User login

Diagnostic Errors in Hospitalized Patients

Abstract

Diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients are a leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality. Significant challenges in defining and measuring diagnostic errors and underlying process failure points have led to considerable variability in reported rates of diagnostic errors and adverse outcomes. In this article, we explore the diagnostic process and its discrete components, emphasizing the centrality of the patient in decision-making as well as the continuous nature of the process. We review the incidence of diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients and different methodological approaches that have been used to arrive at these estimates. We discuss different but interdependent provider- and system-related process-failure points that lead to diagnostic errors. We examine specific challenges related to measurement of diagnostic errors and describe traditional and novel approaches that are being used to obtain the most precise estimates. Finally, we examine various patient-, provider-, and organizational-level interventions that have been proposed to improve diagnostic safety in hospitalized patients.

Keywords: diagnostic error, hospital medicine, patient safety.

Diagnosis is defined as a “pre-existing set of categories agreed upon by the medical profession to designate a specific condition.”1 The diagnostic process involves obtaining a clinical history, performing a physical examination, conducting diagnostic testing, and consulting with other clinical providers to gather data that are relevant to understanding the underlying disease processes. This exercise involves generating hypotheses and updating prior probabilities as more information and evidence become available. Throughout this process of information gathering, integration, and interpretation, there is an ongoing assessment of whether sufficient and necessary knowledge has been obtained to make an accurate diagnosis and provide appropriate treatment.2

Diagnostic error is defined as a missed opportunity to make a timely diagnosis as part of this iterative process, including the failure of communicating the diagnosis to the patient in a timely manner.3 It can be categorized as a missed, delayed, or incorrect diagnosis based on available evidence at the time. Establishing the correct diagnosis has important implications. A timely and precise diagnosis ensures the patient the highest probability of having a positive health outcome that reflects an appropriate understanding of underlying disease processes and is consistent with their overall goals of care.3 When diagnostic errors occur, they can cause patient harm. Adverse events due to medical errors, including diagnostic errors, are estimated to be the third leading cause of death in the United States.4 Most people will experience at least 1 diagnostic error in their lifetime. In the 2015 National Academy of Medicine report Improving Diagnosis in Healthcare, diagnostic errors were identified as a major hazard as well as an opportunity to improve patient outcomes.2

Diagnostic errors during hospitalizations are especially concerning, as they are more likely to be implicated in a wider spectrum of harm, including permanent disability and death. This has become even more relevant for hospital medicine physicians and other clinical providers as they encounter increasing cognitive and administrative workloads, rising dissatisfaction and burnout, and unique obstacles such as night-time scheduling.5

Incidence of Diagnostic Errors in Hospitalized Patients

Several methodological approaches have been used to estimate the incidence of diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients. These include retrospective reviews of a sample of all hospital admissions, evaluations of selected adverse outcomes including autopsy studies, patient and provider surveys, and malpractice claims. Laboratory testing audits and secondary reviews in other diagnostic subspecialities (eg, radiology, pathology, and microbiology) are also essential to improving diagnostic performance in these specialized fields, which in turn affects overall hospital diagnostic error rates.6-8 These diverse approaches provide unique insights regarding our ability to assess the degree to which potential harms, ranging from temporary impairment to permanent disability, to death, are attributable to different failure points in the diagnostic process.

