User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Scattered Flesh-Colored Papules in a Linear Array in the Setting of Diffuse Skin Thickening

The Diagnosis: Scleromyxedema

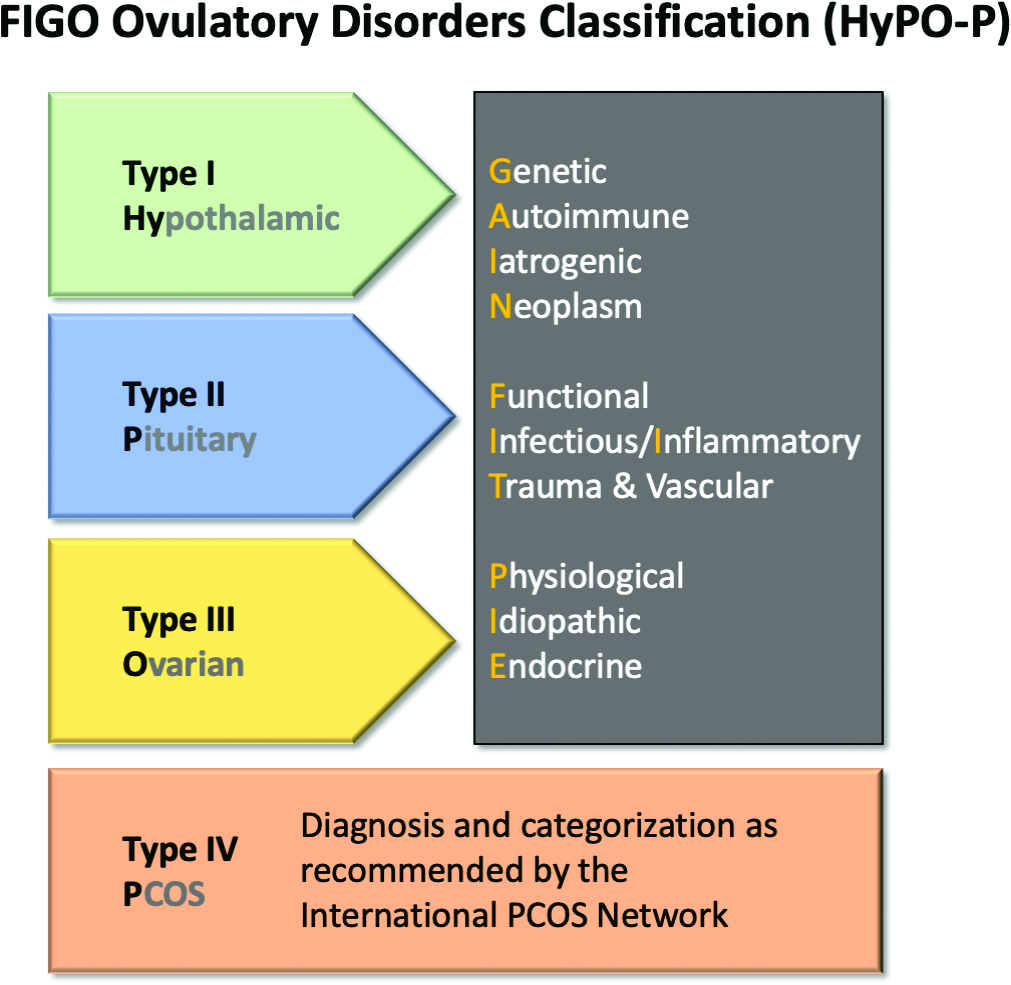

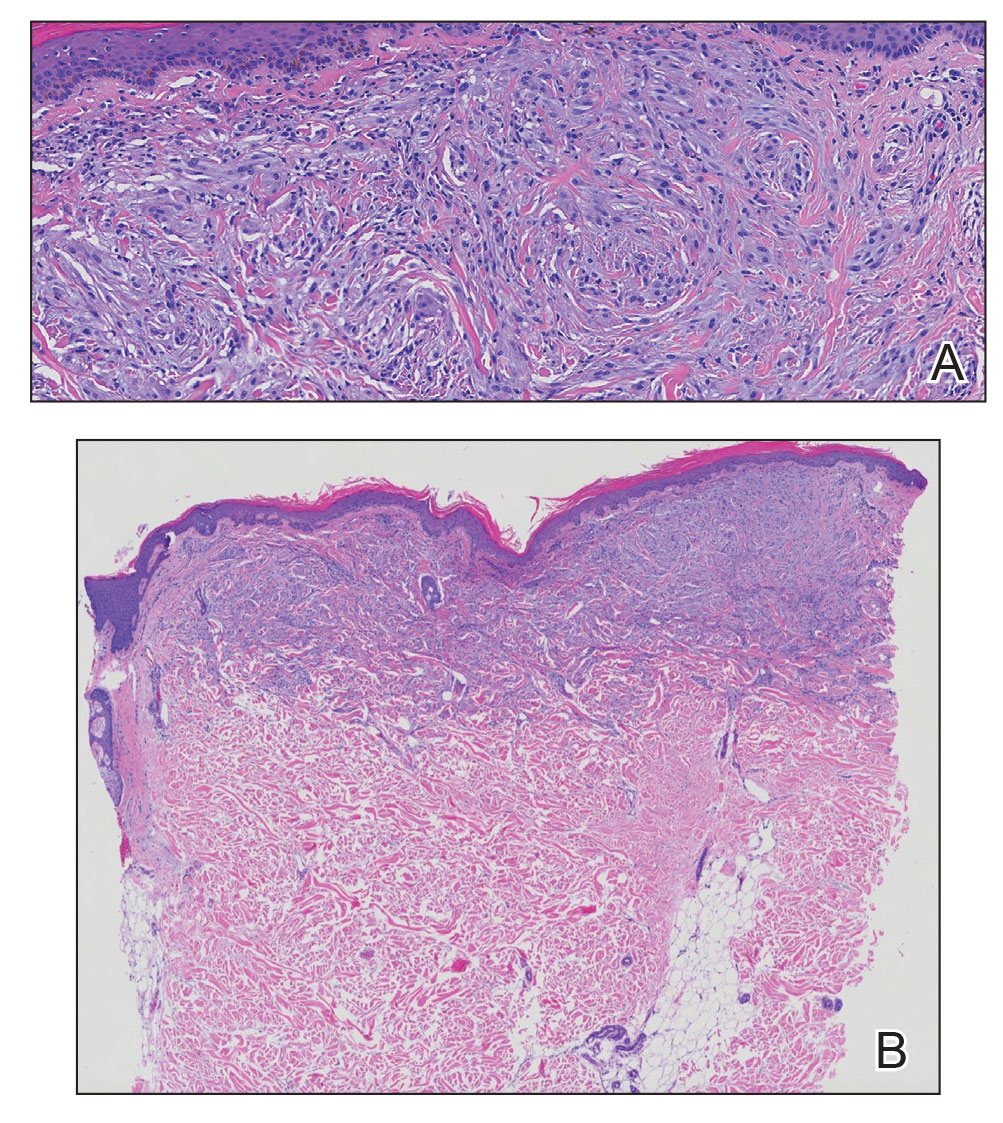

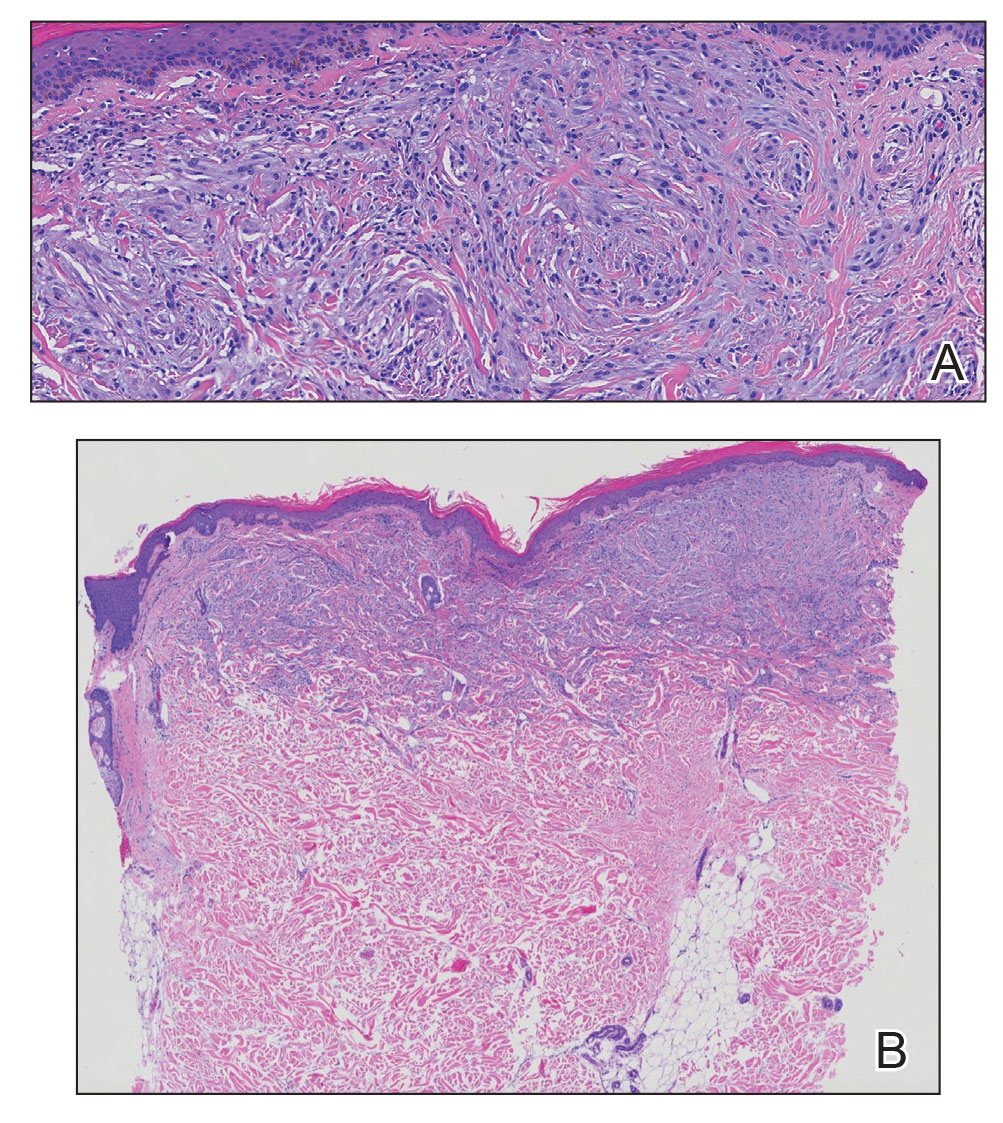

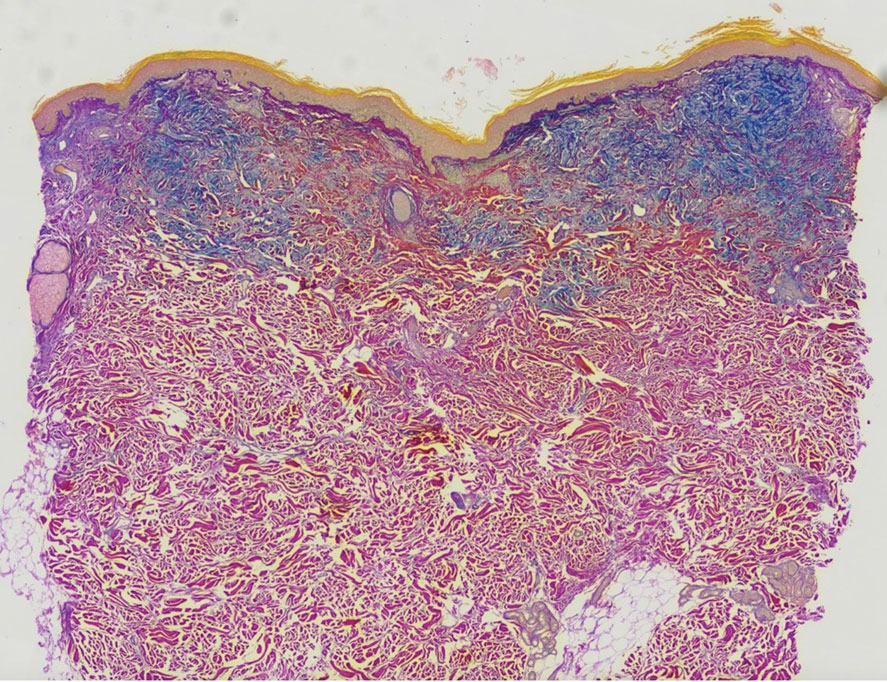

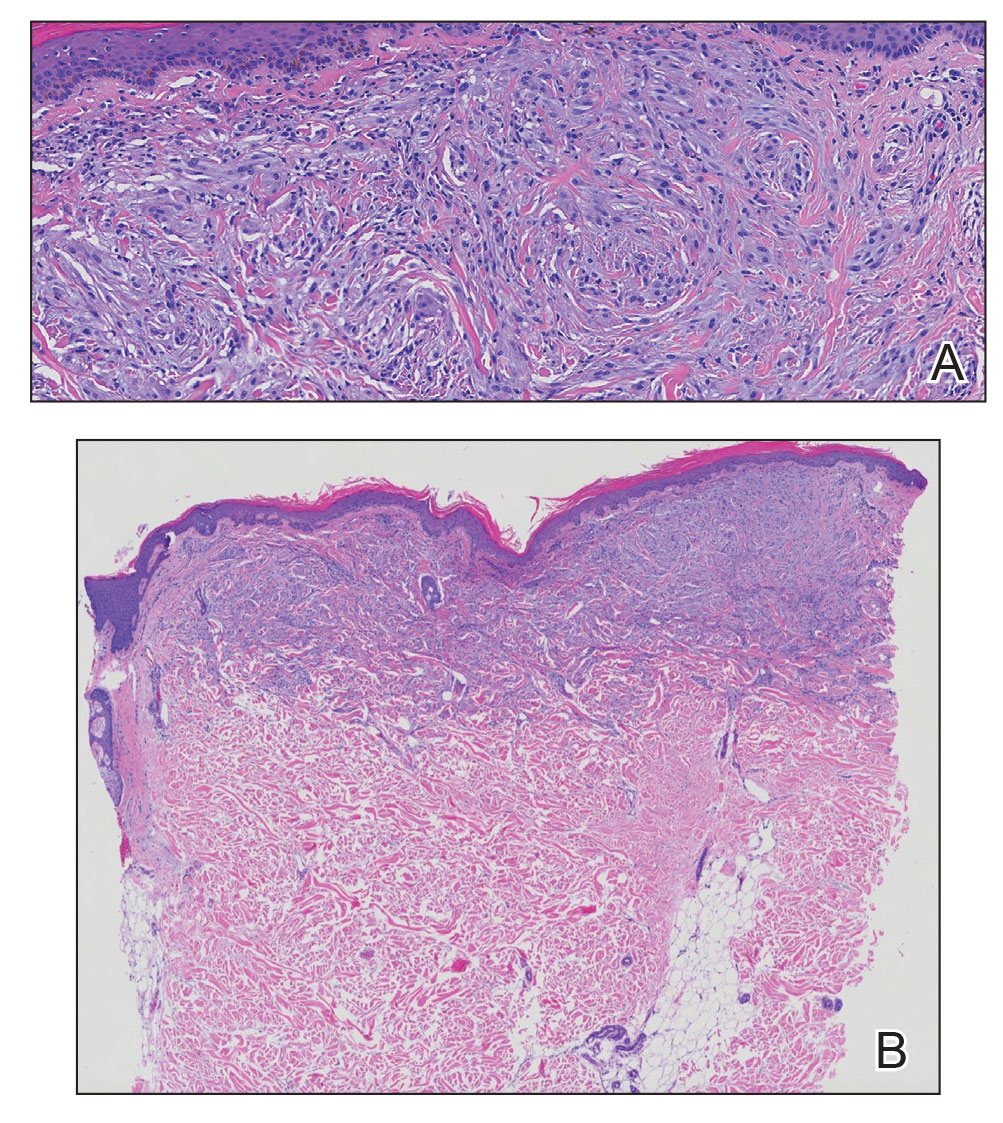

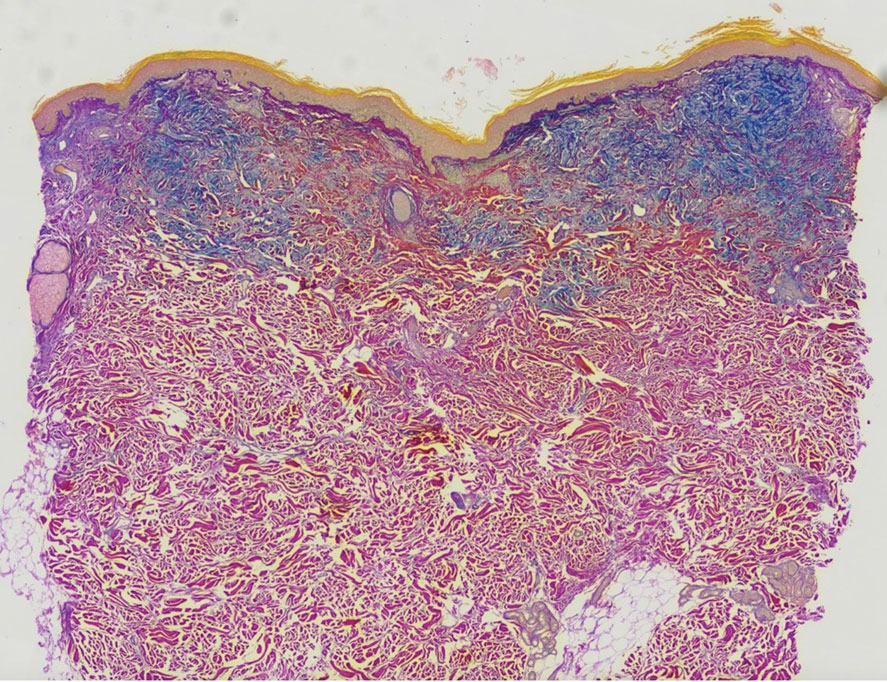

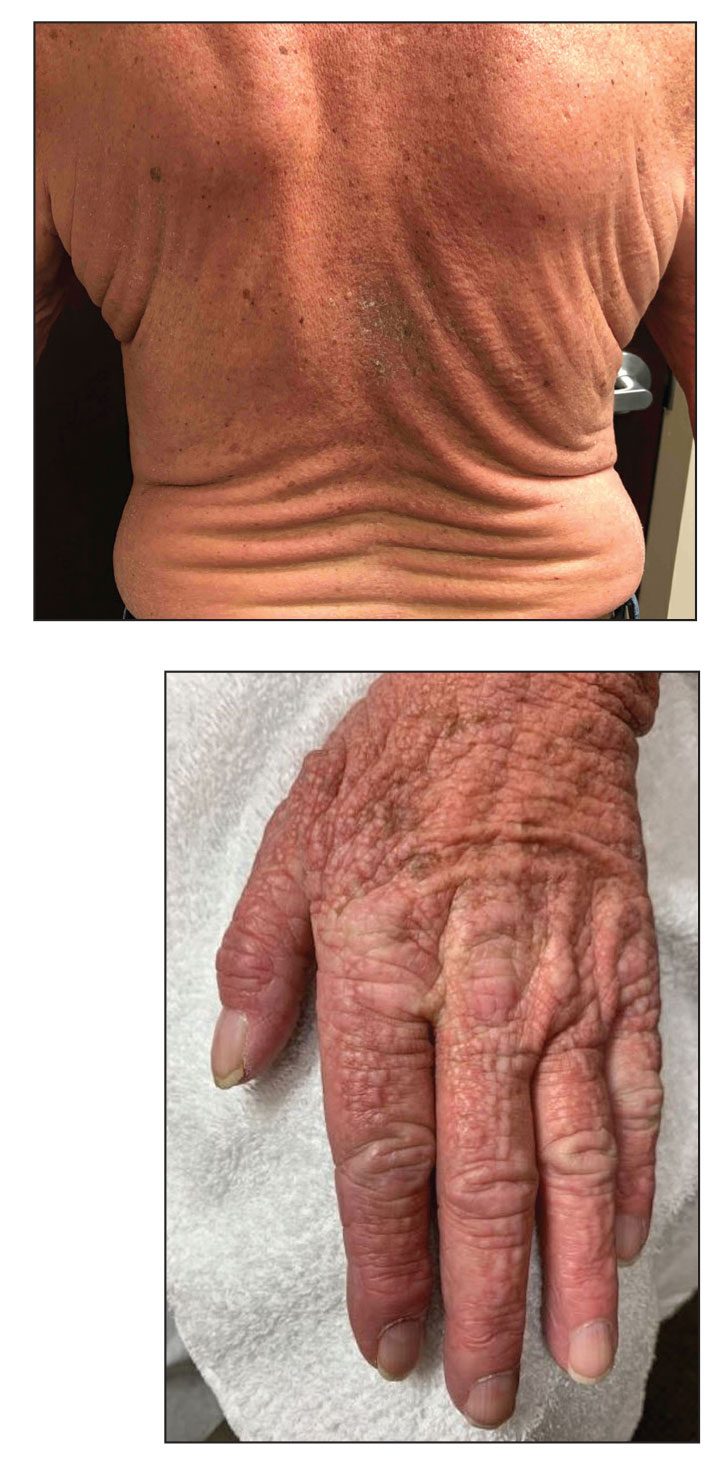

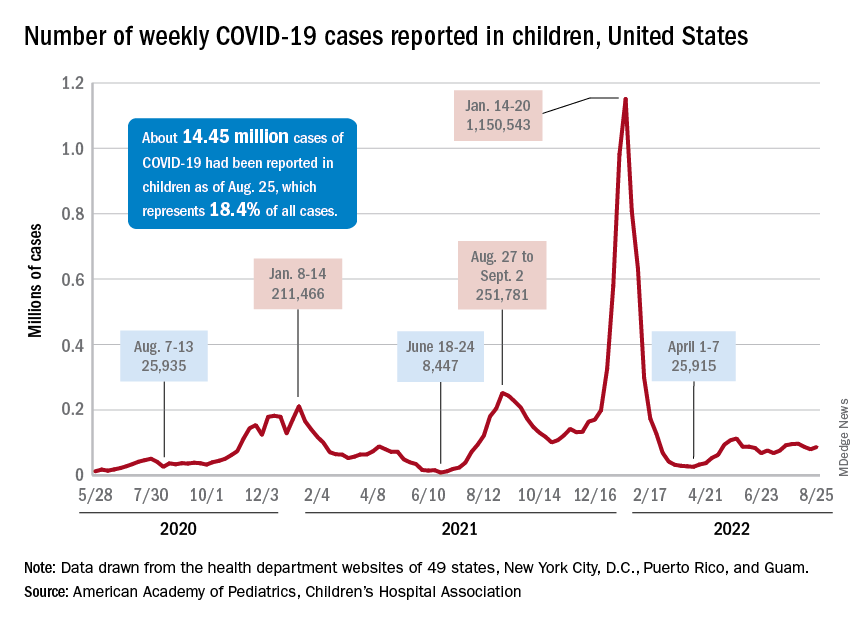

A punch biopsy of the upper back performed at an outside institution revealed increased histiocytes and abundant interstitial mucin confined to the papillary dermis (Figures 1 and 2), consistent with the lichen myxedematosus (LM) papules that may be seen in scleromyxedema. Serum protein electrophoresis revealed the presence of a protein of restricted mobility on the gamma region that occupied 5.3% of the total protein (0.3 g/dL). Urine protein electrophoresis showed free kappa light chain monoclonal protein in the gamma region. Immunofixation electrophoresis revealed the presence of IgG kappa monoclonal protein in the gamma region with 10% monotype kappa cells. The presence of Raynaud phenomenon and positive antinuclear antibody (1:320, speckled) was noted. Laboratory studies for thyroid-stimulating hormone, C-reactive protein, Scl-70 antibody, myositis panel, ribonucleoprotein antibody, Smith antibody, Sjögren syndrome–related antigens A and B antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and RNA polymerase III antibody all were within reference range. Our patient was treated with monthly intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and he noted substantial improvement in skin findings after 3 months of IVIG.

