User login

Topical roflumilast approved for psoriasis in adults and adolescents

.

Roflumilast is a selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4), the first approved for treating psoriasis, according to manufacturer Arcutis Biotherapeutics. The company announced the approval on July 29. Oral roflumilast (Daliresp ) was approved in 2011 for treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).“It’s a breakthrough topical therapy,” says Mark G. Lebwohl, MD, dean of clinical therapeutics and professor of dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and principal investigator in trials of topical roflumilast. In an interview, Dr. Lebwohl noted that the treatment significantly reduced psoriasis symptoms in both short- and long-term trials.

In addition, two features of this treatment set it apart from other topical psoriasis treatments, he said. Roflumilast is not a steroid, so does not have the risk for topical steroid-related side effects associated with chronic use, and, in clinical trials, topical roflumilast was effective in treating psoriasis in intertriginous areas, including the buttocks, underarms, and beneath the breasts, which are difficult to treat.

FDA approval is based on data from two phase 3 randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials, according to Arcutis. The primary endpoint was Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) success, defined as clear or almost clear with at least a two-grade improvement from baseline, and at least a two-grade IGA score improvement from baseline at 8 weeks.

At 8 weeks, 42.4% and 37.5% of the patients treated with topical roflumilast achieved an IGA success rate compared with 6.1% and 6.9% in the control groups, respectively (P < .0001 for both studies).

Treated patients also experienced significant improvements compared with those in the vehicle groups in secondary endpoints in the trials: Those included Intertriginous IGA (I-IGA) Success, Psoriasis Area Severity Index–75 (PASI-75), reductions in itch based on the Worst Itch–Numerical Rating Scale (WI-NRS), and self-reported psoriasis symptoms diary (PSD).

In the studies, 72% and 68% of patients treated with roflumilast met the I-IGA endpoint at 8 weeks versus 14% and 17%, respectively, of those on vehicle (P < .0001 for both studies).

In addition, by week 2, some participants treated with roflumilast had experienced reduced itchiness in both studies. At 8 weeks, among those with a WI-NRS score of 4 or more at baseline, 67% and 69% of the treated patients had at least a four-point reduction in the WI-NRS versus 26% and 33%, respectively, among those on vehicle (P < .0001 for both studies), according to the company.

In general, the cream was well tolerated. There were reports of diarrhea (3%), headache (2%), insomnia (1%), nausea (1%), application-site pain (1%), upper respiratory tract infections (1%), and urinary tract infections (1%). However, Dr. Lebwohl noted that these events were also observed in the control group.

“The study was unequivocal about the improvement in the intertriginous sites,” Dr. Lebwohl said. He contrasts that to the data from other nonsteroidal topicals, which he said can be associated with a rash or irritation in sensitive areas.

Dr. Lebwohl noted that PDE4 is an enzyme that increases inflammation and decreases anti-inflammatory mediators and that inhibiting PDE4 may interrupt some of the inflammation response responsible for psoriasis symptoms, as it has for other conditions such as atopic dermatitis. Data from the 8-week phase 3 trials and yearlong phase 2b, open-label studies support that hypothesis.

“I’m always excited for new psoriasis treatments to broaden our treatment armamentarium,” said Lauren E. Ploch, MD, a dermatologist who practices in Augusta, Ga., and Aiken, S.C., who was asked to comment on the approval.

Even a symptom that seems benign, like itching, Dr. Ploch added, can lead to reduced sleep and increased irritability. Referring to the data on the treatment in the sensitive, intertriginous areas, she noted that the skin in these areas is often thinner, so treatment with steroids can cause further thinning and damage to the skin. If roflumilast doesn’t cause burning, itching, or thinning, it will be a great option to treat these areas, she said in an interview. She was not involved in the trials.

Roflumilast cream will be marketed under the trade name Zoryve, and is expected to be available by mid-August, according to Arcutis.

Roflumilast cream is also under review in Canada for treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults and adolescents.

The studies were funded by Arcutis Biotherapeutics. Dr. Lebwohl reported receiving grant support and consulting fees from Arcutis. Dr. Ploch reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

Roflumilast is a selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4), the first approved for treating psoriasis, according to manufacturer Arcutis Biotherapeutics. The company announced the approval on July 29. Oral roflumilast (Daliresp ) was approved in 2011 for treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).“It’s a breakthrough topical therapy,” says Mark G. Lebwohl, MD, dean of clinical therapeutics and professor of dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and principal investigator in trials of topical roflumilast. In an interview, Dr. Lebwohl noted that the treatment significantly reduced psoriasis symptoms in both short- and long-term trials.

In addition, two features of this treatment set it apart from other topical psoriasis treatments, he said. Roflumilast is not a steroid, so does not have the risk for topical steroid-related side effects associated with chronic use, and, in clinical trials, topical roflumilast was effective in treating psoriasis in intertriginous areas, including the buttocks, underarms, and beneath the breasts, which are difficult to treat.

FDA approval is based on data from two phase 3 randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials, according to Arcutis. The primary endpoint was Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) success, defined as clear or almost clear with at least a two-grade improvement from baseline, and at least a two-grade IGA score improvement from baseline at 8 weeks.

At 8 weeks, 42.4% and 37.5% of the patients treated with topical roflumilast achieved an IGA success rate compared with 6.1% and 6.9% in the control groups, respectively (P < .0001 for both studies).

Treated patients also experienced significant improvements compared with those in the vehicle groups in secondary endpoints in the trials: Those included Intertriginous IGA (I-IGA) Success, Psoriasis Area Severity Index–75 (PASI-75), reductions in itch based on the Worst Itch–Numerical Rating Scale (WI-NRS), and self-reported psoriasis symptoms diary (PSD).

In the studies, 72% and 68% of patients treated with roflumilast met the I-IGA endpoint at 8 weeks versus 14% and 17%, respectively, of those on vehicle (P < .0001 for both studies).

In addition, by week 2, some participants treated with roflumilast had experienced reduced itchiness in both studies. At 8 weeks, among those with a WI-NRS score of 4 or more at baseline, 67% and 69% of the treated patients had at least a four-point reduction in the WI-NRS versus 26% and 33%, respectively, among those on vehicle (P < .0001 for both studies), according to the company.

In general, the cream was well tolerated. There were reports of diarrhea (3%), headache (2%), insomnia (1%), nausea (1%), application-site pain (1%), upper respiratory tract infections (1%), and urinary tract infections (1%). However, Dr. Lebwohl noted that these events were also observed in the control group.

“The study was unequivocal about the improvement in the intertriginous sites,” Dr. Lebwohl said. He contrasts that to the data from other nonsteroidal topicals, which he said can be associated with a rash or irritation in sensitive areas.

Dr. Lebwohl noted that PDE4 is an enzyme that increases inflammation and decreases anti-inflammatory mediators and that inhibiting PDE4 may interrupt some of the inflammation response responsible for psoriasis symptoms, as it has for other conditions such as atopic dermatitis. Data from the 8-week phase 3 trials and yearlong phase 2b, open-label studies support that hypothesis.

“I’m always excited for new psoriasis treatments to broaden our treatment armamentarium,” said Lauren E. Ploch, MD, a dermatologist who practices in Augusta, Ga., and Aiken, S.C., who was asked to comment on the approval.

Even a symptom that seems benign, like itching, Dr. Ploch added, can lead to reduced sleep and increased irritability. Referring to the data on the treatment in the sensitive, intertriginous areas, she noted that the skin in these areas is often thinner, so treatment with steroids can cause further thinning and damage to the skin. If roflumilast doesn’t cause burning, itching, or thinning, it will be a great option to treat these areas, she said in an interview. She was not involved in the trials.

Roflumilast cream will be marketed under the trade name Zoryve, and is expected to be available by mid-August, according to Arcutis.

Roflumilast cream is also under review in Canada for treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults and adolescents.

