User login

Nicotinamide does not prevent skin cancer after organ transplant

published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“No signal of efficacy was observed,” said investigators led by Nicholas Allen, MPH, of the University of Sydney department of dermatology.

These results fill an “important gap in our understanding” and “will probably change the practice of many skin-cancer physicians,” two experts on the topic commented in a related editorial.

The editorialists are David Miller, MD, PhD, a dermatologist and medical oncologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Kevin Emerick, MD, a head and neck surgeon as Massachusetts Eye and Ear, both in Boston.

Transplant patients have 50 times the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers – also known as keratinocyte cancers – than the general public, owing to immunosuppression, and their lesions are more aggressive and are more likely to metastasize, they explain.

Nicotinamide (vitamin B3) has been shown to prevent nonmelanoma skin cancers in healthy, immunocompetent people, so physicians routinely prescribe it to transplant patients on the assumption that it will do the same for them, they comment.

The Australian investigators decided to put the assumption to the test.

The team randomly assigned 79 patients who had undergone solid-organ transplant to receive nicotinamide 500 mg twice a day and 79 other patients to receive twice-daily placebo for a year. Participants underwent dermatology exams every 3 months to check for new lesions.

The participants were at high risk for new lesions; some had had more than 40 in the previous 5 years. The two groups were well balanced; kidney transplants were the most common.

At 12 months, there was virtually no difference in the incidence of new nonmelanoma skin cancers: 207 in the nicotinamide group and 210 in the placebo group (P = .96).

There was also no significant difference in squamous cell and basal cell carcinoma counts or actinic keratosis counts.

“The interpretation of the results is straightforward: nicotinamide lacks clinical usefulness in preventing the development of keratinocyte carcinomas in solid-organ transplant recipients,” the team concludes.

As for why nicotinamide didn’t work in the trial, the investigators say it could be because it is not potent enough to overcome the stifling of antitumor immunity and DNA-repair enzymes with immunosuppression.

Fewer than half of participants in the trial reported using sunscreen at any point during the study, which is in line with past reports that transplant patients don’t routinely use sunscreen.

Two other strategies for preventing squamous cell carcinoma after transplant – use of oral retinoids and mTOR inhibitors – are problematic for various reasons, and use was low in both study arms.

Editorialists Dr. Miller and Dr. Emerick suggest a possible new approach: immune checkpoint inhibitors before transplant to reduce the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer afterward. They say the strategy should be explored and that ongoing efforts to minimize or eliminate the need for immunosuppression after transplant are promising.

The investigators originally planned to enroll 254 persons, but the trial was stopped early because of poor recruitment. Potential participants may already have been taking nicotinamide, which is commonly used, and that may have affected recruitment, the investigators say.

The work was funded by Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council. Dr. Allen has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. One investigator has received speaker’s fees from BMS. Another is a consultant for many companies, including Amgen, BMS, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck. Dr. Emerick is an advisor for Regeneron, Sanofi, and Castle Biosciences. Dr. Miller is a researcher or consultant for those companies as well as Pfizer and others and has stock options in Avstera.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“No signal of efficacy was observed,” said investigators led by Nicholas Allen, MPH, of the University of Sydney department of dermatology.

These results fill an “important gap in our understanding” and “will probably change the practice of many skin-cancer physicians,” two experts on the topic commented in a related editorial.

The editorialists are David Miller, MD, PhD, a dermatologist and medical oncologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Kevin Emerick, MD, a head and neck surgeon as Massachusetts Eye and Ear, both in Boston.

Transplant patients have 50 times the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers – also known as keratinocyte cancers – than the general public, owing to immunosuppression, and their lesions are more aggressive and are more likely to metastasize, they explain.

Nicotinamide (vitamin B3) has been shown to prevent nonmelanoma skin cancers in healthy, immunocompetent people, so physicians routinely prescribe it to transplant patients on the assumption that it will do the same for them, they comment.

The Australian investigators decided to put the assumption to the test.

The team randomly assigned 79 patients who had undergone solid-organ transplant to receive nicotinamide 500 mg twice a day and 79 other patients to receive twice-daily placebo for a year. Participants underwent dermatology exams every 3 months to check for new lesions.

The participants were at high risk for new lesions; some had had more than 40 in the previous 5 years. The two groups were well balanced; kidney transplants were the most common.

At 12 months, there was virtually no difference in the incidence of new nonmelanoma skin cancers: 207 in the nicotinamide group and 210 in the placebo group (P = .96).

There was also no significant difference in squamous cell and basal cell carcinoma counts or actinic keratosis counts.

“The interpretation of the results is straightforward: nicotinamide lacks clinical usefulness in preventing the development of keratinocyte carcinomas in solid-organ transplant recipients,” the team concludes.

As for why nicotinamide didn’t work in the trial, the investigators say it could be because it is not potent enough to overcome the stifling of antitumor immunity and DNA-repair enzymes with immunosuppression.

Fewer than half of participants in the trial reported using sunscreen at any point during the study, which is in line with past reports that transplant patients don’t routinely use sunscreen.

Two other strategies for preventing squamous cell carcinoma after transplant – use of oral retinoids and mTOR inhibitors – are problematic for various reasons, and use was low in both study arms.

Editorialists Dr. Miller and Dr. Emerick suggest a possible new approach: immune checkpoint inhibitors before transplant to reduce the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer afterward. They say the strategy should be explored and that ongoing efforts to minimize or eliminate the need for immunosuppression after transplant are promising.

The investigators originally planned to enroll 254 persons, but the trial was stopped early because of poor recruitment. Potential participants may already have been taking nicotinamide, which is commonly used, and that may have affected recruitment, the investigators say.

The work was funded by Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council. Dr. Allen has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. One investigator has received speaker’s fees from BMS. Another is a consultant for many companies, including Amgen, BMS, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck. Dr. Emerick is an advisor for Regeneron, Sanofi, and Castle Biosciences. Dr. Miller is a researcher or consultant for those companies as well as Pfizer and others and has stock options in Avstera.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“No signal of efficacy was observed,” said investigators led by Nicholas Allen, MPH, of the University of Sydney department of dermatology.

These results fill an “important gap in our understanding” and “will probably change the practice of many skin-cancer physicians,” two experts on the topic commented in a related editorial.

The editorialists are David Miller, MD, PhD, a dermatologist and medical oncologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Kevin Emerick, MD, a head and neck surgeon as Massachusetts Eye and Ear, both in Boston.

Transplant patients have 50 times the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers – also known as keratinocyte cancers – than the general public, owing to immunosuppression, and their lesions are more aggressive and are more likely to metastasize, they explain.

Nicotinamide (vitamin B3) has been shown to prevent nonmelanoma skin cancers in healthy, immunocompetent people, so physicians routinely prescribe it to transplant patients on the assumption that it will do the same for them, they comment.

The Australian investigators decided to put the assumption to the test.

The team randomly assigned 79 patients who had undergone solid-organ transplant to receive nicotinamide 500 mg twice a day and 79 other patients to receive twice-daily placebo for a year. Participants underwent dermatology exams every 3 months to check for new lesions.

The participants were at high risk for new lesions; some had had more than 40 in the previous 5 years. The two groups were well balanced; kidney transplants were the most common.

At 12 months, there was virtually no difference in the incidence of new nonmelanoma skin cancers: 207 in the nicotinamide group and 210 in the placebo group (P = .96).

There was also no significant difference in squamous cell and basal cell carcinoma counts or actinic keratosis counts.

“The interpretation of the results is straightforward: nicotinamide lacks clinical usefulness in preventing the development of keratinocyte carcinomas in solid-organ transplant recipients,” the team concludes.

As for why nicotinamide didn’t work in the trial, the investigators say it could be because it is not potent enough to overcome the stifling of antitumor immunity and DNA-repair enzymes with immunosuppression.

Fewer than half of participants in the trial reported using sunscreen at any point during the study, which is in line with past reports that transplant patients don’t routinely use sunscreen.

Two other strategies for preventing squamous cell carcinoma after transplant – use of oral retinoids and mTOR inhibitors – are problematic for various reasons, and use was low in both study arms.

Editorialists Dr. Miller and Dr. Emerick suggest a possible new approach: immune checkpoint inhibitors before transplant to reduce the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer afterward. They say the strategy should be explored and that ongoing efforts to minimize or eliminate the need for immunosuppression after transplant are promising.

The investigators originally planned to enroll 254 persons, but the trial was stopped early because of poor recruitment. Potential participants may already have been taking nicotinamide, which is commonly used, and that may have affected recruitment, the investigators say.

The work was funded by Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council. Dr. Allen has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. One investigator has received speaker’s fees from BMS. Another is a consultant for many companies, including Amgen, BMS, GlaxoSmithKline, and Merck. Dr. Emerick is an advisor for Regeneron, Sanofi, and Castle Biosciences. Dr. Miller is a researcher or consultant for those companies as well as Pfizer and others and has stock options in Avstera.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Epithelioma Cuniculatum (Plantar Verrucous Carcinoma): A Systematic Review of Treatment Options

Verrucous carcinoma (VC) is an uncommon type of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) that most commonly affects men in the fifth to sixth decades of life. 1 The tumor grows slowly over a decade or more and does not frequently metastasize but has a high propensity for recurrence and local invasion. 2 There are 3 main subtypes of VC classified by anatomic site: oral florid papillomatosis (oral cavity), Buschke-Lowenstein tumor (anogenital region), and epithelioma cuniculatum (EC)(feet). 3 Epithelioma cuniculatum, also known as carcinoma cuniculatum or papillomatosis cutis carcinoides, most commonly presents as a solitary, warty or cauliflowerlike, exophytic mass with keratin-filled sinus tracts and malodorous discharge. 4 Diabetic foot ulcers and chronic inflammatory conditions are predisposing risk factors for EC, and it can result in difficulty walking/immobility, pain, and bleeding depending on anatomic involvement. 5-9

