User login

Reduction in S aureus skin infections may reduce the risk for eczema herpeticum in atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: Among patients with atopic dermatitis (AD), those with vs without a history of Staphylococcus aureus skin infections have significantly higher odds of having a history of eczema herpeticum (EH).

Major finding: Patients with AD and with vs without a history of S aureus skin infections had a 6.60-fold increased risk of having a history of EH (adjusted odds ratio 6.60; P = .002).

Study details: This multicenter, clinical registry study included 112 patients with AD and with (n = 56) or without (n = 56) a history of EH, matched by age and AD severity.

Disclosures: This study was supported partly by a National Eczema Association Engagement Research Grant. Several authors declared serving as consultants or investigator for or receiving grants, personal fees, or clinical trial support from various organizations.

Source: Moran MC et al. History of S. aureus skin infection significantly associates with history of eczema herpeticum in patients with atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023 (Aug 24). doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-00996-y

Key clinical point: Among patients with atopic dermatitis (AD), those with vs without a history of Staphylococcus aureus skin infections have significantly higher odds of having a history of eczema herpeticum (EH).

Major finding: Patients with AD and with vs without a history of S aureus skin infections had a 6.60-fold increased risk of having a history of EH (adjusted odds ratio 6.60; P = .002).

Study details: This multicenter, clinical registry study included 112 patients with AD and with (n = 56) or without (n = 56) a history of EH, matched by age and AD severity.

Disclosures: This study was supported partly by a National Eczema Association Engagement Research Grant. Several authors declared serving as consultants or investigator for or receiving grants, personal fees, or clinical trial support from various organizations.

Source: Moran MC et al. History of S. aureus skin infection significantly associates with history of eczema herpeticum in patients with atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023 (Aug 24). doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-00996-y

Key clinical point: Among patients with atopic dermatitis (AD), those with vs without a history of Staphylococcus aureus skin infections have significantly higher odds of having a history of eczema herpeticum (EH).

Major finding: Patients with AD and with vs without a history of S aureus skin infections had a 6.60-fold increased risk of having a history of EH (adjusted odds ratio 6.60; P = .002).

Study details: This multicenter, clinical registry study included 112 patients with AD and with (n = 56) or without (n = 56) a history of EH, matched by age and AD severity.

Disclosures: This study was supported partly by a National Eczema Association Engagement Research Grant. Several authors declared serving as consultants or investigator for or receiving grants, personal fees, or clinical trial support from various organizations.

Source: Moran MC et al. History of S. aureus skin infection significantly associates with history of eczema herpeticum in patients with atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023 (Aug 24). doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-00996-y

Dupilumab rapidly controls atopic dermatitis symptoms in children

Key clinical point: Dupilumab rapidly improves the severity of atopic dermatitis (AD) symptoms and shows a favorable safety profile in children with moderate-to-severe AD.

Major finding: Dupilumab significantly reduced the mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score at weeks 16, 24, and 52 (all P < .0001) and from weeks 16 to 24 (P < .01) and weeks 16 to 52 (P < .001). By week 52, 86.8% of patients had achieved a ≥ 75% improvement in the EASI score. No serious adverse events were observed, and none of the children discontinued treatment.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective, observational, real-life study including 96 children (age 6-11 years) with moderate-to-severe AD inadequately controlled with conventional topical therapies who received dupilumab (300 mg on days 1 and 15 and 300 mg every 4 weeks).

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Several authors reported receiving honoraria, travel support, or personal fees from or serving as consultants, investigators, speakers, or advisory board members for or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Patruno C et al. A 52-week multicenter retrospective real-world study on effectiveness and safety of dupilumab in children with atopic dermatitis aged from 6 to 11 years. J Dermatolog Treat. 2023;34:2246602 (Aug 14). doi: 10.1080/09546634.2023.2246602

Key clinical point: Dupilumab rapidly improves the severity of atopic dermatitis (AD) symptoms and shows a favorable safety profile in children with moderate-to-severe AD.

Major finding: Dupilumab significantly reduced the mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score at weeks 16, 24, and 52 (all P < .0001) and from weeks 16 to 24 (P < .01) and weeks 16 to 52 (P < .001). By week 52, 86.8% of patients had achieved a ≥ 75% improvement in the EASI score. No serious adverse events were observed, and none of the children discontinued treatment.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective, observational, real-life study including 96 children (age 6-11 years) with moderate-to-severe AD inadequately controlled with conventional topical therapies who received dupilumab (300 mg on days 1 and 15 and 300 mg every 4 weeks).

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Several authors reported receiving honoraria, travel support, or personal fees from or serving as consultants, investigators, speakers, or advisory board members for or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Patruno C et al. A 52-week multicenter retrospective real-world study on effectiveness and safety of dupilumab in children with atopic dermatitis aged from 6 to 11 years. J Dermatolog Treat. 2023;34:2246602 (Aug 14). doi: 10.1080/09546634.2023.2246602

Key clinical point: Dupilumab rapidly improves the severity of atopic dermatitis (AD) symptoms and shows a favorable safety profile in children with moderate-to-severe AD.

Major finding: Dupilumab significantly reduced the mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score at weeks 16, 24, and 52 (all P < .0001) and from weeks 16 to 24 (P < .01) and weeks 16 to 52 (P < .001). By week 52, 86.8% of patients had achieved a ≥ 75% improvement in the EASI score. No serious adverse events were observed, and none of the children discontinued treatment.

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective, observational, real-life study including 96 children (age 6-11 years) with moderate-to-severe AD inadequately controlled with conventional topical therapies who received dupilumab (300 mg on days 1 and 15 and 300 mg every 4 weeks).

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. Several authors reported receiving honoraria, travel support, or personal fees from or serving as consultants, investigators, speakers, or advisory board members for or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Patruno C et al. A 52-week multicenter retrospective real-world study on effectiveness and safety of dupilumab in children with atopic dermatitis aged from 6 to 11 years. J Dermatolog Treat. 2023;34:2246602 (Aug 14). doi: 10.1080/09546634.2023.2246602

Implementation of an Automated Phone Call Distribution System in an Inpatient Pharmacy Setting

Pharmacy call centers have been successfully implemented in outpatient and specialty pharmacy settings.1 A centralized pharmacy call center gives patients immediate access to a pharmacist who can view their health records to answer specific questions or fulfill medication renewal requests.2-4 Little literature exists to describe its use in an inpatient setting.

Inpatient pharmacies receive numerous calls from health care professionals and patients. Challenges related to phone calls in the inpatient pharmacy setting may include interruptions, distractions, low accountability, poor efficiency, lack of optimal resources, and staffing.5 An unequal distribution and lack of accountability may exist when answering phone calls for the inpatient pharmacy team, which may contribute to long hold times and call abandonment rates. Phone calls also may be directed inefficiently between clinical pharmacists (CPs) and pharmacy technicians. Team member time related to answering phone calls may not be captured or measured.

The Edward Hines, Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital (EHJVAH) in Illinois offers primary, extended, and specialty care and is a tertiary care referral center. The facility operates 483 beds and serves 6 community-based outpatient clinics.

Implementation

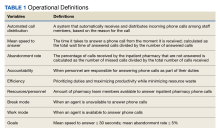

A new inpatient pharmacy service phone line extension was implemented. Data used to report quality metrics were obtained from the Global Navigator (GNAV), an information system that records calls, tracks the performance of agents, and coordinates personnel scheduling. The effectiveness of the ACD system was evaluated by quality metric goals of mean speed to answer ≤ 30 seconds and mean abandonment rate ≤ 5%. This project was determined to be quality improvement and was not reviewed by the EHJVAH Institutional Review Board.