The studies were funded by Arcutis Biotherapeutics. Dr. Lebwohl reported receiving grant support and consulting fees from Arcutis. Dr. Ploch reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

Roflumilast is a selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4), the first approved for treating psoriasis, according to manufacturer Arcutis Biotherapeutics. The company announced the approval on July 29. Oral roflumilast (Daliresp ) was approved in 2011 for treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).“It’s a breakthrough topical therapy,” says Mark G. Lebwohl, MD, dean of clinical therapeutics and professor of dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and principal investigator in trials of topical roflumilast. In an interview, Dr. Lebwohl noted that the treatment significantly reduced psoriasis symptoms in both short- and long-term trials.

In addition, two features of this treatment set it apart from other topical psoriasis treatments, he said. Roflumilast is not a steroid, so does not have the risk for topical steroid-related side effects associated with chronic use, and, in clinical trials, topical roflumilast was effective in treating psoriasis in intertriginous areas, including the buttocks, underarms, and beneath the breasts, which are difficult to treat.

FDA approval is based on data from two phase 3 randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials, according to Arcutis. The primary endpoint was Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) success, defined as clear or almost clear with at least a two-grade improvement from baseline, and at least a two-grade IGA score improvement from baseline at 8 weeks.

At 8 weeks, 42.4% and 37.5% of the patients treated with topical roflumilast achieved an IGA success rate compared with 6.1% and 6.9% in the control groups, respectively (P < .0001 for both studies).

Treated patients also experienced significant improvements compared with those in the vehicle groups in secondary endpoints in the trials: Those included Intertriginous IGA (I-IGA) Success, Psoriasis Area Severity Index–75 (PASI-75), reductions in itch based on the Worst Itch–Numerical Rating Scale (WI-NRS), and self-reported psoriasis symptoms diary (PSD).

In the studies, 72% and 68% of patients treated with roflumilast met the I-IGA endpoint at 8 weeks versus 14% and 17%, respectively, of those on vehicle (P < .0001 for both studies).

In addition, by week 2, some participants treated with roflumilast had experienced reduced itchiness in both studies. At 8 weeks, among those with a WI-NRS score of 4 or more at baseline, 67% and 69% of the treated patients had at least a four-point reduction in the WI-NRS versus 26% and 33%, respectively, among those on vehicle (P < .0001 for both studies), according to the company.

In general, the cream was well tolerated. There were reports of diarrhea (3%), headache (2%), insomnia (1%), nausea (1%), application-site pain (1%), upper respiratory tract infections (1%), and urinary tract infections (1%). However, Dr. Lebwohl noted that these events were also observed in the control group.

“The study was unequivocal about the improvement in the intertriginous sites,” Dr. Lebwohl said. He contrasts that to the data from other nonsteroidal topicals, which he said can be associated with a rash or irritation in sensitive areas.

Dr. Lebwohl noted that PDE4 is an enzyme that increases inflammation and decreases anti-inflammatory mediators and that inhibiting PDE4 may interrupt some of the inflammation response responsible for psoriasis symptoms, as it has for other conditions such as atopic dermatitis. Data from the 8-week phase 3 trials and yearlong phase 2b, open-label studies support that hypothesis.

“I’m always excited for new psoriasis treatments to broaden our treatment armamentarium,” said Lauren E. Ploch, MD, a dermatologist who practices in Augusta, Ga., and Aiken, S.C., who was asked to comment on the approval.

Even a symptom that seems benign, like itching, Dr. Ploch added, can lead to reduced sleep and increased irritability. Referring to the data on the treatment in the sensitive, intertriginous areas, she noted that the skin in these areas is often thinner, so treatment with steroids can cause further thinning and damage to the skin. If roflumilast doesn’t cause burning, itching, or thinning, it will be a great option to treat these areas, she said in an interview. She was not involved in the trials.

Roflumilast cream will be marketed under the trade name Zoryve, and is expected to be available by mid-August, according to Arcutis.

Roflumilast cream is also under review in Canada for treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults and adolescents.

The studies were funded by Arcutis Biotherapeutics. Dr. Lebwohl reported receiving grant support and consulting fees from Arcutis. Dr. Ploch reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Questionnaire for patients with psoriasis might identify risk of axial involvement

Preliminary findings are encouraging

NEW YORK – A questionnaire-based screening tool appears to accelerate the time to diagnosis of axial involvement in patients presenting with psoriasis but no clinical signs of joint pain, according to a study called ATTRACT that was presented at the annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

The risk of a delayed diagnosis of an axial component in patients with psoriasis, meaning a delay in the underlying diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (PsA), is substantial, according to Devis Benfaremo, MD, of the department of clinical and molecular science at Marche Polytechnic University, Ancona, Italy.

There is “no consensus for the best strategy to achieve early detection of joint disease” in patients presenting with psoriasis, but Dr. Benfaremo pointed out that missing axial involvement is a particular problem because it is far more likely than swollen joints to be missed on clinical examination.

While about one in three patients with psoriasis have or will develop psoriatic arthritis, according to the National Psoriasis Foundation, delays in diagnosis are common, according to Dr. Benfaremo. In patients with undiagnosed PsA characterized by axial involvement alone, subtle symptoms can be overlooked or attributed to other causes.

There are several screening questionnaires to detect joint symptoms in patients presenting with psoriasis, such as the five-question Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool, but the questionnaire tested in the ATTRACT trial is focused on detecting axial involvement specifically. It was characterized as the first to do so.

In the ongoing ATTRACT study, 253 patients with psoriasis but no history of PsA or axial disease have been enrolled so far. In the study, patients are screened for PsA based on a patient-completed yes-or-no questionnaire, which takes only a few minutes to complete.

“It is a validated questionnaire for axial [spondyloarthritis], but we have adopted it for detection of psoriasis patients with PsA,” Dr. Benfaremo explained.

The questionnaire for axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) was initially evaluated and validated by Fabian Proft, MD, head of the clinical trials unit at Charité Hospital, Berlin. In addition to a patient self-completed questionnaire, Dr. Proft and coinvestigators have also created a related questionnaire to be administered by physicians.

In the ATTRACT study, patients completed the questionnaire on an electronic device in the waiting room. Positive answers to specific questions about symptoms, which addressed back pain and joint function as well as joint symptoms, divided patients into three groups:

- Group A patients did not respond positively to any of the symptom questions that would prompt suspicion of axial disease. These represented about one-third of those screened so far.

- Group B patients were those who answered positively to at least two questions that related to a high suspicion of axial involvement. These represented 45% of patients.

- The remaining patients were placed in Group C, a category of intermediate risk based on positive responses to some, but not all, questions relating to axial symptoms.

Those in group B are being referred to rheumatology. Patients in group C are given “conditional” eligibility based on the presence of additional risk factors.

AxSpA screening tool ‘makes sense’ for potential use in PsA

The primary outcome of the ATTRACT trial is early identification of axial PsA. Correctly identifying patients with or without peripheral joint involvement is one of several secondary outcomes. The identification of patients who fulfill Assessment Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) criteria for axSpA is another secondary outcome.

Of the 114 patients placed in group B and analyzed so far, 87 have completed an assessment by a rheumatologist with laboratory analyses and imaging, as well as a clinical examination.

Of those 87 assessed by a rheumatologist, 17 did not have either axial or peripheral inflammation. Another 19 were diagnosed with axial disease, including 14 who met ASAS criteria. A total of 10 were classified as having PsA with peripheral inflammation, according to Classification for Psoriatic Arthritis criteria, and 41 are still being considered for a diagnosis of axial or peripheral PsA on the basis of further workup.

“Among the patients with axial PsA, only 10% had elevated C-reactive protein levels,” according to Dr. Benfaremo, echoing previous evidence that inflammatory biomarkers by themselves have limited value for identifying psoriasis patients at high risk of joint involvement.

