User login

Children with resistant UTIs unexpectedly may respond to discordant antibiotics

Children with urinary tract infections (UTIs) may improve clinically, and pyuria may resolve, during empiric treatment with an antibiotic that turns out to be discordant, according a retrospective study in Pediatrics.

“The low rate of care escalation and high rate of clinical improvement while on discordant antibiotics suggests that, for most patients, it would be reasonable to continue current empiric antibiotic practices until urine culture sensitivities return,” said first author Marie E. Wang, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues.

The researchers examined the initial clinical response and escalation of care for 316 children with UTIs who received therapy to which the infecting isolate was not susceptible. The study included patients who had infections that were resistant to third-generation cephalosporins – that is, urinalysis found that the infections were not susceptible to ceftriaxone or cefotaxime in vitro. Before the resistant organisms were identified, however, the patients were started on discordant antibiotics.

Escalation of care was uncommon

The patients had a median age of 2.4 years, and 78% were girls. Approximately 90% were started on a cephalosporin, and about 65% received a first-generation cephalosporin. Patients presented during 2012-2017 to one of five children’s hospitals or to a large managed care organization with 10 hospitals in the United States. The investigators defined care escalation as a visit to the emergency department, hospitalization, or transfer to the ICU.

In all, seven patients (2%) had escalation of care on discordant antibiotics. Four children visited an emergency department without hospitalization, and three children were hospitalized because of persistent symptoms.

Among 230 cases for which the researchers had data about clinical response at a median follow-up of 3 days, 84% “had overall clinical improvement while on discordant antibiotics,” the authors said.

For 22 children who had repeat urine testing while on discordant antibiotics, 53% had resolution of pyuria, and 32% had improvement of pyuria, whereas 16% did not have improvement. Of the three patients without improvement, one had no change, and two had worsening.

Of 17 patients who had a repeat urine culture on discordant therapy, 65% had a negative repeat culture, and 18% grew the same pathogen with a decreased colony count. Two patients had a colony count that remained unchanged, and one patient had an increased colony count.

Small studies outside the United States have reported similar results, the researchers noted. Spontaneous resolution of UTIs or antibiotics reaching a sufficient concentration in the urine and renal parenchyma to achieve a clinical response are possible explanations for the findings, they wrote.

“Few children required escalation of care and most experienced initial clinical improvement,” noted Dr. Wang and colleagues. “Furthermore, in the small group of children that underwent repeat urine testing while on discordant therapy, most had resolution or improvement in pyuria and sterilization of their urine cultures. Our findings suggest that Additionally, given that these patients initially received what would generally be considered inadequate treatment, our findings may provide some insight into the natural history of UTIs and/or trigger further investigation into the relationship between in vitro urine culture susceptibilities and in vivo clinical response to treatment.”

‘Caution is needed’

The study “highlights an intriguing observation about children with UTIs unexpectedly responding to discordant antibiotic therapy,” Tej K. Mattoo, MD, and Basim I. Asmar, MD, wrote in an accompanying commentary.(doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3512). Dr. Mattoo and Dr. Asmar, a pediatric nephrologist and a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, respectively, at Wayne State University and affiliated with Children’s Hospital of Michigan, both in Detroit.

In an inpatient setting, it may be easy for physicians to reassess patients “once urine culture results reveal resistance to the treating antibiotic,” they noted. In an ambulatory setting, however, “it is likely that some patients will receive a full course of an antibiotic that does not have in vitro activity against the urinary pathogen.”

Physicians have a responsibility to use antibiotics judiciously, they said. Widely accepted principles include avoiding repeated courses of antibiotics, diagnosing UTIs appropriately, and not treating asymptomatic bacteriuria.

The study had no external funding. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Wang ME et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1608.

This article was updated 2/4/2020.

Children with urinary tract infections (UTIs) may improve clinically, and pyuria may resolve, during empiric treatment with an antibiotic that turns out to be discordant, according a retrospective study in Pediatrics.

“The low rate of care escalation and high rate of clinical improvement while on discordant antibiotics suggests that, for most patients, it would be reasonable to continue current empiric antibiotic practices until urine culture sensitivities return,” said first author Marie E. Wang, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues.

The researchers examined the initial clinical response and escalation of care for 316 children with UTIs who received therapy to which the infecting isolate was not susceptible. The study included patients who had infections that were resistant to third-generation cephalosporins – that is, urinalysis found that the infections were not susceptible to ceftriaxone or cefotaxime in vitro. Before the resistant organisms were identified, however, the patients were started on discordant antibiotics.

Escalation of care was uncommon

The patients had a median age of 2.4 years, and 78% were girls. Approximately 90% were started on a cephalosporin, and about 65% received a first-generation cephalosporin. Patients presented during 2012-2017 to one of five children’s hospitals or to a large managed care organization with 10 hospitals in the United States. The investigators defined care escalation as a visit to the emergency department, hospitalization, or transfer to the ICU.

In all, seven patients (2%) had escalation of care on discordant antibiotics. Four children visited an emergency department without hospitalization, and three children were hospitalized because of persistent symptoms.

Among 230 cases for which the researchers had data about clinical response at a median follow-up of 3 days, 84% “had overall clinical improvement while on discordant antibiotics,” the authors said.

For 22 children who had repeat urine testing while on discordant antibiotics, 53% had resolution of pyuria, and 32% had improvement of pyuria, whereas 16% did not have improvement. Of the three patients without improvement, one had no change, and two had worsening.

Of 17 patients who had a repeat urine culture on discordant therapy, 65% had a negative repeat culture, and 18% grew the same pathogen with a decreased colony count. Two patients had a colony count that remained unchanged, and one patient had an increased colony count.

Small studies outside the United States have reported similar results, the researchers noted. Spontaneous resolution of UTIs or antibiotics reaching a sufficient concentration in the urine and renal parenchyma to achieve a clinical response are possible explanations for the findings, they wrote.

“Few children required escalation of care and most experienced initial clinical improvement,” noted Dr. Wang and colleagues. “Furthermore, in the small group of children that underwent repeat urine testing while on discordant therapy, most had resolution or improvement in pyuria and sterilization of their urine cultures. Our findings suggest that Additionally, given that these patients initially received what would generally be considered inadequate treatment, our findings may provide some insight into the natural history of UTIs and/or trigger further investigation into the relationship between in vitro urine culture susceptibilities and in vivo clinical response to treatment.”

‘Caution is needed’

The study “highlights an intriguing observation about children with UTIs unexpectedly responding to discordant antibiotic therapy,” Tej K. Mattoo, MD, and Basim I. Asmar, MD, wrote in an accompanying commentary.(doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3512). Dr. Mattoo and Dr. Asmar, a pediatric nephrologist and a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, respectively, at Wayne State University and affiliated with Children’s Hospital of Michigan, both in Detroit.

In an inpatient setting, it may be easy for physicians to reassess patients “once urine culture results reveal resistance to the treating antibiotic,” they noted. In an ambulatory setting, however, “it is likely that some patients will receive a full course of an antibiotic that does not have in vitro activity against the urinary pathogen.”

Physicians have a responsibility to use antibiotics judiciously, they said. Widely accepted principles include avoiding repeated courses of antibiotics, diagnosing UTIs appropriately, and not treating asymptomatic bacteriuria.

The study had no external funding. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Wang ME et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1608.

This article was updated 2/4/2020.

Children with urinary tract infections (UTIs) may improve clinically, and pyuria may resolve, during empiric treatment with an antibiotic that turns out to be discordant, according a retrospective study in Pediatrics.