Localized lichen myxedematosus is a rare idiopathic cutaneous disease that clinically is characterized by waxy indurated papules and histologically is characterized by diffuse mucin deposition and fibroblast proliferation in the upper dermis.1 Scleromyxedema is a diffuse variant of LM in which the papules and plaques of LM are associated with skin thickening involving almost the entire body and associated systemic disease. The exact mechanism of this disease is unknown, but the most widely accepted hypothesis is that immunoglobulins and cytokines contribute to the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans and thereby the deposition of mucin in the dermis.2 Scleromyxedema has a chronic course and generally responds poorly to existing treatments.1 Partial improvement has been demonstrated in treatment with topical calcineurin inhibitors and topical steroids.2

The differential diagnosis in our patient included scleromyxedema, scleredema, scleroderma, LM, and reticular erythematosus mucinosis. He was diagnosed with scleromyxedema with kappa monoclonal gammopathy. Scleromyxedema is a rare disorder involving the deposition of mucinous material in the papillary dermis that causes the formation of infiltrative skin lesions.3 The etiology is unknown, but the presence of a monoclonal protein is an important characteristic of this disorder. It is important to rule out thyroid disease as a possible etiology before concluding that the disease process is driven by the monoclonal gammopathy; this will help determine appropriate therapies.4,5 Usually the monoclonal protein is associated with the IgG lambda subtype. Intravenous immunoglobulin often is considered as a first-line treatment of scleromyxedema and usually is administered at a dosage of 2 g/kg divided over 2 to 5 consecutive days per month.3 Previously, our patient had been treated with IVIG for 3 years for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and had stopped 1 to 2 years before his cutaneous symptoms started. Generally, scleromyxedema patients must stay on IVIG long-term to prevent relapse, typically every 6 to 8 weeks. Second-line treatments for scleromyxedema include systemic corticosteroids and thalidomide.6 Scleromyxedema and LM have several clinical and histopathologic features in common. Our patient’s biopsy revealed increased mucin deposition associated with fibroblast proliferation confined to the superficial dermis. These histologic changes can be seen in the setting of either LM or scleromyxedema. Our patient’s diffuse skin thickening and monoclonal gammopathy were more characteristic of scleromyxedema. In contrast, LM is a localized eruption with no internal organ manifestations and no associated systemic disease, such as monoclonal gammopathy and thyroid disease.

Scleredema adultorum of Buschke (also referred to as scleredema) is a rare idiopathic dermatologic condition characterized by thickening and tightening of the skin that leads to firm, nonpitting, woody edema that initially involves the upper back and neck but can spread to the face, scalp, and shoulders; importantly, scleredema spares the hands and feet.7 Scleredema has been associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections, and monoclonal gammopathy.8 Although our patient did have a monoclonal gammopathy, he also experienced prominent hand involvement with diffuse skin thickening, which is not typical of scleredema. Additionally, biopsy of scleredema would show increased mucin but would not show the proliferation of fibroblasts that was seen in our patient’s biopsy. Furthermore, scleredema has more profound diffuse superficial and deep mucin deposition compared to scleromyxedema. Scleroderma is an autoimmune cutaneous condition that is divided into 2 categories: localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis (SSc).9 Localized scleroderma (also called morphea) often is characterized by indurated hyperpigmented or hypopigmented lesions. There is an absence of Raynaud phenomenon, telangiectasia, and systemic disease.9 Systemic sclerosis is further divided into 2 categories—limited cutaneous and diffuse cutaneous—which are differentiated by the extent of organ system involvement. Limited cutaneous SSc involves calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, skin sclerosis distal to the elbows and knees, and telangiectasia.9 Diffuse cutaneous SSc is characterized by Raynaud phenomenon; cutaneous sclerosis proximal to the elbows and knees; and fibrosis of the gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, and cardiac systems.9 Scl-70 antibodies are specific for diffuse cutaneous SSc, and centromere antibodies are specific for limited cutaneous SSc. Scleromyxedema shares many of the same clinical symptoms as scleroderma; therefore, histopathologic examination is important for differentiating these disorders. Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by thickened collagen bundles associated with a variable degree of perivascular and interstitial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation. No increased dermal mucin is present.9 Our patient did not have the clinical cutaneous features of localized scleroderma and lacked the signs of internal organ involvement that typically are found in SSc. He did have Raynaud phenomenon but did not have matlike telangiectases or Scl-70 or centromere antibodies.

Reticular erythematosus mucinosis (REM) is a rare inflammatory cutaneous disease that is characterized by diffuse reticular erythematous macules or papules that may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus.10 Reticular erythematosus mucinosis most frequently affects middle-aged women and appears on the trunk.9 Our patient was not part of the demographic group most frequently affected by REM. More importantly, our patient’s lesions were not erythematous or reticular in appearance, making the diagnosis of REM unlikely. Furthermore, REM has no associated cutaneous sclerosis or induration.

- Nofal A, Amer H, Alakad R, et al. Lichen myxedematosus: diagnostic criteria, classification, and severity grading. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:284-290.

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosus (LM)(discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:8.

- Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: a systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191-1201.

- Hazan E, Griffin TD Jr, Jabbour SA, et al. Scleromyxedema in a patient with thyroid disease: an atypical case or a case for revised criteria? Cutis. 2020;105:E6-E10.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Hoffman JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449-1467.

- Beers WH, Ince AI, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Miguel D, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of scleroderma adultorum Buschke: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:305-309.

- Rongioletti F, Ferreli C, Atzori L, et al. Scleroderma with an update about clinicopathological correlation. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:208-215.

- Ocanha-Xavier JP, Cola-Senra CO, Xavier-Junior JCC. Reticular erythematous mucinosis: literature review and case report of a 24-year-old patient with systemic erythematosus lupus. Lupus. 2021;30:325-335.

The Diagnosis: Scleromyxedema

A punch biopsy of the upper back performed at an outside institution revealed increased histiocytes and abundant interstitial mucin confined to the papillary dermis (Figures 1 and 2), consistent with the lichen myxedematosus (LM) papules that may be seen in scleromyxedema. Serum protein electrophoresis revealed the presence of a protein of restricted mobility on the gamma region that occupied 5.3% of the total protein (0.3 g/dL). Urine protein electrophoresis showed free kappa light chain monoclonal protein in the gamma region. Immunofixation electrophoresis revealed the presence of IgG kappa monoclonal protein in the gamma region with 10% monotype kappa cells. The presence of Raynaud phenomenon and positive antinuclear antibody (1:320, speckled) was noted. Laboratory studies for thyroid-stimulating hormone, C-reactive protein, Scl-70 antibody, myositis panel, ribonucleoprotein antibody, Smith antibody, Sjögren syndrome–related antigens A and B antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and RNA polymerase III antibody all were within reference range. Our patient was treated with monthly intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and he noted substantial improvement in skin findings after 3 months of IVIG.

Localized lichen myxedematosus is a rare idiopathic cutaneous disease that clinically is characterized by waxy indurated papules and histologically is characterized by diffuse mucin deposition and fibroblast proliferation in the upper dermis.1 Scleromyxedema is a diffuse variant of LM in which the papules and plaques of LM are associated with skin thickening involving almost the entire body and associated systemic disease. The exact mechanism of this disease is unknown, but the most widely accepted hypothesis is that immunoglobulins and cytokines contribute to the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans and thereby the deposition of mucin in the dermis.2 Scleromyxedema has a chronic course and generally responds poorly to existing treatments.1 Partial improvement has been demonstrated in treatment with topical calcineurin inhibitors and topical steroids.2

The differential diagnosis in our patient included scleromyxedema, scleredema, scleroderma, LM, and reticular erythematosus mucinosis. He was diagnosed with scleromyxedema with kappa monoclonal gammopathy. Scleromyxedema is a rare disorder involving the deposition of mucinous material in the papillary dermis that causes the formation of infiltrative skin lesions.3 The etiology is unknown, but the presence of a monoclonal protein is an important characteristic of this disorder. It is important to rule out thyroid disease as a possible etiology before concluding that the disease process is driven by the monoclonal gammopathy; this will help determine appropriate therapies.4,5 Usually the monoclonal protein is associated with the IgG lambda subtype. Intravenous immunoglobulin often is considered as a first-line treatment of scleromyxedema and usually is administered at a dosage of 2 g/kg divided over 2 to 5 consecutive days per month.3 Previously, our patient had been treated with IVIG for 3 years for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and had stopped 1 to 2 years before his cutaneous symptoms started. Generally, scleromyxedema patients must stay on IVIG long-term to prevent relapse, typically every 6 to 8 weeks. Second-line treatments for scleromyxedema include systemic corticosteroids and thalidomide.6 Scleromyxedema and LM have several clinical and histopathologic features in common. Our patient’s biopsy revealed increased mucin deposition associated with fibroblast proliferation confined to the superficial dermis. These histologic changes can be seen in the setting of either LM or scleromyxedema. Our patient’s diffuse skin thickening and monoclonal gammopathy were more characteristic of scleromyxedema. In contrast, LM is a localized eruption with no internal organ manifestations and no associated systemic disease, such as monoclonal gammopathy and thyroid disease.

