User login

Frailty may affect the expression of dementia

according to research published online ahead of print Jan. 17 in Lancet Neurology. Data suggest that frailty reduces the threshold for Alzheimer’s disease pathology to cause cognitive decline. Frailty also may contribute to other mechanisms that cause dementia, such as inflammation and immunosenescence, said the investigators.

“While more research is needed, given that frailty is potentially reversible, it is possible that helping people to maintain function and independence in later life could reduce both dementia risk and the severity of debilitating symptoms common in this disease,” said Professor Kenneth Rockwood, MD, of the Nova Scotia Health Authority and Dalhousie University in Halifax, N.S., in a press release.

More susceptible to dementia?

The presence of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles is not a sufficient condition for the clinical expression of dementia. Some patients with a high degree of Alzheimer’s disease pathology have no apparent cognitive decline. Other factors therefore may modify the relationship between pathology and dementia.

Most people who develop Alzheimer’s disease dementia are older than 65 years, and many of these patients are frail. Frailty is understood as a decreased physiologic reserve and an increased risk for adverse health outcomes. Dr. Rockwood and his colleagues hypothesized that frailty moderates the clinical expression of dementia in relation to Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

To test their hypothesis, the investigators performed a cross-sectional analysis of data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project, which collects clinical and pathologic data from adults older than 59 years without dementia at baseline who live in Illinois. Since 1997, participants have undergone annual clinical and neuropsychological evaluations, and the cohort has been followed for 21 years. For their analysis, Dr. Rockwood and his colleagues included participants without dementia or with Alzheimer’s dementia at their last clinical assessment. Eligible participants had died, and complete autopsy data were available for them.

The researchers measured Alzheimer’s disease pathology using a summary measure of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic and diffuse plaques. Clinical diagnoses of Alzheimer’s dementia were based on clinician consensus. Dr. Rockwood and his colleagues retrospectively created a 41-item frailty index from variables (e.g., symptoms, signs, comorbidities, and function) that were obtained at each clinical evaluation.

Logistic regression and moderation modeling allowed the investigators to evaluate relationships between Alzheimer’s disease pathology, frailty, and Alzheimer’s dementia. Dr. Rockwood and hus colleagues adjusted all analyses for age, sex, and education.

In all, 456 participants were included in the analysis. The sample’s mean age at death was 89.7 years, and 69% of participants were women. At participants’ last clinical assessment, 242 (53%) had possible or probable Alzheimer’s dementia.

The sample’s mean frailty index was 0.42. The median frailty index was 0.41, a value similar to the threshold commonly used to distinguish between moderate and severe frailty. People with high frailty index scores (i.e., 0.41 or greater) were older, had lower Mini-Mental State Examination scores, were more likely to have a diagnosis of dementia, and had a higher Braak stage than those with moderate or low frailty index scores.

Significant interaction between frailty and Alzheimer’s disease

After the investigators adjusted for age, sex, and education, frailty (odds ratio, 1.76) and Alzheimer’s disease pathology (OR, 4.81) were independently associated with Alzheimer’s dementia. When the investigators added frailty to the model for the relationship between Alzheimer’s disease pathology and Alzheimer’s dementia, the model fit improved. They found a significant interaction between frailty and Alzheimer’s disease pathology (OR, 0.73). People with a low amount of frailty were better able to tolerate Alzheimer’s disease pathology, and people with higher amounts of frailty were more likely to have more Alzheimer’s disease pathology and clinical dementia.

One of the study’s limitations is that it is a secondary analysis, according to Dr. Rockwood and his colleagues. In addition, frailty was measured close to participants’ time of death, and the measurements may thus reflect terminal decline. Participant deaths resulting from causes other than those related to dementia might have confounded the results. Finally, the sample came entirely from people living in retirement homes in Illinois, which might have introduced bias. Future research should use a population-based sample, said the authors.

Frailty could be a basis for risk stratification and could inform the management and treatment of older adults, said Dr. Rockwood and his colleagues. The study results have “the potential to improve our understanding of disease expression, explain failures in pharmacologic treatment, and aid in the development of more appropriate therapeutic targets, approaches, and measurements of success,” they concluded.

The study had no source of funding. The authors reported receiving fees and grants from DGI Clinical, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Sanofi. Authors also received support from governmental bodies such as the National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

SOURCE: Wallace LMK et al. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:177-84.

The results of the study by Rockwood and colleagues confirm the strong links between frailty and Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, said Francesco Panza, MD, PhD, of the University of Bari (Italy) Aldo Moro, and his colleagues in an accompanying editorial.

Frailty is primary or preclinical when it is not directly associated with a specific disease or when the patient has no substantial disability. Frailty is considered secondary or clinical when it is associated with known comorbidities (e.g., cardiovascular disease or depression). “This distinction is central in identifying frailty phenotypes with the potential to predict and prevent dementia, using novel models of risk that introduce modifiable factors,” wrote Dr. Panza and his colleagues.

“In light of current knowledge on the cognitive frailty phenotype, secondary preventive strategies for cognitive impairment and physical frailty can be suggested,” they added. “For instance, individualized multidomain interventions can target physical, nutritional, cognitive, and psychological domains that might delay the progression to overt dementia and secondary occurrence of adverse health-related outcomes, such as disability, hospitalization, and mortality.”

Dr. Panza, Madia Lozupone, MD, PhD , and Giancarlo Logroscino, MD, PhD , are affiliated with the neurodegenerative disease unit in the department of basic medicine, neuroscience, and sense organs at the University of Bari (Italy) Aldo Moro. The above remarks come from an editorial that these authors wrote to accompany the study by Rockwood et al. The authors declared no competing interests.

The results of the study by Rockwood and colleagues confirm the strong links between frailty and Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, said Francesco Panza, MD, PhD, of the University of Bari (Italy) Aldo Moro, and his colleagues in an accompanying editorial.

Frailty is primary or preclinical when it is not directly associated with a specific disease or when the patient has no substantial disability. Frailty is considered secondary or clinical when it is associated with known comorbidities (e.g., cardiovascular disease or depression). “This distinction is central in identifying frailty phenotypes with the potential to predict and prevent dementia, using novel models of risk that introduce modifiable factors,” wrote Dr. Panza and his colleagues.

“In light of current knowledge on the cognitive frailty phenotype, secondary preventive strategies for cognitive impairment and physical frailty can be suggested,” they added. “For instance, individualized multidomain interventions can target physical, nutritional, cognitive, and psychological domains that might delay the progression to overt dementia and secondary occurrence of adverse health-related outcomes, such as disability, hospitalization, and mortality.”

Dr. Panza, Madia Lozupone, MD, PhD , and Giancarlo Logroscino, MD, PhD , are affiliated with the neurodegenerative disease unit in the department of basic medicine, neuroscience, and sense organs at the University of Bari (Italy) Aldo Moro. The above remarks come from an editorial that these authors wrote to accompany the study by Rockwood et al. The authors declared no competing interests.

The results of the study by Rockwood and colleagues confirm the strong links between frailty and Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, said Francesco Panza, MD, PhD, of the University of Bari (Italy) Aldo Moro, and his colleagues in an accompanying editorial.

Frailty is primary or preclinical when it is not directly associated with a specific disease or when the patient has no substantial disability. Frailty is considered secondary or clinical when it is associated with known comorbidities (e.g., cardiovascular disease or depression). “This distinction is central in identifying frailty phenotypes with the potential to predict and prevent dementia, using novel models of risk that introduce modifiable factors,” wrote Dr. Panza and his colleagues.

“In light of current knowledge on the cognitive frailty phenotype, secondary preventive strategies for cognitive impairment and physical frailty can be suggested,” they added. “For instance, individualized multidomain interventions can target physical, nutritional, cognitive, and psychological domains that might delay the progression to overt dementia and secondary occurrence of adverse health-related outcomes, such as disability, hospitalization, and mortality.”

Dr. Panza, Madia Lozupone, MD, PhD , and Giancarlo Logroscino, MD, PhD , are affiliated with the neurodegenerative disease unit in the department of basic medicine, neuroscience, and sense organs at the University of Bari (Italy) Aldo Moro. The above remarks come from an editorial that these authors wrote to accompany the study by Rockwood et al. The authors declared no competing interests.

according to research published online ahead of print Jan. 17 in Lancet Neurology. Data suggest that frailty reduces the threshold for Alzheimer’s disease pathology to cause cognitive decline. Frailty also may contribute to other mechanisms that cause dementia, such as inflammation and immunosenescence, said the investigators.

