, up from the decade-long average of 53 firearms-related deaths annually from 2010 to 2020.

Traffic-related causes ranked third for cause of death in 2022, accounting for 56 deaths.

“While overall line-of-duty deaths are trending down, the continuing trend of greater-than-average firearms-related deaths continues to be a serious concern,” Marcia Ferranto, the organization’s chief executive officer, said in a news release. “Using and reporting on this data allows us to highlight the continuing cost of maintaining our democracy, regrettably measured in the lives of the many law enforcement professionals who sacrifice everything fulfilling their promise to serve and protect.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A new report says 70 officers died of COVID-related causes after getting the virus while on the job. The number is down dramatically from 2021, when 405 officer deaths were attributed to COVID.

The annual count was published Wednesday by the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund.

In total, 226 officers died in the line of duty in 2022, which is a decrease of 61% from 2021.

The decrease “is almost entirely related to the significant reduction in COVID-19 deaths,” the report stated. The authors said the decline was likely due to “reduced infection rates and the broad availability and use of vaccinations.”

Reported deaths included federal, state, tribal, and local law enforcement officers.

Firearms-related fatalities were the second-leading cause of death among officers, with 64 in 2022. That count sustains a 21% increase seen in 2021, up from the decade-long average of 53 firearms-related deaths annually from 2010 to 2020.

Traffic-related causes ranked third for cause of death in 2022, accounting for 56 deaths.

“While overall line-of-duty deaths are trending down, the continuing trend of greater-than-average firearms-related deaths continues to be a serious concern,” Marcia Ferranto, the organization’s chief executive officer, said in a news release. “Using and reporting on this data allows us to highlight the continuing cost of maintaining our democracy, regrettably measured in the lives of the many law enforcement professionals who sacrifice everything fulfilling their promise to serve and protect.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A new report says 70 officers died of COVID-related causes after getting the virus while on the job. The number is down dramatically from 2021, when 405 officer deaths were attributed to COVID.

The annual count was published Wednesday by the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund.

In total, 226 officers died in the line of duty in 2022, which is a decrease of 61% from 2021.

The decrease “is almost entirely related to the significant reduction in COVID-19 deaths,” the report stated. The authors said the decline was likely due to “reduced infection rates and the broad availability and use of vaccinations.”

Reported deaths included federal, state, tribal, and local law enforcement officers.

Firearms-related fatalities were the second-leading cause of death among officers, with 64 in 2022. That count sustains a 21% increase seen in 2021, up from the decade-long average of 53 firearms-related deaths annually from 2010 to 2020.

Traffic-related causes ranked third for cause of death in 2022, accounting for 56 deaths.

“While overall line-of-duty deaths are trending down, the continuing trend of greater-than-average firearms-related deaths continues to be a serious concern,” Marcia Ferranto, the organization’s chief executive officer, said in a news release. “Using and reporting on this data allows us to highlight the continuing cost of maintaining our democracy, regrettably measured in the lives of the many law enforcement professionals who sacrifice everything fulfilling their promise to serve and protect.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Long COVID comes into focus, showing older patients fare worse

These findings help define long COVID, guiding providers and patients through the recovery process, Barak Mizrahi, MSc, of KI Research Institute, Kfar Malal, Israel, and colleagues reported.

“To provide efficient continuous treatment and prevent adverse events related to potential long term effects and delayed symptoms of COVID-19, determining the magnitude and severity of this phenomenon and distinguishing it from similar clinical manifestations that occur normally or following infections with other pathogens is essential,” the investigators wrote in The BMJ.

To this end, they conducted a retrospective, nationwide cohort study involving 1,913,234 people who took a polymerase chain reaction test for SARS-CoV-2 between March 1, 2020, and Oct. 1, 2021. They compared a range of long-term outcomes at different intervals post infection, and compared these trends across subgroups sorted by age, sex, and variant. Outcomes ranged broadly, including respiratory disorders, cough, arthralgia, weakness, hair loss, and others.

