User login

Guidelines for assessing cancer risk may need updating

The authors of the clinical trial suggest that these guidelines may need to be revised.

Individuals with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) have an 80% lifetime risk of breast cancer and are at greater risk of ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, and melanoma. Those with Lynch syndrome (LS) have an 80% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer, a 60% lifetime risk of endometrial cancer, and heightened risk of upper gastrointestinal, urinary tract, skin, and other tumors, said study coauthor N. Jewel Samadder, MD in a statement.

The National Cancer Control Network has guidelines for determining family risk for colorectal cancer and breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancer to identify individuals who should be screened for LS and HBOC, but these rely on personal and family health histories.

“These criteria were created at a time when genetic testing was cost prohibitive and thus aimed to identify those at the greatest chance of being a mutation carrier in the absence of population-wide whole-exome sequencing. However, [LS and HBOC] are poorly identified in current practice, and many patients are not aware of their cancer risk,” said Dr. Samadder, professor of medicine and coleader of the precision oncology program at the Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center, Phoenix, in the statement.

Whole-exome sequencing covers only protein-coding regions of the genome, which is less than 2% of the total genome but includes more than 85% of known disease-related genetic variants, according to Emily Gay, who presented the trial results (Abstract 5768) on April 18 at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

“In recent years, the cost of whole-exome sequencing has been rapidly decreasing, allowing us to complete this test on saliva samples from thousands, if not tens of thousands of patients covering large populations and large health systems,” said Ms. Gay, a genetic counseling graduate student at the University of Arizona, during her presentation.

She described results from the TAPESTRY clinical trial, with 44,306 participants from Mayo Clinic centers in Arizona, Florida, and Minnesota, who were identified as definitely or likely to be harboring pathogenic mutations and consented to whole-exome sequencing from saliva samples. They used electronic health records to determine whether patients would satisfy the testing criteria from NCCN guidelines.

The researchers identified 1.24% of participants to be carriers of HBOC or LS. Of the HBOC carriers, 62.8% were female, and of the LS carriers, 62.6% were female. The percentages of HBOC and LS carriers who were White were 88.6 and 94.5, respectively. The median age of both groups was 57 years. Of HBOC carriers, 47.3% had personal histories of cancers; for LS carries, the percentage was 44.2.

Of HBOC carriers, 49.1% had been previously unaware of their genetic condition, while an even higher percentage of patients with LS – 59.3% – fell into that category. Thirty-two percent of those with HBOC and 56.2% of those with LS would not have qualified for screening using the relevant NCCN guidelines.

“Most strikingly,” 63.8% of individuals with mutations in the MSH6 gene and 83.7% of those mutations in the PMS2 gene would not have met NCCN criteria, Ms. Gay said.

Having a cancer type not known to be related to a genetic syndrome was a reason for 58.6% of individuals failing to meet NCCN guidelines, while 60.5% did not meet the guidelines because of an insufficient number of relatives known to have a history of cancer, and 63.3% did not because they had no personal history of cancer. Among individuals with a pathogenic mutation who met NCCN criteria, 34% were not aware of their condition.

“This suggests that the NCCN guidelines are underutilized in clinical practice, potentially due to the busy schedule of clinicians or because the complexity of using these criteria,” said Ms. Gay.

The numbers were even more striking among minorities: “There is additional data analysis and research needed in this area, but based on our preliminary findings, we saw that nearly 50% of the individuals who are [part of an underrepresented minority group] did not meet criteria, compared with 32% of the white cohort,” said Ms. Gay.

Asked what new NCCN guidelines should be, Ms. Gay replied: “I think maybe limiting the number of relatives that you have to have with a certain type of cancer, especially as we see families get smaller and smaller, especially in the United States – that family data isn’t necessarily available or as useful. And then also, I think, incorporating in the size of a family into the calculation, so more of maybe a point-based system like we see with other genetic conditions rather than a ‘yes you meet or no, you don’t.’ More of a range to say ‘you fall on the low-risk, medium-risk, or high-risk stage,’” said Ms. Gay.

During the Q&A period, session cochair Andrew Godwin, PhD, who is a professor of molecular oncology and pathology at University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, said he wondered if whole-exome sequencing was capable of picking up cancer risk mutations that standard targeted tests don’t look for.

Dr. Samadder, who was in the audience, answered the question, saying that targeted tests are actually better at picking up some types of mutations like intronic mutations, single-nucleotide polymorphisms, and deletions.

“There are some limitations to whole-exome sequencing. Our estimate here of 1.2% [of participants carrying HBOC or LS mutations] is probably an underestimate. There are additional variants that exome sequencing probably doesn’t pick up easily or as well. That’s why we qualify that exome sequencing is a screening test, not a diagnostic,” he continued.

Ms. Gay and Dr. Samadder have no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Godwin has financial relationships with Clara Biotech, VITRAC Therapeutics, and Sinochips Diagnostics.

The authors of the clinical trial suggest that these guidelines may need to be revised.

Individuals with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) have an 80% lifetime risk of breast cancer and are at greater risk of ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, and melanoma. Those with Lynch syndrome (LS) have an 80% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer, a 60% lifetime risk of endometrial cancer, and heightened risk of upper gastrointestinal, urinary tract, skin, and other tumors, said study coauthor N. Jewel Samadder, MD in a statement.

The National Cancer Control Network has guidelines for determining family risk for colorectal cancer and breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancer to identify individuals who should be screened for LS and HBOC, but these rely on personal and family health histories.

“These criteria were created at a time when genetic testing was cost prohibitive and thus aimed to identify those at the greatest chance of being a mutation carrier in the absence of population-wide whole-exome sequencing. However, [LS and HBOC] are poorly identified in current practice, and many patients are not aware of their cancer risk,” said Dr. Samadder, professor of medicine and coleader of the precision oncology program at the Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center, Phoenix, in the statement.

Whole-exome sequencing covers only protein-coding regions of the genome, which is less than 2% of the total genome but includes more than 85% of known disease-related genetic variants, according to Emily Gay, who presented the trial results (Abstract 5768) on April 18 at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

“In recent years, the cost of whole-exome sequencing has been rapidly decreasing, allowing us to complete this test on saliva samples from thousands, if not tens of thousands of patients covering large populations and large health systems,” said Ms. Gay, a genetic counseling graduate student at the University of Arizona, during her presentation.

She described results from the TAPESTRY clinical trial, with 44,306 participants from Mayo Clinic centers in Arizona, Florida, and Minnesota, who were identified as definitely or likely to be harboring pathogenic mutations and consented to whole-exome sequencing from saliva samples. They used electronic health records to determine whether patients would satisfy the testing criteria from NCCN guidelines.

The researchers identified 1.24% of participants to be carriers of HBOC or LS. Of the HBOC carriers, 62.8% were female, and of the LS carriers, 62.6% were female. The percentages of HBOC and LS carriers who were White were 88.6 and 94.5, respectively. The median age of both groups was 57 years. Of HBOC carriers, 47.3% had personal histories of cancers; for LS carries, the percentage was 44.2.

Of HBOC carriers, 49.1% had been previously unaware of their genetic condition, while an even higher percentage of patients with LS – 59.3% – fell into that category. Thirty-two percent of those with HBOC and 56.2% of those with LS would not have qualified for screening using the relevant NCCN guidelines.

“Most strikingly,” 63.8% of individuals with mutations in the MSH6 gene and 83.7% of those mutations in the PMS2 gene would not have met NCCN criteria, Ms. Gay said.

Having a cancer type not known to be related to a genetic syndrome was a reason for 58.6% of individuals failing to meet NCCN guidelines, while 60.5% did not meet the guidelines because of an insufficient number of relatives known to have a history of cancer, and 63.3% did not because they had no personal history of cancer. Among individuals with a pathogenic mutation who met NCCN criteria, 34% were not aware of their condition.

“This suggests that the NCCN guidelines are underutilized in clinical practice, potentially due to the busy schedule of clinicians or because the complexity of using these criteria,” said Ms. Gay.

The numbers were even more striking among minorities: “There is additional data analysis and research needed in this area, but based on our preliminary findings, we saw that nearly 50% of the individuals who are [part of an underrepresented minority group] did not meet criteria, compared with 32% of the white cohort,” said Ms. Gay.

Asked what new NCCN guidelines should be, Ms. Gay replied: “I think maybe limiting the number of relatives that you have to have with a certain type of cancer, especially as we see families get smaller and smaller, especially in the United States – that family data isn’t necessarily available or as useful. And then also, I think, incorporating in the size of a family into the calculation, so more of maybe a point-based system like we see with other genetic conditions rather than a ‘yes you meet or no, you don’t.’ More of a range to say ‘you fall on the low-risk, medium-risk, or high-risk stage,’” said Ms. Gay.

During the Q&A period, session cochair Andrew Godwin, PhD, who is a professor of molecular oncology and pathology at University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, said he wondered if whole-exome sequencing was capable of picking up cancer risk mutations that standard targeted tests don’t look for.

Dr. Samadder, who was in the audience, answered the question, saying that targeted tests are actually better at picking up some types of mutations like intronic mutations, single-nucleotide polymorphisms, and deletions.

“There are some limitations to whole-exome sequencing. Our estimate here of 1.2% [of participants carrying HBOC or LS mutations] is probably an underestimate. There are additional variants that exome sequencing probably doesn’t pick up easily or as well. That’s why we qualify that exome sequencing is a screening test, not a diagnostic,” he continued.

Ms. Gay and Dr. Samadder have no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Godwin has financial relationships with Clara Biotech, VITRAC Therapeutics, and Sinochips Diagnostics.

The authors of the clinical trial suggest that these guidelines may need to be revised.

Individuals with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) have an 80% lifetime risk of breast cancer and are at greater risk of ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, and melanoma. Those with Lynch syndrome (LS) have an 80% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer, a 60% lifetime risk of endometrial cancer, and heightened risk of upper gastrointestinal, urinary tract, skin, and other tumors, said study coauthor N. Jewel Samadder, MD in a statement.

The National Cancer Control Network has guidelines for determining family risk for colorectal cancer and breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancer to identify individuals who should be screened for LS and HBOC, but these rely on personal and family health histories.

“These criteria were created at a time when genetic testing was cost prohibitive and thus aimed to identify those at the greatest chance of being a mutation carrier in the absence of population-wide whole-exome sequencing. However, [LS and HBOC] are poorly identified in current practice, and many patients are not aware of their cancer risk,” said Dr. Samadder, professor of medicine and coleader of the precision oncology program at the Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center, Phoenix, in the statement.

Whole-exome sequencing covers only protein-coding regions of the genome, which is less than 2% of the total genome but includes more than 85% of known disease-related genetic variants, according to Emily Gay, who presented the trial results (Abstract 5768) on April 18 at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

“In recent years, the cost of whole-exome sequencing has been rapidly decreasing, allowing us to complete this test on saliva samples from thousands, if not tens of thousands of patients covering large populations and large health systems,” said Ms. Gay, a genetic counseling graduate student at the University of Arizona, during her presentation.

She described results from the TAPESTRY clinical trial, with 44,306 participants from Mayo Clinic centers in Arizona, Florida, and Minnesota, who were identified as definitely or likely to be harboring pathogenic mutations and consented to whole-exome sequencing from saliva samples. They used electronic health records to determine whether patients would satisfy the testing criteria from NCCN guidelines.

The researchers identified 1.24% of participants to be carriers of HBOC or LS. Of the HBOC carriers, 62.8% were female, and of the LS carriers, 62.6% were female. The percentages of HBOC and LS carriers who were White were 88.6 and 94.5, respectively. The median age of both groups was 57 years. Of HBOC carriers, 47.3% had personal histories of cancers; for LS carries, the percentage was 44.2.