“While more research is needed, given that frailty is potentially reversible, it is possible that helping people to maintain function and independence in later life could reduce both dementia risk and the severity of debilitating symptoms common in this disease,” said Professor Kenneth Rockwood, MD, of the Nova Scotia Health Authority and Dalhousie University in Halifax, N.S., in a press release.

More susceptible to dementia?

The presence of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles is not a sufficient condition for the clinical expression of dementia. Some patients with a high degree of Alzheimer’s disease pathology have no apparent cognitive decline. Other factors therefore may modify the relationship between pathology and dementia.

Most people who develop Alzheimer’s disease dementia are older than 65 years, and many of these patients are frail. Frailty is understood as a decreased physiologic reserve and an increased risk for adverse health outcomes. Dr. Rockwood and his colleagues hypothesized that frailty moderates the clinical expression of dementia in relation to Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

To test their hypothesis, the investigators performed a cross-sectional analysis of data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project, which collects clinical and pathologic data from adults older than 59 years without dementia at baseline who live in Illinois. Since 1997, participants have undergone annual clinical and neuropsychological evaluations, and the cohort has been followed for 21 years. For their analysis, Dr. Rockwood and his colleagues included participants without dementia or with Alzheimer’s dementia at their last clinical assessment. Eligible participants had died, and complete autopsy data were available for them.

The researchers measured Alzheimer’s disease pathology using a summary measure of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic and diffuse plaques. Clinical diagnoses of Alzheimer’s dementia were based on clinician consensus. Dr. Rockwood and his colleagues retrospectively created a 41-item frailty index from variables (e.g., symptoms, signs, comorbidities, and function) that were obtained at each clinical evaluation.

Logistic regression and moderation modeling allowed the investigators to evaluate relationships between Alzheimer’s disease pathology, frailty, and Alzheimer’s dementia. Dr. Rockwood and hus colleagues adjusted all analyses for age, sex, and education.

In all, 456 participants were included in the analysis. The sample’s mean age at death was 89.7 years, and 69% of participants were women. At participants’ last clinical assessment, 242 (53%) had possible or probable Alzheimer’s dementia.

The sample’s mean frailty index was 0.42. The median frailty index was 0.41, a value similar to the threshold commonly used to distinguish between moderate and severe frailty. People with high frailty index scores (i.e., 0.41 or greater) were older, had lower Mini-Mental State Examination scores, were more likely to have a diagnosis of dementia, and had a higher Braak stage than those with moderate or low frailty index scores.

Significant interaction between frailty and Alzheimer’s disease

After the investigators adjusted for age, sex, and education, frailty (odds ratio, 1.76) and Alzheimer’s disease pathology (OR, 4.81) were independently associated with Alzheimer’s dementia. When the investigators added frailty to the model for the relationship between Alzheimer’s disease pathology and Alzheimer’s dementia, the model fit improved. They found a significant interaction between frailty and Alzheimer’s disease pathology (OR, 0.73). People with a low amount of frailty were better able to tolerate Alzheimer’s disease pathology, and people with higher amounts of frailty were more likely to have more Alzheimer’s disease pathology and clinical dementia.

One of the study’s limitations is that it is a secondary analysis, according to Dr. Rockwood and his colleagues. In addition, frailty was measured close to participants’ time of death, and the measurements may thus reflect terminal decline. Participant deaths resulting from causes other than those related to dementia might have confounded the results. Finally, the sample came entirely from people living in retirement homes in Illinois, which might have introduced bias. Future research should use a population-based sample, said the authors.

Frailty could be a basis for risk stratification and could inform the management and treatment of older adults, said Dr. Rockwood and his colleagues. The study results have “the potential to improve our understanding of disease expression, explain failures in pharmacologic treatment, and aid in the development of more appropriate therapeutic targets, approaches, and measurements of success,” they concluded.

The study had no source of funding. The authors reported receiving fees and grants from DGI Clinical, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Sanofi. Authors also received support from governmental bodies such as the National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

SOURCE: Wallace LMK et al. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:177-84.

according to research published online ahead of print Jan. 17 in Lancet Neurology. Data suggest that frailty reduces the threshold for Alzheimer’s disease pathology to cause cognitive decline. Frailty also may contribute to other mechanisms that cause dementia, such as inflammation and immunosenescence, said the investigators.

“While more research is needed, given that frailty is potentially reversible, it is possible that helping people to maintain function and independence in later life could reduce both dementia risk and the severity of debilitating symptoms common in this disease,” said Professor Kenneth Rockwood, MD, of the Nova Scotia Health Authority and Dalhousie University in Halifax, N.S., in a press release.

More susceptible to dementia?

The presence of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles is not a sufficient condition for the clinical expression of dementia. Some patients with a high degree of Alzheimer’s disease pathology have no apparent cognitive decline. Other factors therefore may modify the relationship between pathology and dementia.

Most people who develop Alzheimer’s disease dementia are older than 65 years, and many of these patients are frail. Frailty is understood as a decreased physiologic reserve and an increased risk for adverse health outcomes. Dr. Rockwood and his colleagues hypothesized that frailty moderates the clinical expression of dementia in relation to Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

To test their hypothesis, the investigators performed a cross-sectional analysis of data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project, which collects clinical and pathologic data from adults older than 59 years without dementia at baseline who live in Illinois. Since 1997, participants have undergone annual clinical and neuropsychological evaluations, and the cohort has been followed for 21 years. For their analysis, Dr. Rockwood and his colleagues included participants without dementia or with Alzheimer’s dementia at their last clinical assessment. Eligible participants had died, and complete autopsy data were available for them.

The researchers measured Alzheimer’s disease pathology using a summary measure of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic and diffuse plaques. Clinical diagnoses of Alzheimer’s dementia were based on clinician consensus. Dr. Rockwood and his colleagues retrospectively created a 41-item frailty index from variables (e.g., symptoms, signs, comorbidities, and function) that were obtained at each clinical evaluation.

Logistic regression and moderation modeling allowed the investigators to evaluate relationships between Alzheimer’s disease pathology, frailty, and Alzheimer’s dementia. Dr. Rockwood and hus colleagues adjusted all analyses for age, sex, and education.

In all, 456 participants were included in the analysis. The sample’s mean age at death was 89.7 years, and 69% of participants were women. At participants’ last clinical assessment, 242 (53%) had possible or probable Alzheimer’s dementia.

The sample’s mean frailty index was 0.42. The median frailty index was 0.41, a value similar to the threshold commonly used to distinguish between moderate and severe frailty. People with high frailty index scores (i.e., 0.41 or greater) were older, had lower Mini-Mental State Examination scores, were more likely to have a diagnosis of dementia, and had a higher Braak stage than those with moderate or low frailty index scores.

Significant interaction between frailty and Alzheimer’s disease

After the investigators adjusted for age, sex, and education, frailty (odds ratio, 1.76) and Alzheimer’s disease pathology (OR, 4.81) were independently associated with Alzheimer’s dementia. When the investigators added frailty to the model for the relationship between Alzheimer’s disease pathology and Alzheimer’s dementia, the model fit improved. They found a significant interaction between frailty and Alzheimer’s disease pathology (OR, 0.73). People with a low amount of frailty were better able to tolerate Alzheimer’s disease pathology, and people with higher amounts of frailty were more likely to have more Alzheimer’s disease pathology and clinical dementia.

One of the study’s limitations is that it is a secondary analysis, according to Dr. Rockwood and his colleagues. In addition, frailty was measured close to participants’ time of death, and the measurements may thus reflect terminal decline. Participant deaths resulting from causes other than those related to dementia might have confounded the results. Finally, the sample came entirely from people living in retirement homes in Illinois, which might have introduced bias. Future research should use a population-based sample, said the authors.

Frailty could be a basis for risk stratification and could inform the management and treatment of older adults, said Dr. Rockwood and his colleagues. The study results have “the potential to improve our understanding of disease expression, explain failures in pharmacologic treatment, and aid in the development of more appropriate therapeutic targets, approaches, and measurements of success,” they concluded.

The study had no source of funding. The authors reported receiving fees and grants from DGI Clinical, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Sanofi. Authors also received support from governmental bodies such as the National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

SOURCE: Wallace LMK et al. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:177-84.

FROM LANCET NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Frailty modifies the association between Alzheimer’s disease pathology and Alzheimer dementia.

Major finding: Frailty index score (odds ratio, 1.76) is independently associated with dementia status.

Study details: A cross-sectional analysis of 456 deceased participants in the Rush Memory and Aging Project.

Disclosures: The study had no outside funding.

