User login

How we treat acute pain could be wrong

In a surprising discovery that flies in the face of conventional medicine,

The paper, published in Science Translational Medicine, suggests that inflammation, a normal part of injury recovery, helps resolve acute pain and prevents it from becoming chronic. Blocking that inflammation may interfere with this process, leading to harder-to-treat pain.

“What we’ve been doing for decades not only appears to be wrong, but appears to be 180 degrees wrong,” says senior study author Jeffrey Mogil, PhD, a professor in the department of psychology at McGill University in Montreal. “You should not be blocking inflammation. You should be letting inflammation happen. That’s what stops chronic pain.”

Inflammation: Nature’s pain reliever

Wanting to know why pain goes away for some but drags on (and on) for others, the researchers looked at pain mechanisms in both humans and mice. They found that a type of white blood cell known as a neutrophil seems to play a key role.

“In analyzing the genes of people suffering from lower back pain, we observed active changes in genes over time in people whose pain went away,” says Luda Diatchenko, PhD, a professor in the faculty of medicine and Canada excellence research chair in human pain genetics at McGill. “Changes in the blood cells and their activity seemed to be the most important factor, especially in cells called neutrophils.”

To test this link, the researchers blocked neutrophils in mice and found the pain lasted 2-10 times longer than normal. Anti-inflammatory drugs, despite providing short-term relief, had the same pain-prolonging effect – though injecting neutrophils into the mice seemed to keep that from happening.

The findings are supported by a separate analysis of 500,000 people in the United Kingdom that showed those taking anti-inflammatory drugs to treat their pain were more likely to have pain 2-10 years later.

“Inflammation occurs for a reason,” says Dr. Mogil, “and it looks like it’s dangerous to interfere with it.”

Rethinking how we treat pain

Neutrophils arrive early during inflammation, at the onset of injury – just when many of us reach for pain medication. This research suggests it might be better not to block inflammation, instead letting the neutrophils “do their thing.” Taking an analgesic that alleviates pain without blocking neutrophils, like acetaminophen, may be better than taking an anti-inflammatory drug or steroid, says Dr. Mogil.

Still, while the findings are compelling, clinical trials are needed to directly compare anti-inflammatory drugs to other painkillers, the researchers said. This research may also lay the groundwork for new drug development for chronic pain patients, Dr. Mogil says.

“Our data strongly suggests that neutrophils act like analgesics themselves, which is potentially useful in terms of analgesic development,” Dr. Mogil says. “And of course, we need new analgesics.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

In a surprising discovery that flies in the face of conventional medicine,

The paper, published in Science Translational Medicine, suggests that inflammation, a normal part of injury recovery, helps resolve acute pain and prevents it from becoming chronic. Blocking that inflammation may interfere with this process, leading to harder-to-treat pain.

“What we’ve been doing for decades not only appears to be wrong, but appears to be 180 degrees wrong,” says senior study author Jeffrey Mogil, PhD, a professor in the department of psychology at McGill University in Montreal. “You should not be blocking inflammation. You should be letting inflammation happen. That’s what stops chronic pain.”

Inflammation: Nature’s pain reliever

Wanting to know why pain goes away for some but drags on (and on) for others, the researchers looked at pain mechanisms in both humans and mice. They found that a type of white blood cell known as a neutrophil seems to play a key role.

“In analyzing the genes of people suffering from lower back pain, we observed active changes in genes over time in people whose pain went away,” says Luda Diatchenko, PhD, a professor in the faculty of medicine and Canada excellence research chair in human pain genetics at McGill. “Changes in the blood cells and their activity seemed to be the most important factor, especially in cells called neutrophils.”

To test this link, the researchers blocked neutrophils in mice and found the pain lasted 2-10 times longer than normal. Anti-inflammatory drugs, despite providing short-term relief, had the same pain-prolonging effect – though injecting neutrophils into the mice seemed to keep that from happening.

The findings are supported by a separate analysis of 500,000 people in the United Kingdom that showed those taking anti-inflammatory drugs to treat their pain were more likely to have pain 2-10 years later.

“Inflammation occurs for a reason,” says Dr. Mogil, “and it looks like it’s dangerous to interfere with it.”

Rethinking how we treat pain

Neutrophils arrive early during inflammation, at the onset of injury – just when many of us reach for pain medication. This research suggests it might be better not to block inflammation, instead letting the neutrophils “do their thing.” Taking an analgesic that alleviates pain without blocking neutrophils, like acetaminophen, may be better than taking an anti-inflammatory drug or steroid, says Dr. Mogil.

Still, while the findings are compelling, clinical trials are needed to directly compare anti-inflammatory drugs to other painkillers, the researchers said. This research may also lay the groundwork for new drug development for chronic pain patients, Dr. Mogil says.

“Our data strongly suggests that neutrophils act like analgesics themselves, which is potentially useful in terms of analgesic development,” Dr. Mogil says. “And of course, we need new analgesics.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

In a surprising discovery that flies in the face of conventional medicine,

The paper, published in Science Translational Medicine, suggests that inflammation, a normal part of injury recovery, helps resolve acute pain and prevents it from becoming chronic. Blocking that inflammation may interfere with this process, leading to harder-to-treat pain.

“What we’ve been doing for decades not only appears to be wrong, but appears to be 180 degrees wrong,” says senior study author Jeffrey Mogil, PhD, a professor in the department of psychology at McGill University in Montreal. “You should not be blocking inflammation. You should be letting inflammation happen. That’s what stops chronic pain.”

Inflammation: Nature’s pain reliever

Wanting to know why pain goes away for some but drags on (and on) for others, the researchers looked at pain mechanisms in both humans and mice. They found that a type of white blood cell known as a neutrophil seems to play a key role.

“In analyzing the genes of people suffering from lower back pain, we observed active changes in genes over time in people whose pain went away,” says Luda Diatchenko, PhD, a professor in the faculty of medicine and Canada excellence research chair in human pain genetics at McGill. “Changes in the blood cells and their activity seemed to be the most important factor, especially in cells called neutrophils.”

To test this link, the researchers blocked neutrophils in mice and found the pain lasted 2-10 times longer than normal. Anti-inflammatory drugs, despite providing short-term relief, had the same pain-prolonging effect – though injecting neutrophils into the mice seemed to keep that from happening.

The findings are supported by a separate analysis of 500,000 people in the United Kingdom that showed those taking anti-inflammatory drugs to treat their pain were more likely to have pain 2-10 years later.

“Inflammation occurs for a reason,” says Dr. Mogil, “and it looks like it’s dangerous to interfere with it.”

Rethinking how we treat pain

Neutrophils arrive early during inflammation, at the onset of injury – just when many of us reach for pain medication. This research suggests it might be better not to block inflammation, instead letting the neutrophils “do their thing.” Taking an analgesic that alleviates pain without blocking neutrophils, like acetaminophen, may be better than taking an anti-inflammatory drug or steroid, says Dr. Mogil.

Still, while the findings are compelling, clinical trials are needed to directly compare anti-inflammatory drugs to other painkillers, the researchers said. This research may also lay the groundwork for new drug development for chronic pain patients, Dr. Mogil says.

“Our data strongly suggests that neutrophils act like analgesics themselves, which is potentially useful in terms of analgesic development,” Dr. Mogil says. “And of course, we need new analgesics.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Migraine relief in 20 minutes using eyedrops?

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 35-year-old woman with no significant past medical history presents for follow-up of migraine. At the previous visit, she was prescribed sumatriptan for abortive therapy. However, she has been having significant adverse effect intolerance from the oral formulation, and the nasal formulation is cost prohibitive. What can you recommend as an alternative abortive therapy for this patient’s migraine?

Migraine is among the most common causes of disability worldwide, affecting more than 10% of the global population.2 The prevalence of migraine is between 2.6% and 21.7% across multiple countries.3 On a scale of 0% to 100%, disability caused by migraine is 43.3%, comparable to the first 2 days after an acute myocardial infarction (42.2%) and severe dementia (43.8%).4

Abortive therapy for acute migraine includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),

Nausea and vomiting, common components of migraine (that are included in International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition [ICHD-3] criteria for migraine5) present obstacles to effective oral administration if experienced by the patient. In addition, for migraine refractory to first-line treatments, abortive options—including the recently approved

Two oral beta-blockers, propranolol and timolol, are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for migraine prophylaxis. Unfortunately, oral beta-blockers are ineffective for abortive treatment.7 Ophthalmic timolol is typically used in the treatment of glaucoma, but there have been case reports describing its benefits in acute migraine treatment.8,9 In addition, ophthalmic timolol is far cheaper than medications such as ubrogepant.10 A 2014 case series of 7 patients discussed ophthalmic beta-blockers as an effective and possibly cheaper option for acute migraine treatment.8 A randomized, crossover, placebo-controlled pilot study of 198 migraine attacks in 10 participants using timolol eyedrops for abortive therapy found timolol was not significantly more effective than placebo.9 However, it was an underpowered pilot study, with a lack of masking and an imperfect placebo. The trial discussed here was a controlled, prospective study investigating topical beta-blockers for acute migraine treatment.

STUDY SUMMARY

Crossover study achieved primary endpoint in pain reduction

This randomized, single-center, double-masked, crossover trial compared timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% with placebo among 43 patients ages 12 or older presenting with a diagnosis of migraine based on ICHD-3 (beta) criteria. Patients were eligible if they had not taken any antimigraine medications for at least 1 month prior to the study and were excluded if they had taken systemic beta-blockers at baseline, or had asthma, bradyarrhythmias, or cardiac dysfunction.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to treatment with timolol maleate 0.5% eyedrops or placebo. At the earliest onset of migraine, patients used 1 drop of timolol maleate 0.5% or placebo in each eye; if they experienced no relief after 10 minutes, they used a second drop or matching placebo. Patients were instructed to score their headache pain on a 10-point scale prior to using the eyedrops and then again 20 minutes after treatment. If a patient had migraine with aura, they were asked to use the eyedrops at the onset of the aura but measure their score at headache onset. If no headaches developed within 20 minutes of the aura, the episode was not included for analysis. All patients were permitted to use their standard oral rescue medication if no relief occurred after 20 minutes of pain onset.

Continue to: The groups were observed...

The groups were observed for 3 months and then followed for a 1-month washout period, during which they received no study medications. The groups were then crossed over to the other treatment and were observed for another 3 months. The primary outcome was a reduction in pain score by 4 or more points, or to 0 on a 10-point pain scale, 20 minutes after treatment. The secondary outcome was nonuse of oral rescue medication.

Forty-three patients were included in a modified intention-to-treat analysis. The primary outcome was achieved in 233 of 284 (82%) timolol-treated migraines, compared to 38 of 271 (14%) placebo-treated migraines (percentage difference = 68 percentage points; 95% CI, 62-74 percentage points; P < .001). The mean pain score at the onset of migraine attacks was 6.01 for those treated with timolol and 5.93 for those treated with placebo. Patients treated with timolol had a reduction in pain of 5.98 points, compared with 0.93 points after using placebo (difference = 5.05; 95% CI, 4.19-5.91). No attacks included in the data required oral rescue medications, and there were no systemic adverse effects from the timolol eyedrops.

WHAT’S NEW

Evidence of benefit as abortive therapy for acute migraine

This randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed evidence to support timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% vs placebo for treatment of acute migraine by significantly reducing pain when taken at the onset of an acute migraine attack.

CAVEATS

Single-center trial, measuring limited response time

The generalizability of this RCT is limited because it was a single-center trial with a study population from a single region in India. It is unknown whether pain relief, adverse effects, or adherence would differ for the global population. Additionally, only migraines with headache were included in the analysis, limiting non-headache migraine subgroup-directed treatment. Also, this trial evaluated only the response to treatment at 20 minutes, and it is unknown if pain response continued for several hours. Headaches that began more than 20 minutes after the onset of aura were not evaluated.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Timolol’s systemic adverse effects require caution

Systemic beta-blocker effects (eg, bradycardia, hypotension, drowsiness, and bronchospasm) from topical timolol have been reported. Caution should be used when prescribing timolol for patients with current cardiovascular and pulmonary conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

- Kurian A, Reghunadhan I, Thilak P, et al. Short-term efficacy and safety of topical β-blockers (timolol maleate ophthalmic solution, 0.5%) in acute migraine: a randomized crossover trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138:1160-1166. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.3676

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:743-800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4

- Yeh WZ, Blizzard L, Taylor BV. What is the actual prevalence of migraine? Brain Behav. 2018;8:e00950. doi: 10.1002/brb3.950

- Leonardi M, Raggi A. Burden of migraine: international perspectives. Neurol Sci. 2013;34(suppl 1):S117-S118. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1387-8

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629-808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658

- Ubrogepant. GoodRx. Accessed May 23, 2022. www.goodrx.com/ubrogepant

- Orr SL, Friedman BW, Christie S, et al. Management of adults with acute migraine in the emergency department: the American Headache Society evidence assessment of parenteral pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2016;56:911-940. doi: 10.1111/head.12835

- 8. Migliazzo CV, Hagan JC III. Beta blocker eye drops for treatment of acute migraine. Mo Med. 2014;111:283-288.

- 9. Cossack M, Nabrinsky E, Turner H, et al. Timolol eyedrops in the treatment of acute migraine attacks: a randomized crossover study. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:1024-1025. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0970

- 10. Timolol. GoodRx. Accessed May 23, 2022. www.goodrx.com/timolol

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 35-year-old woman with no significant past medical history presents for follow-up of migraine. At the previous visit, she was prescribed sumatriptan for abortive therapy. However, she has been having significant adverse effect intolerance from the oral formulation, and the nasal formulation is cost prohibitive. What can you recommend as an alternative abortive therapy for this patient’s migraine?

Migraine is among the most common causes of disability worldwide, affecting more than 10% of the global population.2 The prevalence of migraine is between 2.6% and 21.7% across multiple countries.3 On a scale of 0% to 100%, disability caused by migraine is 43.3%, comparable to the first 2 days after an acute myocardial infarction (42.2%) and severe dementia (43.8%).4

Abortive therapy for acute migraine includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),

Nausea and vomiting, common components of migraine (that are included in International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition [ICHD-3] criteria for migraine5) present obstacles to effective oral administration if experienced by the patient. In addition, for migraine refractory to first-line treatments, abortive options—including the recently approved

Two oral beta-blockers, propranolol and timolol, are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for migraine prophylaxis. Unfortunately, oral beta-blockers are ineffective for abortive treatment.7 Ophthalmic timolol is typically used in the treatment of glaucoma, but there have been case reports describing its benefits in acute migraine treatment.8,9 In addition, ophthalmic timolol is far cheaper than medications such as ubrogepant.10 A 2014 case series of 7 patients discussed ophthalmic beta-blockers as an effective and possibly cheaper option for acute migraine treatment.8 A randomized, crossover, placebo-controlled pilot study of 198 migraine attacks in 10 participants using timolol eyedrops for abortive therapy found timolol was not significantly more effective than placebo.9 However, it was an underpowered pilot study, with a lack of masking and an imperfect placebo. The trial discussed here was a controlled, prospective study investigating topical beta-blockers for acute migraine treatment.

