User login

Content Analysis of Psoriasis and Eczema Direct-to-Consumer Advertisements

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertisements are an important and influential source of health-related information for Americans. In 1997, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) relaxed regulations and permitted DTC drug advertisements to be televised. Now, via television alone, the average American is exposed to more than 30 hours annually of DTC advertisements for drugs,1 which exceeds, by far, the amount of time the average American spends with his/her physician.2 The United States spends $9.6 billion on DTC advertisements per year, of which $605 million is spent exclusively on DTC advertisements for dermatologic conditions—one of the highest amounts of spending for DTC advertisements, second only to diabetes.3

The increase in advertising for dermatologic conditions is reflective of the rapid growth in the number of treatment options available for chronic skin diseases, especially psoriasis. Since 2004, 11 biologics and 1 oral medication were FDA approved for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. Despite the expansion of treatment options for psoriasis, knowledge and understanding of psoriasis and its treatments generally are poor,4,5 and undertreatment of psoriasis continues to be common.6 Data also suggest existing age and racial disparities in psoriasis treatment in the United States, whereby patients who are older or Black are less likely to receive biologic therapies.7-9 Although the exact causes of these disparities remain unclear, one study found that Black patients with psoriasis were less familiar with biologics compared to White patients,10 which suggests that the racial disparity in biologic treatment of psoriasis could be due to less exposure to and thus recognition of biologics as treatments of psoriasis among Black patients.

Some data suggest that DTC advertisements may affect drug uptake by encouraging patients to request advertised medications from their medical providers.11,12 As such, DTC advertisements are a potentially important source of exposure and information for patients. However, is it possible that DTC advertisements also may contribute to widening knowledge gaps among certain populations, and thus treatment disparities, by neglecting certain groups and targeting others with their content? In an effort to answer this question, we performed an analysis of DTC advertisements for psoriasis and eczema with special attention to advertisement placement, character representation, and disease-related content. We specifically targeted advertisements for psoriasis and eczema, as advertisements for the former are rampant and advertisements for the latter are on the rise because of emerging therapies. We hypothesized that age and racial/ethnic diversity among advertisement characters is poor, and disease-related content is lacking.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Sample

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of televised DTC advertisements for psoriasis and eczema over 14 consecutive days (July 1, 2018, to July 14, 2018). We accessed Nielsen’s top 10 lists, specifically Prime Broadcast Network TV-United States and Prime Broadcast Programs Among African-American, from June 2018 and identified the networks with the greatest potential exposure to American consumers: ABC, CBS, FOX, and NBC.13,14 Each day, programming aired from 5

The FDA identifies DTC advertisement types as product-claim, reminder, and help-seeking advertisements. Product-claim advertisements are required to include the following information for the drug of interest: name; at least 1 FDA-approved indication; the most notable risks; and reference to a toll-free telephone number, website, or print advertisement by which a detailed summary of risks and benefits can be accessed. Reminder advertisements include the name of the drug but no information about the drug’s use.15 Help-seeking advertisements describe a disease or condition without referencing a specific drug treatment. Product-claim, reminder, and help-seeking advertisements for psoriasis or eczema that aired during the recorded time frame were included for analysis; advertisements that aired during sporting events and special programming were excluded.

DTC Advertisement Coding

Advertisement placement (ie, network, day of the week, time, associated television program), type, and target disease were documented for all advertisements included in the study. The content of each unique advertisement for psoriasis and eczema also was documented electronically in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) as follows: characteristics of affected individuals and disease-related content. Advertisement coding was performed independently by 2 graduate students (A.H. and C.W.). First, one-third of the advertisements were randomly selected to be coded by both students. Intercoder agreement between the 2 students was 95.3%. Coding disagreements were primarily due to misunderstanding of definitions and were resolved through consensus. Subsequently, the remaining advertisements were randomly distributed between the 2 students, and each advertisement was coded by 1 student.

Statistical Analysis

All data were summarized descriptively with counts and frequencies using Stata 15 (StataCorp).

Results

We identified 297 DTC advertisements addressing 25 different conditions during our study period. CBS, ABC, NBC, and FOX aired 44.4%, 26.3%, 24.4%, and 5.1% of advertisements, respectively. Overall, DTC advertisements were least likely to air on Saturdays and between the hours of 5

Psoriasis DTC Advertisements

There were 5 unique psoriasis DTC advertisements, all of which were product-claim advertisements, with 1 each for secukinumab (Cosentyx [Novartis]), ixekizumab (Taltz [Eli Lilly and Company]), and guselkumab (Tremfya [Janssen Biotech, Inc]), and 2 for adalimumab (Humira [AbbVie Inc]). The advertisements aired on ABC (n=5 [38.5%]), CBS (n=5 [38.5%]), and NBC (n=3 [23.1%]). Most advertisements aired on weekdays (61.5%) between 6