The findings are preliminary, but Dr. Benfaremo reported that the questionnaire is showing promise for the routine stratification of patients who should be considered for a rheumatology consultation.

If further analyses validate the clinical utility of these stratifications, there is the potential for a substantial acceleration to the diagnosis of PsA.

When contacted to comment about this work, Dr. Proft said that there is an important need for new strategies reduce delay in the diagnosis of PsA among patients presenting with psoriasis. He thinks the screening tool he developed for axSpA “makes sense” as a potential tool in PsA.

“If validated, this could be a very useful for earlier identification of PsA,” Dr. Proft said. He reiterated the importance of focusing on axial involvement.

“Previous screening tools have focused on symptoms of PsA more generally, but inflammation in the peripheral joints is something that you can easily see in most patients,” he said.

In addition to the patient-completed questionnaire and the physician-administered questionnaire, Dr. Proft has also evaluated an online self-referral tool for patients.

“If we can diagnose PsA earlier in the course of disease, we can start treatment earlier, prevent or delay joint damage, and potentially improve outcomes for patients,” Dr. Proft said. He considers this an important direction of research.

Dr. Benfaremo and Dr. Proft reported no potential conflicts of interest.

Preliminary findings are encouraging

Preliminary findings are encouraging

NEW YORK – A questionnaire-based screening tool appears to accelerate the time to diagnosis of axial involvement in patients presenting with psoriasis but no clinical signs of joint pain, according to a study called ATTRACT that was presented at the annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

The risk of a delayed diagnosis of an axial component in patients with psoriasis, meaning a delay in the underlying diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (PsA), is substantial, according to Devis Benfaremo, MD, of the department of clinical and molecular science at Marche Polytechnic University, Ancona, Italy.

There is “no consensus for the best strategy to achieve early detection of joint disease” in patients presenting with psoriasis, but Dr. Benfaremo pointed out that missing axial involvement is a particular problem because it is far more likely than swollen joints to be missed on clinical examination.

While about one in three patients with psoriasis have or will develop psoriatic arthritis, according to the National Psoriasis Foundation, delays in diagnosis are common, according to Dr. Benfaremo. In patients with undiagnosed PsA characterized by axial involvement alone, subtle symptoms can be overlooked or attributed to other causes.

There are several screening questionnaires to detect joint symptoms in patients presenting with psoriasis, such as the five-question Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool, but the questionnaire tested in the ATTRACT trial is focused on detecting axial involvement specifically. It was characterized as the first to do so.

In the ongoing ATTRACT study, 253 patients with psoriasis but no history of PsA or axial disease have been enrolled so far. In the study, patients are screened for PsA based on a patient-completed yes-or-no questionnaire, which takes only a few minutes to complete.

“It is a validated questionnaire for axial [spondyloarthritis], but we have adopted it for detection of psoriasis patients with PsA,” Dr. Benfaremo explained.

The questionnaire for axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) was initially evaluated and validated by Fabian Proft, MD, head of the clinical trials unit at Charité Hospital, Berlin. In addition to a patient self-completed questionnaire, Dr. Proft and coinvestigators have also created a related questionnaire to be administered by physicians.

In the ATTRACT study, patients completed the questionnaire on an electronic device in the waiting room. Positive answers to specific questions about symptoms, which addressed back pain and joint function as well as joint symptoms, divided patients into three groups:

- Group A patients did not respond positively to any of the symptom questions that would prompt suspicion of axial disease. These represented about one-third of those screened so far.

- Group B patients were those who answered positively to at least two questions that related to a high suspicion of axial involvement. These represented 45% of patients.

- The remaining patients were placed in Group C, a category of intermediate risk based on positive responses to some, but not all, questions relating to axial symptoms.

Those in group B are being referred to rheumatology. Patients in group C are given “conditional” eligibility based on the presence of additional risk factors.

AxSpA screening tool ‘makes sense’ for potential use in PsA

The primary outcome of the ATTRACT trial is early identification of axial PsA. Correctly identifying patients with or without peripheral joint involvement is one of several secondary outcomes. The identification of patients who fulfill Assessment Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) criteria for axSpA is another secondary outcome.

Of the 114 patients placed in group B and analyzed so far, 87 have completed an assessment by a rheumatologist with laboratory analyses and imaging, as well as a clinical examination.

Of those 87 assessed by a rheumatologist, 17 did not have either axial or peripheral inflammation. Another 19 were diagnosed with axial disease, including 14 who met ASAS criteria. A total of 10 were classified as having PsA with peripheral inflammation, according to Classification for Psoriatic Arthritis criteria, and 41 are still being considered for a diagnosis of axial or peripheral PsA on the basis of further workup.

“Among the patients with axial PsA, only 10% had elevated C-reactive protein levels,” according to Dr. Benfaremo, echoing previous evidence that inflammatory biomarkers by themselves have limited value for identifying psoriasis patients at high risk of joint involvement.

The findings are preliminary, but Dr. Benfaremo reported that the questionnaire is showing promise for the routine stratification of patients who should be considered for a rheumatology consultation.

If further analyses validate the clinical utility of these stratifications, there is the potential for a substantial acceleration to the diagnosis of PsA.

When contacted to comment about this work, Dr. Proft said that there is an important need for new strategies reduce delay in the diagnosis of PsA among patients presenting with psoriasis. He thinks the screening tool he developed for axSpA “makes sense” as a potential tool in PsA.

“If validated, this could be a very useful for earlier identification of PsA,” Dr. Proft said. He reiterated the importance of focusing on axial involvement.

“Previous screening tools have focused on symptoms of PsA more generally, but inflammation in the peripheral joints is something that you can easily see in most patients,” he said.

In addition to the patient-completed questionnaire and the physician-administered questionnaire, Dr. Proft has also evaluated an online self-referral tool for patients.

“If we can diagnose PsA earlier in the course of disease, we can start treatment earlier, prevent or delay joint damage, and potentially improve outcomes for patients,” Dr. Proft said. He considers this an important direction of research.

Dr. Benfaremo and Dr. Proft reported no potential conflicts of interest.

NEW YORK – A questionnaire-based screening tool appears to accelerate the time to diagnosis of axial involvement in patients presenting with psoriasis but no clinical signs of joint pain, according to a study called ATTRACT that was presented at the annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

The risk of a delayed diagnosis of an axial component in patients with psoriasis, meaning a delay in the underlying diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (PsA), is substantial, according to Devis Benfaremo, MD, of the department of clinical and molecular science at Marche Polytechnic University, Ancona, Italy.

There is “no consensus for the best strategy to achieve early detection of joint disease” in patients presenting with psoriasis, but Dr. Benfaremo pointed out that missing axial involvement is a particular problem because it is far more likely than swollen joints to be missed on clinical examination.

While about one in three patients with psoriasis have or will develop psoriatic arthritis, according to the National Psoriasis Foundation, delays in diagnosis are common, according to Dr. Benfaremo. In patients with undiagnosed PsA characterized by axial involvement alone, subtle symptoms can be overlooked or attributed to other causes.

There are several screening questionnaires to detect joint symptoms in patients presenting with psoriasis, such as the five-question Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool, but the questionnaire tested in the ATTRACT trial is focused on detecting axial involvement specifically. It was characterized as the first to do so.

In the ongoing ATTRACT study, 253 patients with psoriasis but no history of PsA or axial disease have been enrolled so far. In the study, patients are screened for PsA based on a patient-completed yes-or-no questionnaire, which takes only a few minutes to complete.

“It is a validated questionnaire for axial [spondyloarthritis], but we have adopted it for detection of psoriasis patients with PsA,” Dr. Benfaremo explained.

The questionnaire for axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) was initially evaluated and validated by Fabian Proft, MD, head of the clinical trials unit at Charité Hospital, Berlin. In addition to a patient self-completed questionnaire, Dr. Proft and coinvestigators have also created a related questionnaire to be administered by physicians.

