User login

Extraordinary Patients Inspired Father of Cancer Immunotherapy

His pioneering research established interleukin-2 (IL-2) as the first U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved cancer immunotherapy in 1992.

To recognize his trailblazing work and other achievements, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) will award Dr. Rosenberg with the 2024 AACR Award for Lifetime Achievement in Cancer Research at its annual meeting in April.

Dr. Rosenberg, a senior investigator for the Center for Cancer Research at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and chief of the NCI Surgery Branch, shared the history behind his novel research and the patient stories that inspired his discoveries, during an interview.

Tell us a little about yourself and where you grew up.

Dr. Rosenberg: I grew up in the Bronx. My parents both immigrated to the United States from Poland as teenagers.

As a young boy, did you always want to become a doctor?

Dr. Rosenberg: I think some defining moments on why I decided to go into medicine occurred when I was 6 or 7 years old. The second world war was over, and many of the horrors of the Holocaust became apparent to me. I was brought up as an Orthodox Jew. My parents were quite religious, and I remember postcards coming in one after another about relatives that had died in the death camps. That had a profound influence on me.

How did that experience impact your aspirations?

Dr. Rosenberg: It was an example to me of how evil certain people and groups can be toward one another. I decided at that point, that I wanted to do something good for people, and medicine seemed the most likely way to do that. But also, I was developing a broad scientific interest. I ended up at the Bronx High School of Science and knew that I not only wanted to practice the medicine of today, but I wanted to play a role in helping develop the medicine.

What led to your interest in cancer treatment?

Dr. Rosenberg: Well, as a medical student and resident, it became clear that the field of cancer needed major improvement. We had three major ways to treat cancer: surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. That could cure about half of the people [who] had cancer. But despite the best application of those three specialties, there were over 600,000 deaths from cancer each year in the United States alone. It was clear to me that new approaches were needed, and I became very interested in taking advantage of the body’s immune system as a source of information to try to make progress.

Were there patients who inspired your research?

Dr. Rosenberg: There were two patients that I saw early in my career that impressed me a great deal. One was a patient that I saw when working in the emergency ward as a resident. A patient came in with right upper quadrant pain that looked like a gallbladder attack. That’s what it was. But when I went through his chart, I saw that he had been at that hospital 12 years earlier with a metastatic gastric cancer. The surgeons had operated. They saw tumor had spread to the liver and could not be removed. They closed the belly, not expecting him to survive. Yet he kept showing up for follow-up visits.

Here he was 12 years later. When I helped operate to take out his gallbladder, there was no evidence of any cancer. The cancer had disappeared in the absence of any external treatment. One of the rarest events in medicine, the spontaneous regression of a cancer. Somehow his body had learned how to destroy the tumor.

Was the second patient’s case as impressive?

Dr. Rosenberg: This patient had received a kidney transplant from a gentleman who died in an auto accident. [The donor’s] kidney contained a cancer deposit, a kidney cancer, unbeknownst to the transplant surgeons. [When the kidney was transplanted], the recipient developed widespread metastatic kidney cancer.

[The recipient] was on immunosuppressive drugs, and so the drugs had to be stopped. [When the immunosuppressive drugs were stopped], the patient’s body rejected the kidney and his cancer disappeared.

That showed me that, in fact, if you could stimulate a strong enough immune reaction, in this case, an [allogeneic] reaction, against foreign tissues from a different individual, that you could make large vascularized, invasive cancers disappear based on immune reactivities. Those were clues that led me toward studying the immune system’s impact on cancer.

From there, how did your work evolve?

Dr. Rosenberg: As chief of the surgery branch at NIH, I began doing research. It was very difficult to manipulate immune cells in the laboratory. They wouldn’t stay alive. But I tried to study immune reactions in patients with cancer to see if there was such a thing as an immune reaction against the cancer. There was no such thing known at the time. There were no cancer antigens and no known immune reactions against the disease in the human.

Around this time, investigators were publishing studies about interleukin-2 (IL-2), or white blood cells known as leukocytes. How did interleukin-2 further your research?

Dr. Rosenberg: The advent of interleukin-2 enabled scientists to grow lymphocytes outside the body. [This] enabled us to grow t-lymphocytes, which are some of the major warriors of the immune system against foreign tissue. After [studying] 66 patients in which we studied interleukin-2 and cells that would develop from it, we finally saw a disappearance of melanoma in a patient that received interleukin-2. And we went on to treat hundreds of patients with that hormone, interleukin-2. In fact, interleukin-2 became the first immunotherapy ever approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of cancer in humans.

How did this finding impact your future discoveries?

Dr. Rosenberg: [It] led to studies of the mechanism of action of interleukin-2 and to do that, we identified a kind of cell called a tumor infiltrating lymphocyte. What better place, intuitively to look for cells doing battle against the cancer than within the cancer itself?

In 1988, we demonstrated for the first time that transfer of lymphocytes with antitumor activity could cause the regression of melanoma. This was a living drug obtained from melanoma deposits that could be grown outside the body and then readministered to the patient under suitable conditions. Interestingly, [in February the FDA approved that drug as treatment for patients with melanoma]. A company developed it to the point where in multi-institutional studies, they reproduced our results.

And we’ve now emphasized the value of using T cell therapy, t cell transfer, for the treatment of patients with the common solid cancers, the cancers that start anywhere from the colon up through the intestine, the stomach, the pancreas, and the esophagus. Solid tumors such as ovarian cancer, uterine cancer and so on, are also potentially susceptible to this T cell therapy.

We’ve published several papers showing in isolated patients that you could cause major regressions, if not complete regressions, of these solid cancers in the liver, in the breast, the cervix, the colon. That’s a major aspect of what we’re doing now.

I think immunotherapy has come to be recognized as a major fourth arm that can be used to attack cancers, adding to surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

What guidance would you have for other physician-investigators or young doctors who want to follow in your path?

Dr. Rosenberg: You have to have a broad base of knowledge. You have to be willing to immerse yourself in a problem so that your mind is working on it when you’re doing things where you can only think. [When] you’re taking a shower, [or] waiting at a red light, your mind is working on this problem because you’re immersed in trying to understand it.

You need to have a laser focus on the goals that you have and not get sidetracked by issues that may be interesting but not directly related to the goals that you’re attempting to achieve.

His pioneering research established interleukin-2 (IL-2) as the first U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved cancer immunotherapy in 1992.

To recognize his trailblazing work and other achievements, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) will award Dr. Rosenberg with the 2024 AACR Award for Lifetime Achievement in Cancer Research at its annual meeting in April.

Dr. Rosenberg, a senior investigator for the Center for Cancer Research at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and chief of the NCI Surgery Branch, shared the history behind his novel research and the patient stories that inspired his discoveries, during an interview.

Tell us a little about yourself and where you grew up.

Dr. Rosenberg: I grew up in the Bronx. My parents both immigrated to the United States from Poland as teenagers.

As a young boy, did you always want to become a doctor?

Dr. Rosenberg: I think some defining moments on why I decided to go into medicine occurred when I was 6 or 7 years old. The second world war was over, and many of the horrors of the Holocaust became apparent to me. I was brought up as an Orthodox Jew. My parents were quite religious, and I remember postcards coming in one after another about relatives that had died in the death camps. That had a profound influence on me.

How did that experience impact your aspirations?

Dr. Rosenberg: It was an example to me of how evil certain people and groups can be toward one another. I decided at that point, that I wanted to do something good for people, and medicine seemed the most likely way to do that. But also, I was developing a broad scientific interest. I ended up at the Bronx High School of Science and knew that I not only wanted to practice the medicine of today, but I wanted to play a role in helping develop the medicine.

What led to your interest in cancer treatment?

Dr. Rosenberg: Well, as a medical student and resident, it became clear that the field of cancer needed major improvement. We had three major ways to treat cancer: surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. That could cure about half of the people [who] had cancer. But despite the best application of those three specialties, there were over 600,000 deaths from cancer each year in the United States alone. It was clear to me that new approaches were needed, and I became very interested in taking advantage of the body’s immune system as a source of information to try to make progress.

Were there patients who inspired your research?

Dr. Rosenberg: There were two patients that I saw early in my career that impressed me a great deal. One was a patient that I saw when working in the emergency ward as a resident. A patient came in with right upper quadrant pain that looked like a gallbladder attack. That’s what it was. But when I went through his chart, I saw that he had been at that hospital 12 years earlier with a metastatic gastric cancer. The surgeons had operated. They saw tumor had spread to the liver and could not be removed. They closed the belly, not expecting him to survive. Yet he kept showing up for follow-up visits.

Here he was 12 years later. When I helped operate to take out his gallbladder, there was no evidence of any cancer. The cancer had disappeared in the absence of any external treatment. One of the rarest events in medicine, the spontaneous regression of a cancer. Somehow his body had learned how to destroy the tumor.

Was the second patient’s case as impressive?

Dr. Rosenberg: This patient had received a kidney transplant from a gentleman who died in an auto accident. [The donor’s] kidney contained a cancer deposit, a kidney cancer, unbeknownst to the transplant surgeons. [When the kidney was transplanted], the recipient developed widespread metastatic kidney cancer.

[The recipient] was on immunosuppressive drugs, and so the drugs had to be stopped. [When the immunosuppressive drugs were stopped], the patient’s body rejected the kidney and his cancer disappeared.

That showed me that, in fact, if you could stimulate a strong enough immune reaction, in this case, an [allogeneic] reaction, against foreign tissues from a different individual, that you could make large vascularized, invasive cancers disappear based on immune reactivities. Those were clues that led me toward studying the immune system’s impact on cancer.

From there, how did your work evolve?

Dr. Rosenberg: As chief of the surgery branch at NIH, I began doing research. It was very difficult to manipulate immune cells in the laboratory. They wouldn’t stay alive. But I tried to study immune reactions in patients with cancer to see if there was such a thing as an immune reaction against the cancer. There was no such thing known at the time. There were no cancer antigens and no known immune reactions against the disease in the human.

Around this time, investigators were publishing studies about interleukin-2 (IL-2), or white blood cells known as leukocytes. How did interleukin-2 further your research?

Dr. Rosenberg: The advent of interleukin-2 enabled scientists to grow lymphocytes outside the body. [This] enabled us to grow t-lymphocytes, which are some of the major warriors of the immune system against foreign tissue. After [studying] 66 patients in which we studied interleukin-2 and cells that would develop from it, we finally saw a disappearance of melanoma in a patient that received interleukin-2. And we went on to treat hundreds of patients with that hormone, interleukin-2. In fact, interleukin-2 became the first immunotherapy ever approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of cancer in humans.

