User login

Low LDL cholesterol may increase women’s risk of hemorrhagic stroke

, according to research published in Neurology.

“Women with very low LDL cholesterol or low triglycerides should be monitored by their doctors for other stroke risk factors that can be modified, like high blood pressure and smoking, in order to reduce their risk of hemorrhagic stroke,” said Pamela M. Rist, ScD, instructor in epidemiology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Additional research is needed to determine how to lower the risk of hemorrhagic stroke in women with very low LDL and low triglycerides.”

Several meta-analyses have indicated that LDL cholesterol levels are inversely associated with the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. Because lipid-lowering treatments are used to prevent cardiovascular disease, this potential association has implications for clinical practice. Most of the studies included in these meta-analyses had low numbers of events among women, which prevented researchers from stratifying their results by sex. Because women are at greater risk of stroke than men, Dr. Rist and her colleagues sought to evaluate the association between lipid levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

An analysis of the Women’s Health Study

The investigators examined data from the Women’s Health Study, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of low-dose aspirin and vitamin E for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer among female American health professionals aged 45 years or older. The study ended in March 2004, but follow-up is ongoing. At regular intervals, the women complete a questionnaire about disease outcomes, including stroke. Some participants agreed to provide a fasting venous blood sample before randomization. With the subjects’ permission, a committee of physicians examined medical records for women who reported a stroke on a follow-up questionnaire.

Dr. Rist and her colleagues analyzed 27,937 samples for levels of LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides. They assigned each sample to one of five cholesterol level categories that were based on Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Cox proportional hazards models enabled the researchers to calculate the hazard ratio of incident hemorrhagic stroke events. They adjusted their results for covariates such as age, smoking status, menopausal status, body mass index, and alcohol consumption.

A U-shaped association

Women in the lowest category of LDL cholesterol level (less than 70 mg/dL) were younger, less likely to have a history of hypertension, and less likely to use cholesterol-lowering drugs than women in the reference group (100.0-129.9 mg/dL). Women with the lowest LDL cholesterol level were more likely to consume alcohol, have a normal weight, engage in physical activity, and be premenopausal than women in the reference group. The investigators confirmed 137 incident hemorrhagic stroke events during a mean 19.3 years of follow-up.

After data adjustment, the researchers found that women with the lowest level of LDL cholesterol had 2.17 times the risk of hemorrhagic stroke, compared with participants in the reference group. They found a trend toward increased risk among women with an LDL cholesterol level of 160 mg/dL or higher, but the result was not statistically significant. The highest risk for intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) was among women with an LDL cholesterol level of less than 70 mg/dL (relative risk, 2.32), followed by women with a level of 160 mg/dL or higher (RR, 1.71).

In addition, after multivariable adjustment, women in the lowest quartile of triglycerides (less than or equal to 74 mg/dL for fasting and less than or equal to 85 mg/dL for nonfasting) had a significantly increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke, compared with women in the highest quartile (RR, 2.00). Low triglyceride levels were associated with an increased risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage, but not with an increased risk of ICH. Neither HDL cholesterol nor total cholesterol was associated with risk of hemorrhagic stroke, the researchers wrote.

Mechanism of increased risk unclear

The researchers do not yet know how low triglyceride and LDL cholesterol levels increase the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. One hypothesis is that low cholesterol promotes necrosis of the arterial medial layer’s smooth muscle cells. This impaired endothelium might be more susceptible to microaneurysms, which are common in patients with ICH, said the researchers.

The prospective design and the large sample size were two of the study’s strengths, but the study had important weaknesses as well, the researchers wrote. For example, few women were premenopausal at baseline, so the investigators could not evaluate whether menopausal status modifies the association between lipid levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke. In addition, lipid levels were measured only at baseline, which prevented an analysis of whether change in lipid levels over time modifies the risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

Dr. Rist reported receiving a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Rist PM et al. Neurology. 2019 April 10. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007454.

, according to research published in Neurology.

“Women with very low LDL cholesterol or low triglycerides should be monitored by their doctors for other stroke risk factors that can be modified, like high blood pressure and smoking, in order to reduce their risk of hemorrhagic stroke,” said Pamela M. Rist, ScD, instructor in epidemiology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Additional research is needed to determine how to lower the risk of hemorrhagic stroke in women with very low LDL and low triglycerides.”

Several meta-analyses have indicated that LDL cholesterol levels are inversely associated with the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. Because lipid-lowering treatments are used to prevent cardiovascular disease, this potential association has implications for clinical practice. Most of the studies included in these meta-analyses had low numbers of events among women, which prevented researchers from stratifying their results by sex. Because women are at greater risk of stroke than men, Dr. Rist and her colleagues sought to evaluate the association between lipid levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

An analysis of the Women’s Health Study

The investigators examined data from the Women’s Health Study, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of low-dose aspirin and vitamin E for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer among female American health professionals aged 45 years or older. The study ended in March 2004, but follow-up is ongoing. At regular intervals, the women complete a questionnaire about disease outcomes, including stroke. Some participants agreed to provide a fasting venous blood sample before randomization. With the subjects’ permission, a committee of physicians examined medical records for women who reported a stroke on a follow-up questionnaire.

Dr. Rist and her colleagues analyzed 27,937 samples for levels of LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides. They assigned each sample to one of five cholesterol level categories that were based on Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Cox proportional hazards models enabled the researchers to calculate the hazard ratio of incident hemorrhagic stroke events. They adjusted their results for covariates such as age, smoking status, menopausal status, body mass index, and alcohol consumption.

A U-shaped association

Women in the lowest category of LDL cholesterol level (less than 70 mg/dL) were younger, less likely to have a history of hypertension, and less likely to use cholesterol-lowering drugs than women in the reference group (100.0-129.9 mg/dL). Women with the lowest LDL cholesterol level were more likely to consume alcohol, have a normal weight, engage in physical activity, and be premenopausal than women in the reference group. The investigators confirmed 137 incident hemorrhagic stroke events during a mean 19.3 years of follow-up.

After data adjustment, the researchers found that women with the lowest level of LDL cholesterol had 2.17 times the risk of hemorrhagic stroke, compared with participants in the reference group. They found a trend toward increased risk among women with an LDL cholesterol level of 160 mg/dL or higher, but the result was not statistically significant. The highest risk for intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) was among women with an LDL cholesterol level of less than 70 mg/dL (relative risk, 2.32), followed by women with a level of 160 mg/dL or higher (RR, 1.71).

In addition, after multivariable adjustment, women in the lowest quartile of triglycerides (less than or equal to 74 mg/dL for fasting and less than or equal to 85 mg/dL for nonfasting) had a significantly increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke, compared with women in the highest quartile (RR, 2.00). Low triglyceride levels were associated with an increased risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage, but not with an increased risk of ICH. Neither HDL cholesterol nor total cholesterol was associated with risk of hemorrhagic stroke, the researchers wrote.

Mechanism of increased risk unclear

The researchers do not yet know how low triglyceride and LDL cholesterol levels increase the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. One hypothesis is that low cholesterol promotes necrosis of the arterial medial layer’s smooth muscle cells. This impaired endothelium might be more susceptible to microaneurysms, which are common in patients with ICH, said the researchers.

The prospective design and the large sample size were two of the study’s strengths, but the study had important weaknesses as well, the researchers wrote. For example, few women were premenopausal at baseline, so the investigators could not evaluate whether menopausal status modifies the association between lipid levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke. In addition, lipid levels were measured only at baseline, which prevented an analysis of whether change in lipid levels over time modifies the risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

Dr. Rist reported receiving a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Rist PM et al. Neurology. 2019 April 10. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007454.

, according to research published in Neurology.