In the ATTRACT study, patients completed the questionnaire on an electronic device in the waiting room. Positive answers to specific questions about symptoms, which addressed back pain and joint function as well as joint symptoms, divided patients into three groups:

- Group A patients did not respond positively to any of the symptom questions that would prompt suspicion of axial disease. These represented about one-third of those screened so far.

- Group B patients were those who answered positively to at least two questions that related to a high suspicion of axial involvement. These represented 45% of patients.

- The remaining patients were placed in Group C, a category of intermediate risk based on positive responses to some, but not all, questions relating to axial symptoms.

Those in group B are being referred to rheumatology. Patients in group C are given “conditional” eligibility based on the presence of additional risk factors.

AxSpA screening tool ‘makes sense’ for potential use in PsA

The primary outcome of the ATTRACT trial is early identification of axial PsA. Correctly identifying patients with or without peripheral joint involvement is one of several secondary outcomes. The identification of patients who fulfill Assessment Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) criteria for axSpA is another secondary outcome.

Of the 114 patients placed in group B and analyzed so far, 87 have completed an assessment by a rheumatologist with laboratory analyses and imaging, as well as a clinical examination.

Of those 87 assessed by a rheumatologist, 17 did not have either axial or peripheral inflammation. Another 19 were diagnosed with axial disease, including 14 who met ASAS criteria. A total of 10 were classified as having PsA with peripheral inflammation, according to Classification for Psoriatic Arthritis criteria, and 41 are still being considered for a diagnosis of axial or peripheral PsA on the basis of further workup.

“Among the patients with axial PsA, only 10% had elevated C-reactive protein levels,” according to Dr. Benfaremo, echoing previous evidence that inflammatory biomarkers by themselves have limited value for identifying psoriasis patients at high risk of joint involvement.

The findings are preliminary, but Dr. Benfaremo reported that the questionnaire is showing promise for the routine stratification of patients who should be considered for a rheumatology consultation.

If further analyses validate the clinical utility of these stratifications, there is the potential for a substantial acceleration to the diagnosis of PsA.

When contacted to comment about this work, Dr. Proft said that there is an important need for new strategies reduce delay in the diagnosis of PsA among patients presenting with psoriasis. He thinks the screening tool he developed for axSpA “makes sense” as a potential tool in PsA.

“If validated, this could be a very useful for earlier identification of PsA,” Dr. Proft said. He reiterated the importance of focusing on axial involvement.

“Previous screening tools have focused on symptoms of PsA more generally, but inflammation in the peripheral joints is something that you can easily see in most patients,” he said.

In addition to the patient-completed questionnaire and the physician-administered questionnaire, Dr. Proft has also evaluated an online self-referral tool for patients.

“If we can diagnose PsA earlier in the course of disease, we can start treatment earlier, prevent or delay joint damage, and potentially improve outcomes for patients,” Dr. Proft said. He considers this an important direction of research.

Dr. Benfaremo and Dr. Proft reported no potential conflicts of interest.

AT GRAPPA 2022

NAFLD strongly correlated with psoriasis, PsA; risk linked to severity

NEW YORK – – and probably in those with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) as well, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis presented at the annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

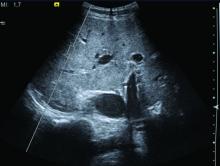

“Our findings imply that psoriatic patients should be screened with an ultrasonographic exam in cases where there are metabolic features that are associated with NAFLD,” reported Francesco Bellinato, MD, a researcher in the section of dermatology and venereology, University of Verona (Italy).

The data are strong. Of 76 nonduplicate publications found in the literature, the 11 observational studies included in the meta-analysis met stringent criteria, including a diagnosis of psoriasis and PsA based on objective criteria, NAFLD confirmed with liver biopsy or imaging, and odds rates calculated with 95% confidence intervals.

From these 11 studies, aggregate data were available for 249,333 psoriatic patients, of which 49% had NAFLD, and 1,491,402 were healthy controls. Among the controls, 36% had NAFLD. Four of the studies were from North America, four from Europe, and three from Asia.

In the pooled data, the risk of NAFLD among those with psoriasis relative to healthy controls fell just short of a twofold increase (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.70-2.26; P < .001). When stratified by studies that confirmed NAFLD by biopsy relative to ultrasonography, there was no significant heterogeneity.

Eight of the studies included an analysis of relative risk in the context of skin lesion severity defined by Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score. Relative to those without NAFLD, psoriatic patients with NAFLD had a significant greater mean PASI score on a pooled weighted mean difference analysis (OR, 3.93; 95% CI, 2.01-5.84; P < .0001).

For PsA relative to no PsA in the five studies that compared risk between these two groups, the risk of NAFLD was again nearly twofold higher. This fell short of conventional definition of statistical significance, but it was associated with a strong trend (OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 0.98-3.43; P = .06).

The risk of NAFLD among patients with psoriasis was not found to vary significantly when assessed by univariable meta-regressions across numerous characteristics, such as sex and body mass index.

In one of the largest of the observational studies included in the meta-analysis by Alexis Ogdie, MD, associate professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues, data were analyzed in more than 1.5 million patients, which included 54,251 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. While the hazard ratio of NAFLD was increased for both psoriasis (HR, 2.23) and PsA (HR, 2.11), it was not elevated in those with RA (HR, 0.96).

Risk by severity, possible mechanisms

This study also included an analysis of NAFLD risk according to psoriasis severity. While risk was still significant among those with mild disease (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.07-1.30), it was almost twofold greater in those with moderate to severe psoriasis (HR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.73-2.87).

Dr. Bellinato conceded that the mechanisms underlying the association between psoriasis and NAFLD are unknown, but he said “metaflammation” is suspected.

“The secretion of proinflammatory, prothrombotic, and oxidative stress mediators in both psoriatic skin and adipose tissue might act systemically and promote insulin resistance and other metabolic derangements that promote the development and progression of NAFLD,” Dr. Bellinato explained.

He thinks that noninvasive screening methods, such as currently used methods to calculate fibrosis score, might be useful for evaluating patients with psoriasis for NAFLD and referring them to a hepatologist when appropriate.

Given the strong association with NAFLD, Dr. Bellinato suggested that “the findings of this meta-analysis pave the way for novel, large, prospective, and histologically based studies.”

The association between psoriasis and NAFLD is clinically relevant, agreed Joel M. Gelfand, MD, vice-chair of clinical research and medical director of the clinical studies unit, department of dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“It is not clear if psoriasis causes fatty liver disease or vice versa, but clinicians should be aware of this association,” he said in an interview. Dr. Gelfand was a coauthor of the study by Dr. Ogdie and colleagues and led another more recent population-based study that implicated methotrexate as a factor in psoriasis-related hepatotoxicity.

If NAFLD is identified in a patient with psoriasis, treatments are limited, but Dr. Gelfand suggested that patients should be made aware of the risk. “Clinicians should encourage patients with psoriasis to take measures to protect their liver, such as avoiding drinking alcohol to excess and trying to maintain a healthy body weight,” he said.

Dr. Bellinato reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gelfand has financial relationships with more than 10 pharmaceutical companies, including those that make therapies for psoriasis.

NEW YORK – – and probably in those with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) as well, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis presented at the annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

“Our findings imply that psoriatic patients should be screened with an ultrasonographic exam in cases where there are metabolic features that are associated with NAFLD,” reported Francesco Bellinato, MD, a researcher in the section of dermatology and venereology, University of Verona (Italy).

The data are strong. Of 76 nonduplicate publications found in the literature, the 11 observational studies included in the meta-analysis met stringent criteria, including a diagnosis of psoriasis and PsA based on objective criteria, NAFLD confirmed with liver biopsy or imaging, and odds rates calculated with 95% confidence intervals.