How did this finding impact your future discoveries?

Dr. Rosenberg: [It] led to studies of the mechanism of action of interleukin-2 and to do that, we identified a kind of cell called a tumor infiltrating lymphocyte. What better place, intuitively to look for cells doing battle against the cancer than within the cancer itself?

In 1988, we demonstrated for the first time that transfer of lymphocytes with antitumor activity could cause the regression of melanoma. This was a living drug obtained from melanoma deposits that could be grown outside the body and then readministered to the patient under suitable conditions. Interestingly, [in February the FDA approved that drug as treatment for patients with melanoma]. A company developed it to the point where in multi-institutional studies, they reproduced our results.

And we’ve now emphasized the value of using T cell therapy, t cell transfer, for the treatment of patients with the common solid cancers, the cancers that start anywhere from the colon up through the intestine, the stomach, the pancreas, and the esophagus. Solid tumors such as ovarian cancer, uterine cancer and so on, are also potentially susceptible to this T cell therapy.

We’ve published several papers showing in isolated patients that you could cause major regressions, if not complete regressions, of these solid cancers in the liver, in the breast, the cervix, the colon. That’s a major aspect of what we’re doing now.

I think immunotherapy has come to be recognized as a major fourth arm that can be used to attack cancers, adding to surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

What guidance would you have for other physician-investigators or young doctors who want to follow in your path?

Dr. Rosenberg: You have to have a broad base of knowledge. You have to be willing to immerse yourself in a problem so that your mind is working on it when you’re doing things where you can only think. [When] you’re taking a shower, [or] waiting at a red light, your mind is working on this problem because you’re immersed in trying to understand it.

You need to have a laser focus on the goals that you have and not get sidetracked by issues that may be interesting but not directly related to the goals that you’re attempting to achieve.

His pioneering research established interleukin-2 (IL-2) as the first U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved cancer immunotherapy in 1992.

To recognize his trailblazing work and other achievements, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) will award Dr. Rosenberg with the 2024 AACR Award for Lifetime Achievement in Cancer Research at its annual meeting in April.

Dr. Rosenberg, a senior investigator for the Center for Cancer Research at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), and chief of the NCI Surgery Branch, shared the history behind his novel research and the patient stories that inspired his discoveries, during an interview.

Tell us a little about yourself and where you grew up.

Dr. Rosenberg: I grew up in the Bronx. My parents both immigrated to the United States from Poland as teenagers.

As a young boy, did you always want to become a doctor?

Dr. Rosenberg: I think some defining moments on why I decided to go into medicine occurred when I was 6 or 7 years old. The second world war was over, and many of the horrors of the Holocaust became apparent to me. I was brought up as an Orthodox Jew. My parents were quite religious, and I remember postcards coming in one after another about relatives that had died in the death camps. That had a profound influence on me.

How did that experience impact your aspirations?

Dr. Rosenberg: It was an example to me of how evil certain people and groups can be toward one another. I decided at that point, that I wanted to do something good for people, and medicine seemed the most likely way to do that. But also, I was developing a broad scientific interest. I ended up at the Bronx High School of Science and knew that I not only wanted to practice the medicine of today, but I wanted to play a role in helping develop the medicine.

What led to your interest in cancer treatment?

Dr. Rosenberg: Well, as a medical student and resident, it became clear that the field of cancer needed major improvement. We had three major ways to treat cancer: surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. That could cure about half of the people [who] had cancer. But despite the best application of those three specialties, there were over 600,000 deaths from cancer each year in the United States alone. It was clear to me that new approaches were needed, and I became very interested in taking advantage of the body’s immune system as a source of information to try to make progress.

Were there patients who inspired your research?

Dr. Rosenberg: There were two patients that I saw early in my career that impressed me a great deal. One was a patient that I saw when working in the emergency ward as a resident. A patient came in with right upper quadrant pain that looked like a gallbladder attack. That’s what it was. But when I went through his chart, I saw that he had been at that hospital 12 years earlier with a metastatic gastric cancer. The surgeons had operated. They saw tumor had spread to the liver and could not be removed. They closed the belly, not expecting him to survive. Yet he kept showing up for follow-up visits.

Here he was 12 years later. When I helped operate to take out his gallbladder, there was no evidence of any cancer. The cancer had disappeared in the absence of any external treatment. One of the rarest events in medicine, the spontaneous regression of a cancer. Somehow his body had learned how to destroy the tumor.

Was the second patient’s case as impressive?

Dr. Rosenberg: This patient had received a kidney transplant from a gentleman who died in an auto accident. [The donor’s] kidney contained a cancer deposit, a kidney cancer, unbeknownst to the transplant surgeons. [When the kidney was transplanted], the recipient developed widespread metastatic kidney cancer.

[The recipient] was on immunosuppressive drugs, and so the drugs had to be stopped. [When the immunosuppressive drugs were stopped], the patient’s body rejected the kidney and his cancer disappeared.

That showed me that, in fact, if you could stimulate a strong enough immune reaction, in this case, an [allogeneic] reaction, against foreign tissues from a different individual, that you could make large vascularized, invasive cancers disappear based on immune reactivities. Those were clues that led me toward studying the immune system’s impact on cancer.

From there, how did your work evolve?

Dr. Rosenberg: As chief of the surgery branch at NIH, I began doing research. It was very difficult to manipulate immune cells in the laboratory. They wouldn’t stay alive. But I tried to study immune reactions in patients with cancer to see if there was such a thing as an immune reaction against the cancer. There was no such thing known at the time. There were no cancer antigens and no known immune reactions against the disease in the human.

Around this time, investigators were publishing studies about interleukin-2 (IL-2), or white blood cells known as leukocytes. How did interleukin-2 further your research?

Dr. Rosenberg: The advent of interleukin-2 enabled scientists to grow lymphocytes outside the body. [This] enabled us to grow t-lymphocytes, which are some of the major warriors of the immune system against foreign tissue. After [studying] 66 patients in which we studied interleukin-2 and cells that would develop from it, we finally saw a disappearance of melanoma in a patient that received interleukin-2. And we went on to treat hundreds of patients with that hormone, interleukin-2. In fact, interleukin-2 became the first immunotherapy ever approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of cancer in humans.

How did this finding impact your future discoveries?

Dr. Rosenberg: [It] led to studies of the mechanism of action of interleukin-2 and to do that, we identified a kind of cell called a tumor infiltrating lymphocyte. What better place, intuitively to look for cells doing battle against the cancer than within the cancer itself?

In 1988, we demonstrated for the first time that transfer of lymphocytes with antitumor activity could cause the regression of melanoma. This was a living drug obtained from melanoma deposits that could be grown outside the body and then readministered to the patient under suitable conditions. Interestingly, [in February the FDA approved that drug as treatment for patients with melanoma]. A company developed it to the point where in multi-institutional studies, they reproduced our results.

And we’ve now emphasized the value of using T cell therapy, t cell transfer, for the treatment of patients with the common solid cancers, the cancers that start anywhere from the colon up through the intestine, the stomach, the pancreas, and the esophagus. Solid tumors such as ovarian cancer, uterine cancer and so on, are also potentially susceptible to this T cell therapy.

We’ve published several papers showing in isolated patients that you could cause major regressions, if not complete regressions, of these solid cancers in the liver, in the breast, the cervix, the colon. That’s a major aspect of what we’re doing now.

I think immunotherapy has come to be recognized as a major fourth arm that can be used to attack cancers, adding to surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

What guidance would you have for other physician-investigators or young doctors who want to follow in your path?

Dr. Rosenberg: You have to have a broad base of knowledge. You have to be willing to immerse yourself in a problem so that your mind is working on it when you’re doing things where you can only think. [When] you’re taking a shower, [or] waiting at a red light, your mind is working on this problem because you’re immersed in trying to understand it.

You need to have a laser focus on the goals that you have and not get sidetracked by issues that may be interesting but not directly related to the goals that you’re attempting to achieve.

Myeloma: FDA Advisers Greenlight Early CAR-T

The FDA asked its Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) to vote on two separate but similar questions at the March 15 meeting. Much of their discussion centered on higher rates of deaths for patients on the CAR-T therapies during early stages of key studies.

ODAC voted 11-0 to say the risk-benefit assessment appeared favorable for a requested broadening of the patient pool for ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel, Carvykti, Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen). J&J is seeking approval for use of the drug for adults with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) who have received at least one prior line of therapy, including a proteasome inhibitor (PI) and an immunomodulatory agent (IMiD), and are refractory to lenalidomide.

ODAC voted 8-3 to say the risk-benefit assessment appeared favorable for a requested broadening of the patient pool for idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel, Abecma, Bristol Myers Squibb). The company is seeking approval of the drug for people with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) who have received an IMiD, a PI, and an anti-CD38 antibody.

The FDA staff will consider ODAC’s votes and recommendations, but is not bound by them. Janssen’s parent company, J&J, said the FDA’s deadline for deciding on the request to change the cilta-cel label is April 5. Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS) said there is not a PDUFA deadline at this time for its application.

Both CAR-T treatments currently are approved for RRMM after 4 or more prior lines of therapy, including an IMiD, PI and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody. Last year BMS and Janssen filed their separate applications, both seeking to have their drugs used earlier in the course of RRMM.

Data provided in support of both requests for expanded use raised alarms at the FDA, with more deaths seen in the early stage of testing among patients given the CAR-T drugs compared to those given standard-of-care regimens, the agency staff said.

The application for cilta-cel rests heavily on the data from the CARTITUDE-4 trial. As reported in The New England Journal of Medicine last year, progression-free survival (PFS) at 12 months was 75.9% (95% CI, 69.4 to 81.1) in the cilta-cel group and 48.6% (95% CI, 41.5 to 55.3) in the standard-care group.

But the FDA staff review focused on worrying signs in the early months of this study. For example, the rate of death in the first 10 months post randomization was higher in the cilta-cel arm (29 of 208; 14%) than in the standard therapy arm (25 of 211; 12%) based on an analysis of the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, the FDA said.

In its review of the ide-cel application, the FDA staff said the median PFS was 13.3 months in the ide-cel arm (95% CI: 11.8, 16.1), and 4.4 months (95% CI: 3.4, 5.9) in the standard of care (SOC) arm.

However, the rate of deaths in the first 9 months post randomization was higher in the ide-cel arm (45/254; 18%) than in the comparator standard-of-care group (15/132; 11%) in the ITT population, the FDA staff said. In the safety analysis population, the rate of deaths from adverse events that occurred within 90 days from starting treatment was 2.7% in the ide-cel arm and 1.6 % in the standard-regimen group.