The ACD system was set up in December 2020. After a 1-month implementation period, metrics were reported to the inpatient pharmacy team and leadership. By January 2021, EHJVAH fully implemented an ACD phone system operated by inpatient pharmacy technicians and CPs. EHJVAH inpatient pharmacy includes CPs who practice without a scope of practice and board-certified pharmacy technicians in 3 shifts. The CPs and pharmacy technicians work in the central pharmacy (the main pharmacy and inpatient pharmacy vault) or are decentralized with responsibility for answering phone calls and making deliveries (pharmacy technicians).

The pharmacy leadership team decided to implement 1 phone line with 2 ACD splits. The first split was directed to pharmacy technicians and the second to CPs. The intention was to streamline calls to be directed to proper team members within the inpatient pharmacy. The CP line also was designed to back up the pharmacy technician line. These calls were equally distributed among staff based on a standard algorithm. The pharmacy greeting stated, “Thank you for contacting the inpatient pharmacy at Hines VA Hospital. For missing doses, unit stock requests, or to speak with a pharmacy technician, please press 1. For clinical questions, order verification, or to speak with a pharmacist, please press 2.” Each inpatient pharmacy team member had a unique system login.

Fourteen ACD phone stations were established in the main pharmacy and in decentralized locations for order verification. The stations were distributed across the pharmacy service to optimize workload, space, and resources.

Training and Communication

Before implementing the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system, the CPs and pharmacy technicians received mandatory ACD training. After the training, pharmacy team members were required to sign off on the training document to indicate that they had completed the course. The pharmacy team was trained on the importance of staffing the phones continuously. As a 24-hour pharmacy service in the acute care setting, any call may be critical for patient care.

A hospital-wide memorandum was distributed via email to all unit managers and hospital staff to educate them on the new ACD phone system, which included a new phone line extension for the inpatient pharmacy. Additionally, the inpatient pharmacy team was trained on the proper way of communicating the ACD phone system process with the hospital staff. The inpatient pharmacy team was notified that there would be an educational period to explain the queue process to hospital staff. Occasionally, hospital staff believed they were speaking to an automated system and hung up before their call was answered. The inpatient pharmacy team was instructed to notify the hospital staff to stay on the line since their call would be answered in the order it was received. Once the inpatient pharmacy team received proper training and felt comfortable with the phone system, it was set up and integrated into the workflow.

Postimplementation Evaluation

Inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system data were collected for 2021. To evaluate the effectiveness of an ACD system, the pharmacy leadership team set up the following metrics and goals for inpatient CPs and inpatient pharmacy technicians for monthly call volume/abandonment rate, mean speed to answer, mean call volume by shift, and the mean abandonment rate by shift.

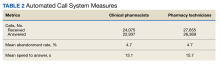

Inpatient pharmacy technicians answered 27,655 calls with a mean call abandonment rate of 4.7%. and a mean 15.6 seconds to answer.

Discussion

Since implementing the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system in January 2021, there have been successes and challenges. The implementation increased accountability and efficiency when answering pharmacy phone calls. An ACD uses an algorithm that ensures equitable distribution of phone calls between CPs and pharmacy technicians. Through this algorithm, the pharmacy team is held more accountable when answering incoming calls. Distributing phone calls equally allows for optimization and balances the workload. The ACD phone system also improved efficiency when answering incoming calls. By incorporating splits when a patient or health care professional calls, ACD routes the question to the appropriate staff member. As a result, CPs spend less time answering questions meant for pharmacy technicians and instead can answer clinical or order verification questions more efficiently.

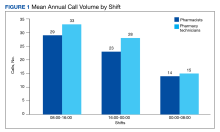

ACD data also allow pharmacy leadership to assess staffing needs, depending on the call volume. Based on ACD data, the busiest time of day was 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM. Based on this information, pharmacy leadership plans to staff more appropriately to have more pharmacy technicians working during the first shift to attend to phone calls.

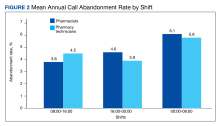

The mean call abandonment rate was 4.7% for both CPs and pharmacy technicians, which met the ≤ 5% goal. The highest call abandonment rate was from midnight to 8

Pharmacy technicians handled a higher total call volume, which may be attributed to more phone calls related to missing doses or unit stock requests compared with clinical questions or order verifications. This information may be beneficial to identify opportunities to improve pharmacy operations.

The main challenges encountered in the ACD implementation process were hardware installation and communication with hospital staff about the changes in the inpatient pharmacy phone system. To implement the new inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system, previous telephones and hardware were removed and replaced. Initially, hardware and installation delays made it difficult for the ACD phone system to operate efficiently in the early months of its implementation. The inpatient pharmacy team depends on the telecommunications system and computers for their daily activities. Delays and issues with the hardware and ACD phone system made it more difficult to provide patient care.

Communication is a continuous challenge to ensure that hospital staff are notified of the new inpatient pharmacy ACD phone number. Over time, the understanding and use of the new ACD phone system have increased dramatically, but there are still opportunities to capture any misdirected calls. Informal feedback was obtained at pharmacy huddles and 1-on-1 discussions with pharmacy staff, and the opinions were mixed. Members of the pharmacy staff expressed that the ACD phone system set up an effective way to triage phone calls. Another positive comment was that the system created a means of accountability for pharmacy phone calls. Critical feedback included challenges with triaging phone calls to appropriate pharmacists, because calls are assigned based on an algorithm, whereas clinical coverage is determined by designated unit daily assignments.

Limitations

There are potential limitations to this quality improvement project. This phone system may not apply to all inpatient hospital pharmacy settings. Potential limitations for implementation at other institutions may include but are not limited to, differing pharmacy practice models (centralized vs decentralized), implementation costs, and internal resources.

Future Goals

To improve the quality of service provided to patients and other hospital staff, the pharmacy leadership team can use the data to ensure that inpatient pharmacy technician resources are being used effectively during times of day with the greatest number of incoming ACD calls. The ACD phone system helps determine whether current resources are being used most efficiently and if they are not, can help identify areas of improvement.

The pharmacy leadership team plans on using reports for pharmacy team members to monitor performance. Reports on individual agent activity capture workload; this may be used as a performance-related metric for future performance plans.

Conclusions

The inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system at EHJVAH is a promising application of available technology. The implementation of the ACD system improved accountability, efficiency, work distribution, and the allocation of resources in the inpatient pharmacy service. The ACD phone system has yielded positive performance metrics including mean speed to answer ≤ 30 seconds and abandonment rate ≤ 5% over 12 months after implementation. With time, users of the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system will become more comfortable with the technology, thus further improving the patient health care quality.

1. Rim MH, Thomas KC, Chandramouli J, Barrus SA, Nickman NA. Implementation and quality assessment of a pharmacy services call center for outpatient pharmacies and specialty pharmacy services in an academic health system. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(10):633-641. doi:10.2146/ajhp170319

2. Patterson BJ, Doucette WR, Urmie JM, McDonough RP. Exploring relationships among pharmacy service use, patronage motives, and patient satisfaction. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2013;53(4):382-389. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2013.12100

3. Walker DM, Sieck CJ, Menser T, Huerta TR, Scheck McAlearney A. Information technology to support patient engagement: where do we stand and where can we go?. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(6):1088-1094. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocx043

4. Menichetti J, Libreri C, Lozza E, Graffigna G. Giving patients a starring role in their own care: a bibliometric analysis of the on-going literature debate. Health Expect. 2016;19(3):516-526. doi:10.1111/hex.12299

5. Raimbault M, Guérin A, Caron É, Lebel D, Bussières J-F. Identifying and reducing distractions and interruptions in a pharmacy department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(3):186-190. doi:10.2146/ajhp120344

Pharmacy call centers have been successfully implemented in outpatient and specialty pharmacy settings.1 A centralized pharmacy call center gives patients immediate access to a pharmacist who can view their health records to answer specific questions or fulfill medication renewal requests.2-4 Little literature exists to describe its use in an inpatient setting.