“Women with very low LDL cholesterol or low triglycerides should be monitored by their doctors for other stroke risk factors that can be modified, like high blood pressure and smoking, in order to reduce their risk of hemorrhagic stroke,” said Pamela M. Rist, ScD, instructor in epidemiology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Additional research is needed to determine how to lower the risk of hemorrhagic stroke in women with very low LDL and low triglycerides.”

Several meta-analyses have indicated that LDL cholesterol levels are inversely associated with the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. Because lipid-lowering treatments are used to prevent cardiovascular disease, this potential association has implications for clinical practice. Most of the studies included in these meta-analyses had low numbers of events among women, which prevented researchers from stratifying their results by sex. Because women are at greater risk of stroke than men, Dr. Rist and her colleagues sought to evaluate the association between lipid levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

An analysis of the Women’s Health Study

The investigators examined data from the Women’s Health Study, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of low-dose aspirin and vitamin E for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer among female American health professionals aged 45 years or older. The study ended in March 2004, but follow-up is ongoing. At regular intervals, the women complete a questionnaire about disease outcomes, including stroke. Some participants agreed to provide a fasting venous blood sample before randomization. With the subjects’ permission, a committee of physicians examined medical records for women who reported a stroke on a follow-up questionnaire.

Dr. Rist and her colleagues analyzed 27,937 samples for levels of LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides. They assigned each sample to one of five cholesterol level categories that were based on Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Cox proportional hazards models enabled the researchers to calculate the hazard ratio of incident hemorrhagic stroke events. They adjusted their results for covariates such as age, smoking status, menopausal status, body mass index, and alcohol consumption.

A U-shaped association

Women in the lowest category of LDL cholesterol level (less than 70 mg/dL) were younger, less likely to have a history of hypertension, and less likely to use cholesterol-lowering drugs than women in the reference group (100.0-129.9 mg/dL). Women with the lowest LDL cholesterol level were more likely to consume alcohol, have a normal weight, engage in physical activity, and be premenopausal than women in the reference group. The investigators confirmed 137 incident hemorrhagic stroke events during a mean 19.3 years of follow-up.

After data adjustment, the researchers found that women with the lowest level of LDL cholesterol had 2.17 times the risk of hemorrhagic stroke, compared with participants in the reference group. They found a trend toward increased risk among women with an LDL cholesterol level of 160 mg/dL or higher, but the result was not statistically significant. The highest risk for intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) was among women with an LDL cholesterol level of less than 70 mg/dL (relative risk, 2.32), followed by women with a level of 160 mg/dL or higher (RR, 1.71).

In addition, after multivariable adjustment, women in the lowest quartile of triglycerides (less than or equal to 74 mg/dL for fasting and less than or equal to 85 mg/dL for nonfasting) had a significantly increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke, compared with women in the highest quartile (RR, 2.00). Low triglyceride levels were associated with an increased risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage, but not with an increased risk of ICH. Neither HDL cholesterol nor total cholesterol was associated with risk of hemorrhagic stroke, the researchers wrote.

Mechanism of increased risk unclear

The researchers do not yet know how low triglyceride and LDL cholesterol levels increase the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. One hypothesis is that low cholesterol promotes necrosis of the arterial medial layer’s smooth muscle cells. This impaired endothelium might be more susceptible to microaneurysms, which are common in patients with ICH, said the researchers.

The prospective design and the large sample size were two of the study’s strengths, but the study had important weaknesses as well, the researchers wrote. For example, few women were premenopausal at baseline, so the investigators could not evaluate whether menopausal status modifies the association between lipid levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke. In addition, lipid levels were measured only at baseline, which prevented an analysis of whether change in lipid levels over time modifies the risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

Dr. Rist reported receiving a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Rist PM et al. Neurology. 2019 April 10. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007454.

FROM NEUROLOGY

FDA modifies safety label for Addyi

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a safety labeling change for flibanserin (Addyi), a treatment for premenopausal women with acquired, generalized hypoactive sexual desire disorder, according to a press release issued April 11 by the agency. Previously, the warning said women should abstain from alcohol entirely.

According to the release, the manufacturer, Sprout, had hoped the FDA would remove the boxed warning and contraindication entirely. However, based on a review of two postmarket research studies, the agency chose to order these modifications to the warnings instead.

The first postmarket study was missing information related to participants’ blood pressure, which FDA officials thought was critical in determining risk; it appeared that this resulted from safety precautions built into the trial. The concern was that not only did this absent information provide further evidence of an interaction but that women at home would not have the benefit of these safety precautions and could suffer serious outcomes, including falls, accidents, and bodily harm. The other postmarketing trial showed that delaying administration of flibanserin until at least 2 hours after consuming alcohol reduced the risk of serious hypotension and syncope.

It is recommended that flibanserin be taken at bedtime because of risks associated with hypotension and syncope, as well as risks associated with central nervous system depression (such as sleepiness). Furthermore, patients are encouraged to discontinue treatment with flibanserin if their hypoactive sexual desire disorder does not improve after 8 weeks. The most common adverse reactions include dizziness, sleepiness, nausea, fatigue, insomnia, and dry mouth.

Full prescribing information is available on the FDA website, as is the full release regarding these safety label modifications.

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a safety labeling change for flibanserin (Addyi), a treatment for premenopausal women with acquired, generalized hypoactive sexual desire disorder, according to a press release issued April 11 by the agency. Previously, the warning said women should abstain from alcohol entirely.

According to the release, the manufacturer, Sprout, had hoped the FDA would remove the boxed warning and contraindication entirely. However, based on a review of two postmarket research studies, the agency chose to order these modifications to the warnings instead.

The first postmarket study was missing information related to participants’ blood pressure, which FDA officials thought was critical in determining risk; it appeared that this resulted from safety precautions built into the trial. The concern was that not only did this absent information provide further evidence of an interaction but that women at home would not have the benefit of these safety precautions and could suffer serious outcomes, including falls, accidents, and bodily harm. The other postmarketing trial showed that delaying administration of flibanserin until at least 2 hours after consuming alcohol reduced the risk of serious hypotension and syncope.

It is recommended that flibanserin be taken at bedtime because of risks associated with hypotension and syncope, as well as risks associated with central nervous system depression (such as sleepiness). Furthermore, patients are encouraged to discontinue treatment with flibanserin if their hypoactive sexual desire disorder does not improve after 8 weeks. The most common adverse reactions include dizziness, sleepiness, nausea, fatigue, insomnia, and dry mouth.

Full prescribing information is available on the FDA website, as is the full release regarding these safety label modifications.

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a safety labeling change for flibanserin (Addyi), a treatment for premenopausal women with acquired, generalized hypoactive sexual desire disorder, according to a press release issued April 11 by the agency. Previously, the warning said women should abstain from alcohol entirely.

According to the release, the manufacturer, Sprout, had hoped the FDA would remove the boxed warning and contraindication entirely. However, based on a review of two postmarket research studies, the agency chose to order these modifications to the warnings instead.

The first postmarket study was missing information related to participants’ blood pressure, which FDA officials thought was critical in determining risk; it appeared that this resulted from safety precautions built into the trial. The concern was that not only did this absent information provide further evidence of an interaction but that women at home would not have the benefit of these safety precautions and could suffer serious outcomes, including falls, accidents, and bodily harm. The other postmarketing trial showed that delaying administration of flibanserin until at least 2 hours after consuming alcohol reduced the risk of serious hypotension and syncope.

It is recommended that flibanserin be taken at bedtime because of risks associated with hypotension and syncope, as well as risks associated with central nervous system depression (such as sleepiness). Furthermore, patients are encouraged to discontinue treatment with flibanserin if their hypoactive sexual desire disorder does not improve after 8 weeks. The most common adverse reactions include dizziness, sleepiness, nausea, fatigue, insomnia, and dry mouth.

