User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

White Spots on the Extremities

The Diagnosis: Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

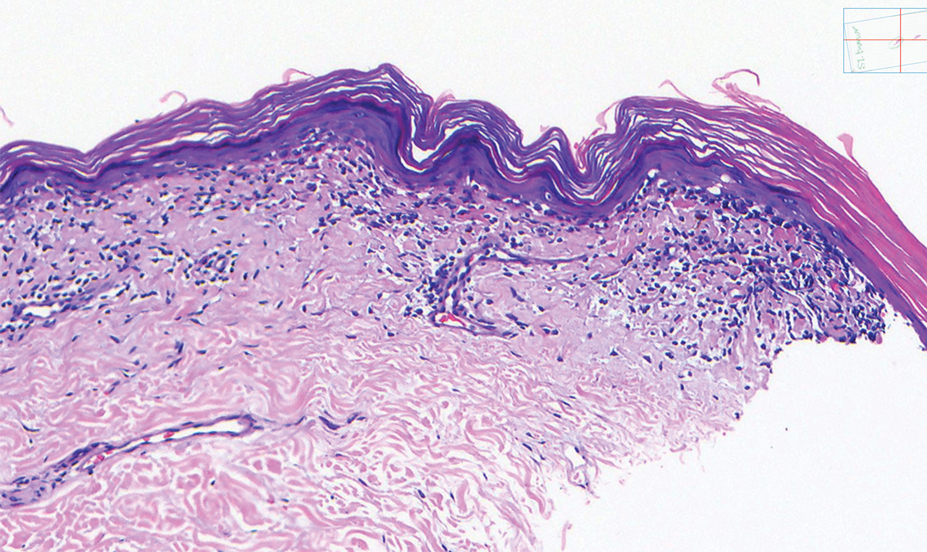

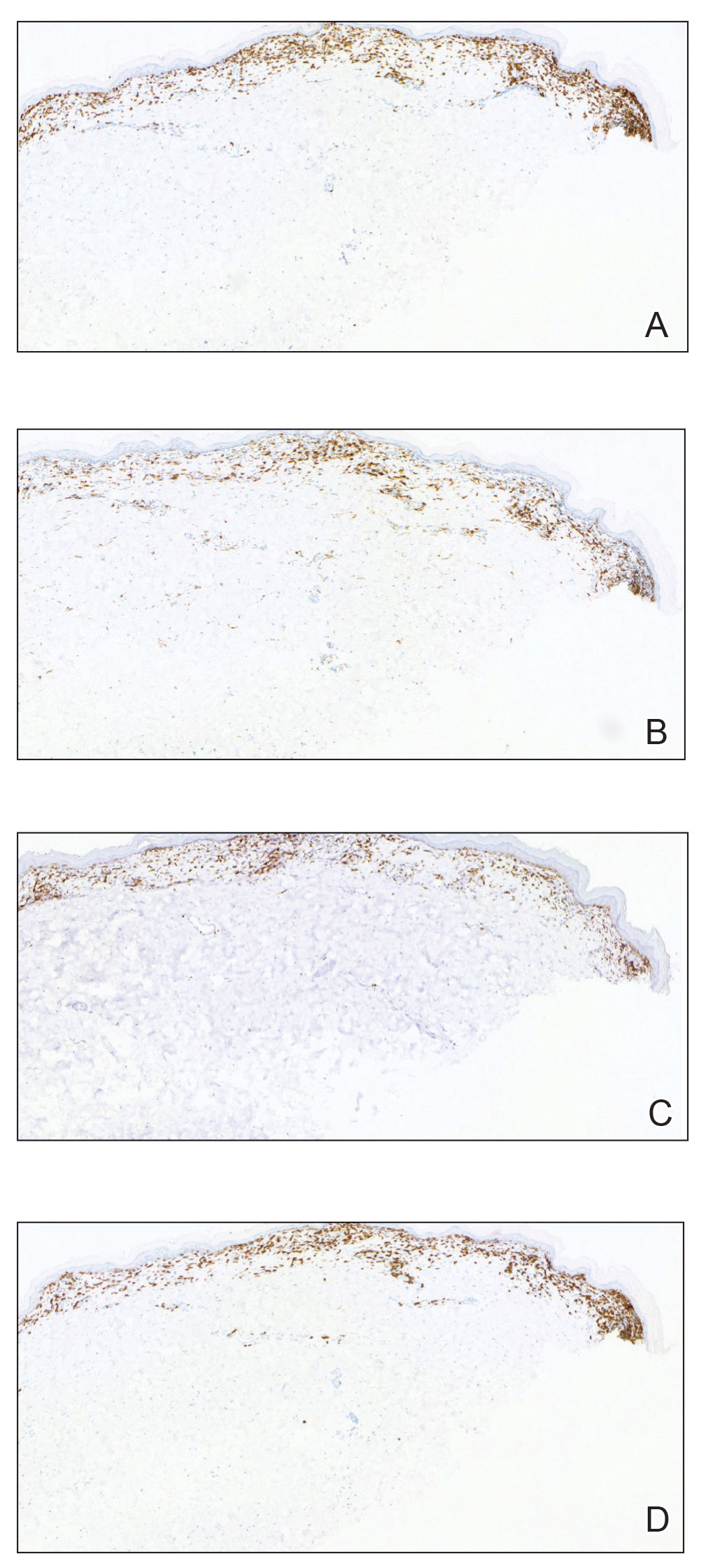

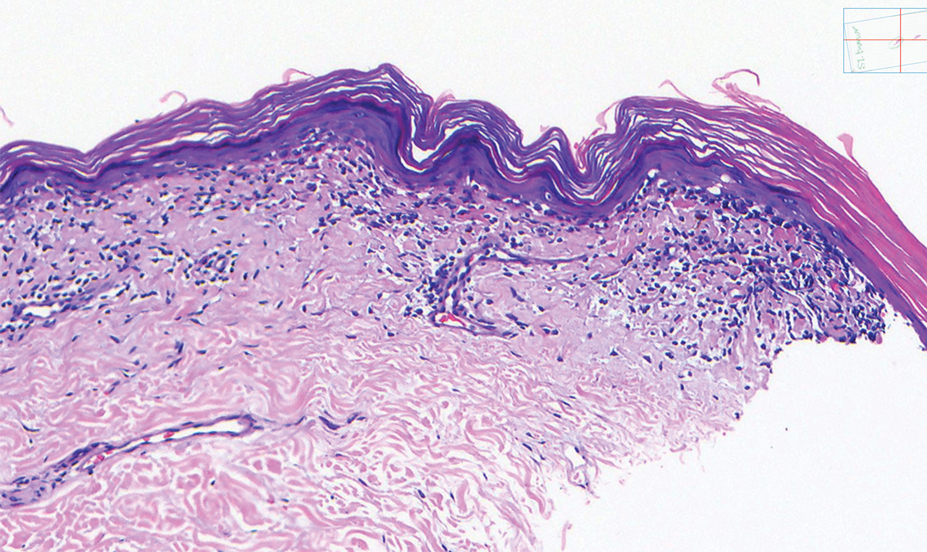

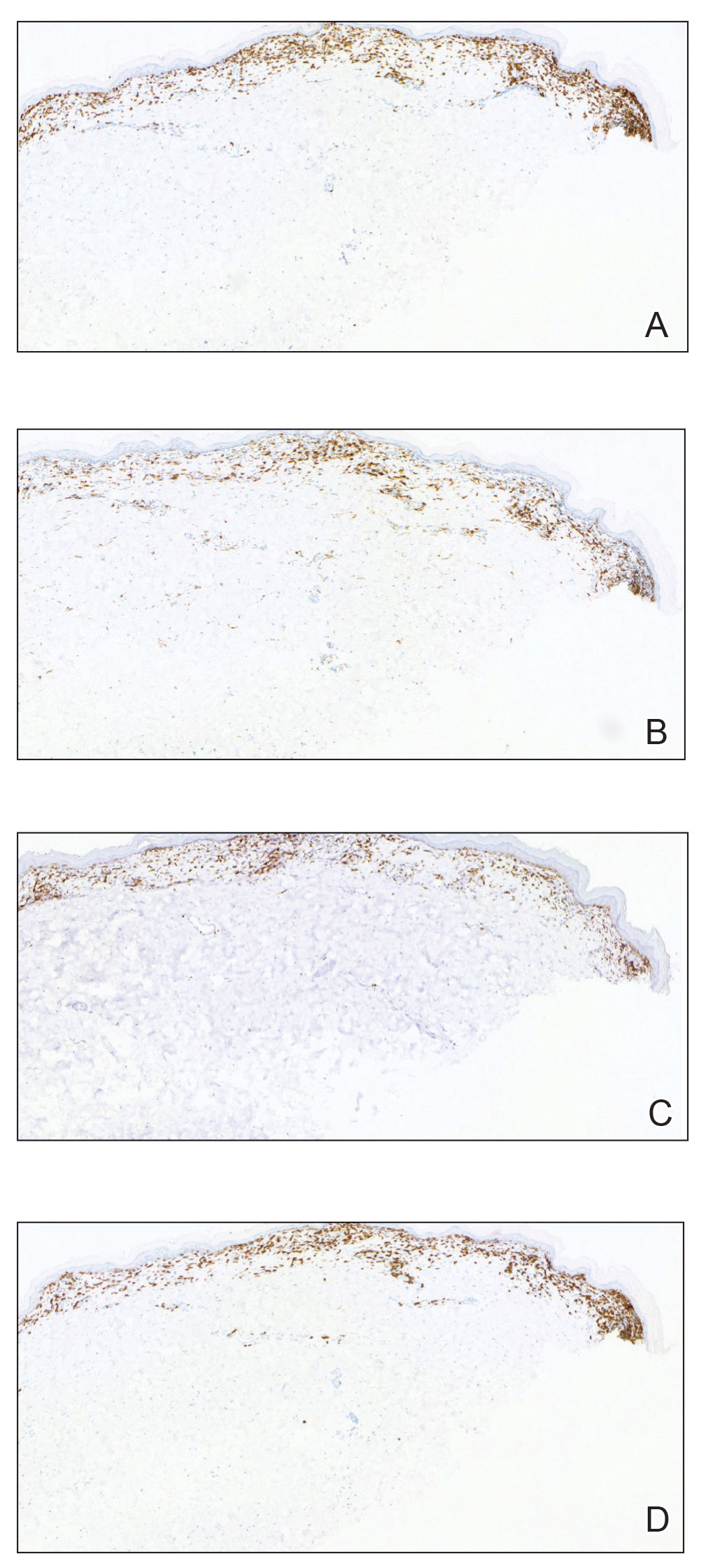

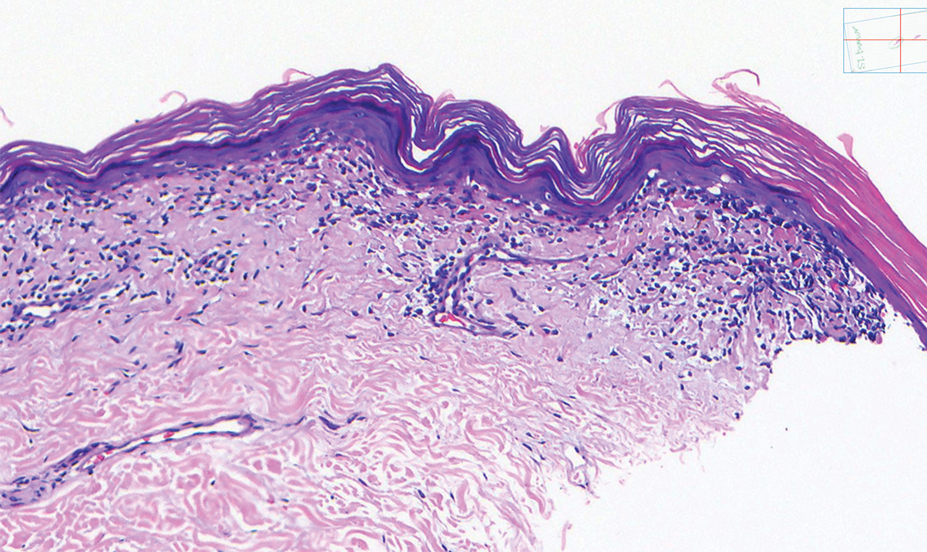

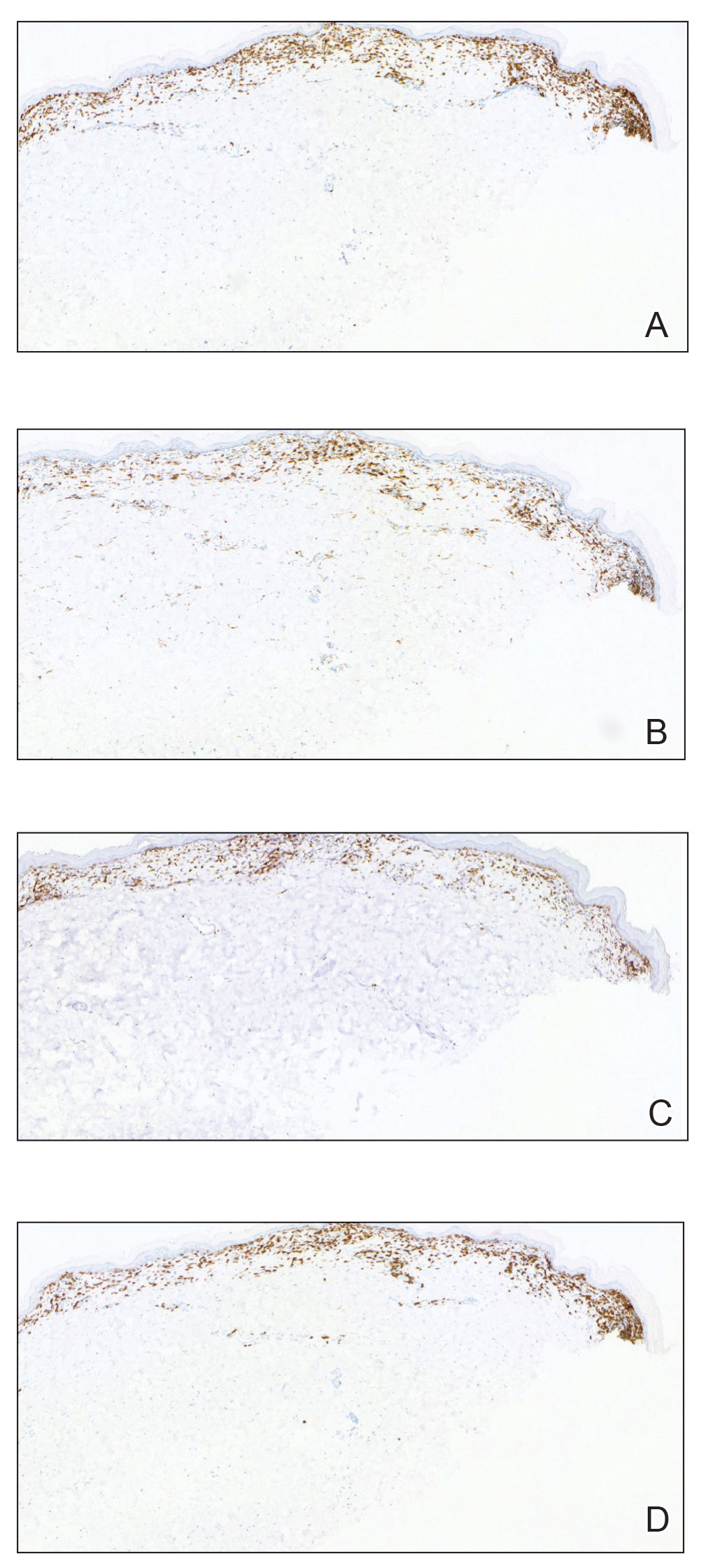

Histopathology showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with expanded cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei of irregular contours in the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical stains of atypical lymphocytes demonstrated the presence of CD3, CD8, and CD5, as well as the absence of CD7 and CD4 lymphocytes (Figure 2). The T-cell γ rearrangement showed polyclonal lymphocytes with 5% tumor cells. The histologic and clinical findings along with our patient’s medical history led to a diagnosis of stage IA (<10% body surface area involvement) hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (hMF).1 Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%; she noted an improvement in her symptoms at 2-month follow-up.

Hypopigmented MF is an uncommon manifestation of MF with unknown prevalence and incidence rates. Mycosis fungoides is considered the most common subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that classically presents as a chronic, indolent, hypopigmented or depigmented macule or patch, commonly with scaling, in sunprotected areas such as the trunk and proximal arms and legs. It predominantly affects younger adults with darker skin tones and may be present in the pediatric population within the first decade of life.1 Classically, MF affects White patients aged 55 to 60 years. Disease progression is slow, with an incidence rate of 10% of tumor or extracutaneous involvement in the early stages of disease. A lack of specificity on the clinical and histopathologic findings in the initial stage often contributes to the diagnostic delay of hMF. As seen in our patient, this disease can be misdiagnosed as tinea versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, vitiligo, pityriasis alba, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, or Hansen disease due to prolonged hypopigmented lesions.2 The clinical findings and histopathologic results including immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of hMF and ruled out pityriasis alba, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, and vitiligo.