From these 11 studies, aggregate data were available for 249,333 psoriatic patients, of which 49% had NAFLD, and 1,491,402 were healthy controls. Among the controls, 36% had NAFLD. Four of the studies were from North America, four from Europe, and three from Asia.

In the pooled data, the risk of NAFLD among those with psoriasis relative to healthy controls fell just short of a twofold increase (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.70-2.26; P < .001). When stratified by studies that confirmed NAFLD by biopsy relative to ultrasonography, there was no significant heterogeneity.

Eight of the studies included an analysis of relative risk in the context of skin lesion severity defined by Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score. Relative to those without NAFLD, psoriatic patients with NAFLD had a significant greater mean PASI score on a pooled weighted mean difference analysis (OR, 3.93; 95% CI, 2.01-5.84; P < .0001).

For PsA relative to no PsA in the five studies that compared risk between these two groups, the risk of NAFLD was again nearly twofold higher. This fell short of conventional definition of statistical significance, but it was associated with a strong trend (OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 0.98-3.43; P = .06).

The risk of NAFLD among patients with psoriasis was not found to vary significantly when assessed by univariable meta-regressions across numerous characteristics, such as sex and body mass index.

In one of the largest of the observational studies included in the meta-analysis by Alexis Ogdie, MD, associate professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues, data were analyzed in more than 1.5 million patients, which included 54,251 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. While the hazard ratio of NAFLD was increased for both psoriasis (HR, 2.23) and PsA (HR, 2.11), it was not elevated in those with RA (HR, 0.96).

Risk by severity, possible mechanisms

This study also included an analysis of NAFLD risk according to psoriasis severity. While risk was still significant among those with mild disease (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.07-1.30), it was almost twofold greater in those with moderate to severe psoriasis (HR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.73-2.87).

Dr. Bellinato conceded that the mechanisms underlying the association between psoriasis and NAFLD are unknown, but he said “metaflammation” is suspected.

“The secretion of proinflammatory, prothrombotic, and oxidative stress mediators in both psoriatic skin and adipose tissue might act systemically and promote insulin resistance and other metabolic derangements that promote the development and progression of NAFLD,” Dr. Bellinato explained.

He thinks that noninvasive screening methods, such as currently used methods to calculate fibrosis score, might be useful for evaluating patients with psoriasis for NAFLD and referring them to a hepatologist when appropriate.

Given the strong association with NAFLD, Dr. Bellinato suggested that “the findings of this meta-analysis pave the way for novel, large, prospective, and histologically based studies.”

The association between psoriasis and NAFLD is clinically relevant, agreed Joel M. Gelfand, MD, vice-chair of clinical research and medical director of the clinical studies unit, department of dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“It is not clear if psoriasis causes fatty liver disease or vice versa, but clinicians should be aware of this association,” he said in an interview. Dr. Gelfand was a coauthor of the study by Dr. Ogdie and colleagues and led another more recent population-based study that implicated methotrexate as a factor in psoriasis-related hepatotoxicity.

If NAFLD is identified in a patient with psoriasis, treatments are limited, but Dr. Gelfand suggested that patients should be made aware of the risk. “Clinicians should encourage patients with psoriasis to take measures to protect their liver, such as avoiding drinking alcohol to excess and trying to maintain a healthy body weight,” he said.

Dr. Bellinato reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gelfand has financial relationships with more than 10 pharmaceutical companies, including those that make therapies for psoriasis.

NEW YORK – – and probably in those with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) as well, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis presented at the annual meeting of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

“Our findings imply that psoriatic patients should be screened with an ultrasonographic exam in cases where there are metabolic features that are associated with NAFLD,” reported Francesco Bellinato, MD, a researcher in the section of dermatology and venereology, University of Verona (Italy).

The data are strong. Of 76 nonduplicate publications found in the literature, the 11 observational studies included in the meta-analysis met stringent criteria, including a diagnosis of psoriasis and PsA based on objective criteria, NAFLD confirmed with liver biopsy or imaging, and odds rates calculated with 95% confidence intervals.

From these 11 studies, aggregate data were available for 249,333 psoriatic patients, of which 49% had NAFLD, and 1,491,402 were healthy controls. Among the controls, 36% had NAFLD. Four of the studies were from North America, four from Europe, and three from Asia.

In the pooled data, the risk of NAFLD among those with psoriasis relative to healthy controls fell just short of a twofold increase (odds ratio, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.70-2.26; P < .001). When stratified by studies that confirmed NAFLD by biopsy relative to ultrasonography, there was no significant heterogeneity.

Eight of the studies included an analysis of relative risk in the context of skin lesion severity defined by Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score. Relative to those without NAFLD, psoriatic patients with NAFLD had a significant greater mean PASI score on a pooled weighted mean difference analysis (OR, 3.93; 95% CI, 2.01-5.84; P < .0001).

For PsA relative to no PsA in the five studies that compared risk between these two groups, the risk of NAFLD was again nearly twofold higher. This fell short of conventional definition of statistical significance, but it was associated with a strong trend (OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 0.98-3.43; P = .06).

The risk of NAFLD among patients with psoriasis was not found to vary significantly when assessed by univariable meta-regressions across numerous characteristics, such as sex and body mass index.

In one of the largest of the observational studies included in the meta-analysis by Alexis Ogdie, MD, associate professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues, data were analyzed in more than 1.5 million patients, which included 54,251 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. While the hazard ratio of NAFLD was increased for both psoriasis (HR, 2.23) and PsA (HR, 2.11), it was not elevated in those with RA (HR, 0.96).

Risk by severity, possible mechanisms

This study also included an analysis of NAFLD risk according to psoriasis severity. While risk was still significant among those with mild disease (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.07-1.30), it was almost twofold greater in those with moderate to severe psoriasis (HR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.73-2.87).

Dr. Bellinato conceded that the mechanisms underlying the association between psoriasis and NAFLD are unknown, but he said “metaflammation” is suspected.

“The secretion of proinflammatory, prothrombotic, and oxidative stress mediators in both psoriatic skin and adipose tissue might act systemically and promote insulin resistance and other metabolic derangements that promote the development and progression of NAFLD,” Dr. Bellinato explained.

He thinks that noninvasive screening methods, such as currently used methods to calculate fibrosis score, might be useful for evaluating patients with psoriasis for NAFLD and referring them to a hepatologist when appropriate.

Given the strong association with NAFLD, Dr. Bellinato suggested that “the findings of this meta-analysis pave the way for novel, large, prospective, and histologically based studies.”

The association between psoriasis and NAFLD is clinically relevant, agreed Joel M. Gelfand, MD, vice-chair of clinical research and medical director of the clinical studies unit, department of dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“It is not clear if psoriasis causes fatty liver disease or vice versa, but clinicians should be aware of this association,” he said in an interview. Dr. Gelfand was a coauthor of the study by Dr. Ogdie and colleagues and led another more recent population-based study that implicated methotrexate as a factor in psoriasis-related hepatotoxicity.

If NAFLD is identified in a patient with psoriasis, treatments are limited, but Dr. Gelfand suggested that patients should be made aware of the risk. “Clinicians should encourage patients with psoriasis to take measures to protect their liver, such as avoiding drinking alcohol to excess and trying to maintain a healthy body weight,” he said.

Dr. Bellinato reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gelfand has financial relationships with more than 10 pharmaceutical companies, including those that make therapies for psoriasis.

AT GRAPPA 2022

Methotrexate’s impact on COVID-19 vaccination: New insights made

Patients who take methotrexate for a variety of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases and pause taking the drug following receipt of a COVID-19 vaccine dose did not have a higher risk of disease flare and had higher antireceptor binding domain (anti-RBD) antibody titers and increased immunogenicity when compared with continuing the drug, three recent studies suggest.