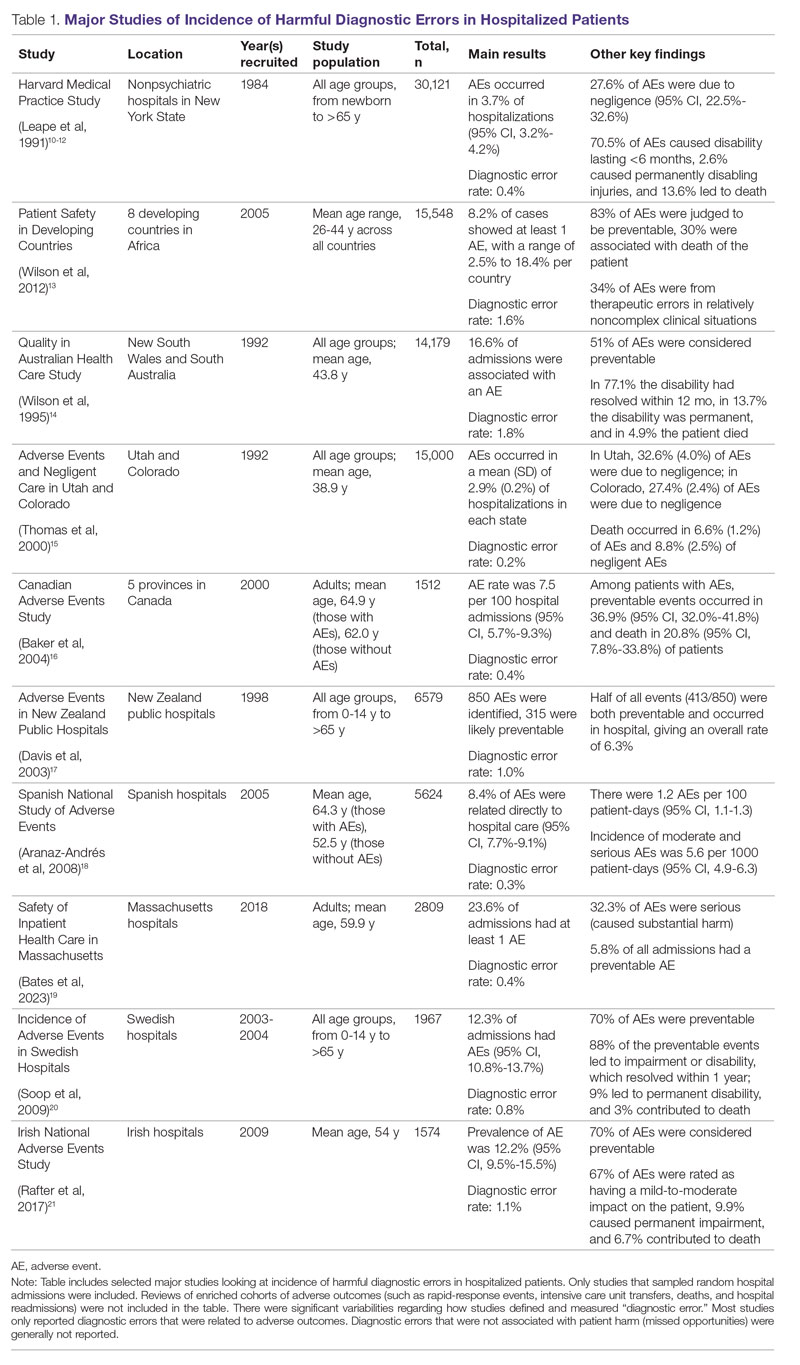

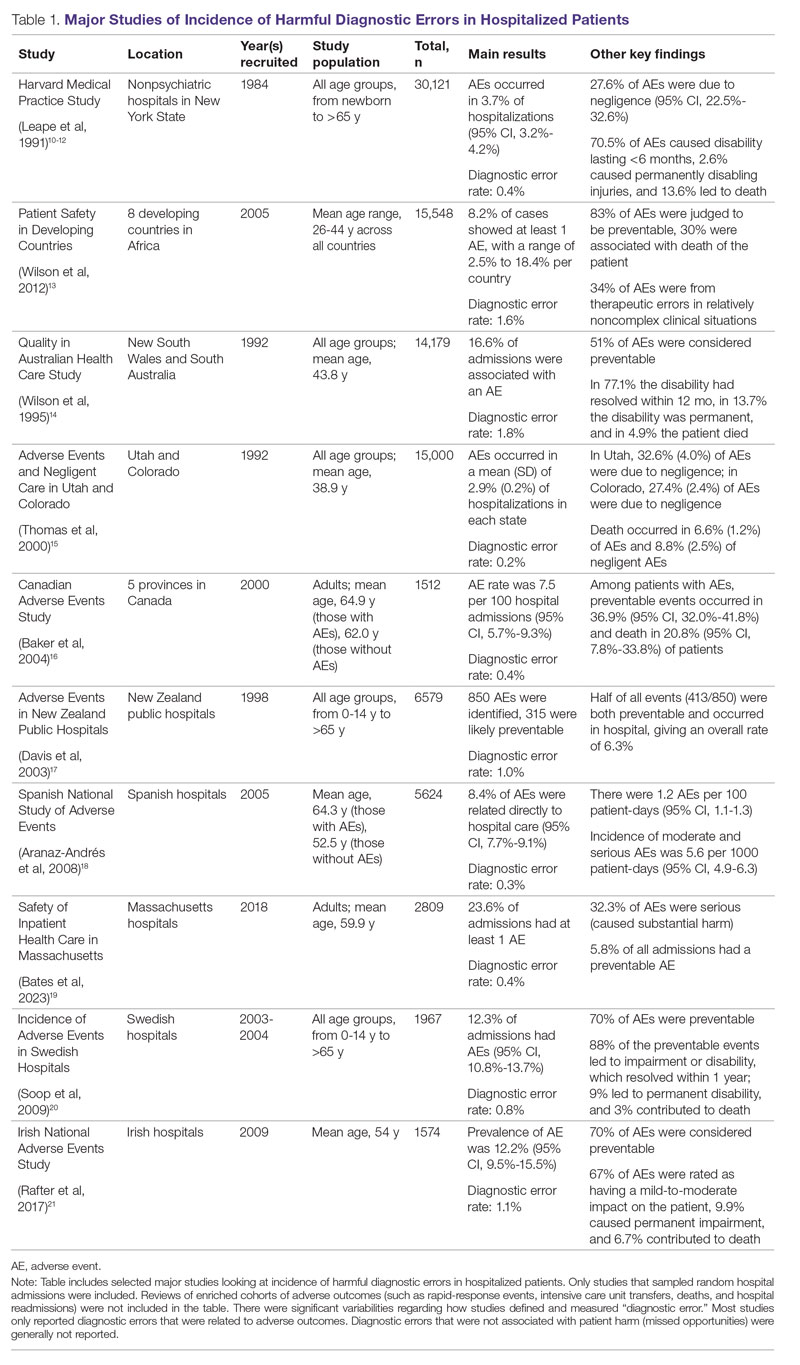

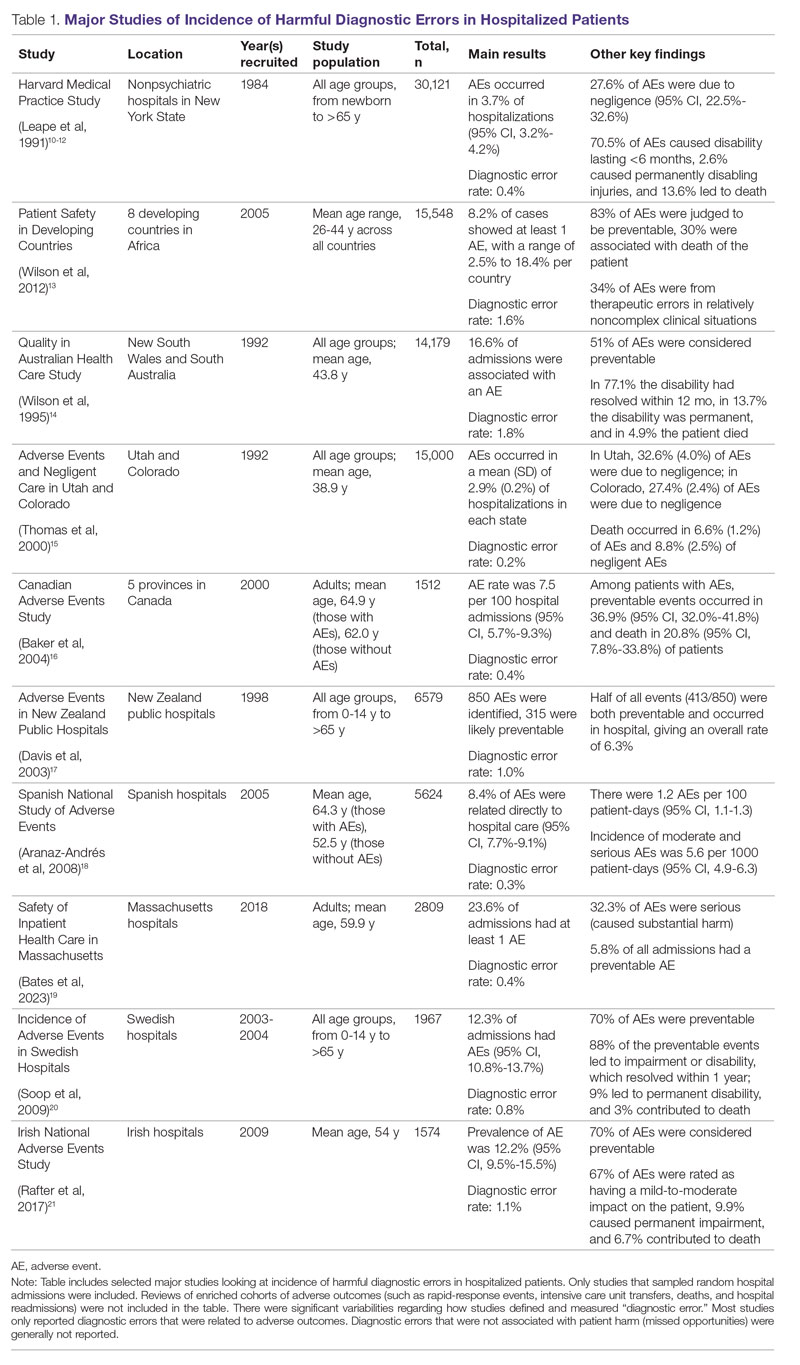

Large retrospective chart reviews of random hospital admissions remain the most accurate way to determine the overall incidence of diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients.9 The Harvard Medical Practice Study, published in 1991, laid the groundwork for measuring the incidence of adverse events in hospitalized patients and assessing their relation to medical error, negligence, and disability. Reviewing 30,121 randomly selected records from 51 randomly selected acute care hospitals in New York State, the study found that adverse events occurred in 3.7% of hospitalizations, diagnostic errors accounted for 13.8% of these events, and these errors were likely attributable to negligence in 74.7% of cases. The study not only outlined individual-level process failures, but also focused attention on some of the systemic causes, setting the agenda for quality improvement research in hospital-based care for years to come.10-12 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 22 hospital admission studies found a pooled rate of 0.7% (95% CI, 0.5%-1.1%) for harmful diagnostic errors.9 It found significant variations in the rates of adverse events, diagnostic errors, and range of diagnoses that were missed. This was primarily because of variabilities in pre-test probabilities in detecting diagnostic errors in these specific cohorts, as well as due to heterogeneity in study definitions and methodologies, especially regarding how they defined and measured “diagnostic error.” The analysis, however, did not account for diagnostic errors that were not related to patient harm (missed opportunities); therefore, it likely significantly underestimated the true incidence of diagnostic errors in these study populations. Table 1 summarizes some of key studies that have examined the incidence of harmful diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients.9-21

The chief limitation of reviewing random hospital admissions is that, since overall rates of diagnostic errors are still relatively low, a large number of case reviews are required to identify a sufficient sample of adverse outcomes to gain a meaningful understanding of the underlying process failure points and develop tools for remediation. Patient and provider surveys or data from malpractice claims can be high-yield starting points for research on process errors.22,23 Reviews of enriched cohorts of adverse outcomes, such as rapid-response events, intensive care unit (ICU) transfers, deaths, and hospital readmissions, can be an efficient way to identify process failures that lead to greatest harm. Depending on the research approach and the types of underlying patient populations sampled, rates of diagnostic errors in these high-risk groups have been estimated to be approximately 5% to 20%, or even higher.6,24-31 For example, a retrospective study of 391 cases of unplanned 7-day readmissions found that 5.6% of cases contained at least 1 diagnostic error during the index admission.32 In a study conducted at 6 Belgian acute-care hospitals, 56% of patients requiring an unplanned transfer to a higher level of care were determined to have had an adverse event, and of these adverse events, 12.4% of cases were associated with errors in diagnosis.29 A systematic review of 16 hospital-based studies estimated that 3.1% of all inpatient deaths were likely preventable, which corresponded to 22,165 deaths annually in the United States.30 Another such review of 31 autopsy studies reported that 28% of autopsied ICU patients had at least 1 misdiagnosis; of these diagnostic errors, 8% were classified as potentially lethal, and 15% were considered major but not lethal.31 Significant drawbacks of such enriched cohort studies, however, are their poor generalizability and inability to detect failure points that do not lead to patient harm (near-miss events).33

Causes of Diagnostic Errors in Hospitalized Patients

All aspects of the diagnostic process are susceptible to errors. These errors stem from a variety of faulty processes, including failure of the patient to engage with the health care system (eg, due to lack of insurance or transportation, or delay in seeking care); failure in information gathering (eg, missed history or exam findings, ordering wrong tests, laboratory errors); failure in information interpretation (eg, exam finding or test result misinterpretation); inaccurate hypothesis generation (eg, due to suboptimal prioritization or weighing of supporting evidence); and failure in communication (eg, with other team members or with the patient).2,34 Reasons for diagnostic process failures vary widely across different health care settings. While clinician assessment errors (eg, failure to consider or alternatively overweigh competing diagnoses) and errors in testing and the monitoring phase (eg, failure to order or follow up diagnostic tests) can lead to a majority of diagnostic errors in some patient populations, in other settings, social (eg, poor health literacy, punitive cultural practices) and economic factors (eg, lack of access to appropriate diagnostic tests or to specialty expertise) play a more prominent role.34,35

