User login

For MD-IQ use only

Should I Stay or Should I Go? Federal Health Care Professional Retirement Dilemmas

Should I Stay or Should I Go? Federal Health Care Professional Retirement Dilemmas

The uselessness of men above sixty years of age and the incalculable benefit it would be in commercial, in political, and in professional life, if as a matter of course, men stopped working at this age.

Sir William Osler1

The first time I remember hearing the word retirement was when I was 5 or 6 years old. My mother told me that my father had been given new orders: either be promoted to general and move to oversee a hospital somewhere far away, or retire from the Army. He was a scholar, teacher, and physician with no interest or aptitude for military politics and health care administration. Reluctantly, he resigned himself to retirement before he had planned. I recall being angry with him, because in my solipsistic child mind he was depriving me of the opportunity to live in a big house across from the parade field, where the generals lived or having a reserved parking spot in front of the post exchange. As a psychiatrist, I suspect that the anger was a primitive defense against the fear of leaving the only home I had ever known on an Army base.

I recently finished reading Michael Bliss’s seminal biography of Sir William Osler (1848-1919), the great Anglo-American physician and medical educator.2 Bliss found few blemishes on Osler’s character or missteps in his stellar career, but one of the few may be his views on retirement. The epigraph is from an address Osler gave before leaving Johns Hopkins for semiretirement in Oxford, England. The farewell speech caused a media controversy with his comments reflecting attitudes that seem ageist today, when many people are active, productive, and happy long past the age of 60 years.3 I do not endorse Osler’s philosophy of aging, nor his exclusion of women (if I did, I would not be around to write this editorial). Not even Osler himself followed his advice: he was active in medicine almost until his death at 70 years old.2

Yet like many of my fellow federal health care practitioners (HCPs), I have been thinking about and planning for retirement earlier than expected, given the memos and directives about voluntary early retirement, deferred resignation, and reductions in force.4,5 The COVID-19 pandemic sadly compelled many burned-out and traumatized HCPs to cross the retirement Rubicon far sooner than they imagined.6

A Google search for information about HCP retirement, particularly among physicians, produces a cascade of advisory articles. They primarily focus on finances, with many pushing their own commercial agenda for retirement planning.7 Although money is a necessary piece of the retirement puzzle, for HCPs it may not be sufficient to ensure a healthy and satisfying retirement. Two other considerations may be even more important to weigh in making the retirement decision, namely timing and meaning.8

For earlier generations of HCPs, work was almost their sole identity. Although younger practitioners are more likely to embrace a better work-life balance, it is still a driving factor for many in the decision to retire.9 It is not just about the cliché of being a workaholic, rather many clinicians continue to enjoy lifelong learning, the rewards of helping people in need, and professional satisfaction. HCPs also spend a longer time training than many other professions; perhaps since we waited so long to practice, we want to stay a little longer.10 For those whose motivation for federal practice was a commitment to service, these may be even more powerful incentives to continue working.

When a nurse, physician, pharmacist, or social worker no longer finds the same gratification and stimulation in their work, whether due to unwelcome changes in the clinical setting or the profession at large, declining health or emotional exhaustion, or the very human need to move onto another phase of life (what Osler likely really meant), then that may be a signal to think hard about retiring. Of course, there have always been—and will continue to be—professionals of all stripes who, even in the most agreeable situation, just cannot wait to retire. Simply because there are so many other ways they want to spend their remaining energy and time: travel, grandchildren, hobbies, even a second career. Because none of us knows how far out our life extends, it is prudent to periodically ask what is the optimal path that combines both purpose and well-being.

All of us as HCPs, and even more as human beings with desires and duties far beyond our respective professions, face a dilemma: a choice between 2 goods that cannot both be fulfilled simultaneously. This is likely why HCPs frequently do what is technically called a phased retirement, a fancy name for working part-time, or retiring from 1 position and taking up another. This temporizes the decision and tempers the bittersweet emotional experience of leaving the profession in one way, and in another, it delays the inevitable.

Over the last few years, I have learned 2 important lessons while watching many of my closest friends retire. First, for those who are still working and those who are retired may seem to inhabit a separate country; hence, special efforts must be made to both appreciate them while they are in our immediate circle of concern and to make efforts to stay in contact once they are emeriti. It is almost as if after being a daily integral aspect of the workplace they have passed into a different dimension of existence. In terms of priorities and mindsets, many of them have. Second, what makes retirement a reality with peace and growth rather than regret and stagnation is owning the decision to retire. There are always constraints: financial, medical, and familial. However, those who retire on their own terms and not primarily in response to fear or uncertainty appear to fare better than those feeling the same pressures who give away their power.11 Having read about retirement in the last months, the best advice I have seen is from Harry Emerson Fosdick, a Protestant minister in the early 20th century: “Don’t simply retire from something; have something to retire to.”12

I have not yet decided about my retirement. Whatever decision you make, remember it is solely yours. After a lifetime of caring for others, retirement is all about caring for yourself.

- Osler W. The Fixed Period. In: Osler W, ed. Aequanimitas With Other Addresses to Medical Students, Nurses and Practitioners of Medicine. 3rd ed. The Blakiston Company; 1932:373-393.

- Bliss M. William Osler: A Life in Medicine. Oxford University Press; 1999.

- Anderson M, Scofield RH. The “Fixed period,” the wildfire news, and an unpublished manuscript: Osler’s farewell speech revisited in geographical breadth and emotional depth. Am J Med Sci. Published online February 11, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2025.02.005

- Obis A. What federal workers should consider before accepting deferred resignation. Federal News Network. April 8, 2025. Accessed April 25, 2025. https://federalnewsnetwork.com/workforce/2025/04/what-federal-workers-should-consider-before-accepting-deferred-resignation/

- Dyer J. VA exempts clinical staff from OPM deferred resignation program. Federal Practitioner. February 11, 2025. Accessed April 28, 2025. https://www.mdedge.com/content/va-exempts-clinical-staff-opm-deferred-resignation-program

- Shyrock T. Retirement planning secrets for physicians. Medical Economics. 2024;101(8). Accessed April 28, 2025. https:// www.medicaleconomics.com/view/retirement-planningsecrets-for-physicians

- Sinsky CA, Brown RL, Stillman MJ, Linzer M. COVID-related stress and work intentions in a sample of US health care workers. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(6):1165-1173. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2021.08.007

- Tabloski PA. Life after retirement. American Nurse. March 3, 2022. Accessed April 25, 2025. https://www.myamericannurse.com/life-after-retirement/

- Chen T-P. Young doctors want work-life balance. Older doctors say that’s not the job. The Wall Street Journal. November 3, 2024. Accessed April 25, 2025. https://www.wsj.com/lifestyle/careers/young-doctors-want-work-life-balance-older-doctors-say-thats-not-the-job-6cb37d48

- Sweeny JF. Physician retirement: Why it’s hard for doctors to retire. Medical Economics. 2019;96(4). Accessed April 25, 2025. https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/physician-retirement-why-its-hard-doctors-retire

- Nelson J. Wisdom for Our Time. W.W. Norton; 1961.

- Silver MP, Hamilton AD, Biswas A, Williams SA. Life after medicine: a systematic review of studies physician’s adjustment to retirement. Arch Community Med Public Health. 2016;2(1):001-007. doi:10.17352/2455-5479.000006

The uselessness of men above sixty years of age and the incalculable benefit it would be in commercial, in political, and in professional life, if as a matter of course, men stopped working at this age.

Sir William Osler1

The first time I remember hearing the word retirement was when I was 5 or 6 years old. My mother told me that my father had been given new orders: either be promoted to general and move to oversee a hospital somewhere far away, or retire from the Army. He was a scholar, teacher, and physician with no interest or aptitude for military politics and health care administration. Reluctantly, he resigned himself to retirement before he had planned. I recall being angry with him, because in my solipsistic child mind he was depriving me of the opportunity to live in a big house across from the parade field, where the generals lived or having a reserved parking spot in front of the post exchange. As a psychiatrist, I suspect that the anger was a primitive defense against the fear of leaving the only home I had ever known on an Army base.

I recently finished reading Michael Bliss’s seminal biography of Sir William Osler (1848-1919), the great Anglo-American physician and medical educator.2 Bliss found few blemishes on Osler’s character or missteps in his stellar career, but one of the few may be his views on retirement. The epigraph is from an address Osler gave before leaving Johns Hopkins for semiretirement in Oxford, England. The farewell speech caused a media controversy with his comments reflecting attitudes that seem ageist today, when many people are active, productive, and happy long past the age of 60 years.3 I do not endorse Osler’s philosophy of aging, nor his exclusion of women (if I did, I would not be around to write this editorial). Not even Osler himself followed his advice: he was active in medicine almost until his death at 70 years old.2

Yet like many of my fellow federal health care practitioners (HCPs), I have been thinking about and planning for retirement earlier than expected, given the memos and directives about voluntary early retirement, deferred resignation, and reductions in force.4,5 The COVID-19 pandemic sadly compelled many burned-out and traumatized HCPs to cross the retirement Rubicon far sooner than they imagined.6

A Google search for information about HCP retirement, particularly among physicians, produces a cascade of advisory articles. They primarily focus on finances, with many pushing their own commercial agenda for retirement planning.7 Although money is a necessary piece of the retirement puzzle, for HCPs it may not be sufficient to ensure a healthy and satisfying retirement. Two other considerations may be even more important to weigh in making the retirement decision, namely timing and meaning.8

For earlier generations of HCPs, work was almost their sole identity. Although younger practitioners are more likely to embrace a better work-life balance, it is still a driving factor for many in the decision to retire.9 It is not just about the cliché of being a workaholic, rather many clinicians continue to enjoy lifelong learning, the rewards of helping people in need, and professional satisfaction. HCPs also spend a longer time training than many other professions; perhaps since we waited so long to practice, we want to stay a little longer.10 For those whose motivation for federal practice was a commitment to service, these may be even more powerful incentives to continue working.

When a nurse, physician, pharmacist, or social worker no longer finds the same gratification and stimulation in their work, whether due to unwelcome changes in the clinical setting or the profession at large, declining health or emotional exhaustion, or the very human need to move onto another phase of life (what Osler likely really meant), then that may be a signal to think hard about retiring. Of course, there have always been—and will continue to be—professionals of all stripes who, even in the most agreeable situation, just cannot wait to retire. Simply because there are so many other ways they want to spend their remaining energy and time: travel, grandchildren, hobbies, even a second career. Because none of us knows how far out our life extends, it is prudent to periodically ask what is the optimal path that combines both purpose and well-being.

All of us as HCPs, and even more as human beings with desires and duties far beyond our respective professions, face a dilemma: a choice between 2 goods that cannot both be fulfilled simultaneously. This is likely why HCPs frequently do what is technically called a phased retirement, a fancy name for working part-time, or retiring from 1 position and taking up another. This temporizes the decision and tempers the bittersweet emotional experience of leaving the profession in one way, and in another, it delays the inevitable.

Over the last few years, I have learned 2 important lessons while watching many of my closest friends retire. First, for those who are still working and those who are retired may seem to inhabit a separate country; hence, special efforts must be made to both appreciate them while they are in our immediate circle of concern and to make efforts to stay in contact once they are emeriti. It is almost as if after being a daily integral aspect of the workplace they have passed into a different dimension of existence. In terms of priorities and mindsets, many of them have. Second, what makes retirement a reality with peace and growth rather than regret and stagnation is owning the decision to retire. There are always constraints: financial, medical, and familial. However, those who retire on their own terms and not primarily in response to fear or uncertainty appear to fare better than those feeling the same pressures who give away their power.11 Having read about retirement in the last months, the best advice I have seen is from Harry Emerson Fosdick, a Protestant minister in the early 20th century: “Don’t simply retire from something; have something to retire to.”12

I have not yet decided about my retirement. Whatever decision you make, remember it is solely yours. After a lifetime of caring for others, retirement is all about caring for yourself.

The uselessness of men above sixty years of age and the incalculable benefit it would be in commercial, in political, and in professional life, if as a matter of course, men stopped working at this age.

Sir William Osler1

The first time I remember hearing the word retirement was when I was 5 or 6 years old. My mother told me that my father had been given new orders: either be promoted to general and move to oversee a hospital somewhere far away, or retire from the Army. He was a scholar, teacher, and physician with no interest or aptitude for military politics and health care administration. Reluctantly, he resigned himself to retirement before he had planned. I recall being angry with him, because in my solipsistic child mind he was depriving me of the opportunity to live in a big house across from the parade field, where the generals lived or having a reserved parking spot in front of the post exchange. As a psychiatrist, I suspect that the anger was a primitive defense against the fear of leaving the only home I had ever known on an Army base.

I recently finished reading Michael Bliss’s seminal biography of Sir William Osler (1848-1919), the great Anglo-American physician and medical educator.2 Bliss found few blemishes on Osler’s character or missteps in his stellar career, but one of the few may be his views on retirement. The epigraph is from an address Osler gave before leaving Johns Hopkins for semiretirement in Oxford, England. The farewell speech caused a media controversy with his comments reflecting attitudes that seem ageist today, when many people are active, productive, and happy long past the age of 60 years.3 I do not endorse Osler’s philosophy of aging, nor his exclusion of women (if I did, I would not be around to write this editorial). Not even Osler himself followed his advice: he was active in medicine almost until his death at 70 years old.2

Yet like many of my fellow federal health care practitioners (HCPs), I have been thinking about and planning for retirement earlier than expected, given the memos and directives about voluntary early retirement, deferred resignation, and reductions in force.4,5 The COVID-19 pandemic sadly compelled many burned-out and traumatized HCPs to cross the retirement Rubicon far sooner than they imagined.6

A Google search for information about HCP retirement, particularly among physicians, produces a cascade of advisory articles. They primarily focus on finances, with many pushing their own commercial agenda for retirement planning.7 Although money is a necessary piece of the retirement puzzle, for HCPs it may not be sufficient to ensure a healthy and satisfying retirement. Two other considerations may be even more important to weigh in making the retirement decision, namely timing and meaning.8

For earlier generations of HCPs, work was almost their sole identity. Although younger practitioners are more likely to embrace a better work-life balance, it is still a driving factor for many in the decision to retire.9 It is not just about the cliché of being a workaholic, rather many clinicians continue to enjoy lifelong learning, the rewards of helping people in need, and professional satisfaction. HCPs also spend a longer time training than many other professions; perhaps since we waited so long to practice, we want to stay a little longer.10 For those whose motivation for federal practice was a commitment to service, these may be even more powerful incentives to continue working.

When a nurse, physician, pharmacist, or social worker no longer finds the same gratification and stimulation in their work, whether due to unwelcome changes in the clinical setting or the profession at large, declining health or emotional exhaustion, or the very human need to move onto another phase of life (what Osler likely really meant), then that may be a signal to think hard about retiring. Of course, there have always been—and will continue to be—professionals of all stripes who, even in the most agreeable situation, just cannot wait to retire. Simply because there are so many other ways they want to spend their remaining energy and time: travel, grandchildren, hobbies, even a second career. Because none of us knows how far out our life extends, it is prudent to periodically ask what is the optimal path that combines both purpose and well-being.

All of us as HCPs, and even more as human beings with desires and duties far beyond our respective professions, face a dilemma: a choice between 2 goods that cannot both be fulfilled simultaneously. This is likely why HCPs frequently do what is technically called a phased retirement, a fancy name for working part-time, or retiring from 1 position and taking up another. This temporizes the decision and tempers the bittersweet emotional experience of leaving the profession in one way, and in another, it delays the inevitable.

Over the last few years, I have learned 2 important lessons while watching many of my closest friends retire. First, for those who are still working and those who are retired may seem to inhabit a separate country; hence, special efforts must be made to both appreciate them while they are in our immediate circle of concern and to make efforts to stay in contact once they are emeriti. It is almost as if after being a daily integral aspect of the workplace they have passed into a different dimension of existence. In terms of priorities and mindsets, many of them have. Second, what makes retirement a reality with peace and growth rather than regret and stagnation is owning the decision to retire. There are always constraints: financial, medical, and familial. However, those who retire on their own terms and not primarily in response to fear or uncertainty appear to fare better than those feeling the same pressures who give away their power.11 Having read about retirement in the last months, the best advice I have seen is from Harry Emerson Fosdick, a Protestant minister in the early 20th century: “Don’t simply retire from something; have something to retire to.”12

I have not yet decided about my retirement. Whatever decision you make, remember it is solely yours. After a lifetime of caring for others, retirement is all about caring for yourself.

- Osler W. The Fixed Period. In: Osler W, ed. Aequanimitas With Other Addresses to Medical Students, Nurses and Practitioners of Medicine. 3rd ed. The Blakiston Company; 1932:373-393.

- Bliss M. William Osler: A Life in Medicine. Oxford University Press; 1999.