STUDY SUMMARY

Crossover study achieved primary endpoint in pain reduction

This randomized, single-center, double-masked, crossover trial compared timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% with placebo among 43 patients ages 12 or older presenting with a diagnosis of migraine based on ICHD-3 (beta) criteria. Patients were eligible if they had not taken any antimigraine medications for at least 1 month prior to the study and were excluded if they had taken systemic beta-blockers at baseline, or had asthma, bradyarrhythmias, or cardiac dysfunction.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to treatment with timolol maleate 0.5% eyedrops or placebo. At the earliest onset of migraine, patients used 1 drop of timolol maleate 0.5% or placebo in each eye; if they experienced no relief after 10 minutes, they used a second drop or matching placebo. Patients were instructed to score their headache pain on a 10-point scale prior to using the eyedrops and then again 20 minutes after treatment. If a patient had migraine with aura, they were asked to use the eyedrops at the onset of the aura but measure their score at headache onset. If no headaches developed within 20 minutes of the aura, the episode was not included for analysis. All patients were permitted to use their standard oral rescue medication if no relief occurred after 20 minutes of pain onset.

Continue to: The groups were observed...

The groups were observed for 3 months and then followed for a 1-month washout period, during which they received no study medications. The groups were then crossed over to the other treatment and were observed for another 3 months. The primary outcome was a reduction in pain score by 4 or more points, or to 0 on a 10-point pain scale, 20 minutes after treatment. The secondary outcome was nonuse of oral rescue medication.

Forty-three patients were included in a modified intention-to-treat analysis. The primary outcome was achieved in 233 of 284 (82%) timolol-treated migraines, compared to 38 of 271 (14%) placebo-treated migraines (percentage difference = 68 percentage points; 95% CI, 62-74 percentage points; P < .001). The mean pain score at the onset of migraine attacks was 6.01 for those treated with timolol and 5.93 for those treated with placebo. Patients treated with timolol had a reduction in pain of 5.98 points, compared with 0.93 points after using placebo (difference = 5.05; 95% CI, 4.19-5.91). No attacks included in the data required oral rescue medications, and there were no systemic adverse effects from the timolol eyedrops.

WHAT’S NEW

Evidence of benefit as abortive therapy for acute migraine

This randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed evidence to support timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% vs placebo for treatment of acute migraine by significantly reducing pain when taken at the onset of an acute migraine attack.

CAVEATS

Single-center trial, measuring limited response time

The generalizability of this RCT is limited because it was a single-center trial with a study population from a single region in India. It is unknown whether pain relief, adverse effects, or adherence would differ for the global population. Additionally, only migraines with headache were included in the analysis, limiting non-headache migraine subgroup-directed treatment. Also, this trial evaluated only the response to treatment at 20 minutes, and it is unknown if pain response continued for several hours. Headaches that began more than 20 minutes after the onset of aura were not evaluated.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Timolol’s systemic adverse effects require caution

Systemic beta-blocker effects (eg, bradycardia, hypotension, drowsiness, and bronchospasm) from topical timolol have been reported. Caution should be used when prescribing timolol for patients with current cardiovascular and pulmonary conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 35-year-old woman with no significant past medical history presents for follow-up of migraine. At the previous visit, she was prescribed sumatriptan for abortive therapy. However, she has been having significant adverse effect intolerance from the oral formulation, and the nasal formulation is cost prohibitive. What can you recommend as an alternative abortive therapy for this patient’s migraine?

Migraine is among the most common causes of disability worldwide, affecting more than 10% of the global population.2 The prevalence of migraine is between 2.6% and 21.7% across multiple countries.3 On a scale of 0% to 100%, disability caused by migraine is 43.3%, comparable to the first 2 days after an acute myocardial infarction (42.2%) and severe dementia (43.8%).4

Abortive therapy for acute migraine includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),

Nausea and vomiting, common components of migraine (that are included in International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition [ICHD-3] criteria for migraine5) present obstacles to effective oral administration if experienced by the patient. In addition, for migraine refractory to first-line treatments, abortive options—including the recently approved

Two oral beta-blockers, propranolol and timolol, are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for migraine prophylaxis. Unfortunately, oral beta-blockers are ineffective for abortive treatment.7 Ophthalmic timolol is typically used in the treatment of glaucoma, but there have been case reports describing its benefits in acute migraine treatment.8,9 In addition, ophthalmic timolol is far cheaper than medications such as ubrogepant.10 A 2014 case series of 7 patients discussed ophthalmic beta-blockers as an effective and possibly cheaper option for acute migraine treatment.8 A randomized, crossover, placebo-controlled pilot study of 198 migraine attacks in 10 participants using timolol eyedrops for abortive therapy found timolol was not significantly more effective than placebo.9 However, it was an underpowered pilot study, with a lack of masking and an imperfect placebo. The trial discussed here was a controlled, prospective study investigating topical beta-blockers for acute migraine treatment.

STUDY SUMMARY

Crossover study achieved primary endpoint in pain reduction

This randomized, single-center, double-masked, crossover trial compared timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% with placebo among 43 patients ages 12 or older presenting with a diagnosis of migraine based on ICHD-3 (beta) criteria. Patients were eligible if they had not taken any antimigraine medications for at least 1 month prior to the study and were excluded if they had taken systemic beta-blockers at baseline, or had asthma, bradyarrhythmias, or cardiac dysfunction.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to treatment with timolol maleate 0.5% eyedrops or placebo. At the earliest onset of migraine, patients used 1 drop of timolol maleate 0.5% or placebo in each eye; if they experienced no relief after 10 minutes, they used a second drop or matching placebo. Patients were instructed to score their headache pain on a 10-point scale prior to using the eyedrops and then again 20 minutes after treatment. If a patient had migraine with aura, they were asked to use the eyedrops at the onset of the aura but measure their score at headache onset. If no headaches developed within 20 minutes of the aura, the episode was not included for analysis. All patients were permitted to use their standard oral rescue medication if no relief occurred after 20 minutes of pain onset.

Continue to: The groups were observed...

The groups were observed for 3 months and then followed for a 1-month washout period, during which they received no study medications. The groups were then crossed over to the other treatment and were observed for another 3 months. The primary outcome was a reduction in pain score by 4 or more points, or to 0 on a 10-point pain scale, 20 minutes after treatment. The secondary outcome was nonuse of oral rescue medication.

Forty-three patients were included in a modified intention-to-treat analysis. The primary outcome was achieved in 233 of 284 (82%) timolol-treated migraines, compared to 38 of 271 (14%) placebo-treated migraines (percentage difference = 68 percentage points; 95% CI, 62-74 percentage points; P < .001). The mean pain score at the onset of migraine attacks was 6.01 for those treated with timolol and 5.93 for those treated with placebo. Patients treated with timolol had a reduction in pain of 5.98 points, compared with 0.93 points after using placebo (difference = 5.05; 95% CI, 4.19-5.91). No attacks included in the data required oral rescue medications, and there were no systemic adverse effects from the timolol eyedrops.

WHAT’S NEW

Evidence of benefit as abortive therapy for acute migraine

This randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed evidence to support timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% vs placebo for treatment of acute migraine by significantly reducing pain when taken at the onset of an acute migraine attack.

CAVEATS

Single-center trial, measuring limited response time

The generalizability of this RCT is limited because it was a single-center trial with a study population from a single region in India. It is unknown whether pain relief, adverse effects, or adherence would differ for the global population. Additionally, only migraines with headache were included in the analysis, limiting non-headache migraine subgroup-directed treatment. Also, this trial evaluated only the response to treatment at 20 minutes, and it is unknown if pain response continued for several hours. Headaches that began more than 20 minutes after the onset of aura were not evaluated.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Timolol’s systemic adverse effects require caution

Systemic beta-blocker effects (eg, bradycardia, hypotension, drowsiness, and bronchospasm) from topical timolol have been reported. Caution should be used when prescribing timolol for patients with current cardiovascular and pulmonary conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

- Kurian A, Reghunadhan I, Thilak P, et al. Short-term efficacy and safety of topical β-blockers (timolol maleate ophthalmic solution, 0.5%) in acute migraine: a randomized crossover trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138:1160-1166. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.3676

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:743-800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4

- Yeh WZ, Blizzard L, Taylor BV. What is the actual prevalence of migraine? Brain Behav. 2018;8:e00950. doi: 10.1002/brb3.950

- Leonardi M, Raggi A. Burden of migraine: international perspectives. Neurol Sci. 2013;34(suppl 1):S117-S118. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1387-8

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629-808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658

- Ubrogepant. GoodRx. Accessed May 23, 2022. www.goodrx.com/ubrogepant

- Orr SL, Friedman BW, Christie S, et al. Management of adults with acute migraine in the emergency department: the American Headache Society evidence assessment of parenteral pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2016;56:911-940. doi: 10.1111/head.12835

- 8. Migliazzo CV, Hagan JC III. Beta blocker eye drops for treatment of acute migraine. Mo Med. 2014;111:283-288.

- 9. Cossack M, Nabrinsky E, Turner H, et al. Timolol eyedrops in the treatment of acute migraine attacks: a randomized crossover study. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:1024-1025. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0970

- 10. Timolol. GoodRx. Accessed May 23, 2022. www.goodrx.com/timolol

- Kurian A, Reghunadhan I, Thilak P, et al. Short-term efficacy and safety of topical β-blockers (timolol maleate ophthalmic solution, 0.5%) in acute migraine: a randomized crossover trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138:1160-1166. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.3676

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:743-800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4

- Yeh WZ, Blizzard L, Taylor BV. What is the actual prevalence of migraine? Brain Behav. 2018;8:e00950. doi: 10.1002/brb3.950

- Leonardi M, Raggi A. Burden of migraine: international perspectives. Neurol Sci. 2013;34(suppl 1):S117-S118. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1387-8

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629-808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658

- Ubrogepant. GoodRx. Accessed May 23, 2022. www.goodrx.com/ubrogepant

- Orr SL, Friedman BW, Christie S, et al. Management of adults with acute migraine in the emergency department: the American Headache Society evidence assessment of parenteral pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2016;56:911-940. doi: 10.1111/head.12835

- 8. Migliazzo CV, Hagan JC III. Beta blocker eye drops for treatment of acute migraine. Mo Med. 2014;111:283-288.

- 9. Cossack M, Nabrinsky E, Turner H, et al. Timolol eyedrops in the treatment of acute migraine attacks: a randomized crossover study. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:1024-1025. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0970

- 10. Timolol. GoodRx. Accessed May 23, 2022. www.goodrx.com/timolol

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider timolol maleate 0.5% eyedrops as a quick and effective abortive therapy for migraine.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single randomized controlled trial.1

Kurian A, Reghunadhan I, Thilak P, et al. Short-term efficacy and safety of topical β-blockers (timolol maleate ophthalmic solution, 0.5%) in acute migraine: a randomized crossover trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138:1160-1166.

New—and surprising—ways to approach migraine pain

Migraine headaches pose a challenge for many patients and their physicians, so new, effective approaches are always welcome. Sometimes new treatments come as total surprises. For example, who would have guessed that timolol eyedrops could be effective for acute migraine?1 Granted, the results (discussed in this issue's PURLs) are from a single randomized trial, but they look very promising.

This is not the only new and innovative treatment for migraine. Everyone knows about the heavily marketed calcium gene-related peptide antagonists, which include monoclonal antibodies and the so-called “gepants.” The monoclonal antibodies and atogepant are approved for migraine prevention, and they do a decent job (although at a high price). In randomized trials, these agents reduced migraine days per month by an average of about 1.5 to 2.5 days compared to placebo.2-5

Ubrogepant and rimegepant are approved for acute migraine treatment. In clinical trials, about 20% of patients taking ubrogepant or rimegepant were pain free at 2 hours post dose, compared to 12% to 14% taking placebo.6,7 Unfortunately, that means 80% of patients still have some pain at 2 hours. By comparison, zolmitriptan performs a bit better, with 34% of patients pain free at 2 hours.8 However, for those who can’t tolerate zolmitriptan, these newer options provide an alternative.

We also now have nonpharmacologic options. The caloric vestibular stimulation device is essentially a headset with ear probes that change temperature, alternating warm and cold. In a randomized controlled trial, it reduced monthly migraine days by 1.1 compared to placebo, from a baseline of 7.7 to 3.9 days.9 It can also be used to treat acute migraine. There is also a vagus nerve–stimulating device that reduced migraine headache severity by 20% on average in 32.2% of patients in 30 minutes. Sham treatment was as effective for 18.5% of patients, giving a number needed to treat of 6 compared to sham.10

And finally, there are complementary and alternative medicine options. Two recent randomized trials demonstrated that ≥ 2000 IU/d of vitamin D reduced monthly migraine days an average of 2 days, which is comparable to the effectiveness of the calcium gene-related peptide antagonists at a fraction of the cost.11,12 In another randomized trial, intranasal 1.5% peppermint oil was as effective as topical 4% lidocaine in providing substantial pain relief for acute migraine; about 42% of patients achieved significant relief with either treatment.13

While we may not have a perfect treatment for our patients with migraine headache, we certainly have many options to choose from.