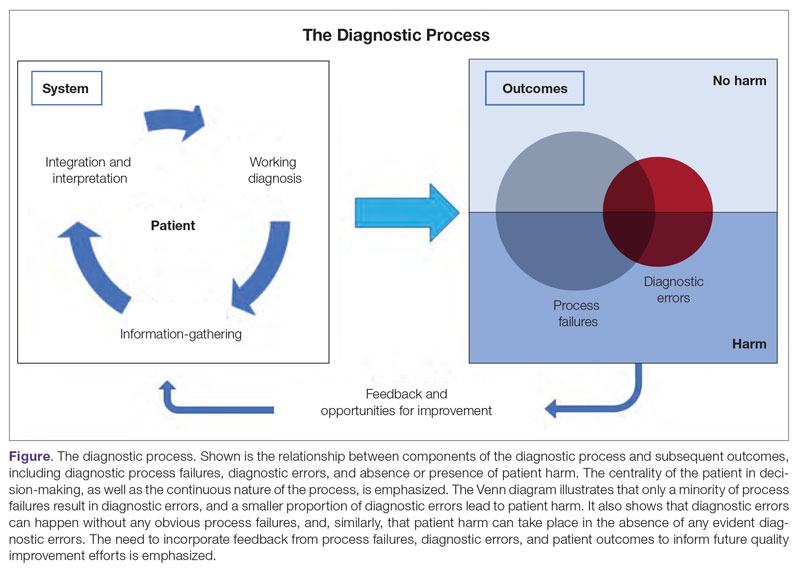

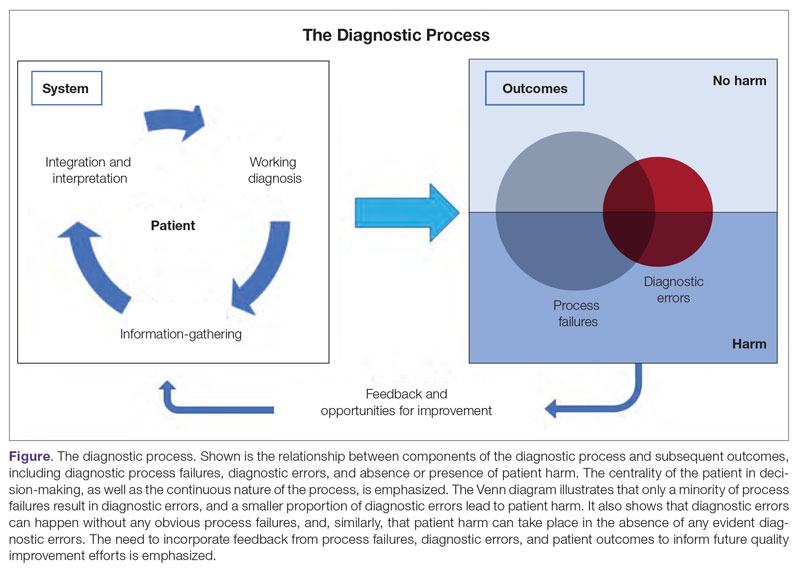

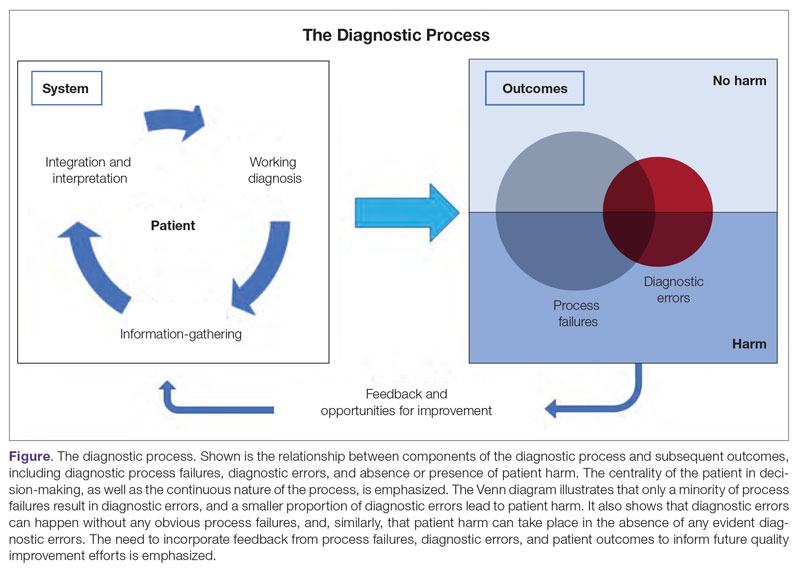

The Figure describes the relationship between components of the diagnostic process and subsequent outcomes, including diagnostic process failures, diagnostic errors, and absence or presence of patient harm.2,36,37 It reemphasizes the centrality of the patient in decision-making and the continuous nature of the process. The Figure also illustrates that only a minority of process failures result in diagnostic errors, and a smaller proportion of diagnostic errors actually lead to patient harm. Conversely, it also shows that diagnostic errors can happen without any obvious process-failure points, and, similarly, patient harm can take place in the absence of any evident diagnostic errors.36-38 Finally, it highlights the need to incorporate feedback from process failures, diagnostic errors, and favorable and unfavorable patient outcomes in order to inform future quality improvement efforts and research.

A significant proportion of diagnostic errors are due to system-related vulnerabilities, such as limitations in availability, adoption or quality of work force training, health informatics resources, and diagnostic capabilities. Lack of institutional culture that promotes safety and transparency also predisposes to diagnostic errors.39,40 The other major domain of process failures is related to cognitive errors in clinician decision-making. Anchoring, confirmation bias, availability bias, and base-rate neglect are some of the common cognitive biases that, along with personality traits (aversion to risk or ambiguity, overconfidence) and affective biases (influence of emotion on decision-making), often determine the degree of utilization of resources and the possibility of suboptimal diagnostic performance.41,42 Further, implicit biases related to age, race, gender, and sexual orientation contribute to disparities in access to health care and outcomes.43 In a large number of cases of preventable adverse outcomes, however, there are multiple interdependent individual and system-related failure points that lead to diagnostic error and patient harm.6,32

Challenges in Defining and Measuring Diagnostic Errors

In order to develop effective, evidence-based interventions to reduce diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients, it is essential to be able to first operationally define, and then accurately measure, diagnostic errors and the process failures that contribute to these errors in a standardized way that is reproducible across different settings.6,44 There are a number of obstacles in this endeavor.

A fundamental problem is that establishing a diagnosis is not a single act but a process. Patterns of symptoms and clinical presentations often differ for the same disease. Information required to make a diagnosis is usually gathered in stages, where the clinician obtains additional data, while considering many possibilities, of which 1 may be ultimately correct. Diagnoses evolve over time and in different care settings. “The most likely diagnosis” is not always the same as “the final correct diagnosis.” Moreover, the diagnostic process is influenced by patients’ individual clinical courses and preferences over time. This makes determination of missed, delayed, or incorrect diagnoses challenging.45,46

For hospitalized patients, generally the goal is to first rule out more serious and acute conditions (eg, pulmonary embolism or stroke), even if their probability is rather low. Conversely, a diagnosis that appears less consequential if delayed (eg, chronic anemia of unclear etiology) might not be pursued on an urgent basis, and is often left to outpatient providers to examine, but still may manifest in downstream harm (eg, delayed diagnosis of gastrointestinal malignancy or recurrent admissions for heart failure due to missed iron-deficiency anemia). Therefore, coming up with disease diagnosis likelihoods in hindsight may turn out to be highly subjective and not always accurate. This can be particularly difficult when clinician and other team deliberations are not recorded in their entirety.47

Another hurdle in the practice of diagnostic medicine is to preserve the balance between underdiagnosing versus pursuing overly aggressive diagnostic approaches. Conducting laboratory, imaging, or other diagnostic studies without a clear shared understanding of how they would affect clinical decision-making (eg, use of prostate-specific antigen to detect prostate cancer) not only leads to increased costs but can also delay appropriate care. Worse, subsequent unnecessary diagnostic tests and treatments can sometimes lead to serious harm.48,49

Finally, retrospective reviews by clinicians are subject to multiple potential limitations that include failure to create well-defined research questions, poorly developed inclusion and exclusion criteria, and issues related to inter- and intra-rater reliability.50 These methodological deficiencies can occur despite following "best practice" guidelines during the study planning, execution, and analysis phases. They further add to the challenge of defining and measuring diagnostic errors.47