Psoriasis Character Portrayal and Disease-Related Content

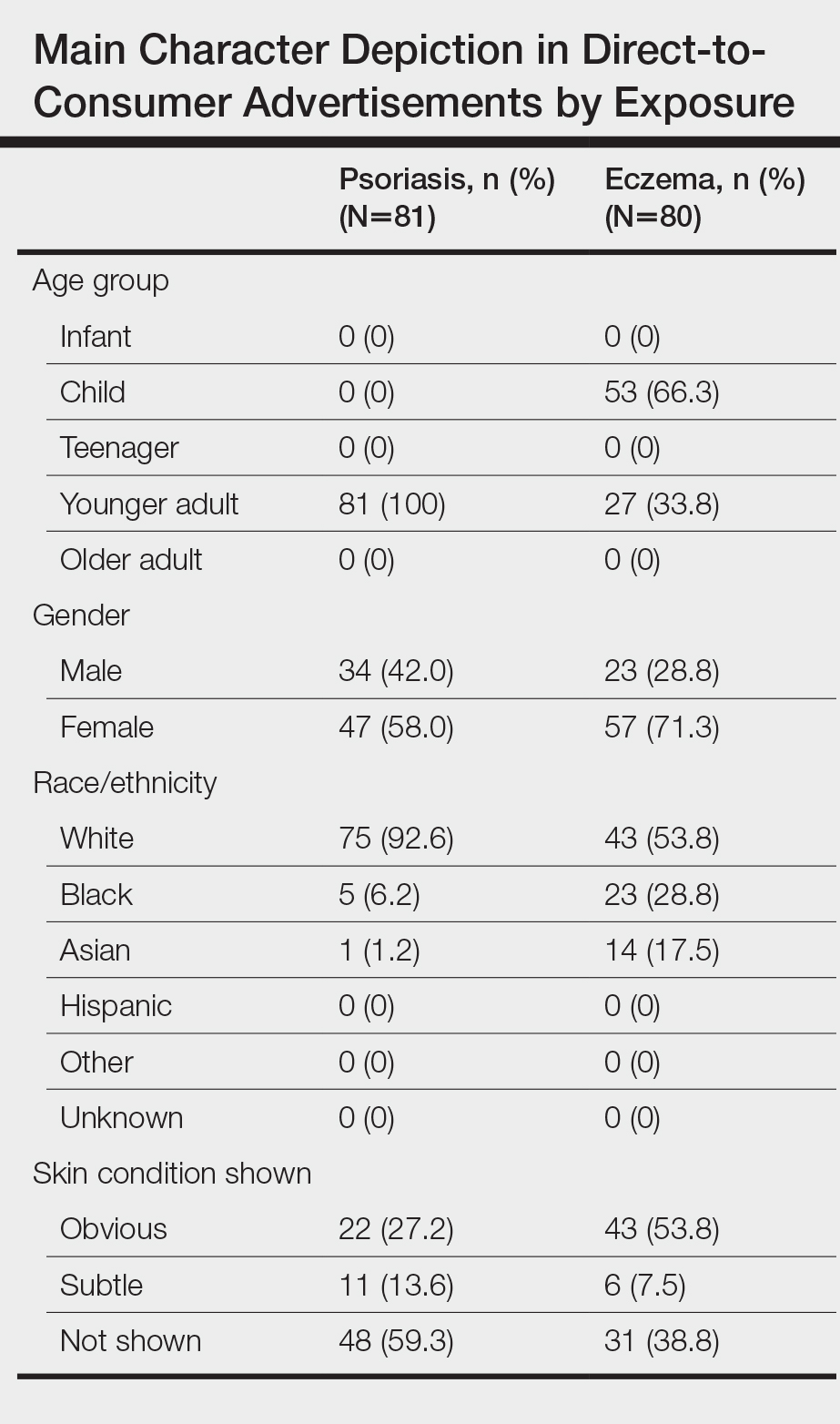

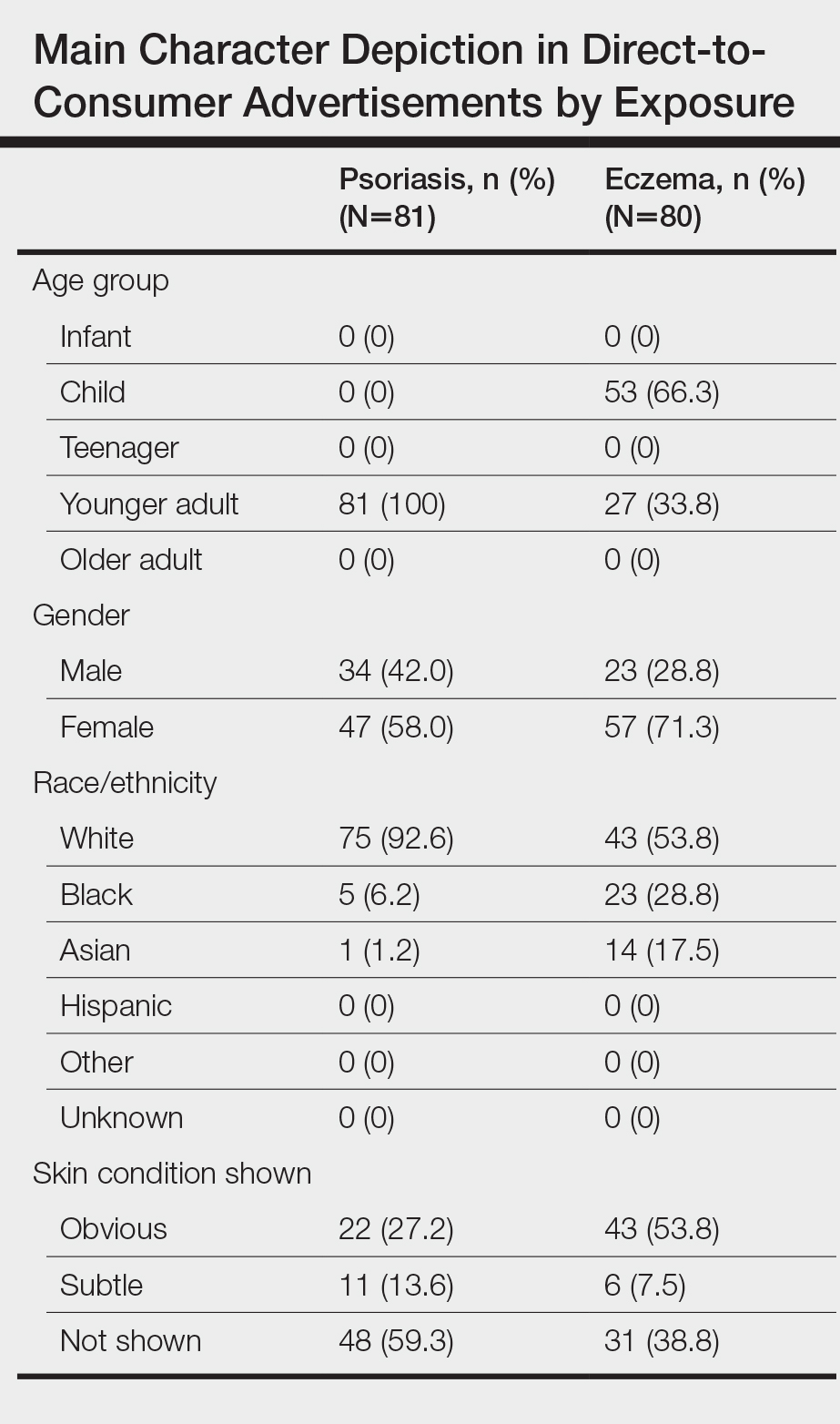

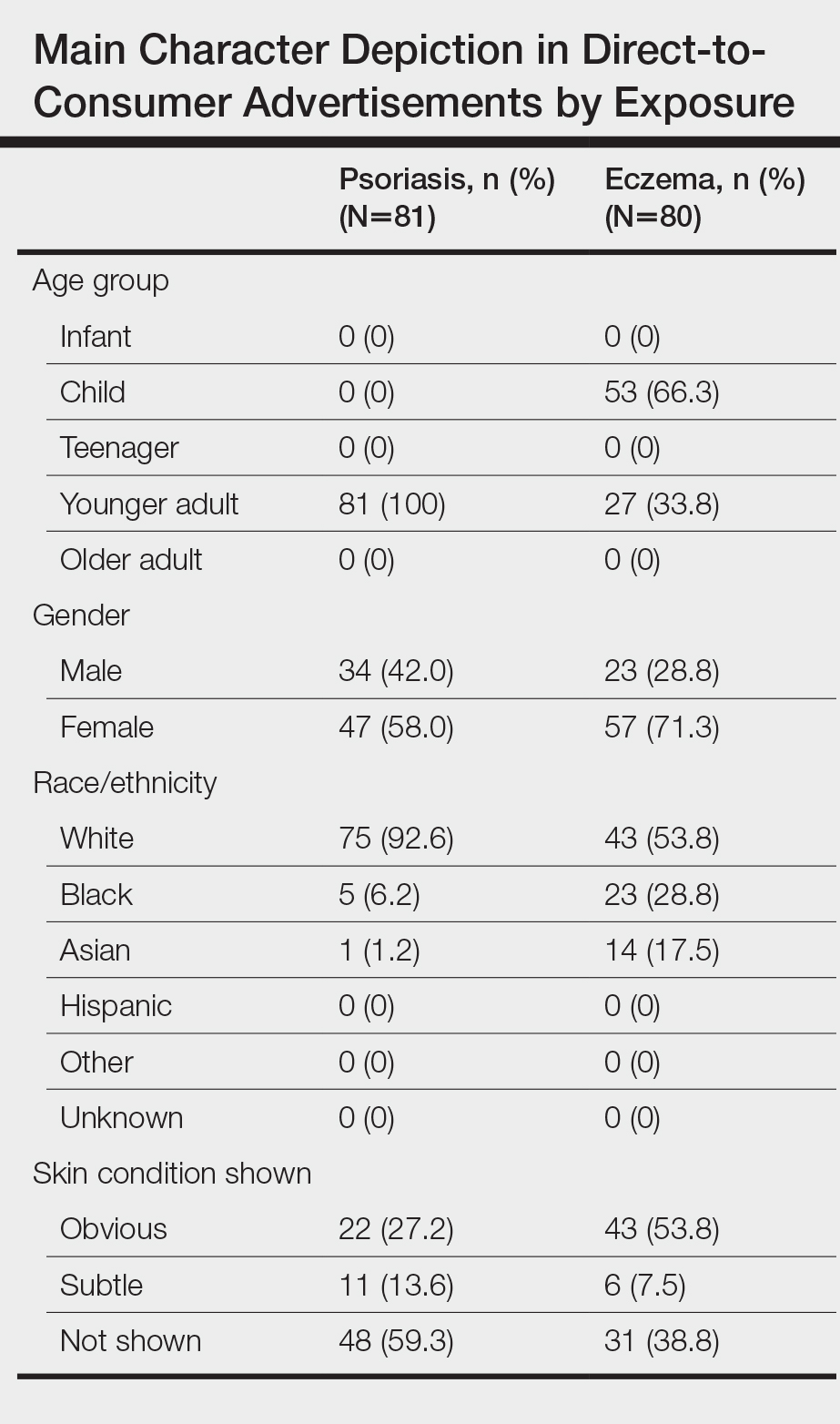

We identified 81 main characters who were depicted as having psoriasis among all advertisements. Characteristics of the affected characters are summarized in the Table. All affected characters were perceived to be younger adults, and there was a slight female predominance (58.0% [47/81]). Most characters were perceived to be White (92.6% [75/81]). Black and Asian characters only represented 6.2% (5/81) and 1.2% (1/81) of all affected individuals, respectively. Notably, the advertisements that featured only White main characters were aired 2.75 times more frequently than the advertisements that included non-White characters.

Psoriasis was shown on the skin of at least 1 character in an obvious depiction (ie, did not require more than 1 viewing) in 84.6% (11/13) of the advertisements. Symptoms of psoriasis (communicated either verbally or visually) were included in only 15.4% (2/13) of advertisements. No advertisements included information on the epidemiology of (ie, prevalence, subpopulations at risk), risk factors for, pathophysiology of, or comorbid diseases associated with psoriasis.

Eczema DTC Advertisements

Among the 27 eczema advertisements aired, there were 4 unique advertisements, of which 3 were product-claim advertisements (all for crisaborole [Eucrisa (Pfizer Inc)]), and 1 was a help-seeking advertisement that was sponsored by Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. The advertisements aired on ABC (n=2 [7.4%]), CBS (n=17 [63.0%]), and NBC (n=8 [29.6%]). All advertisements aired on weekdays between 7

Eczema Character Portrayal and Disease-Related Content

We identified 80 main characters who were depicted to be affected by eczema among all advertisements. Characteristics of the affected characters are summarized in the Table. Most of the affected characters were perceived to be White (53.8% [43/80]) and female (71.3% [57/80]). Other races depicted included Black (28.8% [23/80]) and Asian (17.5% [14/80]). Each unique eczema advertisement included at least 1 non-White main character. Most eczema main characters were perceived to be children (66.3% [53/80]), followed by younger adults (33.8% [27/80]). No infants, teenagers, or older adults were shown as being affected by eczema.

Skin manifestations of eczema were portrayed on at least 1 character in all of the advertisements; 77.8% (21/27) of the advertisements had at least 1 obvious depiction. Symptoms of eczema and the mechanism of disease (pathophysiology) were each included in 44.4% (12/27) of advertisements. This information was included exclusively in the single help-seeking advertisement, which also referenced a website for additional disease-related information. No advertisements included information on the epidemiology of, risk factors for, or comorbid diseases associated with eczema.

Comment

In our study of televised DTC advertisements for psoriasis and eczema in the United States, we identified underrepresentation of racial/ethnic minorities and specific age groups (older adults for psoriasis and all adults for eczema) across all advertisements. Although psoriasis is suggested to be less prevalent among minority patients (1.3%–1.9% among Black patients and 1.6% among Hispanic patients) compared to White patients (2%–4%),16,17 minority vs White representation in psoriasis DTC advertisements was disproportionately lower than population-based prevalence estimates. Direct-to-consumer advertisements for eczema included more minority characters than psoriasis advertisements; however, minority representation remained inadequate considering that childhood eczema is more prevalent among Black vs White children,18 and adult eczema is at least as prevalent among minority patients compared to White patients.19 Not only was minority representation in all advertisements poor, but advertisement placement also was suboptimal, particularly for reaching Black viewers. FOX network was home to 2 of the top 3 primetime broadcast programs among Black viewers around the study period,13 yet no DTC advertisements were aired on FOX.