Full prescribing information is available on the FDA website, as is the full release regarding these safety label modifications.

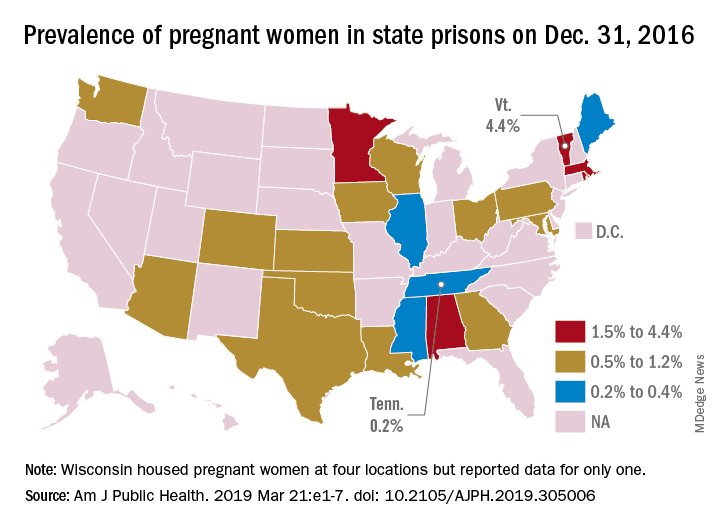

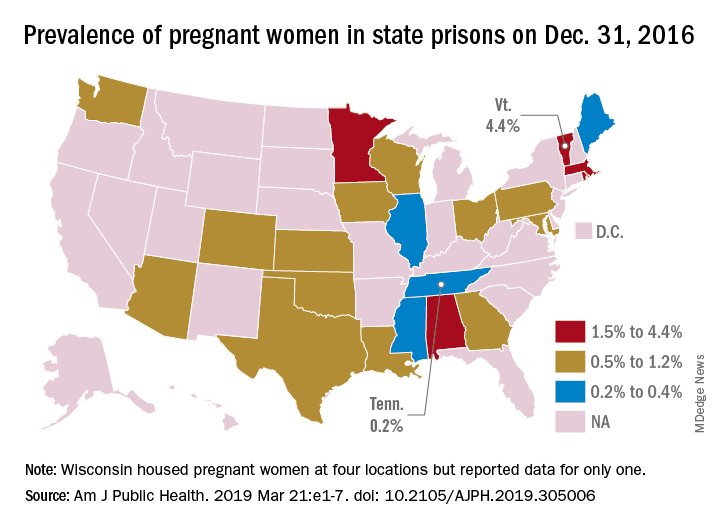

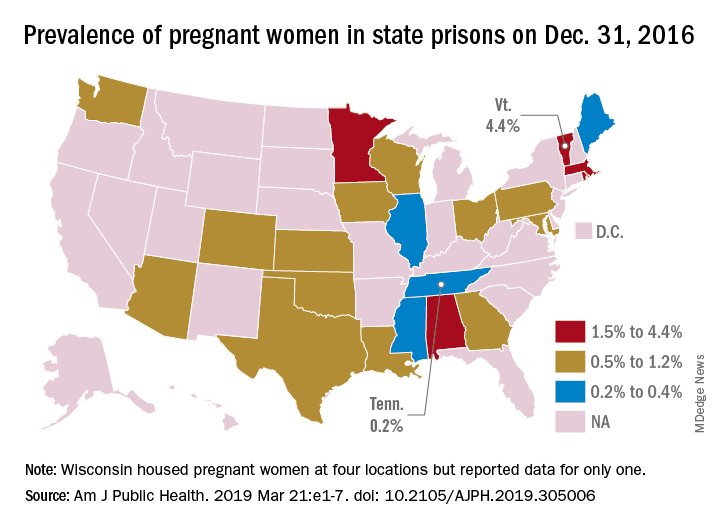

First-of-its-kind study looks at pregnancies in prison

according to a systematic study believed to be the first of its kind.

That works out to 0.6% of the 56,262 women housed in the 23 prison systems on Dec. 31, 2016, Carolyn Sufrin, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her associates wrote in the American Journal of Public Health.

Nearly 1,400 pregnant women were admitted to the 26 federal prisons that house women and 22 state prison systems over a 1-year period in 2016-2017. The prisons involved in the study represent 57% of all women incarcerated in the United States, they noted.

Among the pregnancies completed while women were in prison, there were 753 live births: 685 at state facilities and 68 at federal sites. About 6% of those births were preterm, compared with almost 10% nationally in 2016, and 32% were cesarean deliveries, Dr. Sufrin and her associates reported.

All but six births occurred in a hospital; three “were attributable to precipitous labor with prison nurses or paramedics in attendance, and details were not available for the others,” they wrote. Of the 8% of non–live birth pregnancies, 6% were miscarriages, 1% were abortions, and the remainder were stillbirths or ectopic pregnancies. There were three newborn deaths and no maternal deaths.

“That prison pregnancy data have previously not been systematically collected or reported signals a glaring disregard for the health and well-being of incarcerated pregnant women. The Bureau of Justice Statistics collects data on deaths during custody but not births during custody. Despite this marginalization, it is important to recognize that incarcerated women are still members of broader society, that most of them will be released, and that some will give birth while in custody; therefore, their pregnancies must be counted,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development. The investigators had no conflicts of interest to report.

SOURCE: Sufrin C et al. Am J Public Health. 2019 Mar 21:e1-7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305006.

according to a systematic study believed to be the first of its kind.

That works out to 0.6% of the 56,262 women housed in the 23 prison systems on Dec. 31, 2016, Carolyn Sufrin, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her associates wrote in the American Journal of Public Health.

Nearly 1,400 pregnant women were admitted to the 26 federal prisons that house women and 22 state prison systems over a 1-year period in 2016-2017. The prisons involved in the study represent 57% of all women incarcerated in the United States, they noted.

Among the pregnancies completed while women were in prison, there were 753 live births: 685 at state facilities and 68 at federal sites. About 6% of those births were preterm, compared with almost 10% nationally in 2016, and 32% were cesarean deliveries, Dr. Sufrin and her associates reported.

All but six births occurred in a hospital; three “were attributable to precipitous labor with prison nurses or paramedics in attendance, and details were not available for the others,” they wrote. Of the 8% of non–live birth pregnancies, 6% were miscarriages, 1% were abortions, and the remainder were stillbirths or ectopic pregnancies. There were three newborn deaths and no maternal deaths.

“That prison pregnancy data have previously not been systematically collected or reported signals a glaring disregard for the health and well-being of incarcerated pregnant women. The Bureau of Justice Statistics collects data on deaths during custody but not births during custody. Despite this marginalization, it is important to recognize that incarcerated women are still members of broader society, that most of them will be released, and that some will give birth while in custody; therefore, their pregnancies must be counted,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development. The investigators had no conflicts of interest to report.

SOURCE: Sufrin C et al. Am J Public Health. 2019 Mar 21:e1-7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305006.

according to a systematic study believed to be the first of its kind.

That works out to 0.6% of the 56,262 women housed in the 23 prison systems on Dec. 31, 2016, Carolyn Sufrin, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her associates wrote in the American Journal of Public Health.

Nearly 1,400 pregnant women were admitted to the 26 federal prisons that house women and 22 state prison systems over a 1-year period in 2016-2017. The prisons involved in the study represent 57% of all women incarcerated in the United States, they noted.

Among the pregnancies completed while women were in prison, there were 753 live births: 685 at state facilities and 68 at federal sites. About 6% of those births were preterm, compared with almost 10% nationally in 2016, and 32% were cesarean deliveries, Dr. Sufrin and her associates reported.