The etiology and pathophysiology of hMF are not fully understood; however, it is hypothesized that melanocyte degeneration, abnormal melanogenesis, and disturbance of melanosome transfer result from the clonal expansion of T helper memory cells. T-cell dyscrasia has been reported to evolve into hMF during etanercept therapy.3 Clinically, hMF presents as hypopigmented papulosquamous, eczematous, or erythrodermic patches, plaques, and tumors with poorly defined atrophied borders. Multiple biopsies of steroid-naive lesions are needed for the diagnosis, as the initial hMF histologic finding cannot be specific for diagnostic confirmation. Common histopathologic findings include a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with epidermotropism, intraepidermal nests of atypical cells, or cerebriform nuclei lymphocytes on hematoxylin and eosin staining. In comparison to classical MF epidermotropism, CD4− and CD8+ atypical cells aid in the diagnosis of hMF. Although hMF carries a good prognosis and a benign clinical course,4 full-body computed tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography as well as laboratory analysis for lactate dehydrogenase should be pursued if lymphadenopathy, systemic symptoms, or advancedstage hMF are present.

Treatment of hMF depends on the disease stage. Psoralen plus UVA and narrowband UVB can be utilized for the initial stages with a relatively fast response and remission of lesions as early as the first 2 months of treatment. In addition to phototherapy, stage IA to IIA mycosis fungoides with localized skin lesions can benefit from topical steroids, topical retinoids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and carmustine. For advanced stages of mycosis fungoides, combination therapy consisting of psoralen plus UVA with an oral retinoid, interferon alfa, and systemic chemotherapy commonly are prescribed. Maintenance therapy is used for prolonging remission; however, long-term phototherapy is not recommended due to the risk for skin cancer. Unfortunately, hMF requires long-term treatment due to its waxing and waning course, and recurrence may occur after complete resolution.5

- Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-960.

- Lambroza E, Cohen SR, Lebwohl M, et al. Hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides: demography, histopathology, and treatment of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:987-993.