The investigators compared hazard ratios for each of these outcomes among patients who tested positive versus those who tested negative at three intervals after testing: 30-90 days, 30-180 days, and 180-360 days. Statistically significant differences in the risks of these outcomes between infected versus uninfected groups suggested that COVID was playing a role.

“The health outcomes that represent long COVID showed a significant increase in both early and late phases,” the investigators wrote. These outcomes included anosmia and dysgeusia, cognitive impairment, dyspnea, weakness, and palpitations. In contrast, chest pain, myalgia, arthralgia, cough, and dizziness were associated with patients who were in the early phase, but not the late phase of long COVID.

“Vaccinated patients with a breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection had a lower risk for dyspnea and similar risk for other outcomes compared with unvaccinated infected patients,” the investigators noted.

For the long COVID outcomes, plots of risk differences over time showed that symptoms tended to get milder or resolve within a few months to a year. Patients 41-60 years were most likely to be impacted by long COVID outcomes, and show least improvement at 1 year, compared with other age groups.

“We believe that these findings will shed light on what is ‘long COVID’, support patients and doctors, and facilitate better and more efficient care,” Mr. Mizrahi and coauthor Maytal Bivas-Benita, PhD said in a joint written comment. “Primary care physicians (and patients) will now more clearly understand what are the symptoms that might be related to COVID and for how long they might linger. This would help physicians monitor the patients efficiently, ease their patients’ concerns and navigate a more efficient disease management.”

They suggested that the findings should hold consistent for future variants, although they could not “rule out the possibility of the emergence of new and more severe variants which will be more virulent and cause a more severe illness.”

One “major limitation” of the study, according to Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, MD, a physiatrist and professor and chair of rehabilitation medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, is the lack of data for fatigue and dysautonomia, which are “the major presentations” that she sees in her long COVID clinic.

“The authors of the article focus on the primary damage being related to the lungs, though we know this is a systemic disease beyond the respiratory system, with endothelial dysfunction and immune dysregulation,” Dr. Verduzco-Gutierrez, who is also director of COVID recovery at the University of Texas Health Science Center, said in an interview.

Although it was reassuring to see that younger adults with long COVID trended toward improvement, she noted that patients 41-60 years “still had pretty significant symptoms” after 12 months.

“That [age group comprises] probably the majority of my patients that I’m seeing in the long COVID clinic,” Dr. Verduzco-Gutierrez said. “If you look at the whole thing, it looks better, but then when you drill down to that age group where you’re seeing patients, then it’s not.”

Dr. Verduzco-Gutierrez is so busy managing patients with long COVID that new appointments in her clinic are now delayed until May 31, so most patients will remain under the care of their primary care providers. She recommended that these physicians follow guidance from the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, who offer consensus statements based on clinical characteristics, with separate recommendations for pediatric patients.

Our understanding of long COVID will continue to improve, and with it, available recommendations, she predicted, but further advances will require persistent effort.

“I think no matter what this [study] shows us, more research is needed,” Dr. Verduzco-Gutierrez said. “We can’t just forget about it, just because there is a population of people who get better. What about the ones who don’t?”

The investigators and Dr. Verduzco-Gutierrez disclosed no conflicts of interest.

These findings help define long COVID, guiding providers and patients through the recovery process, Barak Mizrahi, MSc, of KI Research Institute, Kfar Malal, Israel, and colleagues reported.

“To provide efficient continuous treatment and prevent adverse events related to potential long term effects and delayed symptoms of COVID-19, determining the magnitude and severity of this phenomenon and distinguishing it from similar clinical manifestations that occur normally or following infections with other pathogens is essential,” the investigators wrote in The BMJ.