All but six births occurred in a hospital; three “were attributable to precipitous labor with prison nurses or paramedics in attendance, and details were not available for the others,” they wrote. Of the 8% of non–live birth pregnancies, 6% were miscarriages, 1% were abortions, and the remainder were stillbirths or ectopic pregnancies. There were three newborn deaths and no maternal deaths.

“That prison pregnancy data have previously not been systematically collected or reported signals a glaring disregard for the health and well-being of incarcerated pregnant women. The Bureau of Justice Statistics collects data on deaths during custody but not births during custody. Despite this marginalization, it is important to recognize that incarcerated women are still members of broader society, that most of them will be released, and that some will give birth while in custody; therefore, their pregnancies must be counted,” the investigators wrote.

The study was supported by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development. The investigators had no conflicts of interest to report.

SOURCE: Sufrin C et al. Am J Public Health. 2019 Mar 21:e1-7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305006.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH

Stress incontinence surgery improves sexual dysfunction

TUCSON, ARIZ. –

The finding comes from a secondary analysis of two randomized, controlled trials comparing Burch colposuspension, autologous fascial slings, retropubic midurethral polypropylene slings, and transobturator midurethral polypropylene slings. The analysis looked at outcomes at 24 months after surgery. Stephanie Glass Clark, MD, a resident at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, presented the results at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

In the secondary analysis of the Stress Incontinence Surgical Treatment Efficacy Trial (SISTEr) and the Trial of Midurethral Slings (TOMUS) trials, Dr. Clark and her fellow researchers looked at the effect of surgical failure on sexual dysfunction outcomes. Subjective failure was defined as self-reported SUI symptoms or self-reported leakage by 3-day voiding diary beyond 3 months after the surgery. Objective failure was defined as any treatment for SUI after the surgery or a positive stress test or pad test beyond 3 months after the surgery.

Participants were excluded from the two studies if they were sexually inactive in the previous 6 months at baseline, at 12 months post baseline, or at 24 months. The studies employed the short form of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12), which had 12 questions with scores ranging from 0 to 4. The secondary analysis sample included 488 women from SISTEr and 436 women from TOMUS.

There were some baseline differences among groups between the two trials, including vaginal deliveries, race/ethnicity, stage of prolapse, and concomitant surgeries performed at time of the anti-incontinence procedure.

All four surgeries were associated with improvements in sexual function, with no statistically significant between-group differences. Mean PISQ-12 scores improved from a range of 31-33 to a range of 36-38 at 24 months. Although there is no published minimum important difference for PISQ-12 scores, an improvement of at least one-half of a standard deviation is generally accepted as clinically meaningful. “In this case, the standard deviation at baseline was just under 3 and so the improvement of each treatment group by more than 1.5 is a clinically meaningful improvement in their sexual function,” Dr. Clark said.

“Sexual dysfunction is a much more common problem than we previously thought, so we’ve been trying to figure out if patients with pelvic floor disorders like stress incontinence are going to have any improvement in sexual dysfunction by surgically treating their stress incontinence. Previously published data had been pretty conflicting,” Dr. Clark added in an interview.

That previous research was mostly retrospective and could have been impacted by patient selection bias. By analyzing clinical trials, the researchers hoped to test their idea that the pelvic floor symptoms themselves may be key to sexual dysfunction and that treating it surgically would improve matters.

The positive result is encouraging, but it still leaves unanswered questions about the mechanism behind the relationship. Dr. Clark wondered whether leaking urine leakage during sex might be the culprit, or whether it is fear or shame associated with the condition.

The answer may come from further analysis of women who were sexually inactive at baseline, but became sexually active over the course of the studies. “I think looking at that patient population in particular is going to be an interesting area of research. Is it that it was completely related to their pelvic floor disorder, and then we fixed it [so] they could have a more fulfilling sexual life?” speculated Dr. Clark.

The study received some funding from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Clark reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Clark SG et al. SGS 2019, Oral Presentation 11.

TUCSON, ARIZ. –

The finding comes from a secondary analysis of two randomized, controlled trials comparing Burch colposuspension, autologous fascial slings, retropubic midurethral polypropylene slings, and transobturator midurethral polypropylene slings. The analysis looked at outcomes at 24 months after surgery. Stephanie Glass Clark, MD, a resident at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, presented the results at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

In the secondary analysis of the Stress Incontinence Surgical Treatment Efficacy Trial (SISTEr) and the Trial of Midurethral Slings (TOMUS) trials, Dr. Clark and her fellow researchers looked at the effect of surgical failure on sexual dysfunction outcomes. Subjective failure was defined as self-reported SUI symptoms or self-reported leakage by 3-day voiding diary beyond 3 months after the surgery. Objective failure was defined as any treatment for SUI after the surgery or a positive stress test or pad test beyond 3 months after the surgery.

Participants were excluded from the two studies if they were sexually inactive in the previous 6 months at baseline, at 12 months post baseline, or at 24 months. The studies employed the short form of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12), which had 12 questions with scores ranging from 0 to 4. The secondary analysis sample included 488 women from SISTEr and 436 women from TOMUS.

There were some baseline differences among groups between the two trials, including vaginal deliveries, race/ethnicity, stage of prolapse, and concomitant surgeries performed at time of the anti-incontinence procedure.

All four surgeries were associated with improvements in sexual function, with no statistically significant between-group differences. Mean PISQ-12 scores improved from a range of 31-33 to a range of 36-38 at 24 months. Although there is no published minimum important difference for PISQ-12 scores, an improvement of at least one-half of a standard deviation is generally accepted as clinically meaningful. “In this case, the standard deviation at baseline was just under 3 and so the improvement of each treatment group by more than 1.5 is a clinically meaningful improvement in their sexual function,” Dr. Clark said.

“Sexual dysfunction is a much more common problem than we previously thought, so we’ve been trying to figure out if patients with pelvic floor disorders like stress incontinence are going to have any improvement in sexual dysfunction by surgically treating their stress incontinence. Previously published data had been pretty conflicting,” Dr. Clark added in an interview.

That previous research was mostly retrospective and could have been impacted by patient selection bias. By analyzing clinical trials, the researchers hoped to test their idea that the pelvic floor symptoms themselves may be key to sexual dysfunction and that treating it surgically would improve matters.

The positive result is encouraging, but it still leaves unanswered questions about the mechanism behind the relationship. Dr. Clark wondered whether leaking urine leakage during sex might be the culprit, or whether it is fear or shame associated with the condition.

The answer may come from further analysis of women who were sexually inactive at baseline, but became sexually active over the course of the studies. “I think looking at that patient population in particular is going to be an interesting area of research. Is it that it was completely related to their pelvic floor disorder, and then we fixed it [so] they could have a more fulfilling sexual life?” speculated Dr. Clark.

The study received some funding from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Clark reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Clark SG et al. SGS 2019, Oral Presentation 11.

TUCSON, ARIZ. –

The finding comes from a secondary analysis of two randomized, controlled trials comparing Burch colposuspension, autologous fascial slings, retropubic midurethral polypropylene slings, and transobturator midurethral polypropylene slings. The analysis looked at outcomes at 24 months after surgery. Stephanie Glass Clark, MD, a resident at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, presented the results at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

In the secondary analysis of the Stress Incontinence Surgical Treatment Efficacy Trial (SISTEr) and the Trial of Midurethral Slings (TOMUS) trials, Dr. Clark and her fellow researchers looked at the effect of surgical failure on sexual dysfunction outcomes. Subjective failure was defined as self-reported SUI symptoms or self-reported leakage by 3-day voiding diary beyond 3 months after the surgery. Objective failure was defined as any treatment for SUI after the surgery or a positive stress test or pad test beyond 3 months after the surgery.

Participants were excluded from the two studies if they were sexually inactive in the previous 6 months at baseline, at 12 months post baseline, or at 24 months. The studies employed the short form of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12), which had 12 questions with scores ranging from 0 to 4. The secondary analysis sample included 488 women from SISTEr and 436 women from TOMUS.