ODAC ultimately appeared more impressed by data indicating the potential benefit, measured as progression-free survival (PFS), of the two drugs under review, than they were concerned about the issues about early deaths raised by FDA staff.

Panelist Jorge J. Nieva, MD, of the University of Southern California said the CAR-T drugs may present another case of “front-loaded risk” as has been noted for other treatments for serious medical procedures, such as allogeneic transplantations and thoracic surgeries.

In response, Robert Sokolic, MD, the branch chief for malignant hematology at FDA, replied that the data raised concerns that did in fact remind him of these procedures.

“I’m a bone marrow transplant physician. And that’s exactly what I said when I saw these curves. This looks like an allogeneic transplant curve,” Dr. Sokolic said.

But there’s a major difference between that procedure and CAR-T in the context being considered at the ODAC meeting, he said.

With allogeneic transplant, physicians “counsel patients. We ask them to accept an upfront burden of increased mortality, because we know that down the line, overall, there’s a benefit in survival,” Dr. Sokolic said.

In contrast, the primary endpoint in the key studies for expansion of CAR-T drugs was progression-free survival (PFS), with overall survival as a second endpoint. The FDA staff in briefing documents noted how overall survival, the gold standard in research, delivers far more reliable answers for patients and doctors in assessing treatments.

In the exchange with Dr. Nieva, Dr. Sokolic noted that there’s far less certainty of benefit at this time when asking patients to consider CAR-T earlier in the progression of MM, especially given the safety concerns.

“We know there’s benefit in PFS. We know there’s a safety concern,” Dr. Sokolic said.“That’s not balanced by an overall survival balance on the tail end. It may be when the data are more mature, but it’s not there yet.”

Describing Risks to Patients

ODAC panelists also stressed a need to help patients understand what’s known — and not yet known — about these CAR-T therapies. It will be very challenging for patients to understand and interpret the data from key studies on these medicines, said ODAC panelist Susan Lattimore, RN, of Oregon Health & Science University. She suggested the FDA seek labeling that would be “overtly transparent” and use lay terms to describe the potential risks and benefits.

In its presentations to the FDA and ODAC, J&J noted that the COVID pandemic has affected testing and that the rate of deaths flips in time to be higher in the comparator group.

In its briefing document for the meeting, BMS emphasized that most of the patients in the ide-cel arm who died in the first 6 months of its trial did not get the study drug. There were 9 deaths in the standard-regimen arm, or 6.8% of the group, compared with 30, or 11.8% in the ide-cel group.

In the ide-cel arm, the majority of early deaths (17/30; 56.7%) occurred in patients who never received ide-cel treatment, with 13 of those 17 dying from disease progression, the company said in its briefing document. The early death rate among patients who received the allocated study treatment was similar between arms (5.1% in the ide-cel arm vs 6.8% in the standard regimen arm),the company said.

In the staff briefing, the FDA said the median PFS was 13.3 months in the ide-cel arm, compared with 4.4 months in the standard of care (SOC) arm. But there was a “clear and persistent increased mortality” for the ide-cel group, compared with the standard regimen arm, with increased rates of death up to 9 months. In addition, the overall survival disadvantage persisted to 15 months after randomization, when the survival curves finally crossed, the FDA staff said in its March 15 presentation.

ODAC Chairman Ravi A. Madan, MD, of the National Cancer Institute, was among the panelists who voted “no” in the ide-cel question. He said the risk-benefit profile of the drug does not appear favorable at this time for expanded use.

“There’s a lot of optimism about moving these therapies earlier in the disease states of multiple myeloma,” Dr. Madan said, calling the PFS data “quite remarkable.

“But for me this data at this level of maturity really didn’t provide convincing evidence that ide-cel earlier had a favorable risk benefit assessment in a proposed indication.”

ODAC panelist Christopher H. Lieu, MD, of the University of Colorado, said he struggled to decide how to vote on the ide-cel question and in the end voted yes.

He said the response to the treatment doesn’t appear to be as durable as hoped, considering the significant burden that CAR-T therapy imposes on patients. However, the PFS data suggest that ide-cel could offer patients with RRMM a chance for significant times off therapy with associated quality of life improvement.

“I do believe that the risk-benefit profile is favorable for this population as a whole,” he said. “But it’s a closer margin than I think we would like and patients will need to have in-depth discussions about the risks and benefits and balance that with the possible benefits with their provider.”

The FDA asked its Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) to vote on two separate but similar questions at the March 15 meeting. Much of their discussion centered on higher rates of deaths for patients on the CAR-T therapies during early stages of key studies.

ODAC voted 11-0 to say the risk-benefit assessment appeared favorable for a requested broadening of the patient pool for ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel, Carvykti, Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen). J&J is seeking approval for use of the drug for adults with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) who have received at least one prior line of therapy, including a proteasome inhibitor (PI) and an immunomodulatory agent (IMiD), and are refractory to lenalidomide.

ODAC voted 8-3 to say the risk-benefit assessment appeared favorable for a requested broadening of the patient pool for idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel, Abecma, Bristol Myers Squibb). The company is seeking approval of the drug for people with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) who have received an IMiD, a PI, and an anti-CD38 antibody.

The FDA staff will consider ODAC’s votes and recommendations, but is not bound by them. Janssen’s parent company, J&J, said the FDA’s deadline for deciding on the request to change the cilta-cel label is April 5. Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS) said there is not a PDUFA deadline at this time for its application.

Both CAR-T treatments currently are approved for RRMM after 4 or more prior lines of therapy, including an IMiD, PI and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody. Last year BMS and Janssen filed their separate applications, both seeking to have their drugs used earlier in the course of RRMM.

Data provided in support of both requests for expanded use raised alarms at the FDA, with more deaths seen in the early stage of testing among patients given the CAR-T drugs compared to those given standard-of-care regimens, the agency staff said.

The application for cilta-cel rests heavily on the data from the CARTITUDE-4 trial. As reported in The New England Journal of Medicine last year, progression-free survival (PFS) at 12 months was 75.9% (95% CI, 69.4 to 81.1) in the cilta-cel group and 48.6% (95% CI, 41.5 to 55.3) in the standard-care group.

But the FDA staff review focused on worrying signs in the early months of this study. For example, the rate of death in the first 10 months post randomization was higher in the cilta-cel arm (29 of 208; 14%) than in the standard therapy arm (25 of 211; 12%) based on an analysis of the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, the FDA said.

In its review of the ide-cel application, the FDA staff said the median PFS was 13.3 months in the ide-cel arm (95% CI: 11.8, 16.1), and 4.4 months (95% CI: 3.4, 5.9) in the standard of care (SOC) arm.

However, the rate of deaths in the first 9 months post randomization was higher in the ide-cel arm (45/254; 18%) than in the comparator standard-of-care group (15/132; 11%) in the ITT population, the FDA staff said. In the safety analysis population, the rate of deaths from adverse events that occurred within 90 days from starting treatment was 2.7% in the ide-cel arm and 1.6 % in the standard-regimen group.

ODAC ultimately appeared more impressed by data indicating the potential benefit, measured as progression-free survival (PFS), of the two drugs under review, than they were concerned about the issues about early deaths raised by FDA staff.

Panelist Jorge J. Nieva, MD, of the University of Southern California said the CAR-T drugs may present another case of “front-loaded risk” as has been noted for other treatments for serious medical procedures, such as allogeneic transplantations and thoracic surgeries.

In response, Robert Sokolic, MD, the branch chief for malignant hematology at FDA, replied that the data raised concerns that did in fact remind him of these procedures.

“I’m a bone marrow transplant physician. And that’s exactly what I said when I saw these curves. This looks like an allogeneic transplant curve,” Dr. Sokolic said.

But there’s a major difference between that procedure and CAR-T in the context being considered at the ODAC meeting, he said.

With allogeneic transplant, physicians “counsel patients. We ask them to accept an upfront burden of increased mortality, because we know that down the line, overall, there’s a benefit in survival,” Dr. Sokolic said.

In contrast, the primary endpoint in the key studies for expansion of CAR-T drugs was progression-free survival (PFS), with overall survival as a second endpoint. The FDA staff in briefing documents noted how overall survival, the gold standard in research, delivers far more reliable answers for patients and doctors in assessing treatments.

In the exchange with Dr. Nieva, Dr. Sokolic noted that there’s far less certainty of benefit at this time when asking patients to consider CAR-T earlier in the progression of MM, especially given the safety concerns.

“We know there’s benefit in PFS. We know there’s a safety concern,” Dr. Sokolic said.“That’s not balanced by an overall survival balance on the tail end. It may be when the data are more mature, but it’s not there yet.”

Describing Risks to Patients

ODAC panelists also stressed a need to help patients understand what’s known — and not yet known — about these CAR-T therapies. It will be very challenging for patients to understand and interpret the data from key studies on these medicines, said ODAC panelist Susan Lattimore, RN, of Oregon Health & Science University. She suggested the FDA seek labeling that would be “overtly transparent” and use lay terms to describe the potential risks and benefits.

In its presentations to the FDA and ODAC, J&J noted that the COVID pandemic has affected testing and that the rate of deaths flips in time to be higher in the comparator group.

In its briefing document for the meeting, BMS emphasized that most of the patients in the ide-cel arm who died in the first 6 months of its trial did not get the study drug. There were 9 deaths in the standard-regimen arm, or 6.8% of the group, compared with 30, or 11.8% in the ide-cel group.

In the ide-cel arm, the majority of early deaths (17/30; 56.7%) occurred in patients who never received ide-cel treatment, with 13 of those 17 dying from disease progression, the company said in its briefing document. The early death rate among patients who received the allocated study treatment was similar between arms (5.1% in the ide-cel arm vs 6.8% in the standard regimen arm),the company said.

In the staff briefing, the FDA said the median PFS was 13.3 months in the ide-cel arm, compared with 4.4 months in the standard of care (SOC) arm. But there was a “clear and persistent increased mortality” for the ide-cel group, compared with the standard regimen arm, with increased rates of death up to 9 months. In addition, the overall survival disadvantage persisted to 15 months after randomization, when the survival curves finally crossed, the FDA staff said in its March 15 presentation.

ODAC Chairman Ravi A. Madan, MD, of the National Cancer Institute, was among the panelists who voted “no” in the ide-cel question. He said the risk-benefit profile of the drug does not appear favorable at this time for expanded use.

“There’s a lot of optimism about moving these therapies earlier in the disease states of multiple myeloma,” Dr. Madan said, calling the PFS data “quite remarkable.