- Chuang GS, Wasserman DI, Byers HR, et al. Hypopigmented T-cell dyscrasia evolving to hypopigmented mycosis fungoides during etanercept therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S121-S122.

- Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/ European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4730-4739.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70:223.e1-17; quiz 240-242.

The Diagnosis: Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

Histopathology showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with expanded cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei of irregular contours in the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical stains of atypical lymphocytes demonstrated the presence of CD3, CD8, and CD5, as well as the absence of CD7 and CD4 lymphocytes (Figure 2). The T-cell γ rearrangement showed polyclonal lymphocytes with 5% tumor cells. The histologic and clinical findings along with our patient’s medical history led to a diagnosis of stage IA (<10% body surface area involvement) hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (hMF).1 Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%; she noted an improvement in her symptoms at 2-month follow-up.

Hypopigmented MF is an uncommon manifestation of MF with unknown prevalence and incidence rates. Mycosis fungoides is considered the most common subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that classically presents as a chronic, indolent, hypopigmented or depigmented macule or patch, commonly with scaling, in sunprotected areas such as the trunk and proximal arms and legs. It predominantly affects younger adults with darker skin tones and may be present in the pediatric population within the first decade of life.1 Classically, MF affects White patients aged 55 to 60 years. Disease progression is slow, with an incidence rate of 10% of tumor or extracutaneous involvement in the early stages of disease. A lack of specificity on the clinical and histopathologic findings in the initial stage often contributes to the diagnostic delay of hMF. As seen in our patient, this disease can be misdiagnosed as tinea versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, vitiligo, pityriasis alba, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, or Hansen disease due to prolonged hypopigmented lesions.2 The clinical findings and histopathologic results including immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of hMF and ruled out pityriasis alba, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, and vitiligo.

The etiology and pathophysiology of hMF are not fully understood; however, it is hypothesized that melanocyte degeneration, abnormal melanogenesis, and disturbance of melanosome transfer result from the clonal expansion of T helper memory cells. T-cell dyscrasia has been reported to evolve into hMF during etanercept therapy.3 Clinically, hMF presents as hypopigmented papulosquamous, eczematous, or erythrodermic patches, plaques, and tumors with poorly defined atrophied borders. Multiple biopsies of steroid-naive lesions are needed for the diagnosis, as the initial hMF histologic finding cannot be specific for diagnostic confirmation. Common histopathologic findings include a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with epidermotropism, intraepidermal nests of atypical cells, or cerebriform nuclei lymphocytes on hematoxylin and eosin staining. In comparison to classical MF epidermotropism, CD4− and CD8+ atypical cells aid in the diagnosis of hMF. Although hMF carries a good prognosis and a benign clinical course,4 full-body computed tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography as well as laboratory analysis for lactate dehydrogenase should be pursued if lymphadenopathy, systemic symptoms, or advancedstage hMF are present.

Treatment of hMF depends on the disease stage. Psoralen plus UVA and narrowband UVB can be utilized for the initial stages with a relatively fast response and remission of lesions as early as the first 2 months of treatment. In addition to phototherapy, stage IA to IIA mycosis fungoides with localized skin lesions can benefit from topical steroids, topical retinoids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and carmustine. For advanced stages of mycosis fungoides, combination therapy consisting of psoralen plus UVA with an oral retinoid, interferon alfa, and systemic chemotherapy commonly are prescribed. Maintenance therapy is used for prolonging remission; however, long-term phototherapy is not recommended due to the risk for skin cancer. Unfortunately, hMF requires long-term treatment due to its waxing and waning course, and recurrence may occur after complete resolution.5

The Diagnosis: Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

Histopathology showed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate with expanded cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei of irregular contours in the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical stains of atypical lymphocytes demonstrated the presence of CD3, CD8, and CD5, as well as the absence of CD7 and CD4 lymphocytes (Figure 2). The T-cell γ rearrangement showed polyclonal lymphocytes with 5% tumor cells. The histologic and clinical findings along with our patient’s medical history led to a diagnosis of stage IA (<10% body surface area involvement) hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (hMF).1 Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%; she noted an improvement in her symptoms at 2-month follow-up.

Hypopigmented MF is an uncommon manifestation of MF with unknown prevalence and incidence rates. Mycosis fungoides is considered the most common subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that classically presents as a chronic, indolent, hypopigmented or depigmented macule or patch, commonly with scaling, in sunprotected areas such as the trunk and proximal arms and legs. It predominantly affects younger adults with darker skin tones and may be present in the pediatric population within the first decade of life.1 Classically, MF affects White patients aged 55 to 60 years. Disease progression is slow, with an incidence rate of 10% of tumor or extracutaneous involvement in the early stages of disease. A lack of specificity on the clinical and histopathologic findings in the initial stage often contributes to the diagnostic delay of hMF. As seen in our patient, this disease can be misdiagnosed as tinea versicolor, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, vitiligo, pityriasis alba, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, or Hansen disease due to prolonged hypopigmented lesions.2 The clinical findings and histopathologic results including immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of hMF and ruled out pityriasis alba, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, subcutaneous lupus erythematosus, and vitiligo.

The etiology and pathophysiology of hMF are not fully understood; however, it is hypothesized that melanocyte degeneration, abnormal melanogenesis, and disturbance of melanosome transfer result from the clonal expansion of T helper memory cells. T-cell dyscrasia has been reported to evolve into hMF during etanercept therapy.3 Clinically, hMF presents as hypopigmented papulosquamous, eczematous, or erythrodermic patches, plaques, and tumors with poorly defined atrophied borders. Multiple biopsies of steroid-naive lesions are needed for the diagnosis, as the initial hMF histologic finding cannot be specific for diagnostic confirmation. Common histopathologic findings include a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with epidermotropism, intraepidermal nests of atypical cells, or cerebriform nuclei lymphocytes on hematoxylin and eosin staining. In comparison to classical MF epidermotropism, CD4− and CD8+ atypical cells aid in the diagnosis of hMF. Although hMF carries a good prognosis and a benign clinical course,4 full-body computed tomography or positron emission tomography/computed tomography as well as laboratory analysis for lactate dehydrogenase should be pursued if lymphadenopathy, systemic symptoms, or advancedstage hMF are present.

Treatment of hMF depends on the disease stage. Psoralen plus UVA and narrowband UVB can be utilized for the initial stages with a relatively fast response and remission of lesions as early as the first 2 months of treatment. In addition to phototherapy, stage IA to IIA mycosis fungoides with localized skin lesions can benefit from topical steroids, topical retinoids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and carmustine. For advanced stages of mycosis fungoides, combination therapy consisting of psoralen plus UVA with an oral retinoid, interferon alfa, and systemic chemotherapy commonly are prescribed. Maintenance therapy is used for prolonging remission; however, long-term phototherapy is not recommended due to the risk for skin cancer. Unfortunately, hMF requires long-term treatment due to its waxing and waning course, and recurrence may occur after complete resolution.5

- Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-960.

- Lambroza E, Cohen SR, Lebwohl M, et al. Hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides: demography, histopathology, and treatment of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:987-993.

- Chuang GS, Wasserman DI, Byers HR, et al. Hypopigmented T-cell dyscrasia evolving to hypopigmented mycosis fungoides during etanercept therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S121-S122.

- Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/ European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4730-4739.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70:223.e1-17; quiz 240-242.

- Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: a review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954-960.

- Lambroza E, Cohen SR, Lebwohl M, et al. Hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides: demography, histopathology, and treatment of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:987-993.

- Chuang GS, Wasserman DI, Byers HR, et al. Hypopigmented T-cell dyscrasia evolving to hypopigmented mycosis fungoides during etanercept therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(5 suppl):S121-S122.

- Agar NS, Wedgeworth E, Crichton S, et al. Survival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/ European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposal. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4730-4739.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014; 70:223.e1-17; quiz 240-242.

A 52-year-old Black woman presented with self-described whitened spots on the arms and legs of 2 years’ duration. She experienced no improvement with ketoconazole cream and topical calcineurin inhibitors prescribed during a prior dermatology visit at an outside institution. She denied pain or pruritus. A review of systems as well as the patient’s medical history were noncontributory. A prior biopsy at an outside institution revealed an interface dermatitis suggestive of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The patient noted social drinking and denied tobacco use. She had no known allergies to medications and currently was on tamoxifen for breast cancer following a right mastectomy. Physical examination showed hypopigmented macules and patches on the left upper arm and right proximal leg. The center of the lesions was not erythematous or scaly. Palpation did not reveal enlarged lymph nodes, and laboratory analyses ruled out low levels of red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets. Punch biopsies from the left arm and right thigh were performed.

New law allows international medical graduates to bypass U.S. residency

Pediatric nephrologist Bryan Carmody, MD, recalls working alongside an extremely experienced neonatologist during his residency. She had managed a neonatal intensive care unit in her home country of Lithuania, but because she wanted to practice in the United States, it took years of repeat training before she was eligible for a medical license.

“She was very accomplished, and she was wonderful to have as a coresident at the time,” Dr. Carmody said in an interview.

The neonatologist now practices at a U.S. academic medical center, but to obtain that position, she had to complete 3 years of pediatric residency and 3 years of fellowship in the United States, Dr. Carmody said.

Such training for international medical graduates (IMGs) is a routine part of obtaining a U.S. medical license, but

The American Medical Association took similar measures at its recent annual meeting, making it easier for IMGs to gain licensure. Because the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine disrupted the process by which some IMGs had their licenses verified, the AMA is now encouraging state licensing boards and other credentialing institutions to accept certification from the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates as verification, rather than requiring documents directly from international medical schools.