“The low rate of care escalation and high rate of clinical improvement while on discordant antibiotics suggests that, for most patients, it would be reasonable to continue current empiric antibiotic practices until urine culture sensitivities return,” said first author Marie E. Wang, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues.

The researchers examined the initial clinical response and escalation of care for 316 children with UTIs who received therapy to which the infecting isolate was not susceptible. The study included patients who had infections that were resistant to third-generation cephalosporins – that is, urinalysis found that the infections were not susceptible to ceftriaxone or cefotaxime in vitro. Before the resistant organisms were identified, however, the patients were started on discordant antibiotics.

Escalation of care was uncommon

The patients had a median age of 2.4 years, and 78% were girls. Approximately 90% were started on a cephalosporin, and about 65% received a first-generation cephalosporin. Patients presented during 2012-2017 to one of five children’s hospitals or to a large managed care organization with 10 hospitals in the United States. The investigators defined care escalation as a visit to the emergency department, hospitalization, or transfer to the ICU.

In all, seven patients (2%) had escalation of care on discordant antibiotics. Four children visited an emergency department without hospitalization, and three children were hospitalized because of persistent symptoms.

Among 230 cases for which the researchers had data about clinical response at a median follow-up of 3 days, 84% “had overall clinical improvement while on discordant antibiotics,” the authors said.

For 22 children who had repeat urine testing while on discordant antibiotics, 53% had resolution of pyuria, and 32% had improvement of pyuria, whereas 16% did not have improvement. Of the three patients without improvement, one had no change, and two had worsening.

Of 17 patients who had a repeat urine culture on discordant therapy, 65% had a negative repeat culture, and 18% grew the same pathogen with a decreased colony count. Two patients had a colony count that remained unchanged, and one patient had an increased colony count.

Small studies outside the United States have reported similar results, the researchers noted. Spontaneous resolution of UTIs or antibiotics reaching a sufficient concentration in the urine and renal parenchyma to achieve a clinical response are possible explanations for the findings, they wrote.

“Few children required escalation of care and most experienced initial clinical improvement,” noted Dr. Wang and colleagues. “Furthermore, in the small group of children that underwent repeat urine testing while on discordant therapy, most had resolution or improvement in pyuria and sterilization of their urine cultures. Our findings suggest that Additionally, given that these patients initially received what would generally be considered inadequate treatment, our findings may provide some insight into the natural history of UTIs and/or trigger further investigation into the relationship between in vitro urine culture susceptibilities and in vivo clinical response to treatment.”

‘Caution is needed’

The study “highlights an intriguing observation about children with UTIs unexpectedly responding to discordant antibiotic therapy,” Tej K. Mattoo, MD, and Basim I. Asmar, MD, wrote in an accompanying commentary.(doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3512). Dr. Mattoo and Dr. Asmar, a pediatric nephrologist and a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, respectively, at Wayne State University and affiliated with Children’s Hospital of Michigan, both in Detroit.

In an inpatient setting, it may be easy for physicians to reassess patients “once urine culture results reveal resistance to the treating antibiotic,” they noted. In an ambulatory setting, however, “it is likely that some patients will receive a full course of an antibiotic that does not have in vitro activity against the urinary pathogen.”

Physicians have a responsibility to use antibiotics judiciously, they said. Widely accepted principles include avoiding repeated courses of antibiotics, diagnosing UTIs appropriately, and not treating asymptomatic bacteriuria.

The study had no external funding. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Wang ME et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1608.

This article was updated 2/4/2020.

FROM PEDIATRICS

SHM Pediatric Core Competencies get fresh update

New core competencies reflect a decade of change

Over the past 10 years, much has changed in the world of pediatric hospital medicine. The annual national PHM conference sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Academic Pediatric Association (APA) is robust; textbooks and journal articles in the field abound; and networks and training in research, quality improvement, and education are successful and ongoing.

Much of this did not exist or was in its infancy back in 2010. Since then, it has grown and greatly evolved. In parallel, medicine and society have changed. These influences on health care, along with the growth of the field over time, prompted a review and revision of the 2010 PHM Core Competencies published by SHM. With support from the society, the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Special Interest Group launched the plan for revision of the PHM Core Competencies.

The selected editors included Sandra Gage, MD, PhD, SFHM, of Phoenix Children’s Hospital; Erin Stucky Fisher, MD, MHM, of UCSD/Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego; Jennifer Maniscalco, MD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Fla.; and Sofia Teferi, MD, SFHM, a pediatric hospitalist based at Bon Secours St. Mary’s Hospital in Richmond, Va. They began their work in 2017 along with six associate editors, meeting every 2 weeks via conference call, dividing the work accordingly.

Dr. Teferi served in a new and critical role as contributing editor. She described her role as a “sweeper” of sorts, bringing her unique perspective to the process. “The other three members are from academic settings, and I’m from a community setting, which is very different,” Dr. Teferi said. “I went through all the chapters to ensure they were inclusive of the community setting.”

According to Dr. Gage, “the purpose of the original PHM Core Competencies was to define the roles and responsibilities of a PHM practitioner. In the intervening 10 years, the field has changed and matured, and we have solidified our role since then.”

Today’s pediatric hospitalists, for instance, may coordinate care in EDs, provide inpatient consultations, engage or lead quality improvement programs, and teach. The demands for pediatric hospital care today go beyond the training provided in a standard pediatric residency. The core competencies need to provide the information necessary, therefore, to ensure pediatric hospital medicine is practiced at its most informed level.

A profession transformed

At the time of the first set of core competencies, there were over 2,500 members in three core societies in which pediatric hospitalists were members: the AAP, the APA, and SHM. As of 2017, those numbers have swelled as the care for children in the hospital setting has shifted away from these patients’ primary care providers.

The original core competencies included 54 chapters, designed to be used independent of the others. They provided a foundation for the creation of pediatric hospital medicine and served to standardize and improve inpatient training practices.

For the new core competencies, every single chapter was reviewed line by line, Dr. Gage said. Many chapters had content modified, and new chapters were added to reflect the evolution of the field and of medicine. “We added about 14 new chapters, adjusted the titles of others, and significantly changed the content of over half,” Dr. Gage explained. “They are fairly broad changes, related to the breadth of the practice today.”

Dr. Teferi noted that practitioners can use the updated competencies with additions to the service lines that have arisen since the last version. “These include areas like step down and newborn nursery, things that weren’t part of our portfolio 10 years ago,” she said. “This reflects the fact that often you’ll see a hospital leader who might want to add to a hospitalist’s portfolio of services because there is no one else to do it. Or maybe community pediatrics no longer want to treat babies, so we add that. The settings vary widely today and we need the competencies to address that.”

Practices within these settings can also vary widely. Teaching, palliative care, airway management, critical care, and anesthesia may all come into play, among other factors. Research opportunities throughout the field also continue to expand.

Dr. Fisher said that the editors and associate editors kept in mind the fact that not every hospital would have all the resources necessary at its fingertips. “The competencies must reflect the realities of the variety of community settings,” she said. “Also, on a national level, the majority of pediatric patients are not seen in a children’s hospital. Community sites are where pediatric hospitalists are not only advocates for care, but can be working with limited resources – the ‘lone soldiers.’ We wanted to make sure the competencies reflect that reality and environment community site or not; academic site or not; tertiary care site or not; rural or not – these are overlapping but independent considerations for all who practice pediatric hospital medicine – a Venn diagram, and the PHM core competencies try to attend to all of those.”

This made Dr. Teferi’s perspective all the more important. “While many, including other editors and associate editors, work in community sites, Dr. Teferi has this as her unique and sole focus. She brought a unique viewpoint to the table,” Dr. Fisher said.

