User login

Nasal Tanning Sprays: Illuminating the Risks of a Popular TikTok Trend

Nasal tanning spray is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining popularity among consumers on TikTok and other social media platforms. The active ingredient in the tanning spray is melanotan II—a synthetic analog of α‒melanocyte-stimulating hormone,1,2 a naturally occurring hormone responsible for skin pigmentation. α‒Melanocyte-stimulating hormone is a derivative of the precursor proopiomelanocortin, an agonist on the melanocortin-1 receptor that promotes formation of eumelanin.1,3 Eumelanin then provides pigmentation to the skin.3 Apart from its use for tanning, melanotan II has been reported to increase sexual function and aid in weight loss.1

Melanotan II is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration; however, injectable formulations can be obtained illegally on the Internet as well as at some tanning salons and beauty parlors.4 Although injectable forms of melanotan II have been used for years to artificially increase skin pigmentation, the newly hyped nasal tanning sprays are drawing the attention of consumers. The synthetic chemical spray is inhaled into the nasal mucosae, where it is readily absorbed into the bloodstream to act on melanocortin receptors throughout the body, thus enhancing skin pigmentation.2 Because melanotan II is not approved, there is no guarantee that the product purchased from those sources is pure; therefore, consumers risk inhaling or injecting contaminated chemicals.5

In a 2017 study, Kirk and Greenfield6 cited self-image as a common concern among participants who expressed a preference for appearing tanned.6 Societal influence and standards to which young adults, particularly young women, often are accustomed drive some to take steps to achieve tanned skin, which they view as more attractive and healthier than untanned skin.7,8

Social media consumption is a significant risk factor for developing or exacerbating body dissatisfaction among impressionable teenagers and young adults, who may be less risk averse and therefore choose to embrace trends such as nasal tanning sprays to enhance their appearance, without considering possible consequences. Most young adults, and even teens, are aware of the risks associated with tanning beds, which may propel them to seek out what they perceive as a less-risky tanning alternative such as a tanner delivered via a nasal route, but it is unlikely that this group is fully informed about the possible dangers of nasal tanning sprays.

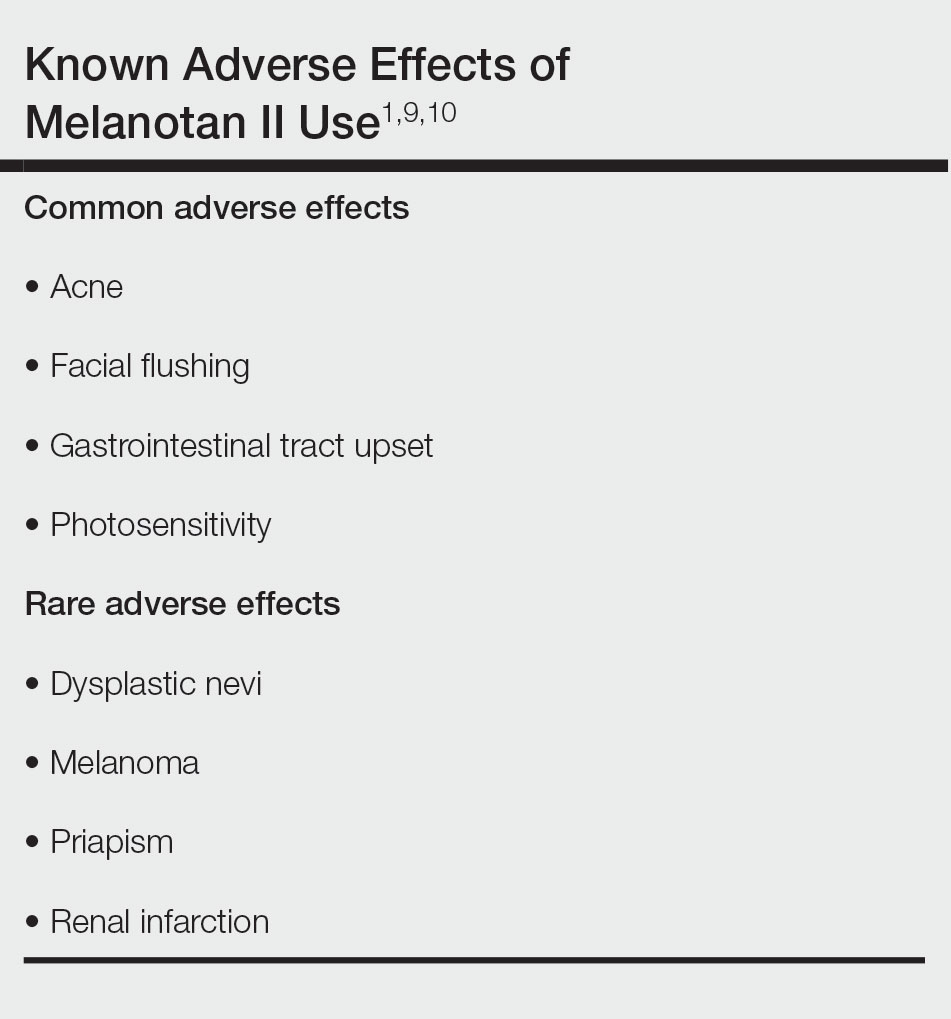

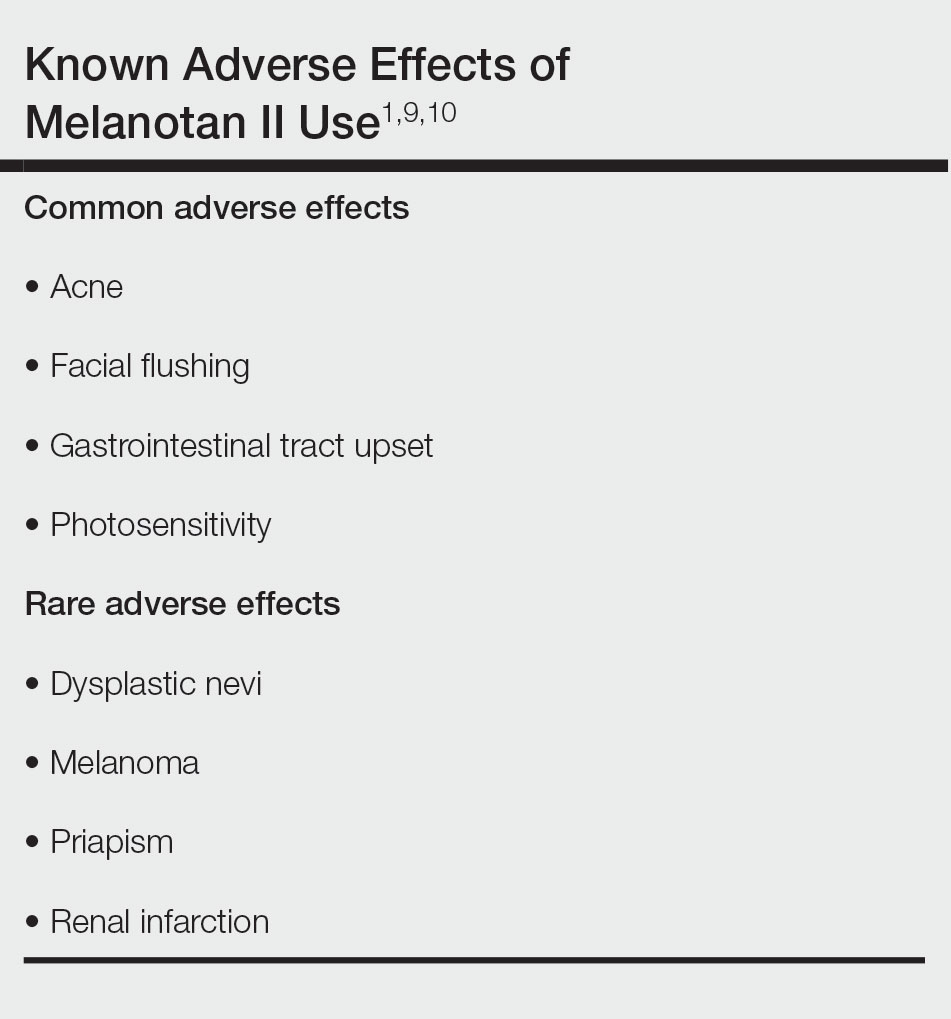

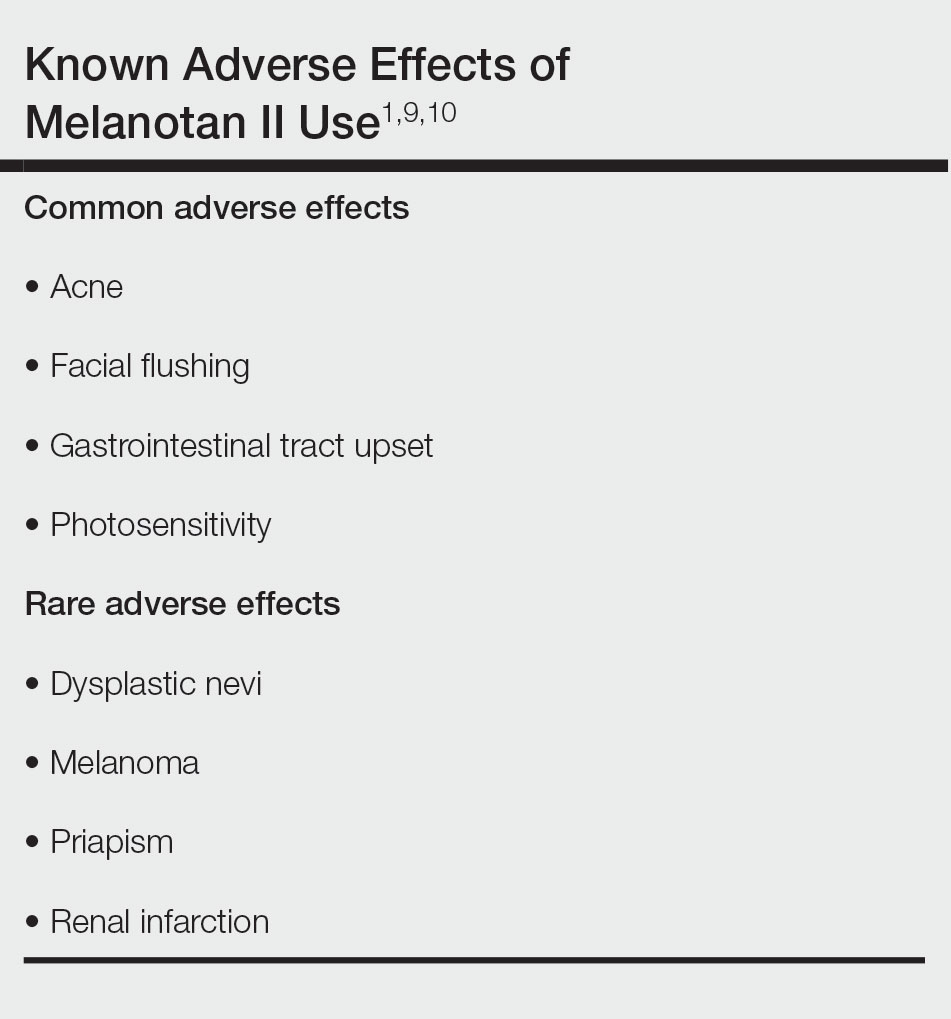

It is crucial for dermatologists and other clinicians to provide awareness and education about the potential harm of nasal tanning sprays. Along with the general risks of using an unregulated substance, common adverse effects include acne, facial flushing, gastrointestinal tract upset, and sensitivity to sunlight (Table).1,9,10 Several case reports have linked melanotan II to cutaneous changes, including dysplastic nevi and even melanoma.1 Less common complications, such as renal infarction and priapism, also have been observed with melanotan II use.9,10

Even with the known risks involving tanning beds and skin cancer, an analysis by Kream et al11 in 2020 showed that 90% (441/488) of tanning-related videos on TikTok promoted a positive view of tanning. Of these TikTok videos involving pro-tanning trends, 3% (12/441) were specifically about melanotan II nasal spray, injection, or both, which has only become more popular since this study was published.11

Dermatologists should be aware of the impact that tanning trends, such as nasal tanning spray, can have on all patients and initiate discussions regarding the risks of using these products with patients as appropriate. Alternatives to nasal tanning sprays such as spray-on tans and self-tanning lotions are safer ways for patients to achieve a tanned look without the health risks associated with melanotan II.