- Anderson M, Scofield RH. The “Fixed period,” the wildfire news, and an unpublished manuscript: Osler’s farewell speech revisited in geographical breadth and emotional depth. Am J Med Sci. Published online February 11, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2025.02.005

- Obis A. What federal workers should consider before accepting deferred resignation. Federal News Network. April 8, 2025. Accessed April 25, 2025. https://federalnewsnetwork.com/workforce/2025/04/what-federal-workers-should-consider-before-accepting-deferred-resignation/

- Dyer J. VA exempts clinical staff from OPM deferred resignation program. Federal Practitioner. February 11, 2025. Accessed April 28, 2025. https://www.mdedge.com/content/va-exempts-clinical-staff-opm-deferred-resignation-program

- Shyrock T. Retirement planning secrets for physicians. Medical Economics. 2024;101(8). Accessed April 28, 2025. https:// www.medicaleconomics.com/view/retirement-planningsecrets-for-physicians

- Sinsky CA, Brown RL, Stillman MJ, Linzer M. COVID-related stress and work intentions in a sample of US health care workers. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(6):1165-1173. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2021.08.007

- Tabloski PA. Life after retirement. American Nurse. March 3, 2022. Accessed April 25, 2025. https://www.myamericannurse.com/life-after-retirement/

- Chen T-P. Young doctors want work-life balance. Older doctors say that’s not the job. The Wall Street Journal. November 3, 2024. Accessed April 25, 2025. https://www.wsj.com/lifestyle/careers/young-doctors-want-work-life-balance-older-doctors-say-thats-not-the-job-6cb37d48

- Sweeny JF. Physician retirement: Why it’s hard for doctors to retire. Medical Economics. 2019;96(4). Accessed April 25, 2025. https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/physician-retirement-why-its-hard-doctors-retire

- Nelson J. Wisdom for Our Time. W.W. Norton; 1961.

- Silver MP, Hamilton AD, Biswas A, Williams SA. Life after medicine: a systematic review of studies physician’s adjustment to retirement. Arch Community Med Public Health. 2016;2(1):001-007. doi:10.17352/2455-5479.000006

- Osler W. The Fixed Period. In: Osler W, ed. Aequanimitas With Other Addresses to Medical Students, Nurses and Practitioners of Medicine. 3rd ed. The Blakiston Company; 1932:373-393.

- Bliss M. William Osler: A Life in Medicine. Oxford University Press; 1999.

- Anderson M, Scofield RH. The “Fixed period,” the wildfire news, and an unpublished manuscript: Osler’s farewell speech revisited in geographical breadth and emotional depth. Am J Med Sci. Published online February 11, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2025.02.005

- Obis A. What federal workers should consider before accepting deferred resignation. Federal News Network. April 8, 2025. Accessed April 25, 2025. https://federalnewsnetwork.com/workforce/2025/04/what-federal-workers-should-consider-before-accepting-deferred-resignation/

- Dyer J. VA exempts clinical staff from OPM deferred resignation program. Federal Practitioner. February 11, 2025. Accessed April 28, 2025. https://www.mdedge.com/content/va-exempts-clinical-staff-opm-deferred-resignation-program

- Shyrock T. Retirement planning secrets for physicians. Medical Economics. 2024;101(8). Accessed April 28, 2025. https:// www.medicaleconomics.com/view/retirement-planningsecrets-for-physicians

- Sinsky CA, Brown RL, Stillman MJ, Linzer M. COVID-related stress and work intentions in a sample of US health care workers. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(6):1165-1173. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2021.08.007

- Tabloski PA. Life after retirement. American Nurse. March 3, 2022. Accessed April 25, 2025. https://www.myamericannurse.com/life-after-retirement/

- Chen T-P. Young doctors want work-life balance. Older doctors say that’s not the job. The Wall Street Journal. November 3, 2024. Accessed April 25, 2025. https://www.wsj.com/lifestyle/careers/young-doctors-want-work-life-balance-older-doctors-say-thats-not-the-job-6cb37d48

- Sweeny JF. Physician retirement: Why it’s hard for doctors to retire. Medical Economics. 2019;96(4). Accessed April 25, 2025. https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/physician-retirement-why-its-hard-doctors-retire

- Nelson J. Wisdom for Our Time. W.W. Norton; 1961.

- Silver MP, Hamilton AD, Biswas A, Williams SA. Life after medicine: a systematic review of studies physician’s adjustment to retirement. Arch Community Med Public Health. 2016;2(1):001-007. doi:10.17352/2455-5479.000006

Should I Stay or Should I Go? Federal Health Care Professional Retirement Dilemmas

Should I Stay or Should I Go? Federal Health Care Professional Retirement Dilemmas

Multiple Firm Papules on the Wrists and Forearms

Multiple Firm Papules on the Wrists and Forearms

THE DIAGNOSIS: Acral Persistent Papular Mucinosis

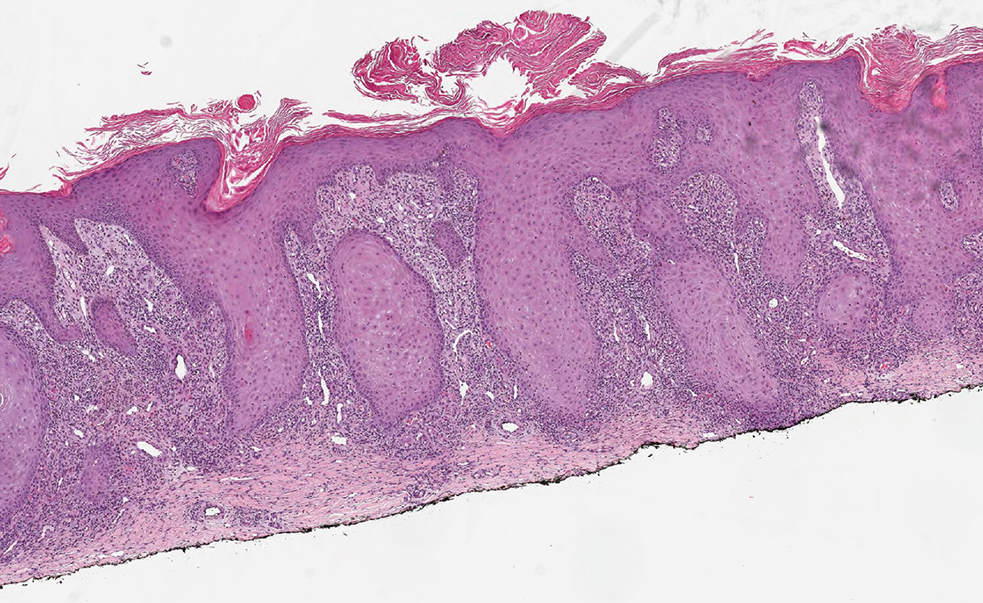

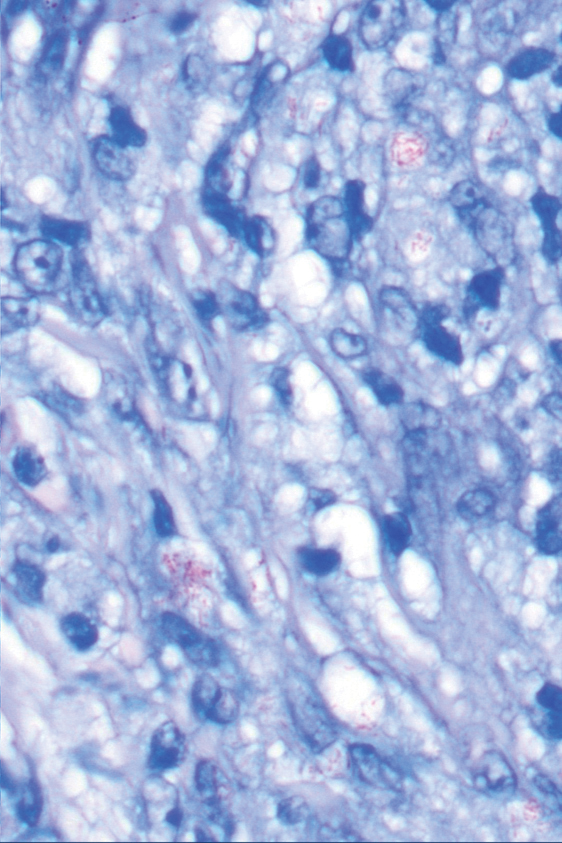

Histopathologic analysis revealed conspicuous interstitial mucin deposition throughout the upper to mid reticular dermis in the absence of a cellular infiltrate or fibroplasia. Colloidal iron staining confirmed the presence of mucin. In correlation with the clinical presentation, a diagnosis of acral persistent papular mucinosis (APPM) was made. The patient was counseled on the benign disease course and lack of associated comorbidities, and additional treatment was not pursued.

Acral persistent papular mucinosis is a rare distinct subtype of cutaneous mucinosis that initially was described by Rongioletti et al1 in 1986. As a localized form of lichen myxedematosus, APPM is characterized by mucin deposition in the dermis with no systemic involvement. The precise pathogenesis remains unclear, although some investigators have suggested that cytokine-mediated stimulation of glycosaminoglycan production may contribute to increased mucin accumulation in the dermis.2 Acral persistent papular mucinosis predominantly affects middle-aged women with a 5:1 female-to-male predominance.3 Clinically, patients present with discrete, nonfollicular, waxy papules that typically measure 2 to 5 mm and are distributed symmetrically on the extensor surfaces of the wrists and forearms. While the lesions generally are asymptomatic, some patients may report mild pruritus. The condition is chronic, with lesions seldom resolving and often increasing in number over time.3

Histologically, APPM is characterized by focal deposits of mucin in the upper reticular dermis with no evidence of increased fibroblast proliferation or fibrosis.4 This feature is pivotal in differentiating APPM from other subtypes of localized lichen myxedematosus and similar dermatoses. Diagnosis of APPM requires exclusion of systemic involvement, including thyroid abnormalities and monoclonal gammopathy, aligning with its classification as a purely cutaneous condition.5 Management of APPM is unclear due to its rarity. Reassurance for patients of its benign nature as well as clinical observation are recommended, though some reports cite benefits of treatment with topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors.6,7 The long-term prognosis for patients with APPM is favorable, although the persistence of and potential increase in lesions over time can be a cosmetic concern.

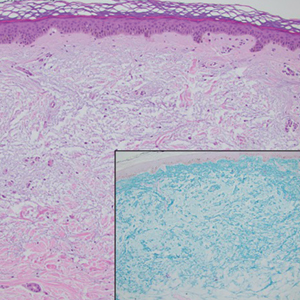

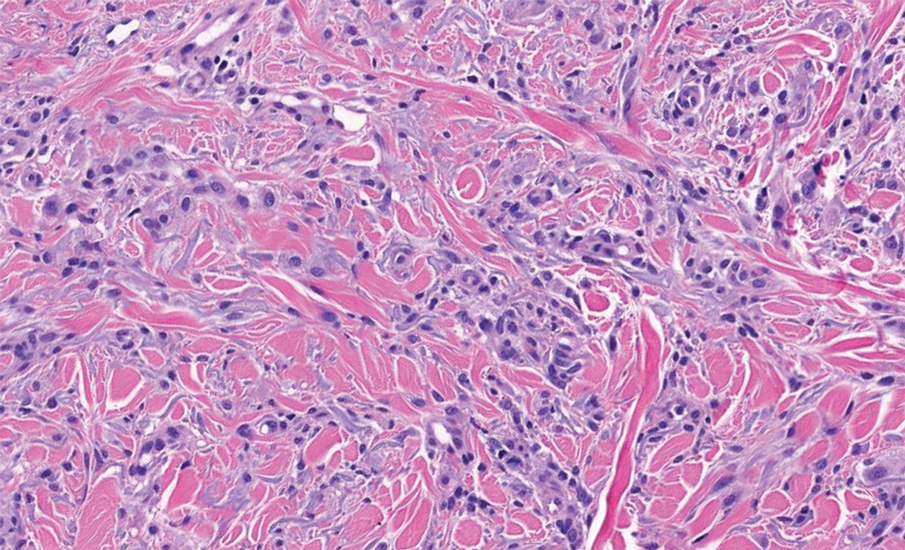

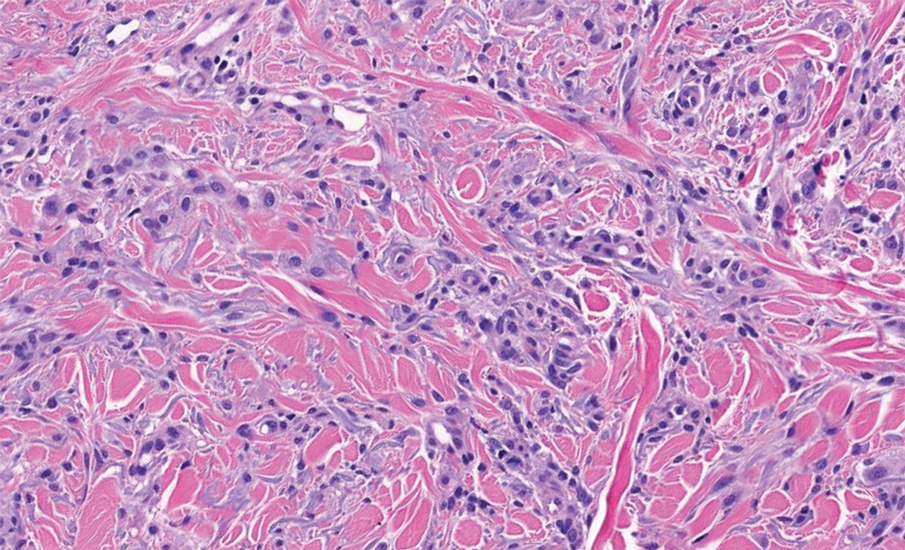

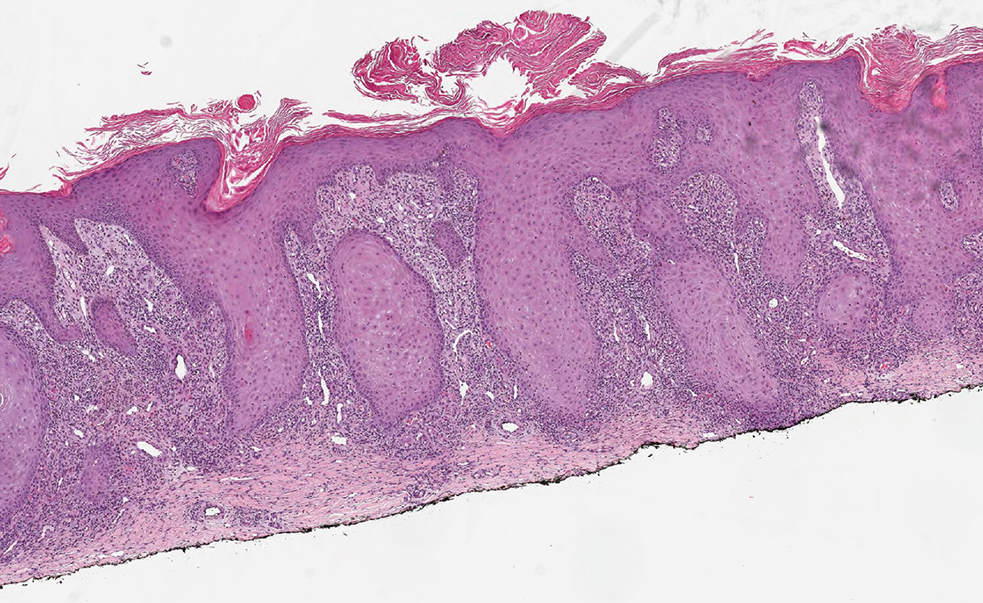

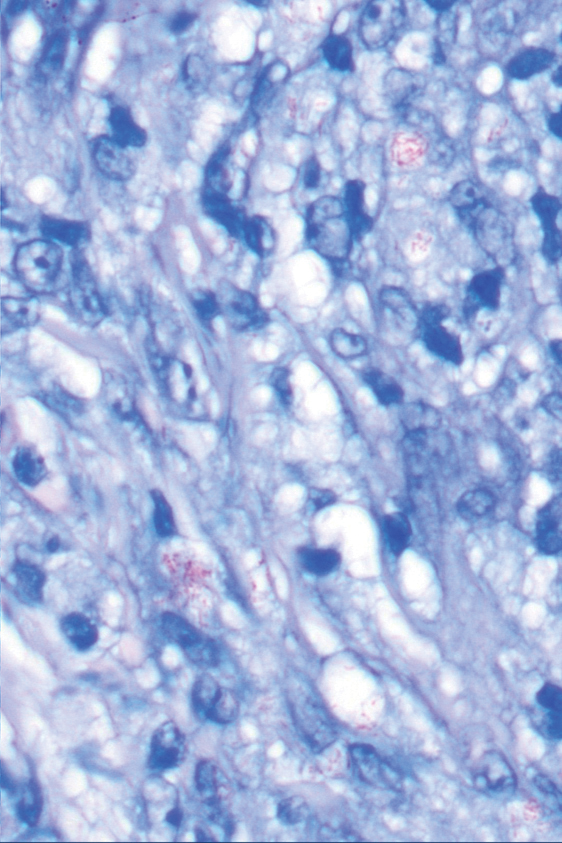

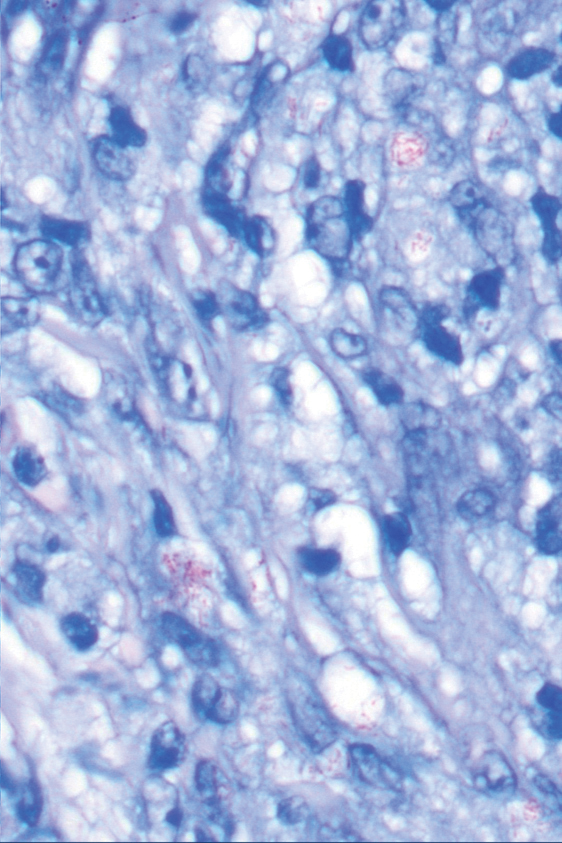

The differential diagnoses for APPM include scleromyxedema, scleredema, and other cutaneous eruptions that manifest as smooth flesh-colored papules, such as granuloma annulare and lichen nitidus.3 Scleromyxedema is a systemic cutaneous mucinosis that is part of the same disease spectrum as lichen myxedematosus. The papular eruption of scleromyxedema is much more widespread, and coalescing of the lesions may lead to characteristic skin thickening, creating leonine facies and deep furrowing over the trunk.8 Extracutaneous manifestations are frequent in scleromyxedema, and up to 90% of patients exhibit evidence of an underlying plasma cell dyscrasia.2 Histopathologically, scleromyxedema shows extensive fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis, in contrast to the findings of APPM (Figure 1).