1. Ge Y, Castelli G. Migraine relief in 20 minutes using eyedrops? J Fam Pract. 2022;71:222-223, 226.

2. Loder E, Renthal W. Calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody treatments for migraine. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:421-422. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7536

3. Silberstein S, Diamond M, Hindiyeh NA, et al. Eptinezumab for the prevention of chronic migraine: efficacy and safety through 24 weeks of treatment in the phase 3 PROMISE-2 (Prevention of migraine via intravenous ALD403 safety and efficacy-2) study. J Headache Pain. 2020;21:120. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01186-3

4. Ament M, Day K, Stauffer VL, et al. Effect of galcanezumab on severity and symptoms of migraine in phase 3 trials in patients with episodic or chronic migraine. J Headache Pain. 2021;22:6. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01215-9

5. Goadsby PJ, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of orally administered atogepant for the prevention of episodic migraine in adults: a double-blind, randomised phase 2b/3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:727-737. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30234-9

6. Lipton RB, Croop R, Stock EG, et al. Rimegepant, an oral calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist, for migraine. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:142-149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811090

7. Lipton RB, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Effect of ubrogepant vs placebo on pain and the most bothersome associated symptom in the acute treatment of migraine: the ACHIEVE II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:1887-1898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16711

8. Bird S, Derry S, Moore R. Zolmitriptan for acute migraine attacks in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD008616. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008616.pub2

9. Wilkinson D, Ade KK, Rogers LL, et al. Preventing episodic migraine with caloric vestibular stimulation: a randomized controlled trial. Headache. 2017;57:1065-1087. doi: 10.1111/head.13120

10. Grazzi L, Tassorelli C, de Tommaso M, et al; PRESTO Study Group. Practical and clinical utility of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) for the acute treatment of migraine: a post hoc analysis of the randomized, sham-controlled, double-blind PRESTO trial. J Headache Pain. 2018;19:98. doi: 10.1186/s10194-018-0928-1

11. Gazerani P, Fuglsang R, Pedersen JG, et al. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel trial of vitamin D3 supplementation in adult patients with migraine. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35:715-723. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2018.1519503

12. Ghorbani Z, Togha M, Rafiee P, et al. Vitamin D3 might improve headache characteristics and protect against inflammation in migraine: a randomized clinical trial. Neurol Sci. 2020;41:1183-1192. doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-04220-8

13. Rafieian-Kopaei M, Hasanpour-Dehkordi A, Lorigooini Z, et al. Comparing the effect of intranasal lidocaine 4% with peppermint essential oil drop 1.5% on migraine attacks: a double-blind clinical trial. Int J Prev Med. 2019;10:121. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_530_17

Migraine headaches pose a challenge for many patients and their physicians, so new, effective approaches are always welcome. Sometimes new treatments come as total surprises. For example, who would have guessed that timolol eyedrops could be effective for acute migraine?1 Granted, the results (discussed in this issue's PURLs) are from a single randomized trial, but they look very promising.

This is not the only new and innovative treatment for migraine. Everyone knows about the heavily marketed calcium gene-related peptide antagonists, which include monoclonal antibodies and the so-called “gepants.” The monoclonal antibodies and atogepant are approved for migraine prevention, and they do a decent job (although at a high price). In randomized trials, these agents reduced migraine days per month by an average of about 1.5 to 2.5 days compared to placebo.2-5

Ubrogepant and rimegepant are approved for acute migraine treatment. In clinical trials, about 20% of patients taking ubrogepant or rimegepant were pain free at 2 hours post dose, compared to 12% to 14% taking placebo.6,7 Unfortunately, that means 80% of patients still have some pain at 2 hours. By comparison, zolmitriptan performs a bit better, with 34% of patients pain free at 2 hours.8 However, for those who can’t tolerate zolmitriptan, these newer options provide an alternative.

We also now have nonpharmacologic options. The caloric vestibular stimulation device is essentially a headset with ear probes that change temperature, alternating warm and cold. In a randomized controlled trial, it reduced monthly migraine days by 1.1 compared to placebo, from a baseline of 7.7 to 3.9 days.9 It can also be used to treat acute migraine. There is also a vagus nerve–stimulating device that reduced migraine headache severity by 20% on average in 32.2% of patients in 30 minutes. Sham treatment was as effective for 18.5% of patients, giving a number needed to treat of 6 compared to sham.10

And finally, there are complementary and alternative medicine options. Two recent randomized trials demonstrated that ≥ 2000 IU/d of vitamin D reduced monthly migraine days an average of 2 days, which is comparable to the effectiveness of the calcium gene-related peptide antagonists at a fraction of the cost.11,12 In another randomized trial, intranasal 1.5% peppermint oil was as effective as topical 4% lidocaine in providing substantial pain relief for acute migraine; about 42% of patients achieved significant relief with either treatment.13

While we may not have a perfect treatment for our patients with migraine headache, we certainly have many options to choose from.

Migraine headaches pose a challenge for many patients and their physicians, so new, effective approaches are always welcome. Sometimes new treatments come as total surprises. For example, who would have guessed that timolol eyedrops could be effective for acute migraine?1 Granted, the results (discussed in this issue's PURLs) are from a single randomized trial, but they look very promising.

This is not the only new and innovative treatment for migraine. Everyone knows about the heavily marketed calcium gene-related peptide antagonists, which include monoclonal antibodies and the so-called “gepants.” The monoclonal antibodies and atogepant are approved for migraine prevention, and they do a decent job (although at a high price). In randomized trials, these agents reduced migraine days per month by an average of about 1.5 to 2.5 days compared to placebo.2-5

Ubrogepant and rimegepant are approved for acute migraine treatment. In clinical trials, about 20% of patients taking ubrogepant or rimegepant were pain free at 2 hours post dose, compared to 12% to 14% taking placebo.6,7 Unfortunately, that means 80% of patients still have some pain at 2 hours. By comparison, zolmitriptan performs a bit better, with 34% of patients pain free at 2 hours.8 However, for those who can’t tolerate zolmitriptan, these newer options provide an alternative.

We also now have nonpharmacologic options. The caloric vestibular stimulation device is essentially a headset with ear probes that change temperature, alternating warm and cold. In a randomized controlled trial, it reduced monthly migraine days by 1.1 compared to placebo, from a baseline of 7.7 to 3.9 days.9 It can also be used to treat acute migraine. There is also a vagus nerve–stimulating device that reduced migraine headache severity by 20% on average in 32.2% of patients in 30 minutes. Sham treatment was as effective for 18.5% of patients, giving a number needed to treat of 6 compared to sham.10

And finally, there are complementary and alternative medicine options. Two recent randomized trials demonstrated that ≥ 2000 IU/d of vitamin D reduced monthly migraine days an average of 2 days, which is comparable to the effectiveness of the calcium gene-related peptide antagonists at a fraction of the cost.11,12 In another randomized trial, intranasal 1.5% peppermint oil was as effective as topical 4% lidocaine in providing substantial pain relief for acute migraine; about 42% of patients achieved significant relief with either treatment.13

While we may not have a perfect treatment for our patients with migraine headache, we certainly have many options to choose from.

1. Ge Y, Castelli G. Migraine relief in 20 minutes using eyedrops? J Fam Pract. 2022;71:222-223, 226.

2. Loder E, Renthal W. Calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody treatments for migraine. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:421-422. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7536

3. Silberstein S, Diamond M, Hindiyeh NA, et al. Eptinezumab for the prevention of chronic migraine: efficacy and safety through 24 weeks of treatment in the phase 3 PROMISE-2 (Prevention of migraine via intravenous ALD403 safety and efficacy-2) study. J Headache Pain. 2020;21:120. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01186-3

4. Ament M, Day K, Stauffer VL, et al. Effect of galcanezumab on severity and symptoms of migraine in phase 3 trials in patients with episodic or chronic migraine. J Headache Pain. 2021;22:6. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01215-9

5. Goadsby PJ, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of orally administered atogepant for the prevention of episodic migraine in adults: a double-blind, randomised phase 2b/3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:727-737. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30234-9

6. Lipton RB, Croop R, Stock EG, et al. Rimegepant, an oral calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist, for migraine. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:142-149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811090

7. Lipton RB, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Effect of ubrogepant vs placebo on pain and the most bothersome associated symptom in the acute treatment of migraine: the ACHIEVE II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:1887-1898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16711

8. Bird S, Derry S, Moore R. Zolmitriptan for acute migraine attacks in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD008616. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008616.pub2

9. Wilkinson D, Ade KK, Rogers LL, et al. Preventing episodic migraine with caloric vestibular stimulation: a randomized controlled trial. Headache. 2017;57:1065-1087. doi: 10.1111/head.13120

10. Grazzi L, Tassorelli C, de Tommaso M, et al; PRESTO Study Group. Practical and clinical utility of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) for the acute treatment of migraine: a post hoc analysis of the randomized, sham-controlled, double-blind PRESTO trial. J Headache Pain. 2018;19:98. doi: 10.1186/s10194-018-0928-1

11. Gazerani P, Fuglsang R, Pedersen JG, et al. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel trial of vitamin D3 supplementation in adult patients with migraine. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35:715-723. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2018.1519503

12. Ghorbani Z, Togha M, Rafiee P, et al. Vitamin D3 might improve headache characteristics and protect against inflammation in migraine: a randomized clinical trial. Neurol Sci. 2020;41:1183-1192. doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-04220-8

13. Rafieian-Kopaei M, Hasanpour-Dehkordi A, Lorigooini Z, et al. Comparing the effect of intranasal lidocaine 4% with peppermint essential oil drop 1.5% on migraine attacks: a double-blind clinical trial. Int J Prev Med. 2019;10:121. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_530_17

1. Ge Y, Castelli G. Migraine relief in 20 minutes using eyedrops? J Fam Pract. 2022;71:222-223, 226.

2. Loder E, Renthal W. Calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibody treatments for migraine. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:421-422. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7536

3. Silberstein S, Diamond M, Hindiyeh NA, et al. Eptinezumab for the prevention of chronic migraine: efficacy and safety through 24 weeks of treatment in the phase 3 PROMISE-2 (Prevention of migraine via intravenous ALD403 safety and efficacy-2) study. J Headache Pain. 2020;21:120. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01186-3

4. Ament M, Day K, Stauffer VL, et al. Effect of galcanezumab on severity and symptoms of migraine in phase 3 trials in patients with episodic or chronic migraine. J Headache Pain. 2021;22:6. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01215-9

5. Goadsby PJ, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of orally administered atogepant for the prevention of episodic migraine in adults: a double-blind, randomised phase 2b/3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:727-737. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30234-9

6. Lipton RB, Croop R, Stock EG, et al. Rimegepant, an oral calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist, for migraine. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:142-149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811090

7. Lipton RB, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Effect of ubrogepant vs placebo on pain and the most bothersome associated symptom in the acute treatment of migraine: the ACHIEVE II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:1887-1898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16711

8. Bird S, Derry S, Moore R. Zolmitriptan for acute migraine attacks in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD008616. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008616.pub2

9. Wilkinson D, Ade KK, Rogers LL, et al. Preventing episodic migraine with caloric vestibular stimulation: a randomized controlled trial. Headache. 2017;57:1065-1087. doi: 10.1111/head.13120

10. Grazzi L, Tassorelli C, de Tommaso M, et al; PRESTO Study Group. Practical and clinical utility of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) for the acute treatment of migraine: a post hoc analysis of the randomized, sham-controlled, double-blind PRESTO trial. J Headache Pain. 2018;19:98. doi: 10.1186/s10194-018-0928-1

11. Gazerani P, Fuglsang R, Pedersen JG, et al. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel trial of vitamin D3 supplementation in adult patients with migraine. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35:715-723. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2018.1519503

12. Ghorbani Z, Togha M, Rafiee P, et al. Vitamin D3 might improve headache characteristics and protect against inflammation in migraine: a randomized clinical trial. Neurol Sci. 2020;41:1183-1192. doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-04220-8

13. Rafieian-Kopaei M, Hasanpour-Dehkordi A, Lorigooini Z, et al. Comparing the effect of intranasal lidocaine 4% with peppermint essential oil drop 1.5% on migraine attacks: a double-blind clinical trial. Int J Prev Med. 2019;10:121. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_530_17