- Habbema L, Halk AB, Neumann M, et al. Risks of unregulated use of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogues: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:975-980. doi:10.1111/ijd.13585

- Why you should never use nasal tanning spray. Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials [Internet]. November 1, 2022. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/nasal-tanning-spray

- Hjuler KF, Lorentzen HF. Melanoma associated with the use of melanotan-II. Dermatology. 2014;228:34-36. doi:10.1159/000356389

- Evans-Brown M, Dawson RT, Chandler M, et al. Use of melanotan I and II in the general population. BMJ. 2009;338:b566. doi:10.116/bmj.b566

- Callaghan DJ III. A glimpse into the underground market of melanotan. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:1-5. doi:10.5070/D3245040036

- Kirk L, Greenfield S. Knowledge and attitudes of UK university students in relation to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure and their sun-related behaviours: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014388. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014388

- Hay JL, Geller AC, Schoenhammer M, et al. Tanning and beauty: mother and teenage daughters in discussion. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1261-1270. doi:10.1177/1359105314551621

- Gillen MM, Markey CN. The role of body image and depression in tanning behaviors and attitudes. Behav Med. 2017;38:74-82.

- Peters B, Hadimeri H, Wahlberg R, et al. Melanotan II: a possible cause of renal infarction: review of the literature and case report. CEN Case Rep. 2020;9:159-161. doi:10.1007/s13730-020-00447-z

- Mallory CW, Lopategui DM, Cordon BH. Melanotan tanning injection: a rare cause of priapism. Sex Med. 2021;9:100298. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100298

- Kream E, Watchmaker JD, Dover JS. TikTok sheds light on tanning: tanning is still popular and emerging trends pose new risks. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1018-1021. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003549

Nasal tanning spray is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining popularity among consumers on TikTok and other social media platforms. The active ingredient in the tanning spray is melanotan II—a synthetic analog of α‒melanocyte-stimulating hormone,1,2 a naturally occurring hormone responsible for skin pigmentation. α‒Melanocyte-stimulating hormone is a derivative of the precursor proopiomelanocortin, an agonist on the melanocortin-1 receptor that promotes formation of eumelanin.1,3 Eumelanin then provides pigmentation to the skin.3 Apart from its use for tanning, melanotan II has been reported to increase sexual function and aid in weight loss.1

Melanotan II is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration; however, injectable formulations can be obtained illegally on the Internet as well as at some tanning salons and beauty parlors.4 Although injectable forms of melanotan II have been used for years to artificially increase skin pigmentation, the newly hyped nasal tanning sprays are drawing the attention of consumers. The synthetic chemical spray is inhaled into the nasal mucosae, where it is readily absorbed into the bloodstream to act on melanocortin receptors throughout the body, thus enhancing skin pigmentation.2 Because melanotan II is not approved, there is no guarantee that the product purchased from those sources is pure; therefore, consumers risk inhaling or injecting contaminated chemicals.5

In a 2017 study, Kirk and Greenfield6 cited self-image as a common concern among participants who expressed a preference for appearing tanned.6 Societal influence and standards to which young adults, particularly young women, often are accustomed drive some to take steps to achieve tanned skin, which they view as more attractive and healthier than untanned skin.7,8

Social media consumption is a significant risk factor for developing or exacerbating body dissatisfaction among impressionable teenagers and young adults, who may be less risk averse and therefore choose to embrace trends such as nasal tanning sprays to enhance their appearance, without considering possible consequences. Most young adults, and even teens, are aware of the risks associated with tanning beds, which may propel them to seek out what they perceive as a less-risky tanning alternative such as a tanner delivered via a nasal route, but it is unlikely that this group is fully informed about the possible dangers of nasal tanning sprays.

It is crucial for dermatologists and other clinicians to provide awareness and education about the potential harm of nasal tanning sprays. Along with the general risks of using an unregulated substance, common adverse effects include acne, facial flushing, gastrointestinal tract upset, and sensitivity to sunlight (Table).1,9,10 Several case reports have linked melanotan II to cutaneous changes, including dysplastic nevi and even melanoma.1 Less common complications, such as renal infarction and priapism, also have been observed with melanotan II use.9,10

Even with the known risks involving tanning beds and skin cancer, an analysis by Kream et al11 in 2020 showed that 90% (441/488) of tanning-related videos on TikTok promoted a positive view of tanning. Of these TikTok videos involving pro-tanning trends, 3% (12/441) were specifically about melanotan II nasal spray, injection, or both, which has only become more popular since this study was published.11

Dermatologists should be aware of the impact that tanning trends, such as nasal tanning spray, can have on all patients and initiate discussions regarding the risks of using these products with patients as appropriate. Alternatives to nasal tanning sprays such as spray-on tans and self-tanning lotions are safer ways for patients to achieve a tanned look without the health risks associated with melanotan II.

Nasal tanning spray is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining popularity among consumers on TikTok and other social media platforms. The active ingredient in the tanning spray is melanotan II—a synthetic analog of α‒melanocyte-stimulating hormone,1,2 a naturally occurring hormone responsible for skin pigmentation. α‒Melanocyte-stimulating hormone is a derivative of the precursor proopiomelanocortin, an agonist on the melanocortin-1 receptor that promotes formation of eumelanin.1,3 Eumelanin then provides pigmentation to the skin.3 Apart from its use for tanning, melanotan II has been reported to increase sexual function and aid in weight loss.1

Melanotan II is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration; however, injectable formulations can be obtained illegally on the Internet as well as at some tanning salons and beauty parlors.4 Although injectable forms of melanotan II have been used for years to artificially increase skin pigmentation, the newly hyped nasal tanning sprays are drawing the attention of consumers. The synthetic chemical spray is inhaled into the nasal mucosae, where it is readily absorbed into the bloodstream to act on melanocortin receptors throughout the body, thus enhancing skin pigmentation.2 Because melanotan II is not approved, there is no guarantee that the product purchased from those sources is pure; therefore, consumers risk inhaling or injecting contaminated chemicals.5

In a 2017 study, Kirk and Greenfield6 cited self-image as a common concern among participants who expressed a preference for appearing tanned.6 Societal influence and standards to which young adults, particularly young women, often are accustomed drive some to take steps to achieve tanned skin, which they view as more attractive and healthier than untanned skin.7,8

Social media consumption is a significant risk factor for developing or exacerbating body dissatisfaction among impressionable teenagers and young adults, who may be less risk averse and therefore choose to embrace trends such as nasal tanning sprays to enhance their appearance, without considering possible consequences. Most young adults, and even teens, are aware of the risks associated with tanning beds, which may propel them to seek out what they perceive as a less-risky tanning alternative such as a tanner delivered via a nasal route, but it is unlikely that this group is fully informed about the possible dangers of nasal tanning sprays.

It is crucial for dermatologists and other clinicians to provide awareness and education about the potential harm of nasal tanning sprays. Along with the general risks of using an unregulated substance, common adverse effects include acne, facial flushing, gastrointestinal tract upset, and sensitivity to sunlight (Table).1,9,10 Several case reports have linked melanotan II to cutaneous changes, including dysplastic nevi and even melanoma.1 Less common complications, such as renal infarction and priapism, also have been observed with melanotan II use.9,10

Even with the known risks involving tanning beds and skin cancer, an analysis by Kream et al11 in 2020 showed that 90% (441/488) of tanning-related videos on TikTok promoted a positive view of tanning. Of these TikTok videos involving pro-tanning trends, 3% (12/441) were specifically about melanotan II nasal spray, injection, or both, which has only become more popular since this study was published.11

Dermatologists should be aware of the impact that tanning trends, such as nasal tanning spray, can have on all patients and initiate discussions regarding the risks of using these products with patients as appropriate. Alternatives to nasal tanning sprays such as spray-on tans and self-tanning lotions are safer ways for patients to achieve a tanned look without the health risks associated with melanotan II.

- Habbema L, Halk AB, Neumann M, et al. Risks of unregulated use of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogues: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:975-980. doi:10.1111/ijd.13585

- Why you should never use nasal tanning spray. Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials [Internet]. November 1, 2022. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/nasal-tanning-spray

- Hjuler KF, Lorentzen HF. Melanoma associated with the use of melanotan-II. Dermatology. 2014;228:34-36. doi:10.1159/000356389

- Evans-Brown M, Dawson RT, Chandler M, et al. Use of melanotan I and II in the general population. BMJ. 2009;338:b566. doi:10.116/bmj.b566

- Callaghan DJ III. A glimpse into the underground market of melanotan. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:1-5. doi:10.5070/D3245040036

- Kirk L, Greenfield S. Knowledge and attitudes of UK university students in relation to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure and their sun-related behaviours: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014388. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014388

- Hay JL, Geller AC, Schoenhammer M, et al. Tanning and beauty: mother and teenage daughters in discussion. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1261-1270. doi:10.1177/1359105314551621

- Gillen MM, Markey CN. The role of body image and depression in tanning behaviors and attitudes. Behav Med. 2017;38:74-82.