“But for me this data at this level of maturity really didn’t provide convincing evidence that ide-cel earlier had a favorable risk benefit assessment in a proposed indication.”

ODAC panelist Christopher H. Lieu, MD, of the University of Colorado, said he struggled to decide how to vote on the ide-cel question and in the end voted yes.

He said the response to the treatment doesn’t appear to be as durable as hoped, considering the significant burden that CAR-T therapy imposes on patients. However, the PFS data suggest that ide-cel could offer patients with RRMM a chance for significant times off therapy with associated quality of life improvement.

“I do believe that the risk-benefit profile is favorable for this population as a whole,” he said. “But it’s a closer margin than I think we would like and patients will need to have in-depth discussions about the risks and benefits and balance that with the possible benefits with their provider.”

The FDA asked its Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) to vote on two separate but similar questions at the March 15 meeting. Much of their discussion centered on higher rates of deaths for patients on the CAR-T therapies during early stages of key studies.

ODAC voted 11-0 to say the risk-benefit assessment appeared favorable for a requested broadening of the patient pool for ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel, Carvykti, Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen). J&J is seeking approval for use of the drug for adults with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) who have received at least one prior line of therapy, including a proteasome inhibitor (PI) and an immunomodulatory agent (IMiD), and are refractory to lenalidomide.

ODAC voted 8-3 to say the risk-benefit assessment appeared favorable for a requested broadening of the patient pool for idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel, Abecma, Bristol Myers Squibb). The company is seeking approval of the drug for people with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) who have received an IMiD, a PI, and an anti-CD38 antibody.

The FDA staff will consider ODAC’s votes and recommendations, but is not bound by them. Janssen’s parent company, J&J, said the FDA’s deadline for deciding on the request to change the cilta-cel label is April 5. Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS) said there is not a PDUFA deadline at this time for its application.

Both CAR-T treatments currently are approved for RRMM after 4 or more prior lines of therapy, including an IMiD, PI and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody. Last year BMS and Janssen filed their separate applications, both seeking to have their drugs used earlier in the course of RRMM.

Data provided in support of both requests for expanded use raised alarms at the FDA, with more deaths seen in the early stage of testing among patients given the CAR-T drugs compared to those given standard-of-care regimens, the agency staff said.

The application for cilta-cel rests heavily on the data from the CARTITUDE-4 trial. As reported in The New England Journal of Medicine last year, progression-free survival (PFS) at 12 months was 75.9% (95% CI, 69.4 to 81.1) in the cilta-cel group and 48.6% (95% CI, 41.5 to 55.3) in the standard-care group.

But the FDA staff review focused on worrying signs in the early months of this study. For example, the rate of death in the first 10 months post randomization was higher in the cilta-cel arm (29 of 208; 14%) than in the standard therapy arm (25 of 211; 12%) based on an analysis of the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, the FDA said.

In its review of the ide-cel application, the FDA staff said the median PFS was 13.3 months in the ide-cel arm (95% CI: 11.8, 16.1), and 4.4 months (95% CI: 3.4, 5.9) in the standard of care (SOC) arm.

However, the rate of deaths in the first 9 months post randomization was higher in the ide-cel arm (45/254; 18%) than in the comparator standard-of-care group (15/132; 11%) in the ITT population, the FDA staff said. In the safety analysis population, the rate of deaths from adverse events that occurred within 90 days from starting treatment was 2.7% in the ide-cel arm and 1.6 % in the standard-regimen group.

ODAC ultimately appeared more impressed by data indicating the potential benefit, measured as progression-free survival (PFS), of the two drugs under review, than they were concerned about the issues about early deaths raised by FDA staff.

Panelist Jorge J. Nieva, MD, of the University of Southern California said the CAR-T drugs may present another case of “front-loaded risk” as has been noted for other treatments for serious medical procedures, such as allogeneic transplantations and thoracic surgeries.

In response, Robert Sokolic, MD, the branch chief for malignant hematology at FDA, replied that the data raised concerns that did in fact remind him of these procedures.

“I’m a bone marrow transplant physician. And that’s exactly what I said when I saw these curves. This looks like an allogeneic transplant curve,” Dr. Sokolic said.

But there’s a major difference between that procedure and CAR-T in the context being considered at the ODAC meeting, he said.

With allogeneic transplant, physicians “counsel patients. We ask them to accept an upfront burden of increased mortality, because we know that down the line, overall, there’s a benefit in survival,” Dr. Sokolic said.

In contrast, the primary endpoint in the key studies for expansion of CAR-T drugs was progression-free survival (PFS), with overall survival as a second endpoint. The FDA staff in briefing documents noted how overall survival, the gold standard in research, delivers far more reliable answers for patients and doctors in assessing treatments.

In the exchange with Dr. Nieva, Dr. Sokolic noted that there’s far less certainty of benefit at this time when asking patients to consider CAR-T earlier in the progression of MM, especially given the safety concerns.

“We know there’s benefit in PFS. We know there’s a safety concern,” Dr. Sokolic said.“That’s not balanced by an overall survival balance on the tail end. It may be when the data are more mature, but it’s not there yet.”

Describing Risks to Patients

ODAC panelists also stressed a need to help patients understand what’s known — and not yet known — about these CAR-T therapies. It will be very challenging for patients to understand and interpret the data from key studies on these medicines, said ODAC panelist Susan Lattimore, RN, of Oregon Health & Science University. She suggested the FDA seek labeling that would be “overtly transparent” and use lay terms to describe the potential risks and benefits.

In its presentations to the FDA and ODAC, J&J noted that the COVID pandemic has affected testing and that the rate of deaths flips in time to be higher in the comparator group.

In its briefing document for the meeting, BMS emphasized that most of the patients in the ide-cel arm who died in the first 6 months of its trial did not get the study drug. There were 9 deaths in the standard-regimen arm, or 6.8% of the group, compared with 30, or 11.8% in the ide-cel group.

In the ide-cel arm, the majority of early deaths (17/30; 56.7%) occurred in patients who never received ide-cel treatment, with 13 of those 17 dying from disease progression, the company said in its briefing document. The early death rate among patients who received the allocated study treatment was similar between arms (5.1% in the ide-cel arm vs 6.8% in the standard regimen arm),the company said.

In the staff briefing, the FDA said the median PFS was 13.3 months in the ide-cel arm, compared with 4.4 months in the standard of care (SOC) arm. But there was a “clear and persistent increased mortality” for the ide-cel group, compared with the standard regimen arm, with increased rates of death up to 9 months. In addition, the overall survival disadvantage persisted to 15 months after randomization, when the survival curves finally crossed, the FDA staff said in its March 15 presentation.

ODAC Chairman Ravi A. Madan, MD, of the National Cancer Institute, was among the panelists who voted “no” in the ide-cel question. He said the risk-benefit profile of the drug does not appear favorable at this time for expanded use.

“There’s a lot of optimism about moving these therapies earlier in the disease states of multiple myeloma,” Dr. Madan said, calling the PFS data “quite remarkable.

“But for me this data at this level of maturity really didn’t provide convincing evidence that ide-cel earlier had a favorable risk benefit assessment in a proposed indication.”

ODAC panelist Christopher H. Lieu, MD, of the University of Colorado, said he struggled to decide how to vote on the ide-cel question and in the end voted yes.

He said the response to the treatment doesn’t appear to be as durable as hoped, considering the significant burden that CAR-T therapy imposes on patients. However, the PFS data suggest that ide-cel could offer patients with RRMM a chance for significant times off therapy with associated quality of life improvement.

“I do believe that the risk-benefit profile is favorable for this population as a whole,” he said. “But it’s a closer margin than I think we would like and patients will need to have in-depth discussions about the risks and benefits and balance that with the possible benefits with their provider.”