Strategies to Improve Measurement of Diagnostic Errors

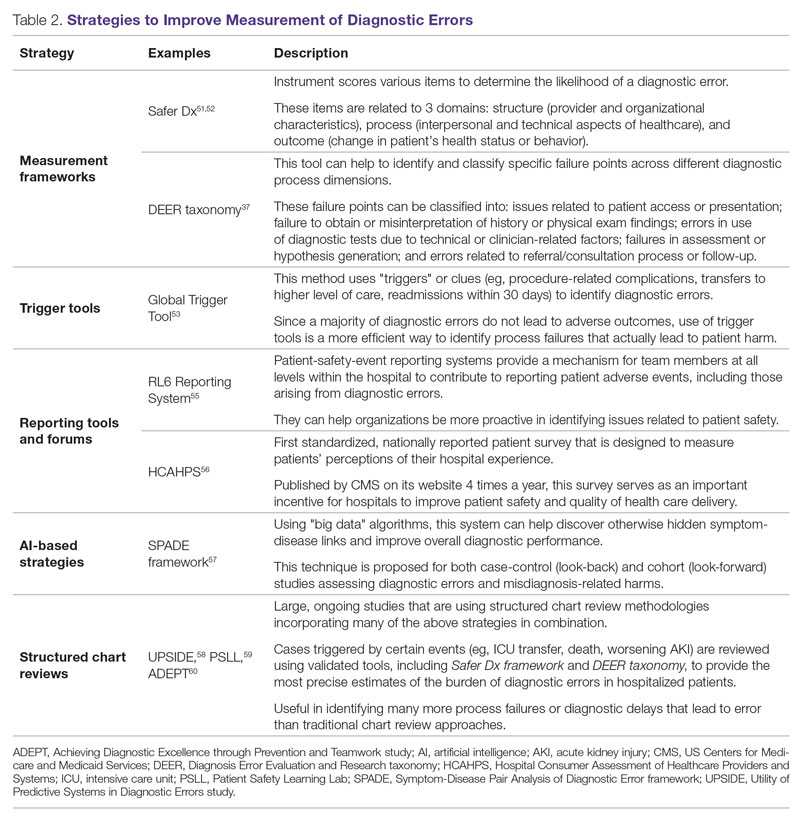

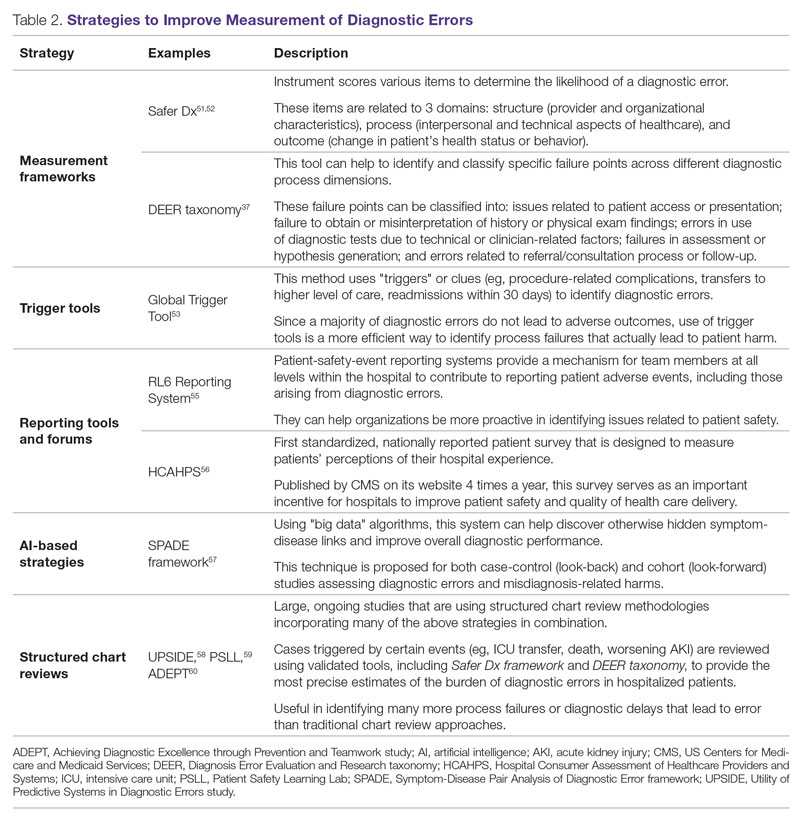

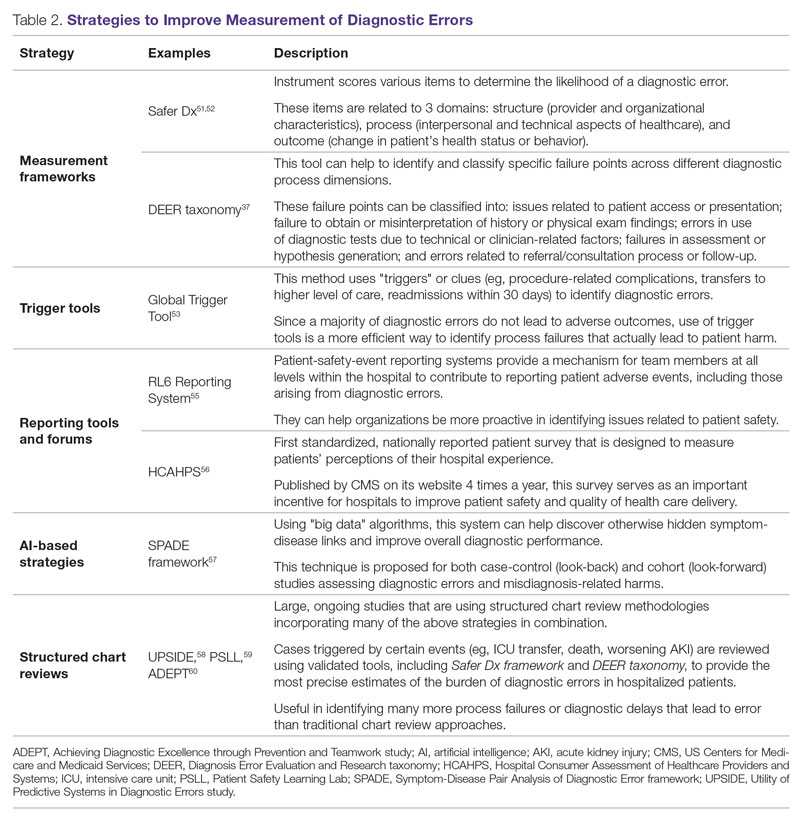

Development of new methodologies to reliably measure diagnostic errors is an area of active research. The advancement of uniform and universally agreed-upon frameworks to define and identify process failure points and diagnostic errors would help reduce measurement error and support development and testing of interventions that could be generalizable across different health care settings. To more accurately define and measure diagnostic errors, several novel approaches have been proposed (Table 2).

The Safer Dx framework is an all-round tool developed to advance the discipline of measuring diagnostic errors. For an episode of care under review, the instrument scores various items to determine the likelihood of a diagnostic error. These items evaluate multiple dimensions affecting diagnostic performance and measurements across 3 broad domains: structure (provider and organizational characteristics—from everyone involved with patient care, to computing infrastructure, to policies and regulations), process (elements of the patient-provider encounter, diagnostic test performance and follow-up, and subspecialty- and referral-specific factors), and outcome (establishing accurate and timely diagnosis as opposed to missed, delayed, or incorrect diagnosis). This instrument has been revised and can be further modified by a variety of stakeholders, including clinicians, health care organizations, and policymakers, to identify potential diagnostic errors in a standardized way for patient safety and quality improvement research.51,52

Use of standardized tools, such as the Diagnosis Error Evaluation and Research (DEER) taxonomy, can help to identify and classify specific failure points across different diagnostic process dimensions.37 These failure points can be classified into: issues related to patient presentation or access to health care; failure to obtain or misinterpretation of history or physical exam findings; errors in use of diagnostics tests due to technical or clinician-related factors; failures in appropriate weighing of evidence and hypothesis generation; errors associated with referral or consultation process; and failure to monitor the patient or obtain timely follow-up.34 The DEER taxonomy can also be modified based on specific research questions and study populations. Further, it can be recategorized to correspond to Safer Dx framework diagnostic process dimensions to provide insights into reasons for specific process failures and to develop new interventions to mitigate errors and patient harm.6

Since a majority of diagnostic errors do not lead to actual harm, use of “triggers” or clues (eg, procedure-related complications, patient falls, transfers to a higher level of care, readmissions within 30 days) can be a more efficient method to identify diagnostic errors and adverse events that do cause harm. The Global Trigger Tool, developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, uses this strategy. This tool has been shown to identify a significantly higher number of serious adverse events than comparable methods.53 This facilitates selection and development of strategies at the institutional level that are most likely to improve patient outcomes.24

Encouraging and facilitating voluntary or prompted reporting from patients and clinicians can also play an important role in capturing diagnostic errors. Patients and clinicians are not only the key stakeholders but are also uniquely placed within the diagnostic process to detect and report potential errors.25,54 Patient-safety-event reporting systems, such as RL6, play a vital role in reporting near-misses and adverse events. These systems provide a mechanism for team members at all levels within the hospital to contribute toward reporting patient adverse events, including those arising from diagnostic errors.55 The Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey is the first standardized, nationally reported patient survey designed to measure patients’ perceptions of their hospital experience. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) publishes HCAHPS results on its website 4 times a year, which serves as an important incentive for hospitals to improve patient safety and quality of health care delivery.56

Another novel approach links multiple symptoms to a range of target diseases using the Symptom-Disease Pair Analysis of Diagnostic Error (SPADE) framework. Using “big data” technologies, this technique can help discover otherwise hidden symptom-disease links and improve overall diagnostic performance. This approach is proposed for both case-control (look-back) and cohort (look-forward) studies assessing diagnostic errors and misdiagnosis-related harms. For example, starting with a known diagnosis with high potential for harm (eg, stroke), the “look-back” approach can be used to identify high-risk symptoms (eg, dizziness, vertigo). In the “look-forward” approach, a single symptom or exposure risk factor known to be frequently misdiagnosed (eg, dizziness) can be analyzed to identify potential adverse disease outcomes (eg, stroke, migraine).57

Many large ongoing studies looking at diagnostic errors among hospitalized patients, such as Utility of Predictive Systems to identify Inpatient Diagnostic Errors (UPSIDE),58 Patient Safety Learning Lab (PSLL),59 and Achieving Diagnostic Excellence through Prevention and Teamwork (ADEPT),60 are using structured chart review methodologies incorporating many of the above strategies in combination. Cases triggered by certain events (eg, ICU transfer, death, rapid response event, new or worsening acute kidney injury) are reviewed using validated tools, including Safer Dx framework and DEER taxonomy, to provide the most precise estimates of the burden of diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients. These estimates may be much higher than previously predicted using traditional chart review approaches.6,24 For example, a recently published study of 2809 random admissions in 11 Massachusetts hospitals identified 978 adverse events but only 10 diagnostic errors (diagnostic error rate, 0.4%).19 This was likely because the trigger method used in the study did not specifically examine the diagnostic process as critically as done by the Safer Dx framework and DEER taxonomy tools, thereby underestimating the total number of diagnostic errors. Further, these ongoing studies (eg, UPSIDE, ADEPT) aim to employ new and upcoming advanced machine-learning methods to create models that can improve overall diagnostic performance. This would pave the way to test and build novel, efficient, and scalable interventions to reduce diagnostic errors and improve patient outcomes.

Strategies to Improve Diagnostic Safety in Hospitalized Patients

Disease-specific biomedical research, as well as advances in laboratory, imaging, and other technologies, play a critical role in improving diagnostic accuracy. However, these technical approaches do not address many of the broader clinician- and system-level failure points and opportunities for improvement. Various patient-, provider-, and organizational-level interventions that could make diagnostic processes more resilient and reduce the risk of error and patient harm have been proposed.61

Among these strategies are approaches to empower patients and their families. Fostering therapeutic relationships between patients and members of the care team is essential to reducing diagnostic errors.62 Facilitating timely access to health records, ensuring transparency in decision making, and tailoring communication strategies to patients’ cultural and educational backgrounds can reduce harm.63 Similarly, at the system level, enhancing communication among different providers by use of tools such as structured handoffs can prevent communication breakdowns and facilitate positive outcomes.64

Interventions targeted at individual health care providers, such as educational programs to improve content-specific knowledge, can enhance diagnostic performance. Regular feedback, strategies to enhance equity, and fostering an environment where all providers are actively encouraged to think critically and participate in the diagnostic process (training programs to use “diagnostic time-outs” and making it a “team sport”) can improve clinical reasoning.65,66 Use of standardized patients can help identify individual-level cognitive failure points and facilitate creation of new interventions to improve clinical decision-making processes.67

Novel health information technologies can further augment these efforts. These include effective documentation by maintaining dynamic and accurate patient histories, problem lists, and medication lists68-70; use of electronic health record–based algorithms to identify potential diagnostic delays for serious conditions71,72; use of telemedicine technologies to improve accessibility and coordination73; application of mobile health and wearable technologies to facilitate data-gathering and care delivery74,75; and use of computerized decision-support tools, including applications to interpret electrocardiograms, imaging studies, and other diagnostic tests.76

Use of precision medicine, powered by new artificial intelligence (AI) tools, is becoming more widespread. Algorithms powered by AI can augment and sometimes even outperform clinician decision-making in areas such as oncology, radiology, and primary care.77 Creation of large biobanks like the All of Us research program can be used to study thousands of environmental and genetic risk factors and health conditions simultaneously, and help identify specific treatments that work best for people of different backgrounds.78 Active research in these areas holds great promise in terms of how and when we diagnose diseases and make appropriate preventative and treatment decisions. Significant scientific, ethical, and regulatory challenges will need to be overcome before these technologies can address some of the most complex problems in health care.79

Finally, diagnostic performance is affected by the external environment, including the functioning of the medical liability system. Diagnostic errors that lead to patient harm are a leading cause of malpractice claims.80 Developing a legal environment, in collaboration with patient advocacy groups and health care organizations, that promotes and facilitates timely disclosure of diagnostic errors could decrease the incentive to hide errors, advance care processes, and improve outcomes.81,82

Conclusion

The burden of diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients is unacceptably high and remains an underemphasized cause of preventable morbidity and mortality. Diagnostic errors often result from a breakdown in multiple interdependent processes that involve patient-, provider-, and system-level factors. Significant challenges remain in defining and identifying diagnostic errors as well as underlying process-failure points. The most effective interventions to reduce diagnostic errors will require greater patient participation in the diagnostic process and a mix of evidence-based interventions that promote individual-provider excellence as well as system-level changes. Further research and collaboration among various stakeholders should help improve diagnostic safety for hospitalized patients.

Corresponding author: Abhishek Goyal, MD, MPH; [email protected]

Disclosures: Dr. Dalal disclosed receiving income ≥ $250 from MayaMD.

1. Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(13):1493-1499. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.13.1493

2. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2015. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/21794

3. Singh H, Graber ML. Improving diagnosis in health care—the next imperative for patient safety. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(26):2493-2495. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1512241

4. Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2139

5. Flanders SA, Centor B, Weber V, McGinn T, Desalvo K, Auerbach A. Challenges and opportunities in academic hospital medicine: report from the academic hospital medicine summit. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(5):636-641. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-0944-6

6. Griffin JA, Carr K, Bersani K, et al. Analyzing diagnostic errors in the acute setting: a process-driven approach. Diagnosis (Berl). 2021;9(1):77-88. doi:10.1515/dx-2021-0033

7. Itri JN, Tappouni RR, McEachern RO, Pesch AJ, Patel SH. Fundamentals of diagnostic error in imaging. RadioGraphics. 2018;38(6):1845-1865. doi:10.1148/rg.2018180021

8. Hammerling JA. A Review of medical errors in laboratory diagnostics and where we are today. Lab Med. 2012;43(2):41-44. doi:10.1309/LM6ER9WJR1IHQAUY

9. Gunderson CG, Bilan VP, Holleck JL, et al. Prevalence of harmful diagnostic errors in hospitalised adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(12):1008-1018. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2019-010822

10. Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):370-376. doi:10.1056/NEJM199102073240604

11. Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):377-384. doi:10.1056/NEJM199102073240605

12. Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Brennan TA, et al. Relation between malpractice claims and adverse events due to negligence. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study III. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(4):245-251. doi:10.1056/NEJM199107253250405

13. Wilson RM, Michel P, Olsen S, et al. Patient safety in developing countries: retrospective estimation of scale and nature of harm to patients in hospital. BMJ. 2012;344:e832. doi:10.1136/bmj.e832

14. Wilson RM, Runciman WB, Gibberd RW, Harrison BT, Newby L, Hamilton JD. The Quality in Australian Health Care Study. Med J Aust. 1995;163(9):458-471. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb124691.x

15. Thomas EJ, Studdert DM, Burstin HR, et al. Incidence and types of adverse events and negligent care in Utah and Colorado. Med Care. 2000;38(3):261-271. doi:10.1097/00005650-200003000-00003

16. Baker GR, Norton PG, Flintoft V, et al. The Canadian Adverse Events Study: the incidence of adverse events among hospital patients in Canada. CMAJ. 2004;170(11):1678-1686. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1040498

17. Davis P, Lay-Yee R, Briant R, Ali W, Scott A, Schug S. Adverse events in New Zealand public hospitals II: preventability and clinical context. N Z Med J. 2003;116(1183):U624.

18. Aranaz-Andrés JM, Aibar-Remón C, Vitaller-Murillo J, et al. Incidence of adverse events related to health care in Spain: results of the Spanish National Study of Adverse Events. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(12):1022-1029. doi:10.1136/jech.2007.065227

19. Bates DW, Levine DM, Salmasian H, et al. The safety of inpatient health care. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(2):142-153. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa2206117

20. Soop M, Fryksmark U, Köster M, Haglund B. The incidence of adverse events in Swedish hospitals: a retrospective medical record review study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2009;21(4):285-291. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzp025

21. Rafter N, Hickey A, Conroy RM, et al. The Irish National Adverse Events Study (INAES): the frequency and nature of adverse events in Irish hospitals—a retrospective record review study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(2):111-119. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004828

22. Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM, Brodie M, et al. Views of practicing physicians and the public on medical errors. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(24):1933-1940. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa022151

23. Saber Tehrani AS, Lee H, Mathews SC, et al. 25-year summary of US malpractice claims for diagnostic errors 1986-2010: an analysis from the National Practitioner Data Bank. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(8):672-680. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001550

24. Malik MA, Motta-Calderon D, Piniella N, et al. A structured approach to EHR surveillance of diagnostic error in acute care: an exploratory analysis of two institutionally-defined case cohorts. Diagnosis (Berl). 2022;9(4):446-457. doi:10.1515/dx-2022-0032

25. Graber ML. The incidence of diagnostic error in medicine. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(suppl 2):ii21-ii27. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001615

26. Bergl PA, Taneja A, El-Kareh R, Singh H, Nanchal RS. Frequency, risk factors, causes, and consequences of diagnostic errors in critically ill medical patients: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(11):e902-e910. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000003976

27. Hogan H, Healey F, Neale G, Thomson R, Vincent C, Black N. Preventable deaths due to problems in care in English acute hospitals: a retrospective case record review study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(9):737-745. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2011-001159

28. Bergl PA, Nanchal RS, Singh H. Diagnostic error in the critically ill: defining the problem and exploring next steps to advance intensive care unit safety. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(8):903-907. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201801-068PS

29. Marquet K, Claes N, De Troy E, et al. One fourth of unplanned transfers to a higher level of care are associated with a highly preventable adverse event: a patient record review in six Belgian hospitals. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):1053-1061. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000000932

30. Rodwin BA, Bilan VP, Merchant NB, et al. Rate of preventable mortality in hospitalized patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(7):2099-2106. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05592-5

31. Winters B, Custer J, Galvagno SM, et al. Diagnostic errors in the intensive care unit: a systematic review of autopsy studies. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(11):894-902. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000803

32. Raffel KE, Kantor MA, Barish P, et al. Prevalence and characterisation of diagnostic error among 7-day all-cause hospital medicine readmissions: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(12):971-979. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2020-010896

33. Weingart SN, Pagovich O, Sands DZ, et al. What can hospitalized patients tell us about adverse events? learning from patient-reported incidents. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):830-836. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0180.x

34. Schiff GD, Hasan O, Kim S, et al. Diagnostic error in medicine: analysis of 583 physician-reported errors. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(20):1881-1887. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.333

35. Singh H, Schiff GD, Graber ML, Onakpoya I, Thompson MJ. The global burden of diagnostic errors in primary care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(6):484-494. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005401

36. Schiff GD, Leape LL. Commentary: how can we make diagnosis safer? Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2012;87(2):135-138. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823f711c

37. Schiff GD, Kim S, Abrams R, et al. Diagnosing diagnosis errors: lessons from a multi-institutional collaborative project. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, Lewin DI, eds. Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation. Volume 2: Concepts and Methodology. AHRQ Publication No. 05-0021-2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2005. Accessed January 16, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK20492/

38. Newman-Toker DE. A unified conceptual model for diagnostic errors: underdiagnosis, overdiagnosis, and misdiagnosis. Diagnosis (Berl). 2014;1(1):43-48. doi:10.1515/dx-2013-0027

39. Abimanyi-Ochom J, Bohingamu Mudiyanselage S, Catchpool M, Firipis M, Wanni Arachchige Dona S, Watts JJ. Strategies to reduce diagnostic errors: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2019;19(1):174. doi:10.1186/s12911-019-0901-1

40. Gupta A, Harrod M, Quinn M, et al. Mind the overlap: how system problems contribute to cognitive failure and diagnostic errors. Diagnosis (Berl). 2018;5(3):151-156. doi:10.1515/dx-2018-0014

41. Saposnik G, Redelmeier D, Ruff CC, Tobler PN. Cognitive biases associated with medical decisions: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:138. doi:10.1186/s12911-016-0377-1

42. Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med. 2003;78(8):775-780. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200308000-00003

43. Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504-1510. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1

44. Zwaan L, Singh H. The challenges in defining and measuring diagnostic error. Diagnosis (Ber). 2015;2(2):97-103. doi:10.1515/dx-2014-0069

45. Arkes HR, Wortmann RL, Saville PD, Harkness AR. Hindsight bias among physicians weighing the likelihood of diagnoses. J Appl Psychol. 1981;66(2):252-254.

46. Singh H. Editorial: Helping health care organizations to define diagnostic errors as missed opportunities in diagnosis. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2014;40(3):99-101. doi:10.1016/s1553-7250(14)40012-6

47. Vassar M, Holzmann M. The retrospective chart review: important methodological considerations. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2013;10:12. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2013.10.12

48. Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(9):605-613. doi:10.1093/jnci/djq099

49. Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. BMJ. 2012;344:e3502. doi:10.1136/bmj.e3502

50. Hayward RA, Hofer TP. Estimating hospital deaths due to medical errors: preventability is in the eye of the reviewer. JAMA. 2001;286(4):415-420. doi:10.1001/jama.286.4.415

51. Singh H, Sittig DF. Advancing the science of measurement of diagnostic errors in healthcare: the Safer Dx framework. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(2):103-110. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003675

52. Singh H, Khanna A, Spitzmueller C, Meyer AND. Recommendations for using the Revised Safer Dx Instrument to help measure and improve diagnostic safety. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019;6(4):315-323. doi:10.1515/dx-2019-0012

53. Classen DC, Resar R, Griffin F, et al. “Global trigger tool” shows that adverse events in hospitals may be ten times greater than previously measured. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):581-589. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0190

54. Schiff GD. Minimizing diagnostic error: the importance of follow-up and feedback. Am J Med. 2008;121(5 suppl):S38-S42. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.02.004

55. Mitchell I, Schuster A, Smith K, Pronovost P, Wu A. Patient safety incident reporting: a qualitative study of thoughts and perceptions of experts 15 years after “To Err is Human.” BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(2):92-99. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004405

56. Mazurenko O, Collum T, Ferdinand A, Menachemi N. Predictors of hospital patient satisfaction as measured by HCAHPS: a systematic review. J Healthc Manag. 2017;62(4):272-283. doi:10.1097/JHM-D-15-00050

57. Liberman AL, Newman-Toker DE. Symptom-Disease Pair Analysis of Diagnostic Error (SPADE): a conceptual framework and methodological approach for unearthing misdiagnosis-related harms using big data. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(7):557-566. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007032

58. Utility of Predictive Systems to Identify Inpatient Diagnostic Errors: the UPSIDE study. NIH RePort/RePORTER. Accessed January 14, 2023. https://reporter.nih.gov/search/rpoHXlEAcEudQV3B9ld8iw/project-details/10020962

59. Overview of Patient Safety Learning Laboratory (PSLL) Projects. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Accessed January 14, 2023. https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/resources/learning-lab/index.html

60. Achieving Diagnostic Excellence through Prevention and Teamwork (ADEPT). NIH RePort/RePORTER. Accessed January 14, 2023. https://reporter.nih.gov/project-details/10642576

61. Zwaan L, Singh H. Diagnostic error in hospitals: finding forests not just the big trees. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(12):961-964. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2020-011099

62. Longtin Y, Sax H, Leape LL, Sheridan SE, Donaldson L, Pittet D. Patient participation: current knowledge and applicability to patient safety. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(1):53-62. doi:10.4065/mcp.2009.0248

63. Murphy DR, Singh H, Berlin L. Communication breakdowns and diagnostic errors: a radiology perspective. Diagnosis (Berl). 2014;1(4):253-261. doi:10.1515/dx-2014-0035

64. Singh H, Naik AD, Rao R, Petersen LA. Reducing diagnostic errors through effective communication: harnessing the power of information technology. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(4):489-494. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0393-z

65. Singh H, Connor DM, Dhaliwal G. Five strategies for clinicians to advance diagnostic excellence. BMJ. 2022;376:e068044. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-068044

66. Yale S, Cohen S, Bordini BJ. Diagnostic time-outs to improve diagnosis. Crit Care Clin. 2022;38(2):185-194. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2021.11.008

67. Schwartz A, Peskin S, Spiro A, Weiner SJ. Impact of unannounced standardized patient audit and feedback on care, documentation, and costs: an experiment and claims analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(1):27-34. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05965-1

68. Carpenter JD, Gorman PN. Using medication list—problem list mismatches as markers of potential error. Proc AMIA Symp. 2002:106-110.