Scleredema adultorum of Buschke (also referred to as scleredema) is a rare idiopathic dermatologic condition characterized by thickening and tightening of the skin that leads to firm, nonpitting, woody edema that initially involves the upper back and neck but can spread to the face, scalp, and shoulders; importantly, scleredema spares the hands and feet.7 Scleredema has been associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections, and monoclonal gammopathy.8 Although our patient did have a monoclonal gammopathy, he also experienced prominent hand involvement with diffuse skin thickening, which is not typical of scleredema. Additionally, biopsy of scleredema would show increased mucin but would not show the proliferation of fibroblasts that was seen in our patient’s biopsy. Furthermore, scleredema has more profound diffuse superficial and deep mucin deposition compared to scleromyxedema. Scleroderma is an autoimmune cutaneous condition that is divided into 2 categories: localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis (SSc).9 Localized scleroderma (also called morphea) often is characterized by indurated hyperpigmented or hypopigmented lesions. There is an absence of Raynaud phenomenon, telangiectasia, and systemic disease.9 Systemic sclerosis is further divided into 2 categories—limited cutaneous and diffuse cutaneous—which are differentiated by the extent of organ system involvement. Limited cutaneous SSc involves calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, skin sclerosis distal to the elbows and knees, and telangiectasia.9 Diffuse cutaneous SSc is characterized by Raynaud phenomenon; cutaneous sclerosis proximal to the elbows and knees; and fibrosis of the gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, and cardiac systems.9 Scl-70 antibodies are specific for diffuse cutaneous SSc, and centromere antibodies are specific for limited cutaneous SSc. Scleromyxedema shares many of the same clinical symptoms as scleroderma; therefore, histopathologic examination is important for differentiating these disorders. Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by thickened collagen bundles associated with a variable degree of perivascular and interstitial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation. No increased dermal mucin is present.9 Our patient did not have the clinical cutaneous features of localized scleroderma and lacked the signs of internal organ involvement that typically are found in SSc. He did have Raynaud phenomenon but did not have matlike telangiectases or Scl-70 or centromere antibodies.

Reticular erythematosus mucinosis (REM) is a rare inflammatory cutaneous disease that is characterized by diffuse reticular erythematous macules or papules that may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus.10 Reticular erythematosus mucinosis most frequently affects middle-aged women and appears on the trunk.9 Our patient was not part of the demographic group most frequently affected by REM. More importantly, our patient’s lesions were not erythematous or reticular in appearance, making the diagnosis of REM unlikely. Furthermore, REM has no associated cutaneous sclerosis or induration.

The Diagnosis: Scleromyxedema

A punch biopsy of the upper back performed at an outside institution revealed increased histiocytes and abundant interstitial mucin confined to the papillary dermis (Figures 1 and 2), consistent with the lichen myxedematosus (LM) papules that may be seen in scleromyxedema. Serum protein electrophoresis revealed the presence of a protein of restricted mobility on the gamma region that occupied 5.3% of the total protein (0.3 g/dL). Urine protein electrophoresis showed free kappa light chain monoclonal protein in the gamma region. Immunofixation electrophoresis revealed the presence of IgG kappa monoclonal protein in the gamma region with 10% monotype kappa cells. The presence of Raynaud phenomenon and positive antinuclear antibody (1:320, speckled) was noted. Laboratory studies for thyroid-stimulating hormone, C-reactive protein, Scl-70 antibody, myositis panel, ribonucleoprotein antibody, Smith antibody, Sjögren syndrome–related antigens A and B antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and RNA polymerase III antibody all were within reference range. Our patient was treated with monthly intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and he noted substantial improvement in skin findings after 3 months of IVIG.

Localized lichen myxedematosus is a rare idiopathic cutaneous disease that clinically is characterized by waxy indurated papules and histologically is characterized by diffuse mucin deposition and fibroblast proliferation in the upper dermis.1 Scleromyxedema is a diffuse variant of LM in which the papules and plaques of LM are associated with skin thickening involving almost the entire body and associated systemic disease. The exact mechanism of this disease is unknown, but the most widely accepted hypothesis is that immunoglobulins and cytokines contribute to the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans and thereby the deposition of mucin in the dermis.2 Scleromyxedema has a chronic course and generally responds poorly to existing treatments.1 Partial improvement has been demonstrated in treatment with topical calcineurin inhibitors and topical steroids.2

The differential diagnosis in our patient included scleromyxedema, scleredema, scleroderma, LM, and reticular erythematosus mucinosis. He was diagnosed with scleromyxedema with kappa monoclonal gammopathy. Scleromyxedema is a rare disorder involving the deposition of mucinous material in the papillary dermis that causes the formation of infiltrative skin lesions.3 The etiology is unknown, but the presence of a monoclonal protein is an important characteristic of this disorder. It is important to rule out thyroid disease as a possible etiology before concluding that the disease process is driven by the monoclonal gammopathy; this will help determine appropriate therapies.4,5 Usually the monoclonal protein is associated with the IgG lambda subtype. Intravenous immunoglobulin often is considered as a first-line treatment of scleromyxedema and usually is administered at a dosage of 2 g/kg divided over 2 to 5 consecutive days per month.3 Previously, our patient had been treated with IVIG for 3 years for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and had stopped 1 to 2 years before his cutaneous symptoms started. Generally, scleromyxedema patients must stay on IVIG long-term to prevent relapse, typically every 6 to 8 weeks. Second-line treatments for scleromyxedema include systemic corticosteroids and thalidomide.6 Scleromyxedema and LM have several clinical and histopathologic features in common. Our patient’s biopsy revealed increased mucin deposition associated with fibroblast proliferation confined to the superficial dermis. These histologic changes can be seen in the setting of either LM or scleromyxedema. Our patient’s diffuse skin thickening and monoclonal gammopathy were more characteristic of scleromyxedema. In contrast, LM is a localized eruption with no internal organ manifestations and no associated systemic disease, such as monoclonal gammopathy and thyroid disease.

Scleredema adultorum of Buschke (also referred to as scleredema) is a rare idiopathic dermatologic condition characterized by thickening and tightening of the skin that leads to firm, nonpitting, woody edema that initially involves the upper back and neck but can spread to the face, scalp, and shoulders; importantly, scleredema spares the hands and feet.7 Scleredema has been associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections, and monoclonal gammopathy.8 Although our patient did have a monoclonal gammopathy, he also experienced prominent hand involvement with diffuse skin thickening, which is not typical of scleredema. Additionally, biopsy of scleredema would show increased mucin but would not show the proliferation of fibroblasts that was seen in our patient’s biopsy. Furthermore, scleredema has more profound diffuse superficial and deep mucin deposition compared to scleromyxedema. Scleroderma is an autoimmune cutaneous condition that is divided into 2 categories: localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis (SSc).9 Localized scleroderma (also called morphea) often is characterized by indurated hyperpigmented or hypopigmented lesions. There is an absence of Raynaud phenomenon, telangiectasia, and systemic disease.9 Systemic sclerosis is further divided into 2 categories—limited cutaneous and diffuse cutaneous—which are differentiated by the extent of organ system involvement. Limited cutaneous SSc involves calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, skin sclerosis distal to the elbows and knees, and telangiectasia.9 Diffuse cutaneous SSc is characterized by Raynaud phenomenon; cutaneous sclerosis proximal to the elbows and knees; and fibrosis of the gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, and cardiac systems.9 Scl-70 antibodies are specific for diffuse cutaneous SSc, and centromere antibodies are specific for limited cutaneous SSc. Scleromyxedema shares many of the same clinical symptoms as scleroderma; therefore, histopathologic examination is important for differentiating these disorders. Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by thickened collagen bundles associated with a variable degree of perivascular and interstitial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation. No increased dermal mucin is present.9 Our patient did not have the clinical cutaneous features of localized scleroderma and lacked the signs of internal organ involvement that typically are found in SSc. He did have Raynaud phenomenon but did not have matlike telangiectases or Scl-70 or centromere antibodies.

Reticular erythematosus mucinosis (REM) is a rare inflammatory cutaneous disease that is characterized by diffuse reticular erythematous macules or papules that may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus.10 Reticular erythematosus mucinosis most frequently affects middle-aged women and appears on the trunk.9 Our patient was not part of the demographic group most frequently affected by REM. More importantly, our patient’s lesions were not erythematous or reticular in appearance, making the diagnosis of REM unlikely. Furthermore, REM has no associated cutaneous sclerosis or induration.

- Nofal A, Amer H, Alakad R, et al. Lichen myxedematosus: diagnostic criteria, classification, and severity grading. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:284-290.

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosus (LM)(discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:8.

- Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: a systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191-1201.

- Hazan E, Griffin TD Jr, Jabbour SA, et al. Scleromyxedema in a patient with thyroid disease: an atypical case or a case for revised criteria? Cutis. 2020;105:E6-E10.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Hoffman JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449-1467.

- Beers WH, Ince AI, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Miguel D, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of scleroderma adultorum Buschke: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:305-309.

- Rongioletti F, Ferreli C, Atzori L, et al. Scleroderma with an update about clinicopathological correlation. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:208-215.

- Ocanha-Xavier JP, Cola-Senra CO, Xavier-Junior JCC. Reticular erythematous mucinosis: literature review and case report of a 24-year-old patient with systemic erythematosus lupus. Lupus. 2021;30:325-335.

- Nofal A, Amer H, Alakad R, et al. Lichen myxedematosus: diagnostic criteria, classification, and severity grading. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:284-290.

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosus (LM)(discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:8.

- Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: a systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191-1201.

- Hazan E, Griffin TD Jr, Jabbour SA, et al. Scleromyxedema in a patient with thyroid disease: an atypical case or a case for revised criteria? Cutis. 2020;105:E6-E10.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Hoffman JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449-1467.

- Beers WH, Ince AI, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Miguel D, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of scleroderma adultorum Buschke: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:305-309.

- Rongioletti F, Ferreli C, Atzori L, et al. Scleroderma with an update about clinicopathological correlation. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:208-215.

- Ocanha-Xavier JP, Cola-Senra CO, Xavier-Junior JCC. Reticular erythematous mucinosis: literature review and case report of a 24-year-old patient with systemic erythematosus lupus. Lupus. 2021;30:325-335.

A 76-year-old man presented to our clinic with diffusely thickened and tightened skin that worsened over the course of 1 year, as well as numerous scattered small, firm, flesh-colored papules arranged in a linear pattern over the face, ears, neck, chest, abdomen, arms, hands, and knees. His symptoms progressed to include substantial skin thickening initially over the thighs followed by the arms, chest, back (top), and face. He developed confluent cobblestonelike plaques over the elbows and hands (bottom) and eventually developed decreased oral aperture limiting oral intake as well as decreased range of motion in the hands. The patient had a deep furrowed appearance of the brow accompanied by discrete, scattered, flesh-colored papules on the forehead and behind the ears. Deep furrows also were present on the back. When the proximal interphalangeal joints of the hands were extended, elevated rings with central depression were seen instead of horizontal folds.

Evolocumab benefits accrue with longer follow-up: FOURIER OLE

Long-term lipid lowering with evolocumab (Repatha) further reduces cardiovascular events, including CV death, without a safety signal, according to results from the FOURIER open-label extension (OLE) study.

In the parent FOURIER trial, treatment with the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor over a median of 2.2 years reduced the primary efficacy endpoint by 15% but showed no CV mortality signal, compared with placebo, in patients with atherosclerotic disease on background statin therapy.

Now with follow-up out to 8.4 years – the longest to date in any PCSK9 study – cardiovascular mortality was cut by 23% in patients who remained on evolocumab, compared with those originally assigned to placebo (3.32% vs. 4.45%; hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.99).

The Kaplan-Meier curves during FOURIER were “essentially superimposed and it was not until the open-label extension period had begun with longer-term follow up that the benefit in terms of cardiovascular mortality reduction became apparent,” said principal investigator Michelle O’Donoghue, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The results were reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and published simultaneously in Circulation.

Pivotal statin trials have median follow-up times of 4-5 years and demonstrated both a lag effect, meaning clinical benefit grew over time, and a legacy effect, where clinical benefit persisted in extended follow-up after the parent study, Dr. O’Donoghue observed.

With shorter follow-up in the parent FOURIER trial, there was evidence of a lag effect with the risk reduction in CV death, MI, and stroke increasing from 16% in the first year to 25% over time with evolocumab.