- Peters B, Hadimeri H, Wahlberg R, et al. Melanotan II: a possible cause of renal infarction: review of the literature and case report. CEN Case Rep. 2020;9:159-161. doi:10.1007/s13730-020-00447-z

- Mallory CW, Lopategui DM, Cordon BH. Melanotan tanning injection: a rare cause of priapism. Sex Med. 2021;9:100298. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100298

- Kream E, Watchmaker JD, Dover JS. TikTok sheds light on tanning: tanning is still popular and emerging trends pose new risks. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1018-1021. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003549

- Habbema L, Halk AB, Neumann M, et al. Risks of unregulated use of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogues: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:975-980. doi:10.1111/ijd.13585

- Why you should never use nasal tanning spray. Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials [Internet]. November 1, 2022. Accessed December 18, 2023. https://health.clevelandclinic.org/nasal-tanning-spray

- Hjuler KF, Lorentzen HF. Melanoma associated with the use of melanotan-II. Dermatology. 2014;228:34-36. doi:10.1159/000356389

- Evans-Brown M, Dawson RT, Chandler M, et al. Use of melanotan I and II in the general population. BMJ. 2009;338:b566. doi:10.116/bmj.b566

- Callaghan DJ III. A glimpse into the underground market of melanotan. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:1-5. doi:10.5070/D3245040036

- Kirk L, Greenfield S. Knowledge and attitudes of UK university students in relation to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) exposure and their sun-related behaviours: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014388. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014388

- Hay JL, Geller AC, Schoenhammer M, et al. Tanning and beauty: mother and teenage daughters in discussion. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:1261-1270. doi:10.1177/1359105314551621

- Gillen MM, Markey CN. The role of body image and depression in tanning behaviors and attitudes. Behav Med. 2017;38:74-82.

- Peters B, Hadimeri H, Wahlberg R, et al. Melanotan II: a possible cause of renal infarction: review of the literature and case report. CEN Case Rep. 2020;9:159-161. doi:10.1007/s13730-020-00447-z

- Mallory CW, Lopategui DM, Cordon BH. Melanotan tanning injection: a rare cause of priapism. Sex Med. 2021;9:100298. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100298

- Kream E, Watchmaker JD, Dover JS. TikTok sheds light on tanning: tanning is still popular and emerging trends pose new risks. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:1018-1021. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003549

PRACTICE POINTS

- Although tanning beds are arguably the most common and dangerous method used by patients to tan their skin, dermatologists should be aware of the other means by which patients may artificially increase skin pigmentation and the risks imposed by undertaking such practices.

- We challenge dermatologists to note the influence of social media on tanning trends and consider creating a platform on these mediums to combat misinformation and promote sun safety and skin health.

- We encourage dermatologists to diligently stay informed about the popular societal trends related to the skin such as the use of nasal tanning products (eg, melanotan I and II) and be proactive in discussing their risks with patients as deemed appropriate.

GVHD raises vitiligo risk in transplant recipients

published online in JAMA Dermatology December 13.

In the cohort study, the greatest risk occurred with hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCTs) and in cases involving GVHD. Kidney and liver transplants carried slight increases in risk.

“The findings suggest that early detection and management of vitiligo lesions can be improved by estimating the likelihood of its development in transplant recipients and implementing a multidisciplinary approach for monitoring,” wrote the authors, from the departments of dermatology and biostatistics, at the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul.

Using claims data from South Korea’s National Health Insurance Service database, the investigators compared vitiligo incidence among 23,829 patients who had undergone solid organ transplantation (SOT) or HSCT between 2010 and 2017 versus that of 119,145 age- and sex-matched controls. At a mean observation time of 4.79 years in the transplant group (and 5.12 years for controls), the adjusted hazard ratio (AHR) for vitiligo among patients who had undergone any transplant was 1.73. AHRs for HSCT, liver transplants, and kidney transplants were 12.69, 1.63, and 1.50, respectively.

Patients who had undergone allogeneic HSCT (AHR, 14.43) or autologous transplants (AHR, 5.71), as well as those with and without GVHD (24.09 and 8.21, respectively) had significantly higher vitiligo risk than the control group.

Among those with GVHD, HSCT recipients (AHR, 16.42) and those with allogeneic grafts (AHR, 16.81) had a higher vitiligo risk than that of control patients.

In a subgroup that included 10,355 transplant recipients who underwent posttransplant health checkups, investigators found the highest vitiligo risk — AHR, 25.09 versus controls — among HSCT recipients with comorbid GVHD. However, patients who underwent SOT, autologous HSCT, or HSCT without GVHD showed no increased vitiligo risk in this analysis. “The results of health checkup data analysis may differ from the initial analysis due to additional adjustments for lifestyle factors and inclusion of only patients who underwent a health checkup,” the authors wrote.

Asked to comment on the results, George Han, MD, PhD, who was not involved with the study, told this news organization, “this is an interesting paper where the primary difference from previous studies is the new association between GVHD in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients and vitiligo.” Prior research had shown higher rates of vitiligo in HSCT recipients without making the GVHD distinction. Dr. Han is associate professor of dermatology in the Hofstra/Northwell Department of Dermatology, Hyde Park, New York.

Although GVHD may not be top-of-mind for dermatologists in daily practice, he said, the study enhances their understanding of vitiligo risk in HSCT recipients. “In some ways,” Dr. Han added, “the association makes sense, as the activated T cells from the graft attacking the skin in the HSCT recipient follow many of the mechanisms of vitiligo, including upregulating interferon gamma and the CXCR3/CXCL10 axis.”

Presently, he said, dermatologists worry more about solid organ recipients than about HSCT recipients because the long-term immunosuppression required by SOT increases the risk of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). “However, the risk of skin cancers also seems to be elevated in HSCT recipients, and in this case the basal cell carcinoma (BCC):SCC ratio is not necessarily reversed as we see in solid organ transplant recipients. So the mechanisms are a bit less clear. Interestingly, acute and chronic GVHD have both been associated with increased risks of BCC and SCC/BCC, respectively.”

Overall, Dr. Han said, any transplant recipient should undergo yearly skin checks not only for skin cancers, but also for other skin conditions such as vitiligo. “It would be nice to see this codified into official guidelines, which can vary considerably but are overall more consistent in solid organ transplant recipients than in HSCT recipients. No such guidelines seem to be available for HSCTs.”

The study was funded by the Basic Research in Science & Engineering program through the National Research Foundation of Korea, which is funded by the country’s Ministry of Education. The study authors had no disclosures. Dr. Han reports no relevant financial interests.

published online in JAMA Dermatology December 13.

In the cohort study, the greatest risk occurred with hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCTs) and in cases involving GVHD. Kidney and liver transplants carried slight increases in risk.

“The findings suggest that early detection and management of vitiligo lesions can be improved by estimating the likelihood of its development in transplant recipients and implementing a multidisciplinary approach for monitoring,” wrote the authors, from the departments of dermatology and biostatistics, at the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul.

Using claims data from South Korea’s National Health Insurance Service database, the investigators compared vitiligo incidence among 23,829 patients who had undergone solid organ transplantation (SOT) or HSCT between 2010 and 2017 versus that of 119,145 age- and sex-matched controls. At a mean observation time of 4.79 years in the transplant group (and 5.12 years for controls), the adjusted hazard ratio (AHR) for vitiligo among patients who had undergone any transplant was 1.73. AHRs for HSCT, liver transplants, and kidney transplants were 12.69, 1.63, and 1.50, respectively.

Patients who had undergone allogeneic HSCT (AHR, 14.43) or autologous transplants (AHR, 5.71), as well as those with and without GVHD (24.09 and 8.21, respectively) had significantly higher vitiligo risk than the control group.

Among those with GVHD, HSCT recipients (AHR, 16.42) and those with allogeneic grafts (AHR, 16.81) had a higher vitiligo risk than that of control patients.

In a subgroup that included 10,355 transplant recipients who underwent posttransplant health checkups, investigators found the highest vitiligo risk — AHR, 25.09 versus controls — among HSCT recipients with comorbid GVHD. However, patients who underwent SOT, autologous HSCT, or HSCT without GVHD showed no increased vitiligo risk in this analysis. “The results of health checkup data analysis may differ from the initial analysis due to additional adjustments for lifestyle factors and inclusion of only patients who underwent a health checkup,” the authors wrote.

Asked to comment on the results, George Han, MD, PhD, who was not involved with the study, told this news organization, “this is an interesting paper where the primary difference from previous studies is the new association between GVHD in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients and vitiligo.” Prior research had shown higher rates of vitiligo in HSCT recipients without making the GVHD distinction. Dr. Han is associate professor of dermatology in the Hofstra/Northwell Department of Dermatology, Hyde Park, New York.

Although GVHD may not be top-of-mind for dermatologists in daily practice, he said, the study enhances their understanding of vitiligo risk in HSCT recipients. “In some ways,” Dr. Han added, “the association makes sense, as the activated T cells from the graft attacking the skin in the HSCT recipient follow many of the mechanisms of vitiligo, including upregulating interferon gamma and the CXCR3/CXCL10 axis.”

Presently, he said, dermatologists worry more about solid organ recipients than about HSCT recipients because the long-term immunosuppression required by SOT increases the risk of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). “However, the risk of skin cancers also seems to be elevated in HSCT recipients, and in this case the basal cell carcinoma (BCC):SCC ratio is not necessarily reversed as we see in solid organ transplant recipients. So the mechanisms are a bit less clear. Interestingly, acute and chronic GVHD have both been associated with increased risks of BCC and SCC/BCC, respectively.”

Overall, Dr. Han said, any transplant recipient should undergo yearly skin checks not only for skin cancers, but also for other skin conditions such as vitiligo. “It would be nice to see this codified into official guidelines, which can vary considerably but are overall more consistent in solid organ transplant recipients than in HSCT recipients. No such guidelines seem to be available for HSCTs.”

The study was funded by the Basic Research in Science & Engineering program through the National Research Foundation of Korea, which is funded by the country’s Ministry of Education. The study authors had no disclosures. Dr. Han reports no relevant financial interests.

published online in JAMA Dermatology December 13.

In the cohort study, the greatest risk occurred with hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCTs) and in cases involving GVHD. Kidney and liver transplants carried slight increases in risk.

“The findings suggest that early detection and management of vitiligo lesions can be improved by estimating the likelihood of its development in transplant recipients and implementing a multidisciplinary approach for monitoring,” wrote the authors, from the departments of dermatology and biostatistics, at the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul.

Using claims data from South Korea’s National Health Insurance Service database, the investigators compared vitiligo incidence among 23,829 patients who had undergone solid organ transplantation (SOT) or HSCT between 2010 and 2017 versus that of 119,145 age- and sex-matched controls. At a mean observation time of 4.79 years in the transplant group (and 5.12 years for controls), the adjusted hazard ratio (AHR) for vitiligo among patients who had undergone any transplant was 1.73. AHRs for HSCT, liver transplants, and kidney transplants were 12.69, 1.63, and 1.50, respectively.

Patients who had undergone allogeneic HSCT (AHR, 14.43) or autologous transplants (AHR, 5.71), as well as those with and without GVHD (24.09 and 8.21, respectively) had significantly higher vitiligo risk than the control group.

Among those with GVHD, HSCT recipients (AHR, 16.42) and those with allogeneic grafts (AHR, 16.81) had a higher vitiligo risk than that of control patients.

In a subgroup that included 10,355 transplant recipients who underwent posttransplant health checkups, investigators found the highest vitiligo risk — AHR, 25.09 versus controls — among HSCT recipients with comorbid GVHD. However, patients who underwent SOT, autologous HSCT, or HSCT without GVHD showed no increased vitiligo risk in this analysis. “The results of health checkup data analysis may differ from the initial analysis due to additional adjustments for lifestyle factors and inclusion of only patients who underwent a health checkup,” the authors wrote.