69. Hron JD, Manzi S, Dionne R, et al. Electronic medication reconciliation and medication errors. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27(4):314-319. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzv046

70. Graber ML, Siegal D, Riah H, Johnston D, Kenyon K. Electronic health record–related events in medical malpractice claims. J Patient Saf. 2019;15(2):77-85. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000240

71. Murphy DR, Wu L, Thomas EJ, Forjuoh SN, Meyer AND, Singh H. Electronic trigger-based intervention to reduce delays in diagnostic evaluation for cancer: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(31):3560-3567. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.61.1301

72. Singh H, Giardina TD, Forjuoh SN, et al. Electronic health record-based surveillance of diagnostic errors in primary care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(2):93-100. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000304

73. Armaignac DL, Saxena A, Rubens M, et al. Impact of telemedicine on mortality, length of stay, and cost among patients in progressive care units: experience from a large healthcare system. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(5):728-735. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002994

74. MacKinnon GE, Brittain EL. Mobile health technologies in cardiopulmonary disease. Chest. 2020;157(3):654-664. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2019.10.015

75. DeVore AD, Wosik J, Hernandez AF. The future of wearables in heart failure patients. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7(11):922-932. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2019.08.008

76. Tsai TL, Fridsma DB, Gatti G. Computer decision support as a source of interpretation error: the case of electrocardiograms. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(5):478-483. doi:10.1197/jamia.M1279

77. Lin SY, Mahoney MR, Sinsky CA. Ten ways artificial intelligence will transform primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8):1626-1630. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05035-1

78. Ramirez AH, Gebo KA, Harris PA. Progress with the All Of Us research program: opening access for researchers. JAMA. 2021;325(24):2441-2442. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.7702

79. Johnson KB, Wei W, Weeraratne D, et al. Precision medicine, AI, and the future of personalized health care. Clin Transl Sci. 2021;14(1):86-93. doi:10.1111/cts.12884

80. Gupta A, Snyder A, Kachalia A, Flanders S, Saint S, Chopra V. Malpractice claims related to diagnostic errors in the hospital. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;27(1):bmjqs-2017-006774. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006774

81. Renkema E, Broekhuis M, Ahaus K. Conditions that influence the impact of malpractice litigation risk on physicians’ behavior regarding patient safety. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):38. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-38

82. Kachalia A, Mello MM, Nallamothu BK, Studdert DM. Legal and policy interventions to improve patient safety. Circulation. 2016;133(7):661-671. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015880

Abstract

Diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients are a leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality. Significant challenges in defining and measuring diagnostic errors and underlying process failure points have led to considerable variability in reported rates of diagnostic errors and adverse outcomes. In this article, we explore the diagnostic process and its discrete components, emphasizing the centrality of the patient in decision-making as well as the continuous nature of the process. We review the incidence of diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients and different methodological approaches that have been used to arrive at these estimates. We discuss different but interdependent provider- and system-related process-failure points that lead to diagnostic errors. We examine specific challenges related to measurement of diagnostic errors and describe traditional and novel approaches that are being used to obtain the most precise estimates. Finally, we examine various patient-, provider-, and organizational-level interventions that have been proposed to improve diagnostic safety in hospitalized patients.

Keywords: diagnostic error, hospital medicine, patient safety.

Diagnosis is defined as a “pre-existing set of categories agreed upon by the medical profession to designate a specific condition.”1 The diagnostic process involves obtaining a clinical history, performing a physical examination, conducting diagnostic testing, and consulting with other clinical providers to gather data that are relevant to understanding the underlying disease processes. This exercise involves generating hypotheses and updating prior probabilities as more information and evidence become available. Throughout this process of information gathering, integration, and interpretation, there is an ongoing assessment of whether sufficient and necessary knowledge has been obtained to make an accurate diagnosis and provide appropriate treatment.2

Diagnostic error is defined as a missed opportunity to make a timely diagnosis as part of this iterative process, including the failure of communicating the diagnosis to the patient in a timely manner.3 It can be categorized as a missed, delayed, or incorrect diagnosis based on available evidence at the time. Establishing the correct diagnosis has important implications. A timely and precise diagnosis ensures the patient the highest probability of having a positive health outcome that reflects an appropriate understanding of underlying disease processes and is consistent with their overall goals of care.3 When diagnostic errors occur, they can cause patient harm. Adverse events due to medical errors, including diagnostic errors, are estimated to be the third leading cause of death in the United States.4 Most people will experience at least 1 diagnostic error in their lifetime. In the 2015 National Academy of Medicine report Improving Diagnosis in Healthcare, diagnostic errors were identified as a major hazard as well as an opportunity to improve patient outcomes.2

Diagnostic errors during hospitalizations are especially concerning, as they are more likely to be implicated in a wider spectrum of harm, including permanent disability and death. This has become even more relevant for hospital medicine physicians and other clinical providers as they encounter increasing cognitive and administrative workloads, rising dissatisfaction and burnout, and unique obstacles such as night-time scheduling.5

Incidence of Diagnostic Errors in Hospitalized Patients

Several methodological approaches have been used to estimate the incidence of diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients. These include retrospective reviews of a sample of all hospital admissions, evaluations of selected adverse outcomes including autopsy studies, patient and provider surveys, and malpractice claims. Laboratory testing audits and secondary reviews in other diagnostic subspecialities (eg, radiology, pathology, and microbiology) are also essential to improving diagnostic performance in these specialized fields, which in turn affects overall hospital diagnostic error rates.6-8 These diverse approaches provide unique insights regarding our ability to assess the degree to which potential harms, ranging from temporary impairment to permanent disability, to death, are attributable to different failure points in the diagnostic process.

Large retrospective chart reviews of random hospital admissions remain the most accurate way to determine the overall incidence of diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients.9 The Harvard Medical Practice Study, published in 1991, laid the groundwork for measuring the incidence of adverse events in hospitalized patients and assessing their relation to medical error, negligence, and disability. Reviewing 30,121 randomly selected records from 51 randomly selected acute care hospitals in New York State, the study found that adverse events occurred in 3.7% of hospitalizations, diagnostic errors accounted for 13.8% of these events, and these errors were likely attributable to negligence in 74.7% of cases. The study not only outlined individual-level process failures, but also focused attention on some of the systemic causes, setting the agenda for quality improvement research in hospital-based care for years to come.10-12 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 22 hospital admission studies found a pooled rate of 0.7% (95% CI, 0.5%-1.1%) for harmful diagnostic errors.9 It found significant variations in the rates of adverse events, diagnostic errors, and range of diagnoses that were missed. This was primarily because of variabilities in pre-test probabilities in detecting diagnostic errors in these specific cohorts, as well as due to heterogeneity in study definitions and methodologies, especially regarding how they defined and measured “diagnostic error.” The analysis, however, did not account for diagnostic errors that were not related to patient harm (missed opportunities); therefore, it likely significantly underestimated the true incidence of diagnostic errors in these study populations. Table 1 summarizes some of key studies that have examined the incidence of harmful diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients.9-21

The chief limitation of reviewing random hospital admissions is that, since overall rates of diagnostic errors are still relatively low, a large number of case reviews are required to identify a sufficient sample of adverse outcomes to gain a meaningful understanding of the underlying process failure points and develop tools for remediation. Patient and provider surveys or data from malpractice claims can be high-yield starting points for research on process errors.22,23 Reviews of enriched cohorts of adverse outcomes, such as rapid-response events, intensive care unit (ICU) transfers, deaths, and hospital readmissions, can be an efficient way to identify process failures that lead to greatest harm. Depending on the research approach and the types of underlying patient populations sampled, rates of diagnostic errors in these high-risk groups have been estimated to be approximately 5% to 20%, or even higher.6,24-31 For example, a retrospective study of 391 cases of unplanned 7-day readmissions found that 5.6% of cases contained at least 1 diagnostic error during the index admission.32 In a study conducted at 6 Belgian acute-care hospitals, 56% of patients requiring an unplanned transfer to a higher level of care were determined to have had an adverse event, and of these adverse events, 12.4% of cases were associated with errors in diagnosis.29 A systematic review of 16 hospital-based studies estimated that 3.1% of all inpatient deaths were likely preventable, which corresponded to 22,165 deaths annually in the United States.30 Another such review of 31 autopsy studies reported that 28% of autopsied ICU patients had at least 1 misdiagnosis; of these diagnostic errors, 8% were classified as potentially lethal, and 15% were considered major but not lethal.31 Significant drawbacks of such enriched cohort studies, however, are their poor generalizability and inability to detect failure points that do not lead to patient harm (near-miss events).33

Causes of Diagnostic Errors in Hospitalized Patients

All aspects of the diagnostic process are susceptible to errors. These errors stem from a variety of faulty processes, including failure of the patient to engage with the health care system (eg, due to lack of insurance or transportation, or delay in seeking care); failure in information gathering (eg, missed history or exam findings, ordering wrong tests, laboratory errors); failure in information interpretation (eg, exam finding or test result misinterpretation); inaccurate hypothesis generation (eg, due to suboptimal prioritization or weighing of supporting evidence); and failure in communication (eg, with other team members or with the patient).2,34 Reasons for diagnostic process failures vary widely across different health care settings. While clinician assessment errors (eg, failure to consider or alternatively overweigh competing diagnoses) and errors in testing and the monitoring phase (eg, failure to order or follow up diagnostic tests) can lead to a majority of diagnostic errors in some patient populations, in other settings, social (eg, poor health literacy, punitive cultural practices) and economic factors (eg, lack of access to appropriate diagnostic tests or to specialty expertise) play a more prominent role.34,35

The Figure describes the relationship between components of the diagnostic process and subsequent outcomes, including diagnostic process failures, diagnostic errors, and absence or presence of patient harm.2,36,37 It reemphasizes the centrality of the patient in decision-making and the continuous nature of the process. The Figure also illustrates that only a minority of process failures result in diagnostic errors, and a smaller proportion of diagnostic errors actually lead to patient harm. Conversely, it also shows that diagnostic errors can happen without any obvious process-failure points, and, similarly, patient harm can take place in the absence of any evident diagnostic errors.36-38 Finally, it highlights the need to incorporate feedback from process failures, diagnostic errors, and favorable and unfavorable patient outcomes in order to inform future quality improvement efforts and research.