FOURIER-OLE enrolled 6,635 patients (3355 randomly assigned to evolocumab and 3280 to placebo), who completed the parent study and self-injected evolocumab subcutaneously with the choice of 140 mg every 2 weeks or 420 mg monthly. Study visits were at week 12 and then every 24 weeks. Median follow-up was 5 years.

Their mean age was 62 years, three-fourths were men, a third had diabetes. Three-fourths were on a high-intensity statin at the time of enrollment in FOURIER, and median LDL cholesterol at randomization was 91 mg/dL (2.4 mmol/L).

At week 12, the median LDL cholesterol was 30 mg/dL (0.78 mmol/L), and this was sustained throughout follow-up, Dr. O’Donoghue reported. Most patients achieved very low LDL cholesterol levels, with 63.2% achieving levels less than 40 mg/dL (1.04 mmol/L) and 26.6% less than 20 mg/dL (0.52 mmol/L).

Patients randomly assigned in the parent trial to evolocumab versus placebo had a 15% lower risk of the primary outcome of CV death, MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization (15.4% vs. 17.5%; HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.75-0.96).

Their risk of CV death, MI, or stroke was 20% lower (9.7% vs. 11.9%; HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.68-0.93), and, as noted previously, 23% lower for CV death.

When major adverse cardiovascular events data were parsed out by year, the largest LDL cholesterol reduction was in years 1 and 2 of the parent study (delta, 62 mg/dL between treatment arms), “highlighting that lag of benefit that continued to accrue with time,” Dr. O’Donoghue said.

“There was then carryover into the extension period, such that there was legacy effect from the LDL [cholesterol] delta that was seen during the parent study,” she said. “This benefit was most apparent early on during open-label extension and then, as one might expect when all patients were being treated with the same therapy, it began to attenuate somewhat with time.”

Although early studies raised concerns that very low LDL cholesterol may be associated with an increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke and neurocognitive effects, the frequency of adverse events did not increase over time with evolocumab exposure.

Annualized incidence rates for patients initially randomized to evolocumab did not exceed those for placebo-treated patients for any of the following events of interest: serious safety events (10% vs. 13%), hemorrhagic stroke (0.04% vs. 0.05%), new-onset diabetes (1.2% vs. 2.3%), muscle-related events (1.2% vs. 1.9%), injection-site reactions (0.4% vs. 0.7%), and drug-related allergic reactions (0.6% vs. 1.1%).

“Long-term use of evolocumab with a median follow-up of more than 7 years appears both safe and well tolerated,” Dr. O’Donoghue said.

Taken together with the continued accrual of cardiovascular benefit, including CV mortality, “these findings argue for early initiation of a marked and sustained LDL cholesterol reduction to maximize benefit,” she concluded.

Translating the benefits

Ulrich Laufs, MD, Leipzig (Germany) University Hospital, Germany, and invited commentator for the session, said the trial addresses two key issues: the long-term safety of low LDL cholesterol lowering and the long-term safety of inhibiting PCSK9, which is highly expressed not only in the liver but also in the brain, small intestine, and kidneys. Indeed, an LDL cholesterol level below 30 mg/dL is lower than the ESC treatment recommendation for very-high-risk patients and is, in fact, lower than most assays are reliable to interpret.

“So it is very important that we have these very clear data showing us that there were no adverse events, also including cataracts and hemorrhagic stroke, and these were on the level of placebo and did not increase over time,” he said.

The question of efficacy is triggered by observations of another PCSK9, the humanized monoclonal antibody bococizumab, which was associated in the SPIRE trial with an increase in LDL cholesterol over time because of neutralizing antibodies. Reassuringly, there was “completely sustained LDL [cholesterol] reduction” with no neutralizing antibodies with the fully human antibody evolocumab in FOURIER-OLE and in recent data from the OSLER-1 study, Dr. Laufs observed.

Acknowledging the potential for selection bias with an OLE program, Dr. Laufs said there are two important open questions: “Can the safety data observed for extracellular PCSK9 inhibition using an antibody be transferred to other mechanisms of PCSK9 inhibition? And obviously, from the perspective of patient care, how can we implement these important data into patient care and improve access to PCSK9 inhibitors?”

With regard to the latter point, he said physicians should be cautious in using the term “plaque regression,” opting instead for prevention and stabilization of atherosclerosis, and when using the term “legacy,” which may be misinterpreted by patients to imply there was cessation of therapy.

“From my perspective, [what] the open-label extension really shows is that earlier treatment is better,” Dr. Laufs said. “This should be our message.”

In a press conference prior to the presentation, ESC commentator Johann Bauersachs, MD, Hannover (Germany) Medical School, said “this is extremely important data because it confirms that it’s safe, and the criticism of the FOURIER study that mortality, cardiovascular mortality, was not reduced is now also reduced.”

Dr. Bauersachs said it would have been unethical to wait 7 years for a placebo-controlled trial and questioned whether data are available and suggestive of a legacy effect among patients who did not participate in the open-label extension.

Dr. O’Donoghue said unfortunately those data aren’t available but that Kaplan-Meier curves for the primary endpoint in the parent trial continued to diverge over time and that there was somewhat of a lag in terms of that divergence. “So, a median follow-up of 2 years may have been insufficient, especially for the emerging cardiovascular mortality that took longer to appear.”

The study was funded by Amgen. Dr. O’Donoghue reported receiving research grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Intarcia, and Novartis, and consulting fees from Amgen, Novartis, AstraZeneca, and Janssen. Dr. Laufs reported receiving honoraria/reimbursement for lecture, study participation, and scientific cooperation with Saarland or Leipzig University, as well as relationships with multiple pharmaceutical and device makers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-term lipid lowering with evolocumab (Repatha) further reduces cardiovascular events, including CV death, without a safety signal, according to results from the FOURIER open-label extension (OLE) study.

In the parent FOURIER trial, treatment with the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor over a median of 2.2 years reduced the primary efficacy endpoint by 15% but showed no CV mortality signal, compared with placebo, in patients with atherosclerotic disease on background statin therapy.

Now with follow-up out to 8.4 years – the longest to date in any PCSK9 study – cardiovascular mortality was cut by 23% in patients who remained on evolocumab, compared with those originally assigned to placebo (3.32% vs. 4.45%; hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.99).

The Kaplan-Meier curves during FOURIER were “essentially superimposed and it was not until the open-label extension period had begun with longer-term follow up that the benefit in terms of cardiovascular mortality reduction became apparent,” said principal investigator Michelle O’Donoghue, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The results were reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and published simultaneously in Circulation.

Pivotal statin trials have median follow-up times of 4-5 years and demonstrated both a lag effect, meaning clinical benefit grew over time, and a legacy effect, where clinical benefit persisted in extended follow-up after the parent study, Dr. O’Donoghue observed.

With shorter follow-up in the parent FOURIER trial, there was evidence of a lag effect with the risk reduction in CV death, MI, and stroke increasing from 16% in the first year to 25% over time with evolocumab.

FOURIER-OLE enrolled 6,635 patients (3355 randomly assigned to evolocumab and 3280 to placebo), who completed the parent study and self-injected evolocumab subcutaneously with the choice of 140 mg every 2 weeks or 420 mg monthly. Study visits were at week 12 and then every 24 weeks. Median follow-up was 5 years.

Their mean age was 62 years, three-fourths were men, a third had diabetes. Three-fourths were on a high-intensity statin at the time of enrollment in FOURIER, and median LDL cholesterol at randomization was 91 mg/dL (2.4 mmol/L).

At week 12, the median LDL cholesterol was 30 mg/dL (0.78 mmol/L), and this was sustained throughout follow-up, Dr. O’Donoghue reported. Most patients achieved very low LDL cholesterol levels, with 63.2% achieving levels less than 40 mg/dL (1.04 mmol/L) and 26.6% less than 20 mg/dL (0.52 mmol/L).

Patients randomly assigned in the parent trial to evolocumab versus placebo had a 15% lower risk of the primary outcome of CV death, MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization (15.4% vs. 17.5%; HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.75-0.96).

Their risk of CV death, MI, or stroke was 20% lower (9.7% vs. 11.9%; HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.68-0.93), and, as noted previously, 23% lower for CV death.

When major adverse cardiovascular events data were parsed out by year, the largest LDL cholesterol reduction was in years 1 and 2 of the parent study (delta, 62 mg/dL between treatment arms), “highlighting that lag of benefit that continued to accrue with time,” Dr. O’Donoghue said.

“There was then carryover into the extension period, such that there was legacy effect from the LDL [cholesterol] delta that was seen during the parent study,” she said. “This benefit was most apparent early on during open-label extension and then, as one might expect when all patients were being treated with the same therapy, it began to attenuate somewhat with time.”

Although early studies raised concerns that very low LDL cholesterol may be associated with an increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke and neurocognitive effects, the frequency of adverse events did not increase over time with evolocumab exposure.

Annualized incidence rates for patients initially randomized to evolocumab did not exceed those for placebo-treated patients for any of the following events of interest: serious safety events (10% vs. 13%), hemorrhagic stroke (0.04% vs. 0.05%), new-onset diabetes (1.2% vs. 2.3%), muscle-related events (1.2% vs. 1.9%), injection-site reactions (0.4% vs. 0.7%), and drug-related allergic reactions (0.6% vs. 1.1%).

“Long-term use of evolocumab with a median follow-up of more than 7 years appears both safe and well tolerated,” Dr. O’Donoghue said.

Taken together with the continued accrual of cardiovascular benefit, including CV mortality, “these findings argue for early initiation of a marked and sustained LDL cholesterol reduction to maximize benefit,” she concluded.

Translating the benefits

Ulrich Laufs, MD, Leipzig (Germany) University Hospital, Germany, and invited commentator for the session, said the trial addresses two key issues: the long-term safety of low LDL cholesterol lowering and the long-term safety of inhibiting PCSK9, which is highly expressed not only in the liver but also in the brain, small intestine, and kidneys. Indeed, an LDL cholesterol level below 30 mg/dL is lower than the ESC treatment recommendation for very-high-risk patients and is, in fact, lower than most assays are reliable to interpret.

“So it is very important that we have these very clear data showing us that there were no adverse events, also including cataracts and hemorrhagic stroke, and these were on the level of placebo and did not increase over time,” he said.

The question of efficacy is triggered by observations of another PCSK9, the humanized monoclonal antibody bococizumab, which was associated in the SPIRE trial with an increase in LDL cholesterol over time because of neutralizing antibodies. Reassuringly, there was “completely sustained LDL [cholesterol] reduction” with no neutralizing antibodies with the fully human antibody evolocumab in FOURIER-OLE and in recent data from the OSLER-1 study, Dr. Laufs observed.

Acknowledging the potential for selection bias with an OLE program, Dr. Laufs said there are two important open questions: “Can the safety data observed for extracellular PCSK9 inhibition using an antibody be transferred to other mechanisms of PCSK9 inhibition? And obviously, from the perspective of patient care, how can we implement these important data into patient care and improve access to PCSK9 inhibitors?”

With regard to the latter point, he said physicians should be cautious in using the term “plaque regression,” opting instead for prevention and stabilization of atherosclerosis, and when using the term “legacy,” which may be misinterpreted by patients to imply there was cessation of therapy.

“From my perspective, [what] the open-label extension really shows is that earlier treatment is better,” Dr. Laufs said. “This should be our message.”

In a press conference prior to the presentation, ESC commentator Johann Bauersachs, MD, Hannover (Germany) Medical School, said “this is extremely important data because it confirms that it’s safe, and the criticism of the FOURIER study that mortality, cardiovascular mortality, was not reduced is now also reduced.”