Asked to comment on the results, George Han, MD, PhD, who was not involved with the study, told this news organization, “this is an interesting paper where the primary difference from previous studies is the new association between GVHD in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients and vitiligo.” Prior research had shown higher rates of vitiligo in HSCT recipients without making the GVHD distinction. Dr. Han is associate professor of dermatology in the Hofstra/Northwell Department of Dermatology, Hyde Park, New York.

Although GVHD may not be top-of-mind for dermatologists in daily practice, he said, the study enhances their understanding of vitiligo risk in HSCT recipients. “In some ways,” Dr. Han added, “the association makes sense, as the activated T cells from the graft attacking the skin in the HSCT recipient follow many of the mechanisms of vitiligo, including upregulating interferon gamma and the CXCR3/CXCL10 axis.”

Presently, he said, dermatologists worry more about solid organ recipients than about HSCT recipients because the long-term immunosuppression required by SOT increases the risk of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). “However, the risk of skin cancers also seems to be elevated in HSCT recipients, and in this case the basal cell carcinoma (BCC):SCC ratio is not necessarily reversed as we see in solid organ transplant recipients. So the mechanisms are a bit less clear. Interestingly, acute and chronic GVHD have both been associated with increased risks of BCC and SCC/BCC, respectively.”

Overall, Dr. Han said, any transplant recipient should undergo yearly skin checks not only for skin cancers, but also for other skin conditions such as vitiligo. “It would be nice to see this codified into official guidelines, which can vary considerably but are overall more consistent in solid organ transplant recipients than in HSCT recipients. No such guidelines seem to be available for HSCTs.”

The study was funded by the Basic Research in Science & Engineering program through the National Research Foundation of Korea, which is funded by the country’s Ministry of Education. The study authors had no disclosures. Dr. Han reports no relevant financial interests.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Dietary supplements may play a role in managing vitiligo

, Ammar Ahmed, MD, associate professor of dermatology at Dell Medical School at the University of Texas, Austin, said at the annual Integrative Dermatology Symposium.

Data on the use of dietary supplements for vitiligo are scarce and of limited quality, but existing studies and current understanding of the pathogenesis of vitiligo have convinced Dr. Ahmed to recommend oral Ginkgo biloba, vitamin C, vitamin E, and alpha-lipoic acid – as well as vitamin D if levels are insufficient – for patients receiving phototherapy, and outside of phototherapy when patients express interest, he said.

Melanocyte stress and subsequent autoimmune destruction appear to be “key pathways at play in vitiligo,” with melanocytes exhibiting increased susceptibility to physiologic stress, including a reduced capacity to manage exposure to reactive oxygen species. “It’s more theory than proven science, but if oxidative damage is one of the key factors [affecting] melanocytes, can we ... reverse the damage to those melanocytes with antioxidants?” he said. “I don’t know, but there’s certainly some emerging evidence that we may.”

There are no human data on the effectiveness of an antioxidant-rich diet for vitiligo, but given its theoretical basis of efficacy, it “seems reasonable to recommend,” said Dr. Ahmed. “When my patients ask me, I tell them to eat a colorful diet – with a lot of colorful fruits and vegetables.” In addition, he said, “we know that individuals with vitiligo, just as patients with psoriasis and other inflammatory disorders, appear to have a higher risk for insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, even after accounting for confounders,” making a healthy diet all the more important.

Two case reports have described improvement with a gluten-free diet, but “that’s it,” he said. “My take is, unless stronger evidence exists, let your patients enjoy their bread.” No other specific diet has been shown to cause, exacerbate, or improve vitiligo, he noted.

Dr. Ahmed offered his views on the literature on this topic, highlighting studies that have caught his eye on antioxidants and other supplements in patients with vitiligo:

Vitamins C and E, and alpha-lipoic acid: In a randomized controlled trial of 35 patients with nonsegmental vitiligo conducted at the San Gallicano Dermatological Institute in Rome, those who received an antioxidant cocktail (alpha-lipoic acid, 100 mg; vitamin C, 100 mg; vitamin E, 40 mg; and polyunsaturated fatty acids) for 2 months before and during narrow-band ultraviolet-B (NB-UVB) therapy had significantly more repigmentation than that of patients who received NB-UVB alone. Forty-seven percent of those in the antioxidant group obtained greater than 75% repigmentation at 6 months vs. 18% in the control arm.

“This is a pretty high-quality trial. They even did in-vitro analysis showing that the antioxidant group had decreased measures of oxidative stress in the melanocytes,” Dr. Ahmed said. A handout he provided to patients receiving UVB therapy includes recommendations for vitamin C, vitamin E, and alpha-lipoic acid supplementation.

Another controlled prospective study of 130 patients with vitiligo, also conducted in Italy, utilized a different antioxidant cocktail in a tablet – Phyllanthus emblica (known as Indian gooseberry), vitamin E, and carotenoids – taken three times a day, in conjunction with standard topical therapy and phototherapy. At 6 months, a significantly higher number of patients receiving the cocktail had mild repigmentation and were less likely to have no repigmentation compared with patients who did not receive the antioxidants. “Nobody did really great, but the cocktail group did a little better,” he said. “So there’s promise.”

Vitamin D: In-vitro studies show that vitamin D may protect melanocytes against oxidative stress, and two small controlled trials showed improvement in vitiligo with vitamin D supplementation (1,500-5,000 IU daily) and no NB-UVB therapy. However, a recent, higher-quality 6-month trial that evaluated 5,000 IU/day of vitamin D in patients with generalized vitiligo showed no advantage over NB-UVB therapy alone. “I tell patients, if you’re insufficient, take vitamin D (supplements) to get your levels up,” Dr. Ahmed sad. “But if you’re already sufficient, I’m not confident there will be a significant benefit.”

Ginkgo biloba: A small double-blind controlled trial randomized 47 patients with limited and slow-spreading vitiligo to receive Ginkgo biloba extract 40 mg three times a day or placebo. At 6 months, 10 patients who received the extract had greater than 75% repigmentation compared with 2 patients in the placebo group. Patients receiving Ginkgo biloba, which has immunomodulatory and antioxidant properties, were also significantly more likely to have disease stabilization.

“I tend to recommend it to patients not doing phototherapy, as well as those receiving phototherapy, especially since the study showed benefit as a monotherapy,” Dr. Ahmed said in an interview after the meeting.

Phenylalanine: Various oral and/or topical formulations of this amino acid and precursor to tyrosine/melanin have been shown to have repigmentation effects when combined with UVA phototherapy or sunlight, but the studies are of limited quality and the oral dosages studied (50 mg/kg per day to 100 mg/kg per day) appear to be a bit high, Dr. Ahmed said at the meeting. “It can add up in cost, and I worry a little about side effects, so I don’t recommend it as much.”

Polypodium leucotomos (PL): This plant extract, from a fern native to Central America and parts of South America, is familiar as a photoprotective supplement, he said, and a few randomized controlled trials show that it may improve repigmentation outcomes, especially on the hands and neck, when combined with NB-UVB in patients with vitiligo.

One of these trials, published in 2021, showed greater than 50% repigmentation at 6 months in 48% of patients with generalized vitiligo who received oral PL (480 mg twice a day) and NB-UVB, versus 22% in patients receiving NB-UVB alone. PL may be “reasonable to consider, though it can get a little pricey,” he said.

Other supplements: Nigella sativa seed oil (black seed oil) and the Ayurvedic herb Picrorhiza kurroa (also known as kutki), have shown some promise and merit further study in vitiligo, Dr. Ahmed said. Data on vitamin B12 and folate are mixed, and there is no evidence of a helpful role of zinc for vitiligo, he noted at the meeting.

Overall, there is a “paucity of large, high-quality trials for [complementary] therapies for vitiligo,” Dr. Ahmed said. “We need big randomized controlled trials ... and we need stratification. The problem is a lot of these studies don’t stratify: Is the patient active or inactive, for instance? Do they have poliosis or not?” Also missing in many studies are data on safety and adverse events. “Is that because of an excellent safety profile or lack of scientific rigor? I don’t know.”

Future approaches to vitiligo management will likely integrate alternative/nutritional modalities with conventional medical treatments, newer targeted therapies, and surgery when necessary, he said. In the case of surgery, he referred to the June 2023 Food and Drug Administration approval of the RECELL Autologous Cell Harvesting Device for repigmentation of stable depigmented vitiligo lesions, an office-based grafting procedure.

The topical Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor ruxolitinib (Opzelura) approved in 2022 for nonsegmental vitiligo, he said, produced “good, not great” results in two pivotal phase 3 trials . At 24 weeks, about 30% of patients on the treatment achieved at least a 75% improvement in the facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI75), compared with about 10% of patients in the placebo groups.

Asked to comment on antioxidant pathways and the potential of complementary therapies for vitiligo, Jason Hawkes, MD, a dermatologist in Rocklin, Calif., who also spoke at the IDS meeting, said that oxidative stress is among the processes that may contribute to melanocyte degeneration seen in vitiligo.

The immunopathogenesis of vitiligo is “multilayered and complex,” he said. “While the T lymphocyte plays a central role in this disease, there are other genetic and biologic processes [including oxidative stress] that also contribute to the destruction of melanocytes.”

Reducing oxidative stress in the body and skin via supplements such as vitamin E, coenzyme Q10, and alpha-lipoic acid “may represent complementary treatments used for the treatment of vitiligo,” said Dr. Hawkes. And as more is learned about the pathogenic role of oxidative stress and its impact on diseases of pigmentation, “therapeutic targeting of the antioxidation-related signaling pathways in the skin may represent a novel treatment for vitiligo or other related conditions.”

Dr. Hawkes disclosed ties with AbbVie, Arcutis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, LEO, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, and UCB. Dr. Hawkes disclosed serving as an investigator and advisory board member for Avita and an investigator for Pfizer.

, Ammar Ahmed, MD, associate professor of dermatology at Dell Medical School at the University of Texas, Austin, said at the annual Integrative Dermatology Symposium.

Data on the use of dietary supplements for vitiligo are scarce and of limited quality, but existing studies and current understanding of the pathogenesis of vitiligo have convinced Dr. Ahmed to recommend oral Ginkgo biloba, vitamin C, vitamin E, and alpha-lipoic acid – as well as vitamin D if levels are insufficient – for patients receiving phototherapy, and outside of phototherapy when patients express interest, he said.

Melanocyte stress and subsequent autoimmune destruction appear to be “key pathways at play in vitiligo,” with melanocytes exhibiting increased susceptibility to physiologic stress, including a reduced capacity to manage exposure to reactive oxygen species. “It’s more theory than proven science, but if oxidative damage is one of the key factors [affecting] melanocytes, can we ... reverse the damage to those melanocytes with antioxidants?” he said. “I don’t know, but there’s certainly some emerging evidence that we may.”