In one study, British researchers examined the effects of a 2-week break in methotrexate therapy on anti-RBD titers following receipt of a third COVID-19 vaccine dose. In their paper published in The Lancet: Respiratory Medicine, they reported results from a randomized, open-label, superiority trial that suggested pausing the drug improved immunogenicity, compared with no break.

In two trials presented at the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) 2022 Congress, a team from India set out to determine whether holding methotrexate after receiving both doses of a COVID-19 vaccine, or holding it only after the second dose, was safe and effective. They found that pausing methotrexate only following the second dose contributed to a lower flare risk, and that patients had higher anti-RBD titers when holding methotrexate for 2 weeks following each dose.

Pausing methotrexate after booster

The 2-week methotrexate break and booster vaccine dose data in the Vaccine Response On Off Methotrexate (VROOM) trial showed that after a month, the geometric mean antispike 1 (S1)-RBD antibody titer was 10,798 U/mL (95% confidence interval [CI], 8,970-12,997) in the group that continued methotrexate and 22,750 U/mL (95% CI, 19,314-26,796) in the group that suspended methotrexate; the geometric mean ratio was 2.19 (P < .0001; mixed-effects model), reported Abhishek Abhishek, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at the University of Nottingham in Nottingham, England, and colleagues.

Prior research showed that stopping methotrexate therapy for 2 weeks following the seasonal influenza vaccine contributed to better vaccine immunity among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, but there was no impact of stopping the drug for up to 4 weeks before vaccination on vaccine-related immunity, the researchers noted.

It is crucial in maximizing long-lasting vaccine protection in people who are possibly susceptible through immune suppression at this point in the COVID-19 vaccination regimen, the study team noted.

“Evidence from this study will be useful for policymakers, national immunization advisory committees, and specialist societies formulating recommendations on the use of methotrexate around the time of COVID-19 vaccination. This evidence will help patients and clinicians make informed choices about the risks and benefits of interrupting methotrexate treatment around the time of COVID-19 vaccination, with implications for the potential to extend such approaches to other therapeutics,” they wrote.

In American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidance for COVID-19 vaccination, the organization advised against using standard synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic medicines such as methotrexate “for 1-2 weeks (as disease activity allows) after each COVID-19 vaccine dose,” given the at-risk population and public health concerns, Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, MMSc, assistant professor of medicine and associate physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Sara K. Tedeschi, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, noted in an accompanying editorial in The Lancet: Respiratory Medicine.

However, when the ACR developed this statement, there was only one trial involving patients with rheumatoid arthritis who paused methotrexate following seasonal influenza vaccination, the editorialists said.

“Although this finding adds to the evidence base to support interruption of methotrexate after vaccination, a shared decision process is needed to weigh the possible benefit of optimizing protection from COVID-19 and the possible risk of underlying disease flare,” they added.

Dr. Abhishek and colleagues assessed 254 patients with immune-mediated inflammatory disease from dermatology and rheumatology clinics across 26 hospitals in the United Kingdom. Participants had been diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, atopic dermatitis, polymyalgia rheumatica, axial spondyloarthritis, and psoriasis without or with arthritis. They had also been taking up to 25 mg of methotrexate per week for 3 months or longer and had received two doses of either the Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine or AstraZeneca/Oxford viral vector vaccine. The booster dose was most often the Pfizer BNT162b2 vaccine (82%). The patients’ mean age was 59 years, with females comprising 61% of the cohort. Participants were randomly assigned 1:1 to either group.

Investigators performing laboratory analysis were masked to cohort assignment, and clinical research staff, data analysts, participants, and researchers were unmasked.

The elevated antibody response of patients who suspended methotrexate was the same across different kinds of immune-mediated inflammatory disease, primary vaccination platform, SARS-CoV-2 infection history, and age.

Notably, no intervention-associated adverse events were reported, the study team noted.

The conclusions that could be drawn from the booster-dose study were limited by the trial’s modest cohort size, the small number of patients in exploratory subgroup analyses, a lack of information about differences in prescription drug behavior, and early termination’s effect on the researchers’ ability to identify differences between subgroups and in secondary outcomes, the authors noted.

Other limitations included a lack of generalizability to patients with active disease who couldn’t stop therapy and were not included in the investigation, and participants were not blinded to what group they were in, the researchers said.

Expert commentary

This current study is consistent with other studies over the last several months showing that methotrexate harms both humoral and cell-mediated COVID-19 responses, noted Kevin Winthrop, MD, MPH, professor of infectious disease and public health at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, who was not involved in the study. “And so now the new wave of studies are like this one, where they are holding methotrexate experimentally and seeing if it makes a difference,” he said.

“The one shortcoming of this study – and so far, the studies to date – is that no one has looked at whether the experimental hold has resulted in a change in T-cell responses, which ... we are [now] recognizing [the importance of] more and more in long-term protection, particularly in severe disease. Theoretically, holding [methotrexate] might help enhance T-cell responses, but that hasn’t been shown experimentally.”

Dr. Winthrop pointed out that one might get the same benefit from holding methotrexate for 1 week instead of 2 and that there likely is a reduced risk of flare-up from underlying autoimmune disease.

It is still not certain that this benefit extends to other vaccines, Dr. Winthrop noted. “It is probably true for most vaccines that if you hold methotrexate for 1 or 2 weeks, you might see some short-term benefit in responsiveness, but you don’t know that there is any clinical meaningfulness of this. That’s going to take other long-term studies. You don’t know how long this benefit lasts.”

Pausing methotrexate during initial COVID vaccine doses

Patients with either rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis had higher anti-RBD antibody titers when methotrexate was stopped after both doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine, or simply after the second dose, than when methotrexate was continued, according to results from two single-center, randomized controlled trials called MIVAC I and II, Anu Sreekanth, MD, of Sree Sudheendra Medical Mission in Kochi, Kerala, India, and colleagues reported at EULAR 2022.

Results from MIVAC I indicated that there was a higher flare rate when methotrexate was stopped after both vaccine doses, but there was no difference in flare rate in MIVAC II when methotrexate was stopped only after the second dose as opposed to stopping it after both doses.

In the MIVAC I trial, 158 unvaccinated patients were randomized 1:1 to a cohort in which methotrexate was held for 2 weeks after both doses and a cohort in which methotrexate was continued despite the vaccine. In MIVAC II, 157 patients continued methotrexate while receiving the first vaccine dose. These patients were subsequently randomized either to continue or to stop methotrexate for 2 weeks following the second dose.

The findings from MIVAC I demonstrated the flare rate was lower in the methotrexate-continue group than in the methotrexate-pause group (8% vs. 25%; P = .005) and that the median anti-RBD titer was significantly higher for the methotrexate-pause group than the methotrexate-continue group (2,484 vs. 1,147; P = .001).

The results from MIVAC II trial indicated that there was no difference in flare rates between the two study groups (7.9% vs. 11.8%; P = .15). Yet, the median anti-RBD titer was significantly higher in the methotrexate-pause cohort than in the methotrexate-continue cohort (2,553 vs. 990; P = .001).

The report suggests there is a flare risk when methotrexate is stopped, Dr. Sreekanth noted. “It appears more logical to hold only after the second dose, as comparable anti-RBD titers are generated” with either approach, Dr. Sreekanth said.

Expert commentary: MIVAC I and II

Inés Colmegna, MD, associate professor at McGill University in Montreal, noted that it was intriguing that the risk of flares in MIVAC II is half of that reported after each of the doses of MIVAC I. “It is also worth emphasizing that despite the reported frequency of flares, the actual disease activity [as measured by the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints] in patients who did or did not withhold methotrexate was similar.

“MIVAC I and II have practical implications as they help to adequately inform patients about the risk and benefit trade of withholding methotrexate post–COVID-19 vaccination,” Dr. Colmegna told this news organization.

“Additional information would help to [further] interpret the findings of these studies, including whether any of the participants were taking any other DMARDs; data on the severity of the flares and functional impact; analysis of factors that predict the risk of flares, such as higher doses of methotrexate; [and change in] disease activity scores pre- and postvaccination,” Dr. Colmegna concluded.