A goal of the core competencies is to make it possible for a pediatric hospitalist to move to a different practice environment and still provide the same level of high-quality care. “It’s difficult but important to grasp the concepts and competencies of various settings,” Dr. Fisher said. “In this way, our competencies are a parallel model to the adult hospitalist competencies.”

The editors surveyed practitioners across the country to gather their input on content, and brought on topic experts to write the new chapters. “If we didn’t have an author for a specific chapter or area from the last set of competencies, we came to a consensus on who the new one should be,” Dr. Gage explained. “We looked for known and accepted experts in the field by reviewing the literature and conference lecturers at all major PHM meetings.”

Once the editors and associate editors worked with authors to refine their chapter(s), the chapters were sent to multiple external reviewers including subgroups of SHM, AAP, and APA, as well as a variety of other associations. They provided input that the editors and associate editors collated, reviewed, and incorporated according to consensus and discussion with the authors.

A preview

As far as the actual changes go, some of new chapters include four common clinical, two core skills, three specialized services, and five health care systems, with many others undergoing content changes, according to Dr. Gage.

Major considerations in developing the new competencies include the national trend of rising mental health issues among young patients. According to the AAP, over the last decade the number of young people aged 6-17 years requiring mental health care has risen from 9% to more than 14%. In outpatient settings, many pediatricians report that half or more of their visits are dedicated to these issues, a number that may spill out into the hospital setting as well.

According to Dr. Fisher, pediatric hospitalists today see increasing numbers of chronic and acute diseases accompanied by mental and behavioral health issues. “We wanted to underscore this complexity in the competencies,” she explained. “We needed to focus new attention on how to identify and treat children with behavioral or psychiatric diagnoses or needs.”

Other new areas of focus include infection care and antimicrobial stewardship. “We see kids on antibiotics in hospital settings and we need to focus on narrowing choices, decreasing use, and shortening duration,” Dr. Gage said.

Dr. Maniscalco said that, overall, the changes represent the evolution of the field. “Pediatric hospitalists are taking on far more patients with acute and complex issues,” she explained. “Our skill set is coming into focus.”

Dr. Gage added that there is an increased need for pediatric hospitalists to be adept at “managing acute psychiatric care and navigating the mental health care arena.”

There’s also the growing need for an understanding of neonatal abstinence and opioid withdrawal syndrome. “This is definitely a hot topic and one that most hospitalists must address today,” Dr. Gage said. “That wasn’t the case a decade ago.”

Hospital care for pediatrics today often means a team effort, including pediatric hospitalists, surgeons, mental health professionals, and others. Often missing from the picture today are primary care physicians, who instead refer a growing percentage of their patients to hospitalists. The pediatric hospitalist’s role has evolved and grown from what it was 10 years ago, as reflected in the competencies.

“We are very much coordinating care and collaborating today in ways we weren’t 10 years ago,” said Dr. Gage. “There’s a lot more attention on creating partnerships. While we may not always be the ones performing procedures, we will most likely take part in patient care, especially as surgeons step farther away from care outside of the OR.”

The field has also become more family centered, said Dr. Gage. “All of health care today is more astute about the participation of families in care,” she said. “We kept that in mind in developing the competencies.”

Also important in this set of competencies was the concept of high-value care using evidence-based medicine.

Into the field

How exactly the core competencies will be utilized from one hospital or setting to the next will vary, said Dr. Fisher. “For some sites, they can aid existing teaching programs, and they will most likely adapt their curriculum to address the new competencies, informing how they teach.”

Even in centers where there isn’t a formal academic role, teaching still occurs. “Pediatric hospitalists have roles on committees and projects, and giving a talk to respiratory therapists, having group meetings – these all involve teaching in some form,” Dr. Fisher said. “Most physicians will determine how they wish to insert the competencies into their own education, as well as use them to educate others.”

Regardless of how they may be used locally, Dr. Fisher anticipates that the entire pediatric hospitalist community will appreciate the updates. “The competencies address our rapidly changing health care environment,” she said. “We believe the field will benefit from the additions and changes.”

Indeed, the core competencies will help standardize and improve consistency of care across the board. Improved efficiencies, economics, and practices are all desired and expected outcomes from the release of the revised competencies.

To ensure that the changes to the competencies are highlighted in settings nationwide, the editors and associate editors hope to present about them at upcoming conferences, including at the SHM 2020 Annual Conference, the Pediatric Hospital Medicine conference, the Pediatric Academic Societies conference, and the American Pediatric Association.

“We want to present to as many venues as possible to bring people up to speed and ensure they are aware of the changes,” Dr. Teferi said. “We’ll be including workshops with visual aids, along with our presentations.”

While this update represents a 10-year evolution, the editors and the SHM Pediatric Special Interest Group do not have an exact time frame for when the core competencies will need another revision. As quickly as the profession is developing, it may be as few as 5 years, but may also be another full decade.

“Like most fields, we will continue to evolve as our roles become better defined and we gain more knowledge,” Dr. Maniscalco said. “The core competencies represent the field whether a senior pediatric hospitalist, a fellow, or an educator. They bring the field together and provide education for everyone. That’s their role.”

New core competencies reflect a decade of change

New core competencies reflect a decade of change

Over the past 10 years, much has changed in the world of pediatric hospital medicine. The annual national PHM conference sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Academic Pediatric Association (APA) is robust; textbooks and journal articles in the field abound; and networks and training in research, quality improvement, and education are successful and ongoing.

Much of this did not exist or was in its infancy back in 2010. Since then, it has grown and greatly evolved. In parallel, medicine and society have changed. These influences on health care, along with the growth of the field over time, prompted a review and revision of the 2010 PHM Core Competencies published by SHM. With support from the society, the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Special Interest Group launched the plan for revision of the PHM Core Competencies.

The selected editors included Sandra Gage, MD, PhD, SFHM, of Phoenix Children’s Hospital; Erin Stucky Fisher, MD, MHM, of UCSD/Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego; Jennifer Maniscalco, MD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Fla.; and Sofia Teferi, MD, SFHM, a pediatric hospitalist based at Bon Secours St. Mary’s Hospital in Richmond, Va. They began their work in 2017 along with six associate editors, meeting every 2 weeks via conference call, dividing the work accordingly.

Dr. Teferi served in a new and critical role as contributing editor. She described her role as a “sweeper” of sorts, bringing her unique perspective to the process. “The other three members are from academic settings, and I’m from a community setting, which is very different,” Dr. Teferi said. “I went through all the chapters to ensure they were inclusive of the community setting.”

According to Dr. Gage, “the purpose of the original PHM Core Competencies was to define the roles and responsibilities of a PHM practitioner. In the intervening 10 years, the field has changed and matured, and we have solidified our role since then.”

Today’s pediatric hospitalists, for instance, may coordinate care in EDs, provide inpatient consultations, engage or lead quality improvement programs, and teach. The demands for pediatric hospital care today go beyond the training provided in a standard pediatric residency. The core competencies need to provide the information necessary, therefore, to ensure pediatric hospital medicine is practiced at its most informed level.

A profession transformed

At the time of the first set of core competencies, there were over 2,500 members in three core societies in which pediatric hospitalists were members: the AAP, the APA, and SHM. As of 2017, those numbers have swelled as the care for children in the hospital setting has shifted away from these patients’ primary care providers.

The original core competencies included 54 chapters, designed to be used independent of the others. They provided a foundation for the creation of pediatric hospital medicine and served to standardize and improve inpatient training practices.