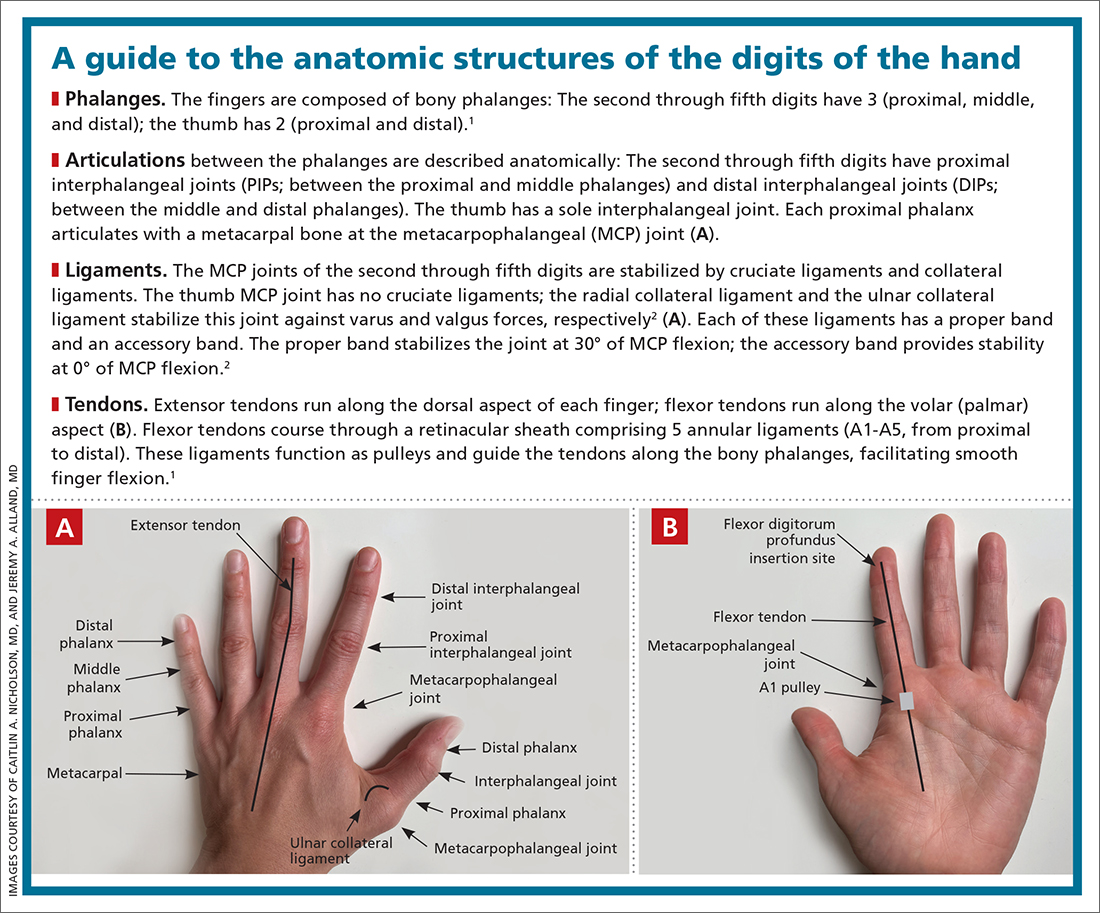

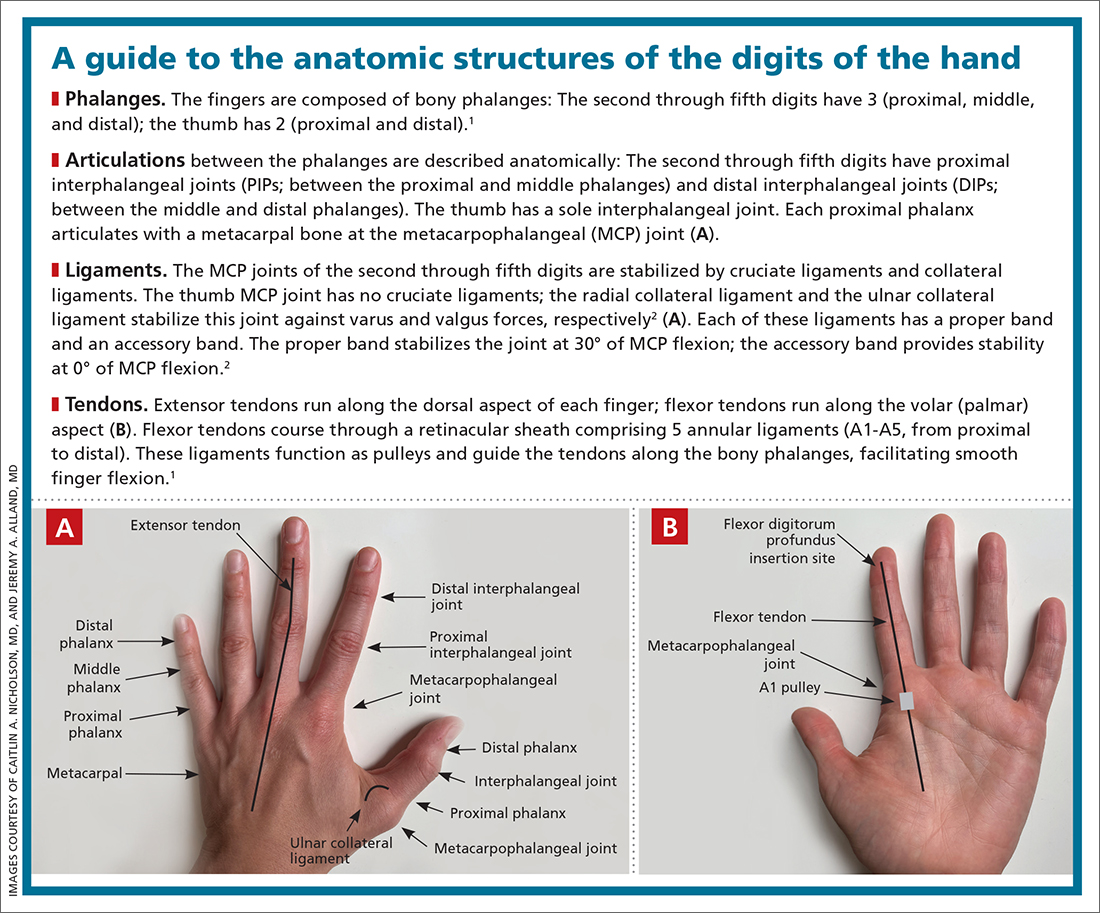

Tips for managing 4 common soft-tissue finger and thumb injuries

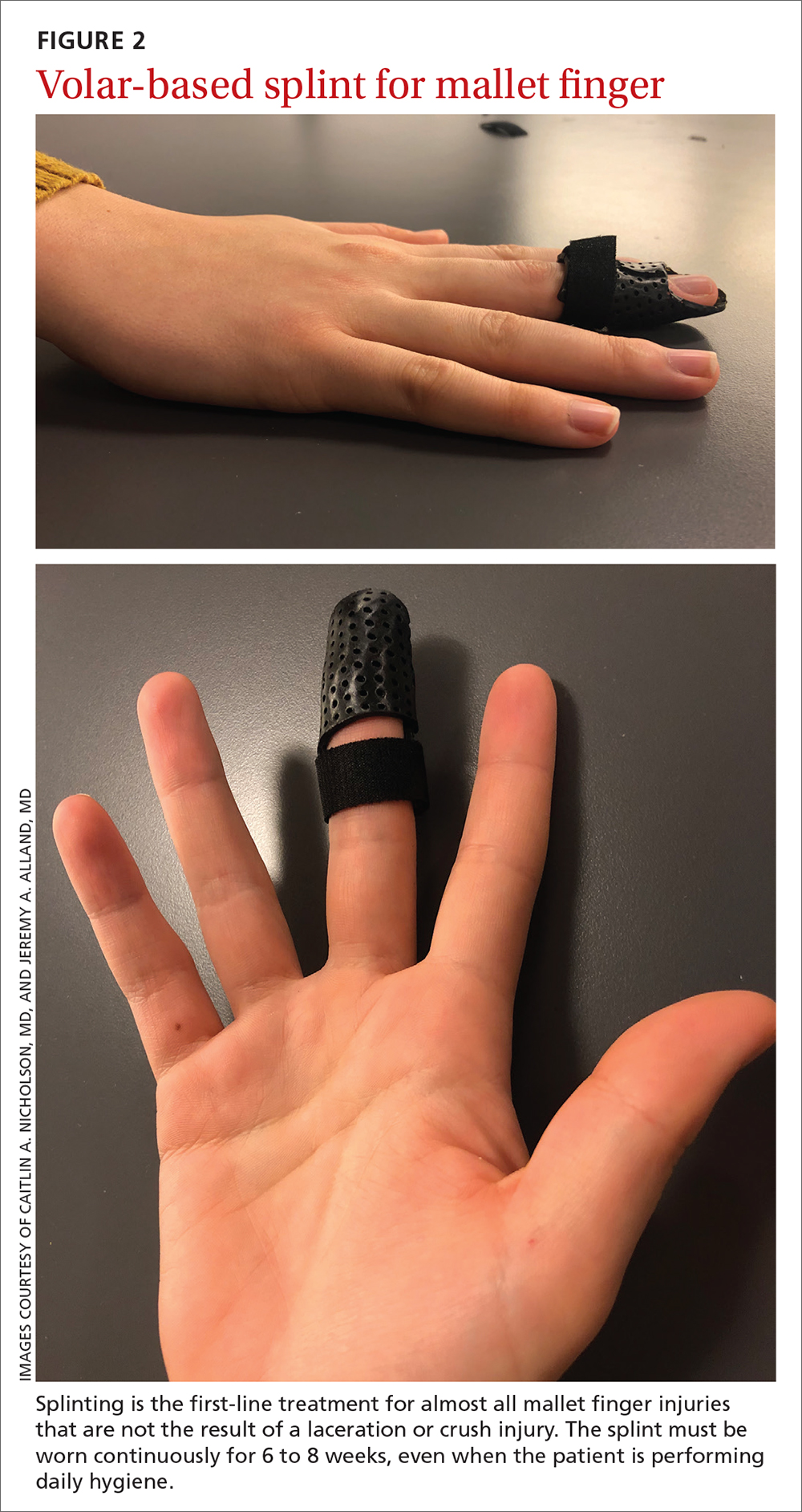

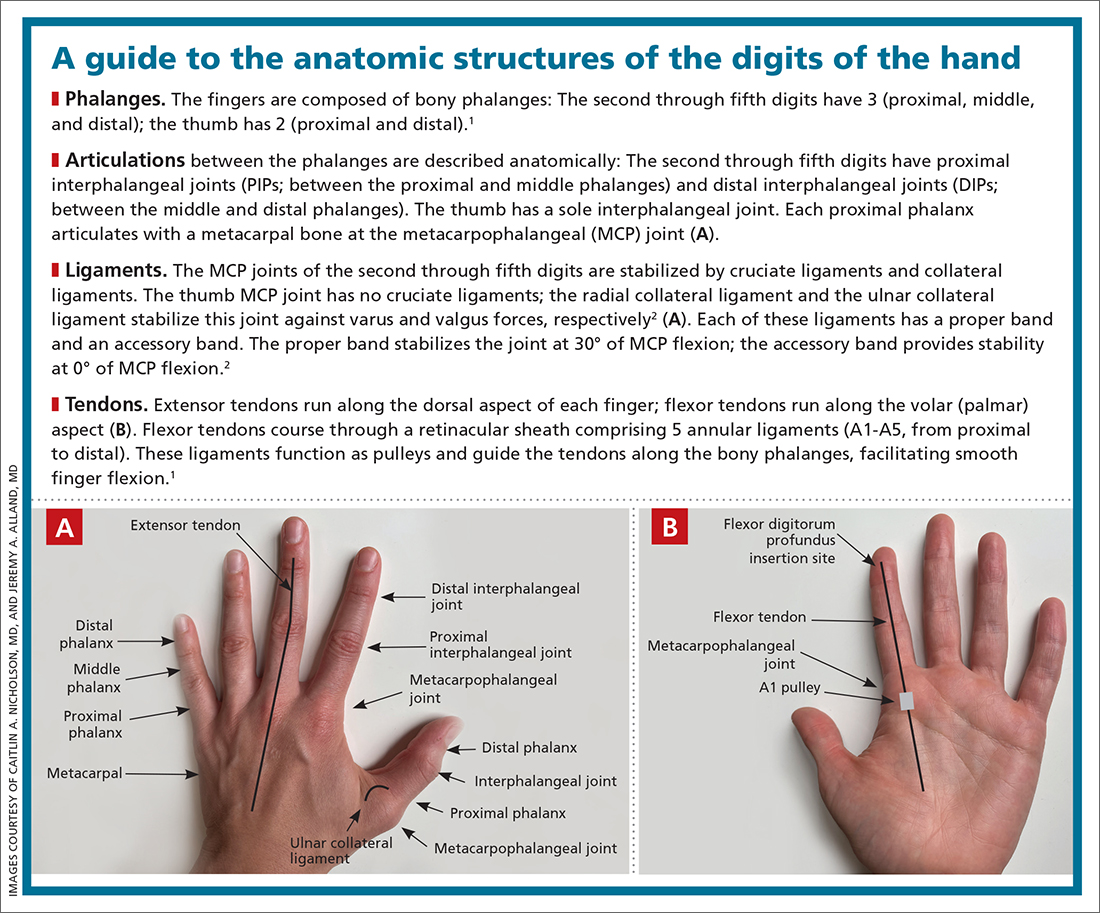

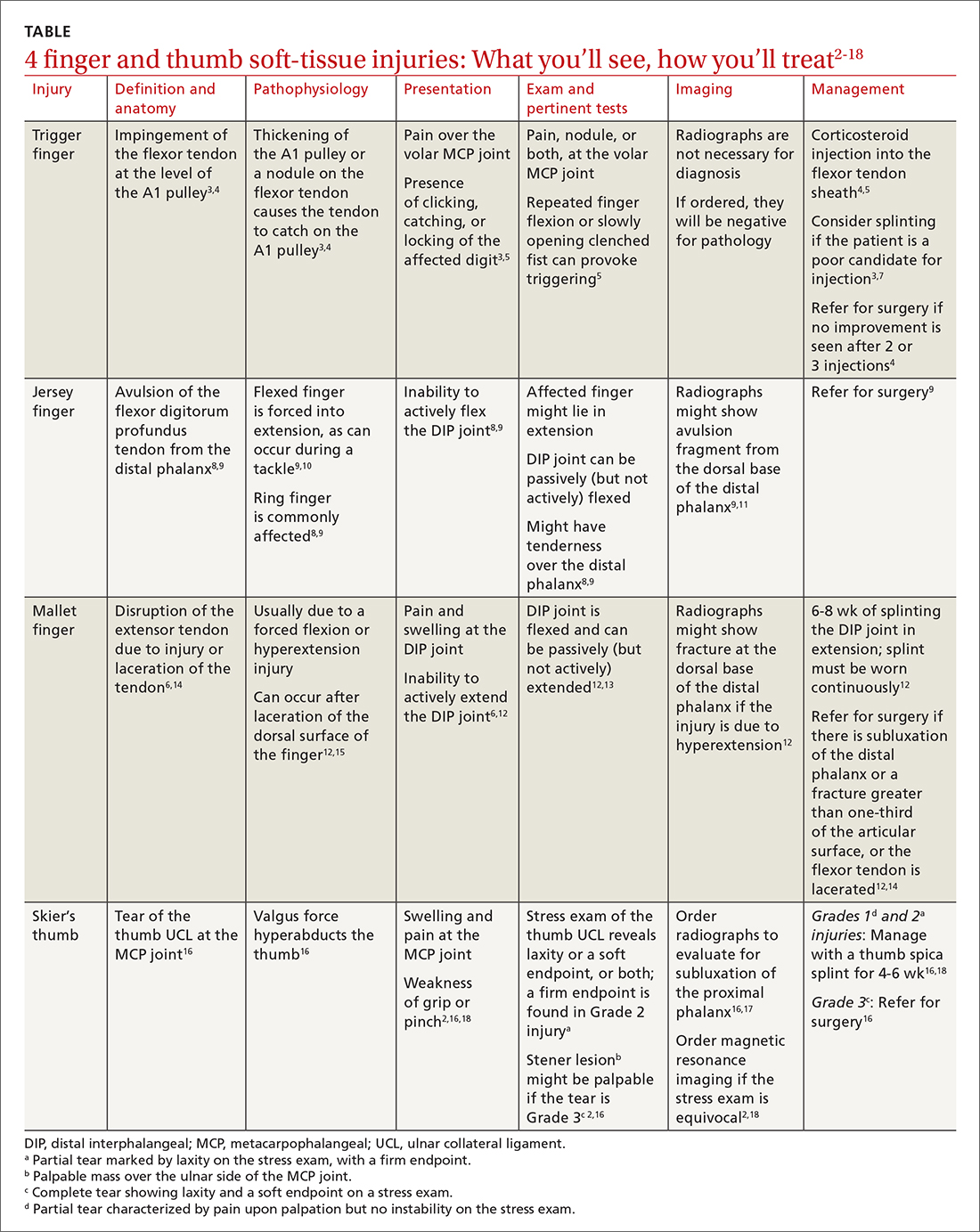

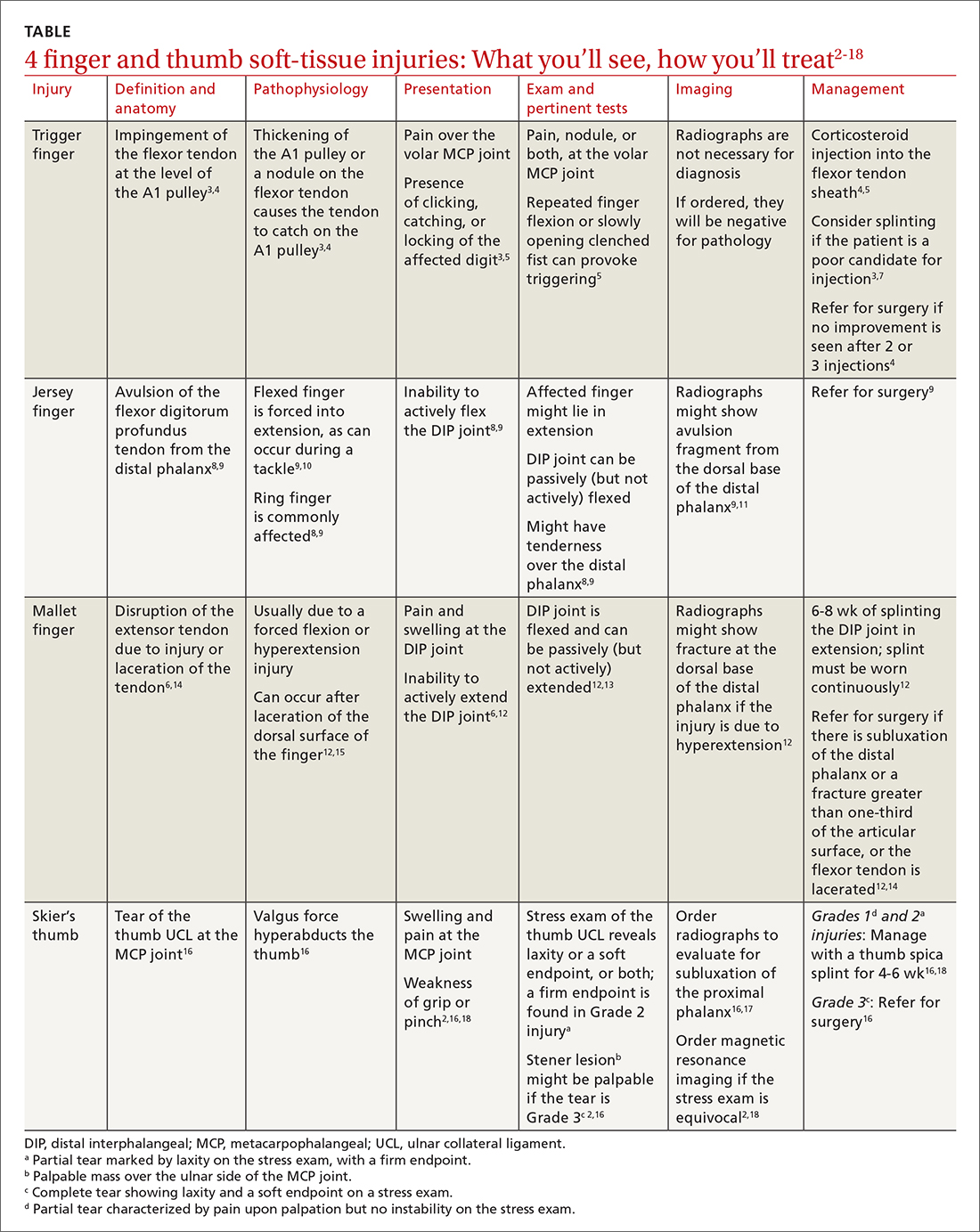

Finger injuries are often seen in the primary care physician’s office. The evidence—and our experience in sports medicine—indicates that many of these injuries can be managed conservatively with bracing or injection; a subset, however, requires surgical referral. In this article, we provide a refresher on finger anatomy (see “A guide to the anatomic structures of the digits of the hand”1,2) and review the diagnosis and management of 4 common soft-tissue finger and thumb injuries in adults: trigger finger, jersey finger, mallet finger, and skier’s thumb (TABLE2-18).

Trigger finger

Also called stenosing flexor tenosynovitis, trigger finger is caused by abnormal flexor tendon movement that results from impingement at the level of the A1 pulley.

Causes and incidence. Impingement usually occurs because of thickening of the A1 pulley but can also be caused by inflammation or a nodule on the flexor tendon.3,4 The A1 pulley at the metacarpal head is the most proximal part of the retinacular sheath and therefore experiences the greatest force upon finger flexion, making it the most common site of inflammation and constriction.4

Trigger finger occurs in 2% to 3% of the general population and in as many as 10% of people with diabetes.5 The condition typically affects the long and ring fingers of the dominant hand; most cases occur in women in the sixth and seventh decades.3-5

Multiple systemic conditions predispose to trigger finger, including endocrine disorders (eg, diabetes, hypothyroidism), inflammatory arthropathies (gout, pseudogout), and autoimmune disorders (rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis).3,5 Diabetes commonly causes bilateral hand and multiple digit involvement, as well as more severe disease.3,5 Occupation is also a risk factor for trigger finger because repetitive movements and manual work can exacerbate triggering.4

Presentation and exam. Patients report pain at the metacarpal head or metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint, difficulty grasping objects, and, possibly, clicking and catching of the digit and locking of the digit in flexion.3,5

On exam, there might be tenderness at the level of the A1 pulley over the volar MCP joint or a palpable nodule. In severe cases, the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint or entire finger can be fixed in flexion.5 Repeated compound finger flexion (eg, closing and opening a fist) or holding a fist for as long as 1 minute and then slowly opening it might provoke triggering.

More than 60% of patients with trigger finger also have carpal tunnel syndrome.5 This makes it important to assess for (1) sensory changes in the distribution of the median nerve and (2) nerve compression, by eliciting Phalen and Tinel signs.4,5

Continue to: Imaging

Imaging. Trigger finger is a clinical diagnosis. Imaging is therefore unnecessary for diagnosis or treatment.5

Treatment. Trigger finger resolves spontaneously in 52% of cases.3 Most patients experience relief in 8 to 12 months.3