Of HBOC carriers, 49.1% had been previously unaware of their genetic condition, while an even higher percentage of patients with LS – 59.3% – fell into that category. Thirty-two percent of those with HBOC and 56.2% of those with LS would not have qualified for screening using the relevant NCCN guidelines.

“Most strikingly,” 63.8% of individuals with mutations in the MSH6 gene and 83.7% of those mutations in the PMS2 gene would not have met NCCN criteria, Ms. Gay said.

Having a cancer type not known to be related to a genetic syndrome was a reason for 58.6% of individuals failing to meet NCCN guidelines, while 60.5% did not meet the guidelines because of an insufficient number of relatives known to have a history of cancer, and 63.3% did not because they had no personal history of cancer. Among individuals with a pathogenic mutation who met NCCN criteria, 34% were not aware of their condition.

“This suggests that the NCCN guidelines are underutilized in clinical practice, potentially due to the busy schedule of clinicians or because the complexity of using these criteria,” said Ms. Gay.

The numbers were even more striking among minorities: “There is additional data analysis and research needed in this area, but based on our preliminary findings, we saw that nearly 50% of the individuals who are [part of an underrepresented minority group] did not meet criteria, compared with 32% of the white cohort,” said Ms. Gay.

Asked what new NCCN guidelines should be, Ms. Gay replied: “I think maybe limiting the number of relatives that you have to have with a certain type of cancer, especially as we see families get smaller and smaller, especially in the United States – that family data isn’t necessarily available or as useful. And then also, I think, incorporating in the size of a family into the calculation, so more of maybe a point-based system like we see with other genetic conditions rather than a ‘yes you meet or no, you don’t.’ More of a range to say ‘you fall on the low-risk, medium-risk, or high-risk stage,’” said Ms. Gay.

During the Q&A period, session cochair Andrew Godwin, PhD, who is a professor of molecular oncology and pathology at University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, said he wondered if whole-exome sequencing was capable of picking up cancer risk mutations that standard targeted tests don’t look for.

Dr. Samadder, who was in the audience, answered the question, saying that targeted tests are actually better at picking up some types of mutations like intronic mutations, single-nucleotide polymorphisms, and deletions.

“There are some limitations to whole-exome sequencing. Our estimate here of 1.2% [of participants carrying HBOC or LS mutations] is probably an underestimate. There are additional variants that exome sequencing probably doesn’t pick up easily or as well. That’s why we qualify that exome sequencing is a screening test, not a diagnostic,” he continued.

Ms. Gay and Dr. Samadder have no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Godwin has financial relationships with Clara Biotech, VITRAC Therapeutics, and Sinochips Diagnostics.

FROM AACR 2023

Acute Onset of Vitiligolike Depigmentation After Nivolumab Therapy for Systemic Melanoma

To the Editor:

Vitiligolike depigmentation has been known to develop around the sites of origin of melanoma or more rarely in patients treated with antimelanoma therapy.1 Vitiligo is characterized by white patchy depigmentation of the skin caused by the loss of functional melanocytes from the epidermis. The exact mechanisms of disease are unknown and multifactorial; however, autoimmunity plays a central role. Interferon gamma (IFN-γ), C-X-C chemokine ligand 10, and IL-22 have been identified as key mediators in an inflammatory cascade leading to the stimulation of the innate immune response against melanocyte antigens.2,3 Research suggests melanoma-associated vitiligolike leukoderma also results from an immune reaction directed against antigenic determinants shared by both normal and malignant melanocytes.3 Vitiligolike lesions have been associated with the use of immunomodulatory agents such as nivolumab, a fully humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody, which blocks the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor that normally is expressed on T cells during the effector phase of T-cell activation.4,5 In the tumor microenvironment, the PD-1 receptor is stimulated, leading to downregulation of the T-cell effector function and destruction of T cells.5 Due to T-cell apoptosis and consequent suppression of the immune response, tumorigenesis continues. By inhibiting the PD-1 receptor, nivolumab increases the number of active T cells and antitumor response. However, the distressing side effect of vitiligolike depigmentation has been reported in 15% to 25% of treated patients.6

In a meta-analysis by Teulings et al,7 patients with new-onset vitiligo and malignant melanoma demonstrated a 2-fold decrease in cancer progression and a 4-fold decreased risk for death vs patients without vitiligo development. Thus, in patients with melanoma, vitiligolike depigmentation should be considered a good prognostic indicator as well as a visible sign of spontaneous or therapy-induced antihumoral immune response against melanocyte differentiation antigens, as it is associated with a notable survival benefit in patients receiving immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma.3 We describe a case of diffuse vitiligolike depigmentation that developed suddenly during nivolumab treatment, causing much distress to the patient.

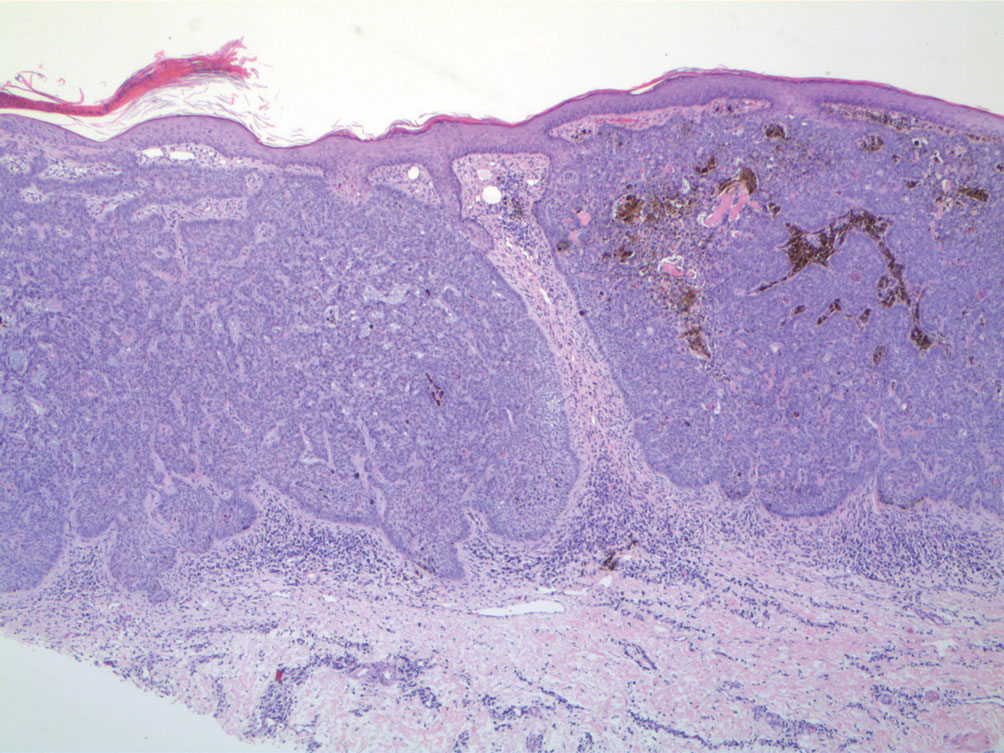

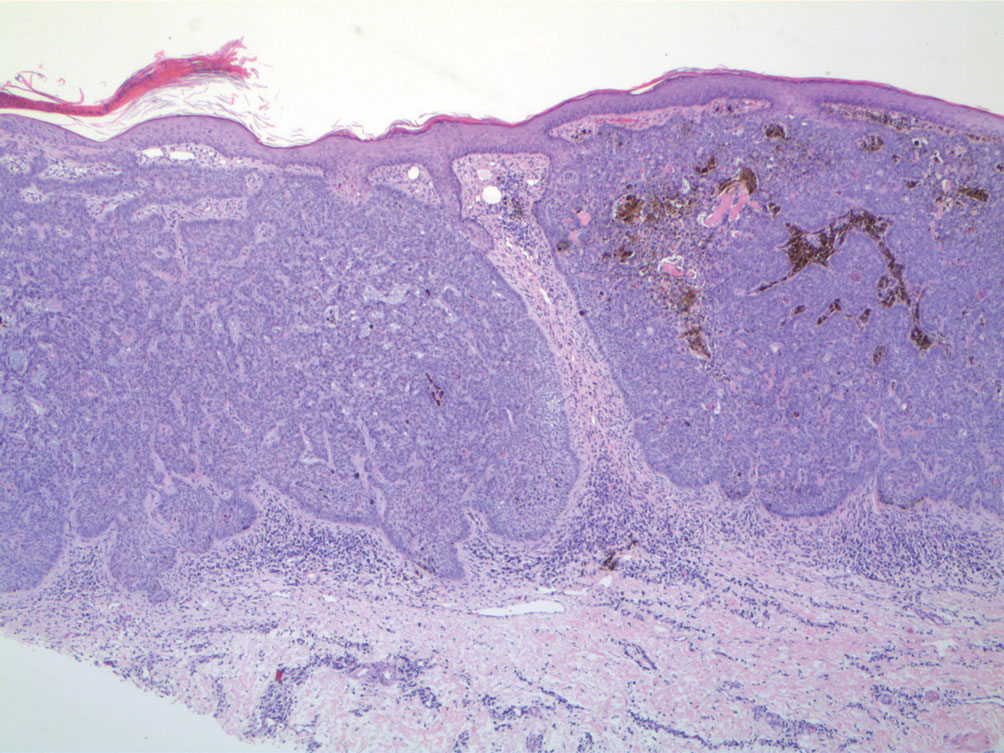

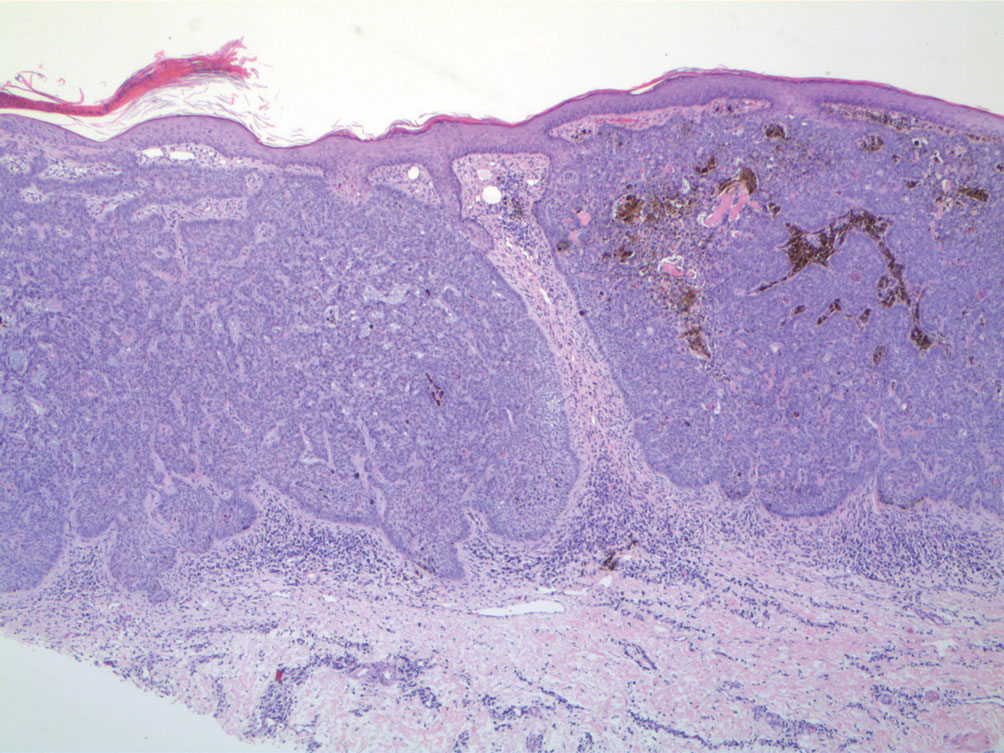

A 75-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a chief concern of sudden diffuse skin discoloration primarily affecting the face, hands, and extremities of 3 weeks’ duration. She had a medical history of metastatic melanoma—the site of the primary melanoma was never identified—and she was undergoing immune-modulating therapy with nivolumab. She was on her fifth month of treatment and was experiencing a robust therapeutic response with a reported 100% clearance of the metastatic melanoma as observed on a positron emission tomography scan. The patchy depigmentation of skin was causing her much distress. Physical examination revealed diffuse patches of hypopigmentation on the trunk, face, and extremities (Figure). Shave biopsies of the right lateral arm demonstrated changes consistent with vitiligo, with an adjacent biopsy illustrating normal skin characteristics. Triamcinolone ointment 0.1% was initiated, with instruction to apply it to affected areas twice daily for 2 weeks. However, there was no improvement, and she discontinued use.