When it comes to Tennessee’s new law, signed by Gov. Bill Lee in April, experienced IMGs who have received medical training abroad can skip U.S. residency requirements and obtain a temporary license to practice medicine in Tennessee if they meet certain qualifications.

The international doctors must demonstrate competency, as determined by the state medical board. In addition, they must have completed a 3-year postgraduate training program in the graduate’s licensing country or otherwise have practiced as a medical professional in which they performed the duties of a physician for at least 3 of the past 5 years outside the United States, according to the new law.

To be approved, IMGs must also have received an employment offer from a Tennessee health care provider that has a residency program accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

If physicians remain in good standing for 2 years, the board will grant them a full and unrestricted license to practice in Tennessee.

“The new legislation opens up a lot of doors for international medical graduates and is also a lifeline for a lot of underserved areas in Tennessee,” said Asim Ansari, MD, a Canadian who attended medical school in the Caribbean and is an advocate for IMGs.

Dr. Ansari is participating in a child and adolescent psychiatry fellowship at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, until he can apply for the sixth time to a residency program. “This could possibly be a model that other states may want to implement in a few years.”

What’s behind the law?

A predicted physician shortage in Tennessee drove the legislation, said Rep. Sabi “Doc” Kumar, MD, vice chair for the Tennessee House Health Committee and a cosponsor of the legislation. Legislators hope the law will mitigate that shortage and boost the number of physicians practicing in underserved areas of the state.

“Considering that one in four physicians in the U.S. are international medical gradates, it was important for us to be able to attract those physicians to Tennessee,” he said.

The Tennessee Board of Medical Examiners will develop administrative rules for the law, which may take up to a year, Rep. Kumar said. He expects the program to be available to IMGs beginning in mid-2024.

Upon completion of the program, IMGs will be able to practice general medicine in Tennessee, not a specialty. Requirements for specialty certification would have to be met through the specialties’ respective boards.

Dr. Carmody, who blogs about medical education, including the new legislation, said in an interview the law will greatly benefit experienced IMGs, who often are bypassed as residency candidates because they graduated years ago. Hospitals also win because they can fill positions that otherwise might sit vacant, he said.

Family physician Sahil Bawa, MD, an IMG from India who recently matched into his specialty, said the Tennessee legislation will help fellow IMGs find U.S. medical jobs.

“It’s very difficult for IMGs to get into residency in the U.S.,” he said. “I’ve seen people with medical degrees from other countries drive Uber or do odd jobs to sustain themselves here. I’ve known a few people who have left and gone back to their home country because they were not accepted into a residency.”

Who benefits most?

Dr. Bawa noted that the legislation would not have helped him, as he needed a visa to practice in the United States and the law does not include the sponsoring of visas. The legislation requires IMGs to show evidence of citizenship or evidence that they are legally entitled to live or work in the United States.

U.S. citizen IMGs who haven’t completed residency or who practiced in another country also are left out of the law, Dr. Carmody said.

“This law is designed to take the most accomplished cream of the crop international medical graduates with the most experience and the most sophisticated skill set and send them to Tennessee. I think that’s the intent,” he said. “But many international medical graduates are U.S. citizens who don’t have the opportunity to practice in countries other than United States or do residencies. A lot of these people are sitting on the sidelines, unable to secure residency positions. I’m sure they would be desperate for a program like this.”

Questions remain

“Just because the doctor can get a [temporary] license without the training doesn’t mean employers are going to be interested in sponsoring those doctors,” said Adam Cohen, an immigration attorney who practices in Memphis. “What is the inclination of these employers to hire these physicians who have undergone training outside the U.S.? And will there be skepticism on the part of employers about the competence of these doctors?”

“Hospital systems will be able to hire experienced practitioners for a very low cost,” Dr. Ansari said. “So now you have these additional bodies who can do the work of a physician, but you don’t have to pay them as much as a physician for 2 years. And because some are desperate to work, they will take lower pay as long as they have a pathway to full licensure in Tennessee. What are the protections for these physicians? Who will cover their insurance? Who will be responsible for them, the attendees? And will the attendees be willing to put their license on the line for them?”

In addition, Dr. Carmody questions what, if anything, will encourage IMGs to work in underserved areas in Tennessee after their 2 years are up and whether there will be any incentives to guide them. He wonders, too, whether the physicians will be stuck practicing in Tennessee following completion of the program.

“Will these physicians only be able to work in Tennessee?” he asked. “I think that’s probably going to be the case, because they’ll be licensed in Tennessee, but to go to another state, they would be missing the required residency training. So it might be these folks are stuck in Tennessee unless other states develop reciprocal arrangements.”

Other states would have to decide whether to recognize the Tennessee license acquired through this pathway, Rep. Kumar said.

He explained that the sponsoring sites would be responsible for providing work-hour restrictions and liability protections. There are currently no incentives in the legislation for IMGs to practice in rural, underserved areas, but the hospitals and communities there generally offer incentives when recruiting, Rep. Kumar said.

“The law definitely has the potential to be helpful,” Mr. Cohen said, “because there’s an ability to place providers in the state without having to go through the bottleneck of limited residency slots. If other states see a positive effect on Tennessee or are exploring ways to alleviate their own shortages, it’s possible [they] might follow suit.”

Rep. Kumar agreed that other states will be watching Tennessee to weigh the law’s success.

“I think the law will have to prove itself and show that Tennessee has benefited from it and that the results have been good,” he said. “We are providing a pioneering way for attracting medical graduates and making it easier for them to obtain a license. I would think other states would want to do that.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pediatric nephrologist Bryan Carmody, MD, recalls working alongside an extremely experienced neonatologist during his residency. She had managed a neonatal intensive care unit in her home country of Lithuania, but because she wanted to practice in the United States, it took years of repeat training before she was eligible for a medical license.

“She was very accomplished, and she was wonderful to have as a coresident at the time,” Dr. Carmody said in an interview.

The neonatologist now practices at a U.S. academic medical center, but to obtain that position, she had to complete 3 years of pediatric residency and 3 years of fellowship in the United States, Dr. Carmody said.

Such training for international medical graduates (IMGs) is a routine part of obtaining a U.S. medical license, but

The American Medical Association took similar measures at its recent annual meeting, making it easier for IMGs to gain licensure. Because the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine disrupted the process by which some IMGs had their licenses verified, the AMA is now encouraging state licensing boards and other credentialing institutions to accept certification from the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates as verification, rather than requiring documents directly from international medical schools.

When it comes to Tennessee’s new law, signed by Gov. Bill Lee in April, experienced IMGs who have received medical training abroad can skip U.S. residency requirements and obtain a temporary license to practice medicine in Tennessee if they meet certain qualifications.

The international doctors must demonstrate competency, as determined by the state medical board. In addition, they must have completed a 3-year postgraduate training program in the graduate’s licensing country or otherwise have practiced as a medical professional in which they performed the duties of a physician for at least 3 of the past 5 years outside the United States, according to the new law.

To be approved, IMGs must also have received an employment offer from a Tennessee health care provider that has a residency program accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

If physicians remain in good standing for 2 years, the board will grant them a full and unrestricted license to practice in Tennessee.

“The new legislation opens up a lot of doors for international medical graduates and is also a lifeline for a lot of underserved areas in Tennessee,” said Asim Ansari, MD, a Canadian who attended medical school in the Caribbean and is an advocate for IMGs.

Dr. Ansari is participating in a child and adolescent psychiatry fellowship at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, until he can apply for the sixth time to a residency program. “This could possibly be a model that other states may want to implement in a few years.”

What’s behind the law?

A predicted physician shortage in Tennessee drove the legislation, said Rep. Sabi “Doc” Kumar, MD, vice chair for the Tennessee House Health Committee and a cosponsor of the legislation. Legislators hope the law will mitigate that shortage and boost the number of physicians practicing in underserved areas of the state.

“Considering that one in four physicians in the U.S. are international medical gradates, it was important for us to be able to attract those physicians to Tennessee,” he said.

The Tennessee Board of Medical Examiners will develop administrative rules for the law, which may take up to a year, Rep. Kumar said. He expects the program to be available to IMGs beginning in mid-2024.

Upon completion of the program, IMGs will be able to practice general medicine in Tennessee, not a specialty. Requirements for specialty certification would have to be met through the specialties’ respective boards.

Dr. Carmody, who blogs about medical education, including the new legislation, said in an interview the law will greatly benefit experienced IMGs, who often are bypassed as residency candidates because they graduated years ago. Hospitals also win because they can fill positions that otherwise might sit vacant, he said.

Family physician Sahil Bawa, MD, an IMG from India who recently matched into his specialty, said the Tennessee legislation will help fellow IMGs find U.S. medical jobs.

“It’s very difficult for IMGs to get into residency in the U.S.,” he said. “I’ve seen people with medical degrees from other countries drive Uber or do odd jobs to sustain themselves here. I’ve known a few people who have left and gone back to their home country because they were not accepted into a residency.”

Who benefits most?

Dr. Bawa noted that the legislation would not have helped him, as he needed a visa to practice in the United States and the law does not include the sponsoring of visas. The legislation requires IMGs to show evidence of citizenship or evidence that they are legally entitled to live or work in the United States.

U.S. citizen IMGs who haven’t completed residency or who practiced in another country also are left out of the law, Dr. Carmody said.

“This law is designed to take the most accomplished cream of the crop international medical graduates with the most experience and the most sophisticated skill set and send them to Tennessee. I think that’s the intent,” he said. “But many international medical graduates are U.S. citizens who don’t have the opportunity to practice in countries other than United States or do residencies. A lot of these people are sitting on the sidelines, unable to secure residency positions. I’m sure they would be desperate for a program like this.”