Source: Wallace LMK et al. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:177-84.

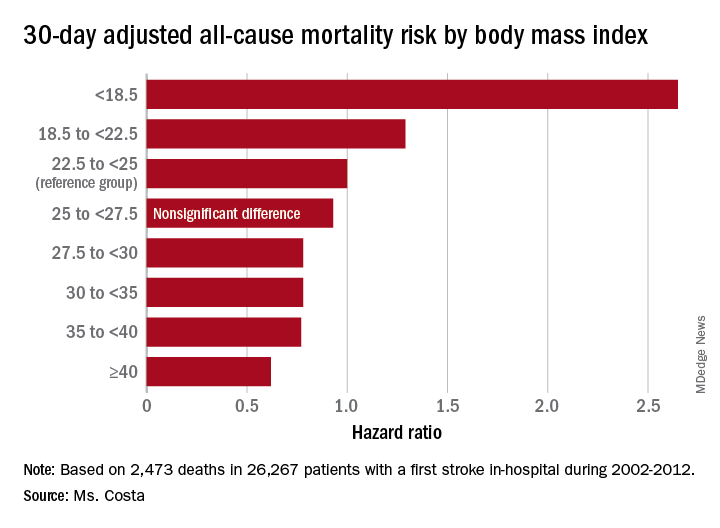

Obesity paradox applies to post-stroke mortality

CHICAGO – Overweight and obese military veterans who experienced an in-hospital stroke had a lower 30-day and 1-year all-cause mortality than did those who were normal weight in a large national study, Lauren Costa reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Underweight patients had a significantly increased mortality risk, added Ms. Costa of the VA Boston Healthcare System.

It’s yet another instance of what is known as the obesity paradox, which has also been described in patients with heart failure, acute coronary syndrome, MI, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and other conditions.

Ms. Costa presented a retrospective study of 26,267 patients in the Veterans Health Administration database who had a first stroke in-hospital during 2002-2012. There were subsequently 14,166 deaths, including 2,473 within the first 30 days and 5,854 in the first year post stroke.

Each patient’s body mass index was calculated based on the average of all BMI measurements obtained 1-24 months prior to the stroke. The analysis of the relationship between BMI and poststroke mortality included extensive statistical adjustment for potential confounders, including age, sex, smoking, cancer, dementia, peripheral artery disease, diabetes, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, use of statins, and antihypertensive therapy.

Breaking down the study population into eight BMI categories, Ms. Costa found that the adjusted risk of 30-day all-cause mortality post stroke was reduced by 22%-38% in patients in the overweight or obese groupings, compared with the reference population with a normal-weight BMI of 22.5 to less than 25 kg/m2.

One-year, all-cause mortality showed the same pattern of BMI-based significant differences.

Of deaths within 30 days post stroke, 34% were stroke-related. In an analysis restricted to that group, the evidence of an obesity paradox was attenuated. Indeed, the only BMI group with an adjusted 30-day stroke-related mortality significantly different from the normal-weight reference group were patients with Class III obesity, defined as a BMI of 40 or more. Their risk was reduced by 45%.

The obesity paradox remains a controversial issue among epidemiologists. The increased mortality associated with being underweight among patients with diseases where the obesity paradox has been documented is widely thought to be caused by frailty and/or an underlying illness not adjusted for in analyses. But the mechanism for the reduced mortality risk in overweight and obese patients seen in the VA stroke study and other studies remains unknown despite much speculation.

Ms. Costa reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

SOURCE: Costa L. Circulation. 2018;138(suppl 1): Abstract 14288.

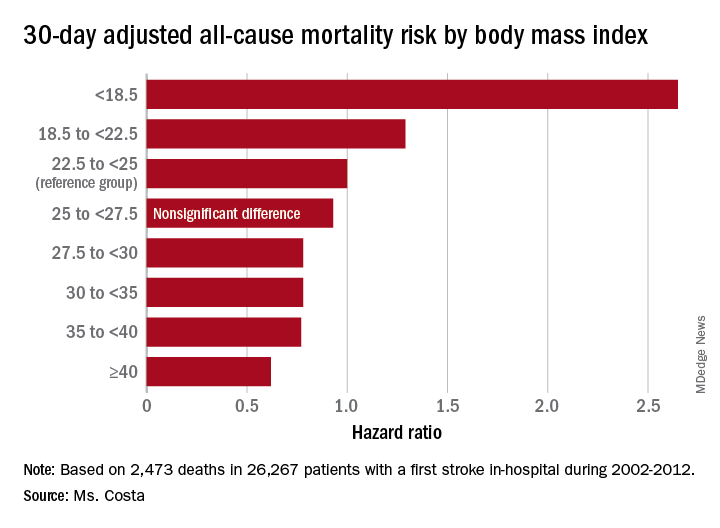

CHICAGO – Overweight and obese military veterans who experienced an in-hospital stroke had a lower 30-day and 1-year all-cause mortality than did those who were normal weight in a large national study, Lauren Costa reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Underweight patients had a significantly increased mortality risk, added Ms. Costa of the VA Boston Healthcare System.

It’s yet another instance of what is known as the obesity paradox, which has also been described in patients with heart failure, acute coronary syndrome, MI, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and other conditions.

Ms. Costa presented a retrospective study of 26,267 patients in the Veterans Health Administration database who had a first stroke in-hospital during 2002-2012. There were subsequently 14,166 deaths, including 2,473 within the first 30 days and 5,854 in the first year post stroke.

Each patient’s body mass index was calculated based on the average of all BMI measurements obtained 1-24 months prior to the stroke. The analysis of the relationship between BMI and poststroke mortality included extensive statistical adjustment for potential confounders, including age, sex, smoking, cancer, dementia, peripheral artery disease, diabetes, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, use of statins, and antihypertensive therapy.

Breaking down the study population into eight BMI categories, Ms. Costa found that the adjusted risk of 30-day all-cause mortality post stroke was reduced by 22%-38% in patients in the overweight or obese groupings, compared with the reference population with a normal-weight BMI of 22.5 to less than 25 kg/m2.

One-year, all-cause mortality showed the same pattern of BMI-based significant differences.

Of deaths within 30 days post stroke, 34% were stroke-related. In an analysis restricted to that group, the evidence of an obesity paradox was attenuated. Indeed, the only BMI group with an adjusted 30-day stroke-related mortality significantly different from the normal-weight reference group were patients with Class III obesity, defined as a BMI of 40 or more. Their risk was reduced by 45%.

The obesity paradox remains a controversial issue among epidemiologists. The increased mortality associated with being underweight among patients with diseases where the obesity paradox has been documented is widely thought to be caused by frailty and/or an underlying illness not adjusted for in analyses. But the mechanism for the reduced mortality risk in overweight and obese patients seen in the VA stroke study and other studies remains unknown despite much speculation.

Ms. Costa reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

SOURCE: Costa L. Circulation. 2018;138(suppl 1): Abstract 14288.

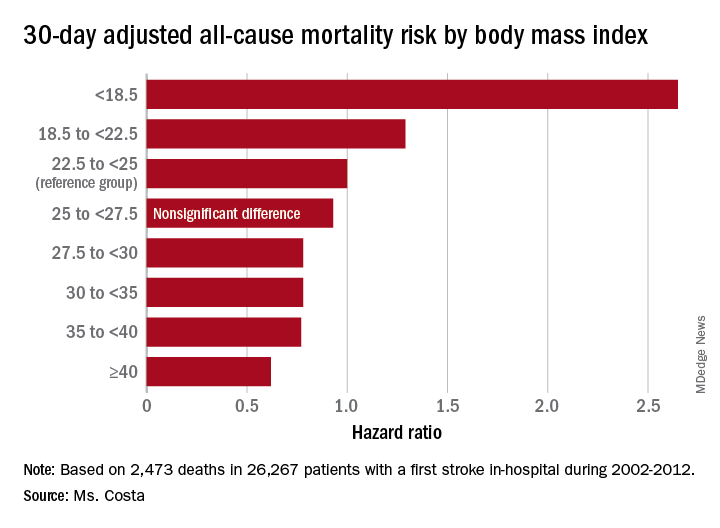

CHICAGO – Overweight and obese military veterans who experienced an in-hospital stroke had a lower 30-day and 1-year all-cause mortality than did those who were normal weight in a large national study, Lauren Costa reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Underweight patients had a significantly increased mortality risk, added Ms. Costa of the VA Boston Healthcare System.

It’s yet another instance of what is known as the obesity paradox, which has also been described in patients with heart failure, acute coronary syndrome, MI, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and other conditions.