At 3-month follow-up, the depigmentation persisted, prompting a trial of hydroquinone cream 4% to be used sparingly in cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face and dorsal aspects of the hands. Additionally, diligent photoprotection was advised. Upon re-evaluation 9 months later, the patient remained in cancer remission, continued nivolumab therapy, and reported improvement in the hypopigmentation with a more even skin color with topical hydroquinone use. She no longer noticed starkly contrasting hypopigmented patches.

Vitiligo is a benign skin condition characterized by white depigmented macules and patches. The key feature of the disorder is loss of functional melanocytes from the cutaneous epidermis and sometimes from the hair follicles, with various theories on the cause. It has been suggested that the disease is multifactorial, involving both genetics and environmental factors.2 Regardless of the exact mechanism, the result is always the same: loss of melanin pigment in cells due to loss of melanocytes.

Autoimmunity plays a central role in the causation of vitiligo and was first suspected as a possible cause due to the association of vitiligo with several other autoimmune disorders, such as thyroiditis.8 An epidemiological survey from the United Kingdom and North America (N=2624) found that 19.4% of vitiligo patients aged 20 years or older also reported a clinical history of autoimmune thyroid disease compared with 2.4% of the overall White population of the same age.9 Interferon gamma, C-X-C chemokine ligand 10, and IL-22 receptors stimulate the innate immune response, resulting in an overactive danger signaling cascade, which leads to proinflammatory signals against melanocyte antigens.2,3 The adaptive immune system also participates in the progression of vitiligo by activating dermal dendritic cells to attack melanocytes along with melanocyte-specific cytotoxic T cells.

Immunomodulatory agents utilized in the treatment of metastatic melanoma have been linked to vitiligolike depigmentation. In those receiving PD-1 immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma, vitiligolike lesions have been reported in 15% to 25% of patients.6 Typically, the PD-1 molecule has a regulatory function on effector T cells. Interaction of the PD-1 receptor with its ligands occurs primarily in peripheral tissue causing apoptosis and downregulation of effector T cells with the goal of decreasing collateral damage to surrounding tissues by active T cells.5 In the tumor microenvironment, however, suppression of the host’s immune response is enhanced by aberrant stimulation of the PD-1 receptor, causing downregulation of the T-cell effector function, T-cell destruction, and apoptosis, which results in continued tumor growth. Nivolumab, a fully humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody, selectively inhibits the PD-1 receptor, disrupting the regulator pathway that would typically end in T-cell destruction.5 Accordingly, the population of active T cells is increased along with the antitumor response.4,10 Nivolumab exhibits success as an immunotherapeutic agent, with an overall survival rate in patients with metastatic melanoma undergoing nivolumab therapy of 41% to 42% at 3 years and 35% at 5 years.11 However, therapeutic manipulation of the host’s immune response does not come without a cost. Vitiligolike lesions have been reported in up to a quarter of patients receiving PD-1 immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma.6

The relationship between vitiligolike depigmentation and melanoma can be explained by the immune activation against antigens associated with melanoma that also are expressed by normal melanocytes. In clinical observations of patients with melanoma and patients with vitiligo, antibodies to human melanocyte antigens were present in 80% (24/30) of patients vs 7% (2/28) in the control group.12 The autoimmune response results from a cross-reaction of melanoma cells that share the same antigens as normal melanocytes, such as melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1), gp100, and tyrosinase.13,14

Development of vitiligolike depigmentation in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with nivolumab has been reported to occur between 2 and 15 months after the start of PD-1 therapy. This side effect of treatment correlates with favorable clinical outcomes.15,16 Enhancing immune recognition of melanocytes in patients with melanoma confers a survival advantage, as studies by Koh et al17 and Norlund et al18 involving patients who developed vitiligolike hypopigmentation associated with malignant melanoma indicated a better prognosis than for those without hypopigmentation. The 5-year survival rate of patients with both malignant melanoma and vitiligo was reported as 60% to 67% when it was estimated that only 30% to 50% of patients should have survived that duration of time.17,18 Similarly, a systematic review of patients with melanoma stages III and IV reported that those with associated hypopigmentation had a 2- to 4-fold decreased risk of disease progression and death compared to patients without depigmentation.7

Use of traditional treatment therapies for vitiligo is based on the ability of the therapy to suppress the immune system. However, in patients with metastatic melanoma undergoing immune-modulating cancer therapies, traditional treatment options may counter the antitumor effects of the targeted immunotherapies and should be used with caution. Our patient displayed improvement in the appearance of her starkly contrasting hypopigmented patches with the use of hydroquinone cream 4%, which induced necrotic death of melanocytes by inhibiting the conversion of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine to melanin by tyrosinase.19 The effect achieved by using topical hydroquinone 4% was a lighter skin appearance in areas of application.

There is no cure for vitiligo, and although it is a benign condition, it can negatively impact a patient's quality of life. In some countries, vitiligo is confused with leprosy, resulting in a social stigma attached to the diagnosis. Many patients are frightened or embarrassed by the diagnosis of vitiligo and its effects, and they often experience discrimination.2 Patients with vitiligo also experience more psychological difficulties such as depression.20 The unpredictability of vitiligo is associated with negative emotions including fear of spreading the lesions, shame, insecurity, and sadness.21 Supportive care measures, including psychological support and counseling, are recommended. Additionally, upon initiation of anti–PD-1 therapies, expectations should be discussed with patients concerning the possibilities of depigmentation and associated treatment results. Although the occurrence of vitiligo may cause the patient concern, it should be communicated that its presence is a positive indicator of a vigorous antimelanoma immunity and an increased survival rate.7

Vitiligolike depigmentation is a known rare adverse effect of nivolumab treatment. Although aesthetically unfavorable for the patient, the development of vitiligolike lesions while undergoing immunotherapy for melanoma may be a sign of a promising clinical outcome due to an effective immune response to melanoma antigens. Our patient remains in remission without any evidence of melanoma after 9 months of therapy, which offers support for a promising outcome for melanoma patients who experience vitiligolike depigmentation.

- de Golian E, Kwong BY, Swetter SM, et al. Cutaneous complications of targeted melanoma therapy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2016;17:57.

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, et al. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386:74-84.

- Ortonne, JP, Passeron, T. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1087-1114.

- Opdivo. Package insert. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2023.

- Ott PA, Hodi FS, Robert C. CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: new immunotherapeutic modalities with durable clinical benefit in melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5300-5309.

- Hwang SJE, Carlos G, Wakade D, et al. Cutaneous adverse events (AEs) of anti-programmed cell death (PD)-1 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma: a single-institution cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:455-461.e1.

- Teulings HE, Limpens J, Jansen SN, et al. Vitiligo-like depigmentation in patients with stage III-IV melanoma receiving immunotherapy and its association with survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:773-781.

- Gey A, Diallo A, Seneschal J, et al. Autoimmune thyroid disease in vitiligo: multivariate analysis indicates intricate pathomechanisms. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:756-761.

- Alkhateeb A, Fain PR, Thody A, et al. Epidemiology of vitiligo and associated autoimmune diseases in Caucasian probands and their families. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:208-214.

- Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320-330.

- Hodi FS, Kluger H, Sznol M, et al. Durable, long-term survival in previously treated patients with advanced melanoma who received nivolumab monotherapy in a phase I trial. Cancer Res. 2016;76(14 suppl):CT001.

- Cui J, Bystryn JC. Melanoma and vitiligo are associated with antibody responses to similar antigens on pigment cells. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:314-318.

- Lynch SA, Bouchard BN, Vijayasaradhi S, et al. Antigens of melanocytes and melanoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1991;10:141-150.

- Sanlorenzo M, Vujic I, Daud A, et al. Pembrolizumab cutaneous adverse events and their association with disease progression. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;15:1206-1212.

- Hua C, Boussemart L, Mateus C, et al. Association of vitiligo with tumor response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:45-51.

- Nakamura Y, Tanaka R, Asami Y, et al. Correlation between vitiligo occurrence and clinical benefit in advanced melanoma patients treated with nivolumab: a multi-institutional retrospective study. J Dermatol. 2017;44:117-122.

- Koh HK, Sober AJ, Nakagawa H, et al. Malignant melanoma and vitiligo-like leukoderma: an electron microscope study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:696-708.

- Nordlund JJ, Kirkwood JM, Forget BM, et al. Vitiligo in patients with metastatic melanoma: a good prognostic sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:689-696.

- Palumbo A, d’Ischia M, Misuraca G, et al. Mechanism of inhibition of melanogenesis by hydroquinone. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1073:85-90.

- Lai YC, Yew YW, Kennedy C, et al. Vitiligo and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:708-718.

- Nogueira LSC, Zancanaro PCQ, Azambuja RD. Vitiligo and emotions. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:41-45.

To the Editor:

Vitiligolike depigmentation has been known to develop around the sites of origin of melanoma or more rarely in patients treated with antimelanoma therapy.1 Vitiligo is characterized by white patchy depigmentation of the skin caused by the loss of functional melanocytes from the epidermis. The exact mechanisms of disease are unknown and multifactorial; however, autoimmunity plays a central role. Interferon gamma (IFN-γ), C-X-C chemokine ligand 10, and IL-22 have been identified as key mediators in an inflammatory cascade leading to the stimulation of the innate immune response against melanocyte antigens.2,3 Research suggests melanoma-associated vitiligolike leukoderma also results from an immune reaction directed against antigenic determinants shared by both normal and malignant melanocytes.3 Vitiligolike lesions have been associated with the use of immunomodulatory agents such as nivolumab, a fully humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody, which blocks the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor that normally is expressed on T cells during the effector phase of T-cell activation.4,5 In the tumor microenvironment, the PD-1 receptor is stimulated, leading to downregulation of the T-cell effector function and destruction of T cells.5 Due to T-cell apoptosis and consequent suppression of the immune response, tumorigenesis continues. By inhibiting the PD-1 receptor, nivolumab increases the number of active T cells and antitumor response. However, the distressing side effect of vitiligolike depigmentation has been reported in 15% to 25% of treated patients.6

In a meta-analysis by Teulings et al,7 patients with new-onset vitiligo and malignant melanoma demonstrated a 2-fold decrease in cancer progression and a 4-fold decreased risk for death vs patients without vitiligo development. Thus, in patients with melanoma, vitiligolike depigmentation should be considered a good prognostic indicator as well as a visible sign of spontaneous or therapy-induced antihumoral immune response against melanocyte differentiation antigens, as it is associated with a notable survival benefit in patients receiving immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma.3 We describe a case of diffuse vitiligolike depigmentation that developed suddenly during nivolumab treatment, causing much distress to the patient.