Inpatient pharmacies receive numerous calls from health care professionals and patients. Challenges related to phone calls in the inpatient pharmacy setting may include interruptions, distractions, low accountability, poor efficiency, lack of optimal resources, and staffing.5 An unequal distribution and lack of accountability may exist when answering phone calls for the inpatient pharmacy team, which may contribute to long hold times and call abandonment rates. Phone calls also may be directed inefficiently between clinical pharmacists (CPs) and pharmacy technicians. Team member time related to answering phone calls may not be captured or measured.

The Edward Hines, Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital (EHJVAH) in Illinois offers primary, extended, and specialty care and is a tertiary care referral center. The facility operates 483 beds and serves 6 community-based outpatient clinics.

Implementation

A new inpatient pharmacy service phone line extension was implemented. Data used to report quality metrics were obtained from the Global Navigator (GNAV), an information system that records calls, tracks the performance of agents, and coordinates personnel scheduling. The effectiveness of the ACD system was evaluated by quality metric goals of mean speed to answer ≤ 30 seconds and mean abandonment rate ≤ 5%. This project was determined to be quality improvement and was not reviewed by the EHJVAH Institutional Review Board.

The ACD system was set up in December 2020. After a 1-month implementation period, metrics were reported to the inpatient pharmacy team and leadership. By January 2021, EHJVAH fully implemented an ACD phone system operated by inpatient pharmacy technicians and CPs. EHJVAH inpatient pharmacy includes CPs who practice without a scope of practice and board-certified pharmacy technicians in 3 shifts. The CPs and pharmacy technicians work in the central pharmacy (the main pharmacy and inpatient pharmacy vault) or are decentralized with responsibility for answering phone calls and making deliveries (pharmacy technicians).

The pharmacy leadership team decided to implement 1 phone line with 2 ACD splits. The first split was directed to pharmacy technicians and the second to CPs. The intention was to streamline calls to be directed to proper team members within the inpatient pharmacy. The CP line also was designed to back up the pharmacy technician line. These calls were equally distributed among staff based on a standard algorithm. The pharmacy greeting stated, “Thank you for contacting the inpatient pharmacy at Hines VA Hospital. For missing doses, unit stock requests, or to speak with a pharmacy technician, please press 1. For clinical questions, order verification, or to speak with a pharmacist, please press 2.” Each inpatient pharmacy team member had a unique system login.

Fourteen ACD phone stations were established in the main pharmacy and in decentralized locations for order verification. The stations were distributed across the pharmacy service to optimize workload, space, and resources.

Training and Communication

Before implementing the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system, the CPs and pharmacy technicians received mandatory ACD training. After the training, pharmacy team members were required to sign off on the training document to indicate that they had completed the course. The pharmacy team was trained on the importance of staffing the phones continuously. As a 24-hour pharmacy service in the acute care setting, any call may be critical for patient care.

A hospital-wide memorandum was distributed via email to all unit managers and hospital staff to educate them on the new ACD phone system, which included a new phone line extension for the inpatient pharmacy. Additionally, the inpatient pharmacy team was trained on the proper way of communicating the ACD phone system process with the hospital staff. The inpatient pharmacy team was notified that there would be an educational period to explain the queue process to hospital staff. Occasionally, hospital staff believed they were speaking to an automated system and hung up before their call was answered. The inpatient pharmacy team was instructed to notify the hospital staff to stay on the line since their call would be answered in the order it was received. Once the inpatient pharmacy team received proper training and felt comfortable with the phone system, it was set up and integrated into the workflow.

Postimplementation Evaluation

Inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system data were collected for 2021. To evaluate the effectiveness of an ACD system, the pharmacy leadership team set up the following metrics and goals for inpatient CPs and inpatient pharmacy technicians for monthly call volume/abandonment rate, mean speed to answer, mean call volume by shift, and the mean abandonment rate by shift.

Inpatient pharmacy technicians answered 27,655 calls with a mean call abandonment rate of 4.7%. and a mean 15.6 seconds to answer.

Discussion

Since implementing the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system in January 2021, there have been successes and challenges. The implementation increased accountability and efficiency when answering pharmacy phone calls. An ACD uses an algorithm that ensures equitable distribution of phone calls between CPs and pharmacy technicians. Through this algorithm, the pharmacy team is held more accountable when answering incoming calls. Distributing phone calls equally allows for optimization and balances the workload. The ACD phone system also improved efficiency when answering incoming calls. By incorporating splits when a patient or health care professional calls, ACD routes the question to the appropriate staff member. As a result, CPs spend less time answering questions meant for pharmacy technicians and instead can answer clinical or order verification questions more efficiently.

ACD data also allow pharmacy leadership to assess staffing needs, depending on the call volume. Based on ACD data, the busiest time of day was 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM. Based on this information, pharmacy leadership plans to staff more appropriately to have more pharmacy technicians working during the first shift to attend to phone calls.

The mean call abandonment rate was 4.7% for both CPs and pharmacy technicians, which met the ≤ 5% goal. The highest call abandonment rate was from midnight to 8

Pharmacy technicians handled a higher total call volume, which may be attributed to more phone calls related to missing doses or unit stock requests compared with clinical questions or order verifications. This information may be beneficial to identify opportunities to improve pharmacy operations.

The main challenges encountered in the ACD implementation process were hardware installation and communication with hospital staff about the changes in the inpatient pharmacy phone system. To implement the new inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system, previous telephones and hardware were removed and replaced. Initially, hardware and installation delays made it difficult for the ACD phone system to operate efficiently in the early months of its implementation. The inpatient pharmacy team depends on the telecommunications system and computers for their daily activities. Delays and issues with the hardware and ACD phone system made it more difficult to provide patient care.

Communication is a continuous challenge to ensure that hospital staff are notified of the new inpatient pharmacy ACD phone number. Over time, the understanding and use of the new ACD phone system have increased dramatically, but there are still opportunities to capture any misdirected calls. Informal feedback was obtained at pharmacy huddles and 1-on-1 discussions with pharmacy staff, and the opinions were mixed. Members of the pharmacy staff expressed that the ACD phone system set up an effective way to triage phone calls. Another positive comment was that the system created a means of accountability for pharmacy phone calls. Critical feedback included challenges with triaging phone calls to appropriate pharmacists, because calls are assigned based on an algorithm, whereas clinical coverage is determined by designated unit daily assignments.

Limitations

There are potential limitations to this quality improvement project. This phone system may not apply to all inpatient hospital pharmacy settings. Potential limitations for implementation at other institutions may include but are not limited to, differing pharmacy practice models (centralized vs decentralized), implementation costs, and internal resources.

Future Goals

To improve the quality of service provided to patients and other hospital staff, the pharmacy leadership team can use the data to ensure that inpatient pharmacy technician resources are being used effectively during times of day with the greatest number of incoming ACD calls. The ACD phone system helps determine whether current resources are being used most efficiently and if they are not, can help identify areas of improvement.

The pharmacy leadership team plans on using reports for pharmacy team members to monitor performance. Reports on individual agent activity capture workload; this may be used as a performance-related metric for future performance plans.

Conclusions

The inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system at EHJVAH is a promising application of available technology. The implementation of the ACD system improved accountability, efficiency, work distribution, and the allocation of resources in the inpatient pharmacy service. The ACD phone system has yielded positive performance metrics including mean speed to answer ≤ 30 seconds and abandonment rate ≤ 5% over 12 months after implementation. With time, users of the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system will become more comfortable with the technology, thus further improving the patient health care quality.

Pharmacy call centers have been successfully implemented in outpatient and specialty pharmacy settings.1 A centralized pharmacy call center gives patients immediate access to a pharmacist who can view their health records to answer specific questions or fulfill medication renewal requests.2-4 Little literature exists to describe its use in an inpatient setting.