Dr. Bauersachs said it would have been unethical to wait 7 years for a placebo-controlled trial and questioned whether data are available and suggestive of a legacy effect among patients who did not participate in the open-label extension.

Dr. O’Donoghue said unfortunately those data aren’t available but that Kaplan-Meier curves for the primary endpoint in the parent trial continued to diverge over time and that there was somewhat of a lag in terms of that divergence. “So, a median follow-up of 2 years may have been insufficient, especially for the emerging cardiovascular mortality that took longer to appear.”

The study was funded by Amgen. Dr. O’Donoghue reported receiving research grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Intarcia, and Novartis, and consulting fees from Amgen, Novartis, AstraZeneca, and Janssen. Dr. Laufs reported receiving honoraria/reimbursement for lecture, study participation, and scientific cooperation with Saarland or Leipzig University, as well as relationships with multiple pharmaceutical and device makers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-term lipid lowering with evolocumab (Repatha) further reduces cardiovascular events, including CV death, without a safety signal, according to results from the FOURIER open-label extension (OLE) study.

In the parent FOURIER trial, treatment with the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor over a median of 2.2 years reduced the primary efficacy endpoint by 15% but showed no CV mortality signal, compared with placebo, in patients with atherosclerotic disease on background statin therapy.

Now with follow-up out to 8.4 years – the longest to date in any PCSK9 study – cardiovascular mortality was cut by 23% in patients who remained on evolocumab, compared with those originally assigned to placebo (3.32% vs. 4.45%; hazard ratio, 0.77; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.99).

The Kaplan-Meier curves during FOURIER were “essentially superimposed and it was not until the open-label extension period had begun with longer-term follow up that the benefit in terms of cardiovascular mortality reduction became apparent,” said principal investigator Michelle O’Donoghue, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The results were reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and published simultaneously in Circulation.

Pivotal statin trials have median follow-up times of 4-5 years and demonstrated both a lag effect, meaning clinical benefit grew over time, and a legacy effect, where clinical benefit persisted in extended follow-up after the parent study, Dr. O’Donoghue observed.

With shorter follow-up in the parent FOURIER trial, there was evidence of a lag effect with the risk reduction in CV death, MI, and stroke increasing from 16% in the first year to 25% over time with evolocumab.

FOURIER-OLE enrolled 6,635 patients (3355 randomly assigned to evolocumab and 3280 to placebo), who completed the parent study and self-injected evolocumab subcutaneously with the choice of 140 mg every 2 weeks or 420 mg monthly. Study visits were at week 12 and then every 24 weeks. Median follow-up was 5 years.

Their mean age was 62 years, three-fourths were men, a third had diabetes. Three-fourths were on a high-intensity statin at the time of enrollment in FOURIER, and median LDL cholesterol at randomization was 91 mg/dL (2.4 mmol/L).

At week 12, the median LDL cholesterol was 30 mg/dL (0.78 mmol/L), and this was sustained throughout follow-up, Dr. O’Donoghue reported. Most patients achieved very low LDL cholesterol levels, with 63.2% achieving levels less than 40 mg/dL (1.04 mmol/L) and 26.6% less than 20 mg/dL (0.52 mmol/L).

Patients randomly assigned in the parent trial to evolocumab versus placebo had a 15% lower risk of the primary outcome of CV death, MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization (15.4% vs. 17.5%; HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.75-0.96).

Their risk of CV death, MI, or stroke was 20% lower (9.7% vs. 11.9%; HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.68-0.93), and, as noted previously, 23% lower for CV death.

When major adverse cardiovascular events data were parsed out by year, the largest LDL cholesterol reduction was in years 1 and 2 of the parent study (delta, 62 mg/dL between treatment arms), “highlighting that lag of benefit that continued to accrue with time,” Dr. O’Donoghue said.

“There was then carryover into the extension period, such that there was legacy effect from the LDL [cholesterol] delta that was seen during the parent study,” she said. “This benefit was most apparent early on during open-label extension and then, as one might expect when all patients were being treated with the same therapy, it began to attenuate somewhat with time.”

Although early studies raised concerns that very low LDL cholesterol may be associated with an increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke and neurocognitive effects, the frequency of adverse events did not increase over time with evolocumab exposure.

Annualized incidence rates for patients initially randomized to evolocumab did not exceed those for placebo-treated patients for any of the following events of interest: serious safety events (10% vs. 13%), hemorrhagic stroke (0.04% vs. 0.05%), new-onset diabetes (1.2% vs. 2.3%), muscle-related events (1.2% vs. 1.9%), injection-site reactions (0.4% vs. 0.7%), and drug-related allergic reactions (0.6% vs. 1.1%).

“Long-term use of evolocumab with a median follow-up of more than 7 years appears both safe and well tolerated,” Dr. O’Donoghue said.

Taken together with the continued accrual of cardiovascular benefit, including CV mortality, “these findings argue for early initiation of a marked and sustained LDL cholesterol reduction to maximize benefit,” she concluded.

Translating the benefits

Ulrich Laufs, MD, Leipzig (Germany) University Hospital, Germany, and invited commentator for the session, said the trial addresses two key issues: the long-term safety of low LDL cholesterol lowering and the long-term safety of inhibiting PCSK9, which is highly expressed not only in the liver but also in the brain, small intestine, and kidneys. Indeed, an LDL cholesterol level below 30 mg/dL is lower than the ESC treatment recommendation for very-high-risk patients and is, in fact, lower than most assays are reliable to interpret.

“So it is very important that we have these very clear data showing us that there were no adverse events, also including cataracts and hemorrhagic stroke, and these were on the level of placebo and did not increase over time,” he said.

The question of efficacy is triggered by observations of another PCSK9, the humanized monoclonal antibody bococizumab, which was associated in the SPIRE trial with an increase in LDL cholesterol over time because of neutralizing antibodies. Reassuringly, there was “completely sustained LDL [cholesterol] reduction” with no neutralizing antibodies with the fully human antibody evolocumab in FOURIER-OLE and in recent data from the OSLER-1 study, Dr. Laufs observed.

Acknowledging the potential for selection bias with an OLE program, Dr. Laufs said there are two important open questions: “Can the safety data observed for extracellular PCSK9 inhibition using an antibody be transferred to other mechanisms of PCSK9 inhibition? And obviously, from the perspective of patient care, how can we implement these important data into patient care and improve access to PCSK9 inhibitors?”

With regard to the latter point, he said physicians should be cautious in using the term “plaque regression,” opting instead for prevention and stabilization of atherosclerosis, and when using the term “legacy,” which may be misinterpreted by patients to imply there was cessation of therapy.

“From my perspective, [what] the open-label extension really shows is that earlier treatment is better,” Dr. Laufs said. “This should be our message.”

In a press conference prior to the presentation, ESC commentator Johann Bauersachs, MD, Hannover (Germany) Medical School, said “this is extremely important data because it confirms that it’s safe, and the criticism of the FOURIER study that mortality, cardiovascular mortality, was not reduced is now also reduced.”

Dr. Bauersachs said it would have been unethical to wait 7 years for a placebo-controlled trial and questioned whether data are available and suggestive of a legacy effect among patients who did not participate in the open-label extension.

Dr. O’Donoghue said unfortunately those data aren’t available but that Kaplan-Meier curves for the primary endpoint in the parent trial continued to diverge over time and that there was somewhat of a lag in terms of that divergence. “So, a median follow-up of 2 years may have been insufficient, especially for the emerging cardiovascular mortality that took longer to appear.”

The study was funded by Amgen. Dr. O’Donoghue reported receiving research grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Intarcia, and Novartis, and consulting fees from Amgen, Novartis, AstraZeneca, and Janssen. Dr. Laufs reported receiving honoraria/reimbursement for lecture, study participation, and scientific cooperation with Saarland or Leipzig University, as well as relationships with multiple pharmaceutical and device makers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2022

New ovulatory disorder classifications from FIGO replace 50-year-old system

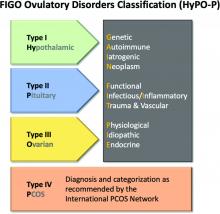

The first major revision in the systematic description of ovulatory disorders in nearly 50 years has been proposed by a consensus of experts organized by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

“The FIGO HyPO-P system for the classification of ovulatory disorders is submitted for consideration as a worldwide standard,” according to the writing committee, who published their methodology and their proposed applications in the International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

The classification system was created to replace the much-modified World Health Organization system first described in 1973. Since that time, many modifications have been proposed to accommodate advances in imaging and new information about underlying pathologies, but there has been no subsequent authoritative reference with these modifications or any other newer organizing system.

The new consensus was developed under the aegis of FIGO, but the development group consisted of representatives from national organizations and the major subspecialty societies. Recognized experts in ovulatory disorders and representatives from lay advocacy organizations also participated.

The HyPO-P system is based largely on anatomy. The acronym refers to ovulatory disorders related to the hypothalamus (type I), the pituitary (type II), and the ovary (type III).

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the most common ovulatory disorders, was given a separate category (type IV) because of its complexity as well as the fact that PCOS is a heterogeneous systemic disorder with manifestations not limited to an impact on ovarian function.

As the first level of classification, three of the four primary categories (I-III) focus attention on the dominant anatomic source of the change in ovulatory function. The original WHO classification system identified as many as seven major groups, but they were based primarily on assays for gonadotropins and estradiol.

The new system “provides a different structure for determining the diagnosis. Blood tests are not a necessary first step,” explained Malcolm G. Munro, MD, clinical professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Munro was the first author of the publication.

The classification system “is not as focused on the specific steps for investigation of ovulatory dysfunction as much as it explains how to structure an investigation of the girl or woman with an ovulatory disorder and then how to characterize the underlying cause,” Dr. Munro said in an interview. “It is designed to allow everyone, whether clinicians, researchers, or patients, to speak the same language.”

New system employs four categories

The four primary categories provide just the first level of classification. The next step is encapsulated in the GAIN-FIT-PIE acronym, which frames the presumed or documented categories of etiologies for the primary categories. GAIN stands for genetic, autoimmune, iatrogenic, or neoplasm etiologies. FIT stands for functional, infectious/inflammatory, or trauma and vascular etiologies. PIE stands for physiological, idiopathic, and endocrine etiologies.

By this methodology, a patient with irregular menses, galactorrhea, and elevated prolactin and an MRI showing a pituitary tumor would be identified a type 2-N, signifying pituitary (type 2) involvement with a neoplasm (N).

A third level of classification permits specific diagnostic entities to be named, allowing the patient in the example above to receive a diagnosis of a prolactin-secreting adenoma.

Not all etiologies can be identified with current diagnostic studies, even assuming clinicians have access to the resources, such as advanced imaging, that will increase diagnostic yield. As a result, the authors acknowledged that the classification system will be “aspirational” in at least some patients, but the structure of this system is expected to lead to greater precision in understanding the causes and defining features of ovulatory disorders, which, in turn, might facilitate new research initiatives.

In the published report, diagnostic protocols based on symptoms were described as being “beyond the spectrum” of this initial description. Rather, Dr. Munro explained that the most important contribution of this new classification system are standardization and communication. The system will be amenable for educating trainees and patients, for communicating between clinicians, and as a framework for research where investigators focus on more homogeneous populations of patients.

“There are many causes of ovulatory disorders that are not related to ovarian function. This is one message. Another is that ovulatory disorders are not binary. They occur on a spectrum. These range from transient instances of delayed or failed ovulation to chronic anovulation,” he said.