A 75-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a chief concern of sudden diffuse skin discoloration primarily affecting the face, hands, and extremities of 3 weeks’ duration. She had a medical history of metastatic melanoma—the site of the primary melanoma was never identified—and she was undergoing immune-modulating therapy with nivolumab. She was on her fifth month of treatment and was experiencing a robust therapeutic response with a reported 100% clearance of the metastatic melanoma as observed on a positron emission tomography scan. The patchy depigmentation of skin was causing her much distress. Physical examination revealed diffuse patches of hypopigmentation on the trunk, face, and extremities (Figure). Shave biopsies of the right lateral arm demonstrated changes consistent with vitiligo, with an adjacent biopsy illustrating normal skin characteristics. Triamcinolone ointment 0.1% was initiated, with instruction to apply it to affected areas twice daily for 2 weeks. However, there was no improvement, and she discontinued use.

At 3-month follow-up, the depigmentation persisted, prompting a trial of hydroquinone cream 4% to be used sparingly in cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face and dorsal aspects of the hands. Additionally, diligent photoprotection was advised. Upon re-evaluation 9 months later, the patient remained in cancer remission, continued nivolumab therapy, and reported improvement in the hypopigmentation with a more even skin color with topical hydroquinone use. She no longer noticed starkly contrasting hypopigmented patches.

Vitiligo is a benign skin condition characterized by white depigmented macules and patches. The key feature of the disorder is loss of functional melanocytes from the cutaneous epidermis and sometimes from the hair follicles, with various theories on the cause. It has been suggested that the disease is multifactorial, involving both genetics and environmental factors.2 Regardless of the exact mechanism, the result is always the same: loss of melanin pigment in cells due to loss of melanocytes.

Autoimmunity plays a central role in the causation of vitiligo and was first suspected as a possible cause due to the association of vitiligo with several other autoimmune disorders, such as thyroiditis.8 An epidemiological survey from the United Kingdom and North America (N=2624) found that 19.4% of vitiligo patients aged 20 years or older also reported a clinical history of autoimmune thyroid disease compared with 2.4% of the overall White population of the same age.9 Interferon gamma, C-X-C chemokine ligand 10, and IL-22 receptors stimulate the innate immune response, resulting in an overactive danger signaling cascade, which leads to proinflammatory signals against melanocyte antigens.2,3 The adaptive immune system also participates in the progression of vitiligo by activating dermal dendritic cells to attack melanocytes along with melanocyte-specific cytotoxic T cells.

Immunomodulatory agents utilized in the treatment of metastatic melanoma have been linked to vitiligolike depigmentation. In those receiving PD-1 immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma, vitiligolike lesions have been reported in 15% to 25% of patients.6 Typically, the PD-1 molecule has a regulatory function on effector T cells. Interaction of the PD-1 receptor with its ligands occurs primarily in peripheral tissue causing apoptosis and downregulation of effector T cells with the goal of decreasing collateral damage to surrounding tissues by active T cells.5 In the tumor microenvironment, however, suppression of the host’s immune response is enhanced by aberrant stimulation of the PD-1 receptor, causing downregulation of the T-cell effector function, T-cell destruction, and apoptosis, which results in continued tumor growth. Nivolumab, a fully humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody, selectively inhibits the PD-1 receptor, disrupting the regulator pathway that would typically end in T-cell destruction.5 Accordingly, the population of active T cells is increased along with the antitumor response.4,10 Nivolumab exhibits success as an immunotherapeutic agent, with an overall survival rate in patients with metastatic melanoma undergoing nivolumab therapy of 41% to 42% at 3 years and 35% at 5 years.11 However, therapeutic manipulation of the host’s immune response does not come without a cost. Vitiligolike lesions have been reported in up to a quarter of patients receiving PD-1 immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma.6

The relationship between vitiligolike depigmentation and melanoma can be explained by the immune activation against antigens associated with melanoma that also are expressed by normal melanocytes. In clinical observations of patients with melanoma and patients with vitiligo, antibodies to human melanocyte antigens were present in 80% (24/30) of patients vs 7% (2/28) in the control group.12 The autoimmune response results from a cross-reaction of melanoma cells that share the same antigens as normal melanocytes, such as melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1), gp100, and tyrosinase.13,14

Development of vitiligolike depigmentation in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with nivolumab has been reported to occur between 2 and 15 months after the start of PD-1 therapy. This side effect of treatment correlates with favorable clinical outcomes.15,16 Enhancing immune recognition of melanocytes in patients with melanoma confers a survival advantage, as studies by Koh et al17 and Norlund et al18 involving patients who developed vitiligolike hypopigmentation associated with malignant melanoma indicated a better prognosis than for those without hypopigmentation. The 5-year survival rate of patients with both malignant melanoma and vitiligo was reported as 60% to 67% when it was estimated that only 30% to 50% of patients should have survived that duration of time.17,18 Similarly, a systematic review of patients with melanoma stages III and IV reported that those with associated hypopigmentation had a 2- to 4-fold decreased risk of disease progression and death compared to patients without depigmentation.7

Use of traditional treatment therapies for vitiligo is based on the ability of the therapy to suppress the immune system. However, in patients with metastatic melanoma undergoing immune-modulating cancer therapies, traditional treatment options may counter the antitumor effects of the targeted immunotherapies and should be used with caution. Our patient displayed improvement in the appearance of her starkly contrasting hypopigmented patches with the use of hydroquinone cream 4%, which induced necrotic death of melanocytes by inhibiting the conversion of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine to melanin by tyrosinase.19 The effect achieved by using topical hydroquinone 4% was a lighter skin appearance in areas of application.

There is no cure for vitiligo, and although it is a benign condition, it can negatively impact a patient's quality of life. In some countries, vitiligo is confused with leprosy, resulting in a social stigma attached to the diagnosis. Many patients are frightened or embarrassed by the diagnosis of vitiligo and its effects, and they often experience discrimination.2 Patients with vitiligo also experience more psychological difficulties such as depression.20 The unpredictability of vitiligo is associated with negative emotions including fear of spreading the lesions, shame, insecurity, and sadness.21 Supportive care measures, including psychological support and counseling, are recommended. Additionally, upon initiation of anti–PD-1 therapies, expectations should be discussed with patients concerning the possibilities of depigmentation and associated treatment results. Although the occurrence of vitiligo may cause the patient concern, it should be communicated that its presence is a positive indicator of a vigorous antimelanoma immunity and an increased survival rate.7

Vitiligolike depigmentation is a known rare adverse effect of nivolumab treatment. Although aesthetically unfavorable for the patient, the development of vitiligolike lesions while undergoing immunotherapy for melanoma may be a sign of a promising clinical outcome due to an effective immune response to melanoma antigens. Our patient remains in remission without any evidence of melanoma after 9 months of therapy, which offers support for a promising outcome for melanoma patients who experience vitiligolike depigmentation.

To the Editor:

Vitiligolike depigmentation has been known to develop around the sites of origin of melanoma or more rarely in patients treated with antimelanoma therapy.1 Vitiligo is characterized by white patchy depigmentation of the skin caused by the loss of functional melanocytes from the epidermis. The exact mechanisms of disease are unknown and multifactorial; however, autoimmunity plays a central role. Interferon gamma (IFN-γ), C-X-C chemokine ligand 10, and IL-22 have been identified as key mediators in an inflammatory cascade leading to the stimulation of the innate immune response against melanocyte antigens.2,3 Research suggests melanoma-associated vitiligolike leukoderma also results from an immune reaction directed against antigenic determinants shared by both normal and malignant melanocytes.3 Vitiligolike lesions have been associated with the use of immunomodulatory agents such as nivolumab, a fully humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody, which blocks the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor that normally is expressed on T cells during the effector phase of T-cell activation.4,5 In the tumor microenvironment, the PD-1 receptor is stimulated, leading to downregulation of the T-cell effector function and destruction of T cells.5 Due to T-cell apoptosis and consequent suppression of the immune response, tumorigenesis continues. By inhibiting the PD-1 receptor, nivolumab increases the number of active T cells and antitumor response. However, the distressing side effect of vitiligolike depigmentation has been reported in 15% to 25% of treated patients.6

In a meta-analysis by Teulings et al,7 patients with new-onset vitiligo and malignant melanoma demonstrated a 2-fold decrease in cancer progression and a 4-fold decreased risk for death vs patients without vitiligo development. Thus, in patients with melanoma, vitiligolike depigmentation should be considered a good prognostic indicator as well as a visible sign of spontaneous or therapy-induced antihumoral immune response against melanocyte differentiation antigens, as it is associated with a notable survival benefit in patients receiving immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma.3 We describe a case of diffuse vitiligolike depigmentation that developed suddenly during nivolumab treatment, causing much distress to the patient.

A 75-year-old woman presented to the clinic with a chief concern of sudden diffuse skin discoloration primarily affecting the face, hands, and extremities of 3 weeks’ duration. She had a medical history of metastatic melanoma—the site of the primary melanoma was never identified—and she was undergoing immune-modulating therapy with nivolumab. She was on her fifth month of treatment and was experiencing a robust therapeutic response with a reported 100% clearance of the metastatic melanoma as observed on a positron emission tomography scan. The patchy depigmentation of skin was causing her much distress. Physical examination revealed diffuse patches of hypopigmentation on the trunk, face, and extremities (Figure). Shave biopsies of the right lateral arm demonstrated changes consistent with vitiligo, with an adjacent biopsy illustrating normal skin characteristics. Triamcinolone ointment 0.1% was initiated, with instruction to apply it to affected areas twice daily for 2 weeks. However, there was no improvement, and she discontinued use.

At 3-month follow-up, the depigmentation persisted, prompting a trial of hydroquinone cream 4% to be used sparingly in cosmetically sensitive areas such as the face and dorsal aspects of the hands. Additionally, diligent photoprotection was advised. Upon re-evaluation 9 months later, the patient remained in cancer remission, continued nivolumab therapy, and reported improvement in the hypopigmentation with a more even skin color with topical hydroquinone use. She no longer noticed starkly contrasting hypopigmented patches.

Vitiligo is a benign skin condition characterized by white depigmented macules and patches. The key feature of the disorder is loss of functional melanocytes from the cutaneous epidermis and sometimes from the hair follicles, with various theories on the cause. It has been suggested that the disease is multifactorial, involving both genetics and environmental factors.2 Regardless of the exact mechanism, the result is always the same: loss of melanin pigment in cells due to loss of melanocytes.

Autoimmunity plays a central role in the causation of vitiligo and was first suspected as a possible cause due to the association of vitiligo with several other autoimmune disorders, such as thyroiditis.8 An epidemiological survey from the United Kingdom and North America (N=2624) found that 19.4% of vitiligo patients aged 20 years or older also reported a clinical history of autoimmune thyroid disease compared with 2.4% of the overall White population of the same age.9 Interferon gamma, C-X-C chemokine ligand 10, and IL-22 receptors stimulate the innate immune response, resulting in an overactive danger signaling cascade, which leads to proinflammatory signals against melanocyte antigens.2,3 The adaptive immune system also participates in the progression of vitiligo by activating dermal dendritic cells to attack melanocytes along with melanocyte-specific cytotoxic T cells.