To this end, they conducted a retrospective, nationwide cohort study involving 1,913,234 people who took a polymerase chain reaction test for SARS-CoV-2 between March 1, 2020, and Oct. 1, 2021. They compared a range of long-term outcomes at different intervals post infection, and compared these trends across subgroups sorted by age, sex, and variant. Outcomes ranged broadly, including respiratory disorders, cough, arthralgia, weakness, hair loss, and others.

The investigators compared hazard ratios for each of these outcomes among patients who tested positive versus those who tested negative at three intervals after testing: 30-90 days, 30-180 days, and 180-360 days. Statistically significant differences in the risks of these outcomes between infected versus uninfected groups suggested that COVID was playing a role.

“The health outcomes that represent long COVID showed a significant increase in both early and late phases,” the investigators wrote. These outcomes included anosmia and dysgeusia, cognitive impairment, dyspnea, weakness, and palpitations. In contrast, chest pain, myalgia, arthralgia, cough, and dizziness were associated with patients who were in the early phase, but not the late phase of long COVID.

“Vaccinated patients with a breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection had a lower risk for dyspnea and similar risk for other outcomes compared with unvaccinated infected patients,” the investigators noted.

For the long COVID outcomes, plots of risk differences over time showed that symptoms tended to get milder or resolve within a few months to a year. Patients 41-60 years were most likely to be impacted by long COVID outcomes, and show least improvement at 1 year, compared with other age groups.

“We believe that these findings will shed light on what is ‘long COVID’, support patients and doctors, and facilitate better and more efficient care,” Mr. Mizrahi and coauthor Maytal Bivas-Benita, PhD said in a joint written comment. “Primary care physicians (and patients) will now more clearly understand what are the symptoms that might be related to COVID and for how long they might linger. This would help physicians monitor the patients efficiently, ease their patients’ concerns and navigate a more efficient disease management.”

They suggested that the findings should hold consistent for future variants, although they could not “rule out the possibility of the emergence of new and more severe variants which will be more virulent and cause a more severe illness.”

One “major limitation” of the study, according to Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, MD, a physiatrist and professor and chair of rehabilitation medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, is the lack of data for fatigue and dysautonomia, which are “the major presentations” that she sees in her long COVID clinic.

“The authors of the article focus on the primary damage being related to the lungs, though we know this is a systemic disease beyond the respiratory system, with endothelial dysfunction and immune dysregulation,” Dr. Verduzco-Gutierrez, who is also director of COVID recovery at the University of Texas Health Science Center, said in an interview.

Although it was reassuring to see that younger adults with long COVID trended toward improvement, she noted that patients 41-60 years “still had pretty significant symptoms” after 12 months.

“That [age group comprises] probably the majority of my patients that I’m seeing in the long COVID clinic,” Dr. Verduzco-Gutierrez said. “If you look at the whole thing, it looks better, but then when you drill down to that age group where you’re seeing patients, then it’s not.”

Dr. Verduzco-Gutierrez is so busy managing patients with long COVID that new appointments in her clinic are now delayed until May 31, so most patients will remain under the care of their primary care providers. She recommended that these physicians follow guidance from the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, who offer consensus statements based on clinical characteristics, with separate recommendations for pediatric patients.

Our understanding of long COVID will continue to improve, and with it, available recommendations, she predicted, but further advances will require persistent effort.

“I think no matter what this [study] shows us, more research is needed,” Dr. Verduzco-Gutierrez said. “We can’t just forget about it, just because there is a population of people who get better. What about the ones who don’t?”

The investigators and Dr. Verduzco-Gutierrez disclosed no conflicts of interest.

These findings help define long COVID, guiding providers and patients through the recovery process, Barak Mizrahi, MSc, of KI Research Institute, Kfar Malal, Israel, and colleagues reported.

“To provide efficient continuous treatment and prevent adverse events related to potential long term effects and delayed symptoms of COVID-19, determining the magnitude and severity of this phenomenon and distinguishing it from similar clinical manifestations that occur normally or following infections with other pathogens is essential,” the investigators wrote in The BMJ.