Ms. Costa presented a retrospective study of 26,267 patients in the Veterans Health Administration database who had a first stroke in-hospital during 2002-2012. There were subsequently 14,166 deaths, including 2,473 within the first 30 days and 5,854 in the first year post stroke.

Each patient’s body mass index was calculated based on the average of all BMI measurements obtained 1-24 months prior to the stroke. The analysis of the relationship between BMI and poststroke mortality included extensive statistical adjustment for potential confounders, including age, sex, smoking, cancer, dementia, peripheral artery disease, diabetes, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, use of statins, and antihypertensive therapy.

Breaking down the study population into eight BMI categories, Ms. Costa found that the adjusted risk of 30-day all-cause mortality post stroke was reduced by 22%-38% in patients in the overweight or obese groupings, compared with the reference population with a normal-weight BMI of 22.5 to less than 25 kg/m2.

One-year, all-cause mortality showed the same pattern of BMI-based significant differences.

Of deaths within 30 days post stroke, 34% were stroke-related. In an analysis restricted to that group, the evidence of an obesity paradox was attenuated. Indeed, the only BMI group with an adjusted 30-day stroke-related mortality significantly different from the normal-weight reference group were patients with Class III obesity, defined as a BMI of 40 or more. Their risk was reduced by 45%.

The obesity paradox remains a controversial issue among epidemiologists. The increased mortality associated with being underweight among patients with diseases where the obesity paradox has been documented is widely thought to be caused by frailty and/or an underlying illness not adjusted for in analyses. But the mechanism for the reduced mortality risk in overweight and obese patients seen in the VA stroke study and other studies remains unknown despite much speculation.

Ms. Costa reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

SOURCE: Costa L. Circulation. 2018;138(suppl 1): Abstract 14288.

REPORTING FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Heavier stroke patients have lower 30-day and 1-year all-cause mortality.

Major finding: The 30-day stroke-related mortality rate after in-hospital stroke was reduced by 45% in VA patients with Class III obesity.

Study details: This retrospective study looked at the relationship between body mass index and post-stroke mortality in more than 26,000 veterans who had an inpatient stroke, with extensive adjustments made for potential confounders.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was sponsored by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Source: Costa L. Circulation. 2018;138(suppl 1): Abstract 14288.

FDA approves generic version of vigabatrin

The drug is approved for the adjunctive treatment of focal seizures in patients aged 10 years and older who have not had an adequate response to other therapies.

The approval was granted to Teva Pharmaceuticals.

An FDA announcement noted that the agency has prioritized the approval of generic versions of drugs to improve access to treatments and to lower drug costs. Vigabatrin had been included on an FDA list of off-patent, off-exclusivity branded drugs without approved generics. The approval of generic vigabatrin “demonstrates that there is an open pathway to approving products like this one,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD.

The label for vigabatrin tablets includes a boxed warning for permanent vision loss. The generic vigabatrin tablets are part of a single shared-system Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program with other drug products containing vigabatrin.

The most common side effects associated with vigabatrin tablets include dizziness, fatigue, sleepiness, involuntary eye movement, tremor, blurred vision, memory impairment, weight gain, joint pain, upper respiratory tract infection, aggression, double vision, abnormal coordination, and a confused state. Serious side effects associated with vigabatrin tablets include permanent vision loss and risk of suicidal thoughts or actions.

The drug is approved for the adjunctive treatment of focal seizures in patients aged 10 years and older who have not had an adequate response to other therapies.

The approval was granted to Teva Pharmaceuticals.

An FDA announcement noted that the agency has prioritized the approval of generic versions of drugs to improve access to treatments and to lower drug costs. Vigabatrin had been included on an FDA list of off-patent, off-exclusivity branded drugs without approved generics. The approval of generic vigabatrin “demonstrates that there is an open pathway to approving products like this one,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD.

The label for vigabatrin tablets includes a boxed warning for permanent vision loss. The generic vigabatrin tablets are part of a single shared-system Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program with other drug products containing vigabatrin.

The most common side effects associated with vigabatrin tablets include dizziness, fatigue, sleepiness, involuntary eye movement, tremor, blurred vision, memory impairment, weight gain, joint pain, upper respiratory tract infection, aggression, double vision, abnormal coordination, and a confused state. Serious side effects associated with vigabatrin tablets include permanent vision loss and risk of suicidal thoughts or actions.

The drug is approved for the adjunctive treatment of focal seizures in patients aged 10 years and older who have not had an adequate response to other therapies.

The approval was granted to Teva Pharmaceuticals.

An FDA announcement noted that the agency has prioritized the approval of generic versions of drugs to improve access to treatments and to lower drug costs. Vigabatrin had been included on an FDA list of off-patent, off-exclusivity branded drugs without approved generics. The approval of generic vigabatrin “demonstrates that there is an open pathway to approving products like this one,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD.

The label for vigabatrin tablets includes a boxed warning for permanent vision loss. The generic vigabatrin tablets are part of a single shared-system Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program with other drug products containing vigabatrin.

The most common side effects associated with vigabatrin tablets include dizziness, fatigue, sleepiness, involuntary eye movement, tremor, blurred vision, memory impairment, weight gain, joint pain, upper respiratory tract infection, aggression, double vision, abnormal coordination, and a confused state. Serious side effects associated with vigabatrin tablets include permanent vision loss and risk of suicidal thoughts or actions.

Prioritize oral route for inpatient opioids with subcutaneous route as alternative

Clinical question: Can adoption of a local opioid standard of practice for hospitalized patients reduce intravenous and overall opioid exposure while providing effective pain control?

Background: Inpatient use of intravenous opioids may be excessive, considering that oral opioids may provide more consistent pain control with less risk of adverse effects. If oral treatment is not possible, subcutaneous administration of opioids is an effective and possibly less addictive alternative to the intravenous route.

Study design: Historical control pilot study.

Setting: Single adult general medicine unit in an urban academic medical center.

Synopsis: A 6-month historical period with 287 patients was compared with a 3-month intervention period with 127 patients. The intervention consisted of a clinical practice standard that was presented to medical and nursing staff via didactic sessions and email. The standard recommended the oral route for opioids in patients tolerating oral intake and endorsed subcutaneous over intravenous administration.

Intravenous doses decreased by 84% (0.06 vs. 0.39 doses/patient-day; P less than .001), the daily rate of patients receiving any parenteral opioid decreased by 57% (6% vs. 14%; P less than .001), and the mean daily overall morphine-milligram equivalents decreased by 31% (6.30 vs. 9.11). Pain scores were unchanged for hospital days 1 through 3 but were significantly improved on day 4 (P = .004) and day 5 (P = .009).

Limitations of this study include the small number of patients on one unit, in one institution, with one clinician group. Attractive features of the intervention include its scalability and potential for augmentation via additional processes such as EHR changes, prescribing restrictions, and pharmacy monitoring.

Bottom line: A standard of practice intervention with peer-to-peer education was associated with decreased intravenous opioid exposure, decreased total opioid exposure, and effective pain control.

Citation: Ackerman AL et al. Association of an opioid standard of practice intervention with intravenous opioid exposure in hospitalized patients. JAMA Int Med. 2018;178(6):759-63.

Dr. Wanner is director, hospital medicine section, and associate chief, division of general internal medicine, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: Can adoption of a local opioid standard of practice for hospitalized patients reduce intravenous and overall opioid exposure while providing effective pain control?

Background: Inpatient use of intravenous opioids may be excessive, considering that oral opioids may provide more consistent pain control with less risk of adverse effects. If oral treatment is not possible, subcutaneous administration of opioids is an effective and possibly less addictive alternative to the intravenous route.

Study design: Historical control pilot study.

Setting: Single adult general medicine unit in an urban academic medical center.

Synopsis: A 6-month historical period with 287 patients was compared with a 3-month intervention period with 127 patients. The intervention consisted of a clinical practice standard that was presented to medical and nursing staff via didactic sessions and email. The standard recommended the oral route for opioids in patients tolerating oral intake and endorsed subcutaneous over intravenous administration.

Intravenous doses decreased by 84% (0.06 vs. 0.39 doses/patient-day; P less than .001), the daily rate of patients receiving any parenteral opioid decreased by 57% (6% vs. 14%; P less than .001), and the mean daily overall morphine-milligram equivalents decreased by 31% (6.30 vs. 9.11). Pain scores were unchanged for hospital days 1 through 3 but were significantly improved on day 4 (P = .004) and day 5 (P = .009).