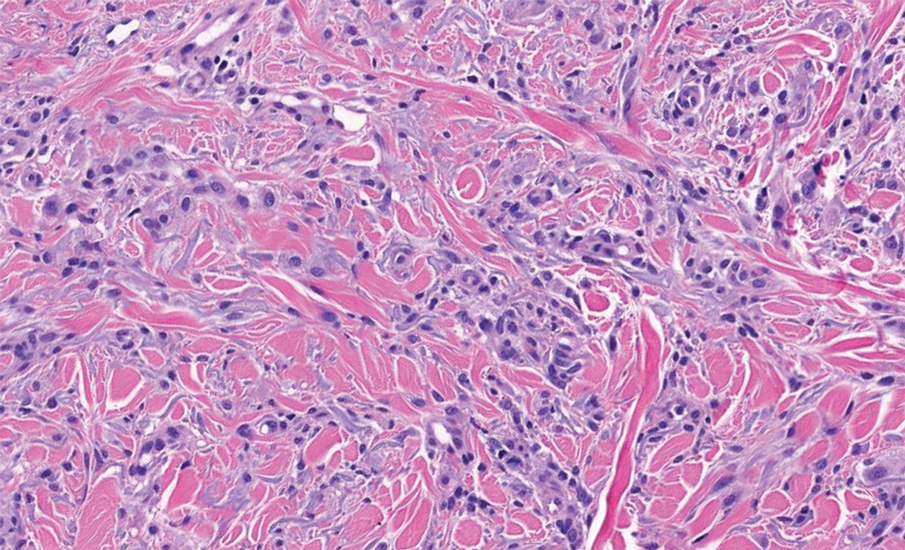

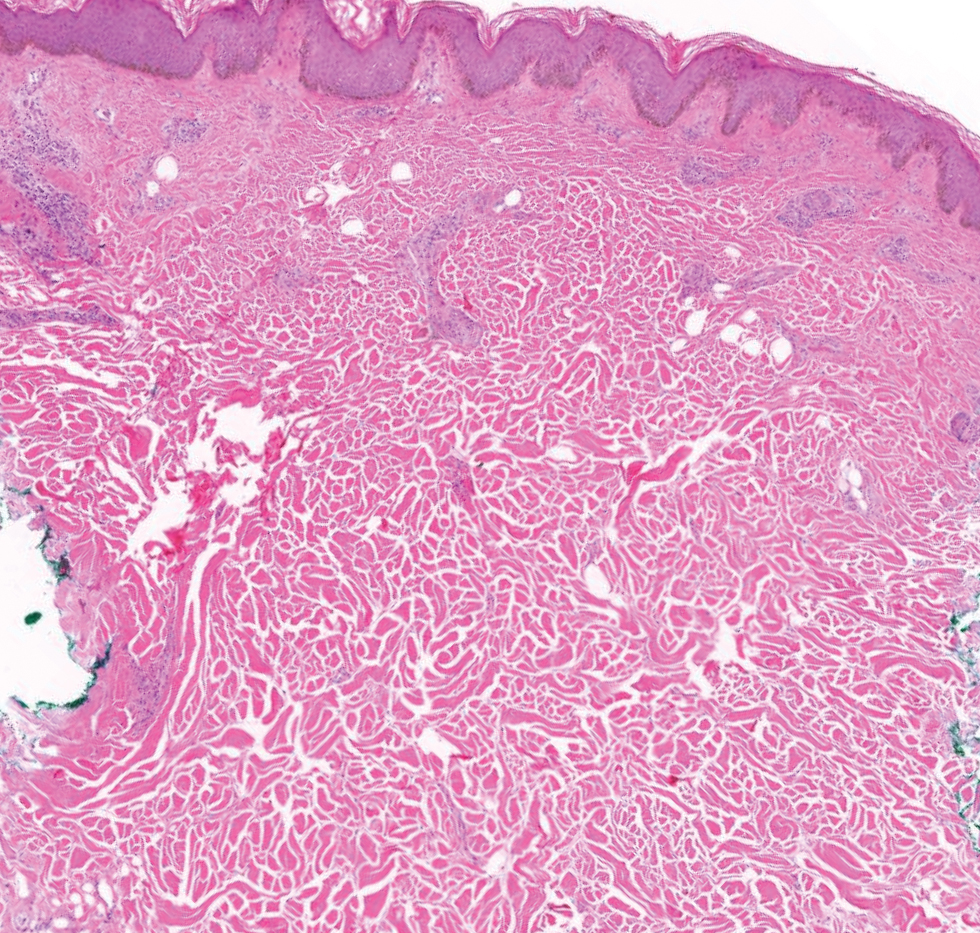

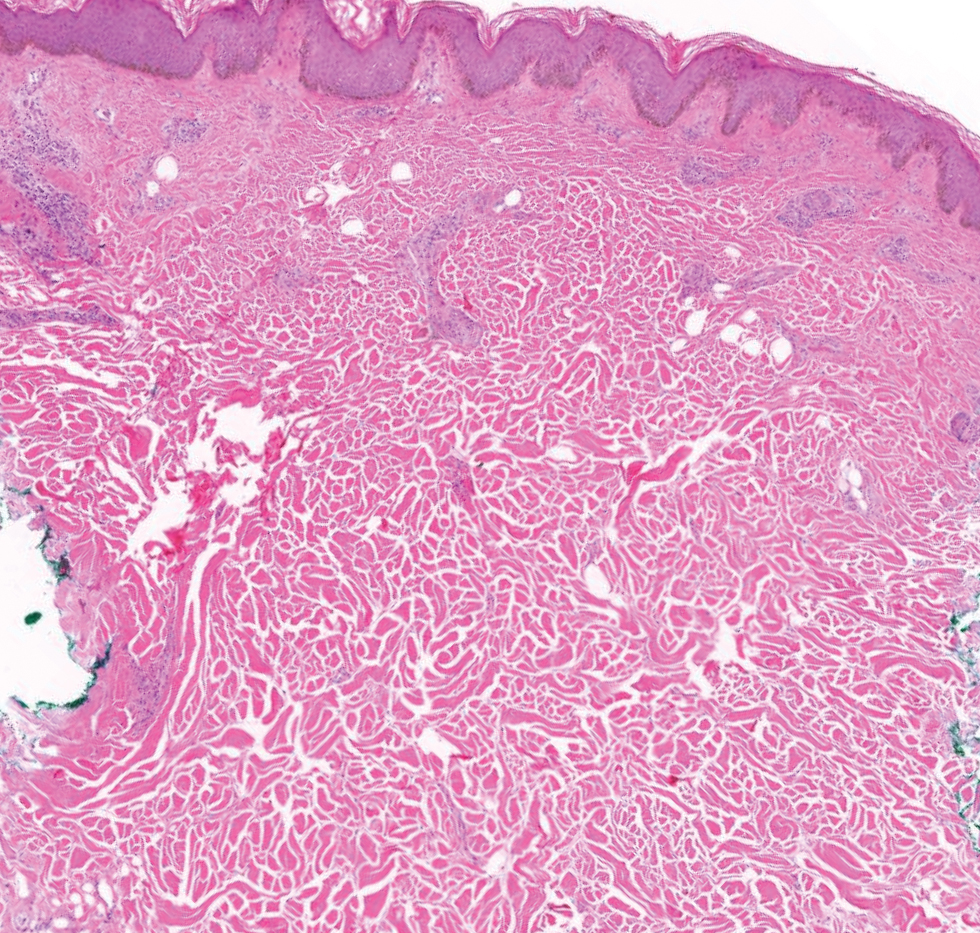

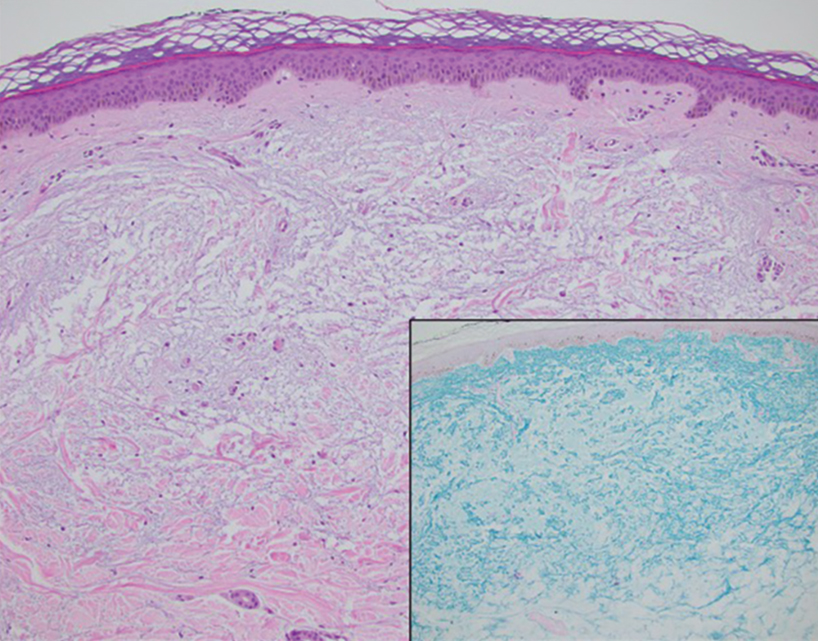

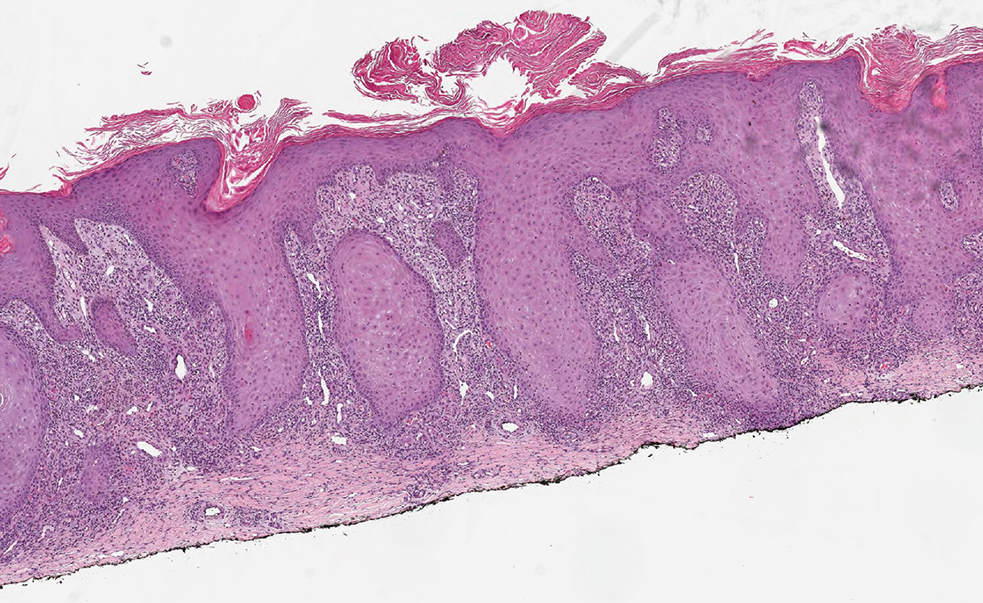

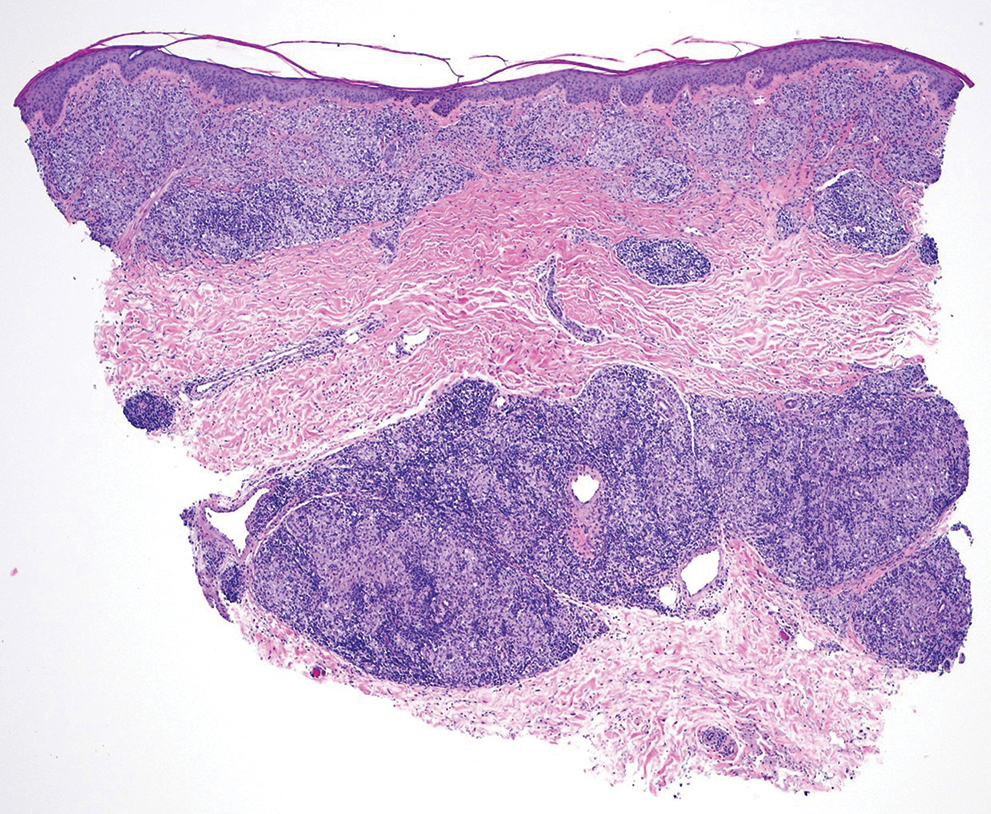

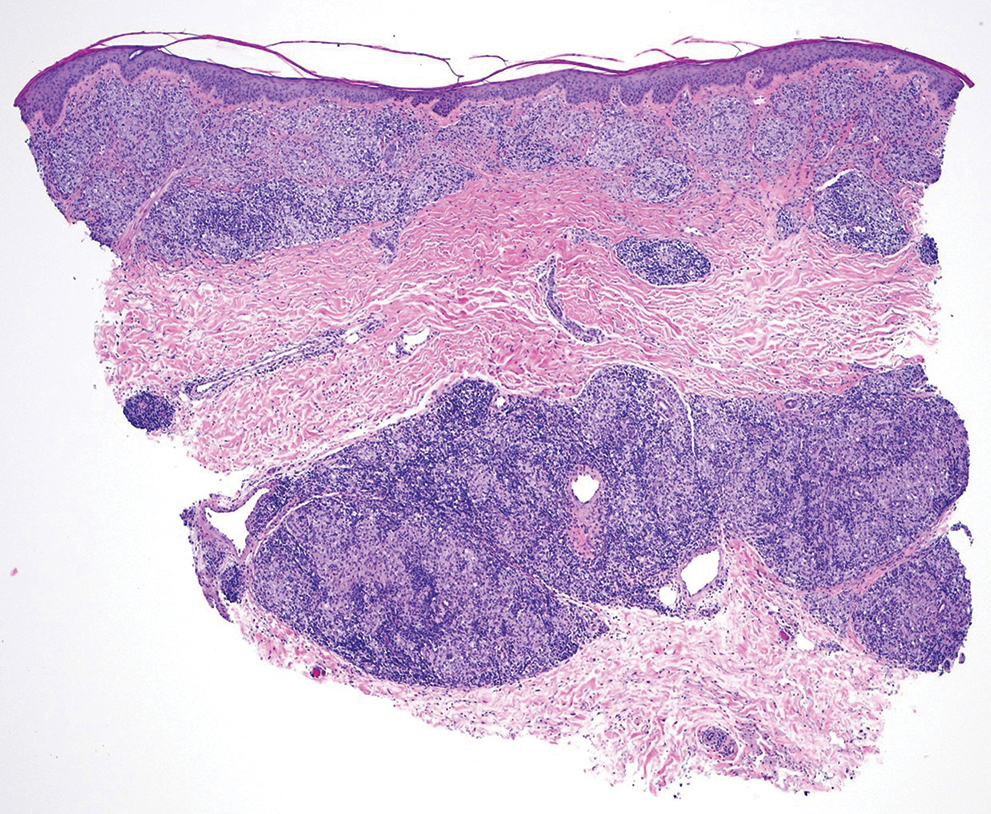

The histopathology of APPM is most similar to scleredema, a rare fibromucinous disorder of the skin associated with diabetes, infection (especially poststreptococcal), or monoclonal gammopathy.9 Biopsy evaluation of scleredema reveals a normal epidermis with mucin deposition between collagen bundles predominantly in the deep reticular dermis as well as absent fibroblast proliferation (Figure 2). Unlike APPM, scleredema manifests with diffuse woody induration with erythema and hyperpigmentation on the posterior neck and upper back.9 On physical examination, the distinct clinical features of scleredema distinguish this condition from APPM and scleromyxedema.