The current literature regarding minority representation in DTC advertisements is mixed. Some studies report underrepresentation of Black and other minority patients across a variety of diseases.20 Other studies suggest that representation of Black patients, in particular, generally is adequate, except among select serious health conditions, and that advertisements depict tokenism or stereotypical roles for minorities.21 Our study provides new and specific insight about the state of racial/ethnic and age diversity, or lack thereof, in DTC advertisements for the skin conditions that currently are most commonly targeted—psoriasis and eczema. Although it remains unclear whether DTC advertisements are good or bad, existing data suggest that potential benefits of DTC advertisements include strengthening of patient-provider relationships, reduction of underdiagnosis and undertreatment of disease, and reduction of disease stigma.22 However, in our analyses, we found disease-specific factual content among all DTC advertisements to be sparse and obvious depictions of skin disease and symptoms to be uncommon, especially for psoriasis. As such, it seems unlikely that existing DTC advertisements for psoriasis and eczema can be expected to contribute to meaningful disease education, reduce underdiagnosis, and reduce the stigmatizing attitudes that have been documented for both skin diseases.23-25

Furthermore, it is important to consider our findings in light of the role that social identity theory plays in marketing. Social identity theory supports the idea that a person’s social identity (eg, age, gender, race/ethnicity) influences his/her behavior, perceptions, and performance.26 The principle of homophily—the tendency for individuals to have positive ties to those who are similar to themselves—is a critical concept in social identity theory and suggests that consumers are more likely to pay attention to and be influenced by sources perceived as similar to themselves.20 Thus, even if the potential benefits of DTC advertisements were to be realized for psoriasis and eczema, the lack of adequate minority and older adult representation raises concerns about whether these benefits would reach a diverse population and if the advertisements might further potentiate existing knowledge and treatment disparities.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. The sampling period was short and might not reflect advertisement content over a longer time course. We did not evaluate other potential sources of information, such as the Internet and social media. Nevertheless, televised DTC advertisements remain a major source of medical and drug information for the general public. We did not directly evaluate viewers’ reactions to the DTC advertisements of interest; however, other literature lends support to the significance of social identity theory and its impact on consumer behavior.26

Conclusion

Our study highlights a lost opportunity among psoriasis and eczema DTC advertisements for patient reach and disease education that may encourage existing and emerging knowledge and treatment disparities for both conditions. Our findings should serve as a call to action to pharmaceutical companies and other organizations involved in creating and supporting DTC advertisements for psoriasis and eczema to increase the educational content, diversify the depicted characters, and optimize advertisement placement.

- Brownfield ED, Bernhardt JM, Phan JL, et al. Direct-to-consumer drug advertisements on network television: an exploration of quantity, frequency, and placement. J Health Commun. 2004;9:491-497.

- Tai-Seale M, McGuire TG, Zhang W. Time allocation in primary care office visits. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1871-1894.

- Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Medical marketing in the United States, 1997-2016. JAMA. 2019;321:80-96.

- Lanigan SW, Farber EM. Patients’ knowledge of psoriasis: pilot study. Cutis. 1990;46:359-362.

- Renzi C, Di Pietro C, Tabolli S. Participation, satisfaction and knowledge level of patients with cutaneous psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:885-888.

- Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J, et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:871-881.e871-830.

- Wu JJ, Lu M, Veverka KA, et al. The journey for US psoriasis patients prescribed a topical: a retrospective database evaluation of patient progression to oral and/or biologic treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:446-453.

- Takeshita J, Gelfand JM, Li P, et al. Psoriasis in the US Medicare population: prevalence, treatment, and factors associated with biologic use. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2955-2963.

- Kerr GS, Qaiyumi S, Richards J, et al. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in African-American patients—the need to measure disease burden. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:1753-1759.

- Takeshita J, Eriksen WT, Raziano VT, et al. Racial differences in perceptions of psoriasis therapies: implications for racial disparities in psoriasis treatment. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:1672-1679.e1.

- Wu MH, Bartz D, Avorn J, et al. Trends in direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription contraceptives. Contraception. 2016;93:398-405.

- Mintzes B, Barer ML, Kravitz RL, et al. How does direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) affect prescribing? a survey in primary care environments with and without legal DTCA. CMAJ. 2003;169:405-412.

- Topten. Nielson website. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/top-ten/. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- Leading ad supported broadcast and cable networks in the United States in 2019, by average number of viewers. Statistia website. https://www.statista.com/statistics/530119/tv-networks-viewers-usa/. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- Prescription drug advertisements. Electronic Code of Federal Regulations website. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=d4f308e364578bda8e55a831638a26c6&mc=true&node=pt21.4.202&rgn=div5. Updated August 12, 2020. Accessed August 12, 2020.

- Gelfand JM, Stern RS, Nijsten T, et al. The prevalence of psoriasis in African Americans: results from a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:23-26.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/health_policy/eczema_skin_problems_tables.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583-590.

- Welch Cline RJ, Young HN. Marketing drugs, marketing health care relationships: a content analysis of visual cues in direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising. Health Commun. 2004;16:131-157.

- Ball JG, Liang A, Lee WN. Representation of African Americans in direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical commercials: a content analysis with implications for health disparities. Health Mark Q. 2009;26:372-390.

- Ventola CL. Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising: therapeutic or toxic? P T. 2011;36:669-674, 681-684.

- Pearl RL, Wan MT, Takeshita J, et al. Stigmatizing attitudes toward persons with psoriasis among laypersons and medical students. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1556-1563.

- Chernyshov PV. Stigmatization and self-perception in children with atopic dermatitis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:159-166.

- Wittkowski A, Richards HL, Griffiths CEM, et al. The impact of psychological and clinical factors on quality of life in individuals with atopic dermatitis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:195-200.

- Forehand MR, Deshpande R, Reed 2nd A. Identity salience and the influence of differential activation of the social self-schema on advertising response. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87:1086-1099.

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertisements are an important and influential source of health-related information for Americans. In 1997, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) relaxed regulations and permitted DTC drug advertisements to be televised. Now, via television alone, the average American is exposed to more than 30 hours annually of DTC advertisements for drugs,1 which exceeds, by far, the amount of time the average American spends with his/her physician.2 The United States spends $9.6 billion on DTC advertisements per year, of which $605 million is spent exclusively on DTC advertisements for dermatologic conditions—one of the highest amounts of spending for DTC advertisements, second only to diabetes.3

The increase in advertising for dermatologic conditions is reflective of the rapid growth in the number of treatment options available for chronic skin diseases, especially psoriasis. Since 2004, 11 biologics and 1 oral medication were FDA approved for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. Despite the expansion of treatment options for psoriasis, knowledge and understanding of psoriasis and its treatments generally are poor,4,5 and undertreatment of psoriasis continues to be common.6 Data also suggest existing age and racial disparities in psoriasis treatment in the United States, whereby patients who are older or Black are less likely to receive biologic therapies.7-9 Although the exact causes of these disparities remain unclear, one study found that Black patients with psoriasis were less familiar with biologics compared to White patients,10 which suggests that the racial disparity in biologic treatment of psoriasis could be due to less exposure to and thus recognition of biologics as treatments of psoriasis among Black patients.

Some data suggest that DTC advertisements may affect drug uptake by encouraging patients to request advertised medications from their medical providers.11,12 As such, DTC advertisements are a potentially important source of exposure and information for patients. However, is it possible that DTC advertisements also may contribute to widening knowledge gaps among certain populations, and thus treatment disparities, by neglecting certain groups and targeting others with their content? In an effort to answer this question, we performed an analysis of DTC advertisements for psoriasis and eczema with special attention to advertisement placement, character representation, and disease-related content. We specifically targeted advertisements for psoriasis and eczema, as advertisements for the former are rampant and advertisements for the latter are on the rise because of emerging therapies. We hypothesized that age and racial/ethnic diversity among advertisement characters is poor, and disease-related content is lacking.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Sample

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of televised DTC advertisements for psoriasis and eczema over 14 consecutive days (July 1, 2018, to July 14, 2018). We accessed Nielsen’s top 10 lists, specifically Prime Broadcast Network TV-United States and Prime Broadcast Programs Among African-American, from June 2018 and identified the networks with the greatest potential exposure to American consumers: ABC, CBS, FOX, and NBC.13,14 Each day, programming aired from 5

The FDA identifies DTC advertisement types as product-claim, reminder, and help-seeking advertisements. Product-claim advertisements are required to include the following information for the drug of interest: name; at least 1 FDA-approved indication; the most notable risks; and reference to a toll-free telephone number, website, or print advertisement by which a detailed summary of risks and benefits can be accessed. Reminder advertisements include the name of the drug but no information about the drug’s use.15 Help-seeking advertisements describe a disease or condition without referencing a specific drug treatment. Product-claim, reminder, and help-seeking advertisements for psoriasis or eczema that aired during the recorded time frame were included for analysis; advertisements that aired during sporting events and special programming were excluded.