There were some baseline differences among groups between the two trials, including vaginal deliveries, race/ethnicity, stage of prolapse, and concomitant surgeries performed at time of the anti-incontinence procedure.

All four surgeries were associated with improvements in sexual function, with no statistically significant between-group differences. Mean PISQ-12 scores improved from a range of 31-33 to a range of 36-38 at 24 months. Although there is no published minimum important difference for PISQ-12 scores, an improvement of at least one-half of a standard deviation is generally accepted as clinically meaningful. “In this case, the standard deviation at baseline was just under 3 and so the improvement of each treatment group by more than 1.5 is a clinically meaningful improvement in their sexual function,” Dr. Clark said.

“Sexual dysfunction is a much more common problem than we previously thought, so we’ve been trying to figure out if patients with pelvic floor disorders like stress incontinence are going to have any improvement in sexual dysfunction by surgically treating their stress incontinence. Previously published data had been pretty conflicting,” Dr. Clark added in an interview.

That previous research was mostly retrospective and could have been impacted by patient selection bias. By analyzing clinical trials, the researchers hoped to test their idea that the pelvic floor symptoms themselves may be key to sexual dysfunction and that treating it surgically would improve matters.

The positive result is encouraging, but it still leaves unanswered questions about the mechanism behind the relationship. Dr. Clark wondered whether leaking urine leakage during sex might be the culprit, or whether it is fear or shame associated with the condition.

The answer may come from further analysis of women who were sexually inactive at baseline, but became sexually active over the course of the studies. “I think looking at that patient population in particular is going to be an interesting area of research. Is it that it was completely related to their pelvic floor disorder, and then we fixed it [so] they could have a more fulfilling sexual life?” speculated Dr. Clark.

The study received some funding from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Clark reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Clark SG et al. SGS 2019, Oral Presentation 11.

REPORTING FROM SGS 2019

Romosozumab gets FDA approval for treating osteoporosis

“These are women who have a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple risk factors or have failed other treatments for osteoporosis,” according to a news release from the agency.

The monthly treatment of two injections (given one after the other at one visit) mainly works by increasing new bone formation, but these effects wane after 12 doses. If patients still need osteoporosis therapy after that maximum of 12 doses, it’s recommended they are put on treatments that reduce bone breakdown. Romosozumab-aqqg is “a monoclonal antibody that blocks the effects of the protein sclerostin,” according to the news release.

The treatment’s efficacy and safety was evaluated in two clinical trials of more than 11,000 women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. In one trial, women received 12 months of either romosozumab-aqqg or placebo. The treatment arm had a 73% lower risk of vertebral fracture than did the placebo arm, and this benefit was maintained over a second year when both groups were switched to denosumab, another osteoporosis therapy. In the second trial, one group received romosozumab-aqqg for 1 year and then a year of alendronate, and the other group received 2 years of alendronate, another osteoporosis therapy, according to the news release. In this trial, the romosozumab-aqqg arm had 50% less risk of vertebral fractures than did the alendronate-only arm, as well as reduced risk of nonvertebral fractures.

Romosozumab-aqqg was associated with higher risks of cardiovascular death, heart attack, and stroke in the alendronate trial, so the treatment comes with a boxed warning regarding those risks and recommends that the drug not be used in patients who have had a heart attack or stroke within the previous year, according to the news release. Common side effects include joint pain and headache, as well as injection-site reactions.

“These are women who have a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple risk factors or have failed other treatments for osteoporosis,” according to a news release from the agency.

The monthly treatment of two injections (given one after the other at one visit) mainly works by increasing new bone formation, but these effects wane after 12 doses. If patients still need osteoporosis therapy after that maximum of 12 doses, it’s recommended they are put on treatments that reduce bone breakdown. Romosozumab-aqqg is “a monoclonal antibody that blocks the effects of the protein sclerostin,” according to the news release.

The treatment’s efficacy and safety was evaluated in two clinical trials of more than 11,000 women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. In one trial, women received 12 months of either romosozumab-aqqg or placebo. The treatment arm had a 73% lower risk of vertebral fracture than did the placebo arm, and this benefit was maintained over a second year when both groups were switched to denosumab, another osteoporosis therapy. In the second trial, one group received romosozumab-aqqg for 1 year and then a year of alendronate, and the other group received 2 years of alendronate, another osteoporosis therapy, according to the news release. In this trial, the romosozumab-aqqg arm had 50% less risk of vertebral fractures than did the alendronate-only arm, as well as reduced risk of nonvertebral fractures.

Romosozumab-aqqg was associated with higher risks of cardiovascular death, heart attack, and stroke in the alendronate trial, so the treatment comes with a boxed warning regarding those risks and recommends that the drug not be used in patients who have had a heart attack or stroke within the previous year, according to the news release. Common side effects include joint pain and headache, as well as injection-site reactions.

“These are women who have a history of osteoporotic fracture or multiple risk factors or have failed other treatments for osteoporosis,” according to a news release from the agency.

The monthly treatment of two injections (given one after the other at one visit) mainly works by increasing new bone formation, but these effects wane after 12 doses. If patients still need osteoporosis therapy after that maximum of 12 doses, it’s recommended they are put on treatments that reduce bone breakdown. Romosozumab-aqqg is “a monoclonal antibody that blocks the effects of the protein sclerostin,” according to the news release.

The treatment’s efficacy and safety was evaluated in two clinical trials of more than 11,000 women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. In one trial, women received 12 months of either romosozumab-aqqg or placebo. The treatment arm had a 73% lower risk of vertebral fracture than did the placebo arm, and this benefit was maintained over a second year when both groups were switched to denosumab, another osteoporosis therapy. In the second trial, one group received romosozumab-aqqg for 1 year and then a year of alendronate, and the other group received 2 years of alendronate, another osteoporosis therapy, according to the news release. In this trial, the romosozumab-aqqg arm had 50% less risk of vertebral fractures than did the alendronate-only arm, as well as reduced risk of nonvertebral fractures.

Romosozumab-aqqg was associated with higher risks of cardiovascular death, heart attack, and stroke in the alendronate trial, so the treatment comes with a boxed warning regarding those risks and recommends that the drug not be used in patients who have had a heart attack or stroke within the previous year, according to the news release. Common side effects include joint pain and headache, as well as injection-site reactions.

Expert gives tips on timing, managing lupus pregnancies

SAN FRANCISCO – Not that many years ago, women with systemic lupus erythematosus were told not to get pregnant. It was just one more lupus heartbreak.

Times have changed, according to Lisa Sammaritano, MD, a lupus specialist and associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

While lupus certainly complicates pregnancy, it by no means rules it out these days. With careful management, the dream of motherhood can become a reality for many women. Dr. Sammaritano shared her insights about timing and treatment at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

It’s important that the disease is under control as much as possible; that means that timing – and contraception – are key. Antiphospholipid antibodies, common in lupus, complicate matters, but there are workarounds, she said.

SAN FRANCISCO – Not that many years ago, women with systemic lupus erythematosus were told not to get pregnant. It was just one more lupus heartbreak.

Times have changed, according to Lisa Sammaritano, MD, a lupus specialist and associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

While lupus certainly complicates pregnancy, it by no means rules it out these days. With careful management, the dream of motherhood can become a reality for many women. Dr. Sammaritano shared her insights about timing and treatment at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

It’s important that the disease is under control as much as possible; that means that timing – and contraception – are key. Antiphospholipid antibodies, common in lupus, complicate matters, but there are workarounds, she said.

SAN FRANCISCO – Not that many years ago, women with systemic lupus erythematosus were told not to get pregnant. It was just one more lupus heartbreak.