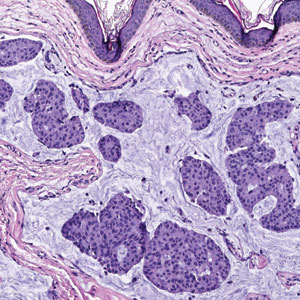

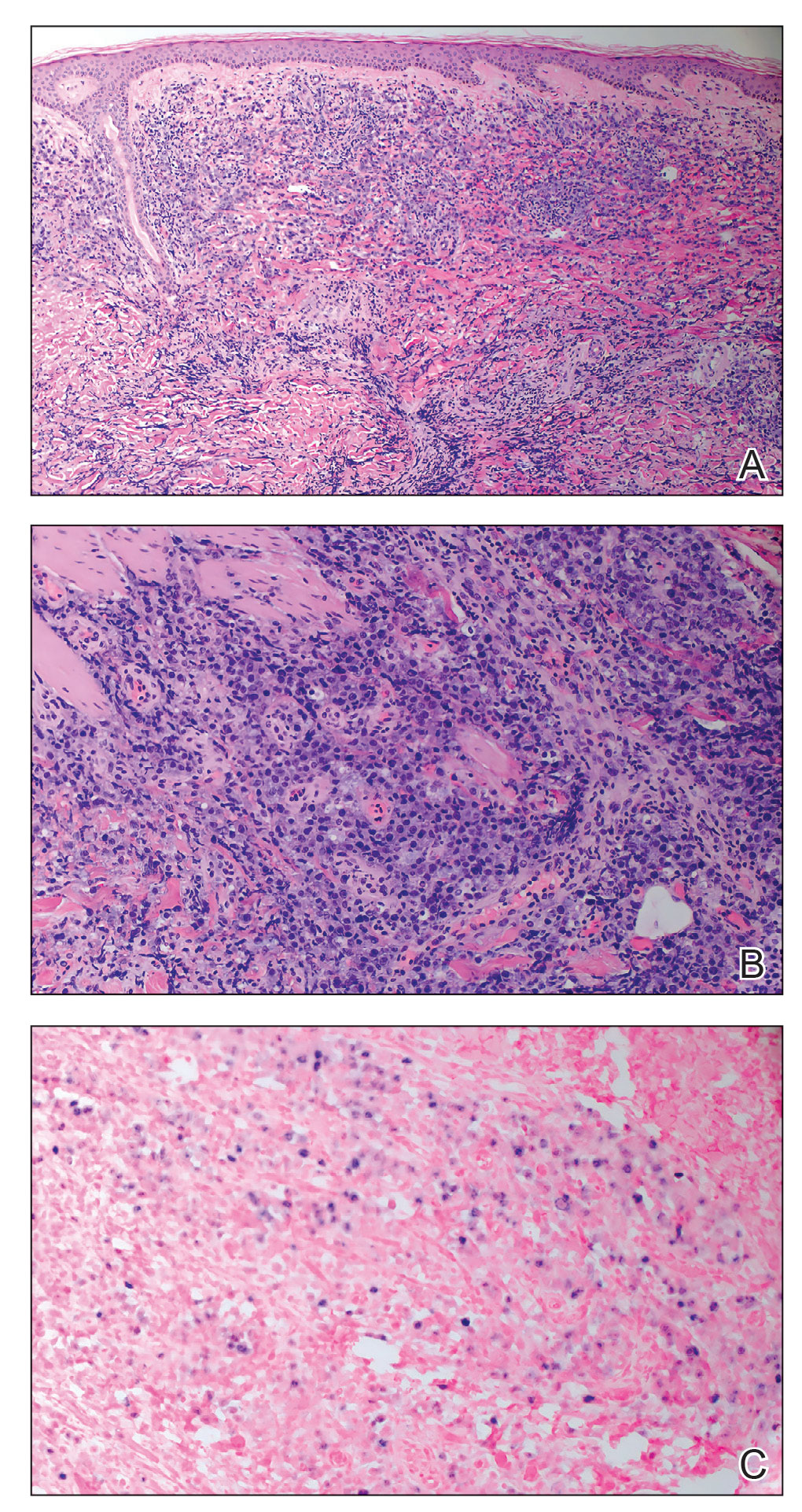

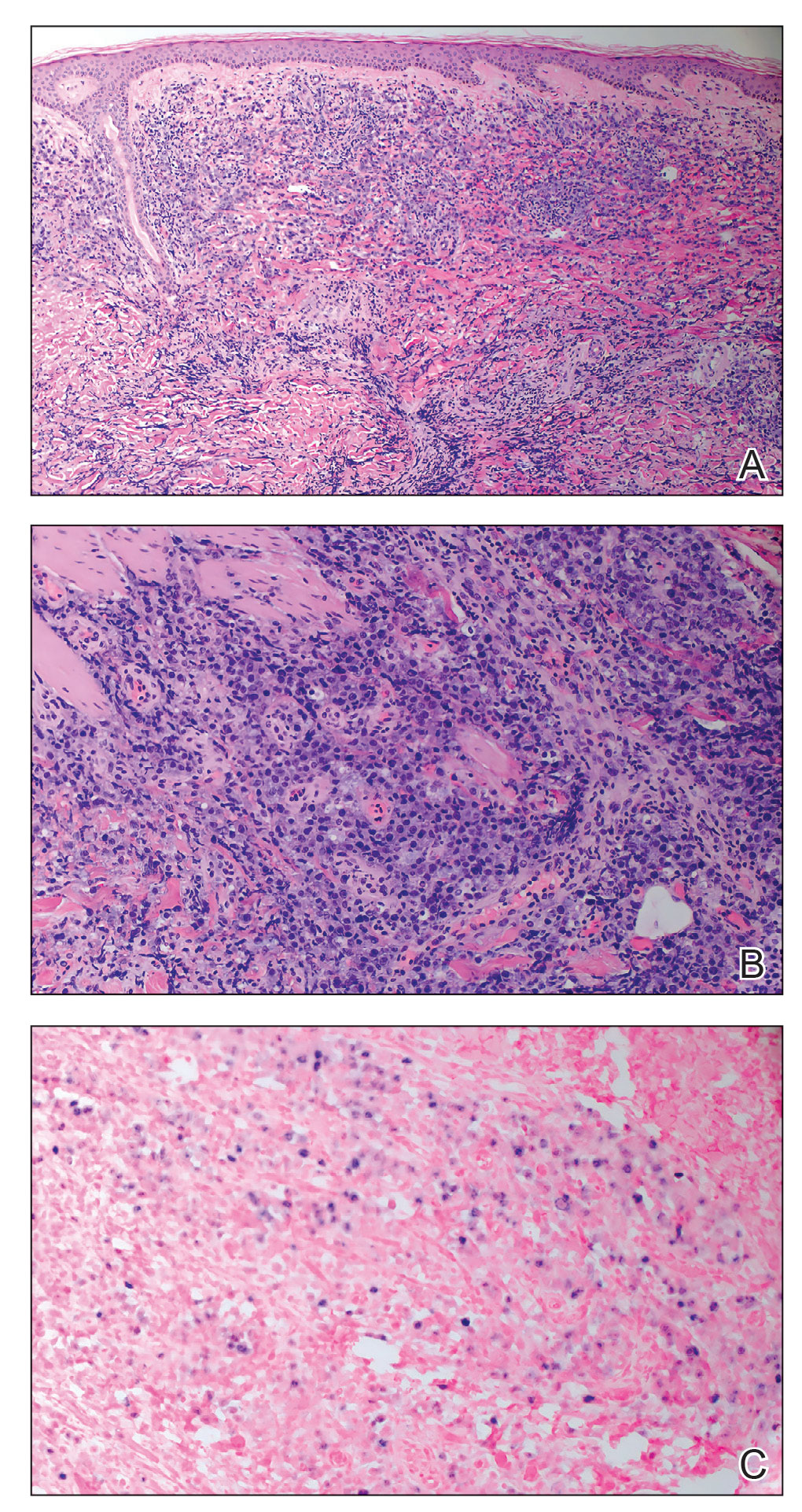

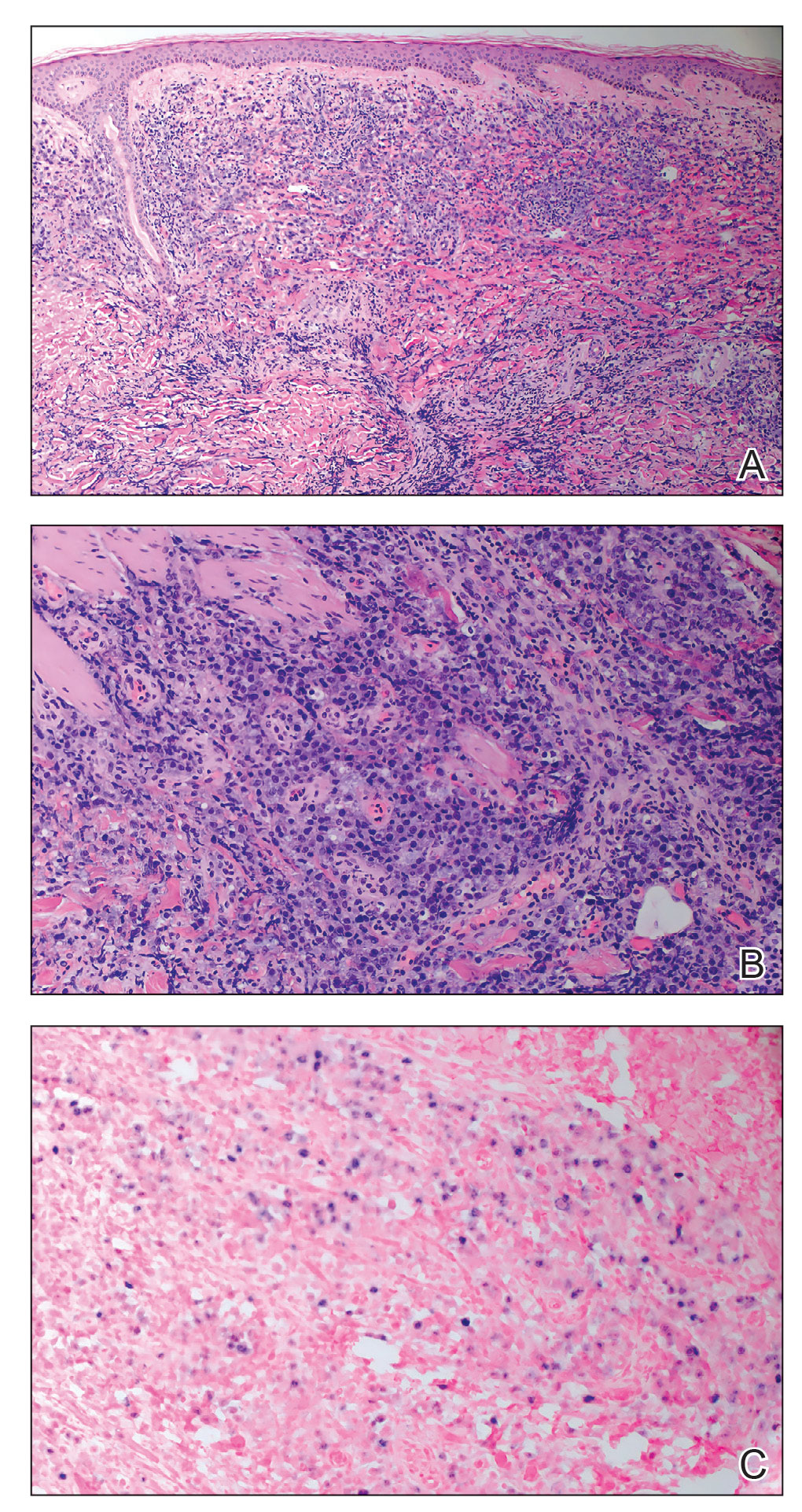

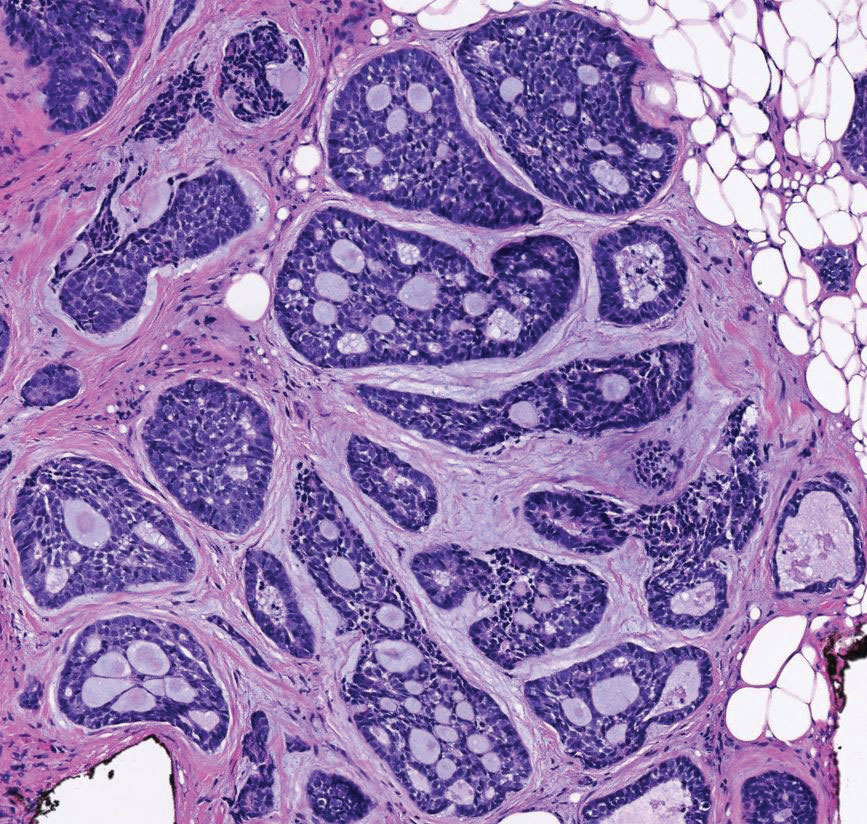

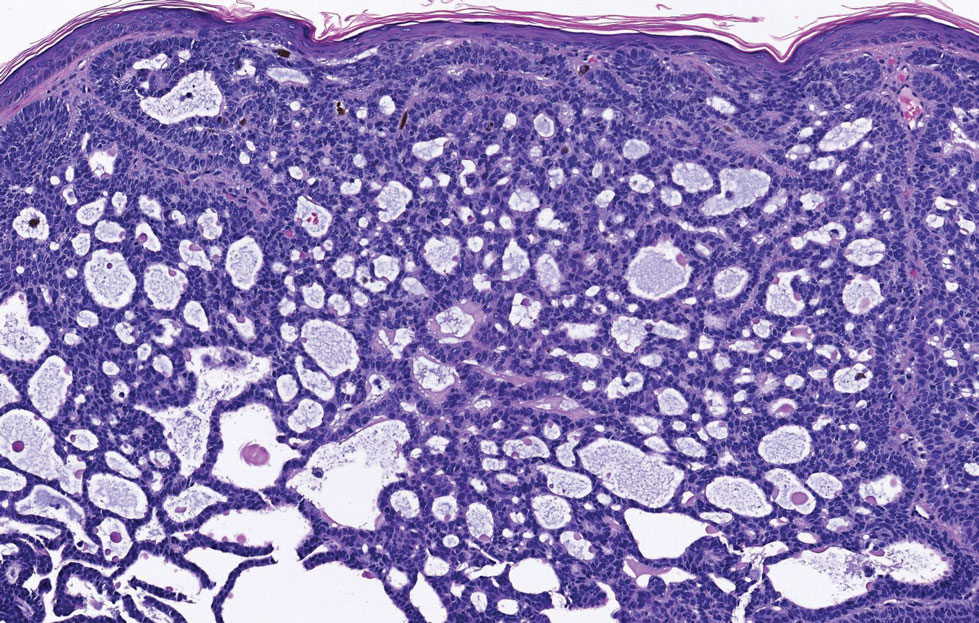

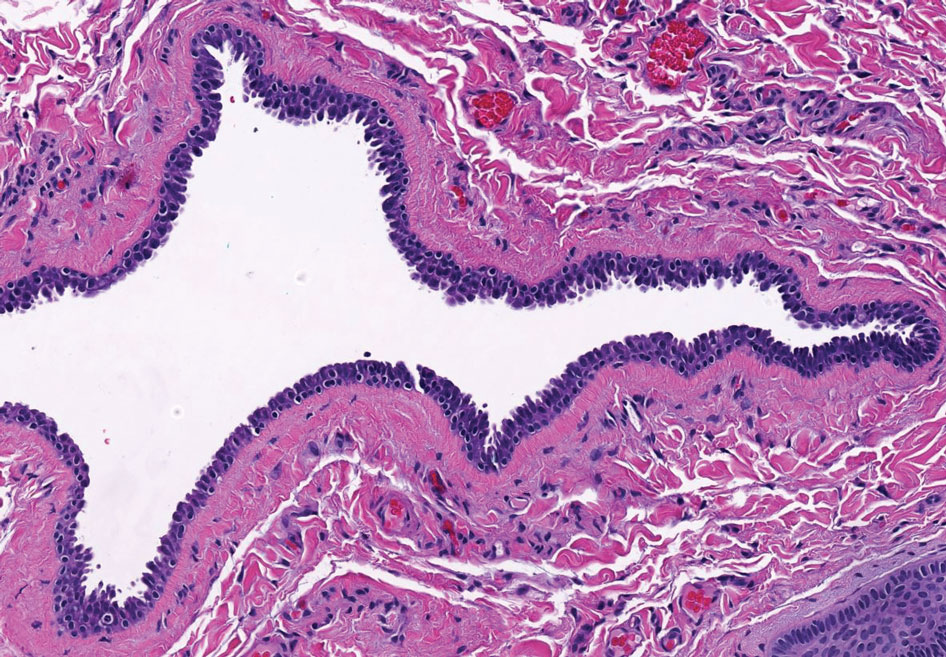

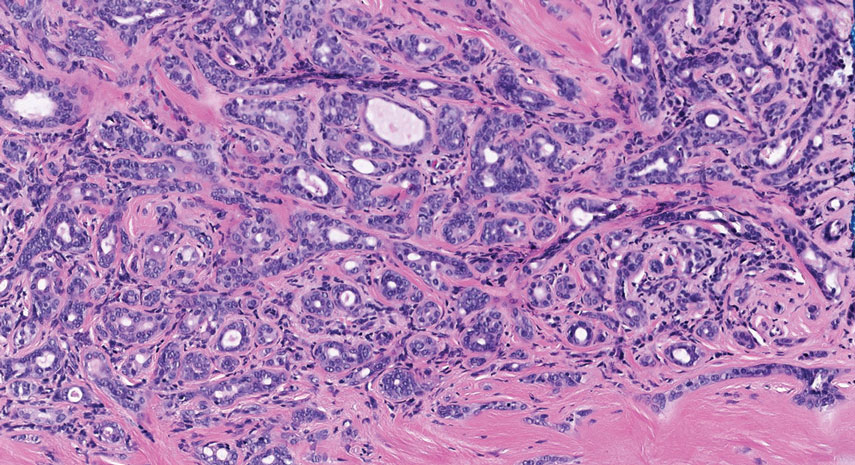

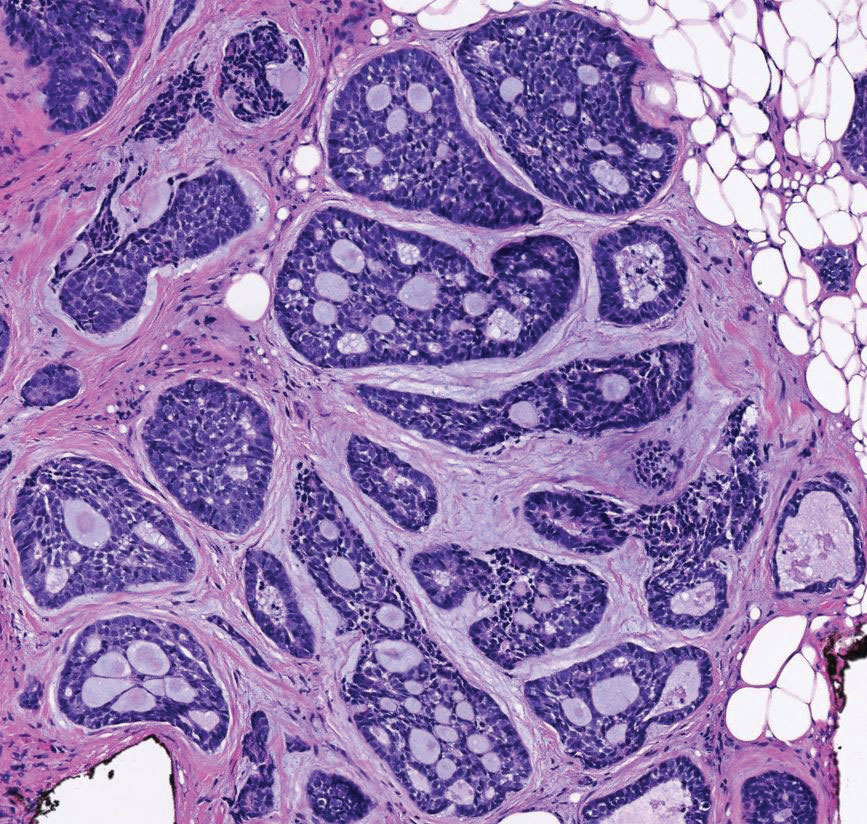

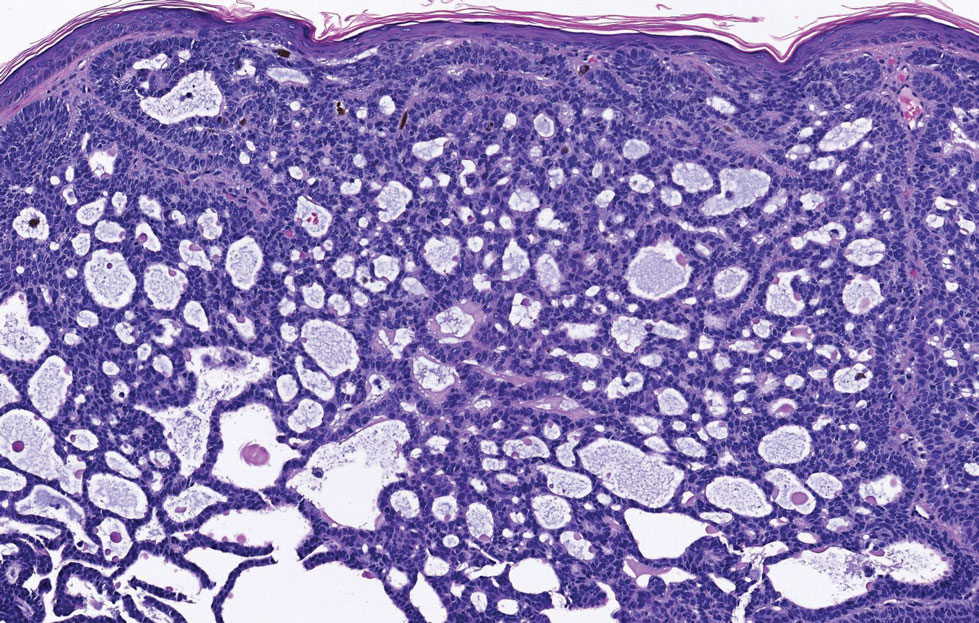

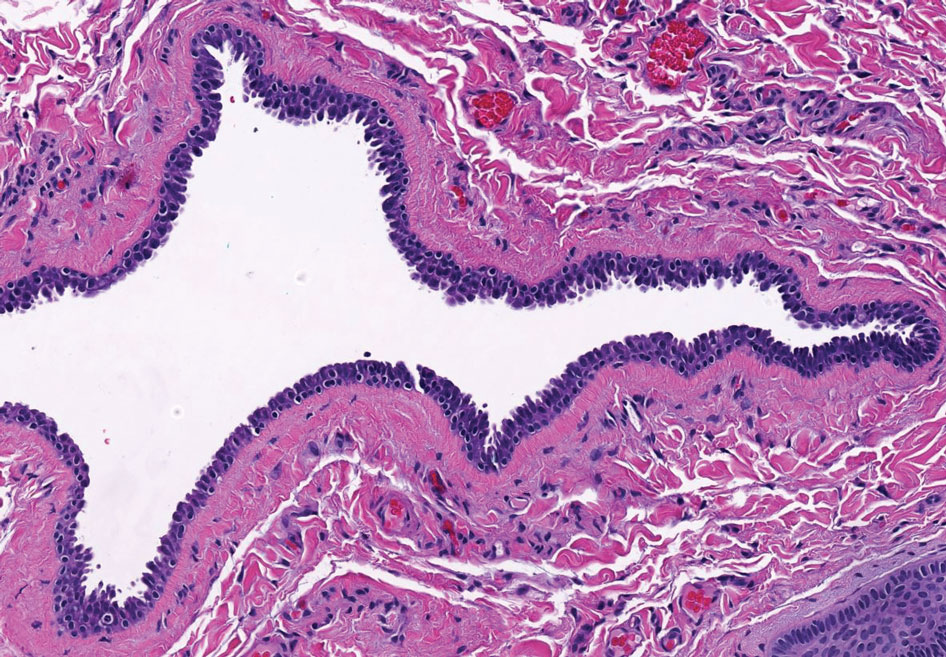

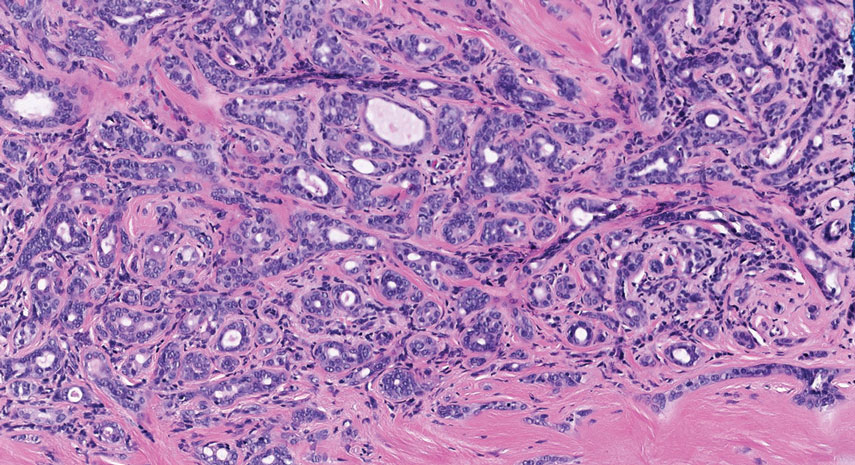

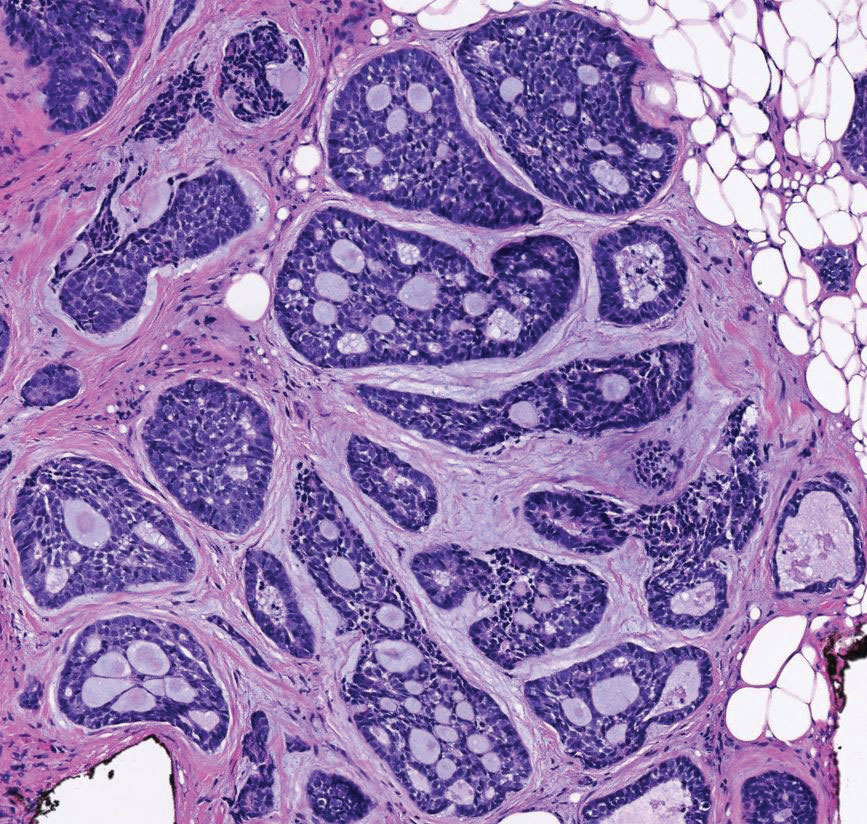

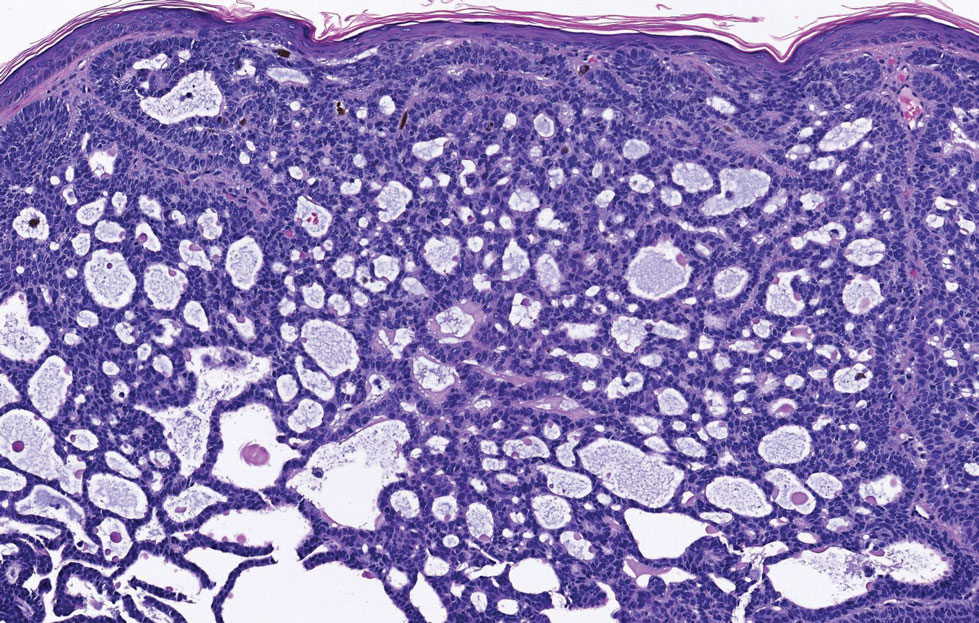

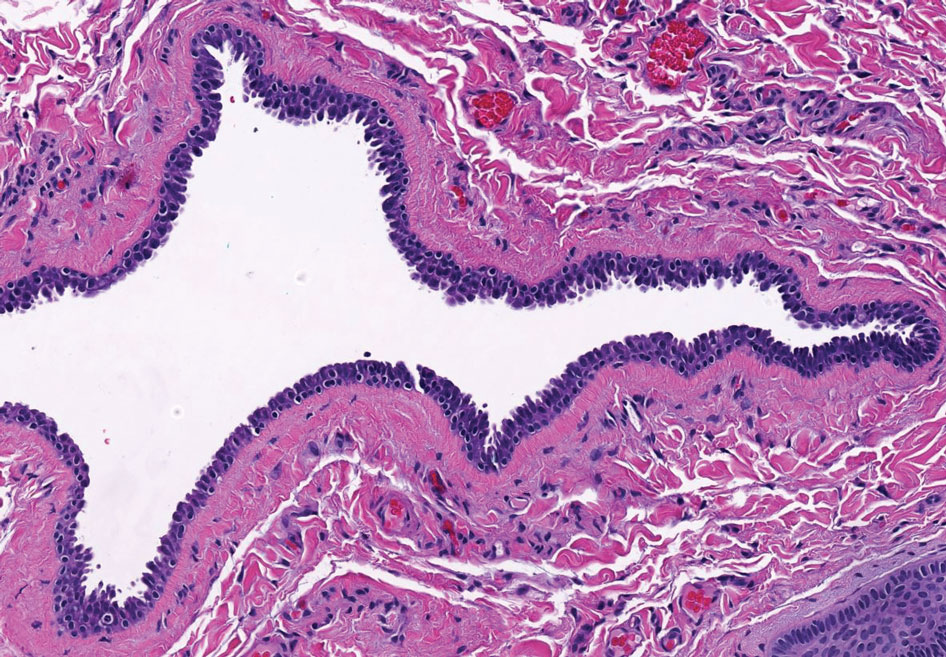

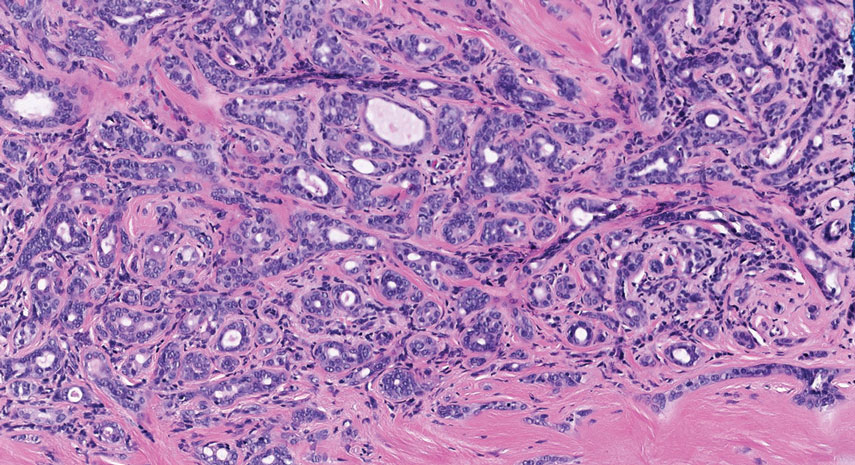

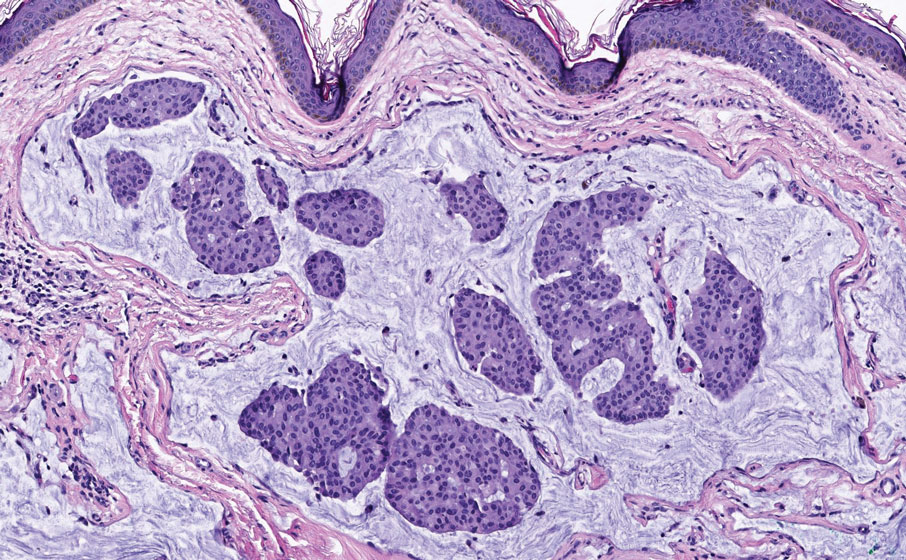

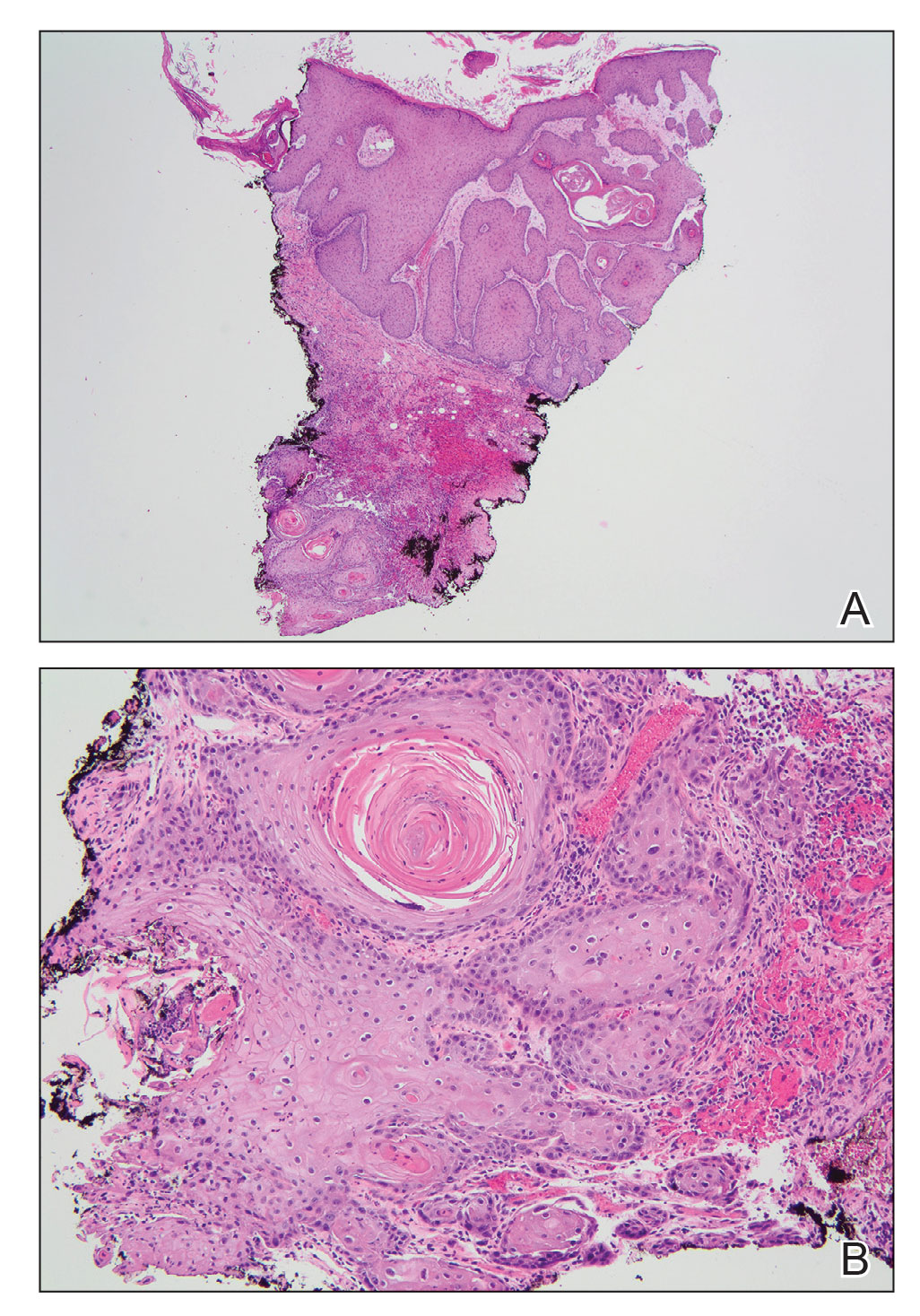

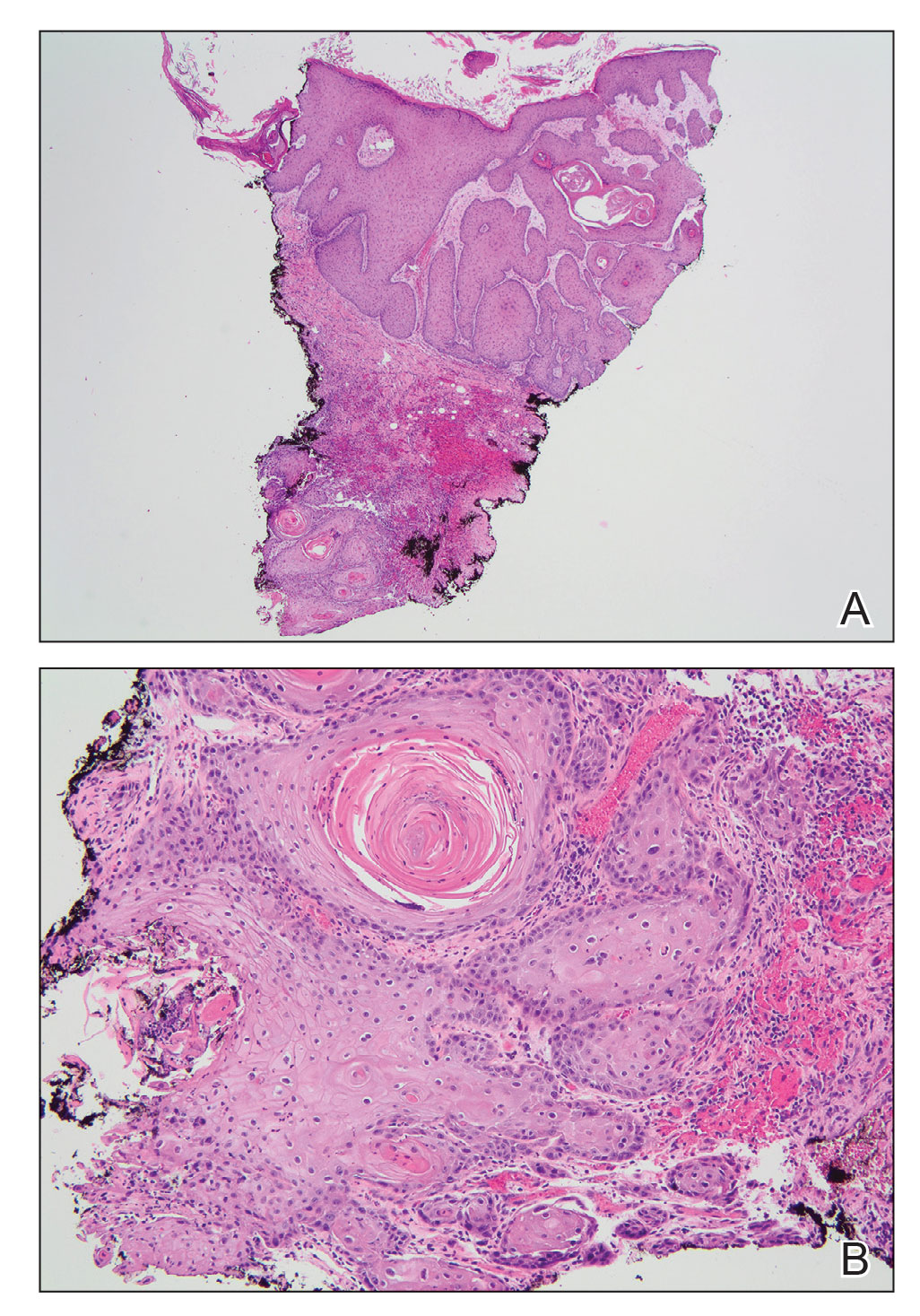

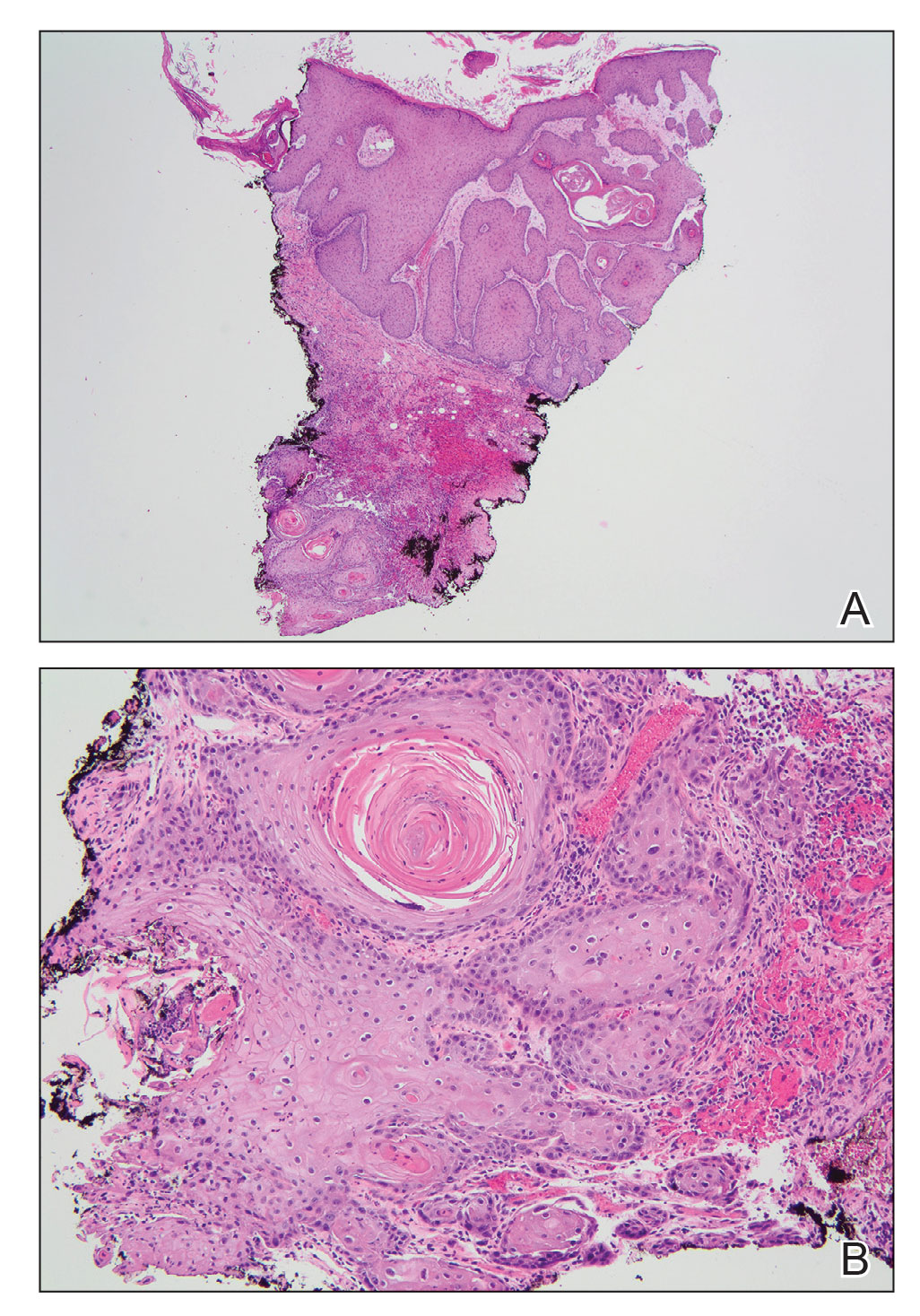

The differential diagnosis for VC includes refractory verruca vulgaris, clavus, SCC, keratoacanthoma, deep fungal or mycobacterial infection, eccrine poroma or porocarcinoma, amelanotic melanoma, and sarcoma.10-13 The slow-growing nature of VC, sampling error of superficial biopsies, and minimal cytological atypia on histologic examination can contribute to delayed diagnosis and appropriate treatment.14 Characteristic histologic features include hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, marked