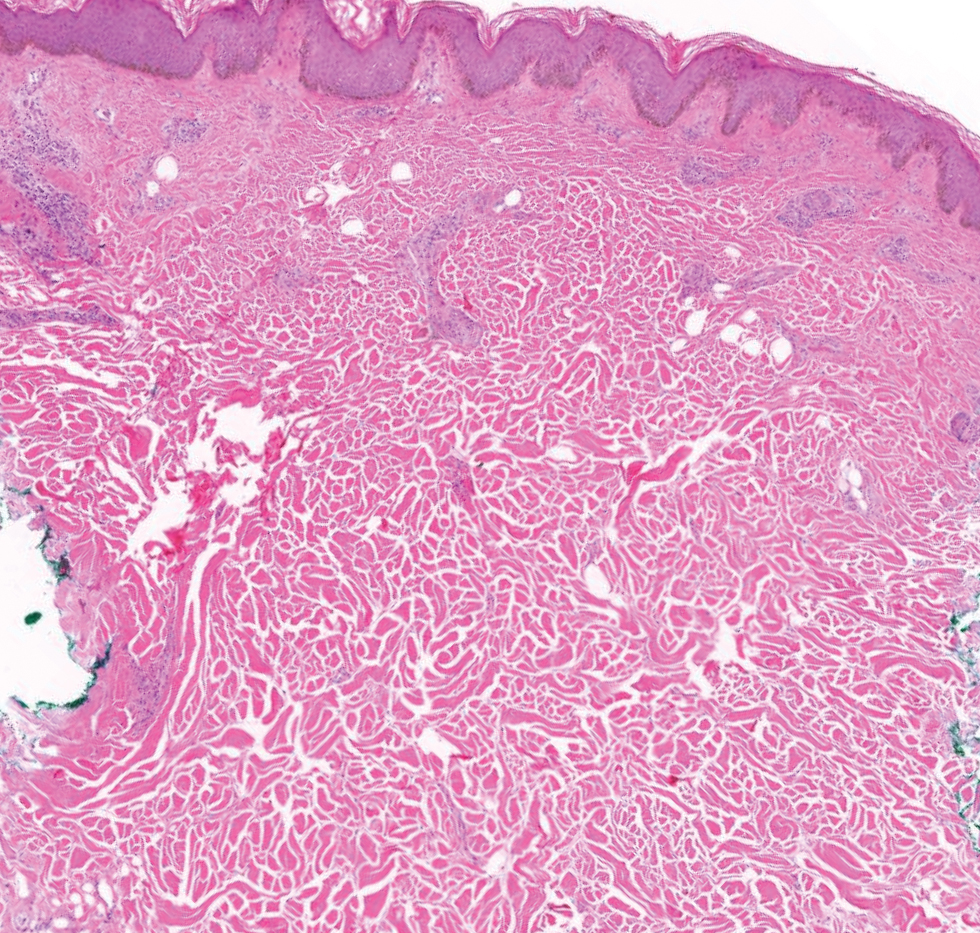

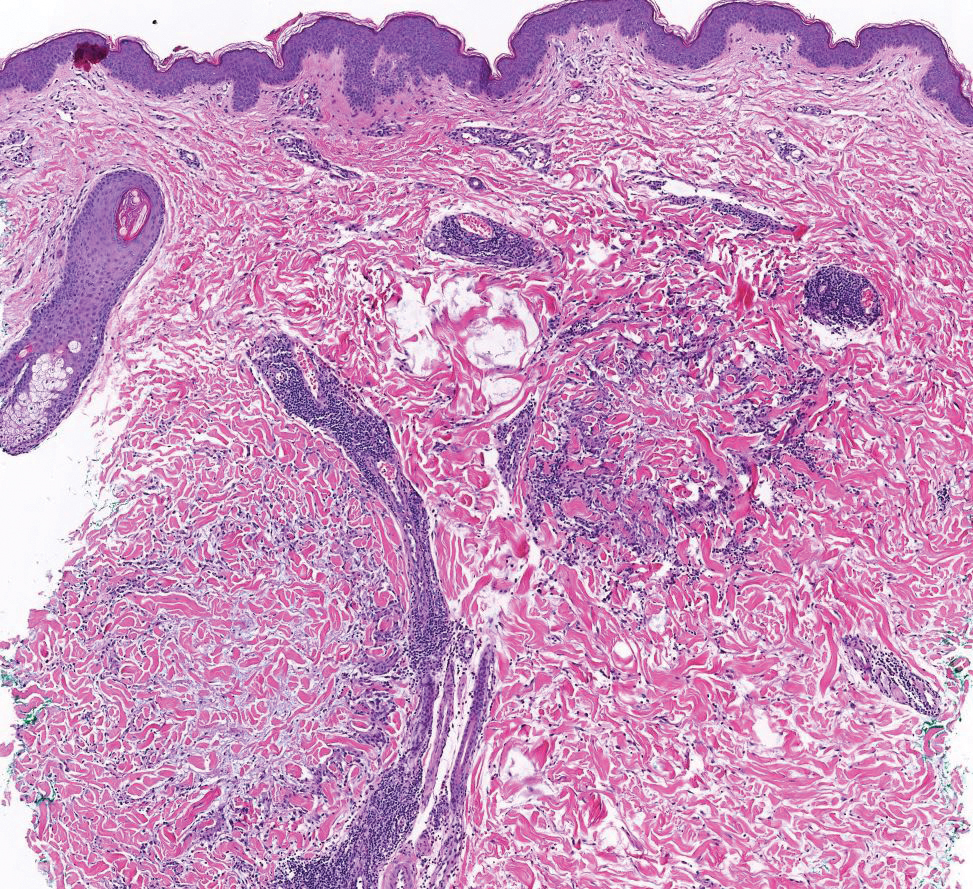

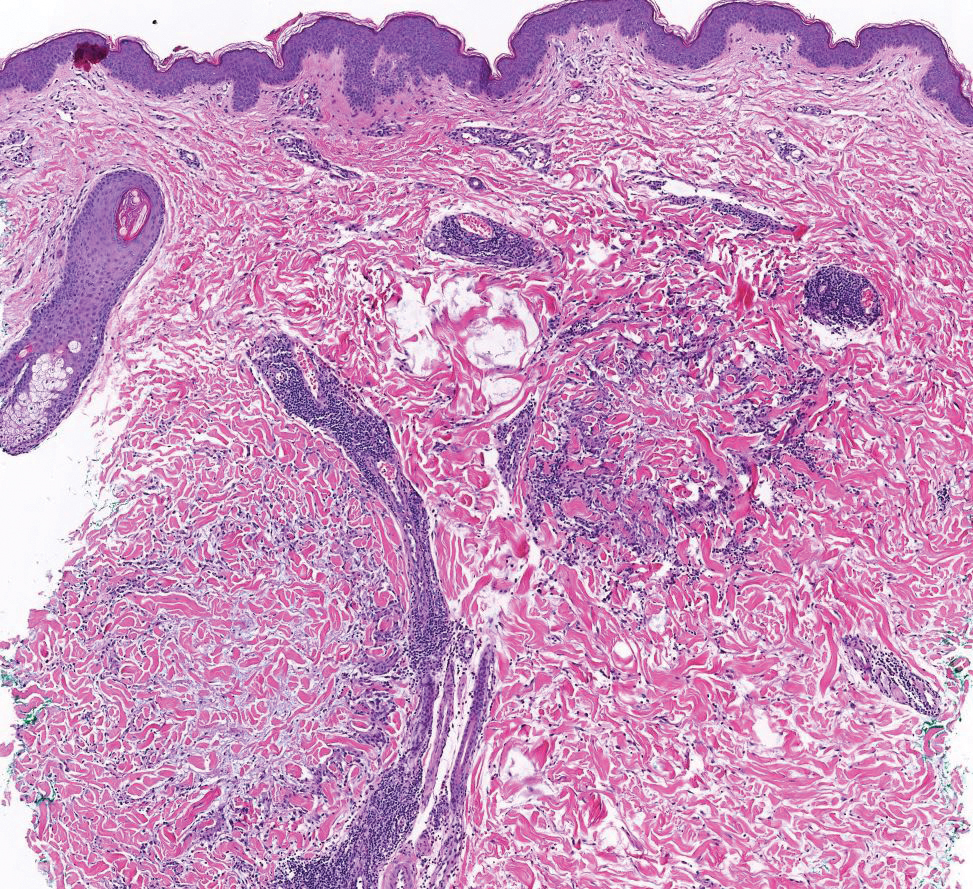

Papular granuloma annulare also was considered in our patient due to the presence of small flesh-colored papules. Histologically, granuloma annulare is characterized by palisading granulomas and mucin deposition in the dermis.10 However, the pattern of mucin deposition differs from that seen in APPM. In granuloma annulare, mucin is observed around foci of degenerated collagen (Figure 3), which was not observed in our patient.10 Additionally, the absence of an inflammatory infiltrate in our patient further ruled out this diagnosis.