Questions remain

“Just because the doctor can get a [temporary] license without the training doesn’t mean employers are going to be interested in sponsoring those doctors,” said Adam Cohen, an immigration attorney who practices in Memphis. “What is the inclination of these employers to hire these physicians who have undergone training outside the U.S.? And will there be skepticism on the part of employers about the competence of these doctors?”

“Hospital systems will be able to hire experienced practitioners for a very low cost,” Dr. Ansari said. “So now you have these additional bodies who can do the work of a physician, but you don’t have to pay them as much as a physician for 2 years. And because some are desperate to work, they will take lower pay as long as they have a pathway to full licensure in Tennessee. What are the protections for these physicians? Who will cover their insurance? Who will be responsible for them, the attendees? And will the attendees be willing to put their license on the line for them?”

In addition, Dr. Carmody questions what, if anything, will encourage IMGs to work in underserved areas in Tennessee after their 2 years are up and whether there will be any incentives to guide them. He wonders, too, whether the physicians will be stuck practicing in Tennessee following completion of the program.

“Will these physicians only be able to work in Tennessee?” he asked. “I think that’s probably going to be the case, because they’ll be licensed in Tennessee, but to go to another state, they would be missing the required residency training. So it might be these folks are stuck in Tennessee unless other states develop reciprocal arrangements.”

Other states would have to decide whether to recognize the Tennessee license acquired through this pathway, Rep. Kumar said.

He explained that the sponsoring sites would be responsible for providing work-hour restrictions and liability protections. There are currently no incentives in the legislation for IMGs to practice in rural, underserved areas, but the hospitals and communities there generally offer incentives when recruiting, Rep. Kumar said.

“The law definitely has the potential to be helpful,” Mr. Cohen said, “because there’s an ability to place providers in the state without having to go through the bottleneck of limited residency slots. If other states see a positive effect on Tennessee or are exploring ways to alleviate their own shortages, it’s possible [they] might follow suit.”

Rep. Kumar agreed that other states will be watching Tennessee to weigh the law’s success.

“I think the law will have to prove itself and show that Tennessee has benefited from it and that the results have been good,” he said. “We are providing a pioneering way for attracting medical graduates and making it easier for them to obtain a license. I would think other states would want to do that.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pediatric nephrologist Bryan Carmody, MD, recalls working alongside an extremely experienced neonatologist during his residency. She had managed a neonatal intensive care unit in her home country of Lithuania, but because she wanted to practice in the United States, it took years of repeat training before she was eligible for a medical license.

“She was very accomplished, and she was wonderful to have as a coresident at the time,” Dr. Carmody said in an interview.

The neonatologist now practices at a U.S. academic medical center, but to obtain that position, she had to complete 3 years of pediatric residency and 3 years of fellowship in the United States, Dr. Carmody said.

Such training for international medical graduates (IMGs) is a routine part of obtaining a U.S. medical license, but

The American Medical Association took similar measures at its recent annual meeting, making it easier for IMGs to gain licensure. Because the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine disrupted the process by which some IMGs had their licenses verified, the AMA is now encouraging state licensing boards and other credentialing institutions to accept certification from the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates as verification, rather than requiring documents directly from international medical schools.

When it comes to Tennessee’s new law, signed by Gov. Bill Lee in April, experienced IMGs who have received medical training abroad can skip U.S. residency requirements and obtain a temporary license to practice medicine in Tennessee if they meet certain qualifications.

The international doctors must demonstrate competency, as determined by the state medical board. In addition, they must have completed a 3-year postgraduate training program in the graduate’s licensing country or otherwise have practiced as a medical professional in which they performed the duties of a physician for at least 3 of the past 5 years outside the United States, according to the new law.

To be approved, IMGs must also have received an employment offer from a Tennessee health care provider that has a residency program accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

If physicians remain in good standing for 2 years, the board will grant them a full and unrestricted license to practice in Tennessee.

“The new legislation opens up a lot of doors for international medical graduates and is also a lifeline for a lot of underserved areas in Tennessee,” said Asim Ansari, MD, a Canadian who attended medical school in the Caribbean and is an advocate for IMGs.

Dr. Ansari is participating in a child and adolescent psychiatry fellowship at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, until he can apply for the sixth time to a residency program. “This could possibly be a model that other states may want to implement in a few years.”

What’s behind the law?

A predicted physician shortage in Tennessee drove the legislation, said Rep. Sabi “Doc” Kumar, MD, vice chair for the Tennessee House Health Committee and a cosponsor of the legislation. Legislators hope the law will mitigate that shortage and boost the number of physicians practicing in underserved areas of the state.

“Considering that one in four physicians in the U.S. are international medical gradates, it was important for us to be able to attract those physicians to Tennessee,” he said.

The Tennessee Board of Medical Examiners will develop administrative rules for the law, which may take up to a year, Rep. Kumar said. He expects the program to be available to IMGs beginning in mid-2024.

Upon completion of the program, IMGs will be able to practice general medicine in Tennessee, not a specialty. Requirements for specialty certification would have to be met through the specialties’ respective boards.

Dr. Carmody, who blogs about medical education, including the new legislation, said in an interview the law will greatly benefit experienced IMGs, who often are bypassed as residency candidates because they graduated years ago. Hospitals also win because they can fill positions that otherwise might sit vacant, he said.

Family physician Sahil Bawa, MD, an IMG from India who recently matched into his specialty, said the Tennessee legislation will help fellow IMGs find U.S. medical jobs.

“It’s very difficult for IMGs to get into residency in the U.S.,” he said. “I’ve seen people with medical degrees from other countries drive Uber or do odd jobs to sustain themselves here. I’ve known a few people who have left and gone back to their home country because they were not accepted into a residency.”

Who benefits most?

Dr. Bawa noted that the legislation would not have helped him, as he needed a visa to practice in the United States and the law does not include the sponsoring of visas. The legislation requires IMGs to show evidence of citizenship or evidence that they are legally entitled to live or work in the United States.

U.S. citizen IMGs who haven’t completed residency or who practiced in another country also are left out of the law, Dr. Carmody said.

“This law is designed to take the most accomplished cream of the crop international medical graduates with the most experience and the most sophisticated skill set and send them to Tennessee. I think that’s the intent,” he said. “But many international medical graduates are U.S. citizens who don’t have the opportunity to practice in countries other than United States or do residencies. A lot of these people are sitting on the sidelines, unable to secure residency positions. I’m sure they would be desperate for a program like this.”

Questions remain

“Just because the doctor can get a [temporary] license without the training doesn’t mean employers are going to be interested in sponsoring those doctors,” said Adam Cohen, an immigration attorney who practices in Memphis. “What is the inclination of these employers to hire these physicians who have undergone training outside the U.S.? And will there be skepticism on the part of employers about the competence of these doctors?”

“Hospital systems will be able to hire experienced practitioners for a very low cost,” Dr. Ansari said. “So now you have these additional bodies who can do the work of a physician, but you don’t have to pay them as much as a physician for 2 years. And because some are desperate to work, they will take lower pay as long as they have a pathway to full licensure in Tennessee. What are the protections for these physicians? Who will cover their insurance? Who will be responsible for them, the attendees? And will the attendees be willing to put their license on the line for them?”

In addition, Dr. Carmody questions what, if anything, will encourage IMGs to work in underserved areas in Tennessee after their 2 years are up and whether there will be any incentives to guide them. He wonders, too, whether the physicians will be stuck practicing in Tennessee following completion of the program.

“Will these physicians only be able to work in Tennessee?” he asked. “I think that’s probably going to be the case, because they’ll be licensed in Tennessee, but to go to another state, they would be missing the required residency training. So it might be these folks are stuck in Tennessee unless other states develop reciprocal arrangements.”

Other states would have to decide whether to recognize the Tennessee license acquired through this pathway, Rep. Kumar said.

He explained that the sponsoring sites would be responsible for providing work-hour restrictions and liability protections. There are currently no incentives in the legislation for IMGs to practice in rural, underserved areas, but the hospitals and communities there generally offer incentives when recruiting, Rep. Kumar said.

“The law definitely has the potential to be helpful,” Mr. Cohen said, “because there’s an ability to place providers in the state without having to go through the bottleneck of limited residency slots. If other states see a positive effect on Tennessee or are exploring ways to alleviate their own shortages, it’s possible [they] might follow suit.”

Rep. Kumar agreed that other states will be watching Tennessee to weigh the law’s success.