Inpatient pharmacies receive numerous calls from health care professionals and patients. Challenges related to phone calls in the inpatient pharmacy setting may include interruptions, distractions, low accountability, poor efficiency, lack of optimal resources, and staffing.5 An unequal distribution and lack of accountability may exist when answering phone calls for the inpatient pharmacy team, which may contribute to long hold times and call abandonment rates. Phone calls also may be directed inefficiently between clinical pharmacists (CPs) and pharmacy technicians. Team member time related to answering phone calls may not be captured or measured.

The Edward Hines, Jr. Veterans Affairs Hospital (EHJVAH) in Illinois offers primary, extended, and specialty care and is a tertiary care referral center. The facility operates 483 beds and serves 6 community-based outpatient clinics.

Implementation

A new inpatient pharmacy service phone line extension was implemented. Data used to report quality metrics were obtained from the Global Navigator (GNAV), an information system that records calls, tracks the performance of agents, and coordinates personnel scheduling. The effectiveness of the ACD system was evaluated by quality metric goals of mean speed to answer ≤ 30 seconds and mean abandonment rate ≤ 5%. This project was determined to be quality improvement and was not reviewed by the EHJVAH Institutional Review Board.

The ACD system was set up in December 2020. After a 1-month implementation period, metrics were reported to the inpatient pharmacy team and leadership. By January 2021, EHJVAH fully implemented an ACD phone system operated by inpatient pharmacy technicians and CPs. EHJVAH inpatient pharmacy includes CPs who practice without a scope of practice and board-certified pharmacy technicians in 3 shifts. The CPs and pharmacy technicians work in the central pharmacy (the main pharmacy and inpatient pharmacy vault) or are decentralized with responsibility for answering phone calls and making deliveries (pharmacy technicians).

The pharmacy leadership team decided to implement 1 phone line with 2 ACD splits. The first split was directed to pharmacy technicians and the second to CPs. The intention was to streamline calls to be directed to proper team members within the inpatient pharmacy. The CP line also was designed to back up the pharmacy technician line. These calls were equally distributed among staff based on a standard algorithm. The pharmacy greeting stated, “Thank you for contacting the inpatient pharmacy at Hines VA Hospital. For missing doses, unit stock requests, or to speak with a pharmacy technician, please press 1. For clinical questions, order verification, or to speak with a pharmacist, please press 2.” Each inpatient pharmacy team member had a unique system login.

Fourteen ACD phone stations were established in the main pharmacy and in decentralized locations for order verification. The stations were distributed across the pharmacy service to optimize workload, space, and resources.

Training and Communication

Before implementing the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system, the CPs and pharmacy technicians received mandatory ACD training. After the training, pharmacy team members were required to sign off on the training document to indicate that they had completed the course. The pharmacy team was trained on the importance of staffing the phones continuously. As a 24-hour pharmacy service in the acute care setting, any call may be critical for patient care.

A hospital-wide memorandum was distributed via email to all unit managers and hospital staff to educate them on the new ACD phone system, which included a new phone line extension for the inpatient pharmacy. Additionally, the inpatient pharmacy team was trained on the proper way of communicating the ACD phone system process with the hospital staff. The inpatient pharmacy team was notified that there would be an educational period to explain the queue process to hospital staff. Occasionally, hospital staff believed they were speaking to an automated system and hung up before their call was answered. The inpatient pharmacy team was instructed to notify the hospital staff to stay on the line since their call would be answered in the order it was received. Once the inpatient pharmacy team received proper training and felt comfortable with the phone system, it was set up and integrated into the workflow.

Postimplementation Evaluation

Inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system data were collected for 2021. To evaluate the effectiveness of an ACD system, the pharmacy leadership team set up the following metrics and goals for inpatient CPs and inpatient pharmacy technicians for monthly call volume/abandonment rate, mean speed to answer, mean call volume by shift, and the mean abandonment rate by shift.

Inpatient pharmacy technicians answered 27,655 calls with a mean call abandonment rate of 4.7%. and a mean 15.6 seconds to answer.

Discussion

Since implementing the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system in January 2021, there have been successes and challenges. The implementation increased accountability and efficiency when answering pharmacy phone calls. An ACD uses an algorithm that ensures equitable distribution of phone calls between CPs and pharmacy technicians. Through this algorithm, the pharmacy team is held more accountable when answering incoming calls. Distributing phone calls equally allows for optimization and balances the workload. The ACD phone system also improved efficiency when answering incoming calls. By incorporating splits when a patient or health care professional calls, ACD routes the question to the appropriate staff member. As a result, CPs spend less time answering questions meant for pharmacy technicians and instead can answer clinical or order verification questions more efficiently.

ACD data also allow pharmacy leadership to assess staffing needs, depending on the call volume. Based on ACD data, the busiest time of day was 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM. Based on this information, pharmacy leadership plans to staff more appropriately to have more pharmacy technicians working during the first shift to attend to phone calls.

The mean call abandonment rate was 4.7% for both CPs and pharmacy technicians, which met the ≤ 5% goal. The highest call abandonment rate was from midnight to 8

Pharmacy technicians handled a higher total call volume, which may be attributed to more phone calls related to missing doses or unit stock requests compared with clinical questions or order verifications. This information may be beneficial to identify opportunities to improve pharmacy operations.

The main challenges encountered in the ACD implementation process were hardware installation and communication with hospital staff about the changes in the inpatient pharmacy phone system. To implement the new inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system, previous telephones and hardware were removed and replaced. Initially, hardware and installation delays made it difficult for the ACD phone system to operate efficiently in the early months of its implementation. The inpatient pharmacy team depends on the telecommunications system and computers for their daily activities. Delays and issues with the hardware and ACD phone system made it more difficult to provide patient care.

Communication is a continuous challenge to ensure that hospital staff are notified of the new inpatient pharmacy ACD phone number. Over time, the understanding and use of the new ACD phone system have increased dramatically, but there are still opportunities to capture any misdirected calls. Informal feedback was obtained at pharmacy huddles and 1-on-1 discussions with pharmacy staff, and the opinions were mixed. Members of the pharmacy staff expressed that the ACD phone system set up an effective way to triage phone calls. Another positive comment was that the system created a means of accountability for pharmacy phone calls. Critical feedback included challenges with triaging phone calls to appropriate pharmacists, because calls are assigned based on an algorithm, whereas clinical coverage is determined by designated unit daily assignments.

Limitations

There are potential limitations to this quality improvement project. This phone system may not apply to all inpatient hospital pharmacy settings. Potential limitations for implementation at other institutions may include but are not limited to, differing pharmacy practice models (centralized vs decentralized), implementation costs, and internal resources.

Future Goals

To improve the quality of service provided to patients and other hospital staff, the pharmacy leadership team can use the data to ensure that inpatient pharmacy technician resources are being used effectively during times of day with the greatest number of incoming ACD calls. The ACD phone system helps determine whether current resources are being used most efficiently and if they are not, can help identify areas of improvement.

The pharmacy leadership team plans on using reports for pharmacy team members to monitor performance. Reports on individual agent activity capture workload; this may be used as a performance-related metric for future performance plans.

Conclusions

The inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system at EHJVAH is a promising application of available technology. The implementation of the ACD system improved accountability, efficiency, work distribution, and the allocation of resources in the inpatient pharmacy service. The ACD phone system has yielded positive performance metrics including mean speed to answer ≤ 30 seconds and abandonment rate ≤ 5% over 12 months after implementation. With time, users of the inpatient pharmacy ACD phone system will become more comfortable with the technology, thus further improving the patient health care quality.