Immunomodulatory agents utilized in the treatment of metastatic melanoma have been linked to vitiligolike depigmentation. In those receiving PD-1 immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma, vitiligolike lesions have been reported in 15% to 25% of patients.6 Typically, the PD-1 molecule has a regulatory function on effector T cells. Interaction of the PD-1 receptor with its ligands occurs primarily in peripheral tissue causing apoptosis and downregulation of effector T cells with the goal of decreasing collateral damage to surrounding tissues by active T cells.5 In the tumor microenvironment, however, suppression of the host’s immune response is enhanced by aberrant stimulation of the PD-1 receptor, causing downregulation of the T-cell effector function, T-cell destruction, and apoptosis, which results in continued tumor growth. Nivolumab, a fully humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody, selectively inhibits the PD-1 receptor, disrupting the regulator pathway that would typically end in T-cell destruction.5 Accordingly, the population of active T cells is increased along with the antitumor response.4,10 Nivolumab exhibits success as an immunotherapeutic agent, with an overall survival rate in patients with metastatic melanoma undergoing nivolumab therapy of 41% to 42% at 3 years and 35% at 5 years.11 However, therapeutic manipulation of the host’s immune response does not come without a cost. Vitiligolike lesions have been reported in up to a quarter of patients receiving PD-1 immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma.6

The relationship between vitiligolike depigmentation and melanoma can be explained by the immune activation against antigens associated with melanoma that also are expressed by normal melanocytes. In clinical observations of patients with melanoma and patients with vitiligo, antibodies to human melanocyte antigens were present in 80% (24/30) of patients vs 7% (2/28) in the control group.12 The autoimmune response results from a cross-reaction of melanoma cells that share the same antigens as normal melanocytes, such as melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1), gp100, and tyrosinase.13,14

Development of vitiligolike depigmentation in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with nivolumab has been reported to occur between 2 and 15 months after the start of PD-1 therapy. This side effect of treatment correlates with favorable clinical outcomes.15,16 Enhancing immune recognition of melanocytes in patients with melanoma confers a survival advantage, as studies by Koh et al17 and Norlund et al18 involving patients who developed vitiligolike hypopigmentation associated with malignant melanoma indicated a better prognosis than for those without hypopigmentation. The 5-year survival rate of patients with both malignant melanoma and vitiligo was reported as 60% to 67% when it was estimated that only 30% to 50% of patients should have survived that duration of time.17,18 Similarly, a systematic review of patients with melanoma stages III and IV reported that those with associated hypopigmentation had a 2- to 4-fold decreased risk of disease progression and death compared to patients without depigmentation.7

Use of traditional treatment therapies for vitiligo is based on the ability of the therapy to suppress the immune system. However, in patients with metastatic melanoma undergoing immune-modulating cancer therapies, traditional treatment options may counter the antitumor effects of the targeted immunotherapies and should be used with caution. Our patient displayed improvement in the appearance of her starkly contrasting hypopigmented patches with the use of hydroquinone cream 4%, which induced necrotic death of melanocytes by inhibiting the conversion of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine to melanin by tyrosinase.19 The effect achieved by using topical hydroquinone 4% was a lighter skin appearance in areas of application.

There is no cure for vitiligo, and although it is a benign condition, it can negatively impact a patient's quality of life. In some countries, vitiligo is confused with leprosy, resulting in a social stigma attached to the diagnosis. Many patients are frightened or embarrassed by the diagnosis of vitiligo and its effects, and they often experience discrimination.2 Patients with vitiligo also experience more psychological difficulties such as depression.20 The unpredictability of vitiligo is associated with negative emotions including fear of spreading the lesions, shame, insecurity, and sadness.21 Supportive care measures, including psychological support and counseling, are recommended. Additionally, upon initiation of anti–PD-1 therapies, expectations should be discussed with patients concerning the possibilities of depigmentation and associated treatment results. Although the occurrence of vitiligo may cause the patient concern, it should be communicated that its presence is a positive indicator of a vigorous antimelanoma immunity and an increased survival rate.7

Vitiligolike depigmentation is a known rare adverse effect of nivolumab treatment. Although aesthetically unfavorable for the patient, the development of vitiligolike lesions while undergoing immunotherapy for melanoma may be a sign of a promising clinical outcome due to an effective immune response to melanoma antigens. Our patient remains in remission without any evidence of melanoma after 9 months of therapy, which offers support for a promising outcome for melanoma patients who experience vitiligolike depigmentation.

- de Golian E, Kwong BY, Swetter SM, et al. Cutaneous complications of targeted melanoma therapy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2016;17:57.

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, et al. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386:74-84.

- Ortonne, JP, Passeron, T. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1087-1114.

- Opdivo. Package insert. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2023.

- Ott PA, Hodi FS, Robert C. CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: new immunotherapeutic modalities with durable clinical benefit in melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5300-5309.

- Hwang SJE, Carlos G, Wakade D, et al. Cutaneous adverse events (AEs) of anti-programmed cell death (PD)-1 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma: a single-institution cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:455-461.e1.

- Teulings HE, Limpens J, Jansen SN, et al. Vitiligo-like depigmentation in patients with stage III-IV melanoma receiving immunotherapy and its association with survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:773-781.

- Gey A, Diallo A, Seneschal J, et al. Autoimmune thyroid disease in vitiligo: multivariate analysis indicates intricate pathomechanisms. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:756-761.

- Alkhateeb A, Fain PR, Thody A, et al. Epidemiology of vitiligo and associated autoimmune diseases in Caucasian probands and their families. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:208-214.

- Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320-330.

- Hodi FS, Kluger H, Sznol M, et al. Durable, long-term survival in previously treated patients with advanced melanoma who received nivolumab monotherapy in a phase I trial. Cancer Res. 2016;76(14 suppl):CT001.

- Cui J, Bystryn JC. Melanoma and vitiligo are associated with antibody responses to similar antigens on pigment cells. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:314-318.

- Lynch SA, Bouchard BN, Vijayasaradhi S, et al. Antigens of melanocytes and melanoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1991;10:141-150.

- Sanlorenzo M, Vujic I, Daud A, et al. Pembrolizumab cutaneous adverse events and their association with disease progression. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;15:1206-1212.

- Hua C, Boussemart L, Mateus C, et al. Association of vitiligo with tumor response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:45-51.

- Nakamura Y, Tanaka R, Asami Y, et al. Correlation between vitiligo occurrence and clinical benefit in advanced melanoma patients treated with nivolumab: a multi-institutional retrospective study. J Dermatol. 2017;44:117-122.

- Koh HK, Sober AJ, Nakagawa H, et al. Malignant melanoma and vitiligo-like leukoderma: an electron microscope study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:696-708.

- Nordlund JJ, Kirkwood JM, Forget BM, et al. Vitiligo in patients with metastatic melanoma: a good prognostic sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:689-696.

- Palumbo A, d’Ischia M, Misuraca G, et al. Mechanism of inhibition of melanogenesis by hydroquinone. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1073:85-90.

- Lai YC, Yew YW, Kennedy C, et al. Vitiligo and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:708-718.

- Nogueira LSC, Zancanaro PCQ, Azambuja RD. Vitiligo and emotions. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:41-45.

- de Golian E, Kwong BY, Swetter SM, et al. Cutaneous complications of targeted melanoma therapy. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2016;17:57.

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, et al. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386:74-84.

- Ortonne, JP, Passeron, T. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1087-1114.

- Opdivo. Package insert. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2023.

- Ott PA, Hodi FS, Robert C. CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: new immunotherapeutic modalities with durable clinical benefit in melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5300-5309.

- Hwang SJE, Carlos G, Wakade D, et al. Cutaneous adverse events (AEs) of anti-programmed cell death (PD)-1 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma: a single-institution cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:455-461.e1.

- Teulings HE, Limpens J, Jansen SN, et al. Vitiligo-like depigmentation in patients with stage III-IV melanoma receiving immunotherapy and its association with survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:773-781.

- Gey A, Diallo A, Seneschal J, et al. Autoimmune thyroid disease in vitiligo: multivariate analysis indicates intricate pathomechanisms. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:756-761.

- Alkhateeb A, Fain PR, Thody A, et al. Epidemiology of vitiligo and associated autoimmune diseases in Caucasian probands and their families. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:208-214.

- Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320-330.

- Hodi FS, Kluger H, Sznol M, et al. Durable, long-term survival in previously treated patients with advanced melanoma who received nivolumab monotherapy in a phase I trial. Cancer Res. 2016;76(14 suppl):CT001.

- Cui J, Bystryn JC. Melanoma and vitiligo are associated with antibody responses to similar antigens on pigment cells. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:314-318.

- Lynch SA, Bouchard BN, Vijayasaradhi S, et al. Antigens of melanocytes and melanoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1991;10:141-150.

- Sanlorenzo M, Vujic I, Daud A, et al. Pembrolizumab cutaneous adverse events and their association with disease progression. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;15:1206-1212.

- Hua C, Boussemart L, Mateus C, et al. Association of vitiligo with tumor response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:45-51.

- Nakamura Y, Tanaka R, Asami Y, et al. Correlation between vitiligo occurrence and clinical benefit in advanced melanoma patients treated with nivolumab: a multi-institutional retrospective study. J Dermatol. 2017;44:117-122.

- Koh HK, Sober AJ, Nakagawa H, et al. Malignant melanoma and vitiligo-like leukoderma: an electron microscope study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:696-708.

- Nordlund JJ, Kirkwood JM, Forget BM, et al. Vitiligo in patients with metastatic melanoma: a good prognostic sign. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:689-696.

- Palumbo A, d’Ischia M, Misuraca G, et al. Mechanism of inhibition of melanogenesis by hydroquinone. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1073:85-90.

- Lai YC, Yew YW, Kennedy C, et al. Vitiligo and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:708-718.

- Nogueira LSC, Zancanaro PCQ, Azambuja RD. Vitiligo and emotions. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:41-45.

Practice Points

- New-onset vitiligo coinciding with malignant melanoma should be considered a good prognostic indicator.

- Daily use of hydroquinone cream 4% in conjunction with diligent photoprotection was shown to even overall skin tone in a patient experiencing leukoderma from nivolumab therapy.

Collision Course of a Basal Cell Carcinoma and Apocrine Hidrocystoma on the Scalp

To the Editor:

A collision tumor is the coexistence of 2 discrete tumors in the same neoplasm, possibly comprising a malignant tumor and a benign tumor, and thereby complicating appropriate diagnosis and treatment. We present a case of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that might have arisen from a nevus sebaceus. Although rare, BCC can coexist with apocrine hidrocystoma. Jayaprakasam and Rene1 reported a case of a collision tumor containing BCC and hidrocystoma on the eyelid.1 We present a case of a BCC on the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that possibly arose from a nevus sebaceus.