Dr. Abhishek disclosed relationships with Springer, UpTodate, Oxford, Immunotec, AstraZeneca, Inflazome, NGM Biopharmaceuticals, Menarini Pharmaceuticals, and Cadila Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Abhishek is cochair of the ACR/EULAR CPPD Classification Criteria Working Group and the OMERACT CPPD Working Group. Dr. Sparks disclosed relationships with Gilead, Boehringer Ingelheim, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and AbbVie, unrelated to this study. Dr. Tedeschi disclosed relationships with ModernaTx and NGM Biopharmaceuticals. Dr. Winthrop disclosed a research grant and serving as a scientific consultant for Pfizer. Dr. Sreekanth and Dr. Colmegna have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients who take methotrexate for a variety of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases and pause taking the drug following receipt of a COVID-19 vaccine dose did not have a higher risk of disease flare and had higher antireceptor binding domain (anti-RBD) antibody titers and increased immunogenicity when compared with continuing the drug, three recent studies suggest.

In one study, British researchers examined the effects of a 2-week break in methotrexate therapy on anti-RBD titers following receipt of a third COVID-19 vaccine dose. In their paper published in The Lancet: Respiratory Medicine, they reported results from a randomized, open-label, superiority trial that suggested pausing the drug improved immunogenicity, compared with no break.

In two trials presented at the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) 2022 Congress, a team from India set out to determine whether holding methotrexate after receiving both doses of a COVID-19 vaccine, or holding it only after the second dose, was safe and effective. They found that pausing methotrexate only following the second dose contributed to a lower flare risk, and that patients had higher anti-RBD titers when holding methotrexate for 2 weeks following each dose.

Pausing methotrexate after booster

The 2-week methotrexate break and booster vaccine dose data in the Vaccine Response On Off Methotrexate (VROOM) trial showed that after a month, the geometric mean antispike 1 (S1)-RBD antibody titer was 10,798 U/mL (95% confidence interval [CI], 8,970-12,997) in the group that continued methotrexate and 22,750 U/mL (95% CI, 19,314-26,796) in the group that suspended methotrexate; the geometric mean ratio was 2.19 (P < .0001; mixed-effects model), reported Abhishek Abhishek, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at the University of Nottingham in Nottingham, England, and colleagues.

Prior research showed that stopping methotrexate therapy for 2 weeks following the seasonal influenza vaccine contributed to better vaccine immunity among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, but there was no impact of stopping the drug for up to 4 weeks before vaccination on vaccine-related immunity, the researchers noted.

It is crucial in maximizing long-lasting vaccine protection in people who are possibly susceptible through immune suppression at this point in the COVID-19 vaccination regimen, the study team noted.

“Evidence from this study will be useful for policymakers, national immunization advisory committees, and specialist societies formulating recommendations on the use of methotrexate around the time of COVID-19 vaccination. This evidence will help patients and clinicians make informed choices about the risks and benefits of interrupting methotrexate treatment around the time of COVID-19 vaccination, with implications for the potential to extend such approaches to other therapeutics,” they wrote.

In American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidance for COVID-19 vaccination, the organization advised against using standard synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic medicines such as methotrexate “for 1-2 weeks (as disease activity allows) after each COVID-19 vaccine dose,” given the at-risk population and public health concerns, Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, MMSc, assistant professor of medicine and associate physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Sara K. Tedeschi, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, noted in an accompanying editorial in The Lancet: Respiratory Medicine.

However, when the ACR developed this statement, there was only one trial involving patients with rheumatoid arthritis who paused methotrexate following seasonal influenza vaccination, the editorialists said.

“Although this finding adds to the evidence base to support interruption of methotrexate after vaccination, a shared decision process is needed to weigh the possible benefit of optimizing protection from COVID-19 and the possible risk of underlying disease flare,” they added.

Dr. Abhishek and colleagues assessed 254 patients with immune-mediated inflammatory disease from dermatology and rheumatology clinics across 26 hospitals in the United Kingdom. Participants had been diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, atopic dermatitis, polymyalgia rheumatica, axial spondyloarthritis, and psoriasis without or with arthritis. They had also been taking up to 25 mg of methotrexate per week for 3 months or longer and had received two doses of either the Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine or AstraZeneca/Oxford viral vector vaccine. The booster dose was most often the Pfizer BNT162b2 vaccine (82%). The patients’ mean age was 59 years, with females comprising 61% of the cohort. Participants were randomly assigned 1:1 to either group.

Investigators performing laboratory analysis were masked to cohort assignment, and clinical research staff, data analysts, participants, and researchers were unmasked.

The elevated antibody response of patients who suspended methotrexate was the same across different kinds of immune-mediated inflammatory disease, primary vaccination platform, SARS-CoV-2 infection history, and age.

Notably, no intervention-associated adverse events were reported, the study team noted.

The conclusions that could be drawn from the booster-dose study were limited by the trial’s modest cohort size, the small number of patients in exploratory subgroup analyses, a lack of information about differences in prescription drug behavior, and early termination’s effect on the researchers’ ability to identify differences between subgroups and in secondary outcomes, the authors noted.

Other limitations included a lack of generalizability to patients with active disease who couldn’t stop therapy and were not included in the investigation, and participants were not blinded to what group they were in, the researchers said.

Expert commentary

This current study is consistent with other studies over the last several months showing that methotrexate harms both humoral and cell-mediated COVID-19 responses, noted Kevin Winthrop, MD, MPH, professor of infectious disease and public health at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, who was not involved in the study. “And so now the new wave of studies are like this one, where they are holding methotrexate experimentally and seeing if it makes a difference,” he said.

“The one shortcoming of this study – and so far, the studies to date – is that no one has looked at whether the experimental hold has resulted in a change in T-cell responses, which ... we are [now] recognizing [the importance of] more and more in long-term protection, particularly in severe disease. Theoretically, holding [methotrexate] might help enhance T-cell responses, but that hasn’t been shown experimentally.”

Dr. Winthrop pointed out that one might get the same benefit from holding methotrexate for 1 week instead of 2 and that there likely is a reduced risk of flare-up from underlying autoimmune disease.

It is still not certain that this benefit extends to other vaccines, Dr. Winthrop noted. “It is probably true for most vaccines that if you hold methotrexate for 1 or 2 weeks, you might see some short-term benefit in responsiveness, but you don’t know that there is any clinical meaningfulness of this. That’s going to take other long-term studies. You don’t know how long this benefit lasts.”

Pausing methotrexate during initial COVID vaccine doses

Patients with either rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis had higher anti-RBD antibody titers when methotrexate was stopped after both doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine, or simply after the second dose, than when methotrexate was continued, according to results from two single-center, randomized controlled trials called MIVAC I and II, Anu Sreekanth, MD, of Sree Sudheendra Medical Mission in Kochi, Kerala, India, and colleagues reported at EULAR 2022.

Results from MIVAC I indicated that there was a higher flare rate when methotrexate was stopped after both vaccine doses, but there was no difference in flare rate in MIVAC II when methotrexate was stopped only after the second dose as opposed to stopping it after both doses.

In the MIVAC I trial, 158 unvaccinated patients were randomized 1:1 to a cohort in which methotrexate was held for 2 weeks after both doses and a cohort in which methotrexate was continued despite the vaccine. In MIVAC II, 157 patients continued methotrexate while receiving the first vaccine dose. These patients were subsequently randomized either to continue or to stop methotrexate for 2 weeks following the second dose.

The findings from MIVAC I demonstrated the flare rate was lower in the methotrexate-continue group than in the methotrexate-pause group (8% vs. 25%; P = .005) and that the median anti-RBD titer was significantly higher for the methotrexate-pause group than the methotrexate-continue group (2,484 vs. 1,147; P = .001).