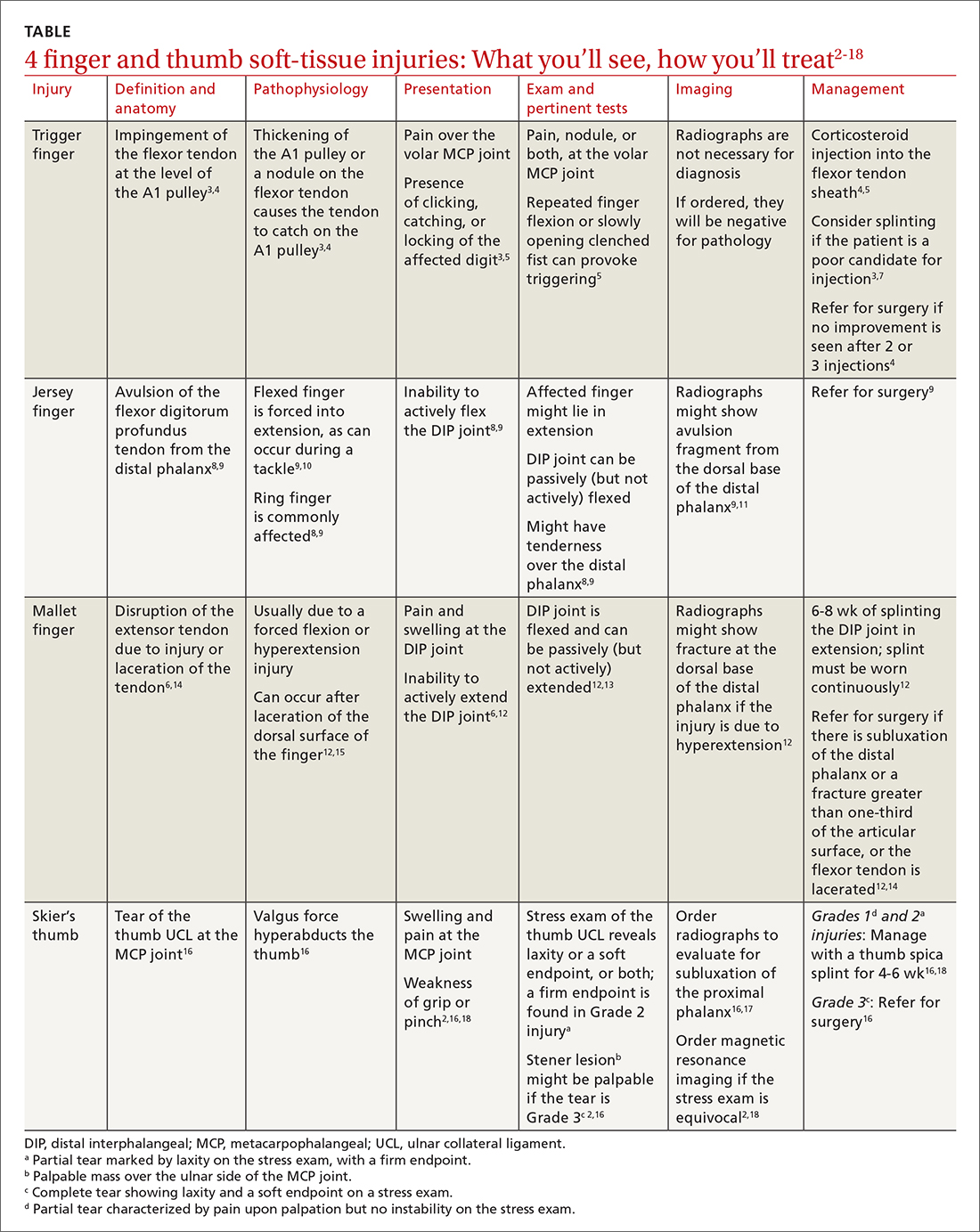

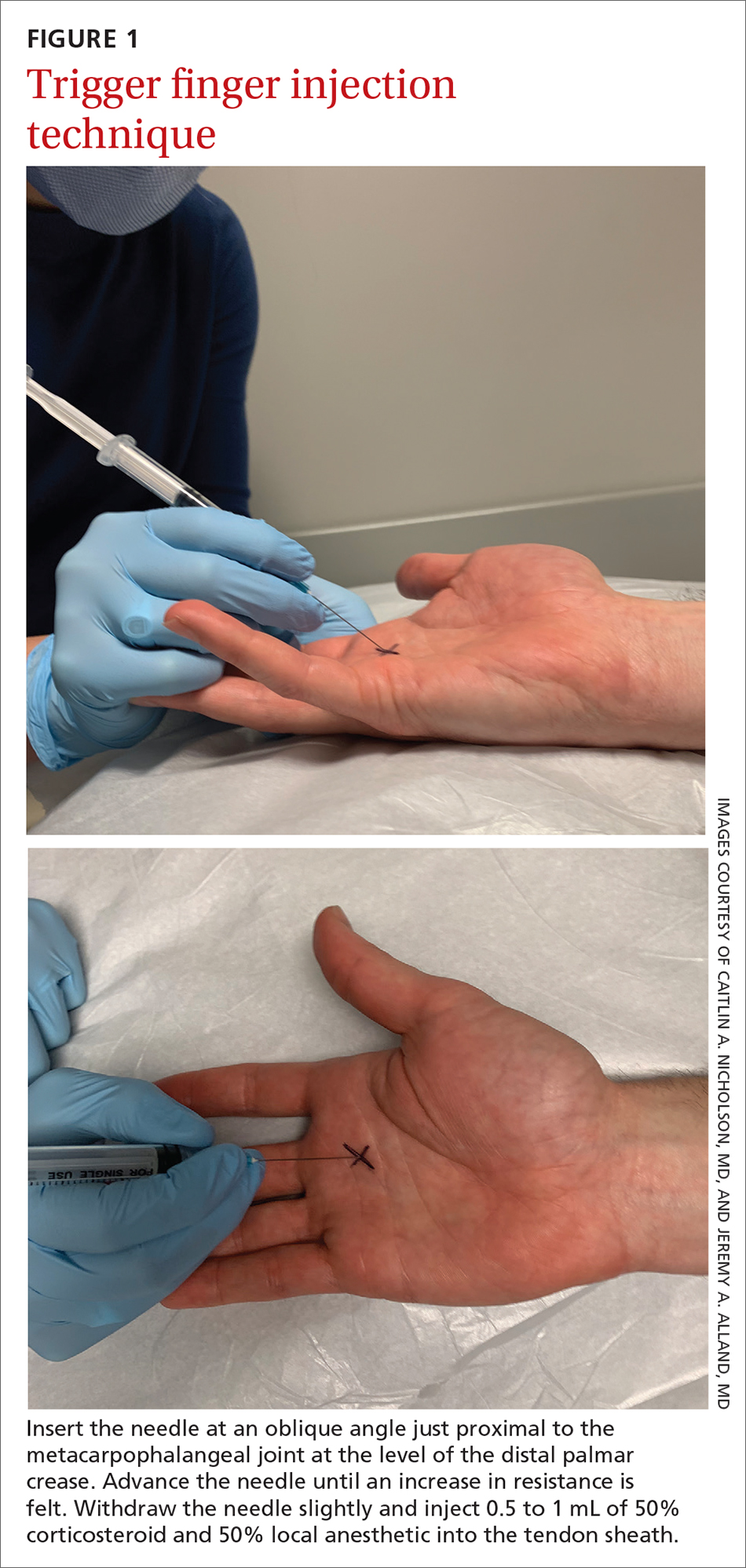

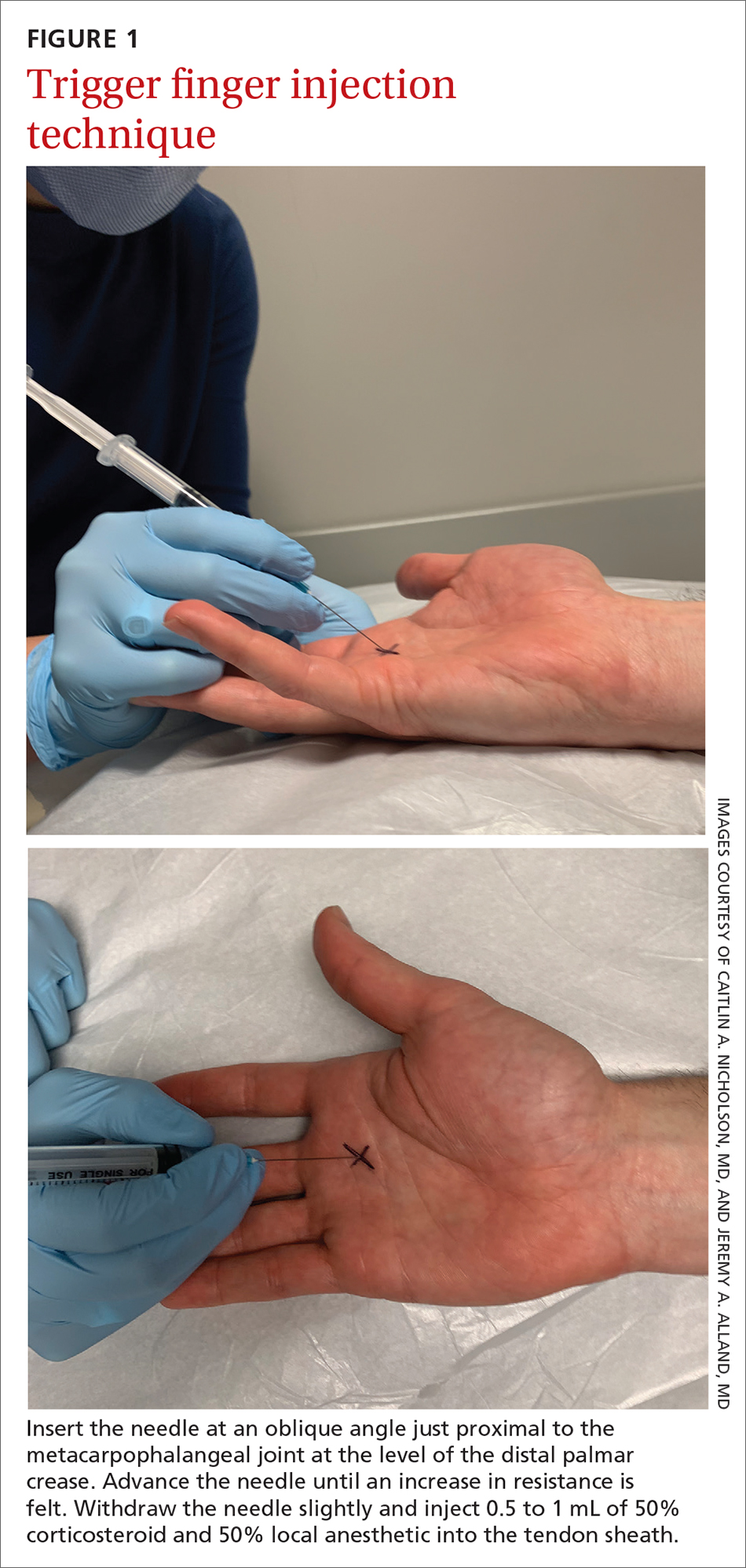

First-line treatment is injection of a corticosteroid into the flexor tendon sheath, which often alleviates symptoms.4,5 Injection is performed at the level of the A1 pulley on the palmar surface, just proximal to the MCP joint at the level of the distal palmar crease6 (FIGURE 1). The needle is inserted at an oblique angle until there is an increase in resistance. The needle is then slightly withdrawn to reposition it in the tendon sheath; 0.5 to 1 mL of 50% corticosteroid and 50% local anesthetic without epinephrine is then injected.6

The cure rate of trigger finger is 57% to 70% with 1 injection and 82% to 86% after 2 injections.3,4,19

Many patients experience symptom relief in 1 to 4 weeks after a corticosteroid injection; however, as many as 56% experience repeat triggering within 6 months—often making multiple injections (maximum, 3 per digit) necessary.19,20 Patients who have a longer duration of symptoms, more severe symptoms, and multiple trigger fingers are less likely to experience relief with injections.3,5

Continue to: Splinting is an effective treatment...

Splinting is an effective treatment for patients who cannot undergo corticosteroid injection or surgery. The MCP or PIP joint is immobilized in extension while movement of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint is maintained. Instruct the patient that the splint must be worn day and night; splinting is continued for ≥ 6 weeks.21 Splinting relieves symptoms in 47% to 70% of cases and is most effective in patients whose symptoms have been present for < 6 months.3,7

Patients whose trigger finger is locked in flexion and those who have not experienced improvement after 2 or 3 corticosteroid injections should be referred for surgery.4 The surgical cure rate is nearly 100%; only 6% of patients experience repeat triggering 6 to 12 months postoperatively.4,7,22

Jersey finger

Causes and incidence. Jersey finger is caused by avulsion injury to the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendon at its insertion on the distal phalanx.8,9 It occurs when a flexed finger is forced into extension, such as when a football or rugby player grabs another player’s jersey during a tackle.9,10 This action causes the FDP tendon to detach from the distal phalanx, sometimes with a bony fragment.9,11 Once detached, the tendon might retract proximally within the finger or to the palm, with consequent loss of its blood supply.9

Although jersey finger is not as common as the other conditions discussed in this article,9 it is important not to miss this diagnosis because of the risk of chronic disability when it is not treated promptly. Seventy-five percent of cases occur in the ring finger, which is more susceptible to injury because it extends past the other digits in a power grip.8,9

Presentation and exam. On exam, the affected finger lies in slight extension compared to the other digits; the patient is unable to actively flex the DIP joint.8,9 There may be tenderness to palpation over the volar distal phalanx. The retracted FDP tendon might be palpable more proximally in the digit.

Continue to: Imaging

Imaging. Anteroposterior (AP), oblique, and lateral radiographs, although unnecessary for diagnosis, are recommended to assess for an avulsion fragment, associated fracture, or dislocation.9,11 Ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging is useful in chronic cases to quantify the degree of tendon retraction.9

Treatment. Refer acute cases of jersey finger for surgical management urgently because most cases require flexor tendon repair within 1 or 2 weeks for a successful outcome.9 Chronic jersey finger, in which injury occurred > 6 weeks before presentation, also requires surgical repair, although not as urgently.9

Complications of jersey finger include flexion contracture at the DIP joint and the so-called quadriga effect, in which the patient is unable to fully flex the fingers adjacent to the injured digit.8 These complications can cause chronic disability in the affected hand, making early diagnosis and referral key to successful treatment.9

Mallet finger

Also called drop finger, mallet finger is a result of loss of active extension at the DIP joint.12,13

Causes and incidence. Mallet finger is a relatively common injury that typically affects the long, ring, or small finger of the dominant hand in young to middle-aged men and older women.12,14,23 The condition is the result of forced flexion or hyperextension injury, which disrupts the extensor tendon.6,14

Continue to: Sudden forced flexion...

Sudden forced flexion of an extended DIP joint during work or sports (eg, catching a ball) is the most common mechanism of injury.12,15 This action causes stretching or tearing of the extensor tendon as well as a possible avulsion fracture of the distal phalanx.13 Mallet finger can also result from a laceration or crush injury of the extensor tendon (open mallet finger) or hyperextension of the DIP joint, causing a fracture at the dorsal base of the distal phalanx.12

Presentation. Through any of the aforementioned mechanisms, the delicate balance between the flexor and extensor tendons is disrupted, causing the patient to present with a flexed DIP joint that can be passively, but not actively, extended.6,12 The DIP joint might also be painful and swollen. Patients whose injury occurred > 4 weeks prior to presentation (chronic mallet finger) might also have a so-called swan-neck deformity, with hyperextension of the PIP joint in the affected finger.12

Imaging. AP, oblique, and lateral radiographs are recommended to assess for bony injury.