DTC Advertisement Coding

Advertisement placement (ie, network, day of the week, time, associated television program), type, and target disease were documented for all advertisements included in the study. The content of each unique advertisement for psoriasis and eczema also was documented electronically in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) as follows: characteristics of affected individuals and disease-related content. Advertisement coding was performed independently by 2 graduate students (A.H. and C.W.). First, one-third of the advertisements were randomly selected to be coded by both students. Intercoder agreement between the 2 students was 95.3%. Coding disagreements were primarily due to misunderstanding of definitions and were resolved through consensus. Subsequently, the remaining advertisements were randomly distributed between the 2 students, and each advertisement was coded by 1 student.

Statistical Analysis

All data were summarized descriptively with counts and frequencies using Stata 15 (StataCorp).

Results

We identified 297 DTC advertisements addressing 25 different conditions during our study period. CBS, ABC, NBC, and FOX aired 44.4%, 26.3%, 24.4%, and 5.1% of advertisements, respectively. Overall, DTC advertisements were least likely to air on Saturdays and between the hours of 5

Psoriasis DTC Advertisements

There were 5 unique psoriasis DTC advertisements, all of which were product-claim advertisements, with 1 each for secukinumab (Cosentyx [Novartis]), ixekizumab (Taltz [Eli Lilly and Company]), and guselkumab (Tremfya [Janssen Biotech, Inc]), and 2 for adalimumab (Humira [AbbVie Inc]). The advertisements aired on ABC (n=5 [38.5%]), CBS (n=5 [38.5%]), and NBC (n=3 [23.1%]). Most advertisements aired on weekdays (61.5%) between 6

Psoriasis Character Portrayal and Disease-Related Content

We identified 81 main characters who were depicted as having psoriasis among all advertisements. Characteristics of the affected characters are summarized in the Table. All affected characters were perceived to be younger adults, and there was a slight female predominance (58.0% [47/81]). Most characters were perceived to be White (92.6% [75/81]). Black and Asian characters only represented 6.2% (5/81) and 1.2% (1/81) of all affected individuals, respectively. Notably, the advertisements that featured only White main characters were aired 2.75 times more frequently than the advertisements that included non-White characters.

Psoriasis was shown on the skin of at least 1 character in an obvious depiction (ie, did not require more than 1 viewing) in 84.6% (11/13) of the advertisements. Symptoms of psoriasis (communicated either verbally or visually) were included in only 15.4% (2/13) of advertisements. No advertisements included information on the epidemiology of (ie, prevalence, subpopulations at risk), risk factors for, pathophysiology of, or comorbid diseases associated with psoriasis.

Eczema DTC Advertisements

Among the 27 eczema advertisements aired, there were 4 unique advertisements, of which 3 were product-claim advertisements (all for crisaborole [Eucrisa (Pfizer Inc)]), and 1 was a help-seeking advertisement that was sponsored by Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. The advertisements aired on ABC (n=2 [7.4%]), CBS (n=17 [63.0%]), and NBC (n=8 [29.6%]). All advertisements aired on weekdays between 7

Eczema Character Portrayal and Disease-Related Content

We identified 80 main characters who were depicted to be affected by eczema among all advertisements. Characteristics of the affected characters are summarized in the Table. Most of the affected characters were perceived to be White (53.8% [43/80]) and female (71.3% [57/80]). Other races depicted included Black (28.8% [23/80]) and Asian (17.5% [14/80]). Each unique eczema advertisement included at least 1 non-White main character. Most eczema main characters were perceived to be children (66.3% [53/80]), followed by younger adults (33.8% [27/80]). No infants, teenagers, or older adults were shown as being affected by eczema.

Skin manifestations of eczema were portrayed on at least 1 character in all of the advertisements; 77.8% (21/27) of the advertisements had at least 1 obvious depiction. Symptoms of eczema and the mechanism of disease (pathophysiology) were each included in 44.4% (12/27) of advertisements. This information was included exclusively in the single help-seeking advertisement, which also referenced a website for additional disease-related information. No advertisements included information on the epidemiology of, risk factors for, or comorbid diseases associated with eczema.

Comment

In our study of televised DTC advertisements for psoriasis and eczema in the United States, we identified underrepresentation of racial/ethnic minorities and specific age groups (older adults for psoriasis and all adults for eczema) across all advertisements. Although psoriasis is suggested to be less prevalent among minority patients (1.3%–1.9% among Black patients and 1.6% among Hispanic patients) compared to White patients (2%–4%),16,17 minority vs White representation in psoriasis DTC advertisements was disproportionately lower than population-based prevalence estimates. Direct-to-consumer advertisements for eczema included more minority characters than psoriasis advertisements; however, minority representation remained inadequate considering that childhood eczema is more prevalent among Black vs White children,18 and adult eczema is at least as prevalent among minority patients compared to White patients.19 Not only was minority representation in all advertisements poor, but advertisement placement also was suboptimal, particularly for reaching Black viewers. FOX network was home to 2 of the top 3 primetime broadcast programs among Black viewers around the study period,13 yet no DTC advertisements were aired on FOX.

The current literature regarding minority representation in DTC advertisements is mixed. Some studies report underrepresentation of Black and other minority patients across a variety of diseases.20 Other studies suggest that representation of Black patients, in particular, generally is adequate, except among select serious health conditions, and that advertisements depict tokenism or stereotypical roles for minorities.21 Our study provides new and specific insight about the state of racial/ethnic and age diversity, or lack thereof, in DTC advertisements for the skin conditions that currently are most commonly targeted—psoriasis and eczema. Although it remains unclear whether DTC advertisements are good or bad, existing data suggest that potential benefits of DTC advertisements include strengthening of patient-provider relationships, reduction of underdiagnosis and undertreatment of disease, and reduction of disease stigma.22 However, in our analyses, we found disease-specific factual content among all DTC advertisements to be sparse and obvious depictions of skin disease and symptoms to be uncommon, especially for psoriasis. As such, it seems unlikely that existing DTC advertisements for psoriasis and eczema can be expected to contribute to meaningful disease education, reduce underdiagnosis, and reduce the stigmatizing attitudes that have been documented for both skin diseases.23-25

Furthermore, it is important to consider our findings in light of the role that social identity theory plays in marketing. Social identity theory supports the idea that a person’s social identity (eg, age, gender, race/ethnicity) influences his/her behavior, perceptions, and performance.26 The principle of homophily—the tendency for individuals to have positive ties to those who are similar to themselves—is a critical concept in social identity theory and suggests that consumers are more likely to pay attention to and be influenced by sources perceived as similar to themselves.20 Thus, even if the potential benefits of DTC advertisements were to be realized for psoriasis and eczema, the lack of adequate minority and older adult representation raises concerns about whether these benefits would reach a diverse population and if the advertisements might further potentiate existing knowledge and treatment disparities.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. The sampling period was short and might not reflect advertisement content over a longer time course. We did not evaluate other potential sources of information, such as the Internet and social media. Nevertheless, televised DTC advertisements remain a major source of medical and drug information for the general public. We did not directly evaluate viewers’ reactions to the DTC advertisements of interest; however, other literature lends support to the significance of social identity theory and its impact on consumer behavior.26

Conclusion

Our study highlights a lost opportunity among psoriasis and eczema DTC advertisements for patient reach and disease education that may encourage existing and emerging knowledge and treatment disparities for both conditions. Our findings should serve as a call to action to pharmaceutical companies and other organizations involved in creating and supporting DTC advertisements for psoriasis and eczema to increase the educational content, diversify the depicted characters, and optimize advertisement placement.

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertisements are an important and influential source of health-related information for Americans. In 1997, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) relaxed regulations and permitted DTC drug advertisements to be televised. Now, via television alone, the average American is exposed to more than 30 hours annually of DTC advertisements for drugs,1 which exceeds, by far, the amount of time the average American spends with his/her physician.2 The United States spends $9.6 billion on DTC advertisements per year, of which $605 million is spent exclusively on DTC advertisements for dermatologic conditions—one of the highest amounts of spending for DTC advertisements, second only to diabetes.3

The increase in advertising for dermatologic conditions is reflective of the rapid growth in the number of treatment options available for chronic skin diseases, especially psoriasis. Since 2004, 11 biologics and 1 oral medication were FDA approved for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. Despite the expansion of treatment options for psoriasis, knowledge and understanding of psoriasis and its treatments generally are poor,4,5 and undertreatment of psoriasis continues to be common.6 Data also suggest existing age and racial disparities in psoriasis treatment in the United States, whereby patients who are older or Black are less likely to receive biologic therapies.7-9 Although the exact causes of these disparities remain unclear, one study found that Black patients with psoriasis were less familiar with biologics compared to White patients,10 which suggests that the racial disparity in biologic treatment of psoriasis could be due to less exposure to and thus recognition of biologics as treatments of psoriasis among Black patients.

Some data suggest that DTC advertisements may affect drug uptake by encouraging patients to request advertised medications from their medical providers.11,12 As such, DTC advertisements are a potentially important source of exposure and information for patients. However, is it possible that DTC advertisements also may contribute to widening knowledge gaps among certain populations, and thus treatment disparities, by neglecting certain groups and targeting others with their content? In an effort to answer this question, we performed an analysis of DTC advertisements for psoriasis and eczema with special attention to advertisement placement, character representation, and disease-related content. We specifically targeted advertisements for psoriasis and eczema, as advertisements for the former are rampant and advertisements for the latter are on the rise because of emerging therapies. We hypothesized that age and racial/ethnic diversity among advertisement characters is poor, and disease-related content is lacking.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Sample

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of televised DTC advertisements for psoriasis and eczema over 14 consecutive days (July 1, 2018, to July 14, 2018). We accessed Nielsen’s top 10 lists, specifically Prime Broadcast Network TV-United States and Prime Broadcast Programs Among African-American, from June 2018 and identified the networks with the greatest potential exposure to American consumers: ABC, CBS, FOX, and NBC.13,14 Each day, programming aired from 5

The FDA identifies DTC advertisement types as product-claim, reminder, and help-seeking advertisements. Product-claim advertisements are required to include the following information for the drug of interest: name; at least 1 FDA-approved indication; the most notable risks; and reference to a toll-free telephone number, website, or print advertisement by which a detailed summary of risks and benefits can be accessed. Reminder advertisements include the name of the drug but no information about the drug’s use.15 Help-seeking advertisements describe a disease or condition without referencing a specific drug treatment. Product-claim, reminder, and help-seeking advertisements for psoriasis or eczema that aired during the recorded time frame were included for analysis; advertisements that aired during sporting events and special programming were excluded.