acanthosis, broad blunt-ended rete ridges with a “bulldozing” architecture, and minimal cytologic atypia and mitoses.5,6 In some cases, pleomorphism and glassy eosinophilic cytoplasmic changes may be more pronounced than that of a common wart though less dramatic than that of conventional SCCs.15 Antigen Ki-67 and tumor protein p53 have been proposed to help differentiate between common plantar verruca, VC, and SCC, but the histologic diagnosis remains challenging, and repeat histopathologic examination often is required.16-19 Following diagnosis, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be necessary to determine tumor extension and assess for deep tissue and bony involvement.20-22

Treatment of EC is particularly challenging because of the anatomic location and need for margin control while maintaining adequate function, preserving healthy tissue, and providing coverage of defects. Surgical excision of EC is the first-line treatment, most commonly by wide local excision (WLE) or amputation. Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) also has been utilized. One review found no recurrences in 5 cases of EC treated with MMS.23 As MMS is a tissue-sparing technique, this is a valuable modality for sites of functional importance such as the feet. Herein, we review various reported EC treatment modalities and outcomes, with an emphasis on recurrence rates for WLE and MMS.

METHODS

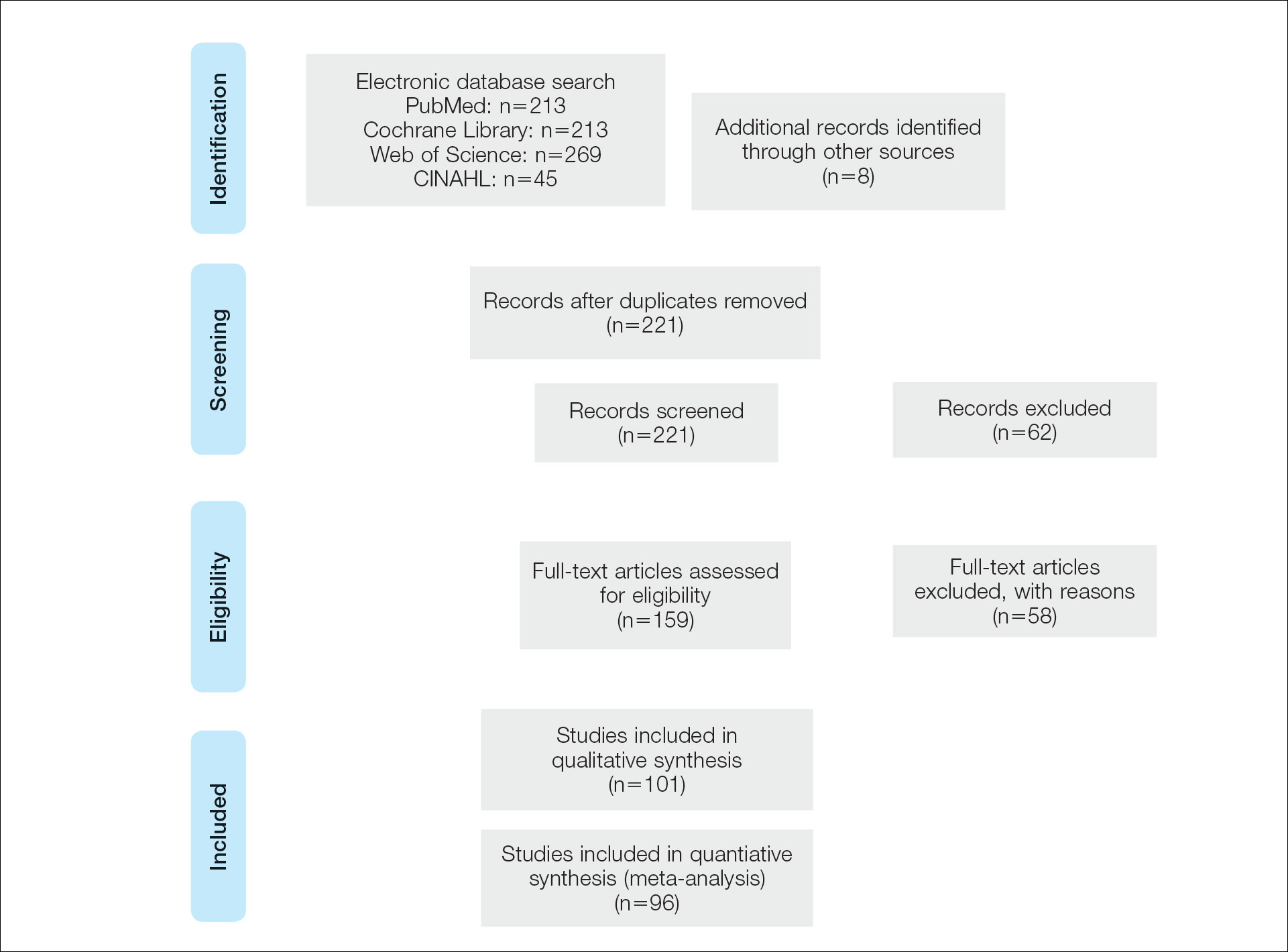

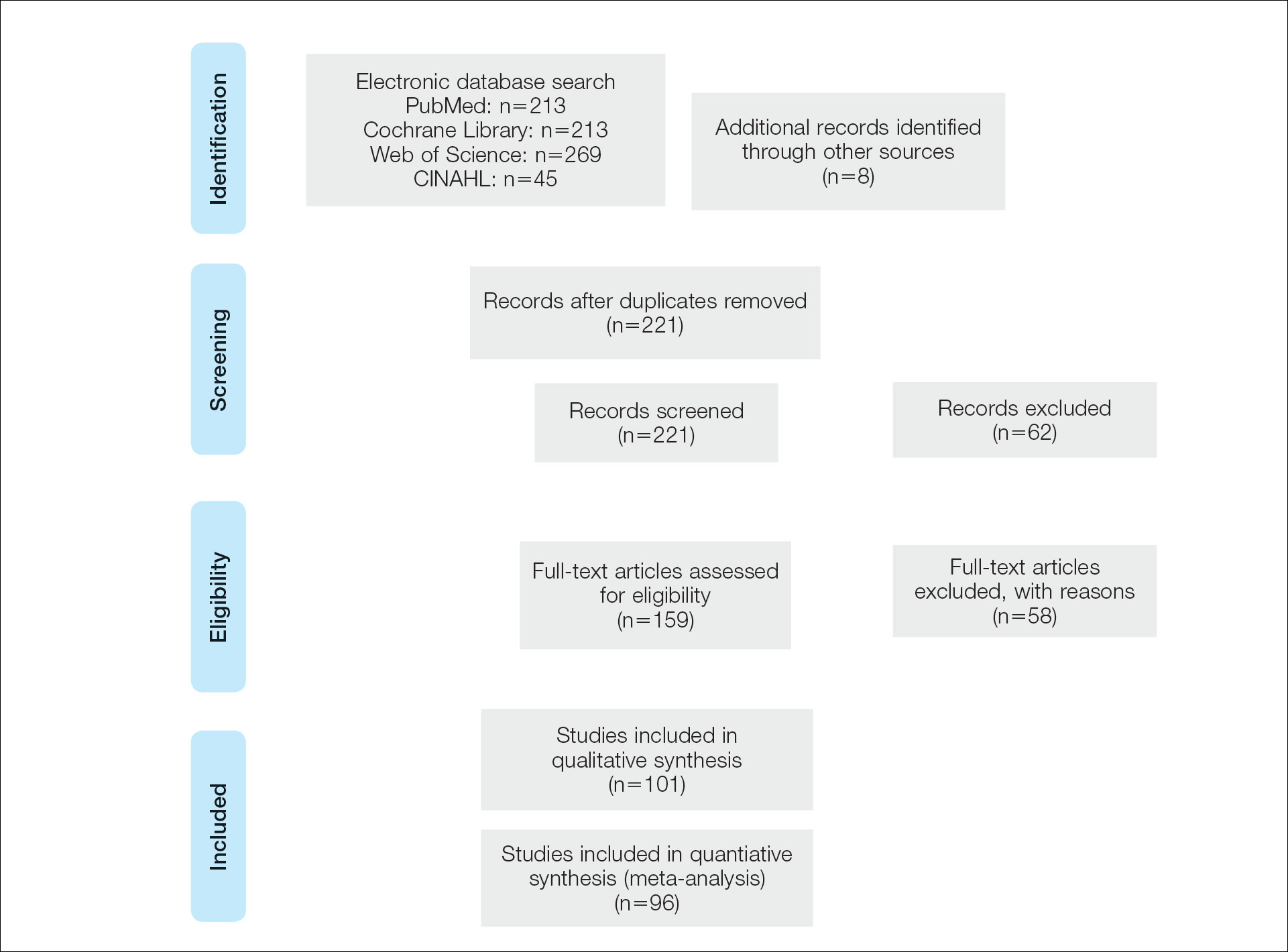

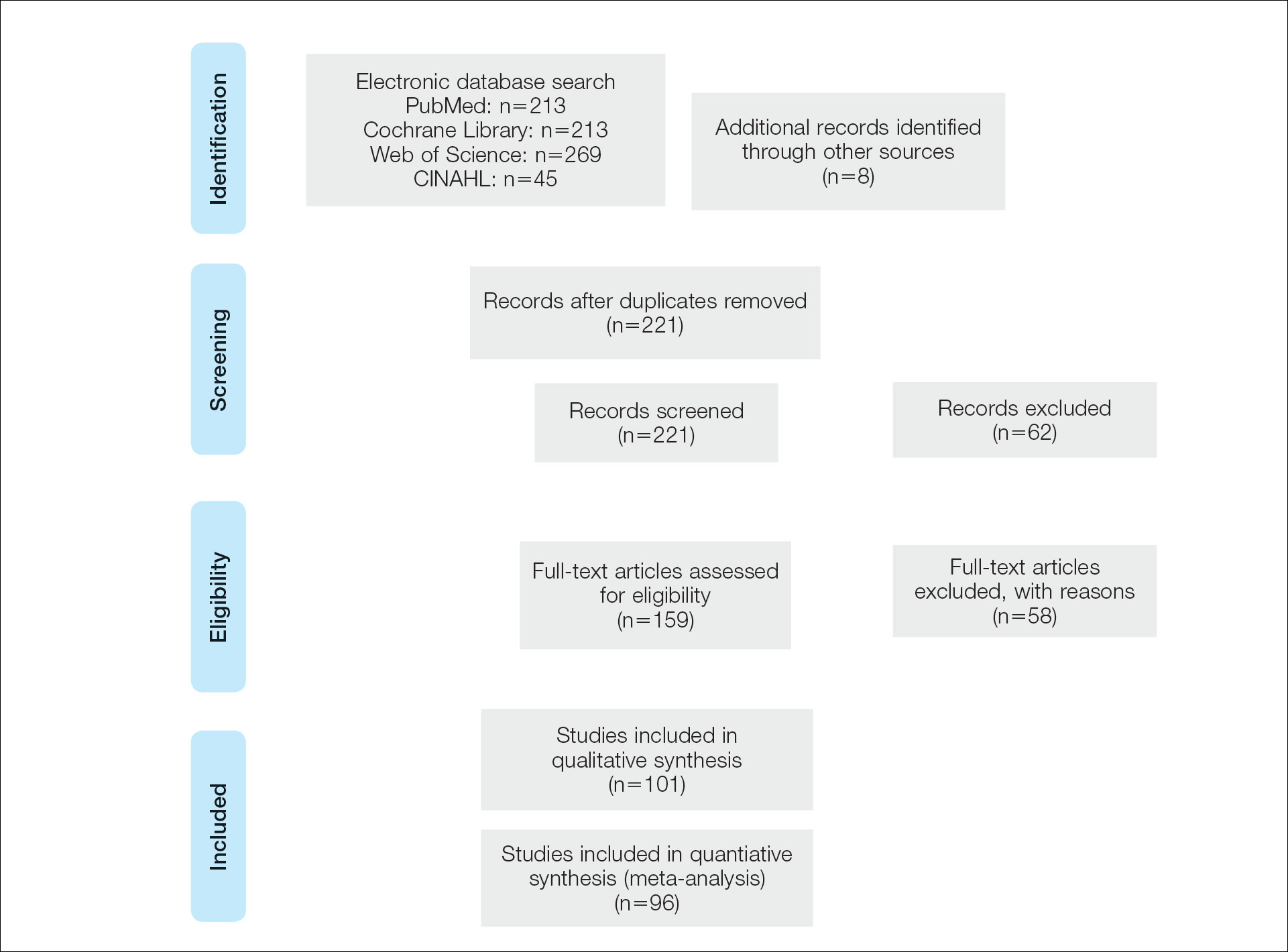

A systematic literature review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE, as well as databases including the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), was performed on January 14, 2020. Two authors (S.S.D. and S.V.C.) independently screened results using the search terms (plantar OR foot) AND (verrucous carcinoma OR epithelioma cuniculatum OR carcinoma cuniculatum). The search terms were chosen according to MeSH subject headings. All articles from the start date of the databases through the search date were screened, and articles pertaining to VC, EC, or carcinoma cuniculatum located on the foot were included. Of these, non–English-language articles were translated and included. Articles reporting VC on a site other than the foot (eg, the oral cavity) or benign verrucous skin lesions were excluded. The reference lists for all articles also were reviewed for additional reports that were absent from the initial search using both included and excluded articles. A full-text review was performed on 221 articles published between 1954 and 2019 per the PRISMA guidelines (Figure).