The results from MIVAC II trial indicated that there was no difference in flare rates between the two study groups (7.9% vs. 11.8%; P = .15). Yet, the median anti-RBD titer was significantly higher in the methotrexate-pause cohort than in the methotrexate-continue cohort (2,553 vs. 990; P = .001).

The report suggests there is a flare risk when methotrexate is stopped, Dr. Sreekanth noted. “It appears more logical to hold only after the second dose, as comparable anti-RBD titers are generated” with either approach, Dr. Sreekanth said.

Expert commentary: MIVAC I and II

Inés Colmegna, MD, associate professor at McGill University in Montreal, noted that it was intriguing that the risk of flares in MIVAC II is half of that reported after each of the doses of MIVAC I. “It is also worth emphasizing that despite the reported frequency of flares, the actual disease activity [as measured by the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints] in patients who did or did not withhold methotrexate was similar.

“MIVAC I and II have practical implications as they help to adequately inform patients about the risk and benefit trade of withholding methotrexate post–COVID-19 vaccination,” Dr. Colmegna told this news organization.

“Additional information would help to [further] interpret the findings of these studies, including whether any of the participants were taking any other DMARDs; data on the severity of the flares and functional impact; analysis of factors that predict the risk of flares, such as higher doses of methotrexate; [and change in] disease activity scores pre- and postvaccination,” Dr. Colmegna concluded.

Dr. Abhishek disclosed relationships with Springer, UpTodate, Oxford, Immunotec, AstraZeneca, Inflazome, NGM Biopharmaceuticals, Menarini Pharmaceuticals, and Cadila Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Abhishek is cochair of the ACR/EULAR CPPD Classification Criteria Working Group and the OMERACT CPPD Working Group. Dr. Sparks disclosed relationships with Gilead, Boehringer Ingelheim, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and AbbVie, unrelated to this study. Dr. Tedeschi disclosed relationships with ModernaTx and NGM Biopharmaceuticals. Dr. Winthrop disclosed a research grant and serving as a scientific consultant for Pfizer. Dr. Sreekanth and Dr. Colmegna have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients who take methotrexate for a variety of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases and pause taking the drug following receipt of a COVID-19 vaccine dose did not have a higher risk of disease flare and had higher antireceptor binding domain (anti-RBD) antibody titers and increased immunogenicity when compared with continuing the drug, three recent studies suggest.

In one study, British researchers examined the effects of a 2-week break in methotrexate therapy on anti-RBD titers following receipt of a third COVID-19 vaccine dose. In their paper published in The Lancet: Respiratory Medicine, they reported results from a randomized, open-label, superiority trial that suggested pausing the drug improved immunogenicity, compared with no break.

In two trials presented at the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) 2022 Congress, a team from India set out to determine whether holding methotrexate after receiving both doses of a COVID-19 vaccine, or holding it only after the second dose, was safe and effective. They found that pausing methotrexate only following the second dose contributed to a lower flare risk, and that patients had higher anti-RBD titers when holding methotrexate for 2 weeks following each dose.

Pausing methotrexate after booster

The 2-week methotrexate break and booster vaccine dose data in the Vaccine Response On Off Methotrexate (VROOM) trial showed that after a month, the geometric mean antispike 1 (S1)-RBD antibody titer was 10,798 U/mL (95% confidence interval [CI], 8,970-12,997) in the group that continued methotrexate and 22,750 U/mL (95% CI, 19,314-26,796) in the group that suspended methotrexate; the geometric mean ratio was 2.19 (P < .0001; mixed-effects model), reported Abhishek Abhishek, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at the University of Nottingham in Nottingham, England, and colleagues.

Prior research showed that stopping methotrexate therapy for 2 weeks following the seasonal influenza vaccine contributed to better vaccine immunity among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, but there was no impact of stopping the drug for up to 4 weeks before vaccination on vaccine-related immunity, the researchers noted.

It is crucial in maximizing long-lasting vaccine protection in people who are possibly susceptible through immune suppression at this point in the COVID-19 vaccination regimen, the study team noted.

“Evidence from this study will be useful for policymakers, national immunization advisory committees, and specialist societies formulating recommendations on the use of methotrexate around the time of COVID-19 vaccination. This evidence will help patients and clinicians make informed choices about the risks and benefits of interrupting methotrexate treatment around the time of COVID-19 vaccination, with implications for the potential to extend such approaches to other therapeutics,” they wrote.

In American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidance for COVID-19 vaccination, the organization advised against using standard synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic medicines such as methotrexate “for 1-2 weeks (as disease activity allows) after each COVID-19 vaccine dose,” given the at-risk population and public health concerns, Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, MMSc, assistant professor of medicine and associate physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Sara K. Tedeschi, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, noted in an accompanying editorial in The Lancet: Respiratory Medicine.

However, when the ACR developed this statement, there was only one trial involving patients with rheumatoid arthritis who paused methotrexate following seasonal influenza vaccination, the editorialists said.

“Although this finding adds to the evidence base to support interruption of methotrexate after vaccination, a shared decision process is needed to weigh the possible benefit of optimizing protection from COVID-19 and the possible risk of underlying disease flare,” they added.

Dr. Abhishek and colleagues assessed 254 patients with immune-mediated inflammatory disease from dermatology and rheumatology clinics across 26 hospitals in the United Kingdom. Participants had been diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, atopic dermatitis, polymyalgia rheumatica, axial spondyloarthritis, and psoriasis without or with arthritis. They had also been taking up to 25 mg of methotrexate per week for 3 months or longer and had received two doses of either the Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine or AstraZeneca/Oxford viral vector vaccine. The booster dose was most often the Pfizer BNT162b2 vaccine (82%). The patients’ mean age was 59 years, with females comprising 61% of the cohort. Participants were randomly assigned 1:1 to either group.

Investigators performing laboratory analysis were masked to cohort assignment, and clinical research staff, data analysts, participants, and researchers were unmasked.

The elevated antibody response of patients who suspended methotrexate was the same across different kinds of immune-mediated inflammatory disease, primary vaccination platform, SARS-CoV-2 infection history, and age.

Notably, no intervention-associated adverse events were reported, the study team noted.

The conclusions that could be drawn from the booster-dose study were limited by the trial’s modest cohort size, the small number of patients in exploratory subgroup analyses, a lack of information about differences in prescription drug behavior, and early termination’s effect on the researchers’ ability to identify differences between subgroups and in secondary outcomes, the authors noted.

Other limitations included a lack of generalizability to patients with active disease who couldn’t stop therapy and were not included in the investigation, and participants were not blinded to what group they were in, the researchers said.

Expert commentary

This current study is consistent with other studies over the last several months showing that methotrexate harms both humoral and cell-mediated COVID-19 responses, noted Kevin Winthrop, MD, MPH, professor of infectious disease and public health at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, who was not involved in the study. “And so now the new wave of studies are like this one, where they are holding methotrexate experimentally and seeing if it makes a difference,” he said.

“The one shortcoming of this study – and so far, the studies to date – is that no one has looked at whether the experimental hold has resulted in a change in T-cell responses, which ... we are [now] recognizing [the importance of] more and more in long-term protection, particularly in severe disease. Theoretically, holding [methotrexate] might help enhance T-cell responses, but that hasn’t been shown experimentally.”

Dr. Winthrop pointed out that one might get the same benefit from holding methotrexate for 1 week instead of 2 and that there likely is a reduced risk of flare-up from underlying autoimmune disease.

It is still not certain that this benefit extends to other vaccines, Dr. Winthrop noted. “It is probably true for most vaccines that if you hold methotrexate for 1 or 2 weeks, you might see some short-term benefit in responsiveness, but you don’t know that there is any clinical meaningfulness of this. That’s going to take other long-term studies. You don’t know how long this benefit lasts.”

Pausing methotrexate during initial COVID vaccine doses