DTC Advertisement Coding

Advertisement placement (ie, network, day of the week, time, associated television program), type, and target disease were documented for all advertisements included in the study. The content of each unique advertisement for psoriasis and eczema also was documented electronically in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) as follows: characteristics of affected individuals and disease-related content. Advertisement coding was performed independently by 2 graduate students (A.H. and C.W.). First, one-third of the advertisements were randomly selected to be coded by both students. Intercoder agreement between the 2 students was 95.3%. Coding disagreements were primarily due to misunderstanding of definitions and were resolved through consensus. Subsequently, the remaining advertisements were randomly distributed between the 2 students, and each advertisement was coded by 1 student.

Statistical Analysis

All data were summarized descriptively with counts and frequencies using Stata 15 (StataCorp).

Results

We identified 297 DTC advertisements addressing 25 different conditions during our study period. CBS, ABC, NBC, and FOX aired 44.4%, 26.3%, 24.4%, and 5.1% of advertisements, respectively. Overall, DTC advertisements were least likely to air on Saturdays and between the hours of 5

Psoriasis DTC Advertisements

There were 5 unique psoriasis DTC advertisements, all of which were product-claim advertisements, with 1 each for secukinumab (Cosentyx [Novartis]), ixekizumab (Taltz [Eli Lilly and Company]), and guselkumab (Tremfya [Janssen Biotech, Inc]), and 2 for adalimumab (Humira [AbbVie Inc]). The advertisements aired on ABC (n=5 [38.5%]), CBS (n=5 [38.5%]), and NBC (n=3 [23.1%]). Most advertisements aired on weekdays (61.5%) between 6

Psoriasis Character Portrayal and Disease-Related Content

We identified 81 main characters who were depicted as having psoriasis among all advertisements. Characteristics of the affected characters are summarized in the Table. All affected characters were perceived to be younger adults, and there was a slight female predominance (58.0% [47/81]). Most characters were perceived to be White (92.6% [75/81]). Black and Asian characters only represented 6.2% (5/81) and 1.2% (1/81) of all affected individuals, respectively. Notably, the advertisements that featured only White main characters were aired 2.75 times more frequently than the advertisements that included non-White characters.

Psoriasis was shown on the skin of at least 1 character in an obvious depiction (ie, did not require more than 1 viewing) in 84.6% (11/13) of the advertisements. Symptoms of psoriasis (communicated either verbally or visually) were included in only 15.4% (2/13) of advertisements. No advertisements included information on the epidemiology of (ie, prevalence, subpopulations at risk), risk factors for, pathophysiology of, or comorbid diseases associated with psoriasis.

Eczema DTC Advertisements

Among the 27 eczema advertisements aired, there were 4 unique advertisements, of which 3 were product-claim advertisements (all for crisaborole [Eucrisa (Pfizer Inc)]), and 1 was a help-seeking advertisement that was sponsored by Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. The advertisements aired on ABC (n=2 [7.4%]), CBS (n=17 [63.0%]), and NBC (n=8 [29.6%]). All advertisements aired on weekdays between 7

Eczema Character Portrayal and Disease-Related Content

We identified 80 main characters who were depicted to be affected by eczema among all advertisements. Characteristics of the affected characters are summarized in the Table. Most of the affected characters were perceived to be White (53.8% [43/80]) and female (71.3% [57/80]). Other races depicted included Black (28.8% [23/80]) and Asian (17.5% [14/80]). Each unique eczema advertisement included at least 1 non-White main character. Most eczema main characters were perceived to be children (66.3% [53/80]), followed by younger adults (33.8% [27/80]). No infants, teenagers, or older adults were shown as being affected by eczema.

Skin manifestations of eczema were portrayed on at least 1 character in all of the advertisements; 77.8% (21/27) of the advertisements had at least 1 obvious depiction. Symptoms of eczema and the mechanism of disease (pathophysiology) were each included in 44.4% (12/27) of advertisements. This information was included exclusively in the single help-seeking advertisement, which also referenced a website for additional disease-related information. No advertisements included information on the epidemiology of, risk factors for, or comorbid diseases associated with eczema.

Comment

In our study of televised DTC advertisements for psoriasis and eczema in the United States, we identified underrepresentation of racial/ethnic minorities and specific age groups (older adults for psoriasis and all adults for eczema) across all advertisements. Although psoriasis is suggested to be less prevalent among minority patients (1.3%–1.9% among Black patients and 1.6% among Hispanic patients) compared to White patients (2%–4%),16,17 minority vs White representation in psoriasis DTC advertisements was disproportionately lower than population-based prevalence estimates. Direct-to-consumer advertisements for eczema included more minority characters than psoriasis advertisements; however, minority representation remained inadequate considering that childhood eczema is more prevalent among Black vs White children,18 and adult eczema is at least as prevalent among minority patients compared to White patients.19 Not only was minority representation in all advertisements poor, but advertisement placement also was suboptimal, particularly for reaching Black viewers. FOX network was home to 2 of the top 3 primetime broadcast programs among Black viewers around the study period,13 yet no DTC advertisements were aired on FOX.

The current literature regarding minority representation in DTC advertisements is mixed. Some studies report underrepresentation of Black and other minority patients across a variety of diseases.20 Other studies suggest that representation of Black patients, in particular, generally is adequate, except among select serious health conditions, and that advertisements depict tokenism or stereotypical roles for minorities.21 Our study provides new and specific insight about the state of racial/ethnic and age diversity, or lack thereof, in DTC advertisements for the skin conditions that currently are most commonly targeted—psoriasis and eczema. Although it remains unclear whether DTC advertisements are good or bad, existing data suggest that potential benefits of DTC advertisements include strengthening of patient-provider relationships, reduction of underdiagnosis and undertreatment of disease, and reduction of disease stigma.22 However, in our analyses, we found disease-specific factual content among all DTC advertisements to be sparse and obvious depictions of skin disease and symptoms to be uncommon, especially for psoriasis. As such, it seems unlikely that existing DTC advertisements for psoriasis and eczema can be expected to contribute to meaningful disease education, reduce underdiagnosis, and reduce the stigmatizing attitudes that have been documented for both skin diseases.23-25

Furthermore, it is important to consider our findings in light of the role that social identity theory plays in marketing. Social identity theory supports the idea that a person’s social identity (eg, age, gender, race/ethnicity) influences his/her behavior, perceptions, and performance.26 The principle of homophily—the tendency for individuals to have positive ties to those who are similar to themselves—is a critical concept in social identity theory and suggests that consumers are more likely to pay attention to and be influenced by sources perceived as similar to themselves.20 Thus, even if the potential benefits of DTC advertisements were to be realized for psoriasis and eczema, the lack of adequate minority and older adult representation raises concerns about whether these benefits would reach a diverse population and if the advertisements might further potentiate existing knowledge and treatment disparities.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. The sampling period was short and might not reflect advertisement content over a longer time course. We did not evaluate other potential sources of information, such as the Internet and social media. Nevertheless, televised DTC advertisements remain a major source of medical and drug information for the general public. We did not directly evaluate viewers’ reactions to the DTC advertisements of interest; however, other literature lends support to the significance of social identity theory and its impact on consumer behavior.26

Conclusion

Our study highlights a lost opportunity among psoriasis and eczema DTC advertisements for patient reach and disease education that may encourage existing and emerging knowledge and treatment disparities for both conditions. Our findings should serve as a call to action to pharmaceutical companies and other organizations involved in creating and supporting DTC advertisements for psoriasis and eczema to increase the educational content, diversify the depicted characters, and optimize advertisement placement.

- Brownfield ED, Bernhardt JM, Phan JL, et al. Direct-to-consumer drug advertisements on network television: an exploration of quantity, frequency, and placement. J Health Commun. 2004;9:491-497.

- Tai-Seale M, McGuire TG, Zhang W. Time allocation in primary care office visits. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1871-1894.

- Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Medical marketing in the United States, 1997-2016. JAMA. 2019;321:80-96.

- Lanigan SW, Farber EM. Patients’ knowledge of psoriasis: pilot study. Cutis. 1990;46:359-362.

- Renzi C, Di Pietro C, Tabolli S. Participation, satisfaction and knowledge level of patients with cutaneous psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:885-888.

- Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J, et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:871-881.e871-830.

- Wu JJ, Lu M, Veverka KA, et al. The journey for US psoriasis patients prescribed a topical: a retrospective database evaluation of patient progression to oral and/or biologic treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:446-453.

- Takeshita J, Gelfand JM, Li P, et al. Psoriasis in the US Medicare population: prevalence, treatment, and factors associated with biologic use. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2955-2963.

- Kerr GS, Qaiyumi S, Richards J, et al. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in African-American patients—the need to measure disease burden. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:1753-1759.