The new system is “ a welcome update,” according to Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of the IVF Center and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, both in Orlando.

Dr. Trolice pointed to the clinical value of placing PCOS in a separate category. He noted that it affects 8%-13% of women, making it the most common single cause of ovulatory dysfunction.

“Another area that required clarification from prior WHO classifications was hyperprolactinemia, which is now placed in the type II category,” Dr. Trolice said in an interview.

Better terminology can help address a complex set of disorders with multiple causes and variable manifestations.

“In the evaluation of ovulation dysfunction, it is important to remember that regular menstrual intervals do not ensure ovulation,” Dr. Trolice pointed out. Even though a serum progesterone level of higher than 3 ng/mL is one of the simplest laboratory markers for ovulation, this level, he noted, “can vary through the luteal phase and even throughout the day.”

The proposed classification system, while providing a framework for describing ovulatory disorders, is designed to be adaptable, permitting advances in the understanding of the causes of ovulatory dysfunction, in the diagnosis of the causes, and in the treatments to be incorporated.

“No system should be considered permanent,” according to Dr. Munro and his coauthors. “Review and careful modification and revision should be carried out regularly.”

Dr. Munro reports financial relationships with AbbVie, American Regent, Daiichi Sankyo, Hologic, Myovant, and Pharmacosmos. Dr. Trolice reports no potential conflicts of interest.

The first major revision in the systematic description of ovulatory disorders in nearly 50 years has been proposed by a consensus of experts organized by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

“The FIGO HyPO-P system for the classification of ovulatory disorders is submitted for consideration as a worldwide standard,” according to the writing committee, who published their methodology and their proposed applications in the International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

The classification system was created to replace the much-modified World Health Organization system first described in 1973. Since that time, many modifications have been proposed to accommodate advances in imaging and new information about underlying pathologies, but there has been no subsequent authoritative reference with these modifications or any other newer organizing system.

The new consensus was developed under the aegis of FIGO, but the development group consisted of representatives from national organizations and the major subspecialty societies. Recognized experts in ovulatory disorders and representatives from lay advocacy organizations also participated.

The HyPO-P system is based largely on anatomy. The acronym refers to ovulatory disorders related to the hypothalamus (type I), the pituitary (type II), and the ovary (type III).

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the most common ovulatory disorders, was given a separate category (type IV) because of its complexity as well as the fact that PCOS is a heterogeneous systemic disorder with manifestations not limited to an impact on ovarian function.

As the first level of classification, three of the four primary categories (I-III) focus attention on the dominant anatomic source of the change in ovulatory function. The original WHO classification system identified as many as seven major groups, but they were based primarily on assays for gonadotropins and estradiol.

The new system “provides a different structure for determining the diagnosis. Blood tests are not a necessary first step,” explained Malcolm G. Munro, MD, clinical professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Munro was the first author of the publication.

The classification system “is not as focused on the specific steps for investigation of ovulatory dysfunction as much as it explains how to structure an investigation of the girl or woman with an ovulatory disorder and then how to characterize the underlying cause,” Dr. Munro said in an interview. “It is designed to allow everyone, whether clinicians, researchers, or patients, to speak the same language.”

New system employs four categories

The four primary categories provide just the first level of classification. The next step is encapsulated in the GAIN-FIT-PIE acronym, which frames the presumed or documented categories of etiologies for the primary categories. GAIN stands for genetic, autoimmune, iatrogenic, or neoplasm etiologies. FIT stands for functional, infectious/inflammatory, or trauma and vascular etiologies. PIE stands for physiological, idiopathic, and endocrine etiologies.

By this methodology, a patient with irregular menses, galactorrhea, and elevated prolactin and an MRI showing a pituitary tumor would be identified a type 2-N, signifying pituitary (type 2) involvement with a neoplasm (N).

A third level of classification permits specific diagnostic entities to be named, allowing the patient in the example above to receive a diagnosis of a prolactin-secreting adenoma.

Not all etiologies can be identified with current diagnostic studies, even assuming clinicians have access to the resources, such as advanced imaging, that will increase diagnostic yield. As a result, the authors acknowledged that the classification system will be “aspirational” in at least some patients, but the structure of this system is expected to lead to greater precision in understanding the causes and defining features of ovulatory disorders, which, in turn, might facilitate new research initiatives.

In the published report, diagnostic protocols based on symptoms were described as being “beyond the spectrum” of this initial description. Rather, Dr. Munro explained that the most important contribution of this new classification system are standardization and communication. The system will be amenable for educating trainees and patients, for communicating between clinicians, and as a framework for research where investigators focus on more homogeneous populations of patients.

“There are many causes of ovulatory disorders that are not related to ovarian function. This is one message. Another is that ovulatory disorders are not binary. They occur on a spectrum. These range from transient instances of delayed or failed ovulation to chronic anovulation,” he said.

The new system is “ a welcome update,” according to Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of the IVF Center and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, both in Orlando.

Dr. Trolice pointed to the clinical value of placing PCOS in a separate category. He noted that it affects 8%-13% of women, making it the most common single cause of ovulatory dysfunction.

“Another area that required clarification from prior WHO classifications was hyperprolactinemia, which is now placed in the type II category,” Dr. Trolice said in an interview.

Better terminology can help address a complex set of disorders with multiple causes and variable manifestations.

“In the evaluation of ovulation dysfunction, it is important to remember that regular menstrual intervals do not ensure ovulation,” Dr. Trolice pointed out. Even though a serum progesterone level of higher than 3 ng/mL is one of the simplest laboratory markers for ovulation, this level, he noted, “can vary through the luteal phase and even throughout the day.”

The proposed classification system, while providing a framework for describing ovulatory disorders, is designed to be adaptable, permitting advances in the understanding of the causes of ovulatory dysfunction, in the diagnosis of the causes, and in the treatments to be incorporated.

“No system should be considered permanent,” according to Dr. Munro and his coauthors. “Review and careful modification and revision should be carried out regularly.”

Dr. Munro reports financial relationships with AbbVie, American Regent, Daiichi Sankyo, Hologic, Myovant, and Pharmacosmos. Dr. Trolice reports no potential conflicts of interest.

The first major revision in the systematic description of ovulatory disorders in nearly 50 years has been proposed by a consensus of experts organized by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

“The FIGO HyPO-P system for the classification of ovulatory disorders is submitted for consideration as a worldwide standard,” according to the writing committee, who published their methodology and their proposed applications in the International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

The classification system was created to replace the much-modified World Health Organization system first described in 1973. Since that time, many modifications have been proposed to accommodate advances in imaging and new information about underlying pathologies, but there has been no subsequent authoritative reference with these modifications or any other newer organizing system.

The new consensus was developed under the aegis of FIGO, but the development group consisted of representatives from national organizations and the major subspecialty societies. Recognized experts in ovulatory disorders and representatives from lay advocacy organizations also participated.

The HyPO-P system is based largely on anatomy. The acronym refers to ovulatory disorders related to the hypothalamus (type I), the pituitary (type II), and the ovary (type III).

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the most common ovulatory disorders, was given a separate category (type IV) because of its complexity as well as the fact that PCOS is a heterogeneous systemic disorder with manifestations not limited to an impact on ovarian function.

As the first level of classification, three of the four primary categories (I-III) focus attention on the dominant anatomic source of the change in ovulatory function. The original WHO classification system identified as many as seven major groups, but they were based primarily on assays for gonadotropins and estradiol.

The new system “provides a different structure for determining the diagnosis. Blood tests are not a necessary first step,” explained Malcolm G. Munro, MD, clinical professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Munro was the first author of the publication.

The classification system “is not as focused on the specific steps for investigation of ovulatory dysfunction as much as it explains how to structure an investigation of the girl or woman with an ovulatory disorder and then how to characterize the underlying cause,” Dr. Munro said in an interview. “It is designed to allow everyone, whether clinicians, researchers, or patients, to speak the same language.”

New system employs four categories

The four primary categories provide just the first level of classification. The next step is encapsulated in the GAIN-FIT-PIE acronym, which frames the presumed or documented categories of etiologies for the primary categories. GAIN stands for genetic, autoimmune, iatrogenic, or neoplasm etiologies. FIT stands for functional, infectious/inflammatory, or trauma and vascular etiologies. PIE stands for physiological, idiopathic, and endocrine etiologies.

By this methodology, a patient with irregular menses, galactorrhea, and elevated prolactin and an MRI showing a pituitary tumor would be identified a type 2-N, signifying pituitary (type 2) involvement with a neoplasm (N).

A third level of classification permits specific diagnostic entities to be named, allowing the patient in the example above to receive a diagnosis of a prolactin-secreting adenoma.

Not all etiologies can be identified with current diagnostic studies, even assuming clinicians have access to the resources, such as advanced imaging, that will increase diagnostic yield. As a result, the authors acknowledged that the classification system will be “aspirational” in at least some patients, but the structure of this system is expected to lead to greater precision in understanding the causes and defining features of ovulatory disorders, which, in turn, might facilitate new research initiatives.

In the published report, diagnostic protocols based on symptoms were described as being “beyond the spectrum” of this initial description. Rather, Dr. Munro explained that the most important contribution of this new classification system are standardization and communication. The system will be amenable for educating trainees and patients, for communicating between clinicians, and as a framework for research where investigators focus on more homogeneous populations of patients.

“There are many causes of ovulatory disorders that are not related to ovarian function. This is one message. Another is that ovulatory disorders are not binary. They occur on a spectrum. These range from transient instances of delayed or failed ovulation to chronic anovulation,” he said.

The new system is “ a welcome update,” according to Mark P. Trolice, MD, director of the IVF Center and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, both in Orlando.

Dr. Trolice pointed to the clinical value of placing PCOS in a separate category. He noted that it affects 8%-13% of women, making it the most common single cause of ovulatory dysfunction.

“Another area that required clarification from prior WHO classifications was hyperprolactinemia, which is now placed in the type II category,” Dr. Trolice said in an interview.

Better terminology can help address a complex set of disorders with multiple causes and variable manifestations.

“In the evaluation of ovulation dysfunction, it is important to remember that regular menstrual intervals do not ensure ovulation,” Dr. Trolice pointed out. Even though a serum progesterone level of higher than 3 ng/mL is one of the simplest laboratory markers for ovulation, this level, he noted, “can vary through the luteal phase and even throughout the day.”

The proposed classification system, while providing a framework for describing ovulatory disorders, is designed to be adaptable, permitting advances in the understanding of the causes of ovulatory dysfunction, in the diagnosis of the causes, and in the treatments to be incorporated.

“No system should be considered permanent,” according to Dr. Munro and his coauthors. “Review and careful modification and revision should be carried out regularly.”