Times have changed, according to Lisa Sammaritano, MD, a lupus specialist and associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

While lupus certainly complicates pregnancy, it by no means rules it out these days. With careful management, the dream of motherhood can become a reality for many women. Dr. Sammaritano shared her insights about timing and treatment at an international congress on systemic lupus erythematosus.

It’s important that the disease is under control as much as possible; that means that timing – and contraception – are key. Antiphospholipid antibodies, common in lupus, complicate matters, but there are workarounds, she said.

AT LUPUS 2019

ACP: Average-risk women under 50 can postpone mammogram

(CBE) for screening in such women of any age, according to a new guideline from the American College of Physicians.

Further, clinicians should discuss whether to screen with mammography in average-risk women aged 40-49 years and consider potential harms and benefits, as well as patient preferences. Providers should discontinue screening average-risk women at age 75 years and women with a life expectancy of 10 years or less, Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, of the ACP and colleagues wrote on behalf of the ACP Clinical Guidelines Committee.

The ACP guidance also addresses the varying recommendations from other organizations on the age at which to start and stop screening and on screening intervals, noting that “areas of disagreement include screening in women aged 40 to 49 years, screening in women aged 75 years or older, and recommended screening intervals,” and stresses the importance of patient input.

“Women should be informed participants in personalized decisions about breast cancer screening,” the authors wrote, adding that those under age 50 years without a clear preference for screening should not be screened.

However, the evidence shows that most average-risk women with no symptoms will benefit from mammography every other year beginning at age 50 years, they said.

The statement, published online April 8 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, was derived from a review of seven existing English-language breast cancer screening guidelines and the evidence cited in those guidelines. It’s intended to be a resource for all clinicians.

It differs from the 2017 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines in that ACOG recommends CBE and does not address screening in those with a life expectancy of less than 10 years. It also differs from the 2016 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines, which make no recommendation on CBE and also do not address screening in those with a life expectancy of less than 10 years.

Other guidelines, such as those from the American College of Radiology, American Cancer Society (ACS), the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, recommend CBE, and the World Health Organization guidelines recommend CBE in low resource settings.

“Although CBE continues to be used as part of the examination of symptomatic women, data are sparse on screening asymptomatic women using CBE alone or combined with mammography,” the ACP guideline authors wrote. “The ACS recommends against CBE in average-risk women of any age because of the lack of demonstrated benefit and the potential for false-positive results.”

The guidance, which does not apply to patients with prior abnormal screening results or those at higher breast cancer risk, also includes an evidence-driven “talking points with patients” section based on frequently asked questions.

An important goal of the ACP Clinical Guidelines Committee in developing the guidance is to reduce overdiagnosis and overtreatment, which affects about 20% of women diagnosed over a 10-year period.

The committee reviewed all national guidelines published in English between January 1, 2013, and November 15, 2017, in the National Guideline Clearinghouse or Guidelines International Network library, and it also selected other guidelines commonly used in clinical practice. The committee evaluated the quality of each by using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument.

Alex Krist, MD, the USPSTF vice-chairperson, offered support for the “shift toward shared decision making that is emerging” and added it’s “part of a larger movement toward empowering people with information not only about the potential benefits but also the potential harms of screening tests.”

“In its 2016 recommendation, the Task Force found that the value of mammography increases with age, with women ages 50-74 benefiting most from screening. For women in their 40s, the Task Force also found that mammography screening every two years can be effective,” he told this publication. “We recommend that the decision to start screening should be an individual one, taking into account a woman’s health history, preferences, and how she values the different potential benefits and harms.”

Dr. Krist further noted that the USPSTF, ACP, and many others “have all affirmed that mammography is an important tool to reduce breast cancer mortality and that the benefits of mammography increase with age.”

Likewise, Robert Smith, PhD, vice president of cancer screening for the ACS, noted that the ACP guidance generally aligns with ACS and USPSTF guidelines because all “support informed decision making starting at age 40, and screening every two years starting at age 50 (USPSTF) or 55 (ACS).”

“The fact that all guidelines are not totally in sync is not unexpected. ... The most important thing to recognize is that all of these guidelines stress that regular mammography plays an important role in breast cancer early detection, and women should be aware of its benefits and limitations, and also remain vigilant and report any breast changes,” he said.

The guidance authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Qaseem A et al., Ann Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.7326/M18-2147.

The ACP guidance statements provide “clarity and simplicity amidst the chaos of diverging guidelines,” Joann G. Elmore, MD, and Christoph I. Lee, MD, wrote in an editorial that accompanied the guideline (Ann Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.7326/M19-0726).

The four statements included in the guidance represent the convergence of differing recommendations, but they also highlight points for physicians to consider in shared decision making with patients, the editorial authors wrote.

Lacking, however, is advice on how clinicians should go about stopping screening in certain patients, they noted.

“We need reliable ways to determine life expectancy given comorbid conditions, as well as methods to appropriately manage the discussion about stopping screening. ... The cessation of routine screening is a highly uncomfortable situation for which we as clinicians currently have little guidance and few tools. At this crossroads of confusion, we need a clear path toward informed, tailored, risk-based screening for breast cancer,” they wrote adding that future guidance statements should “move beyond emphasizing variation across guidelines and instead provide more advice on how to implement high-value screening and deimplement low-value screening.”

Dr. Elmore is with the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Lee is with the University of Washington, Seattle.

The ACP guidance statements provide “clarity and simplicity amidst the chaos of diverging guidelines,” Joann G. Elmore, MD, and Christoph I. Lee, MD, wrote in an editorial that accompanied the guideline (Ann Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.7326/M19-0726).

The four statements included in the guidance represent the convergence of differing recommendations, but they also highlight points for physicians to consider in shared decision making with patients, the editorial authors wrote.

Lacking, however, is advice on how clinicians should go about stopping screening in certain patients, they noted.

“We need reliable ways to determine life expectancy given comorbid conditions, as well as methods to appropriately manage the discussion about stopping screening. ... The cessation of routine screening is a highly uncomfortable situation for which we as clinicians currently have little guidance and few tools. At this crossroads of confusion, we need a clear path toward informed, tailored, risk-based screening for breast cancer,” they wrote adding that future guidance statements should “move beyond emphasizing variation across guidelines and instead provide more advice on how to implement high-value screening and deimplement low-value screening.”

Dr. Elmore is with the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Lee is with the University of Washington, Seattle.

The ACP guidance statements provide “clarity and simplicity amidst the chaos of diverging guidelines,” Joann G. Elmore, MD, and Christoph I. Lee, MD, wrote in an editorial that accompanied the guideline (Ann Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.7326/M19-0726).

The four statements included in the guidance represent the convergence of differing recommendations, but they also highlight points for physicians to consider in shared decision making with patients, the editorial authors wrote.

Lacking, however, is advice on how clinicians should go about stopping screening in certain patients, they noted.

“We need reliable ways to determine life expectancy given comorbid conditions, as well as methods to appropriately manage the discussion about stopping screening. ... The cessation of routine screening is a highly uncomfortable situation for which we as clinicians currently have little guidance and few tools. At this crossroads of confusion, we need a clear path toward informed, tailored, risk-based screening for breast cancer,” they wrote adding that future guidance statements should “move beyond emphasizing variation across guidelines and instead provide more advice on how to implement high-value screening and deimplement low-value screening.”

Dr. Elmore is with the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Lee is with the University of Washington, Seattle.

(CBE) for screening in such women of any age, according to a new guideline from the American College of Physicians.

Further, clinicians should discuss whether to screen with mammography in average-risk women aged 40-49 years and consider potential harms and benefits, as well as patient preferences. Providers should discontinue screening average-risk women at age 75 years and women with a life expectancy of 10 years or less, Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, of the ACP and colleagues wrote on behalf of the ACP Clinical Guidelines Committee.