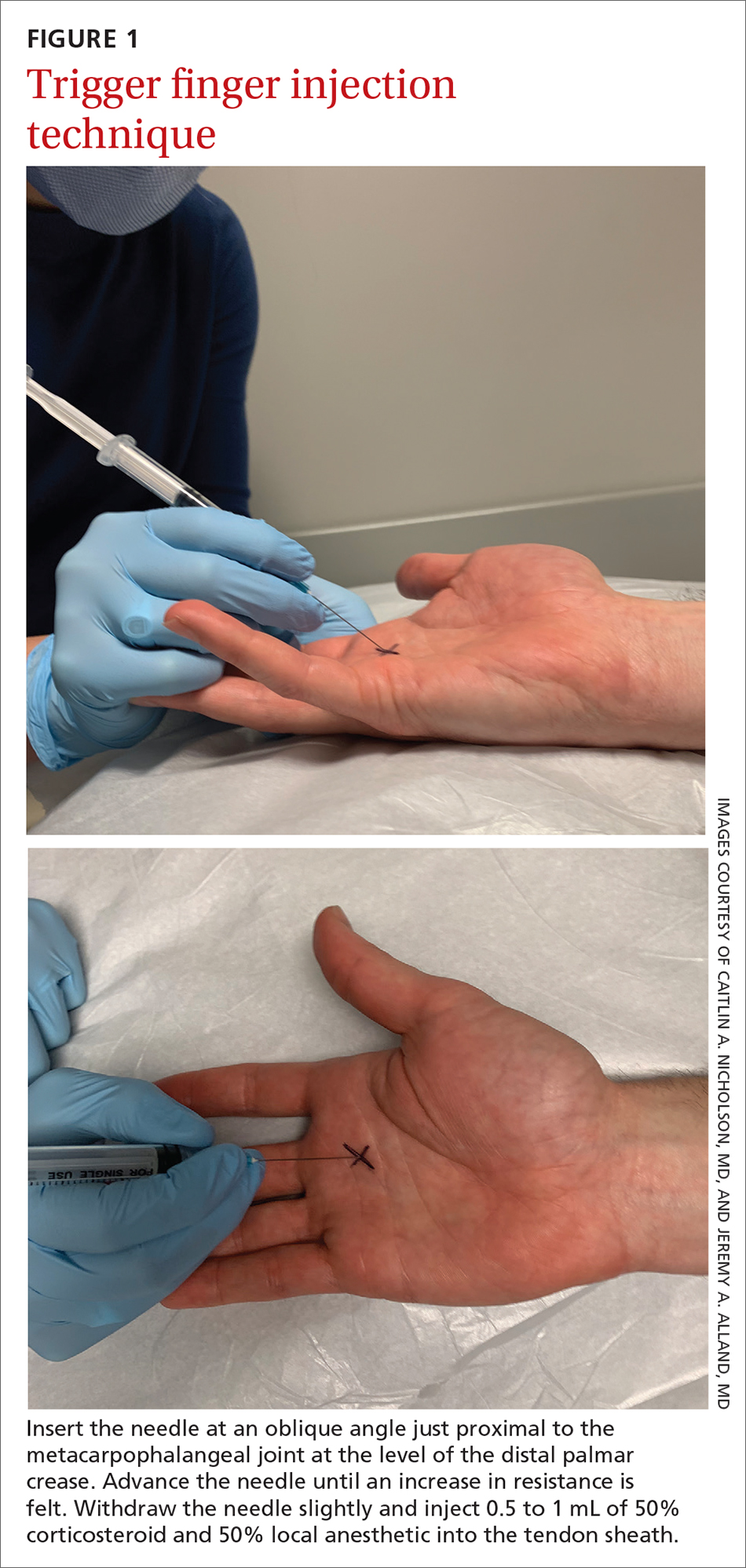

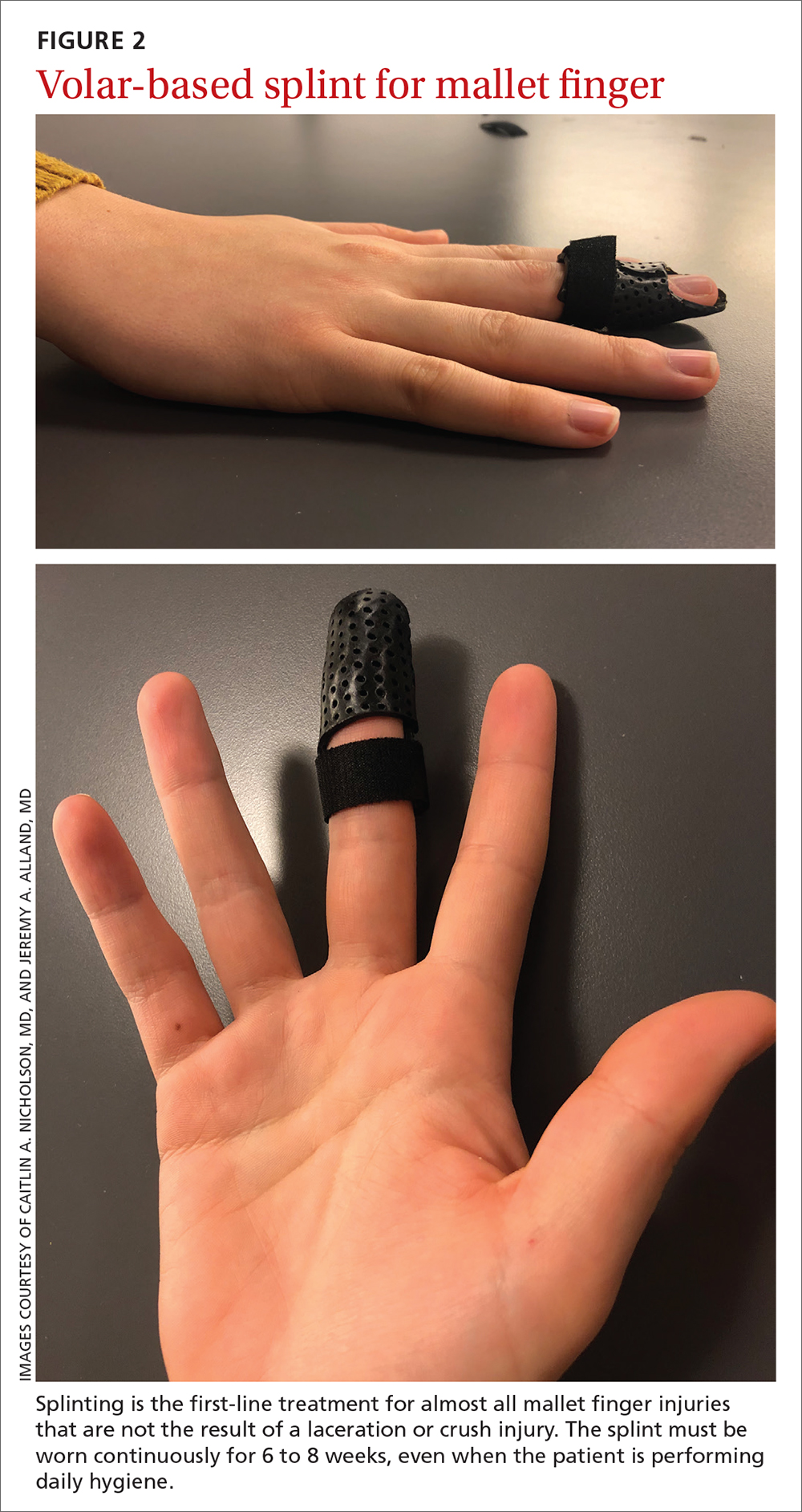

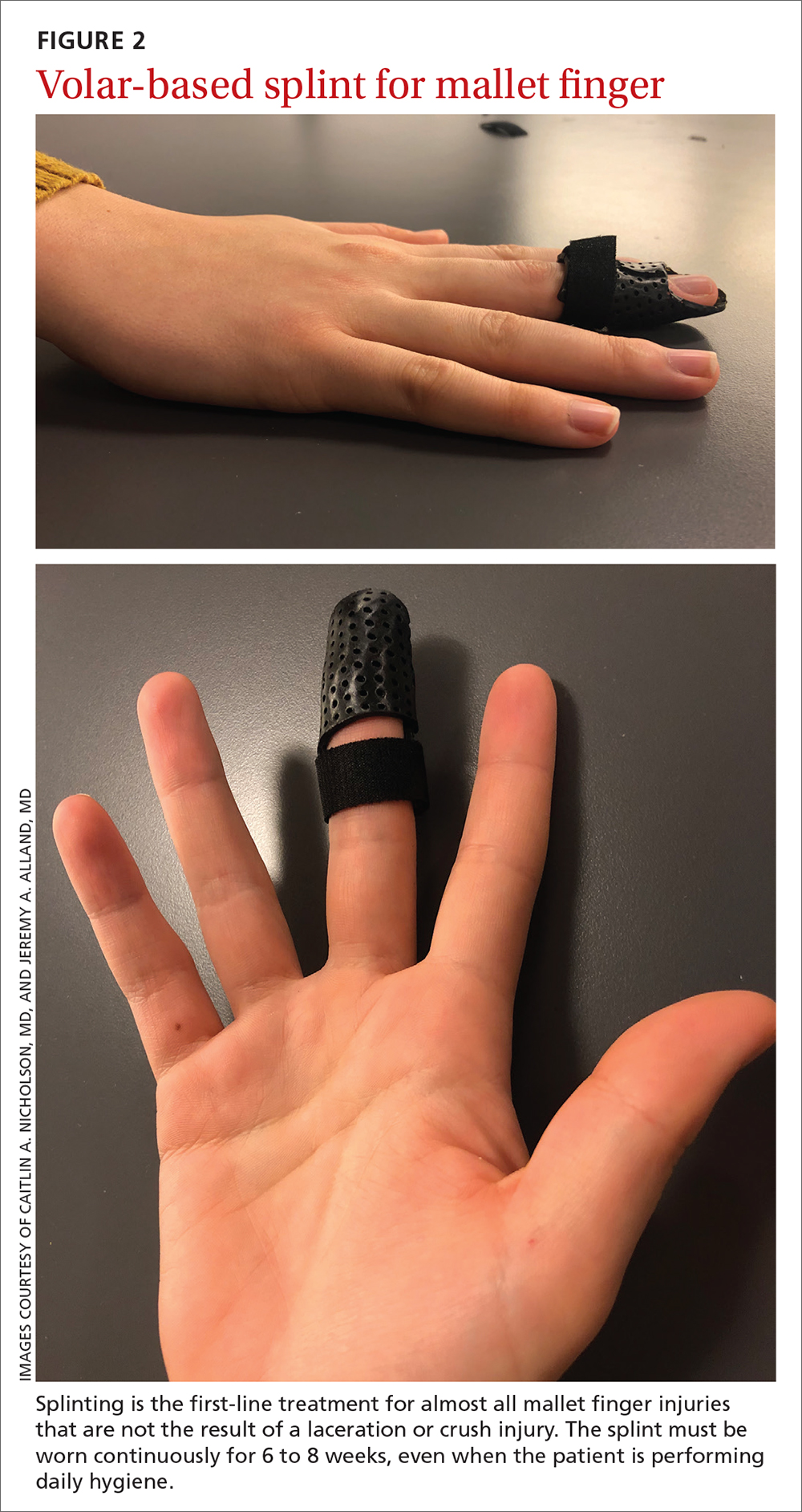

Treatment. Splinting is the first-line treatment for almost all mallet finger injuries that are not the result of a laceration or crush injury. Immobilize the DIP joint in extension for 6 to 8 weeks, with an additional 2 to 4 weeks of splinting at night.6,12 The splint must be worn continuously in the initial 6 to 8 weeks, and the DIP joint should remain in extension—even when the patient is performing daily hygiene.12 It is imperative that patients comply with that period of continuous immobilization; if the DIP joint is allowed to flex, the course of treatment must be restarted.13

Many different types of splints exist; functional outcomes are equivalent across all of them.24,25 In our practice, we manage mallet finger with a volar-based splint (FIGURE 2), which is associated with fewer dermatologic complications and has provided the most success for our patients.23

Continue to: Surgical repair of mallet finger injury...

Surgical repair of mallet finger injury is indicated in any of these situations12,14:

- injury is caused by laceration

- there is volar subluxation of the DIP joint

- more than one-third of the articular surface is involved in an avulsion fracture.

Patients who cannot comply with wearing a splint 24 hours per day or whose occupation precludes wearing a splint at all (eg, surgeons, dentists, musicians) are also surgical candidates.12

Surgical and conservative treatments have similar clinical and functional outcomes, including loss of approximately 5° to 7° of active extension and an increased risk of DIP joint osteoarthritis.12,14,24 Patients with chronic mallet finger can be managed with 6 weeks of splinting initially but will likely require surgery.6,12,13

Skier’s thumb

This relatively common injury is a tear of the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) at the MCP joint of the thumb.16

Causes and incidence. Skier’s thumb occurs when a valgus force hyperabducts the thumb,16 and is so named because the injury is often seen in recreational skiers who fall while holding a ski pole.15-17 It can also occur in racquet sports when a ball or racquet strikes the ulnar side of thumb.16