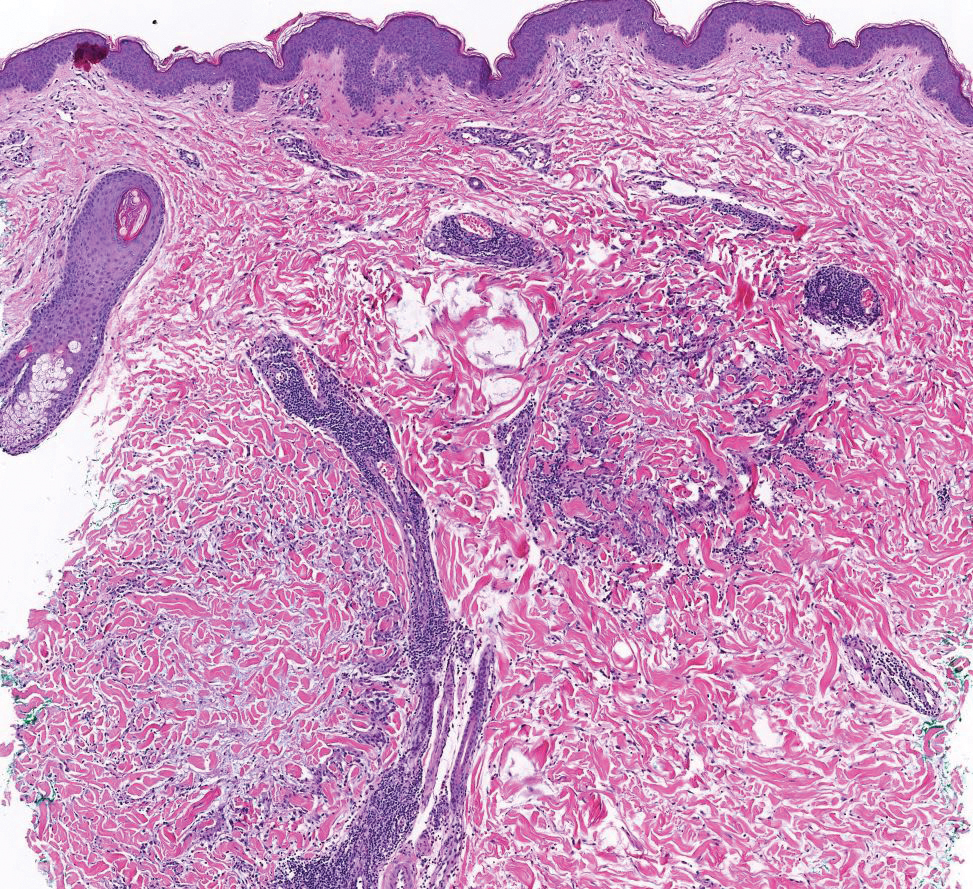

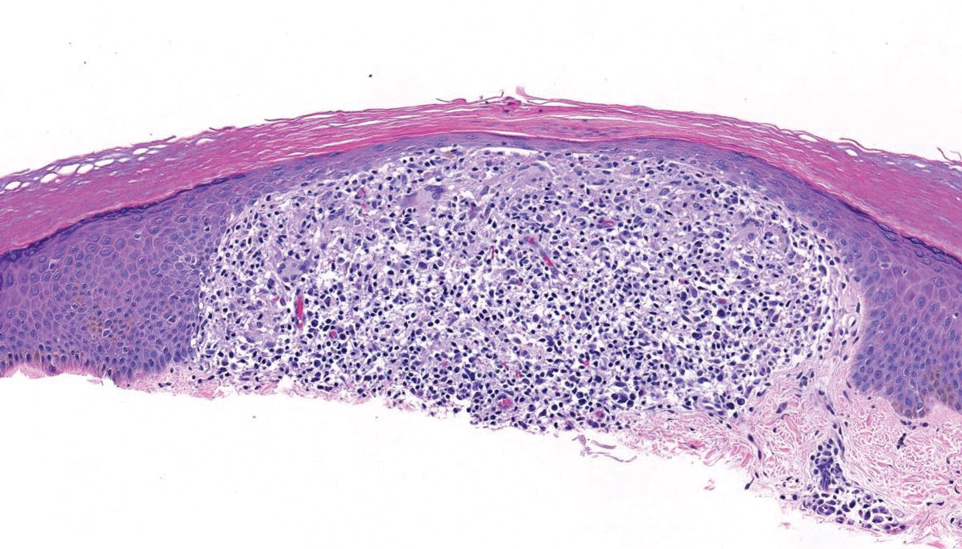

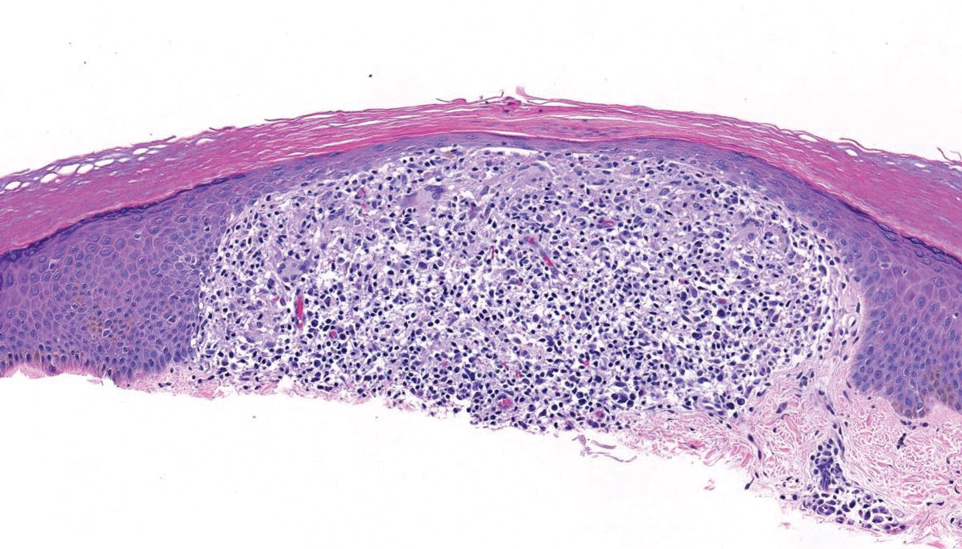

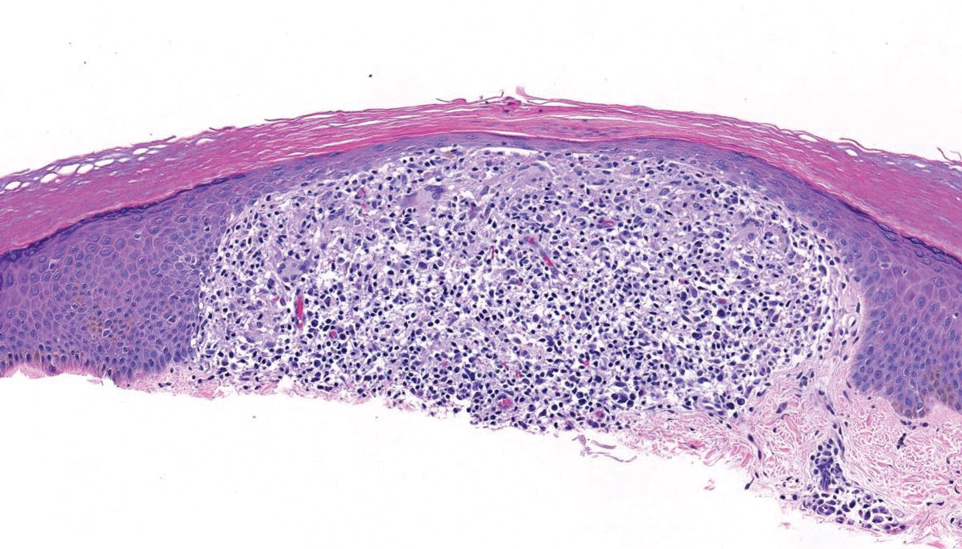

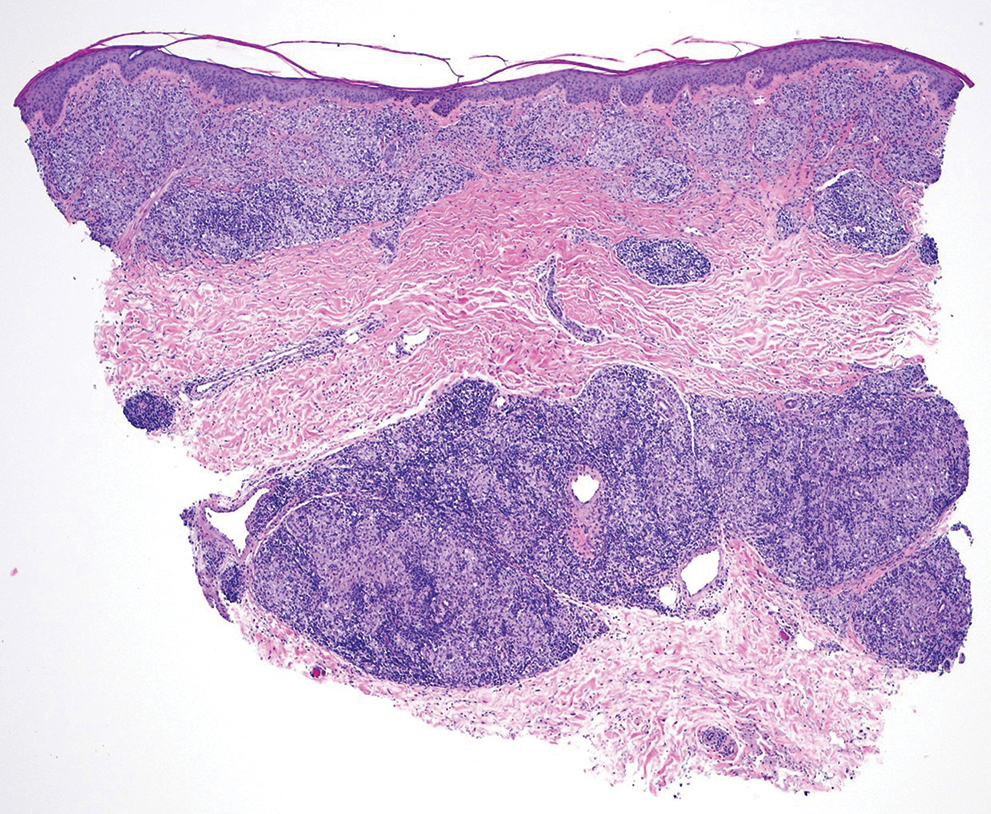

Lichen nitidus also could be considered in the differential diagnosis for ACCM. It typically manifests with minute, clustered, monomorphous papules with a predilection for the chest, abdomen, flexural forearms, and genitalia. The histology of lichen nitidus is distinct, showing a well-circumscribed lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis bordered by epidermal ridges, resembling a ball and clutch appearance (Figure 4).11

Although the clinical differential diagnosis in our patient was broad, histopathologic evaluation played a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis of APPM. This benign condition could be overlooked by patients and physicians; thorough clinical evaluation is necessary to rule out systemic mucinoses, which are associated with higher risks of morbidity and mortality.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Acral persistent papular mucinosis: a new entity. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1237-1239. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1986.01660230027002

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosus (LM)(discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt3xp109qd.

- Rongioletti F, Ferreli C, Atzori L. Acral persistent papular mucinosis. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:211-214. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.10.001

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous mucinoses: microscopic criteria for diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:257-267. doi:10.1097/00000372- 200106000-00022

- Rongioletti F. Lichen myxedematosus (papular mucinosis): new concepts and perspectives for an old disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:100-104. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2006.04.001

- Jun JY, Oh SH, Shim JH, et al. Acral persistent papular mucinosis with partial response to tacrolimus ointment. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:517-519. doi:10.5021/ad.2016.28.4.517

- Rongioletti F, Zaccaria E, Cozzani E, et al. Treatment of localized lichen myxedematosus of discrete type with tacrolimus ointment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:530-532. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.021

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2013.01.007

- Rongioletti F, Kaiser F, Cinotti E, et al. Scleredema. a multicentre study of characteristics, comorbidities, course and therapy in 44 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2399-2404. doi:10.1111/jdv.13272

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Al-Mutairi N, Hassanein A, Nour-Eldin O, et al. Generalized lichen nitidus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:158-160. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2005.22215.x

THE DIAGNOSIS: Acral Persistent Papular Mucinosis

Histopathologic analysis revealed conspicuous interstitial mucin deposition throughout the upper to mid reticular dermis in the absence of a cellular infiltrate or fibroplasia. Colloidal iron staining confirmed the presence of mucin. In correlation with the clinical presentation, a diagnosis of acral persistent papular mucinosis (APPM) was made. The patient was counseled on the benign disease course and lack of associated comorbidities, and additional treatment was not pursued.

Acral persistent papular mucinosis is a rare distinct subtype of cutaneous mucinosis that initially was described by Rongioletti et al1 in 1986. As a localized form of lichen myxedematosus, APPM is characterized by mucin deposition in the dermis with no systemic involvement. The precise pathogenesis remains unclear, although some investigators have suggested that cytokine-mediated stimulation of glycosaminoglycan production may contribute to increased mucin accumulation in the dermis.2 Acral persistent papular mucinosis predominantly affects middle-aged women with a 5:1 female-to-male predominance.3 Clinically, patients present with discrete, nonfollicular, waxy papules that typically measure 2 to 5 mm and are distributed symmetrically on the extensor surfaces of the wrists and forearms. While the lesions generally are asymptomatic, some patients may report mild pruritus. The condition is chronic, with lesions seldom resolving and often increasing in number over time.3

Histologically, APPM is characterized by focal deposits of mucin in the upper reticular dermis with no evidence of increased fibroblast proliferation or fibrosis.4 This feature is pivotal in differentiating APPM from other subtypes of localized lichen myxedematosus and similar dermatoses. Diagnosis of APPM requires exclusion of systemic involvement, including thyroid abnormalities and monoclonal gammopathy, aligning with its classification as a purely cutaneous condition.5 Management of APPM is unclear due to its rarity. Reassurance for patients of its benign nature as well as clinical observation are recommended, though some reports cite benefits of treatment with topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors.6,7 The long-term prognosis for patients with APPM is favorable, although the persistence of and potential increase in lesions over time can be a cosmetic concern.

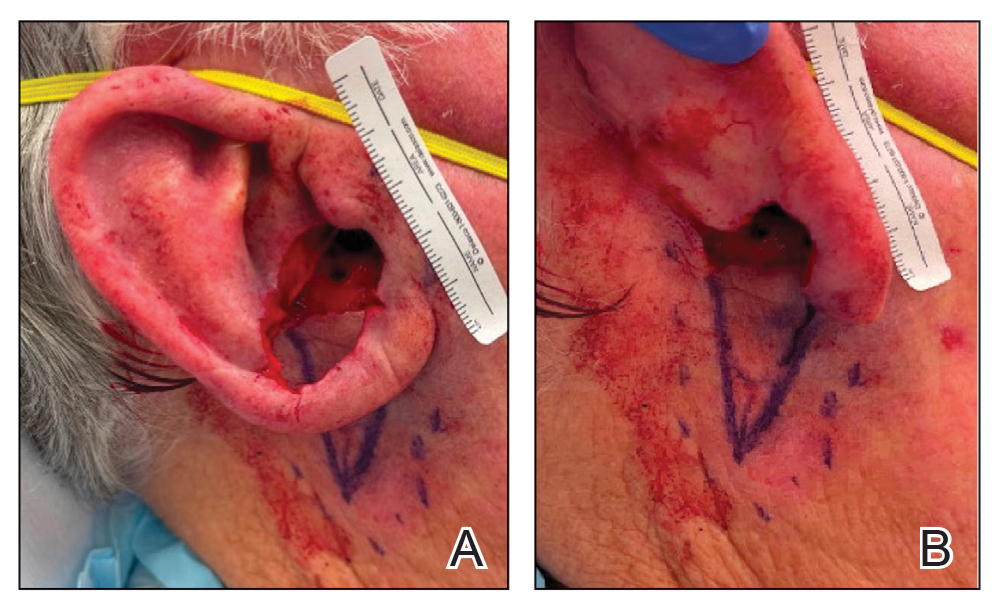

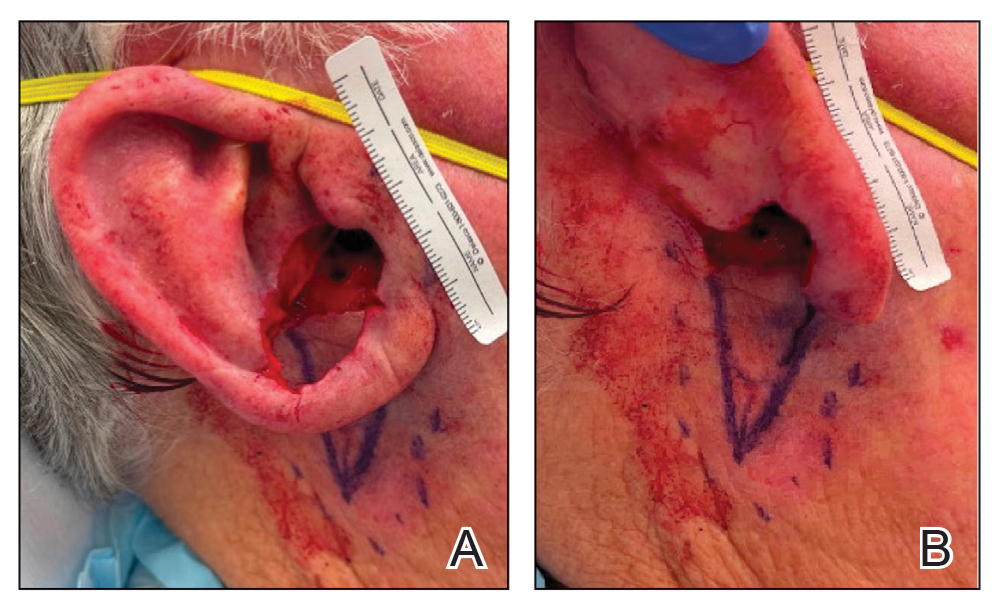

The differential diagnoses for APPM include scleromyxedema, scleredema, and other cutaneous eruptions that manifest as smooth flesh-colored papules, such as granuloma annulare and lichen nitidus.3 Scleromyxedema is a systemic cutaneous mucinosis that is part of the same disease spectrum as lichen myxedematosus. The papular eruption of scleromyxedema is much more widespread, and coalescing of the lesions may lead to characteristic skin thickening, creating leonine facies and deep furrowing over the trunk.8 Extracutaneous manifestations are frequent in scleromyxedema, and up to 90% of patients exhibit evidence of an underlying plasma cell dyscrasia.2 Histopathologically, scleromyxedema shows extensive fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis, in contrast to the findings of APPM (Figure 1).

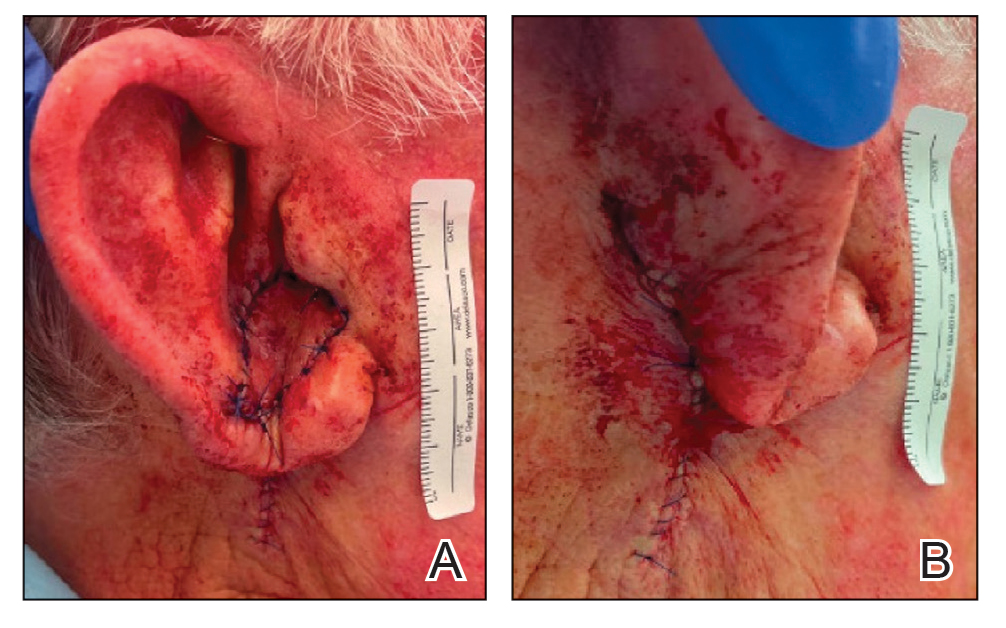

The histopathology of APPM is most similar to scleredema, a rare fibromucinous disorder of the skin associated with diabetes, infection (especially poststreptococcal), or monoclonal gammopathy.9 Biopsy evaluation of scleredema reveals a normal epidermis with mucin deposition between collagen bundles predominantly in the deep reticular dermis as well as absent fibroblast proliferation (Figure 2). Unlike APPM, scleredema manifests with diffuse woody induration with erythema and hyperpigmentation on the posterior neck and upper back.9 On physical examination, the distinct clinical features of scleredema distinguish this condition from APPM and scleromyxedema.

Papular granuloma annulare also was considered in our patient due to the presence of small flesh-colored papules. Histologically, granuloma annulare is characterized by palisading granulomas and mucin deposition in the dermis.10 However, the pattern of mucin deposition differs from that seen in APPM. In granuloma annulare, mucin is observed around foci of degenerated collagen (Figure 3), which was not observed in our patient.10 Additionally, the absence of an inflammatory infiltrate in our patient further ruled out this diagnosis.

Lichen nitidus also could be considered in the differential diagnosis for ACCM. It typically manifests with minute, clustered, monomorphous papules with a predilection for the chest, abdomen, flexural forearms, and genitalia. The histology of lichen nitidus is distinct, showing a well-circumscribed lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis bordered by epidermal ridges, resembling a ball and clutch appearance (Figure 4).11

Although the clinical differential diagnosis in our patient was broad, histopathologic evaluation played a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis of APPM. This benign condition could be overlooked by patients and physicians; thorough clinical evaluation is necessary to rule out systemic mucinoses, which are associated with higher risks of morbidity and mortality.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Acral Persistent Papular Mucinosis

Histopathologic analysis revealed conspicuous interstitial mucin deposition throughout the upper to mid reticular dermis in the absence of a cellular infiltrate or fibroplasia. Colloidal iron staining confirmed the presence of mucin. In correlation with the clinical presentation, a diagnosis of acral persistent papular mucinosis (APPM) was made. The patient was counseled on the benign disease course and lack of associated comorbidities, and additional treatment was not pursued.

Acral persistent papular mucinosis is a rare distinct subtype of cutaneous mucinosis that initially was described by Rongioletti et al1 in 1986. As a localized form of lichen myxedematosus, APPM is characterized by mucin deposition in the dermis with no systemic involvement. The precise pathogenesis remains unclear, although some investigators have suggested that cytokine-mediated stimulation of glycosaminoglycan production may contribute to increased mucin accumulation in the dermis.2 Acral persistent papular mucinosis predominantly affects middle-aged women with a 5:1 female-to-male predominance.3 Clinically, patients present with discrete, nonfollicular, waxy papules that typically measure 2 to 5 mm and are distributed symmetrically on the extensor surfaces of the wrists and forearms. While the lesions generally are asymptomatic, some patients may report mild pruritus. The condition is chronic, with lesions seldom resolving and often increasing in number over time.3

Histologically, APPM is characterized by focal deposits of mucin in the upper reticular dermis with no evidence of increased fibroblast proliferation or fibrosis.4 This feature is pivotal in differentiating APPM from other subtypes of localized lichen myxedematosus and similar dermatoses. Diagnosis of APPM requires exclusion of systemic involvement, including thyroid abnormalities and monoclonal gammopathy, aligning with its classification as a purely cutaneous condition.5 Management of APPM is unclear due to its rarity. Reassurance for patients of its benign nature as well as clinical observation are recommended, though some reports cite benefits of treatment with topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors.6,7 The long-term prognosis for patients with APPM is favorable, although the persistence of and potential increase in lesions over time can be a cosmetic concern.

The differential diagnoses for APPM include scleromyxedema, scleredema, and other cutaneous eruptions that manifest as smooth flesh-colored papules, such as granuloma annulare and lichen nitidus.3 Scleromyxedema is a systemic cutaneous mucinosis that is part of the same disease spectrum as lichen myxedematosus. The papular eruption of scleromyxedema is much more widespread, and coalescing of the lesions may lead to characteristic skin thickening, creating leonine facies and deep furrowing over the trunk.8 Extracutaneous manifestations are frequent in scleromyxedema, and up to 90% of patients exhibit evidence of an underlying plasma cell dyscrasia.2 Histopathologically, scleromyxedema shows extensive fibroblast proliferation and fibrosis, in contrast to the findings of APPM (Figure 1).