A total of 101 articles were included in the study for qualitative analysis. Nearly all articles identified were case reports, giving an evidence level of 5 by the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine rating scale. Five articles reported data on multiple patients without individual demographic or clinical details and were excluded from analysis. Of the remaining 96 articles, information about patient characteristics, tumor size, treatment modality, and recurrence were extracted for 115 cases.

RESULTS

Of the 115 cases that were reviewed, 81 (70%) were male and 33 (29%) were female with a male-to-female ratio of 2.4:1. Ages of the patients ranged from 18 to 88 years; the mean and median age was 56 years. Nearly all reported cases of EC affected the plantar surface of one foot, with 4 reports of tumors affecting both feet.24-27 One case affecting both feet reported known exposure to lead arsenate pesticides27; all others were associated with a clinical history of chronic ulcers or warts persisting for several years to decades. Other less common sites of EC included the dorsal foot, interdigital web space, and subungual digit.28-30 The most common location reported was the anterior ball of the foot. Tumors were reported to arise within pre-existing lesions, such as hypertrophic lichen planus or chronic foot wounds associated with diabetes mellitus or leprosy.31-35 Tumor size ranged from 1 to 22 cm with a median of 4.5 cm.

Eight cases were reported to be associated with human papillomavirus; low-risk types 6 and 11 and high-risk types 16 and 18 were found in 6 cases.36-41 Two cases reported association with human papillomavirus type 2.7,42

Metastases to dermal and subdermal lymphatics, regional lymph nodes, and the lungs were reported in 3 cases, repectively.43-45 Of these, one primary tumor had received low-dose irradiation in the form of X-ray therapy.45

Treatment Modalities

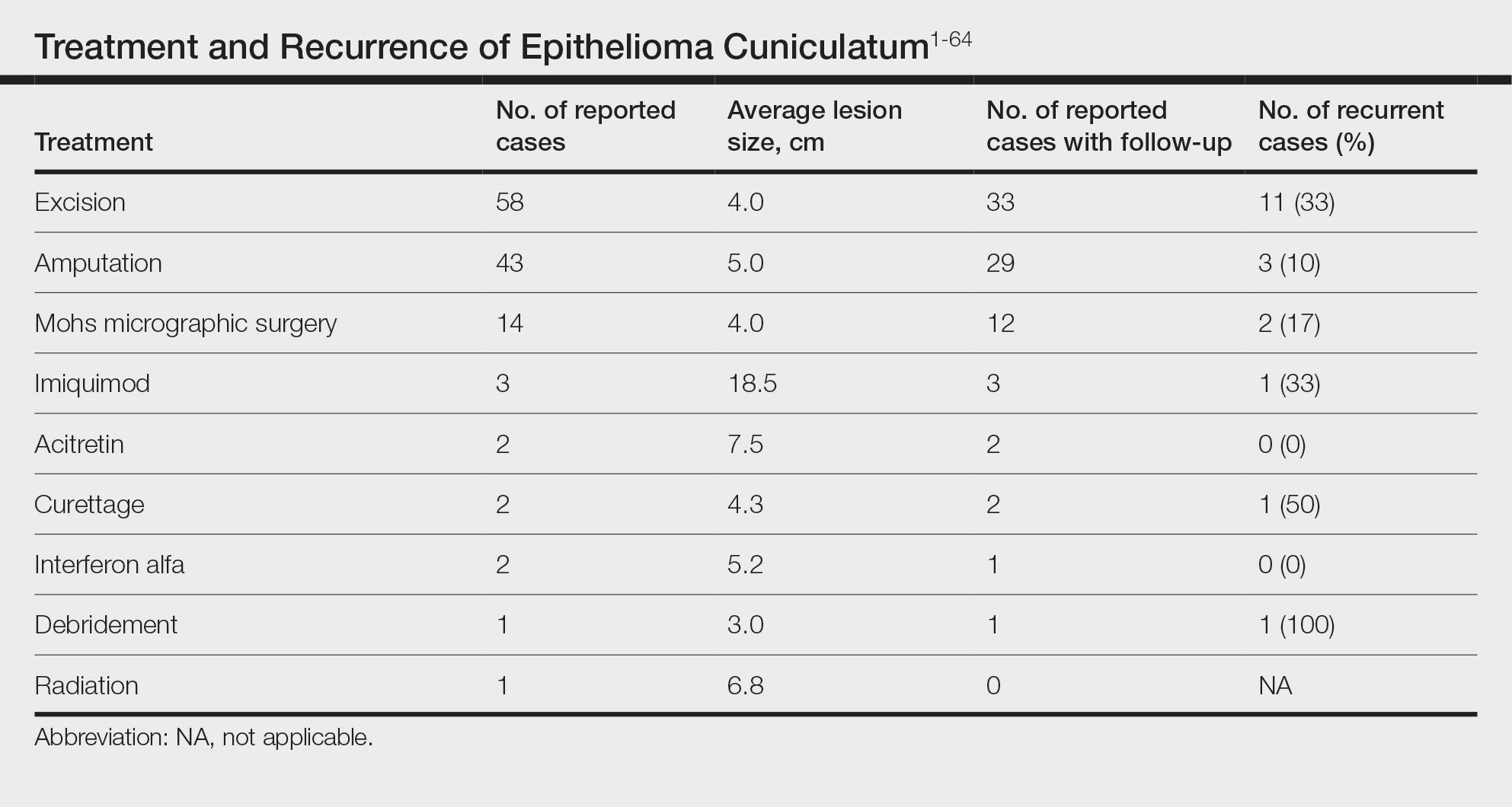

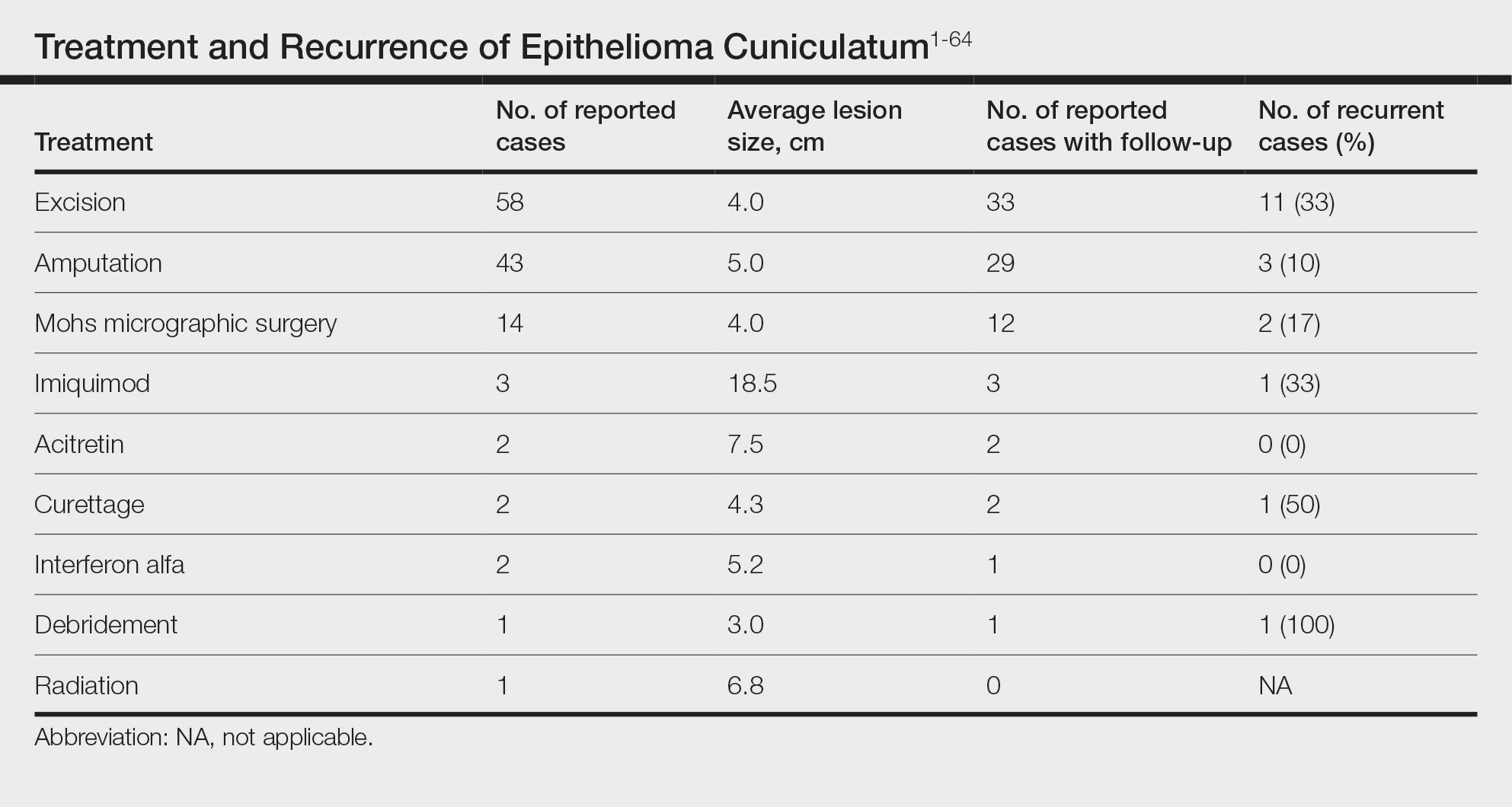

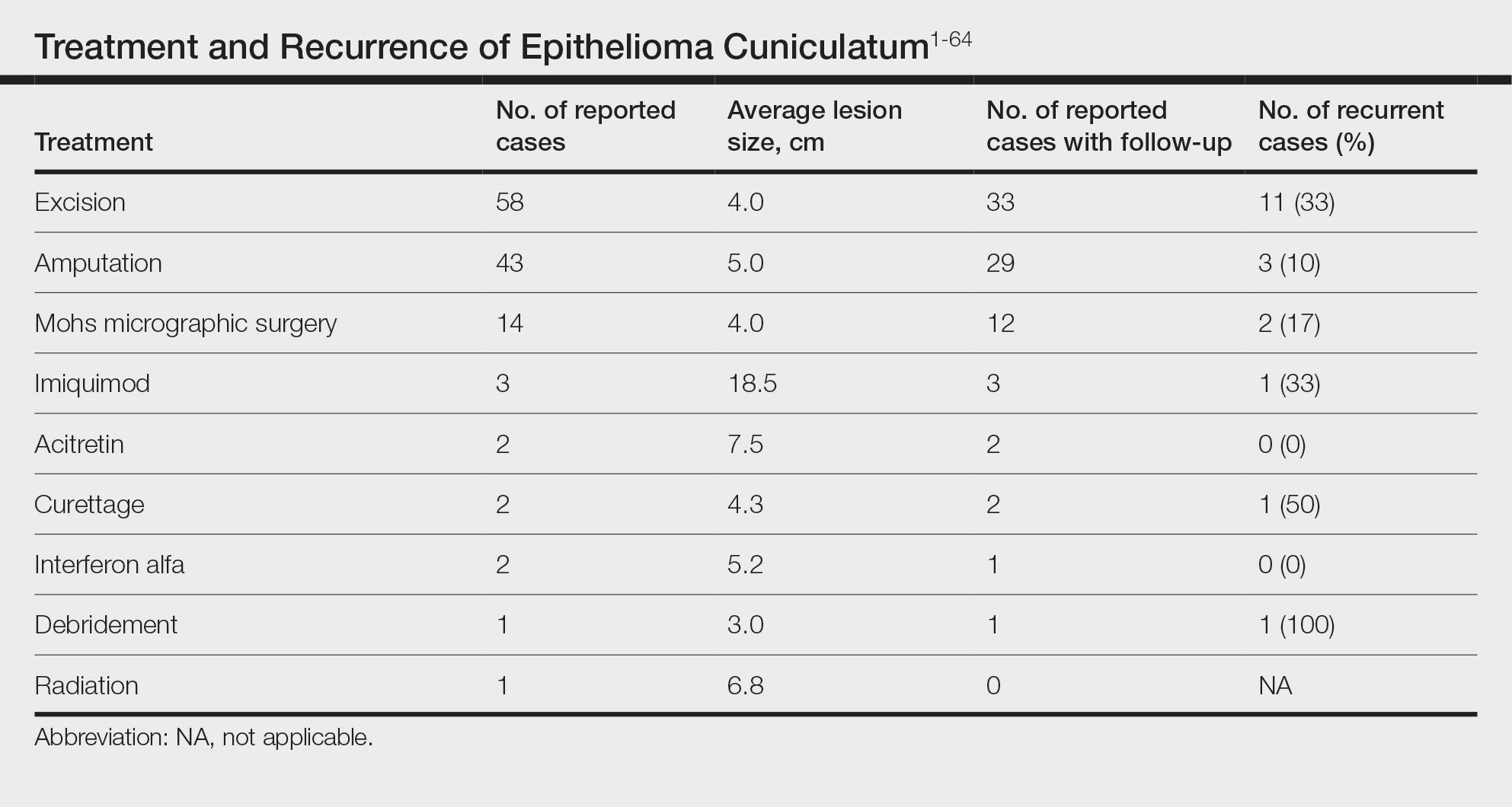

The cases of EC that we reviewed included treatment with surgical and systemic therapies as well as other modalities such as acitretin, interferon alfa, topical imiquimod, curettage, debridement, electrodesiccation, and radiation. The Table includes a complete summary of the treatments we analyzed.

Surgical Therapy—The majority (91% [105/115]) of cases were treated surgically. The most common treatment modality was WLE (50% [58/115]), followed by amputation (37% [43/115]) and MMS (12% [14/115]).

Wide local excision was the most frequently reported treatment, with excision margins of at least 5 mm to 1 cm.48 Incidence of recurrence was reported for 57% (33/58) of cases treated with WLE; of these, the recurrence rate was 33% (11/33). For patients with EC recurrence, the most common secondary treatment was repeat excision with wider margins (1–2 cm) or amputation (5/11).49-52 Few postoperative complications were reported but included pain, infection, and difficulty walking, which were mostly associated with repair modality (eg, split-thickness skin grafts, rotational flaps).53 Amputation was the second most common treatment modality, with a 67% (29/43) incidence of recurrence. Types of amputation included transmetatarsal ray amputation (7/43 [16%]), foot or forefoot amputation (2/43 [5%]), above-the-knee amputation (1/43 [2%]), and below-the-knee amputation (1/43 [2%]). Complications associated with amputation included infection and requirement of prosthetics for ambulation. Split-thickness skin grafts and rotational flaps were the most common surgical repairs performed.52,53

Mohs micrographic surgery was the least frequently reported surgical treatment modality. Both traditional MMS on fresh tissue and “slow Mohs,” with formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue examination over several days, were performed for EC with horizontal en face sectioning.54-56 Incidence of recurrence was reported for 86% (12/14) of MMS cases. Of these, recurrence was seen in 17% (2/12) that utilized a flat horizontal processing of tissue sections coupled with saucerlike excisions to enable examination of the entire undersurface and margins. In one case, the patient was treated with MMS with recurrence noted 1 month later; thus, repeat MMS was performed, and the tumor was found to be entwined around the flexor tendon.57 The tendon was removed, and clear margins were obtained. Follow-up 3 years after the second MMS revealed no signs of recurrence.57 In the other case, the patient had a particularly aggressive course with bilateral VC in the setting of diabetic ulcers that was treated with WLE prior to MMS and recurrence still noted after MMS.26 No complications were reported with MMS.