Limitations of this study include the small number of patients on one unit, in one institution, with one clinician group. Attractive features of the intervention include its scalability and potential for augmentation via additional processes such as EHR changes, prescribing restrictions, and pharmacy monitoring.

Bottom line: A standard of practice intervention with peer-to-peer education was associated with decreased intravenous opioid exposure, decreased total opioid exposure, and effective pain control.

Citation: Ackerman AL et al. Association of an opioid standard of practice intervention with intravenous opioid exposure in hospitalized patients. JAMA Int Med. 2018;178(6):759-63.

Dr. Wanner is director, hospital medicine section, and associate chief, division of general internal medicine, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: Can adoption of a local opioid standard of practice for hospitalized patients reduce intravenous and overall opioid exposure while providing effective pain control?

Background: Inpatient use of intravenous opioids may be excessive, considering that oral opioids may provide more consistent pain control with less risk of adverse effects. If oral treatment is not possible, subcutaneous administration of opioids is an effective and possibly less addictive alternative to the intravenous route.

Study design: Historical control pilot study.

Setting: Single adult general medicine unit in an urban academic medical center.

Synopsis: A 6-month historical period with 287 patients was compared with a 3-month intervention period with 127 patients. The intervention consisted of a clinical practice standard that was presented to medical and nursing staff via didactic sessions and email. The standard recommended the oral route for opioids in patients tolerating oral intake and endorsed subcutaneous over intravenous administration.

Intravenous doses decreased by 84% (0.06 vs. 0.39 doses/patient-day; P less than .001), the daily rate of patients receiving any parenteral opioid decreased by 57% (6% vs. 14%; P less than .001), and the mean daily overall morphine-milligram equivalents decreased by 31% (6.30 vs. 9.11). Pain scores were unchanged for hospital days 1 through 3 but were significantly improved on day 4 (P = .004) and day 5 (P = .009).

Limitations of this study include the small number of patients on one unit, in one institution, with one clinician group. Attractive features of the intervention include its scalability and potential for augmentation via additional processes such as EHR changes, prescribing restrictions, and pharmacy monitoring.

Bottom line: A standard of practice intervention with peer-to-peer education was associated with decreased intravenous opioid exposure, decreased total opioid exposure, and effective pain control.

Citation: Ackerman AL et al. Association of an opioid standard of practice intervention with intravenous opioid exposure in hospitalized patients. JAMA Int Med. 2018;178(6):759-63.

Dr. Wanner is director, hospital medicine section, and associate chief, division of general internal medicine, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

DMTs, stem cell transplants both reduce disease progression in MS

Disease-modifying therapies give patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis a lower risk of developing secondary progressive disease that may only be topped in specific patients with highly active disease by the use of nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, according to findings from two studies published online Jan. 15 in JAMA.

The first study found that interferon-beta, glatiramer acetate (Copaxone), fingolimod (Gilenya), natalizumab (Tysabri), and alemtuzumab (Lemtrada) are associated with a lower risk of conversion to secondary progressive MS, compared with no treatment. Initial treatment with the newer therapies provided a greater risk reduction, compared with initial treatment with interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate.

The second study, described as “the first randomized trial of HSCT [nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation] in patients with relapsing-remitting MS,” suggests that HSCT prolongs the time to disease progression, compared with disease-modifying therapies (DMTs). It also suggests that HSCT can lead to clinical improvement.

DMTs reduced risk of conversion to secondary progressive MS

Few previous studies have examined the association between DMTs and the risk of conversion from relapsing-remitting MS to secondary progressive MS. Those that have analyzed this association have not used a validated definition of secondary progressive MS. J. William L. Brown, MD, of the University of Cambridge, England, and his colleagues used a validated definition of secondary progressive MS that was published in 2016 to investigate how DMTs affect the rate of conversion, compared with no treatment. The researchers also compared the risk reduction provided by fingolimod, alemtuzumab, or natalizumab with that provided by interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate.

Dr. Brown and his colleagues analyzed prospectively collected clinical data from an international observational cohort study called MSBase. Eligible participants had relapsing-remitting MS, the complete MSBase minimum data set, at least one Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score recorded within 6 months before baseline, and at least two EDSS scores recorded after baseline. Participants initiated a DMT or began clinical monitoring during 1988-2012. The population had a minimum follow-up duration of 4 years. Patients who stopped their initial therapy within 6 months and those participating in clinical trials were excluded.

The primary outcome was conversion to secondary progressive MS. Dr. Brown and his colleagues defined this outcome as an EDSS increase of 1 point for participants with a baseline EDSS score of 5.5 or less and as an increase of 0.5 points for participants with a baseline EDSS score higher than 5.5. This increase had to occur in the absence of relapses and be confirmed at a subsequent visit 3 or fewer months later. In addition, the increased EDSS score had to be 4 or more.

After excluding ineligible participants, the investigators matched 1,555 patients from 68 centers in 21 countries. Each therapy analyzed was associated with reduced risk of converting to secondary progressive MS, compared with no treatment. The hazard ratios for conversion were 0.71 for interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate, 0.37 for fingolimod, 0.61 for natalizumab, and 0.52 for alemtuzumab, compared with no treatment.

Treatment with interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate within 5 years of disease onset was associated with a reduced risk of conversion (HR, 0.77), compared with treatment later than 5 years after disease onset. Similarly, patients who escalated treatment from interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate to any of the other three DMTs within 5 years of disease onset had a significantly lower risk of conversion (HR, 0.76) than did those who escalated later. Furthermore, initial treatment with fingolimod, alemtuzumab, or natalizumab was associated with a significantly reduced risk of conversion (HR, 0.66), compared with initial treatment with interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate.

One of the study’s limitations is its observational design, which precludes the determination of causality, Dr. Brown and his colleagues said. In addition, functional score subcomponents of the EDSS were unavailable, which prevented the researchers from using the definition of secondary progressive MS with the best combination of sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. Some analyses were limited by small numbers of patients, and the study did not evaluate the risks associated with DMTs. Nevertheless, “these findings, considered along with these therapies’ risks, may help inform decisions about DMT selection,” the authors concluded.

Financial support for this study was provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the University of Melbourne. Dr. Brown received a Next Generation Fellowship funded by the Grand Charity of the Freemasons and an MSBase 2017 Fellowship. Alemtuzumab studies conducted in Cambridge were supported by the National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre and the MS Society UK.

HSCT delayed disease progression

In a previous case series, Richard K. Burt, MD, of Northwestern University in Chicago, and his colleagues found that patients with relapsing-remitting MS who underwent nonmyeloablative HSCT had neurologic improvement and a 70% likelihood of having a 4-year period of disease remission. Dr. Burt and his colleagues undertook the MS international stem cell transplant trial to compare the effects of nonmyeloablative HSCT with those of continued DMT treatment on disease progression in participants with highly active relapsing-remitting MS.

The researchers enrolled 110 participants at four international centers into their open-label trial. Eligible participants had two or more clinical relapses or one relapse and at least one gadolinium-enhancing lesion at a separate time within the previous 12 months, despite DMT treatment. The investigators also required participants to have an EDSS score between 2.0 and 6.0. Patients with primary or secondary progressive MS were excluded.

Dr. Burt and his colleagues randomized participants to receive HSCT or an approved DMT that was more effective or in a different class than the one they were receiving at baseline. Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus) was not administered during the study because it had not yet been approved. The investigators excluded alemtuzumab because of its association with persistent lymphopenia and autoimmune disorders. After 1 year of treatment, patients receiving a DMT who had disability progression could cross over to the HSCT arm. Patients randomized to HSCT stopped taking their usual DMT.

Time to disease progression was the study’s primary endpoint. The investigators defined disease progression as an increase in EDSS score of at least 1 point on two evaluations 6 months apart after at least 1 year of treatment. The increase was required to result from MS. The neurologist who recorded participants’ EDSS evaluations was blinded to treatment group assignment.

The researchers randomized 55 patients to each study arm. Approximately 66% of participants were women, and the sample’s mean age was 36 years. There were no significant baseline differences between groups on demographic, clinical, or imaging characteristics. Three patients in the HSCT group were withdrawn from the study, and four in the DMT group were lost to follow-up after seeking HSCT at outside facilities.

Three patients in the HSCT group and 34 patients in the DMT group had disease progression. Mean follow-up duration was 2.8 years. The investigators could not calculate the median time to progression in the HSCT group because too few events occurred. Median time to progression was 24 months in the DMT group (HR, 0.07). During the first year, mean EDSS scores decreased (indicating improvement) from 3.38 to 2.36 in the HSCT group. Mean EDSS scores increased from 3.31 to 3.98 in the DMT group. No participants died, and no patients who received HSCT-developed nonhematopoietic grade 4 toxicities.