1. Rim MH, Thomas KC, Chandramouli J, Barrus SA, Nickman NA. Implementation and quality assessment of a pharmacy services call center for outpatient pharmacies and specialty pharmacy services in an academic health system. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(10):633-641. doi:10.2146/ajhp170319

2. Patterson BJ, Doucette WR, Urmie JM, McDonough RP. Exploring relationships among pharmacy service use, patronage motives, and patient satisfaction. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2013;53(4):382-389. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2013.12100

3. Walker DM, Sieck CJ, Menser T, Huerta TR, Scheck McAlearney A. Information technology to support patient engagement: where do we stand and where can we go?. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(6):1088-1094. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocx043

4. Menichetti J, Libreri C, Lozza E, Graffigna G. Giving patients a starring role in their own care: a bibliometric analysis of the on-going literature debate. Health Expect. 2016;19(3):516-526. doi:10.1111/hex.12299

5. Raimbault M, Guérin A, Caron É, Lebel D, Bussières J-F. Identifying and reducing distractions and interruptions in a pharmacy department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(3):186-190. doi:10.2146/ajhp120344

1. Rim MH, Thomas KC, Chandramouli J, Barrus SA, Nickman NA. Implementation and quality assessment of a pharmacy services call center for outpatient pharmacies and specialty pharmacy services in an academic health system. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(10):633-641. doi:10.2146/ajhp170319

2. Patterson BJ, Doucette WR, Urmie JM, McDonough RP. Exploring relationships among pharmacy service use, patronage motives, and patient satisfaction. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2013;53(4):382-389. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2013.12100

3. Walker DM, Sieck CJ, Menser T, Huerta TR, Scheck McAlearney A. Information technology to support patient engagement: where do we stand and where can we go?. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(6):1088-1094. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocx043

4. Menichetti J, Libreri C, Lozza E, Graffigna G. Giving patients a starring role in their own care: a bibliometric analysis of the on-going literature debate. Health Expect. 2016;19(3):516-526. doi:10.1111/hex.12299

5. Raimbault M, Guérin A, Caron É, Lebel D, Bussières J-F. Identifying and reducing distractions and interruptions in a pharmacy department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(3):186-190. doi:10.2146/ajhp120344

Severe atopic dermatitis raises risks for cardiovascular disease and venous thromboembolism

Key clinical point: Severe atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with higher risks for venous thromboembolism and cardiovascular diseases in both children and adults.

Major finding: Children with severe AD vs those without AD had a significantly increased risk (adjusted hazard ratio; 95% CI) for cerebrovascular accidents (2.43; 1.13-5.22), diabetes (1.46; 1.06-2.01), and deep vein thrombosis (DVT; 2.13; 1.17-3.87). Among adults, the severe AD vs non-AD group had a significantly higher risk for cerebrovascular accidents (1.21; 1.13-1.30), diabetes (1.15; 1.09-1.22), dyslipidemia (1.11; 1.06-1.17), myocardial infarction (1.27; 1.15-1.39), DVT (1.64; 1.49-1.82), and pulmonary embolism (1.39; 1.21-1.60).

Study details: This population-based cohort study included 409,431 children (age < 18 years) and 625,083 adults with AD who were matched with 1,809,029 children and 2,678,888 adults without AD, respectively.

Disclosures: This study was supported by a contract from Pfizer, Inc. Some authors declared serving as consultants for or receiving research grants, honoraria, or consulting fees from various sources, including Pfizer. AR Lemeshow declared being an employee of Pfizer, Inc.

Source: Wan J, Chiesa Fuxench ZC, et al. Incidence of cardiovascular disease and venous thromboembolism in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023 (Aug 10). doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.08.007

Key clinical point: Severe atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with higher risks for venous thromboembolism and cardiovascular diseases in both children and adults.

Major finding: Children with severe AD vs those without AD had a significantly increased risk (adjusted hazard ratio; 95% CI) for cerebrovascular accidents (2.43; 1.13-5.22), diabetes (1.46; 1.06-2.01), and deep vein thrombosis (DVT; 2.13; 1.17-3.87). Among adults, the severe AD vs non-AD group had a significantly higher risk for cerebrovascular accidents (1.21; 1.13-1.30), diabetes (1.15; 1.09-1.22), dyslipidemia (1.11; 1.06-1.17), myocardial infarction (1.27; 1.15-1.39), DVT (1.64; 1.49-1.82), and pulmonary embolism (1.39; 1.21-1.60).

Study details: This population-based cohort study included 409,431 children (age < 18 years) and 625,083 adults with AD who were matched with 1,809,029 children and 2,678,888 adults without AD, respectively.

Disclosures: This study was supported by a contract from Pfizer, Inc. Some authors declared serving as consultants for or receiving research grants, honoraria, or consulting fees from various sources, including Pfizer. AR Lemeshow declared being an employee of Pfizer, Inc.

Source: Wan J, Chiesa Fuxench ZC, et al. Incidence of cardiovascular disease and venous thromboembolism in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023 (Aug 10). doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.08.007

Key clinical point: Severe atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with higher risks for venous thromboembolism and cardiovascular diseases in both children and adults.

Major finding: Children with severe AD vs those without AD had a significantly increased risk (adjusted hazard ratio; 95% CI) for cerebrovascular accidents (2.43; 1.13-5.22), diabetes (1.46; 1.06-2.01), and deep vein thrombosis (DVT; 2.13; 1.17-3.87). Among adults, the severe AD vs non-AD group had a significantly higher risk for cerebrovascular accidents (1.21; 1.13-1.30), diabetes (1.15; 1.09-1.22), dyslipidemia (1.11; 1.06-1.17), myocardial infarction (1.27; 1.15-1.39), DVT (1.64; 1.49-1.82), and pulmonary embolism (1.39; 1.21-1.60).

Study details: This population-based cohort study included 409,431 children (age < 18 years) and 625,083 adults with AD who were matched with 1,809,029 children and 2,678,888 adults without AD, respectively.

Disclosures: This study was supported by a contract from Pfizer, Inc. Some authors declared serving as consultants for or receiving research grants, honoraria, or consulting fees from various sources, including Pfizer. AR Lemeshow declared being an employee of Pfizer, Inc.

Source: Wan J, Chiesa Fuxench ZC, et al. Incidence of cardiovascular disease and venous thromboembolism in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023 (Aug 10). doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.08.007

Atopic dermatitis increases the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults

Key clinical point: Adults with newly diagnosed atopic dermatitis (AD) have a 44% increased risk of subsequently developing type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Major finding: The risk for new-onset T2D was significantly higher in adults with newly diagnosed AD vs control individuals without AD (adjusted hazard ratio 1.44; P < .001), with the risk being significantly greater in both men and women with AD (both P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective cohort study including 36,692 adult patients with AD and 36,692 matched control individuals who had never been diagnosed with AD.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology and others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Won Lee S et al. Risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2023;110883 (Aug 16). doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2023.110883

Key clinical point: Adults with newly diagnosed atopic dermatitis (AD) have a 44% increased risk of subsequently developing type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Major finding: The risk for new-onset T2D was significantly higher in adults with newly diagnosed AD vs control individuals without AD (adjusted hazard ratio 1.44; P < .001), with the risk being significantly greater in both men and women with AD (both P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective cohort study including 36,692 adult patients with AD and 36,692 matched control individuals who had never been diagnosed with AD.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology and others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Won Lee S et al. Risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2023;110883 (Aug 16). doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2023.110883

Key clinical point: Adults with newly diagnosed atopic dermatitis (AD) have a 44% increased risk of subsequently developing type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Major finding: The risk for new-onset T2D was significantly higher in adults with newly diagnosed AD vs control individuals without AD (adjusted hazard ratio 1.44; P < .001), with the risk being significantly greater in both men and women with AD (both P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective cohort study including 36,692 adult patients with AD and 36,692 matched control individuals who had never been diagnosed with AD.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology and others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Won Lee S et al. Risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2023;110883 (Aug 16). doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2023.110883

Tralokinumab is safe and effective in older patients with atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: Tralokinumab is well tolerated and effective in older adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: Compared with the placebo group, a significantly higher proportion of patients in ECZTRA 1 and 2 achieved ≥ 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index score (33.9% vs 4.76%; P < .001) and an Investigator’s Global Assessment 0 or 1 score (16.95% vs 0%; P < .001) in the tralokinumab group at week 16. The adverse event (AE) rate was comparable between the groups; however, fewer patients discontinued treatment due to AE in the tralokinumab vs placebo group (5.3% vs 6.9%).