- Takeshita J, Eriksen WT, Raziano VT, et al. Racial differences in perceptions of psoriasis therapies: implications for racial disparities in psoriasis treatment. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:1672-1679.e1.

- Wu MH, Bartz D, Avorn J, et al. Trends in direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription contraceptives. Contraception. 2016;93:398-405.

- Mintzes B, Barer ML, Kravitz RL, et al. How does direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) affect prescribing? a survey in primary care environments with and without legal DTCA. CMAJ. 2003;169:405-412.

- Topten. Nielson website. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/top-ten/. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- Leading ad supported broadcast and cable networks in the United States in 2019, by average number of viewers. Statistia website. https://www.statista.com/statistics/530119/tv-networks-viewers-usa/. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- Prescription drug advertisements. Electronic Code of Federal Regulations website. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=d4f308e364578bda8e55a831638a26c6&mc=true&node=pt21.4.202&rgn=div5. Updated August 12, 2020. Accessed August 12, 2020.

- Gelfand JM, Stern RS, Nijsten T, et al. The prevalence of psoriasis in African Americans: results from a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:23-26.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/health_policy/eczema_skin_problems_tables.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583-590.

- Welch Cline RJ, Young HN. Marketing drugs, marketing health care relationships: a content analysis of visual cues in direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising. Health Commun. 2004;16:131-157.

- Ball JG, Liang A, Lee WN. Representation of African Americans in direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical commercials: a content analysis with implications for health disparities. Health Mark Q. 2009;26:372-390.

- Ventola CL. Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising: therapeutic or toxic? P T. 2011;36:669-674, 681-684.

- Pearl RL, Wan MT, Takeshita J, et al. Stigmatizing attitudes toward persons with psoriasis among laypersons and medical students. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1556-1563.

- Chernyshov PV. Stigmatization and self-perception in children with atopic dermatitis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:159-166.

- Wittkowski A, Richards HL, Griffiths CEM, et al. The impact of psychological and clinical factors on quality of life in individuals with atopic dermatitis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:195-200.

- Forehand MR, Deshpande R, Reed 2nd A. Identity salience and the influence of differential activation of the social self-schema on advertising response. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87:1086-1099.

- Brownfield ED, Bernhardt JM, Phan JL, et al. Direct-to-consumer drug advertisements on network television: an exploration of quantity, frequency, and placement. J Health Commun. 2004;9:491-497.

- Tai-Seale M, McGuire TG, Zhang W. Time allocation in primary care office visits. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1871-1894.

- Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Medical marketing in the United States, 1997-2016. JAMA. 2019;321:80-96.

- Lanigan SW, Farber EM. Patients’ knowledge of psoriasis: pilot study. Cutis. 1990;46:359-362.

- Renzi C, Di Pietro C, Tabolli S. Participation, satisfaction and knowledge level of patients with cutaneous psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:885-888.

- Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J, et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:871-881.e871-830.

- Wu JJ, Lu M, Veverka KA, et al. The journey for US psoriasis patients prescribed a topical: a retrospective database evaluation of patient progression to oral and/or biologic treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:446-453.

- Takeshita J, Gelfand JM, Li P, et al. Psoriasis in the US Medicare population: prevalence, treatment, and factors associated with biologic use. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2955-2963.

- Kerr GS, Qaiyumi S, Richards J, et al. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in African-American patients—the need to measure disease burden. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:1753-1759.

- Takeshita J, Eriksen WT, Raziano VT, et al. Racial differences in perceptions of psoriasis therapies: implications for racial disparities in psoriasis treatment. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:1672-1679.e1.

- Wu MH, Bartz D, Avorn J, et al. Trends in direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription contraceptives. Contraception. 2016;93:398-405.

- Mintzes B, Barer ML, Kravitz RL, et al. How does direct-to-consumer advertising (DTCA) affect prescribing? a survey in primary care environments with and without legal DTCA. CMAJ. 2003;169:405-412.

- Topten. Nielson website. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/top-ten/. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- Leading ad supported broadcast and cable networks in the United States in 2019, by average number of viewers. Statistia website. https://www.statista.com/statistics/530119/tv-networks-viewers-usa/. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- Prescription drug advertisements. Electronic Code of Federal Regulations website. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=d4f308e364578bda8e55a831638a26c6&mc=true&node=pt21.4.202&rgn=div5. Updated August 12, 2020. Accessed August 12, 2020.

- Gelfand JM, Stern RS, Nijsten T, et al. The prevalence of psoriasis in African Americans: results from a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:23-26.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/health_policy/eczema_skin_problems_tables.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic dermatitis in America study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583-590.

- Welch Cline RJ, Young HN. Marketing drugs, marketing health care relationships: a content analysis of visual cues in direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising. Health Commun. 2004;16:131-157.

- Ball JG, Liang A, Lee WN. Representation of African Americans in direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical commercials: a content analysis with implications for health disparities. Health Mark Q. 2009;26:372-390.

- Ventola CL. Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising: therapeutic or toxic? P T. 2011;36:669-674, 681-684.

- Pearl RL, Wan MT, Takeshita J, et al. Stigmatizing attitudes toward persons with psoriasis among laypersons and medical students. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1556-1563.

- Chernyshov PV. Stigmatization and self-perception in children with atopic dermatitis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:159-166.

- Wittkowski A, Richards HL, Griffiths CEM, et al. The impact of psychological and clinical factors on quality of life in individuals with atopic dermatitis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:195-200.

- Forehand MR, Deshpande R, Reed 2nd A. Identity salience and the influence of differential activation of the social self-schema on advertising response. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87:1086-1099.

Practice Points

- Racial/ethnic minorities and older adults are underrepresented in direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertisements for psoriasis and eczema.

- Character representation in psoriasis DTC advertisements, in particular, mirrors existing age and racial disparities in treatment with biologics.

- Disease-specific factual content was sparse, and obvious depictions of skin disease and symptoms were uncommon, especially among psoriasis DTC advertisements.

- Dermatologists should be aware of these deficiencies in psoriasis and eczema DTC advertisements and take care not to further reinforce existing knowledge gaps and inequitable treatment patterns among patients.

Psoriasis, PsA, and pregnancy: Tailoring treatment with increasing data

With an average age of diagnosis of 28 years, and one of two incidence peaks occurring at 15-30 years, psoriasis affects many women in the midst of their reproductive years. The prospect of pregnancy – or the reality of a surprise pregnancy – drives questions about heritability of the disease in offspring, the impact of the disease on pregnancy outcomes and breastfeeding, and how to best balance risks of treatments with risks of uncontrolled psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

While answers to these questions are not always clear, discussions about pregnancy and psoriasis management “shouldn’t be scary,” said Jenny E. Murase, MD, a dermatologist who speaks and writes widely about her research and experience with psoriasis and pregnancy. “We have access to information and data and educational resources to [work with] and reassure our patients – we just need to use it. Right now, there’s unnecessary suffering [with some patients unnecessarily stopping all treatment].”

Much has been learned in the past 2 decades about the course of psoriasis in pregnancy, and pregnancy outcomes data on the safety of biologics during pregnancy are increasingly emerging – particularly for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha inhibitors.

Ideally, since half of all pregnancies are unplanned, the implications of therapeutic options should be discussed with all women with psoriasis who are of reproductive age, whether they are sexually active or not. “The onus is on us to make sure that we’re considering the possibility [that our patient] could become pregnant without consulting us first,” said Dr. Murase, associate professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of medical consultative dermatology for the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group in Mountain View, Calif.

Lisa R. Sammaritano, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and a rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, both in New York, urges similar attention for PsA. “Pregnancy is best planned while patients have quiescent disease on pregnancy-compatible medications,” she said. “We encourage [more] rheumatologists to be actively involved in pregnancy planning [in order] to guide therapy.”

The impact of estrogen

Dr. Murase was inspired to study psoriasis and pregnancy in part by a patient she met as a medical student. “She had severe psoriasis covering her body, and she said that the only times her psoriasis cleared was during her three pregnancies,” Dr. Murase recalled. “I wondered: What about the pregnancies resulted in such a substantial reduction of her psoriasis?”

She subsequently led a study, published in 2005, of 47 pregnant and 27 nonpregnant patients with psoriasis. More than half of the patients – 55% – reported improvements in their psoriasis during pregnancy, 21% reported no change, and 23% reported worsening. Among the 16 patients who had 10% or greater psoriatic body surface area (BSA) involvement and reported improvements, lesions decreased by 84%.

In the postpartum period, only 9% reported improvement, 26% reported no change, and 65% reported worsening. The increased BSA values observed 6 weeks postpartum did not exceed those of the first trimester, suggesting a return to the patients’ baseline status.

Earlier and smaller retrospective studies had also shown that approximately half of patients improve during pregnancy, and it was believed that progesterone was most likely responsible for this improvement. Dr. Murase’s study moved the needle in that it examined BSA in pregnancy and the postpartum period. It also turned the spotlight on estrogen: Patients who had higher levels of improvement also had higher levels of estradiol, estrone, and the ratio of estrogen to progesterone. However, there was no correlation between psoriatic change and levels of progesterone.

To promote fetal survival, pregnancy triggers a shift from Th1 cell–mediated immunity – and Th17 immunity – to Th2 immunity. While there’s no proof of a causative effect, increased estrogen appears to play a role in this shift and in the reduced production of Th1 and Th17 cytokines. Psoriasis is believed to be primarily a Th17-mediated disease, with some Th1 involvement, so this down-regulation can result in improved disease status, Dr. Murase said. (A host of other autoimmune diseases categorized as Th1 mediated similarly tend to improve during pregnancy, she added.)