“To our knowledge, this is the first randomized trial of HSCT in patients with relapsing-remitting MS,” Dr. Burt and his colleagues said. Although observational studies have found similar EDSS improvements following HSCT, “this degree of improvement has not been demonstrated in pharmaceutical trials even with more intensive DMT such as alemtuzumab,” they concluded.

The Danhakl Family Foundation, the Cumming Foundation, the McNamara Purcell Foundation, Morgan Stanley, and the National Institute for Health Research Sheffield Clinical Research Facility provided financial support for this study. No pharmaceutical companies supported the study.

SOURCEs: Brown JWL et al. JAMA. 2019;321(2):175-87. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.20588.; and Burt RK et al. JAMA. 2019;321(2):165-74. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.18743.

The study by Brown et al. provides evidence that DMTs slow the appearance of persistent disabilities in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), Harold Atkins, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Jan 15;321[2]:153-4). Although disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) may suppress clinical signs of disease activity for long periods in some patients, these therapies slow MS rather than halt it. DMTs require long-term administration and may cause intolerable side effects that impair patients’ quality of life. These therapies also may result in complications such as severe depression or progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

“The study by Burt et al. ... provides a rigorous indication that HSCT [hematopoietic stem cell transplantation] can be an effective treatment for selected patients with MS,” Dr. Atkins said. Treating physicians, however, have concerns about this procedure, which is resource-intensive and “requires specialized medical and nursing expertise and dedicated hospital infrastructure to minimize its risks.” Many patients in the study had moderate to severe acute toxicity following treatment, and patient selection thus requires caution.

An important limitation of the study is that participants did not have access to alemtuzumab or ocrelizumab, which arguably are the most effective DMTs, Dr. Atkins said. The study began in 2005, when fewer DMTs were available. “The inclusion of patients who were less than optimally treated in the DMT group needs to be considered when interpreting the results of this study,” Dr. Atkins said.

Furthermore, Burt and colleagues studied patients with highly active MS, but “only a small proportion of the MS patient population exhibits this degree of activity,” he added. The results therefore may not be generalizable. Nevertheless, “even with the limitations of the trial, the results support a role for HSCT delivered at centers that are experienced in the clinical care of patients with highly active MS,” Dr. Atkins concluded.

Dr. Atkins is affiliated with the Ottawa Hospital Blood and Marrow Transplant Program at the University of Ottawa in Ontario. He reported no conflicts of interest.

The study by Brown et al. provides evidence that DMTs slow the appearance of persistent disabilities in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), Harold Atkins, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Jan 15;321[2]:153-4). Although disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) may suppress clinical signs of disease activity for long periods in some patients, these therapies slow MS rather than halt it. DMTs require long-term administration and may cause intolerable side effects that impair patients’ quality of life. These therapies also may result in complications such as severe depression or progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

“The study by Burt et al. ... provides a rigorous indication that HSCT [hematopoietic stem cell transplantation] can be an effective treatment for selected patients with MS,” Dr. Atkins said. Treating physicians, however, have concerns about this procedure, which is resource-intensive and “requires specialized medical and nursing expertise and dedicated hospital infrastructure to minimize its risks.” Many patients in the study had moderate to severe acute toxicity following treatment, and patient selection thus requires caution.

An important limitation of the study is that participants did not have access to alemtuzumab or ocrelizumab, which arguably are the most effective DMTs, Dr. Atkins said. The study began in 2005, when fewer DMTs were available. “The inclusion of patients who were less than optimally treated in the DMT group needs to be considered when interpreting the results of this study,” Dr. Atkins said.

Furthermore, Burt and colleagues studied patients with highly active MS, but “only a small proportion of the MS patient population exhibits this degree of activity,” he added. The results therefore may not be generalizable. Nevertheless, “even with the limitations of the trial, the results support a role for HSCT delivered at centers that are experienced in the clinical care of patients with highly active MS,” Dr. Atkins concluded.

Dr. Atkins is affiliated with the Ottawa Hospital Blood and Marrow Transplant Program at the University of Ottawa in Ontario. He reported no conflicts of interest.

The study by Brown et al. provides evidence that DMTs slow the appearance of persistent disabilities in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), Harold Atkins, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Jan 15;321[2]:153-4). Although disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) may suppress clinical signs of disease activity for long periods in some patients, these therapies slow MS rather than halt it. DMTs require long-term administration and may cause intolerable side effects that impair patients’ quality of life. These therapies also may result in complications such as severe depression or progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

“The study by Burt et al. ... provides a rigorous indication that HSCT [hematopoietic stem cell transplantation] can be an effective treatment for selected patients with MS,” Dr. Atkins said. Treating physicians, however, have concerns about this procedure, which is resource-intensive and “requires specialized medical and nursing expertise and dedicated hospital infrastructure to minimize its risks.” Many patients in the study had moderate to severe acute toxicity following treatment, and patient selection thus requires caution.

An important limitation of the study is that participants did not have access to alemtuzumab or ocrelizumab, which arguably are the most effective DMTs, Dr. Atkins said. The study began in 2005, when fewer DMTs were available. “The inclusion of patients who were less than optimally treated in the DMT group needs to be considered when interpreting the results of this study,” Dr. Atkins said.

Furthermore, Burt and colleagues studied patients with highly active MS, but “only a small proportion of the MS patient population exhibits this degree of activity,” he added. The results therefore may not be generalizable. Nevertheless, “even with the limitations of the trial, the results support a role for HSCT delivered at centers that are experienced in the clinical care of patients with highly active MS,” Dr. Atkins concluded.

Dr. Atkins is affiliated with the Ottawa Hospital Blood and Marrow Transplant Program at the University of Ottawa in Ontario. He reported no conflicts of interest.

Disease-modifying therapies give patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis a lower risk of developing secondary progressive disease that may only be topped in specific patients with highly active disease by the use of nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, according to findings from two studies published online Jan. 15 in JAMA.

The first study found that interferon-beta, glatiramer acetate (Copaxone), fingolimod (Gilenya), natalizumab (Tysabri), and alemtuzumab (Lemtrada) are associated with a lower risk of conversion to secondary progressive MS, compared with no treatment. Initial treatment with the newer therapies provided a greater risk reduction, compared with initial treatment with interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate.

The second study, described as “the first randomized trial of HSCT [nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation] in patients with relapsing-remitting MS,” suggests that HSCT prolongs the time to disease progression, compared with disease-modifying therapies (DMTs). It also suggests that HSCT can lead to clinical improvement.

DMTs reduced risk of conversion to secondary progressive MS

Few previous studies have examined the association between DMTs and the risk of conversion from relapsing-remitting MS to secondary progressive MS. Those that have analyzed this association have not used a validated definition of secondary progressive MS. J. William L. Brown, MD, of the University of Cambridge, England, and his colleagues used a validated definition of secondary progressive MS that was published in 2016 to investigate how DMTs affect the rate of conversion, compared with no treatment. The researchers also compared the risk reduction provided by fingolimod, alemtuzumab, or natalizumab with that provided by interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate.

Dr. Brown and his colleagues analyzed prospectively collected clinical data from an international observational cohort study called MSBase. Eligible participants had relapsing-remitting MS, the complete MSBase minimum data set, at least one Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score recorded within 6 months before baseline, and at least two EDSS scores recorded after baseline. Participants initiated a DMT or began clinical monitoring during 1988-2012. The population had a minimum follow-up duration of 4 years. Patients who stopped their initial therapy within 6 months and those participating in clinical trials were excluded.

The primary outcome was conversion to secondary progressive MS. Dr. Brown and his colleagues defined this outcome as an EDSS increase of 1 point for participants with a baseline EDSS score of 5.5 or less and as an increase of 0.5 points for participants with a baseline EDSS score higher than 5.5. This increase had to occur in the absence of relapses and be confirmed at a subsequent visit 3 or fewer months later. In addition, the increased EDSS score had to be 4 or more.

After excluding ineligible participants, the investigators matched 1,555 patients from 68 centers in 21 countries. Each therapy analyzed was associated with reduced risk of converting to secondary progressive MS, compared with no treatment. The hazard ratios for conversion were 0.71 for interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate, 0.37 for fingolimod, 0.61 for natalizumab, and 0.52 for alemtuzumab, compared with no treatment.