Dr. Munro reports financial relationships with AbbVie, American Regent, Daiichi Sankyo, Hologic, Myovant, and Pharmacosmos. Dr. Trolice reports no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF GYNECOLOGY AND OBSTETRICS

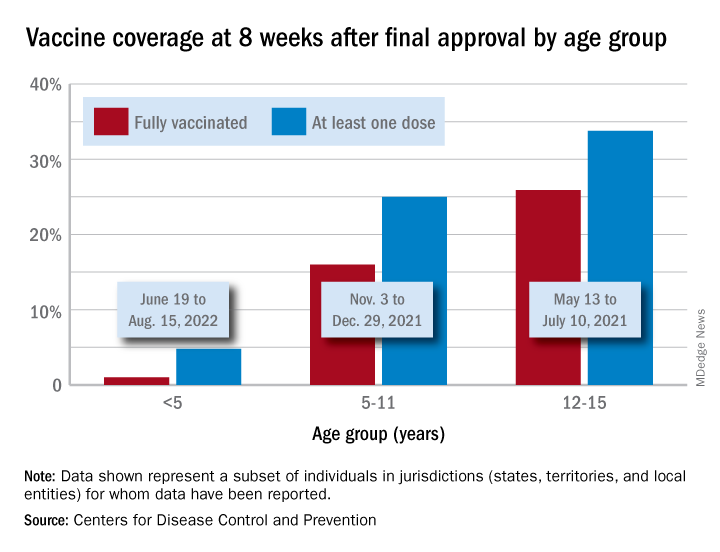

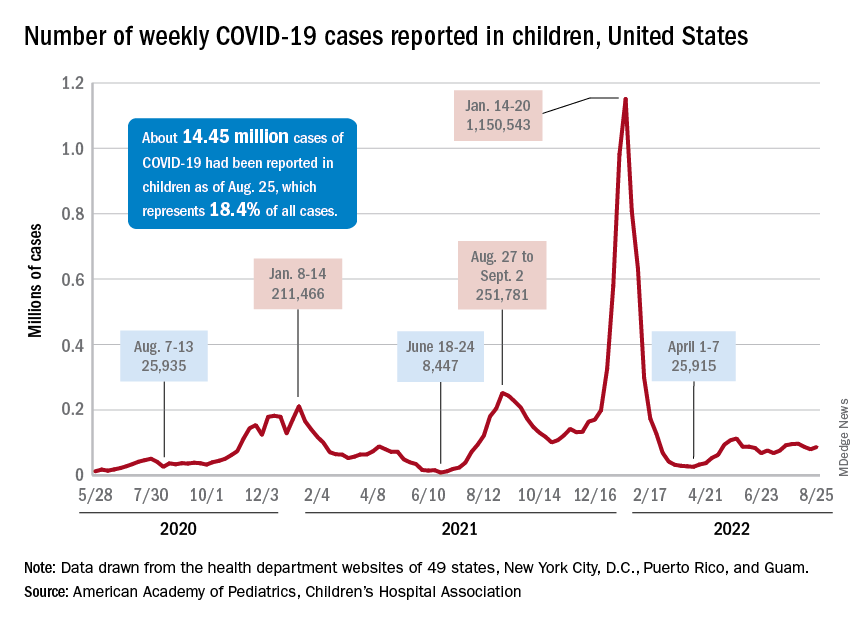

Children and COVID: New cases increase; hospital admissions could follow

New cases of COVID-19 in children were up again after 2 weeks of declines, and preliminary data suggest that hospitalizations may be on the rise as well.

, based on data collected by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association from state and territorial health departments.

A similar increase seems to be reflected by hospital-level data. The latest 7-day (Aug. 21-27) average is 305 new admissions with diagnosed COVID per day among children aged 0-17 years, compared with 290 per day for the week of Aug. 14-20, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported, while also noting the potential for reporting delays in the most recent 7-day period.

Daily hospital admissions for COVID had been headed downward through the first half of August, falling from 0.46 per 100,000 population at the end of July to 0.40 on Aug. 19, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Since then, however, admissions have gone the other way, with the preliminary nature of the latest data suggesting that the numbers will be even higher as more hospitals report over the next few days.

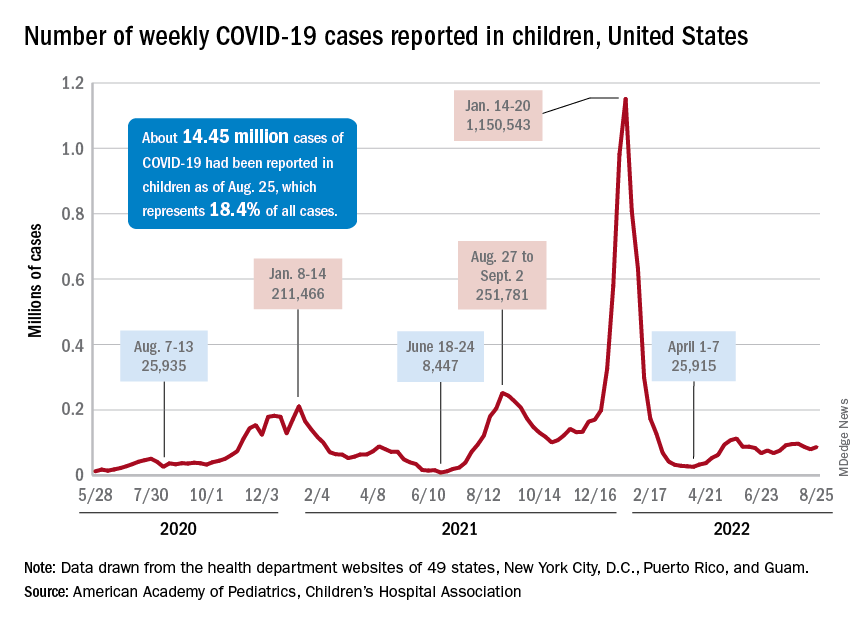

Vaccine initiations continue to fall

Initiations among school-age children have fallen for 3 consecutive weeks since Aug. 3, when numbers receiving their first vaccinations reached late-summer highs for those aged 5-11 and 12-17 years. Children under age 5, included in the CDC data for the first time on Aug. 11 as separate groups – under 2 years and 2-4 years – have had vaccine initiations drop by 8.0% and 19.8% over the 2 following weeks, the CDC said.

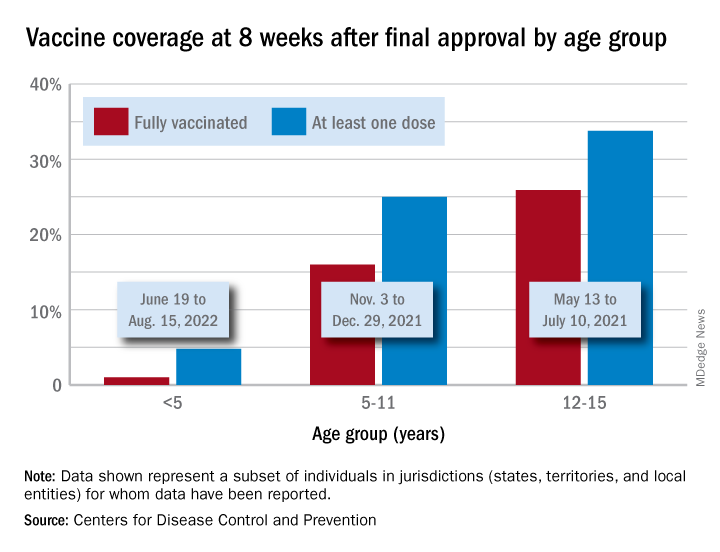

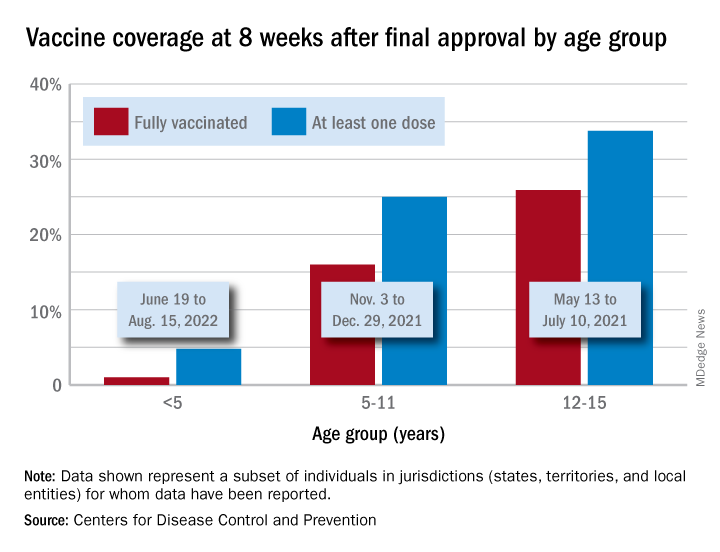

Through their first 8 weeks of vaccine eligibility (June 19 to Aug. 15), 4.8% of children under 5 years of age had received a first vaccination and 1.0% were fully vaccinated. For the two other age groups (5-11 and 12-15) who became eligible after the very first emergency authorization back in 2020, the respective proportions were 25.0% and 16.0% (5-11) and 33.8% and 26.1% (12-15) through the first 8 weeks, according to CDC data.

New cases of COVID-19 in children were up again after 2 weeks of declines, and preliminary data suggest that hospitalizations may be on the rise as well.

, based on data collected by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association from state and territorial health departments.

A similar increase seems to be reflected by hospital-level data. The latest 7-day (Aug. 21-27) average is 305 new admissions with diagnosed COVID per day among children aged 0-17 years, compared with 290 per day for the week of Aug. 14-20, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported, while also noting the potential for reporting delays in the most recent 7-day period.

Daily hospital admissions for COVID had been headed downward through the first half of August, falling from 0.46 per 100,000 population at the end of July to 0.40 on Aug. 19, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Since then, however, admissions have gone the other way, with the preliminary nature of the latest data suggesting that the numbers will be even higher as more hospitals report over the next few days.

Vaccine initiations continue to fall

Initiations among school-age children have fallen for 3 consecutive weeks since Aug. 3, when numbers receiving their first vaccinations reached late-summer highs for those aged 5-11 and 12-17 years. Children under age 5, included in the CDC data for the first time on Aug. 11 as separate groups – under 2 years and 2-4 years – have had vaccine initiations drop by 8.0% and 19.8% over the 2 following weeks, the CDC said.

Through their first 8 weeks of vaccine eligibility (June 19 to Aug. 15), 4.8% of children under 5 years of age had received a first vaccination and 1.0% were fully vaccinated. For the two other age groups (5-11 and 12-15) who became eligible after the very first emergency authorization back in 2020, the respective proportions were 25.0% and 16.0% (5-11) and 33.8% and 26.1% (12-15) through the first 8 weeks, according to CDC data.

New cases of COVID-19 in children were up again after 2 weeks of declines, and preliminary data suggest that hospitalizations may be on the rise as well.

, based on data collected by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association from state and territorial health departments.

A similar increase seems to be reflected by hospital-level data. The latest 7-day (Aug. 21-27) average is 305 new admissions with diagnosed COVID per day among children aged 0-17 years, compared with 290 per day for the week of Aug. 14-20, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported, while also noting the potential for reporting delays in the most recent 7-day period.

Daily hospital admissions for COVID had been headed downward through the first half of August, falling from 0.46 per 100,000 population at the end of July to 0.40 on Aug. 19, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Since then, however, admissions have gone the other way, with the preliminary nature of the latest data suggesting that the numbers will be even higher as more hospitals report over the next few days.

Vaccine initiations continue to fall

Initiations among school-age children have fallen for 3 consecutive weeks since Aug. 3, when numbers receiving their first vaccinations reached late-summer highs for those aged 5-11 and 12-17 years. Children under age 5, included in the CDC data for the first time on Aug. 11 as separate groups – under 2 years and 2-4 years – have had vaccine initiations drop by 8.0% and 19.8% over the 2 following weeks, the CDC said.

Through their first 8 weeks of vaccine eligibility (June 19 to Aug. 15), 4.8% of children under 5 years of age had received a first vaccination and 1.0% were fully vaccinated. For the two other age groups (5-11 and 12-15) who became eligible after the very first emergency authorization back in 2020, the respective proportions were 25.0% and 16.0% (5-11) and 33.8% and 26.1% (12-15) through the first 8 weeks, according to CDC data.