For the new core competencies, every single chapter was reviewed line by line, Dr. Gage said. Many chapters had content modified, and new chapters were added to reflect the evolution of the field and of medicine. “We added about 14 new chapters, adjusted the titles of others, and significantly changed the content of over half,” Dr. Gage explained. “They are fairly broad changes, related to the breadth of the practice today.”

Dr. Teferi noted that practitioners can use the updated competencies with additions to the service lines that have arisen since the last version. “These include areas like step down and newborn nursery, things that weren’t part of our portfolio 10 years ago,” she said. “This reflects the fact that often you’ll see a hospital leader who might want to add to a hospitalist’s portfolio of services because there is no one else to do it. Or maybe community pediatrics no longer want to treat babies, so we add that. The settings vary widely today and we need the competencies to address that.”

Practices within these settings can also vary widely. Teaching, palliative care, airway management, critical care, and anesthesia may all come into play, among other factors. Research opportunities throughout the field also continue to expand.

Dr. Fisher said that the editors and associate editors kept in mind the fact that not every hospital would have all the resources necessary at its fingertips. “The competencies must reflect the realities of the variety of community settings,” she said. “Also, on a national level, the majority of pediatric patients are not seen in a children’s hospital. Community sites are where pediatric hospitalists are not only advocates for care, but can be working with limited resources – the ‘lone soldiers.’ We wanted to make sure the competencies reflect that reality and environment community site or not; academic site or not; tertiary care site or not; rural or not – these are overlapping but independent considerations for all who practice pediatric hospital medicine – a Venn diagram, and the PHM core competencies try to attend to all of those.”

This made Dr. Teferi’s perspective all the more important. “While many, including other editors and associate editors, work in community sites, Dr. Teferi has this as her unique and sole focus. She brought a unique viewpoint to the table,” Dr. Fisher said.

A goal of the core competencies is to make it possible for a pediatric hospitalist to move to a different practice environment and still provide the same level of high-quality care. “It’s difficult but important to grasp the concepts and competencies of various settings,” Dr. Fisher said. “In this way, our competencies are a parallel model to the adult hospitalist competencies.”

The editors surveyed practitioners across the country to gather their input on content, and brought on topic experts to write the new chapters. “If we didn’t have an author for a specific chapter or area from the last set of competencies, we came to a consensus on who the new one should be,” Dr. Gage explained. “We looked for known and accepted experts in the field by reviewing the literature and conference lecturers at all major PHM meetings.”

Once the editors and associate editors worked with authors to refine their chapter(s), the chapters were sent to multiple external reviewers including subgroups of SHM, AAP, and APA, as well as a variety of other associations. They provided input that the editors and associate editors collated, reviewed, and incorporated according to consensus and discussion with the authors.

A preview

As far as the actual changes go, some of new chapters include four common clinical, two core skills, three specialized services, and five health care systems, with many others undergoing content changes, according to Dr. Gage.

Major considerations in developing the new competencies include the national trend of rising mental health issues among young patients. According to the AAP, over the last decade the number of young people aged 6-17 years requiring mental health care has risen from 9% to more than 14%. In outpatient settings, many pediatricians report that half or more of their visits are dedicated to these issues, a number that may spill out into the hospital setting as well.

According to Dr. Fisher, pediatric hospitalists today see increasing numbers of chronic and acute diseases accompanied by mental and behavioral health issues. “We wanted to underscore this complexity in the competencies,” she explained. “We needed to focus new attention on how to identify and treat children with behavioral or psychiatric diagnoses or needs.”

Other new areas of focus include infection care and antimicrobial stewardship. “We see kids on antibiotics in hospital settings and we need to focus on narrowing choices, decreasing use, and shortening duration,” Dr. Gage said.

Dr. Maniscalco said that, overall, the changes represent the evolution of the field. “Pediatric hospitalists are taking on far more patients with acute and complex issues,” she explained. “Our skill set is coming into focus.”

Dr. Gage added that there is an increased need for pediatric hospitalists to be adept at “managing acute psychiatric care and navigating the mental health care arena.”

There’s also the growing need for an understanding of neonatal abstinence and opioid withdrawal syndrome. “This is definitely a hot topic and one that most hospitalists must address today,” Dr. Gage said. “That wasn’t the case a decade ago.”

Hospital care for pediatrics today often means a team effort, including pediatric hospitalists, surgeons, mental health professionals, and others. Often missing from the picture today are primary care physicians, who instead refer a growing percentage of their patients to hospitalists. The pediatric hospitalist’s role has evolved and grown from what it was 10 years ago, as reflected in the competencies.

“We are very much coordinating care and collaborating today in ways we weren’t 10 years ago,” said Dr. Gage. “There’s a lot more attention on creating partnerships. While we may not always be the ones performing procedures, we will most likely take part in patient care, especially as surgeons step farther away from care outside of the OR.”

The field has also become more family centered, said Dr. Gage. “All of health care today is more astute about the participation of families in care,” she said. “We kept that in mind in developing the competencies.”

Also important in this set of competencies was the concept of high-value care using evidence-based medicine.

Into the field

How exactly the core competencies will be utilized from one hospital or setting to the next will vary, said Dr. Fisher. “For some sites, they can aid existing teaching programs, and they will most likely adapt their curriculum to address the new competencies, informing how they teach.”

Even in centers where there isn’t a formal academic role, teaching still occurs. “Pediatric hospitalists have roles on committees and projects, and giving a talk to respiratory therapists, having group meetings – these all involve teaching in some form,” Dr. Fisher said. “Most physicians will determine how they wish to insert the competencies into their own education, as well as use them to educate others.”

Regardless of how they may be used locally, Dr. Fisher anticipates that the entire pediatric hospitalist community will appreciate the updates. “The competencies address our rapidly changing health care environment,” she said. “We believe the field will benefit from the additions and changes.”

Indeed, the core competencies will help standardize and improve consistency of care across the board. Improved efficiencies, economics, and practices are all desired and expected outcomes from the release of the revised competencies.

To ensure that the changes to the competencies are highlighted in settings nationwide, the editors and associate editors hope to present about them at upcoming conferences, including at the SHM 2020 Annual Conference, the Pediatric Hospital Medicine conference, the Pediatric Academic Societies conference, and the American Pediatric Association.

“We want to present to as many venues as possible to bring people up to speed and ensure they are aware of the changes,” Dr. Teferi said. “We’ll be including workshops with visual aids, along with our presentations.”

While this update represents a 10-year evolution, the editors and the SHM Pediatric Special Interest Group do not have an exact time frame for when the core competencies will need another revision. As quickly as the profession is developing, it may be as few as 5 years, but may also be another full decade.

“Like most fields, we will continue to evolve as our roles become better defined and we gain more knowledge,” Dr. Maniscalco said. “The core competencies represent the field whether a senior pediatric hospitalist, a fellow, or an educator. They bring the field together and provide education for everyone. That’s their role.”

Over the past 10 years, much has changed in the world of pediatric hospital medicine. The annual national PHM conference sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Academic Pediatric Association (APA) is robust; textbooks and journal articles in the field abound; and networks and training in research, quality improvement, and education are successful and ongoing.

Much of this did not exist or was in its infancy back in 2010. Since then, it has grown and greatly evolved. In parallel, medicine and society have changed. These influences on health care, along with the growth of the field over time, prompted a review and revision of the 2010 PHM Core Competencies published by SHM. With support from the society, the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Special Interest Group launched the plan for revision of the PHM Core Competencies.

The selected editors included Sandra Gage, MD, PhD, SFHM, of Phoenix Children’s Hospital; Erin Stucky Fisher, MD, MHM, of UCSD/Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego; Jennifer Maniscalco, MD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, Fla.; and Sofia Teferi, MD, SFHM, a pediatric hospitalist based at Bon Secours St. Mary’s Hospital in Richmond, Va. They began their work in 2017 along with six associate editors, meeting every 2 weeks via conference call, dividing the work accordingly.