The histopathology of APPM is most similar to scleredema, a rare fibromucinous disorder of the skin associated with diabetes, infection (especially poststreptococcal), or monoclonal gammopathy.9 Biopsy evaluation of scleredema reveals a normal epidermis with mucin deposition between collagen bundles predominantly in the deep reticular dermis as well as absent fibroblast proliferation (Figure 2). Unlike APPM, scleredema manifests with diffuse woody induration with erythema and hyperpigmentation on the posterior neck and upper back.9 On physical examination, the distinct clinical features of scleredema distinguish this condition from APPM and scleromyxedema.

Papular granuloma annulare also was considered in our patient due to the presence of small flesh-colored papules. Histologically, granuloma annulare is characterized by palisading granulomas and mucin deposition in the dermis.10 However, the pattern of mucin deposition differs from that seen in APPM. In granuloma annulare, mucin is observed around foci of degenerated collagen (Figure 3), which was not observed in our patient.10 Additionally, the absence of an inflammatory infiltrate in our patient further ruled out this diagnosis.

Lichen nitidus also could be considered in the differential diagnosis for ACCM. It typically manifests with minute, clustered, monomorphous papules with a predilection for the chest, abdomen, flexural forearms, and genitalia. The histology of lichen nitidus is distinct, showing a well-circumscribed lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis bordered by epidermal ridges, resembling a ball and clutch appearance (Figure 4).11

Although the clinical differential diagnosis in our patient was broad, histopathologic evaluation played a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis of APPM. This benign condition could be overlooked by patients and physicians; thorough clinical evaluation is necessary to rule out systemic mucinoses, which are associated with higher risks of morbidity and mortality.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Acral persistent papular mucinosis: a new entity. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1237-1239. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1986.01660230027002

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosus (LM)(discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt3xp109qd.

- Rongioletti F, Ferreli C, Atzori L. Acral persistent papular mucinosis. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:211-214. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.10.001

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous mucinoses: microscopic criteria for diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:257-267. doi:10.1097/00000372- 200106000-00022

- Rongioletti F. Lichen myxedematosus (papular mucinosis): new concepts and perspectives for an old disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:100-104. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2006.04.001

- Jun JY, Oh SH, Shim JH, et al. Acral persistent papular mucinosis with partial response to tacrolimus ointment. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:517-519. doi:10.5021/ad.2016.28.4.517

- Rongioletti F, Zaccaria E, Cozzani E, et al. Treatment of localized lichen myxedematosus of discrete type with tacrolimus ointment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:530-532. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.021

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2013.01.007

- Rongioletti F, Kaiser F, Cinotti E, et al. Scleredema. a multicentre study of characteristics, comorbidities, course and therapy in 44 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2399-2404. doi:10.1111/jdv.13272

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Al-Mutairi N, Hassanein A, Nour-Eldin O, et al. Generalized lichen nitidus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:158-160. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2005.22215.x

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Acral persistent papular mucinosis: a new entity. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1237-1239. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1986.01660230027002

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosus (LM)(discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt3xp109qd.

- Rongioletti F, Ferreli C, Atzori L. Acral persistent papular mucinosis. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:211-214. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.10.001

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous mucinoses: microscopic criteria for diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:257-267. doi:10.1097/00000372- 200106000-00022

- Rongioletti F. Lichen myxedematosus (papular mucinosis): new concepts and perspectives for an old disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:100-104. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2006.04.001

- Jun JY, Oh SH, Shim JH, et al. Acral persistent papular mucinosis with partial response to tacrolimus ointment. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:517-519. doi:10.5021/ad.2016.28.4.517

- Rongioletti F, Zaccaria E, Cozzani E, et al. Treatment of localized lichen myxedematosus of discrete type with tacrolimus ointment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:530-532. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.021

- Rongioletti F, Merlo G, Cinotti E, et al. Scleromyxedema: a multicenter study of characteristics, comorbidities, course, and therapy in 30 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:66-72. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2013.01.007

- Rongioletti F, Kaiser F, Cinotti E, et al. Scleredema. a multicentre study of characteristics, comorbidities, course and therapy in 44 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2399-2404. doi:10.1111/jdv.13272

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Al-Mutairi N, Hassanein A, Nour-Eldin O, et al. Generalized lichen nitidus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:158-160. doi:10.1111 /j.1525-1470.2005.22215.x

Multiple Firm Papules on the Wrists and Forearms

Multiple Firm Papules on the Wrists and Forearms

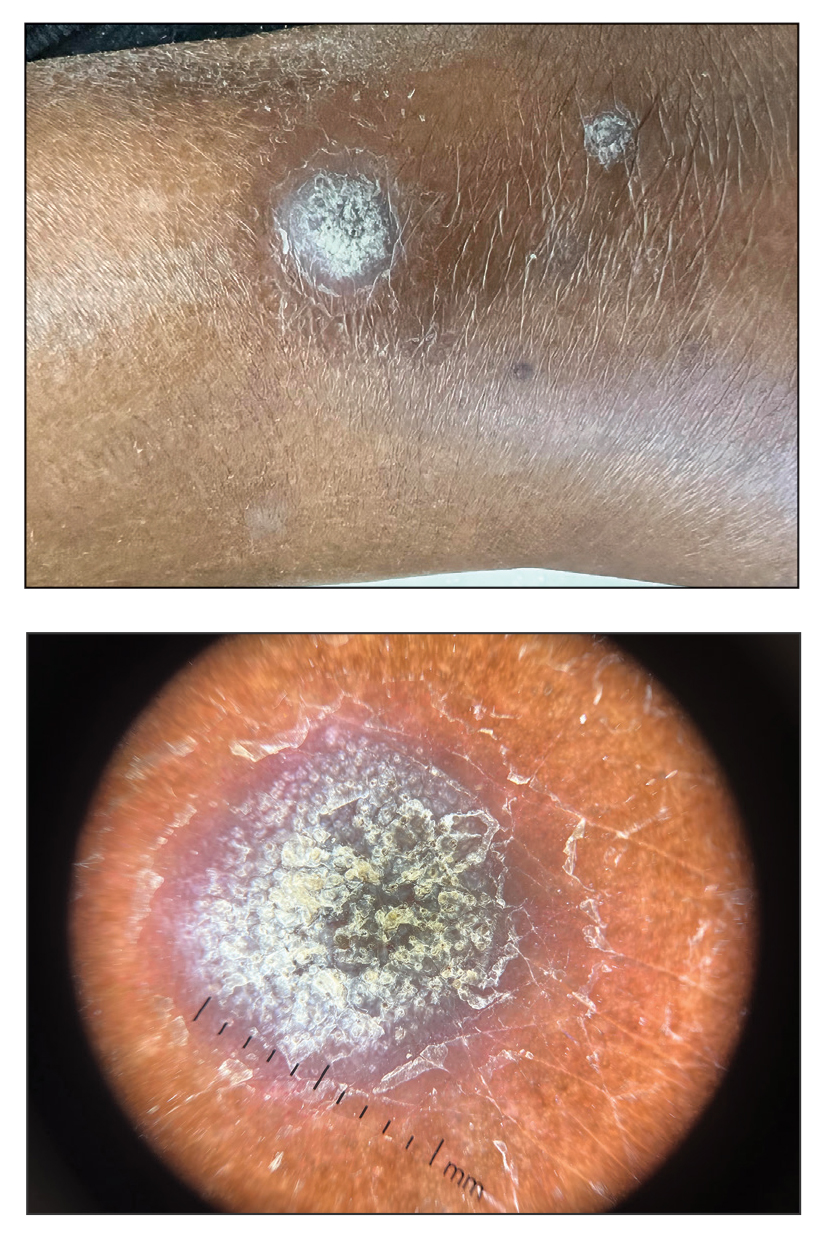

A 69-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with persistent asymptomatic skin lesions on the wrists and forearms of several months’ duration. The lesions had slowly grown in number over the past few months with no identifiable triggers. The patient reported no known history of injury or trauma to the affected sites and was not taking any prescription medications other than daily vitamins. She denied any family history of similar lesions and was otherwise healthy. Physical examination revealed multiple waxy, firm, hypopigmented, 3- to 5-mm papules located exclusively on the dorsal wrists and forearms. No extracutaneous involvement was observed. A 4-mm punch biopsy from the forearm was obtained.

Bridging the Knowledge-Action Gap in Skin Cancer Prevention Among US Military Personnel

Bridging the Knowledge-Action Gap in Skin Cancer Prevention Among US Military Personnel

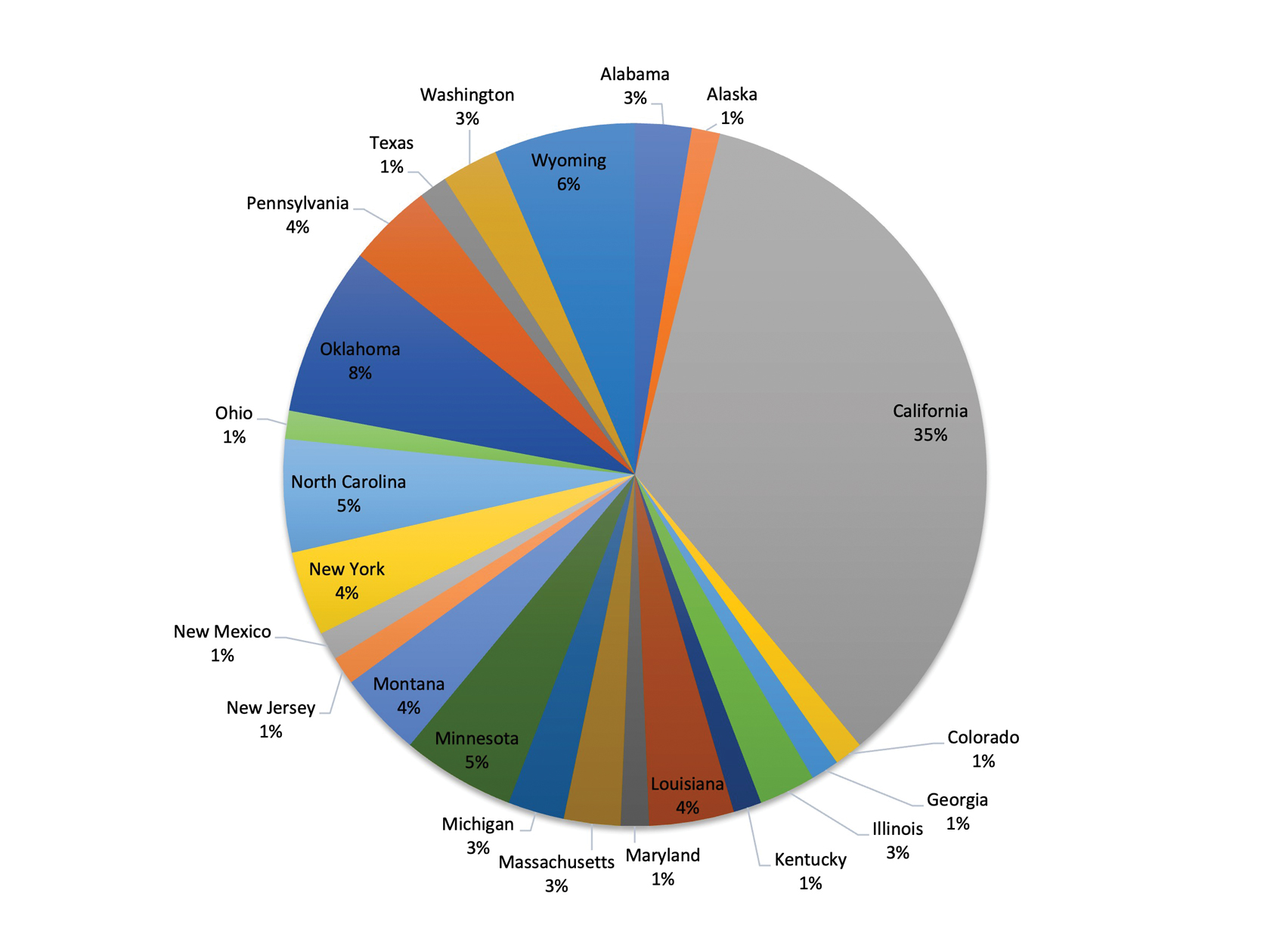

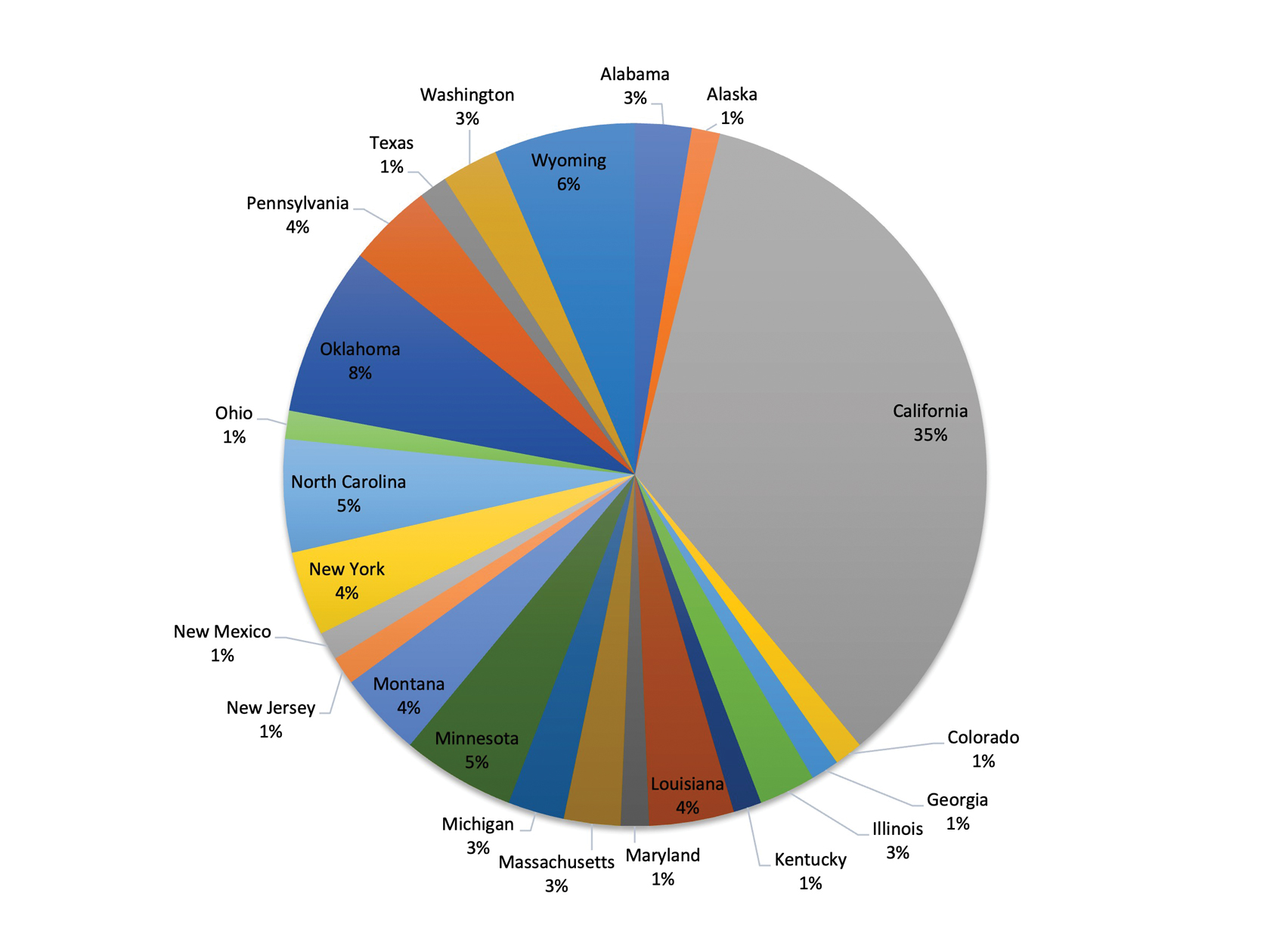

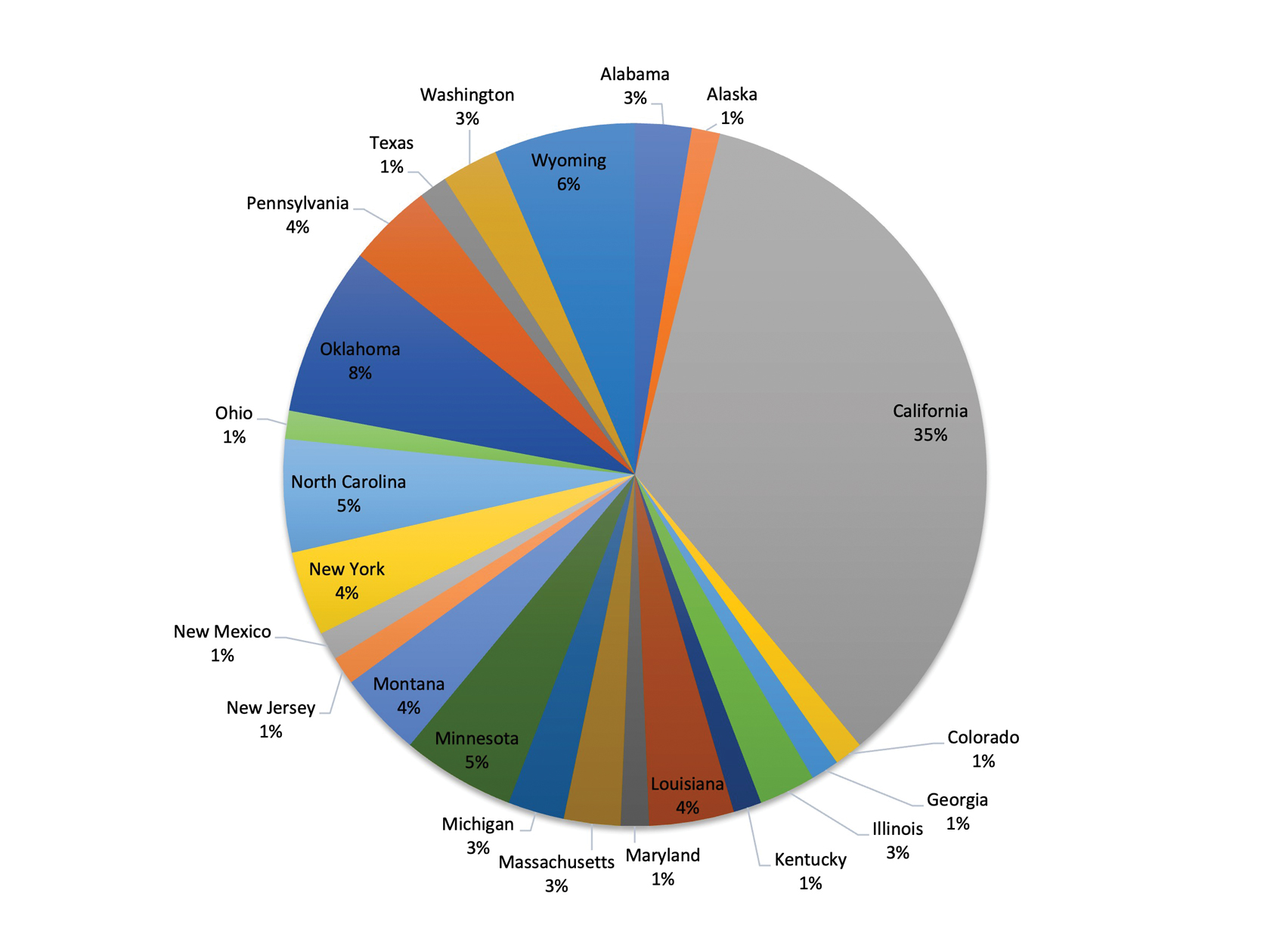

Skin cancer is a major health concern for military service members, who experience notably higher incidence rates than the general population.1 Active-duty military personnel are particularly vulnerable to prolonged sun exposure due to deployments, specialized training, and everyday outdoor duties.1 Despite skin cancer being the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in active-duty service members,2 tracking and documenting the quantity and diversity of these risk factors remain limited. This knowledge gap comes at high cost, simultaneously impairing military medicine preventive measures while burdening the military health care system with substantial expenditures.3 These findings underscore the critical need for targeted surveillance, early-detection programs, and policy-driven interventions to mitigate these medical and economic concerns.