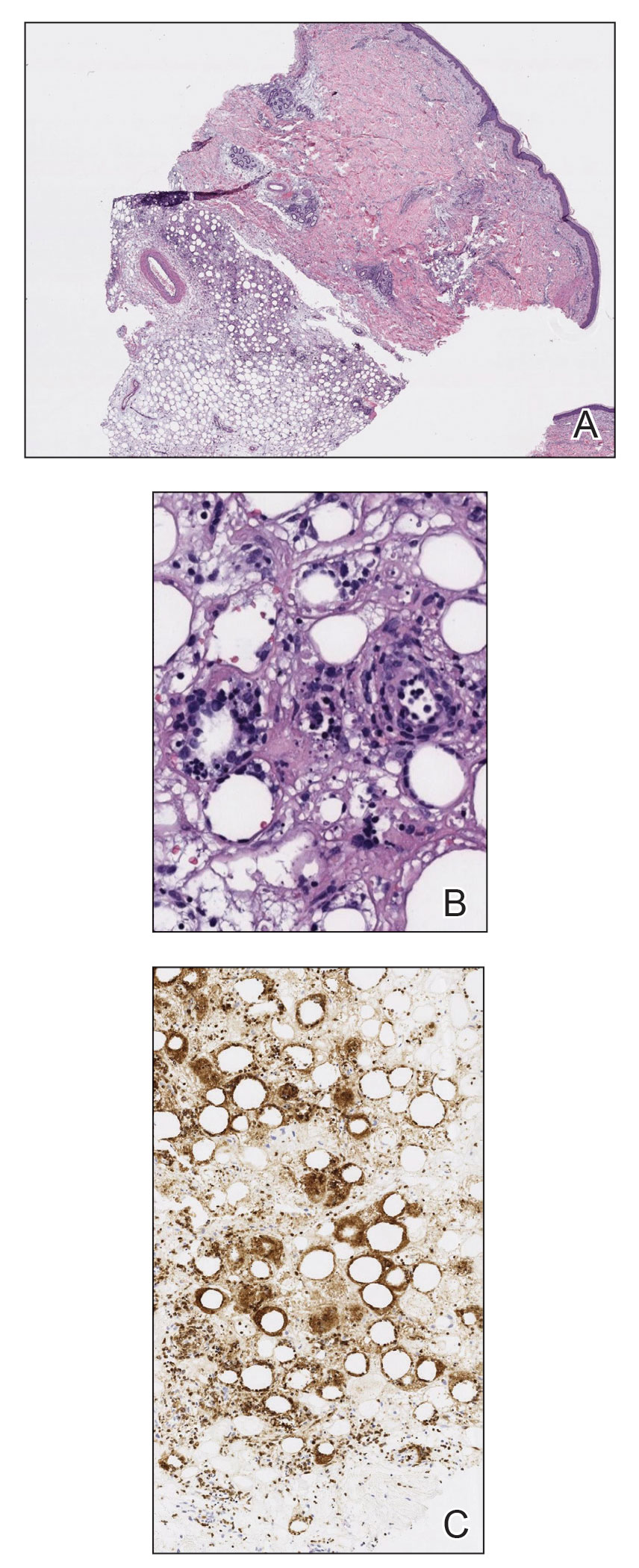

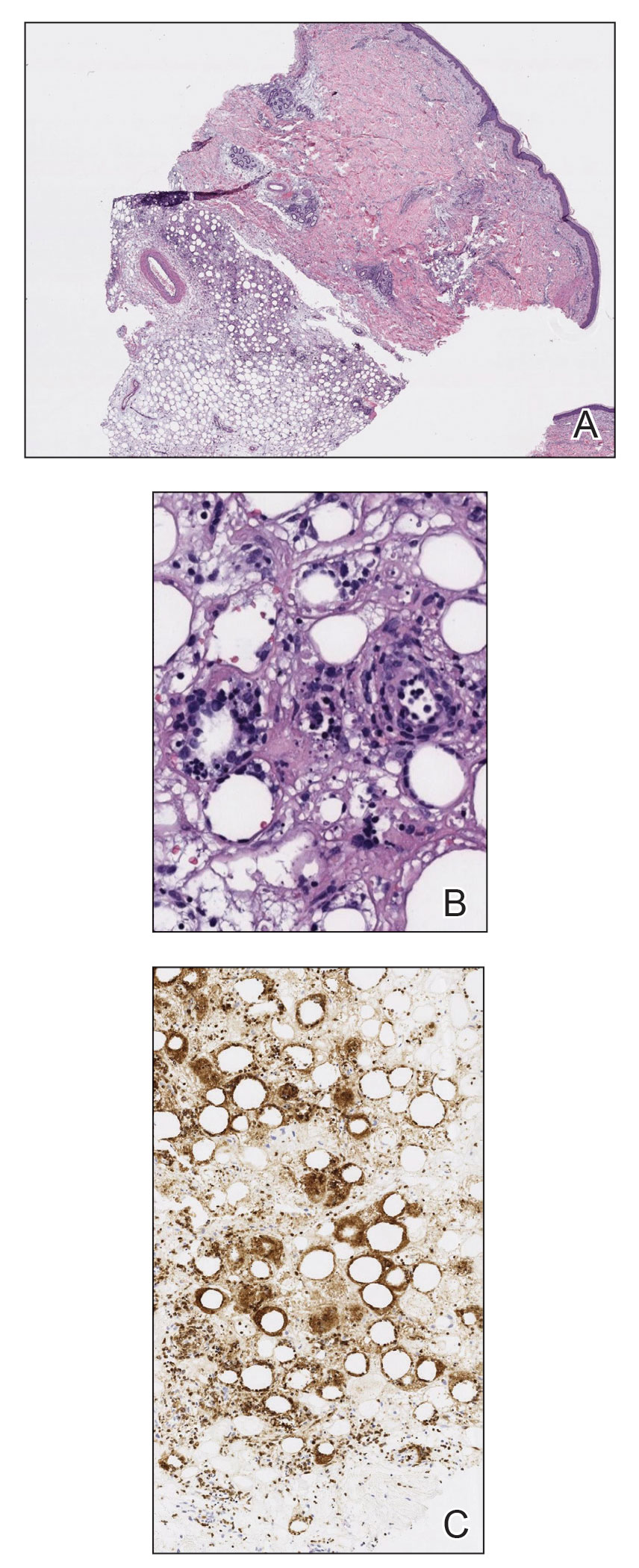

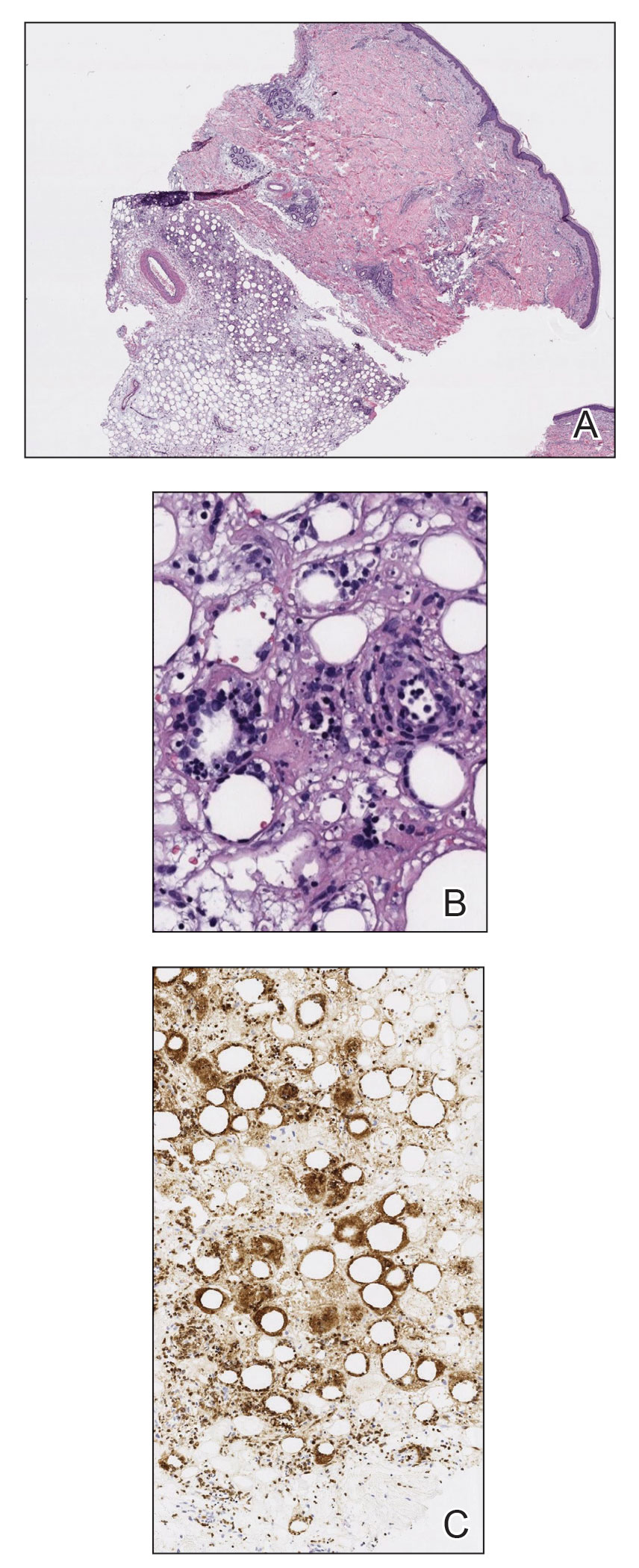

A 92-year-old Black woman with a biopsy-confirmed primary BCC of the left parietal scalp presented for Mohs micrographic surgery. The pathology report from an outside facility was reviewed. The initial diagnosis had been made with 2 punch biopsies from separate areas of the large nodule—one consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC (Figure 1), and the other revealed nodular ulcerated BCC. Physical examination prior to Mohs surgery revealed a mobile, flesh-colored, 6.2×6.0-cm nodule with minimal overlying hair on the left parietal scalp (Figure 2). During stage-I processing by the histopathology laboratory, large cystic structures were encountered; en face frozen sections showed a cystic tumor. Excised tissue was submitted for permanent processing to aid in diagnosis; the initial diagnostic biopsy slides were requested from the outside facility for review.