Treatment with interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate within 5 years of disease onset was associated with a reduced risk of conversion (HR, 0.77), compared with treatment later than 5 years after disease onset. Similarly, patients who escalated treatment from interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate to any of the other three DMTs within 5 years of disease onset had a significantly lower risk of conversion (HR, 0.76) than did those who escalated later. Furthermore, initial treatment with fingolimod, alemtuzumab, or natalizumab was associated with a significantly reduced risk of conversion (HR, 0.66), compared with initial treatment with interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate.

One of the study’s limitations is its observational design, which precludes the determination of causality, Dr. Brown and his colleagues said. In addition, functional score subcomponents of the EDSS were unavailable, which prevented the researchers from using the definition of secondary progressive MS with the best combination of sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. Some analyses were limited by small numbers of patients, and the study did not evaluate the risks associated with DMTs. Nevertheless, “these findings, considered along with these therapies’ risks, may help inform decisions about DMT selection,” the authors concluded.

Financial support for this study was provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the University of Melbourne. Dr. Brown received a Next Generation Fellowship funded by the Grand Charity of the Freemasons and an MSBase 2017 Fellowship. Alemtuzumab studies conducted in Cambridge were supported by the National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre and the MS Society UK.

HSCT delayed disease progression

In a previous case series, Richard K. Burt, MD, of Northwestern University in Chicago, and his colleagues found that patients with relapsing-remitting MS who underwent nonmyeloablative HSCT had neurologic improvement and a 70% likelihood of having a 4-year period of disease remission. Dr. Burt and his colleagues undertook the MS international stem cell transplant trial to compare the effects of nonmyeloablative HSCT with those of continued DMT treatment on disease progression in participants with highly active relapsing-remitting MS.

The researchers enrolled 110 participants at four international centers into their open-label trial. Eligible participants had two or more clinical relapses or one relapse and at least one gadolinium-enhancing lesion at a separate time within the previous 12 months, despite DMT treatment. The investigators also required participants to have an EDSS score between 2.0 and 6.0. Patients with primary or secondary progressive MS were excluded.

Dr. Burt and his colleagues randomized participants to receive HSCT or an approved DMT that was more effective or in a different class than the one they were receiving at baseline. Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus) was not administered during the study because it had not yet been approved. The investigators excluded alemtuzumab because of its association with persistent lymphopenia and autoimmune disorders. After 1 year of treatment, patients receiving a DMT who had disability progression could cross over to the HSCT arm. Patients randomized to HSCT stopped taking their usual DMT.

Time to disease progression was the study’s primary endpoint. The investigators defined disease progression as an increase in EDSS score of at least 1 point on two evaluations 6 months apart after at least 1 year of treatment. The increase was required to result from MS. The neurologist who recorded participants’ EDSS evaluations was blinded to treatment group assignment.

The researchers randomized 55 patients to each study arm. Approximately 66% of participants were women, and the sample’s mean age was 36 years. There were no significant baseline differences between groups on demographic, clinical, or imaging characteristics. Three patients in the HSCT group were withdrawn from the study, and four in the DMT group were lost to follow-up after seeking HSCT at outside facilities.

Three patients in the HSCT group and 34 patients in the DMT group had disease progression. Mean follow-up duration was 2.8 years. The investigators could not calculate the median time to progression in the HSCT group because too few events occurred. Median time to progression was 24 months in the DMT group (HR, 0.07). During the first year, mean EDSS scores decreased (indicating improvement) from 3.38 to 2.36 in the HSCT group. Mean EDSS scores increased from 3.31 to 3.98 in the DMT group. No participants died, and no patients who received HSCT-developed nonhematopoietic grade 4 toxicities.

“To our knowledge, this is the first randomized trial of HSCT in patients with relapsing-remitting MS,” Dr. Burt and his colleagues said. Although observational studies have found similar EDSS improvements following HSCT, “this degree of improvement has not been demonstrated in pharmaceutical trials even with more intensive DMT such as alemtuzumab,” they concluded.

The Danhakl Family Foundation, the Cumming Foundation, the McNamara Purcell Foundation, Morgan Stanley, and the National Institute for Health Research Sheffield Clinical Research Facility provided financial support for this study. No pharmaceutical companies supported the study.

SOURCEs: Brown JWL et al. JAMA. 2019;321(2):175-87. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.20588.; and Burt RK et al. JAMA. 2019;321(2):165-74. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.18743.

Disease-modifying therapies give patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis a lower risk of developing secondary progressive disease that may only be topped in specific patients with highly active disease by the use of nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, according to findings from two studies published online Jan. 15 in JAMA.

The first study found that interferon-beta, glatiramer acetate (Copaxone), fingolimod (Gilenya), natalizumab (Tysabri), and alemtuzumab (Lemtrada) are associated with a lower risk of conversion to secondary progressive MS, compared with no treatment. Initial treatment with the newer therapies provided a greater risk reduction, compared with initial treatment with interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate.

The second study, described as “the first randomized trial of HSCT [nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation] in patients with relapsing-remitting MS,” suggests that HSCT prolongs the time to disease progression, compared with disease-modifying therapies (DMTs). It also suggests that HSCT can lead to clinical improvement.

DMTs reduced risk of conversion to secondary progressive MS

Few previous studies have examined the association between DMTs and the risk of conversion from relapsing-remitting MS to secondary progressive MS. Those that have analyzed this association have not used a validated definition of secondary progressive MS. J. William L. Brown, MD, of the University of Cambridge, England, and his colleagues used a validated definition of secondary progressive MS that was published in 2016 to investigate how DMTs affect the rate of conversion, compared with no treatment. The researchers also compared the risk reduction provided by fingolimod, alemtuzumab, or natalizumab with that provided by interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate.

Dr. Brown and his colleagues analyzed prospectively collected clinical data from an international observational cohort study called MSBase. Eligible participants had relapsing-remitting MS, the complete MSBase minimum data set, at least one Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score recorded within 6 months before baseline, and at least two EDSS scores recorded after baseline. Participants initiated a DMT or began clinical monitoring during 1988-2012. The population had a minimum follow-up duration of 4 years. Patients who stopped their initial therapy within 6 months and those participating in clinical trials were excluded.

The primary outcome was conversion to secondary progressive MS. Dr. Brown and his colleagues defined this outcome as an EDSS increase of 1 point for participants with a baseline EDSS score of 5.5 or less and as an increase of 0.5 points for participants with a baseline EDSS score higher than 5.5. This increase had to occur in the absence of relapses and be confirmed at a subsequent visit 3 or fewer months later. In addition, the increased EDSS score had to be 4 or more.

After excluding ineligible participants, the investigators matched 1,555 patients from 68 centers in 21 countries. Each therapy analyzed was associated with reduced risk of converting to secondary progressive MS, compared with no treatment. The hazard ratios for conversion were 0.71 for interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate, 0.37 for fingolimod, 0.61 for natalizumab, and 0.52 for alemtuzumab, compared with no treatment.

Treatment with interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate within 5 years of disease onset was associated with a reduced risk of conversion (HR, 0.77), compared with treatment later than 5 years after disease onset. Similarly, patients who escalated treatment from interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate to any of the other three DMTs within 5 years of disease onset had a significantly lower risk of conversion (HR, 0.76) than did those who escalated later. Furthermore, initial treatment with fingolimod, alemtuzumab, or natalizumab was associated with a significantly reduced risk of conversion (HR, 0.66), compared with initial treatment with interferon-beta or glatiramer acetate.

One of the study’s limitations is its observational design, which precludes the determination of causality, Dr. Brown and his colleagues said. In addition, functional score subcomponents of the EDSS were unavailable, which prevented the researchers from using the definition of secondary progressive MS with the best combination of sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. Some analyses were limited by small numbers of patients, and the study did not evaluate the risks associated with DMTs. Nevertheless, “these findings, considered along with these therapies’ risks, may help inform decisions about DMT selection,” the authors concluded.

Financial support for this study was provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the University of Melbourne. Dr. Brown received a Next Generation Fellowship funded by the Grand Charity of the Freemasons and an MSBase 2017 Fellowship. Alemtuzumab studies conducted in Cambridge were supported by the National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre and the MS Society UK.

HSCT delayed disease progression

In a previous case series, Richard K. Burt, MD, of Northwestern University in Chicago, and his colleagues found that patients with relapsing-remitting MS who underwent nonmyeloablative HSCT had neurologic improvement and a 70% likelihood of having a 4-year period of disease remission. Dr. Burt and his colleagues undertook the MS international stem cell transplant trial to compare the effects of nonmyeloablative HSCT with those of continued DMT treatment on disease progression in participants with highly active relapsing-remitting MS.