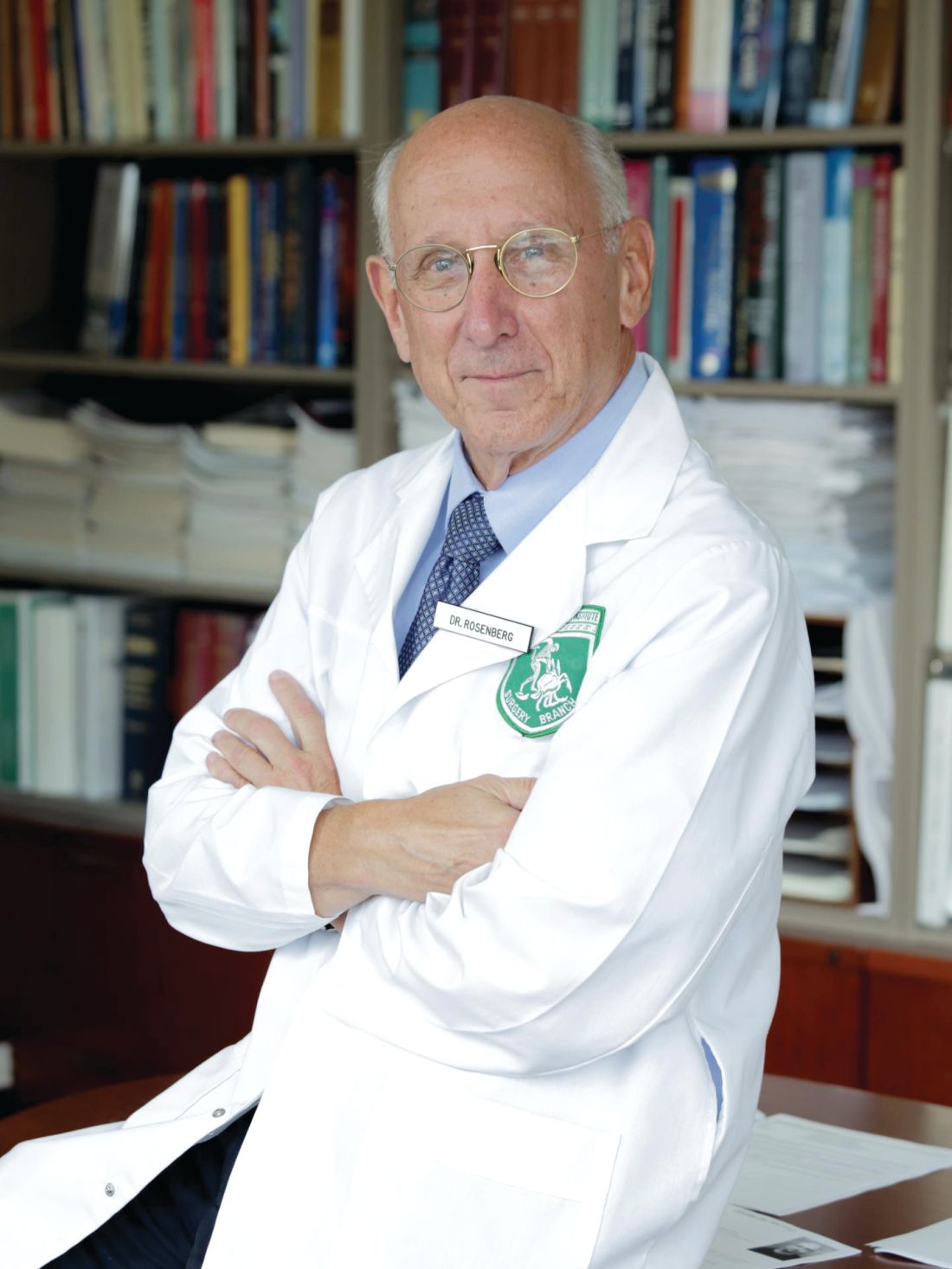

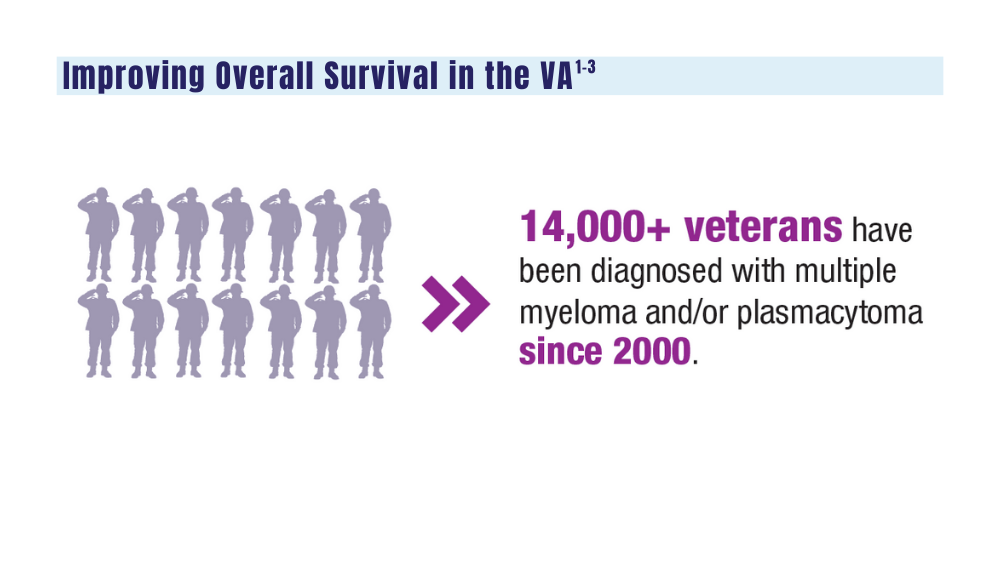

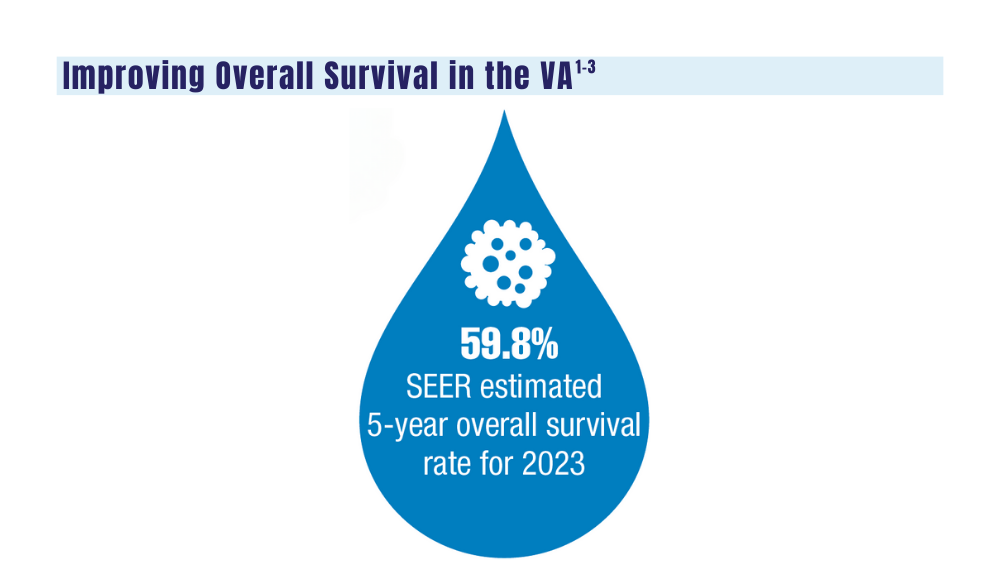

Cancer Data Trends 2024: Multiple Myeloma

1. Mahmood S, Gupta P, Ma H. Impact of time period of diagnosis, race, and military exposures on the survival of US military veterans with multiple myeloma and/or plasmacytoma. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16 suppl). Abstract e20061. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2023.41.16_suppl.e20061

2. National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: myeloma. Accessed January 2, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html

3. Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Terpos E, et al. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up [published correction appears in Ann Oncol. 2022;33(1):117]. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(3):309-322. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.014

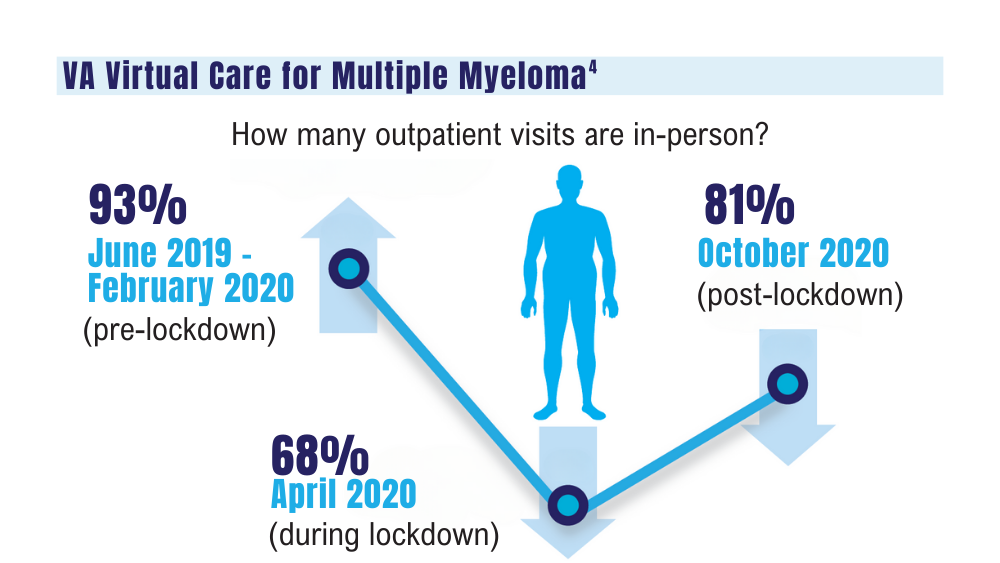

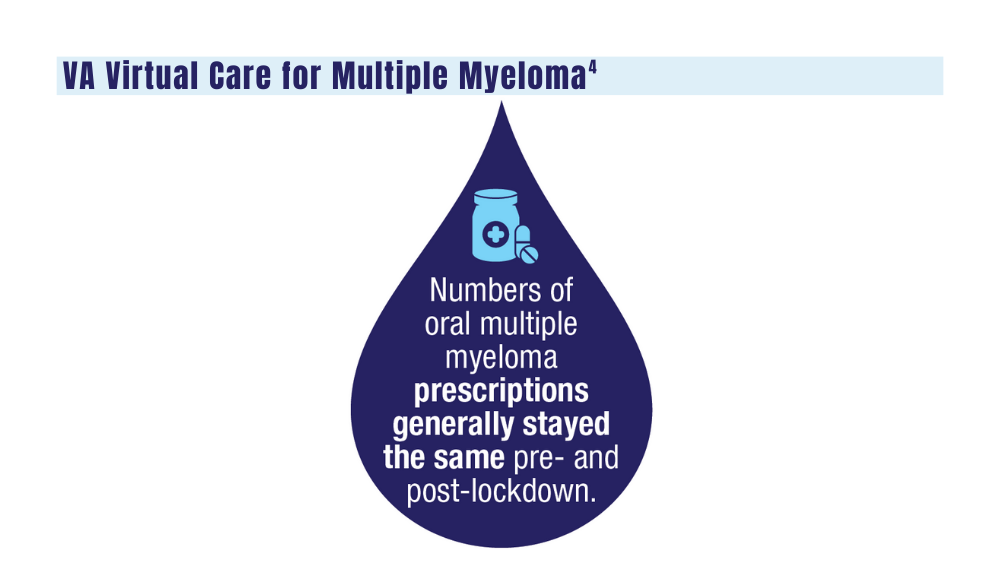

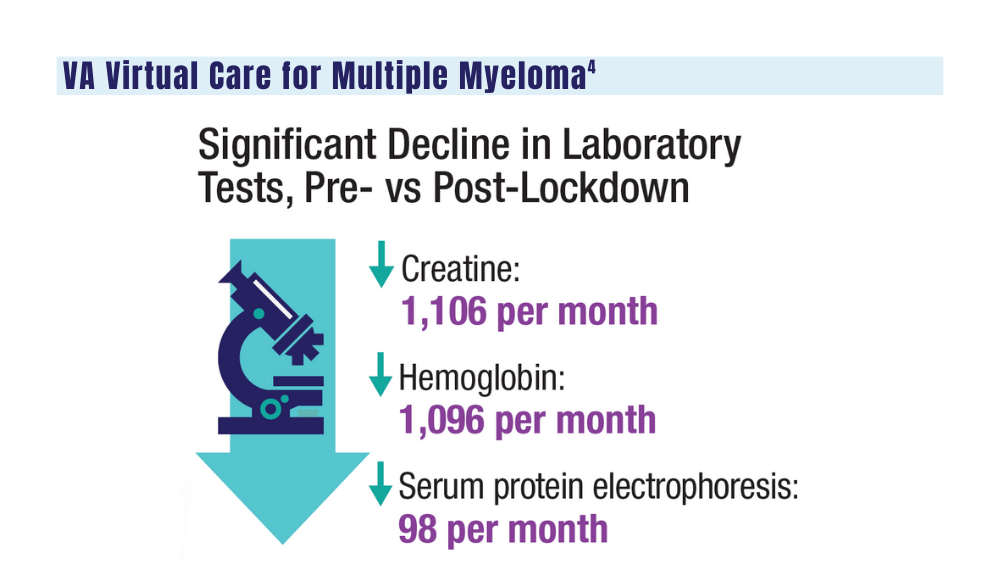

4. Su CT, Chen JC, Sussman JB. Virtual care for multiple myeloma in the COVID-19 era: interrupted time series analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Leuk Lymphoma. 2023;64(5):1035-1039. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2023.2189989