Dr. Teferi served in a new and critical role as contributing editor. She described her role as a “sweeper” of sorts, bringing her unique perspective to the process. “The other three members are from academic settings, and I’m from a community setting, which is very different,” Dr. Teferi said. “I went through all the chapters to ensure they were inclusive of the community setting.”

According to Dr. Gage, “the purpose of the original PHM Core Competencies was to define the roles and responsibilities of a PHM practitioner. In the intervening 10 years, the field has changed and matured, and we have solidified our role since then.”

Today’s pediatric hospitalists, for instance, may coordinate care in EDs, provide inpatient consultations, engage or lead quality improvement programs, and teach. The demands for pediatric hospital care today go beyond the training provided in a standard pediatric residency. The core competencies need to provide the information necessary, therefore, to ensure pediatric hospital medicine is practiced at its most informed level.

A profession transformed

At the time of the first set of core competencies, there were over 2,500 members in three core societies in which pediatric hospitalists were members: the AAP, the APA, and SHM. As of 2017, those numbers have swelled as the care for children in the hospital setting has shifted away from these patients’ primary care providers.

The original core competencies included 54 chapters, designed to be used independent of the others. They provided a foundation for the creation of pediatric hospital medicine and served to standardize and improve inpatient training practices.

For the new core competencies, every single chapter was reviewed line by line, Dr. Gage said. Many chapters had content modified, and new chapters were added to reflect the evolution of the field and of medicine. “We added about 14 new chapters, adjusted the titles of others, and significantly changed the content of over half,” Dr. Gage explained. “They are fairly broad changes, related to the breadth of the practice today.”

Dr. Teferi noted that practitioners can use the updated competencies with additions to the service lines that have arisen since the last version. “These include areas like step down and newborn nursery, things that weren’t part of our portfolio 10 years ago,” she said. “This reflects the fact that often you’ll see a hospital leader who might want to add to a hospitalist’s portfolio of services because there is no one else to do it. Or maybe community pediatrics no longer want to treat babies, so we add that. The settings vary widely today and we need the competencies to address that.”

Practices within these settings can also vary widely. Teaching, palliative care, airway management, critical care, and anesthesia may all come into play, among other factors. Research opportunities throughout the field also continue to expand.

Dr. Fisher said that the editors and associate editors kept in mind the fact that not every hospital would have all the resources necessary at its fingertips. “The competencies must reflect the realities of the variety of community settings,” she said. “Also, on a national level, the majority of pediatric patients are not seen in a children’s hospital. Community sites are where pediatric hospitalists are not only advocates for care, but can be working with limited resources – the ‘lone soldiers.’ We wanted to make sure the competencies reflect that reality and environment community site or not; academic site or not; tertiary care site or not; rural or not – these are overlapping but independent considerations for all who practice pediatric hospital medicine – a Venn diagram, and the PHM core competencies try to attend to all of those.”

This made Dr. Teferi’s perspective all the more important. “While many, including other editors and associate editors, work in community sites, Dr. Teferi has this as her unique and sole focus. She brought a unique viewpoint to the table,” Dr. Fisher said.

A goal of the core competencies is to make it possible for a pediatric hospitalist to move to a different practice environment and still provide the same level of high-quality care. “It’s difficult but important to grasp the concepts and competencies of various settings,” Dr. Fisher said. “In this way, our competencies are a parallel model to the adult hospitalist competencies.”

The editors surveyed practitioners across the country to gather their input on content, and brought on topic experts to write the new chapters. “If we didn’t have an author for a specific chapter or area from the last set of competencies, we came to a consensus on who the new one should be,” Dr. Gage explained. “We looked for known and accepted experts in the field by reviewing the literature and conference lecturers at all major PHM meetings.”

Once the editors and associate editors worked with authors to refine their chapter(s), the chapters were sent to multiple external reviewers including subgroups of SHM, AAP, and APA, as well as a variety of other associations. They provided input that the editors and associate editors collated, reviewed, and incorporated according to consensus and discussion with the authors.

A preview

As far as the actual changes go, some of new chapters include four common clinical, two core skills, three specialized services, and five health care systems, with many others undergoing content changes, according to Dr. Gage.

Major considerations in developing the new competencies include the national trend of rising mental health issues among young patients. According to the AAP, over the last decade the number of young people aged 6-17 years requiring mental health care has risen from 9% to more than 14%. In outpatient settings, many pediatricians report that half or more of their visits are dedicated to these issues, a number that may spill out into the hospital setting as well.

According to Dr. Fisher, pediatric hospitalists today see increasing numbers of chronic and acute diseases accompanied by mental and behavioral health issues. “We wanted to underscore this complexity in the competencies,” she explained. “We needed to focus new attention on how to identify and treat children with behavioral or psychiatric diagnoses or needs.”

Other new areas of focus include infection care and antimicrobial stewardship. “We see kids on antibiotics in hospital settings and we need to focus on narrowing choices, decreasing use, and shortening duration,” Dr. Gage said.

Dr. Maniscalco said that, overall, the changes represent the evolution of the field. “Pediatric hospitalists are taking on far more patients with acute and complex issues,” she explained. “Our skill set is coming into focus.”

Dr. Gage added that there is an increased need for pediatric hospitalists to be adept at “managing acute psychiatric care and navigating the mental health care arena.”

There’s also the growing need for an understanding of neonatal abstinence and opioid withdrawal syndrome. “This is definitely a hot topic and one that most hospitalists must address today,” Dr. Gage said. “That wasn’t the case a decade ago.”

Hospital care for pediatrics today often means a team effort, including pediatric hospitalists, surgeons, mental health professionals, and others. Often missing from the picture today are primary care physicians, who instead refer a growing percentage of their patients to hospitalists. The pediatric hospitalist’s role has evolved and grown from what it was 10 years ago, as reflected in the competencies.

“We are very much coordinating care and collaborating today in ways we weren’t 10 years ago,” said Dr. Gage. “There’s a lot more attention on creating partnerships. While we may not always be the ones performing procedures, we will most likely take part in patient care, especially as surgeons step farther away from care outside of the OR.”

The field has also become more family centered, said Dr. Gage. “All of health care today is more astute about the participation of families in care,” she said. “We kept that in mind in developing the competencies.”

Also important in this set of competencies was the concept of high-value care using evidence-based medicine.

Into the field

How exactly the core competencies will be utilized from one hospital or setting to the next will vary, said Dr. Fisher. “For some sites, they can aid existing teaching programs, and they will most likely adapt their curriculum to address the new competencies, informing how they teach.”

Even in centers where there isn’t a formal academic role, teaching still occurs. “Pediatric hospitalists have roles on committees and projects, and giving a talk to respiratory therapists, having group meetings – these all involve teaching in some form,” Dr. Fisher said. “Most physicians will determine how they wish to insert the competencies into their own education, as well as use them to educate others.”

Regardless of how they may be used locally, Dr. Fisher anticipates that the entire pediatric hospitalist community will appreciate the updates. “The competencies address our rapidly changing health care environment,” she said. “We believe the field will benefit from the additions and changes.”

Indeed, the core competencies will help standardize and improve consistency of care across the board. Improved efficiencies, economics, and practices are all desired and expected outcomes from the release of the revised competencies.

To ensure that the changes to the competencies are highlighted in settings nationwide, the editors and associate editors hope to present about them at upcoming conferences, including at the SHM 2020 Annual Conference, the Pediatric Hospital Medicine conference, the Pediatric Academic Societies conference, and the American Pediatric Association.