To this end, they conducted a retrospective, nationwide cohort study involving 1,913,234 people who took a polymerase chain reaction test for SARS-CoV-2 between March 1, 2020, and Oct. 1, 2021. They compared a range of long-term outcomes at different intervals post infection, and compared these trends across subgroups sorted by age, sex, and variant. Outcomes ranged broadly, including respiratory disorders, cough, arthralgia, weakness, hair loss, and others.

The investigators compared hazard ratios for each of these outcomes among patients who tested positive versus those who tested negative at three intervals after testing: 30-90 days, 30-180 days, and 180-360 days. Statistically significant differences in the risks of these outcomes between infected versus uninfected groups suggested that COVID was playing a role.

“The health outcomes that represent long COVID showed a significant increase in both early and late phases,” the investigators wrote. These outcomes included anosmia and dysgeusia, cognitive impairment, dyspnea, weakness, and palpitations. In contrast, chest pain, myalgia, arthralgia, cough, and dizziness were associated with patients who were in the early phase, but not the late phase of long COVID.

“Vaccinated patients with a breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection had a lower risk for dyspnea and similar risk for other outcomes compared with unvaccinated infected patients,” the investigators noted.

For the long COVID outcomes, plots of risk differences over time showed that symptoms tended to get milder or resolve within a few months to a year. Patients 41-60 years were most likely to be impacted by long COVID outcomes, and show least improvement at 1 year, compared with other age groups.

“We believe that these findings will shed light on what is ‘long COVID’, support patients and doctors, and facilitate better and more efficient care,” Mr. Mizrahi and coauthor Maytal Bivas-Benita, PhD said in a joint written comment. “Primary care physicians (and patients) will now more clearly understand what are the symptoms that might be related to COVID and for how long they might linger. This would help physicians monitor the patients efficiently, ease their patients’ concerns and navigate a more efficient disease management.”

They suggested that the findings should hold consistent for future variants, although they could not “rule out the possibility of the emergence of new and more severe variants which will be more virulent and cause a more severe illness.”

One “major limitation” of the study, according to Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, MD, a physiatrist and professor and chair of rehabilitation medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, is the lack of data for fatigue and dysautonomia, which are “the major presentations” that she sees in her long COVID clinic.

“The authors of the article focus on the primary damage being related to the lungs, though we know this is a systemic disease beyond the respiratory system, with endothelial dysfunction and immune dysregulation,” Dr. Verduzco-Gutierrez, who is also director of COVID recovery at the University of Texas Health Science Center, said in an interview.

Although it was reassuring to see that younger adults with long COVID trended toward improvement, she noted that patients 41-60 years “still had pretty significant symptoms” after 12 months.

“That [age group comprises] probably the majority of my patients that I’m seeing in the long COVID clinic,” Dr. Verduzco-Gutierrez said. “If you look at the whole thing, it looks better, but then when you drill down to that age group where you’re seeing patients, then it’s not.”

Dr. Verduzco-Gutierrez is so busy managing patients with long COVID that new appointments in her clinic are now delayed until May 31, so most patients will remain under the care of their primary care providers. She recommended that these physicians follow guidance from the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, who offer consensus statements based on clinical characteristics, with separate recommendations for pediatric patients.

Our understanding of long COVID will continue to improve, and with it, available recommendations, she predicted, but further advances will require persistent effort.

“I think no matter what this [study] shows us, more research is needed,” Dr. Verduzco-Gutierrez said. “We can’t just forget about it, just because there is a population of people who get better. What about the ones who don’t?”

The investigators and Dr. Verduzco-Gutierrez disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE BMJ

Strong support to provide DAA therapy to all patients with HCV

, a large, real-world analysis finds.

Improved outcomes were seen among patients without cirrhosis, those with compensated cirrhosis, and those with existing liver decompensation, the authors noted.