“I think the law will have to prove itself and show that Tennessee has benefited from it and that the results have been good,” he said. “We are providing a pioneering way for attracting medical graduates and making it easier for them to obtain a license. I would think other states would want to do that.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Imaging techniques will revolutionize cancer detection, expert predicts

PHOENIX –

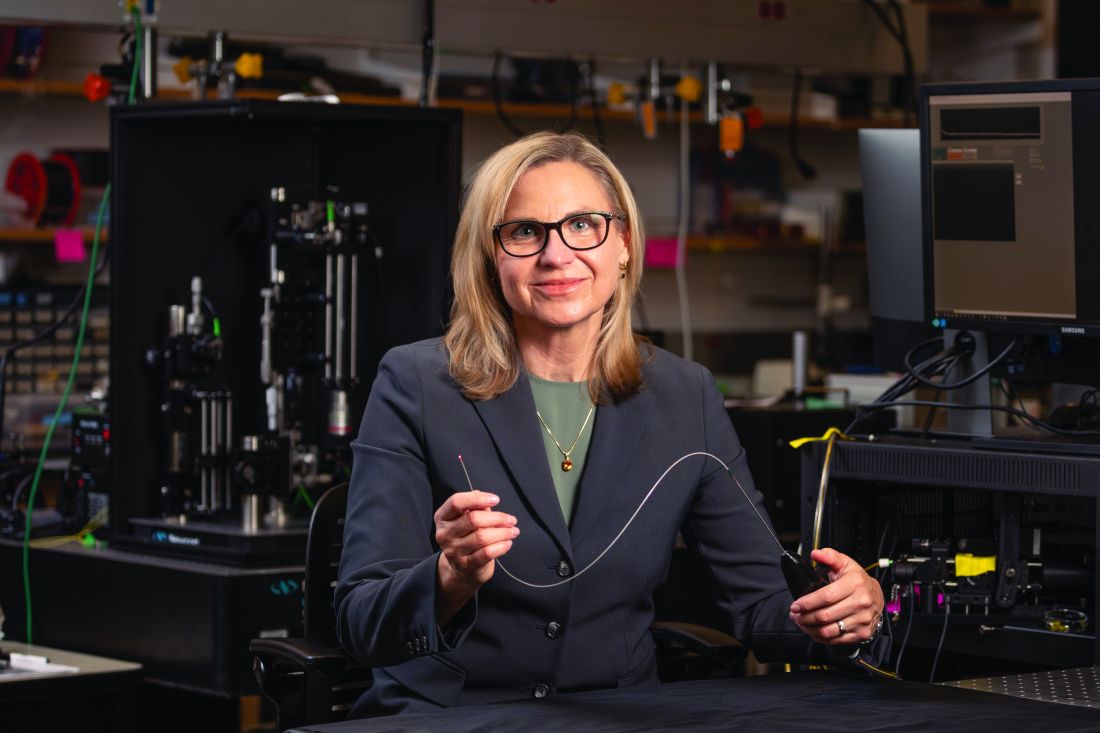

In a lecture during a multispecialty roundup of cutting-edge energy-based device applications at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, Dr. Barton, a biomedical engineer who directs the BIO5 Institute at the University of Arizona, Tucson, said that while no current modality exists to enable physicians in dermatology and other specialties to view internal structures throughout the entire body with cellular resolution, refining existing technologies is a good way to start.

In 2011, renowned cancer researchers Douglas Hanahan, PhD, and Robert A. Weinberg, PhD, proposed six hallmarks of cancer, which include sustaining proliferative signaling, evading growth suppressors, resisting cell death, enabling replicative immortality, inducing angiogenesis, and activating invasion and metastasis. Each hallmark poses unique imaging challenges. For example, enabling replicative immortality “means that the cell nuclei change size and shape; they change their position,” said Dr. Barton, who is also professor of biomedical engineering and optical sciences at the university. “If we want to see that, we’re going to need an imaging modality that’s subcellular in resolution.”

Similarly, if clinicians want to view how proliferative signaling is changing, “that means being able to visualize the cell surface receptors; those are even smaller to actually visualize,” she said. “But we have technologies where we can target those receptors with fluorophores. And then we can look at large areas very quickly.” Meanwhile, the ability of cancer cells to resist cell death and evade growth suppressors often results in thickening of epithelium throughout the body. “So, if we can measure the thickness of the epithelium, we can see that there’s something wrong with that tissue,” she said.

As for cancer’s propensity for invasion and metastasis, “here, we’re looking at how the collagen structure [between the cells] has changed and whether there’s layer breakdown or not. Optical imaging can detect cancer. However, high resolution optical techniques can only image about 1 mm deep, so unless you’re looking at the skin or the eye, you’re going to have to develop an endoscope to be able to view these hallmarks.”

OCT images the tissue microstructure, generally in a resolution of 2-20 microns, at a depth of 1-2 mm, and it measures reflected light. When possible, Dr. Barton combines OCT with laser-induced fluorescence for enhanced accuracy of detection of cancer. Induced fluorescence senses molecular information with the natural fluorophores in the body or with targeted exogenous agents. Then there’s multiphoton microscopy, an advanced imaging technique that enables clinicians to view cellular and subcellular events within living tissue. Early models of this technology “took up entire benches” in physics labs, Dr. Barton said, but she and other investigators are designing smaller devices for use in clinics. “This is exciting, because not only do we [view] subcellular structure with this modality, but it can also be highly sensitive to collagen structure,” she said.

Ovarian cancer model

In a model of ovarian cancer, she and colleagues externalized the ovaries of a mouse, imaged the organs, put them back in, and reassessed them at 8 weeks. “This model develops cancer very quickly,” said Dr. Barton, who once worked for McDonnell Douglas on the Space Station program. At 8 weeks, using fluorescence and targeted agents with a tabletop multiphoton microscopy system, they observed that the proliferation signals of cancer had begun. “So, with an agent targeted to the folate receptor or to other receptors that are implicated in cancer development, we can see that ovaries and fallopian tubes are lighting up,” she said.

With proof of concept established with the mouse study, she and other researchers are drawing from technological advances to create tiny laser systems for use in the clinic to image a variety of structures in the human body. Optics advances include bulk optics and all-fiber designs where engineers can create an imaging probe that’s only 125 microns in diameter, “or maybe even as small as 70 microns in diameter,” she said. “We can do fabrications on the tips of endoscopes to redirect the light and focus it. We can also do 3-D printing and spiral scanning to create miniature devices to make new advances. That means that instead of just white light imaging of the colon or the lung like we have had in the past, we can start moving into smaller structures, such as the eustachian tube, the fallopian tube, the bile ducts, or making miniature devices for brain biopsies, lung biopsies, and maybe being able to get into bronchioles and arterioles.”

According to Dr. Barton, prior research has demonstrated that cerebral vasculature can be imaged with a catheter 400 microns in diameter, the spaces in the lungs can be imaged with a needle that is 310 microns in diameter, and the inner structures of the eustachian tube can be viewed with an endoscope 1 mm in diameter.

She and her colleagues are developing an OCT/fluorescence imaging falloposcope that is 0.8 mm in diameter, flexible, and steerable, as a tool for early detection of ovarian cancer in humans. “It’s now known that most ovarian cancer starts in the fallopian tubes,” Dr. Barton said. “It’s metastatic disease when those cells break off from the fallopian tubes and go to the ovaries. We wanted to create an imaging system where we created a fiber bundle that we could navigate with white light and with fluorescence so that we can see these early stages of cancer [and] how they fluoresce differently. We also wanted to have an OCT system so that we could image through the wall of the fallopian tube and look for that layer thickening and other precursors to ovarian cancer.”

To date, in vivo testing in healthy women has demonstrated that the miniature endoscope is able to reach the fallopian tubes through the natural orifice of the vagina and uterus. “That is pretty exciting,” she said. “The images may not be of the highest quality, but we are advancing.”

Dr. Barton reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

PHOENIX –

In a lecture during a multispecialty roundup of cutting-edge energy-based device applications at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, Dr. Barton, a biomedical engineer who directs the BIO5 Institute at the University of Arizona, Tucson, said that while no current modality exists to enable physicians in dermatology and other specialties to view internal structures throughout the entire body with cellular resolution, refining existing technologies is a good way to start.

In 2011, renowned cancer researchers Douglas Hanahan, PhD, and Robert A. Weinberg, PhD, proposed six hallmarks of cancer, which include sustaining proliferative signaling, evading growth suppressors, resisting cell death, enabling replicative immortality, inducing angiogenesis, and activating invasion and metastasis. Each hallmark poses unique imaging challenges. For example, enabling replicative immortality “means that the cell nuclei change size and shape; they change their position,” said Dr. Barton, who is also professor of biomedical engineering and optical sciences at the university. “If we want to see that, we’re going to need an imaging modality that’s subcellular in resolution.”

Similarly, if clinicians want to view how proliferative signaling is changing, “that means being able to visualize the cell surface receptors; those are even smaller to actually visualize,” she said. “But we have technologies where we can target those receptors with fluorophores. And then we can look at large areas very quickly.” Meanwhile, the ability of cancer cells to resist cell death and evade growth suppressors often results in thickening of epithelium throughout the body. “So, if we can measure the thickness of the epithelium, we can see that there’s something wrong with that tissue,” she said.

As for cancer’s propensity for invasion and metastasis, “here, we’re looking at how the collagen structure [between the cells] has changed and whether there’s layer breakdown or not. Optical imaging can detect cancer. However, high resolution optical techniques can only image about 1 mm deep, so unless you’re looking at the skin or the eye, you’re going to have to develop an endoscope to be able to view these hallmarks.”

OCT images the tissue microstructure, generally in a resolution of 2-20 microns, at a depth of 1-2 mm, and it measures reflected light. When possible, Dr. Barton combines OCT with laser-induced fluorescence for enhanced accuracy of detection of cancer. Induced fluorescence senses molecular information with the natural fluorophores in the body or with targeted exogenous agents. Then there’s multiphoton microscopy, an advanced imaging technique that enables clinicians to view cellular and subcellular events within living tissue. Early models of this technology “took up entire benches” in physics labs, Dr. Barton said, but she and other investigators are designing smaller devices for use in clinics. “This is exciting, because not only do we [view] subcellular structure with this modality, but it can also be highly sensitive to collagen structure,” she said.

Ovarian cancer model

In a model of ovarian cancer, she and colleagues externalized the ovaries of a mouse, imaged the organs, put them back in, and reassessed them at 8 weeks. “This model develops cancer very quickly,” said Dr. Barton, who once worked for McDonnell Douglas on the Space Station program. At 8 weeks, using fluorescence and targeted agents with a tabletop multiphoton microscopy system, they observed that the proliferation signals of cancer had begun. “So, with an agent targeted to the folate receptor or to other receptors that are implicated in cancer development, we can see that ovaries and fallopian tubes are lighting up,” she said.