Study details: Findings are from a post hoc analysis of ECZTRA 1, 2, and 3 trials and included 104 older patients (≥65 years) with AD who received tralokinumab (n = 75) or placebo (n = 29).

Disclosures: This study was supported by LEO Pharma. Two authors declared being employees of LEO Pharma. Some authors declared receiving grants, personal fees, or consulting fees from LEO Pharma and other sources.

Source: Merola JF et al. Safety and efficacy of tralokinumab in older adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A secondary analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2023 (Aug 23). doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2626

Key clinical point: Tralokinumab is well tolerated and effective in older adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: Compared with the placebo group, a significantly higher proportion of patients in ECZTRA 1 and 2 achieved ≥ 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index score (33.9% vs 4.76%; P < .001) and an Investigator’s Global Assessment 0 or 1 score (16.95% vs 0%; P < .001) in the tralokinumab group at week 16. The adverse event (AE) rate was comparable between the groups; however, fewer patients discontinued treatment due to AE in the tralokinumab vs placebo group (5.3% vs 6.9%).

Study details: Findings are from a post hoc analysis of ECZTRA 1, 2, and 3 trials and included 104 older patients (≥65 years) with AD who received tralokinumab (n = 75) or placebo (n = 29).

Disclosures: This study was supported by LEO Pharma. Two authors declared being employees of LEO Pharma. Some authors declared receiving grants, personal fees, or consulting fees from LEO Pharma and other sources.

Source: Merola JF et al. Safety and efficacy of tralokinumab in older adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A secondary analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2023 (Aug 23). doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2626

Key clinical point: Tralokinumab is well tolerated and effective in older adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: Compared with the placebo group, a significantly higher proportion of patients in ECZTRA 1 and 2 achieved ≥ 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index score (33.9% vs 4.76%; P < .001) and an Investigator’s Global Assessment 0 or 1 score (16.95% vs 0%; P < .001) in the tralokinumab group at week 16. The adverse event (AE) rate was comparable between the groups; however, fewer patients discontinued treatment due to AE in the tralokinumab vs placebo group (5.3% vs 6.9%).

Study details: Findings are from a post hoc analysis of ECZTRA 1, 2, and 3 trials and included 104 older patients (≥65 years) with AD who received tralokinumab (n = 75) or placebo (n = 29).

Disclosures: This study was supported by LEO Pharma. Two authors declared being employees of LEO Pharma. Some authors declared receiving grants, personal fees, or consulting fees from LEO Pharma and other sources.

Source: Merola JF et al. Safety and efficacy of tralokinumab in older adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A secondary analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2023 (Aug 23). doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2626

Using Active Surveillance to Identify Monoclonal Antibody Candidates Among COVID-19–Positive Veterans in the Atlanta VA Health Care System

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, monoclonal antibody (Mab) therapy was the only outpatient therapy for patients with COVID-19 experiencing mild-to-moderate symptoms. The Blocking Viral Attachment and Cell Entry with SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies (BLAZE-1) and the REGN-COV2 (Regeneron) clinical trials found participants treated with Mab had a shorter duration of symptoms and fewer hospitalizations compared with those receiving placebo.1,2 Mab therapy was most efficacious early in the disease course, and the initial US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of Mab therapies required use within 10 days of symptom onset.3

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been felt disproportionately among marginalized racial and ethnic groups in the US. The COVID-19 Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network found that non-Hispanic Black persons have significantly higher rates of hospitalization and death by COVID-19 compared with White persons.4-7 However, marginalized groups are underrepresented in the receipt of therapeutic agents for COVID-19. From March 2020 through August 2021, the mean monthly Mab use among Black patients (2.8%) was lower compared with White patients (4.0%), and Black patients received Mab 22.4% less often than White patients.7

The Mab clinical trials BLAZE-1 and REGN-COV2 study populations consisted of > 80% White participants.1,2 Receipt of COVID-19 outpatient treatments may not align with the disease burden in marginalized racial and ethnic groups, leading to health disparities. Although not exhaustive, reasons for these disparities include patient, health care practitioner, and systems-level issues: patient awareness, trust, and engagement with the health care system; health care practitioner awareness and advocacy to pursue COVID-19 treatment for the patient; and health care capacity to provide the medication and service.7

Here, we describe a novel, quality improvement initiative at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Health Care System (AVAHCS) in Georgia that paired a proactive laboratory-based surveillance strategy to identify and engage veterans for Mab. By centralizing the surveillance and outreach process, we sought to reduce barriers to the Mab referral process and optimize access to life-saving medication.

Implementation

AVAHCS serves a diverse population of more than 129,000 (50.8% non-Hispanic Black veterans, 37.5% White veterans, and 11.7% of other races) at a main medical campus and 18 surrounding community-based outpatient clinics. From December 28, 2020, to August 31, 2021, veterans with a positive COVID-19 nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test at AVAHCS were screened daily. A central Mab team consisting of infectious disease (ID) clinical pharmacists and physicians reviewed daily lists of positive laboratory results and identified high-risk individuals for Mab eligibility, using the FDA EUA inclusion criteria. Eligible patients were called by a Mab team member to discuss Mab treatment, provide anticipatory guidance, obtain verbal consent, and schedule the infusion. Conventional referrals from non-Mab team members (eg, primary care physicians) were also accepted into the screening process and underwent the same procedures and risk prioritization strategy as those identified by the Mab team.

Clinic resources allowed for 1 to 2 patients per day to be given Mab, increasing to a maximum of 5 patients per day during the COVID-19 Delta variant surge. We followed our best clinical judgment in prioritizing patient selection, and we aligned our practice with the standards of our affiliated partner, Emory University. In circumstances where patients who were Mab-eligible outnumbered infusion availability, patients were prioritized using the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) COVID-19 (VACO) Index for 30-day COVID-19 mortality.8 As COVID-19 variants developed resistance to the recommended Mab infusions, bamlanivimab, bamlanivimab-etesevimab, or casirivimab-imdevimab, local protocols adapted to EUA revisions. The Mab team also adopted FDA eligibility criteria revisions as they were available.9,10

We describe the outcomes of our centralized screening process for Mab therapy, as measured by screening, uptake, and time to receipt of Mab from screening. We also describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of Mab recipients. Clinical outcomes include postinfusion adverse events (AEs) at day 1 and day 7, emergency department (ED) visits, inpatient hospitalization, and death.

Results

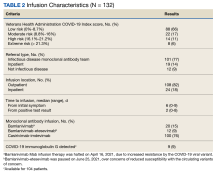

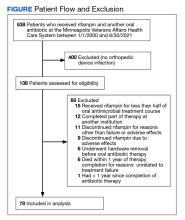

The Mab team screened 2028 veterans who were COVID-19 positive between December 28, 2020, and August 31, 2021, and identified 289 veterans (14%) who met the EUA criteria. One hundred thirty-two veterans (46%) completed Mab infusion, and of the remaining 145 veterans, 124 (86%) declined treatment, and 21 (14%) veterans did not complete Mab infusion largely due to not keeping the appointment. The Mab team active surveillance strategy identified 101 of 132 infusion candidates (77%); 82% had outpatient Mab infusion.

The mean age of veterans who received Mab was 55 years (range, 29-90), and 75% of veterans were aged ≥ 65 years; most were male (84%) and 86 (65%) identified as non-Hispanic Black individuals (Table 1).

Postinfusion AEs reported at day 1 and day 7 occurred for 38 veterans (29%) and 11 veterans (8%), respectively. Sixteen patients (12%) had postinfusion ED visit, and 12 patients (9%) required hospitalization. Eleven of the 12 hospitalized patients (92%) had worsening respiratory symptoms. No deaths occurred in the 132 patients who received Mab.