There are no human data on the effectiveness of an antioxidant-rich diet for vitiligo, but given its theoretical basis of efficacy, it “seems reasonable to recommend,” said Dr. Ahmed. “When my patients ask me, I tell them to eat a colorful diet – with a lot of colorful fruits and vegetables.” In addition, he said, “we know that individuals with vitiligo, just as patients with psoriasis and other inflammatory disorders, appear to have a higher risk for insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, even after accounting for confounders,” making a healthy diet all the more important.

Two case reports have described improvement with a gluten-free diet, but “that’s it,” he said. “My take is, unless stronger evidence exists, let your patients enjoy their bread.” No other specific diet has been shown to cause, exacerbate, or improve vitiligo, he noted.

Dr. Ahmed offered his views on the literature on this topic, highlighting studies that have caught his eye on antioxidants and other supplements in patients with vitiligo:

Vitamins C and E, and alpha-lipoic acid: In a randomized controlled trial of 35 patients with nonsegmental vitiligo conducted at the San Gallicano Dermatological Institute in Rome, those who received an antioxidant cocktail (alpha-lipoic acid, 100 mg; vitamin C, 100 mg; vitamin E, 40 mg; and polyunsaturated fatty acids) for 2 months before and during narrow-band ultraviolet-B (NB-UVB) therapy had significantly more repigmentation than that of patients who received NB-UVB alone. Forty-seven percent of those in the antioxidant group obtained greater than 75% repigmentation at 6 months vs. 18% in the control arm.

“This is a pretty high-quality trial. They even did in-vitro analysis showing that the antioxidant group had decreased measures of oxidative stress in the melanocytes,” Dr. Ahmed said. A handout he provided to patients receiving UVB therapy includes recommendations for vitamin C, vitamin E, and alpha-lipoic acid supplementation.

Another controlled prospective study of 130 patients with vitiligo, also conducted in Italy, utilized a different antioxidant cocktail in a tablet – Phyllanthus emblica (known as Indian gooseberry), vitamin E, and carotenoids – taken three times a day, in conjunction with standard topical therapy and phototherapy. At 6 months, a significantly higher number of patients receiving the cocktail had mild repigmentation and were less likely to have no repigmentation compared with patients who did not receive the antioxidants. “Nobody did really great, but the cocktail group did a little better,” he said. “So there’s promise.”

Vitamin D: In-vitro studies show that vitamin D may protect melanocytes against oxidative stress, and two small controlled trials showed improvement in vitiligo with vitamin D supplementation (1,500-5,000 IU daily) and no NB-UVB therapy. However, a recent, higher-quality 6-month trial that evaluated 5,000 IU/day of vitamin D in patients with generalized vitiligo showed no advantage over NB-UVB therapy alone. “I tell patients, if you’re insufficient, take vitamin D (supplements) to get your levels up,” Dr. Ahmed sad. “But if you’re already sufficient, I’m not confident there will be a significant benefit.”

Ginkgo biloba: A small double-blind controlled trial randomized 47 patients with limited and slow-spreading vitiligo to receive Ginkgo biloba extract 40 mg three times a day or placebo. At 6 months, 10 patients who received the extract had greater than 75% repigmentation compared with 2 patients in the placebo group. Patients receiving Ginkgo biloba, which has immunomodulatory and antioxidant properties, were also significantly more likely to have disease stabilization.

“I tend to recommend it to patients not doing phototherapy, as well as those receiving phototherapy, especially since the study showed benefit as a monotherapy,” Dr. Ahmed said in an interview after the meeting.

Phenylalanine: Various oral and/or topical formulations of this amino acid and precursor to tyrosine/melanin have been shown to have repigmentation effects when combined with UVA phototherapy or sunlight, but the studies are of limited quality and the oral dosages studied (50 mg/kg per day to 100 mg/kg per day) appear to be a bit high, Dr. Ahmed said at the meeting. “It can add up in cost, and I worry a little about side effects, so I don’t recommend it as much.”

Polypodium leucotomos (PL): This plant extract, from a fern native to Central America and parts of South America, is familiar as a photoprotective supplement, he said, and a few randomized controlled trials show that it may improve repigmentation outcomes, especially on the hands and neck, when combined with NB-UVB in patients with vitiligo.

One of these trials, published in 2021, showed greater than 50% repigmentation at 6 months in 48% of patients with generalized vitiligo who received oral PL (480 mg twice a day) and NB-UVB, versus 22% in patients receiving NB-UVB alone. PL may be “reasonable to consider, though it can get a little pricey,” he said.

Other supplements: Nigella sativa seed oil (black seed oil) and the Ayurvedic herb Picrorhiza kurroa (also known as kutki), have shown some promise and merit further study in vitiligo, Dr. Ahmed said. Data on vitamin B12 and folate are mixed, and there is no evidence of a helpful role of zinc for vitiligo, he noted at the meeting.

Overall, there is a “paucity of large, high-quality trials for [complementary] therapies for vitiligo,” Dr. Ahmed said. “We need big randomized controlled trials ... and we need stratification. The problem is a lot of these studies don’t stratify: Is the patient active or inactive, for instance? Do they have poliosis or not?” Also missing in many studies are data on safety and adverse events. “Is that because of an excellent safety profile or lack of scientific rigor? I don’t know.”

Future approaches to vitiligo management will likely integrate alternative/nutritional modalities with conventional medical treatments, newer targeted therapies, and surgery when necessary, he said. In the case of surgery, he referred to the June 2023 Food and Drug Administration approval of the RECELL Autologous Cell Harvesting Device for repigmentation of stable depigmented vitiligo lesions, an office-based grafting procedure.

The topical Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor ruxolitinib (Opzelura) approved in 2022 for nonsegmental vitiligo, he said, produced “good, not great” results in two pivotal phase 3 trials . At 24 weeks, about 30% of patients on the treatment achieved at least a 75% improvement in the facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI75), compared with about 10% of patients in the placebo groups.

Asked to comment on antioxidant pathways and the potential of complementary therapies for vitiligo, Jason Hawkes, MD, a dermatologist in Rocklin, Calif., who also spoke at the IDS meeting, said that oxidative stress is among the processes that may contribute to melanocyte degeneration seen in vitiligo.

The immunopathogenesis of vitiligo is “multilayered and complex,” he said. “While the T lymphocyte plays a central role in this disease, there are other genetic and biologic processes [including oxidative stress] that also contribute to the destruction of melanocytes.”

Reducing oxidative stress in the body and skin via supplements such as vitamin E, coenzyme Q10, and alpha-lipoic acid “may represent complementary treatments used for the treatment of vitiligo,” said Dr. Hawkes. And as more is learned about the pathogenic role of oxidative stress and its impact on diseases of pigmentation, “therapeutic targeting of the antioxidation-related signaling pathways in the skin may represent a novel treatment for vitiligo or other related conditions.”

Dr. Hawkes disclosed ties with AbbVie, Arcutis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, LEO, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, and UCB. Dr. Hawkes disclosed serving as an investigator and advisory board member for Avita and an investigator for Pfizer.

, Ammar Ahmed, MD, associate professor of dermatology at Dell Medical School at the University of Texas, Austin, said at the annual Integrative Dermatology Symposium.

Data on the use of dietary supplements for vitiligo are scarce and of limited quality, but existing studies and current understanding of the pathogenesis of vitiligo have convinced Dr. Ahmed to recommend oral Ginkgo biloba, vitamin C, vitamin E, and alpha-lipoic acid – as well as vitamin D if levels are insufficient – for patients receiving phototherapy, and outside of phototherapy when patients express interest, he said.

Melanocyte stress and subsequent autoimmune destruction appear to be “key pathways at play in vitiligo,” with melanocytes exhibiting increased susceptibility to physiologic stress, including a reduced capacity to manage exposure to reactive oxygen species. “It’s more theory than proven science, but if oxidative damage is one of the key factors [affecting] melanocytes, can we ... reverse the damage to those melanocytes with antioxidants?” he said. “I don’t know, but there’s certainly some emerging evidence that we may.”

There are no human data on the effectiveness of an antioxidant-rich diet for vitiligo, but given its theoretical basis of efficacy, it “seems reasonable to recommend,” said Dr. Ahmed. “When my patients ask me, I tell them to eat a colorful diet – with a lot of colorful fruits and vegetables.” In addition, he said, “we know that individuals with vitiligo, just as patients with psoriasis and other inflammatory disorders, appear to have a higher risk for insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, even after accounting for confounders,” making a healthy diet all the more important.

Two case reports have described improvement with a gluten-free diet, but “that’s it,” he said. “My take is, unless stronger evidence exists, let your patients enjoy their bread.” No other specific diet has been shown to cause, exacerbate, or improve vitiligo, he noted.

Dr. Ahmed offered his views on the literature on this topic, highlighting studies that have caught his eye on antioxidants and other supplements in patients with vitiligo:

Vitamins C and E, and alpha-lipoic acid: In a randomized controlled trial of 35 patients with nonsegmental vitiligo conducted at the San Gallicano Dermatological Institute in Rome, those who received an antioxidant cocktail (alpha-lipoic acid, 100 mg; vitamin C, 100 mg; vitamin E, 40 mg; and polyunsaturated fatty acids) for 2 months before and during narrow-band ultraviolet-B (NB-UVB) therapy had significantly more repigmentation than that of patients who received NB-UVB alone. Forty-seven percent of those in the antioxidant group obtained greater than 75% repigmentation at 6 months vs. 18% in the control arm.

“This is a pretty high-quality trial. They even did in-vitro analysis showing that the antioxidant group had decreased measures of oxidative stress in the melanocytes,” Dr. Ahmed said. A handout he provided to patients receiving UVB therapy includes recommendations for vitamin C, vitamin E, and alpha-lipoic acid supplementation.

Another controlled prospective study of 130 patients with vitiligo, also conducted in Italy, utilized a different antioxidant cocktail in a tablet – Phyllanthus emblica (known as Indian gooseberry), vitamin E, and carotenoids – taken three times a day, in conjunction with standard topical therapy and phototherapy. At 6 months, a significantly higher number of patients receiving the cocktail had mild repigmentation and were less likely to have no repigmentation compared with patients who did not receive the antioxidants. “Nobody did really great, but the cocktail group did a little better,” he said. “So there’s promise.”

Vitamin D: In-vitro studies show that vitamin D may protect melanocytes against oxidative stress, and two small controlled trials showed improvement in vitiligo with vitamin D supplementation (1,500-5,000 IU daily) and no NB-UVB therapy. However, a recent, higher-quality 6-month trial that evaluated 5,000 IU/day of vitamin D in patients with generalized vitiligo showed no advantage over NB-UVB therapy alone. “I tell patients, if you’re insufficient, take vitamin D (supplements) to get your levels up,” Dr. Ahmed sad. “But if you’re already sufficient, I’m not confident there will be a significant benefit.”

Ginkgo biloba: A small double-blind controlled trial randomized 47 patients with limited and slow-spreading vitiligo to receive Ginkgo biloba extract 40 mg three times a day or placebo. At 6 months, 10 patients who received the extract had greater than 75% repigmentation compared with 2 patients in the placebo group. Patients receiving Ginkgo biloba, which has immunomodulatory and antioxidant properties, were also significantly more likely to have disease stabilization.