Information on the effect of pregnancy on PsA is “conflicting,” Dr. Sammaritano said. “Some [of a limited number of studies] suggest a beneficial effect as is generally seen for rheumatoid arthritis. Others, however, have found an increased risk of disease activity during pregnancy ... It may be that psoriatic arthritis can be quite variable from patient to patient in its clinical presentation.”

At least one study, Dr. Sammaritano added, “has shown that the arthritis in pregnancy patients with PsA did not improve, compared to control nonpregnant patients, while the psoriasis rash did improve.”

The mixed findings don’t surprise Dr. Murase. “It harder to quantify joint disease in general,” she said. “And during pregnancy, physiologic changes relating to the pregnancy itself can cause discomfort – your joints ache. The numbers [of improved] cases aren’t as high with PsA, but it’s a more complex question.”

In the postpartum period, however, research findings “all suggest an increased risk of flare” of PsA, Dr. Sammaritano said, just as with psoriasis.

Assessing risk of treatment

Understanding the immunologic effects of pregnancy on psoriasis and PsA – and appreciating the concept of a hormonal component – is an important part of treatment decision making. So is understanding pregnancy outcomes data.

Researchers have looked at a host of pregnancy outcomes – including congenital malformations, preterm birth, spontaneous abortion, low birth weight, macrosomia, and gestational diabetes and hypertension – in women with psoriasis or psoriasis/PsA, compared with control groups. Some studies have suggested a link between disease activity and pregnancy complications or adverse pregnancy outcomes, “just as a result of having moderate to severe disease,” while others have found no evidence of increased risk, Dr. Murase said.

“It’s a bit unclear and a difficult question to answer; it depends on what study you look at and what data you believe. It would be nice to have some clarity, but basically the jury is still out,” said Dr. Murase, who, with coauthors Alice B. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and Caitriona Ryan, MD, of the Blackrock Clinic and Charles Institute of Dermatology, University College Dublin, discussed the pregnancy outcomes data in a recently published review of psoriasis in women.

“In my opinion, because we have therapies that are so low risk and well tolerated, it’s better to make sure that the inflammatory cascade and inflammation created by psoriasis is under control,” she said. “So whether or not the pregnancy itself causes the patient to go into remission, or whether you have to use therapy to help the patient stay in remission, it’s important to control the inflammation.”

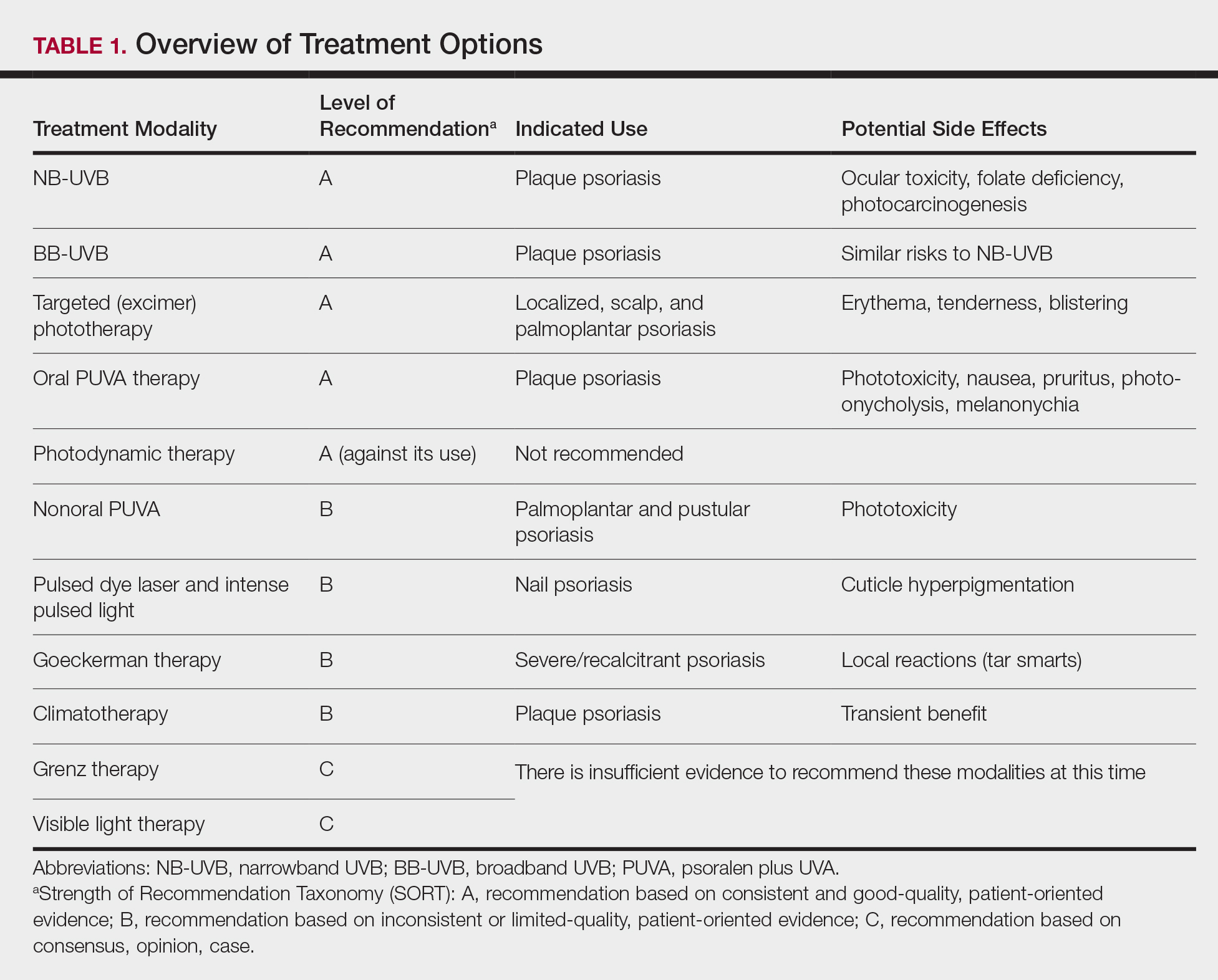

Contraindicated in pregnancy are oral psoralen, methotrexate, and acitretin, the latter of which should be avoided for several years before pregnancy and “therefore shouldn’t be used in a woman of childbearing age,” said Dr. Murase. Methotrexate, said Dr. Sammaritano, should generally be stopped 1-3 months prior to conception.

For psoriasis, the therapy that’s “classically considered the safest in pregnancy is UVB light therapy, specifically the 300-nm wavelength of light, which works really well as an anti-inflammatory,” Dr. Murase said. Because of the potential for maternal folate degradation with phototherapy and the long-known association of folate deficiency with neural tube defects, women of childbearing age who are receiving light therapy should take daily folic acid supplementation. (She prescribes a daily prenatal vitamin containing at least 1 mg of folic acid for women who are utilizing light therapy.)

Many topical agents can be used during pregnancy, Dr. Murase said. Topical corticosteroids, she noted, have the most safety-affirming data of any topical medication.

Regarding oral therapies, Dr. Murase recommends against the use of apremilast (Otezla) for her patients. “It’s not contraindicated, but the animal studies don’t look promising, so I don’t use that one in women of childbearing age just in case. There’s just very little data to support the safety of this medication [in pregnancy].”

There are no therapeutic guidelines in the United States for guiding the management of psoriasis in women who are considering pregnancy. In 2012, the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation published a review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women, the “closest thing to guidelines that we’ve had,” said Dr. Murase. (Now almost a decade old, the review addresses TNF inhibitors but does not cover the anti-interleukin agents more recently approved for moderate to severe psoriasis and PsA.)

For treating PsA, rheumatologists now have the American College of Rheumatology’s first guideline for the management of reproductive health in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases to reference. The 2020 guideline does not address PsA specifically, but its section on pregnancy and lactation includes recommendations on biologic and other therapies used to treat the disease.

Guidelines aside, physician-patient discussions over drug safety have the potential to be much more meaningful now that drug labels offer clinical summaries, data, and risk summaries regarding potential use in pregnancy. The labels have “more of a narrative, which is a more useful way to counsel patients and make risk-benefit decisions” than the former system of five-letter categories, said Dr. Murase. (The changes were made per the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule of 2015.)

MothertoBaby, a service of the nonprofit Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, also provides good evidence-based information to physicians and mothers, Dr. Sammaritano noted.

The use of biologic therapies

In a 2017 review of biologic safety for patients with psoriasis during pregnancy, Alexa B. Kimball, MD, MPH, professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston; Martina L. Porter, MD, currently with the department of dermatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston; and Stephen J. Lockwood, MD, MPH, of the department of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, concluded that an increasing body of literature suggests that biologic agents can be used during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Anti-TNF agents “should be considered over IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors due to the increased availability of long-term data,” they wrote.

“In general,” said Dr. Murase, “there’s more and more data coming out from gastroenterology and rheumatology to reassure patients and prescribing physicians that the TNF-blocker class is likely safe to use in pregnancy,” particularly during the first trimester and early second trimester, when the transport of maternal antibodies across the placenta is “essentially nonexistent.” In the third trimester, the active transport of IgG antibodies increases rapidly.

If possible, said Dr. Sammaritano, who served as lead author of the ACR’s reproductive health guideline, TNF inhibitors “will be stopped prior to the third trimester to avoid [the possibility of] high drug levels in the infant at birth, which raises concern for immunosuppression in the newborn. If disease is very active, however, they can be continued throughout the pregnancy.”