Overall, recurrence was most frequently reported with WLE (11/33 [33%]), followed by MMS (2/12 [17%]) and amputation (3/29 [10%]). When comparing WLE and amputation, the relationship between treatment modality and recurrence was statistically significant using a χ2 test of independence (χ2=4.7; P=.03). However, results were not significant with Yates correction for continuity (χ2=3.4; P=.06). The χ2 test of independence showed no significant association between treatment method and recurrence when comparing WLE with MMS (χ2=1.2; P=.28). Reported follow-up times varied greatly from a few months to 10 years.

Systemic Therapy—Of the total cases, only 2 cases reported treatment with acitretin and 2 utilized interferon alfa.58,59 In one case, treatment of EC with interferon alfa alone required more aggressive therapy (ie, amputation).58 Neither of the 2 cases using acitretin reported recurrence.59,60 Complications of acitretin therapy included cheilitis and transaminitis.60

Other Treatment Modalities—Three cases utilized imiquimod, with 2 cases of imiquimod monotherapy and 1 case of imiquimod in combination with electrodesiccation and WLE.37 One of the cases of EC treated with imiquimod monotherapy recurred and required WLE.61

There were reports of other treatments including curettage alone (2% [2/115]),40,62 debridement alone (1% [1/115]),40 electrodesiccation (1% [1/115]),37 and radiation (1% [1/115]).43 Recurrence was found with curettage alone and debridement alone. Electrodesiccation was reported in conjunction with WLE without recurrence. Radiation was used to treat a case of VC that had metastasized to the lymph nodes; no follow-up was described.43

COMMENT

Epithelioma cuniculatum is an indolent malignancy of the plantar foot that likely is frequently underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed because of location, sampling error, and challenges in histopathologic diagnosis. Once diagnosed, surgical removal with margin control is the first-line therapy for EC. Our review found a number of surgical, systemic, and other treatment modalities that have been used to treat EC, but there remains a lack of evidence to provide clear guidelines as to which therapies are most effective. Current data on the treatment of EC largely are limited to case reports and case series. To date, there are no reports of higher-quality studies or randomized controlled trials to assess the efficacy of various treatment modalities.

Our review found that WLE is the most common treatment modality for EC, followed by amputation and MMS. Three cases43-45 that reported metastasis to lymph nodes also were treated with fine-needle aspiration or biopsy, and it is recommended that sentinel lymph node biopsy be performed when there is a history of radiation exposure or clinically and sonographically unsuspicious lymph nodes, while dissection of regional nodes should be performed if lymph node metastasis is suspected.53 Additional treatments reported included acitretin, interferon alfa, topical imiquimod, curettage, debridement, and electrodesiccation, but because of the limited number of cases and variable efficacy, no conclusions can be made on the utility of these alternative modalities.

The lowest rate of reported recurrence was found with amputation, followed by MMS and WLE. Amputation is the most aggressive treatment option, but its superiority in lower recurrence rates was not statistically significant when compared with either WLE or MMS after Yates correction. Despite treatment with radical surgery, recurrence is still possible and may be associated with factors including greater size (>2 cm) and depth (>4 mm), poor histologic differentiation, perineural involvement, failure of previous treatments, and immunosuppression.63 No statistically significant difference in recurrence rates was found among surgical methods, though data trended toward lower rates of recurrence with MMS compared with WLE, as recurrence with MMS was only reported in 2 cases.25,56

The efficacy of MMS is well documented for tumors with contiguous growth and enables maximum preservation of normal tissue structure and function with complete margin visualization. Thus, our results are in agreement with those of prior studies,54-56,64 suggesting that MMS is associated with lower recurrence rates for EC than WLE. Future studies and reporting of MMS for EC are particularly important because of the functional importance of the plantar foot.

It is important to note that there are local and systemic risk factors that increase the likelihood of developing EC and facilitate tumor growth, including antecedent trauma to the lesion site, chronic irritation or infection, and immunosuppression (HIV related or iatrogenic medication induced). These risk factors may play a role in the treatment modality utilized (eg, more aggressive EC may be treated with amputation instead of WLE). Underlying patient comorbidities could potentially affect recurrence rates, which is a variable we could not control for in our analysis.

Our findings are limited by study design, with supporting evidence consisting of case reports and series. The review is limited by interstudy variability and heterogeneity of results. Additionally, recurrence is not reported in all cases and may be a source of sampling bias. Further complicating the generalizability of these results is the lack of follow-up to evaluate morbidity and quality of life after treatment.

CONCLUSION

This review suggests that MMS is associated with lower recurrence rates than WLE for the treatment of EC. Further investigation of MMS for EC with appropriate follow-up is necessary to identify whether MMS is associated with lower recurrence and less functional impairment. Nonsurgical treatments, including topical imiquimod, interferon alfa, and acitretin, may be useful in cases where surgical therapies are contraindicated, but there is little evidence to support these treatment modalities. Treatment guidelines for EC are not established, and appropriate treatment guidelines should be developed in the future.

- McKee PH, Wilkinson JD, Black MM, et al. Carcinoma (epithelioma) cuniculatum: a clinicopathological study of nineteen cases and review of the literature. Histopathology. 1981;5:425-436.

- Aird I, Johnson HD, Lennox B, et al. Epithelioma cuniculatum: a variety of squamous carcinoma peculiar to the foot. Br J Surg. 1954;42:245-250.

- Seremet S, Erdemir AT, Kiremitci U, et al. Unusually early-onset plantar verrucous carcinoma. Cutis. 2019;104:34-36.

- Spyriounis PK, Tentis D, Sparveri IF, et al. Plantar epithelioma cuniculatum. a case report with review of the literature. Eur J Plast Surg. 2004;27:253-256.

- Ho J, Diven G, Bu J, et al. An ulcerating verrucous plaque on the foot. verrucous carcinoma (epithelioma cuniculatum). Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:547-548, 550-551.

- Kao GF, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Carcinoma cuniculatum (verrucous carcinoma of the skin): a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases with ultrastructural observations. Cancer. 1982;49:2395-2403.

- Zielonka E, Goldschmidt D, de Fontaine S. Verrucous carcinoma or epithelioma cuniculatum plantare. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1997;23:86-87.

- Dogan G, Oram Y, Hazneci E, et al. Three cases of verrucous carcinoma. Australas J Dermatol. 1998;39:251-254.

- Schwartz RA, Burgess GH. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot. J Surg Oncol. 1980;14:333-339.

- McKay C, McBride P, Muir J. Plantar verrucous carcinoma masquerading as toe web intertrigo. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:2010-2012.

- Shenoy AS, Waghmare RS, Kavishwar VS, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of foot. Foot. 2011;21:207-208.

- Lozzi G, Perris K. Carcinoma cuniculatum. CMAJ. 2007;177:249-251.

- Schein O, Orenstein A, Bar-Meir E. Plantar verrucous carcicoma (epithelioma cuniculatum): rare form of the common wart. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8:885.

- Rheingold LM, Roth LM. Carcinoma of the skin of the foot exhibiting some verrucous features. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;61:605-609.

- Klima M, Kurtis B, Jordan PH. Verrucous carcinoma of skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1980;7:88-98.

- Nakamura Y, Kashiwagi K, Nakamura A, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot diagnosed using p53 and Ki-67 immunostaining in a patient with diabetic neuropathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:257-259.

- Costache M, Desa LT, Mitrache LE, et al. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma—report of three cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:383-388.

- Terada T. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin: a report on 5 Japanese cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15:175-180.

- Noel JC, Heenen M, Peny MO, et al. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen distribution in verrucous carcinoma of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:868-873.

- García-Gavín J, González-Vilas D, Rodríguez-Pazos L, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot affecting the bone: utility of the computed tomography scanner. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:3-5.

- Wasserman PL, Taylor RC, Pinillia J, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot and enhancement assessment by MRI. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38:393-395.

- Bhushan MH, Ferguson JE, Hutchinson CE. Carcinoma cuniculatum of the foot assessed by magnetic resonance scanning. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:419-422.

- Penera KE, Manji KA, Craig AB, et al. Atypical presentation of verrucous carcinoma: a case study and review of the literature. Foot Ankle Spec. 2013;6:318-322.

- Suen K, Wijeratne S, Patrikios J. An unusual case of bilateral verrucous carcinoma of the foot (epithelioma cuniculatum). J Surg Case Rep. 2012;2012:rjs020.

- Riccio C, King K, Elston JB, et al. Bilateral plantar verrucous carcinoma. Eplasty. 2016;16:ic46.

- Di Palma V, Stone JP, Schell A, et al. Mistaken diabetic ulcers: a case of bilateral foot verrucous carcinoma. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2018;2018:4192657.

- Seehafer JR, Muller SA, Dicken CH. Bilateral verrucous carcinoma of the feet. Orthop Surv. 1979;3:205.

- Tosti A, Morelli R, Fanti PA, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of the nail apparatus: report of three cases. Dermatology. 1993;186:217-221.

- Melo CR, Melo IS, Souza LP. Epithelioma cuniculatum, a verrucous carcinoma of the foot. report of 2 cases. Dermatologica. 1981;163:338-342.

- Van Geertruyden JP, Olemans C, Laporte M, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the nail bed. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:327-328.

- Thakur BK, Verma S, Raphael V. Verrucous carcinoma developing in a long standing case of ulcerative lichen planus of sole: a rare case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:399-401.

- Mayron R, Grimwood RE, Siegle RJ, et al. Verrucous carcinoma arising in ulcerative lichen planus of the soles. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:547-551.

- Boussofara L, Belajouza-Noueiri C, Ghariani N, et al. Verrucous epidermoid carcinoma as a complication in cutaneous lichen planus [article in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2006;133:404-405.

- Khullar G, Mittal S, Sharma S. Verrucous carcinoma on the foot arising in a chronic neuropathic ulcer of leprosy. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:245-246.

- Ochsner PE, Hausman R, Olsthoorn PGM. Epithelioma cunicalutum developing in a neuropathic ulcer of leprous etiology. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1979;94:227-231.

- Ray R, Bhagat A, Vasudevan B, et al. A rare case of plantar epithelioma cuniculatum arising from a wart. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:485-487.

- Imko-Walczuk B, Cegielska A, Placek W, et al. Human papillomavirus-related verrucous carcinoma in a renal transplant patient after long-term immunosuppression: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2014;46:2916-2919.

- Floristán MU, Feltes RA, Sáenz JC, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot associated with human papillomavirus type 18. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:433-435.

- Sasaoka R, Morimura T, Mihara M, et al. Detection of human pupillomavirus type 16 DNA in two cases of verriicous carcinoma of the foot. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:983984.

- Schell BJ, Rosen T, Rády P, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot associated with human papillomavirus type 16. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:49-55.

- Knobler RM, Schneider S, Neumann RA, et al. DNA dot‐blot hybridization implicates human papillomavirus type 11‐DNA in epithelioma cuniculatum. J Med Virol. 1989;29:33-37.

- Noel JC, Peny MO, Detremmerie O, et al. Demonstration of human papillomavirus type 2 in a verrucous carcinoma of the foot. Dermatology. 1993;187:58-61.

- Jungmann J, Vogt T, Müller CSL. Giant verrucous carcinoma of the lower extremity in women with dementia. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr2012006357.

- McKee PH, Wilkinson JD, Corbett MF, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum: a case metastasizing to skin and lymph nodes. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1981;6:613-618.

- Owen WR, Wolfe ID, Burnett JW, et al. Epithelioma cuniculatum. South Med J. 1978;71:477-479.

- Patel AN, Bedforth N, Varma S. Pain-free treatment of carcinoma cuniculatum on the heel using Mohs micrographic surgery and ultrasonography-guided sciatic nerve block. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:569-571.

- Padilla RS, Bailin PL, Howard WR, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and its management by Mohs’ surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:442-447.

- Kotwal M, Poflee S, Bobhate S. Carcinoma cuniculatum at various anatomical sites. Indian J Dermatol. 2005;50:216-220.

- Arefi M, Philipone E, Caprioli R, et al. A case of verrucous carcinoma (epithelioma cuniculatum) of the heel mimicking infected epidermal cyst and gout. Foot Ankle Spec. 2008;1:297-299.

- Trebing D, Brunner M, Kröning Y, et al. Young man with verrucous heel tumor [article in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2003;9:739-741.

- Thompson SG. Epithelioma cuniculatum: an unusual tumour of the foot. Br J Plast Surg. 1965;18:214-217.

- Thomas EJ, Graves NC, Meritt SM. Carcinoma cuniculatum: an atypical presentation in the foot. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;53:356-359.

- Koch H, Kowatsch E, Hödl S, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin: long-term follow-up results following surgical therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1124-1130.

- Mallatt BD, Ceilley RI, Dryer RF. Management of verrucous carcinoma on a foot by a combination of chemosurgery and plastic repair: report of a case. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1980;6:532-534.

- Mohs FE, Sahl WJ. Chemosurgery for verrucous carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1979;5:302-306.

- Alkalay R, Alcalay J, Shiri J. Plantar verrucous carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery: a case report and literature review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:68-73.

- Mora RG. Microscopically controlled surgery (Mohs’ chemosurgery) for treatment of verrucous squamous cell carcinoma of the foot (epithelioma cuniculatum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:354-362.

- Risse L, Negrier P, Dang PM, et al. Treatment of verrucous carcinoma with recombinant alfa-interferon. Dermatology. 1995;190:142-144.

- Rogozin´ski TT, Schwartz RA, Towpik E. Verrucous carcinoma in Unna-Thost hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:1061-1062.

- Kuan YZ, Hsu HC, Kuo TT, et al. Multiple verrucous carcinomas treated with acitretin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2 suppl):S29-S32.

- Schalock PC, Kornik RI, Baughman RD, et al. Treatment of verrucous carcinoma with topical imiquimod. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:233-234.

- Brown SM, Freeman RG. Epithelioma cuniculatum. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1295-1296.

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL, et al. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:976-990.

- Swanson NA, Taylor WB. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: literature review and treatment by the Mohs’ chemosurgery technique. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:794-797.

Verrucous carcinoma (VC) is an uncommon type of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) that most commonly affects men in the fifth to sixth decades of life. 1 The tumor grows slowly over a decade or more and does not frequently metastasize but has a high propensity for recurrence and local invasion. 2 There are 3 main subtypes of VC classified by anatomic site: oral florid papillomatosis (oral cavity), Buschke-Lowenstein tumor (anogenital region), and epithelioma cuniculatum (EC)(feet). 3 Epithelioma cuniculatum, also known as carcinoma cuniculatum or papillomatosis cutis carcinoides, most commonly presents as a solitary, warty or cauliflowerlike, exophytic mass with keratin-filled sinus tracts and malodorous discharge. 4 Diabetic foot ulcers and chronic inflammatory conditions are predisposing risk factors for EC, and it can result in difficulty walking/immobility, pain, and bleeding depending on anatomic involvement. 5-9

The differential diagnosis for VC includes refractory verruca vulgaris, clavus, SCC, keratoacanthoma, deep fungal or mycobacterial infection, eccrine poroma or porocarcinoma, amelanotic melanoma, and sarcoma.10-13 The slow-growing nature of VC, sampling error of superficial biopsies, and minimal cytological atypia on histologic examination can contribute to delayed diagnosis and appropriate treatment.14 Characteristic histologic features include hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, marked acanthosis, broad blunt-ended rete ridges with a “bulldozing” architecture, and minimal cytologic atypia and mitoses.5,6 In some cases, pleomorphism and glassy eosinophilic cytoplasmic changes may be more pronounced than that of a common wart though less dramatic than that of conventional SCCs.15 Antigen Ki-67 and tumor protein p53 have been proposed to help differentiate between common plantar verruca, VC, and SCC, but the histologic diagnosis remains challenging, and repeat histopathologic examination often is required.16-19 Following diagnosis, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be necessary to determine tumor extension and assess for deep tissue and bony involvement.20-22

Treatment of EC is particularly challenging because of the anatomic location and need for margin control while maintaining adequate function, preserving healthy tissue, and providing coverage of defects. Surgical excision of EC is the first-line treatment, most commonly by wide local excision (WLE) or amputation. Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) also has been utilized. One review found no recurrences in 5 cases of EC treated with MMS.23 As MMS is a tissue-sparing technique, this is a valuable modality for sites of functional importance such as the feet. Herein, we review various reported EC treatment modalities and outcomes, with an emphasis on recurrence rates for WLE and MMS.