With proof of concept established with the mouse study, she and other researchers are drawing from technological advances to create tiny laser systems for use in the clinic to image a variety of structures in the human body. Optics advances include bulk optics and all-fiber designs where engineers can create an imaging probe that’s only 125 microns in diameter, “or maybe even as small as 70 microns in diameter,” she said. “We can do fabrications on the tips of endoscopes to redirect the light and focus it. We can also do 3-D printing and spiral scanning to create miniature devices to make new advances. That means that instead of just white light imaging of the colon or the lung like we have had in the past, we can start moving into smaller structures, such as the eustachian tube, the fallopian tube, the bile ducts, or making miniature devices for brain biopsies, lung biopsies, and maybe being able to get into bronchioles and arterioles.”

According to Dr. Barton, prior research has demonstrated that cerebral vasculature can be imaged with a catheter 400 microns in diameter, the spaces in the lungs can be imaged with a needle that is 310 microns in diameter, and the inner structures of the eustachian tube can be viewed with an endoscope 1 mm in diameter.

She and her colleagues are developing an OCT/fluorescence imaging falloposcope that is 0.8 mm in diameter, flexible, and steerable, as a tool for early detection of ovarian cancer in humans. “It’s now known that most ovarian cancer starts in the fallopian tubes,” Dr. Barton said. “It’s metastatic disease when those cells break off from the fallopian tubes and go to the ovaries. We wanted to create an imaging system where we created a fiber bundle that we could navigate with white light and with fluorescence so that we can see these early stages of cancer [and] how they fluoresce differently. We also wanted to have an OCT system so that we could image through the wall of the fallopian tube and look for that layer thickening and other precursors to ovarian cancer.”

To date, in vivo testing in healthy women has demonstrated that the miniature endoscope is able to reach the fallopian tubes through the natural orifice of the vagina and uterus. “That is pretty exciting,” she said. “The images may not be of the highest quality, but we are advancing.”

Dr. Barton reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

PHOENIX –

In a lecture during a multispecialty roundup of cutting-edge energy-based device applications at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, Dr. Barton, a biomedical engineer who directs the BIO5 Institute at the University of Arizona, Tucson, said that while no current modality exists to enable physicians in dermatology and other specialties to view internal structures throughout the entire body with cellular resolution, refining existing technologies is a good way to start.

In 2011, renowned cancer researchers Douglas Hanahan, PhD, and Robert A. Weinberg, PhD, proposed six hallmarks of cancer, which include sustaining proliferative signaling, evading growth suppressors, resisting cell death, enabling replicative immortality, inducing angiogenesis, and activating invasion and metastasis. Each hallmark poses unique imaging challenges. For example, enabling replicative immortality “means that the cell nuclei change size and shape; they change their position,” said Dr. Barton, who is also professor of biomedical engineering and optical sciences at the university. “If we want to see that, we’re going to need an imaging modality that’s subcellular in resolution.”

Similarly, if clinicians want to view how proliferative signaling is changing, “that means being able to visualize the cell surface receptors; those are even smaller to actually visualize,” she said. “But we have technologies where we can target those receptors with fluorophores. And then we can look at large areas very quickly.” Meanwhile, the ability of cancer cells to resist cell death and evade growth suppressors often results in thickening of epithelium throughout the body. “So, if we can measure the thickness of the epithelium, we can see that there’s something wrong with that tissue,” she said.

As for cancer’s propensity for invasion and metastasis, “here, we’re looking at how the collagen structure [between the cells] has changed and whether there’s layer breakdown or not. Optical imaging can detect cancer. However, high resolution optical techniques can only image about 1 mm deep, so unless you’re looking at the skin or the eye, you’re going to have to develop an endoscope to be able to view these hallmarks.”

OCT images the tissue microstructure, generally in a resolution of 2-20 microns, at a depth of 1-2 mm, and it measures reflected light. When possible, Dr. Barton combines OCT with laser-induced fluorescence for enhanced accuracy of detection of cancer. Induced fluorescence senses molecular information with the natural fluorophores in the body or with targeted exogenous agents. Then there’s multiphoton microscopy, an advanced imaging technique that enables clinicians to view cellular and subcellular events within living tissue. Early models of this technology “took up entire benches” in physics labs, Dr. Barton said, but she and other investigators are designing smaller devices for use in clinics. “This is exciting, because not only do we [view] subcellular structure with this modality, but it can also be highly sensitive to collagen structure,” she said.

Ovarian cancer model

In a model of ovarian cancer, she and colleagues externalized the ovaries of a mouse, imaged the organs, put them back in, and reassessed them at 8 weeks. “This model develops cancer very quickly,” said Dr. Barton, who once worked for McDonnell Douglas on the Space Station program. At 8 weeks, using fluorescence and targeted agents with a tabletop multiphoton microscopy system, they observed that the proliferation signals of cancer had begun. “So, with an agent targeted to the folate receptor or to other receptors that are implicated in cancer development, we can see that ovaries and fallopian tubes are lighting up,” she said.

With proof of concept established with the mouse study, she and other researchers are drawing from technological advances to create tiny laser systems for use in the clinic to image a variety of structures in the human body. Optics advances include bulk optics and all-fiber designs where engineers can create an imaging probe that’s only 125 microns in diameter, “or maybe even as small as 70 microns in diameter,” she said. “We can do fabrications on the tips of endoscopes to redirect the light and focus it. We can also do 3-D printing and spiral scanning to create miniature devices to make new advances. That means that instead of just white light imaging of the colon or the lung like we have had in the past, we can start moving into smaller structures, such as the eustachian tube, the fallopian tube, the bile ducts, or making miniature devices for brain biopsies, lung biopsies, and maybe being able to get into bronchioles and arterioles.”

According to Dr. Barton, prior research has demonstrated that cerebral vasculature can be imaged with a catheter 400 microns in diameter, the spaces in the lungs can be imaged with a needle that is 310 microns in diameter, and the inner structures of the eustachian tube can be viewed with an endoscope 1 mm in diameter.

She and her colleagues are developing an OCT/fluorescence imaging falloposcope that is 0.8 mm in diameter, flexible, and steerable, as a tool for early detection of ovarian cancer in humans. “It’s now known that most ovarian cancer starts in the fallopian tubes,” Dr. Barton said. “It’s metastatic disease when those cells break off from the fallopian tubes and go to the ovaries. We wanted to create an imaging system where we created a fiber bundle that we could navigate with white light and with fluorescence so that we can see these early stages of cancer [and] how they fluoresce differently. We also wanted to have an OCT system so that we could image through the wall of the fallopian tube and look for that layer thickening and other precursors to ovarian cancer.”

To date, in vivo testing in healthy women has demonstrated that the miniature endoscope is able to reach the fallopian tubes through the natural orifice of the vagina and uterus. “That is pretty exciting,” she said. “The images may not be of the highest quality, but we are advancing.”

Dr. Barton reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT ASLMS 2023

The metaverse is the dermatologist’s ally

MADRID – There are endless possibilities within the dermoverse (a term coined by joining “dermatology” and “metaverse”), from a robot office assistant to the brand new world it offers for virtual training and simulation.

A group of dermatologists expert in new technologies came together at the 50th National Congress of the Spanish Academy for Dermatology and Venereology to discuss the metaverse: that sum of all virtual spaces that bridges physical and digital reality, where users interact through their avatars and where these experts are discovering new opportunities for treating their patients. The metaverse and AI offer a massive opportunity for improving telehealth visits, immersive surgical planning, or virtual training using 3-D skin models. These are just a few examples of what this technology may eventually provide.

“The possibilities offered by the metaverse in the field of dermatology could be endless,” explained Miriam Fernández-Parrado, MD, dermatologist at Navarre Hospital, Pamplona, Spain. To her, “the metaverse could mean a step forward in teledermatology, which has come of age as a result of the pandemic.” These past few years have shown that it’s possible to perform some screenings online. This, in turn, has produced significant time and cost savings, along with greater efficacy in initial screening and early detection of serious diseases.

The overall percentage of cases that are potentially treatable in absentia is estimated to exceed 70%. “This isn’t a matter of replacing in-person visits but of finding a quality alternative that, far from dehumanizing the doctor-patient relationship, helps to satisfy the growing need for this relationship,” said Dr. Fernández-Parrado.

Always on duty

Julián Conejo-Mir, MD, PhD, professor and head of dermatology at the Virgen del Rocío Hospital in Seville, Spain, told this news organization that AI will help with day-to-day interactions with patients. It’s already a reality. “But to say that with a simple photo, we can address 70% of dermatology cases without being physically present with our patients – I don’t think that will become a reality in the next 20 years.”

Currently, algorithms can identify tumors with high success rates (80%-90%) using photographs and dermoscopic images; rates increase significantly when both kinds of images are available. These high success rates are possible because tumor morphology is stationary. “However, for inflammatory conditions, accurate diagnosis generally doesn’t exceed 60%, since these are conditions in which morphology can change a lot from one day to the next and can vary significantly, depending on their anatomic location or the patient’s age.”

Maybe once metaclinics, with 3-D virtual reality, have been established and clinicians can see the patient in real time from their offices, the rate of accurate diagnosis will reach 70%, especially with patients who have limited mobility or who live at a distance from the hospital. “But that’s still 10-15 years away, since more powerful computers are needed, most likely quantum computers,” cautioned Dr. Conejo-Mir.

The patient’s ally

In clinical practice, facilitating access to the dermoverse may help reduce pain and divert the patient’s attention, especially during in-person visits that require bothersome or uncomfortable interventions. “This is especially effective in pediatric dermatology, since settings of immersive virtual reality may contribute to relaxation among children,” explained Dr. Fernández-Parrado. She also sees potential applications among patients who need surgery. The metaverse would allow them to preview a simulation of their operation before undergoing it, thus reducing their anxiety and allaying their fears about these procedures.

Two lines are being pursued: automated diagnosis for telehealth consultations, which are primarily for tumors, and robotic office assistants.