Continue to: In chronic cases...

In chronic cases, the UCL can be injured by occupational demands and is termed gamekeeper’s thumb because it was first described in this population, who killed game by breaking the animal's neck between the thumb and index finger against the ground.16,18 A UCL tear causes instability at the thumb MCP joint, which affects a person’s ability to grip and pinch.2,16,18

Presentation. On exam, the affected thumb is swollen and, possibly, bruised. There might be radial deviation and volar subluxation of the proximal phalanx. The ulnar side of the MCP joint is tender to palpation.16 If the distal UCL is torn completely, it can displace proximally and present as a palpable mass over the ulnar side of the MCP joint, known as a Stener lesion.16

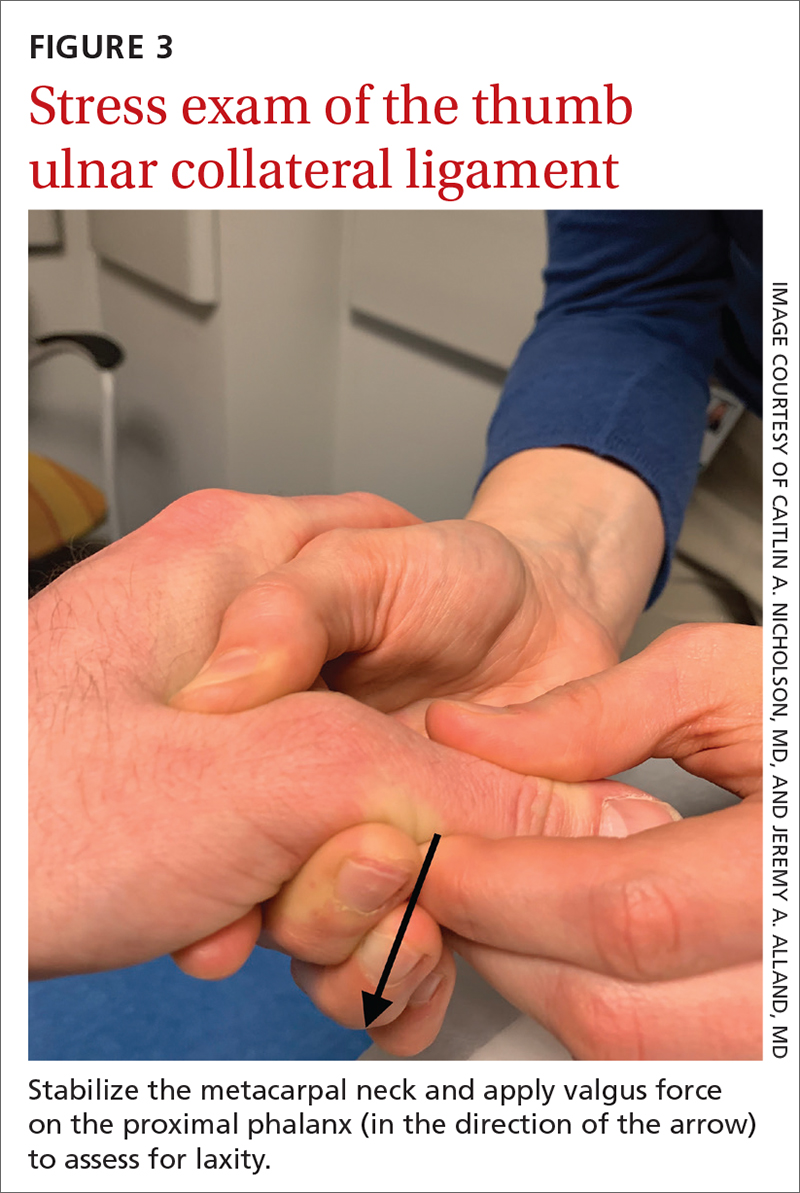

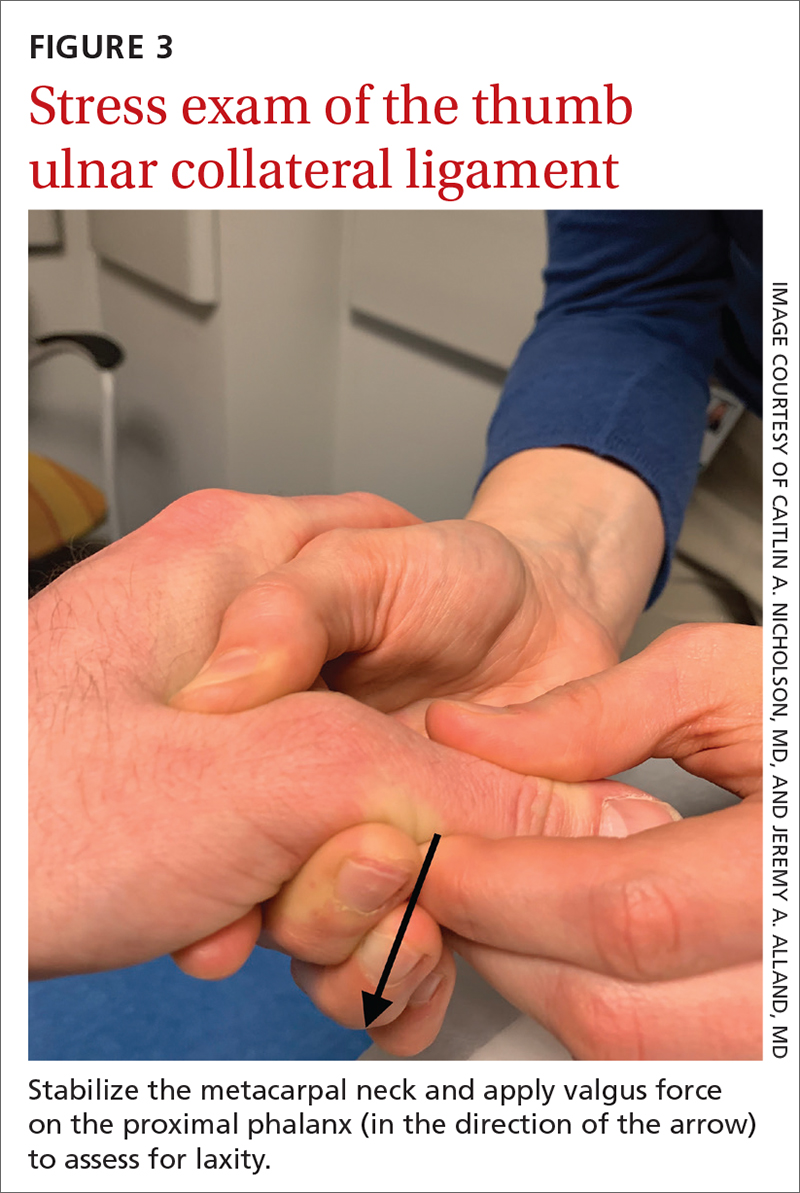

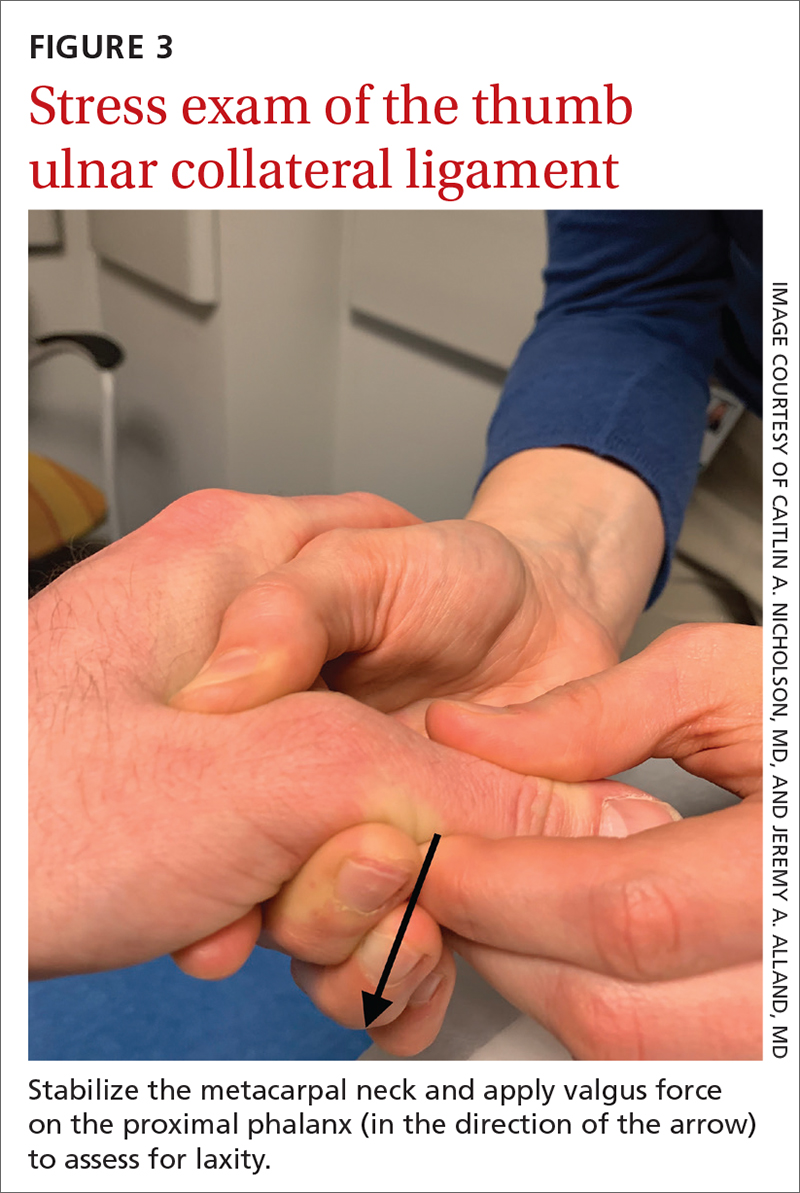

Stress testing of the MCP joint is the most important part of the physical exam for skier’s thumb. Stabilize the metacarpal neck and apply a valgus stress on the proximal phalanx at both 0° and 30° of MCP flexion (FIGURE 3), which allows for assessment of both the proper and accessory bands of the UCL.2,16 (A common pitfall during stress testing is to allow the MCP joint to rotate, which can mimic instability.2) Intra-articular local anesthesia might be necessary for this exam because it can be painful.16,18,26 A stress exam should assess for laxity and a soft or firm endpoint; the result should be compared to that of a stress exam on the contralateral side.16,17

Imaging. AP, oblique, and lateral radiographs of the thumb should be obtained to assess for instability, avulsion injury, and associated fracture. Subluxation (volar or radial) or supination of the proximal phalanx relative to the metacarpal on imaging suggests MCP instability of the MCP joint.16,17

If the stress exam is equivocal, magnetic resonance imaging is recommended for further assessment.2,18

Continue to: Stress radiographs...