“I tend to recommend it to patients not doing phototherapy, as well as those receiving phototherapy, especially since the study showed benefit as a monotherapy,” Dr. Ahmed said in an interview after the meeting.

Phenylalanine: Various oral and/or topical formulations of this amino acid and precursor to tyrosine/melanin have been shown to have repigmentation effects when combined with UVA phototherapy or sunlight, but the studies are of limited quality and the oral dosages studied (50 mg/kg per day to 100 mg/kg per day) appear to be a bit high, Dr. Ahmed said at the meeting. “It can add up in cost, and I worry a little about side effects, so I don’t recommend it as much.”

Polypodium leucotomos (PL): This plant extract, from a fern native to Central America and parts of South America, is familiar as a photoprotective supplement, he said, and a few randomized controlled trials show that it may improve repigmentation outcomes, especially on the hands and neck, when combined with NB-UVB in patients with vitiligo.

One of these trials, published in 2021, showed greater than 50% repigmentation at 6 months in 48% of patients with generalized vitiligo who received oral PL (480 mg twice a day) and NB-UVB, versus 22% in patients receiving NB-UVB alone. PL may be “reasonable to consider, though it can get a little pricey,” he said.

Other supplements: Nigella sativa seed oil (black seed oil) and the Ayurvedic herb Picrorhiza kurroa (also known as kutki), have shown some promise and merit further study in vitiligo, Dr. Ahmed said. Data on vitamin B12 and folate are mixed, and there is no evidence of a helpful role of zinc for vitiligo, he noted at the meeting.

Overall, there is a “paucity of large, high-quality trials for [complementary] therapies for vitiligo,” Dr. Ahmed said. “We need big randomized controlled trials ... and we need stratification. The problem is a lot of these studies don’t stratify: Is the patient active or inactive, for instance? Do they have poliosis or not?” Also missing in many studies are data on safety and adverse events. “Is that because of an excellent safety profile or lack of scientific rigor? I don’t know.”

Future approaches to vitiligo management will likely integrate alternative/nutritional modalities with conventional medical treatments, newer targeted therapies, and surgery when necessary, he said. In the case of surgery, he referred to the June 2023 Food and Drug Administration approval of the RECELL Autologous Cell Harvesting Device for repigmentation of stable depigmented vitiligo lesions, an office-based grafting procedure.

The topical Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor ruxolitinib (Opzelura) approved in 2022 for nonsegmental vitiligo, he said, produced “good, not great” results in two pivotal phase 3 trials . At 24 weeks, about 30% of patients on the treatment achieved at least a 75% improvement in the facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI75), compared with about 10% of patients in the placebo groups.

Asked to comment on antioxidant pathways and the potential of complementary therapies for vitiligo, Jason Hawkes, MD, a dermatologist in Rocklin, Calif., who also spoke at the IDS meeting, said that oxidative stress is among the processes that may contribute to melanocyte degeneration seen in vitiligo.

The immunopathogenesis of vitiligo is “multilayered and complex,” he said. “While the T lymphocyte plays a central role in this disease, there are other genetic and biologic processes [including oxidative stress] that also contribute to the destruction of melanocytes.”

Reducing oxidative stress in the body and skin via supplements such as vitamin E, coenzyme Q10, and alpha-lipoic acid “may represent complementary treatments used for the treatment of vitiligo,” said Dr. Hawkes. And as more is learned about the pathogenic role of oxidative stress and its impact on diseases of pigmentation, “therapeutic targeting of the antioxidation-related signaling pathways in the skin may represent a novel treatment for vitiligo or other related conditions.”

Dr. Hawkes disclosed ties with AbbVie, Arcutis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, LEO, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, and UCB. Dr. Hawkes disclosed serving as an investigator and advisory board member for Avita and an investigator for Pfizer.