“We want to present to as many venues as possible to bring people up to speed and ensure they are aware of the changes,” Dr. Teferi said. “We’ll be including workshops with visual aids, along with our presentations.”

While this update represents a 10-year evolution, the editors and the SHM Pediatric Special Interest Group do not have an exact time frame for when the core competencies will need another revision. As quickly as the profession is developing, it may be as few as 5 years, but may also be another full decade.

“Like most fields, we will continue to evolve as our roles become better defined and we gain more knowledge,” Dr. Maniscalco said. “The core competencies represent the field whether a senior pediatric hospitalist, a fellow, or an educator. They bring the field together and provide education for everyone. That’s their role.”

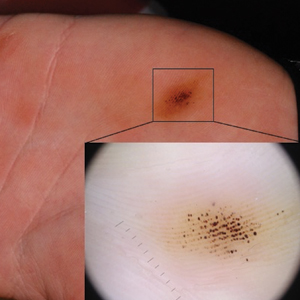

Rash on hands and feet

Lichenoid dermatoses are a heterogeneous group of diseases with varying clinical presentations. The term “lichenoid” refers to the popular lesions of certain skin disorders of which lichen planus (LP) is the prototype. The papules are shiny, flat topped, polygonal, of different sizes, and occur in clusters creating a pattern that resembles lichen growing on a rock. Lichenoid eruptions are quite common in children and can result from many different origins. In most instances the precise mechanism of disease is not known, although it is usually believed to be immunologic in nature. Certain disorders are common in children, whereas others more often affect the adult population.

Lichen striatus, lichen nitidus (LN), and lichen spinulosus are lichenoid lesions that are more common in children than adults.

LN – as seen in the patient described here – is an uncommon benign inflammatory skin disease, primarily of children. Individual lesions are sharply demarcated, pinpoint to pinhead sized, round or polygonal, and strikingly monomorphous in nature. The papules are usually flesh colored, however, the color varies from yellow and brown to violet hues depending on the background color of the patient’s skin. This variation in color is in contrast with LP which is characteristically violaceous. The surfaces of the papules are flat, shiny, and slightly elevated. They may have a fine scale or a hyperkeratotic plug. The lesions tend to occur in groups, primarily on the abdomen, chest, glans penis, and upper extremities. The Koebner phenomenon is observed and is a hallmark for the disorder. LN is generally asymptomatic, unlike LP, which is exceedingly pruritic.

The cause of LN is unknown; however, it has been proposed that LN, in particular generalized LN, may be associated with immune alterations in the patient. The course of LN is slowly progressive with a tendency toward remission. The lesions can remain stationary for years; however, they sometimes disappear spontaneously and completely.

The differential diagnosis of LN beyond the entities discussed above includes frictional lichenoid eruption, lichenoid drug eruption, LP, and keratosis pilaris.

LP is the classic lichenoid eruption. It is rare in children and occurs most frequently in individuals aged 30-60 years. LP usually manifests as an extremely pruritic eruption of flat-topped polygonal and violaceous papules that often have fine linear white scales known as Wickham striae. The distribution is usually bilateral and symmetric with most of the papules and plaques located on the legs, flexor wrists, neck, and genitalia. The lesions may exhibit the Koebner phenomenon, appearing in a linear pattern along the site of a scratch. Generally, in childhood cases there is reported itching, and oral and nail lesions are less common.

Frictional lichenoid eruption occurs in childhood. The lesions consist of lichenoid papules with regular borders 1-2 mm in diameter that generally are asymptomatic, although they may be mildly pruritic. The papules are found in a very characteristic distribution with almost exclusive involvement of the backs of the hands, fingers, elbows, and knees with occasional involvement of the extensor forearms and cheeks. This disorder occurs in predisposed children who have been exposed to significant frictional force during play, and typically resolves spontaneously after removal of the stimulus.

Keratosis pilaris is a rash that usually is found on the outer areas of the upper arms, upper thighs, buttocks, and cheeks. It consists of small bumps that are flesh colored to red. The bumps generally don’t hurt or itch.

The lack of symptoms and spontaneous healing have rendered treatment unnecessary in most cases. LN generally is self-limiting, thus treatment may not be necessary. However, topical treatment with mid- to high-potency corticosteroids has hastened resolution of lesions in some children, as have topical dinitrochlorobenzene and systemic treatment with psoralens, astemizole, etretinate, and psoralen-UVA.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Eichenfield nor Dr. Bhatti has any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

Pickert A. Cutis. 2012 Sep;90(3):E1-3. https://mdedge-files-live.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/files/s3fs-public/Document/September-2017/0900300E1.pdf Tziotzios C et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Nov;79(5):789-804. Tilly JJ et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Oct;51(4):606-24.

Lichenoid dermatoses are a heterogeneous group of diseases with varying clinical presentations. The term “lichenoid” refers to the popular lesions of certain skin disorders of which lichen planus (LP) is the prototype. The papules are shiny, flat topped, polygonal, of different sizes, and occur in clusters creating a pattern that resembles lichen growing on a rock. Lichenoid eruptions are quite common in children and can result from many different origins. In most instances the precise mechanism of disease is not known, although it is usually believed to be immunologic in nature. Certain disorders are common in children, whereas others more often affect the adult population.

Lichen striatus, lichen nitidus (LN), and lichen spinulosus are lichenoid lesions that are more common in children than adults.

LN – as seen in the patient described here – is an uncommon benign inflammatory skin disease, primarily of children. Individual lesions are sharply demarcated, pinpoint to pinhead sized, round or polygonal, and strikingly monomorphous in nature. The papules are usually flesh colored, however, the color varies from yellow and brown to violet hues depending on the background color of the patient’s skin. This variation in color is in contrast with LP which is characteristically violaceous. The surfaces of the papules are flat, shiny, and slightly elevated. They may have a fine scale or a hyperkeratotic plug. The lesions tend to occur in groups, primarily on the abdomen, chest, glans penis, and upper extremities. The Koebner phenomenon is observed and is a hallmark for the disorder. LN is generally asymptomatic, unlike LP, which is exceedingly pruritic.

The cause of LN is unknown; however, it has been proposed that LN, in particular generalized LN, may be associated with immune alterations in the patient. The course of LN is slowly progressive with a tendency toward remission. The lesions can remain stationary for years; however, they sometimes disappear spontaneously and completely.

The differential diagnosis of LN beyond the entities discussed above includes frictional lichenoid eruption, lichenoid drug eruption, LP, and keratosis pilaris.

LP is the classic lichenoid eruption. It is rare in children and occurs most frequently in individuals aged 30-60 years. LP usually manifests as an extremely pruritic eruption of flat-topped polygonal and violaceous papules that often have fine linear white scales known as Wickham striae. The distribution is usually bilateral and symmetric with most of the papules and plaques located on the legs, flexor wrists, neck, and genitalia. The lesions may exhibit the Koebner phenomenon, appearing in a linear pattern along the site of a scratch. Generally, in childhood cases there is reported itching, and oral and nail lesions are less common.

Frictional lichenoid eruption occurs in childhood. The lesions consist of lichenoid papules with regular borders 1-2 mm in diameter that generally are asymptomatic, although they may be mildly pruritic. The papules are found in a very characteristic distribution with almost exclusive involvement of the backs of the hands, fingers, elbows, and knees with occasional involvement of the extensor forearms and cheeks. This disorder occurs in predisposed children who have been exposed to significant frictional force during play, and typically resolves spontaneously after removal of the stimulus.