A significant proportion of diagnostic errors are due to system-related vulnerabilities, such as limitations in availability, adoption or quality of work force training, health informatics resources, and diagnostic capabilities. Lack of institutional culture that promotes safety and transparency also predisposes to diagnostic errors.39,40 The other major domain of process failures is related to cognitive errors in clinician decision-making. Anchoring, confirmation bias, availability bias, and base-rate neglect are some of the common cognitive biases that, along with personality traits (aversion to risk or ambiguity, overconfidence) and affective biases (influence of emotion on decision-making), often determine the degree of utilization of resources and the possibility of suboptimal diagnostic performance.41,42 Further, implicit biases related to age, race, gender, and sexual orientation contribute to disparities in access to health care and outcomes.43 In a large number of cases of preventable adverse outcomes, however, there are multiple interdependent individual and system-related failure points that lead to diagnostic error and patient harm.6,32

Challenges in Defining and Measuring Diagnostic Errors

In order to develop effective, evidence-based interventions to reduce diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients, it is essential to be able to first operationally define, and then accurately measure, diagnostic errors and the process failures that contribute to these errors in a standardized way that is reproducible across different settings.6,44 There are a number of obstacles in this endeavor.

A fundamental problem is that establishing a diagnosis is not a single act but a process. Patterns of symptoms and clinical presentations often differ for the same disease. Information required to make a diagnosis is usually gathered in stages, where the clinician obtains additional data, while considering many possibilities, of which 1 may be ultimately correct. Diagnoses evolve over time and in different care settings. “The most likely diagnosis” is not always the same as “the final correct diagnosis.” Moreover, the diagnostic process is influenced by patients’ individual clinical courses and preferences over time. This makes determination of missed, delayed, or incorrect diagnoses challenging.45,46

For hospitalized patients, generally the goal is to first rule out more serious and acute conditions (eg, pulmonary embolism or stroke), even if their probability is rather low. Conversely, a diagnosis that appears less consequential if delayed (eg, chronic anemia of unclear etiology) might not be pursued on an urgent basis, and is often left to outpatient providers to examine, but still may manifest in downstream harm (eg, delayed diagnosis of gastrointestinal malignancy or recurrent admissions for heart failure due to missed iron-deficiency anemia). Therefore, coming up with disease diagnosis likelihoods in hindsight may turn out to be highly subjective and not always accurate. This can be particularly difficult when clinician and other team deliberations are not recorded in their entirety.47

Another hurdle in the practice of diagnostic medicine is to preserve the balance between underdiagnosing versus pursuing overly aggressive diagnostic approaches. Conducting laboratory, imaging, or other diagnostic studies without a clear shared understanding of how they would affect clinical decision-making (eg, use of prostate-specific antigen to detect prostate cancer) not only leads to increased costs but can also delay appropriate care. Worse, subsequent unnecessary diagnostic tests and treatments can sometimes lead to serious harm.48,49

Finally, retrospective reviews by clinicians are subject to multiple potential limitations that include failure to create well-defined research questions, poorly developed inclusion and exclusion criteria, and issues related to inter- and intra-rater reliability.50 These methodological deficiencies can occur despite following "best practice" guidelines during the study planning, execution, and analysis phases. They further add to the challenge of defining and measuring diagnostic errors.47

Strategies to Improve Measurement of Diagnostic Errors

Development of new methodologies to reliably measure diagnostic errors is an area of active research. The advancement of uniform and universally agreed-upon frameworks to define and identify process failure points and diagnostic errors would help reduce measurement error and support development and testing of interventions that could be generalizable across different health care settings. To more accurately define and measure diagnostic errors, several novel approaches have been proposed (Table 2).

The Safer Dx framework is an all-round tool developed to advance the discipline of measuring diagnostic errors. For an episode of care under review, the instrument scores various items to determine the likelihood of a diagnostic error. These items evaluate multiple dimensions affecting diagnostic performance and measurements across 3 broad domains: structure (provider and organizational characteristics—from everyone involved with patient care, to computing infrastructure, to policies and regulations), process (elements of the patient-provider encounter, diagnostic test performance and follow-up, and subspecialty- and referral-specific factors), and outcome (establishing accurate and timely diagnosis as opposed to missed, delayed, or incorrect diagnosis). This instrument has been revised and can be further modified by a variety of stakeholders, including clinicians, health care organizations, and policymakers, to identify potential diagnostic errors in a standardized way for patient safety and quality improvement research.51,52

Use of standardized tools, such as the Diagnosis Error Evaluation and Research (DEER) taxonomy, can help to identify and classify specific failure points across different diagnostic process dimensions.37 These failure points can be classified into: issues related to patient presentation or access to health care; failure to obtain or misinterpretation of history or physical exam findings; errors in use of diagnostics tests due to technical or clinician-related factors; failures in appropriate weighing of evidence and hypothesis generation; errors associated with referral or consultation process; and failure to monitor the patient or obtain timely follow-up.34 The DEER taxonomy can also be modified based on specific research questions and study populations. Further, it can be recategorized to correspond to Safer Dx framework diagnostic process dimensions to provide insights into reasons for specific process failures and to develop new interventions to mitigate errors and patient harm.6

Since a majority of diagnostic errors do not lead to actual harm, use of “triggers” or clues (eg, procedure-related complications, patient falls, transfers to a higher level of care, readmissions within 30 days) can be a more efficient method to identify diagnostic errors and adverse events that do cause harm. The Global Trigger Tool, developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, uses this strategy. This tool has been shown to identify a significantly higher number of serious adverse events than comparable methods.53 This facilitates selection and development of strategies at the institutional level that are most likely to improve patient outcomes.24

Encouraging and facilitating voluntary or prompted reporting from patients and clinicians can also play an important role in capturing diagnostic errors. Patients and clinicians are not only the key stakeholders but are also uniquely placed within the diagnostic process to detect and report potential errors.25,54 Patient-safety-event reporting systems, such as RL6, play a vital role in reporting near-misses and adverse events. These systems provide a mechanism for team members at all levels within the hospital to contribute toward reporting patient adverse events, including those arising from diagnostic errors.55 The Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey is the first standardized, nationally reported patient survey designed to measure patients’ perceptions of their hospital experience. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) publishes HCAHPS results on its website 4 times a year, which serves as an important incentive for hospitals to improve patient safety and quality of health care delivery.56

Another novel approach links multiple symptoms to a range of target diseases using the Symptom-Disease Pair Analysis of Diagnostic Error (SPADE) framework. Using “big data” technologies, this technique can help discover otherwise hidden symptom-disease links and improve overall diagnostic performance. This approach is proposed for both case-control (look-back) and cohort (look-forward) studies assessing diagnostic errors and misdiagnosis-related harms. For example, starting with a known diagnosis with high potential for harm (eg, stroke), the “look-back” approach can be used to identify high-risk symptoms (eg, dizziness, vertigo). In the “look-forward” approach, a single symptom or exposure risk factor known to be frequently misdiagnosed (eg, dizziness) can be analyzed to identify potential adverse disease outcomes (eg, stroke, migraine).57

Many large ongoing studies looking at diagnostic errors among hospitalized patients, such as Utility of Predictive Systems to identify Inpatient Diagnostic Errors (UPSIDE),58 Patient Safety Learning Lab (PSLL),59 and Achieving Diagnostic Excellence through Prevention and Teamwork (ADEPT),60 are using structured chart review methodologies incorporating many of the above strategies in combination. Cases triggered by certain events (eg, ICU transfer, death, rapid response event, new or worsening acute kidney injury) are reviewed using validated tools, including Safer Dx framework and DEER taxonomy, to provide the most precise estimates of the burden of diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients. These estimates may be much higher than previously predicted using traditional chart review approaches.6,24 For example, a recently published study of 2809 random admissions in 11 Massachusetts hospitals identified 978 adverse events but only 10 diagnostic errors (diagnostic error rate, 0.4%).19 This was likely because the trigger method used in the study did not specifically examine the diagnostic process as critically as done by the Safer Dx framework and DEER taxonomy tools, thereby underestimating the total number of diagnostic errors. Further, these ongoing studies (eg, UPSIDE, ADEPT) aim to employ new and upcoming advanced machine-learning methods to create models that can improve overall diagnostic performance. This would pave the way to test and build novel, efficient, and scalable interventions to reduce diagnostic errors and improve patient outcomes.