Skin cancer has been recognized as a major health risk to the military population for decades, yet incidence and prevalence remain high. This phenomenon is closely linked to the inherent responsibilities and expectations of active-duty military members, including outdoor physical training, field exercises, standing in formation, and outdoor working environments—all of which can occur during peak sunlight hours. These risks are further elevated at duty stations in geographic regions with high levels of UV exposure, such as those in tropical and arid regions of the world. Certain military occupational specialties and missions may further introduce unique risk factors; for instance, pilots with frequent high-altitude missions experience heightened UV exposure and melanoma risk.4 Secondary to compounding determinants, the aviation, diving, and nuclear subgroups of the military community are particularly vulnerable to skin cancer.5

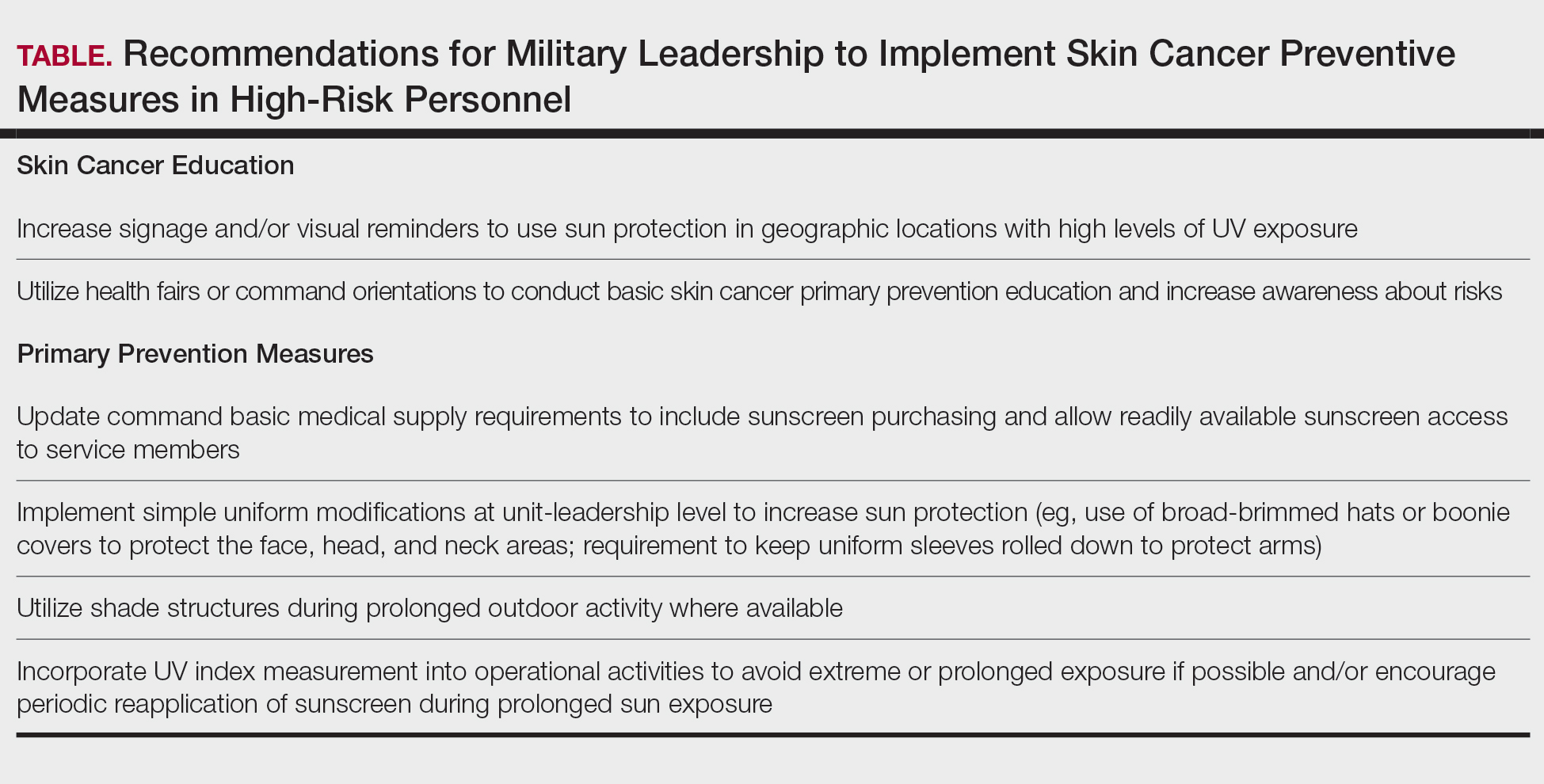

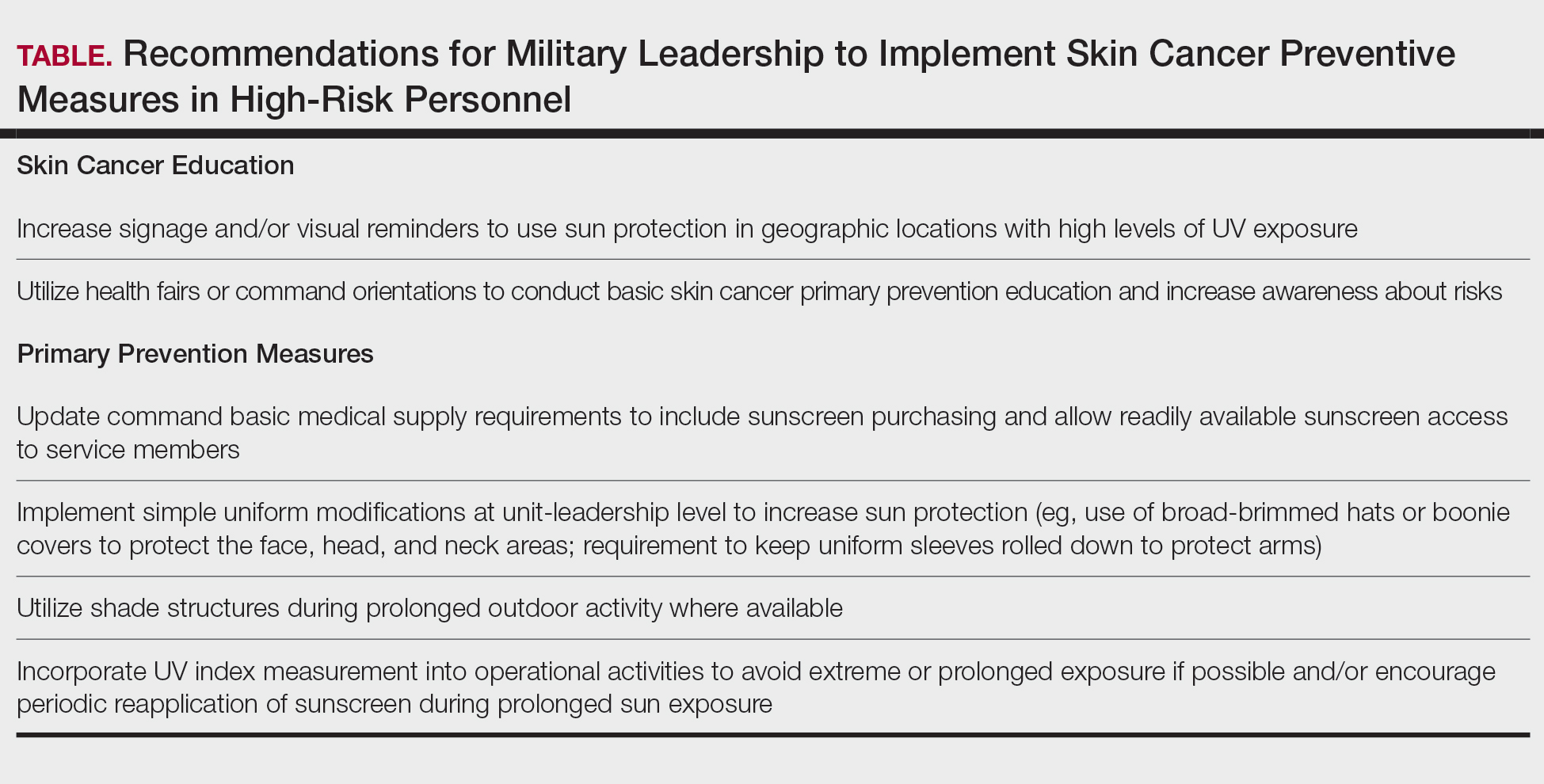

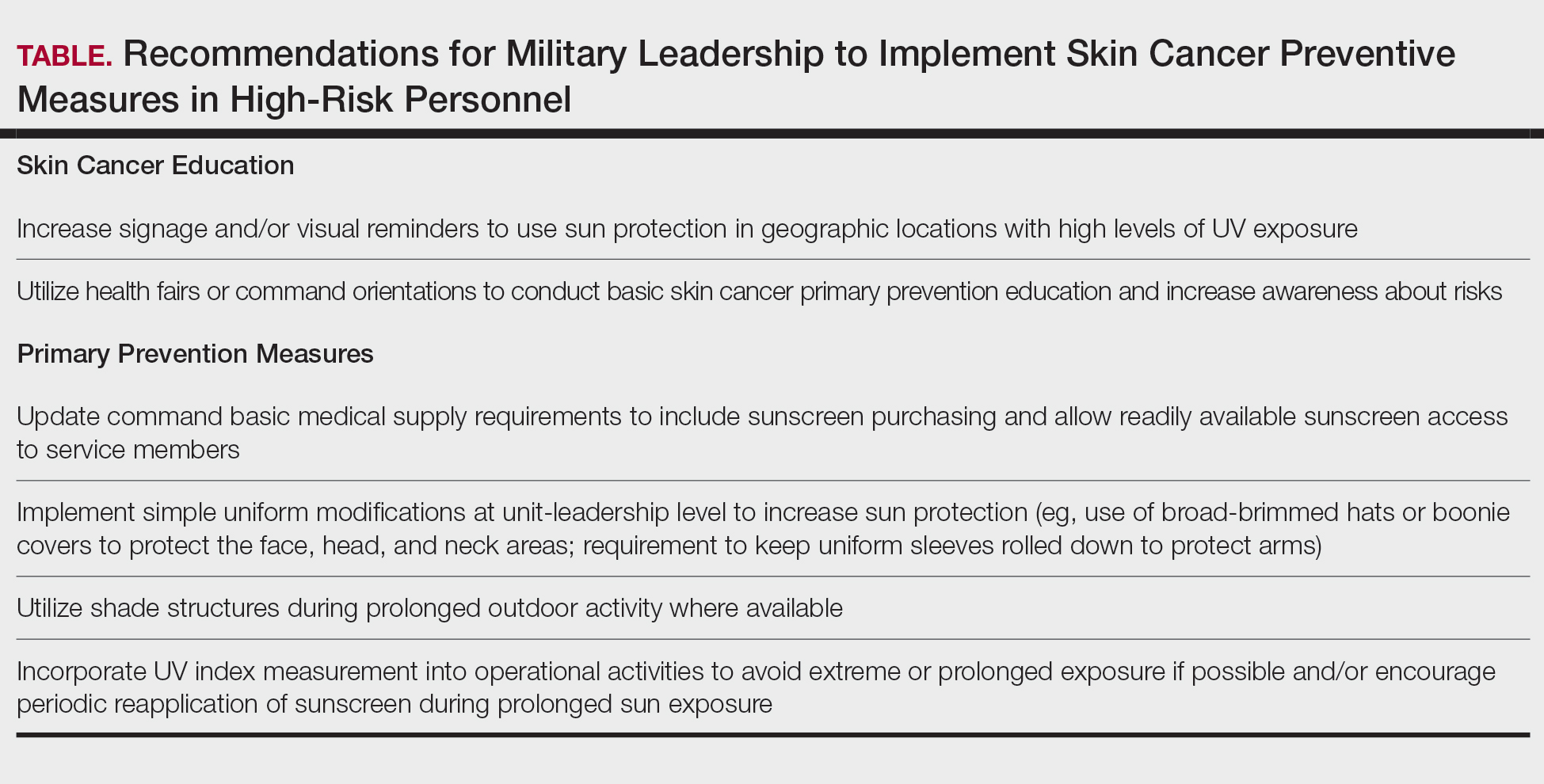

Despite well-documented risks, considerable gaps remain in quantifying and analyzing variations in UV exposure across military occupations, duty locations, and operational roles. Factors such as the existence of over 150 distinct military occupational specialties, frequent geographic relocations, and routine work in austere environments contribute to a wide range of UV exposure profiles that remain insufficiently characterized. This lack of comprehensive exposure data hinders the development of large-scale, targeted skin cancer prevention strategies. Initial approaches to addressing these challenges include enhanced surveillance, education, and policy initiatives. The Table presents practical recommendations for military leadership to consider in implementing preventive measures for skin cancer. Herein, we outline broader systemic strategies to bridge knowledge gaps and address underrecognized occupational risk factors for skin cancer in military service members; these elements include proposed modifications to the electronic Periodic Health Assessment (ePHA) and the development of standardized, military-specific screening and prevention guidelines to support early detection and resource optimization.

Skin Cancer Education for Service Members

Sunscreen and Signage—Diligent primary prevention offers a promising avenue for mitigating skin cancer incidence in military service members. Basic education and precautionary messaging on photoprotection can be widely implemented to simultaneously educate service members on the dangers of sun exposure while reinforcing healthy behaviors in real time. Simple low-cost initiatives such as strategically placed visual signage reminding service members to apply sunscreen in high UV environments can support consistent sun-safe practices. Educational efforts also should emphasize proper sunscreen use, including application on high-risk anatomic sites (eg, the face, neck, scalp, dorsal hands, and ears) and the essentiality of using sufficient quantities of broad-spectrum sunscreen for effective protection. Incorporating this guidance into training materials, briefings, and visual reminders allow seamless integration of photoprotection into service members’ daily routines without compromising operational efficiency.6 Younger service members, who may be less likely to prioritize preventive behaviors, may be particularly responsive to sun safety reminders in training areas, bases, and deployment zones.7 Health fairs and orientation briefs in high-UV regions also offer potential opportunities for targeted education.

Resources for Sun Protection in the Military

Sunscreen—Although sunscreen is critical in minimizing the risk for UV-induced skin cancer, its widespread use in the military is hindered by practical challenges related to accessibility and the need for consistent reapplication; for instance, providing free sunscreen dispensers at institutions for staff working under intense or prolonged UV exposure may improve sunscreen accessibility and use.8 Including sunscreen in standard-issue gear offers another logical way to embed its use into operational readiness as part of the routine protective measures.