FROM IDS 2023

Hyperpigmented Flexural Plaques, Hypohidrosis, and Hypotrichosis

The Diagnosis: Lelis Syndrome

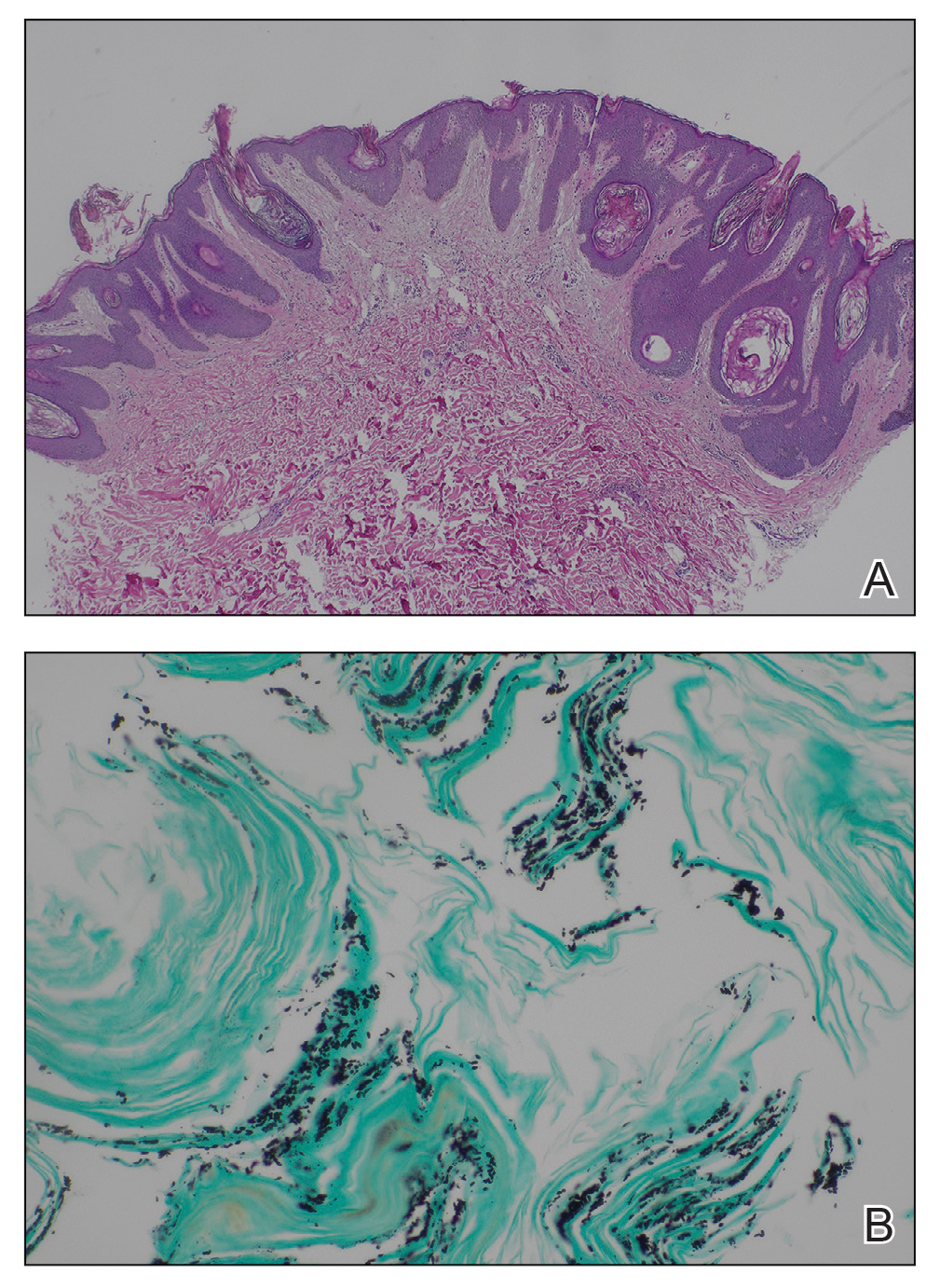

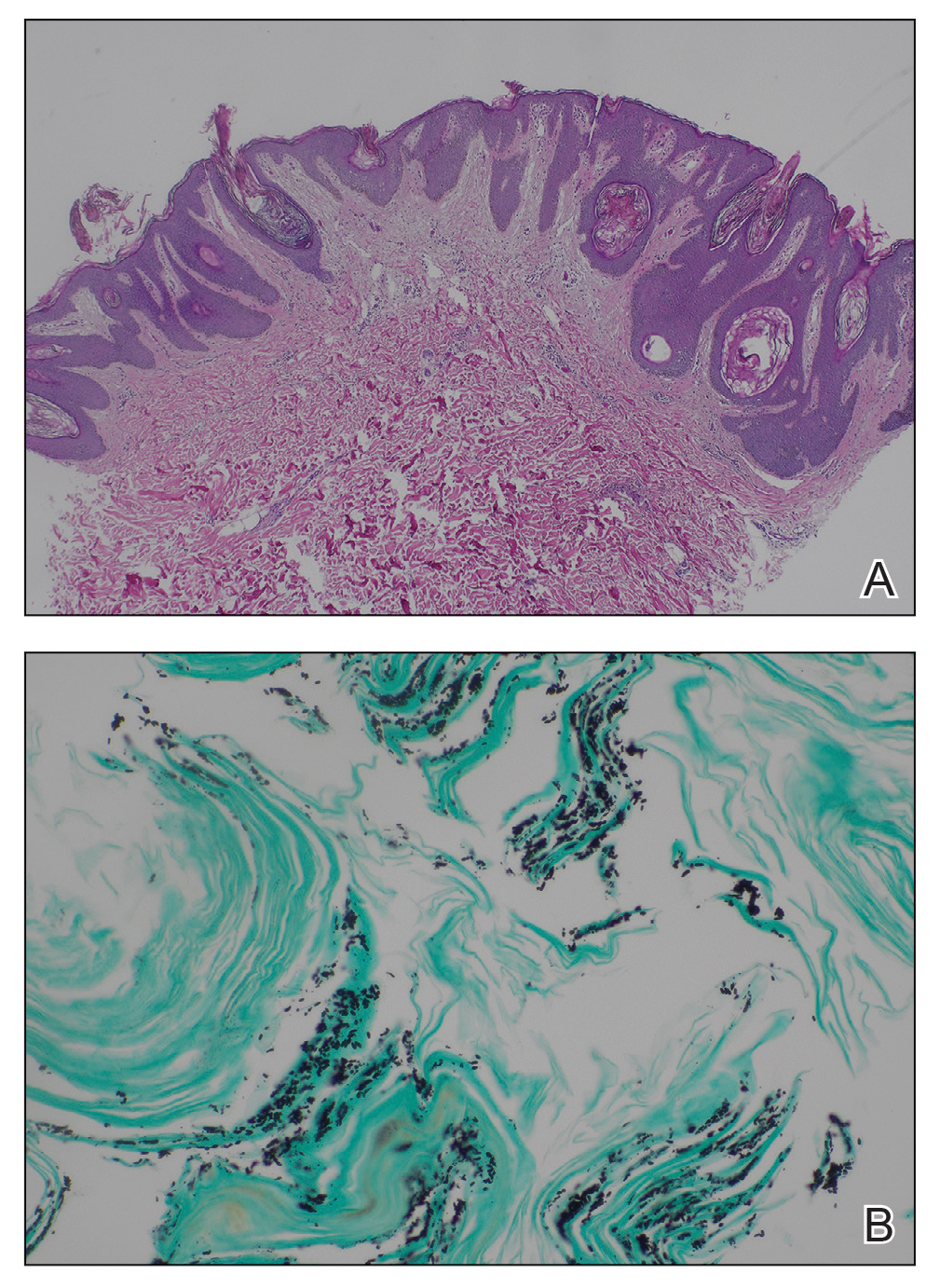

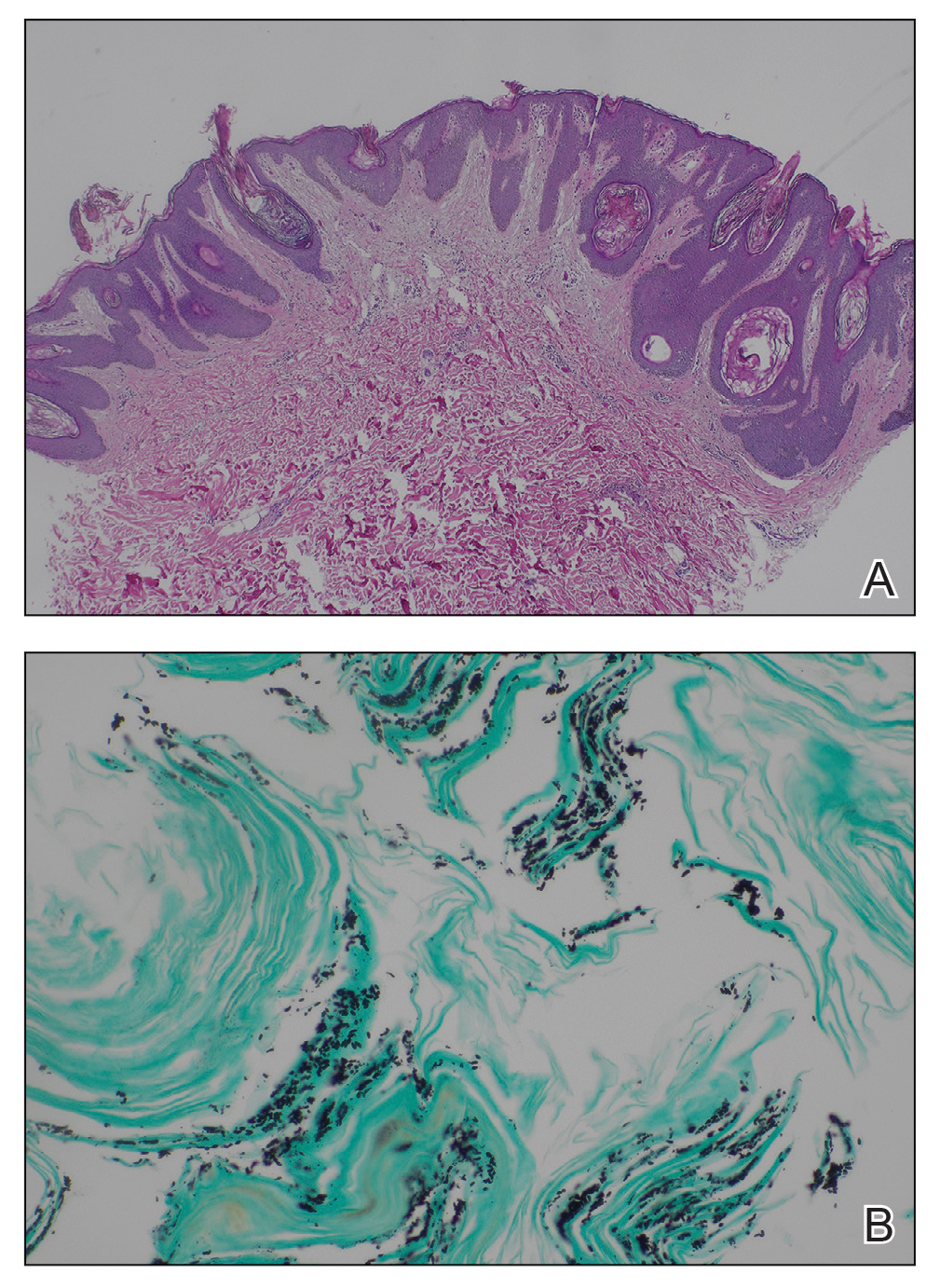

Histopathology revealed spongiotic dermatitis with marked acanthosis and hyperkeratosis (Figure, A) with fungal colonization of the stratum corneum (Figure, B). Our patient was diagnosed with Lelis syndrome (also referred to as ectodermal dysplasia with acanthosis nigricans syndrome), a rare condition with hypotrichosis and hypohidrosis resulting from ectodermal dysplasia.1,2 The pruritic rash was diagnosed as chronic dermatitis due to fungal colonization in the setting of acanthosis nigricans. The fungal infection was treated with a 4-week course of oral fluconazole 200 mg/wk, ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily, and discontinuation of topical steroids, resulting in the thinning of the plaques on the neck and antecubital fossae as well as resolution of the pruritus. Following antifungal treatment, our patient was started on tazarotene cream 0.1% for acanthosis nigricans.

Ectodermal dysplasias are inherited disorders with abnormalities of the skin, hair, sweat glands, nails, teeth, and sometimes internal organs.3 Patients with Lelis syndrome may have other manifestations of ectodermal dysplasia in addition to hypohidrosis and hypotrichosis, including deafness and abnormal dentition,1,3 as seen in our patient. Intellectual disability has been described in many types of ectodermal dysplasia, including Lelis syndrome, but the association may be obscured by neurologic damage after repeat episodes of hyperthermia in infancy due to anhidrosis or hypohidrosis.4

When evaluating the differential diagnoses, the presence of hypotrichosis and hypohidrosis indicating ectodermal dysplasia is key. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis presents with hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and focal acanthosis on histopathology. It can present on the neck and antecubital fossae; however, it is not associated with hypohidrosis and hypotrichosis.5 Although activating fibroblast growth factor receptor, FGFR, mutations have been implicated in the development of acanthosis nigricans in a variety of syndromes, these diagnoses are associated with abnormalities in skeletal development such as craniosynostosis and short stature; hypotrichosis and hypohidrosis are not seen.6,7 HAIR-AN (hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and acanthosis nigricans) syndrome typically presents in the prepubertal period with obesity and insulin resistance; acanthosis nigricans and alopecia can occur due to insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism, but concurrent clitoromegaly and hirsutism are common.6 Sudden onset of extensive acanthosis nigricans also is among the paraneoplastic dermatoses; it has been associated with multiple malignancies, but in these cases, hypotrichosis and hypohidrosis are not observed. Adenocarcinomas are the most common neoplasms associated with paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans, which occurs through growth factor secretion by tumor cells stimulating hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis.6

Lelis syndrome is rare, and our case is unique because the patient had severe manifestations of acanthosis nigricans and hypotrichosis. Because the inheritance pattern and specific genetics of the condition have not been fully elucidated, the diagnosis primarily is clinical.1,8 Diagnosis may be complicated by the variety of other signs that can accompany acanthosis nigricans, hypohidrosis, and hypotrichosis.1,2 The condition also may alter or obscure presentation of other dermatologic conditions, as in our case.

Although there is no cure for Lelis syndrome, one case report described treatment with acitretin that resulted in marked improvement of the patient’s hyperkeratosis and acanthosis nigricans.9 Due to lack of health insurance coverage of acitretin, our patient was started on tazarotene cream 0.1% for acanthosis nigricans. General treatment of ectodermal dysplasia primarily consists of multidisciplinary symptom management, including careful monitoring of temperature and heat intolerance as well as provision of dental prosthetics.4,10 For ectodermal dysplasias caused by identified genetic mutations, prenatal interventions targeting gene pathways offer potentially curative treatment.10 However, for Lelis syndrome, along with many other disorders of ectodermal dysplasia, mitigation of signs and symptoms remains the primary treatment objective. Despite its rarity, increased awareness of Lelis syndrome is important to increase knowledge of ectodermal dysplasia syndromes and allow for the investigation of potential treatment options.

- Steiner CE, Cintra ML, Marques-de-Faria AP. Ectodermal dysplasia with acanthosis nigricans (Lelis syndrome). Am J Med Genet. 2002;113:381-384. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.10787

- Lelis J. Autosomal recessive ectodermal dysplasia. Cutis. 1992; 49:435-437.

- Itin PH, Fistarol SK. Ectodermal dysplasias. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2004;131C:45-51. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.30033

- Blüschke G, Nüsken KD, Schneider H. Prevalence and prevention of severe complications of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia in infancy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:397-399. doi:10.1016/j .earlhumdev.2010.04.008

- Le C, Bedocs PM. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459130/

- Das A, Datta D, Kassir M, et al. Acanthosis nigricans: a review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:1857-1865. doi:10.1111/jocd.13544

- Torley D, Bellus GA, Munro CS. Genes, growth factors and acanthosis nigricans. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1096-1101. doi:10 .1046/j.1365-2133.2002.05150.x

- van Steensel MAM, van der Hout AH. Lelis syndrome may be a manifestation of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:1612-1613. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.32945

- Yoshimura AM, Neves Ferreira Velho PE, Ferreira Magalhães R, et al. Lelis’ syndrome: treatment with acitretin. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47: 1330-1331. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03874.x

- Schneider H. Ectodermal dysplasias: new perspectives on the treatment of so far immedicable genetic disorders. Front Genet. 2022;13:1000744. doi:10.3389/fgene.2022.1000744

The Diagnosis: Lelis Syndrome

Histopathology revealed spongiotic dermatitis with marked acanthosis and hyperkeratosis (Figure, A) with fungal colonization of the stratum corneum (Figure, B). Our patient was diagnosed with Lelis syndrome (also referred to as ectodermal dysplasia with acanthosis nigricans syndrome), a rare condition with hypotrichosis and hypohidrosis resulting from ectodermal dysplasia.1,2 The pruritic rash was diagnosed as chronic dermatitis due to fungal colonization in the setting of acanthosis nigricans. The fungal infection was treated with a 4-week course of oral fluconazole 200 mg/wk, ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily, and discontinuation of topical steroids, resulting in the thinning of the plaques on the neck and antecubital fossae as well as resolution of the pruritus. Following antifungal treatment, our patient was started on tazarotene cream 0.1% for acanthosis nigricans.