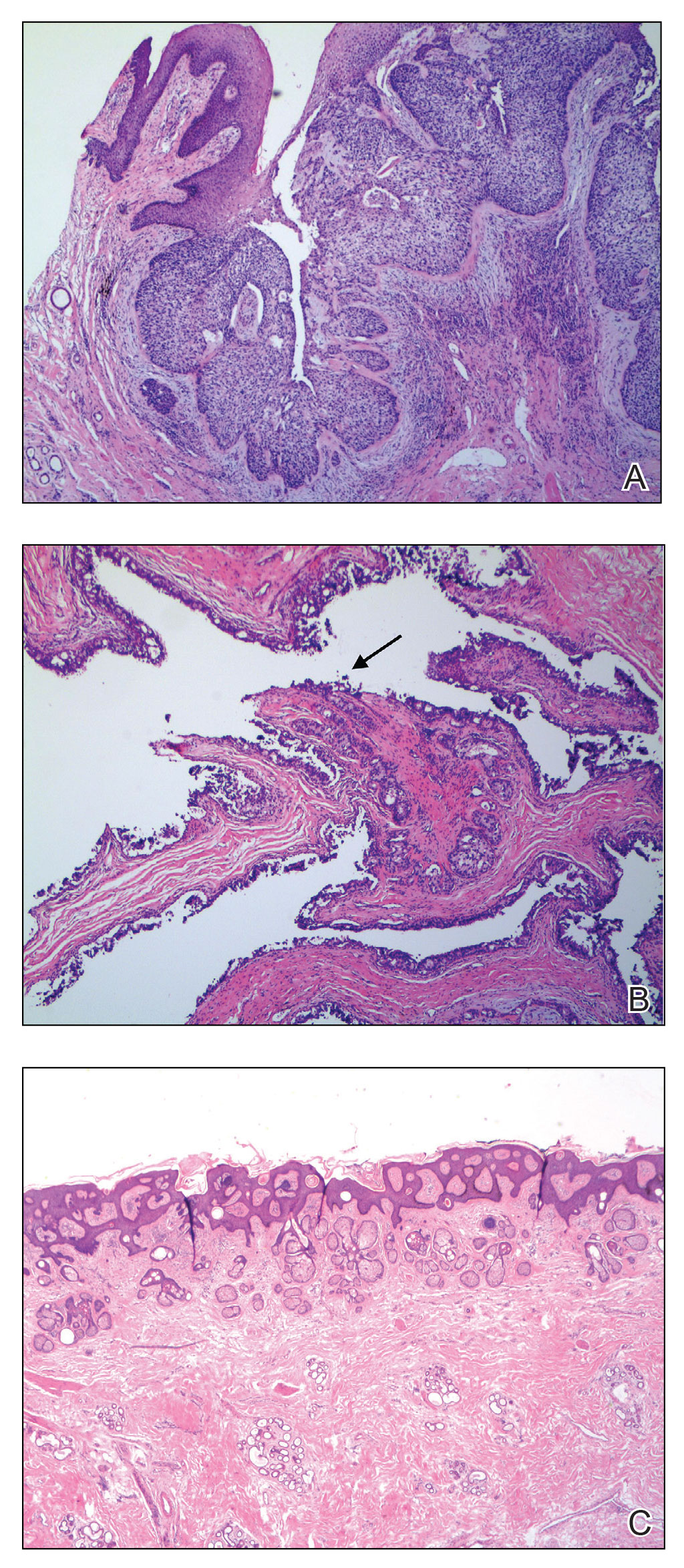

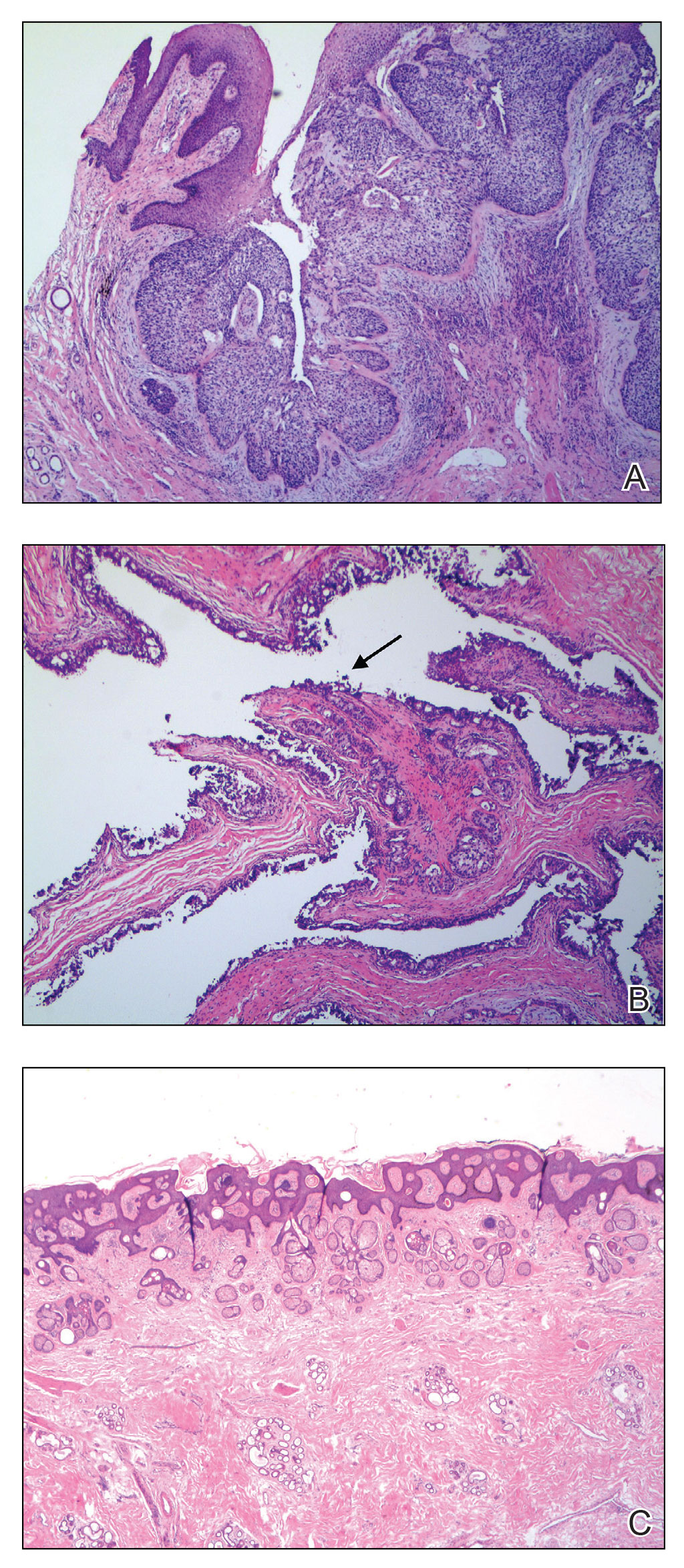

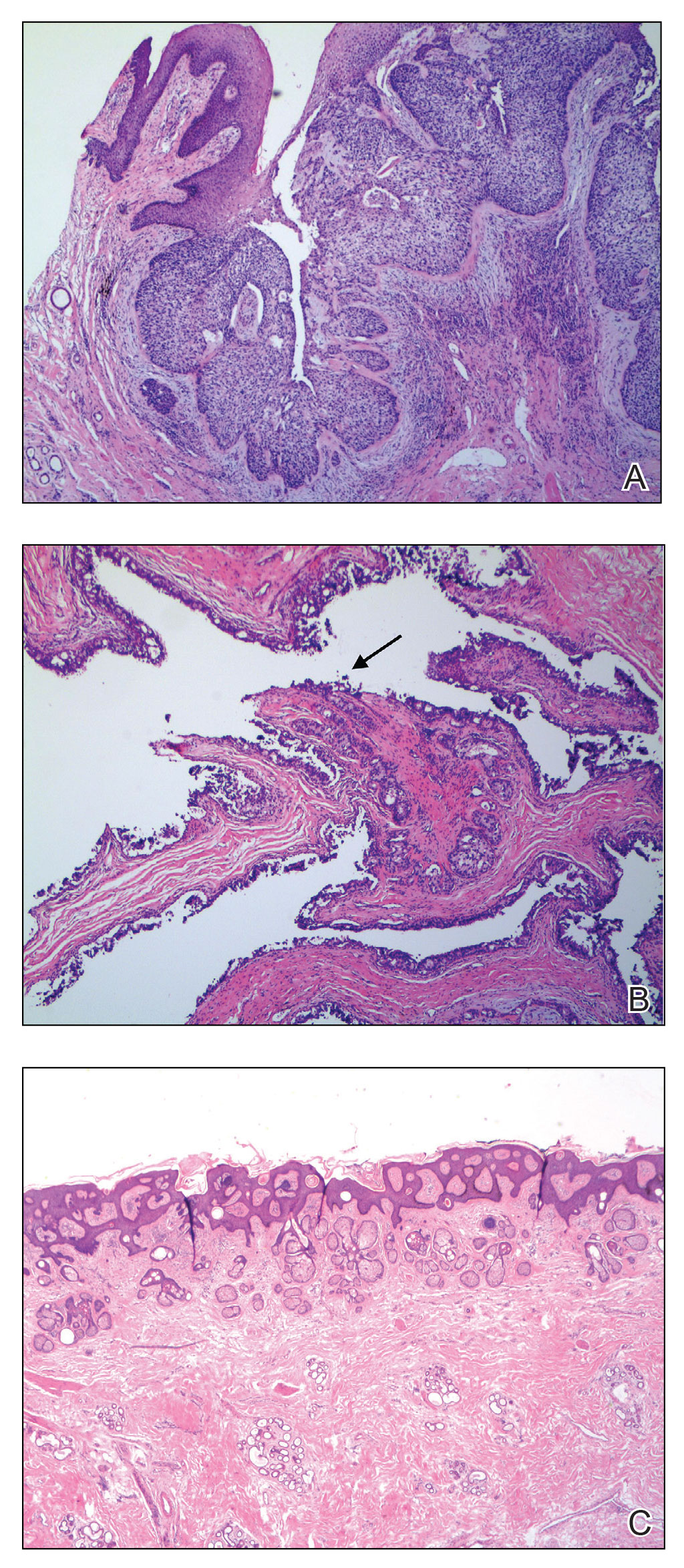

The initial diagnostic biopsy slides were reviewed and found to be consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC, as previously reported. Findings from hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue obtained from Mohs sections were consistent with a combined neoplasm comprising BCC (Figure 3A) and apocrine hidrocystoma (Figure 3B). In addition, one section was characterized by acanthosis, papillomatosis, and sebaceous glands—similar to findings that are seen in a nevus sebaceus (Figure 3C).

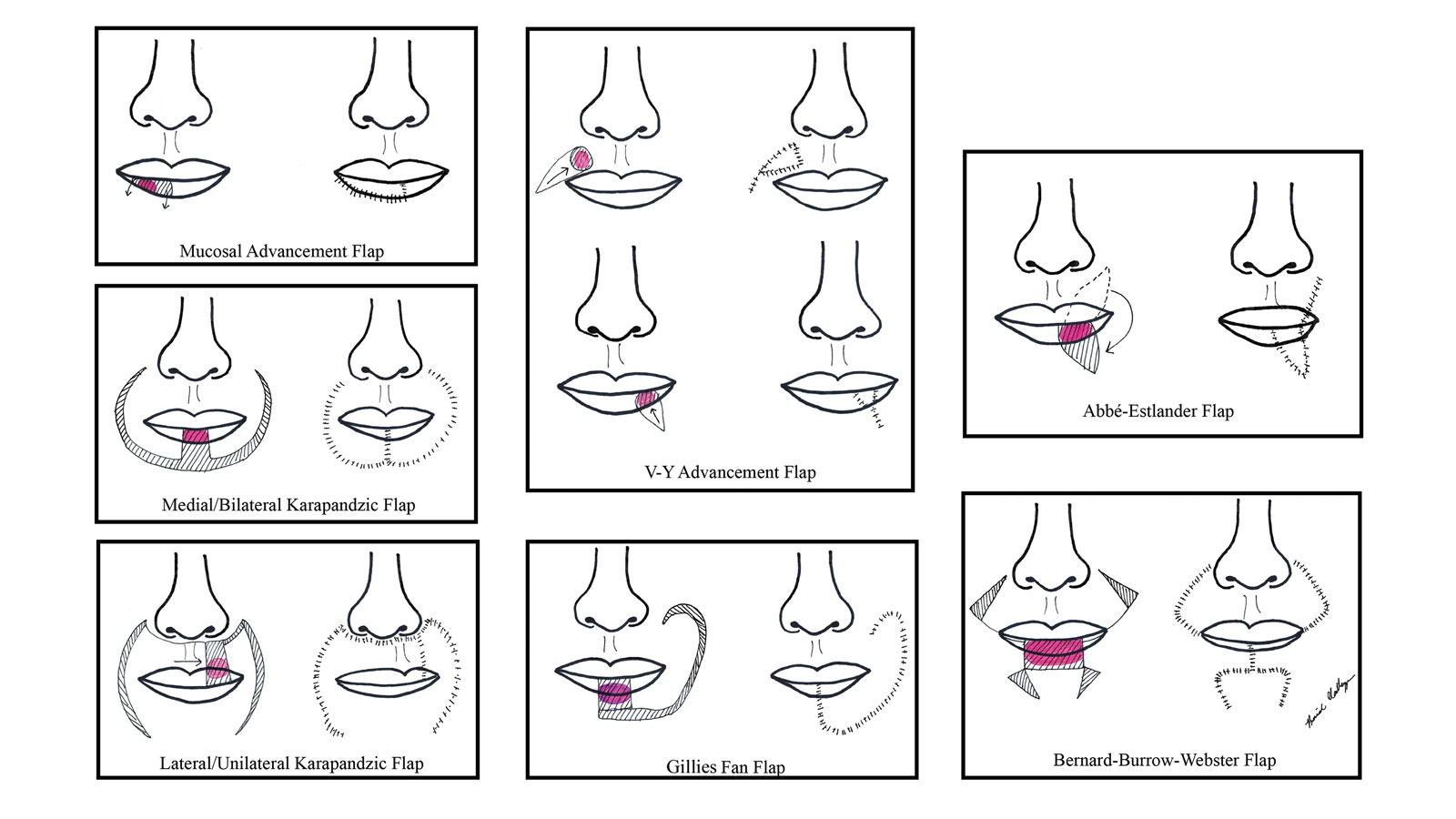

The BCC was cleared after stage I; the final wound size was 7×6.6 cm. Although benign apocrine hidrocystoma was still evident at the margin, further excision was not performed at the request of the patient and her family. Partial primary wound closure was performed with pulley sutures. A xenograft was placed over the unclosed central portion. The wound was permitted to heal by second intention.