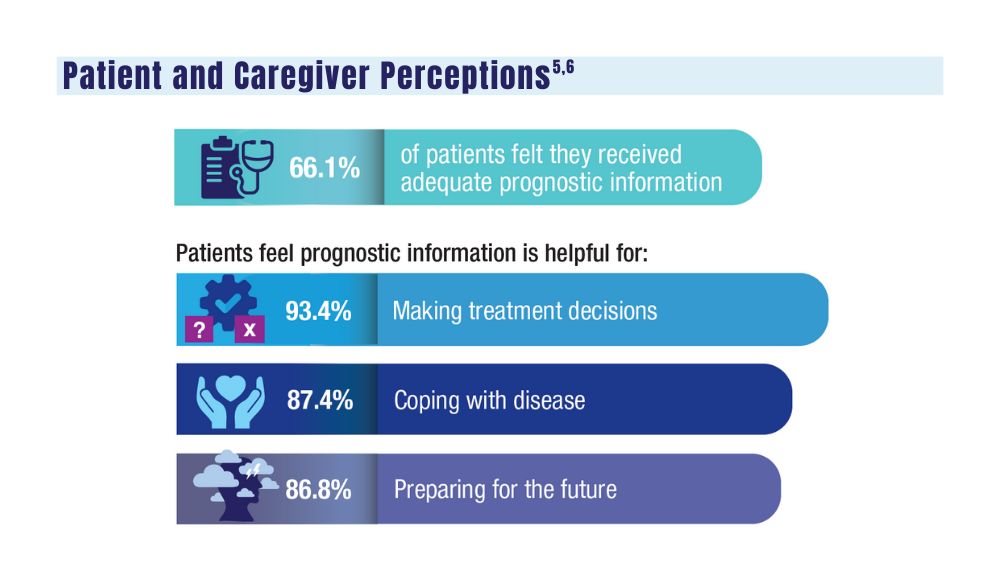

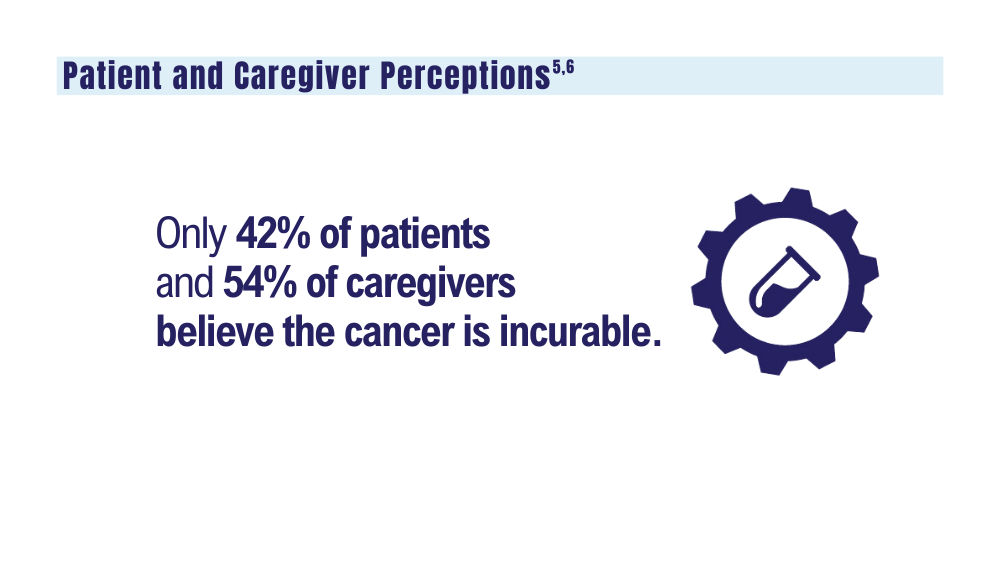

5. O’Donnell EK, Shapiro YN, Yee AJ, et al. Quality of life, psychological distress, and prognostic perceptions in patients with multiple myeloma. Cancer. 2022;128(10):1996-2004. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34134

6. O’Donnell EK, Shapiro YN, Yee AJ, et al. Quality of life, psychological distress, and prognostic perceptions in caregivers of patients with multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 2022;6(17):4967-4974. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022007127

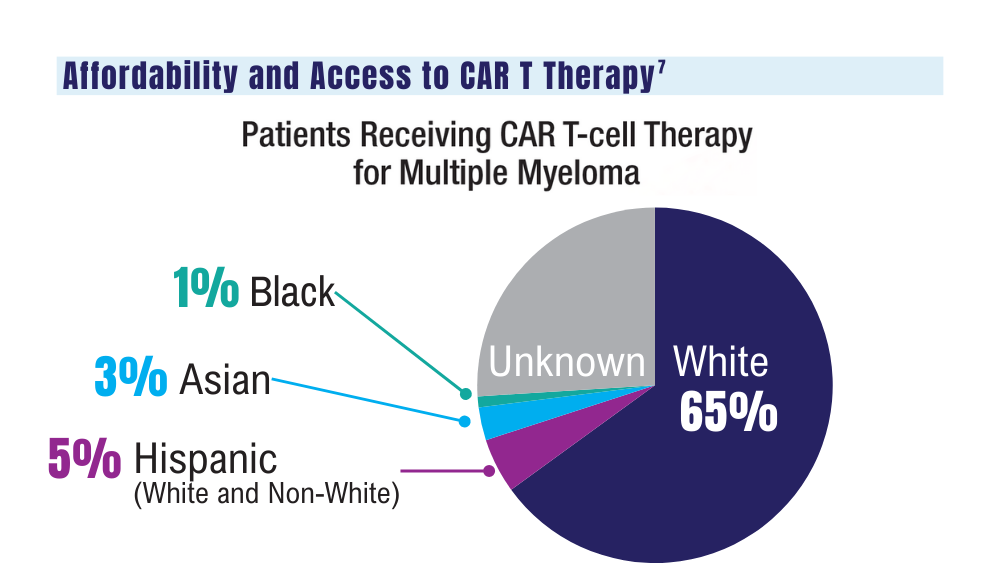

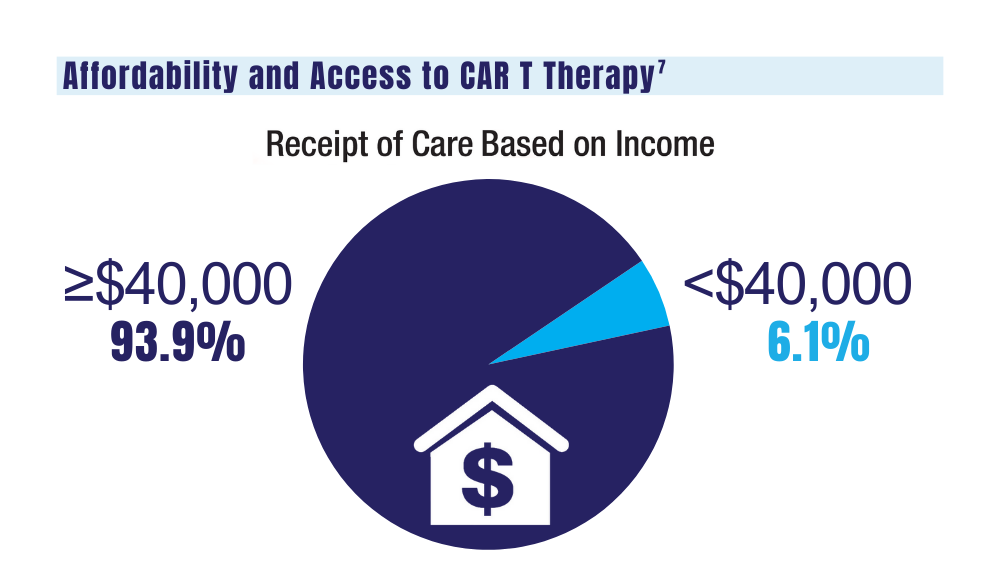

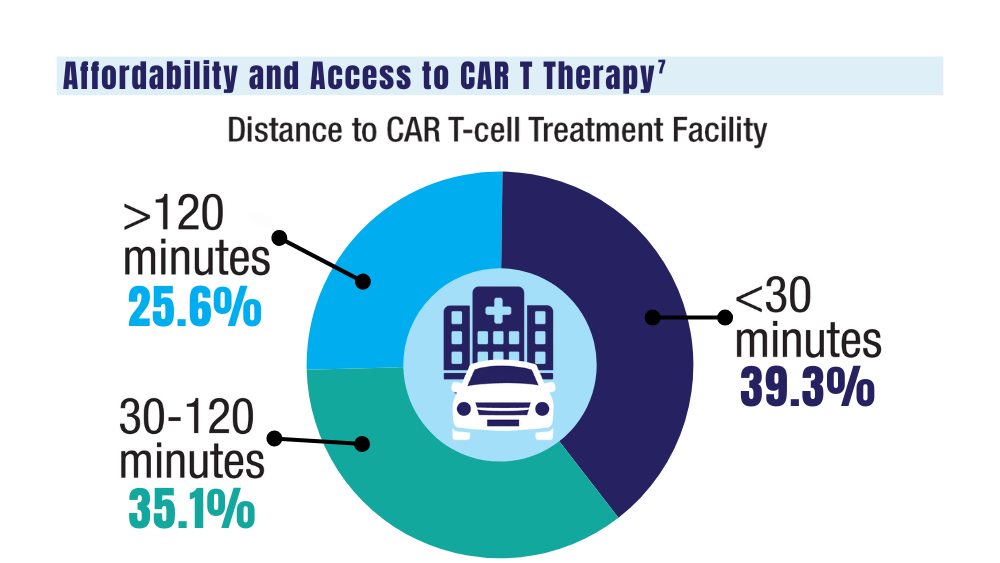

7. Ahmed N, Shahzad M, Shippey E, et al. Socioeconomic and racial disparity in chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy access. Transplant Cell Ther. 2022;28(7):358-364. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2022.04.008