The researchers enrolled 110 participants at four international centers into their open-label trial. Eligible participants had two or more clinical relapses or one relapse and at least one gadolinium-enhancing lesion at a separate time within the previous 12 months, despite DMT treatment. The investigators also required participants to have an EDSS score between 2.0 and 6.0. Patients with primary or secondary progressive MS were excluded.

Dr. Burt and his colleagues randomized participants to receive HSCT or an approved DMT that was more effective or in a different class than the one they were receiving at baseline. Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus) was not administered during the study because it had not yet been approved. The investigators excluded alemtuzumab because of its association with persistent lymphopenia and autoimmune disorders. After 1 year of treatment, patients receiving a DMT who had disability progression could cross over to the HSCT arm. Patients randomized to HSCT stopped taking their usual DMT.

Time to disease progression was the study’s primary endpoint. The investigators defined disease progression as an increase in EDSS score of at least 1 point on two evaluations 6 months apart after at least 1 year of treatment. The increase was required to result from MS. The neurologist who recorded participants’ EDSS evaluations was blinded to treatment group assignment.

The researchers randomized 55 patients to each study arm. Approximately 66% of participants were women, and the sample’s mean age was 36 years. There were no significant baseline differences between groups on demographic, clinical, or imaging characteristics. Three patients in the HSCT group were withdrawn from the study, and four in the DMT group were lost to follow-up after seeking HSCT at outside facilities.

Three patients in the HSCT group and 34 patients in the DMT group had disease progression. Mean follow-up duration was 2.8 years. The investigators could not calculate the median time to progression in the HSCT group because too few events occurred. Median time to progression was 24 months in the DMT group (HR, 0.07). During the first year, mean EDSS scores decreased (indicating improvement) from 3.38 to 2.36 in the HSCT group. Mean EDSS scores increased from 3.31 to 3.98 in the DMT group. No participants died, and no patients who received HSCT-developed nonhematopoietic grade 4 toxicities.

“To our knowledge, this is the first randomized trial of HSCT in patients with relapsing-remitting MS,” Dr. Burt and his colleagues said. Although observational studies have found similar EDSS improvements following HSCT, “this degree of improvement has not been demonstrated in pharmaceutical trials even with more intensive DMT such as alemtuzumab,” they concluded.

The Danhakl Family Foundation, the Cumming Foundation, the McNamara Purcell Foundation, Morgan Stanley, and the National Institute for Health Research Sheffield Clinical Research Facility provided financial support for this study. No pharmaceutical companies supported the study.

SOURCEs: Brown JWL et al. JAMA. 2019;321(2):175-87. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.20588.; and Burt RK et al. JAMA. 2019;321(2):165-74. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.18743.

FROM JAMA

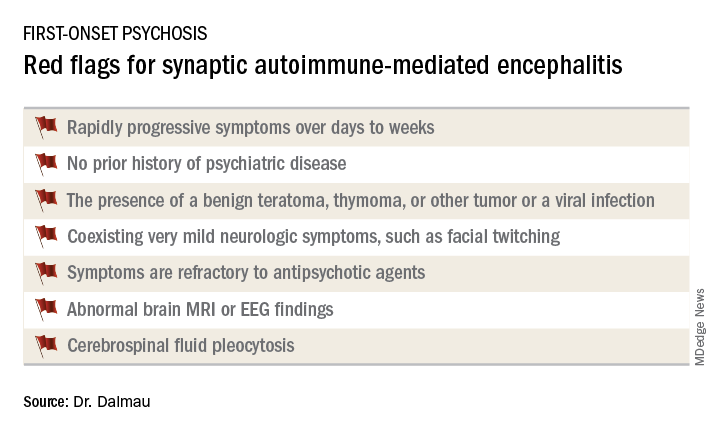

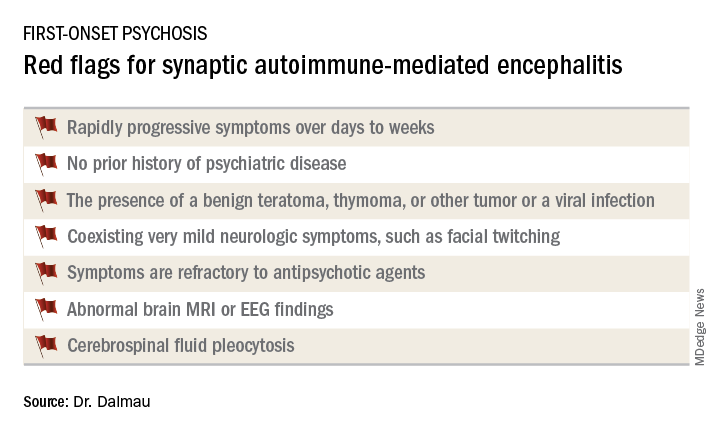

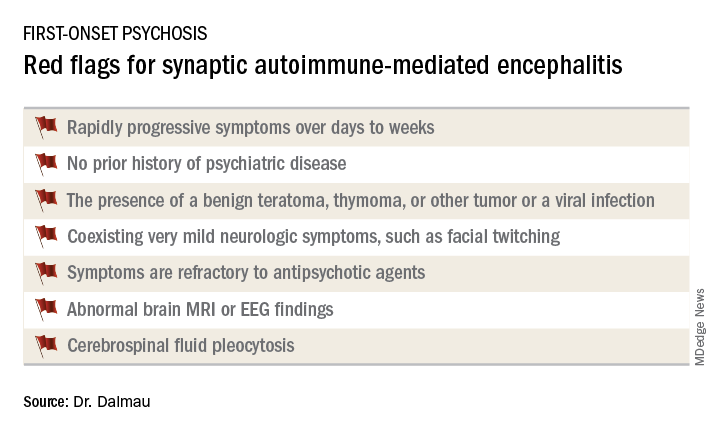

Know the red flags for synaptic autoimmune psychosis

BARCELONA – Consider the possibility of an autoantibody-related etiology in all cases of first-onset psychosis, Josep Dalmau, MD, PhD, urged at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

“There are patients in our clinics all of us – neurologists and psychiatrists – are missing. These patients are believed to have psychiatric presentations, but they do not. They are autoimmune,” said Dr. Dalmau, professor of neurology at the University of Barcelona.

Dr. Dalmau urged psychiatrists to become familiar with the red flags suggestive of synaptic autoimmunity as the underlying cause of first-episode, out-of-the-blue psychosis.

“If you have a patient with a classical presentation of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, you probably won’t find antibodies,” according to the neurologist.

It’s important to have a high index of suspicion, because anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis is treatable with immunotherapy. And firm evidence shows that earlier recognition and treatment lead to improved outcomes. Also, the disorder is refractory to antipsychotics; indeed,

Manifestations of anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis follow a characteristic pattern, beginning with a prodromal flulike phase lasting several days to a week. This is followed by acute-onset bizarre behavioral changes, irritability, and psychosis with delusions and/or hallucinations, often progressing to catatonia. After 1-4 weeks of this, florid neurologic symptoms usually appear, including seizures, abnormal movements, autonomic dysregulation, and hypoventilation requiring prolonged ICU support for weeks to months. This is followed by a prolonged recovery phase lasting 5-24 months, and a period marked by deficits in executive function and working memory, impulsivity, and disinhibition. Impressively, the patient has no memory of the illness.

In one large series of patients with confirmed anti–NMDA receptor encephalitis reported by Dr. Dalmau and coinvestigators, psychiatric symptoms occurred in isolation without subsequent neurologic involvement in just 4% of cases (JAMA Neurol. 2013 Sep 1;70[9]:1133-9).

Dr. Dalmau was senior author of an international cohort study including 577 patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis with serial follow-up for 24 months. The study provided an unprecedented picture of the epidemiology and clinical features of the disorder.

“It’s a disease predominantly of women and young people,” he observed.

Indeed, the median age of the study population was 21 years, and 37% of subjects were less than 18 years of age. Roughly 80% of patients were female and most of them had a benign ovarian teratoma, which played a key role in their neuropsychiatric disease (Lancet Neurol. 2013 Feb;12[2]:157-65). These benign tumors express the NMDA receptor in ectopic nerve tissue, triggering a systemic immune response.

One or more relapses – again treatable via immunotherapy – occurred in 12% of patients during 24 months of follow-up.

When a red flag suggestive of synaptic autoimmunity is present, it’s important to obtain a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample for analysis, along with an EEG and/or brain MRI.