The ACP guidance also addresses the varying recommendations from other organizations on the age at which to start and stop screening and on screening intervals, noting that “areas of disagreement include screening in women aged 40 to 49 years, screening in women aged 75 years or older, and recommended screening intervals,” and stresses the importance of patient input.

“Women should be informed participants in personalized decisions about breast cancer screening,” the authors wrote, adding that those under age 50 years without a clear preference for screening should not be screened.

However, the evidence shows that most average-risk women with no symptoms will benefit from mammography every other year beginning at age 50 years, they said.

The statement, published online April 8 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, was derived from a review of seven existing English-language breast cancer screening guidelines and the evidence cited in those guidelines. It’s intended to be a resource for all clinicians.

It differs from the 2017 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines in that ACOG recommends CBE and does not address screening in those with a life expectancy of less than 10 years. It also differs from the 2016 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines, which make no recommendation on CBE and also do not address screening in those with a life expectancy of less than 10 years.

Other guidelines, such as those from the American College of Radiology, American Cancer Society (ACS), the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, recommend CBE, and the World Health Organization guidelines recommend CBE in low resource settings.

“Although CBE continues to be used as part of the examination of symptomatic women, data are sparse on screening asymptomatic women using CBE alone or combined with mammography,” the ACP guideline authors wrote. “The ACS recommends against CBE in average-risk women of any age because of the lack of demonstrated benefit and the potential for false-positive results.”

The guidance, which does not apply to patients with prior abnormal screening results or those at higher breast cancer risk, also includes an evidence-driven “talking points with patients” section based on frequently asked questions.

An important goal of the ACP Clinical Guidelines Committee in developing the guidance is to reduce overdiagnosis and overtreatment, which affects about 20% of women diagnosed over a 10-year period.

The committee reviewed all national guidelines published in English between January 1, 2013, and November 15, 2017, in the National Guideline Clearinghouse or Guidelines International Network library, and it also selected other guidelines commonly used in clinical practice. The committee evaluated the quality of each by using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument.

Alex Krist, MD, the USPSTF vice-chairperson, offered support for the “shift toward shared decision making that is emerging” and added it’s “part of a larger movement toward empowering people with information not only about the potential benefits but also the potential harms of screening tests.”

“In its 2016 recommendation, the Task Force found that the value of mammography increases with age, with women ages 50-74 benefiting most from screening. For women in their 40s, the Task Force also found that mammography screening every two years can be effective,” he told this publication. “We recommend that the decision to start screening should be an individual one, taking into account a woman’s health history, preferences, and how she values the different potential benefits and harms.”

Dr. Krist further noted that the USPSTF, ACP, and many others “have all affirmed that mammography is an important tool to reduce breast cancer mortality and that the benefits of mammography increase with age.”

Likewise, Robert Smith, PhD, vice president of cancer screening for the ACS, noted that the ACP guidance generally aligns with ACS and USPSTF guidelines because all “support informed decision making starting at age 40, and screening every two years starting at age 50 (USPSTF) or 55 (ACS).”

“The fact that all guidelines are not totally in sync is not unexpected. ... The most important thing to recognize is that all of these guidelines stress that regular mammography plays an important role in breast cancer early detection, and women should be aware of its benefits and limitations, and also remain vigilant and report any breast changes,” he said.

The guidance authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Qaseem A et al., Ann Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.7326/M18-2147.

(CBE) for screening in such women of any age, according to a new guideline from the American College of Physicians.

Further, clinicians should discuss whether to screen with mammography in average-risk women aged 40-49 years and consider potential harms and benefits, as well as patient preferences. Providers should discontinue screening average-risk women at age 75 years and women with a life expectancy of 10 years or less, Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, of the ACP and colleagues wrote on behalf of the ACP Clinical Guidelines Committee.

The ACP guidance also addresses the varying recommendations from other organizations on the age at which to start and stop screening and on screening intervals, noting that “areas of disagreement include screening in women aged 40 to 49 years, screening in women aged 75 years or older, and recommended screening intervals,” and stresses the importance of patient input.

“Women should be informed participants in personalized decisions about breast cancer screening,” the authors wrote, adding that those under age 50 years without a clear preference for screening should not be screened.

However, the evidence shows that most average-risk women with no symptoms will benefit from mammography every other year beginning at age 50 years, they said.

The statement, published online April 8 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, was derived from a review of seven existing English-language breast cancer screening guidelines and the evidence cited in those guidelines. It’s intended to be a resource for all clinicians.

It differs from the 2017 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines in that ACOG recommends CBE and does not address screening in those with a life expectancy of less than 10 years. It also differs from the 2016 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines, which make no recommendation on CBE and also do not address screening in those with a life expectancy of less than 10 years.

Other guidelines, such as those from the American College of Radiology, American Cancer Society (ACS), the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, recommend CBE, and the World Health Organization guidelines recommend CBE in low resource settings.

“Although CBE continues to be used as part of the examination of symptomatic women, data are sparse on screening asymptomatic women using CBE alone or combined with mammography,” the ACP guideline authors wrote. “The ACS recommends against CBE in average-risk women of any age because of the lack of demonstrated benefit and the potential for false-positive results.”

The guidance, which does not apply to patients with prior abnormal screening results or those at higher breast cancer risk, also includes an evidence-driven “talking points with patients” section based on frequently asked questions.

An important goal of the ACP Clinical Guidelines Committee in developing the guidance is to reduce overdiagnosis and overtreatment, which affects about 20% of women diagnosed over a 10-year period.

The committee reviewed all national guidelines published in English between January 1, 2013, and November 15, 2017, in the National Guideline Clearinghouse or Guidelines International Network library, and it also selected other guidelines commonly used in clinical practice. The committee evaluated the quality of each by using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument.

Alex Krist, MD, the USPSTF vice-chairperson, offered support for the “shift toward shared decision making that is emerging” and added it’s “part of a larger movement toward empowering people with information not only about the potential benefits but also the potential harms of screening tests.”

“In its 2016 recommendation, the Task Force found that the value of mammography increases with age, with women ages 50-74 benefiting most from screening. For women in their 40s, the Task Force also found that mammography screening every two years can be effective,” he told this publication. “We recommend that the decision to start screening should be an individual one, taking into account a woman’s health history, preferences, and how she values the different potential benefits and harms.”

Dr. Krist further noted that the USPSTF, ACP, and many others “have all affirmed that mammography is an important tool to reduce breast cancer mortality and that the benefits of mammography increase with age.”

Likewise, Robert Smith, PhD, vice president of cancer screening for the ACS, noted that the ACP guidance generally aligns with ACS and USPSTF guidelines because all “support informed decision making starting at age 40, and screening every two years starting at age 50 (USPSTF) or 55 (ACS).”

“The fact that all guidelines are not totally in sync is not unexpected. ... The most important thing to recognize is that all of these guidelines stress that regular mammography plays an important role in breast cancer early detection, and women should be aware of its benefits and limitations, and also remain vigilant and report any breast changes,” he said.

The guidance authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Qaseem A et al., Ann Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.7326/M18-2147.

REPORTING FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Brexanolone approval ‘marks an important milestone’

In March 2019, the Food and Drug Administration approved a novel medication, Zulresso (brexanolone), for the treatment of postpartum depression. Brexanolone is the first FDA-approved medication for the treatment of postpartum depression, a serious illness that affects nearly one in nine women soon after giving birth.1

Mothers with postpartum depression experience feelings of sadness, irritability, and anxiety, as well as isolation from their loved ones (including their new baby) and exhaustion. The feelings of sadness and anxiety can be extreme, and can interfere with a woman’s ability to care for herself or her family. In some cases, these symptoms can be life threatening. Indeed, the most common cause of maternal death after childbirth in the developed world is suicide.2 Because of the severity of the symptoms and their impact on the family, postpartum depression usually requires treatment.