Ectodermal dysplasias are inherited disorders with abnormalities of the skin, hair, sweat glands, nails, teeth, and sometimes internal organs.3 Patients with Lelis syndrome may have other manifestations of ectodermal dysplasia in addition to hypohidrosis and hypotrichosis, including deafness and abnormal dentition,1,3 as seen in our patient. Intellectual disability has been described in many types of ectodermal dysplasia, including Lelis syndrome, but the association may be obscured by neurologic damage after repeat episodes of hyperthermia in infancy due to anhidrosis or hypohidrosis.4

When evaluating the differential diagnoses, the presence of hypotrichosis and hypohidrosis indicating ectodermal dysplasia is key. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis presents with hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and focal acanthosis on histopathology. It can present on the neck and antecubital fossae; however, it is not associated with hypohidrosis and hypotrichosis.5 Although activating fibroblast growth factor receptor, FGFR, mutations have been implicated in the development of acanthosis nigricans in a variety of syndromes, these diagnoses are associated with abnormalities in skeletal development such as craniosynostosis and short stature; hypotrichosis and hypohidrosis are not seen.6,7 HAIR-AN (hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and acanthosis nigricans) syndrome typically presents in the prepubertal period with obesity and insulin resistance; acanthosis nigricans and alopecia can occur due to insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism, but concurrent clitoromegaly and hirsutism are common.6 Sudden onset of extensive acanthosis nigricans also is among the paraneoplastic dermatoses; it has been associated with multiple malignancies, but in these cases, hypotrichosis and hypohidrosis are not observed. Adenocarcinomas are the most common neoplasms associated with paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans, which occurs through growth factor secretion by tumor cells stimulating hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis.6

Lelis syndrome is rare, and our case is unique because the patient had severe manifestations of acanthosis nigricans and hypotrichosis. Because the inheritance pattern and specific genetics of the condition have not been fully elucidated, the diagnosis primarily is clinical.1,8 Diagnosis may be complicated by the variety of other signs that can accompany acanthosis nigricans, hypohidrosis, and hypotrichosis.1,2 The condition also may alter or obscure presentation of other dermatologic conditions, as in our case.

Although there is no cure for Lelis syndrome, one case report described treatment with acitretin that resulted in marked improvement of the patient’s hyperkeratosis and acanthosis nigricans.9 Due to lack of health insurance coverage of acitretin, our patient was started on tazarotene cream 0.1% for acanthosis nigricans. General treatment of ectodermal dysplasia primarily consists of multidisciplinary symptom management, including careful monitoring of temperature and heat intolerance as well as provision of dental prosthetics.4,10 For ectodermal dysplasias caused by identified genetic mutations, prenatal interventions targeting gene pathways offer potentially curative treatment.10 However, for Lelis syndrome, along with many other disorders of ectodermal dysplasia, mitigation of signs and symptoms remains the primary treatment objective. Despite its rarity, increased awareness of Lelis syndrome is important to increase knowledge of ectodermal dysplasia syndromes and allow for the investigation of potential treatment options.

The Diagnosis: Lelis Syndrome

Histopathology revealed spongiotic dermatitis with marked acanthosis and hyperkeratosis (Figure, A) with fungal colonization of the stratum corneum (Figure, B). Our patient was diagnosed with Lelis syndrome (also referred to as ectodermal dysplasia with acanthosis nigricans syndrome), a rare condition with hypotrichosis and hypohidrosis resulting from ectodermal dysplasia.1,2 The pruritic rash was diagnosed as chronic dermatitis due to fungal colonization in the setting of acanthosis nigricans. The fungal infection was treated with a 4-week course of oral fluconazole 200 mg/wk, ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily, and discontinuation of topical steroids, resulting in the thinning of the plaques on the neck and antecubital fossae as well as resolution of the pruritus. Following antifungal treatment, our patient was started on tazarotene cream 0.1% for acanthosis nigricans.

Ectodermal dysplasias are inherited disorders with abnormalities of the skin, hair, sweat glands, nails, teeth, and sometimes internal organs.3 Patients with Lelis syndrome may have other manifestations of ectodermal dysplasia in addition to hypohidrosis and hypotrichosis, including deafness and abnormal dentition,1,3 as seen in our patient. Intellectual disability has been described in many types of ectodermal dysplasia, including Lelis syndrome, but the association may be obscured by neurologic damage after repeat episodes of hyperthermia in infancy due to anhidrosis or hypohidrosis.4

When evaluating the differential diagnoses, the presence of hypotrichosis and hypohidrosis indicating ectodermal dysplasia is key. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis presents with hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and focal acanthosis on histopathology. It can present on the neck and antecubital fossae; however, it is not associated with hypohidrosis and hypotrichosis.5 Although activating fibroblast growth factor receptor, FGFR, mutations have been implicated in the development of acanthosis nigricans in a variety of syndromes, these diagnoses are associated with abnormalities in skeletal development such as craniosynostosis and short stature; hypotrichosis and hypohidrosis are not seen.6,7 HAIR-AN (hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, and acanthosis nigricans) syndrome typically presents in the prepubertal period with obesity and insulin resistance; acanthosis nigricans and alopecia can occur due to insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism, but concurrent clitoromegaly and hirsutism are common.6 Sudden onset of extensive acanthosis nigricans also is among the paraneoplastic dermatoses; it has been associated with multiple malignancies, but in these cases, hypotrichosis and hypohidrosis are not observed. Adenocarcinomas are the most common neoplasms associated with paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans, which occurs through growth factor secretion by tumor cells stimulating hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis.6

Lelis syndrome is rare, and our case is unique because the patient had severe manifestations of acanthosis nigricans and hypotrichosis. Because the inheritance pattern and specific genetics of the condition have not been fully elucidated, the diagnosis primarily is clinical.1,8 Diagnosis may be complicated by the variety of other signs that can accompany acanthosis nigricans, hypohidrosis, and hypotrichosis.1,2 The condition also may alter or obscure presentation of other dermatologic conditions, as in our case.

Although there is no cure for Lelis syndrome, one case report described treatment with acitretin that resulted in marked improvement of the patient’s hyperkeratosis and acanthosis nigricans.9 Due to lack of health insurance coverage of acitretin, our patient was started on tazarotene cream 0.1% for acanthosis nigricans. General treatment of ectodermal dysplasia primarily consists of multidisciplinary symptom management, including careful monitoring of temperature and heat intolerance as well as provision of dental prosthetics.4,10 For ectodermal dysplasias caused by identified genetic mutations, prenatal interventions targeting gene pathways offer potentially curative treatment.10 However, for Lelis syndrome, along with many other disorders of ectodermal dysplasia, mitigation of signs and symptoms remains the primary treatment objective. Despite its rarity, increased awareness of Lelis syndrome is important to increase knowledge of ectodermal dysplasia syndromes and allow for the investigation of potential treatment options.

- Steiner CE, Cintra ML, Marques-de-Faria AP. Ectodermal dysplasia with acanthosis nigricans (Lelis syndrome). Am J Med Genet. 2002;113:381-384. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.10787

- Lelis J. Autosomal recessive ectodermal dysplasia. Cutis. 1992; 49:435-437.

- Itin PH, Fistarol SK. Ectodermal dysplasias. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2004;131C:45-51. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.30033

- Blüschke G, Nüsken KD, Schneider H. Prevalence and prevention of severe complications of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia in infancy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:397-399. doi:10.1016/j .earlhumdev.2010.04.008

- Le C, Bedocs PM. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459130/

- Das A, Datta D, Kassir M, et al. Acanthosis nigricans: a review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:1857-1865. doi:10.1111/jocd.13544

- Torley D, Bellus GA, Munro CS. Genes, growth factors and acanthosis nigricans. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1096-1101. doi:10 .1046/j.1365-2133.2002.05150.x

- van Steensel MAM, van der Hout AH. Lelis syndrome may be a manifestation of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:1612-1613. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.32945

- Yoshimura AM, Neves Ferreira Velho PE, Ferreira Magalhães R, et al. Lelis’ syndrome: treatment with acitretin. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47: 1330-1331. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03874.x

- Schneider H. Ectodermal dysplasias: new perspectives on the treatment of so far immedicable genetic disorders. Front Genet. 2022;13:1000744. doi:10.3389/fgene.2022.1000744

- Steiner CE, Cintra ML, Marques-de-Faria AP. Ectodermal dysplasia with acanthosis nigricans (Lelis syndrome). Am J Med Genet. 2002;113:381-384. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.10787

- Lelis J. Autosomal recessive ectodermal dysplasia. Cutis. 1992; 49:435-437.

- Itin PH, Fistarol SK. Ectodermal dysplasias. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2004;131C:45-51. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.30033

- Blüschke G, Nüsken KD, Schneider H. Prevalence and prevention of severe complications of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia in infancy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86:397-399. doi:10.1016/j .earlhumdev.2010.04.008

- Le C, Bedocs PM. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459130/

- Das A, Datta D, Kassir M, et al. Acanthosis nigricans: a review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:1857-1865. doi:10.1111/jocd.13544

- Torley D, Bellus GA, Munro CS. Genes, growth factors and acanthosis nigricans. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1096-1101. doi:10 .1046/j.1365-2133.2002.05150.x

- van Steensel MAM, van der Hout AH. Lelis syndrome may be a manifestation of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:1612-1613. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.32945

- Yoshimura AM, Neves Ferreira Velho PE, Ferreira Magalhães R, et al. Lelis’ syndrome: treatment with acitretin. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47: 1330-1331. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03874.x

- Schneider H. Ectodermal dysplasias: new perspectives on the treatment of so far immedicable genetic disorders. Front Genet. 2022;13:1000744. doi:10.3389/fgene.2022.1000744

A 61-year-old woman with a history of hypohidrosis and deafness presented with a pruritic rash on the neck and antecubital fossae of several years’ duration. Prior treatment with topical corticosteroids failed to resolve the rash. Physical examination revealed thick, velvety, hyperpigmented plaques on the inframammary folds, axillae, groin, posterior neck, and antecubital fossae with lichenification of the latter 2 areas. Many pedunculated papules were seen on the face, chest, shoulders, and trunk, as well as diffuse hair thinning, particularly of the frontal and vertex scalp. Eyebrows, eyelashes, and axillary hair were absent. Two 5-mm punch biopsies of the antecubital fossa and inframammary fold were obtained for histopathologic analysis.

Parent concerns a factor when treating eczema in children with darker skin types

NEW YORK –

Skin diseases pose a greater risk of both hyper- and hypopigmentation in patients with darker skin types, but the fear and concern that this raises for permanent disfigurement is not limited to Blacks, Dr. Heath, assistant professor of pediatric dermatology at Temple University, Philadelphia, said at the Skin of Color Update 2023.

“Culturally, pigmentation changes can be huge. For people of Indian descent, for example, pigmentary changes like light spots on the skin might be an obstacle to marriage, so it can really be life changing,” she added.

In patients with darker skin tones presenting with an inflammatory skin disease, such as AD or psoriasis, Dr. Heath advised asking specifically about change in skin tone even if it is not readily apparent. In pediatric patients, it is also appropriate to include parents in this conversation.

Consider the parent’s perspective

“When you are taking care of a child or adolescent, the patient is likely to be concerned about changes in pigmentation, but it is important to remember that the adult in the room might have had their own journey with brown skin and has dealt with the burden of pigment changes,” Dr. Heath said.