Stress radiographs (ie, radiographs of the thumb with valgus stress applied at the MCP joint) can aid in diagnosis but are controversial. Some experts think that these stress views can further damage the UCL; others recommend against them because they carry a false-negative rate ≥ 25%.15,16 If you choose to perform stress views, order standard radiographs beforehand to rule out bony injury.17

Treatment. UCL tears are classified as 3 tiers to guide treatment.

- Grade 1 injury (a partial tear) is characterized by pain upon palpation but no instability on the stress exam.

- Grade 2 injury (also a partial tear) is marked by laxity on the stress exam with a firm endpoint.

- Grade 3 injury (complete tear) shows laxity and a soft endpoint on a stress exam16,17; Stener lesions are seen only in grade 3 tears.16,17

Grades 1 and 2 UCL tears without fracture or with a nondisplaced avulsion fracture can be managed nonoperatively by immobilizing the thumb in a spica splint or cast for 4 to 6 weeks.16,18 The MCP joint is immobilized and the interphalangeal joint is allowed to move freely.2,16,17

Grade 3 injuries should be referred to a hand specialist for surgical repair.16 Patients presenting > 12 weeks after acute injury or with a chronic UCL tear should also be referred for surgical repair.16

CORRESPONDENCE

Caitlin A. Nicholson, MD, 1611 West Harrison Street, Suite 300, Chicago, IL 60612; [email protected]

1. Hirt B, Seyhan H, Wagner M, et al. Hand and Wrist Anatomy and Biomechanics: A Comprehensive Guide. Thieme; 2017:57,58,71,72,75-80.

2. Daley D, Geary M, Gaston RG. Thumb metacarpophalangeal ulnar and radial collateral ligament injuries. Clin Sports Med. 2020;39:443-455. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2019.12.003

3. Gil JA, Hresko AM, Weiss AC. Current concepts in the management of trigger finger in adults. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28:e642-e650. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00614

4. Henton J, Jain A, Medhurst C, et al. Adult trigger finger. BMJ. 2012;345:e5743. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5743

5. Bates T, Dunn J. Trigger finger. Orthobullets [Internet]. Updated December 8, 2021. Accessed April 14, 2022. www.orthobullets.com/hand/6027/trigger-finger

6. Chhabra AB, Deal ND. Soft tissue injuries of the wrist and hand. In: O’Connor FG, Casa DJ, Davis BA, et al. ACSM’s Sports Medicine: A Comprehensive Review. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012:370-373.

7. Ballard TNS, Kozlow JH. Trigger finger in adults. CMAJ. 2016;188:61. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150225

8. Vitale M. Jersey finger. Orthobullets [Internet]. Updated May 22, 2021. 2019. Accessed April 15, 2022. www.orthobullets.com/hand/6015/jersey-finger

9. Shapiro LM, Kamal RN. Evaluation and treatment of flexor tendon and pulley injuries in athletes. Clin Sports Med. 2020;39:279-297. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2019.12.004

10. Goodson A, Morgan M, Rajeswaran G, et al. Current management of Jersey finger in rugby players: case series and literature review. Hand Surg. 2010;15:103-107. doi: 10.1142/S0218810410004710

11. Lapegue F, Andre A, Brun C, et al. Traumatic flexor tendon injuries. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015;96:1279-1292. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2015.09.010

12. Bendre AA, Hartigan BJ, Kalainov DM. Mallet finger. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:336-344. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200509000-00007

13. Lamaris GA, Matthew MK. The diagnosis and management of mallet finger injuries. Hand (N Y). 2017;12:223-228. doi: 10.1177/1558944716642763

14. Sheth U. Mallet finger. Orthobullets [Internet]. Updated August 5, 2021. Accessed April 15, 2022. www.orthobullets.com/hand/6014/mallet-finger

15. Weintraub MD, Hansford BG, Stilwill SE, et al. Avulsion injuries of the hand and wrist. Radiographics. 2020;40:163-180. doi: 10.1148/rg.2020190085

16. Avery III DM, Inkellis ER, Carlson MG. Thumb collateral ligament injuries in the athlete. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10:28-37. doi: 10.1007/s12178-017-9381-z

17. Steffes MJ. Thumb collateral ligament injury. Orthobullets [Internet]. Updated February 18, 2022. Accessed April 15, 2022. www.orthobullets.com/hand/6040/thumb-collateral-ligament-injury

18. Madan SS, Pai DR, Kaur A, et al. Injury to ulnar collateral ligament of thumb. Orthop Surg. 2014;6:1-7. doi: 10.1111/os.12084

19. Dardas AZ, VandenBerg J, Shen T, et al. Long-term effectiveness of repeat corticosteroid injections for trigger finger. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42:227-235. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.02.001

20. Huisstede BM, Gladdines S, Randsdorp MS, et al. Effectiveness of conservative, surgical, and postsurgical interventions for trigger finger, Dupuytren disease, and de Quervain disease: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99:1635-1649.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.07.014

21. Lunsford D, Valdes K, Hengy S. Conservative management of trigger finger: a systematic review. J Hand Ther. 2019;32:212-221. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2017.10.016

22. Fiorini HJ, Tamaoki MJ, Lenza M, et al. Surgery for trigger finger. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD009860. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009860.pub2

23. Salazar Botero S, Hidalgo Diaz JJ, Benaïda A, et al. Review of acute traumatic closed mallet finger injuries in adults. Arch Plast Surg. 2016;43:134-144. doi: 10.5999/aps.2016.43.2.134

24. Lin JS, Samora JB. Surgical and nonsurgical management of mallet finger: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43:146-163.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.10.004

25. Handoll H, Vaghela MV. Interventions for treating mallet finger injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD004574. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004574.pub2

26. Pulos N, Shin AY. Treatment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the thumb: a critical analysis review. JBJS Rev. 2017;5:e3. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.16.00051

Finger injuries are often seen in the primary care physician’s office. The evidence—and our experience in sports medicine—indicates that many of these injuries can be managed conservatively with bracing or injection; a subset, however, requires surgical referral. In this article, we provide a refresher on finger anatomy (see “A guide to the anatomic structures of the digits of the hand”1,2) and review the diagnosis and management of 4 common soft-tissue finger and thumb injuries in adults: trigger finger, jersey finger, mallet finger, and skier’s thumb (TABLE2-18).

Trigger finger

Also called stenosing flexor tenosynovitis, trigger finger is caused by abnormal flexor tendon movement that results from impingement at the level of the A1 pulley.

Causes and incidence. Impingement usually occurs because of thickening of the A1 pulley but can also be caused by inflammation or a nodule on the flexor tendon.3,4 The A1 pulley at the metacarpal head is the most proximal part of the retinacular sheath and therefore experiences the greatest force upon finger flexion, making it the most common site of inflammation and constriction.4

Trigger finger occurs in 2% to 3% of the general population and in as many as 10% of people with diabetes.5 The condition typically affects the long and ring fingers of the dominant hand; most cases occur in women in the sixth and seventh decades.3-5

Multiple systemic conditions predispose to trigger finger, including endocrine disorders (eg, diabetes, hypothyroidism), inflammatory arthropathies (gout, pseudogout), and autoimmune disorders (rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis).3,5 Diabetes commonly causes bilateral hand and multiple digit involvement, as well as more severe disease.3,5 Occupation is also a risk factor for trigger finger because repetitive movements and manual work can exacerbate triggering.4

Presentation and exam. Patients report pain at the metacarpal head or metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint, difficulty grasping objects, and, possibly, clicking and catching of the digit and locking of the digit in flexion.3,5

On exam, there might be tenderness at the level of the A1 pulley over the volar MCP joint or a palpable nodule. In severe cases, the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint or entire finger can be fixed in flexion.5 Repeated compound finger flexion (eg, closing and opening a fist) or holding a fist for as long as 1 minute and then slowly opening it might provoke triggering.

More than 60% of patients with trigger finger also have carpal tunnel syndrome.5 This makes it important to assess for (1) sensory changes in the distribution of the median nerve and (2) nerve compression, by eliciting Phalen and Tinel signs.4,5

Continue to: Imaging

Imaging. Trigger finger is a clinical diagnosis. Imaging is therefore unnecessary for diagnosis or treatment.5

Treatment. Trigger finger resolves spontaneously in 52% of cases.3 Most patients experience relief in 8 to 12 months.3

First-line treatment is injection of a corticosteroid into the flexor tendon sheath, which often alleviates symptoms.4,5 Injection is performed at the level of the A1 pulley on the palmar surface, just proximal to the MCP joint at the level of the distal palmar crease6 (FIGURE 1). The needle is inserted at an oblique angle until there is an increase in resistance. The needle is then slightly withdrawn to reposition it in the tendon sheath; 0.5 to 1 mL of 50% corticosteroid and 50% local anesthetic without epinephrine is then injected.6

The cure rate of trigger finger is 57% to 70% with 1 injection and 82% to 86% after 2 injections.3,4,19

Many patients experience symptom relief in 1 to 4 weeks after a corticosteroid injection; however, as many as 56% experience repeat triggering within 6 months—often making multiple injections (maximum, 3 per digit) necessary.19,20 Patients who have a longer duration of symptoms, more severe symptoms, and multiple trigger fingers are less likely to experience relief with injections.3,5

Continue to: Splinting is an effective treatment...

Splinting is an effective treatment for patients who cannot undergo corticosteroid injection or surgery. The MCP or PIP joint is immobilized in extension while movement of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint is maintained. Instruct the patient that the splint must be worn day and night; splinting is continued for ≥ 6 weeks.21 Splinting relieves symptoms in 47% to 70% of cases and is most effective in patients whose symptoms have been present for < 6 months.3,7

Patients whose trigger finger is locked in flexion and those who have not experienced improvement after 2 or 3 corticosteroid injections should be referred for surgery.4 The surgical cure rate is nearly 100%; only 6% of patients experience repeat triggering 6 to 12 months postoperatively.4,7,22

Jersey finger

Causes and incidence. Jersey finger is caused by avulsion injury to the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendon at its insertion on the distal phalanx.8,9 It occurs when a flexed finger is forced into extension, such as when a football or rugby player grabs another player’s jersey during a tackle.9,10 This action causes the FDP tendon to detach from the distal phalanx, sometimes with a bony fragment.9,11 Once detached, the tendon might retract proximally within the finger or to the palm, with consequent loss of its blood supply.9

Although jersey finger is not as common as the other conditions discussed in this article,9 it is important not to miss this diagnosis because of the risk of chronic disability when it is not treated promptly. Seventy-five percent of cases occur in the ring finger, which is more susceptible to injury because it extends past the other digits in a power grip.8,9

Presentation and exam. On exam, the affected finger lies in slight extension compared to the other digits; the patient is unable to actively flex the DIP joint.8,9 There may be tenderness to palpation over the volar distal phalanx. The retracted FDP tendon might be palpable more proximally in the digit.

Continue to: Imaging

Imaging. Anteroposterior (AP), oblique, and lateral radiographs, although unnecessary for diagnosis, are recommended to assess for an avulsion fragment, associated fracture, or dislocation.9,11 Ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging is useful in chronic cases to quantify the degree of tendon retraction.9

Treatment. Refer acute cases of jersey finger for surgical management urgently because most cases require flexor tendon repair within 1 or 2 weeks for a successful outcome.9 Chronic jersey finger, in which injury occurred > 6 weeks before presentation, also requires surgical repair, although not as urgently.9

Complications of jersey finger include flexion contracture at the DIP joint and the so-called quadriga effect, in which the patient is unable to fully flex the fingers adjacent to the injured digit.8 These complications can cause chronic disability in the affected hand, making early diagnosis and referral key to successful treatment.9

Mallet finger

Also called drop finger, mallet finger is a result of loss of active extension at the DIP joint.12,13

Causes and incidence. Mallet finger is a relatively common injury that typically affects the long, ring, or small finger of the dominant hand in young to middle-aged men and older women.12,14,23 The condition is the result of forced flexion or hyperextension injury, which disrupts the extensor tendon.6,14

Continue to: Sudden forced flexion...

Sudden forced flexion of an extended DIP joint during work or sports (eg, catching a ball) is the most common mechanism of injury.12,15 This action causes stretching or tearing of the extensor tendon as well as a possible avulsion fracture of the distal phalanx.13 Mallet finger can also result from a laceration or crush injury of the extensor tendon (open mallet finger) or hyperextension of the DIP joint, causing a fracture at the dorsal base of the distal phalanx.12

Presentation. Through any of the aforementioned mechanisms, the delicate balance between the flexor and extensor tendons is disrupted, causing the patient to present with a flexed DIP joint that can be passively, but not actively, extended.6,12 The DIP joint might also be painful and swollen. Patients whose injury occurred > 4 weeks prior to presentation (chronic mallet finger) might also have a so-called swan-neck deformity, with hyperextension of the PIP joint in the affected finger.12

Imaging. AP, oblique, and lateral radiographs are recommended to assess for bony injury.