METHODS

A systematic literature review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE, as well as databases including the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), was performed on January 14, 2020. Two authors (S.S.D. and S.V.C.) independently screened results using the search terms (plantar OR foot) AND (verrucous carcinoma OR epithelioma cuniculatum OR carcinoma cuniculatum). The search terms were chosen according to MeSH subject headings. All articles from the start date of the databases through the search date were screened, and articles pertaining to VC, EC, or carcinoma cuniculatum located on the foot were included. Of these, non–English-language articles were translated and included. Articles reporting VC on a site other than the foot (eg, the oral cavity) or benign verrucous skin lesions were excluded. The reference lists for all articles also were reviewed for additional reports that were absent from the initial search using both included and excluded articles. A full-text review was performed on 221 articles published between 1954 and 2019 per the PRISMA guidelines (Figure).

A total of 101 articles were included in the study for qualitative analysis. Nearly all articles identified were case reports, giving an evidence level of 5 by the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine rating scale. Five articles reported data on multiple patients without individual demographic or clinical details and were excluded from analysis. Of the remaining 96 articles, information about patient characteristics, tumor size, treatment modality, and recurrence were extracted for 115 cases.

RESULTS

Of the 115 cases that were reviewed, 81 (70%) were male and 33 (29%) were female with a male-to-female ratio of 2.4:1. Ages of the patients ranged from 18 to 88 years; the mean and median age was 56 years. Nearly all reported cases of EC affected the plantar surface of one foot, with 4 reports of tumors affecting both feet.24-27 One case affecting both feet reported known exposure to lead arsenate pesticides27; all others were associated with a clinical history of chronic ulcers or warts persisting for several years to decades. Other less common sites of EC included the dorsal foot, interdigital web space, and subungual digit.28-30 The most common location reported was the anterior ball of the foot. Tumors were reported to arise within pre-existing lesions, such as hypertrophic lichen planus or chronic foot wounds associated with diabetes mellitus or leprosy.31-35 Tumor size ranged from 1 to 22 cm with a median of 4.5 cm.

Eight cases were reported to be associated with human papillomavirus; low-risk types 6 and 11 and high-risk types 16 and 18 were found in 6 cases.36-41 Two cases reported association with human papillomavirus type 2.7,42

Metastases to dermal and subdermal lymphatics, regional lymph nodes, and the lungs were reported in 3 cases, repectively.43-45 Of these, one primary tumor had received low-dose irradiation in the form of X-ray therapy.45

Treatment Modalities

The cases of EC that we reviewed included treatment with surgical and systemic therapies as well as other modalities such as acitretin, interferon alfa, topical imiquimod, curettage, debridement, electrodesiccation, and radiation. The Table includes a complete summary of the treatments we analyzed.

Surgical Therapy—The majority (91% [105/115]) of cases were treated surgically. The most common treatment modality was WLE (50% [58/115]), followed by amputation (37% [43/115]) and MMS (12% [14/115]).

Wide local excision was the most frequently reported treatment, with excision margins of at least 5 mm to 1 cm.48 Incidence of recurrence was reported for 57% (33/58) of cases treated with WLE; of these, the recurrence rate was 33% (11/33). For patients with EC recurrence, the most common secondary treatment was repeat excision with wider margins (1–2 cm) or amputation (5/11).49-52 Few postoperative complications were reported but included pain, infection, and difficulty walking, which were mostly associated with repair modality (eg, split-thickness skin grafts, rotational flaps).53 Amputation was the second most common treatment modality, with a 67% (29/43) incidence of recurrence. Types of amputation included transmetatarsal ray amputation (7/43 [16%]), foot or forefoot amputation (2/43 [5%]), above-the-knee amputation (1/43 [2%]), and below-the-knee amputation (1/43 [2%]). Complications associated with amputation included infection and requirement of prosthetics for ambulation. Split-thickness skin grafts and rotational flaps were the most common surgical repairs performed.52,53

Mohs micrographic surgery was the least frequently reported surgical treatment modality. Both traditional MMS on fresh tissue and “slow Mohs,” with formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue examination over several days, were performed for EC with horizontal en face sectioning.54-56 Incidence of recurrence was reported for 86% (12/14) of MMS cases. Of these, recurrence was seen in 17% (2/12) that utilized a flat horizontal processing of tissue sections coupled with saucerlike excisions to enable examination of the entire undersurface and margins. In one case, the patient was treated with MMS with recurrence noted 1 month later; thus, repeat MMS was performed, and the tumor was found to be entwined around the flexor tendon.57 The tendon was removed, and clear margins were obtained. Follow-up 3 years after the second MMS revealed no signs of recurrence.57 In the other case, the patient had a particularly aggressive course with bilateral VC in the setting of diabetic ulcers that was treated with WLE prior to MMS and recurrence still noted after MMS.26 No complications were reported with MMS.

Overall, recurrence was most frequently reported with WLE (11/33 [33%]), followed by MMS (2/12 [17%]) and amputation (3/29 [10%]). When comparing WLE and amputation, the relationship between treatment modality and recurrence was statistically significant using a χ2 test of independence (χ2=4.7; P=.03). However, results were not significant with Yates correction for continuity (χ2=3.4; P=.06). The χ2 test of independence showed no significant association between treatment method and recurrence when comparing WLE with MMS (χ2=1.2; P=.28). Reported follow-up times varied greatly from a few months to 10 years.

Systemic Therapy—Of the total cases, only 2 cases reported treatment with acitretin and 2 utilized interferon alfa.58,59 In one case, treatment of EC with interferon alfa alone required more aggressive therapy (ie, amputation).58 Neither of the 2 cases using acitretin reported recurrence.59,60 Complications of acitretin therapy included cheilitis and transaminitis.60

Other Treatment Modalities—Three cases utilized imiquimod, with 2 cases of imiquimod monotherapy and 1 case of imiquimod in combination with electrodesiccation and WLE.37 One of the cases of EC treated with imiquimod monotherapy recurred and required WLE.61

There were reports of other treatments including curettage alone (2% [2/115]),40,62 debridement alone (1% [1/115]),40 electrodesiccation (1% [1/115]),37 and radiation (1% [1/115]).43 Recurrence was found with curettage alone and debridement alone. Electrodesiccation was reported in conjunction with WLE without recurrence. Radiation was used to treat a case of VC that had metastasized to the lymph nodes; no follow-up was described.43

COMMENT

Epithelioma cuniculatum is an indolent malignancy of the plantar foot that likely is frequently underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed because of location, sampling error, and challenges in histopathologic diagnosis. Once diagnosed, surgical removal with margin control is the first-line therapy for EC. Our review found a number of surgical, systemic, and other treatment modalities that have been used to treat EC, but there remains a lack of evidence to provide clear guidelines as to which therapies are most effective. Current data on the treatment of EC largely are limited to case reports and case series. To date, there are no reports of higher-quality studies or randomized controlled trials to assess the efficacy of various treatment modalities.

Our review found that WLE is the most common treatment modality for EC, followed by amputation and MMS. Three cases43-45 that reported metastasis to lymph nodes also were treated with fine-needle aspiration or biopsy, and it is recommended that sentinel lymph node biopsy be performed when there is a history of radiation exposure or clinically and sonographically unsuspicious lymph nodes, while dissection of regional nodes should be performed if lymph node metastasis is suspected.53 Additional treatments reported included acitretin, interferon alfa, topical imiquimod, curettage, debridement, and electrodesiccation, but because of the limited number of cases and variable efficacy, no conclusions can be made on the utility of these alternative modalities.

The lowest rate of reported recurrence was found with amputation, followed by MMS and WLE. Amputation is the most aggressive treatment option, but its superiority in lower recurrence rates was not statistically significant when compared with either WLE or MMS after Yates correction. Despite treatment with radical surgery, recurrence is still possible and may be associated with factors including greater size (>2 cm) and depth (>4 mm), poor histologic differentiation, perineural involvement, failure of previous treatments, and immunosuppression.63 No statistically significant difference in recurrence rates was found among surgical methods, though data trended toward lower rates of recurrence with MMS compared with WLE, as recurrence with MMS was only reported in 2 cases.25,56

The efficacy of MMS is well documented for tumors with contiguous growth and enables maximum preservation of normal tissue structure and function with complete margin visualization. Thus, our results are in agreement with those of prior studies,54-56,64 suggesting that MMS is associated with lower recurrence rates for EC than WLE. Future studies and reporting of MMS for EC are particularly important because of the functional importance of the plantar foot.

It is important to note that there are local and systemic risk factors that increase the likelihood of developing EC and facilitate tumor growth, including antecedent trauma to the lesion site, chronic irritation or infection, and immunosuppression (HIV related or iatrogenic medication induced). These risk factors may play a role in the treatment modality utilized (eg, more aggressive EC may be treated with amputation instead of WLE). Underlying patient comorbidities could potentially affect recurrence rates, which is a variable we could not control for in our analysis.

Our findings are limited by study design, with supporting evidence consisting of case reports and series. The review is limited by interstudy variability and heterogeneity of results. Additionally, recurrence is not reported in all cases and may be a source of sampling bias. Further complicating the generalizability of these results is the lack of follow-up to evaluate morbidity and quality of life after treatment.

CONCLUSION

This review suggests that MMS is associated with lower recurrence rates than WLE for the treatment of EC. Further investigation of MMS for EC with appropriate follow-up is necessary to identify whether MMS is associated with lower recurrence and less functional impairment. Nonsurgical treatments, including topical imiquimod, interferon alfa, and acitretin, may be useful in cases where surgical therapies are contraindicated, but there is little evidence to support these treatment modalities. Treatment guidelines for EC are not established, and appropriate treatment guidelines should be developed in the future.

Verrucous carcinoma (VC) is an uncommon type of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) that most commonly affects men in the fifth to sixth decades of life. 1 The tumor grows slowly over a decade or more and does not frequently metastasize but has a high propensity for recurrence and local invasion. 2 There are 3 main subtypes of VC classified by anatomic site: oral florid papillomatosis (oral cavity), Buschke-Lowenstein tumor (anogenital region), and epithelioma cuniculatum (EC)(feet). 3 Epithelioma cuniculatum, also known as carcinoma cuniculatum or papillomatosis cutis carcinoides, most commonly presents as a solitary, warty or cauliflowerlike, exophytic mass with keratin-filled sinus tracts and malodorous discharge. 4 Diabetic foot ulcers and chronic inflammatory conditions are predisposing risk factors for EC, and it can result in difficulty walking/immobility, pain, and bleeding depending on anatomic involvement. 5-9

The differential diagnosis for VC includes refractory verruca vulgaris, clavus, SCC, keratoacanthoma, deep fungal or mycobacterial infection, eccrine poroma or porocarcinoma, amelanotic melanoma, and sarcoma.10-13 The slow-growing nature of VC, sampling error of superficial biopsies, and minimal cytological atypia on histologic examination can contribute to delayed diagnosis and appropriate treatment.14 Characteristic histologic features include hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, marked acanthosis, broad blunt-ended rete ridges with a “bulldozing” architecture, and minimal cytologic atypia and mitoses.5,6 In some cases, pleomorphism and glassy eosinophilic cytoplasmic changes may be more pronounced than that of a common wart though less dramatic than that of conventional SCCs.15 Antigen Ki-67 and tumor protein p53 have been proposed to help differentiate between common plantar verruca, VC, and SCC, but the histologic diagnosis remains challenging, and repeat histopathologic examination often is required.16-19 Following diagnosis, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be necessary to determine tumor extension and assess for deep tissue and bony involvement.20-22

Treatment of EC is particularly challenging because of the anatomic location and need for margin control while maintaining adequate function, preserving healthy tissue, and providing coverage of defects. Surgical excision of EC is the first-line treatment, most commonly by wide local excision (WLE) or amputation. Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) also has been utilized. One review found no recurrences in 5 cases of EC treated with MMS.23 As MMS is a tissue-sparing technique, this is a valuable modality for sites of functional importance such as the feet. Herein, we review various reported EC treatment modalities and outcomes, with an emphasis on recurrence rates for WLE and MMS.

METHODS

A systematic literature review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE, as well as databases including the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), was performed on January 14, 2020. Two authors (S.S.D. and S.V.C.) independently screened results using the search terms (plantar OR foot) AND (verrucous carcinoma OR epithelioma cuniculatum OR carcinoma cuniculatum). The search terms were chosen according to MeSH subject headings. All articles from the start date of the databases through the search date were screened, and articles pertaining to VC, EC, or carcinoma cuniculatum located on the foot were included. Of these, non–English-language articles were translated and included. Articles reporting VC on a site other than the foot (eg, the oral cavity) or benign verrucous skin lesions were excluded. The reference lists for all articles also were reviewed for additional reports that were absent from the initial search using both included and excluded articles. A full-text review was performed on 221 articles published between 1954 and 2019 per the PRISMA guidelines (Figure).

A total of 101 articles were included in the study for qualitative analysis. Nearly all articles identified were case reports, giving an evidence level of 5 by the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine rating scale. Five articles reported data on multiple patients without individual demographic or clinical details and were excluded from analysis. Of the remaining 96 articles, information about patient characteristics, tumor size, treatment modality, and recurrence were extracted for 115 cases.

RESULTS

Of the 115 cases that were reviewed, 81 (70%) were male and 33 (29%) were female with a male-to-female ratio of 2.4:1. Ages of the patients ranged from 18 to 88 years; the mean and median age was 56 years. Nearly all reported cases of EC affected the plantar surface of one foot, with 4 reports of tumors affecting both feet.24-27 One case affecting both feet reported known exposure to lead arsenate pesticides27; all others were associated with a clinical history of chronic ulcers or warts persisting for several years to decades. Other less common sites of EC included the dorsal foot, interdigital web space, and subungual digit.28-30 The most common location reported was the anterior ball of the foot. Tumors were reported to arise within pre-existing lesions, such as hypertrophic lichen planus or chronic foot wounds associated with diabetes mellitus or leprosy.31-35 Tumor size ranged from 1 to 22 cm with a median of 4.5 cm.

Eight cases were reported to be associated with human papillomavirus; low-risk types 6 and 11 and high-risk types 16 and 18 were found in 6 cases.36-41 Two cases reported association with human papillomavirus type 2.7,42

Metastases to dermal and subdermal lymphatics, regional lymph nodes, and the lungs were reported in 3 cases, repectively.43-45 Of these, one primary tumor had received low-dose irradiation in the form of X-ray therapy.45

Treatment Modalities

The cases of EC that we reviewed included treatment with surgical and systemic therapies as well as other modalities such as acitretin, interferon alfa, topical imiquimod, curettage, debridement, electrodesiccation, and radiation. The Table includes a complete summary of the treatments we analyzed.

Surgical Therapy—The majority (91% [105/115]) of cases were treated surgically. The most common treatment modality was WLE (50% [58/115]), followed by amputation (37% [43/115]) and MMS (12% [14/115]).

Wide local excision was the most frequently reported treatment, with excision margins of at least 5 mm to 1 cm.48 Incidence of recurrence was reported for 57% (33/58) of cases treated with WLE; of these, the recurrence rate was 33% (11/33). For patients with EC recurrence, the most common secondary treatment was repeat excision with wider margins (1–2 cm) or amputation (5/11).49-52 Few postoperative complications were reported but included pain, infection, and difficulty walking, which were mostly associated with repair modality (eg, split-thickness skin grafts, rotational flaps).53 Amputation was the second most common treatment modality, with a 67% (29/43) incidence of recurrence. Types of amputation included transmetatarsal ray amputation (7/43 [16%]), foot or forefoot amputation (2/43 [5%]), above-the-knee amputation (1/43 [2%]), and below-the-knee amputation (1/43 [2%]). Complications associated with amputation included infection and requirement of prosthetics for ambulation. Split-thickness skin grafts and rotational flaps were the most common surgical repairs performed.52,53

Mohs micrographic surgery was the least frequently reported surgical treatment modality. Both traditional MMS on fresh tissue and “slow Mohs,” with formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue examination over several days, were performed for EC with horizontal en face sectioning.54-56 Incidence of recurrence was reported for 86% (12/14) of MMS cases. Of these, recurrence was seen in 17% (2/12) that utilized a flat horizontal processing of tissue sections coupled with saucerlike excisions to enable examination of the entire undersurface and margins. In one case, the patient was treated with MMS with recurrence noted 1 month later; thus, repeat MMS was performed, and the tumor was found to be entwined around the flexor tendon.57 The tendon was removed, and clear margins were obtained. Follow-up 3 years after the second MMS revealed no signs of recurrence.57 In the other case, the patient had a particularly aggressive course with bilateral VC in the setting of diabetic ulcers that was treated with WLE prior to MMS and recurrence still noted after MMS.26 No complications were reported with MMS.

Overall, recurrence was most frequently reported with WLE (11/33 [33%]), followed by MMS (2/12 [17%]) and amputation (3/29 [10%]). When comparing WLE and amputation, the relationship between treatment modality and recurrence was statistically significant using a χ2 test of independence (χ2=4.7; P=.03). However, results were not significant with Yates correction for continuity (χ2=3.4; P=.06). The χ2 test of independence showed no significant association between treatment method and recurrence when comparing WLE with MMS (χ2=1.2; P=.28). Reported follow-up times varied greatly from a few months to 10 years.