The TNF inhibitor certolizumab pegol (Cimzia) has the advantage of being transported only minimally across the placenta, if at all, she and Dr. Murase both explained. “To be actively carried across, antibodies need what’s called an Fc region for the placenta to grab onto,” Dr. Murase said. Certolizumab – a pegylated anti–binding fragment antibody – lacks this Fc region.

Two recent studies – CRIB and a UCB Pharma safety database analysis – showed “essentially no medication crossing – there were barely detectable levels,” Dr. Murase said. Certolizumab’s label contains this information and other clinical trial data as well as findings from safety database analyses/surveillance registries.

“Before we had much data for the biologics, I’d advise transitioning patients to light therapy from their biologics and a lot of times their psoriasis would improve, but it was more of a dance,” she said. “Now we tend to look at [certolizumab] when they’re of childbearing age and keep them on the treatment. I know that the baby is not being immunosuppressed.”

Consideration of the use of certolizumab when treatment with biologic agents is required throughout the pregnancy is a recommendation included in Dr. Kimball’s 2017 review.

As newer anti-interleukin agents – the IL-12/23 and IL-17 inhibitors – play a growing role in the treatment of psoriasis and PsA, questions loom about their safety profile. Dr. Murase and Dr. Sammaritano are waiting for more data. “In general,” Dr. Sammaritano said, “we recommend stopping them at the time pregnancy is detected, based on a lack of data at this time.”

Small-molecule drugs are also less well studied, she noted. “Because of their low molecular weight, we anticipate they will easily cross the placenta, so we recommend avoiding use during pregnancy until more information is available.”

Postpartum care

The good news, both experts say, is that the vast majority of medications, including biologics, are safe to use during breastfeeding. Methotrexate should be avoided, Dr. Sammaritano pointed out, and the impact of novel small-molecule therapies on breast milk has not been studied.

In her 2019 review of psoriasis in women, Dr. Murase and coauthors wrote that too many dermatologists believe that breastfeeding women should either not be on biologics or are uncertain about biologic use during breastfeeding. However, “biologics are considered compatible for use while breastfeeding due to their large molecular size and the proteolytic environment in the neonatal gastrointestinal tract,” they added.

Counseling and support for breastfeeding is especially important for women with psoriasis, Dr. Murase emphasized. “Breastfeeding is very traumatizing to the skin, and psoriasis can form in skin that’s injured. I have my patients set up an office visit very soon after the pregnancy to make sure they’re doing alright with their breastfeeding and that they’re coating their nipple area with some type of moisturizer and keeping the health of their nipples in good shape.”

Timely reviews of therapy and adjustments are also a priority, she said. “We need to prepare for 6 weeks post partum” when psoriasis will often flare without treatment.

Dr. Murase disclosed that she is a consultant for Dermira, UCB Pharma, Sanofi, Ferndale, and Regeneron. She is also coeditor in chief of the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. Dr. Sammaritano reported that she has no disclosures relating to the treatment of PsA.

With an average age of diagnosis of 28 years, and one of two incidence peaks occurring at 15-30 years, psoriasis affects many women in the midst of their reproductive years. The prospect of pregnancy – or the reality of a surprise pregnancy – drives questions about heritability of the disease in offspring, the impact of the disease on pregnancy outcomes and breastfeeding, and how to best balance risks of treatments with risks of uncontrolled psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

While answers to these questions are not always clear, discussions about pregnancy and psoriasis management “shouldn’t be scary,” said Jenny E. Murase, MD, a dermatologist who speaks and writes widely about her research and experience with psoriasis and pregnancy. “We have access to information and data and educational resources to [work with] and reassure our patients – we just need to use it. Right now, there’s unnecessary suffering [with some patients unnecessarily stopping all treatment].”

Much has been learned in the past 2 decades about the course of psoriasis in pregnancy, and pregnancy outcomes data on the safety of biologics during pregnancy are increasingly emerging – particularly for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha inhibitors.

Ideally, since half of all pregnancies are unplanned, the implications of therapeutic options should be discussed with all women with psoriasis who are of reproductive age, whether they are sexually active or not. “The onus is on us to make sure that we’re considering the possibility [that our patient] could become pregnant without consulting us first,” said Dr. Murase, associate professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of medical consultative dermatology for the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group in Mountain View, Calif.

Lisa R. Sammaritano, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and a rheumatologist at the Hospital for Special Surgery, both in New York, urges similar attention for PsA. “Pregnancy is best planned while patients have quiescent disease on pregnancy-compatible medications,” she said. “We encourage [more] rheumatologists to be actively involved in pregnancy planning [in order] to guide therapy.”

The impact of estrogen

Dr. Murase was inspired to study psoriasis and pregnancy in part by a patient she met as a medical student. “She had severe psoriasis covering her body, and she said that the only times her psoriasis cleared was during her three pregnancies,” Dr. Murase recalled. “I wondered: What about the pregnancies resulted in such a substantial reduction of her psoriasis?”

She subsequently led a study, published in 2005, of 47 pregnant and 27 nonpregnant patients with psoriasis. More than half of the patients – 55% – reported improvements in their psoriasis during pregnancy, 21% reported no change, and 23% reported worsening. Among the 16 patients who had 10% or greater psoriatic body surface area (BSA) involvement and reported improvements, lesions decreased by 84%.

In the postpartum period, only 9% reported improvement, 26% reported no change, and 65% reported worsening. The increased BSA values observed 6 weeks postpartum did not exceed those of the first trimester, suggesting a return to the patients’ baseline status.

Earlier and smaller retrospective studies had also shown that approximately half of patients improve during pregnancy, and it was believed that progesterone was most likely responsible for this improvement. Dr. Murase’s study moved the needle in that it examined BSA in pregnancy and the postpartum period. It also turned the spotlight on estrogen: Patients who had higher levels of improvement also had higher levels of estradiol, estrone, and the ratio of estrogen to progesterone. However, there was no correlation between psoriatic change and levels of progesterone.

To promote fetal survival, pregnancy triggers a shift from Th1 cell–mediated immunity – and Th17 immunity – to Th2 immunity. While there’s no proof of a causative effect, increased estrogen appears to play a role in this shift and in the reduced production of Th1 and Th17 cytokines. Psoriasis is believed to be primarily a Th17-mediated disease, with some Th1 involvement, so this down-regulation can result in improved disease status, Dr. Murase said. (A host of other autoimmune diseases categorized as Th1 mediated similarly tend to improve during pregnancy, she added.)

Information on the effect of pregnancy on PsA is “conflicting,” Dr. Sammaritano said. “Some [of a limited number of studies] suggest a beneficial effect as is generally seen for rheumatoid arthritis. Others, however, have found an increased risk of disease activity during pregnancy ... It may be that psoriatic arthritis can be quite variable from patient to patient in its clinical presentation.”

At least one study, Dr. Sammaritano added, “has shown that the arthritis in pregnancy patients with PsA did not improve, compared to control nonpregnant patients, while the psoriasis rash did improve.”

The mixed findings don’t surprise Dr. Murase. “It harder to quantify joint disease in general,” she said. “And during pregnancy, physiologic changes relating to the pregnancy itself can cause discomfort – your joints ache. The numbers [of improved] cases aren’t as high with PsA, but it’s a more complex question.”

In the postpartum period, however, research findings “all suggest an increased risk of flare” of PsA, Dr. Sammaritano said, just as with psoriasis.

Assessing risk of treatment

Understanding the immunologic effects of pregnancy on psoriasis and PsA – and appreciating the concept of a hormonal component – is an important part of treatment decision making. So is understanding pregnancy outcomes data.

Researchers have looked at a host of pregnancy outcomes – including congenital malformations, preterm birth, spontaneous abortion, low birth weight, macrosomia, and gestational diabetes and hypertension – in women with psoriasis or psoriasis/PsA, compared with control groups. Some studies have suggested a link between disease activity and pregnancy complications or adverse pregnancy outcomes, “just as a result of having moderate to severe disease,” while others have found no evidence of increased risk, Dr. Murase said.

“It’s a bit unclear and a difficult question to answer; it depends on what study you look at and what data you believe. It would be nice to have some clarity, but basically the jury is still out,” said Dr. Murase, who, with coauthors Alice B. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and Caitriona Ryan, MD, of the Blackrock Clinic and Charles Institute of Dermatology, University College Dublin, discussed the pregnancy outcomes data in a recently published review of psoriasis in women.

“In my opinion, because we have therapies that are so low risk and well tolerated, it’s better to make sure that the inflammatory cascade and inflammation created by psoriasis is under control,” she said. “So whether or not the pregnancy itself causes the patient to go into remission, or whether you have to use therapy to help the patient stay in remission, it’s important to control the inflammation.”

Contraindicated in pregnancy are oral psoralen, methotrexate, and acitretin, the latter of which should be avoided for several years before pregnancy and “therefore shouldn’t be used in a woman of childbearing age,” said Dr. Murase. Methotrexate, said Dr. Sammaritano, should generally be stopped 1-3 months prior to conception.

For psoriasis, the therapy that’s “classically considered the safest in pregnancy is UVB light therapy, specifically the 300-nm wavelength of light, which works really well as an anti-inflammatory,” Dr. Murase said. Because of the potential for maternal folate degradation with phototherapy and the long-known association of folate deficiency with neural tube defects, women of childbearing age who are receiving light therapy should take daily folic acid supplementation. (She prescribes a daily prenatal vitamin containing at least 1 mg of folic acid for women who are utilizing light therapy.)