Discussion

This novel initiative to optimize access to outpatient COVID-19 treatment demonstrated how the Mab team proactively screened and reached out to eligible veterans with COVID-19 promptly. This approach removed layers in the traditional referral process that could be barriers to accessing care. More than three-quarters of patients who received Mab were identified through this strategy, and the uptake was high at 46%. Conventional passive referrals were suboptimal for identifying candidates, which was also the case at a neighboring institution.

In an Emory University study, referrals to the Mab clinic were made through a traditional, decentralized referral system and resulted in a lower uptake of Mab treatment (4.6%).11 One of the key advantages of the AVAHCS program was that we were able to provide individual education about COVID-19 and counsel on the benefits and risks of therapy. Having a structured, telehealth follow-up plan provided additional reassurance and support to the patient. These personalized patient connections likely helped increase acceptance of the Mab therapy.

Our surveillance and outreach strategy had high uptake among Black patients (65%), which exceeded the proportion of AVAHCS Black veterans (54%).12 In the Emory study, just 30% of the participants were Black patients.11 In a study of bamlanivimab use in Chicago, Black individuals represented just 11% of the study population. White patients were more likely to receive bamlanivimab compared with others races, and the likelihood of receiving bamlanivimab was significantly worse for Black patients (odds ratio, 0.28) compared with White patients.13 These studies highlight the disparity in COVID-19 outpatient treatment that does not reflect the racial and minority group representation of the community at large.

Limitations

The VHA medication allocation system at times created a significant mismatch in supply and demand, which significantly limited the AVAHCS Mab program. VHA facilities nationwide with Mab programs received discrete allocations through the US Department of Health and Human Services via VHA pharmacy benefits management services. Despite our large catchment, AVAHCS was allocated 6 or fewer doses of Mab per week during the evaluated period.

Without formal national guidance in the early period of Mab, the AVAHCS Mab team conferred with Emory University Mab clinicians as well as at other VHA facilities in the country to develop an optimal approach to resource allocation. The Mab team considered all EUA criteria to be as inclusive as possible. However, during times of high demand, our utilitarian approach tried to identify the highest-risk patients who would benefit the most from Mab. The VACO index was validated in early 2021, which facilitated decision making when demand was greater than supply. One limitation of the VACO index is its exclusion of several original Mab EUA criteria, including weight, hypertension, and nonmalignancy-related immunosuppression, into its algorithm.3,8

Conclusions

Through proactive screening and direct outreach to patients, the AVAHCS was able to achieve timely administration of Mab infusion that was well within the initial EUA time frame of 10 days and comparable with the time frame in the REGN-COV2 and BLAZE-1 trials. Improving access to resources by changing the referral structure helped engage veterans who may have otherwise missed the time frame for Mab therapy. The experience of the Mab infusion program at the AVAHCS provided valuable insight into how a health care system could effectively screen a large population and distribute the limited resource of Mab therapy in a timely and proportionate fashion among its represented demographic groups.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Veterans Health Administration VISN 7 Clinical Resource Hub and Tele Primary Care group for their support.

1. Chen P, Nirula A, Heller B, et al; BLAZE-1 Investigators. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 in outpatients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(3):229-237. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2029849

2. Weinreich DM, Sivapalasingam S, Norton T, et al; Trial Investigators. REGN-COV2, a neutralizing antibody cocktail, in outpatients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(3):238-251. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035002

3. US Food and Drug Administration. Fact sheet for health care providers, emergency use authorization (EUA) of bamlanivimab and etesevimab. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/media/145802/download

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-associated hospitalization surveillance network (COVID-net). Updated March 24, 2023. Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covid-net/purpose-methods.html

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Provisional COVID-19 deaths: distribution of deaths by race and Hispanic origin. Updated July 26, 2023. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Provisional-COVID-19-Deaths-Distribution-of-Deaths/pj7m-y5uh

6. Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, Seoane L. Hospitalization and mortality among Black patients and White patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2534-2543. doi:10.1056NEJMsa2011686

7. Wiltz JL, Feehan AK, Mollinari AM, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in receipt of medications for treatment of COVID-19 - United States, March 2020-August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(3):96-102. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7103e1

8. King JT Jr, Yoon JS, Rentsch CT, et al. Development and validation of a 30-day mortality index based on pre-existing medical administrative data from 13,323 COVID-19 patients: the Veterans Health Administration COVID-19 (VACO) Index. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0241825. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0241825

9. US Food and Drug Administration, Office of Media Affairs. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA revokes emergency use authorization for monoclonal antibody bamlanivimab. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-revokes-emergency-use-authorization-monoclonal-antibody-bamlanivimab

10. National Institutes of Health. Information on COVID-19 treatment, prevention and research. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov

11. Anderson B, Smith Z, Edupuganti S, Yan X, Masi CM, Wu HM. Effect of monoclonal antibody treatment on clinical outcomes in ambulatory patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(7):ofab315. Published 2021 Jun 12. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab315

12. United States Census Bureau. Quick facts: DeKalb County, Georgia. Updated July 1, 2022. Accessed August 8, 2023. www.census.gov/quickfacts/dekalbcountygeorgia

13. Kumar R, Wu EL, Stosor V, et al. Real-world experience of bamlanivimab for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74(1):24-31. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab305

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, monoclonal antibody (Mab) therapy was the only outpatient therapy for patients with COVID-19 experiencing mild-to-moderate symptoms. The Blocking Viral Attachment and Cell Entry with SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies (BLAZE-1) and the REGN-COV2 (Regeneron) clinical trials found participants treated with Mab had a shorter duration of symptoms and fewer hospitalizations compared with those receiving placebo.1,2 Mab therapy was most efficacious early in the disease course, and the initial US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of Mab therapies required use within 10 days of symptom onset.3

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been felt disproportionately among marginalized racial and ethnic groups in the US. The COVID-19 Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network found that non-Hispanic Black persons have significantly higher rates of hospitalization and death by COVID-19 compared with White persons.4-7 However, marginalized groups are underrepresented in the receipt of therapeutic agents for COVID-19. From March 2020 through August 2021, the mean monthly Mab use among Black patients (2.8%) was lower compared with White patients (4.0%), and Black patients received Mab 22.4% less often than White patients.7

The Mab clinical trials BLAZE-1 and REGN-COV2 study populations consisted of > 80% White participants.1,2 Receipt of COVID-19 outpatient treatments may not align with the disease burden in marginalized racial and ethnic groups, leading to health disparities. Although not exhaustive, reasons for these disparities include patient, health care practitioner, and systems-level issues: patient awareness, trust, and engagement with the health care system; health care practitioner awareness and advocacy to pursue COVID-19 treatment for the patient; and health care capacity to provide the medication and service.7

Here, we describe a novel, quality improvement initiative at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Health Care System (AVAHCS) in Georgia that paired a proactive laboratory-based surveillance strategy to identify and engage veterans for Mab. By centralizing the surveillance and outreach process, we sought to reduce barriers to the Mab referral process and optimize access to life-saving medication.

Implementation

AVAHCS serves a diverse population of more than 129,000 (50.8% non-Hispanic Black veterans, 37.5% White veterans, and 11.7% of other races) at a main medical campus and 18 surrounding community-based outpatient clinics. From December 28, 2020, to August 31, 2021, veterans with a positive COVID-19 nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test at AVAHCS were screened daily. A central Mab team consisting of infectious disease (ID) clinical pharmacists and physicians reviewed daily lists of positive laboratory results and identified high-risk individuals for Mab eligibility, using the FDA EUA inclusion criteria. Eligible patients were called by a Mab team member to discuss Mab treatment, provide anticipatory guidance, obtain verbal consent, and schedule the infusion. Conventional referrals from non-Mab team members (eg, primary care physicians) were also accepted into the screening process and underwent the same procedures and risk prioritization strategy as those identified by the Mab team.