Keratosis pilaris is a rash that usually is found on the outer areas of the upper arms, upper thighs, buttocks, and cheeks. It consists of small bumps that are flesh colored to red. The bumps generally don’t hurt or itch.

The lack of symptoms and spontaneous healing have rendered treatment unnecessary in most cases. LN generally is self-limiting, thus treatment may not be necessary. However, topical treatment with mid- to high-potency corticosteroids has hastened resolution of lesions in some children, as have topical dinitrochlorobenzene and systemic treatment with psoralens, astemizole, etretinate, and psoralen-UVA.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Eichenfield nor Dr. Bhatti has any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

Pickert A. Cutis. 2012 Sep;90(3):E1-3. https://mdedge-files-live.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/files/s3fs-public/Document/September-2017/0900300E1.pdf Tziotzios C et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Nov;79(5):789-804. Tilly JJ et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Oct;51(4):606-24.

Lichenoid dermatoses are a heterogeneous group of diseases with varying clinical presentations. The term “lichenoid” refers to the popular lesions of certain skin disorders of which lichen planus (LP) is the prototype. The papules are shiny, flat topped, polygonal, of different sizes, and occur in clusters creating a pattern that resembles lichen growing on a rock. Lichenoid eruptions are quite common in children and can result from many different origins. In most instances the precise mechanism of disease is not known, although it is usually believed to be immunologic in nature. Certain disorders are common in children, whereas others more often affect the adult population.

Lichen striatus, lichen nitidus (LN), and lichen spinulosus are lichenoid lesions that are more common in children than adults.

LN – as seen in the patient described here – is an uncommon benign inflammatory skin disease, primarily of children. Individual lesions are sharply demarcated, pinpoint to pinhead sized, round or polygonal, and strikingly monomorphous in nature. The papules are usually flesh colored, however, the color varies from yellow and brown to violet hues depending on the background color of the patient’s skin. This variation in color is in contrast with LP which is characteristically violaceous. The surfaces of the papules are flat, shiny, and slightly elevated. They may have a fine scale or a hyperkeratotic plug. The lesions tend to occur in groups, primarily on the abdomen, chest, glans penis, and upper extremities. The Koebner phenomenon is observed and is a hallmark for the disorder. LN is generally asymptomatic, unlike LP, which is exceedingly pruritic.

The cause of LN is unknown; however, it has been proposed that LN, in particular generalized LN, may be associated with immune alterations in the patient. The course of LN is slowly progressive with a tendency toward remission. The lesions can remain stationary for years; however, they sometimes disappear spontaneously and completely.

The differential diagnosis of LN beyond the entities discussed above includes frictional lichenoid eruption, lichenoid drug eruption, LP, and keratosis pilaris.

LP is the classic lichenoid eruption. It is rare in children and occurs most frequently in individuals aged 30-60 years. LP usually manifests as an extremely pruritic eruption of flat-topped polygonal and violaceous papules that often have fine linear white scales known as Wickham striae. The distribution is usually bilateral and symmetric with most of the papules and plaques located on the legs, flexor wrists, neck, and genitalia. The lesions may exhibit the Koebner phenomenon, appearing in a linear pattern along the site of a scratch. Generally, in childhood cases there is reported itching, and oral and nail lesions are less common.

Frictional lichenoid eruption occurs in childhood. The lesions consist of lichenoid papules with regular borders 1-2 mm in diameter that generally are asymptomatic, although they may be mildly pruritic. The papules are found in a very characteristic distribution with almost exclusive involvement of the backs of the hands, fingers, elbows, and knees with occasional involvement of the extensor forearms and cheeks. This disorder occurs in predisposed children who have been exposed to significant frictional force during play, and typically resolves spontaneously after removal of the stimulus.

Keratosis pilaris is a rash that usually is found on the outer areas of the upper arms, upper thighs, buttocks, and cheeks. It consists of small bumps that are flesh colored to red. The bumps generally don’t hurt or itch.

The lack of symptoms and spontaneous healing have rendered treatment unnecessary in most cases. LN generally is self-limiting, thus treatment may not be necessary. However, topical treatment with mid- to high-potency corticosteroids has hastened resolution of lesions in some children, as have topical dinitrochlorobenzene and systemic treatment with psoralens, astemizole, etretinate, and psoralen-UVA.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Bhatti is a research fellow in pediatric dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego. Neither Dr. Eichenfield nor Dr. Bhatti has any relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

References

Pickert A. Cutis. 2012 Sep;90(3):E1-3. https://mdedge-files-live.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/files/s3fs-public/Document/September-2017/0900300E1.pdf Tziotzios C et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Nov;79(5):789-804. Tilly JJ et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004 Oct;51(4):606-24.

A 9-year-old healthy Kuwaiti male with no significant past medical history presents with a rash on his hands and feet that has been present for 3 years.

His mother reports that he has been seen by dermatologists in various countries and was last seen by a dermatologist in Kuwait 3 years ago. At that time, he was told that it was dryness and advised to not shower daily. Since then he has been taking showers three times weekly and using Cetaphil once weekly without improvement. He was seen by his pediatrician 6 months ago, diagnosed with xerosis, and was given hydrocortisone 2.5% to use twice daily, again without any improvement.

The rash is not itchy, and he has no oral lesions or nail involvement. Exam revealed lichenoid papules on bilateral dorsal hands and feet, bilateral upper arms, bilateral axilla, lower abdomen, and left upper chest.

Community pediatric care is diminishing

The mantra of community hospital administrators is that pediatric care does not pay. Neonatal intensive care pays. For pediatrics, it is similar to how football programs (Medicare patients) support minor sports (pediatrics and obstetrics) at colleges. However, fewer even mildly sick newborns are cared for at community hospitals, which has led to a centralization of neonatal and pediatric care and a loss of pediatric expertise at the affected hospitals.

Pediatric hospitalists are hired to cover the pediatric floor, the emergency department, and labor and delivery, then fired over empty pediatric beds. The rationale expressed is that pediatricians have done such a good job in preventive care that children rarely need hospitalization, so why have a pediatric inpatient unit? It is true that preventive care has been an integral part of primary care for children. Significantly less that 1% of child office visits result in hospitalization.

Advocate Health Care has closed inpatient pediatric units at Illinois Masonic, on Chicago’s North Side, Good Samaritan in Downers Grove, and Good Shepherd in Barrington. Units also have been closed at Mount Sinai in North Lawndale, Norwegian American on Chicago’s West Side, Little Company of Mary in Evergreen Park, and Alexian Brothers in Elk Grove.

As a Chicago-area pediatrician for more than 30 years, I have learned several things about community-based pediatric care:

1. Pediatrics is a geographic specialty. Parents will travel to shop, but would rather walk or have a short ride to their children’s medical providers. Secondary care should be community based, and hospitalization, if necessary, should be close by as well.

2. Hospitals that ceased delivering pediatric inpatient care lost their child-friendliness and pediatric competence, becoming uncomfortable delivering almost any care for children (e.g., sedated MRIs and EEGs, x-rays and ultrasounds, ECGs and echocardiograms, and emergency care).

3. In almost all hospitals, after pediatrics was gone eventually so passed obstetrics (another less remunerative specialty). Sick newborns need immediate, competent care. Most pediatric hospitalizations are short term, often overnight. Delaying newborn care is a medicolegal nightmare. and exposes the child and his or her family to a potentially dangerous drive or helicopter ride.

4. As pediatric subspecialty care becomes more centralized, parents are asked to travel for hours to see a pediatric specialist. There are times when that is necessary (e.g., cardiovascular surgery). Pediatric subspecialists, such as pediatric otolaryngologists, then leave community hospitals, forcing even minor surgeries (e.g., ear ventilation tubes) to be done at a center. In rural areas, this could mean hours of travel, lost work days, and family disruption.