Uniform Modifications—Adapting military uniforms and practices to improve sun protection plays a critical role in reducing skin cancer risk. Targeted protective gear for commonly sun-exposed areas can help mitigate UV exposure. One practical option is the use of wide-brimmed headgear (eg, boonie hats), which provide more face and neck coverage than standard-issue military caps, or covers. The wide-brimmed headgear currently is only selectively authorized during specific scenarios, such as field operations and training exercises, or at the discretion of unit-level leadership. Wide-brimmed headgear, already used by many service members, has been associated with up to a 17% reduction in UV exposure to inadequately protected areas, potentially lowering skin cancer risk.9,10 Similarly, a “sleeves-down” policy—requiring sleeves to remain unrolled and covering the forearms during outdoor activities—offers a simple way to minimize sun exposure without necessitating additional gear. Other specialized clothing items, including UV-blocking neck gaiters, photoprotective clothing, and lightweight gloves, also may be appropriate for high-risk groups and can be implemented in a relatively straightforward manner.

Shade Structures and UV Index Monitoring—Aside from uniform adaptation, physical barrier intervention can further complement skin cancer prevention efforts in the military. Shade structures offer a straightforward way to reduce UV exposure during prolonged outdoor activities. Incorporating daily UV index monitoring into operational guidance can help inform adjustments to training schedules and guide the implementation of additional sun protection measures, such as mandatory sunscreen application, use of wide-brimmed hats, or increased access to shaded rest areas during heavy sunlight hours. Currently, outdoor physical training is restricted during periods of high heat index, measured via Wet Bulb Globe Temperature, to reduce heat-related injuries. We argue that avoidance of nonoperational outdoor activity during peak UV index hours also should be incorporated into standardized policies. This intervention is of particular benefit to service members stationed in regions with a high UV index year-round, such as those stationed in the Middle East, Guam, Okinawa, and southern coastal United States bases.

Policy Changes to Support Photoprotective Measures

Annual Risk Factor Screening‐Screening—Effective secondary prevention efforts by military dermatologists remain an important measure in reducing the burden of skin cancer among military personnel; however, these efforts have become increasingly challenging due to 2 main factors—the diversity of military occupational specialties and their associated unique occupational risks as well as the limited availability of military dermatologists across all branches (approximately 100 active-duty dermatologists for nearly 3 million service members).11 Therefore, targeted interventions that enhance risk assessment, refined screening protocols, and leveraging of existing military health networks can improve early skin cancer detection while optimizing resource allocation.

The ePHA is an online screening tool used annually by all service members to evaluate their overall health. Presently, the ePHA lacks specific questions to assess sun exposure and skin cancer risks. Integrating annual skin cancer risk factor assessments into the ePHA would offer a practical and straightforward approach to identifying at-risk individuals, as suggested by Newnam et al12 in 2022. Skin cancer risk factor assessments allow for targeted data collection related to sun exposure history, family history, and personal risk factors, which can be used to determine individualized risk stratification to assess the need for early secondary prevention measures and specialist referral. These ePHA data can also support population-based analyses to inform preventive strategies and address knowledge gaps related to high-risk exposures, such as extended field exercises or assignments in high-UV regions, that may impede effective skin cancer prevention.

Development of Military-Specific Screening Guidelines—Given the limited number of military dermatologists, a standardized risk-assessment tool could enhance early detection of skin cancer and streamline the referral process. We propose a military-specific skin cancer screening algorithm or risk nomogram that could help to consolidate risk factors into a clear and actionable framework for more efficient triage and appropriate allocation of dermatologic resources and manpower. This nomogram could be developed by military dermatologists and then implemented on a command level, affording primary care providers a useful tool to expedite evaluation of individuals at higher risk for skin cancer while simultaneously promoting judicious use of limited dermatology resources.

Although the United States Preventive Services Task Force does not universally recommend routine skin cancer screenings for asymptomatic adults, military service members are exposed to higher occupational risks than the general population, as previously mentioned. Currently, there is no standardized screening guideline across all military services due to the unique nature and exposure risks for each branch of service and their varied occupations; however, we propose the development of basic standardized screening guidelines by adapting the framework of the United States Preventive Services Task Force and adjusting for military-specific UV exposure and occupational risks to improve early detection of skin cancer. These guidelines could be updated and tailored appropriately when additional population-based data are collected and analyzed through ePHA.

Critiques and Limitations of Implementation

Several challenges and limitations must be considered when attempting to integrate large-scale preventive measures for skin cancer within the US military. A primary concern is the extent to which military resources should be allocated to prevention when off-duty sun exposure remains largely beyond institutional control. Although military health initiatives can address workplace risk through education and policy, individual decisions during both work and leisure time remain a major variable that cannot be feasibly controlled. Cultural and operational barriers also pose challenges; for instance, the US Marine Corps maintains a strong cultural identity tied to uniform appearance, making it difficult to implement widespread changes to clothing-based sun-protection measures. Institutional changes, particularly those involving uniforms, likely will face substantial administrative resistance and potential operational limitations. When broad uniform modifications are unattainable, a more feasible approach may be to encourage unit-level leadership to authorize and promote the frequent use of nonuniform protective measures.

Furthermore, integrating additional skin cancer risk questions into the already extensive ePHA means extra time required to complete the assessment; this adds to service members’ administrative burden, potentially leading to reduced timely compliance, rushed responses, and survey fatigue, which threaten data quality. If new items are to be included, they should be carefully selected for efficiency and clinical relevance. Existing validated questionnaires such as those from the study by Lyford et al7 published in 2021 can serve as a foundation.

Another critical limitation is access to dermatologic care for active-duty service members. Raising awareness of skin cancer risk without ensuring adequate resources may create ethical concerns, particularly in high-risk environments such as the Middle East and Indo-Pacific. Additionally, because skin cancer often develops years or decades after exposure, securing early buy-in from service members and their leaders can be challenging. These concerns make it clear that, while skin cancer prevention is important, implementing widespread measures is not straightforward and requires a practical and balanced approach.

Final Thoughts

Implementing prevention strategies for skin cancer in the military requires balancing evidence-based recommendations with the practical realities of military culture, resource limitations, and operational demands. Challenges remain for dermatologists in providing targeted recommendations due to the multifaceted nature of military roles, including over 150 Navy Military Occupational Specialties, limited familiarity with the unique UV exposure risks associated with each occupation, and variability in local and regional policies on uniform wear, physical training requirements, and other operational practices. Although targeted prevention measures are difficult to establish in the setting of these knowledge gaps, leveraging unit-level leadership to align with existing screening guidelines and optimizing primary prevention measures can be meaningful steps toward reducing skin cancer risk for military service members while maintaining mission readiness.

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancerincidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

- Lee T, Taubman SB, Williams VF. Incident diagnoses of non-melanoma skin cancer, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2005-2014. MSMR. 2016;23:2-6.

- Krivda KR, Watson NL, Lyford WH, et al. The burden of skin cancer in the military health system, 2017-2022. Cutis. 2024;113:200-215. doi:10.12788/cutis.1015

- Sanlorenzo M, Wehner MR, Linos E, et al. The risk of melanoma in airline pilots and cabin crew: a meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:51-58. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1077

- Brundage JF, Williams VF, Stahlman S, et al. Incidence rates of malignant melanoma in relation to years of military service, overall and in selected military occupational groups, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2001-2015. MMSR. 2017;24:8-14.

- Subramaniam P, Olsen CM, Thompson BS, et al, for the QSkin Sun and Health Study Investigators. Anatomical distributions of basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in a population-based study in Queensland, Australia. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:175-182. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4070

- Lyford WH, Crotty A, Logemann NF. Sun exposure prevention practices within U.S. naval aviation. Mil Med. 2021;186:1169-1175. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab099

- Wood M, Raisanen T, Polcari I. Observational study of free public sunscreen dispenser use at a major US outdoor event. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:164-166.

- Schissel D. Operation shadow warrior: a quantitative analysis of the ultraviolet radiation protection demonstrated by various headgear. Mil Med. 2001;166:783-785.

- Milch JM, Logemann NF. Photoprotection prevents skin cancer: let’s make it fashionable to wear sun-protective clothing. Cutis. 2017;99:89-92.

- Association of Military Dermatologists. (n.d.). Military dermatology. https://militaryderm.org/military-dermatology/

- Newnam R, Le-Jenkins U, Rutledge C, et al. The association of skin cancer prevention knowledge, sun-protective attitudes, and sunprotective behaviors in a Navy population. Mil Med. 2024;189:1-7. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac285

Skin cancer is a major health concern for military service members, who experience notably higher incidence rates than the general population.1 Active-duty military personnel are particularly vulnerable to prolonged sun exposure due to deployments, specialized training, and everyday outdoor duties.1 Despite skin cancer being the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in active-duty service members,2 tracking and documenting the quantity and diversity of these risk factors remain limited. This knowledge gap comes at high cost, simultaneously impairing military medicine preventive measures while burdening the military health care system with substantial expenditures.3 These findings underscore the critical need for targeted surveillance, early-detection programs, and policy-driven interventions to mitigate these medical and economic concerns.

Skin cancer has been recognized as a major health risk to the military population for decades, yet incidence and prevalence remain high. This phenomenon is closely linked to the inherent responsibilities and expectations of active-duty military members, including outdoor physical training, field exercises, standing in formation, and outdoor working environments—all of which can occur during peak sunlight hours. These risks are further elevated at duty stations in geographic regions with high levels of UV exposure, such as those in tropical and arid regions of the world. Certain military occupational specialties and missions may further introduce unique risk factors; for instance, pilots with frequent high-altitude missions experience heightened UV exposure and melanoma risk.4 Secondary to compounding determinants, the aviation, diving, and nuclear subgroups of the military community are particularly vulnerable to skin cancer.5

Despite well-documented risks, considerable gaps remain in quantifying and analyzing variations in UV exposure across military occupations, duty locations, and operational roles. Factors such as the existence of over 150 distinct military occupational specialties, frequent geographic relocations, and routine work in austere environments contribute to a wide range of UV exposure profiles that remain insufficiently characterized. This lack of comprehensive exposure data hinders the development of large-scale, targeted skin cancer prevention strategies. Initial approaches to addressing these challenges include enhanced surveillance, education, and policy initiatives. The Table presents practical recommendations for military leadership to consider in implementing preventive measures for skin cancer. Herein, we outline broader systemic strategies to bridge knowledge gaps and address underrecognized occupational risk factors for skin cancer in military service members; these elements include proposed modifications to the electronic Periodic Health Assessment (ePHA) and the development of standardized, military-specific screening and prevention guidelines to support early detection and resource optimization.

Skin Cancer Education for Service Members

Sunscreen and Signage—Diligent primary prevention offers a promising avenue for mitigating skin cancer incidence in military service members. Basic education and precautionary messaging on photoprotection can be widely implemented to simultaneously educate service members on the dangers of sun exposure while reinforcing healthy behaviors in real time. Simple low-cost initiatives such as strategically placed visual signage reminding service members to apply sunscreen in high UV environments can support consistent sun-safe practices. Educational efforts also should emphasize proper sunscreen use, including application on high-risk anatomic sites (eg, the face, neck, scalp, dorsal hands, and ears) and the essentiality of using sufficient quantities of broad-spectrum sunscreen for effective protection. Incorporating this guidance into training materials, briefings, and visual reminders allow seamless integration of photoprotection into service members’ daily routines without compromising operational efficiency.6 Younger service members, who may be less likely to prioritize preventive behaviors, may be particularly responsive to sun safety reminders in training areas, bases, and deployment zones.7 Health fairs and orientation briefs in high-UV regions also offer potential opportunities for targeted education.

Resources for Sun Protection in the Military

Sunscreen—Although sunscreen is critical in minimizing the risk for UV-induced skin cancer, its widespread use in the military is hindered by practical challenges related to accessibility and the need for consistent reapplication; for instance, providing free sunscreen dispensers at institutions for staff working under intense or prolonged UV exposure may improve sunscreen accessibility and use.8 Including sunscreen in standard-issue gear offers another logical way to embed its use into operational readiness as part of the routine protective measures.

Uniform Modifications—Adapting military uniforms and practices to improve sun protection plays a critical role in reducing skin cancer risk. Targeted protective gear for commonly sun-exposed areas can help mitigate UV exposure. One practical option is the use of wide-brimmed headgear (eg, boonie hats), which provide more face and neck coverage than standard-issue military caps, or covers. The wide-brimmed headgear currently is only selectively authorized during specific scenarios, such as field operations and training exercises, or at the discretion of unit-level leadership. Wide-brimmed headgear, already used by many service members, has been associated with up to a 17% reduction in UV exposure to inadequately protected areas, potentially lowering skin cancer risk.9,10 Similarly, a “sleeves-down” policy—requiring sleeves to remain unrolled and covering the forearms during outdoor activities—offers a simple way to minimize sun exposure without necessitating additional gear. Other specialized clothing items, including UV-blocking neck gaiters, photoprotective clothing, and lightweight gloves, also may be appropriate for high-risk groups and can be implemented in a relatively straightforward manner.

Shade Structures and UV Index Monitoring—Aside from uniform adaptation, physical barrier intervention can further complement skin cancer prevention efforts in the military. Shade structures offer a straightforward way to reduce UV exposure during prolonged outdoor activities. Incorporating daily UV index monitoring into operational guidance can help inform adjustments to training schedules and guide the implementation of additional sun protection measures, such as mandatory sunscreen application, use of wide-brimmed hats, or increased access to shaded rest areas during heavy sunlight hours. Currently, outdoor physical training is restricted during periods of high heat index, measured via Wet Bulb Globe Temperature, to reduce heat-related injuries. We argue that avoidance of nonoperational outdoor activity during peak UV index hours also should be incorporated into standardized policies. This intervention is of particular benefit to service members stationed in regions with a high UV index year-round, such as those stationed in the Middle East, Guam, Okinawa, and southern coastal United States bases.

Policy Changes to Support Photoprotective Measures

Annual Risk Factor Screening‐Screening—Effective secondary prevention efforts by military dermatologists remain an important measure in reducing the burden of skin cancer among military personnel; however, these efforts have become increasingly challenging due to 2 main factors—the diversity of military occupational specialties and their associated unique occupational risks as well as the limited availability of military dermatologists across all branches (approximately 100 active-duty dermatologists for nearly 3 million service members).11 Therefore, targeted interventions that enhance risk assessment, refined screening protocols, and leveraging of existing military health networks can improve early skin cancer detection while optimizing resource allocation.

The ePHA is an online screening tool used annually by all service members to evaluate their overall health. Presently, the ePHA lacks specific questions to assess sun exposure and skin cancer risks. Integrating annual skin cancer risk factor assessments into the ePHA would offer a practical and straightforward approach to identifying at-risk individuals, as suggested by Newnam et al12 in 2022. Skin cancer risk factor assessments allow for targeted data collection related to sun exposure history, family history, and personal risk factors, which can be used to determine individualized risk stratification to assess the need for early secondary prevention measures and specialist referral. These ePHA data can also support population-based analyses to inform preventive strategies and address knowledge gaps related to high-risk exposures, such as extended field exercises or assignments in high-UV regions, that may impede effective skin cancer prevention.

Development of Military-Specific Screening Guidelines—Given the limited number of military dermatologists, a standardized risk-assessment tool could enhance early detection of skin cancer and streamline the referral process. We propose a military-specific skin cancer screening algorithm or risk nomogram that could help to consolidate risk factors into a clear and actionable framework for more efficient triage and appropriate allocation of dermatologic resources and manpower. This nomogram could be developed by military dermatologists and then implemented on a command level, affording primary care providers a useful tool to expedite evaluation of individuals at higher risk for skin cancer while simultaneously promoting judicious use of limited dermatology resources.

Although the United States Preventive Services Task Force does not universally recommend routine skin cancer screenings for asymptomatic adults, military service members are exposed to higher occupational risks than the general population, as previously mentioned. Currently, there is no standardized screening guideline across all military services due to the unique nature and exposure risks for each branch of service and their varied occupations; however, we propose the development of basic standardized screening guidelines by adapting the framework of the United States Preventive Services Task Force and adjusting for military-specific UV exposure and occupational risks to improve early detection of skin cancer. These guidelines could be updated and tailored appropriately when additional population-based data are collected and analyzed through ePHA.

Critiques and Limitations of Implementation

Several challenges and limitations must be considered when attempting to integrate large-scale preventive measures for skin cancer within the US military. A primary concern is the extent to which military resources should be allocated to prevention when off-duty sun exposure remains largely beyond institutional control. Although military health initiatives can address workplace risk through education and policy, individual decisions during both work and leisure time remain a major variable that cannot be feasibly controlled. Cultural and operational barriers also pose challenges; for instance, the US Marine Corps maintains a strong cultural identity tied to uniform appearance, making it difficult to implement widespread changes to clothing-based sun-protection measures. Institutional changes, particularly those involving uniforms, likely will face substantial administrative resistance and potential operational limitations. When broad uniform modifications are unattainable, a more feasible approach may be to encourage unit-level leadership to authorize and promote the frequent use of nonuniform protective measures.

Furthermore, integrating additional skin cancer risk questions into the already extensive ePHA means extra time required to complete the assessment; this adds to service members’ administrative burden, potentially leading to reduced timely compliance, rushed responses, and survey fatigue, which threaten data quality. If new items are to be included, they should be carefully selected for efficiency and clinical relevance. Existing validated questionnaires such as those from the study by Lyford et al7 published in 2021 can serve as a foundation.

Another critical limitation is access to dermatologic care for active-duty service members. Raising awareness of skin cancer risk without ensuring adequate resources may create ethical concerns, particularly in high-risk environments such as the Middle East and Indo-Pacific. Additionally, because skin cancer often develops years or decades after exposure, securing early buy-in from service members and their leaders can be challenging. These concerns make it clear that, while skin cancer prevention is important, implementing widespread measures is not straightforward and requires a practical and balanced approach.

Final Thoughts