The clinical differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule includes a pilar cyst, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, cutaneous metastasis, adnexal tumor, atypical fibroxanthoma, and collision tumor. A collision tumor—the association of 2 or more benign or malignant neoplasms—represents a well-known pitfall in making a correct clinical and pathologic diagnosis.2 Many theories have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of collision tumors. Some authors have speculated that they arise from involvement of related cell types.1 Other theories include induction by cytokines and growth factors secreted from one tumor that provides an ideal environment for proliferation of other cell types, a field cancerization effect of sun-damaged skin, or a coincidence.2

In our case, it is possible that the 2 tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus. One retrospective study of 706 cases of nevus sebaceus (707 specimens) found that 22.5% of cases developed secondary proliferation; of those cases, 18.9% were benign.3 Additionally, in 4.2% of cases of nevus sebaceus, proliferation of 2 or more tumors developed. The most common malignant neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was BCC, followed by squamous cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma. The most common benign neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was trichoblastoma, followed by syringocystadenoma papilliferum.3

Our case highlights the possibility of a sampling error when performing a biopsy of any large neoplasm. Additionally, Mohs surgeons should maintain high clinical suspicion for collision tumors when encountering a large tumor with pathology inconsistent with the original biopsy. Apocrine hidrocystoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a large cystic mass of the scalp. Also, it is important to recognize that malignant lesions, such as BCC, can coexist with another benign tumor. Basal cell carcinoma is rare in Black patients, supporting our belief that our patient’s tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus.

It also is important for Mohs surgeons to consider any potential discrepancy between the initial pathology report and Mohs intraoperative pathology that can impact diagnosis, the aggressiveness of the tumors identified, and how such aggressiveness may affect management options.4,5 Some dermatology practices request biopsy slides from patients who are referred for Mohs micrographic surgery for internal review by a dermatopathologist before surgery is performed; however, this protocol requires additional time and adds costs for the overall health care system.4 One study found that internal review of outside biopsy slides resulted in a change in diagnosis in 2.2% of patients (N=3345)—affecting management in 61% of cases in which the diagnosis was changed.4 Another study (N=163) found that the reported aggressiveness of 50.5% of nonmelanoma cases in an initial biopsy report was changed during Mohs micrographic surgery.5 Mohs surgeons should be aware that discrepancies can occur, and if a discrepancy is discovered, the procedure may be paused until the initial biopsy slide is reviewed and further information is collected.

- Jayaprakasam A, Rene C. A benign or malignant eyelid lump—can you tell? an unusual collision tumour highlighting the difficulty differentiating a hidrocystoma from a basal cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Reports. 2012;2012:bcr1220115307. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5307

- Miteva M, Herschthal D, Ricotti C, et al. A rare case of a cutaneous squamomelanocytic tumor: revisiting the histogenesis of combined neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:599-603. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181a88116

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.004

- Butler ST, Youker SR, Mandrell J, et al. The importance of reviewing pathology specimens before Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:407-412. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.01056.x

- Stiegel E, Lam C, Schowalter M, et al. Correlation between original biopsy pathology and Mohs intraoperative pathology. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:193-197. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001276

To the Editor:

A collision tumor is the coexistence of 2 discrete tumors in the same neoplasm, possibly comprising a malignant tumor and a benign tumor, and thereby complicating appropriate diagnosis and treatment. We present a case of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that might have arisen from a nevus sebaceus. Although rare, BCC can coexist with apocrine hidrocystoma. Jayaprakasam and Rene1 reported a case of a collision tumor containing BCC and hidrocystoma on the eyelid.1 We present a case of a BCC on the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that possibly arose from a nevus sebaceus.

A 92-year-old Black woman with a biopsy-confirmed primary BCC of the left parietal scalp presented for Mohs micrographic surgery. The pathology report from an outside facility was reviewed. The initial diagnosis had been made with 2 punch biopsies from separate areas of the large nodule—one consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC (Figure 1), and the other revealed nodular ulcerated BCC. Physical examination prior to Mohs surgery revealed a mobile, flesh-colored, 6.2×6.0-cm nodule with minimal overlying hair on the left parietal scalp (Figure 2). During stage-I processing by the histopathology laboratory, large cystic structures were encountered; en face frozen sections showed a cystic tumor. Excised tissue was submitted for permanent processing to aid in diagnosis; the initial diagnostic biopsy slides were requested from the outside facility for review.

The initial diagnostic biopsy slides were reviewed and found to be consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC, as previously reported. Findings from hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue obtained from Mohs sections were consistent with a combined neoplasm comprising BCC (Figure 3A) and apocrine hidrocystoma (Figure 3B). In addition, one section was characterized by acanthosis, papillomatosis, and sebaceous glands—similar to findings that are seen in a nevus sebaceus (Figure 3C).

The BCC was cleared after stage I; the final wound size was 7×6.6 cm. Although benign apocrine hidrocystoma was still evident at the margin, further excision was not performed at the request of the patient and her family. Partial primary wound closure was performed with pulley sutures. A xenograft was placed over the unclosed central portion. The wound was permitted to heal by second intention.

The clinical differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule includes a pilar cyst, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, cutaneous metastasis, adnexal tumor, atypical fibroxanthoma, and collision tumor. A collision tumor—the association of 2 or more benign or malignant neoplasms—represents a well-known pitfall in making a correct clinical and pathologic diagnosis.2 Many theories have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of collision tumors. Some authors have speculated that they arise from involvement of related cell types.1 Other theories include induction by cytokines and growth factors secreted from one tumor that provides an ideal environment for proliferation of other cell types, a field cancerization effect of sun-damaged skin, or a coincidence.2

In our case, it is possible that the 2 tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus. One retrospective study of 706 cases of nevus sebaceus (707 specimens) found that 22.5% of cases developed secondary proliferation; of those cases, 18.9% were benign.3 Additionally, in 4.2% of cases of nevus sebaceus, proliferation of 2 or more tumors developed. The most common malignant neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was BCC, followed by squamous cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma. The most common benign neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was trichoblastoma, followed by syringocystadenoma papilliferum.3

Our case highlights the possibility of a sampling error when performing a biopsy of any large neoplasm. Additionally, Mohs surgeons should maintain high clinical suspicion for collision tumors when encountering a large tumor with pathology inconsistent with the original biopsy. Apocrine hidrocystoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a large cystic mass of the scalp. Also, it is important to recognize that malignant lesions, such as BCC, can coexist with another benign tumor. Basal cell carcinoma is rare in Black patients, supporting our belief that our patient’s tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus.

It also is important for Mohs surgeons to consider any potential discrepancy between the initial pathology report and Mohs intraoperative pathology that can impact diagnosis, the aggressiveness of the tumors identified, and how such aggressiveness may affect management options.4,5 Some dermatology practices request biopsy slides from patients who are referred for Mohs micrographic surgery for internal review by a dermatopathologist before surgery is performed; however, this protocol requires additional time and adds costs for the overall health care system.4 One study found that internal review of outside biopsy slides resulted in a change in diagnosis in 2.2% of patients (N=3345)—affecting management in 61% of cases in which the diagnosis was changed.4 Another study (N=163) found that the reported aggressiveness of 50.5% of nonmelanoma cases in an initial biopsy report was changed during Mohs micrographic surgery.5 Mohs surgeons should be aware that discrepancies can occur, and if a discrepancy is discovered, the procedure may be paused until the initial biopsy slide is reviewed and further information is collected.

To the Editor:

A collision tumor is the coexistence of 2 discrete tumors in the same neoplasm, possibly comprising a malignant tumor and a benign tumor, and thereby complicating appropriate diagnosis and treatment. We present a case of a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that might have arisen from a nevus sebaceus. Although rare, BCC can coexist with apocrine hidrocystoma. Jayaprakasam and Rene1 reported a case of a collision tumor containing BCC and hidrocystoma on the eyelid.1 We present a case of a BCC on the scalp that was later found to be in collision with an apocrine hidrocystoma that possibly arose from a nevus sebaceus.

A 92-year-old Black woman with a biopsy-confirmed primary BCC of the left parietal scalp presented for Mohs micrographic surgery. The pathology report from an outside facility was reviewed. The initial diagnosis had been made with 2 punch biopsies from separate areas of the large nodule—one consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC (Figure 1), and the other revealed nodular ulcerated BCC. Physical examination prior to Mohs surgery revealed a mobile, flesh-colored, 6.2×6.0-cm nodule with minimal overlying hair on the left parietal scalp (Figure 2). During stage-I processing by the histopathology laboratory, large cystic structures were encountered; en face frozen sections showed a cystic tumor. Excised tissue was submitted for permanent processing to aid in diagnosis; the initial diagnostic biopsy slides were requested from the outside facility for review.

The initial diagnostic biopsy slides were reviewed and found to be consistent with nodular and pigmented BCC, as previously reported. Findings from hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue obtained from Mohs sections were consistent with a combined neoplasm comprising BCC (Figure 3A) and apocrine hidrocystoma (Figure 3B). In addition, one section was characterized by acanthosis, papillomatosis, and sebaceous glands—similar to findings that are seen in a nevus sebaceus (Figure 3C).

The BCC was cleared after stage I; the final wound size was 7×6.6 cm. Although benign apocrine hidrocystoma was still evident at the margin, further excision was not performed at the request of the patient and her family. Partial primary wound closure was performed with pulley sutures. A xenograft was placed over the unclosed central portion. The wound was permitted to heal by second intention.

The clinical differential diagnosis of a scalp nodule includes a pilar cyst, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, cutaneous metastasis, adnexal tumor, atypical fibroxanthoma, and collision tumor. A collision tumor—the association of 2 or more benign or malignant neoplasms—represents a well-known pitfall in making a correct clinical and pathologic diagnosis.2 Many theories have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of collision tumors. Some authors have speculated that they arise from involvement of related cell types.1 Other theories include induction by cytokines and growth factors secreted from one tumor that provides an ideal environment for proliferation of other cell types, a field cancerization effect of sun-damaged skin, or a coincidence.2

In our case, it is possible that the 2 tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus. One retrospective study of 706 cases of nevus sebaceus (707 specimens) found that 22.5% of cases developed secondary proliferation; of those cases, 18.9% were benign.3 Additionally, in 4.2% of cases of nevus sebaceus, proliferation of 2 or more tumors developed. The most common malignant neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was BCC, followed by squamous cell carcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma. The most common benign neoplasm to develop from nevus sebaceus was trichoblastoma, followed by syringocystadenoma papilliferum.3

Our case highlights the possibility of a sampling error when performing a biopsy of any large neoplasm. Additionally, Mohs surgeons should maintain high clinical suspicion for collision tumors when encountering a large tumor with pathology inconsistent with the original biopsy. Apocrine hidrocystoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a large cystic mass of the scalp. Also, it is important to recognize that malignant lesions, such as BCC, can coexist with another benign tumor. Basal cell carcinoma is rare in Black patients, supporting our belief that our patient’s tumors arose from a nevus sebaceus.

It also is important for Mohs surgeons to consider any potential discrepancy between the initial pathology report and Mohs intraoperative pathology that can impact diagnosis, the aggressiveness of the tumors identified, and how such aggressiveness may affect management options.4,5 Some dermatology practices request biopsy slides from patients who are referred for Mohs micrographic surgery for internal review by a dermatopathologist before surgery is performed; however, this protocol requires additional time and adds costs for the overall health care system.4 One study found that internal review of outside biopsy slides resulted in a change in diagnosis in 2.2% of patients (N=3345)—affecting management in 61% of cases in which the diagnosis was changed.4 Another study (N=163) found that the reported aggressiveness of 50.5% of nonmelanoma cases in an initial biopsy report was changed during Mohs micrographic surgery.5 Mohs surgeons should be aware that discrepancies can occur, and if a discrepancy is discovered, the procedure may be paused until the initial biopsy slide is reviewed and further information is collected.

- Jayaprakasam A, Rene C. A benign or malignant eyelid lump—can you tell? an unusual collision tumour highlighting the difficulty differentiating a hidrocystoma from a basal cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Reports. 2012;2012:bcr1220115307. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5307