Clinic resources allowed for 1 to 2 patients per day to be given Mab, increasing to a maximum of 5 patients per day during the COVID-19 Delta variant surge. We followed our best clinical judgment in prioritizing patient selection, and we aligned our practice with the standards of our affiliated partner, Emory University. In circumstances where patients who were Mab-eligible outnumbered infusion availability, patients were prioritized using the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) COVID-19 (VACO) Index for 30-day COVID-19 mortality.8 As COVID-19 variants developed resistance to the recommended Mab infusions, bamlanivimab, bamlanivimab-etesevimab, or casirivimab-imdevimab, local protocols adapted to EUA revisions. The Mab team also adopted FDA eligibility criteria revisions as they were available.9,10

We describe the outcomes of our centralized screening process for Mab therapy, as measured by screening, uptake, and time to receipt of Mab from screening. We also describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of Mab recipients. Clinical outcomes include postinfusion adverse events (AEs) at day 1 and day 7, emergency department (ED) visits, inpatient hospitalization, and death.

Results

The Mab team screened 2028 veterans who were COVID-19 positive between December 28, 2020, and August 31, 2021, and identified 289 veterans (14%) who met the EUA criteria. One hundred thirty-two veterans (46%) completed Mab infusion, and of the remaining 145 veterans, 124 (86%) declined treatment, and 21 (14%) veterans did not complete Mab infusion largely due to not keeping the appointment. The Mab team active surveillance strategy identified 101 of 132 infusion candidates (77%); 82% had outpatient Mab infusion.

The mean age of veterans who received Mab was 55 years (range, 29-90), and 75% of veterans were aged ≥ 65 years; most were male (84%) and 86 (65%) identified as non-Hispanic Black individuals (Table 1).

Postinfusion AEs reported at day 1 and day 7 occurred for 38 veterans (29%) and 11 veterans (8%), respectively. Sixteen patients (12%) had postinfusion ED visit, and 12 patients (9%) required hospitalization. Eleven of the 12 hospitalized patients (92%) had worsening respiratory symptoms. No deaths occurred in the 132 patients who received Mab.

Discussion

This novel initiative to optimize access to outpatient COVID-19 treatment demonstrated how the Mab team proactively screened and reached out to eligible veterans with COVID-19 promptly. This approach removed layers in the traditional referral process that could be barriers to accessing care. More than three-quarters of patients who received Mab were identified through this strategy, and the uptake was high at 46%. Conventional passive referrals were suboptimal for identifying candidates, which was also the case at a neighboring institution.

In an Emory University study, referrals to the Mab clinic were made through a traditional, decentralized referral system and resulted in a lower uptake of Mab treatment (4.6%).11 One of the key advantages of the AVAHCS program was that we were able to provide individual education about COVID-19 and counsel on the benefits and risks of therapy. Having a structured, telehealth follow-up plan provided additional reassurance and support to the patient. These personalized patient connections likely helped increase acceptance of the Mab therapy.

Our surveillance and outreach strategy had high uptake among Black patients (65%), which exceeded the proportion of AVAHCS Black veterans (54%).12 In the Emory study, just 30% of the participants were Black patients.11 In a study of bamlanivimab use in Chicago, Black individuals represented just 11% of the study population. White patients were more likely to receive bamlanivimab compared with others races, and the likelihood of receiving bamlanivimab was significantly worse for Black patients (odds ratio, 0.28) compared with White patients.13 These studies highlight the disparity in COVID-19 outpatient treatment that does not reflect the racial and minority group representation of the community at large.

Limitations

The VHA medication allocation system at times created a significant mismatch in supply and demand, which significantly limited the AVAHCS Mab program. VHA facilities nationwide with Mab programs received discrete allocations through the US Department of Health and Human Services via VHA pharmacy benefits management services. Despite our large catchment, AVAHCS was allocated 6 or fewer doses of Mab per week during the evaluated period.

Without formal national guidance in the early period of Mab, the AVAHCS Mab team conferred with Emory University Mab clinicians as well as at other VHA facilities in the country to develop an optimal approach to resource allocation. The Mab team considered all EUA criteria to be as inclusive as possible. However, during times of high demand, our utilitarian approach tried to identify the highest-risk patients who would benefit the most from Mab. The VACO index was validated in early 2021, which facilitated decision making when demand was greater than supply. One limitation of the VACO index is its exclusion of several original Mab EUA criteria, including weight, hypertension, and nonmalignancy-related immunosuppression, into its algorithm.3,8

Conclusions

Through proactive screening and direct outreach to patients, the AVAHCS was able to achieve timely administration of Mab infusion that was well within the initial EUA time frame of 10 days and comparable with the time frame in the REGN-COV2 and BLAZE-1 trials. Improving access to resources by changing the referral structure helped engage veterans who may have otherwise missed the time frame for Mab therapy. The experience of the Mab infusion program at the AVAHCS provided valuable insight into how a health care system could effectively screen a large population and distribute the limited resource of Mab therapy in a timely and proportionate fashion among its represented demographic groups.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Veterans Health Administration VISN 7 Clinical Resource Hub and Tele Primary Care group for their support.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, monoclonal antibody (Mab) therapy was the only outpatient therapy for patients with COVID-19 experiencing mild-to-moderate symptoms. The Blocking Viral Attachment and Cell Entry with SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies (BLAZE-1) and the REGN-COV2 (Regeneron) clinical trials found participants treated with Mab had a shorter duration of symptoms and fewer hospitalizations compared with those receiving placebo.1,2 Mab therapy was most efficacious early in the disease course, and the initial US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of Mab therapies required use within 10 days of symptom onset.3

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been felt disproportionately among marginalized racial and ethnic groups in the US. The COVID-19 Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network found that non-Hispanic Black persons have significantly higher rates of hospitalization and death by COVID-19 compared with White persons.4-7 However, marginalized groups are underrepresented in the receipt of therapeutic agents for COVID-19. From March 2020 through August 2021, the mean monthly Mab use among Black patients (2.8%) was lower compared with White patients (4.0%), and Black patients received Mab 22.4% less often than White patients.7

The Mab clinical trials BLAZE-1 and REGN-COV2 study populations consisted of > 80% White participants.1,2 Receipt of COVID-19 outpatient treatments may not align with the disease burden in marginalized racial and ethnic groups, leading to health disparities. Although not exhaustive, reasons for these disparities include patient, health care practitioner, and systems-level issues: patient awareness, trust, and engagement with the health care system; health care practitioner awareness and advocacy to pursue COVID-19 treatment for the patient; and health care capacity to provide the medication and service.7

Here, we describe a novel, quality improvement initiative at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Health Care System (AVAHCS) in Georgia that paired a proactive laboratory-based surveillance strategy to identify and engage veterans for Mab. By centralizing the surveillance and outreach process, we sought to reduce barriers to the Mab referral process and optimize access to life-saving medication.

Implementation

AVAHCS serves a diverse population of more than 129,000 (50.8% non-Hispanic Black veterans, 37.5% White veterans, and 11.7% of other races) at a main medical campus and 18 surrounding community-based outpatient clinics. From December 28, 2020, to August 31, 2021, veterans with a positive COVID-19 nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test at AVAHCS were screened daily. A central Mab team consisting of infectious disease (ID) clinical pharmacists and physicians reviewed daily lists of positive laboratory results and identified high-risk individuals for Mab eligibility, using the FDA EUA inclusion criteria. Eligible patients were called by a Mab team member to discuss Mab treatment, provide anticipatory guidance, obtain verbal consent, and schedule the infusion. Conventional referrals from non-Mab team members (eg, primary care physicians) were also accepted into the screening process and underwent the same procedures and risk prioritization strategy as those identified by the Mab team.