Strategies to Improve Diagnostic Safety in Hospitalized Patients

Disease-specific biomedical research, as well as advances in laboratory, imaging, and other technologies, play a critical role in improving diagnostic accuracy. However, these technical approaches do not address many of the broader clinician- and system-level failure points and opportunities for improvement. Various patient-, provider-, and organizational-level interventions that could make diagnostic processes more resilient and reduce the risk of error and patient harm have been proposed.61

Among these strategies are approaches to empower patients and their families. Fostering therapeutic relationships between patients and members of the care team is essential to reducing diagnostic errors.62 Facilitating timely access to health records, ensuring transparency in decision making, and tailoring communication strategies to patients’ cultural and educational backgrounds can reduce harm.63 Similarly, at the system level, enhancing communication among different providers by use of tools such as structured handoffs can prevent communication breakdowns and facilitate positive outcomes.64

Interventions targeted at individual health care providers, such as educational programs to improve content-specific knowledge, can enhance diagnostic performance. Regular feedback, strategies to enhance equity, and fostering an environment where all providers are actively encouraged to think critically and participate in the diagnostic process (training programs to use “diagnostic time-outs” and making it a “team sport”) can improve clinical reasoning.65,66 Use of standardized patients can help identify individual-level cognitive failure points and facilitate creation of new interventions to improve clinical decision-making processes.67

Novel health information technologies can further augment these efforts. These include effective documentation by maintaining dynamic and accurate patient histories, problem lists, and medication lists68-70; use of electronic health record–based algorithms to identify potential diagnostic delays for serious conditions71,72; use of telemedicine technologies to improve accessibility and coordination73; application of mobile health and wearable technologies to facilitate data-gathering and care delivery74,75; and use of computerized decision-support tools, including applications to interpret electrocardiograms, imaging studies, and other diagnostic tests.76

Use of precision medicine, powered by new artificial intelligence (AI) tools, is becoming more widespread. Algorithms powered by AI can augment and sometimes even outperform clinician decision-making in areas such as oncology, radiology, and primary care.77 Creation of large biobanks like the All of Us research program can be used to study thousands of environmental and genetic risk factors and health conditions simultaneously, and help identify specific treatments that work best for people of different backgrounds.78 Active research in these areas holds great promise in terms of how and when we diagnose diseases and make appropriate preventative and treatment decisions. Significant scientific, ethical, and regulatory challenges will need to be overcome before these technologies can address some of the most complex problems in health care.79

Finally, diagnostic performance is affected by the external environment, including the functioning of the medical liability system. Diagnostic errors that lead to patient harm are a leading cause of malpractice claims.80 Developing a legal environment, in collaboration with patient advocacy groups and health care organizations, that promotes and facilitates timely disclosure of diagnostic errors could decrease the incentive to hide errors, advance care processes, and improve outcomes.81,82

Conclusion

The burden of diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients is unacceptably high and remains an underemphasized cause of preventable morbidity and mortality. Diagnostic errors often result from a breakdown in multiple interdependent processes that involve patient-, provider-, and system-level factors. Significant challenges remain in defining and identifying diagnostic errors as well as underlying process-failure points. The most effective interventions to reduce diagnostic errors will require greater patient participation in the diagnostic process and a mix of evidence-based interventions that promote individual-provider excellence as well as system-level changes. Further research and collaboration among various stakeholders should help improve diagnostic safety for hospitalized patients.

Corresponding author: Abhishek Goyal, MD, MPH; [email protected]

Disclosures: Dr. Dalal disclosed receiving income ≥ $250 from MayaMD.

Abstract

Diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients are a leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality. Significant challenges in defining and measuring diagnostic errors and underlying process failure points have led to considerable variability in reported rates of diagnostic errors and adverse outcomes. In this article, we explore the diagnostic process and its discrete components, emphasizing the centrality of the patient in decision-making as well as the continuous nature of the process. We review the incidence of diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients and different methodological approaches that have been used to arrive at these estimates. We discuss different but interdependent provider- and system-related process-failure points that lead to diagnostic errors. We examine specific challenges related to measurement of diagnostic errors and describe traditional and novel approaches that are being used to obtain the most precise estimates. Finally, we examine various patient-, provider-, and organizational-level interventions that have been proposed to improve diagnostic safety in hospitalized patients.

Keywords: diagnostic error, hospital medicine, patient safety.

Diagnosis is defined as a “pre-existing set of categories agreed upon by the medical profession to designate a specific condition.”1 The diagnostic process involves obtaining a clinical history, performing a physical examination, conducting diagnostic testing, and consulting with other clinical providers to gather data that are relevant to understanding the underlying disease processes. This exercise involves generating hypotheses and updating prior probabilities as more information and evidence become available. Throughout this process of information gathering, integration, and interpretation, there is an ongoing assessment of whether sufficient and necessary knowledge has been obtained to make an accurate diagnosis and provide appropriate treatment.2

Diagnostic error is defined as a missed opportunity to make a timely diagnosis as part of this iterative process, including the failure of communicating the diagnosis to the patient in a timely manner.3 It can be categorized as a missed, delayed, or incorrect diagnosis based on available evidence at the time. Establishing the correct diagnosis has important implications. A timely and precise diagnosis ensures the patient the highest probability of having a positive health outcome that reflects an appropriate understanding of underlying disease processes and is consistent with their overall goals of care.3 When diagnostic errors occur, they can cause patient harm. Adverse events due to medical errors, including diagnostic errors, are estimated to be the third leading cause of death in the United States.4 Most people will experience at least 1 diagnostic error in their lifetime. In the 2015 National Academy of Medicine report Improving Diagnosis in Healthcare, diagnostic errors were identified as a major hazard as well as an opportunity to improve patient outcomes.2

Diagnostic errors during hospitalizations are especially concerning, as they are more likely to be implicated in a wider spectrum of harm, including permanent disability and death. This has become even more relevant for hospital medicine physicians and other clinical providers as they encounter increasing cognitive and administrative workloads, rising dissatisfaction and burnout, and unique obstacles such as night-time scheduling.5

Incidence of Diagnostic Errors in Hospitalized Patients

Several methodological approaches have been used to estimate the incidence of diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients. These include retrospective reviews of a sample of all hospital admissions, evaluations of selected adverse outcomes including autopsy studies, patient and provider surveys, and malpractice claims. Laboratory testing audits and secondary reviews in other diagnostic subspecialities (eg, radiology, pathology, and microbiology) are also essential to improving diagnostic performance in these specialized fields, which in turn affects overall hospital diagnostic error rates.6-8 These diverse approaches provide unique insights regarding our ability to assess the degree to which potential harms, ranging from temporary impairment to permanent disability, to death, are attributable to different failure points in the diagnostic process.

Large retrospective chart reviews of random hospital admissions remain the most accurate way to determine the overall incidence of diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients.9 The Harvard Medical Practice Study, published in 1991, laid the groundwork for measuring the incidence of adverse events in hospitalized patients and assessing their relation to medical error, negligence, and disability. Reviewing 30,121 randomly selected records from 51 randomly selected acute care hospitals in New York State, the study found that adverse events occurred in 3.7% of hospitalizations, diagnostic errors accounted for 13.8% of these events, and these errors were likely attributable to negligence in 74.7% of cases. The study not only outlined individual-level process failures, but also focused attention on some of the systemic causes, setting the agenda for quality improvement research in hospital-based care for years to come.10-12 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 22 hospital admission studies found a pooled rate of 0.7% (95% CI, 0.5%-1.1%) for harmful diagnostic errors.9 It found significant variations in the rates of adverse events, diagnostic errors, and range of diagnoses that were missed. This was primarily because of variabilities in pre-test probabilities in detecting diagnostic errors in these specific cohorts, as well as due to heterogeneity in study definitions and methodologies, especially regarding how they defined and measured “diagnostic error.” The analysis, however, did not account for diagnostic errors that were not related to patient harm (missed opportunities); therefore, it likely significantly underestimated the true incidence of diagnostic errors in these study populations. Table 1 summarizes some of key studies that have examined the incidence of harmful diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients.9-21

The chief limitation of reviewing random hospital admissions is that, since overall rates of diagnostic errors are still relatively low, a large number of case reviews are required to identify a sufficient sample of adverse outcomes to gain a meaningful understanding of the underlying process failure points and develop tools for remediation. Patient and provider surveys or data from malpractice claims can be high-yield starting points for research on process errors.22,23 Reviews of enriched cohorts of adverse outcomes, such as rapid-response events, intensive care unit (ICU) transfers, deaths, and hospital readmissions, can be an efficient way to identify process failures that lead to greatest harm. Depending on the research approach and the types of underlying patient populations sampled, rates of diagnostic errors in these high-risk groups have been estimated to be approximately 5% to 20%, or even higher.6,24-31 For example, a retrospective study of 391 cases of unplanned 7-day readmissions found that 5.6% of cases contained at least 1 diagnostic error during the index admission.32 In a study conducted at 6 Belgian acute-care hospitals, 56% of patients requiring an unplanned transfer to a higher level of care were determined to have had an adverse event, and of these adverse events, 12.4% of cases were associated with errors in diagnosis.29 A systematic review of 16 hospital-based studies estimated that 3.1% of all inpatient deaths were likely preventable, which corresponded to 22,165 deaths annually in the United States.30 Another such review of 31 autopsy studies reported that 28% of autopsied ICU patients had at least 1 misdiagnosis; of these diagnostic errors, 8% were classified as potentially lethal, and 15% were considered major but not lethal.31 Significant drawbacks of such enriched cohort studies, however, are their poor generalizability and inability to detect failure points that do not lead to patient harm (near-miss events).33

Causes of Diagnostic Errors in Hospitalized Patients

All aspects of the diagnostic process are susceptible to errors. These errors stem from a variety of faulty processes, including failure of the patient to engage with the health care system (eg, due to lack of insurance or transportation, or delay in seeking care); failure in information gathering (eg, missed history or exam findings, ordering wrong tests, laboratory errors); failure in information interpretation (eg, exam finding or test result misinterpretation); inaccurate hypothesis generation (eg, due to suboptimal prioritization or weighing of supporting evidence); and failure in communication (eg, with other team members or with the patient).2,34 Reasons for diagnostic process failures vary widely across different health care settings. While clinician assessment errors (eg, failure to consider or alternatively overweigh competing diagnoses) and errors in testing and the monitoring phase (eg, failure to order or follow up diagnostic tests) can lead to a majority of diagnostic errors in some patient populations, in other settings, social (eg, poor health literacy, punitive cultural practices) and economic factors (eg, lack of access to appropriate diagnostic tests or to specialty expertise) play a more prominent role.34,35

The Figure describes the relationship between components of the diagnostic process and subsequent outcomes, including diagnostic process failures, diagnostic errors, and absence or presence of patient harm.2,36,37 It reemphasizes the centrality of the patient in decision-making and the continuous nature of the process. The Figure also illustrates that only a minority of process failures result in diagnostic errors, and a smaller proportion of diagnostic errors actually lead to patient harm. Conversely, it also shows that diagnostic errors can happen without any obvious process-failure points, and, similarly, patient harm can take place in the absence of any evident diagnostic errors.36-38 Finally, it highlights the need to incorporate feedback from process failures, diagnostic errors, and favorable and unfavorable patient outcomes in order to inform future quality improvement efforts and research.