1. Mahmood S, Gupta P, Ma H. Impact of time period of diagnosis, race, and military exposures on the survival of US military veterans with multiple myeloma and/or plasmacytoma. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16 suppl). Abstract e20061. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2023.41.16_suppl.e20061

2. National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: myeloma. Accessed January 2, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html

3. Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Terpos E, et al. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up [published correction appears in Ann Oncol. 2022;33(1):117]. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(3):309-322. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.014

4. Su CT, Chen JC, Sussman JB. Virtual care for multiple myeloma in the COVID-19 era: interrupted time series analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Leuk Lymphoma. 2023;64(5):1035-1039. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2023.2189989

5. O’Donnell EK, Shapiro YN, Yee AJ, et al. Quality of life, psychological distress, and prognostic perceptions in patients with multiple myeloma. Cancer. 2022;128(10):1996-2004. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34134

6. O’Donnell EK, Shapiro YN, Yee AJ, et al. Quality of life, psychological distress, and prognostic perceptions in caregivers of patients with multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 2022;6(17):4967-4974. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022007127

7. Ahmed N, Shahzad M, Shippey E, et al. Socioeconomic and racial disparity in chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy access. Transplant Cell Ther. 2022;28(7):358-364. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2022.04.008

1. Mahmood S, Gupta P, Ma H. Impact of time period of diagnosis, race, and military exposures on the survival of US military veterans with multiple myeloma and/or plasmacytoma. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16 suppl). Abstract e20061. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2023.41.16_suppl.e20061

2. National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: myeloma. Accessed January 2, 2024. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/mulmy.html

3. Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Terpos E, et al. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up [published correction appears in Ann Oncol. 2022;33(1):117]. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(3):309-322. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.014

4. Su CT, Chen JC, Sussman JB. Virtual care for multiple myeloma in the COVID-19 era: interrupted time series analysis of Veterans Health Administration data. Leuk Lymphoma. 2023;64(5):1035-1039. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2023.2189989

5. O’Donnell EK, Shapiro YN, Yee AJ, et al. Quality of life, psychological distress, and prognostic perceptions in patients with multiple myeloma. Cancer. 2022;128(10):1996-2004. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34134

6. O’Donnell EK, Shapiro YN, Yee AJ, et al. Quality of life, psychological distress, and prognostic perceptions in caregivers of patients with multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 2022;6(17):4967-4974. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022007127

7. Ahmed N, Shahzad M, Shippey E, et al. Socioeconomic and racial disparity in chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy access. Transplant Cell Ther. 2022;28(7):358-364. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2022.04.008

Cancer Data Trends 2024

The annual issue of Cancer Data Trends, produced in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), highlights the latest research in some of the top cancers impacting US veterans.

Click to view the Digital Edition.

In this issue:

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Special care for veterans, changes in staging, and biomarkers for early diagnosis

Lung Cancer

Guideline updates and racial disparities in veterans

Multiple Myeloma

Improving survival in the VA

Colorectal Cancer

Barriers to follow-up colonoscopies after FIT testing

B-Cell Lymphomas

Findings from the VA's National TeleOncology Program and recent therapy updates

Breast Cancer

A look at the VA's Risk Assessment Pipeline and incidence among veterans vs the general population

Genitourinary Cancers

Molecular testing in prostate cancer, improving survival for metastatic RCC, and links between bladder cancer and Agent Orange exposure

The annual issue of Cancer Data Trends, produced in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), highlights the latest research in some of the top cancers impacting US veterans.

Click to view the Digital Edition.

In this issue:

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Special care for veterans, changes in staging, and biomarkers for early diagnosis

Lung Cancer

Guideline updates and racial disparities in veterans

Multiple Myeloma

Improving survival in the VA

Colorectal Cancer

Barriers to follow-up colonoscopies after FIT testing

B-Cell Lymphomas

Findings from the VA's National TeleOncology Program and recent therapy updates

Breast Cancer

A look at the VA's Risk Assessment Pipeline and incidence among veterans vs the general population

Genitourinary Cancers

Molecular testing in prostate cancer, improving survival for metastatic RCC, and links between bladder cancer and Agent Orange exposure

The annual issue of Cancer Data Trends, produced in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), highlights the latest research in some of the top cancers impacting US veterans.

Click to view the Digital Edition.

In this issue:

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Special care for veterans, changes in staging, and biomarkers for early diagnosis

Lung Cancer

Guideline updates and racial disparities in veterans

Multiple Myeloma

Improving survival in the VA

Colorectal Cancer

Barriers to follow-up colonoscopies after FIT testing

B-Cell Lymphomas

Findings from the VA's National TeleOncology Program and recent therapy updates

Breast Cancer

A look at the VA's Risk Assessment Pipeline and incidence among veterans vs the general population

Genitourinary Cancers

Molecular testing in prostate cancer, improving survival for metastatic RCC, and links between bladder cancer and Agent Orange exposure

Consider These Factors in an Academic Radiation Oncology Position

TOPLINE:

— and accept an offer if the practice is “great” in at least two of those areas and “good” in the third, experts say in a recent editorial.

METHODOLOGY:

- Many physicians choose to go into academic medicine because they want to stay involved in research and education while still treating patients.

- However, graduating radiation oncology residents often lack or have limited guidance on what to look for in a prospective job and how to assess their contract.

- This recent editorial provides guidance to radiation oncologists seeking academic positions. The authors advise prospective employees to evaluate three main factors — compensation, daily duties, and location — as well as provide tips for identifying red flags in each category.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compensation: Prospective faculty should assess both direct compensation, that is, salary, and indirect compensation, which typically includes retirement contributions and other perks. For direct compensation, what is the base salary? Is extra work compensated? How does the salary offer measure up to salary data reported by national agencies? Also: Don’t overlook uncompensated duties, such as time in tumor boards or in meetings, which may be time-consuming, and make sure compensation terms are clearly delineated in a contract and equitable among physicians in a specific rank.

- Daily duties: When it comes to daily life on the job, a prospective employee should consider many factors, including the cancer center’s excitement to hire you, the reputation of the faculty and leaders at the organization, employee turnover rates, diversity among faculty, and the time line of career advancement.

- Location: The location of the job encompasses the geography — such as distance from home to work, the number of practices covered, cost of living, and the area itself — as well as the atmosphere for conducting research and publishing.

- Finally, carefully review the job contract. All the key aspects of the job, including compensation and benefits, should be clearly stated in the contract to “improve communication of expectations.”

IN PRACTICE:

“A prospective faculty member can ask 100 questions, but they can’t make 100 demands; consideration of the three domains can help to focus negotiation efforts where the efforts are needed,” the authors noted.

SOURCE:

This editorial, led by Nicholas G. Zaorsky from the Department of Radiation Oncology, University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio, was published online in Practical Radiation Oncology

DISCLOSURES:

The lead author declared being supported by the American Cancer Society and National Institutes of Health. He also reported having ties with many other sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

— and accept an offer if the practice is “great” in at least two of those areas and “good” in the third, experts say in a recent editorial.

METHODOLOGY:

- Many physicians choose to go into academic medicine because they want to stay involved in research and education while still treating patients.

- However, graduating radiation oncology residents often lack or have limited guidance on what to look for in a prospective job and how to assess their contract.

- This recent editorial provides guidance to radiation oncologists seeking academic positions. The authors advise prospective employees to evaluate three main factors — compensation, daily duties, and location — as well as provide tips for identifying red flags in each category.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compensation: Prospective faculty should assess both direct compensation, that is, salary, and indirect compensation, which typically includes retirement contributions and other perks. For direct compensation, what is the base salary? Is extra work compensated? How does the salary offer measure up to salary data reported by national agencies? Also: Don’t overlook uncompensated duties, such as time in tumor boards or in meetings, which may be time-consuming, and make sure compensation terms are clearly delineated in a contract and equitable among physicians in a specific rank.

- Daily duties: When it comes to daily life on the job, a prospective employee should consider many factors, including the cancer center’s excitement to hire you, the reputation of the faculty and leaders at the organization, employee turnover rates, diversity among faculty, and the time line of career advancement.

- Location: The location of the job encompasses the geography — such as distance from home to work, the number of practices covered, cost of living, and the area itself — as well as the atmosphere for conducting research and publishing.

- Finally, carefully review the job contract. All the key aspects of the job, including compensation and benefits, should be clearly stated in the contract to “improve communication of expectations.”

IN PRACTICE:

“A prospective faculty member can ask 100 questions, but they can’t make 100 demands; consideration of the three domains can help to focus negotiation efforts where the efforts are needed,” the authors noted.

SOURCE:

This editorial, led by Nicholas G. Zaorsky from the Department of Radiation Oncology, University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio, was published online in Practical Radiation Oncology

DISCLOSURES:

The lead author declared being supported by the American Cancer Society and National Institutes of Health. He also reported having ties with many other sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

— and accept an offer if the practice is “great” in at least two of those areas and “good” in the third, experts say in a recent editorial.

METHODOLOGY:

- Many physicians choose to go into academic medicine because they want to stay involved in research and education while still treating patients.

- However, graduating radiation oncology residents often lack or have limited guidance on what to look for in a prospective job and how to assess their contract.

- This recent editorial provides guidance to radiation oncologists seeking academic positions. The authors advise prospective employees to evaluate three main factors — compensation, daily duties, and location — as well as provide tips for identifying red flags in each category.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compensation: Prospective faculty should assess both direct compensation, that is, salary, and indirect compensation, which typically includes retirement contributions and other perks. For direct compensation, what is the base salary? Is extra work compensated? How does the salary offer measure up to salary data reported by national agencies? Also: Don’t overlook uncompensated duties, such as time in tumor boards or in meetings, which may be time-consuming, and make sure compensation terms are clearly delineated in a contract and equitable among physicians in a specific rank.

- Daily duties: When it comes to daily life on the job, a prospective employee should consider many factors, including the cancer center’s excitement to hire you, the reputation of the faculty and leaders at the organization, employee turnover rates, diversity among faculty, and the time line of career advancement.

- Location: The location of the job encompasses the geography — such as distance from home to work, the number of practices covered, cost of living, and the area itself — as well as the atmosphere for conducting research and publishing.

- Finally, carefully review the job contract. All the key aspects of the job, including compensation and benefits, should be clearly stated in the contract to “improve communication of expectations.”

IN PRACTICE:

“A prospective faculty member can ask 100 questions, but they can’t make 100 demands; consideration of the three domains can help to focus negotiation efforts where the efforts are needed,” the authors noted.