5. Children’s hospitals get uninsured and publicly insured children sent hundreds of miles, because there were no subspecialists in the community who would care for these children.

What is the solution, in our profit-focused health care system?

1. Hospitals’ Certificates of Need could include a mandate for pediatric care.

2. Children’s hospitals could be made responsible for community-based care within their geographic catchment areas.

3. The state or the federal government could mandate and financially support community-based hospital care.

4. Deciding what level of care might be appropriate for each community could depend upon closeness to a pediatric hospital, health problems in the community, and the availability of pediatric specialists.

5. A condition for medical licensure might be that a community-based pediatric subspecialist is required to care for a proportion of the uninsured or publicly insured children in his or her area.

6. Reimbursements for pediatric care need to rise enough to make caring for children worth it.

The major decision point regarding care for children cannot be financial, but must instead embrace the needs of each affected community. If quality health care is a right, and not a privilege, then it is time to stop closing pediatric inpatient units, and, instead, look for creative ways to better care for our children.

This process has led to pediatric care being available only in designated centers. The centralization of pediatric care has progressed from 30 years ago, when most community hospitals had inpatient pediatric units, to the search for innovative ways to fill pediatric beds in the mid-90s (sick day care, flex- or shared pediatric units), to the wholesale closure of community pediatric inpatient beds, from 2000 to the present. I have, unfortunately, seen this firsthand, watching the rise of pediatric mega-hospitals and the demise of community pediatrics. It is a simple financial argument. Care for children simply does not pay nearly as well as does care for adults, especially Medicaid patients. Pediatricians are the poorest paid practicing doctors (public health doctors are paid less).

It is true that pediatricians always have been at the forefront of preventive medicine, and that pediatric patients almost always get better, in spite of our best-intentioned interventions. So community-based pediatricians admit very few patients.

With the loss of pediatric units, community hospitals lose their comfort caring for children. This includes phlebotomy, x-ray, trauma, surgery, and behavioral health. And eroding community hospital pediatric expertise has catastrophic implications for rural hospitals, where parents may have to drive for hours to find a child-friendly emergency department.

Is there an answer?

1. Hospitals are responsible for the patients they serve, including children. Why should a hospital be able to close pediatric services so easily?

2. Every hospital that sees children, through the emergency department, needs to have a pediatrician available to evaluate a child, 24/7.

3. There needs to be an observation unit for children, with pediatric staffing, for overnight stays.

4. Pediatric hospitalists should be staffing community hospitals.

5. Pediatric behavioral health resources need to be available, e.g., inpatient psychiatry, partial hospitalization programs, intensive outpatient programs.

6. Telehealth communication is not adequate to address acute care problems, because the hospital caring for the child has to have the proper equipment and adequate expertise to carry out the recommendations of the teleconsultant.

If we accept that our children will shape the future, we must allow them to survive and thrive. Is health care a right or a privilege, and is it just for adults or for children, too?

Dr. Ochs is in private practice at Ravenswood Pediatrics in Chicago. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

The mantra of community hospital administrators is that pediatric care does not pay. Neonatal intensive care pays. For pediatrics, it is similar to how football programs (Medicare patients) support minor sports (pediatrics and obstetrics) at colleges. However, fewer even mildly sick newborns are cared for at community hospitals, which has led to a centralization of neonatal and pediatric care and a loss of pediatric expertise at the affected hospitals.

Pediatric hospitalists are hired to cover the pediatric floor, the emergency department, and labor and delivery, then fired over empty pediatric beds. The rationale expressed is that pediatricians have done such a good job in preventive care that children rarely need hospitalization, so why have a pediatric inpatient unit? It is true that preventive care has been an integral part of primary care for children. Significantly less that 1% of child office visits result in hospitalization.

Advocate Health Care has closed inpatient pediatric units at Illinois Masonic, on Chicago’s North Side, Good Samaritan in Downers Grove, and Good Shepherd in Barrington. Units also have been closed at Mount Sinai in North Lawndale, Norwegian American on Chicago’s West Side, Little Company of Mary in Evergreen Park, and Alexian Brothers in Elk Grove.

As a Chicago-area pediatrician for more than 30 years, I have learned several things about community-based pediatric care:

1. Pediatrics is a geographic specialty. Parents will travel to shop, but would rather walk or have a short ride to their children’s medical providers. Secondary care should be community based, and hospitalization, if necessary, should be close by as well.

2. Hospitals that ceased delivering pediatric inpatient care lost their child-friendliness and pediatric competence, becoming uncomfortable delivering almost any care for children (e.g., sedated MRIs and EEGs, x-rays and ultrasounds, ECGs and echocardiograms, and emergency care).

3. In almost all hospitals, after pediatrics was gone eventually so passed obstetrics (another less remunerative specialty). Sick newborns need immediate, competent care. Most pediatric hospitalizations are short term, often overnight. Delaying newborn care is a medicolegal nightmare. and exposes the child and his or her family to a potentially dangerous drive or helicopter ride.

4. As pediatric subspecialty care becomes more centralized, parents are asked to travel for hours to see a pediatric specialist. There are times when that is necessary (e.g., cardiovascular surgery). Pediatric subspecialists, such as pediatric otolaryngologists, then leave community hospitals, forcing even minor surgeries (e.g., ear ventilation tubes) to be done at a center. In rural areas, this could mean hours of travel, lost work days, and family disruption.

5. Children’s hospitals get uninsured and publicly insured children sent hundreds of miles, because there were no subspecialists in the community who would care for these children.

What is the solution, in our profit-focused health care system?

1. Hospitals’ Certificates of Need could include a mandate for pediatric care.

2. Children’s hospitals could be made responsible for community-based care within their geographic catchment areas.

3. The state or the federal government could mandate and financially support community-based hospital care.

4. Deciding what level of care might be appropriate for each community could depend upon closeness to a pediatric hospital, health problems in the community, and the availability of pediatric specialists.

5. A condition for medical licensure might be that a community-based pediatric subspecialist is required to care for a proportion of the uninsured or publicly insured children in his or her area.

6. Reimbursements for pediatric care need to rise enough to make caring for children worth it.

The major decision point regarding care for children cannot be financial, but must instead embrace the needs of each affected community. If quality health care is a right, and not a privilege, then it is time to stop closing pediatric inpatient units, and, instead, look for creative ways to better care for our children.

This process has led to pediatric care being available only in designated centers. The centralization of pediatric care has progressed from 30 years ago, when most community hospitals had inpatient pediatric units, to the search for innovative ways to fill pediatric beds in the mid-90s (sick day care, flex- or shared pediatric units), to the wholesale closure of community pediatric inpatient beds, from 2000 to the present. I have, unfortunately, seen this firsthand, watching the rise of pediatric mega-hospitals and the demise of community pediatrics. It is a simple financial argument. Care for children simply does not pay nearly as well as does care for adults, especially Medicaid patients. Pediatricians are the poorest paid practicing doctors (public health doctors are paid less).

It is true that pediatricians always have been at the forefront of preventive medicine, and that pediatric patients almost always get better, in spite of our best-intentioned interventions. So community-based pediatricians admit very few patients.

With the loss of pediatric units, community hospitals lose their comfort caring for children. This includes phlebotomy, x-ray, trauma, surgery, and behavioral health. And eroding community hospital pediatric expertise has catastrophic implications for rural hospitals, where parents may have to drive for hours to find a child-friendly emergency department.

Is there an answer?