“We have been using the first one in clinical practice, and we can achieve a success rate of 85%-90%.” The second one is much more complex, “and we’re having a hard time moving it forward within our research team, since it doesn’t involve only one algorithm. Instead, it requires five algorithms working together simultaneously (chatbot, automatic writing, image analysis, selecting the most appropriate treatment, ability to make recommendations, and even an additional one involving feelings),” explained Dr. Conejo-Mir.

A wise consultant

Dr. Conejo-Mir offered examples of how this might work in the near future. “In under 5 years, you’ll be able to sit in front of a computer or your smartphone, talk to an avatar that we’re able to select (sex, appearance, age, kind/serious), show the avatar your lesions, and it will tell us a basic diagnostic impression and even the treatment.”

With virtual learning, physicians can also gather knowledge or take refresher courses, using skin models in augmented reality with tumors and other skin lesions, or using immersive simulation courses that aid learning. Digital models that replicate the anatomy and elasticity of the skin or other characteristics unique to the patient can be used to reach decisions regarding surgeries and to practice interventions before entering the operating room, explained Dr. Fernández-Parrado.

Optimal virtual training

Virtual reality and simulation will doubtless play a major role in this promising field of using these devices for training purposes. “There will be virtual dermatology clinics or metaclinics, where you can do everything with virtual simulated patients, from gaining experience in interviews or health histories (even with patients who are difficult to deal with), to taking biopsies and performing interventions,” said Dr. Conejo-Mir.

A recent study titled “How the World Sees the Metaverse and Extended Reality” gathered data from 29 countries regarding the next 10 years. One of the greatest benefits of this technology is expected in health resources (59%), even more than in the trading of digital assets. While it is difficult to predict when the dermoverse will be in operation, Dr. Fernández-Parrado says she’s a techno-optimist. Together with Dr. Héctor Perandones, MD, a dermatologist at the University Healthcare Complex in León, Spain, and coauthor with Dr. Fernández-Parrado of the article, “A New Universe in Dermatology: From Metaverse to Dermoverse,” she’s convinced that “if we can imagine it, we can create it.”

A differential diagnostician

Over the past 10 years, AI has become a major ally of dermatology, providing new techniques that simplify the diagnosis and treatment of patients. There are many applications for which it adds tremendous value in dermatology: establishing precise differential diagnoses for common diseases, such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, or acne; eveloping personalized therapeutic protocols; and predicting medium- and long-term outcomes.

Furthermore, in onco-dermatology, AI has helped to automate the diagnosis of skin tumors by making it possible to differentiate between melanocytic and nonmelanocytic lesions. This distinction promotes early diagnosis and helps produce screening systems that are capable of prioritizing cases on the basis of their seriousness.

When asked whether any group has published any promising tools with good preliminary results, Dr. Conejo-Mir stated that his group has produced three articles that have been published in top-ranking journals. In these articles, “we explain our experience with artificial intelligence in Mohs surgery, in automated diagnosis, and for calculating the thickness of melanomas.” The eight-person research team, which comprises dermatologists and software engineers, has been working together in this area for the past 4 years.

Aesthetic dermatology

Unlike other specialists, dermatologists have 4-D vision when it comes to aesthetics, since they are also skin experts. AI plays a major role in aesthetic dermatology. It supports this specialty by providing a greater analytic capacity and by evaluating the procedure and technique to be used. “It’s going to help us think and make decisions. It has taken great strides in aesthetic dermatology, especially when it comes to techniques and products. There have been products like collagen, hyaluronic acid, then thread lifts ... Also, different techniques have been developed, like Botox, for example. Before, Botox was given following one method. Now, there are other methods,” explained Dr. Conejo-Mir.

He explained, “We have analyzed the facial image to detect wrinkles, spots, enlarged pores, et cetera, to see whether there are any lesions, and, depending on what the machine says you have, it provides you with a personalized treatment. It tells you the pattern of care that the patient should follow. It also tells you what you’re going to do, whether or not there is any problem, depending on the location and on what the person is like, et cetera. Then, for follow-up, you’re given an AI program that tells you if you’re doing well or not. Lastly, it gives you product recommendations.

“We are among the specialties that are going through the most change,” said Dr. Conejo-Mir.

An intrusive technology?

AI will be a tremendous help in decision-making, to the point where “in 4 or 5 years, it will become indispensable, just like the loupe in years past, and then the dermatoscope.” However, the machine will have to depend on human beings. “They won’t replace us, but they will become unavoidable assistants in our day-to-day medical practice.”

Questions have arisen regarding the potential dangers of these new technologies, like that of reducing the number of dermatologists within the population, and whether they might encourage intrusiveness. Dr. Conejo-Mir made no bones about it. “AI will never cut back the number of specialists. That is false. When AI supports us in teledermatology, even currently on our team, it spits out information, but the one making the decision is the practitioner, not the machine.”

AI is a tool but is not in itself something that treats patients. It is akin to the dermatoscope. Dermatologists use these tools every day, and they help arrive at diagnoses in difficult cases, but they are not a replacement for humans. “At least for the next 50 years, then we’ll see. In 2050 is when they say AI will surpass humans in its intelligence and reasoning capacity,” said Dr. Conejo-Mir.

Dr. Conejo-Mir has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish Edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

MADRID – There are endless possibilities within the dermoverse (a term coined by joining “dermatology” and “metaverse”), from a robot office assistant to the brand new world it offers for virtual training and simulation.

A group of dermatologists expert in new technologies came together at the 50th National Congress of the Spanish Academy for Dermatology and Venereology to discuss the metaverse: that sum of all virtual spaces that bridges physical and digital reality, where users interact through their avatars and where these experts are discovering new opportunities for treating their patients. The metaverse and AI offer a massive opportunity for improving telehealth visits, immersive surgical planning, or virtual training using 3-D skin models. These are just a few examples of what this technology may eventually provide.

“The possibilities offered by the metaverse in the field of dermatology could be endless,” explained Miriam Fernández-Parrado, MD, dermatologist at Navarre Hospital, Pamplona, Spain. To her, “the metaverse could mean a step forward in teledermatology, which has come of age as a result of the pandemic.” These past few years have shown that it’s possible to perform some screenings online. This, in turn, has produced significant time and cost savings, along with greater efficacy in initial screening and early detection of serious diseases.

The overall percentage of cases that are potentially treatable in absentia is estimated to exceed 70%. “This isn’t a matter of replacing in-person visits but of finding a quality alternative that, far from dehumanizing the doctor-patient relationship, helps to satisfy the growing need for this relationship,” said Dr. Fernández-Parrado.

Always on duty

Julián Conejo-Mir, MD, PhD, professor and head of dermatology at the Virgen del Rocío Hospital in Seville, Spain, told this news organization that AI will help with day-to-day interactions with patients. It’s already a reality. “But to say that with a simple photo, we can address 70% of dermatology cases without being physically present with our patients – I don’t think that will become a reality in the next 20 years.”

Currently, algorithms can identify tumors with high success rates (80%-90%) using photographs and dermoscopic images; rates increase significantly when both kinds of images are available. These high success rates are possible because tumor morphology is stationary. “However, for inflammatory conditions, accurate diagnosis generally doesn’t exceed 60%, since these are conditions in which morphology can change a lot from one day to the next and can vary significantly, depending on their anatomic location or the patient’s age.”

Maybe once metaclinics, with 3-D virtual reality, have been established and clinicians can see the patient in real time from their offices, the rate of accurate diagnosis will reach 70%, especially with patients who have limited mobility or who live at a distance from the hospital. “But that’s still 10-15 years away, since more powerful computers are needed, most likely quantum computers,” cautioned Dr. Conejo-Mir.

The patient’s ally

In clinical practice, facilitating access to the dermoverse may help reduce pain and divert the patient’s attention, especially during in-person visits that require bothersome or uncomfortable interventions. “This is especially effective in pediatric dermatology, since settings of immersive virtual reality may contribute to relaxation among children,” explained Dr. Fernández-Parrado. She also sees potential applications among patients who need surgery. The metaverse would allow them to preview a simulation of their operation before undergoing it, thus reducing their anxiety and allaying their fears about these procedures.

Two lines are being pursued: automated diagnosis for telehealth consultations, which are primarily for tumors, and robotic office assistants.

“We have been using the first one in clinical practice, and we can achieve a success rate of 85%-90%.” The second one is much more complex, “and we’re having a hard time moving it forward within our research team, since it doesn’t involve only one algorithm. Instead, it requires five algorithms working together simultaneously (chatbot, automatic writing, image analysis, selecting the most appropriate treatment, ability to make recommendations, and even an additional one involving feelings),” explained Dr. Conejo-Mir.

A wise consultant

Dr. Conejo-Mir offered examples of how this might work in the near future. “In under 5 years, you’ll be able to sit in front of a computer or your smartphone, talk to an avatar that we’re able to select (sex, appearance, age, kind/serious), show the avatar your lesions, and it will tell us a basic diagnostic impression and even the treatment.”

With virtual learning, physicians can also gather knowledge or take refresher courses, using skin models in augmented reality with tumors and other skin lesions, or using immersive simulation courses that aid learning. Digital models that replicate the anatomy and elasticity of the skin or other characteristics unique to the patient can be used to reach decisions regarding surgeries and to practice interventions before entering the operating room, explained Dr. Fernández-Parrado.

Optimal virtual training

Virtual reality and simulation will doubtless play a major role in this promising field of using these devices for training purposes. “There will be virtual dermatology clinics or metaclinics, where you can do everything with virtual simulated patients, from gaining experience in interviews or health histories (even with patients who are difficult to deal with), to taking biopsies and performing interventions,” said Dr. Conejo-Mir.