SOURCE:

This editorial, led by Nicholas G. Zaorsky from the Department of Radiation Oncology, University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center, Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio, was published online in Practical Radiation Oncology

DISCLOSURES:

The lead author declared being supported by the American Cancer Society and National Institutes of Health. He also reported having ties with many other sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Look Beyond BMI: Metabolic Factors’ Link to Cancer Explained

The new research finds that adults with persistent metabolic syndrome that worsens over time are at increased risk for any type of cancer.

The conditions that make up metabolic syndrome (high blood pressure, high blood sugar, increased abdominal adiposity, and high cholesterol and triglycerides) have been associated with an increased risk of diseases, including heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes, wrote Li Deng, PhD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, and colleagues.

However, a single assessment of metabolic syndrome at one point in time is inadequate to show an association with cancer risk over time, they said. In the current study, the researchers used models to examine the association between trajectory patterns of metabolic syndrome over time and the risk of overall and specific cancer types. They also examined the impact of chronic inflammation concurrent with metabolic syndrome.

What We Know About Metabolic Syndrome and Cancer Risk

A systematic review and meta-analysis published in Diabetes Care in 2012 showed an association between the presence of metabolic syndrome and an increased risk of various cancers including liver, bladder, pancreatic, breast, and colorectal.

More recently, a 2020 study published in Diabetes showed evidence of increased risk for certain cancers (pancreatic, kidney, uterine, cervical) but no increased risk for cancer overall.

In addition, a 2022 study by some of the current study researchers of the same Chinese cohort focused on the role of inflammation in combination with metabolic syndrome on colorectal cancer specifically, and found an increased risk for cancer when both metabolic syndrome and inflammation were present.

However, the reasons for this association between metabolic syndrome and cancer remain unclear, and the effect of the fluctuating nature of metabolic syndrome over time on long-term cancer risk has not been explored, the researchers wrote.

“There is emerging evidence that even normal weight individuals who are metabolically unhealthy may be at an elevated cancer risk, and we need better metrics to define the underlying metabolic dysfunction in obesity,” Sheetal Hardikar, MBBS, PhD, MPH, an investigator at the Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah, said in an interview.

Dr. Hardikar, who serves as assistant professor in the department of population health sciences at the University of Utah, was not involved in the current study. She and her colleagues published a research paper on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2023 that showed an increased risk of obesity-related cancer.

What New Study Adds to Related Research

Previous studies have consistently reported an approximately 30% increased risk of cancer with metabolic syndrome, Dr. Hardikar said. “What is unique about this study is the examination of metabolic syndrome trajectories over four years, and not just the presence of metabolic syndrome at one point in time,” she said.

In the new study, published in Cancer on March 11 (doi: 10.1002/cncr.35235), 44,115 adults in China were separated into four trajectories based on metabolic syndrome scores for the period from 2006 to 2010. The scores were based on clinical evidence of metabolic syndrome, defined using the International Diabetes Federation criteria of central obesity and the presence of at least two other factors including increased triglycerides, decreased HDL cholesterol, high blood pressure (or treatment for previously diagnosed hypertension), and increased fasting plasma glucose (or previous diagnosis of type 2 diabetes).

The average age of the participants was 49 years; the mean body mass index ranged from approximately 22 kg/m2 in the low-stable group to approximately 28 kg/m2 in the elevated-increasing group.

The four trajectories of metabolic syndrome were low-stable (10.56% of participants), moderate-low (40.84%), moderate-high (41.46%), and elevated-increasing (7.14%), based on trends from the individuals’ initial physical exams on entering the study.

Over a median follow-up period of 9.4 years (from 2010 to 2021), 2,271 cancer diagnoses were reported in the study population. Those with an elevated-increasing metabolic syndrome trajectory had 1.3 times the risk of any cancer compared with those in the low-stable group. Risk for breast cancer, endometrial cancer, kidney cancer, colorectal cancer, and liver cancer in the highest trajectory group were 2.1, 3.3, 4.5, 2.5, and 1.6 times higher, respectively, compared to the lowest group. The increased risk in the elevated-trajectory group for all cancer types persisted when the low-stable, moderate-low, and moderate-high trajectory pattern groups were combined.

The researchers also examined the impact of chronic inflammation and found that individuals with persistently high metabolic syndrome scores and concurrent chronic inflammation had the highest risks of breast, endometrial, colon, and liver cancer. However, individuals with persistently high metabolic syndrome scores and no concurrent chronic inflammation had the highest risk of kidney cancer.

What Are the Limitations of This Research?

The researchers of the current study acknowledged the lack of information on other causes of cancer, including dietary habits, hepatitis C infection, and Helicobacter pylori infection. Other limitations include the focus only on individuals from a single community of mainly middle-aged men in China that may not generalize to other populations.

Also, the metabolic syndrome trajectories did not change much over time, which may be related to the short 4-year study period.

Using the International Diabetes Federation criteria was another limitation, because it prevented the assessment of cancer risk in normal weight individuals with metabolic dysfunction, Dr. Hardikar noted.

Does Metabolic Syndrome Cause Cancer?

“This research suggests that proactive and continuous management of metabolic syndrome may serve as an essential strategy in preventing cancer,” senior author Han-Ping Shi, MD, PhD, of Capital Medical University in Beijing, noted in a statement on the study.

More research is needed to assess the impact of these interventions on cancer risk. However, the data from the current study can guide future research that may lead to more targeted treatments and more effective preventive strategies, he continued.

“Current evidence based on this study and many other reports strongly suggests an increased risk for cancer associated with metabolic syndrome,” Dr. Hardikar said in an interview. The data serve as a reminder to clinicians to look beyond BMI as the only measure of obesity, and to consider metabolic factors together to identify individuals at increased risk for cancer, she said.

“We must continue to educate patients about obesity and all the chronic conditions it may lead to, but we cannot ignore this emerging phenotype of being of normal weight but metabolically unhealthy,” Dr. Hardikar emphasized.

What Additional Research is Needed?

Looking ahead, “we need well-designed interventions to test causality for metabolic syndrome and cancer risk, though the evidence from the observational studies is very strong,” Dr. Hardikar said.

In addition, a consensus is needed to better define metabolic dysfunction,and to explore cancer risk in normal weight but metabolically unhealthy individuals, she said.

The study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China. The researchers and Dr. Hardikar had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The new research finds that adults with persistent metabolic syndrome that worsens over time are at increased risk for any type of cancer.

The conditions that make up metabolic syndrome (high blood pressure, high blood sugar, increased abdominal adiposity, and high cholesterol and triglycerides) have been associated with an increased risk of diseases, including heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes, wrote Li Deng, PhD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, and colleagues.

However, a single assessment of metabolic syndrome at one point in time is inadequate to show an association with cancer risk over time, they said. In the current study, the researchers used models to examine the association between trajectory patterns of metabolic syndrome over time and the risk of overall and specific cancer types. They also examined the impact of chronic inflammation concurrent with metabolic syndrome.

What We Know About Metabolic Syndrome and Cancer Risk

A systematic review and meta-analysis published in Diabetes Care in 2012 showed an association between the presence of metabolic syndrome and an increased risk of various cancers including liver, bladder, pancreatic, breast, and colorectal.

More recently, a 2020 study published in Diabetes showed evidence of increased risk for certain cancers (pancreatic, kidney, uterine, cervical) but no increased risk for cancer overall.

In addition, a 2022 study by some of the current study researchers of the same Chinese cohort focused on the role of inflammation in combination with metabolic syndrome on colorectal cancer specifically, and found an increased risk for cancer when both metabolic syndrome and inflammation were present.

However, the reasons for this association between metabolic syndrome and cancer remain unclear, and the effect of the fluctuating nature of metabolic syndrome over time on long-term cancer risk has not been explored, the researchers wrote.

“There is emerging evidence that even normal weight individuals who are metabolically unhealthy may be at an elevated cancer risk, and we need better metrics to define the underlying metabolic dysfunction in obesity,” Sheetal Hardikar, MBBS, PhD, MPH, an investigator at the Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah, said in an interview.

Dr. Hardikar, who serves as assistant professor in the department of population health sciences at the University of Utah, was not involved in the current study. She and her colleagues published a research paper on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2023 that showed an increased risk of obesity-related cancer.

What New Study Adds to Related Research

Previous studies have consistently reported an approximately 30% increased risk of cancer with metabolic syndrome, Dr. Hardikar said. “What is unique about this study is the examination of metabolic syndrome trajectories over four years, and not just the presence of metabolic syndrome at one point in time,” she said.

In the new study, published in Cancer on March 11 (doi: 10.1002/cncr.35235), 44,115 adults in China were separated into four trajectories based on metabolic syndrome scores for the period from 2006 to 2010. The scores were based on clinical evidence of metabolic syndrome, defined using the International Diabetes Federation criteria of central obesity and the presence of at least two other factors including increased triglycerides, decreased HDL cholesterol, high blood pressure (or treatment for previously diagnosed hypertension), and increased fasting plasma glucose (or previous diagnosis of type 2 diabetes).

The average age of the participants was 49 years; the mean body mass index ranged from approximately 22 kg/m2 in the low-stable group to approximately 28 kg/m2 in the elevated-increasing group.

The four trajectories of metabolic syndrome were low-stable (10.56% of participants), moderate-low (40.84%), moderate-high (41.46%), and elevated-increasing (7.14%), based on trends from the individuals’ initial physical exams on entering the study.

Over a median follow-up period of 9.4 years (from 2010 to 2021), 2,271 cancer diagnoses were reported in the study population. Those with an elevated-increasing metabolic syndrome trajectory had 1.3 times the risk of any cancer compared with those in the low-stable group. Risk for breast cancer, endometrial cancer, kidney cancer, colorectal cancer, and liver cancer in the highest trajectory group were 2.1, 3.3, 4.5, 2.5, and 1.6 times higher, respectively, compared to the lowest group. The increased risk in the elevated-trajectory group for all cancer types persisted when the low-stable, moderate-low, and moderate-high trajectory pattern groups were combined.

The researchers also examined the impact of chronic inflammation and found that individuals with persistently high metabolic syndrome scores and concurrent chronic inflammation had the highest risks of breast, endometrial, colon, and liver cancer. However, individuals with persistently high metabolic syndrome scores and no concurrent chronic inflammation had the highest risk of kidney cancer.

What Are the Limitations of This Research?

The researchers of the current study acknowledged the lack of information on other causes of cancer, including dietary habits, hepatitis C infection, and Helicobacter pylori infection. Other limitations include the focus only on individuals from a single community of mainly middle-aged men in China that may not generalize to other populations.