Until now, there have been no drugs specifically approved to treat postpartum depression. Commonly, postpartum depression is treated with medications that previously were approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder, despite limited evidence documenting their efficacy for postpartum depression. Other putative treatment alternatives include psychotherapy, estrogen therapy, and neuromodulation, such as electroconvulsive therapy and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Each of these treatments can take weeks or longer to take effect, time that is of elevated importance given the rapidly developing mother-infant relationship in the early postpartum period. Brexanolone addresses both the issue of efficacy and speed of onset, representing a major step forward in the care of women suffering from postpartum depression.

Importantly, the approval of brexanolone marks an important milestone for the psychiatric research community in general and the National Institute of Mental Health in particular, as it represents a compelling example of successful bench-to-bedside translation of basic neuroscience findings to benefit patients. As we have noted elsewhere,3 the research underlying the discovery of endogenous neurosteroids and their role in modulating GABA receptors laid the foundation for the development of brexanolone, an intravenous formulation of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone. The recognition that allopregnanolone was a protective factor induced by stress, that it derived from progesterone, and that its peripheral blood levels were dramatically reduced in the early postpartum period led to the hypothesis that it might be useful as a treatment for postpartum depression.

Sage Therapeutics took on the task of testing this hypothesis, designing a program, in consultation with the FDA, to test the efficacy of allopregnanolone in women with postpartum depression in a series of randomized, placebo-controlled studies assessing brexanolone. 4,5 It is a significant accomplishment of Sage Therapeutics to not only successfully complete the therapeutic program of studies (given past experience with difficulties recruiting these women for placebo-controlled treatment trials) but as well to demonstrate a robust therapeutic effect.

Although the FDA’s approval of a new and novel treatment is exciting for many women, there are still limitations to the broader use of brexanolone. It is delivered intravenously, requires an overnight stay in a certified medical center, and is likely to be considerably expensive, according to early reports – potentially limiting the access to the treatment. There also are potentially serious side effects, such as sedation, dizziness, or sudden loss of consciousness. Nonetheless, this is a promising first step and hopefully will spur further efforts to identify and optimize additional strategies to treat postpartum depression. In fact, other formulations of allopregnanolone and novel analogs to treat postpartum depression already are under study, including some that are orally bioavailable.6,7,8

Several important questions remain to be answered about both brexanolone and postpartum depression: What is the underlying mechanism through which allopregnanolone acts in the brain and reduces depressive symptoms? Is the mechanism unique to postpartum women, or might brexanolone also be effective in nonreproductive depressions in women and men? What causes postpartum depression, and what are the risk factors involved for women who develop this serious condition? Future work will focus on these and other important questions to the benefit of women who have suffered with this condition.

The FDA approval of brexanolone represents the second approval in a month of a new antidepressant treatment targeting different molecules in the brain. In early March 2019, the agency approved Spravato (esketamine) nasal spray as a therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Like brexanolone, esketamine is a fast-acting antidepressant that works through a novel mechanism, completely different from other antidepressants. These new treatment approvals are encouraging, as there has been a paucity for many years in approving new effective treatments for mood disorders.

However, treatment development in psychiatry still has a long way to go and the full underlying neurobiology of mood disorders, including postpartum depression, remains poorly understood. Many challenges are ahead of us in our efforts to develop new treatments and increase our understanding of mental illnesses. Nevertheless, the approval of brexanolone is an important milestone, giving hope to the many women who suffer from postpartum depression, and paving the way for the development of additional novel and effective medications to treat this serious and sometimes life-threatening condition.

Dr. Gordon is the director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the lead federal agency for research on mental disorders. He oversees an extensive research portfolio of basic and clinical research that seeks to transform the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses, paving the way for prevention, recovery, and cure. Dr. Hillefors works at the NIMH and oversees the Translational Therapeutics Program in the division of translational research, focusing on the development of novel treatments and biomarkers and early phase clinical trials. She received her MD and PhD in neuroscience at the Karolinska Institute, Sweden. Dr. Schmidt joined the NIMH in 1986 after completing his psychiatric residency at the University of Toronto. He is the chief of the Section on Behavioral Endocrinology, within the Intramural Research Program at the NIMH, where his laboratory studies the relationship between hormones, stress, and mood – particularly in the areas of postpartum depression, severe premenstrual dysphoria, and perimenopausal depression.

References

1. J Psychiatric Res. 2018 Sep;104:235-48.

2. Br J Psychiatry. 2003 Oct;183:279-81.

3. NIMH Director’s Messages. 2019 Mar 20.

4. Lancet. 2017 Jul 29;390(10093):480-9.

5. Lancet. 2018 Sep 22; 392(10152):1058-70.

6. Sage Therapeutics News. 2019 Jan 7.

7. Marinus Pharmaceuticals. 2017 Jun 27.

8. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03460756. 2019 Mar.

In March 2019, the Food and Drug Administration approved a novel medication, Zulresso (brexanolone), for the treatment of postpartum depression. Brexanolone is the first FDA-approved medication for the treatment of postpartum depression, a serious illness that affects nearly one in nine women soon after giving birth.1

Mothers with postpartum depression experience feelings of sadness, irritability, and anxiety, as well as isolation from their loved ones (including their new baby) and exhaustion. The feelings of sadness and anxiety can be extreme, and can interfere with a woman’s ability to care for herself or her family. In some cases, these symptoms can be life threatening. Indeed, the most common cause of maternal death after childbirth in the developed world is suicide.2 Because of the severity of the symptoms and their impact on the family, postpartum depression usually requires treatment.

Until now, there have been no drugs specifically approved to treat postpartum depression. Commonly, postpartum depression is treated with medications that previously were approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder, despite limited evidence documenting their efficacy for postpartum depression. Other putative treatment alternatives include psychotherapy, estrogen therapy, and neuromodulation, such as electroconvulsive therapy and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Each of these treatments can take weeks or longer to take effect, time that is of elevated importance given the rapidly developing mother-infant relationship in the early postpartum period. Brexanolone addresses both the issue of efficacy and speed of onset, representing a major step forward in the care of women suffering from postpartum depression.

Importantly, the approval of brexanolone marks an important milestone for the psychiatric research community in general and the National Institute of Mental Health in particular, as it represents a compelling example of successful bench-to-bedside translation of basic neuroscience findings to benefit patients. As we have noted elsewhere,3 the research underlying the discovery of endogenous neurosteroids and their role in modulating GABA receptors laid the foundation for the development of brexanolone, an intravenous formulation of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone. The recognition that allopregnanolone was a protective factor induced by stress, that it derived from progesterone, and that its peripheral blood levels were dramatically reduced in the early postpartum period led to the hypothesis that it might be useful as a treatment for postpartum depression.

Sage Therapeutics took on the task of testing this hypothesis, designing a program, in consultation with the FDA, to test the efficacy of allopregnanolone in women with postpartum depression in a series of randomized, placebo-controlled studies assessing brexanolone. 4,5 It is a significant accomplishment of Sage Therapeutics to not only successfully complete the therapeutic program of studies (given past experience with difficulties recruiting these women for placebo-controlled treatment trials) but as well to demonstrate a robust therapeutic effect.

Although the FDA’s approval of a new and novel treatment is exciting for many women, there are still limitations to the broader use of brexanolone. It is delivered intravenously, requires an overnight stay in a certified medical center, and is likely to be considerably expensive, according to early reports – potentially limiting the access to the treatment. There also are potentially serious side effects, such as sedation, dizziness, or sudden loss of consciousness. Nonetheless, this is a promising first step and hopefully will spur further efforts to identify and optimize additional strategies to treat postpartum depression. In fact, other formulations of allopregnanolone and novel analogs to treat postpartum depression already are under study, including some that are orally bioavailable.6,7,8