Systemic Therapy—Of the total cases, only 2 cases reported treatment with acitretin and 2 utilized interferon alfa.58,59 In one case, treatment of EC with interferon alfa alone required more aggressive therapy (ie, amputation).58 Neither of the 2 cases using acitretin reported recurrence.59,60 Complications of acitretin therapy included cheilitis and transaminitis.60

Other Treatment Modalities—Three cases utilized imiquimod, with 2 cases of imiquimod monotherapy and 1 case of imiquimod in combination with electrodesiccation and WLE.37 One of the cases of EC treated with imiquimod monotherapy recurred and required WLE.61

There were reports of other treatments including curettage alone (2% [2/115]),40,62 debridement alone (1% [1/115]),40 electrodesiccation (1% [1/115]),37 and radiation (1% [1/115]).43 Recurrence was found with curettage alone and debridement alone. Electrodesiccation was reported in conjunction with WLE without recurrence. Radiation was used to treat a case of VC that had metastasized to the lymph nodes; no follow-up was described.43

COMMENT

Epithelioma cuniculatum is an indolent malignancy of the plantar foot that likely is frequently underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed because of location, sampling error, and challenges in histopathologic diagnosis. Once diagnosed, surgical removal with margin control is the first-line therapy for EC. Our review found a number of surgical, systemic, and other treatment modalities that have been used to treat EC, but there remains a lack of evidence to provide clear guidelines as to which therapies are most effective. Current data on the treatment of EC largely are limited to case reports and case series. To date, there are no reports of higher-quality studies or randomized controlled trials to assess the efficacy of various treatment modalities.

Our review found that WLE is the most common treatment modality for EC, followed by amputation and MMS. Three cases43-45 that reported metastasis to lymph nodes also were treated with fine-needle aspiration or biopsy, and it is recommended that sentinel lymph node biopsy be performed when there is a history of radiation exposure or clinically and sonographically unsuspicious lymph nodes, while dissection of regional nodes should be performed if lymph node metastasis is suspected.53 Additional treatments reported included acitretin, interferon alfa, topical imiquimod, curettage, debridement, and electrodesiccation, but because of the limited number of cases and variable efficacy, no conclusions can be made on the utility of these alternative modalities.

The lowest rate of reported recurrence was found with amputation, followed by MMS and WLE. Amputation is the most aggressive treatment option, but its superiority in lower recurrence rates was not statistically significant when compared with either WLE or MMS after Yates correction. Despite treatment with radical surgery, recurrence is still possible and may be associated with factors including greater size (>2 cm) and depth (>4 mm), poor histologic differentiation, perineural involvement, failure of previous treatments, and immunosuppression.63 No statistically significant difference in recurrence rates was found among surgical methods, though data trended toward lower rates of recurrence with MMS compared with WLE, as recurrence with MMS was only reported in 2 cases.25,56

The efficacy of MMS is well documented for tumors with contiguous growth and enables maximum preservation of normal tissue structure and function with complete margin visualization. Thus, our results are in agreement with those of prior studies,54-56,64 suggesting that MMS is associated with lower recurrence rates for EC than WLE. Future studies and reporting of MMS for EC are particularly important because of the functional importance of the plantar foot.

It is important to note that there are local and systemic risk factors that increase the likelihood of developing EC and facilitate tumor growth, including antecedent trauma to the lesion site, chronic irritation or infection, and immunosuppression (HIV related or iatrogenic medication induced). These risk factors may play a role in the treatment modality utilized (eg, more aggressive EC may be treated with amputation instead of WLE). Underlying patient comorbidities could potentially affect recurrence rates, which is a variable we could not control for in our analysis.

Our findings are limited by study design, with supporting evidence consisting of case reports and series. The review is limited by interstudy variability and heterogeneity of results. Additionally, recurrence is not reported in all cases and may be a source of sampling bias. Further complicating the generalizability of these results is the lack of follow-up to evaluate morbidity and quality of life after treatment.

CONCLUSION

This review suggests that MMS is associated with lower recurrence rates than WLE for the treatment of EC. Further investigation of MMS for EC with appropriate follow-up is necessary to identify whether MMS is associated with lower recurrence and less functional impairment. Nonsurgical treatments, including topical imiquimod, interferon alfa, and acitretin, may be useful in cases where surgical therapies are contraindicated, but there is little evidence to support these treatment modalities. Treatment guidelines for EC are not established, and appropriate treatment guidelines should be developed in the future.

- McKee PH, Wilkinson JD, Black MM, et al. Carcinoma (epithelioma) cuniculatum: a clinicopathological study of nineteen cases and review of the literature. Histopathology. 1981;5:425-436.

- Aird I, Johnson HD, Lennox B, et al. Epithelioma cuniculatum: a variety of squamous carcinoma peculiar to the foot. Br J Surg. 1954;42:245-250.

- Seremet S, Erdemir AT, Kiremitci U, et al. Unusually early-onset plantar verrucous carcinoma. Cutis. 2019;104:34-36.

- Spyriounis PK, Tentis D, Sparveri IF, et al. Plantar epithelioma cuniculatum. a case report with review of the literature. Eur J Plast Surg. 2004;27:253-256.

- Ho J, Diven G, Bu J, et al. An ulcerating verrucous plaque on the foot. verrucous carcinoma (epithelioma cuniculatum). Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:547-548, 550-551.

- Kao GF, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Carcinoma cuniculatum (verrucous carcinoma of the skin): a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases with ultrastructural observations. Cancer. 1982;49:2395-2403.

- Zielonka E, Goldschmidt D, de Fontaine S. Verrucous carcinoma or epithelioma cuniculatum plantare. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1997;23:86-87.

- Dogan G, Oram Y, Hazneci E, et al. Three cases of verrucous carcinoma. Australas J Dermatol. 1998;39:251-254.

- Schwartz RA, Burgess GH. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot. J Surg Oncol. 1980;14:333-339.

- McKay C, McBride P, Muir J. Plantar verrucous carcinoma masquerading as toe web intertrigo. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:2010-2012.

- Shenoy AS, Waghmare RS, Kavishwar VS, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of foot. Foot. 2011;21:207-208.

- Lozzi G, Perris K. Carcinoma cuniculatum. CMAJ. 2007;177:249-251.

- Schein O, Orenstein A, Bar-Meir E. Plantar verrucous carcicoma (epithelioma cuniculatum): rare form of the common wart. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8:885.

- Rheingold LM, Roth LM. Carcinoma of the skin of the foot exhibiting some verrucous features. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;61:605-609.

- Klima M, Kurtis B, Jordan PH. Verrucous carcinoma of skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1980;7:88-98.

- Nakamura Y, Kashiwagi K, Nakamura A, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot diagnosed using p53 and Ki-67 immunostaining in a patient with diabetic neuropathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:257-259.

- Costache M, Desa LT, Mitrache LE, et al. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma—report of three cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:383-388.

- Terada T. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin: a report on 5 Japanese cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15:175-180.

- Noel JC, Heenen M, Peny MO, et al. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen distribution in verrucous carcinoma of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:868-873.

- García-Gavín J, González-Vilas D, Rodríguez-Pazos L, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot affecting the bone: utility of the computed tomography scanner. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:3-5.

- Wasserman PL, Taylor RC, Pinillia J, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot and enhancement assessment by MRI. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38:393-395.

- Bhushan MH, Ferguson JE, Hutchinson CE. Carcinoma cuniculatum of the foot assessed by magnetic resonance scanning. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:419-422.

- Penera KE, Manji KA, Craig AB, et al. Atypical presentation of verrucous carcinoma: a case study and review of the literature. Foot Ankle Spec. 2013;6:318-322.

- Suen K, Wijeratne S, Patrikios J. An unusual case of bilateral verrucous carcinoma of the foot (epithelioma cuniculatum). J Surg Case Rep. 2012;2012:rjs020.

- Riccio C, King K, Elston JB, et al. Bilateral plantar verrucous carcinoma. Eplasty. 2016;16:ic46.

- Di Palma V, Stone JP, Schell A, et al. Mistaken diabetic ulcers: a case of bilateral foot verrucous carcinoma. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2018;2018:4192657.

- Seehafer JR, Muller SA, Dicken CH. Bilateral verrucous carcinoma of the feet. Orthop Surv. 1979;3:205.

- Tosti A, Morelli R, Fanti PA, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of the nail apparatus: report of three cases. Dermatology. 1993;186:217-221.

- Melo CR, Melo IS, Souza LP. Epithelioma cuniculatum, a verrucous carcinoma of the foot. report of 2 cases. Dermatologica. 1981;163:338-342.

- Van Geertruyden JP, Olemans C, Laporte M, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the nail bed. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:327-328.

- Thakur BK, Verma S, Raphael V. Verrucous carcinoma developing in a long standing case of ulcerative lichen planus of sole: a rare case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:399-401.

- Mayron R, Grimwood RE, Siegle RJ, et al. Verrucous carcinoma arising in ulcerative lichen planus of the soles. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:547-551.

- Boussofara L, Belajouza-Noueiri C, Ghariani N, et al. Verrucous epidermoid carcinoma as a complication in cutaneous lichen planus [article in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2006;133:404-405.

- Khullar G, Mittal S, Sharma S. Verrucous carcinoma on the foot arising in a chronic neuropathic ulcer of leprosy. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:245-246.

- Ochsner PE, Hausman R, Olsthoorn PGM. Epithelioma cunicalutum developing in a neuropathic ulcer of leprous etiology. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1979;94:227-231.

- Ray R, Bhagat A, Vasudevan B, et al. A rare case of plantar epithelioma cuniculatum arising from a wart. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:485-487.

- Imko-Walczuk B, Cegielska A, Placek W, et al. Human papillomavirus-related verrucous carcinoma in a renal transplant patient after long-term immunosuppression: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2014;46:2916-2919.

- Floristán MU, Feltes RA, Sáenz JC, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot associated with human papillomavirus type 18. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:433-435.

- Sasaoka R, Morimura T, Mihara M, et al. Detection of human pupillomavirus type 16 DNA in two cases of verriicous carcinoma of the foot. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:983984.

- Schell BJ, Rosen T, Rády P, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot associated with human papillomavirus type 16. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:49-55.

- Knobler RM, Schneider S, Neumann RA, et al. DNA dot‐blot hybridization implicates human papillomavirus type 11‐DNA in epithelioma cuniculatum. J Med Virol. 1989;29:33-37.

- Noel JC, Peny MO, Detremmerie O, et al. Demonstration of human papillomavirus type 2 in a verrucous carcinoma of the foot. Dermatology. 1993;187:58-61.

- Jungmann J, Vogt T, Müller CSL. Giant verrucous carcinoma of the lower extremity in women with dementia. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr2012006357.

- McKee PH, Wilkinson JD, Corbett MF, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum: a case metastasizing to skin and lymph nodes. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1981;6:613-618.

- Owen WR, Wolfe ID, Burnett JW, et al. Epithelioma cuniculatum. South Med J. 1978;71:477-479.

- Patel AN, Bedforth N, Varma S. Pain-free treatment of carcinoma cuniculatum on the heel using Mohs micrographic surgery and ultrasonography-guided sciatic nerve block. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:569-571.

- Padilla RS, Bailin PL, Howard WR, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and its management by Mohs’ surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:442-447.

- Kotwal M, Poflee S, Bobhate S. Carcinoma cuniculatum at various anatomical sites. Indian J Dermatol. 2005;50:216-220.

- Arefi M, Philipone E, Caprioli R, et al. A case of verrucous carcinoma (epithelioma cuniculatum) of the heel mimicking infected epidermal cyst and gout. Foot Ankle Spec. 2008;1:297-299.

- Trebing D, Brunner M, Kröning Y, et al. Young man with verrucous heel tumor [article in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2003;9:739-741.

- Thompson SG. Epithelioma cuniculatum: an unusual tumour of the foot. Br J Plast Surg. 1965;18:214-217.

- Thomas EJ, Graves NC, Meritt SM. Carcinoma cuniculatum: an atypical presentation in the foot. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;53:356-359.

- Koch H, Kowatsch E, Hödl S, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin: long-term follow-up results following surgical therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1124-1130.

- Mallatt BD, Ceilley RI, Dryer RF. Management of verrucous carcinoma on a foot by a combination of chemosurgery and plastic repair: report of a case. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1980;6:532-534.

- Mohs FE, Sahl WJ. Chemosurgery for verrucous carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1979;5:302-306.

- Alkalay R, Alcalay J, Shiri J. Plantar verrucous carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery: a case report and literature review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:68-73.

- Mora RG. Microscopically controlled surgery (Mohs’ chemosurgery) for treatment of verrucous squamous cell carcinoma of the foot (epithelioma cuniculatum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:354-362.

- Risse L, Negrier P, Dang PM, et al. Treatment of verrucous carcinoma with recombinant alfa-interferon. Dermatology. 1995;190:142-144.

- Rogozin´ski TT, Schwartz RA, Towpik E. Verrucous carcinoma in Unna-Thost hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:1061-1062.

- Kuan YZ, Hsu HC, Kuo TT, et al. Multiple verrucous carcinomas treated with acitretin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2 suppl):S29-S32.

- Schalock PC, Kornik RI, Baughman RD, et al. Treatment of verrucous carcinoma with topical imiquimod. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:233-234.

- Brown SM, Freeman RG. Epithelioma cuniculatum. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1295-1296.

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL, et al. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:976-990.

- Swanson NA, Taylor WB. Plantar verrucous carcinoma: literature review and treatment by the Mohs’ chemosurgery technique. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:794-797.

- McKee PH, Wilkinson JD, Black MM, et al. Carcinoma (epithelioma) cuniculatum: a clinicopathological study of nineteen cases and review of the literature. Histopathology. 1981;5:425-436.

- Aird I, Johnson HD, Lennox B, et al. Epithelioma cuniculatum: a variety of squamous carcinoma peculiar to the foot. Br J Surg. 1954;42:245-250.

- Seremet S, Erdemir AT, Kiremitci U, et al. Unusually early-onset plantar verrucous carcinoma. Cutis. 2019;104:34-36.

- Spyriounis PK, Tentis D, Sparveri IF, et al. Plantar epithelioma cuniculatum. a case report with review of the literature. Eur J Plast Surg. 2004;27:253-256.

- Ho J, Diven G, Bu J, et al. An ulcerating verrucous plaque on the foot. verrucous carcinoma (epithelioma cuniculatum). Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:547-548, 550-551.

- Kao GF, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Carcinoma cuniculatum (verrucous carcinoma of the skin): a clinicopathologic study of 46 cases with ultrastructural observations. Cancer. 1982;49:2395-2403.

- Zielonka E, Goldschmidt D, de Fontaine S. Verrucous carcinoma or epithelioma cuniculatum plantare. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1997;23:86-87.

- Dogan G, Oram Y, Hazneci E, et al. Three cases of verrucous carcinoma. Australas J Dermatol. 1998;39:251-254.

- Schwartz RA, Burgess GH. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot. J Surg Oncol. 1980;14:333-339.

- McKay C, McBride P, Muir J. Plantar verrucous carcinoma masquerading as toe web intertrigo. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:2010-2012.

- Shenoy AS, Waghmare RS, Kavishwar VS, et al. Carcinoma cuniculatum of foot. Foot. 2011;21:207-208.

- Lozzi G, Perris K. Carcinoma cuniculatum. CMAJ. 2007;177:249-251.

- Schein O, Orenstein A, Bar-Meir E. Plantar verrucous carcicoma (epithelioma cuniculatum): rare form of the common wart. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8:885.

- Rheingold LM, Roth LM. Carcinoma of the skin of the foot exhibiting some verrucous features. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;61:605-609.

- Klima M, Kurtis B, Jordan PH. Verrucous carcinoma of skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1980;7:88-98.

- Nakamura Y, Kashiwagi K, Nakamura A, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot diagnosed using p53 and Ki-67 immunostaining in a patient with diabetic neuropathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:257-259.

- Costache M, Desa LT, Mitrache LE, et al. Cutaneous verrucous carcinoma—report of three cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:383-388.

- Terada T. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin: a report on 5 Japanese cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15:175-180.

- Noel JC, Heenen M, Peny MO, et al. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen distribution in verrucous carcinoma of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:868-873.

- García-Gavín J, González-Vilas D, Rodríguez-Pazos L, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot affecting the bone: utility of the computed tomography scanner. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:3-5.

- Wasserman PL, Taylor RC, Pinillia J, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the foot and enhancement assessment by MRI. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38:393-395.

- Bhushan MH, Ferguson JE, Hutchinson CE. Carcinoma cuniculatum of the foot assessed by magnetic resonance scanning. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:419-422.

- Penera KE, Manji KA, Craig AB, et al. Atypical presentation of verrucous carcinoma: a case study and review of the literature. Foot Ankle Spec. 2013;6:318-322.

- Suen K, Wijeratne S, Patrikios J. An unusual case of bilateral verrucous carcinoma of the foot (epithelioma cuniculatum). J Surg Case Rep. 2012;2012:rjs020.

- Riccio C, King K, Elston JB, et al. Bilateral plantar verrucous carcinoma. Eplasty. 2016;16:ic46.

- Di Palma V, Stone JP, Schell A, et al. Mistaken diabetic ulcers: a case of bilateral foot verrucous carcinoma. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2018;2018:4192657.